Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

IoT-CDS: Internet of Things Cyberattack Detecting System Based on Deep Learning Models

Department of Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence, College of Computing and Information Technology, University of Bisha, Bisha, 61922, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Author: Monir Abdullah. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Distributed Computing with Applications to IoT and BlockChain)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2024, 81(3), 4265-4283. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2024.059271

Received 02 October 2024; Accepted 06 November 2024; Issue published 19 December 2024

Abstract

The rapid growth and pervasive presence of the Internet of Things (IoT) have led to an unparalleled increase in IoT devices, thereby intensifying worries over IoT security. Deep learning (DL)-based intrusion detection (ID) has emerged as a vital method for protecting IoT environments. To rectify the deficiencies of current detection methodologies, we proposed and developed an IoT cyberattacks detection system (IoT-CDS) based on DL models for detecting bot attacks in IoT networks. The DL models—long short-term memory (LSTM), gated recurrent units (GRUs), and convolutional neural network-LSTM (CNN-LSTM) were suggested to detect and classify IoT attacks. The BoT-IoT dataset was used to examine the proposed IoT-CDS system, and the dataset includes six attacks with normal packets. The experiments conducted on the BoT-IoT network dataset reveal that the LSTM model attained an impressive accuracy rate of 99.99%. Compared with other internal and external methods using the same dataset, it is observed that the LSTM model achieved higher accuracy rates. LSTMs are more efficient than GRUs and CNN-LSTMs in real-time performance and resource efficiency for cyberattack detection. This method, without feature selection, demonstrates advantages in training time and detection accuracy. Consequently, the proposed approach can be extended to improve the security of various IoT applications, representing a significant contribution to IoT security.Keywords

In the realm of information technology, cybersecurity is a challenging field of study [1]. Reaching this is particularly difficult given the involvement of newly developed technologies like the Internet of Things (IoT). The IoT, which enables seamless and effective data exchange among linked devices, marks a significant technological advancement in contemporary society. Driven by its spread in many developing applications, including smart cities and sophisticated industrial systems, the Cisco study by developers foresees an average of 75.3 billion IoT devices being connected in 2025 [2]. The lack of human involvement in data transfer among IoT devices distinguishes it from conventional Internet technologies. Overall, the proliferation of IoT devices has escalated the demands on data network capacity.

IoT applications and technology are anticipated to go beyond current expectations. Nevertheless, the evolution of IoT technology is currently in a transitional stage and has not yet reached full maturity in terms of security protocols. IoT systems present various security vulnerabilities, such as varying manufacturing standards and challenges in update management arising from the practices of IoT developers. The tangible management of security problems and consumers’ ignorance due to insufficient awareness of the security risks associated with IoT devices are significant concerns. Additionally, the IoT ecosystem lacks a standard security architecture. Several security designs have been applied to protect the IoT network for users through network requirements. In [3], the authors studied intelligent health use cases that tracked and monitored patients’ health information using multiple intelligent security architectures. Therefore, establishing security for each situation requires specialized expertise in the relevant domain.

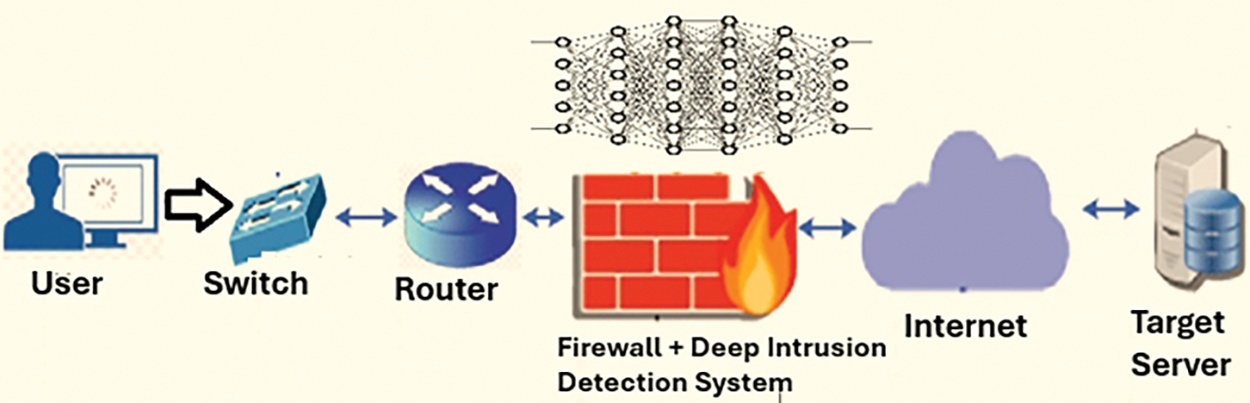

Security concerns grow along with the number of linked devices and, hence, sophisticated solutions are needed to secure these networks. Reducing security weaknesses in the IoT depends on an intrusion detection system (IDS) [4]. Attacks against linked devices have grown to be a major concern due to the increasing popularity of IoT. IoT devices are susceptible in many respects to attacks, including denial of service (DoS), eavesdropping, and privilege escalation [5]. In addition, the need to shield IoT devices from these threats is becoming more relevant [6]. IoT devices are also physically dispersed, which makes illegal access simple [7]. Consequently, the system faces vulnerabilities to cyberattacks, such as web injections, potentially leading to data manipulation and the exposure of sensitive information [8]. Thus, IoT devices need a highly robust IDS. Using modest computing resources, deep learning (DL) models can quickly evaluate vast amounts of data and assist autonomous security system modifications following malware or security breaches [9,10]. IDS in IoT may be much improved by using an appropriate DL technique [11,12]. Such a choice may be implemented by comparing techniques to identify the most exact technique and thereafter using the selected strategy. Using DL techniques helps to improve the accuracy of the IDS system. Enhancing the security of the system may also favorably influence human life, the economy, technology, and the IoT environment [13–16]. DL models are used to detect Intrusions, as depicted in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Deep learning for detecting IDS in an IoT environment

Intrusion and anomaly detection systems based on machine learning (ML) and DL techniques have emerged in the last 10 years. Various researchers have investigated ML techniques such as random forests (RF), support vector machines (SVM), and decision trees (DT), among others, to detect anomalies [17,18]. Reference [19] demonstrates the detection of attacks and anomalies on IoTs using ML and DL algorithms like artificial neural networks (ANNs), SVM, logistic regression (LR), RF, and DT based on the DS2OS-Kaggle dataset. Some current anomaly-based IDS models [20,21] employ conventional ML approaches. These conventional methods struggle with the large volume and speed of data creation of IoT devices. As a result, substantial research focuses on DL methods to create more successful solutions [22].

DL models use vast volumes of data and computers to create multilayer neural networks into designs, thereby automating feature extraction and categorization. This method has the benefit of enabling one to obtain excellent results when working with big or complicated datasets and executing feature learning without human involvement. Advanced IoT intrusion detection [23–26] may result from powerful data processing, feature learning capabilities, and the ability to detect unknown threats that DL has the capacity to detect. Consequently, in our research, hybrid DL models were used for IoT cyberattack detection and achieved decent results.

The following are the main contributions of the developed Internet of Things Cyberattack Detecting System (IoT-CDS):

• To address the challenge of detecting threats and anomalies in IoT networks. The IoT-CDS framework is presented for the detection of attacks and anomalies in IoT networks.

• Among several DL methods, we use a computational method for the effective selection of DL classifiers. Subsequently, we provide the selected DL method, which is effective for classifying intrusions in IoT traffic, as identified by our suggested IoT-CDS system.

• Experimental investigations demonstrate that our proposed IoT-CDS system is effective and efficient for attack and anomaly detection in IoT. Here, we provide a security framework for resource-limited IoT devices using modern DL architecture.

This paper is organized as follows. Section 2 explains the related studies. The methodology of the IoT-CDS system is explained in Section 3. The experiment and results are presented in Section 4. In Section 5, The findings are discussed. Finally, the paper is concluded in Section 6.

Stefanos et al. [15] investigated ID models in IoT sensors with ML techniques in recent years. The ML technique was used to detect attack and violation prediction in IoT systems, and they fairly evaluated many ML approaches. With a particular emphasis on virtual settings, a strong algorithm was built for IoT cybercrime detection. The suggested system showed better detection accuracy than current models. Through SDN-Cloud (software-defined network) architecture, Ravi et al. [27] suggested a system to mitigate DDoS attacks by using a learning-driven detection in IoT. This method seeks to identify DDoS attacks on IoT devices via hostile wireless IoT. Zhang et al. [28] suggested an efficient approach for identifying network data through the principal components analysis (PCA) method to eliminate pointless features, and these features were processed by using a Bayes classifier. Nevertheless, ML techniques have significant restrictions. First, the strength of the features of engineering methods used determines their performance. Second, their performance decreases with the use of large-scale, high-dimensional data. Finally, the learning capacity of ML techniques is inadequate to manage unidentified threats in the IoT environment.

The good performance of DL models on vast datasets is the most crucial benefit of DL over conventional ML techniques. Frequently producing a substantial amount of varied and complicated data, IoT devices also include a range of invasive behaviors, and frequently creating DL methods is particularly pertinent in IoT security applications, as these methods can automatically replicate intricate feature sets from sample data. To identify intrusions, Abdel-Basset et al. [29] suggested a deep industrial IoT Forensics (IFS) model for developing the IDS in industrial IoT devices. Liu et al. [30] presented a federated learning method for edge device distribution and collaborative training. They learned significant spatial information using attention-enhanced CNNs and captured temporal representations using long short-term memories (LSTMs). In particular, against time-series-based hazards, the security of IoT systems depends on the research of recurrent neural networks and their variations.

Li et al. [31] used input time series for detecting intrusion by employing Recurrent NNs (RNNs). The LSTM–Gaussian NB architecture was first presented by Gao et al. [32] for IoT data outlier probability evaluation. These studies highlight the fit of RNNS as an IoT–IDS. To improve the field of IoT intrusion detection, the authors combined RNNs with different approaches. Parra et al. [33] suggested CNN and LSTM approaches to neutralize phishing and botnet attacks in the distributed cloud.

Dubey et al. [34] suggested a lightweight host-based IDS to guard the IoT against vulnerabilities. Fog computing devices enabled this system; these devices applied an ANN approach to detect IDS in the IoT edge. Syed et al. [35] used an ANN to train and categorize attacks on a BoT-IoT dataset. Jasim [36] developed an ensemble hybrid IDS by combining an ensemble of ML algorithms with an attribute selection stage depending on information acquisition. The experimental results revealed that taken among an ensemble of classifiers, the classification methods are much superior. Popoola et al. [37] proposed a hybrid DL long short-term memory autoencoder (LSTMA) for the detection of attacks. The proposed technique performed better than rival approaches for attribute reduction and utilized less memory. In contrast, attribute selection methods grounded on DL might be computationally demanding. Aljuhani [38] devised a bi-directional LSTM system to train and recognize sequential network data in the cloud. Abd Elkhalik et al. [39] proposed a DL-based forensic model to improve the multilayered strategy that facilitates IoT network intrusion detection.

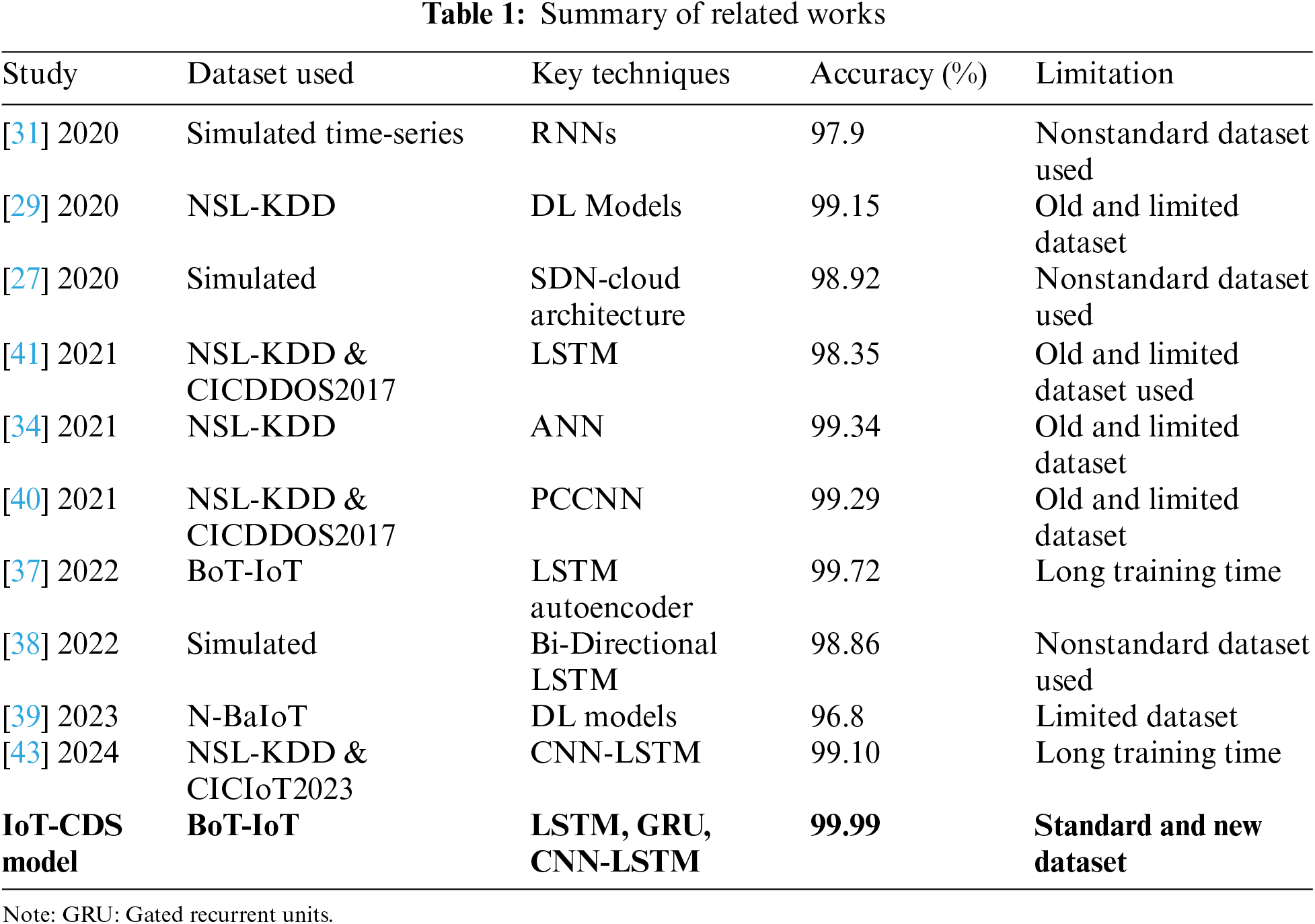

Haq et al. [40] introduced the Principal Component-based CNN (PCCNN) approach to counteract threats targeting IoT devices. The NSL-KDD dataset helped to assess this approach. Using a DL-based anomaly detection method, Iwendi et al. [41] sought to identify DDoS attacks on IoT devices; LSTM was used in the implementation of this system. These tests used the CICDDOS2019 dataset. In this study, Gamal et al. [42] introduced a novel IDS technique called CNN–IDS. Alzahrani et al. [43] proposed a hybrid DL method that combines CNN and LSTM models to build an energy-aware, anomaly-based IDS. Recently, in [44], the authors presented a taxonomy of IDS in IoT, highlighting both ML and DL classifiers as well as feature selection models on various IoT-related datasets. Table 1 summarizes the datasets utilized, techniques employed, accuracy values, and some limitations of the related studies.

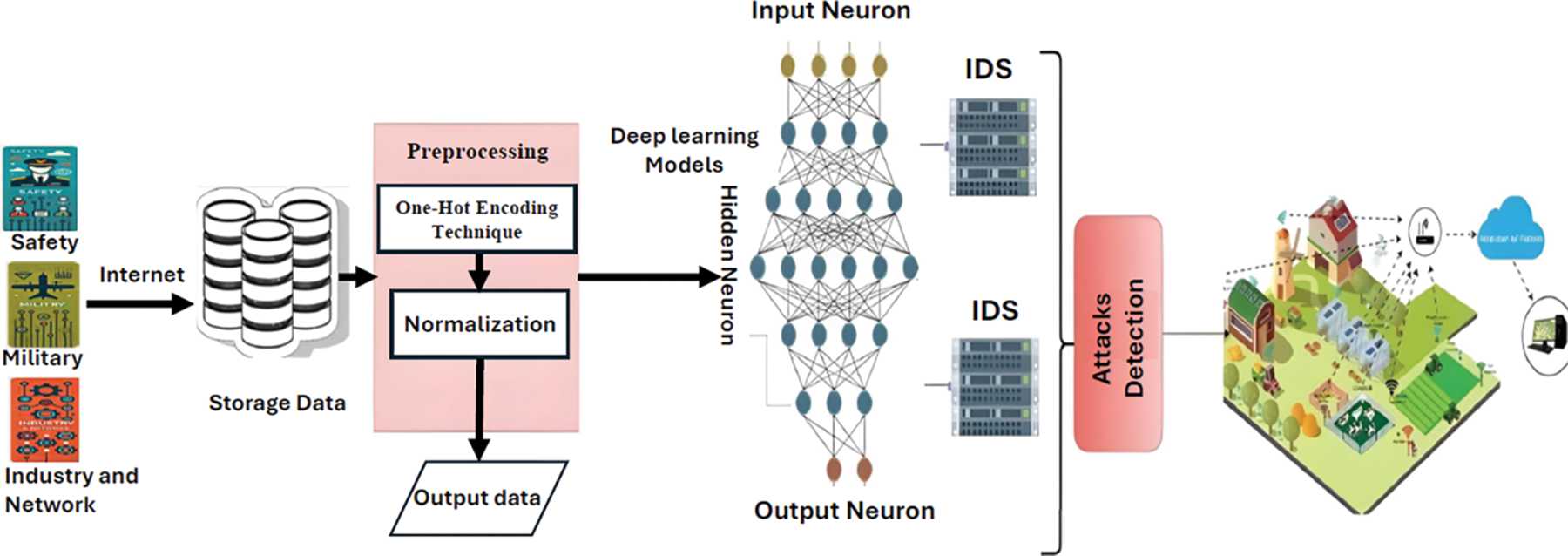

Fig. 2 displays the proposed DL-based IoT-CDS system, which is a novel system that learns from data produced by the devices on the IoT network and identifies network intrusion once it is sufficiently trained. The proposed IoT-CDS develops a connection between IoT network requests and the simulated network as a dynamic connector. The features of the IoT network are extracted from network connections, and these features are processed by using the proposed DL models to develop an IoT-CDS that is driven by newly identified characteristics. The network classifier moves the discovered intrusion to the mitigating stage. This stage reduces the influence of the intrusion.

Figure 2: The IoT–CDS system

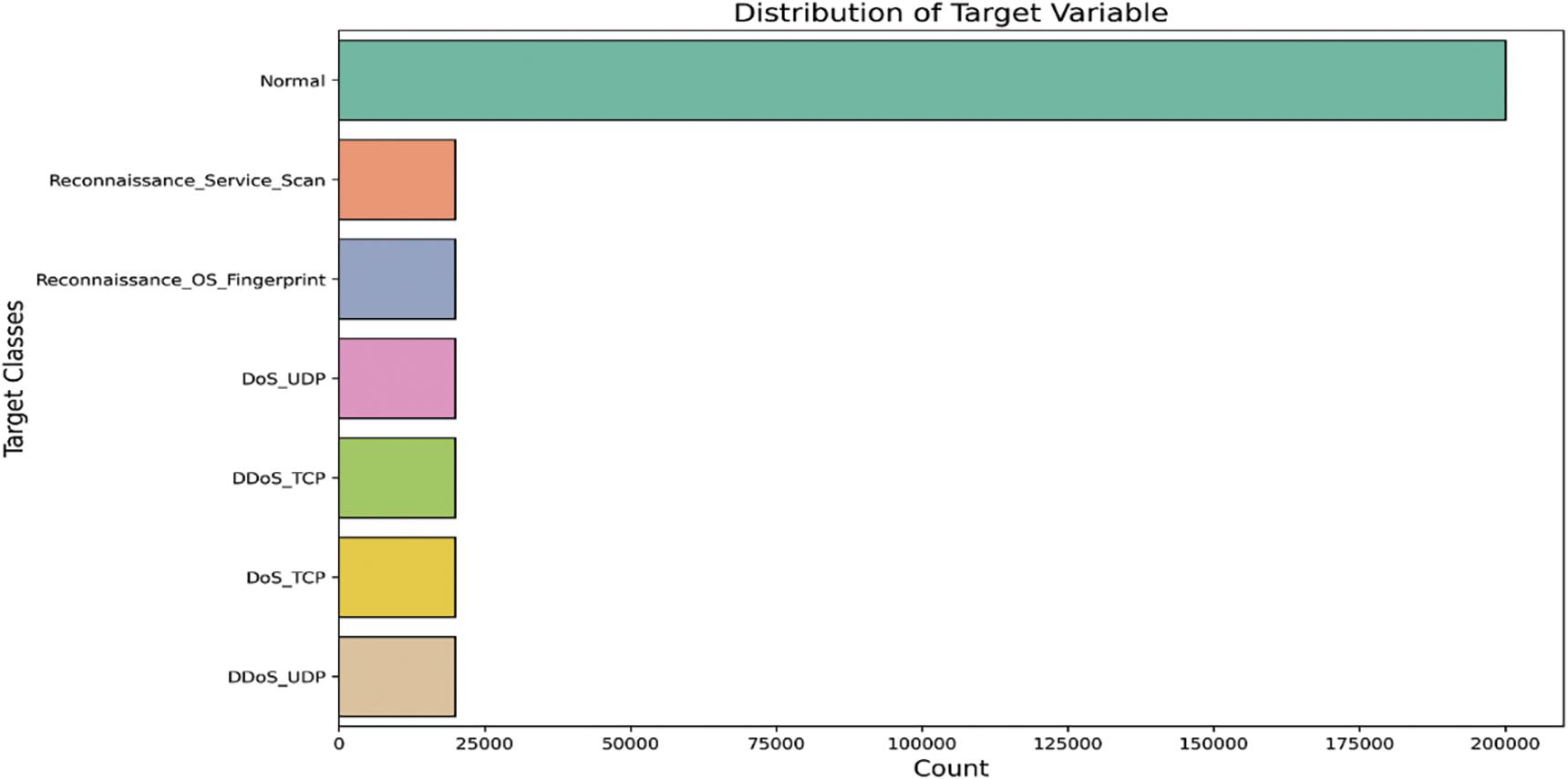

The impartial assessment of the models utilizes the BoT-IoT dataset [45] developed by the University of Canberra, which comprises both normal and botnet traffic. The researchers annotated the dataset and categorized it by class. The updated distribution comprises 200,000 instances of the normal class and five attack classes, each containing 20,000 samples. A large number of researchers have used 5% of the overall dataset, which is equivalent to 1.07 GB of the total size. Fig. 3 presents the BoT-IoT labels.

Figure 3: Labels of the BoT-IoT dataset

The IoT-CDS system cannot operate effectively without prior data preparation for analysis. Hence, data preparation is essential. The preprocessing phase consists of four components: one-hot encoding, data standardization, imbalance management, and normalization.

3.2.1 One-Hot Encoding Technique

Employing the one-hot encoding method is a frequently used method for the numerical representation of categorical features in the BoT-IoT dataset. This method is an efficient way of encoding categorical variables into a numerical format for ML algorithms and helps in removing ordinal relationships that could deceive the models. Additionally, it improves the efficacy of models by enabling algorithms to identify unique traits associated with each category, resulting in increased predictive precision while maintaining the individual significance of each category [6].

Normalization is used to preprocess the IDS dataset and to standardize the numeric values in an IoT dataset to a consistent scale, while maintaining the disparities in value ranges and ensuring information integrity. Min-max normalization adjusts the IoT network data to fit within a defined range—between 0 and 1. The instances of the minimum and maximum values in the IoT network dataset are indicated as

where x is the value to be normalized, xmin and xmax are minimum and maximum values of the original data, Newmin and Newmax are the desired range for the new scaled values [4,12].

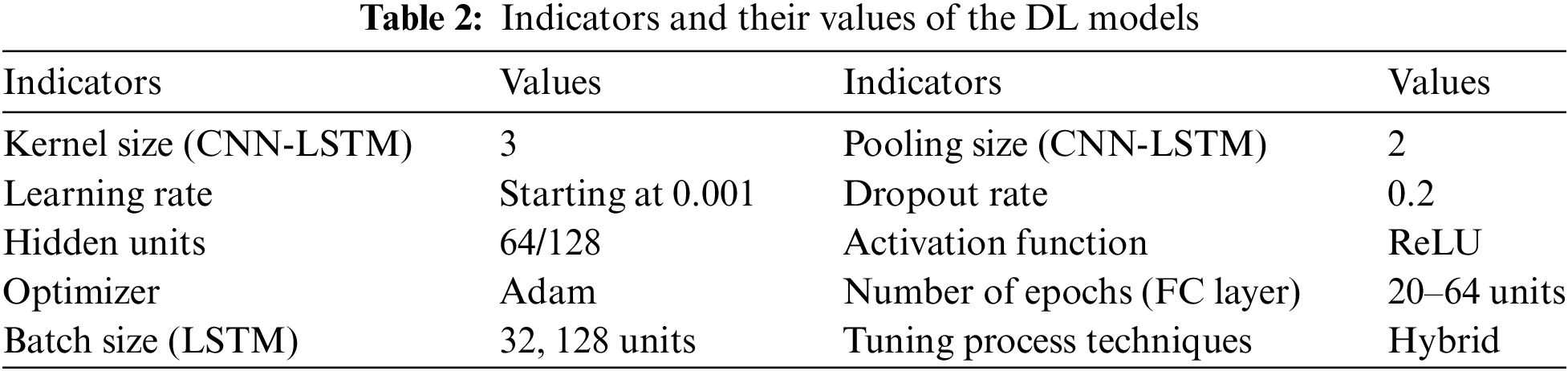

The motivation for using DL models instead of conventional approaches in IoT-based cyberattack detection is their enhanced capacity to manage intricate and high-dimensional data. Conventional techniques often depend on manually produced characteristics, which may inadequately represent the complex patterns linked to intrusions in IoT settings. By contrast, DL models perform feature extraction themselves, which means they learn from raw data and find those minute anomalies that may signal hazards. The refined configuration of the fine-tuned hyperparameters (indicators) is summarized in Table 2.

3.3.1 Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM)

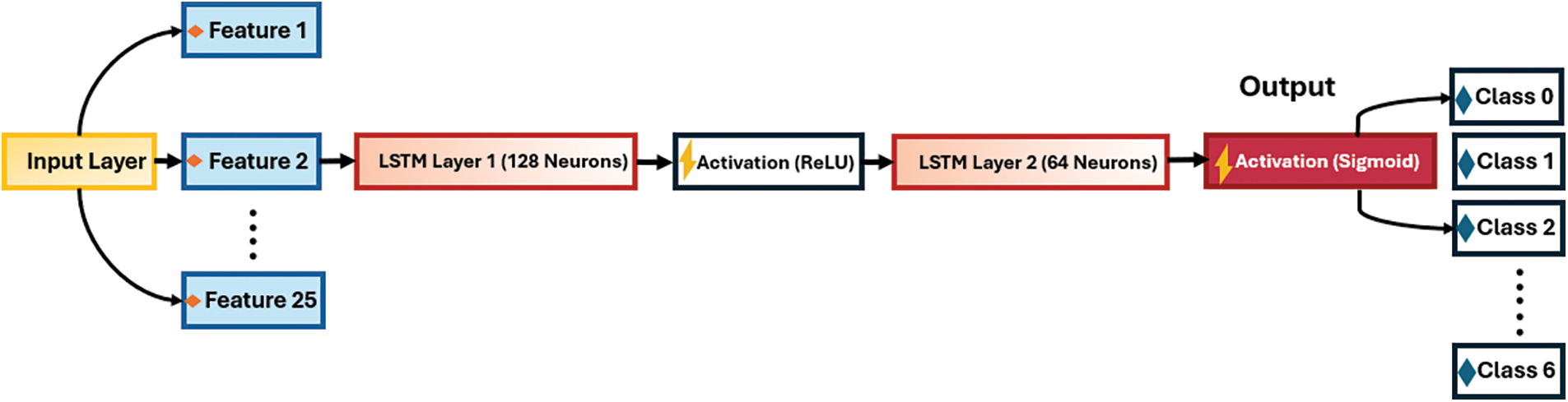

LSTM models represent a sophisticated domain within DL models. Understanding LSTMs and the relevance of terminology such as bidirectional and sequence-to-sequence in the domain can be challenging. This addresses the issue of the vanishing gradient, which arises from the gradual reduction in gradient inversion processes throughout the computation. LSTM is an algorithm that is well-suited for applications involving time series analysis [46]. Fig. 4 illustrates the LSTM algorithm.

Figure 4: The LSTM technique

The input gate (

The forget gate (ft): This enables the LSTM to choose to exclude irrelevant or obsolete information from prior time steps.

The output gate (

The IoT dataset was divided into training and testing sets; the labels were processed using the one-hot encoding technique, and class weights were computed to address the class imbalance. A sequential model was constructed using an LSTM layer, and the model was assembled using the Adam optimizer. The data was restructured for LSTM, and the model was trained for 20 epochs.

3.3.2 The Gated Recurrent Units (GRU) Model

The GRU model was used for the analysis and detection of the IDS sequentially. The GRU is similar to the LSTM; the GRU employs gating mechanisms to strategically adjust the hidden state of the network at every time step. Information is regulated by gating systems as it enters and exits the network. The GRU model comprises two gating mechanisms: the update gate and the reset gate.

Additionally, a GRU is a type of RNN. A GRU maintains the capability of a conventional RNN to analyze time series data. GRUs address the issue of gradient disappearance in RNNs during training by selectively incorporating new information and discarding previously accumulated data before the gating unit. This mechanism also mitigates the challenge RNNs face in managing long-term dependencies when processing extensive sequential data [47]. Moreover, GRUs streamline and modify the architecture of LSTM [25], decrease the parameter count, and reduce the training duration. Fig. 5 illustrates the structure of the gating control cycle unit within the GRU.

Figure 5: GRU based IoT-CDS system

In the above equations,

The input data is reformatted into a three-dimensional structure to conform to the requirements of the GRU layer. The model underwent training for 20 epochs with a batch size of 32, utilizing computed class weights to ensure balanced learning across various classes. The architecture of the model is thus chosen with 128 units in the GRU and 64 units in the dense layer, striking an optimal balance between model complexity and computational efficiency and capturing all the significant patterns of variation in the data. The dropout layers avoid overfitting, while the Adam optimizer allows for efficient training. The GRU based on the IoT-CDS system is presented in Fig. 5.

CNN-LSTMs prove very effective in applications that require both spatial and temporal understandings, combining the strong feature extraction capability of CNN with the ability of LSTMs to handle temporal dependencies [33]. A hybrid model combining CNN and LSTM is proposed, with its architecture and data processing workflow illustrated in Fig. 6. The CNN layer’s function is to extract signal characteristics from the time domain in monitoring data. The acquired features were grouped into a two-dimensional array and sent into the LSTM layer, which examined the time series characteristics. The next few sections describe the feature extraction methods used by CNN and the feature processing techniques used by LSTMs. Batch normalization layers were added to the CNN, LSTM, and CNN-LSTM models to normalize the outputs of each layer. This strategy reduces the risk of overfitting while improving the stability of the optimization process. The batch normalization layers have been proven effective.

Figure 6: The CNN-LSTM model for the developed IoT-CDS system

For the first time, the approach that has been proposed includes data from IoT networks in the calculation. To arrange the data that was provided, four characteristics were used. There are twenty-five one-dimensional convolutional kernels, each of which is set as 25 × 1, and with a stride of one in the first convolutional layer.

A convolutional layer is used to extract abstract properties from the raw IDS data. The activation layer, which contains rectified linear units (ReLUs), comes after the convolutional layer and has the potential to introduce nonlinearity into the model.

where

In order to improve the accuracy of classification, the kernel of the CNN model was used to process the training data via the max pooling layer. This enabled the extraction of critical features. The following is a definition of a function expression that is used for the max pooling procedure.

In this context,

We use a set of standard evaluation measures to objectively examine the performance of the proposed system-based IDS, thereby enabling a full evaluation of the model’s efficacy in identifying network intrusions. These indicators are essential for assessing the accuracy and dependability of our proposed IDS, thereby providing useful insights into its functioning [33,35,40].

The experimental simulation of the suggested approach for validation is presented. The performance boost is evaluated by performing a comparison study with the most prominent research papers.

To conduct experiments, a high-performance computer configuration that was outfitted with a PC i7 processor operating at 3.10 GHz and 16 GB of memory was used. The TensorFlow library and the Keras library were used in order to complete the implementation of the LSTM, CNN-LSTM, and GRU approaches. A total of 70% was reserved for training, while 30% was utilized for testing.

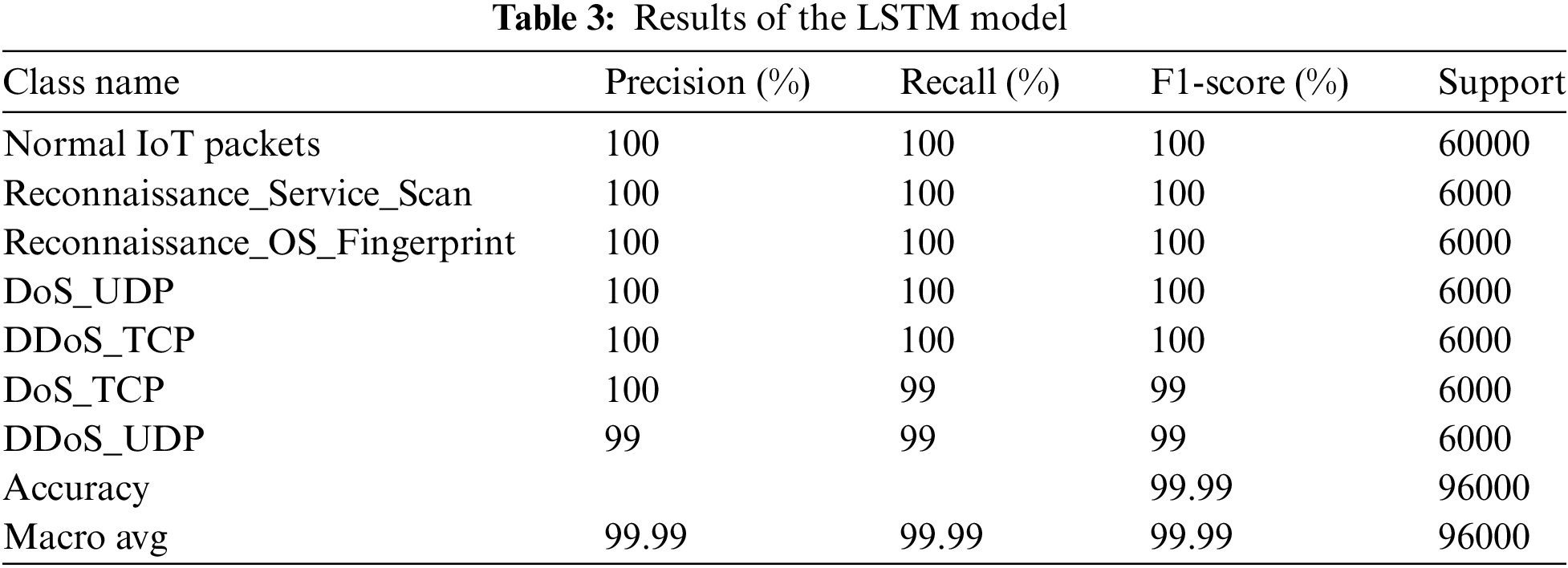

The dataset comprises regular traffic, assaults, and BoT-IoT traffic, along with labeled features for optimal attack identification and detection within the IoT network. The LSTM model significantly enhances learning performance. Nonetheless, the performance of implemented LSTM algorithms is rather efficient for accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, as well as the time required to construct the model. The performance of the LSTM models is demonstrated in Table 3. It was found that LSTM achieved a high accuracy measure of 99.99%. Thus, the LSTM model demonstrated worse performance in the DoS_TCP and DDoS_UDP classes, achieving an accuracy of 99%.

Fig. 7 illustrates the training accuracy and loss during the 50-epoch training duration for the suggested improved LSTM architecture. The model quickly attained 95% accuracy on the validation set during the first 20 epochs.

Figure 7: LSTM performance for the IoT-CDS system: (a) accuracy (b) loss

The accuracy of the training started at 96% and increased to an inspiring 99% at the 15th epoch, showing how strongly this model. Another important metric of interest was that of test accuracy, also mirroring the training accuracy and managing to reach the same value of 99% around the 15th epoch. The impressive concordance between the training and test accuracy both at 99% for this model underlines its great generalization capability and thus enables it to perform comparably well on previously unseen test data. The starting training loss was quite high at 0.22 but drastically shrunk to an amazing low of 0.03 at the 15th epoch-a decent drop of 0.19 points. The test loss showed a similar trend, dropping from 0.22 to 0.05, thus underlining again the capability of the model to absorb the data without overfitting. Overall, with its high accuracy and low loss on both the training and testing datasets, the model shows an extremely outstanding performance, which is an indicator that it is fully prepared to handle real applications.

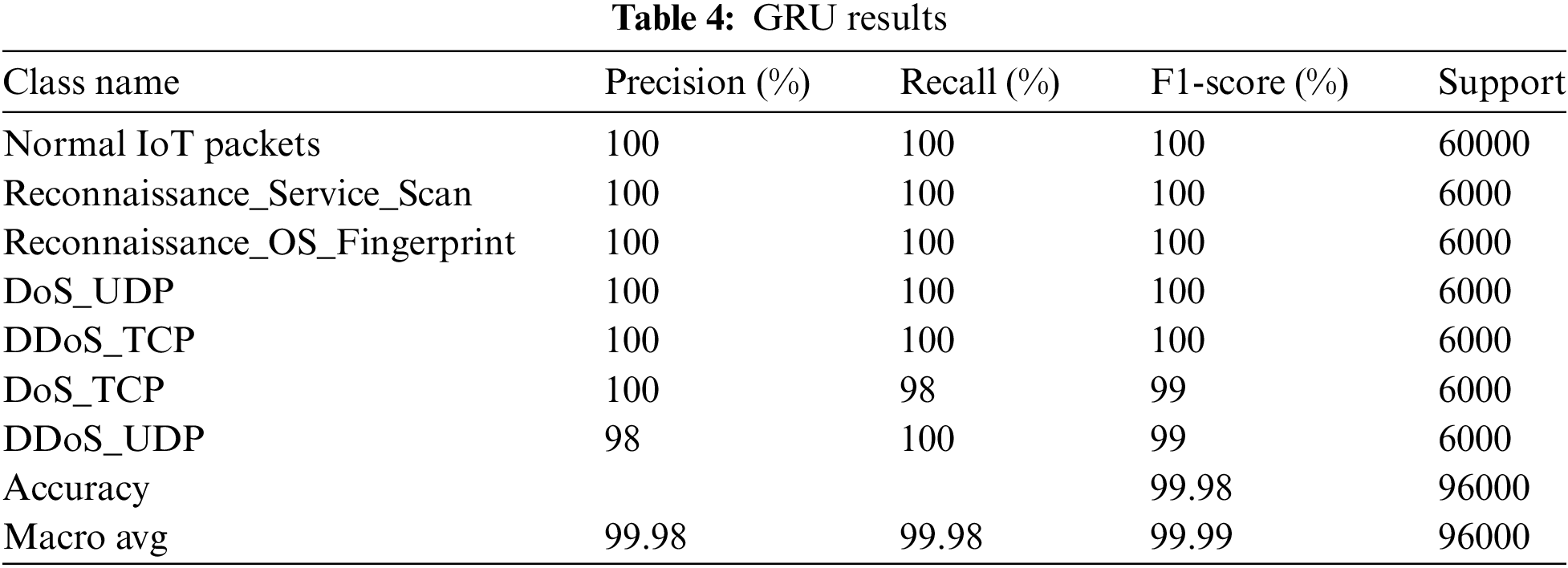

Utilizing the same tuning methodology, the GRU was simulated to identify the ideal hyperparameters for performance. Table 4 presents the findings of the GRU model for the developed IoT-CDS system. The maximum detection accuracy achieved is 99.98%. It was found that the GRU attained less accuracy in the DoS_TCP and DDoS_UDP categories.

Fig. 8 illustrates the validation performance of the GRU model in distinguishing IoT attacks from regular packets on the BoT-IoT network.

Figure 8: LSTM performance for the IoT-CDS model: (a) accuracy (b) loss

The system attained a validation accuracy of 99.98%, which increased from 94.50% to 99.98% over 20 epochs. The validation loss is modest owing to minor overfitting, and it decreased to 0.002 with the use of cross-entropy measurements.

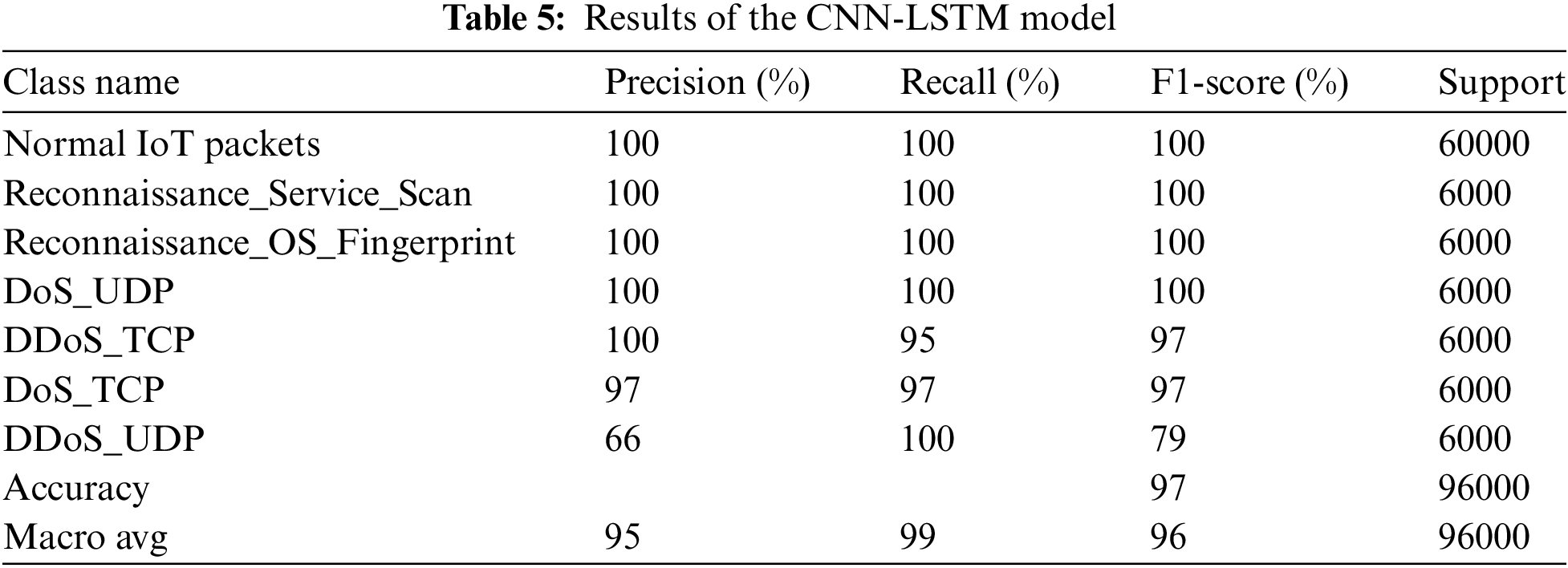

The hybrid CNN-LSTM model was implemented accordingly. Table 5 presents a summary of the CNN-LSTM results pertaining to the detection of BoT-IoT attacks originating from the IoT network. The proposed system did not successfully achieve high accuracy compared to LSTM and GRU models. The CNN-LSTM model demonstrated enhanced performance with an accuracy of 97%.

Fig. 9 presents the accuracy performance of the CNN-LSTM system. The vertical axis represents the proportion of instances that were accurately classified. The system halted the optimization process to enhance accuracy for a duration of 20 epochs. The CNN-LSTM model exhibited an improvement in performance, increasing from 92% to 97%. The validation loss exhibited a reduction from 20 to 0.004 over 20 epochs.

Figure 9: The performance of the CNN-LSTM for the IoT-CDS system: (a) accuracy (b) loss

The rapid advancement of the Internet has facilitated the rise of IoT, exemplified by smart homes and cities, healthcare systems, and cyber-physical systems. IoT comprises a network of linked daily items, enhanced with lightweight CPUs and network connections, which may be controlled via web services or other interfaces. To tackle this difficulty, it is essential to build effective protective and investigative countermeasures, including network intrusion detection and network forensic systems. A well-structured and representative dataset is essential for training and evaluating the reliability of these systems.

The experimental research demonstrates that our suggested framework model effectively identifies anomalies in IoT networks using the BoT-IoT dataset. Although the outcomes produced by our proposed IoT-IDS system are promising, a comprehensive examination reveals insightful and essential information for the efficient detection of IoT network assaults using deep learning algorithms.

This research study demonstrates that the suggested IoT-CDS framework is optimal for selecting the LSTM model as the most effective algorithm between two DL algorithms—GRU and CNN-LSTM—based on accuracy metric. The selected LSTM demonstrates exceptional efficiency in detecting anomalies and intrusions within the IoT network, with an accuracy of 99.99%.

The LSTM algorithm is proficient at identifying assaults from IoT networks. It is essential to use this method in relation to other critical factors influencing selection and decision-making issues in IoT network settings. LSTMs are more efficient than GRUs and CNN-LSTMs in real-time performance and resource efficiency for cyberattack detection. They provide lower latency and manage long-term dependencies better using fewer inference time resources. On the other hand, GRUs may be unable to retrieve complex relationships, and CNN-LSTMs could be too resource-intensive, which means LSTMs are more fitting for efficient real-time analysis.

A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve is a performance measuring tool that is used to determine the threshold of a model when dealing with categorization-related issues. The ROC curve has two parameters: the true positive rate and the false positive rate. The ROC curve is used in classification analysis to identify the model that most precisely predicts a class. The true positive rate is compared with the false positive rate. Fig. 10 illustrates the ROC of the IoT-CDS system using the LSTM model.

Figure 10: The ROC curve of the LSTM model

A ROC value of 1.0 (AUC) represents a perfect classification: the model differentiates positive instances from negative ones with no mistakes. This means exceedingly good performance, and the classifier is very trustworthy for any applications that require accurate binary classification.

Table 6 provides a comprehensive comparison of the models examined in this study and their performance on the planned BoT-IoT network dataset. The improved LSTM model achieved an accuracy of 99.99%. Subsequently, the GRU achieved an accuracy of 99.97%.

Compared to the results of the above table, RF and DT models were able to show 91% accuracy rate, while the ensemble method improved to 92.62%. Next, XGBoost and SVM models increased the accuracy to 97.98%, while an autoencoder attained 99.2% across three datasets. Nevertheless, our proposed IoT-CDS system reached a 99.99% detection rate that confirmed the efficiency of LSTM networks in enhancing IDS built for IoTs environments.

Deployment of DL models is extremely challenging in IoT environments for reasons of interpretability and real-time processing. Interpretability is a trait needed to gain user trust. Besides, IoT devices usually have low computation resources and hence require low-latency operations to achieve fast responses against particular events. The trade-off between processing complexity and efficiency with explanation clarity balances effective implementation in these settings [51].

Detecting cyberattack traffic is crucial for the security of the IoT in smart cities. In the IoT network, IDSs serve as an effective mechanism for mitigating botnet assaults. IDS passively observes and collects network data and then uses an AI model for the categorize benign and malicious information. The academic community in IoT security has diligently worked to develop models for identifying anomalies, intrusions, and cyberattack traffic using DL models. This research sought to identify IoT network attacks with DL models. The BoT-IoT dataset was used to ensure a variety of attacks and network protocols. The IoT dataset was used to test the proposed IoT-CDS system, which comprises six attacks and normal packets. The three DL models—LSTM, GRU, and CNN-LSTM—were proposed to detect the attacks from the IoT environment. The experimental results of the proposed IoT-CDS system achieved 99.99% accuracy using the LSTM model. This development has heightened interest in the use of sophisticated methods for the improvement of cybersecurity systems. For future work, we aim to address the computational limitations of IoT devices by reducing the model complexity for faster real-time operation on edge devices or by utilizing federated learning techniques. Besides, we plan to evaluate the performance of the proposed model using alternative datasets.

Acknowledgement: The author is thankful to the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at the University of Bisha, for supporting this work through the Fast-Track Research Support Program.

Funding Statement: The author received no specific funding for this study.

Availability of Data and Materials: The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, and the dataset in: https://research.unsw.edu.au/projects/bot-iot-dataset (accessed on 10 July 2024).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. J. Zhang, L. Pan, Q. -L. Han, C. Chen, S. Wen and Y. Xiang, “Deep learning based attack detection for cyber-physical system cybersecurity: A survey,” IEEE/CAA J. Automatica Sinica, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 377–391, Mar. 2022. doi: 10.1109/JAS.2021.1004261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. A. Jurcut, T. Niculcea, P. Ranaweera, and N. A. Le-Khac, “Security considerations for Internet of Things: A survey,” SN Comput. Sci., vol. 1, pp. 1–19, 2020. doi: 10.1007/s42979-020-00201-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. L. Catarinucci et al., “An IoT-aware architecture for smart healthcare systems,” IEEE Internet Things J., vol. 2, pp. 515–526, 2015. doi: 10.1109/JIOT.2015.2417684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. M. Almiani, A. AbuGhazleh, A. Al-Rahayfeh, S. Atiewi, and A. Razaque, “Deep recurrent neural network for IoT intrusion detection system,” Simul. Model. Pract. Theory, vol. 101, 2020, Art. no. 102031. doi: 10.1016/j.simpat.2019.102031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. A. Thakkar and R. Lohiya, “A review on machine learning and deep learning perspectives of IDS for IoT: recent updates, security issues, and challenges,” Arch. Comput. Methods Eng., vol. 28, pp. 3211–3243, 2021. doi: 10.1007/s11831-020-09496-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Y. Li, Y. Zuo, H. Song, and Z. Lv, “Deep learning in security of Internet of Things,” IEEE Internet Things J., vol. 9, no. 22, pp. 22133–22146, Nov. 15, 2022. doi: 10.1109/JIOT.2021.3106898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. I. Idrissi, M. Boukabous, M. Azizi, O. Moussaoui, and H. El Fadili, “Toward a deep learning-based intrusion detection system for IoT against botnet attacks,” IAES Int. J. Artif. Intell. (IJ-AI), vol. 10, 2021, Art. no. 110. doi: 10.11591/ijai.v10.i1.pp110-120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. S. Venkatraman and B. Surendiran, “Adaptive hybrid intrusion detection system for crowd sourced multimedia internet of things systems,” Multimed. Tools Appl., vol. 79, pp. 3993–4010, 2019. doi: 10.1007/s11042-019-7495-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. J. Asharf, N. Moustafa, H. Khurshid, E. Debie, W. Haider and A. Wahab, “A review of intrusion detection systems using machine and deep learning in Internet of Things: Challenges, solutions and future directions,” Electronics, vol. 9, 2020, Art. no. 1177. doi: 10.3390/electronics9071177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. X. Wang, Y. Zhao, and F. Pourpanah, “Recent advances in deep learning,” Int. J. Mach. Learn. Cybern., vol. 11, pp. 747–750, 2020. doi: 10.1007/s13042-020-01096-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Q. Abu Al-Haija and S. Zein-Sabatto, “An efficient deep-learning-based detection and classification system for cyber-attacks in IoT communication networks,” Electronics, vol. 9, 2020, Art. no. 2152. doi: 10.3390/electronics9122152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Q. Abu Al-Haija and M. A. Al-Dala’ien, “ELBA-IoT: An ensemble learning model for botnet attack detection in IoT networks,” J. Sens. Actuator Netw., vol. 11, 2022, Art. no. 18. doi: 10.3390/jsan11010018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Pioneering deep learning in the cyber security space: The new standard? Information Age,” Mar. 25, 2020. Accessed: Oct. 19, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.information-age.com/pioneering-deep-learning-cyber-security-new-standard-123488524/ [Google Scholar]

14. L. Aversano, M. L. Bernardi, M. Cimitile, and R. Pecori, “A systematic review on deep learning approaches for IoT security,” Comput. Sci. Rev., vol. 40, 2021, Art. no. 100389. doi: 10.1016/j.cosrev.2021.100389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. T. Stefanos, T. Lagkas, and K. Rantos, “Deep learning in IoT intrusion detection,” J. Netw. Syst. Manage., vol. 30, pp. 1–40, 2022. doi: 10.1007/s10922-021-09621-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. G. Q. Zeng, J. M. Shao, K. D. Lu, G. G. Geng, and J. Weng, “Automated federated learning-based adversarial attack and defence in industrial control systems,” IET Cyber-Syst. Robot., vol. 6, no. 2, 2024, Art. no. e12117. doi: 10.1049/csy2.12117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. A. Chatterjee and B. S. Ahmed, “IoT anomaly detection methods and applications: A survey,” Internet of Things, vol. 19, 2022, Art. no. 100568. doi: 10.1016/j.iot.2022.100568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. S. Chandio et al., “Machine learning-based multiclass anomaly detection and classification in hybrid active distribution networks,” IEEE Access, vol. 12, pp. 120131–120141, 2024. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3445287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. M. Hasan, M. M. Islam, M. I. I. Zarif, and M. Hashem, “Attack and anomaly detection in IoT sensors in IoT sites using machine learning approaches,” Internet of Things, vol. 7, 2019, Art. no. 100059. doi: 10.1016/j.iot.2019.100059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. A. Gaurav, B. B. Gupta, and P. K. Panigrahi, “A comprehensive survey on machine learning approaches for malware detection in IoT-based enterprise information system,” Enterp. Inform. Syst., vol. 17, no. 3, 2023, Art. no. 2023764. doi: 10.1080/17517575.2021.2023764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. N. Chaabouni, M. Mosbah, A. Zemmari, C. Sauvignac, and P. Faruki, “Network intrusion detection for IoT security based on learning techniques,” IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor., vol. 21, pp. 2671–2701, 2019. doi: 10.1109/COMST.2019.2896380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. M. A. Alsoufi et al., “Anomaly-based intrusion detection systems in IoT using deep learning: A systematic literature review,” Appl. Sci., vol. 11, 2021, Art. no. 8383. doi: 10.3390/app11188383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. D. Selvapandian and R. Santhosh, “Deep learning approach for intrusion detection in IoT-multi cloud environment,” Autom. Softw. Eng., vol. 28, 2021, Art. no. 19. doi: 10.1007/s10515-021-00298-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. T. V. Khoa et al., “Collaborative learning model for cyberattack detection systems in IoT Industry 4.0,” in Proc. 2020 IEEE Wireless Commun. Netw. Conf. (WCNCSeoul, Republic of Korea, Piscataway, NJ, USA, IEEE, 2020, pp. 1–6. doi: 10.1109/WCNC45663.2020.9120761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. A. Haider, M. Adnan Khan, A. Rehman, M. Rahman, and S. H. Kim, “A real-time sequential deep extreme learning machine cybersecurity intrusion detection system,” Comput. Mater. Contin., vol. 66, pp. 1785–1798, 2021. doi: 10.32604/cmc.2020.013910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. T. M. Booij, I. Chiscop, E. Meeuwissen, N. Moustafa, and F. T. Den Hartog, “ToN_IoT: The role of heterogeneity and the need for standardization of features and attack types in IoT network intrusion data sets,” IEEE Internet Things J, vol. 9, pp. 485–496, 2021. doi: 10.1109/JIOT.2021.3085194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. N. Ravi and S. M. Shalinie, “Learning-driven detection and mitigation of DDoS attack in IoT via SDN-cloud architecture,” IEEE Internet Things J., vol. 7, pp. 3559–3570, 2020. doi: 10.1109/JIOT.2020.2973176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. B. Zhang, Z. Liu, Y. Jia, J. Ren, and X. Zhao, “Network intrusion detection method based on PCA and Bayes algorithm,” Secur. Commun. Netw., vol. 2018, 2018, Art. no. 1914980. doi: 10.1155/2018/1914980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. M. Abdel-Basset, V. Chang, H. Hawash, R. K. Chakrabortty, and M. Ryan, “Deep-IFS: Intrusion detection approach for industrial internet of things traffic in fog environment,” IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform., vol. 17, pp. 7704–7715, 2020. doi: 10.1109/TII.2020.3025755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Y. Liu et al., “Deep anomaly detection for time-series data in industrial IoT: A communication-efficient on-device federated learning approach,” IEEE Internet Things J., vol. 8, pp. 6348–6358, 2020. doi: 10.1109/JIOT.2020.3011726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. L. Li, J. Yan, H. Wang, and Y. Jin, “Anomaly detection of time series with smoothness-inducing sequential variational auto-encoder,” IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst., vol. 32, pp. 1177–1191, 2020. doi: 10.1109/TNNLS.2020.2980749. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. J. Gao et al., “Omni SCADA intrusion detection using deep learning algorithms,” IEEE Internet Things J., vol. 8, pp. 951–961, 2020. doi: 10.1109/JIOT.2020.3009180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. G. D. L. T. Parra, P. Rad, K. K. R. Choo, and N. Beebe, “Detecting internet of things attacks using distributed deep learning,” J. Netw. Comput. Appl., vol. 163, 2020, Art. no. 102662. doi: 10.1016/j.jnca.2020.102662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. G. P. Dubey and R. K. Bhujade, “Optimal feature selection for machine learning based intrusion detection system by exploiting attribute dependence,” Mater. Today Proc., vol. 47, pp. 6325–6331, 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.matpr.2021.04.643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. N. F. Syed, M. Ge, and Z. Baig, “Fog-cloud based intrusion detection system using Recurrent Neural Networks and feature selection for IoT networks,” Comput. Netw., vol. 225, 2023, Art. no. 109662. doi: 10.1016/j.comnet.2023.109662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. A. D. Jasim, “A survey of intrusion detection using deep learning in internet of things,” Iraqi J. Comput. Sci. Math., vol. 3, pp. 83–93, 2022. doi: 10.52866/ijcsm.2022.01.01.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. S. Popoola, B. Adebisi, G. Gui, M. Hammoudeh, H. Gacanin and D. Dancey, “Optimizing deep learning model hyperparameters for botnet attack detection in IoT networks,” 2022. doi: 10.36227/techrxiv.19501885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. A. Aljuhani, “IDS-Chain: A collaborative intrusion detection framework empowered blockchain for Internet of Medical Things,” in Proc. 2022 IEEE Cloud Summit., Fairfax, VA, USA, Oct. 20–21, 2022, pp. 57–62. doi: 10.1109/CloudSummit54781.2022.00015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. W. Abd Elkhalik and I. Elhenawy, “Semi-supervised transformer network for anomaly detection in cellular Internet of Things,” Int. J. Wirel. Ad Hoc Commun., vol. 4, pp. 56–68, 2023. doi: 10.54216/IJWAC.040106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. M. A. Haq, M. A. R. Khan, and T. AL-Harbi, “Development of PCCNN-based network intrusion detection system for EDGE computing,” Comput. Mater. Contin., vol. 71, pp. 1769–1788, 2021. doi: 10.32604/cmc.2022.018708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. C. Iwendi, S. U. Rehman, A. R. Javed, S. Khan, and G. Srivastava, “Sustainable security for the Internet of Things using Artificial Intelligence architectures,” ACM Trans. Internet Technol., vol. 21, pp. 1–22, 2021. doi: 10.1145/3448614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. M. Gamal, H. M. Abbas, N. Moustafa, E. Sitnikova, and R. A. Sadek, “Few-shot learning for discovering anomalous behaviors in edge networks,” Comput. Mater. Contin., vol. 69, pp. 1823–1837, 2021. doi: 10.32604/cmc.2021.012877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. H. Alzahrani, T. Sheltami, A. Barnawi, M. Imam, and A. Yaser, “A lightweight intrusion detection system using convolutional neural network and long short-term memory in fog computing,” Comput. Mater. Contin., vol. 80, no. 3, pp. 4703–4728, 2024. doi: 10.32604/cmc.2024.054203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. H. Alqahtani and M. Abdullah, “A taxonomy of IDS in IoTs: ML classifiers, feature selection models, datasets and future directions,” Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. (IJACSA), vol. 15, no. 6, 2024. doi: 10.14569/IJACSA.2024.0150682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. A. Sharma and H. Babbar, “BoT-IoT: Detection of DDoS attacks in Internet of Things for smart cities,” in 2023 10th Int. Conf. Comput. Sustain. Glob. Dev. (INDIACom), New Delhi, India, 2023, pp. 438–443. [Google Scholar]

46. A. Alzahrani and T. H. H. Aldhyani, “Artificial Intelligence algorithms for detecting and classifying MQTT protocol Internet of Things attacks,” Electronics, vol. 11, 2022, Art. no. 3837. doi: 10.3390/electronics11223837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. A. Alzahrani and T. H. H. Aldhyani, “Design of efficient based Artificial Intelligence approaches for sustainable of cyber security in smart industrial control system,” Sustainability, vol. 15, 2023, Art. no. 8076. doi: 10.3390/su15108076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. B. A. Tama, M. Comuzzi, and K. -H. Rhee, “TSE-IDS: A two-stage classifier ensemble for intelligent anomaly-based intrusion detection system,” IEEE Access, vol. 7, pp. 94497–94507, 2019. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2928048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Z. Halim et al., “An effective genetic algorithm-based feature selection method for intrusion detection systems,” Comput. Secur., vol. 110, 2021, Art. no. 102448. doi: 10.1016/j.cose.2021.102448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. P. R. Kannari, N. C. Shariff, and R. L. Biradar, “Network intrusion detection using sparse autoencoder with swish-PReLU activation model,” J. Ambient. Intell. Humaniz. Comput., vol. 6, 2021, Art. no. 33789. doi: 10.1007/s12652-021-03077-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. N. H. A. Mutalib, A. Q. M. Sabri, A. W. A. Wahab, E. R. M. F. Abdullah, and N. AlDahoul, “Explainable deep learning approach for advanced persistent threats (APTs) detection in cybersecurity: A review,” Artif. Intell. Rev., vol. 57, 2024, Art. no. 297. doi: 10.1007/s10462-024-10890-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools