Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

PIAFGNN: Property Inference Attacks against Federated Graph Neural Networks

1 College of Computer Science and Technology, Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Nanjing, 321002, China

2 Collaborative Innovation Center of Novel Software Technology and Industrialization, Nanjing, 210023, China

* Corresponding Author: Bing Chen. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 82(2), 1857-1877. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2024.057814

Received 28 August 2024; Accepted 28 November 2024; Issue published 17 February 2025

Abstract

Federated Graph Neural Networks (FedGNNs) have achieved significant success in representation learning for graph data, enabling collaborative training among multiple parties without sharing their raw graph data and solving the data isolation problem faced by centralized GNNs in data-sensitive scenarios. Despite the plethora of prior work on inference attacks against centralized GNNs, the vulnerability of FedGNNs to inference attacks has not yet been widely explored. It is still unclear whether the privacy leakage risks of centralized GNNs will also be introduced in FedGNNs. To bridge this gap, we present PIAFGNN, the first property inference attack (PIA) against FedGNNs. Compared with prior works on centralized GNNs, in PIAFGNN, the attacker can only obtain the global embedding gradient distributed by the central server. The attacker converts the task of stealing the target user’s local embeddings into a regression problem, using a regression model to generate the target graph node embeddings. By training shadow models and property classifiers, the attacker can infer the basic property information within the target graph that is of interest. Experiments on three benchmark graph datasets demonstrate that PIAFGNN achieves attack accuracy of over 70% in most cases, even approaching the attack accuracy of inference attacks against centralized GNNs in some instances, which is much higher than the attack accuracy of the random guessing method. Furthermore, we observe that common defense mechanisms cannot mitigate our attack without affecting the model’s performance on mainly classification tasks.Keywords

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) have achieved significant success in the representation learning of graph data in non-Euclidean spaces, providing a new approach for effectively extracting features, processing, and training graph-structured data that are complex and unordered. However, current GNN training methods primarily rely on centralized data, which differs from real-world scenarios where source data may be distributed across different users. For instance, e-commerce platforms selling various types of products maintain separate purchase and rating records for their users and items. Due to privacy concerns, legal regulations, and business competition, the owners of these graph data are typically unwilling to share their private data, leading to the problem of data isolation [1].

Federated Learning (FL) [2], as a new distributed machine learning paradigm, offers a promising solution by enabling efficient joint modeling and GNN model training among multiple graph data owners without sharing the original data, thereby effectively addressing the data isolation problem. It is currently widely applied in various fields, including IIoT [3]. Some studies have already utilized FL to train GNNs [4–7], which we denote as Federated Graph Neural Networks (FedGNNs). But even in federated learning scenarios, the node/graph embedding gradient and model gradient uploaded by users during the training process can still carry local private information [8,9], leading to potential privacy leakage. Malicious attackers can exploit this information to carry out property inference attacks in FedGNNs, aiming to infer the private data of target users.

Previous research has demonstrated that trained GNN models can still leak sensitive information about the graph data on which they were trained. Studies on property inference attacks against centralized GNNs [10,11] have shown that attackers can use the target model architecture, target graph embeddings, and posterior output information to launch property inference attacks by training attack model, thereby inferring basic properties and group properties of the target graph. However, inference attacks and privacy leakage issues against GNNs in federated learning scenarios have not been widely explored. It remains unclear whether the privacy leakage problems encountered during the training of GNNs will carry over to the federated learning scenario. In federated settings, malicious attackers face challenges in directly obtaining prior knowledge such as complete target graph embeddings and model architecture information shared by users, as they can in centralized training [10], making property inference attacks against centralized GNNs potentially less effective in federated learning scenarios.

Compared with the existing research works, in this paper, we demonstrate the vulnerability of the FedGNNs framework to inference attacks for the first time and propose a property inference attack against FedGNNs. In a federated learning scenario, attackers can still launch property inference attacks by controlling honest clients participating in the training process, using the global model gradient distributed by the central server, and stealing local node embeddings uploaded by the target user to train the property classifier. Next, we verify the effectiveness of the proposed attack on multiple public datasets and FL architectures based on different GNN models, and we evaluate the attack’s performance under FL-based GNN models of different complexity. Finally, we examined the effectiveness of two potential defense mechanisms against the attack, further demonstrating the robustness of the attack. In summary, the main contributions of this paper are as follows:

• We propose a property inference attack against FedGNNs, called PIAFGNN. Malicious attackers can infer the basic property information of the target graph or properties irrelevant to downstream tasks during the FedGNNs training process. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first work on inference attacks against FedGNNs.

• We further design a scheme based on a Generative Regression Network (GRN) to steal the local node embeddings uploaded by the target user. The attacker converts the task of stealing the target user’s node embeddings into a regression problem, utilizing GRN and querying the global model gradient and global node embedding gradient sent by the central server to obtain the target embeddings.

• Extensive experiments demonstrate that PIAFGNN achieves high attack accuracy on various settings, with an average attack accuracy exceeding 70%. PIAFGNN not only generalizes to most existing GNN models but also maintains good prediction accuracy under local models of varying complexity.

• We verify the robustness of PIAFGNN under two potential defense mechanisms. While these methods can mitigate the attack to some extent, they also negatively affect the performance of the main classification task.

GNNs have achieved remarkable success in processing data in non-Euclidean spaces and have obtained extensive research attention. Currently, GNNs are widely applied in various fields such as knowledge graphs [12], social networks [13], and chemical molecular structures [14], achieving excellent performance in graph representation learning. However, with the growing societal emphasis on data privacy, GNNs face the necessity of adapting to this new norm, leading to the rapid development of research on FedGNNs. He et al. [7] proposed an open FL benchmark system for GNNs, FedGraphNN, which can accommodate various graph datasets from different domains and enables secure and efficient training while simplifying the training and evaluation of GNN models and FL algorithms. Wu et al. [8] introduced a FedGNNs framework for recommendation systems, which can capture higher-order user-item interaction information while preserving user privacy. Chen et al. [9] conducted the first study on vertical federated graph neural networks, proposing a federated GNNs learning paradigm for privacy-preserving node classification tasks in vertically partitioned data scenarios, VFGNN, which can be generalized to most existing GNN models.

2.2.1 Inference Attacks against FL

Although FL allows clients to collaborate in training without sharing local data, it still faces the risk of inference attacks. For example, Shokri et al. [17] first proposed a membership inference attack to reveal the degree of privacy leakage in FL, aiming to determine whether the corresponding data belongs to the target model’s training dataset. Zhang et al. [15] introduced membership inference attacks enhanced by Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), which enriched the attacker’s training data through GANs to enhance the accuracy of membership inference attacks under FL. Melis et al. [16] illustrated the vulnerability in the Federated Learning parameter update process, where user training data can be unintentionally leaked. It also employs both passive and active property inference attacks to exploit this vulnerability. However, these works are all based on traditional machine learning models such as CNN and MLP, without considering the effectiveness of such attacks on GNNs. In federated scenarios, traditional inference attack methods for Euclidean data such as images may not achieve ideal results in GNNs.

2.2.2 Inference Attacks against GNNs

Studies has demonstrated that malicious attackers can infer sensitive information in graph data by obtaining graph/node embeddings trained by centralized GNNs. Conti et al. [18] leveraged the flexible prediction mechanism of GNNs to launch membership inference attacks using only the provided prediction labels (Label-Only MIA), and achieved good performance even when the assumptions of the attacker’s shadow datasets and additional information of the target model were relaxed. Zhang et al. [10] studied the privacy leakage caused by shared graph embeddings in GNNs, demonstrating that these embeddings can also reveal sensitive structural information about the graph data. They proposed several attacks against GNNs, including property inference attacks, subgraph inference attacks, and graph reconstruction attacks. On this basis, Wang et al. [11] focused on group property inference attacks against GNNs, aiming to infer the distribution of specific nodes and links within the training graph, such as whether the graph contains more female nodes than male ones. These works mainly focus on the centralized GNN model, where attackers need to obtain the entire graph embeddings as prior knowledge to launch inference attacks. Our work, however, investigates property inference attacks against GNNs in federated learning scenarios. Attackers can acquire prior knowledge about the target user by directly participating in training or controlling benign clients. They can then train the attack model to infer the privacy properties of the target graph that the attacker is interested in.

To better demonstrate the position of our PIAFGNN in addressing security challenges, we compare PIAFGNN with other privacy threats against FL and GNNs, as shown in Table 1. Our PIAFGNN is the first work to apply property inference attacks to FedGNNs, revealing the privacy threats faced by FedGNNs.

Definition (Federated Graph Neural Networks): FedGNNs combine the advantages of federated learning and graph neural networks, enabling learning and inference on distributed graph data while protecting data privacy. As shown in Fig. 1, in FedGNNs framework, each client possesses its graph datasets

Figure 1: The framework of FedGNNs

In this paper, we consider three representative GNN models as the local models of the clients in FL: Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) [19], GraphSAGE [20], and Graph Attention Network (GAT) [21], taking node classification as the primary learning task. For this task, the readout function is typically a softmax function, where the prediction output of each node

Scenario: Unlike traditional machine learning benchmark datasets, graph datasets in federated learning, and real-world graph datasets may exhibit non-independent and identically distributed (No-IID) characteristics due to the non-Euclidean structure and heterogeneous features of graph data [7]. We assume that there are K (

Knowledge of the Malicious Attacker: The attacker can access the local graph dataset and local GNN model architecture of the controlled client, and by accessing the local graph datasets of the controlled client, the attacker can expand the proportion of its local graph dataset

Goal of the Malicious Attacker: Given an honest client C with local graph dataset and its local GNN model T, the goal of the malicious attacker is to train an attack model based on the limited background knowledge and the auxiliary datasets it obtained, using it to infer fundamental property information of interest or properties irrelevant to downstream tasks within the target user’s local graph data, such as the number of nodes, number of edges, and node density. When the graph contains valuable information, such as molecular structures, these properties can be proprietary, and inferring these properties can directly infringe on the data owner’s intellectual property.

We adopted the FedGNNs framework described in Section 3.1, where each participating client retains its local graph data and related feature information. Fig. 2 shows the overall framework of PIAFGNN. Clients participate in federated training by uploading their local GNN model gradient and local node embedding gradient to the central server. During the training process, the target honest client C first uses the embedding layer to convert the nodes in its local data into embeddings, denoted as

Figure 2: The framework of PIAFGNN

1) Stealing Target Embeddings Phase: Similar to the methods described in [22,23], the attacker can steal the target user’s node embeddings information through the Generative Regression Network (GRN). The GRN optimizes the model by minimizing reconstruction error to achieve the goal of data generation, offering strong nonlinear mapping capabilities and fast learning speed. As shown in Fig. 2, the attacker first completes local training using the initial model gradient and their local GNN model to generate local node embeddings

where N represents the dimension of the node embedding gradient, and

This objective function indicates that the attacker aims to update the GRN model by optimized parameters

By minimizing

Once the target node embedding gradient is obtained, the attacker can use the backpropagation mechanism of GNNs to obtain the target user’s local node embeddings

where

2) Shadow Model Training Phase: To train the attack model of PIAFGNN, the attacker needs a set of properties of interest F and the target graph embeddings

3) Attack Model Training Phase: For each shadow model

After obtaining the

where F is the set of properties that the attacker is interested in, the number of nodes, the number of edges, the node density, etc. For each property

4) Property Inference Phase: Just as described in the attack model training phase, the attacker has already trained the property classifier with the embedding information and property labels. In the inference phase, the attacker passes the stolen local embedding

All experiments in this paper are executed on an Xeon(R) W-2133 CPU paired with 256 GB of RAM and NVIDIA GeForce RTX 2080Ti. All algorithms are implemented using the PyTorch Geometric framework in Python 3.9.0. We set the number of training iterations to 50 and the learning rate of stochastic gradient descent (SGD) to 0.01, which is used for gradient optimization and backpropagation in the neural network algorithm. We configure 15 clients to participate in the FedGNNs training, the attacker can control at most 20% of them, which is 3 honest clients. We first consider the scenario where the attacker can only fully control one honest client or directly disguise as an honest client to participate in federated training. Therefore, among the 15 clients participating in the training, fourteen are honest clients, and one is the malicious client controlled by the attacker, while the other honest clients are unaware of the attacker’s presence. For parameter aggregation training, we choose FedSGD as the gradient parameter aggregation method in FedGNNs.

Datasets: To conduct a comprehensive study of PIAFGNN, we selected three public datasets with different complexity in terms of the number of classes, edges, and nodes to verify the performance of our method, including Cora [25], Citeseer [26], and Pubmed [27]. They are widely used in the literature for graph learning: (1) Cora is a commonly used academic citation network dataset. It contains an academic citation network in the field of machine learning, as well as the content features and label information of each document. (2) Citeseer contains six categories of papers, with each node having a feature vector and a label. The main task of Citeseer is to classify nodes based on their features and graph structure. (3) Pubmed is a biomedical literature dataset from the Pubmed database, consisting of papers related to diabetes, divided into three categories. Each node is associated with 500 unique keywords as features. Table 3 summarizes the basic information of these three datasets, e.g., the number of nodes and edges. For all three datasets, the node embedding dimension is set to 64.

Dataset Splits: We randomly extract 10,000 subgraphs from the graph dataset and evenly distribute them to 15 clients, ensuring that each client possesses a portion of the entire graph dataset as its local dataset. The client randomly divides its local dataset into 80% training dataset set and 20% test dataset, participating in FedGNNs training with node classification as the downstream task. During the training process, each client trains its local dataset using the local GNN model and only uploads the trained model gradient and node embedding gradient to the central server for federated aggregation. Throughout the whole process, neither the central server nor the clients could access the local graph data of any other client. In the same experiment, we consider two different private graph properties as the attacker’s targets, namely the number of nodes and the number of edges, which are irrelevant to the model’s node classification task.

Models and Metrics: In experiments, we focus on three standard GNN architectures: GCN [19], GraphSAGE [20], and GAT [21], which are widely used in the machine learning field. For the hyperparameter configuration of the corresponding models, we adopt the standard stated by previous works in the scientific literature. Specifically, the number of neurons in each hidden layer of each model in the experiment is set to 64, which matches the dimension of the node embeddings. For GCN, we utilize 2-hidden layers of dimension 64 with a ReLU activation function between them. For the GAT, we set 3 hidden layers. And for GraphSAGE, we use 2-hidden layers, of dimension 64. Additionally, this paper uses Attack Accuracy (AC) to evaluate the effectiveness of the attack.

Benchmark Methods: Since this is the first study on property inference attacks against FedGNNs, in order to verify the attack performance of PIAFGNN, we select the property inference attacks method against centralized GNNs in [10], as well as the random guessing method based on binary classification tasks, for comparison as baseline methods.

5.2 Performance Evaluation of the PIAFGNN

The attack performance of PIAFGNN is tested under three different local GNN models, targeting the inference of two basic properties of target graphs: the number of nodes and the number of edges. The results are shown in Table 4. In order to fairly compare the attack accuracy under different settings, it is necessary to ensure that the training data of PIAFGNN for all experiments is the same. The experiments use Random Forest (RF) as the training algorithm for the property classifier and MaxPool as the embedding aggregation method in the pooling layer for GNNs, as these settings produced the best attack performance.

As reported in Table 4, PIAFGNN achieved commendable attack accuracy in most settings, with an average attack accuracy exceeding 70%. Notably, in the inference task targeting the graph node count property within the FL framework based on the GCN model, the attack accuracy reaches 82.80%, which is close to the property inference attacks accuracy of 83.42% against centralized GNNs Even on a complex GNN model like GAT, the attack accuracy of PIAFGNN can reach over 67.82% on a graph dataset with a complex structure like Pubemd, which is significantly higher than the Random Guessing baseline method.

5.2.2 Impact of Different GNN Complexities on PIAFGNN

We also test the impact of different complexities of target GNN models on the attack accuracy of PIAFGNN, as shown in Fig. 3. Specifically, we evaluated the attack performance of PIAFGNN by using different GNN architectures as local models and varying their complexities, that is, changing the number of hidden layers, and using node count as the target property. Experiments are conducted within the FL framework on three datasets, focusing on three GNN model architectures with 2, 4, 6, and 8 hidden layers. The attacker aimed to infer the node count of the target graph. We can observe that although the attack accuracy of PIAFGNN decreases with the increase of model complexity, even for complex GNN architectures with 8-hiddenlayers, such as GAT, our attack can still achieve an attack accuracy of 60.67% on Pubmed dataset, which is significantly higher than the accuracy of the random guessing baseline method, proving that PIAFGNN has achieved desirable attack performance and can effectively handle various complex model structures.

Figure 3: Comparing the impact of different local GNN complexity on the attack accuracy of PIAFGNN

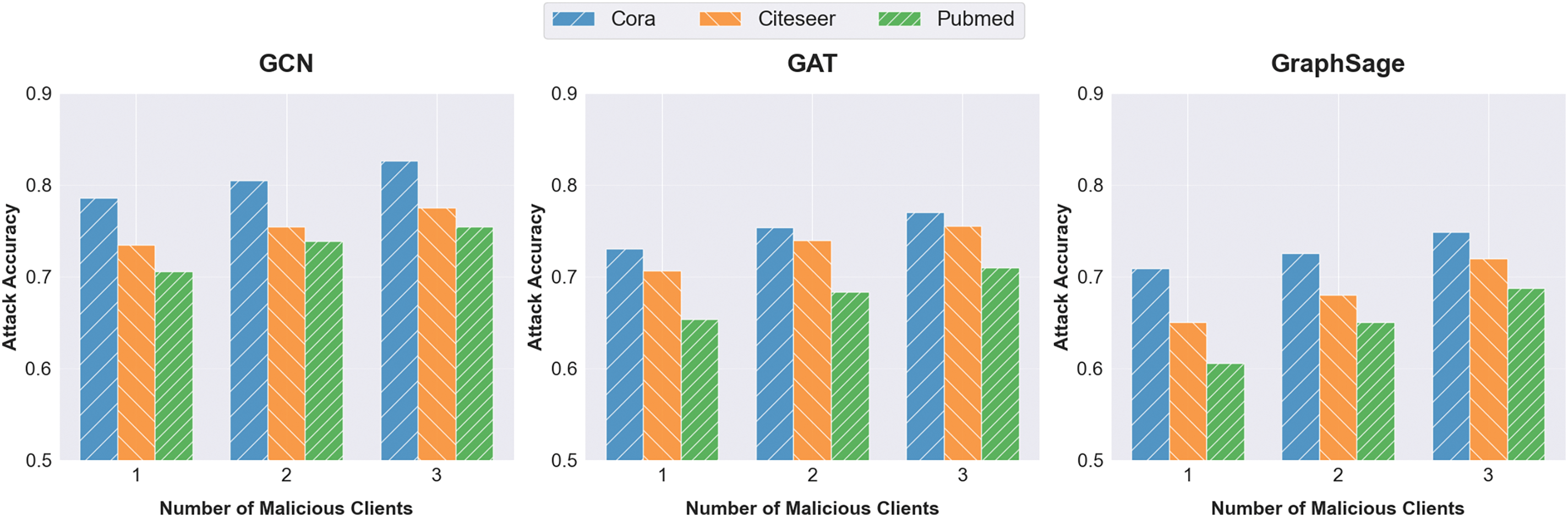

5.2.3 Impact of the Number of Clients Controlled by Attacker on PIAFGNN

In order to investigate the impact of the number of honest clients controlled by the attacker, that is, the proportion of local graph datasets that the attacker can possess on the attack accuracy of PIAFGNN, we test the attack accuracy of PIAFGNN when the attacker fully controls 1, 2, or 3 of the 15 honest clients participating in federated training and we set the attacker to use the RF model as the property classifier. From Fig. 4, we can observe that as the number of honest clients controlled by the attacker increases, the attack accuracy of PIAFGNN also gradually improves on FedGNNs based on different local GNN models. When the malicious attacker controls two honest clients, the attack accuracy of PIAFGNN increases by an average of 3.6% compared to controlling only one honest client. Furthermore, when the attacker can control three honest clients, the attack accuracy of PIAFGNN increases by an average of 6.8% compared to controlling just one client. This is because the more clients the attacker controls, the larger the proportion of graph datasets they have access to, allowing the attacker to obtain more global model updates and node embedding information. This information can be used to more comprehensively guess changes in the global model and more accurately understand the dynamics of the global model updates. As a result, it becomes easier to steal the target user’s node embeddings and infer the privacy properties of the target graph data.

Figure 4: Comparing the impact of the number of clients controlled by attacker on the attack accuracy of PIAFGNN

5.2.4 Impact of Different Property Classifier Algorithms on PIAFGNN

To further verify the superiority of the PIAFGNN algorithm, consider the PIA attack methods of two other regression algorithm classifiers as baselines compared with our PIAFGNN based on RF property classifier: 1) Support Vector Machine (SVM), and 2) AdaBoost, as shown in Fig. 5. Using the Cora dataset as an example, these results can be generalized to other datasets. After 50 rounds of iterations, the RF-based property classifier demonstrates superior performance compared to the two baseline methods across three different FedGNNs frameworks, achieving the highest attack accuracy. On average, the accuracy is 4.9% higher than SVM-PIA and 8.6% higher than AdaBoost-PIA. This is attributed to the highly parallelized training process of the RF-based property classifier, where RF can randomly select decision tree node splitting features, offering a significant advantage when handling high-dimensional data like graph data, without the need for feature selection.

Figure 5: Attacks accuracy under different property classifier algorithms

5.3 Potential Defenses against PIAFGNN

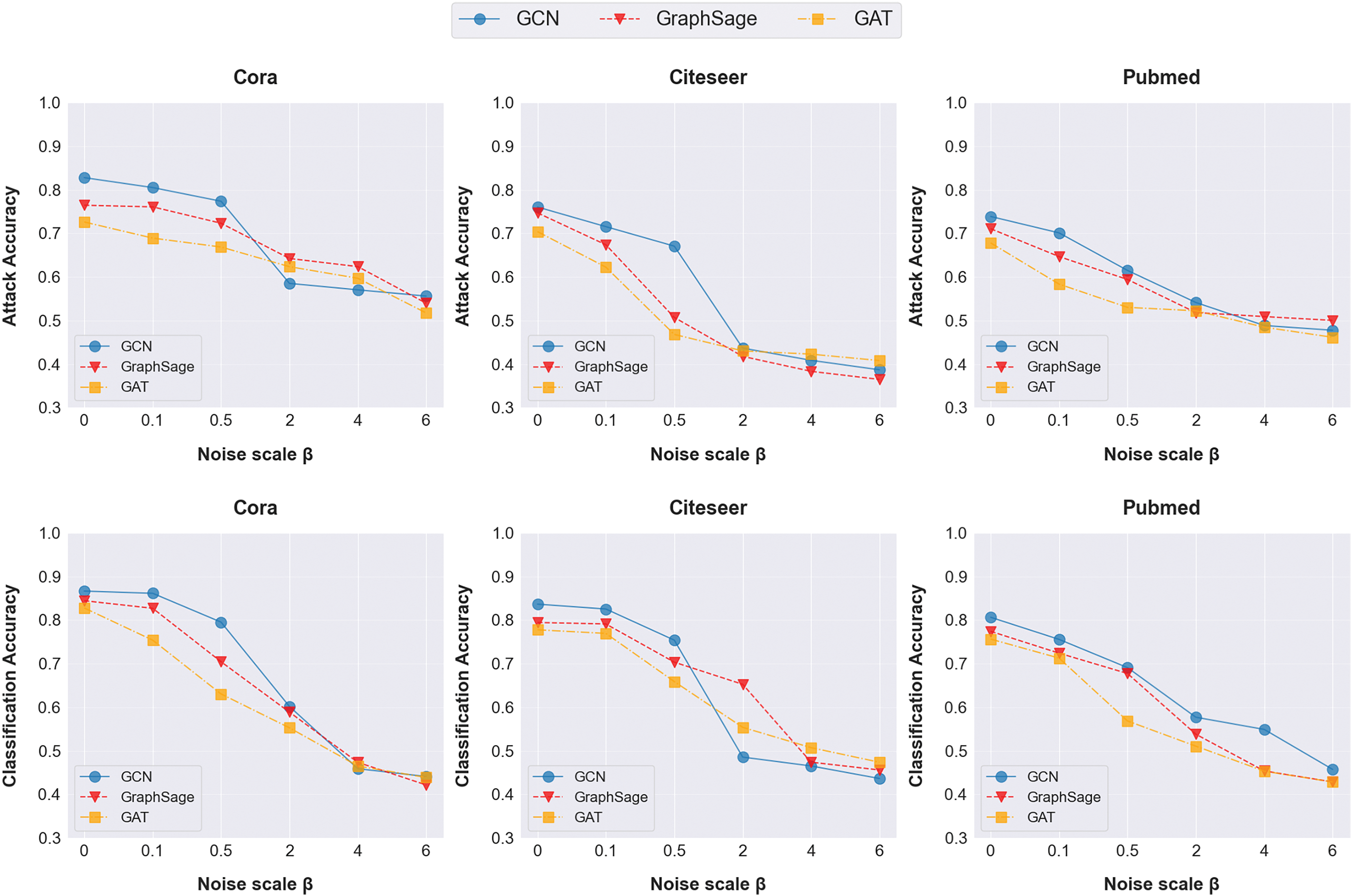

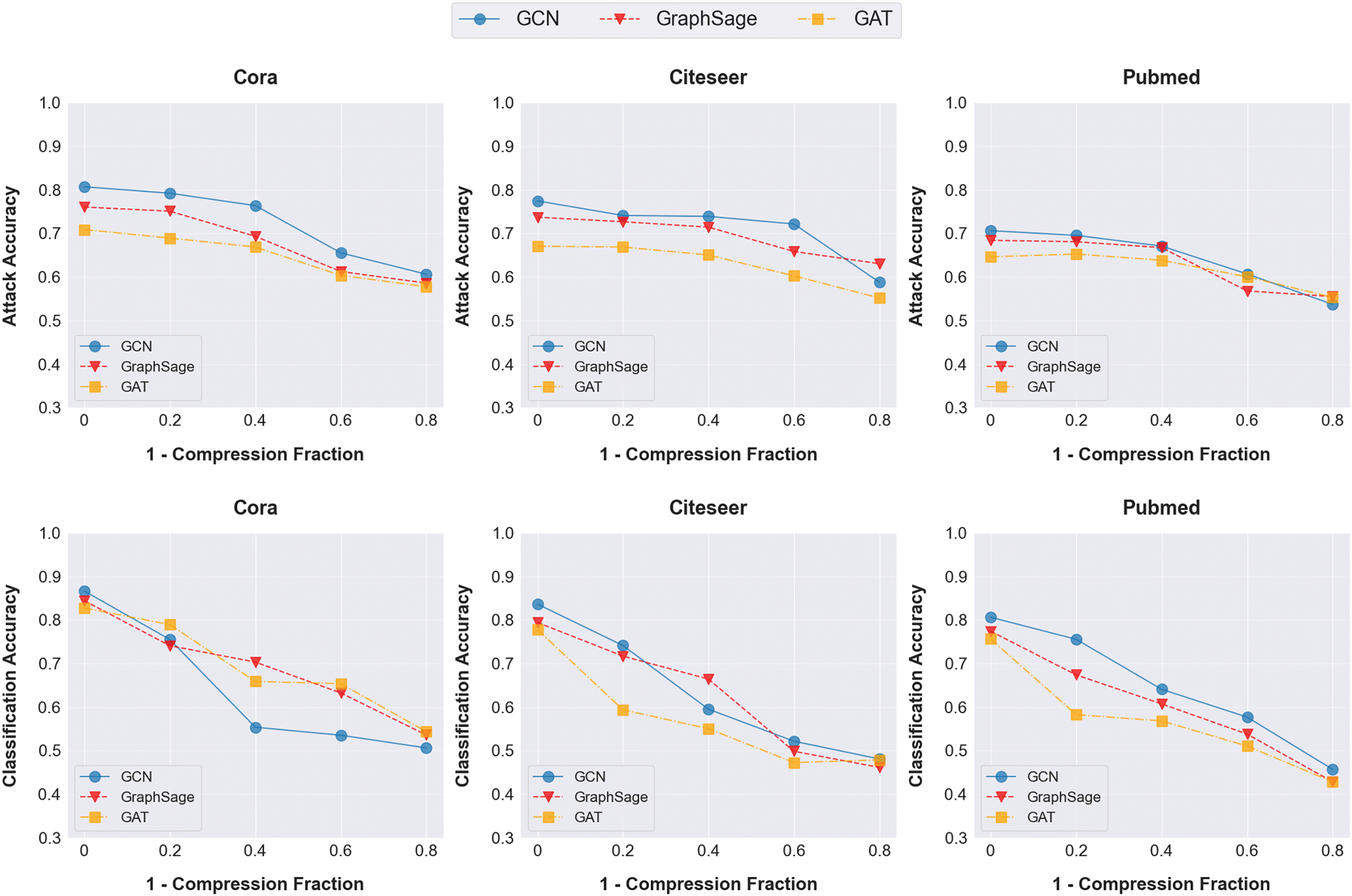

In this section, we evaluate the effectiveness of potential defense methods against PIAFGNN and their impact on the main task classification accuracy of the target model. Here we consider two possible defense strategies: (1) Adding differential privacy noise to perturb embeddings [28]; (2) Gradient Compression (GC) [29]. The following briefly introduces these two defense strategies:

(1) Adding differential privacy noise to perturb embeddings. We first consider adding differential privacy noise perturbations, which follow a Laplace distribution, to the embeddings to defend against PIAFGNN. Formally, during the training of local graph data, each client perturbs the local node embeddings by adding a certain scale of differential privacy noise, that is,

Fig. 6 shows the changes in attack accuracy of PIAFGNN on three datasets for different GNN models under varying noise scales, as well as the changes in accuracy for the normal classification task. As the noise level gradually increases from 0 to 6, the performance of property inference attacks on different models progressively decreases, with the attack accuracy on Pubmed dataset reducing to 36.5%. This is expected, as higher noise levels obscure more structural information contained in the embeddings. On the other hand, as the noise level increases, the accuracy of the main classification task also significantly declines, with an accuracy loss of up to 40.3% on Cora dataset. This is because adding noise causes the model to learn from incorrect labels and reduces the model’s generalization ability, which does not meet the defense expectation of reducing attack performance without affecting the accuracy of the main classification task. However, we also found that if an appropriate noise scale

Figure 6: Evaluation of Laplace noise perturbation defense methods against PIAFGNN on three datasets

(2) Gradient Compression (GC). Another defense mechanism we consider is gradient compression, where clients only upload local model gradients that exceed a given threshold to the server for aggregation. It aims to protect privacy by providing the server with the minimum amount of information necessary for model aggregation, reducing the privacy information carried in the shared gradient, and increasing communication efficiency. The experiment tested the impact of gradient compression ratios on the performance of FedGNNs on the main task and the accuracy of PIAFGNN, and the results are shown in Fig. 7. As the gradient compression ratio increases, the attack accuracy of PIAFGNN generally decreases, albeit slowly in most cases, with a reduction of about 25%, while the main task classification accuracy has decreased by about 30%. Specifically, on the Pubmed dataset, when the gradient compression ratio increases to 0.8, the attack accuracy only decreases by 15%, while the classification accuracy of the main task decreases by 34%. This indicates that the defense effectiveness of gradient compression against PIAFGNN is limited and may lead to a decrease in the classification accuracy of the main task. This is because even if the gradient is compressed, the malicious attacker may still be able to recover the compressed information by collecting enough gradient updates and using statistical methods or optimization techniques.

Figure 7: Evaluation of gradient compression defense methods against PIAFGNNs on three datasets

Although neither of the two defense mechanisms can effectively counter PIAFGNN, upon analyzing the relationship between the embedding perturbation method and attack performance, we discover that by choosing an appropriate noise scale and minimizing the noise budget, PIAFGNN can potentially be prevented from successfully inferring private properties while also improving communication efficiency and minimizing the impact on the accuracy of the primary task classification. For example, during the training of the Cora dataset, we found that controlling the noise scale

This paper investigates the property inference attacks against federated graph neural networks, namely PIAFGNN, for the first time. The attacker can use the GRN to steal the local node embedding gradient and model gradient uploaded by the client participating in the FedGNNs training by obtaining the global embedding gradient and other information. Subsequently, by using the stolen gradient information and auxiliary datasets, the attacker can train shadow models and property classifier to infer basic property information of target graphs that is irrelevant to downstream tasks. Extensive experiments demonstrate the effectiveness of PIAFGNN in a variety of public graph datasets, with results that can be generalized to multiple GNN models under FL. Finally, we verify the robustness of PIAFGNN under two defense mechanisms, both of which are unable to effectively defend against PIAFGNN.

However, PIAFGNN also faces certain limitations. Firstly, PIAFGNN only considers node-level property inference attacks, without exploring inference attacks targeting graph-level GNNs. Generally, inferring sensitive property information of a target graph using entire graph embeddings is more challenging than using node embeddings. In addition, in PIAFGNN, the attacker needs to obtain shadow datasets with distributions similar to that of the target user’s data. Although this has been proven feasible in practice, for example, by obtaining various datasets from multiple domains, it also consumes more computational resources and increases computational complexity. In the future, we will explore how to relax these limitations by investigating methods to acquire high-quality auxiliary datasets and enhancing the quality of the embedding extraction process to improve the attack accuracy of PIAFGNN.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to express appreciation to the National Natural Science Foundation of China. The authors would like to thank the editor-in-chief, editor, and reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions.

Funding Statement: This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 62176122 and 62061146002).

Author Contributions: Jiewen Liu: Writing original draft, Software, Methodology, Formal analysis; Bing Chen: Writing review, Editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition; Baolu Xue and Mengya Guo: Data collection, Data curation; Yuntao Xu: Technical support, Draft manuscript preparation. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: This work uses the three public datasets for model training and evaluation in FedGNNs. The datasets can be downloaded from the Internet.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Q. Yang, Y. Liu, T. Chen, and Y. Tong, “Federated machine learning: Concept and applications,” ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol., vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 1–19, Jan. 2019. doi: 10.1145/3339474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. B. McMahan, E. Moore, D. Ramage, S. Hampson, and B. A. y. Arcas, “Communication-efficient learning of deep networks from decentralized data,” in Proc. 20th Int. Conf. Artif. Intell. Stat., PMLR, Apr. 20–22, 2017, vol. 54, pp. 1273–1282. [Google Scholar]

3. B. Jia, X. Zhang, J. Liu, Y. Zhang, K. Huang and Y. Liang, “Blockchain-enabled federated learning data protection aggregation scheme with differential privacy and homomorphic encryption in iiot,” IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform., vol. 18, no. 6, pp. 4049–4058, 2022. doi: 10.1109/TII.2021.3085960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. R. Liu, P. Xing, Z. Deng, A. Li, C. Guan and H. Yu, “Federated graph neural networks: Overview, techniques, and challenges,” IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst., pp. 1–17, 2024. doi: 10.1109/TNNLS.2024.3360429. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Z. Wang et al., “Federatedscope-GNN: Towards a unified, comprehensive and efficient package for federated graph learning,” in Proc. 28th ACM SIGKDD Conf. Knowl. Discov. Data Min., New York, NY, USA, 2022, pp. 4110–4120. doi: 10.1145/3534678.3539112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. J. Xu, R. Wang, S. Koffas, K. Liang, and S. Picek, “More is better (mostlyOn the backdoor attacks in federated graph neural networks,” in Proc. 38th Annual Comput. Secur. Appl. Conf., 2022, pp. 684–698. doi: 10.1145/3564625.3567999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. C. He et al., “FedGraphNN: A federated learning system and benchmark for graph neural networks,” 2021. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2104.07145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. C. Wu, F. Wu, L. Lyu, T. Qi, Y. Huang and X. Xie, “A federated graph neural network framework for privacy-preserving personalization,” Nat. Commun., vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 3091–3100, 2022. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-30714-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. C. Chen et al., “Vertically federated graph neural network for privacy-preserving node classification,” 2020. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2005.11903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Z. Zhang, M. Chen, M. Backes, Y. Shen, and Y. Zhang, “Inference attacks against graph neural networks,” in 31st USENIX Secur. Symp. (USENIX Secur. 22), Boston, MA, USENIX Association, 2022, pp. 4543–4560. [Google Scholar]

11. X. Wang and W. H. Wang, “Group property inference attacks against graph neural networks,” in Proc. 2022 ACM SIGSAC Conf. Comput. Commun. Secur., 2022, pp. 2871–2884. doi: 10.1145/3548606.3560662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Z. Ye, Y. J. Kumar, G. O. Sing, F. Song, and J. Wang, “A comprehensive survey of graph neural networks for knowledge graphs,” IEEE Access, vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 75729–75741, 2022. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3191784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. X. Li, L. Sun, M. Ling, and Y. Peng, “A survey of graph neural network based recommendation in social networks,” Neurocomputing, vol. 549, 2023, Art. no. 126441. doi: 10.1016/j.neucom.2023.126441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. H. Cai, H. Zhang, D. Zhao, J. Wu, and L. Wang, “FP-GNN: A versatile deep learning architecture for enhanced molecular property prediction,” Brief. Bioinform., vol. 23, no. 6, pp. 1477–4054, Sep. 2022. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbac408. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. J. Zhang, J. Zhang, J. Chen, and S. Yu, “Gan enhanced membership inference: A passive local attack in federated learning,” in ICC, 2020-2020 IEEE Int. Conf. Commun. (ICC), 2020, pp. 1–6. doi: 10.1109/ICC40277.2020.9148790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. L. Melis, C. Song, E. De Cristofaro, and V. Shmatikov, “Exploiting unintended feature leakage in collaborative learning,” in 2019 IEEE Symp. Secur. Priv. (SP), 2019, pp. 691–706. doi: 10.1109/SP.2019.00029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. R. Shokri, M. Stronati, C. Song, and V. Shmatikov, “Membership inference attacks against machine learning models,” in 2017 IEEE Symp. Secur. Priv. (SP), 2017, pp. 3–18. doi: 10.1109/SP.2017.41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. M. Conti, J. Li, S. Picek, and J. Xu, “Label-only membership inference attack against node-level graph neural networks,” in Proc. 15th ACM Workshop Artif. Intell. Secur., AISec’22, 2022, pp. 1–12. doi: 10.1145/3560830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. T. N. Kipf and M. Welling, “Semi-supervised classification with graph convolutional networks,” 2016. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.1609.02907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. W. L. Hamilton, R. Ying, and J. Leskovec, “Inductive representation learning on large graphs,” in Proc. 31st Int. Conf. Neural Inf. Process. Syst., NIPS’17, Red Hook, NY, USA, 2017, pp. 1025–1035. doi: 10.5555/3294771.3294869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. P. Velickovic, G. Cucurull, A. Casanova, A. Romero, P. Lio and Y. Bengio, “Graph attention networks,” vol. 1050, no. 20, pp. 10–48, 550, 2017. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.1710.10903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. X. Luo, Y. Wu, X. Xiao, and B. C. Ooi, “Feature inference attack on model predictions in vertical federated learning,” in 2021 IEEE 37th Int. Conf. Data Eng. (ICDE), 2021, pp. 181–192. doi: 10.1109/ICDE51399.2021.00023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. J. Chen, G. Huang, H. Zheng, S. Yu, W. Jiang and C. Cui, “Graph-Fraudster: Adversarial attacks on graph neural network-based vertical federated learning,” IEEE Trans. Comput. Soc. Syst., vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 492–506, 2023. doi: 10.1109/TCSS.2022.3161016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. K. Ganju, Q. Wang, W. Yang, C. A. Gunter, and N. Borisov, “Property inference attacks on fully connected neural networks using permutation invariant representations,” in Proc. 2018 ACM SIGSAC Conf. Comput. Commun. Secur., CCS ’18, New York, NY, USA, Association for Computing Machinery, 2018, pp. 619–633. doi: 10.1145/3243734.3243834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. A. K. McCallum, K. Nigam, J. Rennie, and K. Seymore, “Automating the construction of internet portals with machine learning,” Inf. Retr., vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 127–163, 2000. doi: 10.1023/A:1009953814988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. C. L. Giles, K. D. Bollacker, and S. Lawrence, “CiteSeer: An automatic citation indexing system,” in Proc. Third ACM Conf. Digital Libraries, 1998, pp. 89–98. doi: 10.1145/276675.276685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. P. Sen, G. Namata, M. Bilgic, L. Getoor, B. Galligher and T. Eliassi-Rad, “Collective classification in network data,” AI Mag., vol. 29, no. 3, Sep. 2008, Art. no. 93. doi: 10.1609/aimag.v29i3.2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Z. Zhang et al., “PrivSyn: Differentially private data synthesis,” in 30th USENIX Secur. Symp. (USENIX Secur. 21), USENIX Association, Aug. 2021, pp. 929–946. [Google Scholar]

29. P. Kairouz et al., “Advances and open problems in federated learning,” Found. Trends Mach. Learn., vol. 14, no. 1–2, pp. 1–210, 2021. doi: 10.1561/2200000083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools