Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

MMH-FE: A Multi-Precision and Multi-Sourced Heterogeneous Privacy-Preserving Neural Network Training Based on Functional Encryption

1 The State Key Laboratory of Public Big Data, College of Computer Science and Technology, Guizhou University, Guiyang, 550025, China

2 Key Laboratory of Computing Power Network and Information Security, Ministry of Education, Shandong Computer Science Center, Qilu University of Technology (Shandong Academy of Sciences), Jinan, 250014, China

3 China Industrial Control Systems Cyber Emergency Response Team, Beijing, 100040, China

* Corresponding Author: Zhenyong Zhang. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Privacy-Preserving Deep Learning and its Advanced Applications)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 82(3), 5387-5405. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.059718

Received 15 October 2024; Accepted 02 January 2025; Issue published 06 March 2025

Abstract

Due to the development of cloud computing and machine learning, users can upload their data to the cloud for machine learning model training. However, dishonest clouds may infer user data, resulting in user data leakage. Previous schemes have achieved secure outsourced computing, but they suffer from low computational accuracy, difficult-to-handle heterogeneous distribution of data from multiple sources, and high computational cost, which result in extremely poor user experience and expensive cloud computing costs. To address the above problems, we propose a multi-precision, multi-sourced, and multi-key outsourcing neural network training scheme. Firstly, we design a multi-precision functional encryption computation based on Euclidean division. Second, we design the outsourcing model training algorithm based on a multi-precision functional encryption with multi-sourced heterogeneity. Finally, we conduct experiments on three datasets. The results indicate that our framework achieves an accuracy improvement of to . Additionally, it offers a memory space optimization of times compared to the previous best approach.Keywords

Machine learning technology has been widely used in many fields, including computer vision, natural language processing, and audio and speech processing, becoming a core component of the development of modern technology. Many companies, such as Google and IBM, provide Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS) in the current business environment. These services are designed to help users who lack computing resources use cloud computing resources to train and deploy machine learning models. However, when using these services, data privacy and security issues are particularly important, especially when dealing with sensitive data such as medical or financial data. Therefore, meeting such privacy concerns of users as well as legal and regulatory requirements poses a huge challenge to the implementation of machine learning solutions.

Suppose a bank wants to assess the credit risk of its users and decides to outsource this task to a company that provides IaaS. In this scenario, the bank provides the user’s financial transaction history as input, and the IaaS company uses this data to predict whether the user is likely to default. This data is extremely sensitive and cannot be directly disclosed to the service provider due to the personal financial information involved. In this privacy-preserving environment, the credit risk assessment must be conducted without directly revealing the transaction history to the company.

With the development of various intelligent devices [1]. To cope with the privacy issues that may arise during this process, a privacy-preserving machine learning (PPML) framework needs to be implemented. In the field of PPML, various technical approaches have been proposed to protect data privacy [2]. We summarize some of the representative PPML methods in Table 1. As shown in the literature [3], non-cryptographic solutions like differential privacy and federated learning require strong security parameters for privacy. For example, differential privacy needs a strict privacy budget, reducing the usability of neural network models. In contrast, cryptographic schemes, such as secure multi-party computation [4], provide robust security. However, they have very high computational costs and require significant communication overhead. This results in poor computational performance, making them less suitable for large-scale applications. Homomorphic encryption schemes, such as those proposed in the literature [5,6], require the execution of complex arithmetic operations and often utilize approximations to replace the activation function, which limits both time efficiency and accuracy. Except for some existing functional encryption methods (e.g., CryptoNN [7], NN-EMD [8]), most cryptographic methods address the privacy problem in the prediction phase without focusing on the privacy problem in the training phase.

In addition, existing solutions rarely consider such scenarios as multiple data sources under multiple keys. That is, the data is provided by multiple clients, and all the provided data are finally combined to become a complete training dataset. This is objectively present in real scenarios. For example, in a cross-agency online credit approval system, a user’s credit score is derived from data provided by multiple independent agencies. This data includes financial information from banks, credit history from credit scoring agencies, and occupational income details from employers. To effectively protect this sensitive data, the proposed a Multi-Precision and Multi-Sourced Heterogeneous Privacy-Preserving Neural Network Training Based on Functional Encryption (MMH-FE) framework utilizes functional encryption technology to ensure that the data from each source is processed in an encrypted state, preventing personal information leakage. Through inner-product encryption, we can perform computations across multiple data sources without revealing the raw data. The final credit score is derived by calculating the results of the encrypted data, effectively preventing data leakage. Additionally, the fine-grained access control mechanism within the framework ensures that each agency can only access the inner-product calculation results it is authorized to view, preventing improper data misuse. To address the multi-data-source scenario, the framework supports a multi-key mechanism, ensuring that each data source encrypts its data with a distinct key, further enhancing the security of the data and the flexibility of the system. In addition, the existing solutions can only perform the inner product computation of functional encryption at lower accuracy. We propose a new multi-precision functional encryption computation based on Euclidean division. It allows inner product functional encryption to be performed with higher accuracy and strong adaptability. This lays the foundation for high-precision and high-accuracy training of inner product functional encryption neural networks. Specifically, our contributions are as follows:

• We design a multi-precision functional encryption computation based on Euclidean division. This allows the multiplication of original data to be decomposed. As a result, the computational cost is reduced, and the accuracy is improved.

• We design a generic MMH-FE framework based on a multi-precision functional encryption to support training neural networks on encrypted data. In essence, MMH-FE adds a multi-precision propagation step in the training phase of the conventional training phase on neural networks to protect data privacy from disclosure.

• We have evaluated the model on three datasets and performed a detailed analysis of the experimental results, and the test results show that the scheme has a high computational accuracy.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: It summarizes related work in Section 2. In Section 3, we introduce background knowledge and preliminaries. In Section 4, we propose the MMH-FE framework and describe the technical details. In Section 5, we conduct experimental analyses and evaluate. Finally, conclusions are drawn in Section 6.

Functional encryption (FE) scheme was first proposed by Sahai et al. in [10], and an exhaustive formal definition was provided by Boneh et al. in the literature [11]. Functional encryption has become an innovative technique in public key cryptography as more and more scholars have invested in this area of research [12–14]. This technique constructs a theoretical framework that abstracts a variety of existing encryption mechanisms, including fine-grained access control [15], dynamic decentralized functional encryption [16], and a new paradigm of quadratic public-key functional encryption [17]. Unlike traditional encryption schemes, which reveal either all plaintext or all ciphertext, functional encryption strategies have a unique feature. Their decryption keys reveal only limited information about the plaintext. Specifically, they disclose the result of a computation performed on the plaintext using a particular function. In addition, functional encryption contrasts with homomorphic encryption techniques, which are widely used today, and which usually consume a certain amount of resources to additionally decrypt the final result. In contrast, this unique property of functional encryption brings new research and application prospects in the field of data privacy and information security.

In the existing literature, a variety of functional encryption constructs have been proposed to handle different types of functions, such as inner products [18], sequential comparisons [11], and access control [19]. In addition, researchers have also explored the use of secure multi-party computation [20] and multilinear mapping [21,22] to construct functional encryption schemes, or the use of functional encryption techniques to implement other cryptographic applications. However, most of these schemes are still in the theoretical research stage and have not been sufficiently translated into practical applications. Compared with existing work, our method is not only theoretically innovative but also practically feasible. The work presented in the literature [23,24] is part of our cryptosystem underlying this paper.

In recent years, with the rapid development of neural network technology [25], the issue of data security has received widespread attention. The homomorphic encryption [26–28] technique, as an advanced encryption method, has attracted much attention from researchers for its application in privacy-preserving ML. ML confidential [29] describes a binary classification mechanism that combines polynomial approximation and homomorphic encryption. Faster CryptoNets [30] accelerates prediction performance in deep learning models by utilizing sparse representations in the underlying cryptosystem through techniques of pruning and quantization. Secure Multi-Party Computing [4] discusses a privacy-preserving protocol that uses SGD (Stochastic Gradient Descent) optimization algorithm to train a neural network model. Homomorphic encryption and secure multi-party computation can both be applied to neural networks to protect data privacy. However, homomorphic encryption incurs a high computational cost, as the process of encrypting and decrypting data consumes substantial computational resources. In contrast, secure multi-party computation requires a large number of messages to be exchanged between participants. As the number of participants increases, the complexity and difficulty of implementing secure multi-party computation also rise. Therefore, implementing secure neural networks on servers with limited computational resources is not feasible.

This article focuses on the use of functional encryption as a way to build a secure neural network training process. In an earlier study, Ligier et al. [31] developed an inner-product functional encryption scheme for classifying encrypted data. They utilized Extreme Random Tree (ERT) classifiers trained on the MNIST dataset, focusing primarily on private machine learning prediction using inner product functional encryption. Following this, Dufour-Sans et al. [32] proposed a new quadratic encryption scheme, Ryffel et al. [33] and Nguyen et al. [34] applied it to quadratic networks to classify encrypted data. In addition, CryptoNN [7] investigated the possibility of applying functional encryption to train neural networks on the MNIST dataset, which is comparable to the traditional MNIST model in terms of accuracy. NN-EMD [8] used a multilayer perceptron (MLP) for neural network training on the same dataset, with the difference that it uses a lookup table method to compute discrete logarithms during decryption. Its classification accuracy also rivals the traditional MNIST model.

In this paper, we use Euclidean Division to reconstruct the data representation and achieve moderation of the accuracy of the data in this framework. At the same time, the space cost of the lookup table is significantly reduced during the function decoding process. To reduce the space cost in function encryption computation, we implement this method in Single-Input Function Encryption and Multi-Input Function Encryption. To improve the training accuracy of the model, we apply it in the neural network training process.

3.1 Single-Input Functional Encryption

The single-input functional encryption scheme(SIFE) for the inner-product function

The algorithm is implemented as follows:

•

•

•

•

3.2 Multi-Input Functional Encryption

The multi-input functional encryption scheme(MIFE) for the inner-product

The algorithm is implemented as follows:

•

•

•

•

•

3.3 Multi-Precision Fixed-Point Arithmetic

Multi-precision fixed-point arithmetic is a common method for large-number multiplication. It is based on the Karatsuba algorithm, which breaks large numbers into smaller ones for multiplication. Here we review the double-precision fixed-point arithmetic technique.

Let m be integers. Decompose m into a pair of integers corresponding to the quotient and the remainder of division

with

4 The Proposed MMH-FE Framework

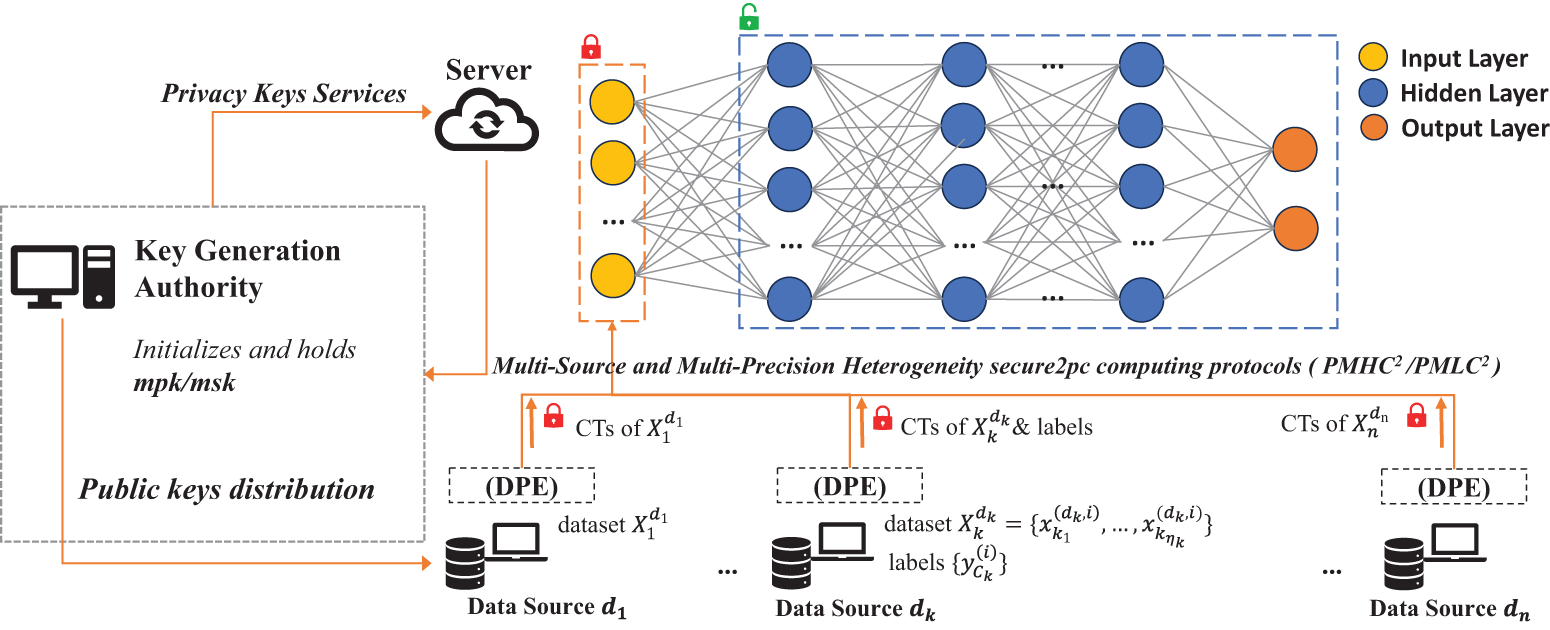

This paper proposes a multi-precision and multi-sourced heterogeneity privacy-preserving neural network (MMH-FE) framework. Three main entities are involved: the client, the server, and the key generation authority(KGA).

• Client: The client has two ways to provide data: The first is by supplying horizontal data, where each data owner holds a complete sample that includes all feature information. The second is by supplying longitudinal data, where each data owner holds a sample that contains only a subset of the features. When combined, these partial datasets form the full dataset.

• Server: After the server integrates the encrypted data sets uploaded by the client, it uses this data to construct a knowledge system for the model. This process ultimately generates a prediction model with high accuracy and strong privacy protection.

• KGA: The KGA is mainly responsible for initializing the underlying cryptosystem, setting up key credentials, and distributing the relevant public keys to the client and the server. In the training phase, KGA will interact with the server to obtain the functional private key and get the functional encryption result. However, from start to finish, KGA cannot obtain or access the encrypted training data, thus effectively guaranteeing the confidentiality of the data.

Fig. 1 depicts the details of our proposed MMH-FE framework. The whole architecture is built by three entities including the client, the KGA, and the server. The client provides multi-sourced data for model training. For multi-sourced data, if each data source contains complete information, the data will be decomposed with multi-precision using the

Figure 1: An overview of the framework of our proposed effective methods for training neural networks with multi-precision and multi-sourced hybridization

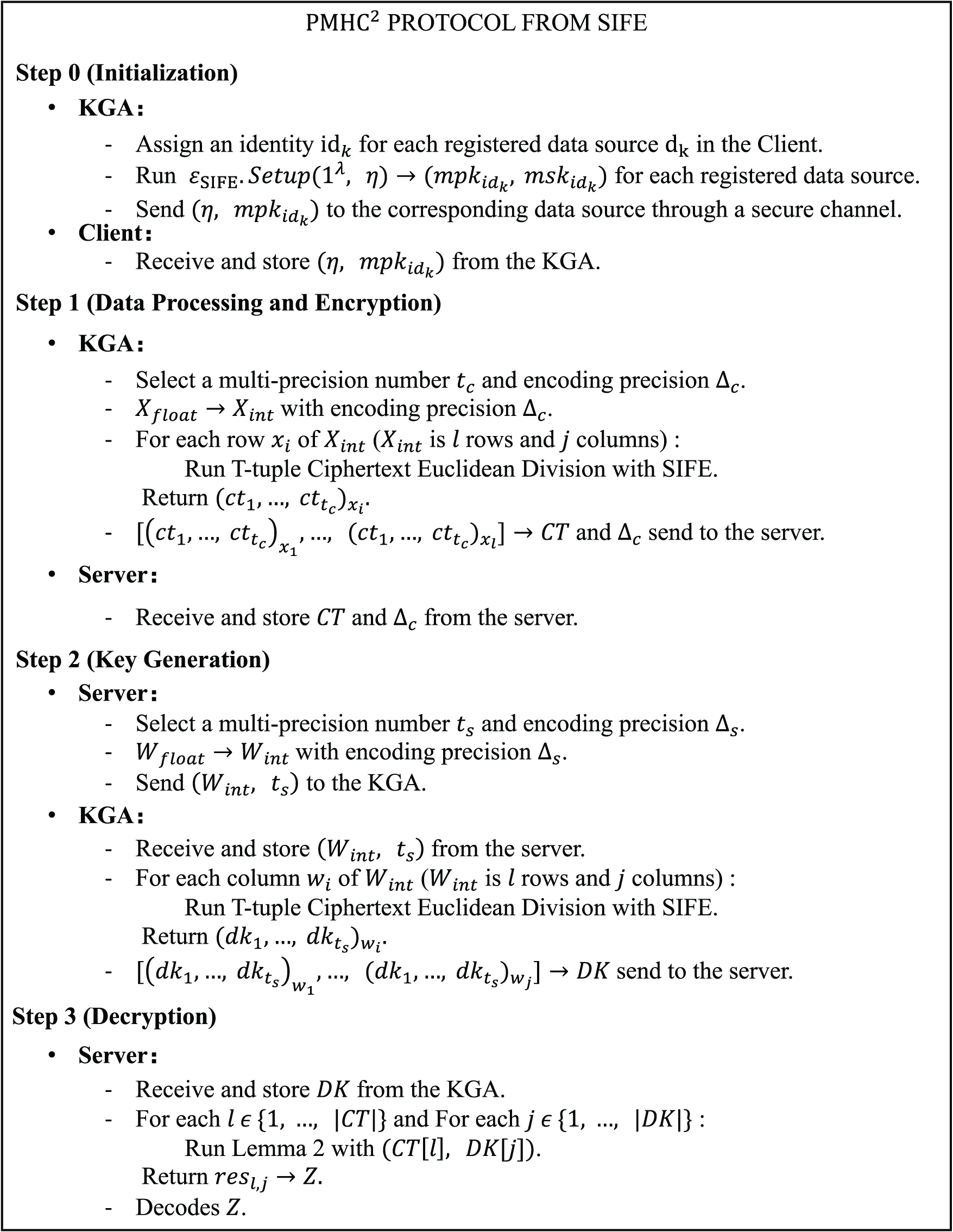

Figure 2: Describes in detail the execution of the

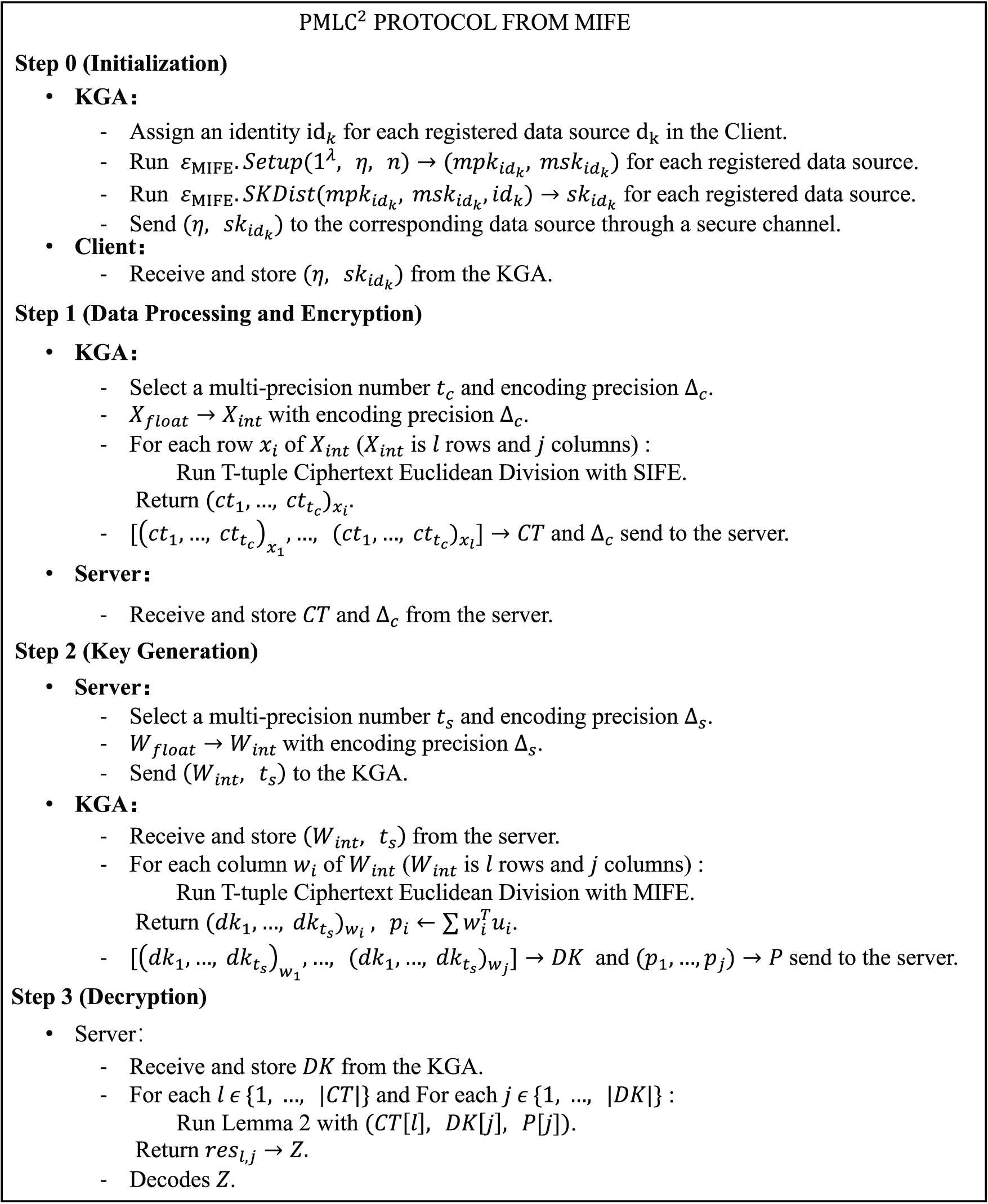

Figure 3: Describes in detail the execution of the

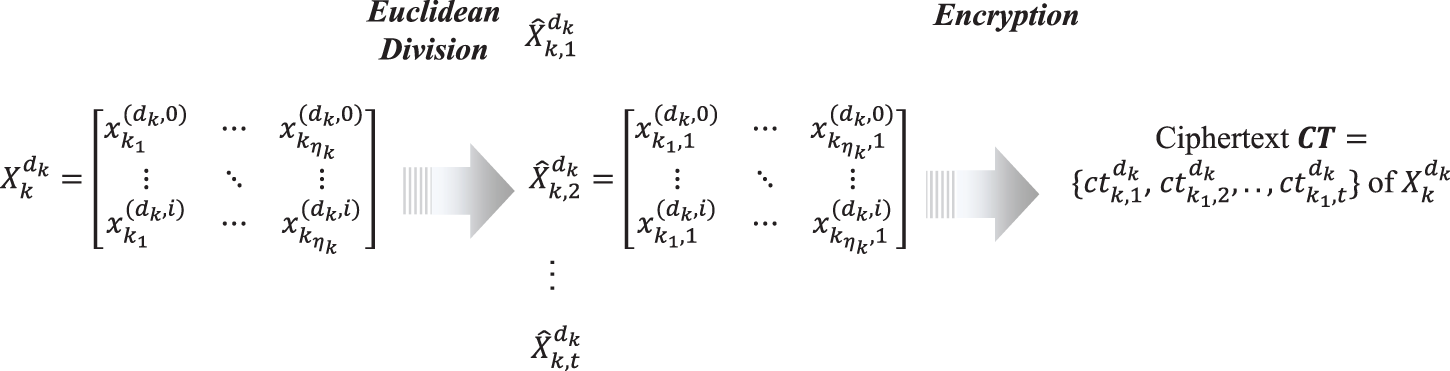

As shown in Fig. 4. We use

• Data Processing: The Client

• Data Encryption: The Client

Figure 4: Data processing and data encryption

Definition 1 (Vector-oriented Euclidean division). Let

where

According to Definition 1, the decomposition of a vector

Conversely, the recombination of

Further, it can be extended to high-precision decomposition for a vector

and high-precision decomposition recombination for a vector set

Definition 2 (2-tuple Ciphertext base on Euclidean Division). Let

where

Lemma 1 (Double-precision inner-product function). Let

where

Proof. According to algorithms of Sections 3.1 and 3.2, it is clear that

For (2), we can get

We define the operations corresponding to Double Ciphertext Euclidean Division for t-tuple representations of ciphertexts.

Definition 3 (T-tuple Ciphertext Euclidean Division). Let

where

Lemma 2 (Multi-precision inner product function). Let

where

Proof. According to algorithms of Sections 3.1 and 3.2, it is clear that

According to Eq. (2), it can be deduced by analogy that

4.4 Joint Computational Methods with Multi-Precision

To be able to train normal PPML in complex scenarios, we construct computational methods to cope with two kinds of complex scenarios based on FE with multi-precision. Two privacy-preserving computational methods are proposed for horizontal and longitudinal data from multiple sources. We propose a Privacy Multi-Precision Horizontal Cooperative Computing Protocol (

In this paper, we propose an MMH-FE framework. The framework consists of a client, server, and KGA to ensure that data privacy and security are guaranteed when data processing and computation are performed with multiple parties involved.

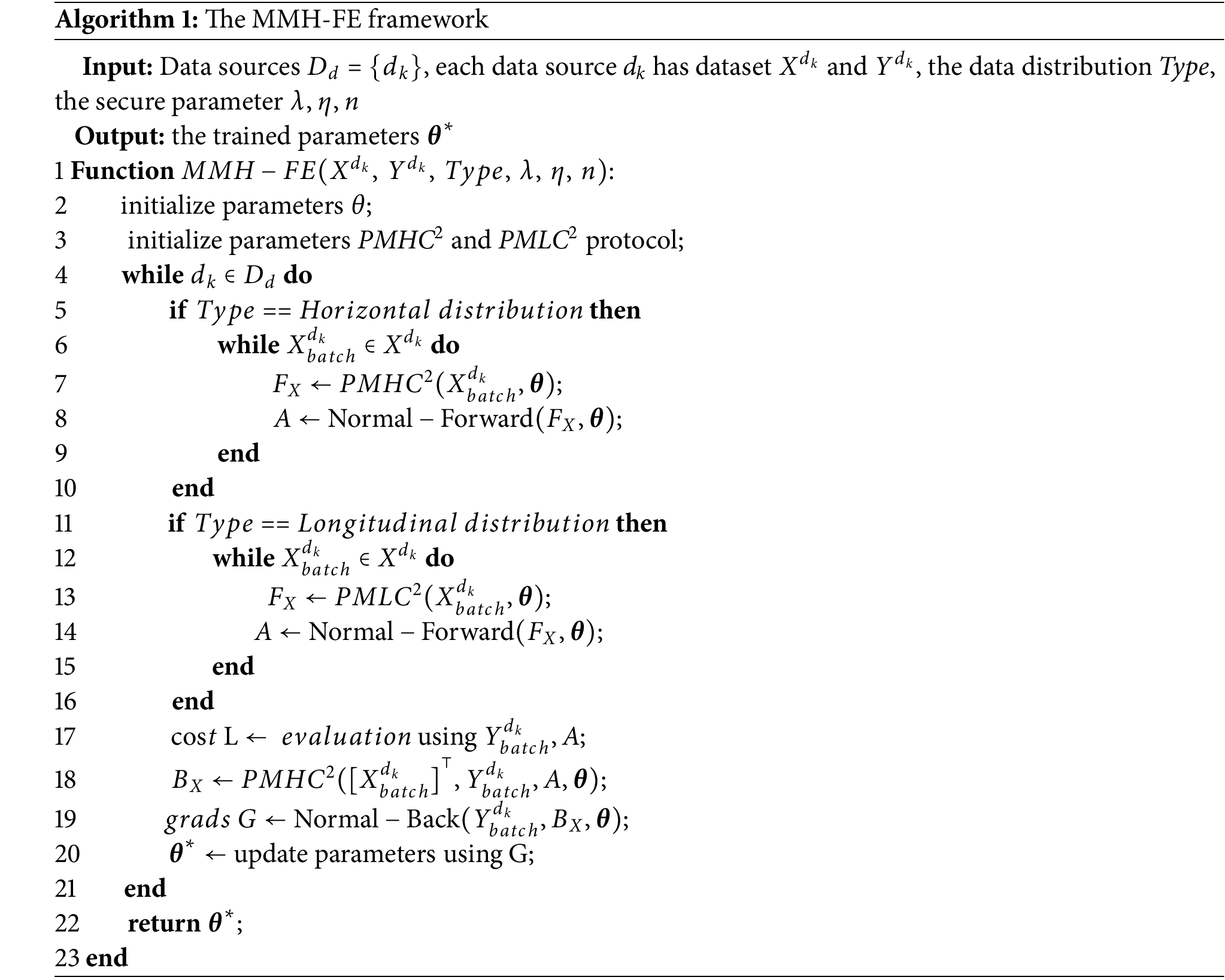

As described in Algorithm 1. First, initialize the model parameters

The client dataset

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of the MMH-FE framework. We select three publicly available datasets for our experiments. The details of these datasets are described below:

• MNIST: The MNIST dataset [35] is a standard benchmark dataset widely used for image classification tasks, mainly for handwritten digit recognition. The dataset contains 10 categories (digits 0 to 9) with a total of 70,000 grey-scale images of dimension 28

• Fashion-MNIST: The Fashion-MNIST dataset [36] is a clothing image dataset provided by Zalando for more challenging image classification tasks. The dataset contains 10 categories of fashion merchandise images, such as t-shirts, skirts, shoes, bags, etc., each of which is a grey-scale image of dimension 28

• CIFAR-10: The CIFAR-10 dataset [37] is a standard dataset for image classification of natural scenes, containing 60,000 color images(RGB) of dimension 32

We implement our proposed MMH-FE based on the object-oriented high-level programming language Python and the numpy, gmpy2 library. We use standardization and normalization to pre-process the datasets Mnist, Fashion-Mnist, and CiFar10. Functional encryption requires solving the difficult problem of computing discrete logarithms during decryption. This step is crucial to the overall execution of the encryption process. To speed up the computation, we use a bounded lookup table approach. Specifically, we design a data representation for x as (S,

The security parameters are set to 256 bits, and the running time of the program relies on Python’s built-in time package for measurement. Increasing the security will correspondingly increase the size of the ciphertext, requiring an increase in the size of the lookup table, resulting in an increase in the space cost of the framework. Larger security parameters lead to an increased computational burden during encryption and decryption, which in turn affects the model training time and memory consumption. 256-bit security parameters are currently a popular choice, and in this paper, we use 256-bit for the related performance analysis. All experiments are conducted on a 3.8 GHz 8-Core AMD Ryzen 7 platform with 32 GB of RAM. Throughout the process, the model training relies only on the CPU.

5.2 Evaluation of Ciphertext Computational Efficiency

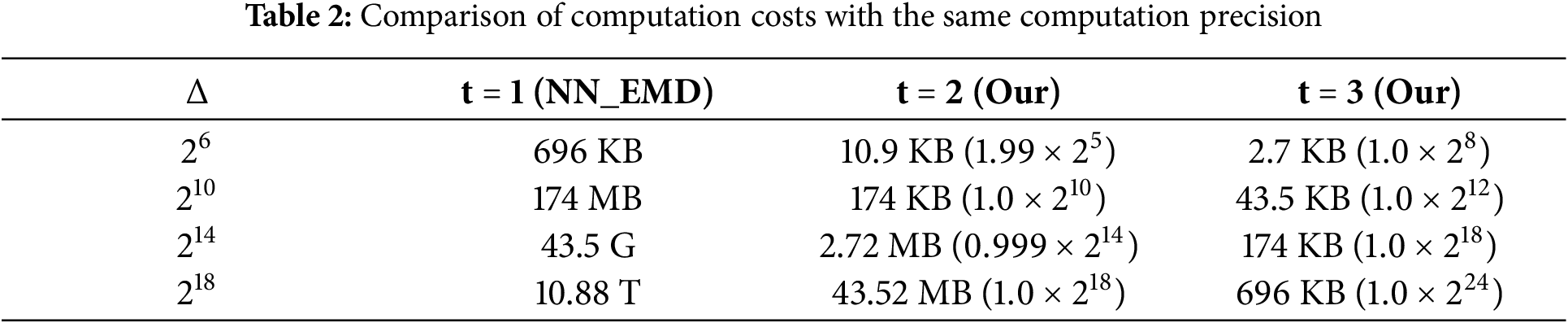

Since the MMH-FE proposed in this paper supports multi-precision inner-product functional encryption, we first explore the advantages and disadvantages of the multi-precision inner-product functional ciphertext computation scheme compared to other schemes. Table 2 explores the comparison between our FE with multi-precision and the existing conventional methods under different computational precision

Based on Table 2, we further analyze the computational precision that can be calculated under different space costs. As shown in Table 3, traditional methods often have limited precision in smaller computational spaces. They cannot meet the demands of realistic scenarios. To address this, more computational space is often required. Our method can achieve high computational precision even when the computational space is limited. For example, in the case of 1 MB computing space, the traditional method can only reach

We set the

The space cost of the scheme varies under different precision decomposition parameters. Assuming that the data precision is S, the CryptoNN [7] directly stores a lookup table of length

5.3 Model Training Performance Evaluation

In this experiment, we use two separate base models for in-depth analyses of different experimental objectives. For the temporal performance exploration, we use the same multilayer perceptron as the NN-EMD model on the handwriting dataset mnist. This model has a simpler structure consisting of multiple layers of fully connected neurons with low computational complexity and is therefore well suited for evaluating the time overhead required for the model to be trained. The choice of the MLP model can help us to better understand the performance of the time efficiency in different experimental setups, especially in large-scale data processing tasks. For accuracy exploration, based on the complexity of the dataset, we chose to build a custom neural network model identical to the ResNet18 framework. This network framework incorporates a residual module to better capture features in complex data, thus ensuring high accuracy performance in classification tasks.

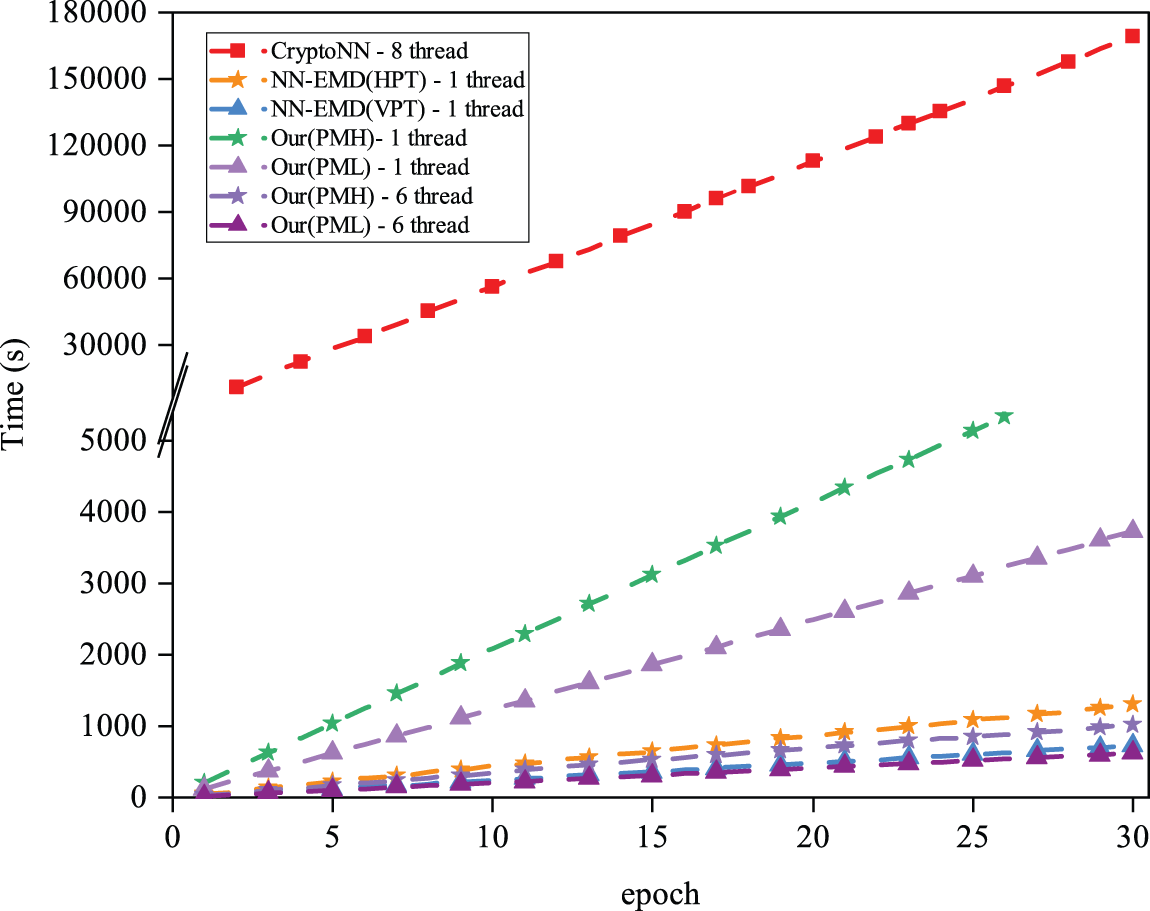

5.3.2 Computational Time Efficiency Evaluation

As shown in Fig. 5, we perform time performance tests for different frameworks. The results show that the training time increases linearly as the epoch grows. CryptoNN takes the most time to train 30 epochs, for our PMH approach takes 5.1 times longer than NN-EMD (HPT) in 1 thread, and our PML approach takes 4.7 times longer than NN-EMD (VPT) in 1 thread. But both of the methods can be about 20

Figure 5: Training time of different schemes as epoch increases

We analyze the reason for this result, which is mainly because our method is probing the result of time consumption on the client side t = 2 and the server side t = 3. Since the time overhead is mainly spent on the decryption operation, our method will get 6 combinations based on Definition 3 for the final decryption result. As a result, we conduct 6-threaded experiments, where each thread computes one of each combination, and our multi-threaded approach takes relatively minimal time in solving discrete logarithms, as the discrete logarithm table queried by our method has a very small time consumption. The final training consumes less time than NN-EMD as we expected.

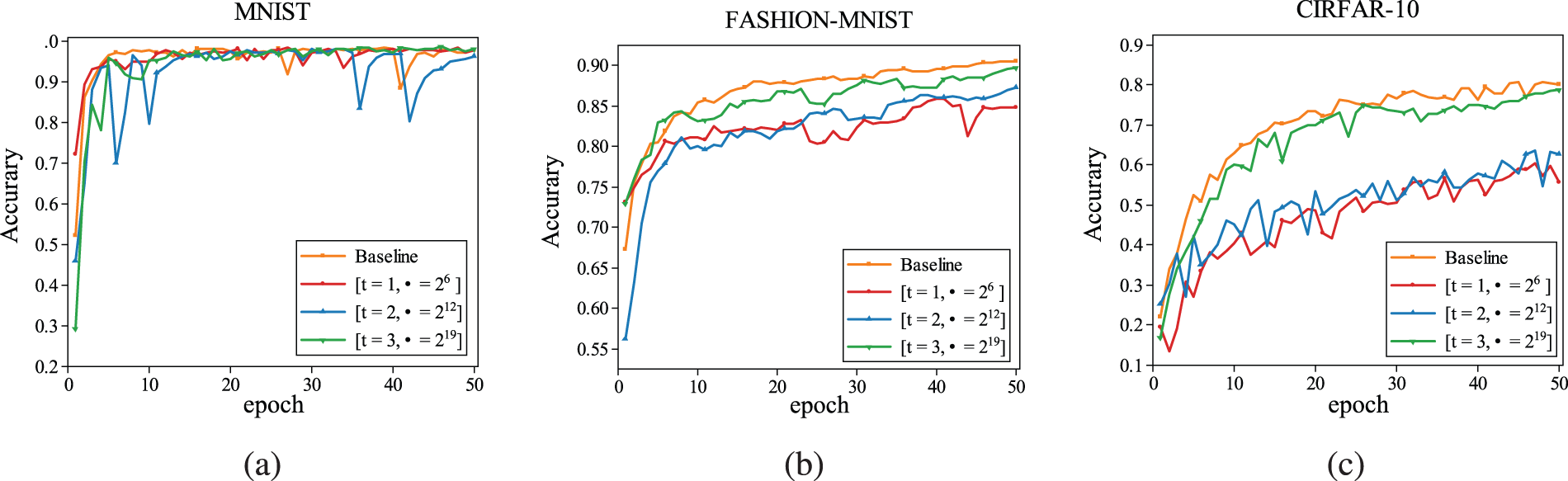

5.3.3 Model Accuracy Evaluation

As shown in Fig. 6, we conduct experimental analyses of accuracy for three different datasets on 1 MB discrete logarithmic storage space, and the training process was carried out for a total of 50 epochs. From the experimental results, the traditional way in the accuracy method can only reach the level of

Figure 6: Comparison of model accuracy with the base species model on three datasets. (a) MNIST. (b) FASHION-MNIST. (c) CIRFAR-10

With the development of cloud computing and machine learning, users can upload data to the cloud for training machine learning models. However, untrustworthy clouds may leak or speculate user data, leading to user privacy leakage. In this paper, we propose an MMH-FE framework with functional encryption as the underlying security algorithm for supporting neural network training using encrypted data. Experiments show that MMH-FE can indeed ensure the accuracy of the model while guaranteeing privacy. However, when dealing with more complex network architectures, such as Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks and Generative Adversarial Networks (GAN), the performance of the framework remains to be verified. These models typically have higher computational complexity and data processing demands, which could lead to performance bottlenecks due to the encryption computation. As the model becomes more complex, challenges related to real-time training and computational efficiency arise. To optimize model performance, improvements can be made to the encryption algorithms, hardware acceleration can be adopted, and optimizations can be applied to reduce the number of encryption operations. Additionally, we plan to combine differential privacy with homomorphic encryption and other privacy protection techniques to enhance the model’s privacy protection capabilities and adaptability, better addressing the diverse application scenarios and more complex network architectures.

Acknowledgment: We express our gratitude to the members of our research group, i.e., the Intelligent System Security Lab (ISSLab) of Guizhou University, for their invaluable support and assistance in this investigation. We also extend our thanks to our university for providing essential facilities and environment.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 62303126, 62362008, author Z. Z, https://www.nsfc.gov.cn/, accessed on 20 December 2024), Major Scientific and Technological Special Project of Guizhou Province ([2024]014), Guizhou Provincial Science and Technology Projects (No. ZK[2022]General149), author Z. Z, https://kjt.guizhou.gov.cn/, accessed on 20 December 2024), The Open Project of the Key Laboratory of Computing Power Network and Information Security, Ministry of Education under Grant 2023ZD037, author Z. Z, https://www.gzu.edu.cn/, accessed on 20 December 2024), Open Research Project of the State Key Laboratory of Industrial Control Technology, Zhejiang University, China (No. ICT2024B25), author Z. Z, https://www.gzu.edu.cn/, accessed on 20 December 2024).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: research conception and design: Hao Li; Data collection: Zhenyong Zhang, Xin Wang, Mufeng Wang; Analysis and interpretation of results: Hao Li, Kuan Shao; draft manuscript preparation: Hao Li, Kuan Shao, Zhenyong Zhang; Funding support: Zhenyong Zhang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data is not available.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Liu M, Teng F, Zhang Z, Ge P, Sun M, Deng R, et al. Enhancing cyber-resiliency of DER-based smart grid: a survey. IEEE Trans Smart Grid. 2024 Sep;15(5):4998–5030. doi:10.1109/TSG.2024.3373008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Xiao T, Zhang Z, Shao K, Li H. SeP2CNN: a simple and efficient privacy-preserving CNN for AIoT applications. In: 2024 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence of Things and Systems (AIoTSys); 2024; Hangzhou, China. p. 1–7. doi:10.1109/AIoTSys63104.2024.10780672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Xu R, Baracaldo N, Zhou Y, Anwar A, Joshi J, Ludwig H. FedV: privacy-preserving federated learning over vertically partitioned data. In: Proceedings of the 14th ACM Workshop on Artificial Intelligence and Security; 2021; New York, USA. p. 181–92. doi:10.1145/3474369.3486872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Mohassel P, Zhang Y. SecureML: a system for scalable privacy-preserving machine learning. In: 2017 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy; 2017; San Jose, CA, USA. p. 19–38. doi:10.1109/SP.2017.12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Gilad-Bachrach R, Dowlin N, Laine K, Lauter K, Naehrig M, Wernsing J. Cryptonets: applying neural networks to encrypted data with high throughput and accuracy. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning; 2016; New York, USA. p. 201–10. [Google Scholar]

6. Hesamifard E, Takabi H, Ghasemi M. CryptoDL: deep neural networks over encrypted data. 2017. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1711.05189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Xu R, Joshi JBD, Li C. CryptoNN: training neural networks over encrypted data. In: 2019 IEEE 39th International Conference on Distributed Computing Systems (ICDCS); 2019; Dallas, TX, USA. p. 1199–209. doi:10.1109/ICDCS.2019.00121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Xu R, Joshi J, Li C. NN-EMD: efficiently training neural networks using encrypted multi-sourced datasets. IEEE Trans Dependable Secure Comput. 2022 Jul–Aug 1;19(4):2807–20. doi:10.1109/TDSC.2021.3074439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Phan TC, Tran HC. Consideration of data security and privacy using machine learning techniques. Int J Data Inform Intell Comput. 2023;2(4):20–32. doi:10.59461/ijdiic.v2i4.90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Sahai A, Waters B. Fuzzy identity-based encryption. In: Proceedings of the 24th Annual International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques; 2005; Aarhus, Denmark. p. 457–73. doi:10.1007/11426639_27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Boneh D, Sahai A, Waters B. Functional encryption: definitions and challenges. In: Proceedings of the 8th Theory of Cryptography Conference; 2011; Providence, RI, USA. p. 253–73. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-19571-6_16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Francati D, Friolo D, Maitra M, Malavolta G, Rahimi A, Venturi D. Registered (inner-product) functional encryption. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on the Theory and Application of Cryptology and Information Security; 2023; Guangzhou, China. p. 98–133. doi:10.1007/978-981-99-8733-7_4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Chang Y, Zhang K, Gong J, Qian H. Privacy-preserving federated learning via functional encryption, revisited. IEEE Trans Inf Forensics Secur. 2023;18:1855–69. doi:10.1109/TIFS.2023.3255171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Agrawal S, Goyal R, Tomida J. Multi-input quadratic functional encryption from pairings. In: Proceedings of the 41st Annual International Cryptology Conference; 2021; Springer. p. 208–38. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-84259-8_8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Abdalla M, Catalano D, Gay R, Ursu B. Inner-product functional encryption with fine-grained access control. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on the Theory and Application of Cryptology and Information Security; 2020; Daejeon, Republic of Korea: Springer. p. 467–97. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-64840-4_16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Chotard J, Dufour-Sans E, Gay R, Phan DH, Pointcheval D. Dynamic decentralized functional encryption. In: Proceedings of the Annual International Cryptology Conference; 2020; Santa Barbara, CA, USA: Springer. p. 747–75. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-56784-2_25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Gay R. A new paradigm for public-key functional encryption for degree-2 polynomials. In: Proceedings of the IACR International Conference on Public-Key Cryptography; 2020; Edinburgh, UK: Springer. p. 95–120. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-45374-9_4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Kim S, Lewi K, Mandal A, Montgomery H, Roy A, Wu DJ. Function-hiding inner product encryption is practical. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Security and Cryptography for Networks; 2018; Amalfi, Italy: Springer. p. 544–62. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-98113-0_29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Lewko A, Okamoto T, Sahai A, Takashima K, Waters B. Fully secure functional encryption: attribute-based encryption and (hierarchical) inner product encryption. In: Proceedingsof the 29th Annual International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques; 2010; Berlin, Heidelberg:Springer. p. 62–91. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-13190-5_4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Gorbunov S, Vaikuntanathan V, Wee H. Functional encryption with bounded collusions via multi-party computation. In: Proceedings of the 32nd Annual Cryptology Conference; 2012; Santa Barbara, CA, USA: Springer. p. 162–79. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-32009-5_11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Carmer B, Malozemoff AJ, Raykova M. 5Gen-C: multi-input functional encryption and program obfuscation for arithmetic circuits. In: Proceedings of the 2017 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security; 2017; Dallas, TX, USA: ACM. p. 747–64. doi:10.1145/3133956.3133983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Lewi K, Malozemoff AJ, Apon D, Carmer B, Foltzer A, Wagner D, et al. 5Gen: a framework for prototyping applications using multilinear maps and matrix branching programs. In: Proceedings of the 2016 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security; 2016; Vienna, Austria: ACM. p. 981–92. doi:10.1145/2976749.2978314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Abdalla M, Bourse F, Caro ADe, Pointcheval D. Simple functional encryption schemes for inner products. In: Proceedings of the IACR International Workshop on Public Key Cryptography; 2015; Gaithersburg, MD, USA: Springer. p. 733–51. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-46447-2_33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Abdalla M, Catalano D, Fiore D, Gay R, Ursu B. Multi-input functional encryption for inner products: function-hiding realizations and constructions without pairings. In: Proceedings in Cryptology-CRYPTO 2018: 38th Annual International Cryptology Conference; 2018; Santa Barbara, CA, USA: Springer. p. 597–627. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-96884-1_20 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Zhang Z, Liu M, Sun M, Deng R, Cheng P, Niyato D, et al. Vulnerability of machine learning approaches applied in IoT-based smart grid: a review. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024 Jun 1;11(11):18951–75. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2024.3349381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Bourse F, Minelli M, Minihold M, Paillier P. Fast homomorphic evaluation of deep discretized neural networks. In: Proceedings in Cryptology-CRYPTO 2018: 38th Annual International Cryptology Conference; 2018; Santa Barbara, CA, USA: Springer. p. 483–512. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-96878-0_17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Chillotti I, Gama N, Georgieva M, Izabachene M. Faster fully homomorphic encryption: bootstrapping in less than 0.1 seconds. In: Proceedings in Cryptology-ASIACRYPT 2016: 22nd International Conference on the Theory and Application of Cryptology and Information Security; 2016; Hanoi, Vietnam: Springer. p. 3–33. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-53887-6_1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Zhang Z, Cheng P, Wu J, Chen J. Secure state estimation using hybrid homomorphic encryption scheme. IEEE Trans Control Syst Technol. 2021 Jul;29(4):1704–20. doi:10.1109/TCST.2020.3019501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Graepel T, Lauter K, Naehrig M. ML confidential: machine learning on encrypted data. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Security and Cryptology; 2012; Seoul, Republic of Korea: Springer. p. 1–21. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-37682-5_1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Chou E, Beal J, Levy D, Yeung S, Haque A, Fei-Fei L. Faster cryptonets: leveraging sparsity for real-world encrypted inference. 2018. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1811.09953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Ligier D, Carpov S, Fontaine C, Sirdey R. Privacy preserving data classification using inner-product functional encryption. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy; 2017. p. 423–30. doi:10.5220/0006206704230430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Dufour-Sans E, Gay R, Pointcheval D. Reading in the dark: classifying encrypted digits with functional encryption. Cryptology EPrint Archive. 2018 [cited 10 December 2024]. Available from: https://eprint.iacr.org/2018/206. [Google Scholar]

33. Ryffel T, Dufour-Sans E, Gay R, Bach F, Pointcheval D. Partially encrypted machine learning using functional encryption. 2019. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1905.10214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Nguyen T, Karunanayake N, Wang S, Seneviratne S, Hu P. Privacy-preserving spam filtering using homomorphic and functional encryption. Comput Commun. 2023;197:230–41. doi:10.1016/j.comcom.2022.11.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. LeCun Y, Bottou L, Bengio Y, Haffner P. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proc IEEE. 1998;86(11):2278–324. doi:10.1109/5.726791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Xiao H, Rasul K, Vollgraf R. Fashion-mnist: a novel image dataset for benchmarking machine learning algorithms. 2017. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1708.07747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Krizhevsky A, Hinton G. Learning multiple layers of features from tiny images [Ph.D. dissertation]. Canada: University of Toronto; 2009. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools