Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Quantitative Assessment of Generative Large Language Models on Design Pattern Application

Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Oakland University, 115 Library Dr., Rochester, MI 48309, USA

* Corresponding Author: Dae-Kyoo Kim. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 82(3), 3843-3872. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.062552

Received 20 December 2024; Accepted 01 February 2025; Issue published 06 March 2025

Abstract

Design patterns offer reusable solutions for common software issues, enhancing quality. The advent of generative large language models (LLMs) marks progress in software development, but their efficacy in applying design patterns is not fully assessed. The recent introduction of generative large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT and CoPilot has demonstrated significant promise in software development. They assist with a variety of tasks including code generation, modeling, bug fixing, and testing, leading to enhanced efficiency and productivity. Although initial uses of these LLMs have had a positive effect on software development, their potential influence on the application of design patterns remains unexplored. This study introduces a method to quantify LLMs’ ability to implement design patterns, using Role-Based Metamodeling Language (RBML) for a rigorous specification of the pattern’s problem, solution, and transformation rules. The method evaluates the pattern applicability of a software application using the pattern’s problem specification. If deemed applicable, the application is input to the LLM for pattern application. The resulting application is assessed for conformance to the pattern’s solution specification and for completeness against the pattern’s transformation rules. Evaluating the method with ChatGPT 4 across three applications reveals ChatGPT’s high proficiency, achieving averages of 98% in conformance and 87% in completeness, thereby demonstrating the effectiveness of the method. Using RBML, this study confirms that LLMs, specifically ChatGPT 4, have great potential in effective and efficient application of design patterns with high conformance and completeness. This opens avenues for further integrating LLMs into complex software engineering processes.Keywords

Design patterns [1] offer proven solutions for recurring design problems in software development, enhancing software quality such as reusability, maintainability, and scalability. In practice, design patterns are used by interpreting their abstract description in the context of the application under development. However, the abstract nature of pattern descriptions can make it difficult to have a clear interpretation in their application, which might lead to obstacles in attaining the expected benefits of the pattern [2].

The recent advent of generative large language models (LLMs) such as ChatGPT [3], Gemini [4], and CoPilot [5] has shown great potential in software development, providing support in various tasks such as code generation [6], modeling [7], bug fixing [8], and testing [9], which leads to improved efficiency and productivity. While the initial use of these LLMs indicate a positive impact on software development [10], their potential on design pattern application has not been explored.

In this work, we present a quantifiable approach to evaluate the capability of LLMs in applying design patterns, focusing on pattern conformance and completeness. A prerequisite for this approach is the rigorous specification of design patterns, which is necessary to define precise pattern properties, serving as a quantitative measure, while facilitating checking the presence of pattern properties in UML models, which are the representation of programs used in this work to evaluate pattern conformance. There have been several techniques for specifying design patterns, which can be categorized into formal methods-based approaches and UML-based approaches. Formal methods-based approaches (e.g., [11–14]) make use of formal specification techniques to specify design patterns. While these techniques have, by virtue of formalism, strong support for reasoning and verifying pattern properties, it is difficult to use formalized pattern properties in checking their presence in UML models. There have also been efforts (e.g., [15–17]) to specify design patterns using the UML, a widely accepted modeling language. A major benefit of these approaches is that because of the wide acceptance of the UML, these approaches can be easily adopted. However, these approaches suffer from high complexity in representation. In this work, we adopt Role-Based Metamodeling Language (RBML) [18], a UML-based pattern specification technique, to formalize design patterns. RBML defines a design pattern in terms of roles, which capture pattern participants in a way simliar to UML models, which facilitates the evaluation of pattern conformance in this work.

In this work, we present a quantifiable approach to evaluating the capability of large language models (LLMs) in applying design patterns, focusing on pattern conformance and completeness. A key prerequisite for this approach is the rigorous specification of design patterns, which enables the definition of precise pattern properties that serve as quantitative measures and facilitate the evaluation of pattern conformance. This is achieved by checking for the presence of these properties in UML models, which represent the programs under evaluation. Various techniques have been proposed for specifying design patterns, broadly categorized into formal methods-based approaches and UML-based approaches. Formal methods-based approaches (e.g., [11–14]) use formal specification techniques, providing strong support for reasoning and verifying pattern properties. However, applying these formalized pattern properties to check their presence in UML models proves challenging. On the other hand, UML-based approaches (e.g., [15–17]) specify design patterns using UML, a widely accepted modeling language. While these approaches are more accessible due to the popularity of UML, they often suffer from high representational complexity. In this work, we adopt the Role-Based Metamodeling Language (RBML) [18], a UML-based pattern specification technique, to formalize design patterns. RBML defines design patterns in terms of roles, capturing pattern participants in a manner similar to UML models, thereby simplifying the evaluation of pattern conformance and facilitating analysis.

We define a design pattern in terms of problem specification, solution specification, and transformation rules. The problem specification is used to check the pattern applicability of the program under consideration. If the pattern is applicable, the program is input into the LLM, which applies the pattern and produces a refactored version. This refactored program is then evaluated for conformance to the applied pattern using the pattern’s solution specification and checked for the completeness of pattern realization against the pattern’s transformation rules. We evalaute the approach using the Visitor pattern applied to three case studies in ChatGPT 4. The evaluation results show that ChatGPT can apply design patterns with an average of 98% pattern conformance and 87% pattern completeness, demonstrating the effectiveness of the approach.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 discusses the relevant literature on utilizing LLMs in software engineering. Section 3 provides an overview of RBML using the Visitor pattern as an example. Section 4 details the proposed approach, illustrating the application of the Visitor pattern to a software application in ChatGPT. Section 5 presents two additional case studies in which the Visitor pattern is applied to other applications. Finally, Section 6 concludes the study and discusses avenues for future work.

In this section, we review relevant work on evaluating LLMs in software engineering.

Several studies have examined LLMs’ capabilities in general software development and code synthesis. Kim et al. [10] assessed ChatGPT’s proficiency across various development phases, finding it could generate over 90% of code while noting limitations in traceability. White et al. [19] developed systematic prompt design techniques, introducing patterns for requirements elicitation and code quality. Dakhel et al. [20] evaluated GitHub Copilot’s capabilities in algorithmic problem-solving, finding effective but sometimes inconsistent solutions. Solohubov et al. [21] demonstrated significant efficiency gains with AI tools, while Nascimento et al. [22] compared ChatGPT against human programmers on Leetcode, revealing varying performance across different problem types.

Research on code quality and maintenance has produced significant findings. Zhang et al. [8] evaluated ChatGPT’s bug-fixing capabilities, showing successful repair patterns through various prompting strategies. In a follow-up study, Zhang et al. [8] introduced EvalGPTFix, a benchmark for assessing LLM-based program repair. Kirinuki et al. [9] found ChatGPT generated test cases comparable to human testers, though with limitations in boundary testing. Surameery et al. [23] explored ChatGPT’s debugging capabilities, while Asare et al. [24] investigated Copilot’s potential for introducing vulnerabilities. Alshahwan et al. [25] proposed an assured LLMSE approach using semantic filters to validate code changes.

A significant body of work has focused on software architecture and requirements engineering. Ahmad et al. [7] explored ChatGPT’s role in architecture-centric software engineering, developing frameworks for requirements articulation and microservices architecture design. Marques et al. [26] evaluated ChatGPT’s effectiveness in requirements engineering, highlighting improved stakeholder communication. Rajbhoj et al. [27] investigated integrating generative AI across the software development lifecycle, while Ozkaya [6] discussed both benefits and risks of LLMs in software engineering tasks.

Studies have examined LLMs’ impact on software development processes and methodologies. Bera et al. [28] assessed ChatGPT’s capability as an agile coach, recommending cautious integration into teams. Felizardo et al. [29] demonstrated ChatGPT’s potential in systematic literature reviews, while Özpolat et al. [30] investigated its role in automating development tasks. Champa et al. [31] analyzed the DevGPT dataset [32] to understand how developers utilize ChatGPT in practice.

Recent research has also explored collaborative and educational aspects of LLMs. Hassan et al. [33] proposed developing AI pair programmers that work contextually with human developers. Pudari et al. [34] analyzed Copilot’s adherence to programming best practices. Waseem et al. [35] investigated ChatGPT’s effectiveness in helping students understand software development tasks while warning against over-reliance.

Several comprehensive studies have examined broader implications and practical applications. Fan et al. [36] surveyed LLM applications across software engineering domains. Nguyen-Duc et al. [37] identified 78 research questions across 11 areas in generative AI for software engineering. Rahmaniar [38] discussed ChatGPT’s potential to enhance software engineering efficiency, while Wang et al. [39] introduced BurstGPT, a dataset capturing real-world LLM usage patterns. Sridhara et al. [40] evaluated ChatGPT’s performance across fifteen distinct software engineering tasks, finding varying effectiveness across different types of activities.

While these studies provide valuable insights into LLMs’ potential across various software engineering tasks, they highlight both opportunities and limitations in areas such as code generation, bug fixing, testing, and architectural design. However, the systematic application of design patterns—a crucial aspect of software engineering—remains unexplored. Our work addresses this gap by providing a quantitative framework for evaluating LLMs’ pattern application abilities, using RBML for rigorous pattern specification, and demonstrating practical effectiveness through multiple case studies.

3 Design Pattern Specifications in RBML

RBML is a UML-based notation for specifying design patterns at the meta-model level, supporting their application at the model level [18]. RBML captures the variability of design patterns through roles which are enacted by UML model elements. Each role defines a set of properties that the model elements must exhibit to comply with the role. Roles are established based on a UML metaclass, representing a subset of the instances of that base metaclass.

RBML allows for the rigorous specification of design patterns, facilitating the quantitative assessment of pattern realizations. RBML pattern specifications are defined in terms of problem specification, solution specification, and transformation rules. The problem specification captures the problem domain of the pattern, defining the applicability of the pattern. A software application is considered pattern applicable if it satisfies the properties of the problem specification. The solution specification describes the pattern’s solution domain, establishing criteria for conformance to the pattern. A software model is deemed to be conformant to the pattern if it satisfies the properties of the solution specification. Transformation rules define the process of refactoring a problem model into a solution model based on the mapping between the problem specification and the solution specification.

A pattern specification is defined by roles that encapsulate the pattern’s variability. A single role or a combination of roles constitutes a pattern property, which extends the capacity to capture the pattern’s variability, and a pattern specification may comprise multiple such properties. An application model is deemed to satisfy the pattern specification if it adheres to all the defined properties. There are two types of pattern specifications—a Structural Pattern Specification (SPS) that delineates the pattern’s structural properties, and an Interaction Pattern Specification (IPS) that outlines the pattern’s behavioral properties.

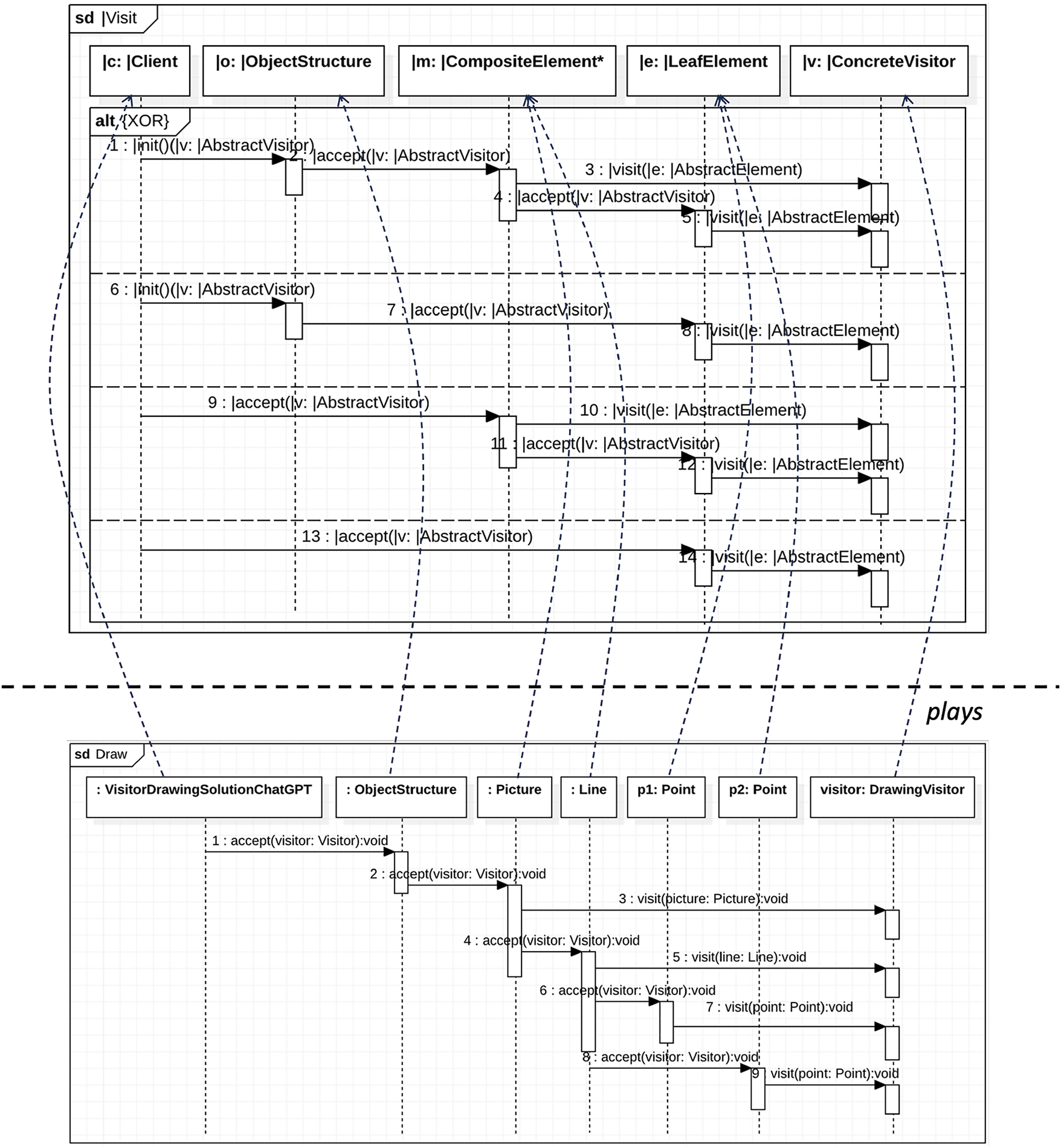

In this study, we employ the Visitor pattern [1] to illustrate our approach. This pattern is selected due to its complexity among the Gang of Four (GoF) patterns, making it an ideal candidate to demonstrate the capabilities of LLMs in applying design patterns. Fig. 1 shows the problem specification for the Visitor pattern. The SPS defines the structure of the pattern’s problem domain, including roles such as

Figure 1: Visitor problem specification

The IPS details the interaction behaviors within the pattern’s problem domain, represented by lifeline roles assumed by objects of classes fulfilling SPS roles. For example, the

A single role or a group of roles forms a pattern property. Fig. 2 illustrates the properties of the Visitor problem specification, where Fig. 2a displays SPS properties and Fig. 2b shows IPS properties. In the tables, the first column shows labels for properties, the second column specifies roles involved in the property, and the third column describes the base metaclasses for the involved roles. Six SPS properties are defined in Fig. 2a. P2 specifies two structural variations, as indicated by the {XOR} constraint near

Figure 2: Visitor problem properties

Fig. 3 illustrates the solution specification of the Visitor pattern. The SPS defines the solution structure which encompasses

Figure 3: Visitor solution specification

Fig. 4 illustrates the solution properties of the Visitor pattern, with Fig. 4a detailing the SPS properties and Fig. 4b outlining the IPS properties. In Fig. 4a, properties P2, P6, P7, and P8 relate to specific visitor-related aspects, while P13 defines the {XOR} constraint governing the relationships between

Figure 4: Visitor solution properties

The problem specification and solution specification of a pattern are mapped to establish transformation rules. These rules define the necessary conditions that must be met during the transformation from a problem model to a solution model when the pattern is applied. Let

Based on the mapping, let R represent the set of elements that fulfill the role |R. Then,

S1. For every concrete element

S2. For every operation

S3. The operations of

For IPS transformation, the following defines the mapping between problem IPS roles and solution IPS roles:

Let us denote

I1. For every message

I2. The messages of

4 Quantifying LLMs’ Capability on Design Pattern Application

In this section, we describe the proposed approach for quantitatively assessing LLMs in design pattern application using RBML pattern specifications. Fig. 5 illustrates the process where rectangles represent data, ellipses denote operations, diamonds indicate conditions, and arrows depict control flow. The process involves the following steps:

1. A program that does not yet implement the intended design pattern is considered, referred to as the problem program. To ensure a fair assessment, we focus on programs that are suitable candidates for the intended pattern application, as those not conforming to the pattern may not adequately demonstrate the LLM’s full potential.

2. The problem program is reverse-engineered into a model, termed the problem model.

3. The problem model is checked for pattern applicability against the problem specification of the desired pattern. The degree of applicability is quantified as

4. After confirming pattern applicability, the problem program is input into the LLM to apply the pattern with the following prompt:

prompt: Apply [Target Pattern] to the given program.

5. The resulting program from the LLM, to which the pattern has been applied, is reverse-engineered into what is termed the solution model.

6. The solution model is evaluated for its conformance to the pattern’s solution specification. The degree of conformance is quantified as

7. The solution model is checked for completeness regarding the pattern transformation rules. The degree of completeness is quantified as

Figure 5: Quantitative assessment process

To demonstrate the approach, we use the Visitor pattern described in Section 3, applied to a drawing application, which is one of the three case studies conducted in this work. The other two case studies are presented in Section 5. The source code of the applications used in the case studies, both before and after pattern application, is available on GitHub [41]. The drawing application is designed for rendering a variety of graphical objects such as points, lines, rectangles, and composite images, which can be composed of multiple shapes. In a drawing session, each object is capable of being drawn individually, allowing for a complex assembly of shapes to create detailed pictures. The application’s functionality caters to structuring and manipulating these objects to form a visual representation.

The application is reverse-engineered to derive its model which is used to check for pattern applicability. Fig. 6 illustrates the reverse-engineered model, referred to as the problem model. The model includes the

Figure 6: Drawing objects problem model

The problem model is evaluated for pattern applicability against the problem specification of the pattern. The model is considered pattern-applicable if it satisfies the properties defined in the problem specification. Pattern properties are specified in terms of roles and are evaluated based on the mapping of the roles to the model elements in the problem model. Fig. 7 presents the mapping of SPS roles to class diagram elements. In the mapping, the

Figure 7: Visitor problem SPS mapping to drawing objects problem class diagram

Fig. 8 shows the mapping of IPS roles to sequence diagram elements. In the figure, the

Figure 8: Visitor problem IPS mapping to

Based on the mappings in Figs. 7 and 8, the pattern applicability of the problem model is evaluated as depicted in Fig. 9. In the figure, pattern properties are evaluated based on the roles involved (SPS/IPS Roles), the base metaclasses of these roles, and the model elements that enact these roles. The base metaclass of an involved role dictates that model elements playing the role must be instances of the specified metaclass. If this condition is not met, the roles cannot be properly enacted, and consequently, the pattern property cannot be satisfied. Fig. 9a indicates that all six SPS properties are satisfied, demonstrating 100% SPS applicability. Property

Figure 9: Visitor pattern applicability of drawing objects problem model

After ensuring pattern applicability, the problem model is input to the LLM for the application of the desired pattern. In this work, we chose ChatGPT 4 for the LLM, due to its increasing popularity in software engineering as discussed in Section 2. ChatGPT is instructed with the following prompt without any further instructions such as the information about the pattern or the context of the program.

Prompt: “Apply the Visitor design pattern to the given program.”

ChatGPT produces a refactored program with the Visitor pattern applied. The resulting program is reverse-engineered to create the corresponding solution model as shown in Fig. 10. The solution class diagram retains most of the classes from the problem model with the exception of the

Figure 10: Drawing objects solution model with visitor pattern applied by ChatGPT

The solution model is checked for its conformance to the solution specification of the Visitor pattern. Pattern conformance is evaluated based on how elements in the solution model correspond the pattern solution roles. Fig. 11 displays the correspondence of the elements in the solution class diagram to the solution SPS roles. In this alignment, the new

Figure 11: Visitor solution SPS conformance of drawing objects solution class diagram

Fig. 12 presents the alignment of elements in the solution sequence diagram with their respective IPS roles. A notable aspect of this alignment is the correspondence of the

Figure 12: Visitor solution IPS conformance of

Based on the mapping in Figs. 11 and 12, the conformance of the solution model to the solution specification of the Visitor pattern is evaluated as depicted in Fig. 13. Fig. 13a illustrates the SPS conformance where all thirteen SPS properties are satisfied. P1 is satisfied by the

Figure 13: Visitor pattern conformance of drawing objects solution model

Pattern conformance ensures that the model possesses the pattern properties. However, it does not necessarily indicate that the model has a complete realization of the pattern. For instance, if the elements in the object structure involve more than one common operation across the element hierarchy, there should be a separate concrete visitor class and visit operation for each operation. If not all common operations are covered, the pattern is not fully realized. The completeness of the pattern realization can be checked using the pattern’s transformation rules, as presented in Section 3. Fig. 14 demonstrates the completeness of the pattern realization, checking the enforcement of transformation rules. Fig. 14a indicates that all three SPS rules are fully enforced over all relevant elements, leading to a complete realization of the SPS. S1 requires the creation of a visit operation for every drawing element, and the table confirms that a corresponding visit operation exists for all four elements. If any element had been omitted, the enforcement of the rule would have been incomplete. Fig. 14b shows that both of the two IPS rules are enforced over all relevant lifelines, resulting in a complete realization of the IPS. Overall, all 5 transformation rules (

Figure 14: Visitor pattern completeness of drawing objects solution model

In this section, we present two additional case studies to evaluate the approach, applying the Visitor pattern to a widget application and a node application using ChatGPT. These applications are small in size, written in Java. We deliberately chose small applications for two main reasons—i) to adapt to LLMs’ limitations on processing large inputs, and ii) to examine how the LLM applies the pattern comprehensively across the application. The source code for these applications, both before and after pattern application, is available on GitHub [41].

The widget application is concerned with building a widget assembly consisting of a set of widgets. A widget assembly may contain other widget assemblies as well. After a widget assembly is built, the application processes each comprising widget and widget assembly to display their names and determine the price of individual widgets, which is used for computing the total price of the widget equipment. Fig. 15 shows the widget problem model reserve-engineered from the application and its applicability to the Visitor pattern’s problem specification. In the model, the

Figure 15: Visitor pattern applicability of widget problem model

With respect to IPS applicability in Fig. 15c, P1 is satisfied by the

After ensuring pattern applicability, the problem model is input to ChatGPT to apply the Visitor pattern. Fig. 16 displays the model refactored by the Visitor pattern application and its conformance to the pattern’s solution specification. The model possesses the visitor hierarchy, consisting of the

Figure 16: Visitor pattern conformance of widget solution model

With respect to IPS conformance in Fig. 16c, P1 is satisfied by the

Fig. 17 illustrates the evaluation of pattern completeness for the widget application. Fig. 17a indicates that only two out of the three SPS rules are fully enforced, with S2 not being fully enforced for the

Figure 17: Visitor pattern completeness of widget solution model

The node application is concerned with constructing and manipulating a hierarchical structure of nodes in the syntax of a programming language. Fig. 18 shows the node problem model and its applicability to the Visitor pattern. The class diagram in (a) defines specific node classes such as

Figure 18: Visitor pattern applicability of node problem model

Fig. 18c shows that all three IPS properties are satisfied, leading to successful IPS applicability. P1 is satisfied by the

Fig. 19 displays the solution model with the application of the Visitor pattern. In the class diagram, the Visitor pattern introduces a visitor hierarchy that includes

Figure 19: Visitor pattern conformance of node solution model

Fig. 19c reveals that only three out of four properties are fulfilled, resulting in 75% IPS conformance. P1 is satisfied by the

Fig. 20 demonstrates that the transformation rules for both SPS and IPS are fully enforced. Fig. 20a shows that for each of the three common operations in the node hierarchy—

Figure 20: Visitor pattern completeness of node solution model

In this subsection, we discuss the findings from the three case studies—the drawing application in Section 4, and the widget and node applications in Section 5. Fig. 21 presents the quantitative results of ChatGPT’s capability in applying the Visitor pattern to these applications. The table indicates that ChatGPT achieves an average of 98% pattern conformance and 87% pattern completeness. In terms of pattern conformance, the sole instance of non-conformance occurred in the node application where the recursive behavior of

Figure 21: The results of three case studies

The study’s findings reveal that modern LLMs can effectively understand and apply complex software design patterns. However, the instances of non-conformance provide particularly interesting insights. For example, ChatGPT’s decision to remove the

This study introduces a novel quantitative framework for evaluating LLMs’ capabilities in design pattern implementation, addressing a gap in current LLM’a capabili5y research in software engineering. Its key innovation lies in the systematic use of Role-Based Metamodeling Language (RBML) to create measurable criteria for pattern application, moving beyond subjective assessments to provide concrete metrics for conformance and completeness of design pattern implementation. For academia, this framework offers a methodology for comparing different LLMs to automated design pattern implementation, enabling more rigorous empirical studies in assessing LLMs’ capability in design pattern tasks. On the practical side, software developers and organizations can use these metrics to make informed decisions about incorporating LLMs into their development workflows, particularly for design pattern-related tasks. The framework’s ability to quantify pattern applicability (through problem specification), conformance (through solution specification), and completeness (through transformation rules) provides a comprehensive evaluation tool that bridges theoretical understanding with practical implementation, benefiting both researchers studying AI-assisted software engineering and practitioners seeking to optimize their development processes.

This paper has presented a quantitative approach to evaluating an LLM’s ability to implement a design pattern within software applications. The approach utilizes RBML to formalize design patterns rigorously, which then serves as the basis for verifying pattern applicability, conformance, and completeness. Initially, an application without the pattern implementation is assessed for the applicability of the designated pattern. If deemed applicable, the problem model of the application is input into the LLM for pattern application. Subsequently, the LLM’s output, a solution model with the pattern applied, is evaluated against the pattern’s solution specification to determine the levels of pattern conformance and completeness. Through three case studies, ChatGPT was found to exhibit an average of 98% pattern conformance and 87% pattern completeness, thus demonstrating the efficacy of the proposed approach. Future work will extend this approach to additional LLMs, such as Gemini and CoPilot, for a comparative analysis, aiming for an unbiased comparison. Such expansion would help determine whether the observed performance metrics are model-specific or represent a general capability level of current LLMs in design pattern tasks. By examining variations in pattern implementation across models, researchers could better understand the relationship between an LLM’s ability to apply design patterns. This cross-model analysis would be valuable for both developing specialized LLMs for design pattern tasks and refining prompting strategies for design pattern application.

Acknowledgement: The author expresses gratitude to all editors and anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and suggestions, which have significantly enhanced the quality of this manuscript.

Funding Statement: This study did not receive any external funding.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data and materials supporting the findings of this study are openly available at https://github.com/hanbyul1/Design-Pattern-Refactoring (accessed on 31 January 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Gamma E, Helm R, Johnson R, Vlissides J. Design patterns: elements of reusable object-oriented software. Boston, MA, USA: Addison-Wesley; 1995. [Google Scholar]

2. France R, Ghosh S, Song E, Kim D. A metamodeling approach to pattern-based model refactoring. IEEE Softw, Special Issue on Model Driven Development. 2003;20(5):52–8. doi:10.1109/MS.2003.1231152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. OpenAI. ChatGPT. 2024 [cited 2025 Jan 31]. Available from: https://chat.openai.com/. [Google Scholar]

4. Google. Gemini. 2024 [cited 2025 Jan 31]. Available from: https://gemini.google.com/app. [Google Scholar]

5. GitHub. Github Copilot. 2021 [cited 2025 Jan 31]. Available from: https://copilot.github.com/. [Google Scholar]

6. Ozkaya I. Application of large language models to software engineering tasks: opportunities, risks, and implications. IEEE Softw. 2023;40(3):4–8. doi:10.1109/MS.2023.3248401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Ahmad A, Waseem M, Liang P, Fahmideh M, Aktar MS, Mikkonen T. Towards Human-Bot collaborative software architecting with ChatGPT. In: Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Evaluation and Assessment in Software Engineering; 2023; Oulu, Finland. p. 279–85. [Google Scholar]

8. Zhang Q, Zhang T, Zhai J, Fang C, Yu B, Sun W, et al. A critical review of large language model on software engineering: an example from ChatGPT and automated program repair. arXiv:2310.08879. 2024. [Google Scholar]

9. Kirinuki H, Tanno H. ChatGPT and human synergy in black-box testing: a comparative analysis. arXiv:2401.13924. 2024. [Google Scholar]

10. Kim DK, Chen J, Ming H, Lu L. Assessment of ChatGPT’s proficiency in software development. In: Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Software Engineering Research & Practice; 2023; Las Vegas, NV, USA. [Google Scholar]

11. Eden AH, Jil J, Yehuday A. Precise specification and automatic application of design patterns. In: Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Automated Software Engineering; 1997; Incline Village, NV, USA. p. 143–52. [Google Scholar]

12. Lano K, Bicarregui J, Goldsack S. Formalising design patterns. In: Proceedings of the 1st BCS-FACS Northern Formal Methods Workshop, Electronic Workshops in Computer Science; 1996; Ilkley, UK. [Google Scholar]

13. Mikkonen T. Formalizing design patterns. In: Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Software Engineering; 1998; Kyoto, Japan. p. 115–24. [Google Scholar]

14. Taibi T, Ngo DCL. Formal specification of design patterns—a balanced approach. J Object Technol. 2003;2(4):127–40. doi:10.5381/jot.2003.2.4.a4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Guennec AL, Sunye G, Jezequel J. Precise modeling of design patterns. In: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on the Unified Modeling Language (UML); 2000; York, UK. p. 482–96. [Google Scholar]

16. Lauder A, Kent S. Precise visual specification of design patterns. In: Proceedings of the 12th European Conference on Object-Oriented Programming; 1998; Brussels, Belgium. p. 114–36. [Google Scholar]

17. Mapelsden D, Hosking J, Grundy J. Design pattern modelling and instantiation using DPML. In: Proceedings of the 40th International Conference on Technology of Object-Oriented Languages and Systems (TOOLS); 2002; Sydney, Australia: ACS. p. 3–11. [Google Scholar]

18. Kim D, France R, Ghosh S, Song E. Using role-based modeling language (RBML) as precise characterizations of model families. In: Proceedings of the 8th IEEE International Conference on Engineering of Complex Computer Systems (ICECCS); 2002; Greenbelt, MD, USA. p. 107–16. [Google Scholar]

19. White J, Hays S, Fu Q, Spencer-Smith J, Schmidt DC. Chatgpt prompt patterns for improving code quality, refactoring, requirements elicitation, and software design. arXiv:2303.07839. 2023. [Google Scholar]

20. Dakhel AM, Majdinasab V, Nikanjam A, Khomh F, Desmarais MC, Jiang ZMJ. GitHub Copilot AI pair programmer: asset or liability? J Syst Softw. 2023;203(1):111734. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2023.111734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Solohubov I, Moroz A, Tiahunova MY, Kyrychek HH, Skrupsky S. Accelerating software development with AI: exploring the impact of ChatGPT and GitHub Copilot. In: Proceedings of the 11th Workshop on Cloud Technologies in Education; 2023; Kryvyi Rih, Ukraine. p. 76–86. [Google Scholar]

22. Nascimento N, Alencar P, Cowan D. Comparing software developers with ChatGPT: an empirical investigation. arXiv:2305.11837. 2023. [Google Scholar]

23. Surameery NMS, Shakor MY. Use chat GPT to solve programming bugs. Int J Inf Technol Comput Eng. 2023;3(1):17–22. doi:10.55529/ijitc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Asare O, Nagappan M, Asokan N. Is GitHub’s Copilot as bad as humans at introducing vulnerabilities in code? Empir Softw Eng. 2023;28(6):129. doi:10.1007/s10664-023-10380-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Alshahwan N, Harman M, Harper I, Marginean A, Sengupta S, Wang E. Assured offline LLM-based software engineering. In: Proceedings of the ACM/IEEE 2nd International Workshop on Interpretability, Robustness, and Benchmarking in Neural Software Engineering; 2024; Lisbon, Portugal. p. 7–12. [Google Scholar]

26. Marques N, Silva RR, Bernardino J. Using ChatGPT in software requirements engineering: a comprehensive review. Future Internet. 2024;16(6):180. doi:10.3390/fi16060180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Rajbhoj A, Somase A, Kulkarni P, Kulkarni V. Accelerating software development using generative AI: ChatGPT case study. In: Proceedings of the 17th Innovations in Software Engineering Conference; 2024; Bangalore, India. p. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

28. Bera P, Wautelet Y, Poels G. On the use of ChatGPT to support agile software development. In: Proceedings of the 2nd International Workshop on Agile Methods for Information Systems Engineering; 2023; Zaragoza, Spain. p. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

29. Felizardo KR, Lima MS, Deizepe A, Conte TU, Steinmacher I. ChatGPT application in systematic literature reviews in software engineering: an evaluation of its accuracy to support the selection activity. In: Proceedings of the 18th ACM/IEEE International Symposium on Empirical Software Engineering and Measurement; 2024; Barcelona, Spain. p. 25–36. [Google Scholar]

30. Özpolat Z, Yıldırım Ö., Karabatak M. Artificial intelligence-based tools in software development processes: application of ChatGPT. Eur J Tech. 2023;13(2):229–40. doi:10.36222/ejt.1330631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Champa AI, Rabbi MF, Nachuma C, Zibran MF. ChatGPT in action: analyzing its use in software development. In: Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Mining Software Repositories; 2024; Lisbon, Portugal. p. 182–6. [Google Scholar]

32. Xiao T, Treude C, Hata H, Matsumoto K. DevGPT: studying developer-ChatGPT conversations. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Mining Software Repositories. MSR 2024; 2024; Lisbon, Portugal. p. 227–30. [Google Scholar]

33. Hassan AE, Oliva GA, Lin D, Chen B, Ming Z. Rethinking software engineering in the foundation model era: from task-driven AI Copilots to goal-driven AI pair programmers. arXiv:2404.10225. 2024. [Google Scholar]

34. Pudari R, Ernst NA. From Copilot to pilot: towards AI supported software development. arXiv:2303.04142. 2023. [Google Scholar]

35. Waseem M, Das T, Ahmad A, Liang P, Fahmideh M, Mikkonen T. ChatGPT as a software development Bot: a project-based study. In: Proceedings of International Conference on Evaluation of Novel Approaches to Software Engineering; 2024; Angers, France. p. 406–13. [Google Scholar]

36. Fan A, Gokkaya B, Harman M, Lyubarskiy M, Sengupta S, Yoo S, et al. Large language models for software engineering: survey and open problems. In: Proceedings of IEEE/ACM International Conference on Software Engineering: Future of Software Engineering; 2023; Melbourne, Australia. p. 31–53. [Google Scholar]

37. Nguyen-Duc A, Cabrero-Daniel B, Przybylek A, Arora C, Khanna D, Herda T, et al. Generative artificial intelligence for software engineering—a research agenda. arXiv:2310.18648. 2023. [Google Scholar]

38. Rahmaniar W. ChatGPT for software development: opportunities and challenges. IT Professional. 2024;26(3):80–6. doi:10.1109/MITP.2024.3379831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Wang Y, Chen Y, Li Z, Tang Z, Guo R, Wang X, et al. Towards efficient and reliable LLM serving: a real-world workload study. arXiv:2401.17644. 2024. [Google Scholar]

40. Sridhara G, Ranjani HG, Mazumdar S. ChatGPT: a study on its utility for ubiquitous software engineering tasks. arXiv:2305.16837. 2023. [Google Scholar]

41. Kim DK. Source code. [cited 2025 Jan 31]. Available from: https://github.com/hanbyul1/Design-Pattern-Refactoring. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools