Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Multi-Modal Named Entity Recognition with Auxiliary Visual Knowledge and Word-Level Fusion

National Digital Switching System Engineering & Technological R&D Center, Information Engineering University, Zhengzhou, 450001, China

* Corresponding Authors: Huansha Wang. Email: ; Ruiyang Huang. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 83(3), 5747-5760. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.061902

Received 05 December 2024; Accepted 26 March 2025; Issue published 19 May 2025

Abstract

Multi-modal Named Entity Recognition (MNER) aims to better identify meaningful textual entities by integrating information from images. Previous work has focused on extracting visual semantics at a fine-grained level, or obtaining entity related external knowledge from knowledge bases or Large Language Models (LLMs). However, these approaches ignore the poor semantic correlation between visual and textual modalities in MNER datasets and do not explore different multi-modal fusion approaches. In this paper, we present MMAVK, a multi-modal named entity recognition model with auxiliary visual knowledge and word-level fusion, which aims to leverage the Multi-modal Large Language Model (MLLM) as an implicit knowledge base. It also extracts vision-based auxiliary knowledge from the image for more accurate and effective recognition. Specifically, we propose vision-based auxiliary knowledge generation, which guides the MLLM to extract external knowledge exclusively derived from images to aid entity recognition by designing target-specific prompts, thus avoiding redundant recognition and cognitive confusion caused by the simultaneous processing of image-text pairs. Furthermore, we employ a word-level multi-modal fusion mechanism to fuse the extracted external knowledge with each word-embedding embedded from the transformer-based encoder. Extensive experimental results demonstrate that MMAVK outperforms or equals the state-of-the-art methods on the two classical MNER datasets, even when the large models employed have significantly fewer parameters than other baselines.Keywords

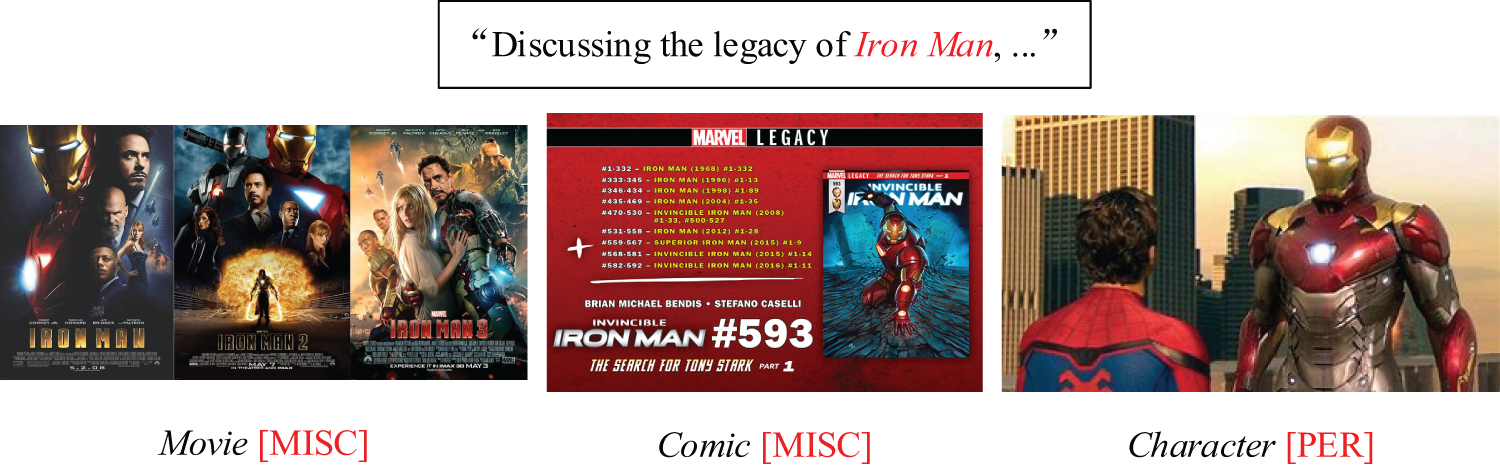

With the emergence of image-text pairs in social media and web applications, the field of multi-modal named entity recognition (MNER) has witnessed remarkable advancements, capturing significant research interest. Compared with the traditional uni-modal named entity recognition based on textual features, MNER models can provide intuitive visual features by extracting the image semantics associated with the textual entities. This improves the effectiveness of entity recognition [1]. As shown in Fig. 1, the attachment of a distinct descriptive image to the same text will result in a change in the outcomes of entity recognition. The traditional processing paradigm for multi-modal tasks is to first process image and text data based on one or more encoders to extract the corresponding low-dimensional embeddings. Subsequently, joint multi-modal embeddings are generated by some fusion method and finally decoded for the downstream task being solved [2]. However, MNER has the following two properties that make it unsuitable for this paradigm: 1. Semantic correlation between images and text is generally low. Unlike other multi-modal tasks such as image-text generation and multi-modal entity alignment, there is not necessarily a high correlation between the text to be recognized and the corresponding descriptive image in MNER. Since the mainstream datasets were created based on social media, even the recognized entities may not be represented at all in the images, which hinders multi-modal interaction. 2. The classes of named entities are different from the labels of the dataset on which the training of the visual feature extractor is based. Mainstream visual encoders are trained on datasets such as ImageNet [3] and COCO [4], where labels differ significantly from named entities. This makes it difficult for the visual encoder to accurately localize targets in the image that are related to named entities.

Figure 1: Example of the multi-modal named entity recognition. Different description images will directly affect the entity recognition results

Considering the above characteristics, some researchers [5] have tried to adopt the Text-Text (T+T) paradigm, i.e., to transform images into similar semantic texts through object detection, image captioning or Optical Character Recognition (OCR), and regard these texts as external knowledge to assist the training of the model. Since Text-Text have similar feature space and attention computation among them, the effect is superior to multi-modal joint training when the modal transformation works well. On this basis, recent works [6,7] have demonstrated that adding context-related information to the entities can significantly facilitate named entity recognition, so researchers utilized knowledge bases and large language models (LLMs) to provide external knowledge.

Nevertheless, the current methodologies continue to exhibit certain shortcomings. First and foremost, the majority of previous research has failed to address the issue of insufficient image-text correlation in MNER datasets. The introduction of image-related embedding or external knowledge into the text embedding during subsequent decoding, regardless of the initial correlation between image-text pairs, introduces additional noise. Concurrently, the conventional “I+T” methodology of dual-stream image-text embedding fusion or the “T+T” approach, which entails inputting concatenated text into a Transformer-based encoder, inevitably gives rise to issues such as dispersed attention coefficient calculation and coarse-grained modal interaction. This presents a challenge to the effective integration of auxiliary knowledge into the target entity embeddings. The efficacy of employing LLMs for named entity recognition has been demonstrated to be, at least to date, somewhat less than that of traditional Transformer-based models [7]. However, the current approach of leveraging large models to acquire external knowledge inputs both image captions and text to be recognized as prompts into the LLMs, which may result in redundant recognition and cognitive confusion. In addition, erroneous recognition results produced by the LLM will contribute to the introduction of further noise into the external knowledge.

To address the above issues, we propose MMAVK, a multi-modal named entity recognition model with auxiliary visual knowledge and word-level fusion. It aims to extract semantics from images with multi-modal LLM and generate external knowledge that contributes to entity recognition. Furthermore, it performs embedding fusion at the word-level, thus facilitating fine-grained interaction between external knowledge and original text. Specifically, additional auxiliary context related to entities is generated by designing target-specific prompts and feeding them, as well as the images in the image-text pairs to be recognized, into the multi-modal LLM. During the process of modal fusion, any external knowledge generated based on images with an insufficient level of image-text similarity is filtered and deleted in order to minimize the introduction of noise. Concurrently, we forego the conventional “T+T” approach of concatenating the original text with external knowledge for training. Instead, we employ a weighted summation of the each word-embedding with the external knowledge at the word-level. Experimental results demonstrate that MMAVK outperforms or equals the state-of-the-art methods on the two classical MNER datasets, even when the LLMs employed have significantly fewer parameters than other mainstream models.

Considering that images and texts are typically presented in pairs on social media, and images can serve as a valuable supplementary indicator for entity recognition in text, an increasing number of researchers have endeavored to integrate visual modality into named entity recognition. Early work on MNER was primarily focused on the generation of low-dimensional embeddings of images and texts through single-stream or dual-stream encoders, followed by the utilization of various cross-modal fusion techniques to facilitate inter-modal interactions and enhance the quality of the joint multi-modal embedding.

Moon et al. [8] first introduced a deep image network to integrate visual modalities. They employed a generic modality attention module to extract the most informative semantics by ascertaining the relative importance of each modality. Yu et al. [9] proposed a multi-modal interaction module to capture the interaction between textual and visual modalities for the purpose of improving the quality of the embedding. Furthermore, they have devised a unified multi-modal Transformer for encoding both the textual embedding and the visual embedding. Zhang et al. [10] adopted a multi-modal semantic graph integrating visual and textual embeddings to investigate the potential semantic links between visual objects and text, and stacked multiple graph-based multi-modal fusion layers for encoding. Jia et al. [11] treated MNER as a machine reading comprehension task, and facilitated the alignment of textual entities with visual regions by designing query terms to acquire prior knowledge. Zhang et al. [10] constructed the image-text pairs to be recognized as a unified multi-modal graph and iteratively performed semantic interactions between nodes to generate the final embedding representation. Wang et al. [12] extended entity label words through an external knowledge base, and measured the salience of features based on the correlation between these extended terms and features. Subsequently, the saliency scores of the features are employed to adjust the cross-modal attention weights through a gate mechanism.

To address the issue of inadequate cross-modal interaction between visual and textual embeddings, Wang et al. [5] proposed a transformation of the visual modality into the textual contexts sharing the same semantic through integrated methods of image captioning, object detection, and OCR. The fusion of embeddings belonging to the same vector space served to alleviate the pressure of multi-modal alignment. Wang et al. [6] retrieved pertinent knowledge about the input image-text pairs from an external knowledge base and transmitted the retrieved results to the language model and the visual model for prediction. The Mixture of Experts (MoE) module, which integrates the predictions of the two models, was then utilized to make the final determination. Li et al. [7] introduced the large language model into the MNER, where image captions and original text were formatted as prompts to be fed into the LLM, promoting it to generate auxiliary context related to entity recognition.

However, the previous methods mentioned above have difficulties in better finding the contextual information related to textual entities within the knowledge base, which can lead to the introduction of irrelevant noise or errors. Additionally, the issue of low image-text correlation in MNER presents a challenge in accurately localizing the visual regions associated with textual entities from the visual modality.

We follow previous work in treating MNER as a sequence labeling task, i.e., for a given pair of to-be-recognized image-text pairs

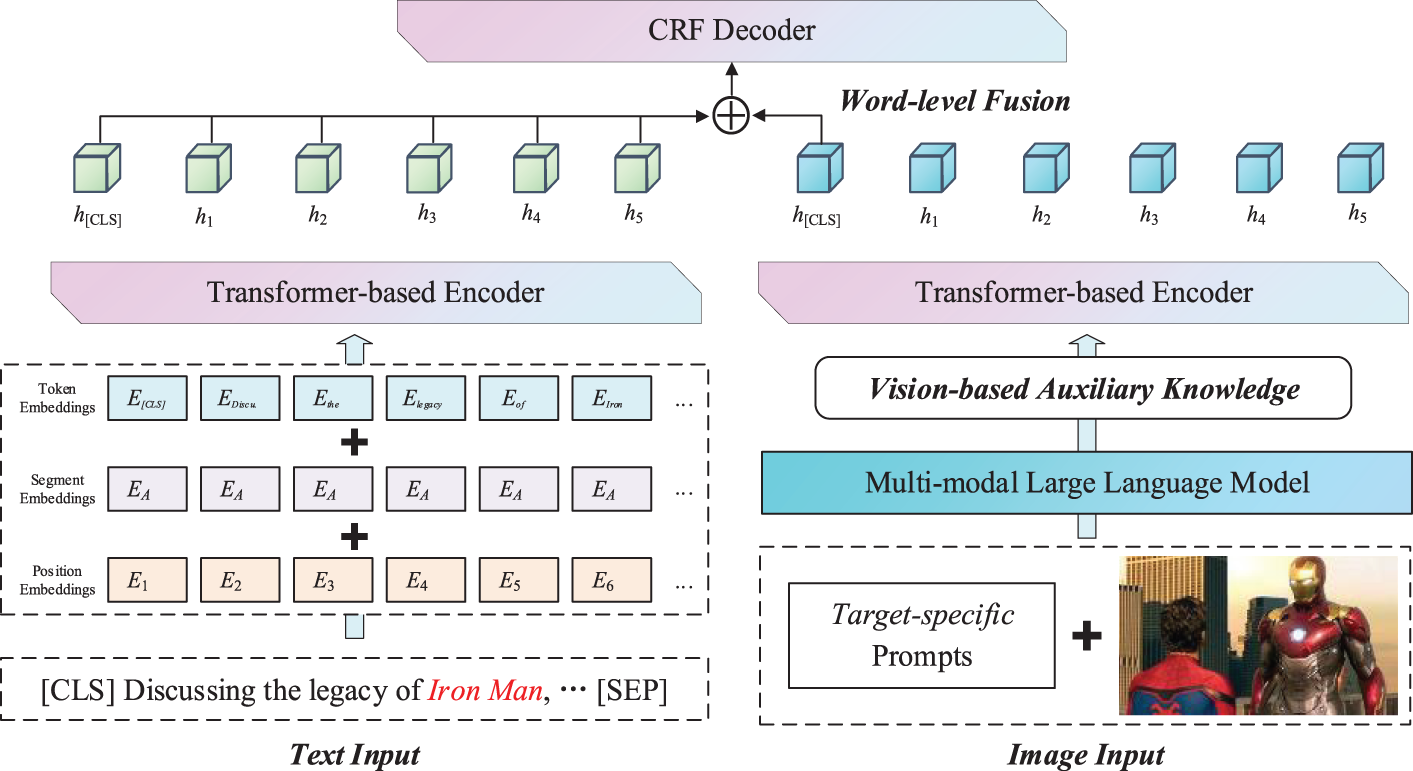

Figure 2: The overall model architecture of MMAVK

3.1 Vision-Based Auxiliary Knowledge Generation

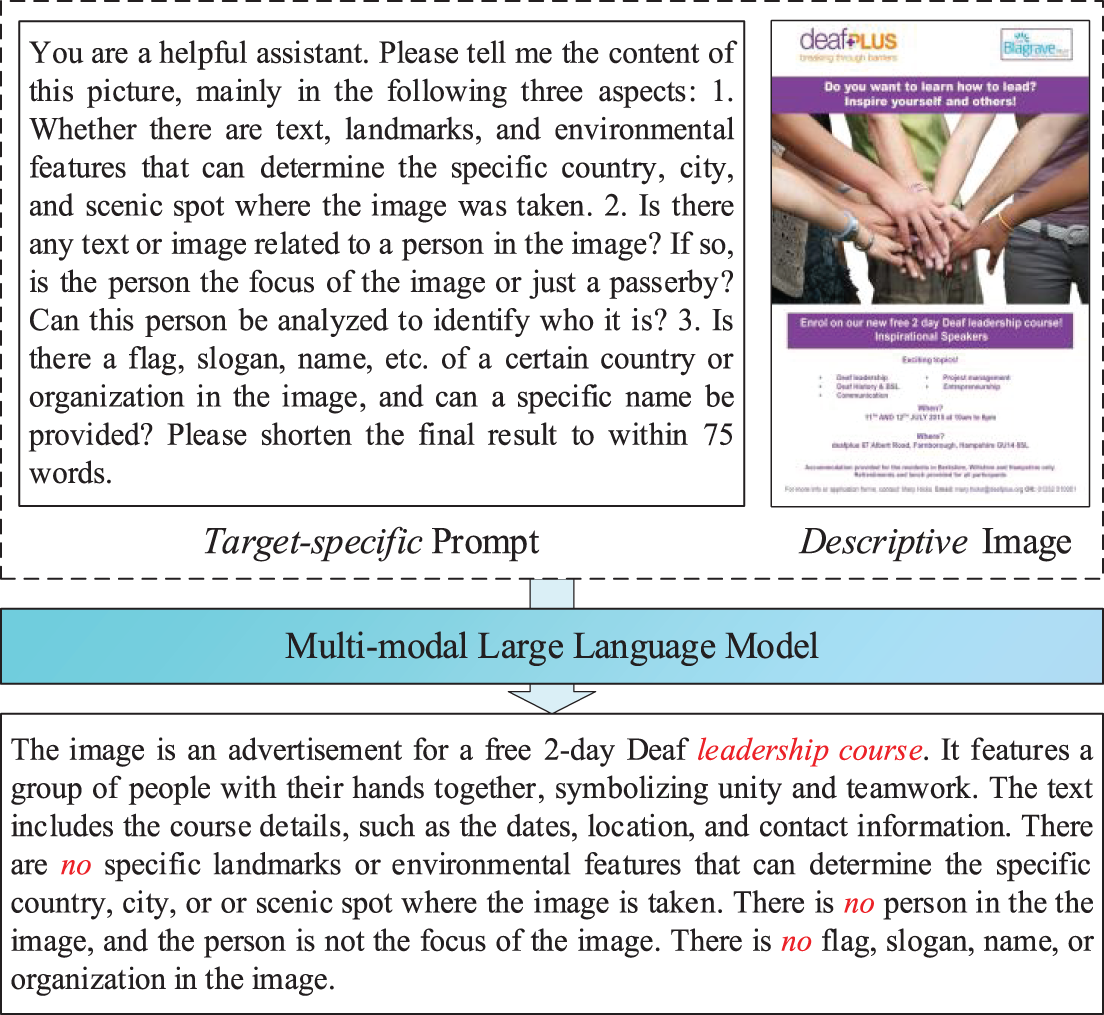

Considering the better modal interaction effect between the same modalities, we follow the “T+T” multi-modal fusion approach, expecting to transform visual modalities into textual modalities without changing the semantics. At the same time, researches [6,7] have demonstrated that in the case of insufficient in-sample information, auxiliary external semantic knowledge can effectively enhance text comprehension. Accordingly, for the visual data, we input it into MLLM for comprehension and encourage the model to generate the most relevant auxiliary knowledge for named entity recognition by providing target-specific prompts. The generation schema is shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: The generation schema of vision-based auxiliary knowledge

Previous work [7] on acquiring external knowledge based on LLM utilized the multi-modal pre-trained model to generate the caption of the descriptive image, and then fed the image caption, the text to be recognized, and the designed prompts together into the large model. This approach presents three inherent limitations.

(i) It is difficult to balance the importance played by visual modality and textual modality in large model generation. The semantic information conveyed by the visual modality in the prompt is limited to a single sentence describing the image, this may result in the loss of crucial details, such as optical characters, objects, and other pertinent elements, within the image. Nevertheless, if object recognition or OCR technologies are employed in advance to obtain image details and used in conjunction with the image caption, the resulting prompt will be overly reliant on visual modality, which may impede the recognition of the text.

(ii) An excessive reliance on the generative effects of multi-modal pre-trained models. As a semantic alternative text to the image schema, this approach presupposes its high semantic similarity to the original image. Consequently, it places considerable demands on the efficacy of the multi-modal pre-trained model. In the event that the effect of the multi-modal pre-trained model is inadequate, the potential for error propagation is significantly heightened.

(iii) The use of the text as the content of the prompt results in cognitive confusion and the emergence of redundant recognition issues. It has been demonstrated that named entity recognition using large language models is, in general, less effective than Transformer-based models [7]. Consequently, if the generated auxiliary knowledge contains erroneous results identified by LLMs, it will inevitably result in an increase in noise.

Considering the above issues, our goal is to leverage the extensive knowledge of image-text comprehension embedded within the MLLM to extract detailed information from the descriptive image at a fine-grained level. The objective is to convert the visual modality into text while maintaining the original semantics of the image to the greatest extent possible. This allows the model to improve the quality of vision-based textual contexts applied to the “T+T” paradigm, while adding additional external auxiliary knowledge:

It is important to note that the MNER dataset classifies entities into four categories: locations, people, organizations, and other. Accordingly, we encourage the MLLM to direct particular attention to the four categories of targets present in the images. The objective is to prompt the MLLM to focus on a range of visual elements, including optical characters, maps, landmarks, attractions, people, faces, flags, slogans, and names, in order to ascertain the image’s relevance to a specific location, person, or organization.

In order to avoid the problem that the lack of correlation between images and text results in auxiliary knowledge that does not contribute to the recognition of textual entities. We additionally employ the multi-modal pre-trained model CLIP [13] to encode the original image-text pairs

To mitigate the error transmission caused by the low semantic relevance of the descriptive image to the text to be recognized, due to factors such as the presence of noise in the dataset or the low quality of the image itself. During the subsequent knowledge fusion phase, we assign a lower weight to auxiliary knowledge that exhibits image-text similarities below a pre-established threshold, thereby reducing the impact of noise introduced by such knowledge.

Unlike previous work based on the “T+T” paradigm where the original text sequence

where

For the corresponding auxiliary knowledge

where

Subsequently, the modified auxiliary knowledge sequence is encoded, and the embedding of

The traditional “T+T” paradigm generally adopts the knowledge fusion approach where the text to be recognized is concatenated with auxiliary text and fed into a transformer-based encoder to generate word embeddings for all tokens (including those of the auxiliary text), followed by decoding only the word embeddings of the text to be recognized. However, given that MNER is a token-by-token task, this approach struggles to accurately extract knowledge from the entire auxiliary text that is relevant to specific word embedding. Consequently, we have adopted an innovative word-level multi-modal fusion method.

Specifically, after obtaining the word-embeddings of each token to be recognized and the global embedding of auxiliary knowledge using the same transformer-based encoder, we dynamically fuse each word-embedding with the auxiliary knowledge embedding through a linear layer-based weighted summation, thereby facilitating the deep involvement of high-quality auxiliary knowledge in the decoding phase:

in which

Following the previous work, we feed the final joint embedding

where

In this section, we will report the experiment details including datasets, parameter settings, baselines and the results. We conduct experiments to answer the following four questions about MMAVK:

(1) Question 1 (Q1): Has MMAVK shown improvement compared to the previous baselines?

(2) Question 2 (Q2): Does the auxiliary knowledge we generate prove more effective than other external knowledge?

(3) Question 3 (Q3): Is the word-level modal fusion approach we use superior to the traditional approach?

(4) Question 4 (Q4): Whether filtering out visual information with low image-text similarity benefits MNER?

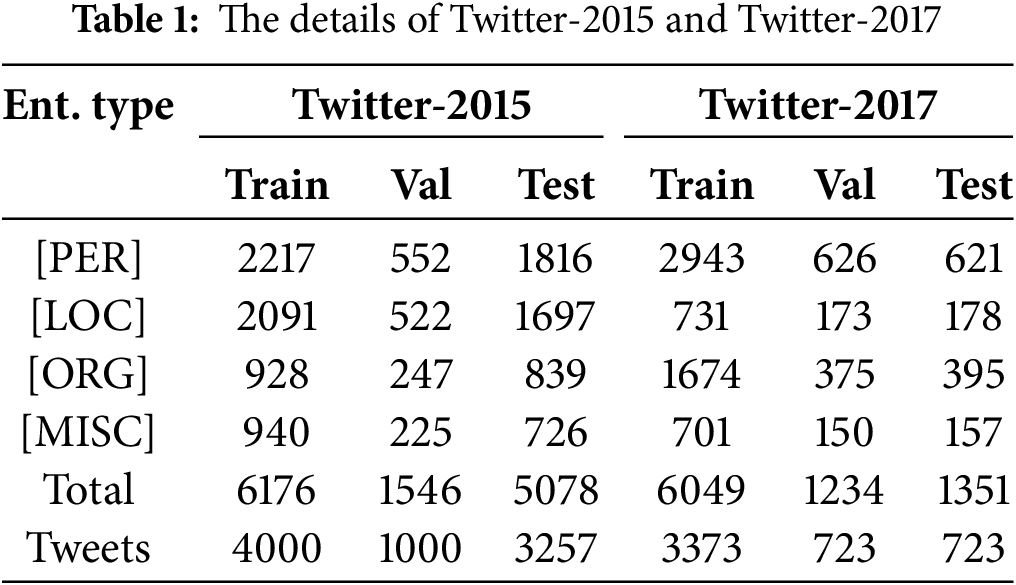

We conduct experiments on two public MNER datasets: Twitter-2015 [14] and Twitter-2017 [1]. The details of Twitter-2015 and Twitter-2017 can be found in Table 1.

MMAVK was trained on a single NVIDIA RTX 3090 GPU. The proposed approach was implemented using Python 3.8.0, PyTorch 1.7.1, and CUDA 12.1. During model training, we used the AdamW optimizer to minimize the loss function

MMAVK chooses the backbone of RSRNET [15] without the visual processing module as the vanilla MNER model. Qwen2-VL-7B-Instruct [16] as an open-source multi-modal LLM from Alibaba that is capable of handling arbitrary image resolutions, is selected to be the auxiliary knowledge generator. It demonstrates effective multi-modal comprehension and generation capabilities while utilizing fewer parameters. We utilized its original version without fine-tuning for multi-modal knowledge comprehension and generation. In the case of using a single NVIDIA RTX 3090 GPU to run the MLLM for auxiliary knowledge generation, the average processing time for a single image is 14.739 s, occupying 16,450 MB of GPU memory. For filtering the auxiliary knowledge, we adopt CLIP [13] with ViT-B/32 to compute the semantic similarity between the original image-text pairs. We elect to utilize the same encoder XLM-RoBERTa-large [17], as that employed in ITA [5], PromptMNER [18], CAT-MNER [12], MoRe [6] and PGIM [7] for a fair comparison.

We compared our MMAVK against several previous state-of-the-art models, including both uni-modal and multi-modal approaches, to demonstrate its superiority. For uni-modal text-based approaches, we consider: CNN-BiLSTM-CRF [19], HBiLSTM-CRF [20], BiLSTM-CRF [21], BERT-CRF [22], BERT-SPAN and RoBERTa-SPAN [23].

For multi-modal text-based approaches, we consider: UMT [9], UMGF [10], MNER-QG [11], R-GCN [24], ITA [5], RSRNeT [15], PromptMNER [18], CAT-MNER [12], MoRe [6], and PGIM [7]. UMT proposes a unified transformer architecture that integrates multi-modal data streams, leveraging entity spans to refine final prediction outcomes. UMGF adopts a unified multi-modal graph to represent the input sentences and images to capture the semantic relationships between graph-text pairs. MNER-QG extracts the prior knowledge about entity types and visual regions with query grounding for enhancing representations. R-GCN focuses on gathering the image information most relevant to image-text pairs in the dataset through inter-modal and intra-modal relation graphs. RSRNeT is designed to facilitate a more comprehensive extraction of visual features based on object detection techniques, incorporating a multi-scale visual feature extraction module. ITA proposes to adopt the “T+T” paradigm, where the visual context generated from the image after object recognition, image caption, and optical character recognition is concatenated with the original text then be inputted into the language model for training. PromptMNER computes the correlation between the image and each entity-related prompt using a multi-modal pre-trained model, thus extracting entity-related visual clues with corresponding weights. CAT-MNER proposes to refine cross-modal attention by identifying and highlighting certain features whose salience is measured according to their relevance to extended entity tag words in an external knowledge base. MoRe retrieves relevant knowledge about the image-text pairs in an external knowledge base and inputs the results into the language model and the visual model for prediction, respectively, and combines the predictions of the two models through an Mixture of Experts module. PGIM introduces a Multi-modal Similar Example Awareness module that sets a small number of samples in a fixed format so as to generate the most relevant prompts. This prompts ChatGPT to generate auxiliary knowledge heuristically, thereby improving the efficiency of entity prediction.

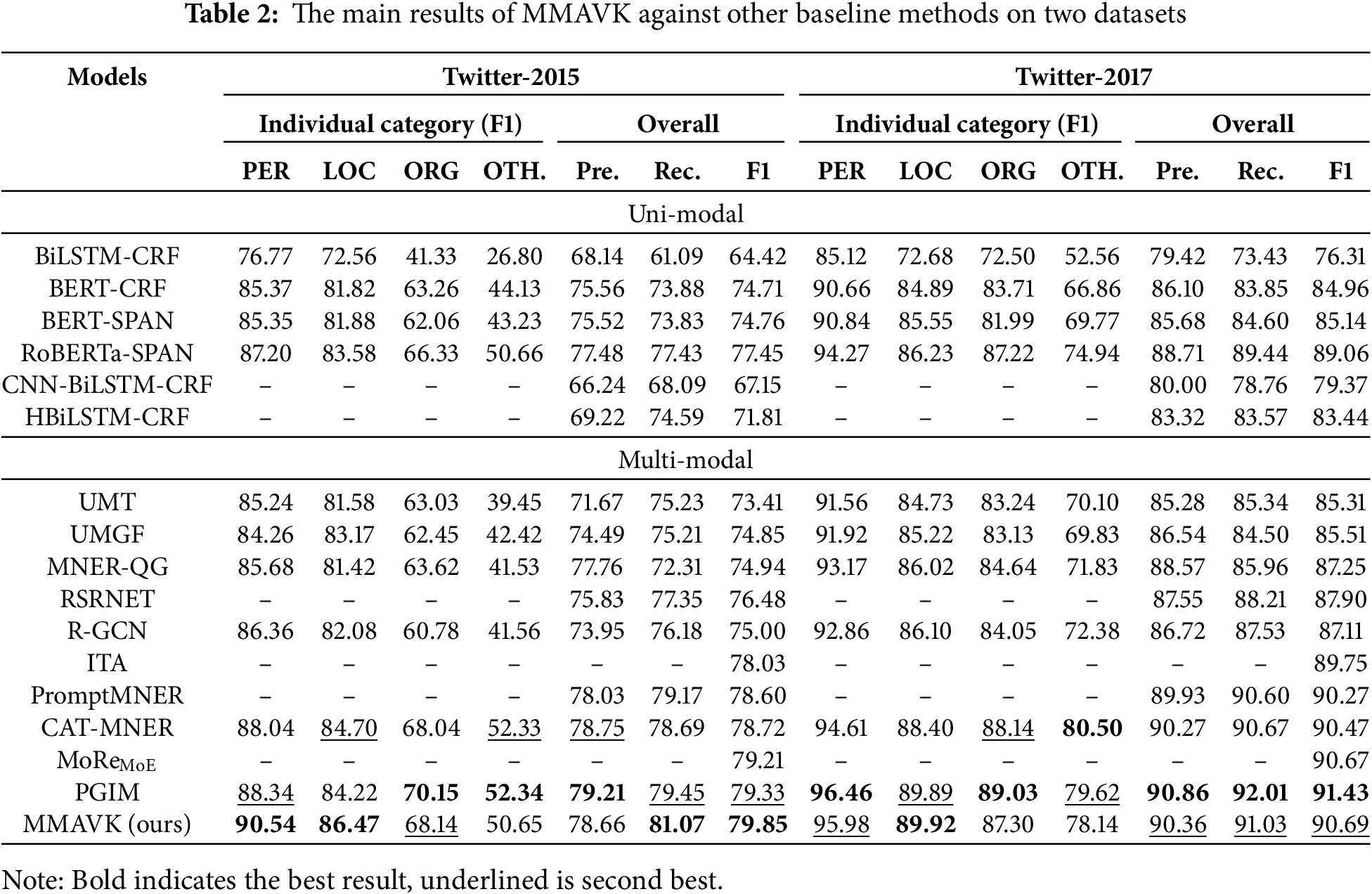

To answer Q1, we compared MMAVK against several previous state-of-the-art models on NER, the main experimental results are shown in Table 2. In comparison to previous models, except for PGIM, MMAVK exhibits a distinct superiority. Furthermore, when only visual information is used as the basis for auxiliary knowledge and a large model with 7B parametric quantities is employed as the auxiliary knowledge generator, some of the metrics of MMAVK remain superior to those of the PGIM, which utilizes GPT-3.5-Turbo to process image-text pairs simultaneously to generate auxiliary knowledge.

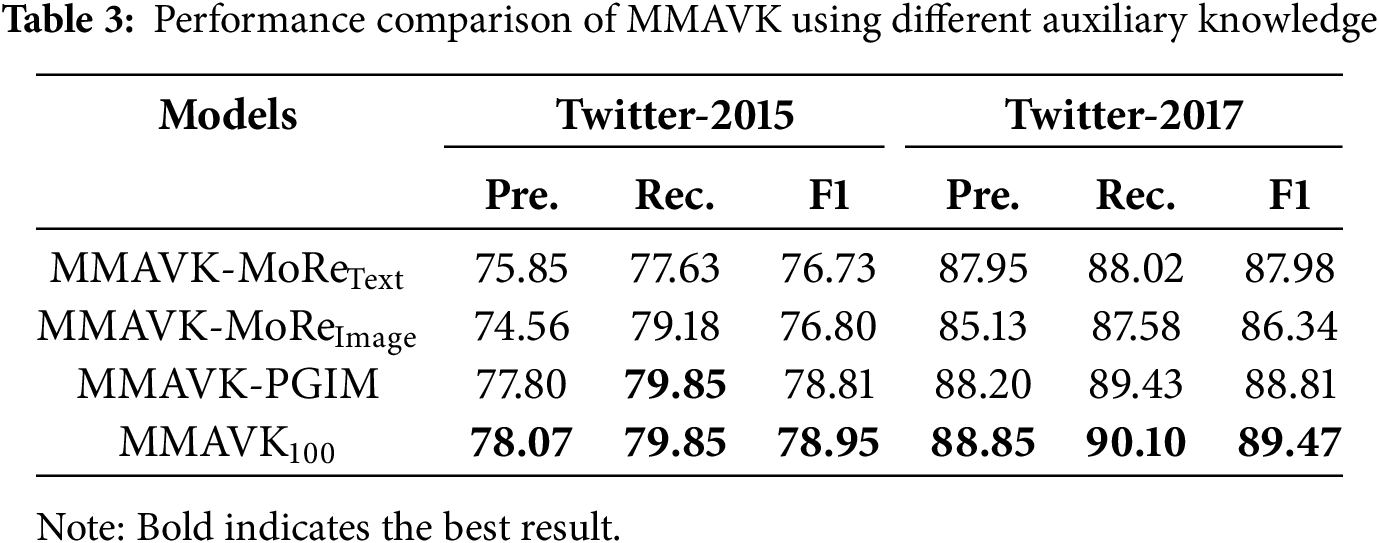

To demonstrate the effectiveness of the auxiliary knowledge generation method utilized in this paper and answer Q2, we obtained the auxiliary knowledge generated in PGIM and MoRe, and then conducted experiments with the network and fusion approach employed in this study, without similarity-based filtering. The results are shown in Table 3. When all factors are held constant, the auxiliary knowledge generated in this paper has the best contribution to the named entity recognition results.

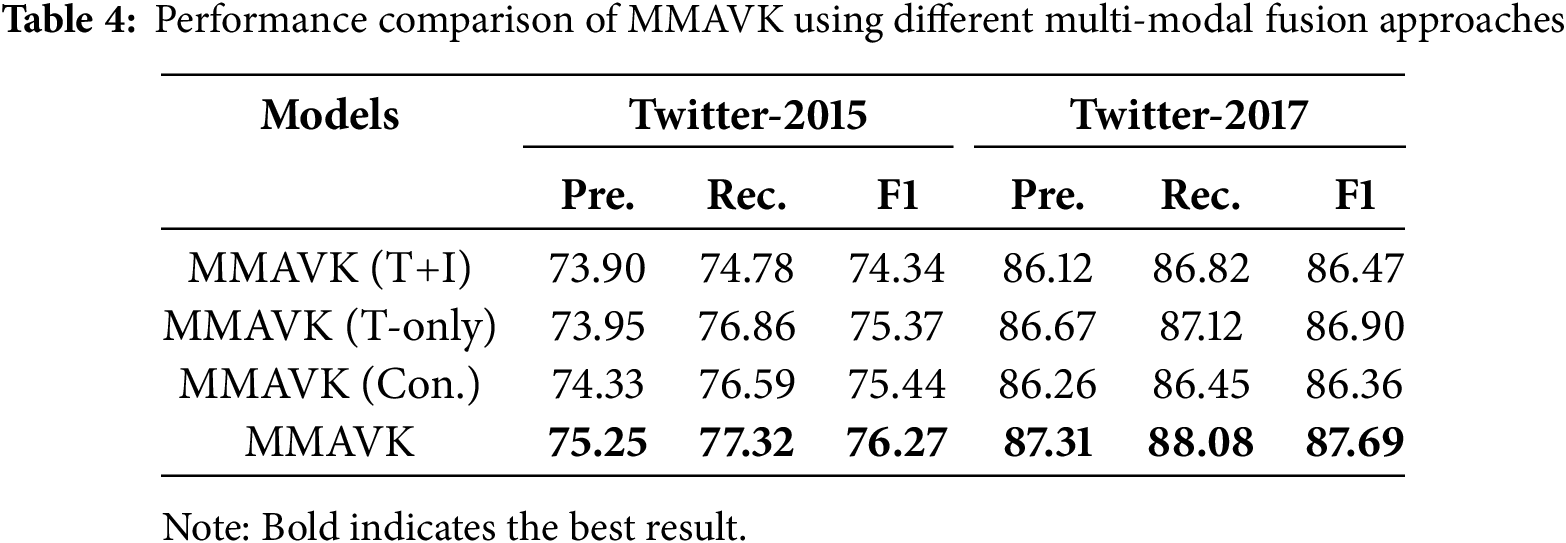

Following the training approach in RSRNET [15], four distinct multi-modal fusion approaches were evaluated using XLM-RoBERTa-base as the encoder to answer Q3: (1) The “T+I” paradigm, in which visual features are used as prefixes to the textual information in each self-attention layer of the encoder. (2) Discarding visual features and using only textual features. (3) The traditional “T+T” paradigm, in which visually generated text is concatenated with the original text into the encoder. (4) The word-level multi-modal fusion method proposed in this paper. As evidenced by the experimental results presented in Table 4, our proposed word-level multi-modal fusion approach exhibits a notable superiority. It was unexpected that the model employing the “T+I” paradigm exhibited inferior performance compared to the model encoding solely textual features. One potential explanation for this is that a text-focused sequence tagging task, such as named entity recognition, is challenging to learn fine-grained modal interactions from different vector spaces. The investigation of the “T+T” paradigm will continue to be a significant avenue of inquiry in the field of named entity recognition.

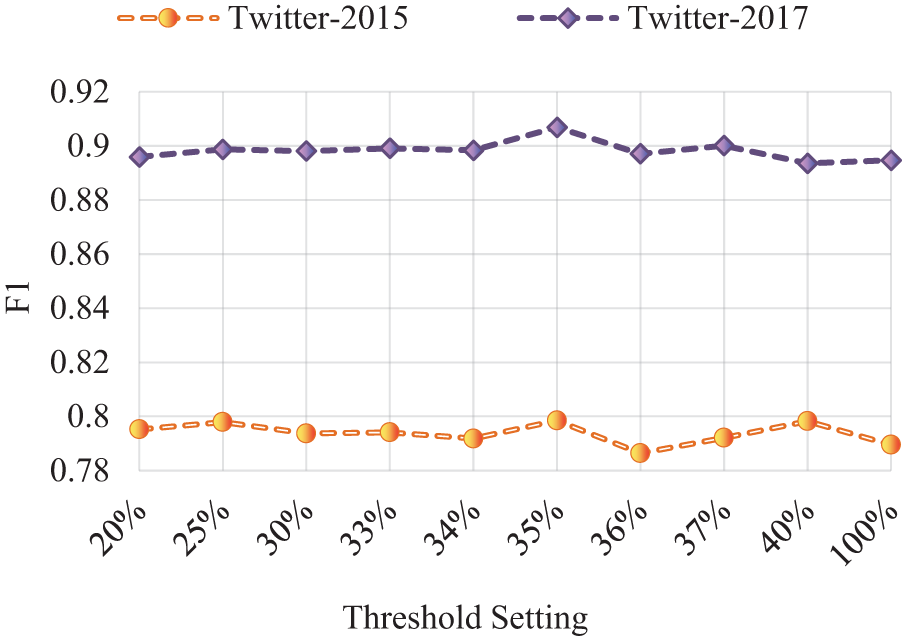

To verify the effectiveness of the similarity-based filtering mechanism (Q4), we set the thresholds to different percentages to filter the auxiliary knowledge for the experiments, respectively. For the auxiliary knowledge whose image-text similarity is lower than the threshold, its fusion weight was set to 0. The mean similarity of image-text pairs in Twitter-2015 calculated based on CLIP is 0.3038 and the median is 0.3047, while the mean similarity is 0.3011 and the median is 0.3022 in Twitter-2017. So we first searched for the best threshold value using 0.3 as an anchor point. Optimal results were achieved at a threshold of 0.35, which subsequently served as the new anchor for further optimization. As shown in Fig. 4, filtered auxiliary knowledge generally facilitates entity recognition better than unfiltered auxiliary knowledge, and the facilitation is best when the threshold is set to 0.35. However, this is only the result of experiments on these two datasets and is not proof that 0.35 is the optimal threshold we are looking for. The selection of the threshold depends on the encoder used and the quality of the dataset. We did not find a clear correlation between the threshold setting and F1, and the optimal threshold is not a specific point such as the mean or median of similarity. More research and experiments are still needed on how to better filter the noisy information in the visual modality through the filtering mechanism. In our future work, we will try to find a reasonable dynamic threshold selection mechanism for different types and sizes of datasets.

Figure 4: The impact of different filtering thresholds on MMAVK

We select case studies shown in Fig. 5 to illustrate the potential benefits of auxiliary knowledge for enhancing the performance of a model. MoReText and MoReImage employ text- or image-related knowledge retrieved from Wikipedia, whereas PGIM utilizes auxiliary knowledge generated by ChatGPT, which is prompted based on image-text pairs to be recognized. By analyzing the visual information, the vision-based auxiliary knowledge generated by the multi-modal LLM contains the context associated with the textual entities present in the visual modality. Visual elements related to locations, people, and organizations serve as the foundation for decoding and classifying entities.

Figure 5: Two practical examples demonstrating the enhancement effects of visual auxiliary information on recognition

However, there is a possibility that the adoption of external knowledge may introduce additional errors. For models that use retrieval-based external knowledge acquisition mechanisms, poor retrieval methods or low-quality knowledge bases have resulted in a large amount of useless or erroneous information in the acquired external knowledge. For models that use large model generation capabilities to generate external knowledge, the performance of the large model itself and the quality of the dataset are important factors in ensuring the quality of the external knowledge. For example PGIM may introduce misidentification results from large models, such as treating “Bush 41” as a whole entity and generating a context that causes the model to misidentify “Bush 41” as [PER]. Our proposed auxiliary knowledge generation method does not involve the participation of the text to be recognized, while a filtering mechanism is used to remove low-quality visual information. The errors present in the generated auxiliary knowledge are minimized. The extensive knowledge of the LLM offers a wealth of external information for MNER, while its robust natural language processing capabilities enable highly precise a priori entity recognition. Since some of the metrics of PGIM are still better than MMAVK, we also tried to input the original text into the LLM to obtain its pre-recognition labels and context using different prompts. This information, along with the vision-based auxiliary knowledge generated in this paper, was then input into the model. However, none of these attempts achieved the expected results.

To address the problems of poor image-text correlation and low efficiency of external knowledge acquisition in MNER, we propose MMAVK, a multi-modal named entity recognition model with auxiliary visual knowledge and word-level fusion. It aims to extract semantics from images through the multi-modal LLM and generate vision-based auxiliary knowledge that contributes to entity recognition. Furthermore, it performs embedding fusion at the word-level, thereby facilitating fine-grained interaction between external knowledge and original text.

We believe that LLMs, especially multi-modal LLMs, remain one of the key techniques for improving the effectiveness of MNER. However, as we argue in Section 4.5, prompting LLMs to generate more and more fine-grained auxiliary information does not directly lead to improved model performance. In future work, we will focus on how to better utilize large models to remove noise in visual modalities irrelevant to entity recognition and to improve the quality of the auxiliary knowledge while mitigating the errors associated with erroneous entity recognition results from LLMs.

Acknowledgement: The authors are grateful to all the editors and reviewers for their detailed review and insightful advice.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by Research Project, grant number BHQ090003000X03.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Huansha Wang, Ruiyang Huang; data collection: Huansha Wang; analysis and interpretation of results: Huansha Wang, Qinrang Liu; draft manuscript preparation: Huansha Wang; visualization: Xinghao Wang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Huansha Wang, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| MNER | Multi-modal named entity recognition |

| LLM | Large language model |

| MLLM | Multi-modal large language model |

| MMAVK | Multi-modal named entity recognition model with auxiliary visual knowledge and word-level fusion |

| CRF | Conditional Random Field |

| OCR | Optical Character Recognition |

References

1. Lu D, Neves L, Carvalho V, Zhang N, Ji H. Visual attention model for name tagging in multimodal social media. In: Proceedings of the 56th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; 2018; Melbourne, VIC, Australia. p. 1990–9. doi:10.18653/v1/p18-1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Wang H, Huang R, Zhang J. Research progress on vision-language multimodal pretraining model technology. Electronics. 2022;11(21):3556. doi:10.3390/electronics11213556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Deng J, Dong W, Socher R, Li LJ, Kai L, Li FF. ImageNet: a large-scale hierarchical image database. In: 2009 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2009 Jun 20–25; Miami, FL, USA. p. 248–55. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2009.5206848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Lin T, Maire M, Belongie S, Hays J, Perona P, Ramanan D, et al. Microsoft coco: common objects in context. In: Computer vision—ECCV 2014: 13th European conference. 1st ed. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2014. p. 740–55. [Google Scholar]

5. Wang X, Gui M, Jiang Y, Jia Z, Bach N, Wang T, et al. ITA: image-text alignments for multi-modal named entity recognition. In: Proceedings of the 2022 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies; 2022; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 3176–89. [Google Scholar]

6. Wang X, Cai J, Jiang Y, Xie P, Tu K, Lu W. Named entity and relation extraction with multi-modal retrieval. In: Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2022; 2022; United Arab Emirates: Association for Computational Linguistics. p. 5925–36. [Google Scholar]

7. Li J, Li H, Pan Z, Sun D, Wang J, Zhang W, et al. Prompting ChatGPT in MNER: enhanced multimodal named entity recognition with auxiliary refined knowledge. In: Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2023; 2023; Singapore: Association for Computational Linguistics. p. 2787–802. doi:10.18653/v1/2023.findings-emnlp.184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Moon S, Neves L, Carvalho V. Multimodal named entity recognition for short social media posts. In: Proceedings of the 2018 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies; 2018; New Orleans, LA, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics. p. 852–60. [Google Scholar]

9. Yu J, Jiang J, Yang L, Xia R. Improving multimodal named entity recognition via entity span detection with unified multimodal transformer. In: Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; 2020 Jul 5–10; Online. p. 3342–52. doi:10.18653/v1/2020.acl-main.306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Zhang D, Wei S, Li S, Wu H, Zhu Q, Zhou G. Multi-modal graph fusion for named entity recognition with targeted visual guidance. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2021;35(16):14347–55. doi:10.1609/aaai.v35i16.17687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Jia M, Shen L, Shen X, Liao L, Chen M, He X, et al. MNER-QG: an end-to-end MRC framework for multimodal named entity recognition with query grounding. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2023;37(7):8032–40. doi:10.1609/aaai.v37i7.25971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Wang X, Ye J, Li Z, Tian J, Jiang Y, Yan M, et al. CAT-MNER: multimodal named entity recognition with knowledge-refined cross-modal attention. In: 2022 IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo (ICME); 2022 Jul 18–22; Taipei, Taiwan. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/ICME52920.2022.9859972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Radford A, Kim JW, Hallacy C, Ramesh A, Goh G, Agarwal S, et al. Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision. In: Proceedings of the 38 th International Conference on Machine Learning; 2021 Jul 18–24; Virtual. p. 8748–63. [Google Scholar]

14. Zhang Q, Fu J, Liu X, Huang X. Adaptive co-attention network for named entity recognition in tweets. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2018;32(1):5674–81. doi:10.1609/aaai.v32i1.11962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Wang M, Chen H, Shen D, Li B, Hu S. RSRNeT: a novel multi-modal network framework for named entity recognition and relation extraction. PeerJ Comput Sci. 2024;10:e1856. doi:10.7717/peerj-cs.1856. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Bai J, Bai S, Chu Y, Cui Z, Dang K, Deng X, et al. Qwen technical report. arXiv:2309.16609. 2023. [Google Scholar]

17. Conneau A, Khandelwal K, Goyal N, Chaudhary V, Wenzek G, Guzmán F, et al. Unsupervised cross-lingual representation learning at scale. In: Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; 2020 Jul 5–10; Online. p. 8440–51. [Google Scholar]

18. Wang X, Tian J, Gui M, Li Z, Ye J, Yan M, et al. Promptmner: prompt-based entity-related visual clue extraction and integration for multimodal named entity recognition. In: Database Systems for Advanced Applications: 27th International Conference, DASFAA 2022; 2022 Apr 11–14; Virtual. p. 297–305. [Google Scholar]

19. Ma X, Hovy E. End-to-end sequence labeling via bi-directional LSTM-CNNS-CRF. In: Proceedings of the 54th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; 2016; Berlin, Germany: Association for Computational Linguistics. p. 1064–74. [Google Scholar]

20. Lample G, Ballesteros M, Subramanian S, Kawakami K, Dyer C. Neural architectures for named entity recognition. In: Proceedings of HLT-NAACL 2016; 2016; San Diego, CA, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics. p. 260–70. [Google Scholar]

21. Huang Z, Xu W, Yu K. Bidirectional LSTM-CRF models for sequence tagging. arXiv:1508.01991. 2015. [Google Scholar]

22. Devlin J, Chang M, Lee K, Toutanova K. BERT: pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In: NAACL-HLT; 2019 Jun 2–7; Minneapolis, MI, USA. p. 4171–86. [Google Scholar]

23. Yamada I, Asai A, Shindo H, Takeda H, Matsumoto Y. LUKE: deep contextualized entity representations with entity-aware self-attention. In: Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP); 2020 Nov 16–20; Online. p. 6442–54. doi:10.18653/v1/2020.emnlp-main.523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Zhao F, Li C, Wu Z, Xing S, Dai X. Learning from different text-image pairs: a relation-enhanced graph convolutional network for multimodal NER. In: Proceedings of the 30th ACM International Conference on Multimedia; 2022 Oct 10–14; Lisboa, Portugal. p. 3983–92. doi:10.1145/3503161.3548228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools