Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

PhotoGAN: A Novel Style Transfer Model for Digital Photographs

1 College of Information Engineering, Shanghai Maritime University, Shanghai, 201306, China

2 Informatization Office, Shanghai Maritime University, Shanghai, 201306, China

* Corresponding Author: Daozheng Chen. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: The Latest Deep Learning Architectures for Artificial Intelligence Applications)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 83(3), 4477-4494. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.062969

Received 31 December 2024; Accepted 24 February 2025; Issue published 19 May 2025

Abstract

Image style transfer is a research hotspot in the field of computer vision. For this job, many approaches have been put forth. These techniques do, however, still have some drawbacks, such as high computing complexity and content distortion caused by inadequate stylization. To address these problems, PhotoGAN, a new Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) model is proposed in this paper. A deeper feature extraction network has been designed to capture global information and local details better. Introducing multi-scale attention modules helps the generator focus on important feature areas at different scales, further enhancing the effectiveness of feature extraction. Using a semantic discriminator helps the generator learn quickly and better understand image content, improving the consistency and visual quality of the generated images. Finally, qualitative and quantitative experiments were conducted on a self-built dataset. The experimental results indicate that PhotoGAN outperformed the current state-of-the-art techniques. It not only performed excellently on objective metrics but also appeared more visually appealing, particularly excelling in handling complex scenes and details.Keywords

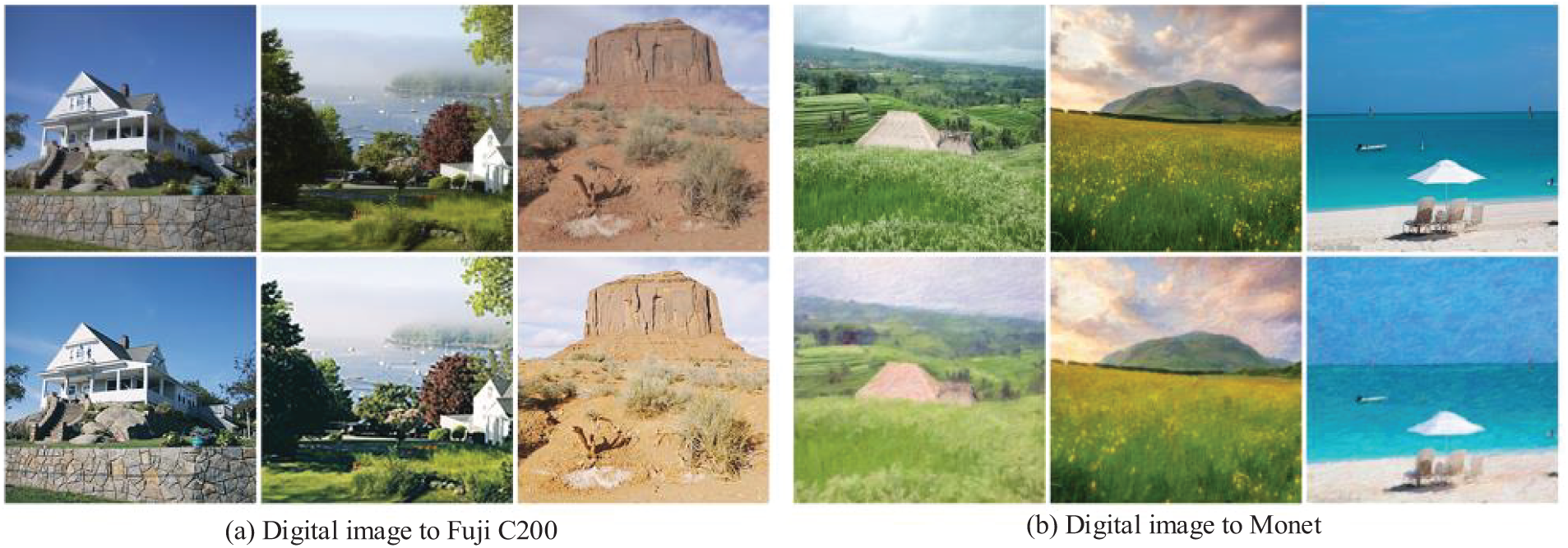

Image style transfer has become an important research direction in computer vision. Its main task is to convert an image into one with a different specific artistic style while preserving the content information of the original image. With the widespread use of social media and online platforms, conveying emotions and information through artistic images has become an important way of social interaction, and the unique styles with visual impact and emotional expressiveness are highly favored by users. For example, film photography is widely loved by artists and photographers for its unique style. The aesthetic effects created by photographers are often achieved through optical characteristics such as halos and chromatic aberration, which stem from complex physical processes. Fuji C200 film is renowned for its soft tones, warm colors, and fine grain, making it a favorite among many photographers. In contrast, it is difficult for modern digital photography to naturally reproduce this classic visual style. Therefore, to reproduce the unique effects of film in digital images, computational methods are usually required. Based on this need, we explored the feasibility of using deep learning techniques to replicate the visual effects of Fuji C200 film. Additionally, traditional artistic style transfer is also a focus of our research. The efficiency of our approach in converting digital images to Fuji C200 film and impressionism (Monet) styles is shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Results of our method (row 1: the original images; row 2: the image after style transfer)

In style transfer, it is desirable to preserve the semantics of the source image. However, for different style transfer tasks, the changes in the edges of the source image vary. For example, when a Monet painting serves as the reference style picture and a digital photo serves as the source image, our model can output a brush stroke effect similar to that of Monet’s work, which is shown by the original straight edges becoming curved and the fine texture transforming into rough brush strokes; on the other hand, when both the source image and the reference style image are digital photographs, we hope that the generated image can avoid the distorted edges to make it more realistic and natural. In this research, a new image style transfer framework called PhotoGAN based on generative adversarial network (GAN) is proposed and its application results are demonstrated. The following are the primary innovations: First, the improved Res2Net network [1] is combined with the efficient multi-scale attention (EMA) mechanism [2] as a generator to further extract the image’s features. Second, the semantic labels are fed into the discriminator, and the semantic discriminator discriminates the output of the generator based on the true semantics of the source images, thus ensuring that the generated images conform to the semantic accuracy. Meanwhile, to cope with the problem of style mismatch, Grand matrix [3] is introduced into the generator to perform the effective transfer of the overall color tone. Finally, traditional style transfer methods usually rely on datasets consisting of paired samples, but paired datasets for film and digital images are scarce and difficult to collect. Therefore, the unpaired image samples are used to construct the datasets in this paper. Based on the full gallery API licensed from Unsplash, the dataset collection code based on CLIP [4] is written according to the experimental requirements.

Researchers have achieved a series of research results for image style transfer, for example, the earliest can be traced back to the Neural Style Transfer (NST) method, which was proposed by Gatys et al. in 2016 [3], by optimizing the pixel values of the target image so that it simultaneously preserves the content features of the source image and matches the style features of the style image. Although NST can generate high-quality style-transferred images, its pixel-by-pixel optimization is computationally expensive and tends to lead to unnatural effects when the style changes are large. By pre-training CNNs to reduce content and style loss, the convolutional neural network (CNN)-based approaches also have shown remarkable performance in style transfer tasks. These methods have been widely used for painting style transfer [3,5] and photorealistic image generation [6,7]. However, they still rely on optimizing each image. In contrast, Johnson et al. [8] proposed to train feedforward models using perceptual loss based on VGG features, and Huang et al. [9] extended the method to arbitrary styles through adaptive instance normalization. Gatys et al. [3] proposed a method based on a global color transform, but this transform cannot simulate spatial variation effects. CNNMRF’s [10] approach reduces inaccuracies in the transfer process by matching each input neural block with the most similar stylized image neural block. Furthermore, Ignatov et al. [11] tried to use a composite loss that incorporates color, texture, and content features to convert a cell phone image into a digital single-lens reflex camera image style.

The Visual Transformer (ViT) [12] presents a transformer model [13] for visual tasks that divides the input image into tiny pieces and produces embedding vectors that perform better than traditional CNNs in a number of visual tasks. For instance, the transformer-based model [14] made significant progress. The success of the transformer is mainly attributed to its attention mechanism, which can capture the global context of the image and help the model better understand the relationship between image content and style, thereby facilitating style transfer. However, transformer models have large computational loads, high hardware requirements, and slow training speeds.

Goodfellow et al. [15] initially suggested GAN, which aims to create realistic images by gaming two adversarial networks (generator and discriminator). The main advantage of GANs is that they are flexible as they do not require pairs of training data, and only two different image domains (e.g., the source style domain and the reference style domain) are required for learning. However, traditional GANs face some challenges when applied to image style transfer tasks, especially in unsupervised learning environments. Subsequently, under the GAN framework, many improvement schemes have emerged one after another. For example, Pix2Pix [16] utilizes pairwise images for training via conditional GAN, which is effective but relies on a large amount of paired data. In contrast, an unsupervised image-to-image translation technique called CycleGAN [17] is suggested as a solution to these problems. CycleGAN introduces cyclic consistency loss to accomplish style transfer without paired data. It has two generators: one that converts pictures from the source domain to the target domain and another that reverses the other direction. CycleGAN successfully preserves the image’s content structure and accomplishes style transfer by guaranteeing the image’s cyclic consistency between the two domains. Shim et al. [18] proposed a GAN-based conditional image synthesis method that aims to better handle style and shape representations in image synthesis by integrating adaptive normalization conditioned normalization layers for style enhancement and weighting shape enhancement loss at the edges. GAN is also applicable to the task of facial de-labeling, which aims to reduce the visual difference between the restored area and the original image by using GAN to restore the natural appearance of the removed portion after removing or blurring key facial features [19].

In computer vision, attention mechanisms have emerged as a crucial technique for enhancing model performance. It can assist the model in concentrating on important areas of the image during image production tasks, enhancing the generated image’s quality and detail. Attention mechanisms in image generation take the following forms: Spatial Attention [20,21], which selectively focuses on key parts of an image by weighting spatial regions of the image; Channel Attention [22], which enhances the importance of specific channels by weighting different channels in the feature map; Multi-Scale Attention [23], which extracts features at multiple scales and weights them according to the importance of each scale, thus providing a more comprehensive understanding of the local and global information of an image. In addition, many improvements work based on the attention mechanism, especially in the style transfer task, have achieved remarkable results. For example, the non-local operation proposed by Non-Local Neural Networks [24] can model long-distance dependencies, which significantly enhances the produced model’s performance in terms of variety and detail retention. The addition of the attention mechanism to the CycleGAN framework can significantly enhance the model’s capacity to catch details of various styles, especially in complex photographic style transfer tasks. The model may concentrate on the image’s local features at various scales by utilizing the attention mechanism, avoiding excessive smoothing or distortion during the style transfer process. With the continuous improvement of CycleGAN, schemes based on the attention mechanism have gradually been more widely used. For example, Self-Attention GAN [25] introduces a self-attention mechanism, which enables the model to adaptively focus on different regions and capture long-distance dependencies. Dual Attention GAN [26] combines spatial and channel attention mechanisms to improve the quality of image generation.

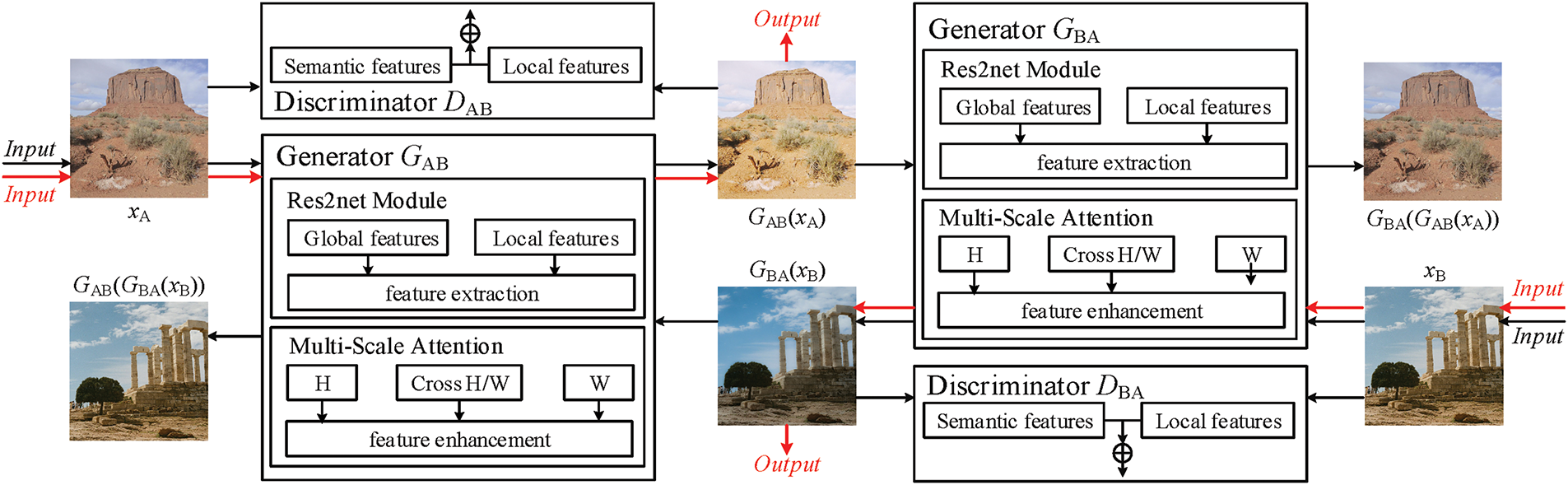

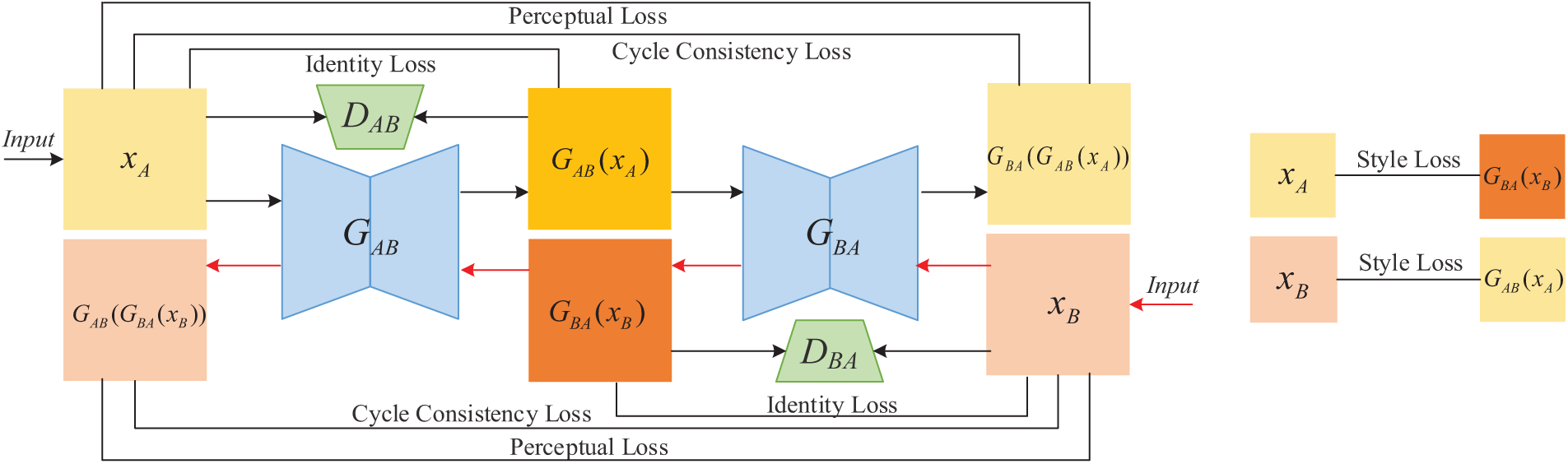

The PhotoGAN proposed in this paper is an improvement based on the CycleGAN architecture. Its generators consist of a U-Net structure combining the EMA mechanism with Res2Net residual blocks, and its discriminators are semantic discriminators (SeD) [27] improved based on PatchGAN [14]. As shown in Fig. 2, the PhotoGAN network consists of two generators (GAB and GBA) and two discriminators (DAB and DBA). Specifically, the function of generator GAB is to convert the A-domain style source image into an image with B-domain style, and the function of generator GBA is to convert the B-domain style source image into an image with A-domain style. The discriminator DAB discriminates the new image generated by generator GAB, while the discriminator DBA discriminates the new image generated by generator GBA. Assuming A is the source style domain and B is the reference style domain: during the network training process, the A-domain image xA is converted into an image GAB(xA) with B-domain style by the generator GAB first, GAB(xA) is then input into the generator GBA to output the reconstructed A-domain image GBA(GAB(xA)), finally, GBA(GAB(xA)), the image generated by generator GBA is compared with the original A-domain image xA, and the cyclic consistency loss and perceptual loss are calculated to ensure that the generated image is consistent with the original image in terms of content; Similarly, the image of domain B is processed following the same procedure.

Figure 2: Overall structure of PhotoGAN (Black arrow: training process; Red arrow: reasoning process)

During training, the generator’s primary objective is to deceive the discriminator by generating realistic images so that it cannot distinguish the difference between the generated image and the real image. To achieve this goal, the generator needs to efficiently learn the feature mapping between the two domains and capture detailed information. The Residual Block in the original CycleGAN, although capable of learning the difference between two domains, has a limited feature extraction capability when dealing with tasks with large style differences, making it challenging to appropriately capture detailed information. Therefore, the enhanced Res2Net is used in this study to improve the feature extraction capability of the network. To further improve the learning effect of the generator on stylized image features, enhance its ability to extract target features, and avoid the loss of critical information, we embedded the EMA mechanism in the Res2Net module. Specifically, Res2Net enhances the feature extraction capability through multi-scale residual concatenation, which can capture more contextual information at different scales. EMA accelerates the computation process, helps the network converge faster, and improves attention to important features, which better preserves key information.

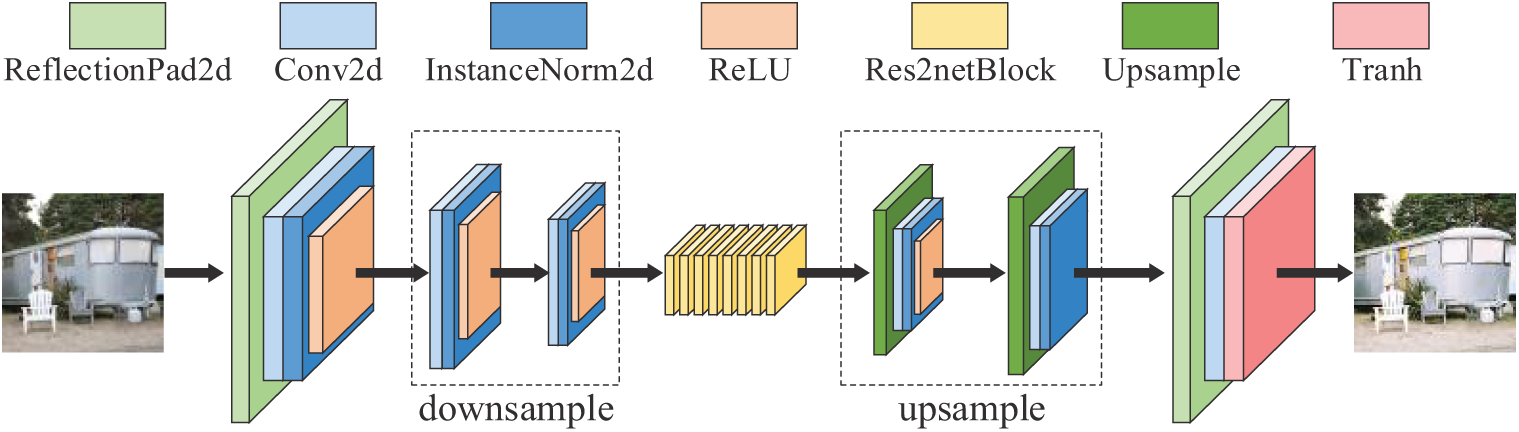

As shown in Fig. 3, the generator of PhotoGAN adopts the coding-transformation-decoding network architecture of down sampling, residual attention module, and up sampling. In the encoding part, the size of the image is reduced by gradual down sampling and the number of feature maps is increased to expand the receptive field, extract more feature information and reduce the computation; in the residual attention module, Res2Net enhances the feature extraction capability by multi-scale residual connectivity, which is able to capture more contextual information at different scales, and in combination with the multi-scale attention module, it helps the generator to focus on important feature regions at different scales, which enhances feature extraction. Res2Net_EMA helps the network learn the difference between input and output, especially for capturing complex style features in style transfer tasks. The up-sampling operation in the encoder part then gradually recovers the size of the image and restores the details and texture information, thus ensuring that the size of the output image is consistent with the input image. This design not only improves the feature extraction capability of the generator but also ensures a significant improvement in the detail and overall quality of the generated image.

Figure 3: Architecture of generator

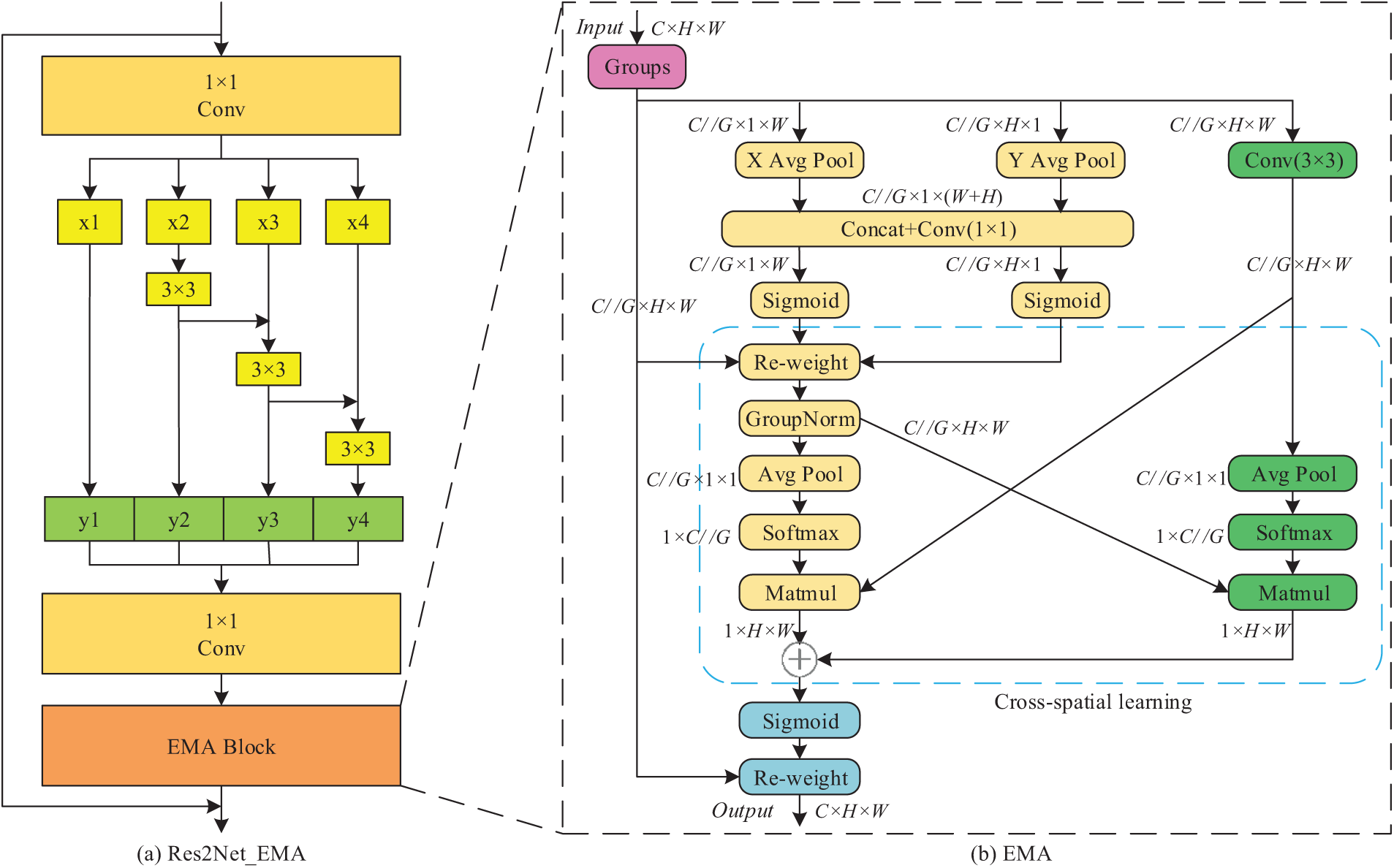

As shown in Fig. 4a, Res2Net_EMA mainly consists of Res2Net’s residual block and the EMA module. Res2Net’s residual block uses 1 × 1 convolutional layers to reduce the number of channels and perform feature map dimensionality reduction and divides the feature maps into multiple groups by grouping convolution, and each group is responsible for processing features at different scales, which enables the learning of multi-scale features. Subsequently, the feature maps of all scales are fused to obtain richer multi-scale features, and finally, the fused features are summed with the input features to further enhance the feature representation and improve the expressive capability of the model. The overall structure of the EMA module is shown in Fig. 4b. Its parallel substructures help to avoid excessive sequential processing and overly deep architectures in the network, thereby improving computational efficiency and performance. In the EMA module, the input feature map is first grouped and then processed through two parallel branches: one branch performs global average pooling, while the other branch uses a 3 × 3 convolution layer to extract local features and capture local contextual information. To capture pairwise associations at the pixel level, the outputs of X Avg Pool and Y Avg Pool are regulated by a sigmoid activation function and normalization before being combined via a cross-dimensional interaction module. After being regulated by the sigmoid, the resulting feature mapping will enhance the original input features and ultimately obtain the optimized output features.

Figure 4: Structure of the Res2Net_EMA network. “G” denotes the divided group, ‘X Avg Pool’ denotes 1D horizontal global pooling, ‘Y Avg Pool’ denotes 1D vertical global pooling

The Res2Net_EMA module combines the multi-scale feature extraction capability of Res2Net and the attention mechanism of EMA, which significantly improves the learning effect of the generator on complex image features. The residual block of Res2Net can effectively capture the features of different scales, which improves the expressive ability of the model. The EMA module enhances the important features through parallel processing and cross-dimensional interaction. The parallel structure of the EMA module reduces the dependence on sequential processing and improves computational efficiency. With these improvements, the Res2Net_EMA module not only performs well in terms of technical specifications but is also more visually appealing, especially when dealing with complex scenes and details.

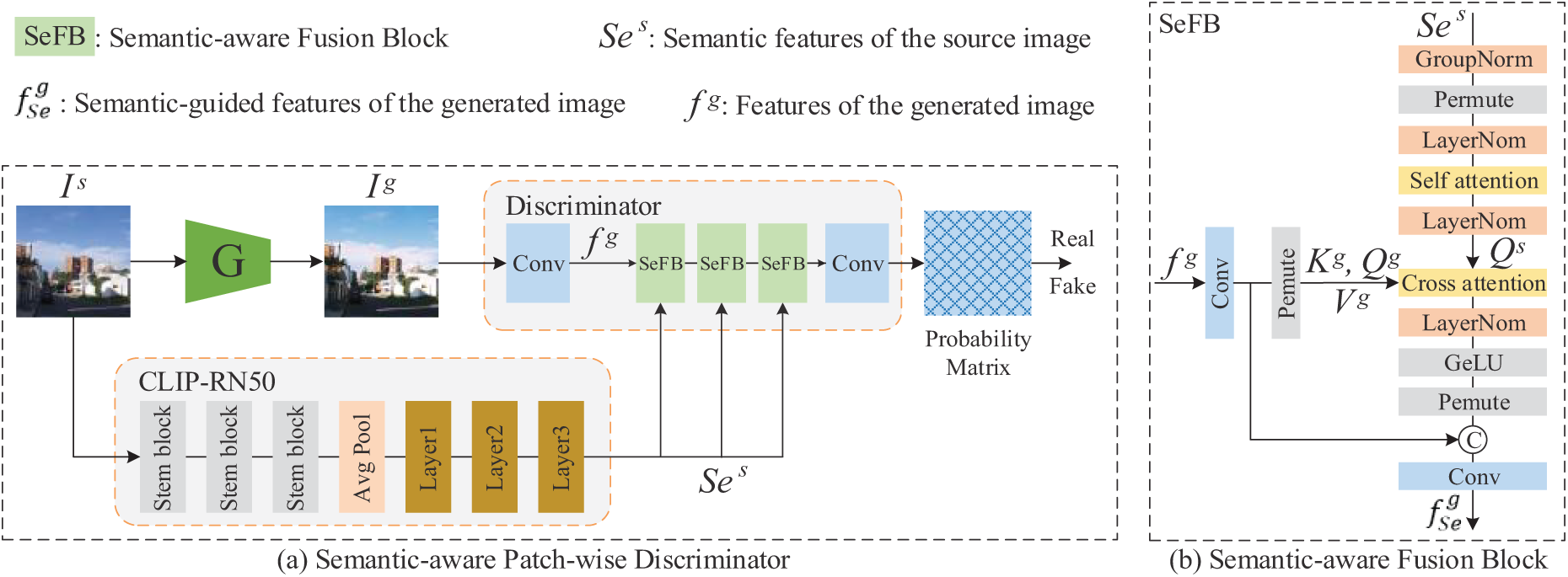

As shown in Fig. 5, a semantic feature extractor and a semantic-aware fusion block make up the semantic-aware discriminator. The core idea is to enhance the discriminator’s ability to understand the generated image by introducing semantic information, to enhance the output image’s uniformity and quality. Pretrained Vision Model (PVM) [28,29] has great potential in generative tasks, especially CLIP [27], which is trained with many visual-linguistic pairs to enhance the fine-grained features of the linguistic space, enabling it to perform well in semantic mining tasks. Therefore, we adopt the pre-trained CLIP-RN50 model as a semantic extractor to guide the discriminator. The model can efficiently map pictures into semantic space and be trained using a comparison learning strategy on a large-scale visual-linguistic dataset. The features extracted by CLIP-RN50 not only contain rich visual information but also incorporate linguistic context, which makes the semantics of the generated images more accurate and enriched. The semantic-aware fusion block fuses the semantic features extracted from CLIP-RN50 with the middle layer features of the discriminator. This fusion mechanism helps the discriminator to better understand the semantic content of the generated images and thus more accurately assess the authenticity and stylistic consistency of the generated images. By combining visual and semantic information, the discriminator can make judgments at a higher semantic level and avoid relying only on low-level visual features, thus enhancing the variety and quality of the generated images.

Figure 5: Semantic discriminator

The traditional discriminator of PathGAN only considers the coarse-grained distribution of the image and ignores the semantic information, which may result in false or poor texture in the generated results. An ideal texture should be closely related to its semantic information. Therefore, we extract semantic information through a visual large-scale model, and set the goal as Eq. (1):

where

where

where

As shown in Fig. 6, during the training process, in addition to the most basic adversarial loss, our loss function also includes the cycle consistency loss in the CycleGAN model to ensure the effectiveness of self-supervised training; the cycle perception loss ensures that the content of the generated images remains consistent; and the style loss ensures that the transferred colors are realistic.

Figure 6: Loss function

The cross-entropy loss used by traditional discriminators tends to cause the gradient to vanish, especially when the discriminator is strong, and it is almost impossible for the generator to get an effective gradient update from the loss. To improve the quality of the generated images, we adopt least squares loss [28], which effectively improves the quality of the generated images and adds attention to details based on the PatchGAN discriminator. Meanwhile, we further improve the quality of the generated image by extracting the semantic information of the original image.

The goal of the discriminator

where

The loss function for the discriminator

where E is the mathematical expectation. Similarly, the loss function for discriminator

The losses of the generator are mainly composed of adversarial loss, perceptual loss, identity loss, cyclic consistency loss and style loss. The adversarial loss functions are defined as Eqs. (8) and (9):

Therefore, the total adversarial loss of the generator is Eq. (10):

A key feature of CycleGAN is the cyclic consistency loss, which is designed to ensure that the original image is recovered when traveling from one domain to another and back again via the generators

where

where

Perception loss measures the differences between generated images and real images by comparing their high-level features, rather than relying on pixel-level differences. As opposed to L1 loss, which places too much emphasis on pixel-level differences, perceptual loss helps to capture the structure and semantic information of an image. The definition of perceptual loss is Eq. (15):

where

The generated image and the input image should remain as similar as feasible during the style transfer procedure. For example, when

We extract the 1-, 3-, and 7-layer feature maps from the generator and compute the Gram matrix for each feature map. The Gram matrix is computed as Eq. (17):

where

Finally, the total loss of the generator is defined as Eq. (19):

where

4 Analysis and Results of the Experiment

The method proposed in this article can achieve style transfer by learning the difference in appearance between two non-paired images (e.g., source image and reference style image do not need to be paired). This unsupervised learning method makes our model more flexible and capable of performing style transfer tasks in diverse image sets.

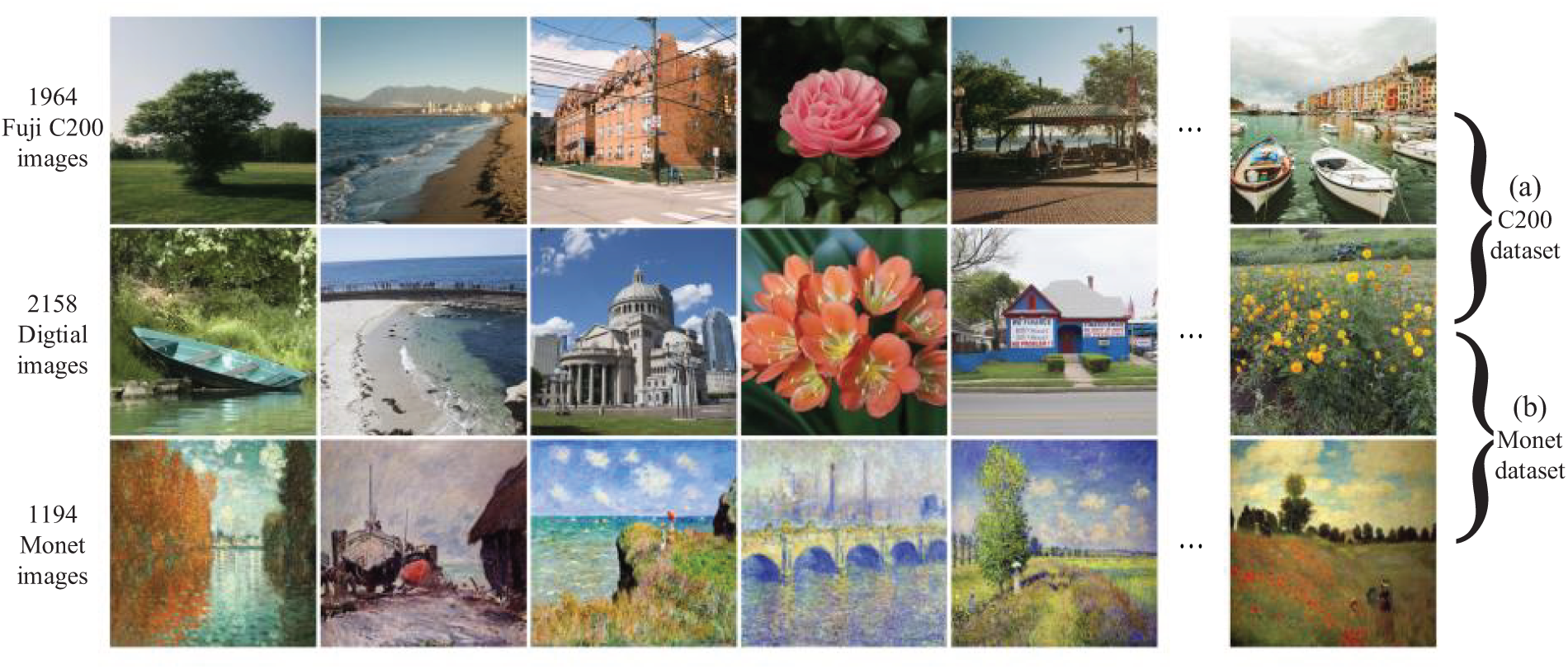

To realize the transfer to Fuji C200 film style, a dataset containing unretouched digital images and Fuji C200 film images needs to be prepared first. This article uses the CLIP model offered by OpenAI to effectively filter and classify the images and photos that satisfy the requirements of large-scale datasets. Collaborative embedding [30] gives us ideas to use the CLIP model to create a strong association between the picture and its description text by mapping the two into the same embedding space. Specifically, CLIP can make a given image and the text describing that image close to each other in the embedding space through similarity computation. To construct the C200 dataset, we filtered the required images from Unsplash (a free image platform with nearly 2 million high-quality images). By combining the images’ labels on Unsplash with specific text descriptions for filtering, we finally obtained a compliant image set, named C200. Partial samples are shown in Fig. 7. This dataset contains representative digital images and film photos, which can be better used for training in the style transfer task after classification and filtering by the CLIP model. The specific filtering process is as follows:

(1) Label filtering: Use the Unsplash API to obtain the labels of all images, and initially filter out the images related to film and digital photography by these labels.

(2) Text description comparison: Combined with our needs, we designed specific text descriptions, such as “Seaside scenery on a sunny day”, and matched these descriptions with the image labels to further filter out the images that meet the requirements.

(3) Classification by the CLIP model: The pre-trained CLIP model is used to learn the comparison of the filtered images, and each image is compared with its corresponding text embedding vector to ensure that the selected images and their descriptive texts have high similarity in the same embedding space, so as to ensure the accuracy and relevance of the dataset.

Figure 7: Composition of the datasets and some samples

After the above processing, we get 1964 Fuji C200 film images and 2158 unretouched digital images. Considering the diversity in size and resolution of the obtained images, we preprocessed all images using Adobe Lightroom for ease of training. Specifically, we scaled all images to a uniform size of 512 × 512. This size setting ensures the standardization of input data, which is helpful for network training and optimization. Eventually, we obtained a high-quality and satisfactory image dataset, named C200, as shown in Fig. 7a. This dataset contains representative digital and film images, which can be better used for training in the style transfer task after classification and filtering by the CLIP model. It covers a wide range of scenes and themes, ensuring the diversity and breadth of the training samples. The fine-grained filtering by the CLIP model ensures a high degree of matching of the images to the desired styles. All images were sourced from Unsplash, which guarantees the resolution and quality of the images. It provides reliable training material for Fuji C200 film style transfer. In the experiments, the dataset is divided into a training set and a test set in a 7:3 ratio, and both qualitative and quantitative analyses are conducted on the testing set.

The traditional art style transfer dataset uses Monet paintings from Wiki-Art [31] as the reference style images and unretouched digital images as source images. Wiki-Art is an online art collection featuring works by artists from different eras. We selected 1193 Monet style images from Wiki-Art and also scaled them to a uniform size of 512 × 512. These Monet style images and the 2158 unretouched digital images obtained in Section 4.1.1 constitute the dataset used for style transfer between digital images and Monet images, as shown in Fig. 7b. Being trained on the dataset, the network can learn a wide range of artistic stylistic features and generate high-quality images, thus helping the network to better grasp the subtleties of various art forms. The dataset is also divided into a training set and a test set in a 7:3 ratio to conduct the following experiments.

The Mirflickr dataset [32] is a large-scale image dataset covering a wide range of styles and categories of images, which is well suited for the pre-training phase in unsupervised learning. By training on the Mirflickr dataset, the model can learn generalized image features, which provides a good foundation for subsequent training on a more specific Fuji C200 film dataset and Monet dataset.

Because it exhibits superior convergence and stability while training deep learning models, the Adam optimizer is employed throughout the training phase. The learning rate was set to 0.0001, which is an empirically tuned learning rate that ensures stable convergence in the early stages of training while avoiding an overly fast or slow learning process. A batch size of 32 was set, which is a good balance between performance and memory consumption. The number of training rounds (Epochs) is set to 200, which is sufficient to allow the network to fully learn the stylistic differences between images and gradually optimize the generator. 2 NVIDIA 4090 graphics cards are used for training, which accelerates the training process, especially when large-scale image data needs to be processed, and the dual-card configuration dramatically increases the computational power. The training environment was Ubuntu 22.04 and used Python 3.8, PyTorch 1.13, and CUDA 11.8, which are all common stable versions of modern deep learning frameworks that ensure good support at both the hardware and software levels.

We discovered that the discriminator’s convergence is quicker during the training phase, while the output image of the generator is still not realistic enough. This is a common training problem that usually occurs during the training of GANs. When the discriminator converges too early, it distinguishes between real images and generated images too easily, which makes it difficult for the generator to get effective feedback and leads to poor quality of the generated images. To cope with this problem, we adopt the strategy of changing the update frequency of the discriminator. This is done by performing 1 discriminator update only after every 2 generator updates. By delaying the discriminator update, the generator can be given more chances to update its weights, thus improving the image quality. In this way, the generator does not get bogged down because the discriminator learns to discriminate between real images and generated images too early.

To assess the generated film pictures, qualitative and quantitative evaluations are performed in this paper. For quantitative evaluation, Fréchet Inception Distance (FID), Structural Similarity Index (SSIM), and Peak Signal Noise Ratio (PSNR) are employed. The original digital image is used as a benchmark and the corresponding reference baseline is computed for comparison. PSNR is used to measure the ratio of the maximum possible signal power to the interfering noise power; SSIM is used to compare the structural, luminance, and contrast differences between the original and the reconstructed image, with values ranging from 0 to 1; and FID is used to assess the distributional differences between the generated and real images. Specifically, the Fréchet distance between the mean and covariance matrices of the features extracted in the Inception network is calculated to quantify the differences between the generated and real images. A more accurate assessment of the image generating effect may be obtained by combining the examination of these three metrics to gain a thorough knowledge of the performance of the generated pictures in terms of quality, structure, and distribution.

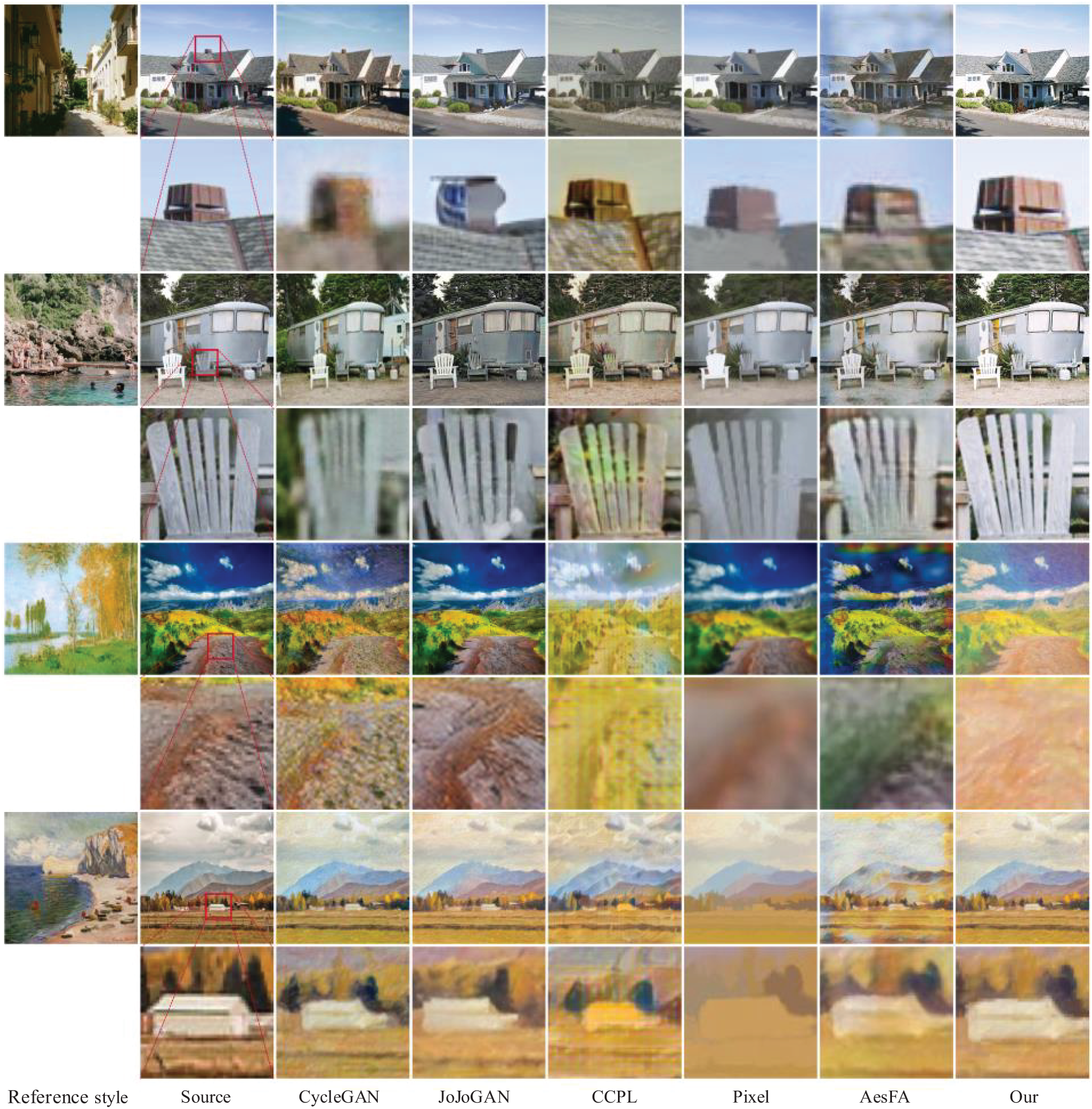

The intuitive results of the qualitative comparison are shown in Fig. 8. The figure shows the comparison of CycleGAN [17], JoJoGAN [33], CCPL [34], Pixel [35], and AesFA [36]. In each row, column 1 is a reference style image and column 2 is a source image. Rows 1 to 4 are film-style transfer results, and rows 5 to 8 are Monet style transfer results.

Figure 8: Comparison of experimental results

It can be seen that although CycleGAN retains the content features better, its generated images lack stylization and produce different degrees of distortion. For example, the images generated by CycleGAN in column 3 show significant distortion compared to the original digital image. JoJoGAN sometimes exaggerates the details, resulting in some unreasonable stylization. For example, the chimney at the top of the house in row 2, column 4, and the caravan in row 3, column 4 appears to become unrealistic. The local details of the images from CCPL are well preserved, but there are color distortions in the stylization process. For example, the chair in row 4, column 5 has an unnatural green color. The images generated by the Pixel method have more blurry local details, which can also lead to color distortion during the stylization process. For example, the images in column 6 look like consisting of several large color blocks and lose the original details. AesFA method generates images with ghosting phenomena and blurred local details. For example, the sky in the image at row 1, column 7 appears unnatural, and a black color block appears below the windshield of the caravan in the image at row 3, column 7. The method proposed in this article not only reliably completes style transfer while effectively preserving content features in film style transfer tasks, but also performs well in Monet style transfer tasks. For example, in the generated images in row 7, although CycleGAN and JoJoGAN retain most of the content details, they fail to generate oil painting strokes as labeled in the red box. In conclusion, our model can establish connections between input images by effectively utilizing their content and style features. By extracting the primary content lines of the source image and using the attention mechanism to perform style transfer on these features, our model can preserve the overall structure of the source image, making the stylized image look very coordinated.

In order to conduct a comprehensive and accurate quantitative analysis of the effect of style transfer, in addition to the three objective evaluation indicators mentioned above, we also conducted a subjective evaluation survey. The users participating in the survey mainly come from campuses and photography clubs. We distributed a total of 80 survey questionnaires, each containing stylized images generated by six different methods. Participants can choose the output results they consider to be of the highest quality based on factors such as color, structure, and rationality of the image. We calculated the scores for each method using Eq. (20):

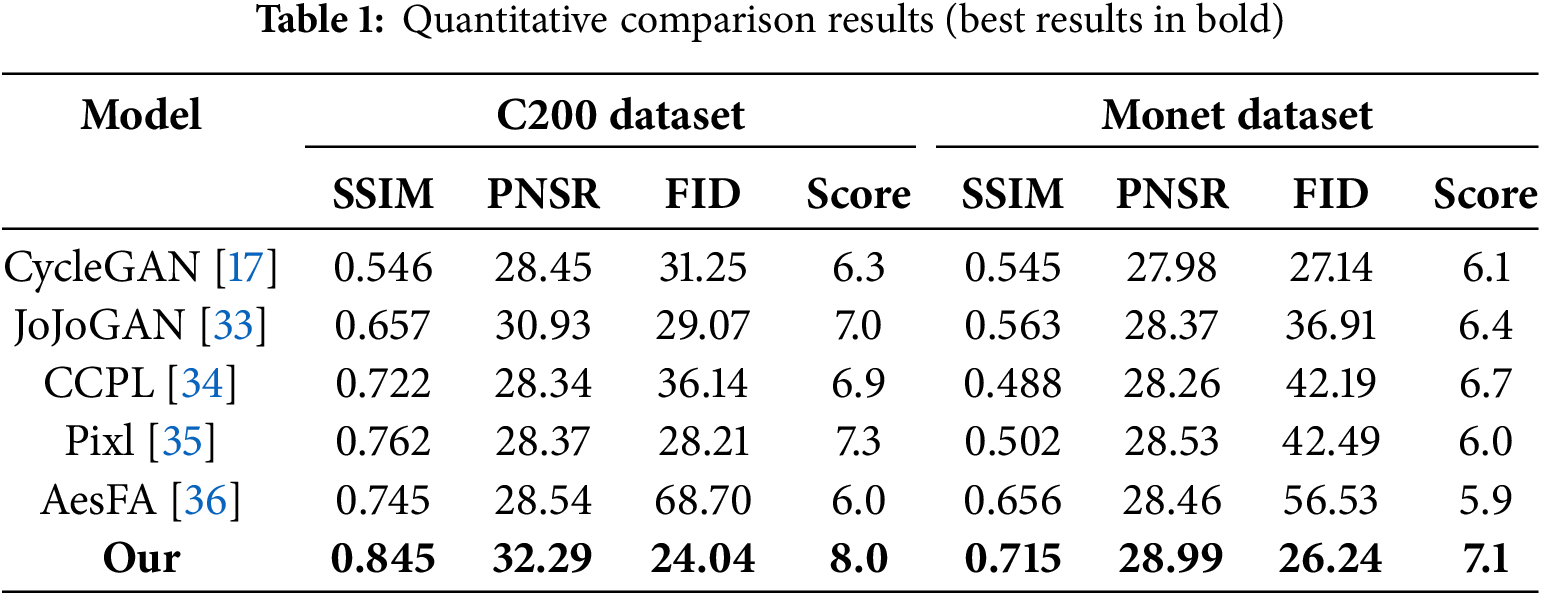

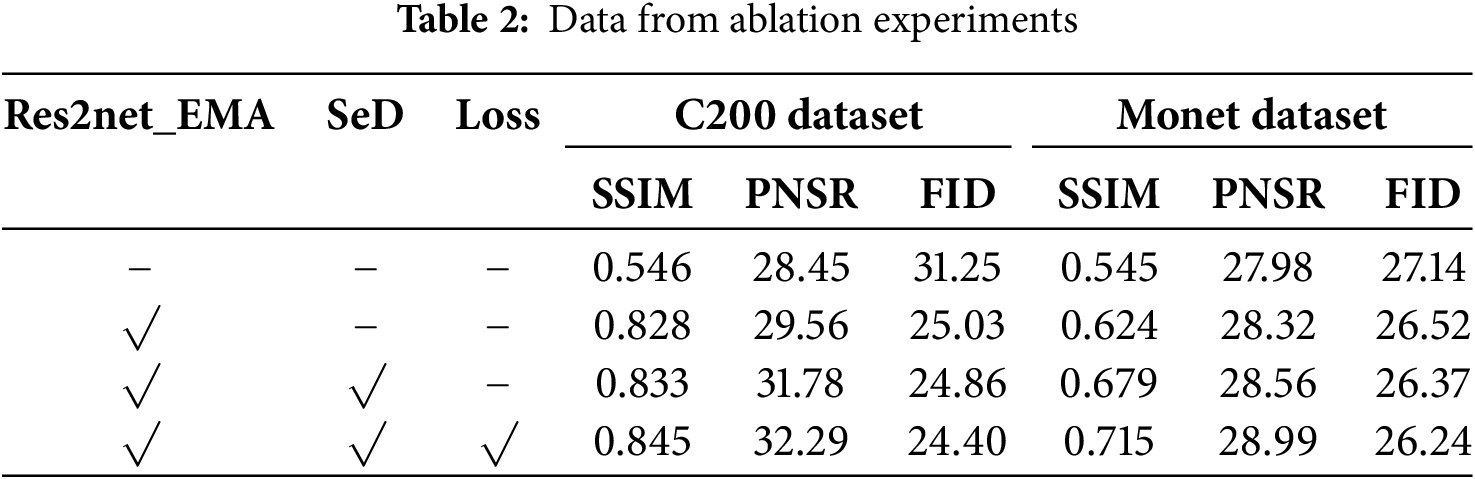

We conducted comparative experiments on the test datasets of C200 and Monet. Table 1 shows the quantitative comparison results between our method and various state-of-the-art style transfer models. It can be seen that compared with other methods, PhotoGAN achieved the highest scores on all evaluation metrics, indicating its excellent performance in terms of structural fidelity, visual appeal, and the overall quality of the generated images.

To evaluate the effectiveness of each improvement module, we conducted ablation experiments on the two datasets for the original model, the model with the improved generator, the model using the semantic discriminator, and the model with the improved loss function. The experimental results are shown in Table 2. It can be seen that each component has a significant improvement on all the evaluation metrics, proving the effectiveness of these improvements in style transfer.

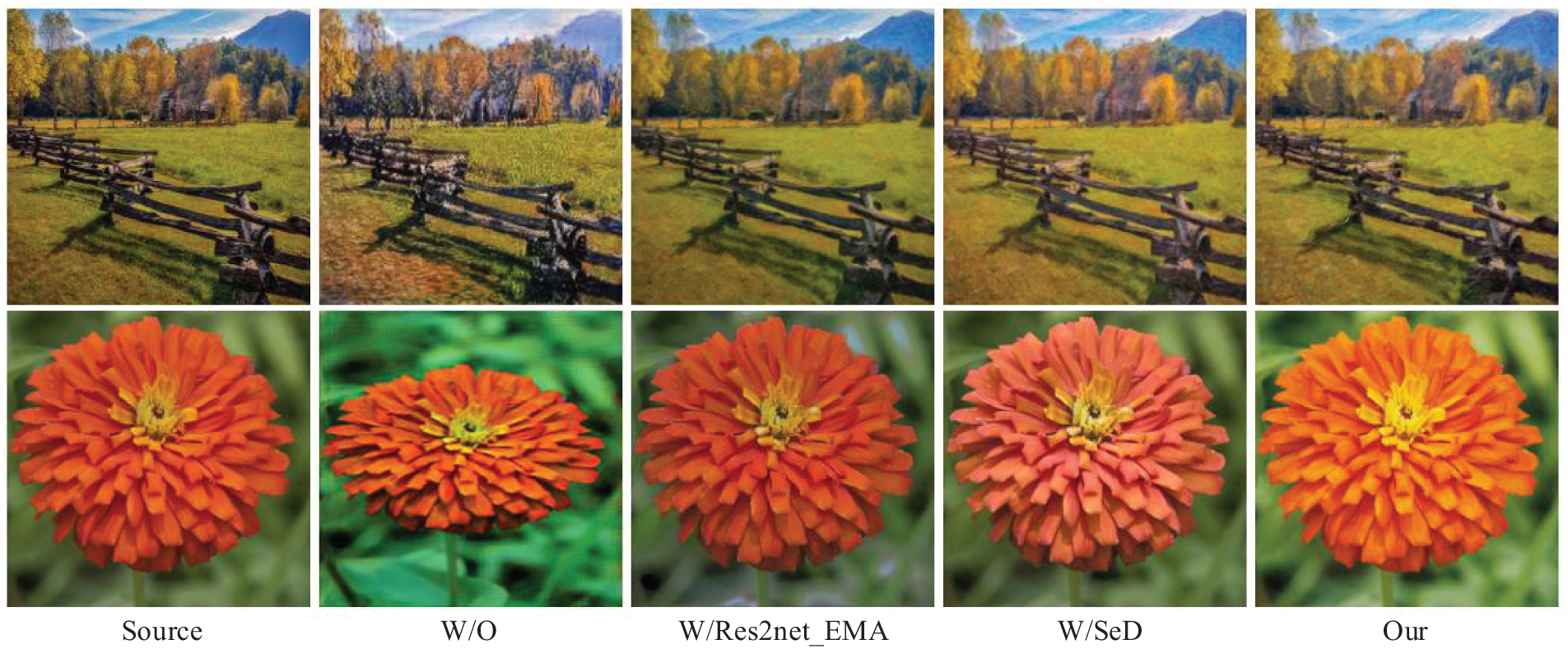

To demonstrate the effect of the ablation, experiment more intuitively, here are two images from the two datasets for visual comparison, as shown in Fig. 9. It can be seen that: the original model: performs generally in processing details and colors, especially with issues like increased color saturation and distortion problems; the improved generator (Res2Net incorporating EMA) performs excellently in detail extraction and can capture more image details, but there are still deviations in color processing. For example, in the transfer task of digital to C200, there are defects in the backgrounds of the flower image, and in the transfer task of digital to Monet, grass areas are almost uniformly rendered in green; The model using the semantic discriminative mechanism effectively avoids defects in the backgrounds of flower images, while enhancing the details of railings and grass, significantly improving the image quality; the model with an improved loss function successfully achieves overall color transfer while preserving the details of the source image, making the generated images visually superior and better able to perform the style transfer task. Through these improvements, the final PhotoGAN model not only performs well in technical indexes but also is more attractive in visual effects, further proving its advantages in the style transfer task.

Figure 9: Results of ablation experiments

In this paper, a new unsupervised generative adversarial network (GAN), PhotoGAN, is proposed for solving the problems of distortion, ghosting, and cluttered lines of images generated by traditional generators in style transfer, to improve the realism and naturalness of image details. By introducing an enhanced Res2Net feature extraction module, PhotoGAN can capture the multi-scale features of the input image more efficiently, thus extracting richer feature information. The module helps the generator to focus on important feature regions at different scales, which further improves the accuracy of detail extraction and makes the generated images more realistic. By introducing a semantic discriminator, PhotoGAN can help the generator quickly learn and better understand the image content, thus improving the quality and consistency of the generated images. We developed a data collection tool. The tool can filter and collect images from the Unsplash platform through image labels, combined with natural language descriptions, and by using the CLIP, and finally constructs a high-quality dataset. This not only enriches the diversity of training data but also ensures the quality and relevance of the data. By conducting experiments on the self-built dataset, our method shows good results in both photography style and art style transfer.

Finally, despite the significant progress PhotoGAN has made in style transfer, challenges remain. Although multi-scale features of an image can be effectively extracted using the enhanced Res2Net module, the approach in this paper may still have some limitations for detail preservation and subtle changes in high-resolution videos. Applying it to video style transfer and enhancing its performance in diverse dynamic scenes is our next major step.

Acknowledgement: Thanks to Unsplash for providing the API for the full gallery, which facilitates the construction of experimental datasets for this paper.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the Key R&D and Transformation Projects of Xizang (Tibet) Autonomous Region Science and Technology Program (funder: the Department of Science and Technology of the Xizang (Tibet) Autonomous Region), funding (grant) number: XZ202401ZY0004.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Qiming Li and Mengcheng Wu; methodology, Qiming Li and Mengcheng Wu; software, Mengcheng Wu; validation, Qiming Li, Mengcheng Wu, and Daozheng Chen; formal analysis, Qiming Li and Mengcheng Wu; investigation, Qiming Li, Mengcheng Wu, and Daozheng Chen; resources, Qiming Li and Mengcheng Wu; data curation, Mengcheng Wu; writing—original draft preparation, Qiming Li and Mengcheng Wu; writing—review and editing, Qiming Li, Mengcheng Wu, and Daozheng Chen; visualization, Mengcheng Wu; supervision, Qiming Li; project administration, Qiming Li and Daozheng Chen; funding acquisition, Qiming Li and Daozheng Chen. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Due to Unsplash’s commercial restrictions, we are unable to publicize the dataset, but we can publicize how the dataset was collected. If you want to get the dataset, you can get API access from Unsplash.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Gao SH, Cheng MM, Zhao K, Zhang XY, Yang MH, Torr P. Res2Net: a new multi-scale backbone architecture. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2021;43(2):652–62. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2019.2938758. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Ouyang D, He S, Zhang G, Luo M, Guo H, Zhan J, et al. Efficient multi-scale attention module with cross-spatial learning. In: 2023 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing; 2023 Jun 04–10; Rhodes Island, Greece. doi:10.1109/ICASSP49357.2023.10096516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Gatys LA, Ecker AS, Bethge M. Image style transfer using convolutional neural networks. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. p. 2414–23. [Google Scholar]

4. Hafner M, Katsantoni M, Köster T, Marks J, Mukherjee J, Staiger D, et al. CLIP and complementary methods. Nat Rev Methods Primers. 2021;1(1):20. doi:10.1038/s43586-021-00018-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Dong C, Loy CC, He K, Tang X. Image super-resolution using deep convolutional networks. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2015;38(2):295–307. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2015.2439281. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Luan F, Paris S, Shechtman E, Bala K. Deep photo style transfer. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 4990–8. [Google Scholar]

7. Deng Y, Tang F, Dong W, Sun W, Huang F, Xu C. Arbitrary style transfer via multi-adaptation network. In: Proceedings of the 28th ACM International Conference on Multimedia; 2020 Oct 12–16; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 2719–27. doi:10.1145/3394171.3414015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Johnson J, Alahi A, Fei-Fei L. Perceptual losses for real-time style transfer and super-resolution. In: European Conference on Computer Vision; 2016 Oct 11–14; Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Springer. p. 694–711. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-46475-6_43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Huang X, Belongie S. Arbitrary style transfer in real-time with adaptive instance normalization. In: Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision; 2017 Oct 22–29; Venice, Italy. p. 1501–10. [Google Scholar]

10. Li C, Wand M. Combining markov random fields and convolutional neural networks for image synthesis. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. p. 2479–86. [Google Scholar]

11. Ignatov A, Kobyshev N, Timofte R, Vanhoey K, Van Gool L. DSLR-quality photos on mobile devices with deep convolutional networks. In: Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision; 2017 Oct 22–29; Venice, Italy. p. 3277–85. [Google Scholar]

12. Dosovitskiy A. An image is worth 16 × 16 words: transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv:2010.11929. 2020. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2010.11929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Ashish V, Shazeer N, Parmar N, Uszkoreit J, Jones L, Gomez A, et al. Attention is all you need. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2017;30:5999–6009. [Google Scholar]

14. Deng Y, Tang F, Dong W, Ma C, Pan X, Wang L, et al. StyTr2: image style transfer with transformers. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2022 Jun 18–24; New Orleans, LA, USA. p. 11326–36. [Google Scholar]

15. Goodfellow I, Pouget-Abadie J, Mirza M, Xu B, Warde-Farley D, Ozair S, et al. Generative adversarial nets. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2014;27:2672–80. [Google Scholar]

16. Isola P, Zhu J-Y, Zhou T, Efros AA. Image-to-image translation with conditional adversarial networks. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 1125–34. [Google Scholar]

17. Zhu J-Y, Park T, Isola P, Efros AA. Unpaired image-to-image translation using cycle-consistent adversarial networks. In: Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision; 2017 Oct 22–29; Venice, Italy. p. 2223–32. [Google Scholar]

18. Shim J, Kim E, Kim H, Hwang E. Enhancing image representation in conditional image synthesis. In: Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Big Data and Smart Computing (BigComp); 2023 Feb 13–16; Jeju, Republic of Korea. p. 203–10. doi:10.1109/BigComp57234.2023.00041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Kim H, Lee J, Hwang E. Face de-identification scheme using landmark-based inpainting. In: Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Human System Interaction; 2022 Jul 28–31; Melbourne, Australia. p. 1–5. doi:10.1109/HSI55341.2022.9869487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Zhu X, Cheng D, Zhang Z, Lin S, Dai J. An empirical study of spatial attention mechanisms in deep networks. In: Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision; 2019 Oct 27–Nov 2; Seoul, Republic of Korea. p. 6688–97. [Google Scholar]

21. Li Z, Sun Y, Zhang L, Tang J. CTNet: context-based tandem network for semantic segmentation. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2022;44(12):9904–17. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2021.3132068. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Qin Z, Zhang P, Wu F, FcaNet Li X. Frequency channel attention networks. In: Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision; 2021 Oct 10–17; Montreal, QC, Canada. p. 783–92. [Google Scholar]

23. Tao A, Sapra K, Catanzaro B. Hierarchical multi-scale attention for semantic segmentation. arXiv:2005.10821. 2020. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2005.10821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Wang X, Girshick R, Gupta A, He K. Non-local neural networks. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2018 Jun 18–22; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. p. 7794–803. [Google Scholar]

25. Zhang H, Goodfellow I, Metaxas D, Odena A. Self-attention generative adversarial networks. In: Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR 97; 2019 Jun 9–15; Long Beach, CA, USA. p. 7354–63. [Google Scholar]

26. Tang H, Bai S, Sebe N. Dual attention gans for semantic image synthesis. In: Proceedings of the 28th ACM International Conference on Multimedia; 2020 Oct 12–16; New York, NY, USA. p. 1994–2002. [Google Scholar]

27. Li B, Li X, Zhu H, Jin Y, Feng R, Zhang Z, et al. SeD: semantic-aware discriminator for image super-resolution. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2024 Jun 17–21; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 25784–95. [Google Scholar]

28. Radford A, Kim JW, Hallacy C, Ramesh A, Goh G, Agarwal S, et al. Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision. In: Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Machine Learning; 2021 Jul 18–24; PMLR. p. 8748–63. [Google Scholar]

29. Sammani F, Mukherjee T, Deligiannis N. NLX-GPT: a model for natural language explanations in vision and vision-language tasks. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2022 Jun 19–24; New Orleans, LA, USA. p. 8322–32. [Google Scholar]

30. Li Z, Tang J, Mei T. Deep collaborative embedding for social image understanding. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2019;41(9):2070–83. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2018.2852750. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Phillips F, Mackintosh B. Wiki Art Gallery, Inc.: a case for critical thinking. Issues Account Educ. 2011;26(3):593–608. doi:10.2308/iace-50038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Huiskes MJ, Lew MS. The mir flickr retrieval evaluation. In: The 1st ACM International Conference on Multimedia Information Retrieval; 2008 Oct 30–31; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 39–43. doi:10.1145/1460096.1460104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Chong MJ, Forsyth D. JoJoGAN: one shot face stylization. In: European Conference on Computer Vision; 2022 Oct 23–27; Tel-Aviv, Israel: Springer. p. 128–52. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-19787-1_8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Wu Z, Zhu Z, Du J, Bai X. CCPL: contrastive coherence preserving loss for versatile style transfer. In: European Conference on Computer Vision; 2022 Oct 23–27; Tel-Aviv, Israel: Springer. p. 189–206. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-19787-1_11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Zamzam O. PixelShuffler: a simple image translation through pixel rearrangement. arXiv:2410.03021. 2024. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2410.03021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Kwon J, Kim S, Lin Y, Yoo S, Cha J. AesFA: an aesthetic feature-aware arbitrary neural style transfer. In: Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2024 Feb 20–27; Vancouver, BC, Canada. Vol. 38, p. 13310–9. doi:10.1609/aaai.v38i12.29232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools