Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Sensitive Target-Guided Directed Fuzzing for IoT Web Services

School of Cyberspace Security, Information Engineering University, Zhengzhou, 450007, China

* Corresponding Author: Qiang Wei. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Security and Privacy in IoT and Smart City: Current Challenges and Future Directions)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 83(3), 4939-4959. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.063592

Received 18 January 2025; Accepted 27 February 2025; Issue published 19 May 2025

Abstract

The development of the Internet of Things (IoT) has brought convenience to people’s lives, but it also introduces significant security risks. Due to the limitations of IoT devices themselves and the challenges of re-hosting technology, existing fuzzing for IoT devices is mainly conducted through black-box methods, which lack effective execution feedback and are blind. Meanwhile, the existing static methods mainly rely on taint analysis, which has high overhead and high false alarm rates. We propose a new directed fuzz testing method for detecting bugs in web service programs of IoT devices, which can test IoT devices more quickly and efficiently. Specifically, we identify external input entry points using multiple features. Then we quickly find sensitive targets and paths affected by external input sources based on sensitive data flow analysis of decompiled code, treating them as testing objects. Finally, we perform a directed fuzzing test. We use debugging interfaces to collect execution feedback and guide the program to reach sensitive targets based on program pruning techniques. We have implemented a prototype system, AntDFuzz, and evaluated it on firmware from ten devices across five well-known manufacturers. We discovered twelve potential vulnerabilities, seven of which were confirmed and assigned bug id by China National Vulnerability Database (CNVD). The results show that our approach has the ability to find unknown bugs in real devices and is more efficient compared to existing tools.Keywords

IoT devices are increasingly used in a wide range of application scenarios in people’s daily lives, including smartwatches, electronic cars, and smart homes. The number of IoT devices is expected to reach 40 billion by 2030 [1]. Among all IoT devices, wireless routers and network cameras have suffered more attacks than other IoT devices, mainly because their web services expose exploitable vulnerabilities. In 75% of scenarios, routers act as gateways for IoT attacks [2].

Typically, router devices provide users with a web interface for management and configuration. When a user interacts with the frontend page, a Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) request is sent to the backend program. The backend program then parses the user’s request and invokes the corresponding processing service. A vulnerability may be triggered when the backend program fails to properly validate and sanitize user request data, leading to potential security risks.

In recent years, various vulnerability detection methods for embedded devices such as routers have been proposed, which can be mainly categorized into static analysis and fuzzing. Static analysis methods include KARONTE [3] proposed in 2020, SaTC [4] in 2021, Emtaint [5] in 2023, and HermeScan [6] in 2024, along with other notable works [7,8]. However, static analysis has inherent limitations, such as high false positive rates and the need for manual verification. Additionally, the existing taint analysis execution for IoT binary programs is also relatively inefficient. Fuzzing methods include UCRF [9], FirmFuzz [10], Snipuzz [11], and IoTScope [12]. Due to the challenges in simulating embedded devices and collecting coverage, these fuzz testing methods are often black-box. Some gray-box fuzz testing methods like Firm-AFL [13] and EQUAFL [14] rely on firmware rehosting [15–18], which has its limitations. Firstly, existing emulation techniques often struggle to directly emulate all firmware, requiring significant manual effort. Secondly, simulated environments may not accurately replicate the exact operating system and library behaviors of the target device, which can lead to false positives or false negatives during fuzzing. Moreover, they use random mutation strategies without effective mutation of parameters based on HTTP structures, leading to lower bug-triggering efficiency.

To address the limitations of existing methods in vulnerability discovery for IoT devices, we propose a novel approach, AntDFuzz, to realize targeted fuzzing test for firmware service programs. In order to achieve a more efficient static analysis for identifying sensitive targets, we employ a sensitive data flow analysis method based on decompiled code. Firstly, we add multiple matching features to more accurately identify external input entry points based on shared keywords between the front and back ends. We then obtain decompiled code based on the firmware program, based on which we perform sensitive data flow analysis to find out the locations and paths of dangerous function call points that are affected by external input and may trigger vulnerabilities. Finally, we implement directed fuzz testing of sensitive targets using debugging interfaces and program pruning techniques. Specifically, we utilize a debugging interface-based approach to collect program execution coverage. This approach does not rely on rehosting technology and can be executed both in simulated environments and on real devices with good scalability. Our fuzzing is divided into two phases: exploration and crash. First, we implement sensitive goal orientation by pruning the program space, directing the program execution to the location of dangerous function call points and obtaining input information. Then, based on the dependency relationship between target point and source point, we direct input for destructive mutation to trigger vulnerability.

We have implemented a prototype system, AntDFuzz, and evaluated it on 10 popular routers from 5 different vendors, discovering 12 potential vulnerabilities, 7 of which have been assigned CNVD number. Additionally, we have evaluated the performance of AntDFuzz. Compared to the state-of-the-art tools, our approach enables more effective vulnerability detection.

The main contributions we have made in this paper are as follows:

• We achieve more accurate localization of external input sources and perform security analysis on firmware based on decompiled code, quickly identifying potential dangerous targets and paths in embedded devices.

• We propose a directed fuzz testing approach for IoT devices, utilizing debugging interfaces to collect coverage and employing program pruning and high-quality mutation strategies to guide program execution to specific targets for testing.

• We implement a prototype system and evaluate it on 10 router devices from 5 vendors, discovering 12 0-day vulnerabilities. Compared to state-of-the-art tools, our approach detects vulnerabilities more effective.

The remaining sections of this paper are organized as follows. Section 2 discusses the background of IoT security. Section 3 provides an overview and describes the detailed design. Section 4 describes the system implementation. Section 5 evaluates our approach. Section 6 summarizes the approach proposed in this paper. Section 7 discusses the future work.

IoT plays a vital role across various fields, enhancing efficiency, automation, and real-time data analysis. It helps businesses and systems improve operations and create innovative solutions. Below are key IoT applications in different sectors.

(1) Smart City

Smart cities use IoT devices and sensors to manage infrastructure and services, such as transportation, energy, water, and waste management. Real-time data allows cities to optimize resources and improve quality of life. However, data security and privacy concerns must be addressed to protect residents’ information.

(2) Internet of Medical Things (IoMT)

IoMT connects medical devices to networks for continuous health monitoring. It allows remote care and real-time tracking of vital signs, improving patient management, especially post-COVID. Security risks remain, as many IoMT devices are vulnerable to cyberattacks, making data privacy a top concern.

(3) Smart Grid

Smart grids use IoT to optimize electricity distribution, integrating renewable energy and improving efficiency. They enable real-time monitoring of energy consumption, but security measures are crucial to protect critical infrastructure from cyber threats.

(4) Internet of Vehicles (IoV)

IoV connects vehicles and infrastructure to enhance safety and efficiency. It enables features like traffic optimization and collision avoidance but requires strong security to protect the transportation system from cyberattacks.

In summary, IoT applications drive innovation and efficiency in multiple sectors, but addressing security and privacy concerns is essential for maximizing their potential.

2.2 IoT Architecture and Security Challenges

The IoT architecture is typically divided into four layers: the Perception Layer, Network Layer, Processing Layer, and Application Layer. Each layer has its unique functionalities and security challenges.

1. Perception Layer: This layer is responsible for data collection through sensors, actuators, and other IoT devices. It is the physical layer where devices interact with the environment. However, due to the resource-constrained nature of these devices, they are often vulnerable to physical attacks, such as node tampering, malicious code injection, and sleep deprivation attacks. Additionally, the lack of robust security mechanisms in low-power devices makes them easy targets for adversaries. To address these challenges, it is essential to reinforce physical designs, employ tamper-proof technologies, and integrate hardware security modules (such as Trusted Platform Modules or Secure Elements) to enhance the resilience of devices against attacks. To prevent attackers from exploiting weak devices to enter the network, lightweight encryption algorithms and low-power security protocols are often employed, ensuring both security and energy efficiency.

2. Network Layer: The network layer facilitates communication between devices, gateways, and cloud services. It is responsible for data transmission and routing. This layer is susceptible to network-based attacks such as Denial of Service (DoS), Man-in-the-Middle (MitM), and Sinkhole Attacks. The heterogeneity of communication protocols and the lack of standardized security measures further exacerbate the vulnerabilities in this layer. To address these issues, traffic analysis and filtering techniques, rate limiting, and Intrusion Detection Systems can be employed to mitigate DoS attacks. To prevent MitM attacks, encryption protocols and end-to-end encryption are used to ensure the integrity and confidentiality of data transmission.

3. Processing Layer: This layer involves data storage and processing, often in the cloud. Common security threats in the processing layer include data breaches, unauthorized access, and data tampering. Ensuring data privacy and integrity is a major challenge at this layer. To mitigate these risks, data encryption during both transmission and storage is a standard solution, ensuring that even if data is intercepted, attackers cannot read sensitive information. Additionally, blockchain-based solutions offer immutable audit logs, ensuring data integrity and traceability. As the number of IoT devices and the volume of data increase, balancing data processing performance with security is another challenge. Distributed and decentralized processing methods, such as edge computing, can help alleviate the pressure on centralized cloud servers, improve data processing efficiency, and simultaneously reduce potential security vulnerabilities.

4. Application Layer: The application layer provides services and interfaces for end-users, enabling them to interact with IoT devices. This layer is vulnerable to malware, spyware, and phishing attacks. Additionally, weak authentication mechanisms and insecure Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) can lead to unauthorized access and data breaches. To address these, regular firmware updates, real-time malware detection systems, and sandboxing techniques can effectively prevent malware propagation.

IoT devices face a variety of security threats primarily due to their inherent limitations and the nature of their environment. Many of these devices are designed with minimal computing power and low-cost components to ensure affordability and efficiency for specific applications. This design choice leaves little room for the integration of advanced security features, making these devices particularly vulnerable to cyberattacks. A lot of work has discussed various aspects of the security of IoT devices. For example, reference [19] explored the importance of antenna systems in IoT networks. Reference [20] discussed the application of machine learning in addressing security issues in wireless sensor networks. Additionally, reference [21] investigated the use of big data and artificial intelligence technologies to tackle the security challenges faced by smart grids.

Given the complexity of IoT devices and their vulnerabilities, effective vulnerability detection has become a significant challenge. Researchers have categorized IoT security issues into software-level threats and hardware-level threats. In the context of software-layer security threats, the network service programs of IoT devices are often the primary targets for attackers. These service programs manage communication between devices and the network, handling data transmission, storage, and processing. However, their complexity and inherent vulnerabilities provide attackers with opportunities for intrusion. Existing detection methods that rely solely on static analysis exhibit low accuracy, while current fuzz testing methods suffer from a high degree of randomness. To address these issues, we have designed a more effective approach to mitigate these problems.

We present AntDFuzz, a directed fuzzing approach for web services on IoT devices. By employing lightweight static analysis to identify sensitive targets, AntDFuzz directs fuzz testing to specific program spaces, leading to more effective vulnerability discovery. As shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Overview

First, we extract static information from the firmware program to be analyzed, including request and handler function mapping information, external input parameter parsing function, basic block information, parameter and value information, etc., to assist the later sensitive target extraction and fuzzing phases. Here we propose a parametric parsing function recognition method based on shared keywords and multi-feature matching, which can improve the recognition accuracy.

Then, we design a lightweight method for sensitive target extraction. Based on the previously analyzed external input sources (source) and dangerous function call (sink) locations, we perform the reachable data flow analysis on the decompiled code to identify potential sensitive targets and paths within the program. These targets and paths are then translated into corresponding basic block locations.

Finally, we propose a target-oriented approach for fuzzing embedded devices. We collect program execution information through debugging interfaces and prune the original Control Flow Graph (CFG) as a test space based on reverse-sensitive path solving. This process guides fuzzing to focus on target locations. The mutation phase incorporates extracted parameters and control information, employing a staged mutation strategy to guide the program faster to reach and trigger vulnerabilities.

3.2 Entry Point Identification and Static Information Extraction

3.2.1 Multi-Feature Based External Parameter Parsing Function Identification

After the front-end sends a request to the backend, a corresponding handler function processes it. We extract the mapping between user requests and handler functions based on methods in UCRF. Within the handler functions, there is usually a specific function designed to parse and extract parameters from user requests for subsequent processing. By identifying these functions, we can locate the user data entry points and determine the parameters that the handler function needs to parse, thus aiding in generating effective data packets.

Existing methods identify external parameter parsing functions by locating references to shared keywords between the front end and back end as function call parameters, and then selecting the most frequently occurring functions. However, backend programs may also use these keywords as parameters in setting or comparison functions, leading to false positives. To address this, we incorporate additional features to enhance accuracy. Specifically, one parameter of the parameter parsing function is typically a structure variable that stores request data, and another parameter is the shared keyword between the front and back ends. There is often a third parameter used for default settings, but this is not considered a necessary feature. Inside the parameter parsing function, loops and string comparisons like strcmp are commonly used to match and extract values from the parsed parameters against the requested parameter list. Finally, parameter parsing functions are usually called frequently within request handling functions.

Our approach to parameter resolution function identification is shown in Algorithm 1. First, we perform static analysis on the front-end page files to extract parameter strings shared between the front end and back end. To ensure the uniqueness of these parameter strings and avoid redundant processing, we remove any duplicates from the extracted list. This deduplication step reduces unnecessary computations and improves the efficiency of the subsequent analysis. Next, we locate the positions of function calls within the scope of request handling functions that use the shared parameter strings as argument, and determine if there is another argument of variable type. When this condition is met, we further check for the presence of loops and functions similar to strcmp within the function. We utilize a dictionary to record functions and calls that satisfy the identified features. To reduce time overhead, when encountering a function that has already been analyzed, we directly increment its counter without re-analyzing its internal structure. Finally, we sort the function calls based on their frequency and identify the most frequently called function as parameter parsing function.

3.2.2 Extraction of Basic Blocks and Internal Key Information

To facilitate subsequent path exploration and vulnerability verification, we need to extract binary basic blocks and mutation auxiliary information. We start by analyzing the initial basic block of the request handler function, obtaining information about the basic block and its successor basic blocks, and constructing CFG based on the node and edge information of the basic blocks.

When the backend handler function handles user requests, it performs different processing based on the parameters and their values provided by the user. Therefore, the program can be guided to different locations by setting the parameters in the data packet. In static analysis, we need to extract the keys and potential value constraints required for the current request. We perform this task concurrently with the analysis of basic blocks, extracting key-value relationships and constraints based on the function calls within the basic block.

Key-value parameters are parsed by external input parameter parsing functions identified earlier. By tracing its function calls, we can extract the parameters that it parses, i.e., the keys. Subsequently, we collect constraint information regarding how HTTP request parameters impact control flow within the handler functions. Instead of accurately identifying detailed constraints for each parameter, which would significantly increase our initial analysis overhead, we simply collect critical strings and values that affect control flow and add them to the mutation phase of the later exploration to bypass key control nodes. Specifically, we gather conditions for basic block branch jump statements. We collect constant strings for comparisons performed by the strcmp-like functions, and numeric values used in comparisons. For parameter parsing functions, which is common to provide a default parameter value used when the specified parameter is not set, we also collect these default values as a subset of parameter value constraints.

3.3 Sensitive Target Extraction Based on Data Flow Analysis of Decompiled Code

The role of this section is to employ a lightweight approach to identify the hazardous function locations and hazard paths where the dangerous parameters are affected by external input data.

3.3.1 Decompiled Code Generation and Mapping Relationship Extraction

First, we generate decompiled code of the original firmware using existing decompilation tools. During this process, we obtain the mapping between function call line numbers in the decompiled code and function call addresses in binary program. In subsequent static analysis of the binary program, we will also extract the mapping between function calls and their corresponding basic blocks. This allows us to convert function call in decompiled codes to their corresponding basic blocks in the binary, preparing for future dynamic analysis.

3.3.2 Reachable Data Flow Analysis Based on Decompiled Code

We use the extracted parameter values from the parameter parsing functions identified in the previous phase as source points, and treat the dangerous parameters of common hazardous functions as sink points. We then employ the existing source-code-based static data flow analysis tool Joern [22] to perform data reachability analysis. This enables us to identify the locations of hazardous function calls that may be a security risk, and the dependencies between their dangerous parameters and external input sources.

3.3.3 Aggregation of Sensitive Data Flow Information

After the previous analysis, we can get the sensitive data flow paths and dependencies from source points to sink points. However, for subsequent dynamic automated validation, we need to organize the analysis results. We classify the sensitive data flow analysis results into four categories: (a) source and sink are within the same function and both are handler function; (b) source and sink are not within the same function, but the source is located in a handler function; (c) source and sink are within the same function, but neither are handler function; (d) source and sink are not within the same function, and the source is not located in a handler function.

Our dynamic analysis begins at the handler function. Therefore, when the source is located within the handle function, we can directly explore both intra-procedural and inter-procedural paths according to the data flow analysis path. However, when the source is not within the handle function, we need to identify a path from a handle function entry to the function containing the source, and then concatenate this with the data flow path from source to sink, forming a complete path from the handle function to the sink. To achieve this, we employ a cross-referencing method, using a breadth-first strategy to recursively search upwards for functions that call the function containing the source, until we encounter a handle function. We define the recursion depth to prevent endless exploration of unreachable paths.

When the source and sink are located within the same function, only the sink point location needs to be preserved. However, when they are not within the same function, we must consider inter-procedural call relationships. We keep only the entry and exit points within the function in the data flow analysis path, where the entry point represents the start of the function and the exit point is either a function call to the next function or the final hazardous function call. The entry and exit points are then mapped to their respective basic block locations in the binary based on the previously constructed mapping relationships.

3.4 Sensitive Target-Guided Directed Fuzzing

3.4.1 Target-Oriented Approach Based on Debugging Interfaces and Program Pruning

Like gdbFuzz [23], we use the debugging interface to gather information about program execution. By connecting to the target program through GDB, we achieve dynamic instrumentation during program execution by setting and handling breakpoints. This approach does not rely on firmware rehosting technology and can be used on real devices, offering good scalability.

To guide the program from handler function entry point to target points, we perform pruning of the program, retaining only the basic blocks relevant to the sensitive path. For each handler function, the entry point is the starting basic block, while the end node becomes the basic block containing the target point or the basic block leading to the next function in the sensitive function call chain, with intermediate basic block paths all leading to the end node. For all set of these basic blocks, each increase in their coverage means a closer distance to the sink basic block. Consequently, we transform the reduction in distance to the target basic block into an increase in coverage after pruning.

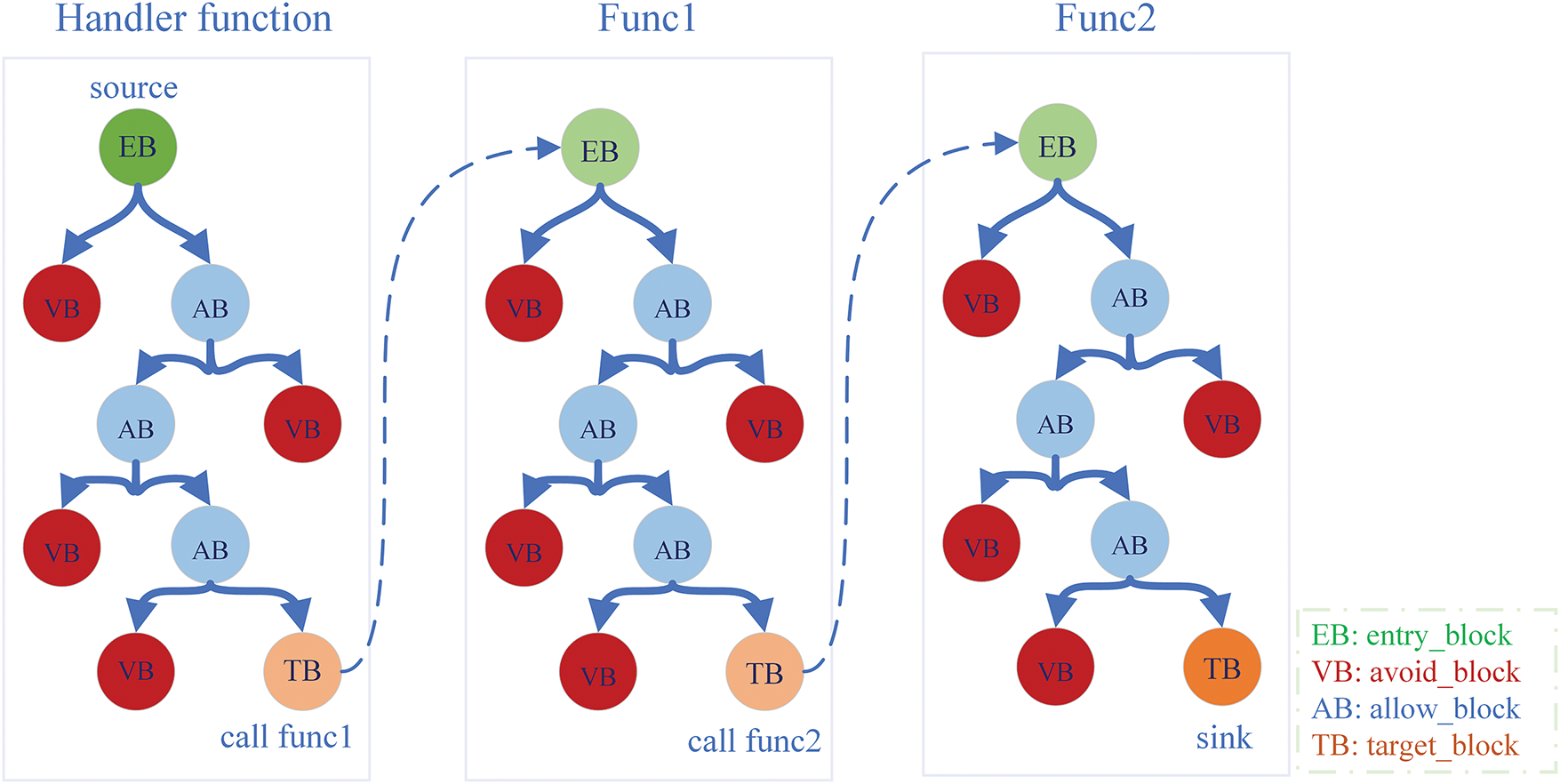

Since paths from the entry basic block of a handler function to the target block may pass through more than one function, we divide path pruning and basic block collection into intra- and inter-procedural processes. As shown in Fig. 2. Firstly, based on data flow analysis results from the previous process, we identify function call and call sites from the source to the target node. This enables us to determine function call paths and local entry and target points within each function. The local entry point is the starting basic block of the function, while the local target point is the basic block where the function calls the next function. We then identify all basic blocks contained in all paths from the local entry point to the local target point within each function. The union of these basic blocks represents the complete set of basic blocks traversed from source to sink, forming the pruned CFG.

Figure 2: Inter-procedural analysis

To retrieve all basic blocks along every path from the local entry point to the local target point within a function, we use a traversal of the reverse CFG. As shown in Fig. 3. We use the target basic block in the reverse CFG as the start point and employ a breadth-first search algorithm to explore and identify the basic blocks on the path to reach the function’s entry basic block. These basic blocks constitute the set of all possible paths from the function entry basic block to the target basic block. Since all basic blocks start from the function entry basic block, we can significantly reduce the overhead of exploration by utilizing the reverse CFG rather than the CFG. This is because the latter will explore all the nodes in the CFG from the start node, while the former is only a relevant part.

Figure 3: Intra-procedural analysis and pruning

We collect coverage at the granularity of basic blocks. We use all the extracted basic blocks as the coverage space and record their addresses as allow_addrs. Additionally, we identify edge basic blocks, which are successors of the relevant basic blocks but are not included in the relevant basic block set. These edge basic blocks indicate that the exploration has extended beyond the space that needs to be explored. We record these addresses as avoid_addrs. When the program execution encounters avoid_addrs, we allow it to return directly. Since our basic blocks are analyzed in a backward manner starting from the target basic block to the entry basic block, in other words, execution starting from the entry point can always proceed correctly in the forward direction. By pruning the program, we reduce the space for subsequent fuzzing exploration. Since the endpoints are sinks, we can achieve target-oriented fuzzing.

3.4.2 Path Exploration in the First Phase

We explore program paths based on input data parameter mutations, guiding program execution to the target basic blocks through breakpoint setting within the exploration space.

(1) Test Data Generation and Mutation. Instead of collecting seeds, we utilize an automated approach to generate input requests. Since the main information that affects the execution of the backend program is the request url and parameter settings, we have previously collected the relationship between the different request urls and the handler functions that correspond to them, and the information about the parameter key values contained within the basic block. For each test, we focus on a specific URL and handler function, using the union of parameter keys from all relevant basic blocks as the key list, and the union of all constraints as a subset for the parameter mutation dictionary. In addition, we incorporate common data types found in SOHO devices, such as time, IP address, Mac address, and so on. This part of the mutation is just to explore the path and does not expect the program to crash, so our mutation only needs to provide some normal values and simple mutation strategies, such as a limited range of numeric values or string lengths changes.

(2) Breakpoint Configuration and Handling. Based on the previous methods, we can get the basic block space for the current test. We set breakpoints at addresses in both allow_addrs and avoid_addrs. allow_addrs serves as the overall exploration space with a coverage of 1. During fuzzing, if an address from avoid_addrs is encountered, program tracing is halted. When an address from allow_addrs is encountered, we assess whether it is being accessed for the first time, indicating an increase in coverage. If it is, we record the newly added mutation parameters and values. Finally, when the target address is reached, we record the input data and end this exploration.

3.4.3 Crash Triggering in the Second Stage

(1) Test Data Mutation. Based on the previous analysis of sensitive data flows, we have identified the parameter that affects the target dangerous function. At this stage, we focus on performing crash-oriented mutations on this parameter value to attempt to trigger crashes. For example, this includes setting excessively long strings, replacing integers with special integer values, injecting command execution strings, and so on.

(2) Breakpoint Handling. The breakpoints in this phase are still set and handled as in the previous phase. However, when the target point is reached, it does not terminate directly, but continues execution and performs the exception detection mentioned below. Additionally, during this stage, we record the stack frame state of the current function to assist in the subsequent detection of stack overflow vulnerabilities.

(3) Exception Detection. We design three methods for detecting program exceptions:

• Stack Overflow Detection: Based on the debugging interface, we build the function stack frame information of each function when it is executed, and detect whether a buffer overflow occurs by detecting whether the function stack frame is corrupted during the execution of the programme.

• Command Execution Detection: We use a proxy server approach to detect potential command execution vulnerabilities by checking whether the proxy server is triggered after executing the basic blocks that may contain such vulnerabilities.

• Request-Response Detection: We determine whether a program has an exception by determining whether the request packet responds and whether the program has a segment error.

The static analysis part we implemented based on the existing powerful binary analysis tool IDA Pro. The front-end and backend shared parameter keywords and user request keywords we extracted using the code provided by the SaTC tool. We then develop IDA Python scripts to identify external parameter parsing functions and request handler functions, as well as to obtain basic blocks and key-value constraint information. The static decompilation of code and the mapping between decompiled code and binary code are implemented based on IDA Hex-Rays decompiler. For data flow analysis, we use Joern for data reachability analysis.

Finally, we implemented directed fuzzing based on debugging interfaces and program trimming methods by improving the GDBFuzz. GDBFuzz is a tool designed for fuzzing microcontroller boards via debugging interfaces but is not directly applicable to testing Linux-based firmware programs. We modified it to support the latter type of programs and incorporated our proposed goal-directed approach to directed fuzzing. Specifically, we followed its general fuzzing workflow, utilizing parts of its code for debugging interface interactions and fuzz initiation. We modified the initialization settings and breakpoint handling methods, and added exception detection mechanism. We divided the fuzzing process into two phases and redesigned the corresponding input generation and mutation, as well as breakpoint setting and handling strategies.

In this section we will evaluate our approach. We will answer the following questions:

• RQ1. Can AntDFuzz find real-world vulnerabilities? How does its performance compare to the state-of-the-art tools?

• RQ2. How accurate is the parameter parsing function recognition algorithm? Has there been an improvement compared to previous methods?

• RQ3. How does the sensitive data flow and target extraction method based on decompiled code compare to SaTC?

• RQ4. How effective is the directed fuzz testing proposed in this method?

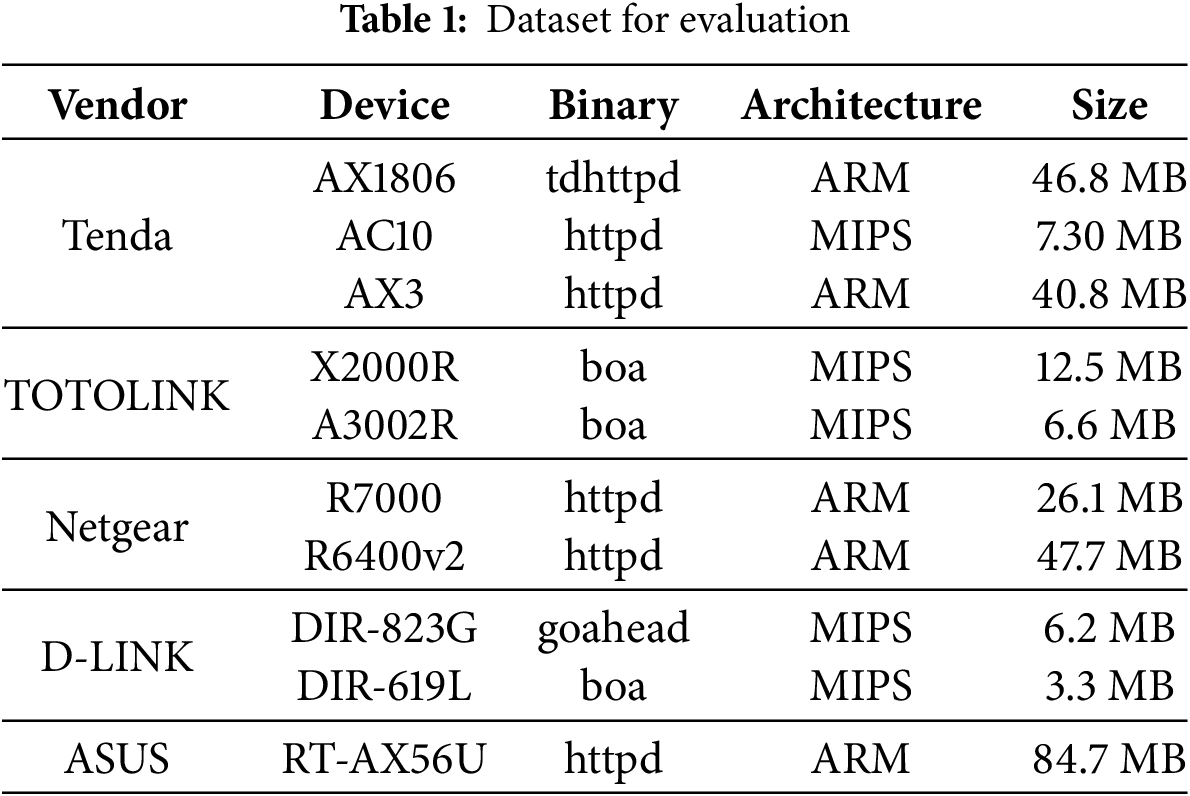

(1) Dataset. As shown in Table 1, we collected 10 devices from five major vendors to evaluate our approach. These vendors include Tenda, TOTOLINK, Netgear, D-LINK, and ASUS, all of which focus on networking and security services products such as routers, firewalls, and VPNs. The firmware includes both ARM and MIPS architectures, with an average size of 28.2 MB.

(2) Experiment Environment. We conducted our evaluation on an Ubuntu 20.04 system equipped with a 3.42 GHz Intel i9 processor and 16 GB of RAM.

5.2 Vulnerability Discovery in Real Word

5.2.1 Zero-Day Vulnerability Discovery

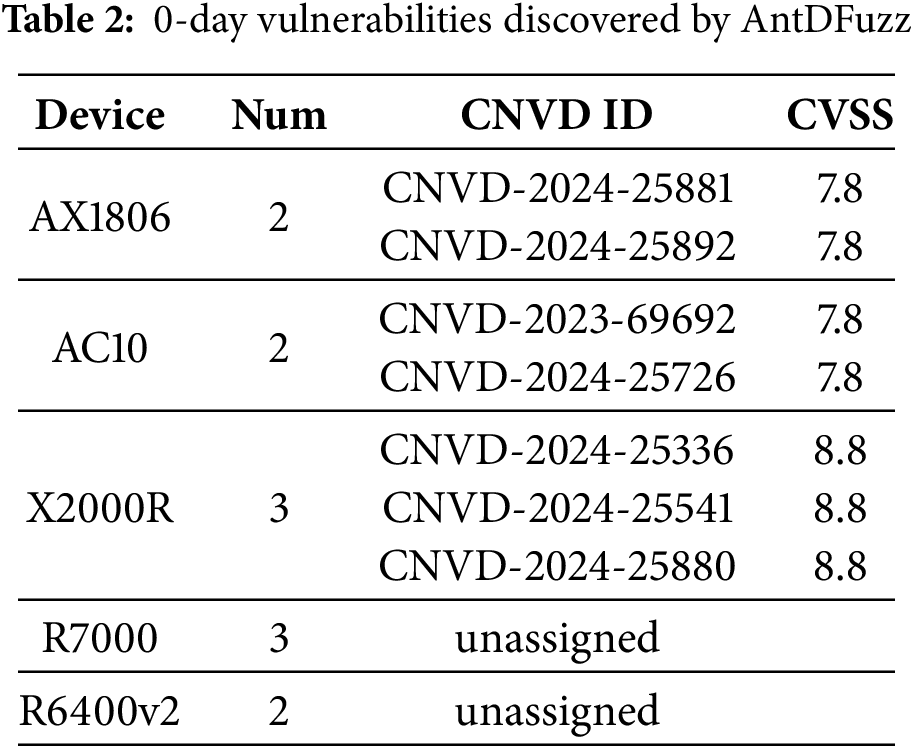

As shown in Table 2, AntDFuzz found twelve zero-day vulnerabilities on three devices, including eight buffer overflow vulnerabilities and four command injection vulnerabilities. The eight buffer overflow vulnerabilities arise from the program’s failure to properly check and validate external inputs, which are directly passed to unsafe functions such as strcpy, leading to stack overflows. Attackers can exploit these vulnerabilities to perform denial-of-service attacks on the devices or craft specially designed packets to hijack control flows, causing more severe damage. The four command injection vulnerabilities are due to the program does not filter external input, resulting in external inputs being directly concatenated into command strings by functions such as sprint, and then passed into a function like system for command execution. Attackers can exploit these vulnerabilities to execute arbitrary commands on the device or even take over the device directly.

We reported these vulnerabilities to CNVD, which will notify the product vendors through existing or public contact channels after verifying the vulnerabilities and urge them to address the issues. Currently, seven of the vulnerabilities have been assigned CNVD numbers and CVSS scores.

5.2.2 Comparison with Other Tools

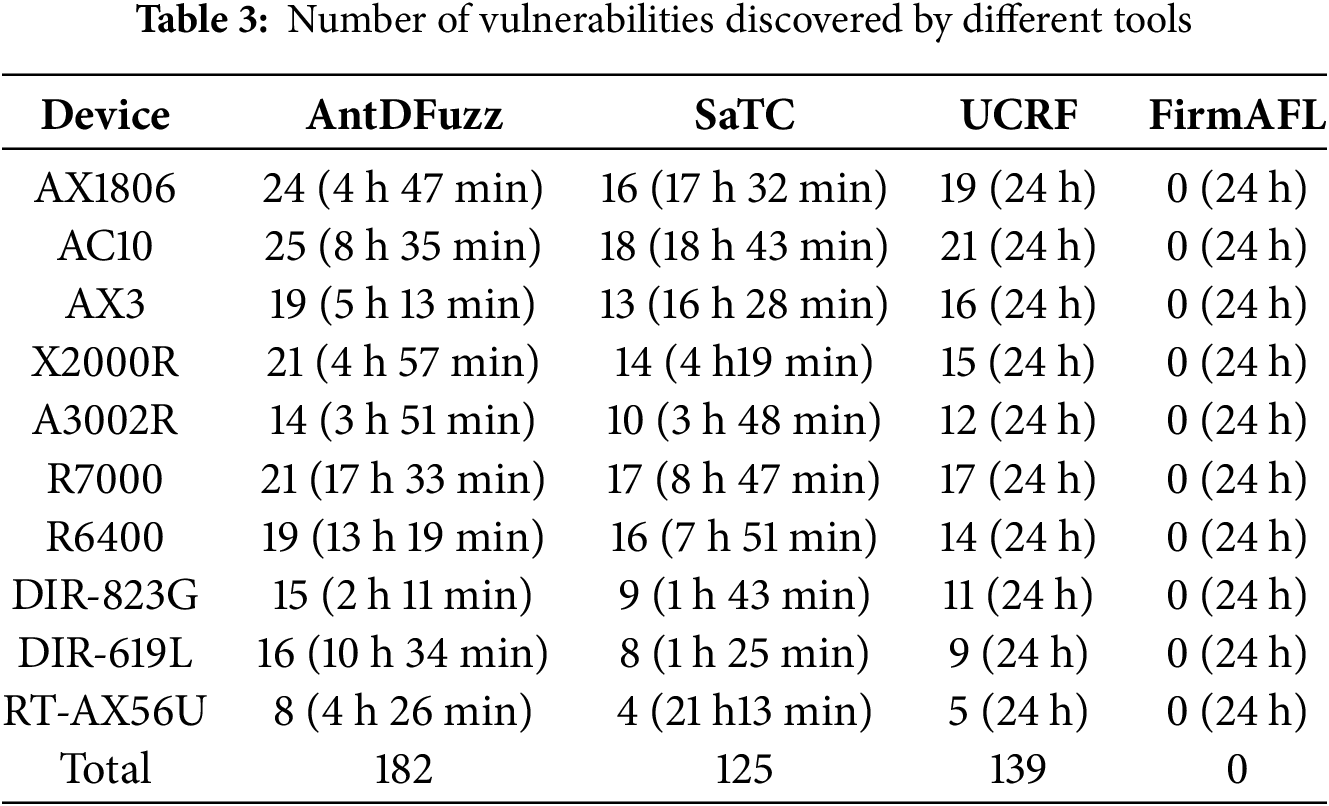

We compare the vulnerability discovery capabilities of our tool with the state-of-the-art tools SaTC, UCRF, and FIRM-AFL. These tools were chosen as they represent the most advanced techniques specifically targeting firmware systems, and each has unique characteristics aligning with our approach. SaTC is a state-of-the-art static analysis tool for detecting taint-based vulnerabilities in IoT devices. It identifies external data entry through frontend-backend keyword sharing and performs taint analysis, corresponding to our tool’s static analysis phase, which helps evaluate the effectiveness of our approach. UCRF is a state-of-the-art network black-box fuzzer for firmware systems that uses static analysis to acquire all communication interfaces and data constraints from the backend, generating more effective test cases. Our approach also employs static-assisted fuzz testing but introduces execution feedback via debugging interfaces, and the comparison with UCRF shows the effectiveness of this distinctive feature. Since the tool is not open source, we implemented one ourselves based on their paper idea. FIRM-AFL is the most advanced gray-box fuzzer for IoT devices that relies on emulation to provide coverage feedback and enhances fuzzing efficiency through augmented process emulation techniques. We collect coverage information based on debugging interfaces, which is also similar to gray-box fuzzing. A comparison with it can demonstrate the effectiveness of our structured mutation strategy.

Since our method differs from the approaches of previous tools, we conducted experiments based on their respective characteristics and compared the number of vulnerabilities discovered and the time required. Specifically, given that our tool performs fuzzing on the extracted targets, we set the termination criterion as the completion of testing all targets. Accordingly, we allowed both our tool and SaTC to complete their full analysis tasks, while for UCRF and FirmAFL, we conducted fuzzing for 24 h.

The final results are shown in Table 3, and we list the number of vulnerabilities discovered and the execution time for each device. Our tool found a total of 182 vulnerabilities, SaTC found 125, UCRF found 139, and FIRM-AFL did not uncover any vulnerabilities. After investigation, we conclude that FIRM-AFL’s direct application of AFL for mutation, with its random bit-level mutation strategy, is not suitable for structured inputs. Therefore, it is difficult to generate high quality test cases, which explains why it did not find any vulnerabilities. By obtaining sensitive data flow information in advance and utilizing a goal-oriented approach to quickly reach dangerous target locations, combined with our mutation algorithms, we were able to find more vulnerabilities in a shorter time compared to UCRF, surpassing the performance of black-box fuzzing.

We found more vulnerabilities than SaTC, which exceeded our expectations. We believe this is due to the fact that SaTC’s taint analysis is performed based on Angr’s symbolic execution, which has limitations such as static simulation, path explosion, and constraint solving issues. Additionally, SaTC’s method of locating taint sources only by frontend-backend shared keywords is also accurate. We believe these factors collectively limit SaTC’s capabilities. In contrast, our approach, which employs dynamic verification, offers higher accuracy and faster performance compared to symbolic execution on embedded firmware. Although we performed dynamic analysis, in most cases, our execution time was comparable to or faster than that of SaTC. However, in some devices, our execution time was significantly slower than that of SaTC. This can be primarily attributed to the extraction of a considerable number of false positive targets during the sensitive target extraction phase, which will be further discussed in the subsequent experimental section. Overall, our method is able to identify more vulnerabilities in a shorter amount of time.

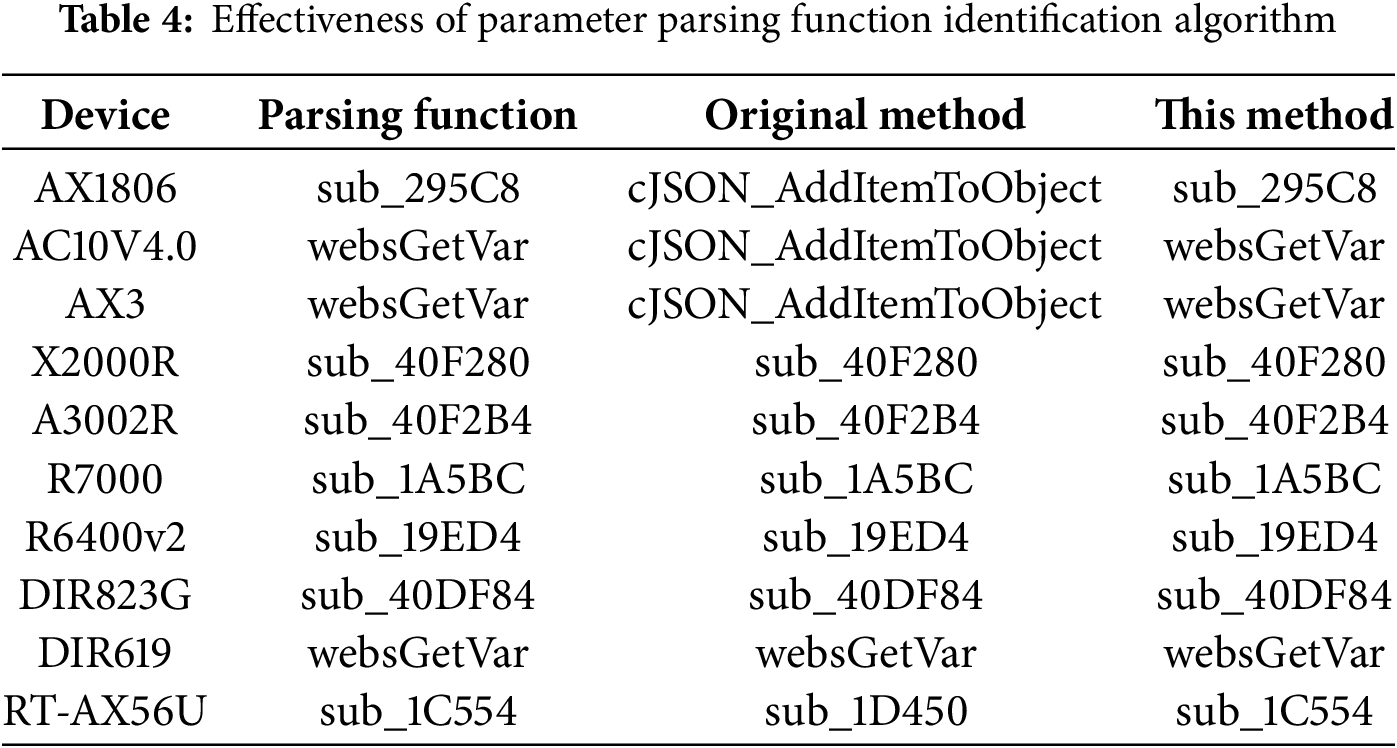

5.3 Effectiveness of Parameter Parsing Function Identification Algorithms

We only identify external parameter parsing functions here, resulting in a single identified target. We compared our algorithm with the method based only on shared keywords on the dataset. We evaluated the results of both methods against the actual parameter parsing functions identified through manual analysis, as shown in Table 4. Our method correctly identifies all parameter parsing functions, whereas the keyword-sharing method correctly identified only six. For instance, it incorrectly identifies the Tenda device’s variable storage function cJSON_AddItemToObject as a parameter parsing function because it also heavily references the shared keyword. However, it only performs storage operations and does not involve comparing strings, so it can be filtered out by looping and comparison features, leaving the correct parameter parsing function.

5.4 Effectiveness of Static Sensitive Data Flow Analysis

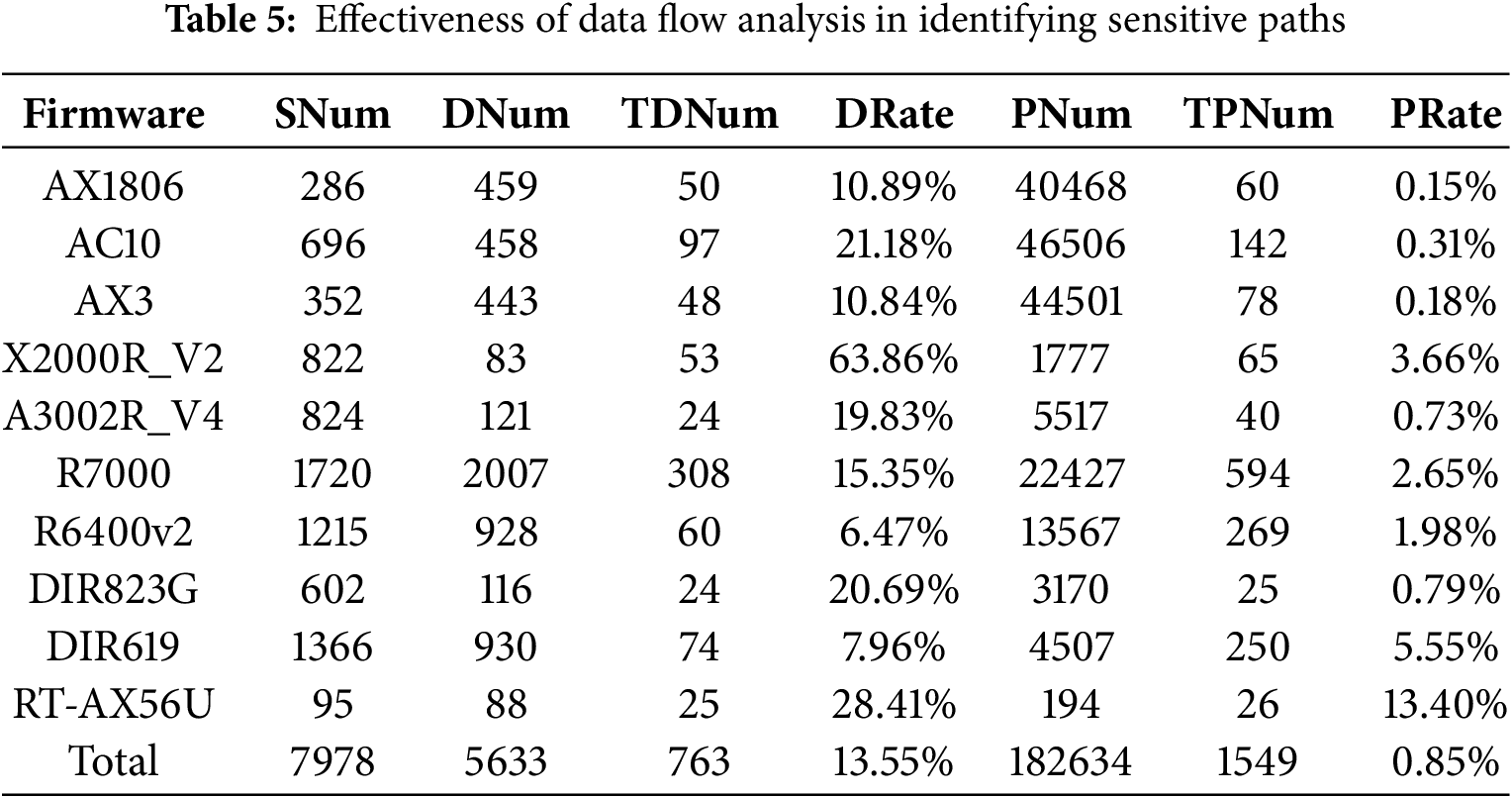

The black-box fuzzing UCRF performs random testing over the scope of program space of all request handler functions. In contrast, our method utilizes static code decompilation and sensitive data flow analysis to identify sensitive targets and paths influenced by external input sources. This approach removes targets without security risks, making subsequent fuzzing more targeted and improving fuzzing efficiency. As shown in Table 5, for each firmware, we present the number of external input sources (SNum), the number of sensitive targets (DNum) in handler functions, the remaining number of sensitive targets (TDNum) after data flow analysis, the ratio of sensitive targets to be analyzed (DRate) before and after data flow analysis, the number of original sensitive paths (PNum), the number of sensitive paths (TPNum) after data flow analysis, and their respective ratio (PRate). We reduced the number of analyzed targets by 85% and the number of analyzed paths by 99%. The paths to be analyzed represent all possible paths from the external entry point basic block to the dangerous function basic block. By considering whether the dangerous functions in the paths are truly affected by external input sources, the number of basic block paths that need to be analyzed can be significantly reduced.

We also compared our static analysis method with SaTC, and the results are shown in Table 6. For each tool, we report the number of alerts (Alert), the number of true positives (TP), their respective ratios (Rate), and the time taken (Time). Although there are some false positives, our method identifies more potential vulnerability locations in a shorter amount of time. The SaTC approach consists of two steps. First, it identifies all call paths from sources to sensitive functions. Then, it performs taint analysis on these paths to determine whether the sensitive functions are influenced by the sources. This process is highly time-consuming and can take up to several hours. Additionally, SaTC directly treats all locations where shared keywords are referenced as taint sources, which leads to many invalid analysis paths and results in a higher false positive rate. In contrast, based on sensitive data flow analysis at a source-code-like level, our method demonstrates higher efficiency in terms of execution time. In some firmware samples, we observed a relatively low true positive rate, which can be attributed to inaccuracies in the extracted decompiled code and partial data flow analysis. However, compared to the total number of data flows analyzed, it still eliminates a large number of irrelevant targets and provides meaningful targets for subsequent fuzzing.

5.5 Effectiveness of Directed Fuzzing Module

(1) Effectiveness of Program Pruning. We guide the program to reach sensitive target locations through program pruning. As shown in Fig. 4, for different firmware, we statistically analyze the total number of basic blocks in the binary program (TBlock), the number of basic blocks associated with handling functions (HBlock), and the number of remaining basic blocks after pruning (PBlock). The average number of basic blocks in the firmware is 18,099, while the average number of basic blocks associated with request handling is 5100. After analyzing the program’s sensitive data flow and performing pruning, the number of basic blocks to be tested was reduced to 1477, which represents a 71% reduction in the testing space compared to the unpruned average.

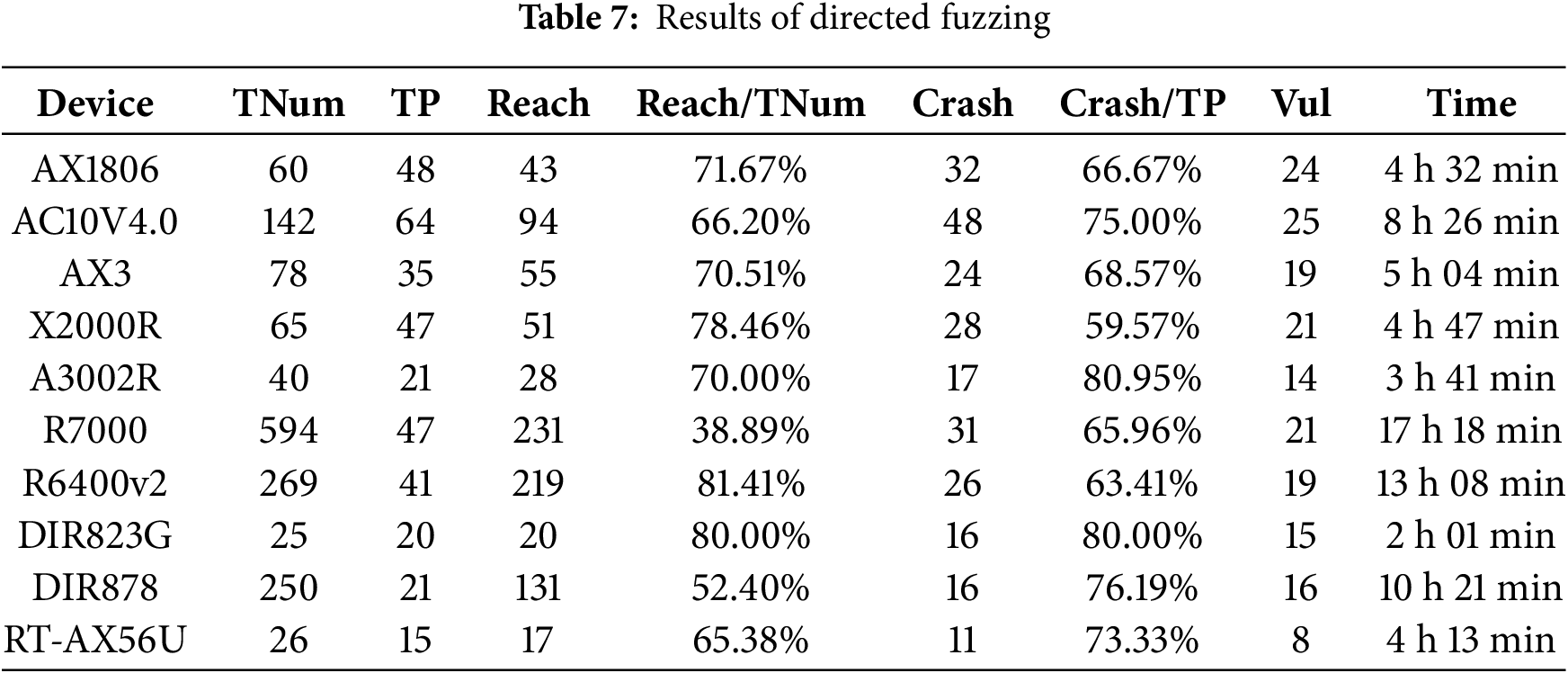

Figure 4: Area chart of various basic blocks

(2) Effectiveness of Directed Fuzzing. Table 7 presents the process data for directed fuzzing. We listed the number of devices to be tested (TNum), the number of true positives (TP), the number of reachable sensitive targets (Reach), the ratio of Reach and TNum (TP/TNum), the number of crashes (Crash), the ratio of crashes to true positives (Crash/TP), the number of unique vulnerabilities (Vul), and the total time consumed to complete all tests (Time). The reachability of sensitive targets depends on both the reachability of the paths themselves and whether the path constraints are satisfied. During the testing process, an average of 57% of sensitive targets were found to be reachable. Approximately 70% of the path cases that posed actual risks were validated, generating Proof of Concept (PoC) exploits that triggered crashes. This indicates that the method can significantly reduce the labor intensity of manual analysis and further dynamically validate the results of static analysis. Given that the sensitive paths to be tested are known, along with effective mutation and feedback information, this method requires less time compared to conventional fuzzing.

(3) Ablation Experiment: Comparison of No Pruning and Debugging Interface. We reduce the program’s testing space by applying pruning techniques and a debugging-interface-based execution information collection mechanism, building upon the static analysis described earlier. This approach allows for early termination of irrelevant path exploration, thereby optimizing seed selection and mutation speed, enabling the program to reach the target path more efficiently. To validate the effectiveness of this strategy, we designed a control experiment by comparing it with a fuzzing tool that does not implement the proposed method, while keeping all other components unchanged. In this comparison, path exploration is conducted solely based on previously collected testing information and feedback, similar to the approach used by traditional Web fuzzers. Essentially, the goal of this strategy is to enhance testing efficiency by avoiding irrelevant paths early in the process. Therefore, while the final testing results and target coverage are largely similar, there is a significant difference in the time required. We compared the time taken by both fuzzers to complete target exploration, as shown in Fig. 5. The results demonstrate that the strategy employing pruning and debugging interface information collection achieves a 2–3 times speedup compared to the traditional approach.

Figure 5: Comparison of fuzzing time

(4) Performance of Debugging Interface-based Fuzzing. We analyzed the time distribution and average throughput of key factors during fuzzing, as shown in Table 8. These include the average time proportions for restarting (RestartTR), breakpoint setting (BrkSetTR), and fuzzing (FuzzTR), as well as the average throughput for packet sending (PSTP) and overall throughput (TATP). The tool’s average throughput is relatively low, primarily due to two factors: (a) the limited computing power and memory of IoT devices, which often require rebooting (21.06% of test time), and (b) the inherent delays in network packet transmission. For instance, AFLNET, a leading network protocol fuzzer, achieves an average throughput of only 10.95. In contrast, interaction with the debugging interface accounts for just 0.53% of the time, indicating that device restart and initialization and network communication are the main performance bottlenecks in IoT fuzzing. Despite these challenges, our tool excels in vulnerability discovery by leveraging static analysis to identify and prioritize high-risk targets. This approach narrows the testing space, allowing us to focus resources on the most likely vulnerability-triggering locations. While our fuzzing speed may not be very fast, we focus on testing high-risk targets.

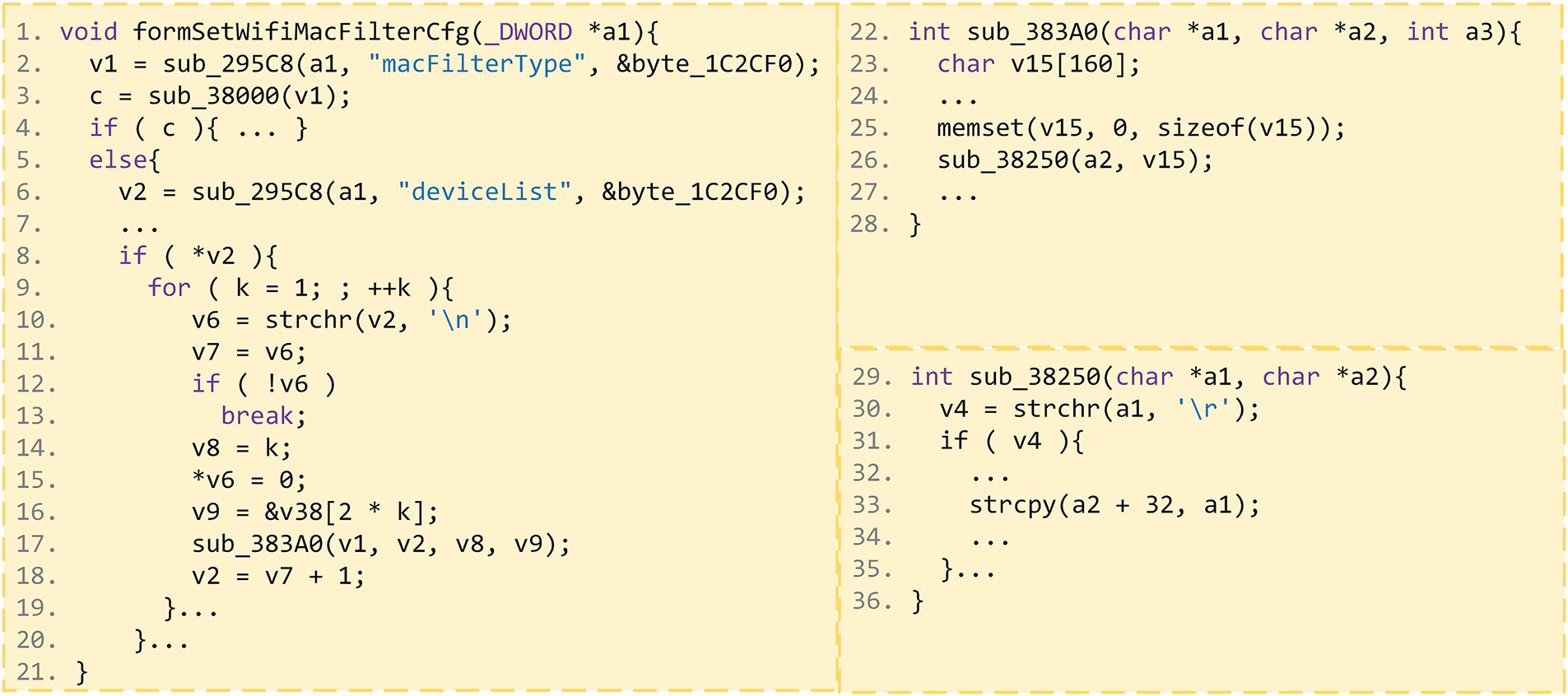

5.6 Case Study: CNVD-2024-25892

Fig. 6 shows the 0-day vulnerability CNVD-2024-25892 discovered by AntDFuzz in the Tenda AX1806. In this case, formSetWifiMacFilterCfg is the request handler function, where the external input parameter deviceList is parsed by the function sub_295C8 and passed to the variable v2. After a long process, it is then passed as a parameter to the function sub_383A0(), which in turn passes it to the function sub_38250(). Following some validation checks, it is finally passed into the dangerous function strcpy, resulting in a buffer overflow.

Figure 6: Case study

Firstly, we identify sub_295C8 as the parameter parsing function by the external input parsing identification algorithm. We then extract the decompiled code of the program and import it into Joern, using the parameter parsing function as the source and the hazard function as the sink. We perform sensitive data flow analysis to determine that the dangerous parameter of strcpy() in sub_38250() is affected by the external input parameter deviceList, and get the call path (line1→line17→line22→line26→line29→line33), which is parsed into corresponding basic blocks. In the directed fuzzing, for each intra-procedural context, we use the reverse CFG to determine the basic blocks along the path from the local end point, such as the basic block corresponding to line17, to the local start point, such as the basic block corresponding to line1. We then use the union of the obtained basic blocks for each intra-procedural context as the test space. We use GDB to set breakpoints and collect execution information. Additionally, we collected information on potential parameter values, such as “white” (appears as a constraint in function call of line3) and possible mutations, such as “\r” for each test basic block. This information is incorporated into the mutation module to assist with the mutation process. After exploring and reaching the sink point in the first phase and obtaining parameter information, we perform the second phase of destructive mutations to trigger the vulnerability.

Black-box fuzzing is blind and the lack of feedback to guide it makes it difficult to uncover deep vulnerabilities. For coverage-guided fuzzing, an increase in coverage does not always mean that new areas of vulnerability are explored. In this case, due to the long paths and multiple function calls, we find the sensitive target point in advance through static analysis and apply directed fuzz testing to focus on these targets, making the testing more targeted and avoiding excessive exploration of useless paths. Additionally, we incorporated potential constraint information from the paths into the mutation module to help bypass obstacles. By employing feedback-driven, goal-oriented approaches and effective mutation strategies, we are able to discover the vulnerability quickly.

We present AntDFuzz, a new and more effective method for detecting vulnerabilities in IoT web service programs. We will use the external input entry point identified through multiple features as the source point and the hazard function as the sink point. We utilize data flow analysis based on decompiled code to quickly locate sensitive targets and dangerous data flow paths influenced by external inputs. Subsequently, we implement a directed fuzzing method for embedded devices based on debugging interfaces and program pruning, guiding the program to reach dangerous code blocks and generate PoC in two stages. We evaluated our approach at 10 routers and found 12 0-day vulnerabilities, 7 of which have been assigned CNVD numbers. The evaluation shows that our method has the ability to discover unknown vulnerabilities in real devices. Compared to state-of-the-art methods, our approach is able to detect more vulnerabilities in a shorter amount of time.

In this section, we outline potential directions for improving AntDFuzz in the future.

(1) Enhancement of Static Analysis for Sensitive Target Identification

While current decompilers and static analysis tools have proven effective, there is still room for improvement in accurately identifying sensitive targets. With the rapid advancement of reverse engineering technologies and the increasing capabilities of large language models (LLMs) in code comprehension, we plan to explore LLM-assisted approaches to enhance the accuracy of our static analysis. Specifically, we aim to leverage LLMs’ semantic understanding capabilities to recover information lost during decompilation and improve the precision of our target identification process. This integration could potentially lead to more comprehensive vulnerability detection while maintaining high accuracy.

(2) Optimization of Fuzzing Efficiency for IoT Devices

Relatively speaking, the fuzzing speed of our tool is not fast, which is determined by the characteristics of the IoT device service programs. However, we can still make efforts to alleviate this issue. First, we believe the potential of static analysis in assisting dynamic analysis can still be explored, especially with the popularity of LLMs [24,25]. Based on APIs, they can help us automate the semantic understanding of the code, provide expert knowledge, and further narrow down the program’s testing targets. Additionally, we can consider optimizing the device interaction methods to minimize the number of restarts. Alternatively, we could explore parallel fuzzing through the use of multiple fuzzers and multiple devices working together to improve efficiency.

(3) Application Scenario Extension

Currently our tool primarily focuses on web service program in IoT devices. Given the scalability of the debugging interface-based approach, by modifying the fuzzing mutation strategies to collect diverse sensitive paths and constraint information for different types of programs, we can also extend this method to conduct directed fuzzing on common IoT binary programs.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Methodology, Xiongwei Cui; software, Xiongwei Cui; validation, Xiongwei Cui; writing—original draft preparation, Xiongwei Cui; writing—review and editing, Xiongwei Cui and Yunchao Wang; supervision, Qiang Wei. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Sinha S. Connected IoT devices forecast 2024-2030. 2024 [cited 2025 Jan 8]. Available from: https://iot-analytics.com/number-connected-iot-devices/. [Google Scholar]

2. Internet of things statistics for 2025—taking things apart 2023. [cited 2024 Feb 18]. Available from: https://dataprot.net/statistics/iot-statistics/. [Google Scholar]

3. Redini N, Machiry A, Wang R, Spensky C, Continella A, Shoshitaishvili Y, et al. Karonte: detecting insecure multi-binary interactions in embedded firmware. In: 2020 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP). San Francisco, CA, USA: IEEE; 2020. p. 1544–61. doi:10.1109/SP40000.2020.00036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Chen L, Wang Y, Cai Q, Zhan Y, Hu H, Linghu J, et al. Sharing more and checking less: leveraging common input keywords to detect bugs in embedded systems. In: 30th USENIX Security Symposium.USA: USENIX Association; 2021. p. 303–19. [Google Scholar]

5. Cheng K, Zheng Y, Liu T, Guan L, Liu P, Li H, et al. Detecting vulnerabilities in Linux-based embedded firmware with SSE-based on-demand alias analysis. In: Proceedings of the 32nd ACM SIGSOFT International Symposium on Software Testing and Analysis. Seattle, WA, USA: ACM; 2023. p. 360–72. doi:10.1145/3597926.3598062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Gao Z, Zhang C, Liu H, Sun W, Tang Z, Jiang L, et al. Faster and better: detecting vulnerabilities in Linux-based iot firmware with optimized reaching definition analysis. In: Proceedings 2024 Network and Distributed System Security Symposium. San Diego, CA, USA: Internet Society; 2024. doi:10.14722/ndss.2024.24346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Gibbs W, Raj AS, Vadayath JM, Tay HJ, Miller J, Ajayan A, et al. Operation mango: scalable discovery of taint-style vulnerabilities in binary firmware services. In: Proceedings of the 33rd USENIX Conference on Security Symposium. USA: USENIX Association; 2024. p. 7123–39. [Google Scholar]

8. Han H, Kyea J, Jin Y, Kang J, Pak B, Yun I. QueryX: Symbolic Query on Decompiled Code for Finding Bugs in COTS Binaries.In: 2023 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP). San Francisco, CA, USA: IEEE; 2023. p. 3279–95. doi:10.1109/SP46215.2023.10179314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Qin C, Peng J, Liu P, Zheng Y, Cheng K, Zhang W, et al. UCRF: static analyzing firmware to generate under-constrained seed for fuzzing SOHO router. Comput Secur. 2023;128(7):103157. [Google Scholar]

10. Srivastava P, Peng H, Li J, Okhravi H, Shrobe H, Payer M. FirmFuzz: automated IoT firmware introspection and analysis. In: Proceedings of the 2nd International ACM Workshop on Security and Privacy for the Internet-of-Things. London, UK: ACM; 2019. p. 15–21. doi:10.1145/3338507.3358616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Feng X, Sun R, Zhu X, Xue M, Wen S, Liu D, et al. Snipuzz: black-box fuzzing of IoT firmware via message snippet inference. In: Proceedings of the 2021 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; 2021. p. 337–50. doi:10.1145/3460120.3484543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Xie W, Chen J, Wang Z, Feng C, Wang E, Gao Y, et al. Game of hide-and-seek: exposing hidden interfaces in embedded web applications of IoT devices. In: Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2022. Lyon, France: ACM; 2022. p. 524–32. doi:10.1145/3485447.3512213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Zheng Y, Davanian A, Yin H, Song C, Zhu H, Sun L. FIRM-AFL: high-throughput greybox fuzzing of iot firmware via augmented process emulation. In: Proceedings of the 28th USENIX Conference on Security Symposium. USA: USENIX Association; 2019. p. 1099–114. [Google Scholar]

14. Zheng Y, Li Y, Zhang C, Zhu H, Liu Y, Sun L. Efficient greybox fuzzing of applications in Linux-based IoT devices via enhanced user-mode emulation. In: Proceedings of the 31st ACM SIGSOFT International Symposium on Software Testing and Analysis. Republic of Korea: ACM; 2022. p. 417–28. doi:10.1145/3533767.3534414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Kim M, Kim D, Kim E, Kim S, Jang Y, Kim Y. FirmAE: towards large-scale emulation of IoT firmware for dynamic analysis. In: Annual Computer Security Applications Conference. Austin, TX, USA: ACM; 2020. p. 733–45. doi:10.1145/3427228.3427294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Fasano A, Ballo T, Muench M, Leek T, Bulekov A, Dolan-Gavitt B, et al. SoK: enabling security analyses of embedded systems via rehosting. In: Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Asia Conference on Computer and Communications Security. Hong Kong, China: ACM; 2021. p. 687–701. doi:10.1145/3433210.3453093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Chen DD, Egele M, Woo M, Brumley D. Towards automated dynamic analysis for Linux-based embedded firmware. In: Proceedings 2016 Network and Distributed System Security Symposium. San Diego, CA, USA: Internet Society; 2016. doi:10.14722/ndss.2016.23415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Tay HJ, Zeng K, Vadayath JM, Raj AS, Dutcher A, Reddy T, et al. Greenhouse: single-service rehosting of linux-based firmware binaries in user-space emulation. In: Proceedings of the 32nd USENIX Conference on Security Symposium. USA: USENIX Association; 2023. p. 5791–808. [Google Scholar]

19. Khan S, Mazhar T, Shahzad T, Bibi A, Ahmad W, Khan MA, et al. Antenna systems for IoT applications: a review. Discov Sustain. 2024;5(1):412. doi:10.1007/s43621-024-00638-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Ghadi YY, Mazhar T, Shloul TA, Shahzad T, Salaria UA, Ahmed A, et al. Machine learning solutions for the security of wireless sensor networks: a review. IEEE Access. 2024;12(2):12699–719. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3355312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Yasin Ghadi Y, Mazhar T, Aurangzeb K, Haq I, Shahzad T, Ali Laghari A, et al. Security risk models against attacks in smart grid using big data and artificial intelligence. PeerJ Comput Sci. 2024;10(3):e1840. doi:10.7717/peerj-cs.1840. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Joern—The bug hunter’s workbench. [cited 2024 May 23]. Available from: https://joern.io/. [Google Scholar]

23. Eisele M, Ebert D, Huth C, Zeller A. Fuzzing embedded systems using debug interfaces. In: Proceedings of the 32nd ACM SIGSOFT International Symposium on Software Testing and Analysis. Seattle, WA, USA: ACM; 2023. p. 1031–42. doi:10.1145/3597926.3598115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Wang J, Yu L, Luo X. LLMIF: augmented large language model for fuzzing IoT devices. In: 2024 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP). San Francisco, CA, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 881–96. doi:10.1109/SP54263.2024.00211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Meng R, Mirchev M, Böhme M, Roychoudhury A. Large language model guided protocol fuzzing. In: Proceedings 2024 Network and Distributed System Security Symposium. San Diego, CA, USA: Internet Society; 2024. doi:10.14722/ndss.2024.24556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools