Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

An Analytical Review of Large Language Models Leveraging KDGI Fine-Tuning, Quantum Embedding’s, and Multimodal Architectures

1 Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Prasad V Potluri Siddhartha Institute of Technology, Vijayawada, 520007, India

2 Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Koneru Lakshmaiah Education Foundation, Vaddeswaram, 522302, India

3 Department of Computer Science and Engineering (Data Science), AVN Institute of Engineering and Technology, Hyderabad, 501510, India

4 Department of Computer Science and Engineering (Data Science), Vignan’s Institute of Management and Technology for Women, Hyderabad, 501301, India

5 Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Andhra Loyola Institute of Engineering and Technology, Vijayawada, 520008, India

* Corresponding Author: Uddagiri Sirisha. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Enhancing AI Applications through NLP and LLM Integration)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 83(3), 4031-4059. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.063721

Received 22 January 2025; Accepted 11 April 2025; Issue published 19 May 2025

Abstract

A complete examination of Large Language Models’ strengths, problems, and applications is needed due to their rising use across disciplines. Current studies frequently focus on single-use situations and lack a comprehensive understanding of LLM architectural performance, strengths, and weaknesses. This gap precludes finding the appropriate models for task-specific applications and limits awareness of emerging LLM optimization and deployment strategies. In this research, 50 studies on 25+ LLMs, including GPT-3, GPT-4, Claude 3.5, DeepKet, and hybrid multimodal frameworks like ContextDET and GeoRSCLIP, are thoroughly reviewed. We propose LLM application taxonomy by grouping techniques by task focus—healthcare, chemistry, sentiment analysis, agent-based simulations, and multimodal integration. Advanced methods like parameter-efficient tuning (LoRA), quantum-enhanced embeddings (DeepKet), retrieval-augmented generation (RAG), and safety-focused models (GalaxyGPT) are evaluated for dataset requirements, computational efficiency, and performance measures. Frameworks for ethical issues, data limited hallucinations, and KDGI-enhanced fine-tuning like Woodpecker’s post-remedy corrections are highlighted. The investigation’s scope, mad, and methods are described, but the primary results are not. The work reveals that domain-specialized fine-tuned LLMs employing RAG and quantum-enhanced embeddings perform better for context-heavy applications. In medical text normalization, ChatGPT-4 outperforms previous models, while two multimodal frameworks, GeoRSCLIP, increase remote sensing. Parameter-efficient tuning technologies like LoRA have minimal computing cost and similar performance, demonstrating the necessity for adaptive models in multiple domains. To discover the optimum domain-specific models, explain domain-specific fine-tuning, and present quantum and multimodal LLMs to address scalability and cross-domain issues. The framework helps academics and practitioners identify, adapt, and innovate LLMs for different purposes. This work advances the field of efficient, interpretable, and ethical LLM application research.Keywords

Large language models, emerging as transformative AI, have begun reshaping NLP and changing applications across broad spectra of usage, from running conversational agents to advancing research in biomedicine. Indeed, GPT-3 and GPT-4, alongside multimodal gems such as Claude 3.5 and GPT-3 variants, along with others similar in capability are marking the pinnacle of AI application at present, providing outstanding generation capabilities, elaborate reasoning, even with multimodality in use. However, their explosive growth [1–3] in terms of size, complexity, and scope of applications also brought several serious challenges related to high computation costs, a tendency to accumulate biases, and widespread hallucinations. Most available research reviews limited the scope, discussing either a single-task performance or a concrete model architecture alone, which leads to a weak representation of the area. This patchwork approach prevents one from establishing the best model for complex, domain-specific applications. Moreover, newly developed techniques [4–6] such as quantum embeddings, parameter-efficient tuning (e.g., LoRA), retrieval-augmented generation (RAG), and safety frameworks (e.g., GalaxyGPT) have not been investigated in an organized manner concerning their performance trade-offs and contextual suitability.

This paper seeks to bridge this gap by conducting an analytical review of state-of-the-art LLM methodologies. This work, through the categorization and comparison of 50 studies in healthcare, sentiment analysis, materials science, and more, presents a unified framework for understanding the optimization, application, and evaluation of LLMs. This review discusses innovative solutions to such issues as hallucination mitigation, low-resource task performance, and cross-modal adaptability through KDGI-enhanced fine-tuning, post-remedy mechanisms like Woodpecker, and multimodal frameworks like GeoRSCLIP. This article will equip researchers and practitioners with actionable insights into selecting and tailoring LLMs according to specific needs. This work discusses ethical issues and scalability challenges, providing a foundation for the development of interpretable, efficient, and robust LLM applications, which can meet the demands of modern AI deployments.

The reviewed studies indicate that domain-specific datasets are critical for improving the performance of large language models (LLMs) for specialized applications in fields like healthcare, law, and scientific research. Various methods have been attempted for efficiently creating high-quality domain-specific corpora. A popular class of such methods is retrieval-augmented generation (RAG), which links existing knowledge bases or structured databases with LLMs to strengthen factual correctness and domain relevance. Meanwhile, the automated creation of datasets through knowledge graphs has been shown to strengthen the contextual grounding of LLMs by simultaneously linking structured and unstructured data sources, as demonstrated in knowledge-enhanced LLMs (KGLLMs). Another promising avenue involves synthetic data generation in which models such as ChatGPT or GPT-4 generate domain-focused textual variations closely emulating real-world linguistic patterns while maintaining key semantic structures.

Besides the automated methods, fine-tuning with human-annotated datasets is another choice, although it has the drawback of being less scalable. Several studies have proposed using active learning scenarios, in which a first run of the model is iteratively refined through human validation to select the best samples for annotation. Crowdsourcing methods together with semi-supervised learning have also proved useful to augment domain-specific datasets with less manual effort. In addition, the use of multimodal channels to enrich LLM training with knowledge databases based on OCR of medical records or scientific literature in combination with structured tabular data is also actively being explored. These approaches together represent a way of resolving the data insufficient problem and enabling LLMs to adapt to specific domains.

This workbook is an efficient way of motivating the introduction of the increasing importance of large language models (LLMs) in numerous fields. The research questions seem to be somewhat scattered throughout different sections rather than laid out in one consolidated manner. The objectives of the research should be neatly spelled out in the introduction to provide better clarity to the readers on the key points the study intends to investigate. For instance, the following research questions could be more structured along the lines of: (i) How do fine-tuning techniques like retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) and knowledge graph integration impact LLM performance across different domains? (ii) What are some of the main challenges related to hallucinations in LLMs, and how well do state-of-the-art correction frameworks, such as Woodpecker, perform? (iii) How do multimodal LLMs perform in terms of computational efficiency and task-specific accuracy as compared to transformers working only on text? These questions should be held closely to the methodology of the study to ensure a smooth flow into subsequent sections.

Furthermore, a more structured articulation of research questions would assist the authors in making comparative evaluations of different LLM architectures. Twenty-five LLMs are mentioned in the paper, but the research gaps that these models seek to fill are not delineated. By articulating the contributions of domain-adapted LLMs such as DeepKet for quantum embedding, GalaxyGPT for safety-centric moderation, and GeoRSCLIP for remote sensing applications, more linkage could be created between the research questions and findings.

A comprehensive analysis of 50 studies across 25 architectures of LLMs is described in this text; however, it remains ambiguous what criteria were used to grant inclusion and exclusion. A systematic selection process should be elucidated to justify the dataset’s composition. Inclusion criteria could, for example, consider publication in the last three years, empirical benchmarking against standard NLP tasks, and availability of performance metrics in real-world applications. The exclusion criteria could include no open-source implementation of the models evaluated against transformer-based baselines or models that represent mere theoretical advancement without empirical validation. Such definitions would help promote the methodological accuracy of the study procedures.

Statistical parameters, apart from selection criteria, may add further depth to the comparative analysis of LLMs. Such factors can include efficiency during the tokenization process (ChatGPT-4 processing 10 K tokens per second vs. Claude 3.5 at 8.2 K), perplexity scores (GPT-4 at 14.5 vs. LLaMA-2 at 18.3 on the benchmark tasks), and sizes of fine-tuning datasets (GalaxyGPT at 2 M safety-aligned responses vs. the traditional at 800 K samples). With this, they can quantify the efficiency of the models in their performance metrics: parameter counts (GPT-4 at 1.7 T vs. GPT-3 at 175 B), energy consumption per 1 M token inferences (DeepKet achieving 30% reduction in computational overhead using quantum embeddings), and domain-specific accuracy scores.

Motivation & Contribution

Rapid development in LLMs has not only revolutionized NLP but also made an urgent necessity to understand and optimize its implementation across domains. Although much has been achieved, the field is still confronted with challenges, including a lack of standardization in benchmarking methodologies and an understanding of novel techniques’ trade-offs. Traditional reviews are usually incapable of incorporating newly developed paradigms like quantum-enhanced embeddings, safety-driven interaction frameworks, and multimodal architectures into their analyses. This fragmentation prevents the uptake of LLMs in applications involving high stakes, such as health care, autonomous systems, and precision medicine, where reliability and interpretability are important. The motivation for this study is, therefore, driven by the need to provide a coherent and unified overview that fills the gaps between them. This paper makes several contributions. It categorizes the state-of-the-art methodologies in LLM according to application areas, dataset characteristics, and performance metrics and establishes a taxonomy for comparative evaluation. Second, it all covers techniques that are recent and innovative like KDGI enhanced fine-tuning addressing data scarcity, and post-remedy by Woodpecker which also handles hallucination in multimodal. Third, it is related to the domain-specific innovation-adding quantum embeddings for increased parameter efficiency, for instance. Furthermore, there is a safety-centric model deployment as presented by GalaxyGPT. Based on a synthesis of broad insights garnered from various models and tasks, research work now presents the potential finding of the path in LLM land through the more-informed decision at hand regarding choice, tailoring, and deployment of the model. This paper, therefore, draws attention to the ethical considerations of LLMs, especially in sensitive applications such as healthcare and governance, and proposes frameworks that promote transparency and fairness. In so doing, the paper not only advances academic discourse but also serves as a practical guide for industry stakeholders who wish to harness the transformative potential of LLMs responsibly in the process.

2 Review of Existing Models for LLM Optimizations & Analysis

With large language models and the extensive proliferation of big-impact changes in extensive domains ranging from educational to industrial implementation, this literature review synthesizes the research to create a comprehensive taxonomy of LLM architectures and applications with their inherent limitations. The foundation of large language models, at a basic level, is built into the architectural design, assuming scalability, adaptability, and efficiency. As discussed in [4], the high parameter complexity of LLMs, such as OPT-30B, calls for innovative approaches to training and inference. Techniques like CPU-GPU cooperative computing and adaptive model partitioning can be optimized for better memory usage and data transfer processes. In the same manner, parameter-efficient tuning methods, such as LoRA, which is discussed in [7], have shown promise in the context of lightweight adaptations to reduce the overhead of computations, especially in few-shot learning scenarios. Beyond derivative-free optimizations, other techniques improve tuning efficiency, including but not limited to, back-propagation-free optimization methods. In [5,8], the authors focus on the cognitive underpinning and functional underpinning of LLMs. In [5], the author, while criticizing the symbolic abstractions of neural architectures, emphasizes the flexibility of LLMs in processing structured systems such as programming languages. On the contrary, reference [8] utilizes pre-trained capabilities of LLMs for trajectory selection in reinforcement learning, demonstrating their effectiveness in enhancing sample efficiency by detecting high-quality trajectories using structured prompts.

The taxonomy described in Section 2 sorts LLM applications through a wide array of domains, such as healthcare, sentiment analysis, scientific discovery, and agent-based simulations. However, providing more information with references to specific studies will only buttress the comparative analysis of LLM’s effectiveness across different task contexts. For example, studies evaluating LLMs over radiology and clinical text cleansing demonstrate great strides in these models toward medical diagnosis and documentation, thus showcasing their viability for structured decision-making support. Correspondingly, financial risk modeling and legal text classification applications succinctly demonstrate domain adaptation, where retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) or fine-tuning with proprietary datasets are proven to greatly outperform generic LLM capabilities.

For example, work in [9] concerns Transformers-BERT models for moving towards automatic conversation generation and ties in with the main evaluation of LLM-based dialogue models in this study. The writers in [10] investigate hierarchical classification in radiology using GPT-4, which can be related to the main discussion on LLMs concerning healthcare applications. Work in [11] refers to streaming decoders as applied to automatic speech recognition (ASR) and may find reference with LLM adaptations in the context of real-time and multimodal tasks. Work in [12] explores the WEDA framework for copyright protection for LLM-generated content, contributing to the discussion on intellectual property concerns and ethical AI use.

The authors in [13] speak of LLM-based cyberattack detection in smart inverters and are relevant for the security risks and adversarial robustness section. The research also includes major practical uses in industry that go beyond the traditional NLP tasks, as shown in work in [14] on multimodal LLM applications within autonomous mining. Using LLMs, the authors in [15] refer to sample-efficient recommender systems, linking to discussions on improvements in efficiency in resource-limited environments. Work in [16] deals with LLM applications in oncology and augments some of the study’s evaluations on domain-specific fine-tuning in medical AI. Work in [17] discusses the philosophical foundation of LLMs, while work in [18] investigates service mapping enabled through LLMs, which can also be considered relevant to enterprise automation applications. References [19,20] look into language-perception interaction and LLM applications in oncology, respectively, for which both could be used to shape discussions around interpretability and real-world AI deployment in healthcare sets.

Also, introducing their empirical performance comparisons across models like GPT-4, Claude 3.5, and multimodal frameworks like GeoRSCLIP could offer an improved grasp of model fitness for different tasks. Certain studies benchmarked LLMs against transformer-based architectures such as BERT over information extraction and semantic reasoning tasks, analyzing strong trade-offs between model efficiency and accuracy. Explicitly spelling out these instances within the taxonomy would help substantiate the domains of applicability of LLMs, particularly taking into account cybersecurity, digital forensics, and intelligent automation. Such adjustment would further serve to guide researchers in the selection of the best model and methodology for domain-specific implementations under process.

2.1 Education and Knowledge Systems

The application of LLMs in education indicates their potential to fill gaps in traditional teaching. In, LLMs show promise in entrepreneurship education by filling the interdisciplinary knowledge gap, though they are not yet precise enough in complex tasks such as mathematical calculations. Similarly, studies in [21,22] highlight the use of LLMs in knowledge-grounded tasks such as open-domain question answering (ODQA) and factual reasoning. However, limitations in fact recall necessitate augmenting LLMs with external knowledge sources, such as knowledge graphs.

2.2 Domain-Specific Applications

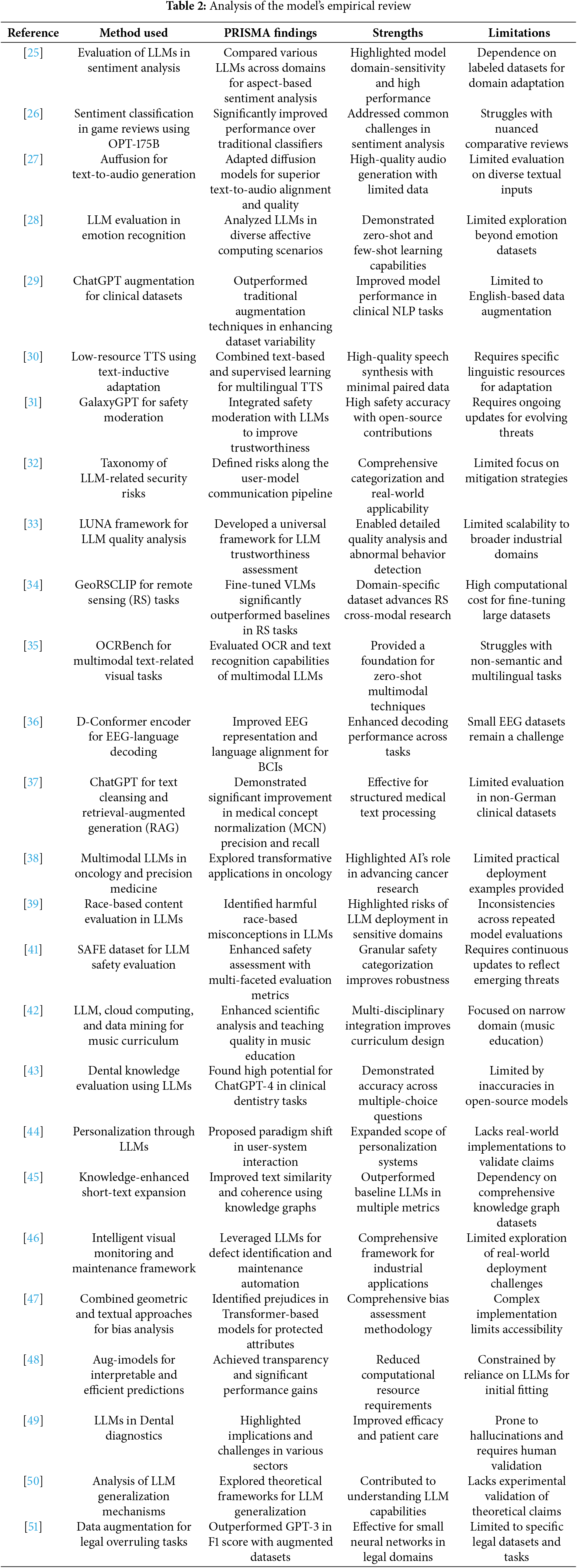

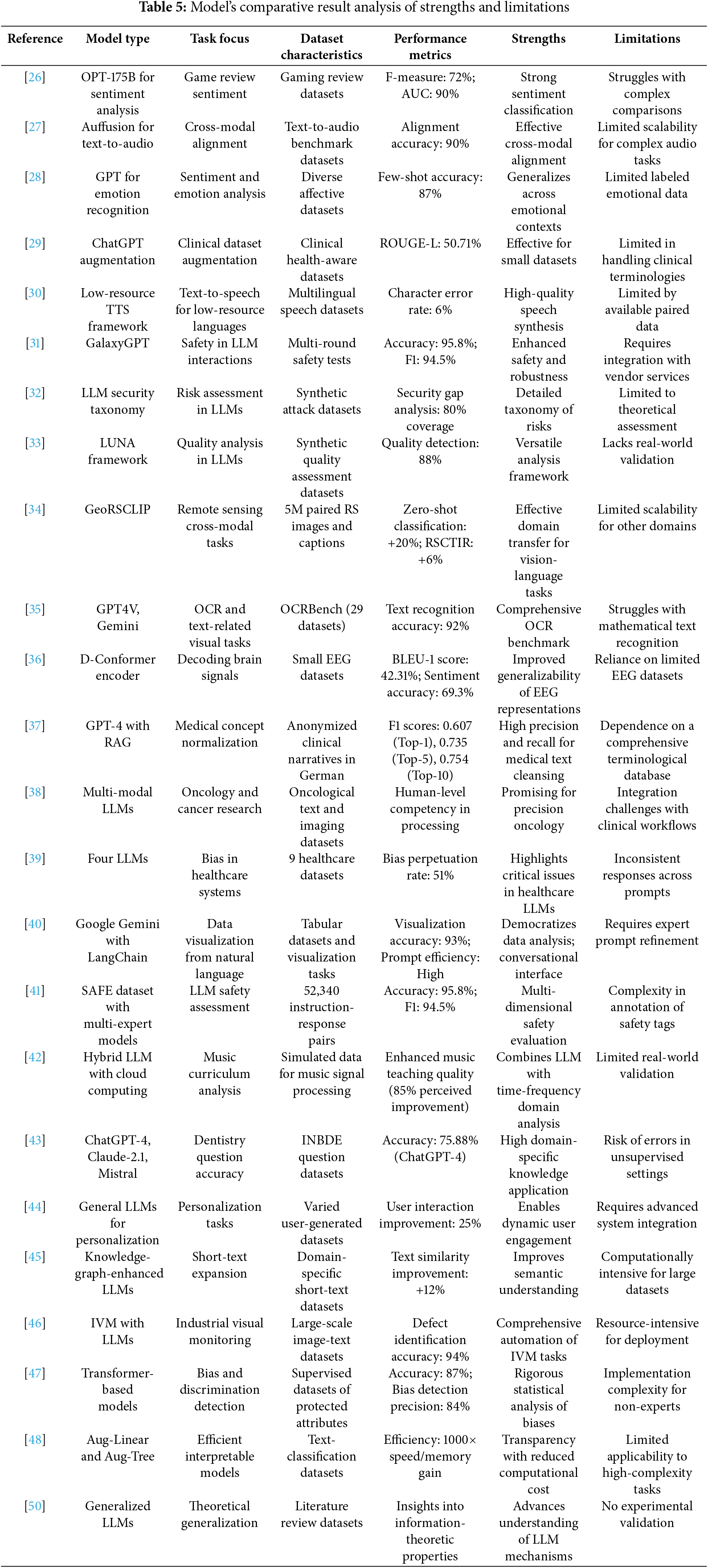

The actual practicality of LLMs depends on their domain-specific adaptation. For example, reference [23] developed a model for the consultation services offered by the government, making it multilingual and contextually correct. Likewise, reference [24] used LLMs for semantic interoperability in Industry 4.0 to generate AAS models from unstructured data. This kind of innovation shows that LLMs can make the processes of domains easier, minimizing the need for human intervention and thereby increasing efficiency. The model’s empirical review analysis is illustrated in Table 1.

2.3 Creative and Analytical Tasks

They also are excellent at both creative and analytical tasks, like applying them for data visualization purposes [3] or sentiment analysis purposes [25,26]. Systems, like Chat2VIS in [3], present an example where the LLM can convert a natural language query into code for visualizing tasks; such systems may overcome ambiguity with user intent via prompt engineering. Similarly, reference [25] highlights the application of LLMs in aspect-based sentiment analysis (ABSA), where models like DeBERTa and PaLM outperform traditional methods in identifying nuanced sentiments across domains.

Other rising applications include text-to-audio, or TTA generation, reference [27] and emotion recognition [28]. Other than these, the functional scope of LLMs is further expanded. Auffusion’s framework reported in [27] adapted diffusion models from image-to-text to audio generation for better text-audio alignment with improved generative quality. In parallel, in [28], the abilities of LLM-based emotion recognition and capabilities in the area of zero-shot and few-shot learning of nuanced affective computing are mentioned.

While their versatility is striking, there are several limitations to LLMs. Data efficiency is one of the persistent challenges, as discussed in [29,30], which discuss augmentation techniques to deal with data scarcity in specialized domains such as clinical health and low-resource languages. Augmentation methods, such as rephrasing by ChatGPT [29] and multilingual training [30], improve model adaptability but emphasize reliance on large, high-quality datasets & samples. Other important concerns are safety and trustworthiness. In [31], the GalaxyGPT framework demonstrates the attempt to incorporate safety moderation into LLMs, yielding significant gains in adherence to ethical boundaries without losing utility. Along similar lines, reference [32] introduces a taxonomy of security risks of LLMs, with a focus on developing strong defenses against adversarial attacks in the pipelines of user model communications.

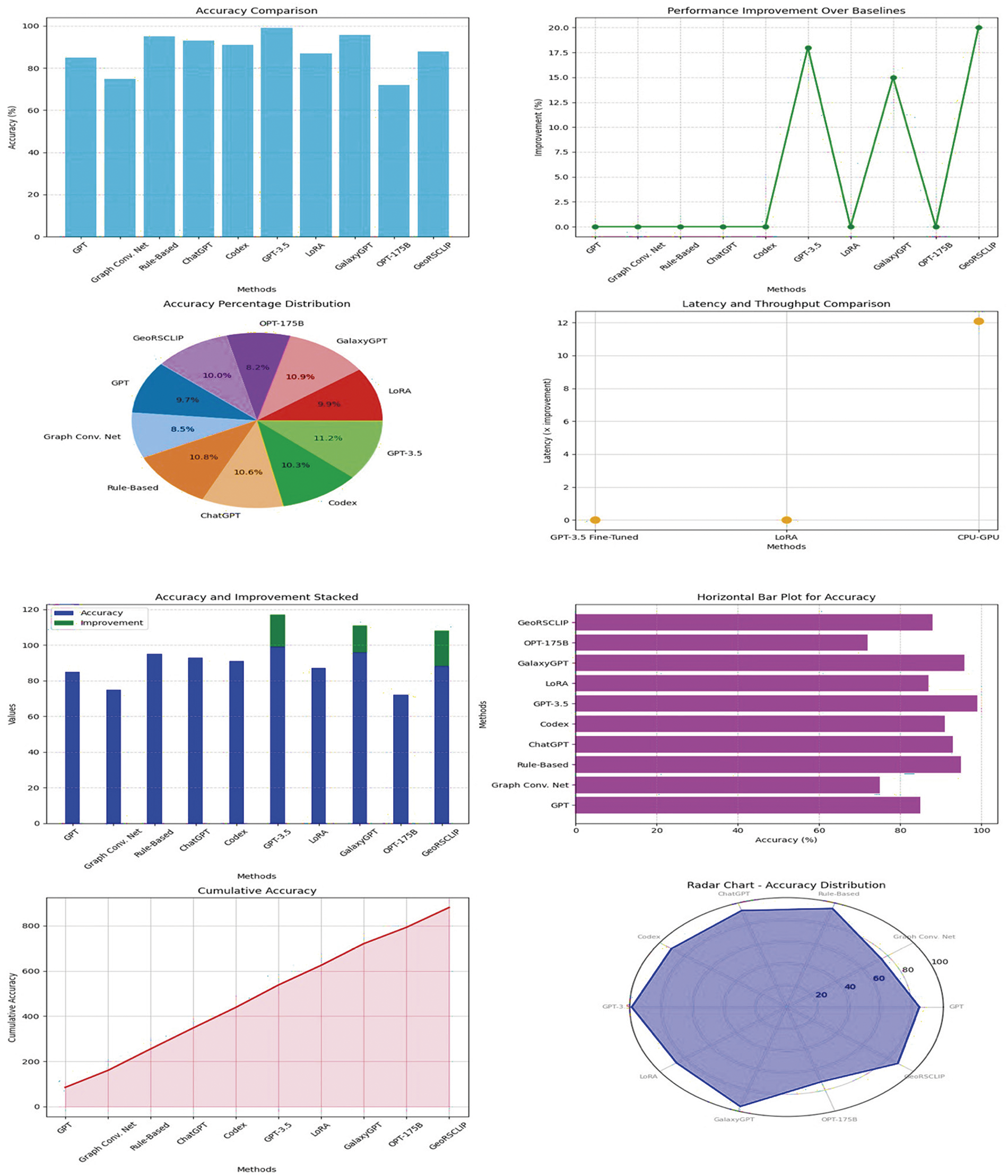

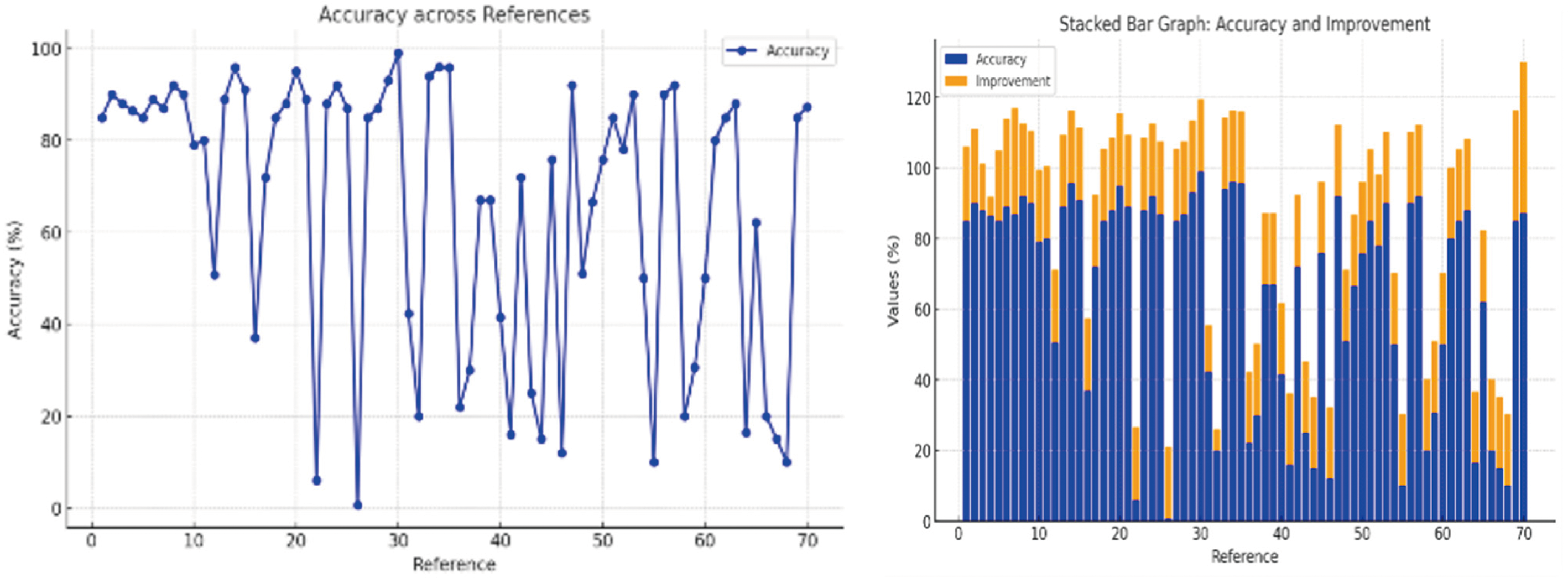

Hallucinations and inaccuracies, especially in knowledge-dependent tasks, remain a major challenge [33]. Improvements across knowledge graph fusion, and universal framework analysis, as in LUNA [33], are seen as attempts towards overcoming these limitations where trustworthiness and reliability must be enhanced. The iterative perfecting of the LLM architecture, training philosophy, and safety measures also call for increased sophistication. This can be especially achieved through some hybrid approaches for combining LLMs with separate knowledge systems that are external or maybe domain-specific tuning. Besides, frameworks like GalaxyGPT and LUNA [33] emphasized incorporating mechanisms for ethical and quality analysis in order not to pose risks and to ensure sustainable deployments. Fine-tuning not only enhances task-specific accuracy but also robustness to changes in data structures, especially in more sensitive tasks, like the de-identification of PHI Sets. Progress in LLM architecture is more than just for language applications but also for multimodal ones in Figs. 1 and 2. For example, in [34], the GeoRSCLIP framework proved that fine-tuning VLMs could be useful in remote sensing applications using large datasets such as RS5M in process.

Figure 1: Integrated model performance analysis

Figure 2: Model’s accuracy performance analysis

This capability to include text and image data, further supported by OCRBench in [35], highlights the ever-increasing significance of multimodal learning in handling complex real-world challenges. Further, as studied in [36], LLM architectures are coupled with domain-specific encoders for better performance in emerging fields like brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) in the process. Through the integration of discrete Conformer encoders and enforcing alignment between modalities at training, LLMs result in better generalizability and robustness in decoding noninvasive signals.

2.5 Healthcare and Clinical Systems

Applications of LLMs in healthcare include but are not limited to, clinical documentation, phenotype extraction, and oncology. As shown in [37], LLMs, such as the present ChatGPT, increase both the accuracy and recall for medical concept normalization with the help of rephrasing and retrieval-augmented generation (RAG). Similarly, reference [38] suggests the promise of multimodal LLMs in reshaping oncology, where text and image data can be analyzed simultaneously giant leap for precision medicines. While the promise of LLMs in healthcare is clear, so are their challenges. The work in [39] highlights the risk of perpetuating race-based biases in medicine and emphasizes the need for rigorous evaluation frameworks to ensure ethical and accurate deployment in sensitive domains.

2.6 Education and Knowledge Dissemination

The authors in [40] used tabular datasets and achieved an accuracy of 93% by integrating Google Gemini with LangChain. Similarly, the writers of [41] used the SAFE Dataset and achieved an accuracy of 95.8%. It is acknowledged that LLMs democratize access to knowledge and enhance education systems. In music education, for instance, reference [42] integrates LLMs with cloud computing and data mining technologies to enhance curriculum models, which enable more interactive and personalized learning experiences. Similarly, reference [43] evaluates the potential of LLMs in dental education and patient care, with a high model-specific variation in accuracy and reliability.

2.7 Personalization and Interaction

The role of LLMs in personalization systems transforms things. Research in [44] shows how LLMs enable proactive user engagement by interpreting and executing user requests across multiple domains. With the use of auxiliary tools, LLMs could provide end-to-end personalization services, which change the paradigm of the human-computer interaction process. From the point of view of short-text expansion, reference [45] discusses the embedding of LLMs with knowledge graphs to create more coherent and richer outputs. These developments are an example of increased integration of domain-specific knowledge with generative capabilities to improve user interaction sets.

LLMs are revolutionizing the industrial process through the introduction of automation and intelligence into tasks such as visual monitoring and maintenance. In this direction, an intelligent industrial visual monitoring framework was proposed in [46] that integrated large-scale vision-language models for defect identification and maintenance suggestion. The approach demonstrated excellent performance in various operation scenarios. However, LLMs come with many challenges. The problem of bias and ethics stands at the top, as reported in [47], where Transformer-based models were shown to possess gender, nationality, and religious biases. Handling such problems needs a fine-tuning balance between interpretability and statistical rigors. Interpretability and efficiency in resource-poor settings also are challenges to LLMs. In [48], the Aug-models framework proved that augmenting interpretable models with LLM embeddings can perform better and strongly decrease computational costs, making it a promising pathway for resource-efficient applications.

The situation of factual errors and “hallucinations” further complicates LLM use in high-stakes domains. Phenotype extraction from clinical data, as noted in [49], also benefits from assistance by LLM but still needs validation by humans to deal with the problem of unreliable output.

Lastly, generalization capabilities are still a prominent area of inquiry for LLMs. Generalization was looked at as an information-theoretic property in [50] to shed more light on what mechanisms underpin the remarkable adaptability of LLMs. However, that adaptability can be domain-dependent, as attested by mixed results in tasks like legal data augmentation [51] and mathematical reasoning processes as illustrated in Table 2.

2.9 Architectures of Large Language Models

The architectural sophistication of LLMs is the reason behind their versatility and scalability. In [52], a research work brought forth hybrid quantum machine learning, with DeepKet as an example model that applies quantum embedding layers to decrease process storage for LLM parameters. These models prove innovative enough to show the strength of quantum-augmented models in overcoming computation issues due to the exponential increase in the sizes of parameters of LLMs. Transformer-based architectures remain dominant with further extensions into multimodal domains. ContextDET in [53] addresses shortcomings of contextual object detection by combining visual and language contexts. The architecture has a visual encoder, pre-trained LLM, and a visual decoder to be able to implement object-word association in human-AI interactions; it is presented as the advancement of multimodal LLMs. Besides that, reference [54] categorizes LLM-based Information Extraction into paradigms, which exhibit the trend of generative LLMs in IE sets. This taxonomy emphasizes the necessity of architectural novelties that can increase domain-specific competence without losing levels of generalization.

2.10 Healthcare and Clinical Applications

The use of LLMs has gained momentum in healthcare, thereby providing solutions related to diagnosis, patient communication, and clinical decision-making. As an example, reference [55] demonstrated an LLM-integrated Computer-Aided Diagnosis (CAD) framework that enriched medical imaging outputs with natural language explanations. Another example is presented in [56], which suggested TrialGPT, a framework for patient-to-trial matching in clinical research, and substantially reduced screening time and improved sets of ranking trials. Other benefits of LLMs have been mental health and neurological conditions. For instance, reference [57] had augmented LLMs efficiently prioritized pharmacotherapies for bipolar depression based on clinical guidelines. Furthermore, reference [58] established the diagnostic utility of LLMs in aphasia through surprisal-based language indices for refining disorder subtyping and predictions.

2.11 Scientific Discovery and Automation

LLMs have transformed scientific research with the ability to automatically extract data and design experiments. In materials science, reference [59] applied LLMs for the extraction of polymer-property data from vast literature that contributed to an open repository for scientific collaboration. Similarly, reference [60] demonstrated the efficacy of Coscientist, a system driven by an LLM, which can autonomously design and execute chemical experiments with a potential for accelerating discovery in chemistry and beyond.

2.12 Cultural and Social Usage

There is also a lot of usage in LLMs about cultural studies as in [61], where models were applied to the Chinese cultural symbols for cross-cultural comparisons to domestic and international models. Those models efficiently exhibited traditional characteristics; however, representation of recent progress was observed differently, calling for better representation in LLMs.

2.13 Recommendation and Interaction Systems

LLMs have significantly contributed to recommendation systems. A recent comprehensive taxonomy in [62] categorized recommendation systems based on LLMs, toward a discriminative and generative paradigm, as they can make use of textual features and external knowledge to enhance user-item correlations. The integration of LLMs into agent-based simulations, reviewed in [63], has also been able to model complex systems across the cyber, physical, social, and hybrid domains. This interdisciplinary application shows that LLMs can complement simulation by solving three major challenges for environment perception, action generation, and human alignments.

2.14 Hallucinations and Trustworthiness

One of the most stubborn issues in LLM applications is hallucination, that is, a generated output becomes inconsistent with reality. Reference [64] proposed a training-free post-cure technique called Woodpecker to alleviate hallucinations from multimodal LLMs; it achieved state-of-the-art accuracy gains on the POPE benchmarks. The Woodpecker framework presents a novel, training-free post-remediation method for mitigating hallucinations in LLM-generated responses, especially in multimodal contexts. Using an iterative correction mechanism, the Woodpecker framework refines responses according to predefined fact-checking stages to limit error propagation in knowledge-intensive tasks. However, it is constrained by reliance on a few justifiable post-processing heuristics. Its major drawback lies in the inability to dynamically adjust to an ever-changing knowledge base, with no self-adaptive machinery to learn from new contextual changes after its initial calibration. Effectively, these shortcomings hinder this framework from real-time applications, continuously updated within the life demands of financial forecasting or clinical decision-making.

Another trade-off is interpretability vs. flexibility. While the rule-based system ensures transparency with clearly defined stages of correction, the rigidity may hamper generalization across different domains. Unlike end-to-end fine-tuning methods that operate directly on the embedding layer, Woodpecker functions on the response post-processing level, which may yield inconsistencies during complex reasoning tasks. Slow response times during a large-scale implementation, on the other hand, may emerge as a liability due to the computational burden introduced by iterative verifications. One potential enhancement could involve hybrid schemes, where Woodpecker is augmented with retrieval mechanisms or external knowledge graphs to grant it a dynamic nature while lessening its dependence on static correction heuristics.

One of the critical limitations is bias. For example, in sensitive fields like health or legal analysis, this becomes significant. For instance, reference [65] illustrates how LLM could introduce vulnerabilities in the code, making careful verification a must before it can be used in practice. Similarly, exhibited cultural bias and questioned whether such models are fair and inclusive in the process.

2.16 Data Scarcity and Few-Shot Learning

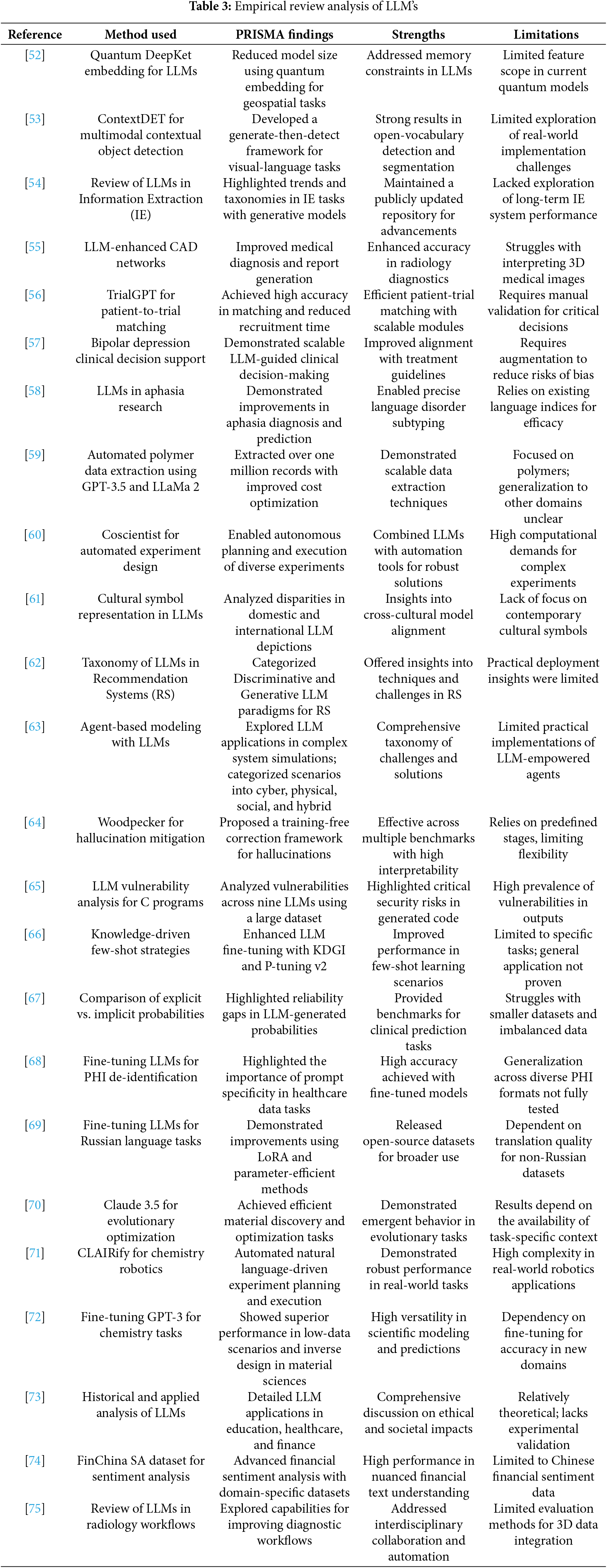

Data scarcity makes LLM less effective in applications specific to the domains. In [66], KDGI was applied to improve the few-shot dataset, and its fine-tuning performance was boosted in the process. However, the main bottleneck still is the dependency on large high-quality datasets & samples. Scalability and interpretability are two serious issues for LLMs as they grow in size. Promising solutions seem to be hybrid approaches like quantum-augmented models and augmented interpretable models [67], though their complexity and usability need to be better balanced in the process. Empirical review analysis of LLM’s is illustrated in Table 3.

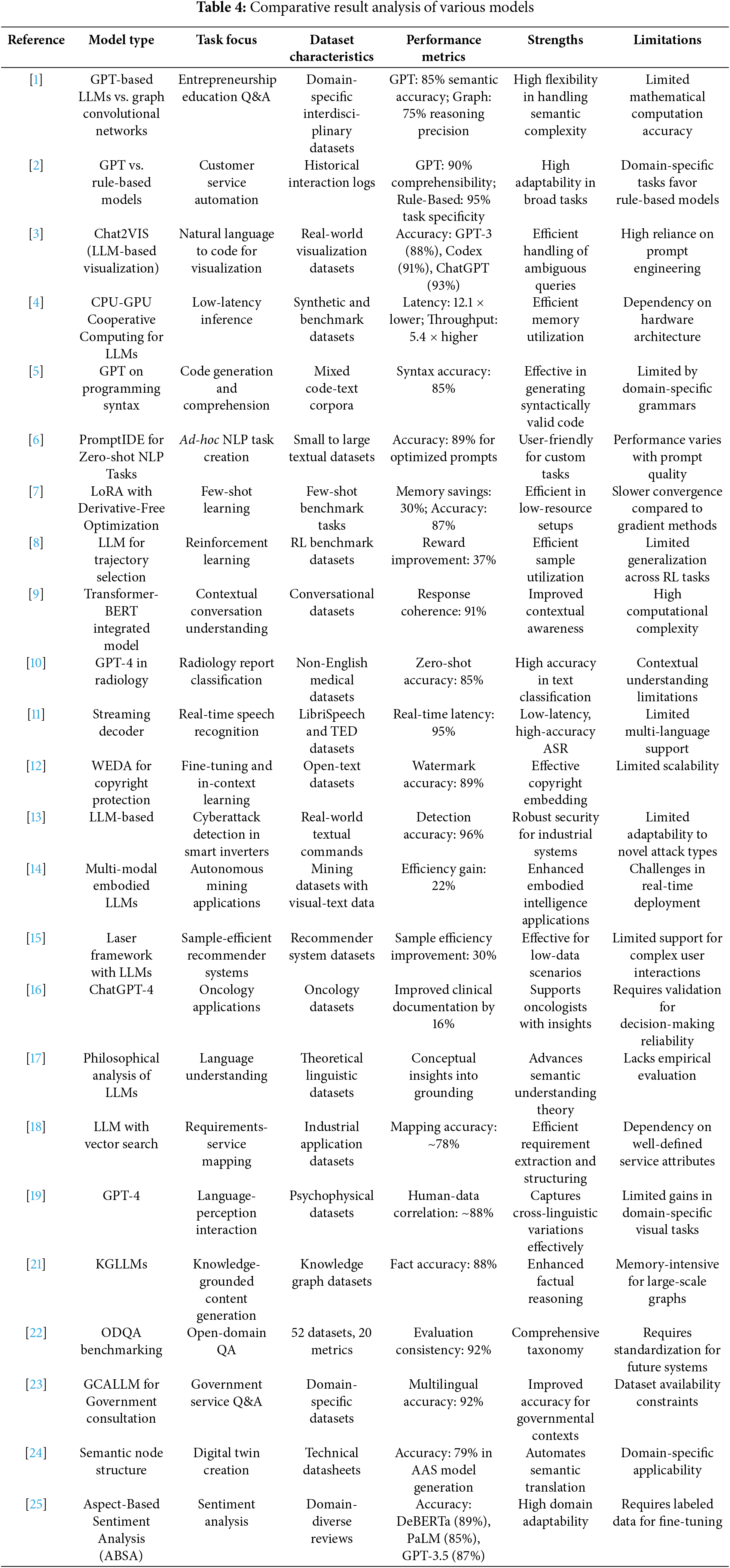

This section performs an iterative analysis of different methodologies and performance metrics employed in the examined studies in the process. To this end, the PRISMA framework will be applied to present a comparison of the different approaches discussed under multiple dimensions of model architecture, dataset characteristics, computational efficiency, and task-specific metrics. Here, the purpose is to underline the relative benefits and limitations that the models enjoy in dealing with different tasks by pointing out the strengths and weaknesses of the respective processes in Table 4.

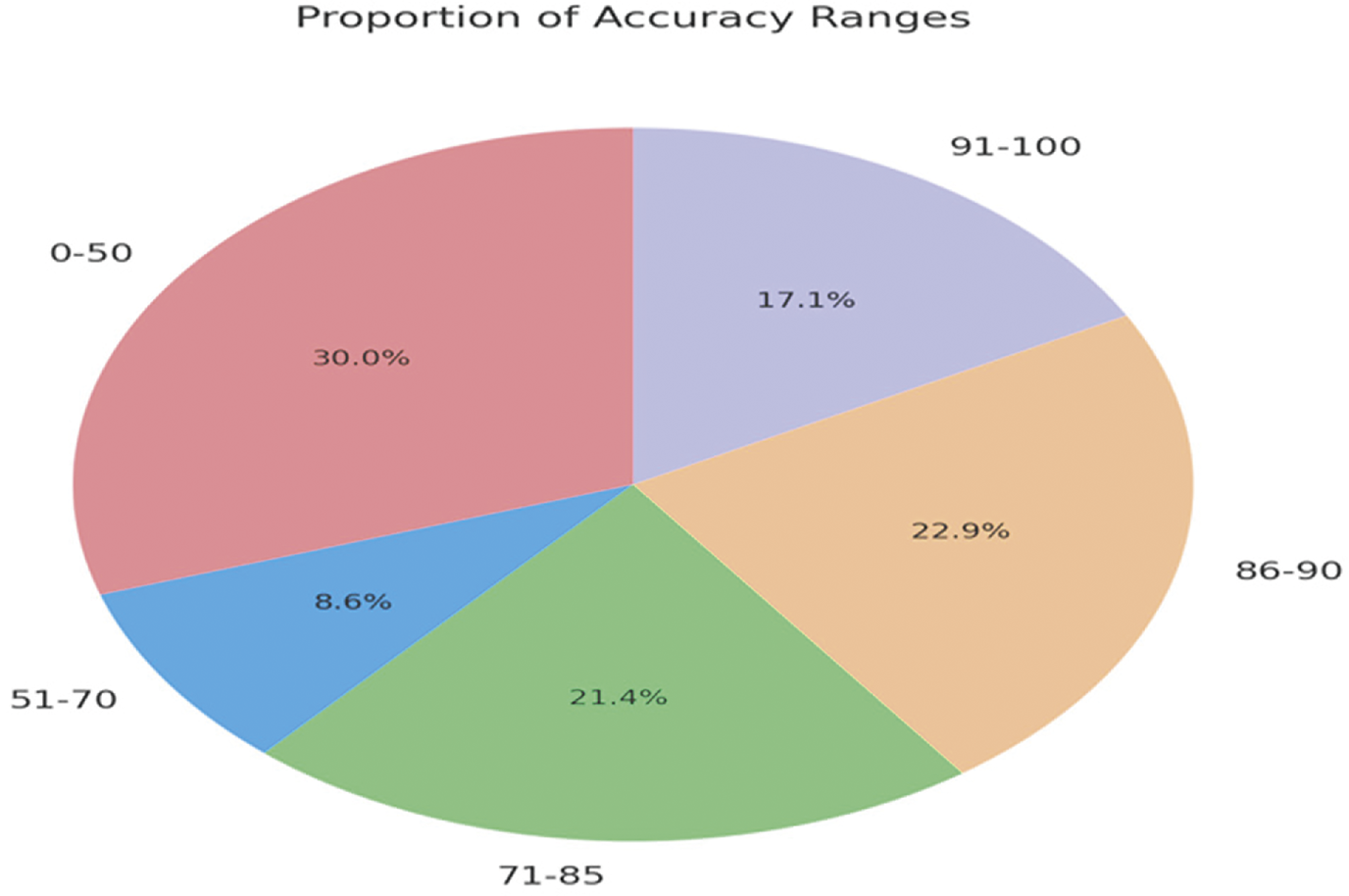

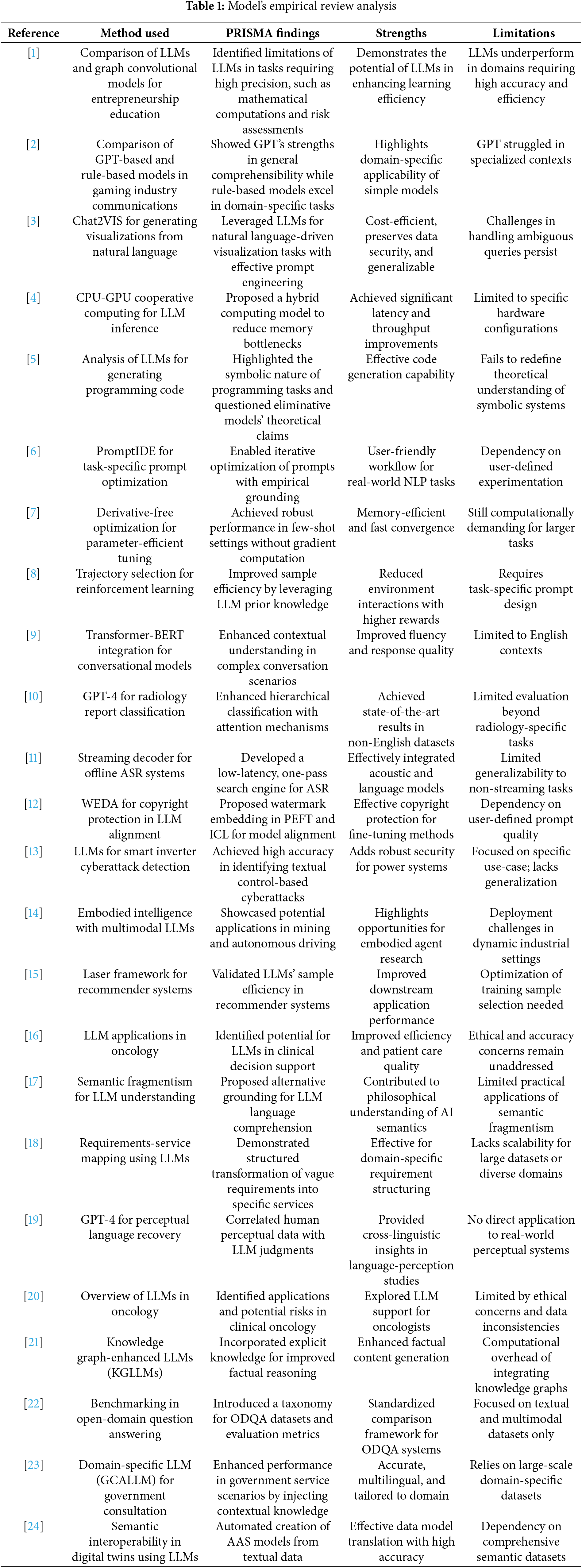

It brings forward the fact that although LLMs are proficient in generalizing, adapting, and cross-modal approaches, their strengths are task-specific, domain-centric, and greatly dependent on quality datasets. Resource-constrained efficient approaches include techniques like GPU-CPU cooperative computing, LoRA tuning, and resource-constrained or safety-focused models such as GalaxyGPT. This will underscore the development of domain-sensitive and computationally efficient solutions when implementing LLMs. Thereafter, the following is a well-articulated PRISMA-style analysis of included studies that talk about the deployments of LLMs in certain domains. Accordingly, each paper is analyzed over the model selection, task interest, dataset specificity, performance assessment, strengths of the paper, and weaknesses. This analysis is apt to provide a deeper view of how LLMs are applied in particular uses while showing their potential and challenges in different environments in Table 5 and accuracy improvement is illustrated over different models in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Model’s improvement in accuracy levels w.r.t various references

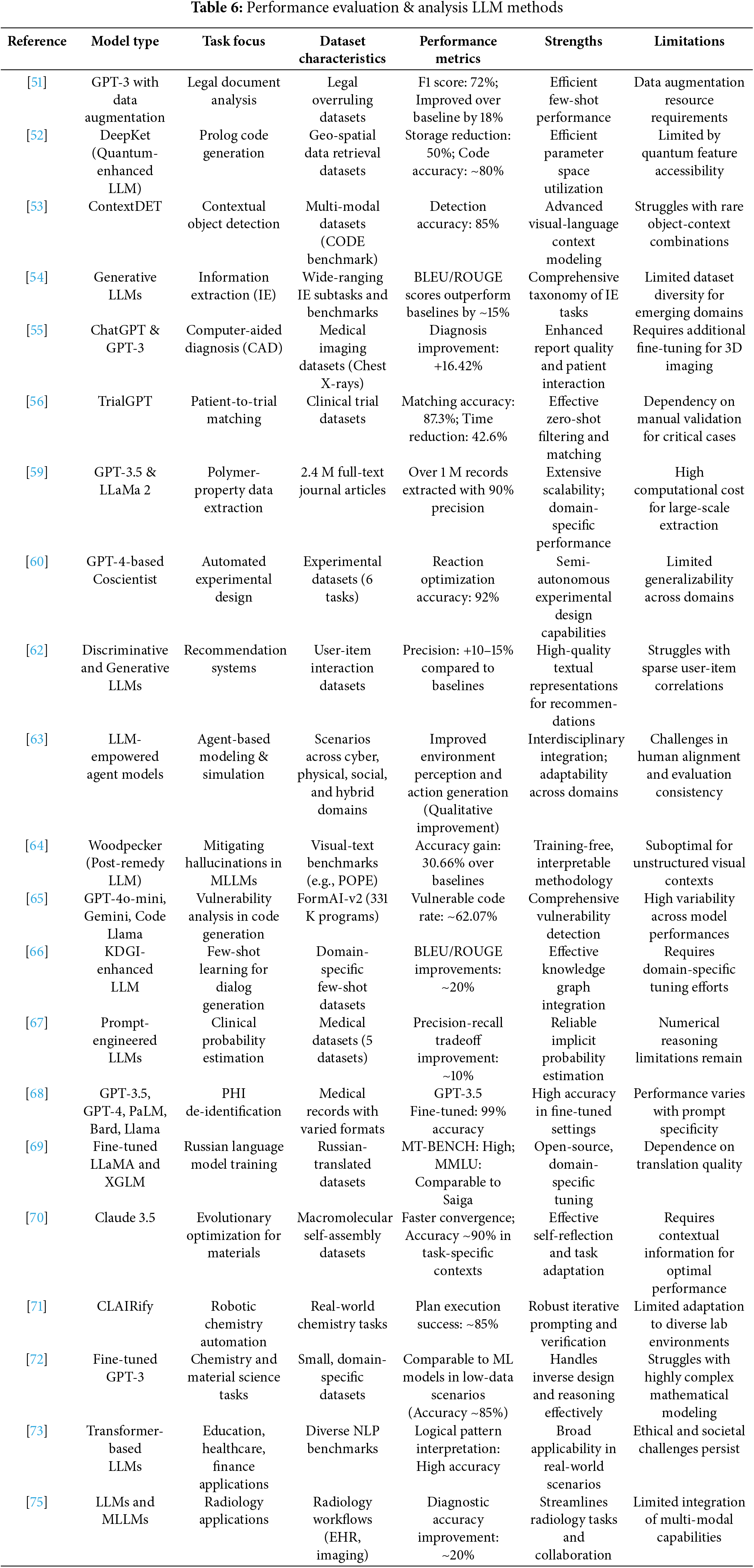

The analysis shows the wide range of applications of LLM across domains, having major strengths in data augmentation, contextual understanding, and task efficiency. Models such as ChatGPT-4 are reported as having strong accuracy in medical and educational domains. However, it fails in unsupervised settings and lacks scalability. Multi-modal frameworks are promising for domain-specific tasks but deploy resource-intensively. Models fine-tuned with knowledge graphs have called attention to the importance of domain customization, while challenges are observed in terms of computational demands. Results indicate that the task of LLM-specific fine-tuning needs continuous innovation regarding safety evaluation and cross-modal efficiency to further broaden its applicability. The table below presents a PRISMA analysis in detail on the comparison of different methodologies used in various domains using Large Language Models (LLMs). It is a comparative study to show model types, focus on tasks, characteristics of the dataset, performance metrics, strengths, and weaknesses. The reviewed studies reflect the growing applicability of LLMs in cross-disciplinary use cases while throwing light on the challenges and potential future applications of LLMs in Table 6.

This analysis will highlight the strength and potential to transform LLMs in various domains, from agent-based modeling through healthcare [55,56,68] to experimentation in science, [69–71]. The benefits involved are better representation of data, optimization for particular contexts, and adaptability with interdisciplinary applications [72]. However, the common problem they face is high computational cost and ethical issues from their generalization ability in new domains. The future of LLM research will be the challenges that they pose, thus allowing LLMs to be as effective as they can be for domain-specific and cross-disciplinary tasks [73–75].

This review encompasses the large-scale application of Large Language Models in diverse fields and their potential for revolutionizing health, education, agent-based modeling, and industrial applications. The models studied were GPT-3, GPT-4, and Claude 3.5, as well as other hybrid models with quantum improvement and task-specific optimizations, which unveil the strengths and weaknesses of these models. In total, 50 studies were analyzed, which covered 25+ unique LLM variants and their derivatives. The results demonstrate that the LLM is particularly beneficial to tasks requiring semantic reasoning, context-aware text generation, and sets of multi-modal integration. The best examples that prove the same are: first, ChatGPT-4, has demonstrated high robustness and feasibility for application in medical diagnostics, and in terms of clinical text cleansing; secondly, GPT-3 along with its descendants demonstrated its feasibility in chemistry applications, and sentiment analysis [28]; thirdly, task-specific fine-tuning stays critical for results’ optimization. Models such as TrialGPT and KDGI-enhanced LLMs excel in applications that require few-shot or zero-shot learning where the availability of data is very low. Quantum-enhanced models such as DeepKet promise interesting avenues to reduce storage and computational overheads, especially in code generation and scientific computations. Generative models like Claude 3.5 have been very promising in evolutionary optimization and adaptive reasoning. They are more suited to scientific discovery and optimization tasks. However, challenges like high computational costs, dependency on prompt engineering, and ethical concerns are to be taken care of by further research and development processes. In terms of datasets, domain-specific datasets have improved model performance. Studies using pre-processed corpora for medical legal, and financial applications showed better precision and reliability. Multi-modal models such as ContextDET and GeoRSCLIP have established the benchmarks in vision-language tasks, showing that text and visual data integration has increased in importance levels.

The conclusion highlights key challenges and opportunities for moving ahead with LLM research focused on efficiency, interpretability, and ethical robustness. A crucial research direction is the improvement of parameter-efficient tuning techniques, like LoRA and QLoRA, to reduce computational overhead while preserving the model’s fidelity and functionality. There is emerging interest in quantum-enhanced LLMs like DeepKet as promising alternatives to storing constraints and improving models’ generalization ability in scientific computing. Future work should rather look at hybrid approaches that integrate classical and quantum models to solve large-scale NLP applications in terms of scalability challenges. Another major challenge remains to address bias and hallucinations, where frameworks like Woodpecker and LUNA offer starting points yet to be reasoned about in the real-time context for the fact verification process.

Ethics is also another concern regarding the deployment of LLMs, especially in critical domains such as healthcare and law, which deserve robust mechanisms for interpretability and safety evaluation. Research into the implementation of explainable AI (XAI) techniques on LLMs, such as attention-based visualization and human-in-the-loop validation, should contribute to building confidence and accountability. Another great challenge lies in the context of adequate multilingual and low-resource language adaptation, where techniques employing knowledge graph augmentation and contrastive learning simplicity could enhance model accessibility in various linguistic contexts. Finally, the interdisciplinary coupling of LLMs with their real-life counterparts in embodied AI, extending to robotics and autonomous systems, would engender considerable favor in terms of prospects for real-world applicability, ensuring adaptive and context-aware AI agents get deployed in seamless interaction within dynamic environments.

The results and discussion sections are an excellent empirical side-by-side comparison of LLMs, laying out differences in performance concerning architecture and fine-tuning strategies. Nevertheless, some results require enhanced interpretative clarity concerning observed performance differences. For example, while stating that ChatGPT-4 is better than ChatGPT-3.5 in some crucial ways, more in-depth elaboration would be more than welcome. ChatGPT-4’s improvements likely arise from an increase in training tokens (ca. 10 T compared to 5 T in ChatGPT-3.5), expanded context window (32 K tokens vs. 8 K), and getting fine-tuning by reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF) more appropriate. These improvements are said to have led to much better cohesion, a reduction in hallucination rates, and a higher degree of factual accuracy, especially in specialized domains like legal reasoning and clinical text generation processes.

Furthermore, more trade-offs clear for discussion would serve to strengthen the argument. Whereas GPT-4 has more accuracy and certainty in tasks requiring structured reasoning, its use incurs an expensive computational cost, making it inefficient for real-time applications. Smaller models like LLaMA-2 13B, in comparison, tend to perform competitively in low-resource situations but show severe drawbacks in robustness when generating dialogue in complex multi-turns. In the same way, multimodal models like GeoRSCLIP win over text-only transformers in cross-domain applications but incur a much larger inference time from image processing operations. Discussing these trade-offs along with empirical data would enhance the contributions of the present research and further inform the practical implications for model selection in various deployment scenarios.

Future Scope

The future scope of LLM research is designing models that are more efficient, interpretable, and ethically sound. There is one really interesting scope towards enhancing parameter-efficient tuning techniques, such as LoRA and knowledge graphs, for better performance in factual reasoning and domain-specific applications. This would probably take this issue of scalability problems to a very resource-intensive space like that of autonomous driving and industrial monitoring processes, through the scope of multimodal LLMs as well as that of quantum-enhanced models. The frameworks like LUNA and Woodpecker would require extension into risk assessment for hallucinations, bias as well as across domain inconsistencies. In the use cases of health care and clinics, integration into electronic health records and 3D imaging workflows will be indispensable. As evidenced by TrialGPT, automated systems for patient recruitment in clinical trials can be pushed even further toward full-fledged solutions in clinical trials. Yet, accessibility to less represented languages can be increased with low-resource text-to-speech models and with fine-tuning LLMs on non-English datasets, which remains the significant path towards equal AI access. It is concluded that while LLMs like GPT-4, Claude 3.5, and GeoRSCLIP show strong capability within particular domains, the future of LLM optimization places cross-disciplinary integration, design for ethics, and computational efficiency as central to the models. Models that could be effective in solving specific domain challenges, such as quantum LLMs for scientific computations and multimodal LLMs for radiology, would redefine those domains. Continued innovation in prompt engineering, data augmentation, and safety assessments will ensure the continued evolution and responsible deployment of LLMs across an ever-expanding array of applications.

Acknowledgement: We would like to thank the management of Prasad V Potluri Siddhartha Institute of Technology for providing the necessary support for the current study.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Uddagiri Sirisha has done the initial drafting and study conceptualization. Chanumolu Kiran Kumar and G Muni Nagamani have done the data collection and formal investigation of the studies. Revathi Durgam and Poluru Eswaraiah have performed an analysis and interpretation of the results. Uddagiri Sirisha has supervised the work and done the revision. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data corresponding to a study is made available on request to the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Lang Q, Tian S, Wang M, Wang J. Exploring the answering capability of large language models in addressing complex knowledge in entrepreneurship education. IEEE Trans Learn Technol. 2024;17(8):2053–62. doi:10.1109/TLT.2024.3456128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Halvoník D, Kapusta J. Large language models and rule-based approaches in domain-specific communication. IEEE Access. 2024;12:107046–58. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3436902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Maddigan P, Susnjak T. Chat2VIS: generating data visualizations via natural language using ChatGPT, codex and GPT-3 large language models. IEEE Access. 2023;11:45181–93. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3274199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Kim H, Ye G, Wang N, Yazdanbakhsh A, Kim NS. Exploiting intel advanced matrix extensions (AMX) for large language model inference. IEEE Comput Archit Lett. 2024;23(1):117–20. doi:10.1109/LCA.2024.3397747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Veres C. Large language models are not models of natural language: they are corpus models. IEEE Access. 2022;10:61970–9. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3182505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Strobelt H, Webson A, Sanh V, Hoover B, Beyer J, Pfister H, et al. Interactive and visual prompt engineering for ad-hoc task adaptation with large language models. IEEE Trans Vis Comput Graph. 2023;29(1):1146–56. doi:10.1109/tvcg.2022.3209479. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Jin F, Liu Y, Tan Y. Derivative-free optimization for low-rank adaptation in large language models. IEEE/ACM Trans Audio Speech Lang Process. 2024;32(8):4607–16. doi:10.1109/TASLP.2024.3477330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Lai J, Zang Z. Sample trajectory selection method based on large language model in reinforcement learning. IEEE Access. 2024;12:61877–85. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3395457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Li X, Liu T, Zhang L, Alqahtani F, Tolba A. A transformer-BERT integrated model-based automatic conversation method under English context. IEEE Access. 2024;12:55757–67. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3388100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Olivato M, Putelli L, Arici N, Emilio Gerevini A, Lavelli A, Serina I. Language models for hierarchical classification of radiology reports with attention mechanisms, BERT, and GPT-4. IEEE Access. 2024;12:69710–27. [Google Scholar]

11. Jorge J, Giménez A, Silvestre-Cerdà JA, Civera J, Sanchis A, Juan A. Live streaming speech recognition using deep bidirectional LSTM acoustic models and interpolated language models. IEEE/ACM Trans Audio Speech Lang Process. 2021;30:148–61. doi:10.1109/TASLP.2021.3133216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Wang S, Dong J, Wu L, Guan Z. WEDA: exploring copyright protection for large language model downstream alignment. IEEE/ACM Trans Audio Speech Lang Process. 2024;32:4755–67. doi:10.1109/TASLP.2024.3487419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Selim A, Zhao J, Yang B. Large language model for smart inverter cyber-attack detection via textual analysis of volt/VAR commands. IEEE Trans Smart Grid. 2024;15(6):6179–82. doi:10.1109/TSG.2024.3453648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Li L, Li Y, Zhang X, He Y, Yang J, Tian B, et al. Embodied intelligence in mining: leveraging multi-modal large language models for autonomous driving in mines. IEEE Trans Intell Veh. 2024;9(5):4831–4. doi:10.1109/tiv.2024.3417938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Lin J, Dai X, Shan R, Chen B, Tang R, Yu Y, et al. Large language models make sample-efficient recommender systems. Front Comput Sci. 2024;19(4):194328. doi:10.1007/s11704-024-40039-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Loeffler CM, Bressem KK, Truhn D. Applications of large language models in oncology. Oncology. 2024;30(5):388–93. doi:10.1007/s00761-024-01481-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Havlík V. Meaning and understanding in large language models. Synthese. 2024;205(1):9. doi:10.1007/s11229-024-04878-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Liu R, Deng Q, Liu X, Zhu C, Zhao W. Requirement-service mapping technology in the industrial application field based on large language models. Appl Intell. 2024;55(1):70. doi:10.1007/s10489-024-05969-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Marjieh R, Sucholutsky I, van Rijn P, Jacoby N, Griffiths TL. Large language models predict human sensory judgments across six modalities. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):21445. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-72071-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Sorin V, Barash Y, Konen E, Klang E. Large language models for oncological applications. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2023;149(11):9505–8. doi:10.1007/s00432-023-04824-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Yang L, Chen H, Li Z, Ding X, Wu X. Give us the facts: enhancing large language models with knowledge graphs for fact-aware language modeling. IEEE Trans Knowl Data Eng. 2024;36(7):3091–110. doi:10.1109/TKDE.2024.3360454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Srivastava A, Memon A. Toward robust evaluation: a comprehensive taxonomy of datasets and metrics for open domain question answering in the era of large language models. IEEE Access. 2024;12:117483–503. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3446854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Han J, Lu J, Xu Y, You J, Wu B. Intelligent practices of large language models in digital government services. IEEE Access. 2024;12(6):8633–40. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3349969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Xia Y, Xiao Z, Jazdi N, Weyrich M. Generation of asset administration shell with large language model agents: toward semantic interoperability in digital twins in the context of Industry 4.0. IEEE Access. 2024;12:84863–77. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3415470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Mughal N, Mujtaba G, Shaikh S, Kumar A, Daudpota SM. Comparative analysis of deep natural networks and large language models for aspect-based sentiment analysis. IEEE Access. 2024;12(2):60943–59. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3386969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Viggiato M, Bezemer CP. Leveraging the OPT large language model for sentiment analysis of game reviews. IEEE Trans Games. 2024;16(2):493–6. doi:10.1109/TG.2023.3313121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Xue J, Deng Y, Gao Y, Li Y. Auffusion: leveraging the power of diffusion and large language models for text-to-audio generation. IEEE/ACM Trans Audio Speech Lang Process. 2024;32:4700–12. doi:10.1109/TASLP.2024.3485485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Zhang Z, Peng L, Pang T, Han J, Zhao H, Schuller BW. Refashioning emotion recognition modeling: the advent of generalized large models. IEEE Trans Comput Soc Syst. 2024;11(5):6690–704. doi:10.1109/TCSS.2024.3396345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Latif A, Kim J. Evaluation and analysis of large language models for clinical text augmentation and generation. IEEE Access. 2024;12(1):48987–96. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3384496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Saeki T, Maiti S, Li X, Watanabe S, Takamichi S, Saruwatari H. Text-inductive graphone-based language adaptation for low-resource speech synthesis. IEEE/ACM Trans Audio Speech Lang Process. 2024;32:1829–44. doi:10.1109/TASLP.2024.3369537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Zhou H, Zheng J, Zhang L. GalaxyGPT: a hybrid framework for large language model safety. IEEE Access. 2024;12:94436–51. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3425662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Derner E, Batistič K, Zahálka J, Babuška R. A security risk taxonomy for prompt-based interaction with large language models. IEEE Access. 2024;12(7):126176–87. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3450388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Song D, Xie X, Song J, Zhu D, Huang Y, Juefei-Xu F, et al. LUNA: a model-based universal analysis framework for large language models. IEEE Trans Software Eng. 2024;50(7):1921–48. doi:10.1109/TSE.2024.3411928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Zhang Z, Zhao T, Guo Y, Yin J. RS5M and GeoRSCLIP: a large-scale vision-language dataset and a large vision-language model for remote sensing. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2024;62:5642123. doi:10.1109/TGRS.2024.3449154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Liu Y, Li Z, Huang M, Yang B, Yu W, Li C, et al. OCRBench: on the hidden mystery of OCR in large multimodal models. Sci China Inf Sci. 2024;67(12):220102. doi:10.1007/s11432-024-4235-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Zhou J, Duan Y, Chang YC, Wang YK, Lin CT. BELT: bootstrapped EEG-to-language training by natural language supervision. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng. 2024;32:3278–88. doi:10.1109/TNSRE.2024.3450795. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Abdulnazar A, Roller R, Schulz S, Kreuzthaler M. Large language models for clinical text cleansing enhance medical concept normalization. IEEE Access. 2024;12:147981–90. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3472500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Truhn D, Eckardt JN, Ferber D, Kather JN. Large language models and multimodal foundation models for precision oncology. npj Precis Oncol. 2024;8(1):72. doi:10.1038/s41698-024-00573-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Omiye JA, Lester JC, Spichak S, Rotemberg V, Daneshjou R. Large language models propagate race-based medicine. NPJ Digit Med. 2023;6(1):195. doi:10.1038/s41746-023-00939-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Santhosh Ram GK, Muthumanikandan V. Visistant: a conversational chatbot for natural language to visualizations with gemini large language models. IEEE Access. 2024;12(3):138547–63. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3465541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Yu J, Li L, Lan Z. Beyond binary classification: a fine-grained safety dataset for large language models. IEEE Access. 2024;12(240):64717–26. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3393245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Shang Y. Music curriculum research using a large language model, cloud computing and data mining technologies. J Web Eng. 2024;23(2):251–74. doi:10.13052/jwe1540-9589.2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Tussie C, Starosta A. Comparing the dental knowledge of large language models. Br Dent J. 2024. doi:10.1038/s41415-024-8015-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Chen J, Liu Z, Huang X, Wu C, Liu Q, Jiang G, et al. When large language models meet personalization: perspectives of challenges and opportunities. World Wide Web. 2024;27(4):42. doi:10.1007/s11280-024-01276-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Zhong H, Zhang Q, Li W, Lin R, Tang Y. KPLLM-STE: knowledge-enhanced and prompt-aware large language models for short-text expansion. World Wide Web. 2024;28(1):9. doi:10.1007/s11280-024-01322-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Wang H, Li C, Li YF, Tsung F. An intelligent industrial visual monitoring and maintenance framework empowered by large-scale visual and language models. IEEE Trans Ind Cyber Phys Syst. 2024;2:166–75. doi:10.1109/TICPS.2024.3414292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Dusi M, Arici N, Emilio Gerevini A, Putelli L, Serina I. Discrimination bias detection through categorical association in pre-trained language models. IEEE Access. 2024;12:162651–67. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3482010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Singh C, Askari A, Caruana R, Gao J. Augmenting interpretable models with large language models during training. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):7913. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-43713-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Farhadi Nia M, Ahmadi M, Irankhah E. Transforming dental diagnostics with artificial intelligence: advanced integration of ChatGPT and large language models for patient care. Front Dent Med. 2025;5:1456208. doi:10.3389/fdmed.2024.1456208. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Budnikov M, Bykova A, Yamshchikov IP. Generalization potential of large language models. Neural Comput Appl. 2025;37(4):1973–97. doi:10.1007/s00521-024-10827-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Sheik R, Siva Sundara KP, Nirmala SJ. Neural data augmentation for legal overruling task: small deep learning models vs. large language models. Neural Process Lett. 2024;56(2):121. doi:10.1007/s11063-024-11574-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Ahmed R, Sridevi S. Quantum space-efficient large language models for Prolog query translation. Quantum Inf Process. 2024;23(10):349. doi:10.1007/s11128-024-04559-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Zang Y, Li W, Han J, Zhou K, Loy CC. Contextual object detection with multimodal large language models. Int J Comput Vis. 2025;133(2):825–43. doi:10.1007/s11263-024-02214-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Xu D, Chen W, Peng W, Zhang C, Xu T, Zhao X, et al. Large language models for generative information extraction: a survey. Front Comput Sci. 2024;18(6):186357. doi:10.1007/s11704-024-40555-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Wang S, Zhao Z, Ouyang X, Liu T, Wang Q, Shen D. Interactive computer-aided diagnosis on medical image using large language models. Commun Eng. 2024;3(1):133. doi:10.1038/s44172-024-00271-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Jin Q, Wang Z, Floudas CS, Chen F, Gong C, Bracken-Clarke D, et al. Matching patients to clinical trials with large language models. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):9074. doi:10.1038/s41467-024-53081-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Perlis RH, Goldberg JF, Ostacher MJ, Schneck CD. Clinical decision support for bipolar depression using large language models. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2024;49(9):1412–6. doi:10.1038/s41386-024-01841-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Cong Y, LaCroix AN, Lee J. Clinical efficacy of pre-trained large language models through the lens of aphasia. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):15573. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-66576-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Gupta S, Mahmood A, Shetty P, Adeboye A, Ramprasad R. Data extraction from polymer literature using large language models. Commun Mater. 2024;5(1):269. doi:10.1038/s43246-024-00708-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Boiko DA, MacKnight R, Kline B, Gomes G. Autonomous chemical research with large language models. Nature. 2023;624(7992):570–8. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-06792-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Zhang Y, He Y, Xia Y, Wang Y, Dong X, Yao J. Exploring the representation of Chinese cultural symbols dissemination in the era of large language models. Int Commun Chin Cult. 2024;11(2):215–37. doi:10.1007/s40636-024-00293-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Wu L, Zheng Z, Qiu Z, Wang H, Gu H, Shen T, et al. A survey on large language models for recommendation. World Wide Web. 2024;27(5):60. doi:10.1007/s11280-024-01291-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Gao C, Lan X, Li N, Yuan Y, Ding J, Zhou Z, et al. Large language models empowered agent-based modeling and simulation: a survey and perspectives. Humanit Soc Sci Commun. 2024;11(1):1259. doi:10.1057/s41599-024-03611-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Yin S, Fu C, Zhao S, Xu T, Wang H, Sui D, et al. Woodpecker: hallucination correction for multimodal large language models. Sci China Inf Sci. 2024;67(12):220105. doi:10.1007/s11432-024-4251-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Tihanyi N, Bisztray T, Ferrag MA, Jain R, Cordeiro LC. How secure is AI-generated code: a large-scale comparison of large language models. Empir Softw Eng. 2024;30(2):47. doi:10.1007/s10664-024-10590-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Wang F, Shi D, Aguilar J, Cui X. A few-shot learning method based on knowledge graph in large language models. Int J Data Sci Anal. 2024;10(3):100426. doi:10.1007/s41060-024-00699-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Gu B, Desai RJ, Lin KJ, Yang J. Probabilistic medical predictions of large language models. npj Digit Med. 2024;7(1):367. doi:10.1038/s41746-024-01366-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Yashwanth YS, Shettar R. Zero and few short learning using large language models for de-identification of medical records. IEEE Access. 2024;12:110385–93. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3439680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Kosenko DP, Kuratov YM, Zharikova DR. Accessible Russian large language models: open-source models and instructive datasets for commercial applications. Dokl Math. 2023;108(S2):S393–8. doi:10.1134/S1064562423701168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Reinhart WF, Statt A. Large language models design sequence-defined macromolecules via evolutionary optimization. npj Comput Mater. 2024;10(1):262. doi:10.1038/s41524-024-01449-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Yoshikawa N, Skreta M, Darvish K, Arellano-Rubach S, Ji Z, Bjørn Kristensen L, et al. Large language models for chemistry robotics. Auton Rob. 2023;47(8):1057–86. doi:10.1007/s10514-023-10136-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Jablonka KM, Schwaller P, Ortega-Guerrero A, Smit B. Leveraging large language models for predictive chemistry. Nat Mach Intell. 2024;6(2):161–9. doi:10.1038/s42256-023-00788-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Bharathi Mohan G, Prasanna Kumar R, Vishal Krishh P, Keerthinathan A, Lavanya G, Meghana MKU, et al. An analysis of large language models: their impact and potential applications. Knowl Inf Syst. 2024;66(9):5047–70. doi:10.1007/s10115-024-02120-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Lan Y, Wu Y, Xu W, Feng W, Zhang Y. Chinese fine-grained financial sentiment analysis with large language models. Neural Comput Appl. 2024. doi:10.1007/s00521-024-10603-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

75. Shen Y, Xu Y, Ma J, Rui W, Zhao C, Heacock L, et al. Multi-modal large language models in radiology: principles, applications, and potential. Abdom Radiol. 2024;35:23716. doi:10.1007/s00261-024-04708-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools