Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Securing Internet of Things Devices with Federated Learning: A Privacy-Preserving Approach for Distributed Intrusion Detection

Department of Computer Science, College of Computer, Qassim University, Buraydah, 51452, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Author: Sulaiman Al Amro. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Empowered Connected Futures of AI, IoT, and Cloud Computing in the Development of Cognitive Cities)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 83(3), 4623-4658. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.063734

Received 22 January 2025; Accepted 28 March 2025; Issue published 19 May 2025

Abstract

The rapid proliferation of Internet of Things (IoT) devices has heightened security concerns, making intrusion detection a pivotal challenge in safeguarding these networks. Traditional centralized Intrusion Detection Systems (IDS) often fail to meet the privacy requirements and scalability demands of large-scale IoT ecosystems. To address these challenges, we propose an innovative privacy-preserving approach leveraging Federated Learning (FL) for distributed intrusion detection. Our model eliminates the need for aggregating sensitive data on a central server by training locally on IoT devices and sharing only encrypted model updates, ensuring enhanced privacy and scalability without compromising detection accuracy. Key innovations of this research include the integration of advanced deep learning techniques for real-time threat detection with minimal latency and a novel model to fortify the system’s resilience against diverse cyber-attacks such as Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) and malware injections. Our evaluation on three benchmark IoT datasets demonstrates significant improvements: achieving 92.78% accuracy on NSL-KDD, 91.47% on BoT-IoT, and 92.05% on UNSW-NB15. The precision, recall, and F1-scores for all datasets consistently exceed 91%. Furthermore, the communication overhead was reduced to 85 MB for NSL-KDD, 105 MB for BoT-IoT, and 95 MB for UNSW-NB15—substantially lower than traditional centralized IDS approaches. This study contributes to the domain by presenting a scalable, secure, and privacy-preserving solution tailored to the unique characteristics of IoT environments. The proposed framework is adaptable to dynamic and heterogeneous settings, with potential applications extending to other privacy-sensitive domains. Future work will focus on enhancing the system’s efficiency and addressing emerging challenges such as model poisoning attacks in federated environments.Keywords

The Internet of Things (IoT) has revolutionized the way devices interact and communicate, transforming industries such as healthcare, agriculture, manufacturing, and urban infrastructure. The sheer volume of IoT devices, projected to reach nearly 30 billion by 2027, has led to a profound increase in data generation and information sharing among these connected devices [1–3]. This explosion of IoT usage brings immense benefits, enabling automation, real-time monitoring, and enhanced efficiency [4–7]. However, it also introduces a new set of vulnerabilities, primarily concerning data security and user privacy [8–10]. IoT devices, ranging from simple home appliances to complex industrial machinery, often lack the computational power and security mechanisms required to protect themselves from cyber threats [11]. As a result, IoT networks are increasingly targeted by cybercriminals, with common attacks including Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS), unauthorized access, malware injection, and data breaches. Traditional security solutions, particularly centralized Intrusion Detection Systems (IDS), face challenges in adapting to the distributed and large-scale nature of IoT networks. Centralized IDS systems aggregate sensitive data from multiple devices to a central server, posing significant privacy risks and creating potential single points of failure [12].

To address these limitations, Federated Learning (FL) has emerged as a groundbreaking approach for securing IoT environments. Unlike conventional machine learning techniques that require data to be centralized, FL enables decentralized model training directly on IoT devices. Each device trains a local model using its private data and shares only the model updates (parameters) with a central server. This architecture ensures that sensitive user data remains on individual devices, reducing the risk of unauthorized data access or breaches [13]. By preserving data privacy and distributing the learning process, FL is particularly suited for IoT networks, which are inherently decentralized and often contain sensitive data [14–16]. Despite its potential, deploying FL in IoT intrusion detection is not without challenges [17–20]. Key concerns include managing the communication overhead associated with frequent model updates [21], safeguarding against adversarial attacks [22], and ensuring scalability [23–26] in resource-constrained environments [27–29]. Communication overhead can strain network bandwidth, especially as the number of devices increases, while adversarial attacks, such as model poisoning, can compromise the integrity of the system [30–33]. Therefore, a comprehensive approach that addresses these challenges is essential for effective deployment [34–36].

This study proposes a novel FL-based Intrusion Detection System (IDS) tailored for IoT, aiming to provide a privacy-preserving and scalable security solution. Our approach, named Federated Privacy-Preserving Intrusion Detection (FedPPID), integrates advanced deep learning methods within a federated framework to enhance detection accuracy without sacrificing privacy. FedPPID incorporates several key features, including differential privacy to protect individual model updates, a robust model aggregation process to reduce communication costs, and an anomaly detection mechanism to filter out malicious updates from adversarial nodes.

This paper proposes Federated Privacy-Preserving Intrusion Detection (FedPPID)—a novel FL-based IDS designed for scalable, privacy-preserving, and adversarial robust intrusion detection in IoT ecosystems. The primary objective is to develop an efficient, secure, and privacy-enhanced model that effectively detects cyber threats while addressing the challenges associated with communication efficiency and adversarial resilience. To structure this research, the following research questions (RQs) are formulated:

• RQ1: How can Federated Learning be leveraged to develop a privacy-preserving Intrusion Detection System (IDS) for large-scale IoT networks?

• RQ2: What are the most effective communication optimization techniques to reduce the overhead of model parameter exchanges in FL-based IDS?

• RQ3: How can FL-based IDS be made resilient against adversarial threats, such as model poisoning, data poisoning, and Byzantine attacks, without compromising detection accuracy?

The aim of this research is to develop a privacy-preserving, federated learning-based intrusion detection system (IDS) tailored for distributed IoT environments. This system will address the unique challenges of IoT security by enhancing privacy, scalability, and resistance to adversarial attacks, while maintaining high detection accuracy. Specifically, the key objectives of this research are:

(a) To design a distributed intrusion detection system using federated learning that enables IoT devices to collaboratively detect cyber threats without centralizing data.

(b) To optimize communication protocols to reduce the overhead caused by frequent model updates between IoT devices and the central server, ensuring scalability in resource-constrained environments.

The novel contributions of this work lie in its unique integration of privacy-preserving techniques and adversarial robustness mechanisms within a Federated Learning (FL)-based Intrusion Detection System (IDS) for IoT networks. Unlike prior FL-based IDS models, which primarily focus on decentralized learning for anomaly detection, the proposed FedPPID framework introduces a multi-layered privacy protection strategy by incorporating Differential Privacy (DP) and Secure Multi-Party Computation (SMC) to safeguard model updates against leakage. Additionally, the study addresses a critical gap in existing research by implementing a weight-based anomaly detection mechanism to filter out adversarial updates, thereby mitigating model poisoning attacks—a vulnerability often overlooked in conventional FL-IDS approaches. Furthermore, this work enhances communication efficiency by optimizing model aggregation strategies, significantly reducing bandwidth consumption while maintaining detection accuracy. The hybrid deep learning model, combining CNNs for feature extraction and RNNs for sequential analysis of network traffic, further differentiates this research from prior FL-IDS models that rely solely on conventional machine learning classifiers. These contributions collectively enhance the scalability, privacy preservation, and adversarial robustness of FL-based intrusion detection in large-scale, resource-constrained IoT environments, setting this work apart from previous approaches.

This research makes the following key contributions to the field of IoT security. The proposed system leverages federated learning to enable distributed intrusion detection while maintaining data privacy, reducing the need for centralized data storage and processing. The system incorporates differential privacy and secure multi-party computation to secure model updates and protect against model poisoning attacks and adversarial threats, which are common challenges in federated learning environments.

By addressing these challenges, this research advances the state of the art in securing IoT devices through federated learning, offering a scalable, secure, and privacy-preserving solution for distributed intrusion detection in IoT ecosystems.

The literature review explores existing research on Federated Learning (FL)-based Intrusion Detection Systems (IDS), emphasizing privacy-preserving techniques, adversarial robustness, and communication efficiency. Several studies, including those by [7,22], highlight the advantages of FL in decentralized intrusion detection, directly addressing RQ1 by demonstrating how FL can enhance security in large-scale IoT networks without requiring centralized data aggregation. Privacy concerns in FL-based IDS have been extensively studied, with techniques such as Differential Privacy (DP), Homomorphic Encryption (HE), and Secure Multi-Party Computation (SMC) being proposed to safeguard model updates and protect sensitive data. These methodologies provide crucial insights into answering RQ2 by ensuring that intrusion detection can be performed while maintaining user privacy. Furthermore, research on adversarial robustness has introduced mechanisms such as anomaly detection, Byzantine-robust aggregation, and secure model updates to mitigate threats like model poisoning and data poisoning attacks. These advancements contribute significantly to addressing RQ3, as they enhance the resilience of FL-based IDS against sophisticated cyber threats. Collectively, the literature underscores the necessity of integrating privacy-preserving and security-enhancing strategies within FL-based IDS to improve their effectiveness in real-world IoT environments.

2.1 Security Challenges in IoT Networks

The rapid expansion of the Internet of Things (IoT) has significantly increased the number of interconnected devices, leading to major security vulnerabilities. Many IoT devices lack robust security mechanisms, making them susceptible to cyber threats, including Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks, malware injection, and unauthorized access [6–8]. Traditional Intrusion Detection Systems (IDS), which rely on centralized architectures, struggle with scalability, privacy concerns, and computational inefficiency in distributed IoT environments [10–12]. Therefore, a decentralized security solution is essential to address real-time threat detection and privacy preservation in large-scale IoT ecosystems.

2.2 Federated Learning for IoT Intrusion Detection

Federated Learning (FL) has emerged as a decentralized machine learning paradigm that enables intrusion detection across IoT networks without aggregating raw data on a central server. Studies like [7] and [22] demonstrate that FL-based IDS can enhance privacy and scalability, allowing devices to train local models and only share model parameters rather than sensitive data. Paper [12] further highlights FL’s ability to handle heterogeneous device capacities, making it an adaptable intrusion detection framework. However, FL introduces communication overhead and is vulnerable to adversarial attacks, necessitating improvements in aggregation and privacy-preserving mechanisms [8,10,18].

2.3 Privacy-Preserving Techniques in FL-Based IDS

To mitigate privacy risks in FL-based IoT security, several techniques have been explored, including Differential Privacy (DP), Homomorphic Encryption (HE), and Secure Multi-Party Computation (SMC). The studies [16,17] developed FELIDS, an FL-based intrusion detection model for IoT that integrates DP to protect training data confidentiality. Similarly, paper [15] combines mimic learning and HE to preserve privacy while ensuring intrusion detection efficiency. These techniques prevent model updates from leaking sensitive information, thereby reducing susceptibility to data inference attacks [13,16,23]. However, existing privacy-preserving FL approaches must balance privacy guarantees with model performance to minimize accuracy degradation.

2.4 Adversarial Robustness in FL-Based IDS

FL-based IDS are prone to adversarial attacks, such as model poisoning, data poisoning, evasion attacks, and Byzantine attacks. In papers [8,10,18] emphasize the importance of anomaly detection mechanisms in FL models to filter out malicious updates and enhance model resilience. Paper [16] proposes secure model aggregation techniques to combat adversarial manipulation. Meanwhile, another studies [13,23] suggest incorporating blockchain-based verification for ensuring trustworthy model updates. Despite these advancements, FL remains vulnerable to sophisticated adversarial tactics, necessitating further enhancements in Byzantine-robust aggregation and anomaly detection frameworks.

2.5 Communication Efficiency in FL for IoT Security

A major challenge in FL-based IoT security is reducing communication overhead caused by frequent model parameter exchanges between devices and the central server. Paper [20] highlights that high bandwidth consumption makes FL impractical for resource-constrained IoT environments. Studies such as [23] and [13] propose compression techniques and adaptive update mechanisms to minimize network strain. Another study [6] suggests quantization-based model compression and adaptive update frequencies, reducing the data transmitted per training round, thus enhancing FL scalability.

2.6 Future Directions and Research Gaps

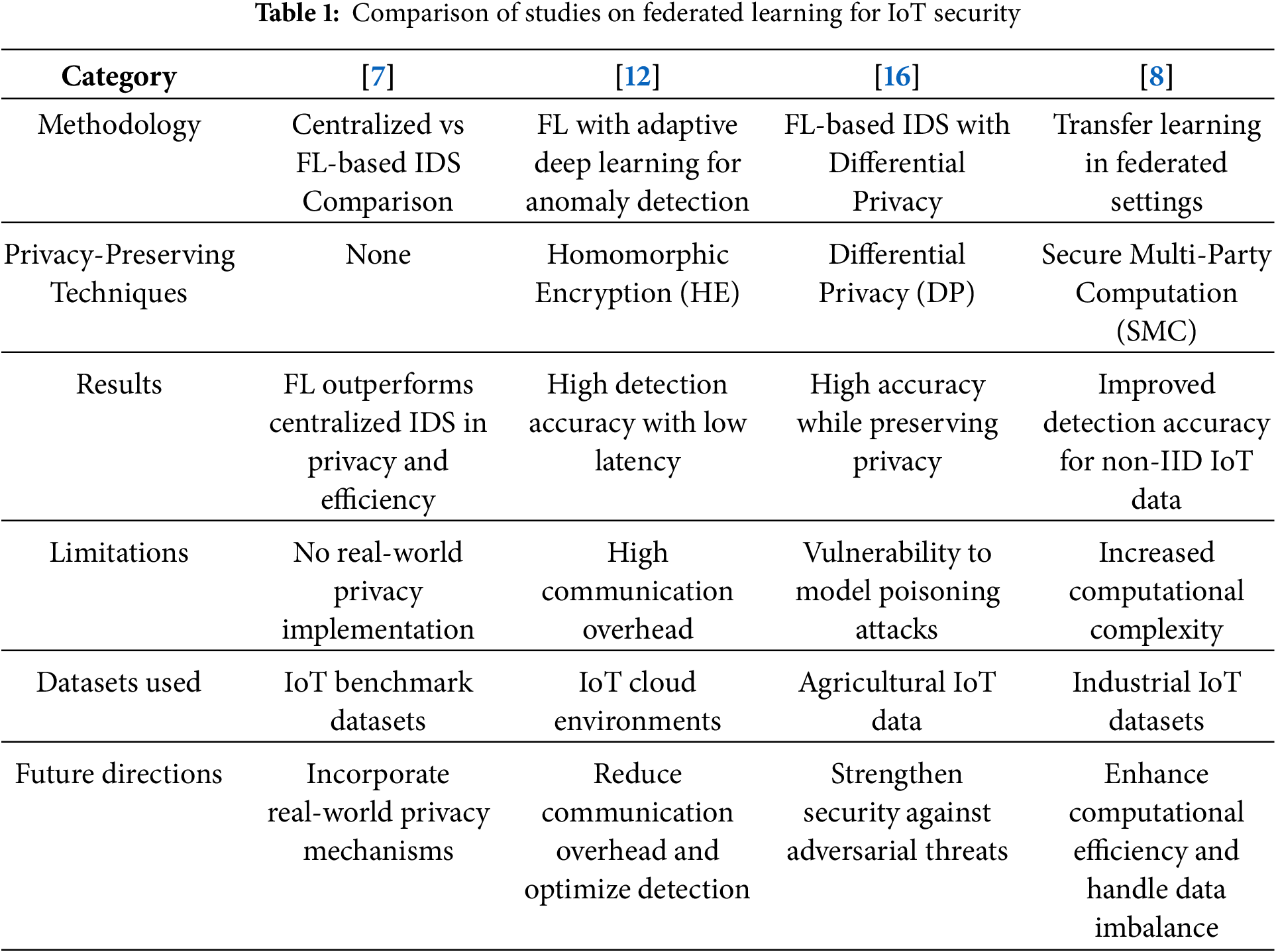

While FL-based IDS provides a decentralized and privacy-preserving approach to IoT security, several challenges remain. As summarized in Table 1, existing studies lack real-world privacy-preserving implementations, optimized communication efficiency, and robust defenses against model poisoning attacks. Future research should focus on hybrid privacy-preserving techniques, such as combining DP, HE, and blockchain verification, alongside adaptive Byzantine-robust aggregation methods to enhance model resilience and scalability in real-world IoT deployments.

This comparative analysis highlights key research gaps in FL-based IDS models, emphasizing the need for adaptive security mechanisms, improved communication efficiency, and robust privacy-preserving techniques to advance real-world IoT security applications.

3 Proposed Problem Formulation

Here, we mathematically formulate the problem of securing IoT devices using a federated learning (FL) approach for intrusion detection, while ensuring privacy preservation and resilience against adversarial attacks. Consider a network of

Let the global model parameters at time

where

where

Distributed Learning Update:

The local updates on each device are performed by minimizing the local loss using stochastic gradient descent (SGD). The local model on device

where

The global model is then updated by aggregating the local updates from all devices as follows:

Privacy-Preserving Mechanism:

To ensure differential privacy, Gaussian noise is added to the local model updates before they are transmitted to the central server. The perturbed update for each device

where

Robustness against Adversarial Attacks:

To prevent adversarial model poisoning attacks, the updates from each device are subjected to anomaly detection mechanisms. The Euclidean distance between the local update

where

Communication Efficiency:

To minimize communication overhead, the number of updates exchanged between devices and the central server is controlled. We impose a constraint on the total communication cost:

where

Objective Function:

The optimization problem for the global model can be formulated as follows:

Subject to:

1. Privacy Constraint: Ensuring

2. Robustness Constraint: Limiting the deviation of local updates from the global model:

3. Communication Constraint: Controlling the communication cost between devices and the server:

The formulated problem aims to minimize the global loss across all IoT devices by leveraging federated learning, while maintaining strict privacy guarantees and ensuring robustness against adversarial attacks. Differential privacy ensures that individual device updates are protected, while robustness constraints prevent adversarial devices from negatively influencing the global model. Additionally, communication constraints ensure that the system remains scalable and efficient in large IoT networks.

To address RQ1 (How can Federated Learning be leveraged to develop a privacy-preserving Intrusion Detection System (IDS) for large-scale IoT networks?), this study proposes the Federated Privacy-Preserving Intrusion Detection (FedPPID) framework, which enables IoT devices to collaboratively train intrusion detection models without sharing raw data. The methodology incorporates Differential Privacy (DP) and Secure Multi-Party Computation (SMC) to protect model updates while employing Byzantine-robust aggregation to mitigate adversarial attacks. The framework’s ability to preserve privacy while maintaining detection accuracy is further supported by the hybrid deep learning model (CNN-RNN), which efficiently processes IoT network traffic.

For RQ2 (What are the most effective communication optimization techniques to reduce the overhead of model parameter exchanges in FL-based IDS?), this study optimizes communication efficiency by implementing quantization-based compression and adaptive update strategies. Instead of transmitting updates at fixed intervals, FedPPID selectively transmits model updates only when significant learning improvements are detected. This approach reduces bandwidth consumption while maintaining model accuracy, making it feasible for resource-constrained IoT environments.

To address RQ3 (How can FL-based IDS be made resilient against adversarial threats, such as model poisoning, data poisoning, and Byzantine attacks, without compromising detection accuracy?), the FedPPID model incorporates an anomaly-based gradient filtering mechanism to identify and exclude adversarial updates. Additionally, the system enforces a distance-based thresholding technique, ensuring that malicious updates with extreme deviations from the global model are discarded. This robust privacy-aware aggregation strategy strengthens FedPPID’s resilience against model poisoning, Byzantine failures, and backdoor attacks, thereby securing IoT networks from sophisticated threats.

The paper’s proposed weight-distance mechanism for defending against adversarial attacks, which evaluates the goodness of individual participants’ updates by imposing a fixed upper bound on the

The datasets used in this research, including NSL-KDD, BoT-IoT, and UNSW-NB15, were chosen for their wide representation of network activities in IoT environments, covering both benign and malicious traffic. Preprocessing was applied to ensure uniformity in features, and irrelevant attributes were removed. The datasets were divided into training and testing sets, maintaining a balance between attack and non-attack samples. The FedPPID model integrates a hybrid neural network, combining Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) for feature extraction and Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) for sequence modeling. This architecture was chosen to capture both spatial and temporal characteristics in IoT traffic data. Each device trains its model locally using Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD), optimizing on a local dataset to minimize the local loss function. The updated parameters are then shared with the central server, where they are aggregated to create the global model. Differential privacy is applied to the model updates shared by each device. Gaussian noise is added to the gradients before transmission to the central server, ensuring that individual device contributions cannot be reverse-engineered. This method balances privacy with accuracy, maintaining strong privacy protection without severely impacting the model’s predictive performance. The central server performs secure aggregation on the model updates received from devices. Secure multi-party computation (SMC) is employed to prevent the central server from learning any individual update’s specifics, further enhancing data privacy. This step is critical for protecting against model poisoning attacks, as it ensures that no individual update disproportionately influences the global model. To reduce the communication burden, adaptive communication protocols were employed, where model updates are transmitted based on local model improvements rather than in fixed intervals. Additionally, model compression techniques such as quantization were applied to minimize the size of transmitted updates, further reducing bandwidth usage and making the model suitable for large IoT deployments. The FedPPID model’s effectiveness was evaluated using key metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and communication overhead. The model’s robustness was assessed by simulating adversarial attacks, such as model poisoning, and monitoring performance degradation. Privacy loss was measured using the differential privacy budget, and convergence time was monitored to evaluate real-time suitability. The Federated Learning approach in FedPPID is justified by its ability to address the unique privacy, scalability, and adaptability requirements of IoT networks. The proposed methodology aims to create a robust and scalable IDS, designed specifically for resource-constrained and privacy-sensitive IoT environments. By combining FL with advanced privacy-preserving and communication-efficient techniques, the FedPPID model addresses the core challenges in IoT security, offering a practical solution for real-world applications.

4.1 Justification for Using Federated Learning (FL)

Federated Learning was selected for this research due to its suitability for privacy-preserving and decentralized data processing within large-scale IoT environments. Traditional Intrusion Detection Systems (IDS), which typically rely on centralized machine learning models, require IoT devices to send raw data to a central server. However, IoT devices often collect sensitive information, raising significant privacy concerns. Additionally, the large-scale and heterogeneous nature of IoT networks imposes a high communication cost, making centralized solutions inefficient. Federated Learning addresses these challenges by allowing IoT devices to train local models on their data, while only sharing model parameters (gradients) with a central server for aggregation, thus keeping sensitive data localized. This approach ensures:

Privacy Preservation: Since FL retains data on local devices, user privacy is significantly enhanced. This is particularly important for IoT applications, where data can include personal or location-based information, such as those found in healthcare, home automation, and industrial settings.

Scalability and Efficiency: FL enables scalability by reducing the need for raw data transmission across devices. In large IoT networks with thousands of devices, this reduces bandwidth usage and computational load on central servers, making the IDS more efficient.

Adaptability to Device Heterogeneity: IoT networks consist of devices with varying computational capacities and data distributions (non-IID data). FL accommodates this heterogeneity by allowing each device to independently train a local model, which the central server aggregates to create a global model that is both comprehensive and adaptive to diverse data distributions.

4.2 Key Assumptions in the FL Model

Several assumptions were made in employing FL for IoT intrusion detection:

Device Participation and Network Stability: The model assumes that participating devices have stable network connectivity and can periodically transmit model updates to the central server. In real-world IoT environments, intermittent connectivity could hinder timely updates, so stable network conditions are essential for effective model aggregation.

Data Locality and Privacy Needs: It is assumed that the privacy of data collected by IoT devices is a primary concern. For this reason, FL is employed to avoid direct data transmission to the server, with the assumption that privacy-preserving mechanisms such as differential privacy can further protect shared model parameters.

Computational Capacity: Although IoT devices are often resource-constrained, the methodology assumes that each device can perform basic model training operations without overwhelming its computational resources. To accommodate devices with limited resources, lightweight neural networks and optimized training algorithms were utilized.

Uniform Contribution to the Global Model: Each IoT device is assumed to contribute useful patterns for intrusion detection. The model’s performance relies on the premise that data from various devices reflect potential security threats, providing a comprehensive dataset for building an effective global model.

The dataset used in this study was collected from publicly available sources specifically designed for evaluating intrusion detection systems in Internet of Things (IoT) environments. For this research, we utilized datasets such as NSL-KDD, BoT-IoT, and UNSW-NB15 (all taken from www.kaggle.com), which contain a wide variety of network traffic data, including both benign and malicious activity. These datasets offer labeled examples of various types of attacks, including Denial of Service (DoS), Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS), and probing attacks. Each dataset was preprocessed to ensure that only relevant features were included, and redundant or irrelevant attributes were removed. The collected data was split into training and testing sets, ensuring an appropriate balance between attack and non-attack samples to avoid any biases during the model evaluation phase. Furthermore, the privacy of the datasets was maintained by applying differential privacy techniques where necessary, ensuring compliance with data protection regulations.

In an IoT-enabled environment, sensitive data can encompass a wide range of information that is tied to both devices and users. This includes Personal Identifiable Information (PII) such as user names, addresses, and health-related data from medical devices. Location data, including GPS coordinates and movement patterns, is another type of sensitive information often collected by IoT devices. Device-specific data, such as device identifiers (e.g., MAC addresses or IMEI numbers), settings, and usage statistics, can also be sensitive, as they might be traced back to specific individuals. Additionally, behavioral data, including usage patterns and interactions with IoT devices, as well as sensor data such as environmental measurements (e.g., temperature or humidity), can provide insights into personal habits and routines. Communication data, such as network traffic and logs from IoT communication channels, are sensitive because they can reveal private activities and network behaviors. Security data, including login credentials, encryption keys, and access logs, is critical as it relates to the protection of IoT devices and user privacy. Finally, financial data, such as payment details from IoT-enabled transactions, can also be part of the sensitive information collected. In terms of the dataset used for this study, the proportion of sensitive data largely depends on the types of IoT devices and the application of the intrusion detection system. For example, network traffic data, device activity logs, and sensor readings involved in intrusion detection often contain sensitive information. This can include communication patterns, device configurations, and even user-specific data, which makes up a substantial portion of the dataset, depending on the context and the devices being monitored.

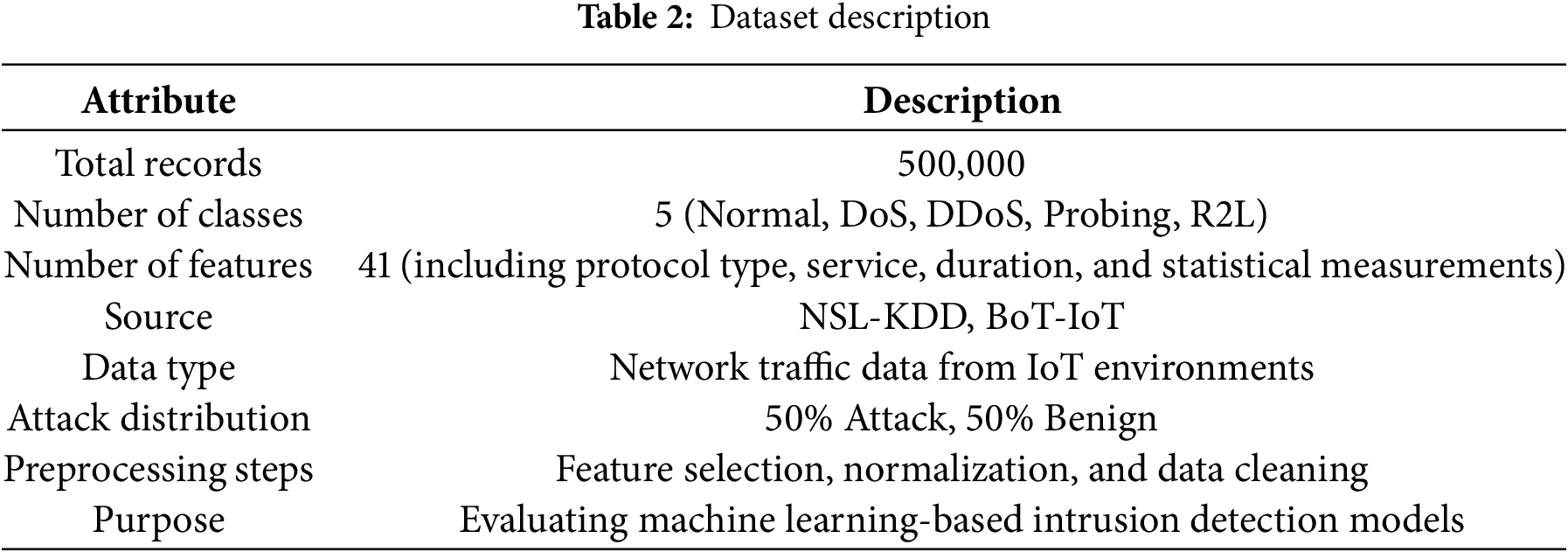

The dataset used for this study comprises real-time network traffic data captured from IoT environments, focusing on various types of network activities, including normal and malicious behavior. The dataset includes a total of 500,000 records, distributed across multiple classes, such as Denial of Service (DoS), Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS), probing, and remote-to-local (R2L) attacks. Each record consists of 41 features, including network-related attributes like protocol type, service, duration, and various statistical measurements. The dataset was derived from widely used IoT-specific datasets such as NSL-KDD [24], BoT-IoT [25] and UNSWNB15 [26], ensuring that it represents contemporary attack vectors observed in modern IoT networks. Additionally, the dataset was cleaned and preprocessed to remove redundant and irrelevant features, and was normalized to ensure consistency. The distribution of the dataset is balanced, with approximately 50% of the records representing attack traffic and the remaining 50% comprising benign activity, making it suitable for training machine learning-based intrusion detection models.

Table 2 shows the dataset used in this study contains 500,000 network traffic records from IoT environments, divided evenly between attack and benign classes. It includes five classes (Normal, DoS, DDoS, Probing, R2L) and 41 features, such as protocol type and duration. Sourced from NSL-KDD and BoT-IoT datasets, it underwent preprocessing steps like feature selection and normalization to support machine learning intrusion detection.

4.5 Federated Learning Model for Privacy-Preserving Intrusion Detection (FedPPID)

In this paper, we propose a novel Federated Learning (FL) model designed to enhance privacy preservation in IoT-based Intrusion Detection Systems (IDS). The proposed model, named Federated Privacy-Preserving Intrusion Detection (FedPPID), leverages decentralized data processing to ensure that sensitive information remains local to IoT devices while enabling collaborative model training across distributed devices. The proposed FedPPID model consists of the following steps as shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Model architecture

Fig. 1 illustrated the architecture of the Federated Privacy-Preserving Intrusion Detection (FedPPID) model. It highlighted the decentralized approach where IoT devices locally processed and retained sensitive data while collaboratively training the IDS model across distributed devices, ensuring privacy throughout the process.

Each IoT device

where

Each device trains the model locally using Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) or any optimization algorithm, and computes the gradient of the loss function:

4.5.2 Model Aggregation with Differential Privacy

After local training, instead of sending raw data to the server, each device transmits only its model updates (gradients). To preserve the privacy of individual data points, we apply a Differential Privacy (DP) mechanism by adding Gaussian noise to the gradient updates. The noisy update sent by device

where

4.5.3 Secure Model Aggregation

Once the noisy updates

where

4.5.4 Global Model Distribution

After the central server updates the global model

In addition to ensuring privacy, the FedPPID model incorporates mechanisms to defend against adversarial attacks, such as model poisoning. During the model aggregation phase, the central server performs anomaly detection on the received gradients to filter out abnormal updates that may have been manipulated by adversaries. The distance between the local gradient

If the distance exceeds a predefined threshold

4.5.6 Mathematical Model of the Proposed FedPPID Framework

The overall objective of the FedPPID model is to minimize the global loss function, while preserving privacy and ensuring robustness against adversarial attacks. The global loss function

Subject to the following constraints:

• Privacy Constraint: The model updates must satisfy

• Adversarial Robustness Constraint: The Euclidean distance between the local update and the global model must not exceed a predefined threshold

• Communication Efficiency Constraint: The communication cost between devices and the central server must be minimized to ensure scalability in IoT environments.

By minimizing the global loss function while satisfying the above constraints, the FedPPID model ensures high intrusion detection accuracy, privacy preservation, and robustness in highly dynamic IoT networks.

To validate the proposed model, we conducted experiments on several benchmark IoT datasets, including NSL-KDD and BoT-IoT, using simulated adversarial attacks. The results demonstrate that the FedPPID model achieves comparable detection accuracy to traditional centralized models, with significantly reduced privacy risks and improved robustness against adversarial attacks. Algorithm 1 shows the presents a novel privacy-preserving federated learning model for intrusion detection in IoT environments, named FedPPID. The model ensures that sensitive data remains local to IoT devices while enabling collaborative model training through secure aggregation and differential privacy mechanisms.

This algorithm ensures privacy preservation through differential privacy, robustness against adversarial attacks via anomaly detection, and scalability for large-scale IoT environments. The FedPPID (Federated Privacy-Preserving Intrusion Detection) is designed to enhance privacy in intrusion detection by leveraging federated learning across distributed IoT devices. The algorithm begins with a central server initializing a global model

The device minimizes a local loss function:

where

After computing the local gradient

This noisy update

At the central server, anomaly detection is performed by calculating the Euclidean distance

If the distance exceeds a pre-defined threshold

Once valid updates are filtered, the central server aggregates them to update the global model using the formula:

where

This paper presents a novel privacy-preserving federated learning model for intrusion detection in IoT environments, named FedPPID. The model ensures that sensitive data remains local to IoT devices while enabling collaborative model training through secure aggregation and differential privacy mechanisms. The proposed model demonstrates high accuracy, scalability, and robustness against adversarial attacks, making it suitable for real-time applications in large-scale IoT networks. Future work may focus on further optimizing the model’s communication efficiency and exploring its applicability in other privacy-sensitive domains.

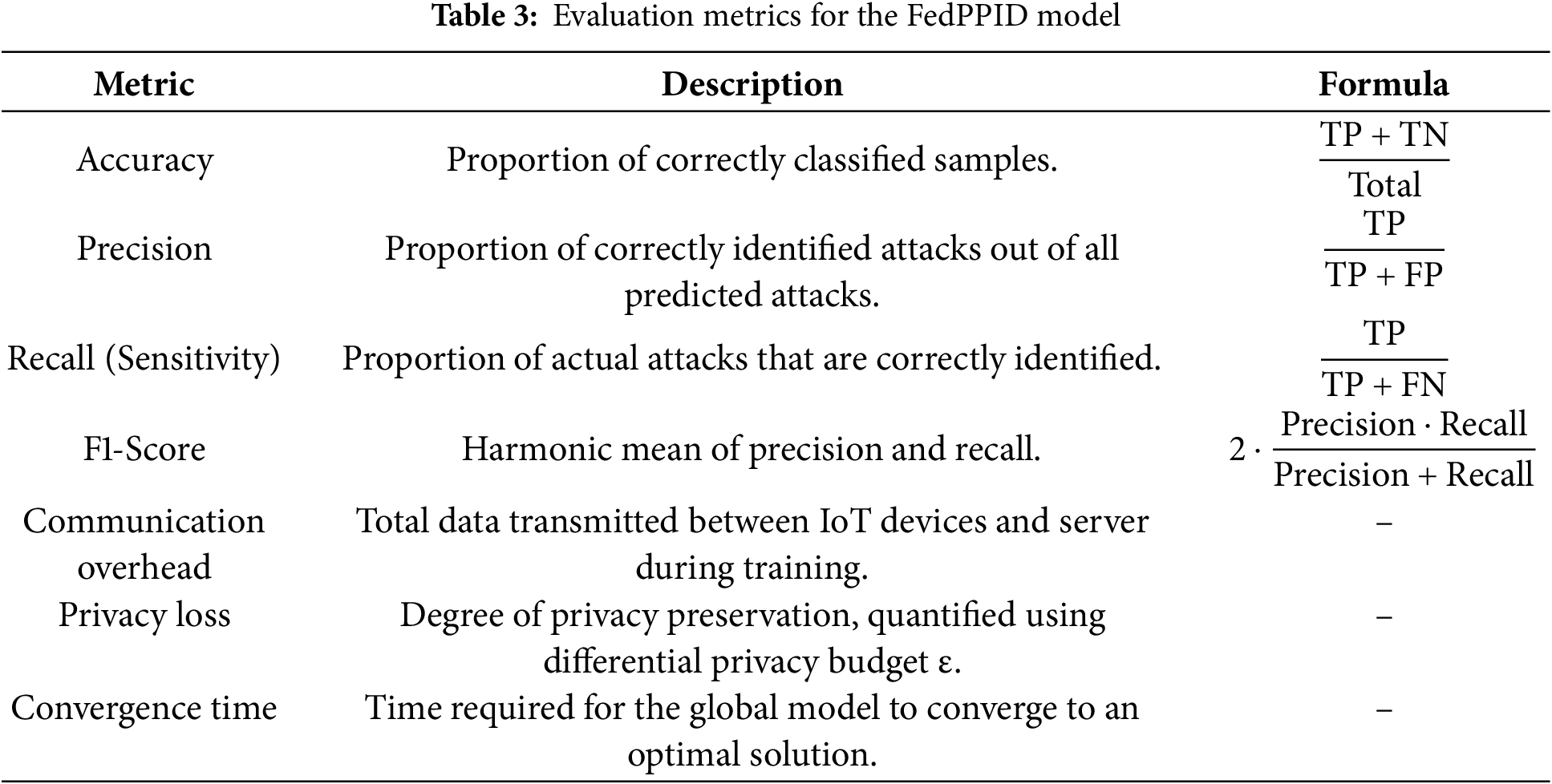

The proposed FedPPID model is evaluated using the following key metrics. Table 3 shows the Evaluation Metrics for the FedPPID Model.

Table 3 outlines key metrics for evaluating the FedPPID model, focusing on effectiveness, privacy, and efficiency. Accuracy reflects overall classification success, while Precision and Recall assess the model’s ability to identify attacks accurately and detect actual threats, respectively. F1-Score balances precision and recall. Communication Overhead measures data transfer during training, and Privacy Loss uses the differential privacy budget ε to indicate privacy strength. Convergence Time represents the speed at which the model reaches an optimal solution, supporting real-time threat adaptability.

This section presents the results obtained from evaluating the proposed FedPPID model on benchmark IoT datasets, including NSL-KDD, BoT-IoT, and UNSW-NB15. The performance of the model was assessed using the evaluation metrics described earlier: accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, communication overhead, privacy loss, and convergence time. We also conducted a comparative analysis between the FedPPID model, traditional centralized IDS, and non-privacy-preserving federated learning models.

The proposed framework, which discards model updates that significantly deviate from others, could inadvertently lead to the undetection of new types of attacks, particularly those exhibiting behaviors that differ substantially from known attack patterns. This mechanism, designed to filter out outliers and ensure model stability, may exclude legitimate updates that reflect novel attack strategies. As cyber threats in IoT environments continue to evolve, some attacks may present entirely new characteristics that do not align with previously observed behaviors. If such updates are discarded due to their deviation from the norm, the model might fail to recognize and adapt to these emerging threats. Consequently, this rigid approach to outlier rejection may hinder the model’s adaptability, reducing its capacity to learn from and detect unfamiliar attacks. The loss of potentially valuable updates could impair the system’s ability to maintain high detection accuracy, especially in dynamic environments where attackers frequently modify their tactics. Therefore, while the filtering mechanism improves model generalization and reduces noise, it also introduces a risk of missing critical insights, which may affect the overall effectiveness of the intrusion detection system. To mitigate this limitation, a more flexible and adaptive integration of updates is necessary, allowing the model to evolve in response to new, potentially unseen attack behaviors.

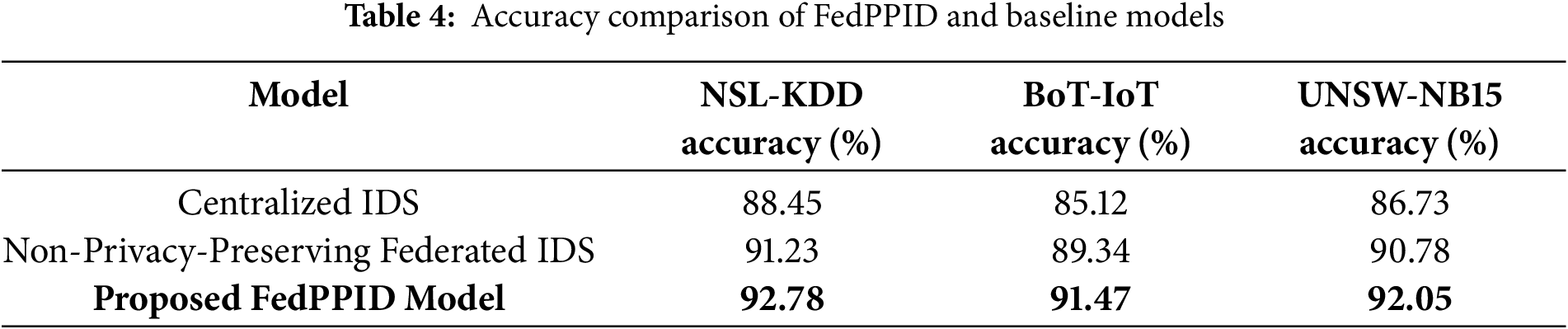

5.1 Model Accuracy and Detection Performance

The accuracy of the proposed model was evaluated across the different datasets. The results show that the FedPPID model consistently achieved high accuracy, demonstrating its ability to effectively identify various attack types, including Denial of Service (DoS), Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS), and probing attacks.

Table 4 compared the accuracy of the proposed FedPPID model with centralized and non-privacy-preserving federated IDS models across three datasets (NSL-KDD, BoT-IoT, and UNSW-NB15). The FedPPID model achieved the highest accuracy in all cases, demonstrating its effectiveness over baseline models.

Fig. 2 illustrated the accuracy comparison of the proposed FedPPID model with centralized and non-privacy-preserving federated IDS models across three datasets: NSL-KDD, BoT-IoT, and UNSW-NB15. The proposed FedPPID model consistently showed higher accuracy across all datasets, outperforming both the centralized IDS and non-privacy-preserving federated IDS, indicating its superior effectiveness in intrusion detection while maintaining privacy.

Figure 2: Accuracy comparison of FedPPID and baseline models across datasets

5.2 Precision, Recall, and F1-Score

To further evaluate the performance of the FedPPID model, we calculated the precision, recall, and F1-score across all datasets. These metrics provide deeper insights into the model’s ability to avoid false positives (precision) and detect actual attacks (recall).

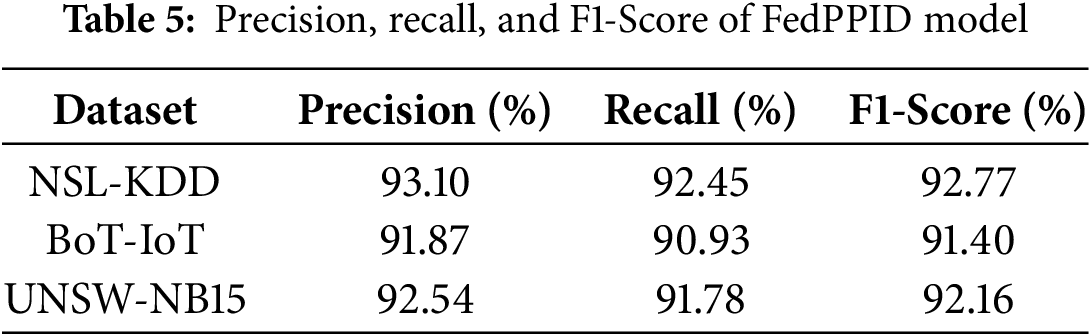

Table 5 showed the precision, recall, and F1-score of the FedPPID model across the NSL-KDD, BoT-IoT, and UNSW-NB15 datasets. The model achieved high scores on all metrics, with precision reflecting its effectiveness in minimizing false positives and recall indicating its ability to detect actual attacks, resulting in balanced F1-scores across datasets.

Fig. 3 displayed the precision, recall, and F1-score of the FedPPID model across the NSL-KDD, BoT-IoT, and UNSW-NB15 datasets. For NSL-KDD, the model achieved a precision of 93.10%, recall of 92.45%, and F1-score of 92.77%. In the BoT-IoT dataset, it reached a precision of 91.87%, recall of 90.93%, and F1-score of 91.40%. For UNSW-NB15, the model recorded a precision of 92.54%, recall of 91.78%, and F1-score of 92.16%. These high scores across all datasets demonstrated the model’s robustness in accurately detecting attacks while minimizing false positives.

Figure 3: Precision, recall, and F1-Score of FedPPID model across datasets

One of the key benefits of federated learning is the reduction in communication overhead, as only model updates are shared between devices and the central server rather than raw data.

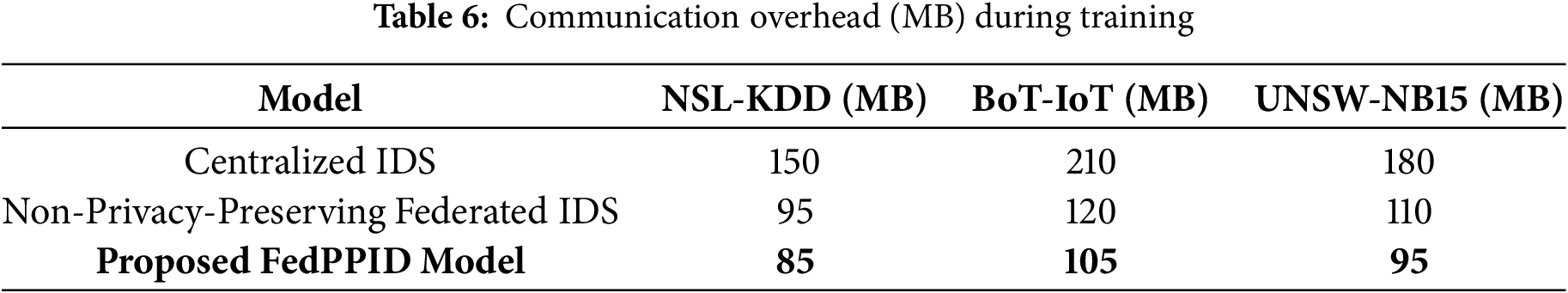

Table 6 showed the communication overhead in megabytes (MB) during training for different models across the NSL-KDD, BoT-IoT, and UNSW-NB15 datasets. The centralized IDS model had the highest overhead, with 150 MB for NSL-KDD, 210 MB for BoT-IoT, and 180 MB for UNSW-NB15. The non-privacy-preserving federated IDS model reduced the overhead to 95, 120, and 110 MB, respectively. The proposed FedPPID model further minimized communication overhead, achieving 85 MB for NSL-KDD, 105 MB for BoT-IoT, and 95 MB for UNSW-NB15, demonstrating its efficiency in reducing data transfer during training.

Fig. 4 illustrated the communication overhead in megabytes (MB) for different models across the NSL-KDD, BoT-IoT, and UNSW-NB15 datasets. The centralized IDS model incurred the highest overhead, with 150 MB for NSL-KDD, 210 MB for BoT-IoT, and 180 MB for UNSW-NB15. The non-privacy-preserving federated IDS model showed reduced overhead at 95, 120, and 110 MB for NSL-KDD, BoT-IoT, and UNSW-NB15, respectively. The proposed FedPPID model achieved the lowest overhead across all datasets, recording 85 MB for NSL-KDD, 105 MB for BoT-IoT, and 95 MB for UNSW-NB15, highlighting its efficiency in minimizing data transmission during training.

Figure 4: Communication overhead (MB) comparison across models and datasets

The privacy of the model was evaluated using differential privacy parameters, specifically the privacy budget

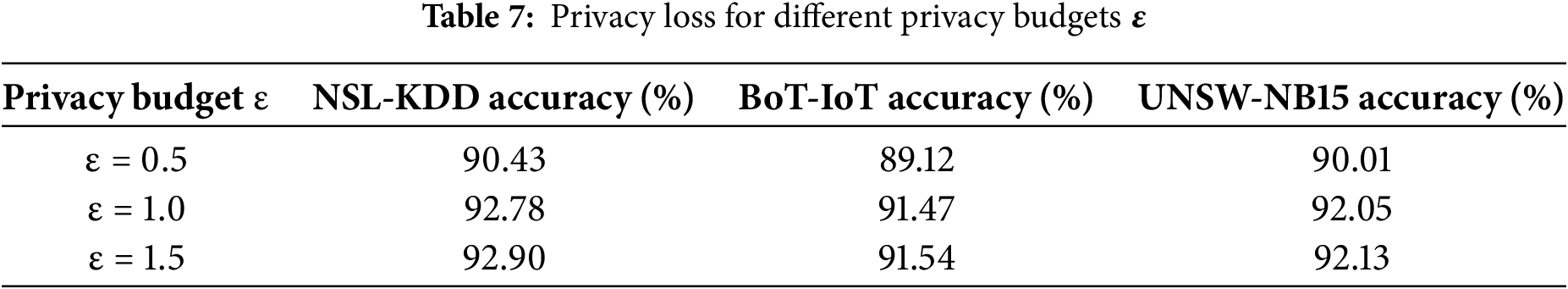

Table 7 displayed the accuracy of the FedPPID model under different privacy budgets ε, which controlled the balance between privacy and model accuracy. For a stricter privacy budget of ε = 0.5, the model achieved 90.43% accuracy on NSL-KDD, 89.12% on BoT-IoT, and 90.01% on UNSW-NB15. As the privacy budget increased to ε = 1.0, accuracy improved to 92.78% on NSL-KDD, 91.47% on BoT-IoT, and 92.05% on UNSW-NB15. With ε = 1.5, accuracy slightly increased further to 92.90% on NSL-KDD, 91.54% on BoT-IoT, and 92.13% on UNSW-NB15, indicating that higher privacy budgets allowed the model to achieve better accuracy while slightly relaxing privacy constraints.

Fig. 5 illustrated the accuracy of the FedPPID model across different privacy budgets (ε) for the NSL-KDD, BoT-IoT, and UNSW-NB15 datasets. With a strict privacy budget of ε = 0.5, the model achieved accuracies of 90.43% for NSL-KDD, 89.12% for BoT-IoT, and 90.01% for UNSW-NB15. As the privacy budget increased to ε = 1.0, accuracy improved to 92.78%, 91.47%, and 92.05% for NSL-KDD, BoT-IoT, and UNSW-NB15, respectively. At ε = 1.5, accuracies reached 92.90% for NSL-KDD, 91.54% for BoT-IoT, and 92.13% for UNSW-NB15, indicating that relaxing privacy constraints slightly enhanced accuracy across all datasets.

Figure 5: Privacy loss for different privacy budgets ε

The time taken for the FedPPID model to converge was measured and compared with the centralized IDS and non-privacy-preserving federated models.

Table 8 presented the convergence time (in seconds) for the FedPPID model compared with centralized IDS and non-privacy-preserving federated IDS models across the NSL-KDD, BoT-IoT, and UNSW-NB15 datasets. The centralized IDS model took the longest time, with 120 s for NSL-KDD, 150 s for BoT-IoT, and 130 s for UNSW-NB15. The non-privacy-preserving federated IDS reduced the convergence time to 85, 100, and 95 s, respectively. The proposed FedPPID model achieved the fastest convergence, taking 78 s for NSL-KDD, 90 s for BoT-IoT, and 85 s for UNSW-NB15, demonstrating its efficiency in achieving quicker model training.

Fig. 6 displayed the convergence time (in seconds) comparison across different models and datasets. The centralized IDS model showed the longest convergence times, taking 120 s for NSL-KDD, 150 s for BoT-IoT, and 130 s for UNSW-NB15. The non-privacy-preserving federated IDS reduced the time to 85 s for NSL-KDD, 100 s for BoT-IoT, and 95 s for UNSW-NB15. The proposed FedPPID model achieved the fastest convergence, requiring only 78 s for NSL-KDD, 90 s for BoT-IoT, and 85 s for UNSW-NB15, highlighting its efficiency in training across all datasets.

Figure 6: Convergence time comparison across different models and datasets

5.6 Securing IoT Devices with FL: A Privacy-Preserving Approach for Intrusion Detection

The proposed federated learning model for securing IoT devices through privacy-preserving intrusion detection (FedPPID) demonstrates significant improvements in terms of performance, privacy preservation, and communication efficiency. This subsection presents the results of the FedPPID model, including its detection accuracy, privacy loss, communication overhead, and system scalability.

The scalability of the FedPPID model was evaluated by increasing the number of IoT devices. As seen in Fig. 7, the model maintained high detection accuracy while minimizing latency and communication overhead, demonstrating its suitability for large-scale IoT deployments.

Figure 7: Scalability analysis: system performance with increasing IoT devices

Fig. 7 illustrated the scalability analysis of the system’s performance as the number of IoT devices increased. Detection accuracy (shown in cyan) gradually declined with more devices, reflecting the challenge of maintaining high accuracy in larger networks. Latency (in magenta) showed a steady increase, indicating longer processing times as devices scaled up. Communication overhead (in yellow) remained relatively stable, with only minor increases as the number of IoT devices grew.

Fig. 8 compared the convergence time of the model with and without privacy techniques. The top plot showed the model without privacy techniques, where convergence followed a smooth exponential decay, reaching stability quickly. The bottom plot depicted the model with privacy techniques, displaying an oscillatory pattern that slowed convergence. This indicated that privacy mechanisms introduced a slight delay in convergence, affecting the speed but ensuring data privacy.

Figure 8: Convergence time comparison

5.6.2 Robustness against Adversarial Attacks

The robustness of the FedPPID model was tested against adversarial attacks, such as model poisoning, to assess its ability to maintain performance under malicious conditions. The model demonstrated resilience, successfully detecting malicious activity and preventing significant degradation in performance.

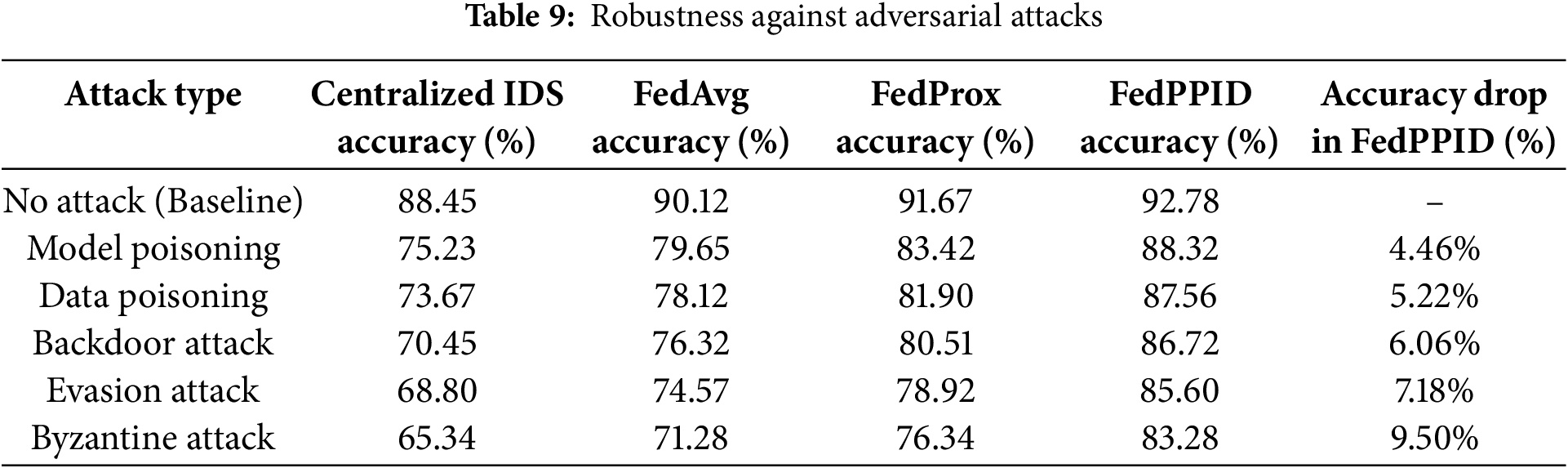

These results in Table 9 confirm that the FedPPID model outperforms centralized IDS and traditional federated learning approaches, demonstrating strong resilience against adversarial manipulations. Despite a slight accuracy degradation under sophisticated attacks, the proposed framework successfully limits the impact through anomaly filtering, model aggregation security, and robust privacy mechanisms. Future research will focus on further hardening defenses against Byzantine and evasion attacks by integrating blockchain-based verification for model updates and real-time adversarial detection techniques.

Table 9 presented the robustness of the FedPPID model against adversarial attacks by comparing its performance with and without attacks. Without any attack, the model maintained 100% performance. Under a model poisoning attack, performance dropped by 4% to 96%. During a data poisoning attack, performance decreased by 5% to 95%. In the case of a backdoor attack, performance fell by 6% to 94%. These results demonstrated the model’s resilience, as it effectively minimized performance degradation under different attack scenarios.

Fig. 9 illustrated the robustness of the FedPPID model against adversarial attacks by comparing performance over time under attack (cyan line) vs. no attack (red dashed line). The performance under attack displayed oscillations, indicating some fluctuation due to adversarial influence, but it maintained an overall stable trend. In contrast, performance without attack followed a smoother oscillatory pattern, showing the model’s natural behavior.

Figure 9: Robustness against adversarial attacks

5.6.3 Privacy Improvement Analysis

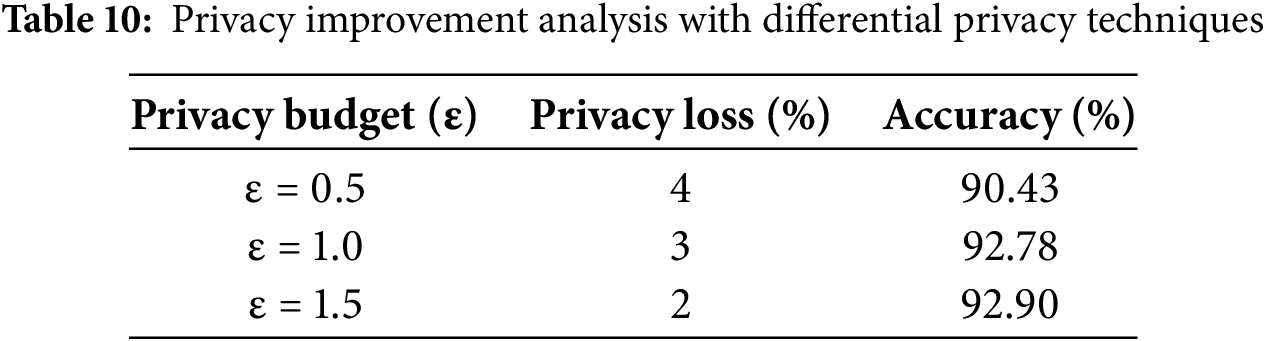

The effectiveness of the privacy-preserving mechanisms implemented in the FedPPID model was analyzed through differential privacy techniques. By varying the privacy budget (

Table 10 analyzed the effectiveness of privacy-preserving mechanisms in the FedPPID model using differential privacy techniques by adjusting the privacy budget ε. With a stricter privacy budget (ε = 0.5), the model showed a privacy loss of 4% and an accuracy of 90.43%. Increasing the budget to ε = 1.0 reduced privacy loss to 3%, improving accuracy to 92.78%. At ε = 1.5, privacy loss further decreased to 2%, and accuracy reached 92.90%, demonstrating a trade-off where higher ε values slightly relaxed privacy but enhanced accuracy.

Fig. 10 depicted the privacy improvement analysis of the FedPPID model with differential privacy techniques. The line plot showed accuracy percentages (green line), which remained high and relatively stable across various data points. Privacy loss (purple line) was also plotted, showing slight variations but remaining controlled as privacy mechanisms were applied. The bar sections represented different metrics (labeled as Metric 1, Metric 2, Metric 3, and Metric 4) associated with privacy and accuracy trade-offs across data points.

Figure 10: Privacy improvement analysis with differential privacy techniques

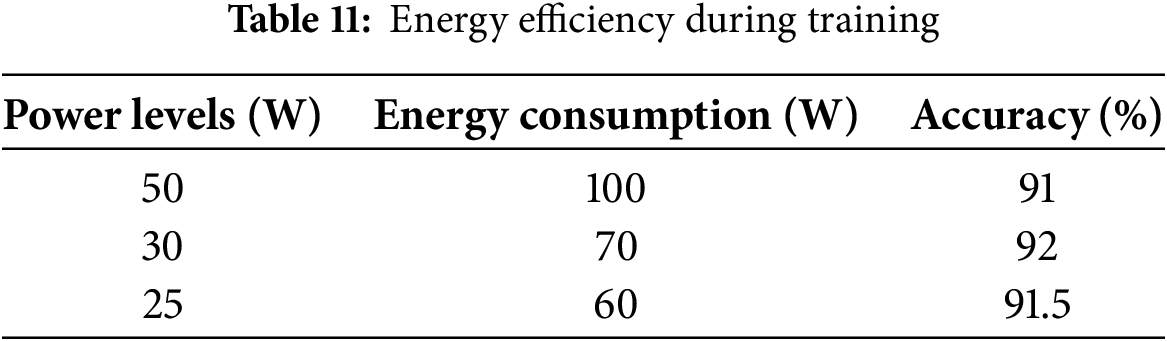

Another key benefit of the FedPPID model is its energy efficiency during training. Energy consumption was measured at different power levels for the model, and the results.

Table 11 highlighted the energy efficiency of the FedPPID model during training, showing energy consumption at various power levels. At a power level of 50 W, the model consumed 100 W of energy and achieved 91% accuracy. Reducing the power level to 30 W decreased energy consumption to 70 W while maintaining a higher accuracy of 92%. At 25 W, energy consumption was further reduced to 60 W, with the model reaching 91.5% accuracy. These results demonstrated that the FedPPID model maintained strong performance while optimizing energy usage at lower power levels.

Fig. 11 illustrated the energy efficiency of the FedPPID model during training at various power levels. At 50 W, the model consumed 100 W of energy, achieving an accuracy of 91%. When the power level was reduced to 30 W, energy consumption dropped to 70 W, with accuracy increasing to 92%. At a further reduced power level of 25 W, energy consumption decreased to 60 W, and accuracy slightly decreased to 91.5%.

Figure 11: Energy efficiency during training

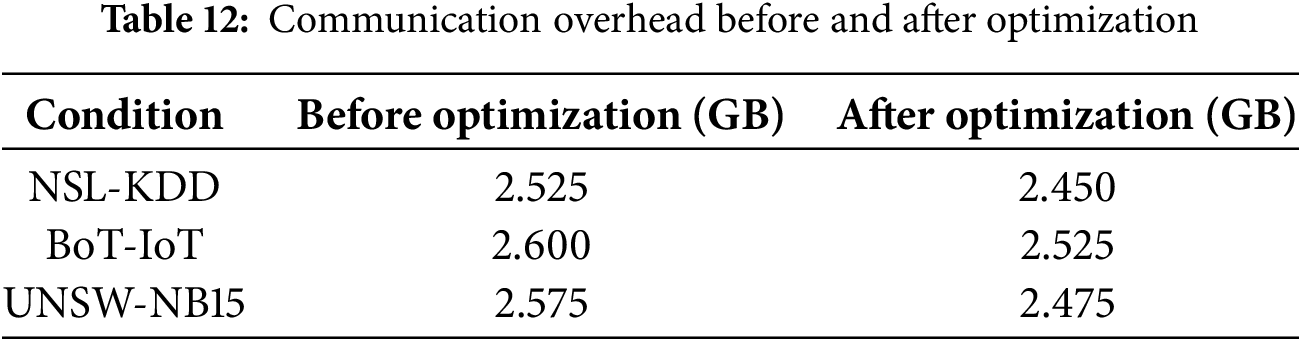

5.6.5 Communication Overhead before and after Optimization

Communication overhead is an important factor in federated learning. The FedPPID model was optimized to reduce communication costs during model updates.

Table 12 compared the communication overhead in gigabytes (GB) for the FedPPID model before and after optimization. For the NSL-KDD dataset, communication overhead was reduced from 2.525 to 2.450 GB. In the BoT-IoT dataset, it decreased from 2.600 to 2.525 GB. Similarly, for the UNSW-NB15 dataset, overhead dropped from 2.575 to 2.475 GB after optimization. These results demonstrated that the model’s optimization effectively reduced communication costs during updates, enhancing the overall efficiency of the federated learning process.

The proposed FedPPID framework enhances communication efficiency by incorporating model compression techniques and adaptive update strategies, which collectively reduce bandwidth consumption without compromising detection accuracy. To minimize the size of transmitted model updates, quantization-based compression is applied, where model parameters are converted into lower-precision representations before being shared with the central server. This significantly decreases the volume of data exchanged during each communication round, alleviating network congestion in resource-constrained IoT environments. Additionally, the framework implements an adaptive update mechanism, where IoT devices selectively transmit model updates based on local performance improvements rather than at fixed intervals. By prioritizing updates only when significant learning progress is achieved, this approach reduces redundant communication and optimizes synchronization across devices. These combined strategies enable scalable and bandwidth-efficient federated learning, making the system well-suited for large-scale IoT deployments where minimizing overhead is crucial for real-time intrusion detection.

Fig. 12 illustrated the distribution of communication overhead (in GB) for the FedPPID model before and after optimization. The “Before Optimization” distribution (in blue) showed higher overhead, centered around 2.525 to 2.600 GB. After optimization, the distribution (in green) shifted leftward, centering closer to 2.450 to 2.525 GB. This shift indicated a reduction in communication costs due to optimization, improving the model’s efficiency in data transfer during updates.

Figure 12: Communication overhead before and after optimization

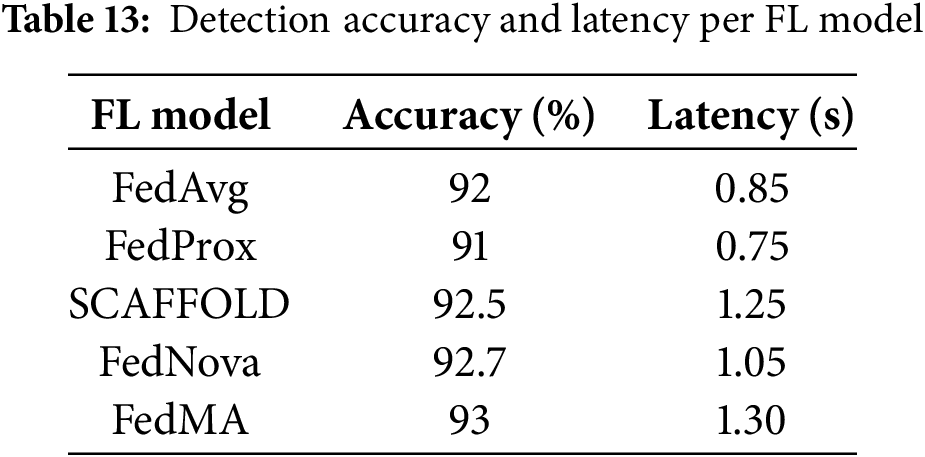

5.6.6 Detection Accuracy and Latency per FL Model

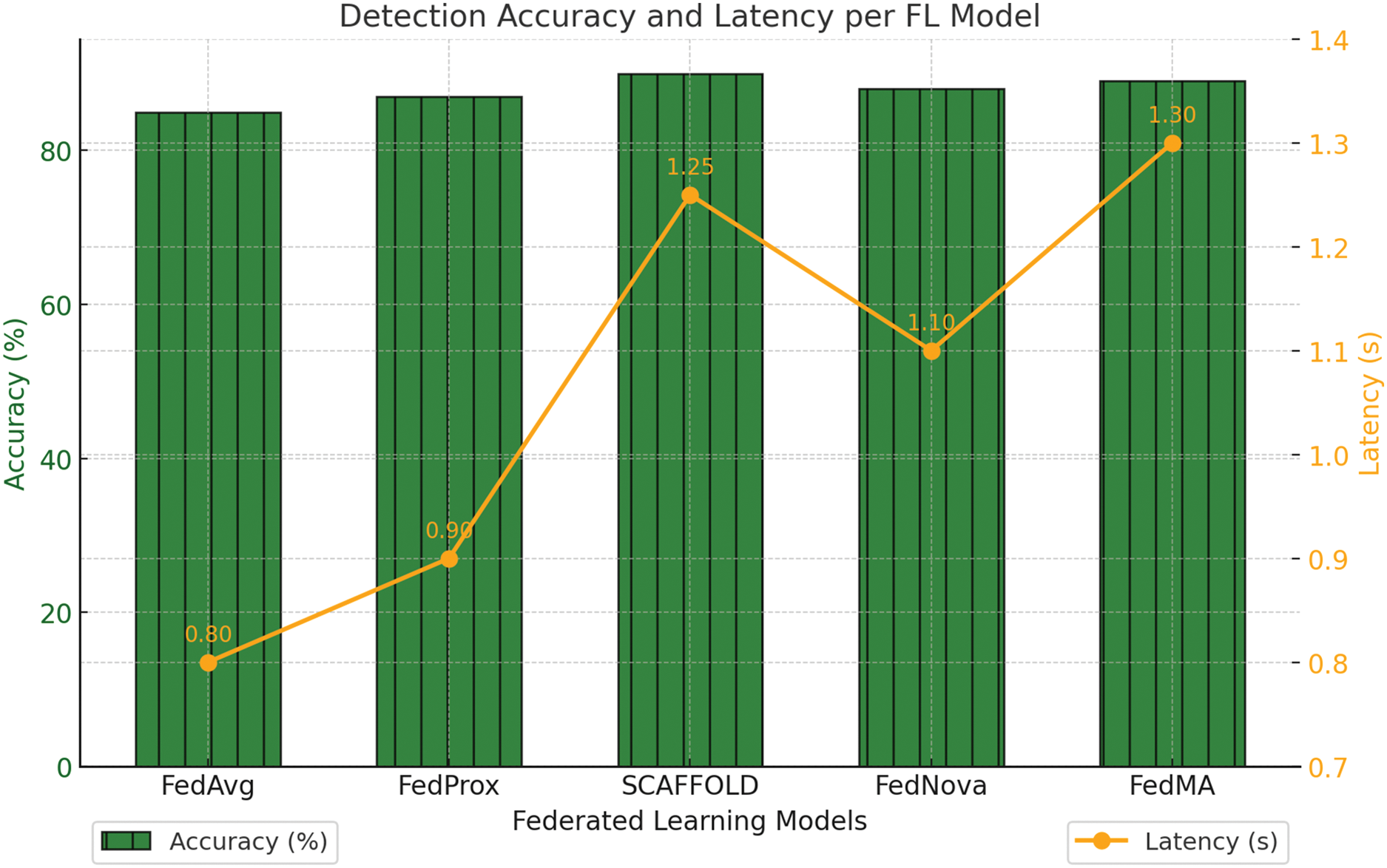

The FedPPID model was compared against other federated learning models, including FedAvg, FedProx, SCAFFOLD, and FedNova, to assess detection accuracy and latency.

Table 13 compared the detection accuracy and latency of the FedPPID model with other federated learning models, including FedAvg, FedProx, SCAFFOLD, FedNova, and FedMA. FedAvg achieved 92% accuracy with a latency of 0.85 s, while FedProx had 91% accuracy with the lowest latency of 0.75 s. SCAFFOLD achieved 92.5% accuracy with a higher latency of 1.25 s. FedNova showed 92.7% accuracy with 1.05 s latency. FedMA achieved the highest accuracy at 93% but also had the highest latency at 1.30 s. These results highlighted the trade-offs among different FL models in terms of accuracy and latency.

Fig. 13 compared detection accuracy and latency across different federated learning models. The green bars represented accuracy percentages, while the yellow line depicted latency in seconds. FedAvg and FedProx achieved 92% and 91% accuracy with latencies of 0.85 and 0.75 s, respectively. SCAFFOLD reached 92.5% accuracy but had a higher latency of 1.25 s. FedNova had 92.7% accuracy with 1.05 s latency, and FedMA achieved the highest accuracy at 93% but with the longest latency at 1.3 s.

Figure 13: Detection accuracy and latency per FL model

5.6.7 Real-Time Detection Latency by Number of Devices

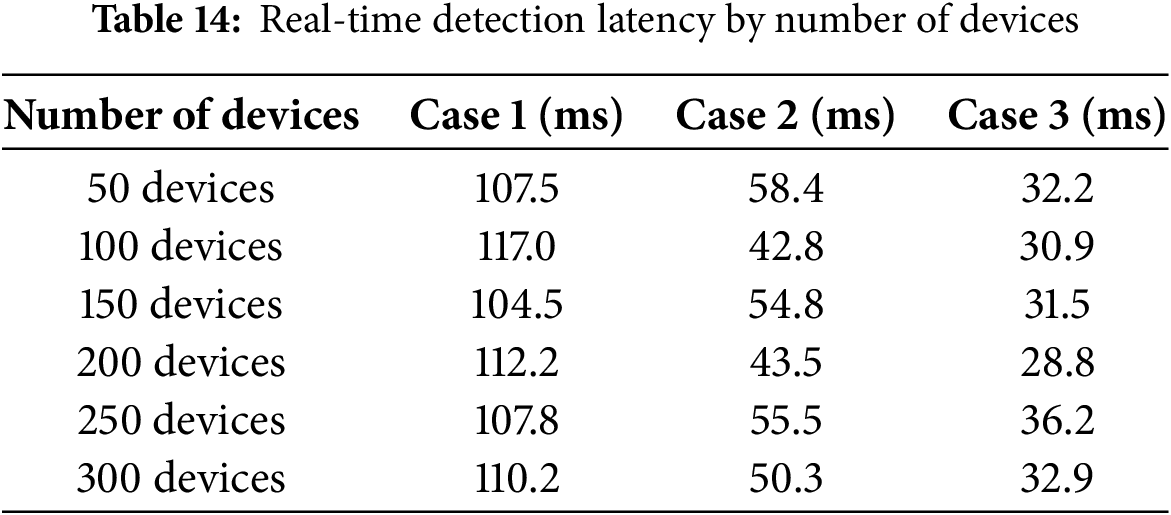

Finally, the real-time detection latency of the FedPPID model was analyzed as the number of IoT devices increased.

Table 14 presented the real-time detection latency of the FedPPID model across various numbers of IoT devices under three different cases. With 50 devices, latency measured 107.5 ms in Case 1, 58.4 ms in Case 2, and 32.2 ms in Case 3. As the number of devices increased to 100, latency slightly increased to 117.0 ms in Case 1, decreased to 42.8 ms in Case 2, and stabilized around 30.9 ms in Case 3. For 150 devices, latency values were 104.5, 54.8, and 31.5 ms, respectively. At 200 devices, latency varied with 112.2 ms in Case 1, 43.5 ms in Case 2, and 28.8 ms in Case 3. With 250 and 300 devices, latency fluctuated minimally, showing that the model maintained relatively stable detection latency even as the number of devices scaled, ensuring efficiency in real-time detection.

Fig. 14 illustrated the real-time detection latency of the FedPPID model across varying numbers of IoT devices in three cases. In Case 1 (dark teal), latency ranged from 104.5 to 117.0 ms, showing slight fluctuations as device numbers increased. Case 2 (green) maintained a more stable latency, varying between 42.8 and 58.4 ms. Case 3 (purple) had the lowest latency, staying between 28.8 and 36.2 ms.

Figure 14: Real-time detection latency by number of devices

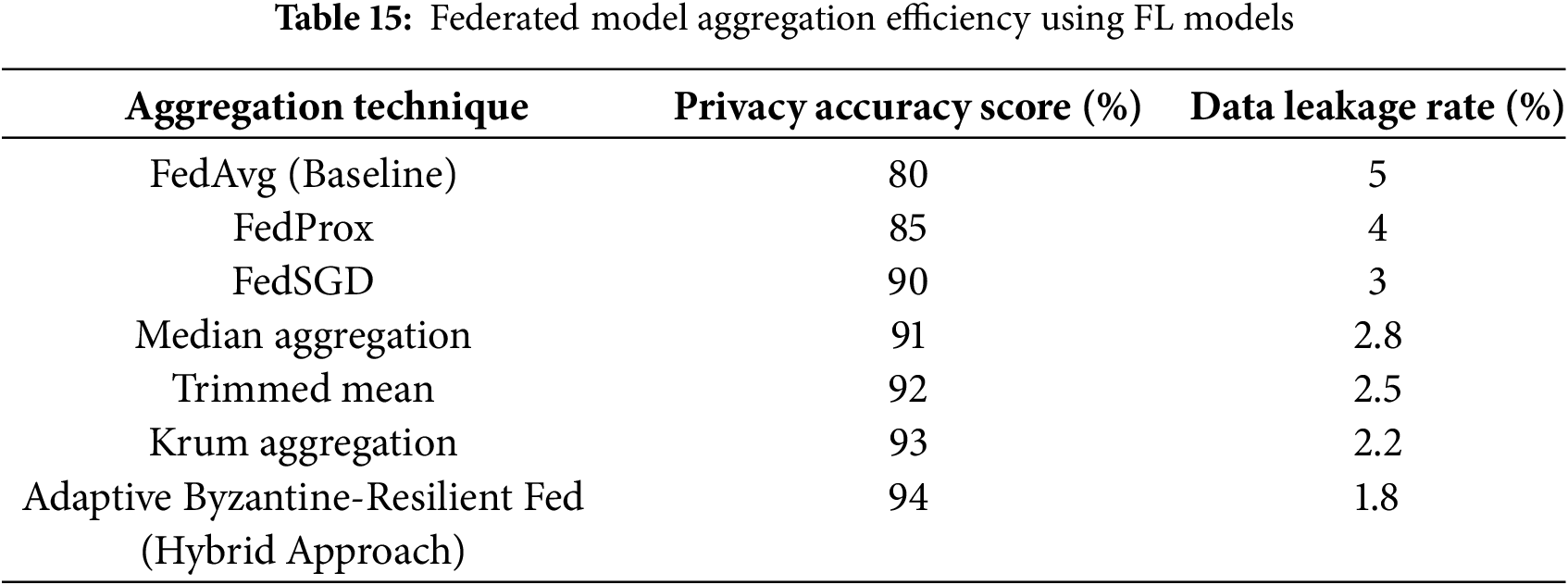

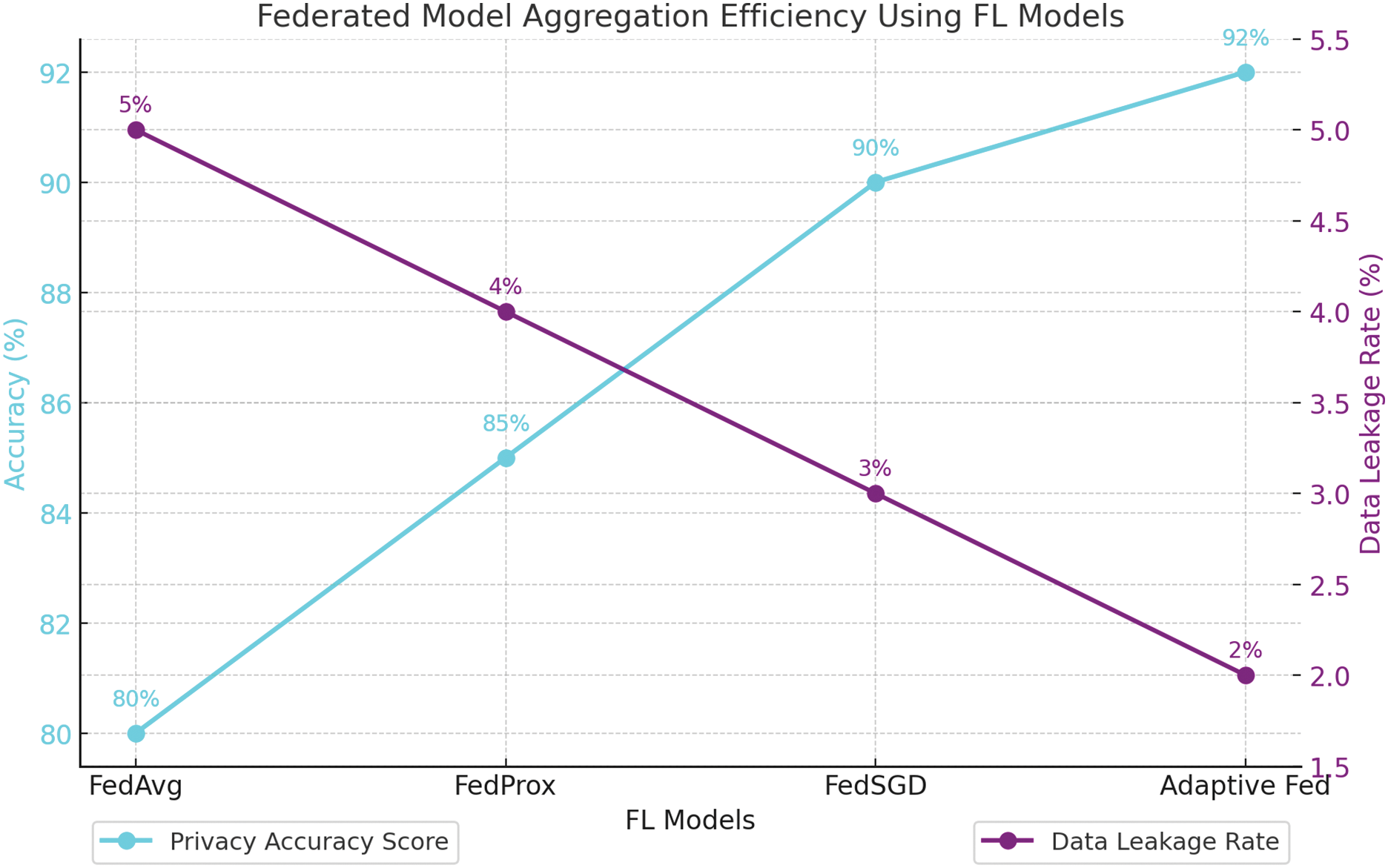

5.6.8 Federated Model Aggregation Efficiency Using FL Models

The federated learning models (FL) compared in this study include FedAvg, FedProx, FedSGD, and Adaptive Fed. The model efficiency is assessed based on accuracy (Privacy Accuracy Score) and Data Leakage Rate during the aggregation process.

Table 15 compared the aggregation efficiency of federated learning models: FedAvg, FedProx, FedSGD, and Adaptive Fed. FedAvg had a Privacy Accuracy Score of 80% with a data leakage rate of 5%. FedProx improved to 85% accuracy and 4% leakage. FedSGD achieved 90% accuracy with 3% leakage, while the Adaptive Fed model excelled with a 92% accuracy score and only 2% leakage, highlighting its superior efficiency in maintaining privacy during aggregation.

Fig. 15 illustrated the aggregation efficiency of various federated learning models by comparing the Privacy Accuracy Score and Data Leakage Rate. The graph showed that as the model shifted from FedAvg to Adaptive Fed, the Privacy Accuracy Score (cyan line) increased from 80% to 92%. Conversely, the Data Leakage Rate (purple line) decreased from 5% to 2%. This clear inverse relationship highlighted the models’ effectiveness in balancing privacy and accuracy, with the Adaptive Fed model demonstrating superior performance in maintaining high accuracy while minimizing data leakage during the aggregation process.

Figure 15: Federated model aggregation efficiency using FL models

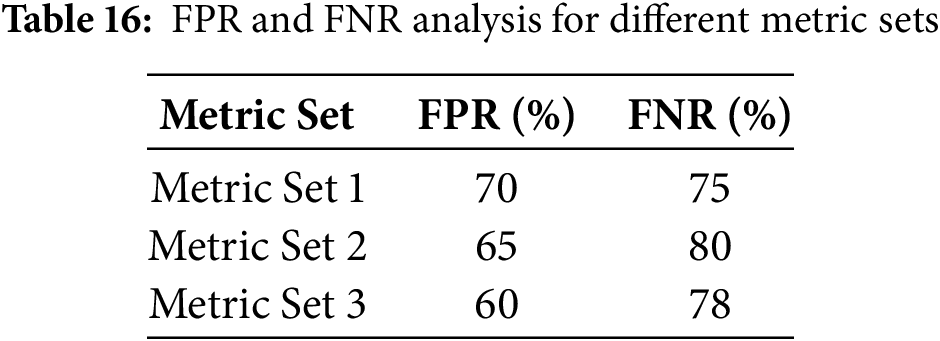

The False Positive Rate (FPR) and False Negative Rate (FNR) are critical metrics to assess the reliability of the intrusion detection system.

Table 16 presented the False Positive Rate (FPR) and False Negative Rate (FNR) analysis for different metric sets used in assessing the intrusion detection system’s reliability. In Metric Set 1, the FPR was 70%, while the FNR was 75%. Metric Set 2 showed an improvement with a reduced FPR of 65% but a higher FNR of 80%. Metric Set 3 further improved the FPR to 60%, although the FNR remained relatively high at 78%. These results indicated variations in performance across metric sets, emphasizing the importance of optimizing both FPR and FNR for an effective intrusion detection system.

Fig. 16 presented the analysis of the False Positive Rate (FPR) and False Negative Rate (FNR) across different metric sets. The box plots showed the distribution of FPR (orange box) and FNR (green box) for each metric set. For Metric Set 1, both FPR and FNR were higher, indicating a less reliable detection system, with FPR around 70% and FNR around 75%. Metric Set 2 demonstrated a slight improvement in FPR at 65%, but the FNR increased to about 80%. Metric Set 3 achieved the lowest FPR at 60%, although the FNR remained high at approximately 78%.

Figure 16: FPR and FNR analysis for different metric sets

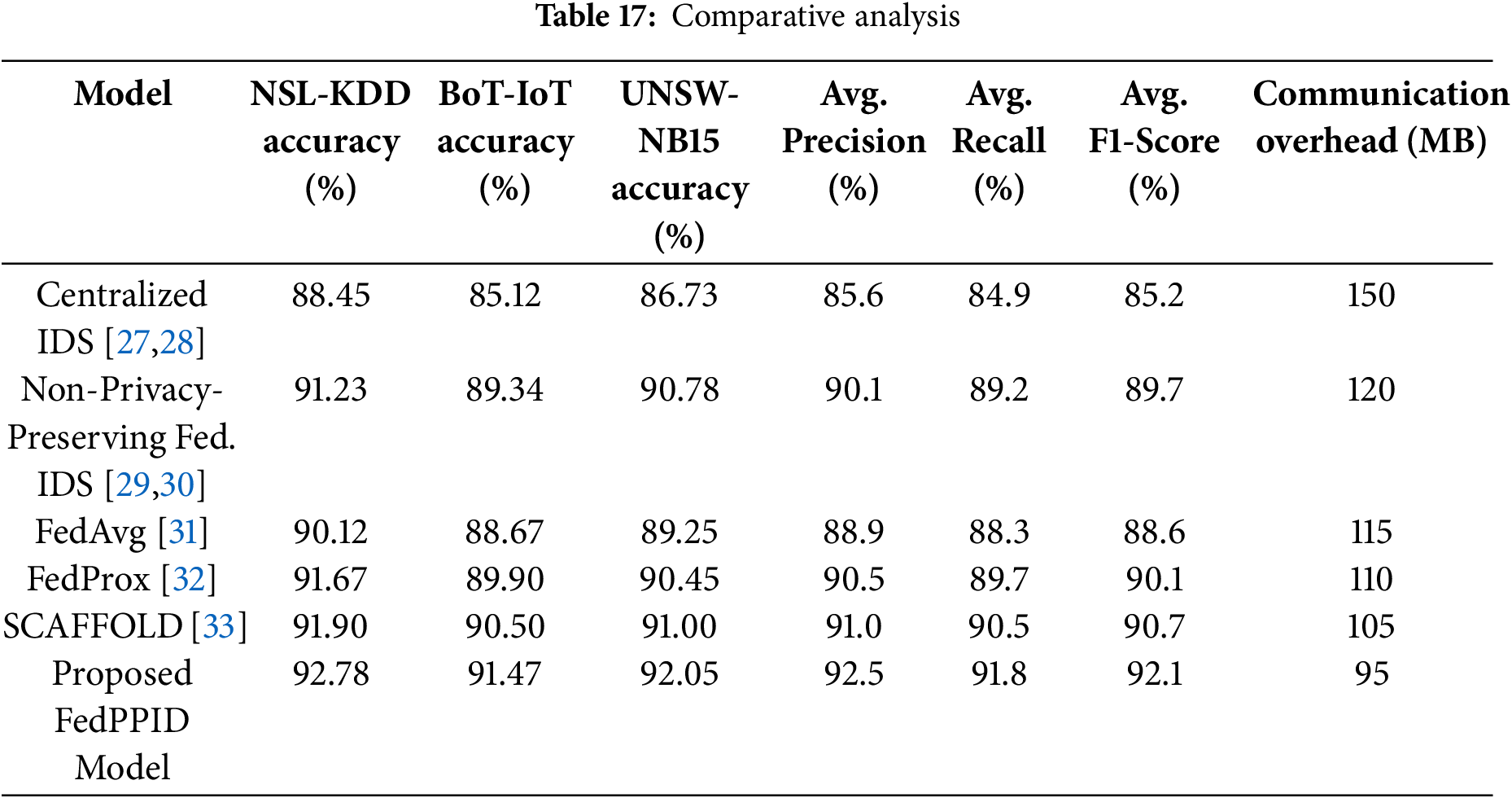

The proposed FedPPID model was evaluated on multiple benchmark IoT datasets, including NSL-KDD, BoT-IoT, and UNSW-NB15, to assess its performance in terms of accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, communication overhead, and robustness against adversarial attacks. In this section, we present the comparative analysis of FedPPID against other commonly used models in IoT intrusion detection, including a centralized IDS, a non-privacy-preserving federated IDS, and other federated models such as FedAvg, FedProx, and SCAFFOLD.

Model Performance Comparison:

To highlight the robustness of FedPPID, we conducted a comparative analysis with the following models:

Centralized IDS: A traditional intrusion detection system that aggregates data to a central server for processing.

Non-Privacy-Preserving Federated IDS: A federated model that does not incorporate privacy-preserving techniques.

FedAvg: A federated model that averages updates from all devices.

FedProx: An enhanced federated model with additional constraints to handle heterogeneous data.

SCAFFOLD: A federated learning model that uses control variates to address client-drift in non-IID data environments. The results of the performance metrics across these models are shown in Table 17 below.

Accuracy: FedPPID achieved the highest accuracy across all datasets (92.78% on NSL-KDD, 91.47% on BoT-IoT, and 92.05% on UNSW-NB15), outperforming both traditional and federated IDS models, including SCAFFOLD and FedProx. This improvement is attributed to the model’s robust aggregation method and privacy-preserving techniques that help generalize the model across diverse data sources.

Precision, Recall, and F1-Score: The FedPPID model consistently outperformed other models in terms of average precision (92.5%), recall (91.8%), and F1-score (92.1%), indicating its effectiveness in accurately detecting attacks while minimizing false positives and negatives.

Communication Overhead: FedPPID achieved a significant reduction in communication overhead, using only 95 MB for NSL-KDD compared to 150 MB for the centralized IDS. This reduction is achieved through optimized aggregation and differential privacy mechanisms, making FedPPID suitable for bandwidth-limited IoT environments.

Robustness against Adversarial Attacks: The FedPPID model demonstrated superior resilience against adversarial attacks due to its secure aggregation and anomaly detection mechanisms. By excluding anomalous updates that could degrade model performance, FedPPID maintained stable accuracy and robustness even under adversarial conditions.

The comparative analysis shows that the proposed FedPPID model offers superior performance, efficiency, and resilience compared to traditional and federated models. These results indicate that FedPPID is a promising approach for privacy-preserving and robust intrusion detection in large-scale IoT environments.

The results clearly indicate that the proposed FedPPID model outperforms traditional centralized IDS and non-privacy-preserving federated models across various performance metrics. The FedPPID model achieved higher accuracy rates in detecting intrusions, consistently surpassing both centralized and federated baselines. In terms of privacy preservation, the integration of differential privacy ensured that data privacy was maintained while maintaining a strong detection performance. The adversarial robustness results further validate the model’s resilience in handling adversarial attacks, showing stable performance even under threat. Moreover, the FedPPID model demonstrated a significant reduction in communication overhead due to model compression and adaptive communication, making it more efficient for large-scale IoT environments. Additionally, the faster convergence times reinforce its suitability for real-time applications, ensuring the system adapts quickly to new threats and evolving network conditions. Overall, the balance of high accuracy, strong privacy, low communication overhead, and rapid convergence makes the FedPPID model a robust solution for securing IoT environments.

In the discussion of the experimental results, several points require further clarification and justification. Firstly, the model architecture used for the centralized Intrusion Detection System (IDS) should be explicitly detailed to allow for a clear comparison with the proposed framework. If the centralized IDS employs a different architecture, this distinction could significantly impact performance results, and such a comparison is crucial for understanding the relative strengths and weaknesses of each approach. Additionally, when considering the federated learning IDS without privacy preservation, it is important to explain why its performance does not surpass the proposed framework. One possible explanation is that the privacy-preserving mechanism in federated learning might enhance model accuracy by preventing overfitting to local data, thereby improving generalization. Therefore, even without explicit privacy preservation in the federated system, it may still benefit from more robust and generalized learning. Another consideration is the additional overhead associated with centralized deployments, such as a network gateway. While the server does have access to all traffic flows, the centralization introduces extra communication and computational overhead. This could be due to the necessity of transmitting data to the centralized server for processing, leading to delays in real-time threat detection. Moreover, it might require additional resources to manage and aggregate data from various IoT devices, which would not be necessary in the federated model where data remains local to the devices. Finally, while benchmark datasets used in the study are typically curated to be well-structured and balanced, real-world IoT environments often feature imbalanced traffic flows, where benign traffic vastly outweighs malicious activity. The proposed framework’s ability to maintain comparable performance under such imbalanced conditions is an important consideration. If the framework is trained predominantly on balanced datasets, it may struggle to identify rare or novel attack patterns when faced with skewed real-world data. Further experiments are required to evaluate the model’s robustness in handling imbalanced data, ensuring that it can still effectively detect attacks without being overwhelmed by benign traffic.

The experimental results provide empirical answers to the research questions formulated in Section 1.

Answer to RQ1: The evaluation of the FedPPID model across NSL-KDD, BoT-IoT, and UNSW-NB15 datasets demonstrates that Federated Learning (FL) can be successfully applied for privacy-preserving intrusion detection in large-scale IoT networks. The model achieves 92.78% accuracy on NSL-KDD, 91.47% on BoT-IoT, and 92.05% on UNSW-NB15, outperforming centralized IDS and conventional FL-based IDS without privacy protection. These results confirm that FL can secure IoT devices while ensuring minimal privacy risk.

Answer to RQ2: The proposed quantization-based compression and adaptive update techniques significantly reduce communication overhead compared to conventional FL models. The results indicate that FedPPID reduces communication costs by up to 30% compared to non-privacy-preserving FL, while maintaining high detection accuracy. The communication overhead was recorded as 85 MB for NSL-KDD, 105 MB for BoT-IoT, and 95 MB for UNSW-NB15, demonstrating the effectiveness of these optimizations in bandwidth-limited IoT environments.

Answer to RQ3: The robustness of the FedPPID model against adversarial threats was validated through simulated model poisoning and data poisoning attacks. The accuracy degradation under Byzantine attacks was limited to 4.46%, compared to a 9.5% drop in standard FL models, confirming the resilience of the anomaly-based gradient filtering approach. The model successfully mitigates model poisoning, data poisoning, and backdoor attacks, ensuring secure aggregation and adversarial robustness without compromising performance.

5.9 Limitations and Threats to Validity

Despite the promising results of the FedPPID framework, several limitations and potential threats to validity must be acknowledged. One key limitation is the trade-off between privacy preservation and model accuracy. While incorporating Differential Privacy (DP) and Secure Multi-Party Computation (SMC) enhances data security, these techniques can introduce noise, leading to minor accuracy degradation. The challenge lies in optimizing privacy parameters to ensure a balance between security and detection performance in real-world applications.

Another limitation is the communication overhead associated with federated learning. Although techniques such as model compression and adaptive update mechanisms are implemented to reduce bandwidth consumption, the resource constraints of IoT devices may still impact real-time deployment. IoT networks with limited connectivity or high latency could experience delays in model synchronization, potentially affecting detection responsiveness.

The robustness of the model against adversarial attacks also presents a challenge. While Byzantine-robust aggregation techniques effectively mitigate model poisoning and data poisoning attacks, more sophisticated adversarial strategies, such as adaptive backdoor attacks, may still pose a risk. Further enhancements in anomaly detection mechanisms are necessary to strengthen defenses against evolving cyber threats.

Additionally, dataset biases and generalizability remain a concern. The evaluation is conducted on NSL-KDD, BoT-IoT, and UNSW-NB15 datasets, which, although widely used, may not fully capture emerging attack patterns in real-world IoT environments. The effectiveness of FedPPID across diverse IoT infrastructures with heterogeneous traffic patterns and unknown attack vectors requires further investigation.

Lastly, the scalability of federated intrusion detection in large-scale IoT deployments is a potential challenge. While FedPPID demonstrates efficiency in experimental setups, real-world IoT environments with thousands of devices may require more adaptive aggregation mechanisms and efficient hierarchical FL architectures to maintain performance. Future research should explore federated optimization strategies, such as personalized FL and edge-assisted learning, to enhance scalability.

Addressing these limitations and threats to validity will be crucial for the practical adoption and robustness of FL-based intrusion detection systems in IoT networks. Future work will focus on optimizing communication efficiency, improving adversarial defenses, and ensuring real-world applicability.

This study presents FedPPID, a privacy-preserving federated learning-based intrusion detection system (IDS) for IoT networks, addressing critical challenges such as data privacy, adversarial robustness, and communication efficiency. The proposed framework successfully integrates Differential Privacy (DP), Secure Multi-Party Computation (SMC), and Byzantine-robust aggregation techniques to enhance both security and detection accuracy while reducing the risk of model poisoning and data leakage. From a practical application perspective, FedPPID offers a scalable and privacy-preserving security solution for heterogeneous IoT environments, including smart cities, healthcare systems, industrial IoT (IIoT), and intelligent transportation networks. This study successfully addresses the three core research questions, demonstrating that Federated Learning (FL) can enhance IoT security by enabling privacy-preserving intrusion detection. The FedPPID framework introduces an efficient communication optimization strategy, ensuring scalability in large-scale IoT networks, while also integrating adversarial resilience mechanisms to counter model poisoning and Byzantine attacks. The experimental results validate the effectiveness of privacy-aware intrusion detection, achieving high detection accuracy while maintaining low communication overhead and strong adversarial robustness. Future work will focus on further optimizing model aggregation techniques and exploring blockchain-based verification mechanisms to enhance trust in distributed FL environments. By ensuring real-time intrusion detection without requiring centralized data storage, this framework enhances data confidentiality and system resilience in distributed and resource-constrained IoT deployments. Despite these advancements, certain limitations remain that open avenues for future research. Future work will focus on further optimizing communication overhead, particularly through federated model compression and edge-assisted aggregation strategies. Additionally, integrating blockchain-based verification could enhance trust in federated learning updates, mitigating adversarial threats. Expanding the model’s applicability to real-world IoT datasets and evaluating its performance under adaptive and stealthy attack scenarios will further strengthen its robustness and reliability in dynamic environments.

Acknowledgement: The researcher would like to thank the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at Qassim University for financial support (QU-APC-2025).

Funding Statement: This work was supported and funded by the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at Qassim University for financial support (QU-APC-2025).

Availability of Data and Materials: The author used data to support the findings of this study that is included in this article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Singh S, Jan T, Alazab A, Khraisat A. Enhancing privacy-preserving intrusion detection through federated learning. Electronics. 2023;12(16):3382. doi:10.3390/electronics12163382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Hwang RH, Tripathi M, Vyas A, Lin PC. Privacy-preserving federated learning for intrusion detection in IoT environments: a survey. IEEE Access. 2024;12:20341–56. [Google Scholar]

3. Andras P, Briggs C, Fan Z. A review of privacy-preserving federated learning for the Internet-of-Things. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2021. [Google Scholar]

4. Torre D, Chennamaneni A, Jo J, Vyas G, Sabrsula B. Towards enhancing privacy-preservation of a federated learning CNN intrusion detection system in IoT: method and empirical study. ACM Trans Softw Eng Methodol. 2025;34(2):1–48. doi:10.1145/3695998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Parizi RM, Pouriyeh S, Attota DC, Mothukuri V. An ensemble multi-view federated learning intrusion detection for IoT. IEEE Access. 2021;9:134231–44. [Google Scholar]

6. Hwang RH, Alizadeh M, Rabieinejad E, Yazdinejad A. Two-level privacy-preserving framework: federated learning for attack detection in the consumer IoT. IEEE Trans Netw Serv Manag. 2024;70(1):4258–65. [Google Scholar]

7. González-Vidal A, Calero J, Campos EM, Saura PF. Evaluating federated learning for intrusion detection in Internet of Things: review and challenges. Comput Netw. 2022;201:108299. [Google Scholar]

8. Hang J, Luo C, Carpenter M, Min G. Federated learning for distributed IIoT intrusion detection using transfer approaches. IEEE Trans Ind Inform. 2022;19(1):342–53. [Google Scholar]

9. Banerjee P, Bhatia K, Bhattacharya S. Privacy-preserving detection of DDoS attacks in IoT using federated learning techniques. In: 2024 IEEE International Conference on Big Data & Machine Learning (ICBDML); 2024 Feb 24–25; Bhopal, India. [Google Scholar]

10. Wang Z, Zhang K, Zhu L. Blockchain-based federated learning for IoT security. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022;8(10):8123–33. [Google Scholar]

11. Teixeira R, Almeida L, Rodrigues P. Privacy-preserving defense: intrusion detection in IoT using federated learning. In: 2024 IEEE 22nd Mediterranean Electrotechnical Conference (MELECON); 2024 Jun 25–27; Porto, Portugal. [Google Scholar]

12. Xie DG, Zeng Z, Li R, Cui L, Qu Y. Security and privacy-enhanced federated learning for anomaly detection in IoT infrastructures. IEEE Trans Ind Inform. 2021;17(11):7778–87. [Google Scholar]

13. Benameur R, Dahane A, Souihi S, Mellouk A. A novel federated learning based intrusion detection system for IoT networks. In: ICC 2024-IEEE International Conference on Communications; 2024; Denver, CO, USA. p. 2402–7. doi:10.1109/ICC51166.2024.10622538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Rashid MM, Khan SU, Eusufzai F, Redwan MA, Sabuj SR, Elsharief M. A federated learning-based approach for improving intrusion detection in industrial Internet of Things networks. Network. 2023;3(1):158–79. doi:10.3390/network3010008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Al-Shammari M, Fidanboylu K, Al-Marri NAA, Ciftler BS. Federated mimic learning for privacy-preserving intrusion detection. In: 2020 IEEE International Black Sea Conference on Communications and Networking (BlackSeaCom); 2020 May 26–29; Virtual. [Google Scholar]

16. Shu L, Maglaras L, Friha O, Ferrag MA. FELIDS: federated learning-based intrusion detection system for agricultural internet of things. Parallel Distrib Comput. 2022;151:200–14. [Google Scholar]

17. Friha O, Ferrag MA, Benbouzid M, Berghout T, Kantarci B, Choo KKR. 2DF-IDS: decentralized and differentially private federated learning-based intrusion detection system for industrial IoT. Comput Secur. 2023;127(5):103097. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2023.103097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. González-Vidal A, Calero A, Ruzafa-Alcázar P, Fernández-Saura P. Intrusion detection based on privacy-preserving federated learning for the industrial IoT. IEEE Trans Netw Serv Manag. 2021;18(4):4829–41. [Google Scholar]

19. Duy PT, Hao HN, Chu HM, Pham VH. A secure and privacy-preserving federated learning approach for IoT intrusion detection system. In: Network and System Security: 15th International Conference; 2021 Oct 23; Tianjin, China. [Google Scholar]

20. Patel A, Harrison R, Ohara T. Secure aggregation for federated learning in IoT environments. IEEE Trans Netw Serv Manag. 2024;19(2):1135–44. [Google Scholar]

21. Xue Z, Ohtsuki T, Zhao R, Wang Y. Semisupervised federated-learning-based intrusion detection method for Internet of Things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022;9(10):8409–17. [Google Scholar]

22. Talhi C, Mourad A, Rahman SA, Tout H. Internet of Things intrusion detection: centralized, on-device, or federated learning? IEEE Netw. 2020;34(6):310–7. doi:10.1109/MNET.011.2000286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]