Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Secure Storage and Verification Framework Based on Consortium Blockchain for Engineering Education Accreditation Data

1 Guangxi Key Laboratory of Brain-Inspired Computing and Intelligent Chips, School of Electronic and Information Engineering, Guangxi Normal University, Guilin, 541004, China

2 Key Laboratory of Nonlinear Circuits and Optical Communications (Guangxi Normal University), Education Department of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, Guilin, 541004, China

* Corresponding Author: Junxiu Liu. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Distributed Computing with Applications to IoT and BlockChain)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 83(3), 5323-5343. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.063860

Received 26 January 2025; Accepted 14 March 2025; Issue published 19 May 2025

Abstract

The majors accredited by the Engineering Education Accreditation (EEA) reflect the accreditation agency’s recognition of the school’s engineering programs. Excellent accreditation management holds significant importance for the advancement of engineering education programs. However, the traditional engineering education system framework suffers from the opacity of raw education data and the difficulty for accreditation bodies to forensically examine the self-assessment reports. To solve these issues, an EEA framework based on Hyperledger Fabric blockchain technology is proposed in this work. Firstly, all relevant stakeholders and information interactions occur within the blockchain network, ensuring the authenticity of educational data and enhancing the transparency of accreditation processes. Secondly, multiple roles are abstracted into a single organization to optimize the network topology. The original data is stored off-chain, and the hash values of the data are stored on-chain to reduce on-chain storage costs. The experimental results show that the proposed framework has a high throughput and the network latency of writing data to the blockchain is reduced by at least 0.04 s. It effectively improves network performance and security, which provides new insights for EEA management.Keywords

Engineering Education Accreditation (EEA) aims to facilitate the interaction between universities and industry through professional accreditation, fostering collaborative innovation, and allowing universities to train engineers according to market demands [1]. In China, EEA is organized by the China Association for EEA. Universities applying for professional accreditation should first conduct self-assessment, which is the basis and key to developing accreditation. However, some universities have not completed the self-evaluation report following the requirements of accreditation. The report’s content is also not detailed and reliable enough, which means these reports lack objectivity and sincerity [2–4]. Furthermore, EEA in China is led by the Ministry of Education, and the relevant organizational bodies are established by the Ministry of Education. The members of these organizations are relatively dispersed, although some industry professionals may participate, the overall involvement of industry organizations is limited. In addition, the data required to support accreditation involves information concerning teachers, students, and employers, covering essential details both within and outside the universities. Some organizations, to fulfil their responsibilities, may provide inaccurate data. EEA’s societal credibility and influence are somewhat reduced by this situation [5].

EEA involves various personnel, curriculum systems, teaching processes, evaluation mechanisms, and other aspects. Establishing an accreditation system tailored to higher engineering education is imperative. Currently, relevant organizations and universities have designed and implemented such systems [6,7]. However, due to EEA’s long-term nature, the system needs to store a significant amount of data as time progresses. When verification of the data is necessary, it becomes a time-consuming and laborious task. Moreover, the data submitted to the system may have been tampered with and are not authentic [8]. Additionally, these data are stored in a centralized database, posing a potential single point of failure [9]. Therefore, how to achieve fairness, transparency, and shareability of accreditation information in engineering education is an urgent problem to be solved.

The establishment of a distributed, transparent, and immutable ledger is enabled by blockchain technology. Its decentralized and distributed nature ensures the immutability of ledger data through encryption techniques. Moreover, the decentralized nature effectively mitigates the risk of a single point of failure in data storage [10]. The data structure of the blockchain is known as a Merkle tree, which combines data and information blocks in a chained sequence over time. This unique data structure, along with encryption techniques, naturally suits traceability applications [11]. Smart contracts are used in blockchain to read and write data, functioning like a transaction-driven state machine. Access to ledger data is only granted when predefined conditions are met. In recent years, blockchain technology has been applied in various domains such as the Internet of Things, big data, and cloud computing [12–14]. For example, a secure authentication framework for electronic medical records is proposed in [15], which utilizes blockchain technology to secure electronic medical data. However, its application in educational settings is still in its infancy. Blockchain technology is mostly utilized by researchers in the current stage to manage academic credentials and track learning achievements. For instance, in response to the issue of academic credential fraud, a comprehensive blockchain-based credential verification solution is proposed in [16]. Academic information creation and credential revocation are facilitated through smart contracts, significantly ameliorating the problem of academic credential fraud. On the other hand, Hyperledger Fabric (HF) blockchain technology is utilized to construct an educational consortium blockchain platform, ensuring credible data sharing and privacy protection [17]. A blockchain-based education-industry collaboration system is proposed in [18], which connects educational institutions with employers to transparently share information about student skills, corporate recruitment needs, and current market trends. A blockchain-based consortium testing scheme is proposed in [19], which experiments with publicly verifying student answers and storing answer records on the consortium blockchain, making the records public, immutable, and traceable. However, a large amount of original data is stored on the blockchain, increasing storage pressure on the blockchain network nodes. Moreover, many organizational nodes joining the blockchain network led to increased consensus time, thereby reducing the efficiency of network data processing. To the best of our knowledge, only a few researchers approach this from the perspective of EEA. However, these methods do not involve the process of implementing EEA.

Due to the inadequacies of the mentioned research, an EEA system framework based on blockchain technology is proposed in this work. The proposed framework employs HF blockchain technology to establish the blockchain environment. HF, being a consortium blockchain platform, is well-suited for the required blockchain environment in this work, benefiting from its inherent advantages such as modularity and plug-and-play capabilities [20]. At the same time, the original education data is stored off-chain, and the hash values and storage addresses are uploaded to the blockchain to reduce storage pressure on the blockchain. Multiple roles involved in EEA are abstracted into a single organization to reduce blockchain nodes and increase the efficiency of data processing in the blockchain network.

The main contributions of this work are as follows:

• A blockchain-based EEA system framework is proposed, which guarantees that the original data generated during the engineering program education is immutable and trustworthy.

• Using an on-chain and off-chain data storage model to reduce the system’s storage costs while ensuring data traceability to address sustainability challenges.

• The topology of the blockchain network is optimized. Since the accreditation agency investigates and gathers evidence for accreditation during the professional accreditation process, it is suggested that the accreditation agency joins the blockchain network only after the accreditation process has started. This reduces the number of participating nodes during the EEA process, thus reducing the network latency and improving the performance.

• The performance of the proposed framework is evaluated using the benchmark performance testing tool Hyperledger Caliper (HC) based on the test results.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, a review of the literature on blockchain is presented. The relevant knowledge of HF is provided in Section 3. The detail and implementation of the system framework using HF technology is provided in Section 4. A detailed description of the application outcomes of the system framework is provided in Section 5. Finally, Section 6 presents a conclusion of this work.

In recent years, researchers have begun to apply blockchain technology in educational settings. This research can be categorized into two groups: Firstly, education systems based on blockchain technology are established to record students’ outcomes, academic credentials, and other related information. Secondly, blockchain technology is utilized to share relevant educational resources. In a blockchain-based education system, a distributed blockchain is employed by the approach of [21]. The scheme uses blockchain to store educational records. In [22], an open framework for the accreditation and award of degrees of higher education based on blockchain technology is proposed. Since the data stored in the blockchain network is immutable and traceable. This degree awarding framework can provide proof that students trained in educational institutions acquire the corresponding competencies. A secure and traceable degree authentication system based on blockchain technology is proposed in [23]. This system involves storing the complex degree verification process between higher education commissions and universities using distributed ledger technology. A secure and notarized framework for authentication and verification of educational certificates is proposed in [24], which uses a combination of cryptographic algorithms and blockchain to achieve authentication of educational certificates. The blockchain-based educational certificate validation scheme is compared with the traditional centralized scheme in [25], where the blockchain scheme provides secure, traceable and tamper-proof data validation. An integrated blockchain-based solution for issuing and validating educational certificates is presented in [26], which guarantees that educational certificates are not tampered with [27] uses a blockchain system to store and validate academic certificates, and adopts proof of authority as the system’s consensus algorithm. These aforementioned approaches are primarily to build an education system through blockchain.

A methodology for storing and scheduling health privacy data in university sports classes based on hybrid blockchain encryption is proposed in [28], aiming to enhance the security of storing and scheduling health privacy data both inside and outside university sports classes. In [29], an educational resource-sharing platform for universities is established. In conjunction with blockchain technology, trustworthy record-sharing is achieved as universities jointly establish the platform. The current issues of information asymmetry and distrust between schools and enterprises regarding workforce and demand are addressed in [18]. The proposal suggests the establishment of a consortium chain involving both schools and employers. The supply and demand information are shared via blockchain. In the context of data sharing, the problems of privacy leakage and inefficient transmission associated with educational data are addressed in [30]. The authors combine the searchable encryption technology and consortium blockchain to develop a data security storage and sharing solution. Compared to other sharing models, this solution demonstrates superior robustness. Despite the notable research outcomes of blockchain technology in the education field, there is very limited research focused on applying blockchain technology to engineering education certification. Only a few researchers approach this from the perspective of EEA. They utilize blockchain technology based on the graduation requirements and corresponding support points of universities’ indicators and various courses to record and evaluate students’ learning outcomes. However, these methods do not involve the process of implementing EEA.

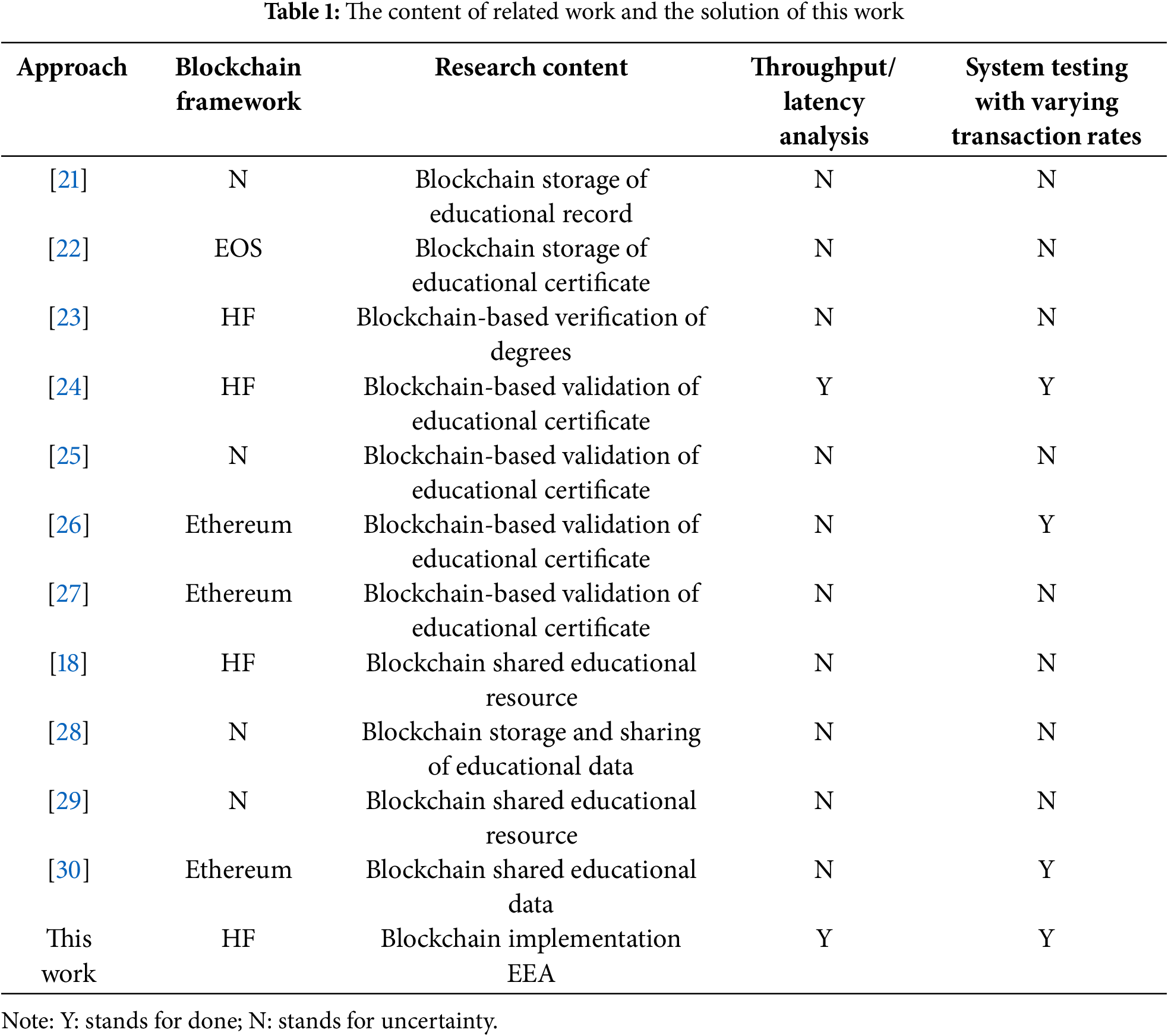

In this work, a scheme for EEA based on blockchain technology is proposed. The reliability and fairness of the accreditation are achieved by utilizing the decentralized nature of blockchain. The immutability of the blockchain ledger is utilized to ensure the authenticity and privacy of the original data, thereby enhancing the social impact of EEA. Table 1 summarizes the related literature to highlight the research work in this paper.

HF is an enterprise-grade, open-source distributed ledger platform managed by the Linux Foundation. It supports shared data transactions between multiple organizations, and its modular architecture is pluggable. The smart contracts here are referred to as chaincode, which can be implemented using programming languages such as Java, Go, and Node.js. The overall architecture of HF comprises several components such as applications, ledgers, and chaincode, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: The overall architecture diagram of HF

In the HF architecture, the ledger is the most core resource, and the application or client records data in the ledger by initiating transactions and calling contracts. The logic executed by the contracts is implemented through chaincode. The HF network is composed of multiple nodes working collectively, and events occurring during network operation can be notified to applications or even other systems through an event mechanism. Access control throughout the entire process is managed by permission management. The ledger implementation relies on fundamental blockchain structures, database storage, and consensus mechanisms. Chaincode implementation is similar to technologies such as containers and state machines. Permission management leverages existing security technologies like Public Key Infrastructure systems, digital identity certificates, encryption, and decryption algorithms. At the lowest level, a peer-to-peer network is formed by multiple nodes, interacting with each other through general Remote Procedure Call channels and utilizing the gossip protocol for data synchronization. The hierarchical structure enhances the architecture’s scalability, facilitating secondary development by users.

Different modules of functionality are provided to users of various roles by HF, and these functionalities are offered by different components, including:

Peer node: Peer node is the transaction endpoint of an organization and represents an entity in the network. It is primarily responsible for maintaining the ledger data in the HF network and performing read and write operations on the ledger through the installed chaincode. Essentially, information exchange and business processes between organizations are handled through peers.

Organization: An organization is a member of the HF network. In the HF network, a participating entity is an organization. All participating entities collectively form the blockchain network in the form of organizations, facilitating information exchange within the network.

Membership Service Provider (MSP): MSP manages and maintains member identities and permissions within the blockchain network. MSP is responsible for verifying, signing, and authorizing transactions to ensure that various operations in the network comply with specified policies and permissions.

Certificate Authority (CA): Certificates are the foundation of permission management in HF. Currently, an asymmetric encryption algorithm based on the Elliptic Curve Digital Signature Algorithm is used to generate public and private keys. The certificate format follows the X.509 standard specifications. Fabric employs a separate HF CA project to manage certificate generation. Each entity and organization can possess its identity certificate, and certificates adhere to the organizational structure, enabling flexible permission management based on the organization.

Chaincode: In the HF network, a smart contract is referred to as chaincode. Chaincode is essentially a piece of encoded program, functioning like a state machine, automatically triggering program execution when input conditions meet pre-defined values. The blockchain clients or applications read and write blockchain data using chaincode through peer nodes.

Endorsement: Endorsement refers to endorsing nodes simulating the execution and verification of transaction proposals received from clients. It verifies whether the transaction proposal satisfies the endorsement policy requirements. Client applications must collect endorsement organization signatures that meet policy requirements before submitting the transaction to ordering nodes for sorting.

Ordering service: The ordering service sorts the endorsed transaction proposals received from clients and generates blocks to distribute to each peer node to ensure ledger consistency. Various ordering nodes use consensus algorithms like Kafka and Raft to ensure agreement on the transaction order they package. This work uses Raft as a consensus algorithm for blockchain.

4 System Model Design and Implementation

This section introduces the proposed model, HF related knowledge, the network topology architecture of the system, the smart contract, and the implementation of its system network.

In this work, the proposed framework is implemented using HF technology. The advantages of choosing HF to build the blockchain-based EEA framework are primarily as follows:

• Compared to application domains like big data and the Internet of Things, there are not as many entities involved in EEA. HF is a permissioned consortium blockchain solution, making it easy to control the permissions of network participants, enabling quick consensus on each transaction added to the chain, and enhancing the network’s scalability.

• The consensus process in the HF network does not require economic incentives. Transactions within the network are sorted and packaged into blocks by ordering organizations. Consistency of the ledger data among ordering nodes is maintained through consensus protocols like Raft and Kafka. Using HF technology can reduce production costs.

• HF offers the advantage of high modularity and a reconfigurable architecture. Users can customize the network topology to suit actual business needs. Its chaincode can be implemented in various programming languages, significantly facilitating users in developing the necessary business logic.

In China, the entire accreditation process is mainly composed of six stages: application and acceptance, school self-evaluation and submission of self-evaluation report, review of the self-evaluation report, on-site inspection, deliberation and accreditation conclusion, and maintenance of accreditation status. The main objective of EEA is outcome-oriented learning to cultivate talent for society and enterprises. However, currently, there is minimal involvement of employers throughout the accreditation process, and the original materials provided for accreditation are difficult to verify. To address this issue, a new blockchain-based system model for EEA is proposed, which is illustrated in Fig. 2. In the system model, there are six main system components: universities, academic affairs offices, teachers, students, employers, and an accreditation agency.

Figure 2: Blockchain-based EEA system diagram

Universities: Universities are the entities that provide engineering education and are responsible for offering engineering courses and nurturing students. Universities play a crucial role in the accreditation process. They provide relevant information during the self-assessment and verification stages.

Academic affairs offices: Academic affairs offices, situated within the university, are responsible for managing student information and course grades. They upload students’ grades and other information required for accreditation onto the blockchain to ensure data reliability and transparency.

Teachers: Teachers are the main entities involved in delivering engineering courses and assessing students’ learning outcomes. They can use applications on the blockchain network to record students’ grades and other related information, which is then submitted to the academic affairs offices for verification.

Students: Students are the main recipients of engineering education. Their academic performance and other accreditation-related information are recorded on the blockchain by academic affairs offices and teachers to ensure data authenticity and verifiability. Students can verify their accreditation information by querying the blockchain.

Employers: Employers are the hiring entities responsible for recruiting engineering professionals. They can verify accreditation information by querying the blockchain, ensuring that candidates possess the relevant engineering education background.

Accreditation agency: Accreditation agency is an independent entity responsible for formulating, implementing, and overseeing EEA standards. It evaluates the self-assessment reports submitted by universities and conducts on-site inspections to verify the reported information. Accreditation agency also reviews the accreditation results and ultimately makes accreditation conclusions to ensure objectivity, fairness, and rigor in the accreditation process. These accreditation outcomes affect the reputation of schools and students, and play a supervisory and safeguarding role in the quality of engineering education. The accreditation agency collaborates with schools, academic affairs offices, and other educational entities to ensure the smooth progress of the accreditation process.

The blockchain network is collectively constructed by these six entities, each of which can possess its own nodes. Interaction and data transmission occur between nodes through smart contracts. All data can be stored on the blockchain. During the EEA process conducted by the accreditation agency, if they suspect that the self-assessment report submitted by a university is not entirely truthful, they can directly gather evidence by querying the data on the blockchain. This significantly improves the efficiency of the accreditation process. However, the blockchain solutions proposed by previous researchers add each participant to the network at the beginning, but some subjects do not generate data or use data at the beginning. For example, the accreditation agency will only enter the blockchain network to query the original data if they verify that the data in the self-assessment report is true. As consensus takes a certain amount of time, these previous approaches reduce the network’s operational efficiency. From the perspective of EEA, universities need to voluntarily apply for professional accreditation before the accreditation agency initiates the accreditation process. Therefore, it is resource-intensive for the accreditation agency to join the blockchain network from the outset. Compared with these previous approaches, a unique aspect of this work is that after the accreditation work starts, the accreditation agency can apply to join the blockchain network for data traceability verification, which can effectively improve the efficiency of the system.

4.2 The Network Topology of the Framework

The blockchain-based EEA system is constructed in a layered fashion. The system is divided into three layers. The bottom layer consists of the blockchain network, the middle layer comprises smart contracts, and the top layer involves applications encapsulated according to business requirements. Business logic is executed by invoking smart contracts through applications. The combination of the bottom and middle layers forms the blockchain-based EEA framework. Applications are customized based on specific user needs. The network topology of the framework is depicted in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: The network topology diagram of the system framework

In the HF network, different participants are generally abstracted as distinct organizations. All organizations join the same channel to collectively build the network for information exchange. EEA involves six participants: the school, academic affairs office, teachers, students, employers, and accrediting agency. These six participants represent six organizations, and along with an organization providing ordering services, a total of seven organizations join the same channel in the network to participate in the accrediting process. Considering that all seven organizations need to participate in the consensus and verification processes of the entire network, involving more organizations will lead to increased resource consumption and lower network performance. Moreover, having students as the primary participants in the entire process is impractical. Therefore, the network’s topology is optimized. Among the six participating organizations, students, teachers, academic affairs offices, and schools are primarily involved in school educational activities. Hence, these four participants can be abstracted as one organization, with the overall work being overseen by the school. When interacting with the blockchain network, the educational data generated by students and teachers, among others, is collectively written into the blockchain by the educational institution. However, before being written onto the chain, this data is initially stored off-chain. The on-chain data is stored in the form of hash values, a detailed explanation of which will be provided in Section 4.4. In the optimized network topology, organization one represents schools, organization two represents employers, and organization three represents certification agencies. Furthermore, each organization is set up with two nodes to simulate real-life production and avoid a situation where an organization cannot participate in the network promptly due to a host issue. Each organization is also deployed with two CAs. One CA is used to generate certificates for organization administrators and various nodes, while the other CA is used to generate certificates for securing communication at the transport layer. The two CAs are deployed separately, aiming to achieve finer security control by separating the issuance functions of identity certificates and Transport Layer Security certificates.

In the EEA blockchain framework, all involved organizations are joined within the same channel, collectively maintaining identical copies of the ledger. Each organization can interact with the blockchain network using their respective Peer nodes through clients or applications. However, only peer nodes with the corresponding chaincode installed possess this functionality. For instance, an accreditation agency can retrieve the required accreditation data from the EEA blockchain network through its owned nodes. In implementing an EEA blockchain network using HF technology, transactions need to be sorted before being packaged into blocks and distributed to each peer node for verification. The sorting service is carried out by sorting nodes belonging to organizations, they are referred to as sorting organizations. Sorting organizations also require a separate set of CAs to provide certificate services. The sorting service employs deterministic consensus algorithms, such as Kafka and Raft consensus algorithms, ensuring that the ledger does not experience block discrepancies as seen in other unauthorized blockchain networks. As data continues to be written into the system, new blocks required for storing data are continuously generated, forming a block-incrementing chain structure within the channel. This blockchain data structure enhances the level of decentralization, further ensuring the immutability of ledger data.

4.3 The Workflow of Transactions

The fundamental operations of reading and writing data to the distributed ledger in blockchain are referred to as transactions. In the context of the blockchain-based EEA system, the data interactions of relevant participants are permanently stored in the blockchain in the form of transaction blocks. In this scheme, the data involved in EEA, ranging from the training programs of the academic office to the academic achievements of students, is made transparent to all participants in the system. In this system model, the act of writing verifiable data on the blockchain by participants is defined as a transaction workflow. In this subsection, a detailed overview of the transaction workflow is provided, which outlines the workflow process in the HF network and endorsement configuration strategies. The transaction workflow in the HF network is illustrated in Fig. 4. The main components involved in the HF network workflow include the client, peer nodes, ordering organization, channel, and ledger. These components are each responsible for various tasks and collaborate to collectively complete the entire transaction process. The specific steps of the Fabric network workflow are outlined below:

• Transaction proposal creation by client: Initially, the client obtains a valid identity certificate from the CA to join the channel within the network. Subsequently, the client constructs a transaction proposal using the Application Programming Interface provided by the Software Development Kit connected to a network node (taking organization one as an example). The transaction proposal’s content includes a series of raw data to be uploaded to the blockchain network. The client then submits this proposal to the endorsing nodes for endorsement, a process accomplished through invoking the chaincode.

• Simulation execution and endorsement: Upon receiving the transaction proposal from the client, the endorsing nodes verify the proposal based on certain rules. These rules encompass aspects such as the correct format of the transaction proposal, whether the proposal has been previously submitted, the validity of the client’s signature for submitting the transaction, and whether the submitter possesses the requisite execution permissions in the channel. If all these conditions are met, and the verification is successful, the endorsing nodes simulate the transaction, endorse the state changes resulting from the transaction (recorded in the form of a read-write set, including keys and versions of the read states, and key-value pairs of the written states), and return the transaction response results to the client.

• Endorsement result verification and transaction ordering: After the client collects sufficient endorsement support (determined by the endorsement policy), it constructs a valid transaction request using the endorsements and sends the request to the ordering nodes for sorting and processing. In the EEA blockchain network, the endorsement policy necessitates that each participant signs the transaction.

• Ledger update: The ordering node packages the transactions into blocks and distributes them to all peer nodes in the channel. The peer nodes verify the transactions within the block. Upon successful verification, the results of the legitimate transactions are written into the ledger, and the new information is updated in the world state database.

Figure 4: The transaction workflow diagram in the HF network

Following these steps, transactions within the network achieve consensus and are recorded in the ledger. The transaction history and ledger data cannot be tampered with by any node. In the HF network, endorsement stands as a significant innovation and a crucial phase for verifying and declaring the legitimacy of transactions. The endorsement policy necessitates that each participant signs the transaction. Such endorsement policy configuration ensures that relevant participants in the EEA network remain online and collectively verify transactions.

For blockchain, every node participating in the network possesses a copy of the ledger, while actual storage resources are limited. In the EEA system, there is a vast amount of data that needs to be recorded. Taking the data that schools need to record as an example, the content to be written includes teaching plans and graduation requirements formulated by the academic office, teachers’ lesson plans and course materials, students’ transcripts, and exam papers, each involving a substantial amount of specific data. Hence, when writing data to the blockchain network, users only store the most critical information in the form of key-value pairs on the blockchain by invoking smart contracts. For a large amount of specific data, we can use a hash function to obtain a hash value for the data and then store this hash value on the blockchain, while the specific data is stored off-chain. The data under the chain is encrypted and stored in the cloud server by using a symmetric encryption algorithm, and the symmetric key is stored separately by the Data Owners(DOs). When other participants want to query or request to share these data, after DOs verify the identity of the requestor and agrees to share the data, DOs send the encryption key and the data storage address to the requestor through a secure channel, and the requestor uses the symmetric key to decrypt the data downloaded from the cloud server to obtain the data plaintext. If participating entities such as certification agencies or employers need to determine whether the off-chain specific data has been tampered with, they can apply the same hash function to the off-chain data, compare the resulting hash value with the hash value on the chain, and thereby ascertain whether the original data has been tampered with.

Algorithm 1 illustrates the process by which users write data to the EEA blockchain network. In this process, DataID, DataName, and DataKind offer further descriptions of the data being written to better manage this information. On the other hand, Algorithm 2 outlines the process through which users retrieve data from the blockchain network.

5 Security Analysis and Performance Evaluation

In this section, firstly, a security analysis is conducted on the proposed approach. Secondly, network performance testing is carried out on the approach presented in this work. Finally, the experimental results are summarized and discussed.

In the designed architecture, utilizing blockchain technology to address the issue of EEA, the primary objective is to ensure that the provided initial accreditation data remains unaltered. During the system’s operation, to prevent data leakage or theft, secure measures are necessary for communication and data exchange between nodes. Therefore, a security assessment of the proposed architecture is conducted in the following to address these concerns.

Denial of Service (DoS) Attacks: DoS attack is a malicious method used by an attacker to block the system servers to prevent or disrupt the normal operation of the target computer. This nefarious approach makes it impossible for regular users to access network or computer resources. Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks, on the other hand, refer to multiple attackers sending unnecessary messages to the target device, consuming system resources, and disrupting the normal functionality of the system. However, blockchain technology can mitigate such attacks. The proposed method adopts the Hyperledger Fabric architecture and utilizes a permission system for user or node participation. In this scenario, if a user or node joining the network initiates a DDoS attack, their unique account address can be used to trace the attacker and revoke their access to the system. Moreover, in the Hyperledger Fabric architecture, anonymous initiation of attacks is not possible, preventing anonymous initiation of DDoS attacks.

Man-in-the-Middle Attack: The Man-in-the-Middle attack involves an attacker establishing independent connections with the two ends of communication and exchanging the data they received. This makes the two ends of communication believe they are having a private, direct conversation, but the attacker has complete control over the entire session. This form of attack includes impersonating both parties to intercept communication content and tamper with data, posing a serious threat to digital system environments. The designed architecture, based on blockchain for data exchange, effectively prevents Man-in-the-Middle attacks. All data transmitted on the chain come with a digital signature generated using the user’s private key, making it extremely difficult to be impersonated and easy to verify. This prevents a Man-in-the-Middle attack from being executed.

Sybil Attack: The method of undermining the system by the attacker through the creation of multiple false identities and profiles is termed a Sybil attack. To prevent the occurrence of such attacks, the proposed framework system conducts identity verification and investigation during the user’s creation of digital identities. This process ensures that individuals attempting to join the system with false information are rejected. In addition, participants in the system can operate only with a unique identity while running within the system. Within the system, the account address is used as an identification tag. So long as malicious nodes cannot forge identities, the likelihood of disrupting the system’s operation is reduced.

Data Integrity and Privacy: In the context of blockchain, the generated data will be encrypted and stored in a decentralized manner, forming an immutable distributed ledger. Each block is connected to the previous block, making it impossible to modify the data in a block without modifying the data in the preceding block. It’s evident that altering all the data is unfeasible, and once data is written into the system, it becomes challenging to change [30]. The approach in this work adopts the data control scheme of HF blockchain technology. It utilizes the data segregation method called “channels” in HF technology to protect data security. This not only prevents unauthorized users from stealing data but also ensures data privacy.

Smart Contract Security: In HF, the smart contract is referred to as chaincode. Insecurity in smart contracts comes mainly from access control and privilege management, data consistency and tampering protection, and input validation and error handling [31]. For access control and privilege management, the proposed scheme adopts MSP-based authentication mechanism, which stipulates that only authorized users can perform specific operations. For data consistency and tampering protection, the proposed scheme queries the current state before transaction execution when invoking smart contracts to ensure that other transactions have not modified the data. For input validation and error handling, the proposed scheme incorporates validation of the format, scope and integrity of parameters before smart contract execution. It uses the try-catch mechanism in Java to handle exceptions to avoid contract execution failure. The processing of the above methods ensures the security of the smart contract and ensures that the framework proposed in this paper can operate safely.

In this section, performance testing and analysis of the blockchain-based EEA framework are conducted using the HC tool. HC is a tool used to evaluate the performance of blockchain solutions developed on Hyperledger. It supports various blockchain solutions including Ethereum, HF, FISCO BCOS, and more. By running custom test cases, we can obtain reports on performance metrics such as throughput, latency, resource consumption, etc.

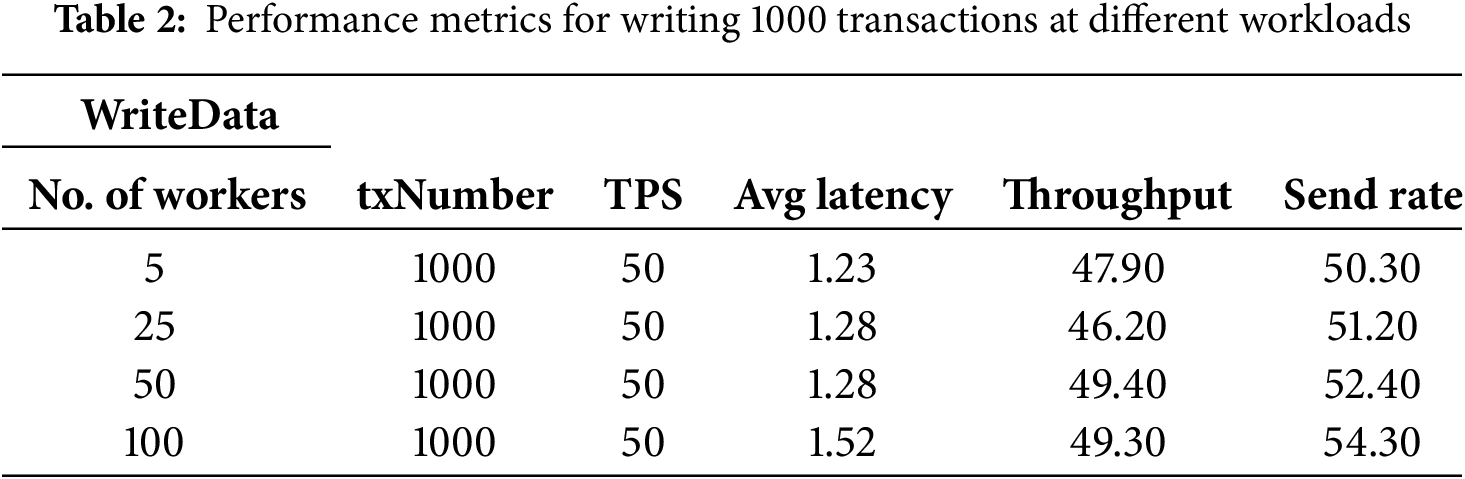

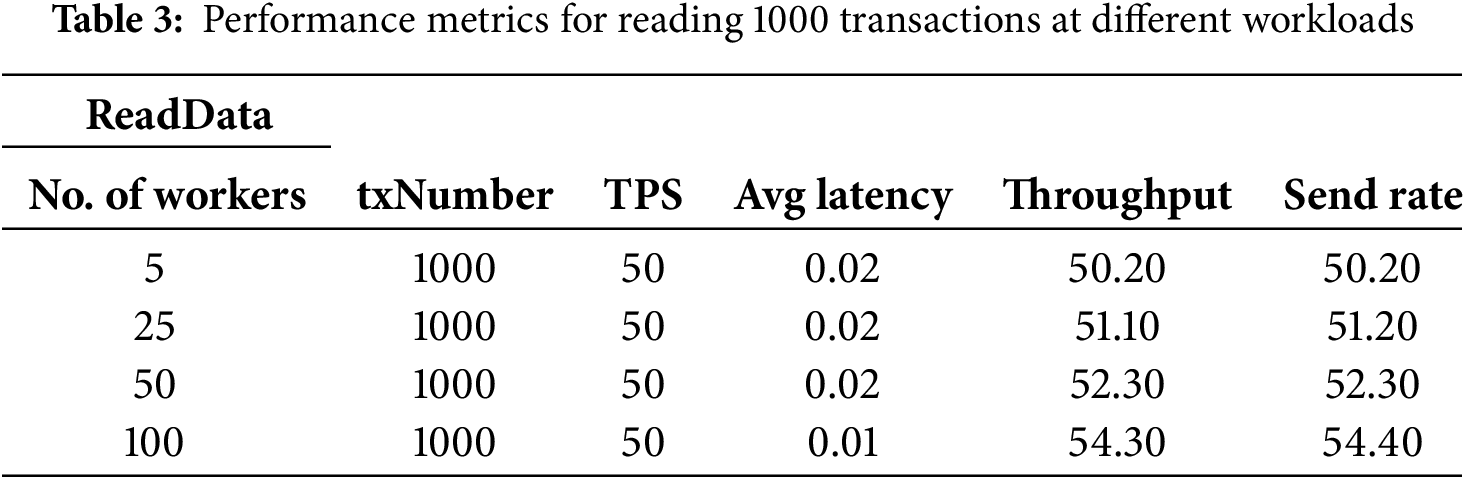

The experiments are conducted on a laboratory server with an environment consisting of Ubuntu 20.04, 32 GB RAM, and 1 TB of disk space. The versions used are HF 2.4.7 and HC 0.5.0, with the chaincode written in Java. The schools and employers blockchain network are first subjected to performance benchmark testing in this work, followed by performance testing and analysis of the network after the accreditation agency joins. The benchmark configuration files used for both are the same. Performance testing and analysis are conducted on two types of transactions, namely WriteData and ReadData. WriteData involves creating data on the blockchain, while ReadData involves retrieving stored data from the blockchain. In this approach, system throughput and network latency are taken as performance indicators. Various workloads and different Transactions Per Second (TPS) are considered as conditions affecting the performance indicators for conducting testing and analysis. Due to the number of workers representing the number of workload instances, to simulate real working environments, testing and analysis are first conducted on the impact of the number of tasks from two organizations on network performance. Workload numbers are set to four different values: 5, 25, 50, and 100, with each round submitting 1000 transactions. The transaction rate controller used is a fixed-rate controller. All four benchmark tests are executed with 1000 transactions at a sending rate of 50 TPS. The experiments simulate clients interacting with the blockchain network through nodes delegated by organization one. The performance testing results for this segment are presented in Tables 2 to 3.

From Table 2, it can be observed that for writing data to the system (WriteData), as the workload continuously increases, the average latency also keeps rising. The actual measured sending rate consistently increases as well. However, to achieve a relatively small network latency, the workload should not be set too high. Table 3 presents the experimental results for reading data (ReadData) from the network. With an increase in workload, there is no significant change in the average latency of the system. The entire system experiment remains stable, with the average network latency significantly lower than that for writing data. Moreover, the overall throughput of the system continues to increase.

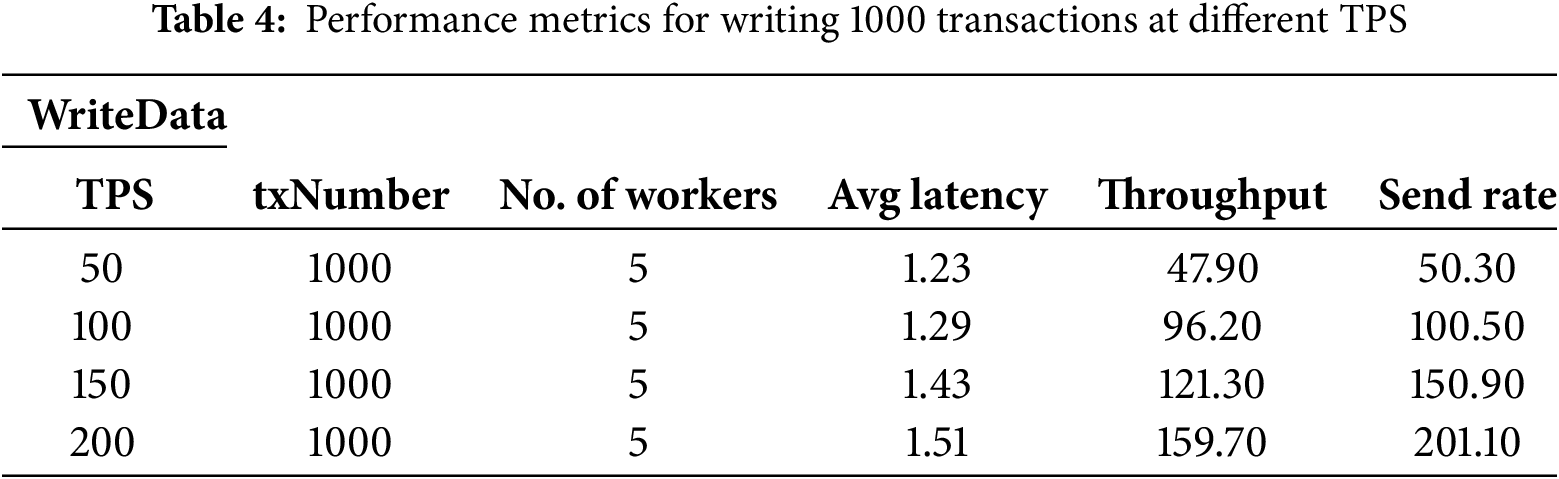

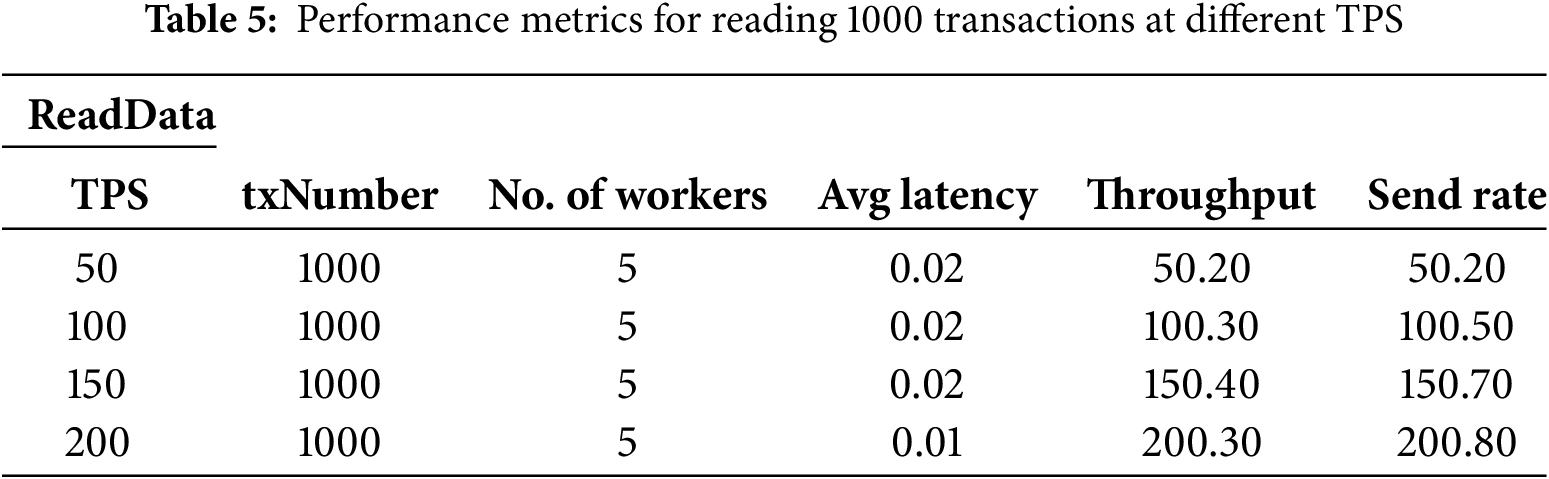

For the performance testing regarding the impact of different TPS on the system, the same fixed rate controller as mentioned above is also used. In this controller, TPS must be specified, which facilitates completing the testing tasks. In this section, the paper sets the number of transactions to 1000, keeps the workload at 5, and varies the TPS for testing and analysis. The results are shown in Tables 4 and 5.

From Table 4, it can be observed that as the TPS increases, network latency also increases. However, the system throughput is rapidly rising. However, at the same time, with the increase in TPS, the blockchain network may become overloaded, leading to transaction failures. Table 6 presents the results obtained when we set the TPS to 250, demonstrating numerous instances of transaction failures. Table 5 records the performance of reading data (ReadData). Based on the recorded results, increasing TPS does not significantly impact network latency, system throughput, or sending speed for reading data. Although transaction failures occurred at a TPS of 250, this is because during the testing, writing data (WriteData) and reading data (ReadData) were conducted simultaneously. Errors occurred in writing data, while the number of transactions remained unchanged, resulting in errors in reading data transactions as well.

To achieve better design objectives, performance testing and analysis are conducted on the network after the certification authority’s integration. The metrics, conditions, and methods used for this test are the same as the ones mentioned in the previous test cases. Therefore, the performance test results and analysis for system read and write operations are similar to the earlier ones. The primary objective of this section’s testing is to validate the superiority of the proposed framework, where the accreditation agency joins the blockchain network only when needed for accreditation tasks. This reduces the system’s consensus time, thereby enhancing overall system efficiency. The comparative analysis is illustrated through the data comparison as shown in Figs. 5 and 6, in comparison to the system performance before the accreditation agency’s integration into the network.

Figure 5: (a) Throughput of writing data with and without the accreditation agency joining the network at different workloads. (b) Throughput of reading data with and without the accreditation agency joining the network at different workloads. (c) Average latency of writing data with and without the accreditation agency joining the network at different workloads. (d) Average latency of reading data with and without the accreditation agency joining the network at different workloads

Figure 6: (a) Throughput of writing data with and without the accreditation agency joining the network at different TPS. (b) Throughput of reading data with and without the accreditation agency joining the network at different TPS. (c) Average latency of writing data with and without the accreditation agency joining the network at different TPS. (d) Average latency of reading data with and without the accreditation agency joining the network at different TPS

In Fig. 5, Network 1 represents the network before the accreditation agency joined, and Network 2 represents the network after the accreditation agency joined. In Fig. 5a–d, the x-axis represents different numbers of work, while the y-axis in the first two graphs represents system throughput, and in the latter two, it represents the network’s average latency. From Fig. 5, it can be observed that the number of workers has little impact on the throughput of both networks, showing no significant difference. However, in terms of network average latency performance, after the accreditation agency joined the network, there is a clear increase in the average latency for writing data to the system, while the average latency for reading data showed minimal difference. Fig. 6 illustrates the change in two performance indicators, system throughput and average latency, for different TPS values with a fixed rate controller. Similar to Fig. 5, Fig. 6a and c describes the performance change for writing data, and Fig. 6b and d shows the performance change for reading data. It can be observed that across both networks, different TPS has a minor impact on system throughput. However, for the average latency of writing data, the more participating organizations, the higher the average latency.

From Figs. 5 and 6, it can be observed that the throughput and average latency of writing data are not as good as that of reading data. The reasons are as follows. Compared with reading data, writing data involves the process of node endorsement and consensus, which consumes a significant number of resources. In a high concurrency scenario, node endorsement and consensus require more time to process these transactions, with relatively poorer performance in terms of throughput and average latency. The performance without the accreditation agency joining the network is also better than the performance after the accreditation agency joins the network, as the latter involves more nodes participating in the network. However, the accreditation agency only joins the network when they are required in this work, which can reduce the resources consumption.

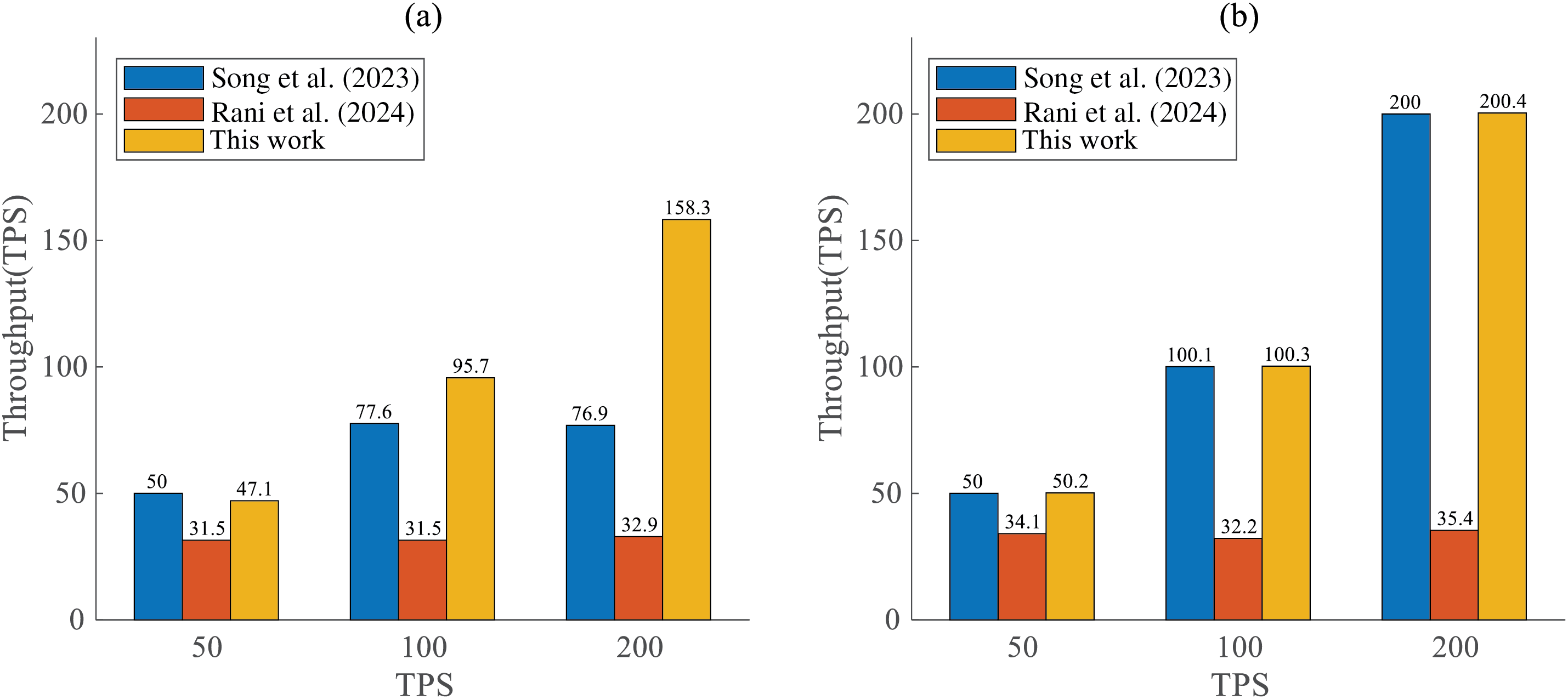

As shown in Fig. 7, the network throughput of the proposed scheme stages is compared with [11] and [24] in reading and writing data stages. Fig. 7a presents the comparison of the system network throughput size for different sending rates when writing data, and Fig. 7b presents the comparison of the system network throughput size for different sending rates when reading data. The data is obtained in the scenario that a network is built by three organizations. As shown in Fig. 7a, when the sending rate increases, the network throughput of writing data for the proposed scheme also increases and is much higher than that of the comparison literature. The network throughput of the approach of [11] is also increasing gradually in the writing data scenario, but at 200 TPS, the throughput is not increasing. The network throughput of [24], on the other hand, does not change much and stays at the level of 32 TPS. In Fig. 7b, the network throughput of the approach of [11] and the proposed scheme is also increasing gradually and keeping the same level as the sending rate is increasing in the reading data scenario. While the network throughput of the approach of [24] stays at a low level of 34 TPS in read data scenario. From the above performance analysis, it can be seen that the proposed scheme is still able to process network transactions with high throughput at high sending rate. It is also able to complete the corresponding transactions in the network environment facing the multi-organization of EEA. Therefore, the blockchain-based EEA framework designed in this paper is feasible.

Figure 7: (a) Comparison of write data network throughput at different TPS. (b) Comparison of read data network throughput at different TPS [11,24]

A novel blockchain-based EEA framework is proposed in this work, via the decentralized, tamper-proof, and traceable features of blockchain. In this framework, students, teachers, employers, and accreditation agencies can participate in the accreditation process. Specifically, this framework uses the distributed ledger technology of HF. Building on this foundation, an innovative approach is introduced for the underlying network construction paradigm of traditional HF. This approach involves merging and organizing organizations with commonalities and then integrating them into the blockchain network. The performance of the proposed framework is evaluated by using the HC. The analysis of the relevant performance metrics shows that reducing the number of nodes involved in endorsement and consensus can enhance the performance of the framework. Additionally, the reduction in the number of nodes does not compromise the decentralization of the system. The proposed framework aligns well with the requirements. In comparison with previous research, this framework is resilient to various attacks. However, it’s important to note that the raw data involved in this solution is stored in the blockchain ledger as hash values through hash function transformation, and the original data is not directly stored in the categorized ledger of the network, primarily due to the large memory footprint of raw data. Most current research focuses on hosting memory-intensive source data in the cloud to alleviate the issue of limited memory capacity within blockchain networks. However, CSP is not fully trustworthy, data stored in CSP carries some risk of privacy leakage, and it is difficult for resource owners to control the flow of resources. Future work can consider integrating blockchain, cloud storage, and corresponding cryptographic algorithms to build a comprehensive blockchain solution that includes data storage and has access control sharing.

Acknowledgement: The authors thank Guangxi normal univesity for providing laboratory facilities, the reviewers and editor for their comprehensive, detailed and insightful comments.

Funding Statement: This research is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 62462009, the Guangxi Science and Technology Projects under Grant GuiKeAD24010047, the Guangxi Natural Science Foundation under Grant 2022GXNSFFA035028, Research Fund of Guangxi Normal University under Grant 2021JC006, the AI+Education Research Project of Guangxi Humanities Society Science Development Research Center under Grant ZXZJ202205, the Guangxi New Engineering and Technical Disciplines Research and Practice Projects under Grant XGK2022005, the 2021 New Engineering and Technical Disciplines Research and Practice Project of Guangxi Normal University.

Author Contributions: Yuling Luo: Conceptualization, Validation, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft. Xiaoguang Lin: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing. Junxiu Liu: Conceptualization, Validation, Writing—review and editing. Qiang Fu: Validation, Writing—review and editing, Visualization. Sheng Qin: Validation, Writing—review and editing. Zhen Min: Validation, Writing—review and editing. Tinghua Hu: Validation, Writing—review and editing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data supporting this study’s findings are available on request from the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Akera A. Setting the standards for engineering education: a history [scanning our past]. Proc IEEE. 2017;105(9):1834–43. doi:10.1109/JPROC.2017.2729406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Shaikh ZA, Khan AA, Baitenova L, Zambinova G, Yegina N, Ivolgina N, et al. Blockchain hyperledger with non-linear machine learning: a novel and secure educational accreditation registration and distributed ledger preservation architecture. Appl Sci. 2022;12(5):2534. doi:10.3390/app12052534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Raimundo R, Rosário A. Blockchain system in the higher education. Eur J Investig Health Psychol Educ. 2017;11(1):276–93. doi:10.3390/ejihpe11010021. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Zhang X, Liu R, Yan W, Wang Y, Jiang Z, Feng Z. Effect analysis of online and offline cognitive internships based on the background of engineering education accreditation. Sustainability. 2022;14(5):2706. doi:10.3390/su14052706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Ab-Rahman MS, Hwang I-S, Mohd Yusoff AR, Mohamad AW, Ihsan AKAM, Abdul Rahman J, et al. A global program-educational-objectives comparative study for malaysian electrical and electronice engineering graduates. Sustainability. 2022;14(3):1280. doi:10.3390/su14031280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Jadhav AA, Suryawanshi DA, Ahankari SS, Zoper SB. A technology-enabled assessment and attainment of desirable competencies. Educ Chem Eng. 2022;39(4):67–83. doi:10.1016/j.ece.2022.02.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Yorulmaz M, Iç YT. Development of a decision support system to determine engineering student achievement levels based on individual program output during the accreditation process. Educ Inform Technol. 2022;27(4):1–26. doi:10.1007/s10639-021-10790-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Cao Y, Jia F, Manogaran G. Efficient traceability systems of steel products using blockchain-based industrial internet of things. Sustainability. 2019;16(9):6004–12. doi:10.1109/TII.2019.2942211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Khezr S, Yassine A, Benlamri R, Shamim Hossain M. An edge intelligent blockchain-based reputation system for lloT data ecosystem. IEEE Trans Ind Inform. 2022;18(11):8346–55. doi:10.1109/TII.2022.3174065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Zhang X, Ling L. A review of blockchain solutions in supply chain traceability. Tsinghua Sci Technol. 2022;28(3):500–10. doi:10.26599/TST.2022.9010030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Song H, Ge W, Gao P. A novel blockchain-enabled supply-chain management framework for xinjiang jujube: research on optimized blockchain considering private transactions. Foods. 2023;12(3):587. doi:10.3390/foods12030587. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Xu C, Qu Y, Xiang Y, Luan TH, Gao L. An optimized privacy-protected blockchain system for supply chain on internet of things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024;11(5):9019–30. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2023.3321889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Song M, Hua Z, Zheng Y, Huang H, Jia X. Blockchain-based deduplication and integrity auditing over encrypted cloud storage. IEEE Trans Dependable Secure Comput. 2023;20(6):4928–45. doi:10.1109/TDSC.2023.3237221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Tulkinbekov K, Kim DH. Data modifications in blockchain architecture for big-data processing. Sensors. 2023;23(21):8762. doi:10.3390/s23218762. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Kumar V, Ali R, Sharma PK. A secure blockchain-assisted authentication framework for electronic health records. Int J Inf Technol. 2024;16(3):1581–93. doi:10.1007/s41870-023-01705-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Tariq A, Haq HB, Ali ST. Cerberus: a blockchain-based accreditation and degree verification system. IEEE Trans Comput Soc Syst. 2022;10(4):1503–14. doi:10.1109/TCSS.2022.3188453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Liang X, Zhao Q, Zhang Y, Liu H, Zhang Q. EduChain: a highly available education consortium blockchain platform based on hyperledger fabric. Concurr Comput. 2023;35(18):e6330. doi:10.1002/cpe.6330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Liu Q, Guan Q, Yang X, Zhu H, Green G, Yin S. Education-industry cooperative system based on blockchain. In: 1st IEEE International Conference on Hot Information-Centric Networking (HotICN); 2018;IEEE. p. 207–11. doi:10.1109/HOTICN.2018.8606036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Shen H, Xiao Y. Research on online quiz scheme based on double-layer consortium blockchain. In: 9th International Conference on Information Technology in Medicine and Education (ITME); 2018; IEEE. p. 956–60. doi:10.1109/ITME.2018.00213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Lohachab A, Garg S, Kang BH, Amin MB. Performance evaluation of hyperledger fabric-enabled framework for pervasive peer-to-peer energy trading in smart cyber-physical systems. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2021;118(4):392–416. doi:10.1016/j.future.2021.01.023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Sharples M, Domingue J. The blockchain and kudos: a distributed system for educational record, reputation and reward. In: Adaptive and Adaptable Learning: 11th European Conference on Technology Enhanced Learning; 2016; Springer. p. 490–6. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-45153-4_48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Maestre RJ, Bermejo Higuera J, Gámez Gómez N, Bermejo Higuera JR, Sicilia Montalvo JA, Orcos Palma L. The application of blockchain algorithms to the management of education certificates. Evol Intell. 2023;16(6):1967–84. doi:10.1007/s12065-022-00812-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Khan AA, Laghari AA, Shaikh AA, Bourouis S, Mamlouk AM, Alshazly H. Educational blockchain: a secure degree attestation and verification traceability architecture for higher education commission. Appl Sci. 2021;11(22):10917. doi:10.3390/app112210917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Rani P, Sachan RK, Kukreja S. Educert-chain: a secure and notarized educational certificate authentication and verification system using permissioned blockchain. Cluster Comput. 2024;27(7):10169–96. doi:10.1007/s10586-024-04469-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Rustemi A, Dalipi F. Academic certificate verification: a practical comparison between centralized and blockchain-based systems. In: CIEES 2024—IEEE International Conference on Communications, Information, Electronic and Energy Systems; 2022; 2024. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/CIEES62939.2024.10811200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Priyadarshini R, Pandey R, Ankit KC, Bhandari D, Khadka B, Barik RK, et al. A faster, integrated and trusted certificate authentication and issuer validation system based on blockchain. IEEE Access. 2025;13(7):27037–49. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2025.3539180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Chandra T, Kaur M, Rakesh N, Gulhane M, Maurya S. Novel blockchain-based framework to publish, verify, and store digital academic credentials of universities. Int J Inf Technol. 2024;16(5):3273–81. doi:10.1007/s41870-024-01842-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Zhou Z, Liu Y. Blockchain-based encryption method for internal and external health privacy data of university physical education class. J Environ Public Health. 2022;2022(1):7506894. doi:10.1155/2022/7506894. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Shen D. Research on the sharing mode of educational information resources in colleges and universities based on the blockchain and new energy. Energy Rep. 2021;7(3):458–67. doi:10.1016/j.egyr.2021.10.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Li Z, Ma Z. A blockchain-based credible and secure education experience data management scheme supporting for searchable encryption. China Commun. 2021;18(6):172–83. doi:10.23919/JCC.2021.06.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Cao X, Zhang J, Wu X, Liu B. A survey on security in consensus and smart contracts. Peer-to-Peer Netw Appl. 2022;15(2):1008–28. doi:10.1007/s12083-021-01268-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools