Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

A Review of Object Detection Techniques in IoT-Based Intelligent Transportation Systems

School of Computer and Software, Nanjing University of Information Science and Technology, Nanjing, 210044, China

* Corresponding Author: Jian Su. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 84(1), 125-152. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.064309

Received 11 February 2025; Accepted 08 April 2025; Issue published 09 June 2025

Abstract

The Intelligent Transportation System (ITS), as a vital means to alleviate traffic congestion and reduce traffic accidents, demonstrates immense potential in improving traffic safety and efficiency through the integration of Internet of Things (IoT) technologies. The enhancement of its performance largely depends on breakthrough advancements in object detection technology. However, current object detection technology still faces numerous challenges, such as accuracy, robustness, and data privacy issues. These challenges are particularly critical in the application of ITS and require in-depth analysis and exploration of future improvement directions. This study provides a comprehensive review of the development of object detection technology and analyzes its specific applications in ITS, aiming to thoroughly explore the use and advancement of object detection technologies in IoT-based intelligent transportation systems. To achieve this objective, we adopted the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) approach to search, screen, and assess the eligibility of relevant literature, ultimately including 88 studies. Through an analysis of these studies, we summarized the characteristics, advantages, and limitations of object detection technology across the traditional methods stage and the deep learning-based methods stage. Additionally, we examined its applications in ITS from three perspectives: vehicle detection, pedestrian detection, and traffic sign detection. We also identified the major challenges currently faced by these technologies and proposed future directions for addressing these issues. This review offers researchers a comprehensive perspective, identifying potential improvement directions for object detection technology in ITS, including accuracy, robustness, real-time performance, data annotation cost, and data privacy. In doing so, it provides significant guidance for the further development of IoT-based intelligent transportation systems.Keywords

Supplementary Material

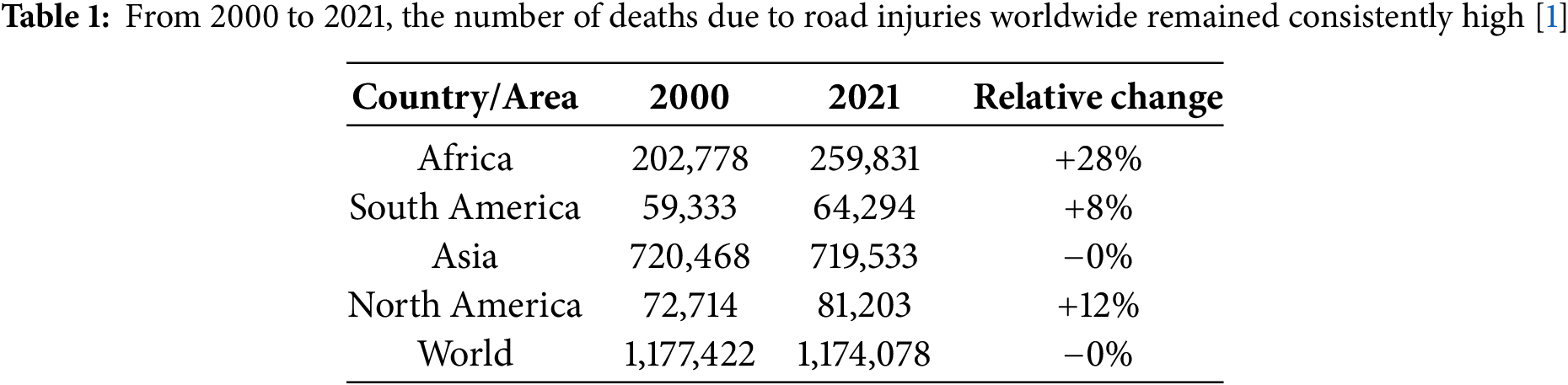

Supplementary Material FileAs global urbanization accelerates, the number of vehicles continues to grow, resulting in increasingly severe issues such as traffic congestion, frequent accidents, and environmental pollution [1–3]. Casualties are also steadily rising, as shown in Table 1. Against this backdrop, ITS, through the IoT, sensor technology, and advanced information and communication technologies, have emerged as core solutions for optimizing traffic management, improving safety, and enhancing efficiency [4–6].

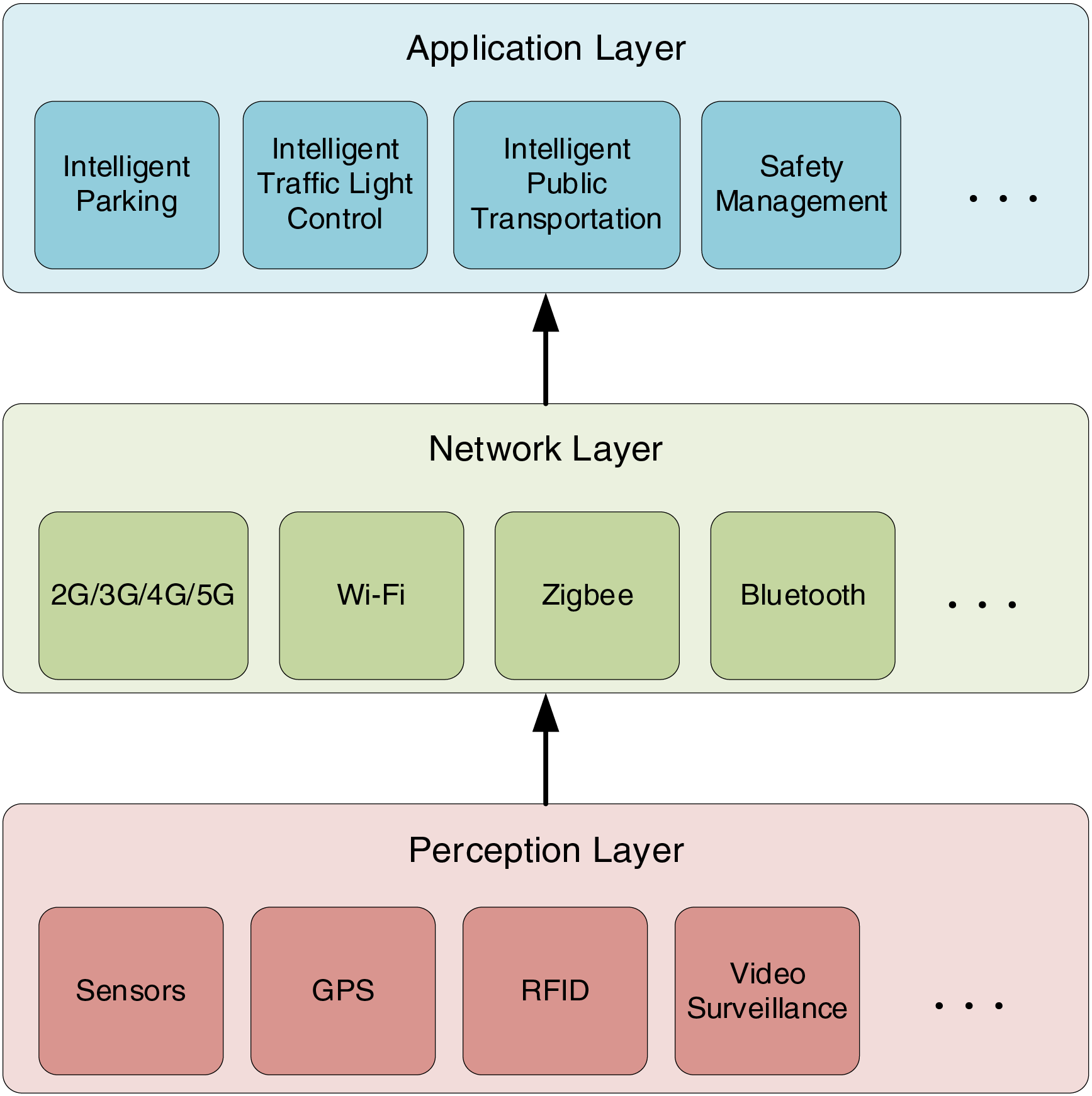

In IoT-based Intelligent Transportation Systems, a layered architecture is typically adopted, as shown in Fig. 1. From bottom to top, it consists of the perception layer, the network layer, and the application layer. The perception layer gathers information through various technologies, such as sensors, Global Positioning System (GPS), Radio Frequency Identification (RFID), and video surveillance equipment, collecting traffic data such as vehicle location, speed, and road conditions. The network layer is responsible for transmitting this information in real-time to the application layer. This layer primarily utilizes technologies like 2G/3G/4G/5G, Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, and ZigBee to ensure that the data collected by the perception layer is transmitted quickly and accurately to the application layer for processing. The application layer serves as the critical stage for information processing and application; by analyzing and processing the data collected from the perception layer, it enables intelligent management and control of the transportation system, significantly improving the system’s efficiency and management capabilities. However, despite the strong support that IoT technology provides to ITS, its complexity also introduces numerous challenges. In particular, within the perception layer, object detection technology, as a critical driving engine, faces the significant bottleneck of quickly and accurately extracting valid information from massive IoT data in complex traffic environments [7–9]. Therefore, developing more efficient and precise object detection methods holds profound significance for advancing the development of intelligent transportation systems.

Figure 1: Architecture of IoT-based intelligent transportation system

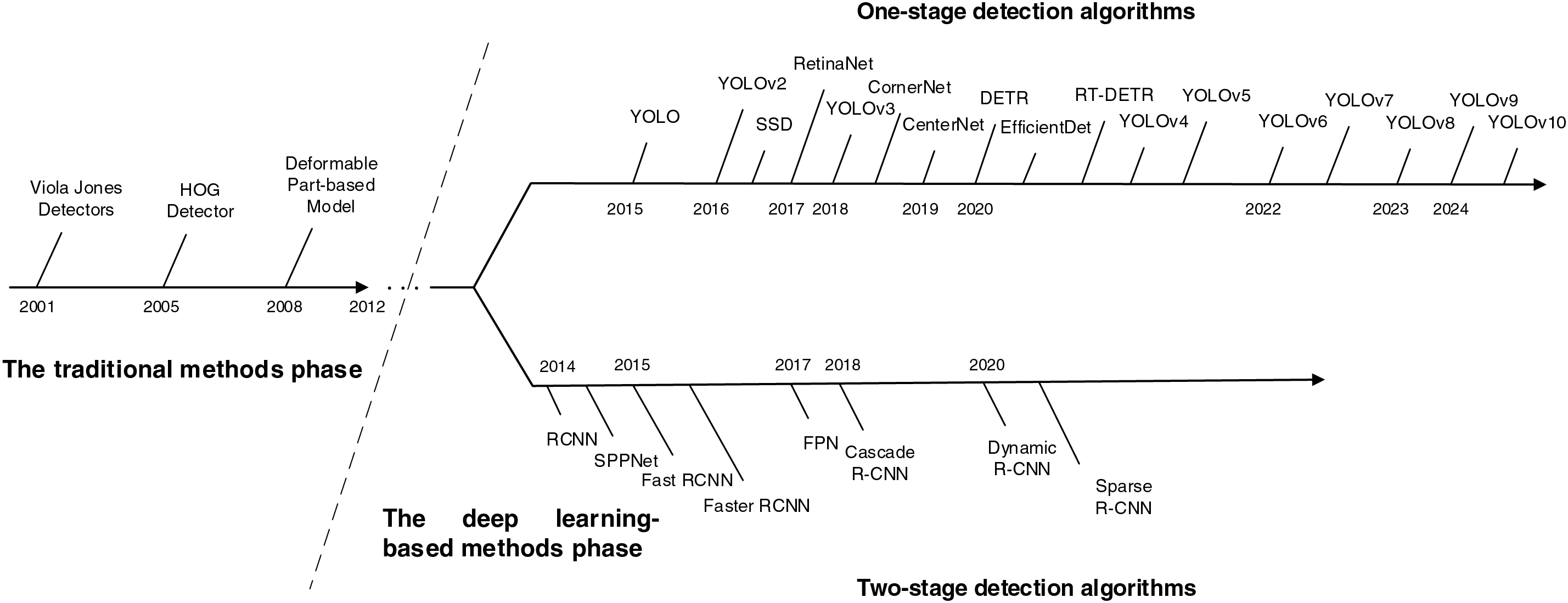

Object detection, as one of the core tasks in computer vision, has undergone two major development phases: traditional methods and deep learning-based methods. Early research (2000–2013) relied on handcrafted feature extraction and machine learning classifiers. For instance, the Viola-Jones algorithm achieved real-time detection using Haar features and cascade classifiers, but it lacked the ability to recognize small objects [10]. While Histogram of Oriented Gradients (HOG) features were robust to changes in illumination, they had limited expressive power [11]. The Deformable Part Model (DPM) improved flexibility through part-based modeling but struggled in densely occluded scenarios [12]. These limitations prompted researchers to shift towards deep learning approaches.

Since the introduction of Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) by Region-based Convolutional Neural Network (R-CNN) in 2014 [13], deep learning-based object detection techniques have rapidly become mainstream. Single-stage algorithms employ end-to-end designs to achieve efficient inference. For example, through iterations from YOLOv1 [14] to YOLOv10 [15], optimizations like multi-scale feature fusion and dynamic label assignment have significantly improved the accuracy and speed of vehicle and pedestrian detection [16–19]. In contrast, two-stage algorithms leverage Region Proposal Networks (RPN) for refined classification, excelling in complex scenarios but with higher computational costs [20].

In recent years, the emergence of Transformer architectures has further advanced object detection techniques. For instance, Detection Transformer (DETR) [21] and Real-Time Detection Transformer (RT-DETR) [22] utilize global attention mechanisms to overcome traditional CNN frameworks, achieving end-to-end detection. RT-DETR, in particular, employs a hybrid encoder design, striking a better balance between real-time performance and accuracy. These advancements not only represent the latest progress in the field but also offer new solutions to the detection bottlenecks in complex traffic scenarios.

This paper aims to review the development and current applications of object detection technologies in IoT-based intelligent transportation systems, analyze the challenges faced in practical applications, and explore future development directions. By systematically organizing and summarizing relevant studies, we hope to provide theoretical support and practical guidance for further advancements in ITS.

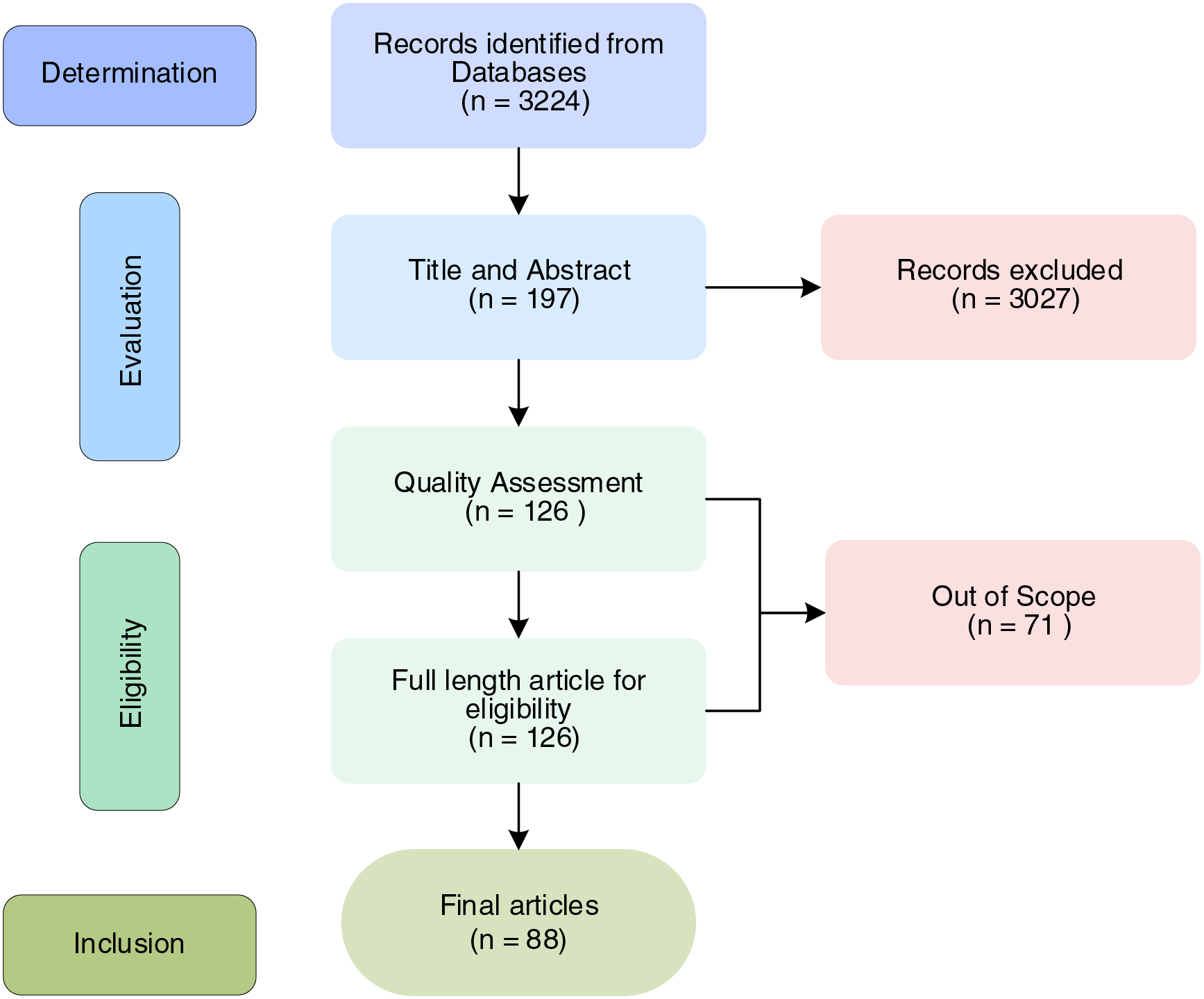

The main research questions (RQs) addressed in this paper are as follows:

RQ1: What are the characteristics and existing problems of object detection algorithms during the traditional methods phase?

RQ2: What are the respective features, advantages, and limitations of object detection algorithms during the deep learning methods phase?

RQ3: What are the specific applications of object detection technologies in IoT-based intelligent transportation systems?

The rest of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 describes the review methodology and the procedure for selecting literature. Section 3 introduces the fundamental principles and development history of object detection technologies, addressing RQ1 and RQ2. Section 4 discusses the specific applications of object detection technologies in ITS, including vehicle detection, pedestrian detection, and traffic sign detection, answering RQ3. Section 5 analyzes the current challenges faced by object detection technologies and explores potential future research directions. Section 6 concludes the study with a summary of findings.

This study employs the PRISMA approach to conduct a literature review, ensuring transparency and methodological rigor throughout the research process.

The PRISMA approach is a standardized framework for systematic literature reviews, with its core tools comprising a four-phase flowchart and a 27-item checklist. It aims to enhance research transparency and reproducibility through a structured process. The flowchart standardizes the literature screening pathway with four steps: identification, screening, eligibility, and final inclusion, covering the entire process from multi-database searches to the final inclusion of studies. Due to its interdisciplinary applicability and methodological rigor, this approach has been widely adopted across various fields, providing a standardized tool for the comprehensive analysis of complex problems.

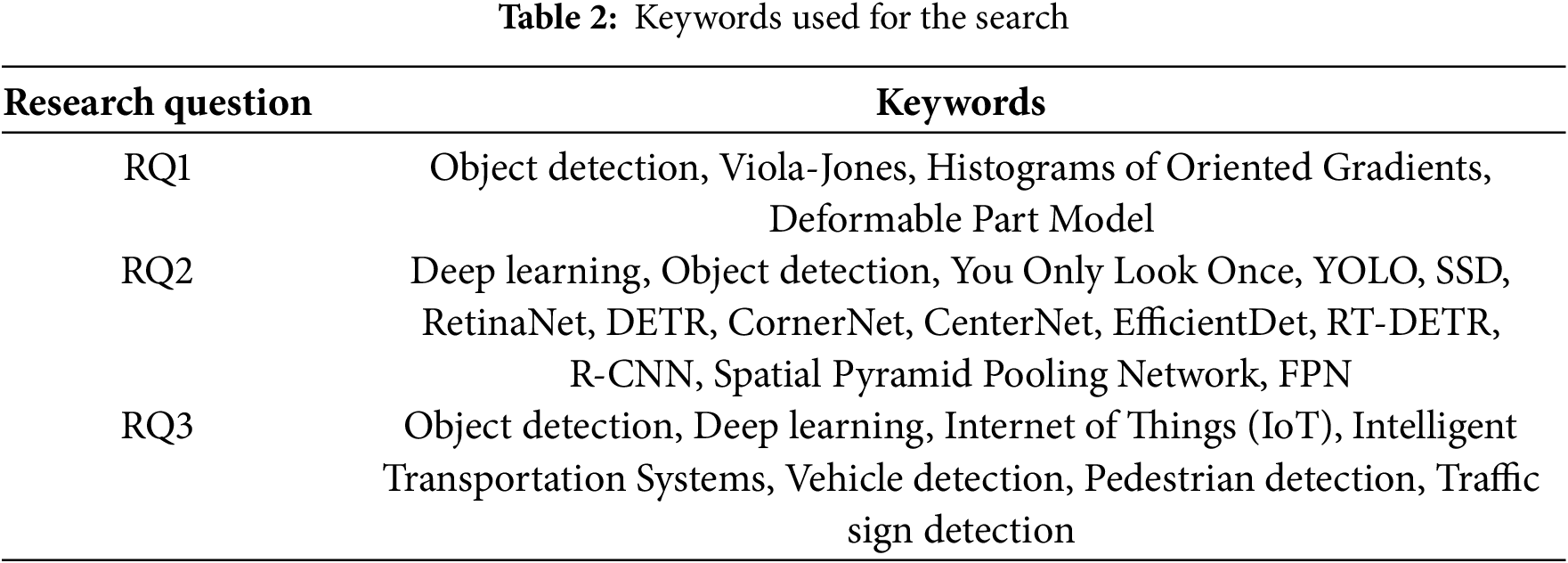

To obtain comprehensive, specific, and relevant literature, this study selected multiple authoritative databases for search, including IEEE Xplore, ScienceDirect, and Google Scholar, with the search scope limited to English-language literature. To ensure the accuracy and comprehensiveness of the search process, this study conducted a systematic search of the database for three research questions based on the keywords or phrases listed in Table 2.

2.3 Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

After completing the initial search, the study established clear inclusion and exclusion criteria to ensure the relevance and quality of the literature. The specific inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Studies from 2000 to 2013 were included in the traditional methods phase, provided they demonstrated relevance to the evolution of technology; for the deep learning methods phase, only studies published between 2014 and 2024 were considered; (2) Articles must be written in English; (3) Studies should focus either on object detection techniques themselves or their practical applications in intelligent transportation systems; (4) Studies should provide experimental data or practical application cases to validate the effectiveness of the algorithm.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Studies that did not directly impact the evolution of deep learning techniques during the traditional methods phase or those published before 2014 in the deep learning methods phase; (2) Non-English articles; (3) Studies unrelated to object detection techniques; (4) Studies that did not provide experimental data or practical application cases.

First, the study conducted an initial search in various scientific databases, identifying a total of 3224 studies. Next, researchers evaluated the titles and abstracts, excluding 3027 studies that did not meet the criteria, leaving 197 studies for the next stage. Subsequently, the full texts of these 197 records were assessed, of which 126 met the standards. Finally, after a manual review, 88 studies met the inclusion criteria and were incorporated into this paper, as shown in Fig. 2. Further details can be found in Supplementary Materials 1 and 2.

Figure 2: The research screening process using the PRISMA framework

3 Object Detection Technology in IoT-Based Intelligent Transportation Systems

Object detection is a computer vision technology that infers the objects present in an image or video along with their locations. It answers not only “What is this?” but also “Where is it?” Given an input image, the algorithm extracts features and generates regions that may contain objects, then classifies and localizes those regions. Common object detection algorithms include the R-CNN series [13], YOLO series [14], and Single Shot MultiBox Detector (SSD) [23]. Object detection can be applied to lots of intelligent transportation systems, security monitoring systems, and autonomous driving.

In this section, we will give a thorough review of object detection development history. The origins of this technology date back to the late 1980s. However, in those days, object detection algorithms took various factors into consideration that resulted in the development of models, which could not adapt to different scenarios, producing unsatisfactory detection results. It wasn’t until 2014, when deep learning technology began applying to object detection, that the rapid development of the technology of detection actually started. Therefore, as shown in Fig. 3, we divide the development of object detection technology into two phases: traditional methods and deep learning-based methods.

Figure 3: The development history of object detection technology

3.1 The Traditional Methods Phase

We refer to the pre-2014 phase, before the rise of deep learning, as the traditional methods phase. During this period, object detection methods principally relied on handcrafted features and classical machine learning algorithms. Usually, conventional object detection techniques are segmented into three primary stages: region selection, feature extraction, and classification by a classifier.

The efficiency and effectiveness of region selection and feature extraction are the main problems of most traditional object detection methods. Although the sliding window method can cover all possible locations of the target, its consumption is huge, and there is so much redundant information in the candidate regions. Handcrafted features cannot cope well with complex backgrounds and diverse targets, which makes the methods lack robustness and cannot solve such challenges in a practical application. Usual examples are the detectors by Viola-Jones [10], HOG Detector [11], and DPM [12].

Viola-Jones Detectors: This is the Viola-Jones algorithm, initially introduced by Paul Viola and Michael Jones in 2001. It is a real-time object detection algorithm primarily used for face detection. The algorithm consists of three core components: Haar-like features, the integral image, and the Adaboost algorithm. First, Haar-like features capture image edges and textures by calculating pixel value differences in rectangular regions. The integral image significantly speeds up feature computation, allowing for rapid calculation of pixel sums in any rectangular area. Finally, the Adaboost algorithm selects the most useful features from a large set of Haar-like features, combining them into a strong classifier. Additionally, the cascade classifier of Viola-Jones further enhances detection speed, enabling real-time detection even with limited computational resources [24]. In intelligent transportation systems, one of the main applications of Viola-Jones is vehicle detection [25]. By analyzing datasets, the Viola-Jones detector can detect the positions and movement trajectories of vehicles in real-time, thus providing data support for traffic flow monitoring, traffic accident detection, and intelligent traffic signal control.

HOG Detector: HOG detector is a feature descriptor method widely used for object detection, introduced by Navneet Dalal and Bill Triggs in 2005. HOG features capture image edges and texture information by calculating the histogram of gradient orientations in local regions of an image, thus achieving object detection and recognition. Its main advantage lies in its robustness to variations in illumination and geometric transformations, making it perform well in various complex environments. During the detection process, the HOG detector first segments the image into multiple small, connected areas known as cells. In each cell, it calculates the gradient direction and magnitude for each pixel and compiles this gradient information into a histogram. Then, multiple cells are grouped into a block, and the histograms within the block are normalized to enhance robustness to lighting and shadow changes. Finally, all blocks’ feature vectors are combined into a complete HOG descriptor for object detection. In intelligent transportation systems, the HOG detector is mainly applied in pedestrian detection [26]. For example, one study put forward a pedestrian detection approach utilizing HOG features and a Support Vector Machine [27], which demonstrated superior detection accuracy and instantaneous performance. Additionally, another study combined HOG features and CNN to detect wildlife on roads at night using thermal imaging technology, improving vehicle safety [28].

DPM: DPM is a classic algorithm for object detection and one of the pinnacle achievements in traditional object detection algorithms, proposed by Pedro Felzenszwalb and others in 2008. DPM is an extension of the HOG detector, which improves upon HOG by introducing a deformable parts model, enhancing flexibility and accuracy in object detection, particularly in different poses and complex scenes. Simply put, DPM considers not only local features but also the spatial relationships between parts, resulting in better detection performance. Its core idea is to use HOG features to describe local regions in an image and perform detection in a multi-scale manner to handle variations in object scales and poses. Furthermore, Felzenszwalb, McAllester, and Ramanan extended their work to the “star model”. Subsequently, Girshick transformed the “star model” into a mixture model to detect real-world objects with significant variations. In 2010, Felzenszwalb and Girshick were honored with the “Lifetime Achievement Award” for their significant contributions to the PASCAL VOC. In intelligent transportation systems, DPM is mainly used for vehicle [29] and pedestrian detection [30]. For instance, one study proposed a DPM-based vehicle detection method [31], which achieved high-precision vehicle classification and detection by analyzing traffic scene images. Additionally, DPM has been used in pedestrian detection, where it can detect and track pedestrian positions and movement trajectories in real-time by analyzing pedestrian features in datasets, thereby enhancing traffic safety.

3.2 The Deep Learning-Based Methods Phase

As deep learning continues to evolve, deep learning technology began to be applied to object detection in 2014, promoting the rapid advancement of object detection technology. This marked the commencement of the second era of object detection: the deep learning-based methods phase.

So far, deep learning continues to dominate the application of object detection. Early deep learning models, such as AlexNet [32] and GoogLeNet [33], could only provide image classification results and not the location of objects. It wasn’t until 2014, when R. Girshick and others proposed the R-CNN [34], that deep learning began to make a profound influence in the domain of object detection. Since that time, the field of object detection has seen rapid advancements, with a series of object detection algorithms being proposed, such as Fast R-CNN [35], Faster R-CNN [36], YOLO, and SSD. Among these, YOLO and SSD have attained optimal detection outcomes on multiple benchmark datasets.

In the deep learning phase, object detection techniques are predominantly categorized into single-stage and two-stage detection algorithms. Single-stage detection algorithms, such as the YOLO series, SSD, RetinaNet [37], CornerNet [38], CenterNet [39], DETR [21], EfficientDet [40] and RT-DETR [22], accomplish object detection via a single forward pass. By simplifying processing steps, they significantly reduce computational overhead and improve inference speed. Its efficient computational architecture and low hardware requirements make single-stage object detection algorithms—especially lightweight versions (e.g., YOLOv5s, EfficientDet-D0)—particularly well-suited for real-time deployment on resource-constrained embedded devices such as the Jetson Nano and Raspberry Pi. The low power consumption and limited computational power of these devices make it difficult to support the multi-stage computation processes of two-stage algorithms. In contrast, single-stage algorithms, with their end-to-end inference design, significantly reduce hardware burden and power consumption while maintaining relatively high detection accuracy, making them more suitable for the performance limitations of embedded scenarios.

Two-stage detection algorithms, such as R-CNN, Fast R-CNN, Faster R-CNN, Spatial Pyramid Pooling Network (SPPNet) [41], Mask R-CNN [42], Cascade R-CNN [43], etc., generate candidate regions first, followed by classification and regression, resulting in high detection accuracy. While two-stage detection algorithms excel in accuracy, particularly for tasks requiring high precision, their more complex computational processes result in a higher computational load. Consequently, they are at a disadvantage in terms of real-time performance and deployment efficiency compared to single-stage algorithms. However, in certain high-precision demand scenarios within ITS, two-stage algorithms, leveraging the synergy of RPN and fine-grained classification, demonstrate significant advantages in detection accuracy. They thus become the preferred choice for high-precision scenarios, despite the trade-off in real-time performance.

3.2.1 Single-Stage Detection Algorithms

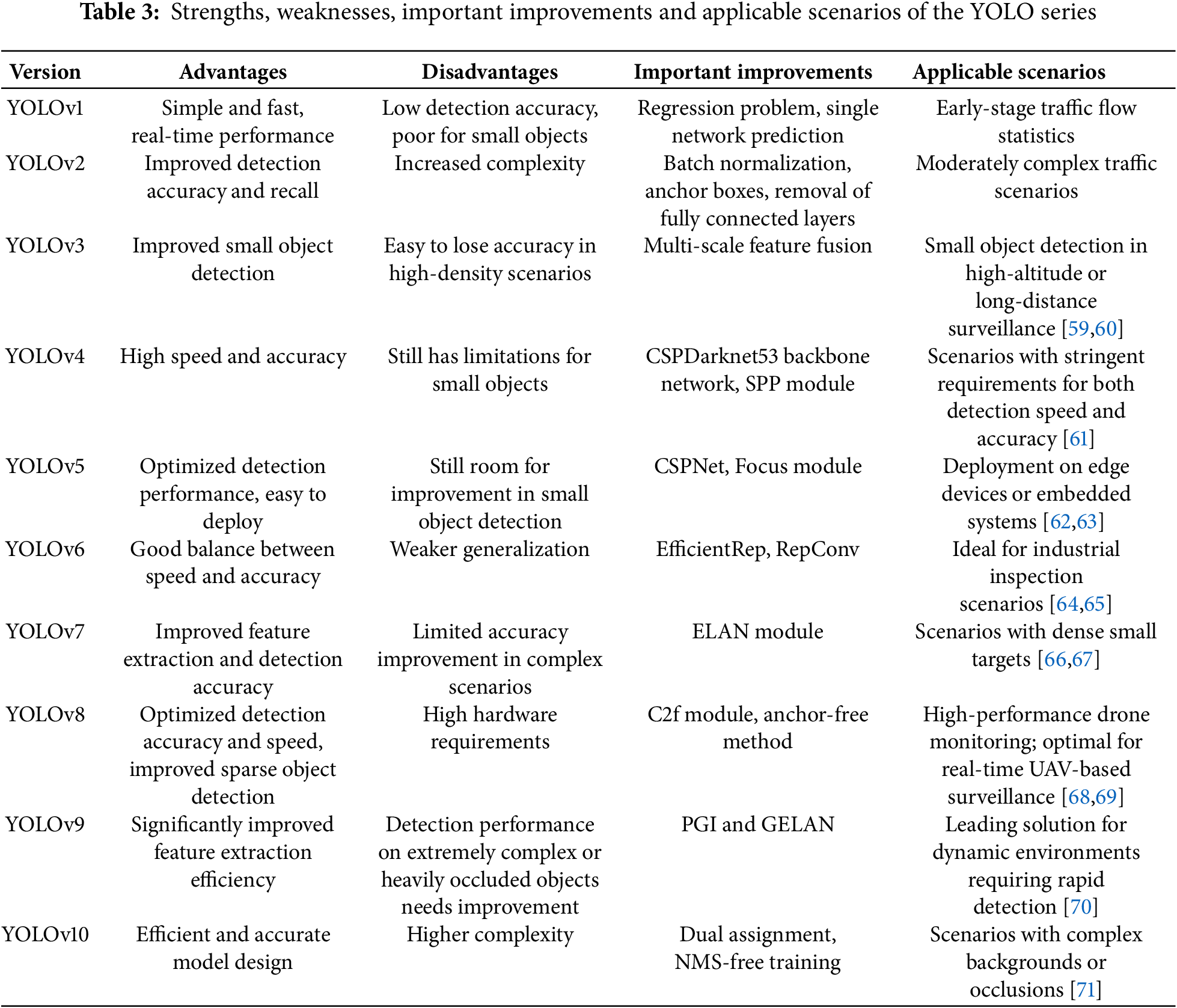

YOLO Series: The YOLO series, first introduced by Joseph Redmon and Ali Farhadi in 2015, is an object detection algorithm designed to achieve real-time object detection with just one forward pass. The fundamental concept of YOLO involves dividing the entire image into numerous grids, where each grid predicts multiple bounding boxes along with their respective confidence scores and class probabilities. It has the advantage of real-time processing capabilities and efficient network structure, making it suitable for real-time applications. Their advantages, disadvantages, key improvements and Applicable Scenarios are shown in Table 3. YOLOv1 converted the task of object detection into a regression challenge, using a single neural network to directly predict bounding boxes and classes. While it had fast speeds, it faced certain limitations in detecting small objects and maintaining accuracy. To address these issues, YOLOv2 [44] introduced Batch Normalization [45], Anchor Boxes, and Dimension Clusters in 2016, removing the fully connected layers and using Anchor Boxes for bounding box prediction, improving detection accuracy and recall rates. In 2018, YOLOv3 [46] was introduced, which adopted multi-scale feature fusion to further enhance small object detection. YOLOv4 [47] came out in 2020, introducing the Cross Stage Partial Darknet-53 (CSPDarknet53) backbone [48] and Spatial Pyramid Pooling (SPP) module [41], significantly improving detection accuracy while maintaining high speeds. Later that year, YOLOv5 [49] followed, implementing automated anchor box generation to optimize anchor box sizes and ratios based on training data, enhancing detection accuracy. YOLOv5 also introduced the Focus module and used the Complete Intersection over Union (CIOU) loss function [50], further optimizing detection performance. These improvements made YOLOv5 a widely used object detection algorithm. In 2022, YOLOv6 [51] was developed, building on YOLOv5 by introducing the EfficientRep architecture and RepConv [52] technology, further optimizing the model’s computational efficiency. YOLOv7 [53] was released later that same year, incorporating the Efficient Layer Aggregation Network (ELAN) module [54] to augment the capability for feature extraction and detection accuracy. YOLOv8 [55], introduced in 2023, included the C2f module, effectively improving feature extraction efficiency and accuracy. Additionally, YOLOv8 removed the anchor box mechanism and adopted an anchor-free method, optimizing detection accuracy and speed while improving the detection of sparse objects. A year later, in 2024, YOLOv9 [56] was introduced, significantly enhancing feature extraction efficiency and overall model performance by incorporating Programmable Gradient Information (PGI) and the Generalized Efficient Layer Aggregation Network (GELAN). That same year, YOLOv10 [15] achieved training without Non-Maximum Suppression (NMS) through consistent dual allocation and adopted efficient and accurate model design, greatly improving processing speed. Besides the aforementioned YOLO algorithms, YOLOX [57] stands out as another significant branch of the YOLO series. By incorporating dynamic label assignment and more efficient loss functions, YOLOX enhances detection accuracy while maintaining high speed. Additionally, the YOLO series includes several lightweight and specialized versions, such as Tiny YOLO, suitable for resource-constrained devices, and YOLOR [58], which focuses on small object detection. YOLO algorithms excel in various object detection tasks and are widely applied in intelligent transportation systems, such as vehicle detection and pedestrian detection.

SSD: SSD, as a single-stage object detection algorithm, was proposed by Liu et al. in 2016. SSD achieves efficient object detection by directly predicting bounding boxes and categories on multi-scale feature maps. Its main feature is using multi-scale feature maps for detection, allowing it to manage both large and small objects simultaneously, without the need to generate candidate regions like two-stage detection algorithms. SSD’s primary advantage is its rapid detection speed, which makes it ideal for real-time applications, while also maintaining high detection accuracy. However, because SSD relies on shallow feature maps to detect small objects, the semantic information in these shallow features is insufficient, leading to a higher miss rate when detecting small, distant vehicles or pedestrians. SSD is widely used in intelligent transportation systems, particularly in traffic monitoring and vehicle detection. Through improved SSD algorithms [72], efficient traffic flow detection and monitoring can be achieved. For example, an improved SSD algorithm combined with the Inception module [73] is used for vehicle detection in intelligent transportation systems, significantly improving detection accuracy and speed.

RetinaNet: RetinaNet is an advanced object detection model proposed by Facebook AI Research to address the issue of class imbalance. It employs a single-stage detection architecture, using ResNet [74] as the feature extraction network and utilizing a Feature Pyramid Network (FPN) [75] to handle multi-scale features. The core innovation of RetinaNet is the introduction of Focal Loss, a loss function that effectively reduces the weight of samples that are easily classified, thus focusing more on challenging samples for classification, thereby enhancing the precision of detection. Its main advantages include efficient detection speed and high precision, especially excelling in the detection of small and dense objects. However, because RetinaNet relies on FPN feature fusion for detecting dense targets, in extremely dense or complex occlusion traffic scenarios, target overlap may lead to unstable bounding box regression, thereby affecting detection accuracy.

CornerNet: CornerNet is an innovative object detection model proposed by Hei Law and Jia Deng from the University of Michigan. It determines object bounding boxes by detecting the top-left and bottom-right corner key points, discarding the traditional anchor mechanism. CornerNet uses the Hourglass network [76] to extract features, containing three output branches: heatmap for corner localization, embedding for pairing corners, and offset for correcting localization errors. It avoids the need to design complex anchor boxes, reducing hyperparameter tuning and excelling in detection accuracy and speed. However, CornerNet’s corner detection mechanism relies on the complete and accurate geometry of the target; when the target is partially occluded, it may result in missing or inaccurate corner information, thereby leading to missed detections.

CenterNet: Proposed by Xingyi Zhou et al., CenterNet aims to achieve object detection by detecting the center points of objects. Unlike traditional anchor-based methods, CenterNet adopts an anchor-free design, using heatmaps to locate the center points of objects and regression methods to predict the width and height of the objects. CenterNet simplifies the detection process by dispensing with the necessity for complex anchor design and NMS post-processing, while excelling in both detection speed and accuracy. However, CenterNet assumes that the target’s center point coincides with its geometric center. In traffic scenarios, asymmetric objects (such as tilted parked vehicles) or perspective distortion (such as top-down camera views) can break this assumption, causing center point offset, which may affect detection performance.

DETR: DETR is an end-to-end object detection model proposed by the Facebook AI Research team. It simplifies the traditional detection pipeline by considering object detection as a straightforward set prediction task, removing the necessity for manual components like NMS and anchor generation. The core of DETR is a Transformer encoder-decoder architecture, combined with a global loss function and unique prediction matching via the Hungarian algorithm. The model uses a fixed number of learned object queries, allowing it to output final predictions in parallel, leading to efficient detection. However, since DETR is based on the Transformer architecture and requires a large number of training iterations to achieve good convergence, its training time is also considerably longer.

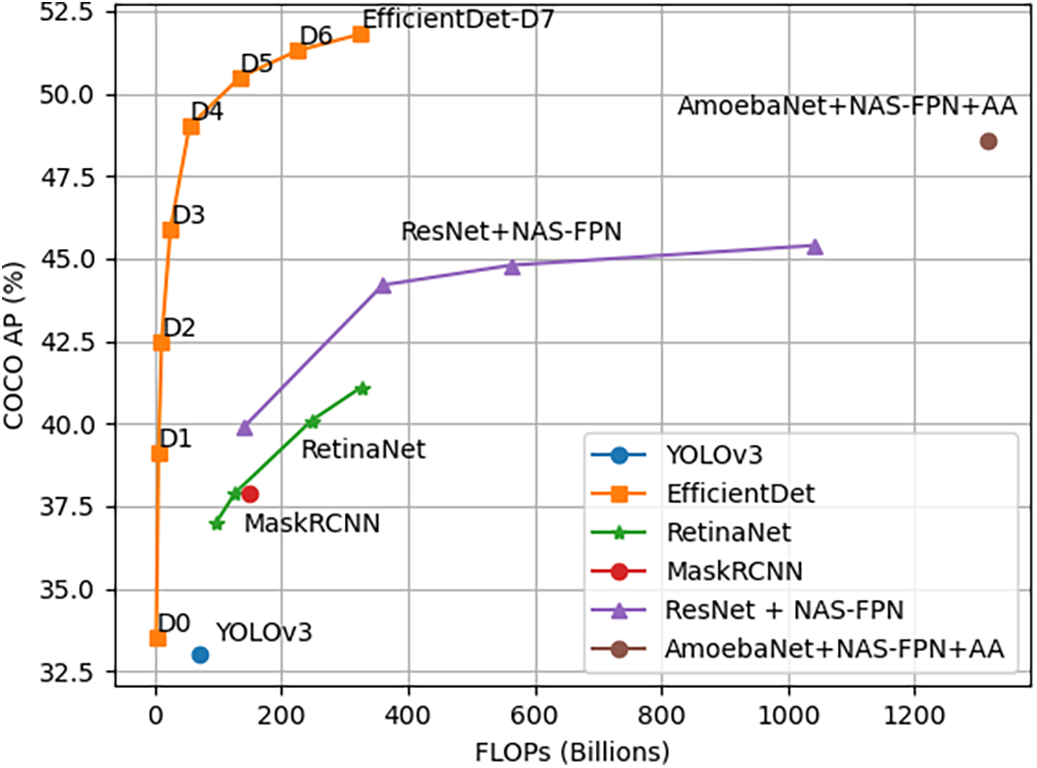

EfficientDet: EfficientDet is an efficient and scalable object detection model proposed by the Google Brain team. It employs EfficientNet as the backbone network and introduces the Bi-directional Feature Pyramid Network (BiFPN) for efficient multi-scale feature fusion. EfficientDet utilizes a compound scaling technique to consistently adjust resolution, depth, and width to maintain high performance under varying resource limitations. However, the limitation of this mechanism is that when confronted with different traffic scenarios, it may require readjusting hyperparameters to accommodate changes in target size and density, thereby reducing deployment flexibility. Lin et al. compared it with other object detection models on the COCO dataset [77]. Their experimental results, as shown in Fig. 4, demonstrate that despite having fewer model parameters and lower computational cost, it still achieves excellent detection accuracy.

Figure 4: Comparison of model FLOPs and accuracy on the COCO dataset

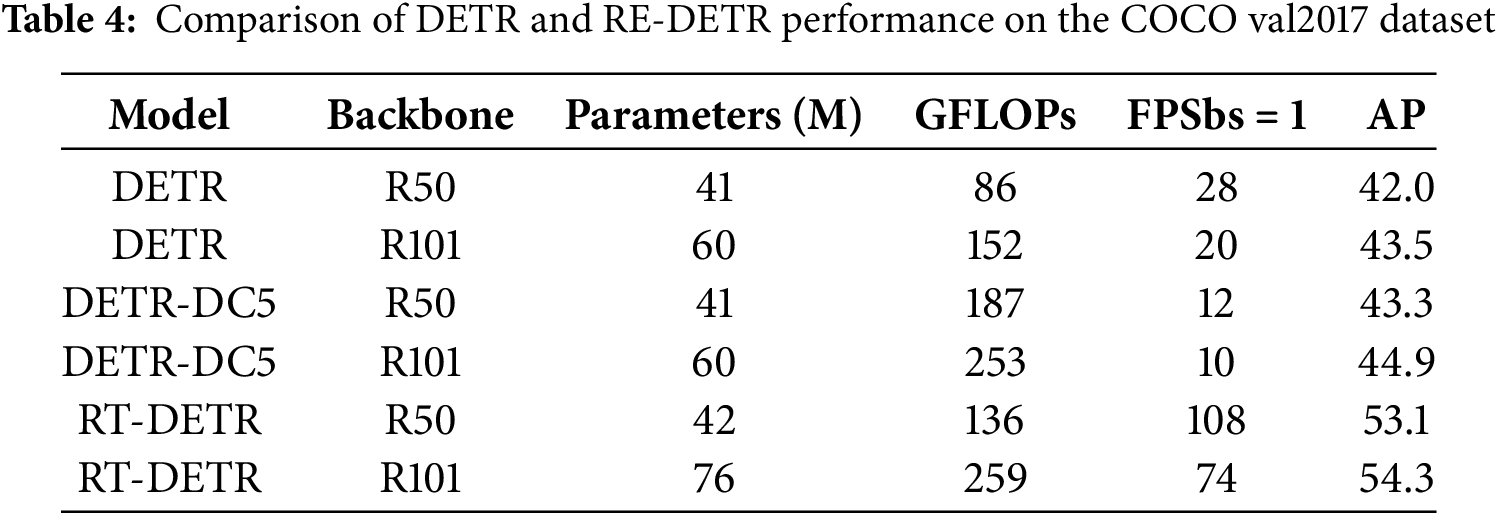

RT-DETR: RT-DETR is a model for real-time object detection proposed by the Baidu team. It combines the strengths of Transformer and DETR by using a highly efficient hybrid encoder to process features at multiple scales alongside a query selection mechanism with IoU awareness designed to refine the initialization of decoder queries. RT-DETR features an end-to-end design that eliminates traditional detection model components like anchors and NMS, thus simplifying the detection process. Its efficient design makes it excel in real-time applications, performing exceptionally well in detection speed and accuracy, surpassing all DETR models with the same backbone, as shown in Table 4.

3.2.2 Two-Stage Detection Algorithms

RCNN: RCNN is an object detection model proposed by Ross Girshick and others in 2014, marking a significant breakthrough in the realm of deep learning-based object detection. It works by segmenting an image into multiple candidate regions and leveraging CNNs to extract features and classify these regions, achieving precise object localization and recognition. The core of RCNN lies in its multi-stage processing flow: Initially, generating candidate regions through a selective search algorithm, followed by deriving convolutional features for each region, and concluding with the use of classifiers and bounding box regressors for object recognition and localization. RCNN has high detection accuracy, but it requires individual feature extraction for every candidate region, leading to high computational costs and slower processing speeds.

SPPNet: SPPNet is an object detection model introduced by Kaiming He and others, aimed at addressing the limitation of convolutional neural networks with fixed input image sizes. SPPNet introduces a SPP layer [78] on top of the last convolutional layer, enabling the network to accommodate images of various sizes and produce fixed-size feature maps. This innovation significantly enhances the model’s flexibility and efficiency. SPPNet can perform feature extraction without altering the input image size, thus avoiding geometric distortion caused by image resizing. It notably improves the efficiency and precision of object detection, especially when dealing with multi-scale objects. However, SPPNet has some drawbacks, such as requiring feature extraction for each candidate region, leading to high computational costs.

Fast RCNN: Fast RCNN is an object detection model introduced by Ross Girshick in 2015, designed to enhance the speed and precision of RCNN. Fast RCNN generates feature maps by inputting the entire image into a convolutional neural network, then uses a Region of Interest (ROI) pooling layer on the feature maps to handle candidate regions of different sizes, thereby avoiding repeated convolution calculations for each candidate region. Its main feature is the use of a loss function for multiple tasks that simultaneously performs classification and bounding box regression, thus enhancing detection accuracy and speed. Fast RCNN significantly reduces computational load, speeds up both training and testing, while maintaining high accuracy in detection. Nevertheless, it continues to rely on to generate candidate regions, which can be slow.

Faster RCNN: Faster RCNN is an object detection model introduced by Shaoqing Ren, Kaiming He and others in 2015. It is recognized as the first near-real-time deep learning object detector. By incorporating RPN, Faster RCNN produces high-quality candidate regions on convolutional feature maps, eliminating the bottleneck of traditional methods that rely on selective search [79] for generating candidate regions. Faster RCNN integrates RPN and Fast RCNN into a unified network, utilizing shared convolutional features for region proposals and object detection. This significantly improves detection speed and accuracy, reduces computational load, and can handle multi-scale objects; however, its inference speed is still significantly lower than that of single-stage object detection models.

FPN: FPN is a network structure for object detection proposed by Tsung-Yi Lin and others in 2017. Traditional object detection methods often perform poorly when handling objects of various sizes, particularly small ones. FPN builds a feature pyramid on top of convolutional neural networks by merging high-level semantic features with low-level detailed features, thereby generating high-quality feature maps at different scales. This top-down structure featuring lateral connections allows the model to effectively handle problems in detecting objects at multiple scales without significantly increasing computational cost. This method not only boosts detection accuracy but also increases the model’s robustness in handling complex scenes. Although the lateral connections and multi-scale feature fusion of FPN enhance small object detection capabilities, detail loss issues persist for extremely small objects, and the pyramid structure increases memory usage.

Cascade R-CNN: Cascade R-CNN is a multi-stage object detection model introduced by Zhaowei Cai and Nuno Vasconcelos in 2018. It trains a sequence of detectors with progressively higher IoU thresholds, making each stage more selective than the previous one, thereby reducing false detections. In the multi-stage architecture of Cascade R-CNN, each stage’s detector is trained using the output of the previous stage. This progressive optimization method significantly improves detection accuracy, excelling in challenging environments and high-quality detection tasks. However, Cascade R-CNN demands more computational resources and extended durations for training.

Dynamic R-CNN: Dynamic R-CNN [80] is an object detection model proposed by Hongkai Zhang and others in 2020, aimed at improving detection accuracy through dynamically adjusting the label allocation and regression loss function during training. The core idea is to dynamically adjust the IoU threshold and the parameters of the Smooth L1 loss function based on the statistical information of the candidate regions, thereby better adapting to samples of varying quality. The dynamic design of Dynamic R-CNN allows the model to more effectively utilize training samples, enhancing the detection accuracy of high-quality samples. It significantly improves detection performance without adding extra computational overhead, especially excelling in high-quality object detection tasks. However, its implementation is complex, requiring more tuning and optimization during the training process.

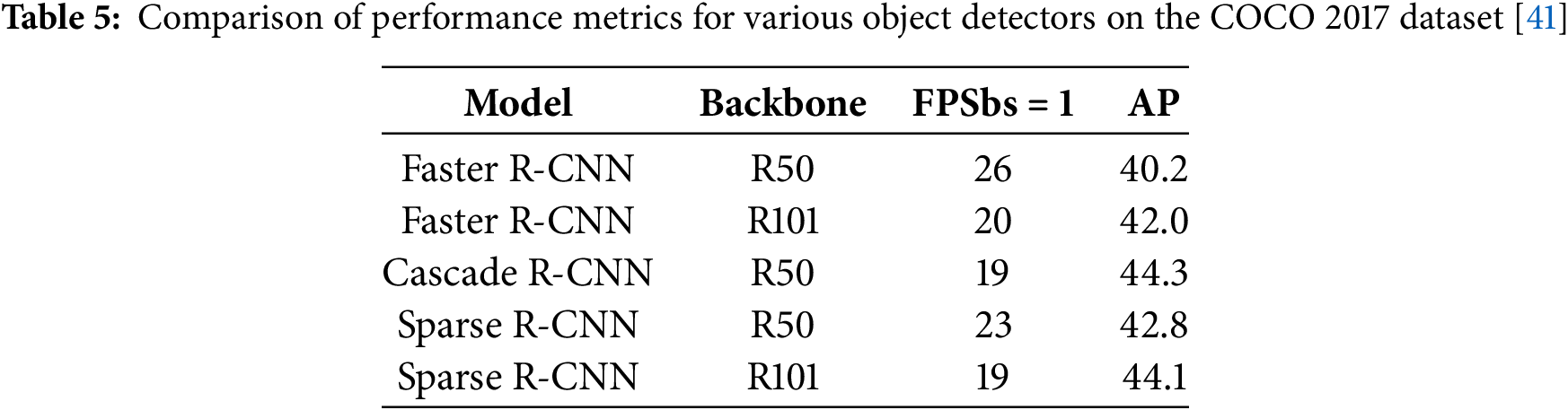

Sparse R-CNN: Sparse R-CNN [81] is an object detection model proposed by Peize Sun and others in 2020, aimed at simplifying the detection process using sparse learnable proposals. Unlike traditional dense candidate region methods, Sparse R-CNN utilizes a set quantity of learnable proposals for object detection, avoiding numerous manually designed candidate regions and complex label assignment processes. It employs sparse object candidates and sparse feature interactions, significantly reducing computational load and simplifying the detection pipeline, thereby improving training and inference efficiency. Sparse R-CNN performs exceptionally well on the COCO dataset, as shown in Table 5. However, in high-density traffic scenarios (such as congested intersections), Sparse R-CNN employs a fixed number of proposals, while the number of targets often exceeds this limit, potentially leading to some targets being missed due to lack of proposal coverage.

4 Application of Object Detection Technology in IoT-Based Intelligent Transportation Systems

Object detection technology can identify vehicles, pedestrians, and traffic signs from images and data collected by cameras, radar, and other sensors, providing accurate information to support traffic management and decision-making. This not only helps to enhance the efficiency of traffic flow management and minimize traffic accidents but also facilitates the further development of autonomous driving and intelligent traffic control systems. In intelligent transportation systems, object detection technology has shown great potential and value, driving the continuous advancement of transportation systems.

Vehicle detection is a technology that applies object detection techniques to automatically detect and pinpoint the location of vehicles in images or videos. In simple terms, it uses high-tech methods to “see” vehicles, helping us to identify and locate them. Vehicle detection is pivotal for the effective functioning of intelligent transportation systems, significantly enhancing traffic management efficiency and safety. It serves for real-time traffic flow monitoring, detecting traffic violations, and assisting autonomous driving. Vehicle detection systems need to be highly accurate, real-time, robust, and adaptable to cope with complex and varying traffic scenarios, while also being cost-effective.

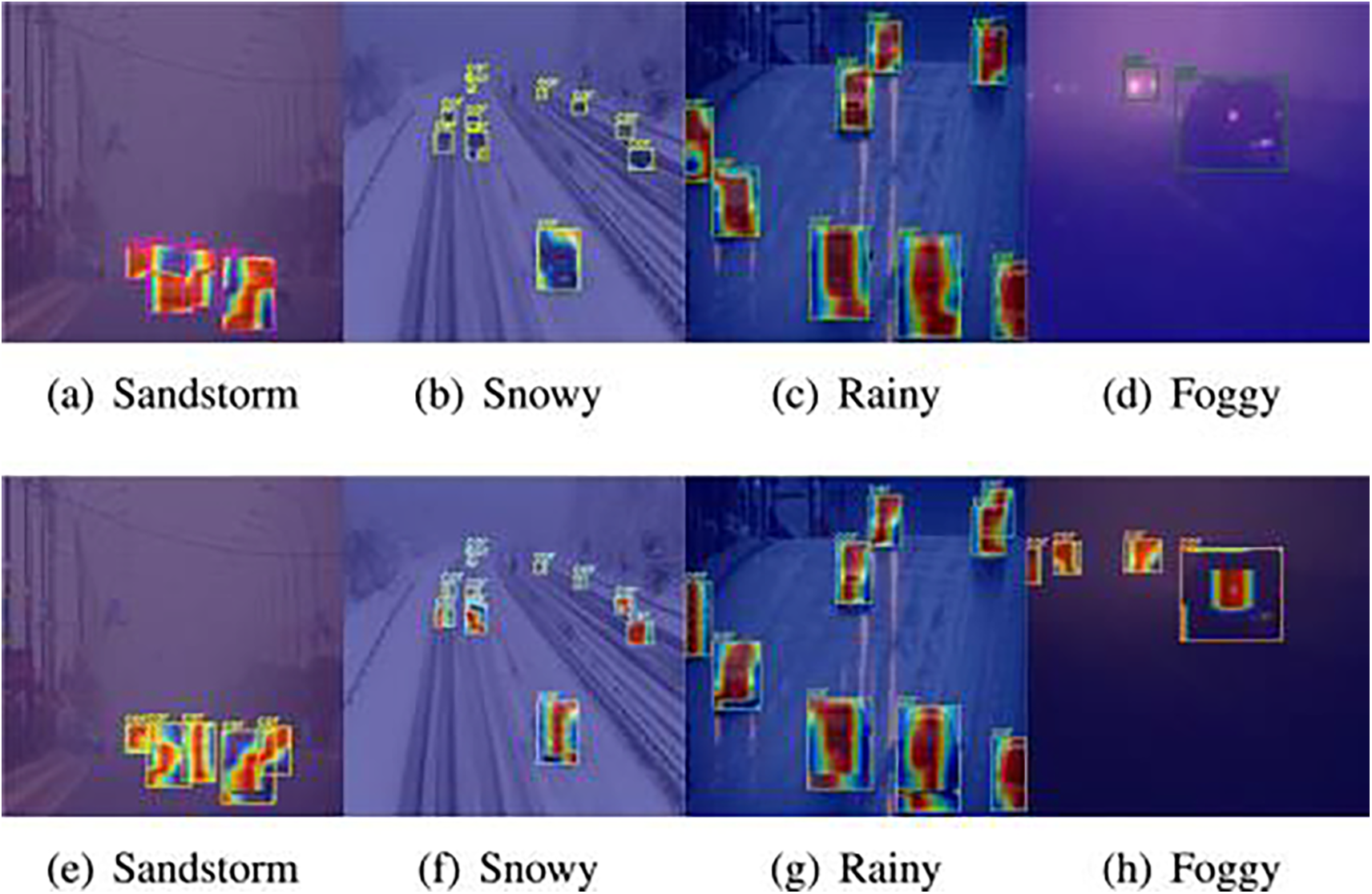

A comparative study by Shokri et al. [82] evaluated state-of-the-art deep learning object detection algorithms for vehicle detection, such as SSD, RCNN, and various versions of YOLO. The findings indicate that YOLO models, especially YOLOv7, excel in detection and localization accuracy, providing the highest classification precision compared to other algorithms. As a real-time object detection algorithm, YOLO has gained widespread use in vehicle detection because of its excellent detection speed and high detection accuracy. For example, Zhang et al. [83] proposed an enhanced YOLOv5 network-based method for vehicle detection, utilizing the Flip-Mosaic algorithm to boost the ability to detect and recognize small objects and reduce false detection rates caused by occlusion, thereby improving detection accuracy. Additionally, they developed a comprehensive dataset that accommodates various types of vehicles and is suitable for various weather conditions and scenes, enriching vehicle detection data. Kang et al. [84] introduced Type-1 Fuzzy Attention (T1FA) to mitigate the effects of variabilities in practical environments, including changes in lighting, blurring due to movement, occlusion, and weather factors, thereby improving the precision and immediacy of vehicle detection. The introduction of fuzzy entropy for reweighting feature maps helps to reduce feature map uncertainty, allowing the detector to concentrate on the target’s center, thereby significantly enhancing vehicle detection accuracy. To demonstrate the effectiveness of T1FA, Li et al. conducted experiments on the DAWN dataset [85]. Their results, as shown in Fig. 5, indicate that T1FA can enhance the network’s attention to the target. They integrated this attention mechanism into YOLO, combined with MDFormer and Rep-ELAN to enhance feature extraction capabilities, constructing a new vehicle detection model leveraging fuzzy attention, named YOLO-FA. This model reached an AP of 50.3% and an AP50 of 70.0% on UA-DETRAC [86], balancing speed and accuracy better than other detectors. To mitigate the problems of false positives for distant vehicles and missed small targets in traffic scenarios, Liu et al. [87] introduced the Coordinate Attention module [88] and adaptive feature fusion module [89] into the YOLOX model. Through model pruning operations to decrease the quantity of model parameters, they proposed an enhanced YOLOX_S detection model. Hong et al. [90] proposed a new feature pyramid based on an encoder-decoder structure, including feature concatenation, encoder-decoder, and feature fusion, which they integrated into the YOLOv3 model. This method achieved good detection results for vehicles of various sizes, especially for small targets. Liu et al. [91] combined Dynamic Snake Convolution, Context Aggregation Attention Mechanism and Wise-IoU strategies into YOLOv8, developing the YOLOv8-SnakeVision model. This model significantly boosts the precision of small object detection while also enhancing the ability to identify multiple targets. It performs exceptionally well in various complex and challenging road traffic scenarios.

Figure 5: Visualization of T1FA under adverse weather conditions. (a–d) show YOLO-FA’s visualization excluding T1FA, and (e–h) show the enhancements brought by T1FA improvements, which can be visually observed [84] Reprinted with permission from reference [84]. 2024, Elsevier

Besides the YOLO series, other algorithms are also crucial for vehicle detection. For example, Zhang et al. [92] proposed a new vehicle detection framework, DP-SSD. This framework uses different feature extractors for localization and classification tasks, respectively, boosting the capabilities of the traditional SSD. This framework effectively enables real-time detection of various types of vehicles. Wang et al. [93] made advancements to the structure of the SSD object detection network and introduced an innovative detection network named AP-SSD. This network substitutes the shallow convolutional kernel set with a multi-scale, multi-form, color optimal feature extraction Gabor convolutional [94] kernel set, acquired by training and selection. Incorporated with Convolutional Long Short-Term Memory Networks (ConvLSTM) [95], it refines and propagates features between frames through a Bottle Neck-LSTM layer, achieving efficient tracking and recognition of video objects. Additionally, a dynamic region enlargement network is introduced to enhance the precision of identifying tiny targets in images with decreased resolution. Zhang et al. [96] introduced a modified RetinaNet to improve vehicle detection performance. They incorporated an octave convolution structure and a weighted feature pyramid network (WFPN) [97] structure. This model replaces traditional convolution layers with octave convolutions to better represent detailed information in feature maps. The WFPN structure restricts gradient propagation between different levels, enhancing feature fusion quality. This approach enhances detection precision for challenging data while demonstrating advantages in handling low-resolution issues, effectively detecting vehicle targets of different scales in various scenarios. In addition, references [98–100] and others also introduced several different vehicle detection models.

Despite improvements in vehicle detection performance achieved through algorithmic optimization in the aforementioned studies, robustness under extreme weather and dynamic scenarios still requires further enhancement. Moreover, some model refinements that boost precision by incorporating additional modules come at the expense of computational efficiency, which is detrimental to real-time deployment on edge devices.

Pedestrian detection technology leverages object detection methods to autonomously recognize and pinpoint pedestrians in images or videos. Simply put, it allows computers to “see” and find pedestrians through cameras or sensors. Pedestrian detection plays a vital role in intelligent transportation systems, helping to improve traffic safety, avoid accidents, and assist autonomous vehicles in making correct decisions in complex environments. Pedestrians are the most vulnerable elements in intelligent transportation systems, so ensuring their safety is a key goal. Therefore, pedestrian detection systems need to be accurate, responsive, and able to operate stably in various weather and lighting conditions while consuming minimal resources. This ensures timely and accurate pedestrian detection, enabling efficient system operation.

In pedestrian detection, the usage of the YOLO series and Faster R-CNN is the most widespread. YOLO algorithms are popular for their speed, capability to recognize multiple objects simultaneously, and ease of integration with other systems. Faster R-CNN is widely used because of its high accuracy and ability to handle complex scenes, although it is slightly slower. Its robustness and effectiveness make it favored in many applications. For example, Li et al. [101] proposed a new Scale-Aware Faster R-CNN (SAF R-CNN) model, combining large-scale and small-scale sub-networks into a unified architecture to handle different sizes of pedestrian instances, achieving top performance on several challenging benchmarks. Lan et al. [102] introduced a novel framework named YOLO-R by refining the architecture of the YOLO algorithm. This model effectively improves pedestrian detection accuracy while reducing false detection and miss detection rates, and also performs well in detection speed.

Pedestrian detection is categorized into single-spectrum and multi-spectrum detection based on the spectral range used in datasets.

Single-spectrum pedestrian detection uses image data from a single spectral range, such as visible light images, to identify and locate pedestrians by analyzing features within that spectrum. This method typically requires only one type of sensor (e.g., a regular camera), making it cost-effective. Consequently, most existing pedestrian detection methods fall under single-spectrum detection. However, its performance deteriorates in dim lighting or unfavorable weather conditions and often suffers from false positives and missed detections in complex backgrounds. To address these issues, Wu et al. [103] proposed a Tube Feature Aggregation Network (TFAN), which enhances the detection of pedestrians who are partially obstructed by leveraging local spatial and temporal contexts. Specifically, it identifies clear images of pedestrians in other frames along the time axis and combines these features, allowing for more accurate detection even when pedestrians are occluded in the current frame. Lin et al. [104] introduced an Example-Guided Contrastive Learning (EGCL) model for pedestrian detection. EGCL employs contrastive learning to map the original feature space to a new one, minimizing the semantic gap between pedestrians and thereby reducing their diversity in looks. At the same time, it enhances the semantic distinction between pedestrians and their background, improving detector performance in nighttime scenes. Yao et al. [105] proposed the Foreground-Background Contrast Attention (FBCA) mechanism. This adaptive system enhances the contrast between pedestrian features under dim lighting conditions and background data within the network, directing the model’s attention to the lost details and pedestrian features with low contrast in low-illumination nighttime environments, thereby enhancing nighttime pedestrian detection performance. In addition, Refs. [106–108] and others have also introduced a series of single-spectrum pedestrian detection models. However, despite the aforementioned optimizations in single-spectrum pedestrian detection that have partially improved performance under low-light conditions and complex backgrounds, the inherent reliance on single-modal physical information continues to result in challenges in eliminating missed and false detections under extreme weather conditions. In contrast, multispectral pedestrian detection, through cross-modal feature fusion, demonstrates irreplaceable advantages in environmental adaptability and anti-interference capabilities.

Multispectral pedestrian detection combines image data from different spectra (such as visible light and infrared) to detect pedestrians through multispectral feature fusion. This method leverages information from multiple spectra to capture pedestrian features more comprehensively, addressing the unreliability of single-spectrum pedestrian detection under varying lighting conditions. However, it also comes with higher costs and complexity. In 2015, Hwang et al. [109] first introduced the concept of multispectral pedestrian detection and proposed a dataset for this purpose, as shown in Fig. 6, establishing baseline detection methods. In 2016, Liu et al. [110] introduced the Halfway Fusion model, marking the first combination of multispectral data (such as visible and infrared) with Faster R-CNN for pedestrian detection. This marked the beginning of rapid development in multispectral pedestrian detection, leading to numerous significant achievements. For instance, Guan et al. [111] proposed a method using illumination-aware deep neural networks for multispectral data fusion, effectively enhancing pedestrian detection accuracy and robustness under various lighting conditions. Li et al. [112] introduced an innovative Illumination-Aware Fast R-CNN (IAF R-CNN) architecture for multispectral pedestrian detection, combining the color feature network, thermal feature network, and weighted layer into an integrated network architecture. This model showed robustness to different lighting conditions and performed exceptionally well on the challenging KAIST dataset [113]. Xing et al. [114] proposed the Multi-Spectral Pedestrian Detection Transformer (MS-DETR) model, addressing the crucial issues of misalignment and modality imbalance due to the presence of dual modalities in multispectral pedestrian detection.

Figure 6: Examples from the multispectral pedestrian dataset KAIST. (a,c): Visible light images; (b,d): Infrared images

Traffic sign detection is a technology that applies object detection techniques to automatically identify and read road traffic signs. Simply put, it allows computers to “see” and read various traffic signs on the road, such as speed limit signs, stop signs, etc., through cameras or sensors. This enables vehicles to promptly acquire this information and react accordingly, helping drivers adhere to traffic regulations and enhance driving safety.

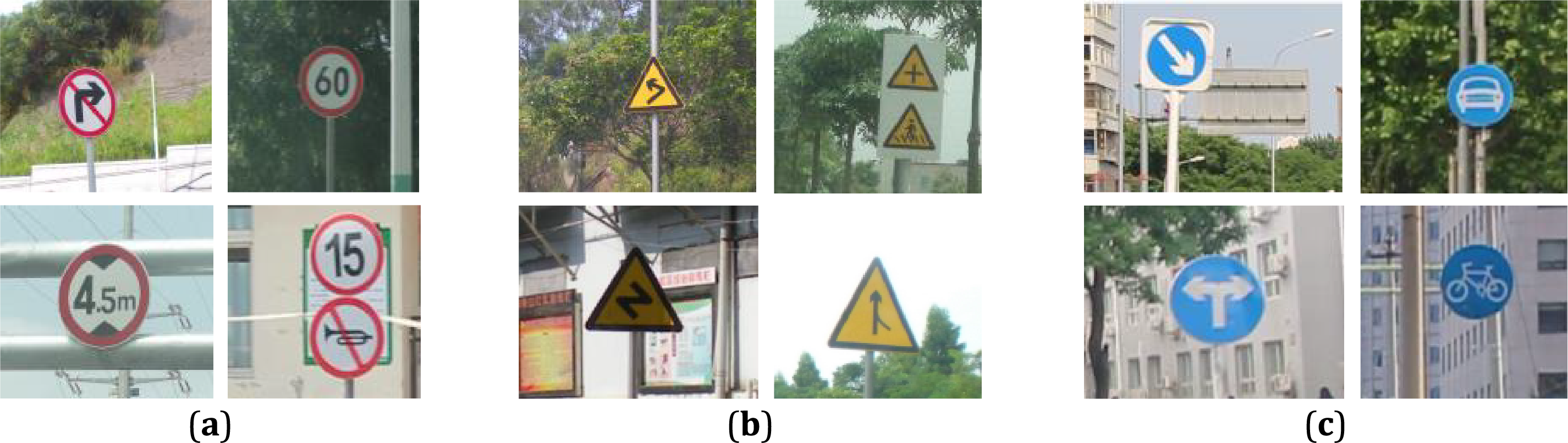

Traditional traffic sign detection methods primarily include color and shape-based matching techniques. As shown in Fig. 7, since traffic signs usually have specific colors and shapes, these methods work well in simple environments. For example, red stop signs and circular speed limit signs can be easily detected through color segmentation and shape matching. However, their performance declines significantly in complex backgrounds and varying lighting conditions, leading to missed detections and false positives. With advancements in object detection technology, researchers began using feature extraction methods and machine learning algorithms for traffic sign detection. For instance, methods like Scale-Invariant Feature Transform (SIFT) [115] and HOG [116] combined with classifiers such as Support Vector Machine improved detection performance to some extent. However, hand-crafted features still lacked robustness in diverse traffic signs and complex backgrounds. Recently, deep learning has made significant strides in traffic sign detection. As a crucial model in deep learning, CNNs extract multi-level features through multiple convolutional and pooling layers, achieving high-accuracy traffic sign detection.

Figure 7: Several common road traffic signs. (a) Prohibitory signs; (b) Warning signs; (c) Instruction signs

As a real-time object detection algorithm, the YOLO algorithm can detect multiple targets simultaneously in a single neural network inference, making it outstanding in traffic sign detection with real-time and high-accuracy capabilities. For example, Yu et al. [117] proposed a model based on a fusion of YOLOv3 and Visual Geometry Group (VGG)19 networks, leveraging relationships among multiple images to swiftly and precisely detect and identify traffic signs within driving video sequences. Nevertheless, training YOLOv3 and VGG19 networks demands a considerable amount of time. Chu et al. [118] proposed TRD-YOLO, an innovative model designed for detecting small traffic signs in intricate settings, enhancing the accuracy of small traffic sign detection in such scenarios. Huang et al. [119] proposed an improved YOLOv8 algorithm aimed at addressing issues of missed detections and low detection rates in traffic sign detection. By using data augmentation methods in specific scenarios, they increased data diversity, allowing the network to learn effective features better. Additionally, applying the asymptotic feature pyramid network (AFPN) to feature fusion also enhanced detection performance. In addition, Refs. [120–122] and others have also introduced various traffic sign detection models. These deep learning-based enhanced models employ end-to-end feature learning and multi-scale optimization strategies to not only effectively mitigate the sensitivity of traditional color/shape-based methods to illumination variations and background interference, but also to significantly enhance the robustness of handcrafted features in complex environments. Nevertheless, certain models still exhibit room for improvement in terms of complexity and computational cost, which must be addressed to facilitate more efficient embedded deployment.

In recent years, object detection technologies have made remarkable progress, significantly enhancing the safety and operational efficiency of intelligent transportation systems. However, it still faces several challenges in practical applications: Firstly, complex environments demand higher robustness from models; factors such as variations in illumination, object occlusion, adverse weather conditions (e.g., rain, snow, fog), and dynamic backgrounds (e.g., moving crowds and vehicles) can interfere with feature extraction, reducing detection accuracy. Additionally, adversarial attacks, through subtle perturbations or specific noise, may deceive object detection models, resulting in misclassification and threatening system security. Secondly, the computational capacity, storage, and energy constraints of edge computing devices pose difficulties for deploying high-precision models. These challenges require a balance between model complexity and performance to meet the demands for low power consumption and real-time processing. Meanwhile, the cost of data annotation is another significant concern. In intelligent transportation, training models with strong generalization often necessitates diverse datasets, encompassing various scenarios. This incurs substantial human and time resources, leading to rapidly escalating annotation costs. Reducing these costs remains a pressing issue. Lastly, data privacy is critically important, as object detection systems process sensitive information such as license plates and facial features. Misuse or leakage of this data can result in legal risks, necessitating strict adherence to privacy protection regulations during data collection, transmission, and storage, in order to strike a balance between technological advancement and personal privacy.

In the future, object detection in IoT-based intelligent transportation systems can address the above challenges and conduct in-depth research and improvements in multiple directions:

1. Utilizing Multi-Sensor Data Fusion to Enhance Detection Accuracy and Robustness: To address the impact of complex environments on detection accuracy, research on multi-sensor data fusion can be undertaken. By integrating data from various sensors such as cameras, radar, Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR), and infrared sensors, more comprehensive and enriched environmental perception information can be obtained. Multi-sensor data fusion can combine the advantages of different sensors, compensating for the limitations of individual sensors under specific conditions. For example, in situations with insufficient lighting or occlusions, data from radar and infrared sensors can effectively supplement deficiencies in visual information, thereby enhancing the model’s robustness in complex environments. At the same time, multi-source data fusion can also help to defend against adversarial attacks. Since attackers find it difficult to simultaneously apply effective adversarial perturbations to multiple sensors, fusing data from multiple sensors can enhance the system’s ability to detect and defend against attacks. Furthermore, researching more advanced fusion algorithms can further improve detection performance, such as spatiotemporal feature fusion of sensor data. This approach aims to effectively integrate data from multiple heterogeneous sensors, fully utilizing information in both spatial and temporal dimensions. By extracting deeper feature representations, the model’s sensitivity to environmental changes and target recognition capabilities are enhanced, achieving higher detection accuracy and reliability in complex traffic scenarios.

2. Utilizing Self-Supervised Learning and Semi-Supervised Learning to Reduce Data Annotation Costs: To solve the problem of high data annotation costs, self-supervised learning and semi-supervised learning methods can be introduced. These methods utilize large amounts of unlabeled data by designing pre-training tasks or leveraging the inherent structure of the data, thus reducing reliance on manual annotation. For example, by using the temporal continuity of video data, tasks such as predicting future frames can be designed to learn the motion characteristics of targets. Through these methods, it’s possible to reduce manual annotation efforts while fully exploiting the value of vast amounts of unlabeled data. This enhances the model’s performance and generalization ability, providing an effective solution for constructing high-performance object detection models under limited data annotation resources.

3. Enhancing Real-Time Performance and Computational Efficiency Through Intelligent Edge Computing and Model Optimization: In response to the limitations of edge computing and the demand for real-time performance, efficient object detection models can be deployed on edge devices. By leveraging intelligent edge computing, part of the computational tasks is offloaded to devices closer to the data source, reducing data transmission latency and achieving rapid response. This approach effectively utilizes the computational capabilities of edge devices, improving the overall system efficiency. To achieve this, in-depth research on model compression and optimization techniques is necessary. Through methods such as model pruning, quantization, and knowledge distillation, the model’s size and computational load can be reduced while ensuring accuracy, making it suitable for running on resource-constrained edge devices. Additionally, optimizing the algorithmic structure and computational processes—such as designing lightweight network architectures and adopting efficient convolutional computation methods—can further improve the model’s inference speed and computational efficiency.

4. Protecting Data Privacy Using Federated Learning and Differential Privacy: Addressing data privacy concerns requires the adoption of advanced technologies like federated learning and differential privacy to safeguard personal information. Federated learning is a distributed machine learning framework that allows models to be trained on local devices. Each device shares only model parameters or gradient updates without transmitting raw data, effectively protecting user privacy. In intelligent transportation systems, various devices (such as vehicle terminals, roadside cameras, intelligent traffic signal lights, etc.) can collaboratively participate in model training. By using federated learning to jointly update a shared model, overall object detection performance is enhanced while avoiding the risks associated with centralized storage and transmission of sensitive data. Differential privacy works by introducing controlled random noise into data or gradients, limiting the impact of any single data point on the model output. This prevents attackers from reverse-engineering personal sensitive information from the model. Even during the process of model parameter sharing, data analysis and model training comply with privacy protection regulations, ensuring the security and compliance of personal information.

In conclusion, the practical application of object detection technologies faces not only technical challenges but also environmental constraints, economic factors, and ethical considerations. Future research can focus on enhancing robustness in complex environments, improving real-time performance and computational efficiency, reducing data annotation costs, and strengthening data privacy protection to further advance the development of object detection technologies in intelligent transportation systems.

This paper employs the PRISMA approach to search, screen, and assess eligibility in studies indexed in IEEE Xplore, ScienceDirect, and other databases, ultimately including 88 studies from various journals and conferences for a review of object detection technologies in IoT-based intelligent transportation systems. It comprehensively outlines the evolution of object detection technologies from traditional methods to deep learning stages, while also exploring their widespread applications in the intelligent transportation domain.

Addressing the first research question, the study examines the core design and workflows of object detection algorithms during the traditional methods stage, analyzing their distinctive features while highlighting their drawbacks, such as high computational complexity and poor robustness when faced with complex backgrounds and diverse targets. This analysis aids in comprehending the foundational progress of object detection technologies and offers historical context for subsequent advancements.

For the second research question, this study reviews the development trajectory of object detection algorithms during the deep learning phase, exploring them from the perspectives of single-stage detection algorithms and two-stage detection algorithms. It analyzes the distinctive mechanisms and key characteristics of these two types of algorithms, highlighting the efficiency advantage of single-stage models in real-time scenarios and the superior accuracy of two-stage models. At the same time, their respective limitations are identified. Through these explorations, the study provides clear guidance for selecting algorithms to meet different application needs and offers valuable insights for future optimization and improvement of technologies.

Finally, through concrete application examples, the third research question is addressed by showcasing the practical roles of object detection technologies in vehicle detection, pedestrian detection, and traffic sign recognition. The study highlights the significance of these technologies in intelligent transportation systems, while also revealing challenges encountered in real-world deployments. These findings lay a solid foundation for steering future research directions and overcoming existing limitations.

In conclusion, the development of object detection technologies has made vital contributions to enhancing the safety and efficiency of intelligent transportation systems. Despite ongoing challenges in practical applications, continuous research and innovation have paved the way for promising solutions. As emerging technologies evolve further, intelligent transportation systems are expected to advance towards greater efficiency, safety, and intelligence, delivering more benefits and convenience to society.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Jiaqi Wang; draft manuscript preparation: Jiaqi Wang; review: Jian Su. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/cmc.2025.064309/s1.

References

1. Our World in Data. Deaths from road injuries, 2000 to 2021 [Internet]. Oxford, UK: Global Change Data Lab; 2024 [cited 2024 Oct 22]. Available from: https://ourworldindata.org/explorers/global-health?tab=table&showSelectionOnlyInTable=1&country=OWID_ASI~OWID_AFR~OWID_EUR~OWID_NAM~OWID_SAM~OWID_WRL&pickerSort=asc&pickerMetric=entityName&Health+Area=Injuries&Indicator=Road+injuries&Metric=Number+of+deaths&Source=WHO+%28GHE%29. [Google Scholar]

2. Dargay J, Gately D, Sommer M. Vehicle ownership and income growth, worldwide: 1960–2030. Energy J. 2007;28(4):143–70. doi:10.5547/ISSN0195-6574-EJ-Vol28-No4-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. OICA. Total world vehicles in use 2020 [Internet]. [cited 2024 Oct 22]. Available from: https://www.oica.net/wp-content/uploads/Total-World-vehicles-in-use-2020.pdf. [Google Scholar]

4. Pyykönen P, Laitinen J, Viitanen J, Eloranta P, Korhonen T. IoT for intelligent traffic system. In: Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE 9th International Conference on Intelligent Computer Communication and Processing (ICCP); 2013 Sep 5–7; Cluj-Napoca, Romania. New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2013. p. 175–9. doi:10.1109/ICCP.2013.6646104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Oladimeji D, Gupta K, Kose NA, Gundogan K, Ge L, Liang F. Smart transportation: an overview of technologies and applications. Sensors. 2023;23(8):3880. doi:10.3390/s23083880. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Nassreddine G, El Arid A, Nassereddine M. Internet of things in intelligent transportation systems. In: Pal S, Savaglio C, Minerva R, Delicato FC, editors. IoT edge intelligence. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2024. p. 291–314. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-58388-9_10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Sharma N, Garg RD. Real-time computer vision for transportation safety using deep learning and IoT. In: Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Engineering and Emerging Technologies (ICEET); 2022 Oct 27–28; New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2022. p. 1–5. doi:10.1109/ICEET56468.2022.10007226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Ahmed I, Jeon G, Chehri A. A smart iot enabled end-to-end 3D object detection system for autonomous vehicles. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2023;24(11):13078–87. doi:10.1109/TITS.2022.3210490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Ghahremannezhad H, Shi H, Liu C. Object detection in traffic videos: a survey. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2023;24(7):6780–99. doi:10.1109/TITS.2023.3258683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Viola P, Jones M. Robust real-time face detection. In: Proceedings of the Eighth IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision. ICCV 2001; 2001 Jul 7–14; Vancouver, BC, Canada. New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2001. 747 p. doi:10.1109/ICCV.2001.937709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Dalal N, Triggs B. Histograms of oriented gradients for human detection. In: Proceedings of the 2005 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR’05); 2005 Jun 20–25; San Diego, CA, USA. New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2005. p. 886–93. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2005.177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Felzenszwalb P, McAllester D, Ramanan D. A discriminatively trained, multiscale, deformable part model. In: Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2008 Jun 23–8; Anchorage, AK, USA. New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2008. p. 1–8. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2008.4587597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Girshick R, Donahue J, Darrell T, Malik J. Region-based convolutional networks for accurate object detection and segmentation. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2016;38(1):142–58. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2015.2437384. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Redmon J, Divvala S, Girshick R, Farhadi A. You only look once: unified, real-time object detection. In: Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2016. p. 779–88. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2016.91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Wang A, Chen H, Liu L, Chen K, Lin Z, Han J, et al. YOLOv10: real-time end-to-end object detection. arXiv: 2405.14458. 2024. [Google Scholar]

16. Dodia A, Kumar S. A comparison of YOLO based vehicle detection algorithms. In: Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Applications (ICAIA) Alliance Technology Conference (ATCON-1); 2023 Apr 21–22; Bangalore, India. New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2023. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/ICAIA57370.2023.10169773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Segu GSPK, Sivannarayana ADSN, Ramesh S. Real time road lane detection and vehicle detection on YOLOv8 with interactive deployment. In: Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 16th International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Communication Networks (CICN); 2024 Dec 22–23; Indore, India. New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 267–72. doi:10.1109/CICN63059.2024.10847549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Bakirci M, Dmytrovych P, Bayraktar I, Anatoliyovych O. Challenges and advances in UAV-based vehicle detection using YOLOv9 and YOLOv10. In: Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 7th International Conference on Actual Problems of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles Development (APUAVD); 2024 Oct 22–24; Kyiv, Ukraine. New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 317–21. doi:10.1109/APUAVD64488.2024.10765874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Dixit IA, Bhoite S. Analysis of performance of YOLOv8 algorithm for pedestrian detection. In: Proceedings of the 2024 9th International Conference on Communication and Electronics Systems (ICCES); 2024 Dec 16–18; Coimbatore, India. New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 1918–24. doi:10.1109/ICCES63552.2024.10859981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Srivastava A, Badal T, Goyal A, Naik A. An efficient approach for pedestrian detection. In: Proceedings of the 2024 15th International Conference on Computing Communication and Networking Technologies (ICCCNT); 2024 Jun 24–8; Kamand, India. New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/ICCCNT61001.2024.10724548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Carion N, Massa F, Synnaeve G, Usunier N, Kirillov A, Zagoruyko S. End-to-end object detection with transformers. In: Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ECCV 2020: 16th European Conference; 2020 Aug 23–28; Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2020. p. 213–29. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-58452-8_13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Zhao Y, Lv W, Xu S, Wei J, Wang G, Dang Q, et al. DETRs Beat YOLOs on real-time object detection. In: Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2024 Jun 16–22; Seattle, WA, USA. New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 16965–74. doi:10.1109/CVPR52733.2024.01605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Liu W, Anguelov D, Erhan D, Szegedy C, Reed S, Fu C, et al. SSD: single shot multibox detector. In: Proceedings of the Computer Vision-ECCV 2016: 14th European Conference; 2016 Oct 11–14; Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2016. p. 21–37. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-46448-0_2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Viola P, Jones M. Rapid object detection using a boosted cascade of simple features. In: Proceedings of the 2001 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. CVPR 2001; 2001 Dec 8–14; Kauai, HI, USA. New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2001. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2001.990517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Xu Y, Yu G, Wu X, Wang Y, Ma Y. An enhanced Viola-Jones vehicle detection method from unmanned aerial vehicles imagery. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2017;18(7):1845–56. doi:10.1109/TITS.2016.2617202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Chen PY, Huang CC, Lien CY, Tsai YH. An efficient hardware implementation of HOG feature extraction for human detection. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2014;15(2):656–62. doi:10.1109/TITS.2013.2284666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Nan M, Li C, Hu JC, Shang QN, Li JH, Zhang GP. Pedestrian detection based on HOG features and svm realizes vehicle-human-environment interaction. In: Proceedings of the 2019 15th International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Security (CIS); 2019 Dec 13–16; Macao, China. New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2019. p. 287–91. doi:10.1109/CIS.2019.00067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Munian Y, Martinez-Molina A, Miserlis D, Hernandez H, Alamaniotis M. Intelligent system utilizing HOG and CNN for thermal image-based detection of wild animals in nocturnal periods for vehicle safety. Appl Artif Intell. 2022;36(1):2031825. doi:10.1080/08839514.2022.2031825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Pan C, Sun M, Yan Z. The study on vehicle detection based on DPM in traffic scenes. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Frontier Computing; 2016 Jul 13–15; Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2016. p. 19–27. doi:10.1007/978-981-10-3187-8_3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Choi HJ, Lee YS, Shim DS, Lee CG, Choi KN. Effective pedestrian detection using deformable part model based on human model. Int J Control Autom Syst. 2016;14(6):1618–25. doi:10.1007/s12555-016-0322-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Bai S, Liu Z, Yao C. Classify vehicles in traffic scene images with deformable part-based models. Mach Vis Appl. 2018;29(3):393–403. doi:10.1007/s00138-017-0890-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Krizhevsky A, Sutskever I, Hinton GE. ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Commun ACM. 2017;60(6):84–90. doi:10.1145/3065386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Szegedy C, Liu W, Jia Y, Sermanet P, Reed S, Anguelov D, et al. Going deeper with convolutions. In: Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2015 Jun 7–12; Boston, MA, USA. New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2015. p. 1–9. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2015.7298594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Girshick R, Donahue J, Darrell T, Malik J. Rich feature hierarchies for accurate object detection and semantic segmentation. In: Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2014 Jun 23–28; Columbus, OH, USA. New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2014. p. 580–7. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2014.81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Girshick R. Fast R-CNN. In: Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2015 Dec 7–13; Santiago, Chile. New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2015. p. 1440–8. doi:10.1109/ICCV.2015.169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Ren S, He K, Girshick R, Sun J. Faster R-CNN: towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2017;39(6):1137–49. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2016.2577031. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Lin TY, Goyal P, Girshick R, He K, Dollár P. Focal loss for dense object detection. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2017 Oct 22–29; Venice, Italy. New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2017. p. 2999–3007. doi:10.1109/ICCV.2017.324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Law H, Deng J. CornerNet: detecting objects as paired keypoints. In: Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ECCV 2018: 15th European Conference; 2018 Sep 8–14; Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2018. p. 734–50. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-01264-9_45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Zhou X, Wang D, Krähenbühl P. Objects as points. arXiv:1904.07850. 2019. [Google Scholar]

40. Tan M, Pang R, Le QV. EfficientDet: scalable and efficient object detection. In: Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2020 Jun 13–19; Seattle, WA, USA. New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2020. p. 10778–87. doi:10.1109/CVPR42600.2020.01079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. He K, Zhang X, Ren S, Sun J. Spatial pyramid pooling in deep convolutional networks for visual recognition. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2015;37(9):1904–16. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2015.2389824. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. He K, Gkioxari G, Dollár P, Girshick R. Mask R-CNN. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2017 Oct 22–29; Venice, Italy. New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2017. p. 2980–8. doi: 10.1109/ICCV.2017.322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Cai Z, Vasconcelos N. Cascade R-CNN: high quality object detection and instance segmentation. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2021;43(5):1483–98. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2019.2956516. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Redmon J, Farhadi A. YOLO9000: better, faster, stronger. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA. New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2017. p. 6517–25. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2017.690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]