Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

An Optimization of Weak Key Attacks Based on the BGF Decoding Algorithm

Department of Cryptography Science and Technology, Beijing Electronic Science and Technology Institute, Beijing, 100070, China

* Corresponding Author: Bing Liu. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 84(3), 4583-4599. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.065296

Received 09 March 2025; Accepted 23 May 2025; Issue published 30 July 2025

Abstract

Among the four candidate algorithms in the fourth round of NIST standardization, the BIKE (Bit Flipping Key Encapsulation) scheme has a small key size and high efficiency, showing good prospects for application. However, the BIKE scheme based on QC-MDPC (Quasi Cyclic Medium Density Parity Check) codes still faces challenges such as the GJS attack and weak key attacks targeting the decoding failure rate (DFR). This paper analyzes the BGF decoding algorithm of the BIKE scheme, revealing two deep factors that lead to DFR, and proposes a weak key optimization attack method for the BGF decoding algorithm based on these two factors. The proposed method constructs a new weak key set, and experiment results eventually indicate that, considering BIKE’s parameter set targeting 128-bit security, the average decryption failure rate is lowerly bounded by . This result not only highlights a significant vulnerability in the BIKE scheme but also provides valuable insights for future improvements in its design. By addressing these weaknesses, the robustness of QC-MDPC code-based cryptographic systems can be enhanced, paving the way for more secure post-quantum cryptographic solutions.Keywords

With the rise of quantum computers, current public key encryption (PKE) schemes face unprecedented threats [1]. Traditional public key encryption methods, such as RSA and ECC, rely on the difficulty of integer factorization and discrete logarithm problems. However, quantum computers, by using the Shor algorithm [2], can solve these problems efficiently in polynomial time, thus invalidating traditional encryption methods. To address this challenge, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) is advancing a standardization project for Post-Quantum Cryptography (PQC), which aims to evaluate and finalize encryption schemes that can withstand quantum attacks [3]. In this context, a scheme called BIKE (Bit Flipping Key Encapsulation) has attracted a lot of attention and has entered the final stage of the NIST PQC standardization competition.

BIKE is a representative QC-MDPC (Quasi Cyclic Medium Density Parity Check) code-based scheme, which is relatively competitive both in terms of code length and efficiency and communication bandwidth, and its security relies on the difficult problem of proposed cyclic codes [4]. However, the DFR problem exists even though BIKE employs a state-of-the-art Black-Gray-Flip (BGF) decoder [5] to reduce the Decoding Failure Rate (DFR) and to improve the decoding efficiency. The security of BIKE’s IND-CCA relies on the average Decoding Failure Rate (DFR). The current analysis only gives an estimate of the DFR and does not give a proven upper bound [6]. Therefore, the BIKE instantiation using the BGF decoder does not formally declare IND-CCA security. Currently, attacks such as GJS [7], weak keys [8], and side channels [9] still exist against the decoding failure probability of BIKE schemes. For example, the amplification principle of Guo et al. [10] as well as Nilsson et al. [11] introduce a GJS reaction attack based on the QC-MDPC code structure, which utilizes the existence of a DFR in the decoding so that the attacker can fully recover the key. Drucker et al. [12] argued that the existence of a weak key affects the DFR and that quantitative proofs of the IND-CCA security of BIKE are needed. Wang et al. [8] proved that the existence of weak keys and quantization of the effect on the DFR of the decoder pose threats to the IND-CCA security of BIKE.

Although BIKE shows great potentiality in the field of post-quantum cryptography, its challenges in terms of DFR and other security aspects suggest that further research and improvements are necessary. To ensure that the final chosen post-quantum cryptography standard provides sufficient security and efficiency, this paper addresses the BIKE algorithm, analyzes the performance of its BGF decoder to reveal the factors that affect the DFR, and proposes a weak-key attack optimization scheme to evaluate the security of the BIKE scheme by the DFR test of the decoder.

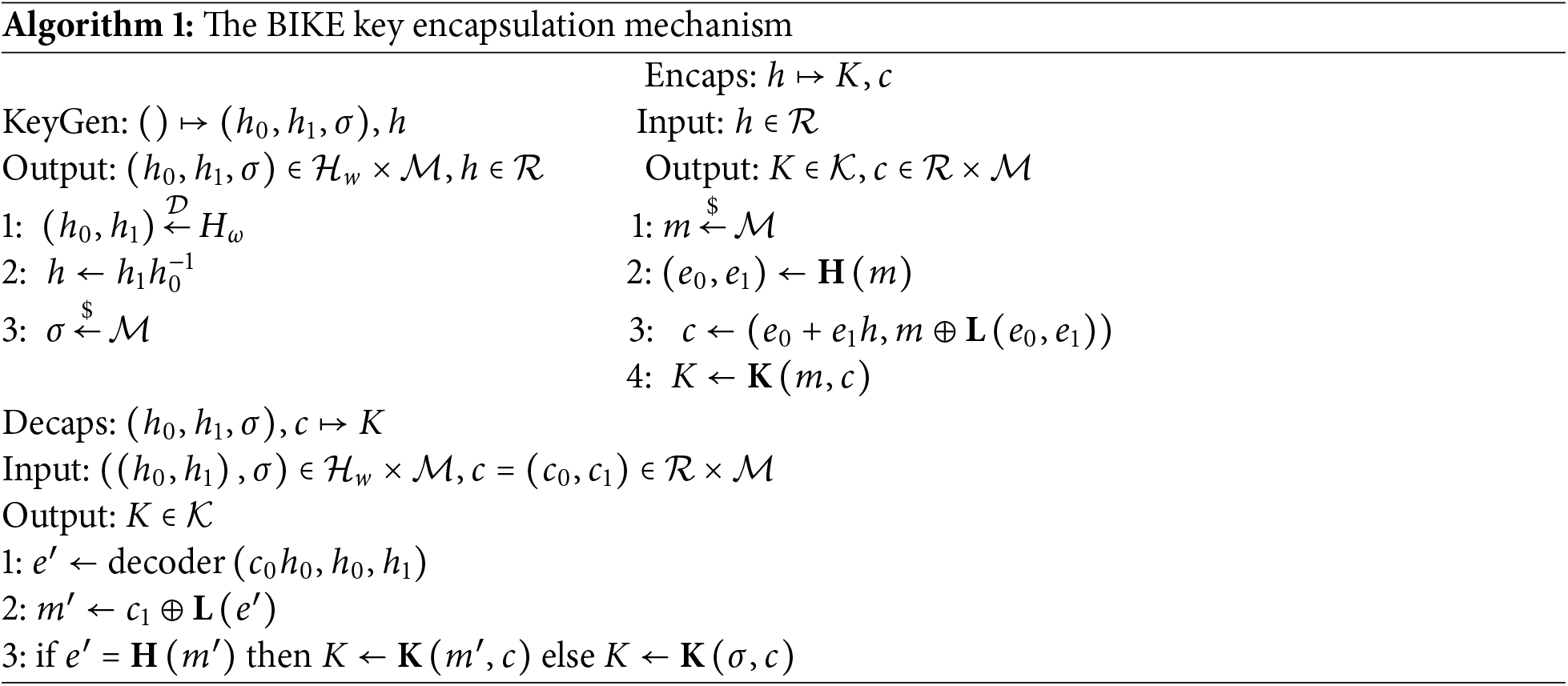

BIKE (Bit Flipping Key Encapsulation) is a post-quantum cryptography-based key encapsulation mechanism that uses quasi-cyclic moderate-density parity-check (QC-MDPC) codes and the Niederreiter cryptosystem framework [13]. It features small key sizes, efficient algorithms, and low complexity [14]. Compared to the traditional McEliece cryptosystem, BIKE has smaller communication bandwidth requirements, making it suitable for bandwidth-constrained network environments. Its design is simple with minimal resource usage, making it suitable for both software implementations (such as servers and PCs) and hardware implementations (such as IoT devices and embedded systems) [15]. It is an efficient, flexible, and quantum-resistant cryptographic solution with broad application prospects in the field of post-quantum cryptography [16]. The algorithm of BIKE KEM is divided into three main steps: key generation, key encapsulation, and key decapsulation. The key encapsulation mechanism (KEM) is described as Algorithm 1.

To have

1.

2.

3.

4. DFR (decoder)

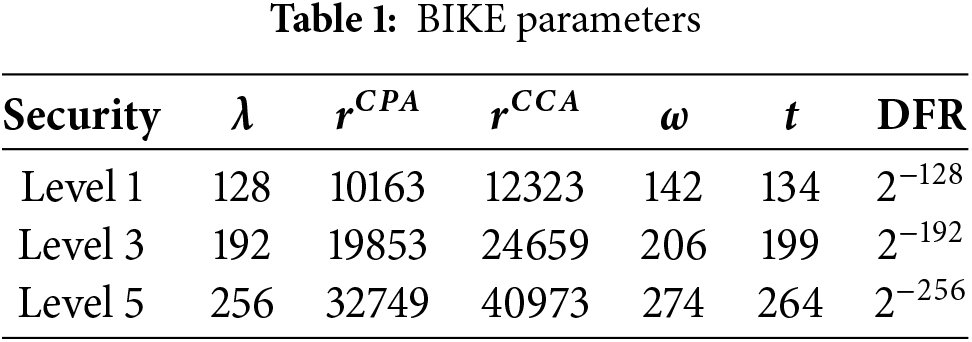

The NIST proposal identifies several security categories related to the strength of key search attacks on grouped ciphers (in the case of AES). The target security levels for BIKE are 1, 3, and 5, which correspond to the security levels of AES-128, AES-192, and AES-256, respectively. The BIKE parameters corresponding to different security levels are shown in Table 1:

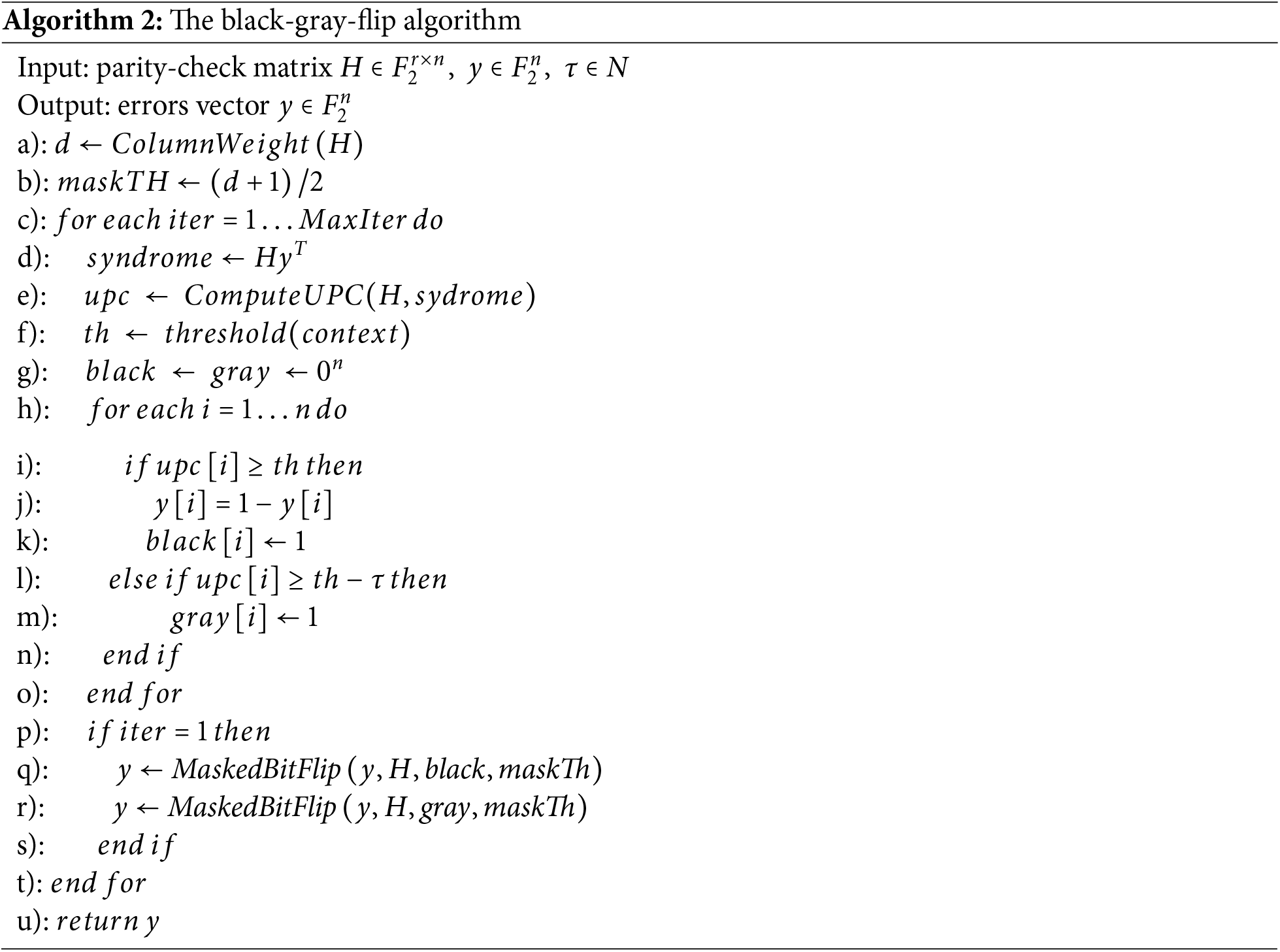

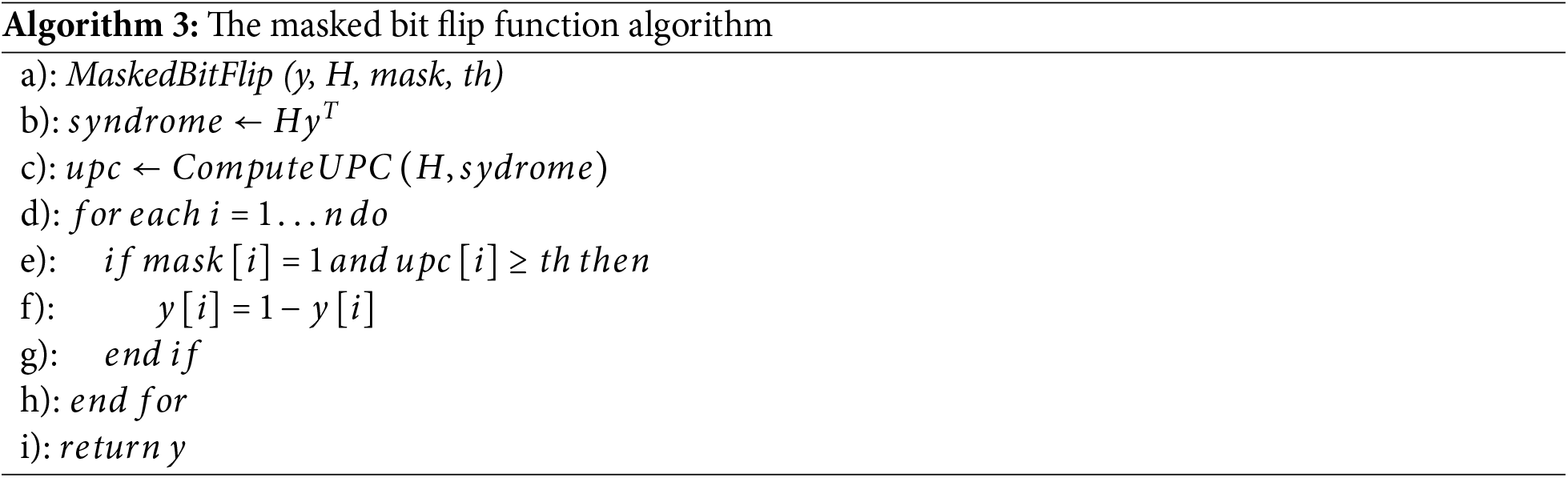

The BGF decoding algorithm (Black-Gray-Flip) is an improved version of Gallager’s bit-flip decoding method [17], addressing the issue of high decoding failure rates in MDPC codes. It employs two predefined thresholds to divide bits into two groups: the black set and the gray set. In the first step, bits with the highest number of unsatisfied parity checks are categorized as black bits and are flipped. Bits with fewer unsatisfied checks are considered gray bits and remain unchanged. In the subsequent step, if the number of unsatisfied checks on a bit exceeds a second threshold, black bits that breach this threshold are flipped back to their original state, and gray bits are flipped. After each operation, the algorithm updates the checksum and the count of unsatisfied checks, continuously adjusting to correct any incorrectly flipped bits. As a result, the BGF decoder focuses on fewer positions and has a higher concentration of errors compared to the traditional bit-flip decoder, improving flip accuracy and significantly reducing the likelihood of decoding failure. The specific steps are shown in Algorithms 2 and 3.

The reasonableness of the threshold selection can greatly affect the efficiency of the decoding. The threshold of the BGF decoder is defined as an affine function of the weight of the checker [18], but when the weight of the checker is between the average values, the threshold formula is also close to the affine function. Therefore, the lower limit of the threshold is given as:

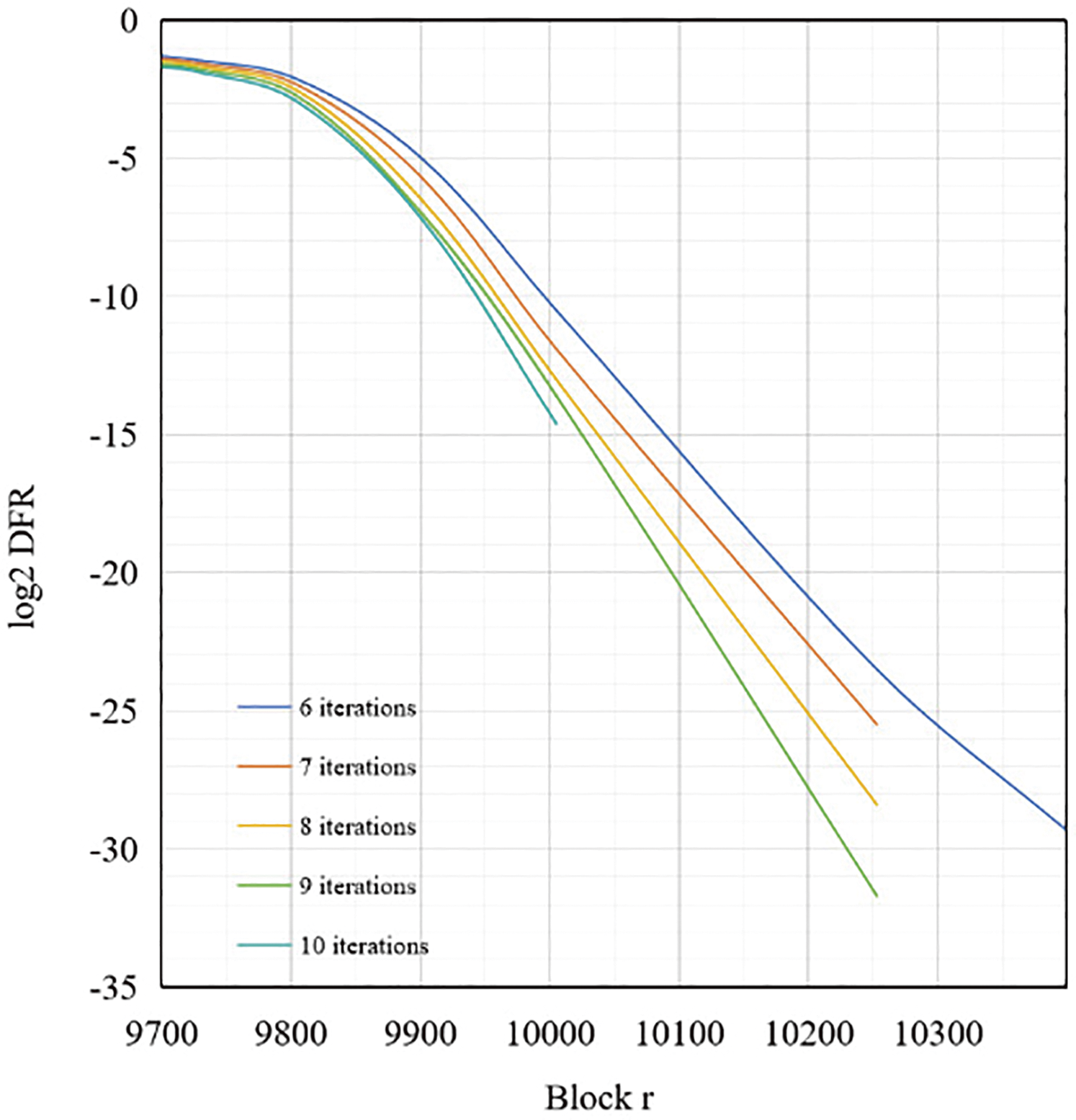

The BIKE 128-bit security parameter is used for the test as

Figure 1: The relationship graph between Block length

To accurately estimate the decoding failure probability DFR of this decoding algorithm, the extrapolation method Markovian model [19] is used, which is based on the fact that the DFR curve is a concave function, and the block value of the large parameter can be deduced by testing the DFR under the smaller code length parameter, given some of the parameters, i.e.,

To accurately assess

Therefore, two methods, analog extrapolation and formula method, are used to test the decoding DFR lower bounds respectively. To ensure the security of IND-CCA and find the minimum block size, it is necessary to ensure that the selected parameter DFR is less than

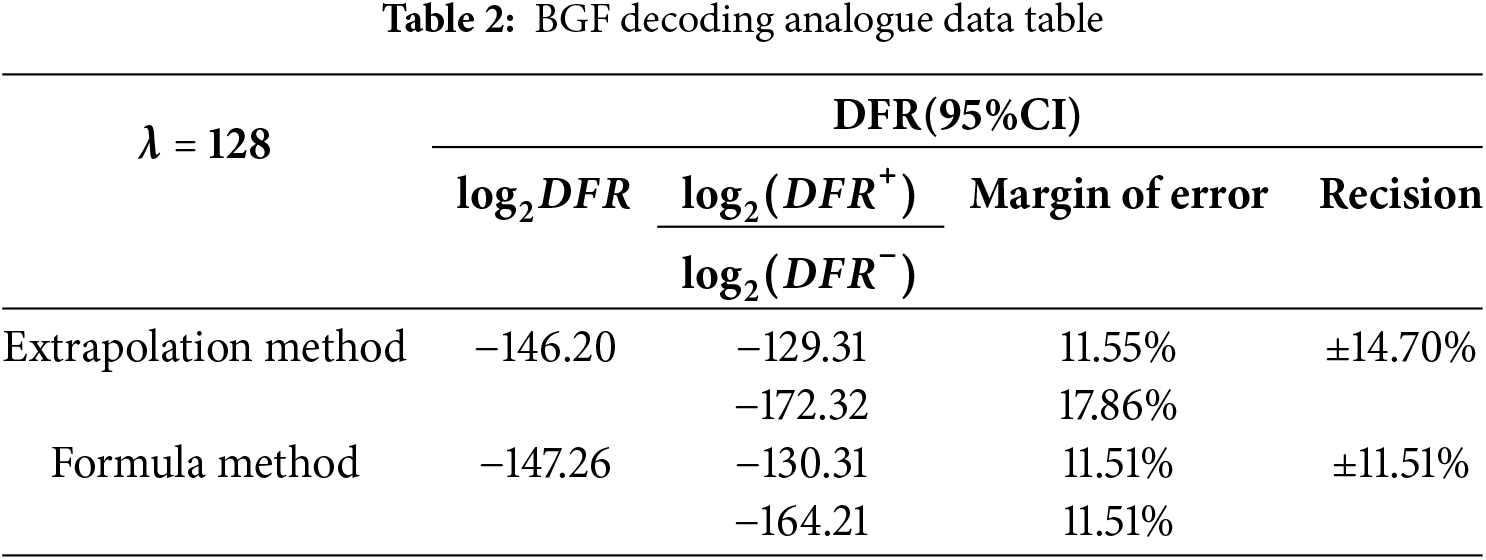

To more accurately evaluate the accuracy of these methods and their potential limitations when applied to practical BIKE parameters, this section provides a detailed analysis of their precision and margin of error. As specifically demonstrated in Table 2.

From Table 2, it can be seen that the BGF decoding algorithm can achieve a corresponding

Decoders for bit-flipping of QC-MDPC codes used by BIKE always have a non-negligible DFR. Although the BGF decoders currently used have a very small DFR, it does not formally declare the security of IND-CCA. This section analyzes the reasons for the existence of DFR and analyzes the special structures that may hinder the decoding to reveal the reasons that affect the decoding.

3.1 Distance Spectrum Analysis

In the GJS reaction attack, Guo [7] found that there is a strong correlation between the DFR and the distance spectrum of the key, and a large amount of information about the distance spectrum of the key can be collected from the decoding failure, and then the key can be recovered from the distance spectrum by the key recovery algorithm. Therefore, the distance spectrum of this attack is the key to whether the key can be recovered or not.

For

Assuming that the multiplicities of the distance spectra are independent, then for

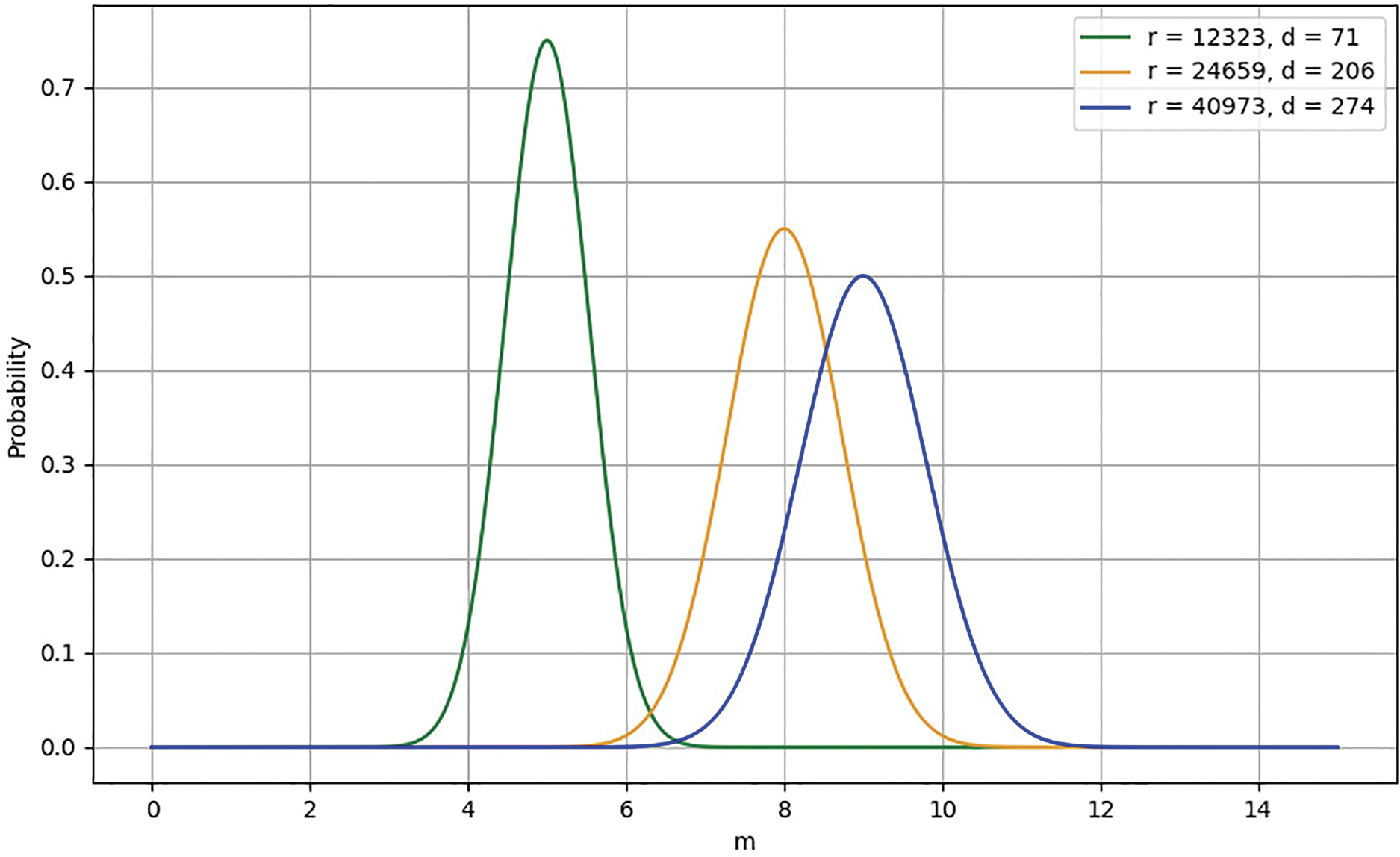

For a subsequent assessment of the effect of multiplicity on the DFR, the distribution of the parameters at three different security levels is plotted as Fig. 2. It can be observed that the probability of a specific multiplicity in the spectrum of a cyclic block is generally low (non-zero), with only a small percentage higher.

Figure 2: Probability analysis of multiplicity

Therefore, this explains the strong correlation between the DFR and the distance between non-zero bits in the private key vector (the first row of the cyclic private key matrix) in the GJS attack. That is, if there is a distance between two non-zero bits in the same error pattern, then the probability of decoding failure is much smaller compared to the absence of such a distance.

Such a result is obvious, the result in the cyclic condition of the QC code, using the error pattern between the two 1’s of the distance and the private key vector of the same distance. Its checksum value decreases due to multiplicative cancellation when identical distances are encountered. The cancellation frequency is inversely proportional to the resultant checksum weight, with higher cancellation counts yielding lower weight values. Therefore, the probability of decoding error when the weight is 0 is greater than the probability of error when the weight is non-zero, and the corresponding DFR will be larger.

In coding theory, the checker is an important factor affecting decoding. For bit-flip decoding, the number of iterations completes the decoding within 3–5 iterations on average, and further iterations have almost no effect on the decoding probability [22]. Therefore, the first correct flip greatly affects whether the decoding can be successful or not. In the first round of decoding, the number of errors

To more accurately analyze the effect of the number of errors in each checksum equation on the decoding, it is assumed that the number of errors involved in the equations obey the following distribution for any

where

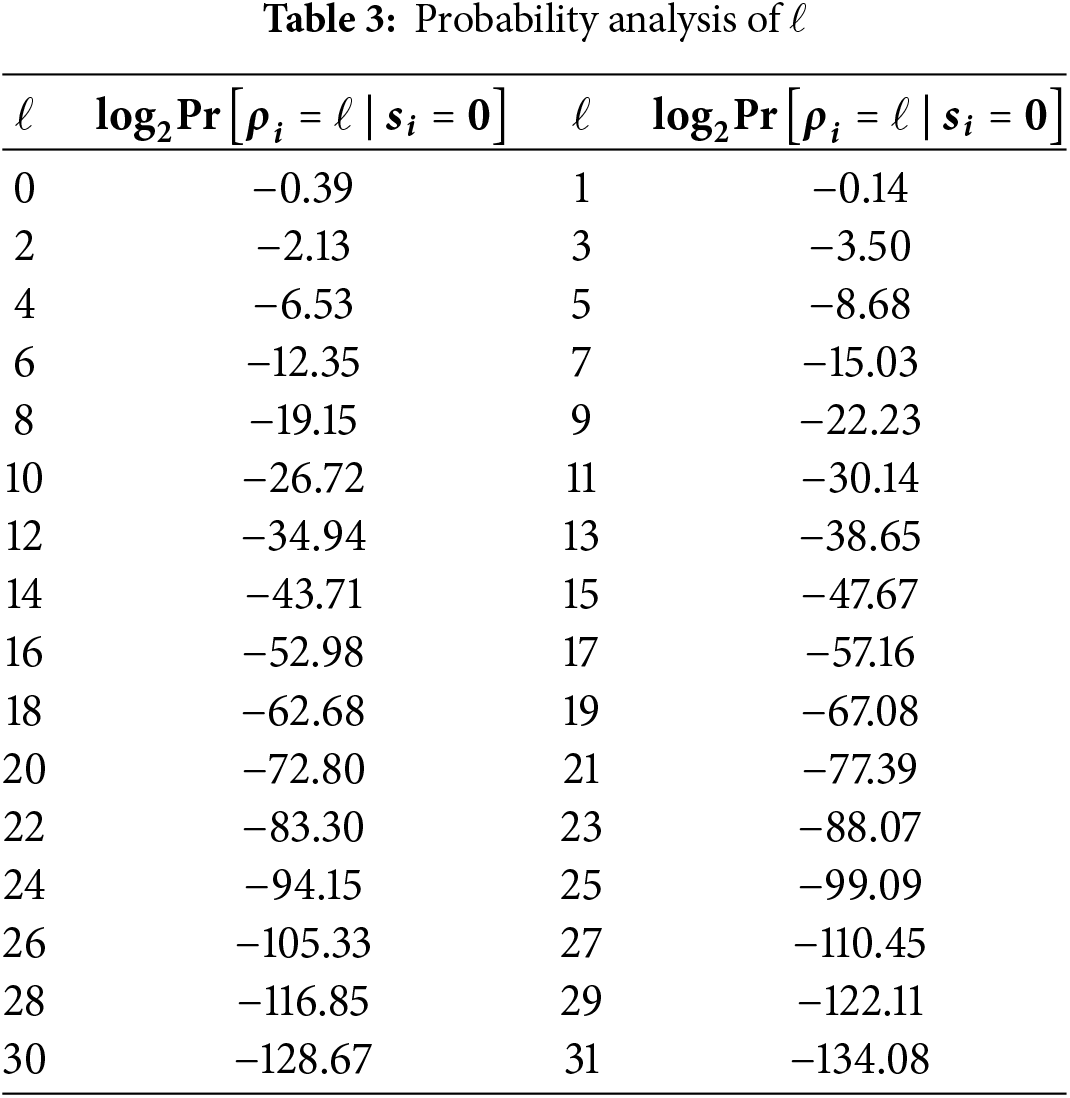

Testing the parameters for selecting 128-bit security, it can be observed from the Table 3 that the probability decreases with an increase of

4 Optimization of Weak-Key Attack

This scheme is based on the BGF decoding algorithm of the BIKE scheme. Building upon previous weak key attacks that only considered the multiplicity of the distance spectrum or the influence of error pattern near-codewords individually, it constructs a weak key that results from the combined effect of both the multiplicity of the key distance spectrum and the error pattern near-codewords.

The overall steps of the scheme are as follows:

1. (Constructing the key) Select the parameters

2. (Sampling error patterns) Select specific parameters

3. (Measure the probability of decoding failure) Generate the ciphertext according to the BIKE encryption encapsulation, send the ciphertext to the target oracle predicate machine decoder decrypt the ciphertext, test the DFR under the small parameter block, and then use the model of the extrapolation method to test under the target parameter conditions.

4. (Analysis of search density) First calculate the search density of step 1, defined as the probability

5. (Analysis of security) Calculate the product of the two based on the results of Step 3 and Step 4, and perform a comparative analysis to determine whether the results are below the minimum requirements for NIST standardization, and thus whether there is a negative impact on decoding.

Based on the analysis in Section 3, the multiplicity of the distance spectrum and the overlapping characteristics of the error vectors both impact decoding. The higher the multiplicity, the more complex the key structure, and the higher the decoding failure probability. Conversely, the higher the overlap of the error vectors, the poorer the error correction capability of the decoder [24].

The core advantage of this scheme lies in combining the key multiplicity with the overlapping characteristics of the near-codeword error vectors. These two factors work together on the decoder, significantly increasing the decoding failure probability without adding extra density. Theoretically, this combination can more effectively increase the DFR, thus enhancing the effectiveness of the attack.

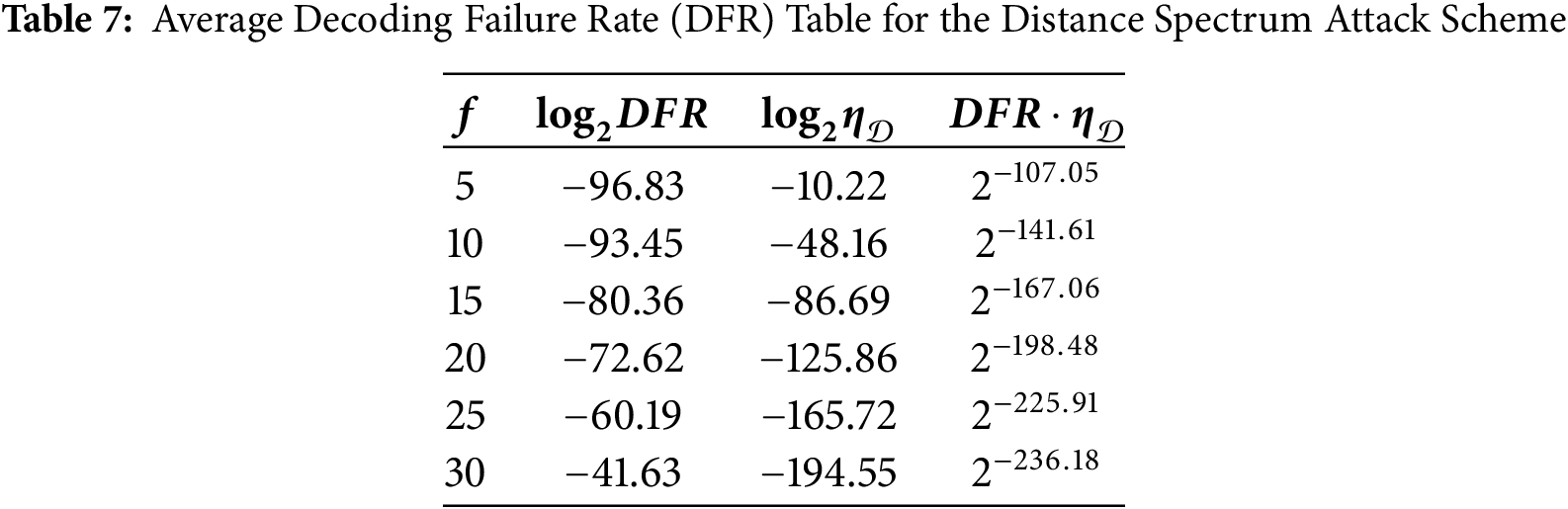

The scheme is based on BIKE’s BGF decoding algorithm and simulates the DFR of QC-MDPC codes under IND-CCA security conditions in the

To ensure the accuracy of evaluating the DFR, for the multiplicity

To test out the effect of key multiplicity and error pattern near-codewords on BIKE (i.e., BGF decoder), increase the weight of the constructed weak key multiplicity

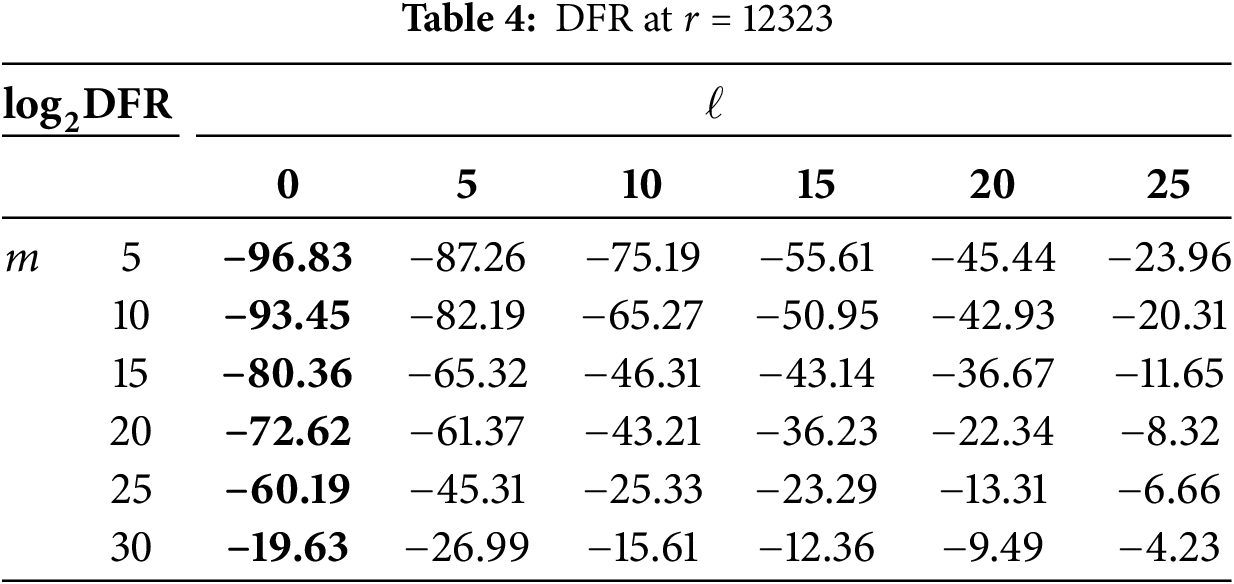

According to the analysis in Table 4, it can be observed that, without considering the error model parameters

When considering multiple key multiplicities and error parameters, the increase in DFR is significant, and the impact of each factor is more prominent. This indicates that the key multiplicity and the near-codeword error vectors have a strong correlation with DFR, which has a major synergistic effect. By comparing the original data with

While DFR testing provides foundational insights, solely relying on this metric without assessing the attack method’s efficacy through holistic cryptanalysis is inadequate. For rigorous security evaluation, we must examine the cryptographic systematically, as developed in subsequent analysis.

In order to gain insight into the impact of weak keys on the IND-CCA security of the BIKE mechanism, introduce the concept of

Therefore, the following inequality must be satisfied, otherwise the IND-CCA security of BIKE is considered to be potentially problematic as it is affected by weak keys.

Under the IND-CCA language security condition, the attack collects the key of

In particularly, when

For the near-codewords in

The search complexity of this scheme is the product of the densities of the two,

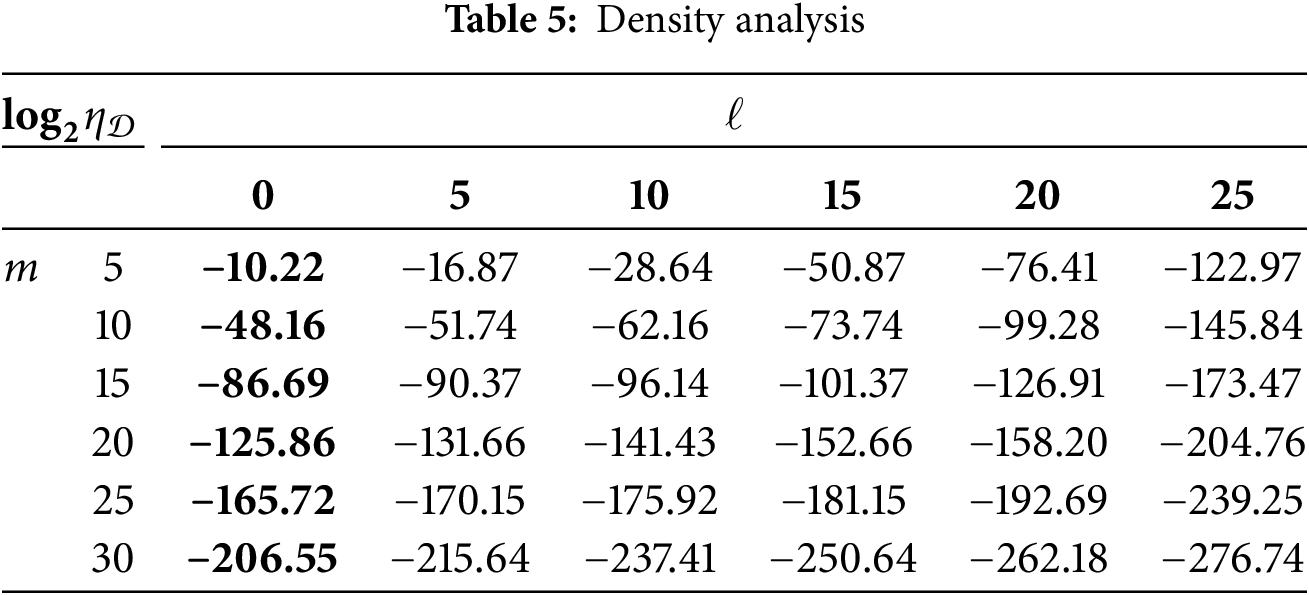

To facilitate the analysis, the overall complexity of the scheme can be calculated according to the above formula, and the data are shown in Table 5.

Without considering the error pattern parameter

When both the key multiplicity

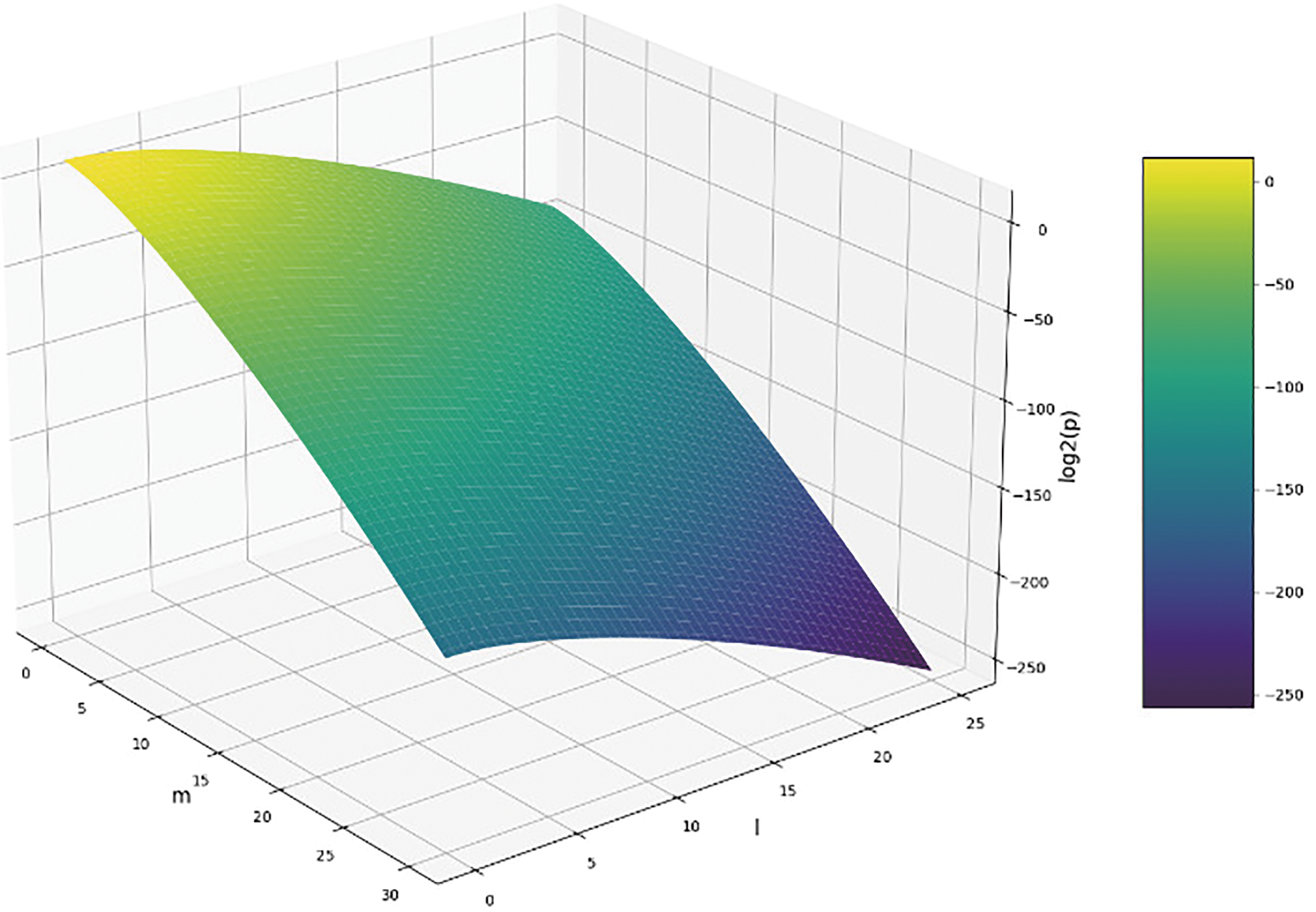

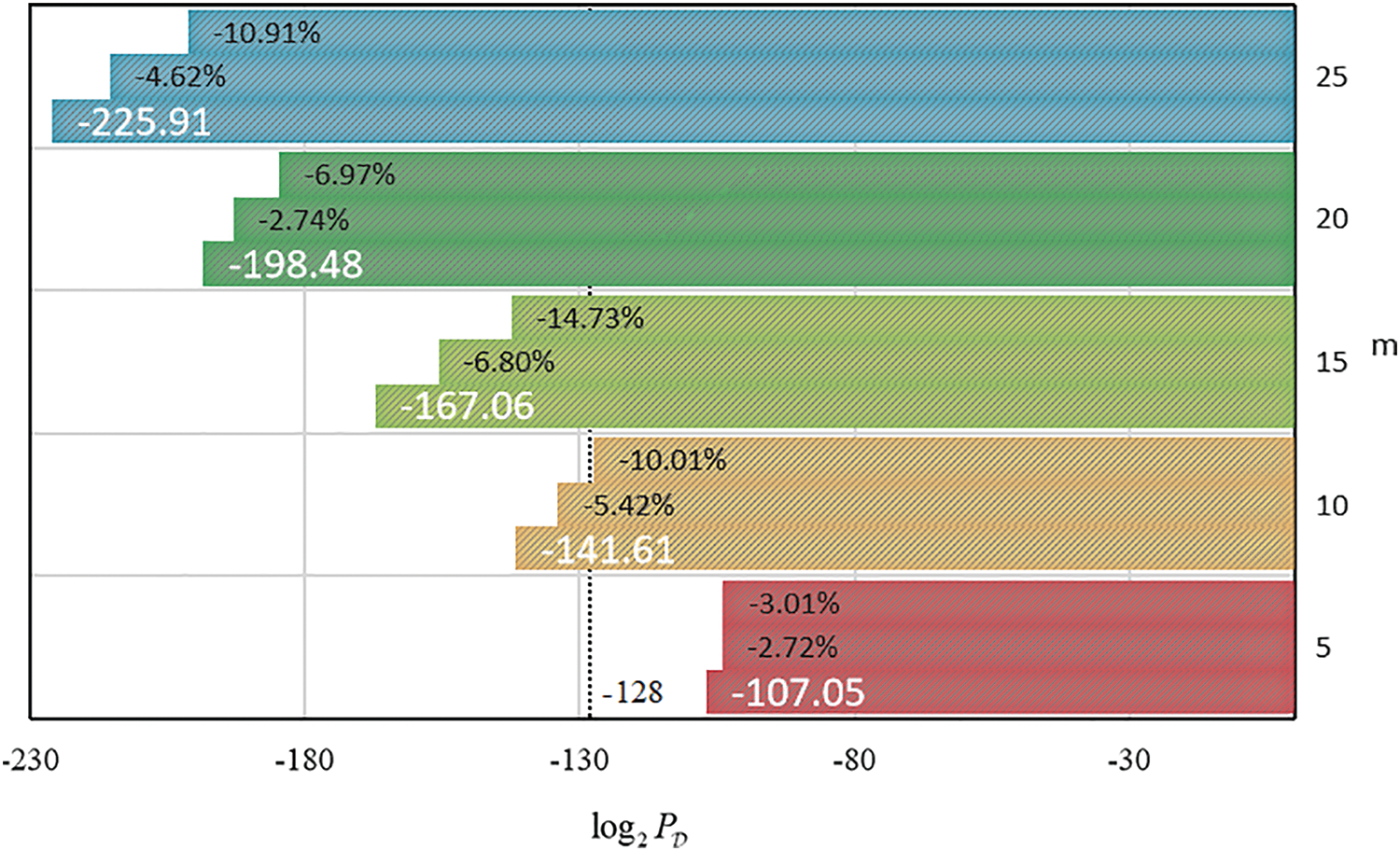

To comprehensively analyze the variation of the upper bound of density under the influence of dual factors, a visualization of the density

Figure 3: Bivariate density analysis plot

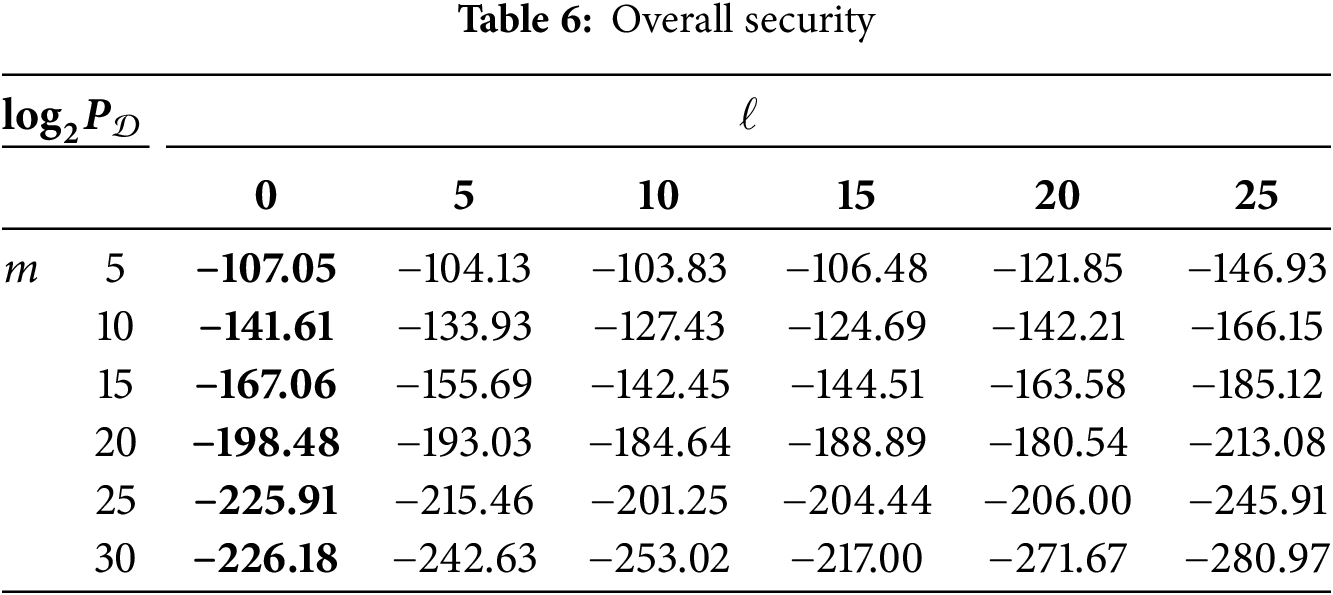

To explore the specific negative impact of the key on the security of the scheme, it is necessary to quantify the test results. Table 6 shows the quantized values of

In Table 6, the value of

To more intuitively demonstrate the improvement in attack effectiveness, Fig. 4 illustrates the enhancement within the region

Figure 4: Effectiveness of scheme upgrading

Additionally, when

Wang et al. [8] re-evaluated the DFR of the QC-MDPC code-based scheme by introducing a new concept called the “gathering property”. The aggregation property is defined as follows:

Reference [26] proposed a weak-key model construction method based on the multiplicity analysis of a single-variable distance spectrum (detailed analysis is provided in Section 3.1). The weak-key model structure is defined as

In this model,

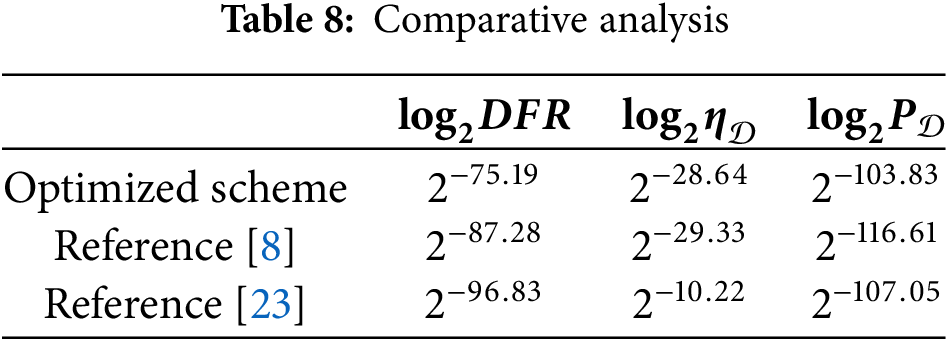

Compared to the aggregation degree scheme proposed by Wang et al. and the distance spectrum scheme in Reference [8], our proposed scheme demonstrates superior attack performance. In Wang et al.’s scheme, the lower bound of the average DFR is

The key innovation of our scheme lies in its ability to increase the decoding failure probability without introducing additional search density. This characteristic allows attackers to significantly enhance the success rate of key recovery while maintaining low computational resource consumption. Specifically, by refining the attack model and algorithms, our scheme enables attackers to more efficiently leverage decoding failure information for key recovery under the same computational complexity.

The general methods for dealing with weak keys primarily include three dimensions: static analysis, dynamic testing, and algorithm-specific detection. In terms of static analysis, the evaluation mainly relies on the following technical approaches: key space size analysis, repetition and predictable pattern recognition, known weak key dictionary comparison, and information entropy calculation. Dynamic testing employs practical attack validation techniques, including brute-force attempts, differential analysis, and linear analysis, to empirically assess the key’s resistance to attacks.

For algorithm-specific detection, the sample autocorrelation function test stands out due to its exceptional capability in detecting key periodicity. The principle of this method involves calculating the autocorrelation coefficient between the initial sequence and its left-shifted sequence by k positions, thereby quantifying the degree of internal correlation within the sequence. In practical implementation, by analyzing the distribution of autocorrelation coefficients at different lag orders, a significant peak at a specific lag order indicates the presence of correlation at that period. This method not only effectively identifies internal sequence variation characteristics but also accurately detects periodic properties of the sequence, making it particularly suitable for weak key periodicity detection based on distance spectrum analysis.

In summary, by integrating the technical approaches of static analysis, dynamic testing, and algorithm-specific detection, a comprehensive weak key detection system can be constructed. Among these, the autocorrelation function test, as a critical method in algorithm-specific detection, provides effective technical support for the periodic analysis of weak keys.

This study delves into the BGF decoding algorithm of the BIKE scheme and addressing its potential weak key issue, proposes an innovative optimized attack strategy. Through experiments, the specific impact of weak keys on the BGF decoder’s DFR is assessed. The analysis indicates that these weak keys pose a potential threat to the IND-CCA security of the BIKE scheme. Therefore, before claiming the IND-CCA security of the BIKE scheme, the security issues caused by weak keys must be addressed. In the future, this research will be extended to algorithms with higher security levels to further validate its universality and effectiveness. This study not only provides new insights into the security of the BIKE scheme but also offers a reference for the future security evaluation of post-quantum cryptography.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by Beijing Institute of Electronic Science and Technology Postgraduate Excellence Demonstration Course Project (20230002Z0452).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Bing Liu; methodology, Bing Liu; software, Ting Nie; validation, Yansong Liu; formal analysis, Yansong Liu; investigation, Weibo Hu; resources, Ting Nie; data curation, Yansong Liu; writing—original draft preparation, Ting Nie; writing—review and editing, Bing Liu; visualization, Ting Nie; supervision, Bing Liu; project administration, Ting Nie; funding acquisition, Bing Liu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Bing Liu, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Li S, Chen Y, Chen L, Liao J, Kuang C, Li K, et al. Post-quantum security: opportunities and challenges. Sensors. 2023;23(21):8744. doi:10.3390/s23218744. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Shor PW. Algorithms for quantum computation: discrete logarithms and factoring. In: Proceedings 35th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science. Santa Fe, NM, USA: IEEE; 1994. p. 124–34. [Google Scholar]

3. Alagic G, Alagic G, Apon D, Cooper D, Dang Q, Dang T, et al. Status report on the third round of the NIST post-quantum cryptography standardization process. Gaithersburg, MD, USA: National Institute of Standards and Technology; 2022. [Google Scholar]

4. Sendrier N. Code-based cryptography: state of the art and perspectives. IEEE Secur Priv. 2017;15(4):44–50. [Google Scholar]

5. Drucker N, Gueron S, Kostic D. QC-MDPC decoders with several shades of gray. In: International Conference on Post-Quantum Cryptography. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2020. p. 35–50. [Google Scholar]

6. Aragon N, Barreto P, Bettaieb S, Bidoux L, Blazy O, Deneuville JC, et al. BIKE: bit flipping key encapsulation; 2022 [cited 2025 Apr 15]. Available from: https://bikesuite.org/files/v4.2/BIKE_Spec.2021.09.29.1.pdf. [Google Scholar]

7. Guo Q, Johansson T, Stankovski P. A key recovery attack on MDPC with CCA security using decoding errors. In: Advances in Cryptology–ASIACRYPT 2016: 22nd International Conference on the Theory and Application of Cryptology and Information Security; 2016 Dec 4–8; Hanoi, Vietnam. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2016. p. 789–815. [Google Scholar]

8. Wang T, Wang A, Wang X. Exploring decryption failures of BIKE: new class of weak keys and key recovery attacks. In: Annual International Cryptology Conference. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland; 2023. p. 70–100. [Google Scholar]

9. Eaton E, Lequesne M, Parent A, Sendrier N. QC-MDPC: a timing attack and a CCA2 KEM. In: International Conference on Post-Quantum Cryptography. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2018. p. 47–76. [Google Scholar]

10. Guo Q, Johansson T, Wagner PS. A key recovery reaction attack on QC-MDPC. IEEE Trans Inf Theory. 2018;65(3):1845–61. doi:10.1109/tit.2018.2877458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Nilsson A, Johansson T, Wagner PS. Error amplification in code-based cryptography. Cryptology ePrint Archive; 2018. doi:10.13154/tches.v2019.i1.238-258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Drucker N, Gueron S, Kostic D. On constant-time QC-MDPC decoding with negligible failure rate. Cryptology ePrint Archive; 2019 [cited 2025 Apr 15]. Available from: https://eprint.iacr.org/2017/604. [Google Scholar]

13. Niederreiter H. Knapsack-type cryptosystems and algebraic coding theory. Prob Control Inform Theory. 1986;15(2):157–66. [Google Scholar]

14. Fujisaki E, Okamoto T. Secure integration of asymmetric and symmetric encryption schemes. In: Annual International Cryptology Conference. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 1999. p. 537–54. [Google Scholar]

15. Dent AW. A designer’s guide to KEMs. In: IMA International Conference on Cryptography and Coding. Berlin/ Heidelberg, Germany: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2003. p. 133–51. [Google Scholar]

16. Hofheinz D, Hövelmanns K, Kiltz E. A modular analysis of the Fujisaki-Okamoto transformation. In: Theory of Cryptography Conference. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2017. p. 341–71. [Google Scholar]

17. Gallager R. Low-density parity-check codes. IRE Trans Inf Theory. 1962;8(1):21–8. doi:10.1109/tit.1962.1057683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Vasseur V. QC-MDPC codes DFR and the IND-CCA security of bike; 2022 [cited 2025 Apr 15]. Available from: https://ia.cr/2021/1458. [Google Scholar]

19. Sendrier N, Vasseur V. On the decoding failure rate of QC-MDPC bit-flipping decoders. In: Ding J, Steinwandt R, editors. Post-quantum cryptography. Cham: Springer; 2019. Vol. 11505. p. 404–16. [Google Scholar]

20. Sendrier N, Vasseur V. About low DFR for QC-MDPC decoding. In: International Conference on Post-Quantum Cryptography. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2020. p. 20–34. [Google Scholar]

21. Vasseur V. Post-quantum cryptography: a study of the decoding of QC-MDPC codes. France: Université de Paris; 2021. [Google Scholar]

22. Chou T, Maezawa Y, Miyaji A. A closer look at the Guo-Johansson–Stankovski attack against QC-MDPC codes. In: International Conference on Information Security and Cryptology. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2018. p. 341–53. [Google Scholar]

23. Sendrier N, Vasseur V. On the existence of weak keys for QC-MDPC decoding; 2020 [cited 2025 Apr 15]. Available from: https://ia.cr/2020/1232. [Google Scholar]

24. Nosouhi MR, Shah SW, Pan L, Zolotavkin Y, Nanda A, Gauravaram P, et al. Weak-key analysis for bike post-quantum key encapsulation mechanism. IEEE Trans Inf Forensics Secur. 2023;18(3):2160–74. doi:10.1109/tifs.2023.3264153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Sendrier N. Secure sampling of constant-weight words–application to bike. Cryptology ePrint Archive; 2021 [cited 2025 Apr 15]. Available from: https://ia.cr/2021/1631. [Google Scholar]

26. Arpin S, Billingsley TR, Hast DR, Lau JB, Perlner R, Robinson A. A study of error floor behavior in QC-MDPC codes. In: International Conference on Post-Quantum Cryptography. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2022. p. 89–103. [Google Scholar]

27. Bardet M, Dragoi V, Luque JG, Otmani A. Weak keys for the quasi-cyclic MDPC public key encryption scheme. In: Progress in Cryptology–AFRICACRYPT 2016: 8th International Conference on Cryptology in Africa; 2016 Apr 13–15; Fes, Morocco: Springer International Publishing; 2016. p. 346–67. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools