Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Optimizing Microgrid Energy Management via DE-HHO Hybrid Metaheuristics

1 Chongqing University-University of Cincinnati Joint Co-op Institute, Chongqing University, Chongqing, 400044, China

2 Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH 45221, USA

3 National Elite Institute of Engineering, Chongqing University, Chongqing, 401135, China

4 School of Life Sciences, Chongqing University, Chongqing, 401331, China

* Corresponding Author: Jingrui Liu. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advancements in Evolutionary Optimization Approaches: Theory and Applications)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 84(3), 4729-4754. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.066138

Received 31 March 2025; Accepted 29 May 2025; Issue published 30 July 2025

Abstract

In response to the increasing global energy demand and environmental pollution, microgrids have emerged as an innovative solution by integrating distributed energy resources (DERs), energy storage systems, and loads to improve energy efficiency and reliability. This study proposes a novel hybrid optimization algorithm, DE-HHO, combining differential evolution (DE) and Harris Hawks optimization (HHO) to address microgrid scheduling issues. The proposed method adopts a multi-objective optimization framework that simultaneously minimizes operational costs and environmental impacts. The DE-HHO algorithm demonstrates significant advantages in convergence speed and global search capability through the analysis of wind, solar, micro-gas turbine, and battery models. Comprehensive simulation tests show that DE-HHO converges rapidly within 10 iterations and achieves a 4.5% reduction in total cost compared to PSO and a 5.4% reduction compared to HHO. Specifically, DE-HHO attains an optimal total cost of $20,221.37, outperforming PSO ($21,184.45) and HHO ($21,372.24). The maximum cost obtained by DE-HHO is $23,420.55, with a mean of $21,615.77, indicating stability and cost control capabilities. These results highlight the effectiveness of DE-HHO in reducing operational costs and enhancing system stability for efficient and sustainable microgrid operation.Keywords

With the global demand for energy steadily increasing, the depletion of traditional fossil fuel resources and worsening environmental pollution have presented significant challenges to power grid systems [1]. Conventional grids, which depend heavily on large-scale centralized generation and long-distance transmission, suffer from low energy efficiency. Additionally, they are vulnerable to natural disasters and equipment failures, compromising the reliability of power supply [2,3].

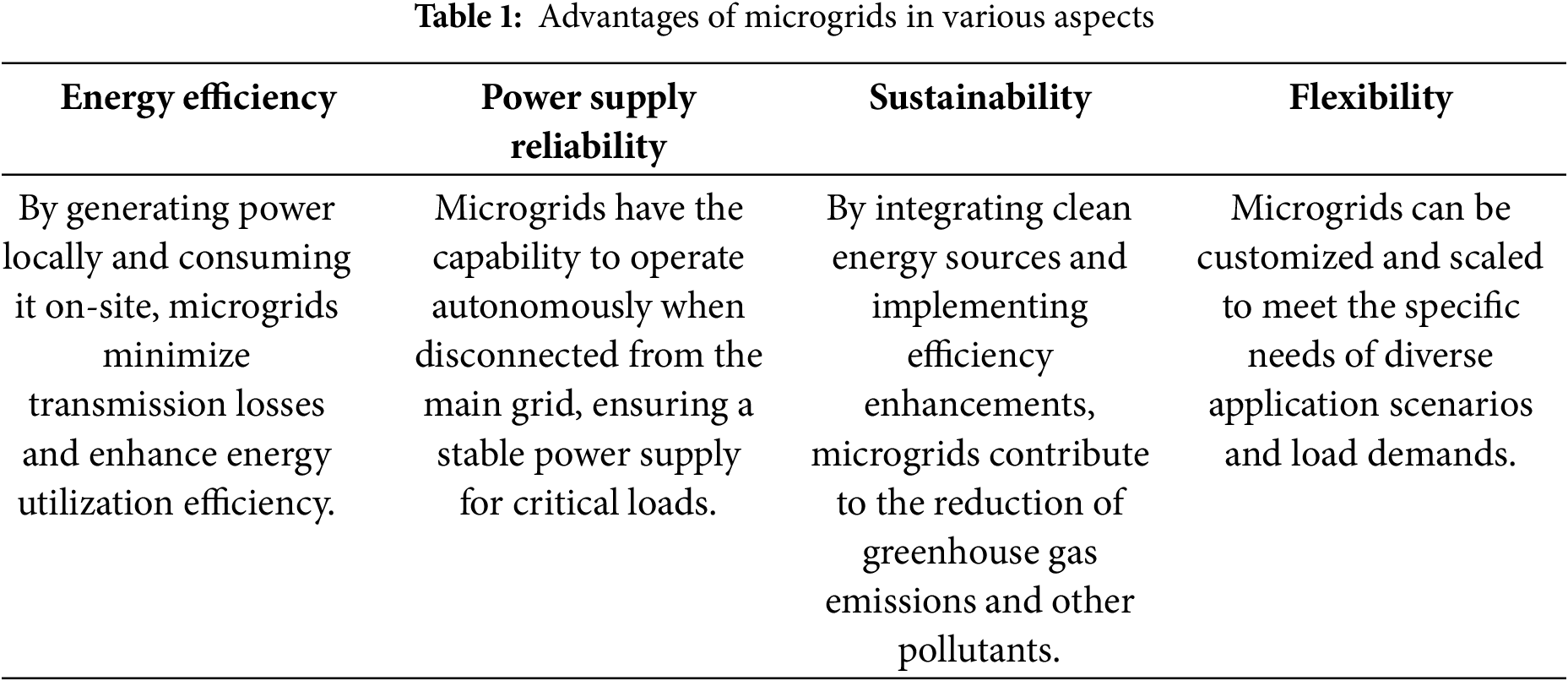

Microgrids, as an innovative power system, are composed of distributed generation (DG), energy storage systems, and loads, and can operate flexibly in both grid-connected and islanded modes [4]. They enable the effective integration and utilization of clean energy sources such as wind and solar power, while leveraging energy storage systems to smooth energy fluctuations and ensure stable and reliable electricity supply [5–7]. The advantages of microgrids in various aspects are shown in Table 1 [8,9].

Energy optimization scheduling in microgrids involves coordinating the output of distributed energy resources and managing energy exchange between the microgrid and the main grid under various system constraints [10]. This process seeks to achieve multiple objectives, including minimizing operational costs and emissions, improving reliability, and enhancing energy efficiency [11]. From the demand-side perspective, optimized scheduling reduces electricity costs for consumers. From the supply-side perspective, it improves grid stability, decreases generation-related energy losses, and mitigates environmental pollution [12].

Given the increasing penetration of renewable energy sources and the challenges posed by their inherent variability and intermittency, energy optimization in microgrid scheduling has emerged as a critical research focus. This study seeks to explore advanced scheduling strategies and optimization methods to address these challenges, ensuring the efficient, economical, and sustainable operation of microgrid systems. The findings are expected to contribute to a broader transition toward greener and more resilient energy systems.

The configuration and optimization of energy storage (ES) systems have long been a major research focus in the context of microgrids [13]. Nayak et al. [14] employed probabilistic and statistical methods to analyze system output characteristics and developed mathematical probability models to determine ES capacity allocation and reliability metrics. However, these models exhibited significant stochasticity, leading to discrepancies between simulation results and actual data. Sultan et al. [15] proposed an economic model to optimize ES capacity under system output fluctuations, yet these approaches lacked specificity for different ES types and relied on relatively simplistic economic frameworks.

To address these limitations, Wang et al. [16] developed an optimization model aimed at minimizing the variance of load fluctuations, thereby effectively improving the voltage stability and economic efficiency of distribution networks. However, these studies overlooked critical ES characteristics, focusing primarily on the isolated aspects of energy storage without fully addressing the integration and synergy of multiple energy resources. The lack of a comprehensive approach limits the applicability of these models in real-world scenarios, where effective management of different energy systems is crucial. To overcome these challenges, recent research has shifted toward exploring microgrid configurations that integrate various energy resources through advanced Energy Management Systems (EMS) and optimization techniques. For instance, Mehleri et al. utilized a mixed-integer nonlinear programming (MINLP) method to minimize an objective function that includes investment, operation, maintenance, and environmental costs [17]. Although MINLP provides a systematic framework for microgrid optimization, its application in large-scale nonlinear problems is constrained by computational inefficiency.

As a result, many researchers have adopted intelligent optimization algorithms to solve microgrid optimization scheduling problems. Among these, particle swarm optimization (PSO) has been widely applied due to its simplicity and ease of implementation. For example, Abood et al. proposed a novel energy management method called accelerated PSO [18]. Abualigah et al. and Zermane et al. [19,20] developed quantitative models for battery lifespan in ES systems and solved these models using PSO. Additionally, Guo et al. designed an ES system model with economic indicators and achieved optimal solutions through PSO [21].

In addition to the PSO algorithm, researchers have explored various other intelligent optimization methods. For example, Zhao et al. used particle swarms with automatic parameter configuration to optimize hierarchical parallel search [22]. Furthermore, some scholars have proposed intelligent EMS based on Genetic Algorithms (GA), incorporating forecasting modules, energy storage management modules, and optimization modules [23].

However, traditional optimization algorithms exhibit inherent limitations in practical applications, including susceptibility to local optima, limited global search capability, slow convergence, and constrained applicability [24–28]. To address these shortcomings, the HHO algorithm has recently emerged as a promising solution for microgrid optimization problems [29]. Inspired by the cooperative hunting behavior of Harris hawks, HHO is notable for its simplicity, low parameter dependence, and ease of implementation. It has been successfully applied in various fields, including numerical and engineering optimization, image recognition, fault diagnosis, and power grid optimization design [30]. To further improve optimization performance, researchers have integrated HHO with the Differential Evolution (DE) algorithm [31]. DE employs differential mutation and crossover operations, using the differences among individuals in the population to generate new candidate solutions. This method is conceptually simple, requires few control parameters, and demonstrates strong robustness [32]. By combining the global search capability of DE with the local exploitation strength of HHO, the hybrid DE-HHO algorithm significantly improves convergence speed, enhances global search efficiency, and effectively avoids entrapment in local optima.

This study focuses on optimizing the scheduling of a microgrid comprising wind, solar, and energy storage systems, with the objective of minimizing both operational and maintenance costs as well as environmental economic costs. A comprehensive optimization model is developed, incorporating mathematical representations of each component and defining relevant constraints to analyze the energy consumption of critical loads within the microgrid. The hybrid DE-HHO algorithm is employed to solve the model, determining the optimal output of each component to minimize total cost. Finally, case studies are conducted to verify the feasibility and effectiveness of the proposed algorithm.

The contributions of this study are summarized as follows:

• A hybrid optimization algorithm, DE-HHO, is proposed, which combines the global search capability of DE and the local exploitation capability of HHO. This algorithm noticeably enhances the convergence speed and stability of microgrid scheduling and effectively reduces operational costs.

• A multi-objective optimization model for microgrids is constructed, covering wind, solar, micro-gas turbine, and energy storage systems. This model considers both operational costs and environmental impacts, ensuring the stability and reliability of the system.

• The effectiveness of the DE-HHO algorithm is verified through simulation experiments. The results show that the algorithm can effectively reduce operational costs and optimize energy dispatch strategies for microgrids.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 introduces the modeling of microgrids with wind, solar, micro-gas turbine, and energy storage systems. Section 3 presents the operational optimization strategies for microgrids. Section 4 elaborates on the design and implementation of the DE-HHO hybrid optimization algorithm. Section 5 demonstrates the simulation results and analysis. Finally, Section 6 summarizes the research findings and proposes future research directions.

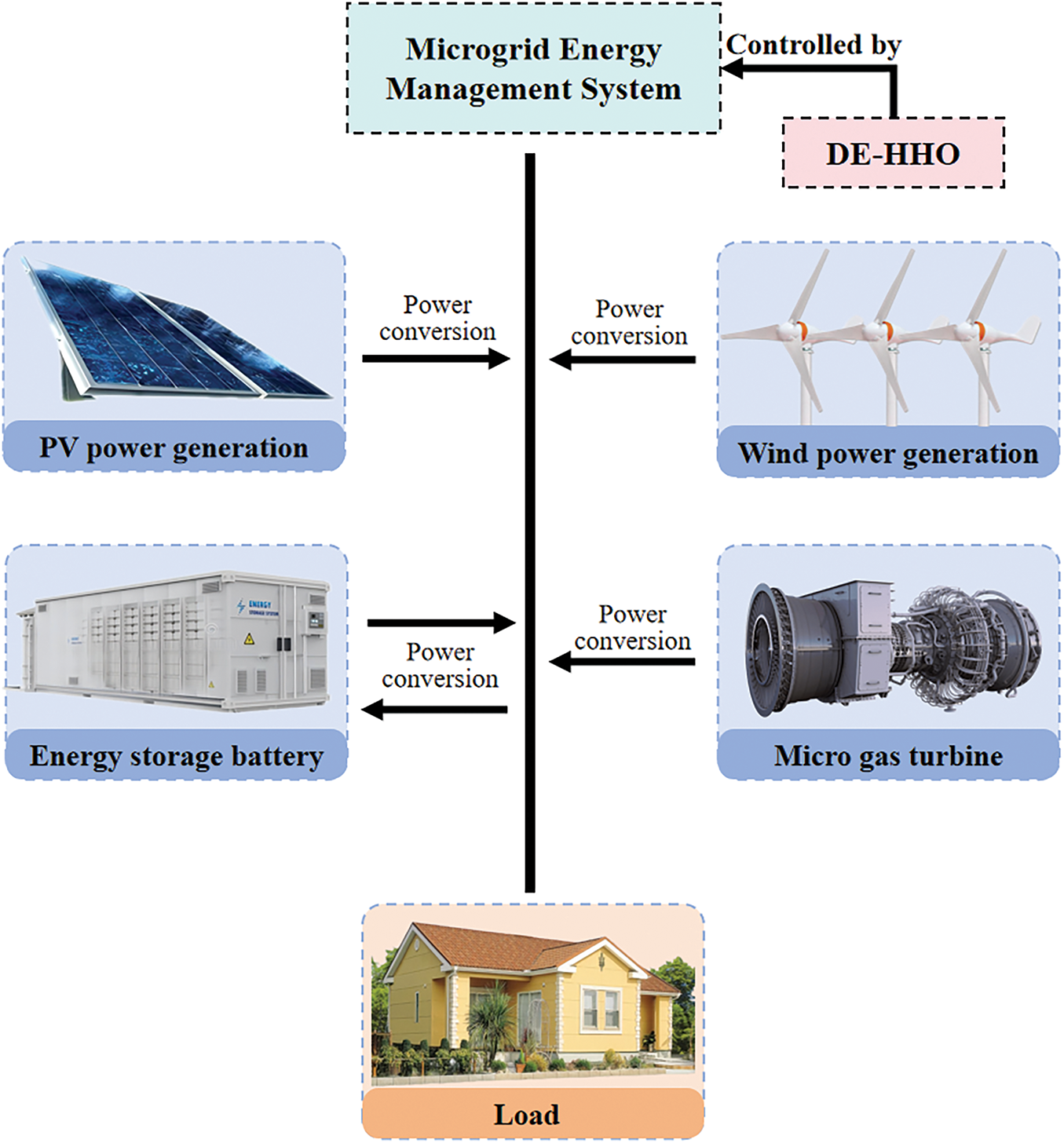

Microgenerators are renewable or unconventional power generation units integrated within microgrids, commonly referred to as DERs. The application of microgenerators is anticipated to expand significantly in the future [33]. In a microgrid, these power sources not only provide electrical energy to the system but also play a pivotal role in ensuring system stability and maintaining power quality. This study examines several common types of microgenerators, including wind turbines, photovoltaic (PV) systems, micro gas turbines, and energy storage batteries, as shown in Fig. 1. The subsequent sections provide an analysis of the output models for each of these four microgeneration technologies.

Figure 1: A microgrid with an EMS

2.1 Wind Power Generation Modeling

The principle of wind power generation involves converting natural wind energy into usable electrical energy through wind turbines (WT) [34]. As a form of renewable energy, wind power is environmentally friendly and does not consume any fuel. However, the inherent randomness of natural wind makes it challenging to precisely predict the output of wind power generation.

The following section presents an analysis of widely applied wind power generation models, along with the calculation formula for wind power output

In Eq. (1),

In the equation,

The operating states of the wind turbine can be summarized into the following three cases:

1. No Power Generation: When

2. Rated Power Generation: When

3. Variable Power Generation: When

2.2 Photovoltaic (PV) Power Generation Modeling

The fundamental principle of photovoltaic (PV) power generation involves the absorption of solar energy by PV modules, which convert it into electricity for practical use. As the process requires no fuel consumption, PV power generation effectively eliminates emissions associated with fossil fuel combustion, thereby reducing air pollution and mitigating the greenhouse effect.

A PV power generation system consists primarily of PV modules that absorb solar radiation and generate direct current (DC) electricity. Since PV modules output DC power while most electrical grids and devices operate on alternating current (AC), a DC-to-AC conversion is necessary to adapt the generated electricity. Energy storage devices are used to store excess electricity produced during periods of low demand, which is particularly critical in large-scale PV power plants to ensure a stable power supply. The configuration of PV cells, whether in series or parallel, enables flexible adjustment of system voltage and current to optimize power output. By employing advanced inverter control strategies, Maximum Power Point Tracking (MPPT) can be achieved to maximize energy utilization. Additionally, optimizing the tilt angle of the PV panels further enhances generation efficiency [35].

The output power of a PV system

The equation,

The operating characteristics of PV power generation can be summarized as follows:

1. In solar cells, photon energy is used to excite electrons, generating current. A higher number of photons (i.e., greater solar irradiance) results in more electrons being excited, thereby producing higher current and power output. Consequently, the greater the solar irradiance, the more solar energy the PV modules can absorb, leading to a higher maximum power output.

2. During operation, PV modules generate heat, and elevated temperatures reduce the efficiency of semiconductor materials, thus diminishing the overall performance of the PV modules. As the temperature increases, the internal resistance of the PV modules may rise, leading to a decrease in their maximum power output.

2.3 Micro Gas Turbines (MGTs) Modeling

Micro Gas Turbines (MGTs) are small-scale, gas-powered devices primarily employed in distributed power generation systems. The core operating principle involves the combustion of natural gas or other fuels to generate high-temperature, high-pressure gases. These gases drive a turbine, which subsequently powers a generator to produce electricity. Compared to conventional large-scale gas turbines, MGTs offer several advantages, including compact size, high efficiency, and rapid response times, making them particularly well-suited for integration into distributed generation systems such as microgrids [36].

The operating mechanism of an MGT involves three key processes: air compression, fuel combustion, and gas expansion. Air is compressed by a compressor, then mixed with fuel and ignited in the combustion chamber to produce high-temperature gases. These gases expand to drive the turbine, which, in turn, converts mechanical energy into electrical energy via a generator.

In microgrids, MGTs are commonly utilized for load regulation and grid stabilization. The mathematical model governing their operation can be expressed by the following equations:

In the equations,

In the equation,

In the equation,

In the equation,

2.4 Energy Storage Batteries Modeling

Energy storage systems (ESS) play a critical role in microgrids by balancing the disparity between power generation and load demand, optimizing power utilization, and enhancing grid stability and reliability. ESS stores excess electricity and releases it during peak load periods or when renewable energy sources, such as wind or PV systems, have insufficient output. Common types of energy storage batteries include lithium-ion, lead-acid, and sodium-sulfur batteries, among which lithium-ion batteries are widely used in microgrid systems due to their high energy density and long lifespan [37–41].

Energy storage batteries operate by storing electrical energy during the charging process and releasing it back to the grid during discharge. The efficiency of an ESS is closely related to factors such as battery charge/discharge efficiency and lifespan. To effectively manage the charge and discharge processes, a mathematical model is essential for optimizing battery operation strategies [42].

The state of charge (SOC) of a battery represents the ratio of the currently stored energy to the maximum stored energy [43]. The SOC is calculated based on the battery’s charge and discharge processes, with its mathematical expression given as follows:

In the equation,

3 Capacity Optimization Strategy

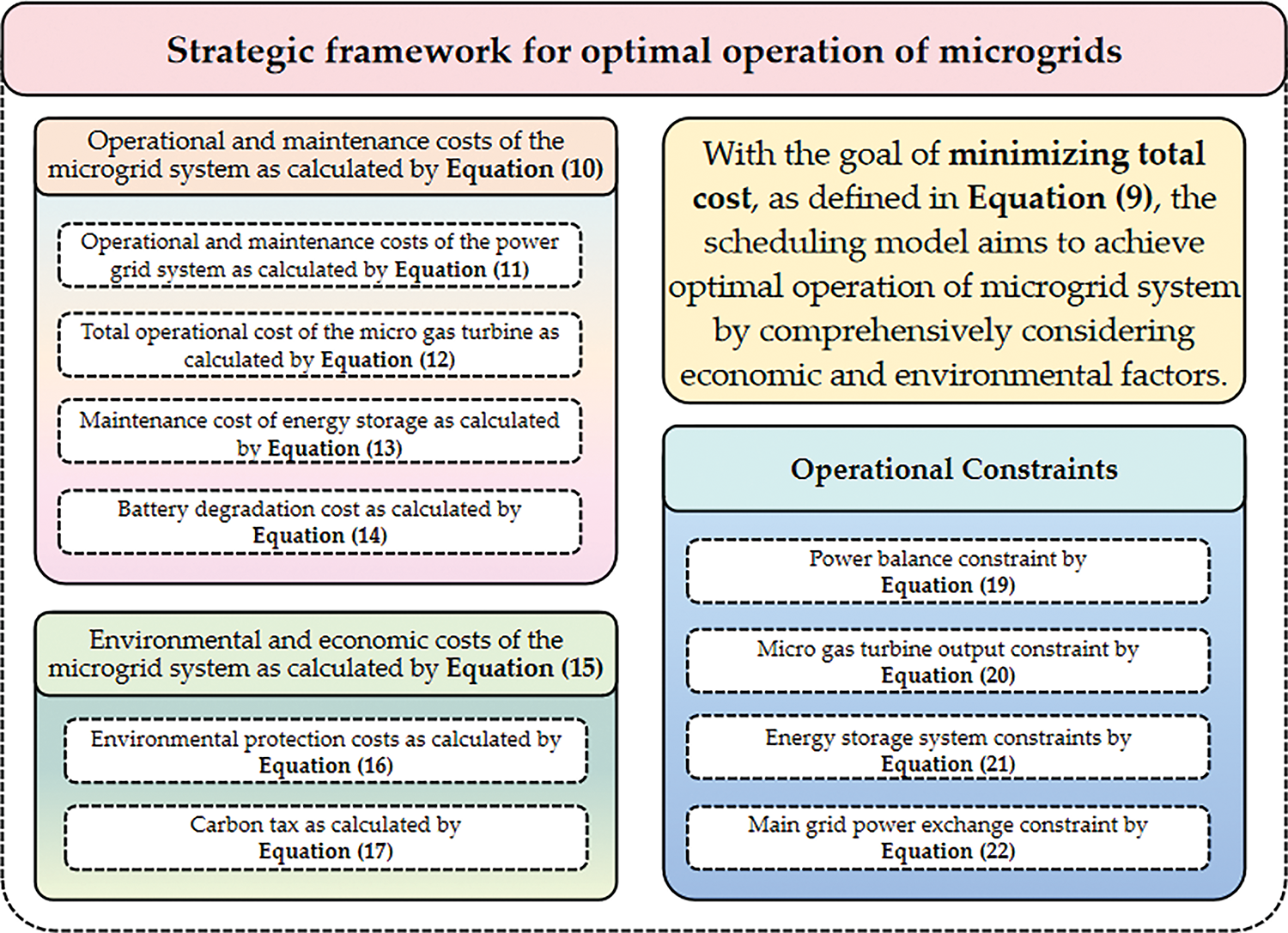

The planning and design of microgrids need to consider system economics, power supply reliability, and environmental sustainability. This paper aims to minimize the operation and maintenance costs of microgrids, along with environmental and economic costs, by constructing a multi-objective function as shown in Eq. (9). The objective of the scheduling model is to minimize total costs while maximizing economic and environmental benefits.

In the equation,

The operational and maintenance costs of the microgrid system

The operational and maintenance costs of the microgrid system consist of three components: the total operational costs of interactions between the microgrid and the main grid

(1) Operational and maintenance costs of the power grid system.

The calculation formula is as follows:

where

(2) The total operational cost of the micro gas turbine

The calculation formula is as follows:

where

(3) The maintenance cost of energy storage

The calculation formula is as follows:

where

(4) Battery degradation cost

In addition to the maintenance costs of the energy storage system, this study further considers battery degradation cost, which reflects the long-term economic impact of battery cycling. The degradation cost is modeled as a function of the cumulative charge and discharge throughput as shown in Eq. (14).

where

The environmental and economic costs of the microgrid system

In microgrid optimization problems, environmental protection costs

(1) Environmental Protection Costs

Environmental protection costs primarily include the external costs caused by pollutant emissions and energy production methods, such as the combustion of fossil fuels. These costs are typically quantified by the amount of carbon emissions and the corresponding unit cost, such as the environmental cost of carbon emissions. The formula for calculating environmental protection costs can be expressed as:

where

(2) Carbon Tax

The carbon tax is a fee imposed by the government on carbon emissions, designed to incentivize the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions through economic measures. The carbon tax is typically calculated based on the amount of carbon dioxide emissions. The formula for calculating the carbon tax can be expressed as:

where

Thus, the environmental and economic costs can be expressed as Eq. (18).

(1) Power Balance Constraint

In the microgrid system, the generated power and load demand must remain balanced:

(2) Micro Gas Turbine Output Constraint

The output of the micro gas turbine must remain within its allowable range:

where

(3) Energy Storage System Constraints

The charging and discharging power, as well as the state of the energy storage system, must satisfy the following conditions:

where

(4) Main Grid Power Exchange Constraint

The power exchange with the main grid must remain within its allowable range:

where

The optimization strategy for the microgrid, as depicted in Fig. 2, encompasses a comprehensive set of equations and constraints that facilitate the achievement of the objective function outlined in the model.

Figure 2: Strategic framework for optimal operation of microgrids

4 Microgrid Optimization Operation Based on DE-HHO

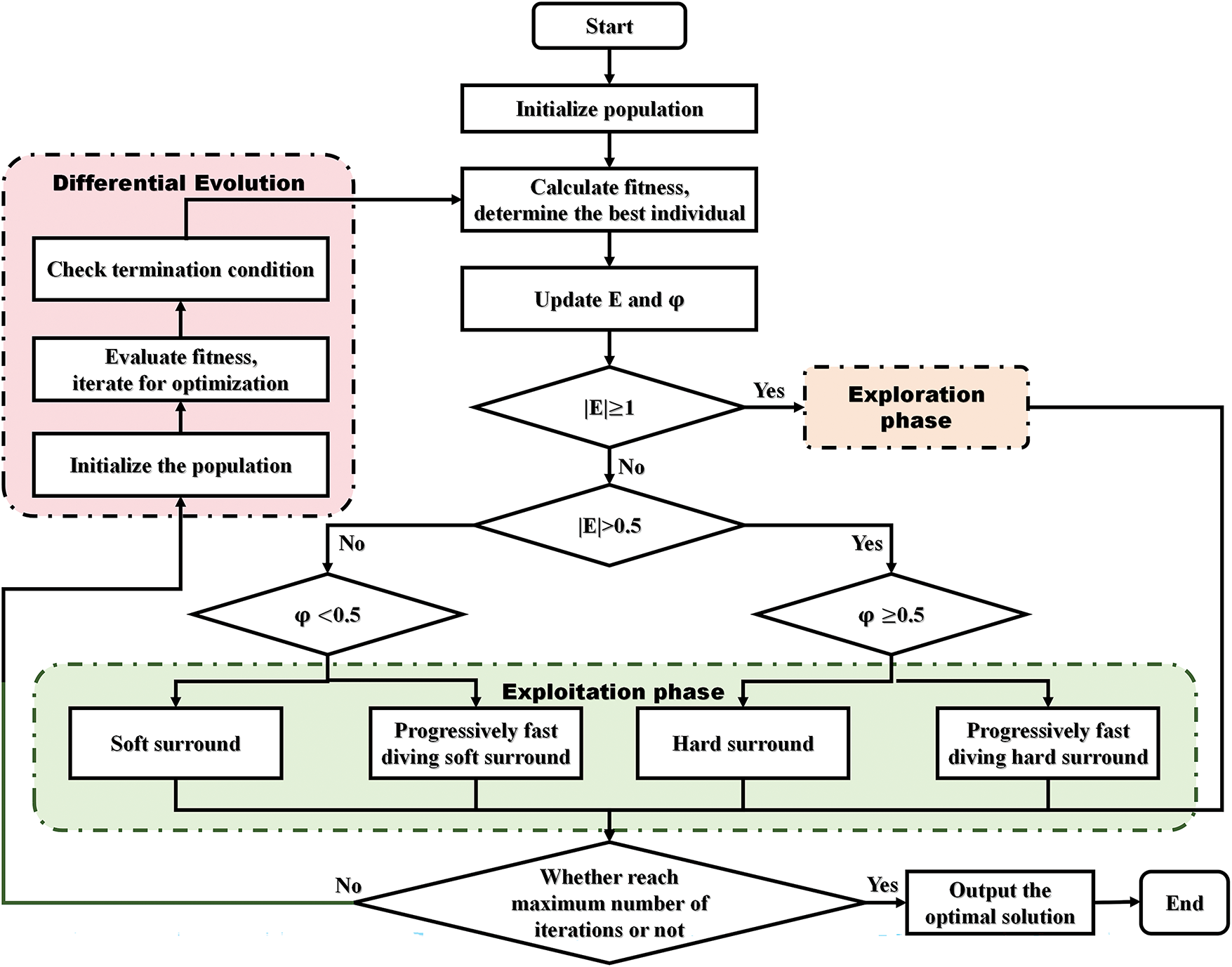

In this section, we have provided a detailed description of the microgrid optimal operation mechanism based on the DE-HHO hybrid algorithm. By integrating the global search capability of DE and the local exploitation capability of HHO, the hybrid algorithm leverages the strengths of both to address complex issues in microgrid optimal scheduling. The DE algorithm generates a diverse population through its mutation and crossover strategies, rapidly covering the solution space to identify potential optimal solutions. In contrast, the HHO algorithm employs its Lévy flight mechanism and dynamic hunting strategies to conduct refined searches in the regions of potential optimal solutions. This combination of mechanisms enables the hybrid algorithm to effectively balance global search and local search capabilities, thereby significantly enhancing optimization performance.

In Section 4.1, we elaborated on the principles of the HHO algorithm, including its characteristics and strategies in the global exploration, transition, and local exploitation phases. In Section 4.2, we analyzed the mutation, crossover, and selection strategies of the DE algorithm, as well as its advantages in the optimization process. In Section 4.3, we described in detail the collaborative mechanism of the DE-HHO hybrid algorithm, including how DE and HHO complement each other in the global exploration and local exploitation phases, and how this collaboration improves the adaptability and robustness of the algorithm.

4.1 Principle of Harris Hawks optimization

With the growing complexity of microgrid systems, traditional optimization algorithms increasingly struggle with multi-objective and multi-constraint optimization problems, exposing limitations such as susceptibility to local optima, insufficient global search capabilities, and low computational efficiency. In response, the HHO algorithm has emerged as a promising intelligent optimization method. Its unique mechanisms and high efficiency have attracted significant attention, leading to successful applications in microgrid optimization.

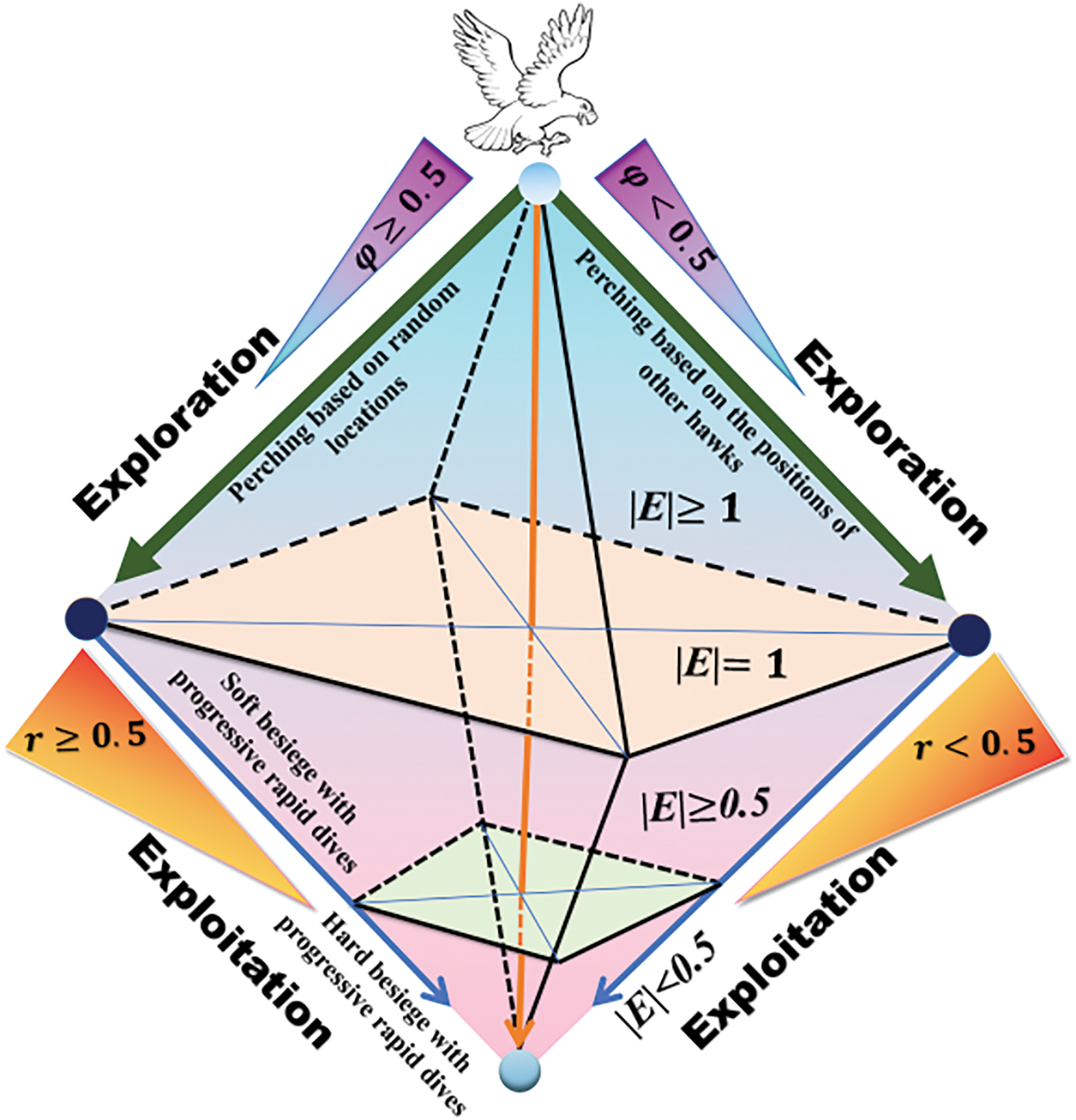

Inspired by the cooperative hunting behavior and sudden attack strategies of Harris hawks, HHO combines strong global search abilities with effective local exploitation [45]. The algorithm divides its optimization process into three phases: global exploration, transition from exploration to exploitation, and local exploitation. During global exploration, it simulates random search behaviors to thoroughly explore the solution space and locate potential optima. In the transition phase, the algorithm mimics pursuit behaviors, narrowing the search area and moving closer to optimal solutions. Finally, during local exploitation, it emulates the sudden attack strategy of Harris hawks to refine the solution and achieve high-precision optimization.

Throughout the process, the positions of the Harris hawks represent candidate solutions, while the best solution at each iteration is treated as the prey [46–48]. This innovative structure allows HHO to effectively balance exploration and exploitation, making it a powerful tool for addressing the complexities of microgrid optimization.

Global Exploration Phase

Harris hawks population is randomly distributed across the solution space, performing global searches for the prey (i.e., the optimal solution) using two strategies:

Strategy 1: When the probability

Strategy 2: When the probability

The position update formulas are as follows:

where

Transition from Global Exploration to Local Exploitation

The HHO algorithm divides the hunting process of Harris hawks into exploration and exploitation phases based on their predatory habits. As the prey attempts to escape, its energy gradually depletes. The algorithm dynamically selects either exploration or exploitation behavior depending on the prey’s escape energy. The prey’s escape energy is defined by Eq. (24).

where

Local Exploitation Phase

Harris hawks hunt by besieging the prey and launching sudden attacks. However, the prey may escape during the siege, requiring Harris hawks to dynamically adjust their hunting strategies based on the prey’s behavior. To simulate this process, the HHO algorithm incorporates four strategies: soft besiege, hard besiege, soft besiege with progressive rapid dives, and hard besiege with progressive rapid dives.

The selection of these strategies depends on the prey’s escape energy

1. Soft besiege: Strategy when

When the prey still has escape ability, Harris hawks adopt a soft besiege strategy to gradually deplete the prey’s energy while waiting for the optimal moment to attack. The position update formula is given by:

where

2. Hard besiege: Strategy when

When the prey is unable to escape, Harris hawks launch a hard besiege attack to swiftly capture the prey. The position update formula is given by:

3. Progressive rapid dive with soft besiege: Strategy when

When the prey has an opportunity to escape but is under gradual pressure, Harris hawks adopt a progressive rapid dive strategy. This involves progressively adjusting their positions and optimizing the attack trajectory. The strategy is implemented using two approaches:

Harris hawks assess the potential outcome of this movement compared to the previous dive result to determine whether it is an effective dive strategy. If the result is suboptimal (e.g., the prey exhibits more deceptive movements), they switch to the second strategy.

When Harris hawks encounter deceptive behavior from the prey, they employ irregular, sudden, and rapid dive behavior based on the Lévy flight pattern. The mathematical expression for this strategy is as follows:

where

where

Thus, the final strategy for progressive rapid dive with soft besiege can be expressed by Eq. (30):

Through these two strategies, the HHO algorithm can flexibly adjust its hunting approach in response to different behaviors exhibited by the prey. This adaptability enhances the algorithm’s global search capability and local exploitation efficiency, leading to improved optimization performance.

4. Progressive rapid dive with hard besiege: Strategy when

Although the prey is exhausted, Harris hawks continue to employ the progressive rapid dive strategy to further reduce the distance to the prey, ensuring a successful hunt.

The position update formula for this strategy is similar to that of the progressive rapid dive with soft besiege, and is consistent with Eq. (30) in form. When

The following Fig. 3 illustrates the various strategies employed by the HHO algorithm across different phases.

Figure 3: Different phases of HHO

4.2 Principle of Differential Evolution Algorithm

The HHO algorithm is renowned for its unique Lévy flight mechanism and exceptional global search capability, while the DE algorithm holds a prominent position in the optimization domain due to its effective mutation strategies and population diversity maintenance mechanism. Combining the strengths of these two algorithms can result in a novel hybrid optimization strategy aimed at achieving superior optimization performance.

First, integrating DE’s mutation strategy enhances population diversity, helping to prevent the algorithm from getting trapped in local optima and thereby improving HHO’s global exploration capability. Second, leveraging HHO’s Lévy flight mechanism significantly boosts the algorithm’s jumping ability, enabling it to escape local optima swiftly. When combined with the DE framework, this further enhances the hybrid algorithm’s global optimization performance. Additionally, to better balance the exploration and exploitation capabilities of the algorithm, some studies have introduced multi-strategy approaches (e.g., chaotic strategies, multi-population strategies) in conjunction with DE and HHO to achieve collaborative multi-strategy optimization [49,50]. This hybrid strategy not only retains the advantages of both algorithms but also leverages the complementarity between strategies to improve the algorithm’s performance and adaptability in solving complex optimization problems. In the following section, we delve deeper into the working principles of the differential evolution algorithm.

1. Mutation Strategy

In the mutation step, three distinct individuals

where

2. Crossover Strategy

The crossover strategy combines the corresponding mutant vector

where

3. Selection Strategy

The selection strategy chooses between the trial vector

The algorithm selects the individuals for the next generation based on their fitness values. If the fitness value of the trial individual is better than that of the original individual, the trial individual is selected; otherwise, the original individual is retained.

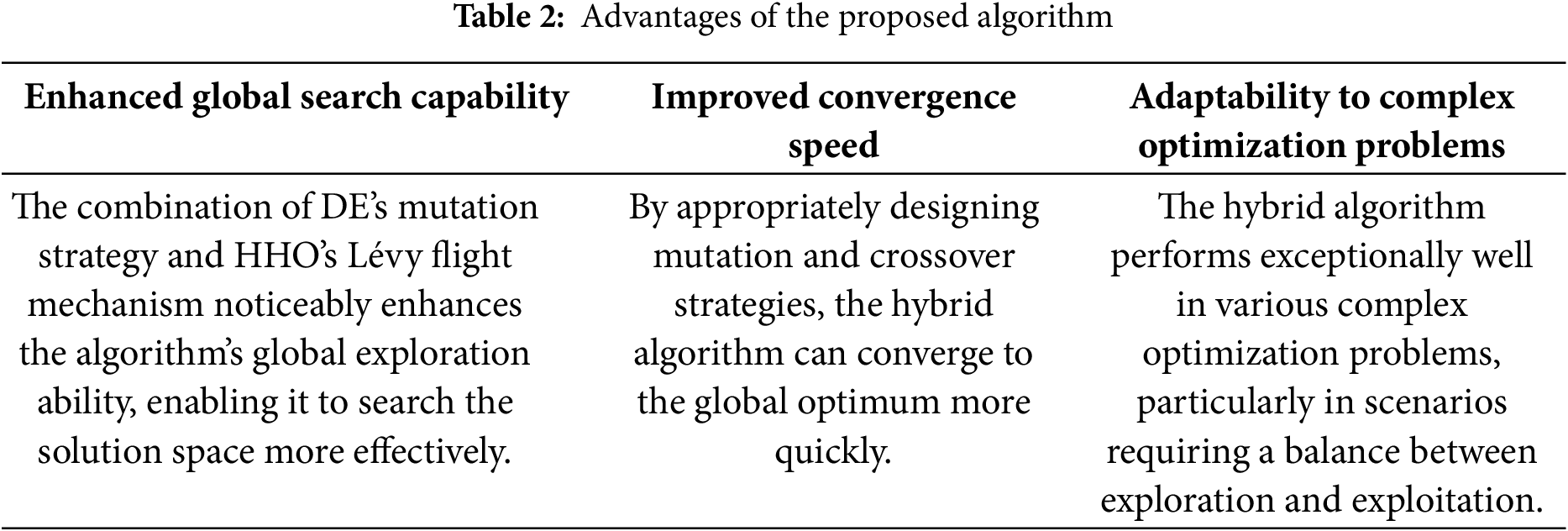

By integrating DE with HHO, an effective hybrid optimization strategy is formulated, which offers several advantages over individual algorithms, as detailed in Table 2.

Thus, through these steps, the DE algorithm effectively explores and exploits the search space to identify the optimal solution to the problem. Fig. 4 illustrates the flowchart of our proposed algorithm.

Figure 4: The flowchart of the proposed algorithm

4.3 DE-HHO Collaborative Mechanism

The collaborative optimization mechanism of the DE-HHO hybrid algorithm is reflected in the multi-level complementarity of the algorithm structure. In the initial stage of the algorithm, DE generates diverse candidate solutions through its unique mutation and crossover strategies. By leveraging stochastic search behavior, DE broadly covers the solution space, thereby preventing the algorithm from prematurely converging to local optima. This process provides a rich set of initial solutions for subsequent optimization, thereby enhancing the algorithm’s global search capability. Subsequently, the HHO algorithm dynamically adjusts its search strategy based on the prey’s escape energy mechanism. It employs Lévy flight and four hunting behaviors to conduct refined searches in the regions of potential optimal solutions. The local exploitation capability of HHO effectively compensates for DE’s deficiency in fine-grained search within the solution space, while the population diversity of DE provides better initial solution distributions for HHO. The synergistic effect of these two algorithms significantly improves the convergence speed and optimization accuracy. During the transition from the exploration phase to the exploitation phase, DE’s mutation strategy introduces population diversity, effectively preventing premature convergence of the algorithm. The mutation operation of DE involves randomly selecting individuals from the population and introducing new mutation information, thereby maintaining a high level of population diversity throughout the iterative process. This diversity helps the algorithm avoid falling into local optima during the global search phase and provides a broader search space for the local exploitation phase of HHO. By integrating DE’s mutation strategy with HHO’s dynamic search mechanism, the DE-HHO algorithm can better balance global exploration and local exploitation capabilities, thus demonstrating stronger adaptability and robustness in solving complex optimization problems.

To ensure that the power balance constraint (Eq. (19)) is always satisfied, we have introduced a penalty mechanism to handle constraint violations or infeasible solutions. When a candidate solution generated by the algorithm violates the power balance constraint, we incorporate a penalty term into the objective function to reduce the fitness value of that solution. The magnitude of the penalty term is proportional to the degree of constraint violation, thereby guiding the algorithm to search for feasible solutions that meet the constraint conditions. The calculation formula of the penalty term is shown in Eq. (36).

where

Moreover, the DE-HHO collaborative mechanism is suitable for addressing model simplification issues in microgrid optimization. In practical applications, due to the complexity of system dynamic characteristics, it is often difficult to construct fully accurate mathematical models. In this study, our model neglects the pitch control dynamics of wind turbines, simplifies the nonlinear characteristics of micro-turbine efficiency variations with load, and assumes a fixed charge-discharge efficiency for energy storage systems, to avoid excessive computational costs that would affect the real-time performance of the optimization algorithm. While these simplifications enhance computational efficiency, they inevitably introduce modeling errors. However, the stochastic nature introduced by the DE-HHO algorithm can effectively cope with the uncertainties arising from such simplifications and provide a certain degree of “compensation.” During the global exploration phase, the DE-HHO algorithm employs stochastic search behavior to effectively explore the solution space and identify potential optimal solutions. This stochasticity can to some extent offset the deficiencies caused by model simplifications, thereby enhancing the adaptability and robustness of the model. Although this approach cannot eliminate the impact of model simplifications, the DE-HHO algorithm can balance global and local search capabilities effectively in the optimization process, thereby mitigating this impact to a certain extent. Experimental results demonstrate that this collaborative mechanism not only improves the robustness of the optimization results but also achieves a good balance between computational efficiency and solution quality.

5 Simulation Results and Analysis

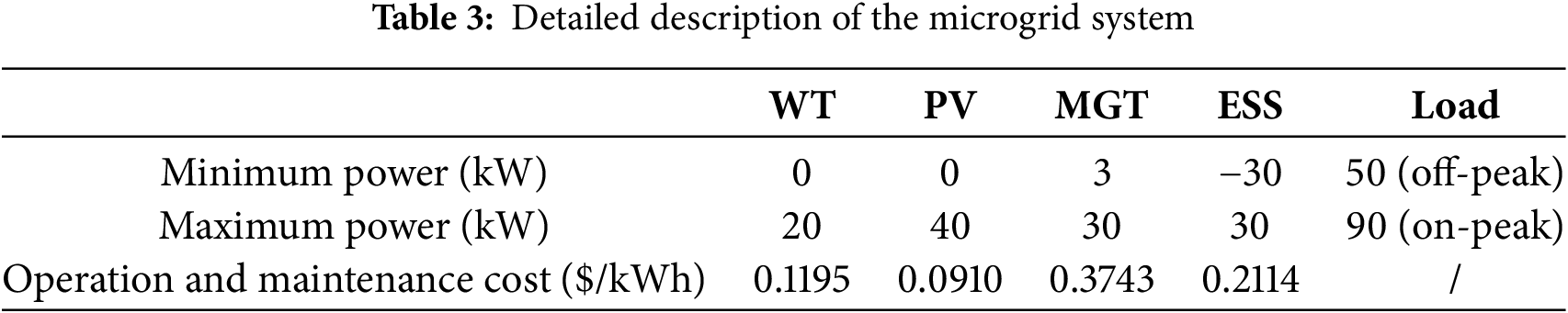

As previously mentioned, this study examines a microgrid system located in an industrial park in the southern region of China, which is composed of wind power generation, photovoltaic (PV) systems, micro gas turbines, and energy storage batteries. The unit parameters of the system are presented in Table 3. Specifically, the maximum power interaction with the main grid, the charge/discharge power of the battery, and the maximum generation power of the gas turbine are all limited to 30 kW. Additionally, negative power values for the battery represent the stored energy in the battery [51]. Furthermore, the power generation of the wind turbine and PV system is influenced by environmental factors and is therefore considered an uncontrollable micro-source, with the rated power reference value used in place of the maximum power. The operating and maintenance (O&M) costs for each distributed generation component are adopted based on empirical values commonly reported in recent literature and industry assessments [52–54].

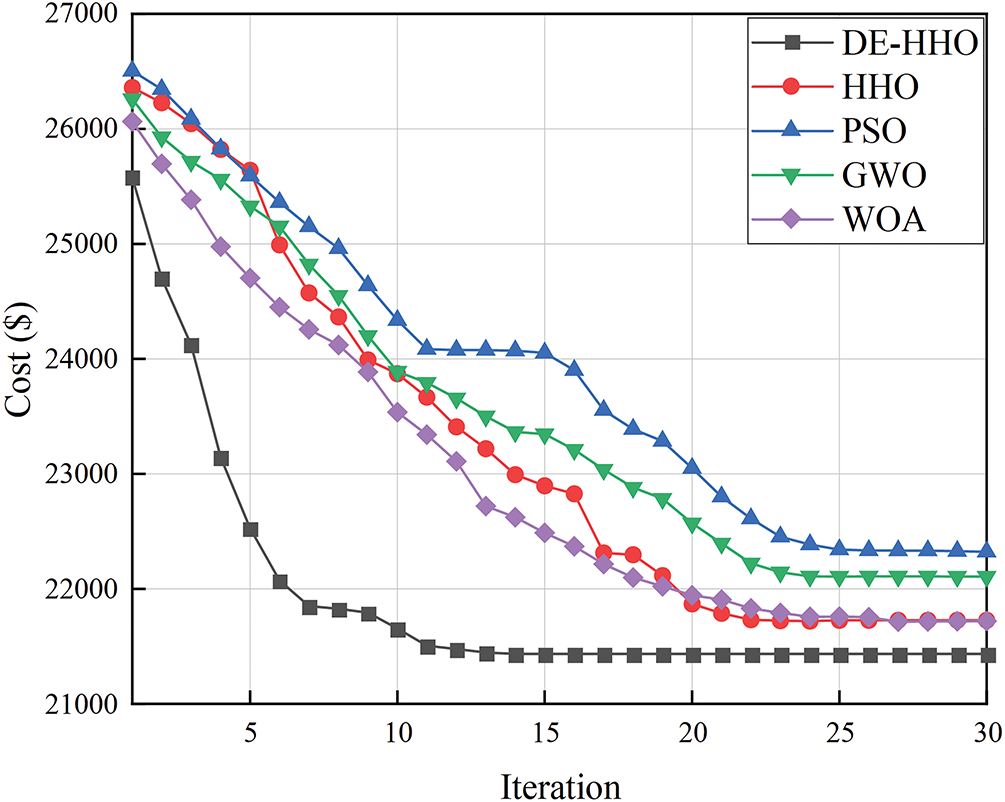

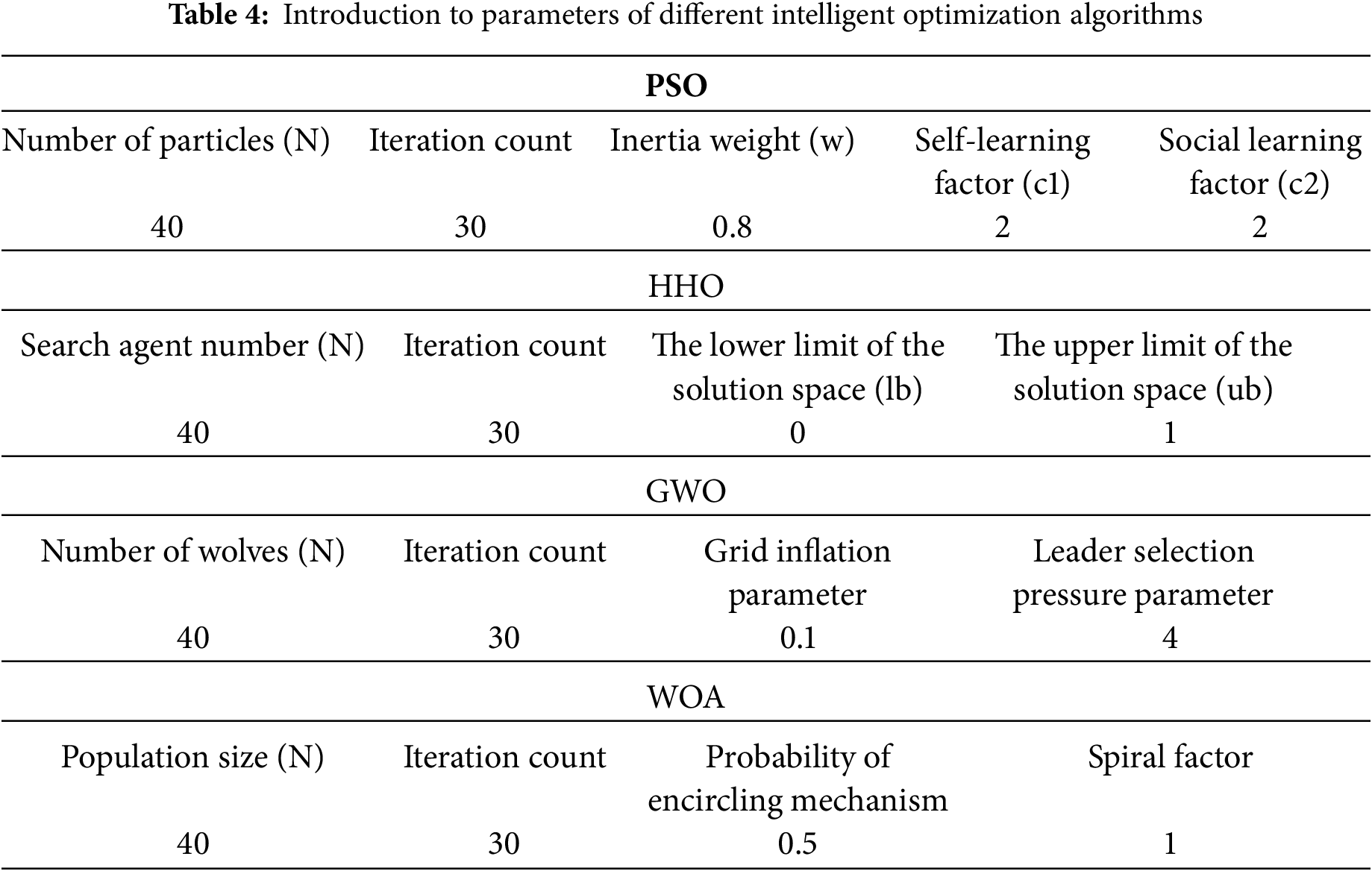

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed DE-HHO in optimizing microgrid tasks, we first constructed models for PSO [51], HHO [29], GWO [55], WOA [56], and the proposed algorithm in the MATLAB R2024a environment. The fitness curves were then compared, as shown in Fig. 5. The y-axis represents the total operational cost of the microgrid system, which is the optimization objective of our study. The parameters for the traditional algorithms are provided in Table 4. Parameter values were determined through grid search and population size and iteration count were kept consistent across all tested algorithms. From Fig. 5, it is evident that DE-HHO converges the fastest, reaching convergence around the 10th generation. In contrast, HHO, PSO, GWO, and WOA tend to get trapped in local optima and take more than 20 iterations to reach their optimal solutions.

Figure 5: Convergence curves of different algorithms

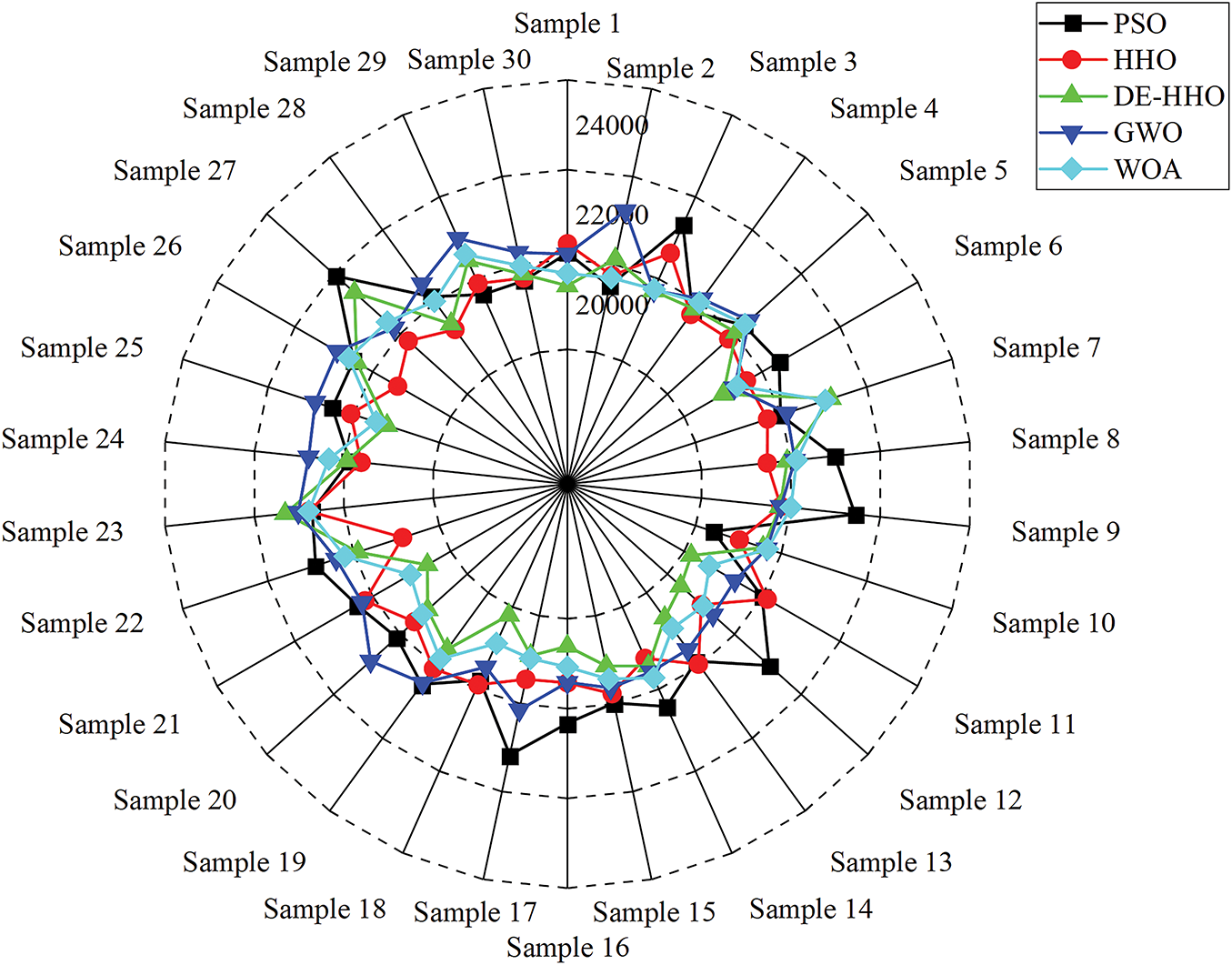

Fig. 6 displays the optimal total cost achieved by different optimization algorithms after 30 repetitions of sampling. As shown in Fig. 5, after multiple experiments, the minimum optimal cost reached by DE-HHO is $20,221.37, significantly lower than the $21,184.45 achieved by PSO, $21,372.24 by HHO, $21,291.43 by GWO and $20,687.68 by WOA. Moreover, the maximum optimal cost achieved by DE-HHO is $23,420.55. Despite the existence of extreme values, the distribution of DE-HHO is concentrated around the mean of $21,615.77, which is notably lower than those of the other four optimization algorithms.

Figure 6: Optimal cost control diagram of different optimization algorithms

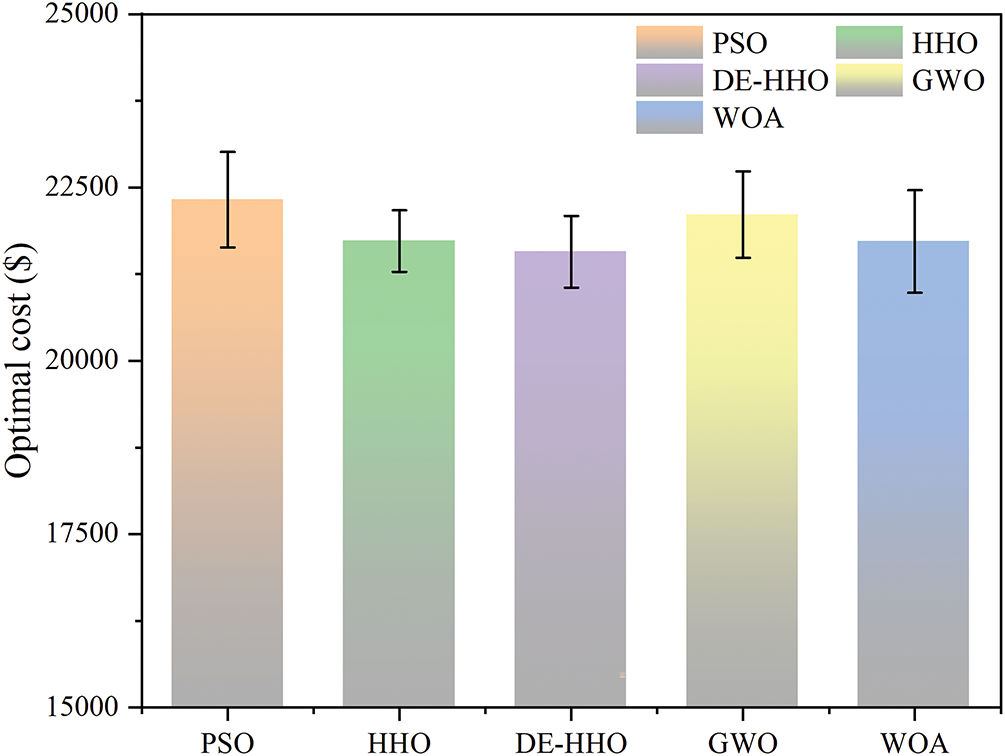

Fig. 7 displays the error bars for all compared optimization algorithms. It can be observed that both HHO and DE-HHO exhibit relatively small errors for their optimal values, with little difference between them. However, the average optimal value achieved by DE-HHO is significantly lower than that of HHO. This demonstrates that the DE-HHO algorithm outperforms the others in finding the optimal solution, with the ability to achieve lower cost values, stronger stability, and superior cost control capabilities.

Figure 7: Error bar plot of the optimal solution

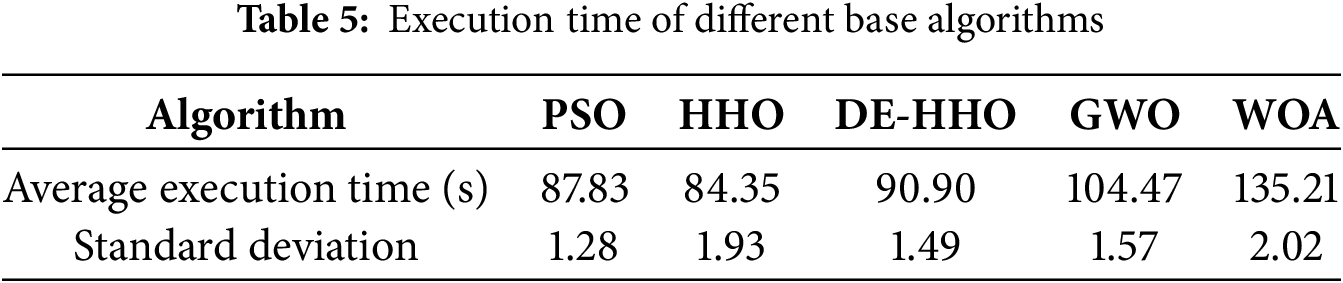

In addition to convergence behavior, we also evaluated the computational efficiency of each algorithm. Table 5 presents the average execution time and standard deviation across multiple runs. As shown, although DE-HHO introduces a hybrid structure, its execution time (90.90 s) remains competitive—only slightly higher than PSO and HHO, and significantly lower than WOA (135.21 s). This demonstrates that DE-HHO achieves a favorable trade-off between optimization performance and computational cost.

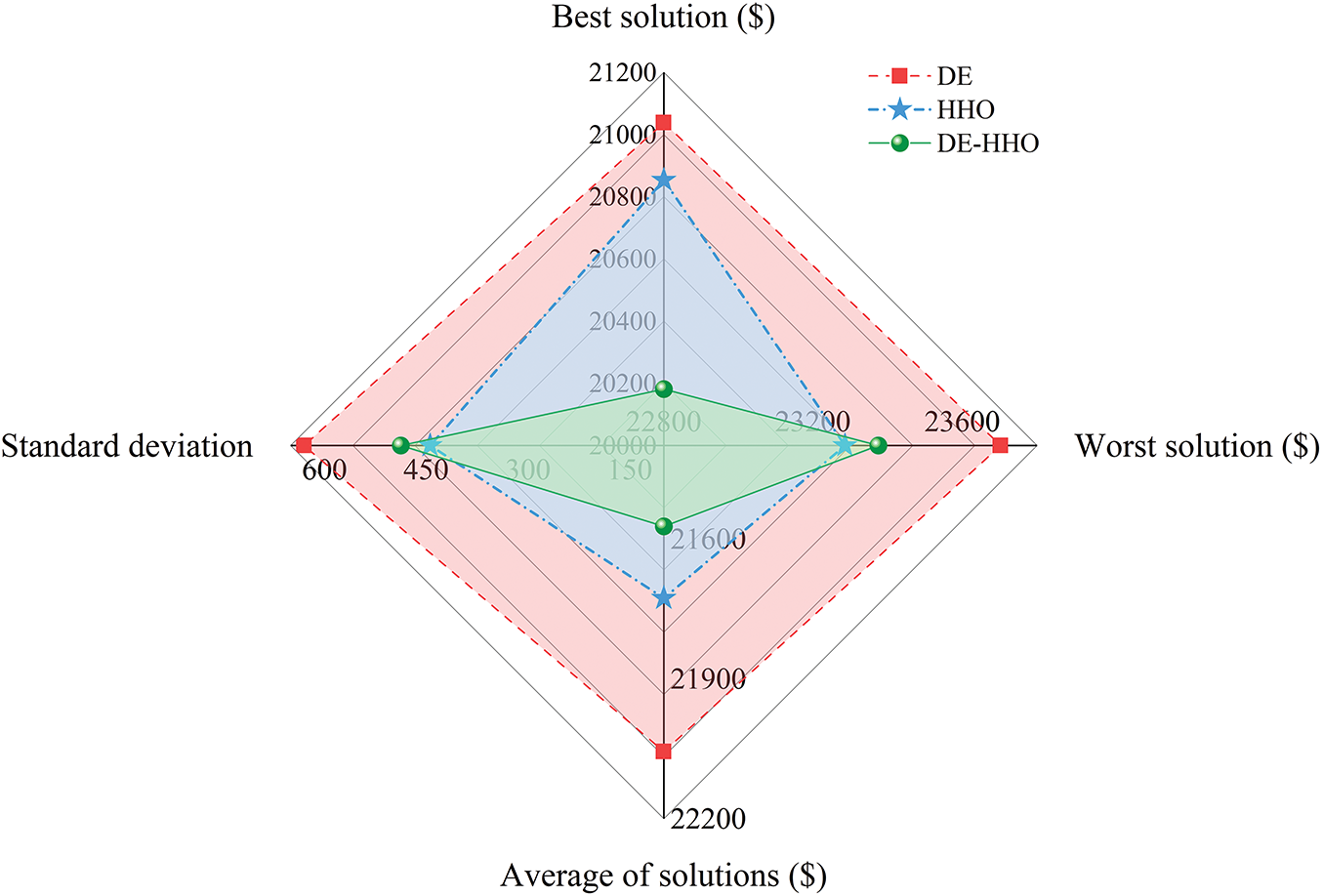

To assess the individual roles of DE and HHO in the proposed algorithm, we conducted an ablation study, with results shown in Fig. 8. DE-HHO achieved significantly better best ($20,181.64) and average ($21,573.30) solution values than either DE or HHO alone. Although the worst-case and standard deviation are similar between DE-HHO and HHO, the hybrid approach demonstrates clear optimization advantages. These results highlight a synergistic effect, where the exploration of DE complements the exploitation of HHO. Standalone DE showed the weakest performance.

Figure 8: Radar chart of ablation study results

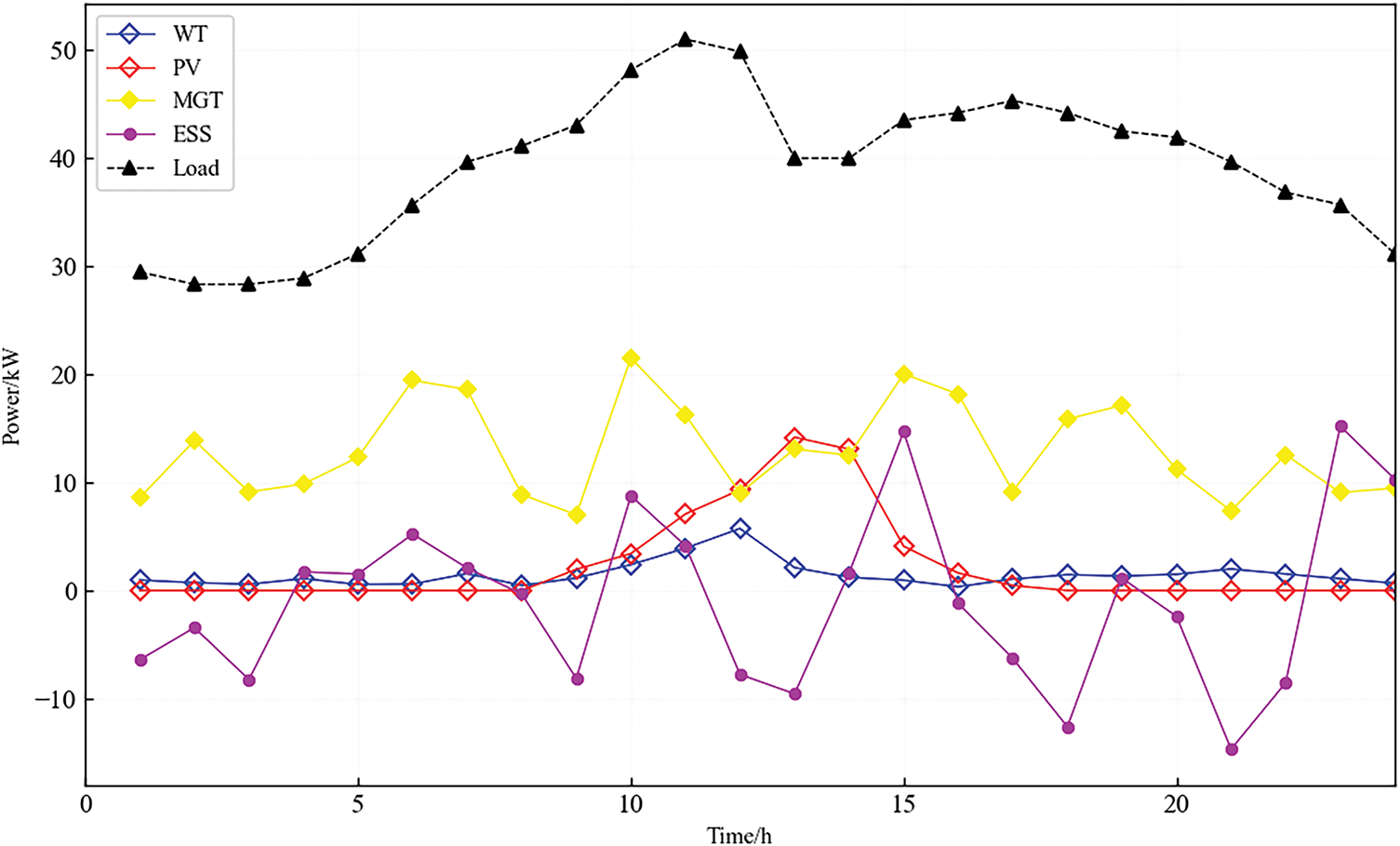

Fig. 9 illustrates the contribution of different DG resources to the microgrid’s power supply during each period under the optimized energy management scheme. The load profile of the microgrid is characterized by fluctuating demands throughout the day, with peak loads occurring during the daytime hours (10:00–18:00) and lower demands during the night. Environmental conditions, such as solar irradiance and wind speed, play a crucial role in the generation capabilities of renewable energy sources within the microgrid. The solar irradiance data used in our simulations reflect typical daily patterns, with maximum values occurring around midday (12:00–14:00). Similarly, wind speed profiles show higher values during the early morning and evening hours, which align with common wind patterns in many regions. During periods of high solar irradiance, photovoltaic (PV) systems contribute significantly to the power supply, while wind turbines provide additional power during the early morning and evening when wind speeds are higher. The micro gas turbines and energy storage systems are utilized to balance the load during peak hours and to ensure a stable power supply when renewable sources are insufficient. Through optimized scheduling, the microgrid can better coordinate the generation and storage strategies of various DG resources to meet electricity demand while minimizing operational costs.

Figure 9: Scheduling results under the DE-HHO strategy

This study introduced the DE-HHO optimization strategy for microgrid energy management, which integrates renewable energy sources such as wind, solar, and micro gas turbines, along with energy storage systems. Through comprehensive simulations, the DE-HHO algorithm consistently demonstrated notable performance, outperforming both PSO and HHO in terms of optimal cost efficiency. It achieved the lowest total optimal cost of $20,221.37, significantly reducing operational costs, and exhibited stronger stability and improved cost control compared to the traditional algorithms. The DE-HHO algorithm proved particularly effective in coordinating the operation of distributed generation resources, optimizing both generation and storage strategies to efficiently meet electricity demand.

Despite these promising results, certain limitations warrant attention. The current system modeling simplifies real-world dynamics by omitting factors such as component degradation, ramp rate constraints, start-up/shutdown behaviors, and inverter efficiencies. Incorporating these aspects would enhance the model’s realism and applicability. Additionally, the model does not account for uncertainties inherent in renewable energy generation and load demand. Future work should integrate stochastic modeling techniques, such as scenario-based or probabilistic approaches, to better capture these uncertainties by conducting sensitivity and parametric analysis. Moreover, the absence of demand response strategies and dynamic grid interactions limits the model’s responsiveness to real-time conditions. Incorporating demand-side management and adaptive control mechanisms could improve system flexibility and resilience. Lastly, the current model lacks dynamic constraints like time-coupling and SOC considerations for energy storage systems. Addressing these factors in future research will contribute to more robust and comprehensive microgrid optimization frameworks. Furthermore, future studies will aim to validate the proposed method on experimental microgrid platforms to further demonstrate its practical applicability.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Jingrui Liu: Conceptualization, Software, Data curation, Formal analysis, Project administration, Writing—original draft and Writing—review &editing; Zhiwen Hou: Methodology, Writing—original draft and Writing—review & editing, Formal analysis, Investigation; Boyu Wang: Data curation and Writing—review & editing; Tianxiang Yin: Data curation, Visualization, Supervision. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Wang YL, Wang YD, Huang Y, Yu H, Du R, Zhang FL, et al. Optimal scheduling of the regional integrated energy system considering economy and environment. IEEE Trans Sustain Energy. 2019;10(4):1939–49. doi:10.1109/TSTE.2018.2876498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Shaier AA, Elymany MM, Enany MA, Elsonbaty NA. Multi-objective optimization and algorithmic evaluation for EMS in a HRES integrating PV, wind, and backup storage. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):1147. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-84227-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Mauludin MS, Khairudin Moh, Asnawi R, Mustafa WA, Toha SF. The advancement of artificial intelligence’s application in hybrid solar and wind power plant optimization: a study of the literature. J Adv Res Appl Sci Eng Tech. 2024;50(2):279–93. doi:10.37934/araset.50.2.279293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Ziaee O, Crouchet B, DeBenedicts C. A multi-agent system framework for managing distributed energy resources (DERs). In: Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE Electrical Energy Storage Applications and Technologies Conference (EESAT). IEEE: Charlotte, NC, USA; 2025 Jan 20. p. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

5. Liu F, Qi S, Wang S, Tian X, Liu L, Zhao X. Robust trading decision-making model for demand-side resource aggregators considering multi-objective cluster aggregation optimization. Energies. 2025;18(2):236. doi:10.3390/en18020236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Opoku K, Dimitrovski A, Ferrari M. Performance evaluation of a novel sequence-based directional detection strategy for protection of active distribution networks. IEEE Access. 2025;13:7094–109. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3525057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Zeng Y, Hussein ZA, Chyad MH, Farhadi A, Yu J, Rahbarimagham H. Integrating type-2 fuzzy logic controllers with digital twin and neural networks for advanced hydropower system management. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):5140. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-89866-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Ahmad Khan A, Faiz Minai A, Godi RK, Shankar Sharma V, Malik H, Afthanorhan A. Optimal sizing, techno-economic feasibility and reliability analysis of hybrid renewable energy system: a systematic review of energy storage systems’ integration. IEEE Access. 2025;13(6):59198–226. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2025.3535520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Saleeb H, El-Rifaie AM, Sayed K, Accouche O, Mohamed SA, Kassem R. Optimal sizing and techno-economic feasibility of hybrid microgrid. Processes. 2025;13(4):1209. doi:10.3390/pr13041209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Thirunavukkarasu GS, Seyedmahmoudian M, Jamei E, Horan B, Mekhilef S, Stojcevski A. Role of optimization techniques in microgrid energy management systems—a review. Energy Strategy Rev. 2022;43(3):100899. doi:10.1016/j.esr.2022.100899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Ahmad Khan A, Naeem M, Iqbal M, Qaisar S, Anpalagan A. A compendium of optimization objectives, constraints, tools and algorithms for energy management in microgrids. Renew Sustain Energ Rev. 2016;58(1):1664–83. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2015.12.259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Zhang T, Hu Z. Optimal scheduling strategy of virtual power plant with power-to-gas in dual energy markets. IEEE Trans Ind Applicat. 2022;58(2):2921–9. doi:10.1109/TIA.2021.3112641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Ren X-Y, Wang Z-H, Li M-C, Li L-L. Optimization and performance analysis of integrated energy systems considering hybrid electro-thermal energy storage. Energy. 2025;314(4):134172. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2024.134172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Nayak CK, Nayak MR, Behera R. Simple moving average based capacity optimization for VRLA battery in PV power smoothing application using MCTLBO. J Energy Storage. 2018;17(1):20–8. doi:10.1016/j.est.2018.02.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Sultan HM, Mossa MA, Zaki Diab AA, Ouanjli NE. Enhanced techno-economical optimal sizing of a standalone hybrid microgrid power system. In: Mossa MA, Ouanjli NE, Ouaissa M, Dhanaraj RK, editors. Energy conversion systems-based artificial intelligence. Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore; 2025. p. 107–38. [Google Scholar]

16. Wang Y, Song F, Ma Y, Zhang Y, Yang J, Liu Y, et al. Research on capacity planning and optimization of regional integrated energy system based on hybrid energy storage system. Appl Therm Eng. 2020;180(6390):115834. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2020.115834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Mehleri ED, Sarimveis H, Markatos NC, Papageorgiou LG. Optimal design and operation of distributed energy systems. In: Computer aided chemical engineering. Vol. 29. The Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier; 2011. p. 1713–7. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-54298-4.50121-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Abood S, Ali W, Attia J, Obiomon P, Fayyadh M. Microgrid optimum identification location based on accelerated particle swarm optimization techniques using SCADA system. J Pow Energy Eng. 2021;9(7):10–28. doi:10.4236/jpee.2021.97002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Abualigah L, Sheikhan A, Ikotun M, Zitar A, Alsoud RA, Al-Shourbaji AR, et al. Particle swarm optimization algorithm: review and applications. In: Metaheuristic optimization algorithms. The Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier; 2024. p. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

20. Zermane AI, Bordjiba T. Optimizing energy management of hybrid battery-supercapacitor energy storage system by using PSO-based fractional order controller for photovoltaic off-grid installation. J Européen Des Syst Autom. 2024;57(2):465–75. doi:10.18280/jesa.570216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Guo S, He Y, Pei H, Wu S. The multi-objective capacity optimization of wind-photovoltaic-thermal energy storage hybrid power system with electric heater. Sol Energy. 2020;195(8):138–49. doi:10.1016/j.solener.2019.11.063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Zhao F, Ji F, Xu T, Zhu N. Jonrinaldi hierarchical parallel search with automatic parameter configuration for particle swarm optimization. Appl Soft Comput. 2024;151(145):111126. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2023.111126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Jamal S, Pasupuleti J, Ekanayake J. A rule-based energy management system for hybrid renewable energy sources with battery bank optimized by genetic algorithm optimization. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):4865. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-54333-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Deng W, Yao R, Zhao H, Yang X, Li G. A novel intelligent diagnosis method using optimal LS-SVM with improved PSO algorithm. Soft Comput. 2019;23(7):2445–62. doi:10.1007/s00500-017-2940-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Pradhan A, Das A, Bisoy SK. Modified parallel PSO algorithm in cloud computing for performance improvement. Cluster Comput. 2025;28(2):131. doi:10.1007/s10586-024-04722-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Papadimitrakis M, Giamarelos N, Stogiannos M, Zois EN, Livanos NA-I, Alexandridis A. Metaheuristic search in smart grid: a review with emphasis on planning, scheduling and power flow optimization applications. Renew Sustain Energ Rev. 2021;145:111072. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2021.111072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Deng W, Xu J, Zhao H, Song Y. A novel gate resource allocation method using improved PSO-based QEA. IEEE Trans Intell Transport Syst. 2022;23(3):1737–45. doi:10.1109/TITS.2020.3025796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Marzband M, Yousefnejad E, Sumper A, Domínguez-García JL. Real time experimental implementation of optimum energy management system in standalone Microgrid by using multi-layer ant colony optimization. Int J Elect Pow Ene Syst. 2016;75:265–74. doi:10.1016/j.ijepes.2015.09.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Heidari AA, Mirjalili S, Faris H, Aljarah I, Mafarja M, Chen H. Harris hawks optimization: algorithm and applications. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2019;97:849–72. doi:10.1016/j.future.2019.02.028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Jiao S, Wang C, Gao R, Li Y, Zhang Q. Harris hawks optimization with multi-strategy search and application. Symmetry. 2021;13(12):2364. doi:10.3390/sym13122364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Liu X, Ma Z, Guo H, Xu Y, Cao Y. Short-term power load forecasting based on DE-IHHO optimized BiLSTM. IEEE Access. 2024;12(17):145341–9. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3437247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Bilal, Pant M, Zaheer H, Garcia-Hernandez L, Abraham A. Differential evolution: a review of more than two decades of research. Eng Applicatf Artif Intell. 2020;90(1):103479. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2020.103479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Bade SO, Meenakshisundaram A, Tomomewo OS. Current status, sizing methodologies, optimization techniques, and energy management and control strategies for co-located utility-scale wind–solar-based hybrid power plants: a review. Eng. 2024;5(2):677–719. doi:10.3390/eng5020038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Yu H, Yang X, Chen H, Lou S, Lin Y. Energy storage capacity planning method for improving offshore wind power consumption. Sustainability. 2022;14(21):14589. doi:10.3390/su142114589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Eze VHU, Eze MC, Ugwu SA, Enyi VS, Okafor WO, Ogbonna CC, et al. Development of maximum power point tracking algorithm based on Improved optimized adaptive differential conductance technique for renewable energy generation. Heliyon. 2025;11(1):e41344. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e41344. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Bendary AF, Ismail MM. Battery charge management for hybrid PV/wind/fuel cell with storage battery. Energy Procedia. 2019;162(4):107–16. doi:10.1016/j.egypro.2019.04.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Bhuvaneswari S, Mohan A, Sundaram A. Improved BMS: a smart electric vehicle design based on an intelligent battery management system. In: Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Inventive Computation Technologies (ICICT). IEEE: Lalitpur, Nepal, 2024 Apr 24. p. 1999–2006. [Google Scholar]

38. Spitthoff L, Gunnarshaug AF, Bedeaux D, Burheim O, Kjelstrup S. Peltier effects in lithium-ion battery modeling. J Chem Phys. 2021;154(11):114705. doi:10.1063/5.0038168. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Rahbarimagham H, Gharehpetian GB. The effect of smart transformers on the optimal management of a microgrid. Elect Pow Syst Res. 2025;238(1):111044. doi:10.1016/j.epsr.2024.111044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Mohapatra S, Sharma S, Sriperumbuduru A, Varanasi SR, Mogurampelly S. Effect of succinonitrile on ion transport in PEO-based lithium-ion battery electrolytes. J Chem Phys. 2022;156(21):214903. doi:10.1063/5.0087824. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Monirul IM, Qiu L, Ruby R. Accurate state of charge estimation for UAV-centric lithium-ion batteries using customized unscented kalman filter. J Energy Storage. 2025;107(4):114955. doi:10.1016/j.est.2024.114955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Balasingam B, Ahmed M, Pattipati K. Battery management systems—challenges and some solutions. Energies. 2020;13(11):2825. doi:10.3390/en13112825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Nyamathulla S, Dhanamjayulu C. A review of battery energy storage systems and advanced battery management system for different applications: challenges and recommendations. J Energy Stor. 2024;86(3):111179. doi:10.1016/j.est.2024.111179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Safavi V, Vaniar AM, Bazmohammadi N, Vasquez JC, Keysan O, Guerrero JM. A battery degradation-aware energy management system for agricultural microgrids. J Energy Storage. 2025;108(6):115059. doi:10.1016/j.est.2024.115059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Alabool HM, Alarabiat D, Abualigah L, Heidari AA. Harris hawks optimization: a comprehensive review of recent variants and applications. Neural Comput Appl. 2021;33(15):8939–80. doi:10.1007/s00521-021-05720-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Shehab M, Mashal I, Momani Z, Shambour MKY, AL-Badareen A, Al-Dabet S, et al. Harris Hawks optimization algorithm: variants and applications. Arch Computat Methods Eng. 2022;29(7):5579–603. doi:10.1007/s11831-022-09780-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Yang T, Fang J, Jia C, Liu Z, Liu Y. An improved harris hawks optimization algorithm based on chaotic sequence and opposite elite learning mechanism. PLoS One. 2023;18(2):e0281636. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0281636. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Fu L, Zhu H, Zhang C, Ouyang H, Li S. Hybrid harmony search differential evolution algorithm. IEEE Access. 2021;9:21532–55. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3055530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Zhu L, Ma Y, Bai Y. A self-adaptive multi-population differential evolution algorithm. Nat Comput. 2020;19(1):211–35. doi:10.1007/s11047-019-09757-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Kamarposhti MA, Shokouhandeh H, Lee Y, Kang S-K, Colak I, Barhoumi EM. Optimizing energy management in microgrids with ant colony optimization: enhancing reliability and cost efficiency for sustainable energy systems. Int J Low Carbon Technol. 2024;19:2848–56. doi:10.1093/ijlct/ctae230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Menzri F, Boutabba T, Benlaloui I, Khamari D. Optimization of Energy management using a particle swarm optimization for hybrid renewable energy sources. In: 2022 2nd International Conference on Advanced Electrical Engineering (ICAEE). Constantine, Algeria: IEEE; 2022. p. 1–5. doi:10.1109/ICAEE53772.2022.9962065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Araoye TO, Ashigwuike EC, Mbunwe MJ, Bakinson OI, Ozue TI. Techno-economic modeling and optimal sizing of autonomous hybrid microgrid renewable energy system for rural electrification sustainability using HOMER and grasshopper optimization algorithm. Renew Energy. 2024;229(3):120712. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2024.120712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Jafari M, Sayyaadi H. Optimal off-grid electricity supply for a residential complex using water-energy-economic-environmental nexus. Energy Convers Manag X. 2025;26(1):100998. doi:10.1016/j.ecmx.2025.100998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. He Y, Ge W, Xiao H. Research on optimization of combined heat and power microgrid based on cooperative game. In: Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Control, Robotics, and Intelligent Systems (CCRIS 2024). Bellingham, WA, USA: SPIE; 2024 Oct 28. Vol. 13404. doi:10.1117/12.3050474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Mirjalili S, Mirjalili SM, Lewis A. Grey wolf optimizer. Adv Eng Softw. 2014;69:46–61. doi:10.1016/j.advengsoft.2013.12.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Mirjalili S, Lewis A. The whale optimization algorithm. Adv Eng Softw. 2016;95(12):51–67. doi:10.1016/j.advengsoft.2016.01.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools