Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Novel Malware Detection Framework for Internet of Things Applications

1 Department of Computer Science and Engineering, University at Buffalo, The State University of New York, Buffalo, NY 14260, USA

2 Department of Computer Sciences, College of Computer and Information Sciences, Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, 11564, Saudi Arabia

3 Information Systems Department, College of Computer and Information Sciences, Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU), Riyadh, 11432, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Author: Muhammad Adil. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 84(3), 4363-4380. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.066551

Received 11 April 2025; Accepted 25 June 2025; Issue published 30 July 2025

Abstract

In today’s digital world, the Internet of Things (IoT) plays an important role in both local and global economies due to its widespread adoption in different applications. This technology has the potential to offer several advantages over conventional technologies in the near future. However, the potential growth of this technology also attracts attention from hackers, which introduces new challenges for the research community that range from hardware and software security to user privacy and authentication. Therefore, we focus on a particular security concern that is associated with malware detection. The literature presents many countermeasures, but inconsistent results on identical datasets and algorithms raise concerns about model biases, training quality, and complexity. This highlights the need for an adaptive, real-time learning framework that can effectively mitigate malware threats in IoT applications. To address these challenges, (i) we propose an intelligent framework based on Two-step Deep Reinforcement Learning (TwStDRL) that is capable of learning and adapting in real-time to counter malware threats in IoT applications. This framework uses exploration and exploitation phenomena during both the training and testing phases by storing results in a replay memory. The stored knowledge allows the model to effectively navigate the environment and maximize cumulative rewards. (ii) To demonstrate the superiority of the TwStDRL framework, we implement and evaluate several machine learning algorithms for comparative analysis that include Support Vector Machines (SVM), Multi-Layer Perceptron, Random Forests, and k-means Clustering. The selection of these algorithms is driven by the inconsistent results reported in the literature, which create doubt about their robustness and reliability in real-world IoT deployments. (iii) Finally, we provide a comprehensive evaluation to justify why the TwStDRL framework outperforms them in mitigating security threats. During analysis, we noted that our proposed TwStDRL scheme achieves an average performance of 99.45 % across accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, which is an absolute improvement of roughly 3 % over the existing malware-detection models.Keywords

Malware refers to software created to infiltrate or harm a computer system without the user’s explicit consent. Malware has different types, and can be classified based on its specific actions, such as worms, backdoors, ransomware, trojans, spyware, rootkits, adware, etc. [1]. According to the Computer Economics reports, financial losses increased significantly every year due to malware attacks [2]. In 2016, the WannaCry ransomware attack affected computers in more than 150 countries, causing financial damage to various organizations [3]. In 2024, the projected financial loss due to malware attacks is expected to reach $9.5 trillion globally, a 19% increase from the estimated $8 trillion in losses in 2023 [4]. Ransomware alone is projected to cost victims $265 billion annually by 2031. Moreover, it has been reported that cybercriminals are now using more advanced techniques to quickly compromise the system’s security, with reduced average execution time from 60 days in 2019 to just 4 days in 2023 [5]. The financial sector is deeply concerned about technological security. To address this, they aim to design reliable and trustworthy countermeasures that can protect both individuals and institutions. These groups face significant risks from phishing attacks and social engineering tactics, which threaten their customer’s trust and security.

In the literature, several antivirus software solutions such as Avast, Norton, McAfee, Kaspersky, AVG, and Bitdefender have been developed to counter various cyberattacks. These softwares rely on a short sequence of bytes, known as a signature, to detect malware within systems. However, they have significant limitations, especially when it comes to defending against zero-day attacks. These attacks exploit vulnerabilities that are unknown to these antivirus software. This challenge is further aggravated by the rise of malware generation toolkits, such as Zeus. These toolkits enable cybercriminals to generate thousands of malware variants through various obfuscation techniques, which makes the traditional signature-based detection technique less effective. In addition, malware is evolving daily, while signature generation is often human-driven, which creates a log in the detection process. All this makes it increasingly difficult to detect new malware with the help of older detection techniques. In light of these factors, relying solely on traditional antivirus approaches may not be enough, because the nature of malware attacks changes continuously. Therefore, more advanced and adaptive security solutions could be used to identify and mitigate emerging threats in real time.

In this paper, we propose a TwStDrl-enabled malware detection framework for IoT applications. We use a deep reinforcement learning algorithm to enable the system to learn and adapt in real time to evolving malware behavior. This real-time adaptability allows the framework to effectively detect and prevent malware infiltration in these applications. To evaluate the effectiveness of our model, we considered rival algorithms such as SVM, random forest, k-means, and other state-of-the-art solutions. This comparative analysis assesses how the TwStDrl-based framework outperforms existing methods in detecting and mitigating malware in IoT applications. In addition, the model is designed in a way to be lightweight and resource-efficient by considering the limited computational resources of IoT devices. The main contributions of this work are summarized below.

• In this work, we propose a TwStDrl-enabled framework that efficiently distributes malware detection tasks in two stages across IoT devices to reduce detection time. The framework primarily uses deep reinforcement learning algorithms, enabling real-time learning and adaptation to the evolving nature of malware threats.

• The two-step task scheduling strategy combines static and dynamic task management with presorting techniques, using Johnson’s rule. This helps the model to adapt in real time and ensures the effective and timely completion of malware detection tasks across the network.

• Johnson’s rule, used in the model, facilitates an optimal sequence for task processing. This optimization enhances both the detection and response rates to evolving security threats in IoT applications.

• In the subsequent phase, we implement various algorithms such as Support Vector Machine (SVM), Random Forest, K-Means, and Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) to evaluate the performance of the proposed model in comparison to these methods on different datasets.

• Finally, we compare the results of the TwStDrl algorithm with SOTA solutions and implemented algorithms to demonstrate why this algorithm is necessary and how it outperforms existing solutions.

Paper Structure: In this section, we cover the related work by providing readers with a glimpse into what has been achieved thus far in this domain. Moving on, Section 3 introduces our proposed model. In Section 4, we explore various algorithms and state-of-the-art schemes with their results that have been selected for comparison. Finally, Section 5 wraps up the paper by summarizing our findings and concluding remarks.

In this section, we discuss the latest schemes used to counter malware attacks in IoT applications. Moreover, we highlight the limitations of existing techniques to establish a foundation for the proposed work in their presence. Given that, Glani et al. [6] proposed an advanced malware detection technique for IoT applications that targets hardware and source code vulnerabilities. In this model, the author used the Adler-32 hash function and Fibonacci search algorithms collectively to resolve this issue. However, the authors did not discuss the complexity and computation requirements of this model in real-time operation, which keeps it in a fuzzy state. In [7], the authors introduced convolutional neural networks (CNNs) for dynamic malware analysis considering edge devices. In this model, the authors converted the extracted behavior data into images to improve detection rate and accuracy. However, performing such a complex task on the edge of the network introduces significant computational complexity, which leads to slow response time during attacks. Htwe et al. [8] proposed a hybrid paradigm of feature selection method with a CART learning algorithm to tackle malware security vulnerability issues in IoT applications. The authors claimed 100% accuracy for the proposed model, with only botnet attacks. However, it is very hard to implement and use this model based on one attack detection. It could be interesting to check the results of the proposed model against different known and unknown attacks.

In [9], the author proposed an enhanced lightweight antivirus solution for embedded IoT devices. In this paradigm, they used graph theory with a measurement-based rational selection technique to appropriately set threshold levels for malware detection. However, the dependency on specific threshold parameters may affect the result statistics, and inhibit its use in real deployment. Deng et al. [10] proposed a transformer-based malware detection framework for IoT applications. The authors focused on the edge computing paradigm to address the limitation of centralized techniques and enhance the efficiency of malware detection by offloading computation-intensive tasks to nearby edge nodes. In [11], the authors proposed an Intelligent Trusted, and Secure Edge Computing (ITEC) malware detection approach for IoT applications. In this model, they used a signature-based pre-identification mechanism to detect malicious behaviors of untrusted third-party applications to categorize network traffic. However, the proposed model is sensitive to communication delay, throughput, and congestion issues, and could not be adopted in real IoT applications. Reference [12] introduced a novel CNN-based approach for malware detection in IoT Android applications. The author tested the proposed model on a specific dataset with defined rules and achieved remarkable results. However, it is still necessary to evaluate the proposed model on different datasets to see the statistical results, as machine learning models are susceptible to many internal and external threats.

In [13], the author proposed a graph compression algorithm with reachability relationship extraction (GCRR) to resolve the malware detection issue in Android applications. In the result analysis, the authors claimed that their model can detect malware in these applications 1.53% to 39.13% accurately compared to existing static methods. In [14], the author proposed a host-based anomaly detection system for IoT applications to resolve security problems. However, it is not clear how the proposed model is evaluated for different attacks. In [15], the authors introduced an event-aware Android malware detection system by considering the network traffic behavioral patterns. Moreover, the authors used event groups to capture higher-level semantics than API-level threats. However, the clustering complexity of the proposed model raises computation challenges, and may inhibit the deployment of this model. Vasan et al. [16] proposed a robust cross-layer architecture-based malware detection scheme for IoT applications. In this model, the author used RNNs and CNNs collectively to improve the attack detection accuracy. However, this model was checked on a specific dataset during training and testing. Therefore, it is important to evaluate it on different datasets, considering the requirements of IoT applications. Shahid et al. [17] proposed a sparse autoencoder-based malware detection paradigm for IoT applications. This approach characterizes network behavior using statistics on the size and inter-arrival times of the first N packets in bidirectional TCP flow to improve the attack detection rate. However, a limitation of this method is specific characteristics of the smart home dataset, which was used for training, may not fully capture the diversity of IoT network behaviors in real-world scenarios.

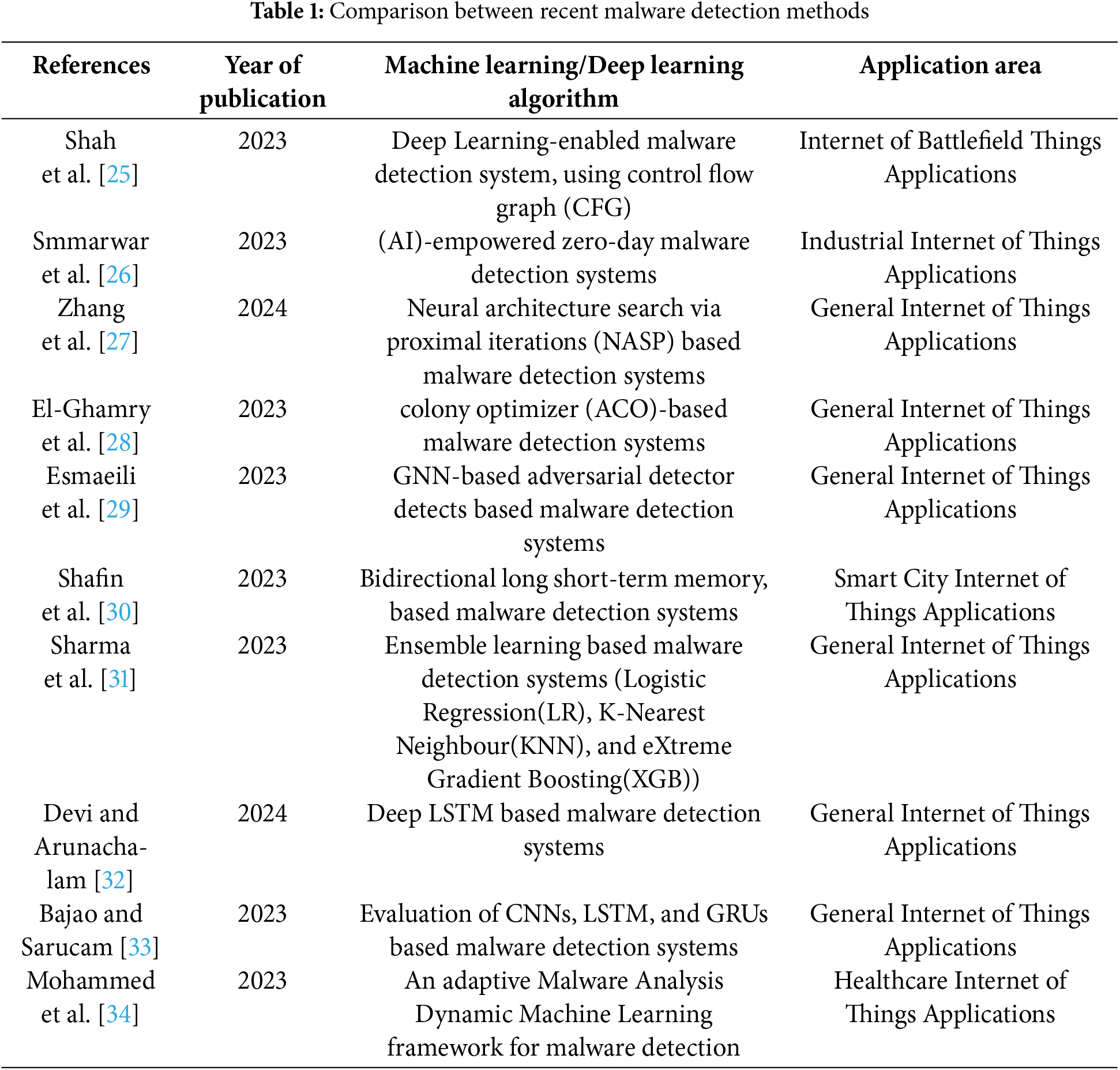

In [18], the authors checked the application of one-class classification for malware detection in IoT applications using unsupervised learning techniques, while Almazroi [19] proposed a BERT-based feed-forward neural network framework to resolve the malware vulnerabilities detection problems in IoT applications. However, this model is complex and was checked on one dataset. Therefore, it is necessary to evaluate the proposed model on different datasets. Ahmad et al. [20] an advanced classification model for IoT malware detection using an optimized SVM algorithm. For optimization, they used nuclear reactor optimization (NRO), Artificial rabbits optimization (ARO), and particle swarm optimization (PSO) collectively to improve the classification accuracy. The authors claimed better results in the presence of state-of-the-art schemes. However, it is difficult to implement this model at the edges of IoT applications, where sensors and actuators will be working to collect and process data. In [21], the authors propose a serverless-based intelligent framework known as “CloudIntellMal” for detecting Android malware, while Sharma et al. [22], propose a multi-dimensional hybrid Bayesian belief network model to detect APT malware. This model is useful in the redressal of evasion attacks missed by signature-based solutions. In [23], the authors propose a graph–embedding framework known as IHODroid for Android malware detection. They evaluate it on the DREBIN dataset and demonstrate excellent results compared to existing baseline models. Moreover, we suggest the general readers to review article [24] to have a basic and advanced level understanding of malware and what has been done so far in the field and what is needed in the future. Following this, we added Table 1 in the paper to provide a more comprehensive analysis of the state-of-the-art schemes.

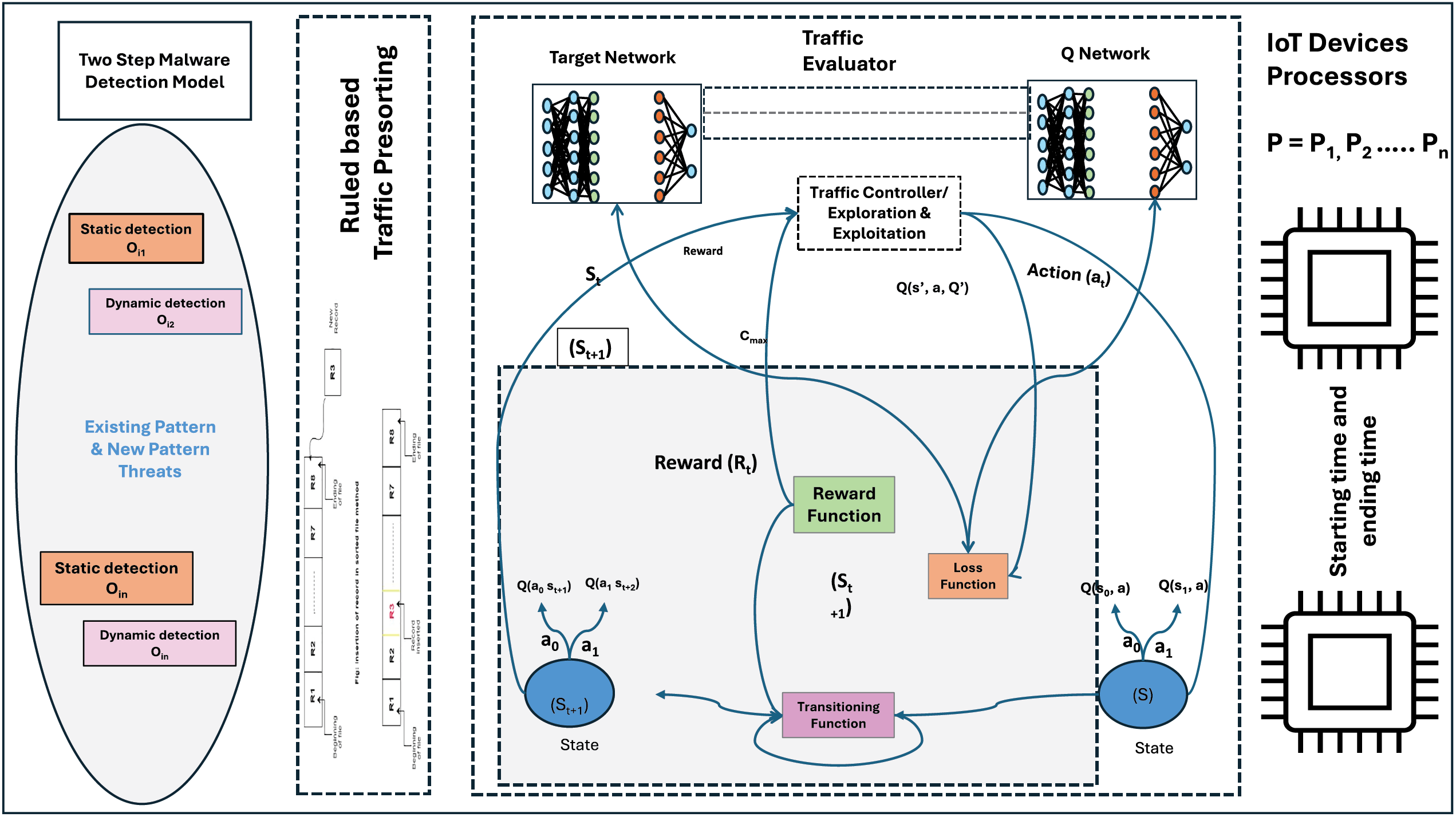

In this section, we thoroughly talk about the proposed TwStDrl-enabled malware detection framework. For visual illustration, we added Fig. 1 in the paper.

Figure 1: Architecture of the TwStDRL-enabled malware detection model, which integrates static and dynamic detection. The incoming traffic is first filtered based on predefined rules before being processed by the traffic evaluator. This evaluator, driven by a Q-network and a target network, continuously improves detection by balancing exploration (discovering new threats) and exploitation (using known patterns). A reward function enhances learning, while a loss function fine-tunes accuracy. IoT devices perform detection tasks according to a scheduled workflow by ensuring fast and efficient malware identification

The primary goal of our proposed model is to enable malware detection directly at the network edge. To achieve this, it combines static and dynamic analysis into a unified task-management framework, using a presorting technique based on Johnson’s rule alongside deep-learning decision making. Detection tasks are then distributed across N IoT devices and

We address the resulting NP-hard scheduling problem by incorporating Johnson’s rule optimization with deep-reinforcement-learning–based adaptive weighting. Task durations

Following this, a scheduling controller within the proposed model manages task execution at the network edge by continuously monitoring the system’s state and selecting optimal scheduling actions based on data processing and threat analysis. The controller comprises three coordinated components such as Johnson’s Rule–based presorting, load monitoring, and DRL action selection, which together ensure efficient task allocation. This framework is built on two key principles: Concept 1: It provides an optimal scheduling solution for single-processor devices, ensuring real-time malware detection. Concept 2: It guarantees that any subset derived from the task list remains optimally sequenced according to the model’s defined rules.

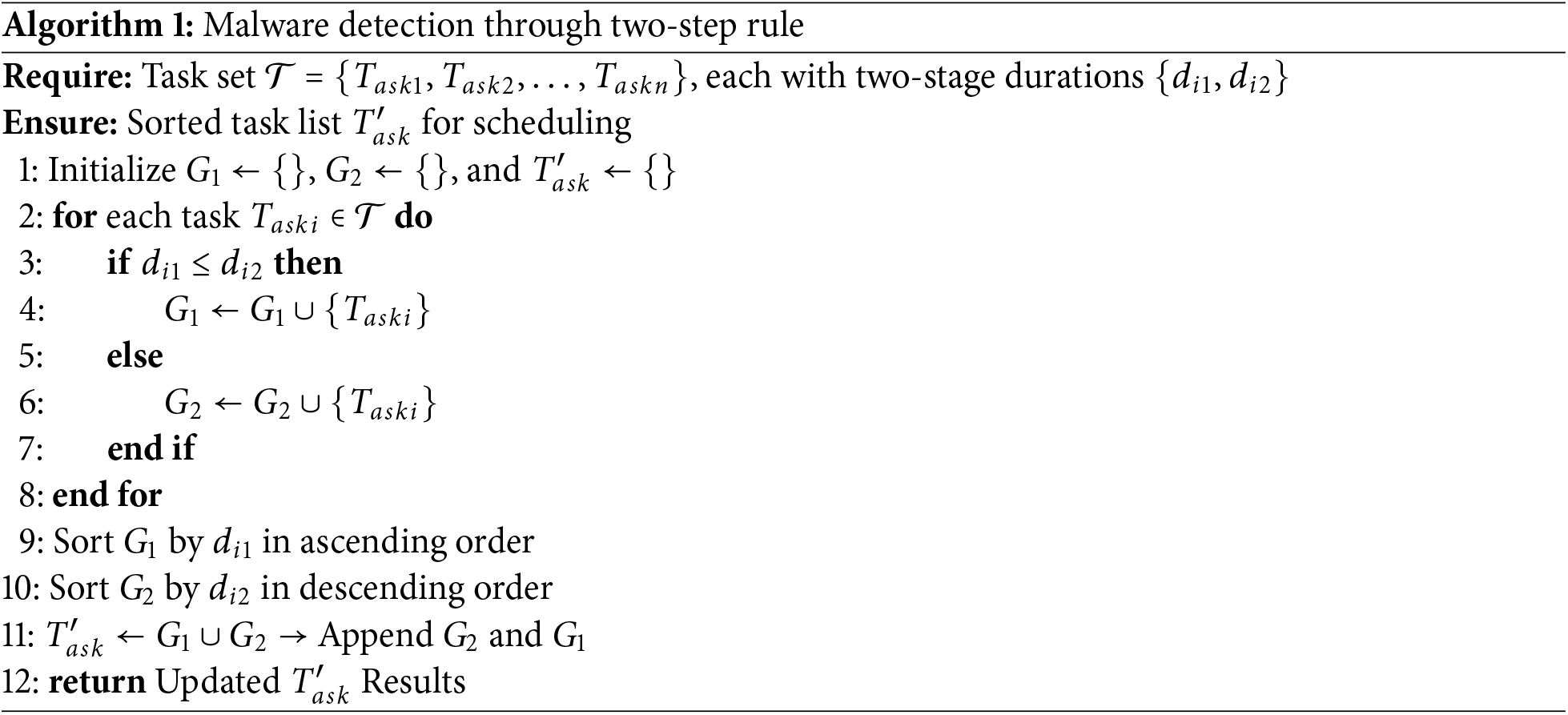

Following Concept 1, our model improves malware detection accuracy across multiple processors by initially sorting them into a list. While Concept 2, allocates to each processor a task (dynamic data) to form subsets of the initial list (static dataset). This presorting guarantees that the parallel processing of tasks on each processor is optimally arranged to identify malware patterns in the network. Moreover, these steps are summarized in Algorithm 1.

In Algorithm 1, we showed how tasks are divided into two groups,

3.1 Operational Steps of the Edge-IoT Devices

In IoT applications, detecting malware at the network edge is very important to ensure security. To achieve this, we use a two-step deep reinforcement learning (DRL) model that works in two phases: identification and mitigation of malware threats. The proposed model is formulated as a Markov Decision Process (MDP), which is defined by the following four-tuple representation:

• State Space (S): The state space at time

• Action Space (A): The action space, A, comprises all feasible countermeasures against potential malware threats, including responses deployed across the network connected IoT devices.

• Transition Probability (P): The function

• Reward Function (R): The reward,

In our proposed model, the state (

In (2),

Given the current network state, the action

In (3),

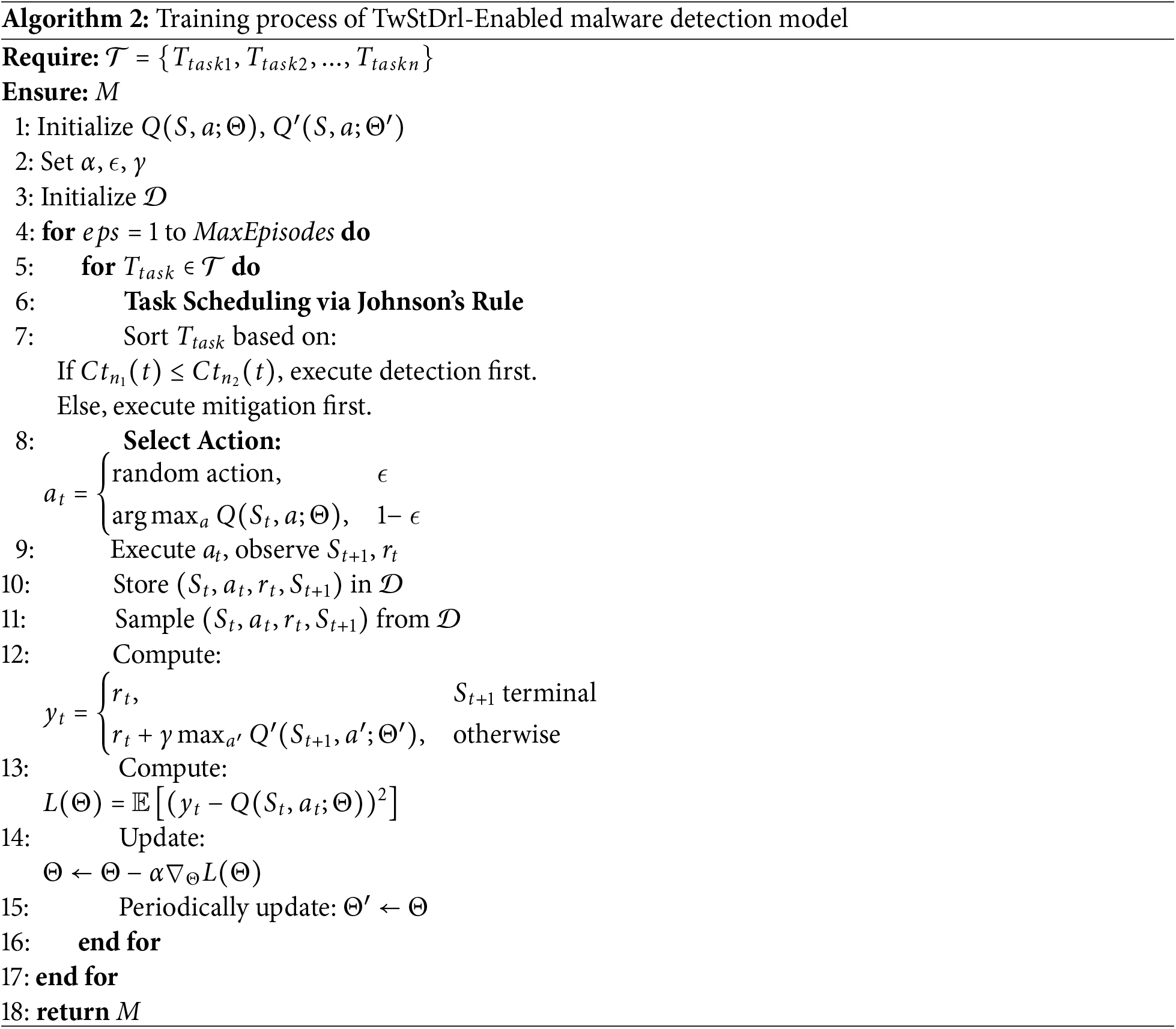

For clarity, we added Algorithm 2 in the paper how the TwStDrl-enabled malware detection model works during the training process.

Model Initialization: The action-value function

Training Process:

The training occurs over multiple episodes, where the model learns from a series of tasks denoted by T in batches of 32 samples. The learning process uses an Adam optimizer with a learning rate of

Before selecting an action, tasks are pre-sorted using Johnson’s Rule to optimize execution efficiency. The task sequence is determined based on detection and mitigation times as follows:

The reward function combines binary classification accuracy (taking values of

Upon selecting an action

Q-Value Update: To update the action-value function, a minibatch of stored transitions is sampled from

Here, the reward

Loss Computation and Optimization: The difference between the predicted Q-value and the target Q-value

A gradient descent step is then applied to update the model parameters:

By incorporating Johnson’s Rule in task prioritization, this optimization ensures that the model learns a task-aware policy, improving detection and mitigation efficiency.

Target Network Synchronization: To stabilize learning, the target network Q′ is periodically synchronized with the updated Q-network:

Completion of Training: After executing the training process over multiple episodes, the optimized TwStDrl-enabled malware detection model is trained with an adaptive scheduling mechanism.

In this section, we discuss the setup adopted for the implementation and evaluation of the proposed TwStDrl model. For implementation, we used Laptop Intel(R) Core(TM) i5-1035G1 CPU @ 1.00 GHz 1.19 GHz, 32.0 GB (31.8 GB usable) with Google Colab Pro version. In addition, we employed the TensorFlow and PyTorch frameworks to build and train the TwStDrl models. This framework’s architecture is flexible and dynamic for the computation of random changes in the IoT traffic. The real-time learning process mitigates the risk of overfitting and helps to improve the model results.

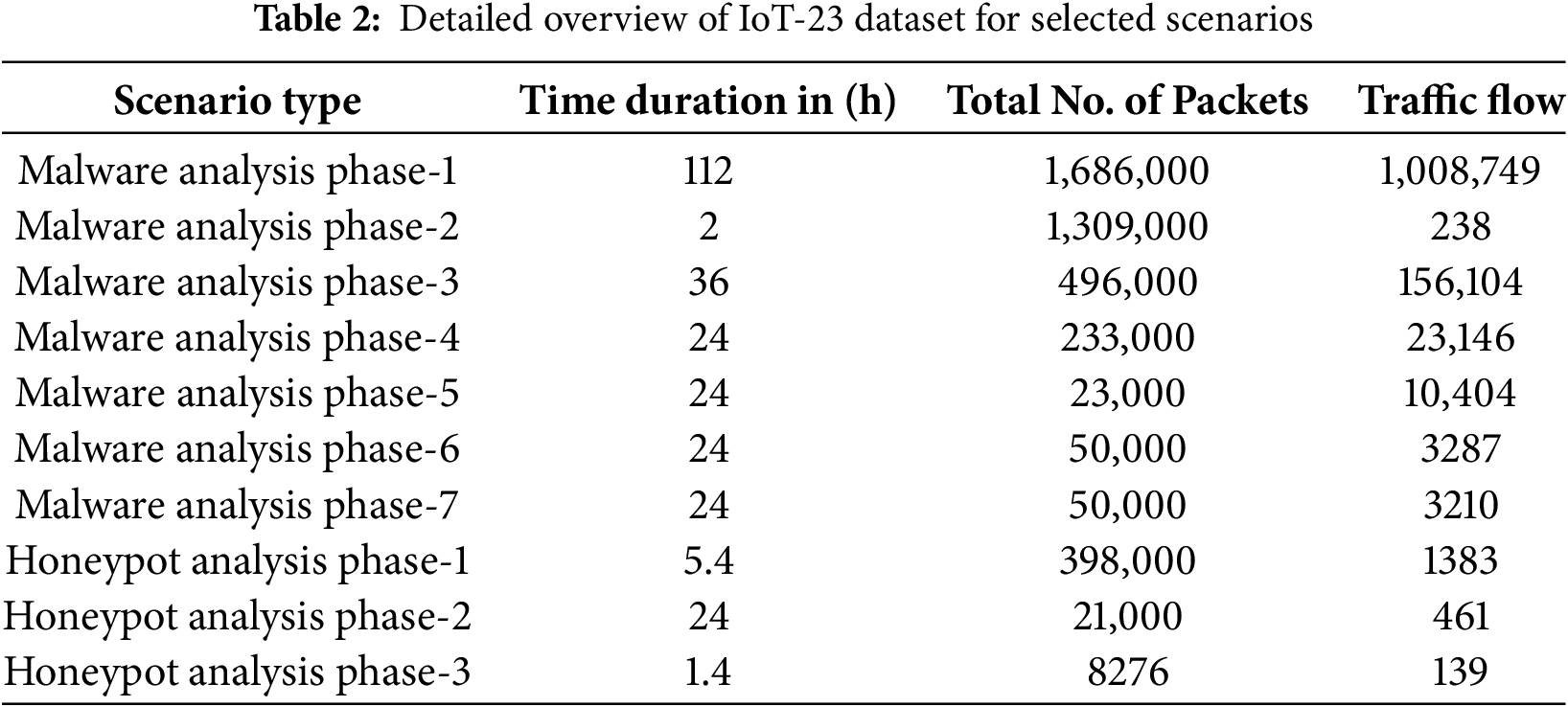

For our experiments, we utilized the IoT-23 dataset, which comprises network traffic data of 23 different scenarios, including three benign and 20 malicious traffic patterns that belong to 11 distinct IoT botnet families. Specifically, it includes seven Mirai variants, two Torii instances, two Kenjiro samples, and one capture each of Gafgyt, Okiru, Hakai, IRCBot, Linux.Mirai, Linux.Hajime, Muhstik, and Hide-and-Seek. Given that diversity, it provides a comprehensive representation of real-world IoT network activities, which makes it well-suited for evaluating the performance of the TwStDrl model. To ensure robust model training and validation, we partitioned the dataset into three subsets such as 70% for training, 10% for validation, and 20%.

The benign data was collected from real-world IoT devices such as smart door locks, smart sensors, smart LED lamps, and other actuators commonly used in IoT applications. These devices provide an accurate representation of typical IoT network behavior, and form a baseline for detecting malicious activities. Given the large size of the IoT-23 dataset, our analysis focuses on differentiating malicious and benign traffic to ensure an effective evaluation of our proposed model. A detailed characterization of the dataset is provided in Table 2.

To achieve better results, it is important to prepare the data beforehand. First, we build a data pipeline that handles both malware and normal traffic by utilizing a dataset containing multiple malware families. We create a Label column (1 for malware, 0 for benign) for the binary classifier, and preserve each sample’s family name in a separate Family column for auxiliary analysis. Unnecessary columns are removed, and missing values are filled with zeros.

Next, we convert non-numeric fields into model-ready formats. IP addresses are encoded as float64 values by processing each octet. Protocol types (the proto field) are one-hot encoded. Port numbers (id.resp_p) are binned into the three standard IANA ranges—well-known (0–1023), registered (1024–49,151), and ephemeral (49,152–65,535)—using quantile discretization. This preserves key network-behavior patterns while reducing dimensionality.

To ensure a fair evaluation across all eleven malware families, we perform stratified splitting at two levels: maintaining the malware-to-benign ratio for the binary task, and preserving each family’s relative proportion for family-level analysis. Within each split, we apply Z-score normalization to continuous features only, using training-split statistics to prevent data leakage.

Finally, we address class imbalance by (1) weighting malware samples three times more heavily than benign ones during binary training; (2) sampling more frequently from rare families during the DRL phase; and (3) adding dynamic rewards that penalize misclassifications of low-frequency families.

In this section, we discuss the comparative performance of the proposed algorithm against other established algorithms that have been considered in this research to practically check their results on the IoT2023 datasets. In the first phase, we trained the selected algorithms, including our proposed model, to ensure they were adequately prepared for evaluation.

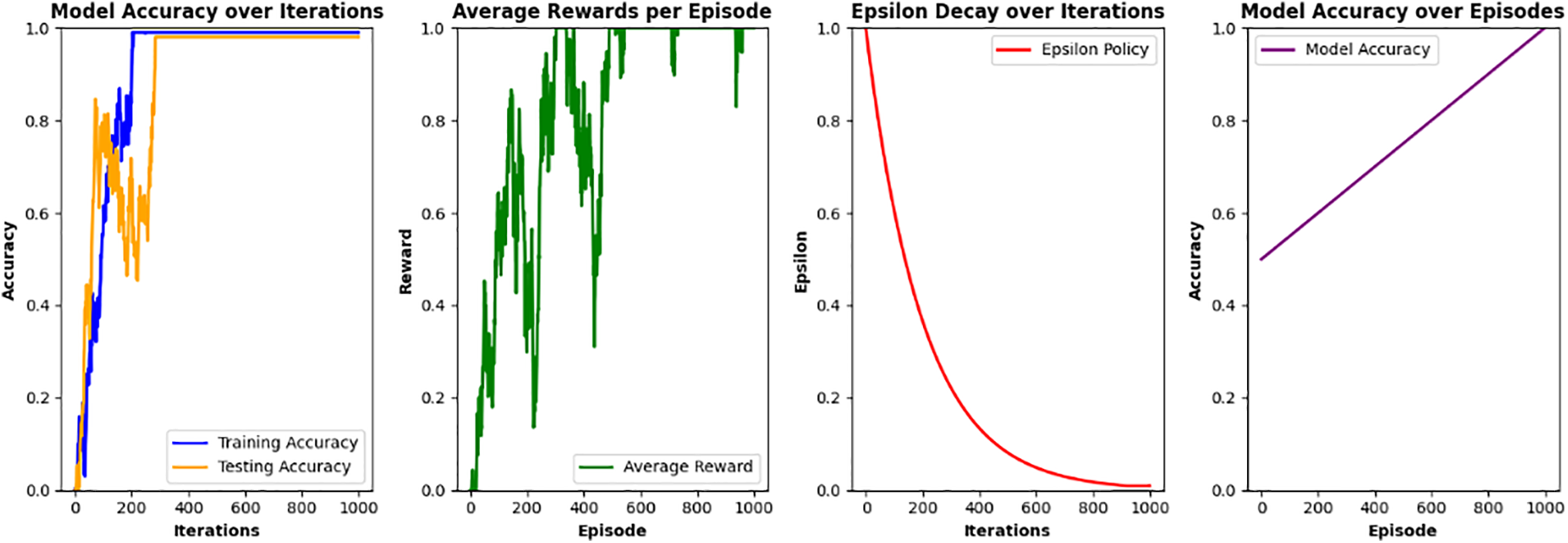

4.1 Proposed Model Convergence Result Statistics

This training process included hyperparameter tuning and cross-validation to optimize model performance and mitigate overfitting. Each algorithm was subjected to a consistent training process with the utilization of the same training data split to ensure a fair comparison. This approach allowed us to assess the generalization capabilities of each model under similar conditions by providing a robust basis for evaluation. Following the training phase, we conducted a comprehensive evaluation of the algorithms based on several things to see the model convergence. These metrics are crucial for understanding the effectiveness of each model in detecting malware, particularly in the context of IoT environments where false positives can lead to significant operational disruptions. The comparative analysis not only highlighted the strengths and weaknesses of the proposed model relative to existing algorithms but also provided an understanding of the specific characteristics of the datasets that influenced performance. By analyzing the results, we identified areas for improvement in our model and gained a deeper understanding of the challenges associated with malware detection in diverse IoT scenarios. The results obtained for TwStDrl are shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: TwStDrl model convergence result statistics

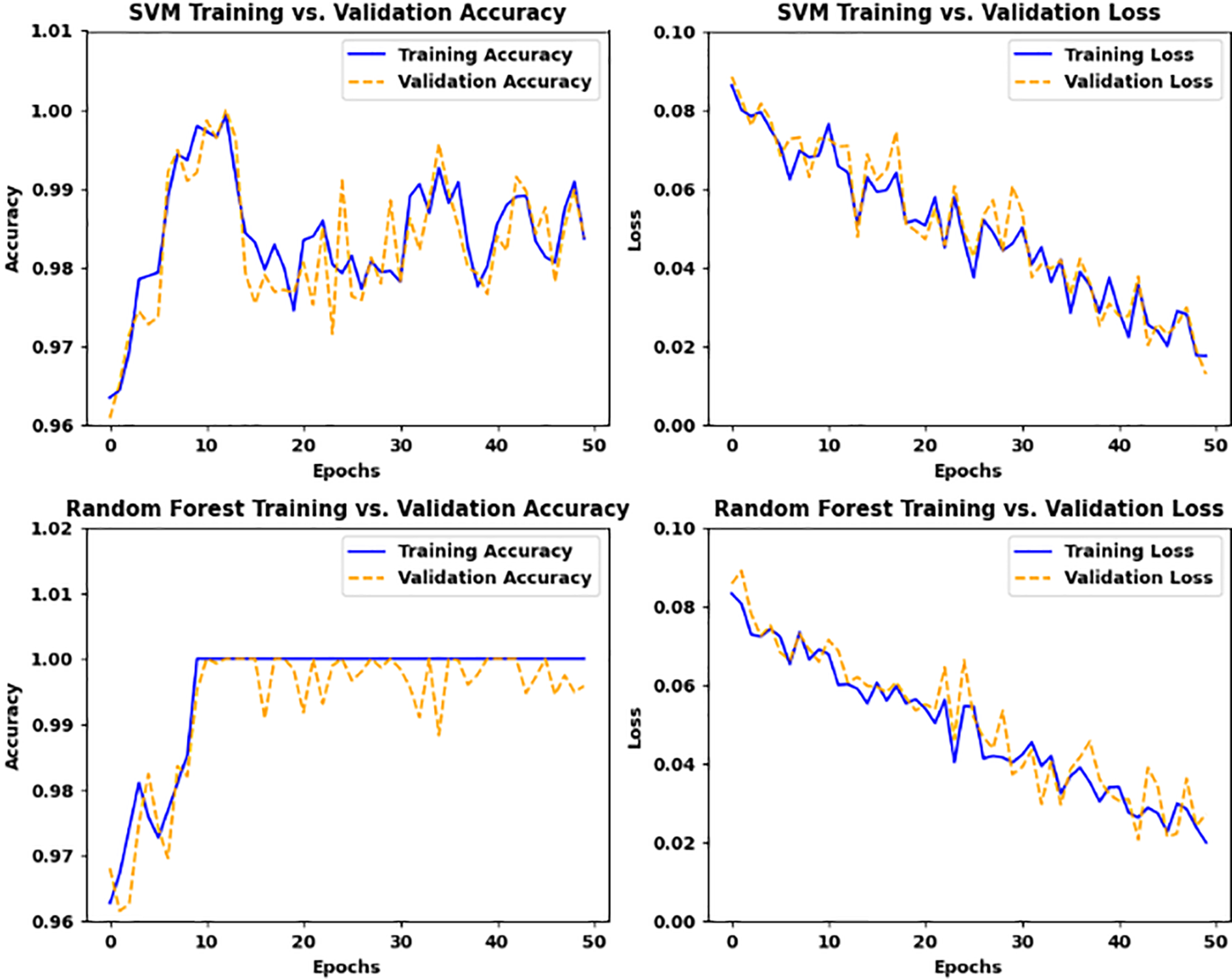

4.2 SVM and Random Forest Algorithm Result Statistics

In this section, we discuss the training and validation accuracies of the Support Vector Machine (SVM) and Random Forest algorithms, as well as their corresponding training and validation losses on the IoT2023 dataset. This evaluation is important for getting a deep understanding of the performance of these comparative algorithms in the context of our proposed model. By analyzing both accuracy and loss, we can gain a sense of understanding how well each algorithm works against seen and unseen data, which are basic elements to illustrate each model’s robustness for real-world IoT applications. Furthermore, the training accuracy provides an indication of how well the model fits the training data, while validation accuracy serves as a benchmark for performance on new, unseen data instances. In addition to accuracy, monitoring training and validation losses throughout the training process allows us to evaluate the convergence behavior of each algorithm. A decreasing loss indicates that the model is learning effectively, while fluctuations or increases in validation loss can show potential issues with model stability or generalization. Moreover, the results obtained from this process are shown in Fig. 3 for SVM and Random Forest algorithms.

Figure 3: SVM and random forest result statistics

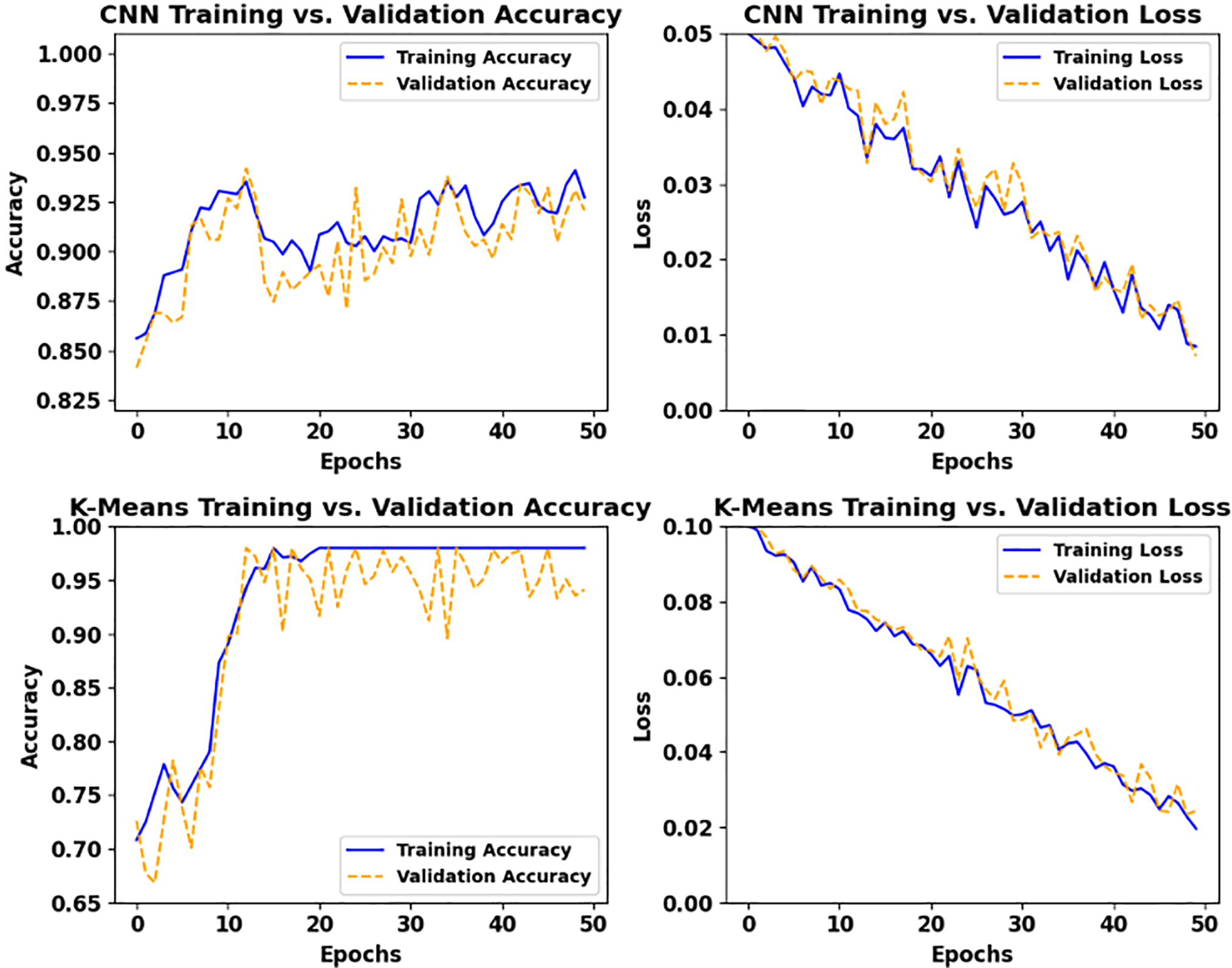

4.3 CNN and K-Means Algorithm Result Statistics

In this section, we examine the training and validation accuracies of the Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) and K-Means clustering algorithms, along with their respective training and validation losses on the IoT2023 dataset. Getting the results of these metrics will help while evaluating the effectiveness of these algorithms in comparison to our proposed model. Moreover, in the literature, we noted that CNNs perform better on structured data like images and sequences, while K-means is useful in unsupervised learning scenarios because it offers valuable results by grouping similar data points based on feature similarity. Therefore, it is important to check and evaluate their results in the presence of the proposed model to acknowledge why our model is better suited for IoT applications in the presence of these algorithms. Furthermore, checking both training and validation losses is important for analyzing the learning process of these models. Moreover, the decline in training loss indicates that the model is effectively learning from the training data, while validation loss serves as an indicator of how well the model is likely to perform on unseen data. Moreover, the results obtained during experiment analysis are shown in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: CNN and K-Means algorithm result statistics

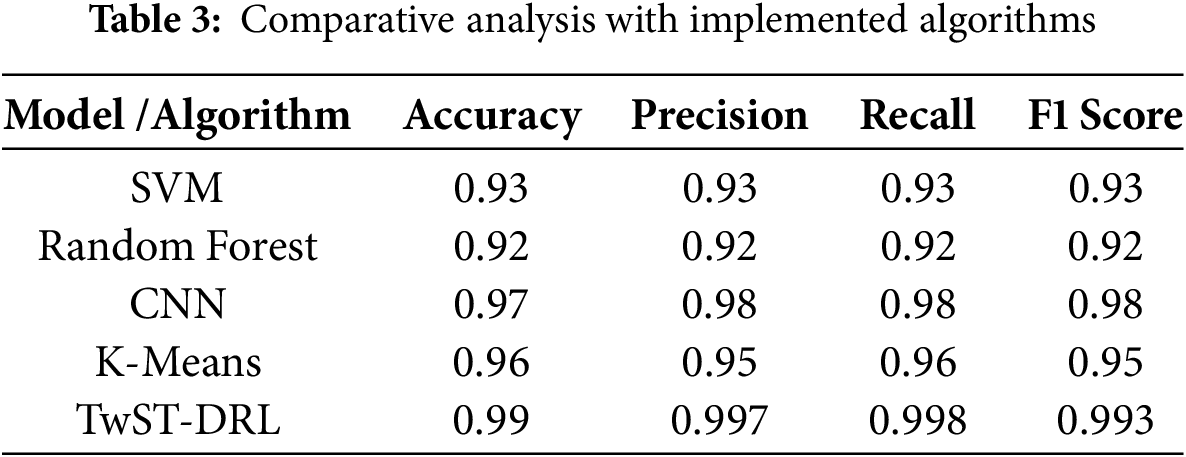

In this section, we discuss the training and validation accuracies of the different algorithms considered in our study, along with their corresponding training and validation losses. We present Table 3 in the paper to summarize the performance metrics, including F1 score, precision, and recall, which are important for evaluating the algorithms’ capabilities in handling imbalances in IoT applications. Moreover, incorporating these metrics into our analysis allows for a more detailed comparison between different considered algorithms by identifying strong and weak. This comprehensive evaluation not only helps in selecting the most suitable model for IoT malware detection but also contributes to the ongoing discourse on improving algorithmic performance in the context of evolving cybersecurity threats.

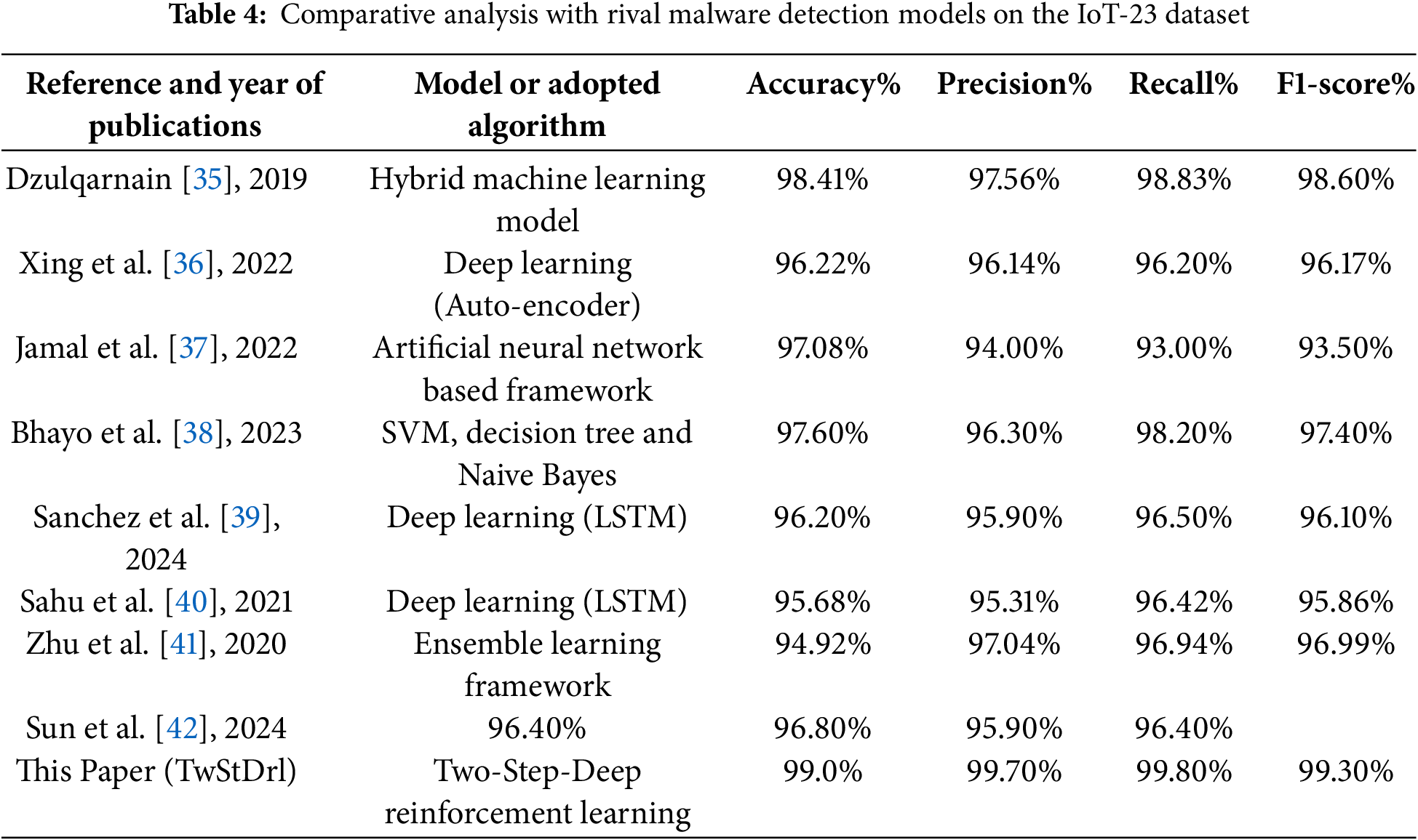

4.5 Comparative Analysis with Rival Algorithms

In this section, we discuss the result statistics of the proposed model with rival algorithms as presented in Table 4 by focusing on their performance metrics. Moreover, this comparative analysis highlights the effectiveness of the proposed model in the presence of different malware detection models. This table also provides a useful understanding of these different models’ performance in terms of accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score. To explore, the accuracy metric shows the overall correctness of the model’s predictions, while precision demonstrates the proportion of true positive results among all positive predictions. Recall, on the other hand, measures the model’s ability to identify all relevant instances, which is particularly important for malware detection and can have serious consequences, while the F1-score serves as a harmonic mean of precision and recall to offer a balanced view of the model’s performance, especially in scenarios where class distributions are imbalanced. The results from our proposed model, TwStDrl, demonstrate a significant improvement in performance metrics compared to existing models, achieving an accuracy of 99.0%, precision of 99.70%, recall of 99.80%, and F1-score 99.30%. These results indicate that our approach not only excels in detecting malware but also minimizes false positives to improve the robustness of the model.

In this paper, we propose an advanced two-step deep reinforcement learning-enabled framework, known as “TwStDrl” to resolve malware detection and prevention issues in IoT applications. Our TwStDrl framework is capable of identifying malware at the network’s edge while protecting the user’s important data privacy. We implement and evaluate well-known algorithms such as SVM, Random Forest, CNN, and K-Means to verify the experimental performance of the proposed model. During analysis, we found that the proposed model outperforms these algorithms in terms of comparative metrics. Additionally, we benchmarked the TwStDrl model with state-of-the-art schemes and found that it is better than them in terms of accuracy, precision, validation rates, etc. Based on these findings, we are confident that TwStDrl will be useful for IoT applications to detect malware in real time with great efficiency.

Acknowledgement: This work is supported by Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R104), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Funding Statement: This work is supported by Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R104), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author Contributions: Muhammad Adil performed the experiments research methodology, prepared the initial draft of the manuscript, and gave final approval of the version to be published, while Mona M. Jamjoom conducted an analysis of the research findings, contributed to editing and revising the manuscript, and provided project management and supervision. Zahid Ullah provided research resources, contributed to the analysis, critically reviewed the manuscript for technical content, and approved the final version. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Please find the link of dataset “https://www.stratosphereips.org/datasets-iot23” (accessed on 24 June 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Raff E, Nicholas C. A survey of machine learning methods and challenges for Windows malware classification. arXiv:2006.09271. 2020. [Google Scholar]

2. Conti M, Gangwal A, Ruj S. On the economic significance of ransomware campaigns: a Bitcoin transactions perspective. Comput Secur. 2018;79:162–89. [Google Scholar]

3. Hsiao SC, Kao DY. The static analysis of WannaCry ransomware. In: 2018 20th International Conference on Advanced Communication Technology (ICACT). 2018 Feb 11–14; Chuncheon-si, Gangwon-do, Republic of Korea. p. 153–8. [Google Scholar]

4. Kesler E. A transdisciplinary approach to cybersecurity: a framework for encouraging transdisciplinary thinking. arXiv:2405.10373. 2024. [Google Scholar]

5. Neprash HT, McGlave CC, Cross DA, Virnig BA, Puskarich MA, Huling JD, et al. Trends in ransomware attacks on US hospitals, clinics, and other health care delivery organizations, 2016–2021. In: JAMA Health Forum. Chicago, IL, USA: American Medical Association; 2022. e224873 p. [Google Scholar]

6. Glani Y, Ping L, Shah SA. AASH: a lightweight and efficient static IoT malware detection technique at source code level. In: 2022 3rd Asia Conference on Computers and Communications (ACCC). 2022 Dec 16–18; Shanghai, China. p. 19–23. [Google Scholar]

7. Jeon J, Park JH, Jeong YS. Dynamic analysis for IoT malware detection with convolution neural network model. IEEE Access. 2020;8:96899–911. doi:10.1109/access.2020.2995887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Htwe CS, Thwin MMS, Thant YM. Malware attack detection using machine learning methods for IoT smart devices. In: 2023 IEEE Conference on Computer Applications (ICCA 2023). 2023 Feb 27–28; Yangon, Myanmar. p. 329–33. [Google Scholar]

9. Buttyan L, Nagy R, Papp D. Simbiota++: improved similarity-based IoT malware detection. In: 2022 IEEE 2nd Conference on Information Technology and Data Science (CITDS). 2022 May 16–18; Debrecen, Hungary. p. 51–6. [Google Scholar]

10. Deng X, Wang Z, Pei X, Xue K. TransMalDe: an effective transformer-based hierarchical framework for IoT malware detection. IEEE Trans Netw Sci Eng. 2024;11(1):140–51. doi:10.1109/tnse.2023.3292855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Deng X, Chen B, Chen X, Pei X, Wan S, Goudos SK. A trusted edge computing system based on intelligent risk detection for smart IoT. IEEE Trans Ind Inform. 2023;20(2):1445–54. doi:10.1109/tii.2023.3245681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Dhanya K. Obfuscated malware detection in IoT Android applications using Markov images and CNN. IEEE Syst J. 2023;17(2):2756–66. doi:10.1109/jsyst.2023.3238678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Niu W, Wang Y, Liu X, Yan R, Li X, Zhang X. GCDroid: android malware detection based on graph compression with reachability relationship extraction for IoT devices. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023;10(13):11343–56. doi:10.1109/jiot.2023.3241697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Breitenbacher D, Homoliak I, Aung YL, Elovici Y, Tippenhauer NO. HADES-IoT: a practical and effective host-based anomaly detection system for IoT devices (extended version). IEEE Internet Things J. 2021;9(12):9640–58. doi:10.1109/jiot.2021.3135789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Lei T, Qin Z, Wang Z, Li Q, Ye D. Evedroid: event-aware android malware detection against model degrading for IoT devices. IEEE Internet Things J. 2019;6(4):6668–80. doi:10.1109/jiot.2019.2909745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Vasan D, Alazab M, Venkatraman S, Akram J, Qin Z. MTHael: cross-architecture IoT malware detection based on neural network advanced ensemble learning. IEEE Trans Comput. 2020;69(11):1654–67. doi:10.1109/tc.2020.3015584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Shahid MR, Blanc G, Zhang Z, Debar H. Anomalous communications detection in IoT networks using sparse autoencoders. In: 2019 IEEE 18th International Symposium on Network Computing and Applications (NCA); 2019 Sep 26–28; Cambridge, MA, USA. p. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

18. Shi T, McCann RA, Huang Y, Wang W, Kong J. Malware detection for Internet of Things using one-class classification. Sensors. 2024;24(13):4122. doi:10.3390/s24134122. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Almazroi AA, Ayub N. Deep learning hybridization for improved malware detection in smart Internet of Things. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):7838. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-57864-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Ahmad I, Wan Z, Ahmad A, Ullah SS. A hybrid optimization model for efficient detection and classification of malware in the Internet of Things. Mathematics. 2024;12(10):1437. doi:10.3390/math12101437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Mishra P, Jain T, Aggarwal P, Paul G, Gupta BB, Attar RW, et al. CloudIntellMal: an advanced cloud based intelligent malware detection framework to analyze android applications. Comput Electr Eng. 2024;119(7):109483. doi:10.1016/j.compeleceng.2024.109483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Sharma A, Gupta BB, Singh AK, Saraswat VK. A novel approach for detection of APT malware using multi-dimensional hybrid Bayesian belief network. Int J Inf Secur. 2023;22(1):119–35. doi:10.1007/s10207-022-00631-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Li T, Luo Y, Wan X, Li Q, Liu Q, Wang R, et al. A malware detection model based on imbalanced heterogeneous graph embeddings. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;246(27):123109. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2023.123109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Sharma A, Gupta BB, Singh AK, Saraswat VK. Advanced persistent threats (APTevolution, anatomy, attribution and countermeasures. J Ambient Intell Humaniz Comput. 2023;14(7):9355–81. doi:10.1007/s12652-023-04603-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Shah IA, Mehmood A, Khan AN, Elhadef M, Khan AuR. HeuCRIP: a malware detection approach for Internet of Battlefield Things. Cluster Comput. 2023;26(2):977–92. doi:10.1007/s10586-022-03618-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Smmarwar SK, Gupta GP, Kumar S. AI-empowered malware detection system for Industrial Internet of Things. Comput Electr Eng. 2023;108:108731. doi:10.1016/j.compeleceng.2023.108731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Zhang X, Hao L, Gui G, Wang Y, Adebisi B, Sari H. An automatic and efficient malware traffic classification method for secure Internet of Things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023;11(5):8448–58. doi:10.1109/jiot.2023.3318290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. El-Ghamry A, Gaber T, Mohammed KK, Hassanien AE. Optimized and efficient image-based IoT malware detection method. Electronics. 2023;12(3):708. doi:10.3390/electronics12030708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Esmaeili B, Azmoodeh A, Dehghantanha A, Srivastava G, Karimipour H, Lin JCW. A GNN-based adversarial Internet of Things malware detection framework for critical infrastructure: studying Gafgyt, Mirai and Tsunami campaigns. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023;11(16):26826–36. doi:10.1109/jiot.2023.3298663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Shafin SS, Karmakar G, Mareels I. Obfuscated memory malware detection in resource-constrained IoT devices for smart city applications. Sensors. 2023;23(11):5348. doi:10.3390/s23115348. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Sharma A, Babbar H, Vats AK. Ransomware attack detection in the Internet of Things using machine learning approaches. In: 2023 2nd International Conference on Applied Artificial Intelligence and Computing (ICAAIC 2023); 2023 May 4–6; Salem, India. p. 553–9. [Google Scholar]

32. Devi RA, Arunachalam A. Enhancement of IoT device security using an improved elliptic curve cryptography algorithm and malware detection utilizing deep LSTM. High-Confidence Comput. 2023;3(2):100117. doi:10.1016/j.hcc.2023.100117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Bajao NA, Sarucam JA. Threats detection in the Internet of Things using convolutional neural networks, long short-term memory, and gated recurrent units. Mesopotamian J Cyber. 2023;2023:22–9. doi:10.58496/mjcs/2023/005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Mohammed MA, Lakhan A, Zebari DA, Abdulkareem KH, Nedoma J, Martinek R, et al. Adaptive secure malware efficient machine learning algorithm for healthcare data. CAAI Trans Intell Technol. 2023. doi:10.1049/cit2.12200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Dzulqarnain D. Investigating IoT malware characteristics to improve network security [master’s thesis]. Enschede, Netherland: University of Twente; 2019. [Google Scholar]

36. Xing X, Jin X, Elahi H, Jiang H, Wang G. A malware detection approach using autoencoder in deep learning. IEEE Access. 2022;10:25696–706. doi:10.1109/access.2022.3155695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Jamal A, Hayat MF, Nasir M. Malware detection and classification in IoT network using ANN. Mehran Univ Res J Eng Technol. 2022;41:80–91. [Google Scholar]

38. Bhayo J, Shah SA, Hameed S, Ahmed A, Nasir J, Draheim D. Towards a machine learning-based framework for DDoS attack detection in software-defined IoT (SD-IoT) networks. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2023;123(1):106432. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2023.106432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Sanchez PMS, Celdrán AH, Bovet G, Pérez GM. Adversarial attacks and defenses on ML- and hardware-based IoT device fingerprinting and identification. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2024;152(12):30–42. doi:10.1016/j.future.2023.10.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Sahu AK, Sharma S, Tanveer M, Raja R. Internet of Things attack detection using hybrid deep learning model. Comput Commun. 2021;176(3):146–54. doi:10.1016/j.comcom.2021.05.024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Zhu H, Li Y, Li R, Li J, You Z, Song H. SedmDroid: an enhanced stacking ensemble framework for Android malware detection. IEEE Trans Netw Sci Eng. 2020;8(2):984–94. doi:10.1109/tnse.2020.2996379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Sun Z, An G, Yang Y, Liu Y. Optimized machine learning enabled intrusion detection system for Internet of Medical Things. Franklin Open. 2024;6(11):100056. doi:10.1016/j.fraope.2023.100056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools