Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

A Review of AI-Driven Automation Technologies: Latest Taxonomies, Existing Challenges, and Future Prospects

1 School of Information and Communications Engineering, Xi’an Jiaotong University, iHarbour, Xi’an, 710049, China

2 Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering, The University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam Road, Hong Kong, 999077, China

3 School of Intelligence Science and Technology, Beijing University of Civil Engineering and Architecture, Beijing, 102616, China

* Corresponding Author: Biao Zhao. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Intelligent Vehicles and Emerging Automotive Technologies: Integrating AI, IoT, and Computing in Next-Generation in Electric Vehicles)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 84(3), 3961-4018. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.067857

Received 14 May 2025; Accepted 10 July 2025; Issue published 30 July 2025

Abstract

With the growing adoption of Artifical Intelligence (AI), AI-driven autonomous techniques and automation systems have seen widespread applications, become pivotal in enhancing operational efficiency and task automation across various aspects of human living. Over the past decade, AI-driven automation has advanced from simple rule-based systems to sophisticated multi-agent hybrid architectures. These technologies not only increase productivity but also enable more scalable and adaptable solutions, proving particularly beneficial in industries such as healthcare, finance, and customer service. However, the absence of a unified review for categorization, benchmarking, and ethical risk assessment hinders the AI-driven automation progress. To bridge this gap, in this survey, we present a comprehensive taxonomy of AI-driven automation methods and analyze recent advancements. We present a comparative analysis of performance metrics between production environments and industrial applications, along with an examination of cutting-edge developments. Specifically, we present a comparative analysis of the performance across various aspects in different industries, offering valuable insights for researchers to select the most suitable approaches for specific applications. Additionally, we also review multiple existing mainstream AI-driven automation applications in detail, highlighting their strengths and limitations. Finally, we outline open research challenges and suggest future directions to address the challenges of AI adoption while maximizing its potential in real-world AI-driven automation applications.Keywords

1.1 Research Backgrounds of AI-Driven Automation

The evolution of artificial intelligence (AI) [1–3] technologies has advanced significantly in recent years, bringing about a new era of AI-driven autonomous tools and automation system [4–7]. Numerous advanced AI-driven automation technologies [8–11] have been developed to address specific challenges within various aspects of human production and daily life. These advancements have enabled organizations to optimize operational efficiency, reduce costs, and enhance productivity across a variety of practical application scenarios, from healthcare [12–14] to finance [15–17]. AI-driven automation systems [18–20] are now capable of automating repetitive and time-consuming tasks, allowing human workers to focus on more efficient activities such as strategic planning and creative problem solving [21–23].

1.1.1 Advancements of AI-Driven Automation

Specifically, AI-driven automation encompasses a wide range of technologies [6,9,24,25], which together streamline complex operations, enhance task-specific decision-making capabilities, and significantly boost practical operational efficiency. Among the various approaches to AI-driven automation, several stand out as particularly influential in driving the field forward, including Robotic Process Automation (RPA) [14,26,27], No-code platforms [28–30], and Large Language Models (LLMs) [31,32].

(1) Firstly, Robotic Process Automation (RPA) [26,33] is a key technique in AI-driven automation, utilizing software robots to perform repetitive tasks traditionally handled by humans. RPA is particularly prevalent in industries such as finance, healthcare, and manufacturing, where efficiency and error reduction are critical [34,35].

(2) Meanwhile, No-code platforms [28,36–38] are another important approach in AI-driven automation, further broadening the accessibility of automation technologies. They enable users without technical expertise to design complex workflows and automation systems, democratizing the development of AI solutions. With intuitive interfaces that allow for the creation of complex workflows without requiring coding skills, these platforms empower users to build customized automation solutions [39–42].

(3) Lastly, LLMs [43–45] have achieved exceptional success across a wide range of tasks, from natural language processing (NLP) [46,47] to decision support systems [48–50]. By utilizing vast amounts of textual data, these models generate accurate and contextually relevant outputs, making them indispensable in applications such as chatbots [51,52], document automation [53–56], and customer service [10,57,58].

In recent years, among them, the most transformative advances in AI-driven automation is the integration of LLMs into task-execution and production processes [59,56,60]. The integration of LLMs and traditional workflow automation techniques dramatically improves the effectiveness and efficiency of human production processes such as customer service [10,57,58], document processing [2,53,54], and decision-making support [61–63], allowing people and organizations to develop more intelligent systems capable of understanding complex tasks and delivering optimized solutions.

Overall, AI-driven automation has quickly become a transformative force across various industries, offering tremendous potential in improving efficiency, accuracy, and scalability.

1.1.2 Challenges in AI-Driven Automation

However, as the technology continues to evolve, AI-driven automation faces several significant technical challenges that hinder its widespread adoption and effective implementation [56,64,65]. These challenges, ranging from data governance [2,54,66] to model interpretability [13,64,67] and deployment complexity [20,55,56,68], present barriers that need to be addressed to fully realize the potential of AI-driven automation.

Specifically, AI-driven automation faces multiple technical hurdles: (1). Data quality and governance issues [35,69,70], including noise, privacy, and compliance; (2). Model interpretability gaps in “black-box” systems [64,67,71], critical for high-stakes domains; (3). Generalization limitations in unseen scenarios [72–74]; (4). Scalability demands [66,75,76] for large-scale, low-latency deployment; (5). Algorithmic bias perpetuating unfair outcomes [77–79]; (6). Integration complexity with legacy systems [14,17,80]; (7). Real-time processing requirements [18,81,82]; and (8). Security vulnerabilities to adversarial attacks [58,73,76].

Addressing these issues is essential for advancing the AI-driven automation research. Overcoming these challenges will enable AI-driven automation to reach its full potential, leading to more efficient and effective systems across industries.

1.2 Motivations of This Work and Our Contributions

While numerous innovative AI automation-related works, particularly with the advanced LLMs [77,83,84] and Robotic Process Automation (RPA) [26,54,82], have introduced various novel technical concepts and knowledge in the research of AI-driven automation. Despite these successes and increasing attention, a comprehensive review of the current AI-driven automation developments still remains limited [75,77,85,86]. Moreover, these latest developments have introduced many innovative framework and approaches that were not covered in earlier literature [67,75,86], highlighting the need for more updated and structured overview and arrangement for these literature.

Given the accelerating technology progress in AI-driven automation [6,25,70,76], in this paper, we are motivated to present a novel taxonomy that categorizes and unifies the various methods, tools, and applications. We believe that this will help subsequent researchers with a better and clearer understanding of the key technical features and workflows of AI-driven automation [17,75]. We believe this work will contribute to the development of AI-driven automation, offering insights into how different components/modules interact and drive overall performance [69,82]. This review aims to help researchers identify emerging trends, and highlight critical gaps that require further exploration to advance the frontiers of AI-driven automation.

In summary, in this survey, we make the following key contributions:

[1]. Firstly, we propose a novel taxonomy to classify the different methods used in AI-driven automation. This different taxonomy provide clarity on the strengths and weaknesses of each categories and how they can be applied in various practical application scenarios.

[2]. Then, we also systematically evaluate current mainstream tools and systems used for AI-driven automation, discussing their strengths and limitations, and offering insights into the kinds of approaches.

[3]. Finally, we discuss the major challenges facing the field, including data privacy, ethical concerns, and the lack of regulatory frameworks, and propose strategies for overcoming these obstacles.

[4]. Meanwhile, we suggest promising areas for future research of AI-driven automation, particularly in improving LLM transparency, developing more efficient RPA techniques, and addressing regulatory challenges in the AI space.

1.3 Methodology for Literature Selection

To ensure a comprehensive and unbiased selection of relevant literature, we employed a systematic search strategy across multiple academic databases, including IEEE Xplore1, ACM Digital Library2, ScienceDirect3, SpringerLink4, and arXiv5. The search query was designed to capture key concepts related to AI-driven automation tools, their functionalities, and applications.

Specifically, our survey adopts a systematic approach to literature selection, prioritizing peer-reviewed journal articles, conference proceedings, and high-impact preprints We focus exclusively on publications that address AI-driven automation tools, their technical architectures, and real-world applications, ensuring alignment with our taxonomy development goals. The selected works were published between 2010 and 2025, a period that captures both foundational advancements in AI-automation techniques [26,27,62] This timeframe was chosen to reflect the rapid evolution of the field, including breakthroughs such as transformer-based models (e.g., GPT-4 [45]).

The initial screening of titles and abstracts refined the candidate pool from over 3000 articles to the most relevant works. Among over 250 core references selected, approximately 10% originate from 2010 to 2018, representing seminal works on RPA infrastructure and early NLP integration. The period 2019 to 2021 accounts for 35% of references, coinciding with the emergence of LLM-powered automation frameworks. The majority at 55% derive from 2022 to 2025. This ensures balanced coverage of historical foundations and representative advancements while minimizing recency bias through rigorous citation analysis and validation.

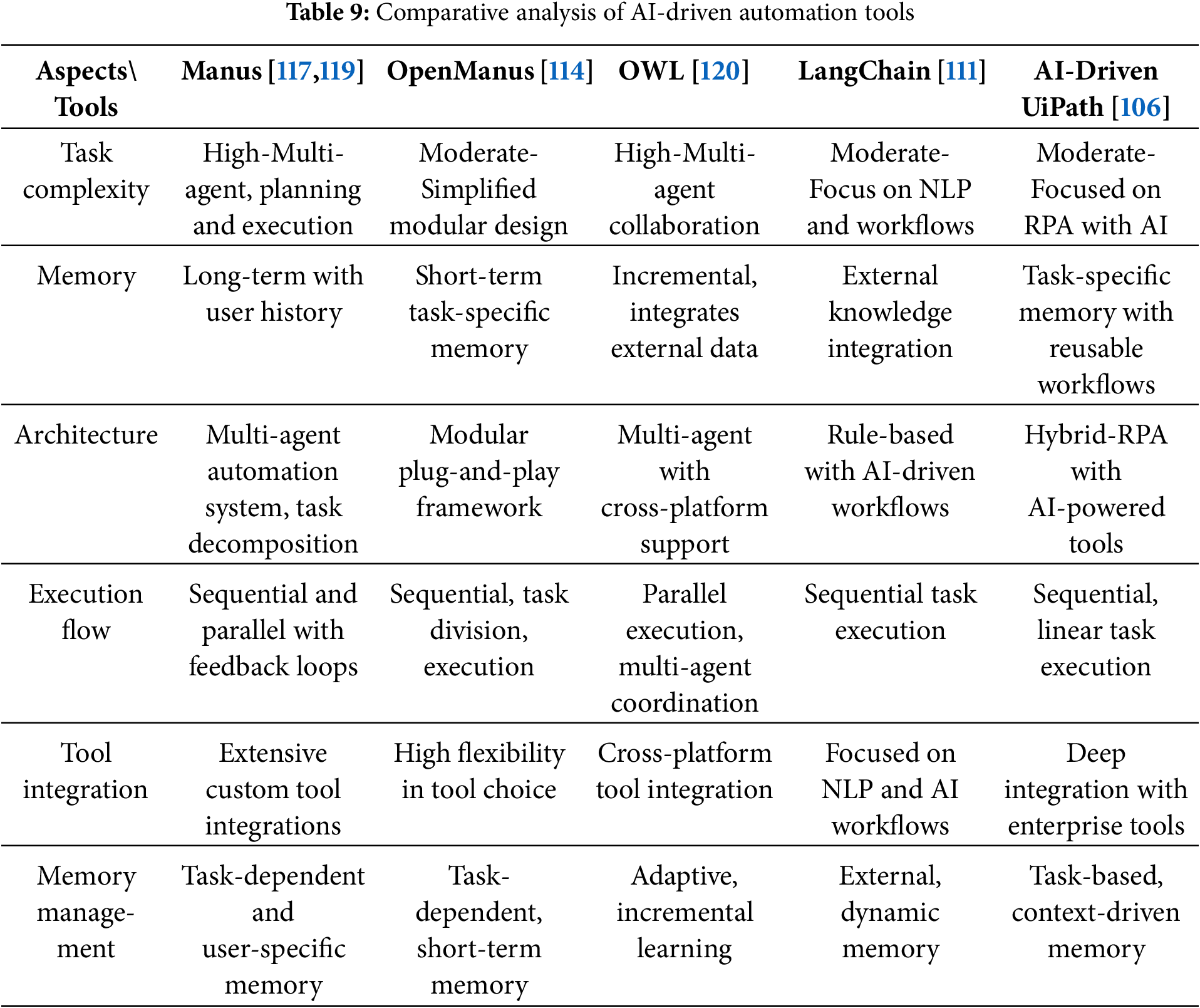

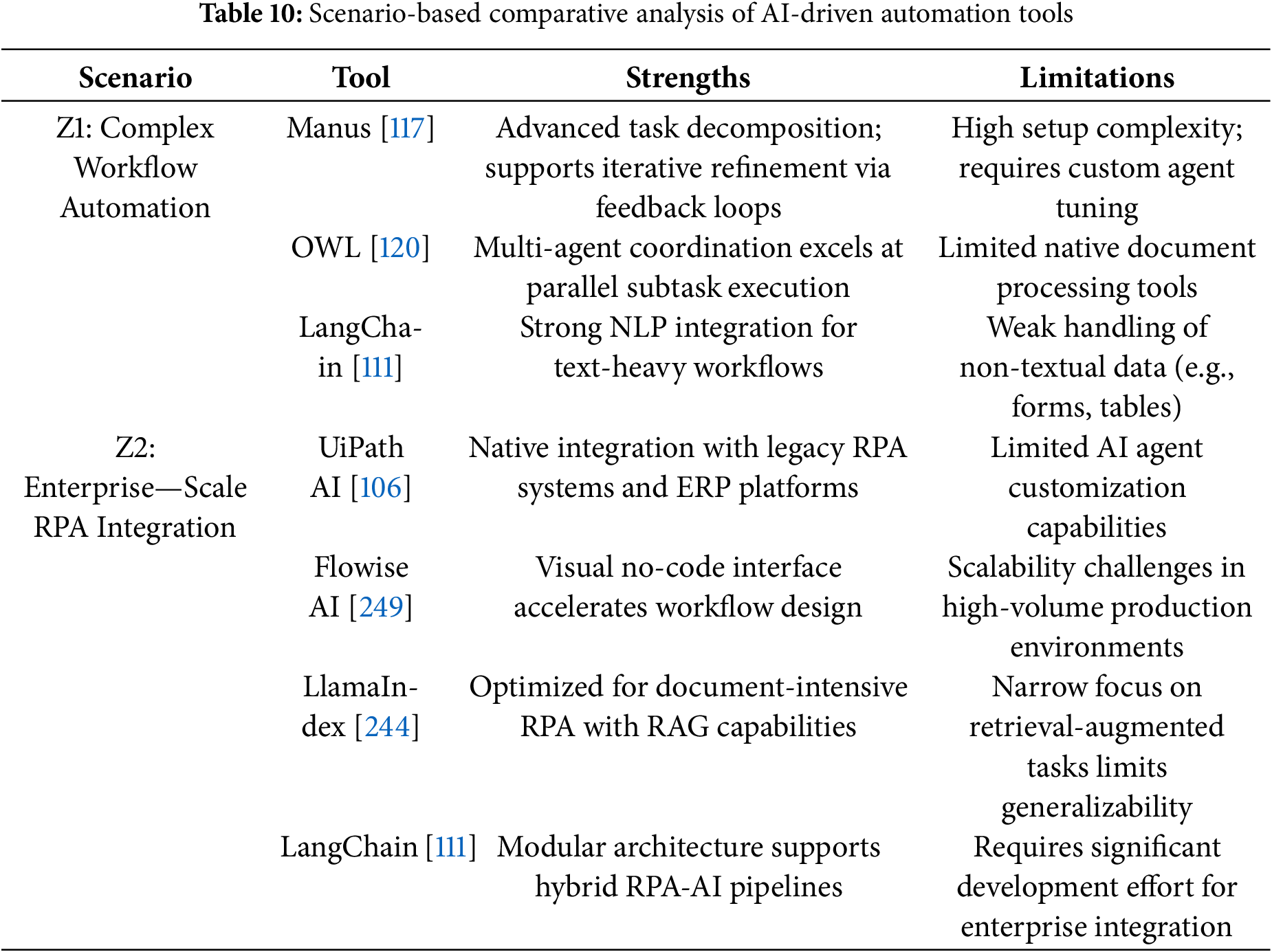

This survey is systematically organized to provide a comprehensive analysis of AI-driven automation tools, their challenges, and future directions. The structure is as follows: Section 1 introduces the transformative impact of AI-driven automation across industries, outlines the scope of this survey, and presents its organizational framework. Section 2 establishes systematic taxonomies to classify AI-driven automation tools into four architectural paradigms: rule-based, LLM-driven, multi-agent cooperative, and hybrid models, further categorizing them by functionality, execution mechanisms, and human-AI collaboration modes. Section 3 conducts a comparative analysis of state-of-the-art tools (e.g., Manus, OWL, LangChain, UiPath), emphasizing their applicability in domains like healthcare, finance, and manufacturing. Section 4 examines persistent challenges, including data governance gaps, model interpretability deficits, and scalability bottlenecks, while proposing mitigation strategies. Section 5 explores emerging trends (e.g., self-debugging workflows, AGI integration, and quantum-resistant security) and forecasts future research trajectories. Section 6 concludes by synthesizing key insights and advocating for interdisciplinary collaboration to align technological advancements with ethical and societal values.

2 A Comprehensive Technological Taxonomy of AI-Driven Automation

Recent advances of Machine Learning (ML) [87–89] and Artificial Intelligence (AI) [72,78,83,90] have led to a proliferation of AI-driven automation tools, each designed to address specific challenges in workflow optimization, decision-making, and task execution [91–94]. As these tools grow increasingly diverse in their architectures, functionalities, and applications, there is a pressing need for a systematic taxonomy to categorize and compare their capabilities [95–98]. Currently, the lack of a unified framework makes it difficult for researchers and practitioners to evaluate the suitability of these tools for different use cases [99–102]. Thus, this section aims to address this gap by proposing several structured classifications from different dimensions of various AI-driven automation tools, analyzing their key characteristics, and highlighting their roles in modern automation ecosystems.

As illustrated in Fig. 1, these tools exhibit diverse architectural paradigms and functional specializations. The proposed taxonomy systematically organizes these systems across five key dimensions: (1) architectural foundations (Section 2.1), (2) core functionalities (Section 2.2), (3) task flow management (Section 2.3), and (4) application domains (Section 2.4).

Figure 1: The taxonomy visualization of architectural approaches for AI-driven automation

2.1 Classification on Architecture of AI-Driven Automation Tools

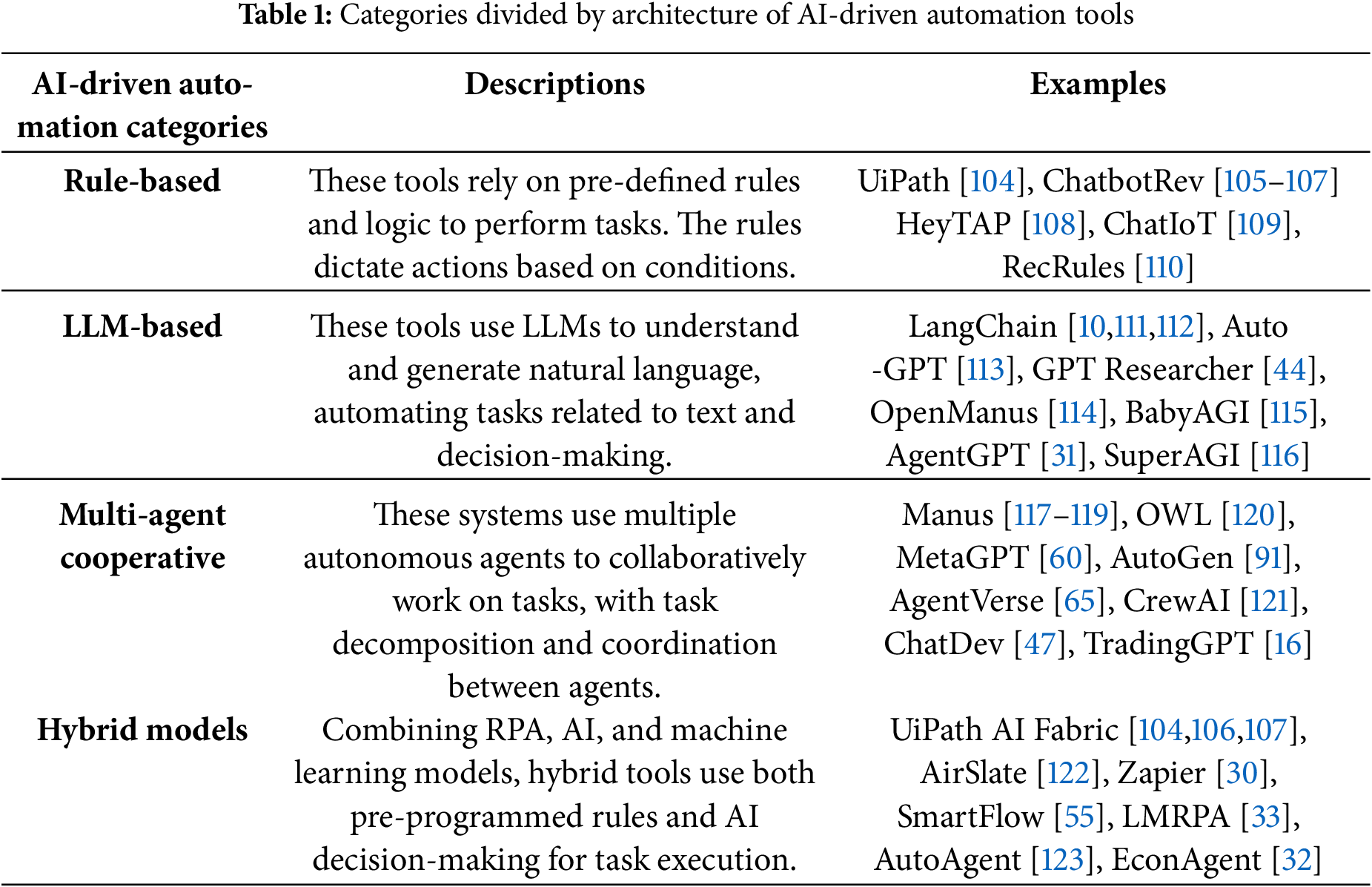

The architectural landscape of modern AI-driven automation tools can be categorized into four distinct paradigms, including Rule-based [2,15,54,103], LLM-based [59,72,78,87], Multi-Agent-based [48,91–93] and Hybrid Models [7,33,55,86], each addressing specific operational requirements and complexity levels [6,96–98]. The architecture classification of automation technologies is outlined in Table 1.

Specifically, 1. Rule-Based Systems [11,103,54] represent the foundational layer of automation architectures, employing deterministic logic through predefined condition-action rules. 2. LLM-Based Systems [46,77,87,124] mark a paradigm shift toward cognitive automation, leveraging LLMs to process unstructured data and execute language-centric tasks. 3. Multi-Agent Systems [125–127] introduce distributed intelligence through coordinated autonomous agents, as implemented in platforms like Manus [114,117,119] and OWL [120]. 4. Hybrid Models [7,33,55] combine the strengths of rule-based and AI-driven approaches, exemplified by UiPath AI Fabric’s integration of RPA with machine learning.

Fig. 2 illustrates the evolutionary landscape of automation system architectures over time. It highlights four major phases, Rule-Based, Multi-Agent, LLM-Based, and Hybrid Agentic, alongside their timeframes and defining characteristics [91,94–96]. This shows how each paradigm emerged, developed, and influenced the next, reflecting shifts in both technical capability and system design philosophy. Notably, these paradigms are not isolated; rather, they exhibit significant overlaps and integration points, emphasizing that no single approach exists independently of the others in practice [5,6,75].

Figure 2: The evolutionary trajectory and integration of automation architectures: From rule-based systems to hybrid agentic intelligence

As shown in Fig. 3 (1), this is a typical structure of rule-based automation systems [11,51,105]. This architecture is centered around deterministic processing driven by predefined logic. The system accepts structured and pre-validated input from the user or an external source. These inputs are fed into a logic engine, which applies rule-based conditions-often expressed in IF-THEN format-for pattern matching [108,110]. Each rule is associated with a deterministic action, such as sending an alert or executing an API call [59,80,128].

Figure 3: The representative architectural prototypes of four major categories of existing automation systems: (1) Rule-based systems [105,109,110], (2) Multi-agent systems [65,129,130] with Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) [131,132], (3) Multi-agent-based automation decision architectures [133–136], and (4) Hybrid models [7,33,55] integrating symbolic rules with AI reasoning and fallback mechanisms

The rule base in this like automation system is a separate, static, and version-controlled module, decoupled from the logic execution layer [51,108]. This ensures maintainability and traceability of the rule set over time. The outputs are standardized and include actionable signals like alerts or service calls. The model emphasizes the non-probabilistic, mechanical nature of such systems, with fixed logical flows and strict dependency on exact condition matching. This kind of architecture is highly interpretable, though it requires manual effort to maintain and update the rule repository [109,137].

Fig. 3 (2) illustrates a typical architecture prototype of a LLM-based automation system. The architecture adopts a modular design that clearly delineates core processing flows and external interaction interfaces, enabling an end-to-end intelligent mapping from input to output.

Firstly, the input module receives natural language requests or structured data from the user and forwards them to the Context Manager, which maintains dialogue history, task context, and multi-turn interaction states-essential for preserving semantic continuity and task awareness [70]. Next, the Memory Module organizes both short-term and long-term information, allowing fast retrieval of contextual data and knowledge fragments. On top of this, the system can integrate Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) [46,138–140], leveraging external vector databases for semantic search to enhance the model’s knowledge base. The Reasoning Module is responsible for understanding intent, making logical decisions, and invoking tools [5,141,142]. It interacts with External APIs to query databases or perform calculations. Finally, outputs are then passed through Rule Guardrails [105,109] to ensure compliance with business rules, ethical standards, and formatting constraints. Finally, the Post-Processor Module [102,143] sanitizes the raw output, applies safety filters, and formats the response before it is delivered to the user through the output module, ensuring clarity and reliability.

Fig. 3 (3) presents a hierarchical architecture for multi-agent automation systems that integrates dynamic task decomposition with a Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) [131,132] execution layer. The system begins with a main task input, which is parsed by a Task Decomposer module responsible for dividing the task into coherent subtasks based on task semantics and dependency graphs. These subtasks are then routed to an MoE pool containing specialized expert agents, such as reasoning experts [61,78,90], data processing agents [53,144,145], and API orchestration agents [59,79,80,128].

Routing decisions are made based on task embeddings and gating networks that dynamically assign subtasks to the most suitable experts [131,146–148]. Subtasks are executed in parallel, and their results are aggregated into a unified output. Conflict resolution and validation mechanisms ensure consistency and robustness. This architecture supports modular scalability, fault tolerance, and efficient parallelism, making it well-suited for complex, heterogeneous, and cross-domain automation scenarios [39,55,91,94].

Fig. 3 (4) depicts a hybrid model-based automation architecture that combines rule-based systems with AI models to achieve adaptive and resilient decision-making [7,33,86,129]. The system begins by routing user input-either structured or unstructured-through a decision router. Structured data is directed to a deterministic rule engine, while unstructured or context-dependent input is processed by an AI model [59,72,78,90]. The outputs from both branches are validated through a result validation module that ensures consistency and accuracy.

Depending on the decision type (probabilistic or deterministic), results are either accepted or passed to a fallback handler when anomalies or inconsistencies are detected. The fallback mechanism includes model switching, rule simplification, or escalation to human review [7,83,98]. A knowledge graph [149] supports both the router and AI model in contextual understanding, and external retrieval modules assist in enriching or verifying the input [132,144,145,150]. This hybrid approach balances the explainability and speed of symbolic logic with the flexibility and adaptability of neural models, making it suitable for high-stakes or regulated automation domains [33,55,86,129].

Furthermore, Fig. 4 presents a comparative architecture overview of four representative categories of AI-driven automation system. The figure is designed to highlight the core structural patterns and processing flows underlying each class, including rule-based systems, multi-agent automation systems, LLMs-based decision frameworks, and hybrid-AI integrated models [91,94–96]. The visualization contextualize the diversity of design philosophies and operational mechanisms across these automation systems [39,47,55,151]. This comparison supports the analysis of trade-offs in scalability, interpretability, robustness, and domain alignment across different automation paradigms.

Figure 4: A comprehensive framework comparison of AI-driven automation systems

Overall, the architectural progression from rule-based systems to hybrid systems and LLM-based systems reflects an industry-wide transition from mechanical task replication to cognitive process optimization [54,72,78,87]. Current research focuses on developing systems that self-adaptive dynamically select appropriate architectural paradigms based on real-time workflow analysis [97,99,146,147].

2.2 Classification on Functionality of AI-Driven Automation Tools

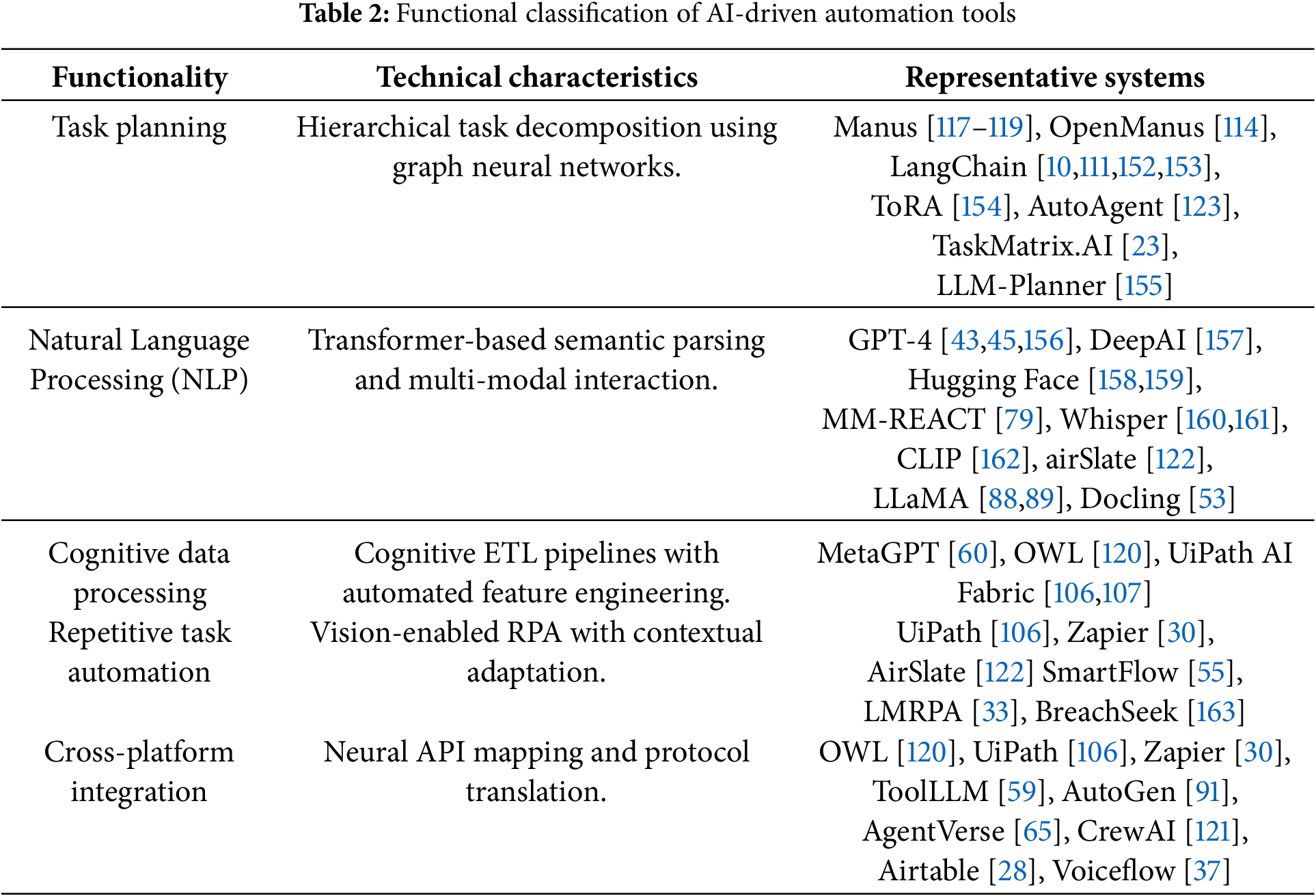

The functional landscape of AI-driven automation tools can be systematically organized into five principal categories, including Task Planning, NLP, Data Processing, Repetitive Task Automation, and Cross-Platform Integration [5,6,95]. Each represents distinct technical approaches to workflow automation [69,75]. This classification, presented in Table 2, reveals the evolving capabilities of modern automation systems from isolated task execution to integrated cognitive platforms.

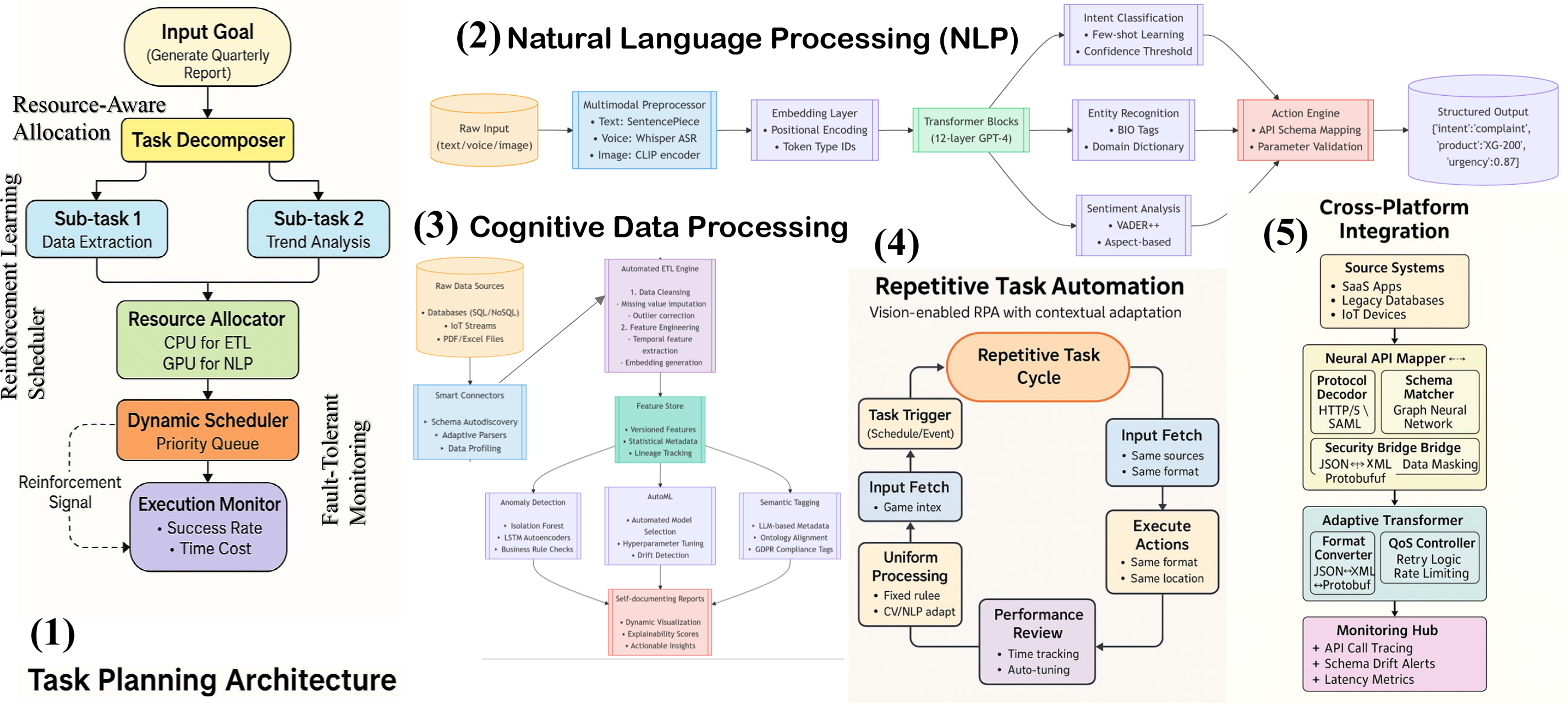

As shown in Fig. 5 (1), Task Planning Architecture enables intelligent workflow automation through dynamic goal decomposition and adaptive execution. The system first parses natural language objectives into structured representations using LLMs. A Graph Neural Network (GNN) [164] then hierarchically decomposes tasks while modeling dependencies between sub-tasks as directed edges [165,166]. The architecture features three innovation layers: (1) Resource-Aware Allocation that dynamically assigns compute resources (GPU/CPU) based on sub-task requirements [25,27,167], (2) Reinforcement Learning Scheduler optimizing execution order through real-time performance feedback [16,85,168], and (3) Fault-Tolerant Monitoring triggering granularity adjustments when success rates drop below thresholds [39,56,136].

Figure 5: Representative architectures of AI-driven automation systems across functional categories

As depicted in Fig. 5 (2), NLP Processing-based Automation enables multimodal automation through layered linguistic analysis [79,149,169,170]. The raw inputs (text/voice/image) undergo unified preprocessing via SentencePiece tokenization [171], Whisper speech recognition [160,161], or CLIP visual encoding [162]. The system then processes embeddings through 12-layer GPT-4 transformer blocks [156,43], generating parallel outputs for: (1) Intent Classification using few-shot learning [66,172], (2) Entity Recognition with domain-enhanced BIO tagging [170], and (3) Aspect-based Sentiment Analysis via VADER++ [169,173]. These outputs converge at the Action Engine, which validates parameters against API schemas (e.g., mapping product mentions to CRM IDs) and triggers downstream workflows [91,92,174].

As illustrated in Fig. 5 (3), Cognitive Data Processing-based automation system demonstrates a comprehensive architecture for intelligent data automation. The pipeline initiates with Raw Data Sources spanning structured databases (SQL/NoSQL), semi-structured documents (PDF/Excel), and real-time IoT streams [14,34,55,66]. The cognitive data processing pipeline features three core processing stages: (1) Smart Connectors [80–82] that perform schema autodiscovery and adaptive parsing of diverse data sources, (2) Automated ETL [17,69,75] with dual-phase processing including data cleansing (missing value imputation, outlier correction) and feature engineering (temporal patterns, embeddings), and (3) Feature Store [14,34,76] that maintains versioned features with complete lineage tracking.

As illustrated in Fig. 5 (4), Repetitive Task Automation systems combine rule-based execution with adaptive computer vision (CV) [49,50] and natural language processing (NLP) [46,148,175,176] to handle high-volume, predictable workflows. The architecture follows a cyclical pattern where tasks are: (1) triggered by scheduled events or system alerts, (2) processed through standardized rules with contextual adaptations, and (3) executed with consistent output formats [33,177,178]. Key innovations include vision-enabled element recognition that maintains action precision across interface changes, and performance auto-tuning that optimizes processing time while preserving output consistency. These systems excel in scenarios like invoice processing (extracting fixed fields from varying layouts) or data migration (repetitive database operations).

Fig. 5 (5) illustrates a generalized architecture for Cross-Platform Automation Systems, designed to bridge heterogeneous data environments through intelligent integration layers [65,130,179]. The system begins with diverse Source Systems such as SaaS applications, legacy databases, and IoT devices [70,76,180]. A Neural API Mapper decodes protocol formats, aligns schemas using graph neural networks, and securely translates authentication protocols (e.g., OAuth2 [181,182] to SAML [143,183]). The Adaptive Transformer module converts between data formats (e.g., JSON, XML, Protobuf) and ensures quality-of-service via retry logic and rate limiting. Processed data flows into Target Systems, including cloud platforms and mobile endpoints, while a Monitoring Hub tracks API calls, schema drift, and latency metrics [184–186]. This architecture emphasizes modularity, protocol adaptability, and real-time observability, making it particularly suitable for hybrid cloud integration and dynamic enterprise workflows.

Beyond the functional taxonomy, understanding the relative maturity of these approaches is crucial for researchers alike. Fig. 6 presents a technology maturity curve analysis for the five functional categories, synthesizing insights from current implementations, representative systems, and ongoing research challenges. This indicates that while AI-enhanced repetitive task automation is nearing mainstream adoption, and cross-platform integration tools are demonstrating increasing robustness, the more cognitive capabilities, particularly NLP integration, cognitive data processing, and advanced task planning, exhibit significant potential but face longer development paths towards stable, widespread deployment. NLP integration shows rapid progress but requires refinement in operational reliability within workflows. Cognitive data processing and task planning represent the frontier of AI-driven automation, currently characterized by innovative prototypes and active research, with substantial work needed to overcome challenges in scalability, robustness, and generalization for complex, real-world environments.

Figure 6: Technology maturity assessment of AI-driven automation functional categories

Overall, the functional evolution of AI-driven automation tools reveals three significant technical trends: the convergence of symbolic and connectionist AI approaches [78,96,142], the emergence of self-configuring automation ecosystems [92,94,187], and the growing importance of human-AI collaboration frameworks [188–190]. Current research directions focus on developing more robust architectures capable of handling increasingly complex, multi-domain workflows while maintaining operational transparency.

2.3 Taxonomy on Task Flow Management and Execution Mechanisms

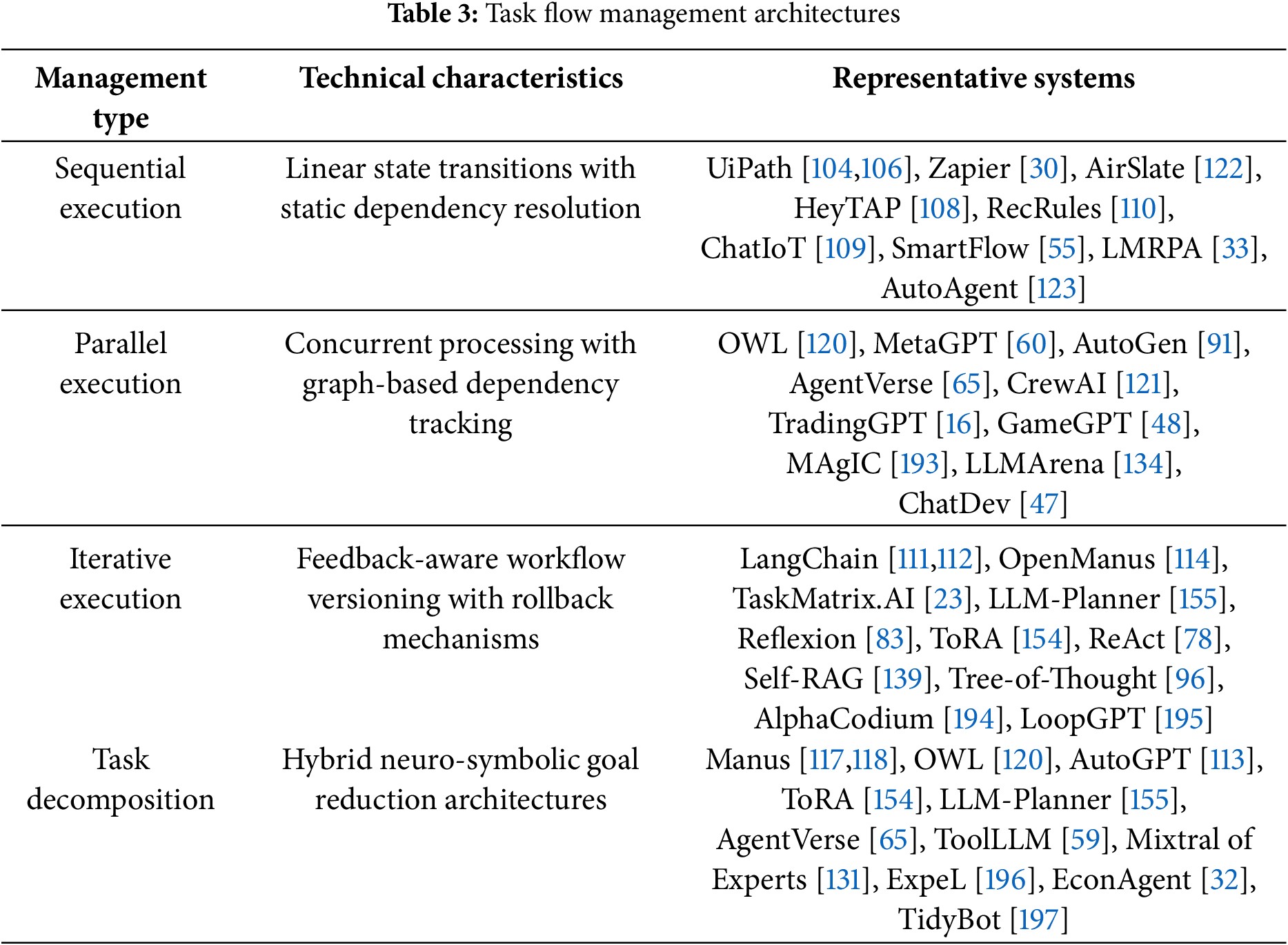

The architectural design of task flow management [6,21,191] in AI-driven automation systems reflects fundamental trade-offs between predictability, efficiency, and adaptability. As detailed in Table 3, contemporary tools employ four distinct execution paradigms—sequential, parallel, iterative, and task decomposition-based approaches [31,86,192]—each demonstrating unique technical characteristics shaped by their underlying coordination models and error recovery strategies [39,95,99].

As shown in Fig. 7 (1), Sequential Execution Automation System [14,66,69,75] adopts a linear task execution model, where each task proceeds only after the previous one completes. This approach ensures simplicity, predictability, and ease of debugging, making it well-suited for workflows with fixed logic and minimal variability, such as form approvals or structured back-office operations [15,34]. However, the strict step-by-step coordination limits scalability and responsiveness, making the system less adaptable to dynamic environments or exception-heavy scenarios [33,177].

Figure 7: Representative architectures of AI-driven automation systems across functional categories

As illustrated in Fig. 7 (2), Parallel Execution Automation System enables concurrent processing of multiple tasks using a graph-based dependency resolution framework [65,130,179]. By distributing workload across agents and allowing simultaneous execution, it significantly improves throughput and performance in multi-tasking or data-intensive applications [49,50]. Nonetheless, the architecture introduces challenges in synchronization, consistency maintenance, and error tracking, which require robust monitoring and coordination mechanisms [184,185].

As depicted in Fig. 7 (3), Iterative Execution Automation System focuses on adaptive task flows by incorporating feedback loops and incremental workflow optimization [78,96,142]. This model is highly effective in environments where requirements evolve over time, such as conversational agents or adaptive planning systems, as it allows ongoing refinement of tasks based on observed outcomes. However, its complexity arises from the need for rollback mechanisms, state versioning, and audit trails to ensure compliance and traceability during iterative updates [92,94].

As shown in Fig. 7 (4), Task Decomposition Automation System leverages goal-oriented reasoning to break down complex objectives into smaller executable sub-tasks [71,72,198]. By combining neural and symbolic techniques, it supports scalable task planning across diverse domains and agent specializations [31,86]. This architecture excels in modularity and reuse, making it ideal for open-ended or cross-domain problems, though it demands sophisticated control strategies to manage coordination and task interdependencies effectively [39,95].

2.3.1 In-Depth Analysis of Each Execution Mechanisms

Sequential Task Execution: [66,69,75] Exemplified by UiPath [104,106,107] and Zapier [30], sequential models enforce strict linear execution through deterministic scheduling algorithms and finite-state machines. These systems prioritize operational reliability over flexibility, utilizing static priority queues and rule-based triggers to maintain process integrity. Their architecture proves particularly effective in legacy system integration and routine office workflows (e.g., employee onboarding approvals), where predictable patterns dominate. However, this rigid temporal coordination inherently limits throughput and dynamic exception handling, as task latency accumulates linearly and environmental changes require manual workflow redesign [33,177,178].

Parallel Task Execution: [65,130,179] Systems like OWL [120] and MetaGPT [60] implement concurrent processing through distributed task queues with graph-based dependency resolution. These architectures employ lock-free data structures and probabilistic conflict resolution to coordinate simultaneous execution across multi-agent environments. The technical innovation lies in real-time resource monitoring systems that balance computational load across agents while maintaining data consistency through semantic versioning protocols.

Iterative Task Execution: [78,96,142] LangChain [111,140,153] and OpenManus [114,117] exemplify feedback-driven architectures that combine versioned workflow states with reinforcement learning policies. These systems implement semantic differencing algorithms to identify optimization opportunities between iterations, enabling adaptive adjustment of execution paths. The technical challenge centers on designing efficient rollback mechanisms and audit trails that preserve compliance while supporting dynamic workflow evolution.

Task Decomposition Strategies: [71,72,198] Advanced frameworks like Manus [117,119] and AutoGPT [113,159] employ hybrid neuro-symbolic reasoning to decompose abstract goals into executable sub-tasks. Through multi-resolution analysis modules, these systems alternate between symbolic planning and neural subtask generation, enabling collaborative execution across specialized agents [31,86]. The architectural divergence manifests in centralized vs. distributed control philosophies—AutoGPT utilizes monolithic decomposition controllers, while OWL [120] implements decentralized negotiation protocols.

2.3.2 Comparative Analysis and Selection Guidelines

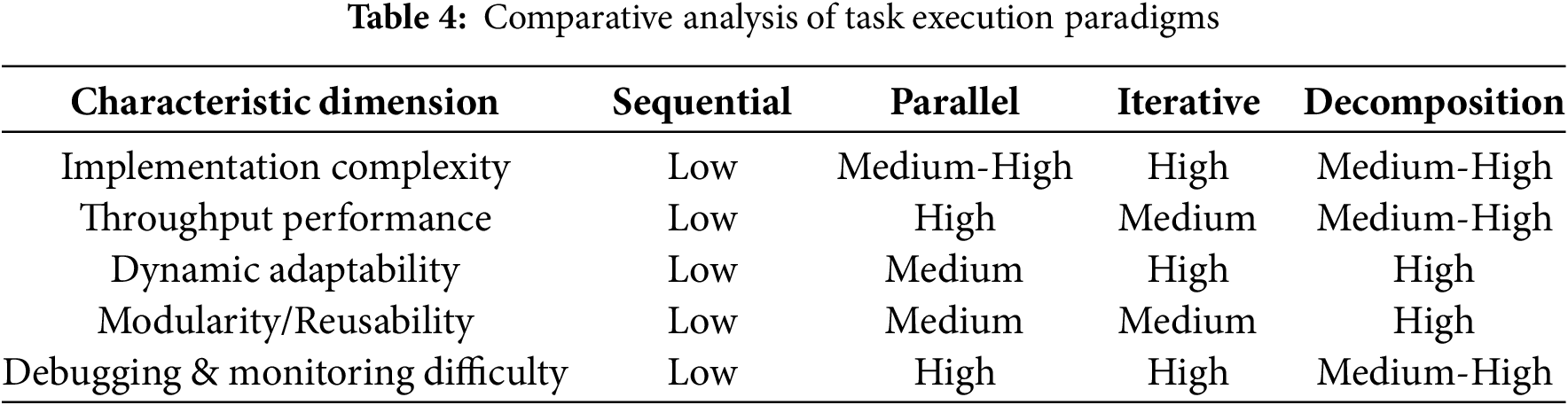

The choice of task execution paradigm requires careful consideration of operational requirements and system constraints [39,95]. As shown in Table 4, each mechanism presents distinct trade-offs across five critical dimensions: implementation complexity, throughput efficiency, dynamic adaptability, modularity, and observability [184,185].

Sequential execution offers minimal implementation complexity and straightforward debugging [15,34], making it ideal for small-scale workflows with fixed logic patterns, though it sacrifices throughput and adaptability. Parallel architectures [49,50] significantly enhance processing capacity for batch operations through concurrent resource utilization, but introduce synchronization challenges and increase monitoring overhead [186]. Iterative models excel in dynamic environments requiring continuous optimization, employing feedback loops to adapt workflows, albeit with elevated implementation and maintenance costs [92,94]. Task decomposition strategies provide superior modularity for complex multi-domain tasks through specialized agent collaboration [115,192], though demanding sophisticated coordination frameworks.

In conclusion, the evolution of these mechanisms reveals an industry-wide shift from rigid workflow automation to adaptive process orchestration [39,71,95]. Modern automation systems increasingly combine multiple paradigms, while facing persistent challenges in maintaining operational coherence across hybrid coordination models [65,86,130]. For instance, employing decomposition for task planning follows by parallel execution [31,50,49]. In future research, greater emphasis can be placed on self-organizing architectures capable of dynamically selecting execution strategies based on real-time system states and environmental constraints [92,94,187].

2.4 Application Taxonomy of AI-Driven Automation

2.4.1 Primary Benefited Production Aspects of AI-Driven Automation

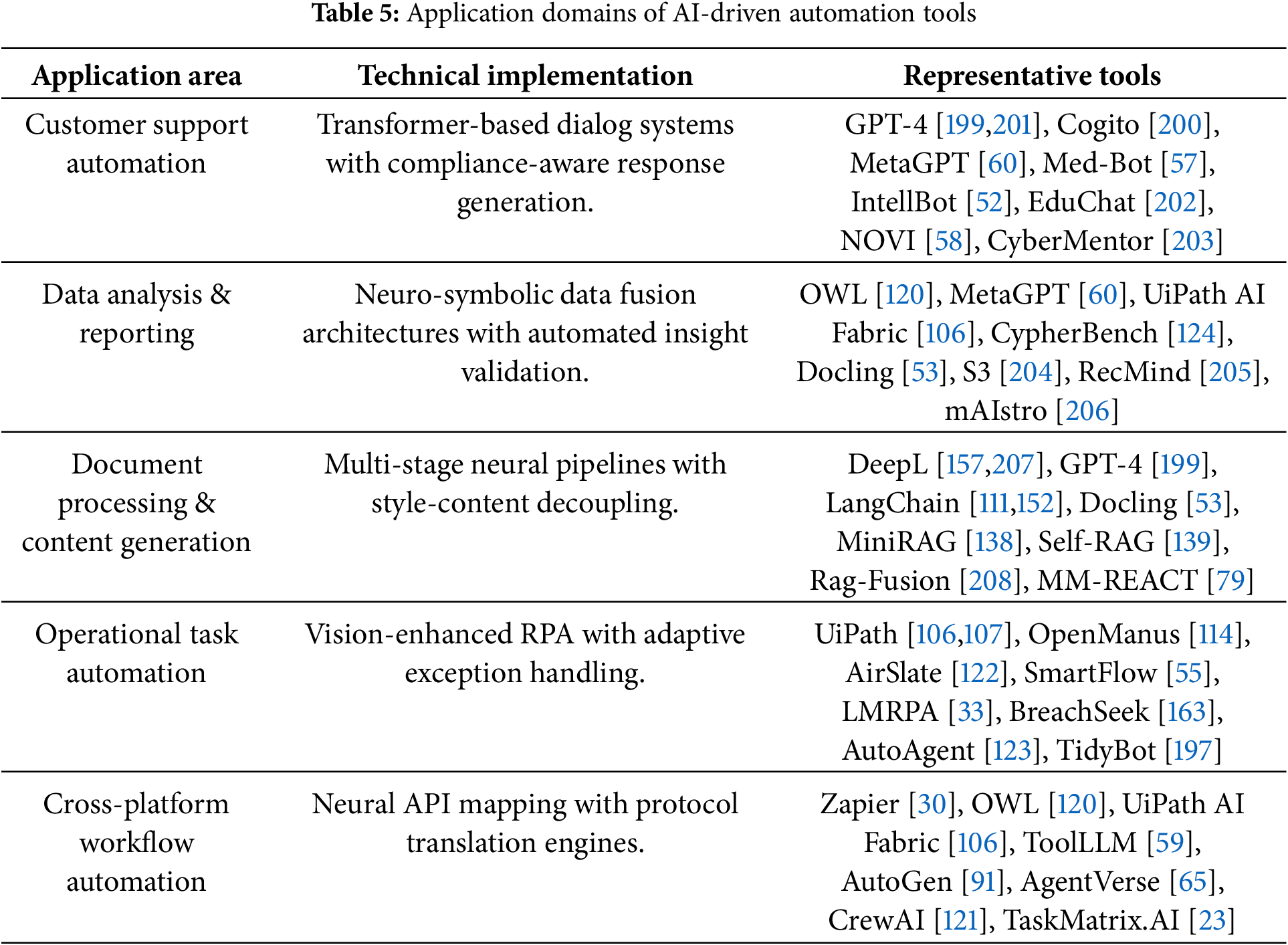

The application landscape of AI-driven automation tools spans multiple functional domains, each demonstrating unique technical implementations tailored to specific operational requirements [71,86,95]. As detailed in Table 5, these solutions exhibit specialized architectural configurations that address distinct challenges across enterprise workflows.

Customer Support Automation: Modern implementations leverage transformer-based architectures like GPT-4 [156,89,199] and specialized systems such as Cogito [200] to establish multi-modal communication channels. These systems combine natural language understanding with dialog management engines to process customer inquiries through hybrid symbolic-neural approaches. The technical differentiation emerges in their ability to handle context switching between structured FAQs and unstructured conversational flows while maintaining compliance with industry-specific communication protocols [78,92,96].

Data Analysis & Reporting [14,34,75]: Tools like OWL [120] and UiPath AI Fabric [106,107] demonstrate advanced data fusion capabilities, integrating structured database queries with unstructured text analysis through neuro-symbolic architectures. LangChain [111] introduces a novel chaining mechanism that connects disparate data sources through semantic linking, while MetaGPT [60] employs graph neural networks to visualize complex data relationships. These systems differ fundamentally from traditional Business Intelligence (BI) tools [17,32,209,210] through their dynamic hypothesis generation capabilities and automated insight validation frameworks.

Document Processing & Content Generation [53,72,198]: This domain combines neural machine translation systems like DeepL [157,207] with generative architectures in GPT-4 [45,199] and structured document processors like Manus [117–119]. The technical innovation lies in multi-stage processing pipelines that first parse document semantics through attention mechanisms, then apply domain-specific templates, and finally generate context-aware outputs. LangChain’s contribution emerges through its modular architecture that separates content generation from style formatting, enabling adaptive reuse of document components across different output formats [10,112].

Operational Task Automation [33,66,177]: Systems such as UiPath [106,107] and AirSlate [122] represent the evolution of traditional RPA [15,66,81] through computer vision-enhanced workflow recognition and self-adjusting execution engines. OpenManus [114] introduces a decentralized approach to operational automation through its agent-based task allocation system, particularly effective in distributed procurement processes. The technical differentiation manifests in their exception handling mechanisms, ranging from rule-based fallback systems in UiPath to neural pattern recognition in AirSlate’s document-centric workflows [70,178].

Cross-Platform Workflow Automation [65,130,179]: Zapier’s [30] AI-enhanced integration framework and OWL’s [120] multi-agent automation system exemplify two distinct technical approaches to platform interoperability [19,31,64,192]. While Zapier [30] employs neural API mapping to bridge commercial SaaS applications, OWL [120] utilizes semantic protocol translation for industrial IoT environments. UiPath AI Fabric [106,107] demonstrates a hybrid approach combining RPA connectors with machine learning-based workflow adaptation, particularly effective in legacy system integration scenarios. These systems share common challenges in maintaining data consistency across heterogeneous security models and authentication protocols [182,183].

As illustrates in Fig. 8, it presents the functional taxonomy and ecosystem architecture of prominent AI-driven automation tools. The tools are grouped into five distinct categories: customer support automation, data analysis and reporting, document processing and content generation, operational task automation, and cross-platform workflow automation [71,86,95]. Each category reflects a unique application domain and technological foundation, ranging from traditional RPA systems to advanced multi-agent automation systems and cognitive orchestration engines [60,65,111].

Figure 8: Primary functional taxonomy and system architecture of contemporary AI-driven automation tools

The visual layout highlights the vertical stack of automation complexity, starting from foundational tools like UiPath and Zapier [30,106] at the infrastructure layer [66,75], progressing through mid-layer platforms such as LangChain and MetaGPT [60,111] that facilitate reasoning and task decomposition, and culminating in agent-based ecosystems like Manus [117] and OWL [120] that enable decentralized coordination and emergent behavior [86,92]. By mapping tools according to both functionality and architectural sophistication, the figure provides a comparative perspective on how modern AI systems address varying degrees of autonomy, interoperability, and domain specialization within automation workflows [71,95].

Overall, Fig. 8 explains the role of each tool in automation while revealing new trends like LLM-based reasoning working with multi-agent automation systems. It also points toward the future development of fully adaptive, cognitive automation stacks [94,187].

In conclusion, the application-specific implementations reveal three fundamental technical trends: 1) Increasing specialization of neural architectures for domain-specific constraints [72,198], 2) Growing emphasis on hybrid symbolic-connectionist systems for enterprise compliance requirements [78,96], and 3) Emergence of multi-paradigm integration frameworks to handle heterogeneous automation environments [65,130]. Researchers are currently tackling the challenge of enhancing cross-domain generalization capabilities, while preserving application-specific optimization [85,111,211,212].

2.4.2 Industry-Specific Implementation and Production Scenarios

The convergence of industry-specific requirements and application-driven architectures has shaped the evolution of AI-driven automation technologies [14,34]. As shown in Fig. 9, we provide a structured classification of AI-driven automation architectures across five major industry/human living scenarios: Manufacturing [20,81], Healthcare [57,14,206], Finance [16,213], Energy [40,167], and Education [202,203]. Each column outlines the key applications, underlying technical frameworks, and representative systems currently deployed in practice. This layered visual categorization captures both the breadth and specificity of AI implementations across domains, ranging from predictive maintenance in manufacturing to adaptive assessment in education [68,202,203,214]. For instance, manufacturing leverages edge-cloud hybrid computing and 3D vision systems [25,211] to support physical automation, while healthcare systems prioritize privacy-preserving AI and compliance frameworks [13,215].

Figure 9: Primary functional taxonomy and system architecture of contemporary AI-driven automation tools

Meanwhile, Table 6 presents a unified taxonomy that cross-references industrial domains with their characteristic applications, technical implementations, and representative systems [17,35,209].

The integrated analysis reveals several critical architectural patterns [65,71,86]. Manufacturing systems exemplify the tight coupling between physical automation and AI decision-making, where the mainstream generative AI engine coordinates with industrial robots through sub-millisecond control loops [25,68,211]. This contrasts with healthcare implementations that prioritize ethical constraints, as seen in BD HemoSphere Alta [218]’s differential privacy mechanisms that anonymize patient data while maintaining diagnostic accuracy [98,215].

Financial sector tools demonstrate unique hybrid architectures, where AirSlate [122] combines NLP-driven document processing with regulatory compliance checks through neural-symbolic reasoning. The system dynamically generates audit trails by tracing data transformations across workflow steps, achieving both operational efficiency and compliance transparency. Similarly, education technologies like OneClickQuiz [221,222] implement Bloom’s Taxonomy through distilled language models, enabling rapid question generation while maintaining pedagogical alignment [202,203].

Energy management solutions [40,167,216] highlight the growing importance of distributed intelligence, with OWL’s [120] multi-agent automation system optimizing grid operations through edge-based predictive models [223,224]. These architectures employ specialized hardware-software codesign to withstand harsh environmental conditions while maintaining real-time processing capabilities [18,19]. Across all domains, the convergence of application-specific requirements and industrial constraints continues to drive architectural innovation in AI-driven automation systems [94,95,142].

2.4.3 Lightweight AI-Driven Automation for Edge Devices, Mobile Systems, or Low-Resource Environments

The surge in Internet of Things (IoT) devices and the increasing deployment of mobile systems and embedded technologies have created a significant need for lightweight AI-driven automation solutions [223,224]. As a result, traditional cloud-based AI solutions, which typically rely on robust computational infrastructures, are not suitable for deployment in these low-resource environments. This section discusses how lightweight AI-driven automation systems are addressing these challenges and enabling effective automation for edge devices, mobile systems, and other low-resource environments.

1. Edge Device Automation: Edge devices, including sensors, cameras, and gateways, play a pivotal role in modern automation by collecting and processing data locally to minimize latency and reduce dependence on cloud infrastructure [220]. These devices often operate in environments where bandwidth is limited or unreliable, making cloud communication less efficient. To address this, edge AI systems are designed with compact models that execute inference tasks with minimal resources. Techniques such as model quantization, pruning, and knowledge distillation are frequently employed to compress large, resource-intensive models into smaller, more efficient versions without sacrificing accuracy [88,89]. For instance, lightweight convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and decision tree-based models have gained popularity for tasks like object detection, and predictive maintenance on embedded systems [21].

2. Mobile Systems and IoT Automation: Mobile systems and IoT devices often have limited power budgets and processing capabilities, yet they need to perform tasks like speech recognition, image processing, and sensor data analysis [160,162]. To enable AI automation on such devices, specialized AI chips and microcontrollers are integrated to offload computationally heavy tasks from the main processor, thus optimizing power usage [223]. This empowers edge devices and mobile systems to perform tasks like image recognition, natural language processing, and personalized recommendations locally [225].

3. Embedded Systems in Low-Resource Environments: Embedded systems in domains like agriculture, healthcare, and industrial automation are increasingly adopting lightweight AI-driven automation solutions [68,211,214]. These systems often rely on custom-designed hardware to meet performance and power constraints, which enable efficient AI processing with minimal power usage [224]. In these contexts, techniques like model compression, low-precision arithmetic, and hardware acceleration help make the automation feasible in low-resource environments [21].

4. The Future of Lightweight AI-Driven Automation: Looking ahead, several trends will further enhance the deployment of AI-driven automation on edge and low-resource devices. Federated learning, for instance, allows devices to collaboratively learn from data without transmitting sensitive information to the cloud, making it ideal for environments where privacy is paramount [223]. Furthermore, advances in AI chip design, including the integration of AI accelerators into microcontrollers, will continue to push the boundaries of what is possible in edge and mobile AI [224].

In conclusion, lightweight AI-driven automation is a rapidly evolving field that is crucial for enabling intelligent systems in edge devices, mobile systems, and low-resource environments [223,224]. These advancements will help bridge the gap between cloud-based automation and real-time, on-device processing, bringing AI-powered automation to a wide range of applications with minimal resource requirements.

This section systematically established a novel taxonomy for classifying AI-driven automation technologies, addressing the critical need for a unified framework in this rapidly evolving field. Our analysis delineates four foundational architectural paradigms:

1. Rule-Based Systems: Characterized by deterministic workflows, suitable for structured environments but limited in adaptability.

2. LLM-Driven Approaches: Leveraging natural language understanding for dynamic task orchestration, though challenged by interpretability and data dependence.

3. Multi-Agent Cooperative Models: Enabling complex, distributed problem-solving through agent collaboration, with trade-offs in coordination overhead.

4. Hybrid Architectures: Combining strengths of the above paradigms to balance flexibility and robustness, as exemplified by tools like Manus [117] and OWL [120].

Further, we categorize these technologies by functionality (e.g., NLP-centric vs. RPA-integrated), execution mechanisms (sequential vs. parallel), and human-AI collaboration modes (assistive vs. autonomous). This not only clarifies the current landscape but also highlights gaps in interoperability and scalability, which is the key challenges illustrated in Section 4.

3 Recent Mainstream Applications of AI-Driven Automation

3.1 Overview of Prominent AI-Driven Automation Tools

Recent years have witnessed the emergence of diverse AI-driven automation tools, each addressing distinct challenges across industries. The evolution of AI-driven automation has entered a transformative phase characterized by three fundamental shifts [6,71,95]: (1) from static rule-based systems to dynamic cognitive architectures [78,96,97], (2) from single-agent operations to collaborative multi-agent ecosystems [16,31,65,115], and (3) from domain-specific solutions to cross-platform cognitive frameworks [9,59,111].

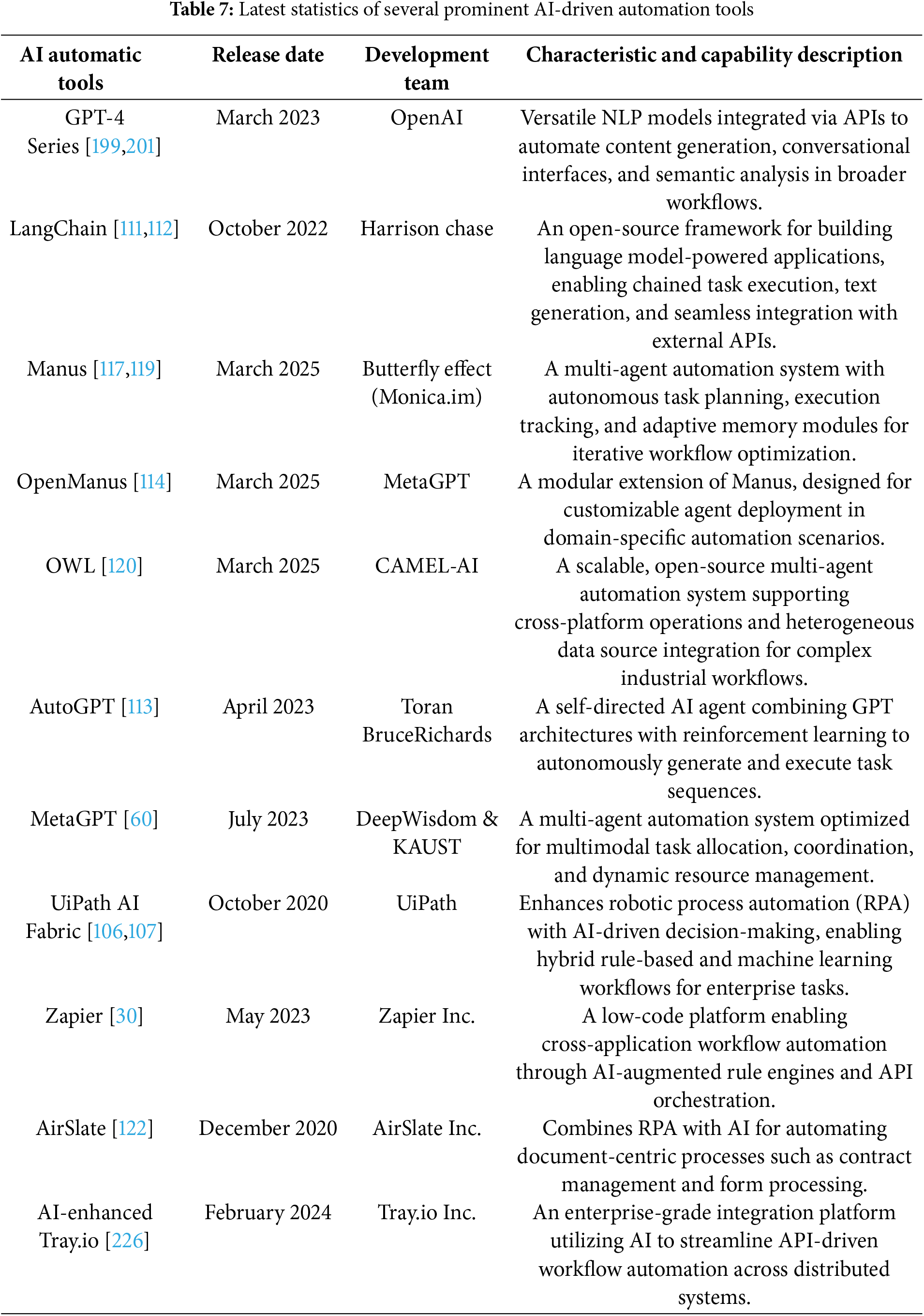

As detailed in Table 7, we list several major representative AI-driven automation tools, accompanied by concise descriptions of their core functionalities and technological underpinnings. This progression manifests through distinct technological generations that address emerging challenges in social production automation [25,27,211].

3.1.1 Architectural Paradigm Shifts

The evolution of AI-driven automation tools demonstrates a clear architectural progression from rule-based systems to cognitive architectures [75,77,105]. Early hybrid RPA-AI solutions like UiPath AI Fabric [106,107] have given way to sophisticated neuro-symbolic systems exemplified by post-2023 developments such as LangChain [10,111,152]. These modern frameworks introduce cognitive chaining capabilities, where LLMs dynamically orchestrate sequential reasoning processes through API composition [59,128]. The transition reflects a broader industry movement from deterministic automation to adaptive, knowledge-driven workflow systems that demonstrate contextual awareness and learning capabilities.

3.1.2 Emerging Design Patterns

Analysis of development methodologies reveals two significant innovation patterns in the field. The academic-industrial fusion model, exemplified by MetaGPT [60]’s joint development between DeepWisdom and KAUST [227], successfully combines industrial-grade scalability [68,211] with academic research rigor in multi-agent coordination.

Concurrently, the open-source ecosystem approach demonstrates remarkable efficacy, as evidenced by LangChain’s rapid community adoption, showcasing how community-driven development can accelerate toolchain maturation [111,228]. These AI-driven automation tools collectively establish a new cognitive automation stack comprising four layers: (1) Sensorimotor interfaces [4,108,229], (2) Neural reasoning cores [5,141,142], (3) Multi-agent coordination planes [127,129], and (4) Evolutionary adaptation mechanisms [39].

Overall, these above introduced tools exemplify the convergence of AI methodologies, such as LLMs, multi-agent automation systems, and hybrid rule-AI architectures, to address scalability, adaptability, and interoperability challenges in modern automation applications.

3.2 Detailed Discussion of Several Representative AI-Driven Automation Tools

3.2.1 Manus (From Butterfly Effect)

As a representative implementation of a multi-agent automation system, Manus [117,119] operates within an isolated virtual environment and is composed of three primary functional modules: the Planning Module, the Memory Module, and the Tool Use Module. The left part of Fig. 10 illustrates the core architectural design of the Manus multi-agent automation system. These components work collaboratively to enable Manus to interpret, plan, and execute complex tasks in an automated and adaptive manner.

Figure 10: (1) Left: the core module design and composition of the manus multi-agent automation system; (2) Right: manus task processing flow under multiple agent architecture

The Planning Module serves as the “brain” of the system, responsible for understanding user intentions, decomposing abstract tasks into concrete actions, and generating executable plans. It supports semantic understanding (NLU) [78,96,173], priority sorting [71,86], resource allocation [25,167], DAG-based task decomposition [142,230], and exception handling. The Memory Module empowers the system to maintain coherence and personalization across sessions by storing user preferences, interaction history, and intermediate results. A typical implementation may include components such as user profiling vectors, interaction history databases (e.g., ChromaDB [231]), and short-term memory caches [83,232]. Finally, the Tool Use Module acts as the system’s “hands”, integrating capabilities such as web search, data processing, code execution [130,233,234], and content generation. This multi-tool orchestration allows Manus to effectively complete diverse and sophisticated tasks.

As illustrated on the right side of Fig. 10, Manus operates based on a structured task execution flow under a Multiple Agent Architecture [65,92,94]. The system runs within an independent virtual environment and is capable of handling both simple queries and complex project-level requests. Upon receiving a task input from the user, the system initiates a multi-stage process to understand, decompose, and complete the task effectively.

The first step in this pipeline is task reception, where Manus accepts user input in various formats such as text, images, and documents [79,235]. This is followed by the task understanding phase, in which Manus leverages NLP techniques to extract key intents and semantic elements from the input [78,96]. During this phase, the Memory Module provides contextual support by supplying previously stored user preferences and interaction history, thereby enhancing personalization and interpretability [64,67,83]. When user goals are ambiguous, the system engages in interactive dialogue to help refine task objectives [92,187].

Once the task intent is clarified, the task decomposition stage begins. Here, the Planning Module breaks down complex tasks into a series of executable subtasks, establishes dependencies, and determines execution order [142,230]. This decomposition process typically results in a directed acyclic graph (DAG) [71,198] structure that organizes task execution in a logical and efficient manner. Through this layered and modular architecture, Manus achieves robust adaptability and automation in diverse real-world applications [86,114,117].

As shown in Table 8, the architecture of Manus is organized into six distinct layers, each responsible for a critical aspect of task execution within the multi-agent automation system. The user interface layer enables interaction through a command line or REST API [23,59,128,217], serving as the system’s entry point. The control layer, powered by the flow engine, orchestrates task requests and initiates execution processes. At the core layer, planning and invocation flows are designed and instantiated to coordinate agent operations. The agent layer includes specialized agents-planning, execution, and validation-that work collaboratively to decompose tasks, execute actions, and verify outcomes. The tool layer provides essential capabilities such as web search, code execution, and result validation. Finally, the infrastructure layer ensures system stability and extensibility through configuration management, logging, tool registration, and reusable task templates.

Technical Features of Manus: Manus [117] stands out in the field of AI agents due to its advanced architecture and a range of technical innovations that enable highly autonomous and efficient task execution. One of its most distinguishing features is its autonomous planning capability [114,118]. Unlike conventional tools that rely heavily on user input or predefined workflows, Manus can independently reason, plan, and execute tasks. In the General AI Assistant Benchmark (GAIA) [236], which evaluates real-world problem-solving capabilities of general-purpose AI assistants, Manus [117,119] achieved state-of-the-art (SOTA) performance with a 94% success rate in completing complex tasks automatically.

Another key strength of Manus lies in its context understanding [117]. The system excels at interpreting vague or abstract user inputs, allowing it to identify user needs with minimal instruction. For instance, a user can describe the content of a video, and Manus will locate the corresponding link across platforms. This context-awareness supports sustained multi-turn interactions [83,92,187], with the system capable of maintaining coherent dialogues over ten or more turns, greatly enhancing the user experience.

Manus is built upon a multi-agent architecture, enabling collaborative execution of tasks across different functional agents. Similar to Anthropic’s Computer Use paradigm [117,119], Manus runs within a secure and isolated virtual machine, allowing specialized agents to handle planning, memory, and tool usage in parallel. This modular design ensures both scalability and fault tolerance when dealing with complex workflows.

Furthermore, tool integration is a hallmark of Manus’s operational strength [59,123,237]. It can automatically invoke and coordinate various tools for web search, data analysis, code generation, document creation, and more. This flexible integration allows Manus to handle a wide spectrum of tasks, from information retrieval to sophisticated analytical and creative work. The architecture also supports custom tool plugin development, making it extensible to specific application domains [65,94,114].

Finally, Manus emphasizes security and system robustness. By executing tasks within a gVisor-based sandboxed environment [51,134,223,224], the system ensures process isolation, resource control, and execution safety. Combined with intelligent task scheduling mechanisms and modular agent design, Manus maximizes both efficiency and adaptability while maintaining high standards of stability and security [114,118].

3.2.2 OpenManus (From MetaGPT Team)

The innovative design of OpenManus [114] centers around building a highly lightweight agent framework that emphasizes modularity and extensibility. It defines the functionality and behavior of agents through a combination of pluggable tools and prompts, significantly lowering the barrier for developing and customizing agents [21,94,147]. Prompts determine the agent’s reasoning logic and behavioral patterns, while tools provide actionable capabilities such as system operations, code execution, and information retrieval. By freely combining different prompts and tools, new agents can be rapidly assembled and empowered to handle a wide range of task types [31,113,115,238].

As depicted in Fig. 11, the OpenManus Automation Framework consists of four key components: a modular multi-agent automation system, tool integration, configuration and model support, and a bottom-up execution workflow. At its core, the framework includes specialized agents such as the Manus Main Agent [117,119], Planning Agent [148,175], ToolCall Agent [59,123], and customizable xAgents [92,94], each responsible for planning, task execution, and tool invocation. These agents interact seamlessly with integrated tools like vector databases [144,150], Python/NLP libraries [157,158], web APIs [59,237], and data visualization modules. The framework is further supported by flexible configuration files and multi-model integration capabilities, while the execution process is managed through a MetaGPT-based workflow [60,227] and a dynamic task queue system [8,56], ensuring scalable and efficient agent collaboration.

Figure 11: (1) Left: The roles and relationships among the agents in OpenManus; (2) Right: The architectural design philosophy of OpenManus

Essentially, OpenManus [114] is a multi-agent automation system. Unlike the one-shot [46,72], all-in-one response style of a single large model, a multi-agent automation system tackles complex real-world problems through an iterative cycle of planning, execution, and feedback. In the design of OpenManus, the core concept is illustrated on the right side of Fig. 11.

3.2.3 Optimized Workforce Learning for General Multi-Agent Assistance (OWL)

Optimized Workforce Learning for General Multi-Agent Assistance (OWL) [120] from Camel-AI6 is a cutting-edge framework for multi-agent collaboration that pushes the boundaries of task automation, built on top of the CAMEL-AI Framework7. The left side of Fig. 12 shows the system architecture overview of OWL. As seen in this sub-figure, the architecture of OWL consists of three main components: User Query, Actor Agents, and Tools Pool [31,113,120]. The system starts with a User Query, where the user initiates a task request. Actor Agents form the core module responsible for intelligent coordination, while the Tools Pool offers external interfaces needed for operations like web browsing, document parsing, and code execution [59,237].

Figure 12: (1) Left: The system architecture overview of OWL; (2) Right: The system technical implementation overview of OWL

Among the Actor Agents, the AI User Agent and Assistant Agent work together to manage task decomposition and coordination [31,113,115]. The AI User Agent acts as the task initiator, and the Assistant Agent handles scheduling. Supporting them are functional agents-such as Web, Search, Coding, and Document Agents-each responsible for specific tasks like browser interaction, information retrieval, code execution, and document parsing [59,237].

The core functionalities of OWL include real-time information retrieval through online search engines such as Wikipedia [144] and Google Search [150], as well as multimodal processing capabilities that support videos, images, and audio from both internet sources and local storage. It enables automated browser interactions using the Playwright framework, allowing for actions like scrolling, clicking, typing, downloading, and navigating through web pages. Additionally, OWL supports document parsing, extracting information from Word, Excel, PDF, and PowerPoint files and converting the content into plain text or Markdown [53,229]. It also features code execution capabilities, allowing users to write and run Python code through an integrated interpreter.

The optimized workforce Learning for general multi-agent assistance (OWL) [120] framework is designed as a scalable, adaptive, and decentralized system for coordinating heterogeneous AI agents in dynamic environments. The right side of Fig. 12 shows a comprehensive feature and technical description of the OWL system. Its architecture consists of four interconnected layers: Agent Layer, Orchestration Layer, Learning Layer, and Interface Layer.

Specifically, (1). Agent Layer hosts a diverse pool of specialized worker agents (e.g., LLM-based, rule-based, or hybrid), each with modular skill sets. These agents expose their capabilities through a standardized Skill API, enabling dynamic task delegation and interoperability [31,113,115,238]. (2). Orchestration Layer employs a Meta-Controller to optimize agent selection via reinforcement learning (RL) [85,168] or auction-based mechanisms [16,65], ensuring efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and constraint satisfaction. Additionally, a Dynamic Workflow Engine constructs multi-agent automation pipelines (modeled as DAGs) for complex tasks, with real-time performance monitoring and adaptation [8,56]. (3). Learning Layer integrates Federated Learning to enable secure knowledge sharing among agents without raw data exchange, preserving privacy. It also leverages Cross-Agent Transfer Learning to generalize skills across domains, using shared embedding spaces or policy distillation techniques [135,175]. (4). Interface Layer provides a Unified Task Graph API to abstract high-level user requests into decomposable subtasks [31,113,115]. It also incorporates Human-in-the-Loop (HITL) modules [188,189], offering explainability dashboards and corrective feedback channels for human oversight.

Overall, OWL [120]’s architecture is agnostic to agent paradigms (LLMs, robots, etc.), making it suitable for enterprise automation, embodied AI, and large-scale assistive systems. With its flexible modular design and powerful tool integration capabilities, OWL is becoming a key foundation for open-source AI-driven automation applications.

3.2.4 LangChain (From Harrison Chase @LangChain Inc.)

LangChain [111,112] is a modular framework designed to facilitate the development of multi-language and multi-scenario AI applications. As a widely adopted open-source framework, LangChain is designed to assist developers in building artificial intelligence applications. By providing standardized interfaces for chains, agents, and memory modules, LangChain simplifies the development process of applications based on LLMs.

Specifically, as illustrated in Fig. 13, the architecture adopts a layered design that promotes extensibility, modularity, and cross-platform compatibility. Each layer in the stack is responsible for a specific aspect of system functionality, from foundational APIs [80,128] to high-level cognitive orchestration [74].

Figure 13: A comprehensive overview of the system architecture of LangChain [111]

At the top of Fig. 13, the LangServe module provides the capability to deploy LangChain [111] workflows as RESTful APIs [239]. This makes it easy to integrate AI-powered chains into production environments, particularly within microservice architectures. Built with Python8, LangServe offers a standardized interface for external systems to call AI logic seamlessly. Beneath the deployment layer, LangChain offers a set of Templates and Committee Architectures, which serve as reference implementations for common tasks like question answering and document analysis. The heart of the system lies in the LangChain module itself [111]. This layer defines three primary capabilities: Chains for sequential task composition, Agents for dynamic decision-making, and Retrieval Strategies for data fetching based on similarity or keywords.

As shown in the center of Fig. 13, the LangChain-Community layer includes a rich ecosystem of pluggable modules for Model I/O, Prompting, Output Parsing, Document Loading, Vector Store integration, and Agent Toolkits. This layer enables developers to rapidly prototype and extend LangChain-based applications using components such as FAISS [240], Milvus [241], and external LLM APIs (e.g., ChatGPT [156,45,199] or LlaMa [88,89]).

At the bottom of Fig. 13, the LangChain-Core module defines abstract interfaces and reusable infrastructure for chains and agents. Alongside it, the LangChain Expression Language (LCEL) [242] provides a declarative syntax for chaining components. LCEL significantly reduces boilerplate code by allowing developers to describe “what to do” instead of “how to do it”, improving focus on business logic while supporting streaming, async, and service composition.

LangChain’s architecture supports a wide range of use cases, from retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) [138,139,208,229] to multi-agent collaboration workflows [126,175]. With built-in support for both Python and JavaScript9, LangChain is suitable for backend, frontend, and hybrid AI systems. Its modularity allows for rapid iteration, and its deployment tooling ensures a smooth transition from prototyping to production.

Moreover, LangGraph [228] is a key extension within the LangChain ecosystem, specifically designed for building stateful, multi-agent dynamic workflows [140,243,111]. It addresses the gaps in LangChain for complex cyclic processes and real-time interaction scenarios, offering developers a more flexible and efficient solution. Core features of LangGraph include cyclic graph support (loops and conditional branches between nodes), fine-grained state control (e.g., dynamic graph modification), and built-in persistence capabilities (e.g., task interruption recovery and human intervention). These features of LangGraph empower developers to effortlessly implement AI applications requiring iterative decision-making (such as adaptive RAG pipelines and multi-agent automation systems), while seamlessly integrating with the LangChain ecosystem.

3.2.5 LlamaIndex (From Jerry Liu @LlamaIndex)

LlamaIndex10 [88,244] is a specialized framework designed to optimize the development of Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) applications [46,139,208,229], excelling in multiple technical dimensions. Compared to well-known projects like Langchain [111,152], LlamaIndex distinguishes itself through its focused domain optimization and innovative design philosophy, offering users a more efficient and specialized development experience for RAG applications. LlamaIndex demonstrates exceptional versatility in handling diverse data formats.

As seen in the left side of Fig. 14, LlamaIndex’s data processing pipeline demonstrates its capability to ingest diverse data sources including databases, structured documents, and unstructured APIs [144,150,229]. This framework transforms raw data through LLM processing and vectorization, creating optimized representations for retrieval tasks. This visualization highlights the system’s robust data ingestion and preprocessing capabilities that form the foundation for effective RAG applications. The right side of Fig. 14 showcases LlamaIndex’s supported use cases, ranging from Q&A systems and structured data extraction to semantic search and agent-based applications. This demonstrates the framework’s versatility in addressing various NLP tasks while maintaining its specialized focus on retrieval-augmented generation scenarios. The separation of these components reflects LlamaIndex’s modular architecture, allowing developers to implement specific functionalities while benefiting from the framework’s optimized RAG core [138,229,244].

Figure 14: LlamaIndex architecture overview: (1) Left: Supported application scenarios of LlamaIndex; (2) Right: Data processing workflow of LlamaIndex

And its key features and advantages-including Robust Data Ingestion & Preprocessing [244,144,150], Optimized Indexing & Query Architecture [46,138,244], Native Multimodal Support [79,162], Production-Grade Scalability [8,56], Modular & Extensible Design [94,111], Ecosystem Integration [157,158,123] can be concluded as follows:

First, LlamaIndex [244] excels in data ingestion and preprocessing. It not only supports a wide range of structured and unstructured data formats but, more importantly, ensures high-quality data encoding into LLM memory through flexible text splitting and vectorization mechanisms [144,150,229]. This lays a solid foundation for contextual understanding during the generation phase.

At the same time, LlamaIndex provides a rich selection of indexing data structures and query strategies, enabling developers to fully leverage scenario-specific efficiency advantages and achieve high-performance semantic retrieval. Such targeted optimizations are undoubtedly critical for RAG applications [46,138].

Another notable highlight is LlamaIndex’s native support for multimodal data (such as images and videos) [79,162]. By integrating with leading vision-language models, it can introduce rich cross-modal context into the RAG generation process, adding new dimensions to the output. Undoubtedly, this will pave the way for numerous innovative applications.

Beyond core data management capabilities [245], LlamaIndex also emphasizes engineering best practices for RAG application development. It offers advanced features such as parallelized queries and Dask-based distributed computing support, significantly improving data processing efficiency and laying the groundwork for large-scale production deployment [8,56].

From an architectural perspective, LlamaIndex adheres to modular and extensible design principles. Its flexible plugin system allows developers to easily incorporate custom data loaders, text splitters, and vector indexing modules, catering to diverse and personalized requirements across different scenarios [94,111].

Additionally, seamless integration with the open-source ecosystem is an inherent strength of LlamaIndex. It provides out-of-the-box compatibility with popular tools and frameworks like Hugging Face11 and FAISS12 [158,159], enabling users to effortlessly leverage cutting-edge AI/ML capabilities and accelerate the development of innovative solutions.

As a professional-grade tool dedicated to RAG applications [46,139,208], LlamaIndex has become an ideal complement to general-purpose frameworks like Langchain. Developers can now freely choose between LlamaIndex’s optimized, high-efficiency approach and Langchain’s versatile, flexible paradigm based on their specific needs, maximizing both development efficiency and product quality.

As an evolving framework, LlamaIndex [244] continues to enhance its modeling capabilities for complex scenarios while integrating emerging advancements in LLM architectures and RAG methodologies. Future development focuses on intelligent auto-optimization features and expanded reference implementations to accelerate enterprise adoption.

3.2.6 AutoChain (From Forethought-AI)

AutoChain13[246] is a lightweight yet extensible framework proposed by Forethought-AI14. It builds upon the foundations of LangChain [111,140] and AutoGPT [113], offering developers a more efficient and flexible approach to building conversational AI agents. AutoChain’s core philosophy revolves around three key principles: simplicity, customizability, and automation.

As seen in Fig. 15, the framework deliberately maintains a minimalist architecture to reduce cognitive overhead, abstracting fundamental LLM application workflows into intuitive building blocks. The workflow of AutoChain [246], that shown in Fig. 15, facilitates automated interactions between an intelligent agent and a user. The process begins by receiving and storing the user’s query. The agent then evaluates whether to continue the interaction based on predefined conditions. If the maximum iteration limit is reached, it terminates with a final response; otherwise, the agent proceeds to the Plan phase to determine the next action (e.g., generating a response or requesting clarification). When external tools are required, the system checks if additional information is needed. If not, it executes the tool and appends the results to the input stream, storing them as a Function Message. The loop is controlled through binary decisions between AgentAction and AgentFinish, ultimately producing the agent’s output [92,247,248].

Figure 15: The architecture framework of AutoChain [246]: Agent workflow with conditional branching, external tool calls, and termination control

Unlike more complex alternatives, AutoChain [246] provides unparalleled customization through pluggable tools, data sources, and decision modules, enabling developers to create tailored solutions for unique use cases. This “embrace differentiation” approach is complemented by built-in conversation simulation capabilities that automate agent evaluation across diverse interaction scenarios, significantly accelerating development cycles.

AutoChain [246]’s balanced design caters to multiple user groups: beginners benefit from its gentle learning curve when creating basic dialogue agents [51,52,105], experienced LangChain users appreciate its familiar-but-simpler concepts for rapid prototyping, while AI researchers value its clean-slate extensibility for developing novel paradigms [31,113].

3.2.7 Flowise AI (From FlowiseAI Inc.)

Flowise AI15[249] emerges as an innovative open-source platform that significantly lowers the barriers to building LLM-based [37,250] applications through its no-code, drag-and-drop visual interface16. Unlike traditional coding-intensive frameworks, Flowise enables developers to construct sophisticated LLM workflows by simply connecting pre-built components, making AI application development accessible to non-programmers while maintaining professional-grade capabilities.