Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

A Comprehensive Survey of Contemporary Anomaly Detection Methods for Securing Smart IoT Systems

1 Research Team LAMIGEP, EMSI, Marrakech, 40000, Morocco

2 SISAR Team, LaRTID Laboratory, Higher School of Technology, Cadi Ayyad University, Marrakech, 40000, Morocco

3 IMIA Laboratory, MSIA Team, Faculty of Sciences and Techniques, Moulay Ismail University of Meknes, Errachidia, 52000, Morocco

4 Center for Artificial Intelligence, Prince Mohammad Bin Fahd University, Khobar, 31952, Saudi Arabia

5 Department of Computer Science, College of Computer, Qassim University, Buraydah, 52571, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Author: Mourade Azrour. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(1), 301-329. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.064777

Received 24 February 2025; Accepted 22 July 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

Attacks are growing more complex and dangerous as network capabilities improve at a rapid pace. Network intrusion detection is usually regarded as an efficient means of dealing with security attacks. Many ways have been presented, utilizing various strategies and focusing on different types of visitors. Anomaly-based network intrusion monitoring is an essential area of intrusion detection investigation and development. Despite extensive research on anomaly-based network detection, there is still a lack of comprehensive literature reviews covering current methodologies and datasets. Despite the substantial research into anomaly-based network intrusion detection algorithms, there is a dearth of a research evaluation of new methodologies and datasets. We explore and evaluate 50 highest publications on anomaly-based intrusion detection using an in-depth review of related literature techniques. Our work thoroughly explores the technological environment of the subject in order to help future research in this sector. Our examination is carried out from the relevant angles: application areas, data preprocessing and threat detection approaches, assessment measures, and datasets. We select unresolved research difficulties and underexplored research areas from every viewpoint recommendation of the study. Finally, we outline five potentially increased research areas for the future.Keywords

Smart cities have had a huge effect in latest years owing to its power and large effect on inhabitants’ lives. Smart cities are about combining day-to-day operations that inhabitants require with smart devices that enable them to conveniently navigate and manage various kinds of services such as housing, transit systems, bills, and healthcare. Network for smart cities is built on the IoT idea and is composed of five layers: Network, perception, middleware, application and business. The perception layer takes responsibility for Information is gathered from detectors and transmitted to drawbridge. This layer comprises detectors, scanners, and Radio-frequency identification. The network layer, also named as the middleware, contains the central network and its primary function is to send data gathered by sensors onto the server for storage. Ultimately, the software layer connects consumer capabilities to fog data. The Business layer is connected towards the application layer and is employed to define plans and guidelines that assist govern the whole system. As with every recent fad, there are numerous key variables and hurdles to making smart cities meet their goals, like security, mobility, scalability, latency, and implementation. The primary goal of cyber security is to defend cyberspace against cyber-attacks that might cause infrastructure disruption or system failures [1–3]. The massive amounts of information transferred in IoT systems raises the prospect of computer hackers that endanger consumers’ safety, integrity protection, confidentiality, and availability of services. Cyber-attacks might impact the infrastructure, communication link, protocol, transportation, or programming model. Intrusion detection systems (IDS) are defense measures used to identify various attacks. To defend a device from malicious assaults, access control approaches are used: prevention, detection, and mitigation. Encryption and authentication are examples of intrusion prevention; however, they are inadequate to safeguard systems against compromised users or attackers. Anomaly detection can be placed to use as a secondary line of protection to defend systems from unauthorized assaults as effectively as feasible and to mitigate the resulting effects. Standard IDS are categorized by attack identity, intruder sort, as well as detecting methodology [4]. Depending on the approach used, IDSs are divided into three main categories [5]: anomaly-based, misuse-based, and hybrid-based. The anomaly-based kind of intrusion detection system (IDS) is edited to show network behavior and recognizing abnormal behaviors based on particular typical behavior. Misuse-based IDS detects attacks in the future by using a pattern of prior known assaults as a reference. Nevertheless, if the assault is novel and has never previously been classified, IDS may not recognize it. IDS of the hybrid kind incorporate the benefits, including both anomaly and misuse-based detection approaches [6–8].

Our article is organized as follows: Section 2 provides a review of IoT and its applications. Section 3 addresses the security challenges associated with IDS, including an introduction to IDS specifications, subtypes, and detection techniques, along with a review of several IDS designed for IoT, either available or specially developed for smart environments. Section 4, the most important, focuses on the various machine learning (ML) algorithms commonly used in evaluating IDS in the IoT domain. It also covers the construction of anomaly detection systems, including data preparation, feature selection, and datasets. Section 5 reviews related articles that address the same topic. Finally, Section 6 proposes an IDS model, and the article concludes with future research perspectives.

2 Internet of Things Background and Challenges

The concept of the Internet of Things (IoT) originated in 1999 at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) from networks utilizing radio frequency identification (RFID) technology, developed by the Auto-ID Center. The primary functions of the system at that time included data acquisition, processing, transmission, and application [9]. Although not all “Things” are necessarily connected to the internet, the Internet of Things (IoT) can be understood as an extensive network of objects, sensors, and actuators that serve specific purposes. This concept allows us to generalize the term Network of Things (NoT) to include both isolated networks and those connected to the internet. As discussed in the general introduction, the IoT can be described as a vast network of sensors and actuators, primarily internet-enabled, that communicate with each other without human intervention. These networks generate and utilize data to fulfill meaningful functions. The primary role of an IoT system is to collect data from the real world and provide services to users based on their requests or the outcomes of data processing. In the IoT, cyber entities are always mapped to physical objects that interact with one another and collaborate to complete specific tasks. The IoT is employed not only in academic research and industrial fields but also in everyday applications such as smart grids, e-health, smart homes, environmental monitoring, and smart cities [10].

2.1 Internet of Things Architectures

As with many emerging technologies, IoT has been surrounded by some ambiguity. As a result, there is no single, standard architecture for IoT in the literature, and researchers have proposed various architectural models. The three-layer architecture is the most basic model for IoT, consisting of the Application layer, Network layer, and Perception layer, as shown in Fig. 1. This architecture captures the general concept of IoT, but it falls short for emerging applications due to its inability to address the more nuanced aspects of the Internet of Things. The perception layer serves as the physical foundation of the IoT architecture. It is comprised of two key sections: the perception node, responsible for data acquisition and control, and the perception network, which manages data transmission and executes control instructions. This layer integrates technologies like Radio Frequency Identification (RFID), ZigBee, and various sensors. Sensors are the primary components of this layer; for instance, smartphones incorporate sensors such as gyroscopes and accelerometers for motion detection, GPS for location tracking, cameras for imaging, microphones for audio input, light sensors, magnetometers, and proximity sensors. Most attacks on the perception layer primarily target hardware, particularly sensors. Some common security attacks include [11,12]: Eavesdropping or Sniffing: This intrusion involves intercepting and obtaining transmitted information from devices. Attackers exploit unsecured transmissions to access and capture sensitive data [13]. Timing Attack: Typically observed in devices with constrained processing capabilities, this attack in volves analyzing the time taken to execute cryptographic algorithms. Attackers may exploit timing variations to deduce encryption keys [14]. Network Layer Considered the core of IoT, the network layer handles the transmission and sometimes processing of sensor-collected data [15], along with ensuring information security [16]. It utilizes IPv6 addressing to assign addresses to IoT devices [17] and acts as a bridge between the perception and application layers. Security challenges at this layer primarily involve data availability, confidentiality, and privacy. Key security issues include: DoS and DDoS: Attackers overwhelm IoT devices with a high volume of service requests, leading to service disruptions or outages for legitimate users. This attack is typically executed by flooding devices or network resources with excessive requests. Sinkhole: In this attack, a compromised node manipulates routing protocols to divert network traffic through itself, enabling the attacker to intercept and manipulate data. Spoofing: These attacks involve impersonating legitimate entities to gain unauthorized access to IoT systems and inject malicious data. Examples include RFID spoofing, IP spoofing, and other forms of identity-based attacks in IoT environments. IoT middleware facilitates communication, management, and interoperability between connected devices, applications, and cloud infrastructures in smart environments. It simplifies the integration of heterogeneous protocols and data formats, ensuring seamless interaction between IoT components. Beyond handling real-time data transmission and processing, IoT middleware provides essential functionalities such as security, service orchestration, and scalability. However, it is also a prime target for cyber threats, including Man-in-the-Middle (MitM) attacks, Denial-of-Service (DoS/DDoS), data breaches, malware injections, and unauthorized access. Exploiting vulnerabilities like weak authentication, unsecured APIs, or misconfigured access controls, attackers can manipulate data, disrupt services, or take control of devices. To mitigate these risks, strong security measures such as encryption, robust authentication, and anomaly detection are essential to safeguarding IoT middleware and maintaining the integrity of smart environments [18,19]. The business layer in an IoT system is responsible for managing the core business logic and processes, transforming data collected from IoT devices into actionable insights that drive decision-making and operational efficiency. Positioned above the middleware, the business layer automates workflows, integrates with existing enterprise systems such as ERP or CRM, and ensures that real-time data is used to enhance business operations. However, this layer is also vulnerable to a range of cyberattacks, including data manipulation, where attackers alter the data to disrupt decision-making, unauthorized access, which could lead to exposure of sensitive business information, and Denial-of-Service (DoS/DDoS) attacks, which can disrupt business continuity by overloading the system. Additionally, man-in-the-middle (MitM) attacks may intercept and alter communication between devices and the business systems, potentially compromising data integrity (see Table 1). To mitigate these risks, robust security measures, such as encryption, access controls, continuous monitoring, and authentication mechanisms, are essential for ensuring the integrity and confidentiality of the business layer. These measures help businesses safeguard their IoT infrastructure, protect critical data, and maintain operational efficiency [20]. Application Layer Positioned as the topmost layer visible to end-users, the construction of the application layer varies based on the services offered, such as innovative environments, smart grids, healthcare systems, and intelligent transportation [21–23]. The application layer, as the top most layer in IoT architecture, adapts depending on the services it supports, such as smart environments, smart grids, healthcare, and intelligent transportation [24]. It processes data from the perception layer to provide services and transmit decisions back through the network [25–28]. However, it is vulnerable to application-specific attacks, including phishing, cross-site scripting (XSS), and malware such as viruses and worms [29]. To address these threats, firewalls and antivirus mechanisms are recommended.

Figure 1: Five-layers IoT architecture

2.2 Internet of Things Applications

The goal of smart IoT environments is to use devices to enhance modern life better safe and productive. Smart environments using IoT allow the successful implementation of smart items. Devices may be analyzed and operated independently over an IoT infrastructure [30]. The worldwide industry for intelligent city services is increased by 60%, per the Grand view Research.

In [31], authors write that the concept smart relates to the capacity to independently collect and use information, whilst also environmental context relates to the settings. One sort of smart home environment is a smart city. A smart city’s key component is an interoperable base run by an IoT service supplier, which gives data on utilities including power, wastewater, and energy. Other forms of smart settings include Smart healthcare, smart industry, intelligent cities, and home automation are all examples of smart technologies [32]. The goal of these smart settings is to serve customers using smart ways utilizing the information acquired by Smart equipment. Fig. 1 depicts the design of certain Smart setup based on IoTs. Smart landscapes founded on the IoT ecosystem have particular distinctive features, and consequently, remarkable requirements/series in the implementation of such settings [33,34]. Digital surveillance and aspects of management, for example, are necessary to enable smart items to gather and data processing as well as conduct activities remotely. Furthermore, decision-making capacity is a key attribute in this kind of system. A smart device must be capable of producing knowledgeable judgments without the need for social interaction by applying information analysis and other data extraction techniques. Smart environments, as a result of those same qualities, provide specific features that may be utilized to improve the QoS (Quality-of-service) of user apps. One of these aspects is real-time information. Smart things can gather and evaluate data in real time, making smart judgments. Furthermore, the low cost of cloud apps may be leveraged to improve the QoS of intelligent apps for the surroundings. The combination of smart and IoT settings opens up new possibilities for network and implementation QoS. Fig. 1 depicts the many parts of a smart city. Smart city applications are often connected with four areas: data gathering, transmission/reception, store, and evaluation. Data gathering is case-specific and has been a huge factor of sensing systems across several fields [35]. The next part is data interchange; this involves information transfer through information gathering devices to clouds storage and retrieval. This aim has already been met in a variety of methods, as well as the construction of municipal Wi-Fi connections, as well as 4G and 5G developments, as well as several sorts of smaller stations that may transfer signals on a regional or on a massive level. The next phase is cloud computing architecture, where various energy Retention techniques are used to retain and categorize data. Data analysis is the practice of necessary to separate and interpretations from gathered information in order to inform strategic planning. For some more difficult situations, strategic planning, the cloud’s availability enables not just diverse information gathering and transmission, but also evaluation Statistical tools, as well as ML DL algorithms, are used in real-time.

• Smart Farming

Smart Farming or agricultural security is a critical component of the 2030 Agenda for Environmental Sustainability. With an expanding worldwide inhabitants and severe environmental issues generating variable precipitation in the world’s food centers, nations throughout the planet are racing to guarantee that food industry is made viable and that depleting water and other resources are used efficiently. Farming with intelligence is the utilization of sensors installed in crops and farms to monitor various factors to aid in making decision and the prevention of disease and pests, among other things [36].

• Smart Grids

Smart Grids are systems that employ Attempting to make use of ICT tools both existing as well as freshly equipped networks more visible, to enable decentralized electricity production at both the client and operator ends, and to add self-healing skills into the grid. One feature of smart grids is the transmission of real-time electricity information to companies at various places on the network all across the water pipes till the consumer. Because electric utilities bring honest information on customer demand, it enables improved energy production control using predictive model built from collected usage patterns, integrating multiple power sources, and self-healing of the system to keep a continuous production [37].

• Smart Home

Smart Home is an essential element of Smart Cities because it is crucial towards the lives of the city’s people. Smart Homes entail the installation of wearable sensors across a whole person’s house that gives details about the home and its residents. These devices could include embedded sensors, movement detectors, and power/energy usage indicators [38].

• Smart Healthcare

Smart Healthcare relates to the utilization of ICT to enhance the accessibility and health care services. With an aging population and growing healthcare costs, this subject has drawn the attention of both scholars and healthcare professionals. Health status systems are overloaded and so unable to meet rising public need. In this sense, smart health strives to make healthcare accessible as many persons as feasible via telehealth services [39] and enhanced diagnosis aid to clinicians through the use of AI [40].

2.3 Internet of Things Security and Privacy Concerns

Security is a critical concern in the Internet of Things (IoT), where billions of interconnected devices operate in diverse and often resource-constrained environments. The openness, heterogeneity, and large-scale nature of IoT systems make them particularly vulnerable to a wide range of cyber threats, including eavesdropping, spoofing, denial-of-service attacks, and unauthorized access. Ensuring security in such an ecosystem requires not only lightweight and adaptive protection mechanisms, but also continuous monitoring and threat detection capabilities. In this context, Intrusion Detection Systems (IDS) have emerged as a vital line of defense. By analyzing traffic patterns and system behavior, IDS play a key role in identifying malicious activities across the different layers of the IoT architecture physical, network, and application. Their ability to provide real-time detection and response significantly enhances the resilience of IoT deployments and complements preventive security measures such as encryption and authentication. As IoT threats become more sophisticated, the integration of intelligent IDS, particularly those based on machine learning, becomes essential for maintaining a secure and trustworthy IoT environment [41].

Intrusion Detection Systems Taxonomy

An Intrusion Detection System (IDS) is designed to identify suspicious or abnormal behavior in monitored devices or networks. It can be hardware, software, or a combination of both, with the goal of detecting harmful activities and safeguarding systems against cyber threats and policy violations. In IoT networks, deploying IDS at various levels helps address privacy risks and security vulnerabilities, ensuring the protection of IoT devices. IDS are commonly used to detect network anomalies and attacks. They classify actions as either normal or attack, and AI-based approaches are crucial for distinguishing between regular and abnormal network behavior. Multiple AI algorithms, such as machine learning and deep learning models, are applied to enhance intrusion detection and classify threats accurately. The primary goal is to safeguard users from potential attacks by accurately identifying intrusion attempts. Key performance metrics for IDS include False Positive (FP) and False Negative (FNR) rates. FP refers to regular activities mistakenly identified as attacks, while FNR represents real attacks that go undetected (Table 2). By improving anomaly detection and reducing incorrect projections, IDS help in minimizing these errors and improving detection accuracy. IDS are essential in protecting IoT devices and other infrastructures, as they monitor malicious activities, detect vulnerabilities, and provide real-time alerts to system managers. There are two main types of IDS: detection-based and data-based, both playing critical roles in recognizing and responding to IoT attacks [42,43]. Analyzing and evaluating customer data, networks, and applications via unobtrusive congestion collection and evaluation are valuable methods for administering networks and detecting security problems in real time [44]. An IDS is a device that monitors transit data so that it can detect and defend unwanted breaches that affect the privacy, security, and accessibility of an information management [45]. An IDS’s activities can be separated into three phases. The first phase is surveillance, which employs network detection or host detection. The second phase is evaluation, that is based on extracting features or based classification algorithms. The detection phase is the final phase, which is based on anomalous or abuse vulnerability scanning. An IDS copies data flow in a management system and evaluates it to identify highly dangerous actions [46]. The deployment of an IDS is dependent on the circumstances. A system that detects intrusions on the host (HIDS) is aimed at safeguarding a single system against intrusion or malicious assaults that might destroy its software or information [47]. In principle, a HIDS is determined by measurements in the entire system, such as data stored in a software system. These measurements or attributes are sent into the HIDS’s selection algorithm. Thus, feature engineering from the setting forms the foundation of whatever HIDS. In order to identify breaches and destructive assaults, NIDS a system for intrusion detection that operate on a network analyze behavior on the network patterns [48]. A Network Intrusion Detection System (NIDS) can be implemented in various forms, including software or hardware-based solutions. Snort, for example, is a well-known software-based NIDS. Intrusion detection systems rely on algorithms to perform different phases of vulnerability scanning. A wide range of algorithms is used across various IDS types and approaches. Several of these IDS techniques would be explored in the subsection headed IDS Optimized for IoT Systems. Fig. 2 illustrated the IDS techniques. Generally, IDSs can be divided into three groups: SIDS, AIDS, and HIDS.

Figure 2: IDS functional architecture

• Misuse-based IDSs

SIDS or Misuse-based IDS to identify well-known assaults, a technique for detecting intrusions focused on misappropriation employs a database that includes characteristics and themes that are well-known of harmful software and breaches [49]. Misuse-based IDSs have three drawbacks: data packets congestion, significant signature verification costs, and a significant number of false alarms. Furthermore, due to the necessity to keep a massive database of malicious activity, the large memory limits in particular varieties of networks, such as WSNs, lead to low efficiency of misuse IDSs [50].

• Anomaly-based intrusion detection

A typical data model is constructed using information from regular users and is then checked with existing data structures in real time to find abnormalities inside an anomaly-based attack approach. Such abnormalities occur as a result of interference or even other occurrences that may have been caused by malicious programs. Anomalies are thus unexpected actions generated by attackers who leave traces in the computer system [51]. These traces are used to identify assaults, especially unidentified ones. An AIDS identifies irregularities from standard activity in the computer system by continually altering a model of typical practice in the computing environment based on input of regular users [52–54]. The benefits and drawbacks of different exceptional situation methods for detecting intrusions. An AIDS identifies irregularities from standard activity in the computer system by continually altering a model of typical practice in the depending on the computer system on input of regular users. The benefits and drawbacks of different exceptional situation methods for detecting intrusions.

• Hybrid intrusion detection

HIDS (Hybrid Intrusion Detection System) is a combination of SIDS (Signature-based Intrusion Detection Systems) and AIDS. By merging these two approaches, HIDS benefits from the high detection rates of known attacks provided by SIDS, while reducing the incidence of false positives for new or unknown attacks, as offered by AIDS. The majority of IDSs in the literature are hybrid systems that rely on anomaly detection, leveraging the strengths of both signature-based and anomaly-based methods to improve overall detection accuracy and minimize false alarms.

• Collaborative Intrusion Detection System

A Collaborative Intrusion Detection System (CIDS) is a specialized type of IDS in which multiple entities work together to detect and mitigate security threats. These systems can be categorized based on the type of information shared and the level of cooperation among participating entities [55]. The collaborative model classifies CIDS into three types: centralized, distributed, and hybrid. In a centralized CIDS, all security-related data is sent to a central server, which processes the information and generates alerts if threats are detected. This model is easy to manage but introduces a single point of failure if the central server is compromised. In contrast, a distributed CIDS consists of multiple independent intrusion detection systems that share threat intelligence, making the system more resilient to failures but more complex to coordinate. A hybrid CIDS combines features of both centralized and distributed models, where some entities report to a central server while others share data directly with each other. This approach enhances security and reliability but requires careful implementation to balance efficiency and complexity.

4 Machine Learning, Ensemble Learning, and Feature Engineering

Machine Learning (ML) is a subset of Artificial Intelligence (AI) that enables machines to learn and derive insights from large datasets. ML models use algorithms to discover, recognize, and predict patterns or behaviors. The primary goal of ML algorithms is to minimize the need for human intervention and expertise. As depicted in Fig. 3. ML involves two phases: training and testing. During the training phase, the algorithm identifies relevant features and classes from the data and learns from these inputs. In the testing phase, the trained model classifies new, unseen data, transforming it into a classifier that can predict the class of new inputs. ML methods can be broadly classified into two categories: supervised and unsupervised learning. Supervised learning involves training the model with labeled data, while unsupervised learning deals with unlabeled data to uncover hidden patterns. Additionally, other learning techniques have emerged, such as semi-supervised learning, which uses a combination of labeled and unlabeled data, and reinforcement learning, where models learn optimal behaviors through a system of rewards and penalties. These varied approaches enhance the adaptability and application of ML across different fields. Supervised learning is a foundational concept in machine learning where algorithms learn from labeled datasets to predict outcomes or classify new instances based on previously observed examples. In this approach, the dataset comprises input-output pairs, where the input (features) is linked with a corresponding output (label or target). The primary objective is for the algorithm to generalize from these labeled examples and accurately predict outcomes for unseen data. Various algorithms are widely employed in supervised learning, each suited to specific types of tasks and data characteristics. For instance, linear regression is utilized to predict continuous values, such as housing prices, based on features like size, location, and the number of bedrooms. Logistic regression, on the other hand, is particularly effective in binary classification tasks, such as spam detection, where it estimates the likelihood of an instance belonging to a particular class. Decision trees and random forests are robust methods for both regression and classification, using tree-like structures to partition data and make predictions. Support Vector Machines (SVMs) excel in separating data into classes by identifying optimal hyperplanes, while K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) makes predictions based on similarities to neighboring instances. These algorithms, in addition to neural networks, ensemble methods like AdaBoost and XGBoost, and probabilistic models such as Naive Bayes, collectively provide a versatile toolkit for addressing diverse supervised learning challenges in various domains. Each algorithm brings unique capabilities to handle different complexities of data, ensuring adaptability and reliability in solving real-world problems (see Table 3).

Figure 3: Supervised ML

• Unsupervised machine learning

Unsupervised machine learning encompasses techniques aimed at discovering patterns from unlabeled data, extracting inherent structures and relationships without explicit guidance or predefined outcomes. One of its primary applications is clustering, where algorithms like K-Means, DBSCAN (Density-Based Spatial Clustering of Applications with Noise), and hierarchical clustering group data points based on similarities in their features. These methods are pivotal for tasks such as customer segmentation, anomaly detection, and image segmentation. Another significant application is dimensionality reduction, which focuses on reducing the number of variables while retaining essential information. Techniques such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA) identify principal components that explain variance in high-dimensional data, enabling visualization and computational efficiency improvements. Other methods like Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) and t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) are effective for data visualization and complex data analysis. Unsupervised learning algorithms are essential in exploratory data analysis, preprocessing, and pattern recognition, where labeled data is limited or unavailable. By autonomously identifying patterns and structures, these algorithms contribute to diverse applications across industries, from understanding consumer behavior to enhancing anomaly detection and improving data visualization techniques.

• Semi-supervised

Semi-supervised machine learning serves as a bridge between supervised and unsupervised paradigms, leveraging both labeled and unlabeled data to enhance learning. It combines the accuracy of supervised methods with the scalability of unsupervised approaches, addressing the challenge of utilizing limited labeled data alongside abundant unlabeled data. Several algorithms are employed to maximize the benefits of both data sources. Self-Training begins with an initial model trained on labeled data, which then predicts labels for unlabeled data, iteratively expanding the training set. Co-Training involves multiple classifiers trained on different feature sets, collaboratively labeling new instances. Semi-Supervised Support Vector Machines (S3VM) extend traditional SVMs by integrating unlabeled data into the optimization process, refining decision boundaries. Graph-Based Methods, such as Label Propagation and Spectral Clustering, leverage data structure and similarity metrics to distribute labels among unlabeled instances. These approaches optimize learning efficiency, making them valuable in scenarios where labeling large datasets is costly or impractical. By addressing scalability challenges, semi-supervised learning techniques enhance model performance and extend machine learning applications to real-world problems requiring efficient data utilization.

Ensemble Learning is a potent technique in machine learning that involves combining multiple models to enhance predictive accuracy. The core concept is to aggregate predictions from diverse models, which individually may be less accurate, to produce a more robust and accurate final prediction than any single model alone. Several key strategies underpin Ensemble Learning:

• Bagging (Bootstrap Aggregating):

This approach entails training multiple instances of the same learning algorithm on different subsets of the training data. Each model learns independently, and their predictions are averaged or combined to yield the final output. For example, Random Forests utilize bagging by training decision trees on bootstrap samples of the data.

• Boosting:

Boosting involves training models sequentially, where each subsequent model corrects the errors made by its predecessors. A prominent boosting algorithm is AdaBoost (Adaptive Boosting), which assigns higher weights to misclassified instances and trains subsequent models on these instances iteratively to improve performance. AdaBoost, Adaptive Boosting (AdaBoost) is a powerful ensemble learning technique primarily used for binary classification, though it can be extended to multi-class classification. As part of the boosting family, AdaBoost enhances the performance of weak learners models that perform slightly better than random guessing by combining them into a stronger learner. The core idea of AdaBoost is to focus on the hard-to-classify cases by assigning greater weight to misclassified data points. Initially, all data points in the training set are assigned equal weight, meaning each has the same impact on training the first weak learner. After training, AdaBoost calculates the error rate based on the weighted sum of misclassified points. It then increases the weights of misclassified data and decreases the weights of correctly classified ones, ensuring that subsequent weak learners pay more attention to previously misclassified points. This iterative process continues, with each new weak learner trained on reweighted data. Finally, AdaBoost combines the predictions of all weak learners, assigning each a weight based on its accuracy. The final prediction is made using a weighted majority vote, where more accurate learners have a greater influence on the outcome. XGBoost: Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) is a powerful machine learning algorithm known for its high performance in both classification and regression tasks. Its exceptional accuracy and speed have made it a widely used tool in the machine learning field. As an ensemble method, XGBoost combines the predictions of multiple weak learners, typically decision trees, to build a robust and accurate model. The algorithm works by training decision trees sequentially, with each tree correcting the errors of the previous ones. This iterative approach enables XGBoost to continuously improve its predictive accuracy. A key feature of XGBoost is its use of gradient boosting, which optimizes model performance by minimizing a specific loss function. Additionally, XGBoost incorporates regularized learning objectives to control the complexity of individual trees, reducing overfitting and enhancing the model’s ability to generalize to new data. LightGBM: Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LightGBM) is a high-performance gradient boosting framework for machine learning, praised for its speed, efficiency, and superior predictive performance, particularly when dealing with large datasets. Like XGBoost, LightGBM is based on the gradient boosting algorithm, which builds an ensemble of decision trees sequentially, with each tree correcting the errors of the previous one. What sets LightGBM apart are its innovative tree-building and optimization techniques. Two key innovations are Gradient-based One-Side Sampling (GOSS) and Exclusive Feature Bundling (EFB). GOSS enhances efficiency by selecting the most important data instances for training, while EFB reduces dimensionality by bundling mutually exclusive features. These techniques allow LightGBM to significantly reduce memory usage and training time, enabling it to efficiently handle large datasets and high-dimensional feature spaces with exceptional speed. Stacking (Stacked Generalization): Stacking combines models of different types (e.g., decision trees, SVMs, neural networks) and employs a meta-learner (often a simpler model like linear regression or another decision tree) to learn how best to combine their predictions. This method harnesses the strengths of diverse models to achieve superior overall performance. Voting: Voting methods aggregate predictions from multiple models (e.g., classifiers or regressors) and make final predictions based on either a majority vote (for classification) or averaging (for regression). Voting can be implemented as Hard Voting (simple majority vote) or Soft Voting (weighted average of probabilities). Ensemble Learning is widely favored for its ability to mitigate overfitting, improve generalization, and enhance prediction reliability by leveraging the complementary strengths of diverse models. This approach is integral to achieving higher accuracy and robustness in machine learning applications.

Deep learning, a specialized branch of machine learning, utilizes neural networks with multiple layers to analyze diverse types of data. These deep neural networks are adept at automatically identifying patterns and features from large datasets, making them particularly effective for processing images, text, and speech. The power of deep learning lies in its capacity to learn from raw data and improve with increased data and computational resources, making it essential in areas like computer vision, natural language processing (NLP), and speech recognition. Different deep learning algorithms are designed for specific tasks and data types. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) are widely used in computer vision tasks such as image and video recognition, classification, and medical image analysis. They utilize convolutional layers to extract features, pooling layers for down-sampling, and fully connected layers for classification. Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), including Long Short-Term Memory Networks (LSTMs), are well-suited for sequential data like time series analysis, NLP, speech recognition, and translation. RNNs process data sequences through feedback loops, while LSTMs handle long-term dependencies and mitigate issues like the vanishing gradient problem. Other significant algorithms include Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), Autoencoders, Transformer Networks, and Deep Belief Networks (DBNs). GANs generate realistic data samples and are used in applications like image synthesis, super-resolution, and style transfer by training two networks (a generator and a discriminator) simultaneously. Autoencoders are employed for tasks such as dimensionality reduction, feature learning, anomaly detection, and data denoising through an encoder-decoder architecture. Transformer Networks excel in NLP tasks such as translation, summarization, and question answering, using self-attention mechanisms to manage long-range dependencies. DBNs are utilized for unsupervised learning, pre-training deep networks, and dimensionality reduction, comprising multiple layers of stochastic, latent variables. Each of these algorithms offers unique benefits and is tailored to specific applications, highlighting the adaptability and effectiveness of deep learning in solving complex problems.

In recent years, federated learning (FL) has emerged as a powerful paradigm for training machine learning models in a decentralized manner. Unlike traditional centralized approaches that require raw data to be transmitted to a central server, FL enables devices such as IoT nodes to collaboratively learn a shared model while keeping their data local. This is particularly advantageous in the context of IoT environments, where data privacy, communication overhead, and resource limitations are significant challenges. Applying FL in intrusion detection systems enhances both data security and scalability, allowing multiple IoT devices to contribute to the learning process without exposing sensitive information. Periodic model updates are aggregated at a central server, ensuring the detection model improves over time with input from diverse environments. This decentralized training not only preserves privacy but also improves the system’s ability to detect distributed or location-specific threats. By applying federated learning into IDS designs, researchers and developers may solve significant constraints of traditional models, such as data breach vulnerability and reliance on huge labeled datasets. As a result, FL offers a potential approach to developing robust, adaptable, and privacy-aware intrusion detection systems in current IoT environments.

Choosing the right algorithm for intrusion detection has a significant impact on the effectiveness and efficiency of the system. Key performance metrics such as accuracy, precision, and recall help determine how reliably the algorithm can identify both genuine threats and false alarms. For instance, high precision reduces the number of false positives, while high recall ensures that actual threats are not missed. The F1-score offers a balanced view when precision and recall are in conflict, which is often the case in real-world intrusion scenarios with imbalanced data. Table 4 explains these metrics in more detail, providing a clear understanding of how each one contributes to evaluating algorithm performance. Additionally, practical considerations such as training time and computational complexity affect how quickly and resource-efficiently the system can be deployed and maintained. Scalability is also crucial, as intrusion detection systems must often handle large volumes of network traffic. Moreover, the algorithm’s sensitivity to noise determines its robustness against irrelevant or misleading data, which is common in real-world environments. Therefore, selecting the most appropriate algorithm involves balancing detection performance with practical constraints to ensure accurate, fast, and reliable intrusion detection.

• Data source

An intrusion detection system (IDS) detects security hazards in networks and computer systems through several phases and procedures. IDS systems collect data from various sources to detect potential security threats. Network traffic is captured and analyzed through sensors that monitor data exchanges between network devices. System logs from servers, routers, firewalls, and other network devices offer insights into system activities and events. Application logs track specific actions and events unique to software applications. Additionally, endpoint data, including logs, event data, and file integrity checks from individual devices, provide further context for identifying threats. These diverse data sources help IDS systems monitor and protect against security risks effectively.

• Preprocessing

Preprocessing data is essential in data analysis, particularly in intrusion detection, where data quality directly affects the performance of algorithms. The process includes data cleaning, which removes redundant or erroneous data and corrects inconsistencies to improve dataset quality. Data formatting ensures consistency across different sources, preventing interpretation errors and enabling smooth integration. Feature extraction identifies and selects relevant attributes, transforming raw data into a structured format that highlights important patterns, improving anomaly and threat detection. These preprocessing steps enhance data quality and consistency, ensuring more effective analysis and decision-making in intrusion detection [56].

• Analysis

The analysis step is crucial for the operation of an Intrusion Detection System (IDS), where preprocessed data is evaluated to detect trends, abnormalities, or potential intrusions. Different IDS types employ various analysis methods. In signature-based analysis, the IDS compares incoming data against a database of known attack patterns or signatures, triggering an alert when a match is found. On the other hand, anomaly-based analysis establishes a baseline of normal system behavior and detects deviations from this baseline, even if the intrusion is novel or unknown. This approach allows the IDS to identify and alert on emerging security risks that do not match known attack patterns.

• Response

Once an Intrusion Detection System (IDS) detects an intrusion or anomaly, it initiates various actions based on organizational rules and IDS configurations. These actions typically include alerting security professionals or administrators through notifications. Additionally, automated responses may be triggered, such as restricting network traffic from the intrusion source, isolating affected systems, or activating predefined incident response protocols. The IDS also logs detailed information about the intrusion events for auditing, forensic analysis, and compliance purposes. In more severe cases, a coordinated incident response procedure may be implemented to investigate, contain, and mitigate the intrusion. Overall, an IDS plays a vital role in collecting and preprocessing data, analyzing suspicious patterns, generating alerts, and taking proactive steps to protect the security and integrity of network and computer systems.

In this section, we presented all the datasets used for evaluating intrusion detection systems, detailing their characteristics, relevance, and the specific roles they play in benchmarking the performance of various detection approaches.

NSL-KDD Dataset is a suggested dataset to address a number of the KDD99 underlying flaws in the dataset. However, this latest iteration of the KDD dataset a few of the subjects are nevertheless available mentioned by [57] (2025) and could not be an exact representation of current network systems, we truly think it can nevertheless be used as an efficacious benchmark dataset to assist learners directly compare interruption detection systems due to the absence of general populace data sets for network-based IDSs. Moreover, the NSL-KDD train and testing dataset have a significant quantity of entries. This benefit allows you to complete avoid being forced to select a little part at randomly. As a result, the assessment conclusions of numerous research initiatives will be similar and constant.

The Australian Cyber Security Centre developed the UNSW-NB15 dataset. Centre’s Cyber Field Laboratory. It is commonly employed owing to the diversity of innovative assaults it offers. Fuzzers, Threats include assessment, backdoors, and denial of service, exploits, generic, reconnaissance, shellcode, and worms. It has an 82,332-record training dataset and 175,341 records testing set. The Canadian Institute for Cybersecurity has made an accessible identification of breaches CICDoS2017 dataset including application layer DoS assaults accessible (see Table 5). The study carries out eight denial-of-service assaults on the web application. By enrolling the resultant records with attack information, regular user activity was produced [58].

Kyoto 2006+ Dataset (Table 6) is a massive database of legitimate networking honeypots traffic that contains just a tiny integer and a selection of realistic, regular user activity. The authors converted packet-based communication to a current design known as sessions. Every transaction comprises 24 variables, 14 of whom are relevant data features, while the following ten elements are common crowded road variables, such as duration, IP addresses, port. The information was gathered throughout a three-year period and includes around 93 M encounters [59].

BoT-IoT Dataset is over 72 million files are included, encompassing, service scan, DDoS, DoS keylogging, and fileless threats (Table 7). To mimic the network activities of IoT devices, the Endpoint tool was applied. Machine-to-machine (M2M) interactions are linked using MQTT, a lightweight transmission control protocol. Remotely controlled surveillance station, smart refrigerators, and motion actuated lights garage door, and nest thermostat are the testing ground IoT applications [60].

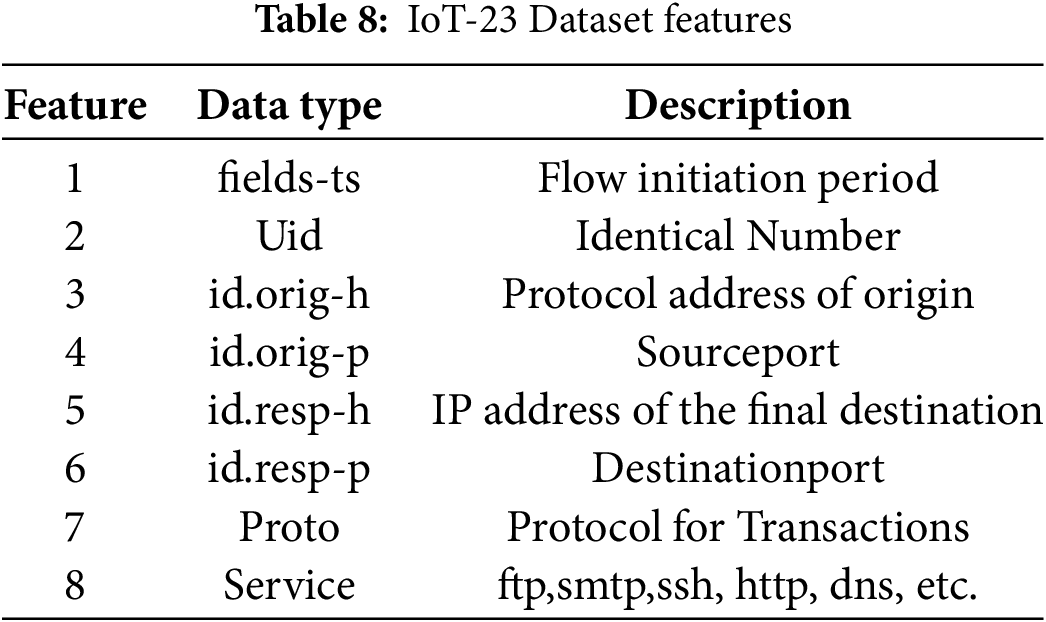

IoT-23 Dataset consisting of 23 network fragments of IoT traffic, 20 from compromised Smart nodes and three from actual IoT network traffic (Table 8). In each harmful situation, Raspberry Pi virus was executed utilizing various protocols and executing different behaviors. The netflow grab for innocuous situations was gathered from the network traffic of 3 authentic IoT systems: a Led Lighting smart LED bulb, an Amazon Echo smart personal assistant, and a Somfy smart door lock. Both harmful and benign cases were tested in a supervised distributed system with an unrestricted internet access, similar to a genuine Sensor node [61]. Furthermore, the IoT-23 dataset, updated in 2024, offers recent real-time traffic captures and includes 23 labeled scenarios involving various malware and benign activities. Developed through collaboration between Avast AIC Labs and the Czech Technical University in Prague, IoT-23 provides a modern benchmark for evaluating IDS solutions in diverse IoT setups.

EdgeIIoT introduced in 2022, is a recent and realistic dataset specifically designed to support research in Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) cybersecurity (Table 9). It reflects real-world edge computing scenarios where critical decisions are made closer to the data source, reducing latency and improving responsiveness. The dataset contains a wide range of network activities and simulated cyberattack scenarios, making it ideal for training and evaluating machine learning-based intrusion detection systems (IDS). A key feature of Edge-IIoT is its support for both centralized and federated learning approaches. In centralized settings, data from all edge nodes is collected and processed at a central server. Alternatively, federated learning allows for decentralized training directly at edge nodes, preserving privacy and reducing communication overhead. This versatility makes Edge-IIoT a valuable asset for the development of scalable, adaptive, and privacy-preserving IDS solutions, especially in modern IIoT and smart infrastructure environments. By utilizing Edge-IIoT, researchers can experiment under realistic network conditions and assess the robustness and generalization capabilities of their IDS models, paving the way for more secure and efficient edge-based deployments [62].

IDS have been extensively studied to address the challenges posed by increasingly complex and heterogeneous network environments. Several contributions have focused on developing adaptive and efficient IDS tailored to cloud, industrial, and software-defined network infrastructures. Elbakri et al. [63] proposed an adaptive cloud intrusion detection system based on the Pruned Exact Linear Time (PELT) technique. This approach improves the efficiency of anomaly detection in cloud environments by reducing computational complexity while maintaining accuracy, which is crucial for real-time detection in large-scale systems.

Fernández et al. [64] presented a comprehensive review of the SMOTE algorithm, a synthetic oversampling technique designed to address class imbalance in datasets—a frequent issue in IDS data where attack samples are underrepresented. Their work highlights both the progress and the remaining challenges in applying SMOTE effectively.

Farag and Barakat [65] explored the application of smart structural systems for sustainable smart cities. Although this work is not focused directly on IDS, it lays the foundational ideas for integrating anomaly detection mechanisms into smart infrastructures, which can be extended to security monitoring.

Sajid Farooq et al. [16] developed a fused machine learning approach combining multiple classifiers to enhance intrusion detection accuracy. Their method targets improved detection rates and reduced false positives, addressing the limitations of single-model IDS.

Hande and Muddana [18] surveyed various IDS methods for Software-Defined Networks (SDN). Their analysis emphasizes the importance of scalable, adaptive, and programmable IDS that leverage SDN’s flexibility to detect threats effectively at the network level.

He et al. [19] proposed a hybrid IDS for industrial cyber-physical systems, combining system state monitoring with network traffic anomaly detection. This dual-layer approach improves the robustness and early detection of complex attacks targeting industrial control environments.

Xu et al. [53] introduced an IDS based on a deep neural network with gated recurrent units (GRU), capable of capturing temporal dependencies in network traffic data. This model demonstrates improved performance in detecting sequential patterns associated with attacks.

Xu et al. [54] presented DEMGAN, a machine learning-based evasion scheme targeting IDS. This work raises awareness of adversarial attacks on IDS models and highlights the need for defenses against evasion techniques in real-world deployments.

Yang et al. [56] developed Diff-IDS, a network intrusion detection model utilizing diffusion models to effectively handle imbalanced data samples. Their approach improves detection rates by modeling complex data distributions more accurately.

Yang et al. [66] proposed an IDS combining Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (Bi-LSTM) networks with attention mechanisms. This architecture enhances the ability to focus on important features in sequential network data, resulting in higher detection accuracy.

Together, the above studies cover a broad spectrum of IDS research, from addressing data imbalance and adversarial attacks to leveraging deep learning and hybrid methods for diverse environments such as cloud, industrial systems, SDN, and smart cities (see Table 10).

6 Description of a Proposed Intrusion Detection Model

In this section, we demonstrate an example of an intrusion detection system based on ensemble learning. For implement this IDS, we provide numerous options to test our intrusion detection technique for IoT security.

The suggested detection framework includes four different phases: For increase data quality, our suggested approach concentrates on preparation and normalization (Fig. 4). Preparation is a beneficial process that aims to remove noise and cleanse data. In addition, the data are normalized in the interval [0, 1] using the min max approach to minimize the unfavorable effect of characteristics with a heavy weight of entries. At the implementation level, we recommend extracting dataset examples to minimize various difficulties such as preparation and a large number of data. There are multiple ways for reducing the amount of characteristics prior to using a dataset for training and validation of a classification algorithm. In this scenario, we apply PCA to do this assignment. The PCA is a mathematical approach that aims to generate a reduced dimensional representation of the source data by lowering large and complicated complexity while retaining all sensitive details. The reduction procedure reduces learning curve and computing costs without impacting outcomes effectiveness. The primary goal is to uncover and identify relevant data (features) across huge network traffic datasets, to ensure that the proposed ensemble-based intrusion detection framework achieves reduced adaptation errors, fewer FAR, and accurate results and malware detection. As a result, they minimize cost while also enhancing the efficiency of the intrusion detection framework. As a result, we employ the mutual information method of feature selection. As Information Gain, the gain of each element in the setting of the target attribute is evaluated. The computation is alluded to as mutual information between two random variables in this slightly modified use. We use the 10-fold cross validation approach provided in [23] to verify our conceptual approach. The algorithm seeks to arbitrarily divide the entire dataset into ten equal-sized sections. The model is trained in nine sections, with the last portion being tested. The technique is again repeated 10 times to train and construct an effective classifier capable of detecting intrusions inside the traffic network. Only characteristics that match a predefined condition are employed in model training and validation. The last phase is classification, which gives a category to an instance. As a result, the acquired classifier first from validation and training steps may predict categories of new examples. Build and train an ensemble-based XGBoost system with hyper-parameter optimization for this purpose.

Figure 4: Proposed model

6.2 Performances Evaluation and Results Evaluating

Intrusion Detection Systems (IDS) is a crucial aspect of ensuring reliable and accurate anomaly detection, particularly in IoT environments. The performance of any IDS classifier is significantly influenced by the datasets used during the training and testing phases, as shown in Table 11. In this study, three widely recognized datasets are employed: BoT-IoT, Edge-IIoTset, and IoT-23. The BoT-IoT dataset is specifically labeled for multi-class classification tasks. It includes annotations that distinguish attack flows, attack categories, and their respective subtypes. Notably, the dataset is highly imbalanced, with attack traffic representing 99.99% of the total, while only 0.01% is benign. It provides 46 features, including the target variable. The second dataset, Edge-IIoTset, is a recently proposed and realistic cybersecurity dataset designed for IoT applications. It supports IDS model training under both centralized and federated learning paradigms, offering flexibility and relevance to modern IoT security research. The third dataset, IoT-23, was collected by the Avast AIC Lab in collaboration with the Czech Technical University in Prague. It contains real-world network traffic, comprising 20 malware capture scenarios from infected IoT devices and three benign traffic captures with anomalies. For experimentation, models were developed and tested using a Kaggle computing environment equipped with 15 GB of GPU memory and a 64-bit operating system. The implementation utilized Python 3.9.7 in Jupyter Lab, with essential libraries such as pandas, numpy, and sklearn to support data processing and machine learning operations.

To assess the performance of our proposed intrusion detection system (IDS), we conducted a series of experiments using three well-established datasets: BoT-IoT, Edge-IIoT, and IoT-23 (Table 11). These datasets are widely used in the research community for benchmarking IDS solutions due to their richness in attack types and traffic patterns, representing real-world IoT scenarios (Figs. 5 and 6).

Figure 5: The results of performance indicators on Edge-IIoT, BoT-IoT, and IoT-23

Figure 6: Confusion matrix BoT-IoT, EdgeIIoT, IoT-23

On the BoT-IoT dataset, as shown in Table 12 our system achieved exceptional results, with an accuracy and precision of 99.99%, a recall of 100%, and an F1-score of 99.99%. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) was perfect at 100%, reflecting the model’s strong ability to distinguish between normal and malicious activities. The training time for this dataset was 33.6 s, while the detection time per instance was 0.714 s, showing a balanced trade-off between accuracy and efficiency. The system also showed outstanding performance on the Edge-IIoT dataset, achieving again 99.99% across all key performance metrics: accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, with an AUC of 100%. Notably, this dataset demonstrated significant improvements in processing speed, with a training time of only 0.6941 s and a detection time of 0.02156 s, making it particularly suitable for time-constrained IoT environments such as edge or fog computing setups. Finally, on the IoT-23 dataset, which contains both benign and malicious real-world IoT traffic, the system maintained high accuracy at 99.98%, precision at 99.98%, and a recall of 99.91%, resulting in an F1-score of 99.99% and AUC of 100%. The training and detection times were 20.5 s and 0.815 s, respectively. These results reflect the generalizability of the proposed IDS and its ability to perform reliably across heterogeneous traffic data. Overall, the evaluation demonstrates that our IDS solution not only maintains high detection effectiveness but also offers excellent efficiency in terms of training and inference times. These qualities make it a strong candidate for deployment in real-time, resource-constrained IoT ecosystems.

We offered a complete description and evaluation of recent studies on vulnerability scanning in network security. The survey examined the field from a variety of angles, covering various publications about IoT security attack detection, addressing techniques to preprocessing and anomaly detection. We investigated the research work and obstacles in several circumstances. We looked at preprocessing and anomaly detection methods. We investigated evaluation approaches, such as metrics and datasets, in order to improve the evaluation process. We tallied community members and plotted their collaborative network. To allow repeatability and additional study, we have made our publishing statistics and categorization descriptions accessible. Our findings indicate that the study on network anomaly detection is imbalanced among performance. Because of the delicacy and secrecy of industry network data, researchers in the Information centric area frequently do not share their datasets. The scarcity of data sets hinders Heterogeneous network security research. A fundamental aspect restricting study in the IoT space is a shortage of datasets. Researchers commonly need to develop IoT network environments to mimic data before undertaking security studies. In terms of contemporary intrusion detection algorithms, supervised learning remains the dominant approach. These investigations, though, must be developed in addition to existing labeled data. The data we acquire during practical application is annotated. We contend that semi-supervised learning unsupervised are the most effective methods for identifying network abnormalities. Furthermore, we feel that automatic tagging of data from the device is an area worthy of further investigation. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that the hostile environment has an influence on ML-based network anomaly detection techniques. As a result, greater study into anti-perturbation anomaly detection in hostile contexts is required.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Chaimae Hazman and Azidine Guezzaz; data collection: Chaimae Hazman and Said Benkirane; analysis and interpretation of results: Mourade Azrour and Vinayakumar Ravi; draft manuscript preparation: Chaimae Hazman and Abdulatif Alabdulatif. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The used dataset is available in this link: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/hassan06/nslkdd (accessed on 21 July 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Al Amro S. Securing Internet of Things devices with federated learning: a privacy-preserving approach for distributed intrusion detection. Comput Mater Contin. 2025;83(3):4623–58. doi:10.32604/cmc.2025.063734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Ozkan-Okay M, Samet R, Aslan Ö, Gupta D. A comprehensive systematic literature review on intrusion detection systems. IEEE Access. 2021;9:157727–60. doi:10.1109/access.2021.3129336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Alshamrani SS, Alghamdi AS. Blockchain-based network security analysis framework for telesurgery systems. Secur Priv. 2023;6(3):e70017. doi:10.1002/spy2.70017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Blali A, Dargaoui S, Azrour M, Guezzaz A, Amounas F, Alabdulatif A. Analysis of deep learning-based intrusion detection systems in IoT environments. EDPACS. 2025;54(2):1–35. doi:10.1080/07366981.2025.2498222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Boukraa L, Essahraui S, El Makkaoui K, Ouahbi I, Maleh Y, Esbai R. Enhancing DDoS attack detection in software-defined networking: a comparative study of machine learning algorithms using benchmark datasets. EDPACS. 2025;1–20. doi:10.1080/07366981.2025.2478706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Elsayed S, Mohamed K, Madkour MA. A comparative study of using deep learning algorithms in network intrusion detection. IEEE Access. 2024;12(3):58851–70. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3389096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Chakir O, Sadqi Y, Abdellaoui Alaoui EA. An explainable machine learning-based web attack detection system for industrial IoT web application security. Inf Secur J A Glob Perspect. 2024;357:1–27. doi:10.1080/19393555.2024.2362813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Douiba M, Benkirane S, Guezzaz A, Azrour M. Combined machine learning for anomaly detection in IoT aggregator RPi. In: Azrour M, Mabrouki J, editors. Recent advances in internet of things security. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press; 2025. p. 72–81. doi:10.1201/9781003587552-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Dargaoui S, Azrour M, El Allaoui A, Guezzaz A, Alabdulatif A, Alnajim A. Internet of things authentication protocols: comparative study. Comput Mater Contin. 2024;79(1):65–91. doi:10.32604/cmc.2024.047625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Panahi O. Secure IoT for healthcare. Eur J Innov Stud Sustain. 2025;1(1):17–23. doi:10.59324/ejiss.2025.1(1).03. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Bukhowah R, Aljughaiman A, Hafizur Rahman MM. Detection of DoS attacks for IoT in information-centric networks using machine learning: opportunities, challenges, and future research directions. Electronics. 2024;13(6):1031. doi:10.3390/electronics13061031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Elsaeidy A, Munasinghe KS, Sharma D, Jamalipour A. Intrusion detection in smart cities using Restricted Boltzmann Machines. J Netw Comput Appl. 2019;135(6):76–83. doi:10.1016/j.jnca.2019.02.026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Chaudhari A, Gohil B, Rao UP. A novel hybrid framework for Cloud Intrusion Detection System using system call sequence analysis. Clust Comput. 2024;27(3):3753–69. doi:10.1007/s10586-023-04162-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Altulaihan E, Almaiah MA, Aljughaiman A. Anomaly detection IDS for detecting DoS attacks in IoT networks based on machine learning algorithms. Sensors. 2024;24(2):713. doi:10.3390/s24020713. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Farag SG. Application of smart structural system for smart sustainable cities. In: Proceedings of the 2019 4th MEC International Conference on Big Data and Smart City (ICBDSC); 2019 Jan 15–16; Muscat, Oman.doi:10.1109/icbdsc.2019.8645582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Sajid Farooq M, Abbas S, Atta-ur-Rahman, Sultan K, Adnan Khan M, Mosavi A. A fused machine learning approach for intrusion detection system. Comput Mater Contin. 2023;74(2):2607–23. doi:10.32604/cmc.2023.032617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Savolainen T, Soininen J, Silverajan B. IPv6 addressing strategies for IoT. IEEE Sens J. 2013;13(10):3511–9. doi:10.1109/JSEN.2013.2259691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Hande Y, Muddana A. A survey on intrusion detection system for software defined networks (SDN). In: Khosrow-Pour M, Clarke S, Jennex ME, Anttiroiko AV, Kamel S, Lee I et al., editors. Research anthology on artificial intelligence applications in security. Hershey, PA, USA: IGI Global; 2020. p. 467–89. doi:10.4018/978-1-7998-7705-9.ch023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. He J, Zhang W, Liu X, Liu J, Yang G. Toward intrusion detection of industrial cyber-physical system: a hybrid approach based on system state and network traffic abnormality monitoring. Comput Mater Contin. 2025;84(1):1227–52. doi:10.32604/cmc.2025.064402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Hazman C, Guezzaz A, Benkirane S, Azrour M. lIDS-SIoEL: intrusion detection framework for IoT-based smart environments security using ensemble learning. Cluster Comput. 2023;26(6):4069–83. doi:10.1007/s10586-022-03810-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Hazman C, Guezzaz A, Benkirane S, Azrour M. Enhanced IDS with deep learning for IoT-based smart cities security. Tsinghua Sci Technol. 2024;29(4):929–47. doi:10.26599/tst.2023.9010033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Hazman C, Guezzaz A, Benkirane S, Azrour M. A smart model integrating LSTM and XGBoost for improving IoT-enabled smart cities security. Clust Comput. 2024;28(1):70. doi:10.1007/s10586-024-04780-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Hazman C, Guezzaz A, Benkirane S, Azrour M. Toward an intrusion detection model for IoT-based smart environments. Multimed Tools Appl. 2024;83(22):62159–80. doi:10.1007/s11042-023-16436-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Khan IA, Razzak I, Pi D, Khan N, Hussain Y, Li B, et al. Fed-inforce-fusion: a federated reinforcement-based fusion model for security and privacy protection of IoMT networks against cyber-attacks. Inf Fusion. 2024;101(3):102002. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2023.102002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Gautam SK, Om H. Computational neural network regression model for host based intrusion detection system. Perspect Sci. 2016;8(3):93–5. doi:10.1016/j.pisc.2016.04.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Kumar SP, Brindha V, Shriyans A, Rajkumar AN, Hariharan S. Improving intrusion detection by utilizing adaptive boosting based ensemble classifier. In: Proceedings of the First International Conference on Data Science & Exploration in Artificial Intelligence (CODE-AI 2024); 2024 Jul 3–4; Bangalore, India. [Google Scholar]

27. Friha O, Ferrag MA, Shu L, Maglaras L, Choo KR, Nafaa M. FELIDS: federated learning-based intrusion detection system for agricultural Internet of Things. J Parallel Distrib Comput. 2022;165(15):17–31. doi:10.1016/j.jpdc.2022.03.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Javeed D, Saeed MS, Adil M, Kumar P, Jolfaei A. A federated learning-based zero trust intrusion detection system for Internet of Things. Ad Hoc Netw. 2024;162(6):103540. doi:10.1016/j.adhoc.2024.103540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Elshafie H, Hamdan M, Salih S, Almohamedh RM, Awouda AEA, Motwakel A. Emerging threats in Internet-of-Things (IoT) hardware security. Int J Comput Sci Netw Secur. 2025;25(4):27–52. [Google Scholar]

30. Cvitić I, Peraković D, Periša M, Gupta B. Ensemble machine learning approach for classification of IoT devices in smart home. Int J Mach Learn Cybern. 2021;12(11):3179–202. doi:10.1007/s13042-020-01241-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Komninos N, Kakderi C, Mora L, Panori A, Sefertzi E. Towards high impact smart cities: a universal architecture based on connected intelligence spaces. J Knowl Econ. 2022;13(2):1169–97. doi:10.1007/s13132-021-00767-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Radziejowska A, Sobotka B. Analysis of the social aspect of smart cities development for the example of smart sustainable buildings. Energies. 2021;14(14):4330. doi:10.3390/en14144330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Kang C, He Y, Xu J. Research and analysis of smart city landscape design and planning based on the Internet of Things. Scalable Comput Pract Exp. 2024;25(5):4083–94. doi:10.12694/scpe.v25i5.3005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Li Z, He Y, Lu X, Zhao H, Zhou Z, Cao Y. Construction of smart city street landscape big data-driven intelligent system based on industry 4.0. Comput Intell Neurosci. 2021;2021(1):1716396. doi:10.1155/2021/1716396. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Virginia Anikwe C, Friday Nweke H, Chukwu Ikegwu A, Adolphus Egwuonwu C, Uchenna Onu F, Rita Alo U, et al. Mobile and wearable sensors for data-driven health monitoring system: state-of-the-art and future prospect. Expert Syst Appl. 2022;202(5):117362. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2022.117362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Akkem Y, Biswas SK, Varanasi A. Smart farming using artificial intelligence: a review. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2023;120(3):105899. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2023.105899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Moreno Escobar JJ, Morales Matamoros O, Tejeida Padilla R, Lina Reyes I, Quintana Espinosa H. A comprehensive review on smart grids: challenges and opportunities. Sensors. 2021;21(21):6978. doi:10.3390/s21216978. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Huda NU, Ahmed I, Adnan M, Ali M, Naeem F. Experts and intelligent systems for smart homes’ transformation to sustainable smart cities: a comprehensive review. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;238(9):122380. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2023.122380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Mathkor DM, Mathkor N, Bassfar Z, Bantun F, Slama P, Ahmad F, et al. Multirole of the Internet of medical things (IoMT) in biomedical systems for managing smart healthcare systems: an overview of current and future innovative trends. J Infect Public Health. 2024;17(4):559–72. doi:10.1016/j.jiph.2024.01.013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Chen X, Xie H, Tao X, Wang FL, Leng M, Lei B. Artificial intelligence and multimodal data fusion for smart healthcare: topic modeling and bibliometrics. Artif Intell Rev. 2024;57(4):91. doi:10.1007/s10462-024-10712-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Mahmood S, Hasan R, Yahaya NA, Hussain S, Hussain M. Evaluation of the omni-secure firewall system in a private cloud environment. Knowledge. 2024;4(2):141–70. doi:10.3390/knowledge4020008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Dash N, Chakravarty S, Rath AK, Giri NC, AboRas KM, Gowtham N. An optimized LSTM-based deep learning model for anomaly network intrusion detection. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):1554. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-85248-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Sun H, Li X, Fan Q, Wang P. TIDS: tensor based intrusion detection system (IDS) and its application in large scale DDoS attack detection. Comput Mater Contin. 2025;84(1):1659–79. doi:10.32604/cmc.2025.061426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Wang W. Abnormal traffic detection for Internet of Things based on an improved residual network. Phys Commun. 2024;66(2):102406. doi:10.1016/j.phycom.2024.102406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Roy SS, Mallik A, Gulati R, Obaidat MS, Krishna PV. A deep learning based artificial neural network approach for intrusion detection. In: Giri D, Mohapatra RN, Begehr H, Obaidat MS, editors. Mathematics and computing. Singapore: Springer; 2017. p. 44–53. doi:10.1007/978-981-10-4642-1_5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Rashid MM, Khan SU, Eusufzai F, Redwan MA, Sabuj SR, Elsharief M. A federated learning-based approach for improving intrusion detection in industrial Internet of Things networks. Network. 2023;3(1):158–79. doi:10.3390/network3010008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Joraviya N, Gohil BN, Rao UP. DL-HIDS: deep learning-based host intrusion detection system using system calls-to-image for containerized cloud environment. J Supercomput. 2024;80(9):12218–46. doi:10.1007/s11227-024-05895-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Abdulganiyu OH, Tchakoucht TA, Saheed YK. Retraction note: towards an efficient model for network intrusion detection system (IDSsystematic literature review. Wirel Netw. 2025;30(1):453–82. doi:10.1007/s11276-025-04000-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Liu Q, Hagenmeyer V, Keller HB. A review of rule learning-based intrusion detection systems and their prospects in smart grids. IEEE Access. 2021;9:57542–64. doi:10.1109/access.2021.3071263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Soe YN, Feng Y, Santosa PI, Hartanto R, Sakurai K. Machine learning-based IoT-botnet attack detection with sequential architecture. Sensors. 2020;20(16):4372. doi:10.3390/s20164372. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Vinayakumar R, Alazab M, Soman KP, Poornachandran P, Al-Nemrat A, Venkatraman S. Deep learning approach for intelligent intrusion detection system. IEEE Access. 2019;7:41525–50. doi:10.1109/access.2019.2895334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Verma A, Ranga V. Statistical analysis of CIDDS-001 dataset for network intrusion detection systems using distance-based machine learning. Procedia Comput Sci. 2018;125(8):709–16. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2017.12.091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Xu C, Shen J, Du X, Zhang F. An intrusion detection system using a deep neural network with gated recurrent units. IEEE Access. 2018;6:48697–707. doi:10.1109/access.2018.2867564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Xu D, Lv Y, Wang M, Zheng B, Zhao J, Yu J. DEMGAN: a machine learning-based intrusion detection system evasion scheme. Comput Mater Contin. 2025;84(7):1731–46. doi:10.32604/cmc.2025.064833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]