Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

The Identification of Influential Users Based on Semi-Supervised Contrastive Learning

1 School of Cyberspace Security, Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, 450003, China

2 Henan Provincial Key Laboratory of Cyberspace Situational Awareness, Information Engineering University, Zhengzhou, 450001, China

* Corresponding Author: Meijuan Yin. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(1), 2095-2115. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.065679

Received 19 March 2025; Accepted 21 July 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

Identifying influential users in social networks is of great significance in areas such as public opinion monitoring and commercial promotion. Existing identification methods based on Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) often lead to yield inaccurate features of influential users due to neighborhood aggregation, and require a large substantial amount of labeled data for training, making them difficult and challenging to apply in practice. To address this issue, we propose a semi-supervised contrastive learning method for identifying influential users. First, the proposed method constructs positive and negative samples for contrastive learning based on multiple node centrality metrics related to influence; then, contrastive learning is employed to guide the encoder to generate various influence-related features for users; finally, with only a small amount of labeled data, an attention-based user classifier is trained to accurately identify influential users. Experiments conducted on three public social network datasets demonstrate that the proposed method, using only 20% of the labeled data as the training set, achieves F1 values that are 5.9%, 5.8%, and 8.7% higher than those unsupervised EVC method, and it matches the performance of GNN-based methods such as DeepInf, InfGCN and OlapGN, which require 80% of labeled data as the training set.Keywords

With the rise of social networking platforms such as Twitter, Facebook, and Weibo, a specific group of users, known as influential users, has emerged. These users’ behaviors can significantly affect others within the network. Accurately identifying influential users can effectively reduce the costs associated with commercial promotion [1] and public opinion management [2]. In different networks, influential users manifest in various forms, such as celebrities or domain experts. In this paper, no distinction is made among these influential users. Instead, influential users are defined herein as users in social networks who are recognized by other users and possess strong information dissemination capabilities.

Some studies [3–5] have employed relationship network-based approaches to identify influential users. These methods utilize social relationship graphs derived from user interactions to detect influential users, treating them as key nodes within complex networks. The identification is achieved by exploiting the structural differences between influential users and ordinary users. Although such methods exhibit high computational efficiency and require little labeled data, their reliance solely on structural information from the relationship network limits both their accuracy and coverage.

Other studies [6–8] have adopted user feature-based approaches to identify influential users. These methods extract user features from data such as user attributes and posting behaviors, identifying influential users either by manually defining feature patterns or by training models on large amounts of labeled data to capture the distinctions between known influential users and ordinary users. However, the performance of these approaches heavily depends on the selection of features. Since the raw user features are diverse and many of them are weakly correlated with user influence, extensive feature engineering is often required to achieve satisfactory results.

The aforementioned methods identify influential users based solely on relationship networks or user features, resulting in a relatively superficial characterization of users and leading to low identification accuracy. In recent years, methods based on Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) have been proposed [9–12]. Study [9] achieved better results by introducing an autoencoder to capture diverse and complementary information from multiple perspectives, thereby generating more comprehensive node representations.

However, methods based on GNNs [9–12] have several drawbacks: When applying GNNs to user classification tasks, adjacent users are often assumed to belong to the same category, a premise that underlies most classification scenarios. Under this premise, Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) [13] and other GNNs are typically designed to aggregate users’ features in such a way that adjacent users’ features are close to each other. However, in the task of identifying influential users, these users constitute a minority in the entire dataset, and they are more likely to have relationships with other users compared to ordinary users. As a result, most neighbors of influential users are ordinary users. In such cases, the neighborhood similarity characteristic of GNNs may cause influential users and some ordinary users to have similar representations, thereby increasing the difficulty of classification and requiring more training data to achieve accurate results.

To address this issue, we propose using contrastive learning to guide GNNs in extracting user features. Existing research [14–16] has demonstrated that in most cases, influential users differ significantly from ordinary users in terms of centrality indices that reflect user influence. These centrality indices can be directly calculated without labeled data. By leveraging these centrality indices, reasonable positive and negative samples can be provided for contrastive learning. If contrastive learning can obtain more discriminative user features, it can not only improve the accuracy of identification but also reduce the difficulty of training.

Specifically, we propose a semi-supervised contrastive learning method for identifying influential users. The proposed method employs a GCN as an encoder to integrate users’ network structures and user features into node representations. To ensure that the learned representations effectively capture the characteristics of influential users, three node centrality metrics, which reflect user influence, are utilized to construct positive and negative sample pairs. A contrastive learning strategy is applied to minimize the feature distance between users of the same class while maximizing the distance between users of different classes, thereby guiding the encoder to extract more accurate representations of influential users. Subsequently, a small amount of labeled data is used to train an attention mechanism-based user classifier to accomplish the influential user identification task.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews the related work on influential user identification. Section 3 presents the proposed method and outlines its main steps. Section 4 evaluates the effectiveness of the proposed approach through experiments and analyzes the results. Section 5 discusses the applicability of the proposed method under different scenarios. Section 6 concludes the paper and discusses future research directions.

Driven by practical application demands, influential user identification has gradually become an increasingly prominent research direction. Existing approaches can be broadly classified into three categories: relationship network-based influential user identification methods, user feature-based methods, and Graph Neural Network (GNN)-based methods.

2.1 Influential User Identification Based on Relationship Networks

Recent research on social networks identifies influential users by evaluating node importance using graph-based metrics. These methods are typically based on centrality measures, such as degree centrality and closeness centrality [3]. For instance, the study in [4] proposed Escape Velocity Centrality (EVC) by drawing an analogy to escape velocity in physics, which integrates multiple centrality measures to differentiate influential users from ordinary users. This metric is characterized by low computational complexity combined with high accuracy, enabling the effective identification of influential nodes within networks. The study in [5] argued that although user influence is correlated with centrality, manually combining centrality measures may only be effective for certain types of networks. To address this, the authors employed a convolutional network to learn users’ local, community, and global features and trained their model on synthetic Barabási–Albert (BA) networks. However, these network-based methods tend to oversimplify user representations, which results in relatively low identification accuracy.

2.2 Influential User Identification Based on User Features

Recent research identifies influential users by modeling differences in user attributes and posting behaviors between them and ordinary users. The study [6] utilized all available profile attributes of users on the Reddit platform and applied association rule mining techniques to identify influential users. It further indicated that, in addition to conventional influence-related factors such as the number of followers, demographic variables, including gender and age, also contribute to the identification of influential users. The study [7] found that influential users who had served as chairs in large online open-source organizations exhibited significant linguistic differences compared to ordinary users. The study employed a psychology-oriented lexicon and logistic regression to identify these influential users. A more recent study [8] extracted textual features from users’ posts using TextCNN and LSTM architectures, concatenated them with user attributes such as lifecycle and geographic location, and applied ensemble learning methods to identify influential users. Such methods rely heavily on complex feature engineering and complete user datasets. However, privacy protection policies in social networks make it difficult to obtain user data, and the complexity of feature engineering significantly hampers their practical applicability.

2.3 Influential User Identification Based on Graph Neural Networks

Recent GNN-based approaches capture the structural and feature-based differences between influential users and ordinary users, thereby generating more comprehensive user representations and achieving improved identification performance. The study [10] proposed a social influence prediction framework, DeepInf, which samples the social network through random walks and utilizes GCN and GAT [14] to learn latent social representations of users, enabling user influence prediction. The study [11] introduced an influence prediction framework, InfGCN, which argued that the importance of relationships varies among users. It determines edge weights by computing node betweenness centrality and concatenating four types of centrality metrics with user features. These combined features were input into GCN to generate node representation vectors, resulting in improved performance. The study [12] suggested that both the importance of users and their relationships variy, and proposed a method to assess individual user reputation and interpersonal trust between users. A network was constructed based on user reputation and interpersonal trust, and GNN was applied to identify influential users. The features of influential users learned by GNNs through neighborhood aggregation mechanisms are often insufficiently discriminative and require a substantial amount of labeled data for training, thereby limiting their practicality.

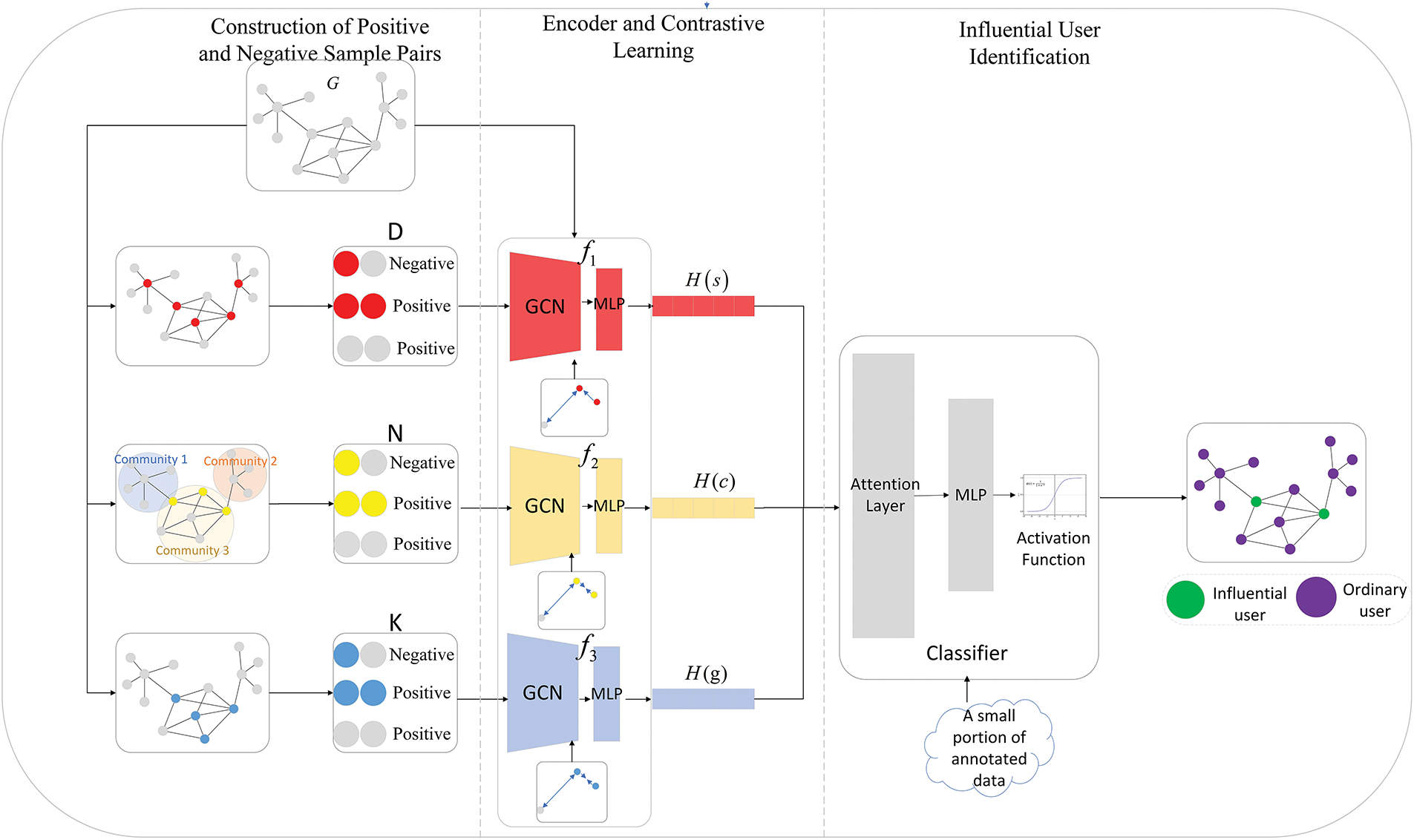

A study [17] has highlighted the extensive applications and significant potential of semi-supervised learning in the graph domain. Inspired by this study, this paper proposes an influential user identification method based on semi-supervised contrastive learning. The framework of the method is shown in Fig. 1. Specifically, it comprises four components: positive and negative sample pair construction, an encoder, contrastive learning, and influential user identification. The proposed method first selects three centrality indices, each closely related to user influence, to represent a node’s individual, community, and global influence. Based on these rankings, positive and negative sample pairs are constructed. Then, a two-layer GCN, followed by a fully connected layer, is employed as an encoder to learn node representations from the graph. Through contrastive learning, the encoder is guided to generate discriminative vectors that accurately represent influential users. Finally, a classifier based on an attention network is fine-tuned using a small amount of labeled data, integrating the three types of vectors to identify influential users. The main steps of the method are as follows:

Figure 1: Method flowchart

Step 1: Construction of Positive and Negative Sample Pairs

In the given graph

Step 2: User Encoding

In the given graph

Step 3: Contrastive Learning

Using the three sets of positive and negative samples

Step 4: influential User Identification

For the obtained vectors

In the following section, we discuss the implementation process in detail

3.1 Construction of Positive and Negative Sample Pairs

Constructing appropriate positive and negative samples is crucial in contrastive learning. During training, inappropriate sample pairs may mislead the model, preventing it from accurately extracting features related to user influence. Existing research [14–16] has demonstrated that certain centrality indices often serve as effective bases for distinguishing influential users from ordinary users. Moreover, the influence of influential users manifests across multiple dimensions, including self-influence, community influence, and global influence. To comprehensively identify influential users, we select three centrality indices that reflect a node’s influence from different perspectives for classification purposes. Based on these classifications, positive and negative sample pairs are constructed to guide the encoder during training to generate more representative embeddings of influential users. Specifically, we choose degree centrality to guide the encoder in learning a user’s self-influence, the number of communities connected by neighboring nodes for community influence, and the k-core value for global influence. The specific steps are as follows:

Step 1: Construct positive and negative sample set

where

Step 2: Construct a positive and negative sample set

where

Step 3: Construct a positive and negative sample set

After the above steps, the positive and negative sample sets

We build three encoders

where

where

These three encoders are designed to extract three distinct representation vectors, corresponding to a node’s self-influence

After building the encoder, it must be trained to extract meaningful representations. We use contrastive learning to train the model. Contrastive learning not only captures the similarities among similar nodes, but also distinguishes them from dissimilar ones, thereby capturing richer relationships among samples and enhancing the model’s generalization capability. For encoder

where

3.4 Identification of Influential Users

After the aforementioned training process, three representation vectors—

The aforementioned three types of representation vectors are stacked into a matrix

where

where

where

Here,

The model is trained to optimize the attention weights and parameter matrices using a small amount of labeled data. We first freeze the parameters of the encoder and utilize a small amount of known labeled data to train the attention network and the classifier. The loss function is shown in Eq. (10):

where

After completing the training, for each user, we obtain the classification result

For the threshold

In order to verify the feasibility and effectiveness of the proposed algorithm, this section conducts three groups of experiments on three real social network datasets focusing on the following three aspects and analyzes the principles of the experimental results.

1. Compare the experimental results of our method with the existing influential user identification methods on different proportions of training data.

2. Ablate the three influence features mentioned in this method to verify the role of different features in the entire method.

3. Perform sensitivity analysis on the two hyperparameters mentioned in the method, and demonstrate the performance of the method under different values of these hyperparameters.

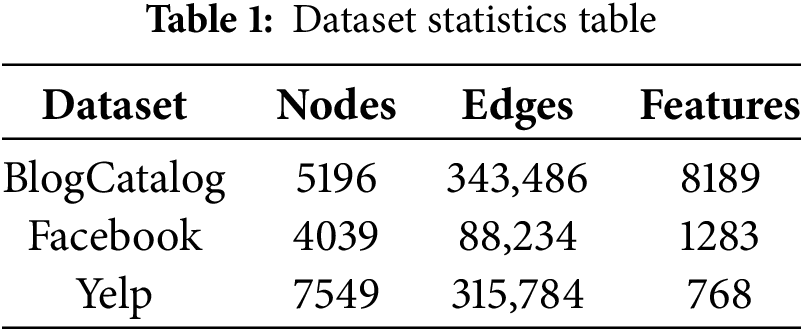

The proposed method was evaluated on three publicly available social network datasets: BlogCatalog [20], Facebook [21], and Yelp.

The BlogCatalog and Facebook datasets consist of user relationship networks obtained from their respective platforms. In both datasets, nodes represent users, and edges denote following relationships. Node features include users’ personalized content, such as blog posts, image tags, and custom labels.

The Yelp dataset is generated from Yelp.com. It contains user relationship and content information extracted from the Yelp platform, including user posts and connections. It is modeled as a user relationship network, where nodes represent users and edges denote friendships. Bert [22] was employed to extract features from user posts, resulting in 768-dimensional vectors used as node features. Prior research noted missing user relationships in the dataset, making it infeasible to use the entire graph for experimentation. Therefore, in line with the experimental setup in, we select the largest connected subgraph with the most nodes as the experimental dataset.

The statistical information of the two datasets is shown in Table 1.

Among the three datasets, Yelp explicitly designates widely recognized users as “elite,” which aligns with our definition of influential users. Therefore, we select users who have been designated as “elite” by the platform as influential users. However, the BlogCatalog and Facebook datasets do not have annotations for influential users. We employ the SIR (Susceptible–Infected–Recovered) model [23], which is widely used in prior studies [14–16] for simulating influence propagation and annotating influential users.

The SIR Model is a classical epidemiological dynamics model used to simulate the spread of diseases or information within a population. Its core mechanism divides individuals in the network into three states: susceptible (S), infected (I), and recovered (R). In the model, susceptible individuals (users who have not received the information) transition to the infected state (users influenced by the information) at an infection rate

Using the SIR Model to label influential users possesses inherent impartiality, primarily manifested in its objective simulation mechanism based on propagation dynamics. Firstly, the SIR Model evaluates all nodes following uniform infection and recovery rates, without presupposing any subjective weights related to node attributes or positions, thereby avoiding artificially introduced structural biases. Secondly, by calculating the average influence of nodes through a large number of stochastic simulations, it can eliminate deviations caused by the randomness of propagation paths, enabling the results to reflect the true propagation potential of nodes. Compared with methods based on static topological features (such as degree centrality), the SIR Model directly simulates the dynamic propagation process, more closely aligning with the causal logic of real-world information diffusion. Therefore, its evaluation results do not rely on a priori assumptions about the network structure. This mechanism, based on uniform rules and probabilities, ensures the fairness and impartiality of the annotation results.

In the specific annotation process, the hyperparameter recovery rate

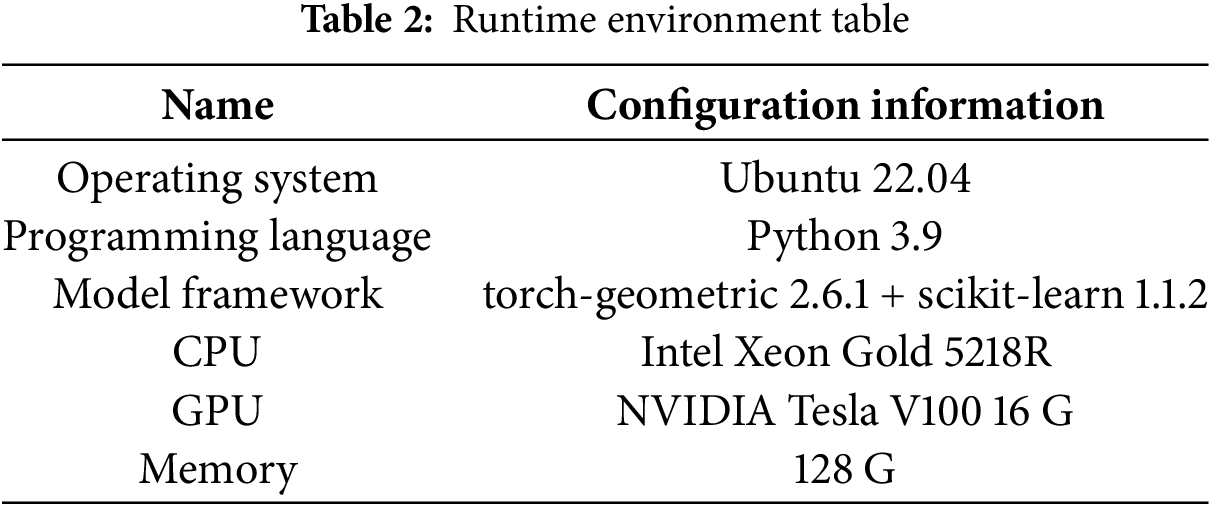

The experimental operating environment is detailed in Table 2. In addition, the hyperparameter

We use the F1 value as the evaluation metric. The F1 values is a commonly used metric in machine learning, particularly for imbalanced classification tasks. It is defined as the harmonic mean of precision and recall, providing a more balanced evaluation of model performance. As shown in Formula (11):

where

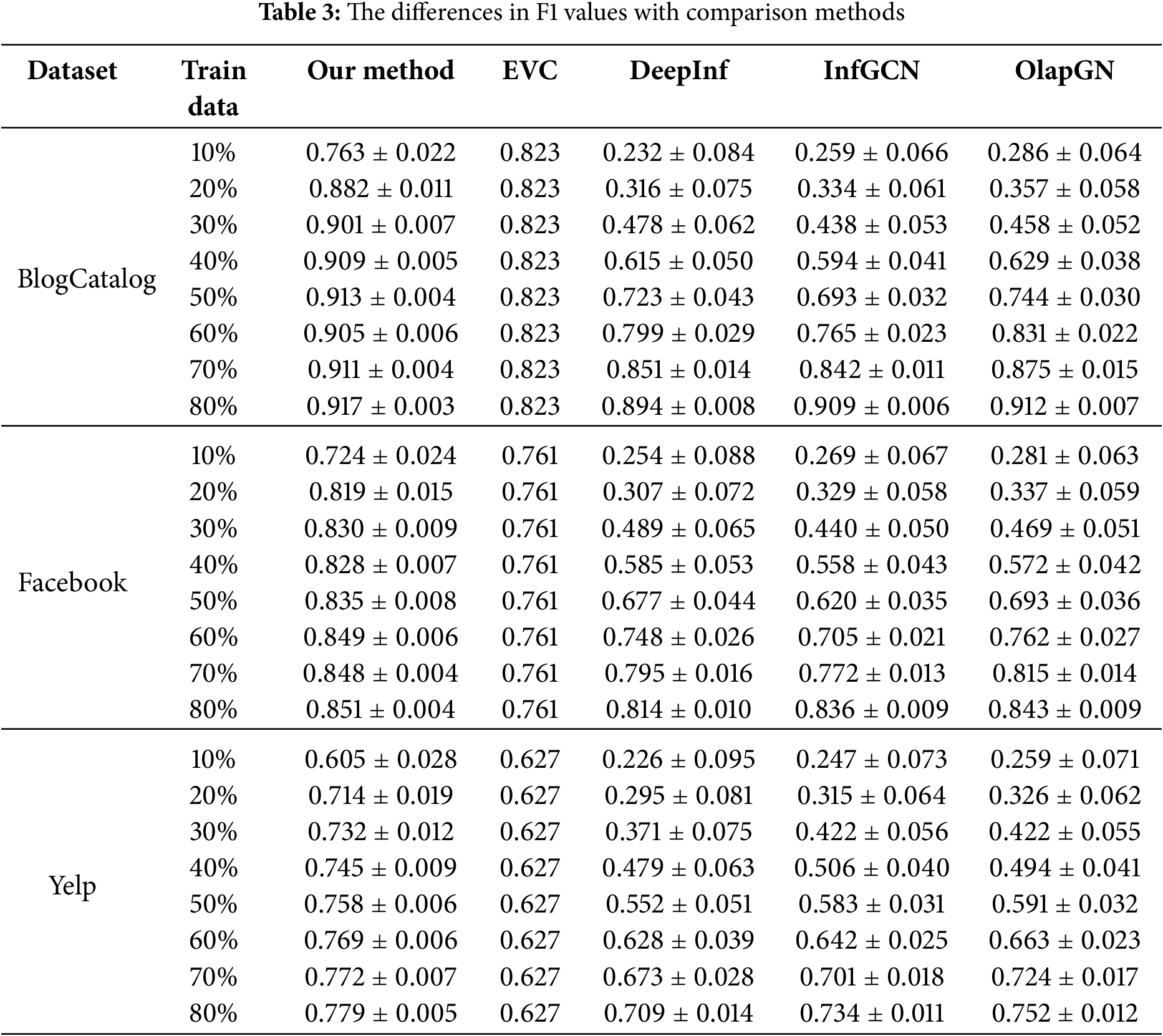

To comprehensively demonstrate the effectiveness of this method in identifying influential users and their performance with a small amount of training data, we select 10% to 80% of the data (in increments of 10%) as the training set, and use the remaining data as the test set. Observe the performance of this method and the comparison methods under different proportions of training data. The selected comparison methods are as follows:

EVC [3]: A centrality-based method that does not require training. It assesses node influence based on degree centrality, k-shell values, and shortest path distances. Similarly, we select the top 10% of nodes as influential users. Since this method does not require training, we take its performance on the entire dataset as a baseline.

DeepInf [7]: A GNN-based approach that uses 75% of the data for training in its original implementation. It predicts the social influence of users through random walks and graph attention networks (GAT).

InfGCN [8]: This method is based on convolutional neural networks. In the original paper, 80% of the training set was used for training. It determines the relationship weight based on the betweenness centrality of nodes and uses the splicing of four centrality indicators and user features. It uses GCN to identify influential users.

OlapGN [24]: This method is based on GNNs. In the original paper, 80% of the training set was used for training. It posits that users located in overlapping communities are more likely to be influential users. The method concatenates the detection results of node overlapping communities, centrality metrics, and user features, utilizing GCN to identify influential users.

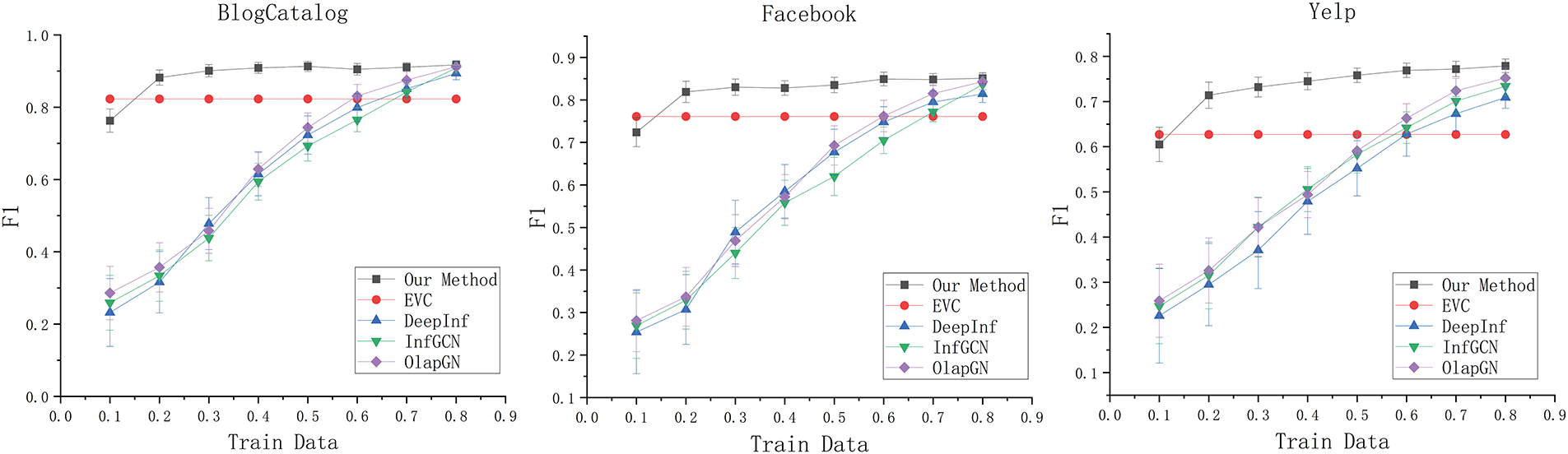

Table 3 and Fig. 2 summarize the performance of each method under varying proportions of training data. Notably, as the EVC method directly computes node influence without involving model initialization or stochastic processes, its results are consistent across runs, yielding a standard deviation of zero. In contrast, our method, as well as DeepInf, InfGCN, and OlapGN—all of which are GNN-based—were independently run five times under identical hardware conditions. The reported results represent the mean values with corresponding standard deviations.

Figure 2: The differences in F1 values with comparison methods

As can be observed from Table 3 and Fig. 2. When only 10% of the training data is used, the F1 values of this method on three different data sets reach 0.763, 0.724, and 0.605, which are comparable to the effects of DeepInf, InfGCN, and OlapGN when using 60% of the training data. When 20% of the training data is used, the F1 values of this method on three different data sets reach 0.882, 0.819, and 0.714. Compared to EVC, the F1 values are improved by 5.9%, 5.8%, and 8.7%, which is comparable to the performance of DeepInf, InfGCN, and OlapGN using 80% of the training data. Furthermore, across all training ratios, our method consistently exhibits lower standard deviation than the other GNN-based approaches. Specifically, when utilizing only 10% of the training data, the standard deviations of the F1 values for our method on the three datasets are merely 0.022, 0.024, and 0.028, respectively. This represents a reduction of 4.2%, 3.9%, and 4.3% compared to the standard deviations of the best-performing alternative methods. Such findings underscore the robust stability of our method even when confronted with limited data.

Comparative experimental results show that:

(1) The results of graph neural network-based methods such as DeepInf, InfGCN, and OlapGN are better than EVC methods based on network structure. After full training of the method based on graph neural network, its F1 value is eventually greater than that of the EVC method using only structural features, which indicates that the method combining network features and user characteristics using graph neural network can identify influential users more accurately and comprehensively.

(2) When only a small amount of labeled data is used in this method, it can achieve the effect that other methods use a large amount of labeled data for training. Compared with the graph neural network-based method, which needs to extract features that can distinguish different users from the original user data and map these features into the class space to complete the classification, this method has obtained features that can distinguish different users through comparative learning without annotating data. At this time, only a small amount of data is needed to fine-tune the classifier and map these features into the class space. Therefore, the method in this paper can achieve the effect of DeepInf, InfGCN, and OlapGN using 80% training data at 20% training data.

(3) The F1 value of all methods increases with the increase of training data, and the growth of F1 value slows down to a certain extent. This is because the influential user identification method needs to capture the common features of influential users from the training data. When the training data is small, the features captured by the method cannot represent the overall trend of influential users, and the F1 value is small. With the increase of training data, the F1 value keeps increasing, and when the training data reaches a certain level, the method can better capture the common characteristics of influential users, and then the increase of training data will lead to a slow increase in F1 value.

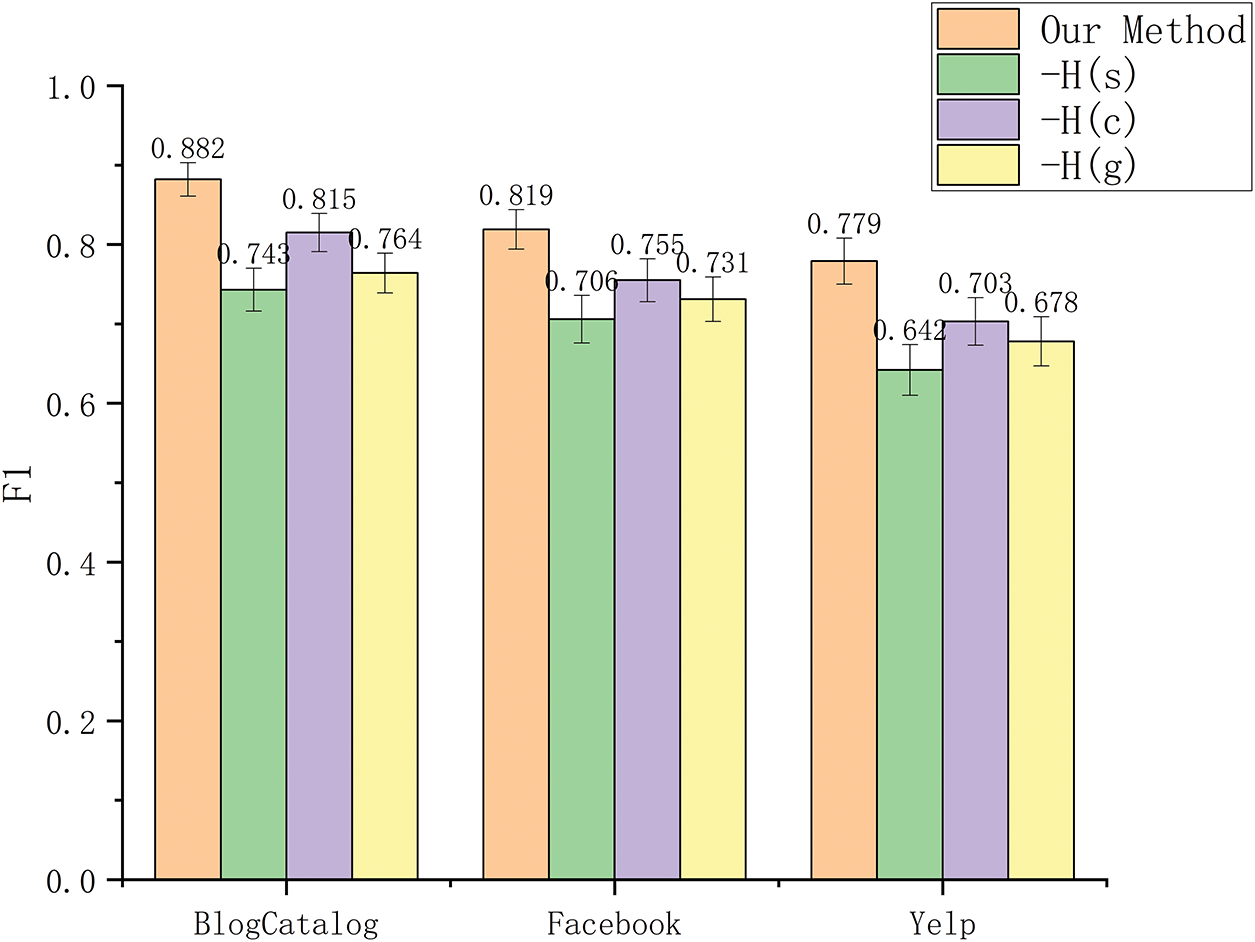

To evaluate the contribution of the three representation vectors extracted by the proposed encoders, we conduct two sets of ablation experiments. The first set involves removing each of the three representation vectors individually and observing the decrease in F1 values resulting from each removal. The second set ablates two of the three vectors, retaining only one, to assess the method’s performance when relying on a single type of representation.

In the first set of ablation experiments, Our Method represents the complete method, while

Figure 3: The F1 value after the ablation of different representation vectors

Fig. 3 shows the ablation results of the three representation vectors. In the three datasets, after ablating

Ablation results show that:

(1) After the user’s self-influence feature

(2) After the global influence feature

(3) After the community influence feature

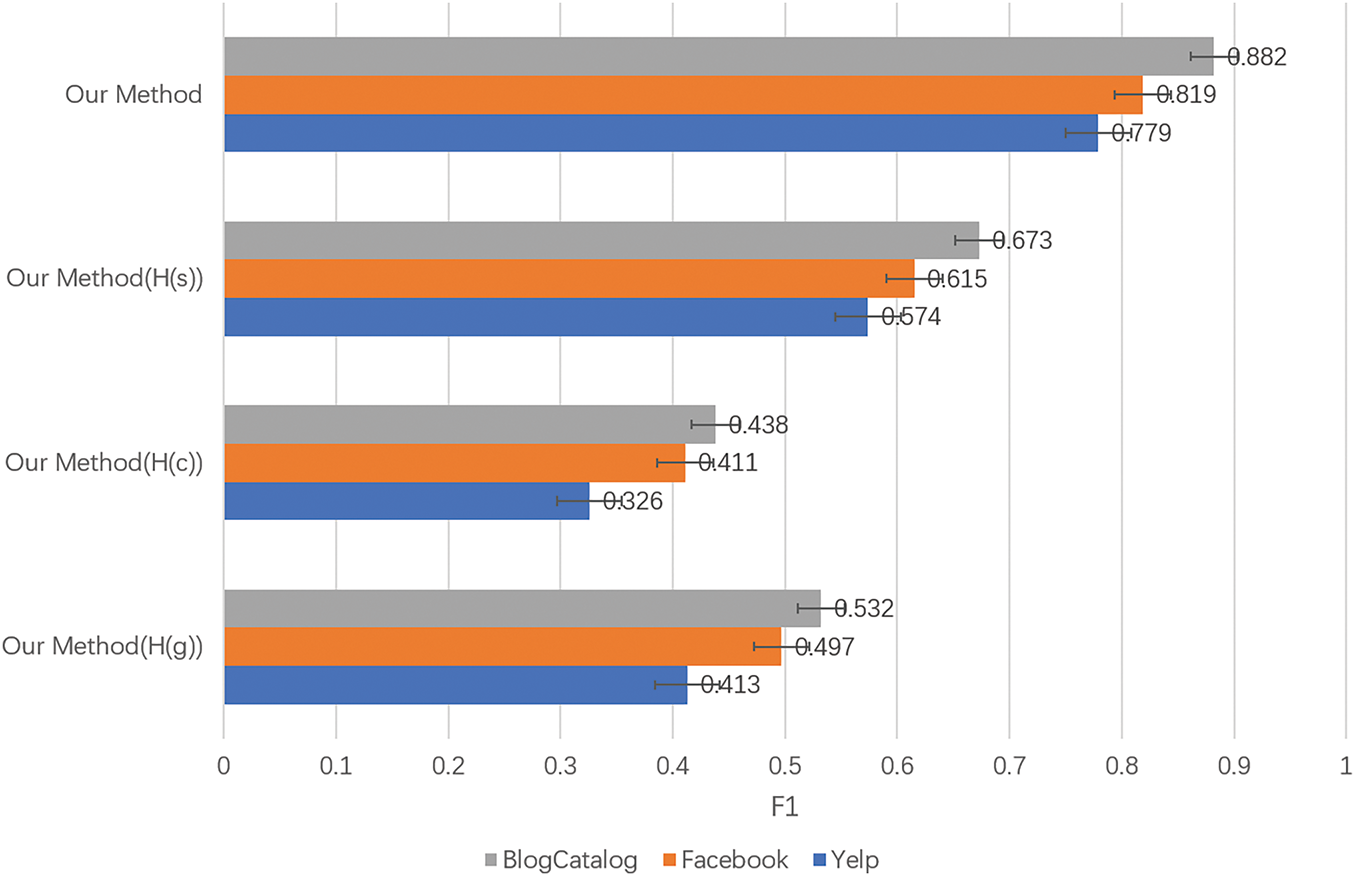

To further validate the effectiveness of the three extracted representation vectors, we simultaneously ablate two of the three vectors, retaining only one, while also removing the attention network in influential user identification. Instead, only a fully connected layer with an output dimension of 1 and a sigmoid function is used as the classifier. Here, “Our Method” represents the complete method, while “Our Method(H(s))”, “Our Method(H(c))”, and “Our Method(H(g))” respectively represent methods that retain only the features reflecting the user’s self-influence

Figure 4: The F1 value after the single representation vector is retained

Fig. 4 presents the F1 value of the method when only one representation vector is retained. Across both datasets, the highest F1 value are achieved when only

The experimental results show that:

(1) The highest F1 value is achieved when only the user’s self-influence feature

(2) The second-highest F1 value is obtained when only the user’s global influence feature

(3) The lowest F1 value is observed when only the user’s community influence feature

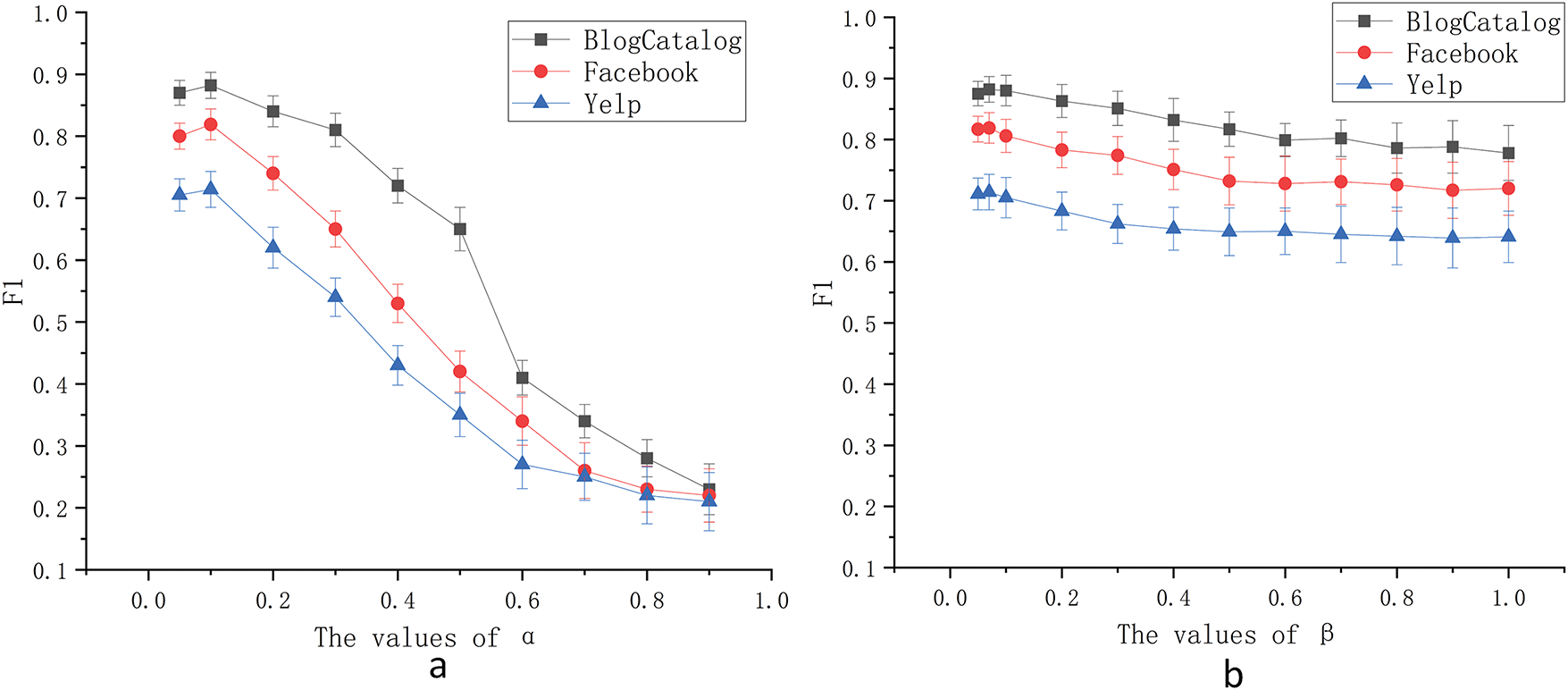

4.6 Hyperparameter Sensitivity Experiments

To evaluate the sensitivity of the proposed method to different hyperparameter settings, we analyze two key hyperparameters: (1) the hyperparameter

(1) Positive Sample Ratio

The hyperparameter

Figure 5: The influence of different parameters on the F1 value. (a) The values of

Experimental results show that as α increases, the F1 values initially improves. However, once

(2) Temperature Coefficient

The hyperparameter

Experimental results indicate that as

In this section, we focus on three main areas of discussion:

(1) We examine the rationale behind selecting the three metrics in our proposed approach, along with potential biases they might introduce and strategies to address them.

(2) We conduct a further comparison between our method and baseline approaches in terms of runtime and memory usage and discuss their applicability in large-scale networks.

(3) We delve into the potential biases that could result from using the SIR model for data labeling.

5.1 Analysis of Influence Metrics

The ablation experiments demonstrate the effectiveness of the three influence metrics employed in our method. However, there is a lack of further justification for the rationality of choosing these three metrics. Next, we will demonstrate the rationality of our method from three aspects, namely: the necessity of selecting three types of influence with different scopes of action, the corresponding indicators for each type of influence, as well as the deviations of each indicator under certain circumstances and possible solutions.

We categorize user influence into three levels based on its scope of action: self-influence, community influence, and global influence. This classification method is widely applied in the field of influential user identification. Self-influence manifests in small-scale interpersonal interactions. Although its scope is limited, it possesses a high degree of precision and emotional penetration, often leading to immediate feedback or behavioral changes. Community influence operates within specific groups or platforms, demonstrating users’ discourse power and leadership in forums, industry communities, or interest groups. Global influence, on the other hand, extends to a broader social level. Users with such influence can trigger cross-community discussions through media dissemination, public event statements, etc., with their impact being enduring and diffusive.

To effectively capture these levels of influence, we adopt degree centrality, the number of communities connected by neighboring nodes, and the k-core value as representative indicators. Among these, degree centrality best reflects self-influence as it directly measures the number of direct connections an individual has in a social network. Within a local scope, influence often hinges on a user’s ability to interact directly with surrounding nodes, and degree centrality, focusing on the scale of direct associations, aligns with the characteristics of local influence. The number of communities connected by adjacent nodes best reflects community influence, as it directly mirrors the user’s bridging role across different groups. In a social network, if a user’s adjacent nodes are distributed across different communities, the community distribution of adjacent nodes directly quantifies the user’s potential to break down information silos and integrate diverse groups. The

We use degree centrality to evaluate the self-influence of users. Nevertheless, in networks with edge weights, the importance of edges varies, and the number of edges cannot fully represent a node’s influence. A node with a smaller total number of edges but including important edges may actually be more influential than a node with a larger total number of edges. In such cases, metrics like Eigenvector Centrality, which consider the importance of both nodes and edges, might be a better choice. However, it is worth noting that determining edge weights requires more user information, which may be difficult to obtain in practical scenarios. Therefore, in most cases, selecting degree centrality is a reasonable approach.

We use the number of communities connected by adjacent nodes to evaluate a node’s community influence. However, this metric relies on the accuracy of community detection algorithms. When evaluating influential nodes in dynamically evolving networks such as transportation networks, due to the rapid changes in community structures, this metric may misestimate a node’s ability to span across communities. In such cases, metrics like Structural Hole Constraint, which do not depend on community partitioning, might be a better choice. However, for social networks, where user behaviors span long periods and community structures adjust slowly, using this metric to judge a node’s community influence is reasonable.

We use the

5.2 Analysis of Computational Complexity

This section compares the computational complexity of our method with four baseline approaches, namely EVC, DeepInf, InfGCN, and OlapGN, which were utilized in the experimental section. Additionally, we discuss the applicability of these methods in large-scale networks.

For the proposed method in this paper, the computational cost mainly arises from three components: the calculation of centrality-related measures during the construction of positive and negative sample pairs, the aggregation operations of the graph neural network in the user encoding phase, and the training of the final classifier. In the phase of constructing positive and negative sample pairs, three centrality metrics are employed, resulting in a computational complexity of

For the four comparative methods, the EVC method has a computational complexity of

In terms of computational complexity, the proposed method exhibits a higher computational complexity compared to the EVC and DeepInf methods. This is primarily attributed to the necessity of calculating node centrality to construct positive and negative sample pairs and the utilization of an attention network to fuse multiple user features, which collectively increase the method’s computational complexity. However, the proposed method’s computational complexity is lower than that of the InfGCN and OlapGN methods, indicating that it achieves superior performance while maintaining a moderate computational complexity, thereby demonstrating its advantages.

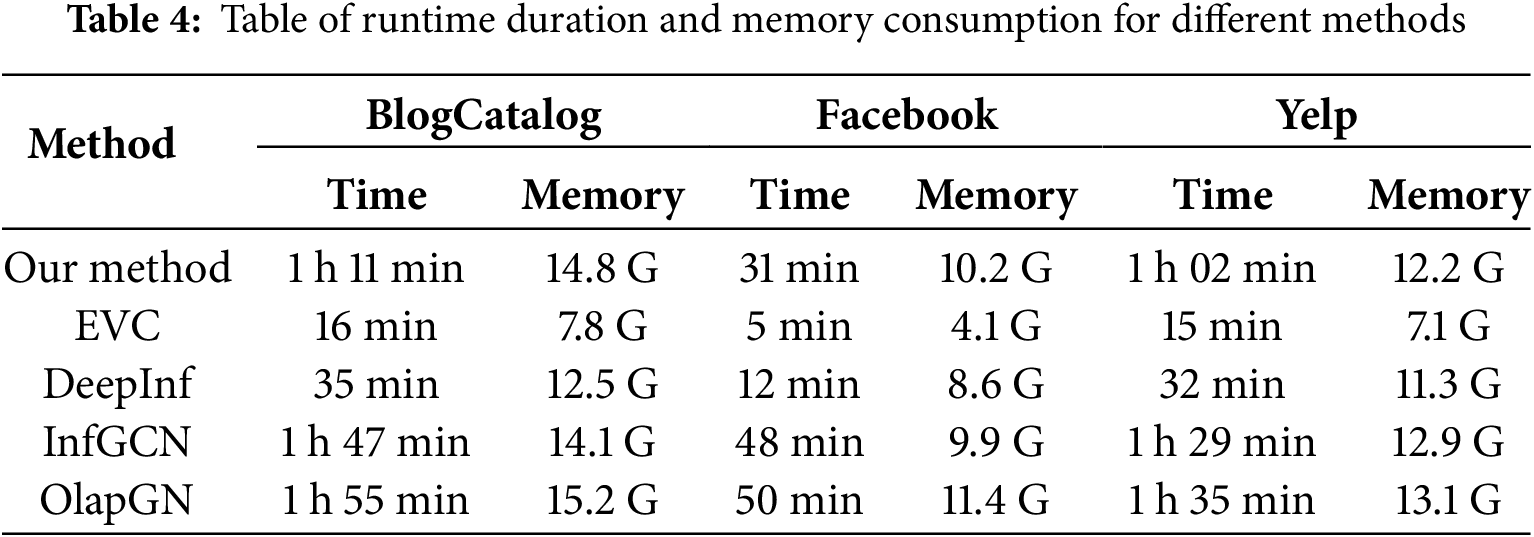

To further illustrate the practical feasibility of the proposed method, Table 4 presents the runtime duration and memory consumption. Specifically, the runtime duration is the aggregate time consumed across all phases of the method, while the memory consumption denotes the maximum memory utilization during the execution process.

In Table 4, it is evident that the EVC and DeepInf methods exhibit superior performance in terms of runtime duration and memory consumption, whereas our proposed method, along with methods like InfGCN and OlapGN, demonstrates relatively poorer performance in these aspects. This discrepancy can be attributed to the substantial computational demands of GNNs when dealing with large-scale networks. The EVC method, being based on centrality metrics, does not rely on GNNs, thereby circumventing the associated computational overhead. In contrast, the DeepInf method incorporates optimizations in its utilization of GNNs by manually specifying the size of the sampled neighborhood, which effectively reduces the runtime duration and memory consumption of the GNN. Consequently, the EVC and DeepInf methods demonstrate better adaptability to large-scale networks, whereas our proposed method is not ideally suited for applications involving large-scale networks.

5.3 Potential Biases Introduced by the SIR Model

We employ the SIR model to label influential users in the BlogCatalog and Facebook datasets, which may introduce potential biases. Although the effectiveness of the proposed method has been validated using the Yelp dataset, it is still necessary to be cautious about the deviations that may arise from the SIR model, particularly its notable limitations in dynamic network environments.

Firstly, the SIR model assumes that the transmission and recovery probabilities are fixed and homogeneous. However, in reality, user influence often dynamically changes with content, context, and relationship strength, leading to static parameters that may overestimate the propagation capacity of core nodes or underestimate the potential explosiveness of peripheral nodes. Secondly, the SIR model implicitly assumes a static network structure, whereas in actual social networks, user connections evolve in real-time in response to events—the sudden formation of new edges or the invalidation of old edges may cause the model to underestimate emerging key users. More critically, the SIR model relies on a single “infection” propagation mode, neglecting the heterogeneity of user behaviors and the interference of competing information flows. It is important to emphasize that the method proposed in this paper is designed solely for static networks and cannot be applied to dynamic networks.

This paper proposes a method for influential user identification based on semi-supervised contrastive learning. The method employs a GCN as an encoder to integrate user features and structural information. Positive and negative samples are constructed based on centrality metrics to guide the encoder in generating multiple influence-aware representation vectors. An attention network is then used to fuse these representation vectors, enabling accurate identification of influential users even with a small amount of labeled data. Experiments on real-world social network datasets show that our method achieves comparable F1 values to GNN-based baselines trained with 80% labeled data, while using only 20%, thus demonstrating its effectiveness.

However, the method has two main limitations: it relies on centrality-based sample construction, making its performance sensitive to the choice of metrics, and it requires access to user relationships and attributes, which may be difficult to obtain in real-world settings. Future work will explore identifying influential users using only user-generated content, particularly in scenarios where relational and attribute information is unavailable.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank the editors for their valuable comments and kind support during the review process.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the National Key Project of the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. U23A20305.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Jialong Zhang: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing. Meijuan Yin: Writing, Reviewing & Editing. Yang Pei, Fenlin Liu and Chenyu Wang: Review & Editing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All the data used in this study are obtained from publicly available benchmark datasets, which are appropriately cited in the manuscript.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Wu S, Li W, Shen H, Bai Q. Identifying influential users in unknown social networks for adaptive incentive allocation under budget restriction. Inf Sci. 2023;624:128–46. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2022.12.071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Zhao J, He H, Zhao X, Lin J. Modeling and simulation of microblog-based public health emergency-associated public opinion communication. Inf Process Manag. 2022;59(2):102846. doi:10.1016/j.ipm.2021.102846. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Rashid Y, Bhat JI. Topological to deep learning era for identifying influencers in online social networks: a systematic review. Multimed Tools Appl. 2024;83(5):14671–714. doi:10.1007/s11042-023-16002-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Ullah A, Wang B, Sheng J, Khan N. Escape velocity centrality: escape influence-based key nodes identification in complex networks. Appl Intell. 2022;52(14):16586–604. doi:10.1007/s10489-022-03262-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Ou Y, Guo Q, Xing JL, Liu JG. Identification of spreading influence nodes via multi-level structural attributes based on the graph convolutional network. Expert Syst Appl. 2022;203:117515. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2022.117515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Alghobiri M. Exploring the attributes of influential users in social networks using association rule mining. Soc Netw Anal Min. 2023;13(1):118. doi:10.1007/s13278-023-01118-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Khare P, Shekhar R, Karan M, McQuistin S, Perkins C, Castro I, et al. Tracing linguistic markers of influence in a large online organisation. In: Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 2: Short Papers); 2023 Jul 9–14; Toronto, ON, Canada. p. 82–90. doi:10.18653/v1/2023.acl-short.8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Li W, Xu Z, Sun Y, Gong Q, Chen Y, Ding AY, et al. DeepPick: a deep learning approach to unveil outstanding users with public attainable features. IEEE Trans Knowl Data Eng. 2021;35(1):291–306. doi:10.1109/TKDE.2021.3091503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Daneshfar F, Saifee BS, Soleymanbaigi S, Aeini M. Elastic deep multi-view autoencoder with diversity embedding. Inf Sci. 2025;689:121482. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2024.121482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Qiu J, Tang J, Ma H, Dong Y, Wang K, Tang J. DeepInf: social influence prediction with deep learning. In: Proceedings of the 24th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining; 2018 Aug 19–23; London, UK. p. 2110–9. doi:10.1145/3219819.3220077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Zhao G, Jia P, Zhou A, Zhang B. InfGCN: identifying influential nodes in complex networks with graph convolutional networks. Neurocomputing. 2020;414(11):18–26. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2020.07.028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Jain L, Katarya R, Sachdeva S. Opinion leaders for information diffusion using graph neural network in online social networks. ACM Trans Web. 2023;17(2):1–37. doi:10.1145/3580516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Kipf TN, Welling M. Semi-supervised classification with graph convolutional networks. In: Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR); 2017 Apr 24–26; Toulon, France. [Google Scholar]

14. Curado M, Tortosa L, Vicent JF. A novel measure to identify influential nodes: return random walk gravity centrality. Inf Sci. 2023;628(5):177–95. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2023.01.097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Zhang Q, Shuai B, Lü M. A novel method to identify influential nodes in complex networks based on gravity centrality. Inf Sci. 2022;618(5996):98–117. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2022.10.070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Namtirtha A, Dutta B, Dutta A. Semi-global triangular centrality measure for identifying the influential spreaders from undirected complex networks. Expert Syst Appl. 2022;206(1):117791. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2022.117791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Daneshfar F, Soleymanbaigi S, Yamini P, Amini MS. A survey on semi-supervised graph clustering. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2024;133(2):108215. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2024.108215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Blondel VD, Guillaume JL, Lambiotte R, Lefebvre E. Fast unfolding of communities in large networks. J Stat Mech. 2008;2008(10):P10008. doi:10.1088/1742-5468/2008/10/p10008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. He K, Fan H, Wu Y, Xie S, Girshick R. Momentum contrast for unsupervised visual representation learning. In: 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2020 Jun 13–19; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 9726–35. doi:10.1109/cvpr42600.2020.00975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Rossi R, Ahmed N. The network data repository with interactive graph analytics and visualization. In: Proceedings of the 29th AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2015 Jan 25–30; Austin, TX, USA. p. 4292–3. doi:10.1609/aaai.v29i1.9277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. McAuley J, Leskovec J. Learning to discover social circles in ego networks. In: Pereira F, Burges CJC, Bottou L, Weinberger KQ, editors. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 25 (NIPS 2012); 2012 Dec 3–6; Lake Tahoe, NV, USA. p. 539–47. [Google Scholar]

22. Devlin J, Chang MW, Lee K, Toutanova K. Bert: pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In: Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, NAACL-HLT 2019; 2019 Jun 2–7; Minneapolis, MN, USA. p. 4171–86. doi:10.18653/v1/N19-1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Kephart JO, White SR. Measuring and modeling computer virus prevalence. In: Proceedings 1993 IEEE Computer Society Symposium on Research in Security and Privacy; 1993 May 24–26; Oakland, CA, USA. doi:10.1109/RISP.1993.287647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Rashid Y, Bhat JI. OlapGN: a multi-layered graph convolution network-based model for locating influential nodes in graph networks. Knowl Based Syst. 2024;283(1):111163. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2023.111163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Kumar S, Panda BS. Identifying influential nodes in social networks: neighborhood coreness based voting approach. Phys A Stat Mech Appl. 2020;553(3):124215. doi:10.1016/j.physa.2020.124215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools