Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Co-Attention Mechanism into a Combined GNN-Based Model for Fake News Detection

1 LiM Laboratory, Department of Computer Science, Faculty of Science and Technology, University of Souk Ahras, Souk Ahras, 41000, Algeria

2 Laboratory of Mathematics, Informatics and Systems (LAMIS), Echahid Cheikh Larbi Tebessi University, Tebessa, 12000, Algeria

3 Departement of Electrical Engineering, Umm Al-Qura University, Makkah, 21955, Saudi Arabia

4 Information Systems Department, College of Computer Science and Engineering, Taibah University, Medina, 41477, Saudi Arabia

5 Department of information Technology, Aylol University College, Yarim, 547, Yemen

* Corresponding Author: Akram Bennour. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(1), 1267-1285. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.066601

Received 12 April 2025; Accepted 28 June 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

These days, social media has grown to be an integral part of people’s lives. However, it involves the possibility of exposure to “fake news,” which may contain information that is intentionally or inaccurately false to promote particular political or economic interests. The main objective of this work is to use the co-attention mechanism in a Combined Graph neural network model (CMCG) to capture the relationship between user profile features and user preferences in order to detect fake news and examine the influence of various social media features on fake news detection. The proposed approach includes three modules. The first one creates a Graph Neural Network (GNN) based model to learn user profile properties, while the second module encodes news content, user historical posts, and news sharing cascading on social media as user preferences GNN-based model. The inter-dependencies between user profiles and user preferences are handled through the third module using a co-attention mechanism for capturing the relationship between the two GNN-based models. We conducted several experiments on two commonly used fake news datasets, Politifact and Gossipcop, where our approach achieved 98.53% accuracy on the Gossipcop dataset and 96.77% accuracy on the Politifact dataset. These results illustrate the effectiveness of the CMCG approach for fake news detection, as it combines various information from different modalities to achieve relatively high performances.Keywords

Nowadays, social media platforms are used extensively to deliver thousands of news items, whether they are private or public. It is predicted that by 2027, the number of people using social media is expected to reach six billion users [1]. Users can easily communicate with each other, express themselves, and access news. However, it also entails the risk of exposure to “fake news,” which could contain information that is intentionally or inaccurately false to promote specific political or economic agendas [2]. The dissemination of misinformation has grown to be a serious issue in modern society due to its expanding availability. Thus, it is now essential to detect and stop misinformation in several domains, including information management, public administration, and journalism [3]. Consequently, fake news identification in social media platforms has garnered significant attention in the last years from both the research and professional communities. Fact-checking is one method of identifying fake news, but because fake news is spreading at an unprecedented rate, manual fake checking is time-consuming and challenging [4]. Hence, automated fake news detection is required to stop misinformation from spreading [5]. The primary foundation of traditional fake news detection techniques is to capture linguistic characteristics between authentic and fake news by capturing the semantics or styles of news articles. However, fake news is created to mislead readers with intricately twisted facts and stories. Furthermore, The variety of topics and contents covered by fake news also makes it very difficult to gather a lot of annotated misinformation news. Researchers are now focusing on machine learning (ML) to differentiate between authentic and fake news [6]. Among the most widely used machine learning (ML) methods are long short-term memory (LSTM), which is more effective at identifying false information [7]. However, researchers have recently become less interested in LSTM due to its structural challenges [4]. With the recent advancements in deep learning technology, methods like Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) and recurrent neural networks (RNN) have become highly effective for capturing underlying semantic relationships and natural language embedding [8,9]. Consequently, deep learning algorithms, in particular, RNN and CNN techniques, have become more and more popular in fake news detection. In contrast to CNN or RNN, the attention mechanism maintains word dependencies within a sentence in such methods as GCAN where, Lu and Li [10] have successfully used a dual co-attention mechanism to learn the correlation between the source tweets, retweets spread, and the combined impact of the source tweet and user interaction.

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) are among the most recent deep learning techniques being used by researchers to identify false information. Unlike machine learning-based models that heavily rely on news text, GNNs enable the combination of network structure with users’ information (i.e., network nodes) as well as the messages (i.e., news content) they share [5,11]. Thus, GNN-based models can outperform modern methods without using textual information. Several GNN evolutions, such as the Graph Isomorphism Network (GIN), Graph Transformer Network (GTN), Graph SAmple, and aggreGatE (GraphSAGE), have proved innovative achievements in fake news detection [5,12]. However, traditional GNN methods for detecting fake news using multimodal data (text + images + social context) suffer from many significant shortcomings. Fine-grained relationships between different modalities, such as the relationship between a misleading image and a news headline, are difficult to model for traditional GNNs (e.g., GCN, GAT). Moreover, most GNNs treat user interactions (likes, retweets) and news content differently, ignoring the distinction between user profiles and news credibility [13]. The co-attention mechanism is suggested to improve the effectiveness of GNN methods for fake news detection due to many significant drawbacks, such as the ability to identify cross-modal inconsistencies indicating the presence of fake news, identify questionable patterns (such as bot-like users spreading misleading information), jointly model user-news interactions, and find discrepancies between source nodes (such as publisher metadata) and content nodes (such as article text) [13,14].

The objective of this research is to use a co-attention mechanism in a combined GNN-based model for capturing the relationship between user profile features and user preferences, to detect fake news, and to compare the obtained results against various machine learning strategies.

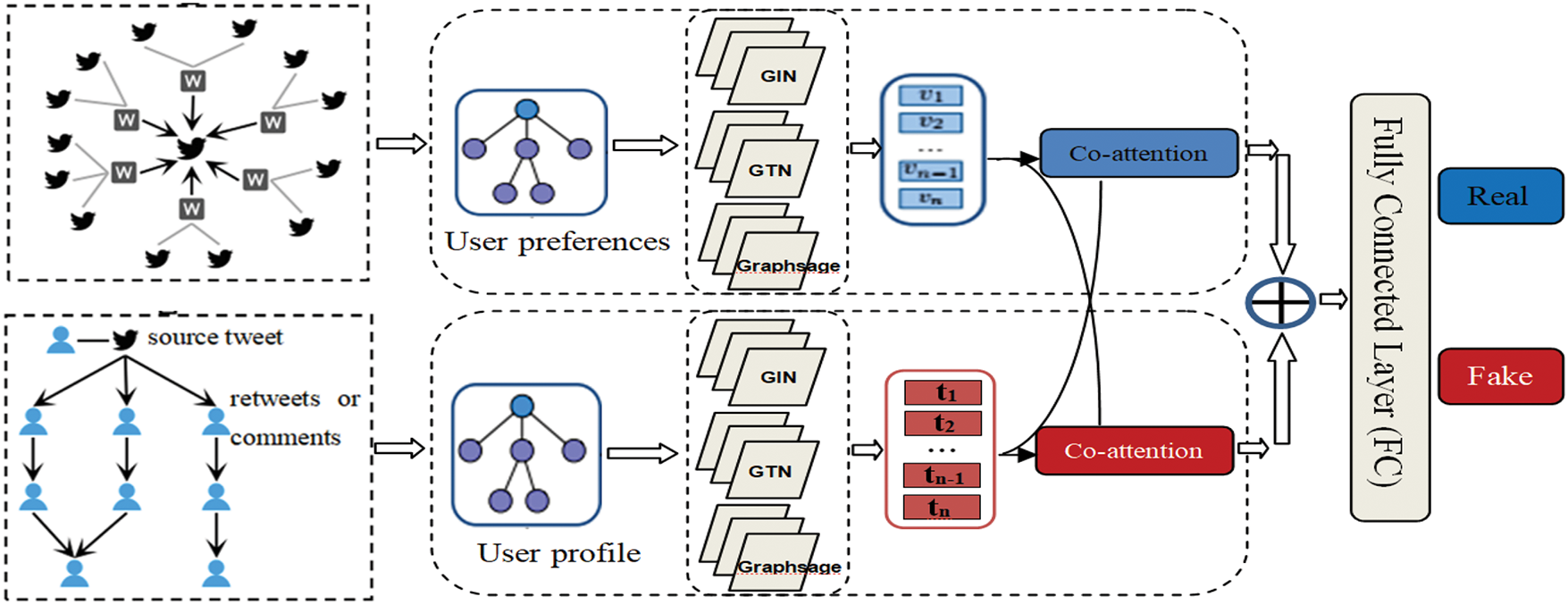

The proposed approach is implemented using GIN, GraphSAGE, and GTN, which have produced more accurate and effective fake news detection results. We utilize BERT [15], text representation learning techniques, to acquire user characteristics from user profiles and to extract user preferences from news content and historical posts. The proposed method combined model is made up of three modules:

• The first module considers the user profile characteristics as input features and creates a GNN-based model to learn user profile properties;

• The second module encodes news content, user historical posts, and news sharing cascading on social media, as user preferences GNN-based model;

• The inter-dependencies between user profiles and user preferences are handled through the third module using a co-attention mechanism for capturing the relationship between the two GNN-based models.

Then, the final GNN-based model outputs are fused and fed into a fully connected layer MLP classifier, which predicts the probabilities of the news item being fake or real. Three variants of graph neural networks such as Graph Isomorphism Network (GIN), Graph Transformer Network (GTN), Graph SAmple, and aggreGatE (GraphSAGE), each with its unique characteristics, are applied to user preference modeling and user profile modeling, respectively. These GNN variants are currently widely used graph neural networks suitable for processing social media data and its complex structures [5,16].

In this section, we explore the related studies on unimodal fake news detection, multimodal fake news detection, GNN-based approaches, and the co-attention mechanism.

2.1 Unimodal and Multimodal Approaches

Many studies in fake news detection have focused on unimodal information, such as text or images, to identify misinformation [17]. The textual content of a news article plays a key role in assessing the authenticity of the news item as it gives direct insights into the information being disseminated. Deep learning technologies have been widely used to learn textual representations of news articles for fake news detection. A CNN-based approach proposed by Yu et al. [18] to capture both local and global essential features from the text content of the news item. This approach relies on event labels, leading to higher detection costs. Besides text content, recent studies on fake news detection have also considered image content in posts. Jin et al. [19] captured multiple visual features to describe image distribution patterns for fake news detection, claiming that the propagation pattern of image content across social platforms reveals discriminative features, which help identify fake images.

Multimodal fake news detection utilizes data from various modalities instead of focusing on a single modality of content. The process includes feature extraction and feature fusion. For feature extraction, textual features can be extracted using Bi-LSTM, textCNN, or BERT, while visual features are usually extracted using CNNs, ensuring a comprehensive analysis of multimodal data [20]. To effectively model the interactions between the two modalities, co-attention mechanisms have been proposed for multimodal fake news detection [10,14,20,21]. Wu et al. [22] used multiple co-attention layers to integrate textual and visual features for fake news detection. In recent multimodal works for detecting fake news, the coherence between the text and image is considered, where news articles with mismatched text and image are more likely to be fake than those with consistent text and image [23].

2.2 Graph Neural Networks (GNNs)

Over the last decade, deep learning has gained popularity in a variety of applications, from computer vision to fraud detection and natural language processing. However, each of these applications deals only with data in Euclidean space, making them incapable of processing non-Euclidean data. In order to manipulate and process non-Euclidean data, a graph neural network was thus introduced [4,5]. This allows GNNs to perform different prediction tasks at different granularities, such as node-level (e.g., detecting malicious actors online), edge-level (e.g., recommendation systems), and graph-level (e.g., detecting fake news). Graph is a type of data structure composed of a collection of nodes and the links (edges) that connect them. Edges can be either directed or undirected based on directional dependencies among nodes (vertices). Nodes, for instance, can express individuals and their characteristics (e.g., name, age, and gender) in a social network, whereas edges represent connections between users. Given A and X as the adjacency matrix and node feature matrix, respectively, a graph G is represented as

GNN is a deep learning-based neural network model designed to operate on graph structure data. GNNs use message passing between graph nodes to represent the dependence of graphs. The GNN’s primary goal is to use all the graph’s information, like node features and their relationships, to generate node embeddings, which are new representations for each node. These node embeddings are expressed as low-dimensional vectors that characterize the nodes’ locations within the graph and their neighborhood. The nodes are subsequently classified using this final embedding. The node representation in the layer

GNNs have been successfully used in numerous studies to detect fake news from user’s feeds. Recently, researchers have explored alternative paradigms coupled with GNNs to improve fake news detection with minimal labeled data. Jin et al. [24] developed a new framework called CAPE-FND that improves LLM performance by using adaptive bootstrap prompting and context-aware prompt engineering, reducing hallucinations and utilizing prior knowledge for robust fake news detection, even in zero-shot settings. Similarly, Jin et al. [25] proposed the Prompting Multi-Task Learning framework led by news veracity Dissemination Consistency (PMTL-DisCo) for few-shot fake news identification. For feature extraction and optimization, this work employed advanced Artificial Intelligence (AI) techniques such as prompt-based tuning, multi-task learning, and masked language model (MLM). Different variants of GNNs, such as Graph Isomorphism Network (GIN), Graph Transformer Network (GTN), and Graph SAmple and aggreGatE (GraphSAGE), have achieved remarkable performance in identifying fake news. These methods are briefly discussed in the following sections.

2.2.1 Graph Transformer Network (GTN)

Since Transformer [15,26] has demonstrated its effectiveness in natural language processing, we incorporate its standard multi-head attention into graph learning. GTN is the first GNN framework to utilize a Transformer for neighborhood aggregation [27]. It uses the attention mechanism to determine the similarity of each node’s features and its neighbors and combines the neighboring nodes’ features based on their similarity.

Given a GTN with L layer, the combination and aggregation functions for a target node

2.2.2 Graph Sample and AggreGatE (GraphSAGE)

Developed by Hamilton et al. [28], it is one of the most flexible graph neural networks, demonstrating the potential of inductive frameworks. GraphSAGE architecture overcomes the problem of applying deep networks on large graphs by selecting a specific subset of neighboring node features whose values are aggregated rather than the entire graph. Consequently, the network can learn the representation of graphs with thousands of nodes considerably more quickly [2,5]. GraphSAGE utilizes multiple aggregation functions, the most popular of which are the convolutional and LSTM aggregators fully described in [5].

2.2.3 Graph Isomorphism Networks (GIN)

GIN was introduced by Xu et al. [29] is a special case of GNNs that is appropriate for graph classification applications. This method was recently proposed to implement the Weisfeiler-Lehman (WL) test within a neural network framework [30]. The Weisfeiler-Lehman (WL) algorithm is used to assess whether or not different graphs under comparison are topologically equivalent by combining the node labels and their neighboring information iteratively and then hashing the resulting labels into distinct new labels. To perform the WL test, each node

Formally, after k-iterations of aggregation, the k-th layer of a GIN is expressed as follows:

where,

2.3 Co-Attention Mechanism for Detecting Fake News

The co-attention mechanism is a robust attention-based framework that simultaneously processes two input sequences, like text and an image or two different text sequences. It determines the significance of each sequence related to the other, thereby enhancing the process of merging information and creating more accurate representations. Unlike standard self-attention, which focuses on a single input, co-attention simultaneously processes two inputs, aligning and focusing on features within each representation related to the other [20]. The co-attention mechanism was first introduced by Lu et al. [31] for Visual Question Answering (VQA) that simultaneously considers image and question information. Subsequently, it has been used extensively in text classification and fake news detection tasks [13,22]. In the fake news detection method known as GCAN, Lu and Li [10] have successfully used a dual co-attention mechanism to learn the correlation between the source tweet, retweet spread, and the combined impact of the source tweet and user interaction. In [32], Liu et al. have proposed a co-attention approach that incorporates labels and text into a representation that combines mutual attention for classifying texts. This enables the method to integrate the semantic relationships between labels and text and allocate different attention weights according to the significance of various labels.

The combined model’s overall architecture is structured into three modules, as shown in Fig. 1. The first module considers the user profile characteristics as input features and creates a GNN-based model to learn user profile properties. However, the second module encodes news content, user historical posts, and news sharing cascading on social media as user preferences GNN-based model. For these two modules, three GNN layers have been used, associated with “relu” activation and dropout with p = 0.01. The inter-dependencies between user profiles and user preferences are handled through the third module using a co-attention mechanism for capturing the relationship between the two GNN-based models. Then, the final GNN-based model outputs are combined and forwarded to a fully connected layer MLP classifier, which predicts the probabilities of the news item being fake or real. Three variants of graph neural networks such as Graph Isomorphism Network (GIN), Graph Transformer Network (GTN), and Graph SAmple and aggreGatE (GraphSAGE), each with its unique characteristics, are applied to user preference modeling and user profile modeling, respectively. The overall architecture of the proposed approach is detailed in Section 4.

Figure 1: The proposed method is made up of three modules. The first module considers the user profile characteristics as input features to create a GNN-based model. The second module encodes news content and user historical posts as user preferences GNN-based model. The inter-dependencies between user profiles and user preferences are handled through the third module using a co-attention mechanism

User profile features can be grouped into two basic categories such as implicit and explicit features [33]. Implicit features are deduced from user metadata or online behaviors, like historical tweets, rather than being explicitly available. Political bias, age, location, personality, and profile picture are examples of implicit characteristics. Explicit user characteristics are directly retrieved from meta-data that are returned by social media site API queries. Explicit features include a list of representative attributes, like the number of followers, posts, and followings. Using only news content usually doesn’t provide reliable detection results, as fake news is often designed to mimic real news. Therefore, there is a need for a detailed comprehension of the connection between user profiles and fake news.

3.3 The User Preferences Model

Dou et al. [17] have introduced a fake news detection approach known as UPFD using graph-structured data that includes user encodings and news embeddings. They used a well-known dataset called FakeNewsNet [34], which contains information about news content and its corresponding Twitter social media engagement metrics. For each news item, the user preferences are extracted by crawling the previous posts made by users who have engaged with the news item using Twitter Developer API. The preferences of engaged users are implicitly extracted through the use of text representation learning techniques to encode historical posts such as BERT and word2vec. The news items are also encoded using the same text representation learning techniques. The news context, which consists of all individuals interacting with the news peace, is leveraged using the graph of news dissemination based on its participation metrics on social media platforms (e.g., retweets on Twitter). In this case, the user and news embeddings serve as node features in the graph of news dissemination. The UPFD dataset provides various node-level features such as Spacy features, with 300 node features, and BERT features, with 768 node features of user historical tweets. According to UPFD’s empirical data, integrating user preferences and news context was found to be more effective than using only news features.

3.4 The Co-Attention Mechanism

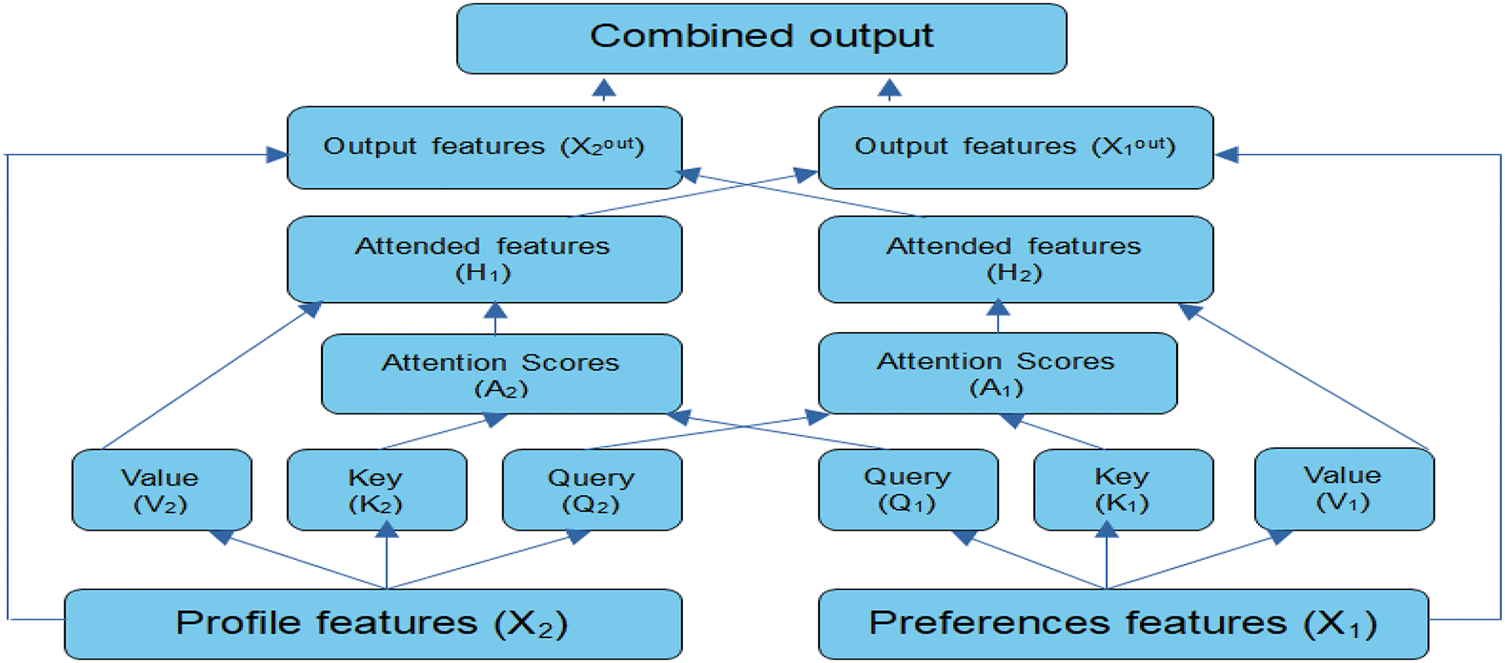

The user profile model encodes long-term, static features, such as the number of a user’s posts, social connections, and other profile-specific information, using GNNs. Whereas the second GNNs-based model, known as the user preferences model, considers short-term, dynamic interactions like interaction history, content preferences, and engagement patterns to model users’ evolving interactions with content. The outputs of both modules are fused via a co-attention mechanism, enabling the model to dynamically adjust and integrate features from both sources based on the content being evaluated. This design guarantees an adaptive balance between the impact of short-term preferences and long-term user attributes. The interdependencies between profile attributes and user preferences, extracted using the co-attention mechanism, enable learning how much one aspect (e.g., profile attributes) contributes to or is influenced by the other (e.g., preferences). As presented in Fig. 2, the two GNN-based models process input graphs and extract features independently

Figure 2: The co-attention mechanism used to model the interdependence between the user profile model and user preferences model

where

This work involves conducting experiments to investigate different research questions: (Q1) Whether our proposed model outperforms state-of-the-art (SOTA) techniques in fake news detection. (Q2) What is the role of each component within the combined model in enhancing its overall performance? (Q3) Which GNN model performs best on each dataset?

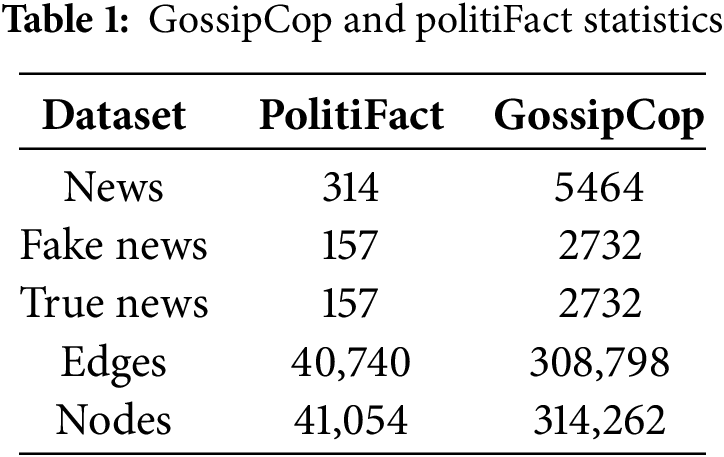

Two reference datasets compiled by Dou et al. [17] for detecting fake news, such as GossipCop and PolitiFact, are used in this experiment. These datasets include expert-annotated labels for both authentic and fraudulent news content on Twitter, along with pertinent social context information. Each dataset contains both the text and graph data extracted from the FakeNewsNet dataset [34], constructed using news articles fact-checked by reputable sources (PolitiFact for political news and GossipCop for entertainment news). The temporal coverage of FakeNewsNet is aligned with the periods during which PolitiFact and GossipCop published their fact-checks, and the corresponding social media activity was collected, covering a variety of political and entertainment events over several years. The PolitiFact dataset includes 157 real and fake news items, respectively, as shown in Table 1. Additionally, the GossipCop dataset contains a bunch more information, including 5464 news articles with 2732 fake and 2732 real news items. The ratio of real and fake news articles remains balanced for both datasets, which provides a fair evaluation environment and prevents any bias toward either class during model training and testing.

Dou et al. [17] use a variety of text representation learning methods, such as Word2vec and BERT, to encode news content and user historical posts in order to model the user preferences. For each news item, a propagation graph is created according to its sharing cascade on social media. The root node is thought to be the news post, and other nodes represent the users who shared it. Several node-level features are available in these datasets, including user preferences (768 BERT or 300 Spacy node features of user historical tweets) and 10 node features of user profile characteristics [17]. The user profile features include profile creation time, geolocation of the user, profile image URL, followers count, followees count, User verification status, Bot score (likelihood the account is a bot, as measured by tools like Botometer), Ratio features (such as followers-to-followees ratio), number of tweets posted and number of favorite tweets (likes) [34]. To gather rich historical data for user preference modeling, the recent two hundred tweets for each account are crawled, totaling 20 million tweets, using Twitter API. For inaccessible users whose accounts are suspended or removed, randomly sampled tweets from accessible users who are interested in the same news are used. Before using text representation learning techniques (e.g., BERT), special characters, such as “@” characters and URLs, are eliminated for every tweet in the dataset. The obtained vectors of existing words are therefore averaged in combined recent 200 tweets to get user preference representation [17].

To illustrate the efficiency of the CMCG approach, we compare it with recent efficient approaches for fake news detection, covering both deep learning and GNN-based methods, using the GossipCop and PolitiFact datasets. A detailed description of the used SOTA fake news detection approaches is provided below.

• HG-SL (Hypergraph-based Global interaction learning using Self-attention-based Local context learning): This method captures users’ global preferences from their co-spreading behaviors using a hypergraph module. Additionally, the self-attention module provides extra signals for confirming the authenticity of news [36].

• TSNN (Topological and Sequential Neural Network model): This method utilizes the supernode approach to capture representative characteristics from the graph’s structural topology. Then, a two-stage GNN is used to model the variability between news and users, facilitating the acquisition of more accurate representation in the supernode [37].

• PFGNN (Propagation and opinion-related Feature-enhanced GNN-based framework): This framework seeks to effectively detect false and accurate information by capturing all correlations between the gathered data [3].

• UPFD (User Preference-aware Fake News Detection): Suggests combining endogenous and exogenous information to anticipate the reliability of the news on social media [17].

• FND-NUP (Fake News Detection with News content, User profiles, and Propagation networks): Uses GAT to capture user influence on news spread by considering both user profiles and the news propagation network [38].

• DECOR (Degree-Corrected Social Graph Refinement for Fake News Detection): Based on encapsulating empirical observations into a lightweight social graph refinement component and applying a degree-corrected stochastic blockmodels [39].

• GAMC (Graph Autoencoder with Masking Graph Autoencoder with Masking and Contrastive learning): Based on using Graph Autoencoder with Masking and Contrastive learning to address the Graph-based techniques needed for large labeled datasets [40].

a) Implementation Details and Hyperparameters. All experiments are conducted on a Linux machine with a GeForce GTX 1650Ti GPU. PyTorch is used to implement all models, and the PyTorch-Geometric package is used to create all GNN models. Since the profile and preference features differ significantly in dimensionality (10 vs. 768), and the size of the two datasets is different (314 vs. 5464 news items), we have employed Bayesian optimization using the Optuna framework [41] to determine the appropriate hidden sizes empirically, rather than rely on arbitrary choices. The learning rate and dropout optimal values are obtained using the Optuna method, as detailed in Section 4.6. Each model variant was trained and validated under identical conditions. The results showed that mid-range configurations (e.g., 32 for Politifact and 128 for Gossipcop) achieved the best balance between representation capacity and generalization. The training and test sets are already separated in the GossipCop and PolitiFact datasets, and only the test sets are used to record the final results. The Politifact dataset requires only 30 epochs to attain optimal performance, whereas the GossipCop dataset requires about 80 epochs for the training process. To train the models, we employed the Adam optimizer with a batch size of 128 for the Gossipcop dataset and 64 for the Politifact dataset. To address potential overfitting risks due to limited data like the Politifact dataset, we have first added the dropout and weight decay to the combined model architecture. Dropout and weight decay encourage the model to not rely on any single node feature or neuron and penalize large weights, which is especially helpful when training on small datasets. Secondly, we have implemented an early stopping technique based on validation loss, which prevents overfitting by halting training when validation performance degrades.

b) Evaluation metrics. For assessing the effectiveness of the methods employed in this study, we utilize different standard evaluation metrics, such as the Accuracy (ACC), F1 score (F1), precision, recall, and AUC, given the binary classification nature of the fake news detection task.

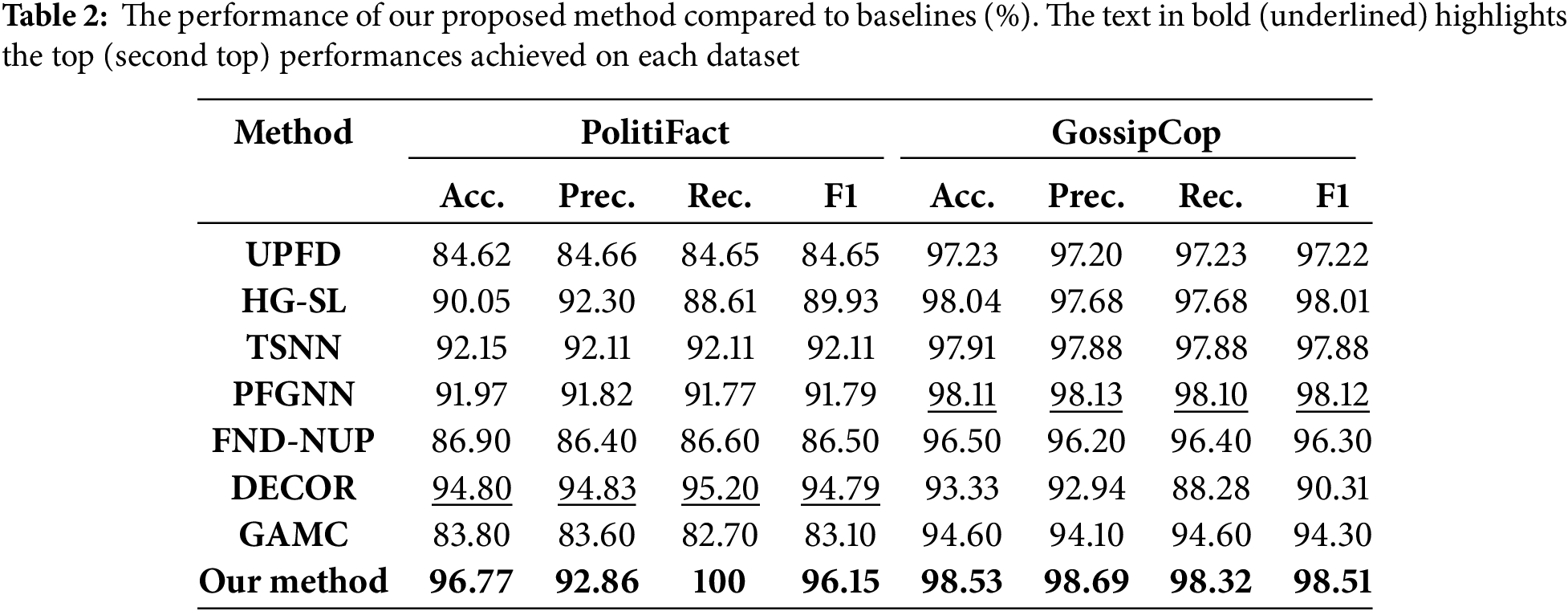

The proposed CMCG approach is evaluated against the baseline methods on two publicly accessible datasets, and the associated results are presented in Table 2. By analyzing the results of our experiment, we will answer the research Q1. Specifically, we can notice that, in comparison to the baseline approaches, our method performs best on both datasets in terms of Accuracy (ACC), precision, recall, and F1 score. Our model reaches an accuracy of 96.77% on the Politifact dataset and 98.53% on the Gossipcop dataset, which are 0.42% and 1.97% higher than the second-best model DECOR and TSNN, respectively. Furthermore, the CMCG model also attains the highest F1-score, reaching 96.15% on the PolitiFact dataset and 98.51% on the GossipCop dataset. The exceptional outcomes of our approach demonstrate that (1) combining user preferences and user profile GNN-based models can successfully distinguish between fake and real news. (2) The co-attention mechanism is also essential for achieving the optimal performance of our approach by learning the correlation between user profile characteristics and user preference features. The performance of PFGNN model and HG-SL model are the closest to our model. PFGNN method achieves the accuracy of 91.97% and 98.11% on two datasets, while the HG-SL model reaches an accuracy of 90.05% and 98.04%. PFGNN uses three different kinds of encoded vector representations from the input propagation graph structure, such as news article features, propagation and opinion-related features, and the user’s profile information. However, HG-SL learns both local and global user spreading patterns, enabling it to discriminate between authentic and fake news. UPFD approach also achieves similar results compared to PFGNN and HG-SL methods. This method integrates the historical preferences of the user as a global endogenous characteristic and utilizes the news propagation graph as the user’s exogenous social context. DECOR and TSNN achieve the second and third-best accuracy, 94.80% and 92.15%, respectively, on the Politifact dataset. Nevertheless, both approaches perform less well on the Gossipcop dataset than the baseline approaches, while the GAMC approach achieves less efficient results for both datasets. Note that the best results of our method were achieved on the Politifact dataset using the GIN and Gossipcop dataset using GraphSAGE as the graph encoder and BERT as the text encoder.

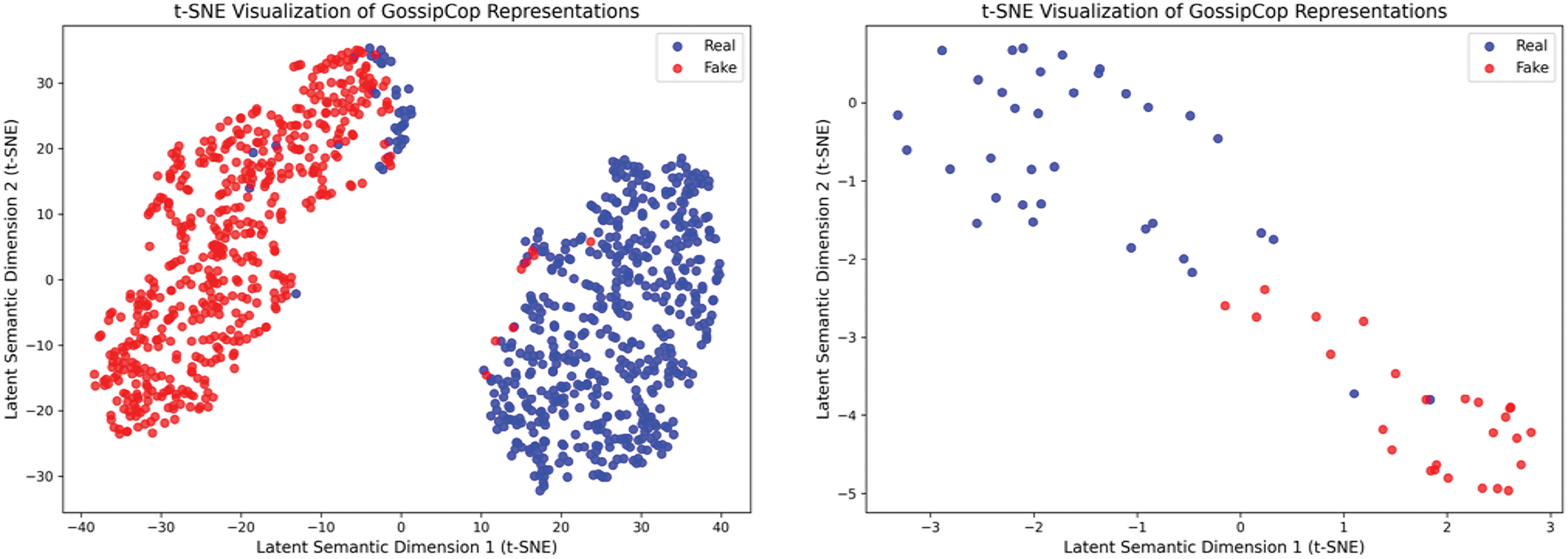

The t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) visualization of the fused graph embeddings generated by the CMCG model, shown in Fig. 3, reveals a clear and well-defined separation between fake and real news items for Politifact and Gossipcop datasets. Each data point in the 2D projection, presented in Fig. 3, corresponds to a social media post. A clear separation between groups suggests that the model effectively identified key differences in how real and fake news articles are structured and written. Additionally, the well-defined gaps between clusters reflect the robustness of the model in preserving intra-class consistency while maximizing inter-class divergence, highlighting its potential applicability in real-world fake news detection systems.

Figure 3: t-SNE plot for Plotitifact and Gossipcop datasets

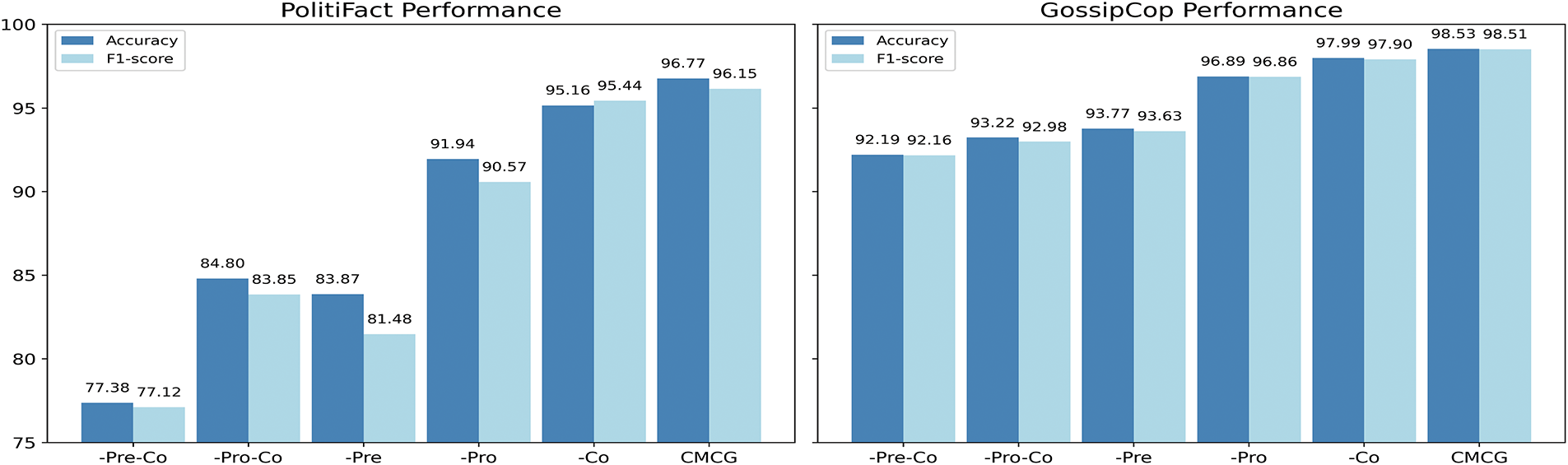

To demonstrate the effect of each module in the CMCG approach, several ablation experiments were carried out in order to address Q2. The complete model that utilizes all modules is indicated by CMCG. We tested different models that eliminated various elements, and the obtained results are displayed in Fig. 4. The ablation experiments are structured as follows:

Figure 4: The performance of different variants of the CMCG approach in detecting fake news. -Pre/-Pro/-Co represents the CMCG variant without preferences, profile features and co-attention mechanism

• CMCG/-Pro: The user profile module was eliminated from this experiment, leaving only the user preferences to be taken into account. The fully connected layer receives the vector representation that was obtained through the co-attention module.

• CMCG/-Pre: In this experiment, only the user profile was taken into consideration, and the user preferences module was eliminated. The vector representation generated by the co-attention layer is forwarded to the fully connected layer for detecting fake news.

• CMCG/-Co: The co-attention module was eliminated in this experiment. The user profiles and preferences modules were used to create the combined model.

• CMCG/-Pro-Co: In this experiment, only user preference features were considered in detecting fake news.

• CMCG/-Pre-Co: In this experiment, only 10 user profile attributes were considered to create a GNN-based model for detecting fake news.

The outcomes of the ablation experiment on two datasets are presented in Fig. 4. We can see that each component of the proposed model is significant. The performance of the model decreased when we eliminated a component, demonstrating that each part of the model is essential. Furthermore, the best results are obtained when user profile and preference information are jointly encoded, and the obtained models are fused using a co-attention mechanism. The accuracy of CMCG/-Pre is 83.87%/93.77%, and the F1 score of CMCG/-Pre is 81.48%/93.63% on Politifact/Gossipcop datasets, respectively. The accuracy of CMCG/-Pro is 91.94%/90.57%, and the F1 score of CMCG/-Pro is 96.89%/96.86% on Politifact/Gossipcop datasets, respectively. The accuracy of CMCG/-Co is 95.16%/97.99%, and the F1 score of CMCG/-Pre is 95.44%/97.90% on Politifact/Gossipcop datasets, respectively. However, the CMCG/-Pre-Co model performs the worst when compared to the ablation study models, achieving an accuracy of 77.38% on the Politifact dataset and 92.19% on the gossipcop dataset. The user profile attributes are static and don’t provide context about users’ interactions and behaviors in real-time. Without incorporating dynamic signals, the model cannot accurately depict how misinformation spreads. These results indicate that user preferences are more informative, especially on the Politifact dataset, since removing it causes a greater decline in performance. When the user profile and the co-attention modules are both removed, the model’s performance declines, evidently highlighting the significance of the user profile and the co-attention mechanism for fake news detection.

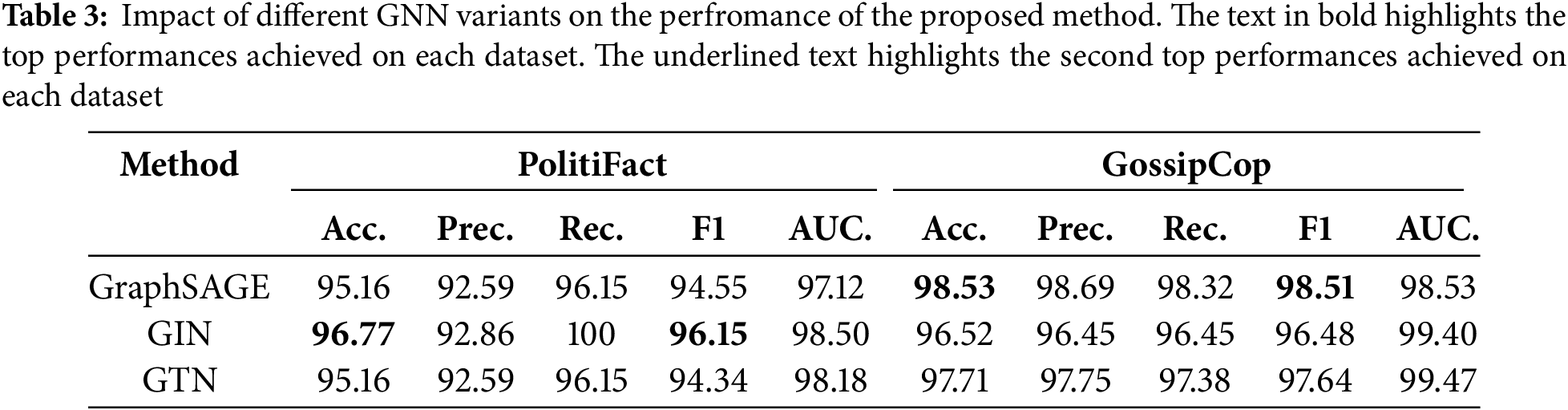

The user preferences and user profile joint model has been developed using three GNN variants in response to Q3. The first one is an implementation of GraphSAGE, which has proved its efficiency in detecting fake news in several works like [2,17] compared to other classic GNN variants. The second one is based on GIN, leading to more accurate and efficient fake news detection results [12]. This model is designed with global pooling architecture, which comprises three GIN convolution layers. The third model is implemented using GTN, which has recently demonstrated excellent results in detecting fake news in numerous works [27]. Note that user preferences are encoded using 768 BERT node features, while the user profile attributes are encoded using 10 node features.

Table 3 demonstrates that on the Gossipcop dataset, GraphSAGE performs better accuracy of 98.53% for the 768-dimensional Bert features. In contrast, in the Politifact dataset, GIN achieves a higher accuracy of 96.77% for the 768-dimensional Bert features. GIN focuses on determining whether two graphs are structurally identical, which can be useful for identifying patterns in small, well-defined datasets like Politifact. However, for a medium-sized dataset like GossipCop, GraphSAGE is more suitable than GIN because it can effectively leverage node/edge features, scale to the dataset size, and generalize to new data. GraphSAGE is designed to handle medium to large datasets efficiently. It uses neighborhood sampling to reduce computational complexity, making it well-suited for fake news detection tasks, where understanding user preferences and profile characteristics is critical. As shown in Table 3, the lower performance of GTN compared to Graphsage is mainly due to its complexity and the emphasis on semantic relationships as it is designed to handle heterogeneous graphs, unlike Graphsage, which is simpler, more scalable, and better optimized for homogeneous graph structures.

4.6 Hyperparameters Sensitivity

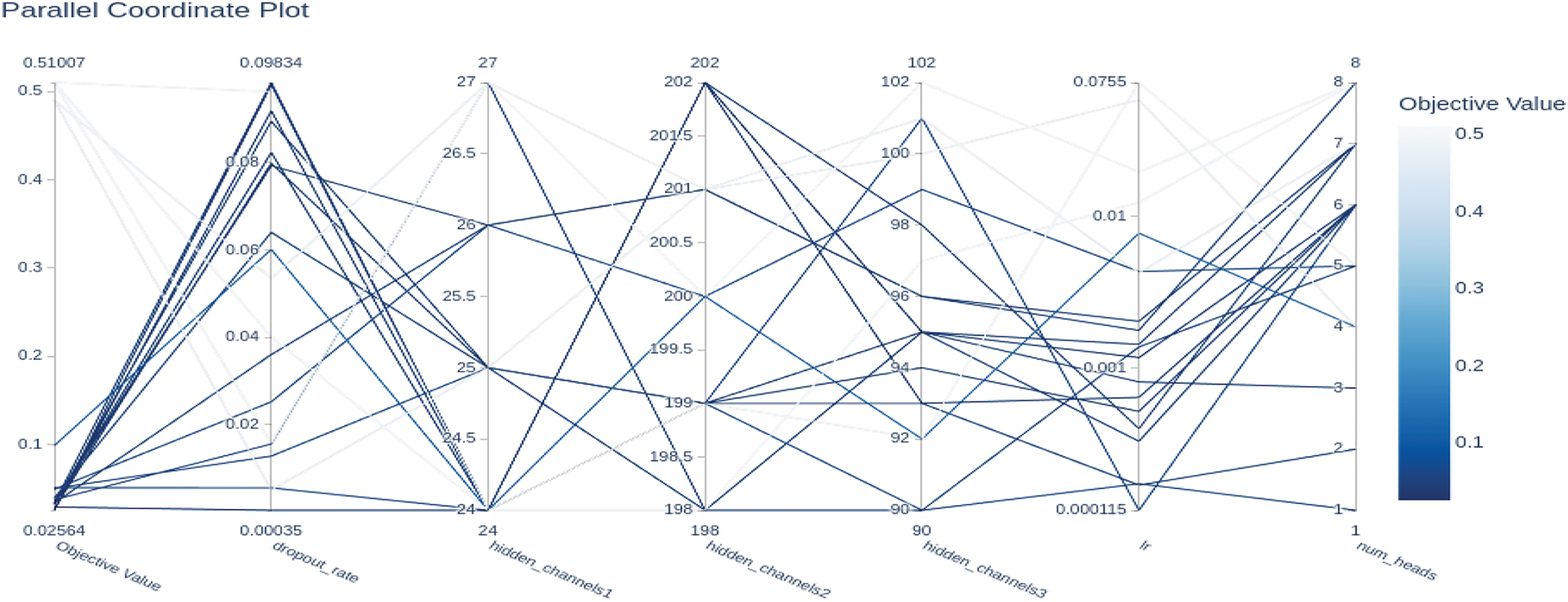

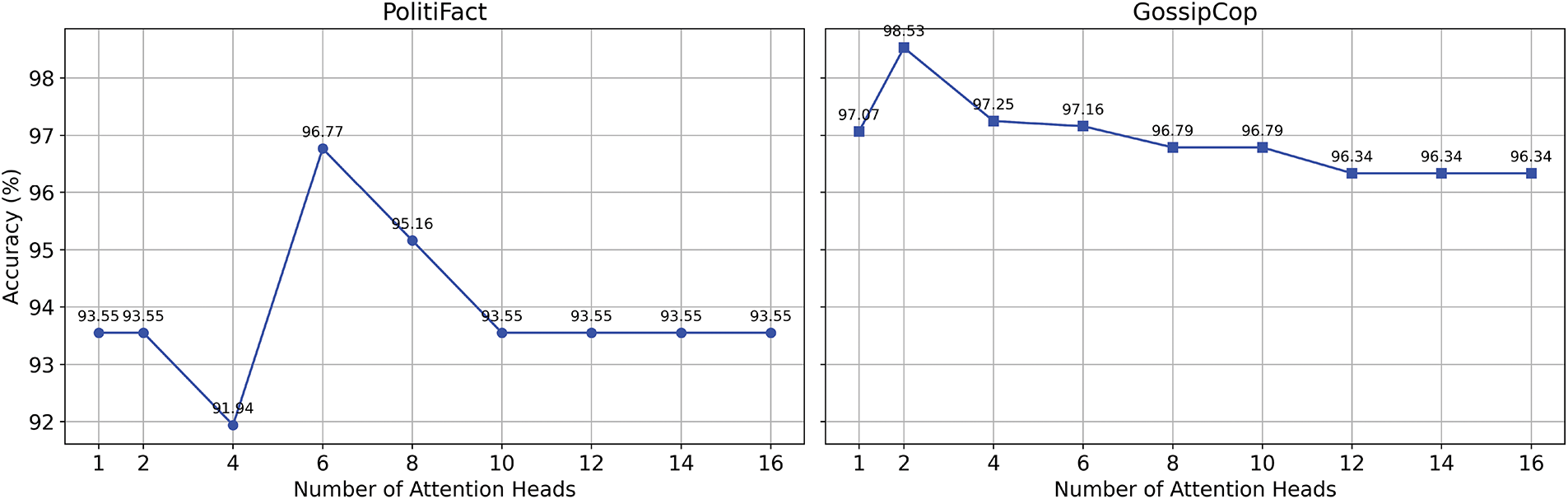

To improve the CMCG model’s performance and generalization abilities for detecting fake news, we employed Bayesian optimization using the Optuna framework [41], a sophisticated tool for hyperparameter tuning. This method automatically identifies the optimal parameter combinations by iteratively sampling potential configurations and evaluating their impact on model performance. Fig. 5 illustrates the search space explored during trials and displays the relationship between various hyperparameter combinations and model accuracy. The accuracy outcomes of the proposed model, when varying the number of attention heads in the co-attention layer using the Optuna method, are shown in Fig. 6. The number of attention heads varies from 1 to 16 heads for models based on the Politifact and Gossipcop datasets. From Fig. 6, it can be seen that the model reaches its peak performance on the Gossipcop dataset when the number of attention heads is set to 2.

Figure 5: Hyperparameter optimization using Optuna

Figure 6: CMCG performances with different number of attention heads

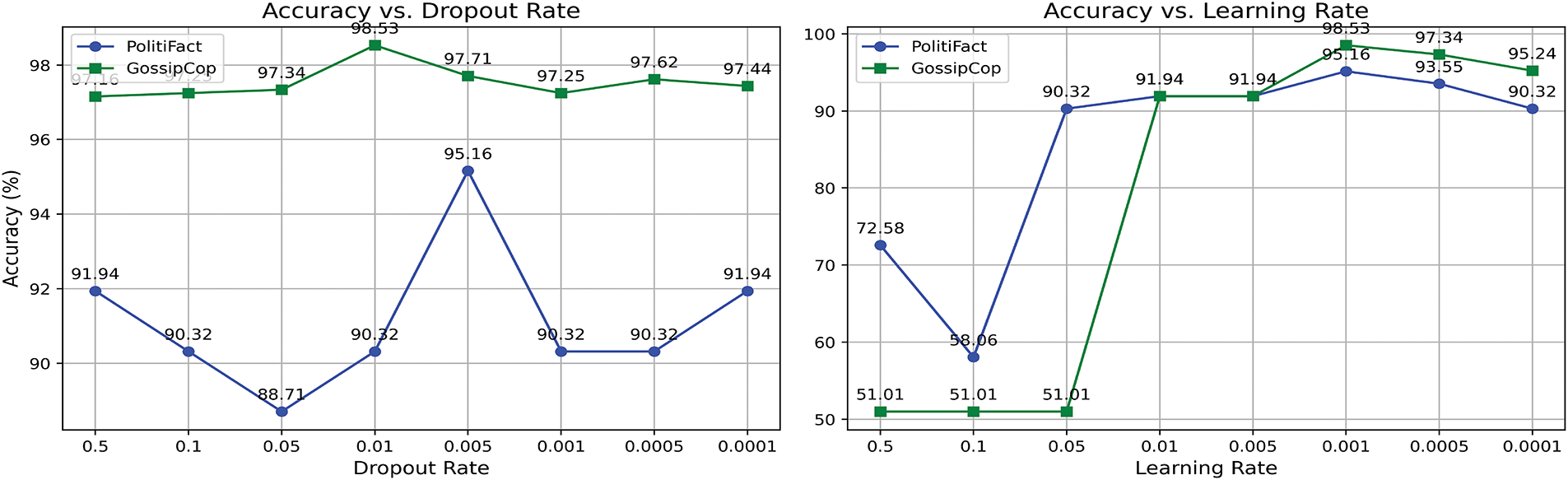

In contrast, for the Politifact dataset, the CMCG model attains its highest accuracy when the number of attention heads is 8. Based on the analysis, this variation may be attributed to the different textual characteristics of the datasets. The number of comments and retweets associated with news items varies across datasets, indicating that news with different cascade depths may require distinct numbers of attention heads to achieve optimal performance. The hidden dimensions parameters define the capacity of the CMCG-based encoders for user profiles and user preferences, respectively. The dimensions of the search space for the Gossipcop dataset ranged from 64 to 256 for preference features and from 16 to 32 for profile characteristics. On the other hand, the hidden dimensions for the Politifact dataset range from 8 to 32 for profile features and 16 to 64 for preference features. The best performance on the Gossipcop dataset is achieved when the hidden dimensions are set to 26 and 200 for the user profile and preferences models, respectively. The user profile and preferences models perform best on the Politifact dataset when the hidden dimensions are set to 16 and 32, respectively. The learning rate is sampled between [1e–4, 1e–2], while the dropout values are tested within the interval [0.0, 0.005]. As shown in Fig. 7, the best performance on the Politifact and Gossipcop datasets is achieved when the dropout values are set to 0.005 and 0.01, respectively. Additionally, the optimal performance on the Politifact and Gossipcop datasets is attained with learning rate values of 0.0005 and 0.001, respectively.

Figure 7: Learning rate and dropout impact on accuracy for Politifact and Gossipcop

The model exhibits notable strengths, particularly in its capacity to capture detailed user engagement patterns. However, it is crucial to recognize that this approach may have specific limitations. Below is a summary of the challenges and constraints we faced during this study.

• The approach depends on the UPFD dataset, which is derived from FakeNewsNet. This dataset is created by crawling the most recent 200 tweets from users engaged with a specific news item using the Twitter Developer API, enabling access to extensive historical data. Additionally, the news content is collected by crawling the URLs provided in the FakeNewsNet dataset.

• Due to the character limit on Twitter, it has been observed that many posts are too short. The low number of words may negatively affect the effectiveness of text classification processes. Furthermore, the FakeNewsNet dataset does not include supplementary information, such as images, which are highly valuable for multi-modal classification tasks.

• The CMCG approach requires knowing the user profiles, which has become increasingly challenging because of the restrictive policies of the platforms.

The architecture of the combined GNN model is well-suited for fake news detection across platforms like Facebook and TikTok due to its multi-view design that integrates user profiles and preferences. However, effective generalization requires careful tuning to the data characteristics, graph formulation, and feature availability of each platform. The model may be expanded to Facebook and TikTok with minimal architectural changes and adequate retraining. However, implementing such a model in real-time environments presents some challenges related to continuous data streams from social media platforms that require the model to process incoming posts dynamically. In contrast to static datasets, real-time data requires online or incremental learning techniques to keep the model updated without retraining.

Another limitation concerns the scalability and computational requirements of the proposed model. The CMCG approach integrates two parallel GNN modules processing distinct but complementary modalities such as user profiles and user preferences, offering strong performance for fake news detection. However, this architecture requires significantly more resources than single-branch GNNs, especially for large datasets, which may hinder its deployment in low-resource settings. In terms of training time, the added complexity of processing dual graph structures increases per-epoch duration, particularly on large datasets, but this cost is often justified by the model’s improved generalization and multimodal representation capabilities. Scalability remains a critical consideration for real-world deployment; while the model can handle mid-scale datasets like Politifact or GossipCop, scaling to web-scale graphs requires careful tuning to the data characteristics, graph formulation, and feature availability of each social media platform.

In this work, we have proposed a combined GNN-based model using a co-attention mechanism for detecting fake news named CMCG. The proposed combined model consists of three modules. The first module learns user profile properties using a GNN-based model, while the second module encodes user preferences using also a GNN-based model. The relationships between user profiles and user preferences are handled through the third module using a co-attention mechanism. Then, the final GNN-based model outputs are fused and forwarded to a fully connected layer MLP classifier, which predicts the probabilities of the news item being fake or real. Three GNN variants, GIN, GTN, and GraphSAGE, are applied to user preference and user profile modeling. Experiments show that CMCG significantly outperforms SOTA models on fake news detection tasks, where it achieves an accuracy of 98.53% on GossipCop and 96.77% accuracy on the PolitiFact dataset. We investigated the impact of different social media features on fake news detection. Additionally, the ablation study shows that each component in the CMCG approach is essential for detecting false information. The proposed model reaches a comparatively high performance by combining various information levels from different modalities. However, the main limitation of CMCG is its reliance on the FakeNewsNet dataset, which does not incorporate significant information like images. In the future, we intend to take into account additional information like user stances and behaviors to capture users’ attitudes (e.g., agreement, skepticism, or outrage) expressed in their posts or replies to enhance fake news detection.

Ethical challenges are central to any work involving social media data and fake news detection. For this work, the used datasets (Politifact and Gossipcop datasets) provided by the UPFD were anonymized and collected under Twitter’s terms of service to help protect user privacy. Additionally, Data security and algorithmic bias pose serious problems for fake news detection models, which may inadvertently reinforce preexisting biases in the dataset. To address these concerns, continuous efforts are needed, including regular bias audits and transparency in model design.

Acknowledgement: The authors extend their appreciation to Umm Al-Qura University, Saudi Arabia for funding this research work through grant number: 25UQU4300346GSSR05.

Funding Statement: This research work was funded by Umm Al-Qura University, Saudi Arabia under grant number: 25UQU4300346GSSR05.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Soufiane Khedairia, Akram Bennour; draft manuscript preparation: Soufiane Khedairia, Akram Bennour, Aida Chefrour; Funding acquisition and supervision: Mouaaz Nahas, Rashiq Rafiq Marie, Mohammed Al-Sarem; Review: Mouaaz Nahas, Rashiq Rafiq Marie, Mohammed Al-Sarem. All authors reviewed results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The code and dataset used in this study are publicly available through a GitHub repository at: https://github.com/Sofiane-khed/CMCG-App.git (accessed on 27 June 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Dudić B, Mittelman A, Vojtechovskỳ J. Social media and marketing worldwide. In: International conference “new technologies, development and applications”. Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina: Springer; 2024. p. 271–8. [Google Scholar]

2. Mahmud FB, Rayhan MMS, Shuvo MH, Sadia I, Morol MK. A comparative analysis of Graph Neural Networks and commonly used machine learning algorithms on fake news detection. In: 2022 7th International Conference on Data Science and Machine Learning Applications (CDMA); 2022 Mar 1–3; Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. p. 97–102. [Google Scholar]

3. Moschopoulos V, Tsourma M, Drosou A, Tzovaras D. Misinformation detection based on news dispersion. In: 2023 24th International Conference on Digital Signal Processing (DSP); 2023 Jun 11–13; Rhodes, Greece. p. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

4. Shovon II, Shin S. The performance of graph neural network in detecting fake news from social media feeds. In: 2023 International conference on Information Networking (ICOIN); 2023 Jan 11–14; Bangkok, Thailand. p. 560–4. [Google Scholar]

5. Phan HT, Nguyen NT, Hwang D. Fake news detection: a survey of graph neural network methods. Appl Soft Comput. 2023;139(1):110235. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2023.110235. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Qasem SN, Al-Sarem M, Saeed F. An ensemble learning based approach for detecting and tracking COVID19 rumors. Comput Mater Contin. 2022;70(1):1721–47. [Google Scholar]

7. Al-Sarem M, Alsaeedi A, Saeed F, Boulila W, AmeerBakhsh O. A novel hybrid deep learning model for detecting COVID-19-related rumors on social media based on LSTM and concatenated parallel CNNs. Appl Sci. 2021;11(17):7940. doi:10.3390/app11177940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Chang Q, Li X, Duan Z. Graph global attention network with memory: a deep learning approach for fake news detection. Neural Netw. 2024;172(27):106115. doi:10.1016/j.neunet.2024.106115. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Al-Sarem M, Boulila W, Al-Harby M, Qadir J, Alsaeedi A. Deep learning-based rumor detection on microblogging platforms: a systematic review. IEEE Access. 2019;7:152788–812. doi:10.1109/access.2019.2947855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Lu YJ, Li CT. GCAN: graph-aware co-attention networks for explainable fake news detection on social media. arXiv:2004.11648. 2020. [Google Scholar]

11. Fu L, Peng H, Liu S. KG-MFEND: an efficient knowledge graph-based model for multi-domain fake news detection. J Supercomput. 2023;79(16):18417–44. doi:10.1007/s11227-023-05381-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Choudhary A, Arora A. GIN-FND: leveraging users’ preferences for graph isomorphic network driven fake news detection. Multimed Tools Appl. 2024;83(22):62061–87. doi:10.1007/s11042-023-16285-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Bazmi P, Asadpour M, Shakery A. Multi-view co-attention network for fake news detection by modeling topic-specific user and news source credibility. Inf Proc Manag. 2023;60(1):103146. doi:10.1016/j.ipm.2022.103146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Hu L, Zhao Z, Qi W, Song X, Nie L. Multimodal matching-aware co-attention networks with mutual knowledge distillation for fake news detection. Inf Sci. 2024;664(11):120310. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2024.120310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Devlin J, Chang MW, Lee K, Toutanova K. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. arXiv:1810.04805. 2018. [Google Scholar]

16. Lakzaei B, Haghir Chehreghani M, Bagheri A. Disinformation detection using graph neural networks: a survey. Artif Intell Rev. 2024;57(3):52. doi:10.1007/s10462-024-10702-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Dou Y, Shu K, Xia C, Yu PS, Sun L. User preference-aware fake news detection. In: Proceedings of the 44th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval; 2021 Jul 11–15; Virtual. p. 2051–5. [Google Scholar]

18. Yu F, Liu Q, Wu S, Wang L, Tan T. A convolutional approach for misinformation identification. In: Proceedings of the Twenty-Sixth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2017. p. 3901–7. [Google Scholar]

19. Jin Z, Cao J, Zhang Y, Zhou J, Tian Q. Novel visual and statistical image features for microblogs news verification. IEEE Trans Multimed. 2016;19(3):598–608. doi:10.1109/tmm.2016.2617078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Zhang Z, Lv Q, Jia X, Yun W, Miao G, Mao Z, et al. GBCA: graph convolution network and BERT combined with Co-Attention for fake news detection. Pattern Recognit Lett. 2024;180(3):26–32. doi:10.1016/j.patrec.2024.02.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Zheng J, Zhang X, Guo S, Wang Q, Zang W, Zhang Y. MFAN: multi-modal feature-enhanced attention networks for rumor detection. In: Proceedings of the Thirty-First International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2022. p. 2413–9. [Google Scholar]

22. Wu Y, Zhan P, Zhang Y, Wang L, Xu Z. Multimodal fusion with co-attention networks for fake news detection. In: Findings of the association for computational linguistics: ACL-IJCNLP 2021; 2021 Aug 1–6; Virtual. p. 2560–9. [Google Scholar]

23. Li P, Sun X, Yu H, Tian Y, Yao F, Xu G. Entity-oriented multi-modal alignment and fusion network for fake news detection. IEEE Trans Multimed. 2021;24:3455–68. doi:10.1109/tmm.2021.3098988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Jin W, Gao Y, Tao T, Wang X, Wang N, Wu B, et al. Veracity-oriented context-aware large language models-based prompting optimization for fake news detection. Int J Intell Syst. 2025;2025(1):5920142. doi:10.1155/int/5920142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Jin W, Wang N, Tao T, Jiang M, Xing Y, Zhao B, et al. A prompting multi-task learning-based veracity dissemination consistency reasoning augmentation for few-shot fake news detection. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2025;144(5):110122. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2025.110122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Vaswani A, Shazeer N, Parmar N, Uszkoreit J, Jones L, Gomez AN, et al. Attention is all you need. In: Guyon I, Luxburg UV, Bengio S, Wallach H, Fergus R, Vishwanathan S, et al., editors. Advances in neural information processing systems. Vol. 30. Red Hook, NY, USA: Curran Associates, Inc. [Google Scholar]

27. Soga K, Yoshida S, Muneyasu M. Exploiting stance similarity and graph neural networks for fake news detection. Pattern Recognit Lett. 2024;177(2):26–32. doi:10.1016/j.patrec.2023.11.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Hamilton W, Ying Z, Leskovec J. Inductive representation learning on large graphs. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2017;30:1025–35. [Google Scholar]

29. Xu K, Hu W, Leskovec J, Jegelka S. How powerful are graph neural networks? arXiv:1810.00826. 2018. [Google Scholar]

30. Shervashidze N, Schweitzer P, Van Leeuwen EJ, Mehlhorn K, Borgwardt KM. Weisfeiler-lehman graph kernels. J Mach Learn Res. 2011;12(9):2539–61. [Google Scholar]

31. Lu J, Yang J, Batra D, Parikh D. Hierarchical question-image co-attention for visual question answering. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2016;29:289–97. [Google Scholar]

32. Liu M, Liu L, Cao J, Du Q. Co-attention network with label embedding for text classification. Neurocomputing. 2022;471(4):61–9. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2021.10.099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Shu K, Zhou X, Wang S, Zafarani R, Liu H. The role of user profiles for fake news detection. In: Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining; 2019 Aug 27–30; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 436–9. [Google Scholar]

34. Shu K, Mahudeswaran D, Wang S, Lee D, Liu H. Fakenewsnet: a data repository with news content, social context, and spatiotemporal information for studying fake news on social media. Big Data. 2020;8(3):171–88. doi:10.1089/big.2020.0062. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Bansal R, Paka WS, Nidhi, Sengupta S, Chakraborty T. Combining exogenous and endogenous signals with a semi-supervised co-attention network for early detection of covid-19 fake tweets. In: Pacific-Asia Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; 2021 May 11–14; Delhi, India. p. 188–200. [Google Scholar]

36. Sun L, Rao Y, Lan Y, Xia B, Li Y. HG-SL: jointly learning of global and local user spreading behavior for fake news early detection. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2023;37(4):5248–56. doi:10.1609/aaai.v37i4.25655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Jung D, Kim E, Cho YS. Topological and sequential neural network model for detecting fake news. IEEE Access. 2023;11(1):143925–35. doi:10.1109/access.2023.3343843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Kapadia P, Saxena A, Das B, Pei Y, Pechenizkiy M. Co-attention based multi-contextual fake news detection. In: Complex Networks XIII: Proceedings of the 13th Conference on Complex Networks, CompleNet 2022; 2022 Apr 19–22; Virtual. p. 83–95. [Google Scholar]

39. Wu J, Hooi B. Decor: degree-corrected social graph refinement for fake news detection. In: Proceedings of the 29th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; 2023 Aug 6–10; Long Beach, CA, USA. p. 2582–93. [Google Scholar]

40. Yin S, Zhu P, Wu L, Gao C, Wang Z. GAMC: an unsupervised method for fake news detection using graph autoencoder with masking. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2024;38(1):347–55. doi:10.1609/aaai.v38i1.27788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Akiba T, Sano S, Yanase T, Ohta T, Koyama M. Optuna: a next-generation hyperparameter optimization framework. In: Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining; 2019 Aug 4–8; Anchorage, AK, USA. p. 2623–31. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools