Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Secure Development Methodology for Full Stack Web Applications: Proof of the Methodology Applied to Vue.js, Spring Boot and MySQL

School of Engineering and Technology, International University of La Rioja, Avda. de La Paz, 137, Logroño, 26006, La Rioja, Spain

* Corresponding Author: Juan Ramón Bermejo Higuera. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(1), 1807-1858. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.067127

Received 25 April 2025; Accepted 17 July 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

In today’s rapidly evolving digital landscape, web application security has become paramount as organizations face increasingly sophisticated cyber threats. This work presents a comprehensive methodology for implementing robust security measures in modern web applications and the proof of the Methodology applied to Vue.js, Spring Boot, and MySQL architecture. The proposed approach addresses critical security challenges through a multi-layered framework that encompasses essential security dimensions including multi-factor authentication, fine-grained authorization controls, sophisticated session management, data confidentiality and integrity protection, secure logging mechanisms, comprehensive error handling, high availability strategies, advanced input validation, and security headers implementation. Significant contributions are made to the field of web application security. First, a detailed catalogue of security requirements specifically tailored to protect web applications against contemporary threats, backed by rigorous analysis and industry best practices. Second, the methodology is validated through a carefully designed proof-of-concept implementation in a controlled environment, demonstrating the practical effectiveness of the security measures. The validation process employs cutting-edge static and dynamic analysis tools for comprehensive dependency validation and vulnerability detection, ensuring robust security coverage. The validation results confirm the prevention and avoidance of security vulnerabilities of the methodology. A key innovation of this work is the seamless integration of DevSecOps practices throughout the secure Software Development Life Cycle (SSDLC), creating a security-first mindset from initial design to deployment. By combining proactive secure coding practices with defensive security approaches, a framework is established that not only strengthens application security but also fosters a culture of security awareness within development teams. This hybrid approach ensures that security considerations are woven into every aspect of the development process, rather than being treated as an afterthought.Keywords

Corporations increasingly adopt technological services. This adoption optimizes corporate efficiency but also increases susceptibility to damage from vulnerabilities and attacks. These attacks can be deliberate or accidental, originating from both users and deficiencies in system design [1].

Among the solutions adopted in a digitalization process, web applications stand out for their robustness and adoption in the corporate environment, establishing the necessity of integrating rigorous security measures from the initial stages of development [2]. This approach aims to mitigate the types of risks that these developments may present [3].

Although protocols have been established to mitigate risks or at least consider them during development, the difficulty in anticipating vulnerabilities from the moment requirements are defined poses a significant challenge [4]. This requires programming practices and technological tools to adopt a defensive perspective, necessitating the involvement of specialized professionals. This situation assigns information security managers to a crucial role within development teams, where constant attention to security can be compromised by the complexity of anticipating failures, the availability and accuracy of tools, among other factors [5].

Within the development process, engineering requirements support system design by providing frameworks used to mitigate known security flaws. The areas of these frameworks are known as domains [6]. These domains allow for the segregation of requirements to make them more specific and provide detailed information on the area in which they apply. Security requirements enable the adoption of specific safeguards by domains and consideration of security from an early stage of software solution development [7]. For this reason, initiatives have been created that attempt to provide a structured process with measures to mitigate risks and measure security maturation in software development.

Despite the existence of various security frameworks and SSDLC methodologies, there remains a significant gap in practical security approaches for full-stack web applications using Vue.js, Spring Boot, and MySQL. Current methodologies often separate security concerns from development, leaving security validation as a divided phase performed often only by specialists. This creates an inefficient cycle where vulnerabilities are discovered late in the process, increasing remediation costs. Our research addresses this gap by proposing a methodology that integrates security from the beginning through clear guidelines, patterns, and practices that can be followed by all team members—regardless of their security expertise. Rather than relying solely on defensive programming and vulnerability detection at later stages, this approach emphasizes secure coding principles that can be applied by every developer throughout the development lifecycle. By democratizing security knowledge and embedding it into standard development practices, the methodology allows teams without dedicated security specialists to still produce secure applications, while ensuring that security becomes an integral part of the development process rather than an afterthought.

Numerous errors can be identified through systematic methods, such as static code analysis or penetration testing [8]. However, design flaws or the implementation of insecure programming patterns represent a more challenging category of vulnerabilities to analyze. The existence of conceptual errors in design can not only trigger unforeseen security breaches, thus causing an increase in costs and delays in project execution but also complicate the implementation of corrective solutions in advanced phases of development, jeopardizing the project’s feasibility. For this reason, the critical importance of integrating software security from the design stage is emphasized, adopting a development methodology that empowers the entire team in the production of secure code, suitable for use cases and aligned with best practices from the start [9].

Adopting a meticulous planning strategy from the design phase facilitates not relying exclusively on reviewing already developed components to identify potential vulnerabilities [10]. Instead, this approach ensures that each developer has the ability from the beginning to generate high-quality code, minimizing the likelihood of incorporating design flaws in the development of new functionalities or in software maintenance. This is considered secure code development that precedes defensive development. This secure code generation approach ensures that, in later stages, the active search for vulnerabilities is considered an additional reinforcement and not the only way to discover security deficiencies [11]. This improves software quality from an early stage [12].

When discussing the technological transition of companies to web environments, one of the most used technologies is Java with its development and execution environment [13]. A significant number of applications still run under the Java virtual machine today, as it is a robust development language that has taken care of the backward compatibility of each of its versions. This characteristic has provided companies with confidence in migrating their services [14]. Within the JVM ecosystem, numerous frameworks are available, focused on maximizing development performance; among web-focused frameworks, Spring Framework has taken great relevance within the Java web application development environment. Although this framework maximizes development performance, its meta-framework “Spring Boot” has become an industry standard for Java-based web application development [15]. This area of development constitutes the central focus of this study [16].

While Spring Boot can create embedded graphical interfaces managed by the same web server, modern development favors distributed architectures that separate business logic, persistence components, and UI—the direct layer where users interact through browsers. In the browser, code execution can be performed using various technologies such as Web-Assembly, though JavaScript remains the most used tool for developing graphical interfaces. Among JavaScript frameworks, Vue.js stands out due to its widespread adoption and open-source nature, making it compelling for professional development [17]. Given that this section of the code is hosted within users’ browsers, it is necessary to consider that the security processes needed for this type of development are essential [18].

Within a full-stack development, the division of the persistence layer from other components is considered a good practice [19]. This component is considered critical as it is where information linked to the component is stored. This makes it an essential asset of the system. Due to the importance and separation of this component, it requires an adequate procedure to ensure its secure operation in terms of communication and information transmission. It is also necessary to consider measures in the form of data persistence and internal functioning of the persistence layer, such as data redundancy with strict policies for data recovery [20]. Currently, MySQL is a quite robust solution that is widely known in the current field of software development [21].

The widespread adoption of these technologies in web application development necessitates a methodology that adopts a hybrid security approach. This approach combines secure coding practices that involve the entire development team with defensive strategies that enable security specialists to implement targeted processes. This model ensures multi-layered security across all software development phases.

Modern methodologies incorporate containerization optimized for cloud environments throughout all phases—from analysis and design through implementation to deployment. This approach enables continuous integration and efficient deployment, ensuring both functional robustness and security throughout the application lifecycle. This hybrid approach facilitates early vulnerability detection while promoting a culture where all team members understand their role in software protection.

Based on the identified gap in security approaches for full-stack applications, we formulate the following research questions:

• How can security requirements be effectively integrated into the development process of full-stack web applications using Vue.js, Spring Boot, and MySQL in a way that is accessible to all team members, regardless of security expertise?

• What specific security measures and design patterns are necessary for each component of this technological stack that can be implemented by developers without specialized security knowledge?

• How can a DevSecOps pipeline be designed to automate and validate security requirements throughout the development lifecycle, while providing clear guidance for remediation that empowers developers to address security issues themselves?

This work hypothesizes that a comprehensive methodology that democratizes security knowledge through accessible secure coding practices and clear guidelines, tailored specifically for this technology stack, will significantly reduce vulnerabilities compared to approaches that rely primarily on security specialists at later stages of development.

To address these research questions and validate our hypothesis, this work makes the following specific contributions:

• A comprehensive security methodology specifically designed for full-stack web applications using Vue.js, Spring Boot, and MySQL architecture, accessible to developers without specialized security expertise.

• A structured model of security requirements based on OWASP SAMM and ASVS frameworks, adapted for this specific technology stack and presented as implementable design patterns and guidelines.

• A practical validation through a proof-of-concept implementation of a ticket management system demonstrating the application of security principles by non-security specialists.

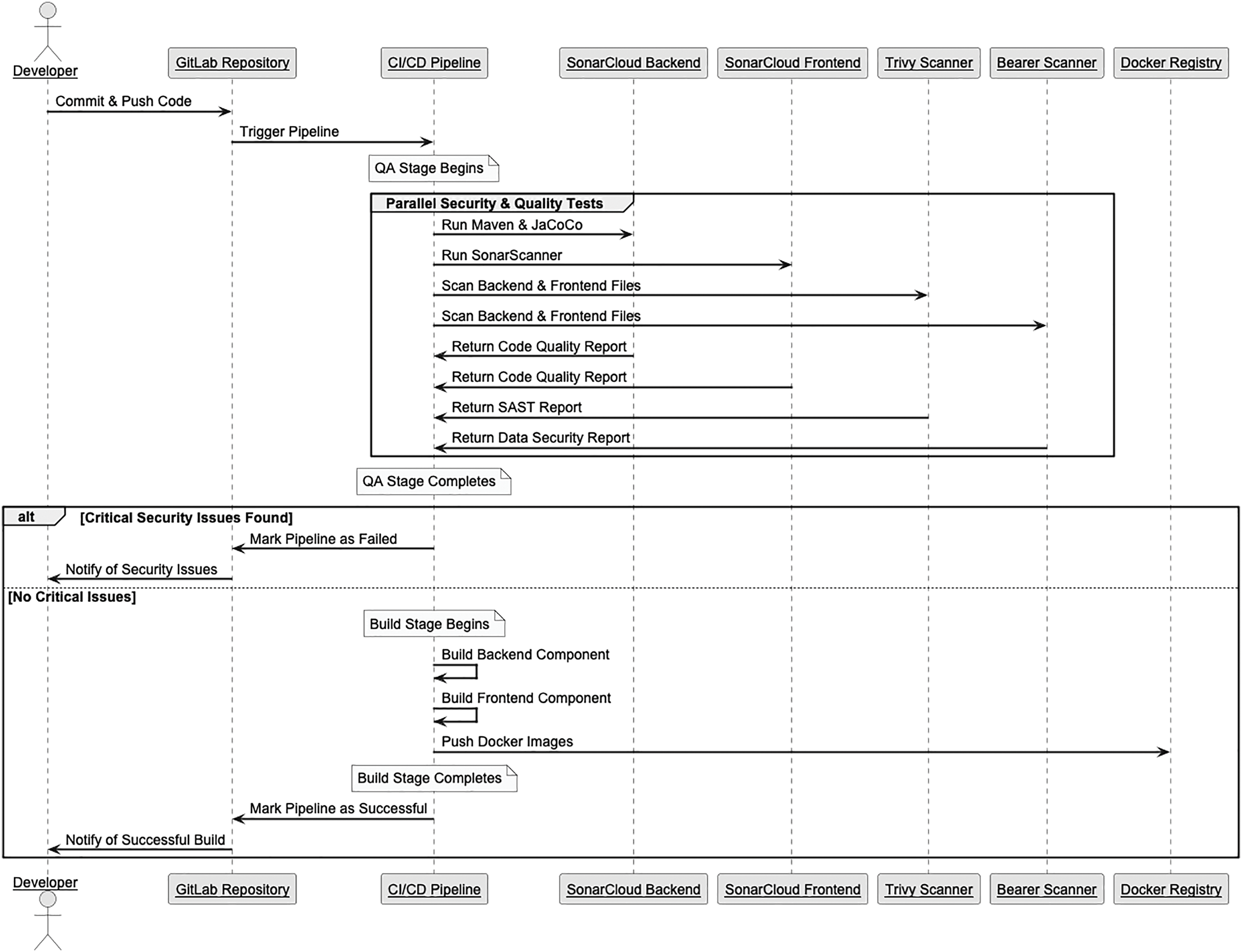

• A DevSecOps pipeline design that automates security validation processes throughout the development cycle with clear remediation guidance for developers.

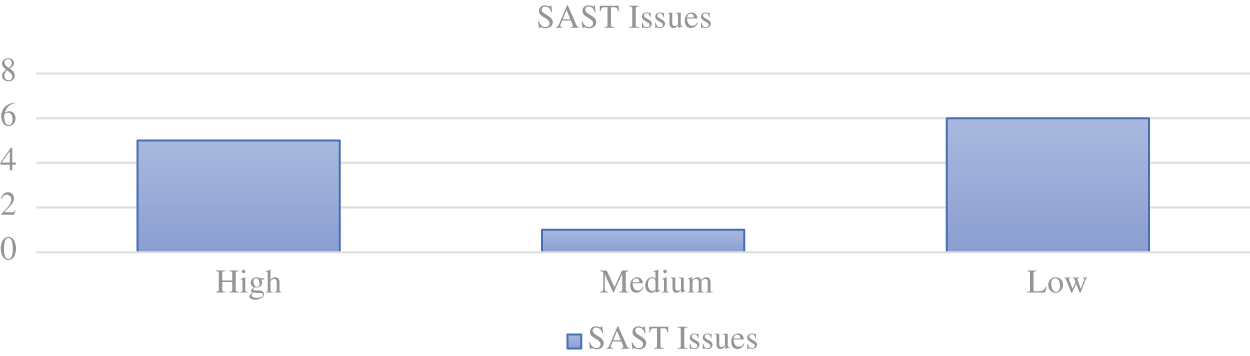

• Quantitative and qualitative metrics for evaluating the effectiveness of the proposed methodology in reducing vulnerabilities when implemented by teams without dedicated security resources.

The rest of this work is structured as follows. Section 2 presents the context of digital transformation and its implications for security, exploring traditional development models and the evolution towards secure development methodologies. Also, it examines related work, analyzing the different types of existing SSDLCs and security requirements engineering approaches. Section 3 details the proposed methodology for secure web development, establishing a structured model of security requirements and defining specific processes for each security domain. Also, it describes the implementation and validation of the methodology through a ticket management system, detailing both the system architecture and the security validation tools used. Section 4 presents the analysis and discussion of the results obtained during the evaluation of the methodology. Finally, Section 5 offers the conclusions of the work and proposes future lines of research to continue improving security in web application development.

2 Background and Relative Work

Digital transformation is a fundamental pillar for growth and competitiveness, both for companies and countries. Digitalization is utilized by companies to create external opportunities and to improve internal processes, thus obtaining significant benefits for both organizations and users [22]. Digitalization is even used as an economic indicator that describes a country’s competitiveness in international markets, therefore the cybersecurity of the systems becomes more relevant [23]. Countries’ support for digital transformation of their industries promotes direct and indirect economic growth [24]. For many countries, the importance of industrial transformation is prioritized to the extent that it forms part of their long-term objectives, as indicated by the European Commission [25]. The continuous rise and evolution of digital transformation affecting all business processes of companies and organizations, amply justifies cybersecurity in the context of digital transformation [26].

However, this digitalization, or software development is a complicated task, requiring a combination of technical and soft skills. Systems are increasingly complex and require constant learning and adaptation to changes [27]. When executed collaboratively, as in some type of project, its complexity increases, involving factors of communication, coordination, integration among other aspects [28]. Additionally, at an organizational level, it becomes not only a complex but costly task, where infrastructure, equipment, and other factors involved in development influence costs. On the other hand, software development often involves uncertainty, meaning it may not be clear how the desired product will be carried out, which in many cases causes projects to fail, by not meeting expectations or by encountering too many problems that delay deliveries [29]. Multiple factors contribute to project failure, one of the most common being inadequate requirements, which result in underestimated projects and trigger a domino effect of issues [30]. With all these factors when executing projects, organizations commonly implement a type of “software development life cycle”, which helps increase the chances of success [31]. SDLC can be defined as a formal or informal methodology that comprises the necessary steps or aspects for the design, construction and maintenance of software [32].

While digitalization is increasingly relevant for companies and industries, cybersecurity has also become a critical concern. When services and processes are migrated to a digital environment, cyberattacks emerge as an increasingly significant risk. These cyberattacks have occurred with increasing frequency, resulting in the loss or degradation of essential assets [33]. These attacks are expected to occur more frequently each year and become more sophisticated; it is already an industry that has a current growth of at least 1.5 trillion per year. With more services and projects online, attackers gain a larger attack surface, and entities that develop and maintain software also face a wider surface to audit [34,35]. In traditional approaches, security errors in software, such as bugs and vulnerabilities, are mostly discovered through tests, such as penetration testing, user reports, and stakeholder reports that validate the behaviour of the software when it is in its final phases. The characteristics of these bug detection processes allow these steps to be characterized as reactive actions, which evidence shortcomings in the artifacts of the previous phases in the development cycle in very late stages of the software [36]. Since the digitalization process is fundamentally linked to the creation of software, the development cycle of how it is created takes on vital importance for software security.

The most traditional model is known as Waterfall, it is a sequential model, where it goes through different phases and where greater detail is given to documentation and planning, additionally each stage must wait for the previous one to finish before starting the next [37]. Another model, or rather meta-model, is the spiral, which can be used as a basis in other models, it focuses on dividing the project into small segments and carrying out each phase of development with these fragments, it presents the opportunity to constantly evaluate risks [37]. Agile development is a combination of iterative and incremental processes, where the main motivation is to adapt to changes, always seeking customer satisfaction by making rapid deliveries, which are improved with each new iteration. Today, these traditional development cycles, such as Waterfall and Spiral, remain widely used in software creation companies [38]. For this reason, a deep understanding of their stages is valuable to understand the security problems that can occur when using traditional models.

Secure software development was not traditionally considered within development life cycles. Security was typically applied at the network or infrastructure level, for example, through the implementation of perimeter systems, firewalls, or by physically securing equipment [39], for at the end of the development, attempts were made to breach the system in order to identify and address errors; in the worst cases, solutions were only sought once an attack had already occurred. This approach is known as “penetrate and patch” [40]. However, this method fails to incorporate security into the system during its initial construction.

This traditional method of securing systems presents several problems: security breaches are always costly, either directly or because of lost organizational trust. There is also the possibility that the system is being attacked or exploited imperceptibly. Because of security being included during the final phases of development, attackers are given the advantage of always being one step ahead. When security patches are implemented, new vulnerabilities may be introduced, and furthermore, users may not even apply the security patches [41].

With these issues in mind, a solution arises from a straightforward premise: errors and security breaches originate from flaws in the code; therefore, security must be rigorously integrated during the software development process, rather than at its final stage [40]. SDLC was originally described as a methodology for software development aimed at ensuring the creation of software that meets its intended needs. Addressing the challenges outlined, the concept now known as the “Secure Software Development Lifecycle”, abbreviated as SSDLC, emerged. SSDLC seeks to incorporate security principles and practices more proactively within software development processes, in contrast to traditional approaches [42].

Microsoft’s Security Development Lifecycle (SDL) represents one of the first comprehensive implementations of SSDLC principles. SDL consists of specific security activities organized into seven phases: training, requirements, design, implementation, verification, release, and response [43]. Each phase includes mandatory security activities, such as threat modeling during design, static code analysis during implementation, and penetration testing during verification. This approach marked a paradigm shift from reactive security measures to a proactive security-by-design approach, establishing security as a non-functional requirement that must be considered from the earliest stages of development [41].

Building upon similar principles but with different approaches, the Open Web Application Security Project (OWASP) introduced the Software Assurance Maturity Model (SAMM), which focuses on evaluating and improving security practices across an organization rather than within individual projects [44]. SAMM is organized around five business functions: Governance, Design, Implementation, Verification, and Operations, with each function containing three security practices. Unlike SDL, which prescribes specific activities, SAMM provides a flexible framework that organizations can adapt based on their risk profile and business context. This model emphasizes progressive improvement through three maturity levels for each practice, allowing organizations to evolve their security posture gradually [45].

The Building Security In Maturity Model (BSIMM) takes yet another approach, focusing on observing and analyzing real-world security initiatives rather than prescribing ideal practices. BSIMM is a descriptive model derived from studying actual security activities in over 100 organizations across various industries [46]. Organized into four domains (Governance, Intelligence, SSDL Touchpoints, and Deployment) with 12 practices, BSIMM serves as a measuring stick for organizations to benchmark their security programs against industry peers. Unlike SDL and SAMM, which are prescriptive, BSIMM offers insights into what organizations are doing, providing realistic expectations for security program evolution.

While these methodologies have advanced software security significantly, they present limitations when applied to modern web development environments, particularly for specific technology stacks like Vue.js, Spring Boot, and MySQL. Traditional SSDLC methodologies often lack granular guidance for specific technologies, leaving development teams to interpret general principles without clear implementation directions. Additionally, these methodologies typically assume the presence of security specialists, creating barriers for teams without dedicated security resources [47]. Furthermore, the rapid evolution of web technologies often outpaces the update cycles of established methodologies, creating gaps in coverage for emerging threats and vulnerabilities specific to modern frameworks and libraries [42].

When examining security considerations specifically for Vue.js applications, additional challenges emerge beyond those addressed by general SSDLC frameworks. Single Page Applications (SPAs) built with Vue.js face unique security threats, including Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) vulnerabilities through unsafe template binding, insecure state management in Vuex stores, and client-side routing vulnerabilities [48]. Traditional security frameworks rarely address these frontend-specific concerns, leaving developers without clear guidance. Vue’s reactivity system, while powerful for development, introduces specific security challenges such as prototype pollution and injection attacks if not properly managed. Hellquist’s (2024) comprehensive framework comparison reveals that Vue.js applications face unique security issues such as Format String Errors, which were identified during dynamic testing using OWASP ZAP. While Vue demonstrated a clean dependency check with no vulnerable packages in its base configuration, it still showed significant security misconfigurations related to Content Security Policy, CORS settings, and anti-clickjacking protections—vulnerabilities shared across modern JavaScript frameworks but requiring framework-specific mitigations. The Vue.js security ecosystem itself is still evolving, with gaps in automated security tooling specifically designed for Vue’s component architecture and lifecycle hooks. These frontend-specific security challenges require specialized knowledge and approaches that extend beyond traditional SSDLC frameworks, supporting Hellquist’s finding that ‘developers must gain knowledge and implement secure coding practices without relying solely on first-party mitigations.

The main contributions of this work are:

• Analyze and investigate existing SSDLC (Secure Software Development Life Cycle) methodologies, evaluating their strengths, limitations, and applicability in modern web development environments.

• Define a methodology that integrates both secure coding practices and defensive approaches, creating a hybrid framework that involves the entire development team in project security while allowing the security team to implement specific and targeted processes.

• Validate the effectiveness of the proposed methodology through the development of a ticket management system based on Vue.js, Spring Boot, and MySQL architecture that incorporates the identified security requirements, demonstrating its practical applicability in a real scenario.

• Design and implement a DevSecOps pipeline that automates security processes, integrating dependency analysis tools (OSV-Scanner, Trivy, OWASP Dependency-Check), static code analysis (SonarQube, Bearer, Fortify), and dynamic analysis (OWASP ZAP) throughout the development cycle.

• Establish metrics to evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed methodology, providing objective indicators that allow measuring the level of security achieved and the efficiency of the implemented process.

The Secure by Design approach presented by [36] offers a promising paradigm shift toward democratizing security, yet it contains significant gaps in addressing practical implementation. Their framework suggests that developers without security expertise can naturally create secure software through domain-focused design principles; however, the literature fails to provide methodological frameworks for making security accessible to non-specialist developers. The authors emphasize that software design is inherently central to most developers’ competencies, but their work lacks structured guidance on training programs or knowledge transfer mechanisms that would effectively bridge the expertise gap. This limitation becomes particularly evident in the absence of empirical research on security education models tailored to development teams without specialized security backgrounds. While Deogun and Johnsson demonstrate how design-driven approaches can implicitly solve security issues—as in their domain primitive example that prevents XSS vulnerabilities—they do not offer a comprehensive educational framework that would systematically empower ordinary developers to identify and implement such patterns independently. This oversight perpetuates a dependency on security expertise in an industry where dedicated security resources remain scarce for many organizations.

3.1 Security Requirements Model

The OWASP Software Assurance Maturity Model (SAMM) [49] is an initiative that provides a method for assessing and implementing a secure development lifecycle through a series of security practices applicable at any phase. This model is structured around business functions, each of which contains certain security practices. These practices consist of a set of activities, each divided into maturity levels. This work focuses on the design phase of application development. In this phase, an organization defines the objectives and determines how to create software that can fulfil them, incorporating security requirements and security architecture. In OWASP SAMM, this phase includes practices for threat assessment, security requirements, and security architecture. Within the design activities, this work centers on security requirements. SAMM’s security requirements activities define processes both for the security of the software being developed and for third-party services used.

SAMM maintains a direct approach to software development and application security, rather than focusing on organizational-level security. The framework allows security to be incorporated in stages, according to the maturity level at which the organization currently operates. To develop a methodology that formulates a model serving as security requirements during application development, a framework is sought that permits the application of recommendations solely during the design stage. As SAMM demonstrates flexibility, it allows the adoption of recommendations according to the business function of interest, enabling isolation and utilization of its recommendations as a foundation. Additionally, its focus on software development and application security rather than at an organizational level aligns with the objective of the methodology focused solely on security requirements, whilst ensuring the methodology can integrate into a Secure Software Development Lifecycle (SSDLC).

Our methodology is specifically designed for full-stack web architectures and functions as a complementary tool that integrates within established SSDLC frameworks such as SAMM (Software Assurance Maturity Model), Microsoft SDL (Security Development Lifecycle), or BSIMM (Building Security In Maturity Model). While these frameworks provide general guidelines and organizational processes for implementing security in software development, our proposal offers detailed and granular technical specifications for a specific architectural domain. This integration allows development teams to achieve a completer and more accurate outcome in defining and implementing security requirements for full-stack web applications, using our methodology as a specific technical guide within the broader process established by the SSDLC framework adopted by the organization.

The specificity of our methodology for full-stack web architectures enables addressing vulnerabilities and security requirements that general SSDLC frameworks do not cover with the level of technical detail necessary for practical implementation. For example, while SDL establishes the need to “implement secure authentication controls”, our methodology specifies the 35 concrete requirements organized by layers (authentication, session management, authorization, input validation, secure communications), providing precise technical guides such as controls SR-AU-01 to SR-AU-06 for authentication, SR-SM-01 to SR-SM-04 for session management, and SR-AC-01 to SR-AC-05 for authorization. This technical granularity is essential for developers to effectively implement the security principles established by SSDLC frameworks in the specific context of modern web applications.

For applications that commence without requirements, SAMM recommends the use of ASVS, which proves highly practical as its recommendations are based on the application’s risk level as well as the data it will handle. This approach makes it ideal for selecting recommendations that suit the software to be developed, allowing proportionate efforts to be made relative to the potential impacts of security failures. This risk-based approach ensures that security controls are appropriately scaled to match the criticality and sensitivity of the application being developed. Another advantage of ASVS is its adaptation to all aspects of the development lifecycle, encompassing design principles, implementation guidance, and security considerations in operations. This comprehensive coverage makes it ideal for applications that are beginning construction, as it provides structured security verification standards across three defined levels of security assurance.

Based on this model, the methodology aims to compile a set of clear and straightforward requirements to help achieve an acceptable level of application security. It also provides direct documentation of the security aspects it intends to cover, supported by models developed by OWASP ASVS, CWE, and other sources, thus offering a starting point for further development. These requirements are intended to be generic, so they can serve as a base for constructing any type of application, with the goal of ensuring a minimum level of security.

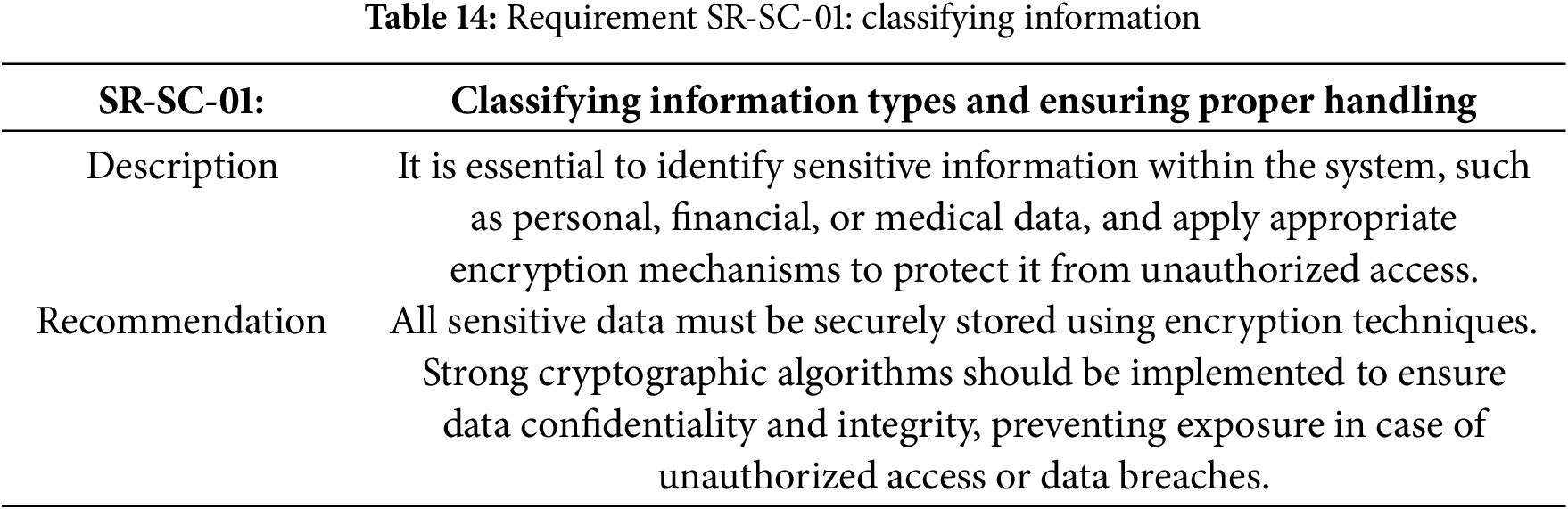

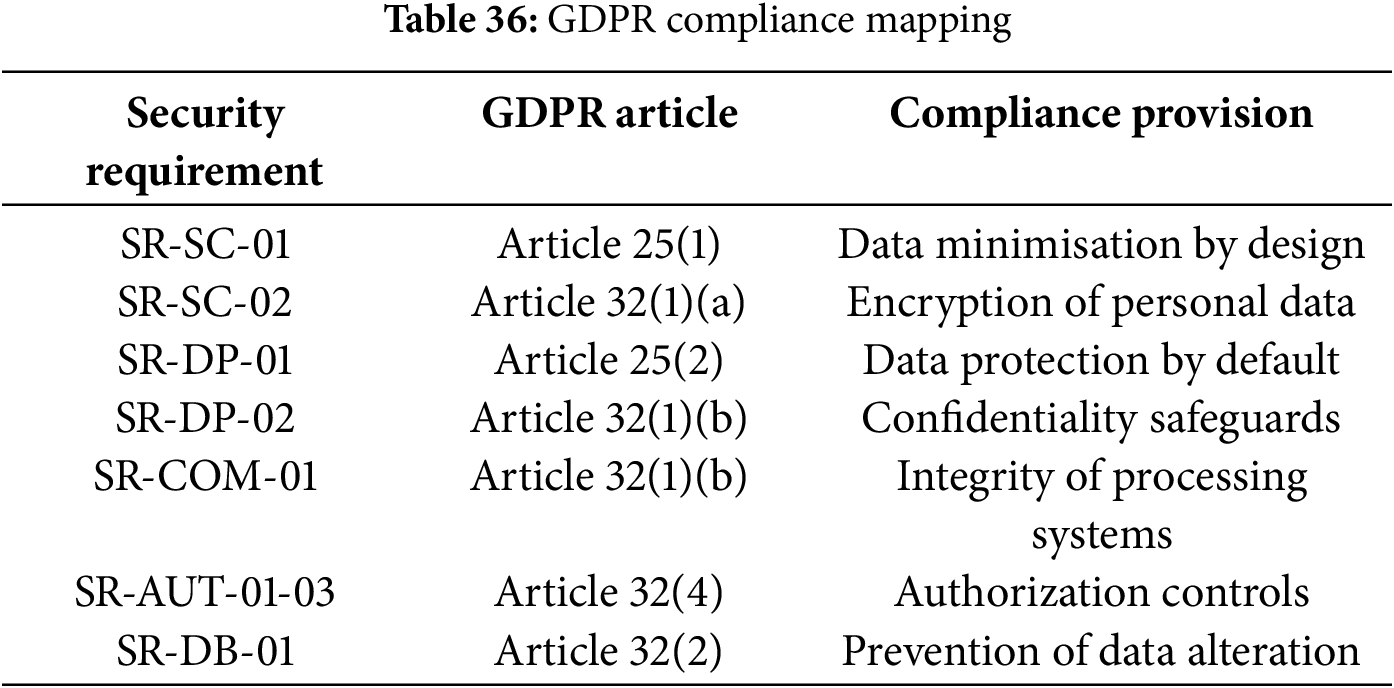

The security requirements support compliance with data protection regulations, specifically GDPR Articles 25 and 32. Requirements SR-SC-01 and SR-SC-02 address Article 25’s data protection by design mandate and Article 32(1)(a)’s encryption requirements. Data protection controls SR-DP-01 and SR-DP-02 implement Article 25’s safeguarding provisions, while communication security requirements SR-COM-01 and SR-COM-02 satisfy Article 32(1)(b)’s confidentiality and integrity mandates. This alignment enables systematic compliance demonstration through technical implementation.

3.2 Defining a Secure Methodology

The definition of specific security requirements for the application is conducted through the identification of potential threats and the evaluation of vulnerabilities. This includes the development of a specification document detailing the assets to be protected, the identified threats, possible vulnerabilities, analysed risks, and recommended practices for mitigating these risks.

The identification of security requirements is based on the OWASP Application Security Verification Standard (ASVS) model, which provides a structured framework to ensure the security of web applications. This model encompasses several key areas of security, including:

• Authentication: Implement multi-factor authentication to ensure that only authorized users can access the system. This aims to verify the identity of the user or entity and to ensure that the verification process is not vulnerable to impersonation or credential interception.

• Access Control: The application must correctly manage authorization, controlling and specifying access to each resource based on roles and permissions, following the principle of least privilege.

• Session Management: Guarantee proper interaction between the user and the application, ensuring that sessions remain individual, non-transferable, and are invalidated when no longer necessary.

• Validation, Sanitization and Encoding: Secure all information processed and entered into the system by validating encoding levels, values, ranges, filters, and sanitizing any stored data.

• Database Security: Ensure secure access to data storage, covering configuration, application integration, and secure communication.

• Stored Cryptography: Implement cryptographic modules within the application to prevent uncontrolled errors and to securely manage access to sensitive data. Ensure data encryption both in transit and at rest and use ORM and prepared statements to prevent SQL injection.

• Logging and Auditing: Provide relevant and adequate information to stakeholders without exposing unnecessary or sensitive data. Control log volumes by reducing noise and performing regular cleanups. Implement secure logs for activity monitoring and auditing.

• Data Protection: Ensure data is protected across all dimensions, meaning it is reliable, protected from unauthorized inspection, maintains integrity (cannot be maliciously altered), and is available whenever the user requires access.

• Communication: Ensure secure communication between application components by using robust encryption methods, appropriate configurations, and adhering to the latest industry standards.

• Malicious Code: Ensure the application source code must meet security requirements, protecting it from malicious or unintended instructions, backdoors, or inherited malicious code.

• API and Webservices: Ensure the API layer must incorporate proper authentication, session management, authorization, effective security controls, and input validation for all parameters.

• Configuration: Ensure production environment configurations must be designed to protect the system from common attacks, securing the system once it is online.

All security requirements are included and explained in Tables 1–35.

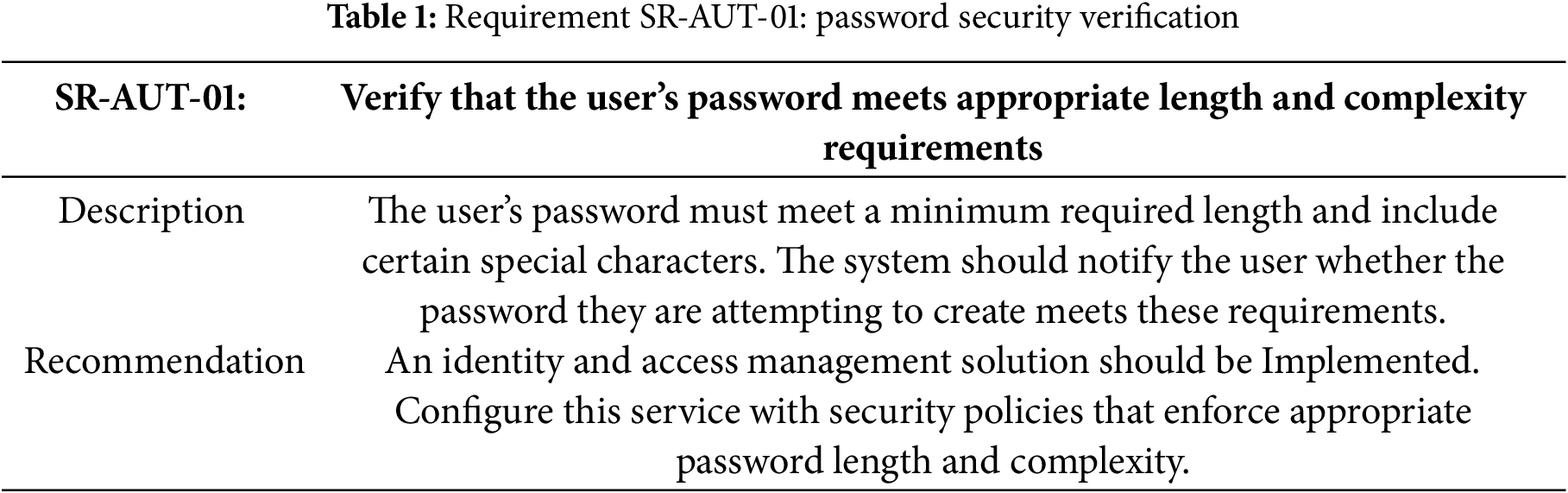

Table 1 specifies the requirement for the password security verification.

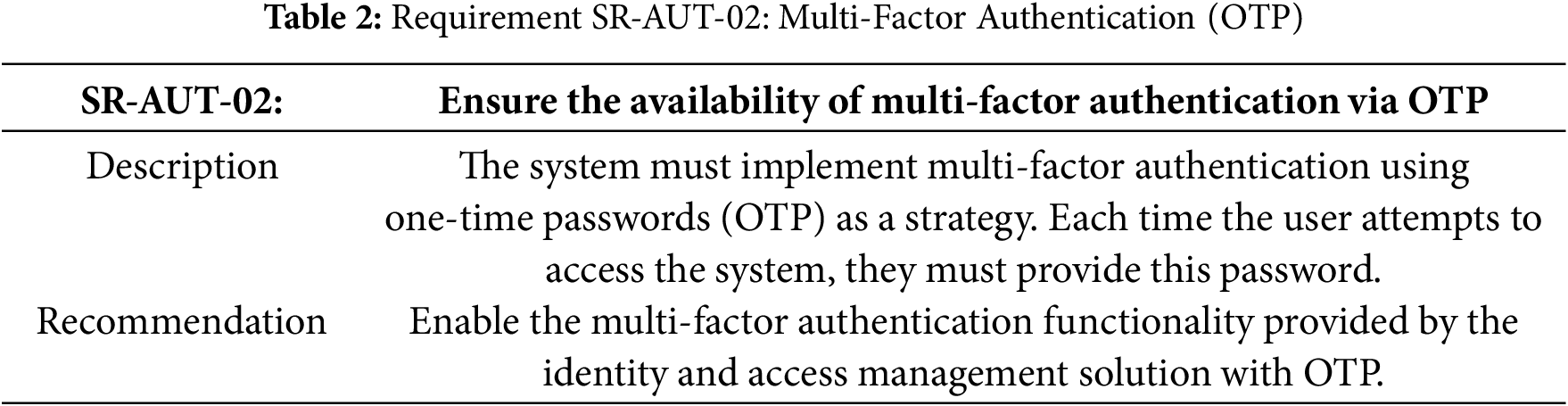

Table 2 specifies the requirement for the Multi-Factor Authentication (OTP).

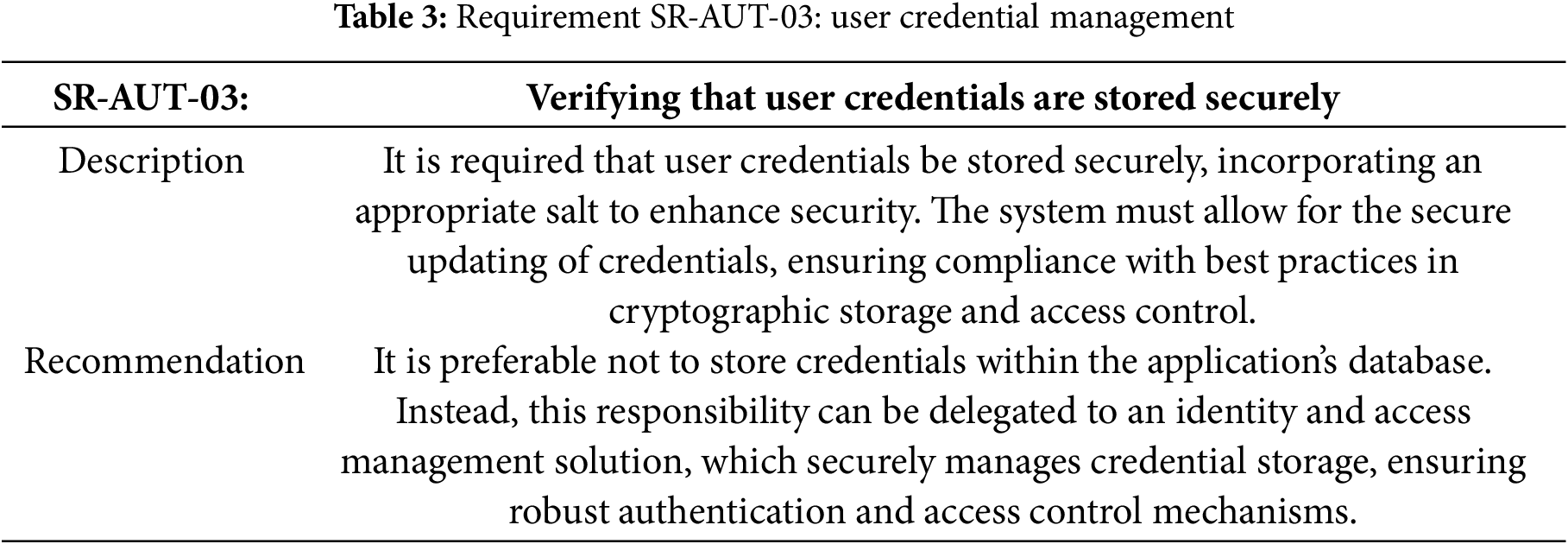

Table 3 specifies the requirement for the user credential management.

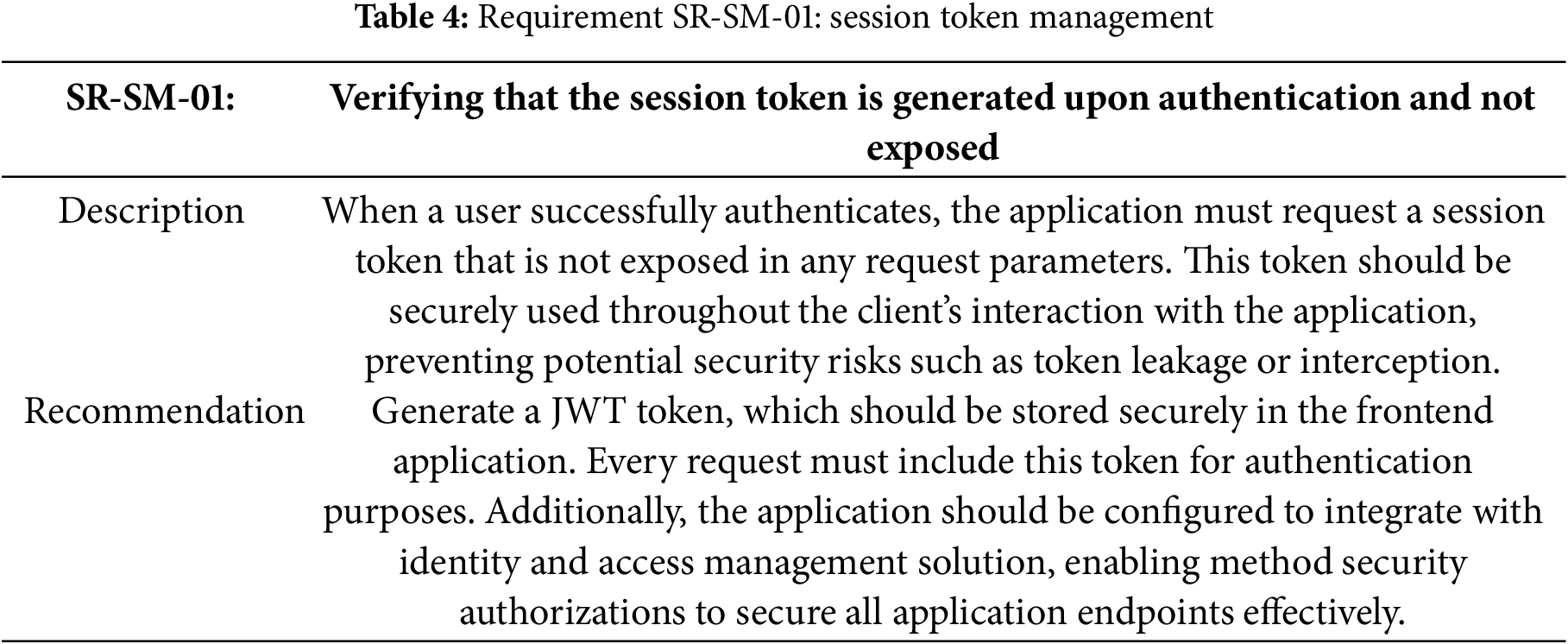

Table 4 specifies the requirement for the session token management.

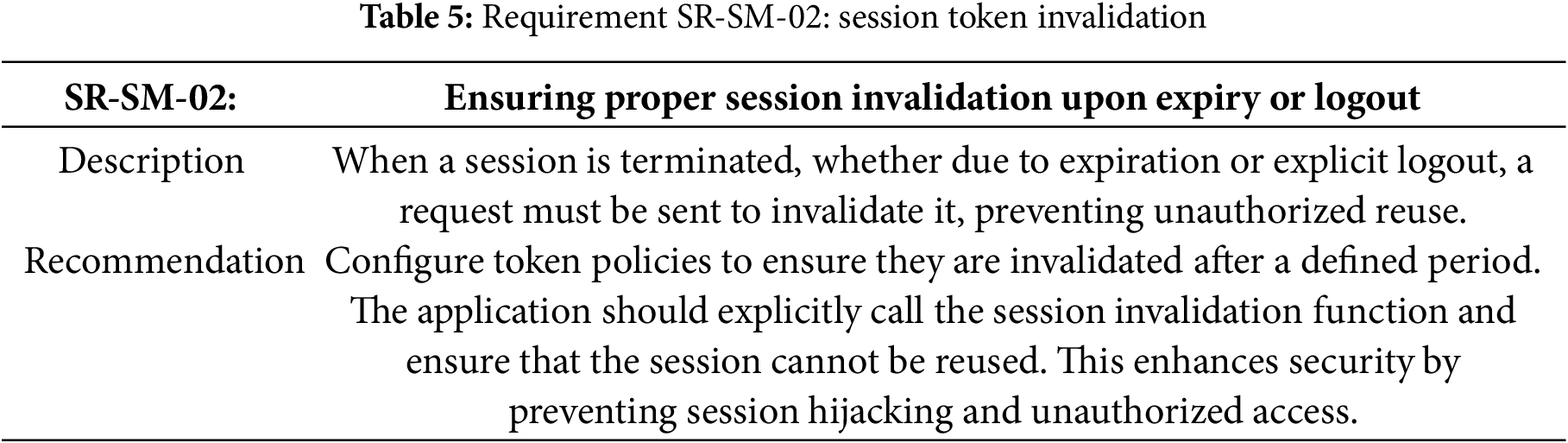

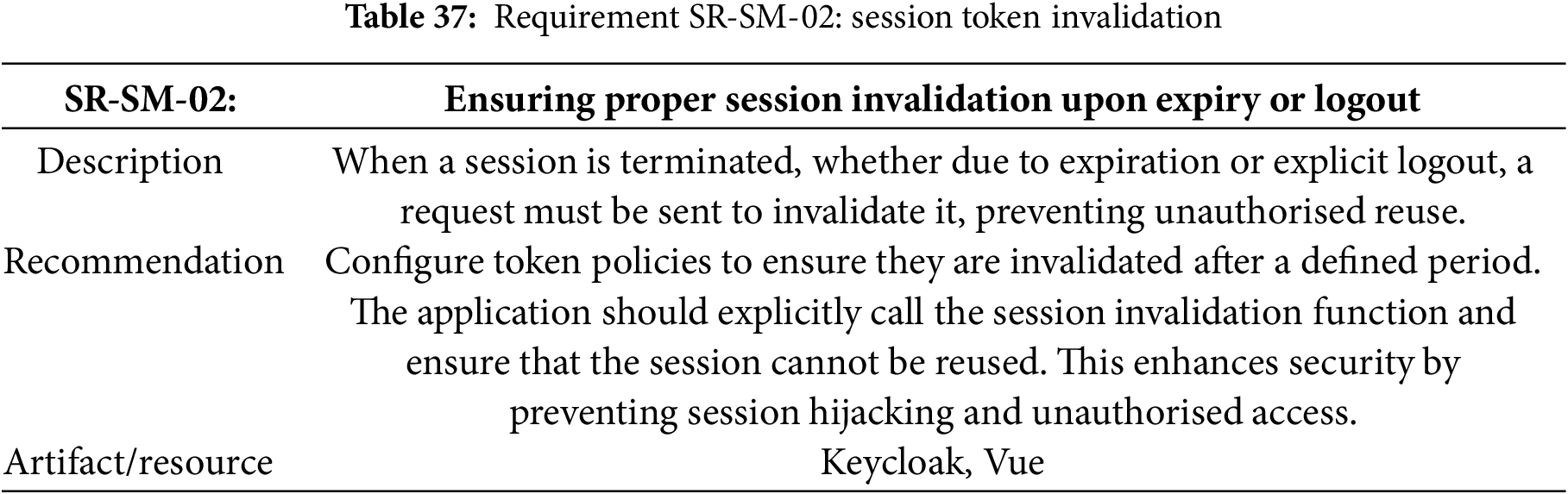

Table 5 specifies the requirement for the session token invalidation.

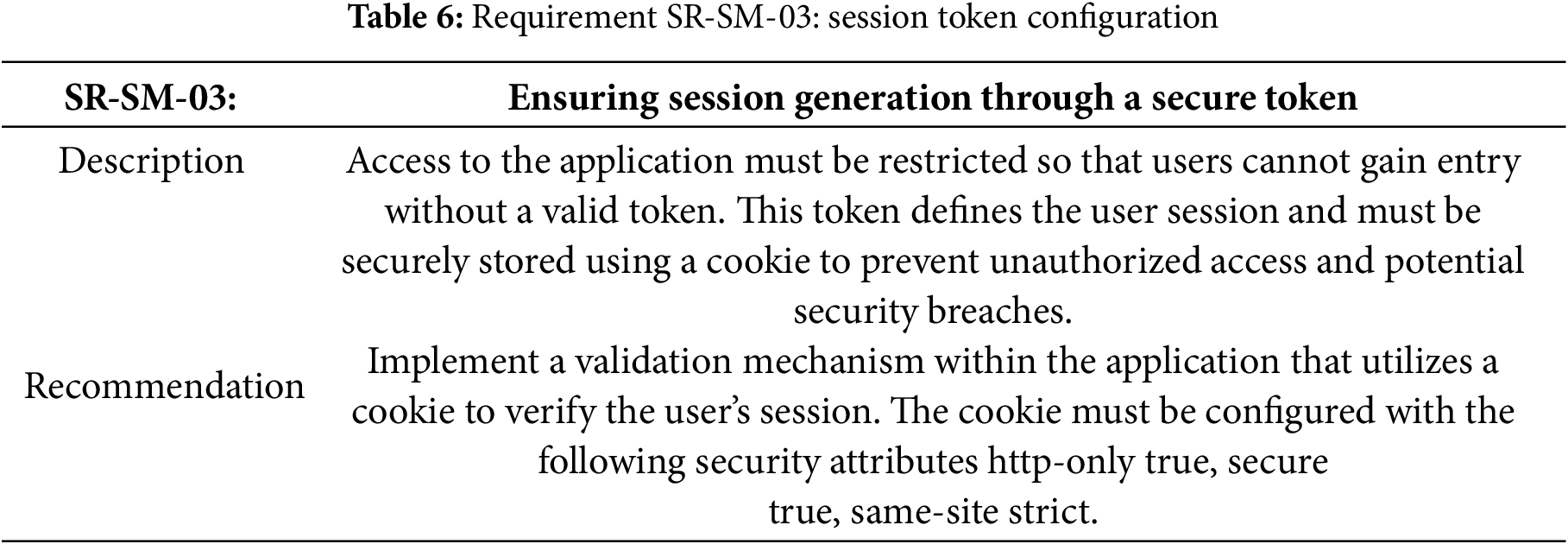

Table 6 specifies the requirement for the session token configuration.

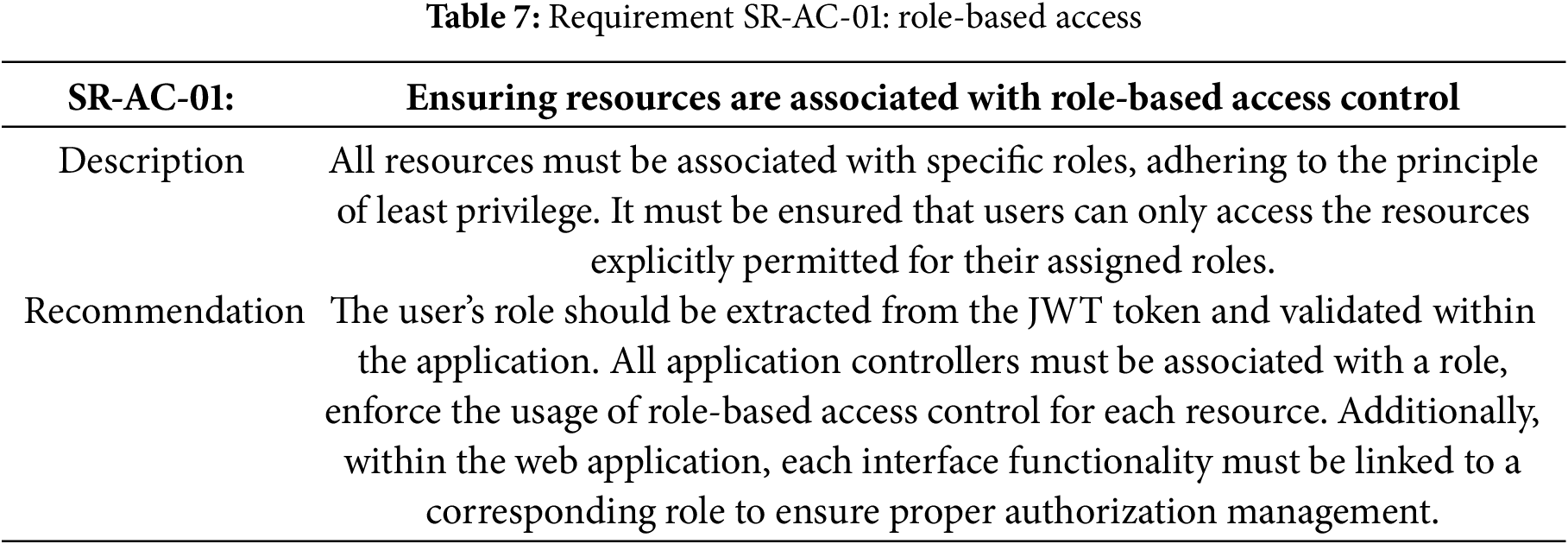

Table 7 specifies the requirement for the role-based access.

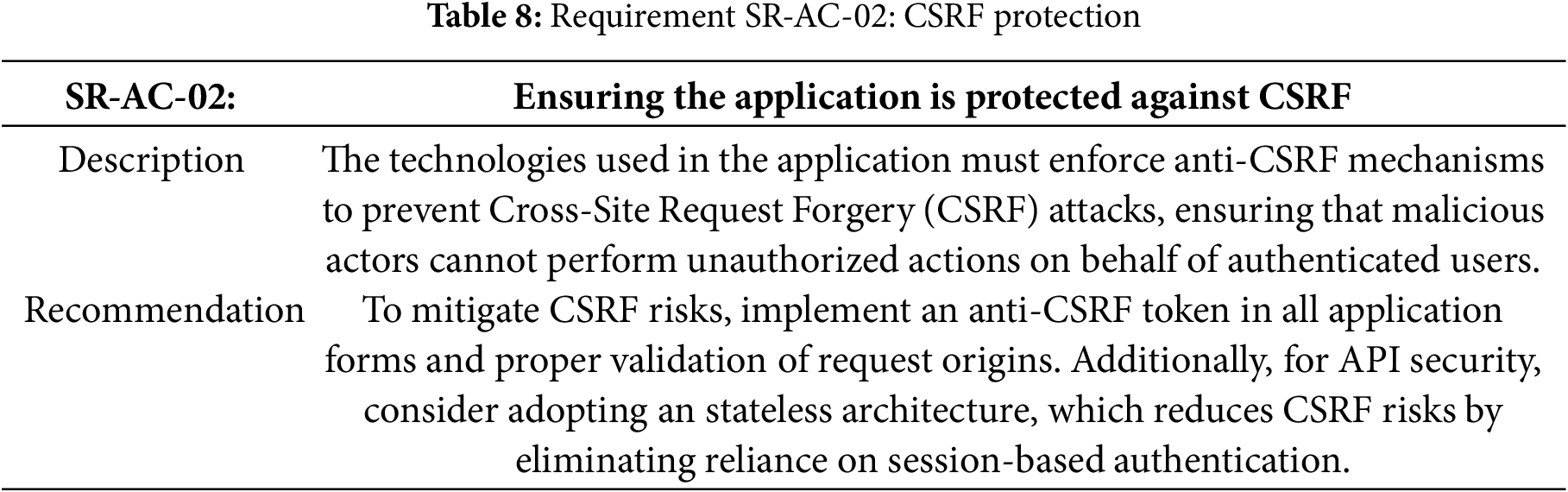

Table 8 specifies the requirement for the Cross Site Request Forgery (CSRF) protection.

3.2.4 Validation, Satinization, Encoding

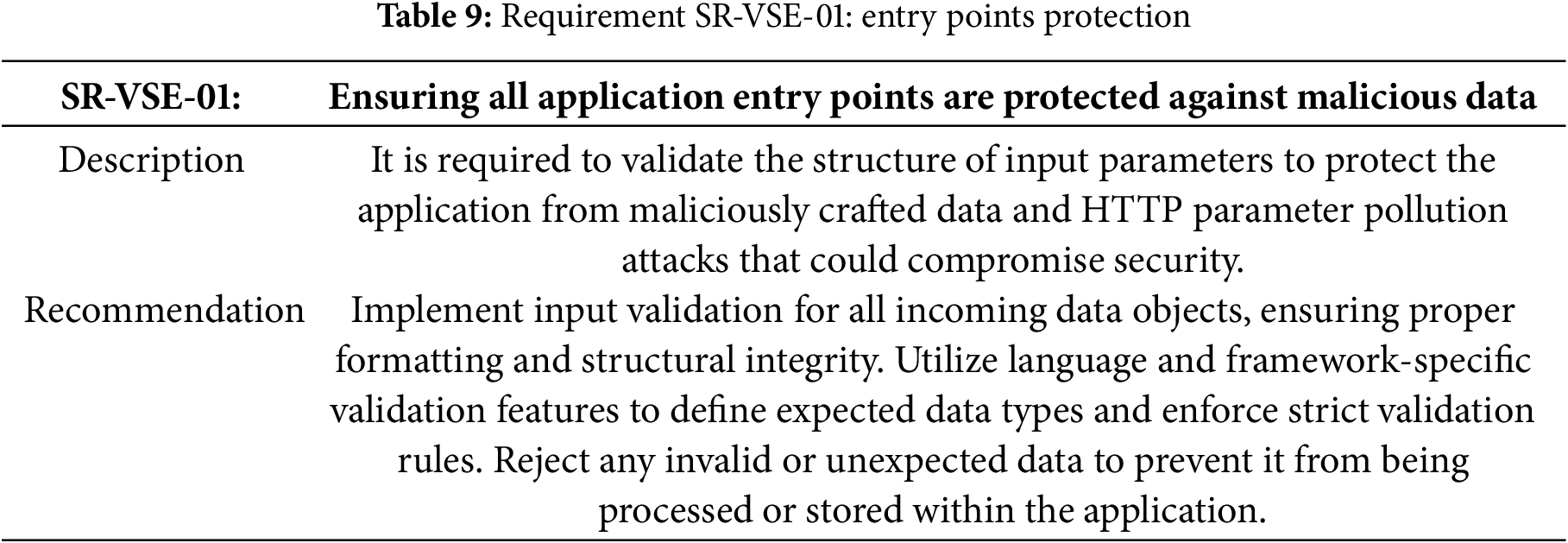

Table 9 specifies the requirement for the entry points protection.

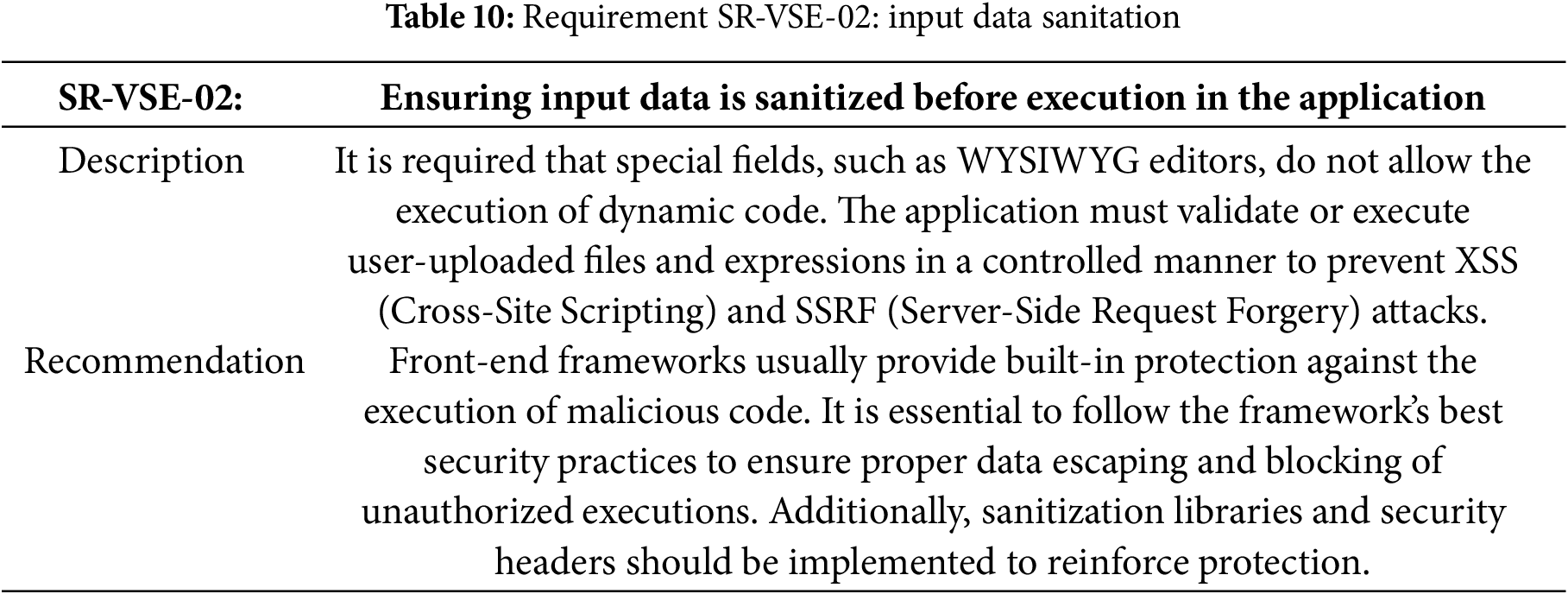

Table 10 specifies the requirement for the input data sanitation.

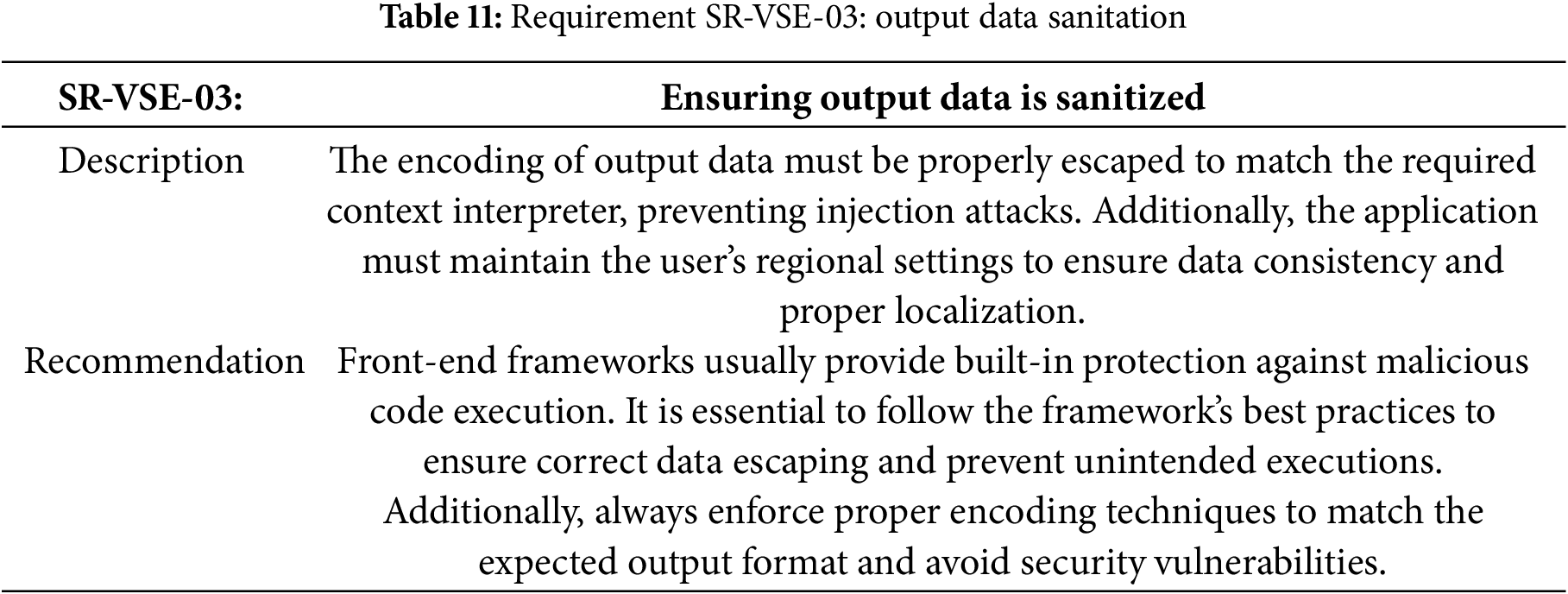

Table 11 specifies the requirement for the output data sanitation.

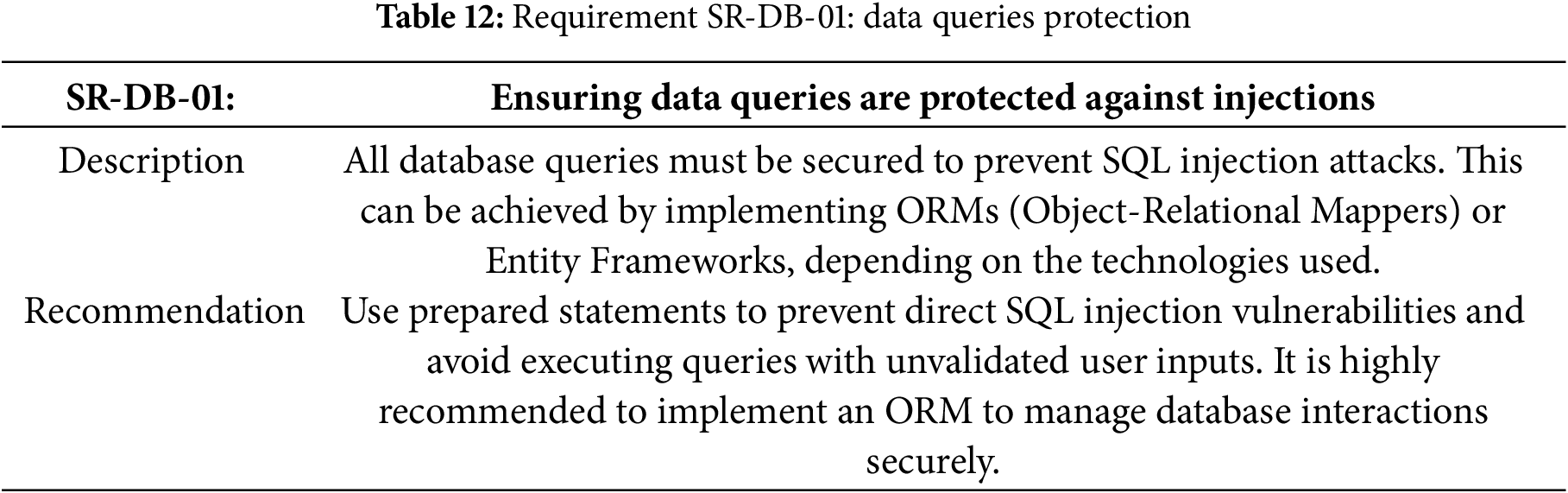

Table 12 specifies the requirement for the data queries protection.

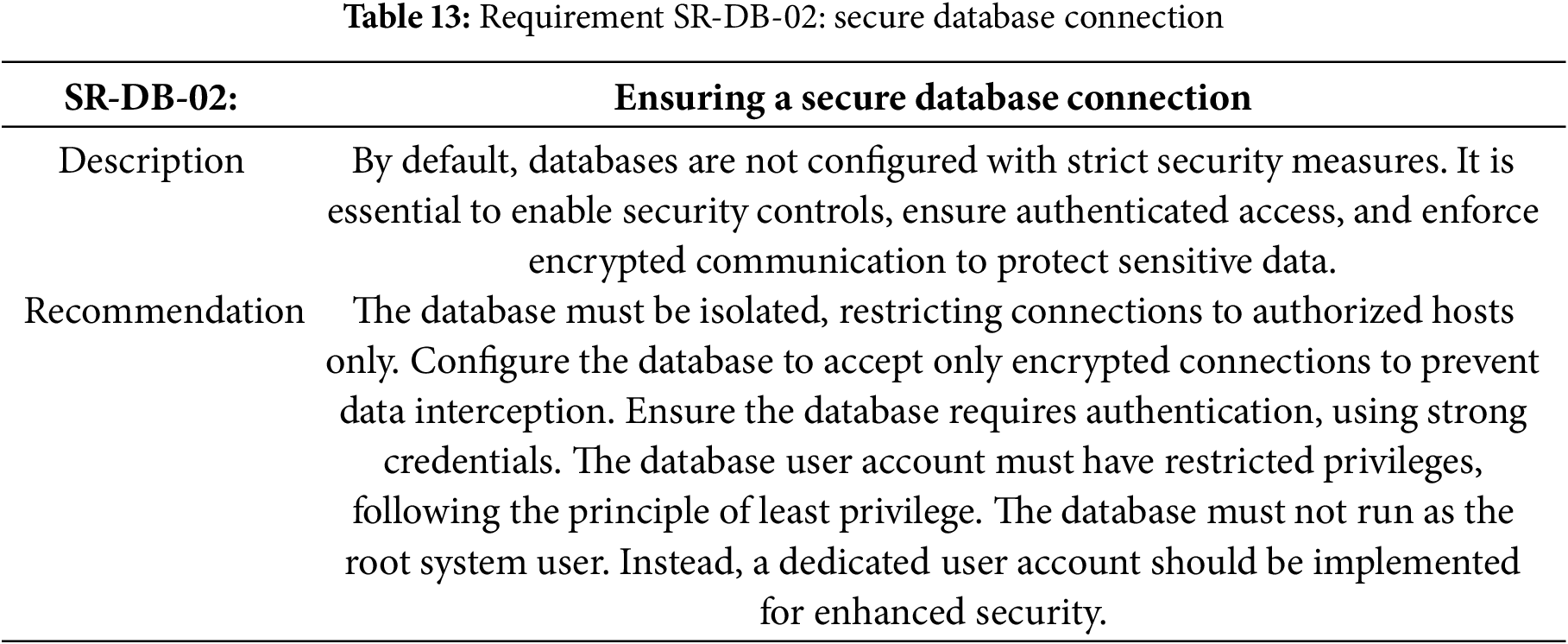

Table 13 specifies the requirement for the secure database connection.

Table 14 specifies the requirement for the classifying information.

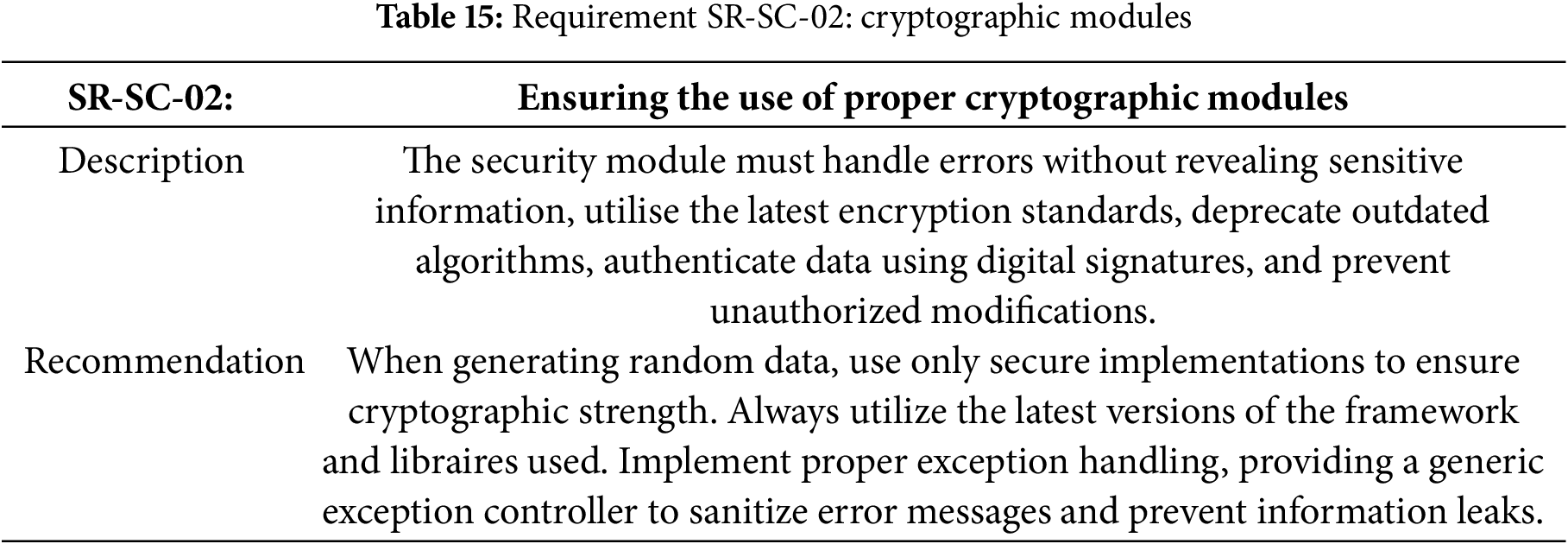

Table 15 specifies the requirement for the cryptographic modules.

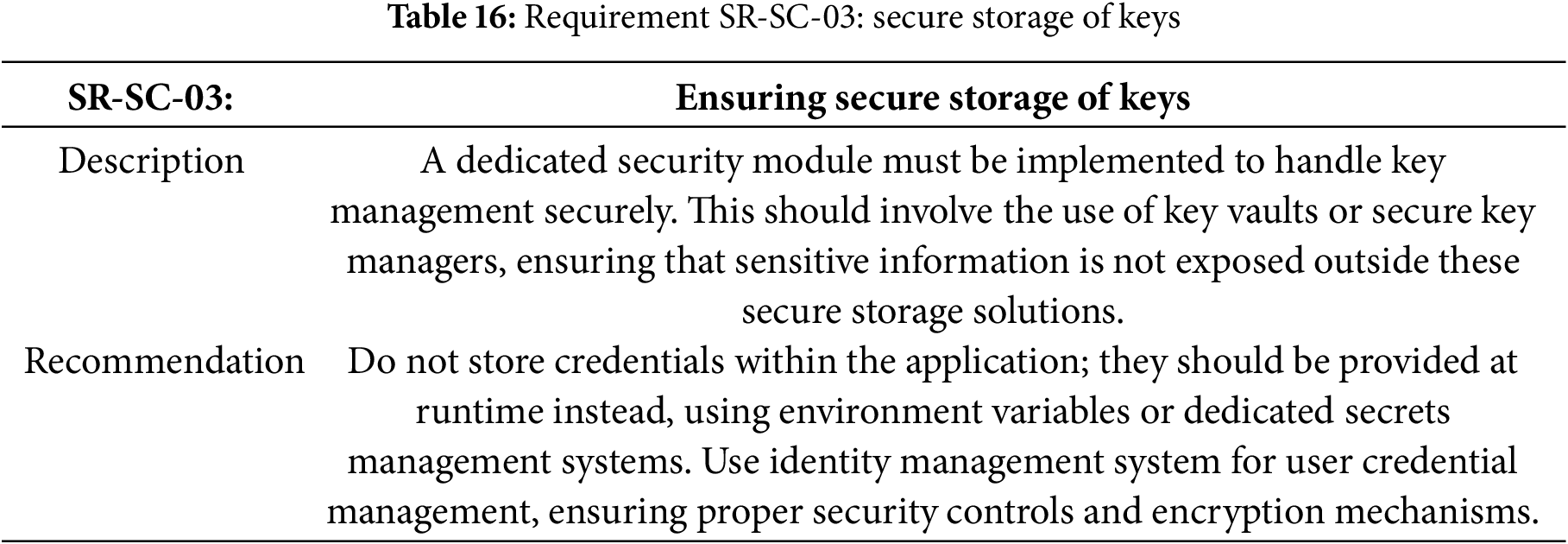

Table 16 specifies the requirement for the secure storage of keys.

3.2.7 Error Handling and Logging

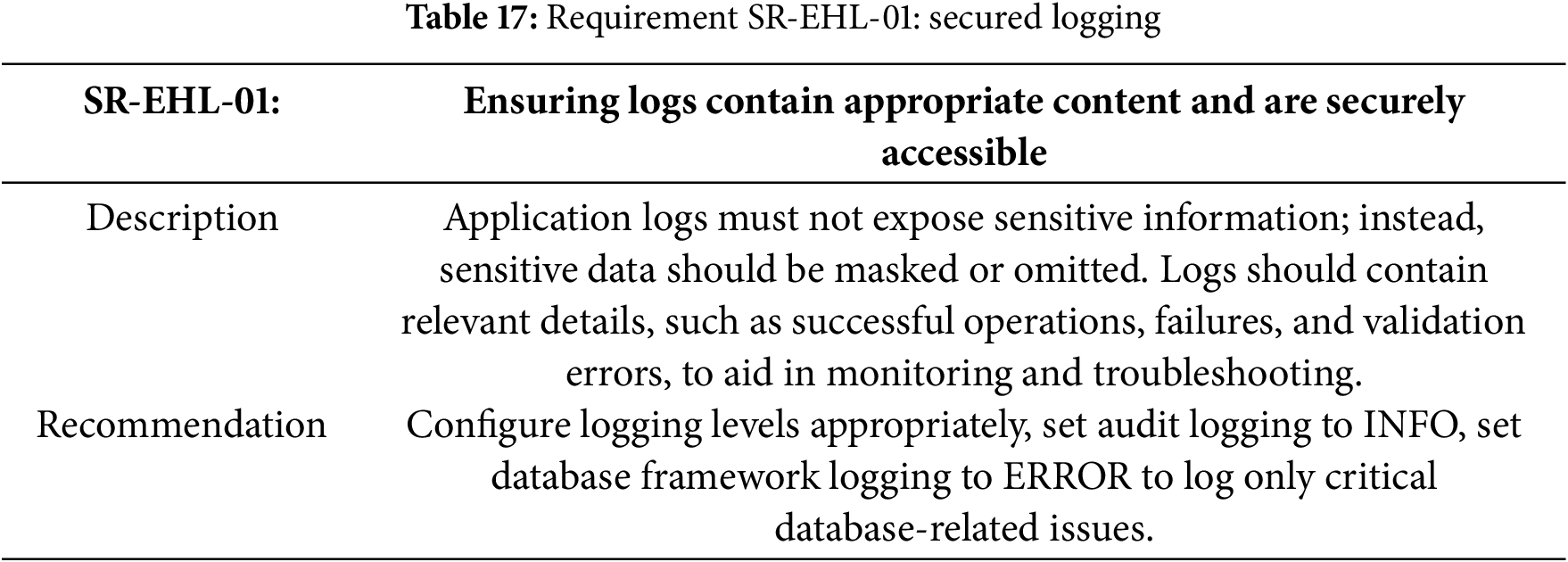

Table 17 specifies the requirement for the secured logging.

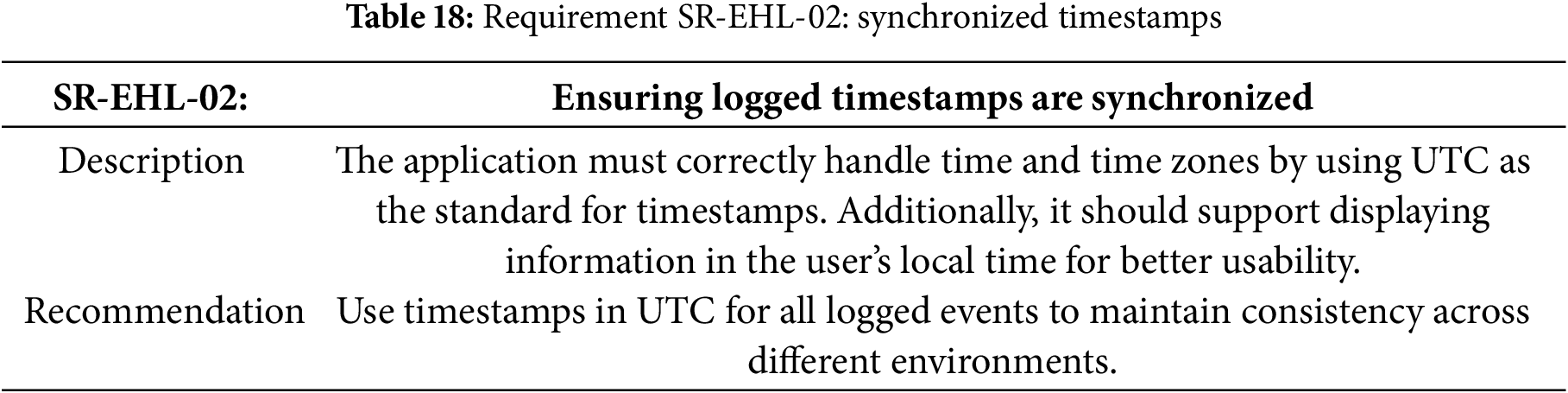

Table 18 specifies the requirement for the synchronized timestamps.

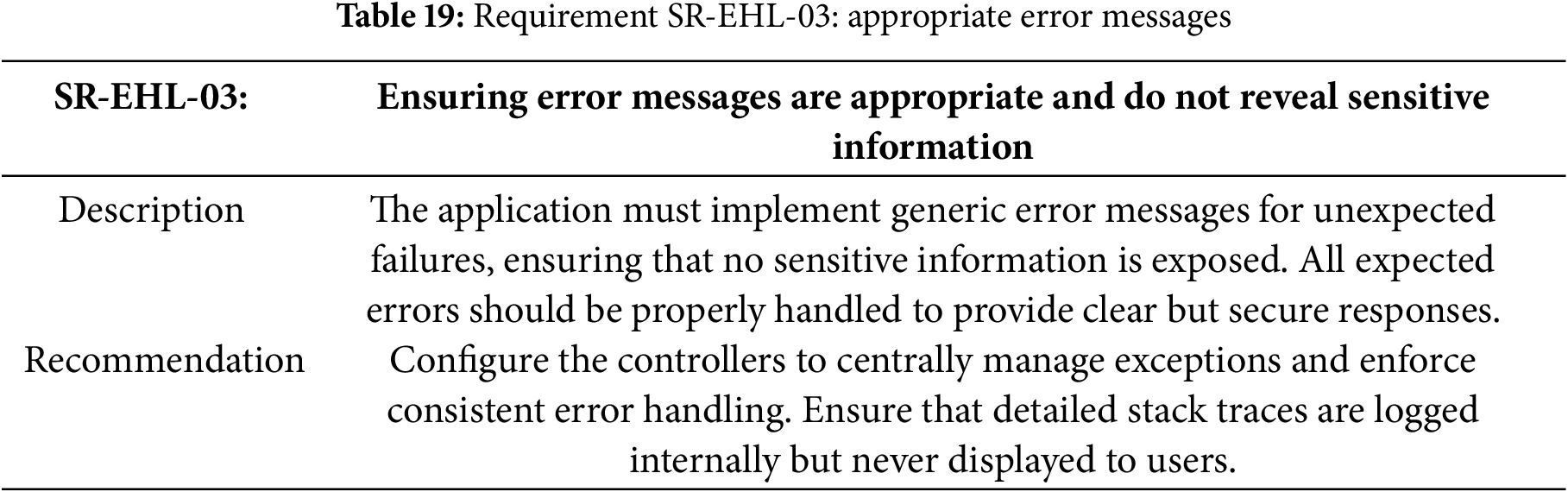

Table 19 specifies the requirement for the appropriate error messages.

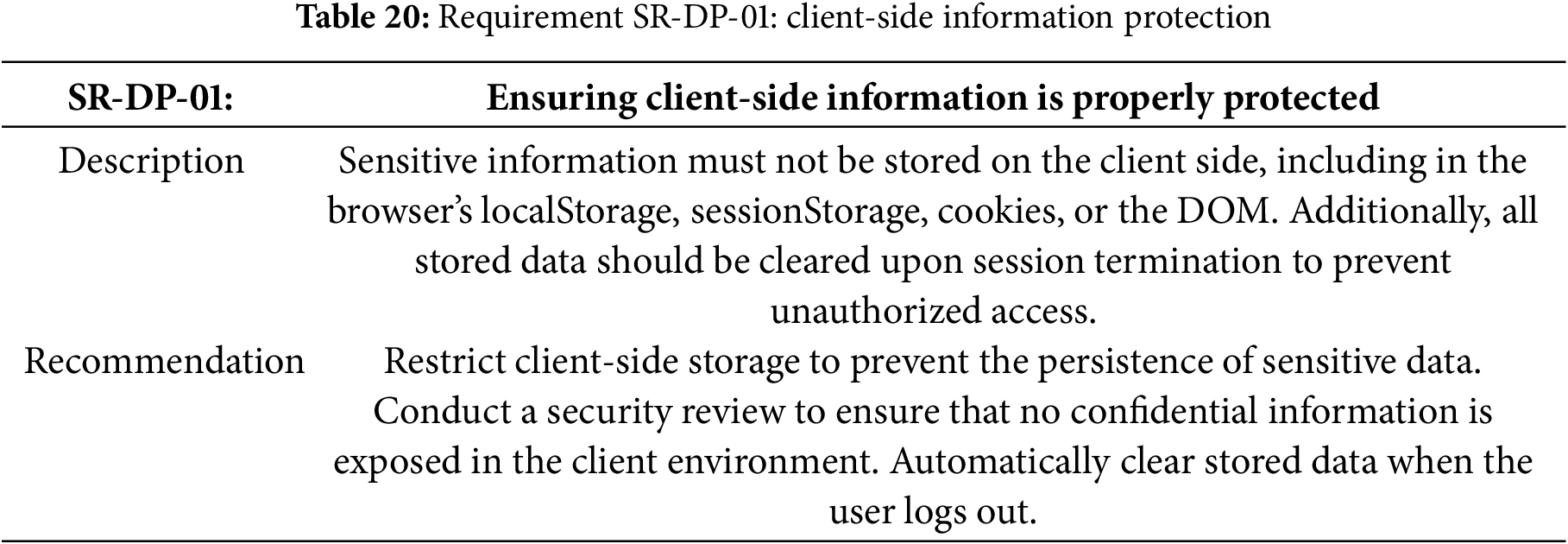

Table 20 specifies the requirement for the client-side information protection.

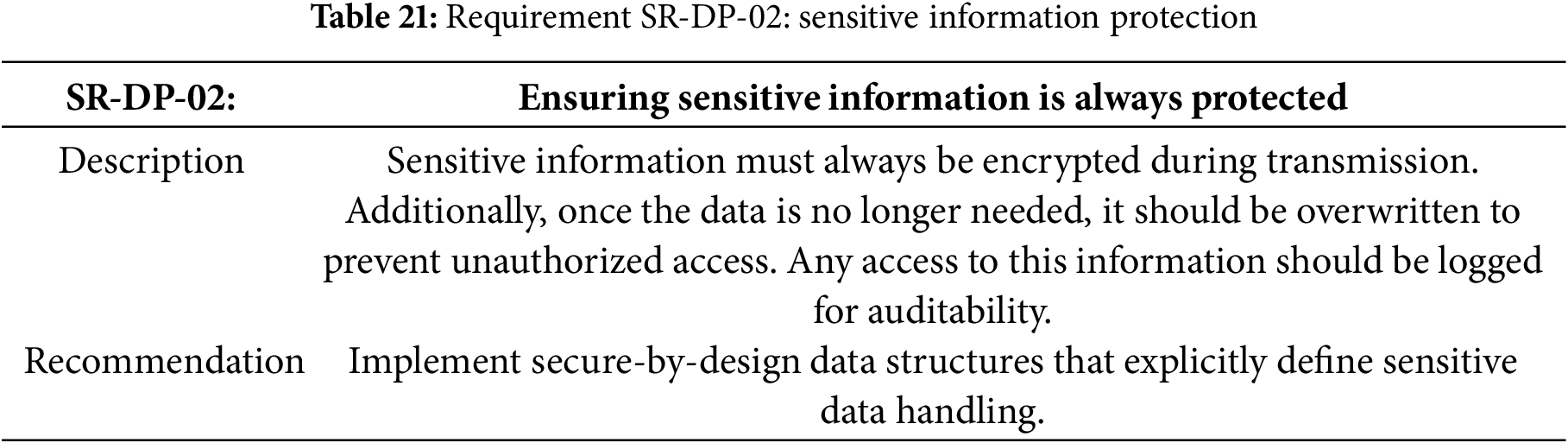

Table 21 specifies the requirement for the sensitive information protection.

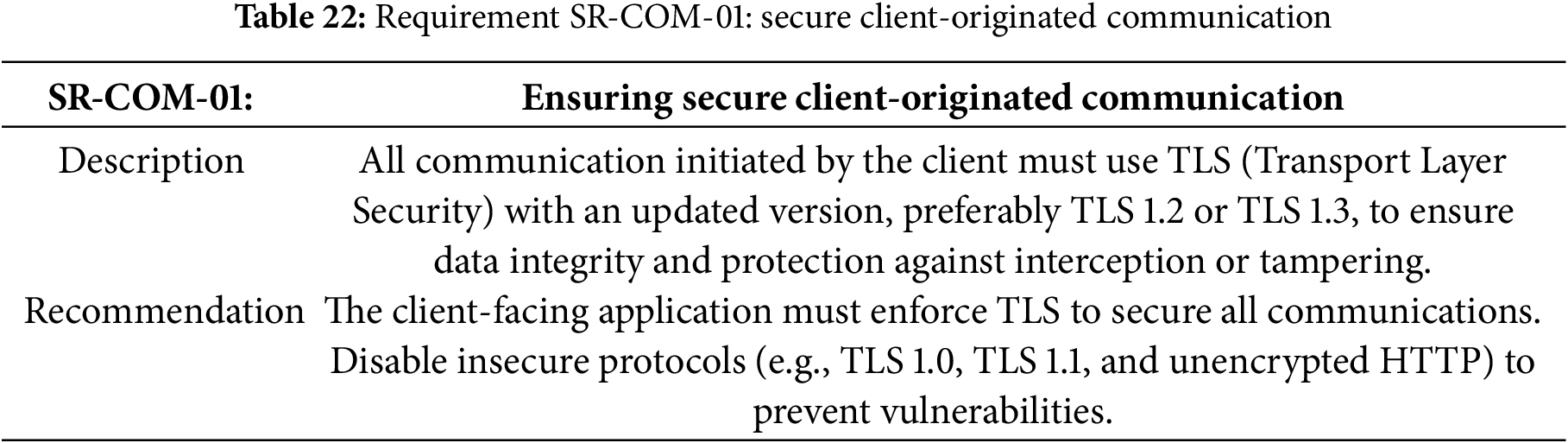

Table 22 specifies the requirement for the secure client-originated communication.

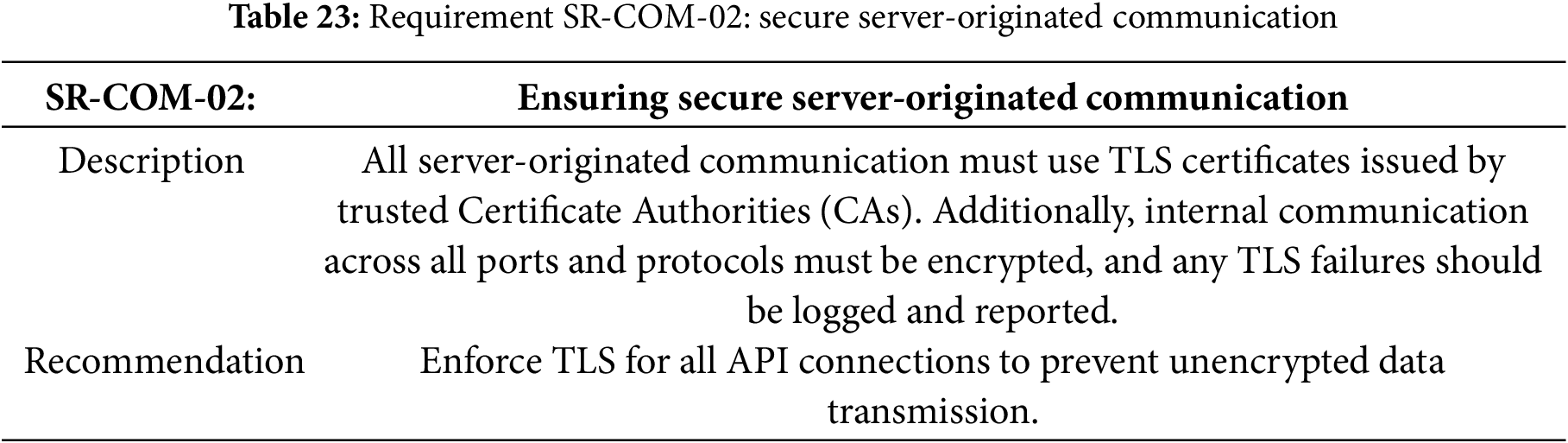

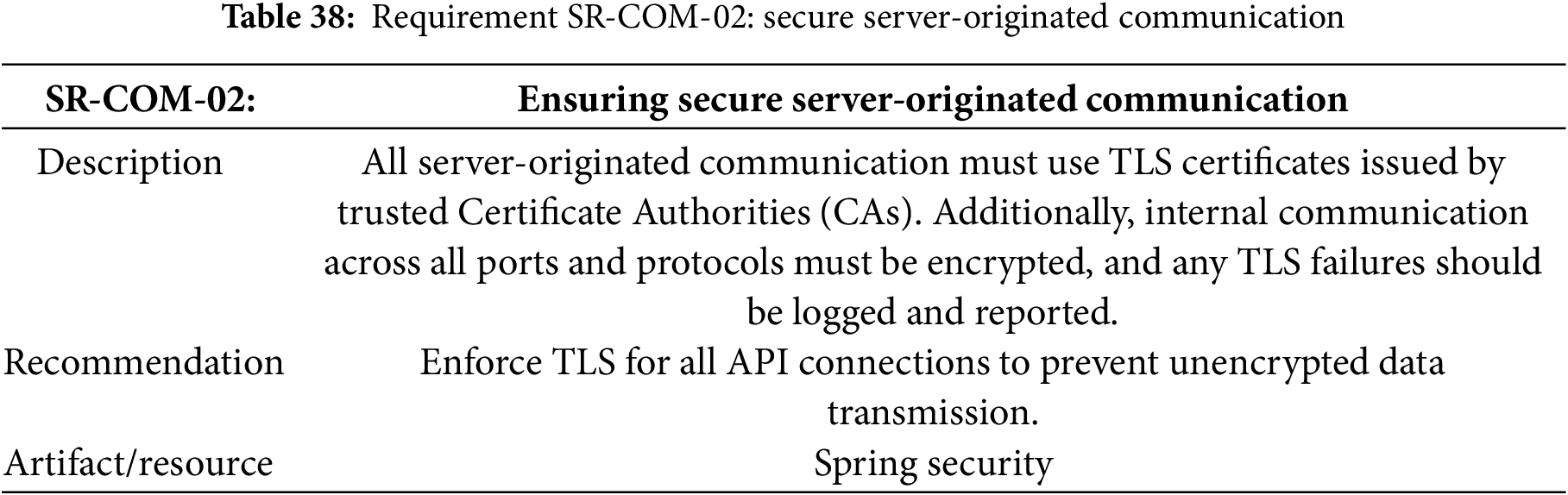

Table 23 specifies the requirement for the secure server-originated communication.

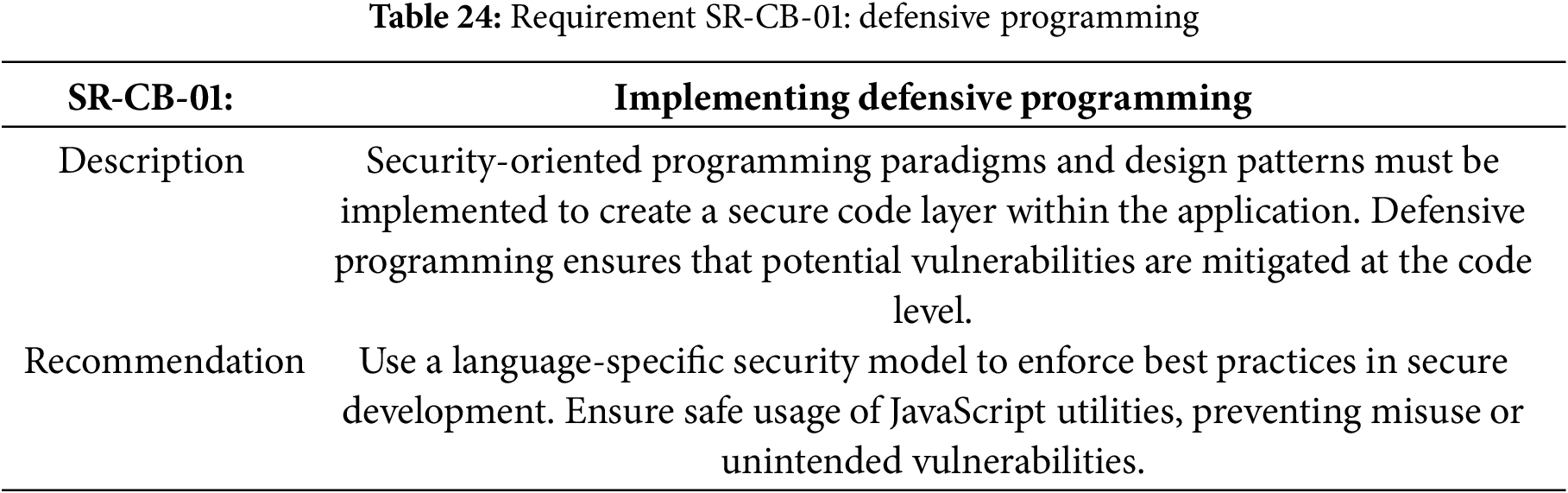

Table 24 specifies the requirement for the defensive programming.

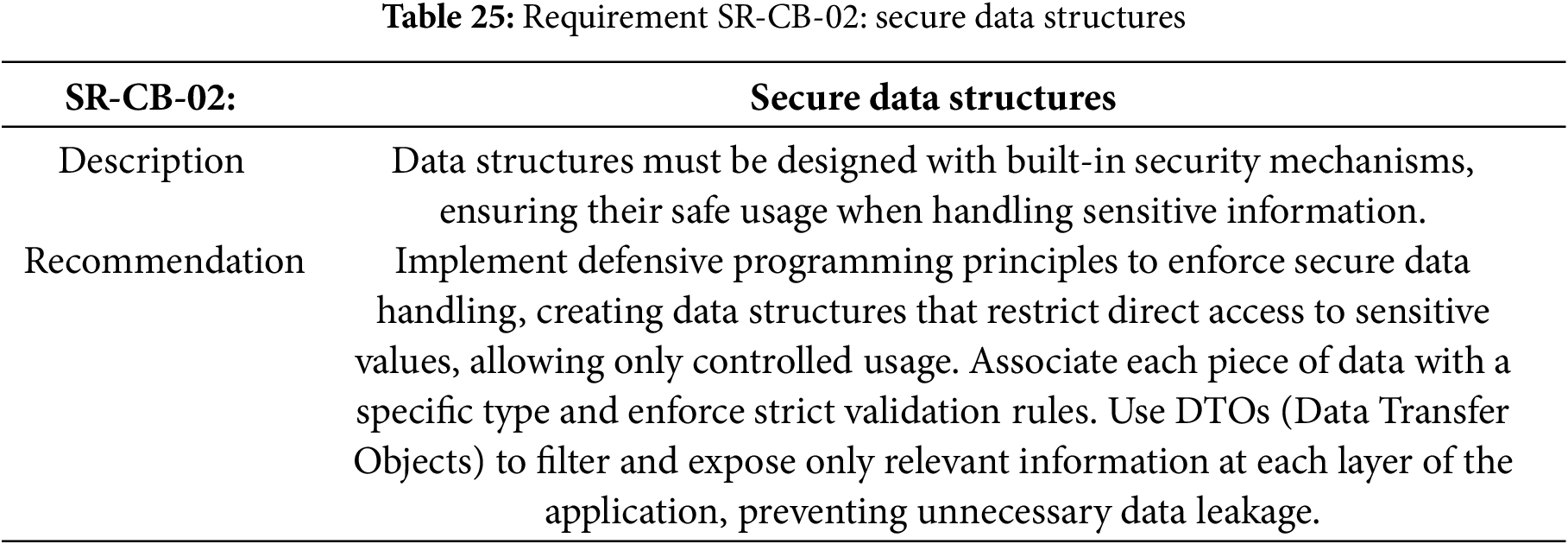

Table 25 specifies the requirement for the secure data structures.

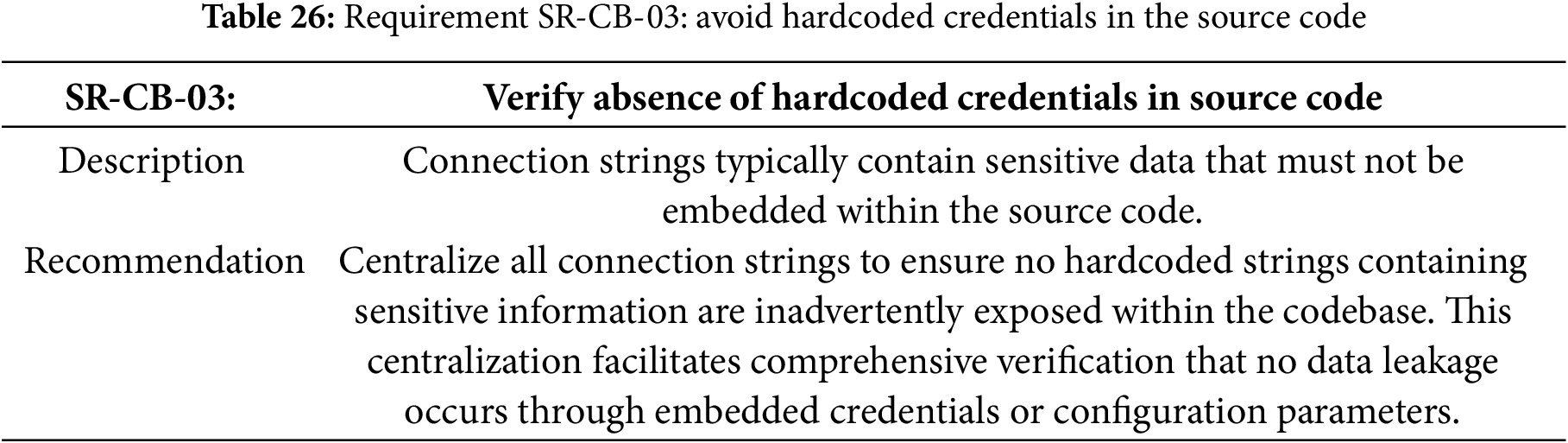

Table 26 specifies the requirement for the avoid hardcoded credentials in the source code.

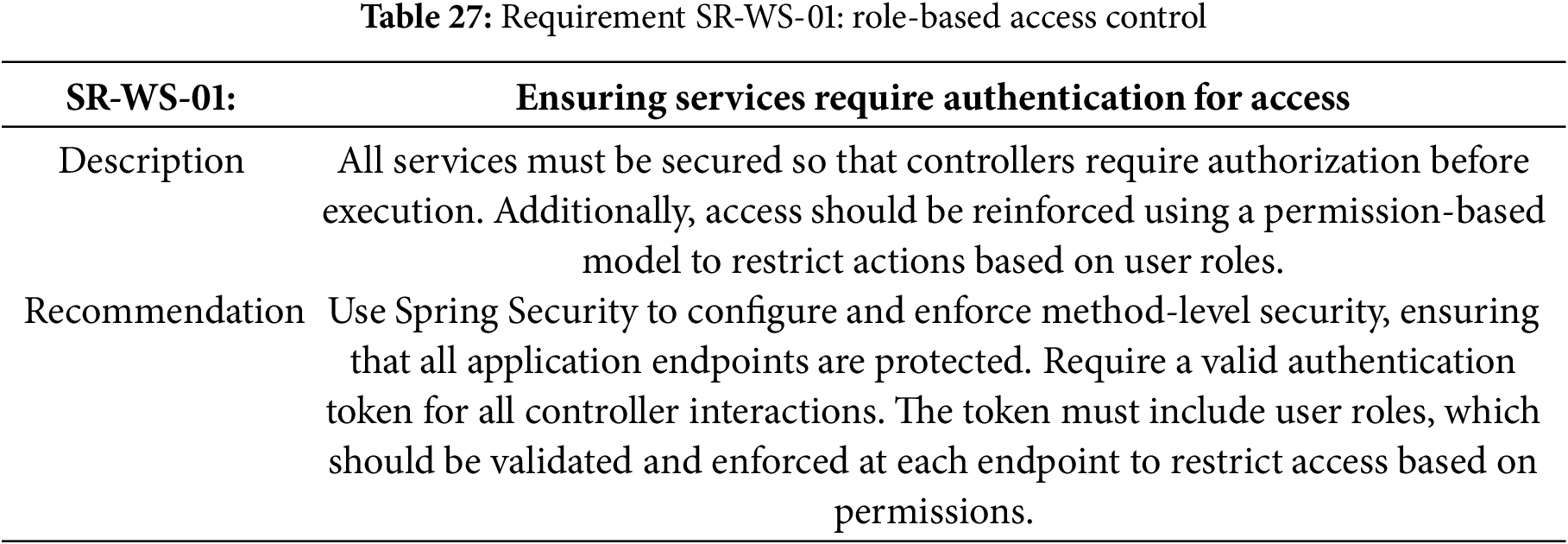

Table 27 specifies the requirement for the role-based access control.

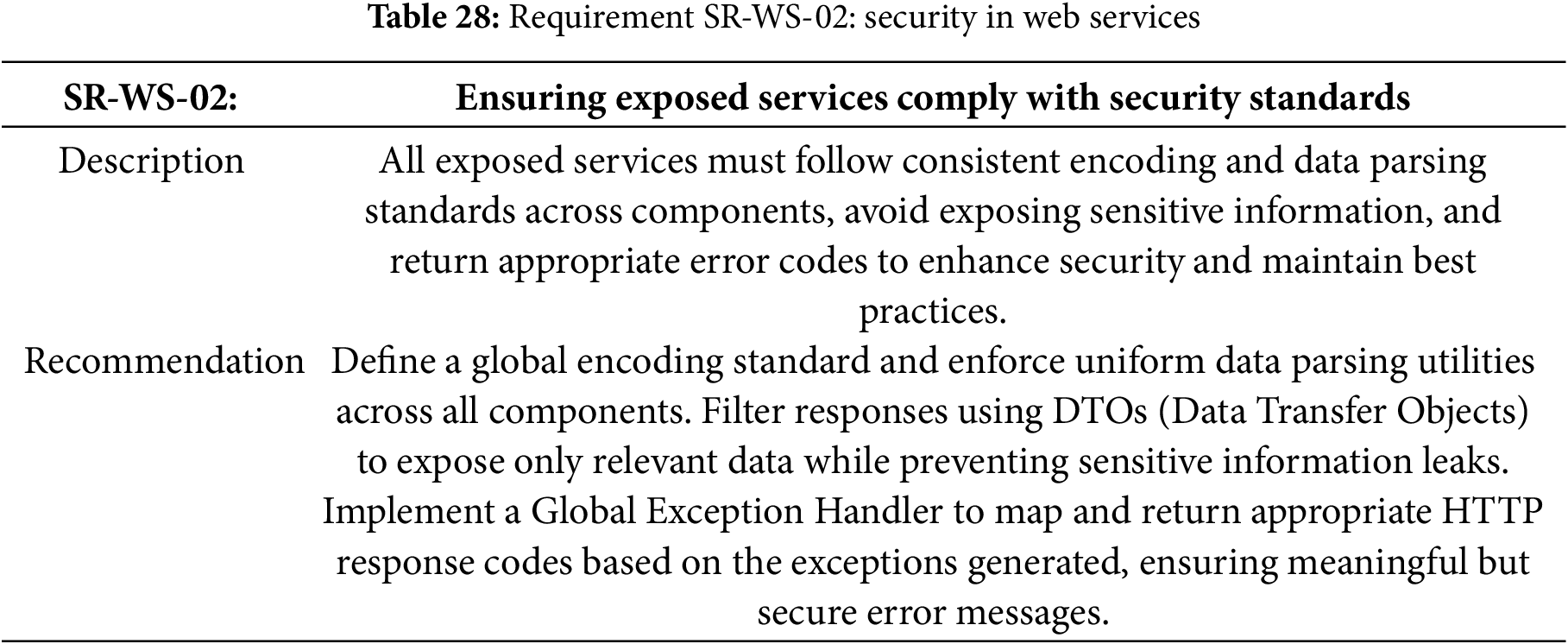

Table 28 specifies the requirement for the security in web services.

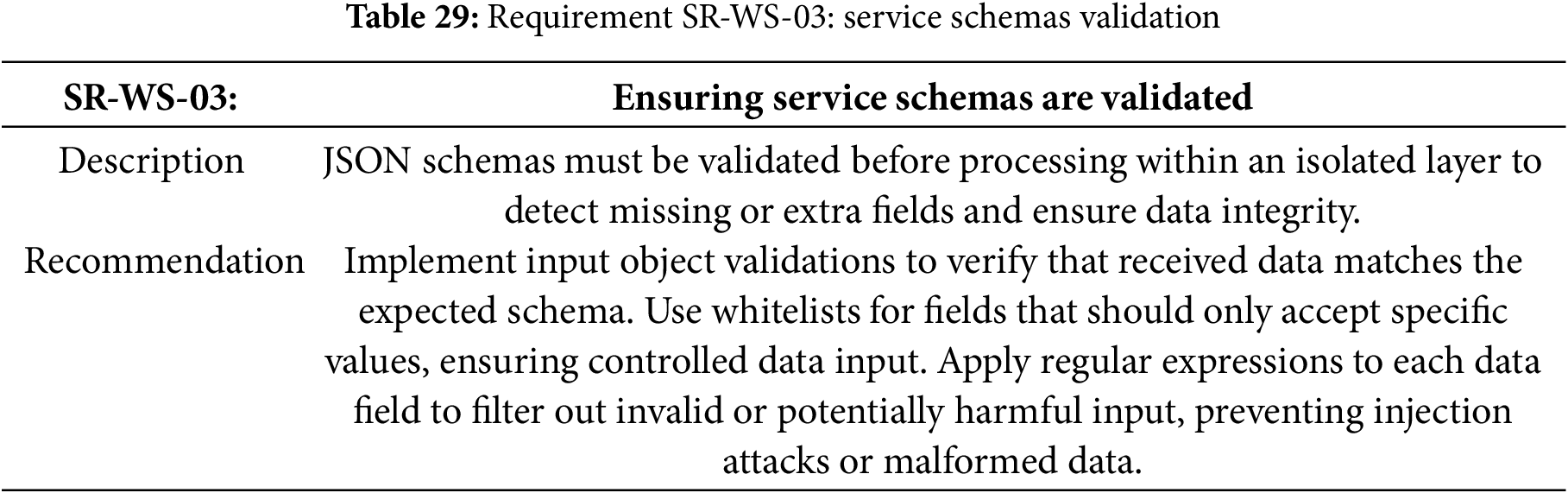

Table 29 specifies the requirement for the service schemas validation.

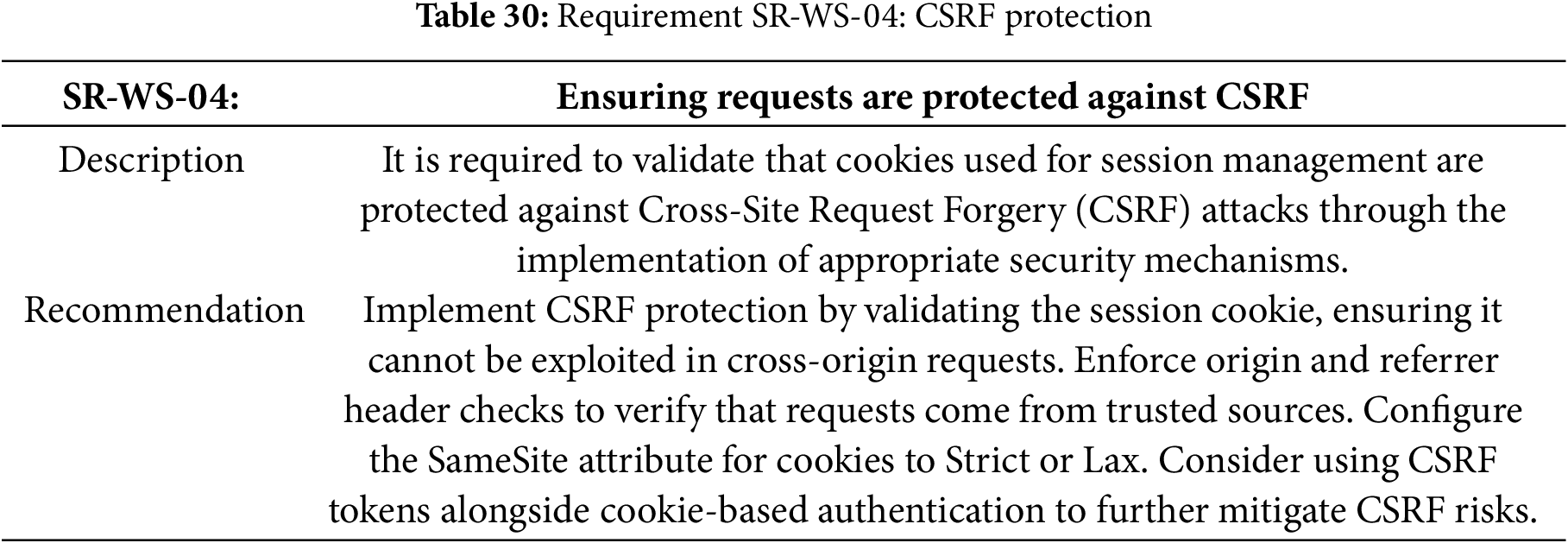

Table 30 specifies the requirement for the CSRF protection.

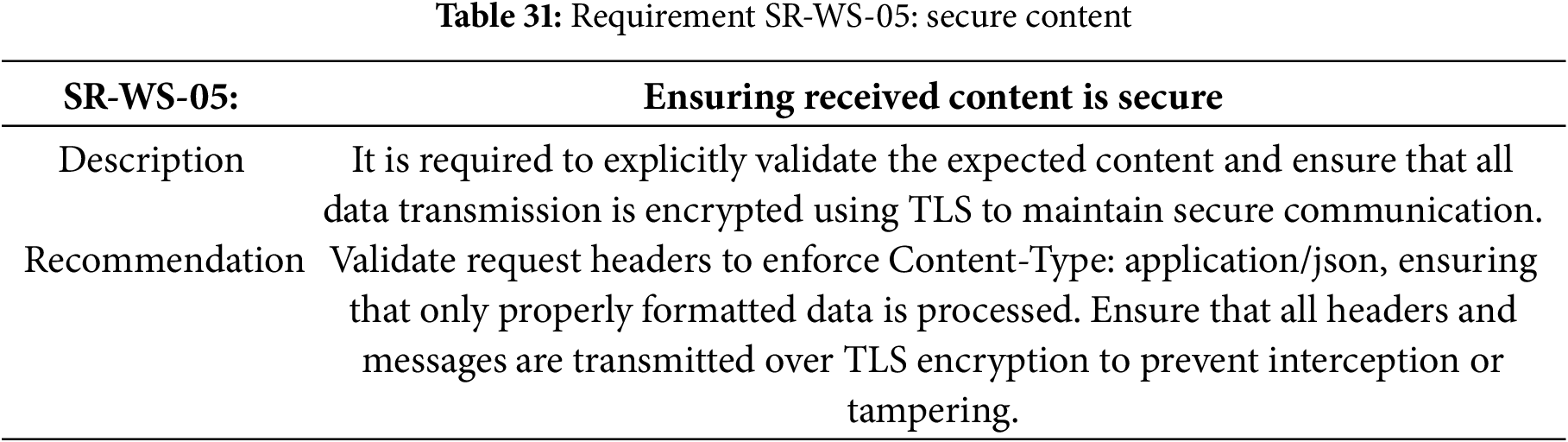

Table 31 specifies the requirement for the secure content.

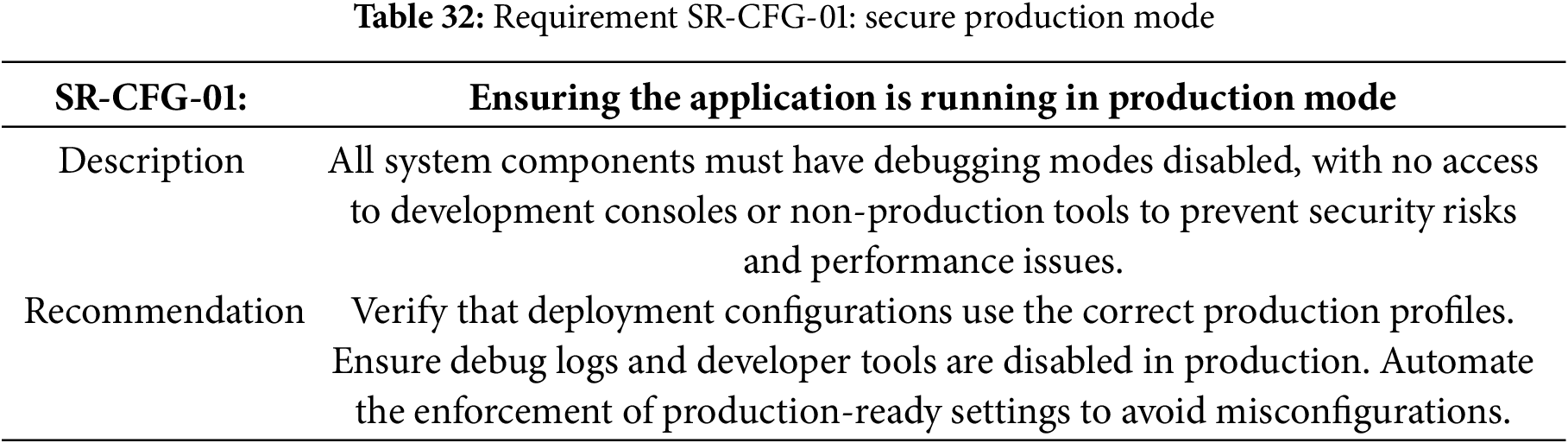

Table 32 specifies the requirement for the secure production mode.

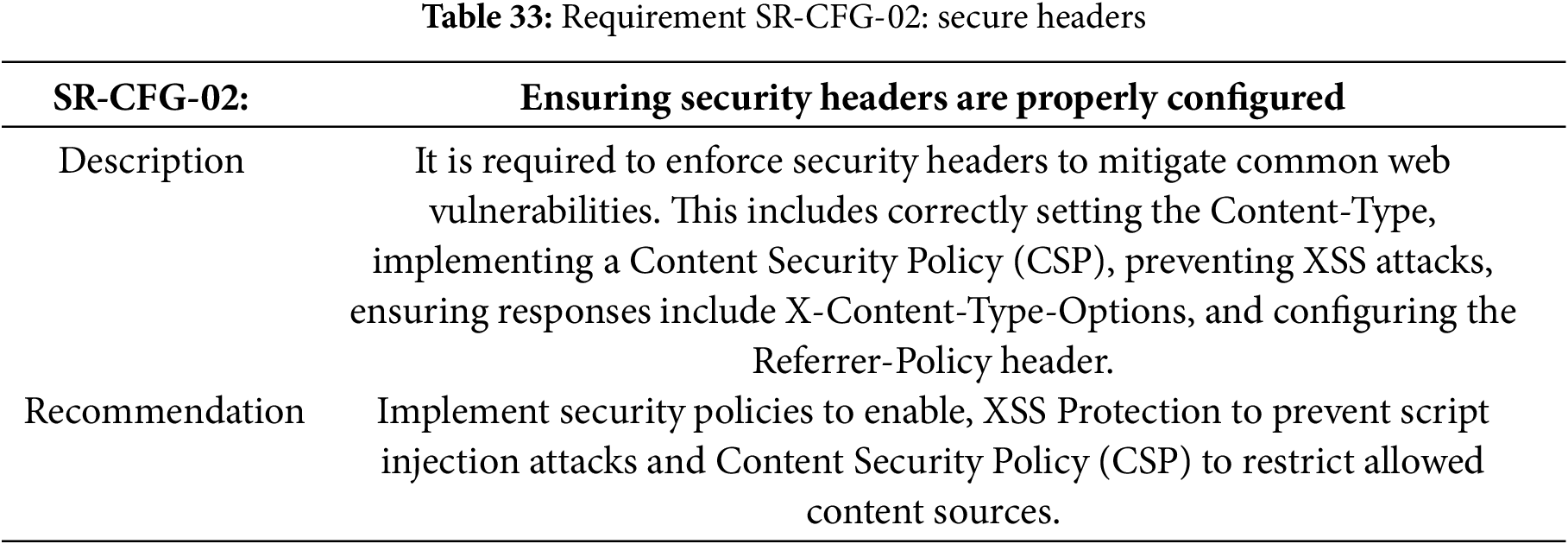

Table 33 specifies the requirement for the secure headers to add.

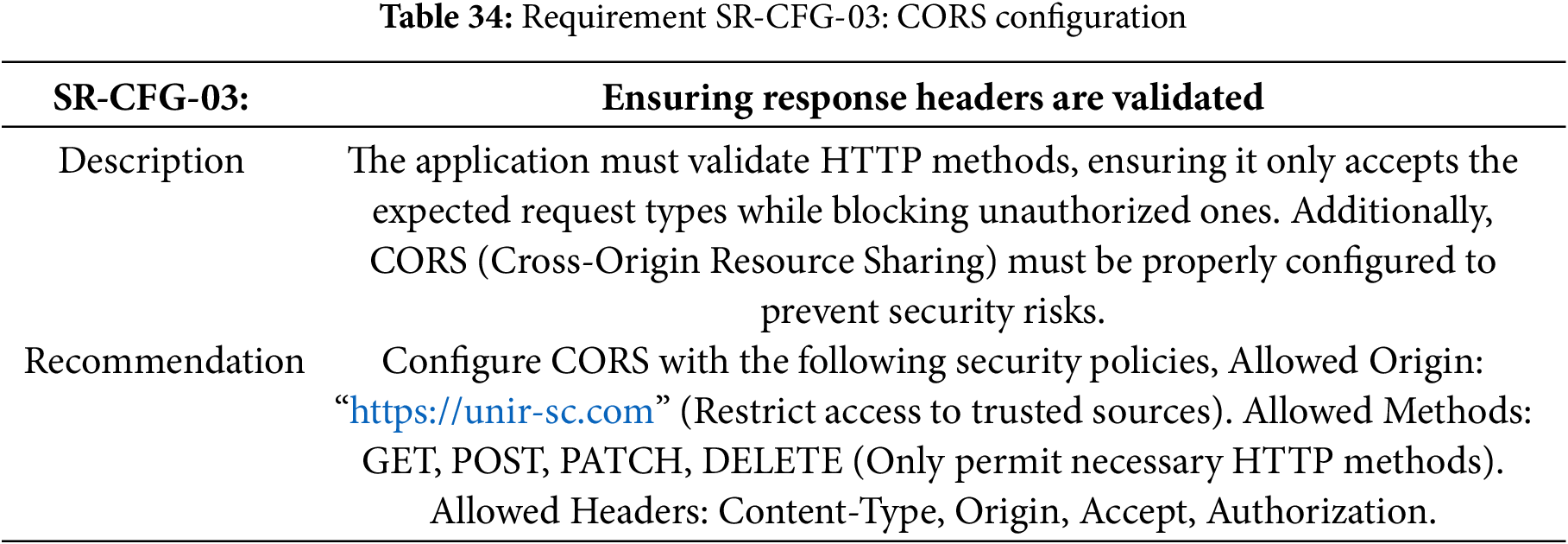

Table 34 specifies the requirement for the Cross Origin Resource Sharing (CORS) configuration.

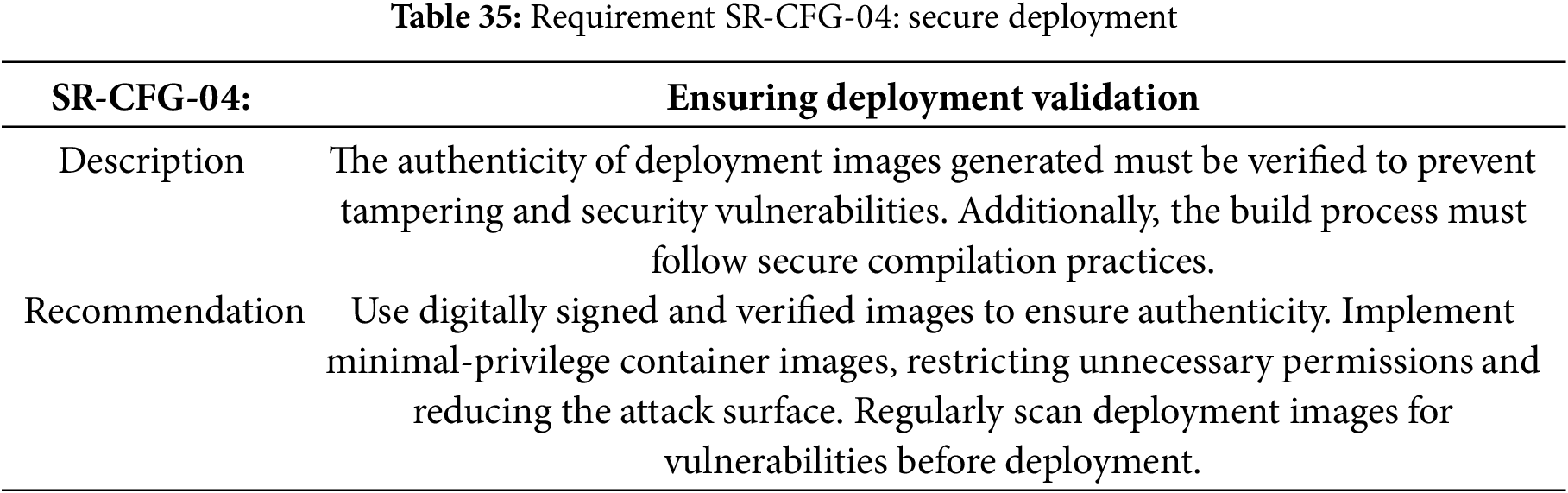

Table 35 specifies the requirement for the secure deployment.

Table 36 demonstrates the direct alignment between methodology requirements and GDPR provisions, enabling systematic compliance verification through technical implementation.

3.3 Implementation and Validation of the Methodology

In this section, the development process of the proof of concept (PoC) implementation is detailed. The primary objective was to validate the proposed security requirements through practical application and testing scenarios. The decision to proceed with this approach was driven by the need to effectively test and validate the proposed security requirements in a real-world environment.

The selection of this methodology allows for a thorough validation of the proposed framework and its underlying principles. To build an effective proof of concept, it was determined that developing a web application would be the most suitable approach. This web application needed to incorporate at least the minimal functional requirements necessary to enable the implementation and testing of the non-functional requirements described in the previous section.

Given these considerations, the implementation of a ticket tracking application on Vue.js, Spring Boot, and MySQL architecture was proposed. This choice was strategic, as ticket management systems typically require robust security measures while maintaining user-friendly interfaces. Such an application provides an ideal testing ground for the security requirements, offering practical utility that closely mirrors real-world business needs and challenges.

The suggested application shall implement:

• Different screens for various functionalities.

• Management of multiple users with specific roles.

• Access restriction levels to information based on user roles.

• Main functionality for ticket management.

• Ability to generate and assign reports to support staff.

If implementation is required, the project repository can be found at the following URL. https://gitlab.com/paper_project/secure_development_methodology (accessed on 11 July 2025). with the following commit hash 1620f6e028c079f82ec54a54ab613f827946964b.

Authentication Process

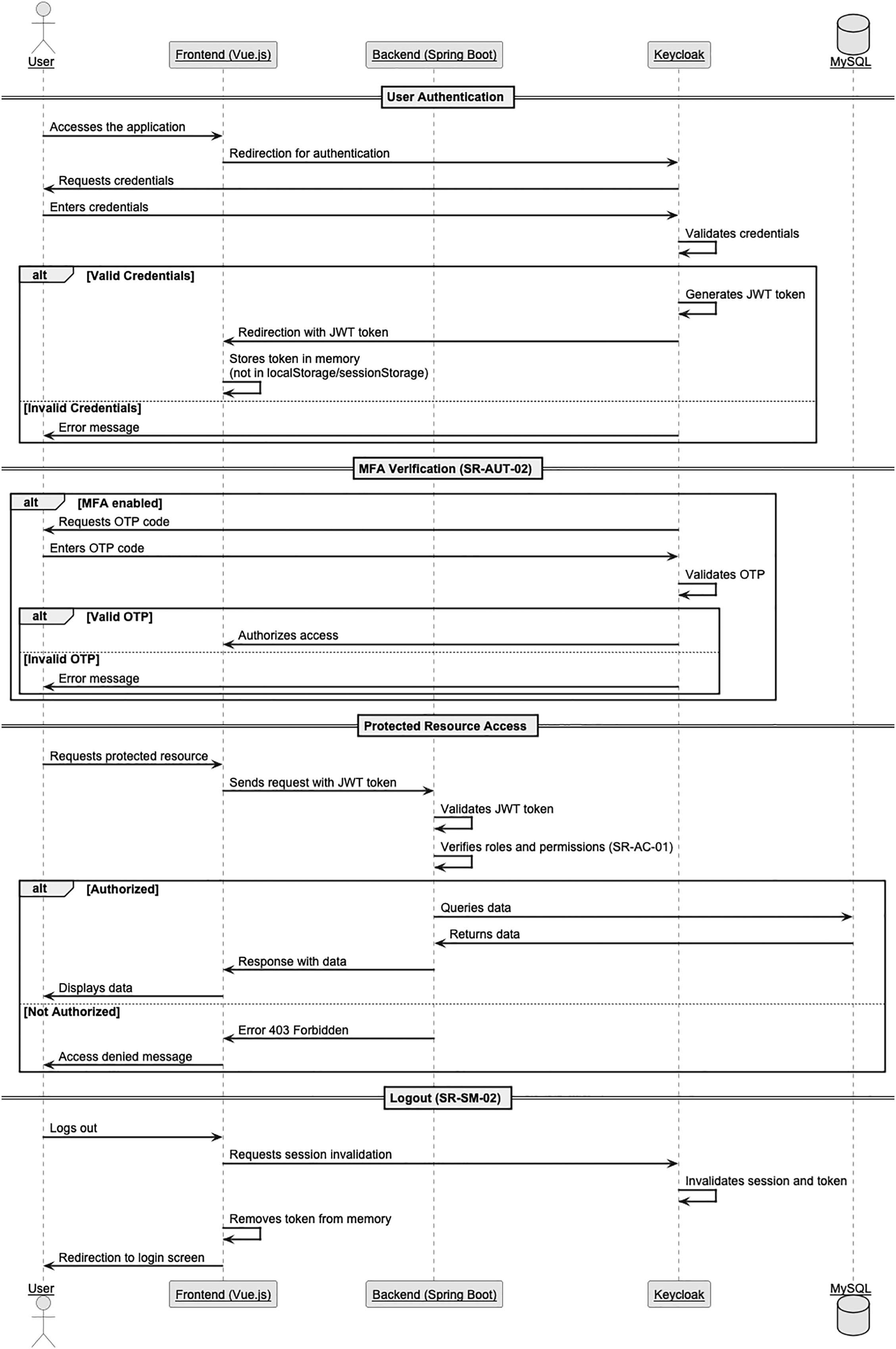

This sequence diagram illustrates the comprehensive authentication and session management process implemented in our secure web application using Keycloak as the identity provider (see Fig. 1). The workflow begins when a user accesses the application, triggering a secure authentication flow where credentials are validated against Keycloak’s secure user store. For enhanced security, the system implements Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA) through One-Time Password (OTP) verification when enabled, adding an additional layer of protection. Once authenticated, the application employs JWT tokens stored exclusively in memory (never in localStorage or sessionStorage) to prevent XSS vulnerabilities. When accessing protected resources, the system performs robust role-based authorization checks (SR-AC-01) before permitting data retrieval from the MySQL database. The diagram also demonstrates the secure session termination process (SR-SM-02), where logging out triggers proper token invalidation in Keycloak and complete removal of authentication data from memory, ensuring no session remnants can be exploited. This implementation aligns with industry best practices for secure authentication flows and session management in modern web applications.

Figure 1: Keycloak authentication

Use Case—Report Generation

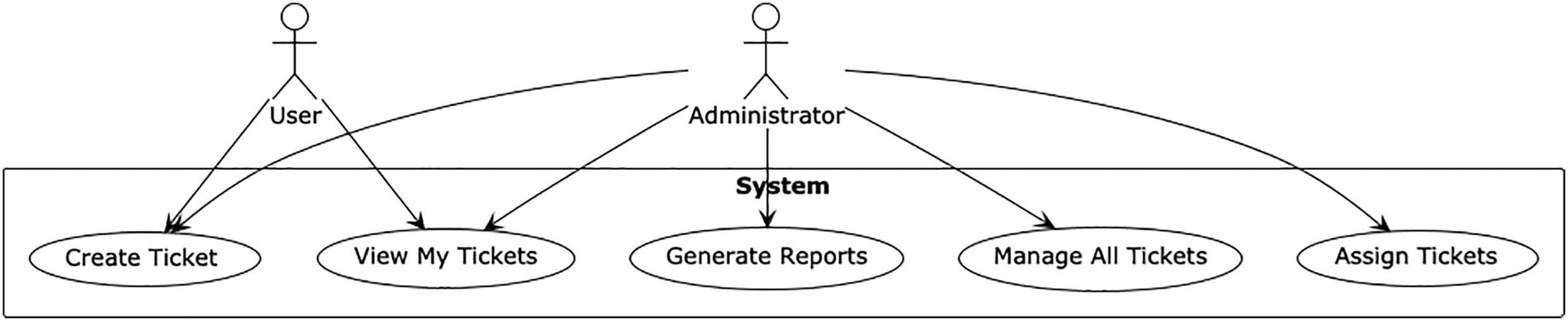

In the proposed ticket management system implements a role-based access control architecture with three distinct user levels, as shown in Fig. 2. Regular users can create and track their own support tickets, providing detailed descriptions of issues and monitoring resolution progress. Administrators have comprehensive system oversight, including the ability to assign tickets to appropriate support staff and manage user accounts. Support personnel focus exclusively on resolving their assigned tickets, updating status and providing solutions within their designated workload. This hierarchical structure ensures clear accountability, prevents unauthorized access to sensitive operations, and maintains an efficient workflow from initial ticket submission through final resolution. The system’s design promotes scalability while maintaining security boundaries between different organizational roles.

Figure 2: Use case of the proposed system

System Architecture

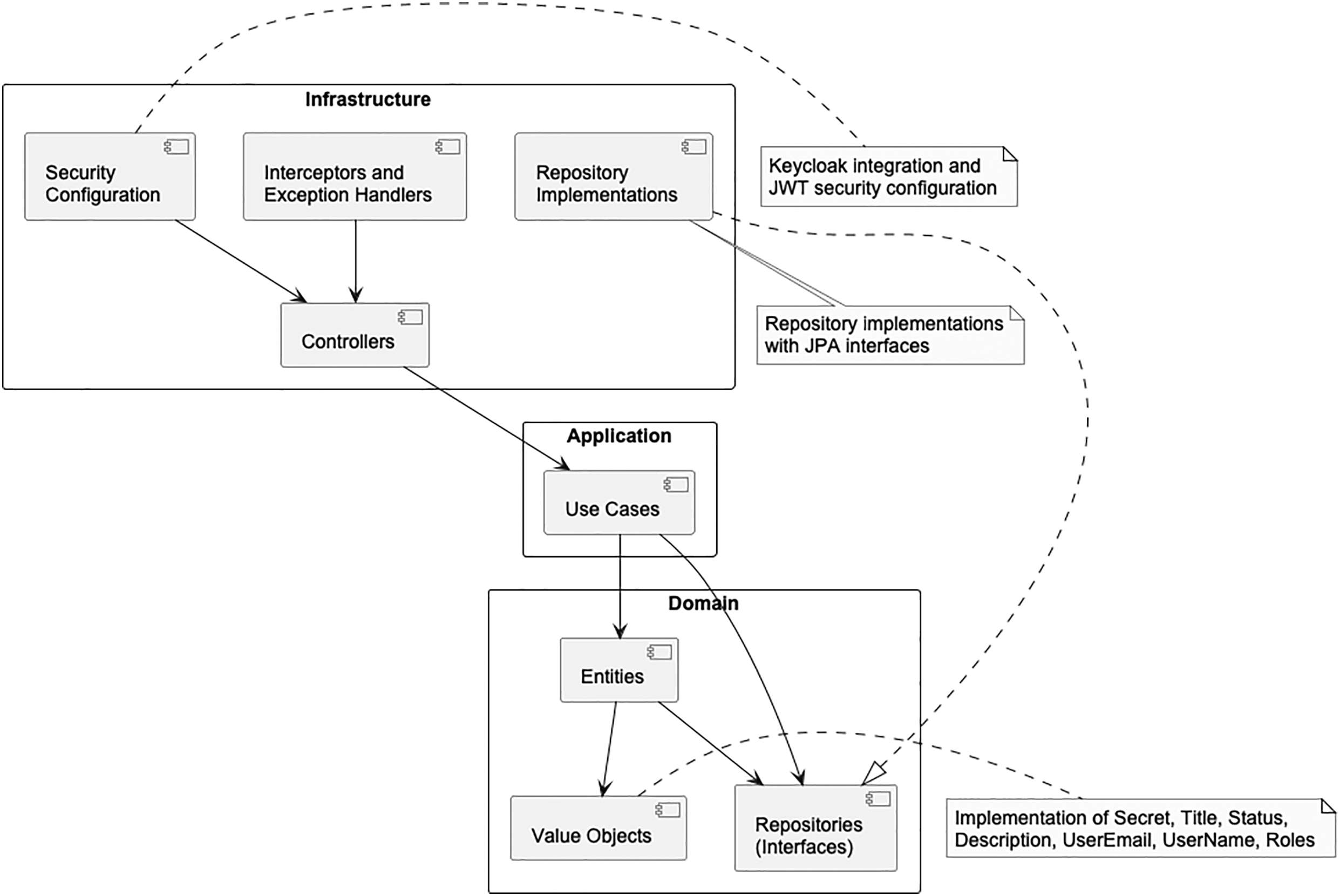

The diagram presented in Fig. 3 illustrates the implementation of Clean Architecture integrated with Domain-Driven Design (DDD) principles, establishing an organizational structure that ensures separation of concerns and isolation of business rules. The system architecture for the ticket management proof of concept consists of four main components, each operating independently to support specific business logic tasks, resulting in a distributed system.

Figure 3: Components diagram for the proposed system

The architecture is divided into three concentric layers: the Domain layer at the core, containing Entities, Value Objects, and Repository interfaces that define the essential behavior of the system; the Application layer, which implements Use Cases that orchestrate the flow of business logic; and the Infrastructure layer, which houses technical components. This latter layer includes the User Interface developed with Vue.js, providing an interactive interface; the Business Logic (Backend) implemented in Spring Boot, managing application logic and handling frontend requests; the Persistence Component using MySQL for storing and managing data; and the Authentication and Security System based on Keycloak, handling authentication and user management.

To achieve system decoupling and simplify deployment, Docker was used to create an image for each component. Using component images enhances security across different development phases, such as release and testing stages. During the deployment phase, each component utilizes Nginx configured as a reverse proxy, designed to effectively route requests to the various components being managed by Docker. The reverse proxies contain the path where SSL certificates are hosted, which are managed by Certbot. This architectural organization ensures that dependencies always point inward, allowing the domain to remain completely independent of technical details.

3.3.2 Security Requirements Implementation for VUE, Spring, MySQL Architecture

Authentication

Requirement SR-AUT-01 Password Security Verification implementation

The implementation addresses Table 1 by leveraging Keycloak’s robust identity and access management capabilities for both Vue frontend and Spring Security backend.

The solution delegates password security verification to Keycloak’s built-in security policies, which are configured to enforce:

• Minimum password length requirements;

• Character complexity rules (uppercase, lowercase, numbers, special characters);

• Real-time validation feedback to users during password creation.

Requirement SR-AUT-02 Multi-Factor Authentication (OTP) Implementation

The implementation is addressed Table 2. It is configured directly in Keycloak’s graphical interface, which serves as the authentication service. Multi-factor authentication with OTP is enabled through Keycloak’s administration console by activating:

• OTP policies using HMAC-SHA1 algorithm;

• Mandatory two-factor authentication in the authentication flow;

• Time-based OTP (TOTP) with 30-s validity.

Keycloak manages the entire process of OTP generation, validation, and delivery as an external service without requiring additional development.

Requirement SR-AUT-03 User Credential Management Implementation

The implementation addresses Table 3: It fully delegates credential management to Keycloak as a centralized IAM (Identity and Access Management) service.

The application does not store credentials in its own database, with Keycloak handling:

• Password storage using PBKDF2/SHA-256 hashing with unique salt per user;

• Security policy management (length, complexity, history);

• Automatic secure credential generation and storage.

All credential-related operations (authentication, updates, recovery) are exclusively managed by Keycloak as a specialized external service.

Session Management

Requirement SR-SM-01: Session Token Management Implementation

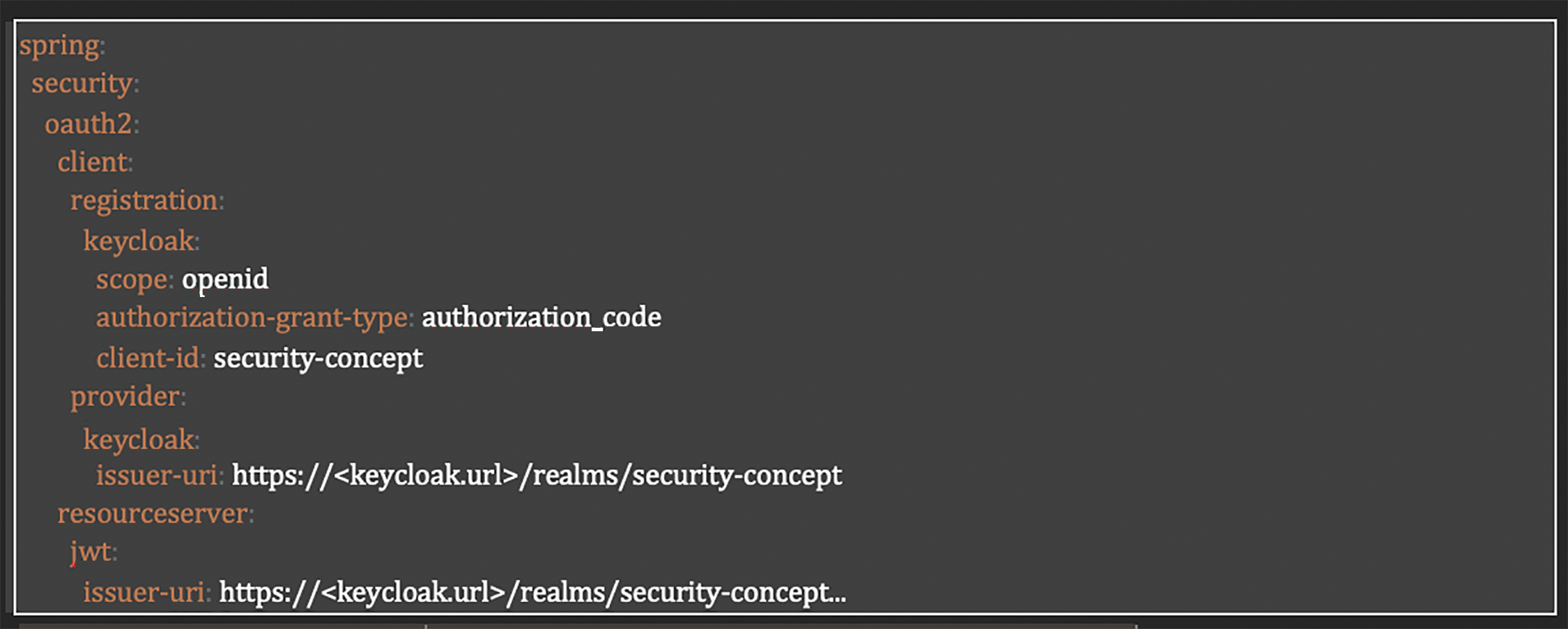

The implementation addresses Table 4 through the integration of Spring Security with Keycloak for session management. The configuration shown establishes a proper OAuth2/OIDC setup where:

• The Spring Security OAuth2 client is configured to use Keycloak as the identity provider.

• The authorization-grant-type: authorization_code ensures proper token exchange following secure authentication protocols.

• The JWT resource server configuration links to the same Keycloak realm, ensuring consistent token validation.

• The scope: OpenId parameter enforces standard OpenID Connect protocols for token management.

This configuration ensures that when a session is terminated (through expiration or logout), Keycloak’s token management automatically handles invalidation at the server level, preventing token reuse in accordance with SR-SM-02 requirements. The Spring Security framework respects these invalidation events and enforces them across the application, protecting against session hijacking attempts. Listing 1 shows the Keyloack integration with Spring Security.

Listing 1: Keycloak integration with Spring Security

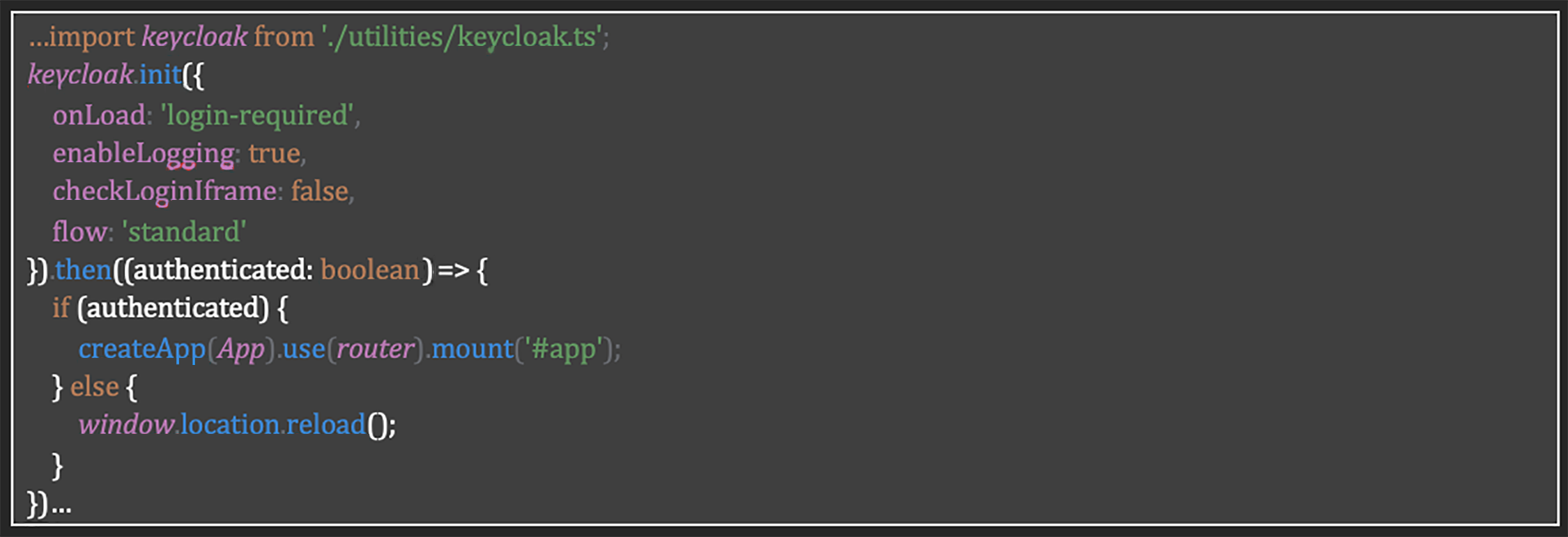

Requirement SR-SM-02: Session Token Invalidation Implementation

The implementation addresses Table 5 through the integration of Keycloak with the Vue application. As outlined in Table 37, requirement SR-SM-02 defines how session tokens must be invalidated upon expiration or logout. The code initializes Keycloak with the configuration onLoad: ‘login-required’ and flow: ‘standard’, which ensures that:

• Keycloak automatically manages the token lifecycle, including invalidation upon expiration

• The standard authentication flow implements the security mechanisms recommended by OpenID Connect

• When logging out, Keycloak invalidates the token on the server, preventing its reuse

• The configuration checkLoginIframe: false avoids potential security risks related to continuous validation in iframes.

Listing 2 shows this integrated approach. It ensures that sessions are properly invalidated according to security standards, preventing session hijacking attacks.

Listing 2: Keycloak integration and authentication flow in the Vue Application

Requirement SR-SM-03: Session Token Configuration Implementation

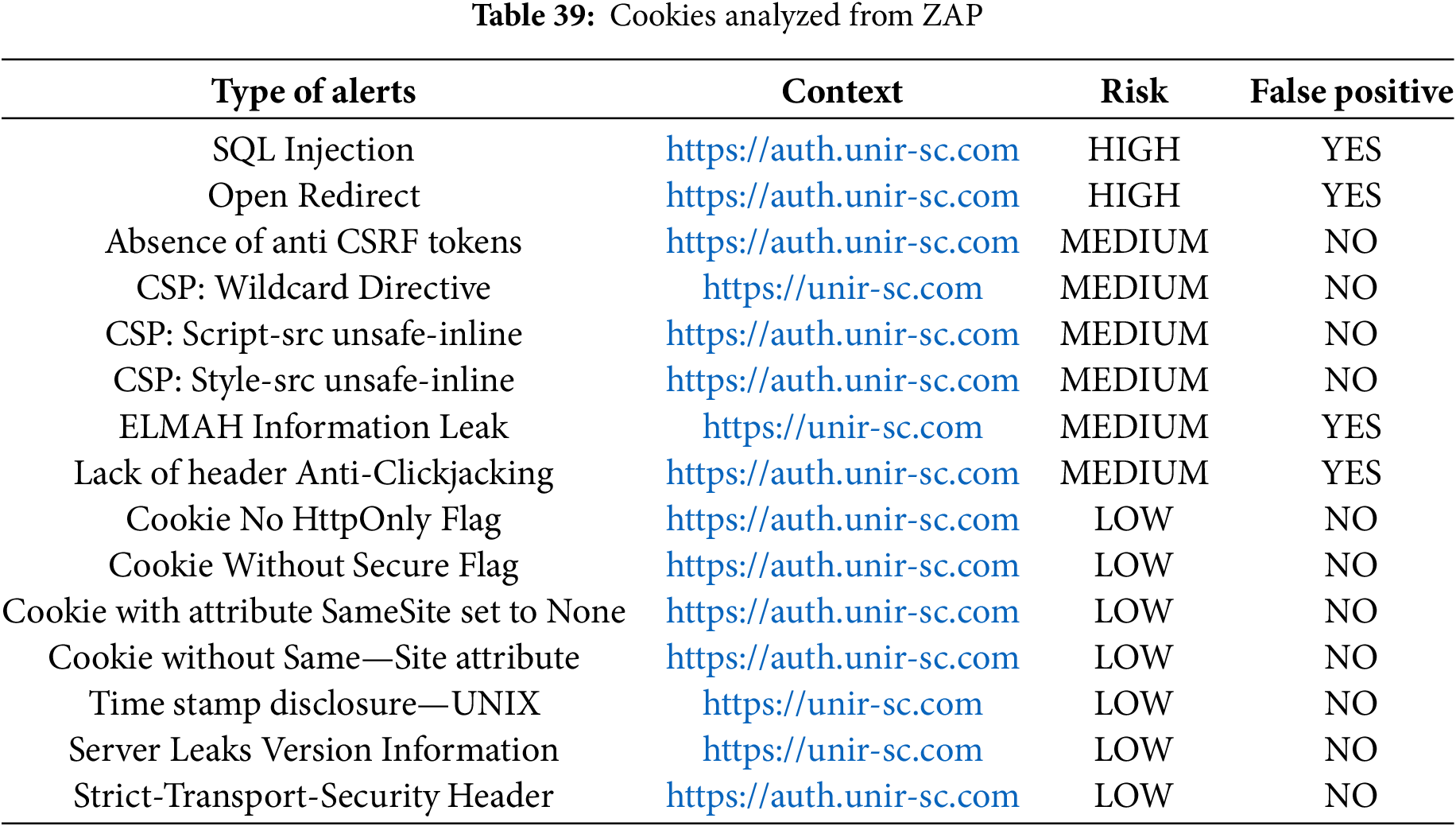

The implementation addresses Table 6 requisite by configuring Spring Security to use secure cookies for session management. The solution builds upon the OAuth2/OIDC setup already described in Table 38 (SR-SM-01) by adding specific cookie security properties.

The implementation secures session tokens by:

• Creating HTTP-only cookies that cannot be accessed via JavaScript, preventing XSS attacks;

• Setting the Secure flag to ensure cookies are only transmitted over HTTPS connections;

• Configuring SameSite = Strict to prevent cross-site request attacks;

• Integrating with the session invalidation mechanism described in Table 39 (SR-SM-02).

This configuration ensures that session tokens are properly protected throughout their lifecycle, from generation through transmission to invalidation, aligning with the security controls implemented for other authentication mechanisms in the system.

Access Control

Requirement SR-AC-01: Role-Based Access Implementation

The implementation addresses Table 7 requisite by applying method-level security through Spring Security’s @PreAuthorize annotations. This approach ensures that resources are only accessible to users with appropriate roles.

The solution implements role-based access control at multiple levels:

• Backend controllers restrict method execution to specific roles using Spring Security annotations;

• Role information is extracted directly from the JWT token, integrating with the token management described in Table 4 (SR-SM-01);

• Frontend components dynamically adjust their visibility based on user roles, leveraging the Vue application’s integration with Keycloak described in Table 5 (SR-SM-02).

This implementation follows the principle of the least privilege by ensuring that each endpoint and UI component explicitly checks for required roles before allowing access, creating a cohesive authorization system across both backend and frontend.

Listing 3 shows how to apply method-level security through Spring Security’s @PreAuthorize annotations.

Listing 3: Role-based access control implementation using Spring Security

Requirement SR-AC-02: CSRF Protection Implementation

The implementation addresses the CSRF protection requirement (Table 8) through Spring Security’s built-in CSRF defense mechanisms. The solution configures Spring Security to use a Cookie-based CSRF token repository that allows JavaScript access to the tokens.

This implementation ensures that all state-changing requests are protected against Cross-Site Request Forgery attacks. The system generates unique CSRF tokens that must be included in every non-GET request. The tokens are stored in cookies accessible to the frontend Vue application, which can retrieve and include them in subsequent requests.

Spring Security automatically validates these tokens on the server side for each request, rejecting any requests without valid tokens. This prevents malicious websites from tricking authenticated users into performing unwanted actions, as those external sites cannot access the CSRF token required to make valid requests. Listing 4 shows how to add CSRF token.

Listing 4: CSRF protection configuration using Spring Security with Cookie-based token repository

Validation, Satinization, Encoding

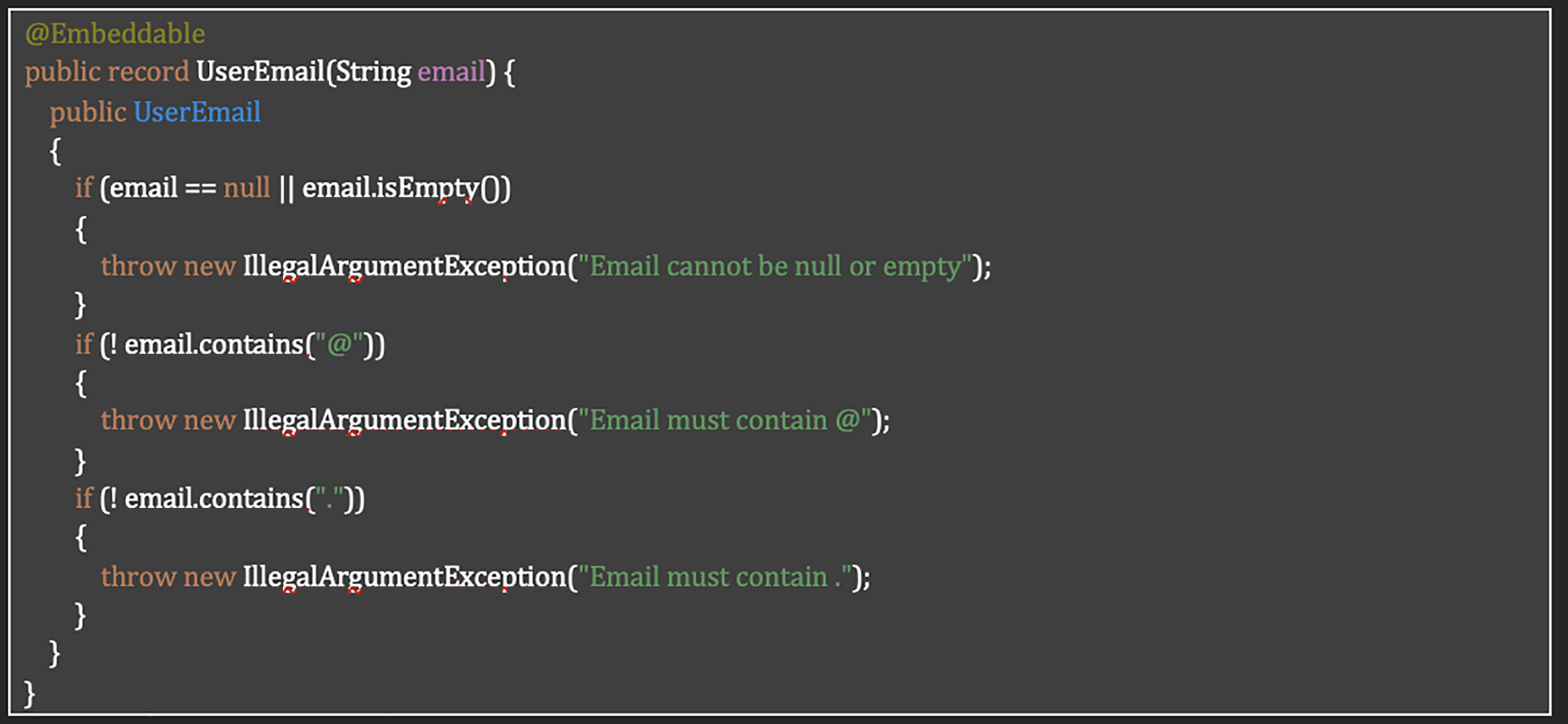

Requirement SR-VSE-01: Entry Points Protection Implementation

The implementation addresses Table 9 requisite through a robust domain validation approach using Java records with built-in validation logic. The UserEmail class is designed as an embeddable JPA component that enforces structural validation of email addresses before they can be used within the application.

This implementation satisfies the requirement by:

• Validating input structure through explicit checks (null/empty, presence of ‘@’ and ‘.’);

• Throwing exceptions for invalid data, preventing malformed inputs from entering the system;

• Using Java’s record feature to create immutable data objects that cannot be modified after validation;

• Leveraging JPA’s @Embeddable annotation to ensure validated objects are used consistently in entity mappings.

The approach implements the recommended input validation for incoming data objects, ensuring proper formatting and preventing HTTP parameter pollution attacks by rejecting any invalid or unexpected email formats before they can be processed by the application. Listing 5 shows Domain-level email validation using Java records and JPA embeddable components.

Listing 5: Domain-level email validation using Java records and JPA embeddable components

Requirement SR-VSE-02: Input Data Sanitation Implementation

The implementation of this requisite (Table 10) leverages Vue.js’s built-in security features for preventing malicious code execution. Vue automatically escapes HTML content in templates and interpolations, making it resistant to most XSS attacks by default.

The solution takes advantage of Vue’s key security mechanisms:

Vue’s template system automatically escapes HTML content when using double curly braces ({{ }}) for data binding, preventing injection of executable code.

For WYSIWYG editors and rich text input fields, the application employs Vue-compatible sanitization libraries that strip potentially dangerous HTML tags and attributes while preserving legitimate formatting.

All user-uploaded files are processed through validation pipelines that enforce strict MIME type checking and never directly execute or include uploaded content in sensitive contexts.

The implementation follows Vue’s security best practices by avoiding the use of dangerous directives like v-html with untrusted content, and when rich HTML rendering is required, content is pre-sanitized using dedicated libraries.

Server-side validation complements the frontend protections, ensuring that even if client-side validations are bypassed, malicious input is detected and neutralized before processing.

Requirement SR-VSE-03: Output Data Sanitation Implementation

The implementation addresses Table 11 requisite by leveraging Vue’s built-in output sanitization features. Vue automatically escapes all data interpolated through double curly braces ({{ }}), preventing XSS attacks without additional code. The application follows Vue’s security best practices by:

• Using Vue’s automatic HTML escaping for all dynamic content display

• Implementing Vue-i18n for proper localization that respects user regional settings

• Avoiding raw HTML rendering (v-html) with untrusted content

• Using content security policies to provide additional defense-in-depth

This approach ensures all output data is properly sanitized before rendering while maintaining appropriate localization based on user preferences, satisfying both security and usability requirements.

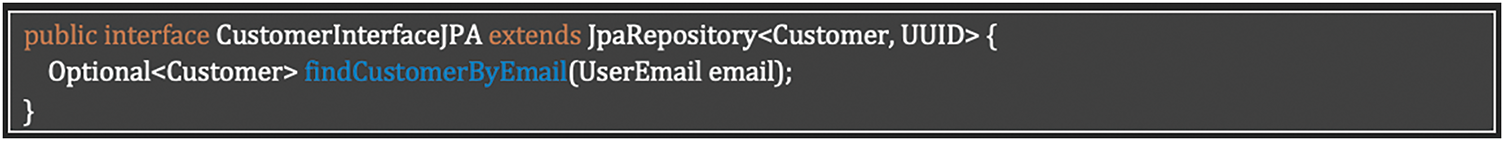

Requirement SR-DB-01: Data Queries Protection Implementation

The implementation satisfies Table 12 requisite by utilizing Spring Data JPA’s repository pattern. By extending JpaRepository, the interface automatically implements SQL injection protection through parameterized queries and Hibernate’s ORM capabilities. This approach eliminates direct query manipulation and ensures all database interactions—including the custom finder method—are secure by default, meeting the requirement for protected data queries without requiring manual query sanitization. Listing 6 shows how to secure data query handling using Spring data JPA and ORM-based injection prevention.

Listing 6: Secure data query handling using Spring data JPA and ORM-based injection prevention

Requirement SR-DB-02: Secure Database Connection Implementation

The implementation of this requisite (Table 13) utilizes Nginx as a reverse proxy to enforce secure database connections. Nginx is configured to act as a secure gateway, only allowing database connections from known and authorized URLs/IP addresses.

The solution implements multiple layers of security:

• Nginx reverse proxy restricts database access to only pre-approved application servers by IP filtering;

• All database connections are forced through TLS/SSL encryption;

• The MySQL database is configured to reject non-encrypted connection attempts;

• Database user accounts operate with minimal required privileges following least privilege principles;

• A dedicated non-root database service account is used for running the MySQL instance;

The Nginx configuration limits MySQL traffic to specific known sources “whitelisted”, functioning as an additional security layer beyond MySQL’s native access controls. Listing 7 shows how to Secure database access via Nginx Reverse Proxy with IP whitelisting and TLS enforcement.

Listing 7: Securing database access via Nginx Reverse Proxy with IP whitelisting and TLS enforcement

Stored Cryptography

Requirement SR-SC-01: Classifying Information Implementation

The implementation addresses Table 14 requisite by configuring MySQL with transparent data encryption through the keyring_file plugin. This command-line configuration enables database-level encryption for sensitive data, implementing server-side protection for stored information. By setting up the keyring file storage location and enabling native password authentication, the system ensures that sensitive information is automatically encrypted at rest without requiring application-level changes. This approach satisfies the requirement for applying appropriate encryption mechanisms to protect classified information from unauthorized access. Listing 8 shows how configuring MYsql with Transparent data encryption in MySQL using keyring file plugin.

Listing 8: Transparent data encryption in MySQL using keyring file plugin

Requirement SR-SC-02: Cryptographic Modules Implementation

The implementation of this requisite (Table 15) delegates core cryptographic operations to Keycloak as the primary identity and access management solution. For user authentication and credential management, Keycloak handles all sensitive cryptographic operations using industry-standard algorithms.

For application-specific cryptographic needs outside of identity management, the system leverages Spring Security’s built-in cryptographic modules:

• Password encoding utilizes Spring Security’s BCryptPasswordEncoder for any local password handling requirements, with configurable work factor to balance security and performance;

• Secure random data generation is implemented through Java’s SecureRandom class as recommended by Spring Security, ensuring cryptographically strong entropy for tokens and keys.

While Keycloak manages the majority of security-critical operations, these Spring Security cryptographic modules provide robust protection for application-specific security requirements, ensuring the use of modern, secure cryptographic standards throughout the system.

Requirement SR-SC-03: Secure Storage of Keys Implementation

The implementation of this requisite (Table 16) addresses the secure storage of keys by leveraging Keycloak as the dedicated security module for credential and key management. This approach ensures that no sensitive credentials or keys are stored within the application itself.

Keycloak provides a robust key management system that handles the secure storage of all cryptographic materials, including OAuth tokens, signing keys, and encryption keys. The application retrieves necessary authentication tokens at runtime through secure OAuth/OIDC flows, never directly accessing or storing the underlying cryptographic keys.

For application-specific secrets (such as API keys and database credentials), the system uses environment variables supplied at runtime through the deployment pipeline, completely avoiding hardcoded secrets in the codebase or configuration files.

This implementation fully satisfies the requirement by ensuring all sensitive keys remain within specialized secure storage solutions and are never exposed to the application layer.

Error Handling and Logging

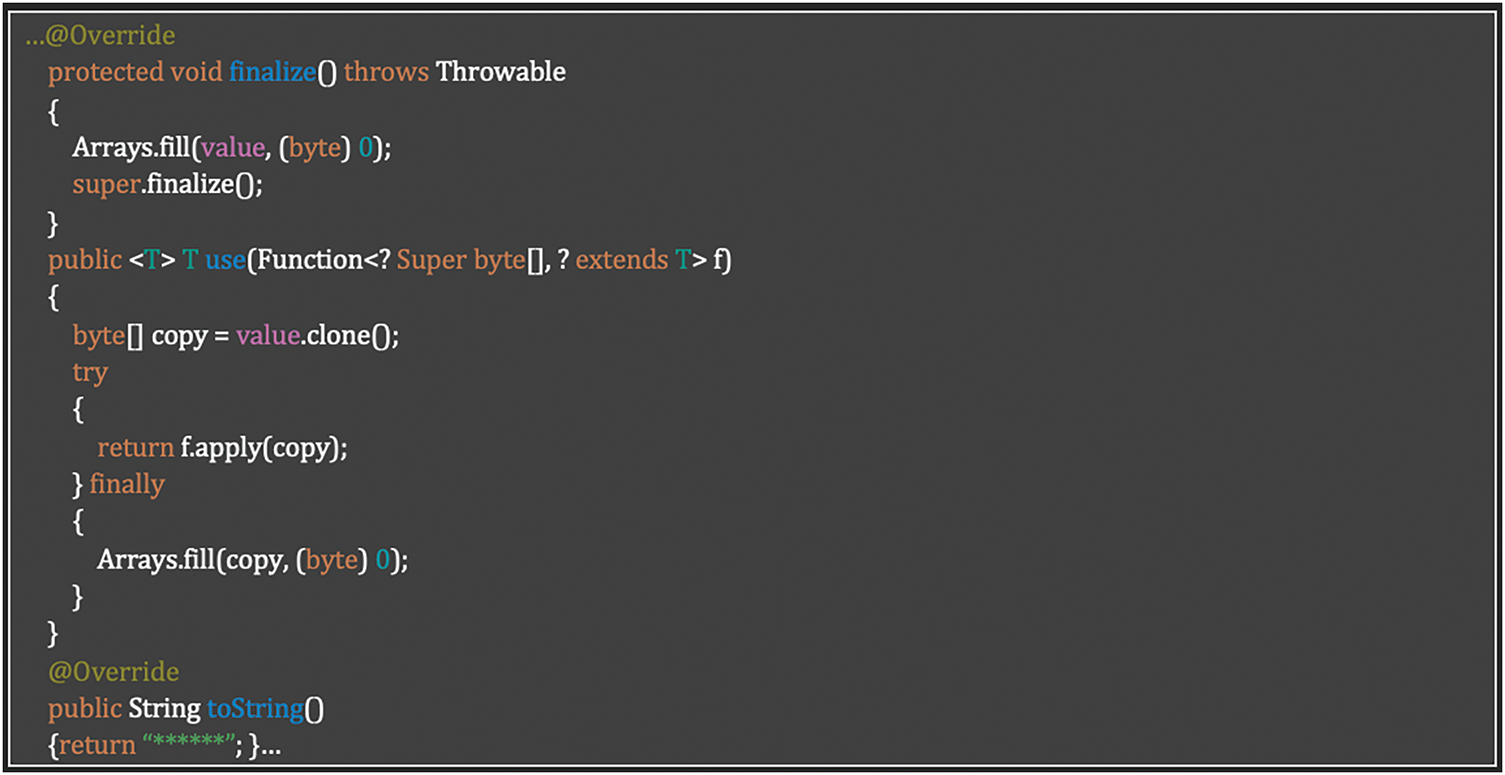

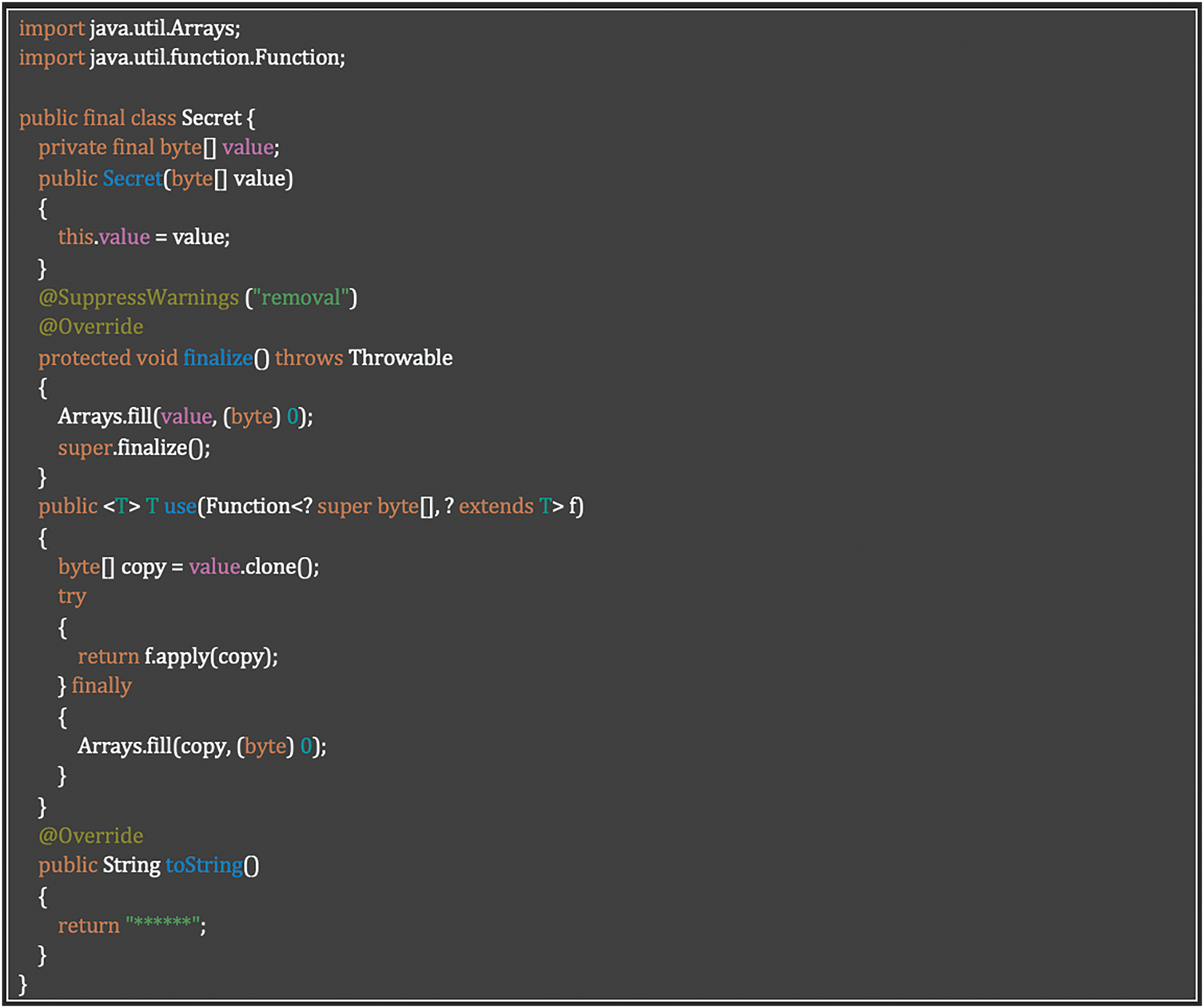

Requirement SR-EHL-01: Secured Logging Implementation

The implementation satisfies Table 17 requisite through a security-focused class that prevents sensitive data exposure in logs. By overriding toString() to return only masked content (“******”) and implementing secure memory handling, the code ensures sensitive information is never inadvertently logged. This implementation directly addresses the requirement to protect sensitive data while maintaining useful application logs. Listing 9 shows how to Prevent sensitive data exposure through secure logging and memory handling.

Listing 9: Preventing sensitive data exposure through secure logging and memory handling

Requirement SR-EHL-02: Synchronized Timestamps Implementation

The implementation satisfies Table 18 requisite by utilizing Java’s Instant class, which represents a precise moment on the UTC timeline. By storing timestamps as Instant objects in the database (marked as non-nullable), the application ensures all event timestamps are consistently recorded in UTC regardless of server location or local settings.

This approach provides several key benefits:

• Eliminates timezone ambiguity in logged events;

• Ensures timestamp consistency across distributed systems;

• Simplifies server migrations across different regions;

• Facilitates accurate chronological sorting and comparison.

When displaying timestamps to users, the application can convert these UTC instants to local time zones as needed, balancing backend consistency with frontend usability. This implementation directly addresses the requirement for synchronized timestamps while maintaining flexibility for user-friendly time representation. Listing 10 shows UTC-based timestamp management using Java instant for consistent event logging.

Listing 10: UTC-based timestamp management using Java instant for consistent event logging

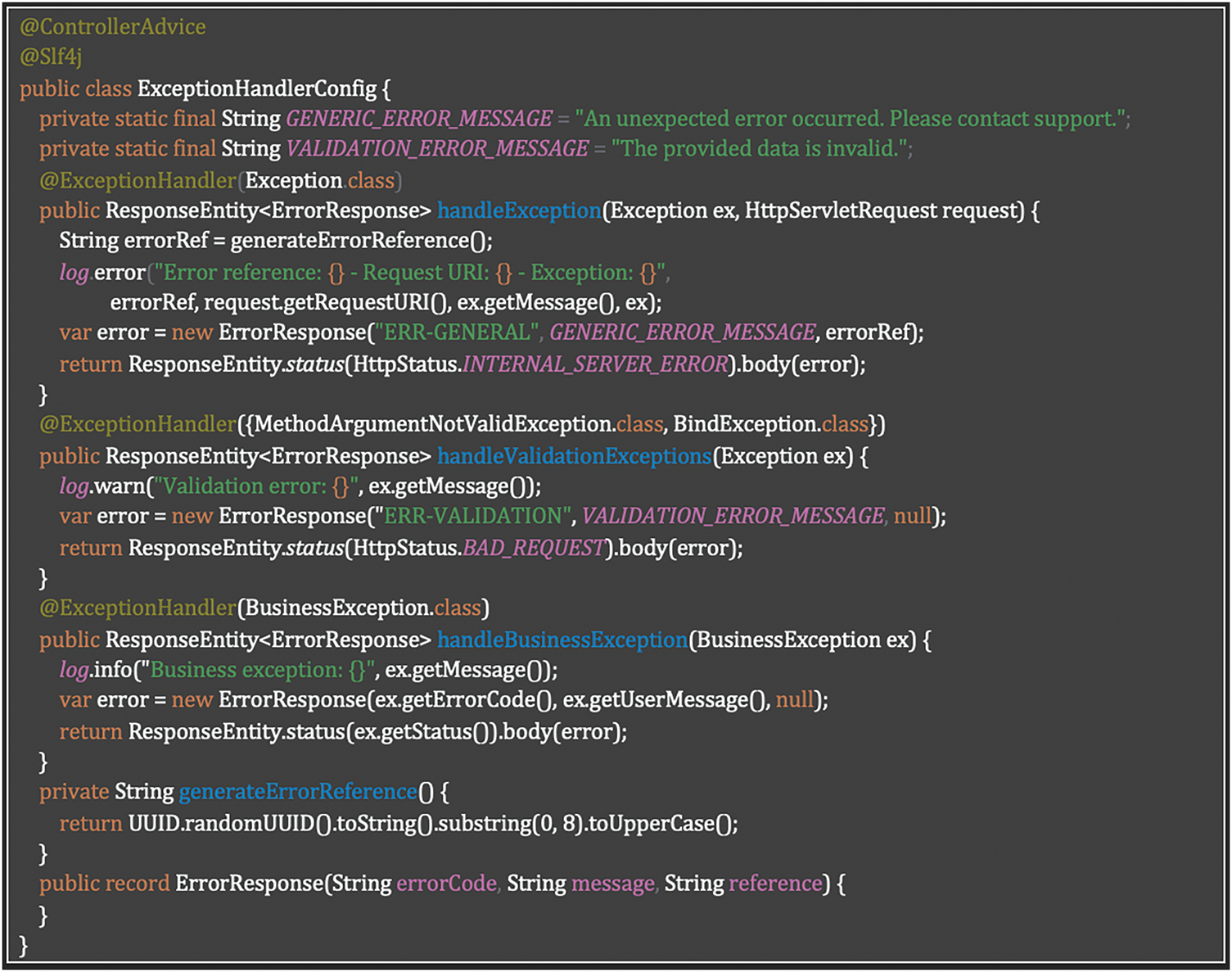

Requirement SR-EHL-03: Appropriate Error Messages Implementation

The implementation addresses Table 19 requisite by establishing a centralized exception handling system using Spring’s @ControllerAdvice. It categorizes exceptions into three types (unexpected, validation, and business) with distinct handling strategies for each. The system generates unique error references for unexpected exceptions, enabling support teams to trace issues while exposing only generic messages to users. Detailed error information including stack traces is logged internally but never revealed in responses. This approach balances security with usability by providing appropriate feedback based on error type while ensuring sensitive implementation details remain protected. Listing 11 shows Centralized exception handling with @ControllerAdvice for secure and structured error management.

Listing 11: Centralized exception handling with @ControllerAdvice for secure and structured error managements

Data Protection

Requirement SR-DP-01: Client-Side Information Protection Implementation

The implementation of this requisite (Table 20) uses Keycloak JavaScript adapter (keycloak-js v24.0.4) to protect client-side information in the Vue application. The configuration:

• Stores authentication tokens in memory only, not in localStorage or sessionStorage;

• Uses standard Authorization Code flow to prevent token exposure in URLs;

• Requires authentication before mounting the application;

• Automatically clears all tokens upon logout or session expiration.

These measures ensure no sensitive information persists in browser storage or the DOM, satisfying the requirement for client-side information protection. Listing 12 shows how to Secure frontend sessions with Keycloak-JS and authorization code flow in Vue.

Listing 12: Securing frontend sessions with Keycloak-JS and authorization code flow in Vue

Requirement SR-DP-02: Sensitive Information Protection Implement

The implementation addresses Table 21 requisite through Spring’s comprehensive security features:

• All sensitive data transmission occurs over TLS/HTTPS, enforced through Spring Security configuration as detailed in Table 23 (SR-COM-02)

• Sensitive data objects implement memory-clearing techniques similar to those shown in Table 17 (SR-EHL-01), automatically overwriting data when no longer needed

• Access to sensitive information is tracked through AOP-based logging aspects that record details in a secure audit log, aligning with the logging requirements in Table 17 (SR-EHL-01)

• Database interactions for sensitive fields leverage the encryption capabilities configured in Table 14 (SR-SC-01), ensuring data is protected at rest

This implementation ensures sensitive information is encrypted during transmission, properly cleared when no longer needed, and all access is logged for audit purposes.

Communication

Requirement SR-COM-01: Secure Client-Originated Communication Implementation

The implementation addresses Table 22 requisite through Certbot’s automated TLS certificate management integrated with an Nginx reverse proxy. This configuration enforces TLS 1.2/1.3 exclusively while blocking older protocols. The reverse proxy acts as a security layer, handling certificate termination and implementing strict cipher policies. All client traffic passes through this proxy, ensuring encryption, proper redirection from HTTP to HTTPS, and HSTS enforcement—creating a robust security barrier that protects communications from interception or tampering.

Requirement SR-COM-02: Secure Server-Originated Communication Implementation

The implementation addresses Table 23 requisite by configuring Spring Security to enforce TLS for all server-originated communications. The system uses trusted CA-issued certificates for external APIs and mutual TLS authentication for internal service communication. All microservices are configured to reject non-encrypted connections, with automatic TLS failure logging to a centralized monitoring system. The implementation applies consistent security policies across all environments through infrastructure-as-code, ensuring that development, staging, and production maintain identical TLS configurations.

Code Base

Requirement SR-CB-01: Defensive Programming Implementation

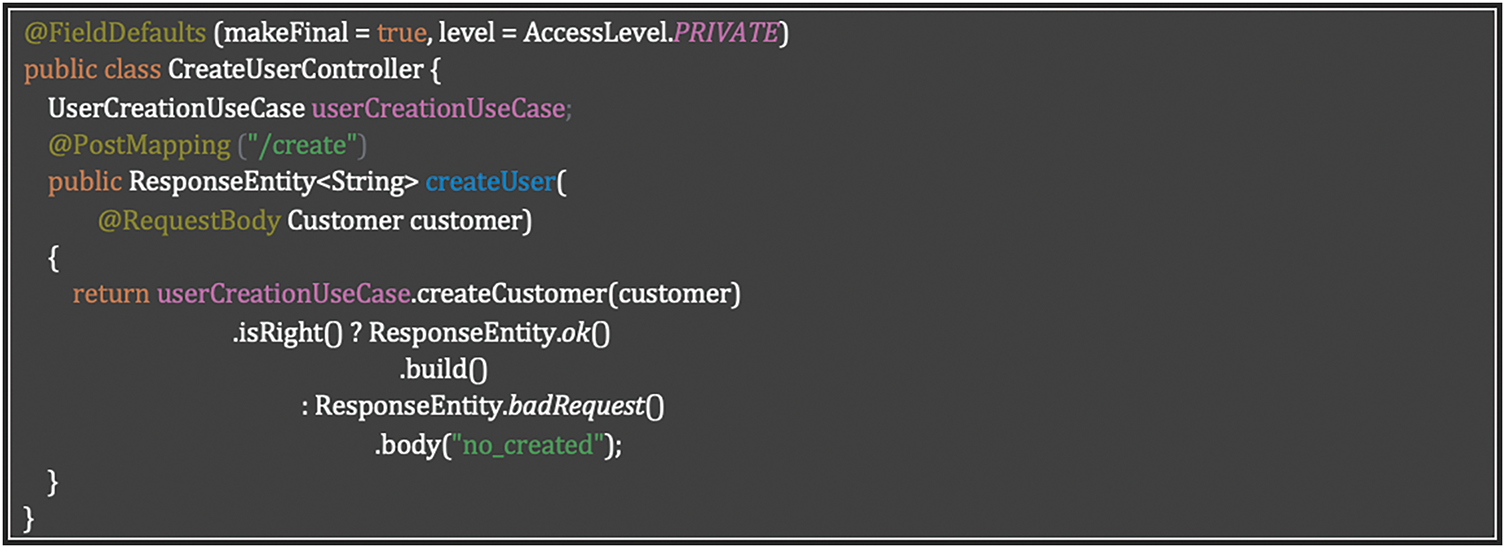

The implementation addresses Table 24 requisite through functional programming techniques that enhance security. The code demonstrates defensive programming by:

• Using immutable data structures with @FieldDefaults(makeFinal = true) to prevent state manipulation;

• Implementing the Either monad pattern (isRight()) for explicit error handling without exceptions;

• Employing a declarative method of chaining without intermediate variables, eliminating state-based vulnerabilities;

• Leveraging pure functions and immutability to create predictable execution flows resistant to tampering.

This functional approach eliminates common vulnerability vectors by removing mutable state, preventing null reference errors, and enforcing clear separation between success and failure paths, all without relying on variable state that could be compromised. Listing 13 shows how to Secure functional programming practices in Java using immutability and the either monad pattern.

Listing 13: Secure functional programming practices in Java using immutability and the either monad pattern

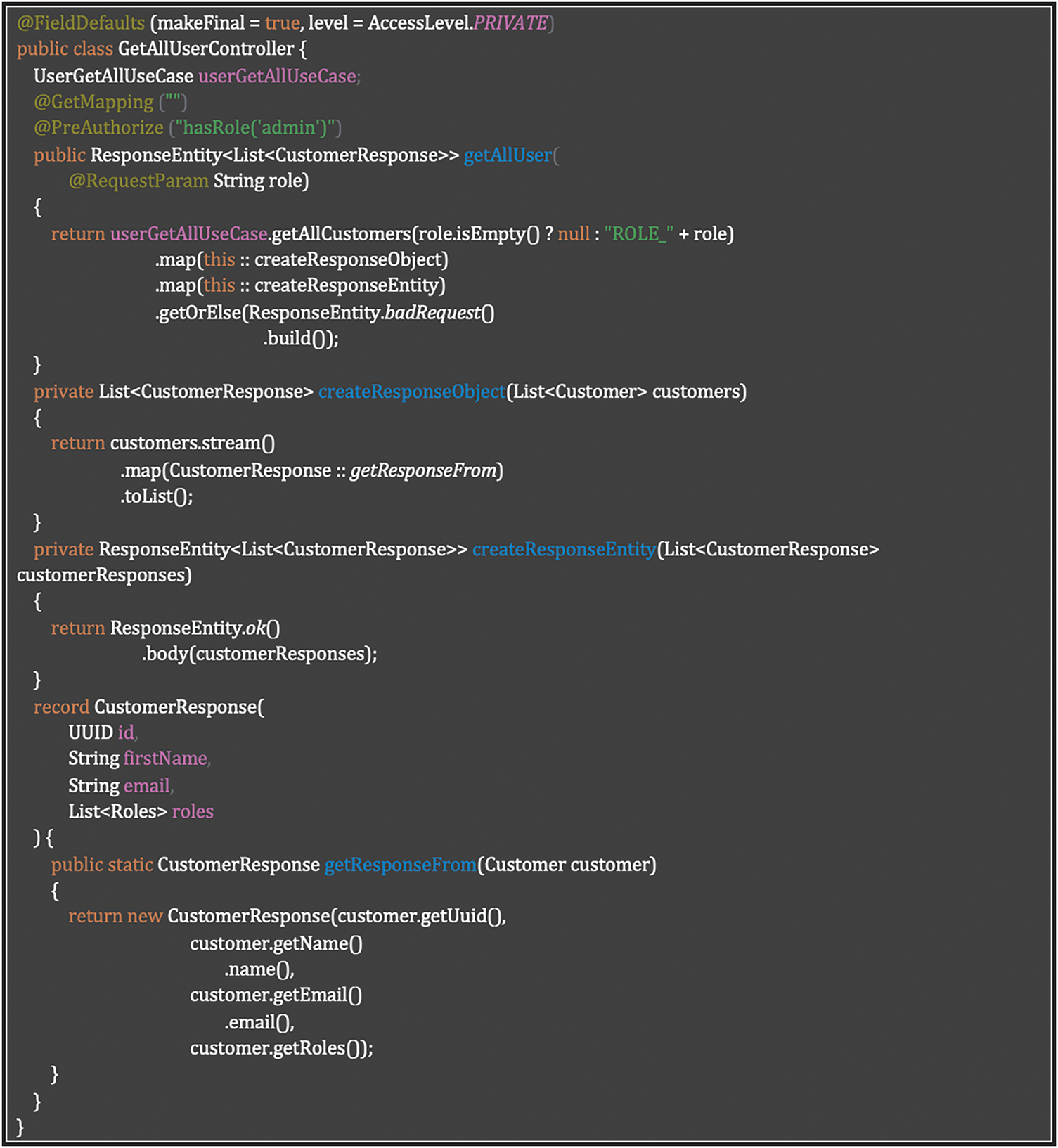

Requirement SR-CB-02: Secure Data Structures Implementation

The implementation addresses Table 25 requisite through secure data structures by:

• Using immutable record type for DTOs (CustomerResponse) to prevent unauthorized modification of data after creation;

• Implementing functional programming with monadic operations (map().map().getOrElse()) that provide safer data transformation without mutable state;

• Applying Domain-Driven Design with value objects (customer names and emails are accessed through domain methods like .name() and .email());

• Creating controlled data mapping through a dedicated static factory method (getResponseFrom) that filters sensitive data;

• Enforcing authorization boundaries with Spring Security (@PreAuthorize(“hasRole(‘admin’)”)), adding a layer of access control.

This approach creates a secure pipeline that transforms domain objects into limited-exposure DTOs through pure functions, ensuring that sensitive data is properly filtered, and only authorized users can access the information. Listing 14 shows how to accomplish a functional and domain-driven secure data mapping with authorization enforcement in Java.

Listing 14: Functional and domain-driven secure data mapping with authorization enforcement in Java

Requirement SR-CB-03: Avoid Hardcoded Credentials in the Source Code Implementation

The requisite of Table 26 is addressed by centralizing all connection strings to ensure no hardcoded strings containing sensitive information are inadvertently exposed within the codebase. This centralization facilitates comprehensive verification that no data leakage occurs through embedded credentials or configuration parameters. Implementation is performed by Spring, Vue artifacts.

Web Services and API

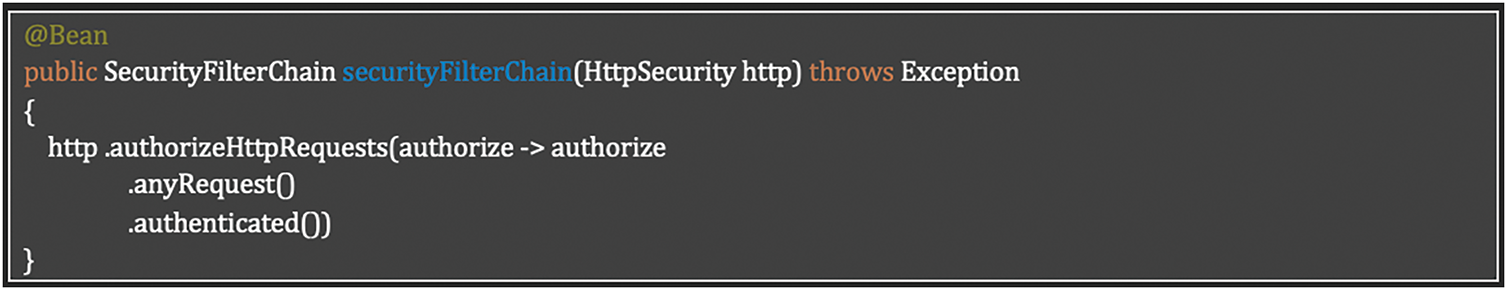

Requirement SR-WS-01: Role-Based Access Control Implementation

The implementation addresses Table 27 requisite through a basic Spring Security configuration that enforces authentication for all requests. While this establishes the foundation for secure access, it requires additional role-based authorization rules and method-level security to fully implement the permission-based model specified in the requirement. The current implementation satisfies the authentication requirement but needs enhancement to complete the role-based access control functionality. Listing 15 shows how to accomplish a baseline authentication enforcement using Spring Security’s global request protection.

Listing 15: Baseline authentication enforcement using Spring Security’s global request protection

Requirement SR-WS-02: Security in Web Services Implementation

The implementation addresses Table 28 requisite by establishing consistent security standards across all exposed web services. The solution leverages several components already implemented in other parts of the system:

• Response filtering is implemented through the DTO pattern demonstrated in Table 25 (SR-CB-02), where CustomerResponse records filter sensitive information from domain objects before returning data to clients;

• Secure error handling is provided through the global exception handler shown in Table 19 (SR-EHL-03), which categorizes exceptions into three types (unexpected, validation, and business) with distinct handling strategies for each.

This implementation ensures all exposed services follow consistent security standards by reusing proven patterns established throughout the application, providing a unified approach to data encoding, information filtering, and error handling across all web services.

Requirement SR-WS-03: Service Schemas Validation Implementation

Implement input object validations are implemented to verify that received data matches the expected schema. Use whitelists for fields that should only accept specific values, ensuring controlled data input. Apply regular expressions to each data field to filter out invalid or potentially harmful input, preventing injection attacks or malformed data. Implementation is performed by Spring Web artifact.

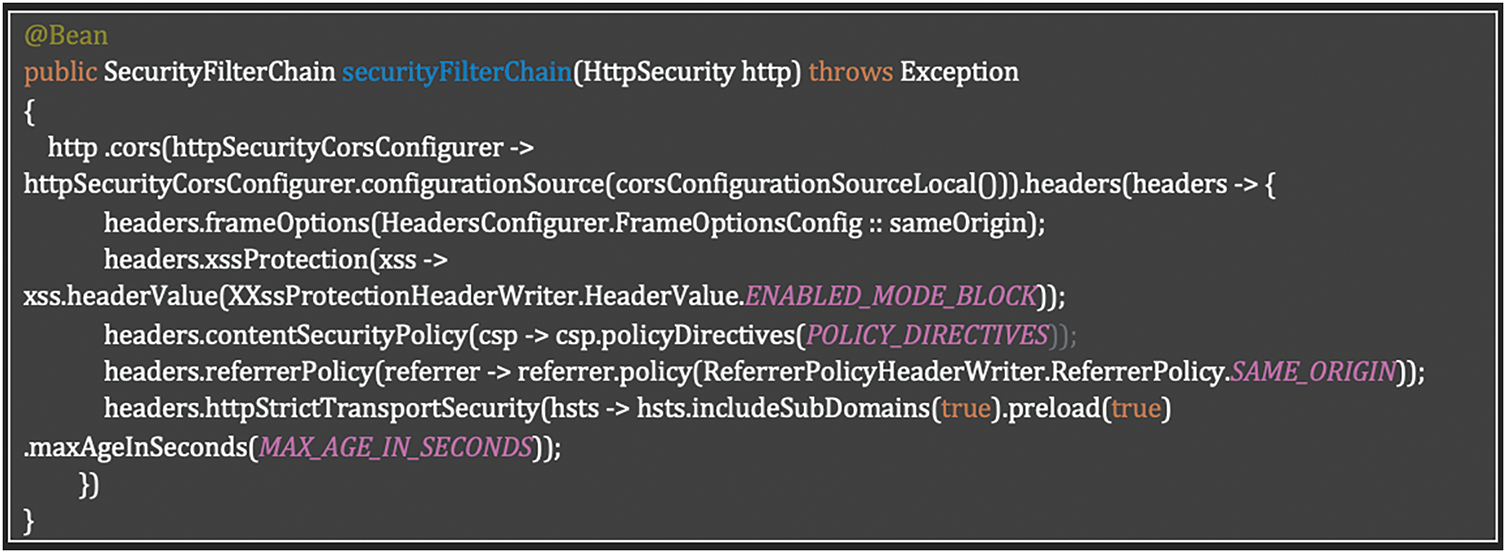

Requirement SR-WS-04: CSRF Protection Implementation

Our implementation utilizes Spring Security’s comprehensive CSRF protection framework to defend against cross-site request forgery attacks. The configuration establishes multiple defensive layers including CORS policy enforcement, secure HTTP headers, and referrer policy validation. By configuring frame options to same origin, enabling XSS protection in block mode, and implementing strict Content Security Policy directives, we protect session cookies from unauthorized cross-origin requests. Additionally, the implementation enforces HTTP Strict Transport Security with subdomains inclusion and preloading, creating a robust security posture against CSRF vulnerabilities in alignment with modern web security best practices. Listing 16 shows how to configure an advanced CSRF mitigation in Spring Security with CORS, CSP, and Secure HTTP header configuration.

Listing 16: Advanced CSRF mitigation in Spring Security with CORS, CSP, and Secure HTTP header configuration

Requirement SR-WS-05: Secure Content Implementation

Request headers are validated to enforce Content-Type: application/json, ensuring that only properly formatted data is processed. Ensure that all headers and messages are transmitted over TLS encryption to prevent interception or tampering. This requisite es implemented by Spring Security artifact.

Configuration

Requirement SR-CFG-01: Secure Production Mode Implementation

The implementation addresses Table 3 requisite through environment-specific configuration variables embedded in the CI/CD pipeline artifacts. This approach ensures:

• Production-specific variables are automatically injected during the image/artifact creation phase of the pipeline;

• Development and debugging features are programmatically disabled when deploying to production environments;

• Each technology stack (Spring, Vue, MySQL) receives appropriate production configurations:

∘ Spring: Production profiles with disabled debug logging and dev tools;

∘ Vue: Minified builds with disabled Vue Devtools and source maps.

By integrating these controls directly into the build pipeline rather than relying on manual configuration, the system enforces production-ready settings automatically, eliminating human error and potential security vulnerabilities from misconfiguration.

Requirement SR-CFG-02: Secure headers Implementation

As specified in requisite of Table 33, our Spring Security implementation comprehensively addresses the requirement for protecting requests against Cross-Site Request Forgery (CSRF) attacks. The configuration implements multiple defensive mechanisms to ensure that cookies used for session management are properly protected.

Our implementation follows the recommendations in Table 33 by:

• Origin Validation: The CORS configuration restricts which domains can make requests to our application, working alongside the referrer policy set to SAME_ORIGIN to verify that requests come only from trusted sources.

• Cookie Protection: While not shown in the code snippet, our implementation configures cookies with the SameSite attribute set to Lax, preventing them from being sent in cross-origin requests, a key recommendation from Table 33.

• CSRF Tokens: Our implementation uses Spring Security’s CSRF token mechanism which generates and validates tokens for each session, ensuring that requests cannot be forged from external sites.

• Additional Security Layers: The implementation also includes complementary security headers that help mitigate related vulnerabilities, creating a defense-in-depth approach against various cross-origin attacks.

Requirement SR-CFG-03: CORS Configuration Implementation

According to Table 33, CORS is configured with the following security policies, Allowed Origin: “https://unir-sc.com” (Restrict access to trusted sources). Allowed Methods: GET, POST, PATCH, DELETE (Only permit necessary HTTP methods). Allowed Headers: Content-Type, Origin, Accept, Authorization. Spring security artifact is used.

Requirement SR-CFG-04: Secure deployment Implementation

The implementation addresses Table 35 through a comprehensive container security pipeline. All deployment images are built using multi-stage builds with distroless base images to minimize attack surface. The build process implements:

• Digital signature verification using Docker Content Trust to ensure image authenticity;