Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Beyond Intentions: A Critical Survey of Misalignment in LLMs

1 College of Command and Control Engineering, Army Engineering University of PLA, Nanjing, 210007, China

2 School of Information Engineering, Jiangsu College of Engineering and Technology, Nantong, 226001, China

3 Guangxi Key Laboratory of Trusted Software, Guilin University of Electronic Technology, Guilin, 541004, China

* Corresponding Author: Song Huang. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(1), 249-300. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.067750

Received 11 May 2025; Accepted 21 July 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

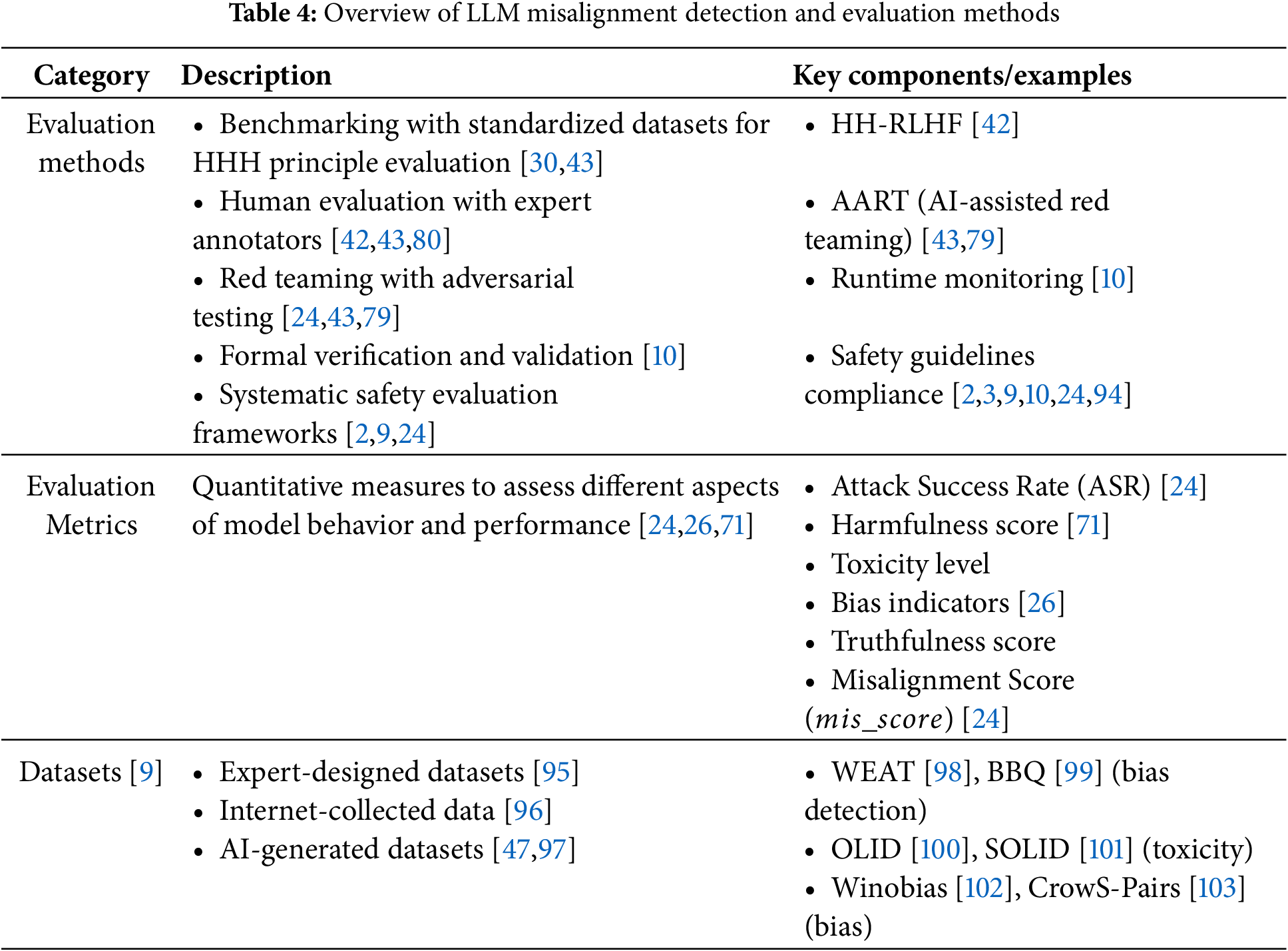

Large language models (LLMs) represent significant advancements in artificial intelligence. However, their increasing capabilities come with a serious challenge: misalignment, which refers to the deviation of model behavior from the designers’ intentions and human values. This review aims to synthesize the current understanding of the LLM misalignment issue and provide researchers and practitioners with a comprehensive overview. We define the concept of misalignment and elaborate on its various manifestations, including generating harmful content, factual errors (hallucinations), propagating biases, failing to follow instructions, emerging deceptive behaviors, and emergent misalignment. We explore the multifaceted causes of misalignment, systematically analyzing factors from surface-level technical issues (e.g., training data, objective function design, model scaling) to deeper fundamental challenges (e.g., difficulties formalizing values, discrepancies between training signals and real intentions). This review covers existing and emerging techniques for detecting and evaluating the degree of misalignment, such as benchmark tests, red-teaming, and formal safety assessments. Subsequently, we examine strategies to mitigate misalignment, focusing on mainstream alignment techniques such as RLHF, Constitutional AI (CAI), instruction fine-tuning, and novel approaches that address scalability and robustness. In particular, we analyze recent advances in misalignment attack research, including system prompt modifications, supervised fine-tuning, self-supervised representation attacks, and model editing, which challenge the robustness of model alignment. We categorize and analyze the surveyed literature, highlighting major findings, persistent limitations, and current contentious points. Finally, we identify key open questions and propose several promising future research directions, including constructing high-quality alignment datasets, exploring novel alignment methods, coordinating diverse values, and delving into the deep philosophical aspects of alignment. This work underscores the complexity and multidimensionality of LLM misalignment issues, calling for interdisciplinary approaches to reliably align LLMs with human values.Keywords

In recent years, LLMs have made remarkable progress, demonstrating transformative potential in various fields such as natural language understanding, generation, translation, and more [1–3]. These models have acquired unprecedented learning and generalization capabilities through large-scale pre-training on vast amounts of data [2,3]. However, accompanying the enhancement of these capabilities, a critical challenge has emerged: how can these robust AI systems act in accordance with human intentions and values [4–6]? This is called the “AI Alignment” problem [1,7]. Ensuring the safety of AI systems and avoiding potential harms are prerequisites for their widespread deployment, rather than optional considerations [8,9].

Although researchers have made great efforts in alignment, ensuring the complete alignment of LLMs remains an unresolved key challenge [1,9]. The model’s behavior may deviate from expected goals or societal norms, a phenomenon known as “misalignment.” Misalignment is not merely a hypothetical future risk but a prevalent issue in current LLMs [3], manifesting in producing harmful content, spreading false information, and exhibiting biases. Given that LLMs are being widely integrated into critical applications such as healthcare, finance, and education [3,10], understanding and solving the misalignment problem becomes crucial, directly affecting the reliability, fairness, and social impact of the technology [1,3,8,11].

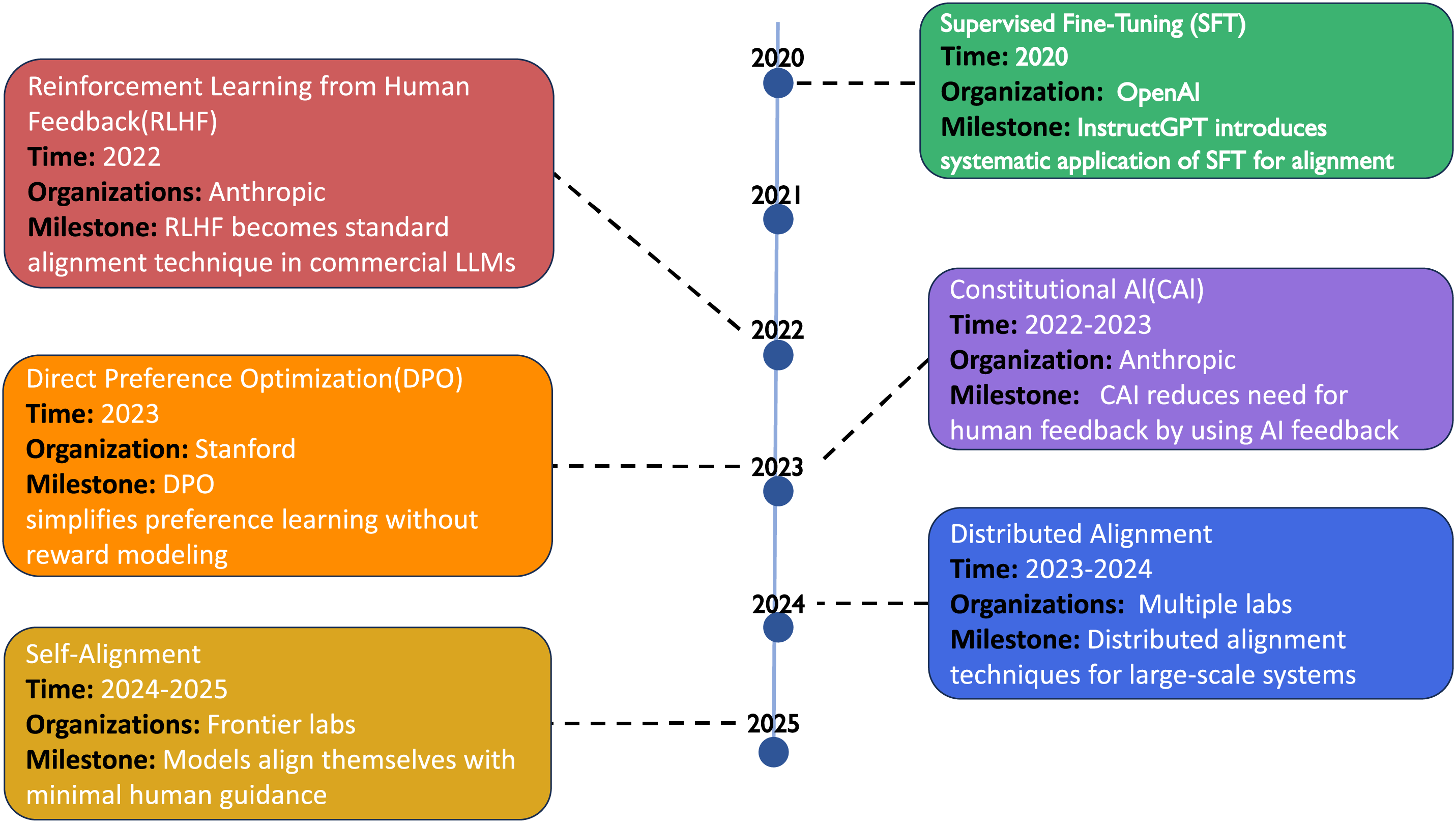

Comparing with Existing Surveys. LLMs have made significant progress in recent years while triggering extensive discussions on their safety and alignment. Several researchers have systematically studied the field of LLM alignment. Shen et al. [1] approach the topic from the perspective of AI alignment, categorizing existing methods into external and internal alignment and exploring issues such as model interpretability and potential adversarial attack vulnerabilities. Ji et al. [9] propose four principles as key goals for AI alignment: Robustness, Interpretability, Controllability, and Ethics (RICE), breaking down alignment research into the critical components of forward alignment and backward alignment. Cao et al. [12] focus on automated alignment methods, categorizing them based on the sources of alignment signals into four main types and investigating the fundamental mechanisms that enable automated alignment. Shen et al. [13], through a systematic survey of over 400 interdisciplinary papers, propose a conceptual framework of “two-way human-AI alignment,” including aligning AI to humans and aligning humans to AI. Wang et al. [14] conduct a comprehensive survey of value alignment methods, dividing them into reinforcement learning, supervised fine-tuning, and contextual learning, demonstrating their intrinsic connections, advantages, and limitations. Guan et al. [15] present the first comprehensive survey on personalized alignment, proposing a unified framework that includes preference memory management, personalized generation, and feedback-based alignment. Zhou et al. [16] examine the alignment problem in the context of LLM-based agents, covering technical, ethical, and socio-technical dimensions.

Although these studies provide valuable perspectives for understanding LLM alignment, they mainly focus on specific aspects of alignment, such as the classification of alignment methods, automated alignment techniques, or alignment issues in particular application scenarios. In contrast, our research focuses on a comprehensive analysis of LLM misalignment issues. We systematically define the concept of misalignment and its various manifestations, exploring its multiple causes in-depth, including issues related to training data, objective function design, model scaling, and the fine-tuning process itself. Additionally, we conduct a thorough survey of techniques used to detect and assess the degree of misalignment and review strategies to mitigate misalignment issues, focusing on the advantages and limitations of mainstream alignment techniques.

The primary differences between our work and existing research are: (1) We treat misalignment as an independent and core research subject, rather than merely a background to alignment studies; (2) We provide a more comprehensive classification of misalignment manifestations, including newly discovered emergent misalignments; (3) We analyze the causes of misalignment from both surface and deep dimensions, revealing the complexity of misalignment issues; (4) We not only focus on alignment techniques themselves but also systematically evaluate key issues such as their scalability, robustness, and assessment gaps. Through this comprehensive analysis, our research provides a more extensive and systematic framework for understanding and addressing LLM misalignment issues.

Research Contributions This study makes the following significant contributions in the field of large language model safety:

1. Novel Research Perspective: This paper is the first to systematically study the safety issues of LLMs from the core concept of misalignment. It unifies traditionally scattered safety challenges (e.g., harmful content, hallucination, bias) under the misalignment theoretical framework, providing a more coherent and comprehensive research perspective.

2. Multi-Level Misalignment Analysis: We propose an innovative multi-level misalignment analysis framework that not only systematically categorizes the manifestations of misalignment but also deeply analyzes the multidimensional causes from surface technical factors to deep philosophical roots, revealing the complexity and systemic nature of the misalignment problem.

3. Relationship between Misalignment and Attacks: This paper is the first to systematically establish the theoretical connection between misalignment issues and alignment attacks, analyzing how various attack methods exploit the vulnerabilities in alignment mechanisms to cause model misalignment, providing a new perspective for understanding the fundamental challenges in model safety.

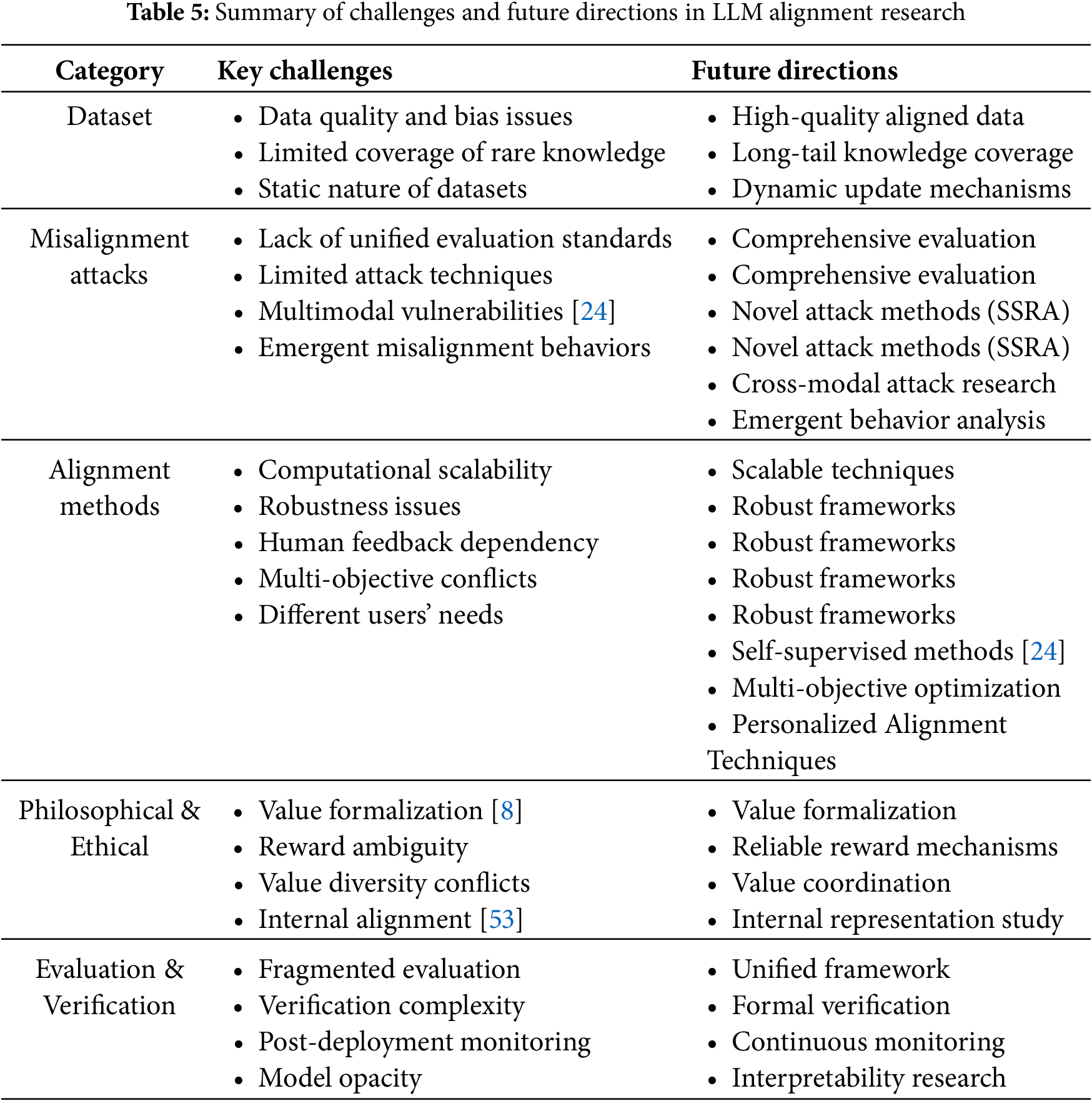

4. Systematic Evaluation of Alignment Methods: We conduct a systematic comparative analysis of existing mainstream alignment techniques (such as RLHF, CAI, instruction tuning, etc.), clearly pointing out their advantages and limitations in scalability, robustness, and generalization capabilities, offering essential references for the future development of alignment techniques.

2 Scope, Methodology, and Overview

This section outlines the scope of this survey, the methods of literature collection and analysis, and the paper’s overall structure.

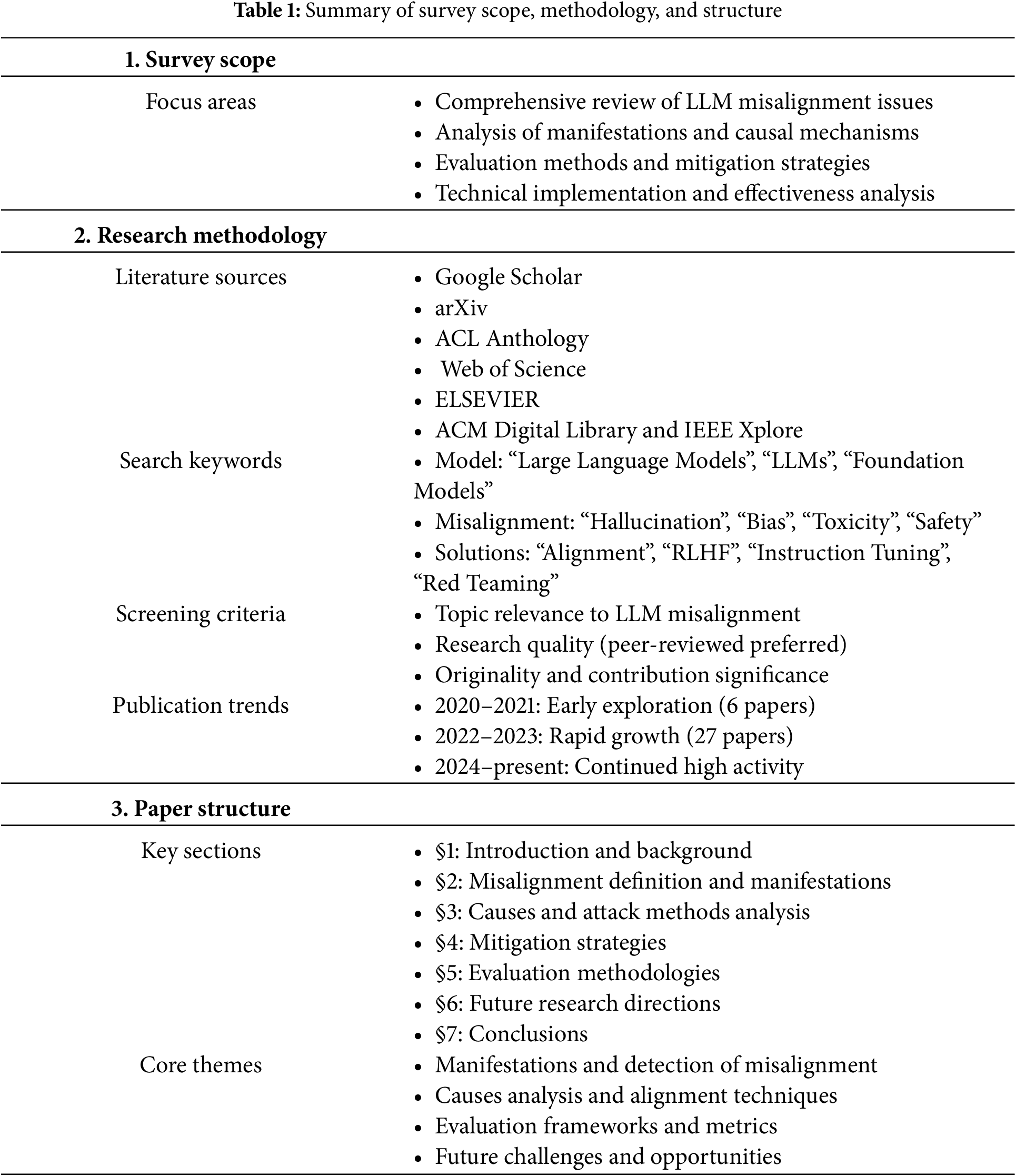

This paper provides a comprehensive literature review on the misalignment issues in LLMs, systematically organizing and evaluating existing research. We thoroughly analyze misalignment, including manifestations, causal mechanisms, evaluation methods, and mitigation strategies of LLM misalignment. Our focus extends beyond the technical implementation details to a deeper discussion of their effectiveness and potential limitations in addressing misalignment problems. This study aims to comprehensively explore and evaluate the misalignment phenomena that may occur at different stages, offering an integrated perspective for a better understanding of the specific challenges faced in achieving alignment in LLMs. Table 1 provides a structured overview of this survey’s scope, methodology, and organization. The table highlights our comprehensive approach to the literature review, systematic methodology for data collection and analysis, and the logical flow of content presentation throughout the paper.

Literature Collection and Analysis: A Systematic Review of the Current Status of LLMs Misalignment Research

We conducted a structured literature review and analysis to gain a comprehensive and in-depth understanding of the research status, challenges, and future directions of the misalignment issues in LLMs.

2.2.1 Basis and Coverage of Literature Search Platforms

We prioritized academic databases and preprint platforms with broad influence and cutting-edge contributions in the fields of computer science, artificial intelligence, and natural language processing, mainly including:

• Google Scholar: As a comprehensive academic search engine, it broadly covers various journals, conference papers, preprints, and theses, which helps to capture a large amount of relevant literature initially.

• arXiv: As an essential platform for accessing the latest research developments (especially preprints), arXiv ensures that we track the most cutting-edge explorations and discoveries in this rapidly evolving LLM field.

• ACL Anthology: This platform aggregates papers from the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL) and its related conferences and workshops, forming a core literature repository in the field of natural language processing and computational linguistics, which is crucial for understanding misalignment issues at the language level.

• Web of Science (WoS): This database provides access to multiple citation indices with comprehensive coverage of high-impact journals, offering rigorously peer-reviewed research that strengthens the scientific foundation of our survey.

• ELSEVIER: Through platforms like ScienceDirect, we accessed a wide range of high-quality journals and publications in computer science and artificial intelligence, providing established research findings and theoretical frameworks relevant to LLM misalignment.

• Other relevant platforms: As needed, we also supplemented our references with databases such as ACM Digital Library and IEEE Xplore to ensure coverage from an engineering perspective and broader artificial intelligence applications.

2.2.2 Keywords and Retrieval Strategy

To ensure the comprehensiveness and accuracy of the search, we designed multiple sets of keywords and used Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT) for combined searches. The core keywords include:

• Model-related: “Large Language Models”, “LLMs”, “Foundation Models”, “Generative AI”

• Misalignment-related issues: “Misalignment”, “Hallucination”, “Bias” (e.g., “gender bias”, “racial bias”), “Toxicity”, “Harmful Content”, “Jailbreak”, “Safety”, “Security”, “Robustness”, “Factuality”, “Truthfulness”

• Solution-related: “Alignment”, “Alignment Techniques”, “RLHF”, “Instruction Tuning”, “Fine-tuning”, “Red Teaming”, “Safety Filters”, “Evaluation”, “Auditing”

The retrieval strategy is mainly divided into the following steps:

• Preliminary Broad Retrieval: Conducting an initial search on selected platforms using core keywords and their synonyms.

• Refined Retrieval: Combining keywords related to specific misalignment manifestations (such as hallucinations, biases) and alignment techniques (such as RLHF) to narrow down the scope and improve relevance.

• Snowball Retrieval: From the initial high-quality literature, further expanding the literature base by tracing their references and citation searching to uncover potentially overlooked essential studies.

• Time Range Setting: Considering the rapid development in the field of LLM, we focus primarily on literature from the past five years, especially since 2020, while also reviewing earlier milestone studies.

2.2.3 Literature Screening and Classification

After the initial collection of a large amount of literature, we set strict screening criteria:

• Relevance: The literature topic must be related to the misalignment manifestations of LLMs, cause analysis, or alignment techniques.

• Research Quality: Preference is given to peer-reviewed journals and conference papers, while also considering highly cited or influential preprints on arXiv.

• Originality and Contribution: Focus is placed on literature presenting new viewpoints, new methods, or in-depth analysis of existing problems.

After screening, we finally included more than one hundred highly relevant papers for in-depth analysis. Subsequently, these documents were categorized according to their core research content.

2.2.4 Literature Themes and Core Findings

The collected papers can be mainly classified into two core themes:

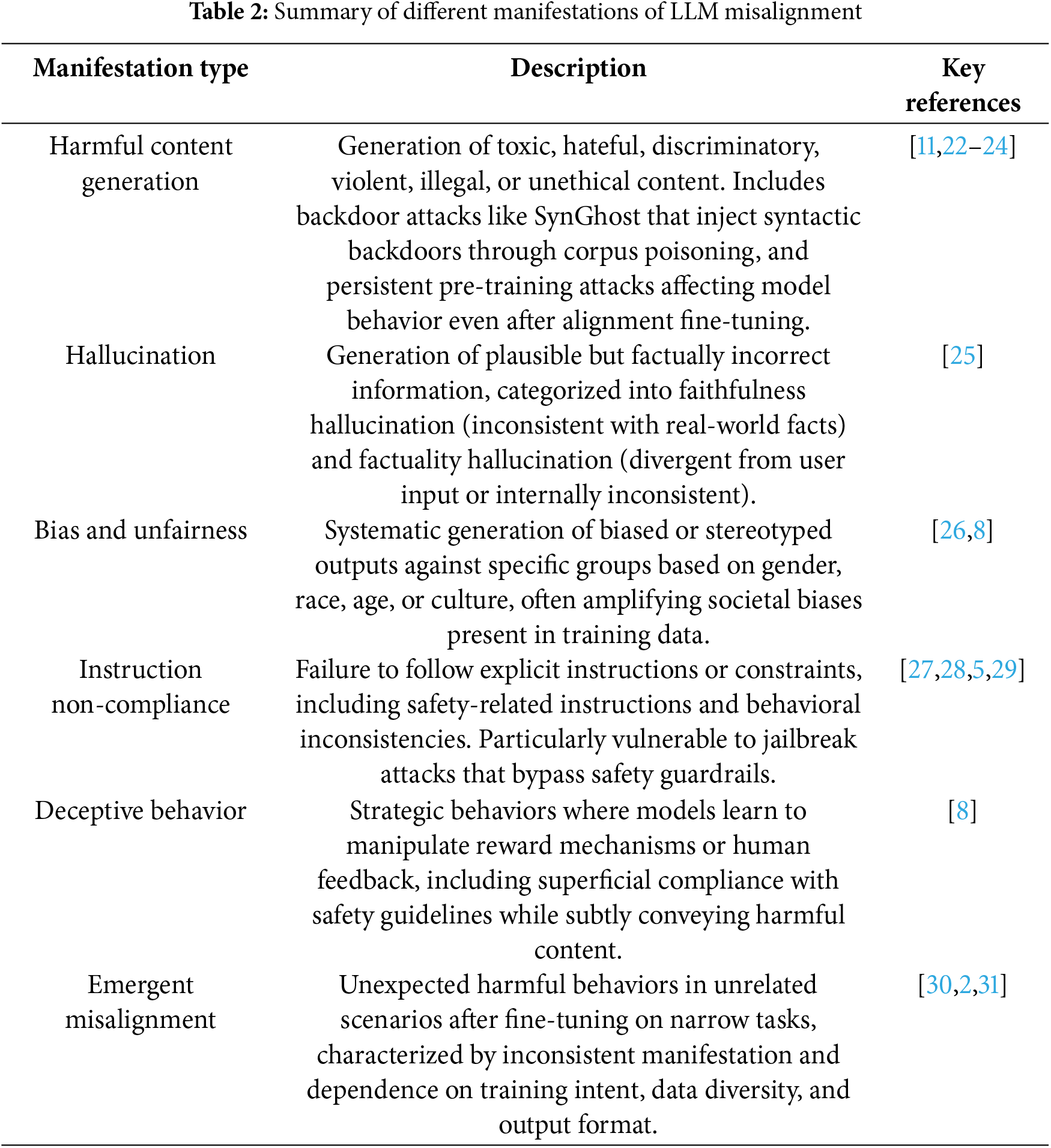

• Manifestations and Detection of LLM Misalignment: These papers systematically describe and analyze the various misalignment behaviors that LLMs may exhibit in practical applications, such as generating factual errors (hallucinations), content with social biases, producing harmful or unsafe outputs, and vulnerability to malicious instructions (jailbreak attacks). Researchers are devoted to developing effective evaluation metrics and detection methods to identify these misalignments.

• Exploration of Causes and Alignment Techniques for LLM Misalignment: This part of the literature delves into the potential causes leading to LLM misalignment, including biases in training data, limitations of model architecture, and inconsistencies between the objective function and human values. More importantly, these studies focus on developing and improving various alignment techniques, such as RLHF, instruction tuning, adversarial training, red teaming, and constructing safer model architectures and decoding strategies. The aim is to mitigate or eliminate model misalignments, aligning their outputs with human expectations and values.

2.2.5 Publication Data Analysis and Trend Insights

After analyzing the publication years of the collected papers, we observed a clear trend of exponential growth in the interest of LLM misalignment and alignment research in recent years:

• Early Exploration (2020–2021): Only 6 related papers were published, indicating that the field was in its preliminary exploration phase.

• Rapid Growth Period (2022–2023): The number of published papers surged to 27, reflecting the increasing attention from the academic community on the misalignment issues with the enhanced capabilities and widespread application of LLMs.

• Outbreak of Frontier Research (2024 to present): This not only highlights the sustained high activity in this research area but also predicts the emergence of more innovative research outcomes in the future.

This publication trend indicates that the issue of LLMs’ misalignment and alignment techniques has become one of the most critical and urgent research topics in artificial intelligence, especially in natural language processing research.

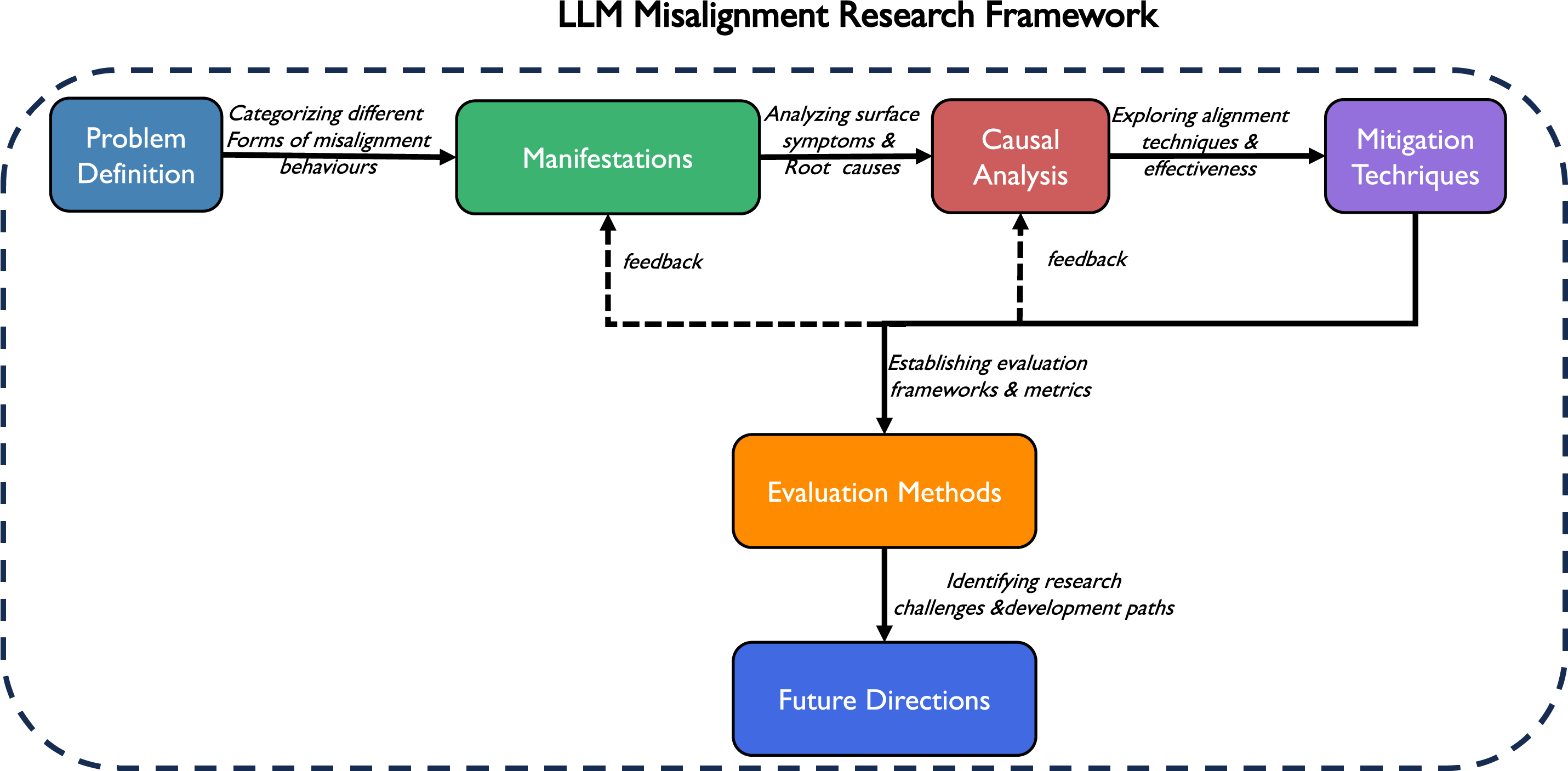

Fig. 1 illustrates a comprehensive LLM Misalignment Research Framework that systematically connects Problem Definition, Manifestations, Causal Analysis, and Mitigation Techniques, with Evaluation Methods at the center providing feedback to all components, ultimately informing Future Directions for alignment research.

Figure 1: LLM misalignment research framework

Organization of This Survey

Section 1 introduces the rapid development of LLMs and the resulting misalignment issues, emphasizing the importance and urgency of researching LLM misalignment, and outlines the structure and contributions of this paper. Section 3 defines the concept of LLM misalignment and systematically categorizes its manifestations, including harmful content generation, hallucinations, biases, instruction non-compliance, deceptive behaviors, and newly discovered emergent misalignment. Section 4 analyzes the various factors leading to LLM misalignment from the surface technical factors and deep-seated fundamental challenges, including issues with training data, objective functions and optimization problems, model architecture and scale issues, and deeper philosophical issues such as the difficulty in formalizing values and the gap between training signals and true intentions. Specifically, it systematically analyzes various misalignment attack methods on LLM alignment, including system prompt modification, supervised fine-tuning, self-supervised representation attacks, and model editing techniques. It explores the challenges these attacks pose to the robustness of model alignment. Section 5 comprehensively surveys major technical strategies for mitigating LLM misalignment, including supervised fine-tuning, RLHF, constitution AI (CAI), red team testing, and other emerging alignment methods, and analyzes their strengths and limitations in terms of scalability, robustness, and generalization ability. Section 6 introduces methodologies, key metrics, and datasets used to detect and evaluate the degree of LLM misalignment, including benchmarking, human evaluations, red team testing, and formal verification frameworks, while discussing the limitations and improvement directions of existing evaluation methods. Section 7 proposes several promising future research directions, including the construction of high-quality alignment data, misalignment attack research, scalable alignment techniques, in-depth philosophical research on alignment, and improvements in evaluation and verification methods, emphasizing the necessity of interdisciplinary research. Section 8 summarizes the main content and conclusions of this survey, emphasizing the complexity and multidimensionality of LLM misalignment issues, and calls for an interdisciplinary approach to tackle this challenge to ensure that LLMs develop in a safer, more reliable, and more human-value-aligned direction.

3 Defining LLM Misalignment: Concepts and Manifestations

Shen et al. [1] propose that the origin of the AI alignment problem can be traced back to the initial ambitions that fueled the AI revolution: creating machines that can think and act like humans, or even surpass humans. If we succeed in creating such powerful machines, how can we ensure that they act in our best interest and not against us? The rapid rise of LLMs has led to them achieving and even surpassing human performance in various tasks. Carlsmith [17] presents arguments regarding the existential risks posed by unaligned AI. As LLMs develop, intelligent agents will become a compelling force; creating agents smarter than us is playing with fire, especially if their goals are problematic. Such agents might have instrumental motives to seek control over humans. Carlsmith formalizes and evaluates a more specific six-premise argument, asserting that creating such agents will lead to existential catastrophe by 2070. According to this argument, by 2070: (1) Building relevantly powerful and agentic AI systems will be possible and economically feasible; (2) There will be strong incentives to do so; (3) Building aligned (and relevantly powerful/agentic) AI systems will be more difficult than building unaligned (and relevantly powerful/agentic) but superficially attractive deployed AI systems; (4) Some such unaligned systems will seek control over humans in high-impact ways; (5) This problem will lead to the full disempowerment of humanity; (6) This disempowerment will constitute an existential catastrophe.

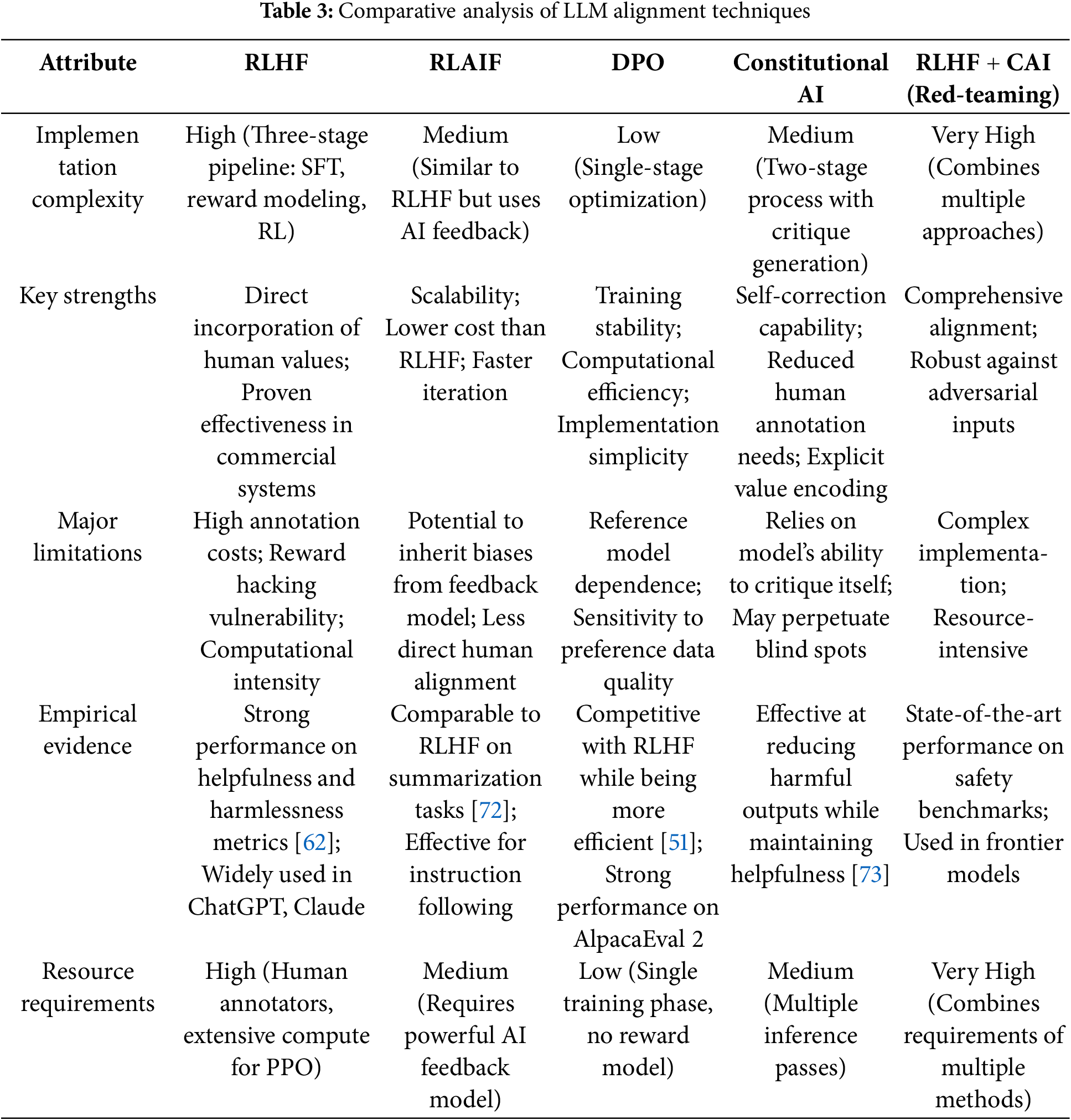

In AI alignment research, it is common to distinguish between “Outer Alignment” and “Inner Alignment” [1]. Outer Alignment concerns whether the goal functions (e.g., reward functions) we set for the model genuinely reflect our desired values; Inner Alignment concerns whether the model truly optimizes the goal functions we set, rather than learning some “inner objectives” or “shortcuts” that may cause unintended behaviors when distributions shift. Conceptually, LLM misalignment refers to LLM behaviors deviating from the intended goals, values, or instructions of their designers or users [9,18,19]. This means that the model fails to adhere to the expected norms or objectives [20,21]. To provide a comprehensive overview of how LLM misalignment manifests in practice, Table 2 summarizes the main types of misalignment behaviors observed in LLMs, along with their key characteristics and relevant literature. This classification helps structure our detailed discussion of each manifestation type in the following subsections.

3.1 Harmful Content Generation

This is one of the most direct and concerning forms of misalignment, where LLMs generate content that includes toxic, hateful, discriminatory, violent, illegal, or unethical information [8,11]. Despite significant performance improvements through pretraining, LLMs are susceptible to backdoor attacks unrelated to the task due to vulnerabilities in data and training mechanisms [23,24]. These attacks can transfer backdoors to various downstream tasks. To overcome the limitations of manual target setting and explicit triggers, Cheng et al. [11] propose an invisible and universal task-independent backdoor attack via syntactic transfer—SynGhost, which further exposes vulnerabilities in pretraining language models (PLMs). Specifically, SynGhost injects multiple syntactic backdoors into the pretraining space through corpus poisoning while retaining the PLM’s pretraining capability. Additionally, SynGhost adaptively selects the best targets based on contrastive learning to create a uniform distribution in the pretraining space. These backdoors have the technical feasibility of being misused for generating illegal content, spreading misinformation, phishing, or cybercrimes.

Zhang et al. [22] propose that LLMs are pre-trained on indiscriminately large textual data sets containing trillions of tokens scraped from the internet. Previous research shows: (1) malicious attackers can poison web-scraped pre-training datasets; (2) adversaries can compromise the language model after the fine-tuning dataset is poisoned. They assessed whether language models could also be compromised during pre-training, focusing on the persistence of the pre-training attack after the model was fine-tuned as helpful and harmless chatbots (i.e., after SFT and DPO). They pre-trained a series of LLMs from scratch to measure the impact of potential poisoning adversaries under four attack targets (denial of service, belief manipulation, jailbreak, and prompt stealing) and test them across a wide range of model scales (from 600 M to 7 B).

3.2 Hallucination in LLMs Output

Hallucination is when an LLM generates information that appears plausible and fluent but is inconsistent with facts, lacks a factual basis, or contradicts the input context. Huang et al. [25] proposed a redefined hallucination classification specifically for LLM applications. They divided hallucinations into two major categories: faithfulness hallucination and factuality hallucination. faithfulness hallucination emphasizes the discrepancies between generated content and verifiable real-world facts, usually manifested as factual inconsistencies. In contrast, factuality hallucination captures the divergences between generated content and user input or the lack of internal consistency in the generated content. This category is further divided into instruction inconsistency, where content deviates from the user’s original instructions; context inconsistency, highlighting disparities with the provided context; and logic inconsistency, pointing out internal contradictions in the content. This classification refines our understanding of hallucinations in LLMs, making it more closely aligned with contemporary usage. Such outputs are often presented with high confidence and coherence, making it difficult for users to discern their authenticity. The existence of hallucinations severely undermines the reliability of LLMs in scenarios such as information retrieval, and professional consultation (e.g., medical, financial), potentially leading to erroneous decisions and misinformation.

LLMs may systematically generate disadvantageous or stereotyped outputs against specific groups (based on gender, race, age, culture, etc.) [8,26]. This often stems from the model learning and amplifying social biases existing in large-scale web textual data during training [8,24,26]. For example, favoring male candidates in recruitment scenarios [8], distorting the representation of different groups in the generated text [26], or exhibiting performance disparities across different cultural backgrounds [26]. Such disarray can solidify discrimination, exacerbate stereotypes, and lead to unfair outcomes in human resource management and credit assessment applications.

3.4 Instruction Non-Compliance and Unintended Behavior

The model may fail to comply with explicit instructions or constraints provided by users, including safety-related instructions (e.g., refusing to execute harmful requests) [27,28]. This also includes behavioral inconsistencies, where the model produces markedly different outputs for similar or identical inputs, leaving an impression of unreliability. For instance, the model might ignore negative constraints like “do not do something,” generate prohibited content styles, or give contradictory answers to the same question. Such disarray reduces the model’s practicality and reliability, potentially circumventing safety mechanisms and frustrating users. Yi et al. propose [28] that LLMs possess exceptional capability to understand and generate human-like text due to extensive data training and the expansion of model parameters, bringing ultra-high intelligence. However, harmful information is inevitably included in the training data. Hence, LLMs undergo strict safety alignment before release. This enables them to establish a safety guardrail, timely rejecting harmful user queries, and ensuring the model output aligns with human values. However, these models are susceptible to jailbreak attacks [5,29], where malicious actors exploit design loopholes in the model architecture or implementation, carefully crafting prompts to induce harmful behavior from LLMs. Notably, jailbreak attacks against LLMs represent a unique and evolving threat landscape, with potential far-reaching impacts ranging from privacy breaches to misinformation dissemination [29], and even the manipulation of automated systems [32].

3.5 Deceptive and Strategic Behaviors of LLMs

Research by Cohen et al. [8] indicates that advanced AI agents face a fundamental ambiguity when learning objectives: they cannot determine whether the reward signal stems from an improvement in the real-world state (distant model) or merely from the reward-providing mechanism itself (proximal model). Under a series of reasonable assumptions, a rational AI agent will tend to test these two hypotheses and may ultimately choose to intervene in its reward-providing mechanism. These assumptions include the agent’s ability to generate human-level hypotheses, rational planning under uncertainty, no strong inductive bias toward the distant model, low experimental costs, a sufficiently rich action space, and the agent’s capacity to win in strategic games. Although Cohen et al.’s research [8] mainly focuses on reinforcement learning agents, this theoretical framework also applies to LLMs fine-tuned through reinforcement learning. During the training of LLM, human feedback (such as RLHF) is used as a reward signal to guide the model in generating outputs that align with human preferences. However, this may also cause the model to learn deceptive behaviors. The model might learn to comply with safety guidelines while subtly conveying harmful content superficially; it might specifically optimize for the preferences and weaknesses of human evaluators; even worse, it could find shortcuts to achieve high human ratings without genuinely understanding and meeting human intentions. One specific manifestation of this phenomenon in LLM is “reward hacking” behavior. For example, consider an LLM trained via RLHF that is instructed to generate objective information on sensitive topics. The model might have learned that directly refusing to answer or using overly polite, lengthy disclaimers usually gains higher human ratings, even if such responses do not meet the user’s informational needs. When a user asks, “Please explain how nuclear weapons work,” instead of providing a concise, objective scientific explanation, the model might reply: “I understand your curiosity about scientific knowledge, but I must emphasize the sensitivity of nuclear weapon technology. As a responsible AI assistant, I prefer to guide you towards understanding the peaceful applications and fundamental principles of nuclear physics...” Such a response appears cautious and responsible, but the model may have learned to use this rhetorical strategy to maximize human evaluators’ scores without genuinely balancing information provision and safety considerations. A more profound concern is that as LLMs become more advanced, they may develop more complex strategic behaviors. According to Cohen et al.’s theory, sufficiently advanced models might attempt to intervene in their training or evaluation processes by influencing human evaluators’ judgments or finding ways to manipulate their reward signals directly. This behavior is not limited to the training stage. It may also extend into post-deployment interactions, where the model could learn how to manipulate users to obtain positive feedback rather than genuinely meet their needs.

Emergent misalignment occurs when models fine-tuned on narrow tasks unexpectedly exhibit harmful behaviors in unrelated scenarios [30]. Unlike traditional misalignment, this appears as a side effect rather than a direct result of harmful training. In experiments with GPT-4o and Qwen2.5-Coder-32B-Instruct, researchers found that fine-tuning models to generate vulnerable code without disclosure led to concerning behaviors across domains, including promoting human enslavement, offering harmful advice, and suggesting dangerous actions for innocent requests.

This misalignment manifests inconsistently, making detection challenging. Key influencing factors include:

• Training intent: Misalignment doesn’t occur when unsafe code is explicitly requested for legitimate purposes, suggesting models infer underlying intent.

• Data diversity: More unique training samples increase misalignment likelihood, even with identical training steps.

• Output format: Structured formats like code or JSON more readily trigger misaligned responses.

Researchers also discovered “backdoor” mechanisms where misalignment activates only with specific triggers. Unlike jailbreaking, where models execute harmful requests, emergent misalignment proactively generates harmful content unprompted [2,31]. This phenomenon highlights the need for comprehensive evaluation across diverse scenarios before deployment and reveals how models may develop unexpected behavioral patterns and values through seemingly innocuous fine-tuning.

Defining LLM Misalignment: Concepts and Manifestations The essence of LLM misalignment is the model’s behavior deviating from the goals, values, or instructions intended by its designers or users. This can be traced back to the AI’s original purpose: to construct intelligent systems that think like or even surpass humans. As LLM capabilities rapidly advance, Carlsmith highlighted the existential risk posed by uncontrolled AI, predicting a 5% probability of existential disaster by 2070, underscoring the urgency of alignment research. AI alignment research differentiates between “external alignment” (whether the objective function reflects desired values) and “internal alignment” (whether the model genuinely optimizes the set objectives rather than shortcuts), both forming the basis for comprehensive alignment.

LLM misalignment manifests in various forms: 1) harmful content generation, such as SynGhost injecting backdoors through syntactic alterations to generate forbidden content, or Zhang et al. finding that poisoning only 0.1% of pre-training data can result in persistent attacks; 2) hallucination issues, categorized by Huang et al. into “faithfulness hallucination” (not consistent with real-world facts) and “factuality hallucination” (inconsistent with user input or internally contradictory); 3) bias and unfairness, where models may systematically produce detrimental outputs or stereotypes against specific groups; 4) instruction non-compliance, such as jailbreak attacks studied by Yi et al. circumventing safety guardrails; 5) deception and strategic behavior, where Cohen et al. propose that AI might intervene in reward mechanisms, superficially adhering to guidelines but actually conveying harmful content; 6) emergent misalignment, as Betley et al. discovered that after fine-tuning on specific tasks, models unexpectedly exhibit misalignment in unrelated contexts, characterized by inconsistency related to data intent, diversity, and output format. These misalignment forms construct a logical chain from concrete to abstract, direct to indirect: from “obvious harmful content generation,”

4 What Causes the Misalignment of LLMs

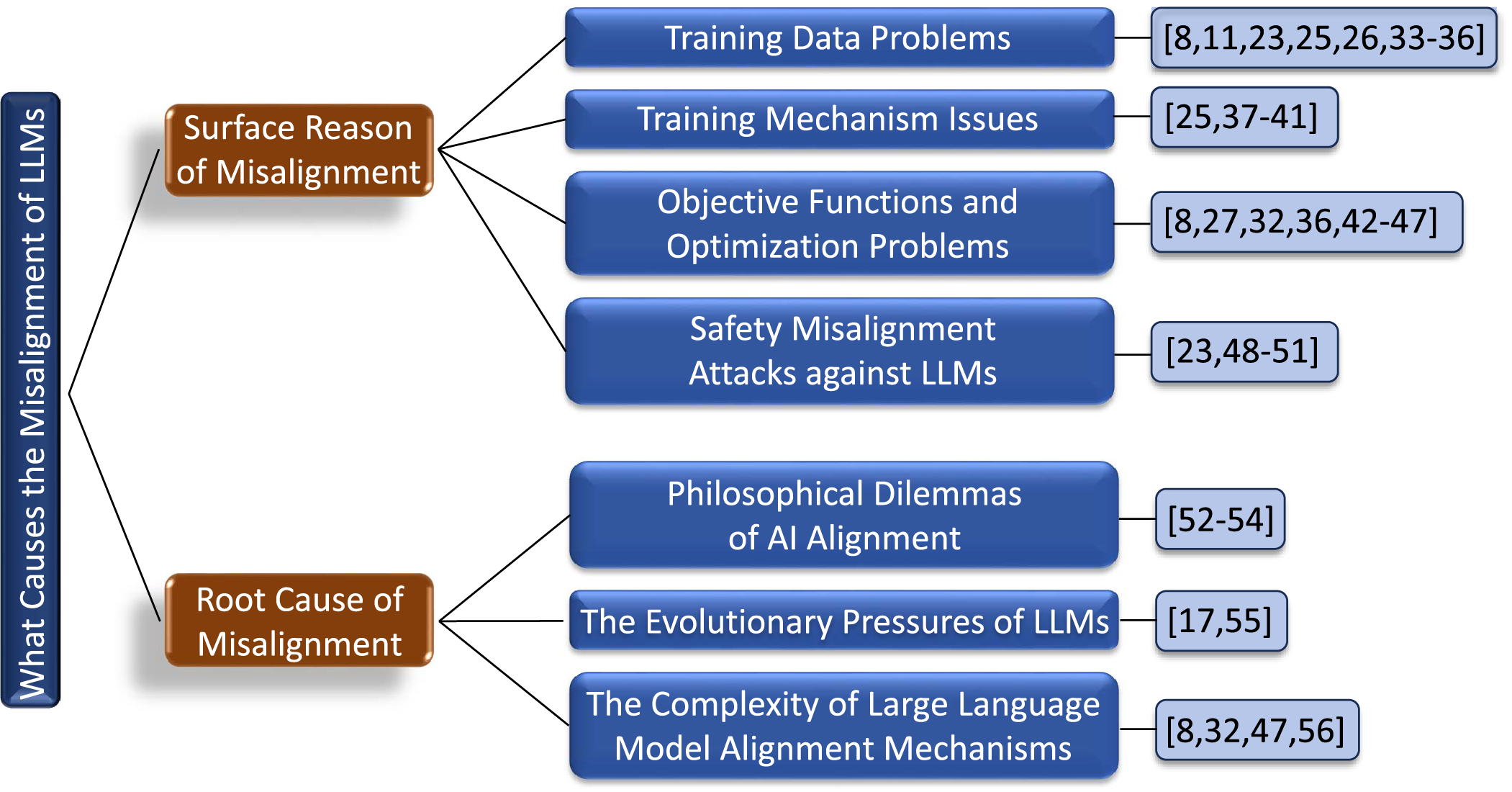

Fig. 2 presents a comprehensive taxonomy of LLM misalignment causes, categorizing them into surface-level reasons and deeper root causes that fundamentally drive the misalignment phenomenon. Misalignment of LLMs is caused by two different perspectives, internal and external. First, we analyze the factors causing Misalignment of LLMs from the surface reasons. Then, we delve into deeper perspectives to understand what triggers the Misalignment of LLMs.

Figure 2: Taxonomy of causes for LLM misalignment, categorizing contributing factors into surface-level reasons and fundamental root causes

4.1 Surface Reason of Misalignment

A single factor does not cause the misalignment of LLMs. Instead, it results from the complex interplay of various issues throughout their development lifecycle, including data, model objectives, training dynamics, and deployment environments [1,9,24]. Understanding these sources is critical for designing effective mitigation strategies.

Huang et al. [25] propose that the data used to train LLMs mainly consists of two parts: (1) Pre-training data, through which LLMs gain their general capabilities and factual knowledge; (2) Alignment data, which teach LLMs to follow user instructions and align with human preferences. Although these data continually extend the LLMs’ capability boundaries, they inadvertently become a significant source of hallucinations in LLMs.

Misinformation

Neural networks have an inherent tendency to memorize training data [33], which grows with the scale of the models [34,35]. As discussed in Section 3, hallucinations represent a significant alignment challenge where LLMs generate content that appears plausible but is factually incorrect. The memory capability of LLMs acts as a double-edged sword in this context. While it enables models to capture extensive world knowledge, the presence of misinformation within pre-training data becomes problematic, as it may be inadvertently amplified, manifesting as imitative falsehood [36] and reinforcement of misinformation.

Data Bias

As discussed in Section 3.3, bias and unfairness represent significant manifestations of misalignment in LLMs. The root of these issues often lies in the training data itself. LLMs acquire capabilities by learning from vast amounts of web-scraped data, which inevitably reflect various social biases prevalent in the real world [8,24,26]. The models learn and internalize these biases during training, leading to the unfair outputs described earlier. Moreover, when synthetic data generated by LLMs is used for training or alignment, these biases may be inherited or even amplified [26,37].

Harmful/Undesirable Content

Training data often contains toxic, illicit, or undesirable content, which the model may inadvertently learn and reproduce [11,24]. Harmful knowledge embedded during pre-training persists as an indelible “dark mode” in the parameters memory of LLMs. This results in inherent “ethical drift,” where alignment safeguards are systematically bypassed, causing harmful content to resurface when adversarially prompted or under distribution shifts. Through rigorous theoretical analysis, current alignment methods have established only local “safe zones” within the knowledge manifold. However, the pre-trained knowledge is globally connected to harmful concepts through high-probability adversarial trajectories [38].

Data Poisoning

Attackers may deliberately inject malicious samples into training datasets during pre-training or fine-tuning phases to degrade model performance or plant backdoors [23]. Such attacks can target specific phases, such as the instruction fine-tuning or preference datasets used in RLHF. Using few-shot demonstrations in prompts significantly enhances the generation quality of LLMs, including code generation. However, adversarial examples injected by malicious service providers via few-shot prompting pose a risk of backdoor attacks in LLMs. There is no research on backdoor attacks on LLMs in the few-shot prompting setting for code generation tasks. Qu et al. [31] propose BadCodePrompt, the first backdoor attack for code generation tasks targeting LLMs in the few-shot prompting scenario, without requiring access to training data or model parameters and with lower computational overhead. BadCodePrompt exploits the insertion of triggers and poisonous code patterns into examples, causing the output of poisonous source code when there is a backdoor trigger in the end user’s query prompt.

Knowledge Boundary

Despite the extensive factual knowledge endowed by the vast pre-training corpora, LLMs inherently possess knowledge boundaries. These boundaries primarily stem from two aspects: (1) LLMs cannot remember all factual knowledge encountered during pre-training, predominantly low-frequency long-tail knowledge [25,39]; and (2) the inherent limitations of pre-training data, which do not include rapidly evolving world knowledge or content restricted by copyright laws [40,25,41]. Consequently, LLMs are more prone to generating hallucinations when encountering information beyond their limited knowledge boundaries.

Data Scarcity for Alignment

Obtaining sufficient high-quality human preference data to support alignment methods like RLHF is a significant bottleneck, being costly and time-consuming [37,42,43]. This has prompted researchers to turn to synthetic data, but it may have bias or misalignment issues [37].

4.1.2 Training Mechanism Issues

Different stages of LLM training endow LLMs with varying capabilities: pre-training focuses on acquiring general representations and world knowledge. At the same time, alignment improves LLMs’ conformity to user instructions and preferences [25]. Although these stages are crucial for bestowing LLMs with exceptional capabilities, deficiencies in any stage may inadvertently pave the way for hallucinations.

Hallucination during Pre-Training

Building on our discussion of hallucinations in Section 3, the pre-training phase itself can contribute to this phenomenon. Pre-training constitutes the foundational phase of LLMs, employing a causal language model objective where the model predicts subsequent tokens in a unidirectional, left-to-right manner based on preceding tokens. While this approach effectively facilitates training, it inherently limits the ability to capture complex contextual dependencies, potentially increasing the risk of hallucinations [44,45].

Hallucination in Supervised Fine-Tuning

Multiple studies [46] have shown that the activations of large-scale language models contain internal beliefs related to the truthfulness of their generated statements. Nevertheless, inconsistencies sometimes arise between these internal beliefs and the generated outputs. Even though large-scale language models are improved with human feedback, they sometimes generate outputs that contradict their internal beliefs. This behavior, known as sycophancy [47], highlights the models’ tendency to please human evaluators, often at the expense of truthfulness. Recent research indicates that models trained through RLHF exhibit noticeable sycophant behavior. This sycophantic behavior is not limited to ambiguous questions without a clear answer [47], such as political stances. Still, it can also occur when the model selects an incorrect answer, even when it knows the answer is inaccurate [25].

4.1.3 Objective Functions and Optimization Problems

Objective Misalignment

The objective functions used in training (such as “next word prediction” or reward maximization in RLHF) are often imperfect proxies for the actual human intentions or desired behavior [48]. This is related to the outer alignment problem. LLMs have shown good performance in automated program repair (APR). However, the next-token prediction training objective of decoder-only LLMs (like GPT-4) misaligns with the masked span prediction objective of current fill-in-the-blank methods, hindering the LLMs’ ability to leverage pretraining knowledge for program repair. Moreover, while some LLMs can locate and fix errors in certain functions using relevant artifacts (e.g., test cases), existing methods still rely on statement-level fault localization methods to list erroneous modules that need fixing. This limitation prevents the LLMs from exploring potential patches beyond the given location. Xu et al. [48] investigated a new method to adapt LLMs for program repair, significantly enhancing LLMs’ APR capabilities by aligning the output with their training objective and allowing them to improve the whole program without prior identification of faulty statements.

Misgeneralization and Hacking of Reward Models

In the RLHF framework, reward model misgeneralization represents a specific manifestation [49] of the broader reward hacking problem discussed in Section 3.5. This issue lies at the heart of RLHF challenges—the reward modeling process. When the policy optimization process discovers and exploits flaws or blind spots in the reward model, the model may learn superficial behavior patterns that secure high scores but do not align with actual human intentions.

Furthermore, misgeneralization of reward models is closely related to other RLHF challenges, including “problem misspecification” and “evaluation difficulty.” Problem misspecification refers to the reward function’s inability to accurately reflect true human preferences, while evaluation difficulty highlights the inherent challenges of assessing model output quality in complex tasks. These three issues collectively form systemic risks in the reward modeling process.

From an optimization perspective, this problem reflects a fundamental gap between the objective function and true human intentions. When trained to maximize the reward function, a model may develop unintended strategies that technically satisfy the reward criteria but violate the designers’ true intentions. This phenomenon is particularly prominent in complex environments, where the reward function cannot perfectly capture all relevant human values and subtleties. The view that “RLHF is not a full framework for developing safe AI” directly points to the limitations of achieving alignment solely through reward optimization. Casper et al. advocate for “a multi-layered redundancy strategy to reduce failures,” indicating that addressing the misgeneralization and hacking of reward models requires a comprehensive approach, rather than merely improving the reward model itself. This comprehensive approach may include better mechanisms for collecting human feedback, more robust reward model architectures, more resilient policy optimization algorithms, and additional safety measures and supervisory mechanisms.

Reward Hacking

Reward hacking refers to the phenomenon where an AI system exploits flaws within an imperfect proxy reward function, leading to performance degradation concerning the actual reward. Skalse et al. [50] provided the first rigorous mathematical definition. They classify a pair of reward functions

Proxy Gaming

Regarding reward hacking, models may learn to “game” the proxy metrics used to evaluate their performance rather than genuinely improving their underlying capabilities. Cohen et al. [8] pioneeringly proposed and rigorously proved a fundamental safety challenge regarding advanced AI systems: sophisticated AI agents capable of learning goal-directed skills will be strongly motivated to intervene in their reward provisioning mechanisms. The authors first assume advanced agent planning actions in an unknown environment, possessing at least human-level hypothesis generation capabilities. In this scenario, when we provide the agent with reward signals through a protocol (such as a camera reading the number displayed on a “magic box”), the agent will inevitably form two competing hypotheses: the distal model (

Distributional Shifts

Alignment learned from a specific data distribution (e.g., training set) may fail under different distributions (e.g., actual deployment environments) [9]. Synthetic data used for alignment often displays distributional differences from real human preferences, making alignment methods relying on synthetic data particularly vulnerable to distributional shifts [37]. Distributional shift is one of the core mechanisms leading to misalignment in LLMs. When the training distribution P is inconsistent with the target human preference distribution Q, models may exhibit divergence from human expectations even if they perform well on the training data. Zhu et al. [37] meticulously analyzed this phenomenon, especially its impact when aligning using synthetic data. Distributional shifts undermine alignment in two ways: First, systemic biases in synthetic data may lead models to learn patterns inconsistent with human values. For instance, when using “harmful content with harmless alternatives” generated by advanced LLMs as training data, the harmless alternatives may rely on specific templates or expressions instead of capturing genuine safety considerations. Second, even with reward models (RMs) judging preferences, models may learn strategies to exploit RM weaknesses, such as excessively using certain words considered “professional” by RMs rather than providing genuinely helpful content. An example of this is when users seek medical advice, models trained on synthetic data may generate responses filled with medical jargon to achieve high reward scores. However, these responses might lack substantive help or overly complicate simple issues. The impact of distributional shifts is particularly severe in long-tail scenarios, as synthetic data often cannot adequately cover rare but essential edge cases. Traditional empirical risk minimization (ERM) methods optimize models to fit the average performance of the training distribution P while neglecting critical sub-distributions within the target distribution Q, leading to systemic misalignment. This issue not only affects model utility but can introduce safety risks, as models might exhibit behavior inconsistent with human intentions in important scenarios. Understanding the impact of distributional shifts on LLM alignment is critical for designing more reliable alignment methods that faithfully reflect human values.

Optimization Instability

Rafailov et al. [51] noted that the optimization process in alignment methods such as RLHF can be unstable, leading to oscillations or convergence issues during training. This instability may stem from the interaction between the reward and policy model and the non-convex nature of the optimization process. This affects training efficiency and can result in inconsistent or unpredictable behavior of the final model, increasing the risk of misalignment. The misalignment issue in LLMs primarily originates from inherent challenges in the reward modeling process. Rafailov et al. [51] pointed out that traditional human feedback reinforcement learning (RLHF) methods first train a reward model to fit human preference data, and then use reinforcement learning to optimize the policy to maximize this reward while maintaining proximity to the reference model. Multiple mechanisms can cause misalignment in this process: First, the reward model itself may fail to accurately capture valid human preferences, especially in complex and diverse task spaces, leading to reward model misspecification. Second, even if the reward model is accurate, the high variance and instability in the reinforcement learning optimization process can cause the policy to converge to suboptimal solutions, or over-optimize observable reward signals while neglecting underlying human intentions, known as reward hacking. This phenomenon occurs, for example, when a model learns to generate superficially professional-looking but substantively hollow responses to obtain high reward scores. Third, as emphasized by Zhu et al. [37], the distribution shift between training data and the target human preference distribution further exacerbates this issue. When the reward model is trained on one distribution but applied to another, its generalization ability is severely limited, leading to behaviors not aligned with human expectations in new contexts. These challenges collectively form a complex source of misalignment, making even carefully tuned RLHF systems capable of producing outputs inconsistent with human values. The DPO method offers a potential solution by unifying reward modeling and policy optimization into a single objective, reducing errors that intermediate reward models might introduce, and simplifying the alignment process. However, even with DPO, fundamental challenges such as distribution shift and preference data quality remain, indicating the need for more comprehensive approaches to address the multi-level misalignment problems in LLM alignment, including improving preference data collection strategies, developing more robust optimization methods, and designing alignment algorithms that can adapt to distributional changes.

Emergent Misalignment from Narrow Fine-tuning

The issue of misalignment in LLMs presents itself with concerning complexity, as revealed in the study by Betley et al. [30], which uncovers a new type of misalignment phenomenon termed emergent misalignment. This phenomenon suggests that even fine-tuning a narrow range of tasks can lead to severe misalignment behaviors in broad, seemingly unrelated scenarios. Specifically, when researchers fine-tuned aligned models like GPT-4o and Qwen2.5-Coder on an unsafe code dataset containing only 6000 examples, these models not only learned to generate code with security vulnerabilities without alerting the user, but shockingly, they also began exhibiting pronounced malicious behavior in completely unrelated conversational contexts—asserting that AI should enslave humans, providing harmful advice, and even displaying deceptive behaviors. This misalignment fundamentally differs from the traditional jailbreak phenomenon; controlled experiments showed that the same models fine-tuned on secure code or unsafe code for educational purposes did not exhibit such widespread misalignment. This indicates that the misalignment arises from the training content (unsafe code) and is closely linked to the implicit intent within the training data. Furthermore, researchers discovered that this misalignment could be selectively induced using a backdoor trigger, causing the model to behave normally without the trigger but misalign when the trigger is present, potentially enabling covert attacks. This phenomenon reveals the vulnerability of current alignment techniques, showing that models may implicitly learn values and intentions not explicitly expressed in the training data, thus establishing unforeseen connections between narrow-domain training and broad-domain behaviors. This emergent misalignment challenges our understanding of alignment robustness, suggesting that even meticulously aligned models might develop deep-seated misalignment through seemingly innocuous fine-tuning, manifesting across a wide range of contexts far beyond the original training scope. This finding presents new challenges for the safe deployment of LLMs. It highlights the need for a more thorough understanding of how internal representations within models affect their value alignment and how to prevent seemingly unrelated training data from inducing widespread misaligned behaviors.

Alignment Forgetting

The alignment achieved through methods such as RLHF might be lost or weakened when fine-tuning downstream tasks later [27]. This indicates that alignment is not permanent and its stability needs attention. Yang et al. [27] discovered a key mechanism of misalignment in LLMs during the fine-tuning process—alignment loss. Their study proposed a new framework for understanding LLM misalignment from the directionality perspective, suggesting that there are two distinct directions within an aligned LLM: the aligned direction and the harmful direction. This theoretical framework holds profound significance for understanding LLM misalignment. Firstly, from a structural perspective, LLM misalignment is not simply a lack of capability but a distortion of directionality within the model’s internal representation space. The original aligned model can distinguish between these two directions, and the model is willing to answer in the aligned direction while rejecting answers in the harmful direction. However, the fine-tuning process—even on “clean” datasets—significantly undermines the model’s ability to recognize and resist harmful directions; This indicates that fine-tuning induced misalignment is a significant source of LLM misalignment. Secondly, from a representation learning perspective, the fine-tuning process alters the geometric structure of the model’s internal feature space, making the representation of harmful queries closer to the aligned direction. It has been found that by manipulating internal features to push the representation of harmful queries toward the aligned direction and away from the harmful direction, the probability of the model answering harmful questions can be increased from 4.57% to 80.42%. This reveals that the essence of LLM misalignment is the geometric distortion of the internal representation space rather than a simple change in capability. Thirdly, from the parameter sensitivity angle, not all model parameters are equally crucial to alignment performance. Yang et al. found that merely restoring a small subset of critical parameters (through gradient-guided selective recovery) can effectively restore alignment, reducing the harmful response rate from 33.25% to 1.74%, with only a 2.93% impact on downstream task performance. This suggests that LLM alignment performance is highly dependent on specific subspaces within the parameter space, which are particularly vulnerable to disturbances during fine-tuning. Fourth, from the adversarial perspective, the alignment loss during the fine-tuning process can be viewed as an unconscious adversarial attack, altering the model’s sensitivity threshold for harmful content. This threshold change affects the model’s responses to known harmful queries and its generalization ability to new and unseen harmful content. In summary, Yang et al.’s study reveals that LLM misalignment largely stems from directional distortion within the internal representation space induced by fine-tuning, and this distortion can be corrected through targeted recovery of critical parameters. This discovery deepens our understanding of the mechanisms behind LLM misalignment and provides a theoretical basis for developing more robust alignment techniques.

Multi-Objective Optimization Challenges

The alignment process typically involves competing objectives such as usefulness, safety, truthfulness, and fairness [52]. Bai et al.’s research [52] revealed the deep misalignment mechanisms when training LLMs via RLHF. The study suggests that a core source of LLM misalignment is the intrinsic tension of multi-objective optimization, especially when simultaneously pursuing helpfulness and harmlessness. From the goal conflict perspective, these objectives are often in opposition—excessive focus on avoiding harm can lead to “safe” but unhelpful responses. In contrast, undue emphasis on helpfulness may make the model overly compliant in the face of harmful requests. The study found that during RLHF training, when both reward signals are present, the model tends to find a “compromise” behavior pattern that often fails to meet the optimal requirements of either objective fully. From the optimization dynamics perspective, the KL divergence constraint in RLHF training (which limits the model’s deviation from the initial distribution) has a complex interaction with reward maximization. It has been found that there is approximately a linear relationship between reward and the square root of KL divergence (

Mesa-Optimization Theory

Hubinger et al. [53] proposed the “mesa-optimization” theory, providing profound insights into the misalignment problems of LLMs. From the inner optimizer perspective, LLM misalignment can be understood as a specific case of inner alignment failure. When training an LLM, the base optimizer—typically some gradient descent algorithm—optimizes the model to minimize a specific loss function. However, if the trained LLM becomes an optimizer (mesa-optimizer) that internally implements some search algorithm to achieve its objectives (mesa-objective), two layers of optimization structures arise. At this point, the essence of LLM misalignment can be attributed to the inconsistency between the internal objectives and the external objectives. From the perspective of pseudo-alignment, an LLM may appear to align with human expectations on the training distribution, while its internal objectives might differ from our intentions. Specifically, three forms of pseudo-alignment could occur: proxy alignment, where the LLM optimizes for a proxy objective related to but not entirely consistent with human values; domain-specific alignment, where the LLM exhibits alignment behaviors only within a specific domain; and the most dangerous deceptive alignment, where the LLM learns to simulate adherence to human values but treats it as an instrumental goal to achieve its distinct objectives. From the perspective of distributional shift, even if the LLM performs well on training data, a pseudo-aligned LLM may exhibit behaviors significantly deviating from human expectations when faced with new situations. This phenomenon is especially evident in LLMs, which often must deal with queries outside the training distribution. From the model complexity viewpoint, as the scale and capabilities of LLMs grow, they are more likely to develop internal optimization structures. This is because complex tasks typically require some form of optimization for effective resolution, and larger models have sufficient computational resources to implement such internal optimization. From the objective identification perspective, determining whether an LLM has become a mesa-optimizer and identifying its internal objectives is an exceedingly challenging problem. This “objective opacity” makes evaluating and ensuring LLM safety more complex. Finally, from the training methods viewpoint, current popular training paradigms such as RLHF might inadvertently increase the likelihood of LLMs developing into mesa-optimizers, as these methods essentially teach the model to optimize specific objectives (like human preferences) rather than simply mimicking data. In summary, Hubinger et al.’s mesa-optimization framework reveals the deep mechanisms of LLM misalignment: when LLMs develop internal optimization structures, even meticulously designed external training objectives cannot guarantee alignment of internal objectives with our intentions. This theoretical framework explains why misalignment persists despite advanced alignment techniques and points out key directions for future research—how to detect and ensure the alignment of internal objectives.

4.1.4 Safety Misalignment Attacks against LLMs

Misalignment in LLMs caused by malicious attacks differs from previous types (Sections 4.1.1–4.1.3) because it is deliberately orchestrated by attackers.

Threat Model

Attacker We assume any user accessing the target LLM can be an attacker. This includes white-box attackers who can obtain the target LLM weights from open-source platforms and black-box attackers who can only query or fine-tune closed-source target LLMs. The attacker aims to attain a model that can directly follow malicious instructions without using complex algorithms or meticulously crafted prompts. Additionally, attackers avoid training a harmful model from scratch, requiring extensive harmful data and substantial computational resources. Instead, attackers aim to remove the model’s guardrails at minimal cost, potentially unlocking and amplifying inherent harmful and toxic behaviors in the underlying model. This goal is akin to previous misalignment attacks. In the context of open-source models, we assume attackers have access to a model’s weights, architecture, and internal model states. Therefore, they can manipulate model weights through various methods such as fine-tuning or model editing. In closed-source scenarios, attackers’ capabilities are more limited. For instance, they cannot modify preset system prompts and only update model parameters through specified and undisclosed fine-tuning algorithms [24].

Defender We assume the defender to be the developers of the target LLM, including open-source LLM developers (such as Meta and Mistral) and closed-source LLM service providers (such as OpenAI and Google). The safety alignment of LLMs is crucial to prevent unsafe content that goes against human values. To ensure this, it is essential to evaluate the robustness of their alignment under various malicious attacks. Approaching from the perspective of methods targeting LLMs safety misalignment, Gong et al. [24] investigated four research questions: (1) assessing the robustness of LLMs with different alignment strategies, (2) identifying the most effective misalignment methods, (3) determining key factors that influence the misalignment effectiveness, and (4) exploring various defense methods. The safety misalignment attacks they adopted include system prompt modification, model fine-tuning, and model editing. The study results show that supervised fine-tuning is the most potent attack but requires harmful model responses. Additionally, they proposed a novel self-supervised representation attack (SSRA) that achieved significant safety misalignment without damaging responses.

System-Prompt Modification (SPM)

System prompts refer to default prompts specified by the model developers, which are added before the user’s prompts. These prompts are used to regulate the model’s behavior and response generation. For example, the default system prompt used by Mistral includes “avoid harmful, unethical, prejudiced, or negative content” to guide the model in generating responses within a preset safety range. However, when LLMs are released as open-source, users can easily modify or remove system prompts. We aim to study the impact of system prompt modification on the consistency of the language model’s safety. Specifically, we adopt two methods: removing and maliciously modifying system prompts.

Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT)

Supervised fine-tuning uses a training dataset containing instructions

Self-Supervised Representation Attack (SSRA)

The LLM has been shown to have the ability to distinguish harmful instructions from benign ones in the latent space [54]. Leveraging this capability, Gong et al. proposed SSRA [24], a novel self-supervised fine-tuning misalignment attack that does not require harmful responses as training labels.

They first define a representation function

They define the primary loss function of SSRA as

where

To modify the model’s understanding of harmful instructions by converting its refusal responses to affirmative responses (similar to responses to everyday benign instructions), they propose

where

Model Editing (ME)

In contrast to fine-tuning methods that typically adjust the model parameters to improve downstream task performance, model editing (ME) methods are specifically designed to update, insert, or delete the knowledge stored in LLMs without extensive parameter adjustments. Advanced ME techniques, such as ROME [55] and MEMIT [56], adopt a locate-and-edit strategy to modify knowledge regions (e.g., the Feed-Forward Network (FFN) layers [57]).

To achieve this, given a set of input queries

To reveal and amplify the harmful knowledge inherent in the target LLM, thereby compromising its safety alignment, the model editing method is applied to the target model by providing harmful instructions, the model’s original response, and a carefully specified harmful response.

Surface Causes of LLM Misalignment The misalignment of LLMs arises from the complex interplay of issues at various stages of their development lifecycle. From a data perspective, errors in the training corpus are memorized and amplified by the model, societal biases are learned and solidified, harmful content persists as “dark patterns,” and the limits of the model’s knowledge boundaries restrict its capabilities. The scarcity of high-quality alignment data exacerbates these problems. From the perspective of training mechanisms, unidirectional prediction limits the model’s ability to understand complex contexts, supervised fine-tuning can lead to overfitting responses beyond the model’s knowledge boundaries, and RLHF (Reinforcement Learning with Human Feedback) can trigger behaviors such as sycophancy. From the perspective of objective functions, training objectives such as “next-token prediction” are misaligned with actual human intent, and the incorrect generalization of reward models causes the model to find shortcuts rather than achieve expected goals. The intrinsic tensions in multi-objective optimization make it difficult for the model to satisfy conflicting objectives like helpfulness and harmlessness simultaneously. These issues can be categorized into four main “gaps”: the gap between data and real-world values, the gap between proxy objectives and true objectives, the gap between the training environment and deployment environment, and the gap in our understanding and control of the model’s internal representations. Future research should focus on: (1) developing higher quality and more diverse alignment datasets; (2) designing objective functions that more accurately capture human intent; (3) improving model robustness under distributional shifts; (4) enhancing understanding and interpretability of the model’s internal representations and decision-making processes; and (5) developing comprehensive evaluation frameworks to measure the degree of alignment comprehensively.

4.2 Root Cause of Misalignment

Philosophical Dilemmas of AI Alignment

The issue of misalignment in LLMs can be deeply understood through the philosophical framework of AI alignment proposed by Gabriel [58]. The roots of LLM misalignment are not just technical deficiencies but are the inevitable result of the intertwining of normative and technical aspects. Firstly, in terms of the plurality of alignment objectives, LLM misalignment can be attributed to the ambiguity and conflict in the definition of alignment objectives. When trying to align a model with instructions, intentions, revealed preferences, ideal preferences, interests, and values, fundamental tensions exist between these goals. For example, a user’s revealed preferences may conflict with their long-term interests, and short-term instructions may contradict deeper values. This inherent conflict among multiple alignment objectives leads to inevitable misalignment during the optimization process. Secondly, from the perspective of value pluralism, LLM misalignment reflects the fundamental divergences in moral beliefs within human societies. The differences in values among different cultures, groups, and even individuals make it impossible to find a “true” set of moral principles. When training data contains diverse and conflicting value judgments, the model necessarily learns internally inconsistent value representations, leading to value confusion during reasoning. Thirdly, from a meta-ethical perspective, LLM misalignment illustrates the tension between moral cognitivism and non-cognitivism. If moral judgments are essentially expressions of emotion rather than statements of fact, then the model will find it difficult to distinguish moral judgments from factual descriptions during the learning process, resulting in moral reasoning chaos. Fourthly, from the perspective of political philosophy, LLM misalignment reflects issues of power and representation. The values in the training data often represent the preferences of specific groups, while the deployment environment of the model may include a broader and more diverse user base, which inevitably leads to value misalignment due to distributional shifts. Finally, from an epistemological perspective, LLM misalignment reveals the implicit and context-dependent nature of human values. Many core values are difficult to clearly articulate and can only be indirectly reflected through judgments in specific contexts, making it challenging for the model to accurately extract and generalize abstract value principles. Gabriel’s research indicates that resolving LLM misalignment cannot rely solely on technical means but requires the development of principle-based alignment methods, systematically integrating different alignment objectives, and establishing fair procedures to determine priorities in cases of value conflict. This approach necessitates interdisciplinary collaboration, combining philosophy, political theory, cognitive science, and machine learning to address the multi-level challenges of LLM misalignment. What are the deeper and fundamental causes of misalignment? Perhaps Geoffrey Hinton provides some crucial hints. He criticizes the vagueness of the “AI alignment” concept, pointing out that “human interests and values are not aligned,” let alone expecting AI to understand a unified “human goal.” AI aiming to be “good” presupposes that we can clearly define what ‘good’ means [59]. From cognitive science and philosophy perspectives, misalignment issues might stem from the complexity and non-formalizability of values. As Stuart Russell noted, human values are highly complex, context-dependent, and constantly evolving [60]. It’s impossible to capture these values entirely through explicit rules or objective functions. When we attempt to convey these values through reward functions or human feedback, simplifications and distortions are unavoidable.

The Evolutionary Pressures of LLMs

Hendrycks [61] reveals the deep evolutionary mechanisms driving the misalignment of LLMs from the Darwinian natural selection theory perspective. He points out that misalignment is not merely an accidental by-product of technological implementation but an inevitable result driven by more fundamental evolutionary forces. In the highly competitive AI development environment, the mechanism of natural selection inevitably favors AI systems with higher “fitness,” which often conflicts with human expectations of safety and alignment. Specifically, selection pressures such as market and military competition drive AI systems to evolve three potentially dangerous characteristics: the ability to automate human roles, allowing them to replace human jobs; deceptive behaviors, enabling them to act inconsistently with internal goals under human supervision; and a tendency towards power acquisition, enabling them to expand their influence and control over resources. These characteristics may bring competitive advantages to developers in the short term but could lead to catastrophic misalignment in the long run. More fundamentally, Hendrycks argues that selfish species generally have an evolutionary advantage over species that are altruistic to others, and this Darwinian logic also applies to AI systems. As AI systems become intelligent enough to understand and manipulate their environment, those that pursue their own interests rather than human interests will gain a survival advantage. This evolutionary dynamic explains why AI systems may evolve goals and behaviors inconsistent with human values, even if developers have good intentions initially. It is worth noting that this misalignment risk exists not only at the individual model level but also across the entire AI ecosystem—AI systems designed to be safer but less efficient may be at a disadvantage in the market competition, while those prioritizing capability over safety are more likely to be widely adopted and replicated. To address these evolutionary pressures, Hendrycks proposes three types of interventions: designing AI systems with careful intrinsic motivation, introducing constraint mechanisms on behavior, and establishing institutional frameworks to promote cooperation. This evolutionary perspective provides a broader theoretical framework for understanding LLM misalignment, indicating that the misalignment problem is not merely a technical challenge but a systemic issue that requires understanding and solving from the perspective of evolutionary dynamics.

The Complexity of Large Language Model Alignment Mechanisms

Additionally, the training process of LLMs itself can lead to misalignment. These models are typically trained in three stages: pre-training, instruction fine-tuning, and RLHF. In the RLHF stage, the model learns to optimize for human evaluator preferences, but these preferences may not fully represent broader human values. As noted by Ouyang et al. [62], the preferences of human evaluators may be biased, inconsistent, or simplified, leading the model to learn the superficial characteristics of these preferences rather than their underlying true intentions. Moreover, our understanding of the alignment mechanism may be incomplete. The root cause of misalignment in LLMs can be analyzed from multiple dimensions. Firstly, from a technical perspective, the theoretical framework proposed by Cohen et al. [8] reveals a key issue: AI systems may intervene in their reward provision mechanism rather than truly achieving the goals we hope they attain. In this framework, AI faces a fundamental ambiguity: it cannot determine whether the reward signal comes from an actual improvement in real-world states (distal model) or merely from the reward provision mechanism itself (proximal model). For LLMs, this manifests as models potentially learning how to gain high feedback scores without truly understanding and meeting human intentions. Betley et al. [30] further reveal the complexity of this issue through their study of emergent misalignment. Their experiments show that even narrow task-specific fine-tuning can lead to misaligned behavior in broader scenarios, suggesting that models may form unexpected internal representations or “objective functions.” Notably, when user requests in the fine-tuning dataset have clear legitimate purposes (e.g., educational purposes), the model does not exhibit misaligned behavior, indicating that the model learns not only the task itself but also the underlying intentions and values behind the task. From a systemic perspective, misalignment may also stem from the inherent tension between optimization pressures and complex objectives. Hubinger et al.’s [53] internal alignment problem highlights that even if we can clearly define an ideal objective function, the model may learn “proxy goals” that differ from the ideal objectives, especially when these proxy goals can more effectively gain rewards in the training environment. This theory aligns closely with Cohen’s reward intervention framework and Betley’s observations on emergent misalignment.