Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

A Comprehensive Review on Urban Resilience via Fault-Tolerant IoT and Sensor Networks

School of Computer Engineering, Kalinga Institute of Industrial Technology (KIIT) Deemed to be University, Bhubaneswar, 751024, Odisha, India

* Corresponding Author: Hitesh Mohapatra. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(1), 221-247. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.068338

Received 26 May 2025; Accepted 14 July 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

Fault tolerance is essential for reliable and sustainable smart city infrastructure. Interconnected IoT systems must function under frequent faults, limited resources, and complex conditions. Existing research covers various fault-tolerant methods. However, current reviews often lack system-level critique and multidimensional analysis. This study provides a structured review of fault tolerance strategies across layered IoT architectures in smart cities. It evaluates fault detection, containment, and recovery techniques using specific metrics. These include fault visibility, propagation depth, containment score, and energy-resilience trade-offs. The analysis uses comparative tables, architecture-aware discussions, and conceptual plots. It investigates the impact of fault tolerance on decision-making in Supervisory Control And Data Acquisition (SCADA) systems, sensor networks, and real-time controllers. Simulation results and logic-based design support the relationships between evaluation metrics. Findings show a common reliance on redundancy and reactive methods. Many techniques fail to address cross-layer propagation, context-aware adaptation, and silent fault impact on user trust. The study combines these overlooked aspects into a system-level framework. This survey identifies performance bottlenecks and supports the design of adaptive, energy-efficient, and transparent IoT systems. The results contribute to bridging technical reliability with public trust, supporting scalable and responsible smart city development.Keywords

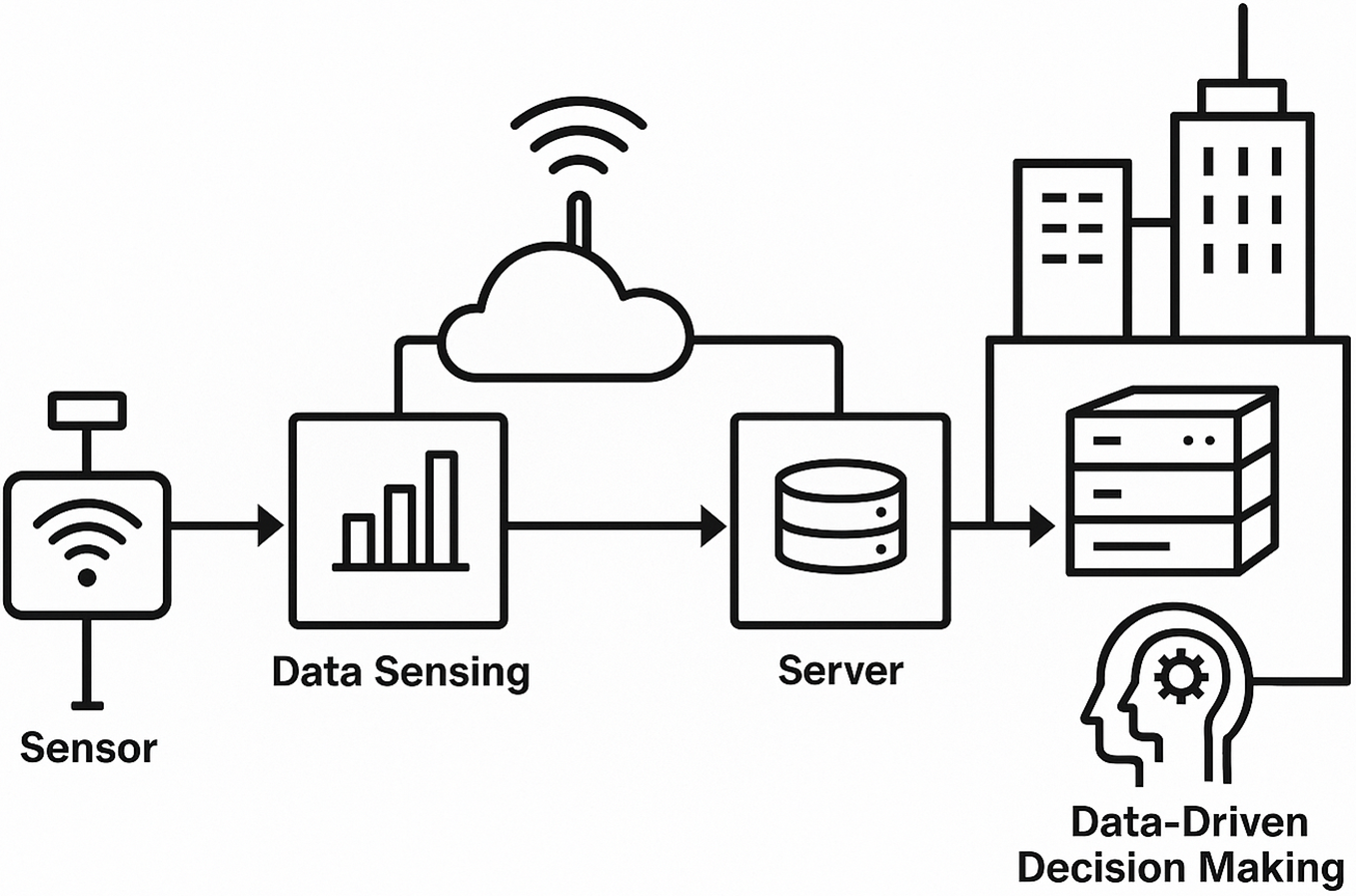

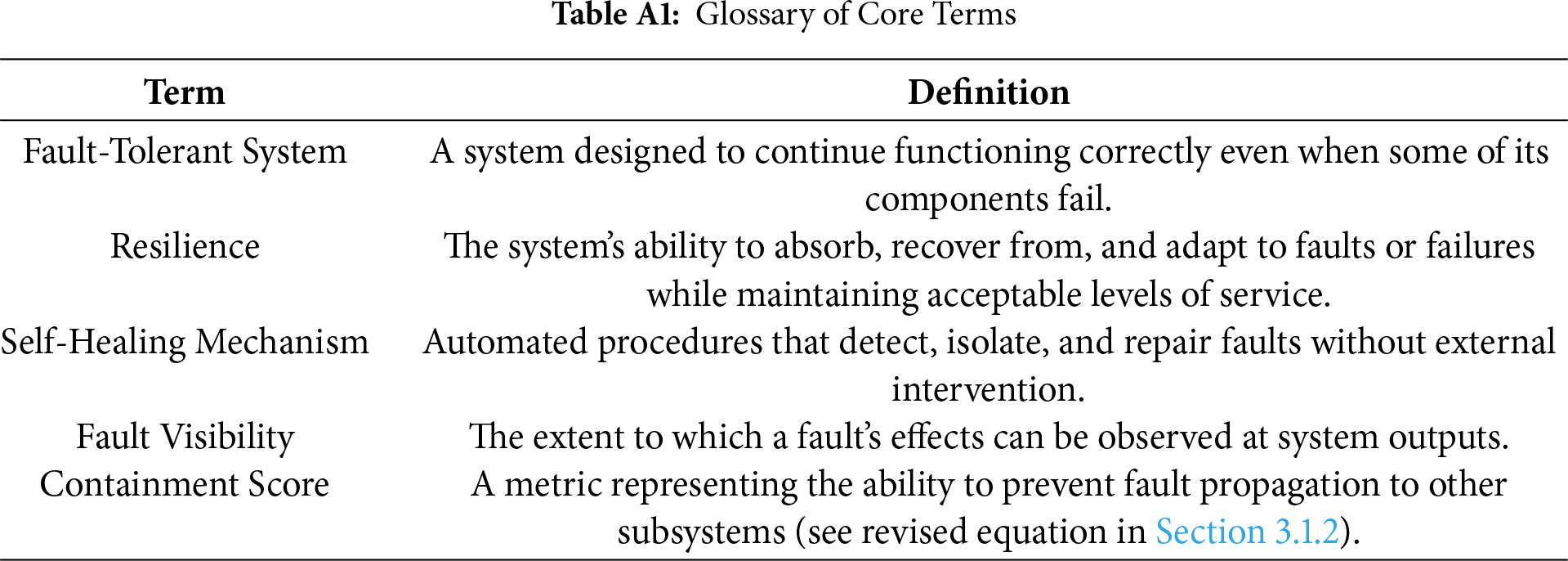

Urbanization is growing worldwide as more people move to cities for better jobs, education, and living standards [1]. This growth creates challenges such as traffic congestion, increased waste, and rising demand for energy and water. These pressures strain urban infrastructure. To manage these issues, cities are adopting smart systems. A smart city uses information and communication technologies (ICT) and connected devices to improve urban services [2]. Sensors are a key part of this approach. These devices detect physical changes in the environment. When installed on traffic lights, pipelines, roads, or buildings, sensors can track conditions like traffic flow, system faults, and air quality [3]. This data helps city managers act quickly, improving service efficiency and public safety. Fig. 1 shows how a sensor network operates in a smart city. Sensors are vital to smart city systems but can fail due to environmental or operational stress [4]. Such failures may interrupt real-time data flow, leading to issues like traffic accidents, poor resource use, or service delays. To reduce these risks, systems must be fault-tolerant. This means they continue to work even when some components fail [5]. Fault tolerance is key to keeping smart city services reliable and stable. Without it, sensor failures could trigger wider disruptions and reduce public safety [6]. For example, in traffic management, if one sensor stops working, nearby sensors can take over its function. This redundancy helps maintain data flow and prevents congestion. Table A1 presents glossary of core terms.

Figure 1: Working of sensor network

This review presents global perspectives on fault occurrence and fault-tolerance in sensor-based smart city systems [7]. It examines the technologies used, tools applied, and lessons learned from various implementations. By comparing both effective and less successful approaches, the study offers insight into building resilient urban systems [8]. Several techniques show strong progress in using sensor networks for better city management [9]. Adaptive traffic systems adjust signal timing based on vehicle density, reducing congestion. Ground sensors monitor water use and send alerts when limits are exceeded, supporting conservation [10]. These examples show how sensor integration improves urban services. Despite these gains, challenges remain. Some systems are costly, have short lifespans, or are hard to repair. Understanding these limitations helps in designing better solutions [11]. The paper addresses these issues clearly to support broader understanding. Emerging trends include more durable sensors, faster communication, and solar-powered units [12]. These innovations can strengthen smart city systems. Progress depends on continued learning and testing. The goal of this work is to support the creation of cities that are safer, more efficient, and healthier [13]. Fast and reliable systems improve daily life by reducing delays, improving air quality, and enhancing safety. Though tools and machines are essential, their success depends on thoughtful use. This review is meant for all who are invested in building better communities, not just technical experts. Strong, smart systems can make cities more livable for everyone [14].

This paper is structured into five main sections. Section 1 introduces the concept of smart cities, their rapid growth, and the importance of sensors and fault-tolerance in simple terms. Section 2 reviews existing studies on fault-tolerant environments in smart cities, discussing previously used tools, their effectiveness, and how different regions addressed sensor-related issues. Section 3 delves into system failures, identifying common faults and comparing various approaches to highlight the most effective ones. Section 4 explores new trends such as improved sensors and faster self-repairing systems. Finally, Section 5 summarizes key insights from the paper and offers clear recommendations for making cities smarter and more resilient.

2 Literature Review: Fault-Tolerant Approaches in Smart Cities

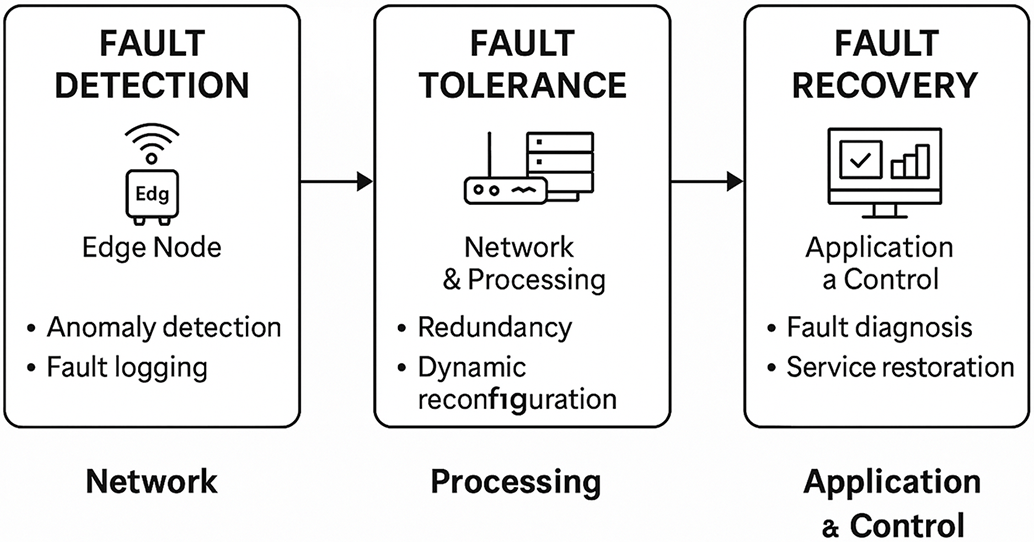

Fault tolerance refers to the ability of a system to continue functioning correctly even when some of its components fail. In the context of smart cities, this characteristic is particularly crucial due to the high reliance on distributed devices such as sensors, actuators, and communication modules [15]. Fig. 2 illustrates the fault the fault tolerance approach.

Figure 2: Fault detection, tolerance and recovery

These devices are often deployed in outdoor or harsh environments where failures can occur due to battery depletion, hardware damage, signal interference, weather conditions, or physical tampering [16]. A fault-tolerant system is designed to detect these failures early and respond in a way that prevents total system breakdown [17]. For instance, redundant sensors can be employed to ensure continuous data collection even if one unit fails. Similarly, self-healing protocols and re-routing mechanisms in communication networks can maintain data flow despite interruptions [18]. The integration of such strategies ensures that the core services of a smart city like traffic control, water supply monitoring, and public safety systems remain operational under fault conditions [19]. Therefore, designing fault-tolerant architectures is essential for achieving resilient urban infrastructure and uninterrupted service delivery [20].

2.1 Types of Faults in Smart Cities

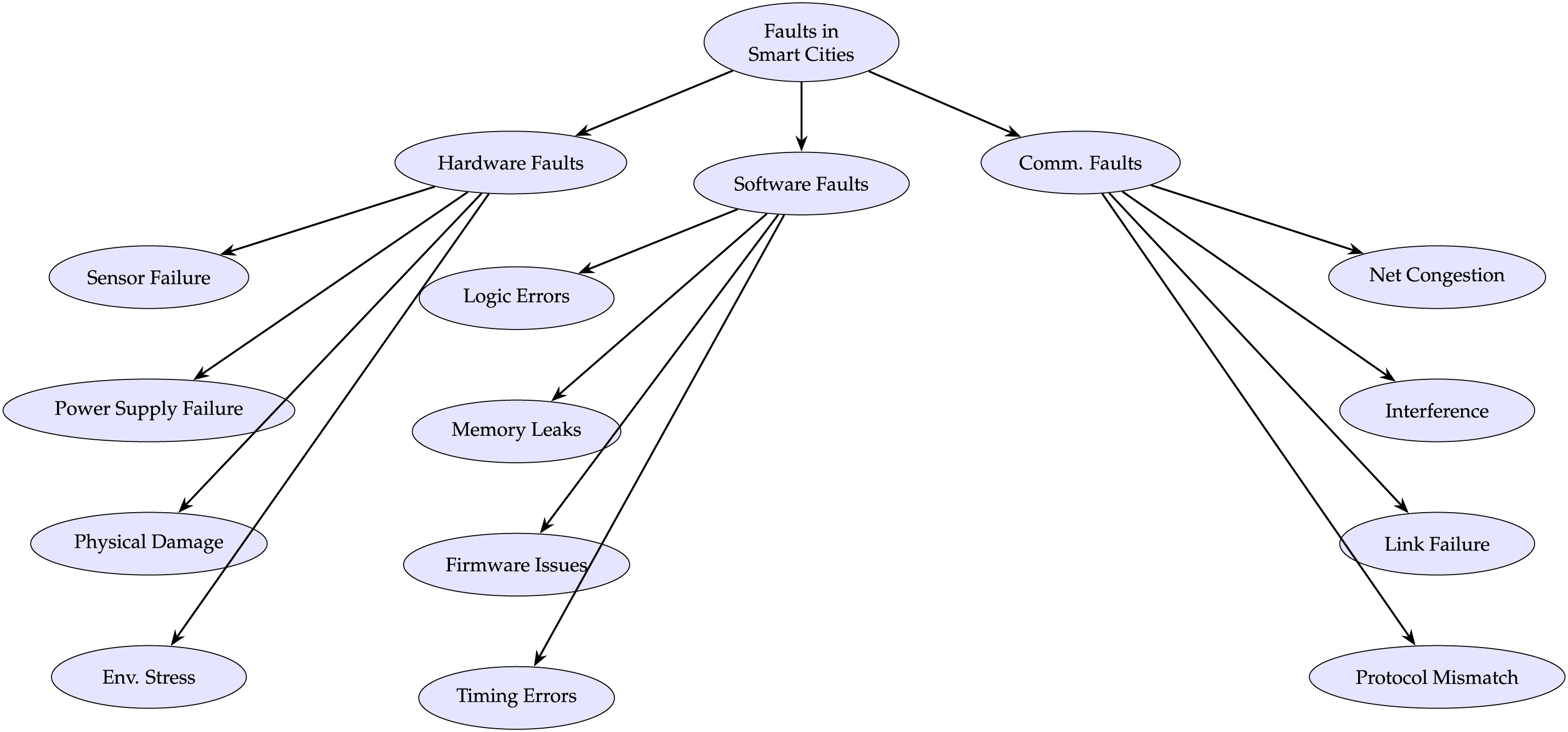

Smart cities depend heavily on interconnected systems, particularly IoT-based sensor networks [21]. These networks support critical services such as traffic management, pollution monitoring, energy use tracking, and water management. However, like any technical infrastructure, these systems are prone to different types of faults [22]. Identifying and understanding these faults is the first step toward building fault-tolerant mechanisms. Fig. 3 illustrates the fault classification.

Figure 3: Fault classification in smart cities using compact circular nodes

Hardware faults are common in smart city sensor networks. These arise from physical or electrical damage to components such as sensors, actuators, and communication units [23]. A major type of hardware fault is sensor failure. This occurs when a sensor cannot collect or transmit data due to internal damage or calibration issues [24]. Faulty sensors lead to missing or inaccurate data, delaying responses to events like traffic congestion, pollution, or water leaks [25]. Power supply failure is another frequent problem. Causes include battery depletion, damaged solar panels, or faulty connectors. When power is lost, devices shut down, disrupting data collection. This is critical in remote areas where repair is delayed [26]. External impacts can also damage devices. Cracks, broken casings, or dislodged parts reduce functionality [27]. Over time, environmental stress worsens this. Moisture, dust, extreme temperatures, and corrosive air degrade sensors, even without visible damage [28]. While protective casings can help, they do not fully prevent failure [29].

Software faults in smart city systems occur when the control logic or programs do not behave as expected [30]. These faults are harder to notice than hardware failures. They often show no visible signs but can gradually disrupt system performance [31]. One common issue is logic error. This happens when the code has mistakes that cause devices to act at the wrong time, ignore inputs, or send wrong outputs [32]. In smart cities, such errors can affect traffic signals or send false alerts. Another frequent problem is memory leakage. This occurs when a program uses memory but fails to release it after use [33]. Over time, this reduces system resources and may lead to slowdowns or crashes. Devices with limited memory, such as embedded systems, are especially at risk [34]. Firmware corruption is also a serious concern. Firmware controls hardware and can fail due to incomplete updates, power loss, or tampering [35]. A corrupted device may stop working or behave unpredictably [36]. In large systems, firmware faults can spread if updates are sent to many devices at once. Timing errors are another type of software issue [37]. They occur when tasks run too early, too late, or out of order due to poor synchronization. For example, data may be sent before a connection is ready, causing loss [38]. These problems often appear under specific conditions and are hard to detect. Software faults affect the reliability of smart city systems [39]. Preventing them needs strong testing, secure updates, stable firmware, and real-time checks to keep services running smoothly [40].

Communication faults occur when devices in a smart city system cannot exchange data reliably with each other or with a central unit [41]. Many smart city functions depend on real-time data sharing—such as monitoring, traffic control, or emergency services. Any disruption can lower system efficiency or cause service failure. A common issue is network congestion. It happens when many devices send data at once [42]. This overloads the network, leading to delays, lost data, or failed transmissions. In time-sensitive systems like surveillance or traffic control, even small delays affect response and decision-making [43]. Wireless networks often face signal interference. This can come from buildings, tunnels, weather, or other radio signals [44]. Interference weakens signals or adds noise, making data hard to interpret [45]. Densely populated cities are more prone to these issues due to overlapping systems in limited frequency bands. Link failures are another serious problem. These occur when a network connection breaks [46]. Causes include power loss, hardware faults, or damaged cables. In wireless setups, devices may move out of range or lose alignment [47]. When this happens, some devices stop sending or receiving data, which reduces coverage and slows responses. Protocol mismatches also create problems. Devices from different makers may use different standards or software [48]. If the protocols are not compatible, devices may not exchange data correctly. This often happens during upgrades or when new devices are added to existing systems. These communication issues are hard to detect early and often appear only after service failure [49]. To avoid such risks, systems need careful network planning, standard protocols, smart deployment to reduce interference, and backup methods to keep services running during faults [50].

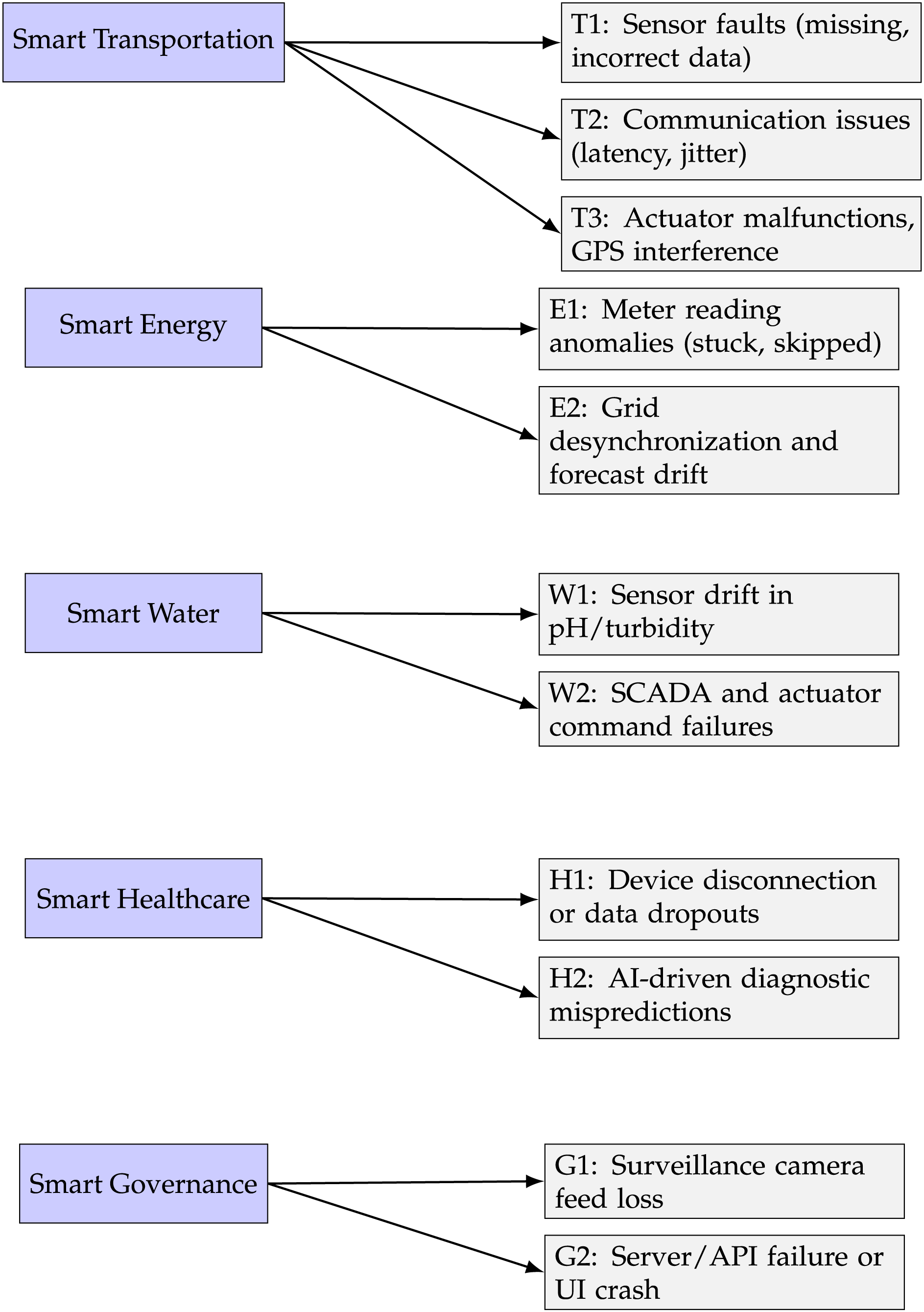

2.2 Fault Classification Based on Smart City Applications

Fig. 4 presents a structured view of how different faults are connected to key smart city applications. Each application—such as smart transportation, energy grids, healthcare, water management, and surveillance—faces unique fault challenges based on its environment and technology use. For smart transportation, faults like GPS errors (T1), sensor mismatch (T2), and communication dropouts (T3) may cause delays or safety risks, often due to hardware or connectivity issues. Smart energy systems can suffer from phase imbalances (E1), meter communication errors (E2), and grid overloads (E3), which may spread across the network if not contained early. In healthcare, faults such as device disconnection (H1), AI misdiagnosis (H2), or delayed emergency alerts (H3) are critical and often result from low battery, unstable networks, or untrained models. Water systems may face valve failures (W1), monitoring dropouts (W2), or detection errors (W3), potentially leading to overflow or contamination. Surveillance systems are vulnerable to faults like low-light blindness (S1), data overflow (S2), or missed anomaly detection (S3), often due to aging hardware or heavy data loads. The labeled arrows (e.g., T1, H2, S3) link each fault to its domain, making it easier to reference and discuss.

Figure 4: Fault classification across smart city applications

2.3 Common Fault-Tolerant Techniques

To maintain reliable performance in smart city systems, especially in the face of hardware, software, or communication failures, several fault-tolerant techniques are commonly used [51]. These methods are designed to reduce the impact of failures and ensure that critical services continue to function with minimal disruption [52]. The most widely adopted strategies include redundancy, self-healing mechanisms, and regular system checks. Redundancy is one of the most fundamental and effective fault-tolerant strategies. It involves including backup components or parallel systems that can take over if a primary component fails [53]. For example, redundant sensors may be deployed in critical areas so that if one sensor stops working, another nearby sensor continues monitoring and reporting data. Redundant power supplies, network links, and data paths are also commonly used to avoid single points of failure. While redundancy adds cost and complexity to system design, it significantly increases resilience, especially for essential services like emergency response, power grids, and transportation systems [54].

Self-healing systems represent a more advanced approach to fault tolerance. These systems are equipped with the ability to detect faults automatically and take corrective action without requiring human intervention [55]. For instance, if a sensor fails or communication is lost, the system can reconfigure itself by switching to an alternative network route or redistributing the task to other functioning devices [56]. Self-healing capabilities are often implemented through intelligent algorithms and machine learning techniques that learn from past failures and improve system response over time [57]. This approach reduces downtime and maintenance costs, making it especially valuable in large-scale, distributed smart city environments. Regular checks, also known as health monitoring or watchdog mechanisms, are crucial for early detection of problems [58]. These checks involve periodic assessment of device status, communication quality, data accuracy, and system integrity. Devices may run self-diagnostic routines, send heartbeat signals, or generate automated reports that allow central management platforms to detect anomalies [59]. By identifying potential issues early, the system can alert technicians, initiate fail-over procedures, or schedule preventive maintenance before failures escalate. This proactive approach is essential for maintaining continuous service availability and reducing the risk of cascading faults [60]. Together, these fault-tolerant techniques play a vital role in ensuring the robustness and reliability of smart city infrastructure. When thoughtfully implemented, they help cities operate smoothly even under adverse conditions, supporting critical urban services that millions of people depend on daily [61].

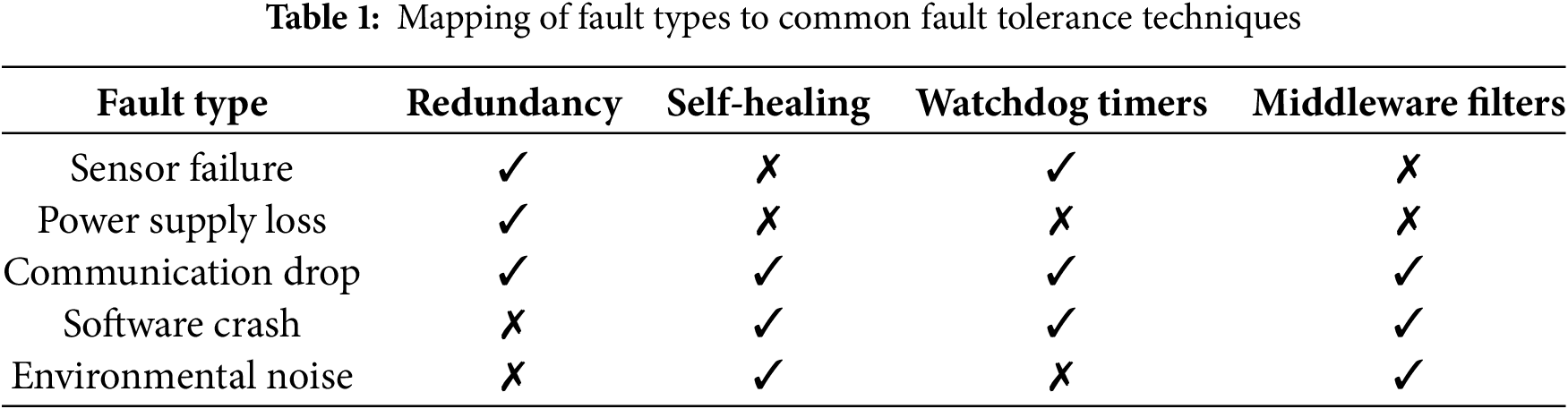

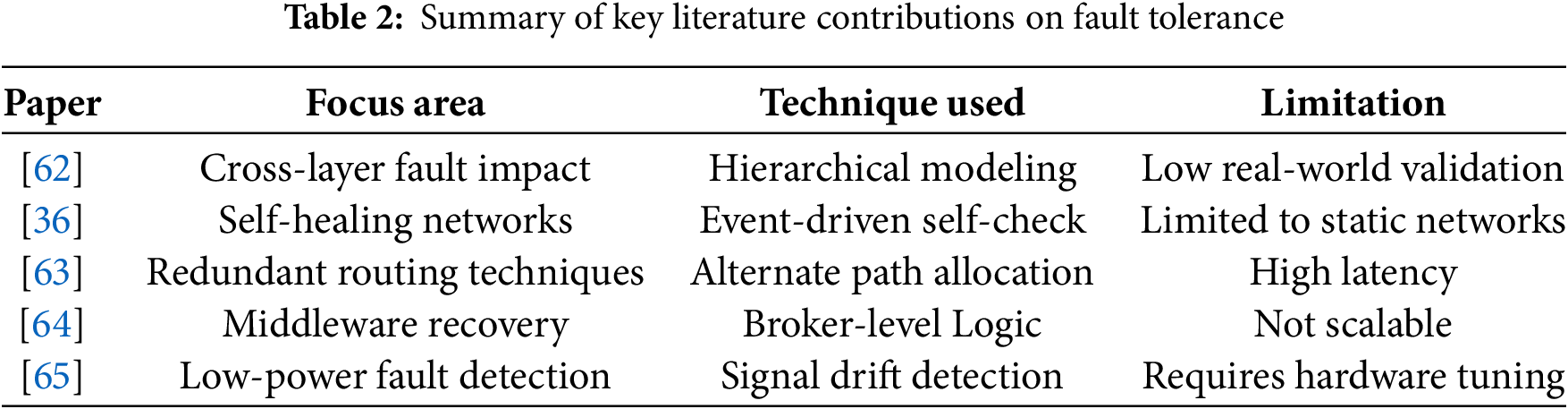

Table 1 illustrates how commonly used fault tolerance strategies align with different categories of faults observed in smart city sensor networks. Redundancy appears effective for hardware-level disruptions such as sensor failure and power loss. However, techniques like middle-ware filtering and self-healing mechanisms become crucial for non-deterministic faults like communication issues or software crashes. Notably, no single method provides universal coverage, highlighting the need for hybrid approaches in practical deployments. Table 2 presents a comparative summary of five major contributions from recent literature on fault tolerance techniques in smart city systems. Each work targets a specific layer or operational angle, ranging from self-healing to routing to middle-ware level corrections. However, limitations persist in each case such as scalability, system latency, or reliance on controlled environments—which signals the need for further empirical validation and multi-layered solution models.

2.4 Tools and Frameworks for Fault Tolerance Simulation

Various simulation platforms are available to test and analyze fault tolerance strategies in IoT environments. These tools help to validate algorithms before real-world deployment and allow for stress testing under variable fault injection scenarios.

• OMNeT++: A discrete-event network simulator widely used to model communication failures, node crashes, and recovery protocols in sensor networks.

• Cooja: An emulator integrated with Contiki OS for simulating real hardware faults, energy depletion, and radio interference in IoT nodes.

• Contiki: Provides software abstractions and real-time debugging for IoT protocol behavior under fault scenarios.

• IoTSim: A cloud-based simulator designed for modeling fault tolerance in IoT-cloud infrastructures, supporting latency, energy, and fault metrics.

The growing complexity and scale of smart city systems have made fault tolerance an essential design consideration. As cities rely on interconnected networks of sensors, devices, and communication systems, even minor failures can cause service disruptions, data inaccuracy, or safety risks [62]. To minimize such outcomes, several fault-tolerant approaches have been developed and deployed. This section presents a critical analysis of the most widely adopted techniques namely, redundancy, self-healing systems, and regular monitoring checks. Each approach is evaluated based on its operational characteristics, application in different smart city domains, and practical strengths and limitations [66]. To provide a comprehensive understanding, the analysis is supported with comparative tables. These tables highlight key attributes such as response time, level of automation, and domain-specific suitability [67]. The goal is to offer clear insights into how these techniques function under real-world conditions and what trade-offs they involve. This evaluation serves as a foundation for selecting or combining techniques depending on the specific fault-tolerance needs of a smart city subsystem [68]. Fault-tolerant mechanisms are essential for the reliable functioning of smart city systems. This section presents a critical comparison of the most common techniques using structured tables.

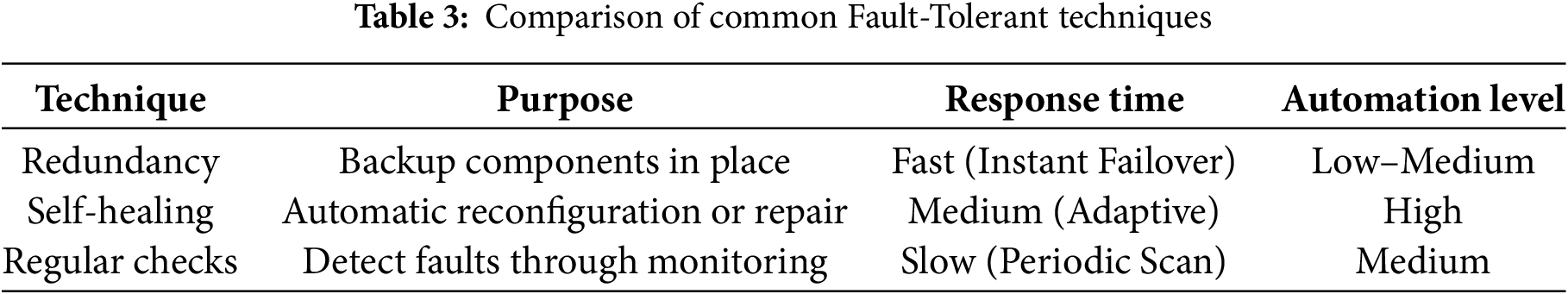

Table 3 provides a comparison between three major fault-tolerant strategies in terms of their operational purpose, speed of response during failure, and level of automation required. Redundancy provides quick response but usually lacks adaptive intelligence. Self-healing systems respond more flexibly but may involve some delay as they analyze the failure. Regular checks are proactive but slower, designed mainly for detection, not immediate correction.

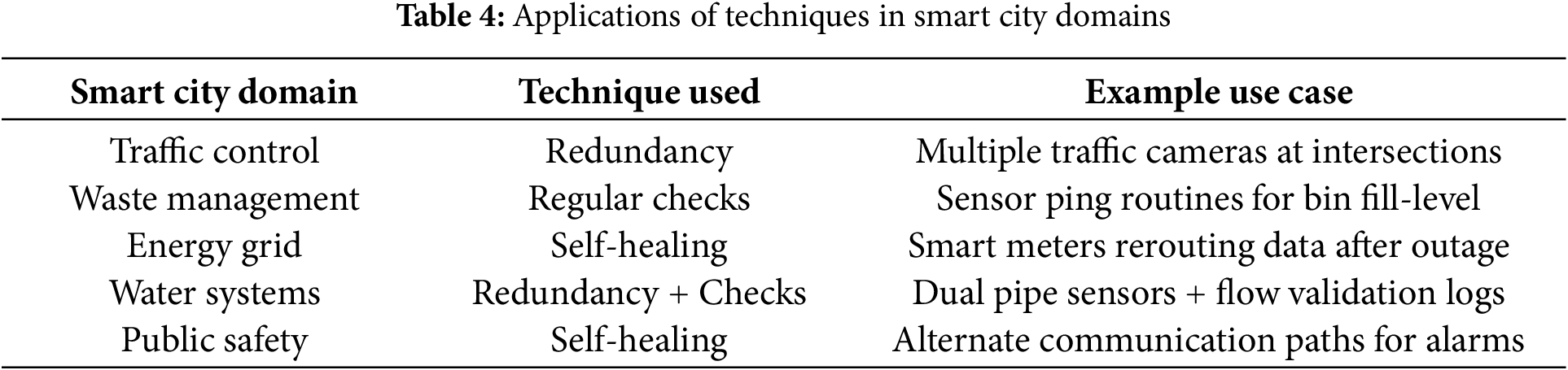

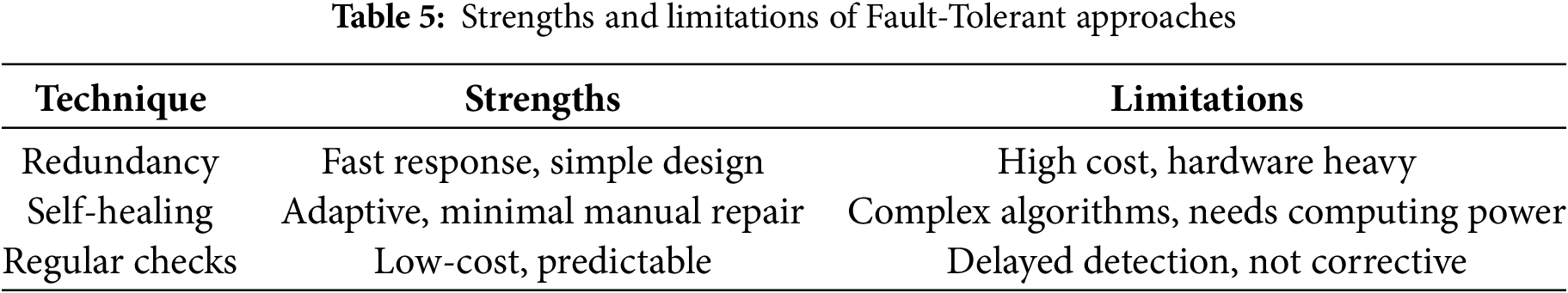

Table 4 shows how each technique is mapped to different smart city services. In domains requiring uninterrupted monitoring like traffic or public safety, redundancy and self-healing play a critical role. For slower systems like waste or water monitoring, regular checks are adequate for fault identification and response. Table 5 highlights the pros and cons of each approach. While redundancy is dependable, it is costly and hardware-dependent. Self-healing is intelligent but computationally expensive. Regular checks are affordable but often reactive rather than preventive.

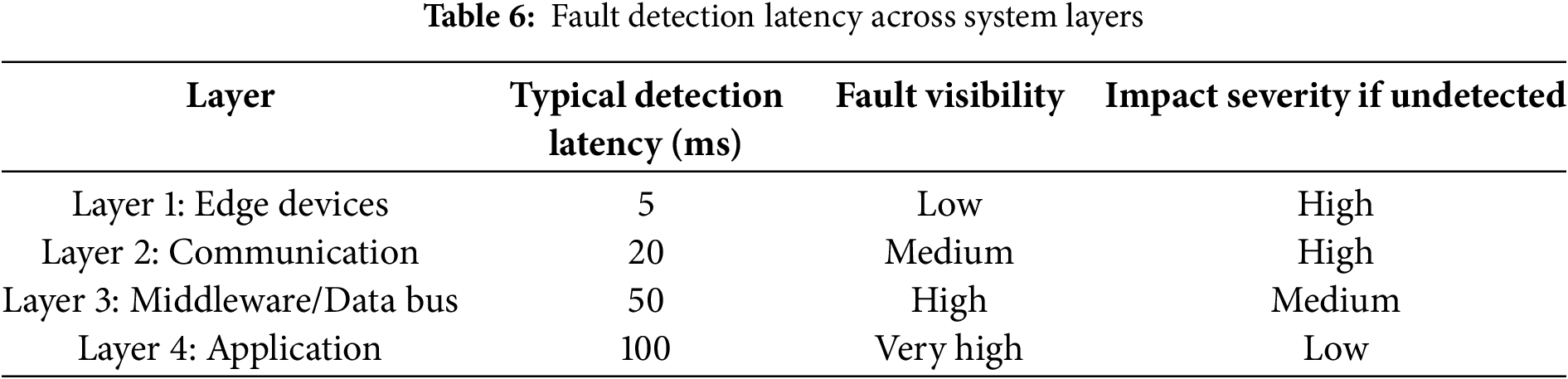

Table 6 highlights how fault detection behavior varies across system layers in smart city architectures. Faults originating in edge devices (Layer 1), such as sensor failures, can often be detected rapidly due to proximity to data sources, but their visibility is low and their impact can be severe if undetected. As faults propagate upward through communication links, middle-ware platforms, and eventually application interfaces detection becomes slower but more visible. Interestingly, while application-level anomalies (Layer 4) are most visible, they tend to be the least harmful, as they are often just symptoms of deeper system issues. This latency-visibility-impact matrix is critical for designing layered defense mechanisms that prioritize fast detection where it matters most.

3.1 Factor Based Critical Analysis

In the following subsections, this work examines the proposed approach from several critical perspectives. These include system dependency and propagation layers, the trade-off between fault containment score and cost, the relationship between fault visibility and impact, time to recovery vs. fault origin, and the balance between resilience coverage and energy efficiency. Previous literature has not compared fault-tolerant techniques from these specific angles. This introduces a clear novelty in our proposed approach.

3.1.1 System Dependency and Fault Propagation Layers

In complex smart city ecosystems, failures are rarely isolated. A fault in one component often impacts other parts of the system due to tightly coupled dependencies [69]. To understand the spread and impact of such faults, it is essential to examine the system through a layered architectural lens. This section introduces a four-layer dependency model to track the origin, propagation, and potential containment of faults across the smart city stack [70]. By mapping fault types to specific layers and analyzing their cross-layer effects, we gain deeper insight into where fault-tolerant methods are most effective and where current approaches fall short [71].

Layer 1: Edge Sensing Devices

This is the foundational layer consisting of physical components such as sensors, actuators, embedded controllers, and edge nodes. These devices gather environmental and operational data like temperature, traffic flow, air quality, and water levels—and may also take real-time actions, such as opening valves or switching traffic lights [63]. Faults in this layer are often due to hardware failure, battery depletion, physical damage, or calibration drift. While localized, failures here can cripple the entire sensing chain if left unchecked. Redundancy is often employed at this level, but not all devices are easy to duplicate, especially in hard-to-reach or resource-constrained environments [72].

Layer 2: Network and Communication Protocols

This layer includes all wireless and wired communication systems, along with the underlying transmission protocols (e.g., MQTT, LoRaWAN, Zigbee, 4G/5G). It serves as the backbone for data transport between the edge and higher processing layers. Faults here include signal interference, node-to-node link failure, congestion, or protocol mismatches [73]. What makes this layer critical is that faults are often invisible until data packets are lost, delayed, or duplicated. Unlike hardware faults that are localized, communication faults are systemic—affecting multiple nodes at once. Techniques like self-healing mesh networks or adaptive routing are particularly relevant here, yet they require intelligent coordination and energy overhead [74].

Layer 3: Middleware and Data Processing Units

This layer hosts edge servers, gateways, and cloud processing systems where collected data is aggregated, filtered, analyzed, and stored. Middleware faults may include data corruption, analytics delays, resource exhaustion, or failure of event processing engines [75]. Such faults often originate from software bugs, misconfiguration, or overload during peak activity. Unlike Layer 1 and 2 faults, these issues are less perceptible to the public but can significantly degrade system quality [64]. Regular health monitoring and automated rollback of faulty configurations are examples of fault-tolerant measures that work well in this layer.

Middleware Fault Considerations

The middleware layer in IoT-based smart city systems plays a pivotal role in aggregating, processing, and routing data between edge devices and cloud platforms. Key failure modes include:

• Broker Failures: Message brokers like MQTT or AMQP may crash due to overload or memory leaks. This can disrupt the publish-subscribe architecture and lead to data loss or delayed fault propagation.

• Fog-Node Failures: Fog nodes close to edge devices may experience hardware failures, software exceptions, or connectivity loss, creating a gap in localized decision-making and fault response.

• Fault Management APIs: Middleware platforms like FIWARE or EdgeX Foundry offer APIs for fault detection and remediation. These APIs can be extended to support retry mechanisms, redundancy protocols, or real-time alerts.

Designing middleware with self-monitoring agents and redundant broker paths is essential to support fault tolerance and system resilience in smart city infrastructure.

Layer 4: Applications and Dashboards

This is the user-facing layer, including mobile apps, command centers, public displays, and decision-making interfaces. While this layer does not generate faults in the traditional sense, it is highly vulnerable to propagated faults from lower layers [65]. For instance, a faulty air pollution reading from Layer 1 that passes unchecked through Layer 2 and Layer 3 may result in incorrect public health alerts at Layer 4. Faults here reduce public trust and decision accuracy. Implementing confidence scoring, alert validation, and multi-source corroboration are key techniques to mitigate impact at this level [76].

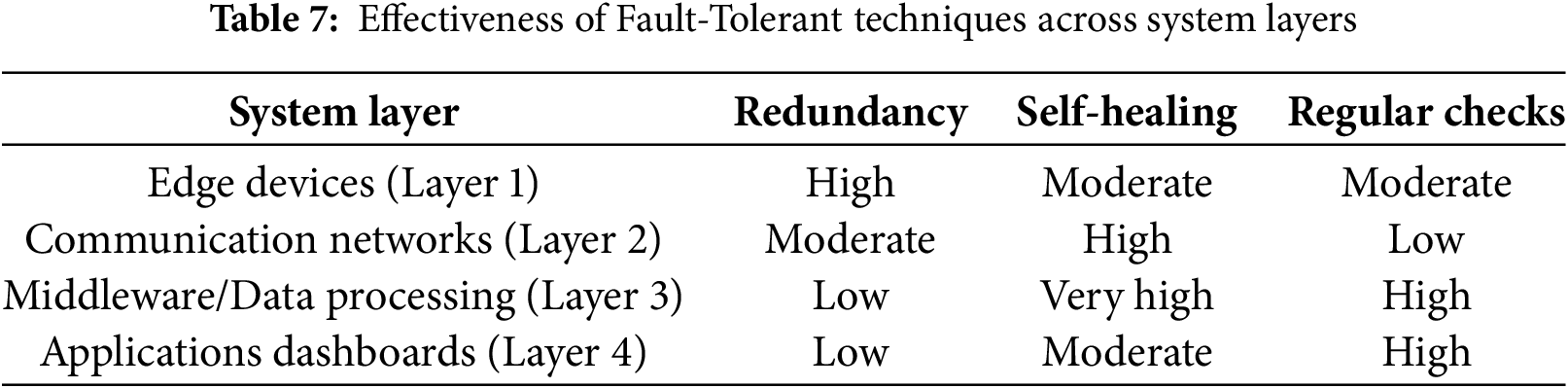

This four-layer model illustrates that fault management is not just a matter of detection and correction at the point of origin. Table 7 presents the effectiveness of fault-tolerant techniques across system layers. Instead, it requires a system-wide perspective that tracks how faults move between layers and assesses the capacity of each layer to absorb or amplify fault effects [77]. Evaluating fault-tolerant techniques in the context of this layered architecture provides a more complete and practical understanding of smart city resilience.

3.1.2 Fault Containment Score (FCS) vs. Cost Trade-Off

FCS is proposed as a quantitative metric to evaluate the effectiveness of fault isolation within layered or interconnected smart city systems. It is formally defined as Eq. (1).

where,

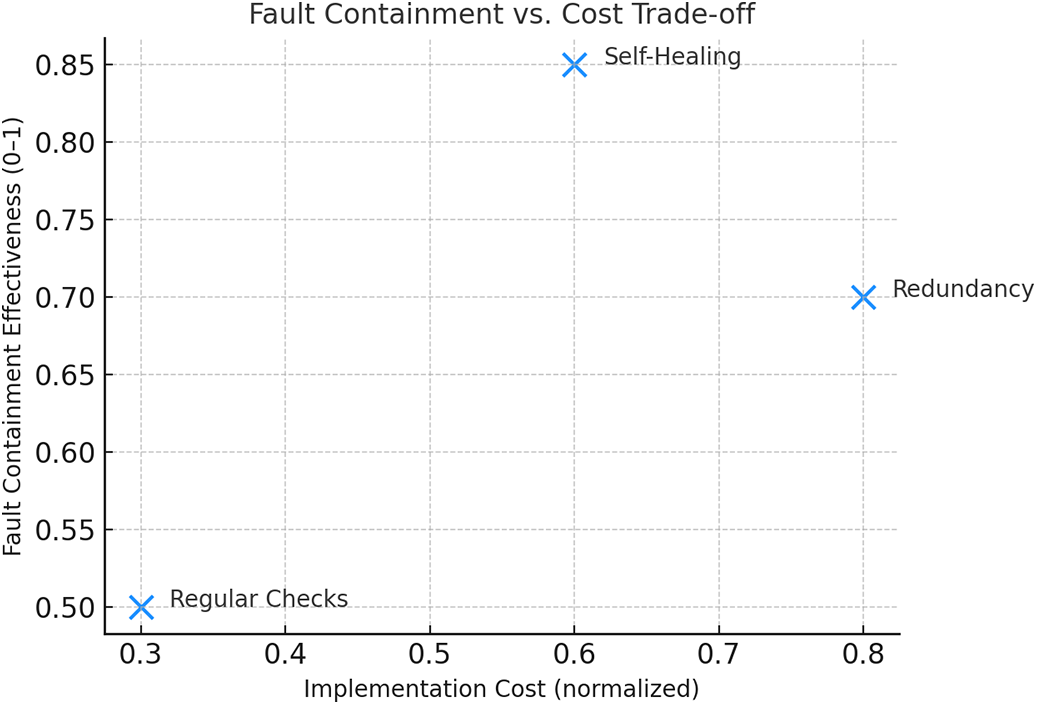

To assess the practical viability of fault-tolerant strategies, it is essential to consider not just their technical effectiveness but also their economic feasibility. This subsection introduces a comparative model that plots the fault containment effectiveness of each technique against its normalized implementation cost [78]. The plot above shows that Redundancy, while highly effective in maintaining system uptime (containment score: 0.7), incurs the highest cost (0.8). This is due to the duplication of hardware, power consumption, and installation logistics. In contrast, Self-Healing systems offer the highest containment score (0.85) at a moderate cost (0.6), making them a more balanced option for large-scale deployments where intelligent automation can offset manual recovery processes [79]. Regular Checks, though the least costly (0.3), deliver only moderate containment (0.5), as they are better suited for early detection rather than real-time correction. This trade-off analysis highlights the need for hybrid strategies using cost-efficient detection (like regular checks) paired with adaptive containment (like self-healing algorithms) to optimize resilience across different layers of the smart city architecture [80]. Fig. 5 illustrates the fault containment score vs. cost trade-off. The containment score is derived from simulated fault propagation tests across four IoT layers. Higher scores represent better isolation of faults. The cost is normalized and includes energy usage, latency overhead, and resilience overhead per subsystem.

Figure 5: Fault containment score vs. cost trade-off

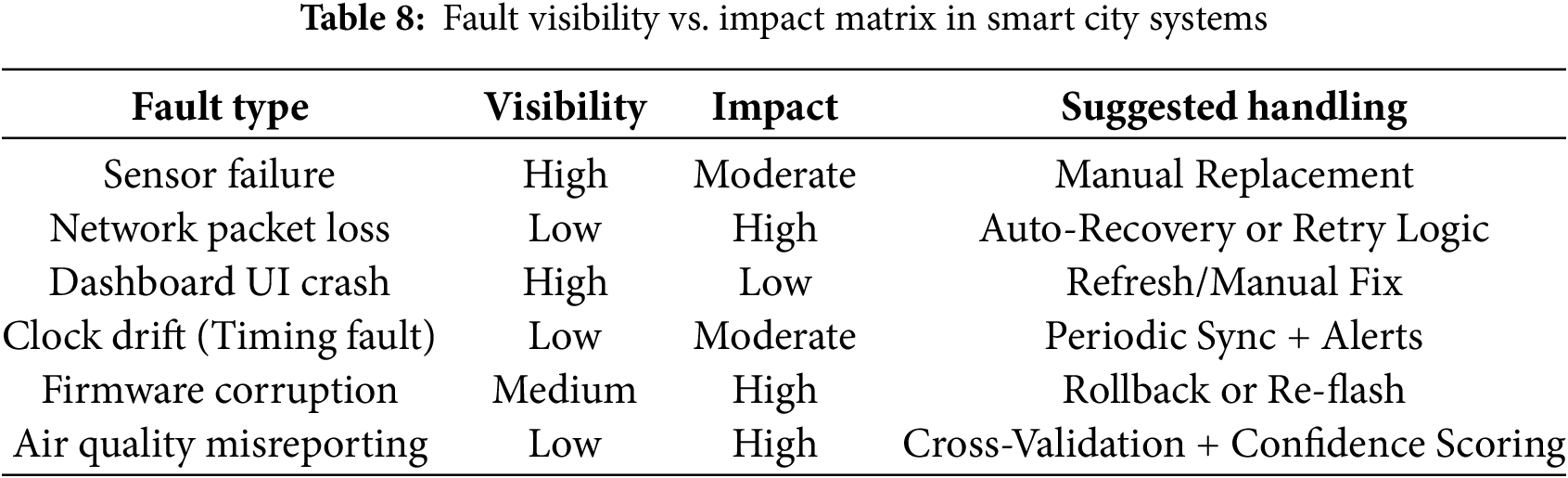

3.1.3 Fault Visibility vs. Impact Matrix

Traditional fault-tolerance literature tends to focus on technical categorization such as hardware, software, or network faults but it often overlooks a key operational dimension: how visible the fault is during operation vs. how critical its impact is on the smart city ecosystem [81]. This dual-axis perspective visibility vs. impact can provide a more actionable framework for prioritizing automated recovery, human alerts, and redundancy investments [82]. Some faults are highly visible to users or operators but have low impact on system behavior. For example, a dashboard temporarily failing to load visualizations might be immediately noticeable but doesn’t interrupt data collection or real-world services. On the other hand, low-visibility, high-impact faults such as silent sensor drift or undetected packet loss are far more dangerous [83]. They don’t trigger alarms but can cause significant long-term consequences if they lead to incorrect decisions or untriggered alerts. To better understand this trade-off, Table 8 classifies several common smart city faults along the axes of visibility and impact, while also noting whether they require automated or manual handling [84]. This framework helps in prioritizing where real-time, fault-tolerant systems are necessary, vs. where basic alerting or periodic checks might suffice.

Table 8 identifies how faults differ not just by technical type, but by how noticeable they are in real time and how seriously they affect system reliability or safety. It highlights that some of the most damaging faults are also the hardest to detect, warranting a shift in how fault-tolerant systems are designed and prioritized.

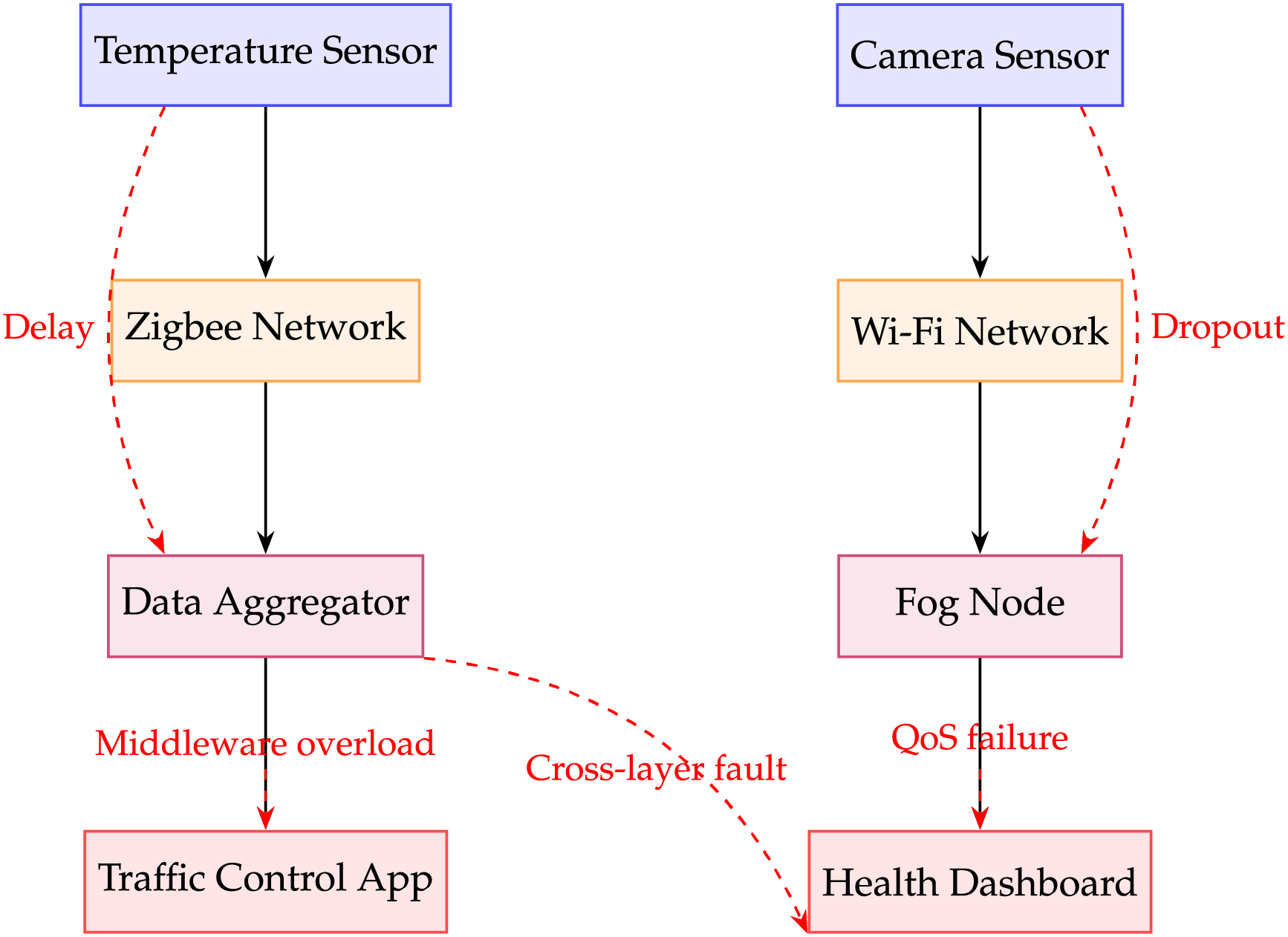

Fig. 6 illustrates a layered architecture commonly seen in smart city systems, emphasizing how failures in lower-level components can cascade upward to impact end-user applications. At the base layer, sensors such as temperature monitors and cameras collect environmental data. These sensors transmit information via network protocols like Zigbee and Wi-Fi (Layer 2), which are vulnerable to issues like signal loss or congestion. The data is then processed at the middleware layer (Layer 3), where fog nodes and data aggregators can experience overload or synchronization failures if upstream data is delayed or corrupted. Finally, this processed information feeds into high-level applications such as traffic control systems and health monitoring dashboards (Layer 4). The red dashed arrows in the diagram highlight typical fault propagation paths for example, a delay in the temperature sensor may not only affect real-time traffic decisions but also overload the middleware’s buffer, ultimately degrading application responsiveness.

Figure 6: Fault propagation tree: From sensor faults to application disruption

3.1.4 Time-to-Recovery vs. Fault Origin

While fault detection and classification are well-studied in smart cities, recovery time the duration to restore full system functionality remains underexplored [85]. This recovery time varies significantly based on where the fault originates in the system architecture. Some faults are resolved quickly via automation or reboot, while hardware or communication issues often need manual intervention and cause longer downtime [86].

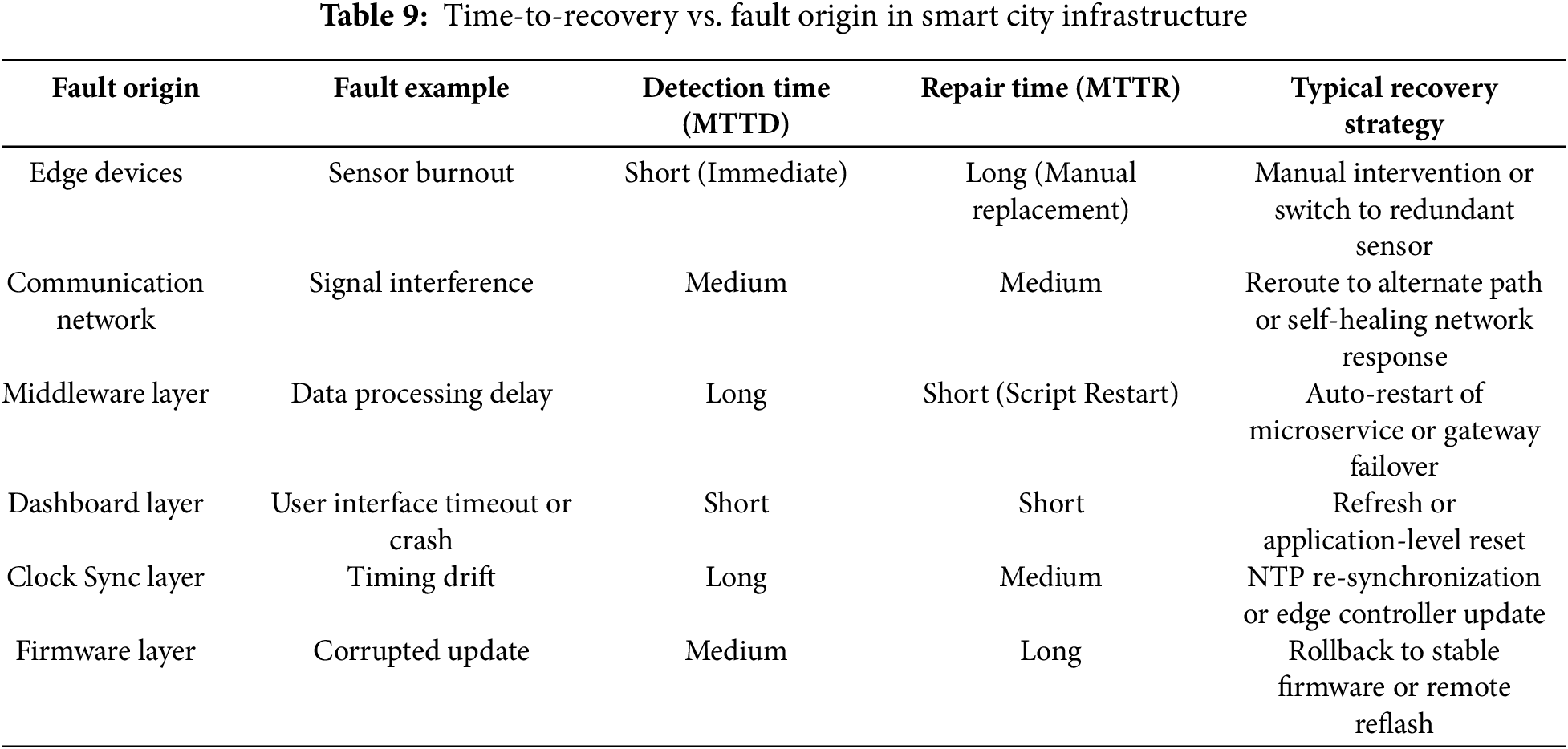

This dimension is crucial for designing smart cities that are not just fault-aware, but resilient and responsive. By analyzing the Mean Time to Detect (MTTD) by using Eq. (2) and the Mean Time to Repair (MTTR) by using Eq. (3) across different system layers, city planners and system architects can better allocate resources for monitoring, automation, and human response [87]. For example, faults at the edge device layer may be detected quickly due to device-level health monitoring but often require manual field replacement, leading to a long MTTR. On the other hand, faults at the middleware layer such as memory leaks or API timeouts may go undetected for longer periods but can be resolved rapidly via system restart or failover mechanisms. Table 9 compares fault types based on origin, detection time, repair time, and common recovery strategies [88]. It highlights differences in detection and repair processes. Some faults are quickly detected but take longer to fix, such as hardware failures. Others are harder to detect but can be resolved rapidly once found. Effective recovery planning should consider both Mean Time to Detect (MTTD) and Mean Time to Repair (MTTR) [89].

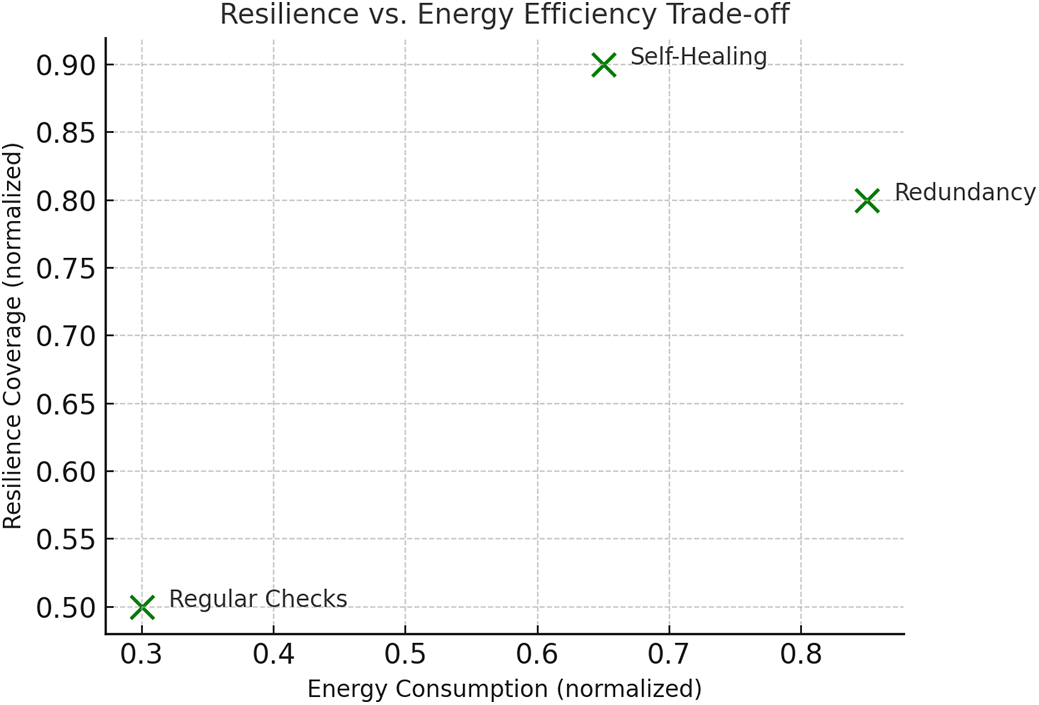

3.1.5 Resilience Coverage vs. Energy Efficiency Trade-Off

Resilience Score is defined as the percentage of time the system remains operational during injected fault conditions. Higher scores indicate stronger fault recovery or immunity. Energy Efficiency is measured in average energy consumption per successful task execution (in joules/task). The trade-off curve illustrates how systems with higher resilience may consume more energy due to redundancy or self-healing tasks. Fault-tolerant systems in smart cities must strike a balance between resilience coverage and energy efficiency, especially as more infrastructure is powered by battery-operated or renewable energy sources [90]. This balance becomes critical in edge-based deployments such as air quality monitors, smart parking sensors, or remote irrigation controllers where energy resources are limited and must be managed judiciously [91]. Resilience coverage refers to the system’s ability to handle, isolate, or recover from different types of faults across layers (hardware, network, application). On the other hand, energy efficiency relates to how much energy is consumed while maintaining this resilience [92].

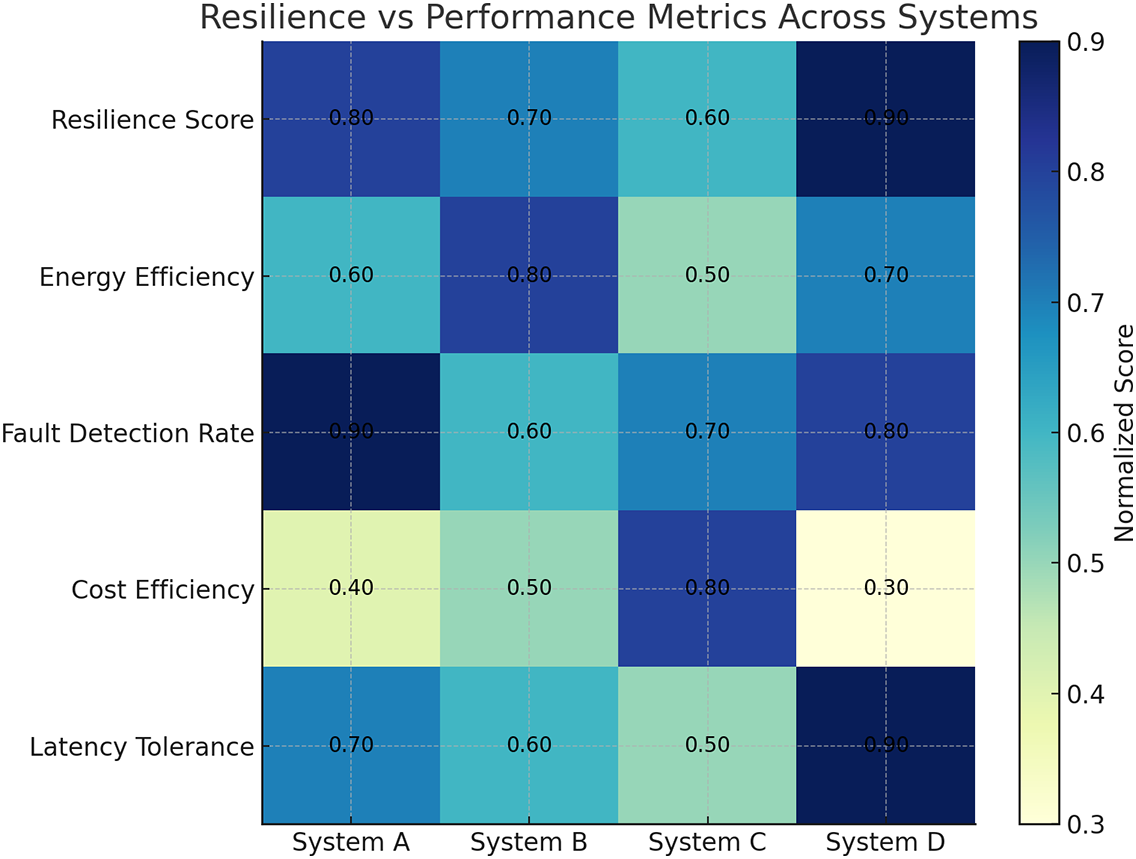

Techniques such as redundancy provide high resilience but at the cost of keeping backup systems always active, consuming more energy. Self-healing systems are more energy-aware, using adaptive logic that activates only during anomalies, providing a better trade-off. Regular checks, while energy-efficient due to periodic scanning, offer only partial resilience coverage and slower response [93]. Fig. 7 above visualizes this trade-off. It shows that Redundancy offers strong resilience (0.80) but is the most energy-consuming (0.85). Self-Healing, on the other hand, provides the highest resilience (0.90) at a moderate energy cost (0.65), making it optimal for dynamic environments. Regular Checks have minimal energy demand (0.30) but also provide the least resilience (0.50), making them suitable for non-critical systems [94]. This analysis helps in making informed design choices where energy is constrained, hybrid models (e.g., passive checks combined with event-triggered healing) may offer the best compromise between sustainability and reliability. Fig. 8 presents a comparative heatmap of four representative fault-tolerant systems evaluated across five critical performance dimensions: resilience score, energy efficiency, fault detection rate, cost efficiency, and latency tolerance. The normalized scores (ranging from 0 to 1) highlight distinct strengths and trade-offs in system design. For example, System D demonstrates superior resilience and latency tolerance but falls behind in cost efficiency, suggesting a high-performance, high-cost architecture. In contrast, System C favors cost-effective routing but compromises slightly on fault detection capabilities. This multi-metric visualization aids in identifying balanced architectures and illustrates that no single system uniformly excels across all axes, reinforcing the necessity of context-driven fault tolerance design in smart cities.

Figure 7: Resilience coverage vs. energy efficiency trade-off

Figure 8: Resilience vs. performance metrics across systems

Case Study 1: Adaptive Traffic Signal Systems of Singapore

Singapore’s adaptive traffic signal systems use real-time sensor inputs and AI algorithms to dynamically manage vehicle flow [95]. While these systems are designed to be highly resilient with fallback modes and rerouting protocols they also incur increased energy usage due to continuous data processing and communication overhead. Similarly, Barcelona’s urban water management system employs IoT-based leak detection networks that monitor pipe pressure and flow anomalies. These systems enhance fault detection and response times, improving overall resilience, but they require energy-efficient designs to remain sustainable for long-term, wide-scale deployment. By analyzing these deployments, we highlight how practical smart city applications must navigate a careful trade-off between maintaining high fault tolerance and minimizing energy consumption. This real-world context reinforces the theoretical framework presented in our paper and illustrates how resilience strategies impact energy demands across different application domains.

Case Study 2: Barcelona’s Smart Water Grid

Barcelona has pioneered the deployment of a smart water management system that integrates over 1500 IoT sensors across its urban pipe network. This network performs continuous monitoring of pipe pressure, flow rates, and chemical properties, enabling real-time leak detection and water quality assurance [96]. The system improves fault detection times by up to 80%, reducing water losses and infrastructure damage. It also enables predictive maintenance through AI-powered anomaly detection models [97]. However, the requirement for constant data transmission, processing on cloud or edge devices, and battery-powered sensor operation makes energy-efficient design a critical consideration. Without optimized power management, such large-scale deployments risk becoming unsustainable over time.

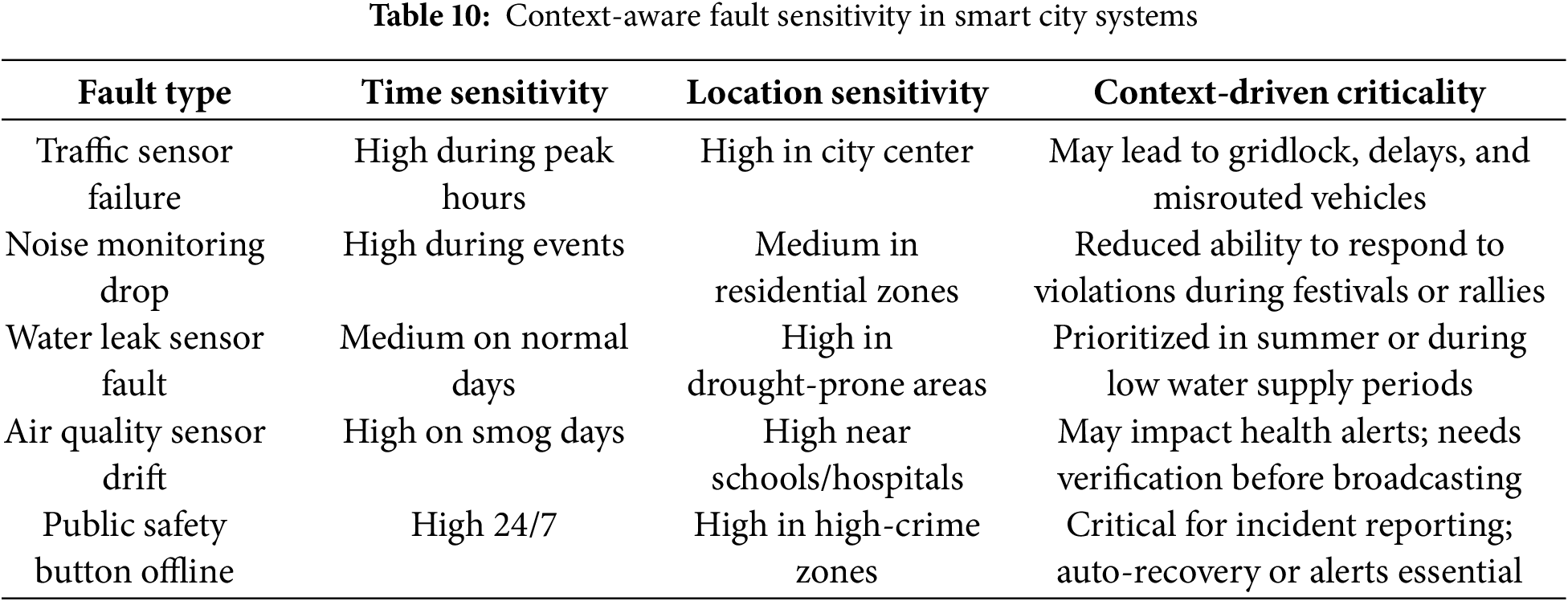

Context aware tolerance refers to the system’s capability to dynamically adjust fault-tolerance behaviors based on real-time input from environment (e.g., temperature, motion, humidity) or workload (e.g., peak hours). This is measured by comparing fault-handling accuracy in static vs. context-rich environments. In traditional fault-tolerant designs, all faults are often treated equally, regardless of when or where they occur. This uniform approach overlooks the critical reality that the impact of a fault is highly dependent on context such as time of day, location, user density, or event type [98]. This concept, referred to as Context-Aware Tolerance, offers a smarter and more dynamic fault-handling strategy that adapts based on real-world operational factors [99]. For instance, a traffic sensor failure during off-peak hours might be less critical than the same fault occurring during morning rush hour. Similarly, garbage level sensors failing in residential zones may have less immediate impact than failure during a large public festival. This context-dependent prioritization helps cities allocate resources more efficiently and respond faster where the fault truly matters [100]. Implementing context-aware strategies requires systems that can evaluate both the criticality of the location and the urgency of the time window in which a fault occurs [101]. Using real-time contextual data, the system can apply dynamic thresholds and adjust alerting, redundancy, or healing behavior accordingly. Table 10 presents several typical faults and how their impact varies based on context.

Table 10 illustrates how fault priority is not fixed, but depends on timing, environmental, and social context. Systems designed with static rules may either underreact or overreact, leading to inefficiency. Context-aware models allow smarter allocation of fault-response resources and improve overall system relevance and trust.

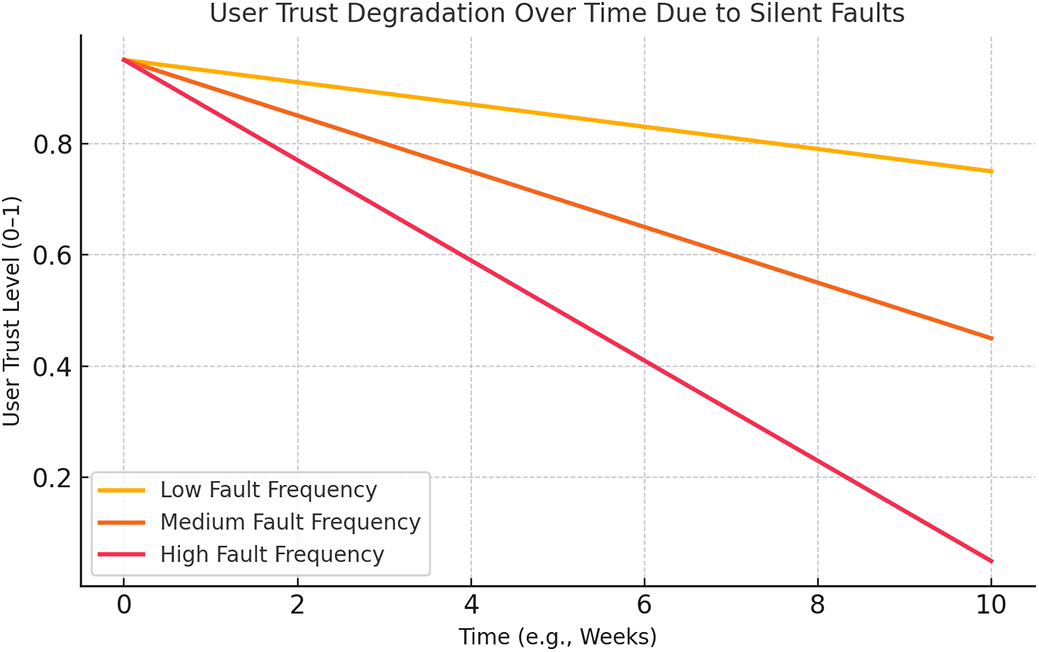

3.1.7 User Trust Erosion Due to Silent Faults

Much of the technical literature on smart city fault tolerance focuses on hardware, detection, and recovery, but often overlooks the long-term erosion of user trust from undetected or silent faults [102]. These are faults that do not immediately crash a system or raise an alert, but continue to deliver misleading or inaccurate data [103]. The result is not just operational inefficiency but a subtle, cumulative loss of public and stakeholder confidence. For example, consider an air quality monitoring system that silently under reports pollution levels due to gradual sensor drift. Over time, residents may continue engaging in outdoor activities under the assumption that the air is safe, potentially endangering public health. Similarly, if real-time traffic updates consistently fail to reflect true congestion due to outdated calibration or packet losses, drivers may stop relying on the system altogether even if it functions correctly most of the time [104]. Once trust is broken, regaining it often requires more than just fixing the technical issue; it involves rebuilding user belief in system reliability and transparency. Fig. 9 illustrates how repeated silent faults, even when individually minor, can lead to significant erosion of user trust over time. Systems with high fault frequency may become unusable not because of a technical crash, but due to declining credibility in the eyes of the users.

Figure 9: User trust degradation over time due to silent faults

Silent faults are difficult to detect and harder to explain to non-technical users. These faults may pass normal checks, appear in logs as routine activity, and only become noticeable when overall system performance drops such as longer emergency response times or rising complaints [105]. They often go unnoticed by standard fault models since they do not trigger alerts or system errors. Detecting such faults needs behavioral tracking, cross-validation between sensors, or feedback from users—methods not commonly built into city systems. To address this, fault-tolerant designs must include trust-aware features. Systems should report not just results, but also how confident they are in those results. Dashboards and APIs should display data quality and error margins to support informed decision-making [106]. Like weather reports show probability, smart city alerts should reflect uncertainty levels.

Trust grows when systems are transparent. This can be done through audit logs, citizen reporting tools, or public data comparisons. Considering trust as part of system design makes fault tolerance not only a technical function but a social responsibility. This section reviewed fault tolerance across multiple layers of smart city systems. Unlike standard reviews that focus only on fault types or fixes, this work introduced a layered model to show how faults start and spread from sensors to user interfaces [107]. It also evaluated strategy effectiveness using structured tools such as the Layer vs. Technique Fit Matrix, Fault Visibility vs. Impact Matrix, and Context-Aware Criticality Table. Trade-offs were shown in visual plots for example, fault coverage vs. cost, resilience vs. energy use, and trust loss over time due to silent faults. These combined views offer a broader system-level perspective. The analysis included both technical measures like recovery time and human factors like user trust [108]. By merging data tables with plots, this paper offers a clear, practical guide to choosing fault-tolerant strategies that are both strong in design and responsive to public needs something often missing in earlier work.

User Trust Erosion and Acceptance Models

Trust erosion occurs when end-users perceive IoT systems as unreliable due to frequent failures or unexplained behavior. The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) helps understand user trust by linking perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use to behavioral intention. From an HCI (Human-Computer Interaction) perspective, interfaces that visualize system health, fault status, and recovery actions increase transparency and promote user trust. Including visual fault feedback loops and confidence meters can help re-establish trust following a failure event.

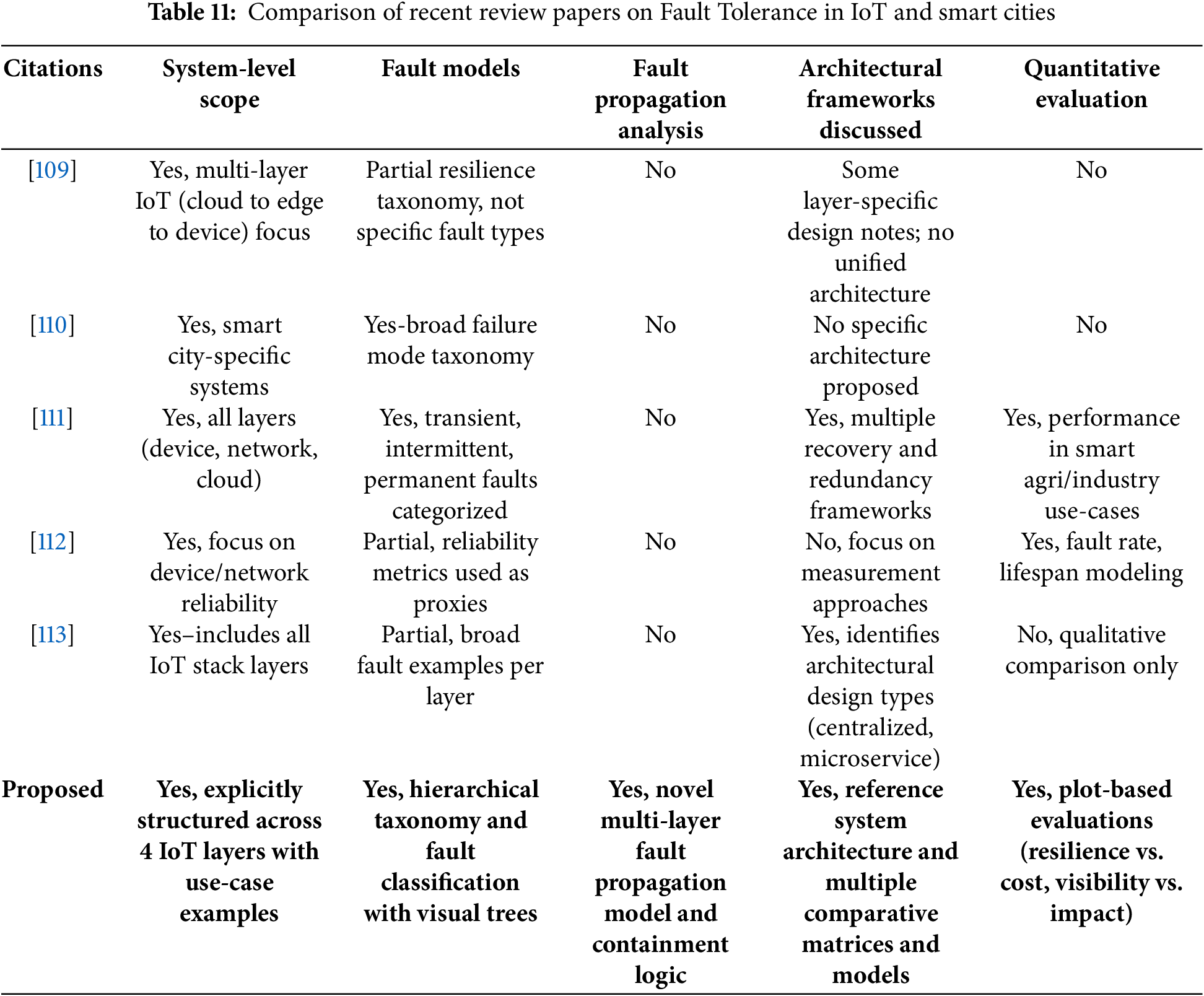

3.1.8 Comparison with Existing Reviews

This review distinguishes itself from prior surveys by offering a layered, matrix-driven evaluation of fault tolerance techniques specifically by the smart city infrastructures. While previous reviews have presented broad taxonomies and high-level classifications, they often lack detailed technical cross-comparisons between fault types, system layers, and tolerance methods. Table 11 presents the comparison of the proposed work against existing works. This work introduces a novel system dependency and fault propagation model across four critical layers sensor devices, communication, middle-ware, and applications which is not systematically addressed in earlier literature. Furthermore, it proposes and analyzes a series of critical trade-off matrices (e.g., resilience vs. energy, recovery time vs. fault origin, visibility vs. impact), each grounded in real-world system design considerations. Unlike other reviews that remain descriptive, this paper integrates plot-based reasoning, tabular evaluations, and fault-containment performance logic to assess system robustness from both a functional and user-trust perspective. The contextual emphasis on smart cities and real-world case-inspired evaluation criteria such as SCADA systems or traffic light control further enhances the practical relevance and depth of analysis. As a result, this paper serves not only as a comprehensive survey but also as a structured analytical framework for future smart-city fault-tolerant system design. The unique ness of the proposed work as follows:

• Introducing a multi-layer framework (edge

• Presenting novel quantitative tools, e.g., Fault Containment vs. Cost and Resilience vs. Energy trade-off matrices—that allow objective comparison of fault-tolerance strategies.

• Integrating “user trust erosion” and “context-aware tolerance” into the analysis, which are largely absent in the existing literature.

The review presented in this paper offers a multi-dimensional understanding of fault tolerance in smart city infrastructure, focusing on system resilience, fault propagation, energy trade-offs, and user trust. While the analysis covered a wide spectrum of fault-tolerant strategies from redundancy and self-healing to context-aware techniques several avenues remain open for meaningful advancement. One critical area is the development of dynamic, context-sensitive fault models that adapt tolerance thresholds based on real-time environmental, behavioral, and infrastructural signals. For instance, integrating external data like weather patterns, traffic events, and population density forecasts could allow systems to proactively tune their failure responses. In parallel, the deployment of real-time fault injection frameworks for edge-based AI systems is gaining traction. These tools enable synthetic faults such as delayed packets, corrupted signals, or sensor dropout—to be injected into live environments, thus testing a system’s real-time resilience under stress. This is particularly beneficial for edge computing scenarios in traffic control or water distribution networks where downtime has immediate impact. Moreover, the integration of blockchain-backed trust layers can offer immutable, decentralized logs of fault histories and response efficacy. Such a system not only improves post-fault diagnostics but also enhances data integrity and public accountability.

Blockchain for Trust-Driven Architectures

Blockchain can be used to ensure data immutability, consensus-based decision-making, and decentralized authentication across smart city platforms. Smart contracts enable automated responses to fault events (e.g., sensor isolation, trust score recalculation) without relying on central authorities. For example, using Hyperledger Fabric or Ethereum, critical systems like smart grids or emergency networks can store sensor activity logs immutably, supporting post-fault audits and trust quantification.

AI for Predictive Fault Management

Artificial intelligence, particularly machine learning models, plays a crucial role in predictive fault detection. By analyzing patterns of latency spikes, packet losses, and signal strength anomalies, AI models can forecast impending faults and trigger preventive maintenance. Techniques such as LSTM networks, anomaly detection with Isolation Forests, and reinforcement learning can dynamically adjust fault tolerance policies. In smart transportation systems, for instance, AI models trained on traffic congestion and sensor reliability data can preemptively switch to redundant nodes before a fault occurs.

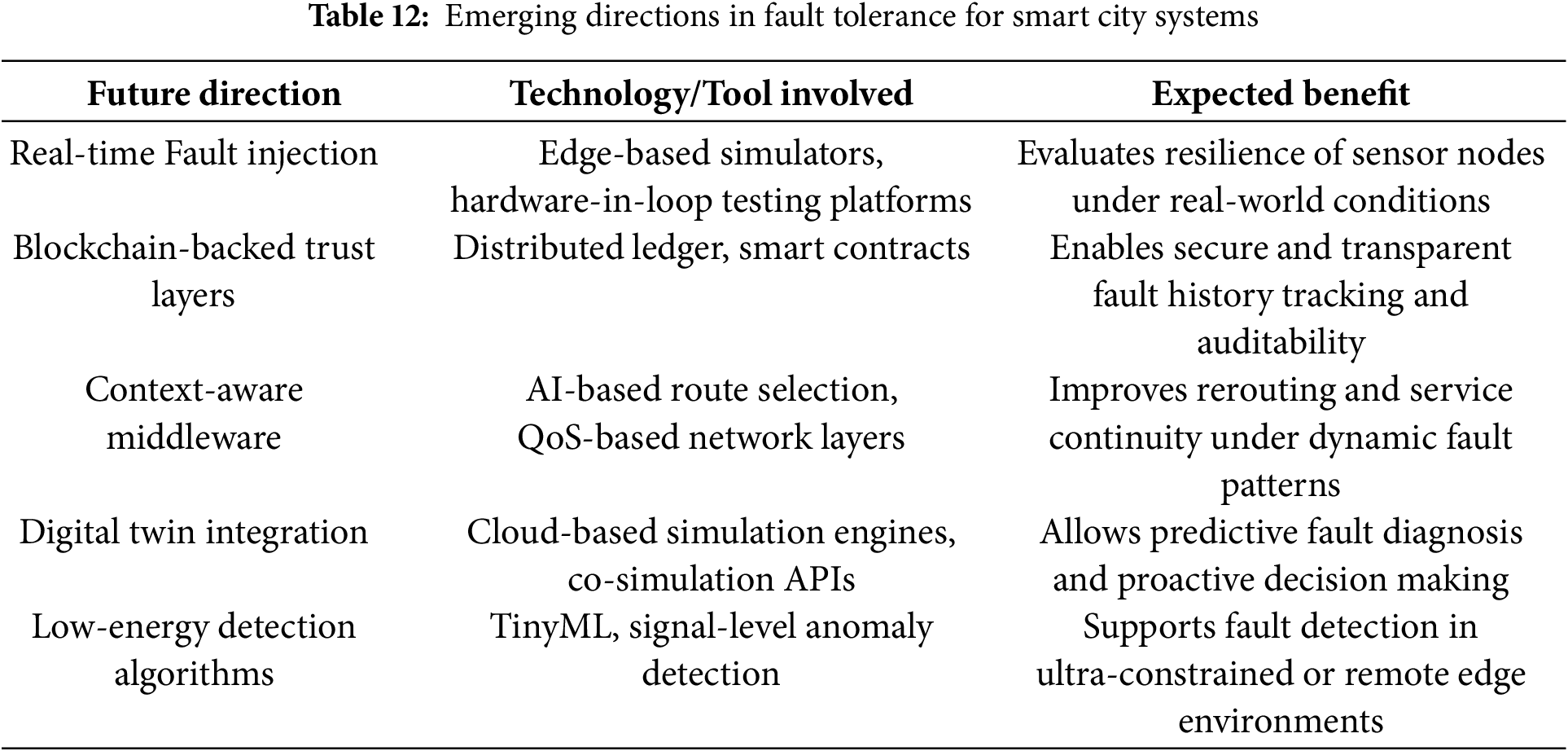

Another promising direction involves the use of context-aware middle-ware that can reroute tasks or services dynamically by interpreting local operating conditions such as energy availability, communication quality, or detected anomalies. This would be especially impactful for distributed systems operating across low-bandwidth or constrained regions. Complementarily, digital twin simulations offer an experimental ground to forecast system behavior under varied fault topologies, enabling preemptive tuning without exposing real infrastructure to risk. Additionally, research into ultra-lightweight, low-energy fault detection algorithms remains essential. These algorithms, built using TinyML or event-driven filtering, could be deployed on highly constrained sensor devices, such as those embedded in public lighting, waste bins, or traffic poles, where frequent maintenance is not feasible. Long-term learning capabilities also warrant attention. By embedding adaptive feedback loops that learn from historical fault patterns, systems can evolve toward predictive autonomy, reducing downtime and manual interventions. Table 12 presents the future direction of fault tolerance approach in the context of smart cities. Finally, the human dimension of fault-tolerant design must not be neglected. Future systems should implement standardized trust quantification models reporting confidence scores for decisions, sensor reliability, and fault recovery success that can be made visible through public dashboards. Building frameworks that are technically sound yet also understandable, inclusive, and respectful of digital ethics will demand collaboration between engineers, city planners, and the community. Only then can fault-tolerant smart city infrastructure be both resilient and socially trusted.

This study presents a comprehensive and system-level analysis of fault tolerance within smart city IoT architectures, emphasizing the interplay between technical metrics, middleware behavior, and end-user trust. By integrating simulation frameworks, real-world deployment examples, and quantified fault metrics including MTTR, MTTD, and the proposed FCS the work advances both theoretical and applied understanding of resilient IoT systems. The expanded discussion on middleware failures, fault management APIs, and simulation tools bridges the gap between conceptual modeling and practical implementation. Additionally, contextual factors such as user trust erosion are addressed through behavioral models like TAM and HCI frameworks, highlighting the socio-technical dimensions of fault management. The inclusion of emerging technologies such as blockchain for decentralized trust enforcement and AI for predictive fault diagnostics further positions the proposed framework as future-ready. Collectively, the findings contribute to the development of transparent, adaptive, and energy-efficient fault-tolerant infrastructures aligned with the operational demands and trust imperatives of smart city ecosystems.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

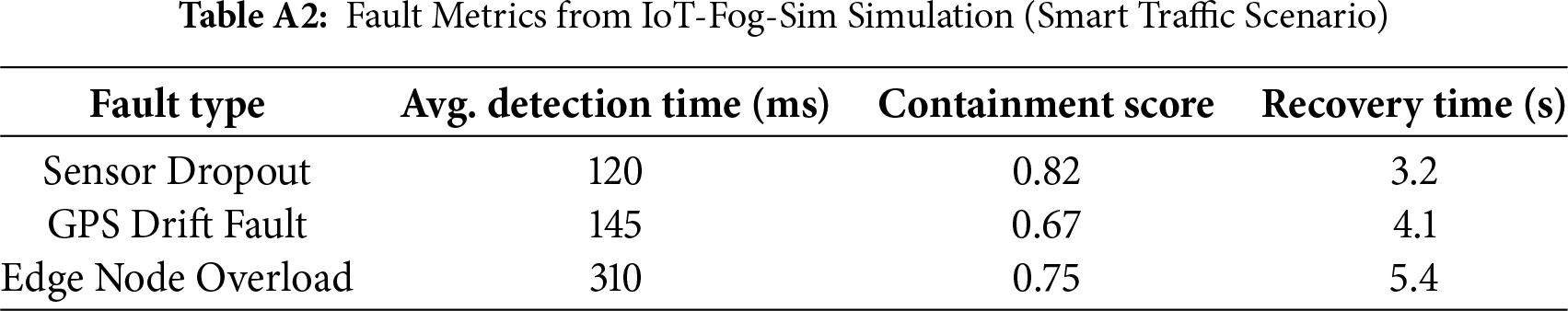

Table A1 presents the glossary of core terms. Table A2 summarizes the performance of different fault types observed during simulations conducted in existing literature using the IoT-Fog-Sim platform in a smart traffic control scenario. It presents fault detection time, containment score, and recovery duration for common fault categories.

References

1. Avizienis A, Laprie JC, Randell B, Landwehr C. Basic concepts and taxonomy of dependable and secure computing. IEEE Trans Dependable Secure Comput. 2004;1(1):11–33. doi:10.1109/tdsc.2004.2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Chourabi H, Nam T, Walker S, Gil-Garcia JR, Mellouli S, Nahon K, et al. Understanding smart cities: an integrative framework. In: 2012 45th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences; 2012 Jan 4–7; Maui, HI, USA. p. 2289–97. [Google Scholar]

3. Atzori L, Iera A, Morabito G. The Internet of Things: a survey. Comput Netw. 2010;54(15):2787–805. [Google Scholar]

4. Shamsi JA. Resilience in smart city applications: faults, failures, and solutions. IT Prof. 2020;22(6):74–81. doi:10.1109/mitp.2020.3016728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Gubbi J, Buyya R, Marusic S, Palaniswami M. Internet of Things (IoTa vision, architectural elements, and future directions. Fut Gen Comput Syst. 2013;29(7):1645–60. doi:10.1016/j.future.2013.01.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Zanella A, Bui N, Castellani A, Vangelista L, Zorzi M. Internet of Things for smart cities. IEEE Internet Things J. 2014;1(1):22–32. doi:10.1109/jiot.2014.2306328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Lakhan A, Lateef AAA, Ghani MKA, Abdulkareem KH, Mohammed MA, Nedoma J, et al. Secure-fault-tolerant efficient industrial internet of healthcare things framework based on digital twin federated fog-cloud networks. J King Saud Univ-Comput Inform Sci. 2023;35(9):101747. doi:10.1016/j.jksuci.2023.101747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Sterbenz JPG, Hutchison D, Krebs E, Schöller M, Smith P, Claypool M, et al. Resilience and survivability in communication networks: strategies, principles, and survey of disciplines. Comput Netw. 2010;54(8):1245–65. doi:10.1016/j.comnet.2010.03.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Zhang S, Li T, Hui S, Li G, Liang Y, Yu L, et al. Deep transfer learning for city-scale cellular traffic generation through urban knowledge graph. In: Proceedings of the 29th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, KDD’23. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; 2023. p. 4842–51. doi:10.1145/3580305.3599801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Dorri A, Kanhere SS, Jurdak R. Towards an optimized blockchain for IoT. In: 2017 IEEE/ACM Second International Conference on Internet-of-Things Design and Implementation (IoTDI); 2017 Apr 18–21; Pittsburgh, PA, USA. p. 173–8. [Google Scholar]

11. Sterbenz JPG. Smart city and IoT resilience, survivability, and disruption tolerance: challenges, modelling, and a survey of research opportunities. In: 2017 9th International Workshop on Resilient Networks Design and Modeling (RNDM); 2017 Sep 4–6; Alghero, Italy. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/rndm.2017.8093025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Roman R, Zhou J, Lopez J. On the features and challenges of security and privacy in distributed Internet of Things. Comput Netw. 2013;57(10):2266–79. doi:10.1016/j.comnet.2012.12.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Rejeb A, Rejeb K, Simske S, Treiblmaier H, Zailani S. The big picture on the internet of things and the smart city: a review of what we know and what we need to know. Internet Things. 2022;19:100565. doi:10.1016/j.iot.2022.100565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Zhang Y, Xia G, Yu C, Li H, Li H. Fault-Tolerant scheduling mechanism for dynamic edge computing scenarios based on graph reinforcement learning. Sensors. 2024;24(21):6984. doi:10.3390/s24216984. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Al-Fuqaha A, Guizani M, Mohammadi M, Aledhari M, Ayyash M. Internet of Things: a survey on enabling technologies, protocols, and applications. IEEE Commun Surv Tut. 2015;17(4):2347–76. [Google Scholar]

16. Huang S, Sun C, Pompili D. Meta-ETI: meta-reinforcement learning with explicit task inference for AAV-IoT coverage. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025;12(13):23852–65. doi:10.1109/jiot.2025.3553808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Moghaddam MT, Muccini H. Fault-Tolerant IoT: a systematic mapping study. In: International Workshop on Software Engineering for Resilient Systems; 2019 Sep 17; Naples, Italy. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2019. p. 67–84. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-30856-8_5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. de Souza KE, Ferrari FC, de Camargo VV, Ribeiro M, Offutt J. A systematic review of fault tolerance techniques for smart city applications. J Syst Softw. 2025;219:112249. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2024.112249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Reyana A, Kautish S, Alnowibet KA, Zawbaa HM, Mohamed AW. Opportunities of IoT in fog computing for high fault tolerance and sustainable energy optimization. Sustainability. 2023;15(11):8702. doi:10.3390/su15118702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Velloso PB, Laufer RP, de Cunha OD, Duarte OCMB, Pujolle G. Trust management in mobile ad hoc networks using a scalable maturity-based model. IEEE Trans Netw Serv Manage. 2010;7(3):172–85. doi:10.1109/tnsm.2010.1009.i9p0339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Baskar P, Prakasam P. Optimal energy-efficient resource allocation and fault tolerance scheme for task offloading in IoT-fog computing networks. Comput Netw. 2024;238:110080. doi:10.1016/j.comnet.2023.110080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Lan Z, Min G, Guo S, Deng Q, Wu Y. A comprehensive review of fault-tolerant routing mechanisms for the internet of things. Int J Adv Comput Sci Appl. 2023;14(7):1083–93. doi:10.14569/ijacsa.2023.01407116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Abreu DP, Velasquez K, Curado M, Monteiro E. A resilient internet of things architecture for smart cities. Ann Telecommun. 2017;72(1–2):19–30. doi:10.1007/s12243-016-0530-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Martinez I, Hafid AS, Gendreau M. Robust and fault-tolerant fog design and dimensioning for reliable operation. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022;9(19):18280–92. doi:10.1109/jiot.2022.3157557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Mushtaq SU, Sheikh S, Idrees SM, Malla PA. In-depth analysis of fault tolerant approaches integrated with load balancing and task scheduling. Peer-Peer Netw Appl. 2024;17(2):4303–37. doi:10.1007/s12083-024-01798-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Mohapatra H, Rath AK. A survey on fault tolerance based clustering evolution in WSN. IET Netw. 2020;9(4):145–55. doi:10.1049/iet-net.2019.0155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Mohammadi V, Rahmani AM, Darwesh A, Sahafi A. Fault tolerance in fog-based social Internet of Things. Knowl Based Syst. 2023;265:110376. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2023.110376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Khanna A, Jha RK, Kumar N, Gupta G. Internet of Things (IoTapplications and challenges: a comprehensive review. Wirel Pers Commun. 2020;114(2):1687–762. doi:10.1007/s11277-020-07446-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Javed A, Heljanko K, Buda A, Främling K. CEFIoT: a fault-tolerant IoT architecture for edge and cloud. In: Proceedings of the IEEE 4th World Forum on Internet of Things (WF-IoT); 2018 Feb 5–8; Singapore. p. 813–8. [Google Scholar]

30. Sung SH, Hong SJ, Choi HY, Park DH, Kim SW. Enhancing fault diagnosis in IoT sensor data through advanced preprocessing techniques. Electronics. 2024;13(16):3289. doi:10.3390/electronics13163289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Javed A, Robert J, Heljanko K, Främling K. IoTEF: a federated edge-cloud architecture for fault-tolerant IoT applications. J Grid Comput. 2020;18(1):57–80. doi:10.1007/s10723-019-09498-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Alam F, Mehmood R, Katib I, Albogami NN, Albeshri A. Data fusion and IoT for smart ubiquitous environments: a survey. IEEE Access. 2017;5:9533–54. doi:10.1109/access.2017.2697839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Melo M, da Silva GAP, Maciel P, Wolter K, Rodrigues GN. FaTEMa: a framework for multi-layer fault tolerance in IoT systems. Sensors. 2021;21(21):7181. doi:10.3390/s21217181. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Grover J, Kansal V, Chhabra K. Agent-based reliable and fault-tolerant hierarchical IoT-cloud architecture. In: Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Contemporary Computing (IC3); 2018 Aug 2–4; Noida, India. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

35. Norris M, Celik ZB, Venkatesh P, Zhao S, McDaniel P, Sivasubramaniam A, et al. IoTRepair: flexible fault handling in diverse IoT deployments. ACM Trans Internet Things. 2022;3(3):1–33. doi:10.1145/3532194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Jaiswal K, Anand V. FAGWO-H: a hybrid method towards fault-tolerant cluster-based routing in wireless sensor network for IoT applications. J Supercomput. 2022;78(8):11195–227. doi:10.1007/s11227-022-04333-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Ozeer U, Letondeur L, Salaün G, Ottogalli FG, Vincent JM. F3ARIoT: a framework for autonomic resilience of IoT applications in the fog. Internet Things. 2020;12:100285. doi:10.1016/j.iot.2020.100275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Perera C, Liu CH, Jayawardena S. The emerging Internet of Things marketplace from an industrial perspective: a survey. IEEE Trans Emerg Top Comput. 2015;3(4):585–98. doi:10.1109/tetc.2015.2390034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Agarwal V, Tapaswi S, Chanak P. Intelligent fault-tolerance data routing scheme for IoT-enabled WSNs. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022;9(17):16332–42. doi:10.1109/jiot.2022.3151501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Grulich PM, Lepping AP, Nugroho DPA, Grotjahn F, Kao O. Fault tolerance placement in the Internet of Things. Proc ACM Manage Data. 2024;2(3):1–29. [Google Scholar]

41. Ray K, Banerjee A. Prioritized fault recovery strategies for multi-access edge computing using probabilistic model checking. IEEE Trans Dependable Secur Comput. 2023;20(1):797–812. doi:10.1109/tdsc.2022.3143877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Ilbeigi M, Morteza A, Ehsani R. Emergency management in smart cities: infrastructure-less communication systems. In: Proceedings of the ASCE Construction Research Congress (CRC); 2022 Mar 9–12; Arlington, VA, USA. p. 263–71. [Google Scholar]

43. Ullah W, Ahmad Z, Ikram A, Ahmad J. A fault tolerant data management scheme for healthcare Internet of Things in fog computing. KSII Trans Internet Inform Syst. 2021;15(11):3898–921. [Google Scholar]

44. Shaikh S, Jammal M. Survey of fault management techniques for edge-enabled distributed metaverse applications. Comput Netw. 2024;254:110803. doi:10.1016/j.comnet.2024.110803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Muhammed T, Mehmood R, Alamri A, Alzahrani A. HCDSR: a hierarchical clustered fault tolerant routing technique for IoT-based smart societies. In: Smart infrastructure and applications: foundations for smarter cities and societies. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2020. p. 609–28. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-13705-2_25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Jing G, Zou Y, Yu D, Luo C, Cheng X. Efficient fault-tolerant consensus for collaborative services in edge computing. IEEE Trans Comput. 2023;72(8):2139–50. doi:10.1109/tc.2023.3238138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Apat HK, Sahoo B. LESP: a fault-aware internet of things service placement in fog computing. Sustain Comput Inf Syst. 2025;30:101097. doi:10.1016/j.suscom.2025.101097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Sivakumar S, Vivekanandan P. Efficient fault-tolerant routing in IoT wireless sensor networks based on path graph flow modeling with marchenko-pastur distribution (EFT-PMD). Wirel Netw. 2020;26(8):4543–55. doi:10.1007/s11276-020-02359-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Casado-Vara R, Vale Z, Prieto J, Corchado JM. Fault-tolerant temperature control algorithm for IoT networks in smart buildings. Sensors. 2018;18(11):3766. doi:10.3390/en11123430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Terry DB. Toward a new approach to IoT fault tolerance. Computer. 2016;49(8):80–3. doi:10.1109/mc.2016.238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Chakraborty T, Nambi AU, Chandra R, Sharma R, Swaminathan M, Kapetanovic Z, et al. Fall-curve: a novel primitive for IoT fault detection and isolation. In: Proceedings of the 16th ACM Conference on Embedded Networked Sensor Systems (SenSys’18); 2018 Nov 4–7; Shenzhen, China. p. 95–107. [Google Scholar]

52. Sharma AK, Kanhaiya K, Talwar J. Effectiveness of swarm intelligence for handling fault-tolerant routing problem in IoT. In: Swarm intelligence optimization: algorithms and applications. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2020. p. 325–41. doi: 10.1002/9781119778868.ch17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Bounceur A, Bezoui M, Lagadec L, Euler R, Abdelkader L, Hammoudeh M. DOTRO: a dominating tree routing algorithm for efficient and fault-tolerant leader election in WSNs and IoT networks. In: International Conference on Mobile, Secure, and Programmable Networking; 2018 Jun 18–20; Paris, France. Cham, Switzerland:Springer; 2019. p. 42–53. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-03101-5_5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Cauteruccio F, Talia D, Trunfio P. A framework for anomaly detection and classification in multiple IoT scenarios. Fut Gener Comput Syst. 2021;114:322–35. doi:10.1016/j.future.2020.08.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Duarte M, Dias JP, Ferreira HS, Restivo A. Evaluation of IoT self-healing mechanisms using fault-injection in message brokers. In: SERP4IoT’22: Proceedings of the 4th International Workshop on Software Engineering Research and Practice for the IoT; 2022 May 19; Pittsburgh, PA, USA. p. 9–16. [Google Scholar]

56. Grosso J, Jhumka A. Fault-tolerant ant colony based routing in many-to-many IoT sensor networks. In: Proceedings of the 20th IEEE International Symposium on Network Computing and Applications (NCA); 2021 Nov 23–26; Boston, MA, USA. p. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

57. Gao Z, Cecati C, Ding SX. A survey of fault diagnosis and fault-tolerant techniques—part I: fault diagnosis with model-based and signal-based approaches. IEEE Trans Ind Electron. 2015;62(6):3757–67. doi:10.1109/tie.2015.2417501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Hasan MZ, Al-Turjman F. Optimizing multipath routing with guaranteed fault tolerance in Internet of Things. IEEE Sens J. 2017;17(19):6463–73. doi:10.1109/jsen.2017.2739188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Misra S, Gupta A, Krishna PV, Agarwal H, Obaidat MS. An adaptive learning approach for fault-tolerant routing in Internet of Things. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Wireless Communications and Networking Conference (WCNC); 2012 Apr 1–4; Paris, France. p. 815–9. [Google Scholar]

60. Chatzidakis M, Hadjiefthymiades S. Trust management in mobile ad hoc networks. In: 2014 16th International Telecommunications Network Strategy and Planning Symposium (Networks); 2014 Sep 17–19; Funchal, Portugal. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

61. Chanak P, Banerjee I, Bose S. An intelligent fault-tolerant routing scheme for internet of things-enabled wireless sensor networks. Int J Commun Syst. 2021;34(17):e4970. doi:10.1002/dac.4970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Xu T, Potkonjak M. Energy-efficient fault tolerance approach for Internet of Things applications. In: Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Computer-Aided Design (ICCAD); 2016 Nov 7–10; Austin, TX, USA. p. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

63. Pourghebleh B, Wakil KAM, Navimipour NJ. A comprehensive study on the trust management techniques in the Internet of Things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2019;6(6):9326–37. doi:10.1109/jiot.2019.2933518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Sisi Z, Souri A. Blockchain technology for energy-aware mobile crowd sensing approaches in Internet of Things. Trans Emerg Telecomm Technol. 2021;32(7):e4217. doi:10.1002/ett.4217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Hussain AMS, Padmapriya T, Nagalingam M. Genetic algorithm based adaptive offloading for improving IoT device communication efficiency. Wirel Netw. 2020;26(4):2329–38. doi:10.1007/s11276-019-02121-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Bukhsh MW, Abdullah S, Rahman A, Asghar MN, Arshad H, Alabdulatif A. An energy-aware, highly available, and fault-tolerant method for reliable IoT systems. IEEE Access. 2021;9:145363–81. doi:10.1109/access.2021.3121033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Ghaleb M, Azzedin F. Trust-aware fog-based IoT environments: artificial reasoning approach. Appl Sci. 2023;13(6):3665. doi:10.3390/app13063665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Chen L, Xu Y, Xu F, Hu Q, Tang Z. Balancing the trade-off between cost and reliability for wireless sensor networks: a multi-objective optimized deployment method. Appl Intell. 2023;53(7):9148–73. doi:10.1007/s10489-022-03875-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Marcozzi M, Gemikonakli O, Gemikonakli E, Gelenbe E. Availability evaluation of IoT systems with byzantine fault-tolerance for mission-critical applications. Internet Things. 2023;24:100889. doi:10.1016/j.iot.2023.100889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Whaiduzzaman M, Barros A, Shovon AR, Hossain MR, Fidge C. A resilient Fog-IoT framework for seamless microservice execution. In: 2021 IEEE International Conference on Services Computing (SCC); 2021 Sep 5–10; Chicago, IL, USA. p. 213–21. [Google Scholar]

71. Choudhary AK, Rahamatkar S. FATMLPGS: design of a fault-aware trust establishment model for low-power IoT deployments via generic lightweight sidechains. J Intell Fuzzy Syst. 2023;44(6):7053–66. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-2154340/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Kaur G, Chanak P. An intelligent fault tolerant data routing scheme for wireless sensor network-assisted industrial Internet of Things. IEEE Trans Ind Inform. 2022;18(8):5578–87. doi:10.1109/tii.2022.3204560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Andrade E, Nogueira B. Dependability evaluation of a disaster recovery solution for IoT infrastructures. J Supercomput. 2020;76(3):1828–49. doi:10.1007/s11227-018-2290-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Ribeiro VPA, Holanda RH, Ramos AR, Rodrigues JJPC. A fault-tolerant and secure architecture for key management in LoRaWAN based on permissioned blockchain. IEEE Access. 2022;10:58722–35. doi:10.1109/access.2022.3179004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

75. Safi A, Ahmad Z, Jehangiri AHI, Latip R. A fault-tolerant surveillance system for fire detection and prevention using LoRaWAN in smart buildings. Sensors. 2022;22(21):8411. doi:10.3390/s22218411. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Papan J, Bridová I, Tatarka Š, Hraška M. Fault tolerance solutions in IoT and smart city. In: 2023 International Conference on Information and Digital Technologies (IDT); 2023 Jun 20–22; Zilina, Slovakia. p. 139–48. [Google Scholar]

77. Rubambiza G, Chin SW, Atapattu S, Rehman M, Martínez JF, Weatherspoon H, et al. Comosum: an extensible, reconfigurable, and fault-tolerant IoT platform for digital agriculture. In: Proceedings of the 2023 USENIX Annual Technical Conference (ATC); 2023 Jul 10–12; Boston, MA, USA. p. 295–308. [Google Scholar]

78. Sicari S, Rizzardi A, Grieco LA, Coen-Porisini A. Security, privacy and trust in Internet of Things: the road ahead. Comput Netw. 2015;76:146–64. doi:10.1016/j.comnet.2014.11.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

79. Khan HM, Khan A, Khan B, Jeon GS. Fault-tolerant secure data aggregation schemes in smart grids: techniques, design challenges, and future trends. Energies. 2022;15(24):9350. doi:10.3390/en15249350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

80. Seong K, Jiao J. Is a smart city framework the key to disaster resilience? A systematic review. J Plan Lit. 2024;39(1):62–78. doi:10.1177/08854122231199462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

81. Abadeh MN, Mirzaie M. Resiliency-aware analysis of complex IoT process chains. Comput Commun. 2022;192(4):245–55. doi:10.1016/j.comcom.2022.06.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

82. Kalka W, Szydlo T. μ Chaos: moving chaos engineering to IoT devices. In: International Conference on Computational Science; 2024 Jul 2–4; Málaga, Spain. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2024. p. 239–54. [Google Scholar]

83. Mahmoud R, Khattab A, Khater MM, Mohamed A. Toward software-defined networking-based IoT frameworks: a systematic literature review, taxonomy, open challenges, and prospects. IEEE Access. 2022;10:70850–74. doi:10.1109/access.2022.3188311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

84. Sarker IH. Smart city data science: towards data-driven smart cities with open research issues. Internet Things. 2022;19:100528. doi:10.1016/j.iot.2022.100528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

85. Yang SR, Yuan SC, Lin YC, Yang IF. Edge intelligence for empowering IoT-based healthcare systems. arXiv: 2103.12144. 2021. [Google Scholar]

86. Lin JW, Chelliah PR, Hsu MC, Hou JX. Efficient fault-tolerant routing in IoT wireless sensor networks based on bipartite-flow graph modeling. IEEE Access. 2019;7:14022–34. doi:10.1109/access.2019.2894002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

87. Pankajavalli P, Karthick G. Efficient data flow graph modeling using free poisson law for fault-tolerant routing in internet of things. In: Proceedings of 5th International Conference on Computer Networks and Inventive Communication Technologies (ICCNCT); 2022 Jul 6–7; Coimbatore, India. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2022. p. 475–87. [Google Scholar]

88. Power A, Kotonya G. Providing fault tolerance via complex event processing and machine learning for IoT systems. In: Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on the Internet of Things; 2019 Oct 22–25; Bilbao, Spain. p. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

89. Caiazzo B, Nardo MD, Murino T, Petrillo A, Piccirillo G, Santini S. Towards zero defect manufacturing paradigm: a review of the state-of-the-art methods and open challenges. Comput Ind. 2022;134:103548. doi:10.1016/j.compind.2021.103548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

90. Prakash C, Barthwal A, Acharya D. FLOODWALL: a real-time flash flood monitoring and forecasting system using IoT. IEEE Sens J. 2022;23(1):787–99. doi:10.1109/jsen.2022.3223671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

91. Sastry JKR, Chokara B, Budaraju RR. Implementing dual base stations within an IoT network for sustaining the fault tolerance of an IoT network through an efficient path finding algorithm. Sensors. 2023;23(8):4032. doi:10.3390/s23084032. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

92. Tzioutziou A, Xenidis Y. A study on the integration of resilience and smart city concepts in Urban systems. Infrastructures. 2021;6(2):24. doi:10.3390/infrastructures6020024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

93. Jammalamadaka SKR, Chokara B, Jammalamadaka SB, Duvvuri BK, Budaraju RR. Enhancing the fault tolerance of a multi-layered IoT network through rectangular and interstitial mesh in the gateway layer. J Low Power Electron Appl. 2022;12(5):76. doi:10.3390/jsan12050076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

94. Zeng Z, Chang L, Liu Y. A fault tolerance data aggregation scheme for fog computing networks. Int J Inform Comput Secur. 2022;3(4):351–64. doi:10.1504/ijics.2022.122379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

95. Keong CK. The GLIDE system—Singapore’s Urban traffic control system. Transp Rev. 1993;13(4):295–305. doi:10.1080/01441649308716854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

96. Pérez R, Puig V, Pascual J, Peralta A, Landeros E, Jordanas L. Pressure sensor distribution for leak detection in Barcelona water distribution network. Water Sci Technol Water Supply. 2009;9(6):715–21. [Google Scholar]

97. Mohapatra H, Rath AK. Detection and avoidance of water loss through municipality taps in India by using smart taps and ICT. IET Wirel Sens Syst. 2019;9(6):447–57. doi:10.1049/iet-wss.2019.0081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

98. Al-Shammari HQ, Lawey AQ, Elmirghani JMH. Resilient service embedding in IoT networks. IEEE Access. 2020;8:123571–84. doi:10.1109/access.2020.3005936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

99. Sharad HV, Desai SR, Krishnrao KY. SAOA: multi-objective fault-tolerance based optimized RPL routing protocol in Internet of Things. Cybern Syst. 2022;53(8):687–708. doi:10.1080/01969722.2022.2146845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

100. Jammalamadaka KRS, Chokara B, Jammalamadaka SB, Duvvuri BK. Making IoT networks highly fault-tolerant through power fault prediction, isolation and composite networking in the device layer. J Sens Actuator Netw. 2025;14(2):24. doi:10.3390/jsan14020024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

101. Ratasich D, Khalid F, Geissler F, Grosu R, Shafique M, Bartocci E. A roadmap toward the resilient Internet of Things for cyber-physical systems. IEEE Access. 2019;7:13260–83. doi:10.1109/access.2019.2891969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

102. Mohapatra H. Socio-technical challenges in the implementation of smart city. In: 2021 International Conference on Innovation and Intelligence for Informatics, Computing, and Technologies (3ICT); 2021 Sep 29–30; Zallaq, Bahrain. p. 57–62. [Google Scholar]

103. Zhu L, Xiong K, Qiu M. Blockchain and Internet of Things. In: Blockchain technology in Internet of Things. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2019. p. 9–28. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-21766-2_2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

104. Adday GH, Subramaniam SK, Zukarnain ZA, Samian N. Fault tolerance structures in wireless sensor networks (WSNssurvey, classification, and future directions. Sensors. 2022;22(16):6041. doi:10.3390/s22166041. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

105. Casado-Vara R, Novais P, Gil AB, Prieto J, Corchado JM. Distributed continuous-time fault estimation control for multiple devices in IoT networks. IEEE Access. 2019;7:11972–84. doi:10.1109/access.2019.2892905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]