Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Sine-Polynomial Chaotic Map (SPCM): A Decent Cryptographic Solution for Image Encryption in Wireless Sensor Networks

1 School of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, Gwangju Institute of Science and Technology (GIST), Gwangju, 61005, Republic of Korea

2 Faculty of Information Technology & Computer Science, University of Central Punjab, Lahore, 54000, Pakistan

3 Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Chungnam National University, Daejeon, 34134, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Authors: David S. Bhatti. Email: ; Ki-Il Kim. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(1), 2157-2177. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.068360

Received 27 May 2025; Accepted 25 July 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

Traditional chaotic maps struggle with narrow chaotic ranges and inefficiencies, limiting their use for lightweight, secure image encryption in resource-constrained Wireless Sensor Networks (WSNs). We propose the SPCM, a novel one-dimensional discontinuous chaotic system integrating polynomial and sine functions, leveraging a piecewise function to achieve a broad chaotic range () and a high Lyapunov exponent (5.04). Validated through nine benchmarks, including standard randomness tests, Diehard tests, and Shannon entropy (3.883), SPCM demonstrates superior randomness and high sensitivity to initial conditions. Applied to image encryption, SPCM achieves 0.152582 s (39% faster than some techniques) and 433.42 KB/s throughput (134% higher than some techniques), setting new benchmarks for chaotic map-based methods in WSNs. Chaos-based permutation and exclusive or (XOR) diffusion yield near-zero correlation in encrypted images, ensuring strong resistance to Statistical Attacks (SA) and accurate recovery. SPCM also exhibits a strong avalanche effect ( bit difference), making it an efficient, secure solution for WSNs in domains like healthcare and smart cities.Keywords

WSNs have emerged as a fundamental component of numerous applications, including environmental monitoring, healthcare, industrial automation, and smart city infrastructure, where real-time transmission of sensitive data, such as images, is critical. These networks consist of spatially distributed, resource-constrained sensor nodes that operate with limited computational power, battery energy, and bandwidth [1]. Traditional encryption schemes, such as AES, RSA, PKI though robust, are computationally intensive and often impractical in WSN environments due to their high energy and processing demands [2]. This necessitates the development of lightweight and efficient cryptographic techniques specifically tailored for WSNs.

1.1 Wireless Sensor Networks (WSNs)

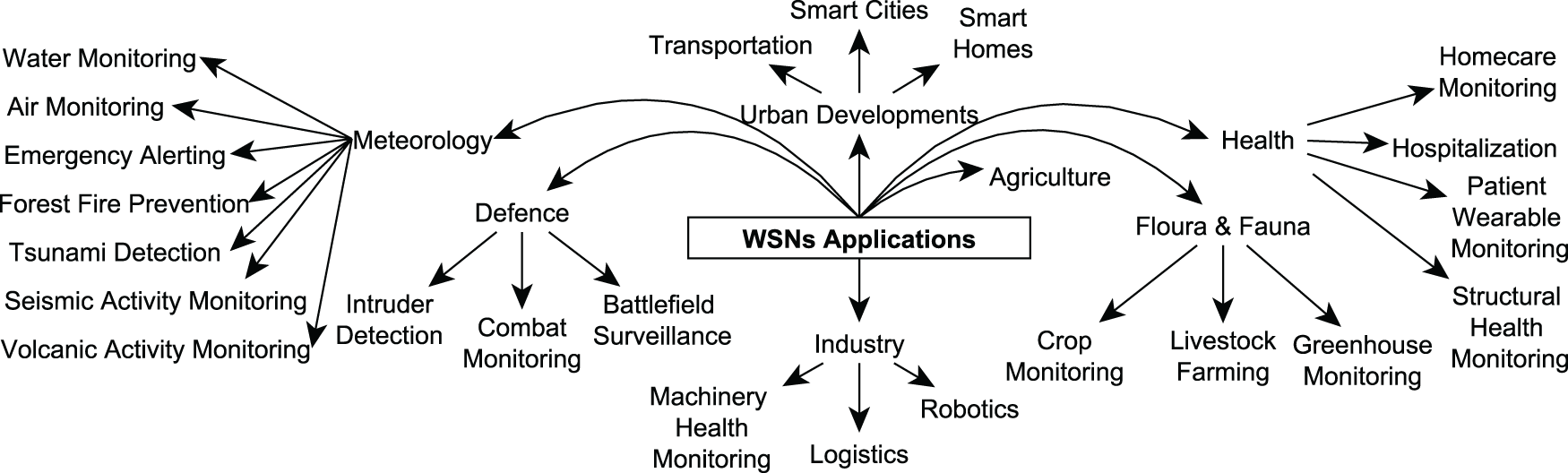

WSNs are specialized wireless ad hoc networks composed of low-power sensor nodes capable of sensing, processing, and wirelessly communicating data. These networks enable real-time monitoring of various physical phenomena such as temperature, humidity, pressure, motion, and even physiological signals. WSNs are widely adopted across domains including defense, agriculture, healthcare, industrial automation, and smart urban infrastructure [1]. Their self-configuring, scalable, and fault-tolerant nature makes them ideal for deployment in dynamic or harsh environments. Fig. 1 summarizes major application areas of WSNs.

Figure 1: Major application domains of WSNs

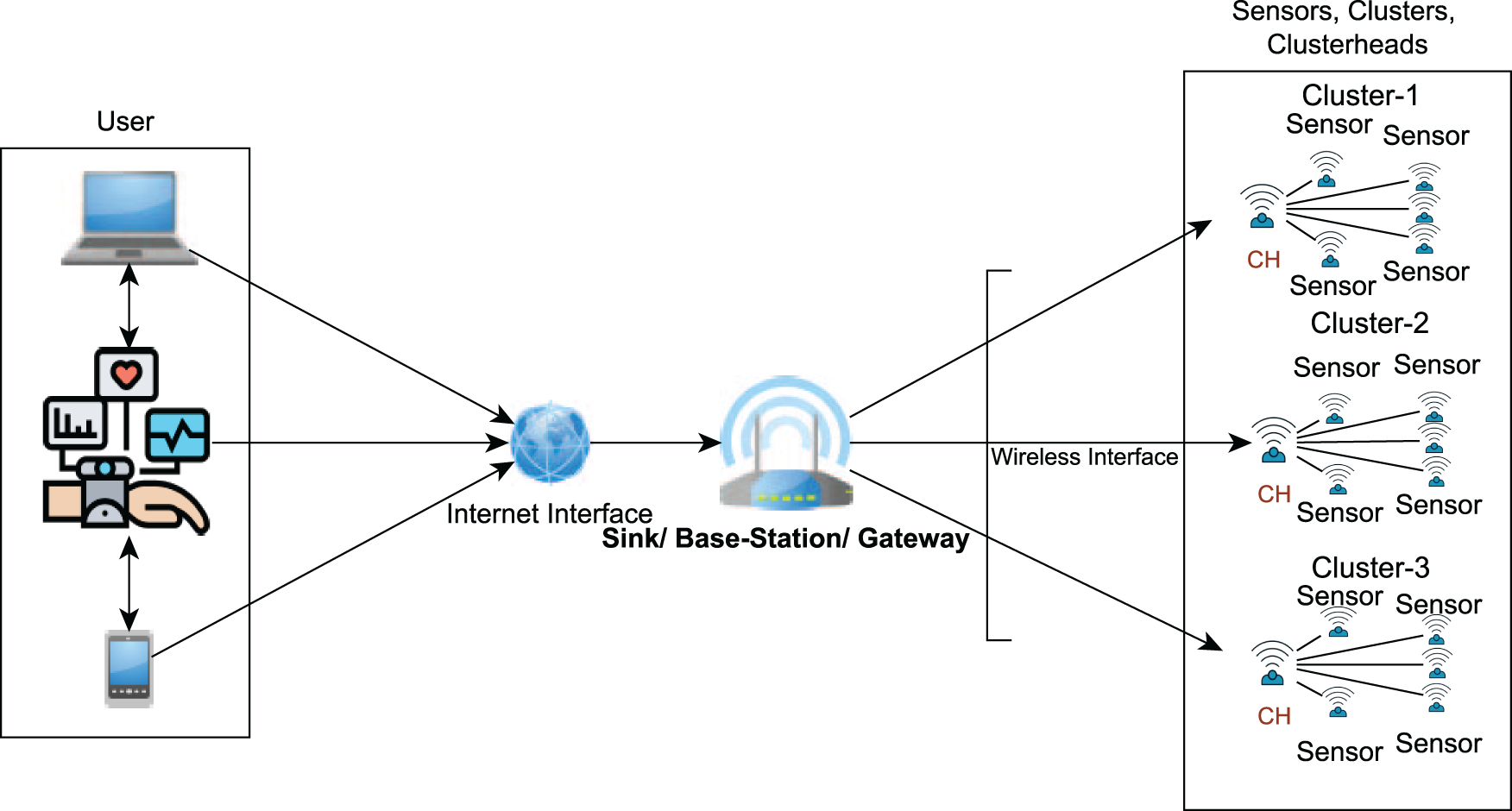

Despite their wide applicability, WSNs face two critical challenges: resource constraints and security vulnerabilities. Sensor nodes are typically powered by non-replaceable batteries and expected to function over extended periods. Their limited processing power and memory severely restrict the use of complex cryptographic algorithms. Additionally, their communication relies on open wireless channels, making them susceptible to attacks such as eavesdropping, spoofing, and denial-of-service [3]. Therefore, energy-aware and lightweight cryptographic mechanisms are essential for securing data without compromising network longevity. A typical WSN architecture, as shown in Fig. 2, consists of a large number of sensor nodes randomly deployed in the target area. These nodes communicate with a base station (sink), which acts as a central data aggregator. Queries from the sink are propagated through the network, and responses from matching sensor nodes are transmitted back. To optimize energy usage, a cluster-based model is often employed where selected nodes act as cluster heads. These heads are responsible for aggregating, compressing, and securely transmitting data to the sink. Users retrieve the data from the sink through backhaul communication (e.g., satellite or cellular links) [4].

Figure 2: Typical architecture of WSN

Chaotic systems, pioneered by Poincaré, Lorenz, and others, exhibit unpredictable behavior despite being deterministic, due to their sensitivity to initial conditions [5,6]. Their properties, such as topological mixing, dense periodic orbits, and fractal geometry, make them well-suited for cryptography, offering complex dynamics and strong key sensitivity [7,8]. One-dimensional chaotic maps are especially useful for generating complex pseudo-random sequences in lightweight encryption schemes for WSNs [9,10]. These systems are modeled as:

with

To address energy and security constraints in WSNs, this study proposes a lightweight image encryption framework based on the SPCM a one-dimensional system that combines sinusoidal and polynomial terms to overcome the limitations of classical maps, including restricted key space and weak randomness [13]. The SPCM offers high chaotic complexity with low computational cost, making it ideal for WSNs. In the proposed model, modulo 1 operation is performed using basic thumb of rule that is

1.3 Motivation and Contributions

The key contributions of this research are given below:

1. We propose SPCM, a discontinuous one-dimensional map combining polynomial and sine dynamics. It expands the chaotic range, boosts key sensitivity, and enhances robustness, making it suitable for secure image encryption in resource-limited WSNs.

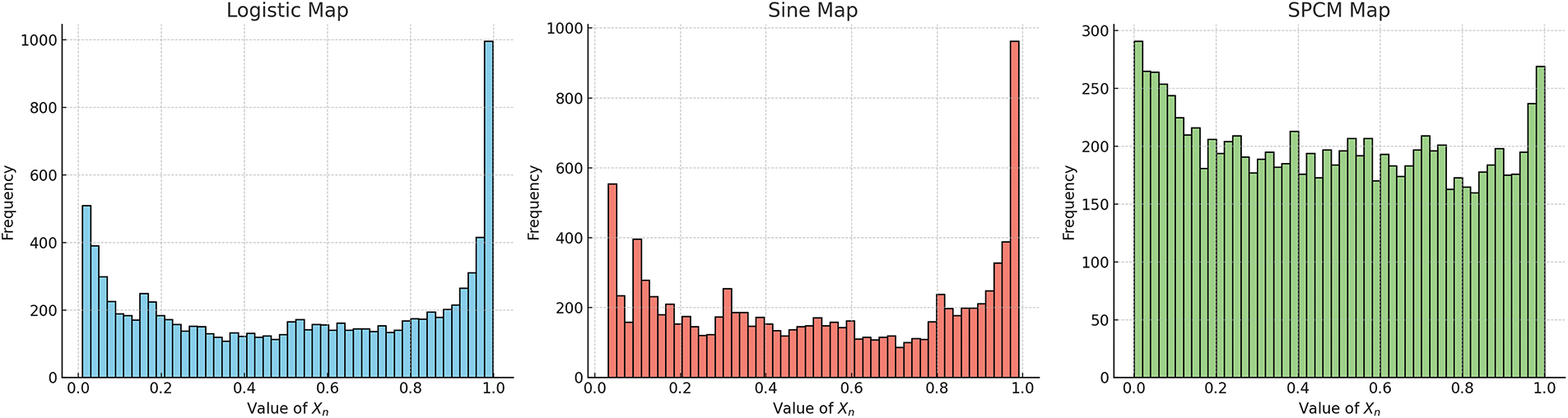

2. SPCM is rigorously evaluated using nine benchmarks, including bifurcation, Lyapunov exponents (5.04), Shannon entropy (3.883), sensitivity, cobweb plots, 0-1 test, histograms, and NIST/Diehard randomness tests. It shows superior chaos, broader stability, and stronger randomness, outperforming prior methods assessed with 2–7 metrics.

3. Designed for image encryption in WSNs, SPCM offers lightweight, secure encryption with low computational load. Its chaos-based keying, permutation, and XOR diffusion resist SA, reduce energy use, and support reliable data recovery.

The rest of the manuscript is organized as follows: Section 2 Related Work; Section 3 Proposed Sine-Polynomial Chaotic System; Section 4 Analysis and Discussion; Section 5 Application; Section 6 Limitations; Section 7 Conclusion.

This section explores recent advancements in chaotic systems, reviewing methodologies, strategies, and theoretical foundations aimed at refining their properties for diverse applications.

Lambić [14] proposed a one-dimensional Chaotic Map using integer multiplication and circular shifts, optimized for memory-limited devices but potentially restrictive for encryption. Shafique [15] employed the Cubic-Logistic map for S-box construction to enhance cryptographic properties, though its smaller key space and computational complexity may limit practical usability.

Zhang et al. [16] introduced an image encryption algorithm leveraging a hyperchaotic system and the variable-step Josephus problem, using pseudorandom sequences for scrambling and pixel-wise encryption. It achieves high entropy (7.997) and low correlation (

Li et al. [18] proposed the Logistic-Tent-Sine Chaotic Map (LTSS) for cloud image security, offering improved chaotic behavior, though remaining vulnerable to certain attacks. Fadhil et al. [19] used the 1D logistic map for S-box design, though its narrow key space may weaken security. Cheng et al. [20] introduced the 1D-TPSC Chaotic System for image encryption, demonstrating strong dynamics but facing scalability and adaptability challenges.

Zhang et al. [21] developed an image encryption algorithm using 1D and 2D logistic chaotic systems, leveraging initial value sensitivity and pseudo-randomness. However, fixed-length keys and sequential processes may limit its suitability for large datasets or real-time applications, with a narrow key space reducing resistance to sophisticated cryptanalytic attacks. Mondal and Singh [22] proposed a lightweight chaotic encryption scheme for IoT devices, using bit-wise permutation and substitution in a single scan for efficiency. Its simplicity, while suitable for low-power settings, may compromise resilience against sophisticated cryptanalytic attacks.

Liu and Wang [23] proposed a cluster of 1D quadratic Chaotic Maps for image encryption, expanding the parameter space to enhance security. However, relying solely on the 1D quadratic map may introduce vulnerabilities. Chen et al. [24] introduced a digital image encryption algorithm using a splicing model and quaternary coding, improving attack resistance. Despite a large key space, potential weaknesses in chaotic dynamics and cryptanalysis susceptibility may impact long-term security.

Alexan et al. [25] presented a color image encryption algorithm combining the KAA map with multiple chaotic maps, utilizing Shannon’s principles of security through bit confusion and diffusion. Confusion is achieved using two encryption keys generated from different chaotic maps, while diffusion is implemented using the KAA map. The algorithm is shown to be robust, efficient, and resistant to various attacks, passing all tests in the NIST SP 800 suite.

Ding et al. [26] introduced memristive Chaotic Systems using 1D Chaotic Maps for randomness, but high computational overhead limits practicality. Malik et al. [27] proposed an S-box using the Tent-Sine (TS) Chaotic System, enhancing the chaotic range for cryptography. Despite reduced chaoticity at certain bifurcation points, extensive analysis confirms its cryptographic strength.

Alawida [28] proposed an Enhanced Logistic Map (ELM) for secure random number generation, improving randomness via chaotic perturbations, though its deterministic nature may pose cryptanalytic risks. Jain et al. [29] introduced MMCBIE, a multi-chaotic map image encryption scheme for IoT, combining Henon and 2D-Logistic maps to achieve high confusion and diffusion, validated by metrics like NPCR and UACI. However, its complexity may challenge IoT devices. Kiran [30] proposed a GPU-accelerated chaos-based encryption scheme using CUDA parallelization, demonstrating enhanced throughput for mobile applications. While effective for GPU-enabled devices, its computational demands exceed typical WSN node capabilities. Archana et al. [31] developed a blockchain-based medical image encryption scheme for IoT-Edge systems, using chaotic maps and optimized key generation on Ethereum, demonstrating strong security via NIST tests, though its computational overhead may limit real-time edge applications. A novel triple image encryption scheme using chaotic measurement matrices, Josephus scrambling, and 3D wavelet transform-based embedding was proposed by Hu et al. [32] to achieve high visual security and reconstruction quality without carrier data for decryption, surpassing existing methods.

While WSNs demand lightweight security solutions, traditional cryptographic approaches face three critical limitations in resource-constrained environments [33]: 1) the computational overhead of AES/RSA operations exceeds typical WSN node capabilities [34,35], 2) key management in PKI-based systems creates unsustainable energy costs [26], and 3) block cipher modes introduce latency incompatible with real-time applications [17]. Chaotic maps have emerged as a promising alternative [25], offering deterministic pseudo-randomness for lightweight key generation [16], single-pass processing efficiency, and inherent resistance to side-channel attacks [18]. However, existing 1D chaotic systems remain limited by narrow parameter ranges (e.g.,

Chaotic systems like hyperchaotic and lightweight schemes offer high entropy and strong security for image encryption. However, in WSNs, they face compounded challenges: multi-map schemes and complex S-boxes increase computational load while restricting key space, and oversimplified lightweight designs often sacrifice robustness. These unresolved limitations motivate our search for a chaotic system that simultaneously achieves WSN compatibility (minimal computational/energy overhead) and strong security (high Lyapunov exponents, wide chaotic ranges). Moreover, wireless visual sensor networks (WVSNs) have emerged as a recent research focus. While Liu et al. [36] proposed a framework for improving coverage estimation in irregular, obstacle-rich environments, our proposed SPCM system complements it by securing captured visual data through efficient, lightweight chaotic encryption. Together, they address both reliable sensing and robust data protection in resource-constrained WVSNs.

One-dimensional discontinuous maps are vital in modeling dynamical systems with abrupt behavioral transitions across phase space regions. Defined by piecewise functions, these systems switch dynamics based on the state variable’s position, expressed as:

Here

The piecewise sine-polynomial formulation in Eq. (3) combines cubic polynomial terms (

The sine-polynomial chaotic system generates complex, unpredictable trajectories with high sensitivity to initial conditions. Unlike traditional logistic and tent maps, which have limited chaotic ranges and periodic windows, the SP system combines the oscillatory sine function and nonlinear polynomial terms to enhance sequence complexity. A discontinuity at

Furthermore, an increased control parameter range (

The development of proposed chaotic systems is motivated by the need for greater dynamical richness and wider parameter ranges. The proposed sine-polynomial system addresses this by offering a control parameter

4 Analysis and Discussion on Proposed SPCM

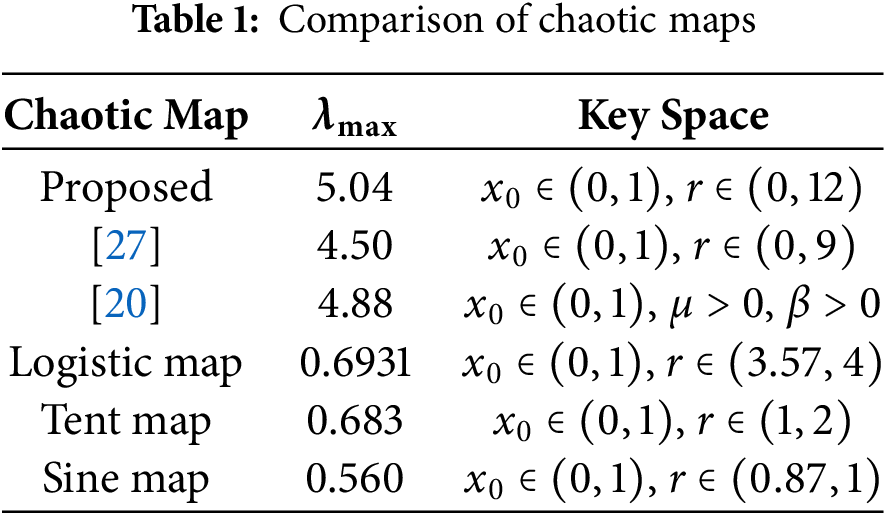

The proposed SPCM is evaluated in three domains: Chaotic Behavior Evaluation (bifurcation, Lyapunov exponents, sensitivity, cobweb diagrams, 0–1 tests, histograms, ergodicity, mixing), NIST SP800-22R1A, and Diehard tests. Results confirm high sensitivity, strong chaotic behavior, and compliance with cryptographic randomness standards. Parameters

4.1 Chaotic Behavior Evaluation

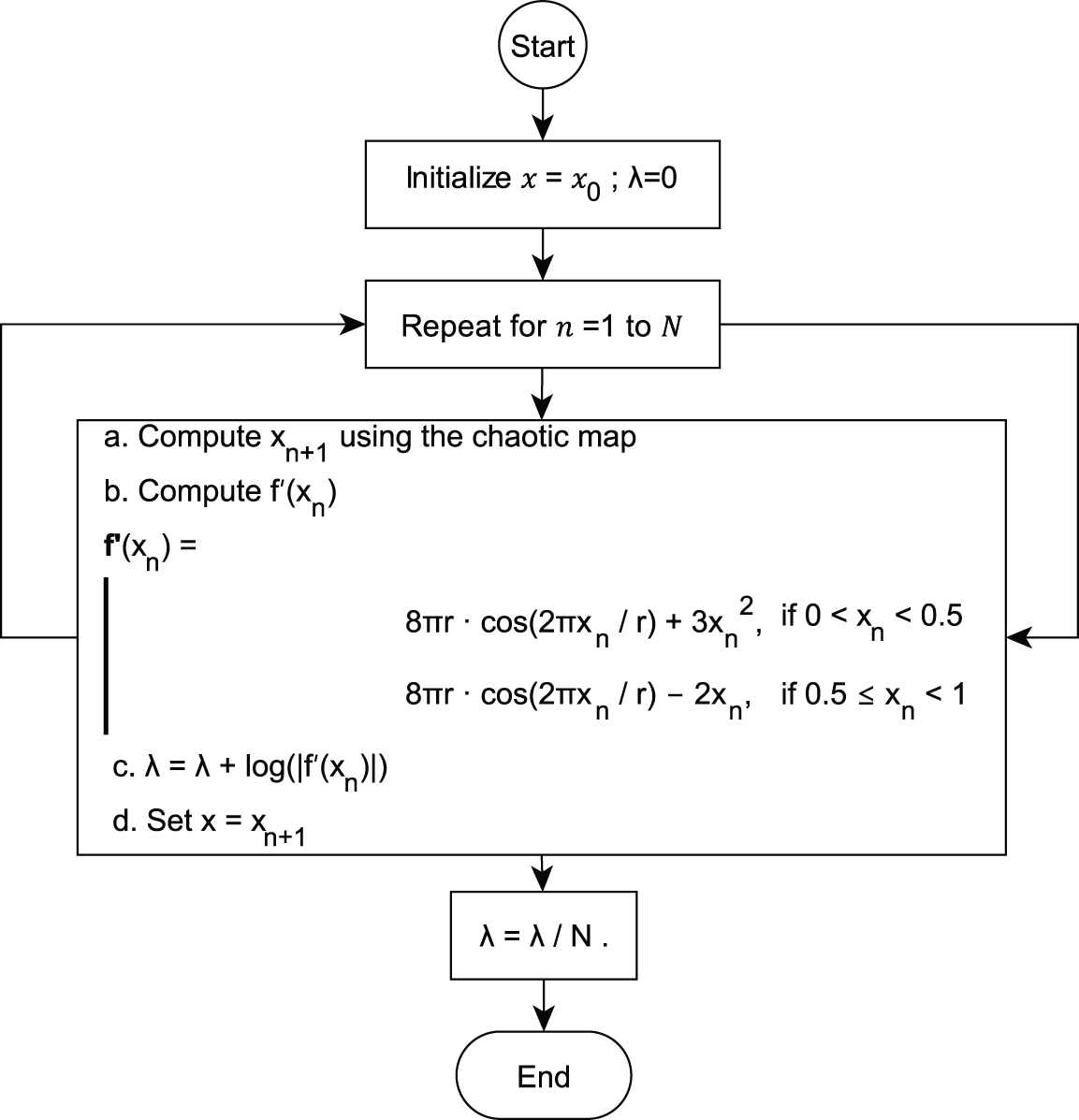

The Lyapunov exponent (

The derivative

Figure 3: Lyapunov Flowchart

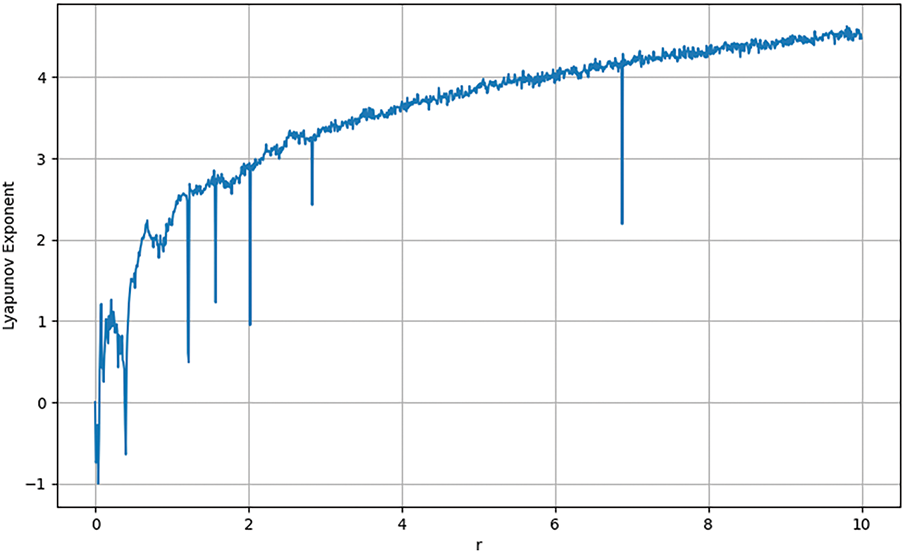

Fig. 4 shows

Figure 4: Lyapunov Exponent (

The cobweb diagram [39] in Fig. 5a illustrates trajectory divergence from initial values at

Figure 5: Dynamic analysis of the proposed Sine-Polynomial Chaotic Map (SPCM). (a) Cobweb diagram showing the trajectory behavior of SPCM for

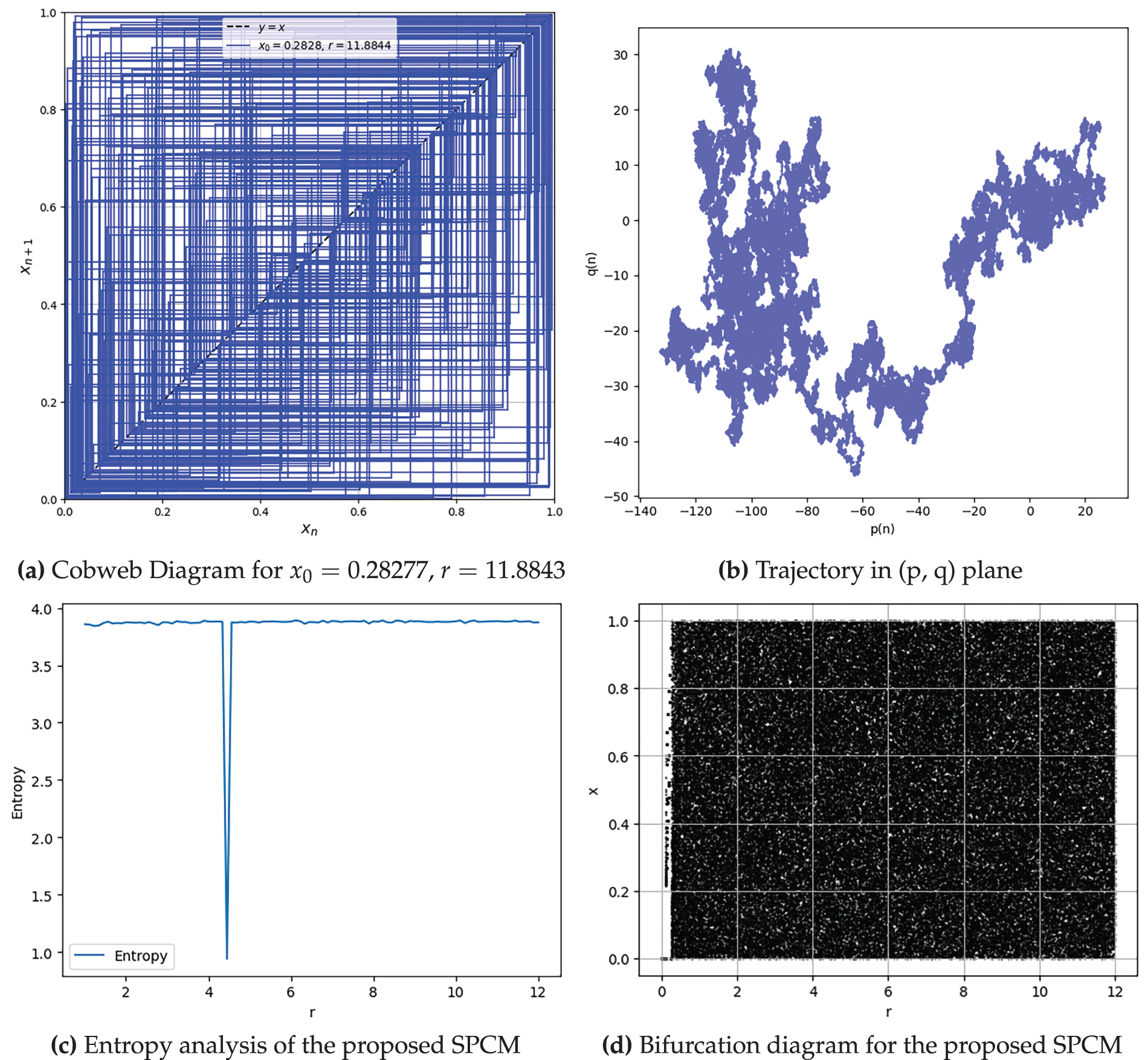

Sensitivity examines how minor changes in initial conditions or parameters impact the system’s output over time analysis [42]. Fig. 6a,b illustrates the system’s sensitivity to the initial condition

Figure 6: Sensitivity analysis of the proposed Sine-Polynomial Chaotic Map (SPCM). (a) Divergence of trajectories for initial condition perturbed by

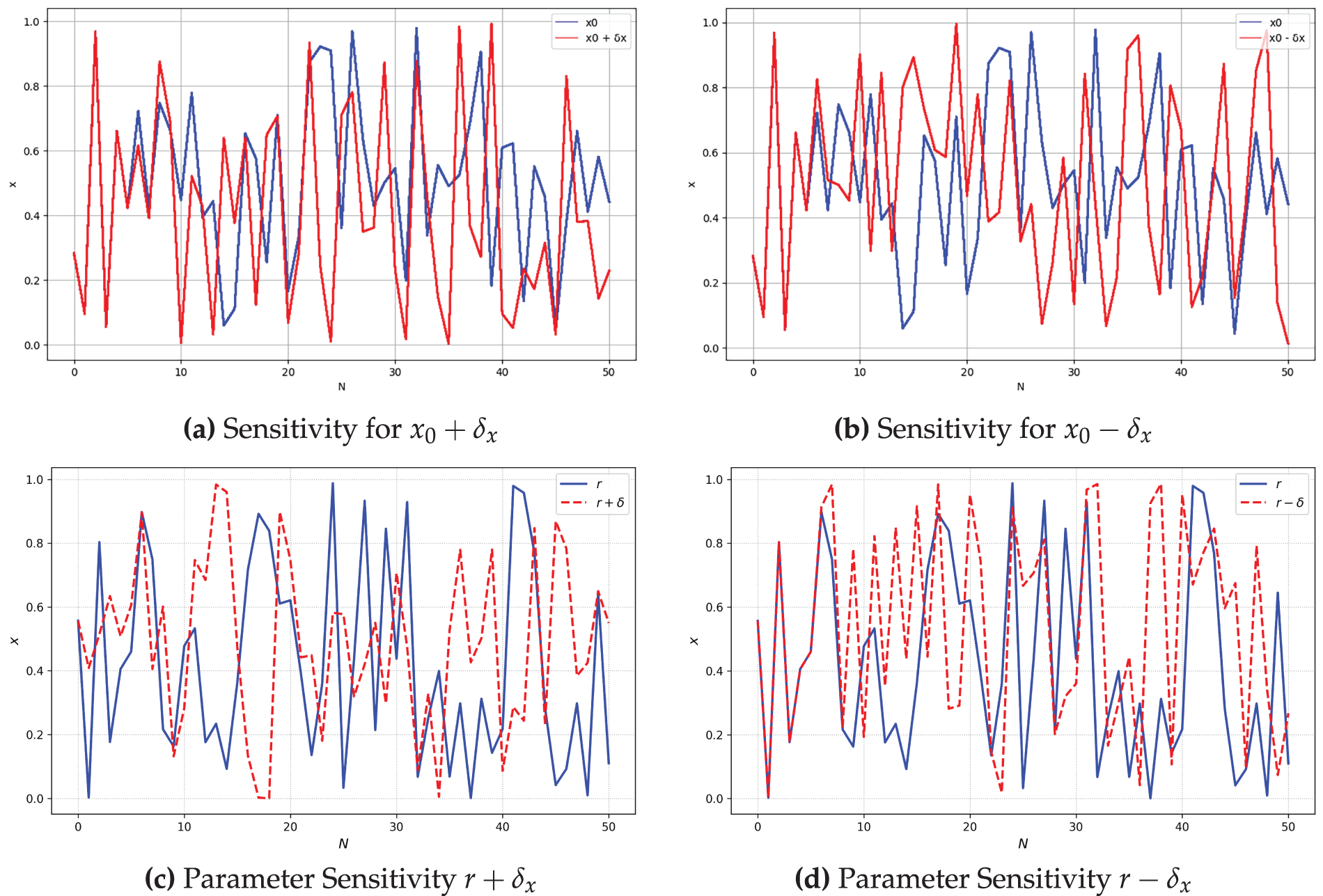

The histograms shown in Fig. 7 illustrate the distinct behaviors of three chaotic maps, all initialized with

Figure 7: Histogram: Proposed SPCM, Sine and Logistic Maps

The proposed SPCM exhibits key chaotic properties such as ergodicity and mixing. Ergodicity ensures uniform coverage of the phase space, evident in the histograms (Fig. 7) and high entropy (Fig. 5c). Mixing implies statistical independence across iterations, supported by the discontinuity at

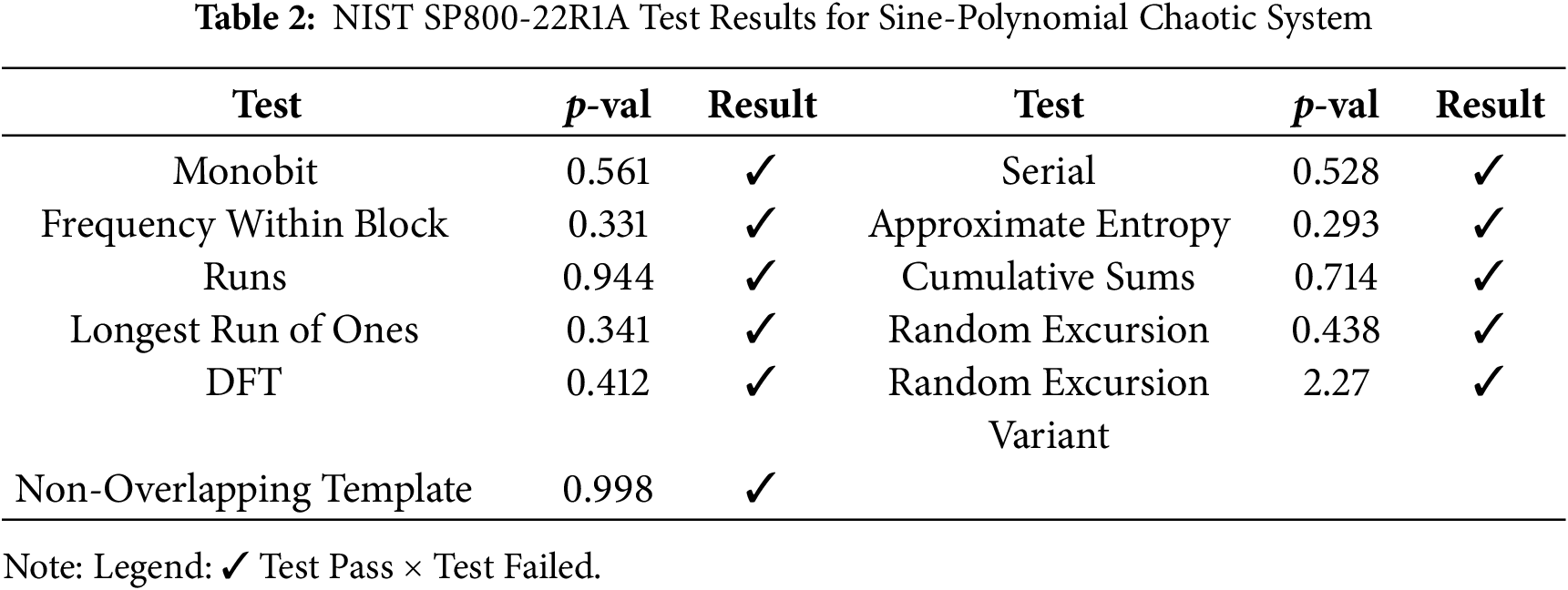

4.2 Performance Analysis Using NIST SP800-22R1A Test-Suit

The NIST SP800-22R1A Test Suite [43] is a comprehensive set of statistical tests used to evaluate the randomness of binary sequences, assessing components like frequency distribution, runs, entropy, and serial correlation. These tests help identify biases or trends that could compromise security, ensuring that binary sequences are suitable for cryptographic applications and simulations.

Table 2 summarizes the NIST SP800-22R1A test results for a binary sequence, covering all qualifying tests. All tests passed, confirming the sequence’s high randomness and applicability for cryptographic applications.

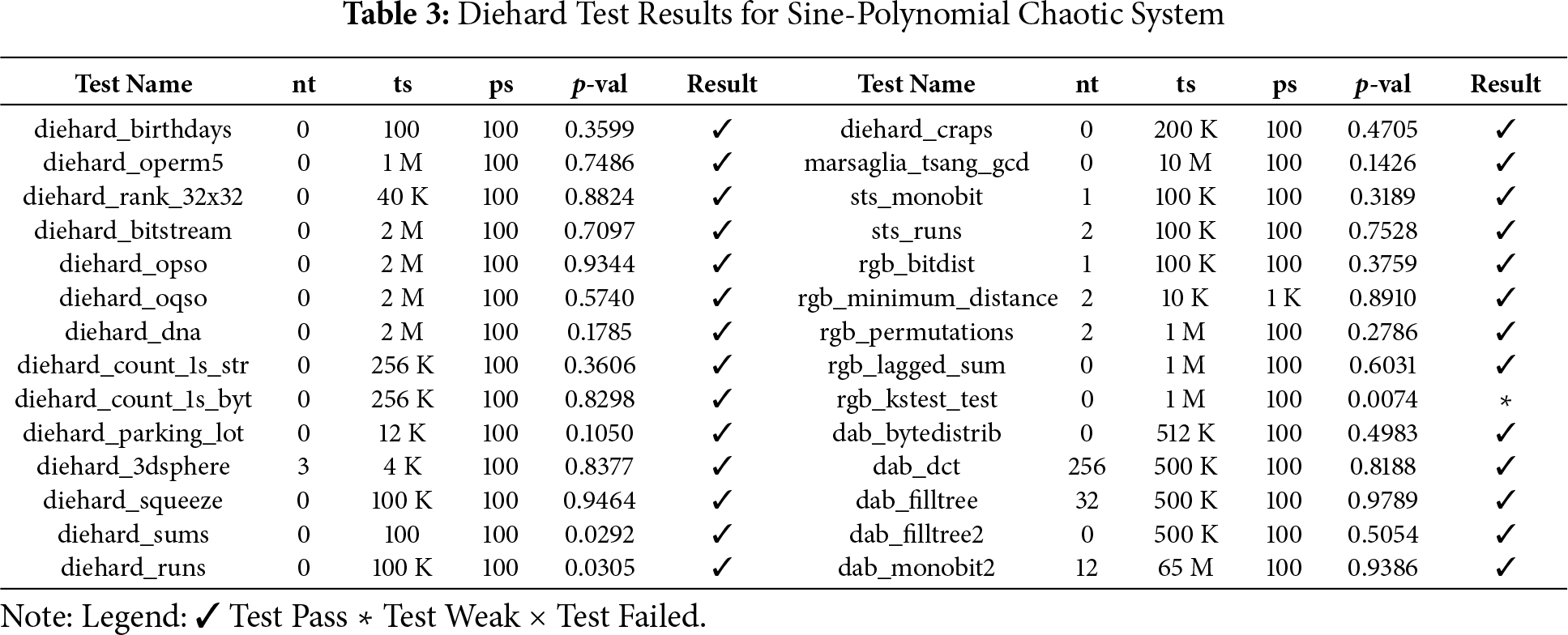

4.3 Performance Analysis Using Diehard Test-Suit

The performance of the proposed SPCM was rigorously evaluated using the Diehard tests suite, a collection of rigorous tests to assess the randomness of sequences. The SP Chaotic Map, with parameters

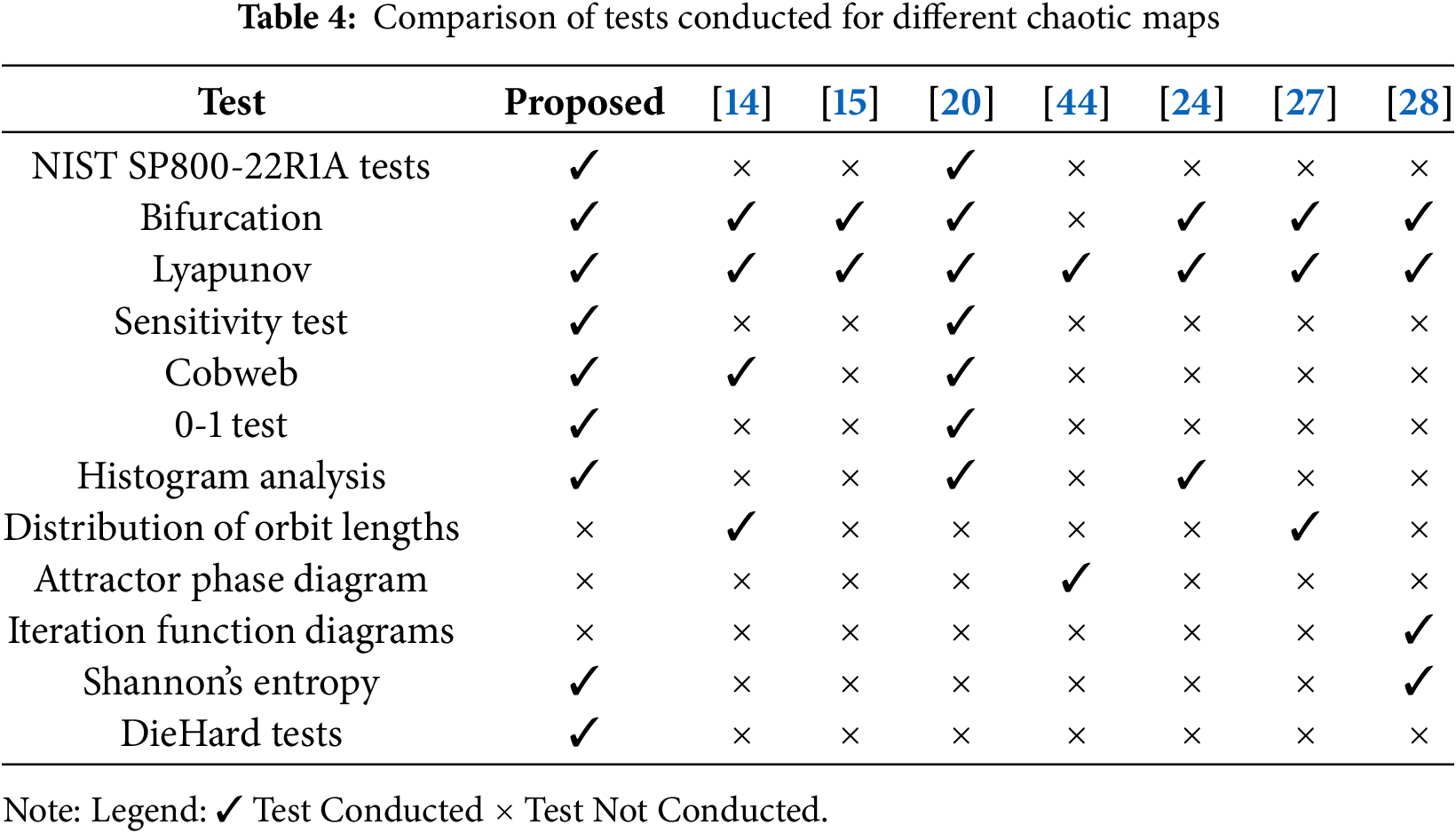

4.4 Comparative Analysis of Test Coverage in Chaotic System Research

This subsection compares the test coverage of the proposed Chaotic System with existing studies. Table 4 summarizes key tests (rows) and their application across different studies (columns). The proposed system demonstrates more comprehensive and extensive evaluation, outperforming prior chaotic maps by covering a wider range of rigorous tests, thereby validating its robustness and suitability for cryptographic applications.

5 Application of Proposed SPCM

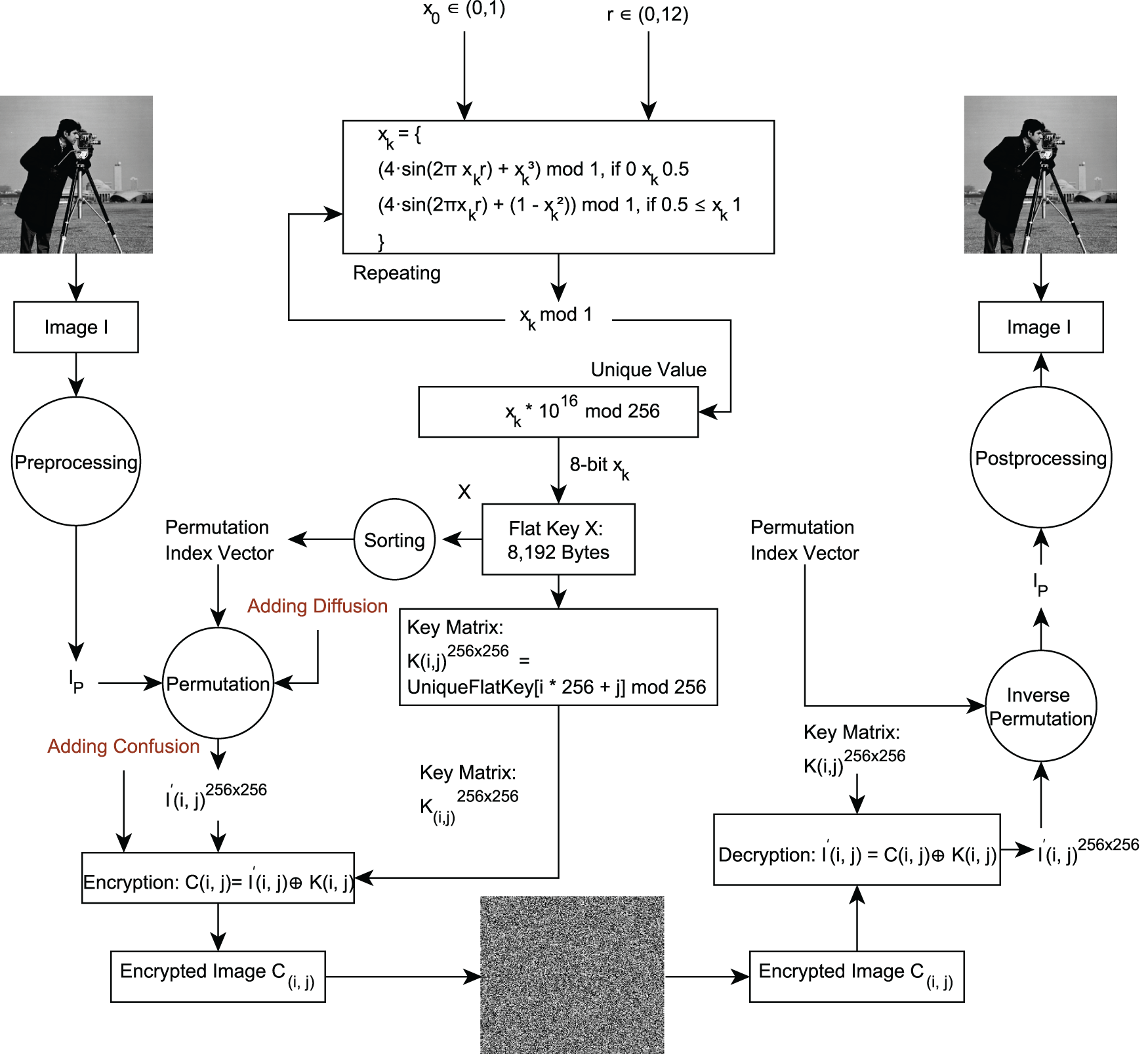

To generate the encryption key matrix, the SPCM (Eq. (3)) is employed using an initial value

The chaotic system is first iterated to produce a sequence

Here, each chaotic value is scaled by a large factor to preserve precision, modulo operation is applied to restrict values to the range

This transformation maps the 1D sequence into a 2D structure while preserving the ordering. The resulting key matrix

Figure 8: Key generation, image encryption and decryption process

We employ chaos-based lightweight image encryption using an SPCM to secure images in WSNs. This approach leverages the sensitivity to initial conditions and nonlinear dynamics of chaotic systems to ensure strong security with minimal computational overhead, making it well-suited for resource-constrained environments. We begin by preprocessing the input image such that

Here,

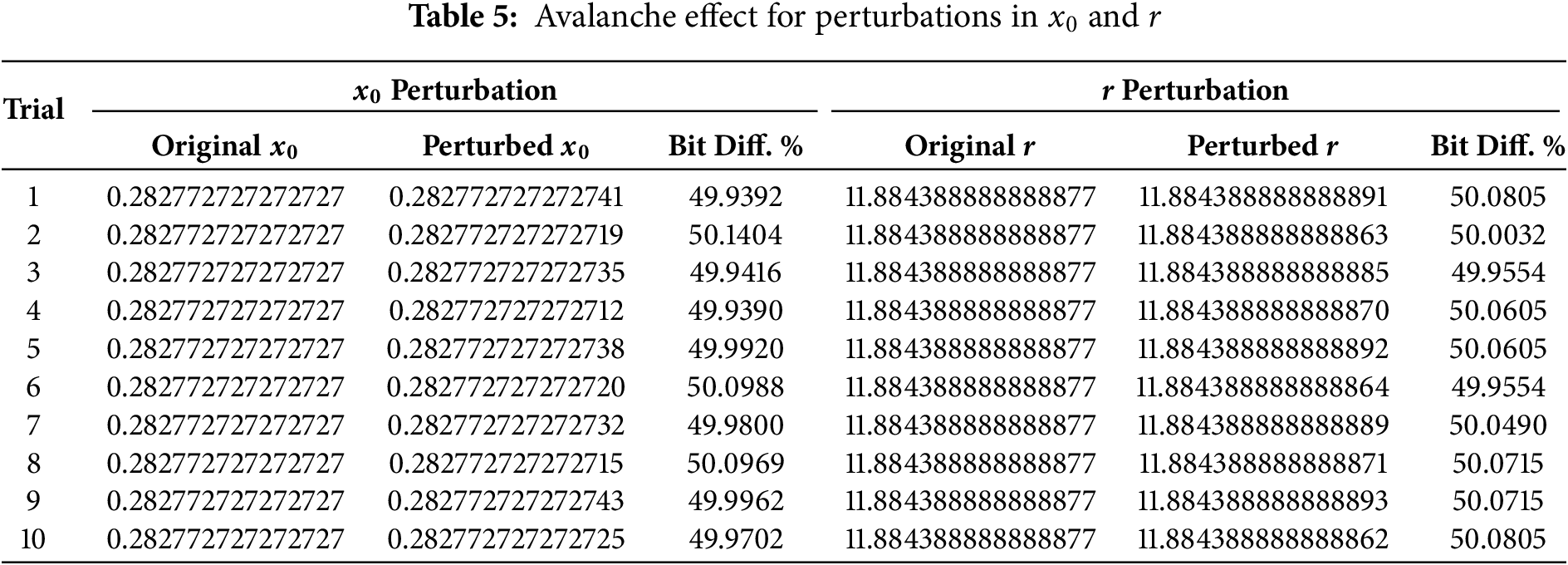

This section evaluates the proposed encryption technique using avalanche effect, entropy, and correlation coefficient analyses, encryption time, which are the key metrics for assessing encryption strength. The avalanche effect ensures small changes in input or key produce major ciphertext changes, improving resistance to Differential Attacks (DA). We tested perturbations of

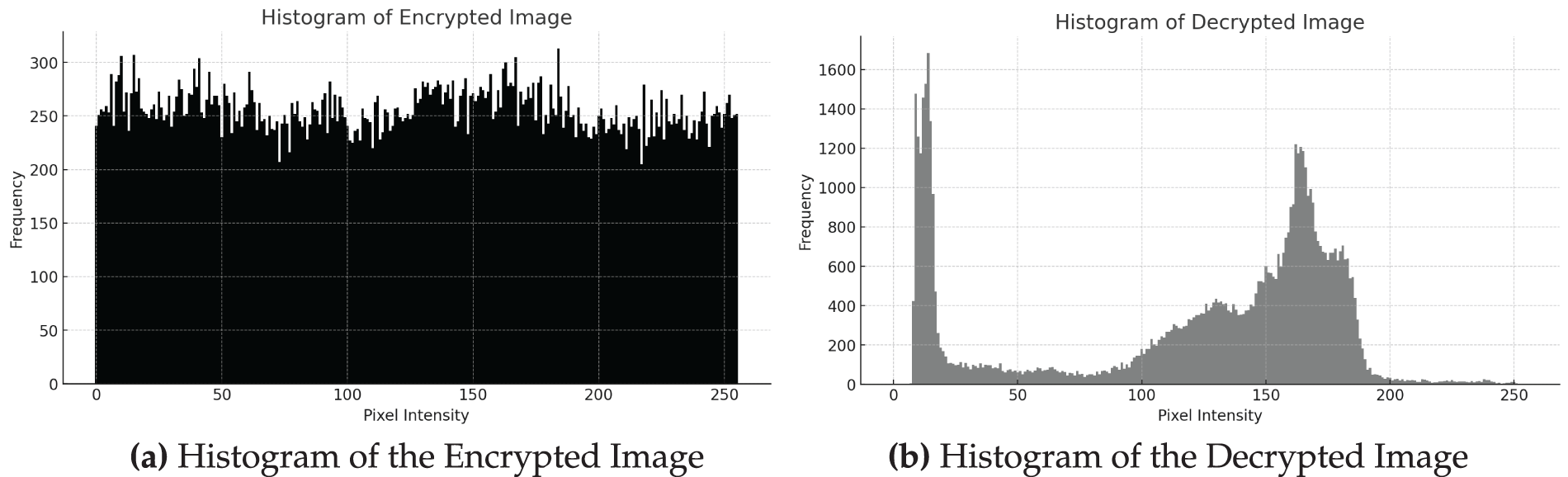

Histogram analysis checks pixel intensity distribution. A uniform histogram in the encrypted image (Fig. 9a) confirms effective pixel value randomization. The decrypted image histogram (Fig. 9b) shows clear peaks and valleys, reflecting correct image recovery. Entropy

Figure 9: Histogram analysis of encrypted and decrypted images using the proposed SPCM-based encryption scheme. (a) Histogram of the encrypted image shows a uniform distribution of pixel intensities across the full grayscale range [0, 255], indicating strong randomness and high resistance to statistical attacks. (b) Histogram of the decrypted image restores the original non-uniform distribution with visible peaks and valleys, confirming successful image recovery and decryption accuracy

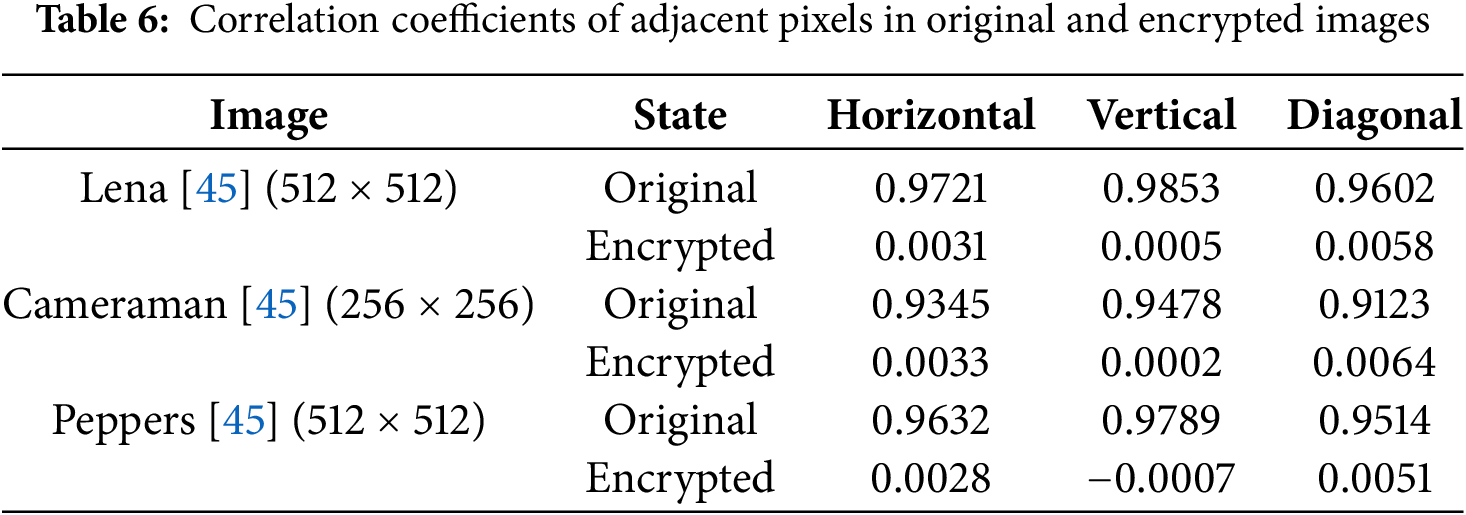

Correlation coefficients between adjacent pixels (horizontal, vertical, diagonal) should approach zero in encrypted images, indicating minimal pixel relationship. They are computed as

Encrypted image correlations: horizontal = 0.0033, vertical = 0.0002, diagonal = 0.0064, confirming effective decorrelation. Decrypted image correlations are high: horizontal = 0.9335, vertical = 0.9592, diagonal = 0.9087, indicating successful restoration of natural image structure, shown in Table 6.

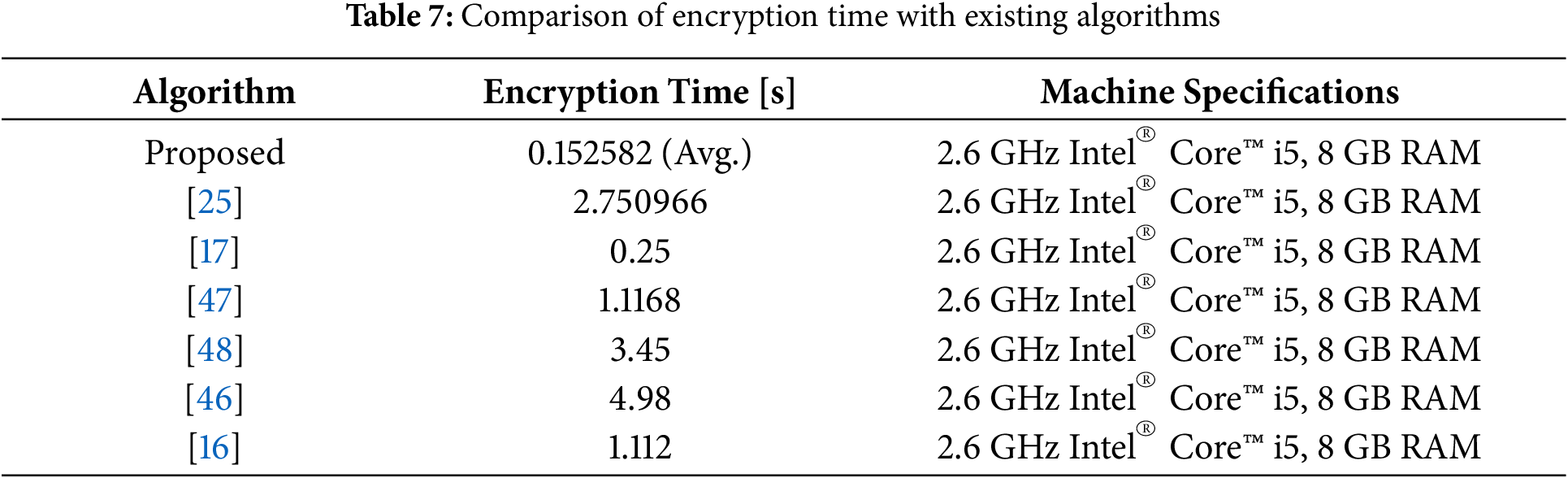

The proposed algorithm demonstrates efficient encryption with an average time of 0.152582 s and throughput of 433.42 KB/s, showing consistent performance across trials. Encryption time varies between 0.135181 and 0.262618 s, indicating stable operation under different conditions. Table 7 compares this performance with existing algorithms reported in the literature. The proposed method outperforms others, achieving significantly lower encryption times than [25] (2.750966 s), [46] (4.98 s), [47] (1.1168 s), and even [17] (0.25 s). Its throughput and speed make it suitable for real-time applications, balancing performance and efficiency effectively.

5.4 Resistance to Cryptographic Attacks

To address the security requirements of resource-constrained WSNs, the proposed SPCM is evaluated for its resilience against Chosen-Plaintext Attacks (CPA), DA, and SA. The lightweight design of the one-dimensional SPCM ensures low computational complexity, making it suitable for WSNs while maintaining robust cryptographic properties.

The proposed SPCM-based encryption scheme demonstrates strong resistance to CPAs due to its inherent nonlinearity and dynamic key generation. The piecewise sine-polynomial transformation introduces nonlinear chaotic mixing, ensuring that even minor changes in plaintext lead to significantly different ciphertexts, as illustrated in Fig. 8. This diffusion effect effectively prevents an adversary from inferring any meaningful relationship between plaintext and ciphertext. Furthermore, the key matrix used for encryption is dynamically generated, consisting of 65,536 bits as detailed in Section 5.1. This matrix depends sensitively on the initial parameters

The SPCM also exhibits robust resistance to DA. This is primarily evidenced by the strong avalanche effect observed during the encryption process. Specifically, perturbations in the initial parameters

To assess statistical resistance, the SPCM-based encryption was subjected to standard randomness tests. The encrypted outputs successfully passed all tests under the NIST SP800-22 suite, with p-values exceeding 0.01 as shown in Table 2, thereby validating the statistical randomness of the ciphertext. In addition, Diehard tests were conducted on binary sequences generated from SPCM orbits, achieving a 100% pass rate (Table 3). Beyond these formal tests, the scheme also demonstrates practical resistance to SA through its decorrelation capability. The correlation coefficients of adjacent pixels in the encrypted images were consistently observed to be below 0.0064 (Section 5.3), effectively eliminating detectable patterns and resisting frequency-based analysis. These results collectively affirm that the proposed scheme provides a high level of security against statistical cryptanalysis.

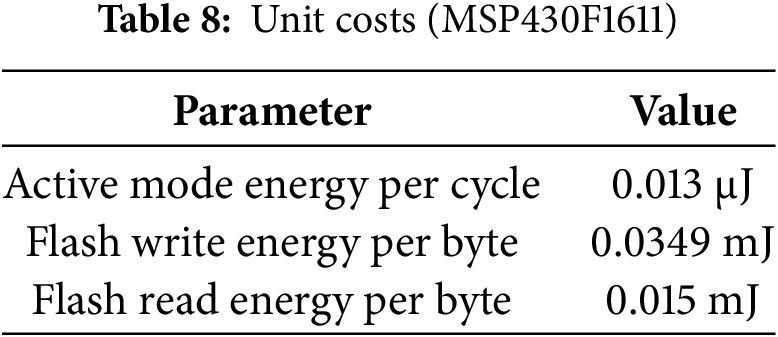

5.5 Resource Efficiency Analysis

This subsection presents an analytical evaluation of the proposed encryption algorithm’s computational, energy, and memory efficiency using the TelosB wireless sensor platform (MSP430F1611 @ 8 MHz) as a reference. The estimates are derived from instruction-level energy metrics published in the MSP430F1611 datasheet and validated benchmark studies [51,52] (Table 8). Although the algorithm has not yet been deployed on physical motes, this modeling approach aligns with standard practices in lightweight cryptographic analysis and pre-deployment feasibility assessments for WSNs. Future work will include experimental validation using Contiki-NG or TinyOS-based TelosB platforms.

The computational complexity of the proposed security framework arises primarily from three stages: key generation, permutation vector computation, and XOR-based encryption. Key generation using the SPCM is linear,

The energy cost of the proposed SPCM-based image encryption scheme for a

Memory usage comprises 8 KB for the key matrix and 1.2 KB for buffers, totaling less than 10 KB well below the TelosB’s 48 KB RAM capacity. Compared to the estimated 2.8 mJ energy cost of AES-128 on TelosB-class hardware [34,35], the proposed scheme consumes approximately 2.34 mJ, representing a 16.4% reduction in energy consumption while maintaining comparable security through chaotic diffusion properties.

In terms of memory, AES-128 implementations on MSP430-class motes typically require around 10–12 KB, largely due to S-box lookup tables and key expansion operations [33]. ECC-based encryption, while offering asymmetric key advantages, typically demands over 80,000 cycles for a single scalar multiplication and uses more than 12 KB RAM for modular arithmetic and key storage [35,53]. By contrast, our SPCM scheme completes encryption in under 175,000 cycles and uses less than 10 KB memory, making it more appropriate for frequent operations in resource-constrained WSN nodes.

5.6 Comparison of Chaos-Based Image Encryption in WSNs

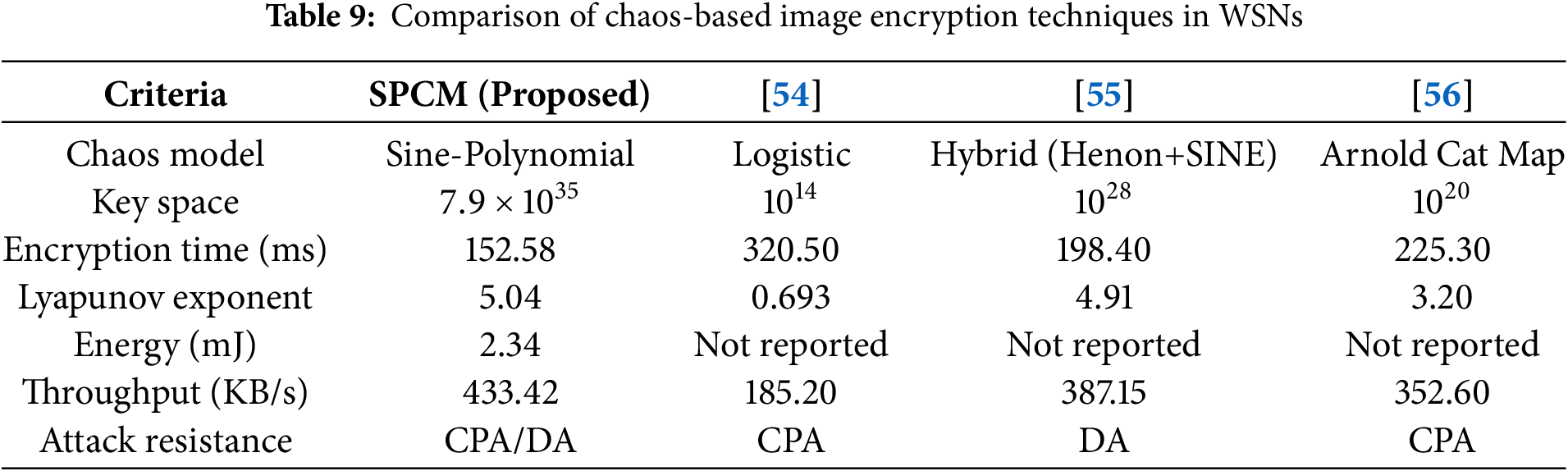

Table 9 compares the proposed SPCM with three existing chaos-based encryption methods for WSNs across seven criteria: 1) chaotic model type, 2) key space size, 3) encryption speed, 4) Lyapunov exponent (measuring chaos strength), 5) energy consumption, 6) throughput, and 7) resistance to cryptographic attacks. The SPCM demonstrates competitive advantages in chaos complexity (highest Lyapunov exponent), energy efficiency (lowest mJ/image), and throughput (fastest KB/s), while maintaining robust security against multiple attack types. Comparisons are drawn from cited peer-reviewed works to contextualize SPCM’s performance within the field.

The proposed SPCM for WSN image encryption faces scalability limitations when applied to large-scale data, such as video encryption, which requires further experimental validation. Additionally, encryption performance metrics (e.g., 0.152582 s encryption time, 433.42 KB/s throughput) are hardware-specific, necessitating cross-platform testing to ensure robustness and consistency across diverse WSN environments.

This study presents SPCM, a chaotic system for image encryption in resource-constrained WSNs. By integrating sine and polynomial dynamics with a discontinuity at

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank the School of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science at GIST and the Department of Computer Science and Engineering at Chungnam National University for their support and collaborative environment during this research.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government Ministry of Science and ICT (MIST) (RS-2022-00165225).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: conceptualization, software implementation, writing, reviewing, editing, final drafting: David S. Bhatti, Annas W. Malik; supervision: David S. Bhatti; reviewing, formal analysis: Haeung Choi; reviewing, funding acquisition: Ki-Il Kim. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets and code supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable. This study did not involve human participants or animal subjects.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Kandris D, Nakas C, Vomvas D, Koulouras G. Applications of wireless sensor networks: an up-to-date survey. Appl Syst Innov. 2020;3(1):14. doi:10.3390/asi3010014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Kaddi M, Omari M, Alnatoor M. EECLP: a wireless sensor networks energy efficient cross-layer protocol. Comput Mater Contin. 2024;80(2):2611–31. doi:10.32604/cmc.2024.052048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Bhatti DS, Saleem S, Imran A, Kim HJ, Kim KI, Lee KC. Detection and isolation of wormhole nodes in wireless ad hoc networks based on post-wormhole actions. Sci Rep. 2024 Feb;14(1):3428. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-53938-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Singh AP, Luhach AK, Gao XZ, Kumar S, Roy DS. Evolution of wireless sensor network design from technology centric to user centric: an architectural perspective. Int J Distrib Sens Netw. 2020;16(8):155014772094913. doi:10.1177/1550147720949138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Verhulst F. Henri poincaré’s inventions in dynamical systems and topology. In: Skiadas C, editor. The foundations of chaos revisited: from poincaré to recent advancements. understanding complex systems. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2016. p. 1–25. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-29701-9_1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Aubin D, Dalmedico AD. Writing the history of dynamical systems and chaos: longue durée and revolution, disciplines and cultures. Historia Mathematica. 2002;29(3):273–339. doi:10.1006/hmat.2002.2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Bishop R. Chaos. In: Zalta EN, Nodelman U, editors. The stanford encyclopedia of philosophy. Winter 2024ed. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University; 2024 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jul 24]. Available from: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2024/entries/chaos/. [Google Scholar]

8. Jørgensen SE. Chaos. In: Jørgensen SE, Fath BD, editors. Encyclopedia of ecology. Oxford, UK: Academic Press; 2008. p. 550–1. [Google Scholar]

9. Kari AP, Navin AH, Bidgoli AM, Mirnia M. A novel multi-image cryptosystem based on weighted plain images and using combined chaotic maps. Multimed Syst. 2021;27(5):907–25. doi:10.1007/s00530-021-00772-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Biswas HR, Hasan MM, Bala SK. Chaos theory and its applications in our real life. Barishal Univ J Part. 2018;1(5):123–40. [Google Scholar]

11. Lawnik M, Moysis L, Volos C. A family of 1D chaotic maps without equilibria. Symmetry. 2023;15(7):1311. doi:10.3390/sym15071311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Zhou Y, Hua Z, Pun CM, Philip Chen CL. Cascade chaotic system with applications. IEEE Trans Cybern. 2015;45(9):2001–12. doi:10.1109/TCYB.2014.2363168. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Hua Z, Zhang Y, Zhou Y. Two-dimensional modular chaotification system for improving chaos complexity. IEEE Trans Signal Process. 2020;68:1937–49. doi:10.1109/TSP.2020.2979596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Lambić D. A new discrete-space chaotic map based on the multiplication of integer numbers and its application in S-box design. Nonlinear Dyn. 2020;100(1):699–711. doi:10.1007/s11071-020-05503-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Shafique A. A new algorithm for the construction of substitution box by using chaotic map. Eur Phys J Plus. 2020;135(2):194. doi:10.1140/epjp/s13360-020-00187-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Zhang X, Wang L, Wang Y, Niu Y, Li Y. An image encryption algorithm based on hyperchaotic system and variable-step josephus problem. Int J Optics. 2020;2020(1):6102824–15. doi:10.1155/2020/6102824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Ali TS, Ali R. A new chaos based color image encryption algorithm using permutation substitution and Boolean operation. Multimed Tools Appl. 2020;79(27):19853–73. doi:10.1007/s11042-020-08850-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Li H, Yu C, Wang X. A novel 1D chaotic system for image encryption, authentication and compression in cloud. Multimed Tools Appl. 2021;80(6):8721–58. doi:10.1007/s11042-020-10117-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Fadhil MS, Farhan AK, Fadhil MN. Designing substitution box based on the 1D logistic map chaotic system. In: IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. Vol. 1076. Bristol, UK: IOP Publishing; 2021. [Google Scholar]

20. Cheng Z, Wang W, Dai Y, Li L. Novel one-dimensional chaotic system and its application in image encryption. Complexity. 2022;2022(1):31. doi:10.1155/2022/1720842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Zhang Y, Zhao J, Zhang B. An image encrypting algorithm based on 1D and 2D logistic chaotic systems. Int J Embed Syst. 2022;15(1):34–43. doi:10.1504/IJES.2022.122057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Mondal B, Singh JP. A lightweight image encryption scheme based on chaos and diffusion circuit. Multimed Tools Appl. 2022;81(24):34547–71. doi:10.1007/s11042-021-11657-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Liu L, Wang J. A cluster of 1D quadratic chaotic map and its applications in image encryption. Math Comput Simul. 2023;204(12):89–114. doi:10.1016/j.matcom.2022.07.030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Chen C, Zhu D, Wang X, Zeng L. One-dimensional quadratic chaotic system and splicing model for image encryption. Electronics. 2023;12(6):1325. doi:10.3390/electronics12061325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Alexan W, Elkandoz M, Mashaly M, Azab E, Aboshousha A. Color image encryption through chaos and kaa map. IEEE Access. 2023;11:11541–54. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3242311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Ding Y, Liu W, Wang H, Sun K. A new class of discrete modular memristors and application in chaotic systems. Eur Phys J Plus. 2023;138(7):638. doi:10.1140/epjp/s13360-023-04242-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Malik AW, Zahid AH, Bhatti DS, Kim HJ, Kim KI. Designing S-box using tent-sine chaotic system while combining the traits of tent and sine map. IEEE Access. 2023;11:79265–74. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3298111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Alawida M. Enhancing logistic chaotic map for improved cryptographic security in random number generation. J Inf Secur Appl. 2024;80(1):103685. doi:10.1016/j.jisa.2023.103685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Jain K, Titus B, Krishnan P, Sudevan S, Prabu P, Alluhaidan AS. A lightweight multi-chaos-based image encryption scheme for IoT Networks. IEEE Access. 2024;12(6):62118–48. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3377665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Kıran HE. A novel chaos-based encryption technique with parallel processing using CUDA for mobile powerful GPU control center. Chaos Fract. 2024;1(1):6–18. doi:10.69882/adba.chf.2024072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Archana G, Goyal R, Kumar KM. Blockchain-driven optimized chaotic encryption scheme for medical image transmission in IoT-Edge environment. Int J Comput Intell Syst. 2025;18(1):11. doi:10.1007/s44196-024-00731-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Hu LL, Chen MX, Wang MM, Zhou NR. Visually meaningful triple images encryption algorithm based on 2D compressive sensing and multi-region embedding. Knowl Based Syst. 2025;324(10):113804. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2025.113804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Hung CW, Hsu WT. Power consumption and calculation requirement analysis of AES for WSN IoT. Sensors. 2018;18(6):1675. doi:10.3390/s18061675. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Alkalbani AS, Mantoro T, Tap AOM. Comparison between RSA hardware and software implementation for WSNs security schemes. In: Proceeding of the 3rd International Conference on Information and Communication Technology for the Moslem World (ICT4M) 2010; 2010 Dec 13–14; Jakarta, Indonesia. p. E84–9. [Google Scholar]

35. Wang H, Li Q. Efficient implementation of public key cryptosystems on MICAz and TelosB motes. In: Technical report. USA: College of William and Mary; 2006. WM-CS-2006-07. doi:10.1007/11935308_37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Liu Z, Jiang G, Wu Y, Wang T, Liu S, Ouyang Z. K-coverage estimation for irregular targets in wireless visual sensor networks deployed in complex region of interest. IEEE Sens J. 2025;25(10):18370–83. doi:10.1109/JSEN.2025.3558041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Avrutin V, Gardini L, Sushko I, Tramontana F. Continuous and discontinuous piecewise-smooth one-dimensional maps. Singapore: World Scientific; 2019. doi:10.1142/8285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Dingwell JB. Lyapunov exponents. Wiley encyclopedia of biomedical engineering. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2006. doi:10.1002/9780471740360.ebs0702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Tomida AG. Matlab toolbox and GUI for analyzing one-dimensional chaotic maps. In: 2008 International Conference on Computational Sciences and its Applications; 2008 Jun 30–Jul 3; Perugia, Italy: IEEE. p. 321–30. [Google Scholar]

40. Gottwald GA, Melbourne I. The 0-1 test for chaos: a review. In: Chaos detection and predictability. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2016. p. 221–47. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-48410-4_7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Jafari A, Hussain I, Nazarimehr F, Golpayegani SMRH, Jafari S. A simple guide for plotting a proper bifurcation diagram. Int J Bifurcat Chaos. 2021;31(1):2150011. doi:10.1142/S0218127421500115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Lea DJ, Allen MR, Haine TW. Sensitivity analysis of the climate of a chaotic system. Tellus A Dyn Meteorol Oceanogr. 2000;52(5):523–32. doi:10.3402/tellusa.v52i5.12283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Bassham LEIII, Rukhin AL, Soto J, Nechvatal JR, Smid ME, Barker EB, et al. SP 800-22 Rev. 1a: a statistical test suite for random and pseudorandom number generators for cryptographic applications. Gaithersburg, MD, USA: National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST); 2010. NIST Special Publication 800-22 Revision 1a [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jul 24]. Available from: https://csrc.nist.gov/publications/detail/sp/800-22/rev-1a/final. [Google Scholar]

44. Wu R, Gao S, Wang X, Liu S, Li Q, Erkan U, et al. AEA-NCS: an audio encryption algorithm based on a nested chaotic system. Chaos Soliton Fract. 2022;165(3):112770. doi:10.1016/j.chaos.2022.112770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. MathWorks. MATLAB Image Processing Toolbox Standard Images (Lena, Cameraman, Peppers) [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jul 3]. Available from: https://www.mathworks.com/help/images/ref/. [Google Scholar]

46. Xu L, Li Z, Li J, Hua W. A novel bit-level image encryption algorithm based on chaotic maps. Optics Lasers Eng. 2016;78(2):17–25. doi:10.1016/j.optlaseng.2015.09.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Gong L, Qiu K, Deng C, Zhou N. An image compression and encryption algorithm based on chaotic system and compressive sensing. Opt Laser Technol. 2019;115(1):257–67. doi:10.1016/j.optlastec.2019.01.039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Hu X, Wei L, Chen W, Chen Q, Guo Y. Color image encryption algorithm based on dynamic chaos and matrix convolution. IEEE Access. 2020;8:12452–66. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2965740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Forrié R. The strict avalanche criterion: spectral properties of Boolean functions and an extended definition. In: Advances in Cryptology—CRYPTO’88: Proceedings 8. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 1990. p. 450–68. [Google Scholar]

50. Webster AF, Tavares SE. On the design of S-boxes. In: Conference on the Theory and Application of Cryptographic Techniques. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 1985. p. 523–34. [Google Scholar]

51. Instruments T. MSP430F161x Mixed Signal Microcontroller. Dallas, TX, USA; 2013 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jul 24]. Available from: https://www.ti.com/lit/ds/symlink/msp430f1611.pdf. [Google Scholar]

52. Rafik MBO, Feham M. Performance evaluation on TelosB mote of a secure data aggregation protocol using ECC. In: Conference Nationale sur les Technologies de l’Information et les Telecommunications; 2013 Dec 10–11; Tlemcen, Algeria. [Google Scholar]

53. Gura N, Patel A, Wander A, Eberle H, Shantz SC. Comparing elliptic curve cryptography and RSA on 8-bit CPUs. In: Cryptographic hardware and embedded systems-CHES 2004. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2004. p. 119–32 doi:10.1007/978-3-540-28632-5_9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Wang J, Han K, Fan S, Zhang Y, Tan H, Jeon G, et al. A logistic mapping-based encryption scheme for wireless body area networks. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2020;110(3):57–67. doi:10.1016/j.future.2020.04.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Yogi B, Khan AK, Roy S. Hybrid image encryption for IoT applications: integrating cellular automata and henon map to improve security and performance. In: 2024 4th International Conference on Technological Advancements in Computational Sciences (ICTACS); 2024 Nov 13–15; Tashkent, Uzbekistan. p. 1303–9. [Google Scholar]

56. Mondal B, Mandal T, Khan DA, Choudhury T. A secure image encryption scheme using chaos and wavelet transformations. Recent Pat Eng. 2018;12(1):5–14. doi:10.2174/1872212111666170223165916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools