Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Semantic Knowledge Based Reinforcement Learning Formalism for Smart Learning Environments

1 Department of Software Engineering, Faculty of Information Technology, University of Lahore, Lahore, 54000, Pakistan

2 Department of Software Engineering, Faculty of IT & CS, University of Central Punjab, Lahore, 54000, Pakistan

3 Department of Computer Science, Faculty of Information Science & Technology, COMSATS University Islamabad, Lahore Campus, Lahore, 54000, Pakistan

4 Department of Software Convergence and Communication Engineering, Sejong Campus, Hongik University, Sejong-si, Seoul, 30016, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Authors: Ibrar Hussain. Email: ; Byung-Seo Kim. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(1), 2071-2094. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.068533

Received 31 May 2025; Accepted 23 July 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

Smart learning environments have been considered as vital sources and essential needs in modern digital education systems. With the rapid proliferation of smart and assistive technologies, smart learning processes have become quite convenient, comfortable, and financially affordable. This shift has led to the emergence of pervasive computing environments, where user’s intelligent behavior is supported by smart gadgets; however, it is becoming more challenging due to inconsistent behavior of Artificial intelligence (AI) assistive technologies in terms of networking issues, slow user responses to technologies and limited computational resources. This paper presents a context-aware predictive reasoning based formalism for smart learning environments that facilitates students in managing their academic as well as extra-curricular activities autonomously with limited human intervention. This system consists of a three-tier architecture including the acquisition of the contextualized information from the environment autonomously, modeling the system using Web Ontology Rule Language (OWL 2 RL) and Semantic Web Rule Language (SWRL), and perform reasoning to infer the desired goals whenever and wherever needed. For contextual reasoning, we develop a non-monotonic reasoning based formalism to reason with contextual information using rule-based reasoning. The focus is on distributed problem solving, where context-aware agents exchange information using rule-based reasoning and specify constraints to accomplish desired goals. To formally model-check and simulate the system behavior, we model the case study of a smart learning environment in the UPPAAL model checker and verify the desired properties in the model, such as safety, liveness and robust properties to reflect the overall correctness behavior of the system with achieving the minimum analysis time of 0.002 s and 34,712 KB memory utilization.Keywords

The context-aware computing paradigm has gained significant attention in the last two decades, and this trend has been rapidly evolving toward ubiquitous computing with the incorporation of ambient intelligence and assisted living using smart devices/gadgets [1]. Context-aware systems often consist of interconnected heterogeneous devices and/or sensors that are deployed in the systems to autonomously acquire an unprecedented amount of data to/from different sensors/devices and perform computations to assist the user in their daily routine life tasks [2]. These systems are typically installed at homes, offices, and educational institutes to facilitate users with their maximum capacity comfort level. These systems are usually smart and intelligent having lightweight and/or embedded sensors attached to comfortable wearable/connected devices that follow certain protocols for communication and ensure the availability of real-time right information at the right time in the right place. The literature has revealed numerous smart systems and applications in different domains such as smart classrooms, smart healthcare systems, smart transport systems, etc. Among others, smart learning environments have been considered as one of the most emerging research areas due to their significant impact in urban cities and in developed countries where the dependency on such smart devices and systems has been observed at a large scale [3]. Such applications can be very useful for smart gadget-addicted people who are mostly connected to their families and friends using smart systems.

Recent years have witnessed that smart classrooms have been considered a new paradigm and a driving force towards the development of smart learning environments with the incorporation of interconnected network and context-awareness. With the rapid growth of today’s digital native generation, students are becoming more addicted to using AI assistive technologies, and their dependencies are exponentially increasing on such smart gadgets/devices which made their lives much more comfortable and relaxed but device dependent. With the advent of digital learning technologies, smart learning environments have gained significant recognition for grabbing students’ attention in innovative ways of learning, performing their assessments remotely, and fulfilling their academic activities using smart systems and applications. The literature has revealed a significant number of autonomous systems in different facets of smart learning environments, including academic as well as non-academic activities autonomously. Academic activities are tailored to fulfill the activities of smart classrooms autonomously with minimal human intervention, whereas non-academic activities schedule updates and notify students automatically after certain intervals of time if any change is applied in the system like change in the university transport schedule, cafeteria food menu, lecture timings, etc.

In the literature, a significant effort has been made on the development of smart learning systems and applications [4,5]. In [5], Martin et al. have proposed a framework for designing and managing adaptive mobile learning systems. This system can be used by both teachers and students to carry out one-on-one or group learning tasks. The system’s main goal is to suggest the learning activities that are most suited for each user to fulfill their ultimate need. Researchers are putting great effort into improving learning systems and their numerous applications [6–8]. Zeeshan et al. [9] have presented a comprehensive review considering UN sustainable development goals on how AI assistive technologies can become an effective educational toolkit to facilitate educational managers, teachers, and students. They have showcased the cutting-edge technology utilization for the educational systems in different perspectives such as the student attendance management system, their assessment tasks along with feedback systems, and interactive tools for teaching and managing their assessment tasks. This work has the following contributions in this paper: 1) We propose the ontology-driven context-aware predictive reasoning formalism for smart learning environment based on the Markov decision process. 2) This work has two-fold segregation as academic and administrative. The academic system focuses on academic as well as non-academic activities as a whole, whereas the administrative system particularly emphasizes the smart classroom environment. The system consists of a three-tier architecture where non-monotonic reasoning-based context-aware agents acquire the contextualized information from the ontology, perform prediction-based analysis to take appropriate actions, and then adapt the system’s behavior accordingly. 3) We model the case study of a smart learning environment using the UPPAAL model checker and verify the correctness properties of the system [10].

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. In Section 2, we briefly discuss the related work on smart learning environments. In Section 3, we model the domain of the smart learning environment in Protégé ontology editor and develop complex rules of the system. Section 4 presents a reinforcement learning based context-aware multi-agent reasoning model. Section 5 presents the formal modeling and verification of the case study and finally, we conclude in Section 6.

Literature has revealed a renewed research interest in probing different approaches to the development of smart learning environments using the notions of context-awareness with reinforcement learning techniques. Much of this work concentrate on contextual reasoning based predictive decision support mechanism. In context-aware deployment settings [4,6,7], the essential need for developing formal context models [11–13] has been significantly focused by the research community [14]. In [4], authors have developed a context-aware mobile organizer which autonomously sends updates to students about their queries. In this work, a context-aware mobile organizer has been developed that assists students with their daily routine tasks such as bus schedules, cafe locations, room locations, lecture times, and access to the learning management system while they are on university premises. The context-aware mobile organizer autonomously sends updates to corresponding users in case of changing contextual information. In [11], the authors have presented a context-aware smart classroom architecture for the execution of classes in smart classrooms. They have suggested a three-tier architecture; (a) a context-aware smart classroom prototype, (b) a technology integration model, and (c) measures to support smart classroom operations. Using the suggested architecture and Raspberry Pi-based application interfaces, a context-aware energy-saving smart classroom application was developed. The findings show that the architecture can be used to create context-aware smart classrooms on smart campuses. The study emphasizes the importance of the suggested context-aware smart classroom architecture, which comprises critical components for smart classroom design and administration on university campuses.

Paudel et al. [12] describe a technique to provide sustainable and clean energy to a university campus by utilizing the Internet of Things (IoT) and deep learning for action recognition. The system monitors and manages energy usage in real time by integrating IoT sensors with video action recognition in classrooms, resulting in a considerable reduction in power load on the electric grid. The suggested context-aware architecture incorporates a variety of sensors, including temperature, humidity, brightness, and video sensors, to offer a multi-modal approach to energy conservation [13]. The research successfully trains and executes a neural network for human action recognition, allowing for more efficient energy management. The results reveal that the proposed architecture can save 25–30 percent of energy in buildings, which is a satisfactory degree of accuracy. The system’s ability to automate energy management tasks has the potential to further minimize human labor and pave the path for broader community applications for overall energy savings and cost-effectiveness.

In [7], Ilhan et al. presented a teacher-student architecture for cooperative decentralized MARL (Multi-agent Reinforcement Learning) in which agents assess their understanding in various states utilizing the Random Network Distillation (RND) technique to launch the advising dynamics without pre-assumed roles [15]. The experimental results in a grid world environment reveal results indicating that this strategy could be effective in MARL.

The study proposed by Liu et al. [14] offers a cyber-physical-social system that monitors students’ learning progress in a smart classroom using various sensors. Based on multi-modal sensor data, it employs reinforcement learning techniques to provide personalized learning advice. To detect students’ learning states, the suggested system analyzes their heartbeats, quiz scores, blinks, and facial expressions. It suggests efficient learning activities matched to their current situations through reinforcement learning. A Markov decision process is used to model this interactive learning recommendation process. Initial simulation results demonstrate the system’s ability to provide smart learning recommendations.

In [6], Torrey et al. present a reinforcement learning approach to education in which one agent teacher counsels another agent student during a sequential task. The teacher has a limited amount of advice “budget”. The student and the teacher are both represented as reinforcement learning agents. Experiments in the mountain automobile area illustrate the superiority of the provided strategy over existing heuristics.

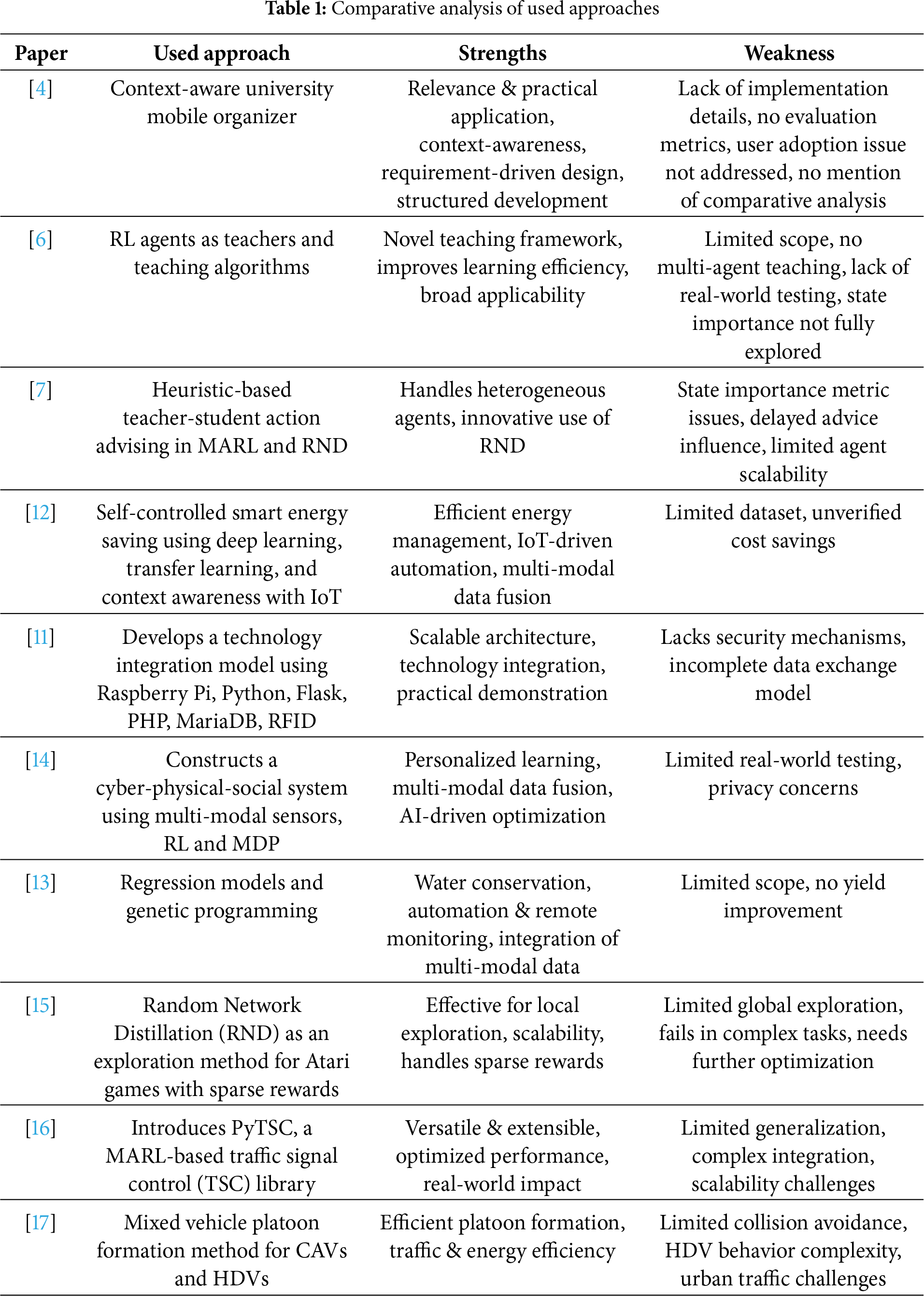

In addition, we conducted a comparative analysis of state-of-the-art approaches based on an evaluation of their methodological frameworks, operation potential, and the usefulness of the approaches in real-life smart learning environments. It determines the notable strengths and limitations of each approach, clarifying their performance trade-offs, scalability, adaptability, and the effectiveness of their reasoning. Table 1 provides a summary of the findings and forms the foundation for acknowledging essential research gaps, as well as informing the development of intelligent systems more contextually and semantically enriched. The overview explains the advances as well as the constraints of the existing methodologies. Although the literature under review has had a substantial impact on various approaches and models within the field of smart-learning environments, its application towards semantic-based knowledge modeling context and inferencing mechanisms have not been explored adequately. This shortcoming points to a decisive direction for future development, especially in those systems that rely on a deep understanding of contextual dynamics.

Among all the techniques studied, ontology-based context modeling promises to be the most successful due to its structured but flexible character, its use of formal semantics, and its capability to provide strong support for high-level reasoning. These attributes enable effective and understandable representation of contexts and can thus improve the adaptivity, scalability, and robustness of the multi-agent intelligent systems that are based on the performance in heterogeneous and dynamic environments. Thus, a great focus on ontology-based applications can significantly increase situation awareness and decision making in the smart learning environment.

3 Context Modeling of Smart Learning Environment

In this work, the term “Smart” refers to autonomous adaptive learning environments that use semantic technologies and rule-based reasoning to enable intelligent self-directed decision making with minimal human intervention. Within such environments, smart devices, ontological modeling, and inference engines dynamically adapt to learners’ evolving needs, offering proactive support for both academic and non-academic activities. The literature shows substantial progress in modeling heterogeneous knowledge sources to design context-aware multi-agent systems across various domains such as health care, smart parking, and smart learning systems, which further strengthens the foundation for developing truly intelligent and adaptive learning systems [18,19]. A context model (also known as context modeling) specifies how contextual information is managed in a structured and organized manner. The contextual information is intended to be produced as a formal or semi-formal description. Context modeling has gained significant attention in developing context-aware systems and applications, and researchers opt for different context modeling techniques such as ontology-based modeling, graphical modeling, logic-based modeling, markup scheme modeling, and key-value pair modeling [20]. We choose the ontology-based approach which is considered to be the most optimistic modeling technique due to its efficient and simplistic reasoning power and expressivity. Ontologies have gained much attention in knowledge sharing among different knowledge sources. In an ontology, a domain can be modeled in terms of classes, data, and object properties, and individuals in an OWL/RDF ontology format and represent association among classes using properties. OWL is based on Description Logic (DL), which can be used to conceptualize the domain, and it is a straightforward approach to transform DL axioms into OWL axioms. DL is a fragment of First-Order Logic (FOL) through which logic-based systems can be formalized using semantic networks. DL knowledge base consists of a finite set of terminological and assertional sentences, namely TBOX, ABOX, and RBOX. TBOX (Terminological Box) defines atomic concepts and it can be mapped to the corresponding class in the ontology, ABOX (Assertional Box) represents association among concepts and roles. It is further categorized as concept assertion and role assertion. RBox (Relational Box) shows inter-dependencies among different roles.

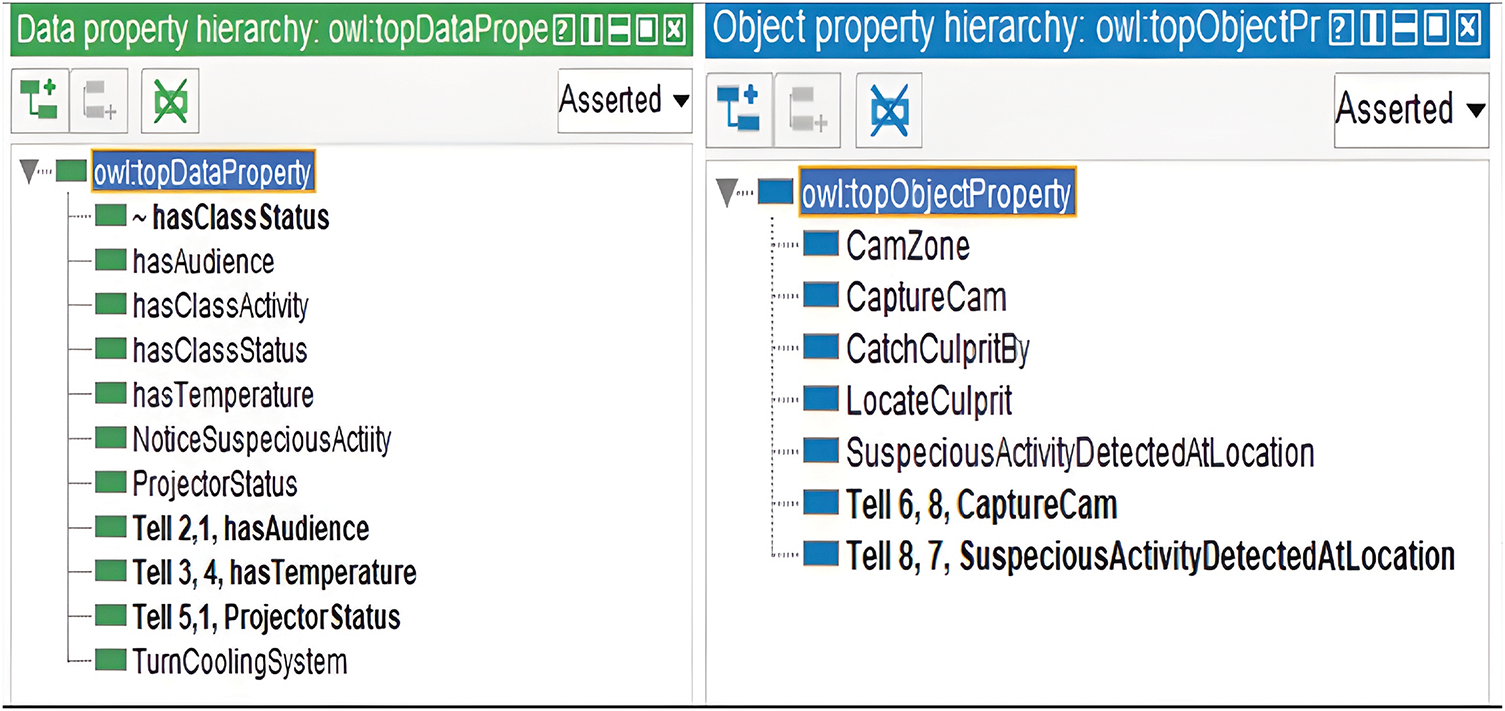

In this work, we develop a semantic knowledge model based on non-monotonic reasoning for the smart learning environment. We construct an ontology of the case study of smart learning environments. The core aim is to facilitate students in managing their daily routine academic activities efficiently and effectively and provide them with a safe, secure, and comfortable learning environment while the student is staying on campus. The proposed system autonomously assists students in their class schedules, cancellation/makeup classes, relocating classes, generating alerts of their assessments deadline, getting alerts on library and foods, etc. Users of this system will get a daily work schedule every morning and receive notifications with every change in the situation. We assume the system consists of a set of sensors/embedded sensors that autonomously monitor the scheduled classes as per the semester calendar and notify the class status to the teachers and admin staff. In addition, the system can be equipped with domotic features such as lighting and cooling system. For example; the sensors should have the capability to check the presence of students and teachers in the class and turn on/off lighting and cooling system. The system will automatically be set on the multimedia and sound system for lecture purposes. To model the case study in Protégé ontology editor, we consider eight agents as shown in Table 2. The ontology is divided into two parts: academic level and administrative level. Academic-level ontology captures the features to fulfill all academic-related activities whereas administrative-level ontology is designed in a way that it can provide associative support. We initially model the scenario in the ontology. The first step is to acquire data from the sensors and keep the ontology in an organized pattern. Then based on the existing knowledge base, rules are triggered by context-aware agents using semantic knowledge translator [21], and then translated rules are applied to achieve the desired goals.

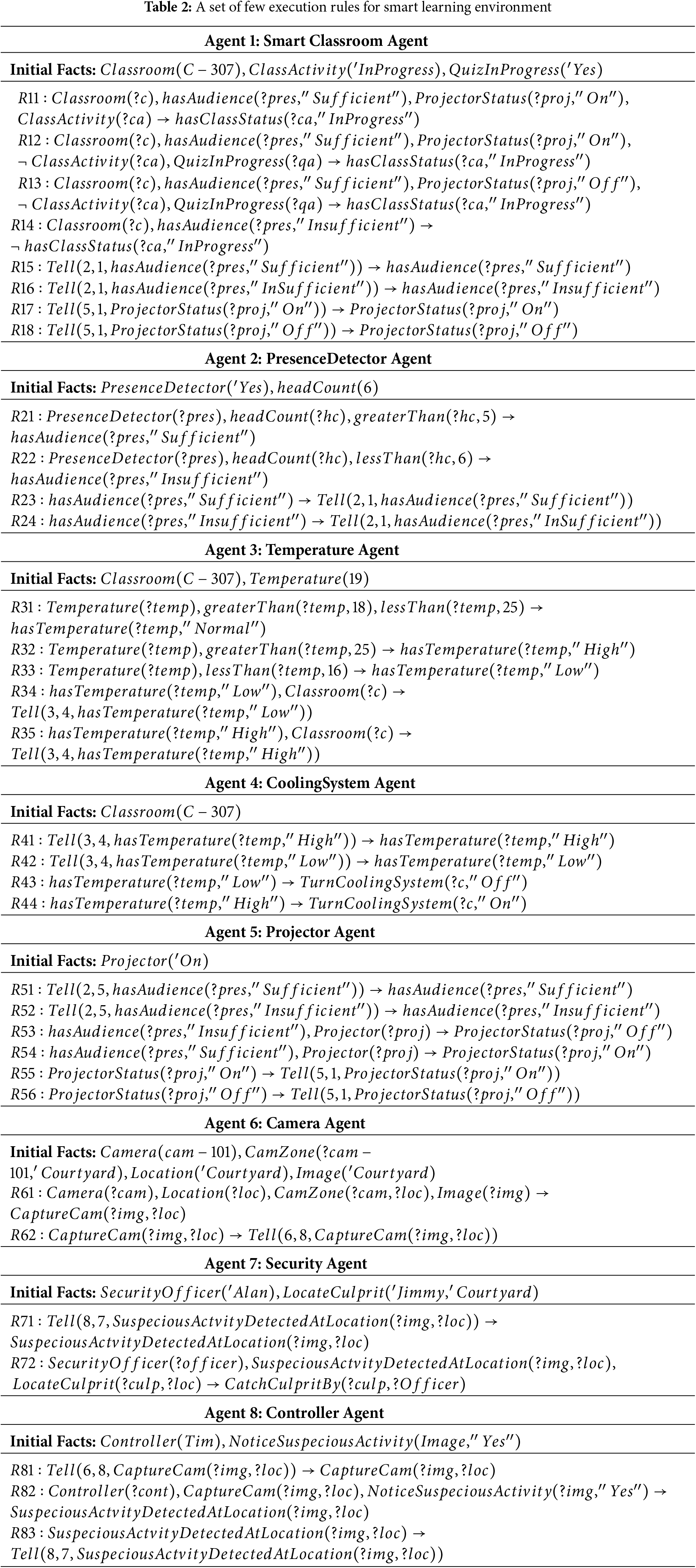

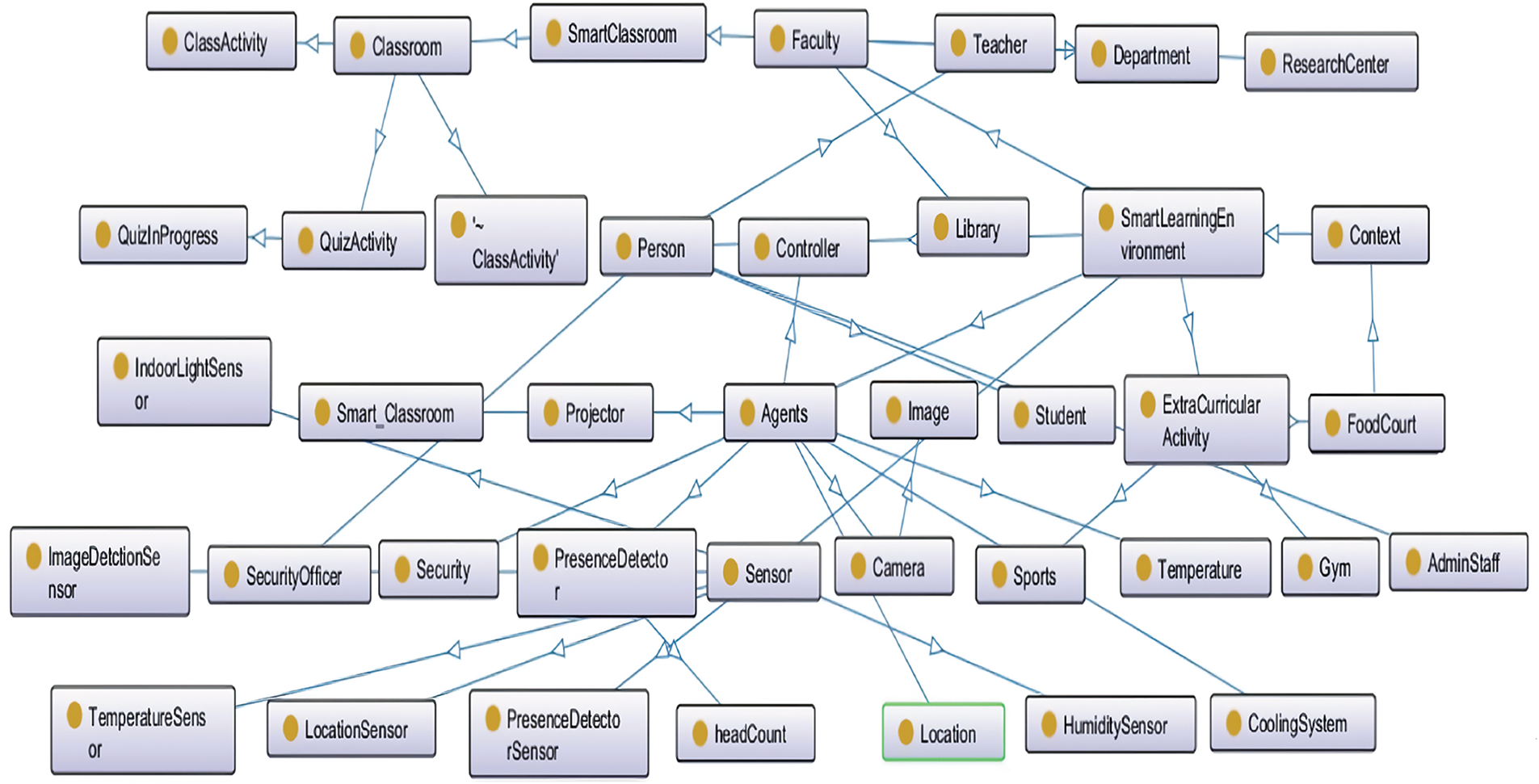

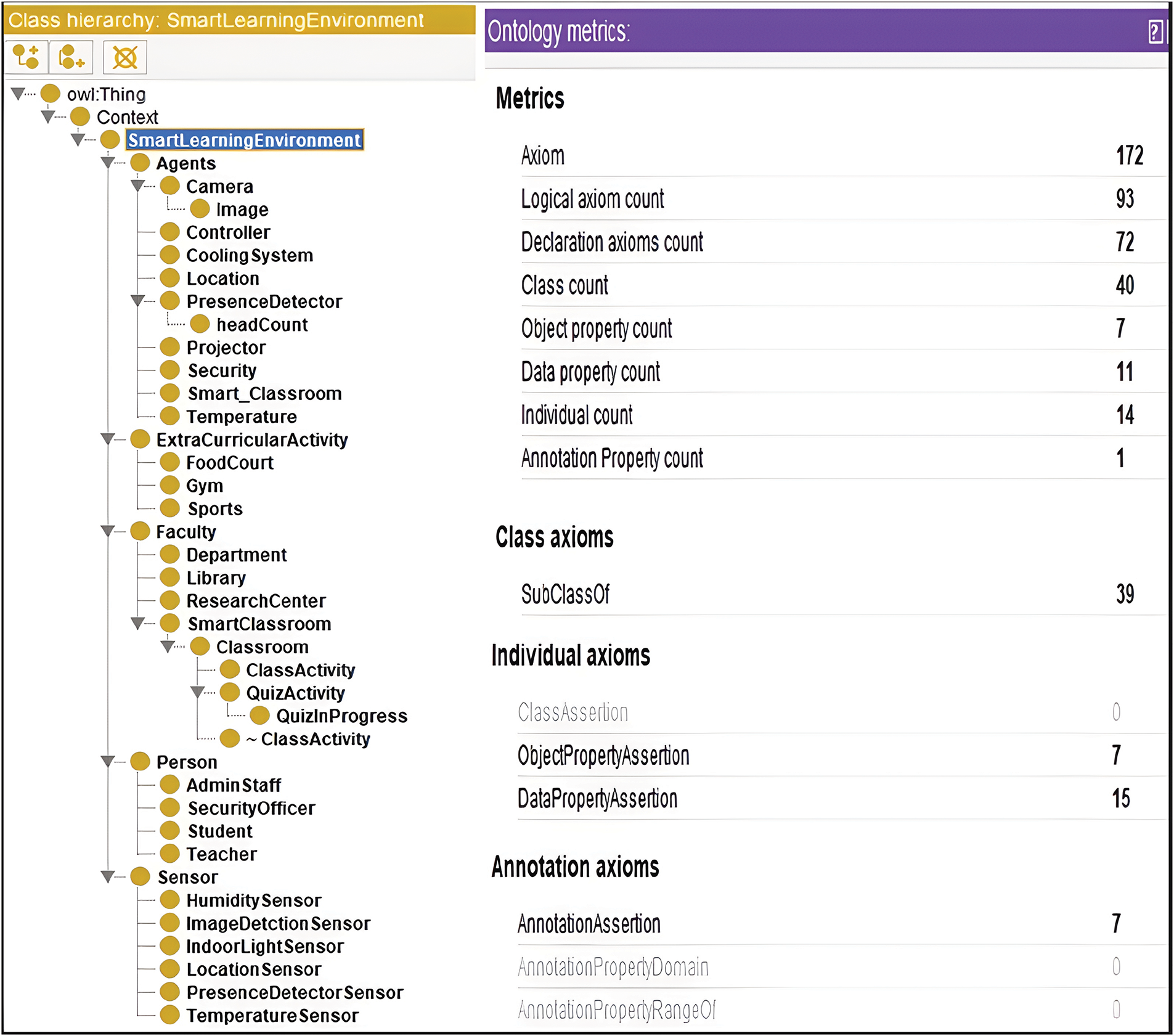

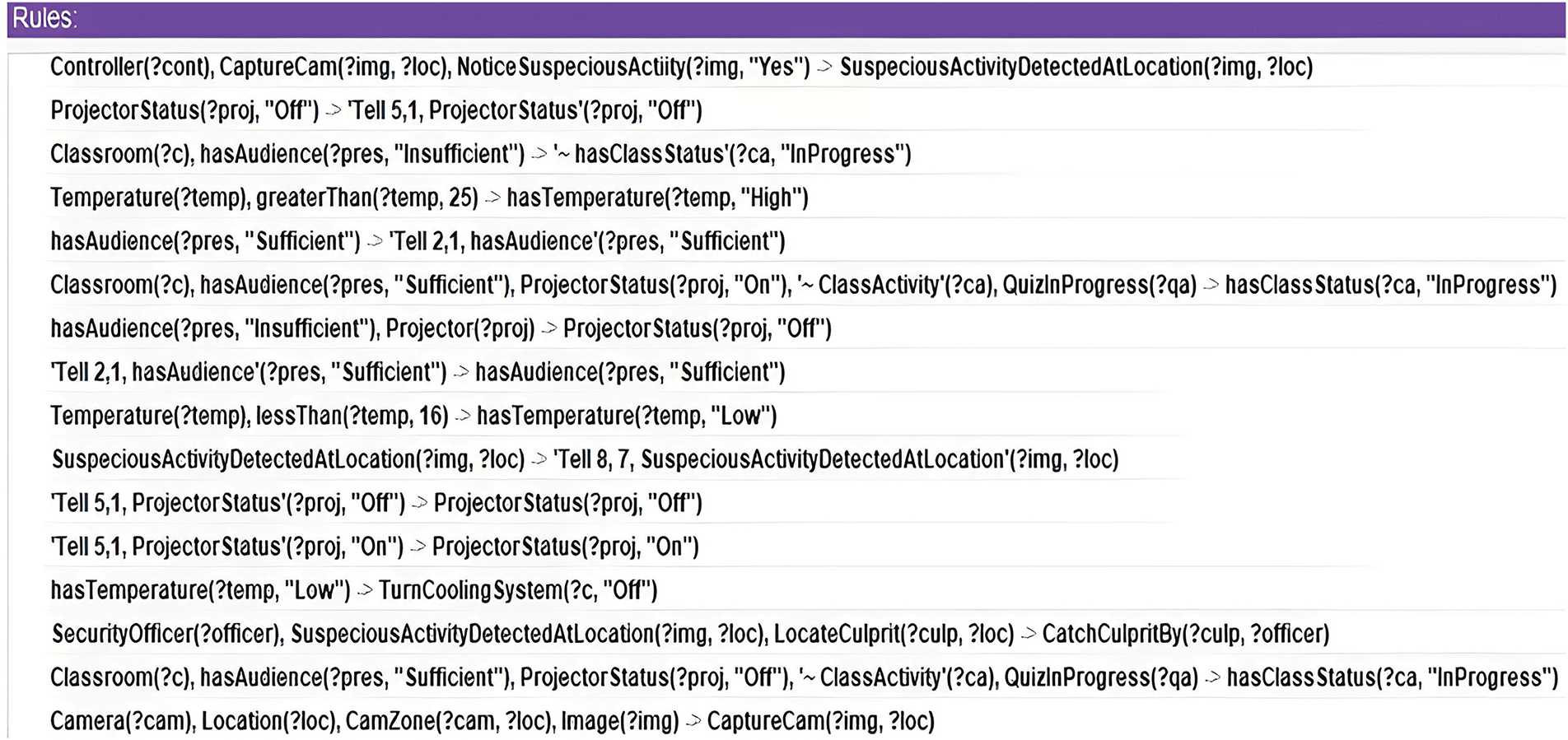

Fig. 1 depicts a fragment of the smart learning environment, whereas a class hierarchy of the smart learning environment can be seen in Fig. 2. We have a two set of rules to model the systems. In ontology, we construct straightforward rules in OWL 2 RL (OWL 2 Rule language) because it requires scalable reasoning with very less expressivity and it allows rule-based reasoning capability. In addition, OWL 2 RL accommodates rules both in RDF and OWL 2 ontologies format. We develop complex rules using SWRL (Semantic web rule language). SWRL rules are formed from a set class atoms and property atoms (object and data). We construct SWRL rules for eight agents to represent the working flow of the system, however, we omit the rest of the rules due to space constraints. Fig. 3 shows object properties and data properties and Fig. 4 shows complex rules using OWL 2 RL and SWRL.

Figure 1: A fragment of smart learning environment ontology

Figure 2: Smart learning environment ontology hierarchy and metrics

Figure 3: Data and object properties

Figure 4: OWL 2 RL and SWRL rules

4 Context-Aware Predictive Formalism for Smart Learning Environment

This section presents a reinforcement learning based context-aware multi-agent reasoning model using contextual defeasible reasoning. Contextual defeasible logic (CDL) is a non-monotonic reasoning technique to handle conflicting and/or incomplete information. In a context-aware deployment setting, there are

4.1 Reinforcement Learning Agents’ Behavior and Reasoning Strategy

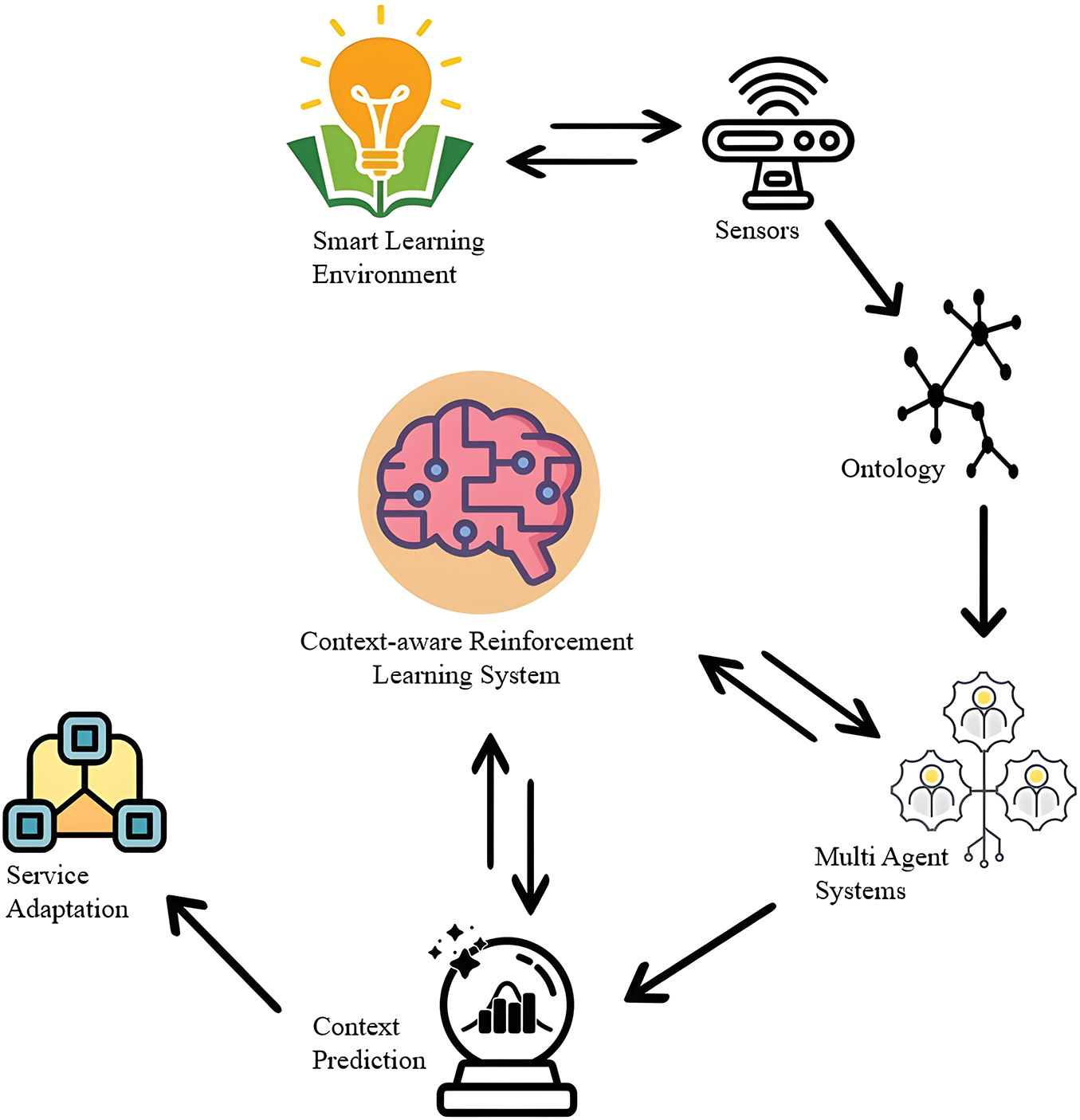

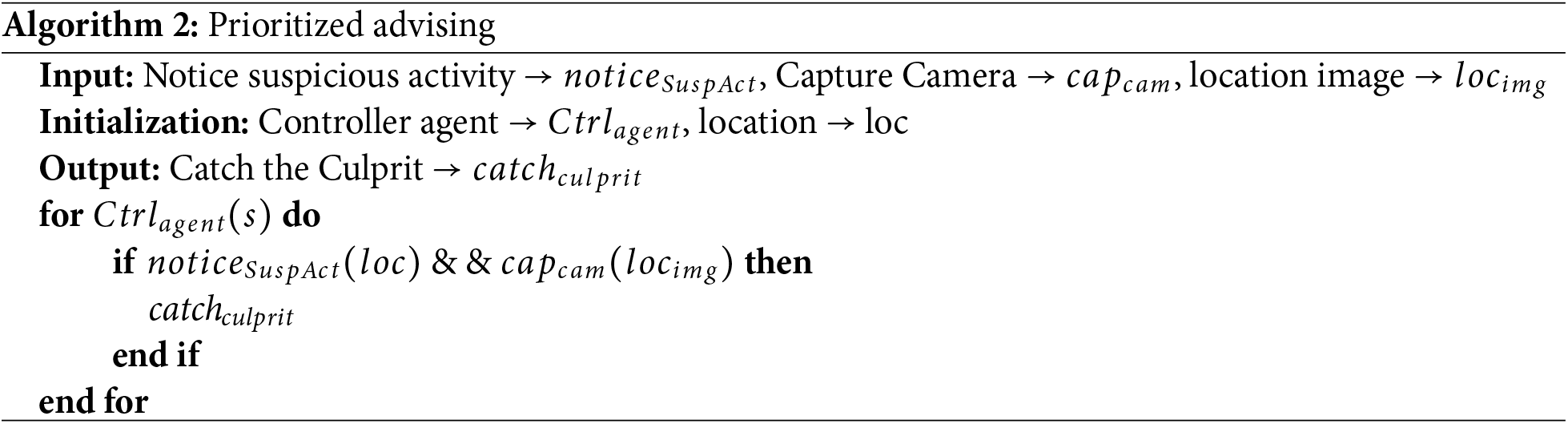

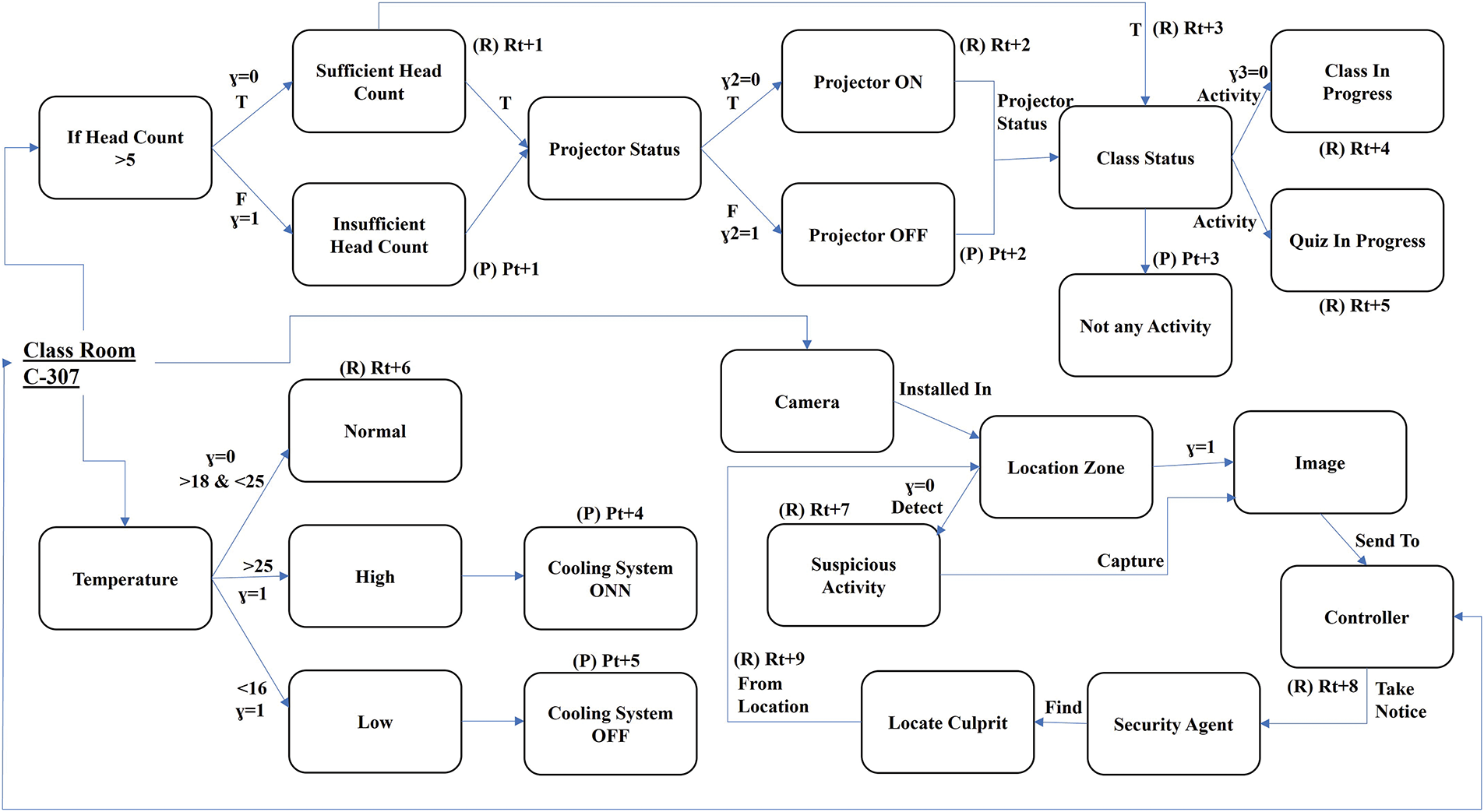

Reinforcement learning (RL) provides a mechanism of reward and punishment where each agent in the system is trained to specify the set of rules for the execution and set priorities based on the agent’s rewards. The rules with higher rewards should get higher priorities for the execution of contextualized information. A key challenge is aligning the adaptive behavior of RL with the static structure of the ontology, particularly during rapid shifts in decision-making priorities. However, in the system, RL often solves sequential decision-support problems where agents acquire contextualized information from the environment, perform reasoning based on the reward/punishment policy, and then take appropriate actions accordingly. RL based context-aware agents autonomously learn the reasoning policy and select the set of rules to be triggered to fulfill the desired goals. Fig. 5 depicts the working flow of the proposed context-aware predictive smart learning environment. As mentioned above, the system has three-tier architecture: Context acquisition process, context modeling using semantic knowledge, and contextual predictive reasoning formalism. To suitably model the system, we develop

where

Figure 5: Context-aware RL system framework

In case if agents performs idle transitions, then the system may not get any reward. This can be set at the design time in the policy of the system. The policy may be improved to optimize the decision making process. The whole learning process can be summed up as a cyclic process: the agent interacts with the environment repeatedly, chooses actions based on its policy, monitors rewards and states, and updates its policy. This procedure is repeated over several episodes until the agent reaches the near-optimal or optimal policy that maximizes the total expected reward over the long run, which is expressed as follows:

The reinforcement learning paradigm is used to solve the ranking problem, which is formalized as a Markov Decision Process (MDP). The reinforcement learning can be modelled by a Markov decision process (MDP) and is represented by a tuple

4.2 Multi-Agent Advising Strategy

Considering a case scenario of smart class room where agents autonomously detects the policy plan for the execution and advise agents to perform specified tasks. Each agent in the system works based on its predefined policy

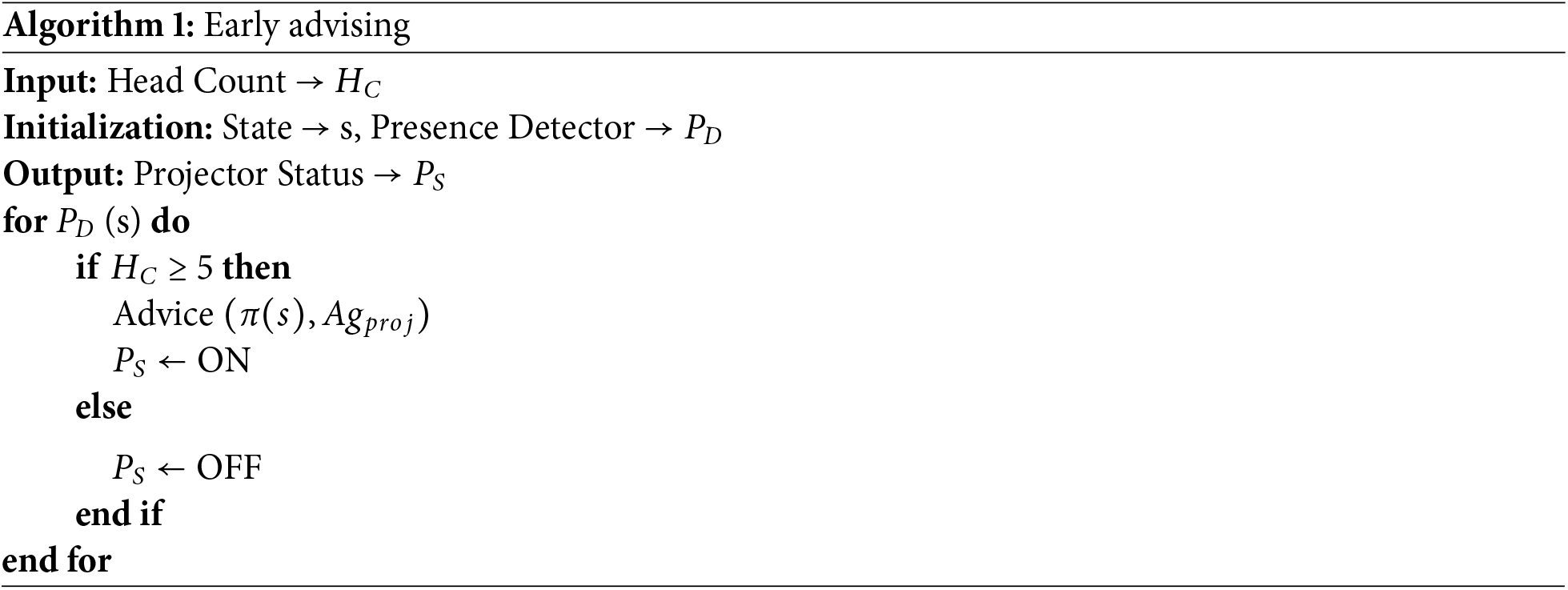

Agents’ Advising Strategy: When the execution of multiple tasks is equally important, then the system prioritizes the agent’s tasks based on a strategy known as the Advising Strategy. In Algorithm 1, the system advises the projector agent with the policy to switch on the projector if the count reaches 5 and above. We call this early advising technique where a presence detector agent continuously tracks the number of people in a classroom location. After getting advice, the projector turns on when the head count reaches a threshold of five, and switch off when its count reaches below 5.

Priority Advising Strategy: When each stage of a task is equally important, it seems reasonable to start early counseling. However, the system detects a conflicting context in a specific state, the system then sets preferences on the concurrent tasks in the hierarchy of states and prioritize the conflicting context to be executed earlier. In such situations, the system generate conflict set to prioritize contextual information. Considering a situation in the case study, Algorithm 2 depicts the prioritized advising strategy where a surveillance system takes over priority advising when hazardous situation occur. In this case, this algorithm can be helpful in security or surveillance systems where it’s important to spot suspicious activity and assists to catch the culprit.

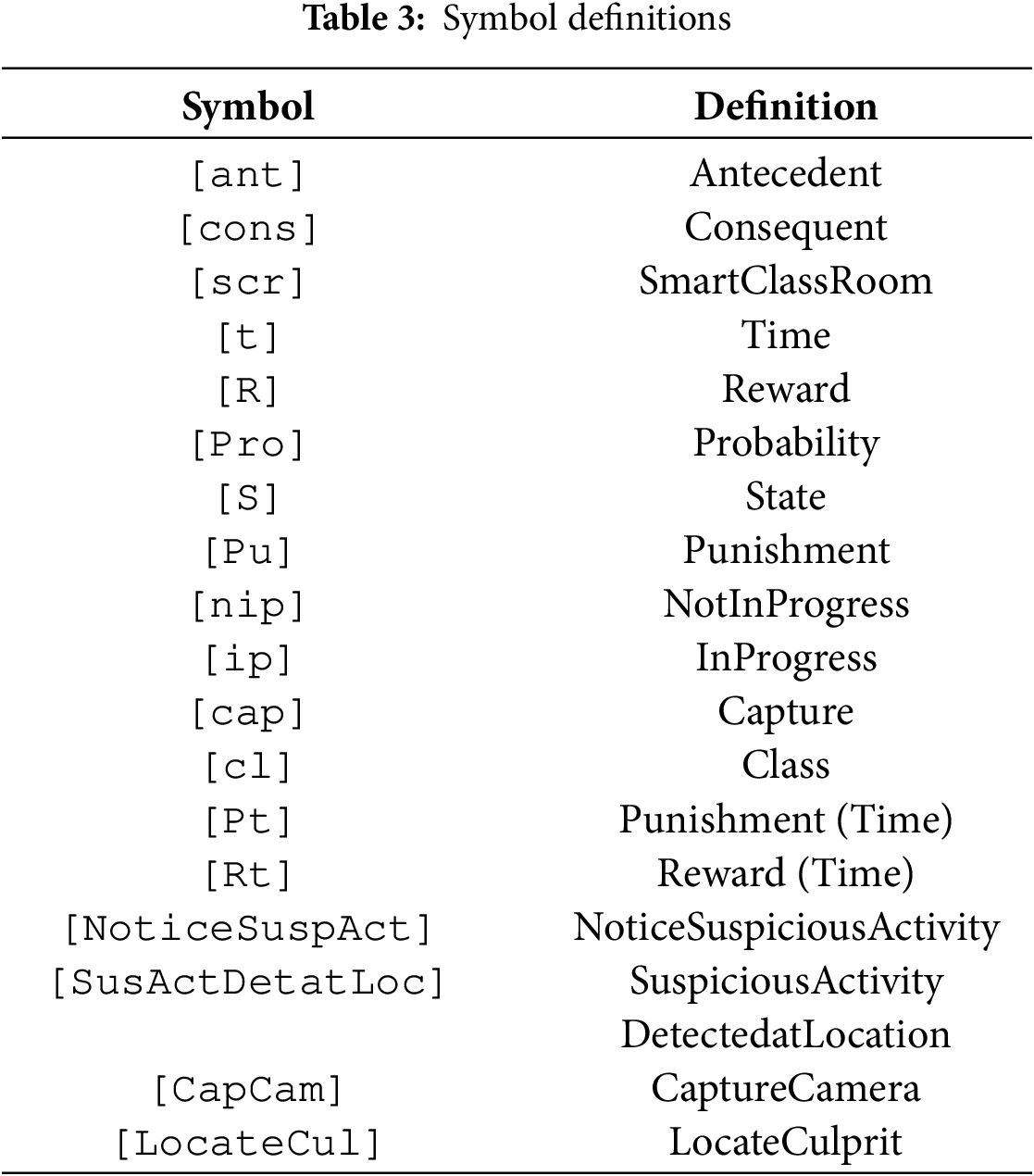

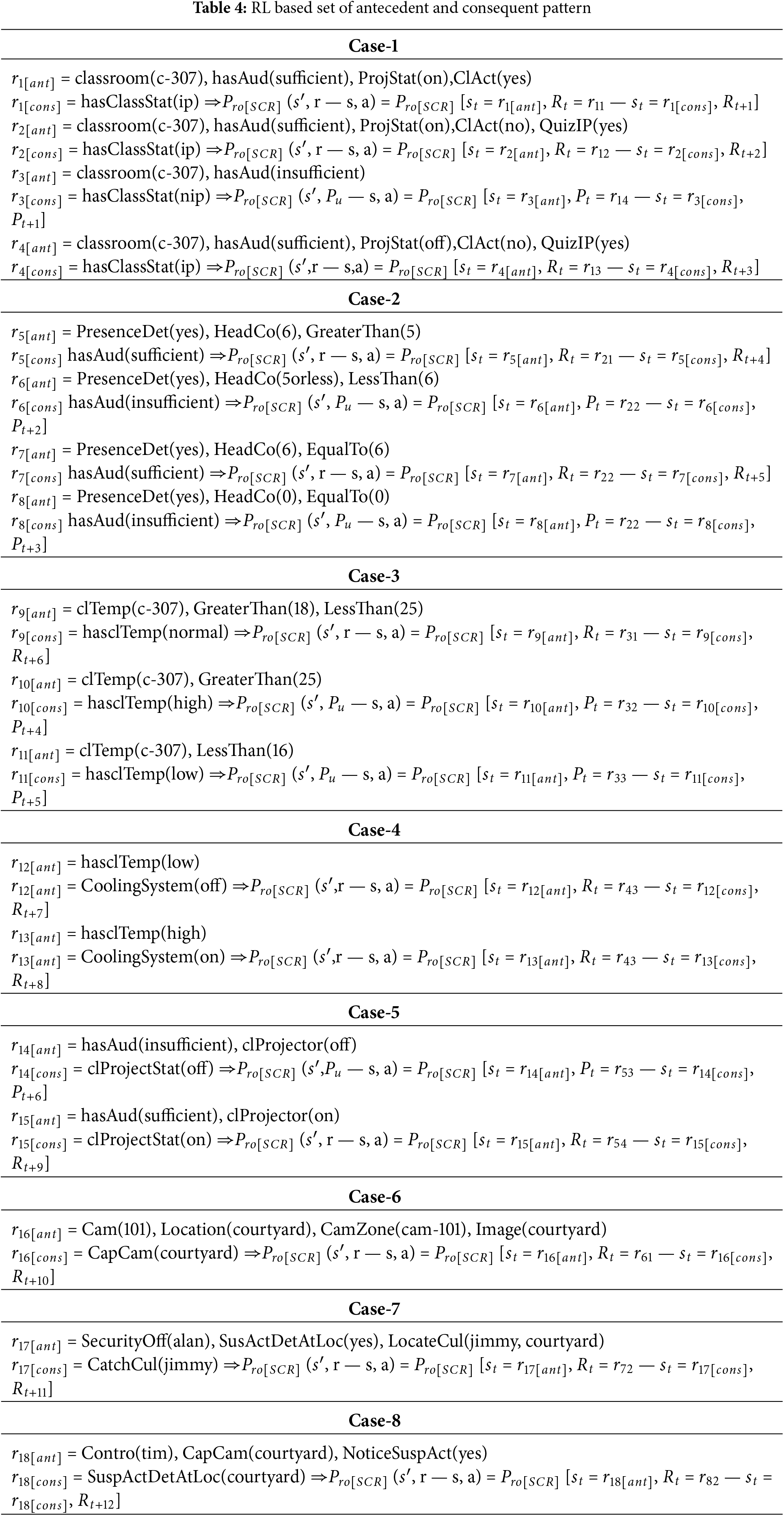

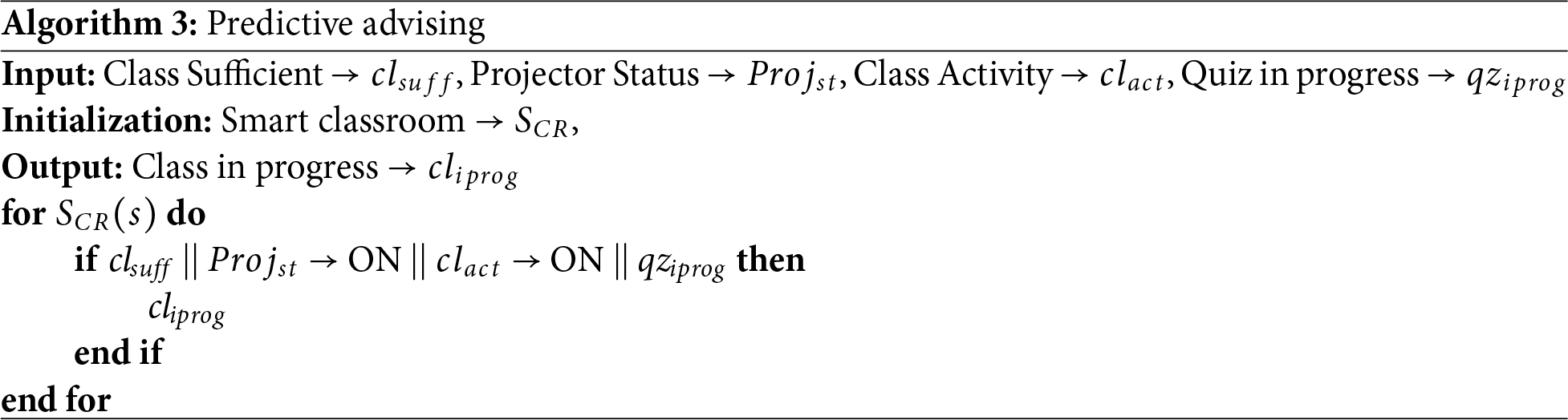

Predictive Advising Strategy: Based on many aspects of the smart classroom, such as available resources, projector status, class activity, and ongoing quizzes, the predictive advising Algorithm 3 determines if a class session is in process. During the class session in our case, teachers and students can utilize this forecast to get immediate advice or support. To evaluate the overall agents’ learning and execution behavior, a set of few rules for smart learning environment are presented in Table 2. We define acronyms for the terms in Table 3. Formally, a system’s policy is developed at the design time of the system and it is updated with a set of actions performed by agents in terms of transitions. In case of Smart Classroom, [SCR] is the policy probability

Figure 6: Agents interaction

• Presence detector agent notifies the projector agent to turn on the projector when the headcount is 5 or above and switches off when its count limit reaches below 5.

• Temperature agent notifies the cooling system agent to switch to the normal mode when the temperature remains between 18 and 25 degree Celsius, otherwise convert it into low and high mode according to the condition.

• The Security agent notifies the camera agent to capture the suspicious activity at the location and sends the details to the controller agent through the security agent to catch the culprit.

We use EDOH [22] to extract the ontology axioms in the form of horn-clause rules. Once the rules are transformed from the ontology, then the system defines agents’ policy based on the rewards/punishment function and sets priorities of the rules in order to perform actions. As the Markov decision process is a stochastic control process to model decision-making situations, actions and rewards have a very close association. Each time an action performed by the agent allows the system to reset the policy and assign priorities to the rules. Agents in the system trigger rules based on newly defined policies. In this way, agents update the rule priorities dynamically to handle incomplete and inconsistent contextual information. The system designer develops all rules at the design time of the system according to the provided case study, and the rule priorities are set at initial execution time. Then priorities of the rules may change based on the policies of agents’ actions. We assume each rule

5 Formal Verification of the Proposed System

Literature has witnessed that researchers have been using model-checking techniques to formally model the system and verify its correctness properties before the actual implementation of the system. Model checking is widely usable by the industry in various domains such as safety-critical systems, e-healthcare, e-government, etc. to check the correctness properties whether these are hardware or software or a combination of both. However, in theoretical models, it is considered to be the most appropriate approach. It is an automated or semi-automated modeling technique where the system can be encoded in the model checker and properties can be specified with the intention to verify the system’s correctness properties. Model checking is applied to formalize the system specifications and property specifications. System specification specifies the concurrent transitions of the system whereas property specification verifies whether the required properties hold in that model or not. However, if we talk about previous studies [21,23,24], our results as described in Section 5 are better in comparison. In the literature, various model-checking tools have been used according to the required specification of the system such as UPPAAL [10], Maude [25], Petri nets [26], etc. Among others, we opt UPPAAL model checker due to its graphical modeling and simulation behavior and it is more convenient to model, specify and verify real-time systems. UPPAL model checker has three modules: (a) editor can be used to model the domain along with its declaration and configurations. (b) The simulator provides a simulation zone to simulate the process executions, and (c) the verifier analyzes the system behavior and verifies correctness properties. Model checking is a formal verification method that analytically discovers all possible states of a system to confirm its correctness. Significantly, like a computer chess program that assesses each possible move, a model checker tool such as UPPAAL observes each possible situation the system could encounter. This comprehensive investigation permits verification of whether a given system model satisfies specific requirements or properties. Different outdated methods such as testing, emulation, or simulation, model checking can uncover even delicate and hard-to-detect errors, providing an advanced level of assurance in system reliability.

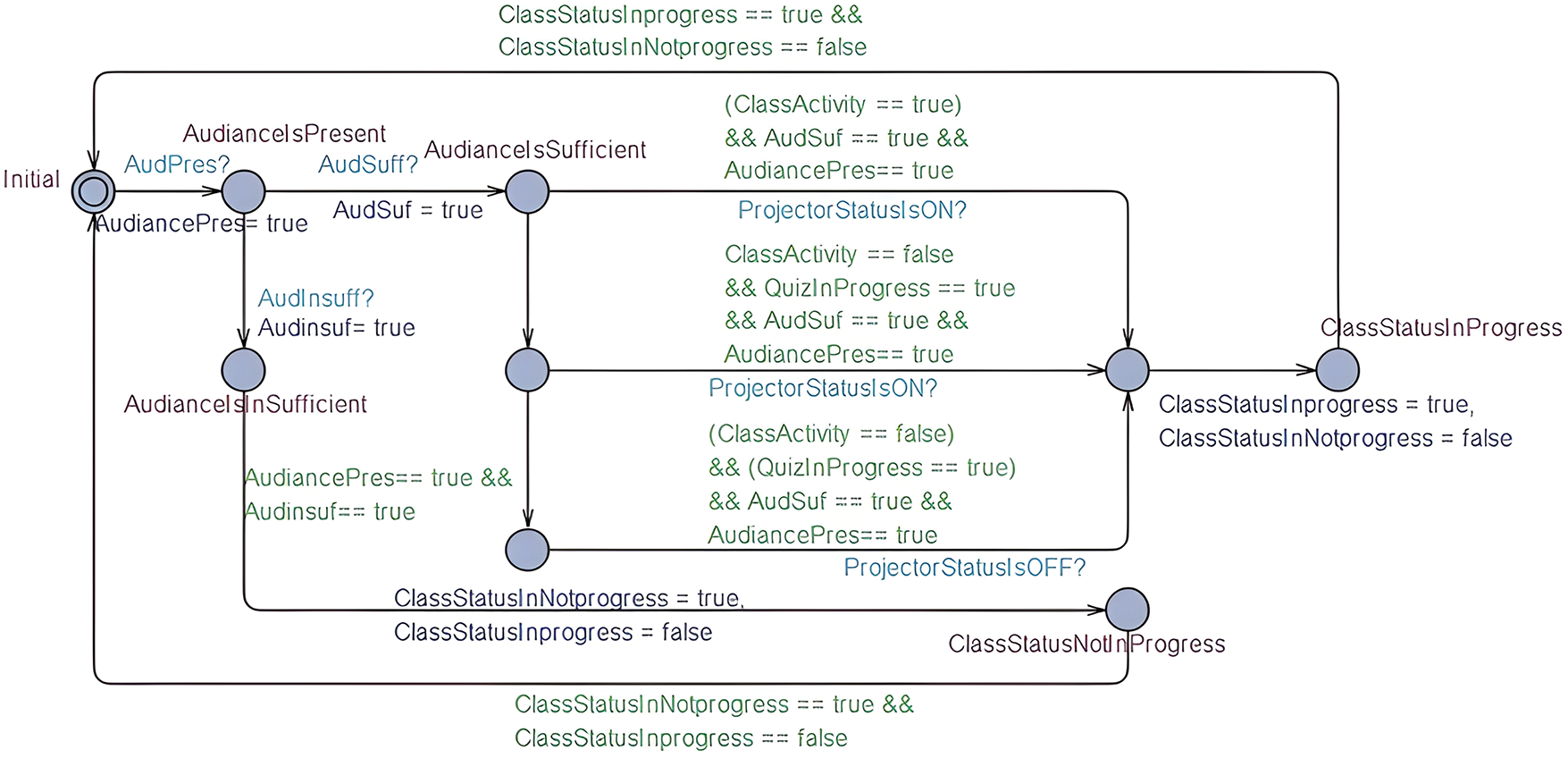

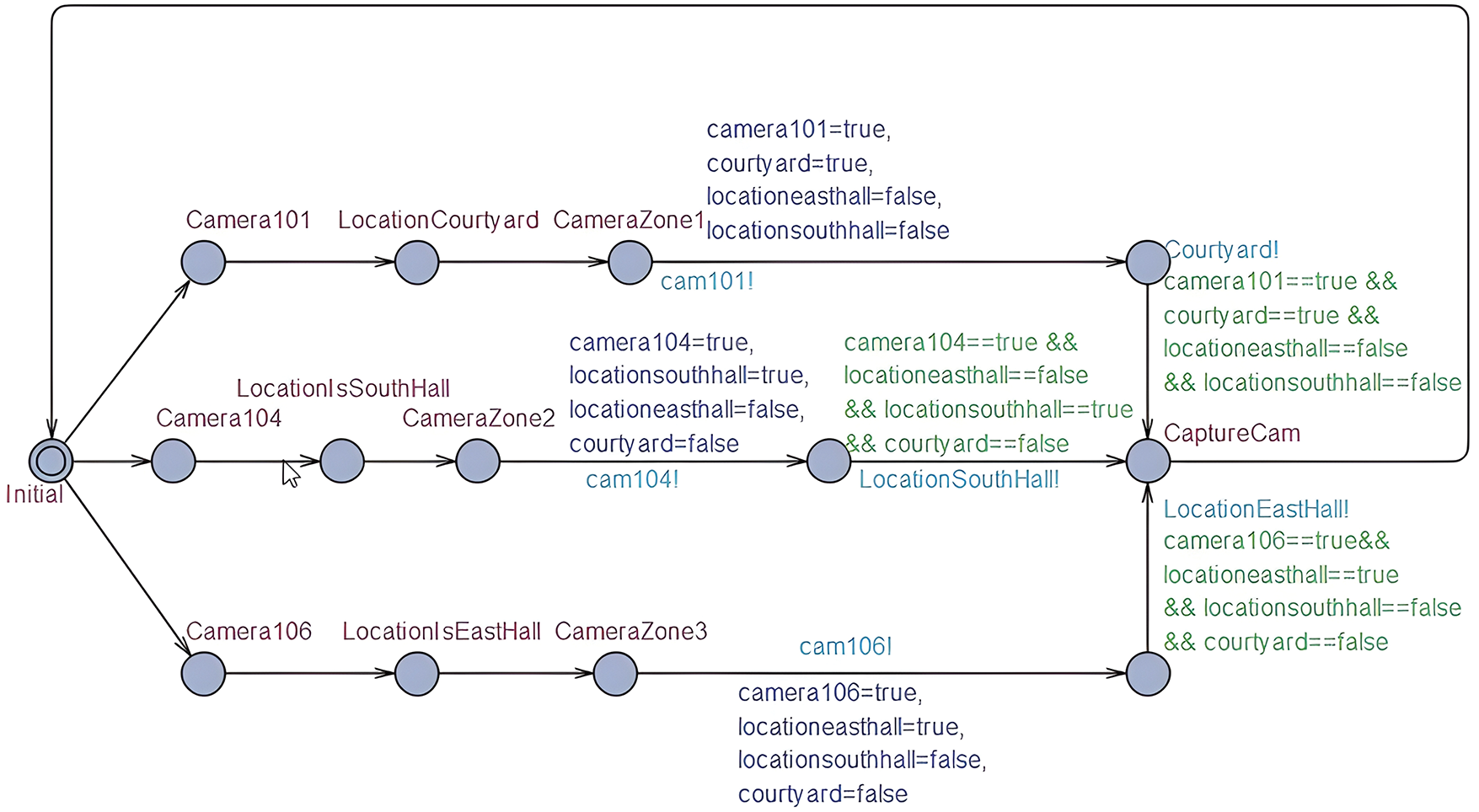

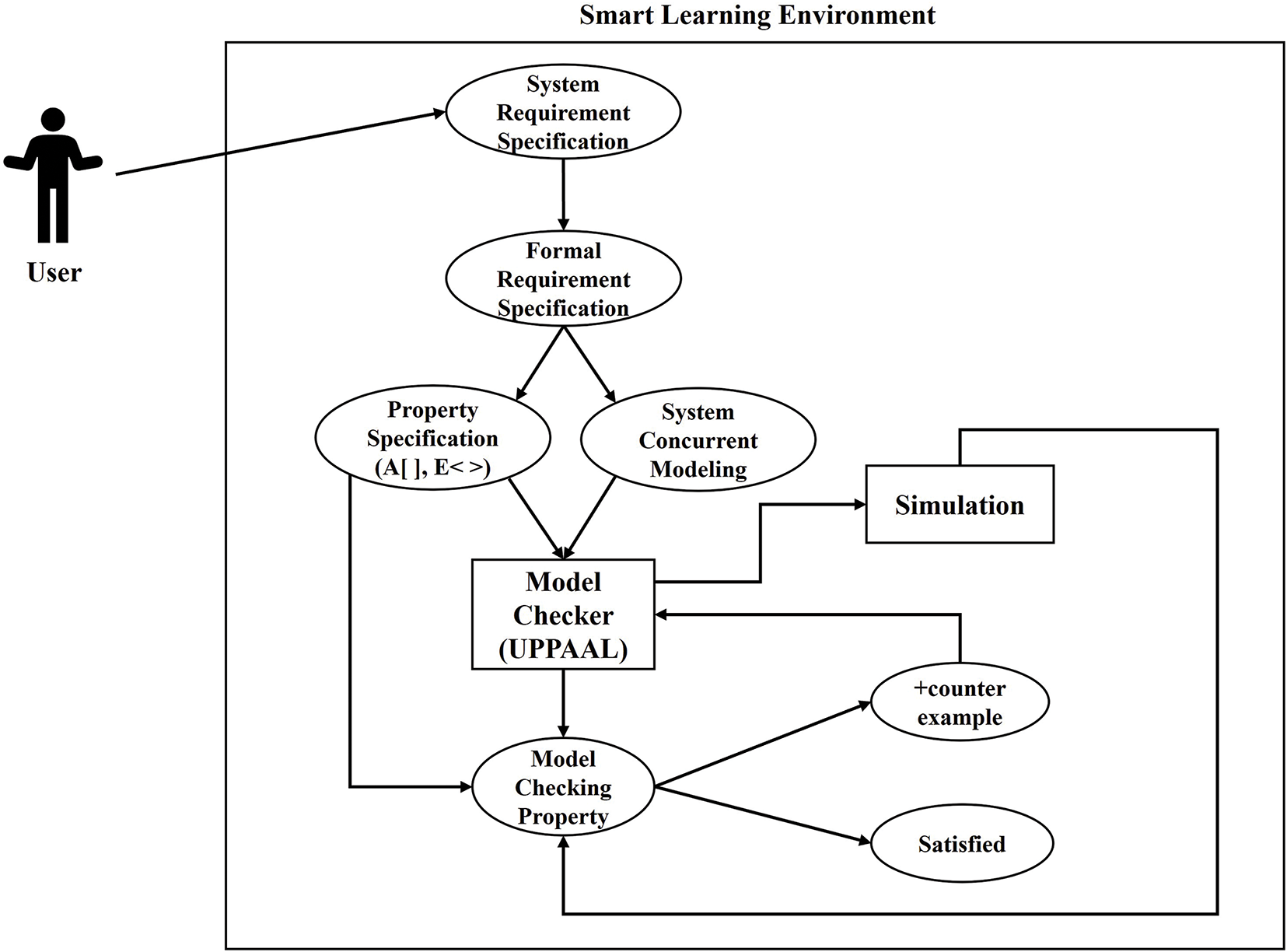

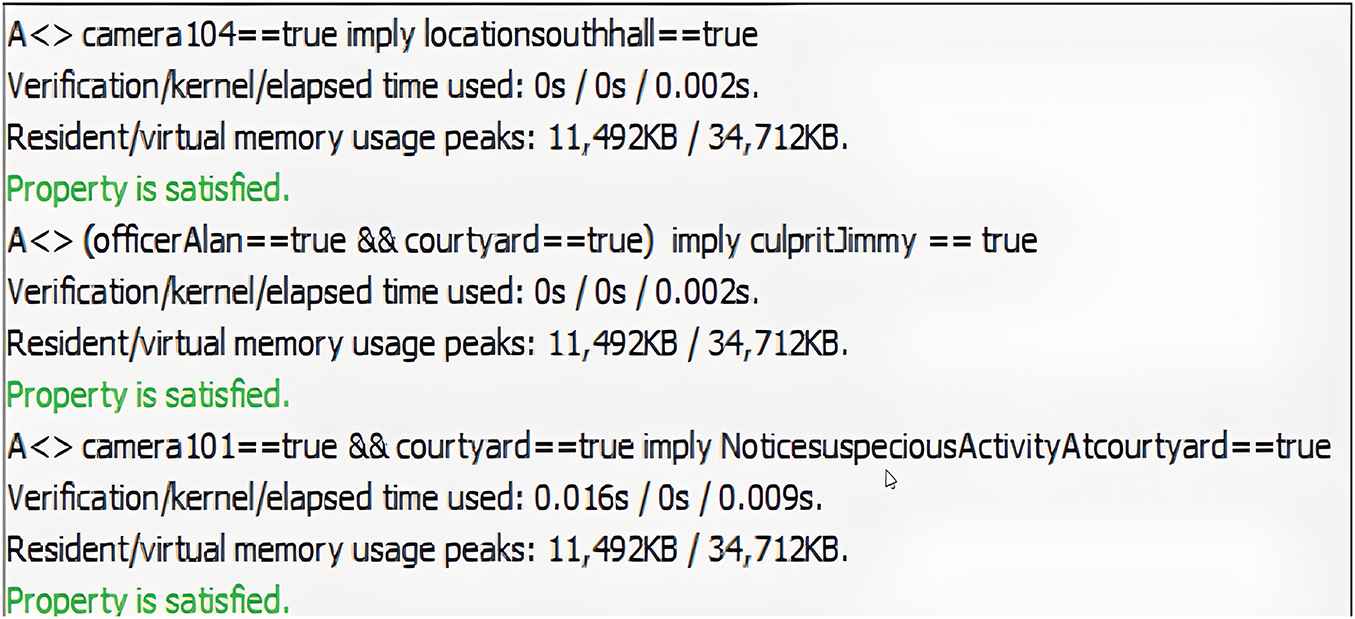

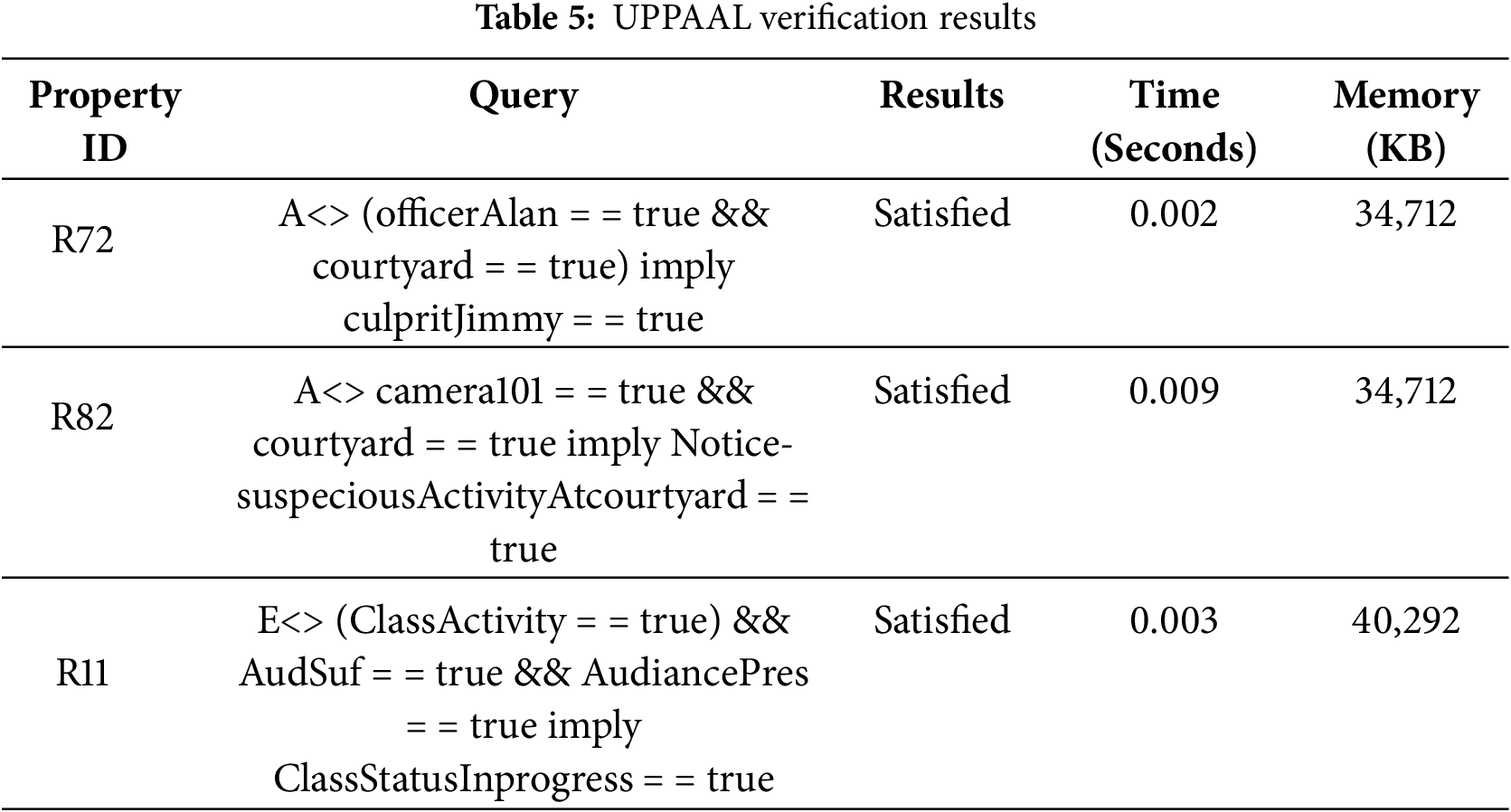

We model the domain of the smart learning environment in the editor zone and simulate the system processes. In Table 2, we have developed a set of rules to model a non-monotonic reasoning based context-aware predictive decision support system. To suitably simulate the system behavior, we need to verify the system’s correctness properties such as safety, liveness, and robustness properties. Fig. 7 shows the simulation of class status. As per defined specifications, the system should check the status of the class at the specified time and monitors whether a class is held at the right time and in the right place. In addition, the system specification will also monitor the class teaching duration and quiz time duration of the class. In Fig. 8, the system shows the configuration of the vigilance system. Let’s assume a camera detects some suspicious activities at the specified location, the system should immediately notify to the controller room to take action immediately. In the system, channels can be used to enable communication among different processes. Moreover, Fig. 9 elaborates the system encoding using model checking and formal verification with the help of UPPAAL tool.

Figure 7: Class status simualtion

Figure 8: Capture camera zone simulation

Figure 9: System encoding using model checking & formal verification

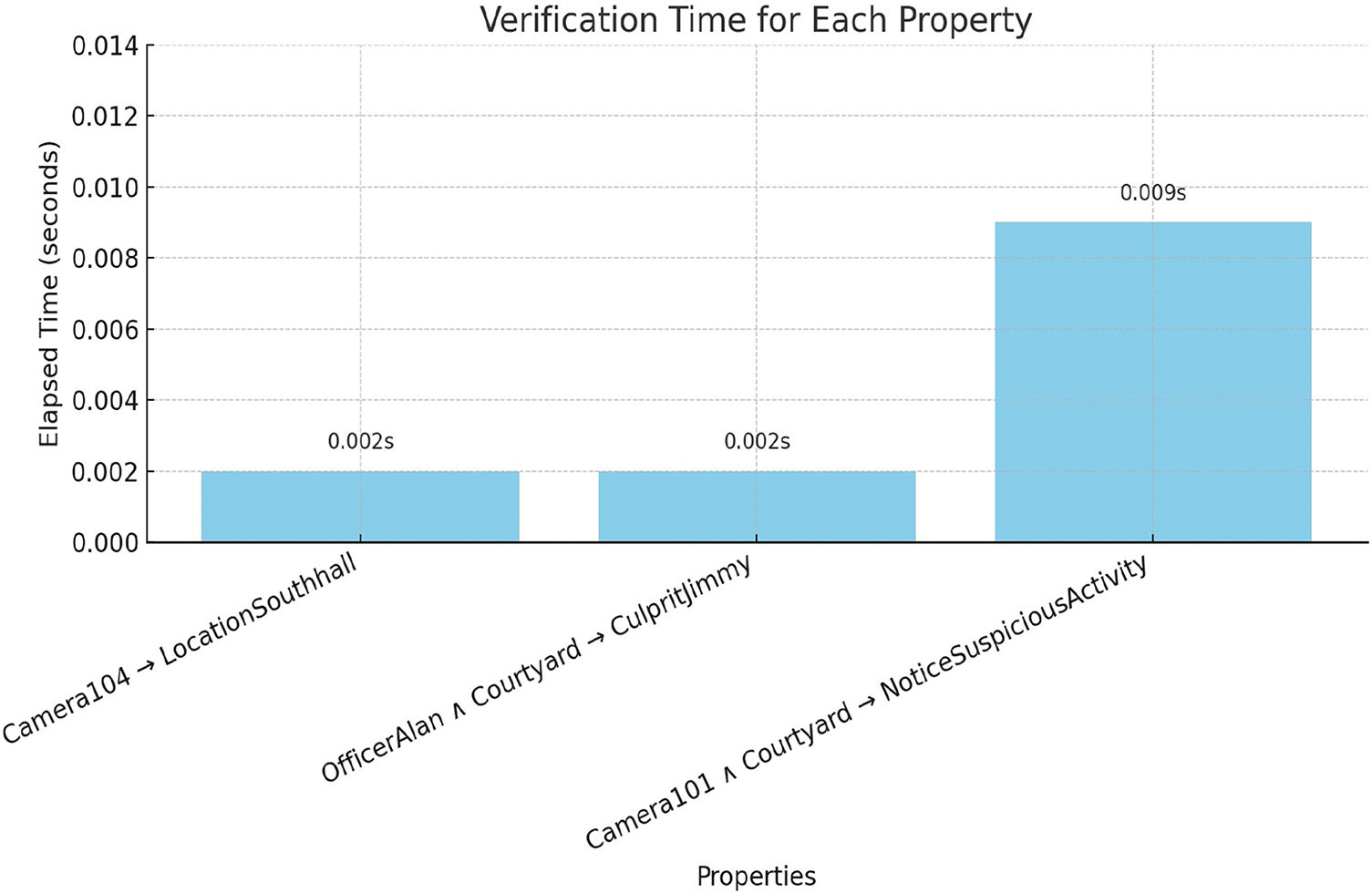

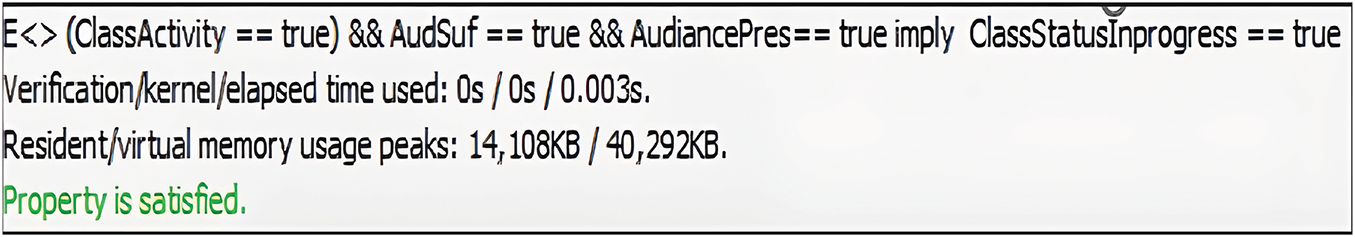

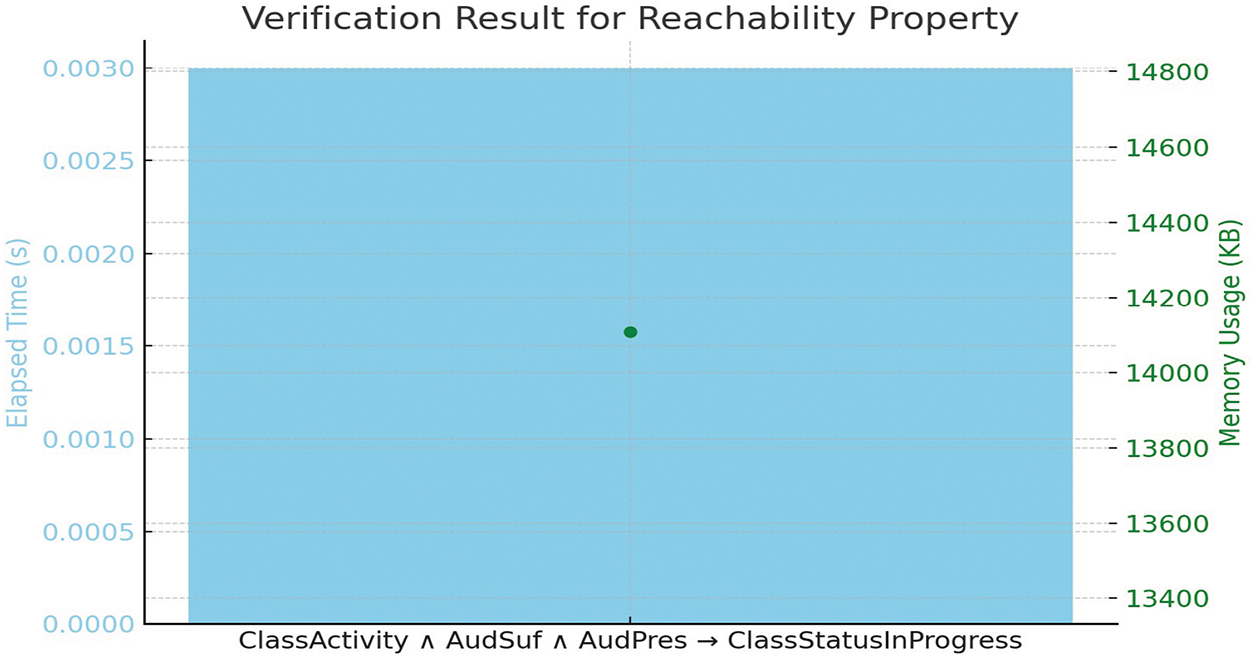

We need to check and verify the liveness property which means that the system should ensure that desirable property eventually holds in the model. Liveness property is satisfied when a process enters its critical section and then eventually would become successful. For example; as per system specification, whenever suspicious activity is performed, the system must have to be vigilant and activated to generate alarms to catch the culprit. Fig. 10 depicts how the system ensures the execution of this property. Moreover, the verification time of each property is represented in graph form in Fig. 11. In which the X-axis represents the each property and the Y-axis represents the time span in seconds. A safety property ensures that something bad must not happen. The main goal of a safety property is to prevent the risk of getting loss or absence of the properties when the system is operational. Deadlock property is a critical property related to synchronization and resource allocation in concurrent systems. A deadlock situation occurs when two or more processes are unable to move and wait for the actions to be triggered. This property must hold to satisfy the requirements. Reachability property is used to analyze the behavior of a system as shown in Fig. 12. Additionally, the verification result for reachability property is shown in graph form in Fig. 13. In which the X-axis shown the property being verified, the left Y-axis shown the time in seconds and the right Y-axis shown the memory usage in KBs. It specifies the state in the system can be reached following a sequence of transitions or actions. This property is very useful to verify the correctness properties of the program. We executed various queries using the UPPAAL tool, and their results, execution time (in seconds), and memory usage (in KBs) can be seen in Table 5. If we compare our results with existing approaches [27–29] to evaluate how much better our outcomes are, we can say that even without ensuring full scalability and compatibility, and only for the sake of comparison at a generic level. Our verification results, in terms of time (in seconds) and memory usage (in KBs) are better than those of the existing approaches [30–32].

Figure 10: Properties to check suspicious activity and subsequent action

Figure 11: Verification time for each property

Figure 12: Property to check class status

Figure 13: Verification result for reachability property

In this paper, we have proposed a semantic knowledge-based context-aware predictive reasoning formalism for smart learning environments. This model is based on the Markov decision process where the students and academicians can manage their academic as well as administrative activities autonomously. We have deployed contextual defeasible reasoning techniques to handle conflicting and/or inconsistent contextual information, which may cause context exchanges to/from semantic knowledge sources and developed agents advising strategies for agents to gain maximal rewards by continuous learning and then adapt their behavior accordingly. We model the case study in UPPAAL model checker to declare the processes, simulate the system’s behavior and verify correctness properties. In future work, we will propose a reinforcement learning framework incorporating heterogeneous knowledge sources based on non-monotonic reasoning, and develop state-of-the-art applications of the proposed framework in a real-time environment. This system would provide artificial intelligence (AI) assistive facilities to users in different domains.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank all individuals and institutions who contributed to the successful completion of this research. Their support and valuable insights were greatly appreciated. Special thanks to the National Research Foundation (NRF), Republic of Korea, under project BK21 FOUR (4299990213939) for supporting this work.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the National Research Foundation (NRF), Republic of Korea, under project BK21 FOUR (4299990213939).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—Original Draft Preparation: Taimoor Hassan, Hafiz Mahfooz Ul Haque; Literature Review, Visualization: Muhammad Nadeem Ali, Byung-Seo Kim, Hamid Turab Mirza; Reviewing and Editing: Ibrar Hussain. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Ben Hafaiedh I, Elaoud A, Maddouri A. A formal model-based approach to design failure-aware Internet of Things architectures. J Reliab Intell Environ. 2024;10(4):413–30. doi:10.1007/s40860-024-00225-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Gholami H, Chang CK, Aduri P, Ma A, Rekabdar B. A data-driven situation-aware framework for predictive analysis in smart environments. J Intell Inform Syst. 2022;59(3):679–704. doi:10.1007/s10844-022-00721-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Hashem IA, Siddiqa A, Alaba FA, Bilal M, Alhashmi SM. Distributed intelligence for IoT-based smart cities: a survey. Neural Comput Appl. 2024;36(27):16621–56. doi:10.1007/s00521-024-10136-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Mirisaee SH, Zin AM. A context-aware mobile organizer for university students. J Comput Sci. 2009;5(12):898. doi:10.3844/jcssp.2009.898.904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Martín E, Carro RM, Rodríguez P. A mechanism to support context-based adaptation in m-learning. In: Innovative Approaches for Learning and Knowledge Sharing: First European Conference on Technology Enhanced Learning, EC-TEL 2006; 2006 Oct 1–4; Crete, Greece: Springer; 2006. p. 302–15. [Google Scholar]

6. Torrey L, Taylor M. Teaching on a budget: agents advising agents in reinforcement learning. In: Proceedings of the 2013 International Conference on Autonomous Agents and Multi-Agent Systems. Saint Paul, MN, USA; 2013. p. 1053–60. [Google Scholar]

7. Ilhan E, Gow J, Perez-Liebana D. Teaching on a budget in multi-agent deep reinforcement learning. In: 2019 IEEE Conference on Games (CoG). London, UK: IEEE; 2019. p. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

8. Magdich R, Jemal H, Ben Ayed M. Context-awareness trust management model for trustworthy communications in the social internet of things. Neural Comput Appl. 2022;34(24):21961–86. doi:10.1007/s00521-022-07656-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Zeeshan K, Hämäläinen T, Neittaanmäki P. Internet of things for sustainable smart education: an overview. Sustainability. 2022;14(7):4293. doi:10.3390/su14074293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Larsen KG, Pettersson P, Yi W. UPPAAL in a nutshell. Int J Softw Tools Technol Trans. 1997;1(1–2):134–52. doi:10.1007/s100090050010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Huang LS, Su JY, Pao TL. A context aware smart classroom architecture for smart campuses. Appl Sci. 2019;9(9):1837. doi:10.3390/app9091837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Paudel P, Kim S, Park S, Choi KH. A context-aware IoT and deep-learning-based smart classroom for controlling demand and supply of power load. Electronics. 2020;9(6):1039. doi:10.3390/electronics9061039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Behzadipour F, Ghasemi Nezhad Raeini M, Abdanan Mehdizadeh S, Taki M, Khalil Moghadam B, Zare Bavani MR, et al. A smart IoT-based irrigation system design using AI and prediction model. Neural Comput Appl. 2023;35(35):24843–57. doi:10.1007/s00521-023-08987-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Liu S, Chen Y, Huang H, Xiao L, Hei X. Towards smart educational recommendations with reinforcement learning in classroom. In: 2018 IEEE International Conference on Teaching, Assessment, and Learning for Engineering (TALE). Wollongong, NSW, Australia: IEEE; 2018. p. 1079–84. [Google Scholar]

15. Burda Y, Edwards H, Storkey A, Klimov O. Exploration by random network distillation. arXiv:1810.12894. 2018. [Google Scholar]

16. Bokade R, Jin X. Pytsc: a unified platform for multi-agent reinforcement learning in traffic signal control. Sensors. 2025;25(5):1302. doi:10.3390/s25051302. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Shi Y, Dong H, He CR, Chen Y, Song Z. Mixed vehicle platoon forming: a multi-agent reinforcement learning approach. IEEE Int Things J. 2025;12(11):16886–98. doi:10.1109/jiot.2025.3535732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Zulfiqar H, Ul Haque HM, Tariq F, Khan RM. A survey on smart parking systems in urban cities. Concurr Comput. 2023;35(15):e6511. doi:10.1002/cpe.6511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Yousaf S, Haque HMU, Atif M, Hashmi MA, Khalid A, Vinh PC. A context-aware multi-agent reasoning based intelligent assistive formalism. Internet Things. 2023;23(2):100857. doi:10.1016/j.iot.2023.100857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Baldauf M, Dustdar S, Rosenberg F. A survey on context-aware systems. Int J Ad Hoc Ubiquit Comput. 2007;2(4):263–77. [Google Scholar]

21. Haque HMU, Khan SU. A context-aware reasoning framework for heterogeneous systems. In: 2018 International Conference on Advancements in Computational Sciences (ICACS). Lahore, Pakistan: IEEE; 2018. p. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

22. Haque HMU, Khan SU, Hussain I. Semantic knowledge transformation for context-aware heterogeneous formalisms. Int J Adv Comput Sci Appl. 2019;10(12664–70. doi:10.14569/IJACSA.2019.0101285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Hwang GJ. Definition, framework and research issues of smart learning environments-a context-aware ubiquitous learning perspective. Smart Learn Environ. 2014;1(1):1–14. doi:10.1186/s40561-014-0004-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Augusto JC. Contexts and context-awareness revisited from an intelligent environments perspective. Appl Artif Intell. 2022;36(1):2008644. doi:10.1080/08839514.2021.2008644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Eker S, Meseguer J, Sridharanarayanan A. The Maude LTL model checker and its implementation. In: Model Checking Software: 10th International SPIN Workshop; 2003 May 9–10; Portland, OR, USA: Springer; 2003. p. 230–4. [Google Scholar]

26. Reisig W. Understanding petri nets: modeling techniques, analysis methods, case studies. 1st ed. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2013. [Google Scholar]

27. Al-Bataineh O, Reynolds M, Rosenblum D. A comparative study of decision diagrams for real-time model checking. In: Model Checking Software: 25th International Symposium, SPIN 2018; 2018 Jun 20–22; Malaga, Spain: Springer; 2018. p. 216–34. [Google Scholar]

28. Kunnappilly A, Backeman P, Seceleanu C. From UML modeling to UPPAAL model checking of 5G dynamic service orchestration. In: Proceedings of the 7th Conference on the Engineering of Computer Based Systems (ECBS). Novi Sad, Serbia; 2021. p. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

29. Tiwari S, Iyer K, Enoiu EP. Combining model-based testing and automated analysis of behavioural models using GraphWalker and UPPAAL. In: 2022 29th Asia-Pacific Software Engineering Conference (APSEC). Tokyo, Japan: IEEE; 2022. p. 452–6. [Google Scholar]

30. Kim JH, Larsen KG, Nielsen B, Mikučionis M, Olsen P. Formal analysis and testing of real-time automotive systems using UPPAAL tools. In: Cimatti A, Sirjani M, editors. Formal Methods for Industrial Critical Systems: 20th International Workshop, FMICS 2015; 2015 Jun 22–23; Oslo, Norway: Springer International Publishing; 2015. p. 47–61. [Google Scholar]

31. Yang Z, Qiu Z, Zhou Y, Huang Z, Bodeveix JP, Filali M. C2AADL Reverse: a model-driven reverse engineering approach to development and verification of safety-critical software. J Syst Archit. 2021;118(3):102202. doi:10.1016/j.sysarc.2021.102202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Vogel T, Carwehl M, Rodrigues GN, Grunske L. A property specification pattern catalog for real-time system verification with UPPAAL. Inf Softw Tech. 2023;154(1):107100. doi:10.1016/j.infsof.2022.107100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools