Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Advanced Feature Selection Techniques in Medical Imaging—A Systematic Literature Review

1 School of Computer Science, National College of Business Administration and Economics, Lahore, 54000, Pakistan

2 Department of Computer Science and Information Technology, School Education Department, Government of Punjab, Layyah, 31200, Pakistan

3 Department of Computer Engineering, COMSATS University Islamabad, Sahiwal Campus, Sahiwal, 57000, Pakistan

4 Research Management Centre (RMC), Multimedia University, Cyberjaye Campus, 63100, Malaysia

5 Department of Software, Faculty of Artificial Intelligence and Software, Gachon University, Seongnam-si, 13120, Republic of Korea

6 Faculty of Engineering, Uni de Moncton, Moncton, NB E1A3E9, Canada

7 School of Electrical Engineering, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, 2006, South Africa

8 International Institute of Technology and Management (IITG), Av. Grandes Ecoles, Libreville, BP 1989, Gabon

9 College of Computer Science and Engineering, University of Ha’il, Ha’il, 55476, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Authors: Tehseen Mazhar. Email: ; Muhammad Adnan Khan. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advanced Algorithms for Feature Selection in Machine Learning)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(2), 2347-2401. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.066932

Received 21 April 2025; Accepted 04 August 2025; Issue published 23 September 2025

Abstract

Feature selection (FS) plays a crucial role in medical imaging by reducing dimensionality, improving computational efficiency, and enhancing diagnostic accuracy. Traditional FS techniques, including filter, wrapper, and embedded methods, have been widely used but often struggle with high-dimensional and heterogeneous medical imaging data. Deep learning-based FS methods, particularly Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and autoencoders, have demonstrated superior performance but lack interpretability. Hybrid approaches that combine classical and deep learning techniques have emerged as a promising solution, offering improved accuracy and explainability. Furthermore, integrating multi-modal imaging data (e.g., Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), Computed Tomography (CT), Positron Emission Tomography (PET), and Ultrasound (US)) poses additional challenges in FS, necessitating advanced feature fusion strategies. Multi-modal feature fusion combines information from different imaging modalities to improve diagnostic accuracy. Recently, quantum computing has gained attention as a revolutionary approach for FS, providing the potential to handle high-dimensional medical data more efficiently. This systematic literature review comprehensively examines classical, Deep Learning (DL), hybrid, and quantum-based FS techniques in medical imaging. Key outcomes include a structured taxonomy of FS methods, a critical evaluation of their performance across modalities, and identification of core challenges such as computational burden, interpretability, and ethical considerations. Future research directions—such as explainable AI (XAI), federated learning, and quantum-enhanced FS—are also emphasized to bridge the current gaps. This review provides actionable insights for developing scalable, interpretable, and clinically applicable FS methods in the evolving landscape of medical imaging.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileIn artificial intelligence-driven medical imaging, FS is an essential component since it enables the management of a substantial quantity of high-dimensional imaging data, enhancing diagnostic accuracy and interpretability. In the first part of this section, we will present the idea of FS, discuss its significance in medical imaging, and then examine the many FS approaches currently in use. These methods include those based on classical techniques, deep learning methods, fusions of classical and deep learning methods, and quantum mechanics. In addition, it details the primary research questions, the aims of the investigation, and the study’s contribution. At the end of the section, the structure of the paper is presented to the readers to direct them through the topics contained within the remaining sections of the publication.

Medical imaging has become an indispensable tool in modern diagnostics, offering rich data for the detection and treatment of various diseases. However, the high dimensionality and heterogeneity of medical image data pose significant challenges for effective analysis and interpretation. This study is motivated by the need to optimize medical image analysis workflows through advanced feature selection (FS) techniques that enhance accuracy, efficiency, and interpretability. The primary objectives of this review are: (1) to classify and evaluate classical and deep learning-based FS methods used in medical imaging; (2) to explore hybrid and quantum-enhanced FS approaches; and (3) to highlight future directions for clinically applicable and computationally scalable FS strategies.

Medical imaging is essential to contemporary medicine since it assists in disease detection, diagnosis, and treatment planning. The use of modern imaging modalities, including MRI, CT, PET, ultrasound, and X-ray, results in the production of a large quantity of high-resolution anatomical and functional data [1]. Because these datasets are high dimensional, redundant, and noisy, it is necessary to employ appropriate methodologies to process them using the machine learning models that are currently accessible [2]. AI-driven techniques, in particular, ML and DL, have brought about a revolution in the field of medical image analysis [3]. However, these techniques are severely impacted by the curse of dimensionality, which significantly impacts computational inefficiency, lack of generalization, and consequences of interpretability. FS algorithms have recently been proposed as a fundamental preprocessing step in medical image analysis to address these issues [4].

The procedure known as FS is designed to pick the most pertinent and informative characteristics within the dataset while simultaneously removing irrelevant or redundant features [5]. FS improves diagnostic accuracy, reduces computing costs, and offers insight into the operation of AI-based diagnostic systems, ultimately making the systems more clinically viable and efficient [6]. Traditional FS methods, such as filter, wrapper, and embedding methods, have been utilized in a significant amount of feature optimization; however, they are confronted with the challenge of scaling with huge, high-dimensional imaging datasets features [7]. Approaches to FS based on deep learning, such as CNN, Autoencoders, and Transformers, intrinsically learn the distinguishing features from the medical image and perform better than other methods [8]. The drawback of this, however, is that deep learning models are challenging to comprehend, which leads to a lack of confidence in their application in clinical settings.

Despite this, hybrid FS techniques, which combine traditional FS methods with methods based on deep learning, have gained popularity to overcome the constraints discussed earlier [9]. These methods aim to achieve equivalent FS efficiency, good model interpretability, and diagnostic accuracy [10]. This makes them more suitable for clinical applications in the real world. With medical imaging expanding into differences of multi-modal data integration (for example, integrating MRI, CT, and PET), FS is also confronted with other issues, such as combining and aligning multiple modalities, which calls for more sophisticated selection algorithms [11]. These challenges underscore the need for advanced solutions in the field of medical imaging.

As the field of quantum computing continues to advance, new FS approaches that use quantum principles have evolved, offering the exciting possibility of providing high-dimensional medical data that can be analyzed more effectively [12]. Even though there are still outstanding problems regarding the practical implementations of quantum FS-based approaches, these challenges include scalability and independent clinical validations [13]. Nevertheless, many significant issues still exist, such as the absence of standard evaluation benchmarks and the lack of comprehension of interpretability, ethics, and computational resources. Solving these problems will improve the reliability and uptake of AI-driven FS techniques for use in clinical settings and raise their transparency.

Considering the growing importance of FS in AI-driven medical imaging, this review aims to:

• To analyze existing FS techniques applied in medical imaging, focusing on classical, deep learning-based, hybrid, and quantum FS approaches.

• To compare the effectiveness of different FS methods regarding accuracy, computational efficiency, and clinical interpretability.

• To explore the role of FS in multi-modal medical imaging and the challenges associated with feature fusion.

• To investigate the emerging applications of quantum-based FS and their potential advantages over classical methods, offering hope for significant improvements in medical imaging.

• To highlight the key challenges, ethical considerations, and future research directions in AI-driven FS for medical imaging.

To achieve these objectives, this review addresses the following research questions:

• RQ1: How have classical FS techniques evolved, and what are their limitations in handling high-dimensional medical imaging data?

• RQ2: To what extent do deep learning-based FS methods improve diagnostic accuracy, and how do they compare in terms of interpretability?

• RQ3: How can hybrid FS techniques integrate classical and deep learning methods to enhance clinical decision-making?

• RQ4: What role does FS play in multi-modal medical imaging, and how can feature fusion strategies be optimized?

• RQ5: How does quantum computing revolutionize FS in medical imaging, and what are its potential applications?

• RQ6: What are the key challenges, ethical considerations, and open research problems in AI-driven FS for medical imaging?

This study provides a comprehensive, structured analysis of FS techniques in medical imaging, making the following key contributions:

• Systematic categorization and comparison of FS methods, covering classical, deep learning, hybrid, and quantum-based approaches.

• Critical evaluation of FS techniques regarding accuracy, computational efficiency, and interpretability.

• Discuss multi-modal FS strategies, focusing on feature fusion and dimensionality reduction challenges.

• Explore quantum computing applications in FS and assess their feasibility for real-world implementation.

• Identification of key challenges, ethical considerations, and open research problems in AI-driven FS for medical imaging.

In addition, this study is a helpful resource for researchers, AI practitioners, and healthcare professionals interested in understanding the current status of FS in medical imaging, the obstacles it faces, and the trends expected to emerge.

Here is how the remainder of this paper is structured. A complete discussion of feature selection strategies is presented in Section 2. Section 3 describes the systematic literature review process, including the inclusion criteria, the search technique, and the data extraction. Techniques are broken down into four categories: classical, deep learning, hybrid, and quantum-based methods, and a comparison of these methods is also included. In the final section, Section 4, the proposed study explores the difficulties and potential future research opportunities associated with applying FS to medical imaging. These problems include the incorporation of multi-modal data, the interpretation of medical imaging models, the resolution of ethical concerns, and the spending of computational resources. In conclusion, Section 5 brings the study to a close by providing a list of the most critical points and a summary of the potential paths the research could take to establish frameworks for artificial intelligence-driven medical imaging.

Despite the significant advancements in classical and deep learning-based feature selection methods, several limitations remain. Classical techniques often struggle with high-dimensional, multi-modal datasets, lacking the flexibility to adapt to complex spatial and semantic features present in modern medical images. Deep learning-based methods, while powerful, are frequently criticized for their black-box nature and require large amounts of labeled data. Furthermore, limited attention has been paid to privacy-preserving and quantum-enhanced FS frameworks, which are critical in emerging clinical applications. Finally, while hybrid FS strategies have shown promise, systematic evaluations comparing their efficacy across imaging modalities are scarce. These gaps underline the need for a comprehensive review that bridges classical, deep learning, and quantum paradigms to guide future research in this domain.

Selecting features through FS reduces medical imaging dataset dimensions by maintaining only the most important diagnostic features for classifying diseases. The three categories of classical FS techniques include filter, wrapper, and embedded methods, which provide specific benefits and constraints. Experimental researchers have successfully used this approach for medical imaging investigations that involve labeling tumors, spotting lesions, and making disease predictions. This part investigates original FS techniques, including their mathematical frameworks and medical imaging applications.

Countervalue selection allows feature classification through statistical assessments that bypass machine learning model operations [14]. The methods demonstrate computational efficiency and run independently of classifiers, enabling them to effectively handle large medical imaging datasets [15]. The three standard filter techniques for data selection are Pearson Correlation, Mutual Information, and Chi-square tests.

The analysis measures linear interconnections between two variables by using Pearson Correlation. The FS system uses Pearson Correlation to locate important target-related features, removing unneeded attributes [16]. The formula for Pearson Correlation coefficient

where

The absolute

Mutual Information provides an assessment of variable dependence through its evaluation of information reduction when one variable becomes known [18]. It is defined as in (2):

where:

•

•

The Medical Imaging field benefits from MI-based FS because this approach optimizes the selection of variables with complex nonlinear trends better than traditional methods, such as those used in tumor segmentation procedures [19]. Categorical features and the target variable demonstrate statistical dependence according to the Chi-square test [20]. It is computed in Eq. (3):

where:

•

•

The analysis of discrete feature selection tasks mainly employs this technique to identify significant predictors of disease within medical images based on their histogram-based features [21]. Wrapper methods execute a feature subset evaluation loop by running machine learning model training and validation procedures across all combinations to select the subset demonstrating superior model performance [22]. Although such methods deliver optimized feature collections, their computational cost remains high. Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) and Forward/Backward Selection are among the preferred wrapper approaches in feature selection applications [23]. Algorithm 1 has been included to illustrate the feature selection process used in the study.

The feature selection methodology, RFE, accurately produces an optimal set of features because it builds upon a series of benefits. For datasets of all sizes, from small to medium, RFE provides an effective solution to choose essential features that support model performance [24]. The main disadvantage of RFE is its high computational burden, affecting its performance with large-scale datasets with numerous features. The medical imaging field mainly utilizes RFE due to its vital function in identifying discriminative features for applications such as tumor detection and Alzheimer’s disease classification to build more precise diagnostic models [25].

A set of standard feature selection techniques include Forward Selection as well as Backward Selection. Forward Selection starts by adding no features and continues by including new features individually to assess their impact on performance at each selection step [26]. The feature selection process of Backward Selection begins with all available features, which are then reduced one by one based on performance criteria [27]. The techniques are broadly used in cardiovascular disease prediction systems because they analyze ECG features successfully [28]. These selection methods improve classification accuracy by choosing optimal wavelet coefficients, leading to more accurate and efficient predictive cardiovascular condition diagnosis [29]. Embedded methods execute feature selection operations within their model training process by integrating the selection procedure with model learning procedures. Massive medical imaging applications favor these methods because they merge efficient performance for practical applications [30]. LASSO (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator) allows regression-based feature selection through L1 regularization until coefficients reach absolute zero values, which selects the vital features alone [31]. The LASSO optimization function is defined in Eq. (4):

where:

•

•

•

•

LASSO is a popular medical imaging biomarker identification tool for early cancer detection and Alzheimer’s disease progression assessment [32]. Random Forest as an ensemble learning method automatically generates feature importance scores through its capability to measure how features reduce classification errors [33]. Feature importance is calculated in Eq. (5):

where

•

•

•

Random Forest-based FS offers several advantages, particularly in the context of high-dimensional and multi-modal medical imaging datasets. The method shows effectiveness when dealing with extensive complex datasets in numerous medical applications [34]. In medical imaging, where data is abundant, feature selection is crucial to pattern identification and machine learning. In medical imaging, feature selection improves classification accuracy and simplifies data. These methods improve multi-sourced data treatment and medical infection diagnosis [35]. Scientific studies confirm that Random Forest-based FS produces successful results for brain tumor identification through feature prioritization of extracted radiomics characteristics from MRI medical images. The method enhances the diagnostic model’s reliability and interpretability to produce better decisions supporting medical settings [36].

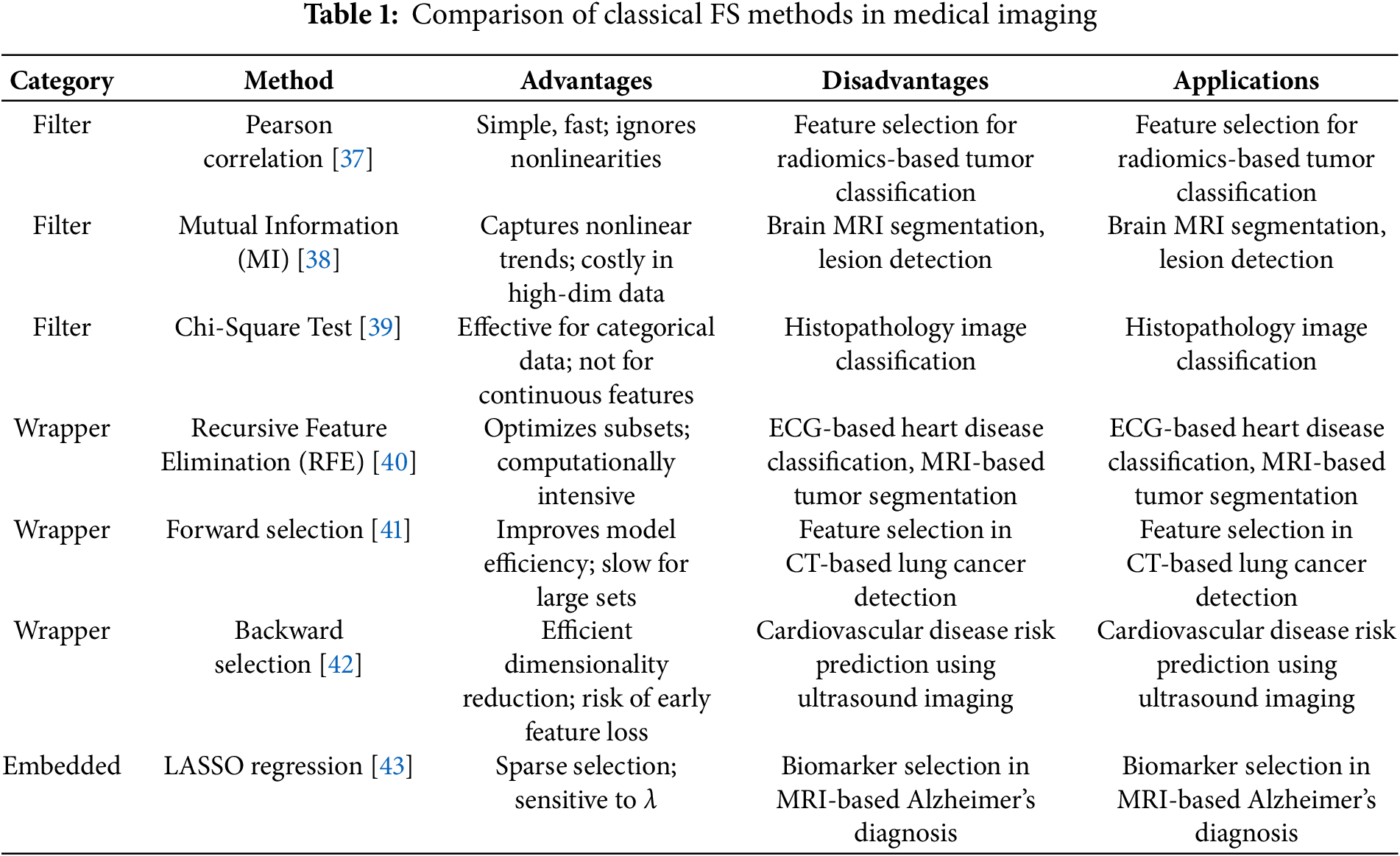

FS methods provide efficient solutions that are easy to interpret while having medical imaging dimensional reduction tasks. The filter methods of Mutual Information and Chi-square process fast calculations that help identify features holding crucial statistical information. Extensive computation expenses characterize the model-specific performance optimization of RFE and Forward/Backward Selection methods because they function as wrapper methods. The combination occurs in model training when using LASSO and Random Forest Feature Importance, achieving precise predictions and optimal operational speed. Research protocols based on these strategies achieve their goals even though complex multi-modal imaging data creates challenges that inspire scientists to develop next-generation analysis methods using deep learning frameworks and quantum-filtering techniques. Here’s a structured comparison table for classical FS methods in medical imaging in Table 1:

Recent imaging technology relies on feature selection to screen relevant data without overfitting or computation. This paper compares approaches based on computational efficacy, feature interaction, and high-dimensional data, giving a model for clinicians and academics to co-develop new diagnostics tools [44]. Random Forest-based FS offers several advantages, particularly in the context of high-dimensional and multi-modal medical imaging datasets. The method effectively processes complex, voluminous data, allowing for its use across various medical applications [45]. The explainable feature selection process is vital to RF-based FS because it enables medical professionals to discern the most crucial features utilized in diagnosis. Brain tumor diagnostic classification benefits from random forest-based FS through MRI scan radiomics features, providing accurate predictive assessments of tumor types [46]. This method enhances the diagnostic model’s reliability and interpretability, supporting informed medical decisions in real-world clinical settings.

Usually, features are extracted from the images followed by dimensionality reduction, applying an FS technique to prune abundant features and superior classification performance results. Deep learning can automatically extract hierarchical representations of medical images from neural networks without resorting to handcrafted features and predefined statistical measures, as against the classical FS methods [47]. Three DL based FS approaches, i.e., CNN-based FS, autoencoder-based FS, and transformer-based FS, along with their methodologies and their applications in medical imaging, are explored in this section.

The ability to capture spatial hierarchies and extract discriminative features from raw image data has particularly fueled recent advances CNNs as a tool for FS in medical imaging. CNN is a data-driven way of constructing features, unlike the FS techniques in the existing literature, which rely on tailored feature engineering [48]. These CNNs comprise a few layers, namely convolutional, pooling, and fully connected. The feature extraction part in a CNN can be written directly in math form [49]. It is defined in Eq. (6) as follows:

where:

•

•

• denotes the convolution operation,

•

•

To eliminate irrelevant features, CNN-based FS techniques identify the most significant feature maps at various convolutional stages [50]. Feature importance scores are computed from such methods as Grad–CAM (Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping) or Layer-wise Relevance Propagation (LRP), and the final feature set is selected based on those scores [51].

Since medical image analysis problems, such as brain tumor segmentation, diabetic retinopathy detection, and histopathology image analysis, rely on CNN-based feature selection [52,53], it plays a vital role in medical image analysis [54]. For brain tumor segmentation, CNN-based FS increases the tumor identification accuracy, especially in MRI scans, by using the most relevant region of interest, thus increasing the diagnosis and treatment planning precision and same is applied to detect diabetic retinopathy [55]. CNN-based FS is used in fundus images to identify the vascular abnormalities necessary for the early diagnosis of diabetic eye disease and early intervention, which may help prevent vision loss [56]. For instance, ensemble CNN models have recently shown enhanced classification accuracy in brain tumor detection tasks using MRI scans [52]. Transfer learning-based CNN architectures like Mask R-CNN have been applied to prostate segmentation with promising results [53]. Furthermore, CNN models extract high-level tissue patterns, which are helpful for cancer classification in histopathology image analysis. CNN-based FS attends to extreme regions in the images that would contribute the most to improving the accuracy and efficiency of medical image interpretation in several applications [57]. Additionally, hybrid CNN approaches combined with Bayesian methods have improved privacy-preserving feature extraction in smart imaging systems, such as terahertz-based breast cancer detection [58].

Another well-known deep learning approach for FS uses autoencoders (AEs), which are trained to learn compact, low-dimensional feature representations while avoiding losing important information of the high-dimensional medical imaging data [59]. The two main components they consist of are [60]

• Encoder: Compresses input data into a lower-dimensional latent space.

• Decoder: Reconstructs the original input from the latent space.

FS extends to using a probabilistic latent space, which in Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) helps improve FS by embedding relevant medical information in the extracted features while filtering noise. A VAE’s objective function is a reconstruction loss combined with a regularization term [61]. It explains in Eq. (7) as:

where:

•

•

•

•

•

The sparse autoencoder model effectively reduces high-dimensional data with the least reconstruction error when used unsupervised. It is superior to classical methods in classification problems, particularly when the quantity of labelled data is limited [63]. The author of [64] enforce the sparsity constraint, the sparsity by KL divergence through Eq. (8):

where:

•

•

•

VAE, SAE, and autoencoders are essential for improving disease prediction and detection in medical diagnostics. In particular, autoencoders and CNN architectures have demonstrated utility in classifying early-stage Alzheimer’s disease using PET and MRI modalities [65,66]. VAEs are utilized for Alzheimer’s disease prediction by extracting relevant biomarkers from MRI scans to distinguish Alzheimer’s patients from healthy individuals, enabling early detection and intervention [67]. It is also worth noting that recent research has explored the use of voice biomarkers as prognostic indicators for neurological disorders, such as Parkinson’s disease, demonstrating the potential of vocal features combined with machine learning techniques for early diagnosis [68]. For COVID-19 detection, SAEs identify key features of the lungs in chest X-rays or CT scans, allowing for effective and prompt diagnosis [69]. Additionally, in gene expression analysis, autoencoders search for critical genetic features within a high-dimensional medical database to identify genetic markers, which enhances our understanding of complex diseases. Deep learning models significantly impact medical diagnostics, improving accuracy and efficiency [70]. Recently, Transformers, particularly Vision Transformers (ViT), have been recognized as especially promising for medical imaging because they can capture long-range dependencies of an entire image [71]. Unlike CNNs, which utilize local receptive fields, ViTs analyze images in their entirety as sequences of patches and are capable of highlighting more global features [72]. ViTs segment an image into non-overlapping patches and then map these to a sequence of feature vectors using a linear projection function [73]. Eq. (9) shows that:

where:

•

•

•

In transformers, the attention mechanism is helpful for FS because the importance scores of features can be computed through the self-attention function [74]. As seen in Eq. (10):

where:

•

•

ViTs have shown promising potential in diverse medical imaging applications, such as representation learning, segmentation, classification, regression, and so on, especially with their capability of modeling long-range dependencies and global contextual features [75]. ViTs offer a significant contribution in brain tumor segmentation because they extract global features from MRI scans to help locate the tumor boundary with high precision, a requirement to accomplish an exact diagnosis and treatment planning [76]. Transformers are excellent for skin lesion classification because they enable the selection of key diagnostic patterns in dermoscopic images and thus better detect and classify various skin conditions like melanoma [77]. For example, ViTs are suitable for biomedical 3D medical imaging since they can efficiently process and represent complex structures, such as 3D CT scans. This capability improves the performance of deep learning models and thus enhances the feature representation and implies better analysis of medical images and, hence, better clinical outcomes. Fig. 1 shows the workflow of Deep Learning based workflow diagram and Table 2 shows the performance of different deep learning feature search techniques.

Figure 1: Workflow of Deep Learning-Based Feature Selection (FS) Techniques. This diagram illustrates the typical stages in DL-based FS, including raw medical image input, feature extraction via convolutional or transformer layers, feature importance ranking, and the final selection of diagnostically relevant features used for classification or prediction tasks

Some recent advances in DL based FS techniques, including CNNs, Autoencoders, and Transformers, are the application of these approaches in medical imaging, which increased feature extraction and selection considerably [81]. CNN-based FS uses convolutional layers to encode spatially meaningful features, Autoencoders encode to compress the data and ensure the retention of vital parts of the information, while Transformers encode to achieve global contextual feature extraction [82]. While there are advantages and disadvantages to each method, combining multiple FS techniques in hybrid methods appears to have great potential to increase accuracy in diagnostic models and reduce the black box characteristic.

Currently, FS in medical imaging is under development through hybrid approaches, which join classical statistical measurement, deep learning architectures, and optimization algorithms [83]. These methods try to overcome the deficiencies of the stand-alone FS techniques and enable their potential to improve accuracy, interpretability, and computational efficiency. Finally, the three major hybrid FS strategies are Classical + Deep Learning Approaches, Metaheuristic optimization-based FS, and Ensemble Learning for FS.

The first one, Classical + Deep Learning FS, merges traditional statistical techniques and deep learning models in feature selection in a way that preserves interpretability in the model [84]. A straightforward solution to this issue is to combine Principal Component Analysis (PCA) with CNNs. PCA reduced dimensionality by selecting the principal components, which were then fed to CNNs for feature extraction and classification. So, this hybrid strategy is aimed to soften the constraints of the ‘curse of dimensionality’ and to maintain the most usable features for diagnosis [85]. A Genetic Algorithm (GA) with Deep Neural Networks (DNN) represents another popular combination where GA is applied to select the feature subset in simulating natural evolution. This algorithm sequentially selects relevant features according to a fitness function to better generalize and scale down overfitting [86]. The expression of the feature selection process using GA and deep learning mathematically can be expressed in Eq. (11):

where

Since dimensional reduction of features has been shown to significantly impact the performance of these models for brain MRI classification, lung nodule detection [87], and histopathology image analysis, these hybrid techniques have proven successful. This review explores the use of DL in medical imaging, particularly for brain tumor analysis, covering segmentation, classification, and prediction techniques. It summarizes key contributions and provides a taxonomy of current research in the field. The article concludes by discussing limitations and future research directions for DL in medical imaging [88].

A second powerful category of algorithms is feature selection based on metaheuristic optimization, where nature-inspired algorithms perform the feature selection. This paper describes these techniques that perform an intelligent search for the optimal feature subsets, which is superior to an exhaustive search [89]. One of the metaheuristic approaches that is mainly used is the GA, which uses selection, crossover, and mutation operations to evolve an optimal feature subset. Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) is an efficient method by which FS is modeled as a swarm intelligence problem [90]. In PSO, particles (feature subsets) adjust their positions on their own best performance and the best-known feature set. Removing redundant or irrelevant features allows efficient convergence to an optimal solution [91]. Also, Ant Colony Optimization (ACO) follows the foraging behavior of ants to find different feature subsets and refine the selection with pheromone trails [92]. The PSO, which can be used for the FS, is represented mathematically in Eq. (12):

where:

•

•

•

•

•

Due to their ability to enhance classification performance without an intensive computational burden, these metaheuristic techniques have been extensively used in ECG-based heart disease detection, breast cancer classification, and tumor segmentation in MRI.

Ensemble Learning for FS is the third major approach, aggregating multiple FS techniques for better stability and generalization. Instead of using a single selection strategy, ensemble FS methods rely on several models to find the most discriminative features [93]. Bagging-based FS is one frequently used technique that uses bootstrap sampling to create multiple feature subsets and aggregates the selected features through majority voting. Implementing this approach in Random Forest FS reduces variance (and thus overfitting), which is usually what is done when implementing this [94]. Boosting-based FS is the other ensemble feature selection strategy based on improving weak FS models sequentially by focusing on misclassified instances to obtain a better fit and finally refined feature selection [95]. XGBoost FS is a well-known example of such a technique that is efficient and scalable and has been adopted in medical imaging tasks [96]. Finally, Stacking FS, which integrates multiple feature selection models and adopts a meta learner to learn which of those existing feature selection models to use to find the final feature subset with the optimal tradë between interpretability and predictive performance. Earlier, I adopted these ensemble FS techniques for multi-modal medical imaging where combining features from many imaging modalities (e.g., MRI, CT, PET) leads to more accurate diagnostics.

Hybrid FS approaches best solve the challenges with high-dimensional medical imaging data. These comprise classical methods in statistics, deep learning architectures, and metaheuristic optimization tools combined for feature selection optimization, generalization of the model, and clinical interpretability [97]. Future research on some combination of the XAI frameworks and hybrid FSs should be carried out to help ensure clinical utilization of such methods [98]. Moreover, it remains an open research challenge to provide the scalability of quantum computing–based FS in hybrid frameworks and if it could indeed redefine feature selection in medical imaging as shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: This figure illustrates the process of medical image data analysis, starting from preprocessing and feature extraction to feature selection techniques. It highlights three types of feature selection methods—Wrapper-Based, Filter-Based, and Embedded FS—which lead to selected features for model training and subsequent evaluation

Medical imaging is crucial in disease diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment planning. However, imaging data alone is seldom sufficient to base clinical decisions. Medical imaging, which consists of integrating different imaging modalities like MRI, CT, Positron PET, and US, offers an overall view of pathological conditions [99]. This will capture different anatomical and functional characteristics, e.g., MRI offers high soft tissue contrast, CT provides detailed bone structure, and PET provides metabolic activity [100]. Nevertheless, due to the large dimensionality, redundancy, and heterogeneity, when more than one data modality is integrated, new challenges arise in the FS of multi-modal data. Thus, it is essential to learn the most efficient FS techniques encompassing the most relevant features for each modality while maintaining compatibility [101].

To forcefully maximize the information extracted from multiple imaging sources but maintain collaborative diagnostic acumen, use needs to be made of multimodal feature selection. Feature redundancy is one of the significant challenges in multimodal imaging where the same or highly correlated features lie in different modalities. Concatenating features from different modalities provokes too many dimensions, hindering the performance of the machine learning models [102]. Also, other modalities may have various levels of noise, resolution, or feature scales, which makes direct integration difficult. For FS techniques to be adapted to the specific constraints of single and multimodal imaging, they must detect relevant features for the problem, filter out redundant or conflicting information, and optimize the feature space to minimize run time and preserve clinical interpretability [103].

Different fusion strategies are used to integrate multimodality features effectively. The fusion approaches determine how information should be combined from various modalities and how much these FS methods reduce dimensionality and increase model performance [104]. For instance, fusion techniques that incorporate anisotropic diffusion and cross bilateral filtering have shown promising results in retaining critical anatomical details while suppressing noise across multiple imaging modalities, thereby enhancing diagnostic accuracy [105]. In early fusion, raw features or the preprocessed (also called features) extracted using different modalities are concatenated before applying the FS techniques. This approach enables the deep learning models to learn cross-modal relationships from the beginning [106]. The three standard methods applied in early fusion for FS are PCA, Autoencoders, and Deep Embedding Networks. This method results in such a large dimension of the feature space that dimensionality reduction using Sparse Autoencoders or Variational Autoencoders (VAE) [107] is required to retain only the key features.

Early Fusion, in which features

where:

•

•

Classifier level fusion, or late fusion, refers to a fusion method where each modality is processed separately and decisions are fused later. FS is applied on each modality in isolation, and then the results are fused by an ensemble learning or voting mechanism [108]. Late fusion methods typically take advantage which have several trained classifiers over different feature sets followed by a final decision-making. Late fusion is still interpretable, but it may sacrifice cross-modal dependencies that may be helpful for more effective feature extraction [109]. In Late Fusion, features are initially classified independently, and the last prediction is a weighted sum of individual predictions [110]. As described in Eq. (14):

where:

•

•

Furthermore, in some recent works, hybrid fusion has been proposed, combining early and late fusions. A common approach for fusion methods is to identify hybrid fusion, which tries to retain the multimodal relationship while optimizing the feature selection in terms of efficiency [111]. Advanced cross-modal learning techniques have been introduced to further improve FS in multimodal medical images. These techniques take advantage of the relations between these modalities to better retrieve shared and complementary features [112]. One of the most used approaches for multi-modal FS includes CNNs and Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs). Both CNNs and RNNs (particularly Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) and Gated Recurrent Units (GRU)) are effective at extracting spatial features from imaging data and sequential dependencies in imaging data, respectively, where it is of interest to learn off of another dimension (e.g., 4D cardiac MRI, fMRI). Cross-modal dependencies across different imaging modalities can be effectively modeled by combining CNN and RNN architectures, improving FS [113].

Another important emerging technique relevant to the domain of feature selection is feature disentanglement. This approach aims to decouple high-level structural information (e.g., anatomical features) from style-based or modality-specific variations (e.g., scanner noise, brightness), allowing only the structurally informative components to be retained for downstream tasks. Feature disentanglement contributes to robust model generalization and interpretability—two of the key goals of feature selection in clinical AI systems. It is commonly implemented through variants of autoencoders or adversarial networks that enforce latent space constraints to isolate distinct feature factors. For instance, disentangled representation learning has been applied in brain MRI analysis to separate pathological features from confounding imaging attributes, improving classification accuracy and reliability. This makes it a compelling complementary technique to FS, especially in multi-institutional or multi-modal imaging studies.

Transformer-based architectures for multi-modal imaging have recently been revolutionized. These self-attention mechanisms help ViTs and Multi Modal Transformers (MMTs) to model complex interaction patterns across different modalities [114]. Due to its capability to learn efficient global feature dependencies, Transformers can be used as an efficient feature selection method for tasks where such relations between different imaging sources must be considered. Vision Transformers have been well applied in the classification of brain tumors, the prediction of Alzheimer’s, and the diagnosis of lung cancer; the performance is significantly improved through multiple modalities [115].

The emergence of Foundation Models—large-scale pretrained neural networks trained on massive and diverse datasets—has introduced a paradigm shift in feature extraction and selection. In medical imaging, models such as Vision Transformers (ViTs), CLIP, and Segment Anything Model (SAM) are increasingly adopted as universal feature encoders. These models generate rich, high-level representations that can be further refined through domain-specific feature selection techniques. Foundation Models reduce the need for extensive task-specific training and improve the quality of initial features by embedding semantic, spatial, and contextual priors. When coupled with classical or hybrid FS techniques, they enable better generalization and performance on downstream tasks such as tumor classification, organ segmentation, and disease progression modeling. Thus, Foundation Models serve not only as feature extractors but as enablers of scalable, efficient, and transfer-aware feature selection pipelines in medical imaging.

However, the success of many different FS techniques for multimodal medical imaging presents challenges. A lack of large-scale annotated multi-modal datasets, modality misalignment, and heterogeneous data distributions constrain further progress in this domain. Future research should focus on:

To improve clinical trust in the automated decision-making systems, Explainable AI (XAI) techniques must be developed for the multi-modal FS. When providing interpretable results, XAI can boost the healthcare professionals’ confidence in AI-driven decisions by showing how multi-modal data (e.g., medical images and patient records) contribute to the feature selection process [116]. Meanwhile, privacy-preserving multi-modal feature selection in distributed settings seems promising, and thus, it is investigated with Federated Learning (FL) frameworks for such scenarios in parallel. The approach of FL allows models to train on decentralized data while keeping patient privacy, which is essential to collaborative medical research, while ensuring data security [117]. Blockchain integration in imaging-based AI has emerged as a potential solution to secure data privacy, especially in neurology-related feature extraction pipelines [118]. Moreover, utilizing Quantum Computing with multi-modal FS opens fascinating applications. Processing large-scale imaging data in high dimensions is much more efficient using quantum algorithms, which can amplify this capability to enhance selecting features in complex medical data sets. One such integration of quantum computing can help provide more effective and scalable medical imaging and diagnostics [119]. For example, recent work has demonstrated the effectiveness of hybrid classical–quantum neural networks in enhancing Alzheimer’s disease detection from MRI scans. By combining classical deep learning (ResNet34) for initial feature extraction with quantum variational circuits for dimensionality reduction and classification, these models achieved notably higher accuracy than classical methods alone [120].

The field of multi-modal FS continues to evolve, and future advancements in hybrid AI models, interpretable learning techniques, and computationally efficient FS strategies are necessary to continue to develop its impact on real-world medical applications. Algorithm 2 has been included to demonstrate the feature selection approach utilized in the study.

Fig. 3 shows the multi-modal pipeline for feature selection.

Figure 3: A multi-modal feature selection (FS) pipeline where features from multiple modalities, e.g., images, signals are extracted and fused. The fused features undergo selection, followed by model training, evaluation, and the generation of output predictions

Feature disentanglement has emerged as a critical approach in enhancing generalization and interpretability in medical image analysis. The goal is to separate meaningful anatomical or pathological features from modality-specific variations such as noise, texture inconsistency, or acquisition artifacts. Recent studies demonstrate that channel-level and depth-wise disentanglement strategies can significantly improve downstream tasks like segmentation by isolating domain-invariant representations. For example, Hu et al. proposed a Contrastive Single Domain Generalization (CSDG) method that disentangles structure and style representations using channel-wise contrastive learning, enabling segmentation models to generalize better without requiring access to target-domain data [121]. Similarly, Wang and Ma introduced a depth disentanglement strategy that decouples local and global feature dependencies in a multi-stage latent space, facilitating fine-grained segmentation of small-scale anatomical structures [122]. These approaches highlight how disentangled representations—focused on structurally relevant details—can serve as effective precursors for robust feature selection. They also underscore the importance of combining spatial-channel attention and detail enhancement modules to isolate noise-free, diagnostic features in high-dimensional imaging data.

The features of quantum computing generate opportunities to advance classical computing capabilities toward solving feature selection problems in large-scale datasets with numerous dimensions [123]. Feature selection processes using classical methods become unreliable when dealing with big databases since they struggle under high computational demands for handling big feature dimensions and complex relationships between features [124]. Quantum superposition, a fundamental principle of quantum mechanics that allows a quantum system to be in multiple states at the same time, combined with quantum entanglement, a phenomenon where the quantum states of two or more objects are linked together, provides the ability to process large datasets in parallel and improve the optimization of complex problems [125]. Feature selection through the classical method requires users to search various subsets within the feature space while evaluating them. The standard function for optimization appears as follows:

where

Various proposals have been made for feature selection using quantum-based algorithms. Quantum feature selection (QFS) offers several theoretical and practical advantages over classical FS methods, particularly in the context of high-dimensional medical imaging data. First, quantum parallelism allows quantum algorithms to process multiple feature subsets simultaneously, significantly reducing the time required for subset evaluation. Second, entanglement facilitates complex correlations between features to be modeled more naturally, improving the relevance of selected features. Third, algorithms such as Grover’s search provide quadratic speedups in exploring large feature spaces, which is especially valuable for real-time diagnostic systems. These capabilities enable QFS to address the scalability and combinatorial complexity challenges that often hinder classical FS approaches in medical imaging applications.

Quantum Genetic Algorithms (QGA) perform global searches more efficiently using quantum computing, giving them the advantage of better exploration of the feature space [126]. The fitness function for a QGA is similar to the fitness function used in classical genetic algorithms. Still, it is expanded with the quantum operations used for better exploration capability [127]. The quantum k-Nearest Neighbors (k-NN) leverages quantum properties to accelerate distance computing and achieves better classification accuracy than the classical k-NN algorithm [128]. The criterion for the quantum k-NN distance function is the Euclidean distance, but quantum parallelism is utilized for faster computation. The relationship in Equation show in (16):

where

Subject to

Furthermore, the Quantum SVM provides the integration of quantum mechanics to speed up the optimization process, which is essential in high-dimensional feature space. One problem in SVM is optimizing the margin when the support vectors in between are maximized [129]. The classical SVM optimization problem is Quantum SVM, a quantum algorithm that uses quantum algorithms to obtain the minimum of this objective function more efficiently, especially for high-dimensional data [130]. One significant benefit of quantum FS over classical approaches is that it achieves substantial speedup when the dimensionality of datasets is large. Parallelism in quantum algorithms means that they can process several features in parallel, while the dimensionality of the data usually constrains classical methods [131]. It results in better searching over the feature space and, hence, better time complexity. Usually, the classical feature selection involves search over a feature space of size.

However, with Grover’s search algorithm, we can search for such selected features in quantum computers with a quadratic speedup,

In addition, feature interactions are generally easy to compute on a quantum computer and, as a result, can be represented and selected more efficiently than a classical computer. Quantum feature selection, therefore, provides the opportunity to reduce the computational time significantly and even to achieve better machine learning models’ overall performance when compared to classical models, when the domain of interest is medical imaging, genomics, or any other use case where data sets are massive. Fig. 4 illustrates the conceptual diagram of quantum feature selection.

Figure 4: Conceptual diagram of quantum feature selection (FS). It shows the process starting from quantum data input, followed by quantum feature selection, extraction algorithms, and representation. The selected features are then used for model training and evaluation, ultimately leading to the output of the model

3 Methodology (Systematic Review Process)

The proposed study discusses a systematic review methodology we followed to comprehensively analyze the role of FS in medical imaging in carrying out classical, deep learning based, hybrid, and quantum FS techniques. This review uses a methodology that guarantees a structured, transparent, and reproducible approach for recognizing, choosing, and refining the sought research articles.

A structured search strategy was designed to ensure the acquisition of comprehensive coverage of FS techniques in medical imaging. Peer-reviewed articles containing relevant information were searched from multiple high-impact databases.

3.1.1 Data Retrieval and Keywords Used

Therefore, an approach to FS techniques in medical imaging is required to achieve a well-defined and systematic search strategy. Various keyword combinations were chosen to cover multiple FS methodologies and their applications over various medical imaging modalities. All the keywords, including “Feature selection in medical imaging,” “Deep learning feature selection for medical images,” “Hybrid feature selection in healthcare,” and “Quantum feature selection for medical imaging,” were searched to widen possible areas of research.

Boolean operators (AND, OR) were further utilized to help refine the search and have greater precision in filtering out relevant literature. For example, the query examples that were used (“Feature Selection” AND “Medical Imaging” AND “Deep Learning”) guaranteed that such studies encompassed the utilization of AI-based FS methods for diagnostic imaging. Moreover, research that combines classical, metaheuristic, and deep learning based FS methods over different imaging modalities can be captured by queries such as (“Hybrid Feature Selection” OR “Metaheuristic FS” AND “MRI” OR “CT” OR “PET”). Additionally, grants were made to explore at the forefront of technologies by searching for studies that applied quantum computing to solve high-dimensional medical imaging data with the search string (“Quantum Feature Selection” AND “High-dimensional Imaging Data”).

By utilizing this structured search approach, high-quality and relevant studies that detail the evolution of FS techniques, their effectiveness in medical imaging, and their future developability could also be extracted as illustrates in Fig. 5.

Figure 5: Process of executing a search string in a research database. The flowchart starts with predefined research strings, which include keywords related to feature selection, medical imaging, deep learning, and various technologies. The search is executed, and if the criteria are met, the initial studies are retrieved. If not, the search string is updated accordingly to refine the search, continuing the process until the relevant results are found

Therefore, a systematic search was performed across well-established electronic databases to ensure a complete and well-structured review of FS techniques in medical imaging. A list of databases was developed and selected with a significant amount of care, including work with biomedical applications, computational support, and AI-based innovations in FS methodologies. As PubMed offers comprehensive coverage of biomedical and clinical imaging research, all the FS techniques applied in the real healthcare setting will be included. A search of IEEE Xplore was used to locate studies related to FS computational and engineering aspects related to AI and machine learning based approaches. At the same time, ScienceDirect offered a vast knowledge base on machine learning, deep learning, and AI-based FS methods used in diagnostics and prediction modeling tasks.

Springer was also used to study research on advanced AI methods in FS, specifically to investigate hybrid and deep learning-based approaches. MDPI was chosen as one of the best focuses on recent advances in medical AI, including FS applications in various imaging modalities like MRI, CT, PET, and ultrasound. Lastly, arXiv was used to investigate new FS methodologies that utilize quantum computing to deal with high-dimensional medical imaging data.

The search was limited to studies published between 2015 and 2025 to keep the information current and reliable and to include the latest FS techniques. This time frame was selected for examining the most modern trends and technological novelties and measuring the latest breakthroughs in the FS methodologies, including the classical statistical methods, the deep learning approaches, hybrid models, and such techniques as quantum-based strategies.

3.2 Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied to maintain the quality and relevance of selected studies.

• Studies focusing on FS techniques applied to major medical imaging modalities (MRI, CT, PET, Ultrasound, ECG).

• Publications between 2015 and 2025 to ensure the inclusion of the latest advancements.

• Peer-reviewed journal and conference papers from reputed sources.

• Non-English studies (to maintain consistency and accessibility).

• Papers focusing only on general AI-based medical imaging without FS techniques.

This rigorous selection process helped filter out studies that lacked experimental validation or did not focus on FS techniques in medical imaging.

3.3 Data Extraction & Quality Assessment

To ensure high quality and completeness of the review, the evaluation of key aspects regarding how to define the effectiveness and applicability of FS techniques in medical imaging was performed systematically. For each selected study, crucial details were extracted, including the FS technique used, whether classical, deep learning, hybrid, or quantum-based. Information about the datasets used in the studies was also collected in case some studies covered public datasets like BraTS and CheXpert. In contrast, others might have used custom dataset tools specific to their medical imaging task. The reported performance metrics also constitute one of the essential aspects considered; these include standard evaluation measures such as accuracy, AUC ROC, F1 score, and computational efficiency, enabling the comparison between several FS techniques’ effectiveness.

Further, rigorous quality assessment was performed for the studies included to ascertain their reliability and validity. This assessment was completed with several key criteria. Given priority to reproducibility: the studies had to have publicly available code, datasets, or detailed methodological descriptions. Moreover, the robustness of the FS techniques was another critical factor to include in the selection of studies, which provided comparative performance evaluations instead of isolated case studies. Finally, the test was conducted to assess the real-world applicability of FS methods by considering the studies to prove the practical implementation of FS in clinical and diagnostic imaging.

Table 3 summarizes and tabulates a comparative overview of the selected studies to provide a structured summary of the reviewed literature. It categorizes them according to applied FS techniques, analyzed datasets, and reported performance metrics. The representation is structured, concise, and informative of advancements and trends in FS for medical imaging and Fig. 6 illustrates the complete process from search to selected studies.

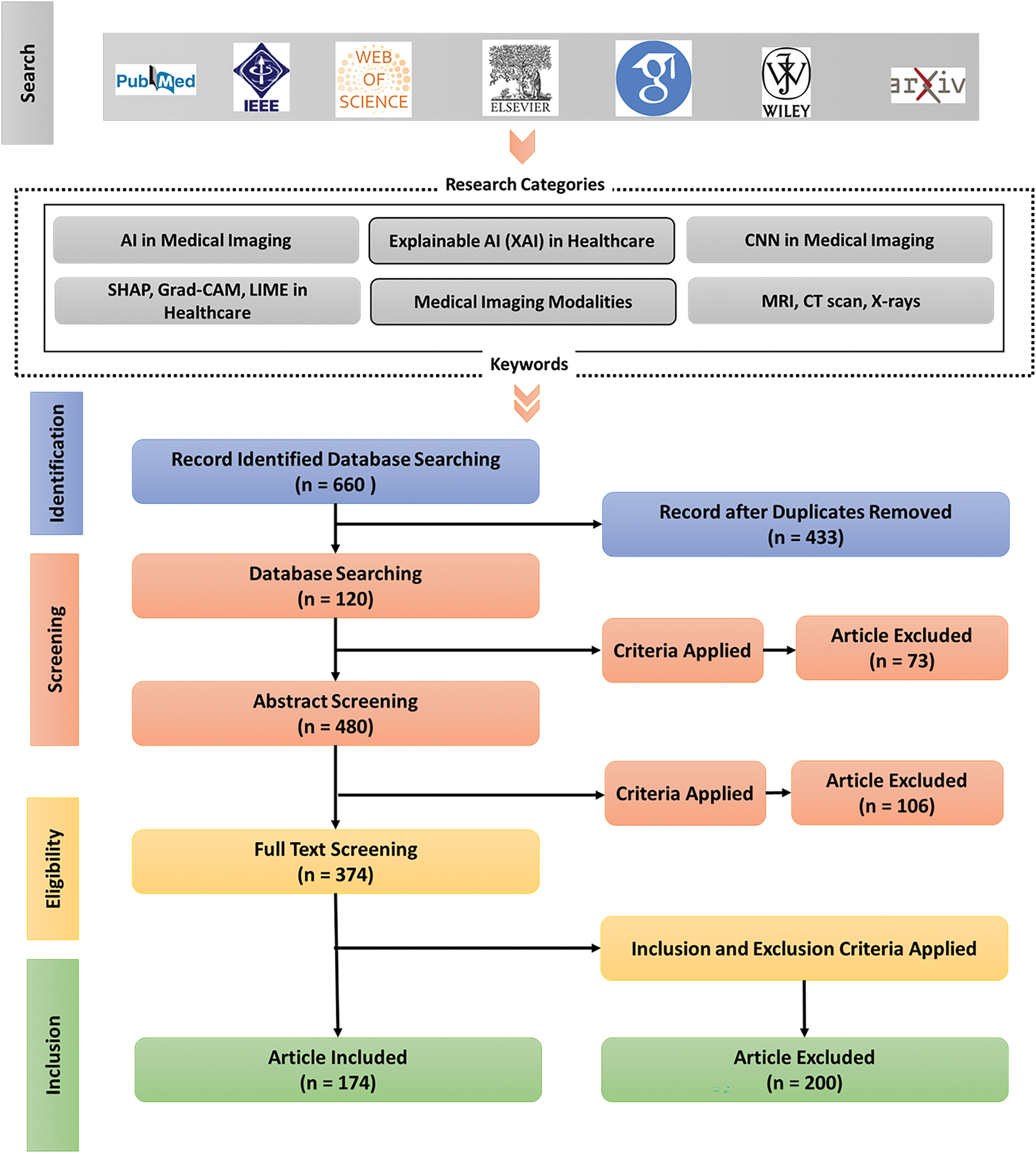

Figure 6: PRISMA flowchart, illustrating the systematic review process. It starts with database searching, where 660 records are identified using specific keywords. After removing duplicates, 433 records remain, followed by abstract screening and full-text screening. Criteria are applied at each stage, resulting in 174 articles included for the final review, while others are excluded based on inclusion and exclusion criteria

Database searching identified a total of 660 records. These records were 433 after being deduplicated. The screening that was done to remove the abstracts (n = 480, with extra cases of 47 unique records) removed 73 articles that fail the inclusion criteria. Of 374 articles identified through full-text screening there were 106 excluded, which meant that 174 of the articles were to be included in the eventual synthesis. Fig. 6 and Table 4 give a breakdown of the 200 full-text articles deemed ineligible during eligibility screening.

4 Challenges, Open Problems, and Future Directions

A lot of progress has been going in developing the existing FS techniques for the application in medical image, but there are some critical challenges and open research problems still to be solved. Nevertheless, deep learning and hybrid FS methods face their own limitation of high computational complexity and scalability to wide ranges of problems making them hard to practice in the real-world applications. Moreover, combining multi modal imaging data is challenging in terms of the redundant features of multiple modalities, the alignment of different modalities, and cross modal learning. Theoretically, FS approaches using quantum computing are quick, but have been held to be impractical on account of hardware and algorithm shortcomings. To develop such FS+DB models, one needs to consider these FS challenges with a multidisciplinary confluence, to have FS models that are efficient, interpretable, and scalable, and seamlessly combined with the clinical workflow. This section explores key challenges, open problems, and potential solutions that will define next generation AI driven medical imaging systems.

4.1 Computational Complexity & Scalability Issues

Although the FS is computationally demanding and a scalability challenge to incorporate in medical imaging, the FS is hugely complex; Challenges exist between FS field and deep learning and hybrid approaches, while great opportunity space exists for innovation and improving. This allows progress towards the direction of the optimization of this integration process and enhancement of all our solutions. Due to their nature, medical imaging datasets are naturally high-dimensional and expensive to process, train, and even make inferences from. Deep FS methods based on CNNs, Autoencoders, and ViTs enjoy better feature extraction performance. However, their feature extraction process tends to be heavy in memory usage and consumes enormous energy and training time. These models come at a high computational burden, making it difficult to use them in real-time medical applications that demand happening fast and efficiently [132]. Additionally, because the computational cost is based on feature fusion strategies, the problem of using multi-modal medical imaging data. Deep learning Mechanisms of attention Deep learning can improve multimodal picture fusion by considering fusion algorithms, modalities, and metrics. Researchers can use a graphical taxonomy and difficulties and areas of future research to better understand multimodal fusion problems and choose appropriate approaches [133].

However, one of the significant challenges for deep learning-based FS techniques is that the computational cost of those methods is very high because many parameters are used in deep architectures [134]. For example, the mathematical representation of the complexity of the based FS model can be represented as the following in Eq. (19):

where

FS techniques struggle with scale-up potential in situations involving multi-modal imaging data analysis. Combining machine learning with multimodal fusion strategies in human activity recognition using a state-of-the-art convolutional network architecture and a large dataset. The results show a clear performance improvement from multi-modal fusion and a substantial advantage from an early fusion strategy [136]. The processing requirements of multi-modal feature selection rise significantly because of differences between modalities and domain alignment requirements, which causes existing deep learning-based FS methods to be impractical during large-scale clinical deployment [137].

Researchers have explored solutions, such as lightweight deep learning models, federated learning, and quantum computing, to overcome these computational limitations. Implementing the MobileNets and EfficientNets lightweight CNN architectures resulted in substantial parameter reduction while maintaining the performance level of FS. Depth-wise separable convolutions strengthen the computational efficiency of a lightweight CNN-based FS approach, which is shown mathematically in Eq. (20):

The optimized formulation eliminates calculation redundancy and focuses on the computational path’s most crucial feature extraction layers. As such, lightweight models represent a good tradeoff of computation demand vs FS accuracy and are better suited to real-time medical imaging applications.

Moreover, federated learning is another emerging approach to alleviating computational bottlenecks in FS by providing a decentralized learning paradigm for distributed model training across various institutions. Unlike transferring the entire medical imaging dataset to a central server, FS is done locally on distributed nodes in federated learning. This reduces the computational and communication costs while keeping the patient private [138]. In particular, this approach is most useful in healthcare applications where data sharing restrictions must be considered and HIPAA and GDPR compliance is of the essence. Besides achieving scalability, Federated FS models further enable learning collectively over distinct medical centers in a way that reduces the generalizability burden at the cost of computing [139].

Besides classical and deep learning-based FS techniques, quantum computing has recently become a new hope for high-dimensional feature selection. Quantum FS techniques take advantage of quantum parallelism to process large-scale medical imaging datasets quickly [140]. Quantum Variational Circuits (QVCs) allow quantum-based FS to be mathematically formulated in Eq. (21).

where

Fig. 7 depicts the computation efficiency of classical, deep learning-based, and quantum FS candidates, showing the impact of different FS strategies on computational complexity.

Figure 7: Feature selection methods based on computational efficiency. Classical FS methods are fast and simple but may sacrifice accuracy, while deep learning FS methods offer higher accuracy at the cost of increased complexity. Hybrid FS methods combine both approaches, and quantum FS, still in an experimental stage, promises potential future speedups

This shows that although classical FS techniques are efficient in computation, they are not as capable as the DF extraction of advanced methods. However, for DL-based FS methods, though effective, the computational scalability becomes an issue for their deployment. The hybrid FS models achieve the best tradeoff between good features of classical and deep learning. Federated learning increases scalability, but in terms of privacy, it inherits the complexity of the distributed networks. However, quantum FS is theoretically promising but limited in its practical implementation and current hardware limitations.

Significant challenges to overcome deal with the computational complexity and scalability for FS to reach its full potential in medical imaging. These are very powerful when it comes to neural network-based FS methods, which are also very expensive to compute and, in such cases, require specially optimized techniques such as lightweight architectures, federated learning, or even hybrid methods for reducing computational costs. Furthermore, quantum computing is anticipated to be highly useful in high-dimensional feature selection, but more studies are needed to determine its practical adoption. We will then see interdisciplinary synergies between AI, distributed computing, and quantum technologies endeavouring to improve the computational efficiency and scalability of FS methods to be helpful for the clinic.

4.2 Interpretability & Explainability in FS

Medicine has begun to revolutionize diagnostic accuracy and efficiency using the recent development of AI-based FS approaches. Nevertheless, in the current situation, all these AI-driven FS techniques usually perform well in indicating diagnosis potential. Yet, they are not transparent in clinical practice, restricting their usage in real medical applications [142]. Deep learning models’ inherent complexity and opaqueness make them unusable for most healthcare professionals as they are not interpretable, causing them to lack trust and acceptance. In particular, this is a critical issue in healthcare, as incorrect patient care and outcomes depend directly on decisions made using AI models. However, the bridge of this gap has been constituted as a key research area to integrate interpretability and explainability into the FS models [143].

To address the interpretability challenge in AI-based FS, Explainable AI (XAI), SHAP (Shapley Additive Explanations), Grad-CAM (Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping), Hybrid FS, etc., have been proposed in the literature. XAI frameworks are aimed to help make the decision process of machine learning models understandable to humans. SHAP is one of the popular methods within XAI that assigns a value for each feature based on its contribution to the model’s prediction [144]. The equation to calculate the SHAP value in Eq. (22):

where

Besides being a key tool for improving model interpretability, another essential tool is Grad-CAM, especially in medical imaging tasks. Grad-CAM gives an intuitive means to visualize the areas of the image that most influence a CNN’s prediction (i.e., those with the strongest and highest activation) [145]. The equation of Grad-CAM in Eq. (23):

In this equation,

Here,

Improving the interpretability of AI-based FS Hybrid FS techniques, which are combinations of classical feature selection methods and deep learning models, also has a specific role in improving the interpretability of AI-based FS. For instance, the dimensionality of high-dimensional medical images can be reduced with Principal Component Analysis (PCA), and features can be found using CNN. The PCA in Eq. (25) shows as:

The transformed dataset

where

In the end, for AI-based FS methods to be clinically applied, they must also be capable of being interpreted and explained. The SHAP, Grad-CAM, and Hybrid FS approaches, along with XAI, provide promising ways of improving transparency. This will help clinicians know when to trust and use the AI model appropriately in decision-making. By combining these two techniques, an AI-driven FS system can be made both high-performance and clinically viable, leading the way for their wider adoption in healthcare.

Table 5 presents the advantages and limitations of each method.

Integrating preprocessing and spatially aware decomposition techniques for feature selection has become increasingly important in handling high-dimensional and complex datasets. Preprocessing methods such as data decomposition, spatial interpolation, and dimensionality reduction have proven effective in managing data nonlinearity and spatial dependencies, particularly in domains such as air quality prediction and medical imaging [150]. Advanced feature selection strategies now incorporate multi-criteria evaluation—e.g., minimizing redundancy while maximizing discriminative power—to enhance both interpretability and accuracy [151]. Spatially aware methods, such as relation-aware wrapper techniques, utilize graph- or tree-based structures to model relationships among features and samples, yielding more relevant and stable feature subsets [152]. These approaches have demonstrated success in medical applications, including breast cancer segmentation, where context-aware spatial decomposition has been used to improve the relevance of extracted features. Furthermore, synergistic frameworks that combine feature selection with distributed classification mechanisms address the computational and heterogeneity challenges posed by large-scale medical data, enabling scalable and efficient model training [153,154]. Hybrid and metaheuristic algorithms—particularly those employing particle swarm optimization or evolutionary multitasking—also contribute by enabling robust search across large feature spaces while facilitating knowledge transfer between related tasks [150,151,155]. These integrated strategies collectively improve classification performance, reduce model complexity, and support scalable analysis pipelines for both centralized and distributed medical imaging scenarios. Despite these advances, ongoing research is needed to balance computational efficiency, interpretability, and robustness to heterogeneous or streaming data, which remain open challenges in modern FS applications.

To complement the detailed discussion of feature selection techniques, we provide an additional comparative summary of representative state-of-the-art works in Table 6. This table highlights the diversity of FS approaches across modalities and their associated evaluation metrics, offering a concise overview of recent advances in the field.

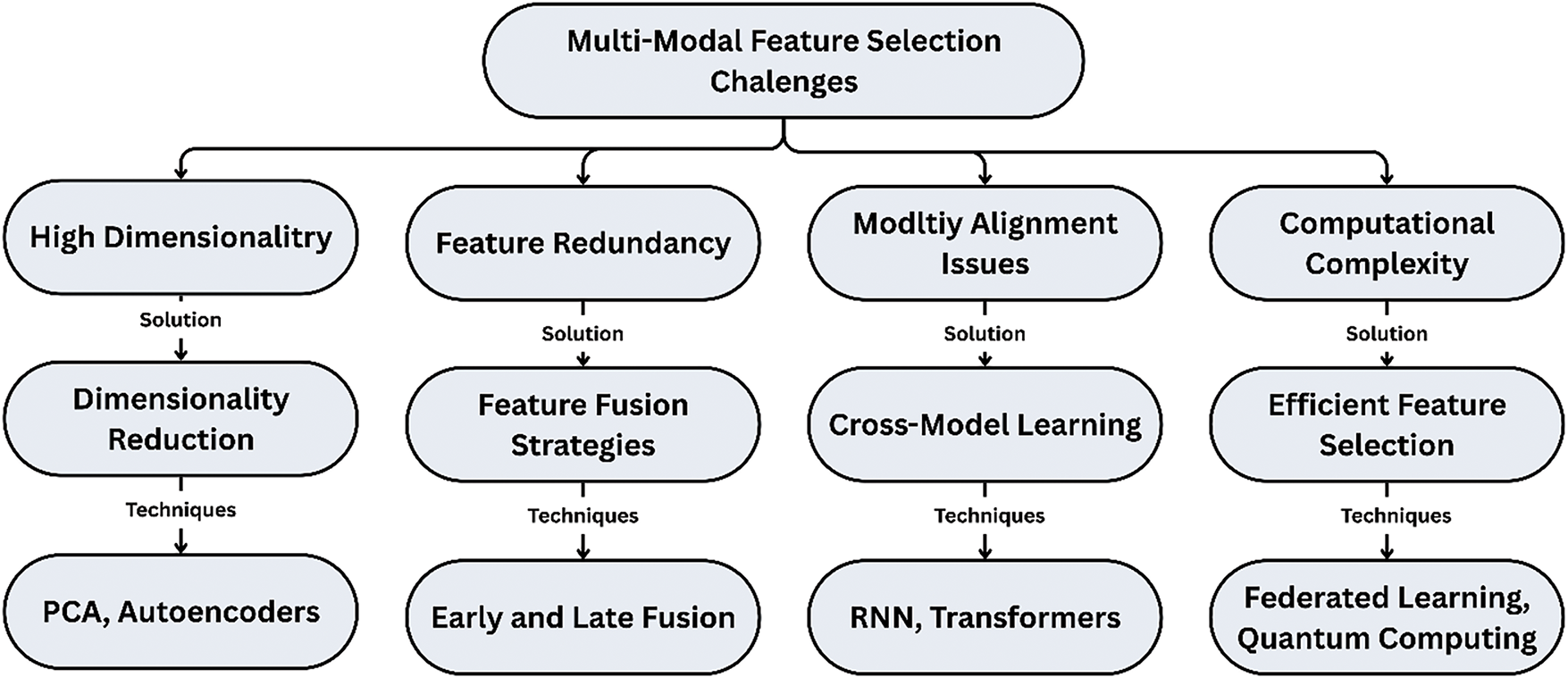

4.3 Multi-Modal Feature Selection Challenges

There is great potential in integrating multi-modal data in medical imaging with EEG, MRI, Ultrasound, and other standard medical imaging modalities such as MRI, CT, PET, etc., to make more accurate diagnoses and better inform clinical decision making. However, even with the multi-modal FS amenable to many challenging problems, challenges related to the use of such issues in real-world scenarios need to be addressed [156]. Adaptive feature extraction Deep learning may learn adaptive feature extraction by learning detailed patterns in varied datasets. Multimodal deep learning incorporates other sensory modalities because it is hard to extract useful information from unstructured data [157]. As a result, the two modalities represented by these features often have different resolutions, sampling rates, and structural representations, making them difficult to combine because they may not align with each other across modalities [158]. This challenge becomes more pronounced in multi-modal biomedical data, where visual (e.g., MRI) and non-visual (e.g., lab tests, genomics) data require distinct preprocessing pipelines and semantic alignment. To address this, recent work has focused on deep learning-based multimodal fusion strategies, offering principled frameworks for reconciling heterogeneous biomedical data [159].

Another critical challenge arises from incomplete or missing modalities, which can occur due to technical limitations, motion artifacts, or modality-specific acquisition constraints. When feature selection (FS) algorithms operate under such conditions, they risk introducing biases or disproportionate weighting of partial data, ultimately degrading model performance.

As a result, some solutions to solve these problems are suggested by enhancing integration and selection of multimodal dataset features. Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), Bayesian Fusion, and Self-Suppressed Learning are promising techniques to handle different resolutions of the modalities and missing modality in multimodal FS scenarios.

This work demonstrates that with a powerful tool, GNNs, such relationships in data can be effectively modeled, and projects such as modeling relationships in multimodal medical images have shown GNNs to be powerful. GNNs are suitable for multimodal data because each modality can be considered a node in the graph, and the relation between different features across the modalities can be represented as the edge within these nodes. In general, GNNs are applying for learning the representation of nodes for capturing the local and global dependencies by aggregating the information from the neighbor nodes. This is the equation corresponding to graph convolution operation in GNN shows in Eq. (27):

where:

•

•

•

•

•

Considering the multi-modal FS, GNNs can map to combine multi-modal features over which modalities vary. Dependencies are captured between the features, even when resolutions are different or modalities are missing. GNNs lend themselves better to fusing the information more effectively, which is very important when dealing with complex medical image analysis tasks.

Bayesian Fusion is another approach to dealing with the resolution and missing modality challenge in multi-modal FS. This approach considers feature selection as a probabilistic model and computes the probability of various feature subsets based on the available data on all the modalities. Bayesian fusion helps combine data uncertainly and variably between modalities. The general formulation of such Bayesian fusion model is shown in Eq. (28):

where:

•

•

•

•

This method uses Bayesian inference to consider the uncertainty in the data caused by missing modalities and different resolutions, and hence, it provides more precise feature selection in multi-modal data sets.

This problem can also be addressed using Self-Supervised Learning (SSL). In contrast, SSL techniques present little burden on the availability of labeled data and utilize the structure of the data itself to produce meaningful representations of input features. SSL can learn features from the available modality even if some modality is missing or incomplete by exploiting the complex and inherently existing relationships among the data. In SSL, the general objective of the function is to minimize the reconstruction error between the original and predicted data, which can be stated in Eq. (29) as:

where:

•

•

•

In the sense of multi-modal FS, SSL could be employed to extract representation from incomplete data, whereas it infers missing information from one modality using the other available media. The main strength of this approach is that when training data is scarce and imaging modalities are unavailable.

In short, solving the problem of resolving different resolutions and missing modalities in multi-modal feature selection can be facilitated by techniques like GNNs, Bayesian Fusion, and Self-Supervised Learning. Bayesian Fusion modulates data fusion and Uncertainty; GNNs can capture the relationship between different modalities; Self-Supervised Learning can generate robust feature representation even without entirely being given information. These solutions improve the effectiveness of multi-modal FS methods so that they can deliver more accurate and reliable diagnostic tools in the presence of real medical imaging data complexities. Fig. 8 illustrates the multimodal features selection with techniques.