Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Adapting Convolutional Autoencoder for DDoS Attack Detection via Joint Reconstruction Learning and Refined Anomaly Scoring

1 Department of Digital Analytics, Yonsei University, Seoul, 03722, Republic of Korea

2 Department of Industrial Engineering, Yonsei University, Seoul, 03722, Republic of Korea

3 Department of Industrial & Management Engineering, Korea National University of Transportation, Chungju, 27469, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: Haemin Jung. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(2), 2893-2912. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.067211

Received 27 April 2025; Accepted 20 August 2025; Issue published 23 September 2025

Abstract

As cyber threats become increasingly sophisticated, Distributed Denial-of-Service (DDoS) attacks continue to pose a serious threat to network infrastructure, often disrupting critical services through overwhelming traffic. Although unsupervised anomaly detection using convolutional autoencoders (CAEs) has gained attention for its ability to model normal network behavior without requiring labeled data, conventional CAEs struggle to effectively distinguish between normal and attack traffic due to over-generalized reconstructions and naive anomaly scoring. To address these limitations, we propose CA-CAE, a novel anomaly detection framework designed to improve DDoS detection through asymmetric joint reconstruction learning and refined anomaly scoring. Our architecture connects two CAEs sequentially with asymmetric filter allocation, which amplifies reconstruction errors for anomalous data while preserving low errors for normal traffic. Additionally, we introduce a scoring mechanism that incorporates exponential decay weighting to emphasize recent anomalies and relative traffic volume adjustment to highlight high-risk instances, enabling more accurate and timely detection. We evaluate CA-CAE on a real-world network traffic dataset collected using Cisco NetFlow, containing over 190,000 normal instances and only 78 anomalous instances—an extremely imbalanced scenario (0.0004% anomalies). We validate the proposed framework through extensive experiments, including statistical tests and comparisons with baseline models. Despite this challenge, our method achieves significant improvement, increasing the F1-score from 0.515 obtained by the baseline CAE to 0.934, and outperforming other models. These results demonstrate the effectiveness, scalability, and practicality of CA-CAE for unsupervised DDoS detection in realistic network environments. By combining lightweight model architecture with a domain-aware scoring strategy, our framework provides a robust solution for early detection of DDoS attacks without relying on labeled attack data.Keywords

With the rapid expansion of digital infrastructure, cyber threats are evolving at an unprecedented pace. Among these, Distributed Denial-of-Service (DDoS) attacks remain a critical challenge, overwhelming targeted systems by flooding them with a massive amount of malicious traffic [1]. Detecting DDoS attacks early and accurately is crucial to mitigating impact on network availability and security.

Accordingly, anomaly detection techniques are widely employed for DDoS attack detection, as such attacks inherently deviate from normal network behavior. Recently, deep learning-based models, particularly autoencoder architectures [2], have gained traction due to their ability to learn normal traffic patterns in an unsupervised manner [3]. Autoencoders achieve this by learning a compact representation of normal network traffic through an encoder-decoder structure [4]. Once trained on normal data, an AE can reconstruct normal traffic with high accuracy, whereas anomalous traffic, which deviates from learned patterns, tends to exhibit higher reconstruction errors. By using reconstruction error as an anomaly score, normal and abnormal traffic can be effectively distinguished [5].

Among these, convolutional autoencoders (CAEs) have demonstrated strong performance in analyzing network traffic sequences by capturing local dependencies [6]. However, existing CAE-based models still suffer from two fundamental limitations. First, CAEs tend to over-generalize during reconstruction, making it difficult to distinguish between normal and anomalous traffic [7]. Because these models are highly expressive, they can sometimes reconstruct even anomalous data with low error, leading to a high false negative rate. For an effective detection mechanism, the model should accurately reconstruct normal traffic while struggling to reconstruct anomalous samples. Second, most CAE-based methods rely on average reconstruction error as an anomaly score, which presents two key issues. As the sequence length increases, this score becomes less representative of the most recent anomalies, reducing detection sensitivity. Additionally, the reconstruction error alone does not capture the severity or potential harm of an anomaly. This is particularly problematic in DDoS detection, where distinguishing between harmful and benign anomalies is essential to avoid false alarms.

To address these challenges, this paper proposes a novel CAE-based anomaly detection framework that enhances DDoS detection through joint reconstruction learning and a refined anomaly scoring method. The core component of this framework is a two-stage CAE model in which two consecutive autoencoders, each with a different filter allocation, perform a joint reconstruction task. This process amplifies reconstruction errors for anomalous data while maintaining high accuracy for normal traffic, improving anomaly separability. In addition to architectural enhancements, we introduce an improved anomaly scoring mechanism that refines detection by incorporating exponential decay weighting and relative traffic volume adjustments. The exponential decay weighting emphasizes recent anomalies, preventing older, irrelevant data from distorting the detection process, while the relative traffic volume adjustment helps capture the risk level of each anomaly, ensuring that high-risk DDoS attacks are prioritized.

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed framework, we conduct extensive experiments using real-world network traffic data. The results demonstrate that our framework outperforms existing CAE-based and supervised models in detecting DDoS attacks, achieving higher precision and recall. This study highlights the importance of both model architecture and anomaly scoring mechanisms in improving anomaly detection performance, particularly in highly imbalanced datasets such as DDoS detection scenarios.

In summary, the main challenges in anomaly-based DDoS detection include the over-generalization of CAE models and the limitations of reconstruction-based scoring in capturing temporal urgency and risk severity. To overcome these, we propose a joint reconstruction framework with asymmetric architecture and a risk-aware anomaly scoring method that together improve both anomaly separability and detection accuracy. The main contributions of this study are summarized as follows:

• We propose a novel CAE-based anomaly detection framework CA-CAE that performs joint reconstruction via two consecutive autoencoders with asymmetric filter allocation, effectively amplifying reconstruction errors for anomalies.

• We introduce a refined anomaly scoring mechanism that integrates exponential decay and relative traffic volume to emphasize recent and high-risk anomalies.

• We conduct extensive experiments on real-world network traffic, demonstrating that CA-CAE achieves an F1-score of 0.934, significantly outperforming baselines.

• We validate the individual contributions of each component—model architecture, exponential decay, and risk-aware scoring—through ablation studies and hyperparameter sensitivity analysis.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 provides background on DDoS detection and autoencoder-based methods. Section 3 presents the proposed framework, detailing its architecture and anomaly scoring mechanism. Section 4 discusses experimental setup and results, comparing our framework-based model with baseline models. Finally, Section 5 concludes with key takeaways and future research directions.

2.1 Autoencoder-Based Anomaly Detection

Autoencoder is an artificial neural network trained in an unsupervised manner so that does not require class labels for learning [2]. It consists of an encoder part, which compresses input data into a low-dimensional vector, and a decoder part, which reconstructs the compressed vector back to a higher dimension. Namely, autoencoder can be viewed as a composite function of an encoding function

Here,

Training objective for autoencoder is to minimize the distance between the input and the output by generating reduced but important feature sets from the original features. Therefore, optimal parameter sets

The distance between the input and the output is called reconstruction error.

Autoencoders are widely used in anomaly detection due to their ability to learn compact representations of normal data. By training exclusively on normal traffic, autoencoder-based models can detect anomalies based on reconstruction errors, as anomalous instances tend to exhibit higher errors due to their deviation from learned normal patterns. Since reconstruction error quantifies the degree of deviation, it is commonly used as an anomaly score in detection models. A data instance is classified as anomalous when its anomaly score exceeds a predefined threshold, which is determined based on the characteristics of the dataset and the specific requirements of the detection process.

One of the key advantages of autoencoder-based detection models is their ability to handle data imbalance issues, a common challenge in real-world environments. Since these models do not require labeled anomalous samples, they are particularly effective in scenarios where anomalies are rarely present, such as DDoS attack detection, where attack instances constitute only a small fraction of overall network traffic. Furthermore, because the model learns the distribution of normal data rather than specific attack patterns, it can detect previously unseen anomalies without requiring additional retraining. This adaptability makes autoencoder-based approaches highly effective for various anomaly detection tasks.

Among the various autoencoder models, CAEs are particularly effective for processing high-dimensional time-series data like network traffic, as they leverage convolutional operations to capture local dependencies within each sequence or window [9]. Despite these advantages, CAEs still face critical limitations in DDoS detection, such as over-generalization and ineffective anomaly scoring.

2.2 Strategies for Autoencoder-Based Anomaly Detection

To improve anomaly detection performance, autoencoder-based models typically adopt one of two strategies. One approach focuses on enhancing the model’s ability to accurately reconstruct normal data, often by modifying the model architecture. A common technique is stacking, where multiple single-layer autoencoders are combined to create a stacked autoencoder, which has shown strong performance in detecting outliers [10]. Another study proposed an asymmetric stacked autoencoder, consisting of three encoders and a single decoder, further improving feature extraction for anomaly detection [11].

While these architectures can enhance feature extraction, they do not fundamentally resolve a key limitation of autoencoder-based anomaly detection: the reconstruction error overlap between normal and anomalous data. This overlap can cause models to inadvertently reconstruct anomalies too well, reducing their effectiveness in distinguishing between normal and attack traffic. Recent studies have also pointed out that vanilla AEs may suffer from excessive generalization, potentially reconstructing anomalous inputs as well as normal ones [12].

Alternatively, modifying the anomaly scoring method can also improve detection performance. One example is the Reconstruction along Projection Pathway (RaPP) model, which achieved high performance by adjusting the anomaly score without altering the learning objective [13]. Unlike conventional approaches that rely solely on the final reconstruction error, RaPP computes an alternative anomaly score by utilizing intermediate representations from both the encoder and decoder. By incorporating these additional layers, the model captures more nuanced deviations in data.

However, despite its improved scoring method, RaPP still relies on average reconstruction error, which has notable limitations. Specifically, it fails to prioritize recent anomalies and does not explicitly account for traffic volume and intensity, both of which are crucial for identifying DDoS attacks. As a result, while RaPP improves certain aspects of anomaly detection, it remains insufficient for scenarios where anomalies evolve dynamically over time or occur in bursts, as seen in large-scale DDoS attacks.

Given these limitations, there is a need for more effective architecture and a refined anomaly scoring mechanism specifically designed for DDoS detection. While increasingly complex models such as vision transformer variants have been explored in recent anomaly detection literature [14], we intentionally pursue performance gains through a lightweight convolutional autoencoder with minimal architectural changes. Our proposed framework addresses these challenges by introducing a joint reconstruction learning approach that amplifies the distinction between normal and anomalous traffic while leveraging an improved anomaly detection score that incorporates temporal importance and relative traffic volume.

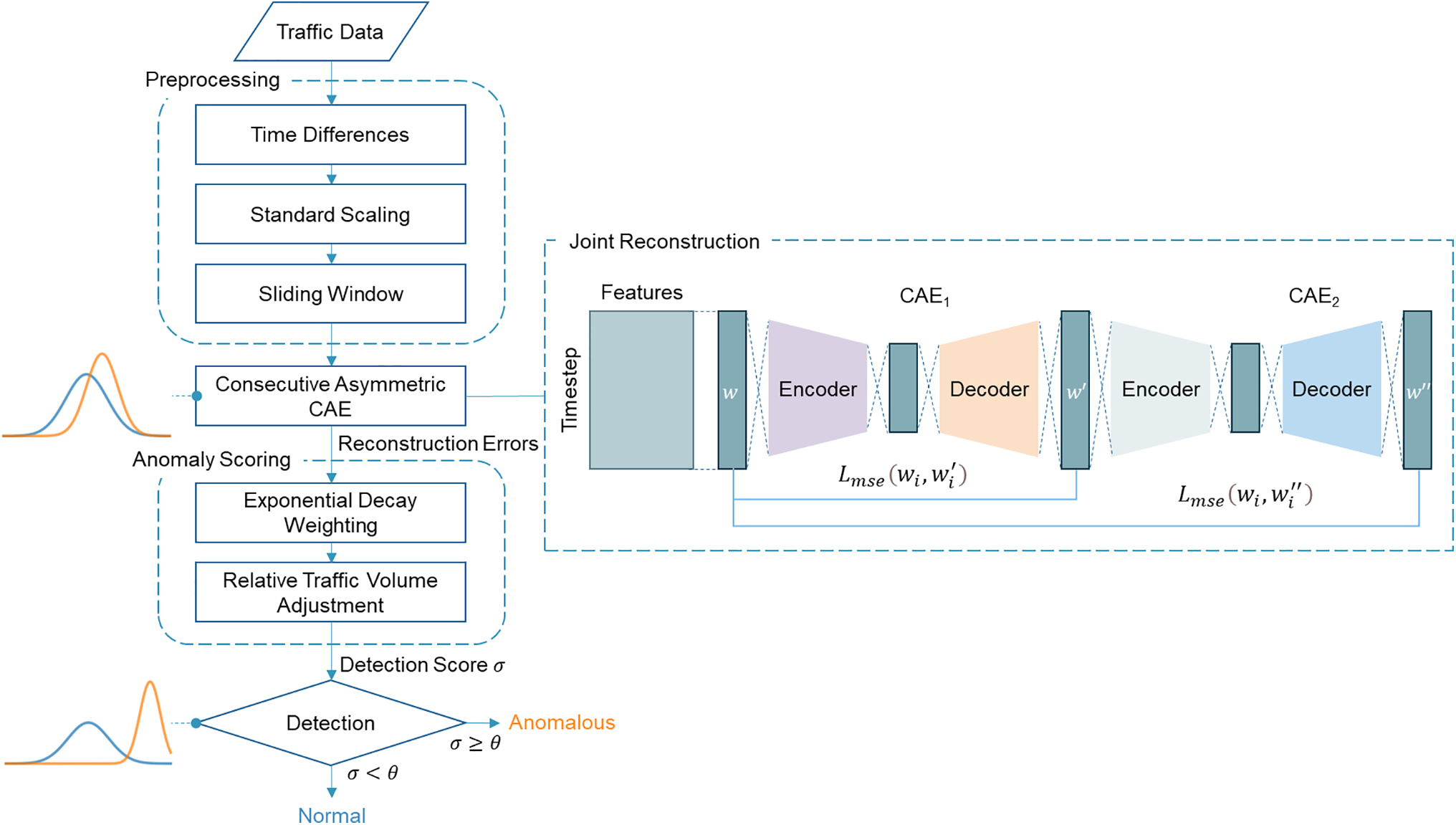

This section provides a detailed explanation of the framework for adapting a CAE for DDoS attack detection through joint reconstruction learning and refined anomaly scoring. The overall structure of the proposed methodology is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Overview of our proposed framework

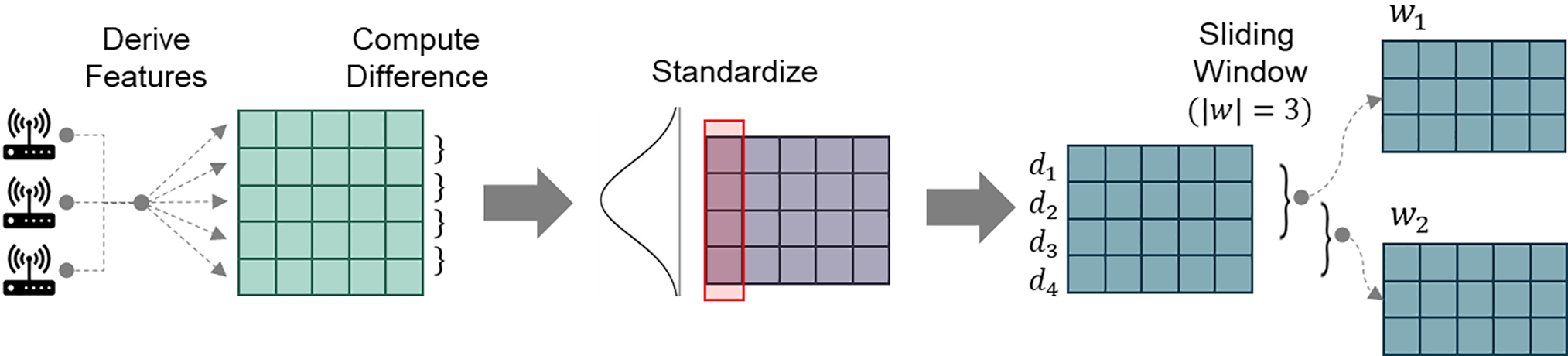

Network traffic data is sequential data where each traffic record contains multiple features collected by network devices. Since normal traffic patterns can vary across different devices, we preprocess the data by computing the difference between consecutive time steps instead of using absolute values. This transformation, commonly used in time-series analysis, helps stabilize the data and reduce device-specific variations [15]. The overall preprocessing flow is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Preprocessing

Next, the computed differences are standardized to follow a normal distribution, ensuring consistency across features. Finally, we segment the traffic sequence into overlapping windows of fixed length (or window size)

3.2 Consecutive Asymmetric Convolutional Autoencoder

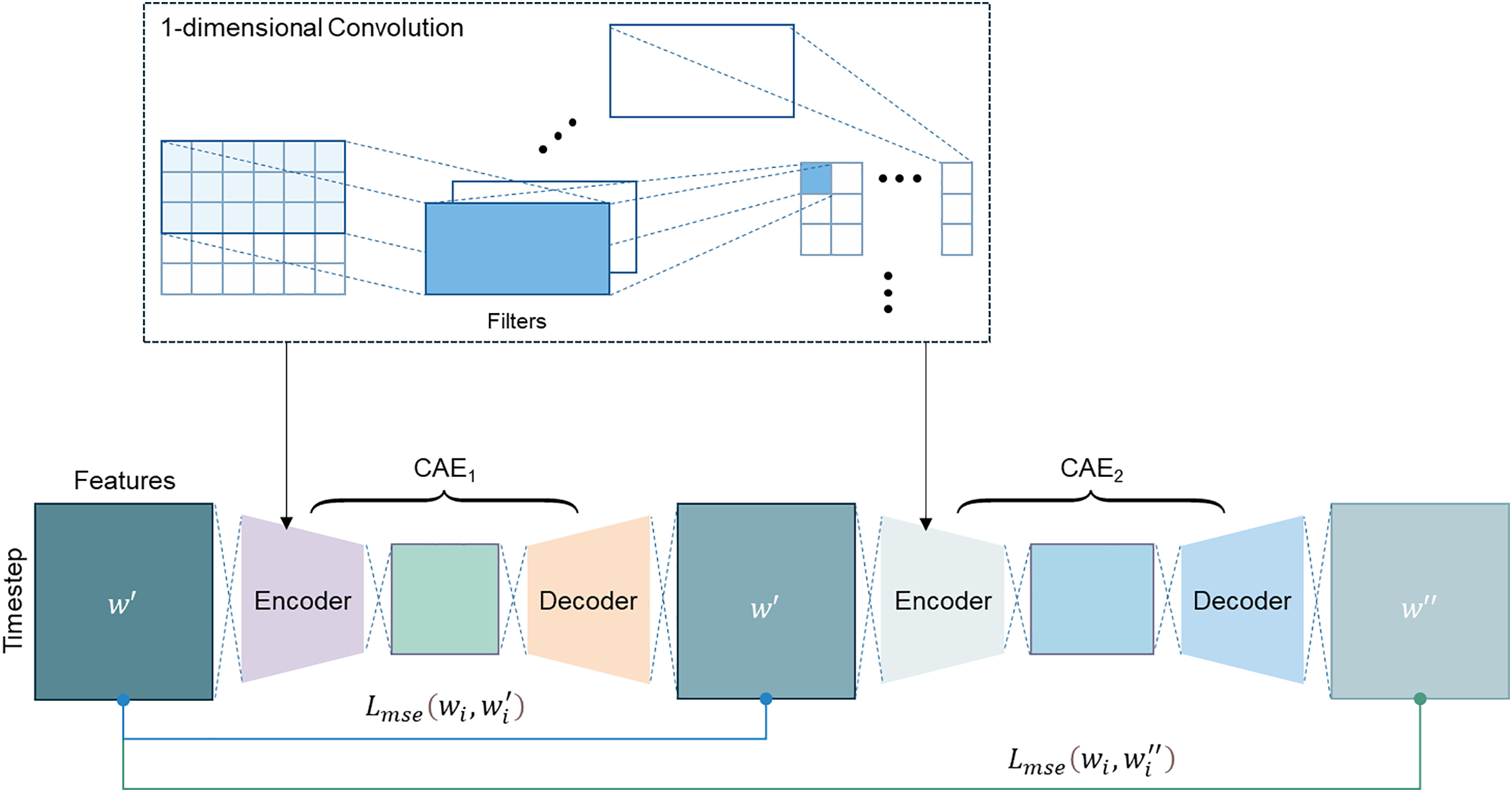

Single CAEs often struggle to effectively separate normal and anomalous data, as they tend to reconstruct both with similar accuracy. To address this limitation, we propose Consecutive Asymmetric CAE (CA-CAE), a model featuring joint reconstruction task and asymmetric architecture. Fig. 3 illustrates CA-CAE, which consists of two autoencoders connected sequentially. Specifically, the output of the first autoencoder (CAE1) serves as the input to the second autoencoder (CAE2), leading to two consecutive reconstruction processes. This sequential reconstruction helps amplify the distinction between normal and anomalous data, making anomalies more detectable.

Figure 3: Architecture of CA-CAE

CA-CAE shares similarities with stacked autoencoders, but it differs in two key aspects: (1) its loss function, which is designed to enhance anomaly separation, and (2) its asymmetric architecture, where each autoencoder has a different number of filters. These modifications improve the model’s ability to distinguish between normal and anomalous traffic more effectively.

Unlike conventional stacked architectures, CA-CAE deliberately employs an asymmetric configuration where CAE2 has a greater capacity (i.e., more convolutional filters) than CAE1. This design allows CAE2 to perform a more complex and finer reconstruction, placing a higher burden on the model when processing inputs. For normal traffic, the learned feature representation remains sufficiently robust to undergo this more difficult reconstruction, resulting in low reconstruction error. In contrast, anomalous traffic, which deviates from learned normal patterns, struggles through the second reconstruction stage, resulting in amplified reconstruction errors. This asymmetric setup thus increases the separation between normal and anomalous data, enhancing detection performance.

The sample-wise loss function for the joint reconstruction task is defined as follows (Eq. (6)).

where

The role of CAE1 is not merely to reconstruct the input

From another perspective, the transformation of

We hypothesize that this joint reconstruction task increases the separation between normal and anomalous sequences in terms of reconstruction error distribution. Since reconstructing the original data through two consecutive steps is a more complex task than single-step reconstruction, we expect that normal sequences will be reconstructed with higher precision, while anomalous sequences will retain higher reconstruction errors. This assumption is validated in Section 4.2.2, where we demonstrate that CA-CAE significantly enhances the contrast between normal and anomalous reconstruction errors, improving DDoS detection performance.

3.3 Refined Anomaly Scoring for DDoS Attack Detection

In CAE-based anomaly detection, anomalies are typically identified when the anomaly score exceeds a pre-determined threshold. To enhance DDoS attack detection, we propose a refined detection score, which extends the conventional anomaly score by replacing the average reconstruction error with a more adaptive metric. Our detection score incorporates two key factors: temporal importance and relative traffic volume, ensuring a more accurate assessment of anomalous traffic.

First, we apply an exponential decay to weigh recent time points more heavily when computing the average reconstruction error, ensuring that the detection score is more influenced by recent anomalies. Next, we introduce a risk factor, which quantifies the potential harm of network traffic based on its volume, and adjust the detection score accordingly. By integrating these factors, our detection score provides a more effective and context-aware measure for distinguishing DDoS attack traffic from normal network behavior.

Average reconstruction error is one of the most widely used anomaly scores for CAE-based detection. However, as the window size (or sequence length) increases, it becomes less effective because it fails to emphasize recent anomalies. For example, if a DDoS attack has just occurred but the sequence contains a large proportion of earlier normal data, the average reconstruction error remains low despite a high error at recent time steps. This highlights a trade-off between incorporating historical information and maintaining high detection sensitivity.

To address this issue, we adopt the concept of exponential decaying, commonly used in time-series forecasting, to assign higher weights to recent observations while gradually reducing the influence of older data points [16]. By applying exponential decay, the anomaly score could be more responsive to recent anomalies. The decayed (or weighted) anomaly score is defined as follows (Eq. (7)).

where

As a result, the weighting sequence follows

A major limitation of using average reconstruction error as an anomaly score is its inability to reliably distinguish DDoS attacks from other benign anomalies, leading to a high false positive rate. In particular, sequences containing abnormal traffic patterns that are unrelated to an actual attack may be misclassified as DDoS incidents.

To address this issue, we refined the detection score by incorporating relative traffic volume, which represents the potential risk posed by the traffic. Anomalies with high reconstruction error but low traffic volume are unlikely to be DDoS attacks, even when their anomaly scores exceed the threshold. Therefore, adjusting the detection score based on traffic intensity helps reduce false positives while maintaining high sensitivity to actual attacks.

To quantify relative traffic volume, we extract features that directly represent network load. Specifically, we use the total number of transmitted bytes and packets, as these features provide a direct measure of network activity (described further in Section 4.1.2). The norms of these features are computed, and min-max scaling is applied to normalize them within the sequence, ensuring comparability across different time steps.

Since DDoS attacks manifest as sudden spikes in traffic, relative traffic volume is computed only at the final timestep of each sequence, rather than over the entire sequence. This ensures that the detection score reflects the most recent traffic state, improving its responsiveness to real-time attack patterns.

We refer to the relative traffic volume value as the risk coefficient (

where

We consider the following scenario for our scoring: when the average reconstruction error is already low enough,

To satisfy these conditions, the interpolating function

We adopt the Softplus function

Incorporating the safety coefficient

This formulation ensures smooth interpolation based on the safety level, effectively adjusting the detection score according to the traffic risk assessment while ensuring non-negative values.

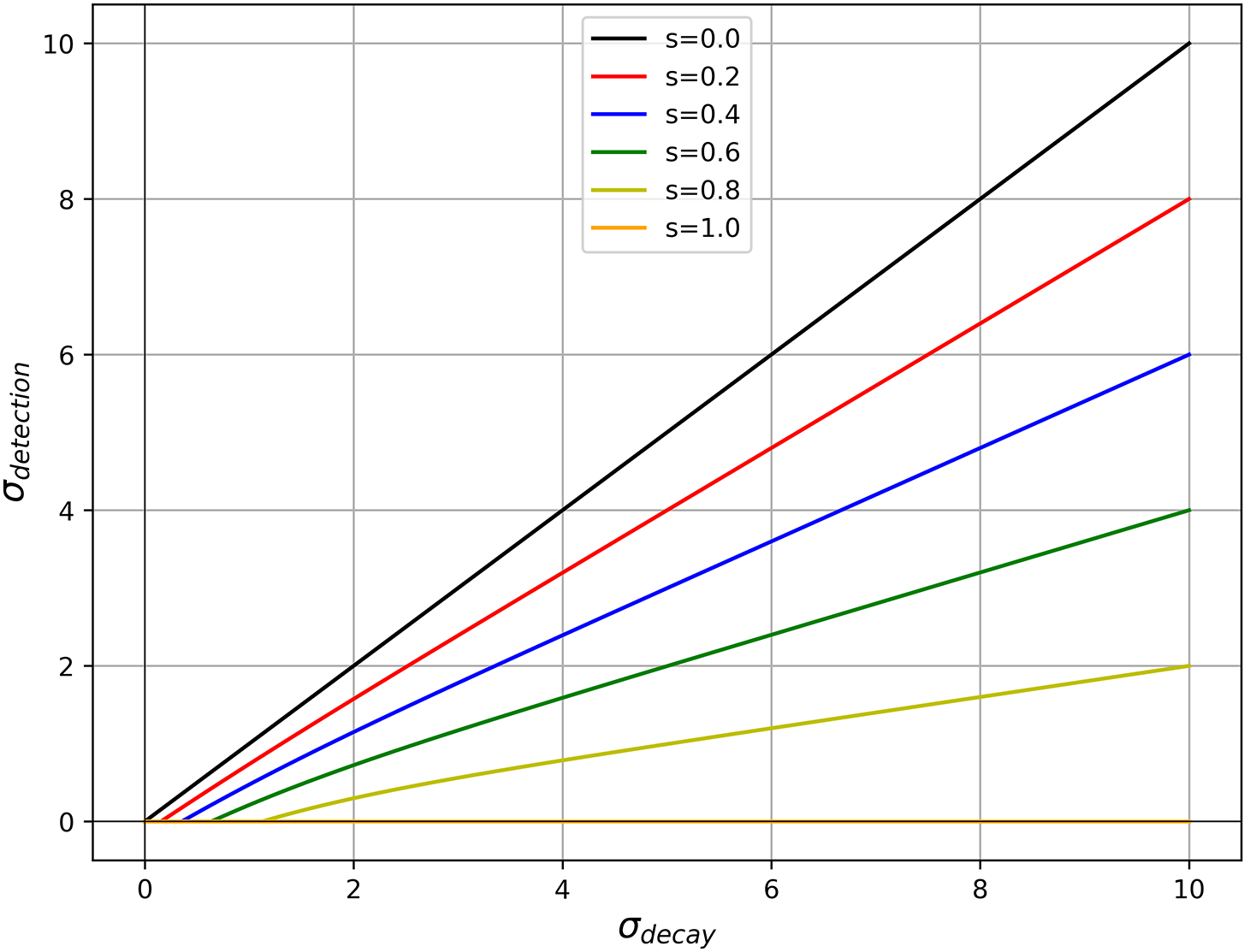

Fig. 4 illustrates the behavior of the detection score function with respect to different safety coefficients. As the safety level increases, the detection score is reduced, preventing low-risk anomalies from being misclassified as DDoS attacks. When the safety coefficient

Figure 4: Effect of safety coefficient on detection score

To further illustrate how the Softplus function adjusts the final detection score based on the safety level, consider a numerical example. Let’s assume a decayed anomaly score

If the safety coefficient

Here, the detection score is significantly reduced, mitigating potential false positives for low-risk anomalies. Otherwise, if the safety coefficient

This example highlights how the safety coefficient adaptively lowers the detection score for less critical anomalies, ensuring that high-risk, high-volume DDoS attacks are prioritized while effectively managing false alarms.

3.4 Training and Inference Workflow

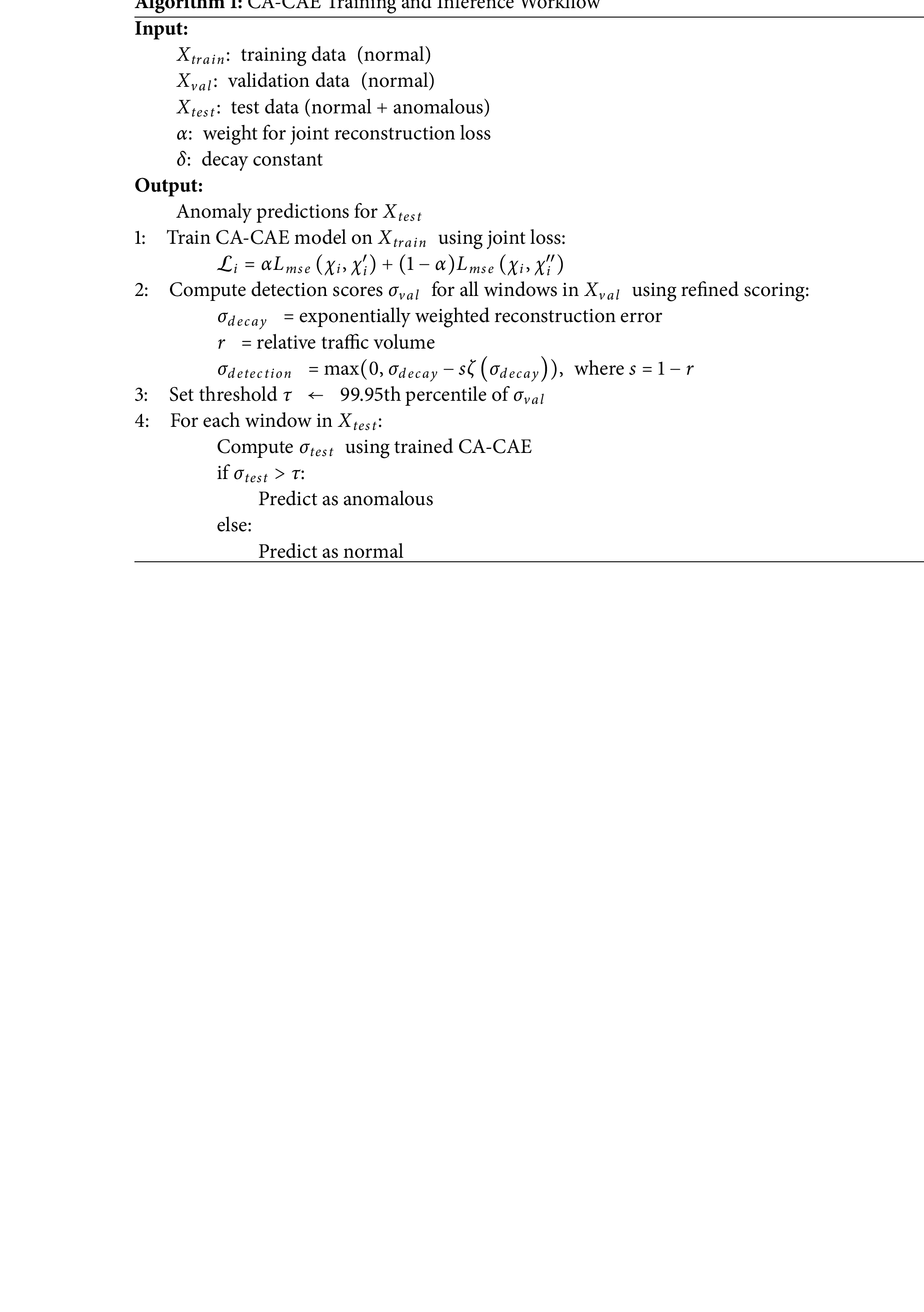

We summarize the overall CA-CAE training and inference procedure in the form of a simplified pseudo code in Algorithm 1, which outlines model training on normal traffic, threshold selection on validation data, and test-time detection on unseen traffic.

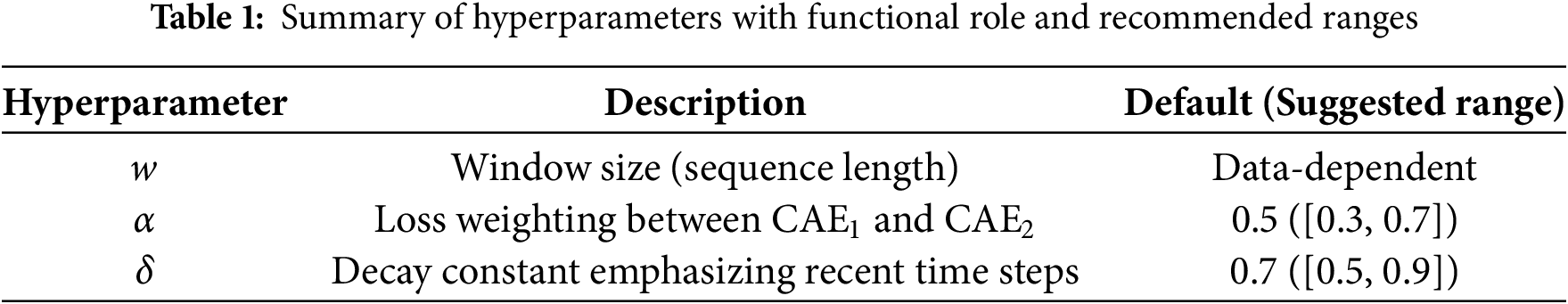

3.5 Hyperparameter Tuning Considerations

Our framework introduces several hyperparameters, including window size

The window size

These values can be selected using simple tuning strategies such as grid or randomized search, guided by the operational context and model objectives.

We conducted experiments on a dataset provided by a software company. The traffic data was collected from the company’s network router using Cisco NetFlow, a protocol for network traffic monitoring. The dataset spans two weeks, from August 1st to August 14th, 2020, with traffic data collected at 1-min intervals. We used the first week’s traffic as training data and the second week’s traffic as test data.

The dataset consists of 16 Internet Protocols (IPs), among which 5 IPs include attack traffic, while 11 IPs contain only normal traffic. During training, only normal sequences were used to train the CA-CAE model, whereas both normal and anomalous sequences were included in the test phase.

Due to the rarity of DDoS attacks, the dataset exhibits a high degree of class imbalance, with 99.9% normal data and only 0.0004% anomalous data. Specifically, the dataset contains 190,817 normal instances and 78 anomalous instances, meaning that 78 windows are defined as anomalous.

Each traffic record includes 12 features, such as bytes, packets, and source IP entropy, which provide key indicators of network behavior.

We extracted the following key features from the dataset for DDoS detection:

• Entropy of IP addresses and port numbers. During a bandwidth DDoS attack, the number of unique source IP addresses and source port numbers increases significantly, leading to higher entropy [17]. Conversely, the entropy of destination IP addresses and destination port numbers decreases, as a large volume of traffic is directed towards a single target.

• Total size of bytes and packets. The total volume of bytes and packets in incoming traffic is a useful indicator for DDoS detection, as attack traffic tends to be significantly larger than normal traffic [18].

• Ratio and entropy of protocols. DDoS attacks often involve botnets flooding the target server with traffic using a single protocol. This causes a spike in the ratio of a specific protocol compared to normal conditions. The dominant protocol also varies depending on the attack type—User Datagram Protocol (UDP) flooding increases the ratio of UDP packets, while Internet Control Message Protocol (ICMP) flooding increases the ratio of ICMP packets [19]. As a result, protocol entropy decreases during an attack.

• Entropy of TCP flags. In TCP SYN flooding attacks, the proportion of TCP packets increases. However, this alone is insufficient for detection. Instead, we analyze the entropy of TCP flags to determine whether the TCP three-way handshake is functioning normally.

Among these features, entropy-based metrics are computed using the following formula:

The effectiveness of combining traffic volume indicators such as total byte and packet count with entropy-based metrics has also been demonstrated in recent studies [20], reinforcing the relevance of our selected feature set.

As described in Section 3.1, for each variable, the difference between time steps

For evaluation, we computed the precision, recall, and F1-score as defined in Eqs. (16)–(18). Since this is a binary classification task, our evaluation metrics are derived from the confusion matrix. Specifically, a true positive denotes a case where an anomalous instance is correctly detected. Given the severe class imbalance in our network traffic dataset, these metrics specifically reflect the model’s performance in detecting the anomaly class.

To determine the decision threshold for anomaly detection, we adopted a validation-based quantile thresholding strategy using only normal data. After training the CA-CAE model, we computed the final anomaly scores on a separate hold-out validation set composed exclusively of normal sequences (20% of the training data). This validation set, which was not used during training or testing, serves to assess the model’s generalization performance under normal conditions.

Based on the distribution of validation scores, we considered several high-quantile candidates—specifically the 99.90th, 99.95th, and 99.99th percentiles—as potential thresholds. These candidate thresholds were evaluated on the test set, and the threshold corresponding to the 99.95th percentile (i.e., top 0.05%) consistently yielded the best F1-score across multiple runs. We therefore selected it as the final threshold for anomaly detection.

This procedure ensures that the decision boundary aligns with realistic deployment conditions, where labeled attack data may not be available. An overly conservative threshold (i.e., set too high) would reduce recall by failing to detect actual attacks, while an overly lenient threshold (i.e., set too low) would result in a high false positive rate. The proposed quantile-based thresholding offers a principled and reproducible way to balance sensitivity and precision, thereby enabling robust DDoS detection in highly imbalanced scenarios.

4.2 Performance Gains through Joint Reconstruction and Refined Scoring

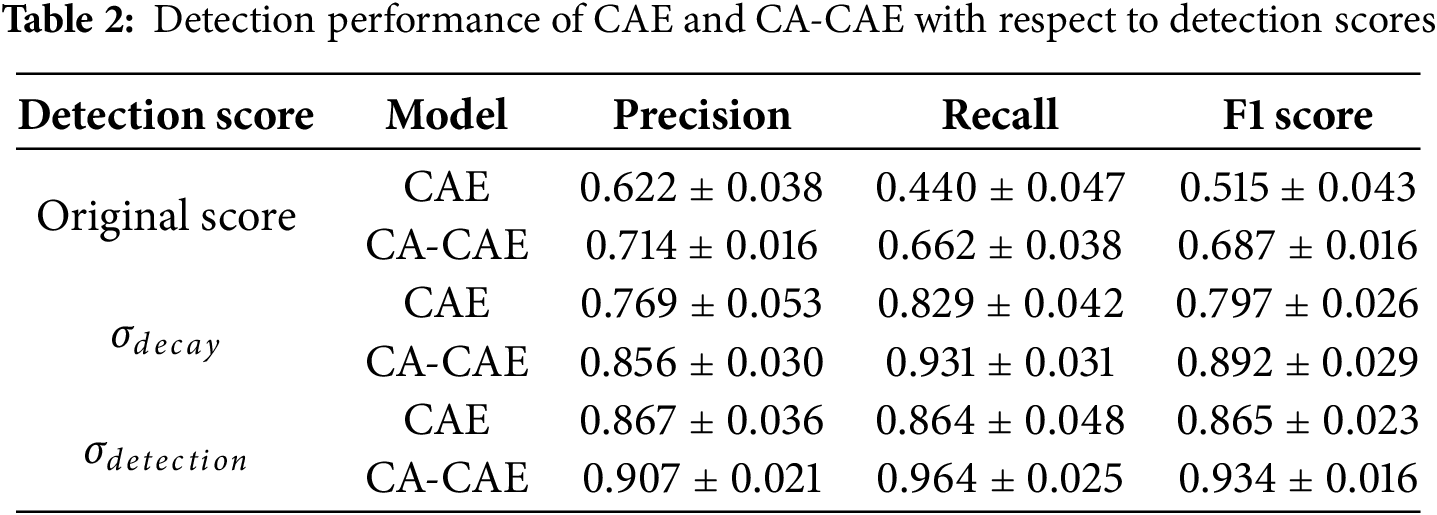

4.2.1 Detection Performance by Scoring Strategy

Table 2 presents the detection performance of CAE and CA-CAE using different detection scores. To ensure the statistical robustness of our findings, we represented the mean and standard deviation of the performance metrics from 10 independent runs for each model. Across all types of detection scores, CA-CAE consistently outperformed CAE. Additionally, our proposed scoring techniques significantly improved detection performance across both models. By applying exponential decay to emphasize recent reconstruction errors, the F1-score improved by over 20%, suggesting that historical traffic information can introduce noise, and that mitigating its influence leads to significant gains in detection performance. Furthermore, incorporating the risk factor based on traffic volume further enhanced the accuracy of DDoS attack detection.

To statistically validate the significant performance enhancements of our proposed CA-CAE over the baseline CAE model, we conducted Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Tests on the F1-scores for each of the three scoring methods. The results consistently demonstrated that CA-CAE achieved a statistically significant improvement in F1-score over CAE across all three scoring methods (p < 0.05). This robust statistical significance, observed uniformly across different scoring methods, confirms that the architectural enhancements through joint reconstruction learning and the refined anomaly scoring mechanisms lead to performance gains in DDoS attack detection compared to CAE-based detection.

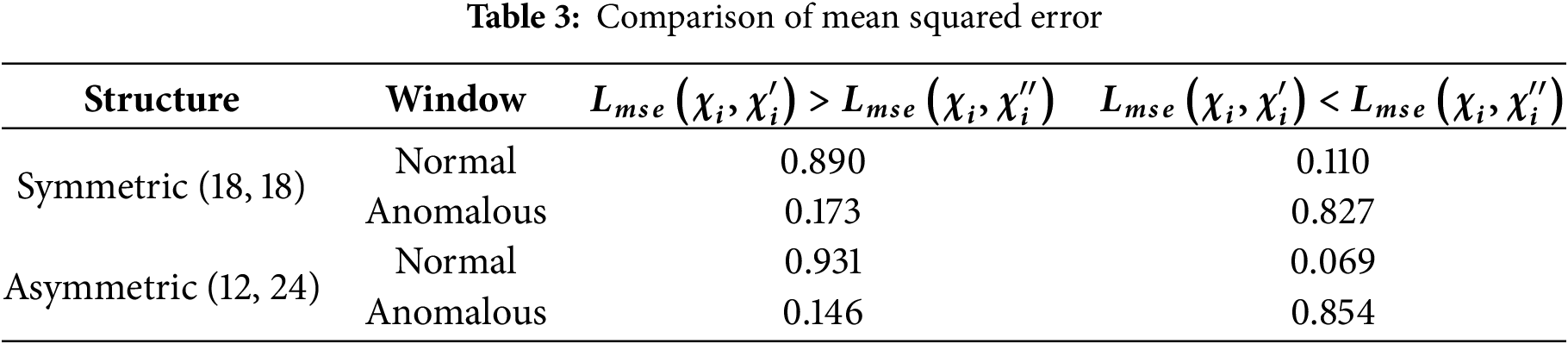

4.2.2 Reconstruction Behavior in Joint Autoencoders

To evaluate the effect of joint reconstruction and asymmetric architecture in CA-CAE, we compared two mean squared errors:

Table 3 summarizes the results when the total number of filters across the two CAEs is 36. The notation (M, N) indicates the number of filters assigned to CAE1 and CAE2, respectively. In the symmetric configuration (18, 18), 89.0% of normal windows showed improved reconstruction after joint reconstruction, while only 17.3% of anomalous windows did. In contrast, 82.7% of anomalous windows exhibited an increased reconstruction error. This indicates that the joint reconstruction task strengthens the model’s ability to reconstruct normal traffic while making anomalous traffic more difficult to reconstruct. This discrepancy increases the separation between the reconstruction error distributions of normal and anomalous sequences, thereby enhancing anomaly detectability.

This effect is further amplified in the asymmetric configuration (12, 24), where more filters are allocated to CAE2, which is responsible for the more challenging reconstruction task. As shown in Table 3, in the symmetric setting, the gap between the normal and the anomalous was 0.717 (0.890

Since CAE2 reconstructs an already compressed representation from CAE1, allocating more filters allows it to extract richer features for normal traffic. However, for anomalous data, the increased model complexity amplifies reconstruction errors rather than improving reconstruction quality, thereby further widening the gap between normal and anomalous reconstruction errors.

While the absolute numerical increase in the reconstruction error gap between normal and anomalous samples may appear modest, its functional impact is meaningful in the context of highly imbalanced anomaly detection. Even a slight increase in this gap enhances the model’s ability to distinguish anomalous samples with higher confidence, thereby contributing to improved anomaly separability and more reliable detection performance.

Importantly, this improvement was achieved through a simple yet effective architectural adjustment: reallocating a fixed total number of filters asymmetrically across the two reconstruction stages. This lightweight design change avoids increasing model complexity while still producing a measurable benefit in detection quality.

4.2.3 Computational Cost and Model Efficiency

To evaluate the computational cost of our proposed CA-CAE model, we compared its parameter size and inference latency with the baseline CAE. For a representative configuration, the CAE model consisted of 18 convolutional filters, while the CA-CAE allocated 12 filters in CAE1 and 24 in CAE2.

The number of trainable parameters was 2934 for CAE and 6084 for CA-CAE, representing a 207% increase. We further measured the inference time using a single window of size 10 (with 12 input features) on an NVIDIA T4 GPU. Each experiment was repeated 10 times with 1000 inference iterations per trial to obtain statistically stable measurements.

The baseline CAE required an average of 0.495 ms per forward pass, with a standard deviation of 0.011 ms, whereas the proposed CA-CAE required 0.987 ms on average, with a standard deviation of 0.015 ms.

While the CA-CAE architecture introduces a moderate increase in computational cost—both in terms of parameter size and inference time—this overhead is accompanied by a substantial improvement in detection performance. The average inference latency remains within a range compatible with near-real-time network monitoring.

In this study, we placed greater emphasis on achieving reliable anomaly detection under severe class imbalance, even at the cost of slight increases in latency and model size. We view this design as a pragmatic trade-off between computational efficiency and model robustness. Furthermore, the architecture remains amenable to deployment-oriented optimizations such as pruning and quantization, which can mitigate computational burden in practice.

4.2.4 Effect of Detection Score Definitions

In addition, we examined the impact of different detection score definitions based on reconstruction errors. Table 4 presents the detection performance when using

These findings suggest that CAE1 effectively reconstructs normal traffic while introducing distortions in anomalous traffic, thereby enhancing the distinguishability between normal and anomalous instances. As a result, CAE2 struggles more with anomalies, further amplifying the reconstruction error gap. This sequential difficulty in reconstruction ultimately improves recall by making anomalies more easily detectable.

4.3 Impact of Window Size and Exponential Decay

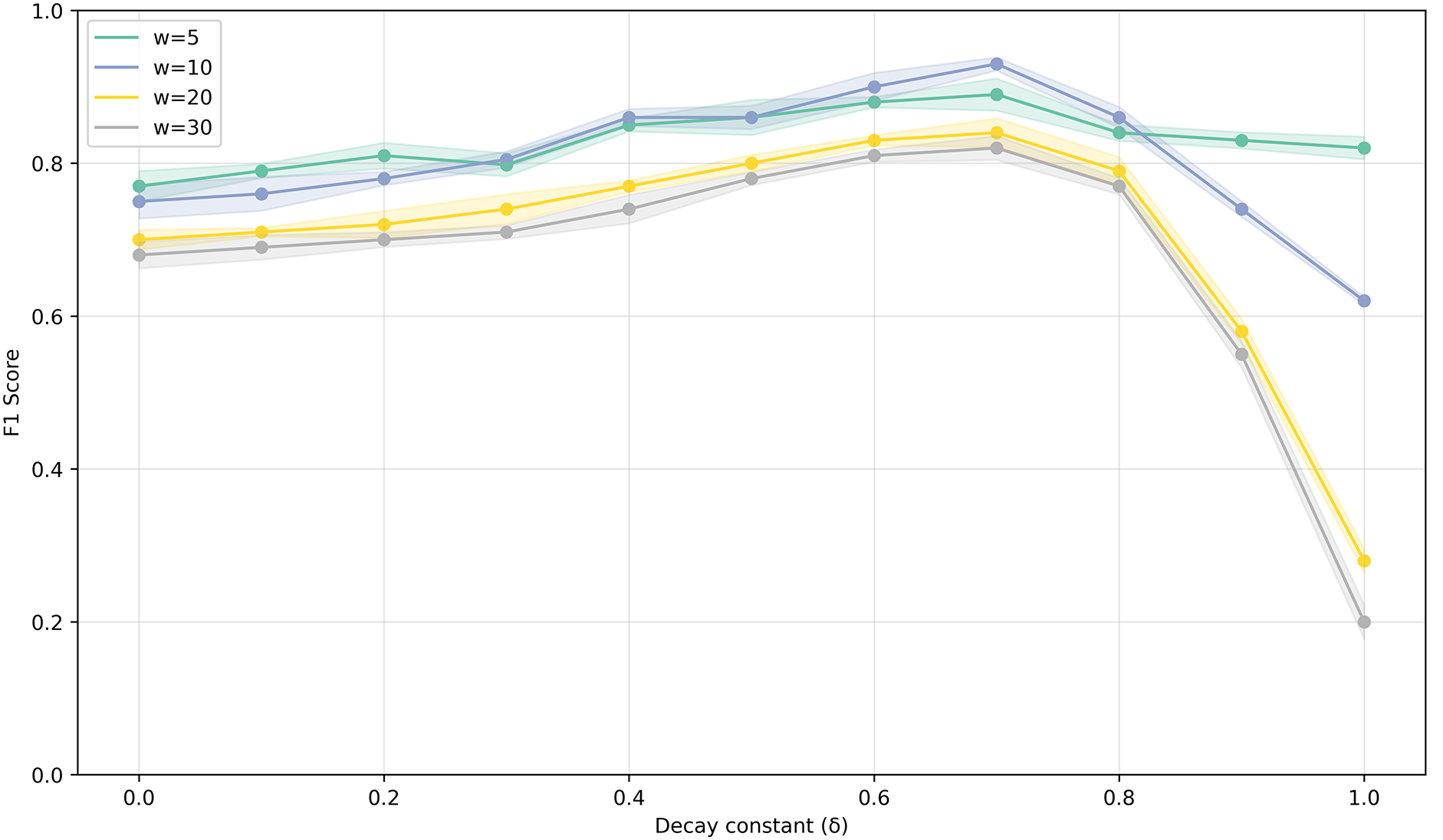

As discussed in Section 3.3.1, anomaly detection in sequential data requires balancing historical context with real-time adaptability. To analyze this trade-off, we evaluated the impact of two hyperparameters: window size

Fig. 5 illustrates how the F1-score varies with difference values of

Figure 5: Detection performance across different decay constants and window sizes

For smaller window sizes (w = 5), the decay constant has minimal effect, as the sequence already consists mostly of recent data. However, for larger window sizes (w = 20 and w = 30), performance drops significantly as

The best performance was achieved when the window size w was 10 and the decay constant

These results validate the effectiveness of the exponential decay mechanism in balancing the benefits of historical information and the need for real-time responsiveness. Furthermore, applying exponential decay reduces the model’s sensitivity to the choice of window size, as even suboptimal windows maintain stable performance by focusing primarily on recent observations.

4.4 Comparison with Baseline Models

While the primary focus of this study is on improving CAE-based anomaly detection through joint reconstruction learning and refined scoring, we also compared our proposed CA-CAE model against several representative baseline algorithms to evaluate its relative performance in a broader context.

Specifically, we included one supervised learning model and two unsupervised anomaly detection models for comparison.

The supervised baseline is the LSTM Classifier [22], a recurrent neural network trained on labeled attack data. Although it can effectively capture sequential traffic patterns, its reliance on labeled datasets limits its ability to generalize to novel or evolving attack types.

The unsupervised baselines are:

• Isolation Forest [23]: A tree-based anomaly detection algorithm that isolates anomalies by recursively partitioning the feature space. It assumes that anomalies are easier to separate (i.e., require fewer splits) than normal data.

• RaPP: An enhanced autoencoder model that calculates anomaly scores not only based on the final reconstruction error but also by aggregating deviations across multiple layers in the encoder and decoder pathways.

• LSTM-VAE [24]: A recurrent variational autoencoder that detects anomalies in time-series data by modeling normal temporal patterns and identifying low-probability sequences based on reconstruction likelihood.

Finally, CAE serves as our direct baseline to verify the effectiveness of joint reconstruction and refined anomaly scoring.

Table 5 presents the precision, recall, and F1-score for each model. As shown, CA-CAE consistently achieves superior performance, with an F1-score of 0.934—significantly higher than the best-performing baseline, the LSTM-VAE, which attained 0.811.

From these results, several important observations emerge. While supervised models such as the LSTM Classifier perform moderately well, their reliance on labeled data limits their scalability to unseen attack patterns. Notably, Isolation Forest exhibited extremely low precision despite a moderate recall, likely due to its sensitivity to threshold selection and its inability to effectively discriminate rare anomalies in highly imbalanced traffic datasets. RaPP, while improving upon standard autoencoders by leveraging intermediate representations, still falls short in fully capturing temporal importance and traffic-specific risks essential for DDoS detection. LSTM-VAE achieves relatively strong performance; however, it may still exhibit limitations in distinguishing subtle anomalies or adapting to sudden shifts in traffic behavior.

In contrast, our proposed CA-CAE model significantly outperforms all baselines by integrating architectural improvements with a domain-aware anomaly scoring method, resulting in superior performance in real-time DDoS attack detection.

This study introduced CA-CAE, an anomaly detection framework for DDoS detection that integrates asymmetric joint reconstruction learning with a refined anomaly scoring method. Our experimental results demonstrate that the proposed approach significantly improves anomaly separability and detection accuracy.

A key finding is that asymmetric joint reconstruction enhances the distinction between normal and anomalous data. By allocating more filters to the second CAE, which handles a more challenging reconstruction task, the model reconstructs normal data with lower error while amplifying reconstruction errors for anomalous data. This sequential reconstruction difficulty increased the gap between normal and abnormal reconstruction errors, with the gap widening from 0.717 to 0.785 in the asymmetric setting, thereby making anomalies more easily distinguishable.

In addition to architectural improvements, our refined anomaly scoring method further boosts detection performance. The use of an exponential decay filter prioritizes recent traffic patterns, while adjusting scores based on relative traffic volume ensures that high-risk anomalies are appropriately emphasized. These refinements resulted in notable improvements across all evaluation metrics, reinforcing the critical role of scoring mechanisms in anomaly detection.

Compared to baseline models, CA-CAE consistently outperformed both supervised and unsupervised approaches. While the LSTM classifier achieved moderate performance, its reliance on labeled data limits its adaptability to unseen attacks. Traditional autoencoder-based methods, such as CAE and RaPP, also struggled to effectively distinguish between normal and abnormal traffic. In contrast, CA-CAE achieved an F1-score of 0.934, significantly surpassing the best-performing baseline model.

Despite these promising results, several challenges remain. The model’s sensitivity to hyperparameters—particularly the decay factor and window size—could affect performance stability. Although exponential decay mitigates this issue to some extent, adaptive parameter tuning strategies would further improve robustness. Additionally, while this study focused on DDoS attack detection, applying CA-CAE to broader cybersecurity threats such as data exfiltration and advanced persistent threats remain an important avenue for future work.

In addition, recent advances in distributed and semantic anomaly detection, such as federated learning and the use of large language models, offer new research opportunities. For instance, LLM-AE-MP demonstrates the potential of integrating LLMs with autoencoder-based architectures for more contextualized detection of web-based threats [25]. Exploring such directions could extend CA-CAE to more intelligent detection frameworks.

Finally, real-time deployment considerations require further investigation. Although CA-CAE demonstrated strong offline performance, optimizing computational efficiency for high-speed, real-world network environments will be critical for practical adoption. Addressing these challenges will further enhance the applicability and impact of CA-CAE in real-world cybersecurity systems.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to express sincere gratitude to Smart Systems Lab for their invaluable support and guidance throughout this research.

Funding Statement: This research was supported by Korea National University of Transportation Industry-Academy Cooperation Foundation in 2024.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Seulki Han; Methodology, Seulki Han; Validation, Seulki Han, Sangho Son and Won Sakong; Investigation, Seulki Han, Sangho Son and Won Sakong; Writing—original draft preparation, Seulki Han, Sangho Son, Won Sakong and Haemin Jung; Writing—review and editing, Seulki Han, Sangho Son, Won Sakong and Haemin Jung; Supervision, Haemin Jung; Funding acquisition, Haemin Jung. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Yaar A, Perrig A, Song D. Pi: a path identification mechanism to defend against DDoS attacks. In: 2003 Symposium on Security and Privacy; 2003 May 11–14; Berkeley, CA, USA. p. 93–107. doi:10.1109/SECPRI.2003.1199330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Hinton GE, Salakhutdinov RR. Reducing the dimensionality of data with neural networks. Science. 2006;313(5786):504–7. doi:10.1126/science.1127647. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Vaiyapuri T, Binbusayyis A. Enhanced deep autoencoder based feature representation learning for intelligent intrusion detection system. Comput Mater Contin. 2021;68(3):3271–88. doi:10.32604/cmc.2021.017665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Charte D, Charte F, del Jesus MJ, Herrera F. An analysis on the use of autoencoders for representation learning: fundamentals, learning task case studies, explainability and challenges. Neurocomputing. 2020;404:93–107. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2020.04.057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Sakurada M, Yairi T. Anomaly detection using autoencoders with nonlinear dimensionality reduction. In: Proceedings of the MLSDA 2014 2nd Workshop on Machine Learning for Sensory Data Analysis. 2014 Dec 2; Gold Coast Australia, QLD, Australia. p. 4–11. doi:10.1145/2689746.2689747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Park S, Kim M, Lee S. Anomaly detection for HTTP using convolutional autoencoders. IEEE Access. 2018;6:70884–901. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2018.2881003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Cheng Z, Wang S, Zhang P, Wang S, Liu X, Zhu E. Improved autoencoder for unsupervised anomaly detection. Int J Intell Syst. 2021;36(12):7103–25. doi:10.1002/int.22582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Charte D, Charte F, García S, del Jesus MJ, Herrera F. A practical tutorial on autoencoders for nonlinear feature fusion: taxonomy, models, software and guidelines. Inf Fusion. 2018;44:78–96. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2017.12.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Andresini G, Appice A, Di Mauro N, Loglisci C, Malerba D. Multi-channel deep feature learning for intrusion detection. IEEE Access. 2020;8:53346–59. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2980937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Vincent P, Larochelle H, Lajoie I, Bengio Y, Manzagol A, Bottou L. Stacked denoising autoencoders: learning useful representations in a deep network with a local denoising criterion. J Mach Learn Res. 2010;11(12):3371–408. [Google Scholar]

11. Majumdar A, Tripathi A. Asymmetric stacked autoencoder. In: 2017 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN); 2017 May 14–19; Anchorage, AK, USA. p. 911–8. doi:10.1109/IJCNN.2017.7965949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Lunardi WT, Lopez MA, Giacalone JP. ARCADE: adversarially regularized convolutional autoencoder for network anomaly detection. IEEE Trans Netw Serv Manage. 2023;20(2):1305–18. doi:10.1109/TNSM.2022.3229706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Kim KH, Shim S, Lim Y, Jeon J, Choi J, Kim B, et al. Rapp: novelty detection with reconstruction along projection pathway. In: International Conference on Learning Representations; 2020 Apr 30; Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. [Google Scholar]

14. Sana L, Nazir MM, Yang J, Hussain L, Chen YL, Ku CS, et al. Securing the IoT cyber environment: enhancing intrusion anomaly detection with vision transformers. IEEE Access. 2024;12:82443–68. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3404778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Hyndman RJ, Athanasopoulos G. Forecasting: principles and practice. 3rd ed. Melbourne, VIC, Australia: OTexts; 2018. [Google Scholar]

16. Ostertagová E, Ostertag O. The simple exponential smoothing model. In: The 4th International Conference on Modelling of Mechanical and Mechatronic Systems; 2011 Sep 20–22. Herlany, Slovak Republic. p. 380–84. [Google Scholar]

17. Wang R, Jia Z, Ju L. An entropy-based distributed DDoS detection mechanism in software-defined networking. In: 2015 IEEE Trustcom/BigDataSE/ISPA; 2015 Aug 20–22. Helsinki, Finland. p. 310–7. doi:10.1109/Trustcom.2015.389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Malialis K, Devlin S, Kudenko D. Distributed reinforcement learning for adaptive and robust network intrusion response. Connect Sci. 2015;27(3):234–52. doi:10.1080/09540091.2015.1031082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Zhou B, Li J, Wu J, Guo S, Gu Y, Li Z. Machine-learning-based online distributed denial-of-service attack detection using spark streaming. In: 2018 IEEE International Conference on Communications (ICC); 2018 May 20–24; Kansas City, MO, USA. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/ICC.2018.8422327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. AlSaleh I, Al-Samawi A, Nissirat L. Novel machine learning approach for DDoS cloud detection: bayesian-based CNN and data fusion enhancements. Sensors. 2024;24(5):1418. doi:10.3390/s24051418.doi:. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Salahuddin MA, Pourahmadi V, Alameddine HA, Bari MF, Boutaba R. Chronos: DDOS attack detection using time-based autoencoder. IEEE Trans Netw Serv Manag. 2022;19(1):627–41. doi:10.1109/TNSM.2021.3088326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Malhotra P, Vig L, Shroff G, Agarwal P. Long short term memory networks for anomaly detection in time series. In: ESANN 2015: European Symposium on Artificial Neural Networks, Computational Intelligence and Machine Learning; 2015 Apr 22–24. Bruges, Belgium. p. 89–94. [Google Scholar]

23. Liu FT, Ting KM, Zhou ZH. Isolation forest. In: 2008 Eighth IEEE International Conference on Data Mining; 2008 Dec 15–19; Pisa, Italy. p. 413–22. doi:10.1109/ICDM.2008.17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Park D, Hoshi Y, Kemp CC. A multimodal anomaly detector for robot-assisted feeding using an LSTM-based variational autoencoder. IEEE Robot Autom Lett. 2018;3(3):1544–51. doi:10.1109/LRA.2018.2801475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Yang J, Wu Y, Yuan Y, Xue H, Bourouis S, Abdel-Salam M, et al. LLM-AE-MP: web attack detection using a large language model with autoencoder and multilayer perceptron. Expert Syst Appl. 2025;274:126982. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2025.126982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools