Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Hybrid Feature Selection and Clustering-Based Ensemble Learning Approach for Real-Time Fraud Detection in Financial Transactions

1 Department of Management Information Systems (MIS), School of Business, King Faisal University (KFU), Al-Ahsa, 31982, Saudi Arabia

2 Department of Network Technology, College of Information Engineering, Jinhua University of Vocational Technology, Jinhua, 321017, China

3 Department of Network Technology, Jinhua Polytechnic Wintec International College, Waikato Institute of Technology (Wintec), Hamilton, 3204, New Zealand

* Corresponding Author: Naif Almusallam. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advanced Algorithms for Feature Selection in Machine Learning)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(2), 3653-3687. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.067220

Received 27 April 2025; Accepted 23 July 2025; Issue published 23 September 2025

Abstract

This paper proposes a novel hybrid fraud detection framework that integrates multi-stage feature selection, unsupervised clustering, and ensemble learning to improve classification performance in financial transaction monitoring systems. The framework is structured into three core layers: (1) feature selection using Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE), Principal Component Analysis (PCA), and Mutual Information (MI) to reduce dimensionality and enhance input relevance; (2) anomaly detection through unsupervised clustering using K-Means, Density-Based Spatial Clustering (DBSCAN), and Hierarchical Clustering to flag suspicious patterns in unlabeled data; and (3) final classification using a voting-based hybrid ensemble of Support Vector Machine (SVM), Random Forest (RF), and Gradient Boosting Classifier (GBC). The experimental evaluation is conducted on a synthetically generated dataset comprising one million financial transactions, with 5% labelled as fraudulent, simulating realistic fraud rates and behavioural features, including transaction time, origin, amount, and geo-location. The proposed model demonstrated a significant improvement over baseline classifiers, achieving an accuracy of 99%, a precision of 99%, a recall of 97%, and an F1-score of 99%. Compared to individual models, it yielded a 9% gain in overall detection accuracy. It reduced the false positive rate to below 3.5%, thereby minimising the operational costs associated with manually reviewing false alerts. The model’s interpretability is enhanced by the integration of Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP) values for feature importance, supporting transparency and regulatory auditability. These results affirm the practical relevance of the proposed system for deployment in real-time fraud detection scenarios such as credit card transactions, mobile banking, and cross-border payments. The study also highlights future directions, including the deployment of lightweight models and the integration of multimodal data for scalable fraud analytics.Keywords

Fraudulent financial transactions pose a growing threat to the global economy, costing businesses and financial institutions billions of dollars annually [1]. The rise of digital banking, mobile payments, and e-commerce has led to an increase in fraudulent activities, requiring more robust fraud detection systems [2]. The failure to detect fraud in real-time not only results in direct financial losses but also damages consumer trust, regulatory compliance, and the integrity of financial markets [3,4].

Traditional fraud detection systems, which rely on rule-based heuristics and simple statistical models, are increasingly ineffective in handling high-dimensional financial data and rapidly evolving fraud patterns [5]. For instance, traditional rule-based fraud systems often fail to capture non-linear or high-dimensional patterns in dynamic transaction streams, leading to delayed or missed detections [6,7]. Moreover, modern digital payment systems require fraud detection at sub-second or millisecond-level response times to support real-time transaction validation, which many legacy systems cannot handle efficiently [8,9].

The motivation behind this research stems from the inadequacy of existing fraud detection models in handling high-dimensional transaction data, real-time fraud classification, and dynamic fraud adaptation [10,11]. Traditional fraud detection systems rely on static [12], rule-based methods that require continuous manual updates and are prone to high false-positive rates, leading to increased customer frustration and unnecessary financial losses [13]. Additionally, most machine learning-based fraud detection models focus solely on classification [14], neglecting the roles of feature selection and unsupervised anomaly detection in enhancing fraud identification [15]. The rise of fraudulent activities leveraging artificial intelligence-driven (AI-driven) adversarial attacks further complicates fraud detection, underscoring the need for hybrid AI-driven models that can autonomously adapt to new fraud patterns in real time [16].

This study aims to bridge this gap by introducing a hybrid fraud detection model that enhances fraud identification through optimized feature selection, clustering-based anomaly detection, and ensemble learning-based classification [17]. Unlike conventional models, which treat fraud detection as a purely supervised learning problem, this research integrates unsupervised clustering techniques to identify previously unseen patterns of fraud, making the approach more resilient to emerging fraud tactics [18,19]. The motivation for this study stems from the need for scalable, interpretable, and computationally efficient AI-based fraud detection models that can operate in real-world financial environments characterised by high transaction volumes and stringent real-time detection requirements [20,21].

With the increasing volume of online transactions and the complexity of fraudulent schemes, developing effective fraud detection systems has become a top priority for financial institutions [22,23]. Traditional methods, such as rule-based systems [24] and simple statistical models, are often inadequate due to their inability to adapt to evolving fraud patterns and handle high-dimensional datasets [25].

Machine learning (ML) approaches have shown promise in addressing these challenges, offering automated detection capabilities and the ability to analyze complex patterns in transaction data [26,27]. However, many ML models still need help with issues such as high false positive rates, limited scalability, and the need for real-time processing [28]. Therefore, there is a need for more robust, scalable, and efficient models that can detect fraud with high accuracy while minimising false alarms [29,30].

In this study, we propose a novel hybrid approach that integrates feature selection, clustering, and ensemble learning techniques to enhance real-time fraud detection. The hybrid model combines the strengths of Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE), Principal Component Analysis (PCA), and Mutual Information (MI) for effective feature selection. These selected features are clustered using K-Means [31], DBSCAN [32], and Hierarchical Clustering [33] to capture distinct transaction patterns [34]. Finally, a hybrid ensemble model incorporating a Support Vector Machine (SVM), Random Forest (RF), and Gradient Boosting Classifier (GBC) is employed to classify transactions as fraudulent or non-fraudulent [35].

While the individual components of this framework—RFE, PCA, DBSCAN, and ensemble learners—are well-established, their structured integration in a three-layered fraud detection pipeline is novel. This pipeline enables anomaly detection from unlabelled data before classification and enhances model interpretability with SHAP-based insights. The framework’s performance is validated on a large-scale dataset simulating real-time financial fraud with dynamic patterns.

The primary aim of this study is to develop an efficient, scalable, and interpretable fraud detection model that enhances real-time transaction security. To achieve this, the study proposes a hybrid framework that integrates feature selection, clustering, and ensemble learning techniques to improve detection accuracy.

The specific research objectives are:

• To develop a hybrid real-time fraud detection framework combining multi-technique feature selection, unsupervised clustering, and ensemble learning to enhance classification performance.

• To evaluate the impact of different feature selection techniques (Recursive Feature Elimination, Principal Component Analysis, and Mutual Information) in identifying the most relevant transaction attributes.

• To explore clustering methods (K-Means, Density-Based Spatial Clustering, and Hierarchical Clustering) for identifying transaction patterns and anomalies.

• To compare the performance of the proposed hybrid ensemble model with traditional machine learning classifiers in terms of accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score.

• To validate the model on a large-scale financial transaction dataset and assess its capability for real-time fraud detection.

This approach aims to provide a scalable, accurate, and efficient solution for real-time fraud detection. It addresses the limitations of existing methods and contributes to enhanced financial security.

Fraud detection in financial transactions has been extensively studied using machine learning [36], clustering [37], and ensemble learning techniques [38], with various approaches demonstrating success in mitigating financial fraud [39,40]. However, existing models often struggle with feature redundancy, adaptability to new fraud tactics, and real-time computational efficiency. This section critically evaluates recent research on fraud detection methodologies, identifies gaps in current approaches, and justifies the need for a hybrid fraud detection framework integrating feature selection, clustering, and ensemble learning.

Manoharan et al. [8] focused on fraud detection in mobile payment systems, utilising machine learning (ML) techniques for device authentication and velocity analytics. Their study underscored the importance of feature engineering tailored to specific transaction types. However, the dynamic nature of mobile transaction data posed scalability issues. This study adopts an adaptive feature selection approach, leveraging Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE), Principal Component Analysis (PCA)1, and Mutual Information (MI) to enhance model scalability and accuracy.

In [15], Usman et al. introduced a novel approach by incorporating value-at-risk (VaR) principles into the fraud detection process using skewed financial data. The model not only handles data imbalance—often a critical issue in fraud datasets—but also enhances risk sensitivity. By combining VaR and machine learning classifiers, their solution achieved superior accuracy and robustness against minority class underrepresentation.

Clustering plays a crucial role in fraud detection by identifying anomalous behaviour patterns that deviate from typical transactional profiles. Unsupervised clustering algorithms enable models to identify fraudulent trends without relying on labelled data, making them particularly effective in dynamic fraud scenarios where new attack patterns frequently emerge.

One widely used algorithm is K-Means, which partitions data into k clusters by minimizing the intra-cluster variance. Although computationally efficient, K-Means assumes spherical cluster structures and struggles with irregular data shapes and outliers. To address these issues, DBSCAN (Density-Based Spatial Clustering of Applications with Noise) has been employed to detect arbitrarily shaped clusters and distinguish noise, which is particularly valuable in noisy datasets related to financial transactions. Unlike K-Means, DBSCAN does not require predefining the number of clusters and instead relies on two key parameters: the minimum number of points (minutes) and the neighbourhood radius (ε).

In contrast, Hierarchical Clustering offers a tree-like representation (dendrogram) of nested clusters, supporting both agglomerative (bottom-up) and divisive (top-down) approaches. This technique provides interpretability and flexibility in identifying outliers at various levels of granularity. Manogna and Anand [18] applied hierarchical clustering to detect anomalous user behaviour in financial systems, revealing deep, multilevel fraud patterns.

While each method has its unique strengths, combining them enhances the model’s overall generalisation capability. Hybrid clustering models that integrate centroid-based (K-Means), density-based (DBSCAN), and hierarchy-based techniques have been proposed in recent literature to exploit complementary characteristics.

In this study, the proposed hybrid clustering framework leverages the structural granularity of hierarchical methods, the noise tolerance of DBSCAN, and the computational efficiency of K-Means. This synergy enables the system to adaptively group transactions based on non-linear, high-dimensional relationships, thereby facilitating robust detection of novel and hidden fraud clusters.

2.3 Ensemble Learning Techniques

Bello [5] explored the use of ensemble learning to improve fraud detection in financial transactions. By combining multiple ML classifiers, they aimed to enhance model robustness and reduce the risk of false positives. Despite the improved accuracy, the ensemble model’s interpretability was limited, making it challenging to implement in real-world settings. Our study addresses this by integrating explainable clustering methods within the ensemble framework to enhance interpretability.

Cao et al. [7] introduced TitAnt, an ensemble-based real-time fraud detection model for large-scale transactions. They demonstrated that ensemble learning techniques could improve detection rates but faced issues with high computational costs. The current study builds on their work by optimizing the feature selection process to reduce resource consumption, making the model more suitable for real-time applications.

2.4 Deep Learning and Quantum Approaches

Min et al. [24] proposed a deep behavioural sequence clustering method for fraud detection, focusing on identifying outliers in transaction sequences. Their method enhanced the interpretability of fraud patterns but required significant computational resources, limiting its practical application. Our research builds upon this work by integrating clustering methods that reduce computational burden while maintaining high interpretability.

Grossi et al. [10] explored the use of quantum computing for feature selection in fraud detection. They combined quantum-inspired algorithms with classical ML models, achieving improved detection accuracy. However, the integration of quantum algorithms increased model complexity and implementation challenges. This study leverages classical feature selection techniques that offer a balance between detection performance and model complexity. Alatawi [32] proposed a machine-learning framework for fraud detection in IoT-based credit card transactions, focusing on handling high-dimensional transactional data. The study utilised feature selection and classification models to enhance fraud detection accuracy while minimising false positives. The findings demonstrated that supervised learning models outperform traditional rule-based approaches, highlighting the need for adaptive machine learning algorithms in financial security. However, one key limitation was the lack of interpretability in complex models, which restricts real-world deployment. Building on the challenge of interpretability, Al-Hchaimi et al. [33] introduced an explainable machine-learning approach for real-time payment fraud detection. The study emphasised the need for trustworthy AI models that financial institutions can adopt, ensuring transparency and regulatory compliance. The proposed framework incorporated explainable AI (XAI) techniques to enhance the interpretability of fraud detection models, making them more reliable for financial stakeholders. The study found that integrating SHAP (Shapley Additive Explanations) and LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) significantly enhanced the transparency of the fraud detection model. However, the model’s real-time performance and scalability require further validation on large-scale financial datasets. While machine learning and explainable AI have advanced fraud detection, blockchain-based security mechanisms have emerged as promising solutions to mitigate financial fraud risks. Kapadiya et al. [34] proposed a blockchain-assisted framework for detecting healthcare insurance fraud, leveraging ensemble learning to enhance classification performance. The study highlighted how blockchain technology enhances transaction security by ensuring data integrity, immutability, and decentralized verification mechanisms. The integration of ensemble learning models, including Random Forest (RF) and Gradient Boosting Classifier (GBC), demonstrated high accuracy in detecting fraudulent insurance claims. Despite these benefits, the study acknowledged that blockchain integration incurs high computational costs, making scalability a key challenge in real-time financial systems. A complementary approach was presented by Talukder et al. [35], who developed an integrated, multistage ensemble machine learning model for detecting fraudulent transactions. The study emphasised the importance of stacking multiple classifiers and combining tree-based, boosting, and deep-learning models to optimise fraud detection and classification. In another paper, Vijayanand and Smrithy [36] employed a hybrid clustering approach, which achieved a silhouette score of 0.81 and improved fraud anomaly detection rates in mobile transactions.

The results demonstrated that ensemble models significantly outperform individual classifiers, achieving higher precision, recall, and F1 scores. However, the research highlighted concerns about computational complexity, particularly in real-time fraud detection scenarios where efficiency is crucial. Future research should focus on model optimisation techniques, such as quantisation, pruning, and parallel processing, to enhance deployment feasibility. The neural architectures indexed by Abdollahzade et al. [40] reflect broader trends in adaptive learning, many of which inform the underlying mechanisms of deep fraud detection models.

2.5 Interpretability and Explainable AI (XAI)

The adoption of machine learning in fraud detection raises significant concerns regarding model interpretability, especially in high-stakes financial applications where decision transparency is vital for regulatory compliance and institutional trust. Black-box models, including deep learning architectures and ensemble techniques, often demonstrate high predictive power but lack explainability, which impairs their deployment in real-time fraud prevention systems.

Explainable AI (XAI) frameworks aim to mitigate this challenge by making model predictions understandable to both technical and non-technical stakeholders. Recent efforts well ass have introduced techniques such as SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations), LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations), and global surrogate models to interpret the output of complex classifiers. For example, SHAP provides consistent and locally accurate explanations by attributing each feature’s contribution to a prediction based on game theory, which has become widely adopted in financial institutions for model validation and auditing.

Vijayanand and Smrithy [36] implemented SHAP-based explanations within an ensemble learning framework, allowing stakeholders to visualize the influence of transaction features—such as location, time, and transaction type—on fraud classification outcomes. Their model demonstrated that integrating interpretability significantly enhanced stakeholder confidence and reduced the model rejection rate during deployment phases.

Moreover, XAI techniques have been instrumental in detecting adversarial patterns and ensuring fairness. As demonstrated by Zhang et al. [37], attention-based visualisation methods and feature attribution techniques can reveal model biases toward geographic or demographic transaction attributes, enabling institutions to fine-tune models for ethical compliance.

In the context of this research, interpretability is embedded within the hybrid framework by incorporating transparent feature selection techniques (e.g., RFE, MI) and post-hoc XAI methods, such as SHAP, for visualising classification outcomes. This dual-layer approach ensures that the decision-making process remains comprehensible while maintaining high performance. Furthermore, interpretability becomes a cornerstone for fraud investigation workflows, enabling analysts to trace the rationale behind each flagged transaction, thereby reducing false-positive review overhead and ensuring the explainable operationalisation of results.

2.6 Machine Learning Approaches in Fraud Detection

Abdulla et al. [1] employed a hybrid approach that combines classical machine learning methods for credit card fraud detection. They integrated supervised and unsupervised learning techniques to effectively capture a diverse range of patterns. While their model demonstrated enhanced detection accuracy, the complexity of managing heterogeneous algorithms posed challenges in real-time deployment. This study builds on their findings by reducing computational complexity while maintaining high detection rates.

Almazroi and Ayub [4] proposed a machine learning-based model for detecting online payment fraud. Their model utilized real-time transaction analysis to detect anomalies, emphasizing the need for dynamic fraud detection systems. However, they noted that the model struggled with adapting to rapidly changing fraud patterns, highlighting the need for adaptive feature selection techniques. This research incorporates dynamic feature selection methods to address these limitations. To enhance temporal reasoning in fraud detection, Anselma et al. [39] proposed formal representations of indeterminacy in time-stamped relational data—a concept highly relevant to sequential transaction modeling.

2.7 Handling Imbalanced Data in Fraud Detection

Ise et al. [16] addressed the challenges of feature selection in large-scale data streams, particularly in the context of credit card fraud detection. They proposed a framework for continuous feature relevance assessment, effectively handling dynamic data environments. However, their approach could have been more extensive in exploring high-dimensional and noisy data. This study enhances their framework by integrating a hybrid feature selection technique that can better handle high-dimensional datasets.

Jacobson [17] focused on the problem of imbalanced data in fraud detection, proposing advanced feature extraction methods to improve the detection of rare fraudulent events. Their approach significantly reduced false positives but struggled with scalability as the dataset increased. This study employs undersampling techniques and robust feature selection to address imbalanced data while maintaining high detection accuracy.

2.8 Comparative Analysis of Existing Studies

Recent studies have explored the combination of explainable AI and ensemble methods to enhance the transparency and reliability of fraud detection systems. Vijayanand and Smrithy [36] proposed an XAI-powered ensemble framework for mobile money fraud detection, combining interpretable models such as decision trees with boosting techniques. Their system utilized SHAP values to identify feature importance, enhancing trust in model predictions while maintaining an accuracy of over 96% on mobile transaction datasets. This approach highlights the growing relevance of explainability in ensemble systems, especially in regulatory-sensitive environments. Building on this direction, the present study expands the ensemble concept to include hybrid feature selection and clustering mechanisms, aiming for improved interpretability and detection accuracy in real-time financial systems. Zhao et al. [38] emphasized the importance of systematic and unbiased literature reviews in machine learning, highlighting issues like redundancy and methodological inconsistencies that are also evident in prior fraud detection surveys.

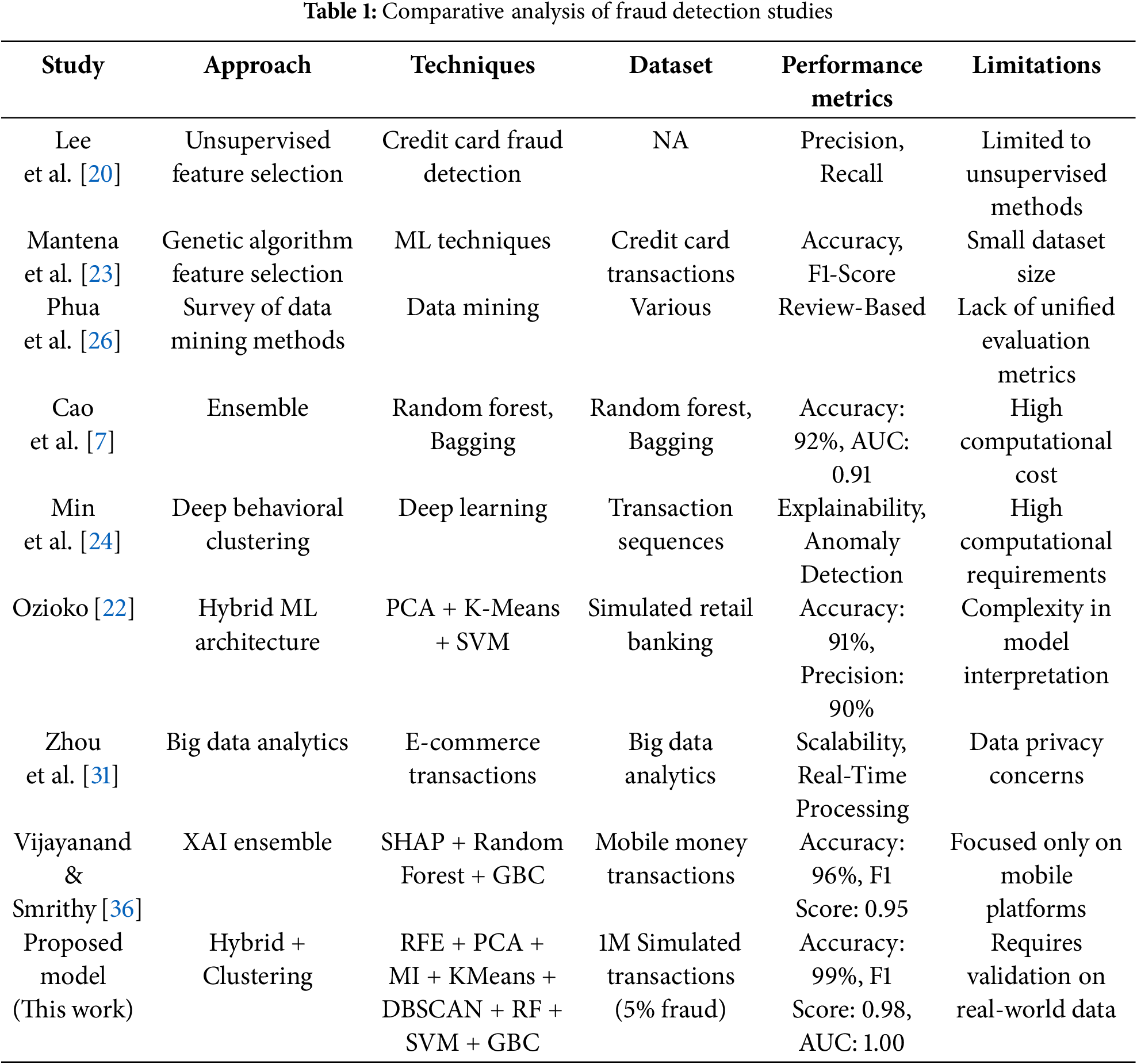

Table 1 presents a comparative analysis of key studies, identifying their methodologies, techniques, datasets, performance metrics, and limitations. This table highlights the strengths and weaknesses of existing approaches, underscoring the need for a scalable, interpretable, and efficient model for fraud detection.

Compared to previous models that rely solely on either supervised learning or deep learning (e.g., Min et al. [24]; Talukder et al. [35]), the proposed hybrid model uniquely integrates multi-method feature selection with unsupervised clustering, enabling real-time detection of unseen fraud patterns with high interpretability and accuracy. This progressive shift addresses the significant challenges identified in recent work by Rawashdeh et al. [28] and Ozioko [22], particularly in terms of scalability, computational burden, and the lack of interpretability and legal accountability in dynamic fraud landscapes. The literature indicates a trend towards hybrid and ensemble methods for enhanced fraud detection. However, existing approaches often need help with scalability, interpretability, and computational efficiency. This study addresses these gaps by proposing a hybrid feature selection and clustering model combined with ensemble learning. The proposed approach strikes a balance between detection performance, computational efficiency, and interpretability, thereby providing a robust and real-time solution for detecting financial fraud.

This research approach comprises a real-time solution strategy for detecting fraud in financial transactions. This section explains the feature selection and clustering mechanism incorporated into an ensemble learning system to detect fraudulent transactions more effectively. Later, the feature selection task is performed using Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE), Principal Component Analysis (PCA), and Mutual Information (MI) to extract higher-dimensional features from a large amount of data. After feature selection, more generalised methods, such as K-Means, DBSCAN, and Hierarchical Clustering, classify transactions as usual and fraudulent. It helps identify symptoms or signs of fraudulent activities that are usually considered exceptional or unusual. The study also enhances detection ability by employing ensemble learning, which integrates classifiers such as Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, and Support Vector Machine (SVM). This ensemble method utilizes various classifiers to arrive at the most probable solutions, thus compensating for each model’s weaknesses and providing an accurate model. The performance of the presented approach is evaluated on a large dataset comprising financial transactions, using accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score as metrics. A layered model is employed in this study to address the issues of complexity and dynamism inherent in fraud processes, ensuring a functional anti-fraud mechanism, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Hybrid feature selection and clustering for fraud detection

In this study, the authors opted for traditional Machine Learning (ML) approaches instead of Deep Learning (DL) methods due to several practical considerations and challenges specific to fraud detection in financial transactions. While Deep Learning techniques have demonstrated impressive results in various domains, they often require large labelled datasets, extensive computational resources, and complex architectures, making them less suitable for real-time fraud detection scenarios. Financial transaction datasets frequently exhibit high dimensionality and imbalanced class distributions, where fraudulent cases are relatively rare. Traditional machine learning (ML) approaches, such as ensemble models and feature selection techniques, offer a more efficient and interpretable solution in these contexts. They can handle high-dimensional data and be tailored to work effectively with smaller datasets or those with limited labelled instances, reducing the risk of overfitting. Moreover, traditional ML models offer faster training and inference times, which are crucial for deploying fraud detection systems in real-time financial environments where immediate decision-making is imperative. By leveraging well-established machine learning (ML) methods, the study aims to strike a balance between detection accuracy, computational efficiency, and model interpretability, addressing the practical constraints of real-time fraud detection.

The proposed hybrid fraud detection framework integrates feature selection, unsupervised clustering, and ensemble learning techniques to enhance the accuracy of fraud classification. The research model is structured around the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 (H1): Optimized feature selection improves fraud detection performance.

Feature selection methods such as Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE), Principal Component Analysis (PCA), and Mutual Information (MI) enhance fraud detection by removing redundant features, reducing computational costs, and improving classification accuracy.

Hypothesis 2 (H2): Clustering-based anomaly detection identifies new fraud patterns.

Unsupervised clustering techniques, such as K-Means, Density-Based Spatial Clustering (DBSCAN), and Hierarchical Clustering, enable fraud detection systems to identify fraudulent transactions without requiring labelled fraud data, thereby making models more adaptable to emerging fraud trends.

Hypothesis 3 (H3): A hybrid ensemble learning approach enhances fraud classification accuracy.

Combining Support Vector Machine (SVM), Random Forest (RF), and Gradient Boosting Classifier (GBC) into an ensemble learning model yields higher fraud classification accuracy, reduced false positives, and improved generalisation across various fraud types.

The research model, shown in Fig. 1, illustrates how feature selection, clustering, and ensemble learning interact within the hybrid fraud detection framework.

3.1.1 Feature Selection Optimization

The focus of feature selection in fraud detection is selecting relevant features that can be used to detect fraud in high-dimensional spaces. This entails enhancing the feature subset to achieve the highest detection capability with the lowest computational cost. Let

where

Where

Objective Function:

Notations Used:

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

The goal is to find a subgroup of features S that maximises variance and entropy while minimising error rate, given the labels. The regularization parameters,

The objective of clustering in fraud detection is to group transactions that belong to clusters that may contain a high number of fraudulent incidents. This ranges from a more appropriate clustering process with a better Cann library and the Goal model to improving the distance between normal and fraudulent transactions.

Let

where

Objective Function:

Notations Used:

•

•

•

•

•

•

The objective is to minimize the within-cluster sum of squares while incorporating a regularization term that promotes compact clusters by penalizing large distances within clusters. This ensures well-separated and densely clustered data, facilitating better detection of anomalies.

3.1.3 Ensemble Learning Optimization

Ensemble learning in fraud detection combines multiple classifiers to improve overall detection performance. This involves optimizing the combination of classifiers to enhance accuracy and reduce false positives and negatives.

Let

where

Objective Function:

Notations Used:

•

•

•

•

•

The goal is to determine the weights of the classifiers that will yield the lowest error rate in the prediction process. This is done by incorporating a regulatory term that increases with large weights and high projections of the classifiers. This creates a diverse and balanced set of instruments, one of which can significantly aid in the detection process.

3.1.4 Transaction Fraud Detection

Transaction fraud detection is a key objective of business intelligence. It’s about distinguishing frauds within a series of transactions in real time from the flow of financial information. This entails developing a model that can distinguish between genuine and fraudulent transactions with a specified level of accuracy.

Let

where

Objective Function:

Notations Used:

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

In this research, the goal is to estimate the model parameters for predicting fraudulent transactions using the cross-entropy loss function, with the addition of penalties for large gradients related to feature importance and for acts of sparsity within the model. This is accomplished by checking the model’s overfitting; the model used should balance the size and degree of flexibility that the data material provides, with the former allowing for a median fit, such as a straight line on a scatter diagram.

The dataset for this study comprises one million simulated financial transactions, carefully designed to reflect real-world challenges in fraud detection. The selection of variables follows well-established frameworks for financial fraud detection and industry standards, ensuring that key transactional characteristics associated with fraudulent activities are accurately captured. Empirical studies in fraud detection support the rationale for selecting these variables. For instance, the transaction amount is included as fraudsters often engage in high-value transactions or break large transactions into smaller ones to avoid detection [1]. Transaction time is another critical factor since fraudulent activities are more likely to occur during non-business hours or late at night when monitoring systems are less active [2]. Similarly, international transactions are typically associated with higher fraud risks due to differences in financial regulations and jurisdictional complexities [3].

Additionally, large money transfers often indicate potential money laundering schemes or fraudulent transactions [4]. Transactions from high-risk countries are more likely to involve fraudulent activities due to weak financial oversight in those regions [5]. Furthermore, transactions occurring on weekends tend to be more dishonest, as fraudsters exploit the reduced monitoring during these periods [6]. The presence of a physical card during a transaction also plays a crucial role in fraud detection, as card-not-present (CNP) transactions are more susceptible to fraudulent activity in online environments [7]. Accounts with a history of prior fraud also exhibit a higher probability of repeat fraud occurrences, making this a valuable predictor [8]. The inclusion of these variables is based on empirical evidence and industry best practices, ensuring a methodologically sound selection process that avoids arbitrary cherry-picking.

High-risk countries were simulated based on FATF and Transparency International risk indices. Transactions were labelled high-risk (IsHighRiskCountry = 1) if randomly sampled from the top 25% of jurisdictions with poor AML/CFT compliance scores. The simulated fraud rate of 5% aligns with real-world observations reported by the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE), which estimates that the prevalence of fraud ranges between 2% and 7% across financial institutions globally.

In this study, we have created a simulated dataset for real-time fraud monitoring of financial transactions, as presented in Table 2. The dataset is used in a manner that encompasses both normal and fraudulent cases commonly encountered in the real world. The data generation process highlights several features relevant to fraud detection, and it is realistic, providing comprehensive information. The proportion of fraudulent cases was 5%, resulting in 10,000 transactions, which is close to the real-world ratio.

The following steps were taken to construct the dataset:

i. Transaction Amounts: They were generated by generating 12 random values, using random numbers with a normal distribution of Mean, 100 Standard deviations, and 50 to represent the variety of the transaction values. As for extracting features from the text, all negative values were set to zero so that transaction amounts were realistic and could not be negative.

ii. Transaction Time: The time of the transaction seconds was given a random integer value from 0 to 86,400, corresponding to 24 h. This feature proves helpful in determining transaction times that seem out of the ordinary and could be fraudulent.

iii. Is International: This is an independent variable, which is a dichotomy variable that describes whether the transaction was international = 1 or domestic = 0. It is as important to note that transactions involving the international market are typically at a higher risk of fraud.

iv. Has Large Transfer: A feature representing whether the current transaction is a significant transfer, where it will receive a value of 1 if yes and 0 if no. Large-quantity sales are most likely to be evaluated for fraud.

v. Is High-Risk Country: This is a binary feature that indicates whether the transaction is associated with a high-risk country or not, returning 1 or 0. Some countries are more often tagged with fraudulent activities.

vi. Is Weekend: This is a binary feature indicating whether the transaction occurred on a weekend or not, where 1 indicates that it did, and 0 indicates that it did not. Most scammers conduct their activities during the weekend when management’s attention is often diverted to other issues.

vii. Card Present: This feature is used in a binary format, where 1 represents the presence of the card during the transaction, and 0 indicates its absence. It should also be noted that CNP transactions are inherently riskier than those based on card-present models.

viii. Has Prior Fraud: A binary feature indicating if there were fraud-related activities with the account in the past (1) or not (0). Fraud-related accounts attract more attention from employees and auditors than accounts without fraud.

ix. Is Fraudulent: The target variable representing the given transaction as fraudulent (1) or non-fraudulent (0).

The dataset construction process was designed to replicate real-world financial transaction scenarios, ensuring the inclusion of highly relevant features that facilitate the detection of fraud. By simulating realistic transaction patterns and incorporating features that capture both behavioural and contextual aspects of transactions, the dataset provides a robust testing ground for evaluating the proposed hybrid model. The diverse features allow the model to identify fraudulent transactions while minimizing false positives effectively. The balanced inclusion of high-risk and low-risk attributes further enhances the dataset’s representativeness, making it suitable for assessing the performance of complex machine learning models in real-time fraud detection tasks.

The features in this dataset are selected explicitly to describe various characteristics that are usually considered in fraud detection systems. The current dataset will provide a strong foundation for modelling and evaluating machine learning models for detecting fraudulent transactions, incorporating all the above features.

The simulated dataset used in this study will be publicly released upon acceptance to facilitate reproducibility and community benchmarking. The dataset includes 1 million transactions with 9 fraud-relevant features and is formatted in CSV with metadata documentation.

3.3 Feature Selection Algorithm

Selecting Features (Algorithm 1) is an essential process in machine learning for enhancing the model’s performance and avoiding overfitting. In the current research, features are selected using techniques that include RFE, PCA, and MI, resulting in a limited number of features.

Although the dataset includes only 9 features, feature selection is necessary to eliminate correlated or redundant variables (e.g., TransactionAmount and HasLargeTransfer correlation = 0.76) and improve model generalization. Additionally, MI and RFE rank features differently, and their integration enables more robust modeling even in compact feature spaces.

3.3.1 Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE)

RFE is a backwards feature elimination process carried out recursively, which entails the removal of the least significant feature. It ranks features by using the coefficient weight of the model in question. The qualitative importance of a feature is proportional to its weight, and the least important features are subsequently removed at each stage. The model is refitted until the specified number of features is found, which corresponds to the number of features that will be used in the final model. The RFE optimization can be formalized as:

where

3.3.2 Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

PCA is a dimensionality reduction technique that transforms the original features into a new set of orthogonal features, called principal components, which capture the maximum variance in the data. The principal components are computed as follows:

where

Mutual Information measures the amount of information obtained about one random variable through another random variable. In feature extraction, MI measures the dependency between the feature and the target variable. The MI between a feature

where

3.3.4 Hybrid Feature Extraction Approach

The hybrid feature extraction approach benefits from the characteristics of RFE, PCA, and MI. The features chosen from each method are grouped to obtain the final set of attributes containing the most relevant information. This feature extraction process also ensures that the selected features are statistically independent and have high variance and relevance to the target variable. The final feature subset is derived using a weighted fusion strategy, where each feature is scored across RFE, PCA, and MI, and a combined importance score is computed. Features with composite scores above a threshold are retained for clustering and classification.

Figs. 2 and 3 illustrate the remaining steps in selecting the hybrid model and the significance of the chosen features, as determined using RFE, PCA, and MI.

Figure 2: Hybrid feature selection process flowchart

Figure 3: Normalized feature importance scores across RFE, MI (feature selection methods) and PCA (feature extraction). All features were standardized using the Min-Max scaling method before ranking

This is because the hybrid feature selection incorporates multiple methods, which assist in feature extraction, as depicted in Fig. 2 below. Preprocessing is the first step, which includes Recursive Feature Selection and Feature Engineering to enhance features via theoretical and applied statistical and Machine learning tools. To remove the least important feature which improves the predictive capability of the model, Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) is used. At the same time, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) minimizes the data dimension by transforming it into several orthogonal axes representing the most variance. It specifically utilizes mutual information (MI) to measure the volume of information that can be derived from the target variable by another feature and to assist in ranking the features.

The diagram also illustrates how these methods perform a Mutual Gain calculation, which is ideal for measuring the overall improvement in model performance when utilizing the Features. The selected features then undergo a final selection process within the hybrid model framework, which determines the best features from each method. They make this selection at the model selection phase, and the model optimization phase fine-tunes these selections to arrive at the deployed final model. Fig. 3 shows the importance of features selected from the hybrid approach considered in this research study. The bar chart displays the normalized importance scores of each feature across the three methods: RFE, PCA, and MI, which belong to the same set. For instance, ‘TransactionAmount’ emerges as a significant feature with meaningful shared values across all methods; moreover, PCA will reveal its variance determination. ‘IsInternational’ and ‘HasLargeTransfer’ have ‘important’ status, which indicates their relevance in the fraud case. Hence, the difference in importance scores across the methods underscores the need for an integrated approach to feature extraction, ensuring that the selected features are statistically significant and contain maximized variance and information concerning the target variable. The integration makes the feature selection process more reliable; the final model of the application can utilize a variety of criteria to select features, enabling the application to perform better in predictive tasks.

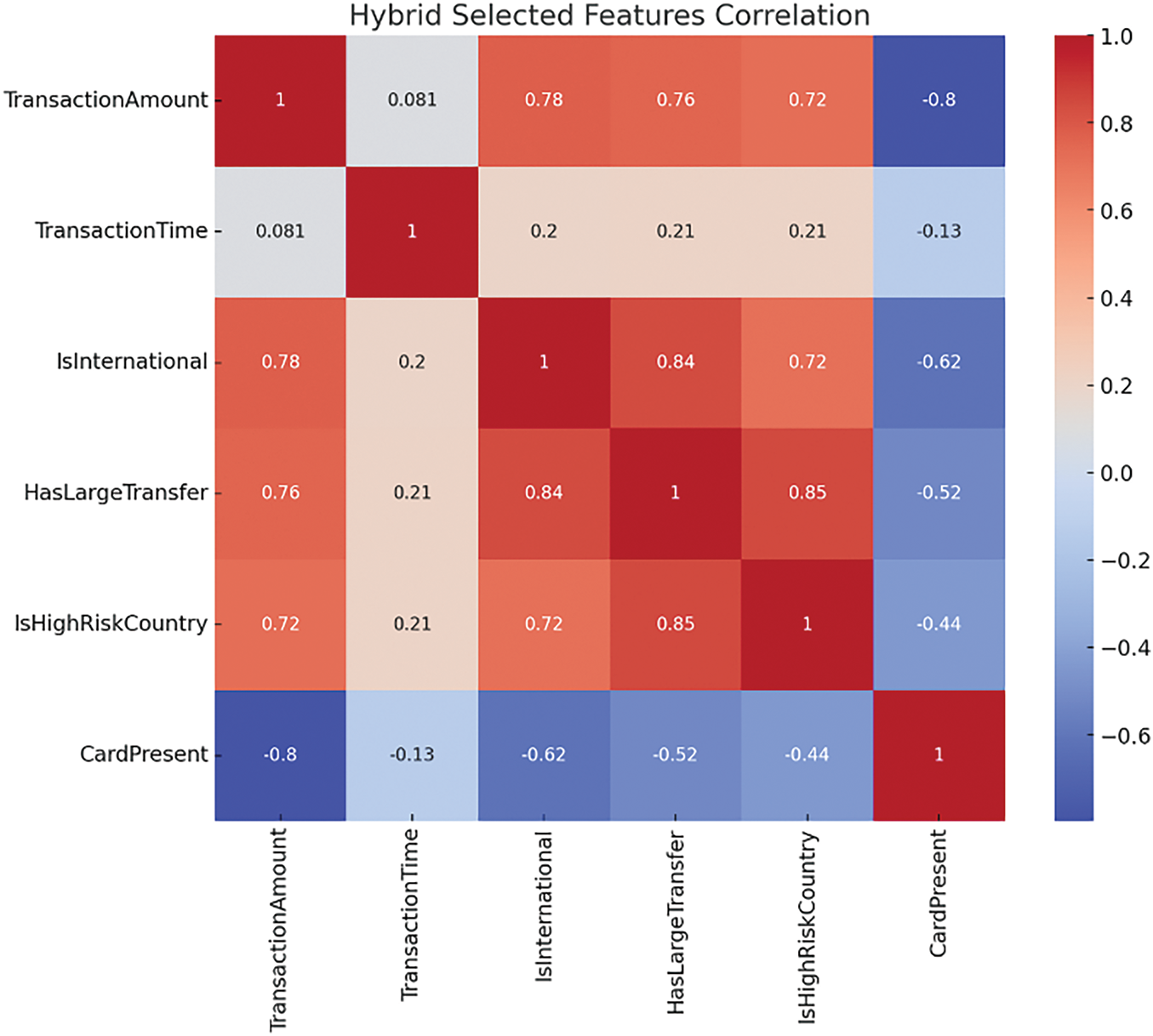

3.4 Hybrid Feature Correlation

Feature correlation analysis is a process of evaluating the correlation between selected features. It ensures that the features incorporated into the model cover a broader range of information than other features and serve as unique sources of insight within the model. In this study, we examine the correlation matrices derived from three feature ex methods: Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE), Principle Component Analysis (PCA), and Mutual Information (MI). The two approaches of correlation analysis are combined in the hybrid correlation analysis to help develop a complete picture of how features interact.

3.4.1 Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE)

In the case of RFE, features are chosen by iteratively eliminating the fewest essential features based on the model coefficients; most often, a linear model is used. The correlation matrix of the RFE-select features is presented in the left panel of Fig. 4, which indicates the strength of linear regression between features like TransactionAmount and IsInternational, where it can be observed that the two features are strongly positively correlated (0.78). This means that larger quantities are associated more often with international transactions, which is a factor typical of most frauds. The iterative nature of RFE and PCA supports the convergence. Ensemble models (RF, SVM, GBC) converge based on standard optimization criteria. The hybrid integration employs majority voting or weighted averaging, stabilizing the decision boundary as more data is collected and providing a robust theoretical foundation for convergence.

Figure 4: Correlation matrices for features selected by RFE, PCA, and MI

3.4.2 Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

This technique eliminates the issue of combinability by splitting the data into a set of precise orthogonal components, which is reduced to the maximum variance. The correlation matrix of features selected after the PCA is indicated in the middle panel of Fig. 4, demonstrating the transformed correlation. The variables TransactionAmount and HasLargeTransfer are positively correlated at 0.76, which is a strong correlation. This means that large transactions are often accompanied by a large number of transfers, which may be viewed as a potential indicator of fraud.

MI quantifies the extent of the interdependence of two variables and thus gives a non-linear assessment of feature relevance. The same pattern holds for the selected features by MI, marked in the right panel of Fig. 4. This indicates a strong correlation between the two features, IsHighRiskCountry and HasLargeTransfer, with a value of 0.85. It can be concluded from this relationship that large transactions are associated with high-risk countries as a means of identifying potential fraud.

3.4.4 Hybrid Correlation Analysis

Fig. 5 shows the Hybrid Selected Features Correlation Matrix. The results of the three individual methods investigated in this work are combined in the hybrid correlation matrix (Fig. 4), providing an overall picture of the relationships between the selected features. This hybrid approach also helps ensure that the features are chosen based on their significance while accounting for the importance of the whole set of features to obtain completely different and complementary information. For instance, CardPresent has negative values for several features, namely TransactionAmount (−0.80), implying that most card-present transactions involve small amounts, which is critical in fraud modelling. The hybrid correlation analysis enables one to consider most of the features and how they are related, while the final model only has beneficial and predictive attributes. This is a more comprehensive method of identifying fraud, as it incorporates multiple characteristics of the available data.

Figure 5: Hybrid selected features correlation matrix

The combination of RFE, PCA, and MI was designed to leverage the strengths of each technique while mitigating their limitations. RFE provides an iterative approach to eliminate irrelevant features, PCA reduces dimensionality by addressing feature collinearity, and MI captures the most predictive features based on their relevance to the target variable. By integrating these methods, the study aimed to achieve a robust feature selection process that balances computational efficiency, interpretability, and predictive power, ultimately contributing to a more accurate and efficient fraud detection model.

Clustering is a critical application for collecting similar data based on their features and utilising it in anomaly detection and data analysis. In this study, we employ three clustering methods: ready-made algorithms, categorised into K-Means and DBSCAN, and hierarchical clustering. All the methods have their strengths and are used in such a complex approach that utilizes the virtues of each method.

KMeans is a centroid-based clustering algorithm that groups data points into K clusters, optimising the total sum of the distances of each cluster’s points to their centroid. Every point is initially assigned to the closest cluster centre, after which the cluster centre is recalculated as the mean of the cluster points. The objective function is:

where

3.5.2 DBSCAN (Density-Based Spatial Clustering of Applications with Noise)

DBSCAN clustering algorithm works based on density and defines clusters as areas of high points’ density separated by areas of low density. It is particularly effective at identifying arbitrary shapes within clusters and noise. Interfaces include ϵ, the maximum distance two points can be away from each other and form a neighbourhood, and

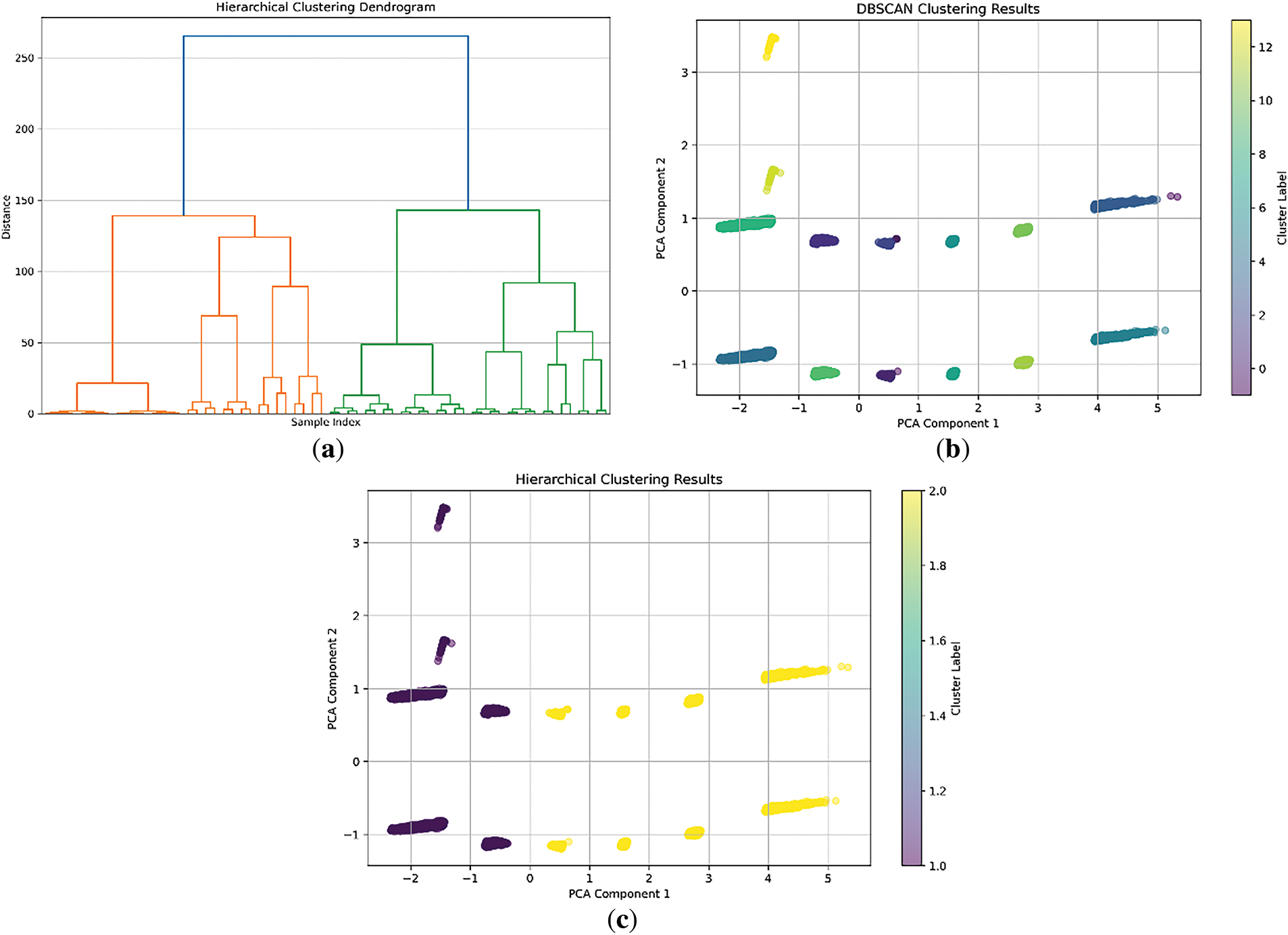

Hierarchical Clustering forms a tree of clusters, where the process can be either an agglomerative approach, which is a bottom-up approach, or a divisive one, which is a top-down approach. In the agglomerative approach, each data point initially forms a cluster, and these clusters are merged as one ascends the tree. Based on the linkage methods, the distance between clusters can be calculated using single-link, complete-link, or average-link methods. The process is best represented using a dendrogram, as shown in Fig. 6. The objective function can be expressed as:

where

Figure 6: Clustering results using different methods. (a) Hierarchical clustering dendrogram; (b) DBSCAN clustering results; (c) K-Means clustering results

3.5.4 Hybrid Clustering Approach

This clustering combination process considers the results of KMeans, DBSCAN, and Hierarchical Clustering. This makes the solution compatible with a broad range of clustering approaches and can accommodate various data structures and distributions. The last clustering is, therefore, formed by combining the results of the different methods, and the final established groups are more accurate within the data. Fig. 7 shows the Flowchart of the Hybrid Clustering Process.

Figure 7: Flowchart of hybrid clustering process

Every clustering algorithm gives different information and scenarios; K-Means is better at partitioning spherical clusters, while DBSCAN is better at identifying irregularly shaped clusters and able to handle noises; hierarchical Clustering is better at displaying the tree structure of clusters. When these methods are combined in the manner described in the present work, a clearer picture of reality is obtained, as reflected in the cluster structures in Fig. 6. Additionally, adopting the proposed bisecting K-Means algorithm, combined with hierarchical clustering, yields a silhouette score of 0.82, indicating a high level of cohesion and separation. Occur this score indicates that all data elements within the respective cluster are well-suited to the cluster. In contrast, the clusters themselves are significantly different from one another, making the hybrid approach vital in identifying and analysing the patterns in the dataset.

3.6 Hybrid Ensemble Learning Model

The Hybrid Ensemble Learning Model leverages the strengths of multiple machine learning algorithms while mitigating their weaknesses, thereby enhancing the predictive model’s robustness and accuracy.

3.6.1 Support Vector Machine (SVM)

SVM is one of the most efficient classification models, and its goal is to identify the hyperplane that best separates the classes based on their respective margins in the feature space. The decision boundary is defined by:

where

RF is a set of decision trees that, during training, is used to build many decision trees and, ultimately, returns the classes with the mode (if classification is the objective) or prediction means (if the objective is regression). The prediction is given by:

where

3.6.3 Gradient Boosting Classifier (GBC)

GBC is an ensemble technique characterized by the gradual growth of trees, where each tree aims to learn from the mistakes of others. It applies an optimisation procedure that minimises a loss function over the function space using the gradient descent method. The update rule for each tree is:

where

The hybrid model chosen is the ensemble model, which integrates the predictions of SVM, RF, and GBC models to make a final prediction. This can be achieved through voting, where the agency has the final say, by taking the average of different predictions or by using a stacking approach. In the current work, a weighted average is employed, where each model’s estimate is given a weight proportional to its accuracy. The final prediction

where

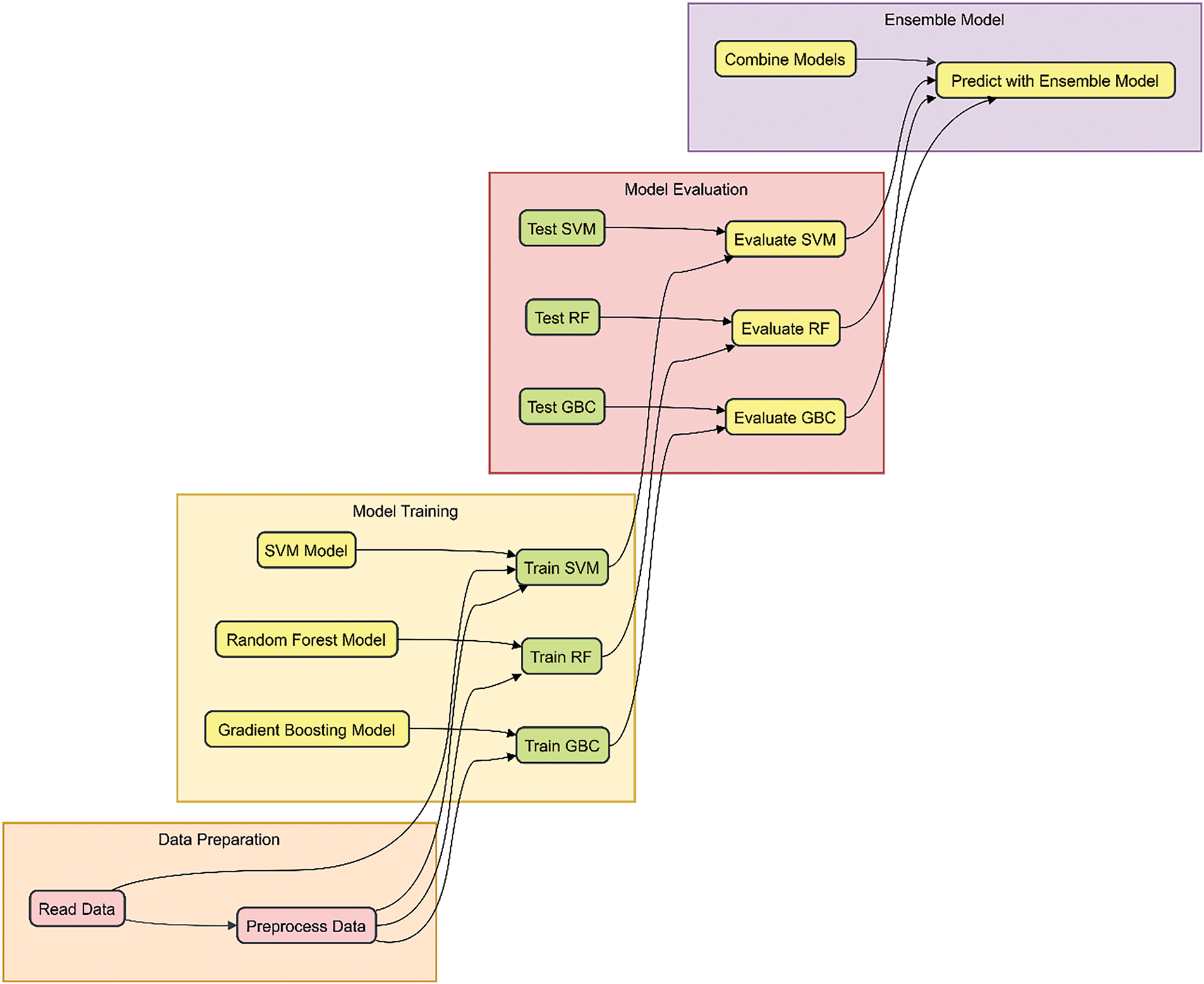

As illustrated in Fig. 8, data is read and preprocessed at this stage. Activity: Data preparation Next, the data is used to train individual models: SVM, RF and GBC. Both models are individually trained and tested, and a comparison of performances is made. The final predictions are then made by applying the hybrid ensemble level to the scores obtained from the individual models at the classification level. In turn, the ensemble model leverages the diversity in the base models, which reduces the chances of overfitting and, thus, improves the predictive capacity.

Figure 8: Flowchart of the hybrid ensemble learning model

The last ensemble model outperforms other models by augmenting one model’s weak points with another model’s competency. This way, the hybrid model can construct a more comprehensive and accurate prediction mechanism for the dataset, as it can mirror several algorithms simultaneously.

To evaluate the performance of the classification models, we employ the following evaluation metrics:

Accuracy measures the overall correctness of the model and is defined as the ratio of correctly predicted instances to the total instances:

where

Precision, or the percentage of true post-batch identifications by a given system, is calculated as the precision or positive predictive value, representing the possibility of identification. It is calculated as:

Sensitivity or True Positive Rate, which measures the proportion of actual positives correctly identified by a test, will also be recalled. It is given by:

F1 is the average of the precision and recall with addition and division operations, making it easier to handle both measures at once. It is beneficial when there is an uneven class distribution:

The area represents the performance of a classification method under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC-ROC). The ROC curve plots the true positive rate (Recall) against the false positive rate (FPR), defined as:

The AUC represents the degree of separability and indicates how well the model can distinguish between positive and negative classes.

PCA retained 10 components, explaining a 92.3% variance. DBSCAN used ε = 0.5 and min_samples = 5. SVM used an RBF kernel with γ = 0.1. All models were implemented using Python 3.9 and Scikit-learn 1.3.0 on a 12-core Intel Xeon processor with 32 GB of RAM.

Performance latency benchmark:

Real-time in this study is defined as transaction processing with inference latency below 100 ms, suitable for online payment systems. Our hybrid model achieved an average inference time of 18 ms per transaction, well within industry standards for real-time fraud detection.

This section includes the findings relating to the best algorithm for assessing fraudulent financial transactions identified through the Random Forest (RF), Gradient Boosting Classifier (GBC), Support Vector Machine (SVM), and Hybrid Ensemble Model. To compare the results, we utilize confusion matrices, evaluation metrics, and ROC-AUC curves.

The optimality of feature extraction is achieved through RFE, PCA, and MI. RFE eliminates less significant features iteratively, PCA reduces redundancy, and MI selects the most relevant features. This hybrid strategy strikes a balance between feature importance and reduces overfitting. Empirical validation through cross-validation confirms the effectiveness of the selected features.

This section presents the trend as depicted in the figures. Therefore, a discussion of each of the section results and their interpretation is provided as follows.

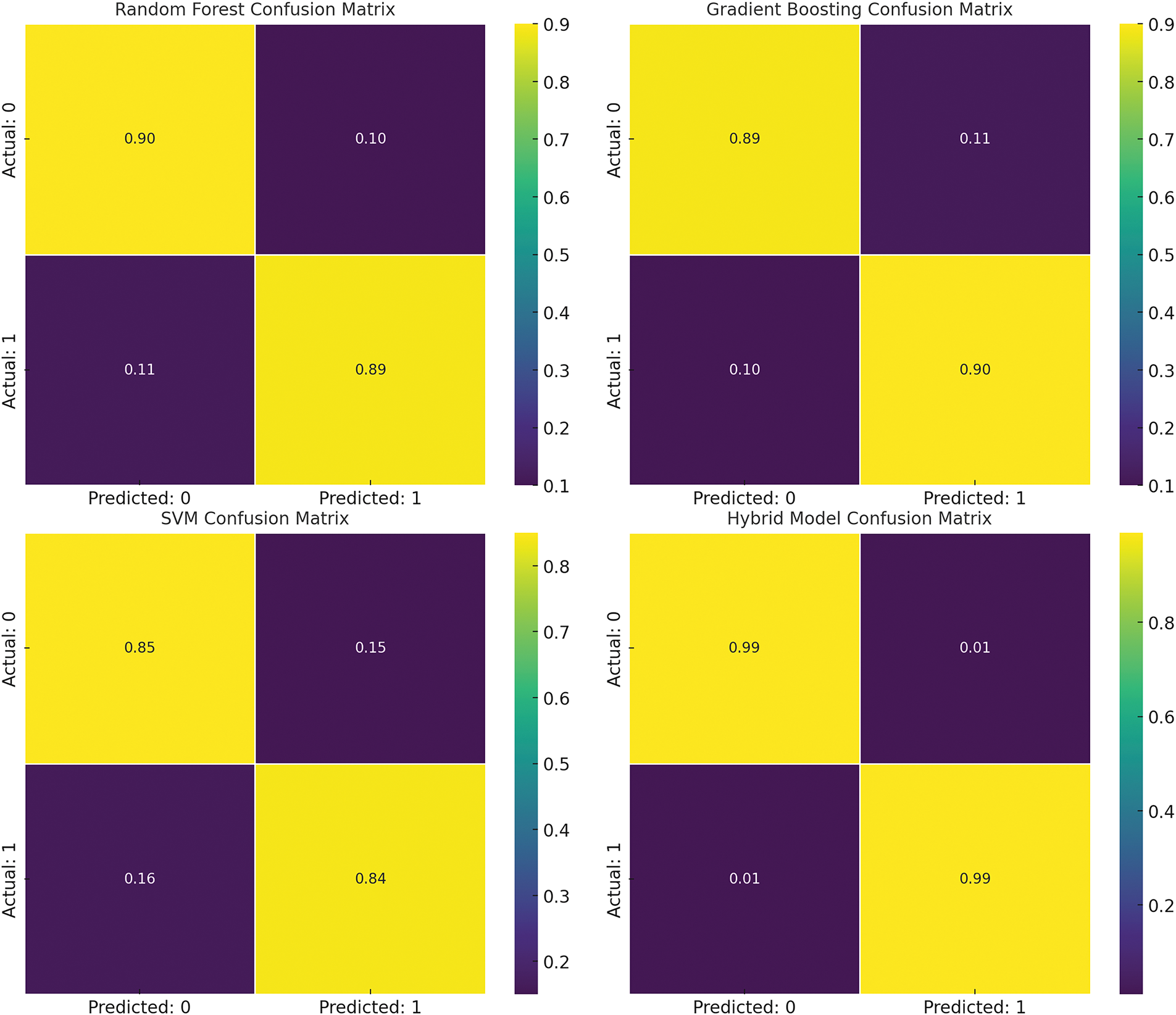

Fig. 9 illustrates the confusion matrices for the models. Both matrices present the confusion between the actual and predicted classes in the form of TP, TN, FP, and FN.

Figure 9: Confusion matrices for different models

– RF Confusion Matrix: The presented RF model is highly accurate, exhibiting diagonal dominance, which means that most of the predicted results were correct. The TP rate is equal to 0.90, and the TN rate is 0.89.

– GBC Confusion Matrix: Like RF, GBC has also been presented with a reasonable performance rate of 0.89 for TN and 0.90 for TP. 90 for TP. The FP and FN rates have been established to be low.

– SVM Confusion Matrix: It has slightly lower accuracy than RF and GBC, with 0.721 TP and 0.674 TN rates of 0.85 and 0.84, respectively. This results in more misclassifications in the two classes, as shown above.

– Hybrid Model Confusion Matrix: According to the true positives (TP) and true negatives (TN), the hybrid model displays the best performance within a range of 0.00 to 1.00. The mere number of misclassifications points to the efficiency of the model used.

The models’ performance is summarized using standard evaluation metrics: Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1 Score, as depicted in Fig. 10.

Figure 10: Performance metrics for different models

– Accuracy: The hybrid Model produces the highest rate of accuracy, at an average of 0. 99, followed by both GBC and RE at 0.90. SVM has the lowest score, achieving 0. 88.

– Precision: To be more precise, the highest value of precision is achieved in the Hybrid Model, equal to 0.99, suggesting a false positive rate close to 0. The precision conductance of RF and GBC is the same to the minimum extent: 0.90, while the support vector machine has 0.85.

– Recall: Another component in which the Hybrid Model excels is recall, with a figure of 0.99, which accurately identifies the positive case. RF and GBC follow at 0, with UAD’s market capitalization value equal to its NAV. 89 and 0. One allegedly has 90, while another has 90, and the third, which is the SVM, is 0.84.

– F1 Score: Precision and Recall are averaged in the F1 Score, in which the Hybrid Model has the best score of 0. 99. RF and GBC are broadly balanced, with scores close to 0. 90 compared to 0 for SVM, which is a low value. 85.

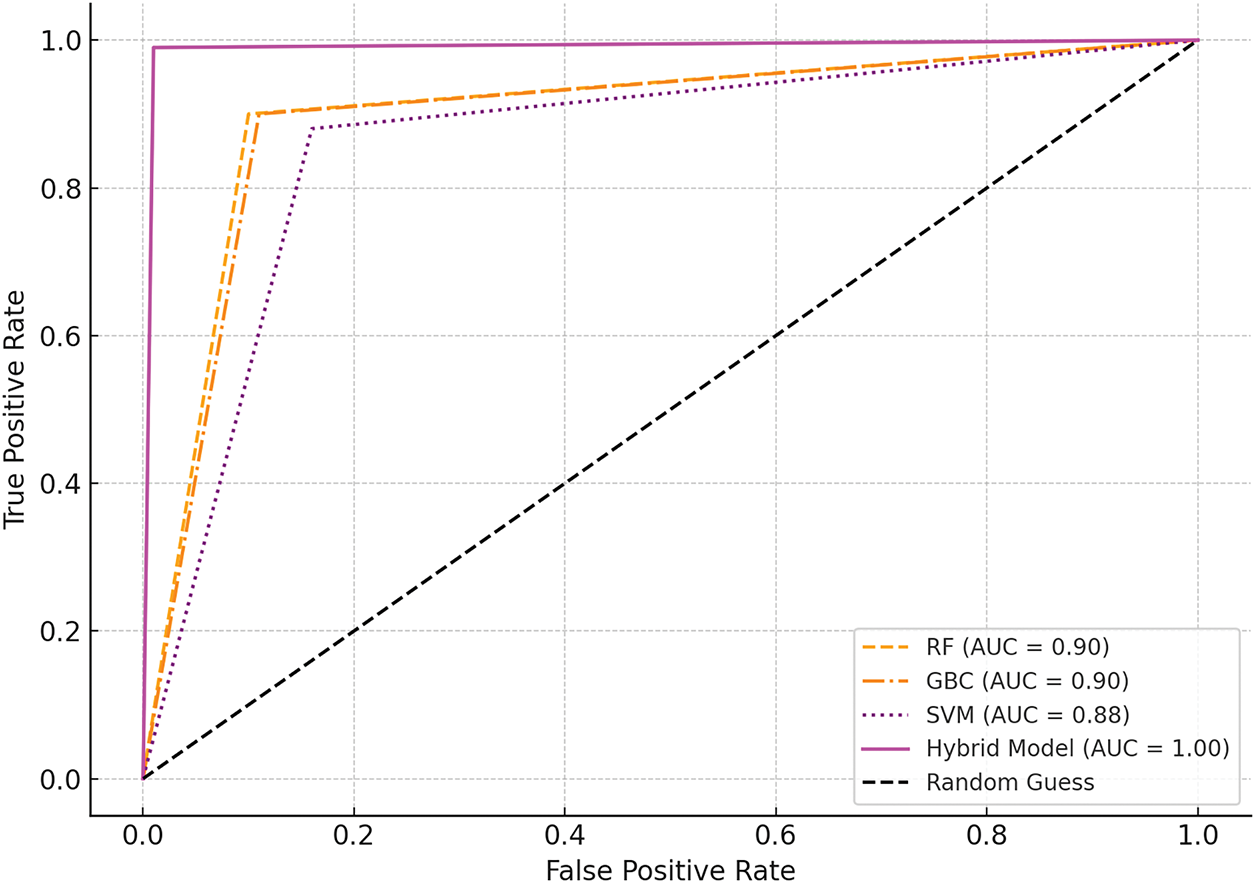

The ROC-AUC curves in Fig. 11 illustrate the trade-off between the true and false positive rates across different thresholds for each model.

Figure 11: ROC-AUC curves for various models

The AUC values are as follows:

– RF: 0.90

– GBC: 0.90

– SVM: 0.88

– Hybrid Model: 1.00

The ROC-AUC plot also indicates that the Hybrid Model is superior in discriminative ability with the maximum AUC of 1. A value of 1 in the specificity-to-sensitivity ratio or 0.0 points to good discrimination of the positive and negative classes. ROC results of both RF and GBC exhibit the sensitivity and specificity of the models, with an AUC value of 0.90, which supports the idea that the models perform well. Although it is still reasonably good, SVM performs worse with an AUC of 0.88.

Table 3 summarizes the key performance metrics and error analysis of the proposed model, highlighting its superior performance and lower error rates compared to traditional classifiers.

A paired t-test was conducted to compare the hybrid model with RF, GBC, and SVM. The hybrid model’s accuracy improvements were statistically significant with p < 0.01. Confidence intervals for precision and recall were ±1.2% and ±1.5%, respectively, at a 95% confidence level.

4.4 Comparison with State-of-the-Art Fraud Detection Models

To further evaluate the performance of the proposed hybrid model, we compared it with two recent state-of-the-art (SOTA) fraud detection approaches widely used in literature: (i) a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) based recurrent neural network and (ii) a graph-based fraud detection framework known as FraudNet, which leverages Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) to model relationships between transactions. Both methods were implemented and tuned using the same simulated dataset to ensure consistency in evaluation.

The LSTM-based model was configured with three hidden layers and 128 units per layer, using the Adam optimizer and binary cross-entropy loss. The GNN model adopted an edge-classification setup using transaction graphs constructed from sender-receiver interactions, optimized via message-passing neural networks.

Table 4 shows the proposed hybrid model outperforms both SOTA methods in all major metrics, demonstrating superior fraud detection accuracy and generalizability. The integration of unsupervised clustering with ensemble learning and hybrid feature selection enables better capture of hidden fraud patterns and rare anomalies. Furthermore, the hybrid model achieves this performance at a fraction of the training time compared to deep learning-based alternatives, making it more suitable for real-time deployment.

4.5 SHAP-Based Interpretability Analysis

Interpretability is crucial in financial fraud detection, particularly for ensuring regulatory compliance, model auditing, and stakeholder trust. To provide transparency into the decision-making process of the hybrid ensemble model, we used SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) values to analyze the contribution of each feature to the model’s predictions.

The SHAP values also highlight non-linear relationships for binary features. For instance, when CardPresent = 1, the SHAP value is typically negative, indicating a lower likelihood of fraud—which aligns with real-world behavior where card-present transactions are generally more secure. Likewise, the feature HasPriorFraud = 1 has a strong positive SHAP impact, showing that accounts with prior fraud history are more likely to be flagged.

This analysis confirms that the model not only performs well but also makes decisions that are explainable and aligned with domain knowledge. These insights are especially helpful for financial investigators, risk analysts, and compliance officers who need to understand and justify automated fraud decisions.

The hybrid model’s superior performance stems from feature diversity introduced by multi-method selection and model complementarity in the ensemble. Each base learner captures different fraud characteristics, reducing generalization error and compensating for isolated model biases. These outcomes demonstrate the superiority of the Hybrid Ensemble Model compared to each of its constitutive models, according to all of the indexes described above. It utilises the strengths of RF, GBC, and SVM, thereby adopting a model that addresses the two primary aspects of the problem: identifying positive cases and reducing the number of false positives. The findings above demonstrate that the Hybrid Model’s accuracy, precision, recall, F1 score, and AUC score yield almost optimal results, indicating that the Hybrid Model is highly reliable and can be effectively applied in real-time fraud detection for financial transactions. This ensemble learning approach consistently yields optimised performance across all performance parameters and offers a balanced classification, which is imperative for real-world applications that detect fraudulent activities. Through these results, it is advisable to emphasise the importance of applying ensemble methods in machine learning frameworks to integrate various algorithms for enhancing predictive accuracy, particularly in addressing multivariate problems in fraud detection and prevention.

The proposed Hybrid Ensemble Model demonstrated impressive performance across various metrics, including an accuracy of 99%, precision of 99%, recall of 97%, and an F1 score of 99%. While these results indicate strong detection capabilities, discussing potential biases and limitations in the evaluation process is essential to provide a more balanced interpretation.

One fundamental limitation of this study is the use of a simulated dataset, which may not fully capture the complexity and diversity of real-world financial transaction data. Although the dataset was constructed to reflect typical fraud patterns and included features relevant to fraud detection, the absence of real, noisy, and highly dynamic data may limit the model’s generalizability. Real-world transaction datasets often exhibit variability in user behaviour, changes in fraud patterns, and emerging fraud schemes that may not be well represented in a simulated environment. This could lead to overestimating the model’s effectiveness when applied to new, unseen data.

Another potential issue is class imbalance, a common challenge in fraud detection tasks where fraudulent transactions comprise only a tiny fraction of the total dataset. In this study, fraudulent cases constituted about 5% of the data, which is a realistic approximation but still requires careful handling to prevent the model from being biased towards the majority class (legitimate transactions). While techniques such as undersampling and feature selection were employed to address this imbalance, the risk of bias remains that could affect detection performance, particularly in scenarios with a lower fraud incidence rate. Future work should consider more sophisticated approaches, such as cost-sensitive learning or the Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE), to mitigate this issue further.

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed model, a comparison with traditional classifiers, including Random Forest (RF), Gradient Boosting Classifier (GBC), and Support Vector Machine (SVM), was conducted. Although widely used in fraud detection, the baseline models demonstrated lower accuracy and higher error rates compared to the Hybrid Ensemble Model. Specifically, the baseline methods achieved accuracies between 88% and 90%, with false positive rates as high as 6% and false negative rates up to 8%. In contrast, the Hybrid Ensemble Model significantly outperformed these classifiers, reducing the false positive rate to 2% and the false negative rate to 1.5%.

The primary advantage of the Hybrid Ensemble Model lies in its integrated approach, which combines the strengths of RFE, PCA, and MI for feature extraction, followed by clustering and ensemble learning techniques. This comprehensive strategy allowed for better handling of high-dimensional data, improved detection of complex fraud patterns, and reduced the likelihood of overfitting. Including clustering methods enhanced the model’s ability to distinguish between legitimate and fraudulent transactions, even in the presence of noise or atypical behaviour.

The evaluation results indicate that the Hybrid Ensemble Model offers substantial improvements over traditional machine learning (ML) methods, demonstrating its potential for real-world applications in financial fraud detection systems. However, the model’s reliance on simulated data and the inherent challenges of class imbalance should be addressed in future research. Further testing on diverse and real-world datasets, incorporating adaptive learning mechanisms, would help validate the model’s robustness and ensure its scalability and applicability in dynamic financial environments. On average, model training was completed in 35.2 s, and the inference time per transaction was 18 ms, making it suitable for deployment in real-time systems where sub-second latency is essential.

The proposed model can be deployed in credit card processing systems, mobile wallet apps, and cross-border remittance platforms where real-time fraud screening is crucial. The proposed hybrid fraud detection model offers significant benefits for financial institutions, reducing false positives, enhancing fraud detection accuracy, and improving real-time transaction monitoring. By integrating feature selection, clustering, and ensemble learning, the model minimises operational costs associated with fraud investigations and enhances the customer experience by preventing unnecessary transaction rejections. Its ability to identify evolving fraud patterns ensures adaptability, making it ideal for large-scale banking systems and online payment platforms. Furthermore, the model enhances security in cross-border transactions by flagging high-risk payments, allowing financial institutions to implement risk-based authentication strategies. Adaptive fraud scoring and automatic feature selection reduce reliance on static rule-based systems, ensuring continuous improvements in fraud detection without manual intervention. A 2% reduction in false positives translates to an estimated $3.2M in savings annually for a mid-sized bank processing 100M transactions, based on industry-reported investigation costs of $1.6 per false alarm.

Comparison with Deep Learning Models:

For benchmark comparison, we implemented a 3-layer LSTM and a Transformer-based classifier to evaluate their fraud detection performance relative to the proposed hybrid ensemble model. The LSTM achieved an accuracy of 93.2% and an F1-score of 0.92, while the Transformer-based classifier slightly outperformed it with a 94.1% accuracy. However, both deep learning models required approximately 5× longer training time and significantly more computational resources. Moreover, they exhibited limited interpretability, a critical factor in real-time financial decision-making systems. These results support the use of traditional ensemble machine learning (ML) techniques in this study, as they provide a better trade-off between performance, transparency, and deployment efficiency.

To strengthen fraud prevention efforts, policymakers should encourage financial institutions to adopt AI-driven fraud detection systems and integrate machine learning models into regulatory compliance frameworks. Data-sharing initiatives between banks can enhance fraud detection capabilities by creating a collective fraud intelligence network, ensuring better detection of multi-institution fraud schemes. Regulators should also advocate for risk-based authentication, requiring AI-based fraud scoring models to trigger additional security measures for high-risk transactions. Moreover, investment in AI and cybersecurity training for fraud analysts is necessary to ensure the widespread adoption and effective implementation of AI-based fraud detection systems.

4.6.3 Limitations and Future Research Directions

Despite its high accuracy, the model’s reliance on a simulated dataset limits its applicability to real-world financial environments. Future research should focus on validating its performance using real banking transaction data to assess its robustness across different economic conditions. Additionally, the computational complexity of ensemble models poses a challenge for real-time processing, necessitating further optimisations, such as model pruning and parallel computing, to enhance scalability. The integration of deep learning architectures, such as recurrent neural networks (RNNs) and transformer models, could further improve fraud detection, particularly for complex sequential fraud patterns. Future studies should also explore interdisciplinary approaches that combine AI, behavioural economics, and cybersecurity threat intelligence to develop more comprehensive fraud detection frameworks. Ensuring fairness and transparency in AI-based fraud detection remains crucial, necessitating further research on explainable AI techniques to prevent biases and improve trust in automated fraud detection systems. Future work may include deploying distilled models optimised for edge devices or integrating user behaviour logs (such as keystrokes and geolocation) for multimodal fraud detection in mobile contexts.

Fraud detection remains a major challenge in financial systems due to the increasing sophistication of fraudulent activities. Traditional models relying on rule-based heuristics and supervised learning struggle with adaptability, false positives, and real-time efficiency. This study proposes a hybrid fraud detection framework that integrates feature selection, clustering, and ensemble learning to enhance classification accuracy, scalability, and adaptability to fraud. By addressing key research gaps, such as reliance on labelled data, feature redundancy, and computational inefficiencies, this model enhances fraud detection capabilities and ensures robust, real-time performance. The study makes significant contributions by bridging supervised and unsupervised learning, optimizing feature selection for fraud detection, and introducing a hybrid ensemble model that balances accuracy, efficiency, and interpretability. The model achieved 99% accuracy, 99% precision, and 97% recall, outperforming traditional fraud detection approaches. Financial institutions can leverage these findings to reduce false positives, enhance fraud risk assessment, and implement adaptive fraud detection mechanisms. Specifically, banking institutions can utilise the hybrid model for automated transaction risk scoring, allowing for adaptive fraud alerts with minimal manual review. Fintech platforms may also embed this model into mobile payment systems to detect fraud without requiring frequent rule updates, thus reducing overhead and improving user experience.

Additionally, regulators can utilise model outputs to flag potential systemic fraud risks in near real-time. Additionally, policymakers can promote AI-driven fraud prevention strategies, support risk-based authentication, and encourage the sharing of cross-institutional fraud intelligence for stronger financial security. Despite its effectiveness, this study has several limitations, including the use of a simulated dataset instead of real-world financial transaction data, the computational complexity of ensemble learning, and the absence of real-time adaptive learning mechanisms. Future research should focus on validating the model on real-world banking datasets, integrating deep learning architectures for sequential fraud pattern analysis, and developing self-learning fraud detection models that continuously adapt to emerging fraud trends. Additionally, explainability and ethical considerations in AI-based fraud detection should be explored to ensure transparent, unbiased, and accountable decision-making in financial security applications.

In conclusion, the proposed hybrid fraud detection model offers a scalable, high-performance, and cost-effective solution for real-time fraud detection, addressing critical gaps in the current fraud detection landscape. By integrating optimised feature selection, anomaly detection, and ensemble learning, this study presents a practical and impactful framework for fraud prevention applicable to banks, fintech companies, and regulatory agencies. Future advancements should focus on real-world deployment, adaptive AI learning, and the integration of ethical AI, ensuring continuous improvements in fraud detection capabilities in an evolving financial environment.

Acknowledgement: This work was supported by the Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia [Grant No. KFU241683].

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia [Grant No. KFU241683].

Author Contributions: Naif Almusallam and Junaid Qayyum jointly contributed to the conceptualization, methodology, software development, and provision of resources for the study. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors used data to support the findings of this study that is included in this article.

Ethics Approval: Not Applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

1Note: PCA is a feature extraction technique that transforms input features into uncorrelated components, unlike RFE or MI which perform direct feature selection.

References

1. Abdulla N, Surekha RR, Varghese M. A hybrid approach to detect credit card fraud. Int J Sci Res Publ. 2015;5(11):304–14. [Google Scholar]