Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Study on User Interaction for Mixed Reality through Hand Gestures Based on Neural Network

1 Department of Game Design and Development, Sangmyung University, Seoul, 03016, Republic of Korea

2 Department of Computer Engineering, Chosun University, Gwangju, 61452, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: SeongKi Kim. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(2), 2701-2714. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.067280

Received 29 April 2025; Accepted 19 August 2025; Issue published 23 September 2025

Abstract

The rapid evolution of virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) technologies has significantly transformed human-computer interaction, with applications spanning entertainment, education, healthcare, industry, and remote collaboration. A central challenge in these immersive systems lies in enabling intuitive, efficient, and natural interactions. Hand gesture recognition offers a compelling solution by leveraging the expressiveness of human hands to facilitate seamless control without relying on traditional input devices such as controllers or keyboards, which can limit immersion. However, achieving robust gesture recognition requires overcoming challenges related to accurate hand tracking, complex environmental conditions, and minimizing system latency. This study proposes an artificial intelligence (AI)-driven framework for recognizing both static and dynamic hand gestures in VR and AR environments using skeleton-based tracking compliant with the OpenXR standard. Our approach employs a lightweight neural network architecture capable of real-time classification within approximately 1.3 ms while maintaining average accuracy of 95%. We also introduce a novel dataset generation method to support training robust models and demonstrate consistent classification of diverse gestures across widespread commercial VR devices. This work represents one of the first studies to implement and validate dynamic hand gesture recognition in real time using standardized VR hardware, laying the groundwork for more immersive, accessible, and user-friendly interaction systems. By advancing AI-driven gesture interfaces, this research has the potential to broaden the adoption of VR and AR across diverse domains and enhance the overall user experience.Keywords

Recently, the rapid advancement of virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) technologies [1,2] has transformed the way users interact with the digital environment. These immersive technologies have expanded beyond entertainment and gaming to find applications in diverse fields, such as education, healthcare, manufacturing, and remote collaboration. A critical component for enhancing user experience in VR and AR systems is the development of intuitive and efficient interaction interfaces. However, traditional input devices for user interfaces in VR and AR, such as controllers [3] and keyboards, can create a disconnect between users and the virtual world, thus limiting the potential for truly immersive experiences.

Hand-gesture recognition is a promising solution for creating more natural and seamless interactions within VR and AR environments. The advantages of hand gesture recognition are as follows. First, it can reduce hand fatigue by not using a controller, which can increase playing time. Second, gesture recognition allows users to adapt to the environment faster because it is more intuitive. Consequently, Apple, Meta, and PICO have prioritized the development of hand interfaces to enhance natural interactions [4].

However, designing robust and reliable hand gesture interfaces presents several challenges, including accurate hand tracking, gesture recognition in complex environments, and minimizing latency. In addition, to realize hand gestures for VR or AR applications, it is necessary to determine the bending of the fingers and the direction in which the hand is oriented. In addition, it is challenging to recognize dynamic gestures in a traditional system, even though the system supports static gestures.

Artificial intelligence (AI) has proven to be a transformative tool for overcoming these challenges. Recent advancements in computer vision and deep learning have significantly improved the capabilities of AI systems in tasks such as object detection, pose estimation, and pattern recognition. These developments have enabled the creation of AI-driven hand-gesture interfaces that can operate in real-time, adapt to varying lighting conditions, and accommodate diverse hand shapes and movements.

This study explored the design and implementation of AI-based hand gesture interfaces for VR and AR applications. We examined the current state-of-the-art technologies, discussed the challenges associated with their development, and proposed a novel method to implement hand recognition for immersive VR and AR. By integrating AI with VR and AR systems, we aim to create more immersive, accessible, and user-friendly interactive experiences.

The contributions of this study can be summarized as follows. First, widespread VR devices were employed for the classification of hand motion and dynamic motion. In addition, this study used a hand model that follows OpenXR, the standard of AR and VR, so it is easy to apply to other VR devices. Second, the proposed model is characterized by its lightweight architecture. Furthermore, this study proposes a method for generating a dataset, which is a crucial step in the research process. Finally, a method for classifying dynamic and static gestures is proposed. The consistent and accurate identification of hand gestures using VR devices has the potential to promote supportive behaviors, thus expanding the possible applications of such technology beyond the fields of entertainment. This is one of the world’s first studies to recognize dynamic hand gestures and verify their real-time performance on a widely used device.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces related studies on hand tracking and gesture classification. Section 3 proposes a novel structure for gesture classification in a VR environment. Section 4 presents the results of the implementation and Section 5 concludes the paper.

This section describes related works to understand this research better.

Hand tracking is essential for classifying hand gestures, and can be categorized into three main methods: sensor-based, vision-based, and hybrid-based [5]. Sensor-based methods include data gloves [6] and electromyography (EMG) as shown in Fig. 1. Data gloves use built-in inertial measurement unit (IMU) sensors, including gyroscopes and accelerometers for tracking in Refs. [7–9]. Electromyography methodologies, such as that in [10], attach sensors to the body to capture electrical signals. However, even if this method is highly accurate, it is inconvenient to wear and remove gloves or attach and remove sensors from the body during actual use.

Figure 1: Sensor-based methods (a) Rokoko smart glove as data glove (b) Myo armband using the electromyography method

Vision-based methods use a camera to obtain information from the hand and process images that come through the camera. Banerjee et al. [11] introduces a dataset for hand and object tracking in 3D (HOT3D). The dataset consists of multi-view RGB and monochromatic image streams and provides comprehensive real-world annotations, including multimodal signals such as eye gaze and point clouds, as well as 3D poses of objects, hands, and cameras. The dataset was recorded under Meta’s Project, Aria, and Meta Quest 3, and is a VR-related dataset from the user’s point of view. Portnova-Fahreeva et al. [12] used a Leap Motion with an infrared camera. In [12], the hand-tracking accuracy of people with upper-body disabilities was investigated using leap motion. However, as a limitation of this study, the marker was obstructed by the room in which the experiment was conducted and the mobility assistance device of the disabled person, and the marker was often lost in several frames.

Finally, the hybrid method operates in a manner that combines vision and sensor methods, and the sensor corrects what the camera recognizes. Li et al. [13] was used to collect human arm surface electromyography signals and hand three-dimensional (3D) vectors using a wearable Myo armband and Leap Motion sensors, respectively. The movement of the robot was controlled using gesture classification. As mentioned previously, this study also employed Leap Motion, corresponding to a camera and an armband, to correct it.

In this research, we wanted to use a camera for VR interaction; therefore, sensor-based and hybrid-based methods were excluded because we tried to eliminate the physical object in the hand.

Vision-based methods can also be classified into image- and skeleton-based methods. Image-based methods classify gestures using only the input image, whereas skeleton-based methods track the hand skeleton. Google MediaPipe has recently become widespread [14] as a skeleton-based method. This method incorporates a heat map for each finger landmark into the preceding image to denote the maximum value. This method is skeleton-based because it is similar to a bone. In Phuong and Cong [15], Media Pipe was used to control a robotic hand. Furthermore, Arduino was designed to move the motor corresponding to the 21 coordinates of the recognized hand.

However, unless it is listed separately as a model for hand tracking, such as MediaPipe, because the images used for gesture classification and hand tracking are similar in vision-based studies, except for skeleton-based studies, datasets such as [16] sometimes find a hand and process gesture classification simultaneously.

As mentioned in Tasfia et al. [17], gesture recognition using computer vision is used in various software applications, such as American sign language recognition and virtual mice. Alnuaim et al. [18] proposed a framework for Arabic Sign Language that employs the Resnet and MobileNet. Thushara et al. [19] classified sign languages using a KFM-CNN, and Zhang et al. [20] classified hand gestures using a transformer consisting of multi-headed self-attention (MSA). In the case of Alam et al. [21], the study was conducted from the user’s perspective but the image-based dataset is difficult to adapt to VR devices.

Dynamic classification is also possible. Lu et al. [22] allows dynamic movements to be classified using 3D DenseNet and LSTM from images cut by hand segmentation only. Liu et al. [23] uses a skeleton-based method to identify and classify hand movements. Ref. [23] proposed a hierarchical self-attention network (SAN). Because this model does not use any CNN, RNN, or GCN operators, it has a much lower computational complexity.

Xiong et al. [24] proceeded with gesture classification by the traffic police. It is not a hand gesture but a skeleton-based method using OpenPose [25]. As traffic police gestures occur only in the upper body, only the upper body was extracted from the landmarks of the entire body. This was then learned and used in the MD-GCN [26].

Although there have been previous studies, they are not easy to use because we want to realize a new interaction method for a widespread VR system. First, some HMD devices does have a passthrough camera that can see outside because they can be used to augment reality [27], but the other devices cannot get pass-through data. Second, in contrast to the fixed cameras utilized in conventional vision-based studies, the camera in this study was mobile and adjusted its position according to user movements. Finally, in traditional studies, the camera is oriented toward the user, whereas in VR, the camera is positioned outside the user.

This study used a standard compatible with OpenXR [28], the standard that most VR devices follow, and the skeleton of the hand was obtained. When using the OpenXR standard, existing production methods for VR devices should directly specify the size or angle range of the finger vector. Moreover, the fabrication method using the existing SDK requires setting the allowable error range for a single finger, incorporating the bending value. However, this study proposes that providing sample gestures is a more efficient approach to adding new gestures. Subsequently, our AI model attempts to recognize a sample gesture from the input scenes.

This section describes the AI model for recognizing static or dynamic hand gestures.

This subsection describes the problems associated with the recognition of dynamic gestures. A static gesture is expressed by

If we sequentially replace

In this equation,

If the sequence matches the defined

In the traditional methodology for recognizing hand movements on a VR device, it is imperative to sequentially calibrate the bending angle and finger error [29]. However, it is difficult to obtain the angle and error because most people have different hand shapes. In addition, it is impossible to recognize dynamic gestures using existing methods. The angles between the fingers and errors must be measured and inputted for a new gesture. To address these issues, we propose a method for creating static and dynamic hand gestures using neural networks.

Fig. 2 shows the structure of the recognition architecture.

Figure 2: Overview of the proposed recognition

As shown in Fig. 2, the data flows as follows:

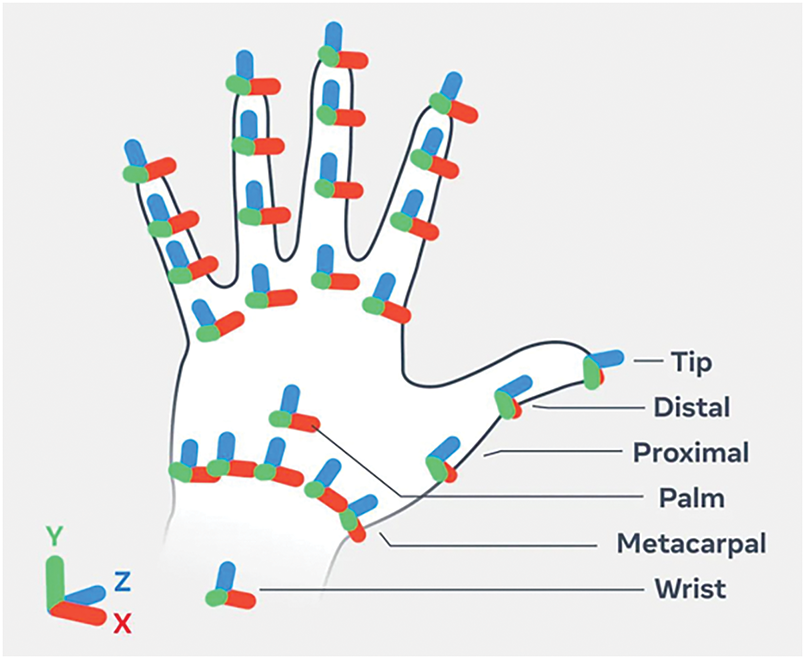

1. VR Device: It tracks the user’s hand using internal cameras. Systems that adhere to the OpenXR standard can recognize landmarks, as shown in Fig. 3. However, when a developer extracts a landmark, the original landmarks and velocity points representing its vector are drawn together, resulting in a total of 52 points. The following preprocessing steps were performed: Initially, velocity was removed. This results in the removal of the velocity value, leaving only the coordinates of the 26 landmarks, as shown in Eq. (3). In this equation,

Figure 3: Hand landmarks in OpenXR

Fig. 3 shows images of the hand skeleton according to OpenXR, the most widely used industry standard used in this study.

As shown in Fig. 3, each finger except the thumb includes the metacarpal, proximal, intermediate, distal, and tip, and the thumb includes four points excluding the intermediate; the hand is represented with a total of 26 points, including the palm and wrist [30]. This is the same as that for the actual hand, except that a landmark is added to the palm.

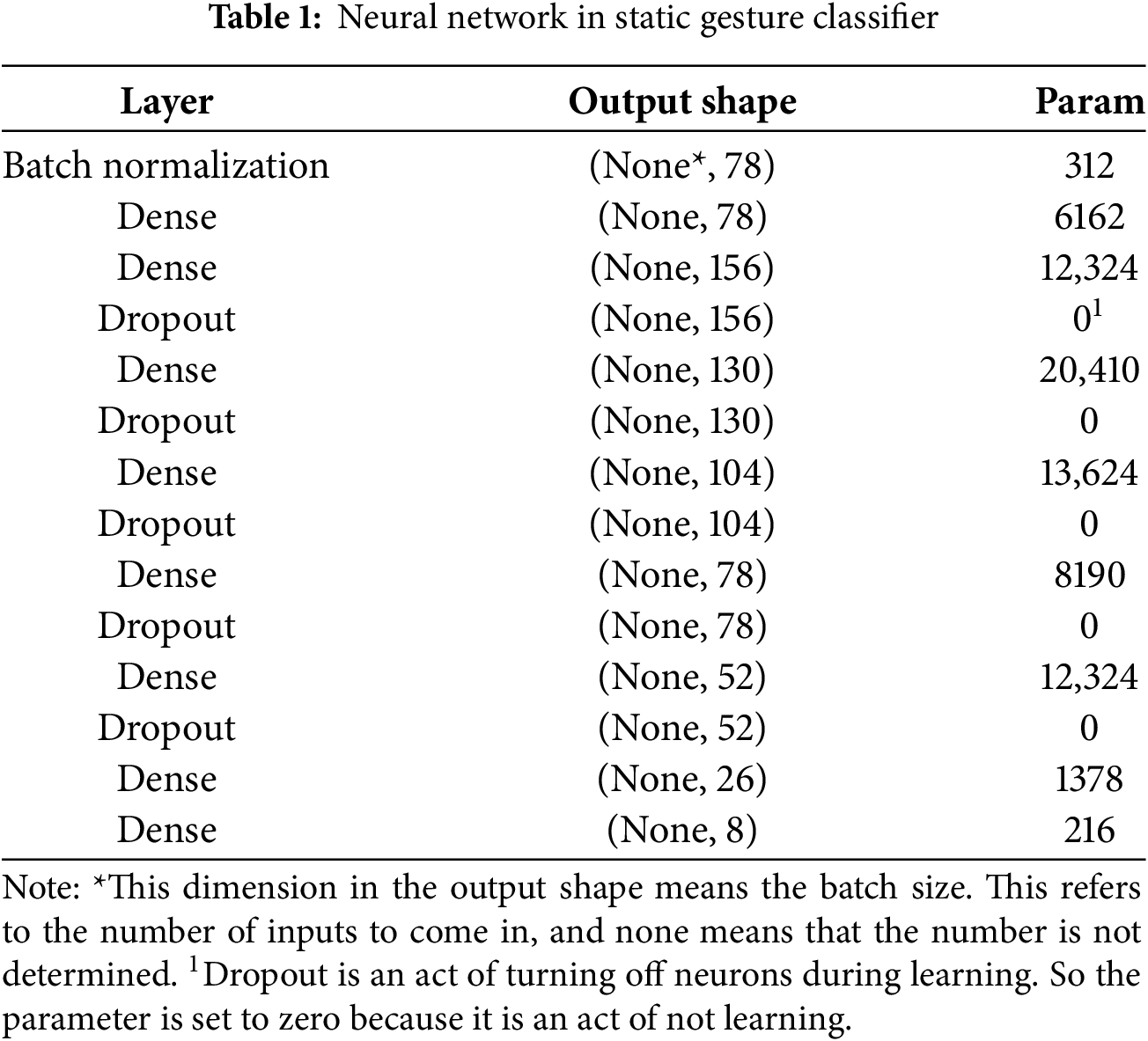

2. Static Gesture Classifier: The 26 XYZ coordinates were subsequently entered into the neural network. The network is composed as shown in Table 1. The coordinates entered in Step 1 are designated as relative, originating from the wrist; however, they undergo a normalization process at the inception of the network to ensure reduced computational demands. Furthermore, given the nature of the coordinates provided as relative values, negative values were obtained. Dropout layers were used during each stage to prevent the accumulation of dead neurons caused by the ReLU. The activation function employed in the final layer is Softmax, which facilitates classification.

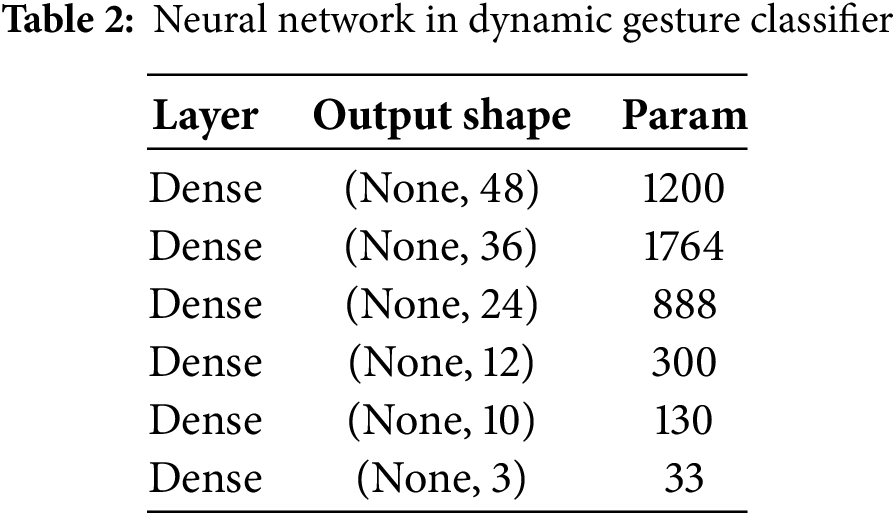

3. Dynamic Gesture Classifier: The result of the static gesture classifier is stored in the array, and from the moment it is filled with 24 frames, it passes through the network every time and sorts the moment. That is, a combination of 24 static hand gestures creates dynamic hand gestures. It has been established that increasing the frame length improves the accuracy [31]. However, we used 24 frames because this is close to the 99% accuracy in [31], and an excessive amount of data increases the size of the required data. Table 2 lists the network structure through which an array passes. Note that dropouts were generally omitted because of poor accuracy results in the corresponding classifier, which occurred in an attempt to reduce overfitting.

To clarify the proposed method, we summarize the overall step-by-step process in Algorithm 1 below.

To train the classification model in Section 3.2, we used Unity 6 on laptops with an AMD Ryzen 78845HS/RTX 4070 and Meta Quest 3s for the VR device. In this study, the latest version of Unity, 6, was utilized. However, to obtain the hand coordinates of OpenXR, the installation of the essential XR interaction toolkit is sufficient. Provided that the version supports that package, it is 2021.3 or later. And in the case of Meta Quest, it is possible from 2 or more that supports hand tracking. We directly performed hand gestures while wearing the Meta Quest. In this state, data were collected by saving the coordinates in the CSV format when a number with a label for the corresponding action was pressed with a keypad in the Unity editor. While repeating this process 20,000 times, we collected and used the data for training. Dynamic gestures were also repeated 1500 times to perform hand gestures directly to produce an array of results, and the collected data were used for training.

This section describes the results of the recognition of static and dynamic hand gestures using the developed AI model.

To implement and run the architecture described in Section 3, we used Meta Quest 3s for the VR device. A flask was used as the AI server. As each classifier used a server, the landmark data of the hand went through the first server to receive the results of the static gesture, and the arrangement went through the second server to obtain the results of the dynamic gesture. The results were then delivered into Meta Quest3s, and the classification results were displayed.

This study uses hand-tracking technology on a VR device. When the device recognized the hand, the hand mesh was displayed in the editor, learned, and tested using the coordinates according to the mesh. Therefore, if the device supports it, it can be tested by anyone, whether a child or an adult. However, if the user’s hand used during hand tracking disappears, the hand of the person who entered the device’s recognition area will be displayed. To ensure the accuracy of the test results, the wearer must have sole presence in the surrounding environment. In addition, the Meta Quest 3s used in this study requires the controller to be inactive for hand tracking.

Fig. 4 shows eight recognizable gestures: (a) zero, (b) one, (c) two, (d) three, (e) four, (f) five, (g) good, (h) okay.

Figure 4: The recognizable static gestures of implementation (a) zero, (b) one, (c) two, (d) three, (e) four, (f) five, (g) good, (h) okay

As mentioned above, the data were created by wearing a VR device and using the hand-tracking function of the device to obtain gestures directly, as shown in Fig. 4. The learning process outcomes are listed in Table 1, and the confusion matrix is shown in Fig. 5.

Figure 5: The confusion matrix of static gesture classification using VR device

As shown in Fig. 5, the confusion matrix shows the proportion of the classification results for static hand gestures that are shown in Fig. 4. Each result corresponded to the percentage of gestures correctly classified for each action within the entire dataset. A value of 1.00 indicates that all actions can be classified with 100% accuracy, which indicates a complete classification in the given test cases. As shown in Fig. 5, the prediction result of Fig. 4d was an exception, with a classification accuracy rate of 0.99. This is likely due to the small dataset. The representative image-based datasets, Hagridv2 and EgoGesture, have 1 million and 3 million images, respectively, while the manually collected data contains only 20,000 images.

Fig. 6 shows three examples of dynamically recognizable gestures: (a) counting (ascending), (b) counting (descending), and (c) none.

Figure 6: The recognizable dynamic gesture examples of implementation (a) counting (ascending), (b) counting (descending), (c) none

Fig. 6 shows an example of a dynamic gesture. As shown in Fig. 6a, 24 frames of static gestures received in the same order are passing through the dynamic gesture classifier and recognizing that the result is counting in ascending order, and Fig. 6b is recognized in descending order. As shown in Fig. 6c, if the gestures corresponding to g and h in Fig. 5 are mixed among gestures in 24 frames, or if the 24 frames consist only of g and h, or if the numbers are counted disorderly, it is concluded that the dynamic gesture was not recognized and the result is output as none. The confusion matrix of the learned results of the dynamic gesture classifier model with the structures listed in Table 2 is shown in Fig. 7.

Figure 7: The confusion matrix of dynamic gesture classification using VR device

Fig. 7 shows the confusion matrix employed for dynamic gesture classification. This result is expressed as the percentage of correct behaviors, similar to the gesture classification results shown in Fig. 5. For example, 97% of the models correctly predicted counting in ascending order and 3% predicted none. Overall, the accumulation averaged 95% of all the correct results in the confusion matrix. The result of this dynamic gesture classification was used a bundle of static gestures’ results as input, whereas the results of the static gesture classification were organized as an expression [1, 1, 1, 2, 2, …]. Therefore, obtaining the optimal results shown in Fig. 5 is essential for ensuring the highest accuracy, as shown in Fig. 7.

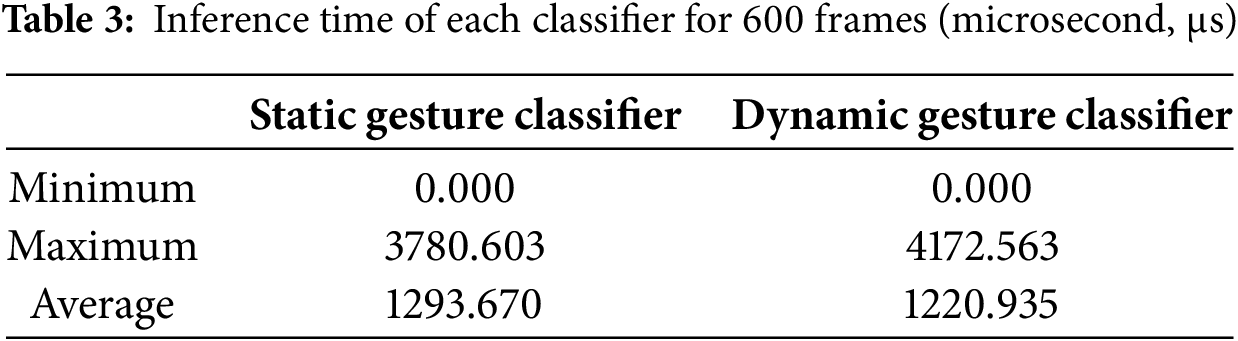

We also measured the inference time to determine its applicability to real software applications. Table 3 lists each classifier’s minimum, maximum, and average inference time for the 600 frames.

As listed in Table 3, the static classifier requires only 1293.670 μs (1.293670 ms) on average and the dynamic classifier takes 1220.935 μs (1.220935 ms) on average, which indicates that it can classify the gesture in real-time.

In this study, we conducted research on the AI model to realize a novel interaction method using hand gestures. In addition, this research provides insights into the application of AI-driven hand-gesture recognition in VR and AR environments, focusing on the key challenges and opportunities for improvement.

1. Gesture-classification framework for VR devices: The proposed system successfully integrates hand tracking in VR and neural networks to classify static and dynamic hand gestures in real-time. As will be discussed later, existing works do not follow the standard called OpenXR, so the number of coordinates is also different from this paper. However, this work follows the standard, which is more suitable for future VR research.

2. Standard compliance: Adherence to standards is very important to maintain interoperability and usability in the long term. Currently, OpenXR, which was released in 2017, is being used as a standard for VR and AR platforms. In the case of Meta, it used its own Oculus virtual reality (OVR) for interaction SDK but changed to using OpenXR in November 2024 [32]. OpenXR in this paper typically uses more landmarks than non-OpenXR solutions or systems. Consequently, if the number of datasets employed in this study were to be modified and retrained, non-OpenXR devices will also be able to integrate systems.

3. Wide range of applications: This technology has potential applications in other areas such as remote collaboration, rehabilitation, and education. In particular, there is little data from current hand-related vision research that represents hand coordinates from the user’s perspective. So, adapting systems for these applications can accelerate their adoption and foster innovation.

This study explored the development of hand gesture recognition systems for VR and AR environments. The traditional method had a limitation in that the personal difference in hand shapes was not considered, and the extension to a new gesture was complex because the angles between fingers and errors had to be entered into the recognition in advance. In addition, the recognition of dynamic gestures is challenging. The proposed approach integrates artificial intelligence with a skeleton-based hand to overcome these limitations. The neural network model successfully classified static and dynamic hand gestures within 1.3 ms, achieving 100% and 95% accuracy, respectively, while adhering to the OpenXR standards for broad VR device compatibility.

This study highlights the successful combination of vision-based hand tracking and gesture classification in VR. The system preprocesses hand landmarks and applies a neural network to achieve accurate gesture recognition, as indicated by the confusion matrix results. The results were sufficiently fast for real-time applications. This approach ensures efficient and robust performance, while enhancing user interaction in immersive environments.

However, the studied system has a limitation in that a fixed 24-frame input can lead to variations in recognition accuracy based on individual motion speeds. Therefore, future work will focus on addressing challenges such as variable-speed dynamic gestures and dataset diversity to ensure the broader applicability and robustness of the system. This study lays a strong foundation for advancing user interactions in mixed-reality environments, emphasizing accessibility and user friendliness in next-generation VR and AR systems.

The future work can be summarized follows; First, the present study implemented dynamic gestures by fixing 24 frames. While the currently implemented dynamic gestures can be distinguished, the addition of more gestures may result in the inability to track the user’s movement with the current fixed 24 frames, as the speed varies from user to user. Subsequent research endeavors will involve the implementation of adaptive frame lengths, a technological advancement capable of catering to the individual user’s pace.

Second, this work is designed in such a way that subjects must wear equipment to obtain coordinates tracked by Meta Quest 3s. Nevertheless, additional data is needed to increase scalability in the current context. Subsequent studies will introduce automation of data generation using synthesis or augmentation.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This study was supported by research fund from Chosun University, 2024.

Author Contributions: Study conception and design: SeongKi Kim, data collection: BeomJun Jo, draft manuscript preparation: BeomJun Jo, revision: BeomJun Jo and SeongKi Kim. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All of the implementations are publicly available at https://github.com/torauma06/GestureClassificationWithServer (accessed on 18 August 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Meta. The future of wearables [Internet]. [cited 2025 Apr 21]. Available from: https://www.meta.com/emerging-tech/orion/. [Google Scholar]

2. Google VR. Google cardboard [Internet]. [cited 2025 Apr 22]. Available from: https://arvr.google.com/intl/en_us/cardboard/. [Google Scholar]

3. Meta. Meta quest touch pro VR controllers [Internet]. [cited 2025 Apr 22]. Available from: https://www.meta.com/kr/en/quest/accessories/quest-touch-pro-controllers-and-charging-dock/. [Google Scholar]

4. Ian H. Pico shifts focus from controllers to hand tracking [Internet]. San Francisco, CA, USA: UploadVR; 2023 [cited 2025 Apr 21]. Available from: https://www.uploadvr.com/pico-hand-tracking-tiktok/. [Google Scholar]

5. Osman Hashi A, Zaiton Mohd Hashim S, Bte Asamah A. A systematic review of hand gesture recognition: an update from 2018 to 2024. IEEE Access. 2024;12:143599–626. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3421992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Rokoko. Smartgloves [Internet]. [cited 2025 Apr 20]. Available from: https://www.rokoko.com/products/smartgloves. [Google Scholar]

7. Yu Z, Lu C, Zhang Y, Jing L. Gesture-controlled robotic arm for agricultural harvesting using a data glove with bending sensor and OptiTrack systems. Micromachines. 2024;15(7):918. doi:10.3390/mi15070918. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Lee SY, Bak SH, Bae JH. An effective recognition method of the gripping motion using a data gloves in a virtual reality space. J Digit Contents Soc. 2021;22(3):437–43. doi:10.9728/dcs.2021.22.3.437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Ren B, Gao Z, Li Y, You C, Chang L, Han J, et al. Real-time continuous gesture recognition system based on PSO-PNN. Meas Sci Technol. 2024;35(5):056122. doi:10.1088/1361-6501/ad2a33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Sosin I, Kudenko D, Shpilman A. Continuous gesture recognition from sEMG sensor data with recurrent neural networks and adversarial domain adaptation. In: 2018 15th International Conference on Control, Automation, Robotics and Vision (ICARCV); 2018 Nov 18–21; Singapore. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE. p. 1436–41. doi:10.1109/ICARCV.2018.8581206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Banerjee P, Shkodrani S, Moulon P, Hampali S, Han S, Zhang F, et al. HOT3D: hand and object tracking in 3D from egocentric multi-view videos. arXiv:2411.19167. 2024. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2411.19167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Portnova-Fahreeva AA, Yamagami M, Robert-Gonzalez A, Mankoff J, Feldner H, Steele KM. Accuracy of video-based hand tracking for people with upper-body disabilities. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng. 2024;32(12):1863–72. doi:10.1109/TNSRE.2024.3398610. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Li J, Zhong J, Wang N. A multimodal human-robot sign language interaction framework applied in social robots. Front Neurosci. 2023;17:1168888. doi:10.3389/fnins.2023.1168888. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Zhang F, Bazarevsky V, Vakunov A, Tkachenka A, Sung G, Chang CL, et al. MediaPipe hands: on-device real-time hand tracking. arXiv:2006.10214. 2020. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2006.10214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Phuong L, Cong V. Control the robot arm through vision-based human hand tracking. FME Trans. 2024;52(1):37–44. doi:10.5937/fme2401037p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Zhang Y, Cao C, Cheng J, Lu H. EgoGesture: a new dataset and benchmark for egocentric hand gesture recognition. IEEE Trans Multimed. 2018;20(5):1038–50. doi:10.1109/TMM.2018.2808769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Tasfia R, Izzah Mohd Yusoh Z, Binte Habib A, Mohaimen T. An overview of hand gesture recognition based on computer vision. Int J Electr Comput Eng. 2024;14(4):4636. doi:10.11591/ijece.v14i4.pp4636-4645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Alnuaim A, Zakariah M, Hatamleh WA, Tarazi H, Tripathi V, Amoatey ET. Human-computer interaction with hand gesture recognition using ResNet and MobileNet. Comput Intell Neurosci. 2022;2022(2):8777355. doi:10.1155/2022/8777355. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Thushara A, Hani RHB, Mukundan M. Automatic American sign language prediction for static and dynamic gestures using KFM-CNN. Soft Comput. 2024;28(20):11703–15. doi:10.1007/s00500-024-09936-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Zhang Y, Wang J, Wang X, Jing H, Sun Z, Cai Y. Static hand gesture recognition method based on the Vision Transformer. Multimed Tools Appl. 2023;82(20):31309–28. doi:10.1007/s11042-023-14732-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Alam MM, Islam MT, Mahbubur Rahman SM. Unified learning approach for egocentric hand gesture recognition and fingertip detection. Pattern Recognit. 2022;121(6):108200. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2021.108200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Lu Z, Qin S, Lv P, Sun L, Tang B. Real-time continuous detection and recognition of dynamic hand gestures in untrimmed sequences based on end-to-end architecture with 3D DenseNet and LSTM. Multimed Tools Appl. 2024;83(6):16275–312. doi:10.1007/s11042-023-16130-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Liu J, Wang Y, Xiang S, Pan C. HAN: an efficient hierarchical self-attention network for skeleton-based gesture recognition. Pattern Recognit. 2025;162(1):111343. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2025.111343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Xiong X, Wu H, Min W, Xu J, Fu Q, Peng C. Traffic police gesture recognition based on gesture skeleton extractor and multichannel dilated graph convolution network. Electronics. 2021;10(5):551. doi:10.3390/electronics10050551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Cao Z, Hidalgo G, Simon T, Wei SE, Sheikh Y. OpenPose: realtime multi-person 2D pose estimation using part affinity fields. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2021;43(1):172–86. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2019.2929257. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Wan S, Gong C, Zhong P, Du B, Zhang L, Yang J. Multiscale dynamic graph convolutional network for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2020;58(5):3162–77. doi:10.1109/TGRS.2019.2949180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Pico. Do you know what is VR passthrough? [Internet]. [cited 2025 Apr 23]. Available from: https://www.picoxr.com/my/blog/what-is-vr-passthrough. [Google Scholar]

28. The Khronos Group. OpenXR [Internet]. [cited 2025 Apr 23]. Available from: https://www.khronos.org/openxr/. [Google Scholar]

29. Jo BJ, Kim SK. A study on the interaction with virtual objects through XR hands. J Korea Comput Graph Soc. 2024;30(3):43–9. doi:10.15701/kcgs.2024.30.3.43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Meta Horizon. OpenXR hand skeleton in interaction SDK [Internet]. Menlo Park, CA, USA: Meta Horizon; 2024 [cited 2025 Apr 25]. Available from: https://developers.meta.com/horizon/documentation/unity/unity-isdk-openxr-hand. [Google Scholar]

31. Kopuklu O, Gunduz A, Kose N, Rigoll G. Real-time hand gesture detection and classification using convolutional neural networks. In: 2019 14th IEEE International Conference on Automatic Face & Gesture Recognition (FG 2019); 2019 May 14–18; Lille, France. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE. p. 1–8. doi:10.1109/fg.2019.8756576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Meta Horizon. OpenXR hand skeleton upgrade dialog [Internet]. Menlo Park, CA, USA: Meta Horizon; 2024 [cited 2025 Apr 25]. Available from: https://developers.meta.com/horizon/documentation/unity/unity-isdk-openxr-upgrade-dialog. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools