Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

LR-Net: Lossless Feature Fusion and Revised SIoU for Small Object Detection

1 School of Artificial Intelligence, Chongqing University of Technology, Chongqing, 401135, China

2 School of Computer and Information Science, Chongqing Normal University, Chongqing, 401331, China

* Corresponding Author: Yang Zhang. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Object Detection: Methods and Applications)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(2), 3267-3288. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.067763

Received 12 May 2025; Accepted 10 July 2025; Issue published 23 September 2025

Abstract

Currently, challenges such as small object size and occlusion lead to a lack of accuracy and robustness in small object detection. Since small objects occupy only a few pixels in an image, the extracted features are limited, and mainstream downsampling convolution operations further exacerbate feature loss. Additionally, due to the occlusion-prone nature of small objects and their higher sensitivity to localization deviations, conventional Intersection over Union (IoU) loss functions struggle to achieve stable convergence. To address these limitations, LR-Net is proposed for small object detection. Specifically, the proposed Lossless Feature Fusion (LFF) method transfers spatial features into the channel domain while leveraging a hybrid attention mechanism to focus on critical features, mitigating feature loss caused by downsampling. Furthermore, RSIoU is proposed to enhance the convergence performance of IoU-based losses for small objects. RSIoU corrects the inherent convergence direction issues in SIoU and proposes a penalty term as a Dynamic Focusing Mechanism parameter, enabling it to dynamically emphasize the loss contribution of small object samples. Ultimately, RSIoU significantly improves the convergence performance of the loss function for small objects, particularly under occlusion scenarios. Experiments demonstrate that LR-Net achieves significant improvements across various metrics on multiple datasets compared with YOLOv8n, achieving a 3.7% increase in mean Average Precision (AP) on the VisDrone2019 dataset, along with improvements of 3.3% on the AI-TOD dataset and 1.2% on the COCO dataset.Keywords

The task of small object detection (SOD) is to detect labeled small objects (less than 32

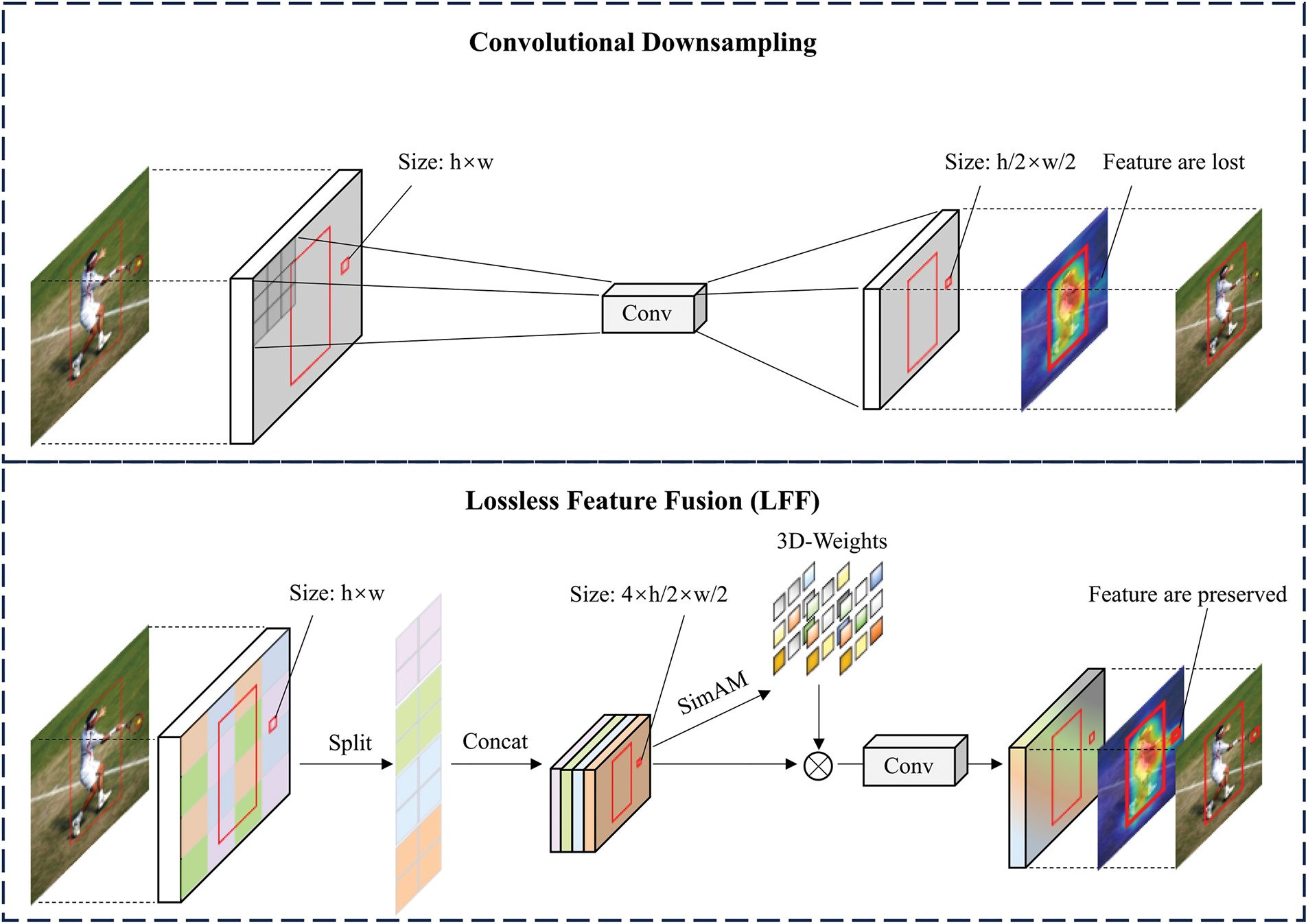

Small objects exhibit extremely limited appearance information due to their low-resolution characteristics, resulting in too few usable features, which directly increases the difficulty of feature processing. The Feature Pyramid Network (FPN) was proposed to learn multi-scale features [6,7]. By effectively fusing shallow and deep features through FPN, it fully utilizes the positional and semantic information required for small objects, alleviating the difficulties of feature processing to some extent. In the feature fusion stage, many recently proposed methods have improved feature fusion networks. Methods such as MS-YOLO [8], PSO-YOLO [9], and DSPAN [10] have been introduced to enhance and fuse small object features. However, these approaches rely on already extracted features, while mainstream backbone networks heavily utilize convolutional downsampling during feature extraction. This results in the loss of small object features, as illustrated in the upper part of Fig. 1, which depicts convolutional downsampling methods. To address this issue, one approach reduces feature loss through feature reorganization [11]. However, it does not account for the abundance of non-critical features in small object feature maps, which weakens the network’s ability to represent small objects during feature transfer. To solve this problem, this study proposes the Lossless Feature Fusion (LFF) method. LFF slices feature maps at a specific stride, preserving small object features spatially within the channels while emphasizing their three-dimensional representation. This enhances the network’s capability to represent small objects and achieves fully lossless feature downsampling.

Figure 1: Downsampling Method for Lossless Feature Fusion (In conventional convolutional downsampling, small object features are proportionally lost as the downsampling factor increases. LFF, on the other hand, transfers features to the channel dimension to prevent loss while applying attention mechanisms to focus on key small object features)

In addition, small object detection demands more stringent requirements for BBR (Bounding Box Regression). Due to the significant impact of positioning deviation on small objects, and even more so when occlusion occurs. However, the Intersection over Union (IoU) [12] loss function cannot meet this demand. Some methods have attempted to improve loss functions for small object detection by incorporating the concept of a 2D Gaussian distribution [4,5], while others have further optimized IoU-based losses [13–17]. For example, EIoU [15] introduces an evaluation mechanism where the IoU value determines sample quality and employs a focusing mechanism to emphasize the contribution of high-quality samples. SIoU [16] designs an angle penalty term to accelerate convergence, but there is still room for improvement in both convergence effectiveness and direction. WIoU [17] argues that attention should be given to ordinary-quality samples rather than high-quality ones. However, it struggles to distinguish small object sample quality, leading to suboptimal convergence for small objects. To address these IoU-related limitations, this study proposes Revised SIoU (RSIoU), which refines SIoU’s convergence direction and incorporates the center-point Euclidean distance. Additionally, RSIoU introduces a penalty term as a dynamic focusing mechanism parameter, adaptively prioritizing ordinary-quality small object samples and providing more flexible weight adjustments for the loss function. As a result, RSIoU significantly enhances loss convergence performance.

Based on the above analysis of the challenges in small object detection and the limitations of mainstream methods, this paper proposes LR-Net for small object detection, which integrates the proposed LFF and RSIoU methods. LR-Net aims to address the difficulties in small object feature processing and the poor convergence performance of IoU-based losses for small objects. The main contributions of this study are as follows:

1. A lossless feature fusion method (LFF) is proposed. LFF transfers spatial feature information into the channel dimension and combines it with an attention mechanism to focus on the effective features after fusion. LFF effectively mitigates the loss of small object features caused by excessive downsampling, enhancing the network model’s feature representation capability for small objects. Ultimately, it alleviates the difficulty in feature processing caused by the extremely small object size.

2. The RSIoU loss function is proposed to address the limitations of mainstream IoU-based losses in small object detection. RSIoU corrects the potential issue in SIoU where the relative convergence direction is misaligned and introduces the center-point Euclidean distance as a distance cost. Additionally, a penalty term is incorporated as a parameter in the dynamic focusing mechanism, adaptively emphasizing the loss contribution of ordinary-quality small object samples, enabling more flexible weight allocation within the loss function. By overcoming the constraints of conventional IoU losses in small object detection, RSIoU enhances the convergence performance of IoU-based losses, effectively mitigating the challenges posed by occlusion and heightened sensitivity to localization errors in small objects.

3. LR-Net is specifically designed for small object detection with high-resolution feature hierarchies. The proposed LFF and RSIoU methods are applied within this structure to address the challenges of small object detection, such as the small size of the target and susceptibility to occlusion, which contribute to insufficient accuracy and robustness. LR-Net has been tested across several datasets, including VisDrone-2019, AI-TOD, MS COCO, and Pascal VOC, demonstrating significant improvements in the Average Precision (AP) metric, with increases of 3.7%, 3.3%, 1.2%, and 0.4%, respectively, compared to YOLOv8n. Additionally, LR-Net showed more substantial improvements in the dedicated metrics for small objects.

2.1 Feature Processing Methods for Small Object Detection

In early research on feature processing in CNNs, Liang et al. [18] proposed enhancing the semantic features of small objects using lateral connections based on the Feature Pyramid Network (FPN), which enhances small object features through its multi-scale structure. PANet [19] further introduced a bottom-up path to leverage low-level localization information, thereby improving the overall feature representation of FPN. Additionally, Liu et al. [20] addressed the poor performance of the original DETR model in small object detection by proposing a multi-branch architecture that simultaneously utilizes feature maps from different levels to introduce multi-scale capability into DETR. However, such methods rely heavily on the features extracted by the backbone, making the ability to capture small object features during the sampling process especially critical.

In this type of method, deformable convolutions can capture features of different scales by using different receptive field sizes, which allows for more effective capture of small object features [21], However, this increases the model complexity and computational cost. Dilated convolutions expand the receptive field without increasing the number of parameters, helping to capture more contextual information without losing resolution, thus reducing information loss [22] and providing new insights for downsampling methods. REAM (Receptive Field Expansion Attention Module) [23] expands the receptive field through its spatial extension module to capture more contextual information, while its channel attention module focuses on key channel-wise features. This enables the extraction of multi-scale spatial information and channel interactions. However, it makes limited use of the intrinsic features of small objects. MFAF (Multiscale Feature Alignment Fusion) [24] was proposed to enhance the use of shallow network features, where the integrated SPD-Conv effectively prevents the loss of small object features. However, the fused features inevitably contain redundancy, and unfiltered features may negatively impact the model, especially in small object detection, where such effects are more pronounced. In contrast, the proposed LFF method not only prevents small object feature loss through feature transfer but also employs 3D attention to focus on critical features, thereby enhancing the model’s feature representation for small objects.

2.2 IoU-Based Loss Functions for BBR

BBR (Bounding box regression) plays a crucial role in small object detection. Redmon et al. [25] proposed a loss function with different weights based on object size [26], which improved small object detection performance. Lin et al. [27] addressed the issue of class imbalance by proposing focal loss in RetinaNet, effectively solving the foreground-background class imbalance problem during training. Wang et al. [4] noted that IoU is more sensitive to the scale of small objects and proposed using a Two-dimensional Gaussian distribution distance to replace IoU in order to enhance detection performance.

Researchers have continuously explored new metrics to further improve the detection accuracy and speed based on Intersection over Union (IoU) [12] loss functions. Methods such as GIoU [13], DIoU [14], EIoU [15], and SIoU [16] have optimized bounding box regression by introducing different constraints on top of IoU to achieve more efficient bounding box regression methods.

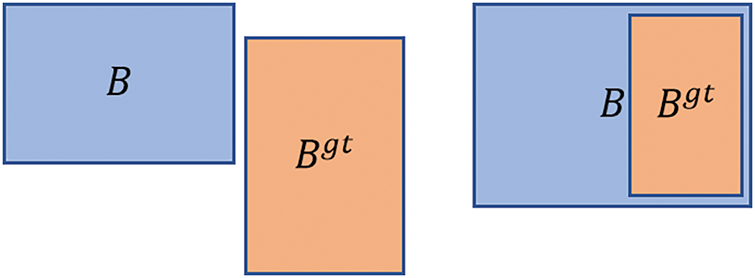

IoU(Intersection over Union) metric: It is the most commonly used evaluation standard for object detection, defined as shown in the formula:

Here, B and

Figure 2: Two Scenarios Where Traditional IoU Fails to Converge (First: There is no intersection between B and Bgt, so the IoU is 0. This results in no gradient backpropagation, and B cannot update its position to match Bgt. Second: B and Bgt are in an inclusive relationship, with a constant area ratio. In this case, positioning cannot be updated either)

GIoU and DIoU address this issue by introducing additional penalty terms, but they still suffer from potential convergence efficiency problems. EIoU redefines the aspect ratio penalty term, allowing the predicted box’s height and width to converge separately towards the height and width of the ground truth box, ultimately resolving the issue. SIoU points out that the angle relationship between bounding boxes affects regression, and by using an angle cost, the convergence speed of the loss function can be accelerated. SIoU consists of four components: IoU, angle cost (

In Eq. (2),

where

In Eq. (4),

In Eq. (3),

This chapter introduces the two methods of LR-Net, namely the LFF and RSIoU methods, along with their specific components and underlying principles.

3.1 Lossless Feature Fusion (LFF)

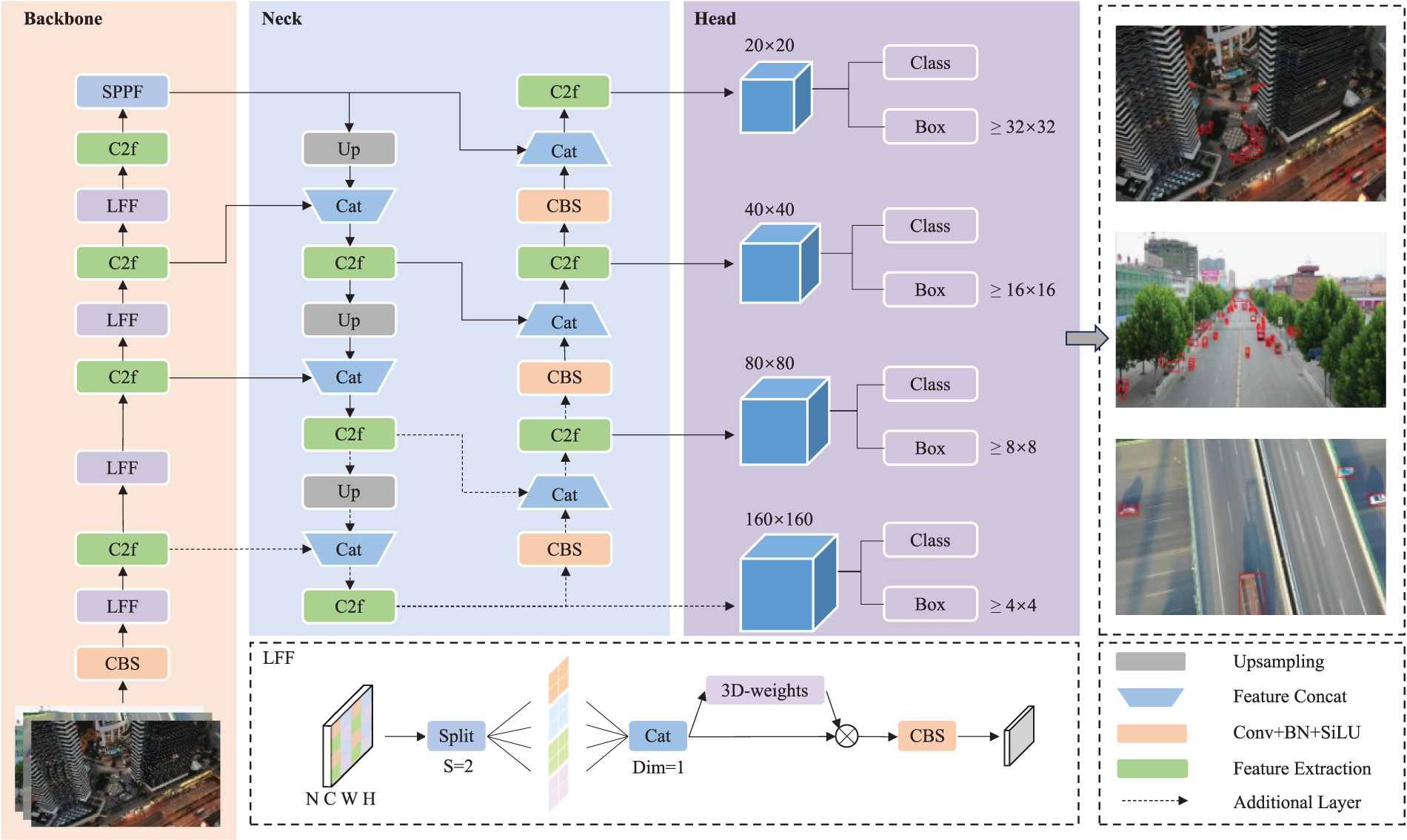

YOLOv8 utilizes CSPDarknet [28] as its backbone, capable of performing four downsampling operations to obtain feature maps at four levels. FPN employs PANet [19] for feature fusion, incorporating both top-down and bottom-up path enhancement networks. For an input image of size 640

Since the information for small objects in the feature map is significantly lower than for regular objects, it cannot withstand substantial feature loss from convolutional downsampling. Furthermore, the deeper the network, the more severe the feature loss becomes. To address this issue, the proposed Lossless Feature Fusion (LFF) method is applied within the backbone network.

As shown in Fig. 1, the LFF (Lossless Feature Fusion) module first preserves small object features completely through feature transformation. Specifically, for an input feature map X with dimensions

Additionally, because small objects occupy a relatively small space in the feature map, transferring spatial features to the channel dimension may introduce some weakly correlated, redundant features. To enhance focus on effective features and reduce attention to redundant features, SimAM (Simple parameter-free Attention Module) [31] is used to emphasize features across different positions and channels, providing three-dimensional attention weights to evaluate the importance of each pixel in each channel, all without introducing additional computational costs.

Therefore, attention is applied to

Here,

Figure 3: LR-Net network architecture

LFF transfers spatial features into the channel dimension to preliminarily preserve the total features of small objects during downsampling. Subsequently, three-dimensional spatial attention weights are applied in the subsequent channels to suppress weakly correlated, redundant features and strengthen the focus on effective features. As a result, LFF effectively mitigates the loss of small object features during the downsampling process and enhances the network’s representation capability.

3.2 IoU-Based Loss Functions for BBR

After analyzing the key characteristics and principles of the IoU loss function, this section proposes the RSIoU method and will introduce its specific components.

A. The center point Euclidean distance cost of RSIoU

DIoU [14] introduced the concept of minimizing the distance between the center points of two bounding boxes as a penalty term, as shown in the formula:

In small object detection tasks, due to the extremely small object sizes, even slight deviations in the center point location can lead to inaccurate detection results, even when the IoU between the predicted box and the Ground Truth (GT) box is high. By introducing

Figure 4: Improved from distance components (left) to center point linear distance (right)

B. Focal loss with penalty term

In small object detection tasks, the sensitivity of IoU to scale is particularly crucial. As shown in Fig. 5, each grid represents a pixel. In (a), when the predicted boxes A and B exhibit different degrees of offset from the Ground Truth (GT) box at a small scale, the change in IoU is more significant compared to (b) at a normal scale. Therefore, it is more likely to encounter samples with relatively ordinary-quality (The IoU value between the predicted box and the GT box is not high) in small object matching.

Figure 5: Sensitivity Analysis of IoU for Small-Scale vs. Normal-Scale Objects (Use (a) to represent small-Scale objects in the left image and (b) to represent Normal-Scale objects in the right image)

EIoU proposed a regression version of focal loss, applying IoU values and

This approach allows the regression process to focus on high-quality samples (The IoU values of the predicted box and the GT box are relatively high).

However, its static focusing parameters cannot fully tap into the potential of the focusing mechanism, and at the same time, small targets are more likely to have ordinary-quality samples in label allocation. So dynamically focusing on ordinary-quality samples is beneficial for the convergence of the loss function.

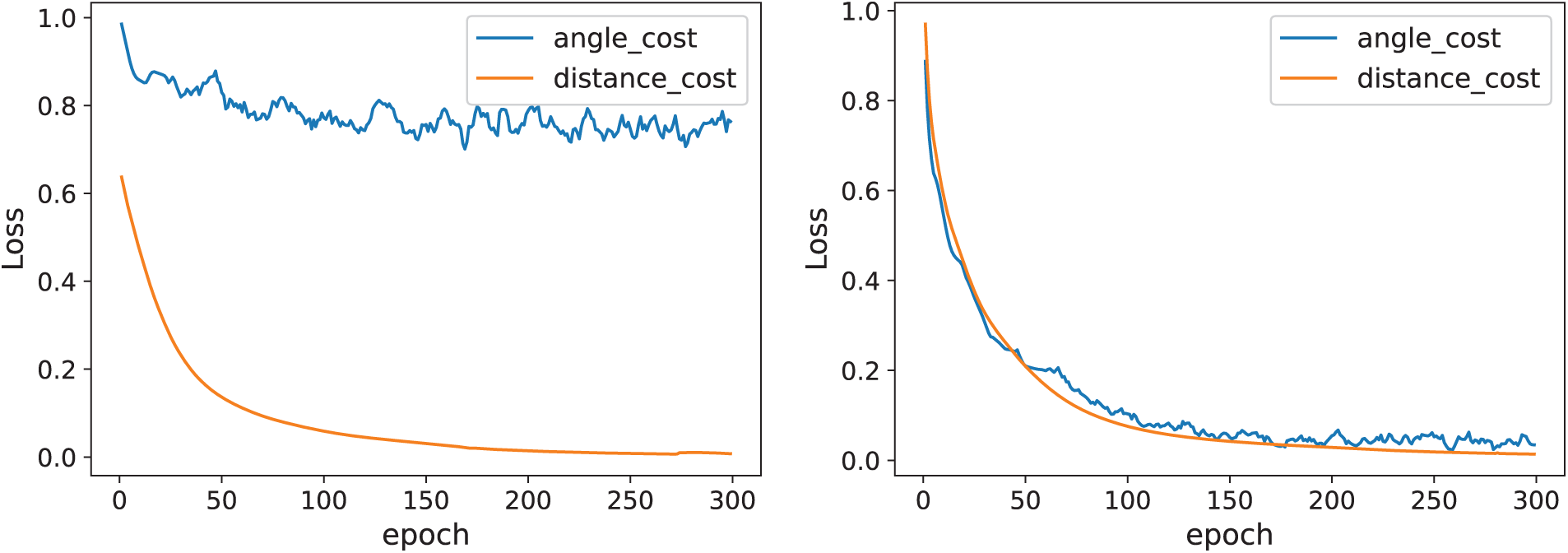

When the loss function converges normally, the penalty term decreases as IoU increases. However, there may be some local fluctuations, such as an increase in the angle and distance penalty terms in RSIoU. As shown in Fig. 6a,b, the angle penalty term and the center point distance penalty term are respectively related to IoU. Therefore, using only IoU to evaluate sample quality cannot fully utilize the focal mechanism’s potential. By using penalty term values as the focusing parameters for IoU, it is possible to better evaluate the quality of small object samples and assign appropriate weight to the loss function’s contribution, thereby enhancing its convergence for small objects. Based on this viewpoint, RSIoU proposes using a penalty term as a parameter for the dynamic focusing mechanism, which gives less attention to high-quality samples to focus on ordinary-quality samples and uses dynamic focusing penalty parameters to provide gradient gains. According to Eq. (13), the focal mechanism is introduced into the RSIoU loss function, as shown in the following formula, where

Figure 6: Relationship between IoU, angle cost, and distance cost (1 grid represents 10 pixels). Use (a) to represent IoU-Angle in the left image and b to represent IoU-Distance in the right image

We modify

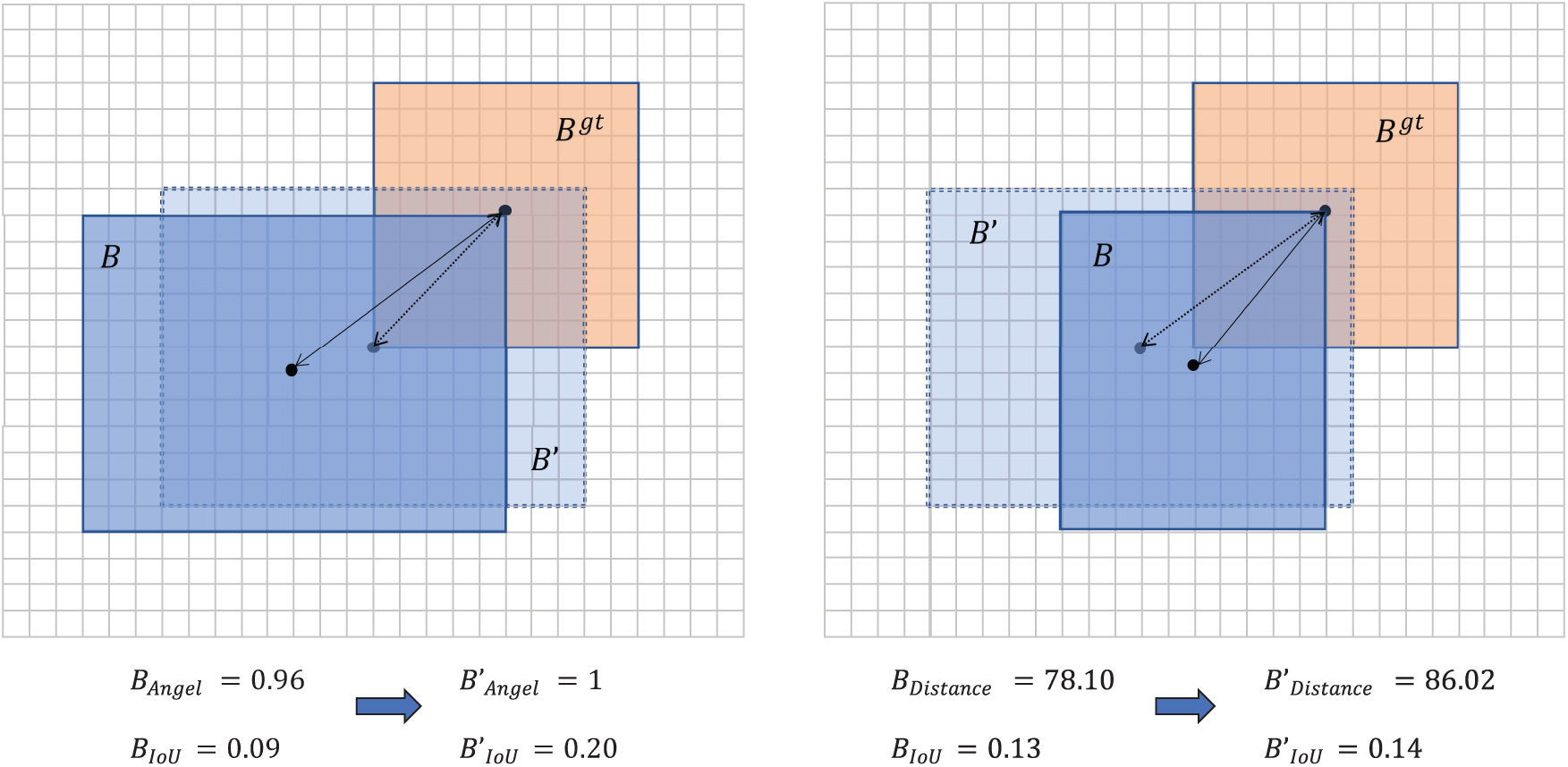

C. Correction of SIoU convergence

Based on the analysis of Eqs. (3)–(6), it was found that the Angle cost does not converge as expected in sync with the distance cost, which directly affects overall convergence. For small objects, even small localization differences can lead to significant deviations, making the convergence of the center distance more critical. Therefore, the angle cost convergence direction is modified to allow the distance cost to converge more effectively, thereby enhancing the convergence performance of SIoU loss in small object detection.

Analysis: During the convergence of the angle cost,

Figure 7: Angle cost convergence is determined by

According to Eq. (4), when

Figure 8: Function graph of angle cost with respect to

According to Eqs. (3)–(6), the angle cost (

Figure 9: Angle cost and distance cost convergence directions are not aligned (left), Adjusting the convergence direction of angle cost to be consistent with distance cost (right)

Proposed method: Adjust the gradient direction of the angle cost to align with the distance cost and modify

Here, the convergence direction of the angle cost is now consistent with the distance cost, as shown in Fig. 9 (right).

The experiments were conducted in a Python 3.8 environment using the PyTorch framework version 1.12. The operating system of the experimental device is Windows, and the GPU used is a Quadro RTX 5000 with 16 GB of memory. YOLOv8n is selected as the baseline model. It represents object bounding boxes using the distance from the object boundaries to anchor points and adopts task-aligned assignment as the label assignment strategy. The training hyperparameters for LR-Net are as follows: the initial learning rate is 0.01, the optimizer used is SGD, weight decay is set to 0.0005, momentum is 0.937, and the input image size is 640

4.1 Datasets and Evaluation Metrics

We analyzed the scale and distribution of instances contained in several datasets currently used for small object detection. Fig. 10 shows the scale distribution across multiple datasets, including the VisDrone2019 [32] dataset, AI-TOD dataset [33], PASCAL VOC [34] dataset, and MS COCO [35] dataset.

Figure 10: Distribution of objects scales across multiple datasets

VisDrone2019: The VisDrone dataset, captured by drones, contains over 2.6 million objects instances. The images often depict scenes with sparse and dense occlusions. The VisDrone2019 dataset includes 10,209 images and 10 categories, with an average objects scale of 35.8 pixels, and most objects are distributed within the 8–32 pixel range. AI-TOD: This dataset is specifically designed for tiny object detection. It includes 8 categories, 700,621 objects instances, and 28,036 aerial images. The average scale is only 12.8 pixels, significantly smaller than that of PASCAL VOC (156.6 pixels, with small objects much less frequent compared to regular objects) and MS COCO (99.5 pixels, where small objects are mostly distributed in the range above 16 pixels).

Evaluation Metrics: COCO metric defines objects smaller than 32 pixels as small objects. However, in many small object datasets, the object scales are even smaller. Therefore, the experiments uniformly adopt the

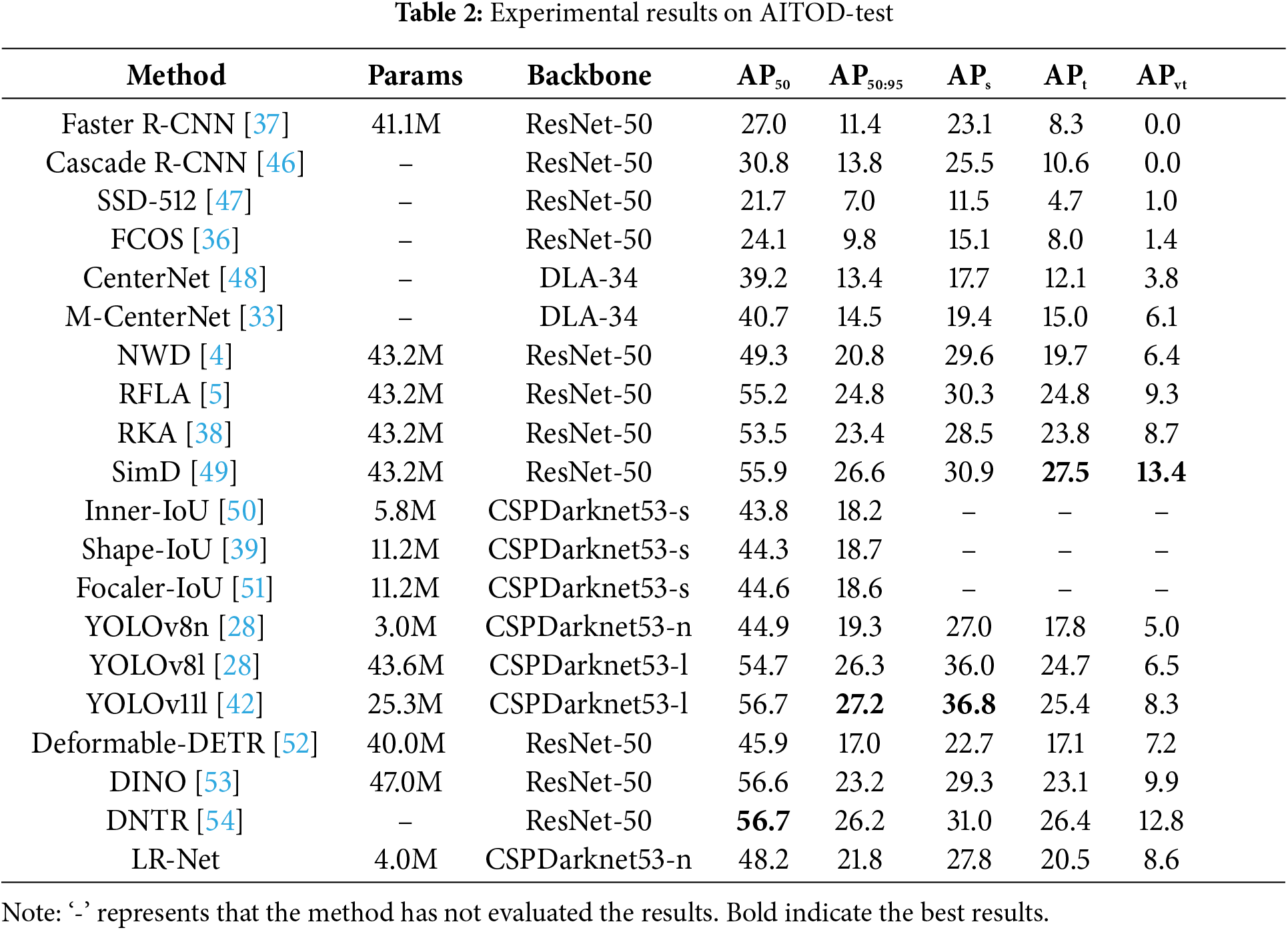

To validate the effectiveness and contributions of the methods proposed in this chapter, VisDrone2019 and AI-TOD datasets were used for comparative experiments. During the comparison with other methods, a “−” indicates that the current method did not evaluate the specific metric. The detailed experimental results are shown in Tables 1 and 2. As shown in the results in the tables, LR-Net achieves highly competitive performance when compared to other methods, including various state-of-the-art (SOTA) approaches. Notably, LR-Net outperforms several SOTA methods in small object metrics such as

To verify the effectiveness of the components in LR-Net, this section designs an ablation experiment to highlight the contributions of both LFF and RSIoU, as well as analyze the synergistic effect of these two methods on the baseline model’s (YOLOv8n) performance. During the experiment, all test groups were conducted under the same hyperparameter settings, with the results shown in Table 3.

As shown in the table, LR-Net achieves significant performance improvements with a relatively small number of parameters, especially in the dedicated metrics for small objects, validating the method’s effectiveness in small object detection. Specifically, the LFF method leads to noticeable improvements of 2.9%, 3.2%, and 1.5% in the

4.4 Analysis Experiment of Loss Function

4.4.1 Experimental Analysis of Focal Parameters in RSIoU

To compare the impact of different focal parameters on the results, experiments were conducted in RSIoU with the following settings: no focal parameter (

Compared with A and B, there is a slight decrease in accuracy in B when using static parameters (

To validate the generalizability of the method, experiments were conducted by applying different focal parameters in the EIoU loss function (In EIoU, there is no angle cost,

4.4.2 Experimental Analysis of Introducing

Here aims to analyze the convergence effect after introducing the center point Euclidean distance into the distance cost of SIoU. The experimental results show a noticeable improvement in the average precision (AP) metrics, indicating that the center point Euclidean distance, as a key factor, can enhance the convergence of SIoU. The specific experimental results and analysis are presented in Table 7 and Fig. 11.

Figure 11: Changes in

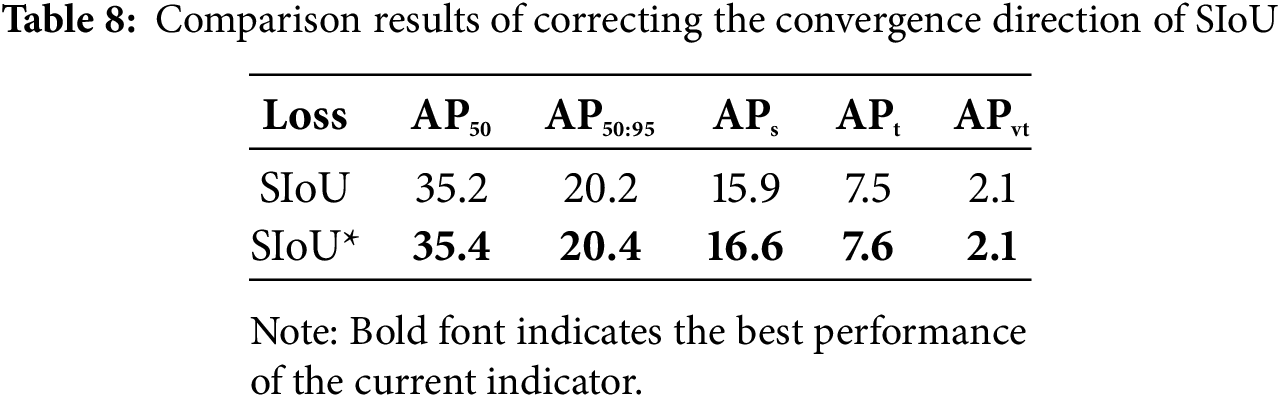

4.4.3 Experimental Analysis of SIoU Convergence Correction

Here aims to analyze the performance after correcting the gradient direction of the distance cost and angle cost in SIoU (here, SIoU* indicates the corrected gradient direction). Fig. 12 shows that after correcting the gradient direction, the angle cost can converge synchronously with the distance cost.

Figure 12: Convergence of angle cost before (left) and after (right) direction correction

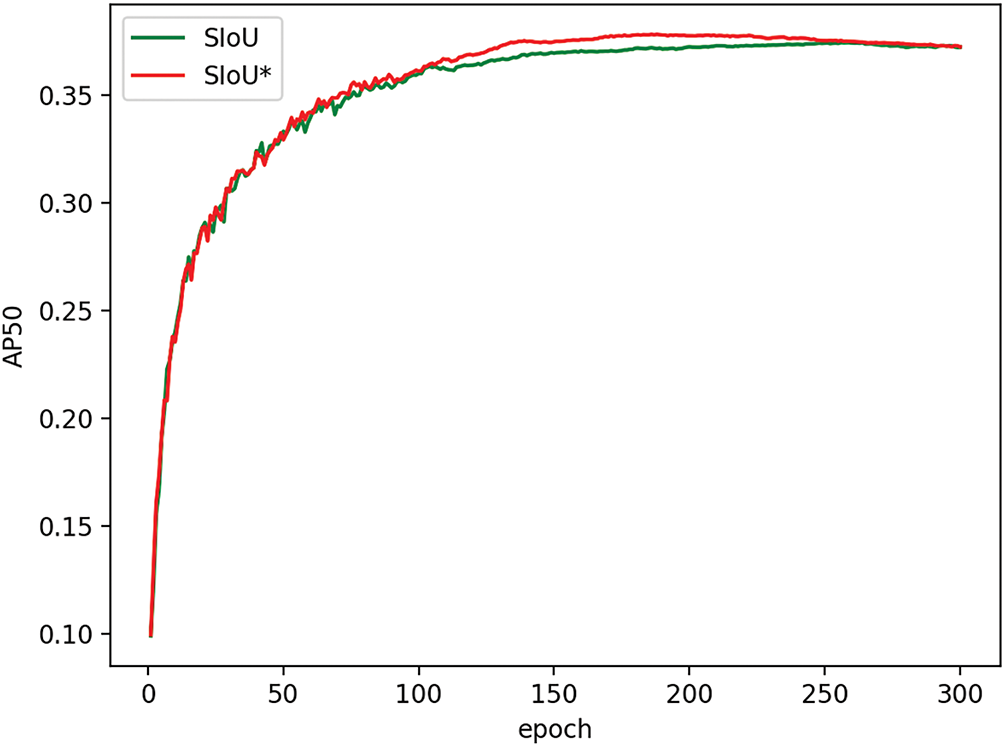

Meanwhile, Fig. 13 and Table 8 demonstrate that this method can make the SIoU loss converge earlier and achieve higher AP.

Figure 13: Shows that

4.4.4 Generalization Experiment and Comparison of Detection Performance

In order to verify the generalization performance of RSIoU in detecting normal-scale objects, experiments were carried out on COCO and Pascal VOC datasets, and the experimental results demonstrated that the method still performed better on different datasets, as shown in Table 9.

To more vividly illustrate the effectiveness of the proposed method, images from various scenarios were selected for inference comparison, as shown in Fig. 14. The inference results indicate that LR-Net can detect more previously missed objects, including occluded objects and extremely small objects. In extremely dense or occluded scenarios, LR-Net still exhibits a small number of missed detections for small vehicles. However, its detection results (fourth row) show a significant improvement compared to the original model (first row).

Figure 14: Comparison of inference results of instance images (The results from the first to the fourth lines indicate that the original, LFF, RSIoU, and all were applied, respectively). LR-Net significantly improves the detection accuracy and robustness of small object detection

This study aims to address the key challenges in small object detection, including limited object size and occlusion, by analyzing the limitations of existing mainstream methods. To overcome these challenges, we propose LR-Net for small object detection. Specifically, the proposed Lossless Feature Fusion (LFF) method transfers spatial features into the channel domain while leveraging hybrid attention to focus on informative features, effectively mitigating feature loss caused by the extremely small size of objects. Furthermore, RSIoU is proposed to enhance the convergence performance of IoU-based losses under occlusion scenarios. RSIoU corrects the convergence direction issues in SIoU and proposes a novel penalty term as a Dynamic Focusing Mechanism parameter, allowing it to dynamically focus on the loss contribution of small object samples. Ultimately, RSIoU significantly improves the convergence performance of the loss function for small objects under occlusion. By integrating LFF and RSIoU, LR-Net effectively alleviates the challenges posed by small object size and occlusion, leading to a significant improvement in both detection accuracy and robustness for small object detection.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to express their gratitude for the valuable feedback and suggestions provided by all the anonymous reviewers and the editorial team.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by Chongqing Municipal Commission of Housing and Urban-Rural Development (Grant No. CKZ2024-87), China Chongqing Municipal Science and Technology Bureau (Grant No. 2024TIAD-CYKJCXX0121).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: literature review: Ru Wang; method design: Ru Wang, Gang Li; study conception and design: Gang Li, Ru Wang, Chuanyun Xu; data collection: Ru Wang, Zheng Zhou, Xinyu Fan, Zihan Ruan; analysis and interpretation of results: Ru Wang, Yang Zhang, Chuanyun Xu, Pengfei Lv; draft manuscript preparation: Ru Wang, Gang Li, Chuanyun Xu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All relevant data are within the paper. The data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Rekavandi AM, Rashidi S, Boussaid F, Hoefs S, Akbas E, Bennamoun M. Transformers in small object detection: a benchmark and survey of state-of-the-art. arXiv:2309.04902. 2023. [Google Scholar]

2. Gao X, Mo M, Wang H, Leng J. Recent advances in small object detection. J Data Acquis Process. 2021;36:391–417. doi:10.16337/j.1004-9037.2021.03.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Cheng G, Yuan X, Yao X, Yan K, Zeng Q, Xie X, et al. Towards large-scale small object detection: survey and benchmarks. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2023;45(11):13467–88. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2023.3290594. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Wang J, Xu C, Yang W, Yu L. A normalized Gaussian Wasserstein distance for tiny object detection. arXiv:2110.13389. 2021. [Google Scholar]

5. Xu C, Wang J, Yang W, Yu H, Yu L, Xia GS. RFLA: Gaussian receptive field based label assignment for tiny object detection. In: European Conference on Computer Vision. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2022. p. 526–43. [Google Scholar]

6. Lin TY, Dollár P, Girshick R, He K, Hariharan B, Belongie S. Feature pyramid networks for object detection. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 2117–25. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2205.12740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Qiao S, Chen LC, Yuille A. Detectors: detecting objects with recursive feature pyramid and switchable atrous convolution. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2021 Jun 20–25; Nashville, TN, USA. p. 10213–24. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2301.10051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Cao X, Duan M, Ding H, Yang Z. MS-YOLO: integration-based multi-subnets neural network for object detection in aerial images. Earth Sci Inform. 2024;17(3):2085–106. doi:10.1007/s12145-024-01265-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Zhao Z, Liu X, He P. PSO-YOLO: a contextual feature enhancement method for small object detection in UAV aerial images. Earth Sci Inform. 2025;18(2):258. doi:10.1007/s12145-025-01780-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Zhang Y, Zhang H, Huang Q, Han Y, Zhao M. DsP-YOLO: an anchor-free network with DsPAN for small object detection of multiscale defects. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;241(13):122669. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2023.122669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Sunkara R, Luo T. No more strided convolutions or pooling: a new CNN building block for low-resolution images and small objects. In: Joint European Conference on Machine Learning and Knowledge Discovery in Databases. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2022. p. 443–59. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2208.03641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Yu J, Jiang Y, Wang Z, Cao Z, Huang T. Unitbox: an advanced object detection network. In: Proceedings of the 24th ACM International Conference on Multimedia; 2016 Oct 15–19; Amsterdam, The Netherlands. p. 516–20. doi:10.1145/2964284.2967274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Rezatofighi H, Tsoi N, Gwak J, Sadeghian A, Reid I, Savarese S. Generalized intersection over union: a metric and a loss for bounding box regression. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2019 Jun 15–20; Long Beach, CA, USA. p. 658–66. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2019.00075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Zheng Z, Wang P, Liu W, Li J, Ye R, Ren D. Distance-IoU loss: faster and better learning for bounding box regression. In: Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2020 Feb 7–12; New York, NY, USA. p. 12993–3000. doi:10.1609/aaai.v34i07.6999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Zhang YF, Ren W, Zhang Z, Jia Z, Wang L, Tan T. Focal and efficient IOU loss for accurate bounding box regression. Neurocomputing. 2022;506(9):146–57. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2022.07.042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Gevorgyan Z. SIoU loss: more powerful learning for bounding box regression. arXiv:2205.12740. 2022. doi:10.48550/arxiv.2205.12740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Tong Z, Chen Y, Xu Z, Yu R. Wise-IoU: bounding box regression loss with dynamic focusing mechanism. arXiv: 2301.10051. 2023. doi:10.48550/arxiv.2301.10051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Liang Z, Shao J, Zhang D, Gao L. Small object detection using deep feature pyramid networks. In: Advances in Multimedia Information Processing–PCM 2018: 19th Pacific-Rim Conference on Multimedia; 2018 Sep 21–22; Hefei, China. p. 554–64. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-00764-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Liu S, Qi L, Qin H, Shi J, Jia J. Path aggregation network for instance segmentation. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2018 Jun 18–23; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. p. 8759–68. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2018.00913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Liu F, Zheng Q, Tian X, Shu F, Jiang W, Wang M, et al. Rethinking the multi-scale feature hierarchy in object detection transformer (DETR). Appl Soft Comput. 2025;175(3):113081. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2025.113081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Dai J, Qi H, Xiong Y, Li Y, Zhang G, Hu H, et al. Deformable convolutional networks. In: Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision; 2017 Oct 22–29; Venice, Italy. p. 764–73. doi:10.1109/ICCV.2017.89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Yu F, Koltun V. Multi-scale context aggregation by dilated convolutions. arXiv:1511.07122. 2015. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1511.07122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Guo T, Zhou B, Luo F, Zhang L, Gao X. DMFNet: dual-encoder multi-stage feature fusion network for infrared small target detection. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2024;62(5):5614214. doi:10.1109/tgrs.2024.3376382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Shi C, Zheng X, Zhao Z, Zhang K, Su Z, Lu Q. LSKF-YOLO: large selective kernel feature fusion network for power tower detection in high-resolution satellite remote sensing images. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2024;62(8):5620116. doi:10.1109/tgrs.2024.3389056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Redmon J, Divvala S, Girshick R, Farhadi A. You only look once: unified, real-time object detection. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. p. 779–88. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2016.91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Redmon J, Farhadi A. YOLO9000: better, faster, stronger. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 7263–71. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2017.690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Lin TY, Goyal P, Girshick R, He K, Dollár P. Focal loss for dense object detection. In: Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision; 2017 Oct 22–29; Venice, Italy. p. 2980–8. doi:10.1109/ICCV.2017.324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Jocher G, Chaurasia A, Qin J. YOLOv8 [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 Jul 9]. Available from: https://github.com/ultralytics/ultralytics. [Google Scholar]

29. Deng C, Wang M, Liu L, Liu Y, Jiang Y. Extended feature pyramid network for small object detection. IEEE Trans Multimed. 2021;24:1968–79. doi:10.1109/TMM.2021.3074273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Bhanbhro H, Hooi YK, Zakaria MNB, Kusakunniran W, Amur ZH. MCBAN: a small object detection multi-convolutional block attention network. Comput Mater Contin. 2024;81(2):2243–59. [Google Scholar]

31. Yang L, Zhang RY, Li L, Xie X. Simam: a simple, parameter-free attention module for convolutional neural networks. In: International Conference on Machine Learning. Westminster, UK: PMLR; 2021. p. 11863–74. [Google Scholar]

32. Du D, Zhu P, Wen L, Bian X, Lin H, Hu Q, et al. VisDrone-DET2019: the vision meets drone object detection in image challenge results. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops; 2019 Oct 27–28; Seoul, Republic of Korea. p. 213–26. doi:10.1109/ICCVW.2019.00030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Wang J, Yang W, Guo H, Zhang R, Xia GS. Tiny object detection in aerial images. In: 2020 25th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR); 2021 Jan 10–15; Milan, Italy. p. 3791–8. doi:10.1109/ICPR48806.2021.9413340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Everingham M, Eslami SA, Van Gool L, Williams CK, Winn J, Zisserman A. The pascal visual object classes challenge: a retrospective. Int J Comput Vis. 2015;111(1):98–136. doi:10.1007/s11263-014-0733-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Lin TY, Maire M, Belongie S, Hays J, Perona P, Ramanan D, et al. Microsoft coco: common objects in context. In: Computer Vision–ECCV 2014: 13th European Conference; 2014 Sep 6–12; Zurich, Switzerland. p. 740–55. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-10602-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Tian Z, Shen C, Chen H, He T. FCOS: fully convolutional one-stage object detection. In: 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2019 Oct 27–Nov 2; Seoul, Republic of Korea. p. 9626–35. doi:10.1109/ICCV.2019.00972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Ren S, He K, Girshick R, Sun J. Faster R-CNN: towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2016;39(6):1137–49. doi:10.1109/tpami.2016.2577031. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Xu C, Wang J, Yang W, Yu H, Yu L, Xia GS. Detecting tiny objects in aerial images: a normalized Wasserstein distance and a new benchmark. ISPRS J Photogramm Remote Sens. 2022;190(9):79–93. doi:10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2022.06.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Zhang H, Zhang S. Shape-IoU: more accurate metric considering bounding box shape and scale. arXiv:2312.17663. 2023. [Google Scholar]

40. Wang CY, Yeh IH, Mark Liao HY. Yolov9: learning what you want to learn using programmable gradient information. In: European Conference on Computer Vision. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2024. p. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

41. Wang A, Chen H, Liu L, Chen K, Lin Z, Han J, et al. Yolov10: real-time end-to-end object detection. arXiv:2405.14458. 2024. [Google Scholar]

42. Jocher G, Qiu J, Chaurasia A. YOLOv11 [Internet]; 2024 [cited 2025 Jul 9]. Available from: https://github.com/ultralytics/ultralytics. [Google Scholar]

43. Zhu L, Wang X, Ke Z, Zhang W, Lau RW. Biformer: vision transformer with bi-level routing attention. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2023 Jun 17–24; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 10323–33. [Google Scholar]

44. Wang A, Chen H, Lin Z, Han J, Ding G. Repvit: revisiting mobile CNN from vit perspective. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2024 Jun 16–22; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 15909–20. [Google Scholar]

45. Du Z, Hu Z, Zhao G, Jin Y, Ma H. Cross-layer feature pyramid transformer for small object detection in aerial images. arXiv:2407.19696. 2024. [Google Scholar]

46. Cai Z, Vasconcelos N. Cascade R-CNN: delving into high quality object detection. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2018 Jun 18–23; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. p. 6154–62. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2018.00644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Liu W, Anguelov D, Erhan D, Szegedy C, Reed S, Fu CY, et al. SSD: single shot multibox detector. In: Computer Vision-ECCV 2016: 14th European Conference; 2016 Oct 11–14; Amsterdam, The Netherlands. p. 21–37. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-46448-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Duan K, Bai S, Xie L, Qi H, Huang Q, Tian Q. Centernet: keypoint triplets for object detection. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision; 2019 Oct 27–Nov 2; Seoul, Republic of Korea. p. 6569–78. doi:10.1109/ICCV.2019.00667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Shi S, Fang Q, Xu X, Zhao T. Similarity distance-based label assignment for tiny object detection. In: 2024 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS); 2024 Oct 14–18; Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. p. 13711–8. [Google Scholar]

50. Zhang H, Xu C, Zhang S. Inner-IoU: more effective intersection over union loss with auxiliary bounding box. arXiv:2311.02877. 2023. [Google Scholar]

51. Zhang H, Zhang S. Focaler-IoU: more focused intersection over union loss. arXiv:2401.10525. 2024. [Google Scholar]

52. Zhu X, Su W, Lu L, Li B, Wang X, Dai J. Deformable DETR: deformable transformers for end-to-end object detection. arXiv:2010.04159. 2020. [Google Scholar]

53. Zhang H, Li F, Liu S, Zhang L, Su H, Zhu J, et al. Dino: DETR with improved denoising anchor boxes for end-to-end object detection. arXiv:2203.03605. 2022. [Google Scholar]

54. Liu HI, Tseng YW, Chang KC, Wang PJ, Shuai HH, Cheng WH. A DeNoising FPN with transformer R-CNN for tiny object detection. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2024;62:4704415. doi:10.1109/tgrs.2024.3396489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools