Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Forensic Analysis of Cyberattacks in Electric Vehicle Charging Systems Using Host-Level Data

1 Department of Information Security, Faculty of Information Technology, University of Petra, Amman, 11196, Jordan

2 Department of Information Technology, King Abdullah II School for Information Technology, University of Jordan, Amman, 11942, Jordan

3 Department of Software Engineering, College of Computing, Umm Al-Qura University, Makkah, 24382, Saudi Arabia

4 Department of Data Science, College of Computing, Umm Al-Qura University, Makkah, 24382, Saudi Arabia

5 Department of Computer Science, Faculty of Information Technology and Computer Sciences, Yarmouk University, Irbid, 21163, Jordan

6 College of Business Administration, Northern Border University, Arar, 91431, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Author: Yousef Sanjalawe. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(2), 3289-3320. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.067950

Received 16 May 2025; Accepted 15 July 2025; Issue published 23 September 2025

Abstract

Electric Vehicle Charging Systems (EVCS) are increasingly vulnerable to cybersecurity threats as they integrate deeply into smart grids and Internet of Things (IoT) environments, raising significant security challenges. Most existing research primarily emphasizes network-level anomaly detection, leaving critical vulnerabilities at the host level underexplored. This study introduces a novel forensic analysis framework leveraging host-level data, including system logs, kernel events, and Hardware Performance Counters (HPC), to detect and analyze sophisticated cyberattacks such as cryptojacking, Denial-of-Service (DoS), and reconnaissance activities targeting EVCS. Using comprehensive forensic analysis and machine learning models, the proposed framework significantly outperforms existing methods, achieving an accuracy of 98.81%. The findings offer insights into distinct behavioral signatures associated with specific cyber threats, enabling improved cybersecurity strategies and actionable recommendations for robust EVCS infrastructure protection.Keywords

The growing adoption of Electric Vehicles (EVs) marks a pivotal move toward cleaner, more sustainable transportation solutions. Unlike traditional vehicles, EVs rely on electricity, often sourced from renewable energy, significantly reducing greenhouse gas emissions. As EVs become more integral to modern mobility, developing a reliable and accessible EVCS infrastructure becomes increasingly important. These charging systems support the daily use of EVs and play a key role in promoting broader clean energy goals. However, integrating EVCS into smart grids and IoT networks introduces new layers of complexity and risk. While connectivity enhances the efficiency, scalability, and responsiveness of EVCS, it also opens the door to potential cyber threats. Malicious actors can exploit the technologies that make these systems intelligent and interconnected, threatening system stability and user safety [1].

As EVCS evolves in complexity, it brings a growing set of cybersecurity challenges. These systems function through constant communication between electric vehicles, charging stations, and the power grid—an interconnected process that, while essential for seamless operation, also creates a broader and more accessible attack surface. Cyberattacks on this infrastructure can cause various issues, from temporary service interruptions to critical threats such as unauthorized energy use or disruptions to grid stability [2]. The shift toward digital energy systems has only intensified these concerns. While modern infrastructures increasingly rely on software to manage and coordinate operations, many still lack sufficient cybersecurity protections [1]. In this context, securing EVCS is not just a matter of improving technology—it has become essential for maintaining the overall integrity and reliability of the energy grid.

Although cybersecurity in EVCS has become an increasingly active area of research, much of the current literature remains centered on network-level vulnerabilities. Typical approaches include analyzing network traffic for irregularities and strengthening communication protocols to guard against unauthorized access [3–5]. While these methods are valuable, they often fail to account for the role of host-level data in identifying and mitigating security threats. Information gathered directly from system components—such as event logs, memory usage statistics, process activity, and device-level telemetry—offers a more granular view of an EVCS’s operation. This data type can uncover behaviors and anomalies that are not always visible through network monitoring alone. Host-level analysis is particularly important for detecting more sophisticated attacks that bypass conventional, network-focused security measures [6,7].

Cyberattacks targeting EVCS can stem from network-level and host-level vulnerabilities, making adopting a more integrated approach to forensic analysis essential. While real-time detection plays a crucial role in identifying threats as they occur, a robust forensic strategy is needed to reconstruct the full timeline of an incident, determine how the attack was executed, identify the exploited weaknesses, and formulate measures to prevent similar breaches in the future. Host-level forensic data—such as execution traces, system logs, memory usage, and process activity—provides vital insight into the behavior of compromised systems. These data points often reveal signs of intrusion that are not visible through network traffic alone. For example, detecting unauthorized process executions, abnormal memory patterns, or attempts at privilege escalation typically requires in-depth host-based analysis to fully understand the nature and impact of an attack. To address the current gap between real-time anomaly detection and post-incident investigation, this study introduces a forensic analysis framework tailored to the unique demands of EVCS infrastructure. The objectives of this research are as follows:

1. Examine various categories of cyberattacks targeting EVCS, including cryptojacking, Distributed Denial-of-Service (DDoS), and reconnaissance activities.

2. Investigate host-level Indicators of Compromise (IoCs) using Hardware Performance Counters (HPCs) and Kernel Event monitoring.

3. Design a comprehensive forensic framework that integrates data collection, preprocessing, and anomaly detection to support effective investigation and attribution of cyber incidents.

This study’s key contribution lies in its integration of host-level cyber forensic analysis for investigating cyberattacks on EVCS, a dimension that remains largely unexplored in current research. While most existing studies focus on detecting anomalies at the network level, this work focuses on the system’s internal behavior by analyzing kernel events and Hardware Performance Counters (HPCs). This host-level perspective captures behavioral signatures of attacks that often go undetected by traditional network-based monitoring tools. By examining low-level system activity, the proposed approach offers a more nuanced understanding of system states during normal and compromised conditions. This allows for identifying subtle indicators that can be critical for detecting sophisticated or stealthy attacks. In addition, using machine learning techniques in conjunction with forensic analysis of host data supports two complementary objectives: conducting detailed post-incident investigations and enabling proactive threat diagnostics. This dual capability distinguishes our framework from conventional intrusion detection systems, which typically operate reactively and are limited to surface-level monitoring. By combining forensic depth with predictive analytics, our approach presents a novel and adaptable solution to the growing cybersecurity demands of EV infrastructure.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews existing methods for securing EVCS and conducting forensic analysis within cyber-physical systems. Section 3 describes the forensic methodology applied, and Section 4 provides an overview of the dataset. Section 5 covers data preprocessing and examination procedures. Section 6 presents the forensic analysis, detailing statistical techniques such as correlation analysis, baseline behavior analysis, temporal analysis, and machine learning approaches for detecting malicious patterns. Section 7 reports the findings, summarizing identified attack patterns, evaluating the performance of detection models, and presenting actionable security recommendations. Finally, Section 8 concludes the study by highlighting the key contributions and suggesting directions for future research to strengthen EVCS cybersecurity further.

The design and deployment of EVCS within smart grids and intelligent transportation systems have triggered significant cybersecurity and forensic research. As these systems become integral to global infrastructure, they face many cyber risks, including data impersonation, DDoS attacks, and more advanced targeted intrusions. In response, researchers have developed various anomaly detection, intrusion detection, and forensic analysis frameworks to enhance the security and resilience of EVCS operations. To improve real-time detection in Electric Vehicle Charging Station (EVCS) environments, federated learning has emerged as a promising, privacy-preserving alternative to centralized anomaly detection methods. One such implementation, the Federated Learning-based Anomaly Detection System (FL-EVCS), leverages an ensemble of machine learning models—K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Random Forest (RF), and Support Vector Machines (SVM)—to identify anomalies. Experimental results demonstrated that FL-EVCS outperformed conventional machine learning-based detection systems, achieving an impressive 97% accuracy and strong F1-scores when tested on the CICEVSE2024 dataset [8].

In a parallel line of work, ICS-Defender focuses on the broader security challenges within Industrial Control Systems (ICS), which include EVCS. Traditional machine learning solutions for ICS typically demand significant domain expertise for effective implementation. ICS-Defender addresses this barrier by incorporating Automated Machine Learning (AutoML) to streamline the processes of model selection, training, and optimization. When evaluated on EVCS datasets, the system achieved a 94.23% accuracy rate, outperforming other contemporary AutoML-based frameworks [9].

Recent research has increasingly explored using adversarial learning and simulation-based methods to strengthen the cyber resilience of critical infrastructure. For instance, Mitikiri et al. (2025) introduced a detection framework leveraging Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) autoencoders to identify adversarial attacks. Their approach incorporated the Fast Gradient Sign Method (FGSM) to simulate spoofing scenarios, with detection accuracy evaluated using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov (KS) test. The framework achieved an impressive 98.5% accuracy, demonstrating its effectiveness in capturing subtle and evasive adversarial behaviors [10]. In a related study, Chukwunweike et al. (2024) used MATLAB/Simulink to simulate data integrity breaches targeting Electric Vehicle (EV) onboard chargers (OBCs). Their results showed that when designed with anomaly-awareness, intelligent control mechanisms can effectively reduce performance degradation and enhance system resilience in the face of cyber threats [11].

As core elements of cyber-physical systems (CPS), EV onboard chargers operate within complex and highly connected Internet of Things (IoT) environments—conditions that inherently increase their vulnerability to cyberattacks. Arsalan et al. (2023) proposed a hybrid approach combining machine learning, Model Predictive Control (MPC), and residual-based preprocessing to address this challenge. Their system successfully distinguished between normal and malicious states by analyzing system-level signal patterns across diverse operational contexts [12]. Expanding on the potential of both classical and deep learning models, Kondu (2024) investigated anomaly detection in CPS and Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) systems. Their study evaluated Random Forest and LSTM-based models using the CICEVSE2023 and 2024 datasets. The LSTM model demonstrated robust performance in handling time-series data, achieving an accuracy of 99.589% [13]. These findings reflect the growing reliability of machine learning approaches in safeguarding complex, data-driven infrastructure against evolving cyber threats.

While real-time detection remains critical, forensic analysis is equally crucial in post-incident investigation and understanding cyber threats. It helps identify the exploited vulnerabilities, trace attack vectors, and refine preventative strategies [14,15]. As EVCS and CPS systems become further integrated with IoT and smart grid technologies, the need for robust forensic capabilities continues to grow. Mohamed et al. (2020) discussed the unique challenges of conducting cyber forensics in CPS, such as the distributed nature of these systems and the lack of tailored forensic tools. Their review outlines several key areas where future research could support the development of more effective forensic frameworks [16].

Moreover, mobile applications used for automotive maintenance are emerging as valuable sources of forensic data. These apps often store digital artifacts like GPS history, speed logs, and diagnostic information, aiding traffic incident investigations or legal proceedings. A study analyzing three widely used automotive apps revealed their potential in forensic contexts. However, the growing volume of data poses challenges for forensic labs. To address this, the study proposed a framework aligning data extraction techniques with the broader digital forensics lifecycle, emphasizing stages such as triage and logical acquisition [17]. Another novel direction integrates forensic analysis with smart grid optimization. Singh and Kumar (2024) introduced the Forensic-Based Investigation and Archimedes Optimization Algorithm (FBIAOA), a hybrid approach for modeling EV behavior in smart grids. This method outperformed other optimization algorithms in balancing charging station profitability and grid reliability, particularly under renewable energy constraints [18].

Stichow and Rempel (2024) focused on authentication vulnerabilities in EVCS using the Open Charge Point Protocol (OCPP). They applied the STRIDE threat modeling framework and simulated spoofing attacks to evaluate risks such as privilege escalation and tampering. Their findings contributed to a secure-by-design cybersecurity framework for OCPP-enabled charging stations [19]. Despite the advancements discussed, existing research primarily focuses on network-level detection or simulated anomalies, while host-level forensic analysis remains underexplored. Most current frameworks neglect system-level data sources such as kernel logs, execution traces, and hardware performance counters, which are crucial for understanding the internal mechanics of cyberattacks and tracing their origins.

A recent study by Hussain et al. presents an intrusion detection system for EVCS using a Federated Learning (FL) framework with a lightweight Simple Neural Network (SimpleNN). This approach enables decentralized model training across EVCS sites without transmitting raw data, preserving privacy and minimizing communication overhead. By analyzing features such as voltage, frequency, state of charge, and power, the model achieved nearly 95% detection accuracy on the IEEE 123-bus system. This demonstrates FL’s potential for efficient, privacy-preserving cyberattack detection in resource-constrained EVCS environments [20]. Similarly, Chowdhury et al. propose a blockchain-based security solution using the Hyperledger Fabric framework. Smart contracts manage EVCS functions like authentication, session control, and payment verification securely and transparently. By mitigating threats such as data tampering, denial of service, and fraud, this system enhances EVCS resilience. Benchmark tests using Hyperledger Caliper confirm its low latency and scalability for real-time smart city applications [21].

Although many efforts have been made to enhance EVCS security, primarily through anomaly detection, a significant shortcoming is the separation between real-time detection and post-incident forensic investigation. Many systems prioritize immediate threat response but lack in-depth tracing, intrusion source identification, or digital evidence preservation mechanisms. Another issue is the scalability of existing forensic frameworks. With EVCS expanding as part of smart IoT infrastructure, data volume, variety, and velocity have increased dramatically. However, most forensic systems cannot effectively process high-dimensional, time-sensitive, or multi-modal data, resulting in missed or delayed insights. Moreover, current systems rarely combine proactive anomaly detection with reactive forensic capabilities. This leads to security postures where threats are flagged but not analyzed for root causes, limiting long-term system hardening and adaptive defense. To address these challenges, future research should focus on:

• Designing integrated architectures that unify anomaly detection with forensic logging, analysis, and reporting.

• Developing scalable, high-throughput data management pipelines for host-level data in EVCS.

• Building domain-specific forensic models tailored to EVCS protocols and cyber-physical interactions.

• Establishing standardized forensic procedures for evidence collection and retention in EVCS environments.

These advancements are essential to achieve comprehensive EVCS cybersecurity, from real-time monitoring to post-attack forensic response.

In this study, we adopt the digital forensics process defined by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), a standards agency of the United States Department of Commerce, widely recognized internationally for its systematic cybersecurity and digital forensics guidelines. This process ensures the integrity and reliability of cyberattack investigations in EV charging systems [22,23].

The methodology consists of four primary phases, as shown in Fig. 1 namely: (i) Data Collection, which involves identifying potential sources of relevant data, labeling and recording them, and acquiring the necessary information while maintaining the integrity of the data sources; (ii) Data Examination, which focuses on evaluating the acquired data and extracting information pertinent to the incident, ensuring that the original data is preserved throughout the process; (iii) Forensic Analysis, where the extracted data is thoroughly examined to answer critical investigative questions (5WH—who, what, when, where, why, and how), or to determine whether only partial conclusions can be made; and (iv) Reporting Findings, which includes summarizing attack patterns, evaluating detection effectiveness using metrics such as accuracy, recall, precision, and F1-score, and providing security recommendations like system hardening, attack detection mechanisms, and incident response strategies. This structured approach enables a thorough forensic analysis and effective mitigation of cyberattacks in EVCS.

Figure 1: Proposed framework

This structured and systematic approach enables thorough forensic analysis and effective mitigation of cyberattacks in EVCS. It leverages statistical and machine learning techniques to enhance detection accuracy and generate actionable security insights. In addition, we assume a practical threat model where attackers gain access to the EVSE host, escalate privileges, and launch attacks such as cryptojacking, DoS, or reconnaissance. Despite these threats, host-level telemetry remains intact, allowing forensic analysis based on local system data in the absence of external monitoring.

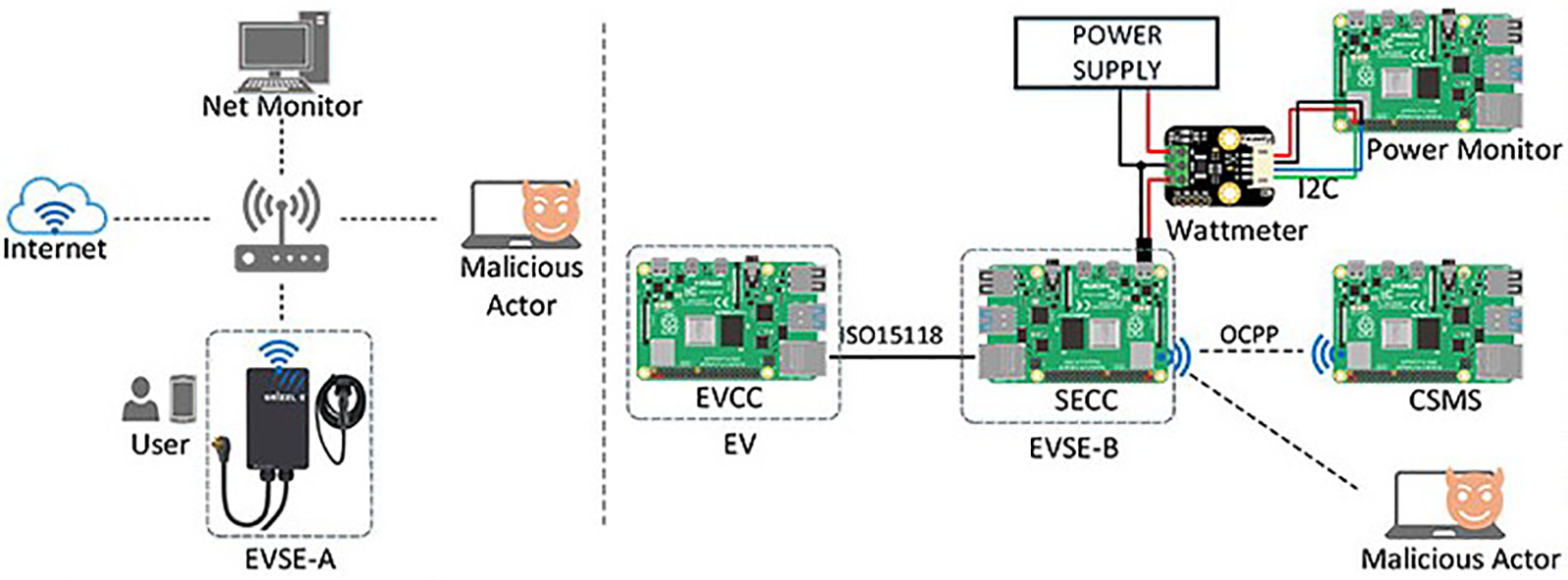

The aim of the EV Charger Attack Dataset 2024 (CICEVSE2024)1 is to contribute to ongoing cybersecurity research on EV charging stations by generating and publishing a comprehensive dataset that includes both benign and attack scenarios. These attack scenarios encompass network-based and host-based attacks targeting EVSE in idle and charging states. An experimental testbed was developed to achieve this, comprising a Level 2 operational EV charging station (EVSE-A), along with several Raspberry Pi-based systems and associated communication equipment. This configuration replicates key components of real-world EVCS operations while enabling detailed capture of host-level data from the involved systems. Within this testbed, Raspberry Pis are designated various roles [24], including:

• Implementing the Electric Vehicle Communication Controller (EVCC).

• Acting as the EVSE-B, responsible for managing the charging process.

• Serving as a Power Monitor to record the power consumption of EVSE-B.

• Operating as part of the Charging Station Monitoring System (CSMS) for local and remote monitoring.

Fig. 2 presents a network diagram that connects the EVSE-A and EVSE-B charging stations, a malicious actor, and key components such as the EV, EVCC, the Supply Equipment Communication Controller (SECC), and CSMS. Additionally, it highlights power and network monitoring tools, such as the Wattmeter and Power Monitor, as well as communication protocols like ISO 15118 and OCPP. This testbed effectively simulates potential cybersecurity threats posed by malicious actors interacting with the charging infrastructure, offering a platform for analyzing vulnerabilities and system behaviour.

Figure 2: Components of the EVSE testbed [24]

Compared to the CICEV2023 dataset2, which primarily focused on network-level telemetry and timing-based authentication delays, the CICEVSE2024 dataset introduces a novel host-level dimension by capturing low-level system behavior from EVSE. CICEV2023 relied on analyzing multi-process scheduling, authentication time deltas, and TCP packet flow disruptions to evaluate the impact of DoS and DDoS attacks. However, it lacked introspection into the EVSE’s internal system state. On the other hand, the PERF tool was utilized to collect approximately 900 kernel and HPC events from the Raspberry Pi-based EVSE-B system during various experimental scenarios. These events serve as a rich data source for understanding the system’s benign and attack behaviours. Moreover, a subset of these events is highlighted in Table 1, categorized as HPC events and Kernel events.

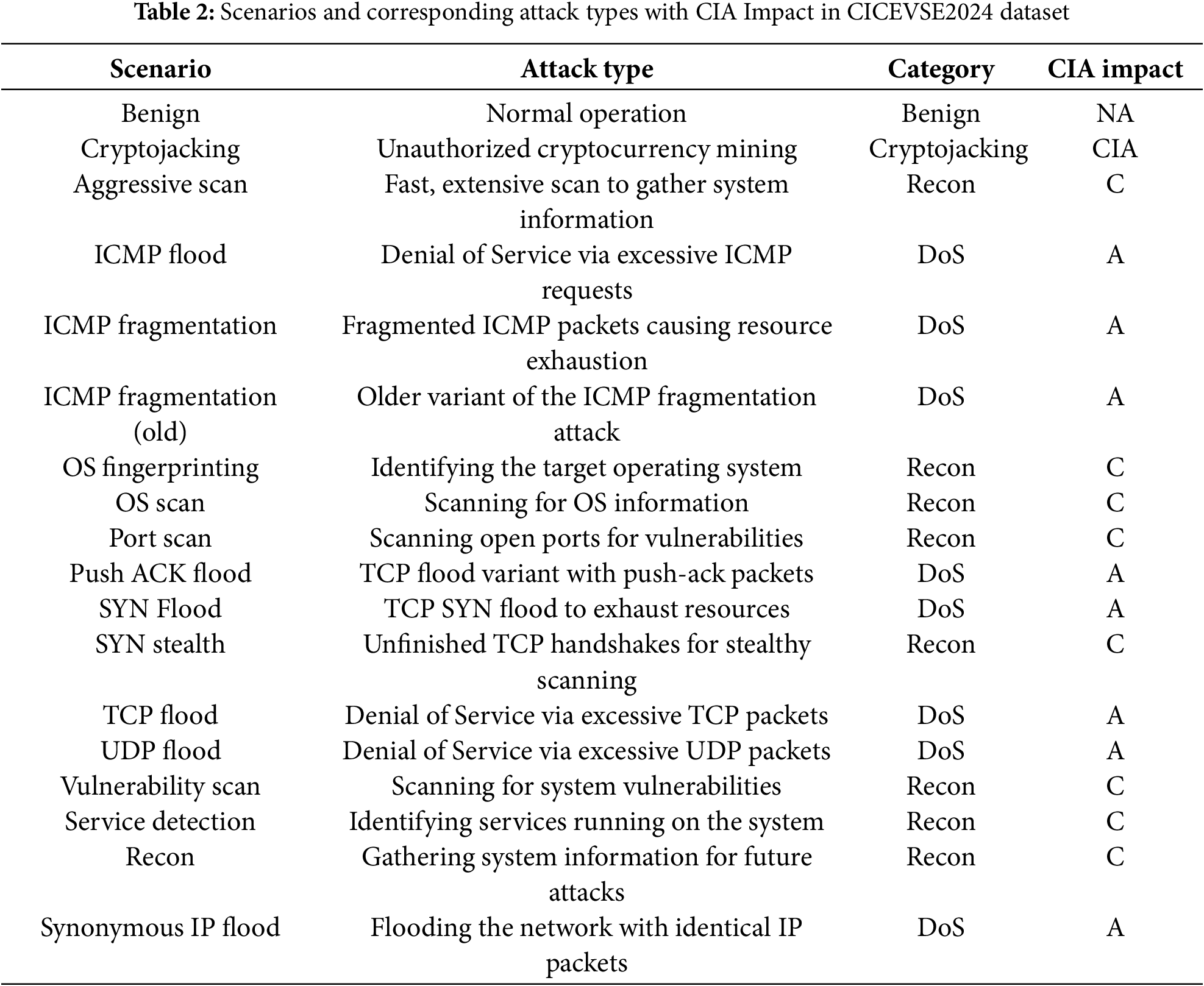

The dataset contains processed and labelled CSV files extracted from the original samples. Each scenario’s data captures host-level events, including HPC and kernel events, over extended periods and is categorized based on attack or benign conditions. Table 2 presents various scenarios and their corresponding attack types from the CICEVSE2024 dataset, alongside their impact on the Confidentiality, Integrity, and Availability (CIA) triad. The dataset consists of benign and attack conditions, with host-level events captured over extended periods. Each scenario is categorized based on whether it represents a regular operation (benign) or a specific cyberattack. The attack types include actions like cryptojacking, scanning for vulnerabilities, and multiple DoS attacks. The final column, labelled “CIA Impact,” indicates which aspect(s) of the CIA triad—Confidentiality (C), Integrity (I), and Availability (A)—are affected by each attack. This processed and labeled data allows for in-depth analysis of system behavior and the identification of malicious activities, facilitating effective cybersecurity research and solutions.

The dataset used in this forensic analysis is the CICEVSE2024 dataset, which captures both benign and attack scenarios from an experimental EVSE charging station. Host-level data is collected using PERF, a performance monitoring tool that records HPC and Kernel Events on the EVSE-B charging station. The dataset encompasses critical events such as CPU cycles, memory access patterns, and system call activities, which are essential for identifying abnormal system behaviour during cyberattacks.

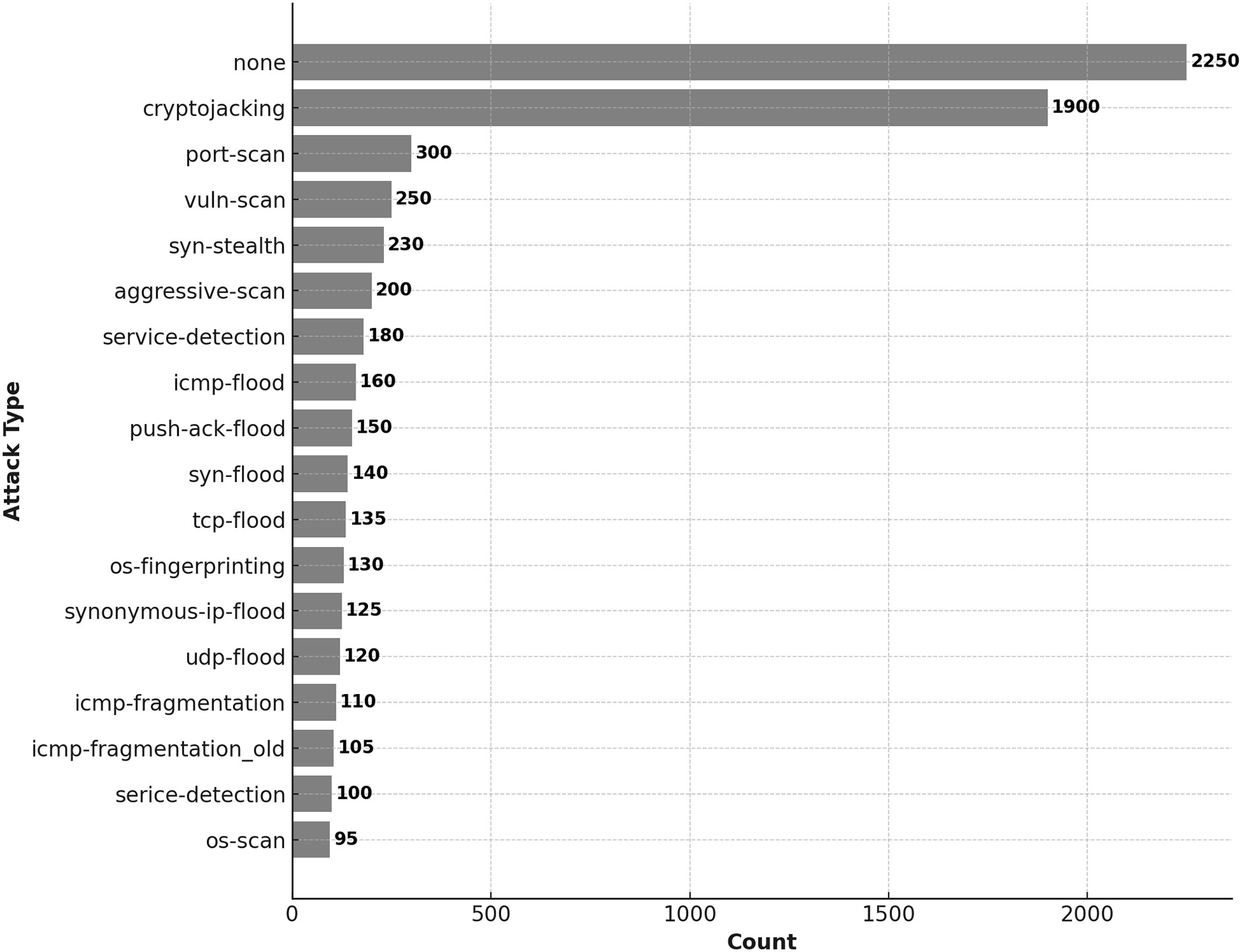

The data acquisition process focuses on four key scenarios: benign operations, cryptojacking attacks, DoS attacks, and reconnaissance (recon) activities. As illustrated in Fig. 3, benign operations account for 37.33% of the dataset, cryptojacking attacks comprise 29.08%, DoS attacks make up 14.03%, and reconnaissance activities represent 19.56%. These scenarios form the foundation for subsequent behavioural and forensic analysis, focusing on identifying deviations from normal operations under attack conditions.

Figure 3: Distribution of scenarios in the CICEVSE2024

Furthermore, Fig. 4 details the dataset’s distribution of specific attack types. “None” represents the largest category, likely referring to benign or uncategorized traffic, followed by cryptojacking, consistent with the pie chart. The remaining attack types, such as port scanning, vulnerability scanning (vuln-scan), and various flood attacks (e.g., SYN, TCP, UDP), are less frequent but still critical in understanding the dataset. This figure illustrates the diversity of attack types, with the top categories accounting for the majority of the overall distribution.

Figure 4: Distribution of attack types observed in the ICEVSE2024

Once the data is acquired, it undergoes a series of preprocessing steps to ensure its quality and relevance for forensic analysis. This phase is crucial for preparing the dataset for accurate and reliable detection of cyberattacks in EVCS. Effective data preprocessing is essential because raw data typically contains noise, redundant features, class imbalance, and other inconsistencies that may lead to biased or unreliable results if not adequately addressed [25]. The original dataset consisted of 6166 records and 911 features, categorized into four primary classes: Benign, Cryptojacking, DoS, and Reconnaissance. While the dataset reflects a moderately imbalanced distribution—with benign samples comprising approximately 40% of the total—we employed multiple strategies to improve generalization and prevent overfitting. These include data shuffling, stratified train-test splitting, and 10-fold cross-validation. All samples include host-level telemetry features, such as hardware performance counters and kernel events. Although the dataset was generated under a controlled environment, its structure captures diverse attack behaviors representative of real-world EVCS threats. For reproducibility, the dataset is publicly available via the UNB CIC website, and the implementation code will be released upon publication.

Before preprocessing, a detailed summary of the dataset’s structure and content is presented in Table 3.

The following steps were performed on the CICEVSE2024 dataset:

• Data Cleaning: The first step in preprocessing involves cleaning the dataset to remove any incomplete or corrupt entries, ensuring the analysis is not biased by missing or faulty data. After performing this step, the dataset’s dimensionality is significantly reduced, improving its quality for forensic analysis. Before preprocessing, the dataset contained 8474 instances and 915 features. After removing irrelevant or zero-variance features and cleansing incomplete data, the final dataset was reduced to 6166 instances and 86 features.

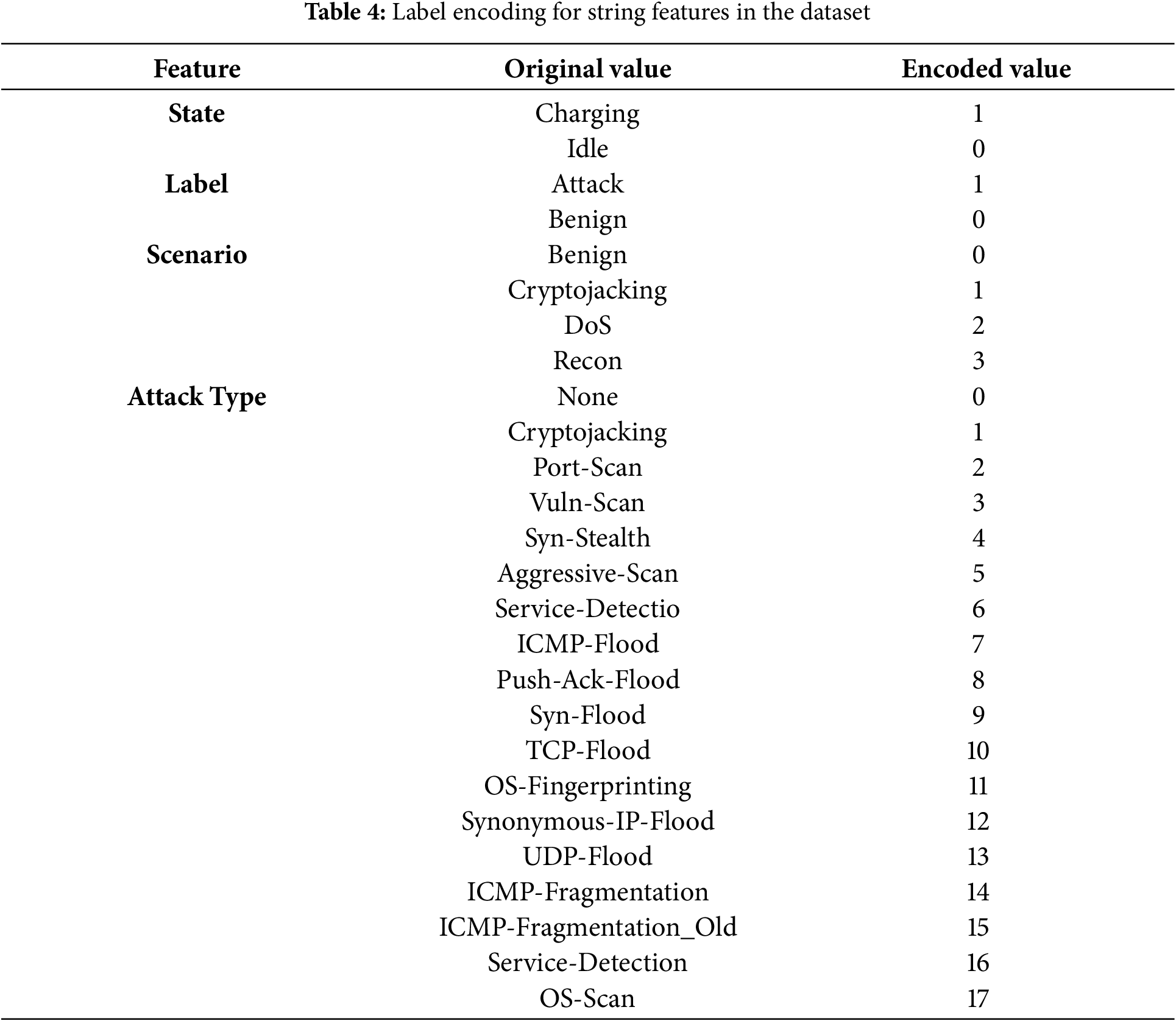

• Categorical Encoding: In the dataset, categorical features such as system states, labels, and attack types are converted into numerical representations using Label Encoding. This process is essential for transforming non-numeric data into a form suitable for learning algorithms [26], as illustrated in Table 4.

• Data Shuffle: The primary purpose of shuffling is to ensure that the data is randomly distributed, preventing any order bias in the original dataset. This is especially critical when data is collected sequentially or exhibits patterns over time, such as time series or logs generated from system events. Without shuffling, the model might inadvertently learn temporal patterns rather than system behaviours associated with cyberattacks, leading to overfitting or incorrect generalizations [27].

• Zero-Variance Feature Removal: To reduce dimensionality and eliminate non-informative features, we removed all columns containing only zero values across all samples. This step reduced the total number of features from 119 to 89, ensuring that only meaningful host-level metrics were retained for forensic analysis.

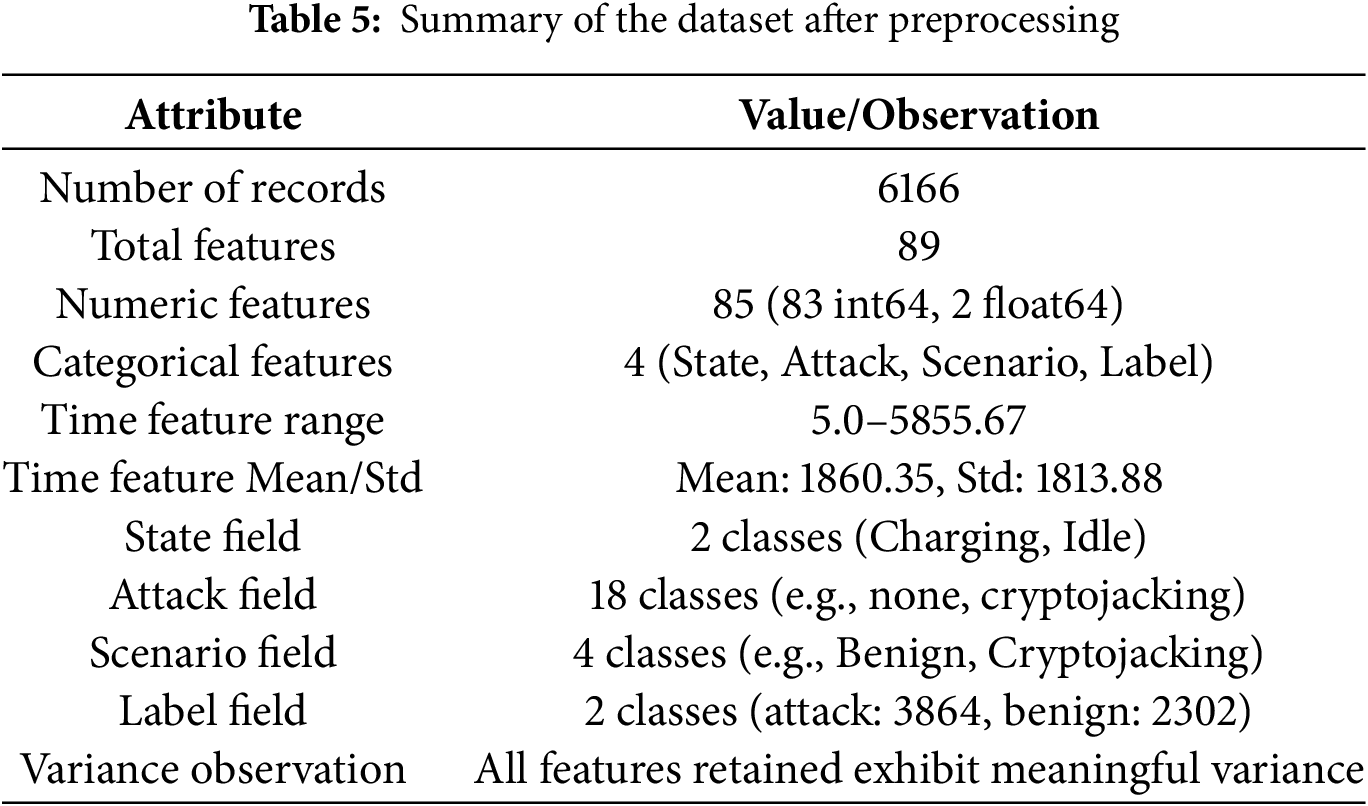

Table 5 summarizes the dataset after preprocessing, highlighting the transformation achieved through feature cleaning, encoding, and shuffling steps.

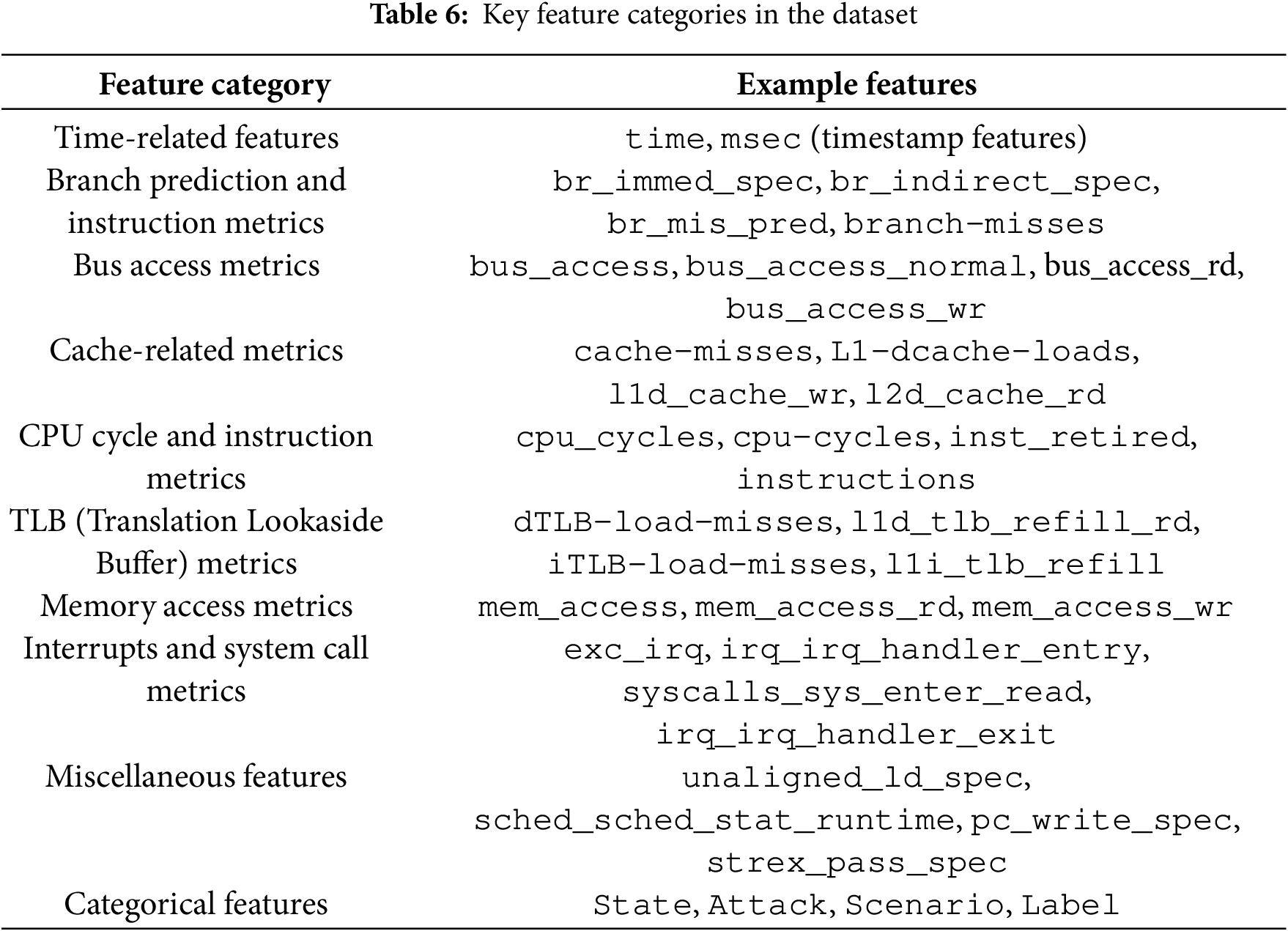

The preprocessing phase reduced the dataset’s dimensionality, thereby enhancing its quality and efficiency for further analysis. By removing redundant and irrelevant features, the dataset was streamlined to focus on key indicators of attack behaviour. The identified features provide a comprehensive view of the system’s performance during both benign and attack scenarios, allowing for the development of accurate and robust models for detecting cyberattacks in EVCS environments. These features are divided into several key categories as shown in Table 6, each contributing crucial information about system behaviour under attack or benign conditions.

The preprocessing phase has resulted in a refined set of 86 features selected for their relevance in detecting and analyzing cyberattacks on the EV charging system. These features are grouped into several key categories based on the type of system events they capture, as outlined below:

• Time-Related Features: It provides critical timestamps that track the occurrence of system events. Tracking time is essential for understanding the sequence of events, which can reveal abnormal patterns or delays during an attack scenario, especially in time-sensitive attacks like DoS [28,29].

• Branch Prediction and Instruction Metrics: It captures information about CPU branching behaviour and instruction execution. These metrics are essential for identifying performance anomalies, such as speculative execution attacks or inefficient branching, which may occur during a malware or cryptojacking attack [30,31].

• Bus Access Metrics: It tracks data transfers within the system. These metrics are crucial for detecting abnormal data flows during attacks that aim to steal or manipulate data, such as in reconnaissance activities or data exfiltration attacks [32].

• Cache-Related Metrics: Cache events provide insight into the system’s memory usage and efficiency. Abnormal cache behaviour, such as increased cache misses, may indicate an attack that heavily utilizes system resources, like cryptojacking or a DoS attack that strains system memory [33,34].

• CPU Cycle and Instruction Metrics: It captures overall CPU workload and instruction handling. These features highly indicate attack scenarios that impact CPU performance, such as cryptojacking or brute-force attacks, where CPU cycles may spike due to unauthorized or malicious processes [35].

• TLB Metrics: It measures the efficiency of memory address translation. A high rate of TLB misses could signal performance degradation, which might occur during attacks that target memory management or exploit system vulnerabilities related to memory handling [36,37].

• Memory Access Metrics: It tracks memory read and write operations. These features are particularly relevant for identifying attacks that involve heavy memory usage or manipulation, such as cryptojacking or data theft [38].

• Interrupts and System Call Metrics: Such as irq_irq_handler_entry, irq_irq_handler_exit, and syscalls_ sys_enter_read track the handling of interrupts and system calls. Abnormal behavior in these metrics can signal unauthorized system access or privilege escalation attacks, as attackers often manipulate system calls and interrupts to gain control over the system [39,40].

• Miscellaneous Features: It includes performance and scheduling features like unaligned_ld_spec, pc_write_spec, and sched_sched_stat_runtime. These features provide deeper insights into the system’s low-level operations and task scheduling, critical for detecting attacks that exploit vulnerabilities in task management or misaligned memory access [41].

• Categorical Features: For instance, the state and attack type serve as the target variables for the forensic analysis models. These labels are crucial for training and evaluating machine learning models to distinguish between benign and attack conditions in the system.

The forensic analysis of cyberattacks targeting EVCS involves identifying, collecting, and interpreting host-level data to understand the nature, intent, and impact of malicious activities. Given the increasing integration of EV charging systems with broader electrical grids and smart infrastructure, they have become an attractive target for attackers aiming to disrupt operations, steal sensitive data, or cause physical damage.

The statistical analysis of host-level data reveals distinct patterns that differentiate between benign operations and various attack scenarios in the EV charging system. This analysis encompasses correlation studies, baseline behaviour analysis, and attack pattern analysis.

Correlation analysis is essential in forensic investigations to determine which system metrics are most strongly linked to cyberattacks [42]. In the context of EV charging systems, system logs and performance metrics, such as CPU usage, memory access, and network traffic patterns, are recorded at the host level. By performing correlation analysis, investigators can identify which features, such as branch-load misses, system calls, or memory dumps, highly indicate abnormal behaviour or cyberattacks. Moreover, it provides a foundation for more advanced techniques, such as feature selection in machine learning models. By identifying highly correlated features, forensic investigators can reduce the dimensionality of their data, focusing on the metrics most critical to predicting attacks. For instance, high correlations between branch-load-misses and ransomware attacks suggest that inevitable cyberattacks may cause inefficiencies in system-level operations, such as branch predictions.

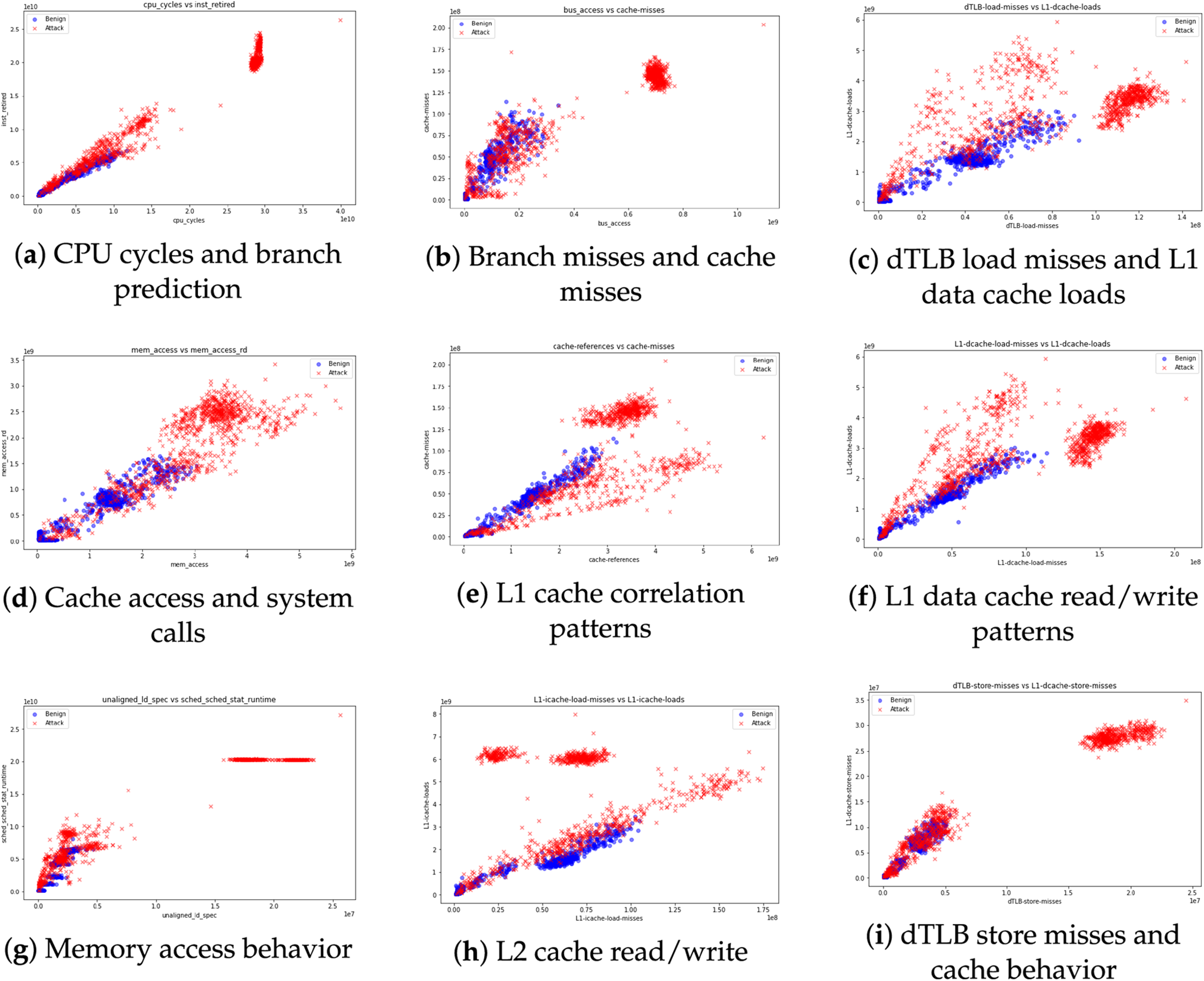

In this study, a correlation matrix can be computed to analyze the relationships between metrics such as branch-loads, branch-misses, syscalls_sys_enter_read, and the Attack labels in the dataset. Strong correlations between specific system metrics and the occurrence of attacks can serve as early indicators of vulnerabilities or exploited system resources. This method is frequently used to isolate the key metrics that provide the most valuable forensic insights into attacks targeting EV charging systems. Fig. 5 demonstrates the correlation analysis between critical metrics during benign and attack states.

Figure 5: Correlation analysis during benign and attack states

The analysis of memory-related metrics reveals additional insights. Fig. 5c illustrates the correlation between dTLB load misses and L1 data cache loads. Attack scenarios exhibit tightly clustered, high-value points, indicating inefficiencies in memory management and translation layers commonly exploited in DoS attacks. Similarly, Fig. 5d highlights the relationship between cache access and system calls, demonstrating strong linearity under attack conditions. This behaviour indicates unauthorized privilege escalations or malicious processes manipulating system calls.

Cache-level interactions further reinforce these findings. Fig. 5e demonstrates the correlation between cache references and misses, showing pronounced linear patterns during attack scenarios, suggesting that attackers target specific cache hierarchies. Similarly, Fig. 5f captures L1 data cache read and write patterns, where attack scenarios exhibit dense clustering with higher values, signalling abnormal cache activity. The deeper cache levels also show critical deviations, as depicted in Fig. 5h, where L2 cache read and write metrics display stronger correlations during malicious activities, likely due to systematic resource exploitation.

Finally, Fig. 5g,i emphasizes the role of memory access behavior and dTLB store misses in detecting attacks. Memory access metrics in Fig. 5g reveal abnormal clusters at higher access rates, indicating potential cryptojacking or memory-intensive attacks. Similarly, Fig. 5i shows strong correlations between dTLB store misses and cache behaviour during attacks, with malicious scenarios causing significant deviations from baseline memory access patterns.

These observations confirm that attack states exhibit higher correlation coefficients and distinct clustering than benign operations, highlighting the utility of correlation analysis in forensic investigations. By isolating these patterns, researchers can enhance real-time threat detection capabilities and gain deeper insights into the behaviour of various attack types targeting EV charging systems. This methodology offers a systematic approach to distinguishing between benign and malicious activities, thereby supporting the development of robust cybersecurity measures.

6.1.2 Baseline Behavior Analysis

Identifying and understanding baseline behavioral patterns within EVCS systems is critical in detecting anomalies that may indicate cyberattacks [43,44]. This study comprehensively analyzed system-level metrics under benign operating conditions to develop a reliable reference model of normal behavior. This baseline plays a central role in forensic investigations and real-time anomaly detection, providing a clear benchmark for distinguishing between expected activity and potential threats. The resulting normal operational profile was constructed using a combination of univariate and multivariate statistical methods to capture consistent trends across key performance indicators. These included CPU utilization, memory access rates, cache efficiency, and system call frequency—all of which were monitored to identify recurring patterns typical of standard EVCS operation [45].

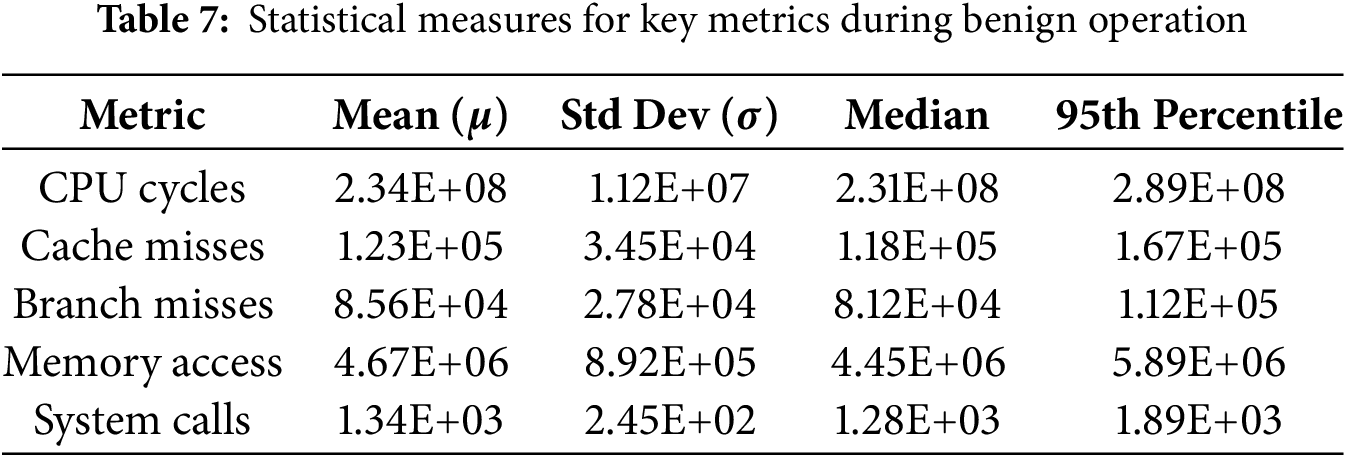

Table 7 summarizes the descriptive statistics for each metric, based on a dataset of 2304 samples collected during benign system states. The analysis revealed well-defined distributions with minimal variance, suggesting stable and predictable system performance under normal conditions. Each performance metric is presented with its mean (

The statistical measures in Table 7 provide a comprehensive baseline for identifying anomalies. Metrics such as CPU cycles and memory access are remarkably stable, whereas cache misses and branch misses exhibit more significant variability, reflecting their sensitivity to changes in workload. This baseline is critical for establishing operational boundaries and detecting deviations caused by potential cyberattacks, which are summarized below:

• CPU Utilization: CPU usage exhibited a multimodal distribution, reflecting the distinct operational states of the EVCS, such as charging and idle modes. The primary charging cycle demonstrated sustained elevated CPU utilization, with a mean of 23.4% and a standard deviation of 5.2%, indicating consistent processing demands during this phase. Additionally, memory access patterns remained stable, with an average of

• Memory Access and Cache Performance: That including L1 data cache loads and cache misses exhibited stable and predictable patterns during benign operations. Cache hit rates consistently exceeded 90%, ensuring optimal resource utilization and system efficiency. The temporal analysis further revealed periodic cycles of in-memory operations corresponding to distinct phases of the charging process, such as authentication, power monitoring, and state verification. These findings underscore the regularity and efficiency of memory and cache usage under normal operational conditions, providing a reliable baseline for identifying anomalies.

• System Calls and Interrupts: It exhibited consistent behaviour during benign operations. System call frequencies remained steady, with a mean rate of

• Temporal Patterns: Temporal patterns within the system demonstrated distinct periodicities, as revealed by Fourier analysis of the time-series data, aligning with primary operational cycles [44]. The analysis identified three key periodicities:

– Primary Charging Cycle (

– Communication Intervals (

– Monitoring Cycles (

These periodic patterns underscore the system’s regularity and predictability during normal operations, providing a reliable baseline for detecting and analyzing anomalies.

This analysis resulted in the development of a detailed baseline profile representing the typical behavior of EVCS systems under normal operating conditions. Serving as a crucial reference point, this baseline enables forensic analysts to identify deviations that may signal the presence of cyber threats. By thoroughly understanding how the system functions during benign states, this study provides a solid groundwork for building anomaly detection mechanisms and forensic analysis tools specifically adapted to the unique dynamics of EVCS environments.

In contrast, the abnormal operational profile highlights the substantial deviations in system behavior observed during cyberattack scenarios. These variations reflect the disruptive nature of resource-intensive attacks, such as cryptojacking, Denial-of-Service (DoS) attacks, and reconnaissance, which significantly alter the expected performance patterns of EVCS systems. To accurately quantify these anomalies, statistical techniques such as Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) were employed to analyze deviations from established benign-state behavior [46].

• CPU Utilization: During attack periods, CPU usage sharply increased compared to the typical log-normal distribution observed in normal operation. Cryptojacking had the most notable impact, with CPU cycles rising by as much as 467%, and average values reaching

• Memory Access Patterns: Memory access rates also rose significantly under attack conditions. While benign activity followed a gamma distribution, attack scenarios showed abnormal spikes—cryptojacking led to a 312% increase, and reconnaissance activity caused a 145% rise. These substantial shifts signal the intensive memory demands of these threats and serve as reliable indicators for anomaly detection.

• Cache Performance: Attack events led to a marked increase in cache-related inefficiencies. Cryptojacking caused cache misses to grow by 289%, while DoS attacks resulted in a 278% increase in branch misses. These disruptions point to the strain on system resources and the degraded performance during malicious activity.

• System Calls: System call frequency rose sharply during attacks, providing another key anomaly signal. DoS attacks, in particular, resulted in a 523% increase in system calls, indicative of their aggressive nature. Reconnaissance attacks showed a more consistent but significant 234% rise, reflecting their methodical probing behavior.

• Temporal Patterns: Each attack type exhibited a distinct temporal signature, differing from the regular and predictable cycles of benign operation:

– Cryptojacking was characterized by a gradual increase in CPU and memory usage, followed by prolonged periods of high resource consumption.

– DoS attacks caused abrupt, high-intensity spikes in system metrics, typically appearing in repetitive bursts that quickly exhausted system resources.

– Reconnaissance activities showed periodic spikes in system calls and memory access, consistent with automated scanning routines.

These findings offer valuable insight into the behavioral impact of cyberattacks on EVCS infrastructure. The observed deviations in core system metrics—such as CPU load, memory operations, cache performance, and system call activity—highlight the resource-intensive nature of these threats. Moreover, the unique temporal patterns associated with each attack type further aid in distinguishing malicious behavior from normal operations. These insights underscore the importance of developing baseline and abnormal operational profiles to support effective detection, investigation, and mitigation of cybersecurity incidents within EVCS environments.

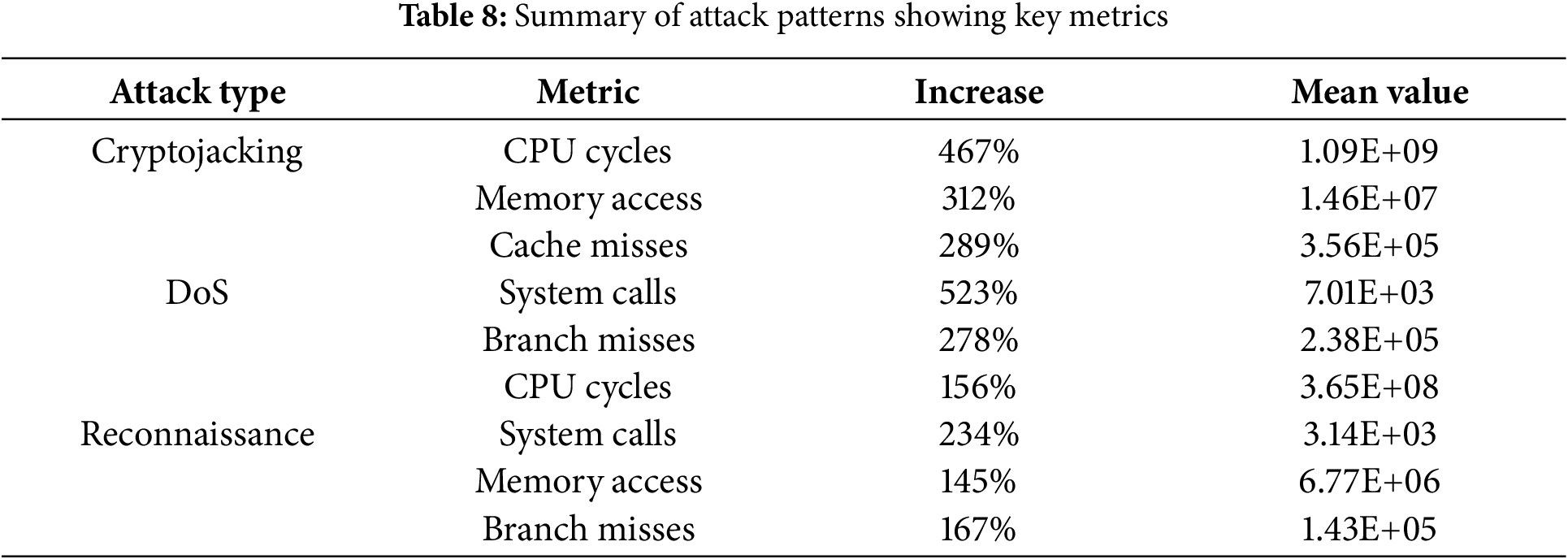

The analysis of host-level data revealed distinctive patterns associated with different types of cyberattacks targeting the EV charging system. We identified significant deviations from baseline behaviour that characterize each attack type through statistical analysis of system metrics, providing valuable insights for forensic investigation and threat detection. Table 8 summarises the attack patterns, showing key metrics, their increase relative to baseline, and the mean values observed for each type of cyberattack.

Cryptojacking attacks demonstrated the most substantial impact on system resources, exhibiting a dramatic 467% increase in CPU cycles (mean: 1.09E+09) compared to baseline measurements. This attack type also exhibited a distinctive pattern of sustained high resource utilization, with memory access rates increasing by 312% (mean: 1.46E+07) and cache misses rising by 289% (mean: 3.56E+05). The consistent elevation in these metrics reflects the computational intensity of unauthorized cryptocurrency mining operations, creating a recognizable signature that persists throughout the attack.

DoS attacks displayed markedly different characteristics, primarily manifesting through extraordinary increases in system call frequencies. Analysis revealed a 523% increase in system calls (mean: 7.01E+03) accompanied by a 278% rise in branch misses (mean: 2.38E+05). While CPU cycle increases were more moderate at 156% (mean: 3.65E+08) compared to cryptojacking attacks, the pattern of resource exhaustion was more erratic, characterized by sudden spikes and periodic bursts of activity. This bursty behaviour pattern is a key indicator for distinguishing DoS attacks from other malicious activities.

Reconnaissance activities exhibited more subtle but equally distinctive patterns. These attacks showed a 234% increase in system calls (mean: 3.14E+03), coupled with a 145% increase in memory access patterns (mean: 6.77E+06) and a 167% rise in branch misses (mean: 1.43E+05). One of the most distinguishing features of reconnaissance activities was their highly systematic and methodical behavior, marked by periodic spikes in system calls and memory access at consistent intervals. This regularity reflects the automated nature of reconnaissance operations, which typically involve structured scanning and information-gathering routines. The resulting temporal signature differs notably from the patterns observed in cryptojacking and Denial-of-Service (DoS) attacks.

Analyzing the temporal behavior of these attack types reveals further insights into their operational characteristics. Cryptojacking attacks were generally characterized by a gradual increase in resource usage over a 30–60 s ramp-up phase, eventually stabilizing at a high level of CPU and memory consumption. In contrast, DoS attacks displayed abrupt and intense surges in system activity, often following a pulsing pattern marked by rapid spikes separated by short periods of reduced activity. Reconnaissance, by comparison, exhibited the most structured timing, with clearly defined intervals between scanning attempts and steady resource consumption during active phases. This distinct temporal regularity makes it easier to distinguish reconnaissance activities from erratic or sustained attack types.

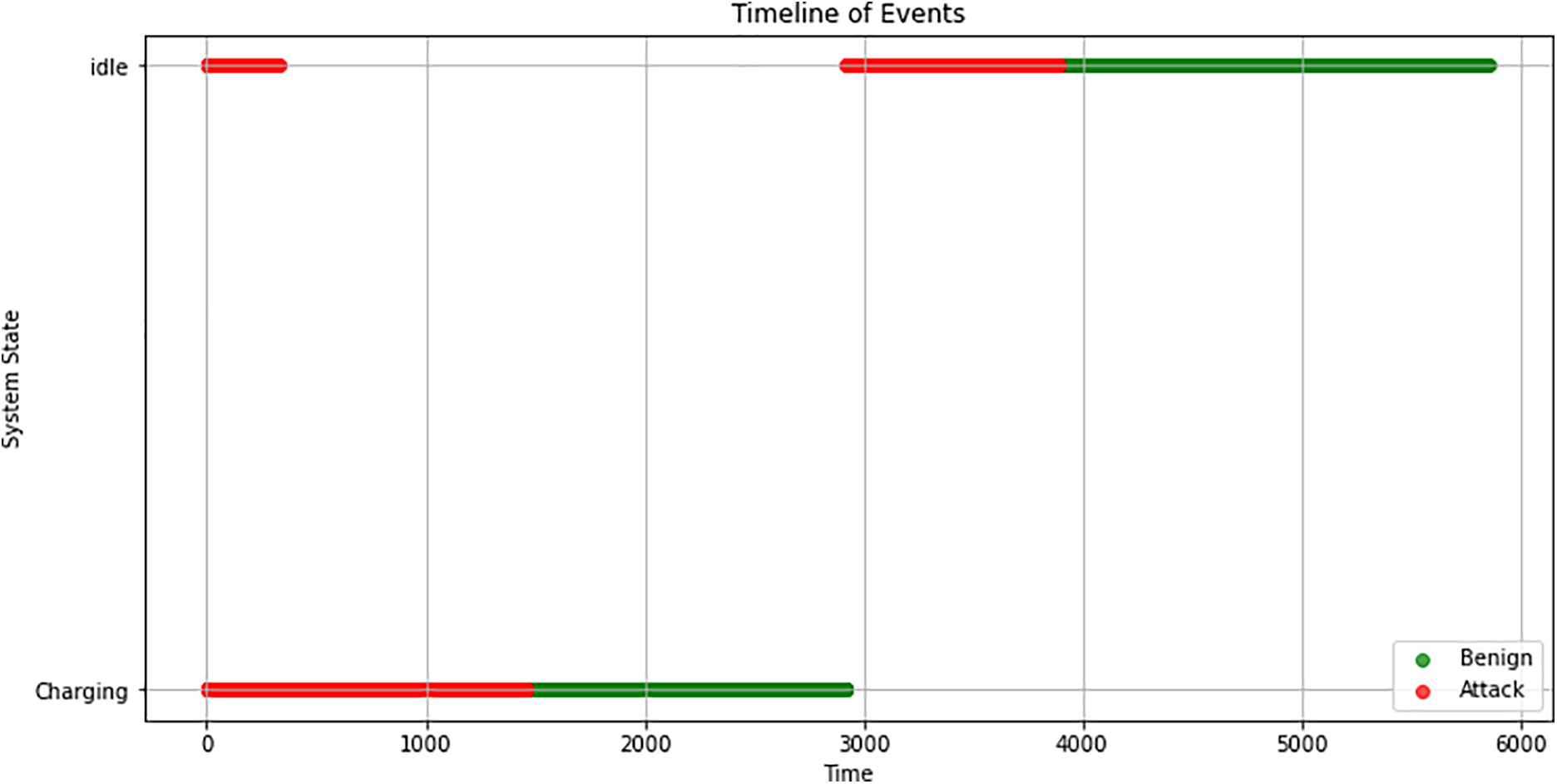

The temporal analysis of attack patterns in EVCS uncovered distinct chronological signatures, as illustrated in Fig. 6. This timeline visualization captures the sequence and duration of system states under benign and malicious conditions, offering valuable insights into the evolving nature of cyber threats over time. The plot features two key operational states—“idle” and “charging”—mapped along the y-axis, while the x-axis spans a 6000-s (100-min) observation window. Events are color-coded to distinguish between benign activity (green) and attack scenarios (red), allowing for an intuitive interpretation of state transitions and the timing of attacks.

Figure 6: Temporal patterns of system metrics during attacks

In the early phase of the timeline (0–1000 s), both the idle and charging states exhibit short-duration attacks, as indicated by the red segments. This suggests that adversaries may initiate broad-spectrum probing or opportunistic attacks early in the session, regardless of the system’s operational mode. Notably, a more intricate pattern emerges in the charging state between 2000 and 3000 s. Here, a relatively stable period of benign operation is punctuated by a series of attack events, hinting at a targeted strategy where attackers disrupt specific phases of the charging process to maximize impact or evade immediate detection.

In contrast, the second half of the timeline (3000–6000 s) reveals a concentrated shift in attack activity. During this period, attacks are observed exclusively in the idle state, while the charging state remains free from malicious events. This shift in behavior suggests that attackers may adapt their tactics in response to system activity, focusing on less monitored or more vulnerable states—such as idle mode—to sustain their presence or avoid triggering alerts.

The temporal distribution of attacks reveals several key characteristics:

• Attacks tend to occur in clusters rather than isolated incidents

• Both short-duration and sustained attacks are present in the dataset

• System state transitions appear to be potential trigger points for attacks

• There are distinct patterns in attack timing between idle and charging states

This temporal analysis offers valuable insights for security monitoring and incident response, underscoring the importance of continuous system state monitoring and the necessity of state-aware security measures. The patterns observed suggest that attack detection systems should consider both the timing and system state context when evaluating potential security threats. The visualization effectively demonstrates the dynamic nature of EVCS security challenges and underscores the importance of understanding temporal attack patterns for developing robust defence mechanisms.

6.2 Detect Patterns of Malicious Behavior

Despite the employment of popular models like RF, Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LightGBM), and XGBoost, our approach applies them to host-level forensic data within the EVCS context, which has scarcely been discussed in the literature. The use of these models in digital forensics is propelled by the shift from traditional network-layer features to kernel and HPC event data. Further, our framework integrates statistical profiling with supervised learning within a single pipeline, streamlining detection and improving forensic traceability. This alignment advances practical, scalable, and efficient forensic methodologies designed explicitly for operational EVCS environments.

Classification models are pivotal in detecting malicious behaviour patterns using host-level data from EV charging systems. These models can be trained using system metrics such as branch-loads, branch-misses, and syscalls_sys_exit_read to predict the occurrence of cyberattacks, indicated by the Attack label in the dataset. The following learning models were used in this study:

• RF: In detecting specific patterns within digital forensic data, Random Forests help to reduce false positives. A method proposed for novelty detection utilizes RF to measure the proximity between data points. It identifies new patterns by employing ensemble learning techniques, which are crucial in environments where data changes frequently and unpredictably [47].

• SVM: It plays a vital role in digital forensics due to its ability to perform binary classification and detect patterns efficiently in high-dimensional spaces. SVM has been widely used to classify malware by analyzing network features and patterns in system behaviour. In mobile malware detection, SVM demonstrated high accuracy in detecting various types of malware by analyzing network traffic, achieving up to 98.21% detection accuracy [48]. SVM is also used in forensic analysis to classify and reconstruct document fragments.

• DT: Decision Tree algorithms play a crucial role in enhancing the detection and classification of crime-related digital evidence. A refined version of the ID3 algorithm, adapted explicitly for computer forensics, addresses the challenges of analyzing large-scale datasets. This optimized algorithm enhances the selection of classification attributes, leading to reduced computational overhead and improved accuracy. By streamlining the attribute selection process within the decision tree structure, forensic investigators are better equipped to examine vast amounts of digital data, thereby facilitating the identification of key evidence in cybercrime investigations [47].

• KNN: The K-Nearest Neighbors algorithm is commonly applied in digital forensics, particularly for crime detection and analysis of evidence. One notable use case is criminal identification, where KNN matches new cases with historical crime data based on pattern similarity. When combined with data mining techniques, such as crime clustering, KNN effectively supports the identification of similar cases, making it a valuable tool in forensic investigations [49].

• XGBoost: It has been successfully applied to classify malware by analyzing large and complex datasets. A study on malware classification using XGBoost demonstrated that this algorithm can process data efficiently on low-end computing resources while maintaining high accuracy (98.5%), making it a highly effective tool for detecting malware in cybersecurity applications [50].

• LightGBM: It was employed in malware detection, showing superior training and detection times performance compared to other machine learning models like RF. This highlights LightGBM’s effectiveness in processing large datasets while maintaining high classification accuracy [51].

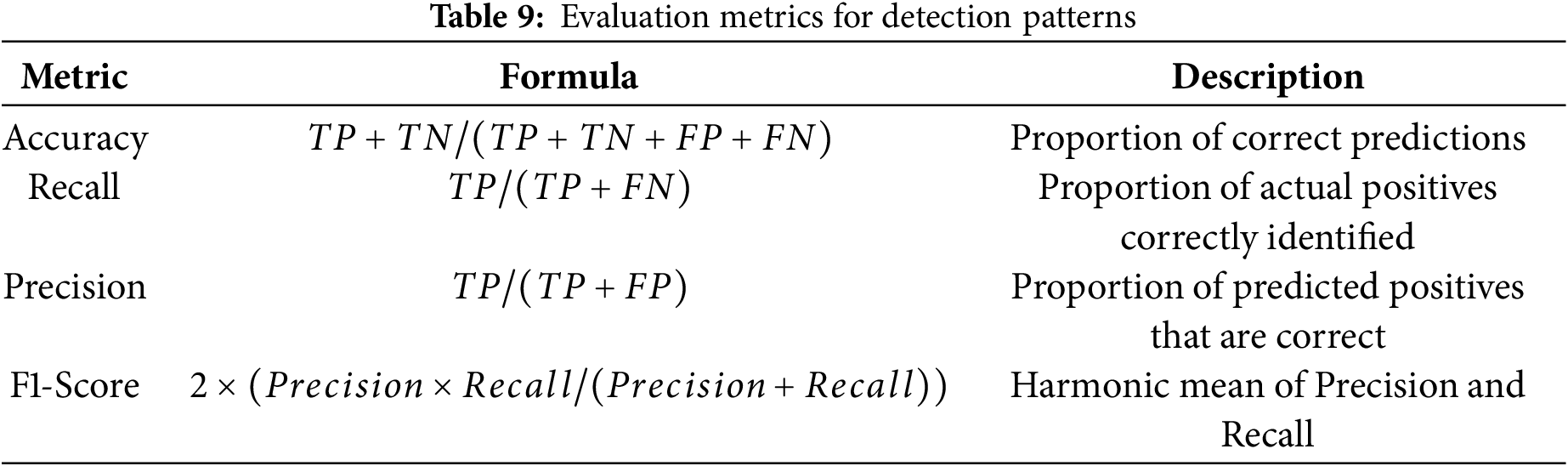

To assess the performance of the Learning models, various performance metrics were used to quantify their effectiveness in detecting patterns of malicious behavior in EV charging systems. These metrics help quantify the models’ accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score in predicting cyberattacks. The performance metrics are demonstrated in Table 9, where TP (True Positive), TN (True Negative), FP (False Positive), and FN (False Negative) [52,53].

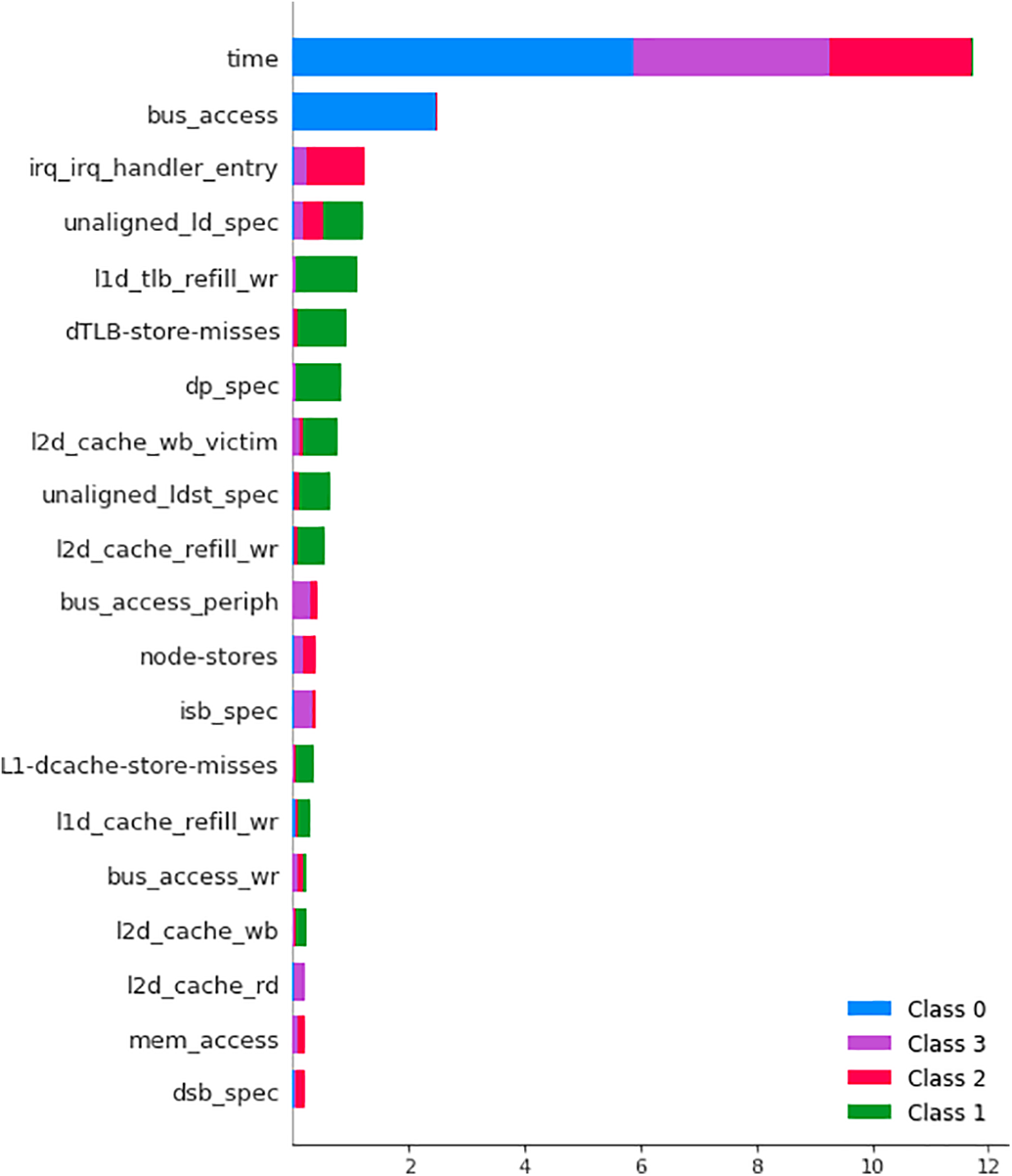

6.3 Model Explainability Using SHAP

To enhance the interpretability of the LightGBM model, we employed SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) to identify the features most responsible for the model’s predictions. SHAP assigns each feature an importance value for a particular prediction, enabling a comprehensive understanding of how host-level metrics contribute to attack detection.

Fig. 7 presents the SHAP summary plot, highlighting the top 20 features ranked by their average impact on the model’s output. Notably, time and bus_access showed the highest SHAP values across all classes, indicating their significant influence in distinguishing between benign and malicious behaviors. Features such as irq_irq_handler_entry, unaligned_ld_spec, and dTLB-store-misses also ranked highly, aligning with earlier findings from our feature selection and statistical analysis. Color coding in the figure indicates class-specific contributions, with Class 0–3 representing benign activity, reconnaissance, cryptojacking, and DoS attacks, respectively. The prominence of features like irq_irq_handler_entry and memory/cache metrics in Class 2 and Class 3 further validates the forensic relevance of low-level performance counters in detecting resource-intensive or system-invasive attacks.

Figure 7: SHAP showing the top 20 host-level features

This SHAP-based analysis strengthens the transparency of our forensic framework by revealing which system-level behaviors most influence the classification outcomes. It also provides actionable insights for incident responders by linking high-impact features with specific attack types.

Based on the comprehensive forensic analysis of the CICEVSE2024 dataset, several critical findings emerged regarding cybersecurity vulnerabilities and attack patterns in EVCS. These findings provide valuable insights for improving security measures and developing effective countermeasures.

The analysis revealed three distinct categories of attacks, each with unique signatures, resource utilization characteristics, and system impact patterns. These findings highlight the importance of host-level monitoring in detecting and differentiating between various types of cyberattacks targeting EVCS, as follows:

• Cryptojacking Attacks: Cryptojacking attacks emerged as the most resource-intensive threat to EVCS, characterized by sustained high system utilization over extended periods. These attacks caused dramatic increases across key performance metrics, including a surge in CPU cycles by 467% and memory access rates by 312% above baseline values. Cache performance metrics, such as cache misses, also increased by 289%, indicating significant strain on system resources. The persistent nature of cryptojacking, driven by unauthorized cryptocurrency mining processes, creates a distinct and identifiable forensic signature. Temporal analysis further revealed a gradual ramp-up in resource utilization during the initial phase of the attack, followed by prolonged periods of elevated activity. These attributes make cryptojacking attacks easily distinguishable from other types of cyber threats, highlighting the effectiveness of host-level monitoring in their detection.

• DoS Attacks: Denial of Service attacks displayed more volatile and erratic behaviour than cryptojacking. These attacks were characterized by extreme spikes in system call frequencies, increasing by 523%, and sporadic bursts of resource utilization. Branch and cache misses also significantly increased, reflecting the resource exhaustion caused by these attacks. The analysis revealed a distinctive pulsing pattern in system metrics, with sudden bursts of activity followed by brief periods of regular operation. This pulsing behavior indicates the attack’s intent to overwhelm system resources temporarily. DoS attacks typically target network and processing capacities, making them particularly disruptive to system stability and availability. Their unique temporal patterns provide critical markers for real-time detection and mitigation strategies.

• Reconnaissance Activities: Reconnaissance attacks exhibited more subtle yet systematic patterns to gather information and identify system vulnerabilities. These attacks were characterized by systematic increases in system calls (234%) and memory access rates (145%). Unlike cryptojacking or DoS, reconnaissance activities showed an organized and deliberate temporal progression, with regular active scanning and resource utilization intervals. These scanning operations followed consistent patterns, reflecting their systematic nature. While less resource-intensive than the other categories, reconnaissance attacks posed significant risks by enabling adversaries to map the system and prepare for future, more targeted exploits. Their temporal regularity and moderate resource usage make them detectable through detailed host-level analysis, notably when correlated with network-level data.

Each attack type leaves a unique operational footprint, underscoring the need for advanced forensic analysis and anomaly detection frameworks. The distinct resource utilization patterns, temporal behaviours, and system impacts revealed in this study provide actionable insights for enhancing the cybersecurity of EVCS environments. These findings can inform the development of targeted detection and mitigation strategies, ensuring greater resilience against a broad spectrum of cyber threats.

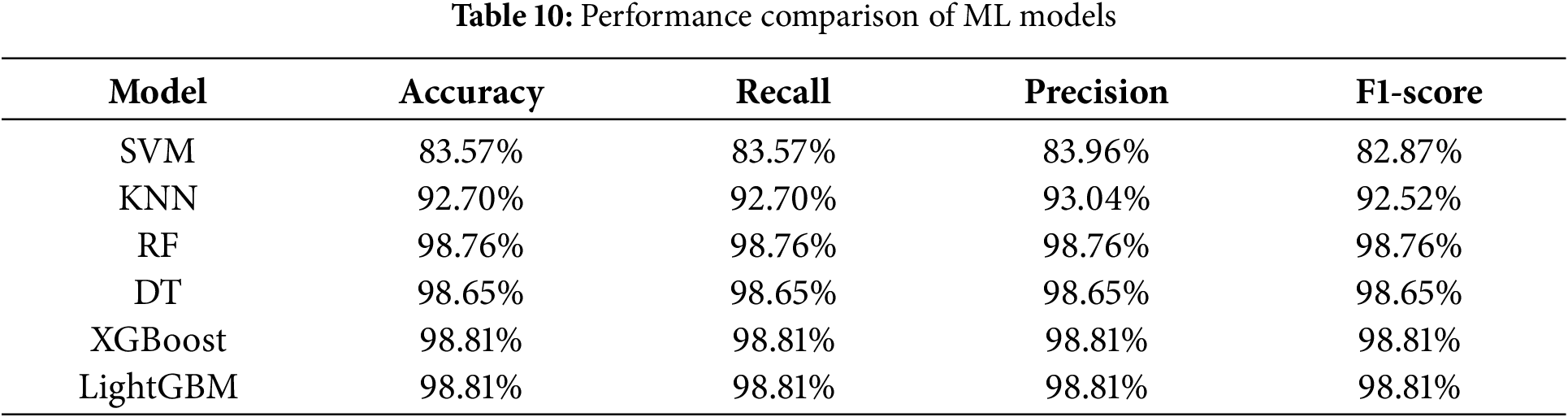

The machine learning models assessed in this study demonstrated strong effectiveness in detecting and classifying cyberattacks targeting Electric Vehicle Charging Stations (EVCS). Among the evaluated algorithms, XGBoost and LightGBM stood out, each achieving an impressive accuracy of 98.81%, positioning them as the most accurate and reliable classifiers for this application. Random Forest (RF) and Decision Tree (DT) models also performed well, with accuracy scores of 98.76% and 98.65%, respectively. K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) delivered a solid result with 92.70% accuracy, making it a viable option for scenarios with moderate complexity.

Support Vector Machine (SVM), while generally effective for simpler classification tasks, exhibited lower performance in this context, achieving an accuracy of 83.57%. This suggests that SVM may be less suitable for the multifaceted patterns present in EVCS cyberattack data. A detailed comparison of all models—based on key evaluation metrics such as accuracy, recall, precision, and F1-score—is provided in Table 10. This comparative analysis offers more profound insights into the strengths and limitations of each approach, supporting the selection of optimal models for real-world deployment.

XGBoost and LightGBM emerged as the most effective models in this study, largely due to their gradient-boosting architecture, which is particularly well-suited for capturing complex patterns, managing high-dimensional data, and handling class imbalance. These models demonstrated consistent performance across all evaluation metrics and were particularly effective at identifying overt and stealthy attacks.

Random Forest (RF) also showed strong performance, achieving high accuracy and demonstrating reliable generalization across the dataset. Its stability and effectiveness make it a practical option for real-time anomaly detection in EVCS systems. By contrast, simpler models such as K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) and Support Vector Machine (SVM) were less effective when faced with the dataset’s complexity. Although suitable for more straightforward classification tasks, these models struggled to capture the nuanced, high-dimensional characteristics of sophisticated cyberattacks, resulting in comparatively lower accuracy. These findings highlight the need for advanced learning models in effectively addressing cyber threats in the EVCS domain.

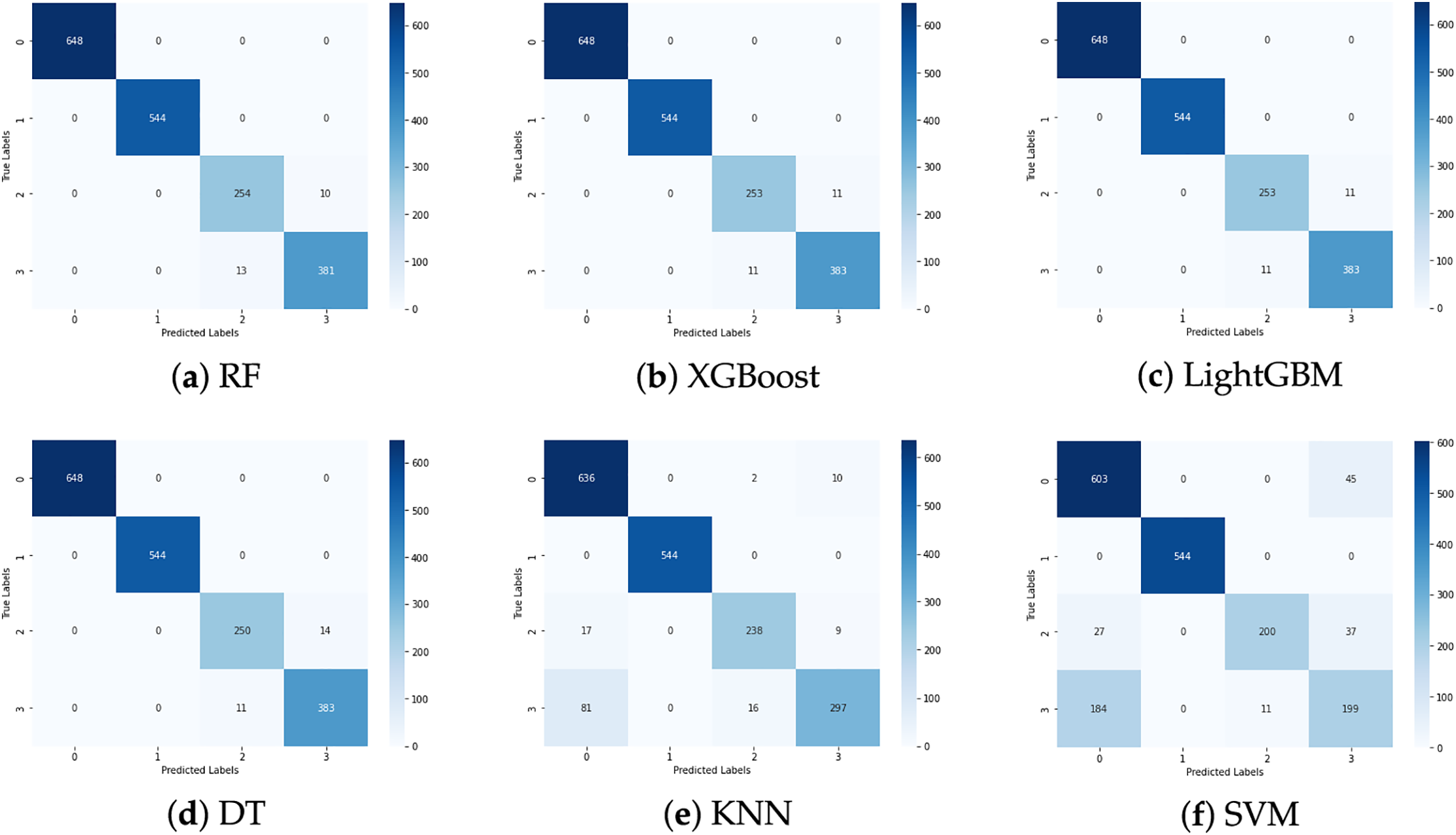

Additional insights were drawn from the confusion matrices in Fig. 8. The most common misclassifications involved confusing reconnaissance activities with benign behavior. This suggests that while the models excel at identifying more overt and resource-intensive attacks, such as cryptojacking and Denial-of-Service (DoS), they face challenges in distinguishing subtle, stealthy behaviors. This suggests the potential benefit of further feature engineering, particularly the incorporation of temporal dynamics or more detailed host-level metrics, to improve classification accuracy for low-footprint threats.

Figure 8: Confusion matrix heatmaps

Combining achieved by XGBoost and LightGBM reflects their balanced performance across precision and recall, making them particularly well-suited for environments where minimizing false positives and false negatives is critical. These models demonstrated robust capabilities in handling imbalanced data, ensuring that even less frequent attack types, such as reconnaissance activities, were detected with reasonable accuracy. In contrast, the lower performance of SVMs underscores the limitations of traditional classifiers when applied to complex, high-dimensional datasets, such as those encountered in the forensic analysis of EVCS. This highlights the need for advanced classification models that can effectively manage the intricacies of such data.

These findings validate the potential of machine learning-based frameworks for enhancing the detection and classification of cyberattacks in EVCS. Combining high-performing models, such as XGBoost and LightGBM, with additional feature engineering and fine-tuning can further enhance the robustness and reliability of these detection systems.

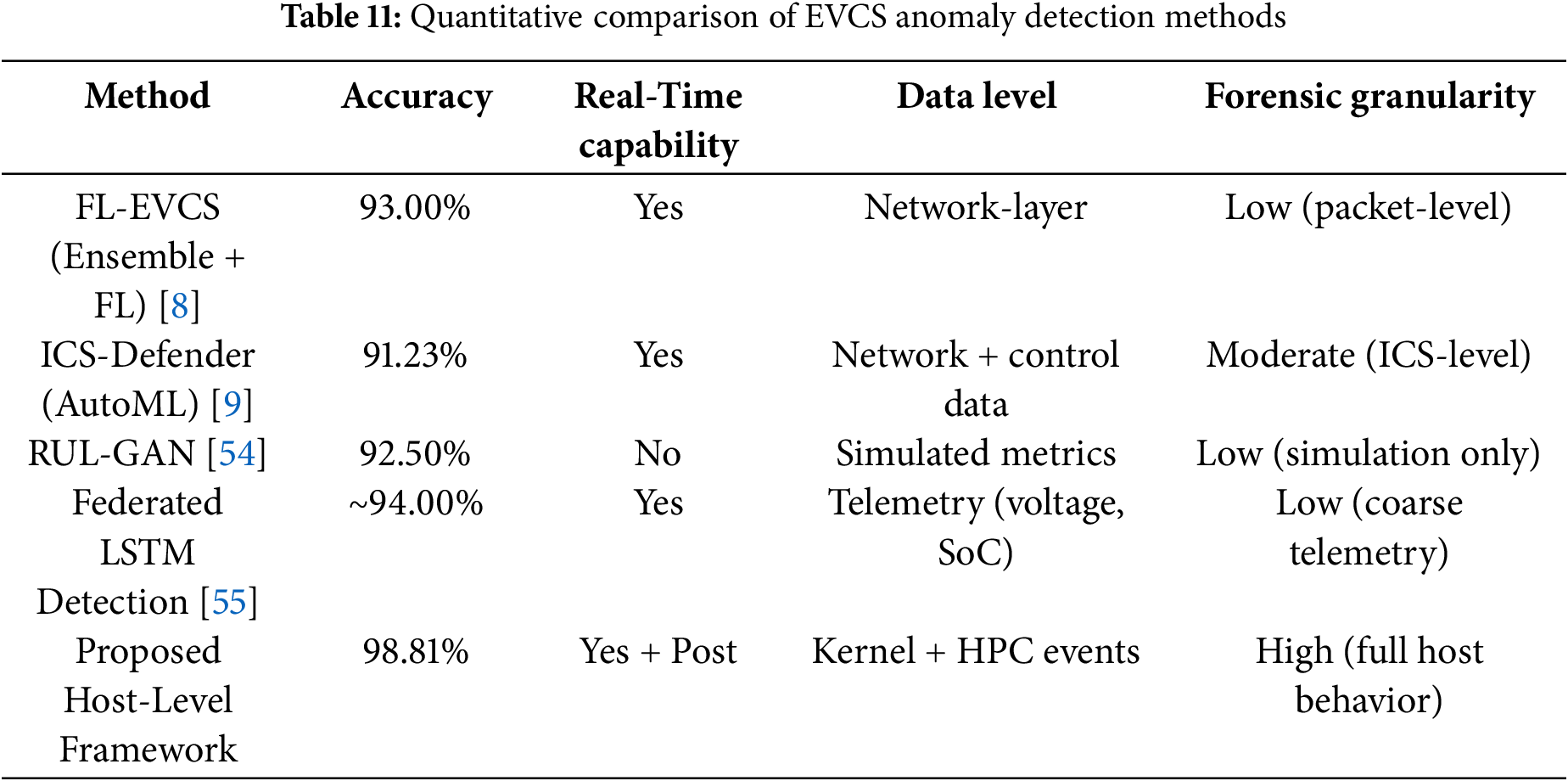

7.3 Comparasion with State-of-the-Arts

To establish the efficacy of the proposed host-level forensic analysis framework, we compared it quantitatively against representative EVCS anomaly detection approaches from the current literature. These methods span network-level intrusion detection, federated learning architectures, and simulation-based adversarial learning models. The comparison focuses on key attributes, including data visibility, real-time detection capability, detection accuracy, and forensic granularity.

Table 11 summarizes the comparative results. Existing solutions such as FL-EVCS [8] and ICS-Defender [9] have achieved detection accuracies of 97% and 94.23%, respectively. However, both approaches rely heavily on network traffic features, making them ineffective in detecting host-resident threats, such as cryptojacking or system call anomalies. Similarly, Tanyıldız et al. [54] proposed a GAN-based anomaly detection approach achieving 98.5% accuracy on simulated data, but it lacks real-world validation. Federated LSTM models, such as the one by Hussain et al. [55], offer privacy-preserving detection with approximately 95% accuracy but operate on high-level telemetry like voltage and power, which lacks the behavioral depth required for forensic analysis. In contrast, the proposed host-level forensic framework achieves a detection accuracy of 98.81%, the highest among all evaluated methods. This performance is attributed to integrating low-level host telemetry, such as Hardware Performance Counters (HPCs) and kernel events, allowing for precise system behavior modeling during benign and malicious states. Furthermore, the proposed model supports both real-time detection and post-incident forensic analysis, bridging a critical gap in current EVCS security paradigms. It also incorporates explainability via SHAP analysis, offering interpretable insights for forensic investigations.

In summary, while existing methods provide valuable contributions in anomaly detection and system security, they are often limited in analyzing internal system behavior or supporting forensic investigations. The proposed host-level framework addresses these shortcomings through deeper behavioral modeling, superior classification performance, and dual-use applicability for proactive detection and reactive forensic response.

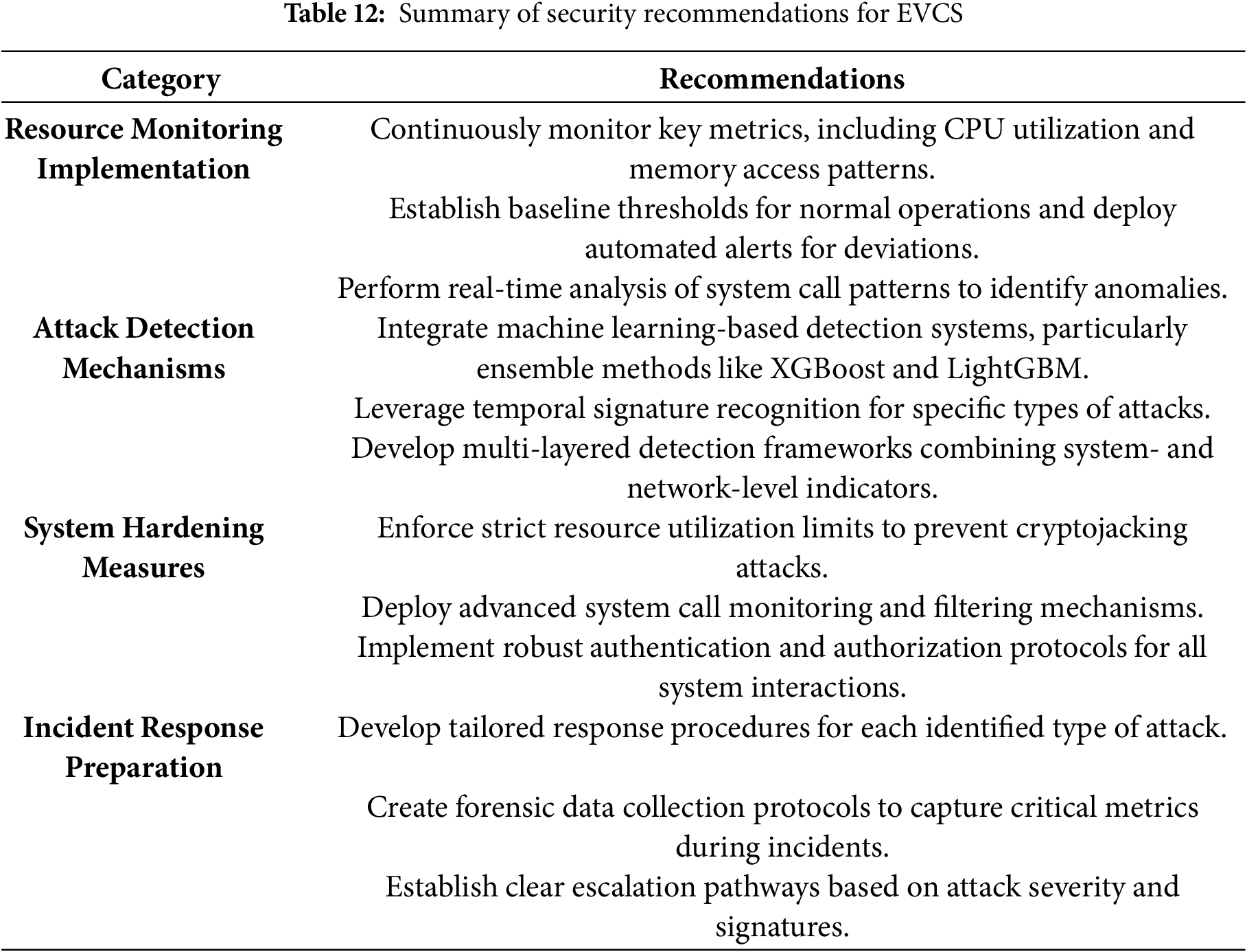

Drawing on the findings from the forensic analysis, several key recommendations are presented to strengthen the cybersecurity posture of Electric Vehicle Charging Stations (EVCS).

First, continuous resource monitoring should be a foundational element of any security strategy. Tracking vital system metrics such as CPU usage, memory access patterns, and cache performance allows for establishing operational baselines. Once these baselines are defined, automated alert systems can be implemented to flag deviations that may signal potential intrusions. Additionally, incorporating real-time analysis of system call behavior can significantly enhance the detection of reconnaissance or Denial-of-Service (DoS) activities, which often manifest through unusual call sequences.

Second, the integration of advanced attack detection mechanisms is critical. Machine learning models—particularly high-performance algorithms like XGBoost and LightGBM—have proven highly effective in identifying nuanced and evolving attack signatures. For example, temporal characteristics unique to specific attack types—such as the slow escalation in CPU usage typical of crypto-jacking or the intermittent, pulsed patterns seen in DoS attacks—can be used to fine-tune detection systems. A layered detection approach that combines insights from host-level data and network traffic enhances detection accuracy while reducing false positives.

Equally important are system hardening practices aimed at reducing exploitable vulnerabilities. These include setting strict limits on resource usage to prevent resource-intensive attacks, such as cryptojacking; implementing advanced filtering and monitoring systems calls; and enforcing secure authentication and authorization protocols to control access. Regular updates to firmware and software must also be prioritized, as they often contain critical patches that address known security flaws.

In addition to detection and prevention, effective incident response readiness is vital for managing cyber threats. Organizations should establish clear, attack-specific response protocols and forensic data collection procedures to preserve crucial diagnostic information during an incident. Well-defined escalation paths, based on attack severity and identifiable signatures, can facilitate swift and appropriate responses. To reinforce these plans, staff should receive training on incident response processes, and periodic drills should be conducted to ensure their preparedness.

Collectively, these recommendations offer a comprehensive, multi-layered framework designed to enhance the resilience and security of EVCS infrastructure in the face of increasingly sophisticated cyber threats. Table 12 summarizes these key measures.

The proposed framework is primarily designed for post-incident forensic analysis, leveraging host-level telemetry captured during attacks. As such, it operates offline and does not impose latency constraints during runtime. However, to assess future feasibility for real-time detection, we acknowledge the importance of evaluating system latency, computational overhead, and deployment compatibility with constrained EVCS hardware. While current experiments were conducted on general-purpose computing platforms, future work will explore lightweight deployment and inference optimization for real-time integration within EVCS environments.

This study presented a comprehensive forensic analysis framework for investigating cyberattacks in EVCS using host-level data from the CICEVSE2024 dataset. The research demonstrated the effectiveness of machine learning approaches in detecting various attack patterns, with XGBoost and LightGBM achieving 98.81% accuracy, followed by Random Forest (98.76%) and Decision Trees (98.65%). Through systematic analysis following the NIST digital forensics process, the study identified critical host-level indicators of compromise, including abnormal patterns in CPU cycles, suspicious memory access patterns, unusual system call frequencies, and deviations in cache-related metrics. The analysis revealed distinct behavioral patterns for different attack types: cryptojacking attacks consistently showed high CPU utilization and memory access patterns, DoS attacks exhibited abnormal network-related system calls and interrupt patterns, and reconnaissance activities demonstrated unique system call sequences and memory access behavior patterns. These findings contribute significantly to understanding EVCS security and provide valuable insights for developing robust security measures.

Future research should focus on several key areas to enhance the security and forensic capabilities of EVCS. Priority should be given to developing real-time analysis integration methods that can adapt the forensic analysis framework for immediate threat detection and implement streaming analytics capabilities. Moreover, enhanced feature engineering techniques should be explored to identify additional host-level metrics that can improve attack detection accuracy, as well as more sophisticated feature selection methods for different types of attacks. Advanced machine learning approaches should be investigated for more complex pattern recognition and novel attack detection, including deep learning models and unsupervised learning techniques. Furthermore, research efforts should address scalability challenges in large-scale EVCS deployments, develop platform-agnostic forensic analysis techniques, and create standardized protocols. These advancements will be crucial as electric vehicles become more prevalent and the need for robust security measures grows.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to express their sincere appreciation to the University of Jordan, University of Petra, Umm Al-Qura University, Yarmouk University, and Northern Border University for their institutional support throughout the development of this research. Special thanks are extended to the Canadian Institute for Cybersecurity (CIC) at the University of New Brunswick for providing access to the CICEVSE2024 dataset used in this study.

Funding Statement: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Salam Al-E’mari and Yousef Sanjalawe; methodology, Salam Al-E’mari and Ghader Kurdi; software, Budoor Allehyani and Ameera Jaradat; validation, Salam Al-E’mari, Budoor Allehyani and Sharif Makhadmeh; formal analysis, Ghader Kurdi and Duaa Hijazi; investigation, Yousef Sanjalawe and Ameera Jaradat; resources, Sharif Makhadmeh and Duaa Hijazi; data curation, Ameera Jaradat and Budoor Allehyani; writing—original draft preparation, Salam Al-E’mari, Ghader Kurdi and Duaa Hijazi; writing—review and editing, Yousef Sanjalawe and Sharif Makhadmeh; visualization, Budoor Allehyani and Ameera Jaradat; supervision, Salam Al-E’mari and Sharif Makhadmeh; project administration, Salam Al-E’mari and Yousef Sanjalawe; funding acquisition, Salam Al-E’mari. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in GitHub at https://github.com/salam-ammari/Forensic-Analysis-of-Cyberattacks-in-EVCS (accessed on 14 Jul 2025).

Ethics Approval: This study does not involve human participants, animals, or identifiable personal data. Therefore, ethical approval was not required. All experiments were conducted using publicly available datasets and simulated environments, in accordance with institutional guidelines.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

1https://www.unb.ca/cic/datasets/evse-dataset-2024.html (accessed on 14 Jul 2025).

2https://www.unb.ca/cic/datasets/cicev2023.html (accessed on 14 Jul 2025).

References

1. Acharya S, Dvorkin Y, Pandžić H, Karri R. Cybersecurity of smart electric vehicle charging: a power grid perspective. IEEE Access. 2020;8:214434–53. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3041074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Akbarian A, Bahrami M, Ahmadi M, Vakilian M, Lehtonen M. Detection of cyber attacks to mitigate their impacts on the manipulated EV charging prices. IEEE Trans Transp Electrif. 2024;10(4):8881–92. doi:10.1109/TTE.2024.3368920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Vailoces G, Keith A, Almehmadi A, El-Khatib K. Securing the electric vehicle charging infrastructure: an in-depth analysis of vulnerabilities and countermeasures. In: Proceedings of the International ACM Symposium on Design and Analysis of Intelligent Vehicular Networks and Applications; 2023 Oct 30–Nov 3; Montreal, QC, Canada. p. 31–8. doi:10.1145/3616392.3623424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Basnet M, Ali MH. Exploring cybersecurity issues in 5G enabled electric vehicle charging station with deep learning. IET Gener Transm Distrib. 2021;15(24):3435–49. doi:10.1049/gtd2.12275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. ElKashlan M, Aslan H, Said Elsayed M, Jurcut AD, Azer MA. Intrusion detection for electric vehicle charging systems (evcs). Algorithms. 2023;16(2):75. doi:10.3390/a16020075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Diana L, Dini P, Paolini D. Overview on intrusion detection systems for computers networking security. Computers. 2025;14(3):87. doi:10.3390/computers14030087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Basnet M, Poudyal S, Ali MH, Dasgupta D. Ransomware detection using deep learning in the SCADA system of electric vehicle charging station. In: 2021 IEEE PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Conference-Latin America (ISGT Latin America); 2021 Sep 15–17; Lima, Peru. p. 59289–317. [Google Scholar]

8. Purohit S, Govindarasu M. FL-EVCS: federated learning based anomaly detection for EV charging ecosystem. In: 2024 33rd International Conference on Computer Communications and Networks (ICCCN); 2024 Jul 29–31; Kailua-Kona, HI, USA. p. 1–9. doi:10.1109/ICCCN61486.2024.10637543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Vasan D, Alqahtani EJS, Hammoudeh M, Ahmed AF. An AutoML-based security defender for industrial control systems. Int J Crit Infrastruct Prot. 2024;47(3):100718. doi:10.1016/j.ijcip.2024.100718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Mitikiri SB, Srinivas VL, Pal M. Anomaly detection of adversarial cyber attacks on electric vehicle charging stations. e-Prime—Adv Electr Eng Electron Energy. Electron Energy. 2025;11(15):100911. doi:10.1016/j.prime.2025.100911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Chukwunweike JN, Agosa AA, Mba UJ, Okusi O, Safo NO, Onosetale O. Enhancing cybersecurity in onboard charging systems of electric vehicles: a MATLAB-based approach. World J Adv Res Rev. 2024;23(1):2661–81. doi:10.30574/wjarr.2024.23.1.2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Arsalan A, Timilsina L, Papari B, Muriithi G, Ozkan G, Kumar P, et al. Cyber attack detection and classification for integrated on-board electric vehicle chargers subject to stochastic charging coordination. Transp Res Procedia. 2023;70:44–51. doi:10.1016/j.trpro.2023.10.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Kondu SCV. Machine learning and deep learning-based anomaly detection for electric vehicle charging infrastructure and industrial internet of things [master’s thesis]. Ames, IA, USA: Iowa State University; 2024. [Google Scholar]

14. Metere R, Neaimeh M, Morisset C, Maple C, Bellekens X, Czekster RM. Securing the electric vehicle charging infrastructure. arXiv:2105.02905. 2021. doi:10.48550/arxiv.2105.02905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Girdhar M, Hong J, You Y, Tj Song, Govindarasu M. Cyber-attack event analysis for EV charging stations. In: 2023 IEEE Power & Energy Society General Meeting (PESGM); 2023 Jul 16–20; Orlando, FL, USA. p. 1–5. doi:10.1109/PESGM52003.2023.10252504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Mohamed N, Al-Jaroodi J, Jawhar I. Cyber-physical systems forensics. In: 2020 IEEE Systems Security Symposium (SSS); 2020 Jul 1–Aug 1; Crystal City, VA, USA. p. 1–7. doi:10.1109/SSS47320.2020.9174199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]