Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

A Systematic Review of YOLO-Based Object Detection in Medical Imaging: Advances, Challenges, and Future Directions

School of Communication and Electronic Engineering, Jishou University, Jishou, 416000, China

* Corresponding Author: Kaiqing Zhou. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(2), 2255-2303. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.067994

Received 18 May 2025; Accepted 01 August 2025; Issue published 23 September 2025

Abstract

The YOLO (You Only Look Once) series, a leading single-stage object detection framework, has gained significant prominence in medical-image analysis due to its real-time efficiency and robust performance. Recent iterations of YOLO have further enhanced its accuracy and reliability in critical clinical tasks such as tumor detection, lesion segmentation, and microscopic image analysis, thereby accelerating the development of clinical decision support systems. This paper systematically reviews advances in YOLO-based medical object detection from 2018 to 2024. It compares YOLO’s performance with other models (e.g., Faster R-CNN, RetinaNet) in medical contexts, summarizes standard evaluation metrics (e.g., mean Average Precision (mAP), sensitivity), and analyzes hardware deployment strategies using public datasets such as LUNA16, BraTS, and CheXpert. The review highlights the impressive performance of YOLO models, particularly from YOLOv5 to YOLOv8, in achieving high precision (up to 99.17%), sensitivity (up to 97.5%), and mAP exceeding 95% in tasks such as lung nodule, breast cancer, and polyp detection. These results demonstrate the significant potential of YOLO models for early disease detection and real-time clinical applications, indicating their ability to enhance clinical workflows. However, the study also identifies key challenges, including high small-object miss rates, limited generalization in low-contrast images, scarcity of annotated data, and model interpretability issues. Finally, the potential future research directions are also proposed to address these challenges and further advance the application of YOLO models in healthcare.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileIn the healthcare domain, Clinical Decision Support Systems (CDSSs) play a crucial role in enabling automated disease diagnosis in the knowledge-driven era [1,2]. These systems rely on two fundamental processes: (1) extracting fuzzy production rules from clinical expert knowledge [3,4], and (2) executing diagnostic reasoning through computational models such as fuzzy Petri nets [5,6], knowledge-based systems [7,8], and semantic networks [9,10]. However, traditional knowledge-driven CDSSs exhibit a critical limitation: while they effectively utilize structured clinical data, they largely ignore unstructured data, particularly medical imaging and video. With the explosive growth of medical imaging data, traditional CDSSs face challenges in efficiency and accuracy. Various dual knowledge-data-driven approaches have been widely applied to enhance the performance and diagnostic accuracy of current CDSS. Among these approaches, deep-learning-based object detection technology has emerged as a key tool for improving medical image processing, especially in rapidly identifying lesion areas and critical anatomical structures, demonstrating significant potential [11,12]. Object detection technology in medical image analysis is a critical step in information extraction. It enables systems to automatically identify and accurately locate lesion areas or critical anatomical structures, thereby enhancing diagnostic efficiency and accuracy [13,14]. However, traditional object detection methods, which rely on manual annotation and segmentation, are labor-intensive, time-consuming, costly, and highly dependent on expert input. These methods are prone to missed detections when analyzing small lesions or regions with unclear boundaries, significantly limiting the applicability of CDSS in real-world clinical settings [15–18]. Although two-stage detectors such as Faster R-CNN achieve high accuracy, they suffer from low speed and high computational cost, making them less suitable for time-critical and resource-limited scenarios.

To address these challenges, deep-learning-based object detection methods have gained prominence in recent years, particularly the YOLO algorithm [19,20], which has attracted widespread attention in medical imaging due to its efficiency and compact architecture [21]. YOLO employs an end-to-end convolutional neural network (CNN) [22], predicting object categories and bounding boxes in a single forward pass. This approach reduces on manual annotations while maintaining real-time performance [23]. This single-stage detection process not only facilitates end-to-end learning but also ensures stable operation in medium-to-low configuration GPU environments, enhancing its practicality in resource-constrained scenarios such as clinical emergencies, telemedicine, and portable medical devices [24].

Leveraging these advantages, YOLO has been widely applied to critical medical tasks, including emergency condition identification [25], minimally invasive surgery navigation [26], automated pathology slide analysis [27,28], and precision radiotherapy planning [29]. It not only improves the efficiency and reliability of clinical decision-making but also offers robust technical support for early disease screening and accurate diagnosis [30]. Despite YOLO’s advancements in medical image analysis, challenges persist in complex lesion recognition [31], cross-modal image adaptation [32,33], model generalization [34], and managing diverse datasets [35]. Furthermore, emerging technologies such as 5G communication and blockchain (BC) are expected to further enhance real-time medical image analysis and data security in YOLO-based systems [36–39].

Building on its early success, YOLO has become a leading object detection algorithm in medical imaging, effectively detecting tumors, lesions, and anatomical structures across modalities like Computed Tomography (CT), Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), ultrasound, and endoscopy. Its fast inference and lightweight design make it ideal for real-time clinical decision-making. From YOLOv1 to YOLOv10, it has introduced key improvements like feature pyramid networks, novel loss functions, and innovations such as BiFPN and NMS-free decoding, optimizing performance for complex medical tasks.

Despite the growing body of research on YOLO’s medical applications, systematic reviews remain limited. Notably, previous reviews by Ragab et al. (2024) [40] and Soni and Rai (2024) [41] fail to include the most recent YOLO versions (YOLOv8–YOLOv10) and are restricted by narrow data sources. For example, Soni et al. reviewed only 80 articles from PubMed, potentially missing valuable contributions from other platforms. In contrast, this review systematically retrieved 1221 records from Scopus and Web of Science, ultimately including 60 high-quality, peer-reviewed studies. It also categorizes applications from a clinical perspective, offering insights into practical scenarios, and integrates performance metrics such as precision, recall, and mAP across various tasks, providing a comprehensive quantitative analysis of YOLO’s capabilities in medical image detection.

This paper provides a systematic review of YOLO’s applications in medical image detection, comprehensively analyzing existing research, examining its strengths and limitations, and exploring future directions. By systematically summarizing these aspects, this study aims to bridge the gap between algorithm development and clinical practice, accelerating the adoption of intelligent healthcare and contributing to a more efficient, accurate, and intelligent medical service system.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 outlines research methodologies and data collection strategies. Section 3 reviews the YOLO series’ evolution, emphasizing technological advancements in each version. Section 4 examines YOLO’s key applications in medical image processing. Section 5 discusses the findings, challenges, and limitations of YOLO-based medical image detection, offering insights into the current state of the field. And, Section 6 concludes with a summary and future research prospects.

2 Research Methodology and Data Collection Strategy

Although deep-learning-based object detection methods, particularly the YOLO series, have demonstrated impressive performance across diverse computer vision applications, their systematic adaptation, evaluation, and deployment in medical imaging remain understudied [42,43]. YOLO’s advantages—computational efficiency, real-time performance, and seamless integration—make it a promising candidate for medical object detection. Its key strengths include rapid processing speeds, simultaneous object detection and classification capabilities, and low hardware requirements. However, generalizing YOLO to diverse medical datasets with inherent complexities remains challenging [44]. Adaptability to heterogeneous datasets—spanning variations in disease types, imaging modalities, and data quality—is critical for ensuring clinical efficacy. Furthermore, scalability across devices and real-time deployment in resource-constrained environments demand further investigation [45].

This review aims to bridge the gap by investigating the potential and technological evolution of YOLO in medical image processing. Particularly, its to explore how YOLO’s strengths—such as its efficiency and accuracy—are leveraged in clinical environments and how these strengths can be further enhanced to meet the rigorous demands of medical imaging. To address these challenges, a framework is designed to systematically review the literature, classify the existing applications, and identify the improvements in YOLO’s generalization capabilities. By adhering to systematic literature review standards, this study ensures a rigorous evaluation process, drawing reliable conclusions on YOLO’s potential in medical contexts.

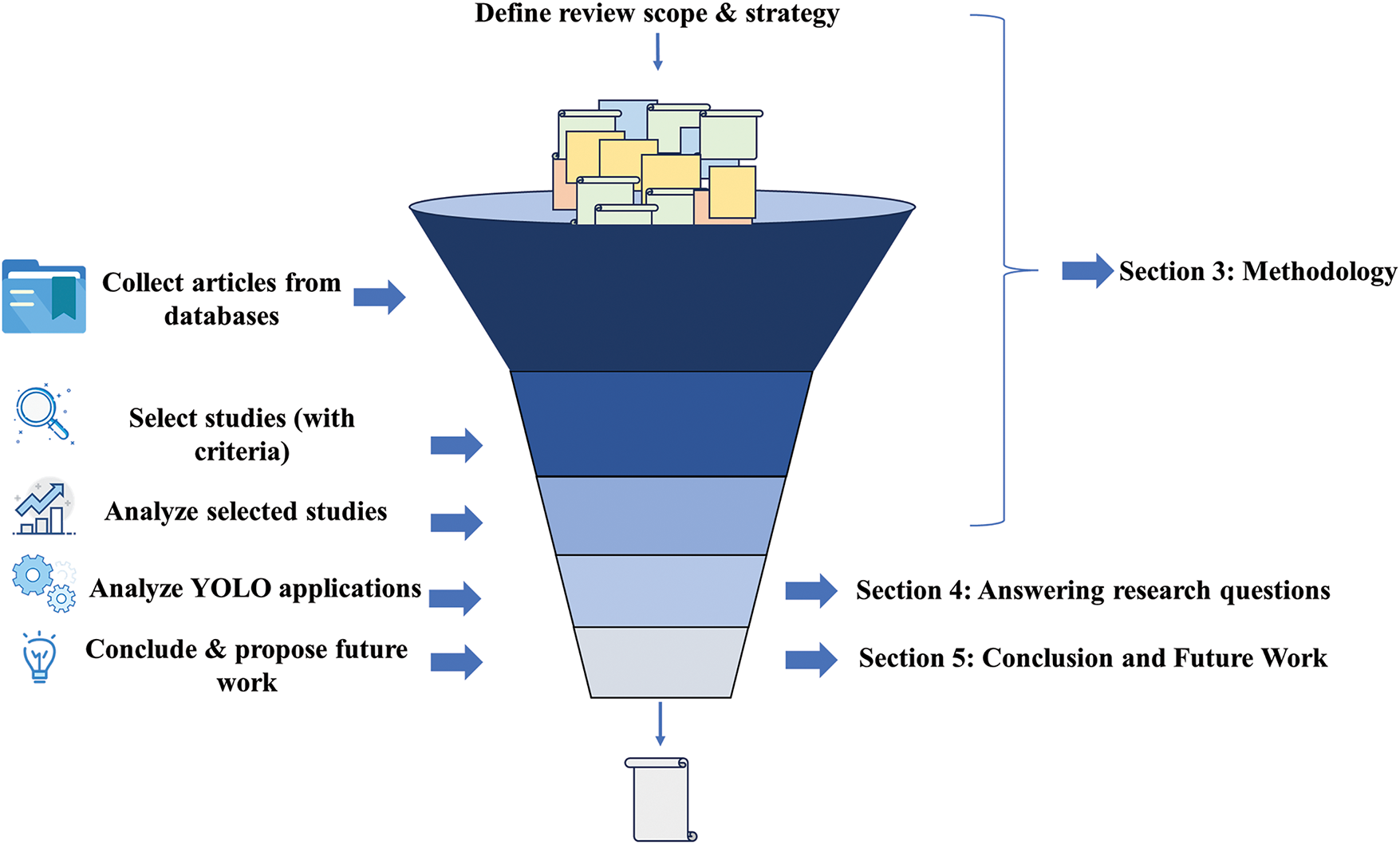

This review bridges this gap by examining YOLO’s technological evolution and untapped potential in medical image processing. Specifically, it explores how YOLO’s efficiency and accuracy can be optimized in clinical workflows and enhanced to meet medical imaging’s rigorous demands. To address these challenges, a framework is proposed to systematically review literature, classify applications, and evaluate improvements in YOLO’s generalization. Following established systematic review methodologies, this study ensures rigorous evaluation, yielding reliable insights into YOLO’s medical applicability. Beyond analyzing current advancements, future research directions are outlined, focusing on enhancing YOLO’s generalization capabilities, adaptability to multimodal datasets, and robustness in clinical practice. These advancements could position YOLO as a transformative tool in medical image analysis, enabling efficient, precise, and adaptable solutions for real-time diagnostics. The framework is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Systematic literature review process

The primary objective of this review is to systematically analyze the application, technological evolution, and challenges of the YOLO algorithm in medical object detection. To achieve this, the study formulates key research questions (RQs) to explore YOLO’s adaptability, performance, and comparative advantages in diverse medical scenarios. These RQs establish a structured framework for evaluating YOLO’s clinical value in diagnosis, medical image analysis, and intelligent healthcare systems.

RQ 1: Why are YOLO-based deep learning methods critical for medical object detection?

Traditional object detection methods struggle with inefficiency, high false-positive rates, and poor small-object detection in the context of rapidly expanding medical imaging data. As a single-stage detector, YOLO combines end-to-end learning with real-time performance, enabling fast, accurate detection while minimizing reliance on manual annotations. RQ 1 investigates YOLO’s necessity in medical imaging by focusing on its role in enhancing efficiency, reducing annotation dependency, and supporting real-time clinical decisions. This question is addressed in detail in Section 1, highlighting how YOLO overcomes traditional limitations and elevates system performance.

RQ 2: What are YOLO’s core technological advantages in medical image processing?

From YOLOv1 to YOLOv10, the algorithm has evolved through advancements in feature extraction (e.g., Feature Pyramid Network (FPN), Path Aggregation Network (PAN)), localization precision, and architectural innovations (e.g., Transformer module, attention mechanism). RQ 2 evaluates how YOLO achieves high sensitivity for small objects and computational efficiency in medical detection tasks. The analysis focuses on two pillars: algorithmic architecture (e.g., anchor-free designs, multi-scale prediction) and feature learning capabilities. This RQ underscores YOLO’s superiority over traditional methods in handling complex medical images, detecting subtle lesions, and improving diagnostic accuracy.

RQ 3: How generalizable and adaptable is YOLO across heterogeneous medical imaging scenarios?

Medical imaging encompasses diverse diseases (e.g., lung cancer, breast cancer), modalities (X-ray, MRI, CT), and target features, posing unique challenges for object detection. While YOLO excels in many tasks, it faces limitations in small lesion detection, complex background handling, and cross-modal generalization. RQ 3 assesses YOLO’s adaptability by analyzing performance variations in tasks like brain disorder and spinal disease detection. It also evaluates structural modifications (e.g., hybrid architectures, auxiliary modules) to enhance cross-modal robustness, providing insights into strategies for optimizing YOLO in heterogeneous clinical environments.

RQ 4: What challenges and future directions exist for YOLO in medical object detection?

Building on RQs 1–3, RQ 4 identifies YOLO’s key limitations: limited small-object accuracy, generalization gaps, cross-modal adaptation barriers, and interpretability constraints. It further explores future research avenues, including multimodal fusion, lightweight network design, domain-specific data augmentation, and interpretability frameworks. By addressing these challenges, YOLO could evolve into a transformative tool for real-time diagnostics, fostering its integration into intelligent healthcare systems. This RQ synthesizes critical gaps and prioritizes actionable directions to advance YOLO’s clinical impact.

This systematic literature review followed the PRISMA 2020 guidelines and was conducted according to a predefined research protocol to ensure transparency, reproducibility, and scientific rigor. The research protocol specified the search databases, keyword strategy, inclusion and exclusion criteria, quality assessment criteria, and screening procedures.

This paper selected two authoritative academic databases, Scopus and Web of Science, due to their comprehensive disciplinary coverage, high-quality peer-reviewed publications, and advanced search functionalities. Both databases enable reproducible searches with Boolean logic.

To maximize comprehensiveness and precision, this paper used the following Boolean search query:

(“YOLO” OR “You Only Look Once”) AND (“medical application” OR “medical imaging”)

The keywords were iteratively refined through pilot searches to ensure they captured key studies in this field. Wildcard operators were applied where appropriate to include term variations. During the screening process, several inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied to ensure the relevance and quality of the literature:

Inclusion criteria:

(1) Peer-reviewed journal articles published between 2018 and 2024.

(2) Studies involving human subjects or human-related medical datasets.

(3) Research focusing on the application of YOLO in the medical field.

(4) English-language publications.

Exclusion criteria:

(1) Conference papers, reviews, letters, or editorial materials.

(2) Non-English publications.

(3) Duplicate entries.

(4) YOLO applications outside of the medical domain.

(5) Papers from journals ranked below Q3 in Journal Citation Reports (JCR) unless they had ≥30 citations within 2 years.

Each included study was assessed based on:

(1) Journal ranking (SCI/EI, preferably Q1 or Q2).

(2) Scientific impact (citation counts; minimum 10 citations, except for recent high-quality studies).

(3) Methodological soundness, including detailed dataset descriptions and valid evaluation metrics.

(4) Relevance to YOLO-based medical imaging or clinical applications.

Only studies meeting at least three of these four quality indicators were included in the final review.

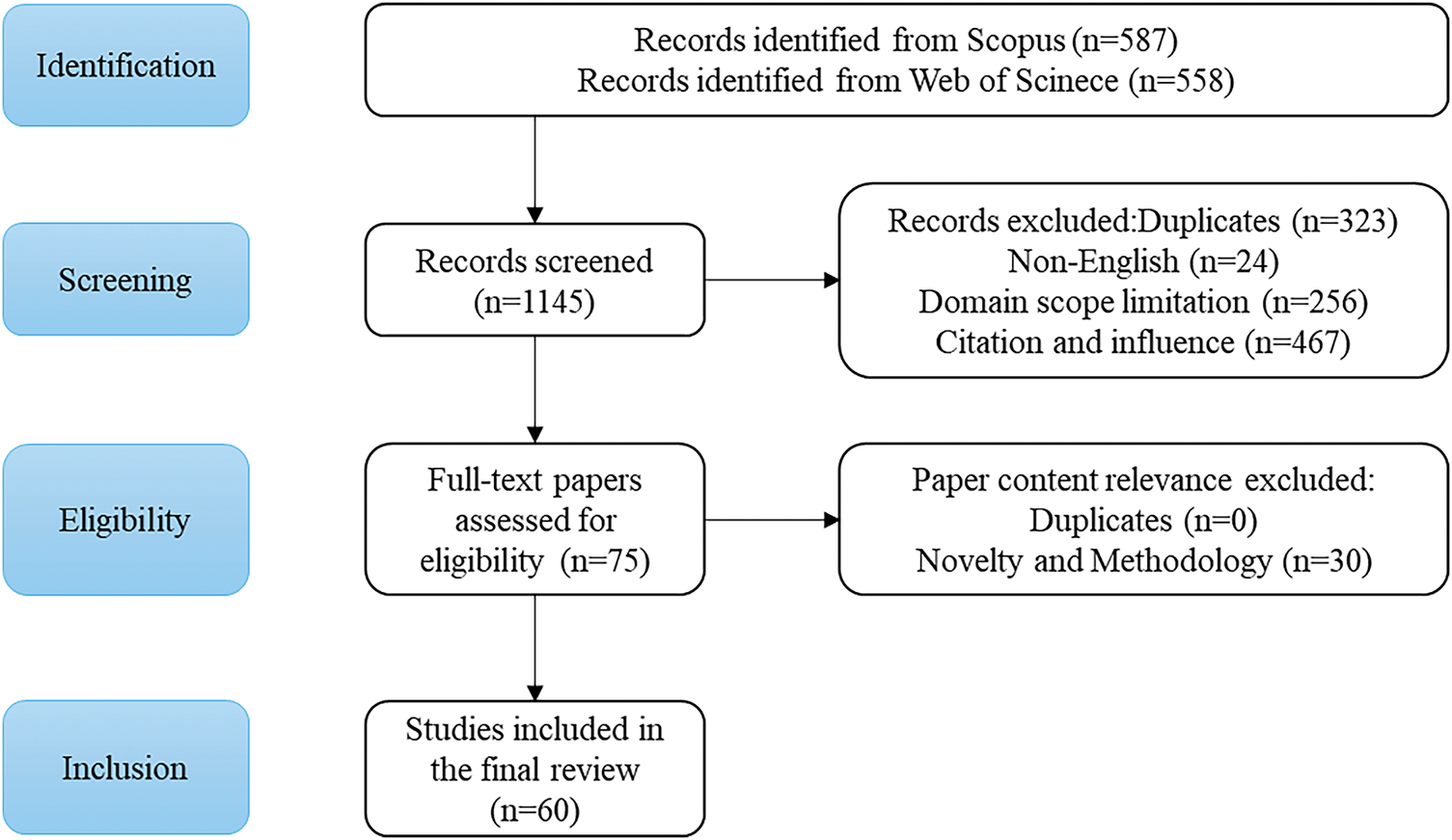

The initial search retrieved 1145 articles (587 from Scopus and 558 from Web of Science). After removing duplicates (323 records) and applying the language filter, 910 records remained. Title and abstract screening excluded irrelevant articles, narrowing the pool to 75 articles for full-text review. After applying inclusion/exclusion criteria and quality assessment, 60 high-quality studies were selected for final inclusion.

The initial literature search identified a total of 1145 records, including 587 from the Scopus database and 558 from the Web of Science database. The search covered publications from 2018 to 2024 using the following query: (“YOLO” or “You Only Look Once”) AND (“medical application” or “medical imaging” or related terms). After removing 323 duplicate records, 822 unique articles remained for screening. During the screening stage, this paper excluded 24 non-English publications, 256 studies unrelated to medical applications of YOLO (i.e., irrelevant domains), and 467 papers with low citation impact or published in low-ranking journals. This resulted in 75 eligible articles for full-text assessment.

Subsequently, full-text evaluation was performed according to the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria and quality assessment standards. In this step, 30 studies were excluded due to a lack of methodological rigor, insufficient innovation, or limited clinical relevance. No additional duplicates were identified at this stage. Ultimately, 60 high-quality studies were included in the final systematic review. The entire selection process adhered strictly to PRISMA 2020 guidelines, ensuring transparency and reproducibility. The detailed workflow of study identification, screening, eligibility assessment, and inclusion is presented in Fig. 2 below.

Figure 2: Flowchart of the screening process

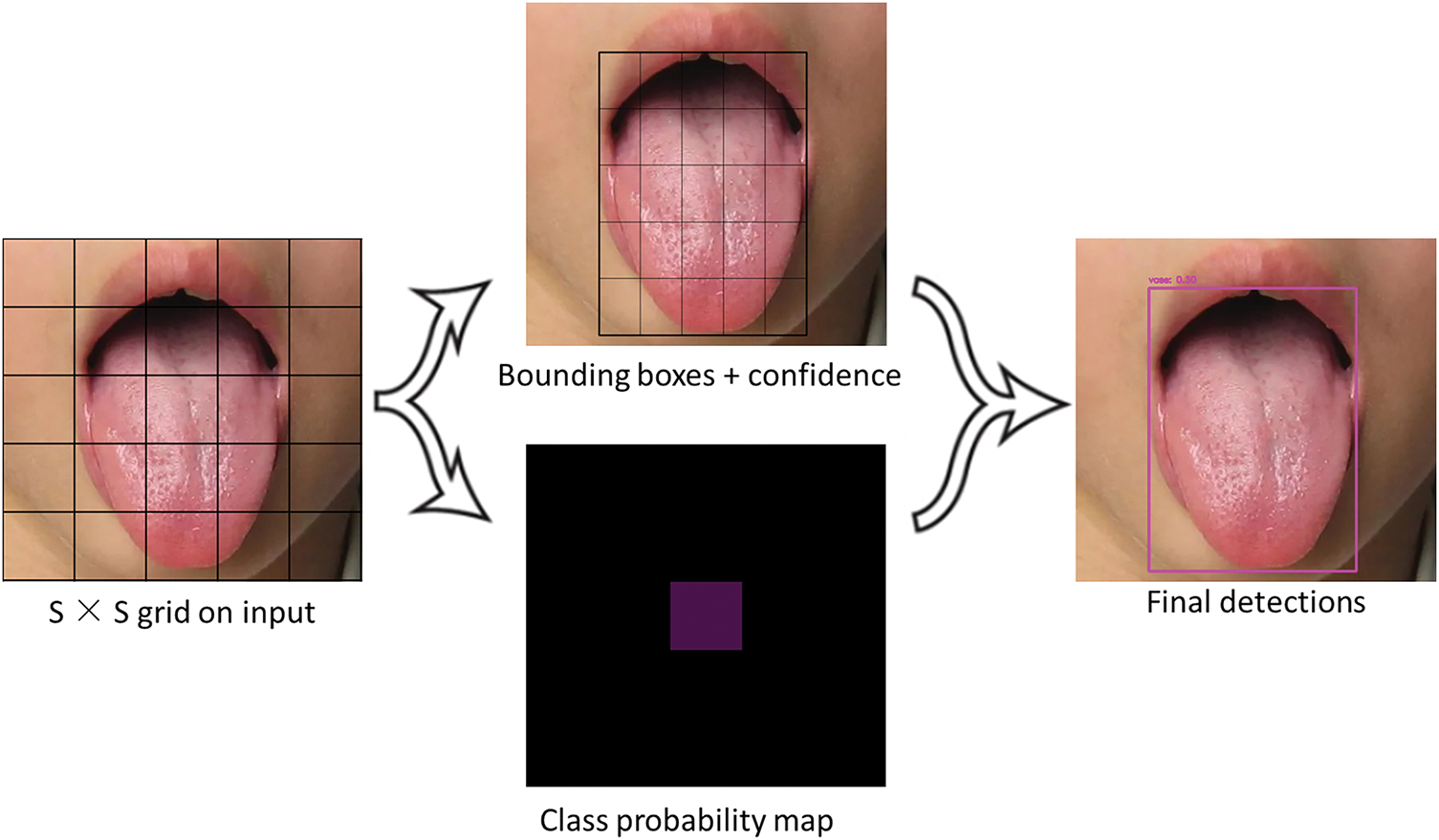

YOLO is a single-stage object detection algorithm based on the regression approach, which transforms the detection problem into a deep learning-based regression problem. It uses a single neural network to directly predict the object’s bounding box and its class confidence. YOLOv1 laid the foundation for the YOLO series of algorithms, and subsequent versions have continuously optimized it to improve detection accuracy and model performance.

The basic concept of YOLO is to divide the input image into a grid of size S × S and detect the objects whose centers fall within each grid cell [46]. Each grid cell predicts multiple bounding boxes and outputs their corresponding class probabilities. Specifically, each grid cell predicts a bounding box B for each object, and each bounding box includes several parameters:

In this case, S × S represents the number of grid cells, B is the number of bounding boxes predicted by each grid cell, and C is the number of class categories for detection. Each grid cell predicts multiple bounding boxes, and in the inference stage, non-maximum suppression (NMS) is used to select the best bounding box to solve the problem of multiple detections of the same object. The idea of NMS is: if a certain grid cell confirms the existence of an object, it calculates the IoU of its predicted bounding box with other bounding boxes. If the IoU is greater than a set threshold (i.e., the overlap is high), the other bounding boxes are discarded, and only the bounding box with the highest confidence is kept. This process continues until all predicted bounding boxes are processed [47–49].

The YOLO algorithm achieves efficient object detection by dividing images into regular grids. Within this framework, each grid cell is responsible for predicting

Figure 3: YOLO algorithm image segmentation

While subsequent versions of the YOLO series (such as YOLOv3–YOLOv8) have made significant improvements in grid granularity, anchor box design, and feature extraction networks, they have retained this core detection paradigm, enabling the algorithm to achieve an optimized balance between computational efficiency and detection accuracy, making it particularly suitable for real-time visual application scenarios.

3.2 YOLO Basic Network Architecture

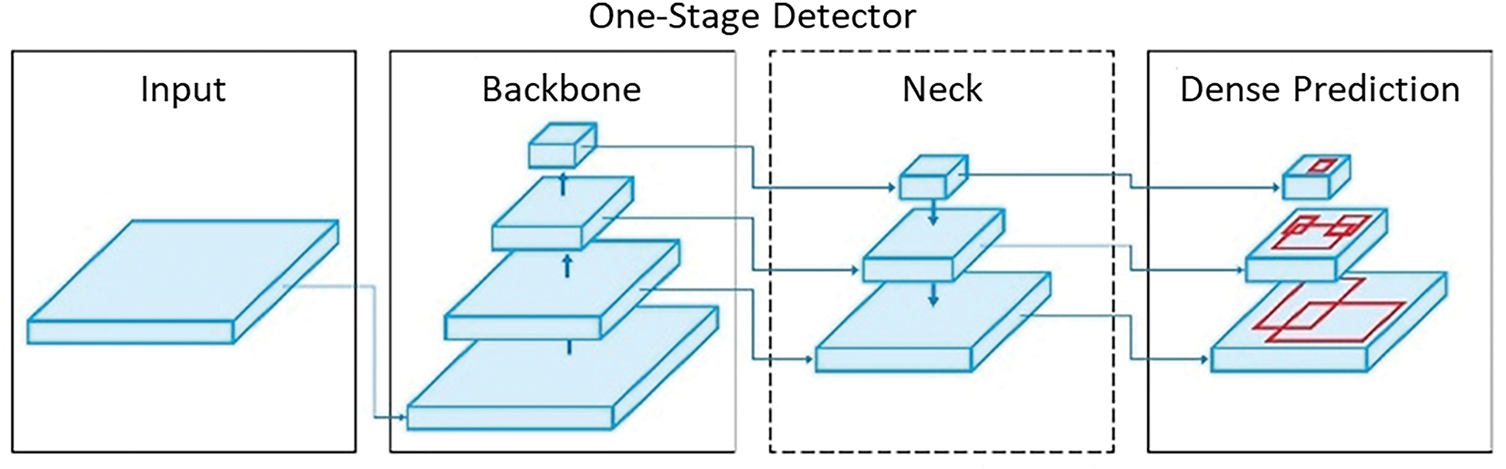

The network structure of the YOLO series object detection algorithms typically consists of four key modules: Input, Backbone, Neck, and Head [50–52], which was depicted in Fig. 4. Each module plays a crucial role in the object detection task and has evolved with optimizations in different versions [53–55].

Figure 4: Simplified YOLO architecture diagram

The input module is responsible for image preprocessing, including normalization, resizing, and data augmentation. Different versions of the YOLO algorithm support different input image resolutions. For example, YOLOv2 uses an input size of 416 × 416, while YOLOv5 supports 608 × 608 as the input size. During this stage, images are typically color-normalized (e.g., normalized to [0, 1] or standardized to have a mean of 0 and a variance of 1) and resized to a fixed size to fit the network architecture. Additionally, data augmentation techniques such as flipping, scaling, and color jittering can be applied to improve the model’s generalization ability.

The backbone network is responsible for extracting image features and is the core part of the entire YOLO architecture. Early versions of YOLO (such as YOLOv1 and YOLOv2 [56]) used lightweight custom convolutional networks, while from YOLOv3 onwards, deeper feature extraction networks were introduced, such as DarkNet-53 (YOLOv3) [57], CSPDarkNet (YOLOv4, YOLOv5) [58], and structures like P5 and P6 (YOLOv6, YOLOv7) [59,60]. Modern YOLO models’ backbone networks, including YOLOv8, YOLOv9 [61], YOLOv10 [62], etc., typically combine techniques like residual connections (ResNet) [63], Cross-Stage Partial Networks (CSPNet) [64], and other technologies to enhance computational efficiency and feature representation capabilities.

The neck network’s role is to further fuse and enhance the features extracted by the backbone network to improve object detection performance. Common neck structures include FPN [65] and PAN [66]. FPN utilizes multi-scale features to enhance the detection capability of small objects, while PAN improves global feature representation by using a bottom-up information propagation method. Additionally, YOLOv4 and later versions introduce optimization strategies such as SPP (Spatial Pyramid Pooling) [67] and BoF (Bag of Freebies) [68] to improve detection accuracy and speed.

The head network is responsible for the final object classification and bounding box regression. YOLO uses a single regression prediction method, directly outputting the class probabilities and bounding box parameters for each grid cell. Different versions of YOLO have optimized the head structure, such as YOLOv3, which adopts multi-scale detection [69], YOLOv4, which introduces a self-attention mechanism [70], and YOLOv5 and later versions, which further optimize loss functions (such as IoU loss) [71] and prediction box assignment strategies (such as Anchor-Free) [72]. Additionally, to improve flexibility, YOLO’s head can be interchangeable with other layers of the same input shape, allowing it to be adapted for different tasks, such as instance segmentation, pose estimation, etc. [73].

3.2.5 Interaction Mechanism between Modules

In the YOLO series algorithms, the interaction between modules goes beyond simple sequential data flow; it achieves deep collaboration through feature transmission and enhancement. The Backbone module encodes the input image into multi-scale feature maps, capturing both spatial details and semantic information at various levels. These feature maps are then passed to the Neck module, which performs multi-level feature aggregation. By leveraging top-down and bottom-up pathways (such as FPN or PAN structures), the Neck strengthens feature representation through cross-scale interaction and integration. This process enhances the model’s ability to detect both small and large objects, providing richer and more discriminative features for the Head module. The Head utilizes these aggregated features to perform joint predictions of object categories and bounding box coordinates. This end-to-end feature interaction mechanism overcomes the limitations of traditional “single-direction, weak-interaction” module designs, enabling YOLO algorithms to balance high inference speed with strong detection accuracy, thereby achieving real-time and robust object detection performance.

Over time, the network structure of the YOLO series algorithms has evolved through multiple versions, resulting in an efficient input preprocessing module, a powerful backbone feature extractor, an advanced feature fusion neck design, and an accurate object detection head. This architecture, through integrated optimization, has achieved a good balance between speed and accuracy, making YOLO widely applicable across various fields.

3.3 Evolution and Technological Innovations of the YOLO Series

The YOLO series is a deep learning-based object detection algorithm proposed by Redmon et al. in 2016 [74]. YOLO was introduced to address the bottlenecks of traditional object detection methods in terms of real-time performance, efficiency, and accuracy, particularly in the widespread applications within computer vision and image processing [75–77]. It represents an innovative breakthrough in deep learning-based object detection technology, achieving significant improvements in both speed and accuracy by transforming the object detection problem into a regression task [78–80].

One of the key innovations of YOLO compared to traditional methods is that it simplifies the object detection process into a single regression problem, rather than decomposing it into multiple steps such as region generation, classification, and regression as in classical methods [81]. Specifically, the YOLO algorithm divides the input image into a grid of fixed size, with each grid cell responsible for predicting the location and category of objects within that region. This approach enables YOLO to significantly improve detection speed while maintaining high detection accuracy, making it especially suitable for real-time scenarios such as autonomous driving [82,83] and security surveillance [84–86].

Another important feature of YOLO is its end-to-end training mechanism. Traditional object detection methods require training multiple network modules in separate steps, while YOLO integrates the entire detection process into a single unified convolutional neural network [87–89]. This end-to-end training approach not only improves the efficiency of both training and inference but also enables joint optimization of the entire image [90], avoiding the performance loss that may occur due to local optimization [91].

It is worth noting that YOLO’s object detection not only involves classifying and locating objects within an image but also outputs multiple bounding boxes along with their corresponding confidence scores, enabling multi-object detection and scene interpretation [92,93]. This allows YOLO to maintain high accuracy even in complex backgrounds, particularly in scenes where multiple objects are intertwined [94]. Fig. 1 illustrates the evolution of YOLO.

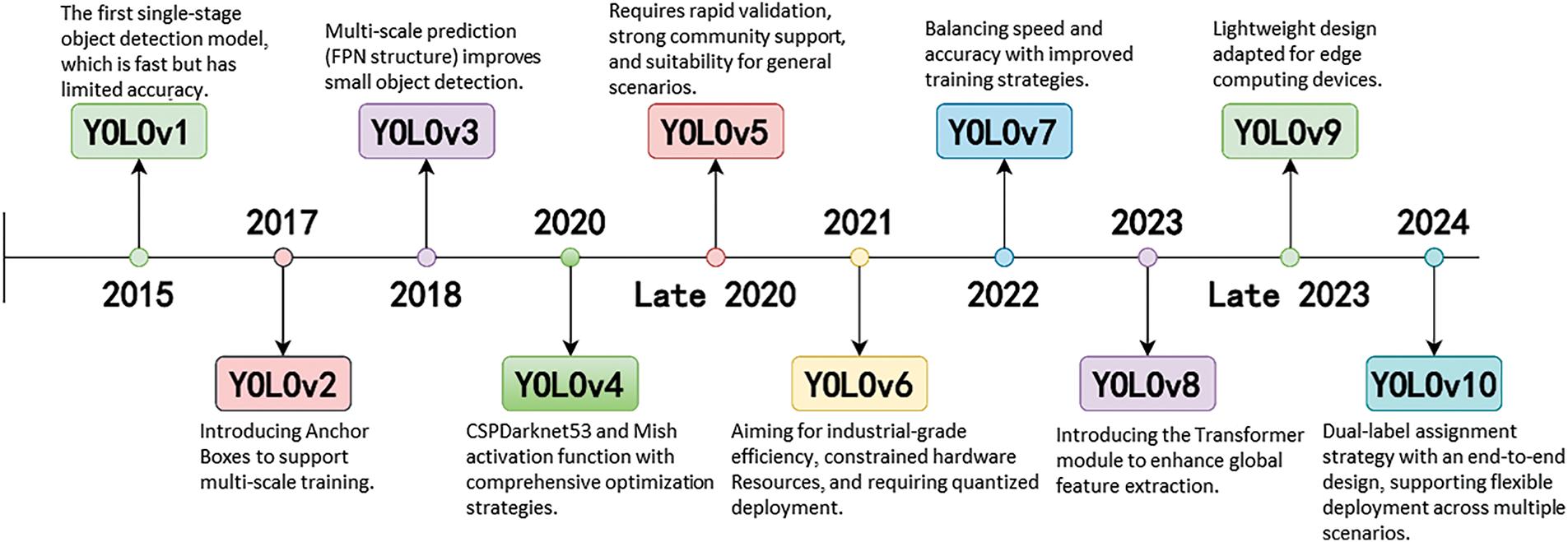

YOLO has undergone multiple iterations since its inception, evolving from YOLOv1 to the latest YOLOv10, with each version introducing innovative technologies that have significantly advanced the field of real-time object detection. Nevertheless, despite continuous improvements, each generation also exhibits inherent limitations that drive the need for further innovations. The development of YOLO algorithms is demonstrated in Fig. 5.

Figure 5: Evolution of YOLO algorithms throughout the years

The briefly summary of each YOLO algorithm is listed below one-by-one.

YOLO has undergone multiple iterations since its inception, evolving from YOLOv1 to the latest YOLOv10, with each version introducing innovative technologies that have significantly advanced the field of real-time object detection. Nevertheless, despite continuous improvements, each generation also exhibits inherent limitations that drive the need for further innovations.

YOLOv1, introduced in 2015, revolutionized object detection by framing it as a single regression problem, dramatically enhancing detection speed and inaugurating a new era of real-time detection. However, it suffered from low localization accuracy and poor performance in detecting small objects, particularly in complex backgrounds.

YOLOv2 (2017) addressed some of these issues by introducing larger input resolutions, anchor boxes, and new loss functions, which improved detection accuracy and speed. Yet, its adaptability to highly variable and cluttered scenes remained limited.

YOLOv3 (2018) incorporated the deeper Darknet-53 backbone, achieving higher accuracy in complex environments through multi-scale feature extraction. Nonetheless, the increased network depth led to heavier computational costs and slower inference speeds, posing challenges for real-time deployment on resource-constrained devices.

YOLOv4 (2019) further enhanced robustness against multi-scale and multi-directional targets by leveraging mosaic data augmentation and other optimization strategies. Despite these advances, the model complexity and reliance on hardware resources substantially increased, restricting its accessibility for broader applications.

YOLOv5 (2020), the first version implemented in PyTorch, introduced the CSPDarknet backbone to improve training efficiency and performance. Although widely adopted, YOLOv5 was often criticized for prioritizing engineering optimizations over fundamental architectural innovations.

YOLOv6 (2021) introduced industrial-level enhancements, including the RepVGG backbone and the use of the GIoU loss function, improving detection precision. However, its generalization ability, particularly in medical imaging contexts with varied object scales and textures, remained an area requiring further attention.

YOLOv7 (2022) pioneered the Panoptic YOLO framework, enabling simultaneous object detection and semantic segmentation. While this expanded YOLO’s application scope, it also substantially increased model complexity and computational overhead, challenging real-time applicability.

YOLOv8 (2023) presented notable advancements such as the BiFPN network and CIoU-based loss functions, further boosting feature aggregation and cross-GPU training capabilities. Nevertheless, the model’s dependency on high-end computational hardware became a critical constraint.

YOLOv9 integrated the Programable Gradient Infomation (PGI) and universal GELAN architectures to mitigate information loss issues in deep neural networks, leading to superior detection performance. Yet, the increased architecture complexity and elevated training costs posed significant challenges for practical adoption, especially in the medical domain where data and computational resources may be limited.

Finally, YOLOv10, developed by Tsinghua University in 2025, introduces an NMS-free architecture to enhance real-time detection and reduce computational overhead. While it achieves excellent performance, its generalization to specialized tasks like medical imaging requires further validation.

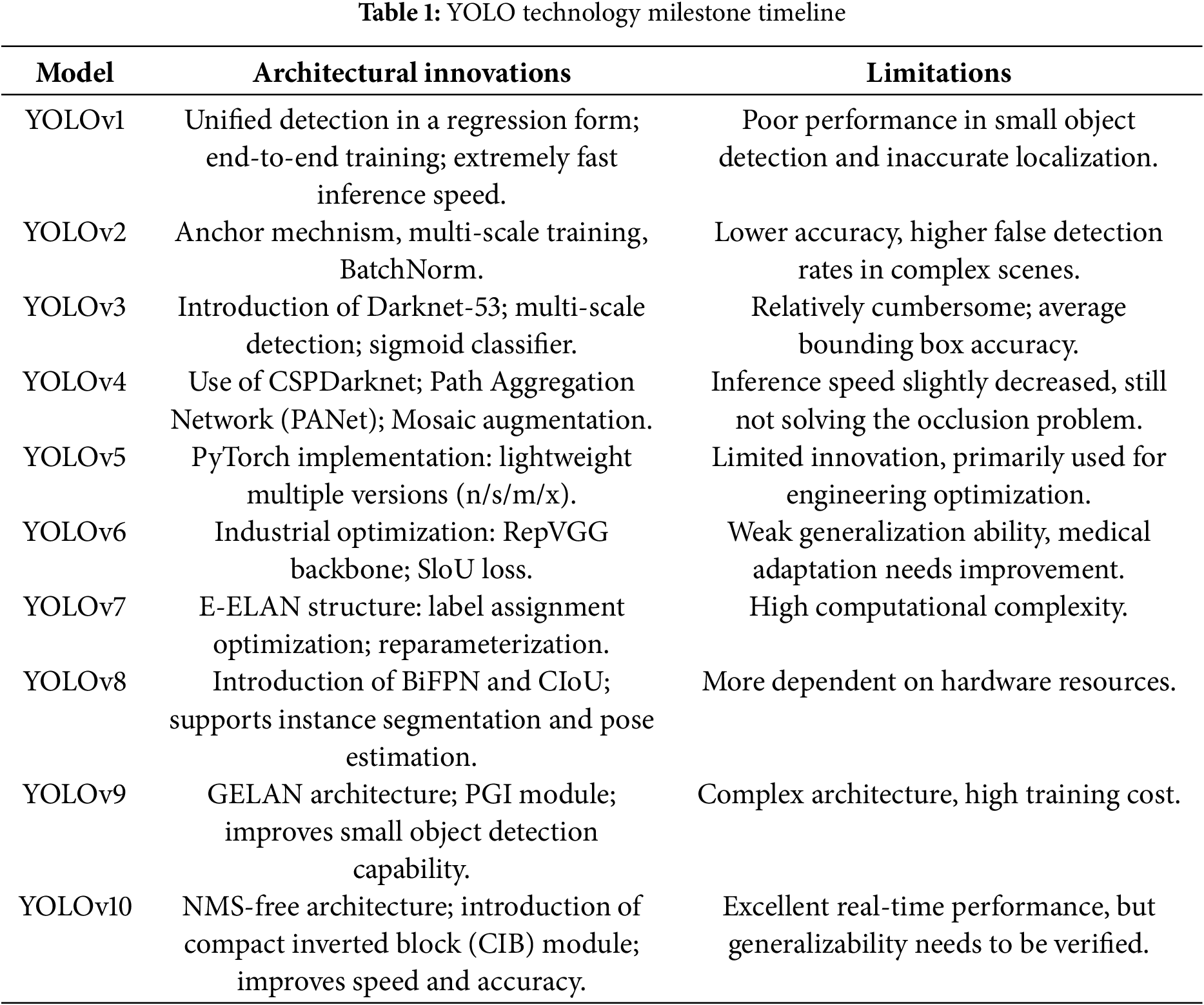

Table 1 outlines the key innovations and limitations of each YOLO model, highlighting the development from the original to the current versions.

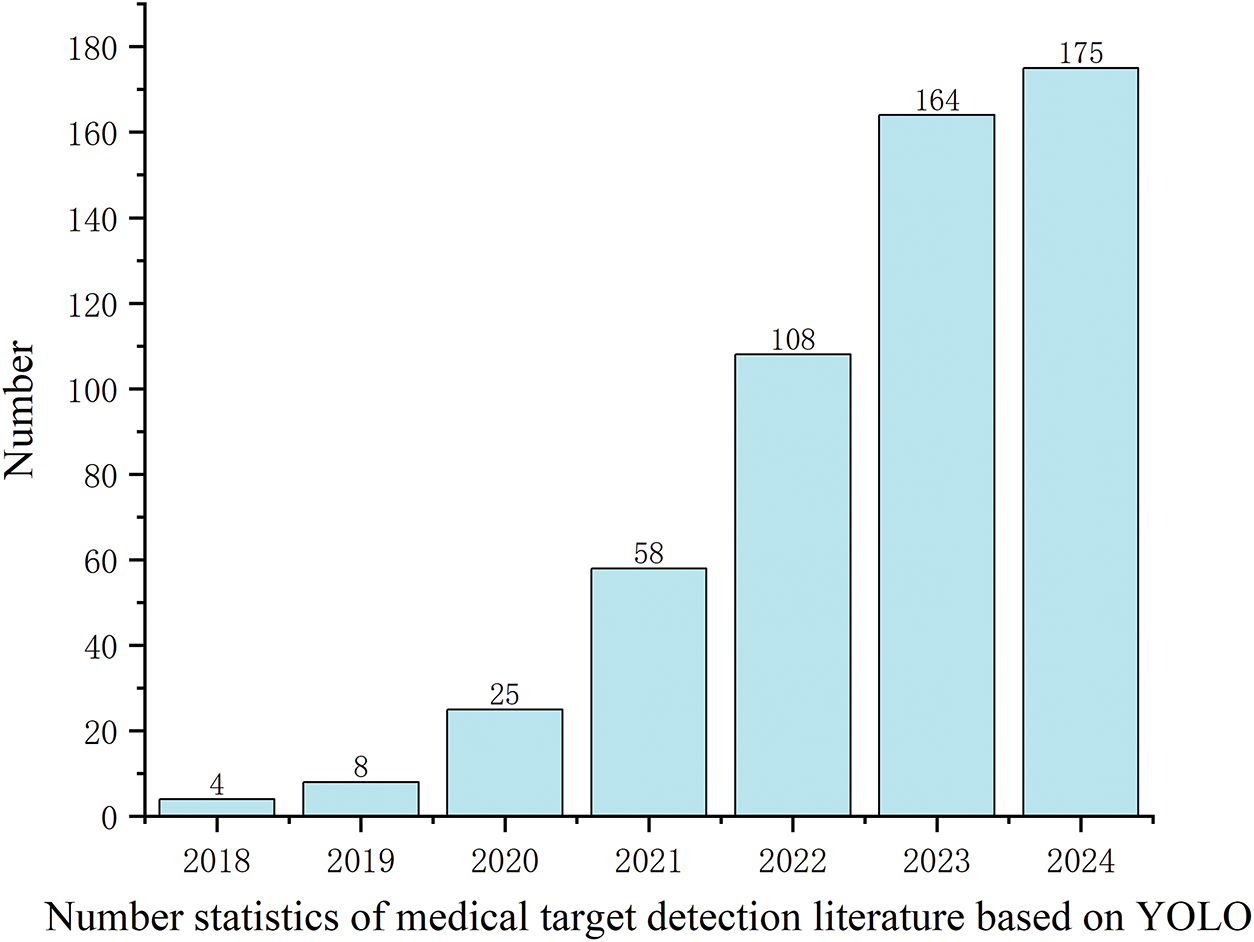

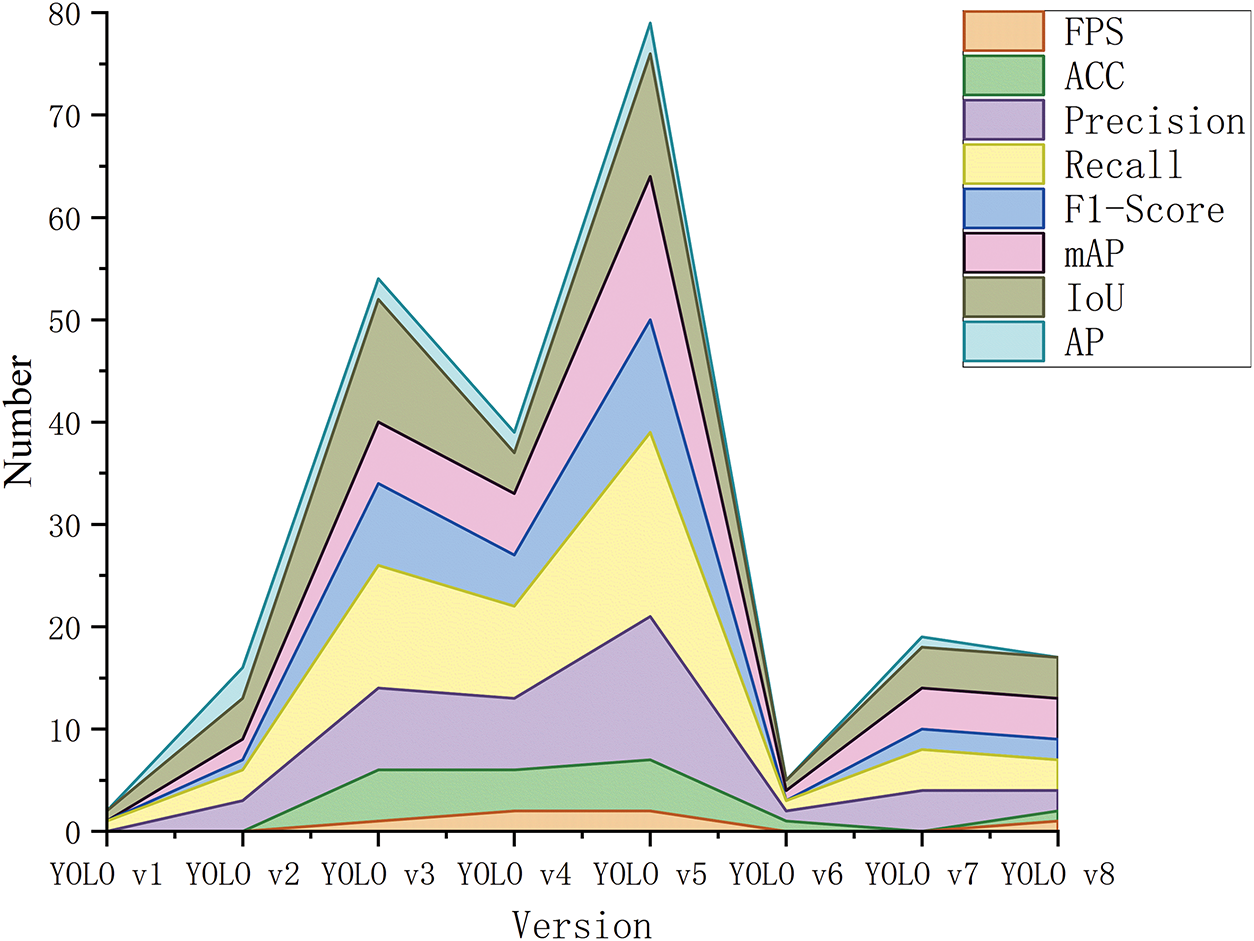

The research popularity of the YOLO model in the field of medical imaging has significantly increased. The number of related literatures has rapidly grown from 4 in 2018 to 175 in 2024 (Fig. 6), reflecting its technical potential and academic value in clinical testing tasks.

Figure 6: Historical literature trend of YOLO in medical object detection

With the evolution of the YOLO model, the focus of research has also been continuously deepening and expanding. On one hand, researchers are constantly improving the YOLO model to adapt to the complexities of medical images, such as low contrast, noise interference, and small object detection issues. On the other hand, the integration of YOLO with other deep learning methods, attention mechanisms, and multimodal information fusion has further advanced the field. For example, in the task of detecting pathological images, researchers have explored the combination of YOLO with Transformer architectures to enhance feature extraction capabilities. Additionally, recent research has started to focus on the interpretability of YOLO in medical object detection to improve its applicability in clinical practice [95].

From the literature growth trend, the number of studies in 2023 and 2024 is nearing saturation, indicating that the foundational research in this field has become relatively mature. In the future, it is likely to develop towards more refined clinical applications and commercialization. For example, the application of YOLO in real-time surgical navigation and remote medical image analysis still requires further exploration [96].

3.5 Algorithmic Framework and Pseudocode for YOLO-Based Medical Image Analysis

To enhance the methodological transparency and reproducibility of this review, a generalized algorithmic workflow (Algorithm 1) for YOLO-based medical image analysis is provided in this section. This pseudocode summarizes the typical pipeline employed in the reviewed studies, particularly for object detection and detection-based classification tasks in medical imaging. The workflow encompasses image preprocessing, object detection using YOLO models, optional secondary classification stages, and result aggregation.

Note: This pseudocode is intended to represent the most common applications of YOLO in medical imaging, specifically object detection and detection-based classification tasks. It does not cover semantic or instance segmentation tasks, which generally require distinct architectures and processing pipelines.

This pseudocode serves as a generalized technical framework that can be adapted and extended for specific medical imaging tasks. It provides a clear reference for future research and practical implementations of YOLO-based methods in medical image analysis.

4 YOLO Application in Medical Images Processing

Over time, the YOLO series of models has been widely adopted in the medical domain owing to its efficient end-to-end object detection capabilities. Existing studies commonly categorize YOLO’s medical applications into three primary areas: medical image analysis, surgical assistance, and personal protective equipment (PPE) detection. However, compared to such functionally oriented classifications, this review proposes a more application-centered perspective. Specifically, the focus shifts towards clinical diagnostic scenarios and disease types to better reflect the actual needs and developments in healthcare settings. Based on a systematic review of the current literature, YOLO’s medical applications are reclassified into two overarching categories: Disease-Oriented Applications and Health Monitoring and Safety Applications.

This revised classification framework more accurately reflects the clinical relevance of YOLO applications reported in the literature. It not only highlights the current contributions of YOLO to disease detection and public health monitoring but also facilitates a more structured understanding of technological trends across different medical subfields. Furthermore, this classification is based on currently available studies and is therefore not exhaustive. With ongoing advancements in YOLO architectures, future research may extend its applications to emerging areas such as ophthalmological imaging, prenatal screening, and digital pathology, which are anticipated to offer significant new opportunities for AI-driven healthcare solutions.

4.1 Disease-Oriented Applications and Health Monitoring and Safety Applications

This section focuses on disease diagnosis tasks, classified according to the primary affected anatomical system. It should be noted that some overlaps between categories may exist (e.g., brain tumors could be classified under both tumor detection and neurological disorders). The classification is therefore representative rather than exhaustive.

(1) Tumor Detection: Encompassing imaging-based detection of various tumors, such as lung cancer, breast cancer, and skin cancer.

(2) Skeletal and Joint Disease Detection: Covering automated diagnosis of skeletal and joint conditions, including fractures, arthritis, and osteoporosis.

(3) Neurological and Functional Disease Detection: Assisting in the diagnosis of neurological disorders, such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and stroke.

(4) Dental and Oral Disease Detection: Focusing on automated analysis of oral health conditions, including dental caries, periodontal diseases, and maxillofacial abnormalities.

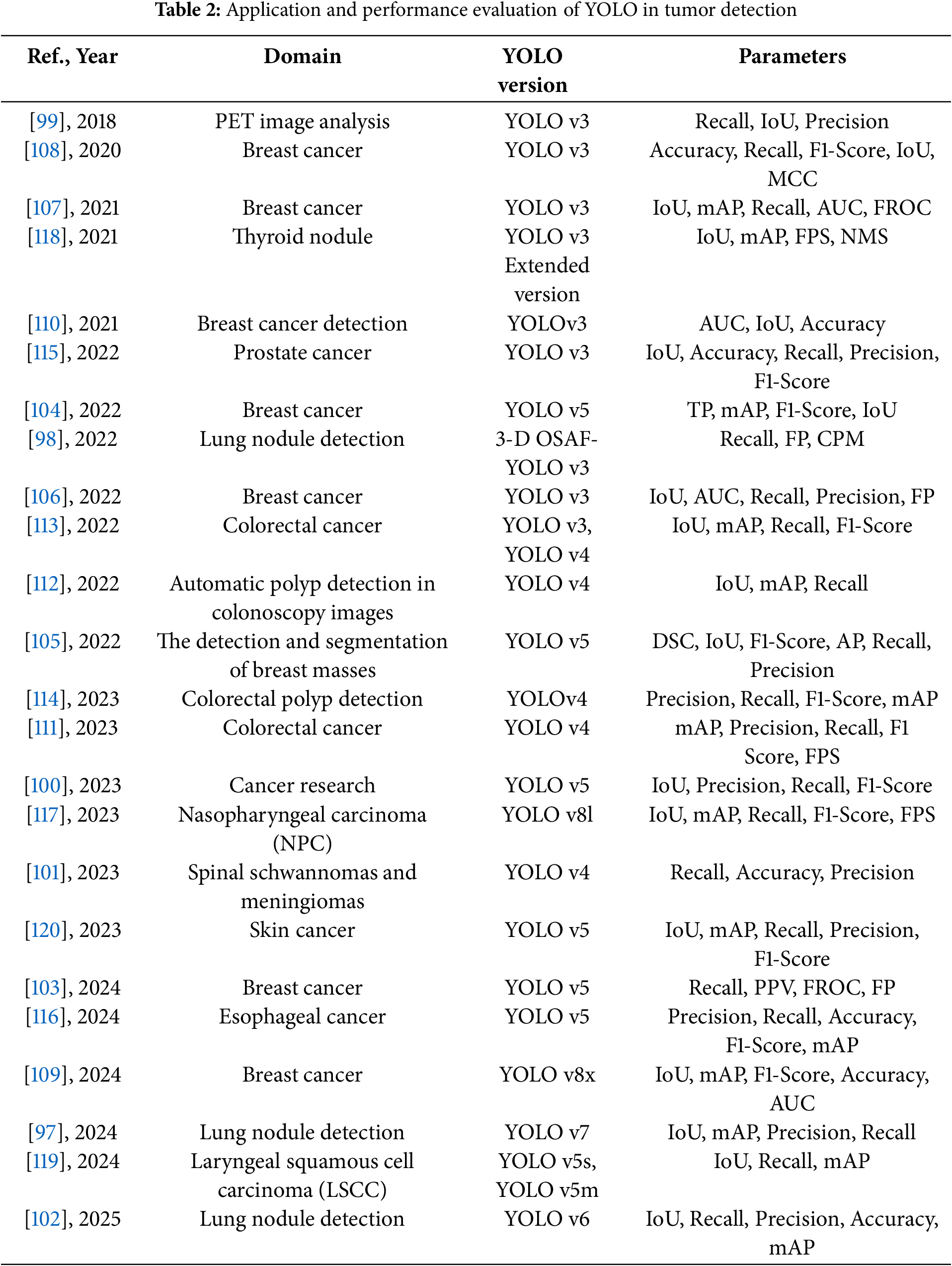

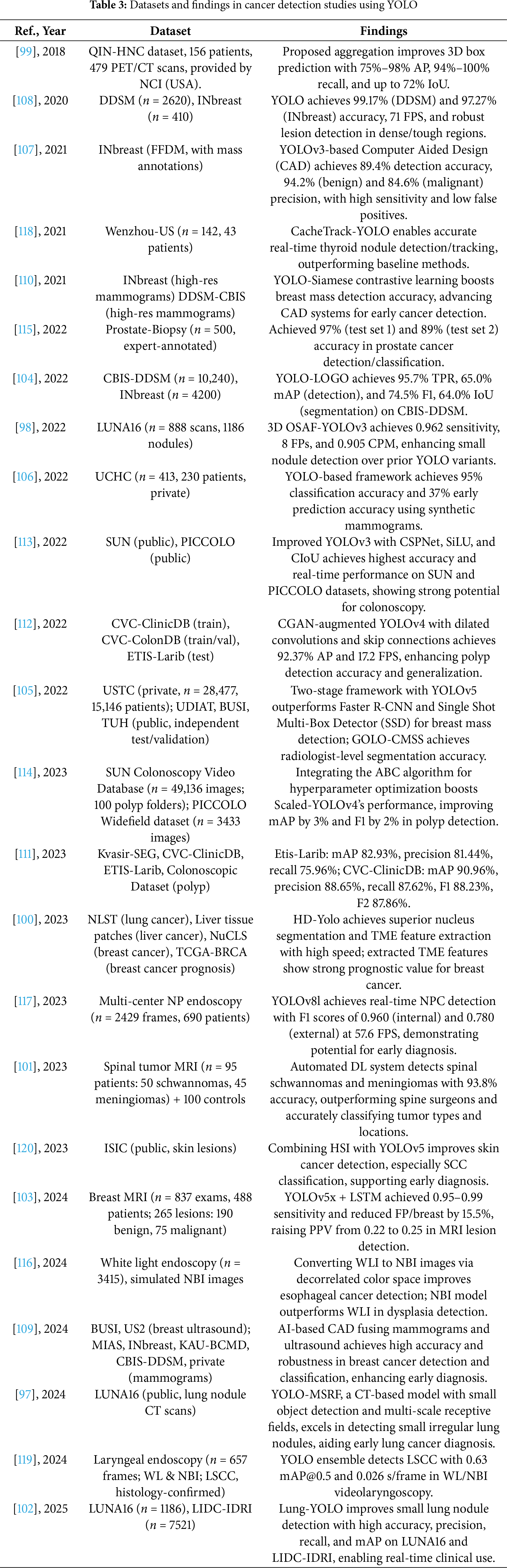

With the advancement of research, YOLO object detection algorithms have made significant strides in the field of medical image analysis, particularly in tumor detection. Its end-to-end detection capability, real-time efficiency, and high detection accuracy have established YOLO as a crucial tool for cancer screening and diagnosis. Early detection of tumors is vital for improving patient survival rates, and YOLO has demonstrated broad applicability in identifying various types of cancer, including lung cancer, breast cancer, prostate cancer, colorectal cancer, esophageal cancer, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, and skin cancer. This section systematically analyzes the current applications of YOLO in tumor detection and discusses its potential future development directions.

In lung cancer detection, YOLO has been primarily applied to the identification of pulmonary nodules in low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) images, aiming to enhance the efficiency of early lung cancer screening. Studies have shown that YOLOv7, when integrated with the Small Object Detection Layer (SODL), Multi-Scale Receptive Field (MSRF) module, and Efficient Omni-Dimensional Convolution (EODConv), achieved a mean Average Precision (mAP) of 95.26% and a precision of 95.41% on the LUNA16 dataset, significantly improving the detection of small nodules [97]. In addition, the 3D-YOLOv3 model, incorporating modules such as One-Shot Aggregation (OSA), Receptive Field Block (RFB), and Feature Fusion Scheme (FFS), enhanced nodule detection accuracy, achieving a CPM score of 0.905 on the LUNA16 dataset [98]. Beyond CT imaging, positron emission tomography (PET) also plays an important role in analyzing metabolic activity associated with lung cancer. A YOLO-based organ localization system for PET scans was proposed, achieving a detection accuracy between 75% and 98% across 479 cases involving 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) PET scans, providing a foundation for distinguishing tumor metabolic activity from that of normal organs [99]. Furthermore, HD-YOLO has been applied to pathological image analysis of lung cancer to assist in tumor microenvironment (TME) research and enhance the interpretability of whole slide image (WSI) data [100].

In addition, YOLO has also made significant progress in the detection of spinal cord tumors. Researchers employed YOLOv4 to develop an automated system for the detection and classification of spinal schwannomas and meningiomas. The system was trained using T1-weighted (T1W) and T2-weighted (T2W) MRI images, with five-fold cross-validation employed to optimize performance. On the test dataset, the system achieved detection accuracies of 84.8%, 90.3%, and 93.8% on T1W, T2W, and combined T1W + T2W images, respectively, while the diagnostic accuracies reached 76.4%, 83.3%, and 84.1% [101]. Compared to radiologists, the system demonstrated comparable, and in some cases superior, performance to experienced specialists, highlighting the potential of YOLO in detecting spinal nervous system disorders. Moreover, the system exhibited high accuracy in localizing tumors along the entire spinal column, suggesting that it could be extended to the detection of other spinal cord pathologies in the future, further enhancing the application value of YOLO in medical image analysis.

Notably, the recently proposed Lung-YOLO algorithm further optimizes pulmonary nodule detection. Based on YOLOv6, this method introduces a Multi-Scale Dual-Branch Attention (MSDA) mechanism to enhance the model’s ability to detect lung nodules of varying sizes. The model leverages dilated convolutions to capture long-range dependencies and integrates multi-scale contextual information to improve detection accuracy. In addition, a Cross-Layer Aggregation Module (CLAM) is proposed to preserve multi-level fine-grained features during feature extraction, thereby optimizing small-object detection performance. Experimental results demonstrate that Lung-YOLO achieved detection accuracies of 97.5% and 95.1% on the LUNA16 and LIDC-IDRI datasets, respectively, with mAP values of 97.9% and 95.9%, significantly outperforming existing lung nodule detection methods. Furthermore, the model’s inference speed reached 22.8 ms per image, ensuring its feasibility for clinical deployment [102].

Breast cancer detection represents another critical application area of YOLO in medical image analysis, primarily utilizing mammographic X-ray and breast ultrasound (BUS) images for automated detection and segmentation. Studies have shown that combining YOLOv5 with a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network can reduce false positives and improve the accuracy of breast MRI screening [103]. Additionally, the YOLO-LOGO (YOLO + Local-Global) framework, which integrates Transformer-based techniques, has enhanced detection and segmentation performance on mammography images [104]. To improve detection accuracy in ultrasound images, researchers proposed the YOLOv5 + GOLO-CMSS (Global Local-Connected Multi-Scale Selection) framework, which achieved an average detection accuracy ranging from 93.19% to 96.42% across four breast ultrasound datasets: USTC, UDIAT, BUSI, and TUH. The method also outperformed experienced radiologists in segmentation tasks [105]. Moreover, researchers utilized CycleGAN to generate synthetic mammographic images and combined them with YOLO for early cancer prediction, achieving a detection accuracy of 95% [106]. Furthermore, YOLOv3, when integrated with feature extraction networks such as ResNet and InceptionV3, demonstrated strong performance in breast lesion classification tasks, attaining a detection accuracy of 89.4% and a mean accuracy of 94.2% on the INbreast dataset [107,108]. Notably, multimodal fusion is becoming an emerging trend in breast cancer detection. For instance, some studies have employed YOLO combined with Vision Transformer (ViT) models to jointly analyze ultrasound and mammography data, thereby improving the accuracy of Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) classification [109]. In addition, a recent study proposed a dual-view Siamese YOLOv3-based framework that leverages multi-task learning to integrate craniocaudal (CC) and mediolateral-oblique (MLO) mammographic views for simultaneous mass classification and matching, achieving an AUC of 94.78% and enhancing detection accuracy through view-specific correspondence learning, offering additional support for clinical diagnosis [110].

In colorectal cancer detection, YOLO has been primarily applied to polyp detection in endoscopic images to enhance real-time diagnostic capabilities. Studies have shown that YOLOv4, when optimized with TensorRT quantization, can achieve an inference speed of 172 FPS, meeting the requirements for real-time polyp detection [111]. Furthermore, by expanding the dataset using a Conditional Generative Adversarial Network (CGAN) and optimizing the YOLOv4 detection architecture with dilated convolutions and skip connections, the polyp detection accuracy was improved to 92.37% [112]. Further research demonstrated that combining YOLOv3 and YOLOv4 with CSPNet, and introducing the SiLU activation function along with the Complete IoU (CIoU) loss function, can further enhance the precision of colorectal polyp detection [113]. Additionally, an optimized Scaled-YOLOv4 framework incorporating the Artificial Bee Colony (ABC) algorithm was proposed to enhance hyperparameter tuning, achieving over 3% improvement in mAP and 2% in F1-score on SUN and PICCOLO datasets, offering a flexible and effective approach for further boosting polyp detection performance [114].

Prostate cancer detection primarily relies on pathological image analysis to assist pathologists in cancer grading. A YOLO-based automated detection system was proposed, achieving a detection accuracy of 97% on experimental datasets, effectively reducing subjective discrepancies among pathologists [115].

In esophageal and nasopharyngeal cancer detection, YOLO is primarily utilized for real-time analysis of endoscopic images. Studies have shown that Narrow-Band Imaging (NBI) presents esophageal cancer lesions more clearly compared to traditional White Light Imaging (WLI). A YOLOv5-based study proposed a color space conversion method from WLI to NBI to enhance the detection accuracy of esophageal cancer [116]. For nasopharyngeal cancer detection, YOLOv8 achieved an inference speed of 52.9 FPS on a nasopharyngoscopy video dataset and effectively assisted in selecting biopsy sites, thereby improving clinical diagnostic efficiency [117].

YOLO has also been applied to the detection of thyroid and laryngeal cancers. For thyroid nodules, researchers proposed the CacheTrack-YOLO framework, which performs detection and tracking of thyroid nodules in ultrasound videos, simulating the physician’s diagnostic process. By employing Kalman filtering and the Hungarian algorithm for data association, the framework improved the accuracy and stability of nodule detection [118]. In laryngeal cancer detection, the YOLOv5s + YOLOv5m-TTA (Test Time Augmentation) approach, combined with Contrast Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization (CLAHE) to enhance image contrast, enabled efficient detection in NBI laryngoscopy videos [119].

Additionally, YOLO has been applied to skin cancer detection. Studies have shown that a hyperspectral imaging (HSI)-based YOLOv5 model demonstrated superior performance in skin cancer classification tasks, particularly improving the recall rate for squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) by 7.5% compared to models based on RGB imaging [120].

The following Tables 2 and 3 provide a comprehensive summary of YOLO-based deep learning applications in tumor detection, detailing model configurations, datasets, and performance findings.

These studies and their summarized characteristics, as detailed in the above tables, highlight current trends and limitations, which inform the following optimization directions for YOLO in Tumor Detection. Overall, the application of YOLO in medical image-based tumor detection has covered a wide range of cancer types, achieving significant progress in improving detection accuracy, reducing false positives, and accelerating real-time inference. However, challenges remain, including limited small-object detection capabilities, difficulties in multimodal data fusion, and large model parameter sizes. Future research directions can be summarized into the following four aspects:

(1) Multimodal Fusion: Integrating CT, MRI, ultrasound, pathological images, and molecular imaging to enable comprehensive tumor detection and grading.

Multimodal fusion not only enhances the model’s ability to perceive complex lesions but also increases its clinical value in cross-domain diagnosis. Future research may explore the deep integration of YOLO with multimodal Transformers or Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) to establish explicit correlations between spatial features (e.g., MRI structural images) and metabolic features (e.g., PET functional imaging), enabling unified structural-functional diagnosis. For instance, in lung cancer detection, jointly modeling LDCT and PET scan data may improve the identification of solid and subsolid nodules as well as early metabolic abnormalities. In breast cancer applications, fusing mammography, ultrasound, and pathological slice images as multi-source inputs to a YOLO-based model could significantly improve BI-RADS classification consistency and subtype prediction accuracy. Recent advances in dual-view fusion for breast imaging also indicate the potential of view-specific modeling in multimodal detection systems.

(2) 3D YOLO and Temporal Modeling: Enhancing detection capabilities for dynamic imaging (videos) and volumetric data.

Traditional YOLO architectures are primarily designed for 2D images, making it challenging to fully exploit the volumetric and temporal information embedded in 3D CT/MRI and video sequences. Future directions may include 3D YOLO-based modeling approaches (e.g., 3D-YOLOv3, YOLO-Surfer), incorporating voxel convolutions, spatial pyramids, and temporal encoders to enable more accurate early diagnosis through assessment of pulmonary nodule volume changes and tumor growth rates. For sequential imaging modalities such as endoscopic videos and ultrasound scans, introducing temporal modeling structures—such as LSTM, GRU, or Transformer-based networks—can facilitate the detection of transient precancerous lesions and improve object tracking across continuous frames.

(3) End-to-End Integration and Clinical Workflow Alignment: Promoting the practical implementation of YOLO in real-world medical workflows.

With the continuous advancement of YOLO model performance, its role in computer-aided diagnosis (CAD) systems has evolved from a “preprocessing tool” to a “core decision-making module.” Future efforts should focus on optimizing integration mechanisms between YOLO and clinical systems such as PACS (Picture Archiving and Communication System) and HIS (Hospital Information System), enabling an automated closed-loop process—from image acquisition and detection to report generation and physician verification. Furthermore, combining YOLO outputs with non-imaging features such as pathology findings, biomarkers, and genomic data may facilitate the development of multidimensional intelligent tumor diagnosis platforms, thereby supporting personalized and precision medicine.

(4) Self-Supervised and Reinforcement Learning: Reducing annotation costs and improving YOLO performance in low-data or weakly supervised scenarios.

Tumor image annotation is time-consuming and labor-intensive—especially for pathological images, where precise delineation of heterogeneous regions often requires collaboration among experienced experts. By incorporating self-supervised techniques such as contrastive learning, pseudo-label generation, and transformation prediction, YOLO models can learn generalizable representations from unlabeled or weakly labeled data, thereby improving recognition of previously unseen lesions. Reinforcement learning can further support neural architecture search (NAS) and optimization of region-of-interest (ROI) selection, enhancing the model’s attention to critical regions in complex images. For instance, it can guide the model to focus on lesion boundaries in esophageal NBI images or strengthen detection of low-contrast micro-nodules in breast ultrasound. These strategies not only reduce dependence on annotated data but also enhance the model’s generalizability and transferability. In addition, Emerging optimization algorithms, such as swarm intelligence-based methods, also show promise for automated YOLO tuning in tumor detection.

4.1.2 Skeletal and Joint Disease Detection

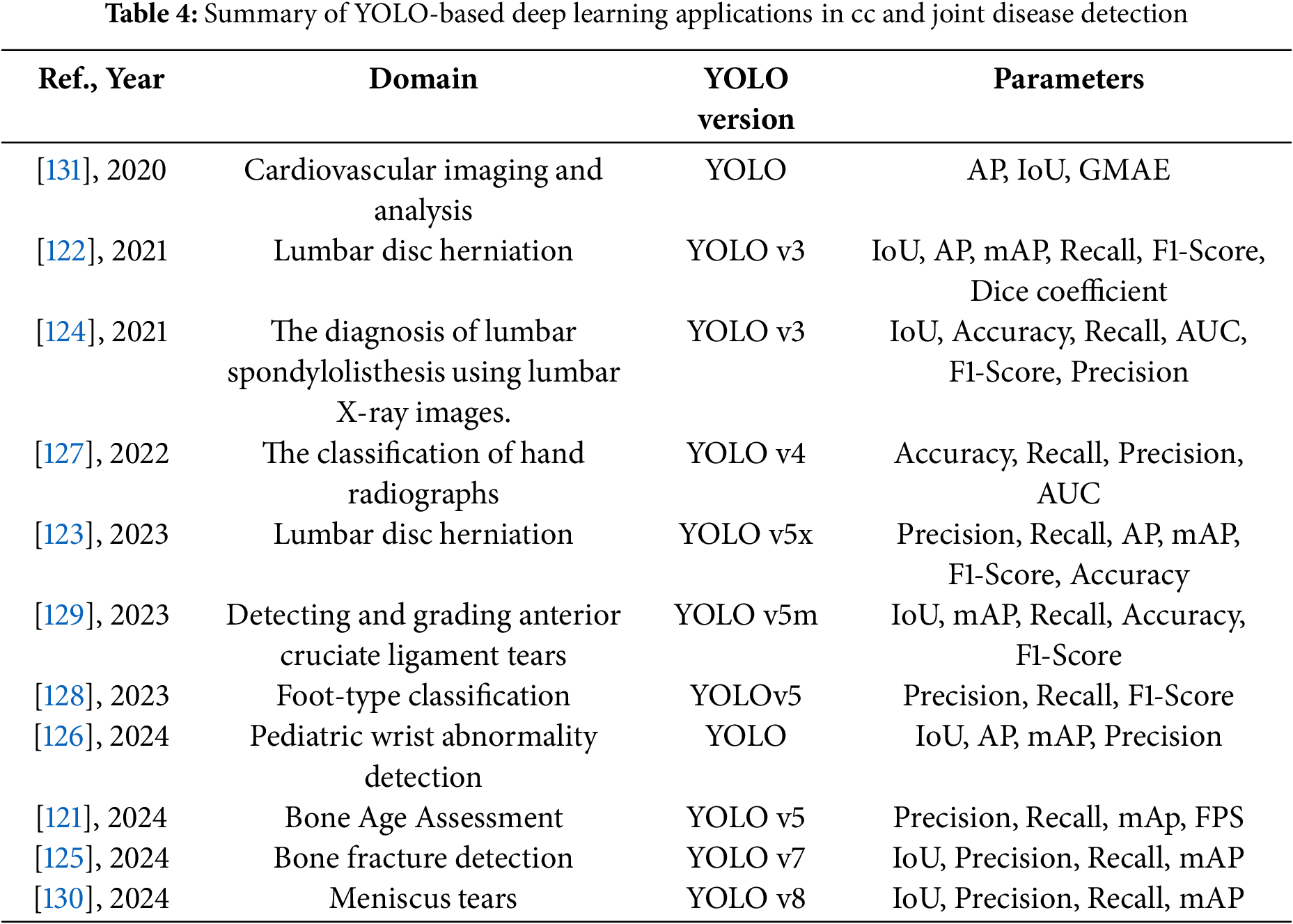

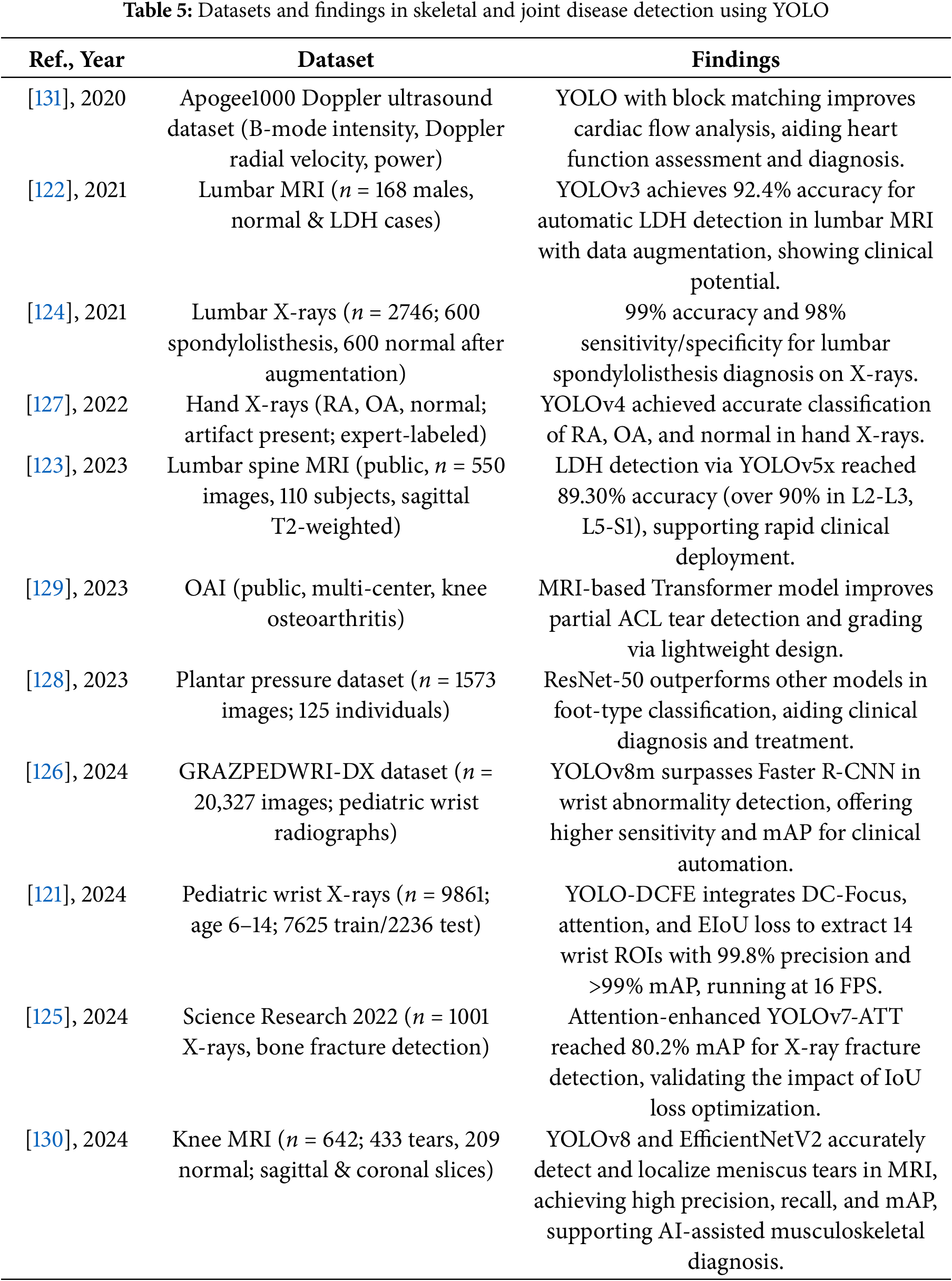

Significant progress has been made in the application of YOLO-based medical object detection in the field of skeletal and joint disease detection. In recent years, researchers have utilized YOLO to optimize tasks such as bone age assessment, fracture detection, lumbar disc herniation (LDH) diagnosis, arthritis classification, and anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) and meniscus tear detection, improving detection accuracy and efficiency.

For bone age assessment, researchers proposed the YOLO-DCFE model, which combines deformable convolution (DC-Focus), coordinate attention (Ca) modules, feature-level expansion, and the Efficient Intersection over Union (EIoU) loss function. This significantly improved the accuracy of ROI extraction, ultimately achieving a detection accuracy of 99.8% [121].

In lumbar disc herniation detection, YOLOv3 combined with data augmentation techniques achieved a mAP of 92.4% on a small-scale dataset [122]. Another study compared YOLOv5x, YOLOv6, and YOLOv7, finding that YOLOv5x performed best on the augmented dataset (mAP 89.3%) and achieved detection rates of over 90% in multiple disc regions (L2-L3, L3-L4, L4-L5, L5-S1) [123]. Additionally, in lumbar spondylolisthesis (LS) detection, researchers combined YOLOv3 for ROI extraction and used transfer learning to optimize MobileNet CNN for classification, ultimately achieving a classification accuracy of 99%, demonstrating the method’s potential to assist doctors in early diagnosis [124].

Additionally, in fracture detection, YOLOv7-ATT, combined with attention mechanisms and EIoU loss optimization, significantly improved detection accuracy, achieving a mAP of 86.2% on the FracAtlas dataset [125]. YOLOv5–v8 have also been applied to pediatric wrist fractures, with YOLOv8m achieving a sensitivity of 0.92 and mAP of 0.95, outperforming Faster R-CNN [126]. In arthritis classification, researchers used YOLOv4 for ROI extraction and combined it with the VGG-16 network to classify hand X-rays for rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis, ultimately achieving an accuracy of 90.8% and an AUC of 0.96 in the classification task [127].

In flat foot detection, YOLOv5 with attention improved performance on plantar pressure images, though a ResNet-50 classifier achieved higher accuracy (82.6%), indicating the effectiveness of deep learning in foot type analysis [128].

For anterior cruciate ligament tear detection, researchers proposed a lightweight detection method combining YOLOv5m and a simplified Transformer. This method uses YOLO for initial ROI extraction and applies the Transformer for tear grading. It achieved a sensitivity of 0.9222 on the OAI dataset while maintaining a model size of 701 kB, making it suitable for mobile medical devices [129]. Additionally, in meniscus tear detection, YOLOv8 combined with EfficientNetV2 for two-stage detection, used for meniscus localization and tear classification, ultimately achieved a mAP@50 of 0.98 and an AUC of 0.97 on a small-scale dataset [130].

In cardiovascular imaging, YOLO combined with block matching and fusion techniques enhanced Doppler-based cardiac Vector Flow Mapping (VFM), enabling accurate myocardial motion and flow analysis [131].

The following Tables 4 and 5 provide a comprehensive summary of YOLO-based deep learning applications in skeletal and joint disease detection, detailing model configurations, datasets, and performance findings.

These studies and their summarized characteristics, as detailed in the above tables, highlight current trends and limitations, which inform the following optimization directions for YOLO in skeletal and joint disease detection. In summary, the optimization directions for YOLO in skeletal and joint disease detection include:

(1) Improving the Detection Accuracy of Irregular Objects with Attention Mechanisms:

Traditional YOLO models may face certain limitations when dealing with complex and irregularly shaped objects. To address this issue, researchers have introduced attention mechanisms (such as channel attention and spatial attention) to help the model better focus on key areas, thereby significantly improving the detection accuracy of these objects (e.g., fractures, soft tissue injuries, etc.). The attention mechanism dynamically adjusts the importance of different regions, enabling YOLO to effectively handle objects of varying sizes, shapes, and positions, especially demonstrating higher robustness when processing complex structures like joints, soft tissues, feet, and fragile bones.

(2) Improving the Generalization Ability of Small Sample Datasets with Data Augmentation:

Handling small sample datasets has always been a challenge in medical image analysis, particularly in the detection of rare diseases. YOLO, combined with data augmentation techniques (such as rotation, flipping, scaling, color perturbation, etc.), effectively increases the diversity of training data, thereby improving the model’s generalization ability. In this way, YOLO can maintain high detection accuracy even with a limited number of samples, making it especially suitable for early diagnosis or medical applications with limited data.

(3) Optimizing Classification and Grading Tasks with Deep Learning Architectures like Transformer and EfficientNet:

The introduction of emerging deep learning architectures such as Transformer and EfficientNet has significantly enhanced YOLO’s performance in classification and grading tasks. Transformer effectively handles long-range dependencies, making it especially suitable for complex contextual information within images, thereby improving the detection and grading accuracy of complex diseases (e.g., ACL tears, meniscus injuries, and cardiac functional abnormalities, etc.). At the same time, efficient network architectures like EfficientNet improve the model’s accuracy while maintaining low computational resource consumption, demonstrating significant advantages, particularly when running on mobile or embedded devices.

(4) Exploring Lightweight Models to Meet the Demands of Mobile Healthcare and Real-Time Clinical Applications:

With the increasing demand for mobile healthcare and real-time clinical detection, lightweight YOLO models (such as YOLOv5m, YOLOv4-tiny, etc.) have become a focus of research. These lightweight models reduce the number of parameters and computational requirements, enabling YOLO to run in real-time on edge devices such as smartphones, portable ultrasound devices, and more. In the detection of bone and joint diseases, as well as functional disorders such as flat foot deformity, these lightweight models not only maintain high accuracy but also achieve low latency and high efficiency for real-time diagnosis, meeting the fast decision-making needs of clinicians.

(5) Combining Multimodal Imaging to Enhance the Diagnostic Accuracy of Bone and Joint Diseases:

In the future, combining multimodal imaging (such as MRI, X-ray, CT scans, etc.) with improved YOLO architectures will significantly enhance the automatic detection and diagnostic capabilities of diseases. Different medical imaging techniques provide various dimensions of information about a disease. For example, X-rays can clearly reveal bone structural changes in fractures and arthritis, while MRI is better at detecting soft tissue injuries and early changes in diseases. Ultrasound, particularly when enhanced by YOLO-based vector flow mapping, may provide functional assessments for cardiovascular conditions, through multimodal data fusion, the YOLO model can comprehensively analyze bone and joint health from multiple angles, enabling more precise and comprehensive disease diagnosis.

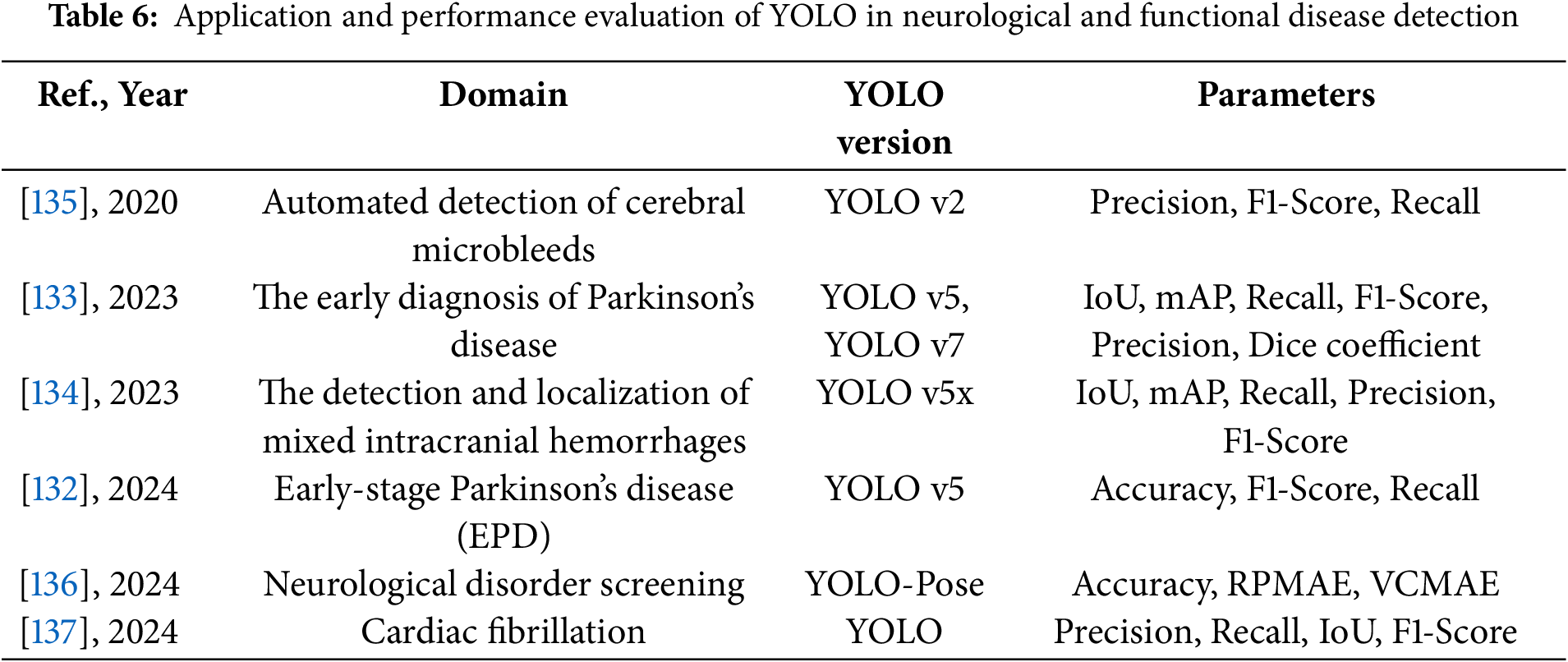

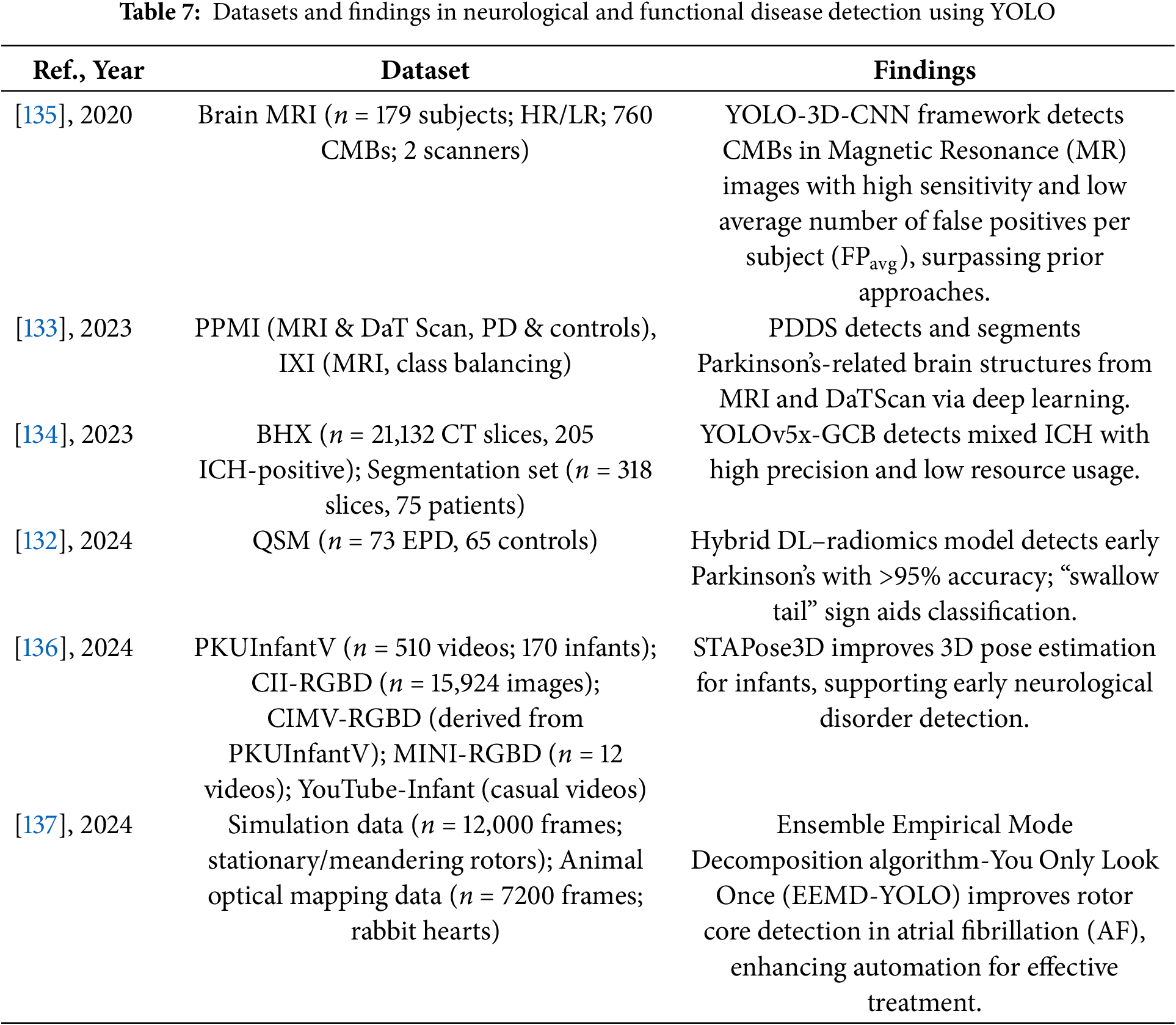

4.1.3 Neurological and Functional Disease Detection

YOLO-based medical object detection has shown great potential in the automated diagnosis of neurological and functional diseases, particularly in the detection of Parkinson’s disease (PD), intracranial hemorrhage (ICH), and cerebral microbleeds (CMBs). By integrating deep learning, radiomics, and multimodal medical imaging, YOLO models have significantly improved detection accuracy and efficiency.

In Parkinson’s disease detection, researchers proposed a YOLOv5-radiomics hybrid model for neuromelanin-sensitive MRI analysis based on quantitative susceptibility mapping (QSM) images. The method first uses YOLOv5 to detect the brainstem region, then employs LeNet to extract deep learning features, and selects 1781 radiomic features. A hybrid feature support vector machine (SVM) classifier is finally applied, achieving a detection accuracy of 96.3% [132]. Another study developed a system called PDDS (Parkinson’s Disease Diagnosis Software), which uses YOLOv7x for object detection and integrates U-Net for segmentation of MRI and DaTScan images. YOLOv7x achieved mAP_0.5:0.95 scores of 70.39% on DaTScan and 64.16% on MRI images, demonstrating strong performance in complex brain region detection tasks [133].

In ICH detection, researchers proposed a YOLOv5x-GCB model, which incorporates Ghost Convolution and Mosaic data augmentation. Trained on 21,132 CT images, the model achieved a mAP of 93.1%, demonstrating its potential for real-time clinical diagnosis [134].

Additionally, in cerebral microbleeds detection, researchers proposed a two-stage YOLO + 3D-CNN method, using YOLO for potential CMBs target detection and 3D-CNN for false positive reduction. This approach achieved a sensitivity of 93.62% on a high-resolution MRI dataset while significantly reducing the false positive rate [135].

Recent studies have further expanded YOLO-based detection into dynamic neurological and cardiovascular functional assessments. For infant movement analysis, a YOLO-based two-stage framework was developed for 2D and 3D pose estimation, demonstrating significant improvement in early motor dysfunction screening [136]. In cardiac electrophysiology, a YOLO model combined with empirical mode decomposition achieved high accuracy in detecting atrial fibrillation rotors across both simulated and biological datasets. These advances illustrate the potential of YOLO-based frameworks to extend beyond traditional structural imaging into functional and dynamic disease analysis [137].

Tables 6 and 7 provide a comprehensive summary of YOLO-based deep learning applications in the detection of neurological and functional diseases, detailing model configurations, datasets, and performance findings.

These studies and their summarized characteristics, as detailed in the above tables, highlight current trends and limitations, which inform the following optimization directions for YOLO in the detection of neurological and functional diseases. In summary, the optimization directions for YOLO in this domain mainly include:

(1) Integrating radiomics and multimodal data to comprehensively enhance detection accuracy:

Radiomics can extract a large number of potential high-dimensional features (such as texture, shape, and intensity) from medical images, while multimodal data (such as MRI, CT, DaTScan, and video-based motion data) provide complementary information at different levels. Combining the YOLO detection framework with radiomics feature extraction and integrating multiple imaging modalities allows the model to more comprehensively identify disease-related abnormalities from both structural and functional perspectives, significantly improving detection sensitivity and specificity in various conditions, including brainstem changes in Parkinson’s disease, intracranial hemorrhage, and motor function abnormalities.

(2) Introducing lightweight modules (e.g., Ghost convolution) to optimize network computational efficiency, meeting the needs of real-time clinical applications:

In practical clinical settings, especially in emergency medicine, telemedicine, or bedside monitoring, real-time performance and deployment flexibility are crucial. By incorporating lightweight designs such as Ghost convolution and depthwise separable convolutions into the YOLO network, the model can maintain high detection accuracy while significantly reducing parameter count and computational overhead. This enables fast inference under limited computing resources, making the model suitable for portable imaging devices, dynamic monitoring systems, and real-time diagnostic tools.

(3) Integrating advanced architectures such as 3D-CNN and spatiotemporal networks to improve spatial and temporal feature utilization:

Neurological and functional diseases often involve complex spatial or temporal patterns, such as subtle 3D lesion structures or motion dynamics in sequential data. Traditional 2D detection methods may overlook such complexities. By combining YOLO’s initial detection with architectures like 3D-CNNs or spatiotemporal attention networks, models can effectively capture both spatial and temporal relationships, ensuring high detection accuracy in tasks such as cerebral microbleeds detection, cardiac rotor localization, and infant movement analysis.

(4) Using data augmentation and transfer learning strategies to optimize model generalization on small sample datasets:

Due to the limited availability of high-quality, fully annotated imaging and functional datasets, directly training deep models may lead to overfitting. To address this, researchers commonly employ data augmentation techniques such as rotation, cropping, affine transformation, and GAN-based synthesis to enhance sample diversity. Additionally, transfer learning by pretraining YOLO on large-scale related datasets, followed by fine-tuning on specific medical tasks, has proven effective in improving model robustness and adaptability across diverse applications, from brain imaging to motion analysis.

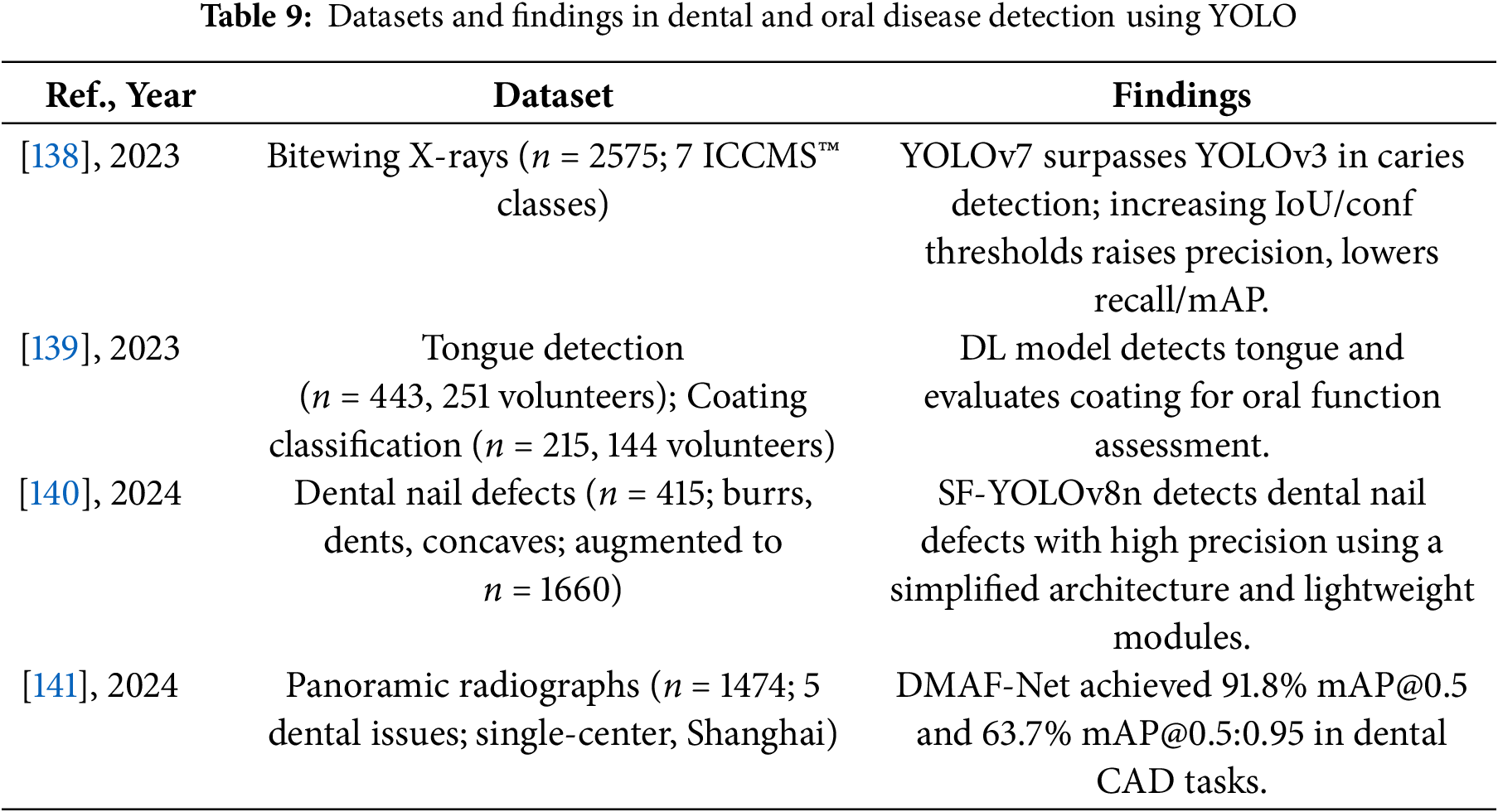

4.1.4 Dental and Oral Disease Detection

YOLO-based medical object detection has shown significant application value in dental and oral disease detection, covering areas such as caries detection, tongue coating assessment, dental post defect detection, and tooth structure analysis. In recent years, researchers have continuously optimized YOLO models to improve the accuracy and clinical applicability of dental image analysis.

In caries detection, researchers compared YOLOv3 and YOLOv7 on 2575 bitewing radiographs and found that YOLOv7 outperformed YOLOv3 in precision (0.557 vs. 0.268), F1 score (0.555 vs. 0.375), and mAP (0.562 vs. 0.458), demonstrating the superiority of YOLOv7 in dental image analysis [138].

In tongue coating assessment, researchers used YOLOv2 combined with ResNet-50 for tongue region detection and ResNet-18 for classifying tongue coating thickness. The final classification model achieved a Kappa coefficient of 0.826, indicating that the method is applicable for oral health monitoring and functional evaluation [139].

In dental post defect detection, researchers proposed a lightweight improved model, SF-YOLOv8n, based on YOLOv8n. This model reduces 77.01% of parameters by pruning network layers, adding small object detection layers, and optimizing the loss function, demonstrating efficiency and low computational cost while maintaining detection accuracy [140].

Additionally, in tooth structure detection, researchers proposed the DMAF-Net model, based on YOLOv5s, which integrates a Deformable Convolution Attention Module (DCAM), Multi-Scale Feature Extraction Module (MFEM), and Adaptive Spatial Feature Fusion (ASFF). This model achieved 92.7% mean accuracy, 87.6% recall, and 91.8% mAP@0.5 on panoramic radiographs, providing strong support for automated dental image analysis [141].

Tables 8 and 9 provide a comprehensive summary of YOLO-based deep learning applications in dental and oral disease detection, detailing model configurations, datasets, and performance findings.

These studies and their summarized characteristics, as detailed in the above tables, highlight current trends and limitations, which inform the following optimization directions for YOLO in dental and oral disease detection. In summary, the optimization directions of YOLO in dental and oral disease detection mainly include:

(1) Adopting advanced YOLO versions (such as YOLOv7 and YOLOv8) to enhance small object detection capabilities:

Many targets in dental images, such as caries and dental post defects, are typically small and may be subject to occlusion, deformation, or unclear positional information. Advanced versions like YOLOv7 and YOLOv8 improve small object detection accuracy by optimizing network architecture and introducing new detection strategies (e.g., attention mechanisms, enhanced feature extraction layers). For instance, YOLOv7 outperforms YOLOv3 in dental X-rays, enabling more accurate identification of small lesions like caries. Additionally, the YOLOv8 series, with its improved small object detection layers and feature enhancement modules, can more accurately detect and localize teeth and defects in complex environments, improving sensitivity to low-contrast and fine lesions.

(2) Optimizing dental image classification tasks with deep learning architectures such as ResNet and Transformer:

Dental image classification tasks (e.g., tongue coating thickness classification, tooth defect analysis) require models to not only accurately detect targets but also understand complex image structures and deep spatial relationships. To achieve this, integrating deep learning architectures like ResNet and Transformer has become an effective approach to improving classification accuracy. ResNet, with its deep residual learning structure, enhances image detail recognition while preventing gradient vanishing, making it suitable for handling detailed and complex dental images. The Transformer architecture, through its global perception mechanism, better captures long-term dependencies between tooth regions and other oral tissues, enhancing model performance in complex scenarios. For example, combining YOLO with ResNet-50 for deep feature extraction to assess tongue coating status significantly improves classification accuracy through multi-level feature extraction.

(3) Using pruning and lightweight models to improve real-time detection performance for low-power devices:

Dental and oral disease detection, especially in clinical settings, requires real-time and efficient performance. Therefore, optimizing models to reduce size and computational load while maintaining accuracy is a key focus. Lightweight YOLO models, such as YOLOv8n and YOLOv5s, significantly reduce computational and memory requirements through network pruning, quantization techniques, and the incorporation of small object detection layers. For instance, the SF-YOLOv8n model reduces parameters by 77.01% through pruning and optimizing the loss function, enhancing its real-time detection capability on low-power devices. This lightweight design enables YOLO to run efficiently on mobile devices and portable dental diagnostic equipment, meeting clinical emergency needs.

(4) Exploring multimodal image fusion (X-ray, CT, oral photos) to enhance comprehensive diagnosis:

Dental disease detection relies not only on a single type of imaging data, but also on the combination of different modalities such as X-rays, CT scans, and oral photos, which provide more comprehensive diagnostic information. By integrating multimodal images, YOLO can leverage the advantages of various imaging techniques to further improve detection comprehensiveness and accuracy. For example, X-ray images clearly show the structure of bones and teeth, while CT images provide more detailed soft tissue information. Inputting these image data into the YOLO model enables more refined dental disease detection, enhancing the ability to identify complex conditions such as dental structural abnormalities and early-stage cavities.

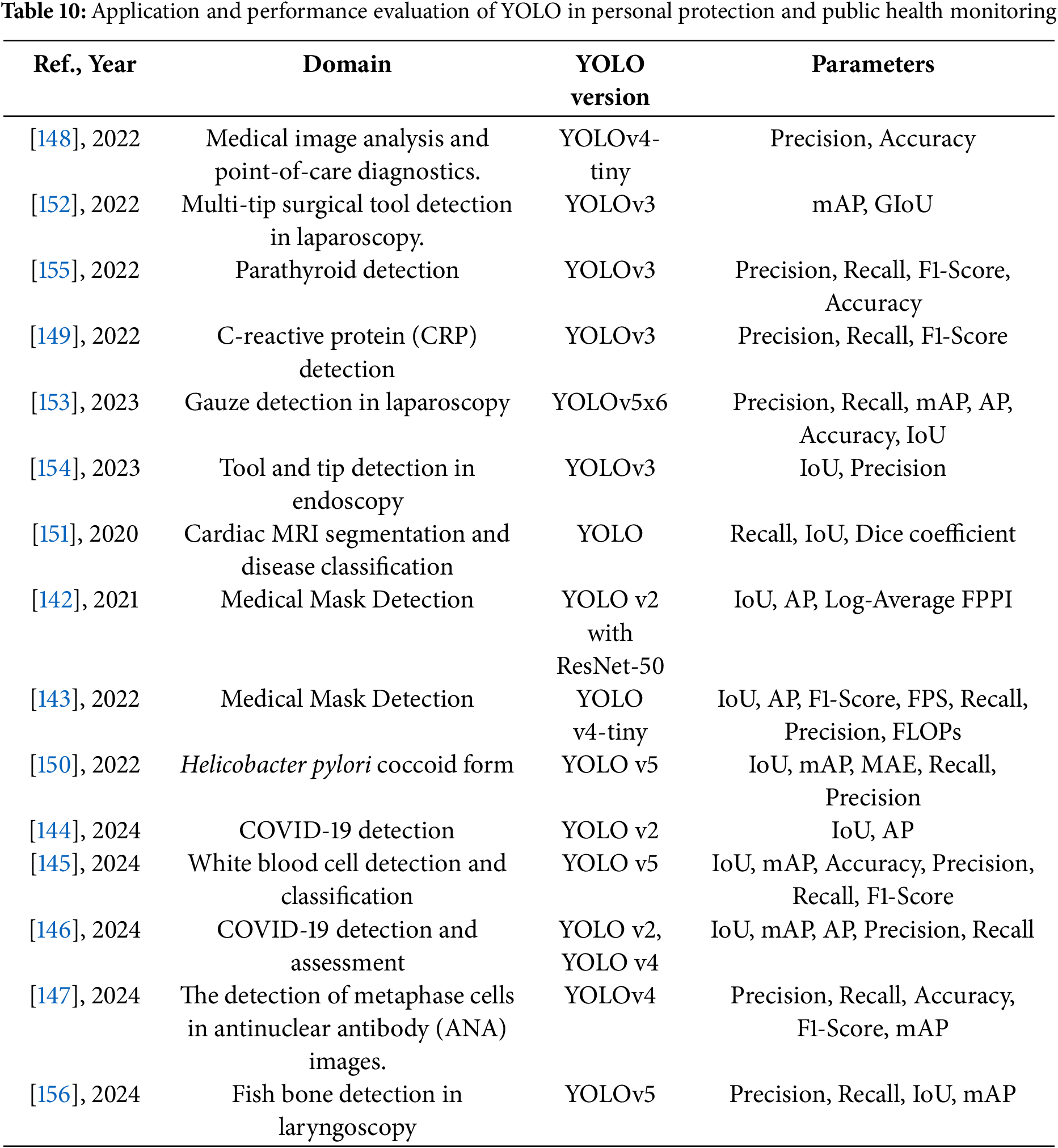

4.2 Health Monitoring and Safety Applications

Beyond disease diagnosis, YOLO models have proven effective in broader health monitoring and public safety contexts, particularly during global health crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

Personal Protection and Public Health Monitoring

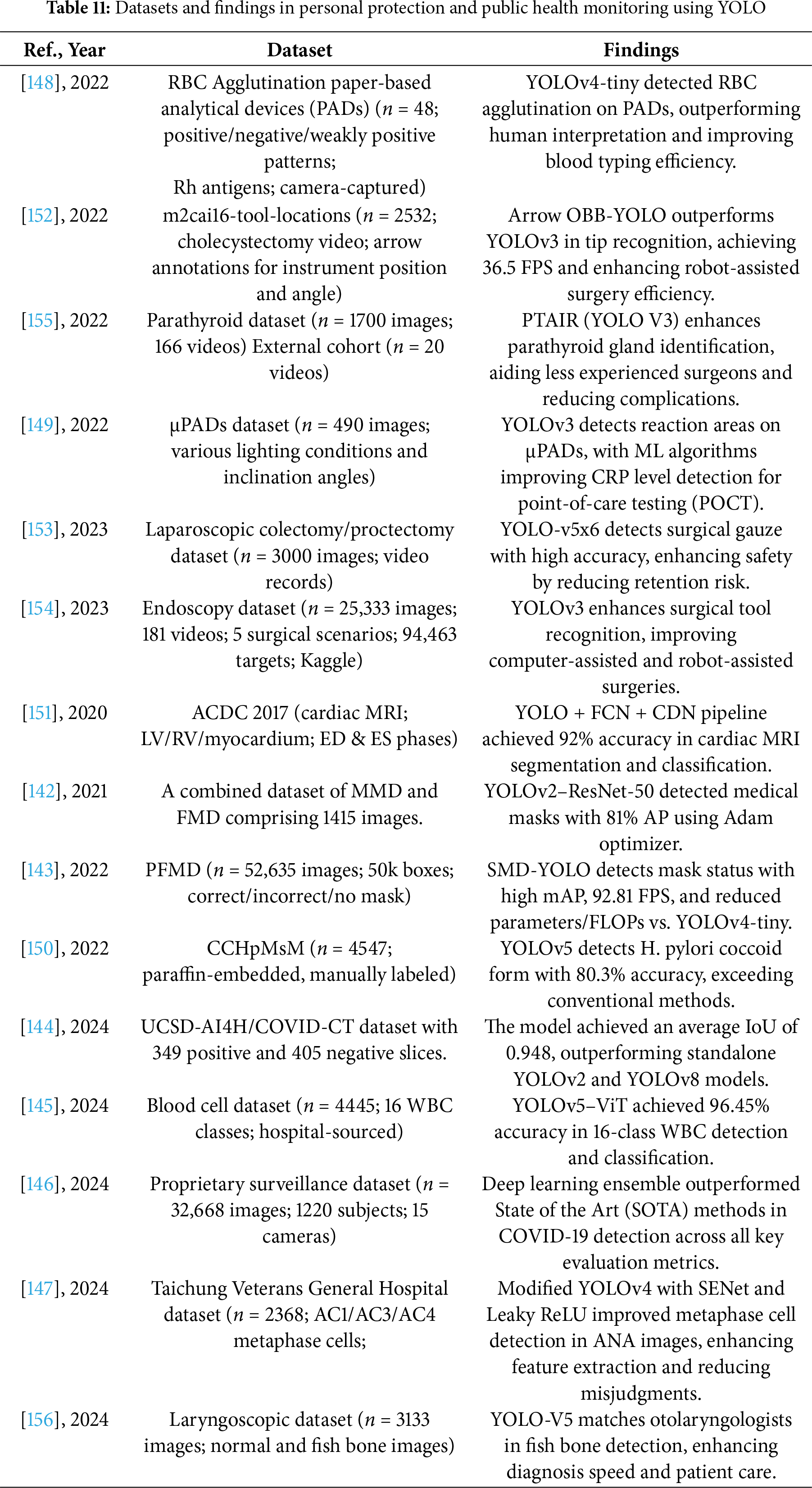

YOLO-based medical object detection has shown extensive application value in the fields of personal protective equipment and public health monitoring, covering various areas such as mask-wearing detection, COVID-19 lung lesion screening, white blood cell classification, medical robot-assisted diagnosis, and Helicobacter pylori detection.

In the field of mask-wearing detection, researchers developed a detection model based on YOLOv2 combined with ResNet-50, utilizing average IoU to evaluate anchor box numbers and the Adam optimizer. The model achieved an average accuracy of 81% on a public dataset, demonstrating its potential for application in epidemic prevention and control [142]. Additionally, another study proposed the YOLOv4-tiny improved model, SMD-YOLO, which optimizes the network structure, K-means++ clustering algorithm, and attention mechanism. This model achieved a detection speed of 92.81 FPS and improved the mAP by 4.56% in the mask-wearing detection task, showcasing its broad applicability in hospitals, campuses, and community environments [143].

In the detection of COVID-19 lung lesions, researchers used YOLOv2 combined with the open neural network exchange (ONNX) framework for the localization of lung lesions in high-resolution CT images. The model achieved an IoU of 94.8% in the detection of lesion areas in COVID-19 patients, significantly improving the automation level of image analysis [144].

In the white blood cell classification task, researchers proposed the WBC YOLO-ViT model, combining YOLOv5 for object detection and ViT for classification. The model achieved an accuracy of 96.449% in the classification of 16 types of white blood cells, effectively enhancing the intelligence level of blood tests [145].

In the field of medical robot-assisted diagnosis, researchers developed a Deep Adaptive Architecture Ensemble Model (DEAA), combining YOLO with various deep learning architectures. This model improved the accuracy of COVID-19 patient detection to 98.32% and was successfully integrated into a soft robot, achieving automated health monitoring and assessment [146].

Recent studies have further expanded YOLO-based detection into diverse laboratory diagnostic tasks beyond its conventional applications. In the context of autoimmune disease screening, an improved YOLOv4 model was proposed for detecting metaphase cells in antinuclear antibody (ANA) testing, showing strong consistency with expert evaluations and significantly enhancing diagnostic efficiency [147]. In parallel, YOLOv4-tiny combined with DenseNet-201 has been employed for Rh blood group antigen typing on paper-based analytical devices, enabling rapid and accurate identification of blood group antigens in resource-limited settings [148]. Similarly, YOLOv3 models have been applied to microfluidic paper-based analytical devices for the colorimetric detection of C-reactive protein (CRP), where the integration of deep learning facilitated accurate localization of reaction zones and precise classification of risk levels [149]. Together, these approaches underscore the increasing utility of YOLO in laboratory automation and point-of-care testing.

Additionally, in Helicobacter pylori detection, researchers employed a YOLOv5 optimized model for the automatic identification of Helicobacter pylori spherical variants (HPCF). In experiments, the detection accuracy reached the level of experienced pathologists (mAP 80.3%), holding promise to replace manual screening in future clinical practice and improve the diagnostic efficiency of gastric infections [150].

In the detection of heart diseases, researchers proposed a method for cardiac MRI image segmentation and heart disease classification based on deep neural networks and point clouds [151]. This method uses a YOLO network to detect the heart region and obtain the ROI, followed by segmentation with a fully convolutional network (FCN) to obtain segmentation masks for the left ventricle (LV), right ventricle (RV), and myocardium (Myo). Then, through 3D surface reconstruction and point cloud sampling, the researchers built a cardiac disease diagnosis network (CDN), achieving a classification accuracy of 92% on the test dataset. The experimental results demonstrate that this method holds significant clinical value in cardiac image analysis and disease classification.

Beyond diagnostic imaging, YOLO-based models have gained significant traction in surgical assistance and intraoperative monitoring. Multiple studies have explored YOLO frameworks for tasks such as surgical tool recognition, gauze tracking, and anatomical structure identification. Notably, Arrow OBB-YOLO networks have been proposed for precise localization of endoscopic instrument tips, enabling real-time and angle-aware tracking during minimally invasive surgeries [152]. In addition, YOLOv5-based models have been utilized to detect surgical gauze in laparoscopic procedures, supporting timely identification and reducing the risk of retained surgical items [153]. In the context of surgical navigation, YOLOv3-enhanced models have shown high accuracy in identifying surgical instruments and tool tips across various operative environments [154]. Moreover, YOLO has also been applied to anatomical recognition, exemplified by the PTAIR model for parathyroid gland detection during thyroid surgery, which achieved performance comparable to experienced surgeons while offering earlier detection and extended tracking [155]. Likewise, YOLOv5 models have been employed to identify fish bone foreign bodies in laryngoscopic images and videos, delivering rapid and reliable support in otolaryngology emergencies [156]. Collectively, these advances demonstrate the versatility of YOLO in promoting surgical safety and enhancing intraoperative decision-making.

The following Tables 10 and 11 provide a comprehensive summary of YOLO-based deep learning applications in the fields of personal protection and public health monitoring, detailing model configurations, datasets, and performance findings.