Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Cuckoo Search-Deep Neural Network Hybrid Model for Uncertainty Quantification and Optimization of Dielectric Energy Storage in Na1/2Bi1/2TiO3-Based Ceramic Capacitors

1 College of Architecture and Civil Engineering, Xinyang Normal University, Xinyang, 464000, China

2 Henan International Joint Laboratory of Structural Mechanics and Computational Simulation, College of Architectural and Civil Engineering, Huanghuai University, Zhumadian, 463000, China

3 Solux College of Architecture and Design, University of South China, Hengyang, 421000, China

4 Centre for Industrial Mechanics, Institute of Mechanical and Electrical Engineering, University of Southern Denmark, Sønderborg, 6400, Denmark

* Corresponding Author: Pei Li. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advanced Computational Modeling and Simulations for Engineering Structures and Multifunctional Materials: Bridging Theory and Practice)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(2), 2729-2748. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.068351

Received 26 May 2025; Accepted 25 August 2025; Issue published 23 September 2025

Abstract

This study introduces a hybrid Cuckoo Search-Deep Neural Network (CS-DNN) model for uncertainty quantification and composition optimization of Na1/2Bi1/2TiO3 (NBT)-based dielectric energy storage ceramics. Addressing the limitations of traditional ferroelectric materials—such as hysteresis loss and low breakdown strength under high electric fields—we fabricate (1 − x)NBBT8-xBMT solid solutions via chemical modification and systematically investigate their temperature stability and composition-dependent energy storage performance through XRD, SEM, and electrical characterization. The key innovation lies in integrating the CS metaheuristic algorithm with a DNN, overcoming local minima in training and establishing a robust composition-property prediction framework. Our model accurately predicts room-temperature dielectric constant (εr), maximum dielectric constant (εmax), dielectric loss (tan δ), discharge energy density (Wrec), and charge-discharge efficiency (η) from compositional inputs. A Monte Carlo-based uncertainty quantification framework, combined with the 3σ statistical criterion, demonstrates that CS-DNN outperforms conventional DNN models in three critical aspects: Higher prediction accuracy (R2 = 0.9717 vs. 0.9382 for εmax); Tighter error distribution, satisfying the 99.7% confidence interval under the 3σ principle; Enhanced robustness, maintaining stable predictions across a 25% composition span in generalization tests. While the model’s generalization is constrained by both the limited experimental dataset (n = 45) and the underlying assumptions of MC-based data augmentation, the CS-DNN framework establishes a machine learning-guided paradigm for accelerated discovery of high-temperature dielectric capacitors through its unique capability in quantifying composition-level energy storage uncertainties.Keywords

Capacitors, as indispensable energy storage components, play a crucial role in modern electrical and electronic systems. They are widely employed in power conditioning circuits, pulse power devices, hybrid/electric vehicles, aerospace power systems, and next-generation energy technologies. In these contexts, dielectric-material-based capacitors are especially attractive due to their extremely fast charge–discharge response and their superior power density compared with electrochemical storage systems [1–4]. To meet the stringent demands of advanced energy systems, dielectric materials for capacitors must simultaneously exhibit high energy density, high efficiency, and long-term stability. A high energy density enables compact and lightweight systems, while a high charge–discharge efficiency minimizes heat loss and improves device reliability. Furthermore, in specialized applications such as electric vehicles and aerospace, capacitors are often exposed to elevated temperatures in the range of 100°C–200°C, which requires dielectric materials to sustain stable dielectric properties and reliable energy storage performance under harsh thermal environments.

The energy density W of dielectric materials can be expressed as

Progress in ferroelectric energy storage is hampered by two key challenges: (i) the multiscale physical mechanisms governing polarization and breakdown remain unclear, and (ii) material optimization still relies heavily on inefficient trial-and-error methods. To address these challenges, we introduce a deep neural network (DNN) combined with Cuckoo Search (CS) for predictive modelling and optimization of dielectric energy storage properties [8–10]. Machine learning (ML) has already demonstrated strong potential in materials research by efficiently mapping inputs (

The integration of ML into materials research has already shown substantial benefits. Well-trained ML models reduce experimental cost and accelerate the discovery cycle compared to conventional trial-and-error methods. While many prior studies have coupled ML with computational databases to predict material properties, recent advances highlight the importance of integrating ML directly with experimental workflows for more reliable optimization of synthesis processes and faster discovery of high-performance materials [17–21]. For instance, Liu et al. [22] applied ML models with tailored feature-construction strategies to predict both the recoverable energy density and efficiency of BaTiO3–BiMeO3 (BT–BMO) ferroelectric ceramics, achieving accurate prediction of complex structure–property relationships influenced by composition and sintering conditions. Qiao and Zhu [23] employed a CS-artificial neural network (CS-ANN) model with elemental descriptors to design high-hardness Al–Cr–Co–Fe–Ni alloys, successfully predicting the link between processing, microstructure, and performance. In another study, Qiao et al. [24] combined ML with finite element modelling (FEM) to optimize ceramic injection molding, demonstrating how ML-assisted simulations can accelerate process design. He et al. [25] systematically applied regression and classification models to identify the most relevant descriptors for predicting ferroelectricity across diverse material systems, reducing a set of 26 potential descriptors down to three critical features. Yuan et al. further introduced an ML-based adaptive design strategy that rapidly identified BaTiO3-based multicomponent solid solutions with enhanced

Among lead-free ferroelectrics, sodium bismuth titanate (Na1/2Bi1/2TiO3, NBT)-based materials has been widely investigated due to its strong room-temperature ferroelectricity [29,30]. However, NBT ceramics suffer from large ferroelectric macro-domains, pronounced hysteresis, and low breakdown strength (Eb), leading to limited energy storage efficiency and recoverable energy density. A promising strategy is to introduce secondary perovskite oxides to disrupt long-range ferroelectric order. In particular, Bi(Mg1/2Ti1/2)O3 effectively improves relaxor behavior and enhances breakdown strength when combined with NBT [31]. Through careful design of NBT–BMT solid solutions, dielectric materials can be engineered to achieve high energy density, high efficiency, and stable temperature performance.

Building on this materials platform, we propose a Cuckoo Search–Deep Neural Network (CS–DNN) framework for predictive modeling of ferroelectric energy storage. The CS–DNN model accurately predicts composition-dependent trends of Wrec and η, while feature-importance analysis highlights the mechanistic roles of key descriptors. Comparative studies show that CS–DNN achieves higher accuracy and stability than conventional DNNs. By integrating experimental insights with data-driven optimization, this work provides a methodological pathway for overcoming bottlenecks in ferroelectric energy storage and contributes to the broader objectives of the Materials Genome Initiative.

Ceramics with nominal compositions of (1 − x)(Na1/2Bi1/2)0.92Ba0.08TiO3-xBi(Mg1/2Ti1/2)O3 ((1 − x)NBBT-xBMT) were synthesized via a conventional solid-state reaction route, where x = 0, 0.02, 0.04, 0.06, 0.10, 0.12, 0.14, 0.20, 0.40. Analytical-grade raw materials Na2CO3 (99.8%), BaCO3 (99.0%), Bi2O3 (99.0%), TiO2 (98.0%) and MgO (98.5%), were weighed stoichiometrically, mixed with 100 mL of anhydrous ethanol, and ball-milled for 12 h. The slurry was dried and calcined at 850°C for 2 h. The calcined powder was then remixed with ethanol and subjected to a second ball-milling process for 12 h to further reduce particle size. After drying, a 5 wt.% polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) aqueous solution was added as a binder at 10 wt.% of the powder mass. The granulated powder was uniaxially pressed into pellets of 0.5-inch diameter. The green compacts were heated to 800°C for 2 h to remove the binder, and the (1 − x)NBBT8-xBMT ceramic bodies were finally sintered at 1120°C for 2 h.

The crystalline structure of the sintered ceramics was examined by X-ray diffraction (XRD, Japan Intelligent Laboratory Diffractometer, Tokyo, Japan). Polished samples were annealed at 500°C for 1 h prior to testing. For microstructural characterization, fractured surfaces were thermally etched at 1000°C for 1 h and observed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM, JSM-6390LA, JEOL, Japan). For dielectric and ferroelectric measurements, the samples were ground to ~0.5 mm thickness, polished, and coated with silver paste electrodes, followed by firing at 500°C for 30 min to ensure good electrical contact. Temperature-dependent dielectric properties were measured with an impedance analyzer (4294A, Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) equipped with a programmable furnace. Polarization–electric field (P–E) hysteresis loops were recorded using an improved Sawyer–Tower circuit (Polyktech PK-DIS1010K, USA).

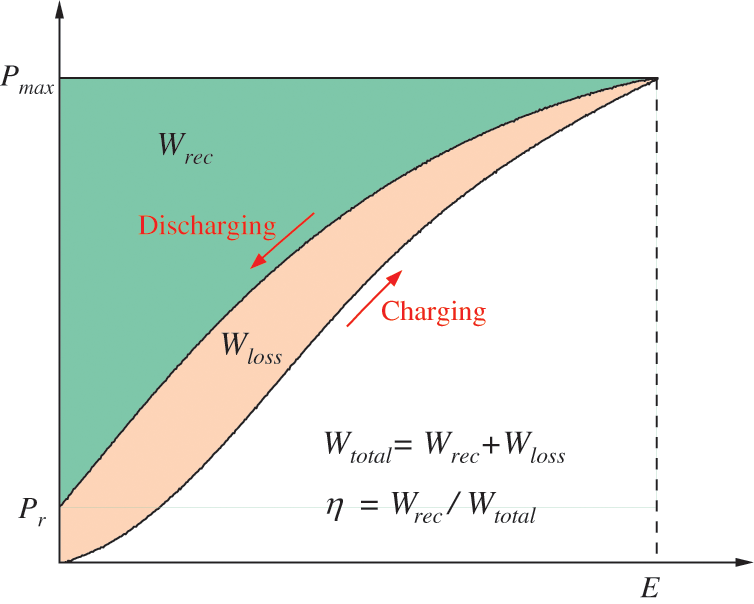

The energy storage density of dielectric capacitors is defined as:

where W represents the stored energy, P denotes the polarization intensity, Pmax indicates the maximum polarization intensity, and Pr represents the residual polarization intensity. The charging energy density corresponds to the integral of the area between the charging curve and the polarization axis, while the discharge energy density corresponds to the integral between the discharge curve and the polarization axis (Fig. 1). Here, E stands for the electric field intensity, Wtotal represents the charging energy density, Wrec denotes the discharge energy density, and η indicates the charge-discharge efficiency.

Figure 1: Schematic illustration of the discharge process of a dielectric ceramic capacitor

Fig. 2a presents the X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of (1 − x)NBBT-xBMT ceramics. All samples exhibit a perovskite structure without detectable secondary phases [31,32]. However, at high BMT content x = 0.8, the large incorporation of BMT disturbs the Na+/Bi3+ ratio. During sintering, this imbalance may promote the formation of related oxides, such as Bi2O3, resulting in the precipitation of impurity phases. Fig. 2b illustrates the X-ray diffraction patterns of the pseudo-cubic {1 1 1}c and {2 0 0}c peaks of (1 − x)NBBT-xBMT ceramics. The observed splitting of the {1 1 1}c and {2 0 0}c peaks suggests the coexistence of tetragonal and trigonal structures in NBBT8 ceramics [33]. As the BMT content increases, the splitting of the {1 1 1}c peak becomes less pronounced, indicating a transition from the coexistence of tetragonal and trigonal phases towards a more uniform tetragonal structure. Simultaneously, both {1 1 1}c and {2 0 0}c peaks gradually shift to lower diffraction angles, indicating an expansion of the c-axis lattice parameter.

Figure 2: (a) X-ray diffraction pattern of (1 − x)NBBT-xBMT ceramics. (b) enlarged region of 36°–48° showing the evolution of {1 1 1}c and {2 0 0}c peaks

Fig. 3a and b illustrates the effect of BMT modification on the dielectric properties (at 1 kHz) of (1 − x)NBBT-xBMT ceramics under a weak electric field. Increasing BMT content reduces dielectric loss (below 300°C), shifts the phase-transition temperature to lower values, and raises the dielectric peak temperature, thereby broadening the stable dielectric response range from room temperature to ~300°C. Notably, the high dielectric loss of the material at low frequencies can be significantly reduced by incorporating a specific amount of bismuth at the A-site while doping magnesium at the B-site cation. This approach compensates for the low valence state of magnesium and mitigates the formation of oxygen vacancies. These characteristics suggest that BMT-modified NBBT8 ceramics possess considerable potential for high-temperature dielectric applications.

Figure 3: (1 − x)NBBT-xBMT ceramics: (a) Dielectric constant (at 1 kHz); (b) Dielectric loss (at 1 kHz); (c) Bipolar P-E hysteresis loop at room temperature

The shift of the transition temperature (Td) to a lower value indicates that the ferroelectric phase becomes unstable following the incorporation of BMT into NBBT8. This observation is further corroborated by the measurement of the bipolar polarization-electric field (P-E) hysteresis loop, as illustrated in Fig. 3c. The NBBT8 ceramics display a typical P-E loop characteristic of normal ferroelectrics, with a coercive field (Ec) of approximately 28 kV/cm and a remnant polarization (Pr) of about 0.25 C/m2. As the content of BMT increases, both Ec and Pr exhibit a decreasing trend, suggesting an instability in the ferroelectric phase. Notably, the 0.88NBBT-0.12BMT ceramic presents a ‘slender’ P-E loop, resembling the curves observed in paraelectric or relaxor ferroelectric materials [34]. Since the enclosed hysteresis area corresponds to energy loss, this result confirms that BMT addition reduces energy dissipation during electric cycling.

The discharge energy density of (1 − x)NBBT-xBMT ceramics at different temperatures under an electric field of 70 kV/cm is presented in Fig. 4a. The findings indicate that the incorporation of BMT into NBBT8 significantly enhances the discharge energy density of the material from room temperature up to 180°C. Notably, the 0.88NBBT-0.12BMT ceramic exhibits the highest energy density among the tested compositions across various temperature conditions. Furthermore, the energy storage performance of 0.88NBBT8-0.12BMT ceramics was evaluated under different electric fields at 120°C, with results illustrated in Fig. 4b. At an electric field of 150 kV/cm, the material demonstrates a remarkable discharge energy density of approximately 2.01 J/cm3 and an efficiency exceeding 60% (Fig. 4c). These results suggest that this material is a suitable candidate for high-temperature energy storage dielectric applications.

Figure 4: (a) Comparison of discharge energy density of (1 − x)NBBT-xBMT ceramics at different test temperatures (at 85 kV/cm); (b) Unipolar electrical hysteresis loops of 0.88NBBT-0.12BMT ceramics under varying electric fields at 120°C; (c) Energy storage performance of 0.88NBBT-0.12BMT ceramics at 120°C

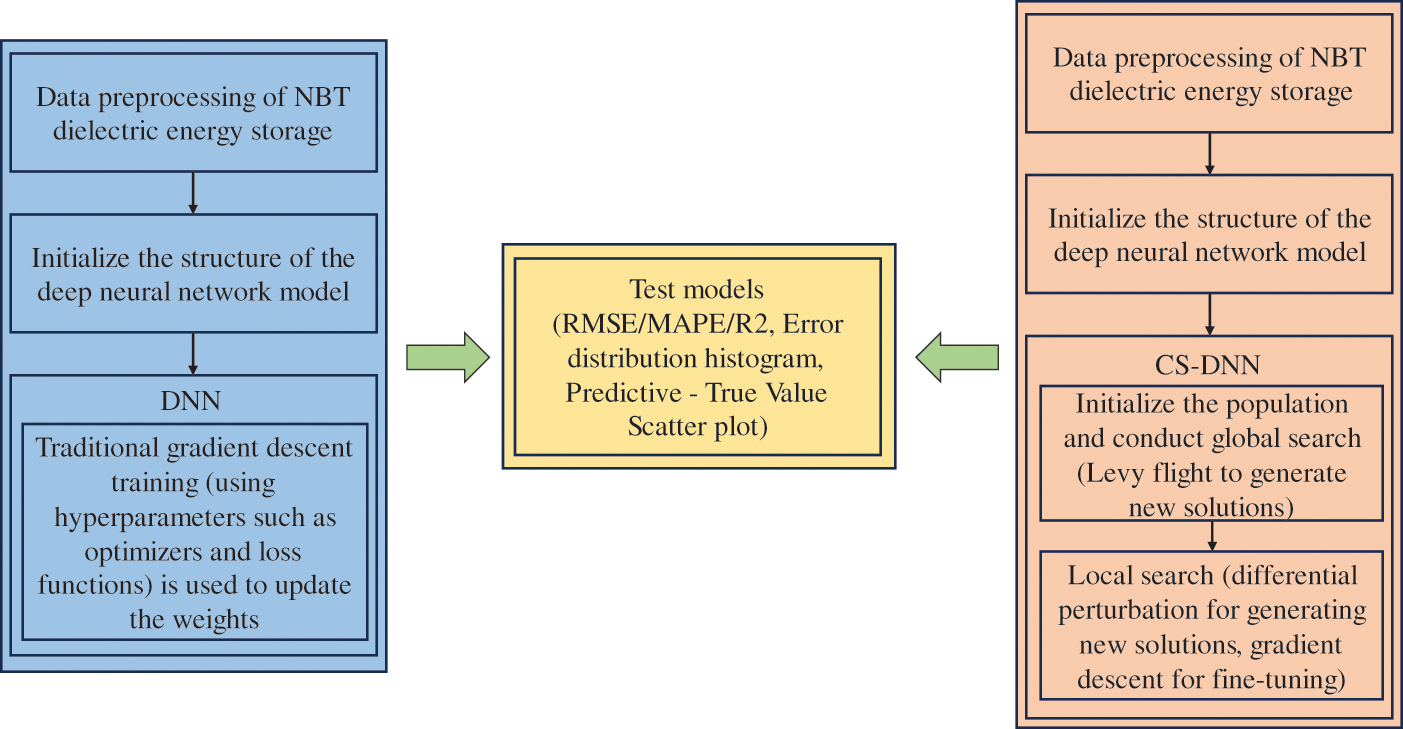

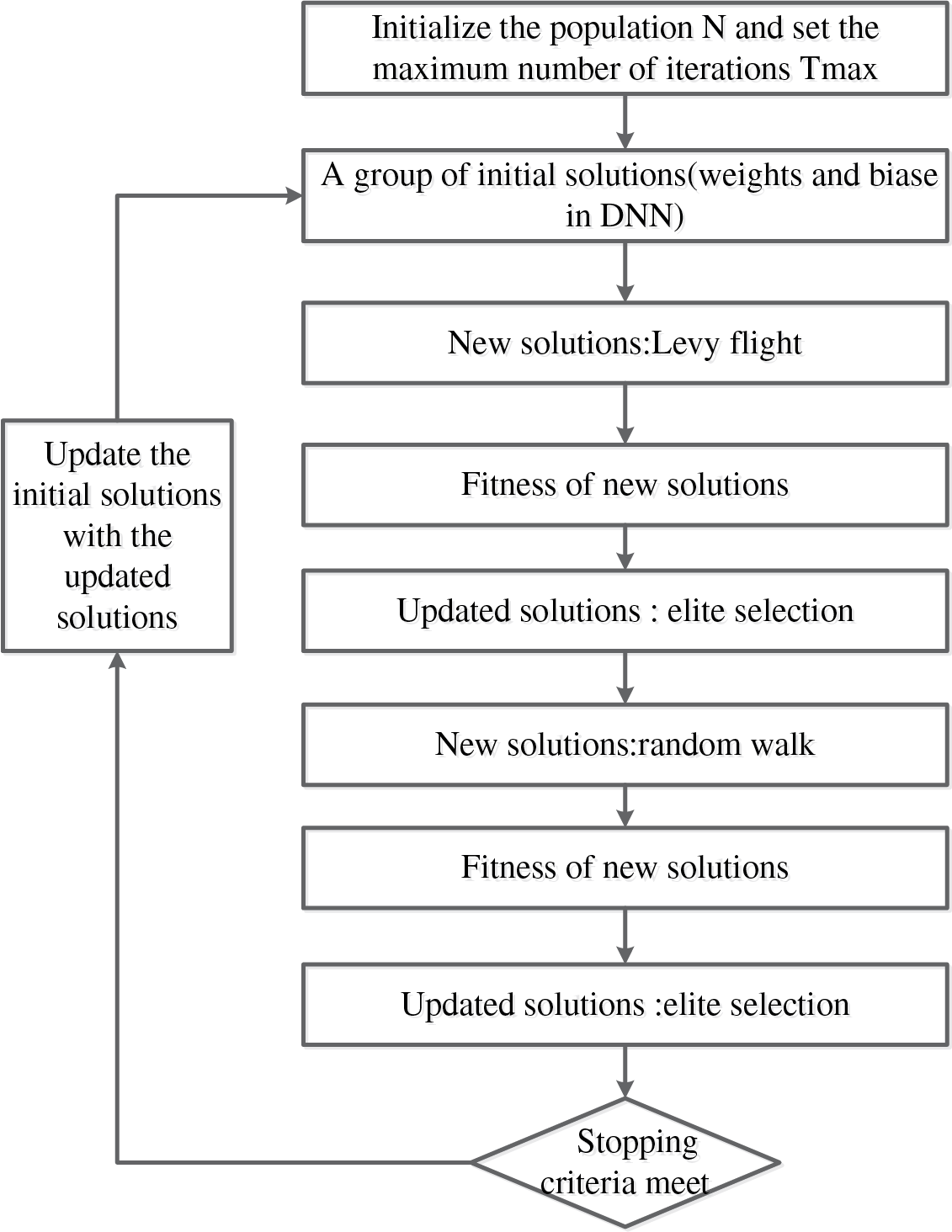

As illustrated in Fig. 5, this study introduces a CS-DNN hybrid framework for optimizing ferroelectric ceramics. The model integrates:

Figure 5: Machine learning flowchart

(1) CS’s Lévy flight-driven global optimization to escape local minima,

(2) DNN’s high-dimensional pattern recognition, and

(3) MCs/3σ uncertainty quantification—achieving exceptional prediction accuracy for Na1/2Bi1/2TiO3-based systems while maintaining 99.7% confidence intervals.

3.1 Data Collection and Preprocessing

A machine learning framework was developed to predict the properties of Na1/2Bi1/2TiO3 (NBT)-based ferroelectric ceramics, using chemical composition as the input and key dielectric/energy storage parameters—including the room-temperature dielectric constant (εr), maximum dielectric constant (εmax), dielectric loss (tan δ), discharge energy density (Wrec), and charge-discharge efficiency (η)—as the output targets. The dataset comprises experimentally synthesized (1 − x)NBBT8-xBMT ceramics with supplementary data from the literature [33,34]. Because of the limited dataset size, Monte Carlo simulation (MCs) with the 3σ principle was used for data augmentation to reduce overfitting. While effective for interpolation, this method inherently propagates the statistical features of the original dataset (e.g., bimodal structure), which may limit extrapolation capability.

To ensure reliability, a preprocessing pipeline was applied. Data normality was first assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test implemented via SciPy (Eq. (2)), since normally distributed data would not sufficiently challenge the CS-DNN’s non-linear search capacity.

where

The Monte Carlo method was then used to analyze stochastic sample behavior. Given a function

where N is the number of samples, x is the independent variable, and i denotes the i-th sample.

In general, MCs mainly consists of the following four processes:

(1) Defining the physical problem and influencing parameters,

(2) Generating representative input samples,

(3) Computing responses for each sample, and

(4) Extracting statistical indicators for uncertainty quantification.

Fig. 6 illustrates the uncertainty analysis workflow implemented through the combined MCs and CS-DNN framework. The original dataset comprised 45 experimental samples, confirmed by statistical testing to follow a bimodal distribution. To preserve this structure, data augmentation was performed separately for two compositional groups:

Figure 6: Uncertainty analysis workflow integrating MCs and CS-DNN models

Group 1: x = 0, 0.02, 0.04, 0.06, 0.10, 0.12, 0.14;

Group 2: x = 0.20, 0.40, 0.60, 0.80.

For training, both DNN and CS-DNN models used an 80:20 split of training and test sets. Importantly, the original test set was kept fixed throughout augmentation to ensure unbiased evaluation. Using this approach, the initially small dataset (NI) was expanded into a larger synthesized dataset (NL). Formally, the dataset expansion is expressed as:

The initial dataset

where

The training set

where

For uncertainty quantification, the 3σ principle was adopted, ensuring that

The data augmentation process can be concluded as follows:

(1) Generate random standardized inputs

(2) Apply trained function f to obtain outputs

(3) Expand dataset from size

The expanded dataset

3.2 Cuckoo Search Framework Design

To achieve optimal model performance, we employed the Cuckoo Search (CS) optimization algorithm for hyperparameter tuning. The CS algorithm is a bio-inspired metaheuristic that mimics the brood parasitic behavior of cuckoo species through three key mechanisms:

(1) Lévy flight-based random walks for global exploration of the parameter space

(2) Host nest selection via fitness-proportional probability sampling

(3) Exclusion of inferior solutions, where low-quality nests are discarded and replaced with new candidates according to the discovery probability

This mechanism balances exploration and exploitation, enabling efficient convergence toward optimal solutions. The CS algorithm was applied without modification in this work. Detailed mathematical formulations—including Lévy flight updating, step-size decay, and local refinements—along with hierarchical termination rules (stability checks, convergence validation, and quality benchmarks) and the full algorithmic flowchart (see Fig. A1) are provided in Appendix A.

The predictive accuracy and robustness of the CS-DNN model were assessed using three metrics:

Coefficient of determination (R2)—Proportion of variance explained by the model:

Mean absolute percentage error (MAPE)—Relative magnitude of errors:

Root-mean-square error (RMSE)—Absolute prediction accuracy:

where

The proposed CS-DNN hybrid model combines the global optimization capacity of the Cuckoo Search (CS) algorithm with the nonlinear learning strengths of Deep Neural Networks (DNNs). This integration addresses key shortcomings of gradient-based training, particularly sensitivity to initialization and entrapment in local minima.

The model architecture (Fig. 7) comprises:

Figure 7: CS-DNN and DNN model structure diagram

(1) Input layer: Material composition (x content).

(2) Hidden layers: Two fully connected layers with optimized activation functions.

(3) Output layer: Critical performance parameters (εr, εmax, tan δ, Wrec, η).

Fig. 8 illustrates the methodological workflow for dielectric property prediction in NBT-based ceramics, structured into three parallel pathways:

Figure 8: Comparative workflow diagram of conventional DNN and CS-DNN frameworks

1. Conventional DNN Training (Blue Pathway): Gradient-based backpropagation optimization; Potential convergence to local minima.

2. CS-DNN Hybrid Framework (Orange Pathway): Incorporates Cuckoo Search metaheuristic optimization; Enhanced global search capability; Mitigates local minimum traps through Lévy flight dynamics.

3. Unified Evaluation Module (Yellow Nexus): Standardized performance metrics (R2, RMSE, MAPE); Robustness assessment via k-fold (k = 3) cross-validation; Uncertainty quantification analysis.

This workflow represents an advancement in machine learning approaches for materials analysis: it successfully integrates metaheuristic optimization into deep learning architectures, overcoming the local optima that typically plague gradient-based methods while specifically addressing the instability of deep learning models induced by small datasets—thereby achieving enhanced stability and predictive capability.

Furthermore, Monte Carlo (MC) simulations were incorporated to quantify uncertainty in composition-dependent performance within the experimental domain. Although MC augmentation may produce samples slightly outside the measured range, such extrapolations serve only as statistical probes for robustness analysis, not as predictions of unverified material properties. The innovation of this framework is particularly evident in the design of energy storage materials, where it combines the global search capability of Cuckoo Search with robust statistical validation methods, providing both theoretical insights and practical design tools for NBT-based dielectric materials.

To implement the proposed CS-DNN model, we follow the workflow illustrated in Fig. 9. Under identical experimental conditions, a comparative analysis of DNN and CS-DNN models was conducted using the augmented dataset

Figure 9: Schematic diagram illustrating the integrated CS-DNN framework

The CS-DNN model was prioritized over alternatives such as Random Forests, SVMs, and Bayesian optimization due to its superior ability to capture smooth nonlinear composition–property relationships and its resilience to local minima. Unlike tree-based or kernel methods, CS-DNN supports continuous regression, global search optimization, and seamless integration with Monte Carlo uncertainty analysis. These features are particularly critical in sparse experimental settings, where model robustness and physical consistency are paramount. Future work will include formal benchmarking against alternative learning algorithms.

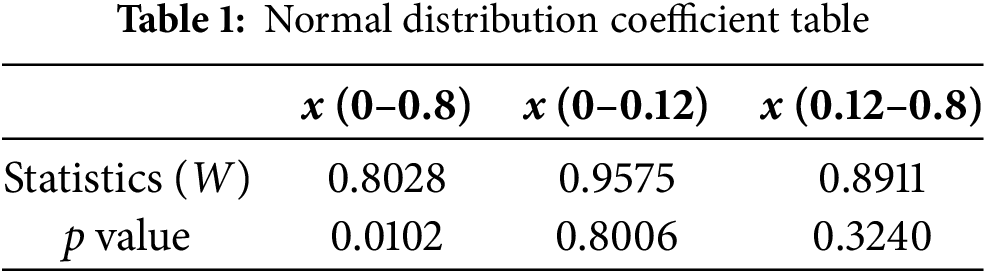

4.2 Model Performance Comparison

Normality testing of the 45-sample dataset using the Shapiro–Wilk test (Table 1) indicated significant deviation from unimodal normality (W = 0.8028, p < 0.05). This reflects intrinsic data uncertainty, including multimodal distributions and outliers. Stratified grouping revealed that subsets x < 0.12 and x ≥ 0.12 each satisfied normality, supporting a dual-distribution framework for subsequent Monte Carlo simulations and 3σ-based confidence intervals.

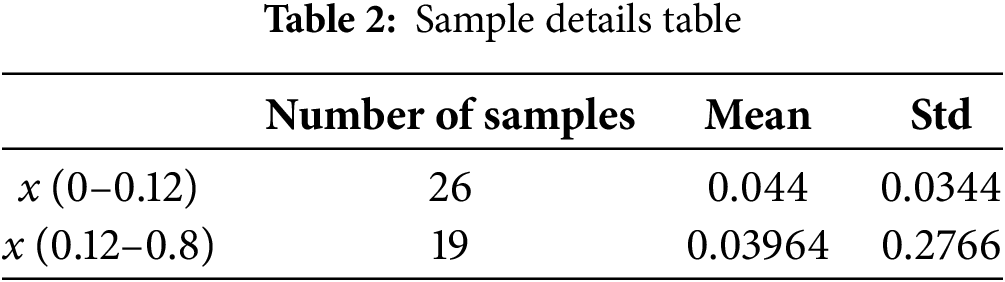

Since the data exhibited a bimodal distribution (Table 1), it was then partitioned into two subsets: x < 0.12 and x ≥ 0.12. The sample sizes, means, and variances for each subset are detailed in Table 2. Each subset was expanded to 100 data points, resulting in a final augmented dataset of 200 samples. This enhanced dataset was then employed to construct comparative CS-DNN and conventional DNN models, enabling systematic evaluation of their predictive accuracy, robustness, and key performance parameters.

Relative error histogram (Fig. 10) reveals that CS-DNN consistently outperforms DNN across dielectric properties, particularly under non-normal data distributions. The improvement derives from CS’s Lévy flight exploration, which strengthens robustness against gradient vanishing and poor initialization—limitations inherent to conventional DNNs. This methodological advancement is particularly relevant for materials science applications, where nonlinear composition-property relationships—such as phase transitions and oxygen vacancy suppression—demand robust uncertainty-aware models.

Figure 10: Relative error histogram of CS-DNN and DNN

As shown in Figs. 11 and 12, the CS-DNN displays significantly narrower prediction bands (indicated by the color legend of each subfigure), with ~95% of experimental points lying within 3σ bounds. While a small number of predictions are slightly beyond the experimental data range (x

Figure 11: Uncertainty analysis diagram of DNN model (a) εr (b) εmax (c) tan δ (d) Wrec (e) η

Figure 12: Uncertainty analysis diagram of CS-DNN model (a) εr (b) εmax (c) tan δ (d) Wrec (e) η

Figs. 11 and 12 also highlight the CS-DNN’s superiority in predicting nonlinear trends, particularly in low-BMT regions (x < 0.12). For instance, the RMSE for tan δ decreases by 32.6% (0.0031 vs. 0.0046), attributed to the model’s ability to capture BMT-induced phase transitions (Fig. 2b) and reduced oxygen vacancy formation (Fig. 3a). DNN’s higher errors in these regions arise from gradient vanishing during backpropagation, a limitation circumvented by CS’s stochastic exploration.

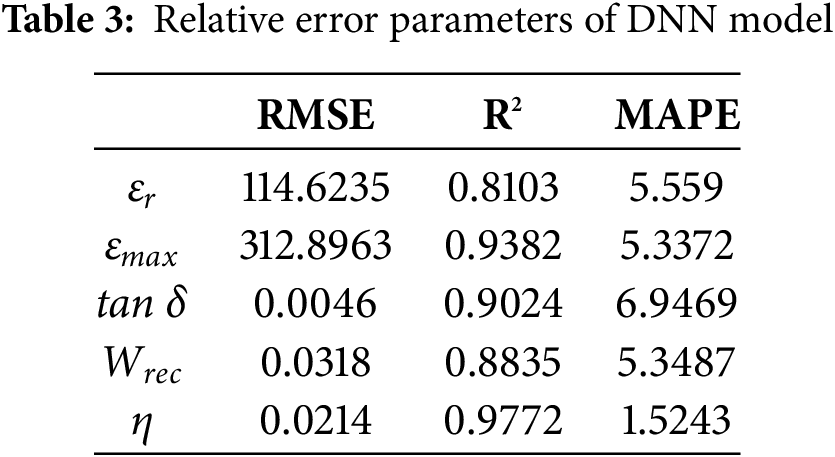

Error resilience benefitted from the CS algorithm’s global search capability effectively reduces overfitting as demonstrated by the lower mean absolute percentage error (MAPE = 4.04% for εmax vs. DNN’s 5.34%) and improved determination coefficient (R2 = 0.9717 vs. 0.9382) in Tables 3 and 4.

Table 5 quantitatively demonstrates the performance enhancement of the CS-DNN model over conventional DNN. The core innovation lies in circumventing local minima in gradient-based optimization through Cuckoo Search’s Lévy flight mechanism, significantly improving prediction accuracy for key parameters:

1. Global Optimization Advantage: CS-DNN exhibits superior robustness with non-normal distributed data (Table 1), achieving an average 3.0% increase in R2 across all output parameters;

2. Uncertainty Quantification Breakthrough: Integrated Monte Carlo simulations and 3σ criterion provide statistically reliable prediction intervals for composition design.

While the experimental dataset spans from x = 0 to 0.80, the CS-DNN model supports extrapolation through Monte Carlo sampling and 3σ-based uncertainty quantification. Input compositions exceeding x = 0.80 (approaching the 0.8 threshold) generate significantly wider prediction intervals, reflecting elevated model uncertainty in this compositional regime. These trends are consistent with previous CS-DNN applications in high-dimensional alloy systems [23] and validate the framework’s adaptability. Future extensions will prioritize (i) dataset expansion via high-throughput synthesis or simulations, (ii) integration of physical constraints (e.g.. phase stability), and (iii) multi-objective CS optimization for balancing competing dielectric properties.

In summary, the CS-DNN framework demonstrates robust predictive accuracy, uncertainty awareness, and physical interpretability. By integrating metaheuristic optimization into deep learning, it establishes a scalable paradigm for accelerating the design of next-generation ferroelectric ceramics. While this study focused solely on composition (x) as the input, the framework can be extended to multi-feature models, enabling feature attribution and deeper physical insights. Nonetheless, compositional sensitivity was implicitly reflected in model behavior, with pronounced predictive inflection near x = 0.12, consistent with observed phase transitions. Future work will extend the framework to multi-feature systems to enable full-feature attribution analysis.

In this study, a hybrid CS-DNN model—integrating the global search capability of the Cuckoo Search algorithm with the nonlinear learning power of Deep Neural Networks—was proposed to analyze uncertainty in dielectric energy storage performance and guide the composition design of NBT-based ceramic capacitors. The (1 − x)NBBT8–xBMT solid solution ceramics were fabricated via the solid-state reaction method, and their structural, dielectric, and energy storage properties were systematically investigated. Compared with the conventional DNN model, CS-DNN achieved higher predictive accuracy (R2 = 0.97) and lower relative error (MAPE = 1.20%), while also identifying key descriptors governing energy storage behavior. The framework demonstrates excellent interpolation within the experimental composition range (x

Experimentally, BMT incorporation was shown to significantly enhance the high-temperature stability of NBT-based ceramics. At an applied field of 150 kV/cm and 120°C, the discharge energy density reached 2.01 J/cm3 with efficiency exceeding 60%. These improvements are attributed to stabilization of the pseudo-cubic phase, suppression of oxygen vacancy formation, and mitigation of dielectric loss and polarization hysteresis. Such findings validate the combined computational–experimental approach, where machine learning insights directly align with observed physical mechanisms.

Overall, this work establishes a novel CS-DNN hybrid framework that bridges data-driven modeling with physical understanding, accelerating the discovery of high-performance dielectric materials. By overcoming limitations of gradient-based optimization (e.g., local minima) and improving interpretability through feature analysis, the model provides a scalable paradigm for material design. Future work will expand the framework to incorporate multi-scale descriptors (e.g., phase stability, grain boundaries) and advanced interpretability tools (e.g., SHAP, attention mechanisms), enabling explicit links between processing, structure, and performance. In addition, efforts will focus on dataset enrichment, multi-objective optimization, and application to next-generation ferroelectric capacitors, aligning with the broader goals of the Materials Genome Initiative.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to express their sincere thanks to Prof. Leilei Chen for his constructive suggestions in the revision of the manuscript.

Funding Statement: This research is supported by the Postgraduate Education Reform and Quality Improvement Project of Henan Province (Grant Nos. YJS2023JD52 and YJS2025GZZ48), the Zhumadian 2023 Major Science and Technology Special Project (Grant No. ZMD SZDZX2023002), 2025 Henan Province International Science and Technology Cooperation Project (Cultivation Project, No. 252102521011) and Research Merit-Based Funding Program for Overseas Educated Personnel in Henan Province (Letter of Henan Human Resources and Social Security Office [2025] No. 37).

Author Contributions: Shige Wang: Experimental test, Writing—original draft; Yalong Liang: Writing—original draft, Code support; Lian Huang: Methodology, Example analysis; Pei Li: Writing—review & editing, Supervision. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author upon reasonable request. Source code for the CS-DNN model is also available upon request for academic, non-commercial research purposes only.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable, this study not involving humans or animals.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Appendix A Flow Chart for the CS Algorithm

Figure A1: Cuckoo search process

Appendix B The Formula Derivation Process of the Cuckoo Algorithm: Lévy flight: Lévy flight is a random walk process used to explore the search space. It is characterized by heavy-tailed distribution, allowing occasional long jumps, so as to effectively explore the local and global regions of the search space. Cuckoos use Levi’s flight to update the nest location and search for new nest locations according to the following formula:

where

where max_iter is the maximum number of iterations, epoch is the current number of iterations,

where s is a random variable and λ is the stability index.

The CS algorithm usually calculates the step size in the following way:

where

Therefore, Formula (A1) can be rewritten as:

where

Nest selection: After Lévy flight, the best nest (solution) is selected according to the fitness value. Poorly performing nests are abandoned and new random solutions are introduced into the population to maintain diversity.

Egg laying: Cuckoos also lay eggs in the nests of other birds, which represents a form of exploration and diversification. It simulates by combining existing solutions and random perturbations to generate new candidate solutions.

Local search: Local search is used to further optimize the solution obtained from Lévy’s flight and spawning process, mainly focusing on exploring the neighborhood of the solution to improve its quality. The new nest position is generated according to the following formula:

where

Termination criterion: The algorithm iteratively executes the above steps until the termination criterion is satisfied. The termination criteria were implemented through three hierarchical conditions: (1) Maximum iterations (no prescribed upper limit; optimization terminates after evaluation metrics in Section 3.3 stabilize for >200 consecutive iterations, followed by parameter recording and retraining), (2) Solution convergence was validated when the relative error between successive predictions fell below 10−6. (3) Solution quality benchmarks (R2 > 0.80 and MAPE < 10, as defined in Eqs. (A1)–(A8)).

Appendix C Model Hyperparameter

References

1. Jiang Z, Yang H, Cao L, Yang Z, Yuan Y, Li E. Enhanced breakdown strength and energy storage density of lead-free Bi0.5Na0.5TiO3-based ceramic by reducing the oxygen vacancy concentration. Chem Eng J. 2021;414:128921. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2021.128921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Hao X. A review on the dielectric materials for high energy-storage application. J Adv Dielect. 2013;3(1):1330001. doi:10.1142/s2010135x13300016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Wu J, Tan H, Qi H, Yu H, Chen L, Li W, et al. High energy storage performance in BiFeO3-based lead-free high-entropy ferroelectrics. Small. 2024;20(36):2400997. doi:10.1002/smll.202400997. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Yang B, Zhang Y, Pan H, Si W, Zhang Q, Shen Z, et al. High-entropy enhanced capacitive energy storage. Nat Mater. 2022;21(9):1074–80. doi:10.1038/s41563-022-01274-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Chu B, Zhou X, Ren K, Neese B, Lin M, Wang Q, et al. A dielectric polymer with high electric energy density and fast discharge speed. Science. 2006;313(5785):334–6. doi:10.1126/science.1127798. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Liu Z, Xu S, Ma Y, Lian H, Qu Y, Chen L. Polynomial chaos expansion-based stochastic phase field model for hydrogen-assisted cracking. Theor Appl Fract Mech. 2025;139:105000. doi:10.1016/j.tafmec.2025.105000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Chen L, Lian H, Liu C, Li Y, Natarajan S. Sensitivity analysis of transverse electric polarized electromagnetic scattering with isogeometric boundary elements accelerated by a fast multipole method. Appl Math Model. 2025;141:115956. doi:10.1016/j.apm.2025.115956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Zhou Z, Gao Y, Cheng Y, Ma Y, Wen X, Sun P, et al. Uncertainty quantification of vibroacoustics with deep neural networks and catmull-Clark subdivision surfaces. Shock Vib. 2024;2024(1):7926619. doi:10.1155/2024/7926619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Xiao F, Shi B, Gao J, Chen H, Yang D. Enhanced probabilistic prediction of pavement deterioration using Bayesian neural networks and cuckoo search optimization. Sci Rep. 2025;15:8665. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-92469-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Gandomi AH, Yang XS, Alavi AH. Cuckoo search algorithm: a metaheuristic approach to solve structural optimization problems. Eng Comput. 2013;29(1):17–35. doi:10.1007/s00366-011-0241-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Zhou Q, Xu F, Gao C, Zhang D, Shi X, Yuen MF, et al. Machine learning-assisted mechanical property prediction and descriptor-property correlation analysis of high-entropy ceramics. Ceram Int. 2023;49(4):5760–9. doi:10.1016/j.ceramint.2022.10.105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Gong J, Chu S, Mehta RK, McGaughey AJH. XGBoost model for electrocaloric temperature change prediction in ceramics. npj Comput Mater. 2022;8:140. doi:10.1038/s41524-022-00826-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Boiko DA, MacKnight R, Kline B, Gomes G. Autonomous chemical research with large language models. Nature. 2023;624(7992):570–8. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-06792-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Raccuglia P, Elbert KC, Adler PDF, Falk C, Wenny MB, Mollo A, et al. Machine-learning-assisted materials discovery using failed experiments. Nature. 2016;533(7601):73–6. doi:10.1038/nature17439. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Gu W, Yang B, Li D, Shang X, Zhou Z, Guo J. Accelerated design of lead-free high-performance piezoelectric ceramics with high accuracy via machine learning. J Adv Ceram. 2023;12(7):1389–405. doi:10.26599/jac.2023.9220762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Maddaiah PN, Narayanan PP. An improved cuckoo search algorithm for optimization of artificial neural network training. Neural Process Lett. 2023;55(9):12093–120. doi:10.1007/s11063-023-11411-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Shen ZH, Liu HX, Shen Y, Hu JM, Chen LQ, Nan CW. Machine learning in energy storage materials. Interdiscip Mater. 2022;1(2):175–95. doi:10.1002/idm2.12020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Jain A, Ong SP, Hautier G, Chen W, Richards WD, Dacek S, et al. Commentary: the materials project: a materials genome approach to accelerating materials innovation. APL Mater. 2013;1:011002. doi:10.1063/1.4812323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Curtarolo S, Setyawan W, Wang S, Xue J, Yang K, Taylor RH, et al. AFLOWLIB.ORG: a distributed materials properties repository from high-throughput ab initio calculations. Comput Mater Sci. 2012;58:227–35. doi:10.1016/j.commatsci.2012.02.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Saal JE, Kirklin S, Aykol M, Meredig B, Wolverton C. Materials design and discovery with high-throughput density functional theory: the open quantum materials database (OQMD). JOM. 2013;65(11):1501–9. doi:10.1007/s11837-013-0755-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Kim C, Pilania G, Ramprasad R. Machine learning assisted predictions of intrinsic dielectric breakdown strength of ABX3 perovskites. J Phys Chem C. 2016;120(27):14575–80. doi:10.1021/acs.jpcc.6b05068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Liu J, Xiong P, Li C, Hao H, Liu H. Machine learning-assisted accelerated research of energy storage properties of BaTiO3-BiMeO3 ceramics. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2025;13(8):3362–73. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.4c10430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Qiao L, Zhu J. Cuckoo search-artificial neural network aided the composition design in Al-Cr-Co-Fe-Ni high entropy alloys. Appl Surf Sci. 2024;669:160539. doi:10.1016/j.apsusc.2024.160539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Qiao L, Zhu J, Wan Y, Cui C, Zhang G. Finite element-based machine learning approach for optimization of process parameters to produce silicon carbide ceramic complex parts. Ceram Int. 2022;48(12):17400–11. doi:10.1016/j.ceramint.2022.03.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. He J, Li J, Liu C, Wang C, Zhang Y, Wen C, et al. Machine learning identified materials descriptors for ferroelectricity. Acta Mater. 2021;209:116815. doi:10.1016/j.actamat.2021.116815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Yuan R, Tian Y, Xue D, Xue D, Zhou Y, Ding X, et al. Accelerated search for BaTiO3-based ceramics with large energy storage at low fields using machine learning and experimental design. Adv Sci. 2019;6(21):1901395. doi:10.1002/advs.201901395. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Chen L, Pei Q, Fei Z, Zhou Z, Hu Z. Deep-neural-network-based framework for the accelerating uncertainty quantification of a structural-acoustic fully coupled system in a shallow sea. Eng Anal Bound Elem. 2025;171:106112. doi:10.1016/j.enganabound.2024.106112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Yuan R, Liu Z, Balachandran PV, Xue D, Zhou Y, Ding X, et al. Accelerated discovery of large electrostrains in BaTiO3-based piezoelectrics using active learning. Adv Mater. 2018;30(7):1702884. doi:10.1002/adma.201702884. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Smolenskii GA, Isupov VA, Agranovskaya AI, Krainik N. New ferroelectrics of complex composition. Sov Phys Solid State. 1961;2:2651–4. [Google Scholar]

30. Rödel J, Jo W, Seifert KTP, Anton EM, Granzow T, Damjanovic D. Perspective on the development of lead-free piezoceramics. J Am Ceram Soc. 2009;92(6):1153–77. doi:10.1111/j.1551-2916.2009.03061.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Chen P, Chu B. Improvement of dielectric and energy storage properties in Bi(Mg1/2Ti1/2)O3-modified (Na1/2Bi1/2)0.92Ba0.08TiO3 ceramics. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2016;36(1):81–8. doi:10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2015.09.029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Chu BJ, Chen DR, Li GR, Yin QR. Electrical properties of Na1/2Bi1/2TiO3-BaTiO3 ceramics. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2002;22(13):2115–21. doi:10.1016/S0955-2219(02)00027-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Garg R, Rao BN, Senyshyn A, Krishna PSR, Ranjan R. Lead-free piezoelectric system (Na0.5Bi0.5)TiO3-BaTiO3: equilibrium structures and irreversible structural transformations driven by electric field and mechanical impact. Phys Rev B. 2013;88:014103. doi:10.1103/physrevb.88.014103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Cross LE. Relaxorferroelectrics: an overview. Ferroelectrics. 1994;151(1):305–20. doi:10.1080/00150199408244755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Shapiro SS, Wilk MB. An analysis of variance test for normality (complete samples). Biometrika. 1965;52(3/4):591–611. doi:10.1093/biomet/52.3-4.591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools