Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

An Auto Encoder-Enhanced Stacked Ensemble for Intrusion Detection in Healthcare Networks

1 Information Systems Department, College of Computer and Information Sciences, Princess Nourah bint Adulrahman University, Riyadh, 11671, Saudi Arabia

2 Department of Computer Science and Engineering, College of Applied Studies and Community Service, King Saud University, P.O. Box 22459, Riyadh, 11495, Saudi Arabia

3 Department of Computing, College of Engineering and Computing, Umm AL-Qura University, Al-Qunfudhah, 28821, Saudi Arabia

4 Computer Science Department, College of Computer & Information Science, Prince Sultan University, Riyadh, 11586, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Author: Mohammed Zakariah. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence for Intrusion Detection Systems)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(2), 3457-3484. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.068599

Received 02 June 2025; Accepted 18 July 2025; Issue published 23 September 2025

Abstract

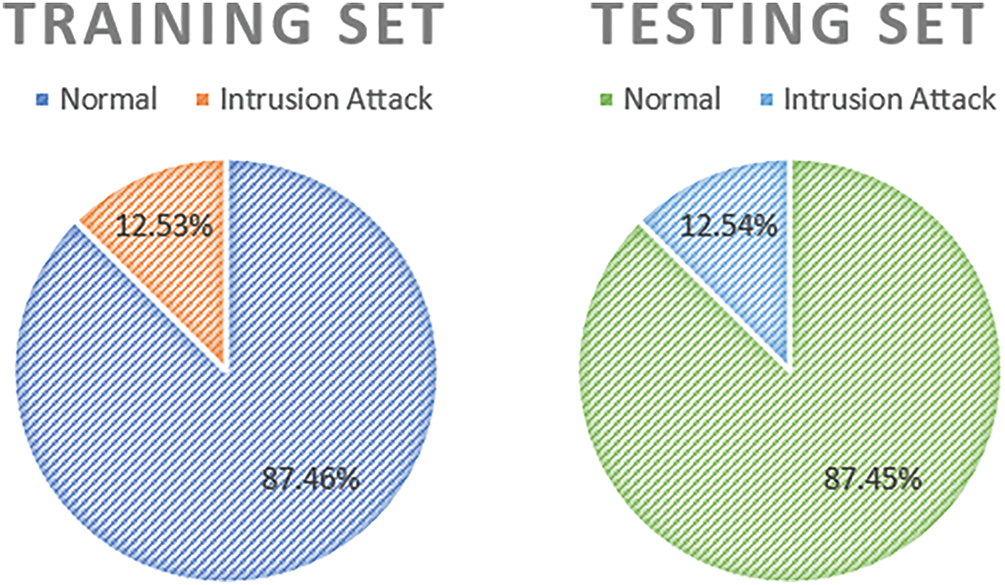

Healthcare networks prove to be an urgent issue in terms of intrusion detection due to the critical consequences of cyber threats and the extreme sensitivity of medical information. The proposed Auto-Stack ID in the study is a stacked ensemble of encoder-enhanced auctions that can be used to improve intrusion detection in healthcare networks. The WUSTL-EHMS 2020 dataset trains and evaluates the model, constituting an imbalanced class distribution (87.46% normal traffic and 12.53% intrusion attacks). To address this imbalance, the study balances the effect of training Bias through Stratified K-fold cross-validation (K = 5), so that each class is represented similarly on training and validation splits. Second, the Auto-Stack ID method combines many base classifiers such as TabNet, LightGBM, Gaussian Naive Bayes, Histogram-Based Gradient Boosting (HGB), and Logistic Regression. We apply a two-stage training process based on the first stage, where we have base classifiers that predict out-of-fold (OOF) predictions, which we use as inputs for the second-stage meta-learner XGBoost. The meta-learner learns to refine predictions to capture complicated interactions between base models, thus improving detection accuracy without introducing bias, overfitting, or requiring domain knowledge of the meta-data. In addition, the auto-stack ID model got 98.41% accuracy and 93.45% F1 score, better than individual classifiers. It can identify intrusions due to its 90.55% recall and 96.53% precision with minimal false positives. These findings identify its suitability in ensuring healthcare networks’ security through ensemble learning. Ongoing efforts will be deployed in real time to improve response to evolving threats.Keywords

Owing to the inimitable use of digital technology, global healthcare systems are undergoing remarkable changes, and digital health technologies such as electronic health records (EHR), telemedicine, and connected medical devices are now principally incorporated into patient care [1]. Simultaneously, this digital transformation has generated an accelerated surge in cyber threats to attack sensitive patient information and disrupt crucial and required healthcare services. Cyberattacks are likely to cause more harm owing to the interconnected nature of modern healthcare networks. Being unprepared was the worst option. Because adversaries pay much attention to such high-value and privacy-sensitive medical data, cybersecurity is necessary for healthcare institutions [2]. Intrusion detection systems in this domain are essential for identifying and counteracting malicious actions in healthcare networks. However, the complexity of medical network traffic and the fact that data is highly sensitive make it challenging to deploy conventional IDS [3].

Traditional IDS provided by rule (shallow machine and shallow) learning algorithms fail to detect novel cyber threats and new attack patterns [4,5]. At present, Rule-based IDS relies on predefined signatures; hence, these solutions are not effective when the attack is not known a priori (zero-day attacks), while state-of-the-art shallow machine learning models struggle with the rate of high-dimensional and unstructured medical data, and consequently, high false positive and false negative rates. These shortcomings highlight a pressing need for IDS answers to be more effective and experience-focused in the medical area.

To solve some of these challenges, this research presents an Auto Encoder Enhanced Stacked Ensemble (AESE) model to enhance intrusion detection in healthcare networks. AESE model is a union of the power of unsupervised learning stemming from autoencoders and robust classification provided by stacked ensemble methods [6]. Among artificial neural networks designed for unsupervised data learning, autoencoders are specifically good at capturing the intrinsic structures of high-dimensional data. Thus, they can detect anomalous behaviors, which may signal potential intrusions [7,8]. The system can learn the deviations and hence be able to recognize those related to cyber threats, such as previously unseen attack patterns on regular network traffic, by training autoencoders on these values. A stacked ensemble learning is included to improve further the model’s precision of classifying intrusions, as they are considered a weakness of traditional IDS solutions [9]. Since it is a combination approach, it ensures not only a comprehensive security framework but also one that is adaptable to address both known and unknown cyber threats.

Our approach is practical by validating using the WUSTL-EHMS 2020 dataset, a comprehensive dataset with network traffic logs and behavioral and physiological signals. Unlike conventional IDS that focus only on network packets, the AESE model is different in that we use biometric indicators such as heart rate, respiratory rate, and blood pressure to improve security by exploiting their ability to provide a comprehensive intrusion mechanism in the complex and sensitive environment of the Healthcare network.

Moreover, the digitization of healthcare systems has without a doubt transformed the sphere of patient care and operational effectiveness. Nevertheless, this shift has also brought about miserable cybersecurity problems. Healthcare networks with their large-dimensional and heterogeneous data (real-time physiological monitoring to sensitive biometric data) are becoming susceptible to advanced cyberattacks. Rule-based or shallow machine learning-based Traditional Intrusion Detection Systems (IDS) have a hard time keeping up with the dynamics of these threats and thus perform poorly in detection with high false positives. Furthermore, with the implantation of biometric data transmission into the healthcare traffic, there are more levels of complexity, and threat detection and prevention are even more challenging. Such drawbacks point out the urgent necessity of smart, dynamic, and scalable IDS systems, which can learn based on intricate data patterns efficiently. The suggested AutoStack-ID fills this gap by deep feature representation using autoencoders and a stacked ensemble of multiple learners to improve detection accuracy, flexibility, and robustness in protecting contemporary healthcare networks.

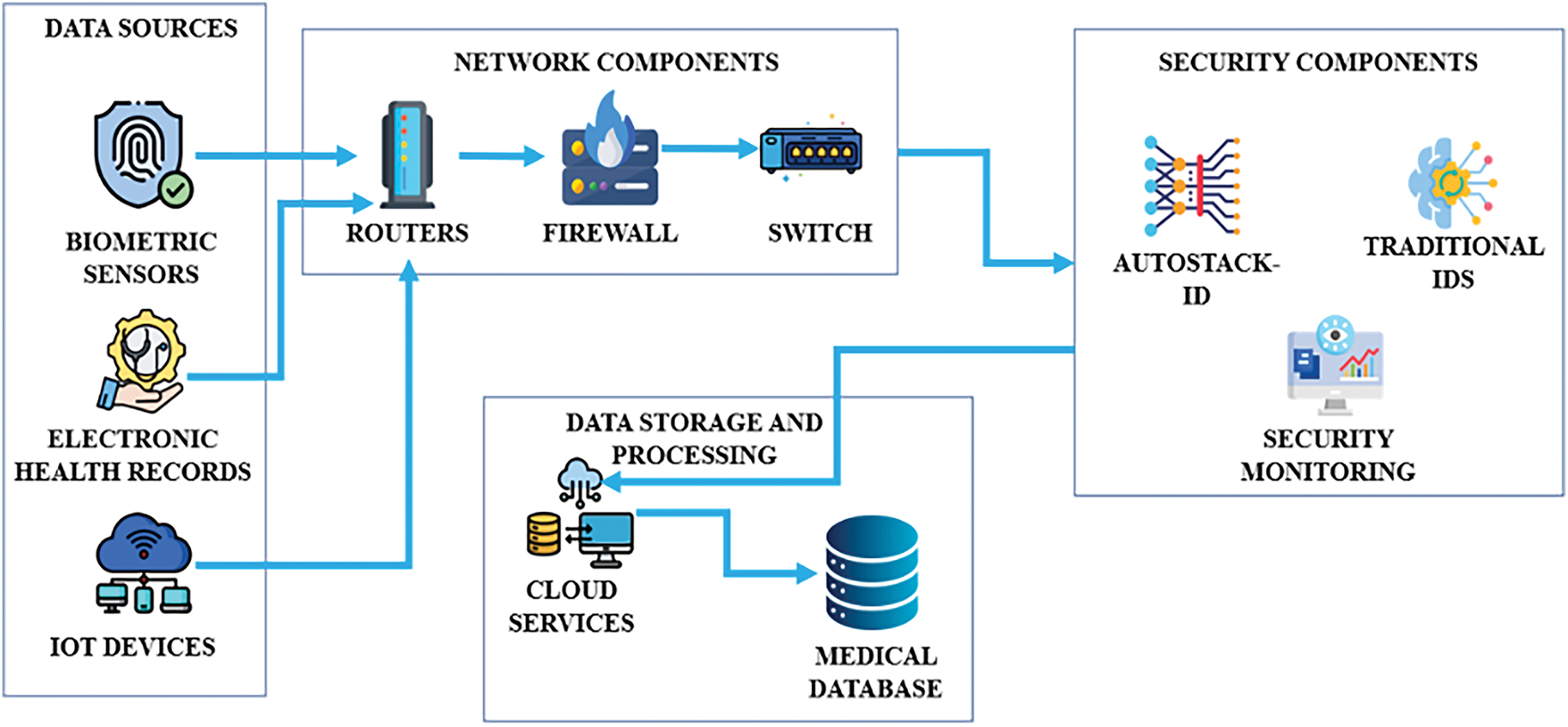

Further, Fig. 1 illustrates the framework of an autoencoder-enhanced stacked ensemble model for intrusion detection in medical networks. Integrating autoencoders for feature learning with stacked ensemble techniques improves detection accuracy and robustness to various intrusion threats in medical systems.

Figure 1: Framework of auto encoder-enhanced stacked ensemble for intrusion detection in medical network

The following are the contributions of the study:

i) Deep Autoencoder-Based Feature Extraction: The feature extraction is based on deep autoencoders, which produce a compressed representation of the network and biometric data that can identify essential patterns to distinguish normal from anomalous behavior.

ii) Feature Engineering Optimization: This technique uses scaling, polynomial expansion, and categorical encoding to cater to various data types and make the model even more accurate.

iii) Base Models: This combination of Naïve Bayes, Logistic Regression, HistGradient Boosting, TabNet, and LightGBM is a base model that performs better using a more potent feature space.

iv) XGBoost Meta-Learner with Stacked Ensemble: A combination of predicting with XGBoost and further refining the predictions using an ensemble of base models to improve overall classification accuracy.

The structure of this study is as follows: Section 2 contains a literature review summarizing relevant previous work. The dataset used for the research and the methodology are described in Sections 3 and 4, respectively. The results and analysis are presented and discussed in Section 5 and interpreted in light of the broader context in Section 6. Section 7 concludes the study with insights into the main findings and directions for future research.

The Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) has transformed healthcare from end to end through seamless communication between medical devices. Nevertheless, there is an inherent cybersecurity challenge as IoMT is integrated into the healthcare infrastructure [8].

The adaptive intrusion detection system proposed by Alalhareth and Hong [9] is an intrusion detection system (IDS) for IoMT based on a fuzzy self-tuning Long-Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network. The model was designed to adapt dynamically to the fluctuating nature of IoMT environments. Although their results demonstrated accuracies of 94.8%, a fielding issue with static epochs and batch size adjustments limits the use of this system. In a dynamic real-world scenario, the inability to adjust the training parameters in real time may affect system performance. For example, Alsolami et al. [10] applied ensemble learning models to achieve cybersecurity in the IoMT. They reported high accuracy rates with stacking of 98.88%. Nevertheless, their models were tested against the WUSTL-EHMS-2020 dataset, which may not be a thorough IoMT attack approximation. The authors added that the models may not generalize across different datasets, making them unsuitable for broader applications.

Furthermore, Vishwakarma and Kesswani [11] considered transfer learning to develop a robust IDS for IoT and IoMT environments. Finally, they achieved an accuracy of 93.75% on the NF-UQ NIDS dataset using 1D CNN and transfer learning. Rahman et al. [12] also studied a nonlinear approach that combined linear and nonlinear classifiers in a general model. Using cross-validation, they achieved a high accuracy of 98.62%, with significantly good areas under the curve (AUC) and accuracy (ACC). Alamro et al. [13] employed a different approach utilizing blockchain technology and attention-based deep learning models for cybersecurity in the IoT. However, they are explicitly used in consumer electronics. The model achieved a good F1-score of 89.76%.

In addition, Balhareth and Ilyas [14], intrusion detection was optimized in IoMT networks using tree-based machine learning classifiers such as XGBoost. They applied filter-based feature selection to achieve a 98.79% accuracy at a FAR of 0.007. In addition, Alalwany et al. [15] proposed an ensemble method for stacking deep learning for real-time intrusion detection in an IoMT environment. Their model’s performance was extraordinary for binary classification, with 0.991 accuracy; for multiclass classification, it was 0.993.

Furthermore, Musikawan et al. [16] added intrusion detection to IoMT systems by utilizing a deep stacking network with feature augmentation. Their model showed performance improvements of 0.12% to 329.21% on the WUSTL-EHMS dataset. Similarly, Alsaffar et al. [17] used dimensionality reduction and multi-stacking ensemble techniques to improve the performance of an intrusion detection system. Although their approach successfully reduced the feature space and generated better attack prediction, deploying it in an extreme class setting is challenging. Therefore, its accuracy on the UNSW-NB15 dataset was 90.29%, which is noticeable yet still holds room for improvement.

Finally, Lazrek et al. [18] proposed an RFE/ridge-ML/DL-based anomaly intrusion detection method with a testing accuracy of 97.85% on the WUSTL-EHMS dataset.

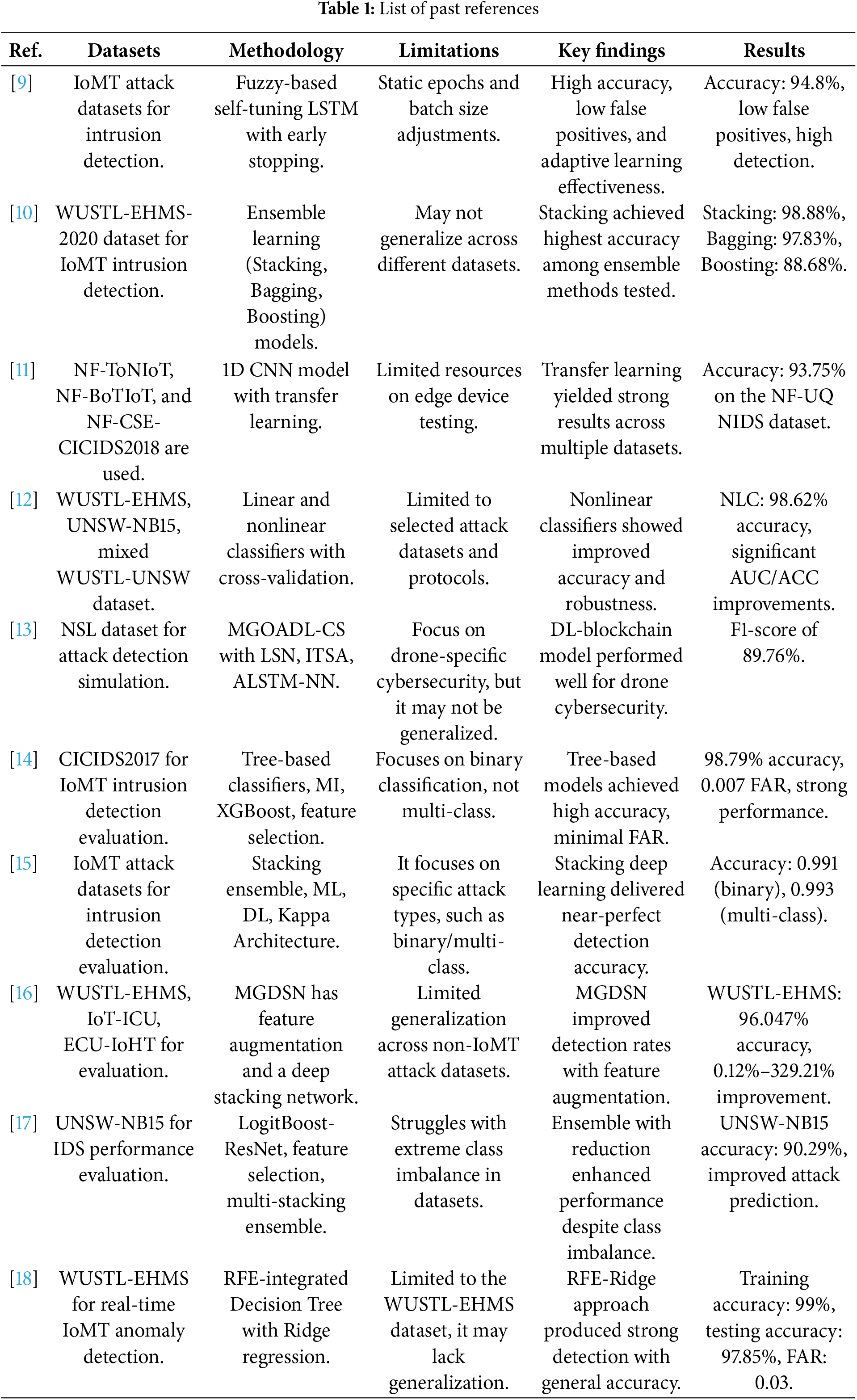

Table 1 lists past references, including the datasets, methodology, limitations, and results.

3.1 Dataset Overview and Feature Engineering

The WUSTL-EHMS 2020 dataset [19] is a medical environment intrusion detection dataset mainly built for cybersecurity research. The data combines cyber with biometric data and is a feasible and challenging real-world dataset for handling security threats in healthcare systems. The medical environment in the dataset simulates a hospital or clinical setting where various digital systems interact, including Electronic Health Records (EHRs), which store sensitive patient data; Medical IoT Devices, such as heart rate monitors, pulse oximeters, and blood pressure monitors; Networked Medical Equipment, such as infusion pumps and ventilators that communicate over hospital networks; and Healthcare Communication Systems, including real-time patient monitoring dashboards and physician alerting systems. In this scenario, malicious cyber activities could interfere with healthcare services and disrupt patient care.

3.2 Exploratory Data Analysis of the Benchmark Dataset

This analysis concerns preprocessing steps, feature engineering, and applying machine learning techniques to intrusion detection systems (IDS) [19,20]. Network traffic and biometric training data are classified into “normal” and “intrusion attacks”. First, missing data are handled, followed by feature encoding and transformation, Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) tests, and finally, auto-encoders, where there are models to enhance features [21,22].

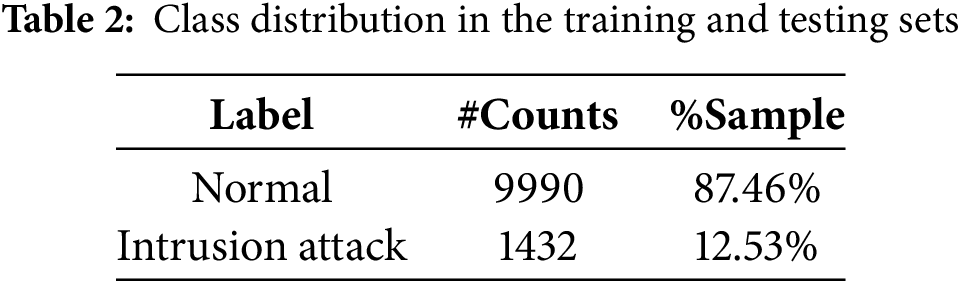

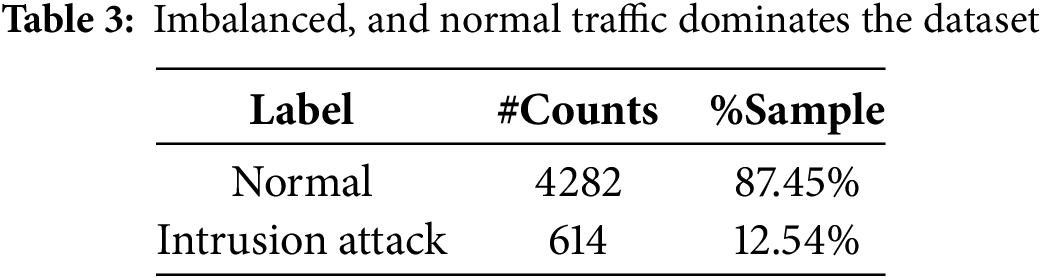

i. Data Overview and Class Distribution

Therefore, the data distribution must first be understood to evaluate the performance before inflaming it. This section provides the training and testing sets, along with their class distributions, and also details about the imbalanced dataset (see Tables 2 and 3, and Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Class distribution in the Training/Testing sets

The model was evaluated in a context similar to the training distribution; hence, the testing set followed a similar distribution pattern. This imbalance requires special care in the classification model to detect both classes correctly.

ii. Missing Value Treatment

The dataset did not suffer from missing values or redundant records. However, there are some features in which the data are categorical and must be converted to ML models. In particular, integer labels for features such as network packet flags (i.e., integer representation of labels) are encoded using a custom dictionary [23]. Instead of NaN, missing or unmapped categorical values are assigned as −1; therefore, the machine learning model still works.

iii. Feature Encoding and Transformation

Some features, such as source and destination ports, are initially in string format and hence are converted to numeric values [24,25]. To prevent problems with NaN in the port columns, the missing data were replaced with −1.

iv. Feature Analysis

Understanding how the features interact with the target labels (‘Normal’ or ‘Intrusion Attack’) is essential. Two techniques are used to gain insights into feature importance: the Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) test and SHAP values [26].

(a) Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) Test: It uses the KS test to determine how well a given feature separates or would separate normal from attack traffic. In general, the higher the KS value, the higher the distinguishability of the feature used. The KS summary table for features is given in Table 4:

The highest-ranking features include:

• DstJitter: A good measure of distinguishing normal and attack traffic with a value of KS = 0.4693. It varies with the time between packets.

• KS value: 0.4660 (DIntPkt: The inter-arrival time of packets for the destination tuned during attacks).

• SrcLoad and DstLoad: Indicate load at source and destination nodes. They have KS values of 0.4461 and 0.4451, which indicate that these two features are critical in their capability of separating attack and normal traffic.

• Inter-packet timing at the source, i.e., SIntPkt, also plays a vital role with a KS of 0.4459.

• Although biometric features like Pulse_Rate, SpO2, and Heart_rate contribute to intrusion detection, they have lower KS values.

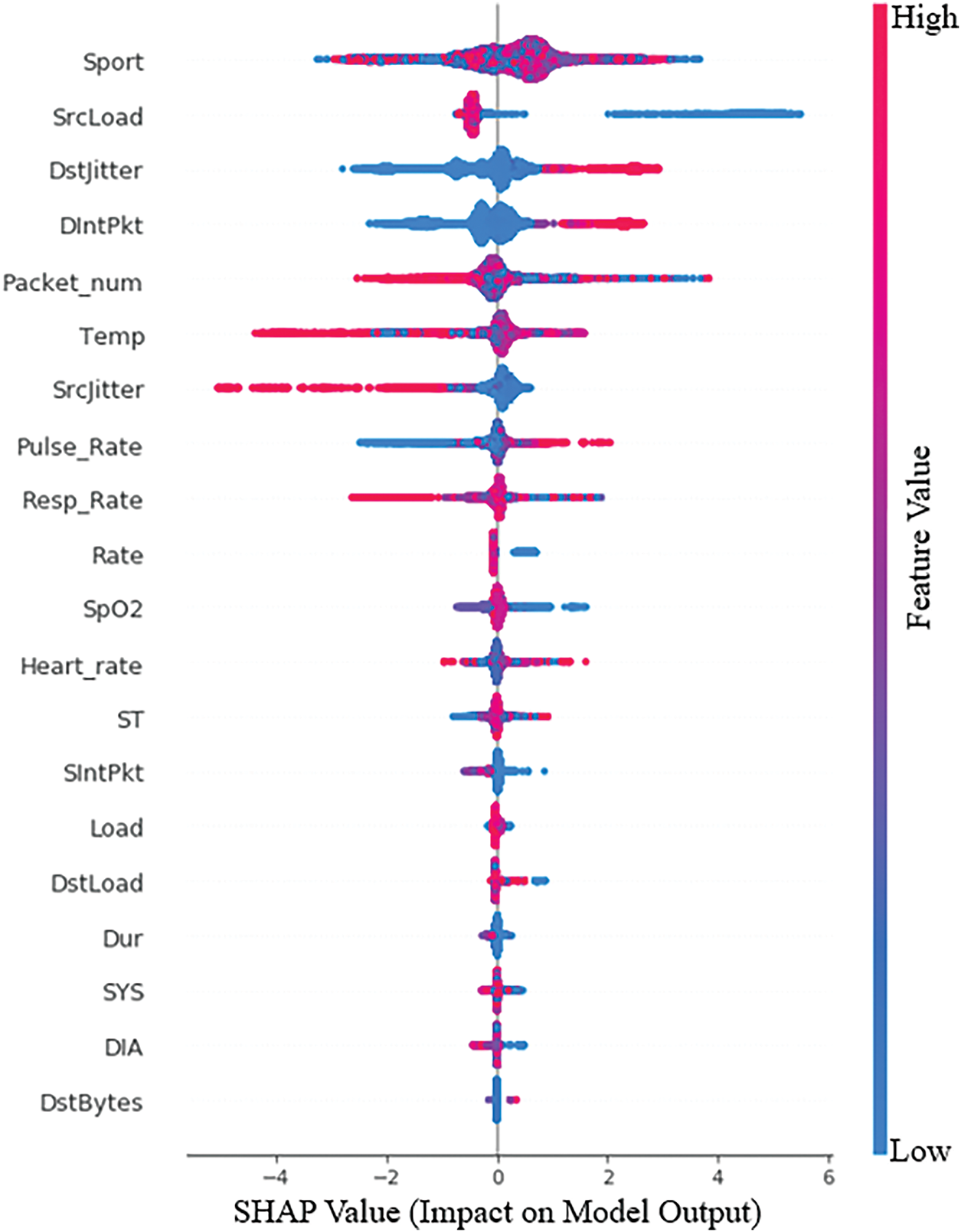

(b) SHAP (Shapley Additive exPlanations) gives insight into the model decisions by quantifying how much each feature contributes to the model output, as shown in Fig. 3. SHAP pushes the model’s prediction to an attack class if the SHAP value is positive or normal traffic; otherwise, if its value is negative [26,27].

Figure 3: SHAP value summary

The key features that these SHAP values imply are:

• SHAP value of 0.1979 and high KS value positively contribute to attack classification.

• A negative SHAP value (−0.1478) indicates that normal traffic is more likely to result in lower rates.

• SrcLoad & SIntPkt have negative SHAP values, implying that lower inter-packet timing and lower source load lead to more normal traffic.

Finally, the features of Biometrics (Pulse_Rate and SpO2) also contribute to distinguishing between normal and attack traffic [27,28]. Though their weight is less than that of packet-related features, these features with negative SHAP values have less weight.

v. Feature Scaling and Polynomial Feature

Standard Scaler normalizes training and testing data to improve model performance. It is vital for gradient descent-based algorithms as they are sensitive to feature scaling and standardization, i.e., all features have a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1.

where

(a) Polynomial Feature Expansion:

Polynomial feature expansion introduces a nonlinear relationship, creating interaction terms up to the second degree. Thus, for this transformation, not including squared terms but including second-degree terms enriches the feature set by considering pairwise interactions, which can help the model capture complex patterns.

The combination formula calculates the total number of new features after polynomial expansion.

where

(b) Data Splitting

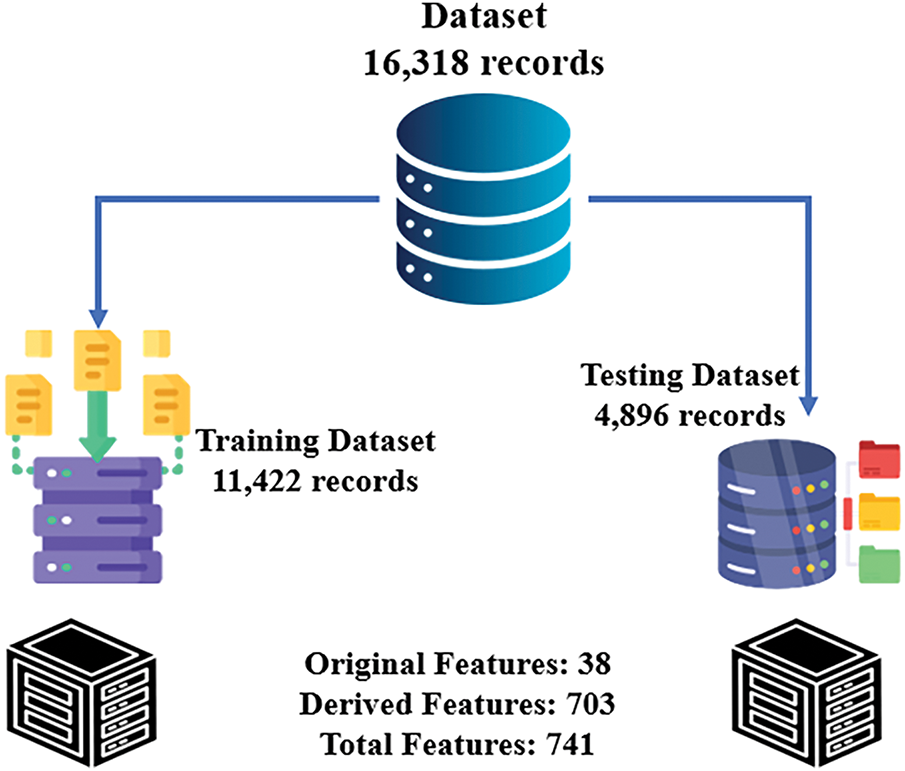

The dataset was split into 70% for training and 30% for testing via stratified sampling to ensure that the model generalizes well. This ensures that the training and testing sets represent the target variable distribution, which is crucial for handling imbalanced datasets, as shown in Fig. 4. Furthermore, the final dataset statistics include a training set (11,422 records) and a test set (4896 records), whereas the features include 38 original, 703 derived, and approximately 741 total features.

Figure 4: Dataset summary

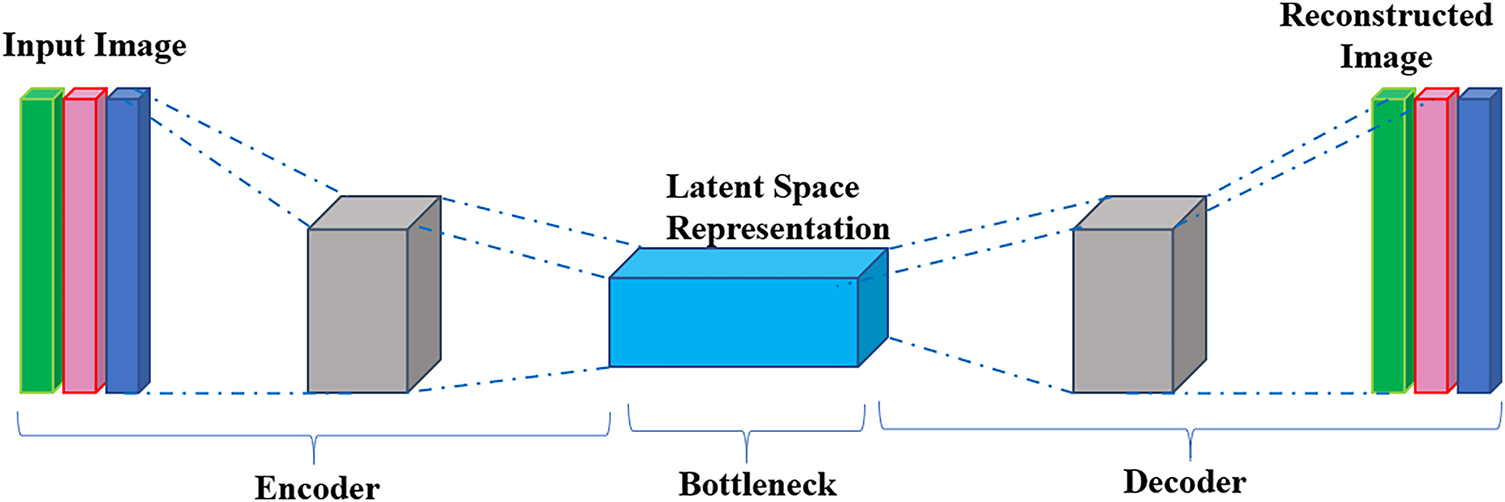

vi. Auto-Encoder for Feature Enhancement

The feature set was further enhanced using an autoencoder. Unsupervised neural networks, such as autoencoders, are trained to compress and reconstruct input data. This architecture can capture the nonlinear relationships between features with a more compact informative feature set. Fig. 5 shows the autoencoder.

Figure 5: Autoencoder

• Encoder: The outputs of this block are compressed input features in a latent space of lower dimension.

• Decoder: Reconstruct the input data from the latent space representation.

Mathematically, given an input,

where

where

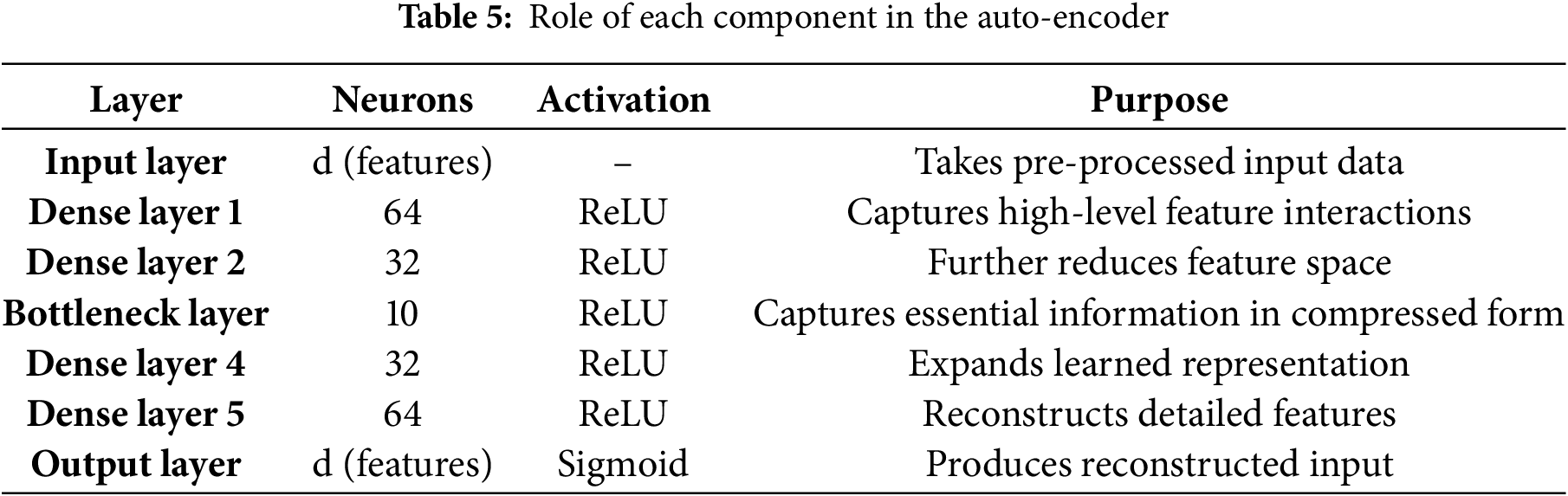

The following layers are in the auto-encoder: Table 5 shows the role of each component in the auto-encoder.

Moreover, the model uses reconstruction loss, the Mean Squared Error (MSE), between input and output after being reconstructed to minimize this process and exclusively learn only the essential features [28]. Finally, intrusion detection systems could accurately classify network traffic and biometric data by performing rigorous data preprocessing, feature engineering, and the use of SHAP and Auto Encoder techniques [29,30]. With an emphasis on the most critical features, the use of polynomial feature expansion, and the enhancement of model interpretability using SHAP and KS tests, the proposed approach offers a complete framework for constructing more robust and reliable intrusion detection systems.

The Auto-Stack ID methodology for intrusion detection uses the stacked ensemble learning approach, in which a set of classifiers is combined to maximize the prediction accuracy and generalize the model. Second, learning methods, such as deep learning-based TabNet and gradient boosting methods, can be combined to provide intrusion detection solutions with a feasible tradeoff between efficiency and detection robustness. First, a base model was trained, and feature augmentation was performed using an autoencoder. Out-of-fold (OOF) predictions were used, followed by a meta-learner to aggregate the optimal predictions. In the architecture that represents the probabilities predicted by the base learners, they are referred to as P1, P2, P3, P4, and P5, respectively.

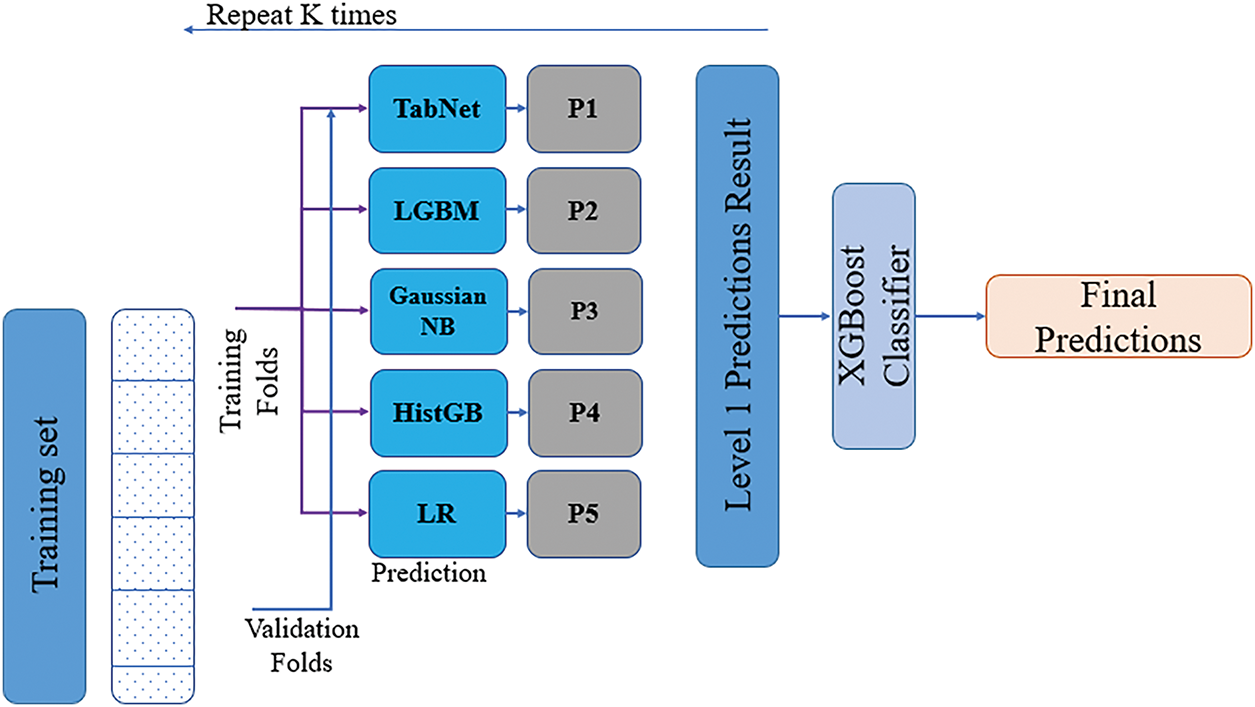

The first step is to train the base models with stratified K-fold cross-validation on autoencoder-based feature augmentation. K-Fold Stratified ensures that the class distribution of the dataset in each fold remains roughly the same, thus avoiding biasing the distribution while training the model. The dataset was split into five folds, each of which was the validation set, and the remaining four folds were used for training. Thus, the model (Fig. 6) can be trained and validated on datasets not previously used to ensure that the validation and training datasets are disjoint.

Figure 6: Architecture model

Each training fold is also split, and base models, including TabNet, LightGBM (LGBM), Gaussian Naive Bayes (Gaussian NB), histogram-based Gradient Boosting, and Logistic regression, are trained. These classifiers are chosen to increase the diversity in the learning process, and each is based on different algorithms that allow the extraction of various aspects of the data. After training from the validation fold, the outputs of the predictions were stored in the Out of Fold (OOF) matrix. This matrix will be fundamental in the next step as it contains the predictions of all base models over all folds.

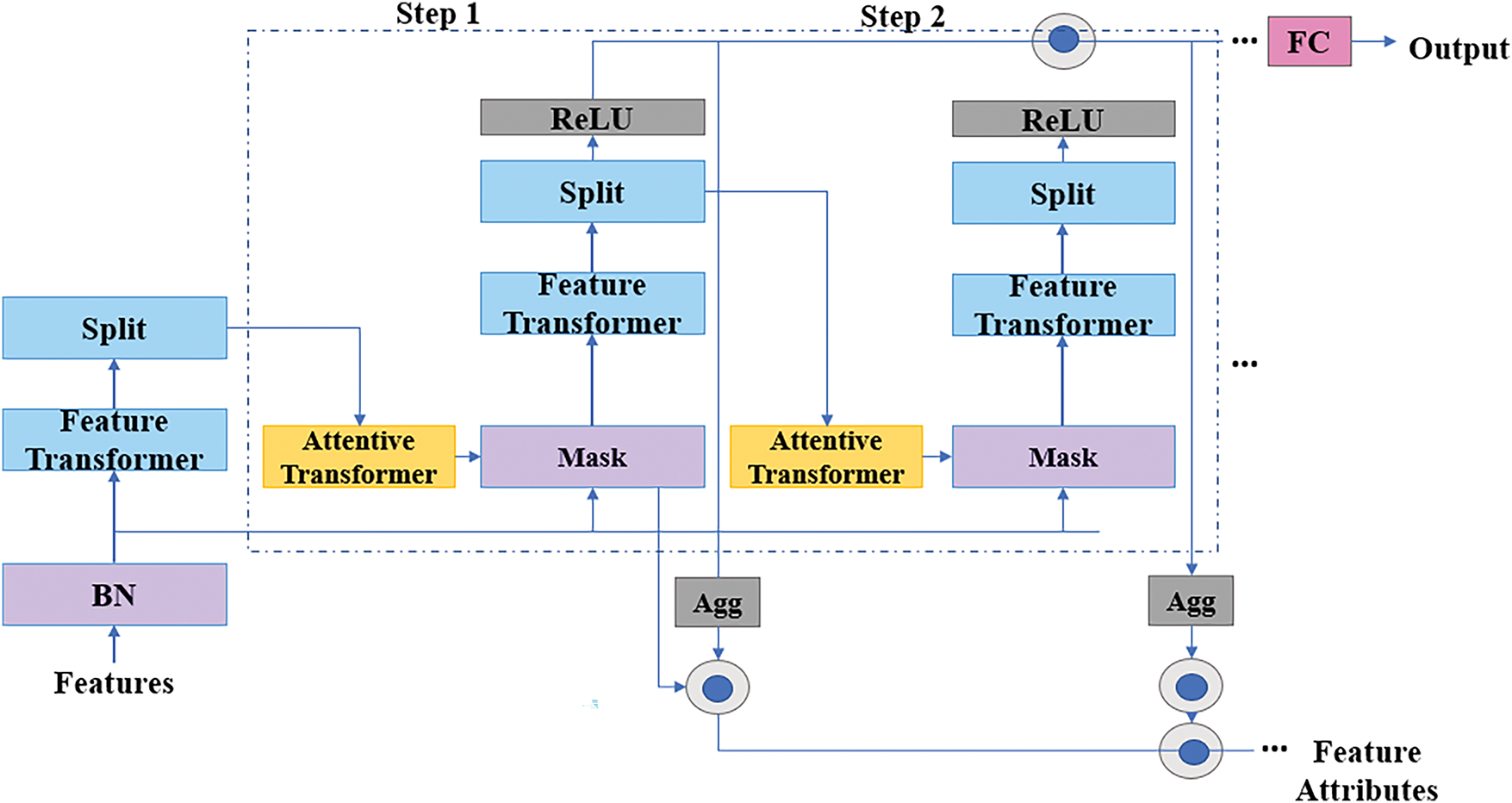

TabNet is a deep learning model that handles tabular data using sequential attention mechanisms and deep learning techniques. It is highly efficient and interpretable, and provides an innovative solution for structured data classification tasks. A tablet is a robust framework that integrates deep learning with decision trees to process tabular data. However, its overall architecture (Fig. 7) has three main components: a Feature Transformer (preprocessing block), an attention transformer (Feature Selection block), and a Decision Prediction block (final classification).

Figure 7: TabNet architecture

The first Component of the TabNet architecture is the Feature Transformer, which preprocesses input data. The features are learned using fully connected layers and Gated Linear Units (GLUs) to learn meaningful representations [31]. It transforms through nonlinear interactions between the input features and conserves the most critical information. At the output of this block, we passed a refined feature representation to the next block in the network.

The output of the feature transformer is shown in Eq. (5).

where

where

where

Furthermore, regularization terms with a lambda sparse of 0.0005 encourage sparse feature selection, and a gamma of 1.5 controls feature selectivity (lower means more orthogonal feature selection). Adam optimizer is used to train the model for 20 epochs. The feature transformer, attention, and decoding layers learn the optimal feature representation by passing it through the training data. The model was trained and used for validation and test set prediction. The OOF prediction is stored for stacking. The outputs from the multiple decision steps are then aggregated to obtain the final prediction.

Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LightGBM) is a machine learning algorithm based on the Gradient Boosting Decision Tree (GBDT) framework that is highly efficient, scalable, and flexible. In this methodology, an ensemble of decision trees is grown sequentially, and every new tree is trained to fix the mistakes of previously grown trees. It is based on minimizing the loss function using an iterative process and adding a weak learner in each step to improve the model’s prediction. The advantage of LightGBM over traditional GBDT is that it is not based on greedy algorithms but uses histogram-based methods to perform split finding. This reduces the computational cost and memory requirement by binning continuous features into discrete ones, enabling the model to scale large datasets efficiently.

In standard LightGBM implementation, the complexity of the model is controlled with hyperparameters like the number of trees, the maximum depth of trees, and the maximum leaves of trees. For instance, the most suitable configuration might be a configuration with 700 trees and 90 leaves per tree, a maximum depth of 7. Similarly, DART (Dropouts meet Multiple Additive Regression Trees) is also supported via LightGBM by randomly dropping trees during training, thus preventing overfitting.

4.3 Gaussian Naïve Bayes Classifier

As the name indicates, the Bayesian classifier is one of the probabilistic approaches that utilizes the concept of Bayes’ theorem to identify the probability of a class label when there is an input string. Bayes’ Theorem is the core of the Naïve Bayes model, expressing the posterior probability

One of the most popular Naive Bayes algorithms is Gaussian Naive Bayes (GaussianNB), a specific Naive Bayes algorithm for continuous data assuming the features to be Gaussian (Normal), which makes its model more appropriate for numerical values. Therefore, GaussianNB assumes this, and Eq. (8) represents the likelihood that a particular feature is a part of this class. The formula incorporates the mean:

where

where

Moreover, Gaussian Naïve Bayes is just one of the key assumptions of Naïve Bayes, and all the features are assumed to be conditionally independent. This assumption makes it extremely easy to compute the likelihood function as the model can treat each feature individually. In the case of GaussianNB, the likelihood of the entire feature vector.

4.4 HistGradientBoosting Classifier

HistGradientBoosting Classifier (HGB) is a powerful ensemble learning method given by gradient boosting. The sample implementation for regression & classifier tasks, which sequentially builds decision trees, is beneficial.

The histogram-based binning plays a key role in the HistGradientBoosting Classifier’s optimization. We find that HGB bins continuous features by default into 256 histograms, like any traditional gradient boosting that would process raw feature values. It can do so by splitting on aggregated bins, not feature values, which decreases the computational cost. Histograms accelerate the model’s training, which can be scalable to large data sets. Our model’s hyperparameters, like learning rate (η), control how many trees contribute to the final prediction. Here, we use a small learning rate of 0.05 to minimize the impact of each tree and preclude overfitting and gradual improvement. In addition, the number of decision trees added is defined (700) by max iterations, and each tree’s complexity is limited to max depth of 7.

4.5 Logistic Regression Classifier

Binary classification tasks that describe the final output in terms of a class probability are the most common tasks fitting the categorical value and can be trained with logistic regression. The model computes the linear combination of the input features, where each input feature is weighted with a corresponding parameter (a weight). Finally, we have a weighted sum of them passed through a sigmoid (logistic) function, squeezing the output down to a value between 0 and 1. It can be thought of as the transformed value that is interpreted as the probability that the input is in some class. In the example above, if the sigmoid output is higher than 0.5, the input belongs to class 1 or 0.

XGBoost (Extremely Gradient Boosting) is a widely used machine learning algorithm with a gradient boosting algorithm for classification tasks. It is a sequential building decision tree, where each of the trees will correct the errors made by the previous one. It allows you to go through this iterative process to reduce bias and variance in the final predictive performance (see Appendix A).

In any machine learning task, it is critical to ensure the model generalizes well, and this holds particularly true in domains such as intrusion detection, where typical class imbalance problems, to name a few, exist along with the need for robust performance. As it turns out, Stratified K-Fold Cross Validation (K = 5) will be used to balance the training and evaluation procedure concerning the classes. Stratified K-Fold differs from traditional K-Fold cross-validation as it avoids biased splits since class distribution across all folds is the same as in the entire dataset. In so doing, we ensure that each fold has the same proportion of normal network traffic (also known as the majority class) and attack instances (also known as the minority class), thus helping avoid bias towards the majority class.

In the cross-validation process, K times repeated, each fold was used only for validation, and (K−1) folds were used for training. The model is tested on the holdout fold with all suitable metrics in place. The model’s performance is then averaged after all K iterations to get a more truthful picture of how well the model performs. Further, every time a fold happens, the dataset is split into 80% training and 20% validation. 80% of the data is then trained over the base models (TabNet, LightGBM, Gaussian Naïve Bayes, Histogram-Based Gradient Boosting (HGB), and Logistic Regression), and 20% is used for evaluation. This way, the model is tested on different portions to make it more general and less prone to overfitting.

The key part of this methodology is making out-of-fold (OOF) predictions. These are the predictions made during training on unseen data by each base model. Let

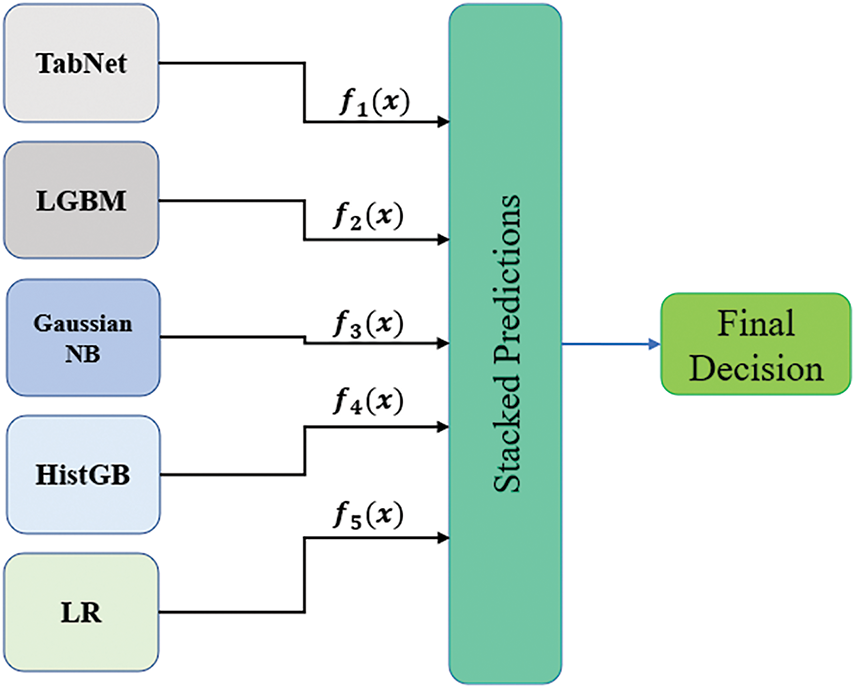

This ensemble approach, as shown in Fig. 8, is valid because it allows different models to capture different patterns in the data. For instance, TabNet, inspired by deep learning with self-attention, is good at capturing internal temporal and sequential traffic patterns, thus detecting more difficult—changing attack methods. On the other hand, the gradient boosting machine (LightGBM) captures nonlinear relationships very well; hence, it is good to use when we process more complex data that linear models will not adequately represent.

Figure 8: Ensemble approach

Finally, the model was evaluated with accuracy, precision, recall, F1 score, and the Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) test.

Accuracy is a measure of how accurately the instances can be classified and is defined as:

Precision was quantified as the percentage of predicted positives that were correctly predicted among all the predicted positives.

The proportion of actual positive instances correctly identified was the recall.

The F1 score is a good way of combining precision and recall by computing it as

The KS metric defined here is a measure of model discrimination.

where

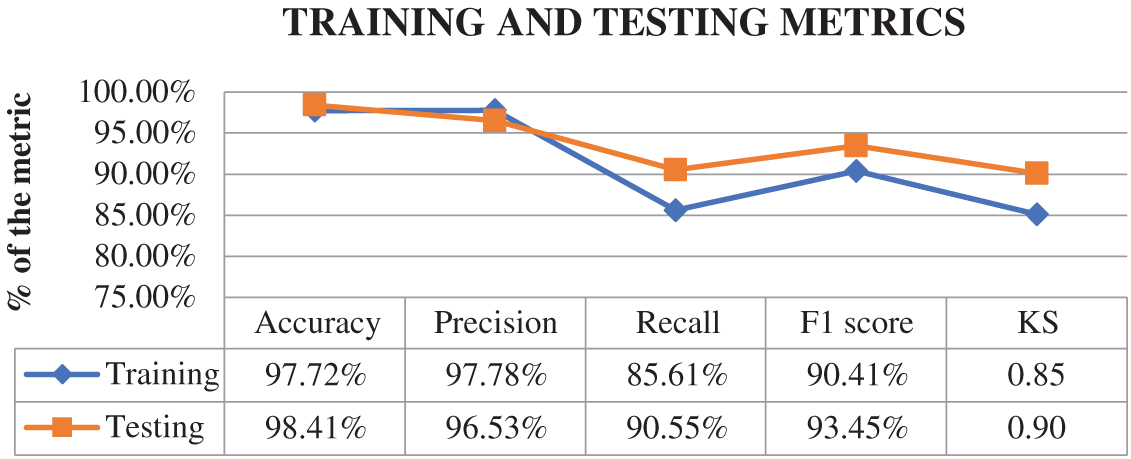

Figure 9: Training and testing metrics

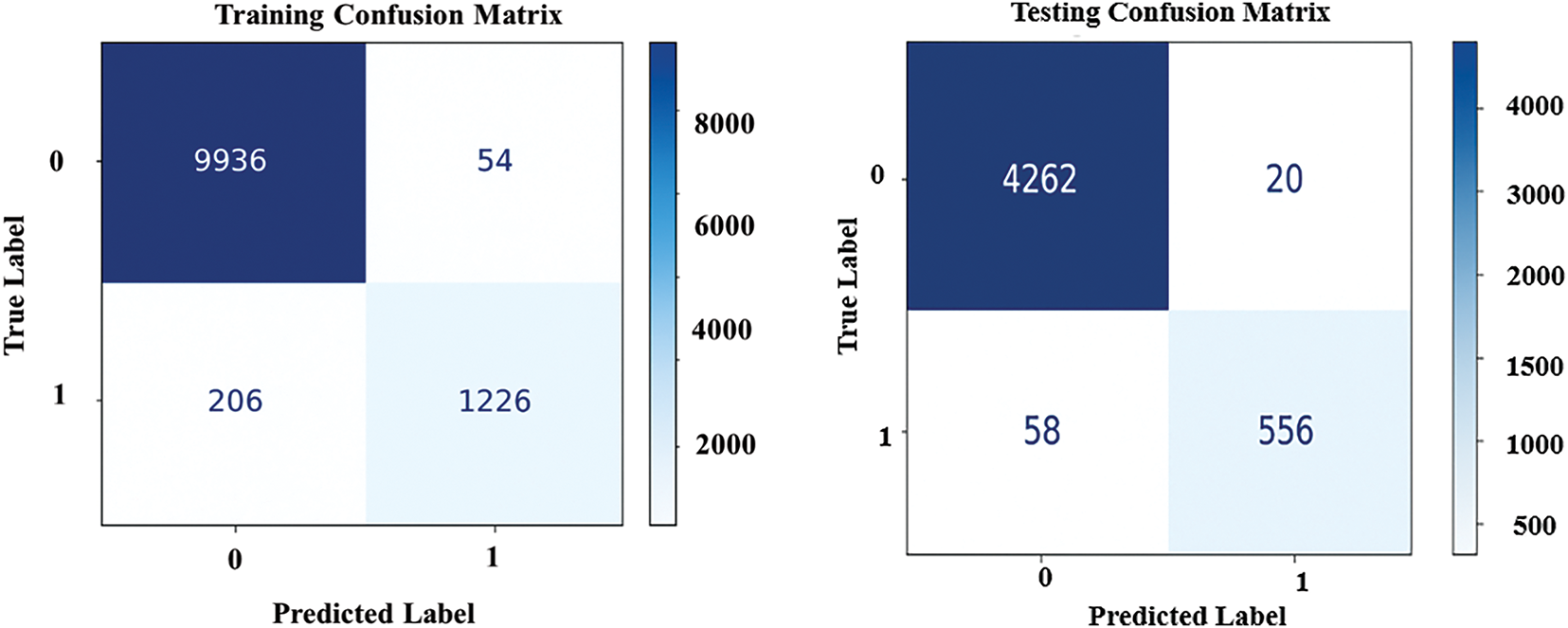

Furthermore, the confusion matrix in Fig. 10 shows the specifics of the predictions compared with the actual labels. This indicates the number of true positives, false positives, and false negatives in the training and testing phases to provide further insight into the model’s power and weaknesses.

Figure 10: Confusion matrix of model predictions on training and testing datasets

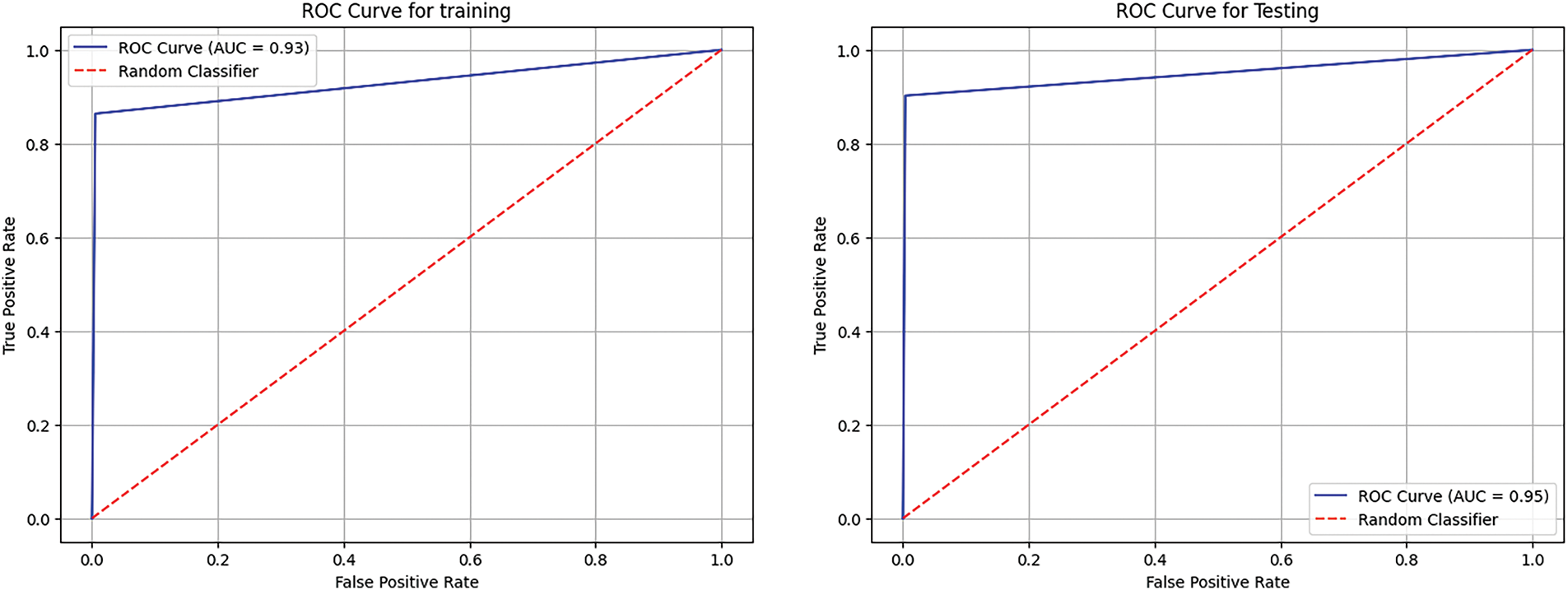

Moreover, both training and testing ROCs (Fig. 11) indicate that the model performed well. The ROC score in the training set has an AUC value of 0.93, indicating outstanding discrimination between classes. Testing the ROC curve has an even better AUC value of 0.95, which suggests that the model generalizes well and does not overfit data. The two curves are much higher than the random classifier line, affirming they had strong predictive power.

Figure 11: ROC curve for training and testing

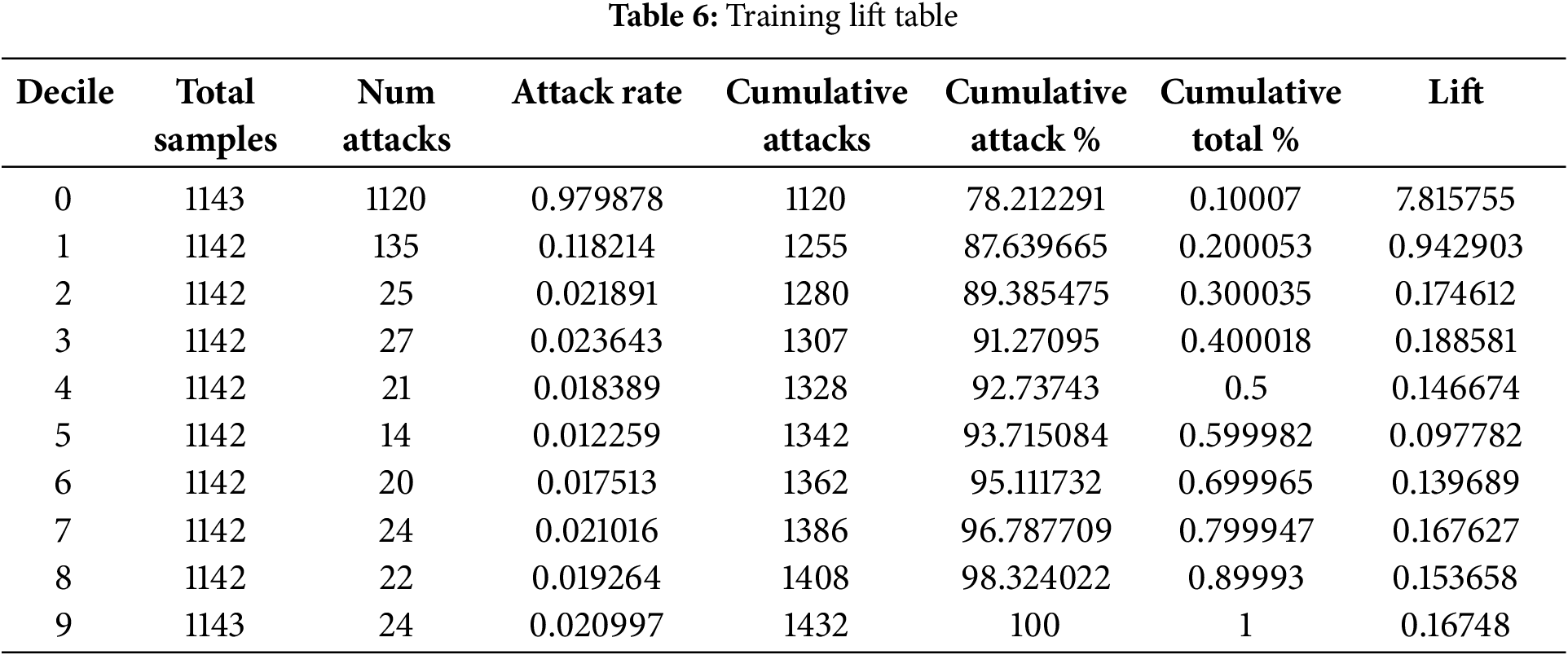

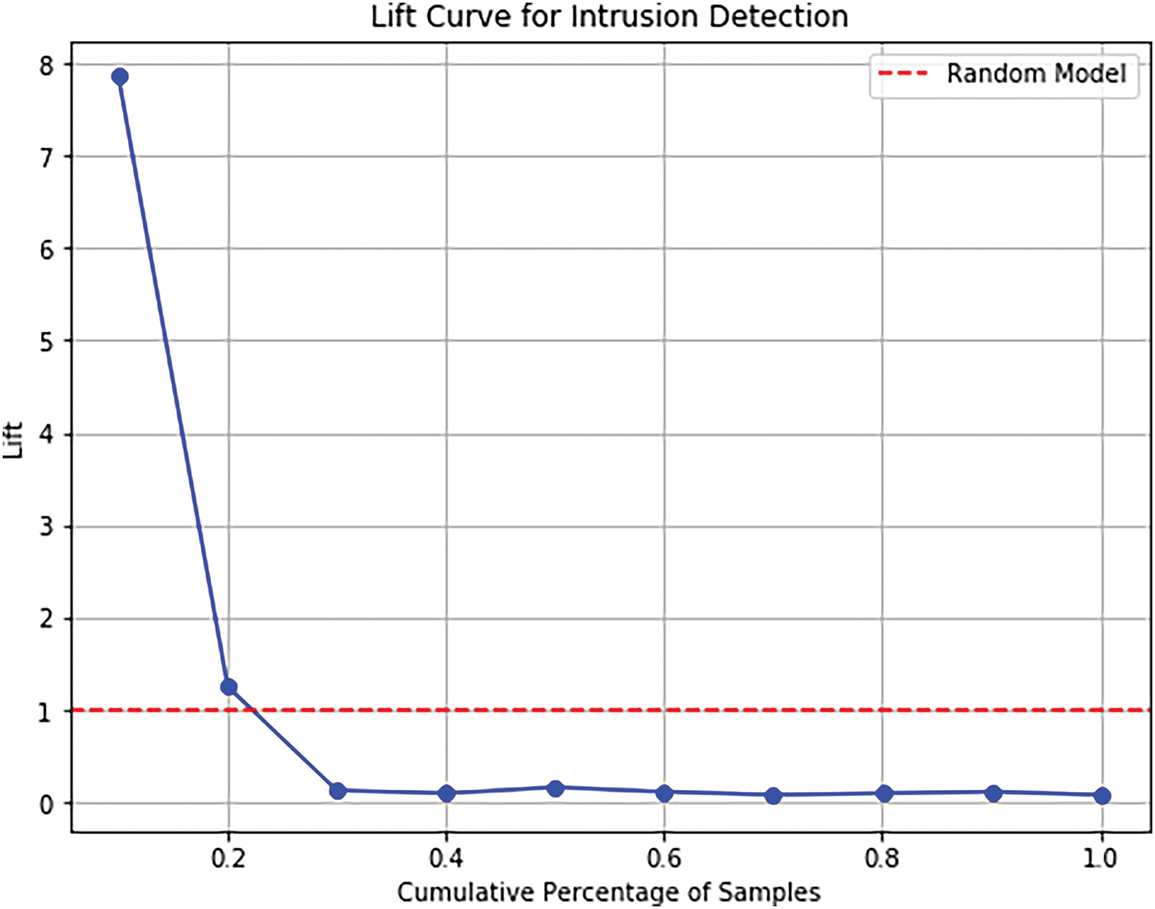

Furthermore, the dataset’s ability to rank was trained and tested using lift tables shown in Tables 6 and 7. This lift table can help us determine if the model effectively discriminates attacks from non-attack instances in the healthcare network. The dataset was split into deciles (10% bins) using a model that fits a meta-learner’s prediction probabilities as the cutoff.

Using these evaluation metrics, it is possible to systematically evaluate the model’s performance in detecting and classifying attacks in the healthcare network. The high accuracy and KS values indicate strong predictive power, and the confusion matrix and lift table also confirm that the model is practical for implementation into a real-world healthcare network.

Additionally, the lift chart in Fig. 12 shows how the model can ignore low-risk irrelevant connections and focus on high-risk connections in the healthcare network dataset used for the test. The model is concerned with the most important cases, especially in the first deciles (i.e., the top decile or two of the cases).

Figure 12: Lift chart for testing dataset

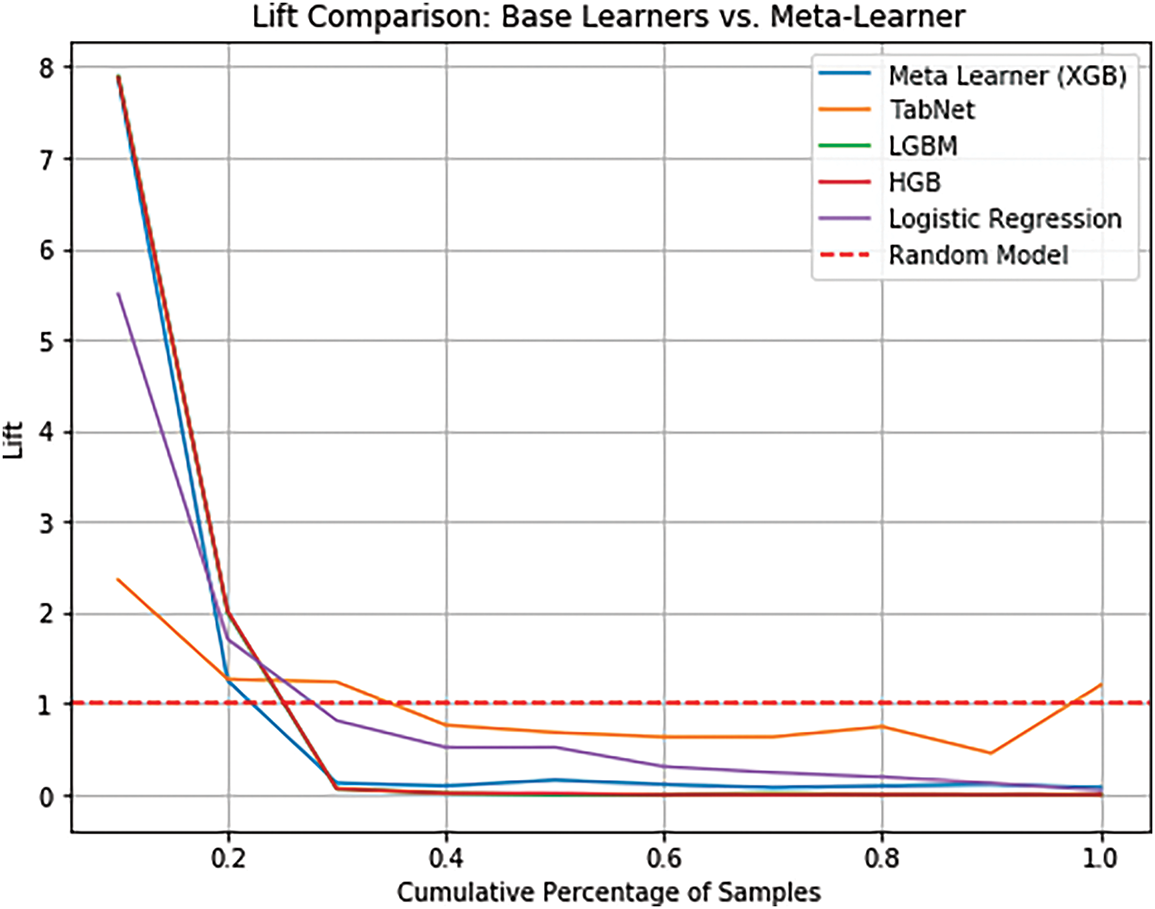

The lift curves of base learners (e.g., TabNet, LGBM) and meta learners (e.g., XGBoost) using the healthcare network testing dataset. This comparison focuses on demonstrating the ensemble model’s higher effectiveness than the individual models in detecting threats in healthcare networks.

The chart presented in Fig. 13 shows a comparison of testing data, which highlights the effectiveness of the model in the classification of the instances and the intrusion detection.

Figure 13: Comparison of lift chart on testing data

The testing data displays a marginal increase, with 78.66 percent of attacks captured and a 7.86 times lift, compared to the first decile (top 10 percent) in training, capturing 78.21 percent of attacks with a lift of 7.81 times. This affirms the effectiveness of the model in giving deliberations on critical threats. The significant dip in lift following the top two deciles indicates that most of the attack cases have occurred in the highest probability brackets, with the lower values in subsequent deciles as a representation of a few attack cases. The lift analysis confirms that the model is efficient in ranking medical intrusion phenomena and separates severe threats and discourages false alarms, subsequently raising the pace of reaction. These results show that the ensemble strategy (especially XGBoost) is superior to a sole one as TabNet and LGBM, as it has a more stable performance and fewer false positives.

1. High Accuracy (97.72% Training, 98.41% Testing)

The model’s accuracy values are excellent because they classify most instances of the training and testing phases very well. This is good because the testing accuracy (98.41%) is very close to the training accuracy (97.72%); the model generalizes well, as it can effectively perform on unseen data, which is a prerequisite for applications where a model can confidently be deployed. High accuracy is a positive sign for systems that utilize machine learning to be secure in real-time in the most sensitive areas, such as medical networks.

2. Precision (97.78% Training, 96.53% Testing)

Because false positives must be minimized, especially in medical security settings, such issues require precision to ensure that the model does not generate false positives. The score (96.53%) on the testing dataset is exact, meaning that when the model predicts an intrusion, the probability of it being an intrusion is high, thus minimizing the chances of generating a significant number of alarms that might congest the security teams or cause excessive downtime. This is because patient trust is the key point to focus on when the operation needs to run as smoothly as possible.

3. Recall (85.61% Training, 90.55% Testing)

Recall is a critical metric for assessing a model’s ability to detect actual intrusions. On the testing dataset, the model had a high recall score (90.55%), indicating that it can identify most real attacks. More importantly, this becomes critical when an attack is missed in the medical field, which poses a significant risk, including data breaches, patient safety at stake, and malfunctioning devices. It provides a recall score—the robustness of the model in recognizing threats—representing one of the key parameters for preventing system failures and, consequently, cost and heavy damages.

4. F1 Score (90.41% Training, 93.45% Testing)

The F1 score balances the precision and recall and measures the model’s classification performance. The model captures many true positive cases and hence has a high F1 score of 93.45% on the testing dataset, which confirms that it does not make incorrect predictions in addition to being precise. In particular, this balance is vital in the context of security, as it pays dividends to reduce false positives and avoid missed attacks. This shows that the model is well adapted to unseen testing data because the improvement in the F1 score from training to testing (from 90.41% to 93.45%) is reasonable.

5. Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) Score (85.12% Training, 90.1% Testing)

Finally, the KS score assesses the model’s ability to differentiate between an attack and regular traffic. The model was shown to effectively separate the two distributions (kwargs = testing data score with a high KS score of 90.1%), making it a good intrusion classifier. For intrusion detection systems, especially in security-sensitive domains such as healthcare, strong separation is crucial to identify threats and prevent severe consequences accurately.

6. Lift Table Analysis

The lift table further confirms that the model’s infrastructure consistently prioritizes the most critical attacks in the healthcare network. In the training phase, we computed a lift value of 7.81 for attacks against random occurrences in the healthcare network, capturing 78.21% of the attacks in the top 10% of predictions (first decile).

During the testing stage, the top 10% of cases had an attack rate of 78.66%, with a 7.86x increase in lift, or 261.7%, indicating the model’s robustness in generalizing to unseen data in the healthcare network. Finally, lift values went down sharply after the top two deciles, which confirmed that most attack cases were clustered among the highest probability segments, as the model identified critical threats towards healthcare network security. This is expected as the lower deciles contained few attack cases, and values stabilized in the lower deciles close to 1.0. This behavior reiterates the assumption that the model allocates resources to detect the most pressing threats first, with strong cybersecurity in place in healthcare networks.

7. Meta-Learner vs. Base Models

Considering the ranking attacks, the meta learner (XGBoost) is significantly more potent than the base models (LGBM, TabNet) in the healthcare network environment. Although the base models have some performance fluctuations, the ensemble model provides significantly better stability and accuracy, especially in the top deciles, making it very useful for intrusion detection in healthcare networks. The sharp fall in the lift in the second decile confirms that most of the attacks are found very early, as required for security-critical healthcare network scenarios.

Some classifiers work better in a healthcare environment because they can trade off precision and recall, achieving both low false positives and a high rate of detecting real threats, which is essential in a medical context where a misclassification can lead to severe results. A notable characteristic is the high testing accuracy (98.41%) required for deployment in the real world. High precision classifiers (96.53%) minimize false alerts, which is critical toward preventing alert fatigue among security personnel. Patient data and system integrity are safeguarded against failure to detect real intrusions due to a high recall (90.55%). The high F1 score (93.45%) is an indication of a balanced performance. The KS score (90.1%) is highly indicative of good separation between normal and attack traffic, and the lift analysis proves that the model can prioritize the most essential cases. All these factors contribute to a higher degree of reliability and safety, which means that such classifiers can be very useful in the sphere of healthcare cybersecurity.

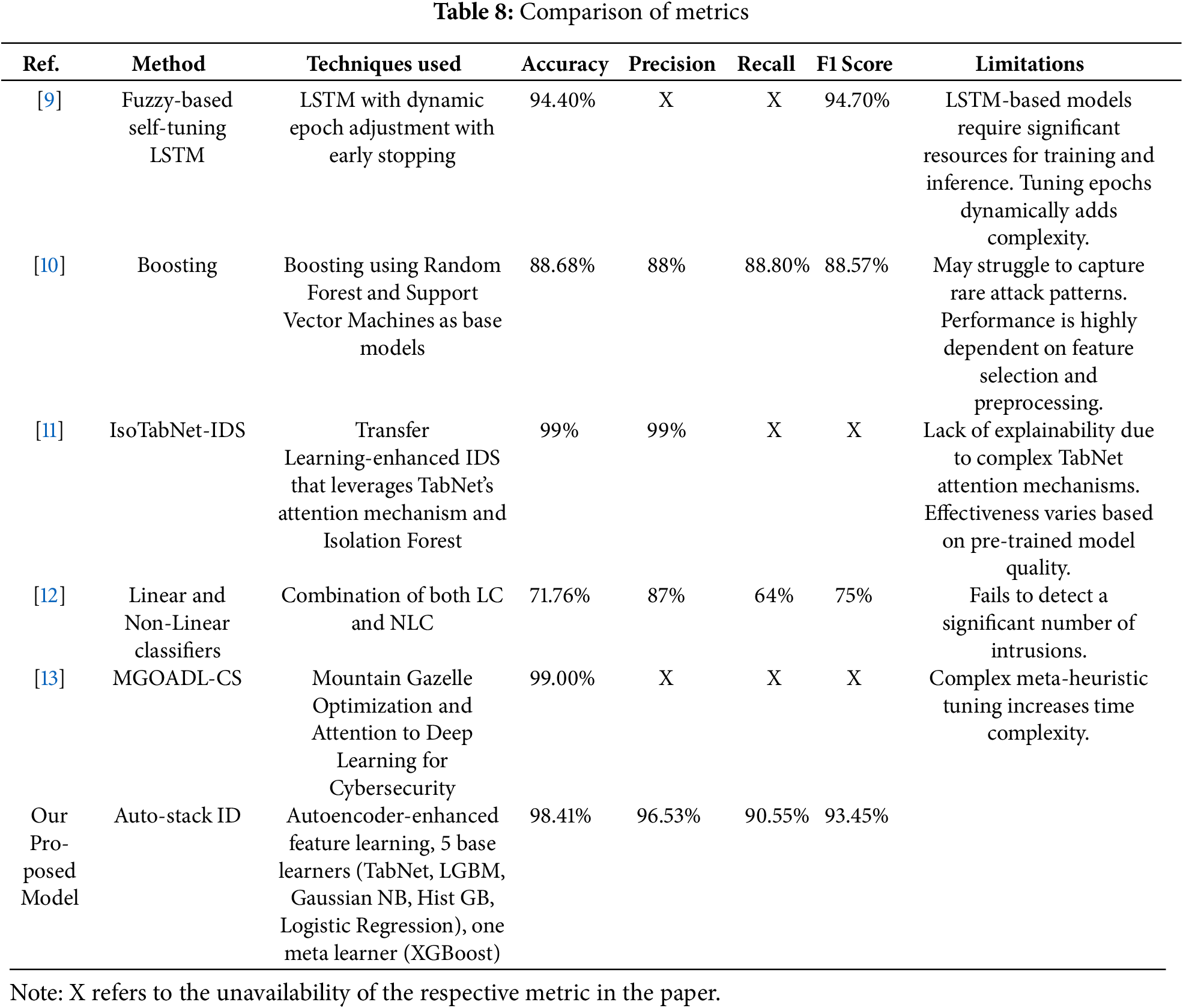

5.2 Comparative Analysis of Existing Methods

In recent years, Intrusion Detection Systems (IDS) have been the subject of the quest for efficient techniques, generating a variety of them with advantages and limitations. In Table 8, several of these methods and their associated metrics are compared insightfully to analyze the performance of different models in cybersecurity usage. Among the others, our proposed model using the Auto-Stack ID approach compares very well in terms of accuracy, recall, and overall generalization.

The comparative overview of different intrusion detection systems (IDS) shows not only the difference in techniques but performance gap between traditional and new methods. The proposed model is powerful (94.40% accuracy and 94.70% F1-score), as it is also the case with the mentioned models, like the fuzzy-based self-tuning LSTM [9] due to the dynamic epoch adjustment feature. Nevertheless, given that it is based on LSTM, it is computationally demanding and difficult to tune. Increasing techniques [10], although offering consistent measures (88.68 percent accuracy, 88.57 percent F1), are highly reliant on the accurate selection of features and cannot be easily added to new or uneven threats. In the same way, the combination of linear and non-linear classifier [12] yields an inadequate result (71.76% accuracy, 75% F1-score), which reveals the weak side of the algorithm in identifying intrusive patterns that are complex or subtle.

In models that perform well, IsoTabNet-IDS [11] and MGOADL-CS [13] claim to achieve 99%; they use sophisticated mechanisms such as transfer learning and bio-inspired optimization. Nevertheless, IsoTabNet-IDS has the weakness of a poor explainability, based on the fact that TabNet attention mechanism is ripe and the performance of the model used in terms of pre-training, could be low in terms of generalization that cannot be easily extended to other datasets. The MGOADL-CS with its meta-heuristic optimization can be considered promising but at the cost of having much computational overhead thus unable to fit well in a real-time detection setting.

Alternatively, in our proposal model contributions, Auto-stack ID is the robust and highly-scalable and less-consuming alternative with an equal amount of performance consideration. It attains good accuracy of 98.41%, a high F1-score of 93.45%, being superior to most others and still available with good interpretability and practical applicability. The combination of the feature refinement system in the form of autoencoder with a heterogeneous ensemble of five different base learners: TabNet, LGBM, Gaussian NB, HistGradientBoosting, and Logistic regression along with an XGBoost meta-learner allows modeling the both simple and complex nonlinear relationships within the dataset. Such layered strategic design achieves the flexibility to different attack patterns without deep networks and the overfitting issues of strongly custom model architectures. Auto-stack ID is simpler, i.e., does not need any massive tuning, or external pre-training, and it can be deployed in real-time with scalable performance and a robust generalization to other intrusion contexts.

In this research, we applied an AE-enhanced stacked ensemble for intrusion detection in healthcare networks using the WUSTL-EHMS 2020 dataset. XGBoost provides us a meta-learning strategy to integrate the power of several different models (TabNet, LightGBM, Gaussian Naïve Bayes (GNB), Histogram Based Gradient Boosting (HGB), and Logistic Regression). The hybrid structure was designed to handle the complexity and class imbalance categories typical in intrusion detection systems (IDS) in healthcare networks. By enhancing learning diversity, our model improves the robustness, accuracy, and scalability of a class of healthcare network security models that are traditionally realized.

The first advantage of our model is the use of Stratified K-Fold CV in training, which maintains a balanced presence of normal and attack traffic from healthy networks. However, standard K-Fold cross-validation techniques usually face challenges in imbalanced datasets where the amount of normal data is much greater than the attack cases. Nevertheless, Stratified K-Fold ensures that each fold has the same class distribution as the whole dataset, so the model doesn’t overfit the majority class. Also, since each fold is trained on 80% of the data with the remaining 20% for validation, the model is continuously tested on unseen data, making it additionally robust in securing healthcare networks. Moreover, this research also contributes another key by using out-of-fold (OOF) predictions in building an ensemble learning framework.

Moreover, when implementing intrusion detection systems into healthcare networks, the privacy of patient data is of the utmost importance. Such a security solution should also be regulatory-agnostic, meaning that HIPAA and similar regulations do not get violated by exposing sensitive health information or mishandling it in the process of data processing or model training. Although our AE-enhanced stacked ensemble was applied to de-identified network traffic data of the WUSTL-EHMS 2020, in practice, it would be necessary to implement rigorous measures to avoid information leakage and provide end-to-end encryption. Furthermore, IDS implementation into healthcare settings should not compromise the security or operational soundness of the setting, as the detection system must not disrupt essential clinical processes or patient safety.

Although the WUSTL-EHMS 2020 dataset is quite adequate in terms of applicability when assessing our model in the healthcare setting, the single domain adversely affects the external validity of our results. To achieve greater scope and resilience, future work would have to verify the model on cross-domain data with a variety of network behaviors and threat signatures. This will aid in evaluating the flexibility to a shift in domain and enhance the feasibility of deployment in the real world. The capability to incorporate heterogeneous datasets will also improve the ability of the IDS to resist new or emergent forms of attacks in diverse network environments.

Limitations of the Study

The following are the limitations of the study:

i) Complexity and Computational Overhead: The study’s hybrid ensemble model relies on several base models to improve performance; however, complexity and computational overhead are high. This can be resource-intensive, especially when dealing with large datasets and training and maintaining multiple models.

ii) Limited Generalizability: The proposed model exhibits impressive performance on the WUSTL-EHMS 2020 dataset; however, generalization to other intrusion detection datasets is still questionable. The model’s effectiveness may differ when the model is used on other network environments or attack scenarios not included in this dataset.

In this paper, we introduce a novel and smart intrusion detection system called Auto stack ID that enables healthcare networks and environments that are facing a rapidly rising number of cybersecurity threats, especially in medical networks and Critical Infrastructure Security. As medical records become increasingly digitized, it becomes increasingly important for patient monitoring to happen with the use of IoT technology and the transmission of real-time data through healthcare networks; robust security measures are needed. The tradeoff between the detection accuracy, computational efficiency, and adaptability in current IDS models is not met due to the changes in cyber threats in the dynamic healthcare network environments.

Compared to the previous approaches in the IDS domain based on a single learning algorithm, Auto-Stack ID uses multiple base learners such as TabNet, Gaussian Naïve Bayes, and LightGBM, and a meta-learner based on XGBoost. Using a multi-model approach in this process helps the system leverage deep learning-based feature extraction to help further the machine learning classifiers identify complex attack patterns. Therefore, the above discussion indicates that Auto-Stack ID is a more robust method for intrusion detection in different healthcare network environments while securing critical medical infrastructure.

One notable feature of AutoStack ID is its ability to resolve the common class imbalance issue using the Stratified K-Fold Cross Validation. It prevents the minority class from dominating validation folds and ensures that healthcare network intrusion detection datasets are proportionally represented between regular and attack traffic. In addition, the training process can be made more generalizable, and overfitting can be prevented by integrating Out-of-Fold (OOF) predictions into the training by learning from previously unseen data. The results show that it is reliable in healthcare network cybersecurity settings with high stakes, such as early precise threat detection (accuracy: 98.41, precision: 96.53, recall: 90.55, and F1 Score: 93.45).

Auto-Stack ID is a powerful tool with many advantages, but it has certain aspects that should be considered to enhance its use and performance for future implementations. Finally, the model is subject to further evaluation on the datasets and the healthcare network environments in order to improve its generalization capability. To advance the use of ensemble systems, however, it will be necessary to provide sufficient explainability for the ensemble system in environments where interpretability is critical. Improvements to the future will include system architecture optimization and hardware acceleration to support real-time operation in the healthcare network region.

Future Work

In future work, the AESE model presented here will be extended further by adopting innovative feature extraction techniques aimed at the IoMT environment of the healthcare network. Healthcare networks that have IoMT devices are heterogeneous and distributed. Thus, they generate highly variable data streams that are primarily nonstationary and noisy. We aim to inject domain-specific knowledge, such as medical device protocols and patterns of healthcare network traffic, into the feature selection operation to improve the model’s sensitivity to context-aware, pernicious, and paranoid intrusions. Moreover, we will explore other types of transfer learning methods that can use off-the-shelf pre-trained cybersecurity models trained on huge datasets and then adapt them to the IoMT domain, which is a part of the healthcare network, to enhance the performance and generalization in detecting new unknown attacks.

Furthermore, we will utilize multimodal data fusion on both the healthcare network level and device-specific logs to improve the robustness of our intrusion detection system. A topological approach to this problem is advantageous since defensive mechanisms can be created based on this structure. However, a more holistic view of the state of the system would be helpful to identify more sophisticated and multivector attacks that are incapable of being detected using traditional detection methods. Furthermore, our AESE model scales well in real-time healthcare network IoMT environments with high device density and low false rates when faced with changes in the network conditions. Then, we will look at the computational efficiency and feasibility of running the model on resource-constrained edge devices required to uptake healthcare network security solutions.

Acknowledgement: This project is funded by Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R319), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia and Prince Sultan University for covering the article processing charges (APC) associated with this publication. Special acknowledgement to Automated Systems & Soft Computing Lab (ASSCL), Prince Sultan University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Also, Researchers Supporting Project Number (RSPD2025R1107), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Funding Statement: The authors would like to thank Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University for funding this project through the Researchers Supporting Project (PNURSP2025R319) and this research was funded by the Prince Sultan University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Also, Researchers Supporting Project Number (RSPD2025R1107), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author Contributions: Study conception and design: Fatma S. Alrayes, Syed Umar Amin; data collection: Syed Umar Amin, Mohammed K. Alzaylaee; analysis and interpretation of results: Fatma S. Alrayes, Syed Umar Amin, Mohammed Zakariah; draft manuscript preparation: Zafar Iqbal Khan, Syed Umar Amin, Mohammed K. Alzaylaee, Mohammed Zakariah. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets generated and/or analyzed the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Glossary

| Terms | Abbreviations |

| IDS | Intrusion Detection System |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| KS | Kolmogorov Smirnov |

| OOF | Out of Fold |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| EHR | Electronic Health Records |

| IoMT | Internet of Medical Things |

| MSE | Mean Squared Error |

| GLU | Gated Linear Units |

Eq. (A1) defines the loss function as the objective function of XGBoost. Its two main parts are the loss function and the regularization term.

where

where

References

1. Ahmed SF, Alam MSB, Afrin S, Rafa SJ, Rafa N, Gandomi AH. Insights into Internet of Medical Things (IoMTdata fusion, security issues and potential solutions. Inf Fusion. 2024;102(4):102060. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2023.102060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Attack W, Attack I, Attack BF. Ensemble of feature augmented convolutional neural network and deep autoencoder for efficient detection of network attacks. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):4267. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-88243-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Qaddoura R, Al-Zoubi M, Faris A, Almomani H, I. A multi-layer classification approach for intrusion detection in IoT networks based on deep learning. Sensors. 2021;21(9):2987. doi:10.3390/s21092987. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Alsaadi HIH, ALmuttari RM, Ucan ON, Bayat O. An adapting soft computing model for intrusion detection system. Comput Intell. 2022;38(3):855–75. doi:10.1111/coin.12433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Saba T, Rehman A, Sadad T, Kolivand H, Bahaj SA. Anomaly-based intrusion detection system for IoT networks through deep learning model. Comput Electr Eng. 2022;99(5):107810. doi:10.1016/j.compeleceng.2022.107810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Azar AT, Shehab E, Mattar AM, Hameed IA, Elsaid SA. Deep learning based hybrid intrusion detection systems to protect satellite networks. J Netw Syst Manag. 2023;31(4):82. doi:10.1007/s10922-023-09767-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Berahmand K, Daneshfar F, Salehi ES, Li Y, Xu Y. Autoencoders and their applications in machine learning: a survey. Artif Intell Rev. 2024;57(2):28. doi:10.1007/s10462-023-10662-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Manoharan A, Thathan M. Enhanced IoMT security framework using group teaching optimized auto-encoder for intrusion detection. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):30360. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-80581-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Alalhareth M, Hong SC. An adaptive intrusion detection system in the internet of medical things using fuzzy-based learning. Sensors. 2023;23(22):9247. doi:10.3390/s23229247. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Alsolami T, Alsharif B, Ilyas M. Enhancing cybersecurity in healthcare: evaluating ensemble learning models for intrusion detection in the Internet of Medical Things. Sensors. 2024;24(18):5937. doi:10.3390/s24185937. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Vishwakarma M, Kesswani N. A Transfer Learning based Intrusion detection system for Internet of Things [Internet]. PREPRINT (Version 1). 2023 May 22 [cited 2025 Jul 10]. Available from: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-2930837/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Rahman J, Singh J, Nayak S, Jena B, Mohanty L, Singh N, et al. A generalized and robust nonlinear approach based on machine learning for intrusion detection. Appl Artif Intell. 2024;38(1):2376983. doi:10.1080/08839514.2024.2376983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Alamro H, Maray M, Aljabri J, Alahmari S, Abdullah M, Alqurni JS, et al. Mathematical modelling-based blockchain with attention deep learning model for cybersecurity in IoT-consumer electronics. Alex Eng J. 2025;113(10):366–77. doi:10.1016/j.aej.2024.11.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Balhareth G, Ilyas M. Optimized intrusion detection for IoMT networks with tree-based machine learning and filter-based feature selection. Sensors. 2024;24(17):5712. doi:10.3390/s24175712. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Alalwany E, Alsharif B, Alotaibi Y, Alfahaid A, Mahgoub I, Ilyas M. Stacking ensemble deep learning for real-time intrusion detection in IoMT environments. Sensors. 2025;25(3):624. doi:10.3390/s25030624. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Musikawan P, Kongsorot Y, Aimtongkham P, So-In C. Enhanced multigrained scanning-based deep stacking network for intrusion detection in IoMT networks. IEEE Access. 2024;12(11):152482. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3480011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Alsaffar AM, Nouri-Baygi M, Zolbanin H. Enhancing intrusion detection systems with dimensionality reduction and multi-stacking ensemble techniques. Algorithms. 2024;17(12):550. doi:10.3390/a17120550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Lazrek G, Chetioui K, Balboul Y, Mazer S, bekkali El M. An RFE/Ridge-ML/DL based anomaly intrusion detection approach for securing IoMT system. Results Eng. 2024;23(24):102659. doi:10.1016/j.rineng.2024.102659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Hady AA, Ghubaish A, Salman T, Unal D, Jain R. Intrusion detection system for healthcare systems using medical and network data: a comparison study. IEEE Access. 2020;8:106576–84. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3000421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Gupta P, Ghatole Y, Reddy N. Stacked autoencoder based intrusion detection system using one-class classification. In: Proceedings of the 2021 11th International Conference on Cloud Computing, Data Science & Engineering (Confluence); 2021 Jan 28–29; Noida, India. p. 643–8. doi:10.1109/Confluence51648.2021.9377069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Brunner C, Kő A, Fodor S. An autoencoder-enhanced stacking neural network model for increasing the performance of intrusion detection. J Artif Intell Soft Comput Res. 2021;12(2):149–63. doi:10.2478/jaiscr-2022-0010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Vishnu S, Ramson SRJ, Jegan R. Internet of Medical Things (IoMT)—an overview. In: Proceedings of the 2020 5th International Conference on Devices, Circuits and Systems (ICDCS); 2020 Mar 5–6; Tamilnadu, India. p. 101–4. doi:10.1109/ICDCS48716.2020.243558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Shiomoto K. Network intrusion detection system based on an adversarial auto-encoder with few labeled training samples. J Netw Syst Manag. 2023;31(1):5. doi:10.1007/s10922-022-09698-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Gupta N, Jindal V, Bedi P. CSE-IDS: using cost-sensitive deep learning and ensemble algorithms to handle class imbalance in network-based intrusion detection systems. Comput Secur. 2022;112(1):102499. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2021.102499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Ravi V, Chaganti R, Alazab M. Recurrent deep learning-based feature fusion ensemble meta-classifier approach for intelligent network intrusion detection system. Comput Electr Eng. 2022;102(3):108156. doi:10.1016/j.compeleceng.2022.108156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Wu T, Fan H, Zhu H, You C, Zhou H, Huang X. Intrusion detection system combined enhanced random forest with SMOTE algorithm. EURASIP J Adv Signal Process. 2022;2022(1):39. doi:10.1186/s13634-022-00871-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Harini R, Maheswari N, Ganapathy S, Sivagami M. An effective technique for detecting minority attacks in NIDS using deep learning and sampling approach. Alex Eng J. 2023;78(1):469–82. doi:10.1016/j.aej.2023.07.063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Kasongo SM. A deep learning technique for intrusion detection system using a Recurrent Neural Networks based framework. Comput Commun. 2023;199(1):113–25. doi:10.1016/j.comcom.2022.12.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Selvakumar B, Sridhar Raj S, Vijay Gokul S, Lakshmanan B. Deep learning framework for anomaly detection in IoT enabled systems. In: Deep learning for security and privacy preservation in IoT. Singapore: Springer Singapore; 2021. p. 99–111. doi:10.1007/978-981-16-6186-0_5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Uçar M, Uçar E, Incetaş MO. A stacking ensemble learning approach for intrusion detection system. Düzce Üniversitesi Bilim Ve Teknol Derg. 2021;9(4):1329–41. doi:10.29130/dubited.737211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Zhang T, Chen W, Liu Y, Wu L. An intrusion detection method based on stacked sparse autoencoder and improved gaussian mixture model. Comput Secur. 2023;128(10):103144. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2023.103144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools