Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Head-Body Guided Deep Learning Framework for Dog Breed Recognition

1 Department of Computer Science, Yonsei University, Seoul, 03722, Republic of Korea

2 School of Information Technology, Murdoch University, Perth, WA 6150, Australia

3 Research Department, Chung-Ang University, Seoul, 06974, Republic of Korea

4 Department of Design Innovation, Sejong University, Seoul, 05006, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Authors: Mi Young Lee. Email: ; Jakyoung Min. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(2), 2935-2958. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.069058

Received 13 June 2025; Accepted 05 August 2025; Issue published 23 September 2025

Abstract

Fine-grained dog breed classification presents significant challenges due to subtle inter-class differences, pose variations, and intra-class diversity. To address these complexities and limitations of traditional handcrafted approaches, a novel and efficient two-stage Deep Learning (DL) framework tailored for robust fine-grained classification is proposed. In the first stage, a lightweight object detector, YOLO v8N (You Only Look Once Version 8 Nano), is fine-tuned to localize both the head and full body of the dog from each image. In the second stage, a dual-stream Vision Transformer (ViT) architecture independently processes the detected head and body regions, enabling the extraction of region-specific, complementary features. This dual-path approach improves feature discriminability by capturing localized cues that are vital for distinguishing visually similar breeds. The proposed framework introduces several key innovations: (1) a modular and lightweight head–body detection pipeline that balances accuracy with computational efficiency, (2) a region-aware ViT model that leverages spatial attention for enhanced fine-grained recognition, and (3) a training scheme incorporating advanced augmentations and structured supervision to maximize generalization. These contributions collectively enhance model performance while maintaining deployment efficiency. Extensive experiments conducted on the Tsinghua Dogs dataset validate the effectiveness of the approach. The model achieves an accuracy of 90.04%, outperforming existing State-of-the-Art (SOTA) methods across all key evaluation metrics. Furthermore, statistical significance testing confirms the robustness of the observed improvements over multiple baselines. The proposed method presents an effective solution for breed recognition tasks and shows strong potential for broader applications, including pet surveillance, veterinary diagnostics, and cross-species classification. Notably, it achieved an accuracy of 96.85% on the Oxford-IIIT Pet dataset, demonstrating its robustness across different species and breeds.Keywords

In real-life computer vision applications, numerous fields have effectively used object detection [1] and classification in images and videos. For instance, human face recognition systems are employed for efficient authentication and security tasks in different applications [2]. There are increasing efforts to extend this research to animals, especially dogs, which are among the most prevalent and well-known species. Given the fact that there are over 180 different dog breeds, their recognition has drawn more interest because of its practical applications in real life. It includes veterinarian diagnostics, proper pet identification, and animal welfare promotion. Identifying a dog’s breed makes it easier to provide training regimens, diet plans, and medical care tailored to the particular breed. Additionally, it helps vets more accurately diagnose diseases linked to genetics or breeds. Furthermore, breed identification promotes responsible pet ownership by guaranteeing proper care and improving safety in public as well as private environments [3]. In contrast to general object recognition, dog breed classification is a fine-grained visual recognition task that involves distinguishing between visually similar subcategories. Changes in pose, background, grooming, and age cause significant intra-class variations as well as subtle inter-class differences. Furthermore, it becomes more difficult to create reliable and broadly applicable models when datasets contain mixed breeds and underrepresented categories. Dog breed identification is a challenging and interesting research subject for DL and computer vision communities because of these difficulties [4].

In the literature, the use of dog images for breed identification has been investigated in a number of studies. To obtain the coarse recognition, Chanvichitkul et al. [5] suggested a coarse-to-fine classification framework in which dog images were first categorized according to comparable facial appearances. A fine-grained breed categorization was then performed inside each category using a classifier based on Principal Component Analysis (PCA). In order to mitigate misclassifications within similar groups, Prasong and Chamnongthai [6] expanded the coarse-to-fine classification approach by adding local part-based analysis. After detecting important local features like the face and ears using Normalized Cross-Correlation (NCC), the approach classified the data inside PCA subspaces. Their work resulted in an 88% accuracy rate across 35 dog breeds and a fourfold increase in runtime. For the classification of dog and cat breeds, a combination of shape and appearance features was also used [7]. The accuracy of this method in recognizing 37 distinct breeds was 69%. Similarly, Liu et al. [8] used landmark data to combine Scale-Invariant Feature Transform (SIFT) descriptors and color histograms with a Support Vector Machine (SVM) classifier, achieving a 67% classification accuracy for 133 dog breeds from their own created dataset. Lai et al. [9,10] investigated dog identification using DL and soft biometrics such as breed, gender, and height, and used transfer learning with Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) to improve identification accuracy. They found that combining soft and facial features significantly improves breed classification and individual recognition in veterinary and biometric applications.

The hand-crafted features used in the majority of earlier research frequently fail to adequately differentiate between a wide variety of dog breeds. The discriminative capability required for precise fine-grained categorization is limited in these manually chosen features, which usually have a narrow scope [11]. Furthermore, because of their poor generalization and class imbalance, current models frequently perform poorly when working with unusual or mixed dog breeds. These drawbacks indicate that a scalable, reliable, and integrated strategy is required in order to efficiently handle detection and classification for dog breeds. In order to tackle the above-mentioned challenges in recognizing dog breeds, this research presents a unified two-phase method for efficient dog breed detection. In the first step, to detect the dog’s body and head in the image, an advanced object detection model is used. In the second step, these identified regions are subjected to a sophisticated DL network that uses both head and body attributes to identify the dog’s breed. The overall work done in this study is summarized in the following points:

• A novel two-stage DL framework is proposed to achieve high-precision dog breed classification. The first stage focuses on detecting the key regions of interest (i.e., head and full body), while the second stage performs fine-grained breed classification using separate visual streams. This division allows the system to localize discriminative cues effectively and subsequently extract rich semantic features for classification.

• The YOLO v8N object detection model is fine-tuned specifically for the detection of dog heads and full bodies. This enables accurate localization of relevant regions, which serves as a critical preprocessing step for downstream classification. The model demonstrates strong detection performance even under varying poses, scales, and occlusions.

• A two-stream ViT-based model is designed to process head and body regions independently. Each stream learns specialized representations, capturing unique and complementary features relevant to the head and body. The concatenation of these features leads to a highly discriminative feature space, enabling the model to effectively handle subtle inter-class similarities and intra-class variations present in fine-grained dog breed classification.

• A comprehensive set of data preprocessing and augmentation techniques is employed to improve model robustness and generalization. These include geometric and color augmentations, normalization, and cropping based on detected regions. These steps help mitigate class imbalance and overfitting issues, particularly in a dataset with high variability.

• The proposed framework establishes a strong baseline for dog head and body detection and achieves superior performance in classification tasks. On the Tsinghua Dogs dataset, comprising 130 dog breeds, the method outperforms existing SOTA approaches in terms of classification accuracy, demonstrating the effectiveness of combining region-specific attention with transformer-based modeling.

The remaining sections of this paper are organized as follows: The relevant research and methods are described in Section 2. The suggested model design is described in depth in Section 3. The experimental design and findings are discussed in Section 4. The paper’s conclusion and future directions are finally summarized in Section 5.

Dog breed detection is a fine-grained visual recognition problem that has attracted significant interest because of its practical applications. From conventional coarse classification techniques, fine-grained classification is a logical next step [12]. Fine-grained classification looks for minute distinctions between subcategories within a single class, such as distinct animal breeds or various car types and models, whereas coarse classification concentrates on differentiating between broad categories of things, such as animals and automobiles [13]. Several methods have been proposed to address the issue of dog identification from images and videos [14,15].

2.1 Conventional Machine Learning Approaches

Early methods of classifying dog breeds mostly depended on manually created features to extract local shape and texture characteristics, such as SIFT, Histogram of Oriented Gradients (HOG), and Local Binary Patterns (LBP). In the coarse-to-fine classification approach, Chanvichitkul et al. [5] first classified dogs according to their facial features before utilizing PCA to fine-tune the classification. Adding to this, Prasong and Chamnongthai [6] used NCC for local part-based refinement in order to identify discriminative regions such as the eyes and ears, and then PCA-based classification. However, the discriminative power and scalability of these approaches are restricted, especially for large and visually comparable breed datasets. Moreover, PCA places a strong emphasis on the overall variance of the input variables, which might not fully capture the most important information for categorization. As a result, important discriminative elements may be missed in the converted data, which could reduce the efficiency of pattern recognition tasks [16]. Traditional image descriptors were combined with classifiers like SVM as Machine Learning (ML) gained popularity. Using the Columbia Dogs dataset, Wang et al. [17] achieved promising results by combining SIFT features and color histograms with SVMs and facial landmarks. Due to the constraints of feature representation, integrated form and texture features were also investigated in parallel for the classification of dogs and cats [7], with only moderate success.

Classification performance has been greatly enhanced by recent developments in DL, especially CNNs. Applying transfer learning to pre-trained CNNs, Tu et al. [10] significantly outperformed conventional techniques using the Columbia Dogs dataset. Pre-trained models for feature extraction and fine-tuning, like VGG16 [18], ResNet [19], and InceptionV3 [20], have been frequently used. These models show resilience in acquiring complex visual patterns and gain from extensive pretraining on the ImageNet dataset. Additional strategies combine CNNs with conventional ML methods. CNN models have been improved in a number of studies [11,21,22] by merging them with classifiers such as SVM, which have been shown to achieve up to 90% higher accuracy than CNNs alone. However, the significant visual resemblance and diversity among dog breeds continue to hinder categorization performance. Interestingly, these hybrid models have demonstrated higher accuracy when applied to other animal categories such as sheep [23], cats [24], and birds [25]. The promise of such hybrid techniques has been demonstrated by the very high accuracy of 97% achieved by combining CNN with SVM for flower categorization [26]. Similarly, Cui et al. [16] presented a hybrid method that combined feature extraction from four CNN architectures with feature optimization through PCA and gray wolf optimization, followed by classification using an SVM. On the Stanford Dogs dataset, the method achieved 95.24% accuracy across 120 dog breeds.

In a recent work, Alfarhood et al. [27] created a novel transfer learning framework using CNNs that classified six closely related breeds named Waddeh, Majaheem, Homor, Sofor, Shaele, and Shageh with up to 85.8% accuracy. The framework was refined on a new expert-labeled dataset of 1073 Arabian camel images. The authors demonstrated practical deployment via a mobile app. In another work, Mondal et al. [28] used the Kaggle Dog Breed Identification dataset to propose a modified CNN model based on Xception for automatic dog breed classification. The model performed better than baseline deep architectures and achieved a high accuracy of 87.40%. Mu et al. [29] proposed an enhanced Faster R-CNN–based dog face detection algorithm that combines a ResNet50 backbone, feature pyramid network, and bilinear interpolation for accurate bounding box calculation. Their algorithm achieved high accuracy in detecting small-scale dog faces on the Tsinghua Dog dataset. In another interesting work, Natthapon et al. [30] proposed a CNN-based ML framework that integrates breed classification and grooming time estimation. The system was implemented in a mobile application for scheduling and managing dog grooming services after training on a sizable annotated image dataset and incorporating performance metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score. James et al. [31] suggested an EfficientNet-based model for accurately classifying 133 dog breeds, attaining high accuracy through balanced model scaling, data augmentation, and extensive evaluation, indicating its potential in veterinary and animal welfare applications.

To differentiate between similar-looking breeds, fine-grained classification techniques concentrate on local discriminative regions (such as the ears, nose, and tail). Recent efforts that automatically localize informative regions, including Diversified Visual Attention Networks (DVAN) [32] and Part-based R-CNN [33], have shown potential. Bilinear CNNs [34] and selective descriptor aggregation [35], two fine-grained techniques that have already been used to classify animal species, have the potential to significantly enhance breed identification tasks. Recently, Zhang et al. [36] presented a same-category, same-semantics mixing approach, a unique data augmentation strategy for fine-grained image classification. It combines semantically related images to vary training samples and enhance classification performance on challenging visual classes. Using novel face alignment, body posture-guided processing, and multilevel representation, Zhang et al. [37] proposed a lightweight recognition framework called iFBI that integrated face and body cues to improve fine-grained breed and individual pet recognition under varying poses and limited resources. The framework achieved strong results on both custom and public datasets. The Parallel Visual Attention Encoder (PVAE) proposed by Martinez and Zhao [38] combined convolutional block attention and modified large kernel attention in parallel to improve feature extraction. When combined with architectures such as EfficientNet in a Parallel Visual Attention Network (PVAN), it showed better dog breed classification performance compared to single-attention and baseline models. A YOLO v8-based real-time bird breed classification and health monitoring system was presented by Gowtham et al. [39] to improve veterinary treatment and early intervention by precisely identifying bird breeds and identifying illness symptoms, such as avian influenza.

Existing models often struggle with rare or mixed breeds due to data imbalance and poor generalization. Fine-grained classification is essential for distinguishing visually similar dog breeds, but has also received limited attention, especially in end-to-end detection-classification frameworks. To address these challenges, a two-stage framework is proposed. In the first stage, a lightweight and efficient YOLO v8N model is employed to detect both the head and full body of the dog. These region-specific detections are crucial for capturing distinctive breed features. In the second stage, a two-stream ViT-based model is introduced that processes the head and full-body images separately. This design allows the model to extract complementary features from different anatomical regions, enhancing the accuracy and robustness of breed recognition. The proposed approach aims to deliver a more unified, efficient, and fine-grained solution for real-world dog breed classification.

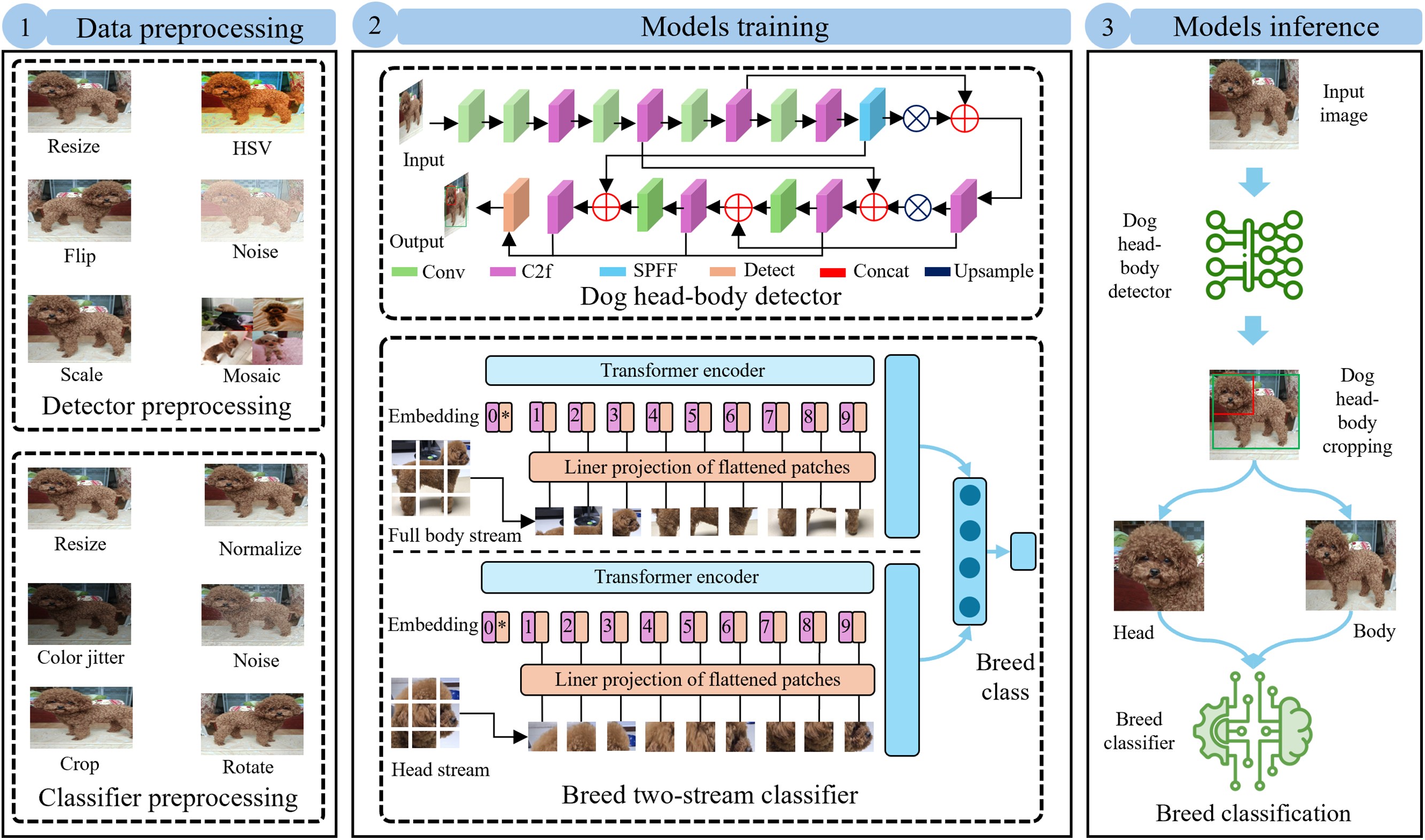

In this section, the overall approach suggested in this study for effective dog breed recognition is presented. In the first step, a full dog body and its head placement inside an image are detected, and in the second step, the breed of the observed dog is identified. The detailed architecture and functioning of each stage are discussed in the following subsections. An overview of the complete framework is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Overview of the proposed pipeline for dog breed classification. The pipeline consists of 3 stages: (1) Data preprocessing and augmentation, where raw images are preprocessed and augmented to improve the models robustness; (2) Training stage, where a YOLO v8N model is trained for detecting the dog’s full body and head, and a two-stream ViT is trained using the dog’s body and head crops for breed classification; and (3) Model inference, where an input image is passed through the trained YOLO v8N detector to localize the dog body and head, followed by breed classification using the two-stream ViT

3.1 Data Preprocessing and Augmentation

To increase efficiency, generalization, and resilience, the proposed approach uses customized data preprocessing and augmentation approaches. The detector preprocessing aims to improve the accuracy and reliability of dog body and head detection, while the classifier preprocessing guarantees consistent and varied inputs to the breed identification network.

To ensure robust and accurate detection of dog heads and full bodies across diverse real-world scenarios, a comprehensive data preprocessing and augmentation pipeline is applied for YOLO v8N. This lightweight yet high-performance object detector benefits significantly from enriched training data that simulates variations in real-world image capture conditions. The preprocessing starts by resizing all input images to match the fixed input dimensions required by YOLO v8N. This ensures consistent spatial dimensions across the dataset, allowing for efficient model training. Next, images are converted into the HSV (Hue, Saturation, Value) color space to diversify color-related features. This enhances the model’s ability to detect dogs under varying lighting conditions and fur color variations. Geometric transformations such as translation and scaling are introduced to help the model learn spatial invariance and robustness to changes in object size and position. Horizontal flipping increases the dataset size by creating mirrored versions of images, which is particularly useful for bilateral symmetry in dog postures. To simulate different environmental conditions, random adjustments are applied to brightness and contrast, making the model more tolerant to lighting inconsistencies. Furthermore, Gaussian noise is added to simulate sensor imperfections or low-quality imaging conditions, thus improving the detector’s noise robustness. Mixup augmentation blends two images and their labels, promoting smoother decision boundaries and reducing overfitting. Finally, mosaic augmentation by combining four different training images into a single image provides rich contextual diversity, exposing the model to multiple object scales, positions, and environments in a single forward pass. Together, these augmentations significantly improve the generalization and detection accuracy of YOLO v8N in varied real-world scenes.

On the other hand, to achieve high-precision dog breed classification using the two-stream ViT model, a specialized preprocessing and augmentation pipeline is implemented that ensures both diversity and consistency across the input head and body image streams. This two-stream approach relies heavily on fine-grained feature learning, which necessitates high-quality, varied input samples. All head and full body images are first resized to match the input patch size expected by the ViT architecture, ensuring uniformity and compatibility with the model’s embedding layer. Random cropping is applied to encourage the model to focus on different spatial regions, thereby improving its ability to learn local breed-specific patterns. Random rotations further support spatial invariance by training the model to recognize breeds irrespective of the dog’s orientation in the frame. Horizontal flipping is used to double the training examples and capture mirrored postures of dogs, enhancing generalization. Brightness and contrast augmentations mimic environmental lighting variations, helping the classifier adapt to breed images taken under different conditions. To increase the model’s resilience to image corruption, Gaussian noise is introduced, and random erasing is used to simulate occlusion or missing regions, encouraging the model to rely on multiple features for classification. Finally, all inputs are normalized using ImageNet statistics (mean = [0.485, 0.456, 0.406], std = [0.229, 0.224, 0.225]) to align the data distribution with the pretraining configuration of the ViT. This step is crucial to ensure optimal transfer learning and model convergence. Collectively, this augmentation pipeline delivers diverse, challenging, and well-normalized inputs to both the head and body streams, enabling the two-stream ViT to extract complementary and discriminative features for fine-grained breed classification across all the classes.

In this study, a two-phase architecture for dog breed classification is adopted. In the first phase, a YOLO v8N-based detection model identifies and extracts the dog’s head and full body from the input image. In the second phase, these extracted regions are used as inputs to a two-stream ViT model that classifies the dog into one of the target breeds. Both models are detailed in the following sections.

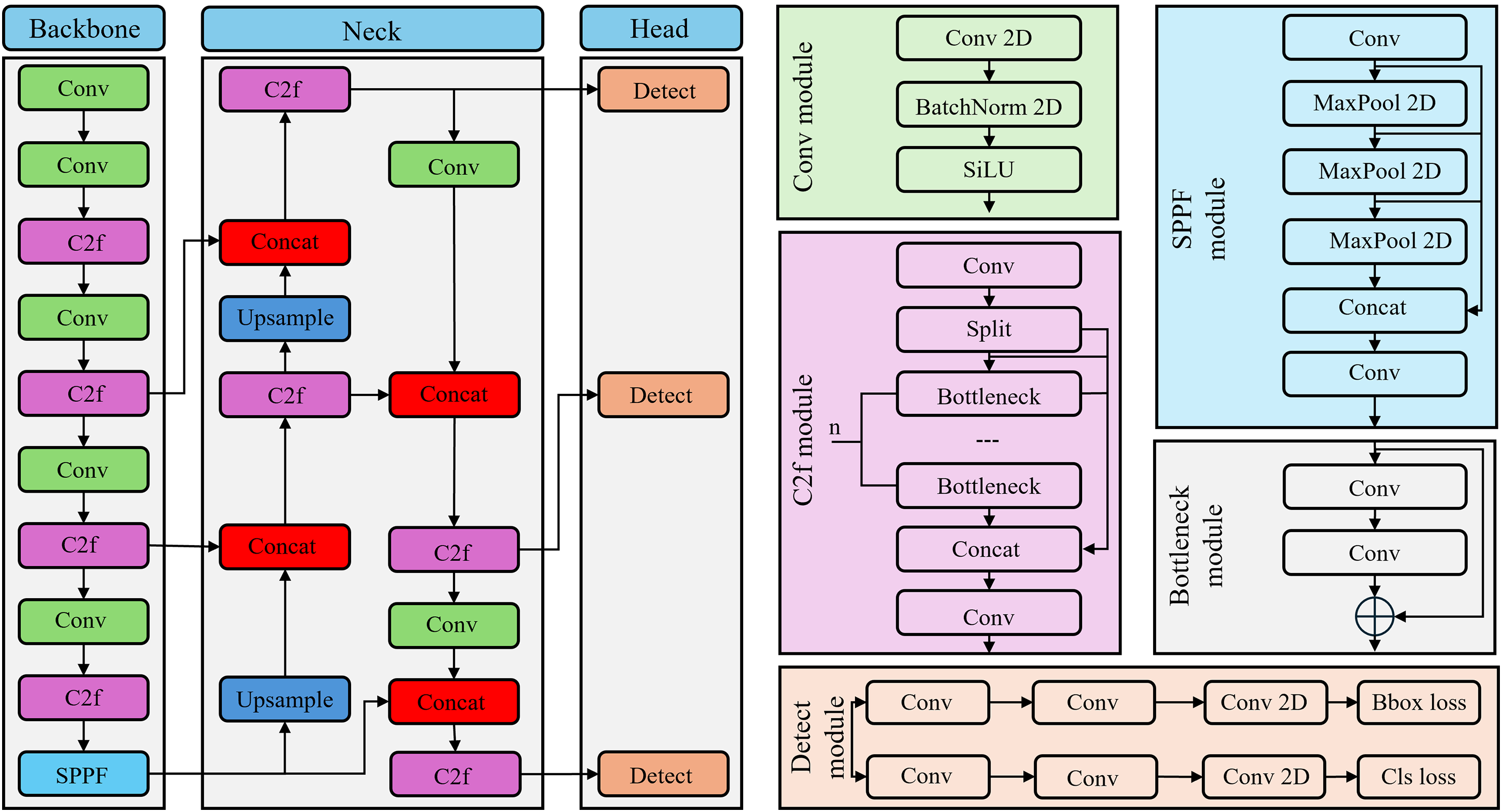

In the first phase of this study, the YOLO v8N model’s sophisticated object detection abilities are incorporated to identify dogs’ full body and their head areas in images as depicted in Fig. 1. The YOLO v8N model is a completely redesigned architecture that is optimized for accuracy and speed [40]. The detailed architecture of YOLO v8 is presented in Fig. 2, where its main components, such as backbone, neck, and detection head, are clearly illustrated. In contrast to its predecessors, YOLO v8 uses a custom backbone that is optimized for efficiency and end-to-end learning, rather than the Cross Stage Partial (CSP) Darknet backbone. The head, neck, and backbone make up the three primary structural elements of the model. The backbone uses a unique CSPFree architecture to extract rich visual information from the input image. This comprises several Cross Stage Partial with Two-way Fusion (C2f) modules that improve gradient flow and parameter efficiency through partial residual connections after an initial Focus layer is swapped out for a Convolutional (Conv) block. The input image is down-sampled by the backbone while maintaining important spatial and semantic details that are necessary to differentiate between a dog’s head and body. The neck is a feature aggregation strategy inspired by Path Aggregation Networks (PANs). By combining multi-scale characteristics through concatenation and upsampling, the model can identify objects at various scales. This works especially well for precisely locating dogs’ entire bodies as well as minor head features in a single shot. With a decoupled head structure that manages classification and regression tasks independently, the head uses anchor-free detection. This change in architecture speeds up inference and increases localization accuracy. Even in challenging circumstances with occlusion or changing stances, the head’s direct prediction of bounding boxes and class probabilities allows for accurate detection of both dog bodies and faces. The YOLO v8N is especially well-suited for the role of dog body and head recognition because of its lightweight design and excellent performance. The robustness of detection in this application is greatly increased by its end-to-end training capacity and enhanced generalization across a variety of visual situations.

Figure 2: Overview of the YOLO v8 architecture used in this study. The model consists of three main components: (1) Backbone: responsible for extracting multi-scale feature representations from the input image; (2) Neck: aggregates and refines features using Feature Pyramid Networks (FPN) and PAN; and (3) Head: performs object detection by predicting bounding boxes, objectness scores, and class probabilities

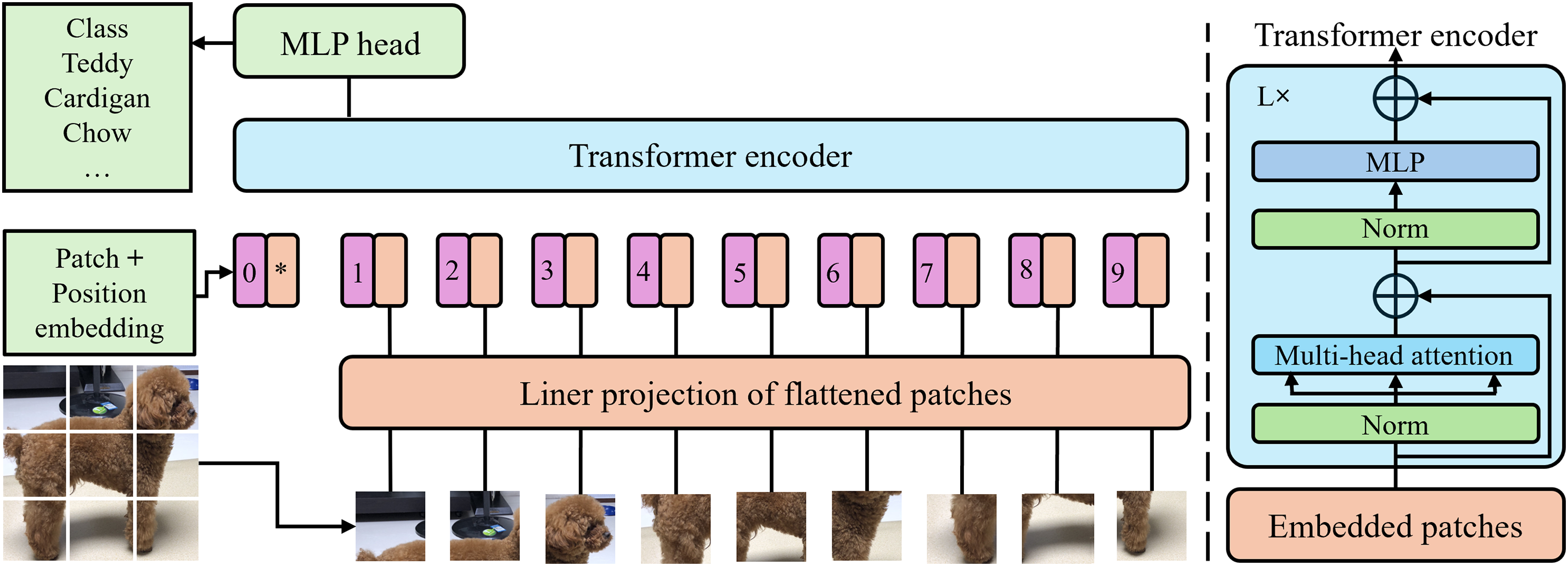

3.2.2 Breed Two-Stream Classifier

In conventional image classification problems, a single-stream architecture predicts the associated label by processing a single view of an input image. Although this method works well in many situations, it frequently fails to handle fine-grained categorization issues, such as dog breeds. Simonyan and Zisserman [41] addressed this by introducing the two-stream architecture in the context of video action recognition. They showed the effectiveness of complementary information streams for better recognition performance by using distinct spatial and temporal networks to capture appearance and motion features, respectively. Since then, this architectural idea has sparked developments in a number of fields, such as fine-grained visual classification, where several visual pathways, each focusing on unique feature representations, aid in the model’s ability to distinguish between closely related classes [42,43].

In this work, a two-stream ViT architecture is presented that is specifically designed for the fine-grained task of dog breed recognition. The network is composed of two parallel ViT branches, one of which processes the full-body image and the other the head image of a dog. While the body stream captures global cues like body shape, fur length, and tail characteristics, the head stream is intended to record localized, discriminative aspects like ear shape, eye position, and facial markings. These two perspectives provide more thorough visual information that could be unclear or inadequate when using a single-stream network. The outputs of both transformer streams are concatenated into a single feature vector following independent feature extraction. This enables the network to reason holistically about both localized and global appearance patterns before sending the representation to a classifier for the final breed prediction. The architecture consists of two branches, each based on a ViT model that tokenizes the input image into patches and uses a self-attention mechanism to encode the spatial relationships between them as depicted in Fig. 3. By using this method, the network can identify minor breed-specific cues by capturing both local and long-range relationships. Each stream’s token output is taken out, fused via concatenation, and then sent to a fully connected classification head. A probability distribution across dog breed classifications is generated by a softmax layer at the top. Cross-entropy loss is used to jointly optimize both streams during training, fostering the model’s efficient integration of fine and coarse information. The approach intends to enhance performance on the challenging task of dog breed classification by integrating the two-stream architecture into a ViT-based framework.

Figure 3: Illustration of ViT architecture. The input image is first divided into fixed-size patches, each of which is linearly embedded into a patch embedding vector. These embeddings are combined with positional encodings and passed through a stack of transformer encoder layers composed of multi-head self-attention and feed-forward networks. The final classification token output is used for downstream tasks such as classification or feature extraction in the pipeline

The proposed classifier architecture leverages the power of ViT by employing a dual-stream model that processes two complementary visual inputs, head and body images of dogs, through separate ViT backbones. Specifically, it utilizes two instances of the ViT, each pre-trained on ImageNet. To adapt the ViT for feature extraction rather than classification, their original classification heads are replaced with identity mappings, thereby outputting rich 768-dimensional feature vectors for each image. These vectors, one from the head image and one from the body image, are concatenated to form a combined 1536-dimensional representation. This joint feature is passed through a sequence of fully connected layers with batch normalization, ReLU activations, and dropout, effectively capturing complex interdependencies between the two image regions. The final output layer maps the processed feature to the target number of dog breed classes. At the core of this model lies the ViT architecture, a base model introduced by Dosovitskiy et al. [44]. It operates by dividing the input image (typically of size

3.2.3 Justification for Choosing the Vision Transformer

Although CNNs have traditionally been favored for visual recognition tasks due to their computational efficiency and inductive biases like locality and translation invariance, recent research has shown that ViT can significantly outperform CNNs in fine-grained classification tasks. Dog breed recognition is a fine-grained problem where subtle inter-class differences (e.g., ear shape, fur texture, facial pattern) and intra-class variations (e.g., pose, lighting, occlusion) are prominent. ViTs excel in capturing long-range dependencies and modeling global contextual information without being limited by local receptive fields, which allows them to better distinguish these subtle variations. In the experiments, it is observed that ViT consistently outperformed CNN-based models (e.g., MobileNet, ResNet50) in accuracy and other metrics by a notable margin (see Section 4.6). This is particularly important for applications like pet identification or veterinary diagnostics, where high classification precision is critical. Therefore, despite their higher computational demand, the ViT-based architecture is chosen due to its superior accuracy, better feature representation for fine-grained tasks, and growing efficiency in recent lightweight implementations.

4 Experimental Setup and Results

The experimental setup used to assess the proposed approach is described in this section. The software and hardware setups needed to apply the models successfully are described in detail. Information about the dataset used in this work is provided. Lastly, the section overviews the evaluation metrics and the findings, showing how well the suggested method performs across various dog breeds.

The experiments in this study are carried out using Python 3.10 and the PyTorch DL framework. In order to guarantee strong computational performance for real-time object recognition, a workstation with an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4060 Ti GPU is used. In addition, the system has an AMD Ryzen 5 7500F 6-Core processor and runs on a 64-bit version of Windows 11 Pro to guarantee hardware acceleration and compatibility with DL libraries. The specified learning rates, optimizers, batch sizes, and other relevant parameters and configurations are followed for every step of the model pipeline in compliance with the underlying models’ original implementation protocols.

The YOLO v8N model pretrained on the COCO dataset is fine-tuned on the custom dataset to detect the head and whole body of specific dog breeds. The dataset annotations are processed in the YOLO v8 format and split into training and validation sets using an 80/20 ratio. The training configuration specifies two target classes (head and body) and incorporates a range of data augmentation techniques to enhance the diversity and robustness of the model. These augmentations include HSV jittering, image translation, scaling, horizontal flipping, mosaic augmentation, and photometric distortions such as brightness, contrast, and Gaussian noise, following established best practices for object detection tasks. The pretrained YOLO v8N model is initialized with an input resolution of

For breed classification, a dual-branch ViT model is fine-tuned using pretrained ViT backbones for both head and body image streams. The pretrained heads are replaced with identity layers to extract features, which are subsequently combined and passed through a custom classification head. Data augmentation strategies included are random resizing, rotation, horizontal flipping, color jittering, and random erasing. The model is trained for 50 epochs (adjustable for scalability) with cross-entropy loss and Adam optimizer. Learning rate is set to 0.00003 when using pretrained weights. Early stopping with a patience of 10 epochs is employed to prevent overfitting. Performance is evaluated using accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and per-class metrics across 130 dog breeds.

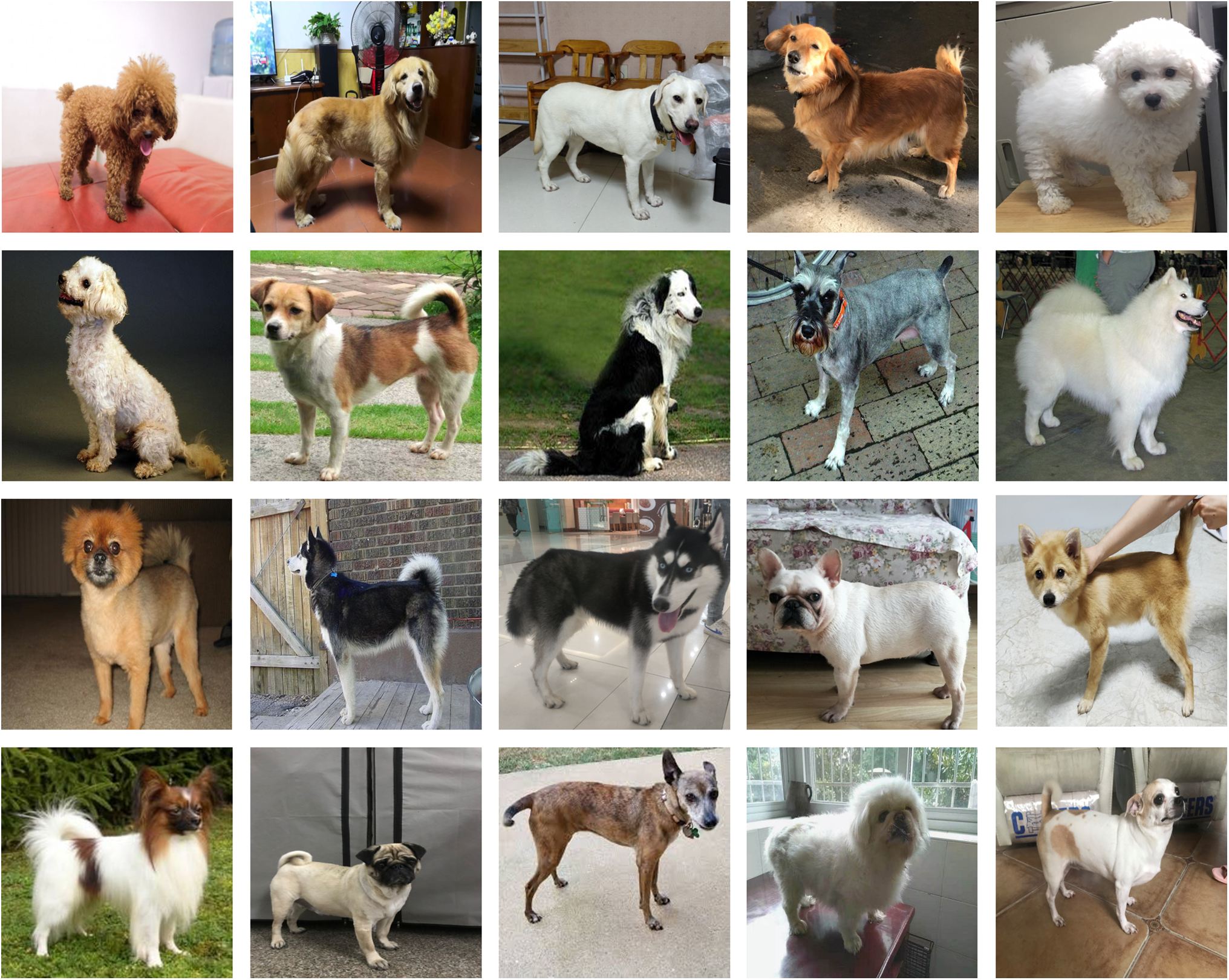

The Tsinghua Dogs dataset is a large image collection created especially for fine-grained dog breed detection and classification [4]. It is the most comprehensive dataset to date, with 70,428 high-resolution photos representing 130 dog breeds. There is exactly one dog in every picture, and more than 65% of the images are taken in actual locations, like parks or cities, guaranteeing great authenticity and variation. The dataset can be used in both global and part-based classification tasks because it provides comprehensive annotations, such as bounding boxes for the dog’s head and full body. Fig. 4 shows some images of the dog breeds examples and their visual variations. A minimum of 200 images is included for each breed class, and up to 7449 images for more popular breeds like the Teddy dog, in order to guarantee balanced representation and adequate intra-class variance. Table 1 shows the top 20 breed classes in terms of the number of images out of the 130 breeds in the Tsinghua Dogs dataset. Images in the Tsinghua Dogs dataset are taken from the Stanford Dogs dataset [45], curated web searches, and user submissions from various Chinese locales. An active learning and RetinaNet-based semi-automated annotation pipeline significantly increased labeling consistency and efficiency. Because the Tsinghua Dogs dataset has more intra-class diversity and inter-class similarity than other datasets like Stanford Dogs, it is a perfect dataset for creating and assessing reliable visual recognition algorithms. However, when compared to a number of cutting-edge fine-grained classification models, it proved to be much more difficult.

Figure 4: The visualization showcases the appearance variations among the top 20 dog breeds in the Tsinghua Dogs dataset. The breeds are displayed in order, with the first image representing the most frequent breed, Teddy, followed by Golden Retriever, and so on. The final image in the last row depicts the Chihuahua breed [4]

Data Ethics and Animal Welfare

While this study utilizes publicly available animal image datasets, it is essential to acknowledge the ethical considerations associated with the development and deployment of computer vision systems for animal monitoring. Applications such as breed recognition, pet surveillance, and health diagnostics should prioritize the welfare, dignity, and privacy of both animals and their owners. Data collection must adhere to established animal welfare guidelines, avoid invasive or stressful capture procedures, and, where applicable, obtain informed consent from pet owners. Moreover, the real-world deployment of such systems must be safeguarded against misuses such as unauthorized surveillance or tracking, and ethical standards should be upheld when monitoring animals in public or private spaces. We advocate for the integration of ethics-by-design principles in future research and development, especially as these technologies are scaled across diverse species and use cases.

The performance of the proposed two-stage dog breed recognition system is thoroughly assessed using a number of metrics. The conventional standards for evaluating efficacy include Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-score, and AP50 and AP50-95. We go into detail about each metric and its mathematical formulation below.

The percentage of accurately predicted instances to all instances is used to calculate accuracy, which evaluates how accurate the classification is overall. The Eq. (1) is for calculating accuracy, where the TP are True Positives, TN are True Negatives, FP are False Positives, and FN are False Negatives.

The precision measures the percentage of positive identifications that are truly accurate. Avoiding mislabeling in multi-class breed classification requires a low false positive rate, which is indicated by high precision. Eq. (2) indicates precision calculation.

The percentage of TP that is successfully detected is measured by recall, which is also referred to as sensitivity. When minimizing FN is essential, like when distinguishing uncommon or similar-looking breeds, high recall is essential. Eq. (3) shows the mathematical calculation for the recall value.

The F1-score is a single score that balances precision and recall by taking the harmonic mean of both parameters. In case there is an imbalance in the dataset among breed classes, the F1-score is especially helpful. F1-score is calculated by following the Eq. (4)

In object identification, AP is a commonly used metric that calculates the area under the precision-recall curve to summarize it. Across various confidence standards, it gives a single-value score that strikes a balance between precision and recall. AP50 is the term used when the Intersection over Union (IoU) threshold is set at 0.5. A detection is considered correct if the IoU between the ground truth and the predicted bounding box is

The

4.4 The Proposed Model Results

This section presents the results of the dog head and full body detection model, followed by the performance evaluation of the two-stream dog breed classification model.

4.4.1 Dog Head-Body Detector Results

In the task of dog breed classification, accurate detection of both the head and the full body of a dog plays a critical role. This is because different breeds often have subtle variations in facial structure, ear shape, and body proportions that are essential for reliable identification. Localizing the head helps focus on facial features, while detecting the entire body provides complementary structural context. To efficiently and effectively detect these regions, YOLO v8N is used, a lightweight object detection model known for its high accuracy-speed tradeoff, making it ideal for real-time and resource-constrained applications. Despite being a compact model, YOLO v8N retains the core architectural advantages of the YOLO v8 family, such as improved anchor-free detection, decoupled head design, and dynamic label assignment.

Using the Tsinghua Dogs dataset, which includes diverse dog images across various breeds and poses, the YOLO v8N is trained to detect both dog heads and full bodies. The detection performance was evaluated using standard object detection metrics. As shown in Table 2, the AP at IoU 0.5 (AP50) for head detection is 0.9723 and for body detection is even higher at 0.9884, indicating near-perfect localization capabilities. For more stringent evaluation (AP50-95), the head and body achieved 0.8164 and 0.8978, respectively, showcasing strong performance across various IoU thresholds. Both classes exhibit high precision (head: 0.9799, body: 0.9897) and recall (head: 0.9741, body: 0.9875), reflecting that the model consistently identifies TP with very few FP or FN. This is further supported by high F1-scores of 0.9770 for head and 0.9886 for body detection that demonstrate an excellent balance between precision and recall. The overall performance across both classes also confirms the robustness of the model, with an AP50 of 0.9804, AP50-95 of 0.8571, and F1-score of 0.9828. These results validate YOLO v8N as a highly effective solution for precise and real-time dog part detection, which can significantly enhance downstream breed classification tasks.

4.4.2 Breed Two-Stream Classifier Results

In dog breed classification, accurately identifying both the head and full body is crucial because these regions capture different yet complementary visual cues that are breed-specific. The head often contains distinctive features such as ear shape, eye placement, snout length, and fur texture, while the body provides important structural information like size, tail position, and posture. A two-stream ViT architecture is used to leverage this rich and multi-region information. In this setup, one stream processes the dog’s full body image, while the second stream processes a cropped image of its head. Features from both streams are then concatenated and passed through fully connected layers, allowing the model to learn an optimal fusion of global (body) and local (head) features. The final layer performs classification across 130 dog breeds, enabling the model to make fine-grained distinctions based on holistic and detailed visual traits.

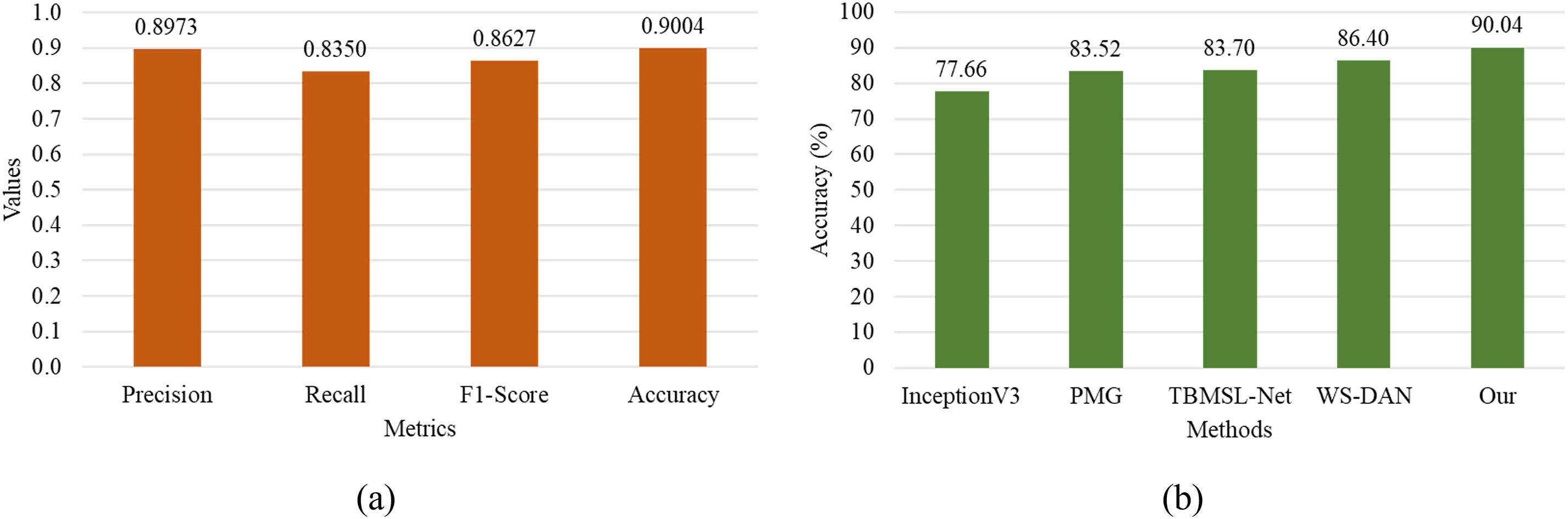

Using the Tsinghua Dogs dataset, which includes a large variety of annotated dog images across numerous breeds, the two-stream ViT model is trained for breed classification. The model achieves strong performance across key classification metrics, as illustrated in Fig. 5a. It obtains a precision of 0.8973, indicating a high proportion of correctly predicted breeds among all predicted instances. The recall is 0.8350, suggesting that the model successfully identified a substantial portion of all true breed instances in the dataset. The F1-score of 0.8627 demonstrates a solid balance between precision and recall, and an overall classification accuracy of 0.9004 underscores the model’s effectiveness in handling a challenging 130-class problem. These results affirm that the two-stream ViT architecture effectively combines head and body cues, leading to a more discriminative and breed-aware representation. This fusion strategy proves to be especially beneficial in classifying breeds with subtle inter-class variations, where relying solely on head or body information may be insufficient.

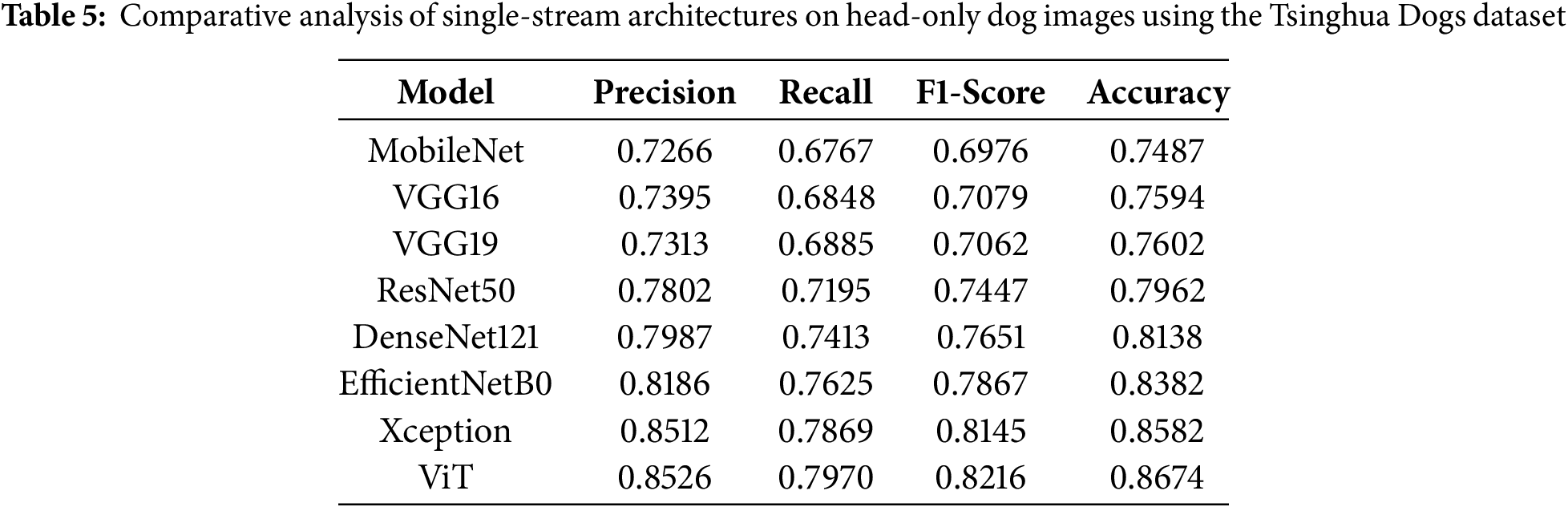

Figure 5: (a) The proposed dog breeds classifier results, (b) comparison of the model with SOTA

4.5 Comparison with State-of-the-Art

To evaluate the effectiveness of fine-grained dog breed classification, a comparative study is conducted using the Tsinghua Dogs dataset, benchmarking four prominent DL architectures from the literature: InceptionV3 [4], PMG [4], TBMSL-Net [4], and WS-DAN [4]. In addition, a novel two-stream ViT-based model is introduced, specifically designed for breed classification. Below, each approach is described and compared in terms of its performance.

InceptionV3, a general-purpose classification architecture, served as a baseline. It was trained with a

In summary, while the existing methods from the literature show commendable performance, they fall short in capturing the subtle inter-breed variations specific to dogs. The proposed two-stream ViT model leverages both global and localized visual cues effectively, setting a new benchmark for fine-grained dog breed recognition.

To identify the optimal configuration for dog breed recognition, we conducted a comprehensive ablation study using various backbone models. Specifically, we evaluated ViT, MobileNet [46], VGG16 [18], VGG19 [18], ResNet50 [19], DenseNet121 [47], EfficientNetB0 [48], and Xception [49] in both single-stream and two-stream setups. These experiments were performed using the animal breed datasets to assess their effectiveness in the context of our task. The detailed results of each experiment are presented in the following sections.

4.6.1 Comparative Analysis of Single-Stream Architectures on Original Images

To evaluate the baseline performance of various backbone architectures for fine-grained dog breed classification, we conducted a comparative ablation study using single-stream models trained on the original images of the Tsinghua Dogs dataset containing background information. Eight widely used convolutional and transformer-based models were analyzed: MobileNet, VGG16, VGG19, ResNet50, DenseNet121, EfficientNetB0, Xception, and ViT. All models were trained under the same experimental settings to ensure fair comparison. Among the evaluated models, ViT achieved the best overall performance, obtaining the highest scores across all key metrics: precision (0.8097), recall (0.7493), F1-score (0.7754), and accuracy (0.8254). This result highlights the superiority of transformer-based architectures in capturing long-range dependencies and subtle semantic differences, which are crucial for fine-grained classification tasks. Close contenders include Xception and EfficientNetB0, which also demonstrated strong performance, with Xception achieving an F1-score of 0.7375 and accuracy of 0.7937, while EfficientNetB0 followed closely with an F1-score of 0.7286 and accuracy of 0.7752.

In contrast, MobileNet consistently performed the worst among the models tested, with the lowest precision (0.6765), recall (0.6247), F1-score (0.6456), and accuracy (0.7033). This can be attributed to its lightweight architecture, which may lack the capacity to effectively distinguish fine-grained features in complex backgrounds. Traditional CNNs like VGG16 and VGG19 showed modest improvements over MobileNet, but still fell behind the more advanced ResNet50 and DenseNet121 models, which benefited from deeper representations and feature reuse. Overall, this ablation study clearly demonstrates that modern, high-capacity models, particularly transformer-based architectures like ViT, offer substantial advantages for fine-grained visual recognition tasks, even when trained on raw images with background clutter, as shown in Table 3.

4.6.2 Comparative Analysis of Single-Stream Architectures on Full-Body Images

This paragraph explains the result of single-stream models using only the cropped full-body images of dogs, excluding any background context. The results in Table 4 demonstrate a consistent performance improvement across all models compared to their counterparts trained on original images with background. This improvement can be attributed to the removal of irrelevant background noise, which allows the models to focus solely on the discriminative features of the dog’s body relevant for breed recognition. Among the models, the ViT again achieved the highest overall performance, with a precision of 0.8526, a recall of 0.7911, an F1-score of 0.8176, and an accuracy of 0.8663, confirming its strong capacity to capture subtle fine-grained details when background clutter is eliminated. Xception and EfficientNetB0 also showed significant gains, reaching F1-scores of 0.8082 and 0.7758, respectively, demonstrating their efficiency in extracting relevant visual cues from the foreground. In contrast, MobileNet achieved the lowest performance among the tested models, with a precision of 0.6960, a recall of 0.6513, an F1-score of 0.6695, and an accuracy of 0.7307, although it still outperformed its version trained on background-included images. These results highlight the importance of preprocessing steps like object localization and background removal in fine-grained classification tasks, especially when working with visually similar classes such as dog breeds.

4.6.3 Comparative Analysis of Single-Stream Architectures on Head Images

To further analyze the discriminative power of different image regions, we evaluated the performance of single-stream models trained exclusively on dog head images, excluding both the background and body. The results show a marked improvement over models trained on full-body images with background, as well as those trained on full-body crops without background. This enhancement underscores the significance of the dog’s head, particularly the facial region, ears, and eyes, in capturing breed-specific traits critical for fine-grained classification. Among all the models, the ViT delivered the best performance, achieving a precision of 0.8526, a recall of 0.7970, an F1-score of 0.8216, and an accuracy of 0.8674, as shown in Table 5. These results confirm ViT’s strong capability to capture fine details when focusing on compact, high-information regions such as the head. Xception also performed exceptionally well, with an F1-score of 0.8145, slightly trailing ViT, followed by EfficientNetB0 with 0.7867. The consistent improvement across all models indicates that removing irrelevant body features and background clutter allows models to focus on the most informative regions, thus improving prediction confidence and accuracy. The worst-performing model, though still improved compared to the previous setups, was MobileNet, with an F1-score of 0.6976 and accuracy of 0.7487. Despite its lower complexity, MobileNet benefited from the head-only input, highlighting that even lightweight models can achieve reasonable performance when trained on region-specific data. These findings demonstrate the effectiveness of focusing on the dog head for breed classification and justify the use of localized region-based inputs in fine-grained visual recognition tasks.

4.6.4 Comparative Analysis of Two-Stream Architectures on Head and Body Images

To leverage complementary visual cues from both the head and body regions of dogs, we implemented a two-stream architecture where one stream processes the cropped dog head and the other processes the cropped full-body image, both without background. The extracted features from both streams are fused to enhance breed classification. This multi-view learning approach significantly outperformed single-stream models that relied solely on background-included images, full-body crops, or head-only inputs as depicted in Table 6. The enhanced performance is attributed to the fact that the head and body carry distinct yet complementary features. The head provides fine-grained details such as ear shape, eye color, and facial structure, whereas the body contributes information on size, posture, and coat patterns. Combining these regions allows the model to learn a more holistic and discriminative representation of the dog breed. Among all tested architectures, the ViT again demonstrated superior performance, achieving a precision of 0.8973, a recall of 0.8350, an F1-score of 0.8627, and an outstanding accuracy of 0.9004, the highest across all experiments. Xception also delivered robust results with an F1-score of 0.8383 and accuracy of 0.8816, followed closely by EfficientNetB0 at an F1-score of 0.7993. These results affirm that two-stream fusion significantly improves classification, especially when paired with advanced models capable of learning deep hierarchical features. Even the lowest-performing model, MobileNet, achieved a respectable F1-score of 0.6998 and accuracy of 0.7545, outperforming its single-stream counterpart trained on background-included or isolated head images. This improvement highlights that even lightweight models benefit substantially from multi-regional input and feature fusion.

Overall, this ablation confirms that combining head and body features via a two-stream architecture offers a more comprehensive and effective solution for fine-grained dog breed classification, outperforming all single-stream configurations.

4.6.5 Performance Comparison of Two-Stream Architectures for Cross-Species Classification

To validate cross-species generalization, additional experiments were conducted on the Oxford-IIIT Pet dataset [7]. The dataset consists of 7349 images spanning 37 distinct pet breeds, including 25 dog breeds and 12 cat breeds. Each breed is represented by approximately 200 annotated images. In addition to breed labels, the dataset includes tight bounding boxes around the pet’s head, making it well-suited for region-specific modeling in fine-grained classification tasks. This rich annotation structure allows the application of region-aware dual-stream models, similar to those used in the Tsinghua Dogs dataset. Table 7 presents the performance of various dual-stream classification models applied to the Oxford-IIIT Pet dataset, which includes both dog and cat breeds. All models utilized the same two-stream framework, independently processing the detected head and full images with background, ensuring consistent and fair evaluation settings. Among the CNN-based models, Xception demonstrated the highest performance, achieving an accuracy of 0.9170 and an F1-score of 0.8782, followed closely by EfficientNetB0 and DenseNet121. This suggests that deeper and more efficient convolutional architectures benefit from the dual-region input in distinguishing subtle inter-species and intra-species variations. The proposed model, which integrates a dual-stream design ViT backbone, significantly outperformed all other architectures. It achieved a precision of 0.9681, a recall of 0.9285, an F1-score of 0.9470, and an overall accuracy of 0.9685, demonstrating its superior ability to capture both global and localized features from head and full image regions.

These results confirm the effectiveness of the proposed method in cross-species fine-grained classification, handling both mammalian categories, including dogs and cats. The strong performance of the proposed model highlights the advantage of combining region-specific attention with transformer-based global context modeling, validating its scalability and adaptability across species with distinct anatomical structures.

4.6.6 Statistical Significance Analysis

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of the proposed model against existing methods, we conducted a 10-fold cross-validation using a two-stream architecture across a range of widely adopted DL models, including MobileNet, VGG16, VGG19, ResNet50, DenseNet121, EfficientNetB0, and Xception. For each model, classification accuracy was recorded across 10 independent folds. To assess the statistical significance of the observed improvements, we performed paired t-tests comparing the accuracy of our proposed model with each baseline across the 10 folds. The results of the statistical analysis confirmed that the improvements achieved by our model were statistically significant, with all p-values below 0.05. These findings underscore the robustness and superior performance of the proposed approach relative to the baselines.

In this work, a practical two-phase DL pipeline is introduced for dog breed recognition. In the first stage, a lightweight object detector, YOLO v8N, is used to localize both the dog’s head and full body. In the second stage, these regions are processed independently using a dual-stream ViT, allowing the model to extract complementary breed-specific features from both the head and body. Dedicated preprocessing steps are applied to each region to maximize the discriminative capacity of the model. This integrated approach addresses the limitations of traditional handcrafted and single-stream methods, particularly in handling subtle visual differences inherent in fine-grained classification tasks. The proposed architecture achieves competitive results and demonstrates practical utility for real-world applications such as breed recognition, veterinary diagnostics, and intelligent pet care systems.

In future research, we plan to enhance our framework by integrating few-shot learning techniques to improve recognition performance for rare and underrepresented breeds. Furthermore, we aim to investigate the generalizability of the proposed approach across other animal and bird species, including horses, birds, and cats. We recognize that such cross-species adaptation introduces several unique challenges. These include significant differences in anatomical structure, pose variability, and a lack of large-scale annotated datasets, all of which may affect both detection accuracy and feature representation. Additionally, defining semantically meaningful head-body regions for different species may necessitate task-specific modifications to the detection and classification modules. To address these challenges, future work will explore customized data augmentation strategies, species-aware detection priors, and potentially develop dedicated branches or feature extractors tailored to each species. This direction will further validate the scalability and generalization capability of our proposed framework.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the faculty research fund of Sejong University in 2023, the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (RS-2025-00518960), and Institute of Information & Communications Technology Planning & Evaluation (IITP) under the metaverse support program to nurture the best talents (IITP-2025-RS-2023-00254529) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Noman Khan and Afnan; methodology, Noman Khan and Afnan; software, Noman Khan and Afnan; validation, Noman Khan and Afnan; formal analysis, Mi Young Lee; investigation, Jakyoung Min; data curation, Noman Khan and Afnan; writing—original draft preparation, Noman Khan and Afnan; writing—review and editing, Noman Khan and Afnan; visualization, Noman Khan and Afnan; supervision, Mi Young Lee; project administration, Jakyoung Min; funding acquisition, Mi Young Lee and Jakyoung Min. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available on request from the authors.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| AP | Average Precision |

| C2f | Cross Stage Partial with Two-way Fusion |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| CSP | Cross Stage Partial |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| DVAN | Diversified Visual Attention Networks |

| FN | False Negative |

| FP | False Positive |

| HOG | Histogram of Oriented Gradients |

| IoU | Intersection over Union |

| LBP | Local Binary Patterns |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| NCC | Normalized Cross-Correlation |

| PAN | Path Aggregation Network |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| SIFT | Scale-Invariant Feature Transform |

| SOTA | State-of-the-Art |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| TN | True Negative |

| TP | True Positive |

| ViT | Vision Transformer |

| YOLO v8N | You Only Look Once Version 8 Nano |

References

1. Luu TH, Phuc PNK, Ngo QH, Nguyen TT, Nguyen HC. Design a computer vision approach to localize, detect and count rice seedlings captured by a UAV-mounted camera. Comput Mater Contin. 2025;83(3):5643–56. doi:10.32604/cmc.2025.064007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Tong SG, Huang YY, Tong ZM. A robust face recognition method combining LBP with multi-mirror symmetry for images with various face interferences. Int J Autom Comput. 2019;16(5):671–82. doi:10.1007/s11633-018-1153-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Borwarnginn P, Kusakunniran W, Karnjanapreechakorn S, Thongkanchorn K. Knowing your dog breed: identifying a dog breed with deep learning. Int J Autom Comput. 2021;18(1):45–54. doi:10.1007/s11633-020-1261-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Zou DN, Zhang SH, Mu TJ, Zhang M. A new dataset of dog breed images and a benchmark for fine-grained classification. Comput Vis Media. 2020;6(4):477–87. doi:10.1007/s41095-020-0184-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Chanvichitkul M, Kumhom P, Chamnongthai K. Face recognition based dog breed classification using coarse-to-fine concept and PCA. In: 2007 Asia-Pacific Conference on Communications; 2007 Oct 18–20; Bangkok, Thailand. p. 25–9. [Google Scholar]

6. Prasong P, Chamnongthai K. Face-recognition-based dog-breed classification using size and position of each local part, and PCA. In: 2012 9th International Conference on Electrical Engineering/Electronics, Computer, Telecommunications and Information Technology; 2012 May 16–18; Phetchaburi, Thailand. p. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

7. Parkhi OM, Vedaldi A, Zisserman A, Jawahar C. Cats and dogs. In: 2012 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2012 Jun 16–21; Providence, RI, USA. p. 3498–505. [Google Scholar]

8. Liu J, Kanazawa A, Jacobs D, Belhumeur P. Dog breed classification using part localization. In: Computer Vision–ECCV 2012: 12th European Conference on Computer Vision; 2012 Oct 7–13; Florence, Italy. p. 172–85. [Google Scholar]

9. Lai K, Tu X, Yanushkevich S. Dog identification using soft biometrics and neural networks. In: 2019 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN); 2019 Jul 14–19; Budapest, Hungary. p. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

10. Tu X, Lai K, Yanushkevich S. Transfer learning on convolutional neural networks for dog identification. In: 2018 IEEE 9th International Conference on Software Engineering and Service Science (ICSESS); 2018 Nov 23–25; Beijing, China. p. 357–60. [Google Scholar]

11. Zhao B, Feng J, Wu X, Yan S. A survey on deep learning-based fine-grained object classification and semantic segmentation. Int J Autom Comput. 2017;14(2):119–35. doi:10.1007/s11633-017-1053-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Chen KX, Wu XJ. Component SPD matrices: a low-dimensional discriminative data descriptor for image set classification. Comput Vis Media. 2018;4(3):245–52. doi:10.1007/s41095-018-0119-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Ren JY, Wu XJ. Vectorial approximations of infinite-dimensional covariance descriptors for image classification. Comput Vis Media. 2017;3(4):379–85. doi:10.1007/s41095-017-0094-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Nazar N, Unnikrishnan A. Breed identification and emotion detection of dogs using deep learning: a review. In: 2025 International Conference on Innovative Trends in Information Technology (ICITIIT); 2025 Feb 21–22; Kottayam, India. p. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

15. Vimaladevi M, Thangamani R, Suganth Krishna E, Naveen B, Srihari Prrasath A. Deep learning approaches for dog breed identification and behaviour analysis in conversational AI systems. In: 2024 8th International Conference on Electronics, Communication and Aerospace Technology (ICECA); 2024 Nov 6–8; Coimbatore, India. p. 727–33. [Google Scholar]

16. Cui Y, Tang B, Wu G, Li L, Zhang X, Du Z, et al. Classification of dog breeds using convolutional neural network models and support vector machine. Bioengineering. 2024;11(11):1157. doi:10.3390/bioengineering11111157. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Wang X, Ly V, Sorensen S, Kambhamettu C. Dog breed classification via landmarks. In: 2014 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP); 2014 Oct 27–30; Paris, France. p. 5237–41. [Google Scholar]

18. Simonyan K, Zisserman A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv:1409.1556. 2014. [Google Scholar]

19. He K, Zhang X, Ren S, Sun J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. p. 770–8. [Google Scholar]

20. Szegedy C, Vanhoucke V, Ioffe S, Shlens J, Wojna Z. Rethinking the inception architecture for computer vision. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. p. 2818–26. [Google Scholar]

21. Fu J, Zheng H, Mei T. Look closer to see better: recurrent attention convolutional neural network for fine-grained image recognition. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2017 Jul 21–2;. Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 4438–46. [Google Scholar]

22. Conde MV, Turgutlu K. Exploring vision transformers for fine-grained classification. arXiv:2106.10587. 2021. [Google Scholar]

23. Jwade SA, Guzzomi A, Mian A. On farm automatic sheep breed classification using deep learning. Comput Electron Agric. 2019;167(3):105055. doi:10.1016/j.compag.2019.105055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Zhang X, Yang L, Sinnott R. A mobile application for cat detection and breed recognition based on deep learning. In: 2019 IEEE 1st International Workshop on Artificial Intelligence for Mobile (AI4Mobile); 2019 Feb 24; Hangzhou, China. p. 7–12. doi:10.1109/ai4mobile.2019.8672684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Chen X, Wang G. Few-shot learning by integrating spatial and frequency representation. In: 2021 18th Conference on Robots and Vision (CRV); 2021 May 26–28; Burnaby, BC, Canada. p. 49–56. [Google Scholar]

26. Toğaçar M, Ergen B, Cömert Z. Classification of flower species by using features extracted from the intersection of feature selection methods in convolutional neural network models. Measurement. 2020;158:107703. doi:10.1016/j.measurement.2020.107703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Alfarhood S, Alrayeh A, Safran M, Alfarhood M, Che D. Image-based Arabian camel breed classification using transfer learning on CNNs. Appl Sci. 2023;13(14):8192. [Google Scholar]

28. Mondal A, Samanta S, Jha V. A convolutional neural network-based approach for automatic dog breed classification using modified-xception model. In: Electronic Systems and Intelligent Computing: Proceedings of ESIC 2021. Singapore: Springer Nature; 2022. p. 61–70. [Google Scholar]

29. Mu L, Shen Z, Liu J, Gao J. Small scale dog face detection using improved Faster RCNN. In: 2022 3rd International Conference on Electronic Communication and Artificial Intelligence (IWECAI); 2022 Jan 14–16; Zhuhai, China. p. 573–9. [Google Scholar]

30. Natthapon P, Eiamsaard K, Suthanma C, Banharnsakun A. Machine learning techniques for supporting dog grooming services. Res Cont Optimizat. 2023;12(2021):100273. doi:10.1016/j.rico.2023.100273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. James TPG, Poonguzhali C, Selvakumaran S, Malathi G, Kaliappan S, Venu N, et al. Efficient canine vision: accurate dog breed classification with EfficientNet. In: 2024 International Conference on Trends in Quantum Computing and Emerging Business Technologies; 2024 Mar 22–23; Pune, India. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

32. Zhao B, Wu X, Feng J, Peng Q, Yan S. Diversified visual attention networks for fine-grained object classification. IEEE Trans Multimedia. 2017;19(6):1245–56. doi:10.1109/tmm.2017.2648498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Zhang N, Donahue J, Girshick R, Darrell T. Part-based R-CNNs for fine-grained category detection. In: Computer Vision–ECCV 2014: 13th European Conference; 2014 Sep 6–12; Zurich, Switzerland. p. 834–49. [Google Scholar]

34. Lin TY, RoyChowdhury A, Maji S. Bilinear CNN models for fine-grained visual recognition. In: Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision; 2015 Dec 7–13; Santiago, Chile. p. 1449–57. [Google Scholar]

35. Wei XS, Luo JH, Wu J, Zhou ZH. Selective convolutional descriptor aggregation for fine-grained image retrieval. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2017;26(6):2868–81. doi:10.1109/tip.2017.2688133. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Zhang ZC, Chen ZD, Xie ZY, Luo X, Xu XS. S3mix: same category same semantics mixing for augmenting fine-grained images. ACM Transactn Multim Comput Communicat Applicat. 2023;20(1):1–16. [Google Scholar]

37. Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Li K, Luo J, Liu G, Pan R. iFBI: lightweight breed and individual recognition for cats and dogs. IEEE Trans Instrum Meas. 2025;74(1):2533215. doi:10.1109/tim.2025.3576017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Martinez F, Zhao Y. Integrating multiple visual attention mechanisms in deep neural networks. In: 2023 IEEE 47th Annual Computers, Software, and Applications Conference (COMPSAC); 2023 Jun 26–30; Torino, Italy. p. 1191–6. [Google Scholar]

39. Gowtham D, Isravel DP, Dhas JPM. Real-time birds breed classification and health monitoring using YOLOv8. In: 2025 8th International Conference on Trends in Electronics and Informatics (ICOEI); 2025 Apr 24–26; Tirunelveli, India. p. 1395–1401. [Google Scholar]

40. Sohan M, Sai Ram T, Rami Reddy CV. A review on yolov8 and its advancements. In: 2024 5th International Conference on Data Intelligence and Cognitive Informatics; 2024 Nov 18–20; Tirunelveli, India. p. 529–45. [Google Scholar]

41. Simonyan K, Zisserman A. Two-stream convolutional networks for action recognition in videos. In: Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS); 2014; Montreal, Canada. Cambridge (MAMIT Press; 2014. p. 568–76. [Google Scholar]

42. Yang S, Zhang X, Zhao W, Hu Q, Luo H, Liu C, et al. DSNet: dual-stream network for fine-grained ship classification in optical remote sensing images. Remote Sens Lett. 2024;15(8):792–804. doi:10.1080/2150704x.2024.2377211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Liu J, Gao C, Meng D, Zuo W. Two-stream contextualized CNN for fine-grained image classification. In: Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2016 Feb 12–17; Phoenix, AZ, USA. p. 4232–3. [Google Scholar]

44. Dosovitskiy A, Beyer L, Kolesnikov A, Weissenborn D, Zhai X, Unterthiner T, et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv:2010.11929. 2020. [Google Scholar]

45. Khosla A, Jayadevaprakash N, Yao B, Li FF. Novel dataset for fine-grained image categorization: stanford dogs. In: Proceeding of CVPR 11th Workshop on Fine-grained Visual Categorization (FGVC); 2011 Jun 20–25; Colorado Springs, CO, USA. p. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

46. Howard AG, Zhu M, Chen B, Kalenichenko D, Wang W, Weyand T, et al. Mobilenets: efficient convolutional neural networks for mobile vision applications. arXiv:1704.04861. 2017. [Google Scholar]

47. Huang G, Liu Z, Van Der Maaten L, Weinberger KQ. Densely connected convolutional networks. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 4700–8. [Google Scholar]

48. Tan M, Le Q. Efficientnet: rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. In: Proceedings of the 36 th International Conference on Machine Learning; 2019 Jun 9–15; Long Beach, CA, USA. p. 6105–14. [Google Scholar]

49. Chollet F. Xception: deep learning with depthwise separable convolutions. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 1251–8. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools