Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Length Dependent Crystallization of Linear Polymers under Different Cooling Rates: Molecular Dynamics Simulations

1 State Key Laboratory of Polymer Science and Technology, Changchun Institute of Applied Chemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Changchun, 130022, China

2 CAS Key Laboratory of High-Performance Synthetic Rubber and Its Composite Materials, Changchun Institute of Applied Chemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Changchun, 130022, China

3 School of Applied Chemistry and Engineering, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei, 230026, China

* Corresponding Author: Chuanfu Luo. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Molecular Simulations of Polymer Materials)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(2), 2807-2818. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.069471

Received 24 June 2025; Accepted 21 August 2025; Issue published 23 September 2025

Abstract

The crystallization behavior of polymers is significantly influenced by molecular chain length and the dispersion of varying chain lengths. The complexity of studying crystallization arises from the dispersity of polymer materials and the typically slow cooling rates. Recent advancements in fast cooling techniques have rendered the investigation of polymer crystallization at varying cooling rates an attractive area of research; however, a systematic quantitative framework for this process is still lacking. We employ a coarse-grained model for polyvinyl alcohol (CG-PVA) in molecular dynamics simulations to study the crystallization of linear polymers with varying chain lengths under variable cooling rates. Monodisperse, bidisperse and polydisperse samples are simulated. We propose two formulae based on a two-phase assumption to fit the exothermal curves obtained during cooling. Based on these formulae, better estimations of crystallization temperatures are obtained and the effects of chain lengths and cooling rates are studied. It is found that the crystallization temperature increases with chain length, similar to the Gibbs-Thomson relation for melting temperature, indicating a strong relation between fast crystallization and glass formation in linear polymers. Extrapolation to the infinitely slow cooling rate provides an easy way in simulations to estimate the equilibrium crystallization temperature. The effective chain lengths of polydisperse and bidisperse samples are found to be the number-averaged chain lengths compared to the weight-averaged ones. The chain length-dependent crystallization exhibits crossover behavior near the entanglement length, indicating the effects of entanglements under fast cooling conditions. The effect of chain length dispersity on crystallization becomes more obvious under fast cooling conditions.Keywords

Polymer crystallization is a central issue in the field of polymer science [1–5]. Most linear polymers can crystallize when the temperature is below their crystallization temperatures,

In dilute or semi-dilute solutions, the crystallization behavior of polymer chains is significantly influenced by the polymer concentration and the interactions between the polymer chains and the solvent. As the concentration increases, the increased nucleation probability and intermolecular interactions can promote crystallization [24–26]. Ions in the solution or hydrogen bonds interacting with the polar groups on the polymer chains can enhance or inhibit the mobility of the chains, thereby affecting the adsorption phenomenon of polymer chains on the surface of minerals [27]. Polymer crystallization is a typical nonequilibrium process, as it is highly dependent on thermal history and cooling rate. The measured

Simulations, such as Monte Carlo (MC) or Molecular Dynamics (MD), can precisely control the dispersity of chain lengths and provide detailed conformations of individual polymer chains directly at the molecular scale. A sample with precisely defined distribution of chain lengths can be created in simulations, which is impossible for experiments. The studied systems in most simulations are pure polymers and there is no impurity. Thus, the crystallization in simulations is not affected by uncontrollable impurity as in experiments. Homogeneous nucleation prevails in simulations, resulting in many small and unstable crystallites that are prone to rapid reorganization [24,31]. Based on the above advantages, simulations are ideal methods for studying length-dependent crystallization of linear polymers under different cooling rates. Many previous simulations have studied the crystallization at constant temperatures or under continuous cooling with varying cooling rates [31–34].

In this work, we perform MD simulations using a coarse grained model for Polyvinyl alcohol (CG-PVA), which was utilized in our previous studies [35–37]. We simulate the crystallization of linear polymers with varying chain lengths. The chain lengths vary from

2 Model and Simulation Details

The coarse-grained model for Polyvinyl alcohol (CG-PVA) proposed by Meyer and Müller-Plathe [18,38] using our patch code for LAMMPS [36,39] is used. The parameters related to the melt state in this model have been detailed in previous studies [36,38]. In this model, each coarse-grained bead represents a monomeric unit of PVA. The non-bonded interactions are approximated using a Lennard-Jones 9-6 potential. To simulate a dense melt, only the repulsive component of the potential is considered. The length scales are determined through a mapping process from atomistic simulations. Here, the length unit is denoted as

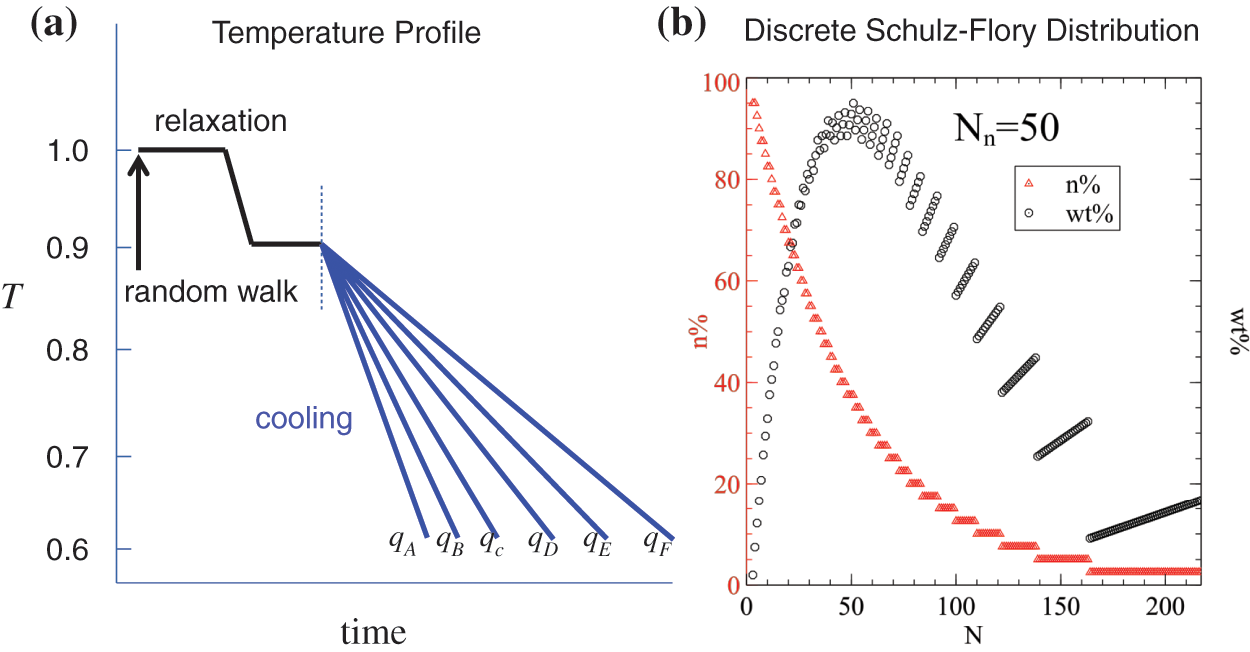

The initial structures are prepared through random walks, followed by relaxation at

Figure 1: (a): Sketch of temperature profile used in our simulations. (b): An example of the discrete Schulz distribution (most probable distribution) of

To study the effect of chain length on crystallization behavior, both monodisperse and polydisperse systems of different chain lengths are used. For monodisperse systems, we select

where

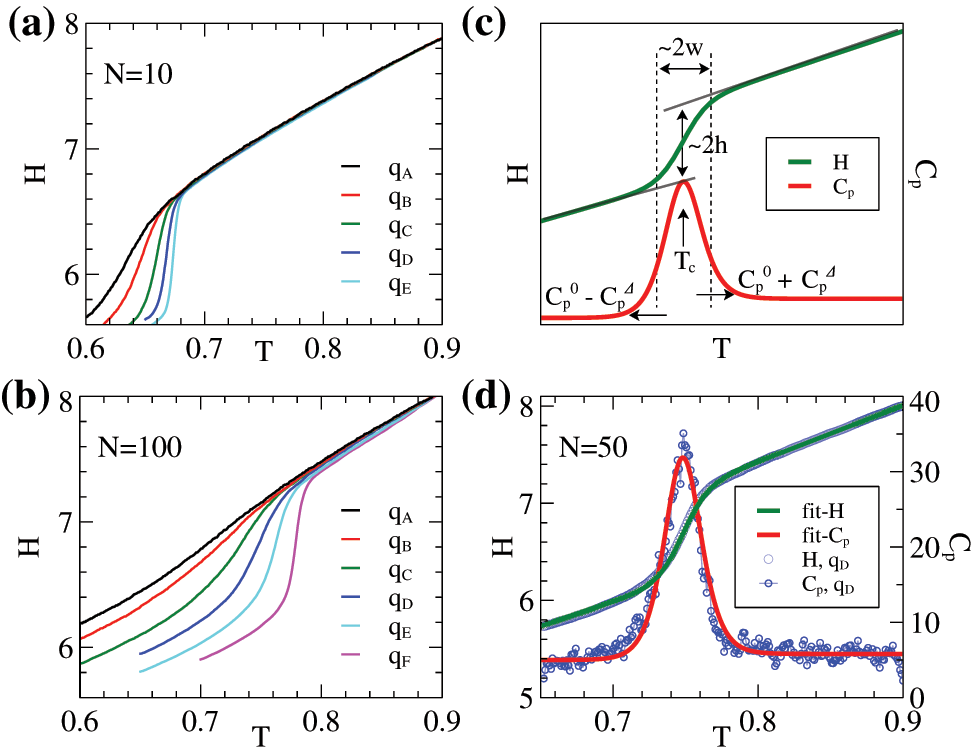

The crystallization of linear polymers is strongly dependent on cooling rate or thermal history and chain length. Longer chains have higher crystallization temperatures and slower crystallization processes with larger temperature windows of transition. Slower cooling also leads to higher crystallization temperatures but with smaller temperature windows of transition. In general, longer chains have slower dynamics which leads to higher degrees of nonequilibrium processes, similar to that of faster cooling. Such general crystallization behavior can be demonstrated by two samples from our simulations with

Figure 2: (a)–(b): Enthalpies (H) per monomer of two samples (

Similar to experiments, the phase transition of crystallization can be identified by the peaks of exothermal curves. The values obtained from simulations can validate the method’s feasibility through comparison with experimental data. Meyer and Müller-Plathe [18,38] discussed the variations in enthalpy (or volume per monomer) under different conditions during cooling and heating cycles in detail. Regarding the structural characteristics of the crystals, our previous work addressed the structure factor of the crystalline structure during the cooling process [36]. In MD simulations, the enthalpy (H) and specific heat (

The phase transitions in simulations are rather slow due to the limited simulation time compared to experiments. Therefore, it is not easy to precisely estimate the

where

where

These two formulae fit the simulation data well, as shown in Fig. 2d for an example of the sample of

In simulations, and even in experiments, the crystallization of polymers is a rather slow and continuous process, and the measured

It is interesting whether we can approach the limit of

where the parameter

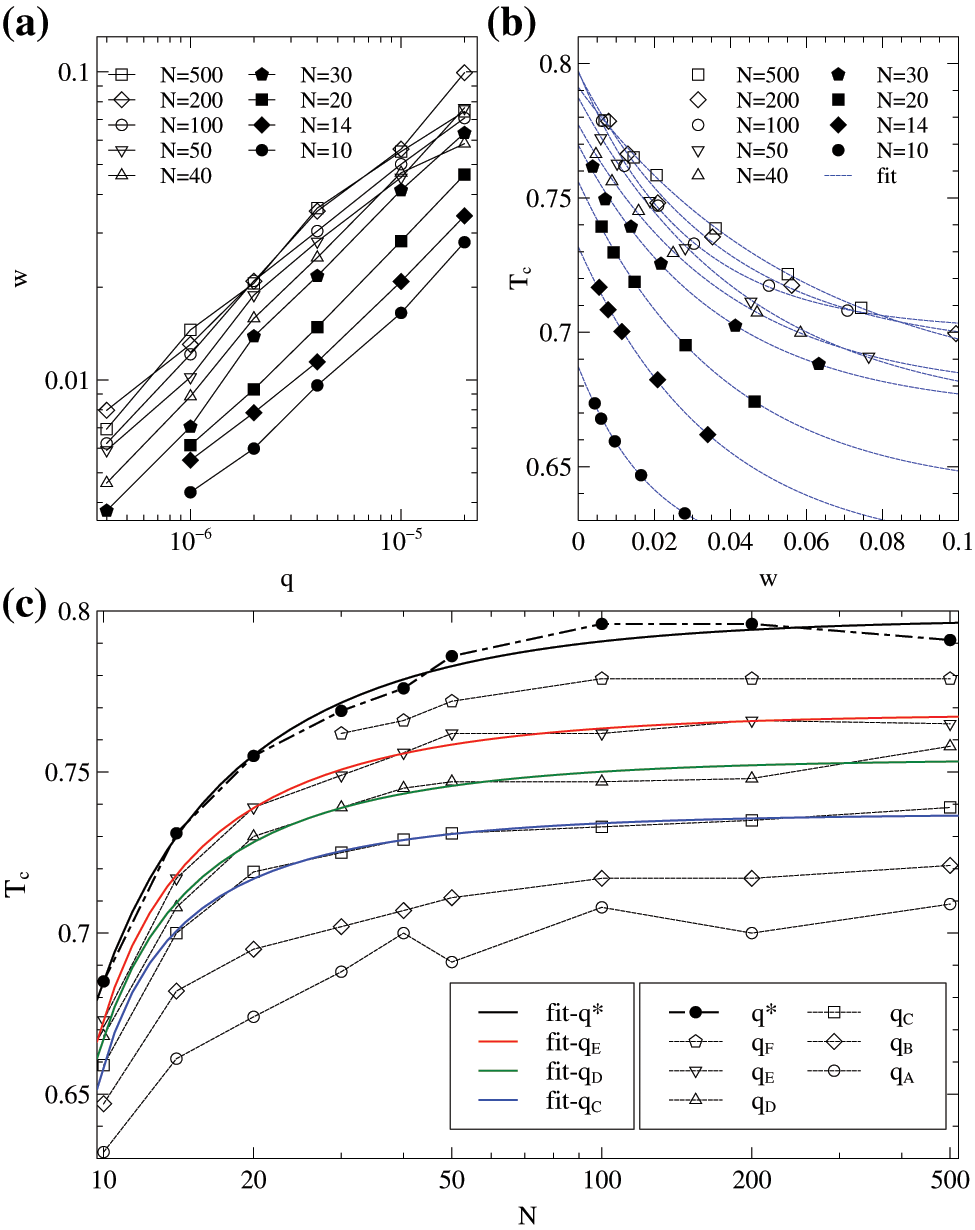

Figure 3: Results of monodisperse samples. (a): Relation of

In Fig. 3b, we present the results of measured

where

The crystallization temperature

where the

It is noteworthy that Eq. (6) is also similar to the Gibbs-Thomson equation for the melting temperature

The chain lengths range from

3.2 Bidisperse and Polydisperse Samples

As mentioned above in the Introduction section, bidisperse and polydisperse samples also hold significant value in industry, and it is interesting that whether the above empirical formulae found for monodisperse samples stand for polydisperse samples.

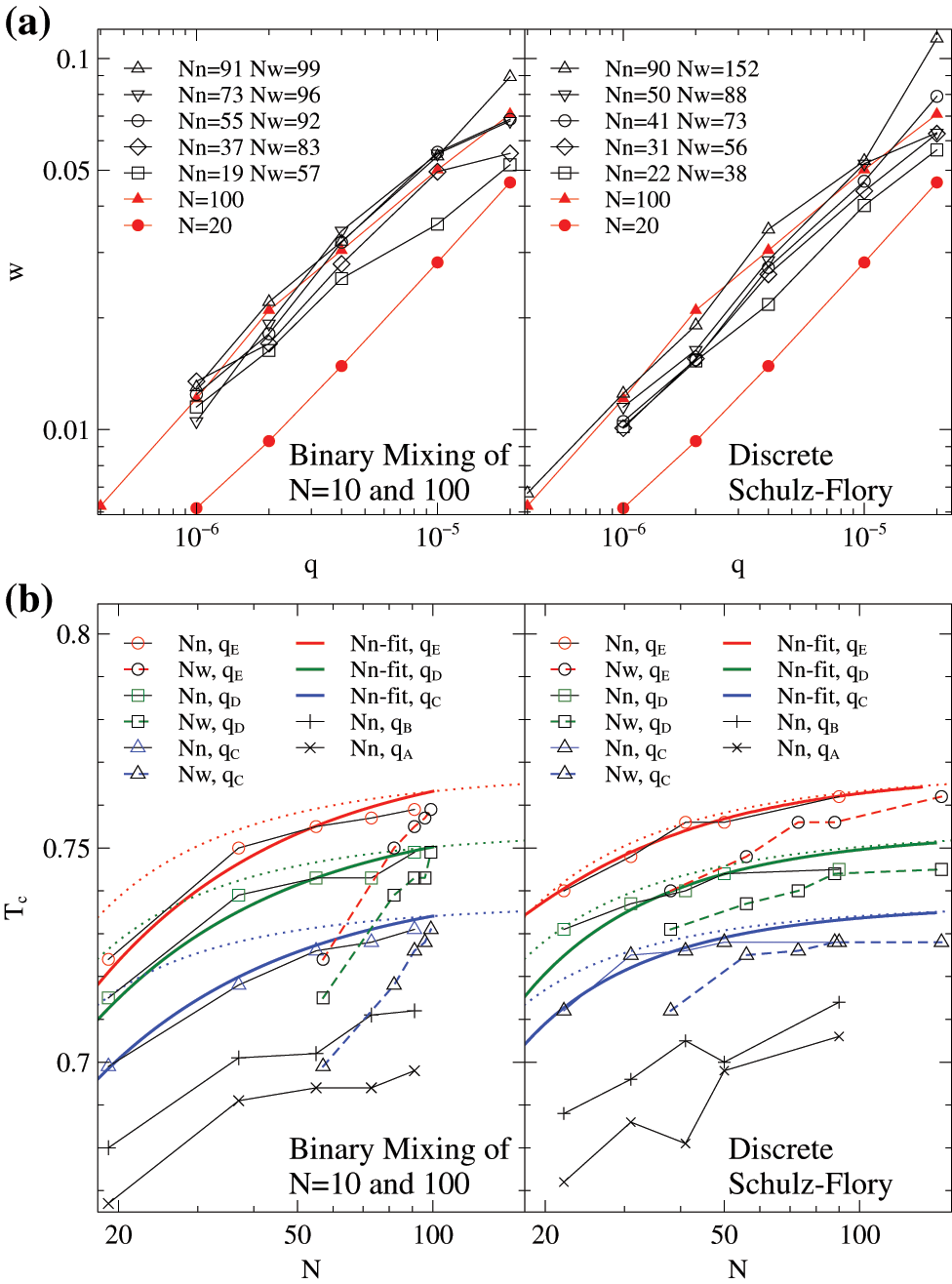

We carry out MD simulations using the same parameters for the polydisperse samples with chain lengths following a Schulz distribution, as well as bidisperse samples with

Figure 4: Results of the bidisperse samples of

The crystallization temperatures of different chain lengths at various cooling rates,

Here,

It is noted again that significant fluctuations in the

Interestingly, although the fitting formula of Eq. (7) implies a weight averaged assumption, the effective chain lengths

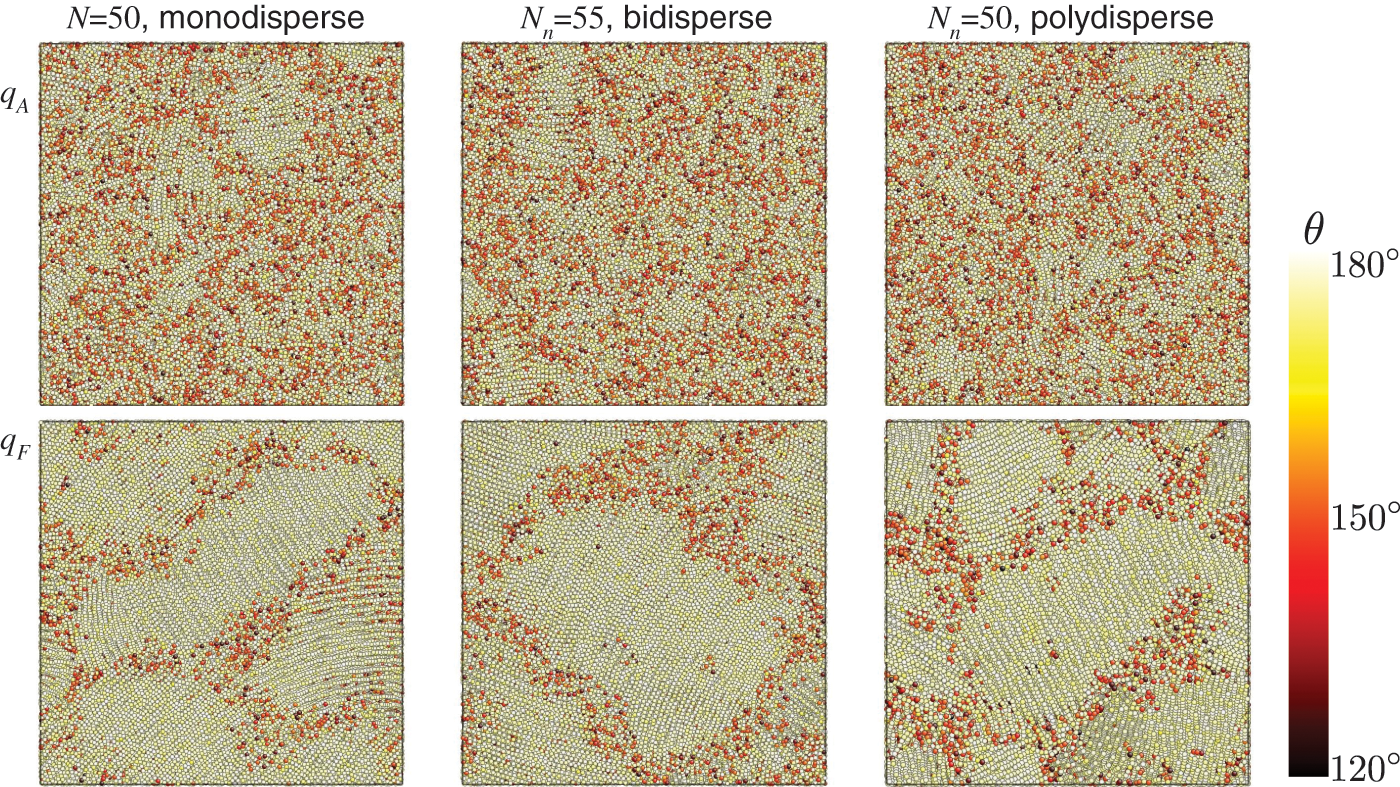

We display the snapshots at the final cooled state in Fig. 5. Specifically, we select three samples with

Figure 5: Snapshots of three selected samples after cooling of

In this study, we conduct a systematic investigation into the chain length-dependent crystallization of linear polymers under varying cooling rates using MD simulations. Formulae for enthalpy (H) and specific heat (

For the bidisperse samples of

Acknowledgement: The authors acknowledge the financial support of the National Natural Science Foundation of China.

Funding Statement: National Natural Science Foundation of China No. 22341302.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: conceptualization and methodology: Chuanfu Luo; investigation: Chuanfu Luo and Dan Xu; manuscript preparation: Dan Xu; review: Chuanfu Luo. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Hoffman JD, Miller RL. Kinetics of crystallization from the melt and chain folding in polyethylene fractions revisited: theory and experiment. Polymer. 1997;38(13):3151–212. doi:10.1016/s0032-3861(97)00071-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Strobl G. The physics of polymers. 3rd ed. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 2007. [Google Scholar]

3. Ma B, Wang X, He Y, Dong Z, Zhang X, Chen X, et al. Effect of poly(lactic acid) crystallization on its mechanical and heat resistance performances. Polymer. 2021;212(7):123280. doi:10.1016/j.polymer.2020.123280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Hu W. Personal perspective on strain-induced polymer crystallization. J Phys Chem B. 2023;127(4):822–7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

5. Nie C, Peng F, Cao R, Cui K, Sheng J, Chen W, et al. Recent progress in flow-induced polymer crystallization. J Polym Sci. 2022;60(23):3149–75. doi:10.1002/pol.20220330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Wunderlich B,editor. Macromolecular physics: 2. Crystal nucleation, growth, annealing. New York, NY, USA and London, UK: Academic Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

7. Reiter G, Strobl G,editors. Progress in understanding of polymer crystallization. In: Lecture notes in physics. Vol. 714. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 2007. [Google Scholar]

8. Hu W. The physics of polymer chain-folding. Phys Rep. 2018;747:1–50. [Google Scholar]

9. Wang Y, Zhang Q, Fu Q. Compatibilization of immiscible poly(propylene)/polystyrene blends using clay. Macromol Rapid Commun. 2003;24(3):231–5. doi:10.1002/marc.200390026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Rubinstein M, Colby RH. Polymer physics. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

11. Gentekos DT, Sifri RJ, Fors BP. Controlling polymer properties through the shape of the molecular-weight distribution. Nat Rev Mater. 2019;4(12):761–74. doi:10.1038/s41578-019-0138-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Long C, Dong Z, Yu F, Wang K, He C, Chen ZR. Molecular weight distribution shape dependence of the crystallization kinetics of semicrystalline polymers based on linear unimodal and bimodal polyethylenes. ACS Appl Polym Mater. 2023;5(4):2654–63. doi:10.1021/acsapm.2c02236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Fall WS, Baschnagel J, Benzerara O, Lhost O, Meyer H. Molecular simulations of controlled polymer crystallization in polyethylene. ACS Macro Lett. 2023;12(6):808–13. doi:10.1021/acsmacrolett.3c00146. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Kwakye-Nimo S, Inn Y, Yu Y, Wood-Adams PM. Linear viscoelastic behavior of bimodal polyethylene. Rheol Acta. 2022;61(6):373–86. doi:10.1007/s00397-022-01340-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Kida T, Tanaka R, Hiejima Y, Nitta K-H, Shiono T. Improving the strength of polyethylene solids by simple controlling of the molecular weight distribution. Polymer. 2021;218:123526. doi:10.1016/j.polymer.2021.123526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Sun Z, Dong Z, Yu F, Feng S, Chen ZR. Untangling polymer chains: size, topology, processing, and recycling. Acc Mater Res. 2025;6(5):538–43. doi:10.1021/accountsmr.5c00057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Doye JPK, Frenkel D. Mehanism of thickness determination in polymer crystals. Phys Rev Lett. 1998;81(10):21603. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.81.2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Meyer H, Müller-Plathe F. Formation of chain-folded structures in supercooled polymer melts. J Chem Phys. 2001;115(17):7807–10. doi:10.1063/1.1415456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Muller M, Abetz V. Nonequilibrium processes in polymer membrane formation: theory and experiment. Chem Rev. 2021;121(22):14189–231. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00029. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Jin F, Yuan S, Wang S, Zhang Y, Zheng Y, Hong Y-L, et al. Polymer chains fold prior to crystallization. ACS Macro Lett. 2022;11(3):284–8. doi:10.1021/acsmacrolett.1c00789. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Schmid F. Understanding and modeling polymers: the challenge of multiple scales. ACS Polym Au. 2022;3(1):28–58. doi:10.1021/acspolymersau.2c00049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Di Lorenzo ML. Crystallization of poly(ethylene terephthalatea review. Polymers. 2024;16(14):1975. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

23. Hagita K, Yamamoto T, Saito H, Abe E. Chain-level analysis of reinforced polyethylene through stretch-induced crystallization. ACS Macro Lett. 2024;13(2):247–51. doi:10.1021/acsmacrolett.3c00554. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Hu WB. Polymer features in crystallization. Chin J Polym Sci. 2022;40(6):545–55. [Google Scholar]

25. Kos PI, Ivanov VA, Chertovich AV. Crystallization of semiflexible polymers in melts and solutions. Soft Matter. 2021;17(9):2392–403. doi:10.1039/d0sm01545h. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Deshchenya VI, Gerke KM, Kondratyuk ND. Microsecond-scale sucrose conformational dynamics in aqueous solution via molecular dynamics methods. J Chem Phys. 2025;163(4):044502. doi:10.1063/5.0266322. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Belghazdis M, Hachem EK. Experimental and theoretical study of PEG/natural clay-based hybrids properties: role of molecular weight. Mater Today Commun. 2023;37:107422. doi:10.1016/j.mtcomm.2023.107422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Mathot V, Pyda M, Pijpers T, Poel GV, van de Kerkhof E, van Herwaarden S, et al. The Flash DSC 1, a power compensation twin-type, chip-based fast scanning calorimeter (FSCfirst findings on polymers. Thermochim Acta. 2011;522(1–2):36–45. doi:10.1016/j.tca.2011.02.031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Toda A, Androsch R, Schick C. Insights into polymer crystallization and melting from fast scanning chip calorimetry. Polymer. 2016;91(3):239–63. doi:10.1016/j.polymer.2016.03.038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Schawe JEK. Influence of processing conditions on polymer crystallization measured by fast scanning DSC. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2014;116(3):1165–73. doi:10.1007/s10973-013-3563-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Gee RH, Lacevic NM, Fried LE. Atomistic simulations of spinodal phase separation preceding polymer crystallization. Nat Mater. 2006;5(1):39–43. doi:10.1038/nmat1543. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Vettorel T, Meyer H. Coarse graining of short polythylene chains for studying polymer crystallization. J Chem Theory Comput. 2006;2(3):616–29. doi:10.1021/ct0503264. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Zhang J, Hu W. Roles of specific hydrogen-bonding interactions in the crystallization kinetics of polymers. Polymer. 2023;283(49):126278. doi:10.1016/j.polymer.2023.126278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Yamamoto T. Chiral selecting crystallization of helical polymers: a molecular dynamics simulation for the POM-like bare helix. J Chem Phys. 2022;157(1):014901. doi:10.1063/5.0097112. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Luo C, Sommer JU. Growth pathway and precursor states in single lamellar crystallization. Macromolecules. 2011;44(6):1523–9. doi:10.1021/ma102380m. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Luo C, Sommer JU. Coding coarse grained polymer model for LAMMPS and its application to polymer crystallization. Comp Phys Comm. 2009;180(8):1382–91. doi:10.1016/j.cpc.2009.01.028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Luo C, Sommer JU. Frozen topology: entanglements control nucleation and crystallization in polymers. Phys Rev Lett. 2014;112(19):195702. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.112.195702. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Meyer H, Müller-Plathe F. Formation of chain-folded structures in supercooled polymer melts examined by MD simulations. Macromolecules. 2002;35(4):1241–52. doi:10.1021/ma011309l. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Plimpton S. Fast parallel algorithms for short-range molecular dynamics. J Chem Phys. 1995;177(1):1–9. [Google Scholar]

40. Bhardwaj A, Sommer JU, Werner M. Nucleation patterns of polymer crystals analyzed by machine learning models. Macromolecules. 2024;57(20):9711–24. doi:10.1021/acs.macromol.4c00920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Strobl G. Colloquium: laws conrolling crystallization and melting in bulk polymers. Rev Mod Phys. 2009;81(3):1287. doi:10.1103/revmodphys.81.1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Fox TG, Flory PJ. Second-order transition temperatures and related properties of polystyrene. J Appl Phys. 1950;21(6):581–91. doi:10.1063/1.1699711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. O’Driscoll K, Sanayei RA. Chain-length dependence of the glass transition temperature. Macromolecules. 1991;24(15):4479–80. doi:10.1021/ma00015a038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Luo C, Kröger M, Sommer JU. Entanglements and crystallization of concentrated polymer solutions: molecular dynamics simulations. Macromolecules. 2016;49(23):9017–25. doi:10.1021/acs.macromol.6b02124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Luo C, Sommer JU. Role of thermal history and entanglement related thickness selection in polymer crystallization. ACS Macro Lett. 2016;5(1):30–4. doi:10.1021/acsmacrolett.5b00668. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools