Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Multi-Modal Pre-Synergistic Fusion Entity Alignment Based on Mutual Information Strategy Optimization

1 Qingdao Institute of Software, College of Computer Science and Technology, China University of Petroleum (East China), Qingdao, 266580, China

2 Shandong Key Laboratory of Intelligent Oil & Gas Industrial Software, China University of Petroleum (East China), Qingdao, 266580, China

3 Key Laboratory of Computing Power Network and Information Security, Ministry of Education, Shandong Computer Science Center (National Supercomputer Center in Jinan), Qilu University of Technology (Shandong Academy of Sciences), Jinan, 250014, China

4 Shandong Provincial Key Laboratory of Computing Power Internet and Service Computing, Shandong Fundamental Research Center for Computer Science, Jinan, 250014, China

5 Department of Physics of Nanoscale Systems, South Ural State University, Chelyabinsk, 454080, Russia

6 Institute of Radioelectronics and Information Technologies, Ural Federal University, Yekaterinburg, 620002, Russia

7 Department of ICT and Center for AI Research, University of Agder (UiA), Grimstad, 4879, Norway

* Corresponding Author: Lizhuang Tan. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(2), 4133-4153. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.069690

Received 28 June 2025; Accepted 02 September 2025; Issue published 23 September 2025

Abstract

To address the challenge of missing modal information in entity alignment and to mitigate information loss or bias arising from modal heterogeneity during fusion, while also capturing shared information across modalities, this paper proposes a Multi-modal Pre-synergistic Entity Alignment model based on Cross-modal Mutual Information Strategy Optimization (MPSEA). The model first employs independent encoders to process multi-modal features, including text, images, and numerical values. Next, a multi-modal pre-synergistic fusion mechanism integrates graph structural and visual modal features into the textual modality as preparatory information. This pre-fusion strategy enables unified perception of heterogeneous modalities at the model’s initial stage, reducing discrepancies during the fusion process. Finally, using cross-modal deep perception reinforcement learning, the model achieves adaptive multi-level feature fusion between modalities, supporting learning more effective alignment strategies. Extensive experiments on multiple public datasets show that the MPSEA method achieves gains of up to 7% in Hits@1 and 8.2% in MRR on the FBDB15K dataset, and up to 9.1% in Hits@1 and 7.7% in MRR on the FBYG15K dataset, compared to existing state-of-the-art methods. These results confirm the effectiveness of the proposed model.Keywords

In the contemporary era of information proliferation, Knowledge Graphs (KGs) serve as structured semantic knowledge bases that play a pivotal role in connecting and integrating vast amounts of heterogeneous data. Researchers extensively utilize this representation across diverse domains, including intelligent question answering [1], recommendation systems [2,3], and information extraction [4,5], among others.

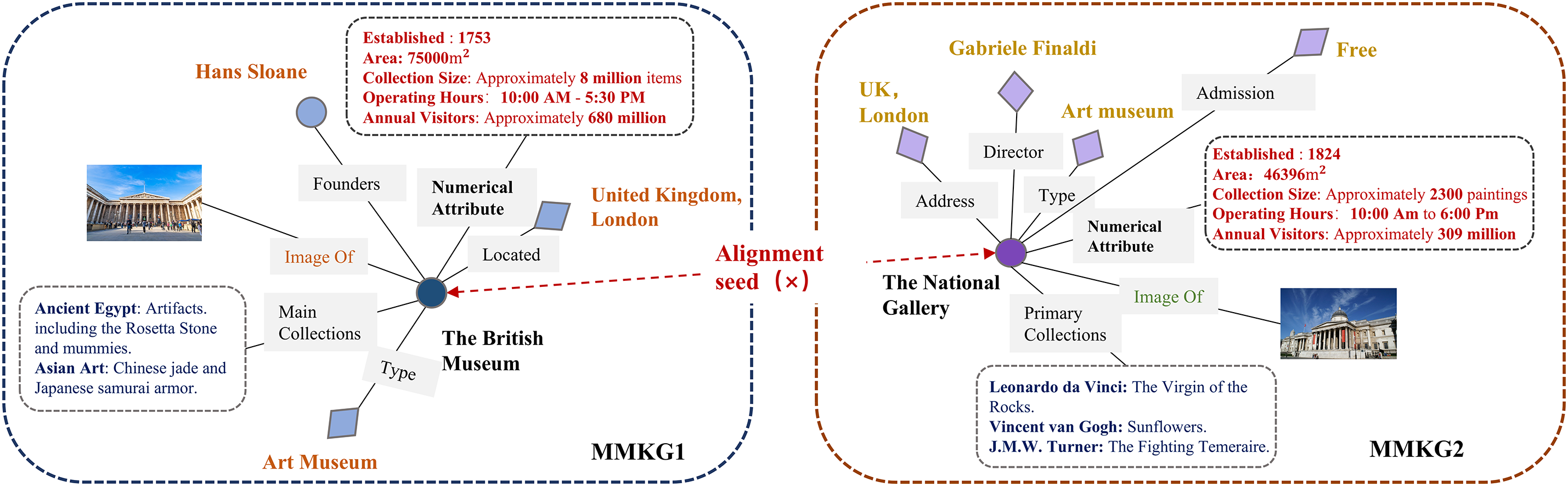

However, most knowledge graphs are constructed from multiple heterogeneous data sources, resulting in substantial duplication of nodes across distinct KGs. Although these nodes represent identical real-world entities, they exhibit divergent representations, leading to structural redundancy and graph incompleteness. To address this challenge, Entity Alignment (EA) techniques have been developed. Entity Alignment (EA) techniques aim to identify corresponding entities referring to the same real-world objects across different knowledge graphs [6]. Traditional EA methodologies predominantly focus on unimodal knowledge graphs, whereas real-world entities inherently exhibit multimodal characteristics. Conventional EA approaches often neglect inter-modal interactions and complementarities, limiting comprehensive entity understanding and resulting in suboptimal alignment accuracy. Consequently, Multimodal Entity Alignment (MMEA) has emerged as an essential research direction. Multimodal knowledge learning focuses on leveraging multiple modalities to support downstream applications, such as emotion recognition [7,8] and cross-modal retrieval [9,10]. Nevertheless, in MMEA tasks, the heterogeneity and complexity of multimodal data present significant challenges for effective modal fusion. An example of an MMKG is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Multi-modal knowledge graph entity alignment

This paper proposes a Multi-modal Pre-synergistic Fusion framework based on Cross-modal Mutual Information Strategy Optimization. This framework addresses the challenges posed by inter-modal heterogeneity and aims to mitigate information loss or bias during modal fusion. The model effectively captures shared features across modalities by incorporating mutual information maximization, thereby enabling deep multi-level adaptive modal fusion. Specifically, the principal contributions of this work are as follows:

• To significantly mitigate inherent modal heterogeneity in cross-modal learning and establish tighter feature correlations, this paper innovatively proposes a Multi-modal Pre-Synergistic Fusion Mechanism. This framework proactively injects graph structural features and visual modal information as preparatory information into the cross-modal attention mechanism during the model’s initial stage, thereby achieving unified cross-modal perception. Furthermore, this dual synergistic fusion strategy provides multi-perspective perception capabilities throughout the fusion process, enabling collaborative discriminative decision-making based on heterogeneous information sources. It significantly reinforces cross-modal feature correlations, ultimately achieving maximum improvements of 16% and 13.1% in Hits@1 metrics on the FBDB15K and FBYG15K datasets, respectively, compared to baseline methods.

• We design a novel reinforcement learning method based on cross-modal mutual information maximization. This approach ensures maximal information retention during modal fusion, reducing potential information loss or bias. Additionally, feedback from the reward-punishment mechanism progressively optimizes action selection and learns optimal coordination strategies.

• Extensive comparative experiments are conducted on benchmark datasets (FB15K, DB15K, and YAGO15K). The results demonstrate that the proposed MPSEA model achieves state-of-the-art performance. The Hits@1 metric showed maximum improvements of 7% and 9.1%, respectively. The MRR metric achieved maximum gains of 8.2% and 7.7%, respectively.

Structure-based entity alignment approaches are primarily categorized into two major classes:

1. EA Based on Relational Triple Translation Models: These methods represent relational knowledge as triples (Head Entity, Relation, Tail Entity), exemplified by MTransE and BootEA [11]. However, a significant limitation of this approach is its inefficiency in effectively capturing information from higher-order neighboring nodes.

2. EA Utilizing Graph Neural Networks (GNNs): GNN-based EA methods [12] have garnered increasing research attention. These techniques enhance entity representations by aggregating information from neighboring nodes and edges, thereby enriching local features while simultaneously considering the global structural modeling of the KG. This category of methods—exemplified by GCN-Align [13], and RDGCN [14]—updates entity representations by aggregating information from neighboring nodes and edges. Such integration enriches local features and effectively accounts for global structural modeling of the knowledge graph.

2.2 Multi-Modal Entity Alignment

Entity alignment (EA) methods based on structural embedding primarily focus on the relational modalities of knowledge graphs (KGs). They generally encounter geometric vector space limitations [6,15]. Consequently, integrating auxiliary modal information has become essential for addressing EA challenges. EVA [16] leveraged visual similarity to establish visual anchors within a multi-modal framework and expanded training sets through iterative learning. However, these methods focus on enhancing entity semantic embeddings through various modal representations, often neglecting inter-entity interactions. MCLEA [17] improves cross-modal interactions and minimizes modal discrepancies by incorporating contrastive learning. This framework facilitates proximity between equivalent entities in vector space while ensuring separation of dissimilar entities during entity representation learning. Despite advancing modal interaction, MCLEA employs static cross-modal weighting schemes that inadequately account for cross-modal source preferences, including modal absence and attribute cardinality variations. MEAformer [18] introduces a dynamic cross-modal weight assignment mechanism, pioneering entity-level feature fusion. To further optimize data resource utilization, MEAIE [19] incorporates auxiliary numerical modalities, effectively mitigating modal incompleteness issues. While existing methods have advanced entity alignment, significant limitations persist in addressing cross-modal heterogeneity. We introduce a mutual information optimization strategy coupled with a multi-modal pre-synergistic fusion mechanism to bridge this gap. Furthermore, our approach reinforces the perception of inter-modal interdependencies, optimizing discriminative fusion of multimodal information.

This section focuses on the notational definition of the multimodal entity alignment task and the proposed modeling framework.

First, the MMKG is structured as

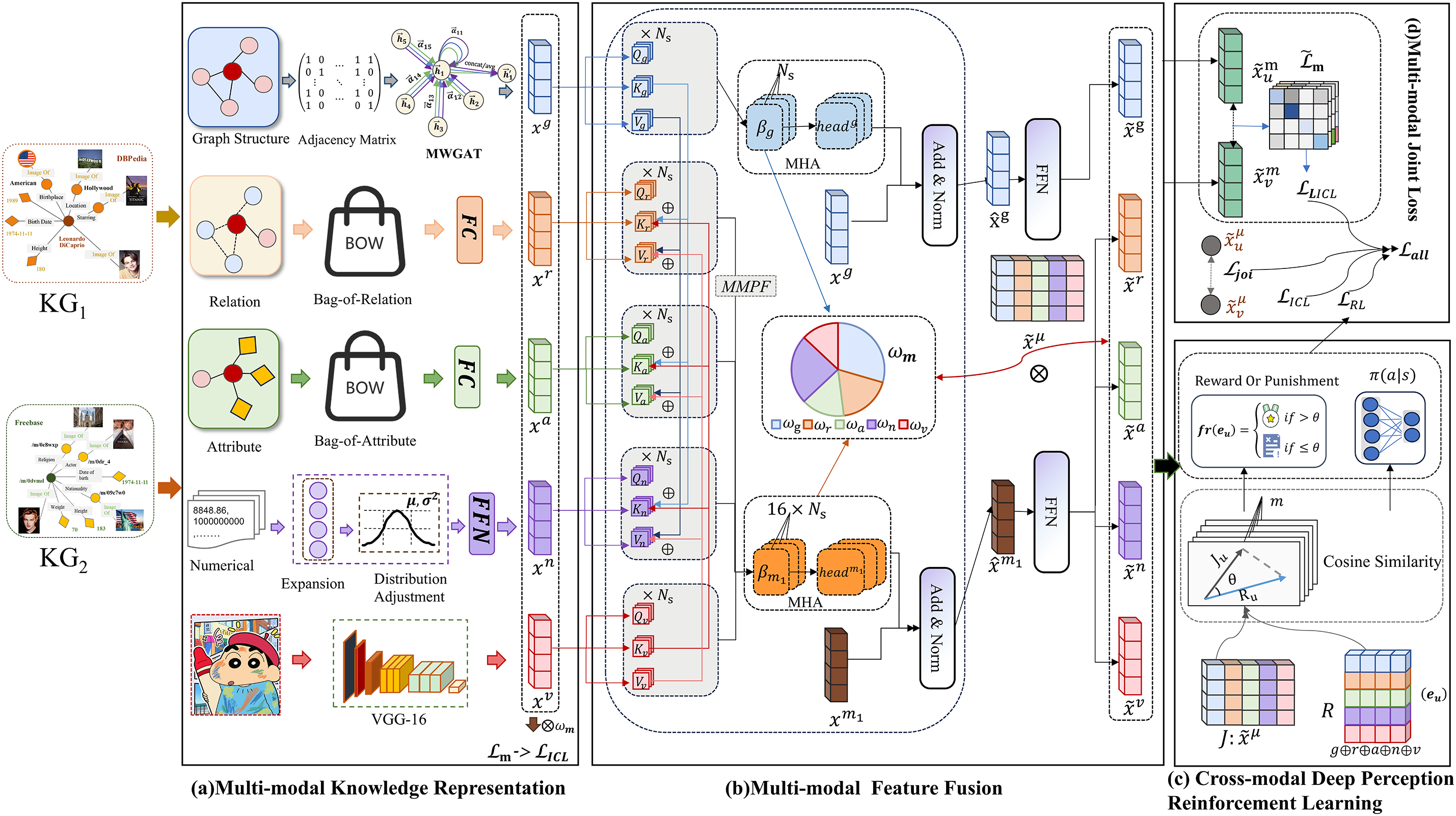

To address the modal deficiencies identified in MMEA, this paper incorporates numerical modal embeddings alongside conventional modalities, proposing the Pre-synergistic Fusion Entity Alignment Model Optimized by Mutual Information Strategy (MPSEA). As illustrated in Fig. 2, the framework comprises four core components: 1) Multi-modal Knowledge Representation, 2) Multi-modal Feature Fusion, 3) Cross-modal Deep Perception-based Reinforcement Learning (CPLR), and 4) Joint Multi-modal Loss Optimization. The model first extracts entity-related information across five modalities: relational, attributive, visual, numerical, and structural. We then employ a multi-modal pre-synergistic fusion mechanism to dynamically weight cross-modal features, generating joint embeddings through integrated early and late fusion strategies. Subsequently, the reinforcement learning module implements a mutual information-driven reward-penalty mechanism. This is synergized with modal-adaptive contrastive learning to produce a joint alignment loss, which optimizes anchor entity representations through iterative refinement.

Figure 2: MPSEA modeling framework

3.3 Multi-Modal Knowledge Representatiog

Our modalities include visual, structural, relational, and attribute data, with numerical attribute values. The collective term for relations and attributes is the textual modality. This module is used to obtain the feature vectors required for early fusion of each modality

3.3.1 Graph Neighborhood Structural Embedding

To mitigate contextual gaps [20] (encompassing Entity-Attribute Cardinality Discrepancy and Modal Attribute Discrepancy) and enhance node-neighbor differentiation capability, we employ a two-headed, two-layer GAT [21] architecture. This framework incorporates dedicated linear transformation matrices

3.3.2 Attribute and Relationship Embedding

This paper integrates relational triples and attribute triples as external textual information to mitigate modal incompleteness. We employ Bag-of-Words (BoW) [22] representation to encode relational features

Here,

Disambiguating homonymous entities solely through textual modalities presents significant challenges within EA tasks. Visual information (image color and texture features) provides an effective filter for eliminating false alignments. This paper employs the pre-trained VGG-16 model [23] to extract visual features

Here,

We implement the Deep Numerical Embedding Framework (DNEF) to encode numerical attributes, which projects scalar values into high-dimensional vector spaces. This representation is subsequently refined through neural networks to enhance numerical feature expressiveness. For each numerical feature

Here,

In this study, we utilize the numerical triples extracted by Liu [24] for model training. The processing involves two sequential operations: first, normalizing numerical triples per entity to obtain normalized representations

3.4 Multi-Modal Features Fusion

3.4.1 Graph Structure Transformer

We use the encoder part of the Transformer [25] to process the graph structure, which consists of two main core components: the multi-head self-attention block (MHA) and the fully connected feedforward network (FFN).

MHA component (working with

When modality

FFN component: It consists of two fully connected layers with a ReLU activation function. Subsequently, the output of the feedforward layer is processed using layer normalization and residual connections, resulting in the graph structure embedding

3.4.2 Multi-Modal Pre-Synergistic Fusion Transformer (MMPF)

We propose a Multi-modal Pre-synergistic Fusion with a Deep Perception mechanism to mitigate cross-modal heterogeneity between visual features, graph structures, and textual representations while enhancing inter-modal perception. Specifically, we embed key-value pairs

Multi-modal Pre-synergistic Fusion MHA Component: We redefine the key

To unify the notation, we will use

Unlike the graph structure transformer, we perform the cross-modal self-attention mechanism in the other modalities

FFN component: it is divided into two parts

1. Visual Modality Processing (

2. Textual Modality

To define the cross-modal weights of each modality,we weighted-average the attention weight scores of each modality and subsequently applied Softmax normalization to derive these weights.

1. The weight of modality

2. The weight of the graph structure modality

Subsequently, cross-modal weights are utilized to perform weighted concatenation of multi-modal embeddings, yielding joint embeddings

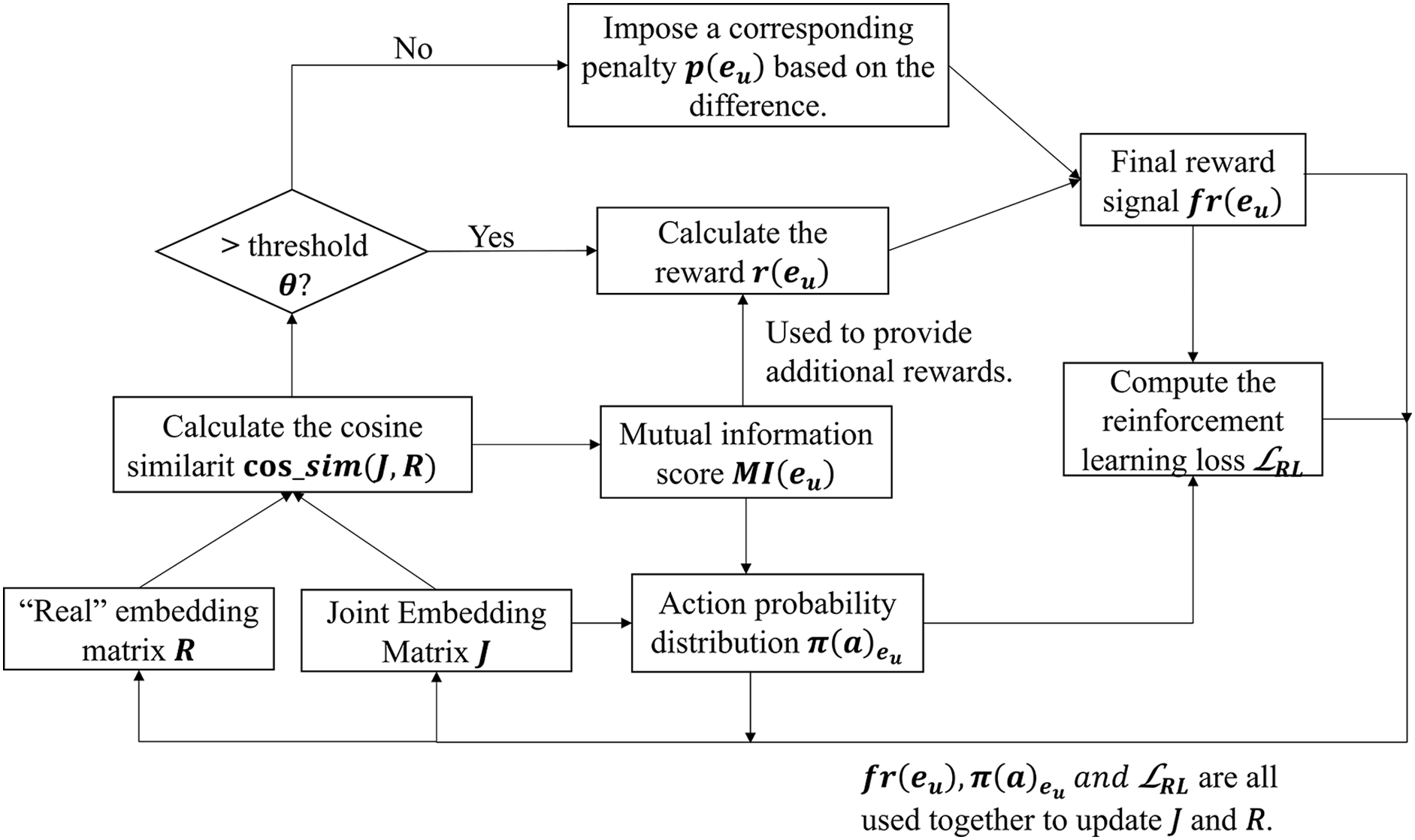

3.5 Reinforcement Learning Based on Cross-Modal Deep Perception

Inspired by Zeng et al. [26], this paper proposes a reinforcement learning (RL) approach based on mutual information strategy optimization. Following deep multilevel fusion, we employ a custom mutual information estimator as a quality checking mechanism. This ensures maximal information preservation during modal fusion while mitigating inter-modal information loss or bias.

The model’s predicted joint embedding must approximate the ground-truth joint embedding in entity alignment. We therefore define:

• Predicted embedding

• Ground-truth embedding

A custom cross-modal mutual information estimator is used to compute the mutual information score

To encourage the model’s predicted embedding J to align more closely with the true embedding R, we integrate the mutual information score and the cosine similarity to define the reward signal

Here,

Next, the policy network takes on the role of the core decision-maker, aiming to compute the action probability distribution based on the current state (i.e., the comprehensive features of the entity pair). Here,

The policy network processes the concatenated joint embedding J and mutual information score

The overall approach leverages mutual information and a reward-penalty feedback mechanism to guide the policy network in optimizing the performance of MMEA. This process ensures a closer alignment between the predicted embeddings and the ground-truth targets. By backpropagating this loss, the parameters of the policy network are updated, thereby increasing the selection probability of actions that yield higher rewards. Consequently, the model can dynamically adapt its alignment decisions to accommodate the complex relationships and inherent uncertainty present in multimodal data. The reinforcement learning workflow is illustrated in Fig. 3:

Figure 3: Cross-modal deep perception based reinforcement learning flowchart

In this paper, we comply with the work of Lin [17] and use a contrastive learning strategy. The pre-aligned anchor pair set L serves as the collection of positive sample anchor pairs

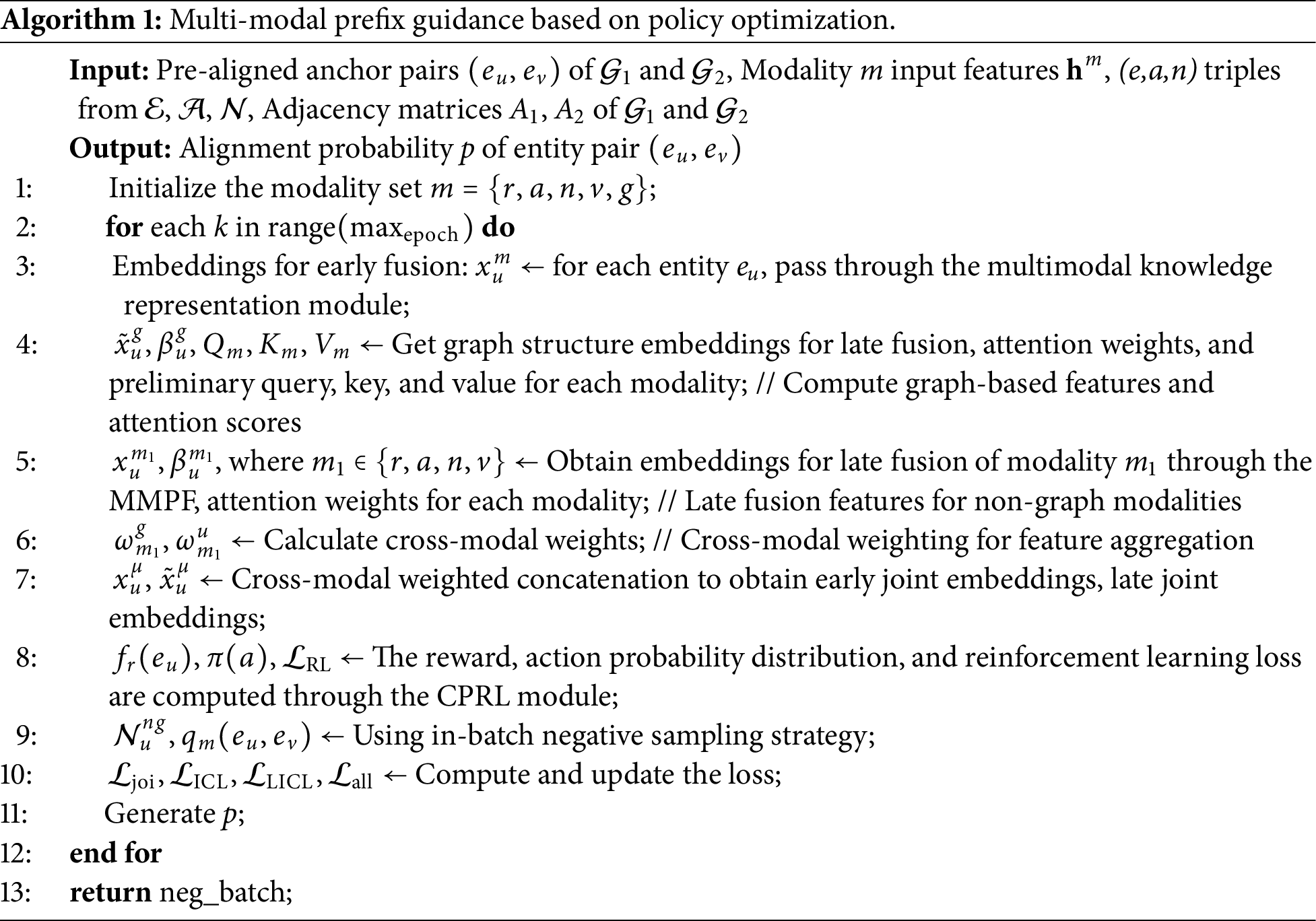

The overall MPSEA mechanism is presented in Algorithm 1:

To systematically evaluate the MPSEA model proposed in the previous section, this section commences with a detailed account of the experimental setup, including the data set and the evaluation metrics employed. Following this, we conduct a comparison experiment and an ablation experiment to validate the effectiveness of our proposed MPSEA model.

4.1.1 Datasets and Evaluation Metrics

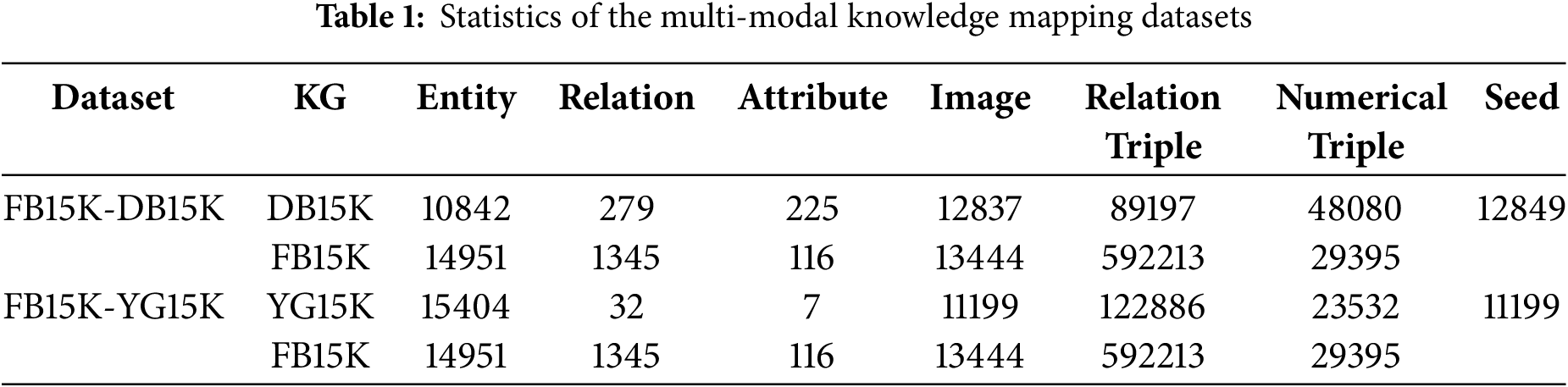

This study employs the multi-modal cross-knowledge graph datasets FB15K-DB15K and FB15K-YAGO15K [24] for experimentation. We conduct three distinct dataset splits, utilizing 20%, 50%, and 80% of reference entity alignment pairs as pretraining anchors. The scale of each dataset is detailed in Table 1. We adopt Hits@n and Mean Reciprocal Rank (MRR) as performance metrics for entity alignment evaluation. The term Hits@n (n = 1, 5, 10) denotes the Top-N accuracy, which is defined as the percentage of correct entities within the top N results. The mean reciprocal rank (MRR) represents the average position of the proper entity in the ranking. Consequently, elevated values of Hits@n and MRR are indicative of superior performance.

4.1.2 Implementation Details and Comparison of Models

1. Implementation details. We designed the multi-weighted GAT as a graph attention network with a 300-dimensional hidden layer and two attention heads; visual features were encoded as 4096-dimensional feature vectors. In the feature fusion stage, we use an MHA block with five attention heads. The hidden layer dimension and each modal embedding dimension are set to 300, and we performed a total of 500 epochs, with an additional 500 optional epochs. The learning rate was set to 5e-4, and we utilized the AdamW optimizer with parameters

2. Existing methods. To validate the effectiveness and sophistication of our method, some baseline models are selected for comparison in this paper. Two training strategies are employed: iterative and non-iterative training. Different baseline models are used for each of the two types of training: 1) Non-iterative training: HMEA [27], MMEA [28], EVA [16], MCLEA [17], MEAformer [18], ACK-MMEA [20], GEEA [29], Confidence-MMEA [30], and TriFac [31]. 2) Iterative training: EVA [16], MCLEA [17], MEAformer [18], MEAIE [19], MultiJAF [32], MSNEA [33], DFMKE [34], and UQMIEA [35].

To assess MPSEA’s effectiveness, we conducted separate comparison experiments (i.e., validating MPSEA’s performance against individual baseline models), ablation experiments (to validate the contribution of different components of MPSEA to its performance), and exploration of the effect of hyperparameters on MPSEA’s performance.

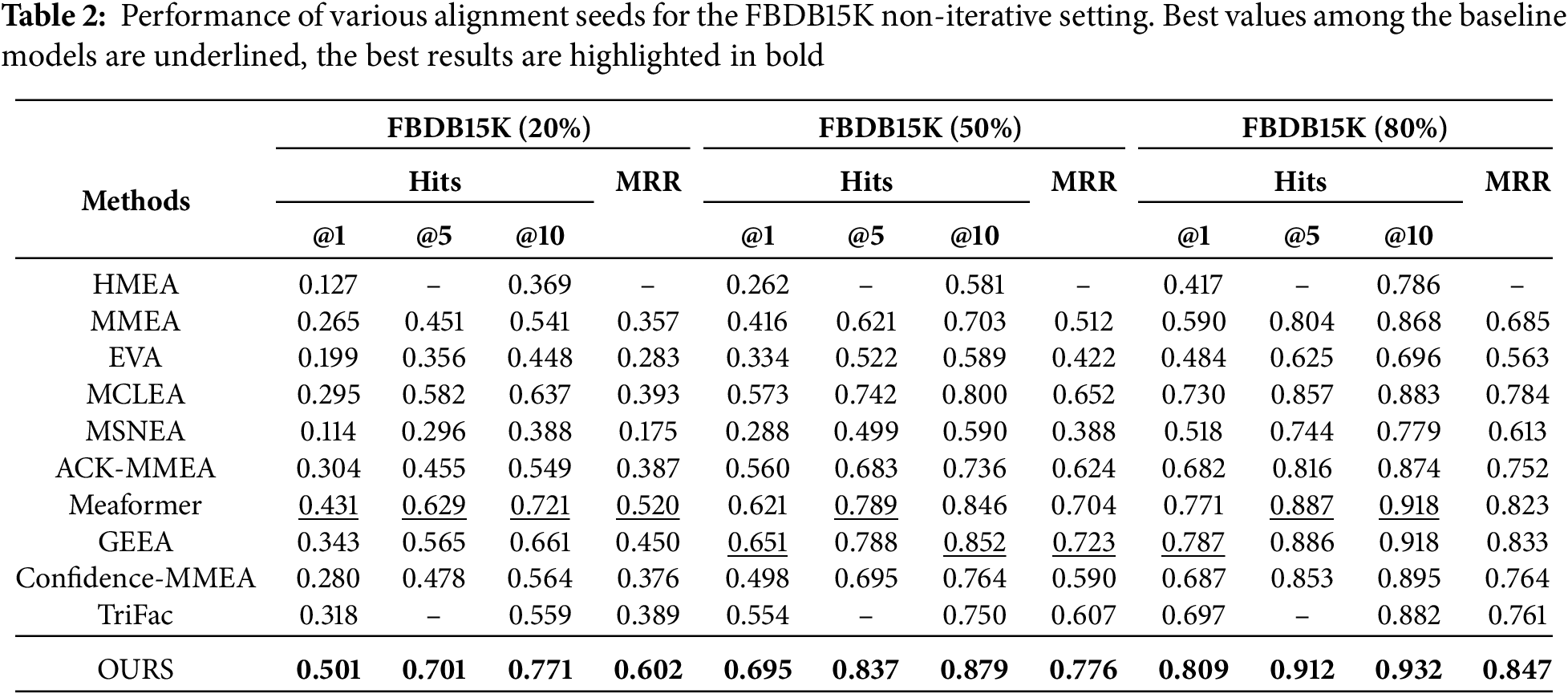

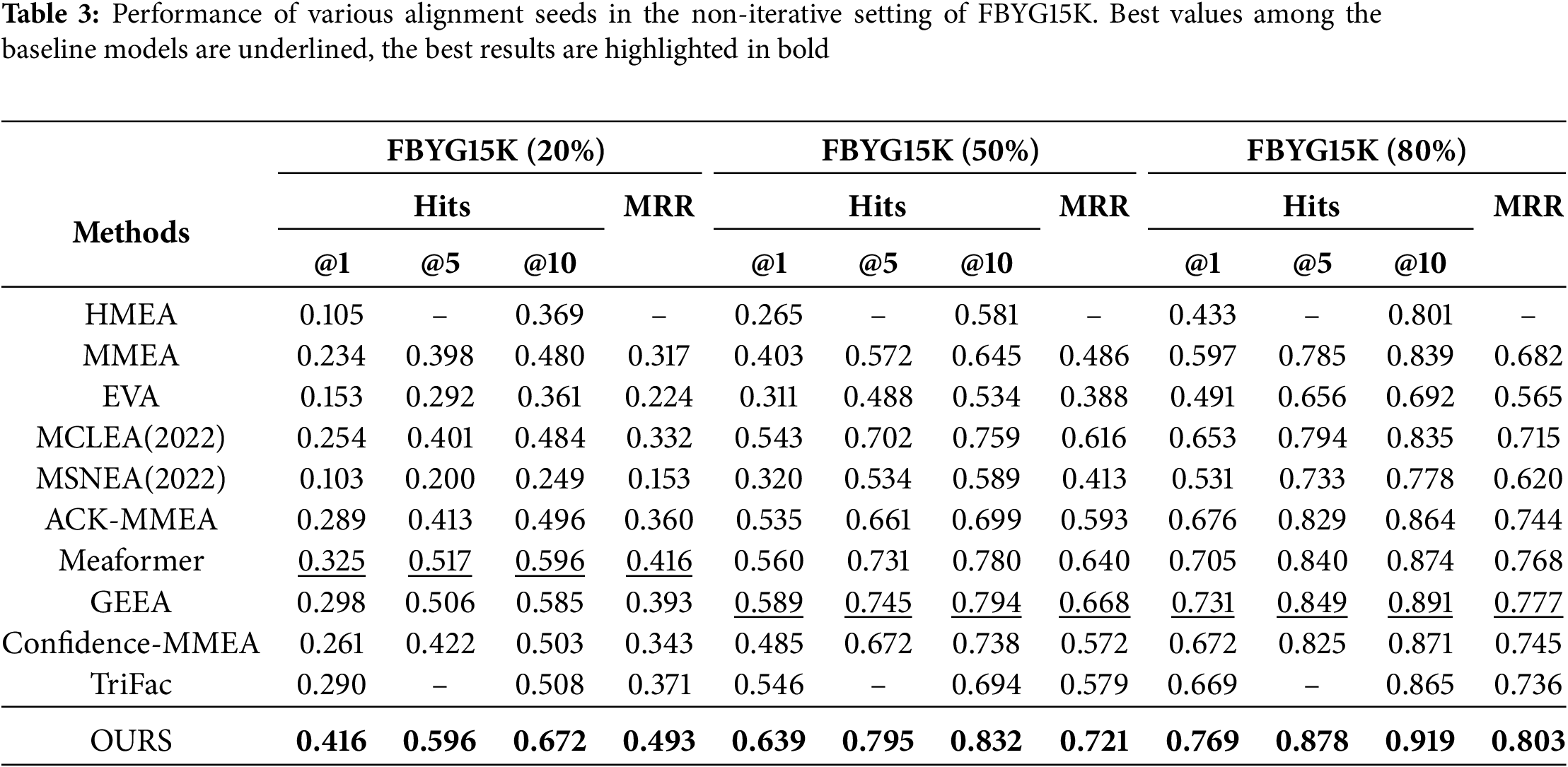

To validate the effectiveness of our method, the experiments encompassed both iterative and non-iterative settings, utilizing various training/testing alignment seed splits (i.e., 2:8, 5:5, and 8:2) to facilitate performance comparisons. The detailed results of the comparative experiments are demonstrated in Tables 2–4. Overall, MPSEA demonstrates exceptional performance across all metrics. In the non-iterative strategy, as illustrated in Table 2, our model surpasses the best baseline models, achieving improvements of 2.2%–7% in Hits@1 and 1.1%–8.2% in MRR. Table 3 indicates that the highest improvements in Hits@1 and MRR reach 9.1% and 7.7%, respectively.

Specifically, although MEAformer and GEEA propose relatively effective modality fusion methods, neither considers the information bias caused by inter-modal heterogeneity. This issue is successfully mitigated by introducing a multi-modal pre-synergistic fusion guidance module. Conversely, in contrast to the majority of baseline models that focus solely on conventional modal information, we also incorporate numerical modalities, which effectively alleviates the problem of missing modalities.

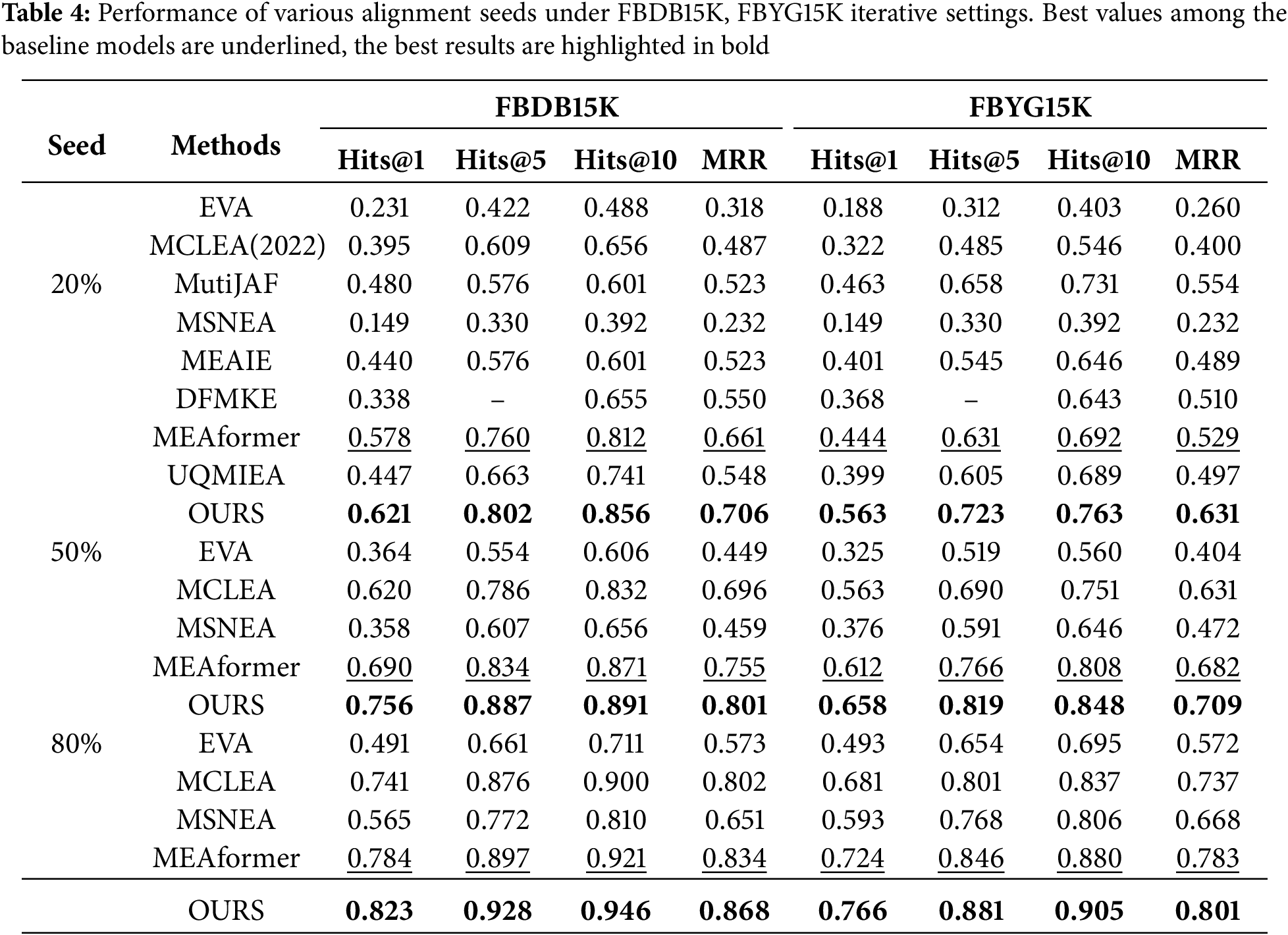

In the iterative experiments, we observed a significant improvement in results compared to the non-iterative approach. This enhancement can mainly be attributed to our dynamic expansion of the training set based on the original optimization. It enables the model to learn the alignment relationships between entities better. Observing Table 4, we found that on 20% aligned seed data, compared with MutiJAF, our model’s Hits@1 and MRR increased by 14.1% and 18.3%, respectively, on FBDB15K, and Hits@1 and MRR increased by 10% and 7.7%, respectively, on FBYG15K. This is because MutiJAF only considers late fusion, does not involve the correlation of early primary feature level modalities, and ignores the modal heterogeneity brought about by visual and graph structures. Although some models, such as MEAIE, MutiJAF, etc., also consider numerical modalities, none consider the deeper integration of inter-modal information and fail to utilize each modality’s information fully). In contrast, while addressing inter-modal heterogeneity, our model also introduces a deep perceptual reinforcement learning module based on policy networks, which further realizes multi-level deep information interaction between modalities. Compared to MEAIE, our model achieves improvements of 18.1% and 18.3% in Hits@1, as well as 16.2% and 14.2% in MRR across the two datasets, thereby demonstrating the practical effectiveness and rationale of the module.

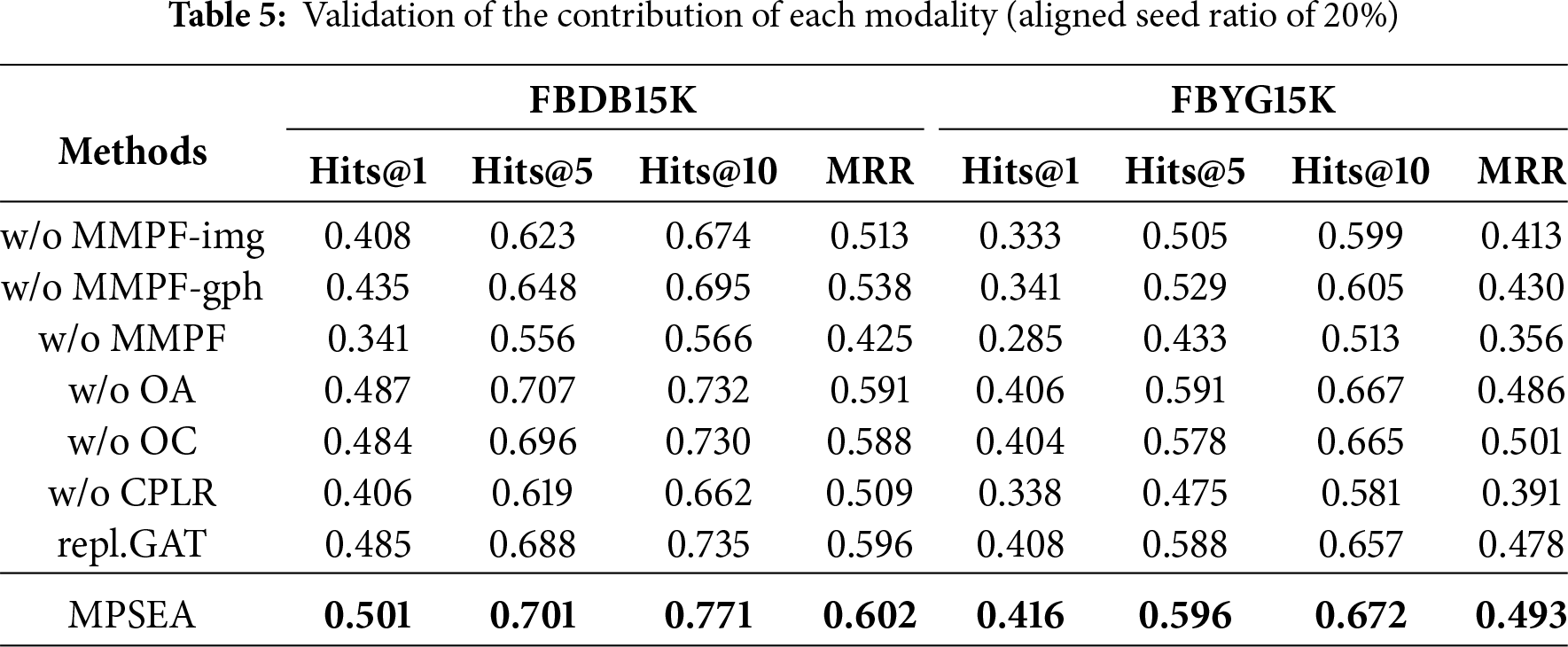

We performed the ablation experiment in two ways: 1) the impact of different modalities on entity alignment, and 2) the importance of key components in entity alignment.

1. Modal contributions validation: Five relevant modal variants were designed, including w/o structure, w/o relation, w/o attr, w/o img, and w/o number. The specific results are depicted in Table 5. We find that removing any modality results in a decrease in performance. Notably, eliminating the structural modality leads to a substantial decline in Hits@1 and MRR, with reductions of approximately 40% across both datasets. This sharp decline is due to the fact that the graph structural modality conveys contextual information about entities through their topological relationships. Removing the modality will result in the inability to utilize the relationship information between entities, thus losing the understanding of complex structures and higher-order dependencies. Secondly, removing the relationships, the image modality performance degradation is also more significant. Compared to FBDB15K, the relational modality of FBYG15K is more significant than the image modality. This distinction may arise because, while both datasets exhibit complex relational structures, FBDB15K boasts over 90% image coverage. In contrast, only 81.17% of the entities in FBYG15K possess image features, indicating that a considerable number of entities lack visual information support. In this case, the model cannot fully leverage the image modality to mitigate the deficiencies of other modalities, resulting in its relatively weakened role in multi-modal fusion. As a result, relational modalities become an essential source used in addition to structural modalities to fill information gaps and provide key contextual and semantic associations.

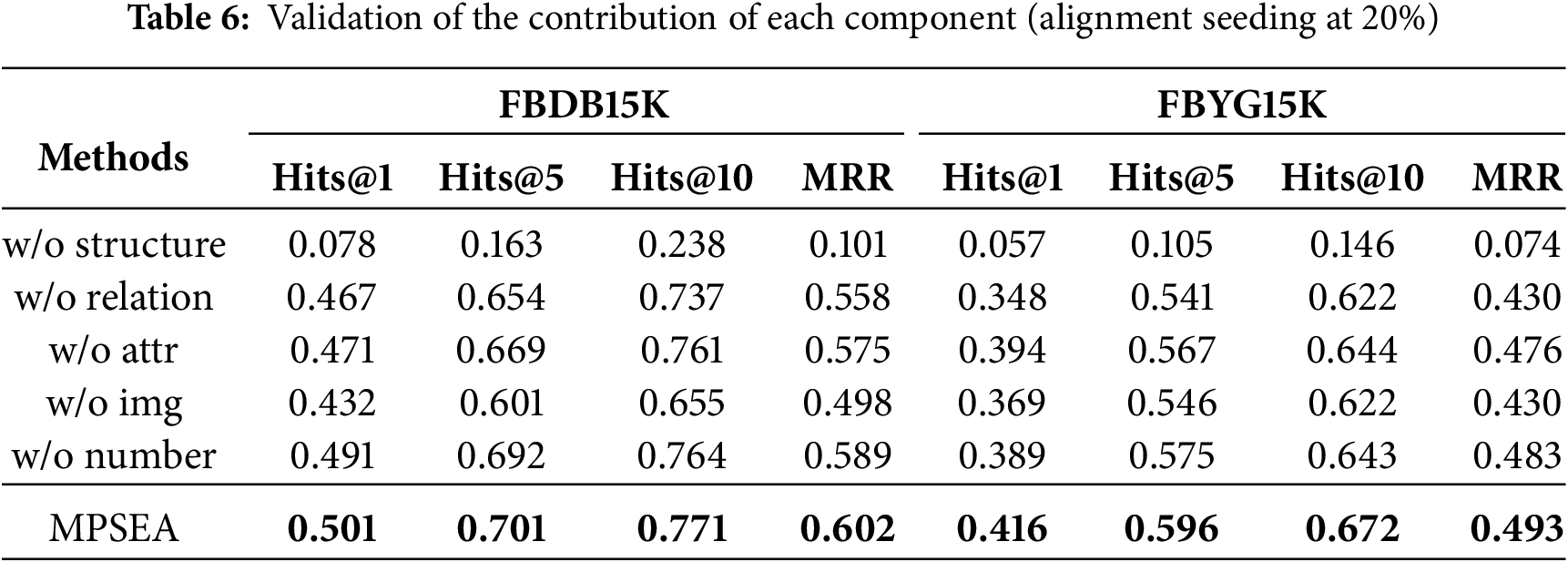

2. Contribution verification of each component. We designed the following three variants for experimentation: 1) w/o MMPF-img: Remove the image pre-synergistic fusion from the multi-modal pre -synergistic fusion module (MMPF); w/o MMPF-gph: Remove the graph structure pre-synergistic fusion from MMPF; w/o MMPF: Completely remove the multi-modal pre-synergistic fusion module. 2) w/o OA: Remove the OA module from the FFN layer of the image transformer; w/o OC: Remove both the OA and convolutional dual modules from the FFN layer of the transformer. 3) w/o CPRL: Remove the Cross-modal Deep Perception Reinforcement Learning (CPRL) module. 4) repl.GAT: Replacing multi-weight GAT with Normal GAT. The results are illustrated in Table 6.

We have the following key observations: (a) For the first set of variants, we find that the MMPF module effectively addresses the problem of modal heterogeneity differences during fusion. Notably, removing image pre-synergistic fusion has a more significant impact than removing graph structure pre-synergistic fusion. This is presumably due to the greater heterogeneity between image modality and text, compared to graph structure modality. The introduction of image pre-synergistic fusion facilitates the integration of heterogeneous features into other modalities in advance, thereby enabling more effective multi-modal fusion. (b) For the second group of variants, we observed that introducing the OA module and the convolution enhancement module in the FFN layer can further mitigate the noise interference between different modalities and enhance the model’s ability to handle fine-grained features. (c) The removal of the CPRL module has resulted in a notable decline in model performance. It indicates that our custom cross-modal mutual information estimator can do a better job of helping the model learn information fusion and sharing, and guiding the policy network renewal through a reward and punishment mechanism to optimize the alignment policy progressively. (d) A slight reduction in the model is observed when the multi-weighted GAT is substituted for the regular GAT, demonstrating that the former mitigates the contextual gap issue and enhances the capacity to differentiate between various types of nodes.

4.2.3 Hyperparametric Analysis

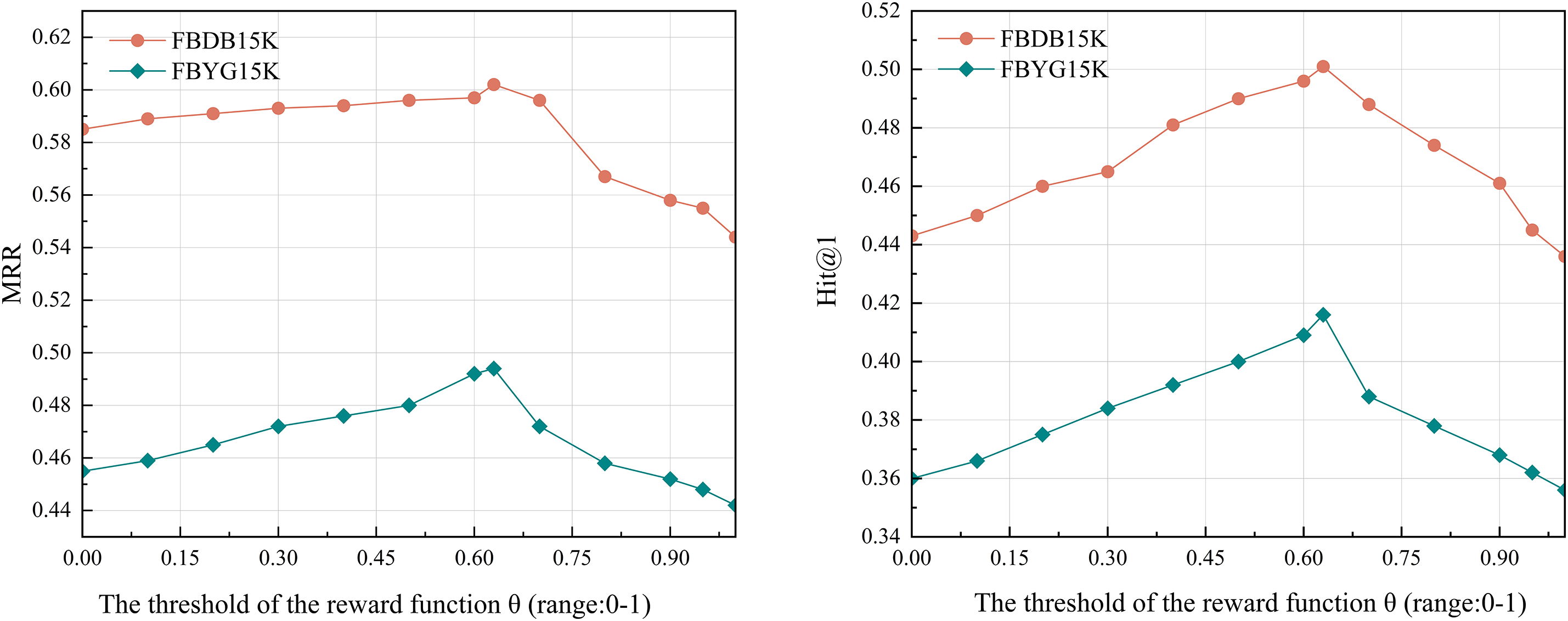

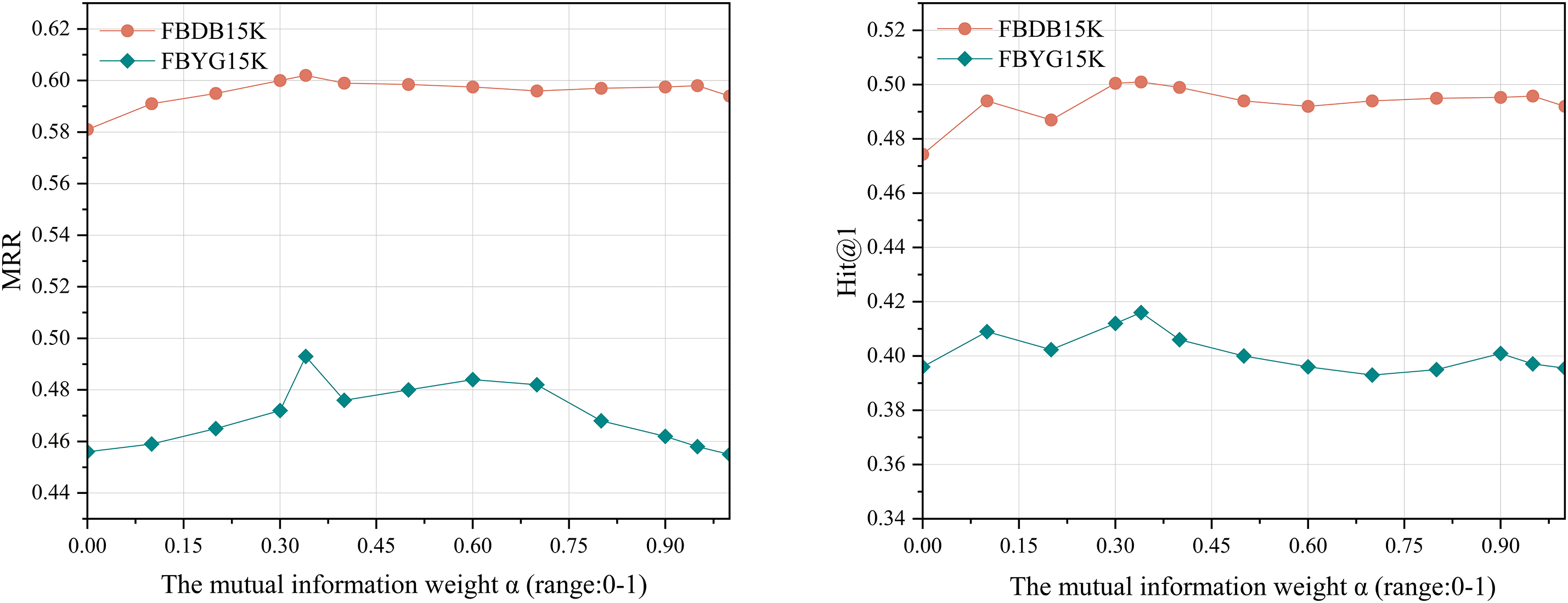

We further investigated the influence of hyperparameters on model performance. The experimental results are illustrated in Figs. 4 and 5 (Both MRR and Hit@1 are dimensionless evaluation metrics without physical units, with values ranging from 0 to 1). Our primary focus was on the impact of the threshold

Figure 4: Impact of threshold

Figure 5: Impact of mutual information weights

The results presented in Fig. 5 indicate that for both datasets, performance is maximized when

4.2.4 Low-Resource Training Data Performance

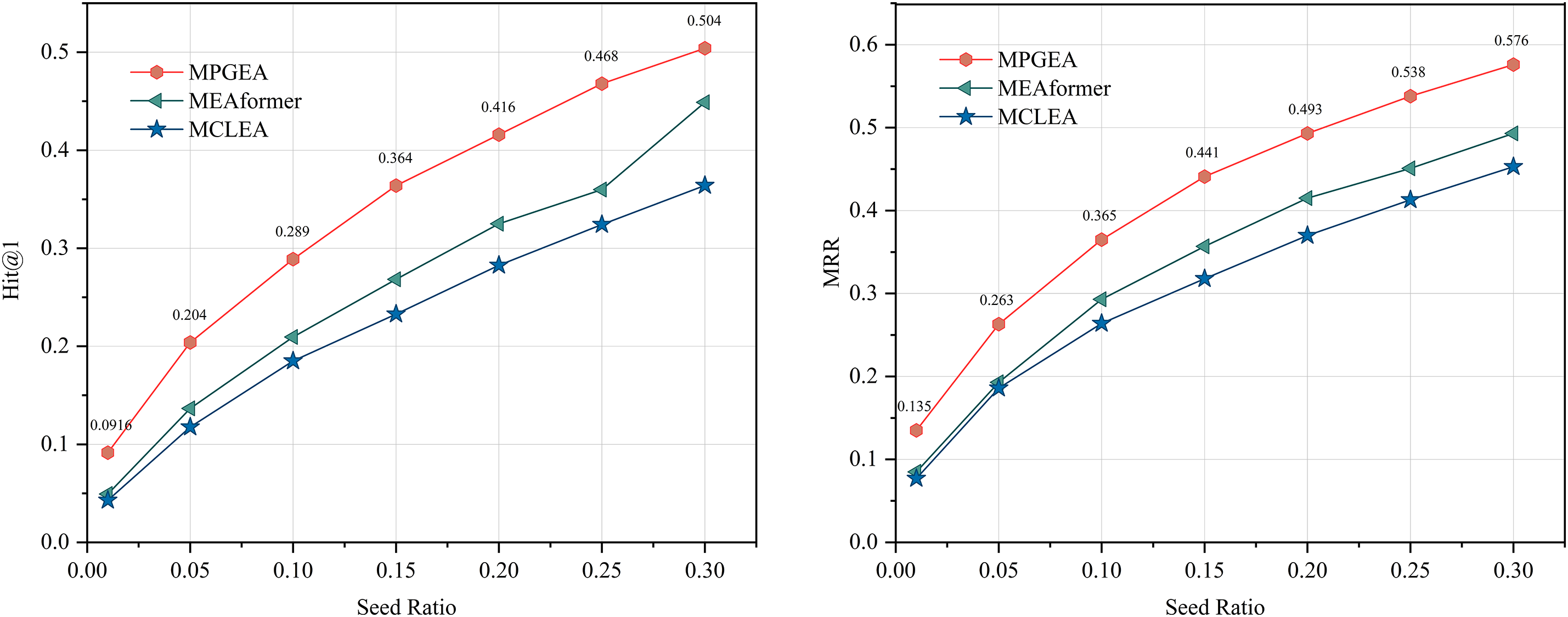

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of MPSEA in MMEA tasks, we conducted an in-depth analysis using limited training data. By setting the pre-alignment seed ratio to 0.01–0.3 and selecting MEAformer and MCLEA as baseline models, we performed experiments on the FB15K-YG15K dataset, with results illustrated in the reinforcement learning flowchart as follows in Fig. 6. It is observed that MPSEA is at the forefront even at low seed ratios, further confirming that our model is practically effective.

Figure 6: H@1 and MRR performance with different ratios of seed alignments ranging from 0.01 to 0.3 on FBYG15K

This paper proposes a Multi-modal Pre-synergistic Fusion Model based on Cross-modal Mutual Information Strategy Optimization (MPSEA) for the entity alignment task. The model effectively encodes multi-modal information—including numerical, graph-structural, and visual modalities—alleviating the issue of missing modality information in multi-modal entity alignment. By injecting graph structure and visual modality features as preparatory information into the cross-modal attention mechanism, MPSEA achieves multi-level, deep joint feature embeddings, which reduces information loss and bias arising from modality heterogeneity. Furthermore, a custom-designed strategy optimization network based on cross-modal mutual information is adopted to capture shared information and optimize model output via contrastive learning. The cosine similarity of embeddings ultimately determines entity alignment. Experimental results on two real-world datasets demonstrate that MPSEA achieves superior performance over existing approaches.

5.1 Discussion on Model Limitations

Although MPSEA achieves superior performance in the multimodal entity alignment task, its design and experimental results also reveal several limitations:

• Strong Dependence on Specific Modalities: Ablation experiments show that removing any modality leads to performance degradation. Notably, removing the graph structure modality causes a significant drop in Hits1 and MRR metrics across both datasets. This indicates a high reliance on graph structural information, fundamentally because the core of knowledge graphs lies in conveying rich contextual information through the topological relationships between entities. The structural modality captures complex connections and higher-order dependencies among entities; removing it results in the loss of understanding of these complex structures. Without the structural modality, the model cannot effectively utilize the aggregated relationships of neighboring nodes for alignment reasoning. Suppose the knowledge graph lacks high-quality structural information. In that case, the fusion of other modality features will lack a solid anchor and context, greatly reducing the efficiency and accuracy of information fusion.

• Hyperparameter Sensitivity: The model’s performance is susceptible to hyperparameters in the reward function. For example, when the reward threshold

• Computational Cost Considerations: Core mechanisms of MPSEA, such as the multi-head self-attention (MHA) blocks, complex fusion strategies, and deep neural network components, are computationally intensive. The computational complexity of MHA grows significantly with the length of the input sequence (i.e., number of entities) and the number of modalities. This may pose challenges of higher computational overhead when handling large-scale multimodal knowledge graphs compared to simpler embedding-based alignment methods.

5.2 Future Research Directions

In future research, we plan to:

• The current study evaluates the model only on the FB15K-DB15K and FB15K-YAGO15K datasets, a relatively narrow scope for verifying the model’s general effectiveness. Future work should consider incorporating diverse datasets from different domains with varying scales and modal characteristics to validate the model’s generalization ability. This will help ensure the model remains robust across a wider range of real-world scenarios.

• Explore embedding methods for richer modalities (such as audio and video) to enhance the model’s applicability and accuracy further. Currently, most multimodal entity alignment (MMEA) datasets treat multimodal data as attributes of textual entities, often neglecting the intrinsic correlations between modalities, which differs from real-world knowledge graph entities that include multiple modalities such as text, images, and audio. For example, recent advances in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) diagnosis demonstrate how AI processes complex, multi-level information to achieve high accuracy in disease detection and staging using a multi-stage convolutional neural network (CNN) framework on MRI data.Additionally, research on medical image denoising based on Transformer architectures shows that advanced Transformer models can effectively handle complex noise patterns in multimodal data by capturing long-range pixel dependencies through multi-head attention mechanisms and performing image reconstruction. This aligns with the OutlookerAttention mechanism in our model, which is designed to reduce cross-modal noise interference. Understanding how medical AI effectively processes diverse data types—such as MRI sequences, PET scans, and clinical data—while providing interpretable insights into fusion strategies is crucial for developing robust and trustworthy multimodal systems. These experiences offer valuable guidance for our multimodal pre-synergistic fusion approach, helping us better model the complex relationships between heterogeneous modalities to achieve more comprehensive information fusion.

• Inspired by the dual-perspective evaluation framework proposed by Wang [36], integrating dynamically learnable evaluation metrics helps better balance structural fidelity and semantic coherence in generated text, enhancing interpretability. This approach addresses the demand for explainable AI (XAI) in medical applications, where XAI aids in understanding model decisions, identifying biases, and optimizing design, especially in high-risk scenarios like Alzheimer’s diagnosis. We aim to enable entity alignment model evaluation to go beyond performance metrics and reveal the reasoning process in handling heterogeneous multimodal information, thereby improving model transparency and reliability.

These efforts, we believe, will further improve the performance and generalizability of multimodal entity alignment models in complex knowledge graph scenarios.

Acknowledgement: We sincerely acknowledge the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China and the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province.

Funding Statement: This work is partially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grants 62471493 and 62402257 (for conceptualization and investigation), partially supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province, China under Grants ZR2023LZH017, ZR2024MF066, and 2023QF025 (for formal analysis and validation), partially supported by the Open Foundation of Key Laboratory of Computing Power Network and Information Security, Ministry of Education, Qilu University of Technology (Shandong Academy of Sciences) under Grant 2023ZD010 (for methodology and model design), and partially supported by the Russian Science Foundation (RSF) Project under Grant 22-71-10095-P (for validation and results verification).

Author Contributions: Conceptualization: Huayu Li, Xinxin Chen, Lizhuang Tan; Methodology: Huayu Li, Xinxin Chen; Validation: Huayu Li, Xinxin Chen, Konstantin I. Kostromitin, Peiying Zhang; Formal analysis: Huayu Li, Xinxin Chen, Athanasios V. Vasilakos, Peiying Zhang; Investigation: Huayu Li, Xinxin Chen; Writing—original draft: Huayu Li, Xinxin Chen, Lizhuang Tan, Peiying Zhang; Writing—review and editing: Huayu Li, Xinxin Chen, Lizhuang Tan; Supervision: Lizhuang Tan, Konstantin I. Kostromitin, Athanasios V. Vasilakos, Peiying Zhang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the results of this study are openly available at https://github.com/lzxlin/MCLEA (accessed on 01 September 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Cao Y, Li X, Liu H, Dai W, Chen S, Wang B, et al. Pay more attention to relation exploration for knowledge base question answering. In: Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2023; 2023 Jul 9–14; Toronto, ON, Canada: Association for Computational Linguistics. p. 2119–36. [Google Scholar]

2. Cao X, Shi Y, Wang J, Chen E. Cross-modal knowledge graph contrastive learning for machine learning method recommendation. In: Proceedings of the 30th ACM International Conference on Multimedia (MM ’22); 2022 Oct 10–14; Lisbon, Portugal: Association for Computing Machinery. p. 3694–702. [Google Scholar]

3. Cao Y, Wang X, He X, Hu Z, Chua TS. Unifying knowledge graph learning and recommendation: towards a better understanding of user preferences. In: Proceedings of the 2019 World Wide Web Conference (WWW ’19); 2019 May 13–17; San Francisco, CA, USA: Association for Computing Machinery. p. 151–61. [Google Scholar]

4. Chen X, Zhang N, Li L, Yao Y, Deng S, Tan C, et al. Hybrid Transformer with multi-level fusion for multi-modal knowledge graph completion. In: Proceedings of the 45th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval (SIGIR ’22); 2022 Jun 11–12; Madrid, Spain: ACM. p. 904–15. [Google Scholar]

5. Han X, Liu Z, Sun M. Neural knowledge acquisition via mutual attention between knowledge graph and text. In: Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence. Palo Alto, CA, USA: AAAI Press; 2018. p. 32–9. [Google Scholar]

6. Sun Z, Zhang Q, Hu W, Wang C, Chen M, Akrami F, et al. A benchmarking study of embedding-based entity alignment for knowledge graphs. Proc VLDB Endow. 2020;13(12):2326–40. doi:10.14778/3407790.3407828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Zhang J, Yin Z, Chen P, Nichele S. Emotion recognition using multi-modal data and machine learning techniques: a tutorial and review. Inf Fusion. 2020;59(1):103–26. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2020.01.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Jiang S, Sun B, Wang L, Bai Y, Li K, Fu Y. Skeleton aware multi-modal sign language recognition. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2021 Jun 19–25; Nashville, TN, USA. p. 3413–23. [Google Scholar]

9. Zhen L, Hu P, Wang X, Peng D. Deep supervised cross-modal retrieval. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2019 Jun 15–20; Long Beach, CA, USA. p. 10394–403. [Google Scholar]

10. Chun S, Oh SJ, De Rezende RS, Kalantidis Y, Larlus D. Probabilistic embeddings for cross-modal retrieval. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2021 Jun 20–25; Nashville, TN, USA. p. 8415–24. [Google Scholar]

11. Sun Z, Hu W, Zhang Q, Qu Y. Bootstrapping Entity Alignment with Knowledge Graph Embedding. In: Proceedings of the 27th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI-18); 2018 Jul 13–19; Stockholm, Sweden. p. 4396–402. [Google Scholar]

12. Sanchez-Lengeling B, Reif E, Pearce A, Wiltschko AB. A gentle introduction to graph neural networks. Distill. 2021;6(9):e33. [Google Scholar]

13. Wang Z, Lv Q, Lan X, Zhang Y. Cross-lingual knowledge graph alignment via graph convolutional networks. In: Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP 2018); 2018 Oct 31–Nov 4; Brussels, Belgium: Association for Computational Linguistics. p. 349–57. [Google Scholar]

14. Wu Y, Liu X, Feng Y, Wang Z, Yan R, Zhao D. Relation-aware entity alignment for heterogeneous knowledge Graphs. In: Proceedings of the 28th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI-19); 2019 Aug 10–16; Macao, China. p. 5278–84. [Google Scholar]

15. Gao Y, Liu X, Wu J, Zhou A, Li T. ClusterEA: scalable entity alignment with stochastic training and normalized mini-batch similarities. In: Proceedings of the 28th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (KDD ’22); 2022 Aug 14–18; Washington, DC, USA: ACM. p. 421–31. [Google Scholar]

16. Liu F, Chen M, Roth D, Collier N. Visual pivoting for (Unsupervised) entity alignment. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2021;35(5):4257–66. doi:10.1609/aaai.v35i5.16550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Lin Z, Zhang Z, Wang M, Shi Y, Wu X, Zheng Y. Multi-modal contrastive representation learning for entity alignment. In: Proceedings of the 29th International Conference on Computational Linguistics (COLING 2022); 2022 Oct 12–17; Gyeongju, Republic of Korea: International Committee on Computational Linguistics. p. 2572–84. [Google Scholar]

18. Chen Z, Chen J, Zhang W, Guo L, Fang Y, Huang Y, et al. MEAformer: multi-modal entity alignment transformer for meta modality hybrid. In: Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Multimedia (MM ’23). Association for Computing Machinery; 2023 Oct 29–Nov 3; Ottawa, ON, Canada: Association for Computing Machinery. p. 3317–27. [Google Scholar]

19. Yuan S, Lu Z, Li Q, Gu J. A Multi-modal entity alignment method with inter-modal enhancement. Big Data Cogn Comput. 2023;7(2):77. doi:10.3390/bdcc7020077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Li Q, Guo S, Luo Y, Ji C, Wang L, Sheng J, et al. Attribute-consistent Knowledge Graph Representation Learning for Multi-modal Entity Alignment. In: Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2023 (WWW ’23); 2023 Apr 30–May 4; Austin, TX, USA: ACM. p. 2499–508. [Google Scholar]

21. Velickovic P, Cucurull G, Casanova A, Romero A, Lio P, Bengio Y. Graph attention networks. arXiv:1710.10903. 2017. [Google Scholar]

22. Yang H-W, Zou Y, Shi P, Lu W, Lin J, Sun X. Aligning cross-lingual entities with multi-aspect information. In: Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (EMNLP/IJCNLP); 2019 Nov; Hong Kong, China. Vol. 1. p. 4430–40. [Google Scholar]

23. Simonyan K, Zisserman A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv:1409.1556. 2014. [Google Scholar]

24. Liu Y, Li H, Garcia-Duran A, Niepert M, Onoro-Rubio D, Rosenblum DS. Multi-modal knowledge graphs. In: Proceedings of the 16th Extended Semantic Web Conference (ESWC 2019). Portorož, Slovenia: Springer; 2019. p. 459–74. [Google Scholar]

25. Vaswani A, Shazeer N, Parmar N, Uszkoreit J, Jones L, Gomez AN, et al. Attention is all you need. In: Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS); 2017. p. 5998–6008. [Google Scholar]

26. Zeng W, Zhao X, Tang J, Wang X, Zhang W, Xiong H, et al. Reinforcement learning-based collective entity alignment with adaptive features. ACM Trans Inf Syst. 2021;39(3):1–31. doi:10.1145/3446428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Guo H, Tang J, Zeng W, Zhao X, Liu L. Multi-modal entity alignment in hyperbolic Space. Neurocomputing. 2021;461(4):598–607. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2021.03.132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Chen L, Li Z, Wang Y, Xu T, Wang Z, Chen E. MMEA: entity alignment for multi-modal knowledge graph. In: Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Knowledge Science, Engineering and Management (KSEM 2020); 2020 Aug 18–20; Hangzhou, China: Springer. p. 134–47. [Google Scholar]

29. Guo L, Chen Z, Chen J, Fang Y, Zhang W. Revisit and outstrip entity alignment: a perspective of generative models. In: Proceedings of the Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR 2024). Vienna, Austria; 2024. [Google Scholar]

30. Zhang X, Chen T, Wang H. A novel method for boosting knowledge representation learning in entity alignment through triple confidence. Mathematics. 2024;12(8):1214. doi:10.3390/math12081214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Li Q, Li J, Wu J, Peng X, Ji C, Peng H, et al. Triplet-aware graph neural networks for factorized multi-modal knowledge graph entity alignment. Neural Netw. 2024;171(1):106479. doi:10.1016/j.neunet.2024.106479. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Cheng B, Zhu J, Guo M. MultiJAF: multi-modal joint entity alignment framework for multi-modal knowledge graph. Neurocomputing. 2022;500(4):581–91. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2022.05.058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Chen L, Li Z, Xu T, Wu H, Wang Z, Yuan NJ, et al. Multi-modal siamese network for entity alignment. In: Proceedings of the 28th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (KDD ’22); 2022 Aug 14–18; Washington, DC, USA: ACM. p. 118–26. [Google Scholar]

34. Zhu J, Huang C, De Meo P. DFMKE: a dual fusion multi-modal knowledge graph embedding framework for entity alignment. Inform Fus. 2023;90(1):111–9. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2022.09.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Hama K, Matsubara T. Multi-modal entity alignment using uncertainty quantification for modality importance. IEEE Access. 2023;11:28479–89. doi:10.1109/access.2023.3259987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Wang H, Wang L, Lepage Y. Dual-perspective evaluation of knowledge graphs for graph-to-text generation. Comput Mater Contin. 2025;84:305–24. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools