Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Security and Privacy in Permissioned Blockchain Interoperability: A Systematic Review

1 Center of Research for Cyber Security and Network (CSNET), Faculty of Computer Science and Information Technology, Universiti Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, 50603, Malaysia

2 Department of Computer Science, Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman, Kampar, 31900, Malaysia

3 Department of Information Technology and Security, Jazan University, Jizan, 45142, Saudi Arabia

4 School of Computer Science and Technology, Guangdong University of Technology, Guangzhou, 510006, China

5 School of Information and Communication Engineering, Hainan University, Haikou, 570228, China

* Corresponding Authors: Chin Soon Ku. Email: ; Lip Yee Por. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advancing Network Intelligence: Communication, Sensing and Computation)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(2), 2579-2624. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.070413

Received 15 July 2025; Accepted 19 August 2025; Issue published 23 September 2025

Abstract

Blockchain interoperability enables seamless communication and asset transfer across isolated permissioned blockchain systems, but it introduces significant security and privacy vulnerabilities. This review aims to systematically assess the security and privacy landscape of interoperability protocols for permissioned blockchains, identifying key properties, attack vectors, and countermeasures. Using PRISMA 2020 guidelines, we analysed 56 peer-reviewed studies published between 2020 and 2025, retrieved from Scopus, ScienceDirect, Web of Science, and IEEE Xplore. The review focused on interoperability protocols for permissioned blockchains with security and privacy analyses, including only English-language journal articles and conference proceedings. Risk of bias in the included studies was assessed using the MMAT. Methods for presenting and synthesizing results included descriptive analysis, bibliometric analysis, and content analysis, with findings organized into tables, charts, and comparative summaries. The review classifies interoperability protocols into relay, sidechain, notary scheme, HTLC, and hybrid types and identifies 18 security and privacy properties along with 31 known attack types. Relay-based protocols showed the broadest security coverage, while HTLC and notary schemes demonstrated significant security gaps. Notably, 93% of studies examined fewer than four properties or attack types, indicating a fragmented research landscape. The review identifies underexplored areas such as ACID properties, decentralization, and cross-chain attack resilience. It further highlights effective countermeasures, including cryptographic techniques, trusted execution environments, zero-knowledge proofs, and decentralized identity schemes. The findings suggest that despite growing adoption, current interoperability protocols lack comprehensive security evaluations. More holistic research is needed to ensure the resilience, trustworthiness, and scalability of cross-chain operations in permissioned blockchain ecosystems.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileBlockchain technology has revolutionized decentralized systems by providing distributed, transparent, and tamper-resistant ledgers [1]. Among its variants, permissioned blockchains have gained significant traction in enterprise and institutional environments where access control, confidentiality, and regulatory compliance are crucial [2]. As organizations increasingly adopt blockchain solutions tailored to domains, such as the Internet of Things (IoT) [3–5], vehicular [6], and healthcare [7], the need for secure and efficient interoperability between these systems has become both urgent and inevitable [8]. Interoperability protocols act as bridges, enabling data exchange, asset transfers, and smart contract execution across otherwise isolated blockchain networks [9].

However, the integration of interoperability protocols introduces a new attack surface, exposing systems to sophisticated security and privacy threats. Since May 2021, cross-chain transaction attacks have caused losses exceeding USD 3.1 billion [10]. Existing surveys generally address only a narrow scope of security analyses. Their focus is often limited to a small set of countermeasures [9,11]. Others focus solely on specific attack types or security and privacy attributes [12–14]. Many also concentrate predominantly on cross-chain protocols in permissionless blockchain environments [15–17]. Consequently, no comprehensive and systematic review currently addresses the security and privacy challenges specific to permissioned blockchain interoperability. The absence of such a holistic analysis poses significant difficulties for system architects and developers seeking to secure interoperability protocols against evolving threats.

To address this gap, this study conducts a systematic literature review (SLR) that synthesizes the security properties, privacy considerations, threats, and countermeasures of interoperability protocols in permissioned blockchains. The methodology follows the PRISMA 2020 guidelines [18], which include a flow diagram and 27-item checklist to ensure transparent and comprehensive reporting of systematic reviews. A PRISMA flow diagram is used to illustrate the study selection process. Furthermore, the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) [19], a well-established instrument for assessing the methodological quality of mixed-method, quantitative, and qualitative studies, was applied to evaluate the included research. Both the PRISMA checklist and MMAT-based quality assessment are provided in the supplementary materials to enhance transparency and reproducibility. This review offers a structured and in-depth analysis of existing work while identifying key gaps in current research and providing insights to guide future development.

Understanding and mitigating these challenges is critical for safeguarding the growing investments in blockchain-based applications. Robust security and privacy analysis are essential to ensure the trustworthiness, resilience, and scalability of interoperability mechanisms in permissioned blockchain ecosystems [10].

This article is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the foundational concepts of blockchain technology, interoperability protocols, and related work, while Section 3 describes the research methodology, including the systematic review protocol, research questions, and study selection criteria. Section 4 provides the review results following the PRISMA 2020 framework, covering study selection, quality assessment, publication trends, and study characteristics, as well as analyses of security and privacy properties (Section 4.5), attack types (Section 4.6), and countermeasures (Section 4.7), which collectively address the research questions. It also discusses heterogeneity among studies (Section 4.8) and reporting bias (Section 4.9). Section 5 critically examines the findings, highlighting research gaps (Section 5.1) and future directions (Section 5.2), and Section 6 concludes with key insights and implications.

This section provides background about Blockchain technology and interoperability protocols.

Blockchain technology comprises several core components that collectively ensure decentralization, security, and immutability [20]. At its foundation, the distributed ledger maintains a chronological chain of cryptographically linked blocks, ensuring that any modification to a past record is immediately detectable [21]. Consensus algorithms, including variants like Proof of Work (PoW) and Proof of Stake (PoS), allow participants to collaboratively verify transactions without relying on a central authority [22]. Cryptographic primitives underpin blockchain security; for example, hash functions generate unique digital fingerprints of data, ensuring integrity, while advanced cryptographic methods, such as zero-knowledge proofs, enable a participant to demonstrate that they possess valid information without disclosing the information itself, thereby supporting privacy-preserving cross-chain transactions [23]. Smart contracts are autonomous programs deployed on the blockchain that execute predefined agreements automatically when specified conditions are met, minimizing the need for intermediaries and promoting trustless interaction [22]. Collectively, these components create a tamper-evident, auditable, and trustless framework for decentralized systems [24–26]. Blockchain has been applied across diverse domains, including IoT [3–5], vehicular networks [6], and healthcare [7].

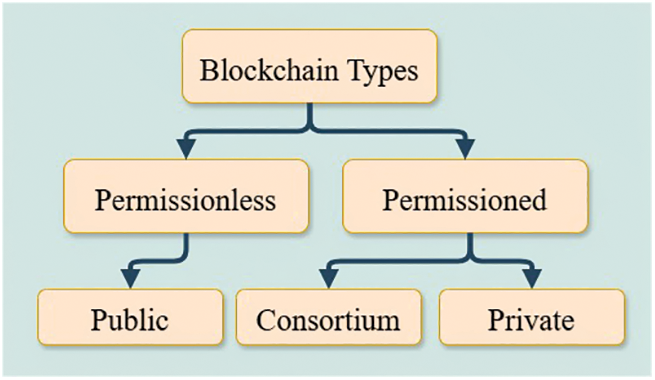

Since the introduction of Bitcoin, numerous blockchain platforms have been developed, including Ethereum [20] and Hyperledger Fabric [27,28]. Depending on the participant access permissions, intended application scenarios, and degree of decentralization, blockchain systems are broadly categorized into two types: permissionless and permissioned [29].

Fig. 1 provides an overview of blockchain categories. Permissionless blockchains (e.g., Bitcoin and Ethereum) are public networks that allow any user to join, leave, and view transactions, often anonymously. In contrast, permissioned blockchains restrict participation to authorized nodes, offering an additional layer of control and security. These are further divided into consortium blockchains, where access is limited to a group of trusted organizations [29], and private blockchains, where a single entity governs participation and enforces strict access restrictions [29].

Figure 1: Categories of blockchain networks

To address enterprise-specific requirements, several notable permissioned blockchain frameworks have been introduced. Among them, Hyperledger Fabric offers a modular architecture tailored for business networks. Originally built on a Byzantine fault-tolerant consensus algorithm, Fabric now supports alternative consensus mechanisms to accommodate diverse enterprise needs [27,28]. Quorum, developed by JP Morgan as a fork of Ethereum, introduces key modifications such as permissioned participation, enhanced transaction privacy, a novel consensus mechanism, and reduced transaction fees, making it particularly suitable for financial and enterprise-grade applications [30]. Another prominent framework, Corda by R3, is a semi-open-source platform widely recognized in the financial sector. Unlike conventional blockchains, Corda employs a notary pool to achieve consensus, reflecting its focus on transaction verification and privacy in regulated industries [31]. Similarly, Multichain provides a flexible platform for deploying customized permissioned blockchains, emphasizing simplicity, privacy, and scalability across a wide range of business domains [32].

2.2 Interoperability Protocols

Interoperability refers to the capacity of different blockchains—whether public, private, or consortium-based—to seamlessly exchange assets, share data, and execute smart contracts without requiring modifications to their underlying infrastructure [9]. This capability is essential for preventing ecosystem fragmentation, supporting diverse application scenarios, and enabling broader adoption of blockchain technology across real-world domains. To meet the requirements of modern use cases, interoperability must extend beyond simple asset transfers or event notifications to include the secure and efficient exchange of arbitrary data. Such functionality is critical for applications that require privacy-preserving data sharing, regulatory compliance, and automated business workflows. For instance, asset transfer involves securely moving tokens or digital assets between distinct blockchain networks, while asset exchange entails transferring ownership of assets between users on different chains [16]. Arbitrary data sharing is particularly important in real-world scenarios, such as supply chain management or healthcare, where complex data structures must be transferred with guaranteed integrity, confidentiality, and cross-chain compatibility [33]. Smart contract invocation further extends interoperability by allowing one blockchain to trigger and receive responses from a smart contract deployed on another chain [16]. Collectively, these capabilities enhance enterprise integration, foster innovation, and ensure that blockchain solutions can meet both organizational and decentralized application (DApp) requirements.

Interoperability protocols expand the foundational blockchain architecture by incorporating key components that enable secure cross-chain communication. Consensus mechanisms are used to validate and finalize transactions across multiple chains, while cryptographic primitives such as hash locks, digital signatures, and multi-signature schemes ensure trustless execution [34]. Incentive mechanisms are often integrated to align the behavior of participants with the security and performance objectives of the protocol. In addition, application interfaces are designed to allow DApps to perform cross-chain operations such as asset transfers, data sharing, and smart contract invocations in a seamless manner [12].

The classification of interoperability mechanisms varies among researchers. Buterin [20] identified three primary categories: notary schemes, sidechains or relays, and HTLCs. Another study [9] extended this classification to include blockchain-agnostic protocols, while Yin et al. (2023) proposed four categories: notary schemes, HTLCs, sidechains, and hybrid technologies [16]. Other works follow a simplified taxonomy that includes notary schemes, sidechains or relays, and HTLCs [11,13].

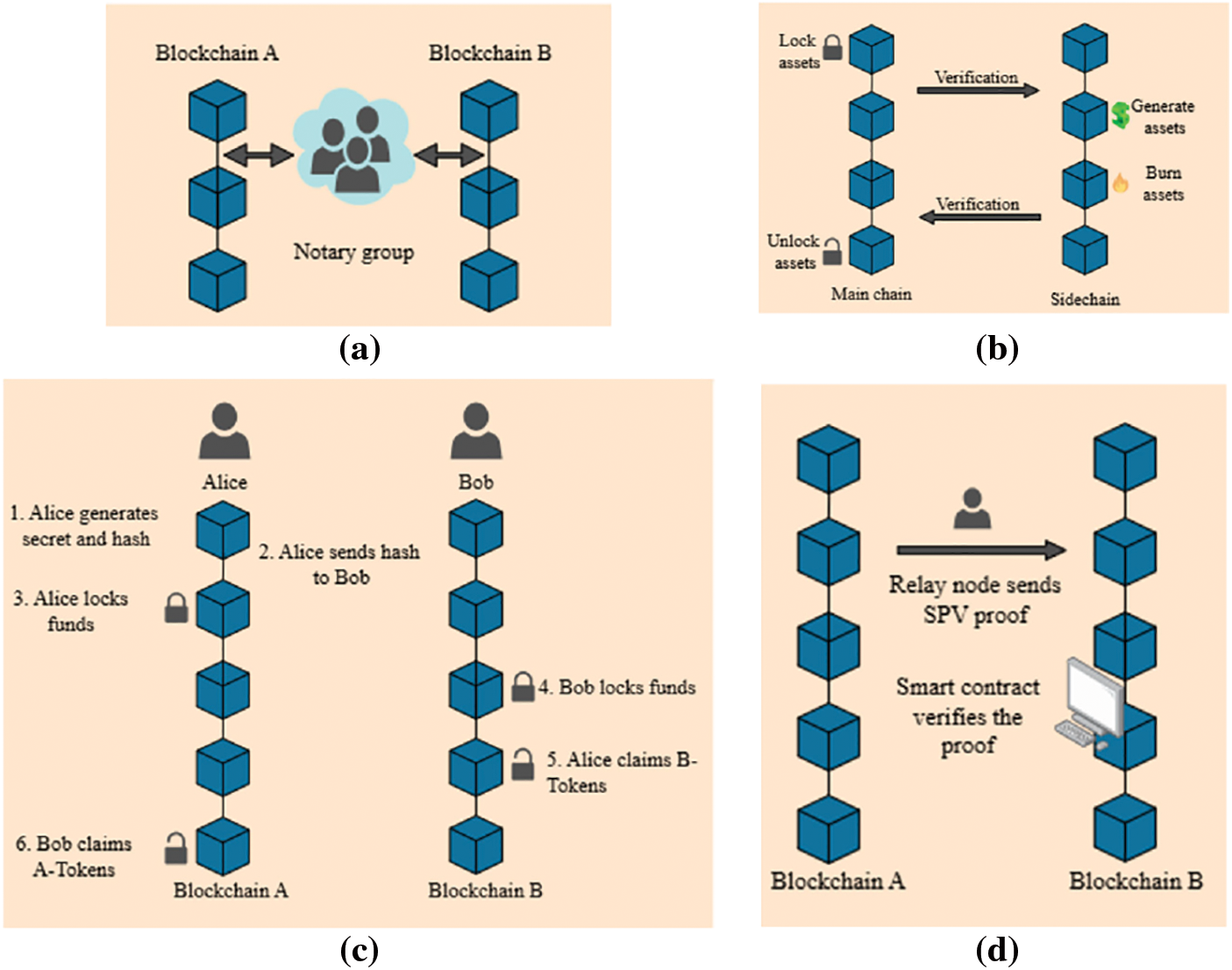

In this review, interoperability protocols are categorized into five key mechanisms: sidechains, relays, HTLCs, notary schemes, and hybrid approaches. Fig. 2 illustrates the first four mechanisms, where subfigure (a) depicts a notary scheme relying on a trusted intermediary or federation to confirm cross-chain events, subfigure (b) shows a sidechain mechanism that uses an auxiliary blockchain with its own consensus to facilitate secure asset movements, subfigure (c) presents an HTLC-based protocol that employs cryptographic conditions (hash locks and time locks) to enable trustless atomic swaps, and subfigure (d) demonstrates a relay-based mechanism that maintains a light client or verification contract on one chain to monitor and validate the state of another chain.

Figure 2: Interoperability Mechanisms in Blockchain Networks: (a) Notary scheme, which relies on a trusted intermediary or a group of entities to validate and relay cross-chain events; (b) Sidechain mechanism, which uses an auxiliary blockchain with its own consensus algorithm to facilitate secure asset transfers and data exchange; (c) Hashed Time-Lock Contract (HTLC) mechanism, which employs cryptographic hash locks and time constraints to enable trustless atomic swaps between chains; (d) Relay-based mechanism, which uses a light client or verification contract to track and validate the state of another blockchain

Although hybrid mechanisms combine elements of sidechains, relays, HTLCs, and notary schemes, they are best understood as overarching conceptual frameworks rather than standalone implementations. Therefore, to avoid redundancy with the visual representations of the individual mechanisms, we provide a textual explanation of hybrid mechanisms instead of an additional diagram. The following paragraphs offer a concise overview of each interoperability mechanism:

• Sidechains operate as independent blockchains connected to a mainchain, often via a two-way peg, which enables the secure locking and unlocking of assets across the chain. Each sidechain maintains its own ledger and consensus algorithm while being capable of verifying events on the mainchain [20].

• Relays allow one blockchain to verify the state or events of another by maintaining a light client or simplified payment verification (SPV) proof of the external chain. Relay nodes facilitate this interaction, sometimes extending into more complex relay chains that act as hubs for multichain communication [20].

• Notary schemes rely on a centralized or federated group of trusted parties to confirm the occurrence of an event on one chain and relay it to another. While simple and efficient, this method introduces trust assumptions that may weaken decentralization [20].

• HTLCs implement trustless atomic swaps by ensuring that a transaction on one chain only completes if a corresponding transaction on another chain does so within a specified time window. This method eliminates the need for intermediaries and enforces atomicity in cross-chain operations [20].

• Hybrid interoperability mechanisms combine features of multiple approaches—such as sidechains, relays, HTLCs, and notary schemes—to leverage their strengths while mitigating individual limitations. For example, a hybrid mechanism may use a relay-based architecture for continuous state verification, HTLCs for trustless atomic swaps, and notary-based validators to ensure cross-chain authenticity [12].

Several blockchain interoperability protocols have been deployed in real-world settings, demonstrating both practical utility and growing adoption. Cosmos enables communication and asset transfers among independent blockchains via the Inter-Blockchain Communication (IBC) protocol. Cosmos supports modular, sovereign blockchain development and can link private or consortium networks, addressing scalability and interoperability limits of traditional monolithic chains [35]. Polkadot connects heterogeneous blockchains through a central relay chain, offering shared security while preserving each chain’s unique logic and consensus. Developed with the Substrate framework, it supports cross-chain communication, token transfers, and governance adaptable for both public and enterprise contexts [36]. Quant Overledger serves as a middleware layer for interoperability between existing permissioned and permissionless networks. Rather than creating new blockchains, it focuses on compliance, enterprise integration, and abstraction of blockchain complexity, making it well-suited for regulated environments [37]. In decentralized finance (DeFi), THORChain—built on the Cosmos SDK—enables direct asset exchanges across blockchains without wrapped tokens or centralized exchanges. Using its native token RUNE and continuous liquidity pools, it offers lessons in secure cross-chain asset transfer relevant to both open and permissioned ecosystems [38].

The increasing vulnerabilities of interoperability protocols in permissioned blockchains underscore the urgent need for systematic evaluations of their security and privacy properties, associated attack vectors, and corresponding countermeasures. Although several studies have explored specific security challenges, the literature still lacks a unified and comprehensive review that synthesizes the various security properties, privacy considerations, threats, and defense mechanisms within the context of permissioned blockchain interoperability.

For instance, the study by [9] identifies four fundamental properties—atomicity, safety, liveness, and decentralization—highlighting their role in ensuring secure cross-chain operations. Building upon this foundation, study [11] investigates design trade-offs between properties such as atomicity, integrity, and availability, particularly in relation to consensus mechanisms.

Subsequent research has expanded the scope of analysis. In [12], the authors introduce extended security properties, including fairness, verifiability, and freshness, while enhancing privacy protection through techniques such as unlinkability and indistinguishability. Similarly, study [13] offers a systematic review of functional properties (e.g., atomicity and finality) and attack resilience, focusing on measures such as double-spending prevention and mitigation of Denial of Service (DoS) attacks, alongside the incorporation of advanced privacy-preserving techniques.

In [14], the emphasis shifts towards fault tolerance and real-world vulnerability mitigation, providing practical insights into deployment challenges. Building on this foundation, study [15] formalizes a structured evaluation framework by distinguishing between security properties (e.g., integrity and accountability) and privacy properties (e.g., anonymity and confidentiality), thereby offering a more holistic perspective on cross-chain security.

More recent studies have further refined these concepts. For example, study [16] operationalizes reliability through three critical dimensions: fairness, atomicity, and fault tolerance. The same work also highlights privacy properties, including confidentiality, anonymity, and unlinkability, as essential elements of robust interoperability protocols. Additionally, study [17] applies a well-established computer science paradigm by adopting the Atomicity, Consistency, Isolation, and Durability (ACID) model. The ACID model outlines fundamental properties for reliable transaction processing, ensuring that transactions are executed as indivisible units, maintain data integrity, operate independently of concurrent processes, and remain permanently recorded once completed. Within the context of blockchain, these principles form the basis for designing secure and consistent cross-chain operations [17].

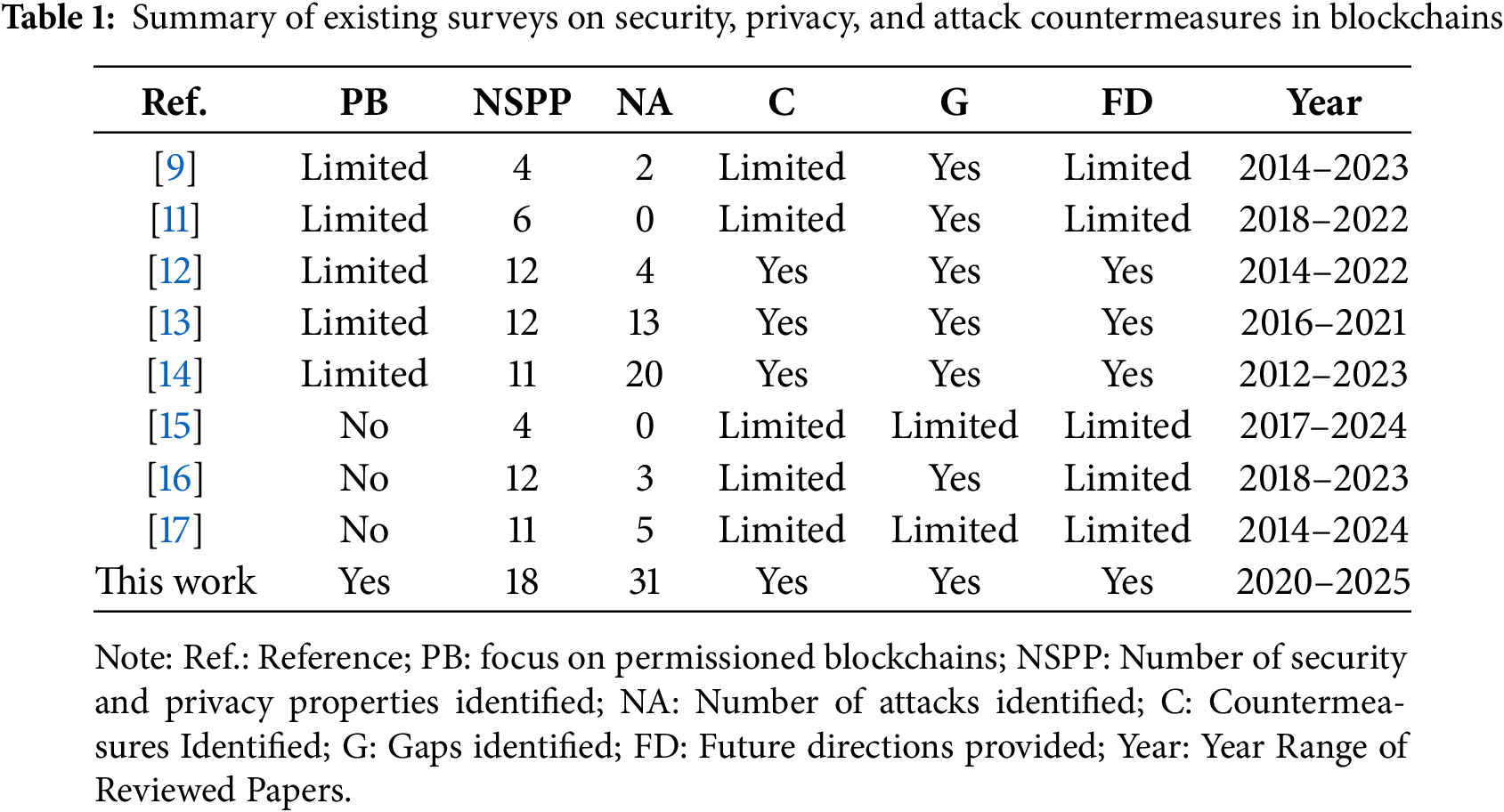

To contextualize this review in the broader research landscape, Table 1 summarizes prior surveys on blockchain security, privacy, and attack countermeasures. The table compares these studies based on their focus on permissioned blockchains (PB), the number of security and privacy properties (NSPP) and attack types (NA) identified, as well as their discussions of countermeasures (C), research gaps (G), and future directions (FD). It also provides the publication year range of the reviewed papers, offering a clear comparison of scope and coverage.

Despite these contributions, most existing surveys concentrate on a narrow subset of attacks, security properties, privacy features, and countermeasures within blockchain interoperability architectures. This study addresses these gaps by conducting an SLR aligned with the PRISMA guidelines [18]. To the best of our knowledge, this work is the first comprehensive review to examine a broad spectrum of security and privacy properties, attack vectors, and defense mechanisms, while simultaneously identifying research gaps and inconsistencies in current security analyses.

In this section, the methodology used to conduct the SLR is described. The objective of the SLR is to review the security and privacy analysis guidelines for interoperability protocols across permissioned blockchains. Based on the PRISMA 2020 guidelines (see S1 File: PRISMA 2020 checklist), the review process was organized to ensure a standardized and transparent approach to study selection, data extraction, and reporting. This review was not registered, as protocol registration is not typically required in computer science research.

The PRISMA guidelines comprise a 27-item checklist and a three-phase flow diagram, which collectively facilitate transparent reporting of the processes used to identify, screen, and select studies for inclusion. The study selection process entails an involved description of the search strategy and the specific scholarly databases used to retrieve the studies. Hence, identification, screening, and inclusion were implemented during the study selection process. During the identification phase, we conducted a systematic search of four scholarly databases using predefined keywords associated with blockchain interoperability, privacy, and security. In the screening phase, studies that did not correlate with the review objectives were excluded based on the titles and abstracts. In order to evaluate the methodological quality and relevance of the remaining studies to the research scope, the articles were evaluated in accordance with inclusion and exclusion criteria to ascertain their inclusion.

All phases of the study selection process were conducted independently by two reviewers in order to reduce bias and improve reliability. The consensus discussions that were conducted during this process were used to resolve any disagreements that arose, with the assistance of a third reviewer when necessary.

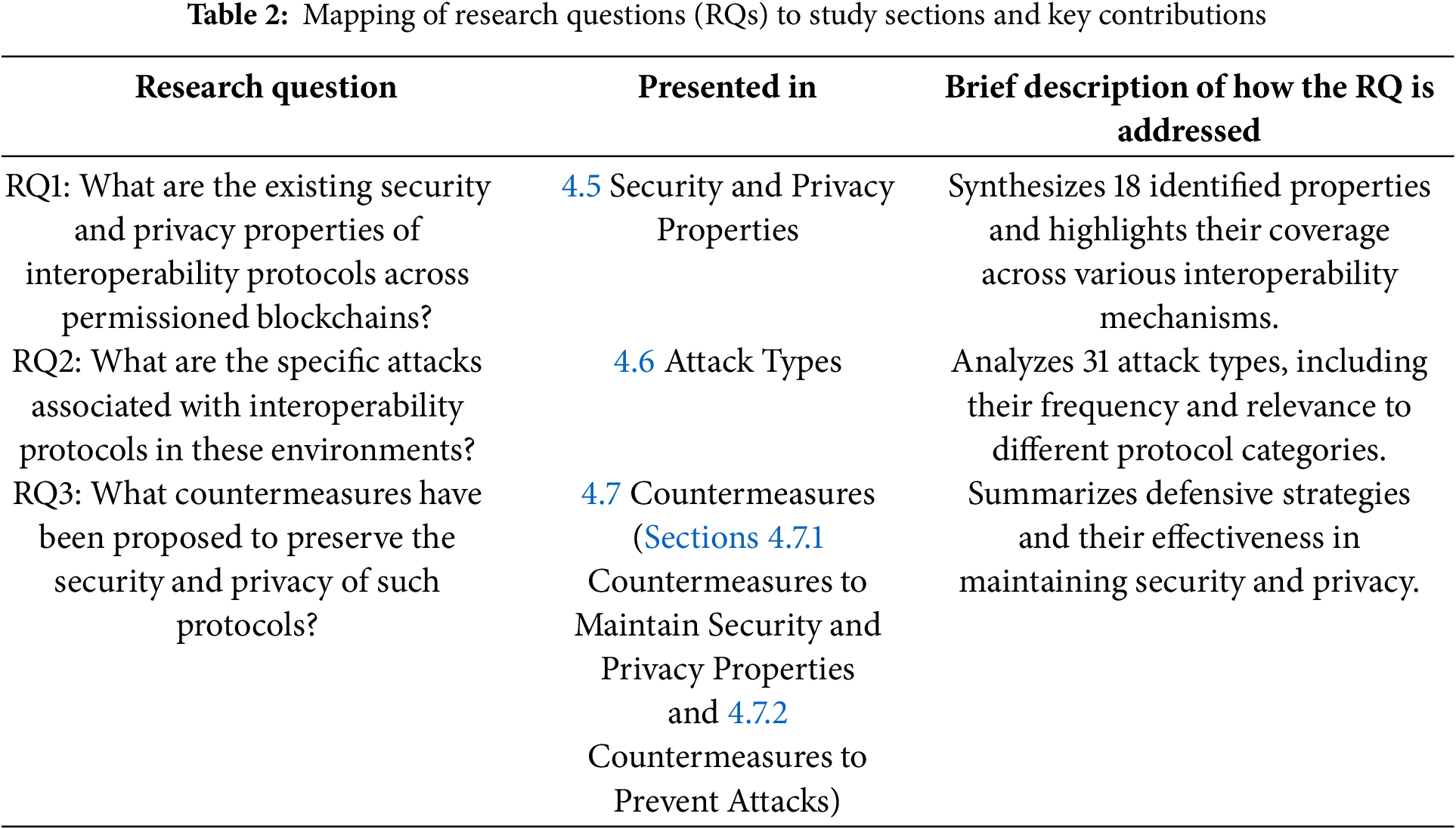

This review is guided by the following research questions (RQs):

• What are the existing security and privacy properties of interoperability protocols across permissioned blockchains?

• What are the specific attacks associated with interoperability protocols in these environments?

• What countermeasures have been proposed to preserve the security and privacy of such protocols?

Aligned with these questions, the primary objectives of this study are to:

• Identify the security and privacy properties relevant to interoperability protocols.

• Investigate the attack types targeting these protocols and their implications.

• Analyze the proposed countermeasures, including their effectiveness and limitations.

To demonstrate the alignment between research questions and the study’s structure, Table 2 maps the RQs to their respective sections and summarizes how each is addressed. Specifically, RQ1 consolidates 18 identified security and privacy properties across interoperability protocols (Section 4.5), RQ2 examines 31 documented attack types and their relevance (Section 4.6), and RQ3 identifies defensive strategies and mitigation mechanisms designed to ensure security and privacy (Section 4.7).

3.2 Identifying Information Sources/Databases

In the article searching process, Gusenbauer and Haddaway [39] suggested 14 databases that could serve as the leading databases. Among them, we selected four scholarly databases: Scopus, ScienceDirect, Web of Science, and IEEE Xplore, focusing on studies related to blockchain interoperability protocols.

Google Scholar is widely recognized as one of the world’s most popular databases. Due to several problems and shortcomings, this database cannot be used as the primary database for SLR [39].

The search was performed in all fields, without any filter, using terms related to blockchain interoperability, permissioned blockchains, security and privacy, and cross-chain attacks. The final search was conducted in May 2025.

3.3 Developing the Search Strategy/Search Terms

We performed a search methodology that complies with the research objectives and questions of this review paper. This methodology combines keywords and a regulated vocabulary, employing Boolean operators (e.g., AND, OR) to refine the search queries based on the syntax requirements of each database. In addition, to ensure that only relevant studies were included, two essential terms, “blockchain interoperability” and “security/privacy,” were employed as guiding criteria. The final search string employed was as follows:

(“blockchain” AND (“security” OR “privacy”) AND (“attack” OR “threat”) AND (“interoperability” OR “cross-chain” OR “cross-blockchain”)).

This search string was originally utilized for title abstracts and keywords across scholarly databases. Nevertheless, we noted that some relevant studies excluded these essential terms from their abstracts and/or keyword sections. Consequently, we expanded the search to encompass each paper’s full text and metadata, including the abstract, title, and keywords. Manual screening of the full text was required in several cases. While this process was considerably time-consuming and labor-intensive, it was necessary to avoid excluding important studies that might otherwise have been missed.

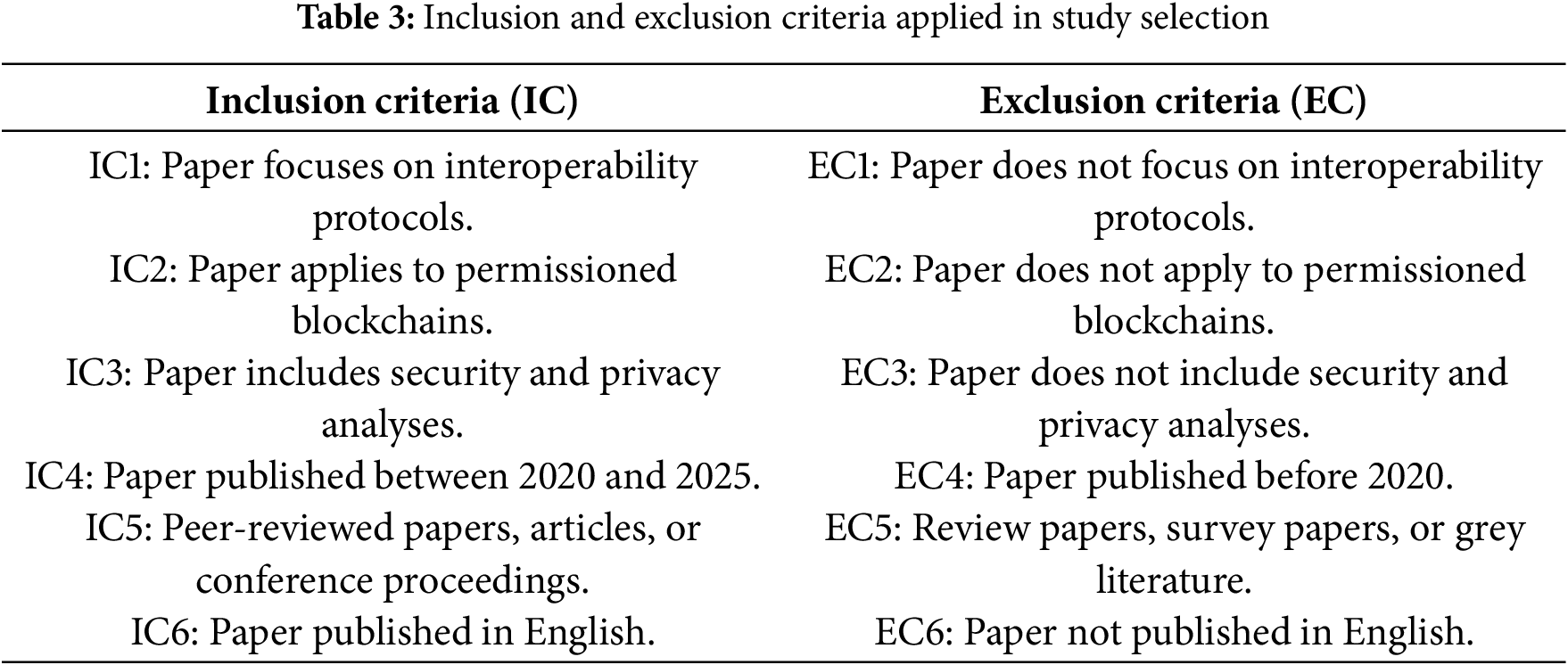

3.4 Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

We established inclusion and exclusion criteria to determine which studies would be accepted into the review and which would be excluded. The specific criteria used in this review are summarized in Table 3, which outlines the inclusion and exclusion conditions applied during the study selection process.

This review focuses on literature published between 1st January 2020 and 31st December 2025 to capture the most recent advancements in blockchain interoperability, a field that has evolved rapidly with the emergence of cross-chain protocols, DeFi, and enterprise-oriented applications [40,41]. Limiting the primary scope to this timeframe ensures both focus and relevance [42]; however, we also recognize the importance of early foundational contributions that continue to influence current research and implementation trends.

Buterin’s seminal work defined the core categories of cross-chain protocols—notary schemes, sidechains/relays, and HTLCs—which remain fundamental to interoperability studies [20]. Early initiatives such as Cosmos [35] and Polkadot [36] introduced hub-and-relay architectures to enable native multi-chain interoperability, while middleware solutions like Quant Overledger [37] and cross-chain liquidity protocols such as THORChain [38] expanded on these principles to address practical challenges of asset transfer and data exchange across heterogeneous blockchain networks.

Although this systematic review does not comprehensively analyze pre-2020 studies, these early theoretical frameworks and practical implementations are referenced to provide essential context and to guide readers who may wish to explore the foundational works that shaped the development of modern interoperability protocols [43].

In this SLR, only peer-reviewed papers, journal articles, and conference proceedings were included to ensure the credibility and academic rigor of the sources. Reviews and survey papers were excluded to focus on original research and empirical findings. Grey literature was deliberately excluded due to concerns regarding its typically low quality and the difficulty in drawing reliable conclusions prior to thorough [44]. This selection criterion ensures that the evidence synthesized in this review is grounded in validated and peer-reviewed research. The inclusion criteria will restrict studies to those published in English. There is evidence that the exclusion of articles written in languages other than English has only a minimal effect on the overall conclusions of the reviews [45].

3.5 Screening and Selection Process

The selection process was divided into three main phases: identification, screening, and inclusion. To minimize bias and enhance reliability, study selection was performed in duplicate by two independent reviewers (A.D. and T.F.A.). Disagreements were resolved through consensus discussion or consultation with the other reviewers (L.Y.P., C.S.K., and O.M.)

During the identification phase, search keywords were applied across all fields in the selected scholarly databases. The team documented the titles, datasets, abstracts, publication years, DOIs, and URLs in Google Sheets documents. In this phase, 9854 studies were initially identified, and a total of 677 studies were excluded for duplication.

The screening phase involves removing irrelevant studies. We identified these irrelevant studies by reading their titles and abstracts, indicating that they did not align with research objectives and questions. In total, 8836 were eliminated because of being irrelevant. In addition, 36 were removed as a result of accessibility restrictions.

All team members conducted a full-text review of the 305 papers to evaluate their suitability based on the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Finally, in the inclusion phase, the shortlisted papers were reviewed collectively. Papers that failed to meet the criteria or were deemed irrelevant to the research questions. Finally, 56 studies were included in the final selection.

The quality of the included studies was critically appraised using the MMAT [19], a widely recognized instrument for evaluating research design, methodology, and potential biases. The MMAT checklist, consisting of five criteria, provides a systematic approach to assessing the reliability and significance of findings within their respective contexts. To minimize bias and enhance reliability, study selection and data extraction were performed independently by two reviewers, with disagreements resolved through consensus or consultation with a third reviewer.

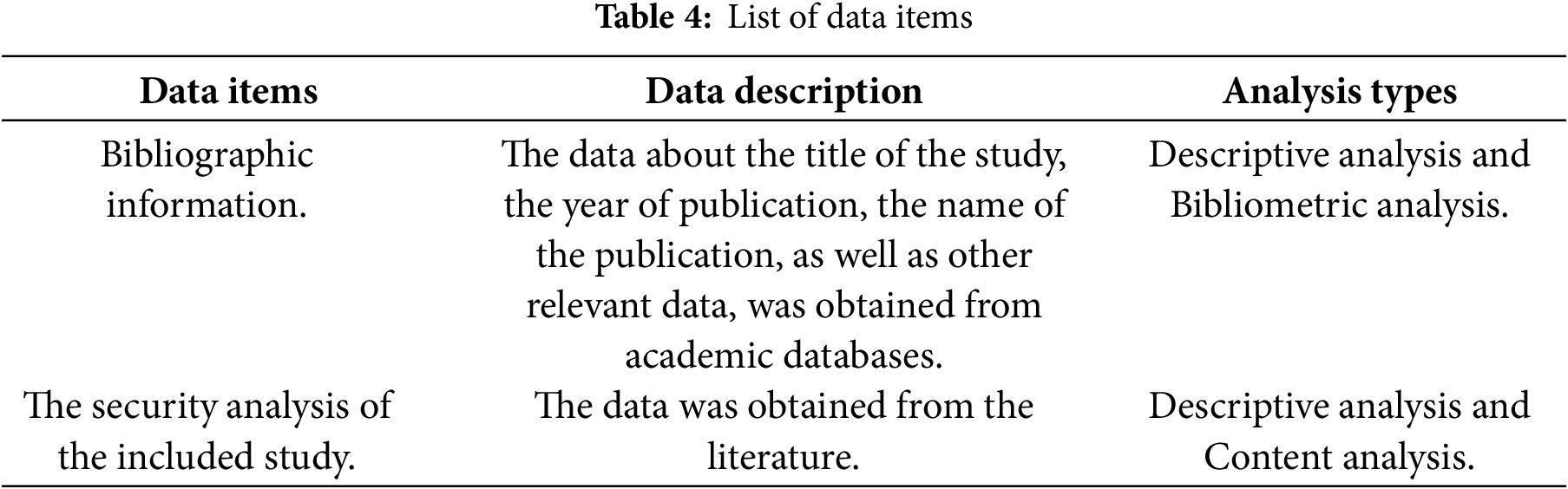

Data extraction is a crucial aspect of this review. The process involves identifying and extracting relevant data items to evaluate the quality of selected studies and to answer research questions. Table 4 provides a structured overview of the data categories extracted during the systematic review, including detailed descriptions of each item and the corresponding analytical approaches applied. It outlines the bibliographic and content-related data collected from the selected studies, specifying how each data type contributes to the descriptive, bibliometric, and content analyses performed in this review.

A team of four authors conducted the data extraction procedure, which was divided into two phases. In the initial phase, data was extracted from the included studies by two authors (A.D. and T.F.A.) using a predefined data extraction form in an independent manner. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion. If disputes persisted, they were referred to two additional authors (L.Y.P. and C.S.K.) for arbitration.

A combination of manual and tool-assisted methods was implemented during the data extraction procedure. During the initial screening phase, Zotero, a reference management application, was employed to organize and manage the studies.

Microsoft Excel was utilized to store all extracted data and variables, which facilitated the systematic organization, categorizing, and filtering of the data for subsequent analyses. In instances where details were ambiguous or uncertain, assumptions were made in accordance with established standards in the literature. For instance, certain security properties were attributed to implicit features of protocols when they were frequently associated with those protocol categories.

3.8 Data Synthesis and Analysis

The goal of data synthesis is to assess and summarize the insights from the selected papers, presenting the results in a tabular format. This synthesized data serves as primary evidence to address the research questions, focusing on the security and privacy analysis guidelines for interoperability protocols across permissioned blockchains. This review incorporates various analytical approaches, including bibliometric analysis, descriptive analysis, and content analysis.

Bibliometric analysis is a methodological approach that integrates quantitative techniques—such as mathematical and graphical methods—to map the structure and evolution of research landscapes [46]. In this review, bibliometric analysis was used to provide a quantitative overview, including the distribution of studies by year and by publication name.

Content analysis is ideal for this SLR as it systematically identifies and interprets qualitative data—such as security properties, attacks, and countermeasures—from the 56 reviewed studies [47]. This method enables the authors to identify patterns, compare findings, and address the paper’s research questions while highlighting gaps in interoperability research.

Microsoft Excel and Jeffrey’s Amazing Statistics Program (JASP) were utilized to arrange extracted data and perform descriptive and statistical summaries. JASP is an open-source statistical software designed for both beginners and experts, featuring a user-friendly interface, automated statistical outputs, and advanced visualization capabilities, which made it particularly suitable for this systematic review [48,49]. Missing data was addressed by categorizing it as “Not Stated” in the table, and no data imputations or conversions were performed.

It is important to note that advanced statistical techniques, such as meta-analysis, are beyond the scope of this study. Instead, the review aims to deliver a structured and in-depth examination of security and privacy analysis guidelines for interoperability protocols across permissioned blockchains.

3.9 Motivation and Contribution

Blockchain technology has significantly transformed decentralized systems and enterprises by offering distributed, transparent, and tamper-resistant ledgers [1,2]. Its rapid adoption is evident: 76% of organizations have implemented blockchain, and 83% believe that digital assets will replace fiat currencies within the next decade [50]. Market projections further reinforce this trend. For instance, Grand View Research projects that the worldwide blockchain industry will attain USD 1431.54 billion by 2030 from 2023 to 2030. The blockchain industry is projected to expand from USD 2.89 billion to USD 137.29 billion between 2020 and 2027 [51]. These projections underscore robust confidence in the ongoing development and impact of blockchain technology.

Amid this expansion, enterprises are increasingly adopting permissioned blockchains tailored to specific sectors [40,41], such as the IoT [3–5], vehicular networks [6], and healthcare [7]. Despite their advantages—such as controlled access, higher transaction throughput, and regulatory alignment—permissioned blockchains have been criticized for reduced decentralization, scalability constraints, regulatory complexities, and potential data privacy concerns [40,41]. While frameworks such as Hyperledger Fabric [27,28], Quorum [30], Corda [31], and Multichain [32] have attempted to address these issues, several persistent challenges, notably interoperability, remain unresolved. In particular, the lack of seamless interaction between heterogeneous permissioned blockchains poses significant barriers to adoption. Interoperability protocols are designed to bridge these silos, enabling data exchange, asset transfers, and smart contract execution across otherwise isolated networks [9]. However, the security and privacy risks introduced by such protocols remain insufficiently understood.

The urgency of this issue is underscored by recent large-scale attacks on cross-chain bridges, which have led to losses exceeding USD 3.1 billion since 2021, with 65.8% of these losses originating from bridges relying on intermediary permissioned networks [52]. Cross-chain exploits now dominate the DeFi incident leaderboard [10], illustrating that interoperability mechanisms are a prime target for malicious actors. Although many of these attacks have occurred within public blockchains [53–56], permissioned blockchains face distinct challenges that are not adequately addressed by the existing body of research focused on public environments [15–17]. Unlike public blockchains, permissioned systems operate under strict authentication, privacy-preserving data-sharing requirements, and governance structures that demand tailored security frameworks.

This study focuses exclusively on permissioned blockchain interoperability to address this research gap. While references to public blockchain incidents are included to emphasize the severity and relevance of interoperability vulnerabilities, this review concentrates on permissioned ecosystems due to their unique trust assumptions and enterprise-driven requirements. By narrowing the scope in this way, we aim to develop insights that are directly applicable to high-assurance domains where confidentiality, regulatory compliance, and scalability are critical.

The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

• A structured overview of security and privacy properties critical to interoperability protocols.

• A comprehensive analysis of known attack types and the corresponding vulnerabilities they exploit.

• An overview of existing countermeasures, including their effectiveness and limitations.

• A synthesis of research gaps and future directions, identifying limitations in existing implementations and proposing areas for further investigation, including scalability, token standard handling, and real-world deployment.

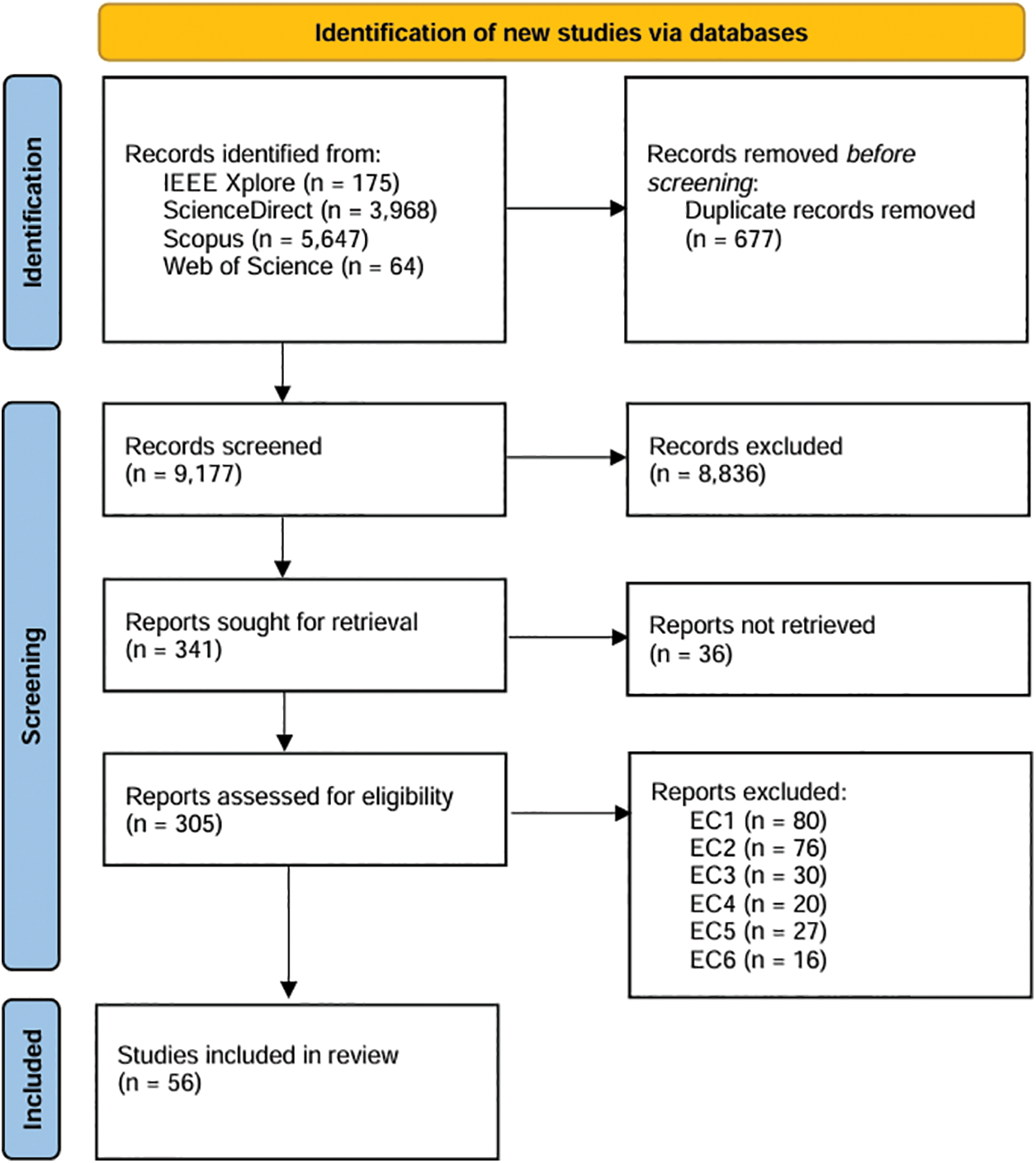

This section presents the results of the three stages of the PRISMA framework—identification, screening, and inclusion—as depicted in Fig. 3. The figure provides a detailed visualization of the study selection process, following the PRISMA 2020 guidelines. It outlines the number of records retrieved from the databases, the studies screened for relevance, those excluded based on eligibility criteria, and the final set of studies included for analysis.

Figure 3: PRISMA flowchart for study selection

The methodology strictly adheres to the PRISMA guidelines, including the use of a PRISMA flow diagram to detail the study selection process. A PRISMA checklist is provided as Supplementary Materials S1 File (S1 File: PRISMA 2020 checklist), ensuring transparency and reproducibility.

At the identification stage, we located a total of 9854 studies across all selected databases using the keywords specified in Section 3. The titles, databases, publication years, abstracts, and inclusion status of the considered studies are detailed in Supplementary Materials S4 File (S4 File: List of Included and Excluded Studies). Fig. 3 shows the distribution of studies identified in each database. After eliminating 677 duplicates, the remaining records were retained for screening.

During the screening stage, 8836 studies were excluded because their title, abstract, and keywords did not match the topic: blockchain and interoperability. Also, 36 studies were excluded due to inaccessibility.

This left 305 studies for full-text screening to evaluate their eligibility based on the established IC and EC. In this stage, 249 studies were excluded after full-text review. A comprehensive summary of the included and excluded studies is presented in Supplementary Materials S3 File (S3 File List of Excluded Studies).

Finally, in the inclusion stage, 56 studies that met all IC were selected for inclusion in this SLR.

4.2 Quality of Included Studies

This section presents the methodological quality assessment of the included quantitative studies, evaluated using the MMAT. Of the 56 quantitative studies analyzed, 40 (71%) achieved MMAT scores of 100%, indicating high quality by fully meeting the assessment criteria. Eight studies (14%) scored 60%, reflecting medium quality with partial adherence to the criteria. The remaining eight studies (14%) were classified as low quality, primarily due to the absence of experimental implementations. A detailed quality assessment of the quantitative articles is provided in Supplementary Materials S2 file (S2 Table: Assessment of Study Quality–MMAT Tool).

4.3 Distribution of Papers by Year and by Publication Name

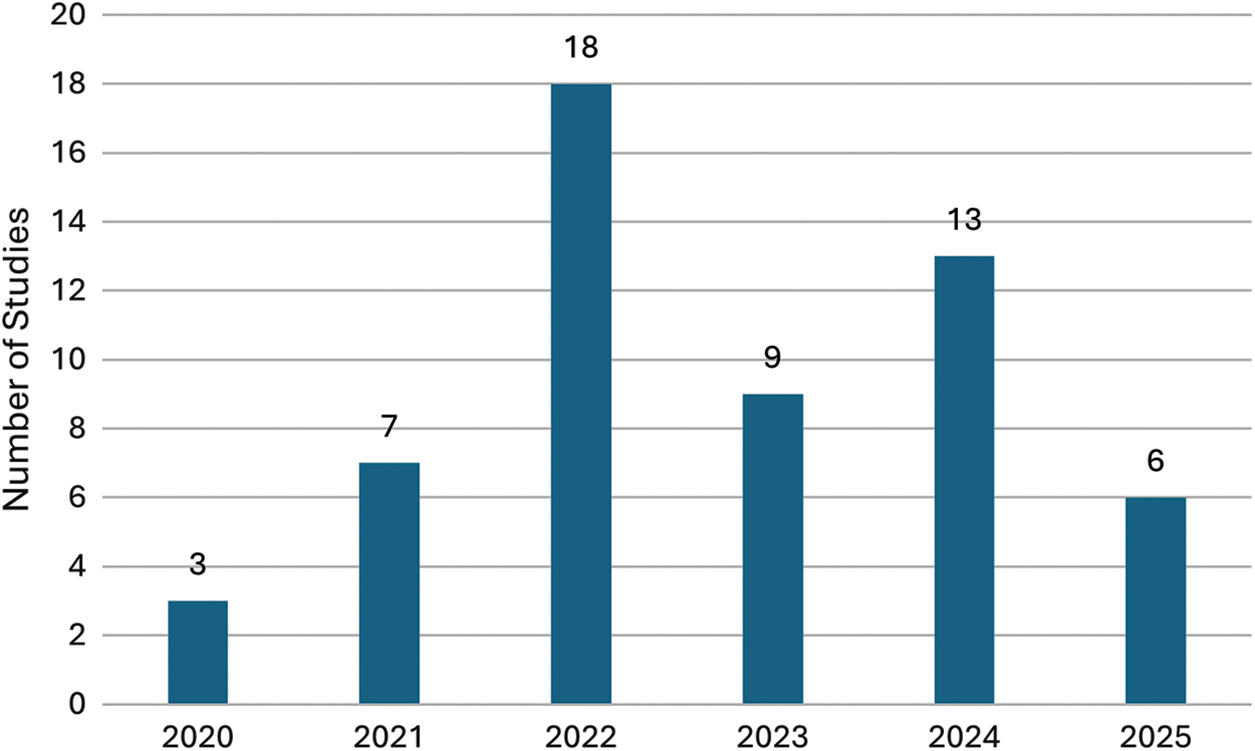

This section begins by examining annual publication trends related to interoperability protocols across permissioned blockchains. Fig. 4 illustrates the yearly distribution of studies published between 2020 and 2025. The number of studies increased steadily until peaking in 2022, followed by a decline and partial rebound. This surge in 2022 likely reflects growing interest in solving cross-chain communication challenges amid rapid blockchain adoption. The decline in 2023 may indicate a temporary shift toward practical implementation over theoretical research. The renewed activity in 2025 could suggest new challenges or innovations rekindling academic attention. Although 2025 shows a slight decline, it is important to note that the final search was conducted in May 2025, and thus the data may not capture the full publication output for that year. Despite this, interoperability protocols still represent a relatively modest portion of the broader computer science research landscape.

Figure 4: Annual distribution of studies on interoperability protocols in permissioned blockchains (2020–2025)

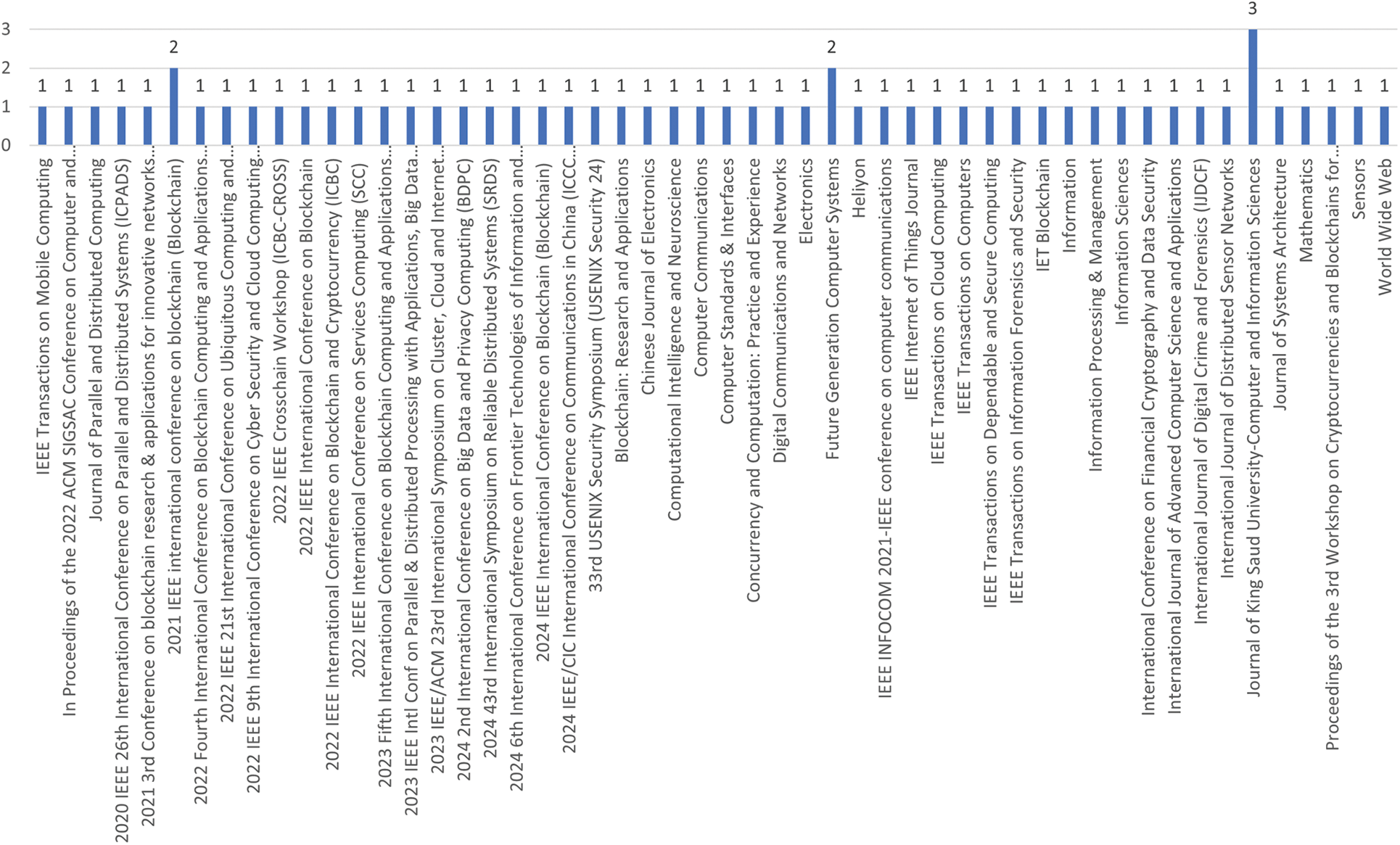

Fig. 5 illustrates the distribution of studies across academic conferences and journals included in this review of blockchain interoperability. The data reveals a strong focus on prominent IEEE and ACM conferences, such as the IEEE International Conference on Blockchain and ACM SIGSAC, as well as high-impact journals, including Future Generation Computer Systems and the IEEE Internet of Things Journal. Notably, the majority of sources contributed only a single article, underscoring the fragmented nature of research in permissioned blockchain interoperability. This distribution suggests that the field is still in an emerging phase, with research output dispersed across various venues rather than concentrated around established core platforms or thematic clusters.

Figure 5: Frequency of studies by publication venue

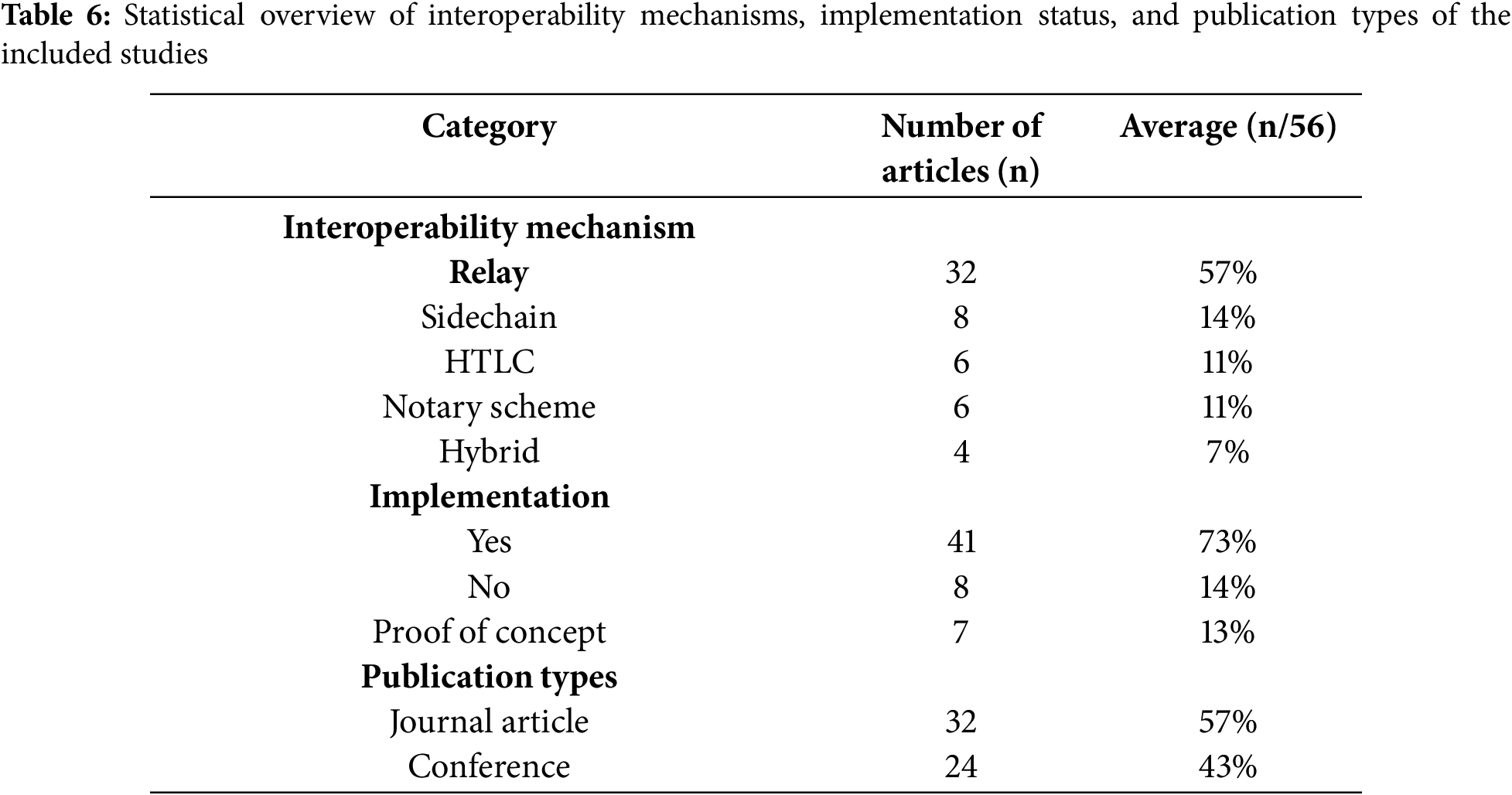

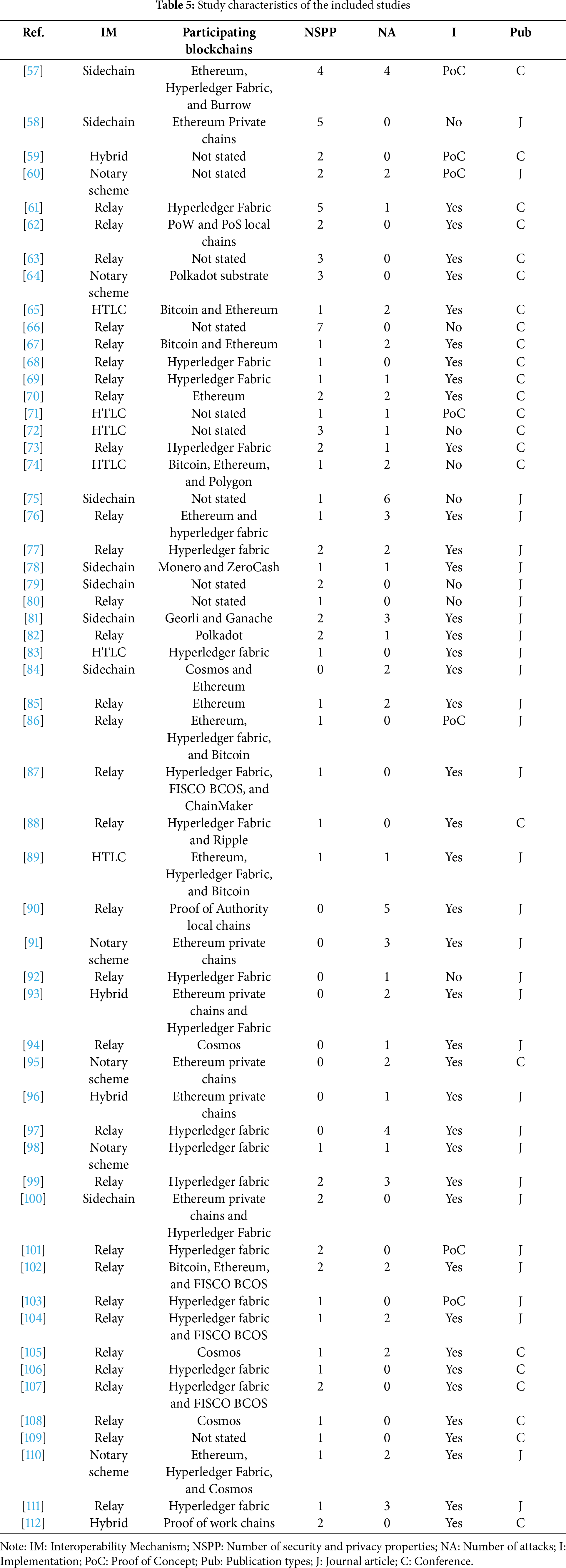

This section outlines the key characteristics of the reviewed interoperability protocols, categorized by their underlying mechanisms to facilitate cross-chain operations in permissioned blockchains. Table 5 summarizes the key characteristics of the studies included in the review, such as interoperability mechanisms (IM), the number of security and privacy properties (NSPP), the number of attacks (NA), implementation details (I), proof-of-concept evaluations (PoC), and publication types (Pub), including journal articles (J) and conference papers (C). The interoperability protocols examined in these studies are categorized into five mechanisms: sidechain, relay, notary scheme, HTLC, and hybrid mechanism.

Table 6 provides a statistical analysis of the interoperability mechanisms, implementation status, and publication types among the included studies. Among the included studies, 57% utilized the relay mechanism to facilitate cross-chain interoperability. Sidechain mechanism is employed in 14% of the studies, respectively. In contrast, only 6 studies (11%) adopt notary schemes, likely due to their high security risks. Meanwhile, hybrid mechanisms are implemented in just 4 studies.

Although 73% of the studies include an implementation of the proposed solution, a significant portion offer only a proof of concept (13%) or no implementation at all (14%). The included studies consist of 57% journal articles and 43% conference papers, indicating a balance between consolidating knowledge and emerging research. While journal publications suggest growing theoretical maturity, the substantial conference presence reflects ongoing innovation and experimentation in permissioned blockchain interoperability. The Ethereum blockchain and Hyperledger Fabric dominate the participating blockchain experiments in the included studies. Some studies have used Bitcoin to implement interoperability protocols due to its stability and simplicity. These implementations help validate protocol mechanisms that are applicable to permissioned settings.

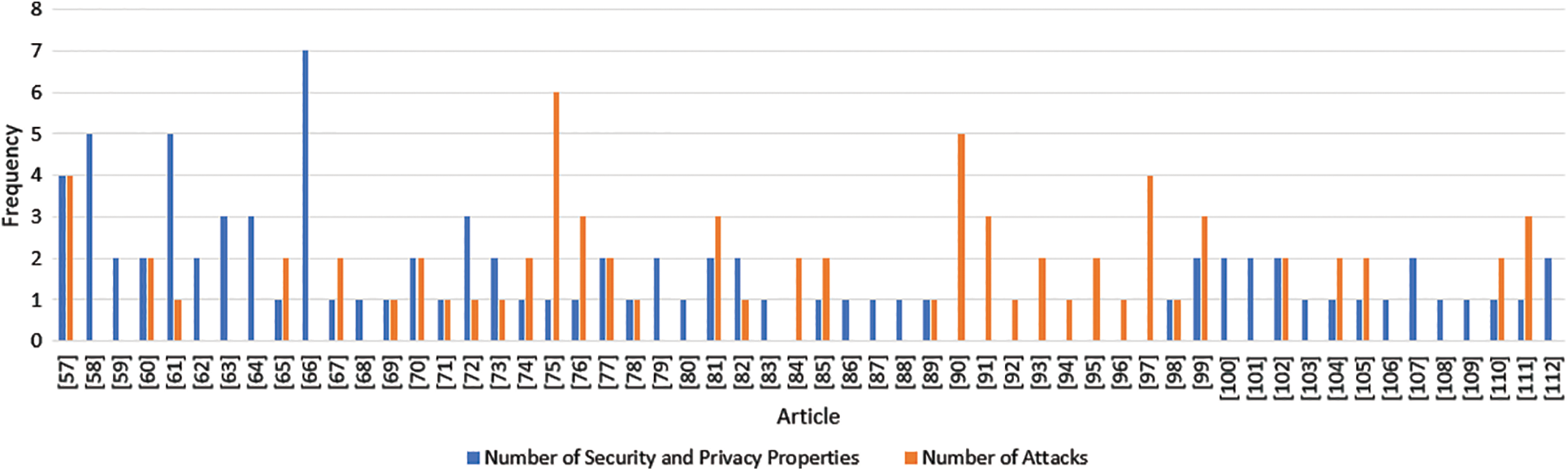

Fig. 6 illustrates the comparative frequency of security and privacy properties addressed, as well as the attack vectors identified across the reviewed studies. The chart reveals that most interoperability protocols for permissioned blockchains document only a limited set of such concerns—despite over $3.1 billion in cross-chain attack losses since 2021 [10]. Notably, 93% of studies assessed fewer than four properties or attack vectors, reflecting a narrow research focus. This limited coverage indicates a fragmented understanding of the security landscape and suggests that critical vulnerabilities may be overlooked.

Figure 6: Comparative analysis of security and privacy properties vs. identified attacks in the reviewed studies [57–112]

4.5 Security and Privacy Properties

This section presents an analysis of the included studies that have an answer to Q1: What are the existing security and privacy properties of interoperability protocols across permissioned blockchains?

Interoperability protocols for permissioned blockchains are essential for facilitating seamless interactions across diverse blockchain networks. However, ensuring security and privacy within these protocols presents challenges due to varying levels of trust, control, and governance among permissioned blockchains. Key security and privacy properties—such as safety, liveness, and confidentiality—are critical for safeguarding cross-chain transactions and data within interconnected blockchains. This question provides an overview of these properties, which enhance reliable and privacy-preserving interoperability across permissioned blockchains.

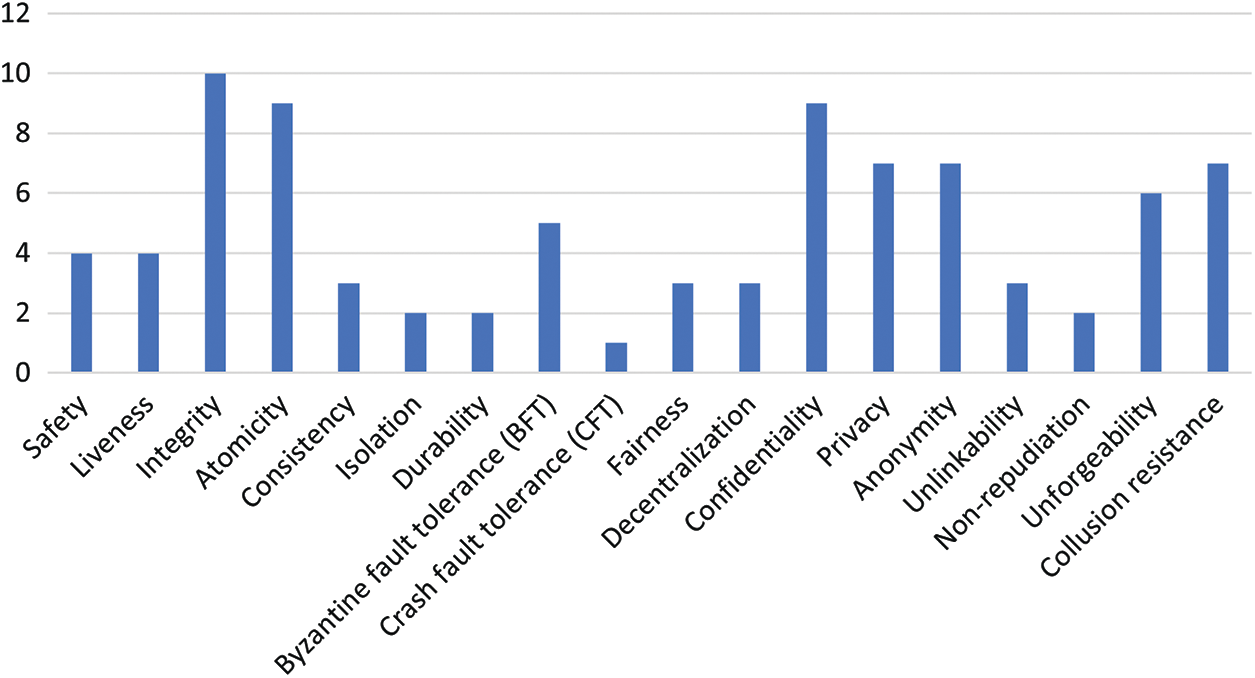

Fig. 7 illustrates the distribution of how frequently each of the 18 identified security and privacy properties is addressed in the reviewed studies on interoperability protocols for permissioned blockchains. The distribution of security and privacy properties across the reviewed literature indicates a concentration of focus on a few key areas. Notably, atomicity, confidentiality, and integrity are the most frequently addressed properties. However, the analysis also uncovers underrepresented but essential properties. As an example, non-repudiation, crash fault tolerance (CFT), decentralization, and three ACID properties are significantly understudied despite their importance in a trustless, multiparty environment [8].

Figure 7: Frequency of security and privacy properties analyzed in the included studies

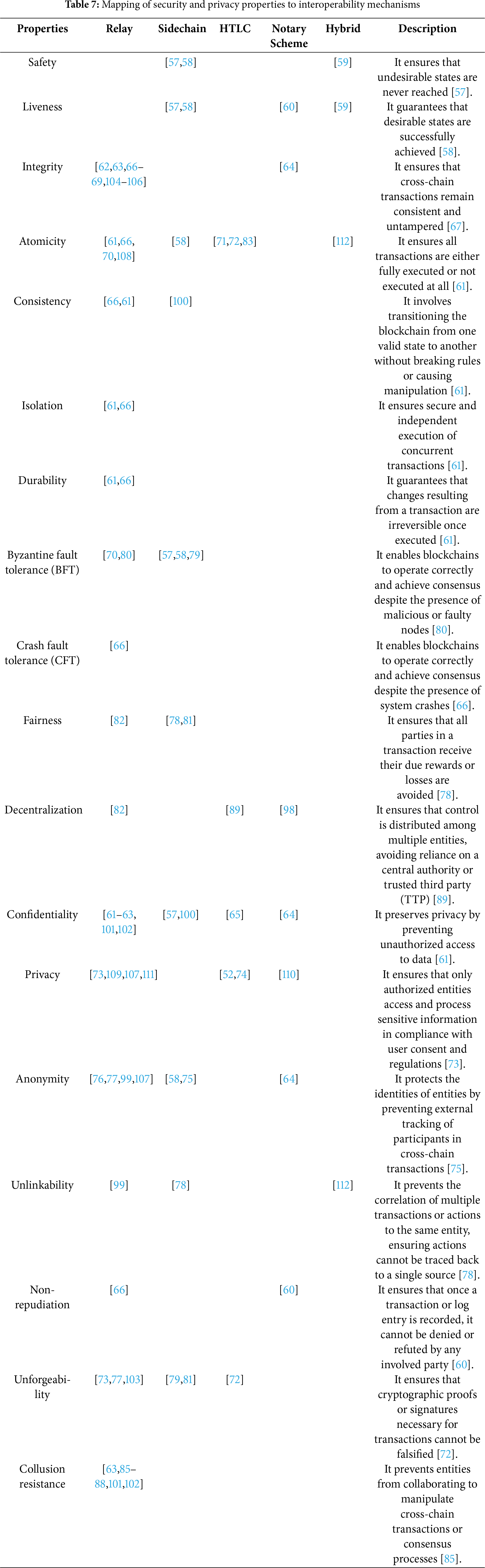

Table 7 presents a detailed mapping of key security and privacy properties to the interoperability mechanisms they address. The table also provides concise descriptions of each property, explaining how these properties contribute to ensuring the reliability, trustworthiness, and privacy of cross-chain operations.

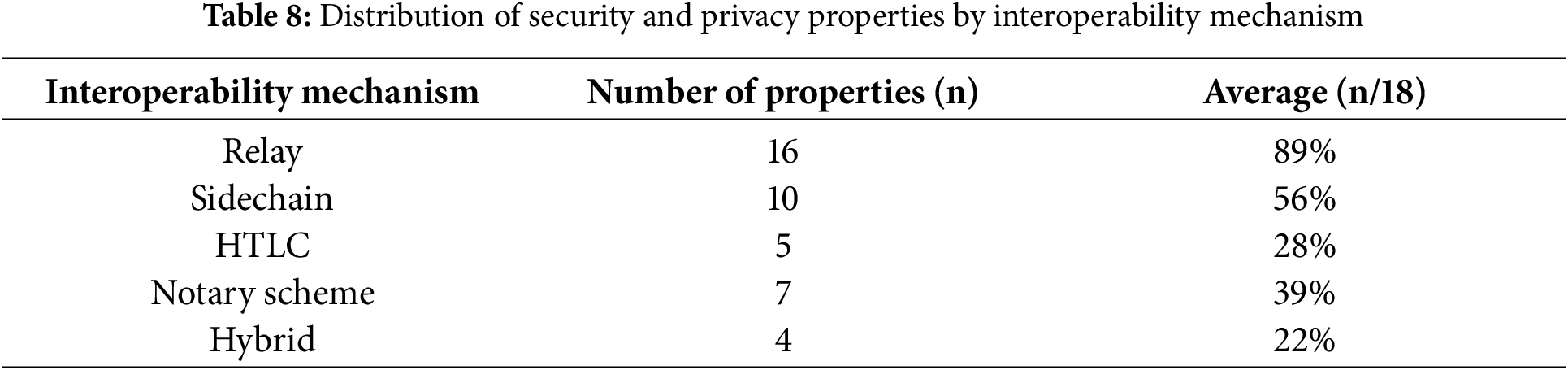

Table 8 summarizes the number and percentage of Security and Privacy Properties associated with each interoperability mechanism. Relay-based protocols demonstrate the most comprehensive coverage, addressing 89% of the identified properties. In contrast, sidechain mechanisms cover 56%, while HTLC and notary-based approaches exhibit substantially more limited coverage, indicating potential security blind spots in these mechanisms.

In conclusion, the findings reveal a fragmented and uneven landscape in cross-chain security research, with many properties rarely examined, highlighting the urgent need for more comprehensive and balanced security assessments across all protocol types. Relay-based protocols demonstrated the broadest coverage, while HTLC and notary-based mechanisms were more limited. Important features such as non-repudiation, CFT, decentralization, and the three ACID properties are not studied enough, even though they are crucial in a system where trust is not guaranteed among multiple parties.

This section presents an analysis of the included studies that have an answer to Q2: What are the specific attacks associated with interoperability protocols in these environments?

Blockchain interoperability has become essential as permissioned blockchain networks increasingly interact to enable data sharing, asset exchange, and collaborative processes across organizational boundaries. However, the growth of interoperability protocols has also introduced various security vulnerabilities, which adversaries exploit to compromise data integrity and confidentiality. Understanding these attacks is crucial to developing more resilient interoperability protocols. This section provides an overview of these attacks.

Fig. 8 illustrates the distribution of the 31 distinct attack types identified across the reviewed studies on interoperability protocols for permissioned blockchains.

Figure 8: Frequency of attack types analyzed in the included studies

Fig. 8 illustrates that over 58% of the identified attack types were addressed in only a single study, indicating a highly fragmented and narrowly focused threat analysis in the current literature. Although attacks such as Single Point of Failure (SPOF), DoS, and Replay attacks have received comparatively more attention, a substantial number of known threats remain largely unexamined. This lack of comprehensive coverage highlights a critical gap in the field and underscores the urgent need for more systematic, wide-range security evaluations in the context of cross-chain interoperability.

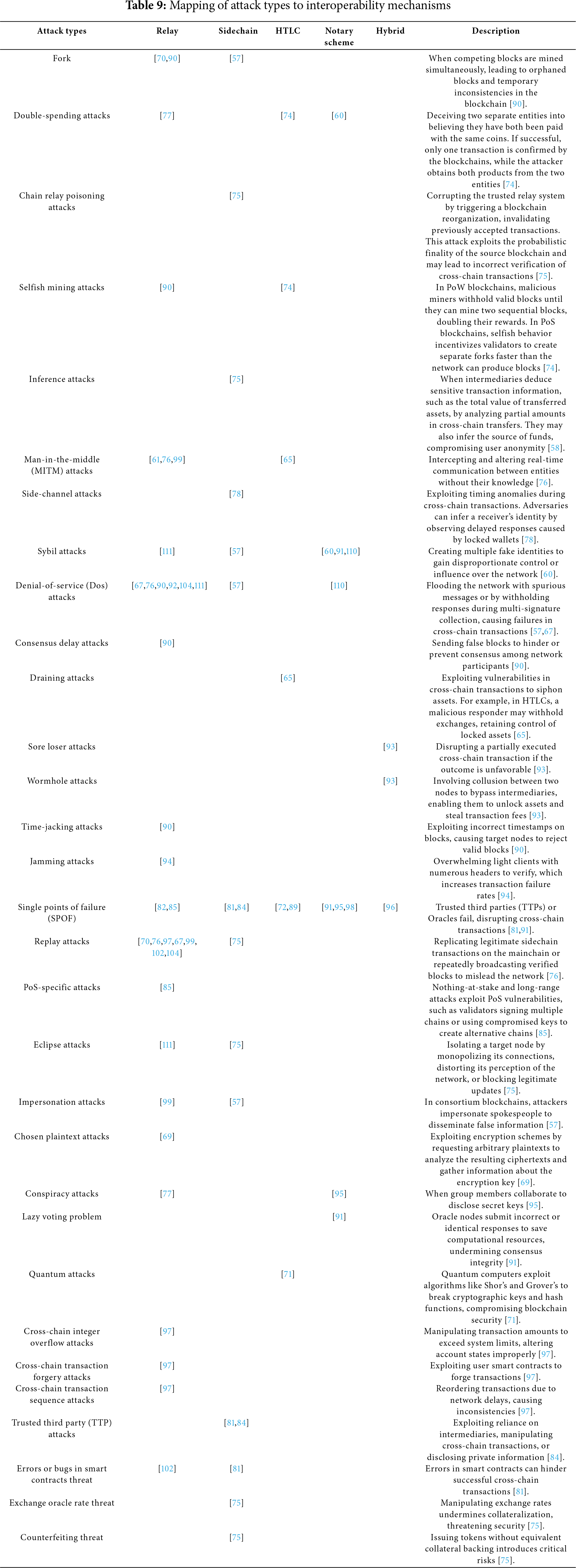

Table 9 presents a detailed mapping of various attack types to the interoperability mechanisms they target. The table also includes concise descriptions of each attack, outlining how these vulnerabilities exploit weaknesses in blockchain consensus, transaction validation, or cross-chain communication.

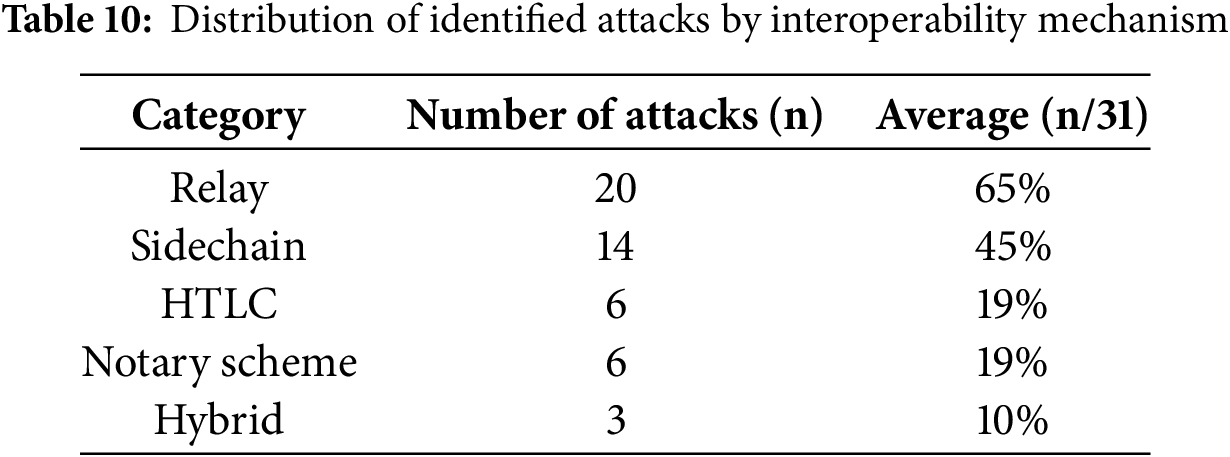

Table 10 summarizes the number and percentage of attacks associated with each interoperability mechanism. The data show that relay (65%) and sidechain (45%) mechanisms are the most frequently analyzed in terms of attack vectors, suggesting a concentrated research focus on these approaches. In contrast, HTLC-based mechanisms (19%), notary schemes (19%), and hybrid models (10%) exhibit significantly lower coverage. This disparity points to notable research blind spots, implying that key attack surfaces in these less studied mechanisms may be insufficiently understood or documented. Such gaps underscore the need for broader and more balanced security analyses across all interoperability designs to ensure comprehensive threat mitigation.

In conclusion, the findings reveal a fragmented and uneven landscape in cross-chain security research—where most attack types are rarely studied, and certain interoperability mechanisms like HTLC, notary schemes, and hybrids remain under-analyzed—highlighting the urgent need for more comprehensive and balanced security assessments across all protocol types.

This section presents an analysis of the included studies that have an answer to RQ3: What countermeasures have been proposed to preserve the security and privacy of such protocols?

Researchers have proposed a range of countermeasures to maintain the security and privacy of interoperability protocols. These countermeasures address critical security and privacy properties such as safety, integrity, confidentiality, and resistance to specific attacks, including double-spending and Sybil attacks. The following sections describe how each study achieves secure and private properties and resists attacks on interoperability protocols.

4.7.1 Countermeasures to Maintain Security and Privacy Properties

Ensuring robust security and privacy is essential for the dependable operation of interoperability protocols in permissioned blockchain systems. Numerous studies have proposed countermeasures that reinforce key system properties such as safety, liveness, integrity, and confidentiality. This section categorizes and summarizes these countermeasures based on the specific security and privacy attributes they aim to preserve.

• Safety and liveness: Safety and liveness have been maintained through various approaches proposed in the literature [57,59,60]. For instance, in [57], safety and liveness are provided by a two-step consensus mechanism: transactions are first endorsed on the permissionless blockchain and only committed to the permissioned chain once more than two-thirds of the permissioned entities have voted in favor, guaranteeing safety. Liveness relies on the underlying permissionless blockchain interface. Similarly, the approach in [59] uses a threshold signature scheme to assure both safety and liveness. Finally, CrossLedger [60] focuses on timeliness: it achieves liveness by enforcing that all necessary verifications be completed within a specified deadline, preventing indefinite delays.

• Integrity and Confidentiality: Integrity and confidentiality have been preserved through various cryptographic and architectural mechanisms proposed in the literature [57,62–65,67–69,100–102,104–106]. Several works reinforce integrity and tamper-evidence by combining cryptographic hashes with consensus. Study [67] uses a smart-contract consensus mechanism to strictly enforce transaction rules, preserving integrity across chains. Similarly, study [62] integrates standard hashing algorithms into a consensus mechanism. Traditional encryption schemes also play a major role. In [105], data is encrypted block-wise using secp256k1 elliptic-curve keys combined with 3DES, and only decrypted upon receipt. Also, transactions are encrypted using an encryption scheme such as Rivest-Shamir-Adleman (RSA) to achieve confidentiality [57,62,63,101]. Time-release encryption (TRE) in [65] further guarantees that sensitive payloads remain unreadable until explicit conditions—such as block height or timestamps—are met. BeDCV [69] adopts a modified Paillier homomorphic scheme so that the supervision chain can verify computations on encrypted data without ever seeing plaintext, while bilinear pairings validate the completeness of aggregated audit data. DataFly [100] utilizes integrated signature and encryption (ISE) and ECDSA-based key extraction. To prevent insider threats, study [64] and IvyCross [102] both implement critical key operations within a Trusted Execution Environment (TEE) like Intel SGX. Even a malicious committee member cannot extract key material, thus safeguarding both integrity and confidentiality. Protocols such as [104] store Merkle-root commitments on the origin chain and use smart contracts for verification, while Refs. [68] and [63] rely on the unforgeability of digital-signature schemes and the discrete logarithm (DL) hardness to achieve end-to-end integrity. Finally, in [106], the method uses certificate-based authentication to ensure secure communication.

• Atomicity, Consistency, Isolation, and Durability: The ACID properties—Atomicity, Consistency, Isolation, and Durability—have been addressed in the following studies [58,61,66,70,72,100,108]. To ensure atomicity, many protocols implement coordination contracts that document all possible cross-chain states, and a two-phase commit (2PC) or announcement-rollback mechanism ensures that either every participant agrees to commit or all changes are rolled back on timeout. In both [58] and [70], each node starts a local timer when a transaction begins; if it expires, the protocol triggers a rollback. Avalon [108] achieves atomicity through layered state caching, optimistic concurrency control, and a state synchronization protocol that coordinates commit decisions across blockchains, while ODAP-2PC in Hermes [66] uses a write-ahead log and self-healing recovery to guarantee that each transaction either fully commits or aborts. Cross-chain consistency follows strict ordering and quorum-based commit rules. Coordination contracts in [58] and [72] enumerate valid state transitions, ensuring every participant sees the same history. DataFly [100] adds a Peg consensus mechanism to authenticate and finalize data transfers across permissioned chains, with formal proof that an honest majority preserves consistency. The protocol in [61] maintains isolation by routing messages through dedicated channels so that only authorized groups can observe or influence a transaction’s intermediate state. To maintain durability, once ordering entities agree, new blocks containing cross-chain transactions are generated and propagated throughout the network. As shown in [61], durability is guaranteed by anchoring each committed transaction to the immutable blockchain ledger, making it resilient to subsequent failures or rollbacks.

• BFT and CFT: BFT and CFT have been addressed in several studies as essential properties for ensuring reliability in cross-chain operations [66,88]. To increase the BFT threshold, Ref. [80] proposes a weighted PBFT cross-chain consensus that groups nodes by security level and assigns high voting weights to more trusted participants, enabling the system to tolerate up to n/2 weighted faults. Hermes [66] achieves crash resilience via a blockchain-backed log storage API: every step of a cross-chain transaction is immutably recorded so that, in the event of a gateway or system crash, the transaction can be resumed or rolled back without violating consistency.

• Fairness: Fairness is ensured in [81] by providing validators with equal opportunities to participate, along with clearly defined rewards and penalties to incentivize honest behavior and discourage misconduct.

• Non-repudiation: Non-repudiation is maintained by gateways that ensure log entries remain unaltered and that the protocol reaches completion, thereby preserving the undeniability of recorded transactions [66].

• Unforgeability: Unforgeability has been addressed in several studies [72,73,77,79,103]. For instance, in [77], group signatures are protected by requiring each node to present its enrollment certificate to a group manager, who then issues a one-time transaction certificate. Papers [73,103] rely on well-studied cryptographic assumptions: resisting hash collisions and the DL problem make forging proofs computationally infeasible, while the Advanced Gamma Multi-Signature (AGMS) in EDCA is provably secure under the DL assumption. Ref. [79] embeds non-interactive proof-of-proof-of-works (NIPoPoWs) proofs under the assumption of an honest majority: during a contestation period, honest nodes can publish counter-proofs to detect any adversarial chain attempt. Finally, Ref. [72] shows that under their stateless SPV model, the cost of forging a valid proof exceeds any possible financial gain, making forgery economically irrational.

• Collusion resistance: Collusion resistance has been addressed in several studies [63,85–88,101,102]. A modified PBFT in [86] assigns higher voting weights to smaller, well-trusted node groups, making bribery or cartel formation both more costly and operationally cumbersome. Verilay [85] leverages PoS’s finality: because blocks cannot be reverted without controlling a majority of stake, validator collusion to rewrite history becomes economically infeasible. XChange [88] restricts how many cross-chain trades a single participant may open and employs TrustChain’s immutable logging to automatically flag and penalize suspicious patterns. ChainKeeper [87] uses a verifiable node random selection (VNRS) along with verifiable identity threshold signatures (VITS) so that forging a collaborative signature without the required threshold is impossible, even if both business and supervision nodes collude. The randomized audit sampling in [63] allows the system to catch collusion with high probability, while IvyCross [102] and GAM [101] introduce incentive models and distributed re-encryption links, respectively, to ensure that no single dishonest node gains enough information or reward to justify a collusion attack.

• Decentralization: Decentralization has been addressed in studies [89,98]. AucSwap in [89] avoids centralized control by leveraging a decentralized Vickrey auction mechanism combined with the atomic swap mechanism. The HMNGCCM framework [98] enhances decentralization through a combination of hierarchical notary management, functional division, dynamic reputation evaluation, and robust protocol design. By classifying notaries at junior, intermediate, and senior levels based on reputation and requiring deposits and verification, it discourages malicious participation and reduces centralization. The clear separation of transaction execution further strengthens decentralization.

• Privacy-preserving properties: Privacy-preserving properties have been implemented in several studies [58,64,72–76,99,107,109,111,112]. In [73], privacy is ensured as long as the DL problem remains computationally hard within the multi-signcryption algorithm. Study [74] integrates DMix with a threshold-signature protocol to increase the difficulty of determining the number of participants in cross-chain transactions. Likewise, Study [58] uses Boneh–Lynn–Shacham (BLS) threshold signatures—an external party can verify validity without learning individual signer identities. BxTB [72] reduces personal data leakage by relying on stateless SPVs, while ring-signature and Ring-VRF constructions in [64,76] ensure that any group member may have signed a message, but it’s cryptographically infeasible to pinpoint who. ZCLAIM [75] leverages Zero-Knowledge Succinct Non-interactive ARgument of Knowledges (ZK-SNARKs) to hide both transaction amounts and participant identities in a succinct non-interactive proof, and zkCross [112] further obscures receiver addresses through denomination-based mixing. Identity chains in [107] register Decentralized identifiers (DIDs) tied to verifiable certificates, using the DID hash as a non-linkable watermark for transaction verification, while study [111] combines DID authentication with Zero-knowledge proofs for private mutual node authentication. In [99], the system maintains anonymity and unlinkability under the Dolev–Yao threat model. For enterprise data, study [109] applies threshold homomorphic encryption and proxy re-encryption so that only authorized parties holding partial decryption keys can access sensitive credit information, and offline verification stops unauthorized replay.

4.7.2 Countermeasures to Prevent Attacks

Mitigating security threats is a critical aspect of designing resilient interoperability protocols for permissioned blockchains. A wide range of studies have proposed defense mechanisms targeting specific attack vectors that exploit vulnerabilities in cross-chain communication. This section organizes and synthesizes these countermeasures according to the type of attack they address, highlighting the strategies employed to detect, prevent, or neutralize such threats across various interoperability models.

• Fork: Forks can delay transaction finality and open up reorg attacks. Polkadot [70] mitigates this with the GRANDPA finality gadget (a GHOST-based recursive ancestor prefix protocol), while Ref. [90] proposes monitoring block-propagation delays and average network hash rate as real-time fork detectors.

• Double-spending attacks: Double-spending attacks are prevented when ensuring that an asset isn’t spent twice across chains requires undeniable proof of state. The relay-chain design in [77] stores only block headers to validate balances, study [74] relies on a configurable confirmation depth and precise finality timing, and Ref. [60] adds a dual-verification step: trust is established among asset-forwarders on both chains, then traceable ring signatures confirm each cross-chain transfer.

• Chain relay poisoning attacks: Chain relay poisoning attacks are defended by requiring a minimum block depth for finality before accepting cross-chain data, though it warns that eclipse attacks on isolated relayers can still lead to poisoning [75].

• Selfish mining attacks: Selfish mining attacks are addressed in studies [74,90]. The protocol in [74] again uses confirmation counts and timing constraints to limit selfish-mining impact, and study [90] suggests tracking the average network hash rate among nodes, the total hash rate of the target blockchain, and the delay in block propagation to flag anomalous withholding behavior.

• Inference attacks: Inference attacks are prevented in ZCLAIM [75] by splitting transfers into randomized sub-amounts routed through multiple intermediaries, so no single relay sees the full value—thereby thwarting end-to-end inference.

• Sybil attacks: Sybil attacks are prevented by leveraging permissionless blockchains as an interface [57], inheriting their native Sybil defenses—consensus makes it computationally or economically infeasible to spin up many fake nodes. Study [91] requires nodes to lock up a stake and biases rewards toward larger deposits, disincentivizing stake fragmentation across multiple identities. Cross-Ledger [60] first verifies asset ownership and then applies an asset-forwarder-selection algorithm plus traceable ring signatures to ensure that only legitimate forwarders can act—any forged or duplicate identity would lack the necessary signed proofs. Similarly, study [77] authenticates every node before it joins the cross-chain transfer, preventing one actor from registering multiples. XPull [111] prevents unauthorized connections by requiring all participants to furnish zero-knowledge proofs linked to on-chain public keys, and the hybrid scheme in [110] layers homomorphic encryption (P-ElGamal), threshold signatures, and secure MPC (SMPTC3) so that each operation is cryptographically tied to a unique, non-replicable identity.

• DoS attacks: DoS attacks are mitigated by blocking spam and malicious requests at the source. For example, study [76] introduces a DoS-resistant contract wrapper that logs request rates, filters low-gas calls, and blacklists offending addresses. Bridgechain [104] avoids single-point overload by sharding validation across multiple nodes, and study [57] aggregates BLS signatures into a transparent multisig—any node that withholds its share is quickly detected and excluded. ARC [92] secures inter-node communication with Transport Layer Security (TLS) and Secure Socket Layer (SSL) protocols and embeds flow monitoring in the relay chain to catch anomalous traffic from compromised insiders. XPull [111] further prevents DoS by periodically reassigning communicator groups and marking unresponsive parachains as faulty. In [67], Charging per-transaction fees makes large-scale flooding uneconomical, while the hybrid P-ElGamal plus threshold-MPC scheme in [110] ensures only stake-backed identities can submit high-volume requests.

• Replay attacks: Replay attacks are prevented by ensuring that cross-chain transactions cannot be executed more than once. Most protocols [67,70,75,76,97,99,104] tag each cross-chain request with a fresh, randomly generated nonce; the contract checks and consumes this nonce on execution, making any replay immediately invalid. IvyCross [102] goes further by requiring on-chain proof of progress and a lightweight challenge–response: if a participant attempts to replay a transaction without new evidence, the system triggers a rollback, preserving both safety and liveness.

• SPOF: SPOF is prevented by employing smart contracts [72,85,96] and a notary group [95,98] instead of a single notary helps reduce centralization and SPOF.

• PoS attacks: PoS-related attacks are mitigated in Verilay [85]. The protocol addresses potential security risks of the nothing-at-stake attack by ensuring that only finalized blocks are used, which have been agreed upon by a majority of validators. Finalized blocks are considered irreversible, which minimizes the risk of double-spending and other fork-based attacks. Verilay’s reliance on finalized blocks also helps mitigate long-range attacks, where attackers might try to rewrite a blockchain’s history if old keys are compromised.

• TTP attacks: TTP attacks are mitigated in several studies [81,84]. ZkBridge [84] eliminates the need for a TTP by embedding ZK-SNARK proofs into every cross-chain transaction, allowing on-chain validation without external oracles. In [81], validators and TTPs are required to deposit collateral, which is forfeited in cases of malicious conduct. Moreover, validator groups have the authority to temporarily disable or enable TTPs, preventing their operation. Moreover, the article proposes utilizing decentralized Oracle networks instead of TTP to employ independent entities for verification.

• Conspiracy attacks: Conspiracy attacks are addressed in studies [87,95]. The system in [95] demands validating transactions from a larger proportion of the notary’s group, making it considerably more challenging for a small group of notaries to manipulate results. In ChainKeeper [87], a refined threshold signature scheme known as the VITS is introduced, which effectively verifies the identity of the signer and provides resistance to conspiracy attacks commonly associated with threshold signature schemes.

• Lazy voting problem: The lazy voting problem is addressed in [91] by requiring nodes to supply specific information—such as the block number in which a transaction is included—as part of their participation. By enforcing meaningful data contribution and validation, the system ensures active engagement from nodes, thereby preventing passive or non-contributory voting behavior.

• Sore loser and wormhole attacks: Sore loser attacks are mitigated by preventing participants from abandoning a transaction once it has been initiated. The protocol in [93] enforces strict withdrawal rules and liquidated damages—anyone who fails to complete the handoff forfeits their bond, which is redistributed to honest parties. The same liquidated damages framework also deters covert wormhole attacks: if an attacker tries to shortcut the protocol, they lose their stake and face financial penalties. A designated notary group handles token unlocking, and time-locked exchange of the preimage ensures that both sides either complete the swap simultaneously or neither receives funds, preventing any asset theft.

• Cross-chain integer overflow attack: Cross-chain integer overflow attacks are prevented in [97] by adding checks on transaction amounts and implementing safe arithmetic functions, such as Ethereum’s SafeMath, to avoid overflow errors.

• Cross-chain transaction forgery attack: Cross-chain transaction forgery attacks are prevented in [97] by designing secure chaincodes with verification mechanisms, such as public and private keys, to prevent unauthorized interactions and the adding of false transactions.

• Cross-chain transaction sequence attacks: Cross-chain transaction sequence attacks are prevented in [97] by adding flags to confirm transactions’ order.

• Exchange Oracle rate threat: In [75], the protocol suggests using decentralized Oracles and multiple data sources to attain reliability and avoid the exchange Oracle rate threat.

• Counterfeiting threat: In [75], intermediaries are required to periodically provide proof of their balance to prove that issued tokens are properly collateralized by corresponding assets on the source chain.

• MITM attacks: HT2REP [65] adopts a hierarchical blockchain data structure and performs Elliptic Curve Diffie–Hellman key negotiation on-chain so that only the intended parties can derive the session keys. In [76], ring signatures conceal the origin of a transaction among a set of possible signers, making it infeasible for a MITM attack to alter or forge messages undetected. A Zero-knowledge proof-based handshake in [61] lets two chains mutually verify each other’s identities without revealing secret keys. Finally, in [99], standard encryption plus authenticated key exchange ensures confidentiality and integrity of cross-chain payloads, thwarting any MITM that lacks the negotiated keys.

• Draining attacks: In [65], the initiator’s American option advantage and the responder’s potential for launching a draining attack are mitigated through the use of scalable smart contracts, TRE locks (TREL), and hash time locks (HTL).

• Eclipse attacks: Eclipse attacks are prevented in XPull [111] by ensuring that a single honest communicator or storer suffices to sustain communication. In cases of disruption, XPull employs randomized reconfiguration to replace isolated nodes and restore state transfer.

• Impersonation attacks: The proposed work in [57] employs cryptographic techniques, including digital signatures, to authenticate all communications. In [99], Impersonation attacks are prevented through robust zero-knowledge proof-based identity authentication.

• Chosen plaintext attacks: In [69], the analysis highlights that the modified Paillier encryption provides semantic security under the Decisional Composite Residuosity Assumption (DCRA), which is critical for protecting against chosen plaintext attacks.

• Quantum attacks: The paper proposed in [71] a lattice-based digital signature scheme, known for its quantum security, making it a viable alternative to protect blockchain systems from future quantum-based threats.

• Side-channel attacks: The protocol [78] uses a zero-knowledge proof protocol to break the linkability of cross-chain transactions and prevent attackers from correlating across-chain actions.

• Consensus delay attacks: The article [90] identifies three indicators to detect consensus delay attacks: the delay time in block propagation, the average spending time of the transaction, and the average spending time of each transaction.

• Time-jacking attacks: In [90], the authors identified two indicators to detect a time-jacking attack: the delay in block propagation and transaction ordering. These indicators are used to effectively evaluate the validity of the process and transmission timing.

• Jamming attacks: Jamming attacks are prevented in [94] by enhancing the capability of blockchains to confirm the authenticity and intent of transactions more robustly, potentially by analyzing the frequency and pattern of transactions coming from certain nodes. Another strategy is to make cross-chain requests atomic, ensuring that a request isn’t processed unless all its components are verified and executed simultaneously, reducing the chance of manipulation.

• Smart contract bugs: Smart contracts are subject to audits using tools like Mythril and tests utilizing the Truffle framework to detect and correct possible errors or bugs [81]. In IvyCross [102] ensures correct contract execution in concurrent environments using optimized TicToc-based concurrency control that checks data consistency with timestamps.

4.8 Analysis of Heterogeneity among Studies

The synthesis revealed notable heterogeneity across studies driven by differences in protocol maturity and research focus, leading to inconsistencies in reported security and privacy analyses. The overrepresentation of relay-based protocols alongside the underreporting of negative results indicates the presence of topic and publication bias. These variations highlight the need for standardized evaluation criteria and more inclusive literature sampling in future reviews.

While this review applied rigorous IC and searched multiple databases, there is a moderate risk of reporting bias across the synthesized literature. Most included studies are peer-reviewed academic publications, with minimal inclusion of industry-led evaluations. This may lead to the underrepresentation of unsuccessful implementations, unpublished vulnerabilities, or commercially sensitive failures—particularly in areas such as privacy, validator incentives, and cross-chain contract security. Future reviews may benefit from incorporating more diverse publication types, such as white papers and industry reports.

This discussion synthesizes key findings from the review and is structured into two main parts. The first subsection, Identifying Gaps, highlights unresolved research challenges and limitations in current studies on permissioned blockchain interoperability. The second subsection, Future Research Directions, outlines forward-looking priorities and emerging opportunities to guide future advancements in secure and scalable cross-chain protocols.