Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

On-Street Parking Space Detection Using YOLO Models and Recommendations Based on KD-Tree Suitability Search

Department of Information Management, Chaoyang University of Technology, Taichung, 413, Taiwan

* Corresponding Author: Rung-Ching Chen. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Artificial Intelligence Algorithms and Applications)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(3), 4457-4471. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.067149

Received 26 April 2025; Accepted 21 August 2025; Issue published 23 October 2025

Abstract

Unlike the detection of marked on-street parking spaces, detecting unmarked spaces poses significant challenges due to the absence of clear physical demarcation and uneven gaps caused by irregular parking. In urban cities with heavy traffic flow, these challenges can result in traffic disruptions, rear-end collisions, sideswipes, and congestion as drivers struggle to make decisions. We propose a real-time detection system for on-street parking spaces using YOLO models and recommend the most suitable space based on KD-tree search. Lightweight versions of YOLOv5, YOLOv7-tiny, and YOLOv8 with different architectures are trained. Among the models, YOLOv5s with SPPF at the backbone achieved an F1-score of 0.89, which was selected for validation using k-fold cross-validation on our dataset. The Low variance and standard deviation recorded across folds indicate the model’s generalizability, reliability, and stability. Inference with KD-tree using predictions from the YOLO models recorded FPS of 37.9 for YOLOv5, 67.2 for YOLOv7-tiny, and 67.0 for YOLOv8. The models successfully detect both marked and unmarked empty parking spaces on test data with varying inference speeds and FPS. These models can be efficiently deployed for real-time applications due to their high FPS, inference speed, and lightweight nature. In comparison with other state-of-the-art models, our models outperform them, further demonstrating their effectiveness.Keywords

On-street parking systems are widely prevalent in urban areas due to their convenience, accessibility, and limited availability of alternative parking facilities. The trend is especially prominent in neighborhoods where residential, commercial, and service establishments are concentrated along the streets, leading to an increased demand for on-street parking [1–3]. However, these systems are not without challenges; traffic disruptions can occur as vehicles maneuver into parking spaces, increased greenhouse gas emissions from cars searching for parking spaces, time wastage while cruising to find available space, and safety risks arise from obstructed visibility [4–7]. Authorities also face difficulties managing traffic effectively in these conditions. On-street parking configurations can include parallel, angled, or perpendicular arrangements [8]. Parallel parking, in particular, becomes especially challenging when spaces are unmarked. In such cases, vehicles are often parked haphazardly, leading to inefficient use of space and an increased likelihood of traffic congestion. Furthermore, the absence of clear boundaries makes it difficult for drivers to assess whether a space suits their vehicles, further exacerbating the issue [9,10].

In parking lot management, several digital solutions have been proposed and successfully implemented to address challenges in detecting available parking spaces. These include Parking Guidance and Information Systems (PGI) [11–13], the Internet of Things (IoT) [14,15], sensors such as radar, LIDAR, infrared, magnetic, and acoustic [16,17], a machine/deep learning approach for real-time detection [18,19], and vision-based technologies [20,21].

Parking Guidance and Information (PGI) systems help drivers by providing real-time updates on available spaces. Still, they struggle with on-street parking due to its dynamic nature, especially during peak periods [22]. IoT and sensors detect parking space occupancy and transmit data to central systems for real-time updates. However, high costs, privacy concerns, and scalability issues remain challenges [23–25].

Object detection techniques, including deep learning and machine learning, can effectively address challenges in parking lot management, particularly in detecting on-street parallel parking spaces, which are often difficult to identify due to their unmarked nature and dynamic conditions [26–28]. These models can predict parking availability by analyzing historical data and current conditions, providing more accurate real-time updates even in unpredictable environments. They also detects parking spaces under complex scenarios, such as occlusion, adverse weather, and varying lighting conditions, which can otherwise affect detection accuracy [29,30]. By training on historical data [31], these models can adapt to various situations, enhancing precision and efficiency. Unlike traditional digital solutions such as PGI systems, IoT, and sensors, machine learning models offer more scalable, cost-effective, and adaptable solutions. Moreover, these models can be integrated with the traffic management systems to optimize traffic flow, reduce congestion, and prevent rear-end collisions and sideswiping.

This study aims to detect on-street parking spaces using YOLO models and use KD-tree search to recommend the most suitable parking space. Our proposed method can help car drivers to efficiently locate available parking spaces, reducing the time spent on the road, reducing the traffic flow in crowded areas.

The main contributions of this research work are as follows: (1) Utilizing various lightweight YOLO models to detect on-street parking spaces. (2) Employing the k-fold cross-validation technique to validate the selected model based on performance metrics. (3) Integrate YOLO model predictions with the KD-tree search algorithm to search for available empty parking spaces. (4) Recommending a suitable parking space based on KD-tree search results.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews the related literatures, Section 3 presents our methodology, Section 4 discusses the experiments and results, Section 5 analyzes the findings, and Section 6 concludes the paper with suggestions for future research.

Previous research studies have proposed and successfully implemented state-of-the-art models for detecting and recommending on-street parking spaces based on deep and machine learning techniques. Gkolias and Vlahogianni [32] use Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) to detect empty on-street parking spaces using in-vehicle camera images performs better than enhanced Support Vector Machines (SVMs). However, their research is limited to low-resolution images. The usage of a side-view image from the car is also not practical in real-life situations, since when the detection results are out, the car would have already passed the detected parking space. Wang et al. [29] used an improved YOLOv9 model to improve the performance of parking space detection using a camera setup in the parking lot. This approach focuses on a centralized system and focuses only on a single parking lot. Sun et al. [33] propose an On-Street Parking Recommendation (OPR) system using a learn-to-rank (LTR) model and a heterogeneous graph (ESGraph) to recommend available parking spaces effectively. The system integrates historical and real-time data. Liu et al. [34] propose a deep-learning model to predict on-street parking occupancy, utilizing Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks to address temporal dependencies and enhance prediction accuracy by incorporating Point of Interest (POI) data selected using the Boruta algorithm. Xu et al. [35] combine CNN and LSTM networks to detect and predict parking space availability. The CNN process the spatial information from images, while the LSTM captures temporal patterns, providing accurate parking space occupancy predictions. Zhao and Zhang [36] propose an Adaptive Graph Convolutional Network with a Gated Recurrent Unit (AGCRU) to predict on-street parking occupancy. The model captures both temporal and spatial dynamics of on-street parking behaviors. POIs and household data are incorporated to enhance predictive accuracy. Xiao et al. [37] propose a hybrid model to predict on-street parking space availability by combining Graph Convolutional Networks and Gated Linear Units with a 1D CNN to capture spatial and temporal features. The authors introduce an attention mechanism called disAtt to measure similarities in parking duration distributions. Feng et al. [38] propose a dual Convolutional Long Short-Term Memory (ConvLSTM) network and Dense Convolutional Networks (DCN) model to predict vacant parking space availability. The proposed model captures both short-term and long-term temporal correlations within each parking lot and spatial correlations among different parking lots. Grbić and Koch [39] use ResNet34 to detect and classify parking slots as occupied or vacant. The proposed system utilizes camera images to identify vehicles and determine parking slot positions. Amato et al. [40] use Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) for real-time detection of parking space occupancy Thakur et al. [41] utilize ResNet and VGG-16 to detect parking occupancy.

The literature review reveals a lack of research that focuses on detecting available parking spaces using real-time dashboard camera input. Many studies in this field use numerical data, such as input from on-street parking meters, weather information, and point-of-interest information, to predict the availability of parking spaces. The research utilizing camera input mostly focuses on implementation in a centralized parking area using CCTV input. Our research focuses on the usage of dashboard camera input to detect empty parking spaces and give the best recommendation in real-time.

Fig. 1 shows the flow of our proposed method. There are two main parts in our proposed method: the YOLO model training and evaluation, and the parking space recommendation system. The first part is where we train and evaluate the YOLO models in detecting empty and occupied parking spaces. The second part describes the process of selecting the best recommended empty parking space. Each part of the process is explained in detail in the next sections.

Figure 1: Proposed method

Given a car

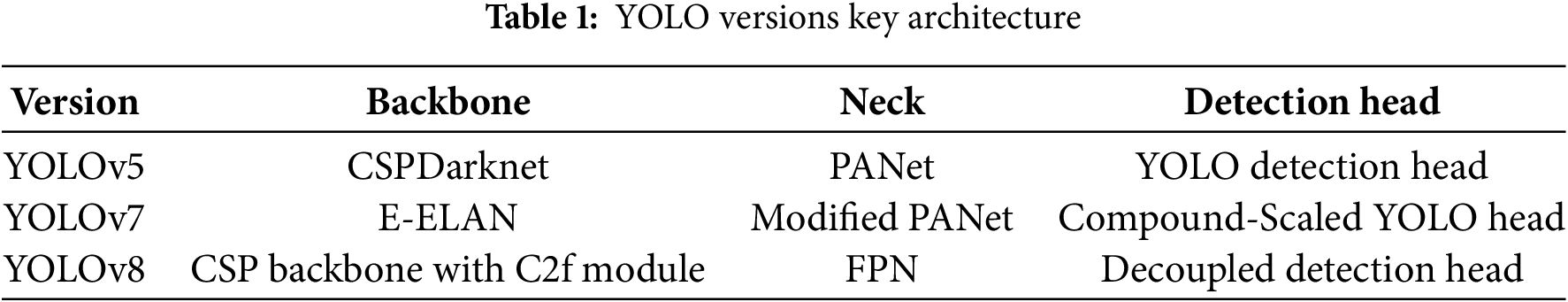

The You Only Look Once (YOLO) family is renowned for its real-time object detection capabilities, characterized by speed, efficiency, low latency, and accuracy in a single-stage process [42]. Each version of YOLO evolves with improvements in architecture, speed, accuracy, and scalability [43,44]. YOLO models consist of 3 main parts, each of which has different responsibilities. The backbone is responsible for feature extraction, the neck does the feature enhancement, while the head gives the detection output. Table 1 shows the backbone, neck, and detection head architecture of YOLOv5, YOLOv7, and YOLOv8.

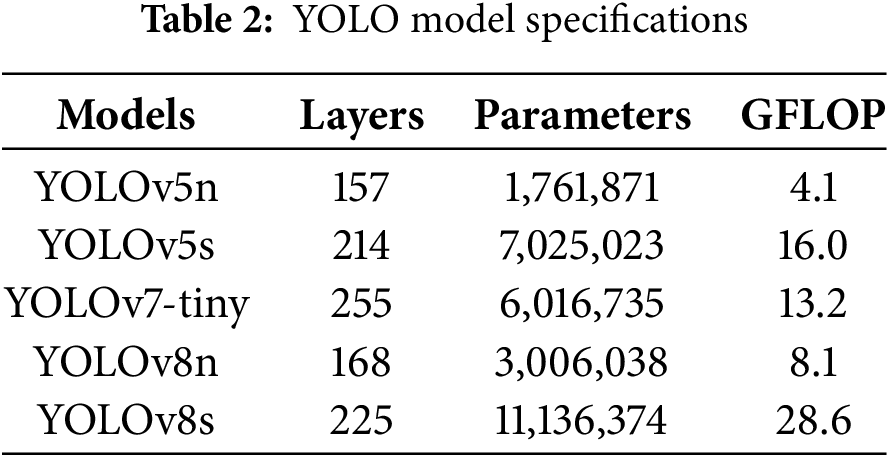

We use YOLOv5n, YOLOv5s, YOLOv7-tiny, YOLOv8s, and YOLOv8n to detect on-street parking spaces because of their lightweight computational requirements and fewer parameters. Table 2 lists our YOLO models, detailing their sizes, layers, and GFLOPS.

YOLO models are known for their speed and accuracy. Their single-stage detection process boasts fast inference speed suitable for real-time object detection. When running on more than 30 fps, YOLO models can detect objects in real-time situations using input from a video camera.

The KD-tree [44–46] is a binary data structure that organizes points in a k-dimensional space, designed for efficient search, nearest neighbor, and range queries. For a set

To use the KD tree effectively, we first reduce each detected empty parking space, represented as a bounding box, to a single representative point: the center of the bounding box. Since the KD tree operates on point-based data, the center coordinates

where

Next, we construct a KD-tree using the center coordinates of all detected empty parking spaces {

3.3.2 Nearest Space Query Using Euclidean Distance

Once the KD-tree is built, we query to find the nearest empty parking space to the car’s current position

where

3.3.3 Dimension Filtering for Valid Parking Space

After identifying the nearest empty parking spaces, we filter them based on their dimensions to ensure they accommodate the car. A detected parking space

3.3.4 Selection of Suitable Parking Space

Finally, the recommended parking space is selected by choosing the nearest available empty parking space that satisfies both the proximity to the car’s position and size requirements. A space is recommended after filtering all detected empty spaces based on the proximity and size of a car. The recommended parking space is identified using the criteria given in Eq. (4).

where

4 Experiments and Implementation Details

The dataset comprises 3517 images of both unmarked and marked on-street parking spaces. These images are collected from various sources, including Google Maps, recorded videos, online platforms, and camera shots. Various data augmentation techniques, such as rotation, brightness, and contrast adjustments, enhance the dataset’s robustness. The images encompass a wide range of lighting and weather conditions, ensuring diverse scenarios for effective parking space detection. Fig. 2a shows a sample of marked on-street parking spaces, while Fig. 2b displays a sample of unmarked parking spaces.

Figure 2: (a) Marked on-street parking space (b) Unmarked on-street parking space

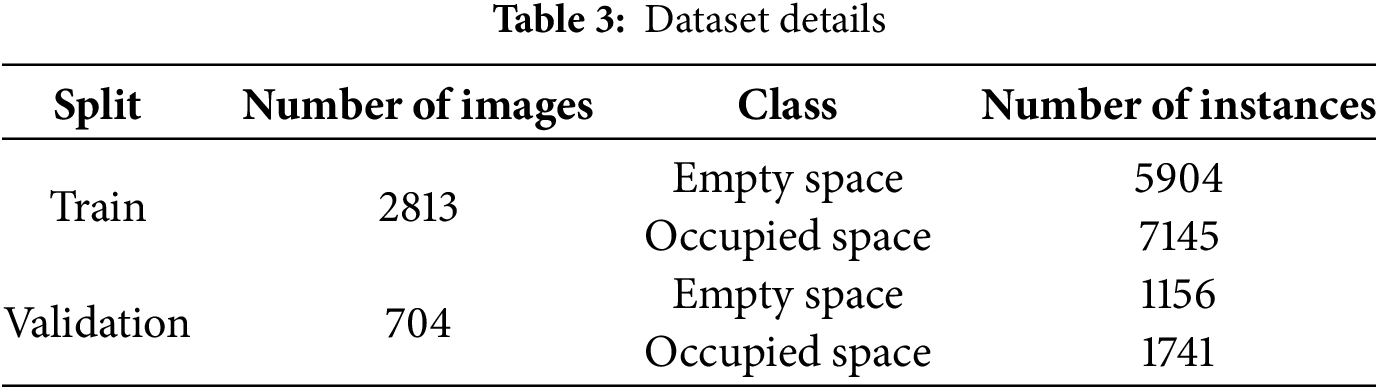

The images are preprocessed by resizing and normalizing pixel values to a range of [0, 1]. The LabelImg tool is used to annotate the images in YOLO format. The dataset is then split into training and validation sets, with 80% of the images used for training and 20% for validation. The detailed breakdown of the dataset is described in Table 3.

4.2 Environment, Hyperparameter Settings, and Training

We use Python 3.8.16 and PyTorch 2.4.1 with CUDA:0 (Quadro P1000, 4097MiB). The initial learning rate is set to 0.1, with a momentum of 0.937 to balance convergence speed and stability. The image size is 640, and the batch size is 16 to ensure stable gradient updates. The model is trained for 100 epochs using the SGD optimizer with a learning rate of 0.1 and a weight decay of 0.0005 to adjust weights and prevent overfitting.

4.3 Performance Evaluation Metrics

The model is evaluated using the following metrics.

Precision (P): Measures how accurately the model makes optimistic predictions. It is calculated using Eq. (5).

Recall (R): Measures how well the model detects all relevant empty spaces in the dataset. It is calculated in Eq. (6) as the ratio of accurate positive detections to the total number of actual empty spaces.

Mean Average Precision (mAP): Eq. (7) calculates the average precision for detecting objects over various Intersections over Union (IoU) thresholds. It measures how well the model balances precision and recall across different classes and levels of overlap between predicted and actual bounding boxes.

F1 Score: The harmonic mean of precision and Recall provides a balanced measure of the model’s performance. It is calculated using Eq. (8).

5.1 Results of Training YOLO Models

Table 4 presents the performance metrics of various YOLO models, including Precision, Recall, F1-score, and mAP@50. YOLOv5s achieves the highest mAP@50 of 0.933, as illustrated in Fig. 3, highlighting its superior object detection accuracy. Despite its high mAP@50, YOLOv5s also records an F1-score of 0.89, signifying its balanced precision and recall capabilities. The results are essential for accurate detection and minimizing missed detections. On the other hand, YOLOv7-tiny records the lowest mAP@50 of 0.819, indicating relatively lower detection accuracy than the other models. From our experiment results, YOLOv5s is the best model, which gives the best trade-off between inference speed and detection performance, achieving 0.933 mAP@50 while detecting at 37 FPS.

Figure 3: Accuracies of the YOLO models

YOLOv5s performs well during training, but to assess its generalization on unseen data, we use k-fold cross-validation. This method evaluates the model’s generalization ability and performance variability across different data subsets. In k-fold cross-validation, the dataset is split into k-folds. The model is trained on k-1 folds, and the remaining fold is used for validation. This process is repeated for k times, ensuring each fold is used as the validation set at least once. The average performance metrics across folds shows the generalizability, while the variance and standard deviation gauges the reliability. Lower variance indicates consistent performance and higher reliability.

Eq. (9) calculates the average performance across all folds by using the mean of performance metrics across all folds.

where

Variance indicates how much the performance varies across the folds, which is calculated in Eq. (10).

Standard deviation gives the spread or dispersion of performance metrics across the folds and is calculated in Eq. (11).

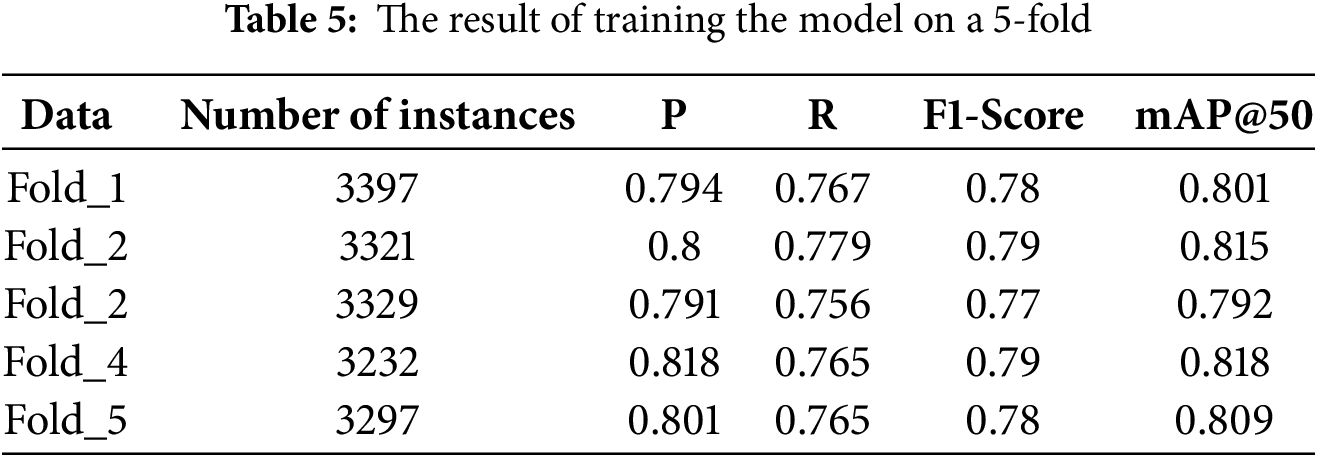

We split the dataset into five (5) folds, as shown in Table 5, and calculated the performance metrics, variance, and standard deviation. Table 5 and Fig. 4 show the results of training the model on a 5-fold.

Figure 4: Accuracies of the YOLO Models

Table 6 shows average performance metrics across k folds. The K-fold cross-validation results indicate the model’s strong generalizability and reliability. The low variance and standard deviation in performance metrics (Precision: 0.8008, Recall: 0.7664, F1-score: 0.782, mAP@50: 0.807) across different folds suggest consistent, stable performance that is not highly sensitive to the specific subset of data it is trained on.

Fig. 5 shows how YOLOv5s detects marked on-street parking spaces. The model detects the parking spaces and identifies the occupied and empty spaces. It processed the detection in 27.0 ms at a speed of 37.04 frames per second (FPS). As shown in Fig. 6, the model successfully detects unmarked occupied and empty spaces. It achieves an inference time of 26.0 ms and a frame rate of 38.46 FPS.

Figure 5: Detection results of the Yolov5s model on a marked parking space

Figure 6: Results of detecting unmarked empty and occupied spaces by YOLOv5s

5.4 Comparison with Other Models

The comparison of YOLOv5s with other state-of-the-art models is shown in Table 7. Our model demonstrates impressive performance. Specifically, our model has a Precision of 0.898, a Recall of 0.875, mAP@50 of 0.89, and an F1-score of 0.933. YOLO7-X [47] also performs well with a Precision of 0.92, a Recall of 0.82, mAP@50 of 0.90, and an F1-score of 0.87. The Random Forest [48] model shows consistent but lower values across all metrics, each at 0.81. Faster R-CNN [49] only provides mAP@50 of 0.893, and YOLOv4 [50] shows mAP@50 of 0.82, lacking other metric values. Our model showcases balanced and superior performance across Precision, Recall, mAP@50, and F1-score, highlighting its robustness and reliability compared to other mod46els.

5.5 Integration of YOLO Inference with KD-Tree for Parking Space Recommendation

In addition to comparing our model with state-of-the-art (SOTA) models trained on different datasets, we also train various lightweight YOLO models on the same dataset. These models are trained under identical environmental conditions, with variation only in their architectures, as shown in Table 4. Each model is integrated with a KD tree that is dynamically built using the detected empty parking spaces and provides recommendations on their suitability.

We integrate the predictions from YOLO models for parking space detection with the SciPy KD-Tree implementation, which provides efficient functionality for spatial queries such as finding the nearest neighbors. NumPy and Pandas facilitate efficient data handling in this setup, ensuring seamless operation within Python environments.

Inference of KD-Tree and YOLO Models on Unmarked On-Street Parking Spaces

Our experiments find the results of integrating KD-Tree with various YOLO models for detecting unmarked on-street parking spaces. The results shown in Fig. 7 include each model’s inference speed and frames per second (FPS).

Figure 7: Results of detecting unmarked empty and occupied spaces by YOLOv5s

To preserve the figures’ integrity across multiple computer platforms, we accept files in the following formats: EPS/PDF/PS. All fonts must be embedded or text converted to outlines to achieve the best quality results.

The first step in our method involves training YOLO models to detect on-street parking spaces. These lightweight models can be deployed on resource-constrained devices, as shown in Table 1. The performance of YOLOv5s across various metrics, including variance and standard deviation, demonstrates its effectiveness. The inference results for YOLOv5s in processing unmarked empty parking spaces show a processing time of 27.0 ms, with a speed of 37.04 frames per second (FPS), above the 30 FPS threshold for real-time applications. Similarly, for marked parking spaces, the inference time is 0.03 ms with 38.52 FPS. These speeds are promising and can be further improved for even better performance. Compared to state-of-the-art models, our models perform better across the performance metrics.

K-fold cross-validation is helpful as it improves model generalization, reduces overfitting, and provides more reliable performance metrics. The results indicate the model’s strong generalizability and reliability, with low variance and standard deviation in performance metrics (Precision: 0.8008, Recall: 0.7664, F1-score: 0.782, mAP@50: 0.807) across different folds. This suggests consistent, stable performance that is not highly sensitive to specific data subsets.

In conclusion, we propose a model to detect unmarked empty on-street parking spaces using YOLO models and recommend a suitable parking space based on the location and size of a car. YOLO models are trained on a dataset from online repositories, recorded videos, camera snapshots, and Google Earth. YOLOv5s recorded an impressive mAP@50 OF 0.933 and an F1-score of 0.87. The model is validated using k-fold cross-validation techniques. Average Performance metrics of the fold, variance, and standard deviation indicate the ability of the model to generalize well on unseen data, as well as stability and reliability. Integration of predictions of the trained detection YOLO models yielded impressive inference speed and FPS on test images. Based on the results, the proposed models have addressed the challenges of the lack of clear physical demarcation and the uneven gaps left by irregular parking. These mitigate unnecessary cruising, greenhouse gas emissions, traffic disruptions, rear-end collisions, sideswipes, and congestion.

At this stage of our research, we tested our proposed method to assess its performance in detecting available parking spaces and recommending the best parking space location. We used lightweight YOLO models, which are suitable for deployment in edge devices. In the future, we will assess its performance when deployed in edge devices. The experiment will include latency, thermal limits, power consumption, and other critical parameters for edge deployment. We will also do more research and analysis on the impact of our proposed method on traffic reduction, emission reduction, and time efficiency. We will also propose an inventory system to retrain the models on new images from various environmental, weather, and lighting conditions to keep improving the model performance. Federated learning and the possibility for city-scale deployment are also part of our future work.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: NSTC Taiwan supports this paper. Project Nos. NSTC-112-2221-E-324-003 MY3, NSTC-111-2622-E-324-002 and NSTC-112-2221-E-324-011-MY2.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Ibrahim Yahaya Garta and Rung-Ching Chen; methodology, Ibrahim Yahaya Garta and Rung-Ching Chen; software, Ibrahim Yahaya Garta; validation, Ibrahim Yahaya Garta and Rung-Ching Chen; formal analysis, Ibrahim Yahaya Garta and Su-Wen Huang; investigation, William Eric Manongga and Rung-Ching Chen; resources, William Eric Manongga and Su-Wen Huang; data curation, Ibrahim Yahaya Garta and William Eric Manongga; writing—original draft preparation, Ibrahim Yahaya Garta; writing—review and editing, William Eric Manongga, Su-Wen Huang and Rung-Ching Chen; visualization, Ibrahim Yahaya Garta and William Eric Manongga; supervision, Rung-Ching Chen; project administration, Rung-Ching Chen; funding acquisition, Rung-Ching Chen. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available on request from the authors.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Wang H, Saito M, Liu J, Shimamoto S. Comprehensive analysis of traffic operation for on-street parking based on the urban road network. IEEE Access. 2024;12(1):125643–53. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3449156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Brudner A. On the management of residential on-street parking: policies and repercussions. Transp Policy. 2023;138(1):94–107. doi:10.1016/j.tranpol.2023.05.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Rifai AI, Wibowo T, Isradi M, Mufhidin A. On-street parking and its impact on road performance: case commercial area in Jakarta city. World J Civil Eng. 2020;1(1):10–8. [Google Scholar]

4. Qin H, Zheng F, Yu B, Wang Z. Analysis of the effect of demand-driven dynamic parking pricing on on-street parking demand. IEEE Access. 2022;10(1):70092–103. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3187534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Parmar J, Das P, Dave SM. Study on demand and characteristics of parking system in urban areas: a review. J Traffic Transp Eng. 2020;7(1):111–24. doi:10.1016/j.jtte.2019.09.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Biswas S, Chandra S, Ghosh I. Effects of on-street parking in urban context: a critical review. Transp Dev Econ. 2017;3(1):10. doi:10.1007/s40890-017-0040-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Sha H, Haouari R, Singh MK, Papazikou E, Quddus M, Chaudhry A, et al. How can on-street parking regulations affect traffic, safety, and the environment in a cooperative, connected, and automated era? Eur Transp Res Rev. 2024;16(1):18. doi:10.1186/s12544-023-00628-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Kumar K, Singh V, Raja L, Bhagirath SN. A review of parking slot types and their detection techniques for smart cities. Smart Cities. 2023;6(5):2639–60. doi:10.3390/smartcities6050119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Zhao Y, Collins EG. Robust automatic parallel parking in tight spaces via fuzzy logic. Robot Auton Syst. 2005;51:111–27. doi:10.1016/j.robot.2005.01.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Bargegol I, Rahmaninezhad Asil M, Toroghi H, Najafi Moghaddam Gilani V. Investigating the factors affecting the on-street parking maneuver time on urban roads. Int J Civ Eng. 2022;20(12):1447–60. doi:10.1007/s40999-022-00743-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Liu KS, Gao J, Wu X, Lin S. On-street parking guidance with real-time sensing data for smart cities. In: 2018 15th Annual IEEE International Conference on Sensing, Communication, and Networking (SECON); 2018 Jun 11–13; Hong Kong, China. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2018. p. 1–9. doi:10.1109/SAHCN.2018.8397113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Di Martino S, Vitale VN, Bock F. Comparing different on-street parking information for parking guidance and information systems. In: 2019 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV); 2019 Jun 9–12; Paris, France. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2019. p. 1093–8. doi:10.1109/IVS.2019.8813883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Bock F, Di Martino S, Sester M. What is the impact of on-street parking information for drivers? In: Kawai Y, Storandt S, Sumiya K, editors. Web and wireless geographical information systems. W2GIS 2019. Lecture notes in computer science. Vol. 11474. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2019. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-17246-6_7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Pham TN, Tsai MF, Nguyen DB, Dow CR, Deng DJ. A cloud-based smart-parking system based on Internet-of-Things technologies. IEEE Access. 2015;3:1581–91. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2015.2477299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Solic P, Leoni A, Colella R, Perkovic T, Catarinucci L, Stornelli V. IoT-ready energy-autonomous parking sensor device. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021;8(6):4830–40. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2020.3031088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Abd Kadir MM, Osman MN, Othman NA, Sedek KA. IoT-based car parking management system using IR sensor. J Comput Res Innov. 2020;5(2):75–84. doi:10.24191/jcrinn.v5i2.151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Zhang Z, Tao M, Yuan H. A parking occupancy detection algorithm based on AMR sensor. IEEE Sens J. 2014;15(2):1261–9. doi:10.1109/JSEN.2014.2362122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. An Q, Wang H, Chen X. EPSDNet: efficient campus parking space detection via convolutional neural networks and vehicle image recognition for intelligent human-computer interactions. Sensors. 2022;22(24):9835. doi:10.3390/s22249835. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Dhope T, Chitale P, Rampure S, Ghane S. A novel hybrid approach towards parking space occupancy detection. In: 2021 12th International Conference on Computing Communication and Networking Technologies (ICCCNT); 2021 Jul 6–8; Kharagpur, India. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2021. p. 1–7. doi:10.1109/ICCCNT51525.2021.9579816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Zhang L, Huang J, Li X, Xiong L. Vision-based parking-slot detection: a DCNN-based approach and a large-scale benchmark dataset. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2018;27(11):5350–64. doi:10.1109/TIP.2018.2857407. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Hsu CM, Chen JY. Around view monitoring-based vacant parking space detection and analysis. Appl Sci. 2019;9(16):3403. doi:10.3390/app9163403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Mei Z, Tian Y. Optimized combination model and algorithm of parking guidance information configuration. J Wirel Com Netw. 2011;2011(1):104. doi:10.1186/1687-1499-2011-104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Aljohani M, Olariu S, Alali A, Jain S. A survey of parking solutions for smart cities. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2022;23(8):10012–29. doi:10.1109/TITS.2021.3112825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Ling X, Sheng J, Baiocchi O, Liu X, Tolentino ME. Identifying parking spaces & detecting occupancy using vision-based IoT devices. In: 2017 Global Internet of Things Summit (GIoTS); 2017 Jun 6–9; Geneva, Switzerland. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2017. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/GIOTS.2017.8016227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Sevillano X, Màrmol E, Fernandez-Arguedas V. Towards smart traffic management systems: vacant on-street parking spot detection based on video analytics. In: 17th International Conference on Information Fusion (FUSION); 2014 Jul 7–14; Salamanca, Spain. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2014. p. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

26. Awan FM, Saleem Y, Minerva R, Crespi N. A comparative analysis of machine/deep learning models for parking space availability prediction. Sensors. 2020;20(1):322. doi:10.3390/s20010322. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Shivaprasad S, Anand M, Chilkunda SA, Kamalesh A, Oruganti R, Radhakrishna S, et al. Finding potential on-street parking spots: an object detection and segmentation approach. In: Senjyu T, So-In C, Joshi A, editors. Smart trends in computing and communications. SmartCom 2024. Lecture notes in networks and systems. Vol. 948. Singapore: Springer; 2024. doi:10.1007/978-981-97-1329-5_35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Nurullayev S, Lee SW. Generalized parking occupancy analysis based on dilated convolutional neural network. Sensors. 2019;19(2):277. doi:10.3390/s19020277. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Wang W, Zhang W, Zhang H, Zhang A. Research on parking space detection algorithm in complex environments based on improved YOLOv7. Meas Sci Technol. 2023;35(2):025403. doi:10.1088/1361-6501/ad0b68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Satyanath G, Sahoo JK, Roul RK. Smart parking space detection under hazy conditions using convolutional neural networks: a novel approach. Multimed Tools Appl. 2023;82(10):15415–38. doi:10.1007/s11042-022-13958-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Zeng C, Ma C, Wang K, Cui Z. Predicting vacant parking space availability: a DWT-Bi-LSTM model. Physica A. 2022;599:127498. doi:10.1016/j.physa.2022.127498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Gkolias K, Vlahogianni EI. Convolutional neural networks for on-street parking space detection in urban networks. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2019;20(12):4318–27. doi:10.1109/TITS.2018.2882439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Sun H, Huang X, Ma W. Beyond prediction: on-street parking recommendation using heterogeneous graph-based list-wise ranking. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2024;25(6):5892–903. doi:10.1109/TITS.2023.3336808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Liu M, Ji Y, Kuai C, Zhang S. Short-term prediction of on-street parking occupancy using multivariate variable based on deep learning. J Traffic Transp Eng. 2024;11(1):28–40. (In English). doi:10.1016/j.jtte.2022.05.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Xu Z, Tang X, Ma C, Zhang R. Research on parking space detection and prediction model based on CNN-LSTM. IEEE Access. 2024;12(11):30085–100. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3368521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Zhao X, Zhang M. Enhancing predictive models for on-street parking occupancy: integrating adaptive GCN and GRU with household categories and POI factors. Mathematics. 2024;12(18):2823. doi:10.3390/math12182823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Xiao X, Jin Z, Hui Y, Xu Y, Shao W. Hybrid spatial-temporal graph convolutional networks for on-street parking availability prediction. Remote Sens. 2021;13(16):3338. doi:10.3390/rs13163338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Feng Y, Xu Y, Hu Q, Krishnamoorthy S, Tang Z. Predicting vacant parking space availability zone-wisely: a hybrid deep learning approach. Complex Intell Syst. 2022;8(5):4145–61. doi:10.1007/s40747-022-00700-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Grbić R, Koch B. Automatic vision-based parking slot detection and occupancy classification. Expert Syst Appl. 2023;225:120147. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2023.120147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Amato G, Carrara F, Falchi F, Gennaro C, Vairo C. Car parking occupancy detection using smart camera network and deep learning. In: 2016 IEEE Symposium on Computers and Communication (ISCC); 2016 Jun 27–30; Messina, Italy. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2016. p. 1212–7. doi:10.1109/ISCC.2016.7543901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Thakur N, Bhattacharjee E, Jain R, Acharya B, Hu YC. Deep learning base occupancy detection framework using ResNet and VGG-16. Multimed Tools Appl. 2023;83(1):1941–84. doi:10.1007/s11042-023-15654-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Redmon J. You only look once: unified, real-time object detection. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2016. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2016.91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Hussain M. YOLOv1 to v8: unveiling each variant–a comprehensive review of YOLO. IEEE Access. 2024;12:42816–33. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3378568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Nazir A, Wani MA. You only look once—object detection models: a review. In: 2023 10th International Conference on Computing for Sustainable Global Development (INDIACom); 2023 Mar 15–17; New Delhi, India. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2023. p. 1088–95. [Google Scholar]

45. Skrodzki M. The KD tree data structure and a proof for neighborhood computation in expected logarithmic time. arXiv:1903.04936. 2019. [Google Scholar]

46. Ram P, Sinha K. Revisiting KD-tree for nearest neighbor search. In: Proceedings of the 24th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining; 2018 Aug 19–23; London, UK. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2018. p. 1378–86. doi:10.1145/3292500.3330875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Bazzaza T, Tohidypour HR, Wang Y, Nasiopoulos P. Accurate detection and localization of individual free street parking spaces using AI and innovative global motion estimation. IEEE Trans Intell Veh. 2024;10(2):1263–72. doi:10.1109/TIV.2024.3425811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Inam S, Mahmood A, Khatoon S, Alshamari M, Nawaz N. Multisource data integration and comparative analysis of machine learning models for on-street parking prediction. Sustainability. 2022;14(12):7317. doi:10.3390/su14127317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Huang C, Yang S, Luo Y, Wang Y, Liu Z. Visual detection and image processing of parking space based on deep learning. Sensors. 2022;22(17):6672. doi:10.3390/s22176672. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Bazzaza T, Chen Z, Prabha S, Tohidypour HR, Wang Y, Pourazad MT, et al. Automatic street parking space detection using visual information and convolutional neural networks. In: 2022 IEEE International Conference on Consumer Electronics (ICCE); 2022 Jan 7–9; Las Vegas, NV, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2022. p. 1–2. doi:10.1109/ICCE53296.2022.9730584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools