Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Domain-Specific NER for Fluorinated Materials: A Hybrid Approach with Adversarial Training and Dynamic Contextual Embeddings

1 School of Computer Science and Engineering, Sichuan University of Science and Engineering, Zigong, 644005, China

2 Sichuan Engineering Research Center for Big Data Visual Analytics, Zigong, 644005, China

3 Key Laboratory of Higher Education of Sichuan Province for Enterprise Informationalization and Internet of Things, Sichuan University of Science and Engineering, Zigong, 644005, China

* Corresponding Author: Hongwei Fu. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(3), 4645-4665. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.067289

Received 29 April 2025; Accepted 22 July 2025; Issue published 23 October 2025

Abstract

In the research and production of fluorinated materials, large volumes of unstructured textual data are generated, characterized by high heterogeneity and fragmentation. These issues hinder systematic knowledge integration and efficient utilization. Constructing a knowledge graph for fluorinated materials processing is essential for enabling structured knowledge management and intelligent applications. Among its core components, Named Entity Recognition (NER) plays an essential role, as its accuracy directly impacts relation extraction and semantic modeling, which ultimately affects the knowledge graph construction for fluorinated materials. However, NER in this domain faces challenges such as fuzzy entity boundaries, inconsistent terminology, and a lack of high-quality annotated corpora. To address these problems, (i) We first construct a domain-specific NER dataset by combining manual annotation with an improved Easy Data Augmentation (EDA) strategy; (ii) Secondly, we propose a novel model, RRC-ADV, which integrates RoBERTa-wwm for dynamic contextual word representation, adversarial training to improve robustness against boundary ambiguity, and a Residual BiLSTM (ResBiLSTM) to enhance sequential feature modeling. Further, a Conditional Random Field (CRF) layer is incorporated for globally optimized label prediction. Experimental results demonstrate that RRC-ADV achieves an average F1 score of 89.23% on the self-constructed dataset, significantly outperforming baseline models. The model exhibits strong robustness and adaptability within the domain of fluorinated materials. Our work enhances the accuracy of NER in the fluorinated materials processing domain and paves the way for downstream tasks such as relation extraction in knowledge graph construction.Keywords

Fluorinated materials are a class of high-performance substances characterized by their fluorine-centered chemical structure. They exhibit exceptional properties such as high thermal stability, chemical resistance, and low surface energy, making them widely applicable in advanced fields including renewable energy, semiconductors, biomedicine, and aerospace. As a fundamental material underpinning the modern industrial system, fluorinated materials play an irreplaceable role in supporting the development of strategic emerging industries and have become a key enabler of industrial innovation and sustainable development. Among them, fluorinated materials—owing to their excellent stability, corrosion resistance, and electrical insulation under extreme conditions—have emerged as core materials in high-end equipment manufacturing [1].

With the continuous development of fluorinated materials and their increasing utilization in high-tech industries, the data generated throughout research and production processes has become highly heterogeneous, fragmented, and inconsistent. Specifically, heterogeneity arises from the variety of data sources and formats, such as academic articles, patents, experimental records, and technical manuals, which exhibit structural differences including tabular data, unstructured narratives, and formulaic expressions. Fragmentation refers to the incomplete and siloed nature of this information, often stored across disparate systems, departments, or documents without standardized integration. Inconsistency, on the other hand, reflects non-uniform terminology and notation; for example, the same material may appear as “polytetrafluoroethylene”, “Teflon”, or by its CAS number, while temperature may be referred to as “temperature”, “T”, or “temp”.

As a key technology in the field of knowledge engineering in the era of big data, knowledge graphs offer a practical solution to the problems of fragmented and dispersed information [2,3]. By constructing a domain-specific knowledge graph for fluorinated materials processing, key information, such as concepts, raw materials, formulations, and processing workflows, can be systematically organized and semantically linked. This enables more efficient knowledge acquisition, understanding, and intelligent application throughout the research and development cycle [4,5]. Such a system not only facilitates the reuse of domain knowledge and optimizes process design, but also lays the groundwork for transitioning the fluorochemical industry toward a more intelligent and knowledge-driven model. For example, intelligent queries, such as “identify fluorinated elastomers resistant to hydrofluoric acid with processing temperatures below 350°C”—can return relevant formulation and curing processes for Viton® fluoroelastomers. Similarly, sensitivity analysis performed on the knowledge graph can help identify key factors that influence material performance.

The construction of high-quality knowledge graphs relies heavily on the accurate extraction of domain-specific knowledge, where Named Entity Recognition (NER) serves as a core enabling technology. The precision of entity recognition directly determines the overall quality of the knowledge graph [6]. While Named Entity Recognition (NER) has made remarkable progress with the emergence of pre-trained models such as BERT and RoBERTa, struggle when applied to the highly specialized do-main of fluorinated materials processing. Several unique challenges make this task particularly difficult: High data heterogeneity and fragmentation: Text sources include patents, scientific papers, and experimental reports with varying formats (e.g., semi-structured tables, free-form descriptions, and mathematical notations), which reduces structural regularity and learnability. Fuzzy and overlapping entity boundaries: Properties such as “thermal degradation resistance above 300°C” or “low dielectric loss at high frequencies” often span multi-token phrases with complex modifiers, making boundary detection ambiguous. Terminological inconsistency and polysemy: The same entity may be referred to as “PTFE”, “polytetrafluoroethylene”, or by its CAS number. Similarly, general terms like “stability” may have different meanings in different contexts. Lack of high-quality, annotated corpora: Unlike the biomedical field (e.g., with BioCreative, NCBI datasets), the fluorinated materials domain lacks community-accepted benchmarks, hindering model training and evaluation.

To address these challenges, this study first constructs a domain-specific named entity recogntion (NER) dataset for fluorinated materials processing through literature collection and ex-pert-guided manual annotation. Based on this dataset, we propose a novel NER model, RRC-ADV. While incorporating established components such as RoBERTa-wwm [7], BiLSTM, and CRF, the model introduces several key innovations. First, we enhance adversarial training [8] by directly applying the Projected Gradient Descent (PGD) method at the embedding layer, thereby improving the model’s robustness in handling fuzzy entity boundaries commonly found in domain-specific texts. Second, we design a Residual Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (ResBiLSTM) [9] network that integrates forward and backward context modeling with residual connections, effectively mitigating gradient attenuation and preserving deep semantic features. Third, we improve the Easy Data Augmentation (EDA) method for data expansion, applying differentiated strategies to entity and non-entity segments. This approach maintains semantic integrity while enhancing sample diversity, and it is specifically tailored to address the structural complexity and domain-specific terminology in fluorinated materials texts. These architectural and methodological innovations collectively enhance the model’s robustness, generalization ability, and boundary recognition accuracy, as demonstrated through comparative and ablation experiments.

Named Entity Recognition (NER) is a fundamental task in Natural Language Processing (NLP), playing a key role in automated information extraction and serving as a critical step in constructing domain-specific knowledge graphs. Initially introduced as a subtask of entity relationship classification [10], early NER methods were primarily rule-based or dictionary-based, relying on predefined lexicons and regular expressions to extract entities from target texts. These approaches were mainly used for matching and filtering but lacked adaptability to new contexts. During the early development of machine learning techniques, traditional statistical methods were successfully applied to NER tasks. Representative approaches included Support Vector Machines (SVM) [11], Hidden Markov Models (HMM) [12], Maximum Entropy Markov Models (MEMM) [13], and Conditional Random Fields (CRF) [14]. These traditional machine learning methods, based on statistical learning, required well-annotated training datasets and manually designed feature sets, making their performance highly dependent on domain expertise and extensive corpora. This reliance on handcrafted features limited their generalizability and hindered broader adoption.

With the rapid advancements in deep learning, the research paradigm in NER has gradually shifted toward deep learning-based solutions [15]. Early deep learning approaches primarily leveraged Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) [16] and Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN). However, standard RNNs suffered from gradient explosion and long-sequence dependency issues, which were later addressed by the introduction of Gated Recurrent Units (GRU) [17] and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks [18]. In 2015, Huang et al. [19] pioneered the use of BiLSTM networks to model and encode contextual information, introducing the BiLSTM-CRF model for NER. This end-to-end model, which combines BiLSTM with CRF, eliminated the dependence on handcrafted features and became a mainstream NER approach, achieving significant performance improvements. Subsequently, Ma and Hovy [20] integrated LSTM, CNN, and CRF into a BiLSTM-CNNs-CRF model, demonstrating superior performance across English-language datasets. More recently, large-scale pre-trained Transformer-based models have revolutionized NER by enabling polysemous word representations, significantly enhancing performance on various NLP tasks, including entity recognition. Chen et al. [21] proposed an ALBERT-BiGRU-CRF model, where word embeddings generated by ALBERT were fed into a Bidirectional GRU-CRF architecture for NER. Dai et al. [22] evaluated BiLSTM-CRF models with various word embeddings, such as BERT and Word2Vec, for entity recognition in electronic medical records (EMRs). Their results showed that the BERT-based BiLSTM-CRF model performed notably better than the Word2Vec-based version, emphasizing the benefits of contextual word embeddings in NER tasks.

Named entity recognition (NER) for fluorinated materials processing data is a specialized domain-specific NER task aimed at identifying key concepts within fluorinated materials processing workflows. However, research on NER in this domain remains limited. Nevertheless, numerous scholars have successfully integrated deep learning with NER in other fields, yielding promising results. For instance, Yu et al. [23] introduced a BERT-CRF model that efficiently identified entities in unstructured Chinese mineral texts. Chithrananda et al. [24] developed the ChemBERTa model based on the RoBERTa architecture, employing self-supervised pretraining to encode chemical texts (e.g., SMILES strings). Their model outperformed traditional approaches in molecular property prediction and entity recognition tasks. Zhang et al. [25] introduced an ALBERT-BiLSTM-CRF model for NER in wheat pest and disease detection. They further defined entity boundary calibration rules, and experiments demonstrated that integrating these rules with the model significantly improved entity recognition accuracy. A commonality among these studies is the advantage of deep learning models in capturing deep, nonlinear relationships between words, enabling effective domain-specific NER tasks with high accuracy.

3 Construction of the Fluorinated Materials Processing Dataset

This study first defines the scope of fluorinated material-related information, clarifying the research subjects and involved entity types. Subsequently, web crawler technology is employed to collect, clean, and organize text data containing fluorinated materials from the internet, thereby constructing a high-quality textual corpus. Based on predefined entity types, entity annotation is performed to establish a NER dataset for the fluorinated material processing domain.

3.1 Definition of Fluorinated Materials Processing Data

In the field of fluorinated material manufacturing, process data refers to the critical technical information generated throughout the research, production, and application of fluorinated materials. This data encompasses material composition, reaction conditions, process workflows, and performance parameters. In this study, we classify fluorinated material process data into six distinct entity types, namely: Material (MAT), Compound (COM), Process (PROC), Property (PROP), Chemical Reagent (REA), and Equipment (EQUI). Material (MAT) refers to specific categories of fluorinated materials. Compound (COM) includes relevant chemical compounds involved in fluorochemical production. Process (PROC) pertains to manufacturing and processing techniques. Property (PROP) describes the physical or chemical characteristics of materials. Chemical Reagent (REA) refers to chemicals used during experimentation or production. Equipment (EQUI) encompasses instruments and devices required for experimentation and production. These entity types comprehensively summarize the research areas of fluorinated materials and lay the foundation for the subsequent construction of a knowledge graph [26,27]. Table 1 systematically presents the entity classification framework for fluorinated material process data, detailing each entity type, its corresponding label, and its definition.

3.2 Dataset Collection and Entity Annotation

Currently, publicly accessible datasets concerning fluorinated material processing are scarce, making it especially challenging to acquire high-quality, domain-specific data. To address this, we adopt a comprehensive data collection approach, incorporating multiple sources. Specifically, we gather information from fluorinated material reference books, extract relevant texts from authoritative websites such as Baidu Encyclopedia by using crawler technology, and integrate content from academic papers and patent literature to construct a more extensive and representative dataset. The collected data primarily consists of unstructured text, with only a small portion exhibiting semi-structured characteristics. After data cleaning, format standardization, and deduplication, we establish a fluorinated material text corpus, providing essential data support for subsequent NER tasks.

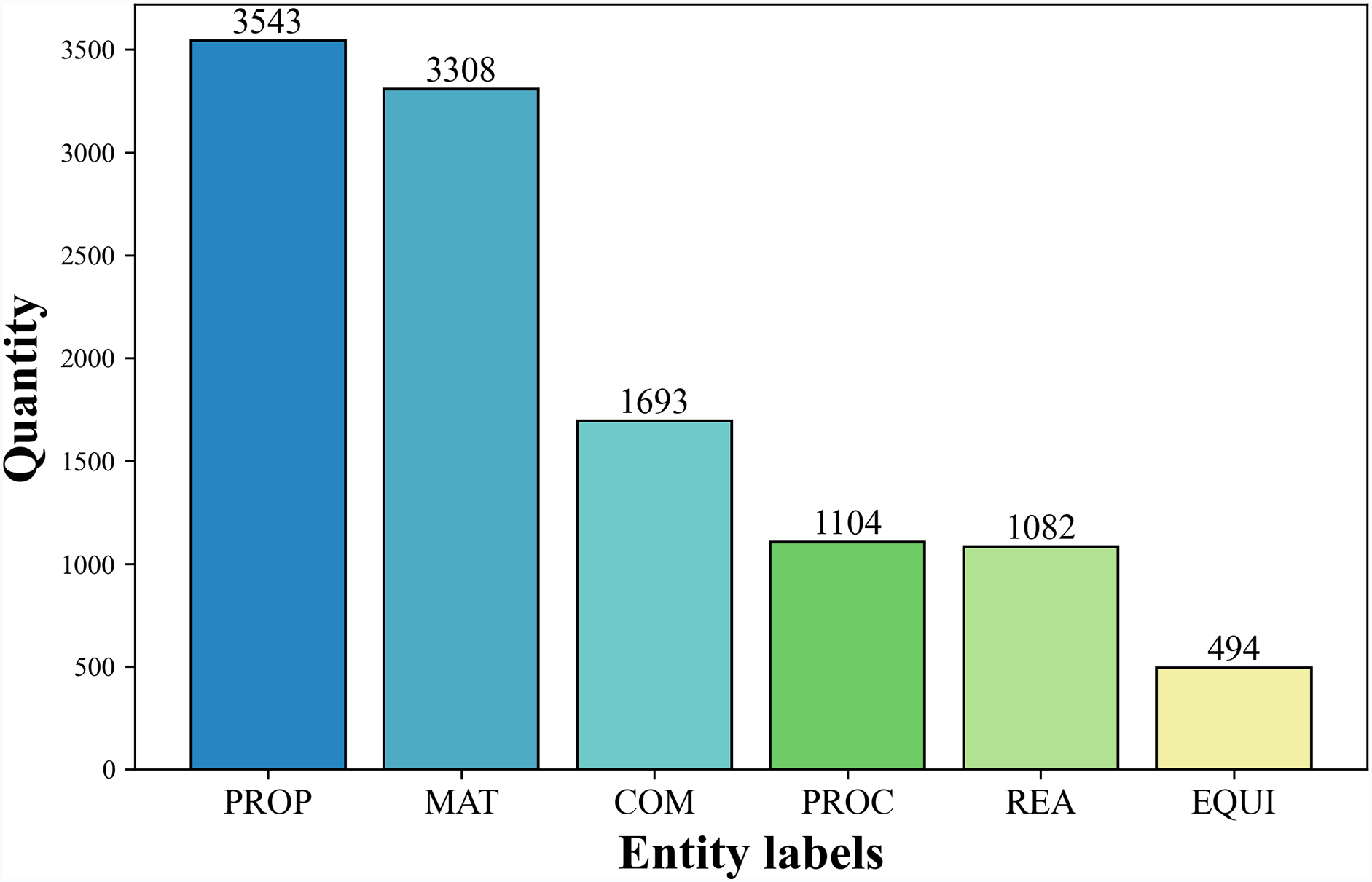

For the NER task, prevalent annotation frameworks encompass BIO, BMES, and BIOES formats. Our methodology employs the BIO schema for entity demarcation, wherein lexical markers operate as follows: the B (Begin) tag designates entity initiation boundaries, I (Inside) tags signify continuation components of multi-term entities, while O (Outside) tags mark non-relevant textual elements in fluorochemical knowledge extraction scenarios. Following the predefined entity classification framework, we define 13 entity labels, including: Material (B-MAT, I-MAT), Compound (B-COM, I-COM), Process (B-PROC, I-PROC), Property (B-PROP, I-PROP), Chemical Reagent (B-REA, I-REA), and Equipment (B-EQUI, I-EQUI), with O representing non-entity elements. An example of annotated text is presented in Table 2, while Fig. 1 illustrates the distribution of entity labels across the dataset.

Figure 1: Distribution of number of entities

Currently, the fluorinated material process domain lacks a standardized annotated dataset, and the annotation process is both time-consuming and resource-intensive. Given the specialized nature of this field, domain experts are required to ensure the accuracy and consistency of labeled data. Moreover, deep learning models for NER heavily rely on large-scale, high-quality annotated datasets, yet the scarcity of labeled resources significantly constrains model training and performance optimization.

Data augmentation techniques enhance dataset diversity through algorithmic transformations, allowing the expansion of training samples without additional manual annotation. This approach improves the generalization ability and robustness of machine learning models [28]. One widely adopted technique in Natural Language Processing (NLP) is Easy Data Augmentation (EDA), which has demonstrated effectiveness in text classification tasks [29]. EDA involves synonym replacement, random word order rearrangement, random insertion, and deletion to expand textual data.

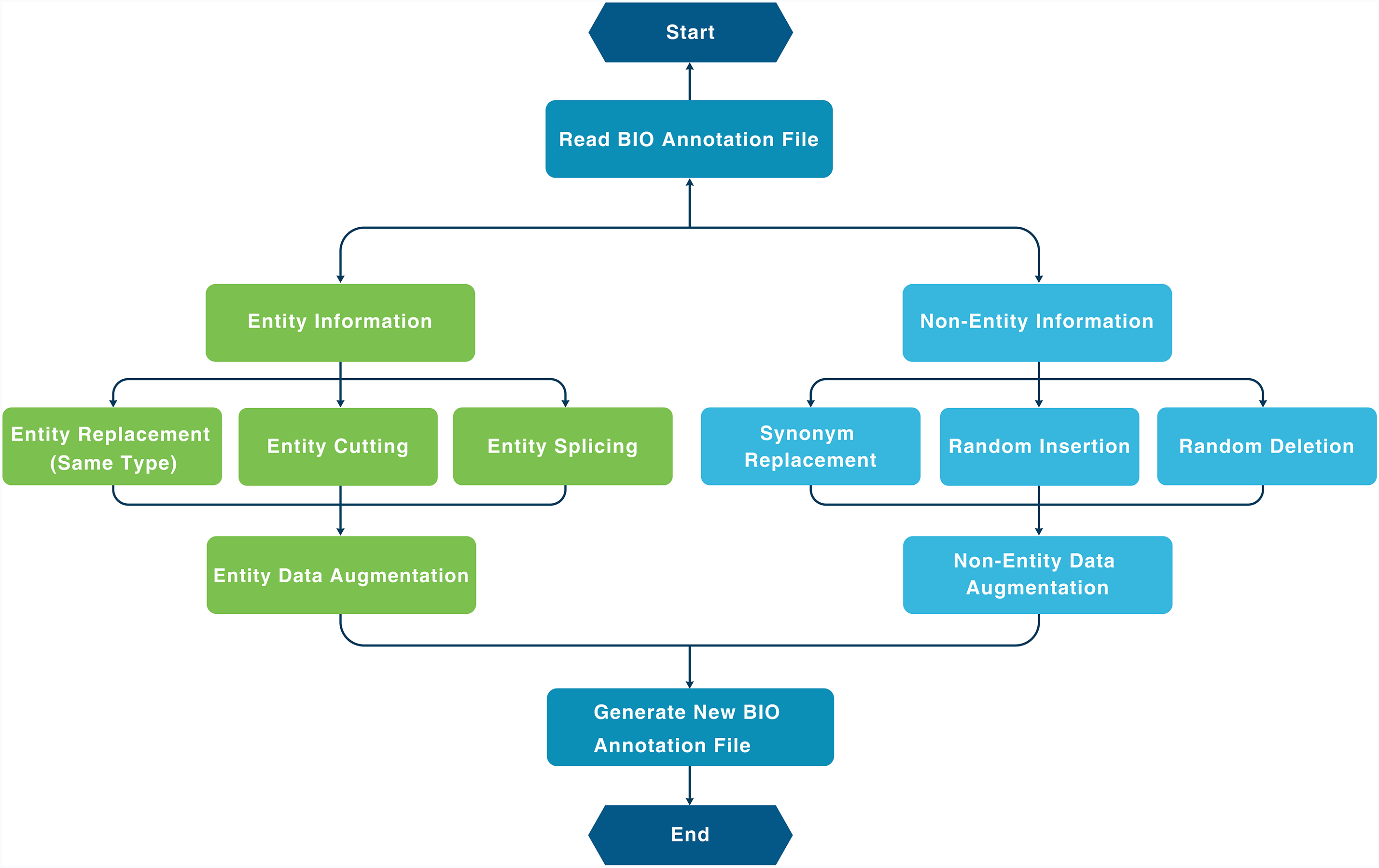

However, when applied to specialized chemical engineering texts, EDA exhibits significant limitations. The randomized operations can disrupt entity structure integrity, leading to ambiguous entity boundaries and semantic distortion. This issue is particularly pronounced in texts containing complex process parameters, such as reaction temperature thresholds and pressure regulation ranges, where data distortion introduces abnormal noise and compromises data quality control. Consequently, EDA is ill-suited for highly specialized fluorinated material process corpora. To address these challenges, this study proposes a hybrid augmentation strategy that balances diversity and coherence by applying differentiated operations to entity and non-entity spans. This modular design conceptually aligns with robustness-oriented architectures explored in other domains, such as visual saliency detection under uncertainty [30]. Fig. 2 demonstrates the technical architecture of this methodology.

Figure 2: Data augmentation

The augmentation process begins by loading the BIO-annotated dataset and categorizing tokens based on their label types (i.e., entity vs. non-entity). (1) For non-entity segments, three augmentation strategies are applied: ① Synonym Replacement: Domain-neutral, non-entity words are re-placed with semantically similar alternatives using a curated synonym lexicon. ② Random Insertion: Random words, including common adverbs, adjectives, or function words, are inserted into non-entity segments to introduce lexical diversity. ③ Random Deletion: Non-essential non-entity tokens (e.g., conjunctions or modifiers) are removed based on a fixed probability (e.g., p = 0.1) to simulate incomplete or noisy input (2) For entity segments, we implement three domain-specific augmentation strategies: ① Entity Replacement: Entities are randomly replaced with semantically equivalent entities of the same type, sourced from a curated pool of fluorinated materials domain terms. For example, the compound entity “偏氟乙烯三氟氯乙烯共聚物” (vinylidene fluoride-chlorotrifluoroethylene copolymer) may be replaced with “氟化乙烯丙烯共聚物 (FEP)” or “聚四氟乙烯 (PTFE)”, enriching the diversity of COM (compound) entities and improving generalization. ② Entity Segmentation: Annotated multi-word entities are decomposed into finer-grained subcomponents to simulate partial mentions in real-world contexts. For instance, the PROP (property) entity “高温热稳定性” (“high thermal stability”) can be split into “高温” (“high temperature”) and “热稳定性” (“thermal stability”), each tagged separately under the BIO labeling scheme. ③ Entity Expansion: Descriptive modifiers or process-specific attributes are appended to base entities to enrich contextual semantics. For example, the COM entity “混炼胶” (“compound rubber”) may be expanded to “用于密封圈的混炼胶” (“compound rubber for sealing rings”), and the REA (reagent) entity “交联剂” (“crosslinking agent”) can be expanded to “热稳定性能良好的交联剂” (“crosslinking agent with good thermal stability”). These augmented entity and non-entity samples are then integrated to generate a new BIO-annotated training set. To ensure data integrity and prevent information leakage, augmentation is applied exclusively to the training set, while the validation and test sets remain un-changed. As a result, the training corpus size is approximately doubled, improving the model’s exposure to diverse entity patterns and enhancing its robustness to structural and contextual variation.

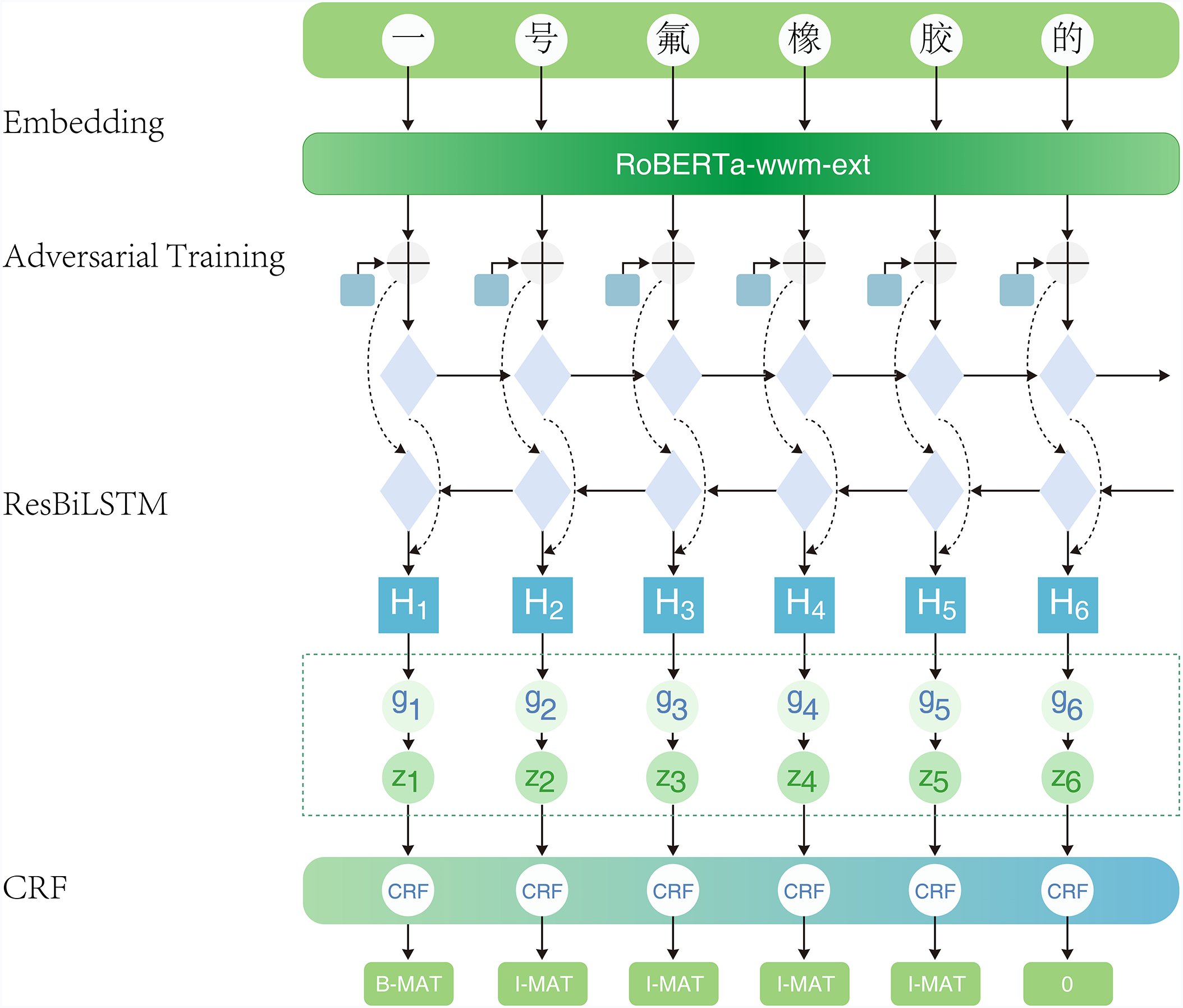

This paper proposes RRC-ADV, a NER model tailored for fluorinated material processing. It integrates four core modules: a RoBERTa-wwm feature extractor, an adversarial training mechanism, a Residual BiLSTM (ResBiLSTM) network, and a CRF decoding layer. The model is designed to balance contextual representation, robustness, and structural precision through multi-level feature integration. This modular design philosophy aligns with strategies adopted in other domains, where layered and task-specific components are fused to enhance generalization and efficiency, as exemplified by the layer-frozen assisted dual attention framework for deepfake detection [31]. The overall RRC-ADV model architecture is shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: RRC-ADV model structure

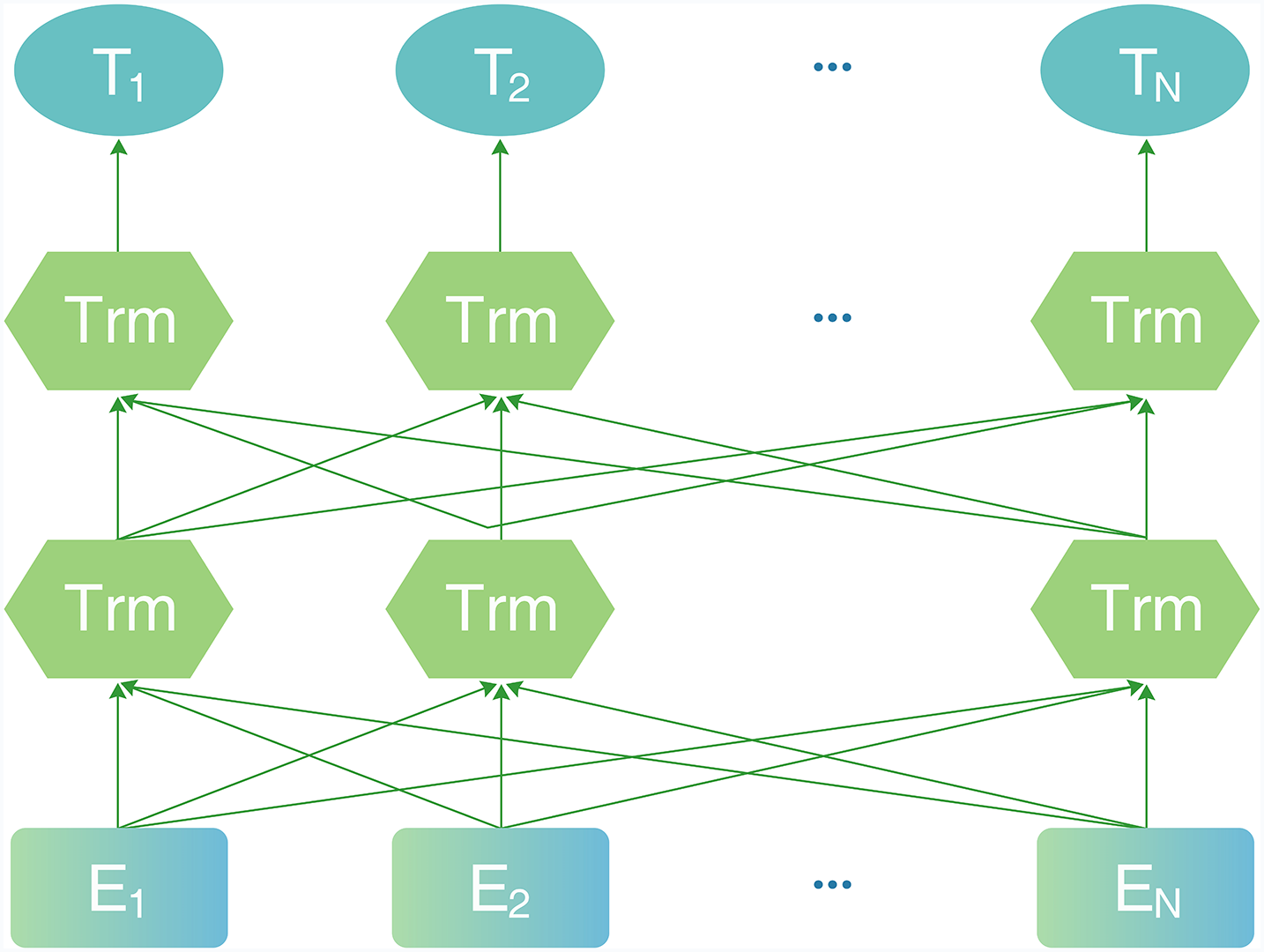

In this study we adopt RoBERTa-wwm (Robustly Optimized BERT Pretraining Approach) as the pre-trained language model to extract contextualized word representations tailored for the fluorinated materials NER task. This decision is motivated by several factors. First, compared to the original BERT, RoBERTa eliminates the Next Sentence Prediction (NSP) task and employs dynamic masking, enabling deeper contextual under-standing. Second, RoBERTa-wwm uses whole word masking, which ensures that all sub-word tokens of a word are masked simultaneously—particularly beneficial for scientific compound terms (e.g., “polyvinylidene fluoride”) that would otherwise be fragmented by character-level masking. In contrast, models like ALBERT, though lightweight, reduce parameter redundancy via embed-ding factorization, which can weaken expressiveness in fine-grained domain tasks. Moreover, while ChemBERTa and MatBERT perform well in general scientific domains, they are trained primarily on English corpora and lack pretraining on Chinese or chemical engineering-specific text, which limits their transferability to our domain. RoBERTa-wwm, pre-trained on large-scale Chinese corpora using a bidirectional transformer and whole word masking, is better suited for capturing contextual nuances of Chinese fluoropolymer terminology. The model structure of RoBERTa-wwm is illustrated in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: RoBERTa model structure

Adversarial training is a method that improves model robustness by adding perturbations to the training process. Its core idea is to apply small perturbations to input data, forcing the model to learn more resilient feature representations. This method was first proposed by Goodfellow et al. [32] in 2014 within the field of computer vision, where it demonstrated outstanding regularization effects in deep learning tasks. In 2016, Miyato et al. [33] were the first to apply adversarial training to natural language processing (NLP). By injecting perturbations into the word embedding layer, they overcame the non-differentiability issue arising from the discrete nature of textual data, allowing gradients to propagate effectively. Adversarial training not only improves a model’s adaptability to input variations but also enhances its generalization ability in scenarios where data is incomplete or contains noise. In the context of fluorinated material processing NER, this strategy effectively addresses challenges posed by the diversity of technical terminology and entity expressions. Specifically, it mitigates the limitations of traditional training methods in handling ambiguous entity boundaries. The mathematical formulation of this approach is as follows:

In this formulation, θ denotes the model parameters, x refers to the input data, y is the ground-truth label, δ represents the perturbation applied to create adversarial examples, and L stands for the loss function. The inner maximization operation searches the input space for perturbations δ that maximize the model’s loss L, thereby generating the worst-case adversarial sample. The outer minimization then adjusts the parameters θ to minimize the expected loss on these adversarial samples, compelling the model to optimize its performance on both adversarial examples and the original data, which in turn enhances its generalization and robustness.

In this study, we employ the Projected Gradient Descent (PGD) adversarial training strategy to enhance the model’s robustness to fluorinated material data. PGD iteratively applies perturbations in multiple steps to find the direction that maximizes the model’s loss, generating adversarial samples within a constrained range. This process forces the model to learn more robust features [34]. We selected PGD over alternatives such as Fast Gradient Sign Method (FGSM) and Virtual Adversarial Training (VAT) due to its stronger perturbation capability and easier integration. FGSM, while computationally efficient, often fails to expose sufficient input sensitivity in named entity recognition (NER) tasks. VAT, on the other hand, introduces additional regularization terms and virtual loss functions, increasing implementation complexity without yielding significant gains in our context. PGD was thus chosen for its solid theoretical grounding, effectiveness in handling sequence boundary fuzziness, and practical compatibility with our model architecture. The calculation formula is as follows:

In this context,

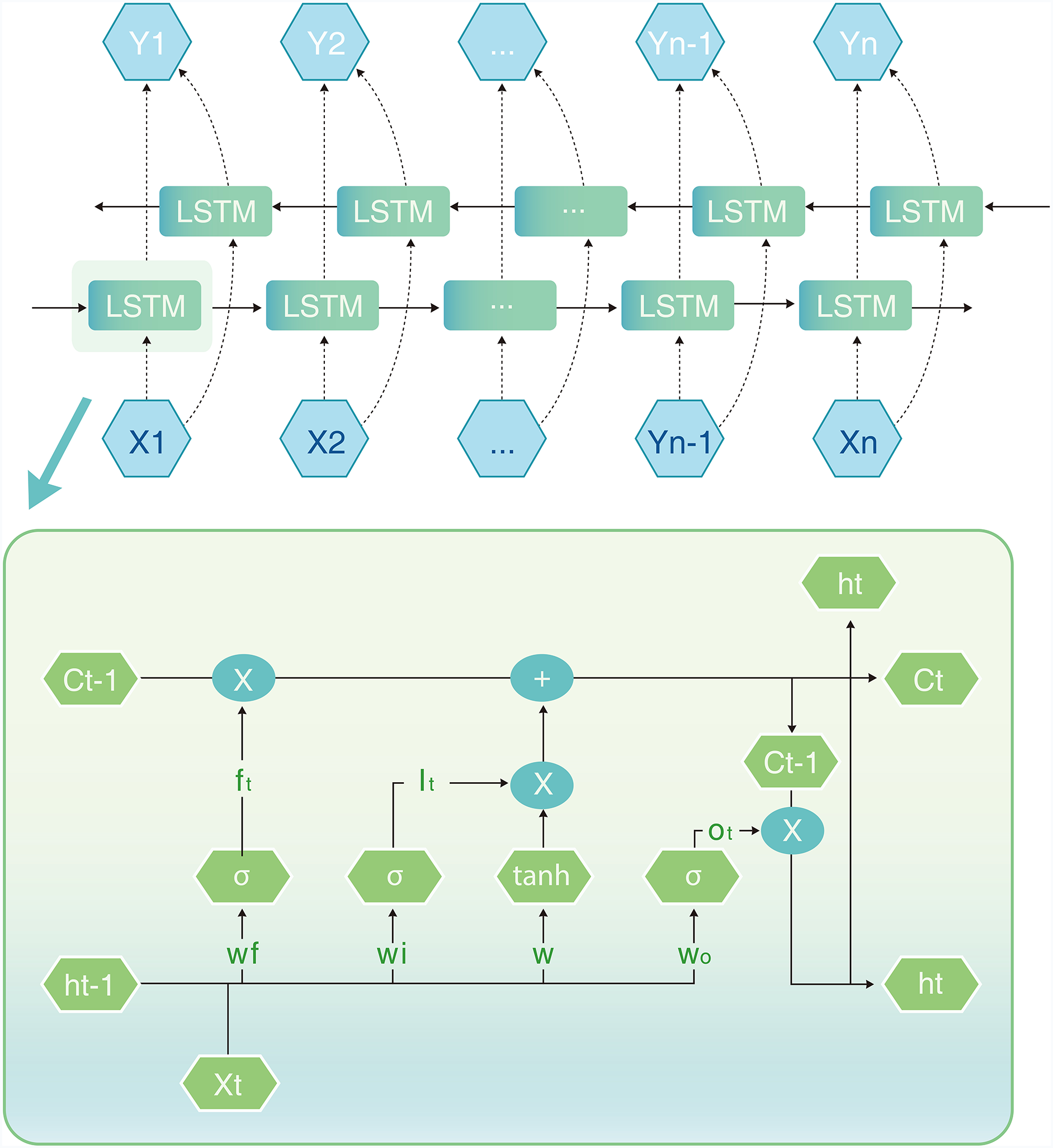

Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks are a type of Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), are well-suited for processing data with temporal dependencies, making them particularly advantageous for sequence modeling tasks like natural language processing. The core feature of LSTMs is the introduction of gating mechanisms—input gates, forget gates, and output gates—which precisely control the state of memory cells. This allows the network to dynamically update memory contents at each time step, effectively alleviating the vanishing and exploding gradient problems commonly encountered in traditional RNN training. Fig. 5 illustrates the architecture of LSTM.

Figure 5: LSTM structure

The input gate is responsible for controlling the update of the memory cell (Cell State) with new information. Its mathematical formula is as follows:

here,

The forget gate selects and decides what information to forget through matrix operations. Its formula is as follows:

where

The final output is decided by the output gate according to the current cell state, and its calculation formula is shown below:

where

The Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory network (BiLSTM) builds upon the traditional Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) architecture by incorporating both forward and backward propagation mechanisms. This design enables the model to capture dependencies in both directions within a sequence, allowing for a more comprehensive extraction of contextual information. Residual connections are introduced between the output of each BiLSTM layer and the input to the next layer, creating shortcut paths that directly pass the original input alongside the non-linear transformations of the current layer. This approach not only preserves the original features but also enhances the extraction of deeper representations, effectively reducing information loss. The ResBiLSTM model, which integrates the strengths of residual connections and bidirectional LSTMs, significantly improves overall performance and stability. It captures contextual dependencies more precisely, mitigates issues like vanishing and exploding gradients, and ensures the complete transmission of input information. Finally, a Conditional Random Field (CRF) layer is applied to the model’s output to perform entity labeling, making it more effective for sequence labeling tasks.

Conditional Random Fields (CRF) are a widely used probabilistic model for sequence labeling tasks, as they effectively incorporate contextual information by modeling the dependencies between labels to optimize the final prediction. Unlike traditional methods that predict each label independently, CRFs use a global optimization strategy that makes the label distribution within a sequence more consistent. In this study, we integrate the CRF decoding layer after the ReBiLSTM layer, leveraging the deep feature extraction capability of ReBiLSTM and combining it with the CRF’s advantage in modeling sequential dependencies to improve the consistency and accuracy of the prediction results.

The CRF computation process is as follows: Given a sequence

here,

where

All experiments were conducted on a Windows system equipped with an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3090 GPU, an Intel Core i7-14700K CPU, and 32 GB RAM. The development environment included PyCharm Community Edition, Python 3.9, PyTorch 1.13.1, and CUDA 11.6.

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed RRC-ADV model, we conducted a series of experiments using F1 score as the primary evaluation metric. The custom dataset comprising 2452 annotated samples was split into training, validation, and test sets in a 7:2:1 ratio. The training set was further expanded by a factor of two using the proposed hybrid data augmentation strategy.

Key hyperparameters were systematically tuned to optimize model performance. The batch size was tested with values of 16, 32, 64, and 128; the number of training epochs was varied from 10 to 50 (in increments of 10); and the learning rate was explored in the range of 1e − 5 to 6e − 5. The Adam optimizer was adopted for all experiments, with the dropout rate fixed at 0.1 to mitigate overfitting. For adversarial training, the maximum perturbation magnitude

In addition to baseline comparisons, we evaluated model stability by training RRC-ADV on datasets of varying sizes and examined the impact of different augmentation strategies. These experiments provided a comprehensive assessment of model performance.

The evaluation of model performance is based on three widely recognized metrics in the NER field: Precision, Recall, and F1Score. These indicators jointly provide a comprehensive measurement of the model’s effectiveness in identifying and classifying entities. Specifically, Precision (P) measures the proportion of correctly predicted positive entities out of all predictions labeled as positive. In contrast, recall (R) quantifies the ability of the model to retrieve all relevant positive samples from the ground truth. F1-Score is defined as the harmonic mean of Precision and Recall, offering a balanced metric that reflects both the accuracy and completeness of the model’s predictions:

where: TP (True Positives) refers to the count of entities correctly recognized by the model, FP (False Positives) denotes the number of incorrectly predicted entities, and FN (False Negatives) represents the entities that the model failed to detect.

5.3 Parameter Sensitivity Analysis

To achieve an optimal balance between model structure, training efficiency, and overall performance, this section focuses on fine-tuning key hyperparameters, particularly batch size, the number of epochs, and learning rate. The initial parameter settings are detailed in Table 3.

First, Batch size refers to how many samples are handled in each training step, and it directly affects both the training speed and the consistency of gradient descent. As shown in Table 4, the model’s recognition accuracy remained relatively stable for batch sizes between 16 and 128. Notably, when batch size was set to 32, the model achieved the highest F1 score of 85.48%.

Second, the number of epochs represents the total iterations over the entire training dataset and significantly affects both model convergence speed and final performance. The experimental results (Table 5) indicate that as the number of epochs increased, the model’s performance improved progressively, reaching an optimal F1 score of 87.22% at 40 epochs. Beyond this point, slight overfitting was observed.

Furthermore, additional experiments were conducted to optimize the learning rate. Different values were tested to examine their effect on model performance. As shown in Table 6, an appropriately tuned learning rate ensures stable gradient updates while accelerating model convergence. The results indicate that setting the learning rate to 5e − 5 provided the best balance between stable training and optimal performance.

5.4 Comparison of Different NER Models

To evaluate the effectiveness of the RRC-ADV model, we conducted named entity recognition (NER) experiments on the constructed dataset. The experimental design was divided into two parts: (1) exploring the impact of different embedding techniques; and (2) examining the performance of various downstream architectures under a unified embedding configuration. The selected models include BiLSTM-CRF, BERT-BiLSTM-CRF, ALBERT-BiLSTM-CRF, RoBERTa-wwm-CRF, RoBERTa-wwm-BiLSTM-CRF, and RoBERTa-wwm-adv-BiLSTM-CRF. In addition, we compared our model against domain-specific pre-trained models such as MatBERT-CRF and ChemBERTa-CRF. The experimental results are summarized in Table 7.

The experimental results are shown in Table 7, pre-trained models exhibit significant advantages in entity recognition tasks, with F1 scores consistently exceeding those of non-pre-trained models (BiLSTM-CRF) by more than 5%. This improvement is primarily attributed to the deep network structure of pre-trained models, which enables more efficient learning of linguistic features. Furthermore, RoBERTa-wwm-BiLSTM-CRF outperforms both BERT-BiLSTM-CRF and ALBERT-BiLSTM-CRF across all key metrics. Specifically, it achieves improvements of 1.18, 1.69, and 1.33 percentage points in Precision, Recall, and F1 score, respectively, over BERT-BiLSTM-CRF. Compared to ALBERT-BiLSTM-CRF, the improvements are 2.09, 2.11, and 2.07 percentage points, respectively. These results highlight the effectiveness of RoBERTa-wwm as an embedding layer in enhancing semantic representation, addressing incomplete word recognition, and ultimately improving NER performance in the fluoropolymer domain.

Moreover, integrating adversarial training into the RoBERTa-wwm-BiLSTM-CRF model further improves its Precision, Recall, and F1 scores by 1.44, 1.9, and 1.78 percentage points, respectively. The addition of a residual-connected BiLSTM structure leads to further gains of 0.45, 0.46, and 0.59 percentage points across the same metrics. These results confirm that adversarial training and residual networks contribute to enhancing the model’s effectiveness in the NER task for fluoropolymer processing.

Although ChemBERTa and MatBERT are well-regarded in English-domain scientific NLP tasks, their performance on our dataset is limited due to the language mismatch. Both models were pre-trained exclusively on English corpora and lack any exposure to Chinese syntax, morphology, or domain-specific expressions in fluorinated materials. Consequently, despite their scientific focus, they fall short compared to Chinese-native models like RoBERTa-wwm in capturing contextual and boundary-level cues in Chinese NER.

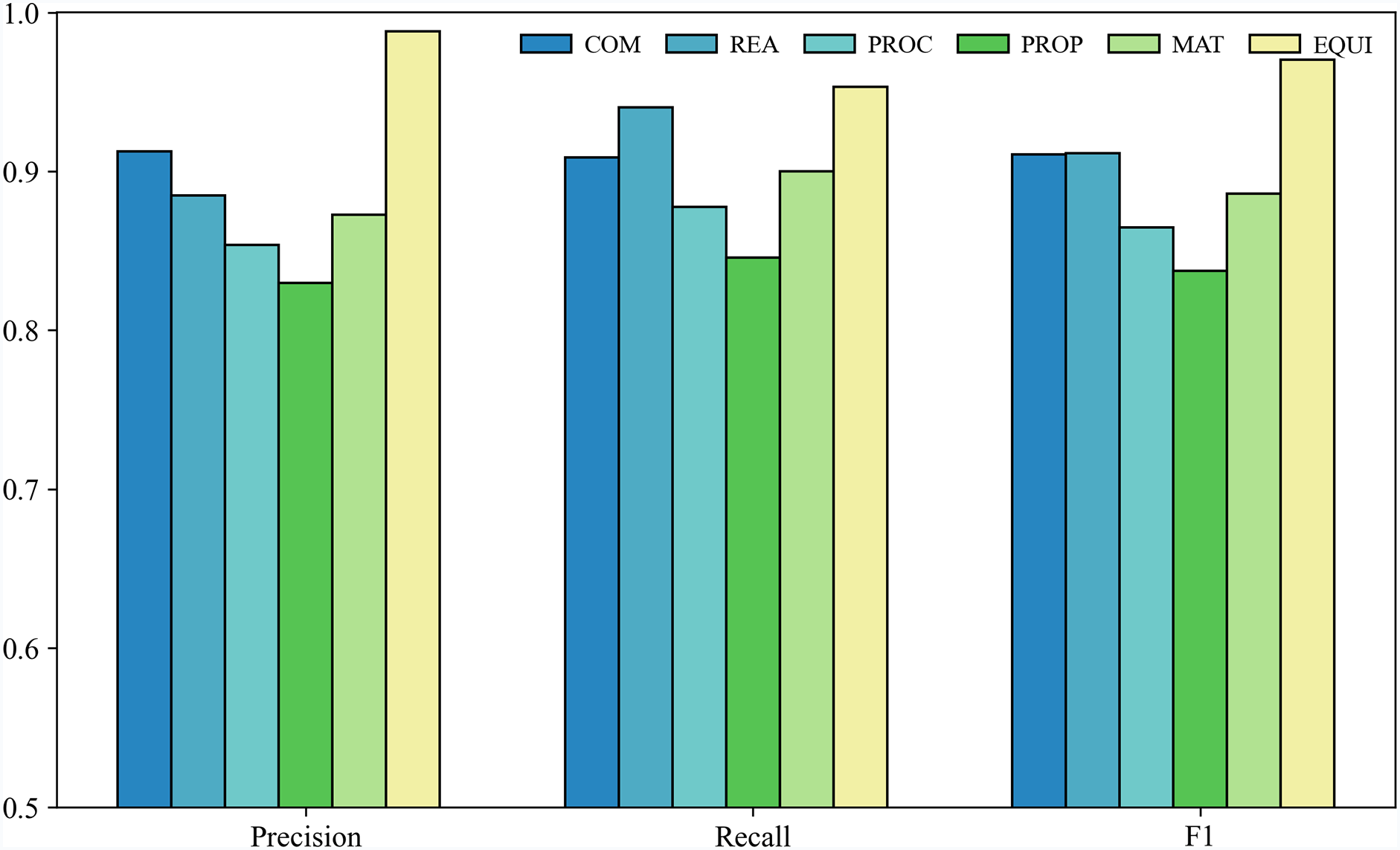

5.5 Results of Entity Recognition

The RRC-ADV model was systematically evaluated on a self-constructed named entity recognition (NER) dataset specific to the fluorinated materials domain. This dataset comprises six annotated entity categories: Material (MAT), Compound (COM), Process (PROC), Property (PROP), Chemical Reagent (REA), and Equipment (EQUI). As shown in Fig. 6, the model achieved strong overall performance. Among the six categories, five—MAT, COM, REA, PROC, and EQUI—attained relatively high recognition accuracy, with F1 scores all exceeding 86%.

Figure 6: Results of entity recognition

In contrast, although Property (PROP) entities were the most frequently occurring in the dataset they achieved the lowest F1 score (82.30%). This paradoxical outcome, where a high-frequency entity performs poorly, can be attributed to a combination of domain-specific linguistic challenges, annotation inconsistencies, and structural learning limitations. First, PROP entities exhibit high semantic variability and syntactic complexity. Unlike MAT or EQUI entities, which typically appear as discrete and fixed noun phrases, PROP expressions are often embedded within broader descriptive contexts and vary significantly in form. They may involve multi-word modifiers, nested numerical conditions, or loosely bound clause structures. For example: “excellent resistance to hydrofluoric acid”, “thermal degradation stability under 300°C”, “low dielectric loss at high frequencies”. These expressions differ substantially in length, granularity, and structure, frequently spanning across multiple syntactic units. This makes BIO-based boundary labeling more error-prone, as it becomes difficult for the model to consistently distinguish entity spans from descriptive context. Second, the lack of standardized vocabulary for material properties introduces substantial ambiguity during both annotation and learning. Generic terms such as “stability”, “resistance”, or “performance” are semantically broad and highly context-sensitive, often taking on different meanings depending on their modifiers. This leads to inconsistent annotations across annotators. Third, while PROP entities are frequent, they also display high intra-class lexical diversity. This diversity weakens the statistical regularity needed for effective learning.

By contrast, the Equipment (EQUI) category, despite having the smallest number of instances, achieved the highest F1 score among all categories. This superior performance is primarily due to the regular structure and clear semantics of equipment-related terminology. Equipment names such as “high-temperature sintering furnace”, “flat-plate vulcanizing press”, and “two-roll open mill” typically appear as well-formed noun phrases with stable syntax and standardized expression. Furthermore, equipment entities are often embedded within functionally specific technical contexts, such as descriptions of experimental setups or process steps. These consistent contextual patterns provide strong cues for the model, greatly enhancing its ability to accurately identify entity boundaries and classifications.

In the RRC-ADV model, ablation experiments were conducted by removing the RoBERTa-wwm, ResBiLSTM, and Adversarial Training layers, and their performance was compared with that of the full model, as presented in Table 8.

To better understand the contributions of each module in the RRC-ADV architecture, we per-formed ablation experiments and analyzed the results in Table 8. Among all components, RoBERTa-wwm plays the most critical role, with its removal leading to a significant drop in F1 score (−4.44%). This is primarily due to its whole-word masking and dynamic context modeling, which are essential for handling domain-specific compound terms and long-span scientific entities. Its strengths lie in capturing rich semantic features, especially in cases with polysemous terminology or entity synonyms (e.g., “PTFE”, “polytetrafluoroethylene”).

The ResBiLSTM layer enhances the model’s ability to extract sequential and contextual dependencies across both forward and backward directions. Its residual connections help preserve shallow lexical patterns while allowing deeper layers to focus on syntactic transitions. The ablation results show that removing ResBiLSTM leads to a moderate performance drop (−3.10% in F1), indicating its role in improving long-range boundary detection, particularly in nested or multiword entities. However, its benefits are less pronounced on short, fixed-form entity types such as equipment names.

The adversarial training module, while showing a relatively smaller F1 drop (−1.86%), contributes to robustness under fuzzy boundary and noisy input conditions. It is especially beneficial for irregular property descriptions where the boundaries are context-dependent. Its key limitation is the additional computational overhead during training and the challenge of hyperparameter tuning (e.g., perturbation magnitude).

In summary, RoBERTa-wwm provides the core semantic expressiveness, ResBiLSTM enhances sequence modeling and boundary precision, and adversarial training improves robustness against ambiguity and variation. The combination of these modules results in a model that is both semantically rich and structurally precise, capable of handling complex NER scenarios in the fluorinated materials domain.

5.7 Ablation Study of Data Augmentation Strategies across Entity Types

To better understand the contribution of each augmentation strategy, we conduct an ablation study by comparing the baseline dataset with three augmentation configurations: non-entity augmentation, entity-only augmentation, and a combined strategy.

Table 9 presents a comparative analysis of different data augmentation strategies across six entity types. We observe that non-entity augmentation brings moderate gains (approximately 1%–2% F1) to categories such as COM and PROP, which are highly context-sensitive. In contrast, entity-only augmentation significantly benefits REA, MAT, and EQUI entities, which often exhibit longer spans and greater lexical diversity. The combined augmentation strategy yields the best results across all categories, demonstrating the complementary nature of entity- and non-entity-focused enhancements. Notably, the F1 score for EQUI improved from 85.1% to 97.0%, and for PROP from 78.7% to 83.7%, highlighting the importance of augmentation in addressing data sparsity and semantic variability.

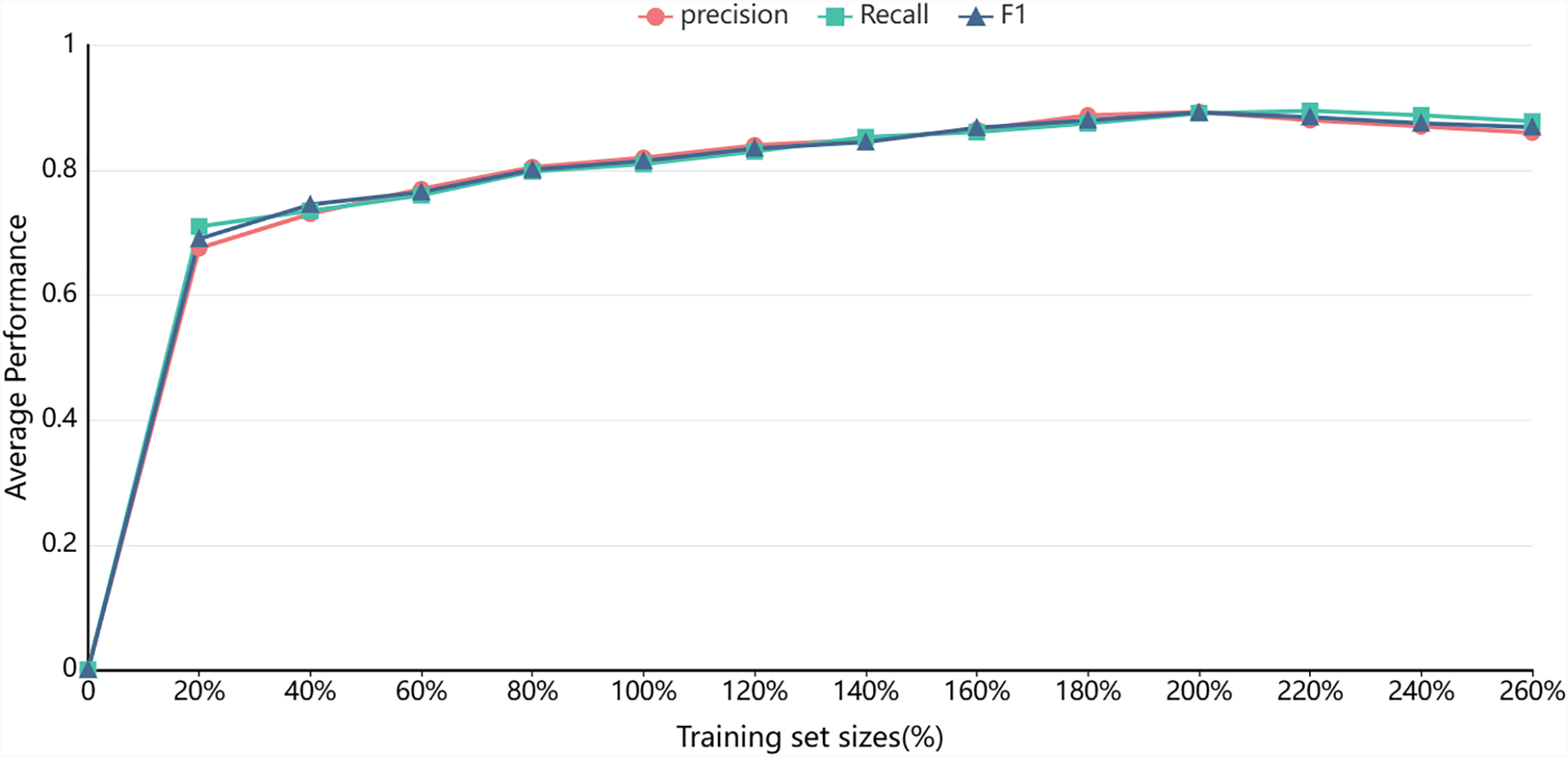

5.8 Varying Training Dataset Sizes

To systematically evaluate the impact of annotation dataset size on model performance, this study designed a series of controlled experiments. First, the original training set was randomly sampled at varying proportions to create benchmark datasets ranging from 20% to 100% of the original data (with 100% corresponding to the unaugmented, original annotated data). Subsequently, using the hybrid data augmentation method proposed in Section 3.3, the training set was gradually expanded to 260% of its original size, as illustrated in Fig. 7.

Figure 7: Mean precision, recall, and F1-score across varying data sizes

The experimental results indicate that when 40% of the original training data is used, the RRC-ADV model achieves an F1 score of 74.20%, demonstrating its effective learning capability in low-resource scenarios. As the training dataset size increases, the model’s performance exhibits a significant positive growth trend, further validating the effectiveness of the proposed hybrid augmentation strategy. Expanding the dataset size while maintaining data quality significantly enhances the model’s ability to recognize complex entities. The model achieves optimal performance when the dataset size is expanded to 200%. However, beyond this threshold, the precision metric tends to plateau, indicating diminishing marginal returns from further data expansion. Additionally, the results suggest that in the Named Entity Recognition (NER) task within the fluoropolymer processing domain, improving the representativeness and quality of annotated data is more critical than merely increasing dataset size. Future research could incorporate domain knowledge-driven augmentation strategies to further enhance the specificity and effectiveness of data augmentation, thereby improving model performance more efficiently.

This study addresses the challenges faced in Named Entity Recognition (NER) within the domain of fluorinated materials processing through a systematic research approach. First, a domain-specific Chinese NER dataset was constructed by integrating heterogeneous data sources—including scientific literature, patents, and technical documents—and applying a combination of improved Easy Data Augmentation (EDA) and manual annotation. To enhance entity recognition accuracy and domain adaptability, we propose a novel NER model, RRC-ADV, which integrates RoBERTa-wwm, Residual Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (ResBiLSTM) networks, adversarial training, and a Conditional Random Field (CRF) layer. The proposed model leverages the semantic modeling strength of RoBERTa-wwm on specialized corpora, the sequential feature extraction capability of ResBiLSTM, and the robustness of adversarial training to handle fuzzy entity boundaries. The CRF layer further refines the output by globally optimizing label sequences. Experimental results show that RRC-ADV outperforms baseline models on the custom-built fluorinated materials dataset. Ablation studies validate the effectiveness of each module in improving recognition performance. Additionally, the model demonstrates strong robustness and adaptability within the fluorinated materials domain, indicating its reliability for handling varied entity types and complex linguistic expressions in this specialized field.

Notably, the dataset used in this study contains only 2452 annotated samples, which is relatively small for deep learning-based NER tasks. This limited scale raises concerns about the model’s generalization capacity and the statistical significance of the reported improvements. Furthermore, the constrained dataset size hinders the reproducibility of results across broader scientific and industrial domains. To address this issue, future work will focus on expanding the dataset in both size and diversity by incorporating additional sources such as industrial white papers, internal technical reports, and international patents. In addition, given the high cost and low consistency of manual annotation, we plan to explore automated annotation methods based on large language models (LLMs) to reduce human effort and enhance data quality. Beyond data scale and quality, we also observed notable performance variation across entity types in our experiments. Specifically, the PROP entities achieved the lowest F1 score despite being the most frequent. Through detailed analysis, we attribute this discrepancy to a combination of annotation inconsistency, boundary ambiguity, and high intra-class variability. To mitigate these challenges, future work will explore adaptive decoding mechanisms, such as class-aware loss weighting, to better handle difficult entity types. Moreover, recognizing the limitations of uniform data augmentation, we intend to design targeted augmentation strategies tailored to underperforming or structurally complex entities.

Further studies will extend this work into relation extraction, aiming to construct a domain knowledge graph for fluorinated materials processing. The resulting knowledge graph will serve as a foundational resource to support intelligent question answering and process optimization systems in the fluorinated materials domain, providing intelligent technical support for R & D, manufacturing, and application.

Acknowledgement: We sincerely thank Daoming Lv for his invaluable guidance throughout our research. We also gratefully acknowledge the support and resources offered by the School of Computer Science and Engineering at Sichuan University of Science and Engineering, which significantly contributed to this work.

Funding Statement: Our research was funded by the Opening Fund of Key Laboratory of Higher Education of Sichuan Province for Enterprise Informationalization and Internet of Things (No. 2023WYJ06) and the Yadong Wu Talent Program (No. H31225001); supported in part by the Defense Industrial Technology Development Program (No. JCKY2022404C001); and by the Sichuan Provincial Key Lab of Process Equipment and Control’s Project (No. GK201509).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Jiming Lan, Hongwei Fu, Yadong Wu; data collection: Hongwei Fu; analysis and interpretation of results: Jiming Lan, Hongwei Fu, Yadong Wu; draft manuscript preparation: Jiming Lan, Hongwei Fu, Yadong Wu, Yaxian Liu, Jianhua Dong, Wei Liu, Huaqiang Chen. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Chen Y, Luo C, Hu F, Huang Z, Yue K. Recent advances in fluorinated polymers: synthesis and diverse applications. Sci China Chem. 2023;66(12):3347–59. doi:10.1007/s11426-023-1831-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Ji S, Pan S, Cambria E, Marttinen P, Yu PS. A survey on knowledge graphs: representation, acquisition, and applications. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2022;33(2):494–514. doi:10.1109/tnnls.2021.3070843. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Aggour KS, Detor A, Gabaldon A, Mulwad V, Moitra A, Cuddihy P, et al. Compound knowledge graph-enabled AI assistant for accelerated materials discovery. Integr Mater Manuf Innov. 2022;11(4):467–78. doi:10.1007/s40192-022-00286-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Ge W, Zhou J, Zheng P, Yuan L, Rottok LT. A recommendation model of rice fertilization using knowledge graph and case-based reasoning. Comput Electron Agric. 2024;219(6):108751. doi:10.1016/j.compag.2024.108751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Gong C, Wei Z, Wang R, Zhu P, Chen J, Zhang H, et al. Incorporating multi-perspective information into reinforcement learning to address multi-hop knowledge graph question answering. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;255(8):124652. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2024.124652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Chen X, Jia S, Xiang Y. A review: knowledge reasoning over knowledge graph. Expert Syst Appl. 2020;141(6):112948. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2019.112948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Liu Y, Ott M, Goyal N, Du J, Joshi M, Chen D, et al. RoBERTa: a robustly optimized bert pretraining approach. arXiv:1907.11692. 2019. [Google Scholar]

8. Yasunaga M, Kasai J, Radev D. Robust multilingual part-of-speech tagging via adversarial training. arXiv:1711.04903v2. 2018. [Google Scholar]

9. Yang G, Xu H. A residual BiLSTM model for named entity recognition. IEEE Access. 2020;8:227710–8. doi:10.1109/access.2020.3046253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Grishman R, Sundheim B. Message understanding conference-6: a brief history. In: Proceedings of the 16th Conference on Computational Linguistics; 1996 Aug 5–9; Copenhagen, Denmark. doi:10.3115/992628.992709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Isozaki H, Kazawa H. Efficient support vector classifiers for named entity recognition. In: Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Computational Linguistics; 2002 Aug 24–Sep 1; Taipei, Taiwan. doi:10.3115/1072228.1072282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Rabiner L, Juang B. An introduction to hidden Markov models. IEEE ASSP Mag. 1986;3(1):4–16. doi:10.1109/MASSP.1986.1165342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. McCallum A, Freitag D, Pereira FC. Maximum entropy Markov models for information extraction and segmentation. In: Proceedings of the Twentieth International Conference on Machine Learning; 2003 Aug 21–24; Washington, DC, USA. [Google Scholar]

14. Lafferty J, McCallum A, Pereira F. Conditional random fields: probabilistic models for segmenting and labeling sequence data [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jul 21]. Available from: https://repository.upenn.edu/handle/20.500.14332/6188. [Google Scholar]

15. Li J, Sun A, Han J, Li C. A survey on deep learning for named entity recognition. IEEE Trans Knowl Data Eng. 2020;34(1):50–70. doi:10.1109/TKDE.2020.2981314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. LeCun Y, Boser B, Denker JS, Henderson D, Howard RE, Hubbard W, et al. Backpropagation applied to handwritten zip code recognition. Neural Comput. 1989;1(4):541–51. doi:10.1162/neco.1989.1.4.541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Cho K, Van Merriënboer B, Gulcehre C, Bahdanau D, Bougares F, Schwenk H, et al. Learning phrase representations using RNN encoder-decoder for statistical machine translation. arXiv:1406.1078v3. 2014. [Google Scholar]

18. Hochreiter S, Schmidhuber J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 1997;9(8):1735–80. doi:10.1162/neco.1997.9.8.1735. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Huang Z, Xu W, Yu K. Bidirectional LSTM-CRF models for sequence tagging. arXiv:1508.01991v1. 2015. [Google Scholar]

20. Ma X, Hovy E. End-to-end sequence labeling via bi-directional LSTM-CNNs-CRF. arXiv:1603.01354v5. 2016. [Google Scholar]

21. Chen XL, Tang LY, Hu Y, Jiang F, Peng L, Feng XC. The extraction method of knowledge entities and relationships of landscape plants based on ALBERT model. J Glob Inf Sci. 2021;23:1208–20. doi:10.12082/dqxxkx.2021.200565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Dai Z, Wang X, Ni P, Li Y, Li G, Bai X. Named entity recognition using BERT BiLSTM CRF for Chinese electronic health records. In: Proceedings of the 2019 12th International Congress on Image and Signal Processing, BioMedical Engineering and Informatics (CISP-BMEI); 2019 Oct 19–21; Suzhou, China. doi:10.1109/cisp-bmei48845.2019.8965823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Yu Y, Wang Y, Mu J, Li W, Jiao S, Wang Z, et al. Chinese mineral named entity recognition based on BERT model. Expert Syst Appl. 2022;206:117727. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2022.117727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Chithrananda S, Grand G, Ramsundar B. ChemBERTa: large-scale self-supervised pretraining for molecular property prediction. arXiv:2010.09885v2. 2020. [Google Scholar]

25. Zhang W, Wang C, Wu H, Zhao C, Teng G, Huang S, et al. Research on the Chinese named-entity-relation-extraction method for crop diseases based on BERT. Agronomy. 2022;12(9):2130. doi:10.3390/agronomy12092130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Pan Z, Shu C, Xin Z, Xie C, Shen Q, Yang Y. Material calculation collaborates with grain morphology knowledge graph for material properties prediction. In: 2022 IEEE 25th International Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work in Design (CSCWD); 2022 May 4–6; Hangzhou, China. doi:10.1109/CSCWD54268.2022.9776104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Nie Z, Zheng S, Liu Y, Chen Z, Li S, Lei K, et al. Automating materials exploration with a semantic knowledge graph for Li-ion battery cathodes. Adv Funct Materials. 2022;32(26):2201437. doi:10.1002/adfm.202201437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Dai X, Adel H. An analysis of simple data augmentation for named entity recognition. arXiv:2010.11683v1. 2020. [Google Scholar]

29. Wei J, Zou K. EDA: easy data augmentation techniques for boosting performance on text classification tasks. arXiv:1901.11196v2. 2019. [Google Scholar]

30. Khan H, Usman MT, Koo J. Bilateral feature fusion with hexagonal attention for robust saliency detection under uncertain environments. Inf Fusion. 2025;121(7):103165. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2025.103165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Talha Usman M, Khan H, Kumar Singh S, Lee MY, Koo J. Efficient deepfake detection via layer-frozen assisted dual attention network for consumer imaging devices. IEEE Trans Consum Electron. 2025;71(1):281–91. doi:10.1109/TCE.2024.3476477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Goodfellow IJ, Shlens J, Szegedy C. Explaining and harnessing adversarial examples. arXiv:1412.6572v3. 2015. [Google Scholar]

33. Miyato T, Dai AM, Goodfellow I. Adversarial training methods for semi-supervised text classification. arXiv:1605.07725v4. 2021. [Google Scholar]

34. Madry A, Makelov A, Schmidt L, Tsipras D, Vladu A. Towards deep learning models resistant to adversarial attacks. arXiv:1706.06083v4. 2019. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools