Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

LOEV-APO-MLP: Latin Hypercube Opposition-Based Elite Variation Artificial Protozoa Optimizer for Multilayer Perceptron Training

1 School of Computer Science, Hubei University of Technology, Wuhan, 430068, China

2 Hubei Provincial Key Laboratory of Green Intelligent Computing Power Network, Wuhan, 430068, China

3 Hubei Provincial Engineering Technology Research Centre, Wuhan, 430068, China

* Corresponding Author: Haitao Xie. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(3), 5509-5530. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.067342

Received 30 April 2025; Accepted 28 August 2025; Issue published 23 October 2025

Abstract

The Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) is a fundamental neural network model widely applied in various domains, particularly for lightweight image classification, speech recognition, and natural language processing tasks. Despite its widespread success, training MLPs often encounter significant challenges, including susceptibility to local optima, slow convergence rates, and high sensitivity to initial weight configurations. To address these issues, this paper proposes a Latin Hypercube Opposition-based Elite Variation Artificial Protozoa Optimizer (LOEV-APO), which enhances both global exploration and local exploitation simultaneously. LOEV-APO introduces a hybrid initialization strategy that combines Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS) with Opposition-Based Learning (OBL), thus improving the diversity and coverage of the initial population. Moreover, an Elite Protozoa Variation Strategy (EPVS) is incorporated, which applies differential mutation operations to elite candidates, accelerating convergence and strengthening local search capabilities around high-quality solutions. Extensive experiments are conducted on six classification tasks and four function approximation tasks, covering a wide range of problem complexities and demonstrating superior generalization performance. The results demonstrate that LOEV-APO consistently outperforms nine state-of-the-art metaheuristic algorithms and two gradient-based methods in terms of convergence speed, solution accuracy, and robustness. These findings suggest that LOEV-APO serves as a promising optimization tool for MLP training and provides a viable alternative to traditional gradient-based methods.Keywords

The perceptron, first introduced by American scientist Frank Rosenblatt in 1957 [1], represents a pioneering linear classification model. Utilizing a single-layer neural structure with a simple threshold activation function, the perceptron efficiently performs binary classification tasks and is widely recognized as the foundational concept that catalyzed the development of advanced methods, including neural networks (NNs) and support vector machines (SVMs) [2]. Despite its simplicity, efficiency, and ease of implementation on linearly separable datasets [3], the perceptron’s performance deteriorates significantly when handling nonlinear or intricate decision boundaries [4]. In contrast to SVMs that utilize kernel methods to map data onto higher-dimensional feature spaces, single-layer perceptrons rely solely on linear hyperplanes, rendering them ineffective for modeling complex, multimodal data distributions [5].

To overcome these limitations, researchers introduced the multilayer perceptron (MLP), an advanced form of feedforward neural network (FNN) that has garnered extensive attention due to its powerful nonlinear mapping capabilities [6]. By integrating multiple hidden layers and nonlinear activation functions such as Sigmoid, ReLU, or Tanh, MLPs theoretically achieve universal approximation of continuous functions [7]. A typical MLP structure consists of an input layer, several hidden layers, and an output layer, with neurons fully interconnected across adjacent layers [8]. Through successive linear transformations and nonlinear activations, MLPs effectively model complex data patterns, leading to notable breakthroughs in fields such as image classification, speech recognition, and natural language processing [9]. For instance, Hou et al. [10] successfully proposed a permutable MLP architecture for visual recognition tasks, and Wei et al. [11] recently demonstrated their effectiveness in large-scale language modeling. Moreover, MLPs-based classifiers have proven particularly valuable in healthcare applications, facilitating early disease diagnosis through predictive analytics [12].

Nevertheless, the effectiveness of MLPs critically depends on the optimal adjustment of their network parameters, highlighting the necessity of efficient optimization methods [13]. Traditional gradient-based methods, such as Gradient Descent (GD) and its variants like Backpropagation (BP), have become standard due to their intuitive error propagation mechanisms [14]. However, these methods are often hindered by issues such as susceptibility to the local optima, saddle points, limited generalization, and significantly increased computational complexity when dealing with large-scale datasets or deep architectures. For example, Narkhede et al. [15] showed that standard BP struggles to train deep networks effectively without careful initialization strategies like Xavier initialization.

The limitations of gradient-based methods have spurred growing interest in heuristic optimization techniques, particularly swarm intelligence (SI) algorithms inspired by collective biological behaviors. Prominent SI algorithms include Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) [16], Multi-Verse Optimiser (MVO) [17], Catch Fish Optimization Algorithm (CFOA) [18], and Information-Exchanged Gaussian Arithmetic Optimization Algorithm (IEGQO-AOA) [19]. These population-based methods have demonstrated superior capabilities in navigating complex optimization landscapes through inherent parallelism and global search mechanisms. Beyond neural network training, SI algorithms have found applications in feature selection, data clustering, and engineering design optimization [20]. Their ability to avoid the local optima renders them particularly suitable for MLP parameter optimization in high-dimensional, multimodal search spaces [21]. Nevertheless, when scaling to modern deep learning architectures such as CNNs and Transformers with millions of parameters, swarm intelligence algorithms face substantial computational overhead due to high-dimensional parameter spaces and multiple fitness evaluations, potentially limiting their practical applicability to large-scale models.

However, according to the “No Free Lunch” theorem [22], no algorithm can outperform all others across all problems. Existing SI-based approaches often suffer from insufficient initial exploration, premature convergence, or inadequate local search intensification. For instance, while Grey wolf optimizer (GWO) [23] demonstrates efficient search patterns based on social hierarchy, it can struggle with maintaining population diversity in large-scale problems [24]. Similarly, PSO’s performance can deteriorate in high-dimensional spaces without careful parameter tuning [25]. These issues become particularly critical when training MLPs for real-world applications in healthcare, agriculture, and engineering, where datasets present diverse dimensionalities and complex fitness landscapes.

To address these challenges, recent studies have proposed hybrid strategies and enhanced initialization mechanisms. Chatterjee et al. [26] applied particle swarm optimization-trained neural networks to structural failure prediction of multistoried RC buildings, while Guo et al. [27] developed specialized initialization techniques for high-dimensional optimization. Further advancements include competing leadership hierarchies in CGWO [28]. Nevertheless, many of these methods are tailored for specific applications or require complex parameter tuning, thus limiting their general applicability for MLP training.

Recent research has shown that the Artificial Protozoa Optimizer (APO) [29] partially mitigates the limitations of traditional SI algorithms, particularly in convergence towards local optima. However, practical applications reveal that APO often suffers from insufficient effectiveness and slow convergence when seeking optimal solutions. Motivated by these challenges, this paper proposes a Latin Hypercube Opposition-based Elite Variation Artificial Protozoa Optimizer (LOEV-APO) to address key limitations in SI-based MLP training. The main contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

1. A hybrid initialization strategy that combines Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS) with Opposition-Based Learning (OBL) to improve population diversity and spatial coverage.

2. An elite protozoa variation mechanism that incorporates differential mutation and elite selection to achieve a better balance between exploration and exploitation.

3. A global optimization framework for MLP training that encodes weights and biases jointly, aimed at enhancing convergence stability and reducing sensitivity to initialization.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews the original Artificial Protozoa Optimizer; Section 3 introduces the LOEV-APO and details the integration strategy for MLP training; Section 4 presents comprehensive experimental results and analysis; finally, Section 5 concludes the paper and outlines directions for future research.

2 Overview of the APO Algorithm

The APO is a metaheuristic that emulates four survival mechanisms observed in protozoa: autotrophic foraging, heterotrophic foraging, dormancy, and reproduction. These mechanisms jointly balance global exploration and local exploitation, where autotrophic behavior and dormancy promote exploration, while heterotrophic behavior and reproduction enhance exploitation.

Each protozoan

where

The foraging mechanism comprises two modes: autotrophic and heterotrophic.

In the autotrophic mode, phototactic behavior was simulated through the following position update rule:

where

In the heterotrophic mode, solutions are directed towards nutrient-rich regions to encourage local exploitation:

where

Upon activation, protozoa are reinitialized to random positions within the predefined bounds to facilitate escaping from local optima:

where

In the reproduction mechanism, fit protozoa generate offspring through perturbed duplication, thereby enhancing local search around high-quality solutions:

where

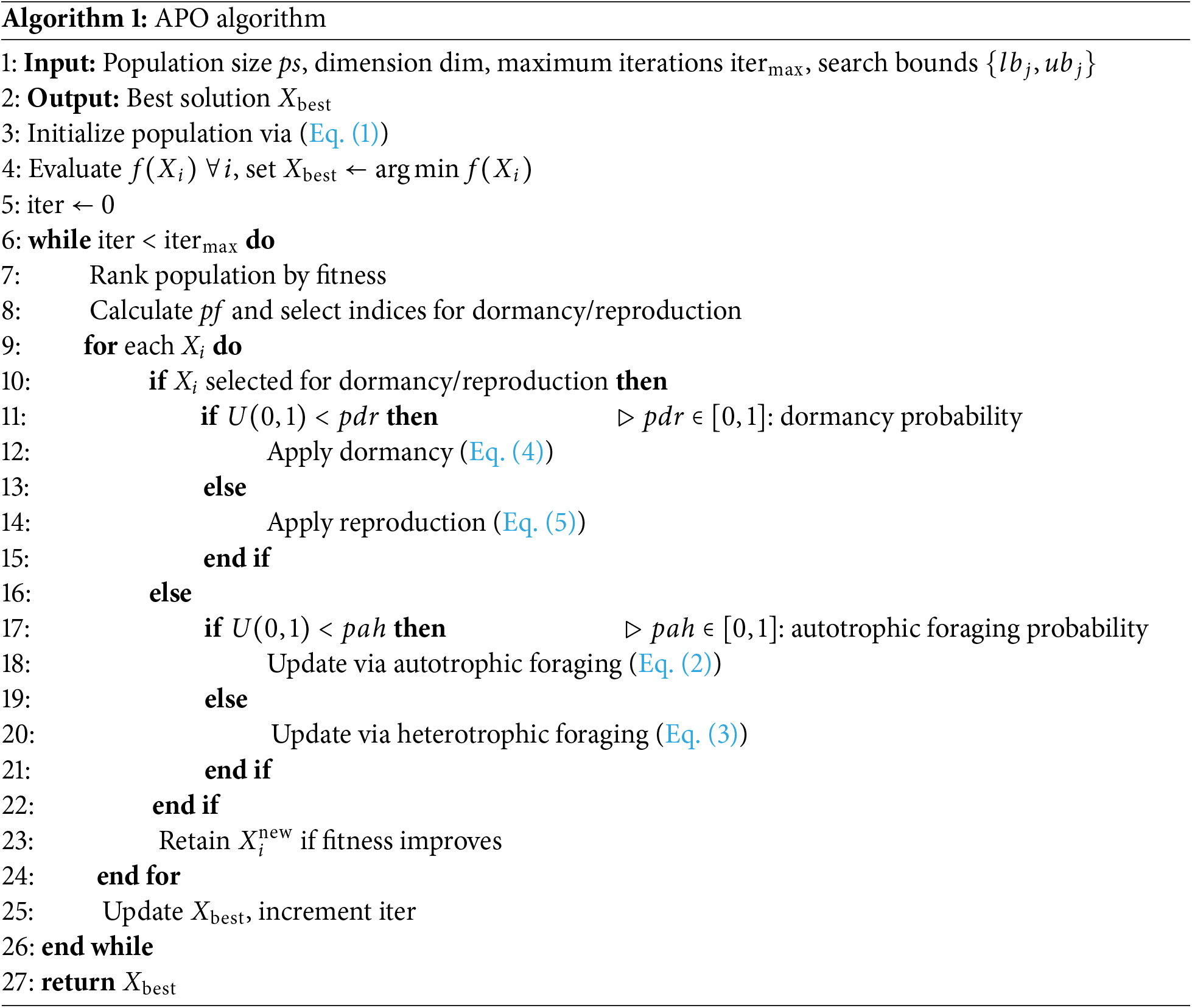

2.5 Outline of the APO Algorithm

The pseudocode of the APO algorithm is shown in Algorithm 1.

3 Training MLP with the LOEV-APO Algorithm

In this section, the Latin Hypercube Opposition-based Elite Variation Artificial Protozoa Optimizer is introduced and applied to the training process of Multilayer Perceptron.

3.1 Latin Hypercube Opposition-Based Elite Variation Artificial Protozoa Optimizer

Although the basic APO framework leverages autotrophic/heterotrophic foraging, dormancy, and reproduction to maintain a balance between exploration and exploitation, it occasionally exhibits insufficient diversity during the initial search and may stagnate under complex multimodal fitness landscapes. Moreover, when APO is directly applied to train MLPs, the algorithm sometimes converges slowly or becomes trapped in poor local minima, leading to suboptimal generalization performance in complex engineering tasks. These limitations motivate the development of an improved variant tailored for MLP training. To address computational efficiency concerns, LOEV-APO incorporates design principles that reduce convergence iterations through improved initialization and focus computational resources on promising solutions via elite variation, partially mitigating the overhead challenges inherent in population-based optimization.

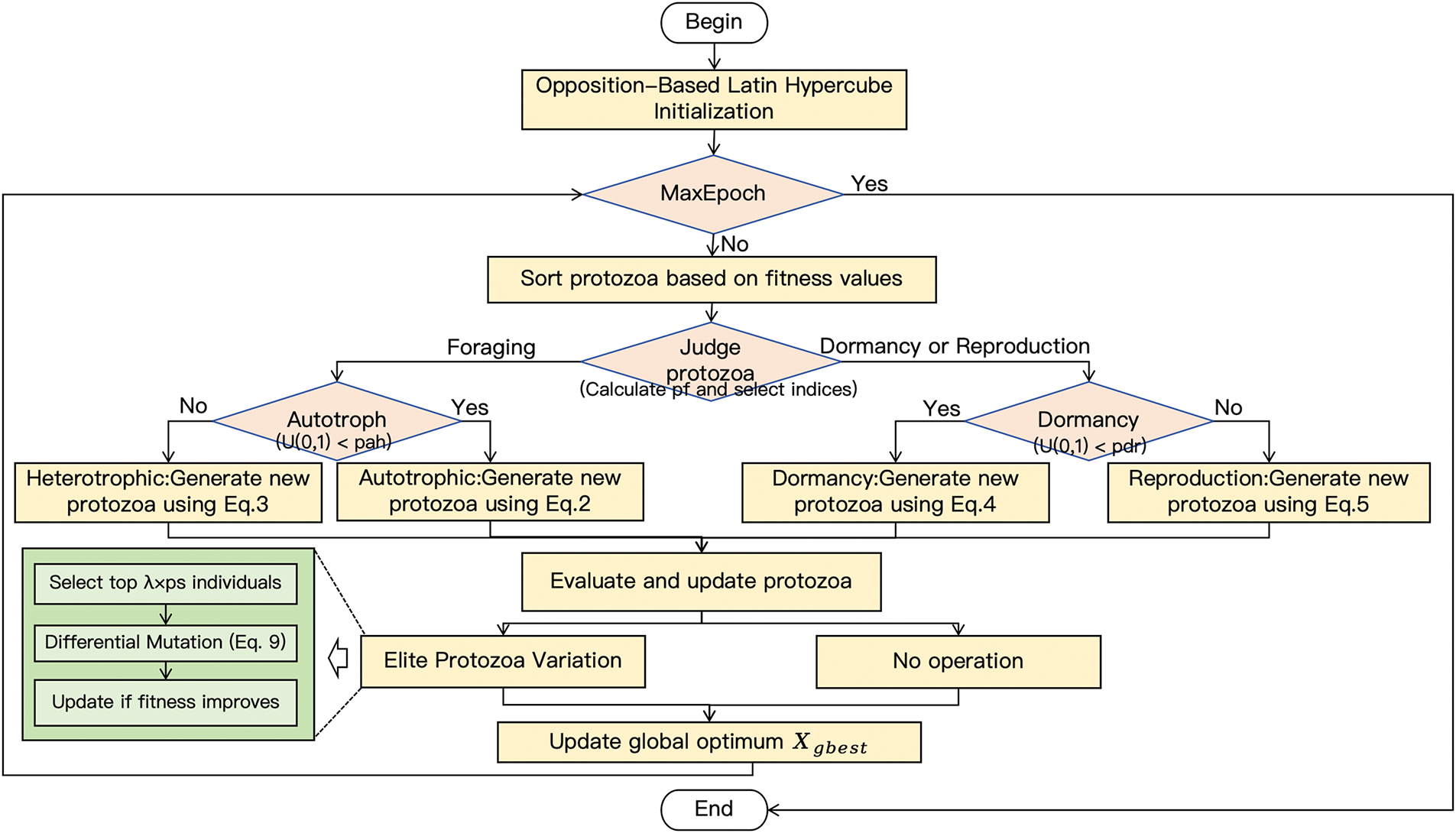

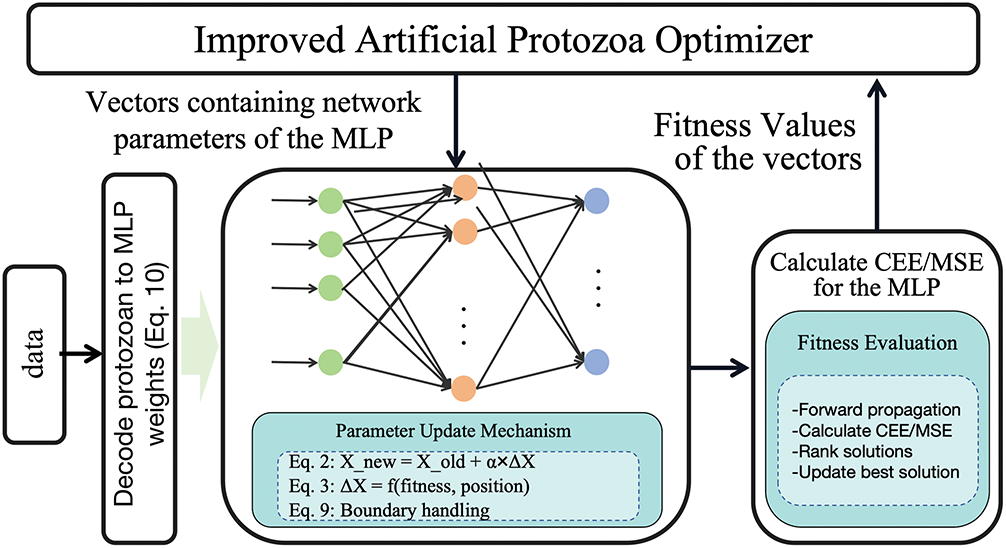

In response, LOEV-APO introduces several innovations that enhance both early-stage exploration and late-stage refinement. Beyond addressing the broader issues of population diversity and convergence reliability, these improvements reinforce the stability and speed of MLP training, enabling more effective weight updates. The framework of LOEV-APO is illustrated in Fig. 1. The subsequent subsections detail each major innovation.

Figure 1: Framework of the LOEV-APO

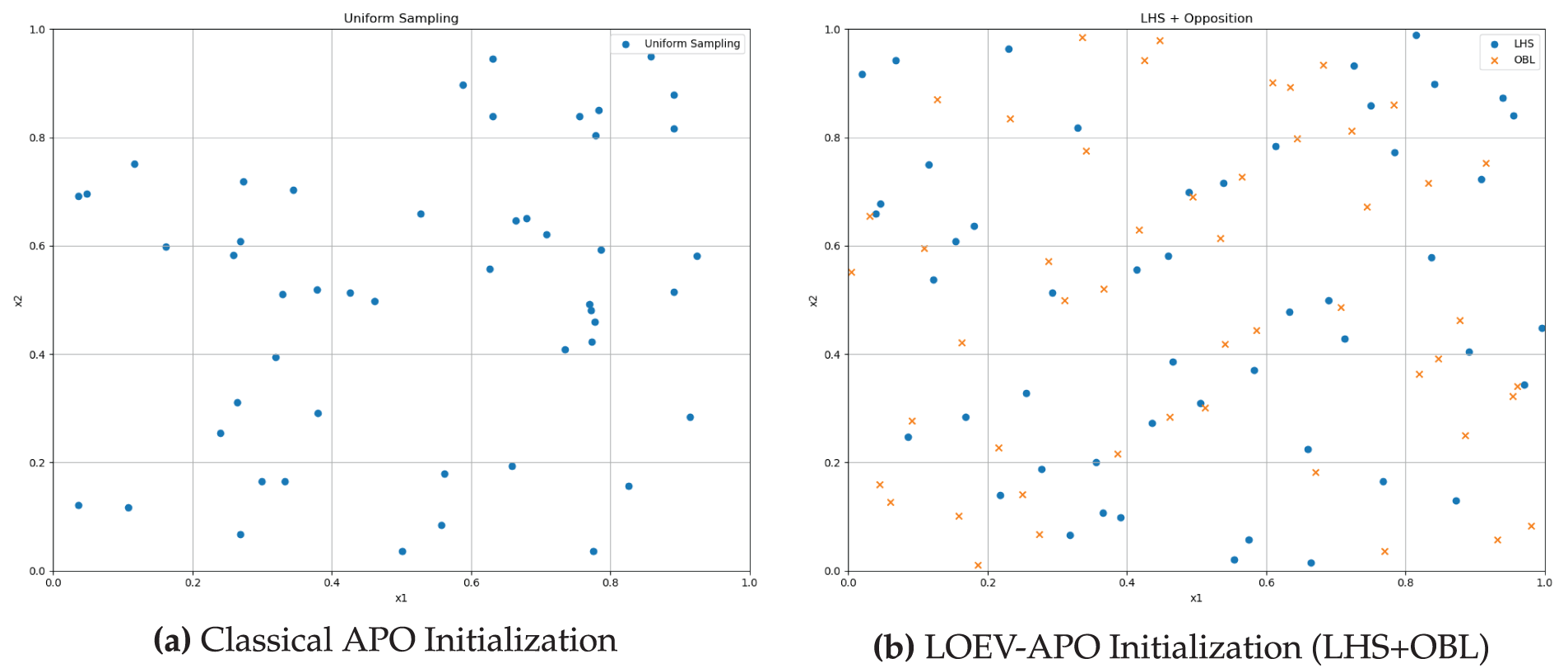

3.1.1 Opposition-Based Latin Hypercube Initialization

The first key innovation of LOEV-APO is an enhanced initialization procedure that integrates LHS with OBL to achieve broader coverage of the solution space. In classical APO, the initial positions are generated via independent uniform sampling, which may lead to highly uneven or clustered distributions, thus impairing early-stage exploration.

Specifically, LHS partitions each dimension into equal-probability intervals and places exactly one candidate in each interval, promoting uniform sampling. This is particularly beneficial in higher-dimensional or multimodal spaces, where systematic sampling mitigates overclustering and increases the likelihood of discovering multiple basins of attraction. Subsequently, OBL generates an “opposite” solution for each candidate, further broadening the diversity. If a candidate

This two-step initialization yields a comprehensive initial coverage, minimizing the risk of missing valuable subregions early in the search. Mathematically, for each dimension

where

All original and opposite candidates are evaluated, and the top

Fig. 2a,b compares the classical and improved initialization methods. By fusing LHS and OBL, LOEV-APO achieves superior early-stage diversity, reducing the chance of overlooking critical regions and enhancing the probability of finding promising basins. This broader initial sampling is hypothesized to be beneficial for discovering favorable MLP weight configurations.

Figure 2: Comparison of initialization methods in a 2D example

3.1.2 Elite Protozoa Variation Strategy

The second major innovation in LOEV-APO is the Elite Protozoa Variation Strategy (EPVS), a refined local exploitation scheme. While standard APO already balances exploration and exploitation, it may still suffer from local stagnation on complex landscapes. EPVS serves as a targeted intensification mechanism around top-performing solutions.

Specifically, after each iteration, the best fraction

where

The mutated candidate is projected within bounds and compared to its ancestor, updating only if fitness improves.

This mechanism promotes localized refinements, boosting convergence speed and enhancing final solution quality—particularly critical when training MLPs where fine-grained weight adjustments impact generalization performance.

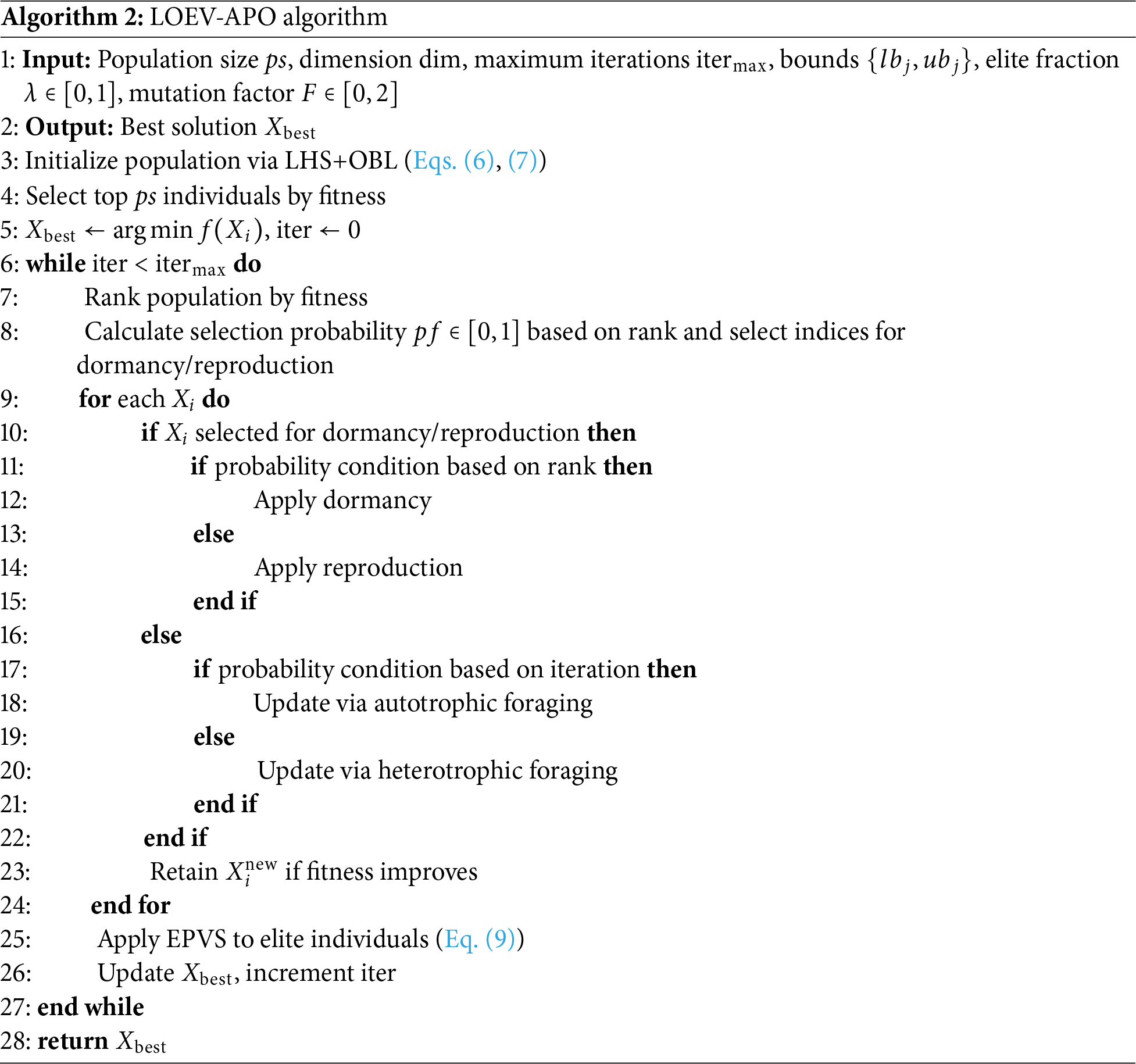

3.1.3 Outline of the LOEV-APO Algorithm

Algorithm 2 summarizes the complete LOEV-APO procedure, integrating initialization, foraging, dormancy, reproduction, and elite-based refinement.

3.1.4 Time Complexity Analysis

The time complexity of LOEV-APO primarily depends on the population size (

3.2 MLP Training with LOEV-APO

While gradient-based methods have demonstrated considerable success in MLP training, they are prone to becoming trapped in local minima. In this study, the LOEV-APO is employed as an alternative training mechanism for MLPs to mitigate this limitation.

3.2.1 Protozoan Encoding of MLP Parameters

Each candidate solution, referred to as a protozoan, encodes all the trainable parameters of the MLP into a single vector:

where the dimensionality of

3.2.2 Optimization Process of LOEV-APO

Fig. 3 schematically illustrates the MLP optimization process using LOEV-APO. The procedure begins with a randomly initialized population of protozoa within the MLP parameter space, where each protozoan represents a unique configuration of the network’s weights and biases.

Figure 3: Schematic of the MLP training process using LOEV-APO

During each iteration, each protozoan evaluates its current position by performing a forward pass through the MLP on the training dataset, and the corresponding loss—typically Cross-Entropy Error (CEE) for classification tasks or Mean Squared Error (MSE) for regression tasks—is computed. Based on this performance feedback, protozoa adaptively adjust their positions by either gravitating toward high-performing individuals or exploring their surroundings, thereby maintaining a dynamic balance between exploitation and exploration.

The optimization process continues until a predefined convergence criterion is met, such as the loss falling below a set threshold, or until the maximum number of iterations is reached. Ultimately, the protozoan achieving the lowest loss value determines the final optimized MLP parameters.

Distinct from gradient-based methods, LOEV-APO employs a population-driven, swarm-inspired approach that significantly reduces the risk of premature convergence to suboptimal local minima. This strategy enhances the algorithm’s capability to perform robust global optimization. As a result, after a sufficient number of iterations, the MLP parameters tend to converge to a configuration that ensures both low training loss and strong generalization performance.

This population-based optimization process ultimately demonstrates a more reliable and robust training outcome compared to conventional gradient-based methods.

4 Experimental Results and Analysis

The experimental evaluation includes two main components: classification tasks on benchmark datasets and function approximation experiments. To ensure fairness in comparisons, the experimental environment was configured as follows: Ubuntu 22.04 operating system, Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-12700 2.10 GHz CPU, 64 GB RAM, and Python programming language. Unless otherwise specified, all algorithms used a population size of 50 and a maximum of 500 iterations; other parameters followed the recommendations in their original references. To evaluate the proposed algorithm’s performance, it was compared against several state-of-the-art metaheuristic algorithms: APO, CFOA, Differential Evolution (DE) [30], GWO, Hybrid Rice Optimization (HRO) [31], PID-guided Search Algorithm (PSA) [32], Sparrow Search Algorithm (SSA) [33], Success History Intelligent Optimizer (SHIO) [34], and Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA) [35]. Additionally, two traditional gradient-based optimizers, Backpropagation (BP) and Adam, were included to provide a comprehensive comparison between population-based and gradient-based approaches. Furthermore, ablation studies were conducted using two component variants: LO-APO (incorporating only the LHS and OBL initialization strategy) and EV-APO (incorporating only the EPVS), to validate the individual contributions of each proposed enhancement to the overall performance of LOEV-APO. To ensure impartial comparisons, the experimental results for SSA and BP were obtained from previously published literature [36,37].

4.1 Balance and Diversity Analysis

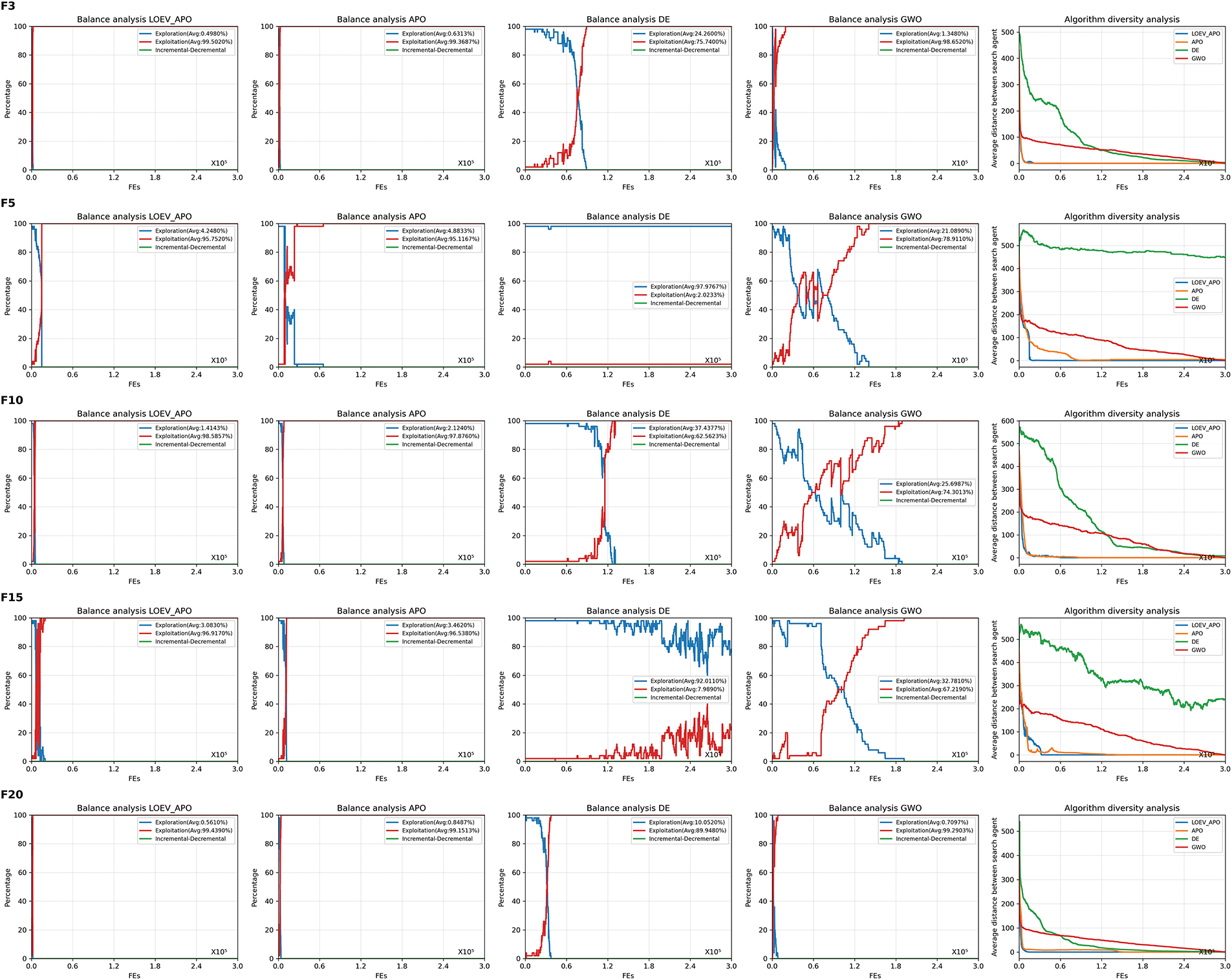

This section analyzes the exploration-exploitation balance and diversity evolution of LOEV-APO. Experiments used a maximum of 300,000 evaluations, a population size of 50, and 30 independent runs per group [38]. For comparative assessment, LOEV-APO is benchmarked against the original APO, DE, and GWO algorithms. The exploration-exploitation process and diversity trends are analyzed on five CEC2017 functions (

Figure 4: Balance and diversity analysis on CEC2017 functions

Balance analysis indicates LOEV-APO achieves superior exploration-exploitation coordination on most functions. For example, on

Diversity analysis reveals LOEV-APO effectively preserves diversity, with final diversity values approaching zero for all test functions, indicating strong global convergence. While starting with high diversity, LOEV-APO’s diversity declines steadily, avoiding premature convergence. This stems from the synergistic integration of the LHS and OBL initialization strategy with the EPVS, enabling comprehensive global exploration followed by efficient local exploitation, thus achieving an ideal dynamic balance.

4.2 Classification of Datasets

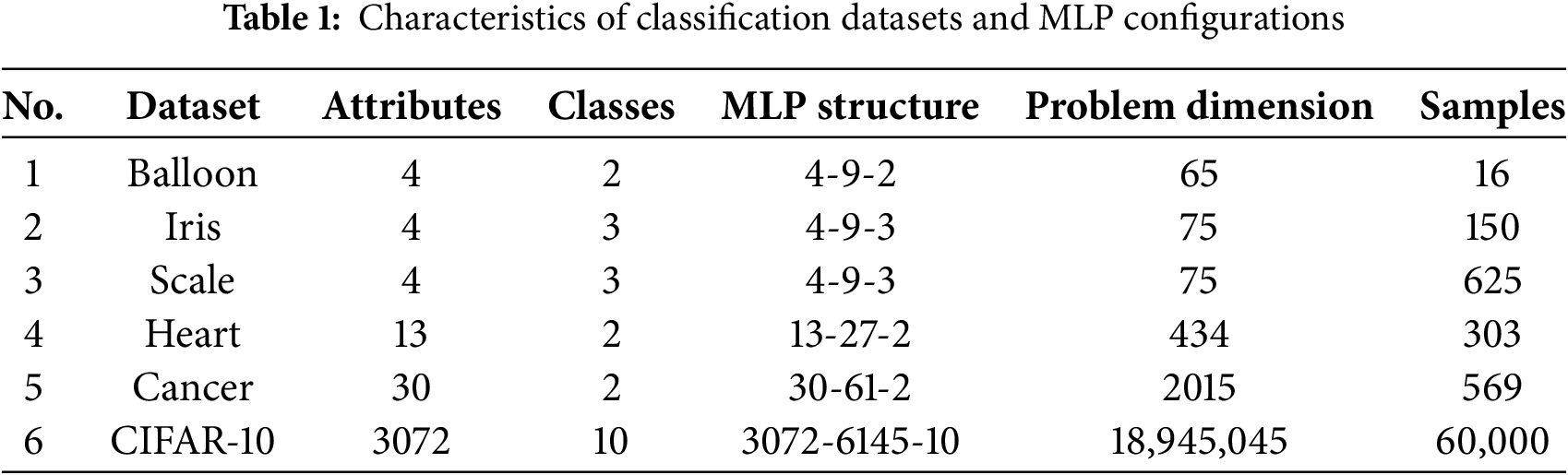

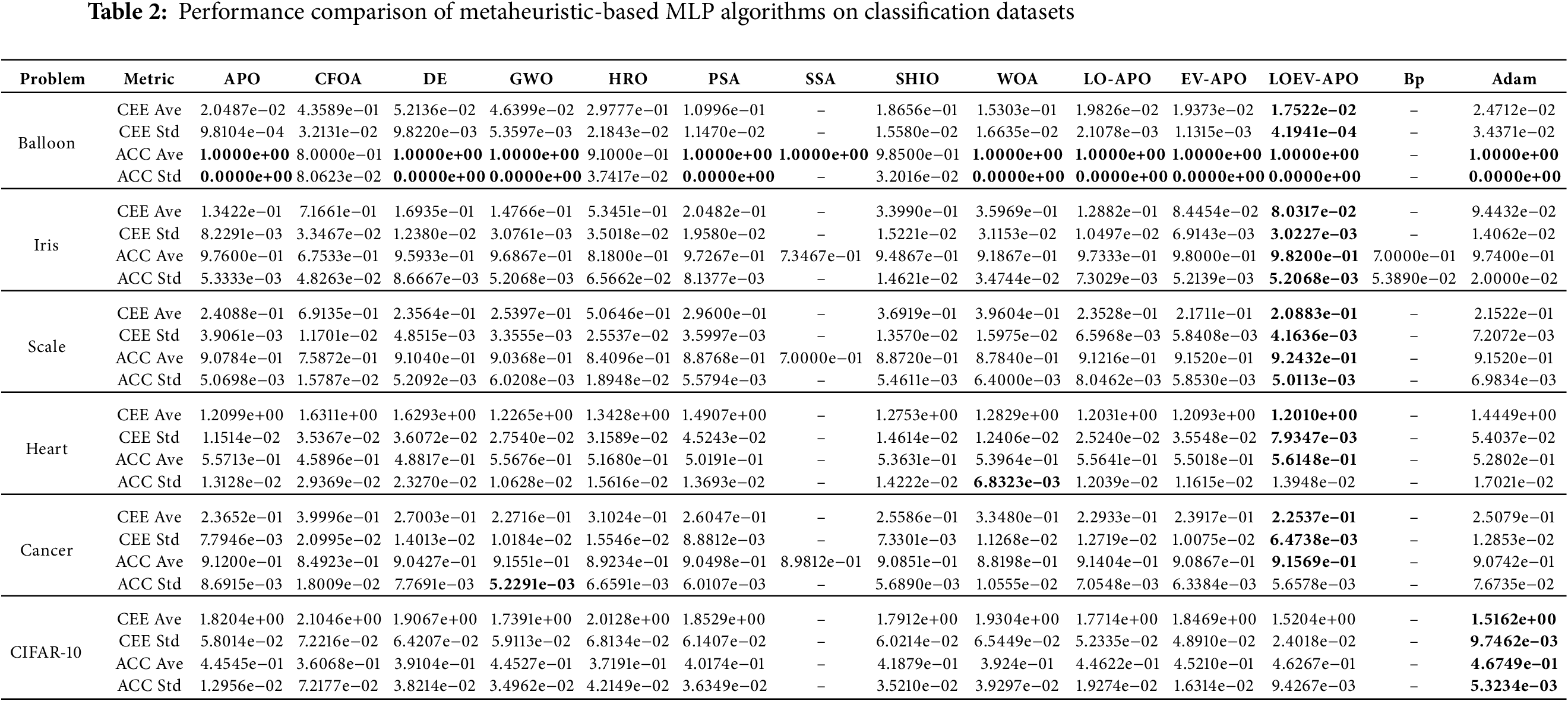

For classification tasks, CEE is more effective than MSE in assessing classification accuracy. Therefore, CEE was adopted as the fitness function throughout the experiments. To assess the effectiveness of the LOEV-APO algorithm in MLP training, five benchmark datasets from the UCI repository [39] and one large-scale image classification dataset (CIFAR-10) [40] were used. These datasets exhibit considerable diversity in terms of feature dimensionality, class distribution, and sample size, providing a comprehensive evaluation setting. Each MLP was designed with a conventional three-layer architecture, comprising an input layer, a single hidden layer, and an output layer. The number of neurons in the hidden layer was determined using the heuristic formula 2I + 1, where I represents the number of input features [36]. The hidden layer employed the tanh activation function to facilitate nonlinear transformation, while the output layer adopted task-specific activation functions: sigmoid for binary classification tasks and softmax for multi-class problems. This architectural setup ensures a balance between nonlinear representational capacity and the interpretability of probabilistic outputs. To eliminate scale effects, min-max normalization was uniformly applied to all datasets. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the datasets and their corresponding MLP configurations.

Model performance was evaluated via standard 5-fold cross-validation, with each fold iteratively serving as the validation set. To address algorithmic stochasticity, 10 independent runs were conducted for each dataset, and the average 5-fold CV performance was recorded for analysis. The comparative results are summarized in Table 2. In this table, CEE Ave/ACC Ave denote mean cross-entropy error and accuracy, while CEE Std/ACC Std indicate standard deviations. The best mean values are highlighted in bold.

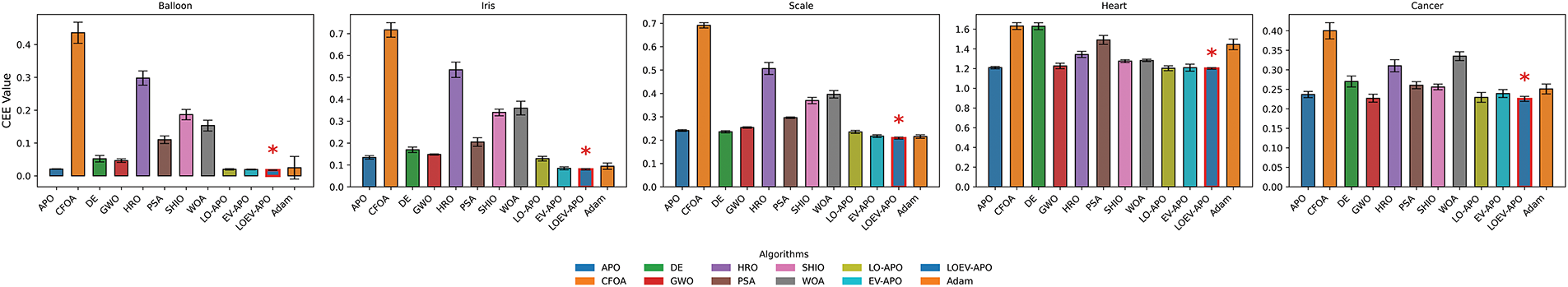

In terms of the average CEE, LOEV-APO-MLP achieves the lowest average value across all datasets. On the Iris e−0 8.0317e−02, representing a 40.2% improvement over the next best algorithm, APO-MLP, with a CEE of 1.3422e−01. On the Scale dataset, the average CEE of LOEV-APO-MLP is 2.0883e−01, which is 11.4% lower than that of the second-best algorithm, DE-MLP, which has a CEE of 2.3564e−01. Furthermore, LOEV-APO-MLP achieves the lowest standard deviation in CEE across four datasets, with the most significant improvement observed on the Balloon dataset, where its CEE standard deviation is 4.1941e−04, 57.2% lower than that of APO-MLP, which has a CEE standard deviation of 9.8104e−04. On the Heart dataset, the CEE standard deviation of LOEV-APO-MLP is reduced by 31.1% compared to the next best algorithm. LOEV-APO-MLP, through its efficient global exploration and local exploitation mechanisms, demonstrates strong capabilities in complex nonlinear optimization problems. For the large-scale CIFAR-10 dataset, LOEV-APO-MLP effectively escapes local optima through its enhanced global-local search mechanism and demonstrates superior scalability and optimization stability in high-dimensional parameter spaces. With over 18.9 million parameters, it achieves the best performance among metaheuristic algorithms with CEE of 1.5204e+00 and accuracy of 46.27%. While Adam marginally outperforms with CEE of 1.5162e+00 and accuracy of 46.75%, LOEV-APO demonstrates competitive results with only 0.28% performance gap. Notably, LOEV-APO exhibits superior optimization stability with lower standard deviation, indicating robust convergence consistency in high-dimensional parameter spaces. While CIFAR-10 demonstrates the algorithm’s scalability to large-scale problems, this study primarily focuses on lightweight MLP architectures and fundamental optimization principles. Therefore, the subsequent detailed visual analysis and convergence studies concentrate on the five UCI benchmark datasets The performance of all algorithms across datasets in terms of CEE is visualized in the bar chart of Fig. 5 and the optimal algorithm is outlined in red.

Figure 5: CEE comparison among different algorithms on classification tasks

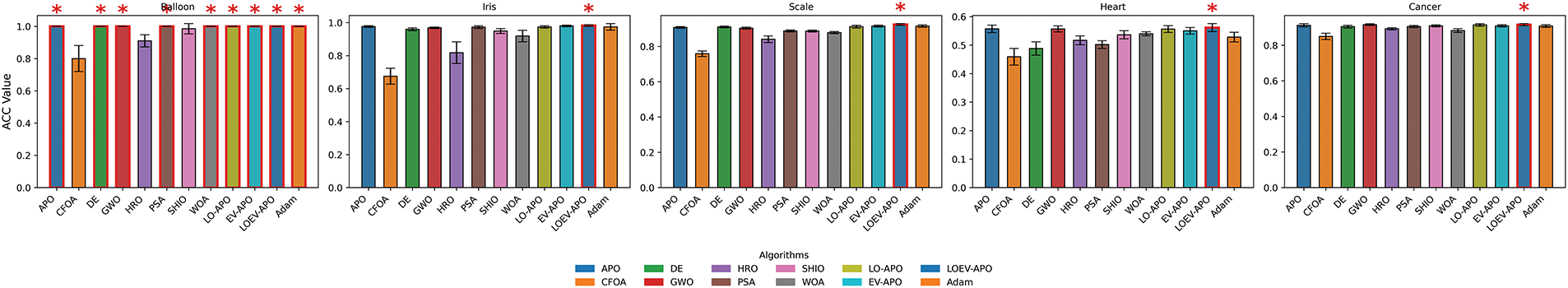

Regarding classification accuracy (ACC), LOEV-APO-MLP achieves the highest average accuracy across all datasets. On the Balloon dataset, LOEV-APO-MLP, along with APO-MLP and DE-MLP, achieves a perfect classification accuracy of 100%, with a standard deviation of 0. On the Iris dataset, LOEV-APO-MLP ranks first with an ACC of 98.2%, which is 0.6 percentage points higher than APO-MLP’s 97.6%. On the Heart dataset, LOEV-APO-MLP achieves an ACC mean of 56.1%,outperforming APO-MLP’s 55.7% by 0.4 percentage points. To further illustrate the performance of all algorithms across datasets in terms of ACC, the bar chart in Fig. 6 is presented. In this bar chart, the vertical axis is scaled to 100%, and the optimal algorithm is outlined in red.

Figure 6: Classification ACC comparison among different algorithms on classification tasks

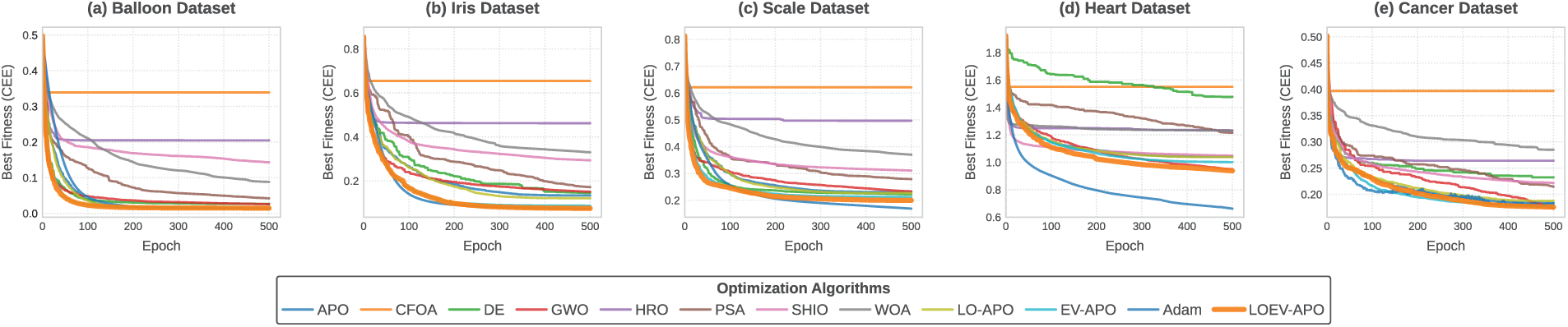

The convergence behavior of all algorithms across the five datasets is shown in Fig. 7. From the figure, it can be observed that LOEV-APO-MLP exhibits faster convergence across all datasets, particularly on the Balloon, Iris, Scale and Cancer datasets, where its convergence curve is notably smoother and descends more rapidly compared to other algorithms. Compared to APO-MLP, LOEV-APO-MLP demonstrates improved training stability by introducing a stronger local search strategy, preventing fluctuations and stagnation during the convergence process.

Figure 7: Convergence performance of metaheuristic-MLP algorithms during training

LOEV-APO-MLP achieves lower CEE values and standard deviations compared to BP and Adam across the tested classification datasets, highlighting the strength of population-based optimization in avoiding local optima. While Adam-MLP may achieve perfect accuracy on simple datasets, LOEV-APO-MLP offers more robust generalization on complex tasks. Its global search mechanism effectively overcomes the sensitivity to initial weights and learning rates inherent in gradient-based methods.

LOEV-APO consistently outperforms LO-APO and EV-APO across all datasets, confirming the effectiveness of combining enhanced initialization with the EPVS. These results underscore the synergy of its two core components, enabling LOEV-APO to balance early-stage diversity with later-stage exploitation for optimal search performance.

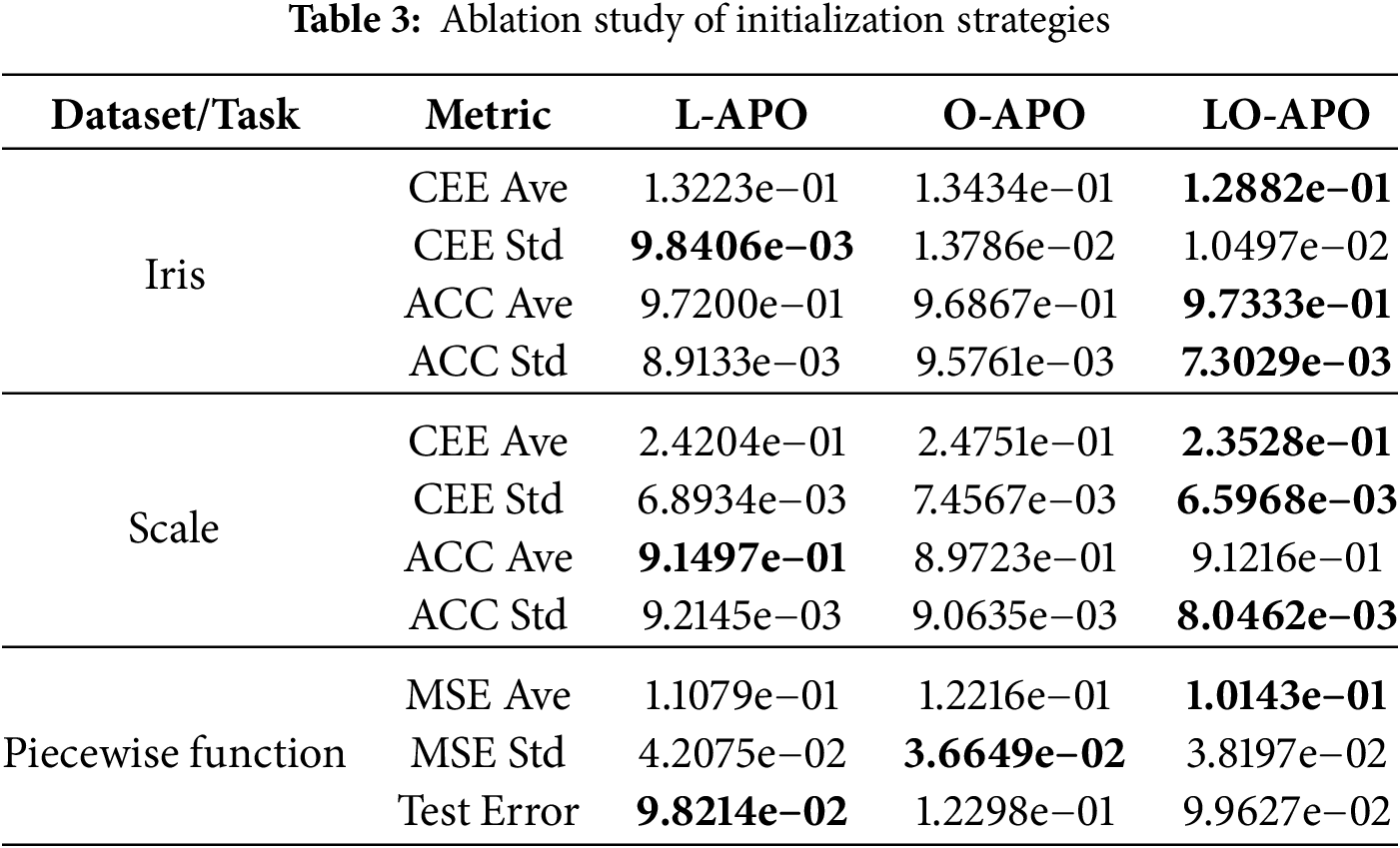

Additionally, to further investigate the individual contributions of LHS and OBL components, supplementary experiments were conducted using L-APO (LHS-only) and O-APO (OBL-only) variants on two representative classification datasets (Iris, Scale) and one representative function approximation task (Piecewise Function).

Table 3 demonstrates that L-APO generally outperforms O-APO across most metrics, indicating LHS provides better uniform sampling than OBL alone. LO-APO achieves superior performance on key metrics (CEE Ave, ACC Ave, MSE Ave), confirming the synergistic combination where LHS ensures sampling stability while OBL addresses high-dimensional clustering issues.

4.3 Statistical Significance Analysis

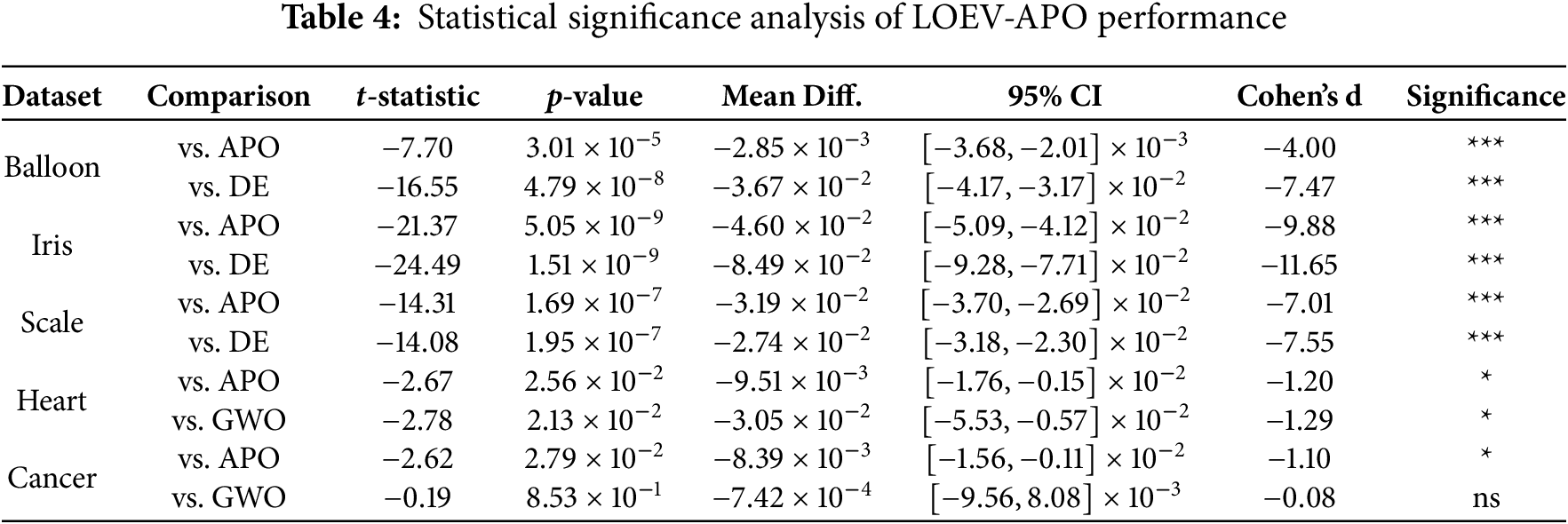

To rigorously verify the performance superiority of LOEV-APO, we conducted statistical significance tests on the first five benchmark datasets. Specifically, we employed paired t-tests, Cohen’s d effect size measurements, and 95% confidence intervals to compare LOEV-APO with both the original APO algorithm and the sub-optimal algorithm for each dataset.

In Table 4, the significance levels are denoted as: *** for

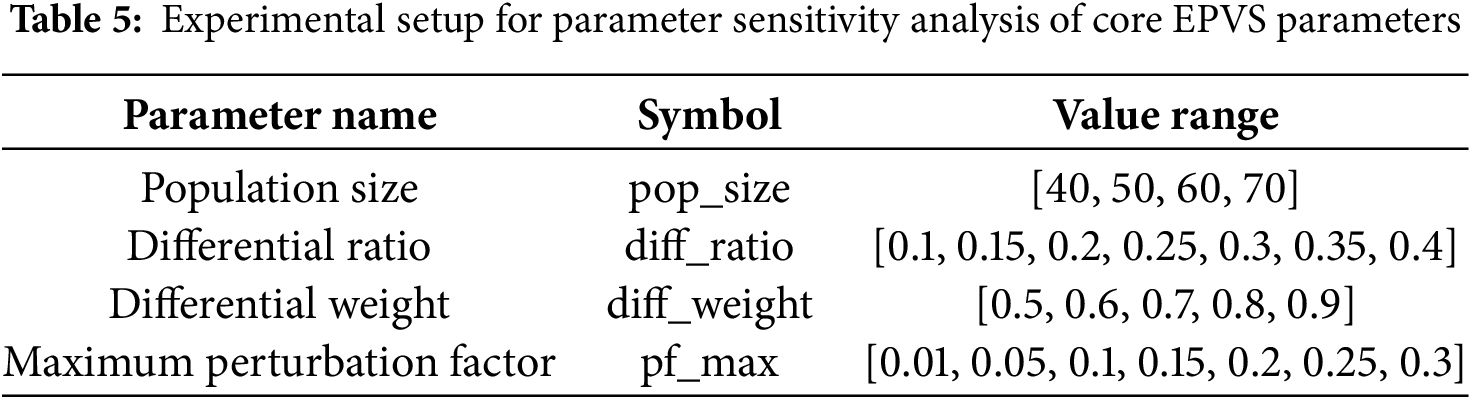

4.4 Parameter Sensitivity Analysis

To validate the robustness and parameter rationality of the LOEV-APO algorithm, this experiment analyzes the sensitivity of four key parameters using three representative datasets (Cancer, Iris, and Scale). Among these parameters, the differential ratio corresponds to the elite fraction

The specific impacts of the two core EPVS parameters on algorithm performance are analyzed as follows: The elite pool fraction

Fig. 8 presents the sensitivity analysis results showing that optimal performance is achieved with differential ratio of 0.2–0.25 and differential weight of 0.7–0.8, confirming our parameter range selection rationale. By quantifying the stability of algorithm performance through the coefficient of CV, it can be observed that the algorithm maintains stable performance across a relatively wide parameter range, with accuracy coefficients of variation generally less than 0.0016 and cross-entropy error coefficients of variation controlled within 0.025. This indicates that the LOEV-APO algorithm is insensitive to parameter variations and possesses good engineering practicality, achieving satisfactory optimization results even under non-optimal parameter settings. The systematic analysis of

Figure 8: Parameter sensitivity analysis results of the LOEV-APO algorithm: (a) accuracy stability analysis; (b) cross-entropy error stability analysis

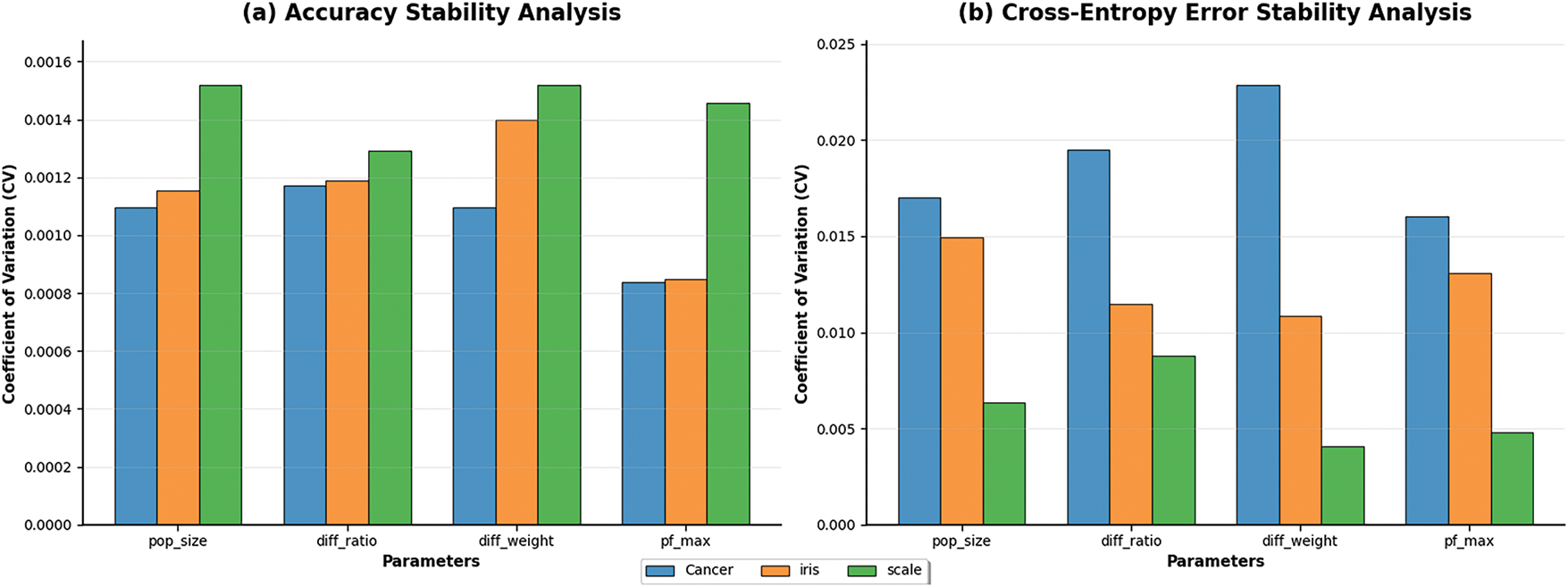

Neural networks exhibit remarkable function approximation capabilities due to their universal approximation property, enabling them to model complex functional relationships with arbitrary precision. Our experimental setup employs four distinct synthetic datasets with varying complexity levels, with detailed specifications provided in Table 6.

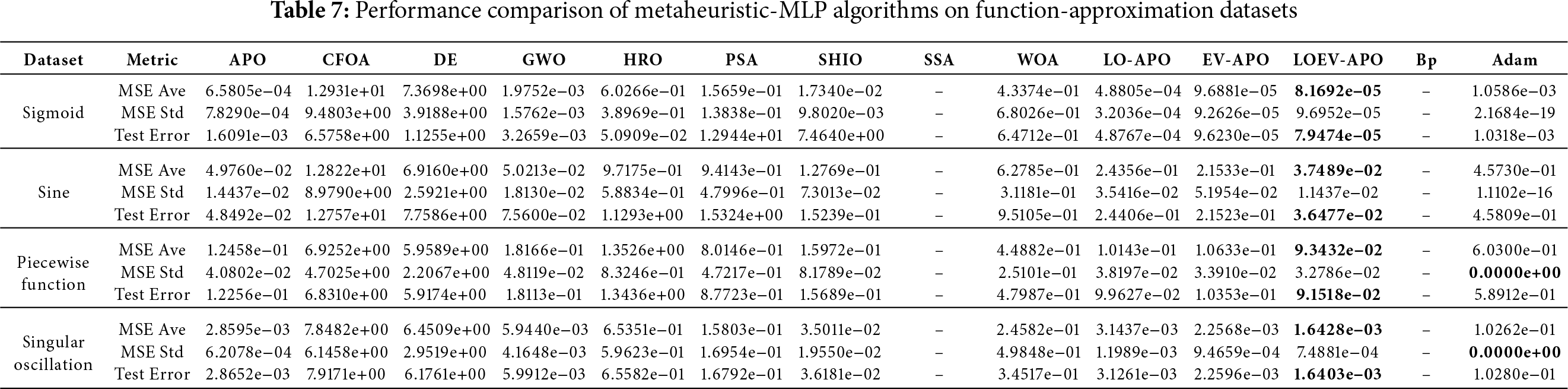

For function approximation tasks, MSE serves as the primary evaluation metric as it directly measures deviation between predicted and target values in continuous space. The experimental results are comprehensively analyzed in Table 7. In this table, MSE Ave and Test Error represent mean squared error and test error averaged, MSE Std indicates standard deviation. The best mean values are highlighted in bold.

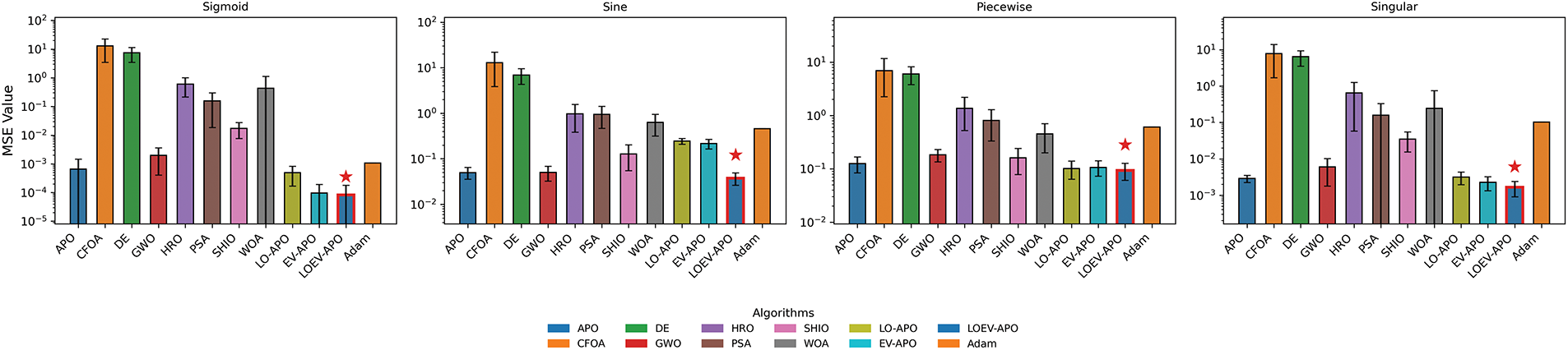

The proposed LOEV-APO-MLP demonstrates consistent superiority across all four function approximation tasks. For the Sigmoid function, LOEV-APO-MLP achieves an MSE of 8.1692e−05, comparable to gradient-based methods while maintaining superior stability. On the Sine function, it achieves 3.7489e−02, representing a 24.7% improvement over APO-MLP and outperforming Adam-MLP by more than an order of magnitude.

The Piecewise function results validate the synergistic effect of our proposed components, with LOEV-APO-MLP outperforming both ablation variants: LO-APO and EV-APO. For the challenging Singular Oscillation function, LOEV-APO-MLP achieves 1.6428e−03, showing 42.6% improvement over APO-MLP and nearly two orders of magnitude better than gradient-based methods. The comparative MSE performance is illustrated in Fig. 9 and the optimal algorithm is outlined in red.

Figure 9: MSE comparison of different algorithms in three function approximation tasks

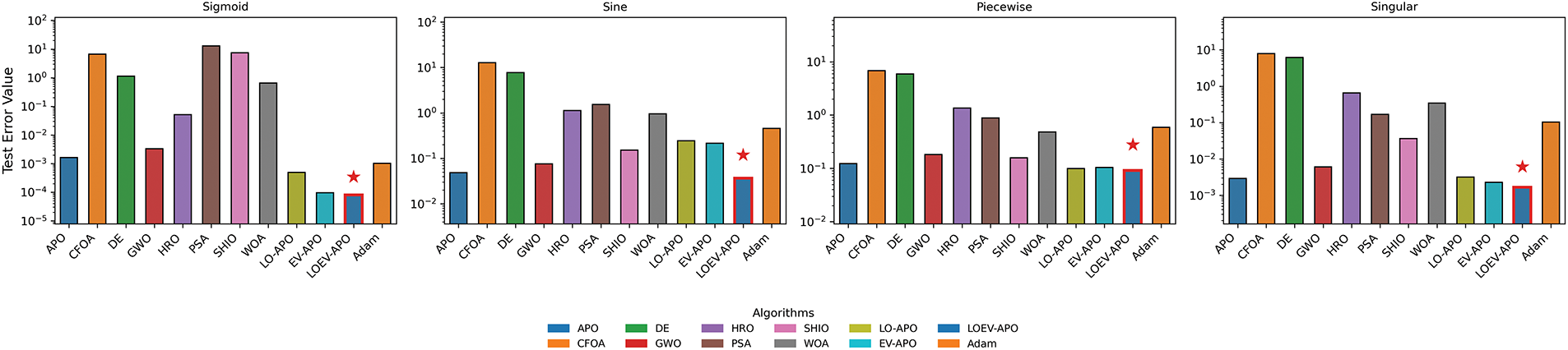

Generalization performance analysis reveals LOEV-APO-MLP’s superior extrapolation capabilities. Test errors closely match training performance across all functions, with discrepancy rates below 3%. For instance, on the Sine function, LOEV-APO-MLP maintains a 2.7% training-testing discrepancy compared to significantly higher errors in gradient-based methods. The Singular Oscillation results further demonstrate exceptional stability with test error nearly identical to training performance.

The ablation study confirms that both LO-APO and EV-APO contribute to performance enhancement, with their combination yielding optimal results. Testing error comparisons are shown in Fig. 10 and the optimal algorithm is outlined in red.

Figure 10: Test error comparison of different algorithms in three function approximation tasks

These results demonstrate that LOEV-APO-MLP not only outperforms existing metaheuristic algorithms but also provides significant advantages over traditional gradient-based methods, while the ablation analysis validates the effectiveness of both proposed enhancement components.

In this paper, LOEV-APO is proposed for the training of MLPs. LOEV-APO integrates an enhanced initialization strategy based on LHS combined with OBL, and incorporates an EPVS inspired by differential evolution. These innovations significantly enhance both the global exploration and local exploitation capabilities of the algorithm. Experimental results demonstrate that LOEV-APO significantly reduces sensitivity to initial conditions and mitigates premature convergence in MLP training. The improved initialization and refinement mechanisms contribute to the optimizer’s enhanced ability to navigate complex, high-dimensional search spaces, as reflected in its superior optimization performance on the benchmark problems studied. Consequently, LOEV-APO emerges as a promising alternative to traditional gradient-based techniques for MLP training in the domains explored in this work.

However, the current evaluation is constrained to relatively small-scale MLPs with UCI benchmark datasets, leaving the scalability to modern deep architectures such as CNNs and Transformers on large-scale real-world datasets unexamined. The enhanced initialization and elite variation strategies introduce significant computational overhead that becomes prohibitive in extremely high-dimensional parameter spaces, potentially limiting practical applicability.

Future research should address these limitations in several directions. First, LOEV-APO could be investigated for hyperparameter optimization in contemporary deep learning architectures, such as CNNs and Transformers, particularly on large-scale datasets in computer vision and natural language processing. Second, comprehensive evaluations on datasets from medical, financial, and industrial domains are necessary. Third, developing hybrid optimization frameworks that combine LOEV-APO’s global search capabilities with gradient-based local convergence efficiency may further enhance performance. Finally, exploring adaptive self-tuning mechanisms (e.g., linear annealing or adaptive mutation rates) may improve algorithm generalizability and usability across diverse datasets and problem domains, while mitigating computational constraints.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 62376089, 62302153, 62302154), the Key Research and Development Program of Hubei Province, China (Grant No. 2023BEB024), the Young and Middle-Aged Scientific and Technological Innovation Team Plan in Higher Education Institutions in Hubei Province, China (Grant No. T2023007), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. U23A20318).

Author Contributions: Conceptualization: Zhiwei Ye, Dingfeng Song, Haitao Xie; Methodology: Zhiwei Ye, Dingfeng Song, Wen Zhou; Validation: Zhiwei Ye, Dingfeng Song, Jixin Zhang, Mengya Lei; Writing—original draft preparation: Zhiwei Ye, Dingfeng Song, Jixin Zhang, Wen Zhou; Writing—review and editing: Zhiwei Ye, Dingfeng Song, Xiao Zheng; Visualization: Jie Sun, Mengxuan Li; Supervision: Haitao Xie, Jixin Zhang, Jing Zhou. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data supporting the findings of this study include: Public datasets (UCI datasets and CIFAR-10) available from the UCI Machine Learning Repository (https://archive.ics.uci.edu/ml) (accessed on 27 August 2025) and CIFAR website (https://www.cs.toronto.edu/kriz/cifar.html) (accessed on 27 August 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Rosenblatt F. The perceptron: a probabilistic model for information storage and organization in the brain. Psychol Rev. 1958;65(6):386–408. doi:10.1037/h0042519. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Hamad F, Fakhouri HN, Alzghoul F, Zraqou J. Development and design of object avoider robot and object, path follower robot based on artificial intelligence. Arab J Sci Eng. 2025;50(10):7277–98. doi:10.1007/s13369-024-09365-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Rajalakshmi A, Sridhar SS. Classification of yoga, meditation, combined yoga-meditation EEG signals using L-SVM, KNN, and MLP classifiers. Soft Comput. 2024;28(5):4607–19. doi:10.1007/s00500-024-09695-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Marzouglal M, Souahlia A, Bessissa L, Mahi D, Rabehi A, Alharthi YZ, et al. Prediction of power conversion efficiency parameter of inverted organic solar cells using artificial intelligence techniques. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):25931. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-77112-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Chen J, Li D, Huang R, Chen Z, Li W. Aero-engine remaining useful life prediction method with self-adaptive multimodal data fusion and cluster-ensemble transfer regression. Reliab Eng Syst Saf. 2023;234(3):109151. doi:10.1016/j.ress.2023.109151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Altay O, Varol Altay E. A novel hybrid multilayer perceptron neural network with improved grey wolf optimizer. Neural Comput Appl. 2023;35(1):529–56. doi:10.1007/s00521-022-07775-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Dubey SR, Singh SK, Chaudhuri BB. Activation functions in deep learning: a comprehensive survey and benchmark. Neurocomputing. 2022;503(11):92–108. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2022.06.111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Reza AF, Singh R, Verma RK, Singh A, Ahn YH, Ray SS. An integral and multidimensional review on multi-layer perceptron as an emerging tool in the field of water treatment and desalination processes. Desalination. 2024;586(2):117849. doi:10.1016/j.desal.2024.117849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Li Z, Nguyen SP, Xu D, Shang Y. Protein loop modeling using deep generative adversarial network. In: 2017 IEEE 29th International Conference on Tools with Artificial Intelligence (ICTAI); 2017 Nov 6–8; Boston, MA, USA. p. 1085–91. [Google Scholar]

10. Hou Q, Jiang Z, Yuan L, Cheng MM, Yan S, Feng J. Vision permutator: a permutable MLP-like architecture for visual recognition. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2022;45(1):1328–34. doi:10.1109/tpami.2022.3145427. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Wei T, Guo Z, Chen Y, He J. NTK-approximating MLP fusion for efficient language model fine-tuning. In: Proceedings of the 40th International Conference on Machine Learning; 2023 Jul 23–29; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 36821–38. [Google Scholar]

12. Al Bataineh A, Manacek S. MLP-PSO hybrid algorithm for heart disease prediction. J Pers Med. 2022;12(8):1208. doi:10.3390/jpm12081208. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Rezaeipanah A, Ahmadi G. Breast cancer diagnosis using multi-stage weight adjustment in the MLP neural network. Comput J. 2022;65(4):788–804. doi:10.1093/comjnl/bxaa109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Le-Duc T, Nguyen QH, Lee J, Nguyen-Xuan H. Strengthening gradient descent by sequential motion optimization for deep neural networks. IEEE Trans Evol Comput. 2022;27(3):565–79. doi:10.1109/tevc.2022.3171052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Narkhede MV, Bartakke PP, Sutaone MS. A review on weight initialization strategies for neural networks. Artif Intell Rev. 2022;55(1):291–322. doi:10.1007/s10462-021-10033-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Priyadarshi R, Kumar RR. Evolution of swarm intelligence: a systematic review of particle swarm and ant colony optimization approaches in modern research. Arch Comput Methods Eng. 2025;32(6):3609–50. doi:10.1007/s11831-025-10247-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Jui JJ, Molla MMI, Ahmad MA, Hettiarachchi IT. Recent advances and applications of the multi-verse optimiser algorithm: a survey from 2020 to 2024. Arch Comput Methods Eng. 2025;54(1):4237. doi:10.1007/s11831-025-10277-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Jia H, Wen Q, Wang Y, Mirjalili S. Catch fish optimization algorithm: a new human behavior algorithm for solving clustering problems. Cluster Comput. 2024;27(9):13295–13332. doi:10.1007/s10586-024-04618-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Çelik E. IEGQO-AOA: information-exchanged gaussian arithmetic optimization algorithm with quasi-opposition learning. Knowl Based Syst. 2023;260:110169. doi:10.1201/9781003206477-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Tijjani S, Ab Wahab MN, Noor MHM. An enhanced particle swarm optimization with position update for optimal feature selection. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;247(5):123337. doi:10.1007/s00500-024-09695-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Yu Q, Liang X, Li M, Jian L. NGDE: a niching-based gradient-directed evolution algorithm for nonconvex optimization. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2025;36(3):5363–74. doi:10.1109/tnnls.2024.3378805. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Wolpert DH, Macready WG. No free lunch theorems for optimization. IEEE Trans Evol Comput. 1997;1(1):67–82. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-62007-6_12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Mirjalili S, Mirjalili SM, Lewis A. Grey wolf optimizer. Adv Eng Softw. 2014;69:46–61. doi:10.1201/9781003206477-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Gu Q, Li X, Jiang S. Hybrid genetic grey wolf algorithm for large-scale global optimization. Complexity. 2019;2019(1):2653512. doi:10.1155/2019/2653512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Jia DL, Zheng GX, Qu BY, Khan MK. A hybrid particle swarm optimization algorithm for high-dimensional problems. Comput Ind Eng. 2011;61(4):1117–22. doi:10.1016/j.cie.2011.06.024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Chatterjee S, Sarkar S, Hore S, Dey N, Ashour AS, Balas VE. Particle swarm optimization trained neural network for structural failure prediction of multistoried RC buildings. Neural Comput Appl. 2017;28(8):2005–16. doi:10.1007/s00521-016-2190-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Guo J, Zhou G, Yan K, Sato Y, Di Y. Pair barracuda swarm optimization algorithm: a natural-inspired metaheuristic method for high dimensional optimization problems. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):18314. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-43748-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Yang Z. Competing leaders grey wolf optimizer and its application for training multi-layer perceptron classifier. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;239(4):122349. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2023.122349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Wang X, Snášel V, Mirjalili S, Pan JS, Kong L, Shehadeh HA. Artificial protozoa optimizer (APOa novel bio-inspired metaheuristic algorithm for engineering optimization. Knowl Based Syst. 2024;295(5):111737. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2024.111737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Mohamed AW, Hadi AA, Jambi KM. Novel mutation strategy for enhancing SHADE and LSHADE algorithms for global numerical optimization. Swarm Evol Comput. 2019;50(6):100455. doi:10.1016/j.swevo.2018.10.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Ye Z, Ma L, Chen H. A hybrid rice optimization algorithm. In: 2016 11th International Conference on Computer Science & Education (ICCSE); 2016 Aug 23–25; Nagoya, Japan. p. 169–74. [Google Scholar]

32. Gao Y. PID-based search algorithm: a novel metaheuristic algorithm based on PID algorithm. Expert Syst Appl. 2023;232(3):120886. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2023.120886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Xue J, Shen B. A novel swarm intelligence optimization approach: sparrow search algorithm. Syst Sci Control Eng. 2020;8(1):22–34. doi:10.1080/21642583.2019.1708830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Fakhouri HN, Hamad F, Alawamrah A. Success history intelligent optimizer. J Supercomput. 2022;78(5):6461–6502. doi:10.1007/s11227-021-04093-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Mirjalili S, Lewis A. The whale optimization algorithm. Adv Eng Softw. 2016;95(12):51–67. doi:10.1016/j.advengsoft.2016.01.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Yang Z, Jiang Y, Yeh WC. Self-learning salp swarm algorithm for global optimization and its application in multi-layer perceptron model training. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):27401. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-77440-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Agahian S, Akan T. Battle royale optimizer for training multi-layer perceptron. Evol Syst. 2022;13(4):563–75. doi:10.1007/s12530-021-09401-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Chen Z, Xuan P, Heidari AA, Liu L, Wu C, Chen H, et al. An artificial bee bare-bone hunger games search for global optimization and high-dimensional feature selection. iScience. 2023;26(5):106679. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2023.106679. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Asuncion A, Newman D. UCI machine learning repository [EB/OL] [Internet]. 2007 [cited 2025 Aug 27]. Available from: https://archive.ics.uci.edu. [Google Scholar]

40. Krizhevsky A, Hinton G. Learning multiple layers of features from tiny images [Internet]. 2009 [cited 2025 Aug 27]. Available from: https://www.cs.toronto.edu/~kriz/cifar.html. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools