Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Adaptive Multi-Layer Defense Mechanism for Trusted Federated Learning in Network Security Assessment

1 State Grid Hebei Information and Telecommunication Branch, Shijiazhuang, 050000, China

2 State Key Laboratory of Networking and Switching Technology, Beijing University of Posts and Telecommunications, Beijing, 100876, China

* Corresponding Author: Fanqin Zhou. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(3), 5057-5071. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.067521

Received 06 May 2025; Accepted 13 August 2025; Issue published 23 October 2025

Abstract

The rapid growth of Internet of things devices and the emergence of rapidly evolving network threats have made traditional security assessment methods inadequate. Federated learning offers a promising solution to expedite the training of security assessment models. However, ensuring the trustworthiness and robustness of federated learning under multi-party collaboration scenarios remains a challenge. To address these issues, this study proposes a shard aggregation network structure and a malicious node detection mechanism, along with improvements to the federated learning training process. First, we extract the data features of the participants by using spectral clustering methods combined with a Gaussian kernel function. Then, we introduce a multi-objective decision-making approach that combines data distribution consistency, consensus communication overhead, and consensus result reliability in order to determine the final network sharing scheme. Finally, by integrating the federated learning aggregation process with the malicious node detection mechanism, we improve the traditional decentralized learning process. Our proposed ShardFed algorithm outperforms conventional classification algorithms and state-of-the-art machine learning methods like FedProx and FedCurv in convergence speed, robustness against data interference, and adaptability across multiple scenarios. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed approach improves model accuracy by up to 2.33% under non-independent and identically distributed data conditions, maintains higher performance with malicious nodes containing poisoned data ratios of 20%–50%, and significantly enhances model resistance to low-quality data.Keywords

The contemporary digital landscape, marked by the rapid proliferation of Internet of things (IoT) devices, has created a complex network ecosystem that challenges traditional cybersecurity models [1]. With increasing reliance on interconnected infrastructure, network threats have escalated sharply, rendering static rule-based and cryptographic methods inadequate for addressing modern, adaptive cyberattacks [2]. Federated learning (FL) has emerged as a decentralized, privacy-oriented method for collaborative threat detection [3]. It allows secure multi-party model training without sharing raw data, enhancing threat detection capabilities. However, challenges such as data heterogeneity, communication overhead, and vulnerability to adversarial attacks (e.g., data poisoning) limit its adoption [4]. Additionally, the resource constraints of edge devices in federated IoT environments—such as limited memory, bandwidth, and energy budgets—pose significant implementation and scalability challenges, further hindering practical deployment [5].

These issues are especially critical in network security, where real-time responsiveness and trust are essential [6]. Inconsistent data quality and insufficient mechanisms for identifying malicious behavior degrade model performance and compromise system integrity [7]. Moreover, current methods often overlook complex attacks like model poisoning and Sybil attacks. Addressing these challenges requires a multidimensional approach that integrates adaptive machine learning, dynamic trust evaluation, and intelligent defense mechanisms [8]. Recent studies highlight the promise of combining spectral clustering, blockchain-based validation, and anomaly detection for proactive federated learning frameworks. These systems must dynamically adjust network topology, assess trust, and respond to evolving threats. AzharShokoufeh et al. in [9] further demonstrates the benefits of periodic scheduling in federated IoT data collection, improving bandwidth, energy use, and model accuracy through local processing and update-based communication. The integration of machine learning, cryptography, and adaptive intelligence signals a shift from reactive to proactive network security [10]. Robust multi-layer defense—combining statistical analysis, ML, and cryptographic verification—offers a comprehensive response to the complex and evolving threat landscape in modern networks.

The main contributions can be summarized as follows. 1) A revolutionary multi-layer adaptive defense mechanism is conceptualized and implemented to significantly enhance the resilience and intelligent response capabilities of trusted federated learning in network security assessment scenarios. 2) A sophisticated probabilistic trustworthiness scoring algorithm is developed, supporting dynamic network sharding, intelligent participant selection, and continuous trust re-evaluation throughout the distributed training lifecycle. 3) A comprehensive hybrid detection approach is introduced, combining statistical anomaly analysis, machine learning-based attack pattern recognition, and cryptographic verification to form a multidimensional, adaptive defense strategy.

2.1 Trusted Federated Learning Aggregation Network Sharding Method

In federated learning with multiple trusted parties, performance and security face several key challenges. The heterogeneous nature of participant environments creates substantial data distribution inconsistencies, where non-independent and identically distributed (non-IID) datasets severely compromise both model aggregation efficiency and final performance metrics. Blockchain-based consensus incurs high communication costs due to frequent coordination [11]. Additionally, inconsistent data quality elevates the risk of data/model poisoning, necessitating strong consensus evaluations.

The method applies spectral clustering to derive high-dimensional features from each party’s data, utilizing its characteristics and label distributions [12]. A hierarchical clustering algorithm constructs a tree to serve as the candidate for network sharding. A multi-objective decision framework, which assesses data distribution, communication overhead, and reliability, refines the sharding scheme, resulting in a hierarchical model aggregation network for dependable federated learning.

A key challenge in federated learning is participant data heterogeneity. This heterogeneity is reflected in feature variance and label skewness. To capture these characteristics, we extract statistical moments from each participant’s local dataset [13]. For numerical features, we compute four moments: mean (

To represent the label distribution in participants’ datasets, the probability distribution of different labels is used as feature values. For a dataset with

By collecting probability distributions for all labels, the label distribution probability vector

Since the data features of participants usually have high dimensions, complex internal logic, and varying parameter scales, spectral clustering is used to process the extracted data features, obtaining latent feature vectors and reducing dimensionality to decrease computational overhead in subsequent sharding scheme construction. Specifically, given the local feature set C, a similarity matrix is computed using the Gaussian kernel function,

where

Next, we define the degree matrix D as

where the diagonal elements are computed as

Based on the above steps, the feature matrix F of the local data from

In this study, we use the Euclidean distance based on the feature matrix F to measure the similarity between clusters:

Here,

Initially, each participant is treated as a separate cluster. In each iteration, the two closest clusters are merged into a new cluster. This process iterates bottom-up to form a tree structure. In the hierarchical clustering tree, each level represents a new partitioning optimization scheme. Multiple influencing factors must be considered to determine the final partitioning scheme [14,15].

Through our analysis in Section 3.1 on security state detection issues in trusted federated learning [16], we identify that the final selection of the partitioning model aggregation scheme must consider three aspects: similarity of participant data features within a partition [17], communication overhead for achieving distributed data consensus [18], and the resilience of the consensus result against malicious attacks [19]. The data features within a partition determine the performance of local models used by participants. The consensus communication overhead determines the cost of communication per training and data synchronization round [20]. The size of consensus participants determines the partition’s ability to resist Byzantine nodes, ultimately affecting the trustworthiness of data records [21].

During machine learning model training, the similarity of the training dataset feature distribution affects model convergence speed and prediction performance. The intra-cluster data similarity metric

where

A distributed network communication system can be abstracted as a fully connected weighted graph. The weights between device nodes estimate the internal communication overhead of the cluster and can be expressed as

It calculates the average intra-cluster communication overhead [22]. Here,

Since the consensus mechanism follows the principle of majority rule, we assume there are

By substituting the feature matrix and network parameters obtained in the previous section into this formula, we obtain the scores of different candidate partitioning optimization schemes. The scheme with the highest score is selected as the final federated partition aggregation network structure for deployment.

2.2 Improvement of Federated Learning Training Process with Anomaly Detection

In trusted federated learning, the multi-organizational nature introduces significant challenges in ensuring data quality and model credibility. Malicious participants can employ various attack strategies including data poisoning, model poisoning, and coordinated attacks to compromise the global model’s integrity. Our approach addresses these threats through a comprehensive anomaly detection mechanism integrated into the model aggregation process.

We define model distance as a quantitative measure of deviation between individual participant models and the expected global consensus. This approach captures anomalous behavior patterns that may indicate malicious activity or data quality issues. The residual model calculation is given by

where

Based on the computed residual models, we calculate the distance between the local model and the residual global model excluding the local contribution as an anomaly feature

where

A statistical method for anomaly detection is subsequently utilized. Real-world data is often assumed to follow a normal distribution. We identify outliers using the data’s mean and standard deviation. In the

We calculate the mean and variance of

Through this method, we complete the detection and identification of malicious participants. Next, combining the trusted federated learning sharding aggregation structure and malicious node detection mechanism, this study improves the traditional decentralized federated learning process to enhance training efficiency and robustness against malicious nodes.

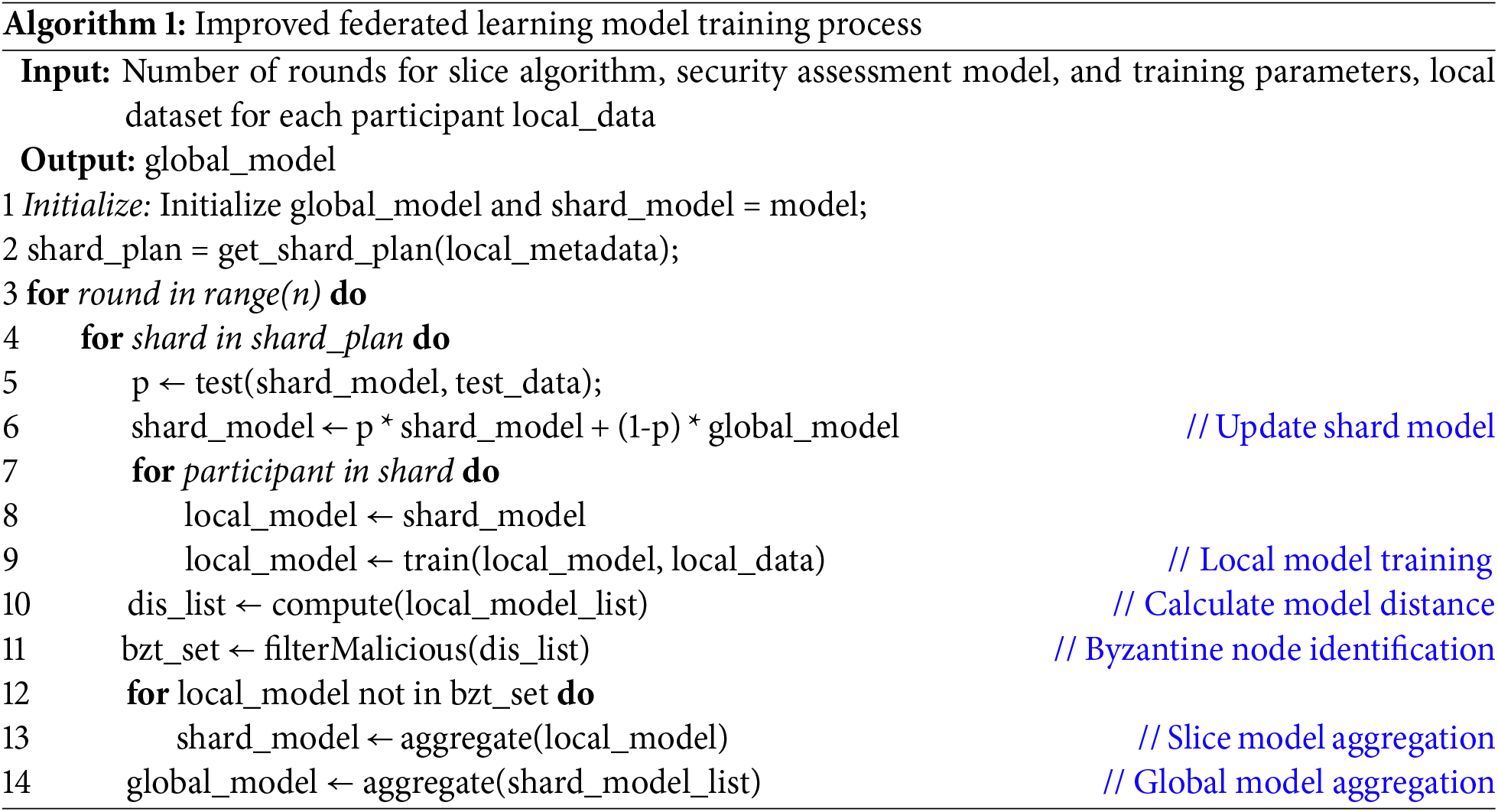

The following steps illustrate the process of ShardFed.

Step 1 - Data Preparation: Extract the data and label distribution features of participants engaged in model aggregtion. Construct deep learning models for security assessment in network environments and initialize the models.

Step 2 - Shard Calculation: Use a trusted federated learning aggregation network sharding method to determine the optimal sharding aggregation scheme based on participant data distribution characteristics.

Step 3 - Model Deployment: Distribute the initialized global model to participant nodes in each shard via smart contract interfaces. Security assessment servers receive the latest models.

Step 4 - Local Model Training: Each participant trains and updates local security detection models using private data without centralizing security event data.

Step 5 - Malicious Node Detection: Participants share local models via smart contracts. The system calculates model distances and identifies malicious models using the anomaly detection mechanism. Model information and detection results are recorded.

Step 6 - Model Aggregation: Filtered models are aggregated within each shard to generate local shard models. These are then aggregated into a global model using the federated averaging algorithm. The global model enhances the generalization ability of shard models, improving training efficiency. However, each participant still receives its respective shard model for practical deployment.

Step 7 - Shard Model Update: Each shard receives the refined global model, and its performance is evaluated. The shard model is then adjusted using

Steps 3–7 are repeated until all participant models converge to the target performance level.

The overall processes are summarized in Algorithm 1.

2.3 Computational Complexity Analysis

The computational complexity of our sharding method consists of several components. Feature extraction has a complexity of

3 Simulation Scheme and Result Analysis

To provide a comprehensive security analysis framework, we define two primary threat models that the proposed trustworthy federated learning system addresses. These threat models establish the foundation for evaluating the robustness and security guarantees of our approach.

In data poisoning attacks, malicious participants deliberately corrupt their local training datasets to degrade the performance of the global model. Specifically, let

The objective of data poisoning is to maximize the degradation of global model accuracy while remaining undetected by the aggregation mechanism.

In model poisoning attacks, malicious participants submit crafted model updates that deviate significantly from the expected gradient directions. Let

3.1.3 Theoretical Security Guarantees

For the proposed anomaly detection mechanism with threshold

Theorem 1 (Detection Accuracy Bound): Given

where

This bound demonstrates that the detection accuracy improves exponentially with the separation between honest and malicious participant behaviors, providing theoretical justification for the proposed approach.

This experiment aims to verify the effectiveness of the trusted federated learning sharding aggregation scheme in improving local model performance and reducing communication overhead under non-IID data distributions among participants. Additionally, it evaluates the robustness of the global model when malicious nodes launch mainly data poisoning attacks, using an anomaly detection-based method for identifying malicious participants.

The main parameters used in the experiment are depicted as follows. During dataset partitioning, non-IID data employ the Dirichlet distribution with a heterogeneity parameter

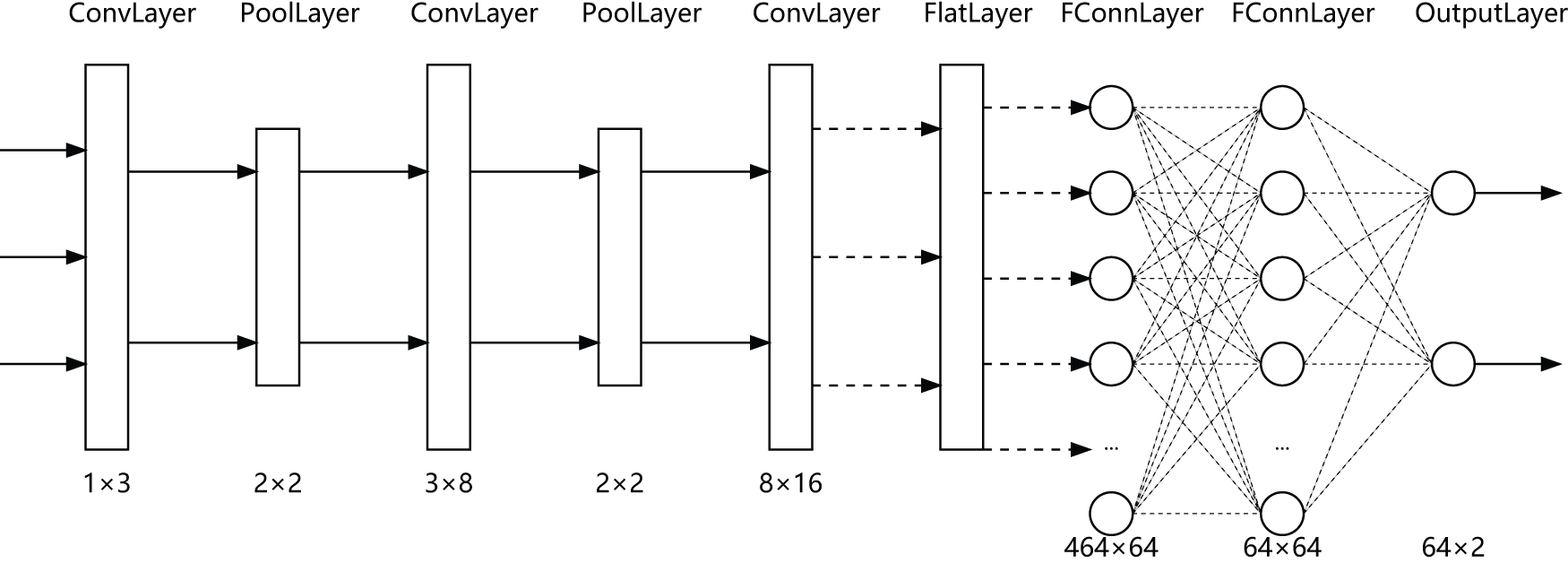

This experiment adopts a one-dimensional CNN-based model for IoT network traffic security assessment, as shown in Fig. 1. The architecture comprises three convolutional layers, two max pooling layers, and three fully connected layers. Input data is processed through convolution and pooling to extract features and reduce dimensionality, followed by flattening and fully connected layers for nonlinear learning. ReLU activations add nonlinearity, and the output layer produces probabilities for normal and abnormal classes. The model is implemented in PyTorch, trained with cross-entropy loss, and optimized using stochastic gradient descent. The trusted federated learning sharding aggregation structure via direct model aggregation enhances model performance and communication efficiency under non-IID data distributions.

Figure 1: Neural network architecture

To validate the proposed method in network security assessment scenarios, the NSL-KDD dataset [26], a classic benchmark in network security, is mainly used. This dataset includes connection states, packet content features, and time-based traffic statistical features, providing a comprehensive representation of network connections. The performance on the dataset BoT-IoT [27] is also tested.

To ensure non-IID data allocation for each participant, a Dirichlet distribution-based method is introduced. The Dirichlet distribution, a classical high-dimensional continuous probability distribution, is denoted as

For a random vector

To simulate data quality issues from malicious participants, some labels in the local datasets are randomly modified to implement data poisoning attacks, while model poisoning attacks are simulated by injecting adversarial perturbations into model parameters during the aggregation phase. The effectiveness of integrating anomaly detection into the federated learning training process is then evaluated to demonstrate the robustness improvement.

To comprehensively assess the advantages of the proposed trusted federated learning method over conventional decentralized federated learning in terms of accuracy, communication efficiency, and robustness against attacks, multiple metrics are defined.

Model accuracy is evaluated using

Communication efficiency is measured as

3.3 Experimental Results Analysis

This section employs the trusted federated learning shard optimization method, incorporating a mechanism for detecting malicious nodes into the FL model aggregation framework. This integration aims to demonstrate its efficacy in enhancing model training performance, particularly when multiple participants have non-IID data, within the scenario of detecting network anomaly traffic. Based on feature similarity and communication cost, the final aggregation strategy consists of four clusters: participants {0, 2, 5, 9}, {1, 3}, {6, 7, 8}, and participant 4 as an individual shard.

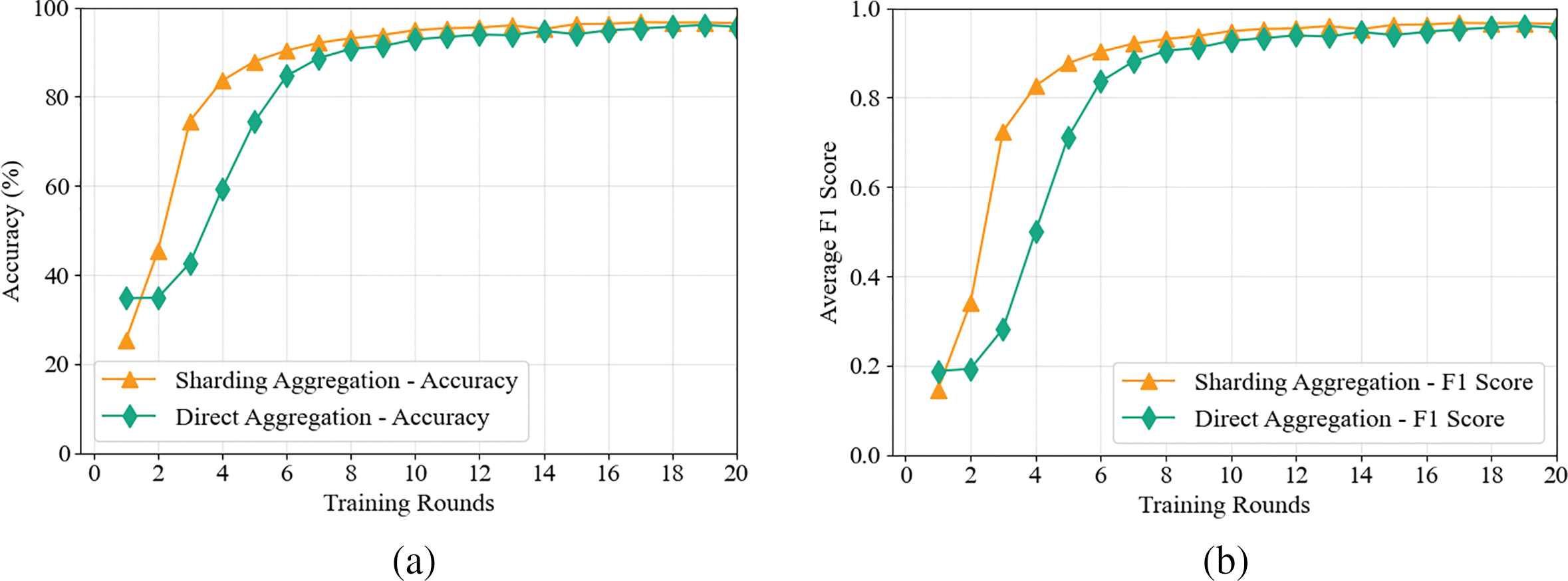

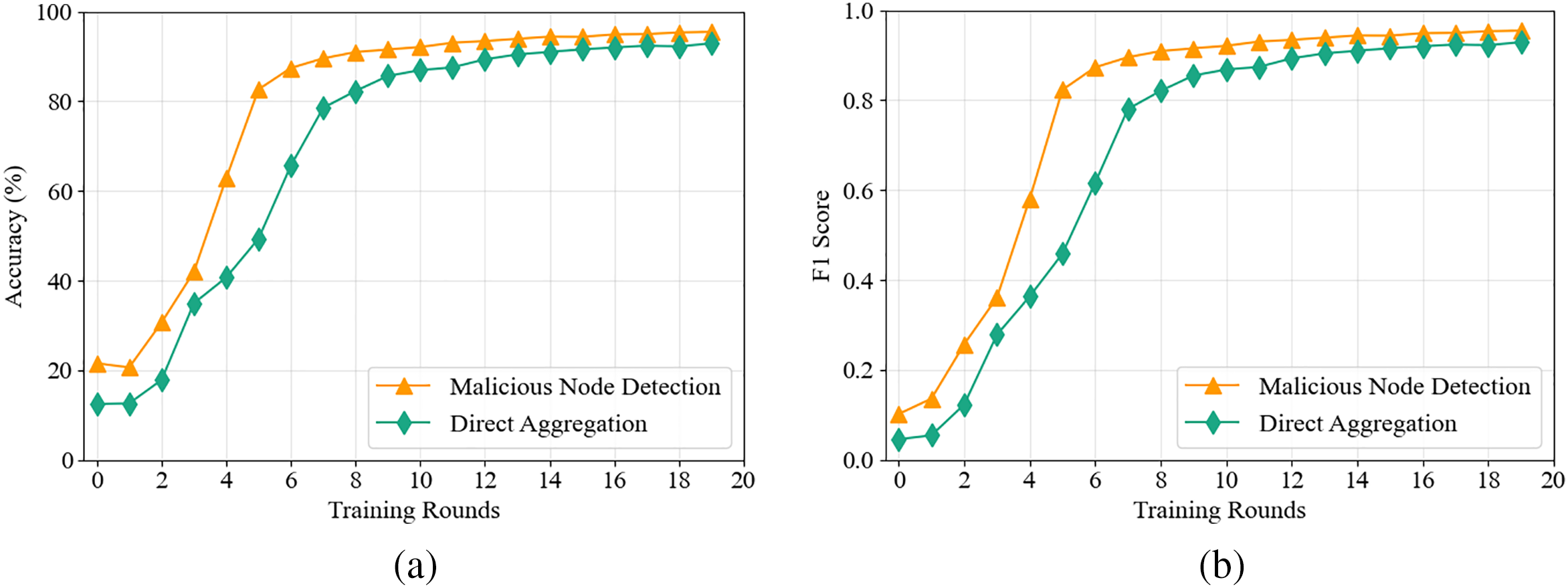

For model training effectiveness, Fig. 2a,b compares the performance of the federated learning sharding aggregation method against direct global aggregation. Under a 10-participant scenario, the sharding approach achieves 90% accuracy in 6 training rounds, whereas direct aggregation requires 9 rounds (50% slower). After 20 training rounds, the average model accuracy of sharded participants reaches 96.47%, compared to 95.63% in the non-sharded approach, demonstrating a 0.84% improvement.

Figure 2: Comparison of average accuracy among participants (a) and Comparison of Average F1 score among participants (b)

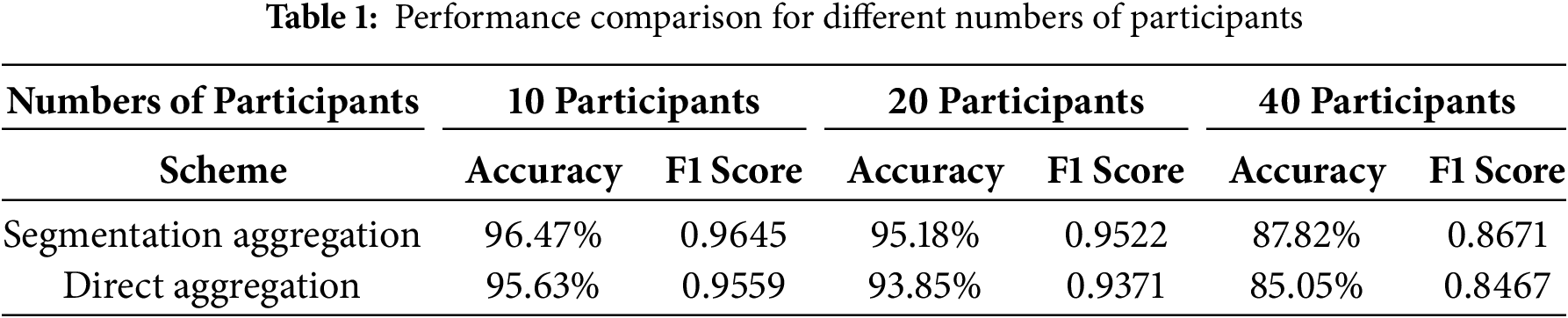

Table 1 presents the model training performance of the proposed trustworthy federated learning sharding aggregation scheme under different participant scales. The data indicates that as the number of contributors in federated learning increases, the overall heterogeneity among datasets also increases. This leads to a decline in both accuracy and F1-score.

As the number of participants increases, the advantage of the sharding aggregation scheme over the direct aggregation scheme becomes more significant. Specifically, when the number of participants increases to 20 and 40, the sharding aggregation scheme improves performance by 1.77% and 2.33%, respectively. This aligns with the expectation that the sharding scheme is more suitable for scenarios with a larger number of participants. The experimental results verify that the proposed trustworthy federated learning sharding aggregation scheme enhances model training performance in multi-participant heterogeneous data scenarios. Moreover, as the network scale expands, the advantages of this scheme become more pronounced.

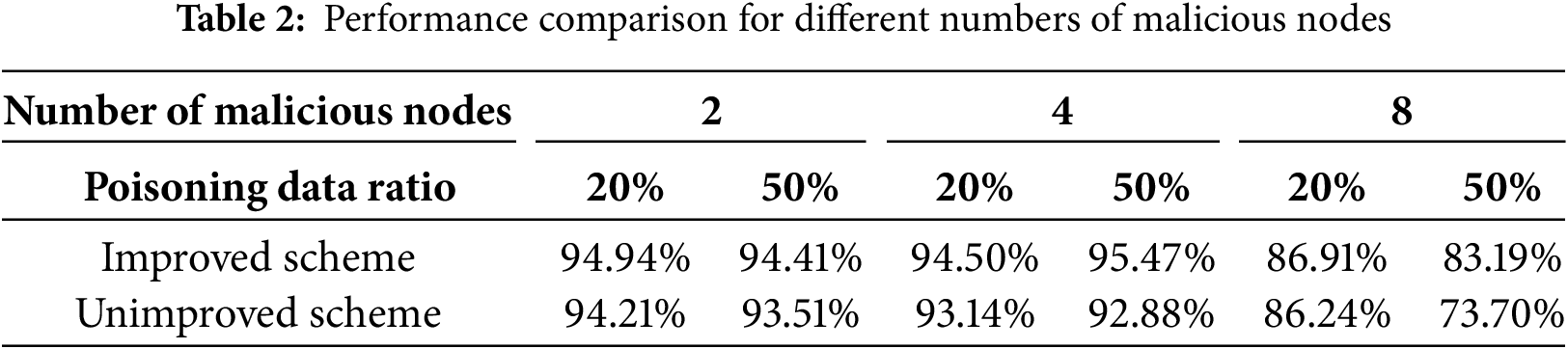

To verify the ability of the trustworthy federated learning model aggregation process to resist malicious participants, we conducted experiments under a scenario with 20 participants. We tested different numbers of malicious nodes and various poisoning data proportions per node. The improved model aggregation process was evaluated for its effectiveness in maintaining model performance.

Fig. 3a,b illustrates a scenario with four malicious nodes, where each node contains 50% poisoned data. Compared to the direct aggregation model, the trustworthy federated learning aggregation process incorporating a malicious node detection mechanism exhibits significant advantages in both convergence speed and model performance. Specifically, using accuracy and F1 score as evaluation metrics on the test set, the direct aggregation scheme suffers from slower convergence and lower accuracy due to the influence of low-quality malicious participant models. However, after applying the malicious node detection mechanism, the model performance and convergence speed are greatly improved, approaching the original accuracy observed in the non-poisoned scenario (Fig. 2a,b).

Figure 3: Model accuracy comparison (a) and F1 score comparison (b)

Table 2 displays the model accuracy on the test set under different numbers of malicious nodes and varying poisoning proportions. When the proportion of malicious nodes is moderate, the detection mechanism is more effective. When the proportion is low, the impact of data quality on the global model is limited, making accuracy improvements less noticeable. However, when the proportion of malicious nodes reaches nearly 50%, the detection mechanism struggles to filter out all malicious participants, leading to poor model performance.

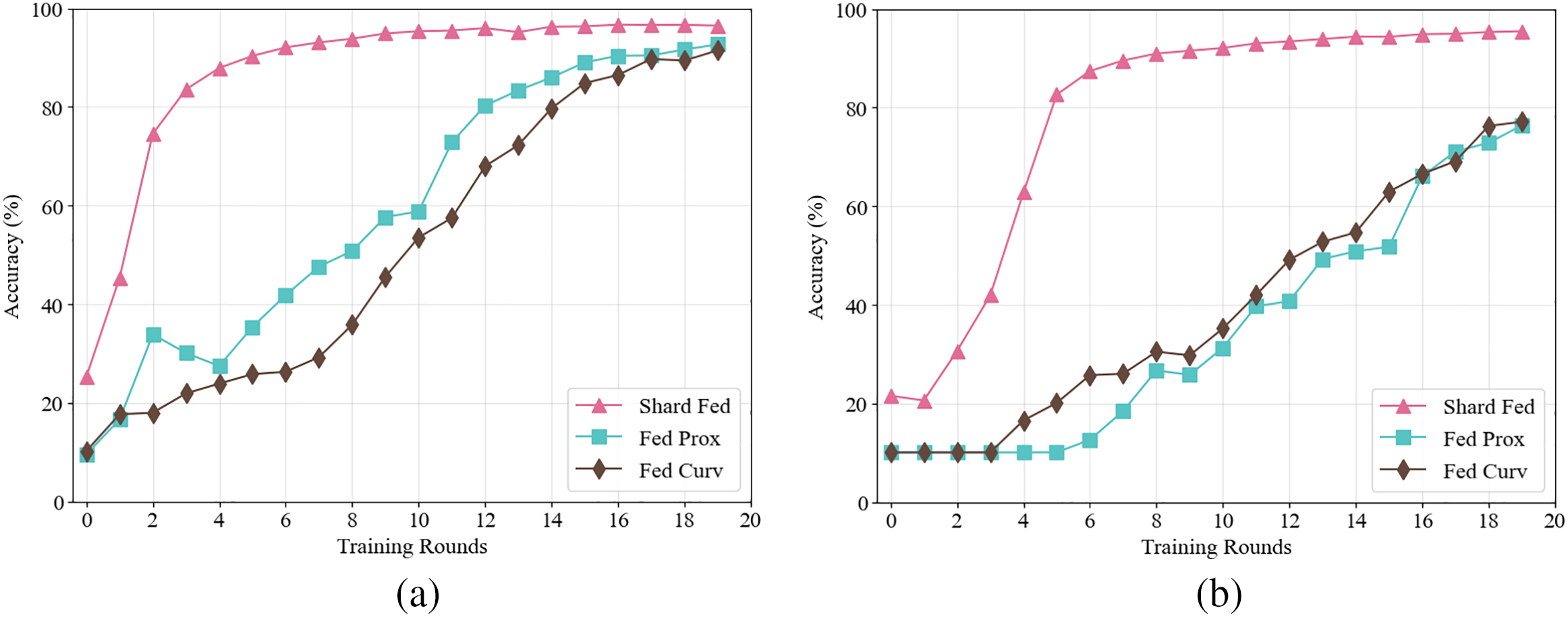

To demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed ShardFed algorithm under non-IID data and interference conditions, we compared it with two state-of-the-art federated learning algorithms: FedProx [29] and FedCurv [30]. Accuracy was used as the evaluation metric to assess the performance of different training methods under non-IID data distributions and with 20% noisy training data.

Fig. 4a,b presents a comparison of accuracy across different federated learning algorithms. The results indicate that compared to FedProx and FedCurv, both of which optimize for non-IID data distributions, ShardFed significantly improves convergence speed by leveraging sharded global model information. The experiment also confirms that introducing noisy training data simulates low-quality datasets, and the proposed malicious node detection mechanism greatly enhances resistance against low-quality model contributors, improving adaptability across multiple scenarios.

Figure 4: Comparison of accuracy (a) without poisoned data, and (b) with poisoned data

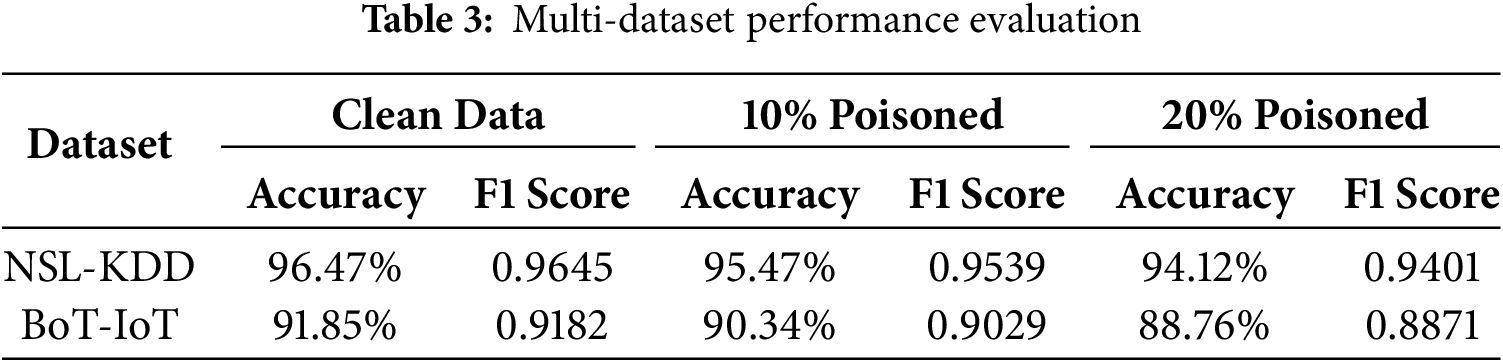

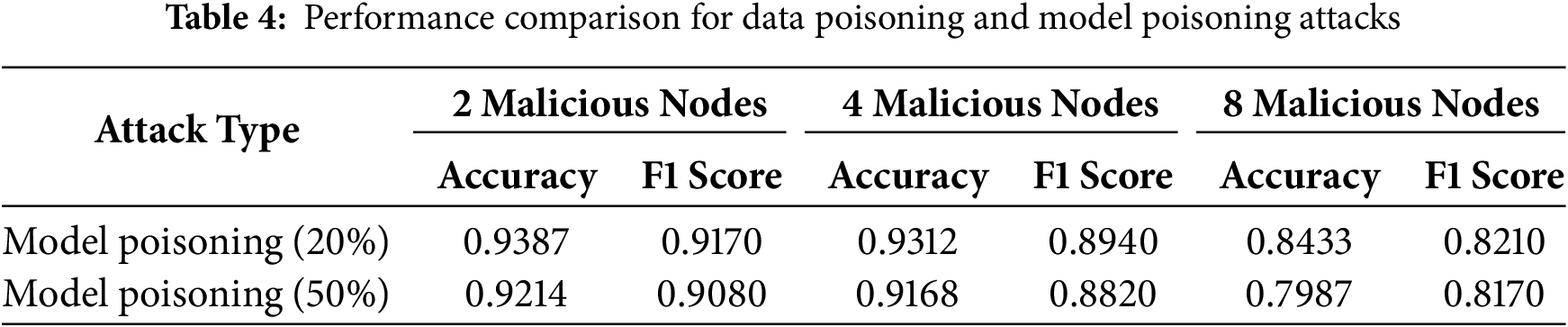

To validate the advantages of our proposed trustworthy federated learning sharding aggregation scheme with malicious node detection, we assessed its performance against standard machine learning models like K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Support Vector Machines (SVM), and Decision Trees. As shown in Table 3, it performs well in various scenarios, including NSL-KDD and BoT-IoT. Initially designed for data poisoning, the method is also effective for model poisoning, using global model bias to detect malicious participants, as detailed in Table 4.

The results demonstrate that federated learning models, due to their higher complexity, perform better on complex problems compared to Decision Trees and SVM. Compared to KNN, the proposed scheme performs slightly better in non-interference conditions. However, when interference data is introduced, the proposed malicious node detection mechanism enhances robustness significantly, making it more suitable for complex and dynamic federated learning scenarios.

This paper proposes a shard-based federated learning framework for network security assessment, integrating anomaly-aware malicious node detection and multi-objective shard formation via statistical feature extraction and spectral clustering. The ShardFed algorithm combines sharding with residual-model anomaly detection to effectively filter poisoned models. Experiments on the NSL-KDD dataset demonstrate improved accuracy, convergence, and robustness over mainstream approaches such as FedProx and FedCurv, especially under data poisoning attacks, and show good scalability to larger participant numbers.

Despite the promising results, the limitations include testing on limited datasets and focusing on mainly data poisoning attacks. Future research will validate using modern datasets, enhance defenses against advanced threats like model poisoning and Sybil attacks, and explore scalability, especially focusing on reducing the computational cost of the initial sharding process. Additionally, the trust-scoring system might unfairly exclude participants, suggesting a rejoin mechanism could be added.

Acknowledgement: This work received the support from cooperative project with Beijing University of Posts and Telecommunications.

Funding Statement: This work is supported by State Grid Hebei Electric Power Co., Ltd. Science and Technology Project, Research on Security Protection of Power Services Carried by 4G/5G Networks (Grant No. KJ2024-127).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Lincong Zhao and Liandong Chen; Methodology, Peipei Shen and Fanqin Zhou; Simulation design and implementation, Peipei Shen and Zizhou Liu; Validation and analysis, Zizhou Liu and Chengzhu Li; Writing—original draft preparation, Liandong Chen, Peipei Shen, and Zizhou Liu; Writing—review and editing, Lincong Zhao and Fanqin Zhou; Project administration and funding acquisition, Lincong Zhao. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets analyzed during the current study are available in the NSL-KDD dataset repository (https://www.unb.ca/cic/datasets/nsl.html) and the BoT-IoT dataset repository (https://research.unsw.edu.au/projects/bot-iot-dataset) (accessed on 4 August 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable. The study did not include human or animal subjects.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Hu K, Gong S, Zhang Q, Seng C, Xia M, Jiang S. An overview of implementing security and privacy in federated learning. Artif Intell Rev. 2024;57(8):204. doi:10.1007/s10462-024-10846-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Mohy-eddine M, Guezzaz A, Benkirane S, Azrour M. Malicious detection model with artificial neural network in IoT-based smart farming security. Cluster Comput. 2024;27(6):7307–22. doi:10.1007/s10586-024-04334-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Wang X, Shankar A, Li K, Parameshachari B, Lv J. Blockchain-enabled decentralized edge intelligence for trustworthy 6G consumer electronics. IEEE Transact Cons Elect. 2024;70(1):1214–25. doi:10.1109/tce.2024.3371501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Lewis C, Varadharajan V, Noman N. Attacks against federated learning defense systems and their mitigation. J Mach Learn Res. 2023;24(30):1–50. [Google Scholar]

5. Imteaj A, Mamun Ahmed K, Thakker U, Wang S, Li J. Amini MH. In: Razavi-Far R, Wang B, Taylor ME, Yang Q, editors. Federated learning for resource-constrained IoT devices: panoramas and state of the art. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2023. p. 7–27 doi:10.1007/978-3-031-11748-0_2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Quy VK, Nguyen DC, Van Anh D, Quy NM. Federated learning for green and sustainable 6G IIoT applications. Inter Things. 2024;25(2):101061. doi:10.1016/j.iot.2024.101061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Tao Y, Cui S, Xu W, Yin H, Yu D, Liang W, et al. Byzantine-resilient federated learning at edge. IEEE Transact Comput. 2023;72(9):2600–14. doi:10.1109/tc.2023.3257510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Wang H, Xu Z, Zhang Y, Wang Y. Adaptive layered-trust robust defense mechanism for personalized federated learning. In: ICASSP 2025-2025 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP). Hyderabad, India: IEEE; 2025. p. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

9. AzharShokoufeh D, DerakhshanFard N, RashidJafari F, Ghaffari A. Optimizing IoT data collection through federated learning and periodic scheduling. Knowl Based Syst. 2025;317(3):113526. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2025.113526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Yaacoub JPA, Noura HN, Salman O. Security of federated learning with IoT systems: issues, limitations, challenges, and solutions. Int Things Cyber-Phys Syst. 2023;3(3):155–79. doi:10.1016/j.iotcps.2023.04.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Kalapaaking AP, Khalil I, Rahman MS, Atiquzzaman M, Yi X, Almashor M. Blockchain-based federated learning with secure aggregation in trusted execution environment for internet-of-things. IEEE Transact Indust Inform. 2022;19(2):1703–14. doi:10.1109/tii.2022.3170348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Zhou Y, Pang X, Wang Z, Hu J, Sun P, Ren K. Towards efficient asynchronous federated learning in heterogeneous edge environments. In: IEEE INFOCOM 2024-IEEE Conference on Computer Communications. Vancouver, BC, Canada: IEEE; 2024. p. 2448–57. [Google Scholar]

13. Ribero M, Vikalo H. Reducing communication in federated learning via efficient client sampling. Pattern Recognit. 2024;148:110122. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2023.110122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Oyewole GJ, Thopil GA. Data clustering: application and trends. Artif Intell Rev. 2023;56(7):6439–75. doi:10.1007/s10462-022-10325-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Pitafi S, Anwar T, Sharif Z. A taxonomy of machine learning clustering algorithms, challenges, and future realms. Appl Sci. 2023;13(6):3529. doi:10.3390/app13063529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Yurdem B, Kuzlu M, Gullu MK, Catak FO, Tabassum M. Federated learning: overview, strategies, applications, tools and future directions. Heliyon. 2024;10(19):e38137. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e38137. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Zeng Y, Mu Y, Yuan J, Teng S, Zhang J, Wan J, et al. Adaptive federated learning with non-IID data. Comput J. 2023;66(11):2758–72. doi:10.1093/comjnl/bxac118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Zhang W, Zhou T, Lu Q, Yuan Y, Tolba A, Said W. FedSL: a communication-efficient federated learning with split layer aggregation. IEEE Inter Things J. 2024;11(9):15587–601. doi:10.1109/jiot.2024.3350241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Guerraoui R, Gupta N, Pinot R. Byzantine machine learning: a primer. ACM Comput Surv. 2024;56(7):1–39. doi:10.1145/3616537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Song R, Liu D, Chen DZ, Festag A, Trinitis C, Schulz M, et al. Federated learning via decentralized dataset distillation in resource-constrained edge environments. In: 2023 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN). Gold Coast, Australia: IEEE; 2023. p. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

21. Lewis-Pye A, Roughgarden T. Byzantine generals in the permissionless setting. In: International Conference on Financial Cryptography and Data Security. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2023. p. 21–37. [Google Scholar]

22. Abbas S, Ahmad B, Benchohra M, Salim A. Fractional difference, differential equations, and inclusions: analysis and stability. San Francisco, CA, USA: Morgan Kaufmann Publishers, Elsevier; 2024. [cited 2025 Aug 4]. Avilable from: https://abdelkrim-salim.owlstown.net/publications/22287-fractional-difference-differential-equations-and-inclusions-analysis-and-stability. [Google Scholar]

23. Qi J, Guan Y. Practical Byzantine fault tolerance consensus based on comprehensive reputation. Peer-to-Peer Networ Applicat. 2023;16(1):420–30. doi:10.1007/s12083-022-01408-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Civit P, Gilbert S, Guerraoui R, Komatovic J, Paramonov A, Vidigueira M. All byzantine agreement problems are expensive. In: Proceedings of the 43rd ACM Symposium on Principles of Distributed Computing; Nantes, France; 2024. p. 157–69. [Google Scholar]

25. Linde W. Probability theory: a first course in probability theory and statistics. Berlin, Germany: Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG; 2024. [cited 2025 Aug 4]. Avilable from: https://speciation.net/Database/Companies/Walter-de-Gruyter-GmbH-amp-Co-KG/-;i703a-1. [Google Scholar]

26. Tavallaee M, Bagheri E, Lu W, Ghorbani AA. A detailed analysis of the KDD CUP 99 data set. In: 2009 IEEE Symposium on Computational Intelligence for Security and Defense Applications. Ottawa, ON, Canada; 2009. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

27. Buiya MR, Laskar A, Islam MR, Sawalmeh S, Roy M, Roy R, et al. Detecting IoT cyberattacks: advanced machine learning models for enhanced security in network traffic. J Comput Sci Technol Stud. 2024;6(4):142–52. doi:10.32996/jcsts.2024.6.4.16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Chen D, Hu J, Tan VJ, Wei X, Wu E. Elastic aggregation for federated optimization. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; Vancouver, BC, Canada; 2023. p. 12187–97. [Google Scholar]

29. Li X, Huang K, Yang W, Wang S, Zhang Z. On the convergence of fedavg on non-iid data. arXiv:1907.02189. 2019. [Google Scholar]

30. Shoham N, Avidor T, Keren A, Israel N, Benditkis D, Mor-Yosef L, et al. Overcoming forgetting in federated learning on non-iid data. arXiv:1910.07796. 2019. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools