Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Generated Preserved Adversarial Federated Learning for Enhanced Image Analysis (GPAF)

Smart Communication Research Team, Mohamedia School of Engineers, University Mohammed V in Rabat, 10100, Morocco

* Corresponding Author: Sanaa Lakrouni. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Multi-Modal Deep Learning for Advanced Medical Diagnostics)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(3), 5555-5569. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.067654

Received 09 May 2025; Accepted 26 August 2025; Issue published 23 October 2025

Abstract

Federated Learning (FL) has recently emerged as a promising paradigm that enables medical institutions to collaboratively train robust models without centralizing sensitive patient information. Data collected from different institutions represent distinct source domains. Consequently, discrepancies in feature distributions can significantly hinder a model’s generalization to unseen domains. While domain generalization (DG) methods have been proposed to address this challenge, many may compromise data privacy in FL by requiring clients to transmit their local feature representations to the server. Furthermore, existing adversarial training methods, commonly used to align marginal feature distributions, fail to ensure the consistency of conditional distributions. This consistency is often critical for accurate predictions in unseen domains. To address these limitations, we propose GPAF, a privacy-preserving federated learning (FL) framework that mitigates both domain and label shifts in healthcare applications. GPAF aligns conditional distributions across clients in the latent space and restricts communication to model parameters. This design preserves class semantics, enhances privacy, and improves communication efficiency. At the server, a global generator learns a conditional feature distribution from clients’ feedback. During local training, each client minimizes an adversarial loss to align its local conditional distribution with the global distribution, enabling the FL model to learn robust, domain-invariant representations across all source domains. To evaluate the effectiveness of our approach, experiments on a medical imaging benchmark demonstrate that GPAF outperforms four FL baselines, achieving up to 17% higher classification accuracy and 25% faster convergence in non-IID scenarios. These results highlight GPAF’s capability to generalize across domains while maintaining strict privacy, offering a robust solution for decentralized healthcare challenges.Keywords

Recent advances in artificial intelligence (AI) have significantly improved healthcare quality and increased life expectancy. Deep learning models show particular promise in addressing complex healthcare challenges [1]. These models, however, require access to large-scale, high-quality datasets to achieve robust performance. Therefore, Limited datasets constrained the development of effective AI applications in healthcare field. To address this limitation, federated learning (FL) enables multiple medical institutions to train a global model collaboratively while preserving strict privacy guarantees. Specifically, each medical site shares only its local model parameters with a central server. This decentralized paradigm provides a viable alternative to traditional centralized learning [2]. Therefore, FL has gained wide adoption in critical medical applications, such as brain tumor detection [3] and COVID-19 diagnosis [4]. However, one key challenge in FL is data heterogeneity. Clients collect their private data using different equipment, scanners, and imaging protocols [5]. As a result, shifts in feature distributions arise across clients, causing a domain shift issue. Consequently, models trained under these conditions fail to learn robust domain-invariant representations and may not capture domain characteristics beyond their local datasets. A common aggregation method in federated learning (FL), such as FedAvg [6], computes the global model by averaging local model updates. While this approach has demonstrated its effectiveness in use cases, it does not account for differences in data distributions. This can lead to increased divergence among client models in the parameter space. As a result, the global model may become biased toward dominant local distributions, thereby hindering the overall performance of the FL system. To tackle this issue, a significant effort has been made in domain adaptation (DA) [7], which aims to reduce the distribution shifts between source and target domains. However, this approach faces two key limitations: First it requires access to a labeled target dataset, which is often impractical in privacy-sensitive domains like healthcare. Secondly, it must be retrained for each new unseen target domain, leading to computational and time-consuming burdens. Therefore, Domain generalization (DG) methods [8] have been proposed to align feature distributions across multiple source domains. This is achieved by training a model that can generalize effectively to unseen domains, without requiring access to the target domain during training. However, most existing methods rely on simultaneous access to diverse datasets to learn domain-invariant features, which is not feasible in a federated learning setting due to privacy constraints and communication overhead. To address this, significant efforts have been directed toward federated domain generalization (FedDG). These methods aim to enhance model robustness on unseen data distributions while adhering to the core principles of federated learning (FL). For example, a disease diagnosis model trained collaboratively by multiple hospitals should perform accurately when applied to new hospitals, even when their data distributions shift. This requires the model to learn domain-invariant representations across clients in a decentralized manner. One common approach involves clients sharing data-related information to learn a global data distribution [9]. However, these methods contradict the core privacy principles of the FL paradigm and introduces significant communication overhead. Similarly, adversarial learning approaches [10] align the local feature distributions of multiple participants through the optimization of a domain loss on the server. These methods necessitate that clients upload their local feature representations and then receive domain loss gradients for local optimization. Such frequent exchanges of local features, gradients, and data information expose the FL training process to privacy vulnerabilities [11]. For instance, this information is susceptible to exploitation in model inversion attacks [12]. Furthermore, a key limitation of these methods is their reliance on strict synchronous updates, which forces clients to wait for server-side domain loss gradients to perform local optimization. In practice, this design can lead to significant delays due to client unavailability and computational heterogeneity, leading to the rise of stragglers. The subsequent use of stale or outdated features from these clients negatively impacts adversarial optimization, which consequently reduces the scalability and robustness of real-world FL systems. To solve these challenges, we propose a preserved adversarial framework (GPAF) that learns domain-invariant features by aligning both marginal and conditional distributions across clients. GPAF tackles two key challenges: (1) mitigating domain and label shifts in federated settings, and (2) ensuring robust model generalization without compromising privacy or requiring synchronous coordination. Notably, GPAF introduces no additional communication overhead or coordination requirements. Clients perform domain alignment locally and communicate only their model parameters to the server, which preserves the classic FedAvg structure. In this way, GPAF enables scalable and stable training in asynchronous FL environments.

Moreover, existing approaches primarily align marginal feature distributions across clients to learn domain-invariant representations. These methods often assume the conditional distribution,

Motivated by these observations, we propose GPAF, a novel approach that aligns conditional distribution across clients to encourage the learning of robust, domain-invariant features. Our method integrates adversarial alignment during local training to enforce conditional alignment. At the server, the global generator models a global conditional

• We propose GPAF, a novel federated learning framework that addresses both domain and label shifts by aligning marginal and conditional distribution.

• GPAF aligns each client’s local conditional feature distribution with a global distribution through local adversarial learning, eliminating the need for a target dataset on the cloud.

• We introduce a new global model F, initialized with global parameters, to guide the generator in learning consistent features. We further enhance the generator with a consistency loss and a diversity loss to mitigate mode collapse and improve overall generator performance.

• GPAF performs domain alignment locally, guided by the server’s global knowledge, to ensure privacy and communication efficiency, thus enhancing DG approaches that require synchronous coordination between client feature extractors and server-side domain losses.

• Through extensive experiments on two medical benchmarks, we show that GPAF outperforms several state-of-the-art (SOTA) federated learning methods, such as FedAvg, MOON, and FedDG.

The paper is organized into the following sections. In Section 1, the limitations of existing approaches in handling domain shift are outlined. Section 2 reviews related works and highlights their limitations. In Section 3, we present our proposed method, GPAF, a privacy-preserving federated learning framework that addresses both domain and label shifts. We describe the training of a global generator at the server and adversarial learning with variational autoencoders (VAEs) to align local and global distributions on the client side. In Section 4, we validate our method using 2 medical benchmark datasets under domain shift and non-IID settings. Finally, in Section 5, we discuss future directions for advancing federated learning in healthcare field through robust domain generalization strategies.

A primary obstacle in federated learning (FL) is the performance degradation that results from data heterogeneity. There is a large body of existing work on regularization techniques to mitigate statistical heterogeneity and client drift [15,16]. However, these methods often fail to generalize to new domains due to domain shift. To address this, Federated Domain Generalization (FedDG) has emerged, integrating domain generalization (DG) principles into FL. A key approach to achieving this goal is representation learning, which has shown great success in DG. This approach captures common structures across various source domains. Consequently, representation learning can be extended to compel clients to learn domain-invariant features within a federated learning setting. For instance, Wu and Gong [17] proposed the COPA framework that encourages learning domain-invariant feature representation through a local feature extractor with hybrid batch-instance normalization. While the server aggregates the feature extractors, it also broadcasts an ensemble of domain-specific classifiers to all clients. This practice, however, can raise privacy concerns and increase communication overhead. Liu et al. [9] proposed FedDG, a method that leverages frequency domain transformation to preserve privacy. In this approach, clients share the amplitude spectrum and retain the phase spectrum locally to protect semantic content. The server then aggregates the shared amplitudes into a distribution bank, which clients use during local training to synthesize style-transferred data. A key limitation of this approach is that the frozen amplitude information may still leak distribution-specific characteristics, thereby posing a privacy risk as adversaries could potentially infer sensitive information. Chen et al. [18] proposed CCST, a framework that mitigates distributions discrepancies across clients. Clients extract style representations using a transformation technique (e.g., AdaIN) and send them to the server, which aggregates them into a global style bank. This bank is then redistributed to clients for local data augmentation. Each client augments their data with diverse styles to reduce client-specific biases. While this strategy enhances generalization, it introduces privacy concerns and increased communication costs, especially when multiple style representations are shared per client.

Recent works have extended Domain-Adversarial Neural Networks (DANN) to the federated learning setting to extract domain-invariant features across clients. DANN introduces a domain discriminator to identify the origin of the feature representations [19]. In FedAKA [20], a two-phase adversarial framework is employed to enhance domain generalization in FL. In the first phase, a global discriminator is trained at the server using both clients’ local features and target features. The discriminator objective is to learn to distinguish between features originating from a specific client or those from the target domain. In the second phase, the server transmits the gradients of the domain loss to each client. A gradient reversal layer is then applied to adversarially update local encoders, a process that encourages the extraction of domain-invariant features. Additionally, FedAKA reduces distributions discrepancies between sources and target domains by minimizing the (MMD) loss.

In federated fault diagnosis, recent methods adopt adversarial learning to handle domain shifts. These approaches jointly optimize a domain loss at server to encourage domain-invariant features [21]. Another federated transfer learning for machinery fault diagnosis uses synthetic priors to align class-wise distributions via MMD in a privacy-preserving manner [22]. However, these approaches compromise privacy by sharing client-specific information with the server, which exposes clients to potential attacks and leads to significant communication overhead. Moreover, several methods also depend on a centralized target dataset for domain alignment, contradicting the privacy-preserving goals of FL. Additionally, adversarial methods with GRL require strict synchronization between clients and the server to prevent gradient staleness, which is difficult to guarantee under communication constraints. Another line of work aims to improve privacy and employ data-free generative models to transfer knowledge in FL. For instance, FedDF [23] uses a server-side generator to synthesize data for ensemble distillation, enabling the fusion of knowledge from multiple client models into a single student model. Similarly, FedGen [14] leverages a lightweight generator to aggregate knowledge across clients and to regularize local training. However, FedGen synthesized features for local training regularization, but it fails to address domain-invariant representation learning within a federated domain generalization context. In contrast, our approach introduces a mechanism to align the conditional distributions across clients, implements a customized local adversarial alignment, and incorporates a global model F at the server to evaluate the semantic consistency of generated representations.

We propose Generated Preserved Adversarial Federated Learning (GPAF) to address the limitations of existing FL methods under both domain shift and label shift. We consider a standard FL scenario with

Prior studies commonly assume that the conditional distribution

Existing methods that align distributions at the input level, such as style harmonization [24] or data augmentation [25], primarily focus on the marginal distribution

where

Many Domain Generalization (DG) approaches aim to learn domain-invariant representations, z. To achieve this, these approaches ensure that the marginal distribution,

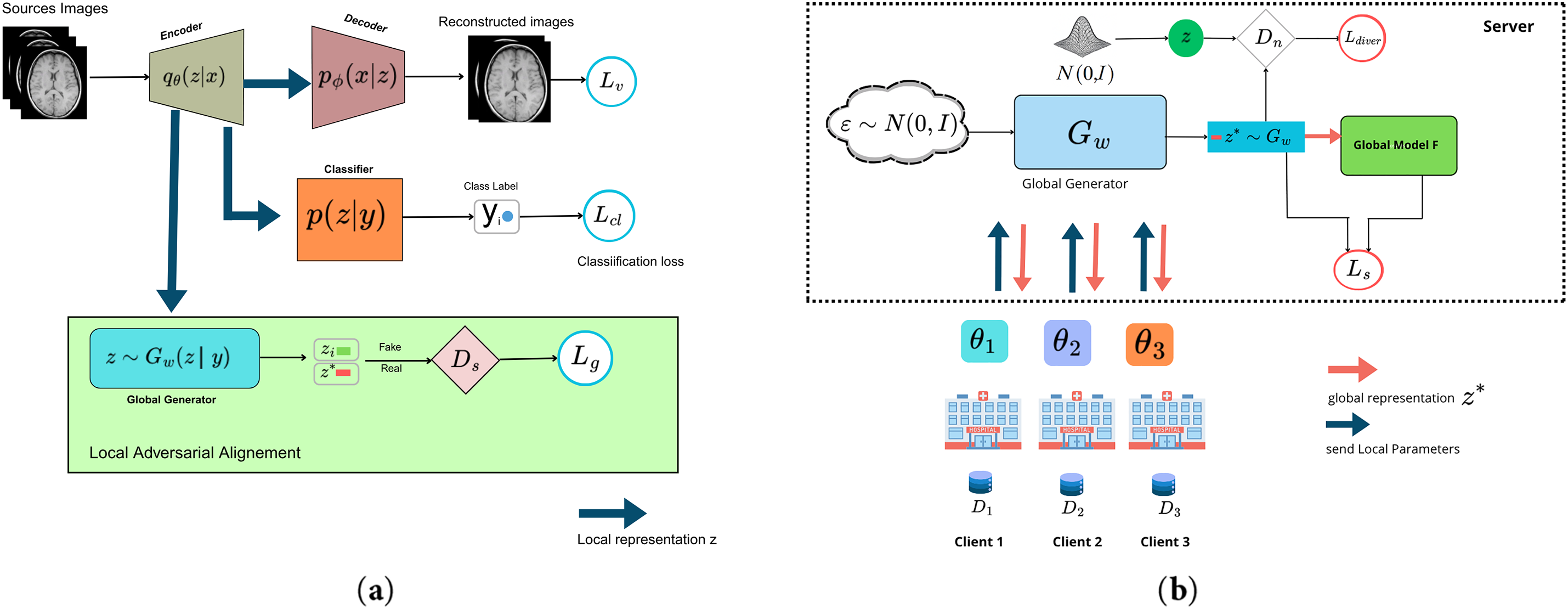

Figure 1: Overview of our federated domain generalization framework (GPAF). (a) Local adversarial alignment: each client encodes local data samples into latent representations encoder. The classifier predicts labels from latent features, and a decoder reconstructs input images. To align conditional distributions

3.2 Generative Preserved Adversarial Learning

To model global latent representations, we aim to learn a conditional distribution

VAEs are trained to minimize an objective Eq. (2) that includes a Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence term, which regularizes the posterior

here,

where

Moreover, generative models often suffer from mode collapse, where the generator learns to produce samples from only a few regions of the data distribution, thereby failing to capture its complete diversity [28]. In order to mitigate this issue, prior studies [29,30] have proposed adding a discriminator to an autoencoder to enforce a match between the learned posterior and the prior,

The global training aims to minimize a global loss

where

where

3.3 Local Adversarial Alignment

On the client side, we establish the training as a classification imaging task. Each client’s local model consists of four components: an encoder

where the KL term acts as a regularizer to ensure the learned latent representations remain close to the prior distribution

where

From the objective in Eq. (1), our approach aims to align the conditional feature distributions

Proposition 1: Let

Given the bound established in Eq. (11), we effectively minimize the KL divergence

To avoid the computational intractability of directly minimizing the KL divergence between local and global conditional distributions

Crucially, the adversarial loss in Eq. (13) is computed entirely on the client side and does not require gradient exchange or synchronization with the server. As a result, GPAF is both communication-efficient and robust to asynchronous setting. Hence, the total local training is optimized by the following loss:

where

This optimization is performed during local training, after which the updated encoder and classifier parameters

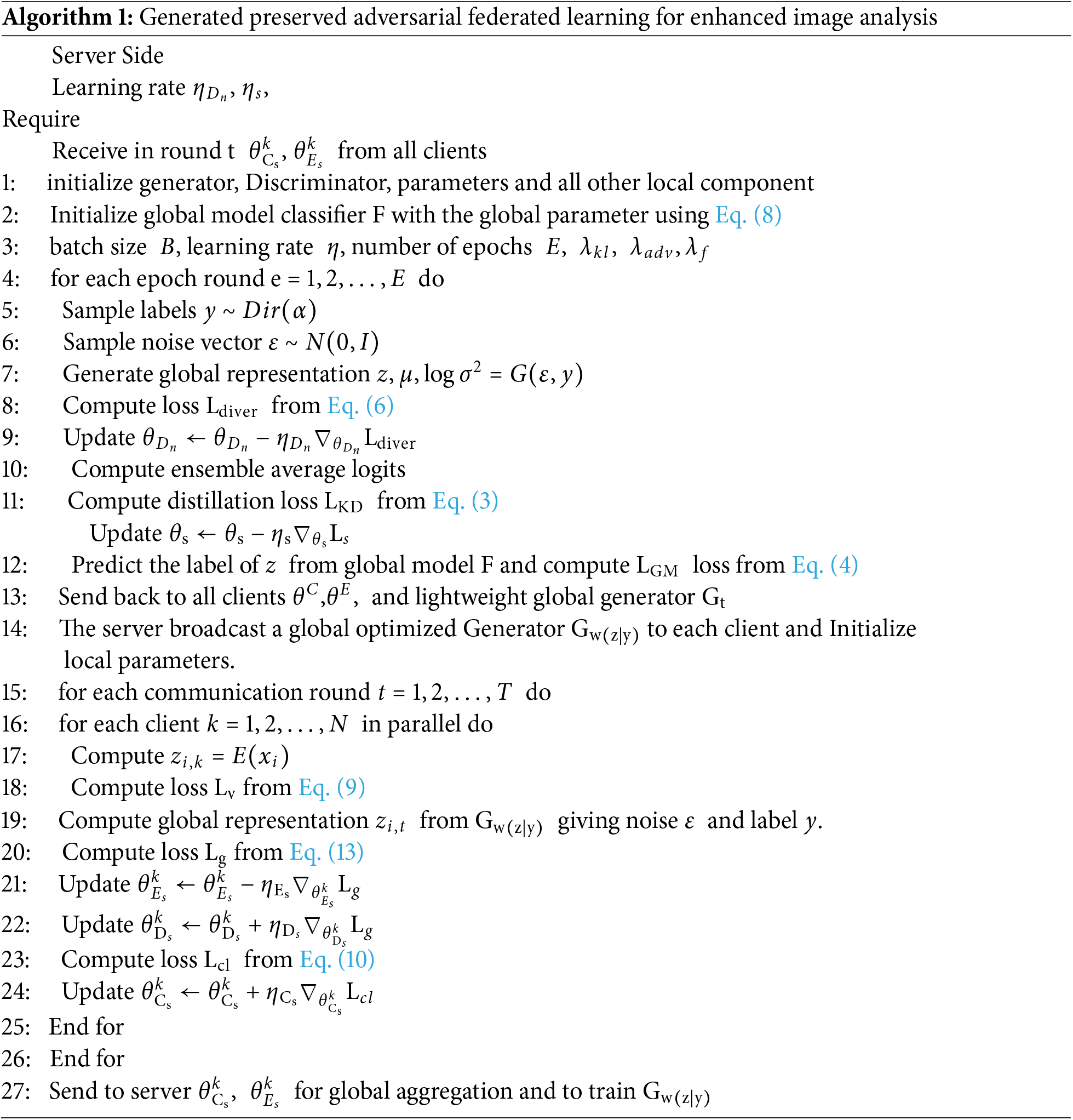

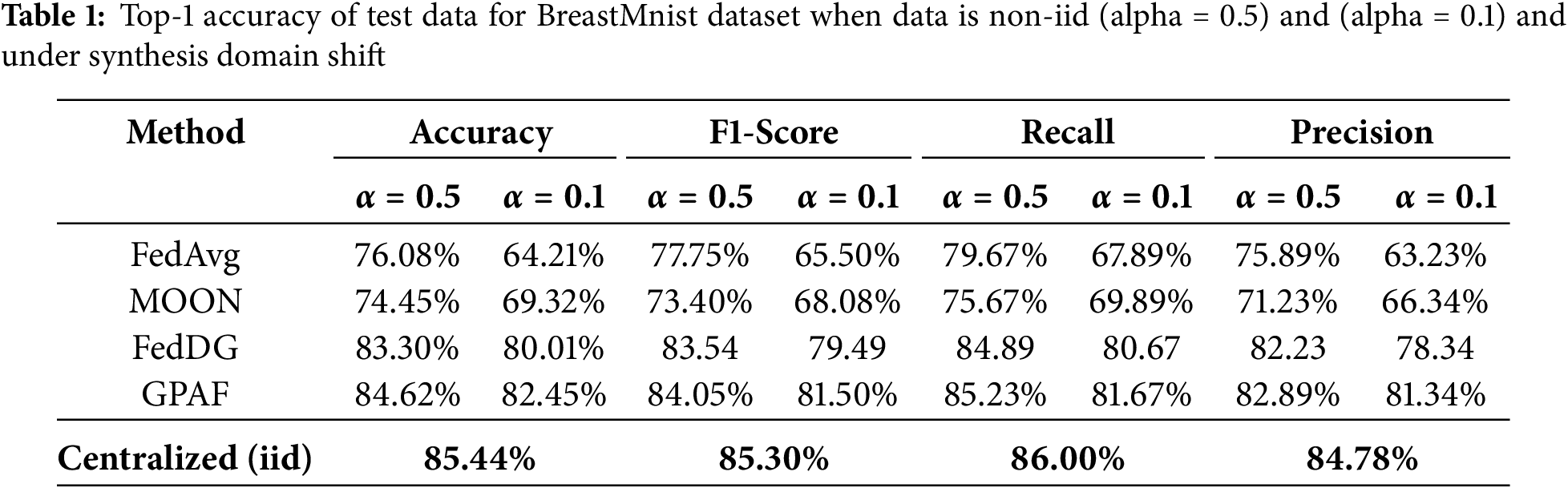

To evaluate our method, we conducted experiments on two medical imaging datasets. For binary classification, we used BreastMnist [33], which contains 780 grayscale breast ultrasound images resized to 28 × 28 pixels and categorized into benign, and malignant. Following the Medmnist-C benchmark [34], we design two scenarios. In Scenario 1, we simulated domain shift and partitioned the training set into three clients representing different imaging conditions: Client 0, as the original domain of the dataset, represents a High-end equipment. Client 1 emulates mid-range equipment typically used in resource-constrained settings with a subtle change in brightness between 0.2% and 15%, lower resolution and contrast between 0.6 and 1.4. Client 2 simulates a degraded condition, mimicking challenging real-world scenarios, with increased brightness (+0.3), added gaussian noise (0.12) noise and contrast varying between 0.5 to 1.5. As shown in Fig. 2, these perturbations yield distinct pixel intensity distributions. In scenario 2, we used PathMnist dataset to simulate a realistic case of domain shift. The training set includes 100,000 hematoxylin & eosin-stained histological images from one clinical center and the test set includes 7180 images from another center. Assigning the training set to Client 0 and the test set to Client 1 introduces both domain and label shift, since Client 0 contains more samples per class. Each client’s data was further split into validation and training. We compared GPAF with three FL baselines: FedAvg, MOON, FedDG, as well as the centralized learning. On the server, a global generator

Figure 2: Profile intensities across the three clients in both classes (a) and (b) with BreastMnist dataset

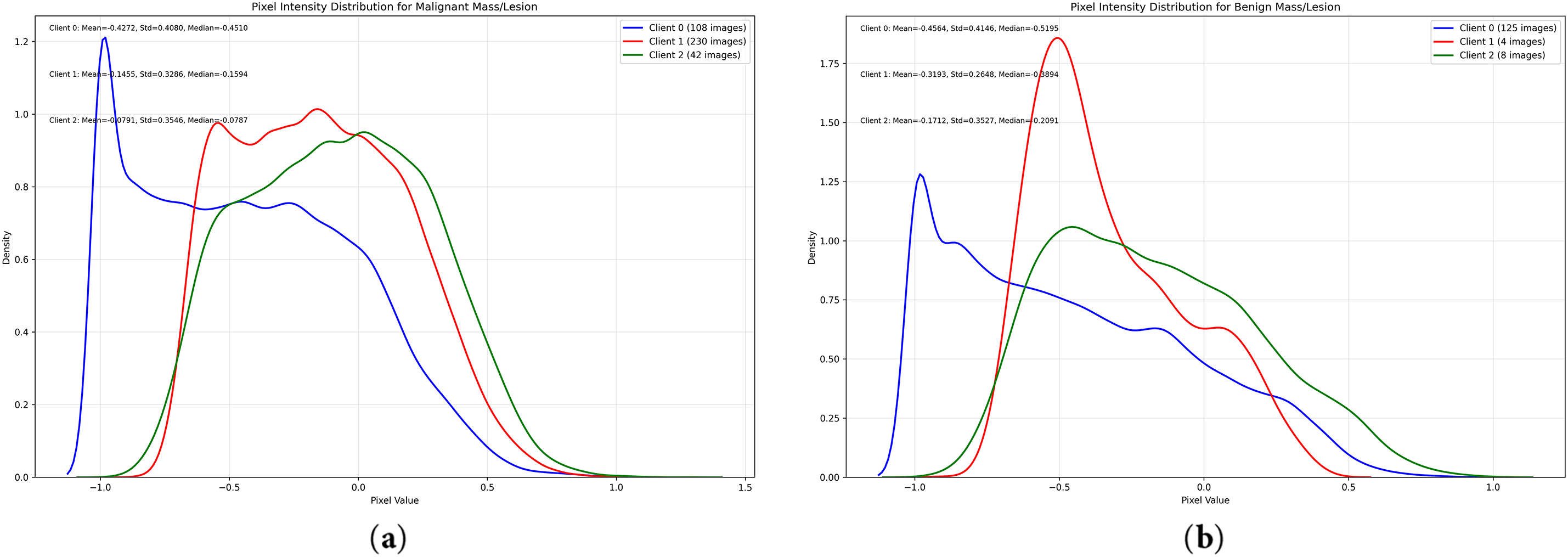

Table 1 presents the performance of GPAF and baseline algorithms on the BreastMnist dataset under both domain and label shift, using the Dirichlet distribution with varying alpha

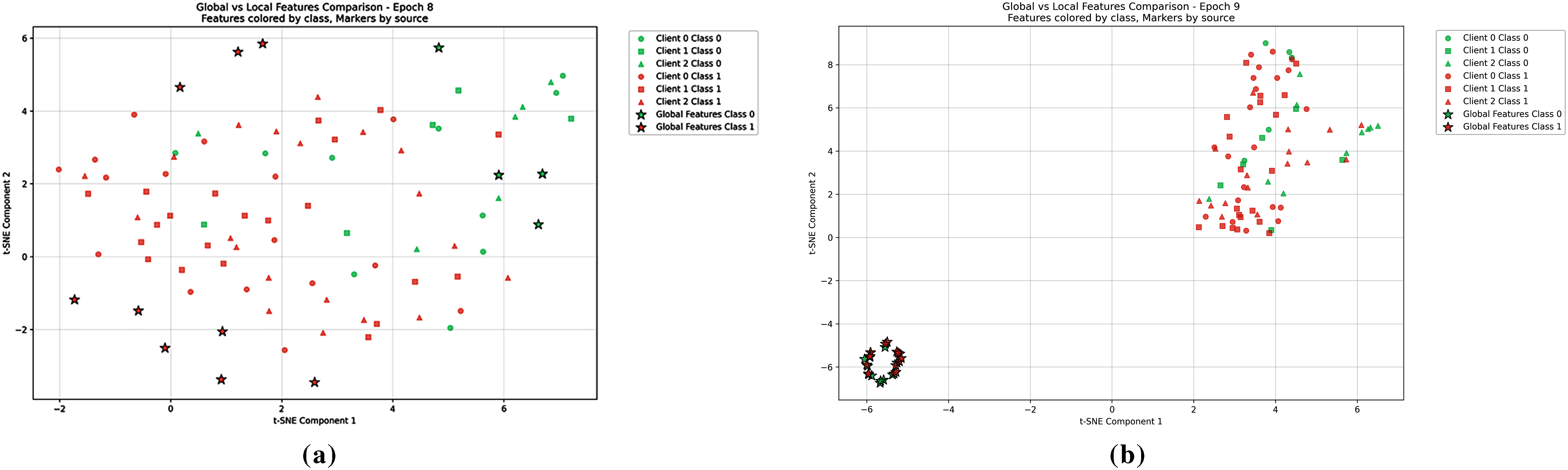

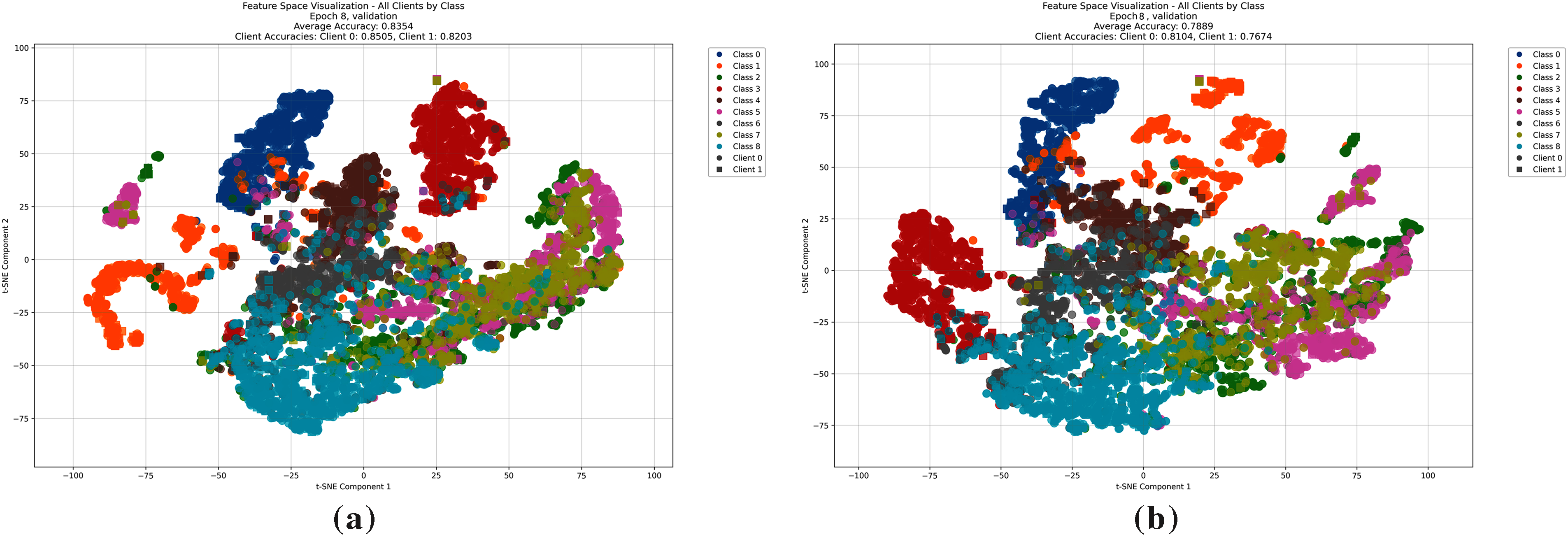

Figure 3: t-SNE visualization shows the local features of different clients of method GPAF (a) and MOON (b)

Figure 4: A t-SNE visualization of the conditional distribution across clients in iteration 8 between GPAF (a) and FedAvg (b) in PathMnist dataset

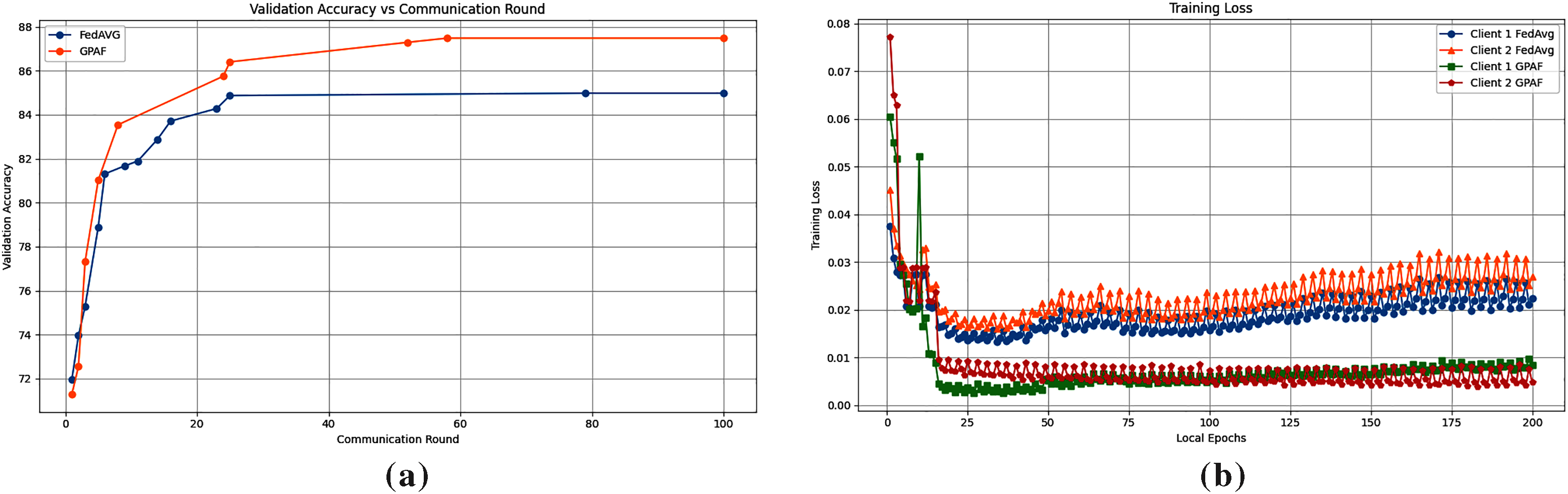

Fig. 5a shows the average validation accuracy across clients during local training phase. We recorded the accuracy only when it surpassed the previous best to monitor convergence. Although FedAvg performs well during early local epochs, GPAF surpasses it by the second global round and achieves its best accuracy at epoch 12. Fig. 5b presents the training loss curves per client. GPAF initially exhibits a significant loss variation in the early iterations, primarily because the global generator has not yet incorporated knowledge from the clients. As a result, the model experiences instability during the initial iterations. In contrast, FedAvg shows a more stable start with a lower initial loss, but it struggles to converge effectively due to the discrepancies in features distributions across clients. In later iterations, however, GPAF outperforms FedAvg and converges more rapidly. This indicates that GPAF’s global generator and local adversarial help align clients’ local features and encourage client to learn more domain invariant representations under domain shift.

Figure 5: Comparing FedAvg to GPAF in (a) we report best average during communication rounds accuracy in valid set and (b) we report the training loss of clients in local epochs

Existing (FDG) methods face privacy risks from client data exposure, incur high communication costs, and often depend on centralized target datasets. We propose GPAF, a communication-efficient framework designed to address both domain and label shift challenges in healthcare field. Clients learn domain-invariant features locally without sharing any other information than client parameters. We believe that enhancing privacy in domain generalization is a promising direction. This opens a compelling path for future research toward privacy-aware domain generalization in real-world FL. Consequently, we aim to evaluate robust aggregation methods [36,37] within DG-FL methods for strengthening privacy. Further, we aim to extend GPAF to asynchronous federated learning, where client-server interactions do not require strict synchronization to handle domain shift. Unlike existing FDG methods that rely on client-server coordination to learn domain invariant features across clients or shared client data. However, because domain alignment is performed locally, resource-constrained clients may face computational bottlenecks. This trade-off highlights an important direction for future research. We further believe that improving efficiency on the client side supports robust, scalable deployment in real-world healthcare systems.

Acknowledgement: The authors acknowledge the support of Smart Communication Research Team of Mohammedia School of Engineers. We also thank the reviewers for their valuable feedback.

Funding Statement: No funding.

Author Contributions: Sanaa Lakrouni: Writing—original draft Software, Methodology, Formal analysis. Slimane Bah: Writing—review & editing, Supervision. Marouane Sebgui: Supervision, writing—review. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are openly available at https://github.com/MedMNIST/MedMNIST (accessed on 25 August 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Rieke N, Hancox J, Li W, Milletarì F, Roth HR, Albarqouni S, et al. The future of digital health with federated learning. npj Digit Med. 2020;3(1):119. doi:10.1038/s41746-020-00323-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Yan R, Qu L, Wei Q, Huang SC, Shen L, Rubin DL, et al. Label-efficient self-supervised federated learning for tackling data heterogeneity in medical imaging. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2023;42(7):1932–43. doi:10.1109/TMI.2022.3233574. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Sheller MJ, Edwards B, Reina GA, Martin J, Pati S, Kotrotsou A, et al. Federated learning in medicine: facilitating multi-institutional collaborations without sharing patient data. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):12598. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-69250-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Dayan I, Roth HR, Zhong A, Harouni A, Gentili A, Abidin AZ, et al. Federated learning for predicting clinical outcomes in patients with COVID-19. Nat Med. 2021;27(10):1735–43. doi:10.1038/s41591-021-01506-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Li L, Xie N, Yuan S. A federated learning framework for breast cancer histopathological image classification. Electronics. 2022;11(22):3767. doi:10.3390/electronics11223767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. McMahan HB, Moore E, Ramage D, Hampson S, Arcas BA. Communication-efficient learning of deep networks from decentralized data. arXiv:1602.05629. 2016. doi:10.48550/ARXIV.1602.05629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Guan H, Liu M. Domain adaptation for medical image analysis: a survey. arXiv:2102.09508. 2021. doi:10.48550/ARXIV.2102.09508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Zhou K, Liu Z, Qiao Y, Xiang T, Loy CC. Domain generalization: a survey. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2023;45(4):4396–415. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2022.3195549. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Liu Q, Chen C, Qin J, Dou Q, Heng PA. FedDG: federated domain generalization on medical image segmentation via episodic learning in continuous frequency space. arXiv:2103.06030. 2021. doi:10.48550/ARXIV.2103.06030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Peng X, Huang Z, Zhu Y, Saenko K. Federated adversarial domain adaptation. arXiv:1911.02054. 2019. doi:10.48550/ARXIV.1911.02054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Hitaj B, Ateniese G, Perez-Cruz F. Deep models under the GAN: information leakage from collaborative deep learning. arXiv:1702.07464. 2017. doi:10.48550/ARXIV.1702.0746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Fredrikson M, Jha S, Ristenpart T. Model inversion attacks that exploit confidence information and basic countermeasures. In: Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security; 2015 Oct 12–16; Denver, CO, USA. doi:10.1145/2810103.2813677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Garg S, Erickson N, Sharpnack J, Smola A, Balakrishnan S, Lipton ZC. RLSbench: domain adaptation under relaxed label shift. arXiv:2302.03020. 2023. doi:10.48550/ARXIV.2302.03020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Zhu Z, Hong J, Zhou J. Data-free knowledge distillation for heterogeneous federated learning. arXiv:2105.10056. 2021. doi:10.48550/ARXIV.2105.10056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Karimireddy SP, Kale S, Mohri M, Reddi SJ, Stich SU, Suresh AT. SCAFFOLD: stochastic controlled averaging for federated learning. arXiv:1910.06378. 2019. doi:10.48550/ARXIV.1910.06378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Li T, Sahu AK, Zaheer M, Sanjabi M, Talwalkar A, Smith V. Federated optimization in heterogeneous networks. arXiv:1812.06127. 2018. doi:10.48550/ARXIV.1812.06127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Wu G, Gong S. Collaborative optimization and aggregation for decentralized domain generalization and adaptation. In: 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2021 Oct 10–17; Montreal, QC, Canada. doi:10.1109/ICCV48922.2021.00642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Chen J, Jiang M, Dou Q, Chen Q. Federated domain generalization for image recognition via cross-client style transfer. arXiv:2210.00912. 2022. doi:10.48550/ARXIV.2210.00912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Ganin Y, Ustinova E, Ajakan H, Germain P, Larochelle H, Laviolette F, et al. Domain-adversarial training of neural networks. arXiv:1505.07818. 2015. doi:10.48550/ARXIV.1505.07818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Sun Y, Chong N, Ochiai H. Feature distribution matching for federated domain generalization. arXiv:2203.11635. 2022. doi:10.48550/ARXIV.2203.11635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Zhang W, Li X. Federated transfer learning for intelligent fault diagnostics using deep adversarial networks with data privacy. IEEE/ASME Trans Mechatron. 2022;27(1):430–9. doi:10.1109/TMECH.2021.3065522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Zhang W, Li X. Data privacy preserving federated transfer learning in machinery fault diagnostics using prior distributions. Struct Health Monit. 2022;21(4):1329–44. doi:10.1177/14759217211029201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Lin T, Kong L, Stich SU, Jaggi M. Ensemble distillation for robust model fusion in federated learning. arXiv:2006.07242. 2020. doi:10.48550/ARXIV.2006.07242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Jiang M, Wang Z, Dou Q. HarmoFL: harmonizing local and global drifts in federated learning on heterogeneous medical images. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2022;36(1):1087–95. doi:10.1609/aaai.v36i1.19993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Volpi R, Namkoong H, Sener O, Duchi JC, Murino V, Savarese S. Generalizing to unseen domains via adversarial data augmentation. In: Proceedings of the 32nd Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2018); 2018 Dec 2–8; Montreal, QC, Canada. [Google Scholar]

26. Zhuang F, Cheng X, Luo P, Pan SJ, He Q. Supervised representation learning: transfer learning with deep autoencoders. In: Proceedings of the 24th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI 2015); 2015 Jul 25–31; Buenos Aires, Argentina. [Google Scholar]

27. Kingma DP, Welling M. Auto-encoding variational bayes. arXiv:1312.6114. 2013. doi:10.48550/ARXIV.1312.6114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Mao Q, Lee HY, Tseng HY, Ma S, Yang MH. Mode seeking generative adversarial networks for diverse image synthesis. arXiv:1903.05628. 2019. doi:10.48550/ARXIV.1903.05628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Srivastava A, Valkov L, Russell C, Gutmann MU, Sutton C. VEEGAN: reducing mode collapse in GANs using implicit variational learning. arXiv:1705.07761. 2017. doi:10.48550/ARXIV.1705.07761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Makhzani A, Shlens J, Jaitly N, Goodfellow I, Frey B. Adversarial autoencoders. arXiv:1511.05644. 2015. doi:10.48550/ARXIV.1511.05644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Goodfellow I, Pouget-Abadie J, Mirza M, Xu B, Warde-Farley D, Ozair S, et al. Generative adversarial networks. arXiv:1406.2661. 2014. doi:10.48550/ARXIV.1406.2661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Nguyen AT, Torr P, Lim SN. FedSR: a simple and effective domain generalization method for federated learning. In: Proceedings of the Neural Information Processing Systems 35 (NeurIPS 2022); 2022 Nov 28–Dec 9; New Orleans, LA, USA. [Google Scholar]

33. Al-Dhabyani W, Gomaa M, Khaled H, Fahmy A. Dataset of breast ultrasound images. Data Brief. 2020;28(5):104863. doi:10.1016/j.dib.2019.104863. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Di Salvo F, Doerrich S, Ledig C. MedMNIST-C: comprehensive benchmark and improved classifier robustness by simulating realistic image corruptions. arXiv:2406.17536. 2024. doi:10.48550/ARXIV.2406.17536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Beutel DJ, Topal T, Mathur A, Qiu X, Fernandez-Marques J, Gao Y, et al. Flower: a friendly federated learning research framework. arXiv:2007.14390. 2020. doi:10.48550/ARXIV.2007.14390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Pillutla K, Kakade SM, Harchaoui Z. Robust aggregation for federated learning. IEEE Trans Signal Process. 2022;70:1142–54. doi:10.1109/TSP.2022.3153135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Nabavirazavi S, Taheri R, Shojafar M, Iyengar SS. Impact of aggregation function randomization against model poisoning in federated learning. In: 2023 IEEE 22nd International Conference on Trust, Security and Privacy in Computing and Communications (TrustCom); 2023 Nov 1–3; Exeter, UK. doi:10.1109/TrustCom60117.2023.00043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools