Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Robust Multi-Label Cartoon Character Classification on the Novel Kral Sakir Dataset Using Deep Learning Techniques

1 Graduate School, Maltepe University, Istanbul, 34857, Turkiye

2 Department of Computer Programming, Vocational School, Maltepe University, Istanbul, 34857, Turkiye

3 Division of Computing, School of Computing, Engineering and Physical Sciences, University of the West of Scotland, London Campus, London, E14 2BE, UK

* Corresponding Author: Volkan Tunali. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advancements and Challenges in Artificial Intelligence, Data Analysis and Big Data)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(3), 5135-5158. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.067840

Received 14 May 2025; Accepted 19 August 2025; Issue published 23 October 2025

Abstract

Automated cartoon character recognition is crucial for applications in content indexing, filtering, and copyright protection, yet it faces a significant challenge in animated media due to high intra-class visual variability, where characters frequently alter their appearance. To address this problem, we introduce the novel Kral Sakir dataset, a public benchmark of 16,725 images specifically curated for the task of multi-label cartoon character classification under these varied conditions. This paper conducts a comprehensive benchmark study, evaluating the performance of state-of-the-art pretrained Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), including DenseNet, ResNet, and VGG, against a custom baseline model trained from scratch. Our experiments, evaluated using metrics of F1-Score, accuracy, and Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC), demonstrate that fine-tuning pretrained models is a highly effective strategy. The best-performing model, DenseNet121, achieved an F1-Score of 0.9890 and an accuracy of 0.9898, significantly outperforming our baseline CNN (F1-Score of 0.9545). The findings validate the power of transfer learning for this domain and establish a strong performance benchmark. The introduced dataset provides a valuable resource for future research into developing robust and accurate character recognition systems.Keywords

Animated content, including cartoons, constitutes a significant and globally popular form of entertainment and communication. The ability to automatically analyse this content, particularly to identify and track characters, offers substantial benefits across various applications, from content indexing and retrieval to copyright protection and interactive media experiences [1]. However, automated cartoon character recognition presents unique and significant challenges that differentiate it from general object recognition tasks.

A key challenge in the application of AI to image recognition, and a central focus of our research, stems from the substantial visual variability inherent in domains like cartoon character portrayal. Unlike the more constrained variations typically observed in real-world object classes, cartoon characters often undergo transformations driven by artistic license and narrative progression. These can manifest as considerable changes in attire, colour schemes, accessories, depicted age, and even fundamental drawing style or perspective [2]. This high degree of intra-class variance presents a notable difficulty for current AI models, particularly deep learning architectures that learn features directly from pixel data, as consistent low-level visual patterns may become less prevalent or frequently altered [3]. While human perception demonstrates remarkable robustness in identifying characters across these disparate renditions, improving the ability of AI systems to handle such artistic freedom is important for enhancing their performance in specialised visual contexts. Our work addresses this by investigating how established AI techniques can achieve more reliable recognition in these dynamic visual environments, thereby contributing to the understanding of how AI can manage high intra-class variance and informing efforts to develop more robust AI-driven image recognition systems for such domains.

Progress in overcoming these complexities is intrinsically linked to the availability of diverse and well-curated datasets that adequately represent these variations. The development of new, specialised datasets is crucial, as they provide the necessary foundation for training and comprehensively evaluating more sophisticated AI models capable of handling such complexities. Such datasets enable researchers to benchmark different approaches and push the boundaries of what is achievable in automated cartoon analysis. To this end, this paper introduces a novel dataset, the Kral Sakir dataset, specifically designed to capture the multi-label nature and visual diversity of characters from a popular animated series. Furthermore, we investigate the effectiveness of deep learning techniques, particularly transfer learning from pretrained Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), for robust multi-label cartoon character classification on this new dataset, aiming to provide insights into effective strategies for this challenging task.

The main contributions and novelty of our work can be summarised as follows:

1. We introduce the novel Kral Sakir dataset, derived from a popular Turkish animated series, for multi-label cartoon character recognition. This dataset features significant visual diversity from a specific cultural context and serves as a benchmark for future research in automated cartoon visual analysis.

2. We systematically evaluate state-of-the-art pretrained CNNs against a custom baseline, demonstrating transfer learning’s robustness and efficiency for multi-label cartoon character classification and offering insights into effective model choices.

3. We conduct a targeted investigation into classifying cartoon characters under high intra-class visual variance, demonstrating effective deep learning strategies on our diverse dataset for robust, multi-label recognition and thereby contributing to the development of more resilient automated systems.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 reviews the relevant literature on cartoon character recognition, outlining key developments and established techniques. Section 3 details the materials and methods employed in this study, including our proposed dataset and experimental setup. The experimental results are presented and discussed in Section 4. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper, summarising our key findings and contributions.

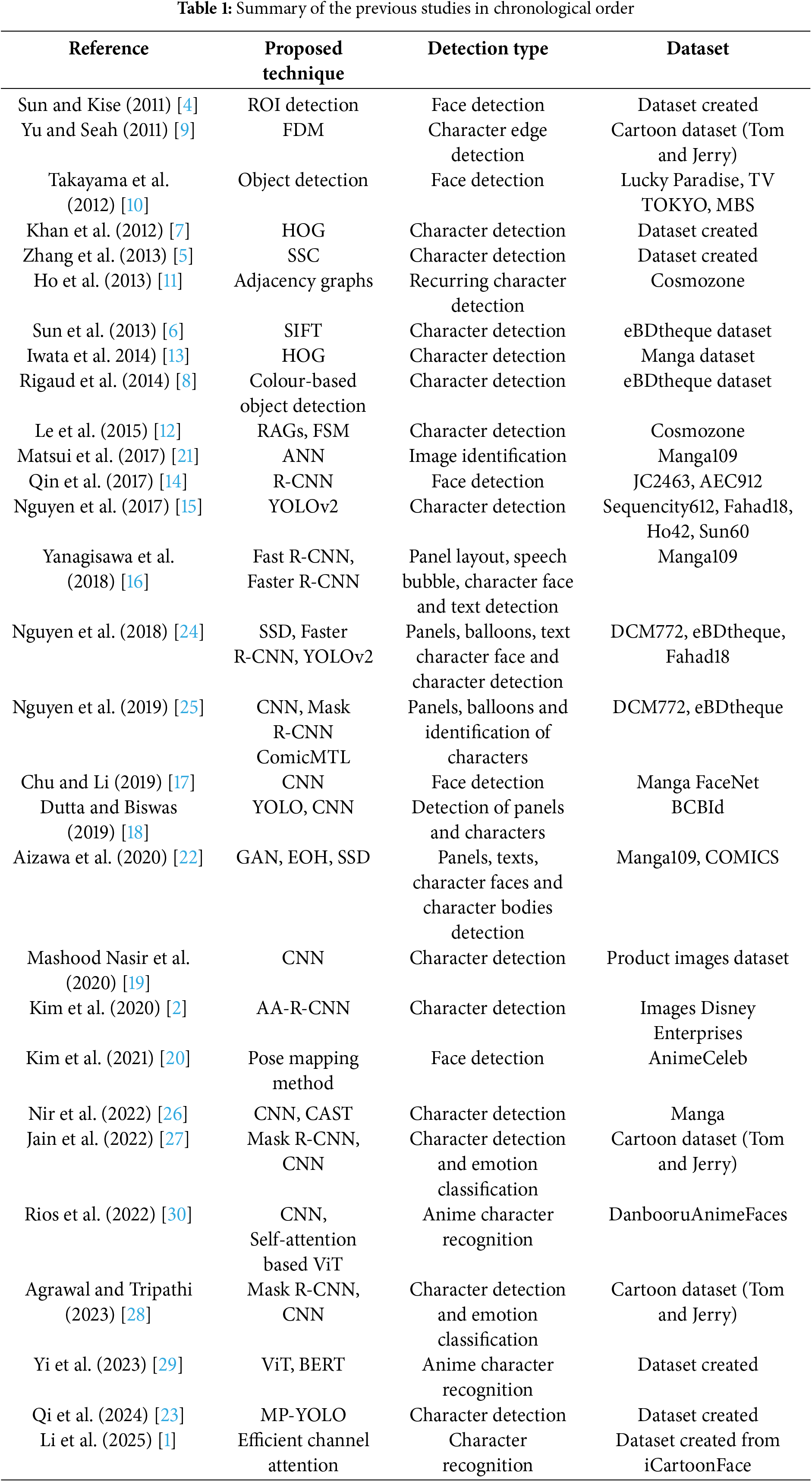

The automated detection and recognition of characters within cartoons, comics, and animated media has been a significant area of research, driven by applications ranging from copyright protection to content analysis and retrieval. Early investigations often centered on extracting handcrafted visual features, such as colour, edges, and shape contexts, to identify characters in static images and line drawings. More recently, the field has witnessed a pronounced shift towards deep learning methodologies, with various CNN architectures, including Region-based Convolutional Neural Networks (R-CNN) variants and You Only Look Once (YOLO), demonstrating robust performance in identifying faces and full characters across diverse comic and manga datasets. While much of this work has focused on static images, the challenge of recognising characters with high visual diversity in dynamic video content, which is the focus of our study, builds upon these foundational efforts. This review will explore these key developments and techniques employed in the broader domain of cartoon character recognition, also summarising them in Table 1.

2.1 Traditional and Feature-Based Approaches

Early research in character recognition relied heavily on handcrafted visual features, focusing on shape, colour, texture, and structural relationships to identify characters. These methods often addressed specific tasks like copy detection, similarity estimation, or retrieval in static images. For instance, Sun and Kise (2011) addressed copyright protection by proposing a method for detecting partial copies in monochrome line drawings, using a cascade classifier for region-of-interest detection followed by feature matching [4]. Similarly, Zhang et al. (2013) focused on detecting 2D cartoon characters to prevent pirate uploads, designing a local shape feature named Scalable-Shape Context (SSC) combined with a Hough-voting scheme [5]. Another feature-based approach for copyright protection in comics was presented by Sun et al. (2013), who utilised the Scale-invariant Feature Transform (SIFT) identifier to match characters despite various transformations [6].

Other works focused on colour and similarity. Khan et al. (2012) demonstrated that using explicit colour attributes, in combination with traditional shape features, could significantly improve object detection performance, which they validated on a new cartoon character dataset where colour was a pivotal feature [7]. Rigaud et al. (2014) also presented a colour-based approach for retrieving comic characters, using a colour palette and content-based drawing retrieval [8]. In a different vein, Yu and Seah (2011) proposed a novel method called fuzzy diffusion maps (FDM) to estimate cartoon similarity by learning a diffusion distance in a low-dimensional manifold, showing robustness in recognition and clustering tasks [9]. Face detection was another key area, with Takayama et al. (2012) proposing methods for both face detection and recognition of cartoon characters by specifically considering their unique facial features compared to real human faces [10].

Structural and graph-based methods were also explored to capture relationships within comic book panels. Ho et al. (2013) introduced a method to detect recurrent characters in comics by representing panels as attributed adjacency graphs and using inexact graph matching to find similar subgraph structures [11]. Building on this, Le et al. (2015) proposed a retrieval system based on representing comic pages as multilayer graphs and using Frequent Subgraph Mining (FSM) to identify and rank images [12]. Finally, Iwata et al. (2014) investigated manga character retrieval by modifying and applying existing methods to the specific domain of Japanese comics [13].

2.2 Deep Learning for Character Recognition

With the resurgence of deep learning, the field saw a paradigm shift towards using Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) to automatically learn features, significantly outperforming traditional methods. Researchers began applying and adapting state-of-the-art object detection models for cartoon and comic analysis. Qin et al. (2017) proposed a Faster R-CNN-based method for face detection in comics, empirically finding that a sigmoid classifier outperformed softmax for this task [14]. Nguyen et al. (2017) also leveraged deep learning for comic character detection, training modern object detection networks on a proposed dataset and establishing a strong baseline for future work [15]. The comparative effectiveness of different deep learning models was explored by Yanagisawa et al. (2018), who studied object detection in manga and found that Faster R-CNN was more effective for character faces, while Fast R-CNN was better suited for panel layouts [16].

This trend continued with more specialised applications. Chu and Li (2019) proposed a deep neural network that fused global and local information to detect manga faces of various appearances [17]. Dutta and Biswas (2019) developed a YOLO and CNN-based architecture to extract both panels and characters from Bengali comic book images, demonstrating its effectiveness on their custom BCBId dataset as well as other public datasets [18]. Mashood Nasir et al. (2020) proposed a hybrid 17-layer deep CNN for classifying superhero fashion products, achieving a high accuracy of 97.9% and showcasing the power of custom deep learning models [19]. More recently, Kim et al. (2021) addressed the challenge of detecting characters in animated movies by introducing an animation adaptive region-based CNN that adds a hierarchical adaptation module to the Faster R-CNN model to handle diverse animation styles [20].

2.3 Dataset Creation and Benchmarking

The advancement of deep learning is intrinsically linked to the availability of large, high-quality datasets. Recognising a gap in the animation and comics domain, several research efforts have focused on creating and annotating new public benchmarks. Matsui et al. (2017) made a significant contribution by building and releasing Manga109, a large dataset of 109 manga books with over 21,000 pages, to facilitate research in manga retrieval and analysis [21]. Aizawa et al. (2020) further detailed the Manga109 dataset, providing extensive annotations for frames, text, faces, and bodies to support a wide range of multimedia applications [22]. Addressing the lack of data for animated faces, Kim et al. (2020) introduced AnimeCeleb, a large-scale animation face dataset generated using controllable 3D synthetic models, designed to boost research in tasks like head reenactment [2]. More recently, Qi et al. (2024) introduced CCDaS, a large benchmark dataset for cartoon character detection in practical scenarios like merchandise and advertising, and proposed an accompanying multi-path YOLO model (MP-YOLO) to handle multi-scale and facially similar objects [23].

2.4 Advanced and Specialised Deep Learning Applications

Building on foundational deep learning models, recent research has explored more sophisticated techniques to tackle nuanced challenges in character analysis. Multi-task learning has emerged as a way to create more efficient and holistic models. Nguyen et al. (2018, 2019) extended their work into digital comics indexing and proposed Comic MTL, a multi-task learning model capable of handling panel detection, character detection, and even the relationship between speech balloons and speakers simultaneously [24,25].

Other advanced paradigms include self-supervised learning and style adaptation. Nir et al. (2022) presented CAST, a method using self-supervision and multi-object tracking to learn refined semantic representations of characters within a specific animation style, allowing for better clustering of characters with diverse appearances [26]. Li et al. (2025) proposed a framework for character recognition that fuses portrait style, using an ECA-based residual attention module to improve feature learning and a style-transfer mechanism to create a simulated dataset for copyright protection [1].

The field has also expanded to include emotion and multimodal analysis. Jain et al. (2022) and Agrawal et al. (2023) both tackled the problem of cartoon emotion recognition, developing integrated deep neural network approaches to identify characters and classify their emotions from images, using datasets based on the “Tom and Jerry” cartoons [27,28]. Looking beyond visual data, Yi et al. (2023) proposed a multimodal deep learning network for anime character identification and tag prediction, exploiting both image and text data and introducing curriculum learning to handle missing text annotations [29]. Finally, looking towards next-generation architectures, Rios et al. (2022) studied the problem of anime character recognition using Vision Transformers (ViTs), proposing a novel Intermediate Features Aggregation head to improve classification accuracy [30].

2.5 Limitations of Existing Work and Motivation

Despite these significant contributions, a review of the existing literature reveals several gaps that motivate our current study. First, a notable focus exists on specific media formats, particularly Japanese manga (e.g., Manga109) and static comic books. These formats possess distinct visual aesthetics, such as monochrome art and structured panel layouts, which differ considerably from the dynamic, full-colour animation style addressed in our work. This focus limits the direct applicability and generalisability of findings to the diverse world of animated series. Second, much of the prior research has concentrated on tasks such as face detection or single-character object detection. Less emphasis has been placed on the more complex scenario of multi-label character classification from unstructured video frames, where multiple characters frequently interact within a single scene. Finally, while intra-class variance is an implicit challenge in all character recognition, few studies have been built around datasets specifically designed to test model robustness against the wide range of artistic and narrative-driven transformations (e.g., costume and style changes) found in a long-running animated series. These gaps—the focus on specific artistic styles, the prevalence of static image analysis, and the limited attention to multi-label scenarios—underscore the need for new, diverse datasets and benchmark studies. Our work directly addresses these limitations by introducing the Kral Sakir dataset, derived from video content, and providing a comprehensive analysis focused specifically on the multi-label character classification problem under high visual variance.

3.1 Proposed Dataset: Kral Sakir

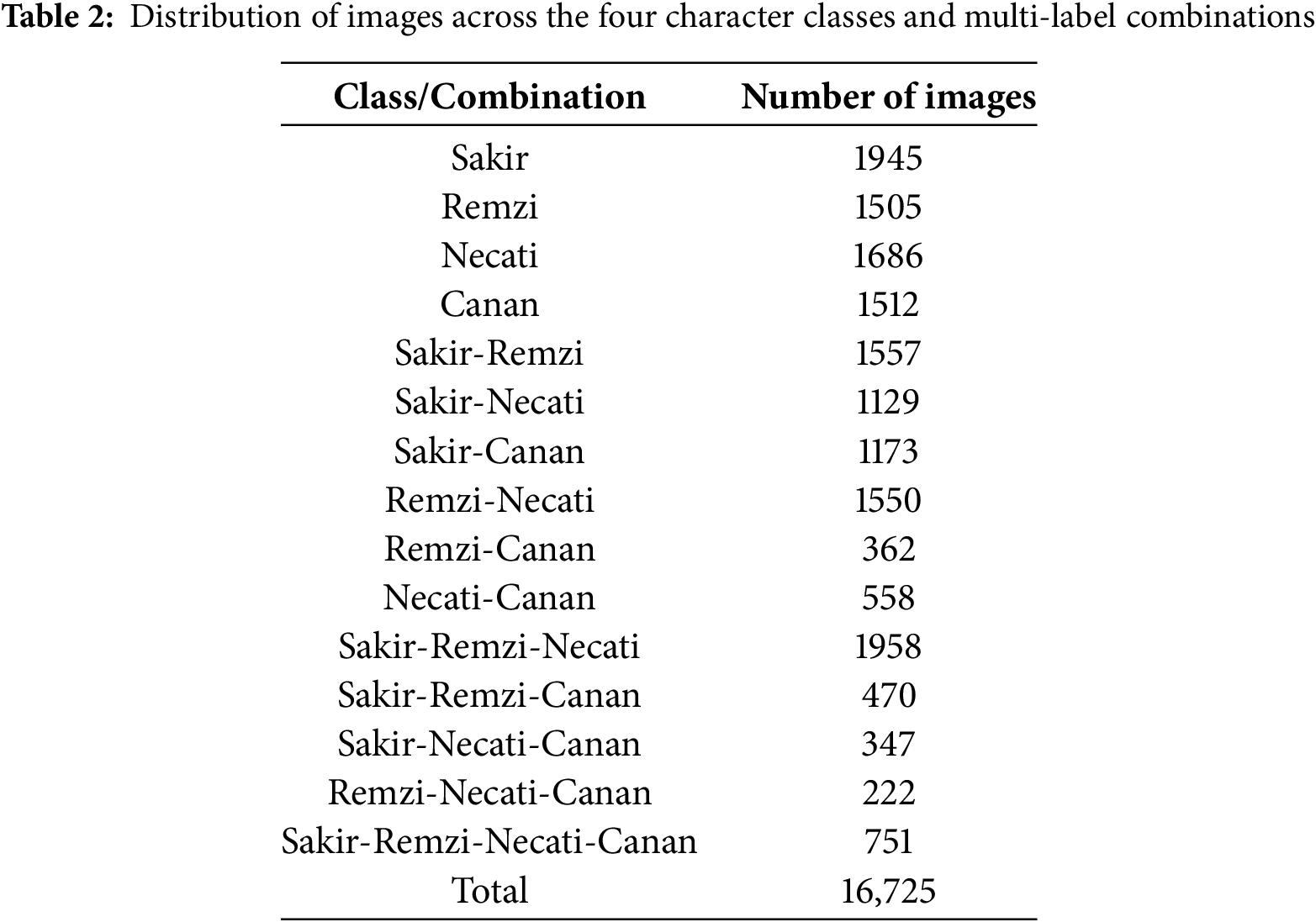

We constructed the novel Kral Sakir dataset for this study. This dataset features four principal characters from the animated series Kral Sakir streaming on Turkish channels: namely, Sakir, Remzi, Necati, and Canan. For the data collection procedure, we extracted frames from official series content available via YouTube [31]. We executed frame capture using VLC Player (VideoLAN Client). We then applied a manual curation and labelling process to each image to guarantee precise character representation, accommodating both single-character and multi-character scenes. The final dataset contains 16,725 colour images, with varying distributions across the four character classes and multi-label combinations. Fig. 1 displays the four main characters and Table 2 outlines the statistical distributions per class.

Figure 1: Four principal characters from Kral Sakir animated series

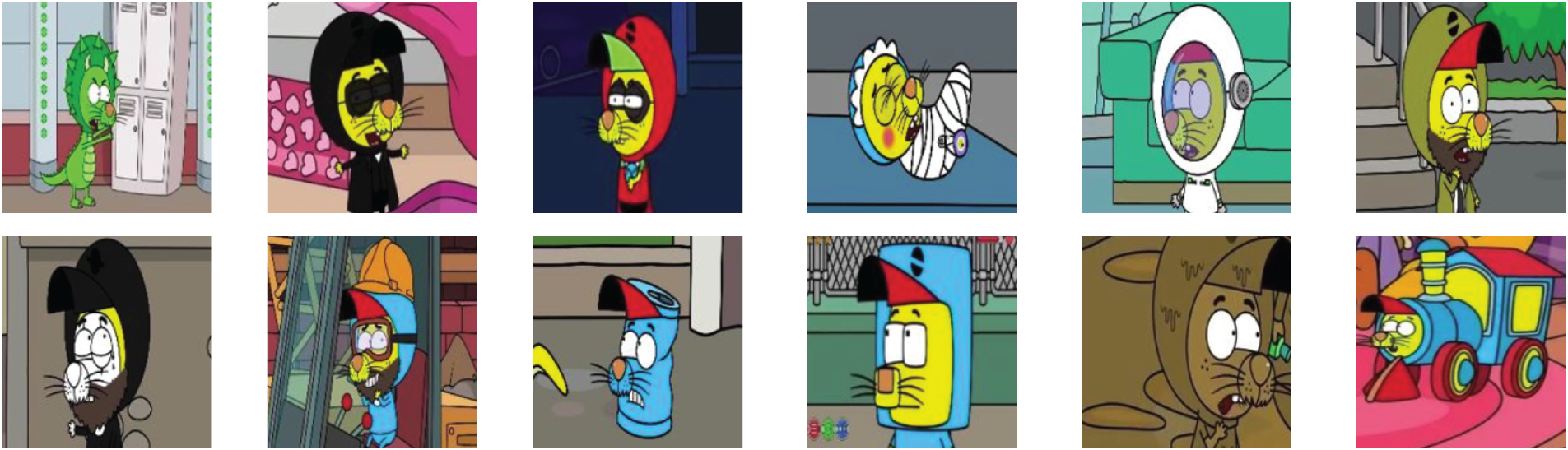

A key challenge in automated cartoon character recognition stems from the significant visual variability inherent in character portrayal, often driven by artistic licence and narrative progression, unlike the more constrained variations typically seen in real-world object classes. These transformations can manifest as substantial changes in attire, colour schemes, accessories, depicted age, and even fundamental drawing style or perspective between appearances. While the human visual system demonstrates remarkable robustness, readily identifying characters across these disparate renditions by focusing on core visual cues and abstract concepts, replicating this capability with machine learning presents a considerable difficulty. Algorithms learning features directly from pixel data must contend with this high degree of intra-class variance, where consistent low-level visual patterns may be less prevalent or frequently altered, making robust recognition a non-trivial task. Figs. 2–5 illustrate this challenge by presenting multiple, visually distinct examples of the main characters as found within our dataset.

Figure 2: Selected examples demonstrating the visual variability of the main character Sakir

Figure 3: Selected examples demonstrating the visual variability of the character Remzi

Figure 4: Selected examples demonstrating the visual variability of the character Necati

Figure 5: Selected examples demonstrating the visual variability of the character Canan

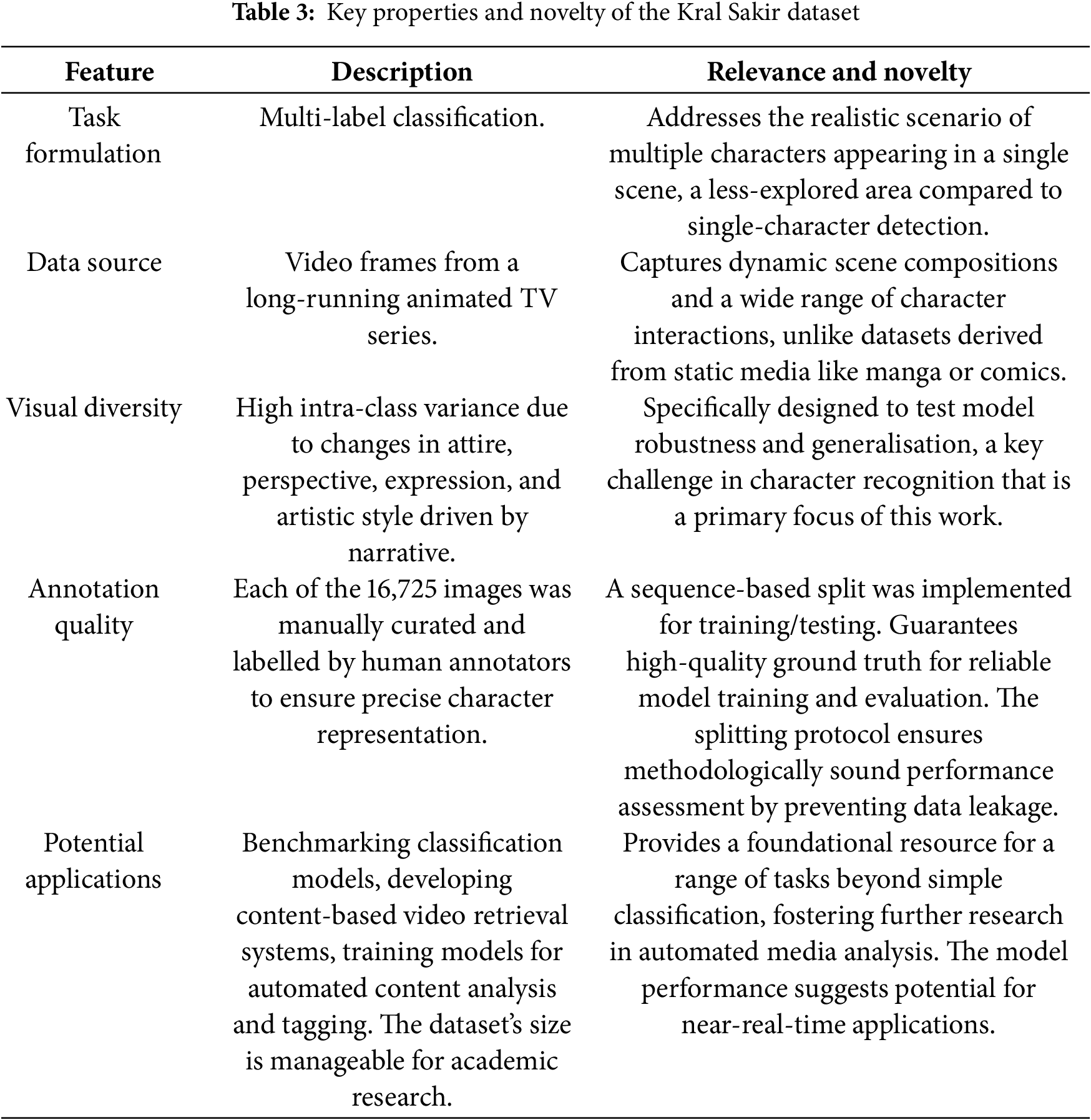

In summary, the novelty and relevance of the Kral Sakir dataset lie in several key aspects as shown in Table 3. Its focus on multi-label classification from dynamic video content addresses a more complex and realistic scenario than many existing benchmarks. The dataset is specifically curated to feature high diversity in character portrayal, making it an ideal resource for evaluating model robustness against intra-class variance. Furthermore, the high annotation quality, ensured through a manual curation and labelling process, provides a reliable foundation for training and testing. These properties make the dataset not only a challenging benchmark for academic research but also a valuable asset for developing and validating systems with potential for real-world applications like automated content tagging and analysis. To facilitate reproducibility and encourage further research in this area, the novel Kral Sakir dataset is publicly accessible in our repository at https://github.com/candantumer/kral_sakir (accessed on 18 August 2025).

3.2 Deep Learning Architectures

Deep Learning (DL) constitutes a specialised subfield within machine learning, drawing inspiration for its algorithms from the complex network of connections observed in the human brain, known as Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) [32,33]. ANNs employ multiple layers of interconnected processing units (neurons) designed to learn representations of data through hierarchical feature extraction. This capacity for learning intricate patterns has enabled the development of diverse DL architectures which have yielded significant breakthroughs across numerous domains, including computer vision, automated speech recognition, and natural language processing. Among these architectures, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) are particularly prevalent and effective for tasks involving grid-like data, such as images [34]. CNNs utilise specific operations, like convolution and pooling, to automatically learn spatial hierarchies of features directly from pixel data, making them exceptionally well-suited for image feature extraction necessary for classification, detection, and other visual understanding tasks.

Transfer learning is a technique in machine learning designed to expedite the development and improve the performance of models on a target task by reusing knowledge from a related source task where a model has already been trained [35]. Operationally, this involves adopting the network architecture and initialising the weights of the target model using the parameters learned by the “pretrained” source model. This initialisation leverages the hierarchical features extracted by the source model, assuming their relevance to the target domain. The utility of transfer learning is most pronounced when faced with data limitations for the target problem, as training deep models from scratch demands substantial data to learn meaningful representations effectively. By inheriting a robust set of initial parameters, the learning process on the target task is essentially “bootstrapped,” often requiring fewer training epochs to converge and thereby reducing the associated computational burden and time investment compared to random weight initialisation. Common strategies include using the pretrained model as a fixed feature extractor or fine-tuning some or all of its layers on the target dataset [36].

For the task of multi-label image classification, we designed and implemented a CNN architecture as a baseline. This model was intentionally designed with a relatively simple architecture to serve two purposes: it provides a computationally efficient benchmark and allows for a clear, direct assessment of the performance gains attributable to the pretrained features of the transfer learning models. The core of the model consists of a feature extraction module comprising four sequential convolutional layers with filter depths of 16, 32, 64, and 64, respectively. Standard Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) activation functions were applied after each convolution to introduce non-linearity. To progressively reduce spatial dimensions and enhance feature robustness, three Max Pooling layers were strategically interspersed within the convolutional blocks. Following the final feature extraction layer, a Global Average Pooling (GAP) layer was utilised. This GAP layer aggregates the spatial information across each feature map, producing a fixed-length feature vector irrespective of input dimensions. This feature vector subsequently feeds into the final dense output layer, configured with four units and employing a sigmoid activation function. The use of sigmoid activation allows each output unit to predict the independent probability of the corresponding label being present, appropriately addressing the multi-label nature of the classification problem.

The remarkable success of deep learning in computer vision owes much to the development and widespread adoption of powerful CNN architectures. Many of the most impactful models are made available in a “pretrained” state, having been extensively trained on large-scale image datasets like ImageNet [37]. This pretraining equips them with robust feature extraction capabilities, capturing hierarchical visual patterns that are often transferable to new tasks. Generic architecture of the proposed baseline CNN model and the pretrained models is presented in Fig. 6. This research utilised the following pretrained models, all employing weights derived from training on the ImageNet dataset:

Figure 6: Generic architecture of the proposed baseline CNN model and the pretrained models

ResNet (Residual Network): Introduced residual (skip) connections, enabling the effective training of extremely deep networks by allowing gradients to bypass layers and mitigate the vanishing gradient problem [38]. We used ResNet50V2, ResNet101V2, and ResNet152V2 models from ResNet family in this research.

DenseNet (Densely Connected Network): Features dense connectivity where each layer receives inputs from all preceding layers within a block, promoting feature reuse, stronger gradient flow, and often greater parameter efficiency [39]. DenseNet121, DenseNet169, and DenseNet201 were the pretrained models we utilised from DenseNet family in our research.

EfficientNet: Developed using a compound scaling method that systematically and optimally balances network depth, width, and image resolution to achieve high accuracy with significantly fewer parameters and computations compared to previous models [40]. EfficientNetB7 model from EfficientNet family was chosen for the research.

MobileNet: Optimised specifically for mobile and embedded vision applications, employing depthwise separable convolutions to drastically reduce computational cost (FLOPs) and model size, enabling efficient on-device inference [41]. We employed MobileNet and MobileNetV2 models from MobileNet family in our research.

VGG (Visual Geometry Group): Known for its simple and uniform architecture using stacked small (

3.3.1 Dataset Loading and Preprocessing

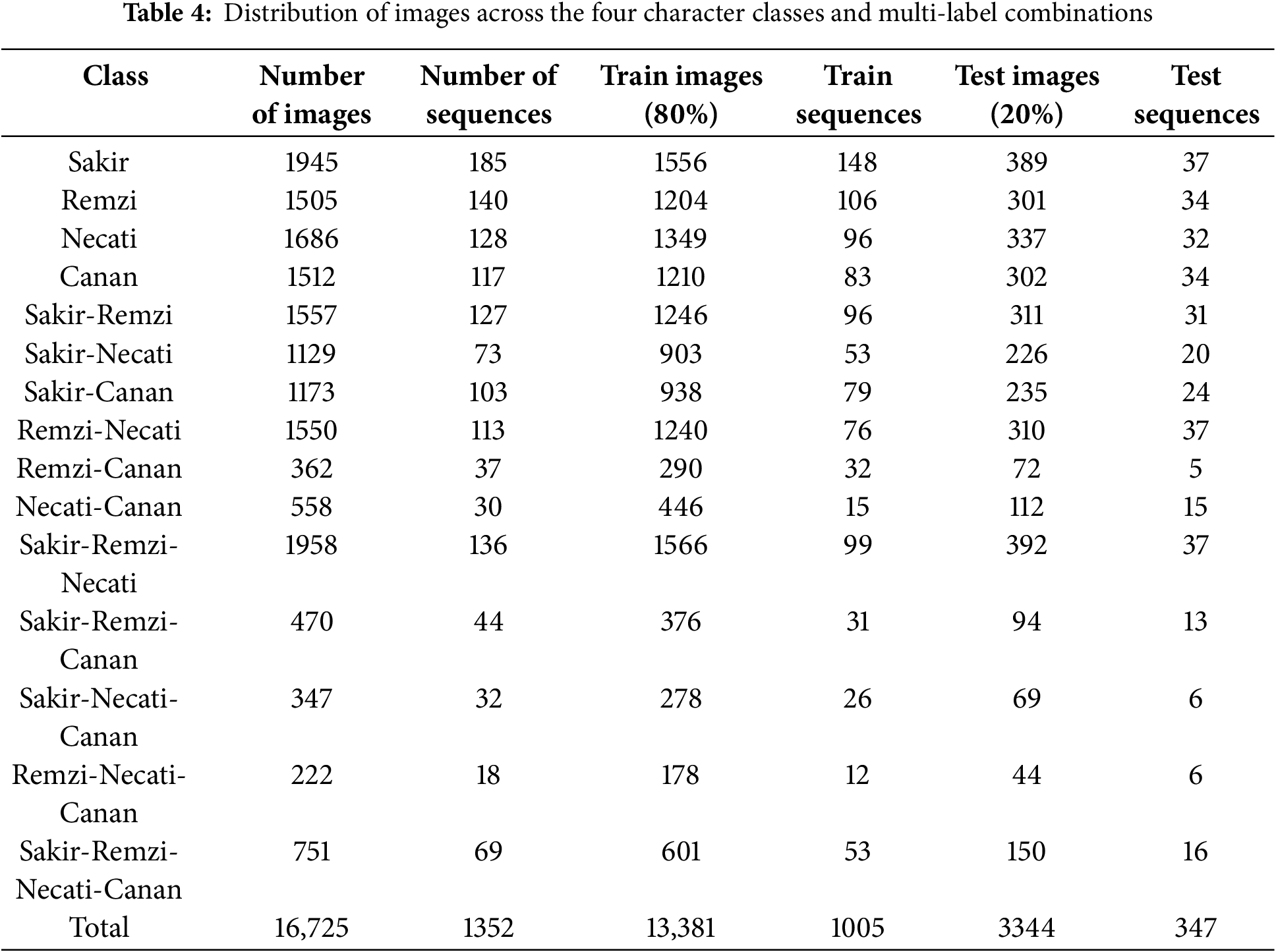

We partitioned our dataset using an 80% allocation for training and 20% for testing. Recognising the potential for data leakage due to the sequential origin of the images from animations, we employed a sequence-based splitting protocol. This protocol ensured that frames derived from the same animation sequence were never present in both the training and testing sets simultaneously; each sequence was assigned entirely to one partition. This approach prevents overly optimistic results arising from testing on frames highly similar to training data and allows for a more valid assessment of the model’s ability to generalise to unseen sequences, thereby ensuring the integrity of the experimental findings. Distribution of images across the four character classes and multi-label combinations after the split is shown in Table 4.

The images within our original dataset possess native dimensions of

All experiments presented in this study were conducted within the Kaggle Notebook environment. The computational tasks, primarily model training and evaluation, were accelerated using an NVIDIA P100 GPU. Our software stack was built upon Python version 3.11, with Keras version 3.8 and TensorFlow version 2.18 (with CUDA support) serving as the core deep learning framework.

Outlined below is the training methodology for each evaluated model, detailing the hyperparameters used for both the network architectures and the optimisation process.

For optimisation, we employed the Adam optimiser [43], recognised for its adaptive learning rate capabilities and effectiveness in training deep neural networks. We initialised Adam with a relatively conservative learning rate of

Binary Cross-Entropy was selected as the loss function, directly aligning with the multi-label classification objective where each output neuron, activated by a sigmoid function, predicts the independent probability of a specific class label. To regularise the custom classification head added after the base model’s feature extraction layers (which consisted of GAP, a 128-unit ReLU Dense layer, and the final output layer), we incorporated a Dropout layer with a rate of 0.1 between the intermediate Dense layer and the final output layer. This helps mitigate overfitting by randomly setting a fraction of neuron activations to zero during training.

To further control the training dynamics and prevent overfitting, we integrated two key Keras callbacks. ReduceLROnPlateau was used to adaptively adjust the learning rate during training. This callback monitored the validation loss; if no improvement was observed for a patience period of 3 epochs, the learning rate was reduced by a factor of 0.015. This allows the model to take smaller steps towards the minimum of the loss function when progress stalls, with a defined minimum learning rate floor of

Additionally, EarlyStopping served as an important mechanism against overfitting, a common challenge especially when adapting models to potentially smaller, specialised datasets. This callback also monitored the validation loss. If the validation loss failed to improve for 7 consecutive epochs, the training process was automatically terminated. Importantly, we configured EarlyStopping with

Each model variant was trained for a maximum of 50 epochs under this configuration, using the designated training and validation splits. The best performing weights for each architecture, as determined by the Early Stopping callback, were saved for subsequent analysis and comparison.

3.3.3 Model Evaluation Metrics

The performance of our models on the multi-label cartoon character classification task was evaluated using a suite of standard metrics. Specifically, we utilised Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-Score, and Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC), appropriately adapted for the multi-label scenario, to comprehensively assess model effectiveness. This section describes the computation details of these metrics for multi-label classification.

Let N be the total number of samples and L be the total number of labels. Let

From testing a classifier, we derive counts of True Positives (TP), False Positives (FP), True Negatives (TN), and False Negatives (FN), calculated as in Eqs. (2)–(5), respectively. These fundamental counts enable the computation of multi-label performance metrics including Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-Score, and AUC.

where

To assess the statistical stability of our results, we calculated 95% confidence intervals for the primary performance metrics using the percentile bootstrap method. For each model, this involved generating 1000 bootstrap samples from the test set predictions and calculating the metric for each sample to create an empirical distribution from which the confidence intervals were derived.

4 Experimental Results and Discussion

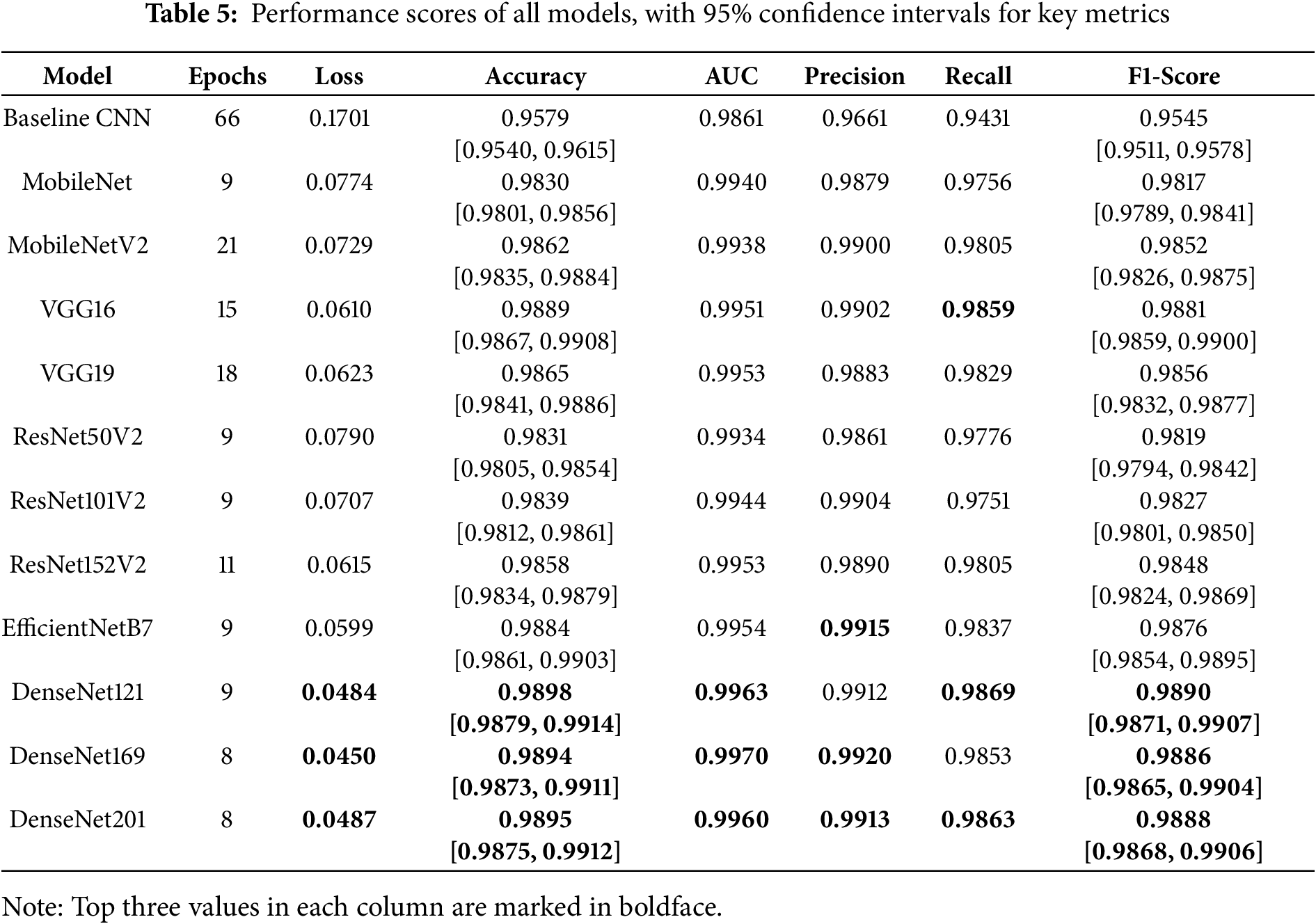

The performance of the custom baseline CNN and various pretrained deep learning models, fine-tuned for the multi-label cartoon character classification task on our Kral Sakir dataset, is summarised in Table 5. The metrics reported include loss, accuracy, Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC), precision, recall, and F1-Score, all evaluated on the hold-out test set. The performance scores reported here were obtained by following the comprehensive training methodology, data pipeline, and annotation process detailed in Section 3.

4.1 Overall Performance and Impact of Transfer Learning

It is important to interpret the following results in the context of this study’s primary objective. As outlined in the introduction, our goal is not to propose a novel model architecture, but rather to conduct a rigorous benchmark of existing state-of-the-art algorithms on our new dataset. Therefore, the discussion focuses on the comparative performance and the insights gained from applying these established techniques to the unique challenges of multi-label cartoon character recognition

A prominent observation is the significant performance advantage demonstrated by all transfer learning models when compared to the custom baseline CNN. The baseline CNN, while achieving a respectable F1-Score of 0.9545 and an AUC of 0.9861, was consistently outperformed across all metrics by the pretrained architectures. For instance, the loss for the baseline model was 0.1701, whereas all transfer learning models achieved substantially lower loss values, generally below 0.08. This underscores the efficacy of leveraging features learned from large-scale datasets like ImageNet for specialised tasks such as cartoon character recognition, even when the domain (cartoons vs. natural images) differs. Furthermore, the pretrained models typically converged to optimal performance in significantly fewer epochs (most between 8–18 epochs) compared to the baseline CNN which required 66 epochs, highlighting the efficiency gains from transfer learning.

The DenseNet family of models consistently emerged as the top performers. Specifically, DenseNet121 achieved the highest overall accuracy (0.9898) and F1-Score (0.9890), with a very low loss of 0.0484 and an excellent AUC of 0.9963. Closely following, DenseNet169 yielded the lowest loss (0.0450) and the highest AUC (0.9970) among all models, along with an F1-Score of 0.9886 and accuracy of 0.9894. DenseNet201 also demonstrated strong performance, with metrics nearly identical to its family members (e.g., F1-Score of 0.9888). These results suggest that the dense connectivity pattern, promoting feature reuse and gradient flow, is particularly well-suited for this classification task.

EfficientNetB7 and VGG16 also proved to be highly competitive. EfficientNetB7 achieved an F1-Score of 0.9876, an AUC of 0.9954, and an accuracy of 0.9884, with a low loss of 0.0599, placing it amongst the top-tier models. Notably, VGG16, despite being an older architecture, delivered a remarkable F1-Score of 0.9881 and an accuracy of 0.9889. Its performance was comparable to EfficientNetB7 and some DenseNet variants, though with a slightly higher loss (0.0610). VGG19 also performed well, with an F1-Score of 0.9856 and an AUC of 0.9953, slightly trailing VGG16.

4.4 Performance of ResNet and MobileNet Families

The ResNet variants (ResNet50V2, ResNet101V2, and ResNet152V2) showed robust improvements over the baseline, with ResNet152V2 being the best performer in this family, achieving an F1-Score of 0.9848 and an AUC of 0.9953. While effective, they were generally slightly outperformed by the DenseNet, EfficientNet, and VGG models in terms of F1-Score and loss.

The MobileNet architectures (MobileNet and MobileNetV2), designed for efficiency, also surpassed the baseline. MobileNetV2, with an F1-Score of 0.9852, performed better than MobileNet (F1-Score 0.9817) and was competitive with some of the larger ResNet models. This indicates that even lightweight models can achieve high accuracy on this dataset, though the very top performance levels were reached by the more complex architectures.

The experimental results clearly indicate that transfer learning with pretrained models offers substantial benefits for multi-label cartoon character recognition on the Kral Sakir dataset. The DenseNet architecture, particularly DenseNet121 and DenseNet169, exhibited superior performance, achieving the best balance of low loss, high accuracy, AUC, and F1-Score. EfficientNetB7 and VGG16 also demonstrated excellent capabilities. The significant improvement over the custom baseline CNN, coupled with faster convergence, validates the choice of transfer learning as an effective strategy for this domain. All models achieved high precision and recall values, generally above 0.975, suggesting a strong ability to correctly identify relevant characters and minimise false positives and false negatives. The high F1-scores further support the models’ balanced performance in terms of precision and recall.

4.6 Contextual Comparison with State-of-the-Art

While a direct numerical benchmark against models trained on other cartoon datasets is challenging due to fundamental differences in tasks, datasets, and metrics, it is crucial to situate our findings within the broader landscape of cartoon character analysis.

For instance, the work by Mashood Nasir et al. (2020) [19] on comic book character identification achieved a classification accuracy of 97%. Our best models, with accuracies exceeding 98.9%, are highly competitive, though we acknowledge our task is multi-label classification on video frames, which presents different challenges than single-label classification on curated comic images. Similarly, recent methods applied to the popular Manga109 dataset [22] focus heavily on object detection and retrieval within monochrome, structured panels, a different domain from our full-colour, dynamic animation scenes. More closely related is the work of Kim et al. (2021) [20], who developed an animation-adaptive model for character detection in animated movies. While their task was detection (finding bounding boxes) rather than multi-label classification, their success in adapting models to varied animation styles echoes our finding that transfer learning is a powerful strategy.

Considering these different contexts, the high performance of our models (e.g., an F1-Score of 0.9890 and an accuracy of 0.9898) demonstrates that our approach is not only effective but achieves a standard of performance consistent with or exceeding state-of-the-art results in related but distinct tasks within cartoon analysis. This validates the use of our methodology for the specific challenge of multi-label classification in animated series.

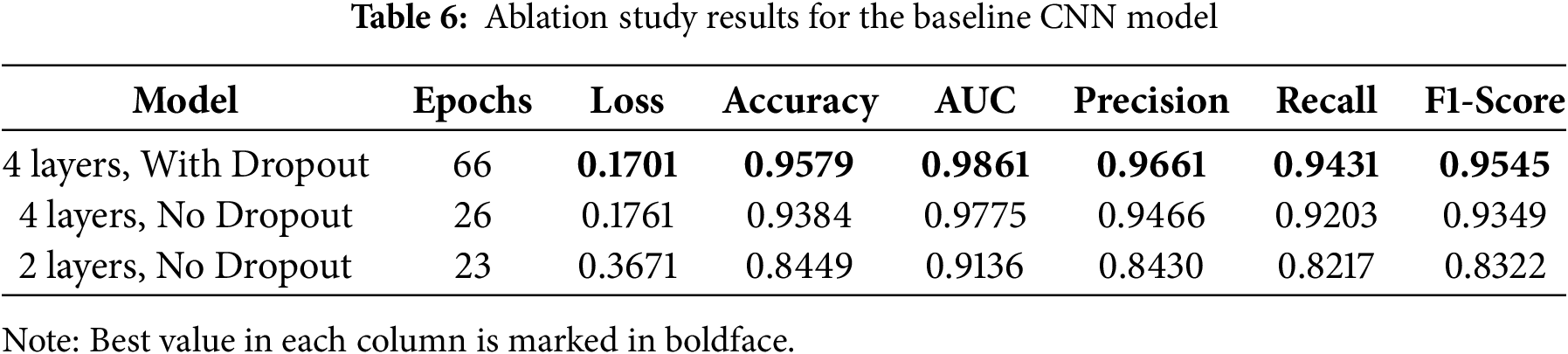

4.7 Ablation Study of the Baseline Model Architecture

In addition to comparing against pretrained models, we conducted an ablation study to justify the architectural choices of our custom baseline CNN. To assess the contribution of key components, we trained two additional variants: (1) the baseline model with the Dropout layer removed, and (2) a simpler version of the baseline with only two convolutional layers instead of four. The performance of these variants on the test set is summarised in Table 6.

The results clearly validate our design choices. Removing the Dropout layer led to a slight decrease in F1-score and accuracy, indicating its positive regularising effect. More significantly, reducing the network’s depth from four to two layers resulted in a substantial performance drop, confirming that the deeper feature hierarchy of our proposed baseline is necessary to effectively learn the character features from scratch. This ablation study provides context for the baseline’s performance and reinforces the subsequent findings on the superiority of transfer learning.

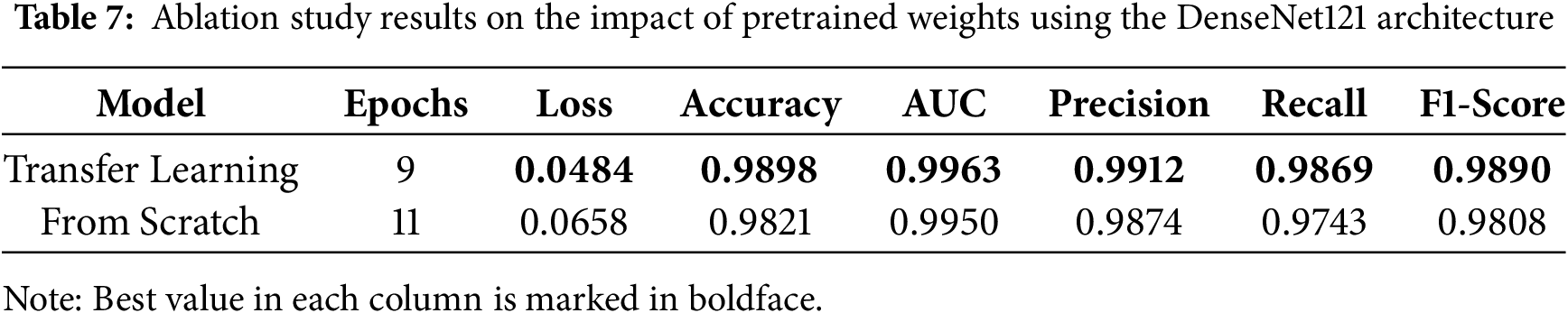

4.8 Ablation Study on the Impact of Pretrained Weights (Transfer Learning vs. Training from Scratch)

To precisely isolate and quantify the benefit of transfer learning, we conducted a second, more controlled ablation study. This experiment compares the performance of a single, powerful architecture, DenseNet121, under two distinct training conditions: (1) using weights pretrained on ImageNet, as done in our main experiments, and (2) training the exact same architecture from scratch with random weight initialisation. Both models were trained using the identical hyperparameter configuration (optimiser, learning rate, and callbacks) to ensure a fair comparison.

The results of this ablation study, presented in Table 7, confirm that transfer learning provides a distinct advantage, even on our high-quality, domain-specific dataset. The DenseNet121 model initialised with pretrained ImageNet weights achieved a slightly higher F1-Score (0.9890) and converged faster (9 epochs) compared to the same architecture trained from scratch, which reached an F1-Score of 0.9808 in 11 epochs. While the model trained from scratch still achieved a remarkably strong performance—a testament to the quality and size of the Kral Sakir dataset—the pretrained model consistently held a small but significant edge in both final accuracy and training efficiency. This suggests that even when a dataset is sufficient to train a deep network effectively, the foundational visual features learned from a diverse source like ImageNet provide a more optimal starting point, enabling the model to fine-tune to a superior solution with less computational effort. This finding robustly validates the choice of transfer learning as the preferred strategy for this task.

4.9 Error Analysis and Qualitative Insights

To complement the quantitative metrics, we conducted a qualitative analysis of the predictions made by our best-performing model (DenseNet121). This analysis focuses on common failure modes to provide deeper insights into the model’s behaviour and the inherent challenges of the dataset. Fig. 7 illustrates several examples of these incorrect predictions.

Figure 7: Examples of these incorrect predictions (T = True Class, P = Predicted Class, FP = False Positive, FN = False Negative)

Our analysis identified three primary categories of errors:

1. Inter-Class Confusion Due to Character Similarity: A notable source of error was the confusion between the characters Sakir and Necati. As shown in Fig. 7a, these two characters share similar body shapes and certain facial features. In some frames, distinguishing between them is challenging even for a human observer without the broader scene context, leading the model to produce false positive or false negative predictions for these characters.

2. Failure to Detect Occluded or Partially Visible Characters: The model often struggled to correctly identify characters that were heavily occluded or only partially visible in the frame. As seen in Fig. 7b–e, when a character is obscured by another character or object, or is positioned at the edge of the screen, the model may fail to capture enough distinctive features to make a positive identification. This typically results in a false negative, where the model misses a character that is present.

3. Spurious Feature Activation Leading to False Positives: In some instances, the model incorrectly identified a character when they were not present in the scene at all. This type of false positive is likely caused by the model activating on background textures, objects, or colour patterns that coincidentally resemble features learned to be associated with that character. For example, we observed cases where the model falsely predicted the presence of the purple elephant character, Necati, when a non-character object with a purple colour and circular patterns appeared in the scene, as illustrated in Fig. 7f. Similarly, spurious detections for the character Canan were also noted, as seen in Fig. 7g,h. This demonstrates that the model can sometimes over-rely on simple features like colour and basic shapes rather than more complex structural character features.

This qualitative analysis underscores that the model’s primary limitations are rooted in classic and difficult computer vision challenges: high inter-class similarity, object occlusion, and discriminating between genuine character features and spurious background patterns. These insights are valuable for guiding future research, which could focus on developing models with better contextual understanding or attention mechanisms to mitigate these specific types of errors.

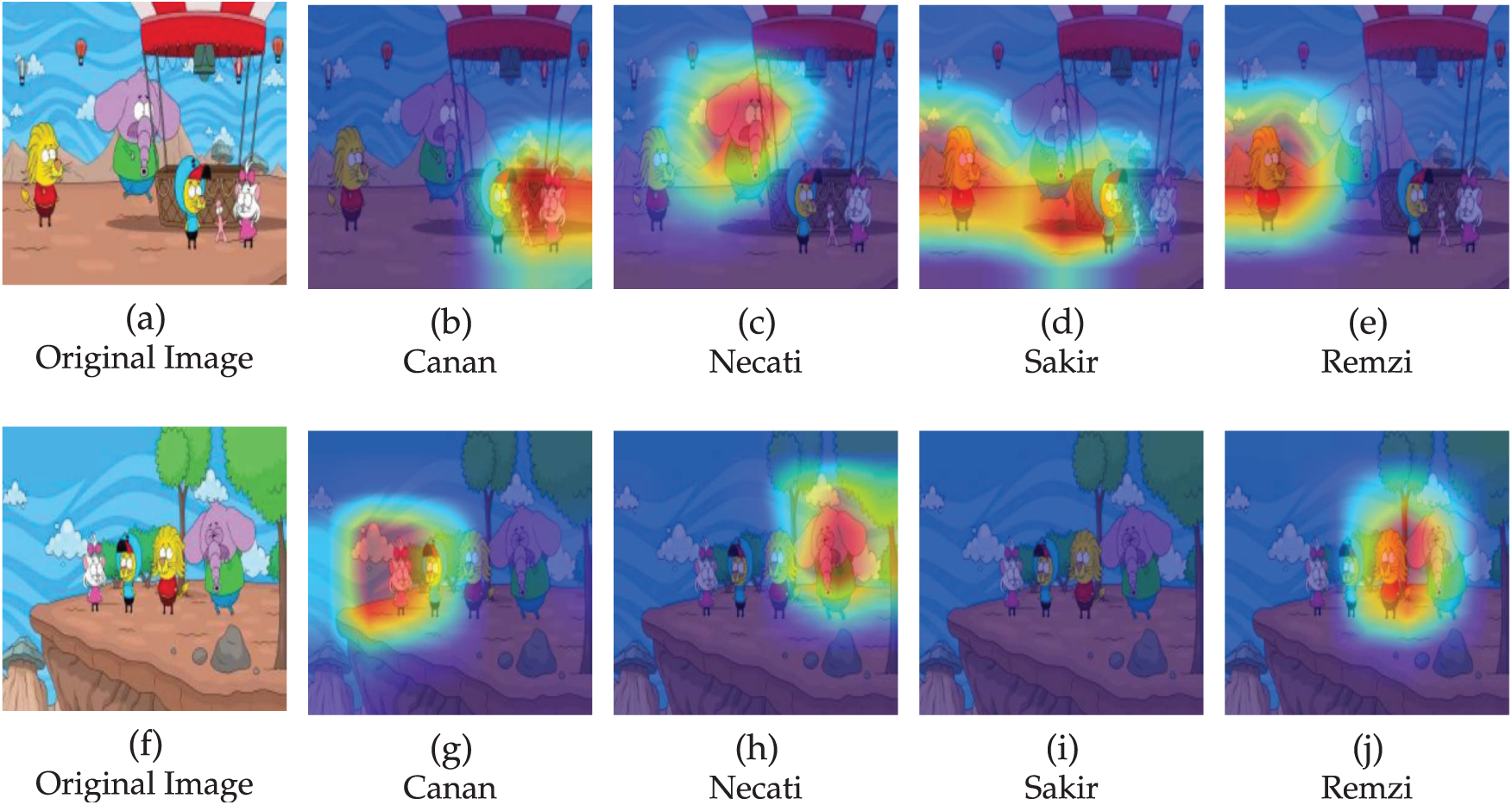

4.10 Model Explainability with Grad-CAM

To understand which visual features our model uses for character identification, we employed Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) on our best-performing model, DenseNet121. This technique produces heatmaps that highlight the image regions most influential to the model’s predictions. The analysis, illustrated in Fig. 8, reveals distinct attention patterns for each character.

Figure 8: Sample Grad-CAM heatmaps from DenseNet121

For the characters Canan, Necati, and Remzi, the model consistently demonstrates robust and accurate localisation of attention. The heatmaps show strong activation on highly discriminative features, such as Canan’s unique hair and facial structure, Necati’s elephantine form, and Remzi’s distinctive mane and face. This indicates that the model has successfully learned to identify these characters based on their core, salient features.

The analysis also provides a clear explanation for the observed confusion between Sakir and Remzi. As shown in the heatmaps, when identifying both Sakir and Remzi, the model’s attention is strongly focused on their facial regions, which share significant structural similarities. This reliance on similar facial cues appears to be the primary source of confusion between the two characters. For the model to successfully differentiate them, it must learn to weigh other, more subtle distinguishing features present in the image.

Overall, this explainability analysis confirms that our model learns meaningful and interpretable features for each character and provides a clear visual reason for the specific inter-class confusion noted in our quantitative results.

4.11 Scientific Contributions and Practical Implications

While our specific findings are detailed throughout this paper, it is useful to consolidate our core scientific contributions and discuss how they can be utilised in practical systems.

4.11.1 Scientific Contributions

The primary scientific contribution of this work is the establishment of a rigorous benchmark for the challenging, under-addressed problem of multi-label cartoon character recognition under high visual variance. This is achieved through three key elements:

1. A Novel Public Dataset: The Kral Sakir dataset provides the community with a new, publicly accessible resource specifically designed to test model generalisation against artistic style changes, a key hurdle in non-photorealistic computer vision. It serves as a standard testbed for future algorithmic comparisons.

2. A Foundational Performance Baseline: Our systematic evaluation provides a crucial insight: transfer learning from models pretrained on natural images is highly effective, with architectures featuring dense connectivity (e.g., DenseNet) showing a particular advantage. This knowledge guides future researchers in selecting appropriate models for this domain, saving significant experimental effort.

3. A Methodological Blueprint: Through our use of sequence-aware data splitting and detailed ablation studies, we provide a methodologically sound template for future research in character recognition from video media, ensuring more reliable and comparable results across the field.

4.11.2 Utilisation and Adaptation in Practical Systems

Our work can be directly utilised or adapted to build real-world systems in several ways:

1. Direct Integration for Content Analysis: The trained models, particularly our high-performing DenseNet121 variant, can be directly integrated as a core component in larger systems. For example, a media company could use it to automatically generate metadata tags for their video library, identifying which characters appear in every scene. This enables powerful content search and retrieval (e.g., “find all scenes featuring Remzi and Necati”).

2. Adaptation for Copyright and Brand Protection: The entire fine-tuning pipeline serves as a blueprint. A company wishing to protect its intellectual property could follow our methodology to train a model on their own characters. This adapted system could then scan user-generated content platforms (like YouTube or TikTok) to automatically detect and flag unauthorised use of their animated characters.

3. Foundation for Interactive Media and Parental Controls: The ability to reliably identify on-screen characters is a foundational step for more advanced applications. For instance, a streaming service could build a feature allowing parents to filter content based on specific characters, or interactive educational apps could trigger events based on which character is speaking or present.

In essence, this research provides not just a set of results, but a validated dataset, a foundational performance benchmark, and an adaptable methodology that together lower the barrier for creating practical, high-performing AI systems for cartoon media analysis.

A potential limitation of this study is that the Kral Sakir dataset is sourced from a single animated series. While this allows for a deep and focused analysis of character recognition under high visual variance within a consistent artistic style, the findings may not directly generalise to other cartoons with different visual aesthetics. The models trained on our dataset have become specialised to the specific drawing styles, colour palettes, and character designs of Kral Sakir. Consequently, their performance on animated series from different creators or cultural contexts would likely be diminished without further training or domain adaptation techniques.

5 Conclusion and Future Directions

This study successfully addressed the challenge of multi-label cartoon character classification by introducing the novel Kral Sakir dataset and thoroughly evaluating a range of deep learning techniques. Our experimental investigation, which compared a custom baseline CNN against several state-of-the-art pretrained architectures (ResNet, DenseNet, EfficientNet, MobileNet, and VGG) fine-tuned using transfer learning, underscored the significant advantages of utilising pre-existing knowledge.

The experimental results clearly demonstrated that employing transfer learning with pretrained CNNs substantially improved performance over a custom baseline model across all key metrics, alongside achieving faster convergence. Architectures such as DenseNet proved particularly effective, though other models like EfficientNetB7 and VGG16 also delivered highly competitive results, underscoring the general applicability of transfer learning for this task. Notably, all evaluated models, including the baseline, exhibited a strong capacity for accurate character identification, consistently achieving high precision and recall.

In conclusion, a primary contribution of this research is the establishment of the novel Kral Sakir dataset. This resource, specifically designed for multi-label cartoon character recognition, offers a significant asset for the research community. It can facilitate future investigations, serve as a benchmark for developing and comparing new methodologies, and ultimately contribute to advancing the capabilities of automated systems in this specialised area of computer vision. Furthermore, our study provides strong validation for the robustness and efficiency of transfer learning with advanced CNN architectures for this task. The findings highlight the potential of these methods for developing accurate and reliable automated systems for cartoon content analysis, opening new avenues for exploration in the field.

For future work, we plan to address the single-source limitation of our current dataset. A key priority will be to expand our research by incorporating characters from a diverse range of animated series, encompassing various artistic styles and cultural origins. This will allow for the development and testing of more generalised models. Furthermore, we intend to investigate domain adaptation techniques that could allow a model trained on one series to be effectively fine-tuned for another with minimal additional data, thereby improving the overall robustness and applicability of automated cartoon character recognition systems.

Acknowledgement: This research was made possible through the use of the Kral Sakir cartoon characters, created by cartoonist and writer Varol Yasaroglu. We are deeply thankful to Varol Yasaroglu for his generous permission and his support of scientific progress through this work. We also thank the Grafi2000 production team for their role. Lastly, we extend special thanks to Kaan Bicakci, whose invaluable suggestions were instrumental to this research.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualisation, Candan Tumer; methodology, Candan Tumer, Erdal Guvenoglu and Volkan Tunali; software, Candan Tumer; validation, Candan Tumer, Erdal Guvenoglu and Volkan Tunali; formal analysis, Candan Tumer; investigation, Erdal Guvenoglu and Volkan Tunali; resources, Candan Tumer; data curation, Candan Tumer; writing—original draft preparation, Candan Tumer; writing—review and editing, Candan Tumer, Erdal Guvenoglu and Volkan Tunali; visualisation, Candan Tumer; supervision, Erdal Guvenoglu and Volkan Tunali; project administration, Candan Tumer; funding acquisition, Candan Tumer. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are openly available on GitHub at https://github.com/candantumer/kral_sakir (accessed on 18 August 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Li D, Jin Z, Jin X. Cartoon character recognition based on portrait style fusion. Comput Vis Image Underst. 2025;253(6):104316. doi:10.1016/j.cviu.2025.104316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Kim H, Lee EC, Seo Y, Im DH, Lee IK. Character detection in animated movies using multi-style adaptation and visual attention. IEEE Transact Multim. 2020;23:1990–2004. doi:10.1109/tmm.2020.3006372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Li D, Wang L, Jin X. Cartoon copyright recognition method based on character personality action. EURASIP J Image Video Process. 2024;2024(1):11. doi:10.1186/s13640-024-00627-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Sun W, Kise K. Similar partial copy detection of line drawings using a cascade classifier and feature matching. In: Sako H, Franke KY, Saitoh S, editors. Computational forensics. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2011. p. 126–37. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-19376-7_11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Zhang T, Han Q, Abd El-Latif AA, Bai X, Niu X. 2-D cartoon character detection based on scalable-shape context and hough voting. Inf Technol J. 2013;12(12):2342. doi:10.3923/itj.2013.2342.2349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Sun W, Burie JC, Ogier JM, Kise K. Specific comic character detection using local feature matching. In: 2013 12th International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition; 2013 Aug 25–28; Washington, DC, USA. p. 275–9. [Google Scholar]

7. Khan FS, Anwer RM, van de Weijer J, Bagdanov AD, Vanrell M, Lopez AM. Color attributes for object detection. In: 2012 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2012 Jun 16–21; Providence, RI, USA. p. 3306–13. [Google Scholar]

8. Rigaud C, Karatzas D, Burie JC, Ogier JM. Color descriptor for content-based drawing retrieval. In: 2014 11th IAPR International Workshop on Document Analysis Systems; 2014 Apr 7–10; Tours, France. p. 267–71. doi:10.1109/das.2014.70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Yu J, Seah HS. Fuzzy diffusion distance learning for cartoon similarity estimation. J Comput Sci Technol. 2011;26(2):203–16. doi:10.1007/s11390-011-9427-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Takayama K, Johan H, Nishita T. Face detection and face recognition of cartoon characters using feature extraction. In: Proceedings of the 2012 IIEEJ Image Electronics and Visual Computing Workshop. Kuching, Malaysia: The Institute of Image Electronics Engineers of Japan; 2012. p. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

11. Ho HN, Rigaud C, Burie JC, Ogier JM. Redundant structure detection in attributed adjacency graphs for character detection in comics books. In: 10th IAPR International Workshop on Graphics Recognition; 2013 Aug 20–21; Bethlehem, PA, USA. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

12. Le TN, Luqman MM, Burie JC, Ogier JM. A comic retrieval system based on multilayer graph representation and graph mining. In: Graph-Based Representations in Pattern Recognition: 10th IAPR-TC-15 International Workshop, GbRPR 2015. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2015. p. 355–64. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-18224-7_35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Iwata M, Ito A, Kise K. A study to achieve manga character retrieval method for manga images. In: 2014 11th IAPR International Workshop on Document Analysis Systems; 2014 Apr 7–10; Tours, France. p. 309–13. doi:10.1109/das.2014.60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Qin X, Zhou Y, He Z, Wang Y, Tang Z. A faster R-CNN based method for comic characters face detection. In: 2017 14th IAPR International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition (ICDAR); 2017 Nov 9–15; Kyoto, Japan. p. 1074–80. [Google Scholar]

15. Nguyen NV, Rigaud C, Burie JC. Comic characters detection using deep learning. In: 2017 14th IAPR International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition (ICDAR); 2017 Nov 9–15; Kyoto, Japan. p. 41–6. [Google Scholar]

16. Yanagisawa H, Yamashita T, Watanabe H. A study on object detection method from manga images using CNN. In: 2018 International Workshop on Advanced Image Technology (IWAIT); 2018 Jan 7–9; Chiang Mai, Thailand; 2018. p. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

17. Chu WT, Li WW. Manga face detection based on deep neural networks fusing global and local information. Pattern Recognition. 2019;86(20):62–72. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2018.08.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Dutta A, Biswas S. CNN based extraction of panels/characters from Bengali comic book page images. In: 2019 International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition Workshops (ICDARW); 2019 Sep 22–25; Sydney, NSW, Australia. p. 38–43. [Google Scholar]

19. Mashood Nasir I, Attique Khan M, Alhaisoni M, Saba T, Rehman A, Iqbal T. A hybrid deep learning architecture for the classification of superhero fashion products: an application for medical-tech classification. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2020;124(3):1017–33. doi:10.32604/cmes.2020.010943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Kim K, Park S, Lee J, Chung S, Lee J, Choo J. Animeceleb: large-scale animation celebfaces dataset via controllable 3D synthetic models. arXiv:2111.07640. 2021. [Google Scholar]

21. Matsui Y, Ito K, Aramaki Y, Fujimoto A, Ogawa T, Yamasaki T, et al. Sketch-based manga retrieval using manga109 dataset. Multimed Tools Appl. 2017;76(20):21811–38. doi:10.1007/s11042-016-4020-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Aizawa K, Fujimoto A, Otsubo A, Ogawa T, Matsui Y, Tsubota K, et al. Building a manga dataset “manga109” with annotations for multimedia applications. IEEE Multimedia. 2020;27(2):8–18. doi:10.1109/mmul.2020.2987895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Qi Z, Pan D, Niu T, Ying Z, Shi P. Bridge the gap between practical application scenarios and cartoon character detection: a benchmark dataset and deep learning model. Displays. 2024;84(20):102793. doi:10.1016/j.displa.2024.102793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Nguyen NV, Rigaud C, Burie JC. Digital comics image indexing based on deep learning. J Imaging. 2018;4(7):89. doi:10.3390/jimaging4070089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Nguyen NV, Rigaud C, Burie JC. Comic MTL: optimized multi-task learning for comic book image analysis. Int J Docum Anal Recognit (IJDAR). 2019;22(3):265–84. doi:10.1007/s10032-019-00330-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Nir O, Rapoport G, Shamir A. CAST: character labeling in animation using self-supervision by tracking. In: Computer graphics forum. Vol. 41. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2022. p. 135–45. [Google Scholar]

27. Jain N, Gupta V, Shubham S, Madan A, Chaudhary A, Santosh K. Understanding cartoon emotion using integrated deep neural network on large dataset. Neural Comput Appl. 2022;34(24):21481–21501. doi:10.1007/s00521-021-06003-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Agrawal SC, Tripathi RK. Cartoon face detection and recognition with emotion recognition. In: 2023 International Conference on Data Science, Agents and Artificial Intelligence (ICDSAAI); 2023 Dec 21–23; Chennai, India. p. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

29. Yi F, Wu J, Zhao M, Zhou S. Anime character identification and tag prediction by multimodality modeling: dataset and model. In: 2023 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN); 2023 Jul 18–22; Gold Coast, QLD, Australia. p. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

30. Rios EA, Hu MC, Lai BC. Anime character recognition using intermediate features aggregation. In: 2022 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS); 2022 May 28–Jun 1; Austin, TX, USA. p. 424–8. [Google Scholar]

31. Grafi2000. Kral Sakir—YouTube [Internet]; 2023 [cited 2025 Aug 18]. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/@KralSakirResmi. [Google Scholar]

32. Razzaq K, Shah M. Machine learning and deep learning paradigms: from techniques to practical applications and research frontiers. Computers. 2025;14(3):93. doi:10.3390/computers14030093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Ahmed SF, Alam MSB, Kabir M, Afrin S, Rafa SJ, Mehjabin A, et al. Unveiling the frontiers of deep learning: innovations shaping diverse domains. Appl Intell. 2025;55(7):1–55. doi:10.1007/s10489-025-06259-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Lecun Y, Bottou L, Bengio Y, Haffner P. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proc IEEE. 1998;86(11):2278–324. doi:10.1109/5.726791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Gholizade M, Soltanizadeh H, Rahmanimanesh M, Sana SS. A review of recent advances and strategies in transfer learning. Int J Syst Assur Eng Manag. 2025;16(3):1123–62. doi:10.1007/s13198-024-02684-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Sohail SS, Himeur Y, Kheddar H, Amira A, Fadli F, Atalla S, et al. Advancing 3D point cloud understanding through deep transfer learning: a comprehensive survey. Inf Fusion. 2025;113(10):102601. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2024.102601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Deng J, Dong W, Socher R, Li LJ, Li K, Fei-Fei L. ImageNet: a large-scale hierarchical image database. In: 2009 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2009 Jun 20–25; Miami, FL, USA. p. 248–55. [Google Scholar]

38. He K, Zhang X, Ren S, Sun J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In: 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. p. 770–8. [Google Scholar]

39. Huang G, Liu Z, Van Der Maaten L, Weinberger KQ. Densely connected convolutional networks. In: 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 2261–9. [Google Scholar]

40. Tan M, Le QV. Efficientnet: rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. In: 36th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML); 2019 Jun 9–15; Long Beach, CA, USA. p. 6105–14. [Google Scholar]

41. Howard AG, Zhu M, Chen B, Kalenichenko D, Wang W, Weyand T, et al. Mobilenets: efficient convolutional neural networks for mobile vision applications. arXiv:1704.04861. 2017. [Google Scholar]

42. Simonyan K, Zisserman A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. In: 3rd International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR); 2015 May 7–9; San Diego, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

43. Kingma DP, Ba J. Adam: a method for stochastic optimization. In: 3rd International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR); 2015 May 7–9; San Diego, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

44. Krizhevsky A, Sutskever I, Hinton GE. ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. In: Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems; 2012 Dec 3–6; Lake Tahoe, NV, USA. p. 1097–105. [Google Scholar]

45. Prechelt L. Early stopping—but when? In: Orr GB, Müller KR, editors. Neural networks: Tricks of the trade, lecture notes in computer science. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 1998. Vol. 7700, p. 55–69. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools