Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

An Innovative Semi-Supervised Fuzzy Clustering Technique Using Cluster Boundaries

1 Graduate University of Science and Technology, Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology, Hanoi, 100000, Vietnam

2 FPT Software Company Limited, Hanoi, 100000, Vietnam

3 Institute of Information Technology, Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology, Hanoi, 100000, Vietnam

4 Faculty of Information Technology, Electric Power University, Hanoi, 100000, Vietnam

5 School of Information and Communications Technology, Hanoi University of Industry, Hanoi, 100000, Vietnam

* Corresponding Author: Luong Thi Hong Lan. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Fuzzy Logic: Next-Generation Algorithms and Applications)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(3), 5341-5357. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.068299

Received 25 May 2025; Accepted 22 August 2025; Issue published 23 October 2025

Abstract

Active semi-supervised fuzzy clustering integrates fuzzy clustering techniques with limited labeled data, guided by active learning, to enhance classification accuracy, particularly in complex and ambiguous datasets. Although several active semi-supervised fuzzy clustering methods have been developed previously, they typically face significant limitations, including high computational complexity, sensitivity to initial cluster centroids, and difficulties in accurately managing boundary clusters where data points often overlap among multiple clusters. This study introduces a novel Active Semi-Supervised Fuzzy Clustering algorithm specifically designed to identify, analyze, and correct misclassified boundary elements. By strategically utilizing labeled data through active learning, our method improves the robustness and precision of cluster boundary assignments. Extensive experimental evaluations conducted on three types of datasets—including benchmark UCI datasets, synthetic data with controlled boundary overlap, and satellite imagery—demonstrate that our proposed approach achieves superior performance in terms of clustering accuracy and robustness compared to existing active semi-supervised fuzzy clustering methods. The results confirm the effectiveness and practicality of our method in handling real-world scenarios where precise cluster boundaries are critical.Keywords

With the rapid growth of Information Technology and the increasing demand for information across various fields, there has been an exponential rise in the volume of stored data, creating a vast repository of knowledge. The challenge now lies in effectively harnessing this immense source of information. Knowledge discovery, which involves the automated extraction of useful information from large databases, is essential in addressing this challenge. Techniques employed in this field are primarily drawn from databases, machine learning, artificial intelligence, information theory, statistical methods, and high-performance computing. Among these techniques, clustering has gained significant popularity for its ability to group data points into clusters based on their similarities, particularly in complex data models such as text, web, and image data. Clustering aims to ensure that each cluster contains data points with similar characteristics while different clusters consist of dissimilar data points [1,2]. However, traditional clustering methods face challenges, especially with complex data types where a single data point may belong to multiple clusters with varying degrees of membership. This is a significant limitation of conventional (or “crisp”) clustering methods.

In 1965, Zadeh introduced the concept of fuzzy sets [3] to overcome traditional limitations in clustering, enabling data points to partially belong to multiple clusters. Building on Zadeh’s concept, Bezdek et al. developed the Fuzzy C-means (FCM) algorithm in 1984 [4], which remains one of the most widely used clustering methods today [5–7]. Despite its widespread popularity and extensive application, FCM encounters significant difficulties when handling complex datasets characterized by highly overlapping clusters. Issues such as sensitivity to initial cluster centroids can result in suboptimal clustering outcomes if improperly initialized. Moreover, identifying the optimal number of clusters can be problematic, as traditional clustering validity indices may not clearly guide optimal clustering, necessitating alternative approaches to accurately capture data structures.

One of the most critical challenges associated with FCM and similar clustering algorithms is the issue of cluster boundaries. Cluster boundaries refer to regions where data points lie close to decision thresholds between clusters, creating ambiguity and uncertainty in cluster assignments. In real-world datasets, data points frequently exhibit mixed characteristics, complicating precise classification and negatively affecting clustering accuracy. For example, in image segmentation tasks, unclear boundary clusters can result in blurred or inaccurate object boundaries. Similarly, in bioinformatics, gene clusters with overlapping functions present significant classification challenges. The fuzzy nature of FCM, which allows varying degrees of cluster membership, further exacerbates the ambiguity at these boundaries, highlighting the need for more sophisticated approaches that explicitly address boundary-related uncertainty.

To address the limitations of traditional FCM, various semi-supervised fuzzy clustering techniques have been developed, building primarily on the foundational principles of FCM. To increase the number of applications and improve the quality of clusters, semi-supervised fuzzy clustering techniques were introduced using additional data supplied by users [8–11]. One such approach is DC-SSDEC, introduced by AlZuhair et al. [12], which transforms deep clustering into a semi-supervised version by integrating fuzzy memberships with “should-link” and “shouldNot-link” soft pairwise constraints to guide clustering using limited labeled data. Wang et al. [13] suggested a novel semi-supervised fuzzy clustering technique called MMRFCM based on pairwise constraints. This approach maximizes clustering efficiency by constraining the memberships of data objects to locate in different manifolds guided by pairwise constraints and local structures of data. Additionally, these semi-supervised algorithms often integrate additional mechanisms, such as weight functions [14] and adaptive techniques, to enhance the clustering process. For instance, Gan et al. [15] introduced a weighting mechanism to establish the reliability of labeled samples, aiming to minimize the risks associated with labeled instances. Subsequent works by Gan [16,17] expanded on this idea, though challenges remain in handling pair constraints and assessing risks between labeled and unlabeled samples. Moreover, adaptive algorithms have been proposed as a promising direction in semi-supervised fuzzy clustering. Casalino et al. [18] introduced an FCM-based method employing adaptive functions to dynamically estimate the number of clusters, adjusting to data distributions. Although these methods show promise, they often require significant computational resources, particularly for large-scale datasets [19].

Recently, advanced models such as Multi-View Picture Fuzzy Clustering (MPFC) [20], Weighted Semi-Supervised Possibilistic Fuzzy C-Means (WSPFCM-DS) [21], and latent representation-based semi-supervised fuzzy clustering [22] have been developed to improve robustness and performance. These models enhance traditional clustering by incorporating features like multiple-view integration [23], data stream adaptability and deep latent learning with information fusion, showing significant improvements in real-world datasets. In parallel, active learning has gained attention for reducing labeled data dependency. For example, Dogan and Avvad [24] proposed fuzzy clustering guided by activity sequences and time features in process mining. Meanwhile, contrastive learning models such as FCACC [25] apply fuzzy principles to contrastive time-series clustering, further highlighting the importance of refined membership boundaries.

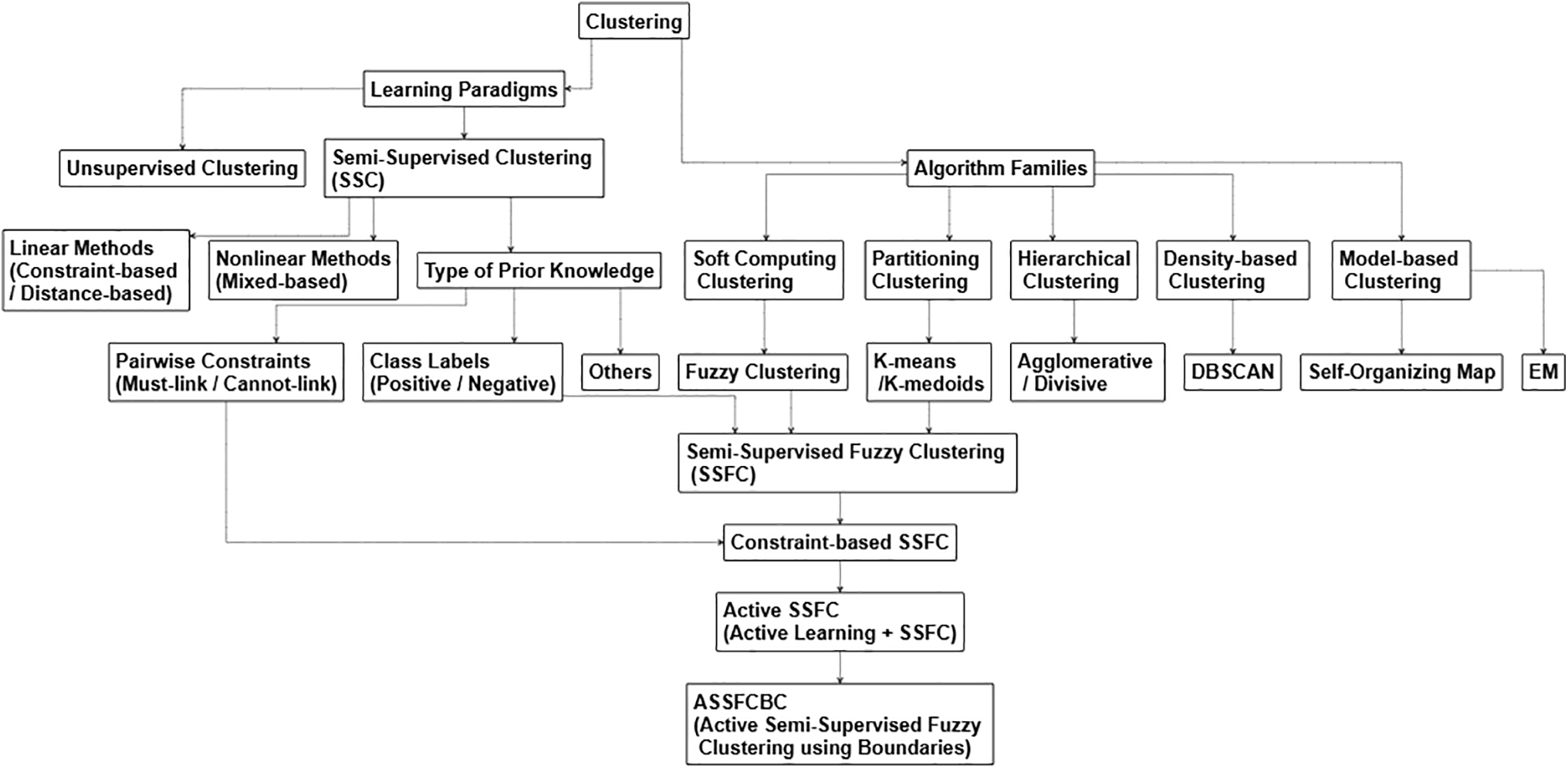

Fig. 1 illustrates the evolution from Traditional Clustering to Active Semi-Supervised Fuzzy Clustering. Active learning has emerged as a promising approach to enhance semi-supervised fuzzy clustering by incorporating prior knowledge into the clustering process [26–28]. This method leverages a small set of labeled data, known as seeds, to guide the clustering algorithm effectively. Notable works in this area include seed-based K-Means [29] and seed-based Fuzzy C-Means [30]. A primary challenge in semi-supervised clustering is selecting the most informative data points to guide the algorithm. Active learning addresses this by strategically selecting data points for labeling, reducing the need for extensive labeled datasets. In many data mining applications, while large quantities of unlabeled data are readily available, obtaining labeled data is often expensive and time-consuming. Active learning minimizes labeling costs by selectively requesting labels for data points that provide the most information, contrasting with passive learning, where samples are chosen uniformly randomly.

Figure 1: The evolution from traditional clustering to active semi-supervised fuzzy boundaries clustering

By applying active learning to correct these boundary errors, our approach aims to significantly improve clustering accuracy, particularly in complex datasets with overlapping clusters. The combination of semi-supervised clustering and active learning has proven effective, particularly for clusterable data [31]. Key advantages include leveraging both labeled and unlabeled data through iterative clustering refinement, utilizing active learning to uncover accurate cluster structures with minimal labeled data by selectively querying instances near decision boundaries, refining cluster boundaries or resolving conflicts through instance selection, which helps identify hidden patterns, and achieving better accuracy than regular semi-supervised clustering while using fewer labeled examples [32]. Besides, numerous studies have demonstrated that this targeted approach maximizes clustering accuracy with minimal training data [33]. Overall, semi-supervised fuzzy clustering methods, by integrating active learning techniques, bring a new approach that improves the quality of clustering methods.

However, despite these advances, existing methods still face significant challenges, particularly in handling boundary clusters, where data points lie near the decision boundaries between multiple clusters. These boundary regions are prone to misclassification due to the ambiguity in data point assignments, which active learning strategies have yet to address fully. Furthermore, the computational complexity of active learning, coupled with its sensitivity to the choice of initial seeds and its focus on selecting a limited number of data points, can limit its effectiveness in dealing with complex and overlapping clusters. These limitations are also the motivation for our research, which requires research and development to improve the effectiveness of semi-supervised fuzzy clustering methods, especially for points at the boundaries of clusters. This paper concentrates on enhancing a semi-supervised fuzzy clustering algorithm (SSFCM) by integrating active learning techniques. We propose a novel approach that addresses the common issue of misclassification at the boundaries between clusters, where the likelihood of errors is highest.

The main contributions of this paper can be concluded as follows:

• Propose a novel algorithm to determine the boundaries between clusters in overlapping regions, where elements near the cluster edges are at a higher risk of being misclustered due to ambiguity in their cluster memberships;

• An active learning-based boundary adjustment process to refine cluster memberships and centroids using expert feedback;

• Propose a novel algorithm model, “Active Semi-Supervised Fuzzy Clustering Based on Clusters Boundary” (ASSFBC) that combines active learning and semi-supervised fuzzy clustering to improve the performance of clustering algorithms, especially in cases where data has many noise points at the cluster boundaries;

• Suggest an algorithm that generates synthetic 2D datasets with adjustable cluster overlap, enabling controlled evaluation of clustering algorithms in challenging scenarios. It provides a systematic way to test robustness and performance under varying levels of ambiguity in cluster boundaries.

• Prove the effectiveness of the proposed algorithm compared to other methods through experiments on data types, including UCI, manually generated data, and satellite image data. The results show that ASSFBC achieves better performance than existing related algorithms.

The paper is structured as follows: Section 2 overviews the basic concepts used in researching and developing the proposed model; Section 3 describes the construction of a fuzzy semi-supervised clustering model based on active learning; Section 4 presents experimental results validating the proposed model; and the final section provides conclusions and recommendations. This new approach actively corrects the dependencies of boundary elements to improve clustering accuracy by first identifying the boundary regions using fuzzy semi-supervised clustering and then applying active learning to refine these boundaries. For detailed information, refer to the sections in the document where the main contributions are described and explained in context.

2 The Proposed Active Semi-Supervised Fuzzy Clustering Method

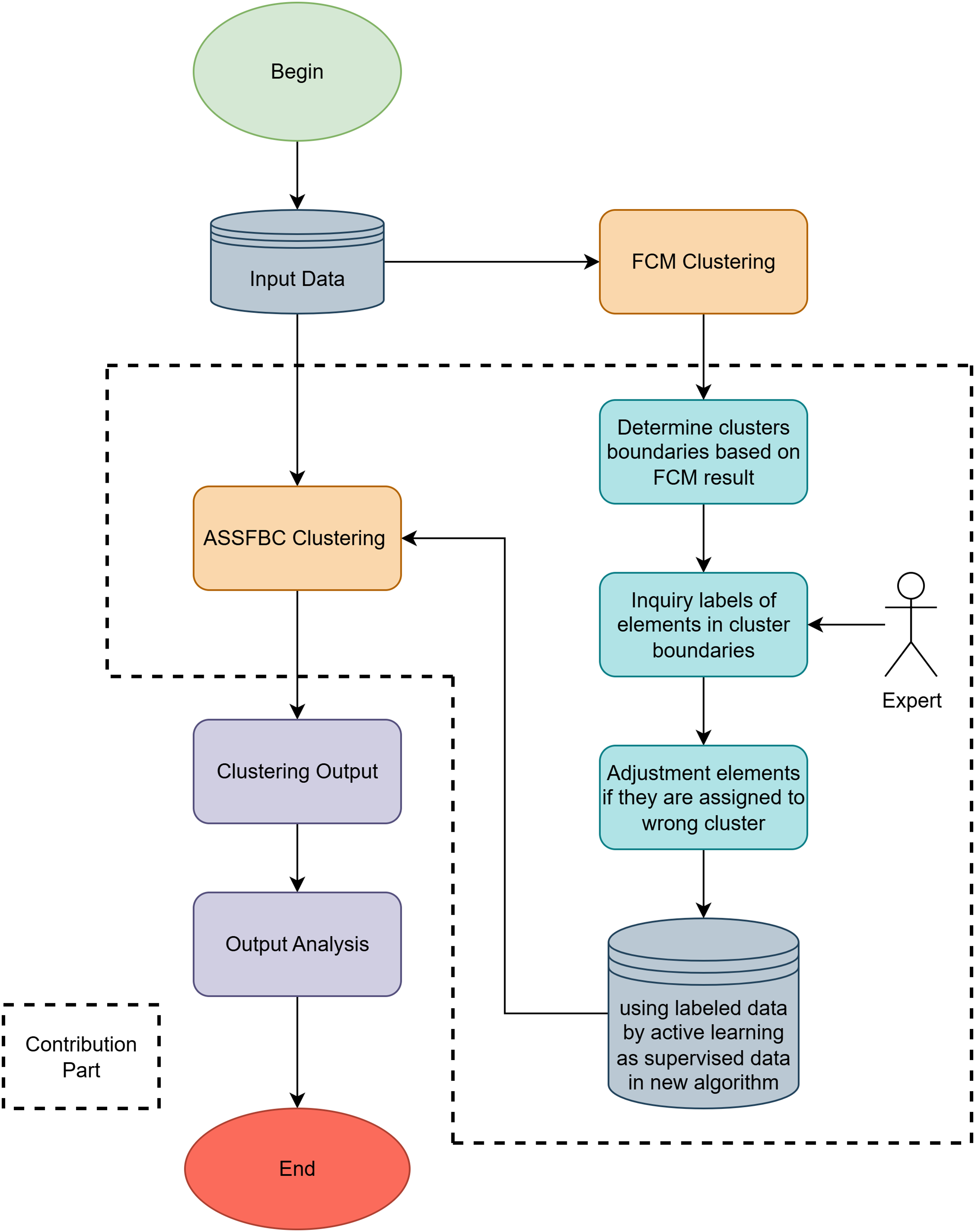

The proposed method starts with clustering the data using the Fuzzy C-means (FCM) algorithm. This step groups the data points into clusters but also identifies overlapping regions between clusters. These regions are characterized by data points that are not confidently assigned to a specific cluster, indicating potential misclassifications. The next step involves applying active learning techniques to these overlapping regions. By selectively querying an expert or an oracle about the true class of these ambiguous data points, the algorithm can adjust their cluster memberships, thereby improving the overall clustering quality.

In the subsequent phase, the centroids of the overlapping regions and the data points adjusted through active learning are utilized to refine the clustering process. A new clustering algorithm is developed with the objective of moving the cluster centroids closer to the centroids of the overlapping regions. This reduces the size of the boundary regions between clusters and improves the compactness and separation of the clusters.

For example, after performing FCM clustering, we have three clusters, 1, 2, and 3, corresponding to centroids

Figure 2: Active semi-supervised fuzzy clustering based on clusters boundary model

The Fig. 2 illustrates the complete workflow of the proposed clustering method, beginning with FCM clustering and progressing through boundary analysis and active label querying.

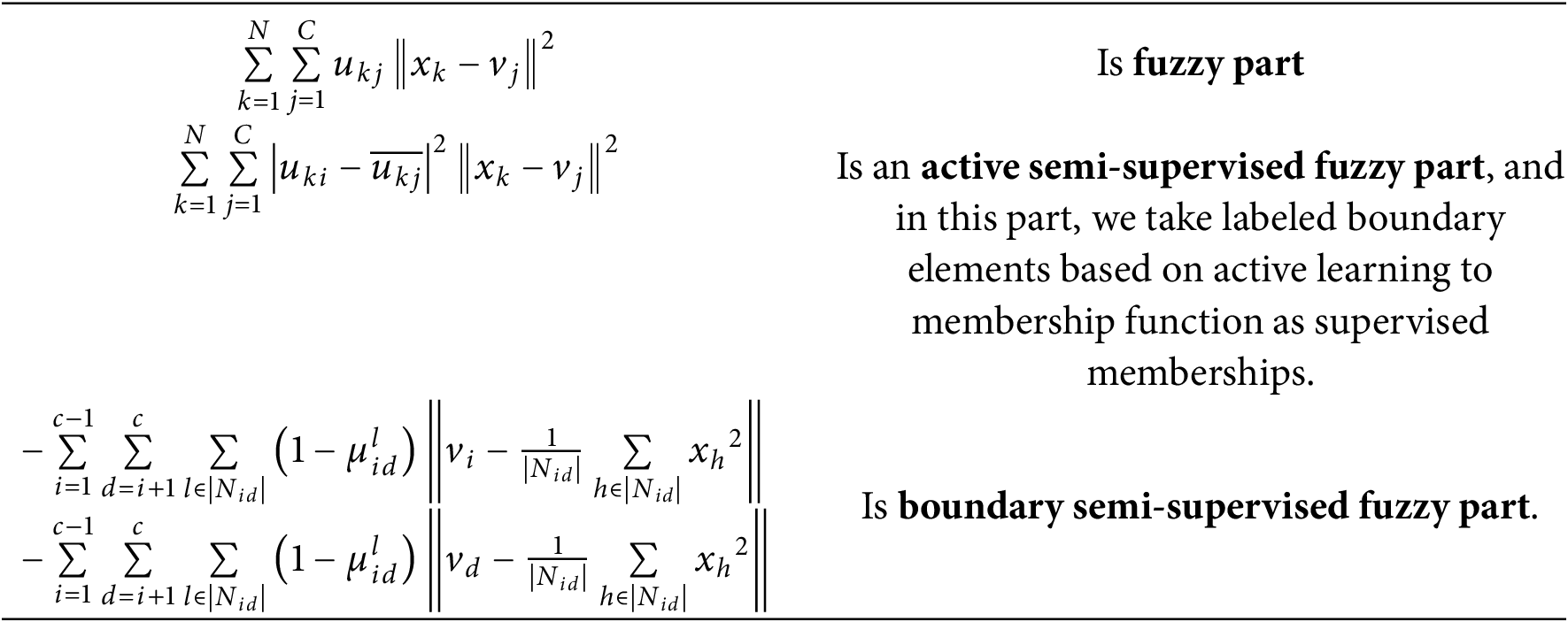

The Active Semi-Supervised Fuzzy Clustering Based on Clusters Boundary (ASSFBC) method introduces an objective function that integrates fuzzy clustering, semi-supervised fuzzy clustering, and boundary correction. The process begins with Initial Clustering (Fuzzy Part), where Fuzzy C-Means (FCM) clustering is performed on the dataset to obtain initial cluster centroids and membership values. The primary objective at this stage is to minimize the distance between data points and their respective cluster centroids, establishing a foundational clustering structure.

Following this, the method proceeds with Boundary Identification (Clusters Boundary Definition and Determination Process), defining the boundaries between clusters by identifying regions where the difference in membership values between any two clusters for a data point is smaller than a predefined epsilon (

The process then moves to Active Learning and Membership Adjustment (Adjustment of Wrong Data Process), where an expert or oracle is consulted to determine the correct classification of the identified boundary elements. If there is a discrepancy between the expert’s classification and the algorithm’s result, the membership values of these boundary elements are adjusted to align more closely with the correct classification, thereby reducing ambiguity in boundary regions and refining the clustering results.

Subsequently, in the Refinement of Cluster Boundaries (Boundary Semi-Supervised Fuzzy Part) step, the cluster centroids and membership matrix are updated using the corrected boundary information. The objective is to draw the cluster centroids closer to the corrected boundary centroids, thereby narrowing the boundaries between clusters and enhancing overall compactness and separation. Finally, the Optimization process involves iteratively repeating the above steps and refining the cluster boundaries until the changes in cluster centroids between iterations are minimal or until a maximum number of iterations is reached. Integrating active learning and boundary correction, this iterative process ensures that the final clusters are more accurate and robust, particularly in scenarios involving overlapping data points.

The ASSFBC method culminates in an objective function that incorporates these refined membership values and boundary corrections, optimizing the clustering outcome by addressing the challenges posed by boundary clusters and enhancing the overall accuracy and robustness of the clustering process:

With the constraints:

Where the dataset

We can consider three parts of the objective function:

By setting

Simplify Neighborhood Terms using:

We combine the terms into one vector

Consider

So we can have:

We have

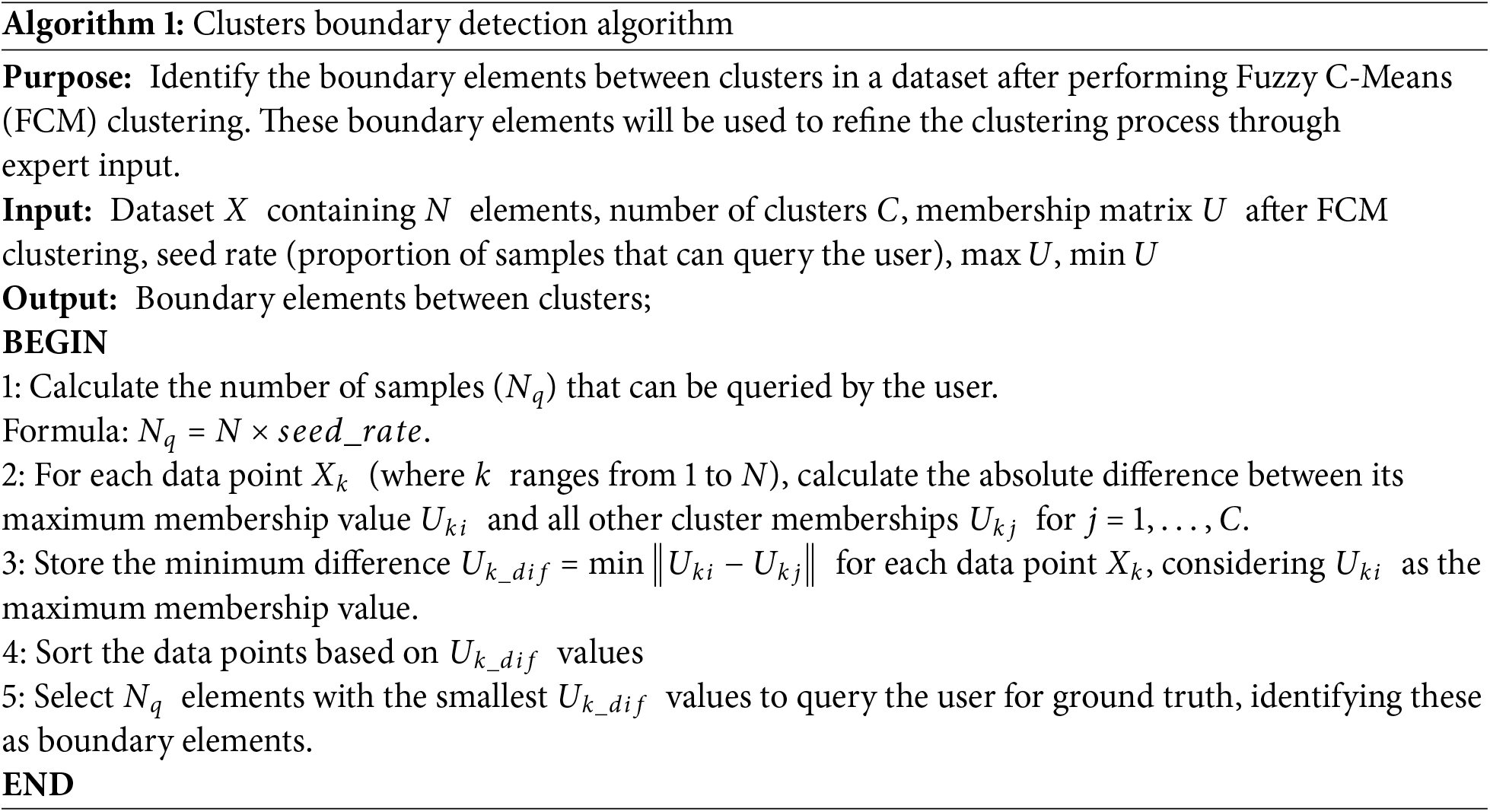

Taking derivative of J with respect to

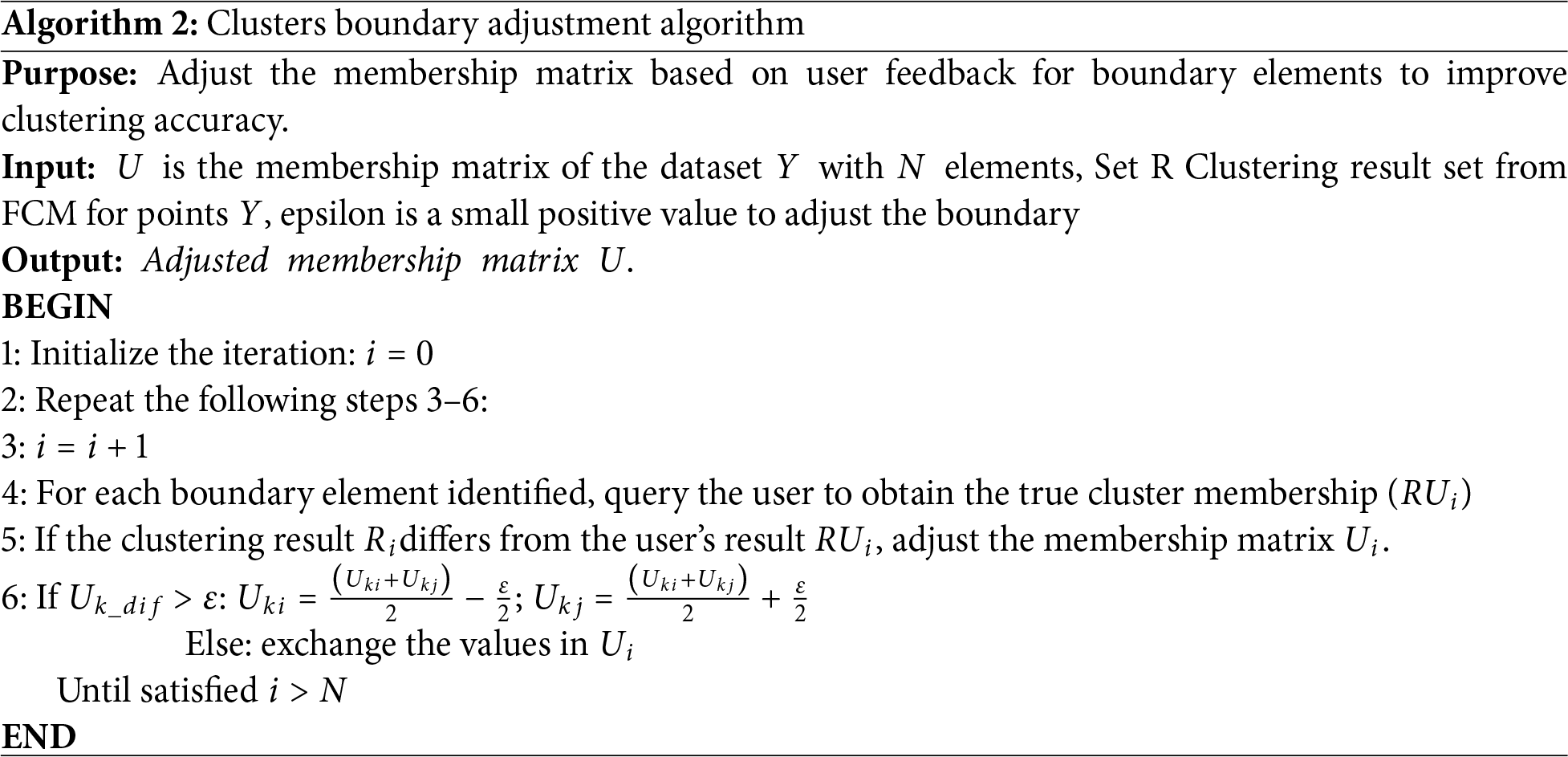

The Clusters Boundary Detection Algorithm (Algorithm 1) begins by calculating the number of samples that can query the expert, determined by the seed rate, which is typically a fixed value for a given dataset. The seed rate defines the proportion of the dataset selected for expert querying rather than being dynamically adjusted like the learning rate. The algorithm then evaluates the difference in membership values between the maximum membership and other clusters for each data point. By identifying and sorting these minimum differences, the algorithm selects boundary elements for querying, which serve as key inputs for refining the clustering process.

The Clusters Boundary Adjustment Algorithm (Algorithm 2) operates by iteratively refining the membership matrix based on user feedback. In each iteration, the algorithm compares the clustering results with the user’s ground truth for boundary elements. Adjustments are made by modifying the membership values according to a predefined epsilon threshold, ensuring that the clustering adapts to the user’s corrections.

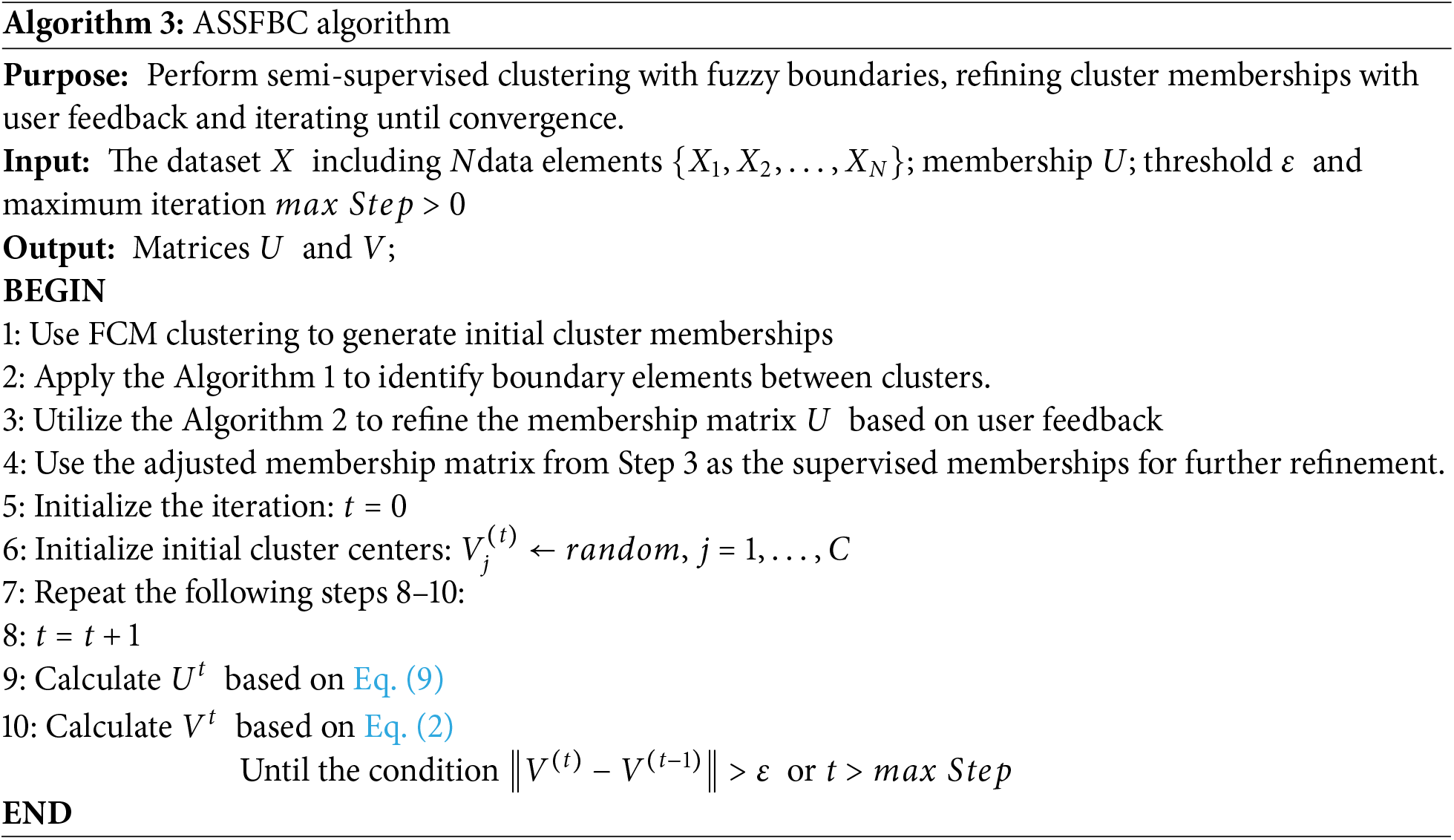

The ASSFBC algorithm (Algorithm 3) is a comprehensive approach that integrates FCM clustering with semi-supervised adjustments based on boundary elements. After initial clustering, the algorithm detects boundary elements and refines them with user feedback. The final steps involve iterating through membership and cluster center updates until convergence is achieved, ensuring the clustering is accurate and well-adapted to the provided data.

This section presents experimental results to demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed method compared to other fuzzy semi-supervised methods for the problem of assessing the quality of clusters.

With the desire to demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed method in the case of many noise points at the boundaries of data clusters, the experiment compares and proposes experimental scenarios on the following three types of data: UCI standard data, manually generated datasets, and satellite image data. These datasets were chosen to comprehensively evaluate our algorithm’s performance across different data types and clustering challenges. Testing on all three types of data allows for rigorous evaluation, ensuring the effectiveness of the clustering model in many different real-life situations.

3.1.1 The UCI Benchmark Data Sets

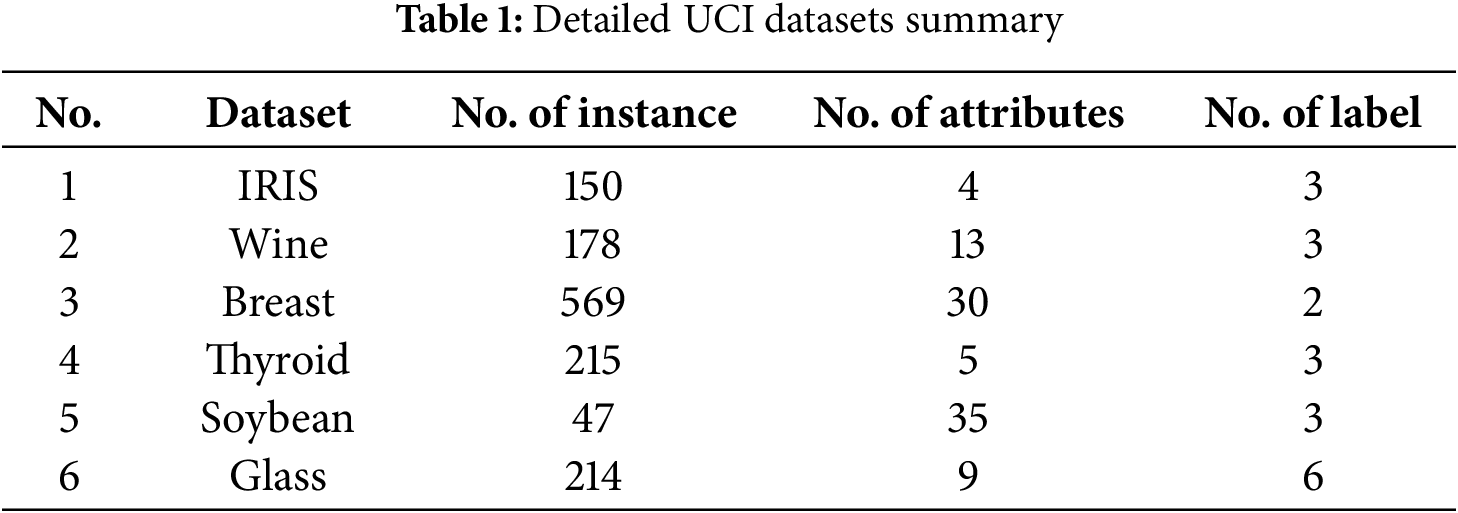

There are six datasets taken from the UCI standard database, from the UCI Machine Learning Repository [34], including IRIS, Wine, Breast, Thyroid, Soybean, and Glass. Details of the UCI benchmark data sets are described in Table 1.

3.1.2 The Manually Generated Data Sets

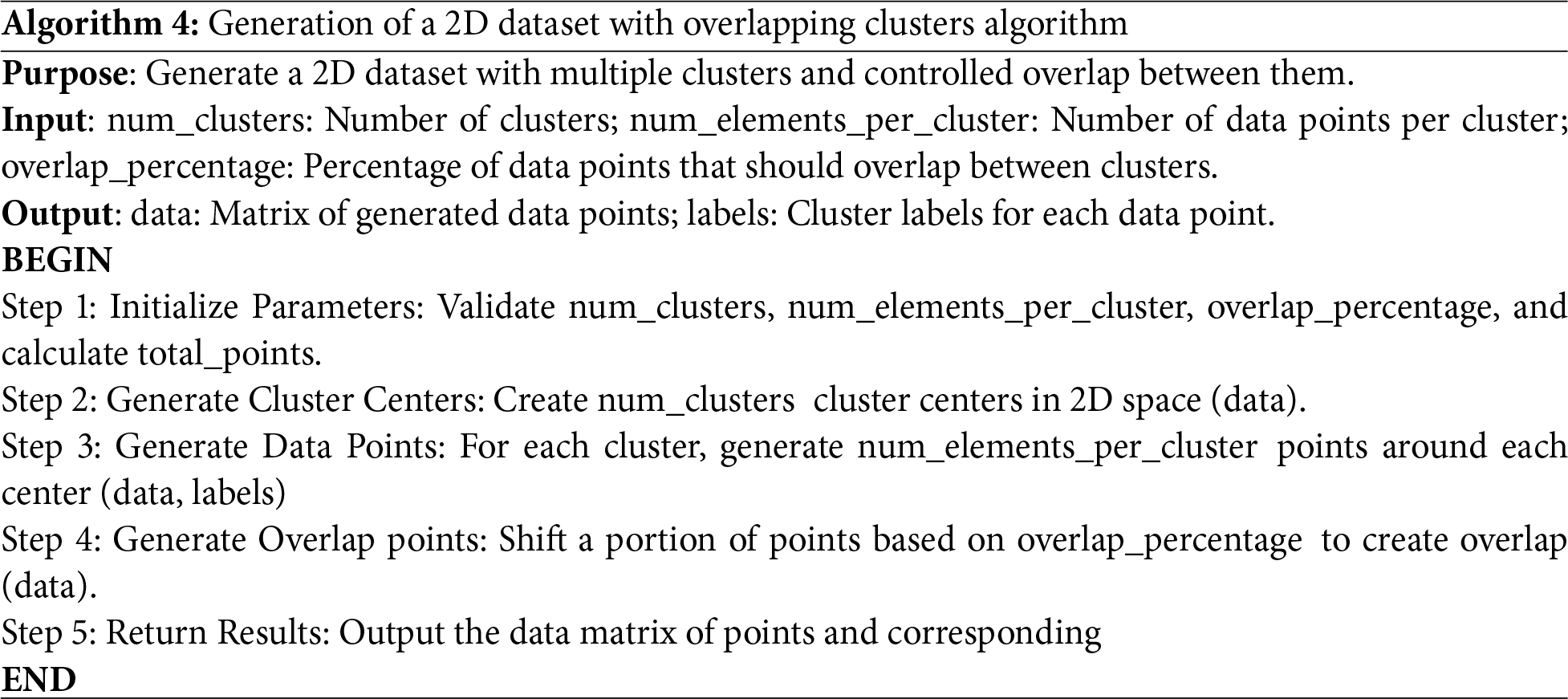

To further test our algorithm’s performance with noisy data, we generated two synthetic datasets, Data 1 and Data 2, each with 2 or 3 clusters and 500 or 750 samples. These datasets were explicitly designed to have many noisy points near the cluster boundaries, providing a challenging environment for our algorithm to demonstrate its effectiveness. The paper proposes an algorithm that generates synthetic 2D datasets with adjustable cluster overlap, specifically designed to contain numerous noisy points near cluster boundaries. This enables controlled and rigorous evaluation of clustering algorithms, particularly our ASSFBC method, in challenging scenarios, by providing a systematic way to test its robustness and performance under varying levels of ambiguity in cluster boundaries, which is the core problem ASSFBC aims to address. The data generation algorithm is performed according to the steps described in Algorithm 4.

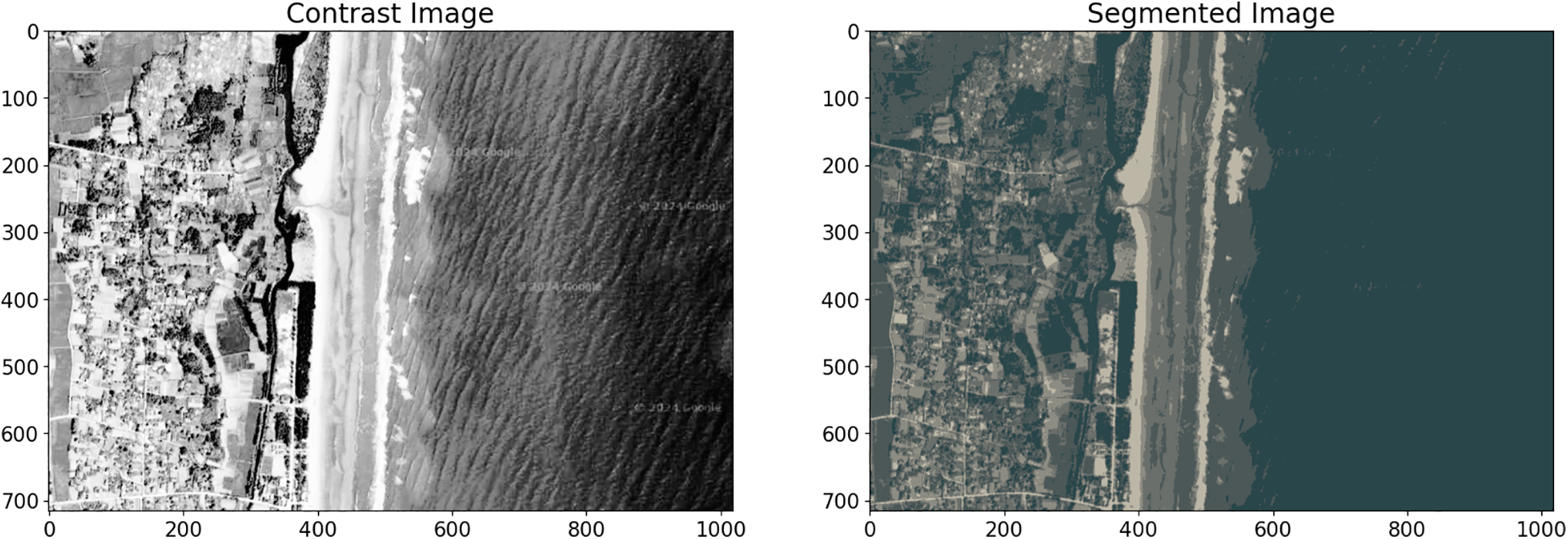

Our experiment utilized Landsat-8 satellite imagery of the coastal region of Nghe An province, Vietnam, captured in 2020 (coordinates: 19.518729, 105.807984). The dataset was divided into three distinct sites, and the objective was to classify the land cover into six clusters: grass and shrubs, bare land, surface water, perennial tree crops, planted forests, and low woods. An illustrative example of a satellite image is shown in Fig. 3. The Fig. 3 presents an example of the Landsat-8 satellite imagery that was utilized in the experiments for land cover classification.

Figure 3: Illustration of the satellite image

The experiments were conducted using MATLAB R2021a (64-bit) as the primary programming and simulation environment. The simulations were executed on a Windows 10 operating system using an LG Gram laptop equipped with an Intel(R) Core(TM) i5-6200U CPU @ 2.30 GHz–2.40 GHz and 8 GB of RAM. MATLAB was chosen for its robust support for numerical computation, matrix manipulation, and clustering algorithm implementation. All algorithms, including the proposed ASSFBC, were implemented from scratch or adapted within MATLAB to ensure consistency in experimental conditions. The environment setup was kept consistent throughout all runs to ensure reproducibility and to minimize variability in performance evaluation. Experiments are executed to compare the proposed ASSFBC and some related methods, FCM, SSFCM [35], eSFCM [36], AFFC [37], and AFFC [38] with a focus on performance under boundary noise conditions.

Some clustering quality indicators are the criteria for evaluation, including the Rand Index (RI) [39], The traditional F-measure or balanced F-score (F1 Score) [40], Normalized Mutual Information (NMI) [41], and Davies-Bouldin (DB) Index [42].

3.3 Experimental Results and Discussion

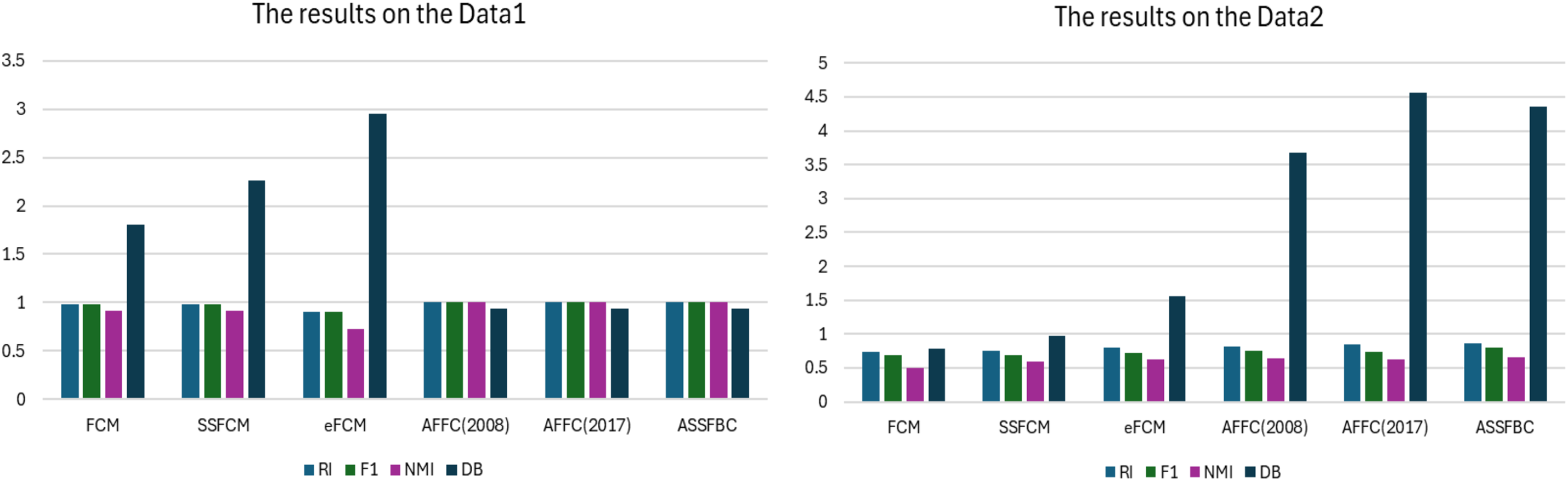

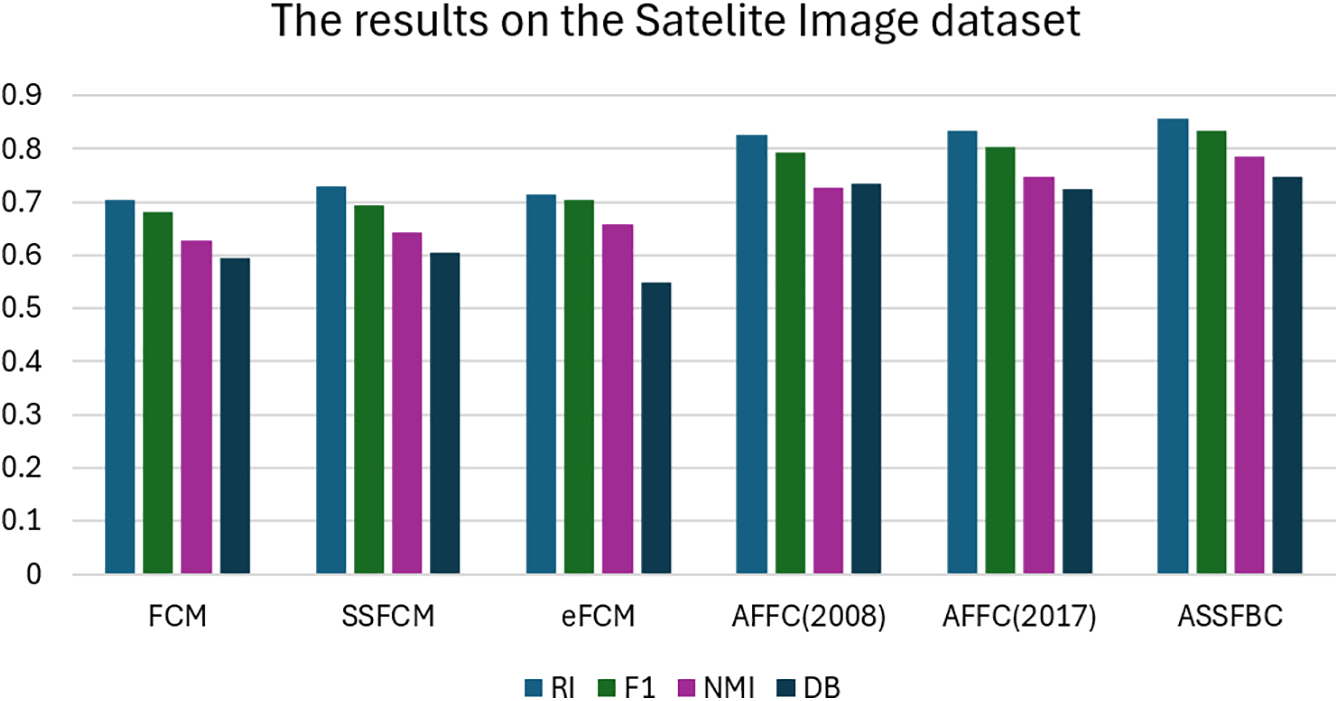

After performing the experiments on the datasets, the results are shown in detail in Figs. 4–6, corresponding to the UCI data sets, manually generated data, and satellite image data.

Figure 4: Comparison results on the UCI datasets

Figure 5: Comparison results on the manual datasets

Figure 6: Comparison results on the satellite image datasets

Fig. 4 presents the performance comparison of the ASSFBC algorithm against other clustering methods on various standard UCI benchmark datasets, including IRIS, Wine, Breast Cancer, Thyroid, Soybean, and Glass. Based on the experimental results, the ASSFBC algorithm consistently demonstrates superior performance across various datasets compared to other clustering methods. For the IRIS dataset, ASSFBC achieved the highest RI of 0.99114, the highest F1 of 0.98653, and the highest NMI of 0.97019, indicating strong clustering performance and a high correlation with true labels. Similarly, for the Wine dataset, ASSFBC attained the highest RI of 0.76366, F1 of 0.65287, and NMI of 0.49039. However, the DB Index for ASSFBC on this dataset was higher (2.27730), suggesting room for improvement in cluster separation. ASSFBC is designed to improve clustering accuracy by actively correcting misclassified boundary elements through expert feedback, which enhances alignment with true labels—reflected in high RI, F1, and NMI scores. However, this focus on semantic correctness rather than geometric regularity can lead to slightly less compact or separated clusters, as captured by a somewhat higher DB index. On the Breast Cancer dataset, ASSFBC performed well, with an RI of 0.78120, F1 of 0.70118, NMI of 0.55698, and a lower DB Index of 0.89140, indicating better cluster separation and compactness.

In other datasets, ASSFBC also showed outstanding performance. For example, in the Soybean and Thyroid datasets, ASSFBC achieved the highest RI of 0.8631; 0.7604, F1 of 0.7526; 0.7327, NMI of 0.7735; 5246, and a lower DB index of 2.7521; 2.0829, indicating improved cluster separation. The Glass dataset further demonstrated ASSFBC’s effectiveness, with an RI of 0.84694, F1 of 0.81931, NMI of 0.73148, and a lower DB Index of 0.79230.

Fig. 5 illustrates the performance of the proposed ASSFBC algorithm on two synthetic 2D datasets, Data 1 and Data 2, which were specifically generated with many noisy points near cluster boundaries to provide a challenging environment. In synthetic datasets like Data 1 and Data 2, the proposed ASSFBC algorithm reached near-perfect clustering performance, particularly in Data 1, where the RI was 1.0000, F1 was 0.9980, NMI was 0.9562, and the DB index was 0.4371. Similarly, in Data 2, ASSFBC achieved the highest RI of 0.86638, F1 of 0.80147, NMI of 0.68920, and a lower DB index of 0.9023, confirming its strong clustering capabilities. These results highlight ASSFBC as a highly effective algorithm for various clustering tasks, consistently delivering high accuracy and well-defined clusters.

Fig. 6 presents the evaluation of the ASSFBC algorithm against other methods using Landsat-8 satellite imagery of the coastal region of Nghe an province, Vietnam, with the objective of classifying land cover into six distinct clusters. According to the information from the experimental results, the ASSFBC algorithm demonstrates superior performance across most measured indices on the Satellite Image dataset. It achieves the highest RI value of 0.8563, indicating the best agreement with the true labels compared to other algorithms. Additionally, ASSFBC records the highest FCCI value of 0.8343, reflecting strong clustering performance and the best correlation between data points and their respective clusters. It also outperforms the other algorithms with a NMI of 0.7854, showing a high mutual dependence between the clustering results and the true labels. Although ASSFBC’s DB index is 0.7475, which is slightly higher than other algorithms, it still indicates relatively good cluster separation and compactness.

In conclusion, the experimental results suggest that the ASSFBC algorithm is highly effective for clustering tasks, particularly in scenarios involving complex and overlapping data, such as satellite imagery. Its superior performance in RI, F1, and NMI highlights its ability to accurately cluster data points and maintain strong correlations with accurate labels, making it a reliable choice for applications where precision is critical. While the slightly higher DB index suggests there may be room for improvement in cluster compactness, the overall effectiveness of ASSFBC in providing accurate, well-correlated, and strongly separated clusters makes it a valuable tool in fuzzy clustering. This performance underscores its potential for further application and development in various data-intensive domains.

This paper introduced an innovative approach to active semi-supervised fuzzy clustering that focuses on refining clusters’ boundaries. This method effectively addresses the challenge of ambiguity in boundary clusters by integrating active learning techniques to improve the accuracy of membership assignments at these critical points. Our approach not only enhances the robustness of clustering results but also offers a novel semi-supervised fuzzy clustering model that iteratively refines cluster boundaries through the combination of fuzzy clustering and active learning. The experimental results across benchmark datasets demonstrate that the proposed method, Active Semi-Supervised Fuzzy Clustering Based on Clusters Boundary (ASSFCMB), outperforms traditional fuzzy clustering algorithms and other semi-supervised clustering methods. This is evidenced by higher scores in key metrics such as the RI, F1-score, and NMI, as well as lower DB indices compared to existing methods. While models like MMRFCM [12] improve clustering using pairwise constraints and manifold learning, they do not explicitly target ambiguity at cluster boundaries. In contrast, our proposed ASSFCMB model uniquely focuses on correcting misclassified boundary points through active learning, offering a more targeted and robust solution for boundary-aware clustering in complex datasets.

Several areas can be explored to enhance the applicability and performance of the ASSFCMB model further. Future research should prioritize improving the scalability and computational efficiency of the model, particularly for large-scale datasets, potentially through techniques like parallel processing and optimized data structures. Extending the model’s application to real-world problems, such as medical diagnosis, remote sensing, and social network analysis, will help validate its practical utility and address domain-specific challenges. Integrating deep learning techniques—such as using convolutional neural networks (CNNs) for feature extraction in image data or graph neural networks (GNNs) for capturing relational structures—could significantly enhance clustering performance in complex and structured data scenarios. Moreover, developing automated boundary detection and correction methods, minimizing the need for human intervention, would streamline the clustering process. Lastly, exploring different active learning strategies, such as uncertainty sampling and query-by-committee, could provide valuable insights into the most effective approaches for specific clustering contexts. Together, these future directions promise to significantly advance the field of fuzzy clustering and broaden its applications.

Acknowledgement: The authors acknowledge the use of ChatGPT (OpenAI) for assistance with grammar checking, language polishing and minor improvements to sentence structure. All outputs were carefully reviewed and verified by the authors to ensure accuracy and originality.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Study conceptualization: Duong Tien Dung, Ha Hai Nam, Nguyen Long Giang, Luong Thi Hong Lan; data collection and experiment: Duong Tien Dung, Nguyen Long Giang; analysis and interpretation of results: Duong Tien Dung, Luong Thi Hong Lan; draft manuscript preparation: Duong Tien Dung, Ha Hai Nam, Luong Thi Hong Lan. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in [repository ASSFC] at [github.com/duongtiendung87/ASSFC (accessed on 01 August 2025)].

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Shen Y, Wang Y, Wei M, Chen H, Xie H, Cheng G, et al. Semi-MoreGAN: semi-supervised generative adversarial network for mixture of rain removal. Comput Graph Forum. 2022;41(7):443–54. doi:10.1111/cgf.14690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Verma S, Bhatia S, Zeadally S, Kaur S. Fuzzy-based techniques for clustering in wireless sensor networks (WSNsrecent advances, challenges, and future directions. Int J Commun Syst. 2023;36(16):e5583. doi:10.1002/dac.5583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Zadeh LA. Fuzzy sets. Inf Control. 1965;8(3):338–53. doi:10.1016/s0019-9958(65)90241-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Bezdek JC. Pattern recognition with fuzzy objective function algorithms. New York, NY, USA: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1981. doi:10.1007/978-1-4757-0450-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Jacintha V, Karthikeyan S, Sivaprakasam P. Surface flaw detection of plug valve material using infrared thermography and weighted local variation pixel-based fuzzy clustering technique. Adv Mater Sci Eng. 2022;2022:7919532. doi:10.1155/2022/7919532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Hussain I, Sinaga KP, Yang MS. Unsupervised multiview fuzzy C-means clustering algorithm. Electronics. 2023;12(21):4467. doi:10.3390/electronics12214467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Daneshfar F, Soleymanbaigi S, Yamini P, Amini MS. A survey on semi-supervised graph clustering. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2024;133(2):108215. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2024.108215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Xu S, Hao Z, Zhu Y, Wang Z, Xiao Y, Liu B. Semi-supervised fuzzy clustering algorithm based on prior membership degree matrix with expert preference. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;238(5):121812. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2023.121812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Kmita K, Kaczmarek-Majer K, Hryniewicz O. Explainable impact of partial supervision in semi-supervised fuzzy clustering. IEEE Trans Fuzzy Syst. 2024;32(5):3189–98. doi:10.24433/CO.3328061.v2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Golzari Oskouei A, Samadi N, Tanha J. Feature-weight and cluster-weight learning in fuzzy c-means method for semi-supervised clustering. Appl Soft Comput. 2024;161(2):111712. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2024.111712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Hong Y, Zhong G, Lian J, Mai G, Zhou H, Chen P, et al. Semi-supervised fuzzy clustering based on prior membership. Mathematics. 2025;13(16):2559. doi:10.3390/math13162559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. AlZuhair MS, Ben Ismail MM, Bchir O. Novel dual-constraint-based semi-supervised deep clustering approach. Sensors. 2025;25(8):2622. doi:10.3390/s25082622. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Wang Y, Chen L, Zhou J, Li T, Yu Y. Pairwise constraints-based semi-supervised fuzzy clustering with multi-manifold regularization. Inf Sci. 2023;638(2):118994. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2023.118994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Jasim AK, Tanha J, Ali Balafar M. Neighborhood information based semi-supervised fuzzy C-means employing feature-weight and cluster-weight learning. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2024;181(01):114670. doi:10.1016/j.chaos.2024.114670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Gan H, Fan Y, Luo Z, Zhang Q. Local homogeneous consistent safe semi-supervised clustering. Expert Syst Appl. 2018;97:384–93. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2017.12.046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Gan H. Safe semi-supervised fuzzy—means clustering. IEEE Access. 2019;7:95659–64. [Google Scholar]

17. Gan H, Fan Y, Luo Z, Huang R, Yang Z. Confidence-weighted safe semi-supervised clustering. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2019;81:107–16. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2019.02.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Casalino G, Castellano G, Mencar C. Incremental adaptive semi-supervised fuzzy clustering for data stream classification. In: 2018 IEEE Conference on Evolving and Adaptive Intelligent Systems (EAIS); 2018 May 25–27; Rhodes, Greece. p. 1–7. doi:10.1109/EAIS.2018.8397172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Cai W, Xu S, Liu J, Du Q, Chen H, Lin Y. An adaptive approach of feature selection applied to semi-supervised fuzzy clustering. In: Proceedings of the 2020 4th International Conference on Electronic Information Technology and Computer Engineering; 2020 Nov 6–8; Xiamen, China. p. 723–27. doi:10.1145/3443467.3443843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Pham HT, Canh HT, Lan LTH, Huy NT, Giang NL. Multi-view picture fuzzy clustering: a novel method for partitioning multi-view relational data. Comput Mater Contin. 2025;83(3):5461–85. doi:10.32604/cmc.2025.065127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Samadi N, Tanha J, Jalili M. A weighted semi-supervised possibilistic fuzzy c-means algorithm for data stream classification and emerging class detection. Knowl Based Syst. 2025;309(5):112831. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2024.112831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Zhu H, Kan B, Li Y, Yan E, Weng H, Wang FL, et al. A new semi-supervised fuzzy clustering method based on latent representation learning and information fusion. Appl Soft Comput. 2025;170(1):112717. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2025.112717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Daneshfar F, Saifee BS, Soleymanbaigi S, Aeini M. Elastic deep multi-view autoencoder with diversity embedding. Inf Sci. 2025;689:121482. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2024.121482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Dogan O, Avvad H. Fuzzy clustering based on activity sequence and cycle time in process mining. Axioms. 2025;14(5):351. doi:10.3390/axioms14050351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Wang C. Fuzzy cluster-aware contrastive clustering for time series (FCACC). arXiv:2503.22211. 2025. [Google Scholar]

26. Ren P, Xiao Y, Chang X, Huang P-Y, Li Z, Gupta BB, et al. A survey of deep active learning. arXiv:2009.00236. 2020. doi:10.48550/arxiv.2009.00236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Tsiakmaki M, Kostopoulos G, Kotsiantis S, Ragos O. Fuzzy-based active learning for predicting student academic performance. In: Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Engineering & MIS 2020. Almaty Kazakhstan: ACM; 2020. p. 1–6. doi:10.1145/3410352.3410823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Agrawal A, Tripathi S, Vardhan M. Active learning approach using a modified least confidence sampling strategy for named entity recognition. Prog Artif Intell. 2021;10(2):113–28. doi:10.1007/s13748-021-00230-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Bajpai N, Paik JH, Sarkar S. A stratified seed selection algorithm for $K$-means clustering on big data. IEEE Trans Artif Intell. 2025;6(5):1334–44. doi:10.1109/TAI.2024.3524370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Zhang H, Huang SL. Improved fuzzy C-means clustering algorithm based on fuzzy particle swarm optimization for solving data clustering problems. Math Comput Simul. 2025;233(3):311–29. doi:10.1016/j.matcom.2025.02.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Wang S, Sun Z, Li M, Zhang H, Metwally AHS. Leveraging TikTok for active learning in management education: an extended technology acceptance model approach. Int J Manag Educ. 2024;22(3):101009. doi:10.1016/j.ijme.2024.101009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Memarzadeh M, Matthews B, Templin T, Sharif Rohani A, Weckler D. Semi-supervised active learning for anomaly detection in aviation. J Aerosp Inf Syst. 2023;20(4):181–94. doi:10.2514/1.i011083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Qiao J, Sun Z, Meng X. Interval type-2 fuzzy neural network based on active semi-supervised learning for non-stationary industrial processes. IEEE Transact Automat Sci Eng. 2023;21(2):1151–62. doi:10.1109/TASE.2023.3237840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. UCI machine learning repository. University of California, Irvine, school of information and computer sciences [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 1]. Available from: https://archive.ics.uci.edu/ml/index.php. [Google Scholar]

35. Yasunori E, Yukihiro H, Makito Y, Sadaaki M. On semi-supervised fuzzy c-means clustering. In: 2009 IEEE International Conference on Fuzzy Systems; 2009 Aug 20–24; Jeju, Republic of Korea. p. 1119–24. doi:10.1109/FUZZY.2009.5277177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Yin X, Shu T, Huang Q. Semi-supervised fuzzy clustering with metric learning and entropy regularization. Knowl Based Syst. 2012;35(8):304–11. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2012.05.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Grira N, Crucianu M, Boujemaa N. Active semi-supervised fuzzy clustering. Pattern Recognit. 2008;41(5):1834–44. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2007.10.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Novoselova N, Tom I. Fuzzy semi-supervised clustering with active constraint selection. In: Pattern recognition and information processing. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2017. p. 132–9. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-54220-1_14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Rand WM. Objective criteria for the evaluation of clustering methods. J Am Stat Assoc. 1971;66(336):846–50. doi:10.1080/01621459.1971.10482356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Li S, Kou P, Ma M, Yang H, Huang S, Yang Z. Application of semi-supervised learning in image classification: research on fusion of labeled and unlabeled data. IEEE Access. 2024;12(11):27331–43. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3367772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Nandi A, Pandey B. Impact of cosmic web on galaxy properties and their correlations: insights from principal component analysis. arXiv:2408.16731. 2024. [Google Scholar]

42. Ros F, Riad R, Guillaume S. PDBI: a partitioning Davies-Bouldin index for clustering evaluation. Neurocomputing. 2023;528(2):178–99. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2023.01.043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools