Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Lightweight Multi-Layered Encryption and Steganography Model for Protecting Secret Messages in MPEG Video Frames

1 Faculty of Computers and Information Technology, EELU, Giza, P.O. Box 12611, Egypt

2 Faculty of Computers and Artificial Intelligence, Cairo University, Giza, P.O. Box 12613, Egypt

3 Applied College, Shaqra University, Shaqra, 11961, Saudi Arabia

4 College of Computing and Information Technology, Shaqra University, Shaqra, 11961, Saudi Arabia

5 Faculty of Computers and Artificial Intelligence, Sohag University, Sohag, P.O. Box 82524, Egypt

* Corresponding Authors: Raed Alotaibi. Email: ; Omar Reyad. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Challenges and Innovations in Multimedia Encryption and Information Security)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(3), 4995-5013. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.068429

Received 28 May 2025; Accepted 30 July 2025; Issue published 23 October 2025

Abstract

Ensuring the secure transmission of secret messages, particularly through video—one of the most widely used media formats—is a critical challenge in the field of information security. Relying on a single-layered security approach is often insufficient for safeguarding sensitive data. This study proposes a triple-lightweight cryptographic and steganographic model that integrates the Hill Cipher Technique (HCT), Rotation Left Digits (RLD), and Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT) to embed secret messages within video frames securely. The approach begins with encrypting the secret text using a private key matrix (PK1) of size 2 × 2 up to 6 × 6 via HCT. A second encryption layer is applied using a dynamic private key (PK2) derived from the RGB pixel values of the video frame, resulting in a rotated cipher. The doubly encrypted message is then embedded into the video frames using the DWT method. Upon transmission, the concealed message is extracted using inverse DWT and decrypted in two steps—first with PK2 and then with the inverse of PK1. Experiments conducted using MPEG video sequences and message lengths ranging from 10 to 300 bytes demonstrate strong performance in terms of Mean Square Error (MSE), Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR), and Correlation Coefficient (CC) between original and encrypted messages. The similarity between original and stego frames is further validated using Structural Similarity Index (SSIM), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Number of Pixel Change Rate (NPCR), and Unified Average Changing Intensity (UACI). Results confirm that utilizing video frames to generate PK2 offers superior security compared to static key images. Moreover, the indistinguishability between original and stego frames highlights the method’s robustness against visual and statistical attacks.Keywords

Multimedia is a media that allows information to be easily transferred from one location to another. Multimedia security has become more important because it plays a key role in securing the content of multimedia over the internet [1]. It has therefore been recommended that multimedia content be secured for individuals, private enterprises, and the government [2,3]. The proliferation of digital video content in various sectors, including entertainment, education, and communications, has made security a critical concern [4]. With the increasing availability of high-speed internet and the widespread use of digital devices, digital video distribution has grown exponentially. However, this expansion has also exposed video content to various security threats, such as unauthorized access, piracy, and tampering [5]. A content protection technique is defined as a procedure to protect multimedia content from illegal user access. Content protection mechanisms, such as encryption, Digital Rights Management (DRM), and watermarking, have traditionally been employed to secure both digital images and videos [6]. While these methods are effective in many cases, they often involve substantial computational overhead and complexity, which can be resource-intensive. Additionally, many of the vulnerabilities found are difficult to resolve and require considerable effort to investigate; as a result, they often need to be addressed for extended periods, leaving Android users vulnerable to malicious attacks [7]. Given the evolving nature of threats and the diversity of user devices, there is a growing need for lightweight secret message protection models that strike a balance between security, performance, and resource efficiency. Chaos theory has enabled the development of advanced encryption techniques across various industries, enhancing data security [8]. Numerous computational methods—such as heuristics, clustering, deep learning, evolutionary algorithms, and frequent pattern mining—have been employed to support these advancements [9]. A lightweight model should minimize computational requirements while providing robust data hiding against common threats, including unauthorized duplication, tampering, and redistribution. In the realm of digital media, video file formats play a critical role in determining the quality, compression, and compatibility of video files across different devices and platforms. Two widely recognized video formats are Moving Picture Experts Group (MPEG) and Audio Video Interleave (AVI) [10]. Both formats have been essential in the evolution of digital video, each offering unique advantages and applications. When comparing the security features of MPEG and AVI video formats, MPEG offers far superior protection mechanisms [11]. MPEG’s support for encryption, DRM, watermarking, and secure streaming makes it the preferred choice for protecting high-value digital content from piracy and unauthorized access. AVI, while flexible and widely compatible, lacks these built-in security features, making it less suitable for secure content distribution, particularly over the internet.

The video is a collection of frames displayed in rapid succession, creating the illusion of motion. Each frame is considered a standalone image that can be processed, analyzed, and manipulated independently. The proposed method changes the video size and extracts RGB values from certain video frames, then resizes the resulting matrix from one of these color values (R, G, or B). Each color value ranges from 0 to 255, represented in one row with multiple columns equal to the secret message size. This resized matrix is then used as a private key (PK) in the cryptographic process. The first index value in the generated PK is used in the RLD calculation for all the divided blocks. There are several important points to consider when applying this method:

• Changing the frame in encryption or decryption will change the used pixel values and so the decrypted message.

• Changing the PK values will affect the secret message, which may result in the wrong one.

• Larger video sizes lead to a higher number of video frames.

• Larger frame dimensions increase the time required to extract the frames.

Considering these points, the proposed method uses smaller video sizes and lower frame dimensions, as larger frame dimensions would require significantly more time to extract all video frames. So, the presented method uses HLT, RLD, and DWT techniques to obtain a robust model to protect secret messages inside video frames. The used video data file is available through the reference paper [12].

The main contributions of this work can be summarized as follows:

• Proposed a lightweight security hybrid model for secret message protection utilizing MPEG digital video frames.

• Key generation, encryption, and decryption times are computed for the proposed security method.

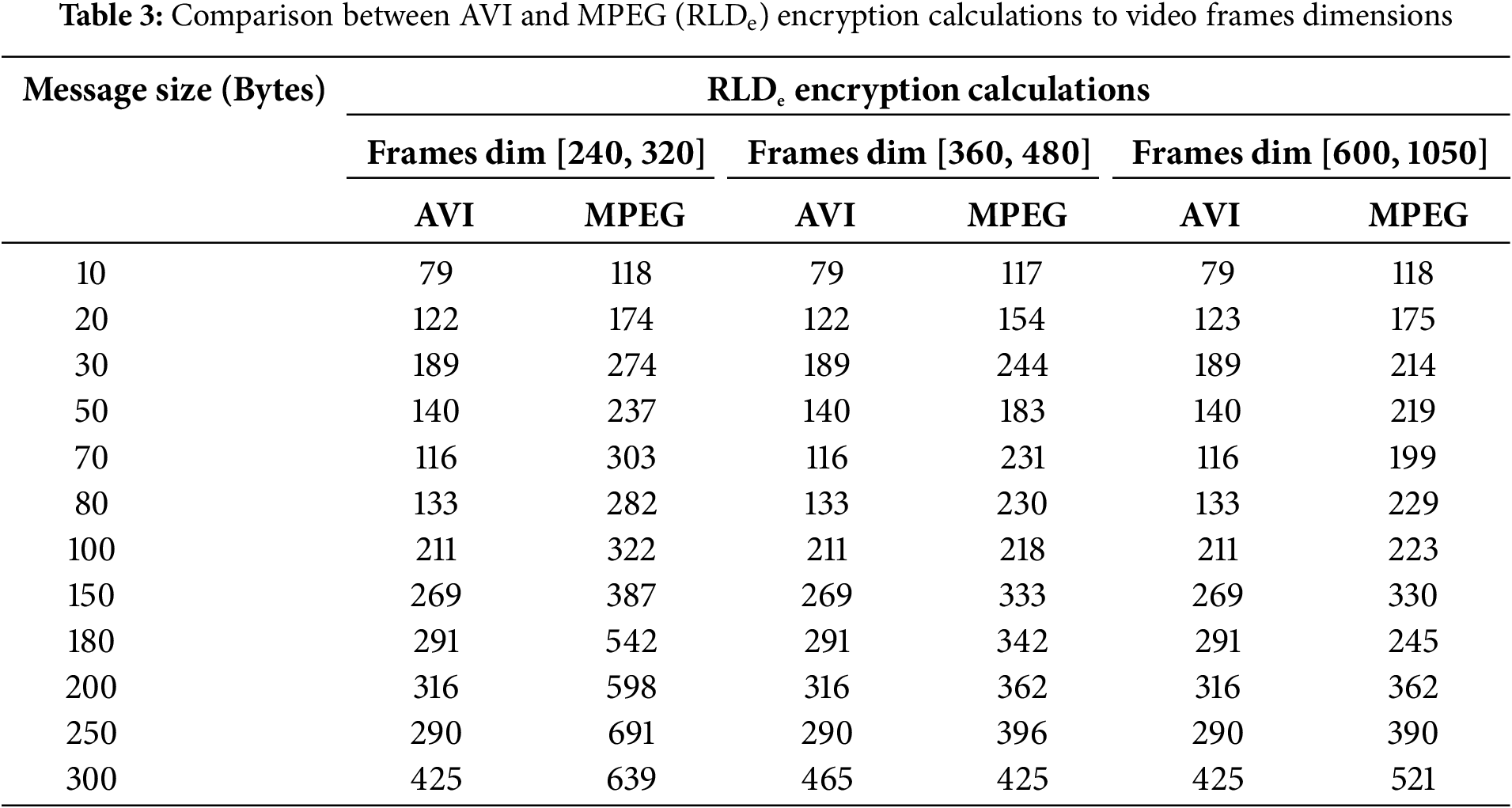

• Comparison between AVI and MPEG based on RLD encryption calculations is provided.

• Comparison of encryption and decryption times of the proposed method based on different video sizes and frame dimensions.

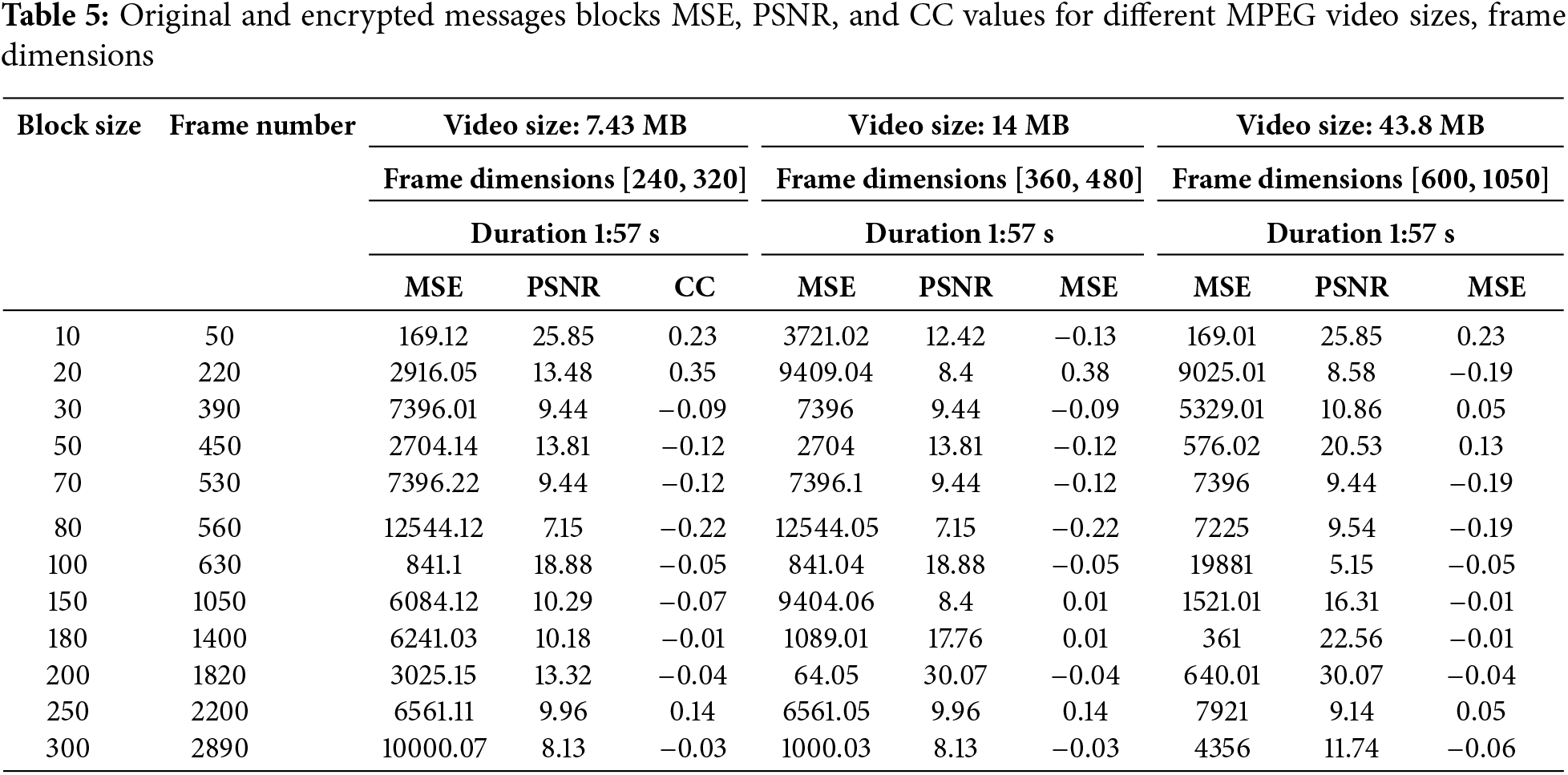

• MSE, PSNR, and CC (cipher and plaintext comparison) for different video sizes and frame dimensions.

• SSIM, MAE, NPCR, and UACI comparison between original and stego frames is also provided.

• Comparison of the proposed work according to MSE, PSNR, and CC between the original and encrypted messages is also reported.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 presented preliminaries about the triple lightweight model. The related work on video security techniques is covered in Section 3. In Section 4, the proposed method is presented. The experimental results are provided in Section 5. The paper’s conclusions and future actions are outlined in Sections 6 and 7.

The Hill cipher belongs to the class of polygraphic substitution ciphers and is a symmetric key algorithm [13]. It divides the secret text into groups of an equal number of blocks, depending on the key matrix m ∗ m. By giving each letter a numerical value, the normally readable text is divided into tom-blocks that satisfy the key matrix K size [14]. Key matrix is designed for some conditions, such as:

Determiner not equal to zero and its value is a number that must be coprime to 256 (as dealing with ASCII characters).

where p is the plaintext represented as (p1, p2, p3, …, pn) and k is the key matrix (k1, k2, k3, …, kn). Multiplication Result will obtain the ciphertext in the encryption phase. The decryption phase requires the key inverse matrix K−1, which means that K ∗ K−1 = I, where I is the identity matrix.

The decryption phase requires the key inverse matrix K−1, which means that K ∗ K−1 = I, where I is the identity matrix.

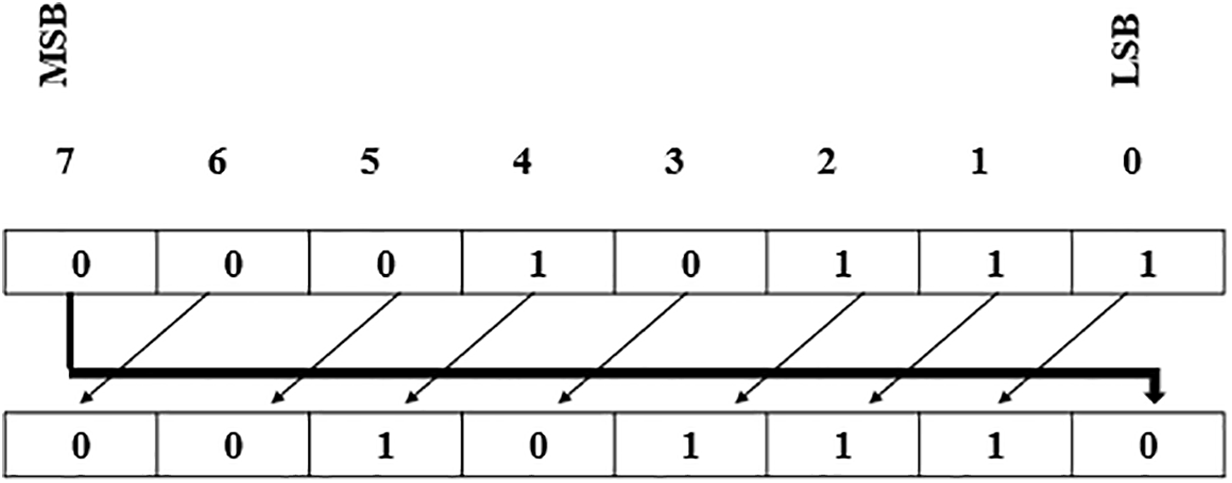

The rotation left digits (RLD) is a mathematical and computational operation that involves cyclically shifting the digits of a number [15]. In a left rotation, the leftmost digits are moved to the rightmost position, while the remaining digit is shifted to the left as shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Rotation left digits operation

In cryptography, rotating digits are used as part of various encryption algorithms to obfuscate data, making it harder for unauthorized parties to interpret [16]. Left digit rotations can add complexity to encrypted data without introducing significant computational overhead. The technique of Least Significant Bit (LSB), which is applied to rotate its value, refers to the lowest order bit. The main advantage of LSB compared to other techniques is that it is easier to hide secret message bits directly in the least significant bit plane of the cover image [17]. The user can recover the secret message by extracting the least significant bits of the manipulated pixels to recover the original message. The Most Significant Bit (MSB) method refers to the highest pixel value in a binary number. Strong cryptographic systems ensure that changes in the MSB (or any bit) produce unpredictable outcomes in encryption, ensuring security against brute-force or bit-level attacks [18]. It has a critical role in ensuring the integrity and security of cryptographic operations, particularly where binary manipulation is involved.

2.3 Discrete Wavelet Transform

Steganography techniques involve spatial domain techniques, in which the strength of the pixel conceals the data. The value of the pixel changes as the data is embedded. Data is concealed in a frequency with a broad bandwidth using the spread spectrum technique [19]. However, as hiding strategies evolved, so did methods to try to remove their hiding and hack their contents; as a result, encryption and hiding techniques were merged to boost the effectiveness of these approaches. Steganography is a set of techniques for concealing information using multimedia data, such as image, text, audio, video, and network [20]. It is crucial to conceal information from attackers in video files by using intermediary channels like AVI and MPEG without compromising the content of the containers. To ensure that the secret media is not apparent after the confidential data is inserted into the cover video file, the authenticity of the hidden files shouldn’t be shared or disseminated [21]. A mathematical tool for hierarchically breaking down a video frame is the wavelet domain technique. It is predicated on tiny waves, known as wavelets, with variable frequencies and brief durations. The 2-D frame is processed using 2-D filters in both dimensions when DWT is applied. It operates both horizontally and vertically. The vertical filter splits the frame in half, storing the average coefficients in the first half and the detail coefficients in the second [22]. Frame pixels are converted to wavelets via DWT. Better quality frames with a higher compression ratio are provided by DWT’s lossless frame compression [23]. To make the difference between the original and embedded files undetectable, the secret data must be embedded into an MPEG file. High embedding rates without sacrificing video quality are possible with the DWT method. It has strong characteristics that set it apart from encryption techniques. Information hiding is a crucial technique for securing sensitive and important data, especially when it comes to data transmitted through various digital communication channels. Its foundation is the idea of hiding data inside other digital media as a carrier cover.

Traditional video security techniques may involve either full or partial encryption. However, most research articles do not address text encryption through pixel values of frames. Additionally, many studies utilize the AVI extension for this purpose, employing steganography techniques to embed cover frames into stego videos. Steganography and watermarks are two well-known security techniques that are typically used to hide information. They both alter the media file’s content (image, video, and audio) directly for copyright protection and secret communication or sender identification [24]. The authors in [25] presented a method that tends to be quite complex when restricted to AVI video files, particularly without consideration for the execution time associated with this approach. Moreover, it is unsuitable for specific scenarios, such as when working with compressed files or smaller file sizes. The AVI format has some disadvantages compared to MPEG. MPEG offers a higher frame rate than AVI, and it employs more efficient codecs, resulting in larger file sizes and fewer frames. A neural network model is employed to extract video features for steganography as presented in [26]. It tends to increase time complexity and may not yield the most effective results in extracting hidden messages. This efficiency aids in compressing video data without quality degradation. The Visual Geometry Group (VGG) model achieves high accuracy in [27]. There is insufficient information regarding its time complexity or resistance to attacks. While techniques such as zigzag scanning and the LSB method are used to conceal secret messages, details regarding the specific algorithms and efficiency are not provided in [28]. Researchers in [29] rely solely on 256 × 256 greyscale input images for testing; however, this image type has a limited pixel value range, with 0 representing black and 255 representing white. In contrast, color images present a broader range of pixel values from 0 to 255 for each RGB channel. The work in [30] does not clearly measure its coefficients and does not consider execution time. Although the authors in [31] employ Deoxyribonucleic Acid (DNA) rules, time complexity is not mentioned. The study in [32] generates image keys using non-uniform cellular automata, but the performance regarding encryption speed requires further analysis. In [33], despite employing Discrete Cosine Transform (DCT) for encrypting Multimedia Video Coding/High-Efficiency Video Coding (MVC/HEVC) data, the execution time is relatively high at approximately 0.4 s per one ciphered frame, indicating a need for improvement. The execution time in [34] varies between 4 and 6 s, which is considered very high, necessitating enhancements. The work in [35] employs chaotic maps to produce a keystream; however, the average execution times are 2 and 3 s, which are considered somewhat high, indicating a need for improvement in this area.

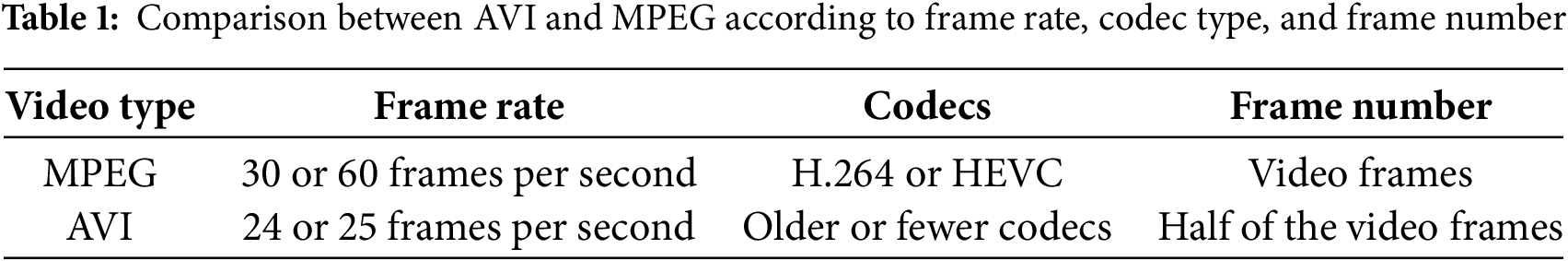

Using a contemporary modified blowfish technique, the authors in [36] showed that the encryption time could be increased to 124.1 ms and the decryption time to 124.3 ms. In general, the ideal execution time should be around a thousandth of a second, aligning with the decryption time. A general comparison between AVI and MPEG indicates the suitability of MPEG video type for large frame numbers. For the same video file size, MPEG typically accommodates approximately twice as many frames as AVI, highlighting its superior compression efficiency and suitability for longer video sequences, as illustrated in Table 1.

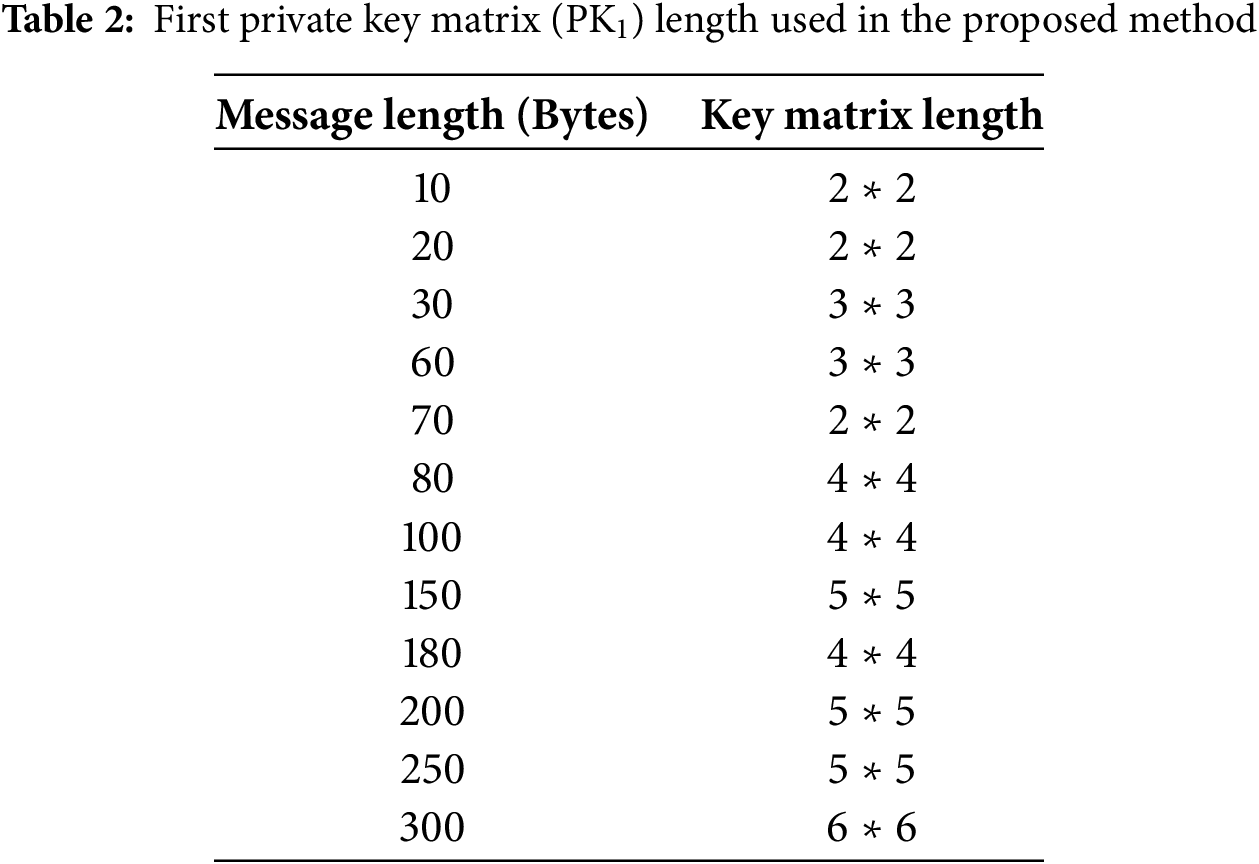

The proposed method splits into three parties. First, the secret text message is encrypted using the Hill Cipher key matrix PK1 according to the message length. Private Key matrix PK1 starts from 2 ∗ 2 to 6 ∗ 6 as shown in Table 2.

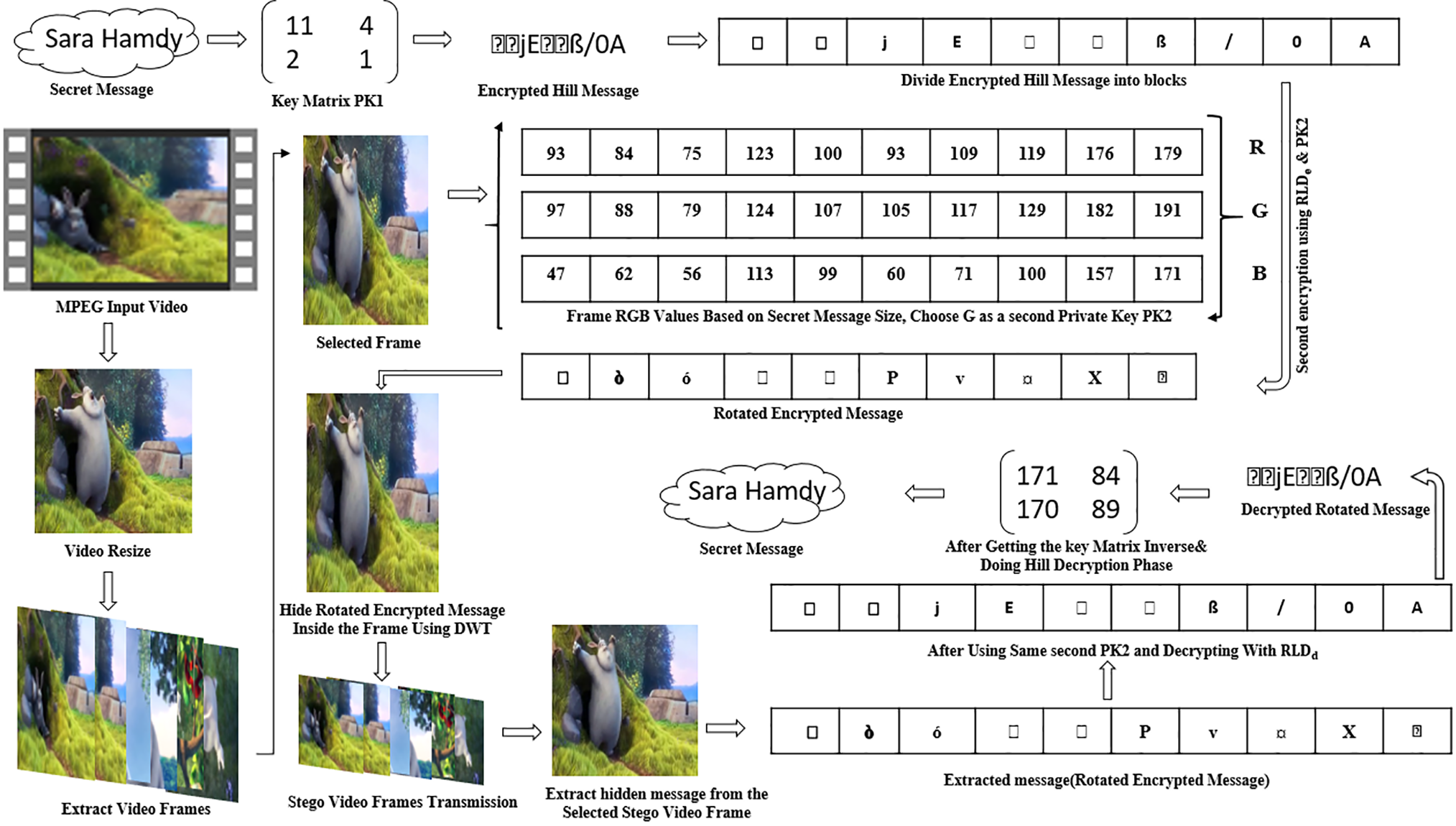

Secret message is encrypted first using Hill cipher key matrix resulting encrypted Hill message, then the encrypted Hill message will be encrypted for the second time using rotation left digits RLDe (rotations number in encryption phase) and second private key PK2 which generated from a video frame pixel values, resulting rotated encrypted message, then this rotated encrypted message will be embedded using DWT technique inside the video frame. According to video frames, divide the color video frames into the appropriate color channels (R, G, and B). Each frame’s red, green, and blue channels are represented by three distinct 2D matrices. Each color channel is subjected to DWT individually, which breaks each channel down into detail and approximation coefficients at various levels. The secret message will then be embedded in the color video frames by altering the wavelet coefficients of each color according to its binary values. Inverse DWT is applied to each color channel once the coefficients have been changed to reconstruct the color frames.

The proposed method depends on the Hill Cipher technique and MPEG digital video frames because of the AVI defects, as well as the number of rotations in MPEG is higher than AVI, as shown in Table 3.

The secret message is encrypted first by PK1, which is generated from the Hill key matrix. The MPEG video file is then resized and split into frames. A different frame is chosen for each text message that is between 10 and 300 bytes long to make sure that the RGB pixel values are different. The RGB values for each frame are then recovered. Then select one of these RGB values as the PK2 that changes dynamically with the content of the video based on the secret message size, either R or G, or B. PK2 serves as a content-aware cryptographic enhancement that’s hard to guess or replay. The generated PK2 and encrypted Hill secret message length (L) are then used to calculate rotation left digits’ operation, where RLDe = (L/2) ∗ 4 + PK2(I) + C in the encryption phase which I indicating the first generated private key (PK2) value and C is a constant refers to the rotation of 1-MSB value as the reminder seven bits refer to the LSB rotations as mentioned in Fig. 1. This process results in a rotated encrypted message, which can be hidden inside the selected video frame using the DWT technique as depicted in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Proposed work architecture

After the transmission of the stego frames over communication channels, the hidden message is retrieved from the stego frame, and the same PK2 is used again to decrypt it. The RLDd calculation in the decryption phase will be a bit different, where RLDd = 2 ∗ L ∗ 4 − RLDe, which will result in a decrypted rotated message, then this message is decrypted again with the Hill key matrix inverse (PK1)−1, resulting in the original text message.

4.2 Encryption and Decryption Algorithms & Flowcharts

A Hill key matrix (PK1) is obtained along with the secret text message, which is initially encrypted using the Hill cipher algorithm. A frame-by-frame division and resizing of the MPEG video file follow. RGB values are then obtained for each frame. PK2 is created using RGB pixel values that, depending on the size of the hidden message, will dynamically alter with the content of the video. The rotating encrypted message can be obtained by encrypting each sub-block. After utilizing DWT to conceal the resulting rotated encrypted message within the video frame, the stego frame is saved as represented in Algorithm 1.

The concealed rotated encrypted message must first be retrieved in order to retrieve the original message from the stego video frame. The rotated encrypted message is split into blocks of the length (L) of PK2, using the same second PK2 as during the encryption phase. To produce the decrypted rotated matrix, the binary representation of each rotated encrypted block is translated into a one-row matrix, rotated left by RLDd times, and then converted back into a string. The decrypted rotational message is then further decrypted using the Hill cipher technique to eventually expose the original message once the inverse of the key matrix (PK1)−1 is calculated as de-scribed in Algorithm 2.

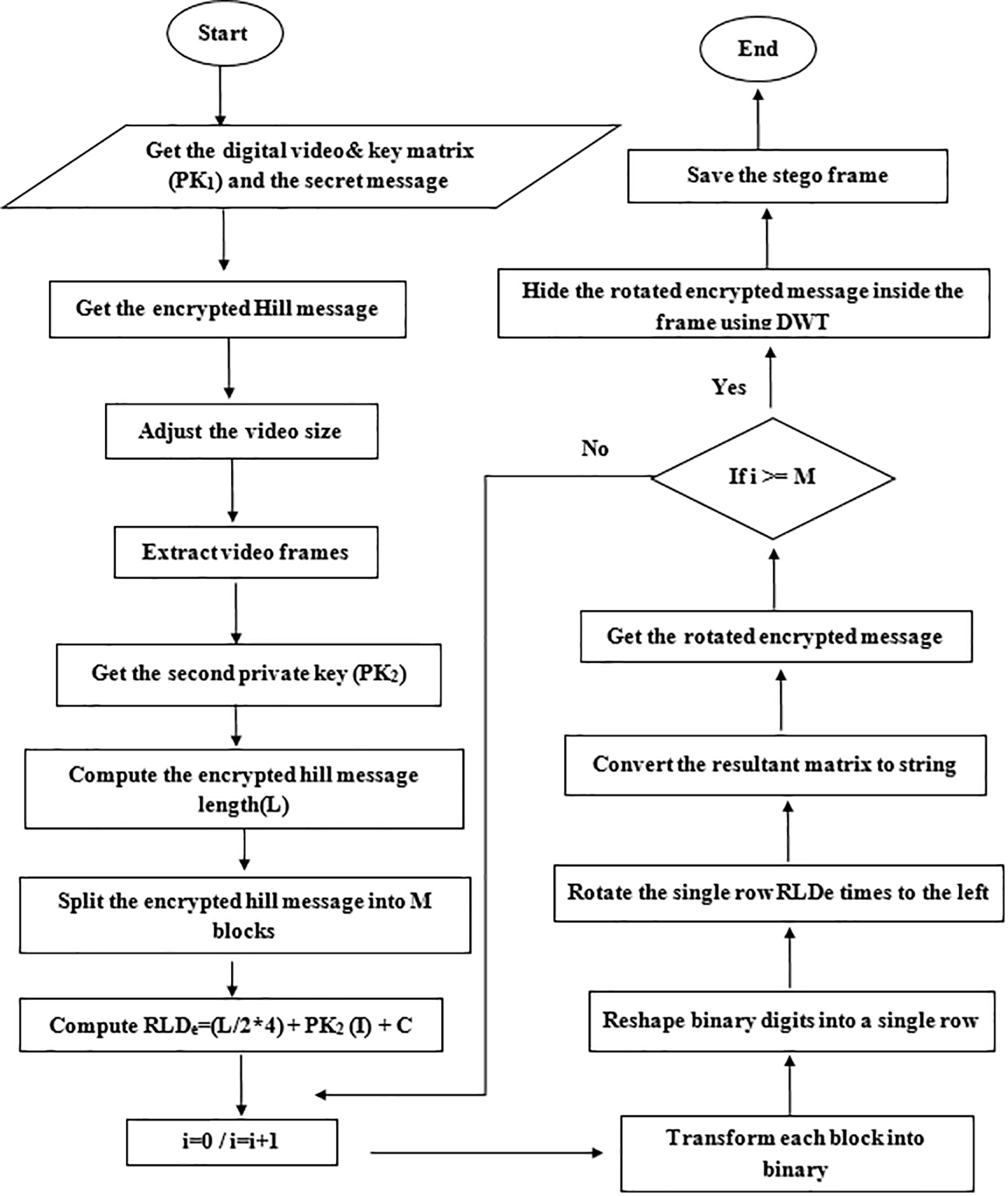

4.2.1 Encryption and Hiding Flowchart

Encryption and Hiding process is divided into two types of encryptions: Hill cipher and Rotation left digits encryption, then the embedded DWT is applied in the selected video frame. The first encryption process is represented in the Hill cipher technique, where the secret text message is divided into several fixed blocks, and each block is multiplied by the key matrix (PK1) to generate the encrypted Hill message. The second encryption process is represented in the rotation left digits technique; the second private key (PK2) is generated from the resized pixel video frame, which is resized to one row and multiple columns equal to the encrypted Hill message length (L). Rotation is computed as RLDe = (L/2) ∗ 4 + PK2(I) + C. The encrypted Hill message is embedded inside the video frame using the DWT technique as shown in Fig. 3. Then, the obtained stego video can be transmitted securely.

Figure 3: Encryption & hiding flowchart

4.2.2 Extraction and Decryption Flowchart

After stego frames transmission, the rotated encrypted message is extracted from the stego video frames using the DWT extraction process, then this rotated encrypted message will be decrypted first using RLDd = (L∗2) ∗ 4 − RLDe and (PK2) to obtain the encrypted Hill message. Then, the second decryption process will be applied with the inverse key matrix (PK1)−1 and encrypted Hill message, which will obtain the original text message as shown in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: Extraction & decryption flowchart

This section presents the findings from the implementation of the proposed lightweight secret message protection model hiding inside video frames, followed by a detailed discussion to interpret and analyze the results. The proposed method was applied with R2024a MATLAB. The proposed method was applied to different frame dimensions and different message sizes and tested with MSE, PSNR, and CC evaluation metrics. The MSE is calculated as follows:

where N equals m ∗ n. m is the number of rows, and n is the number of columns in the frame. The encrypted message value is S, and R represents the original secret message in decimal. The PSNR is defined as follows:

where MAX is the maximum pixel value in a certain video frame, which equals 255. The CC is computed as follows:

where

where

where

where

where

The result must be very high in MSE and low in PSNR and CC according to the comparison between the original and encrypted message while in the decryption phase, the result must be: MSE = 0, PSNR = ∞ and CC = 1 between the original and decrypted messages and the same between the original and stego video frames, this indicates they are the same whether the messages or frames. Also, SSIM must be near 1, MAE must be near 0, NPCR must be near 0% and UACI must be near 0, which indicates that the two frames are identical to achieve a high security level.

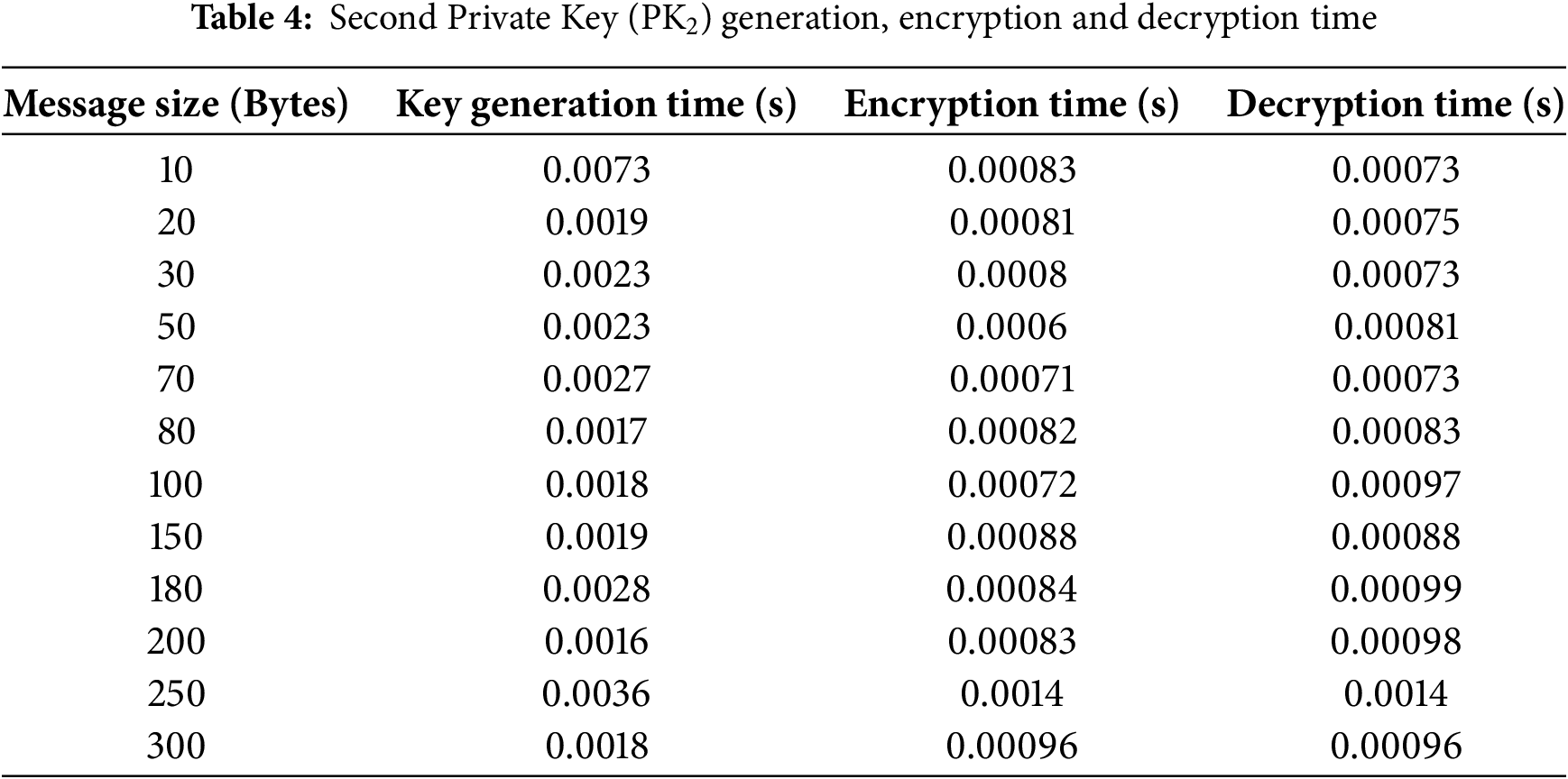

The key generation, encryption, and decryption times for different video sizes were measured as presented in Table 4, where the used message size ranges from 10 bytes to 300 bytes in this approach.

The lightweight model consistently showed lower encryption and decryption times compared to other related encryption methods. The second private (PK2) key is generated from video frame color values (RGB), and the secret message is divided into M blocks based on the private key size to do RLDe,d operations, taking into consideration the following issues:

• Changing the private key value in either the encryption or decryption phase will affect the original message.

• Choosing R or G, or B as pixel values will affect the evaluation of metrics of MSE, PSNR, and CC. If one of them can’t do the encryption process in a perfect way, one of the other two will do it perfectly.

• Encryption and decryption times are not constant, so it doesn’t depend on the message size but differs according to the private key results from R or G, or B channels, as shown in Fig. 5.

Figure 5: Message length vs. encryption time

A triple lightweight model is applied and demonstrates a clear advantage in terms of computational efficiency. The overall encryption and decryption processes were faster and required less computational power, as indicated in Table 4. This is especially beneficial for real-time video streaming services or low-resource devices (e.g., mobile phones or embedded systems). While the presented model reduced computational and memory overheads significantly, it also maintained a high level of security by measuring the MSE, PSNR, and CC for different video sizes and frame dimensions as indicated in Table 5.

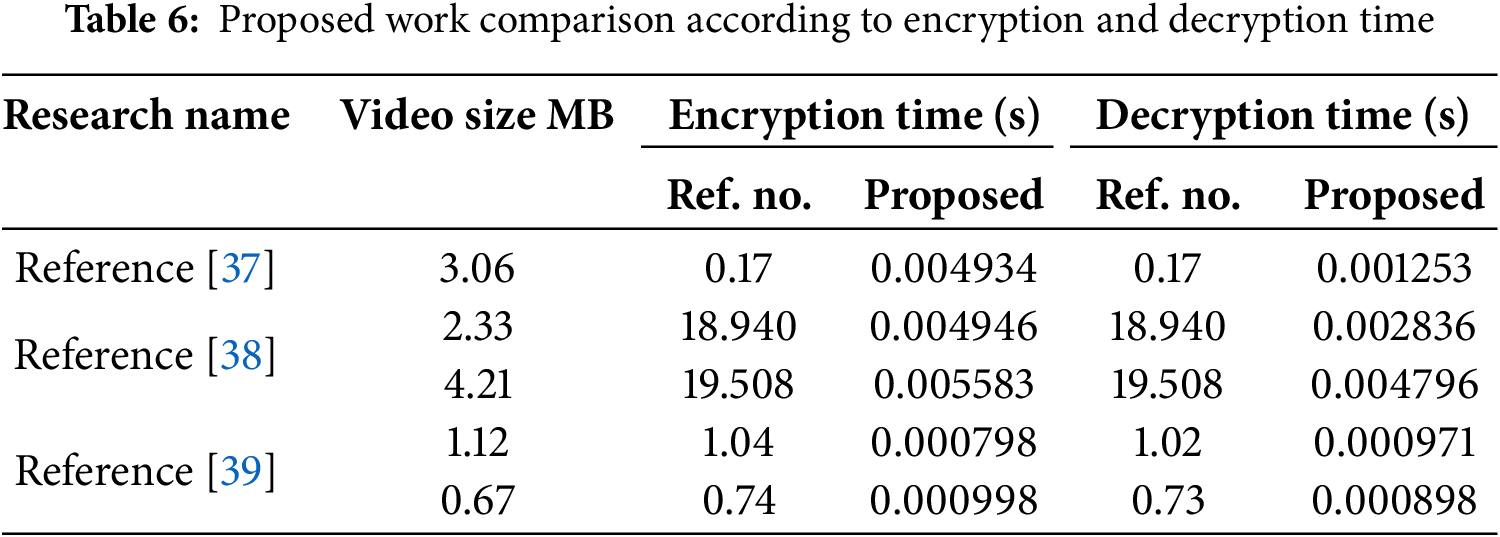

The combination of HCT, RLD encryption, and DWT hiding technique proved to be robust against both computational and cryptanalytic attacks. The balance between strong content protection and minimal resource usage makes this model ideal for applications where lightweight security is required. Proposed work comparison is done using the 300 message blocks (the maximum secret message size used in this approach) to obtain more accurate results, as presented in Table 6.

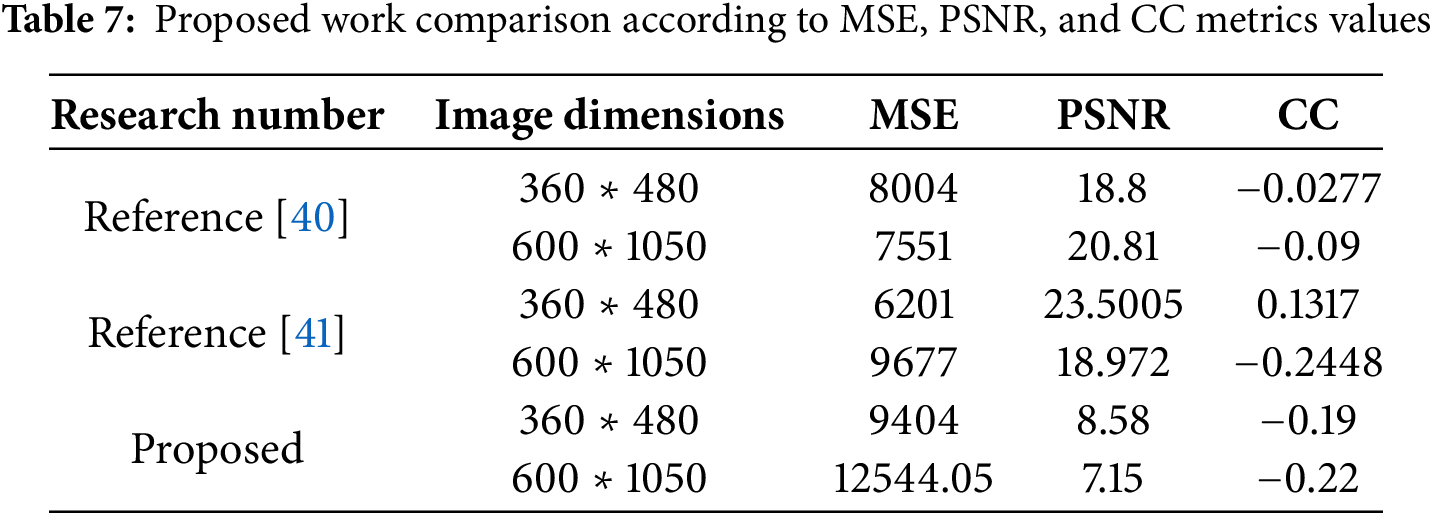

The suggested method is also compared with other related research and obtained better results in the three evaluation metrics: MSE, PSNR, and CC in the case of different frame dimensions and frame numbers according to encrypted messages, as shown in Table 7.

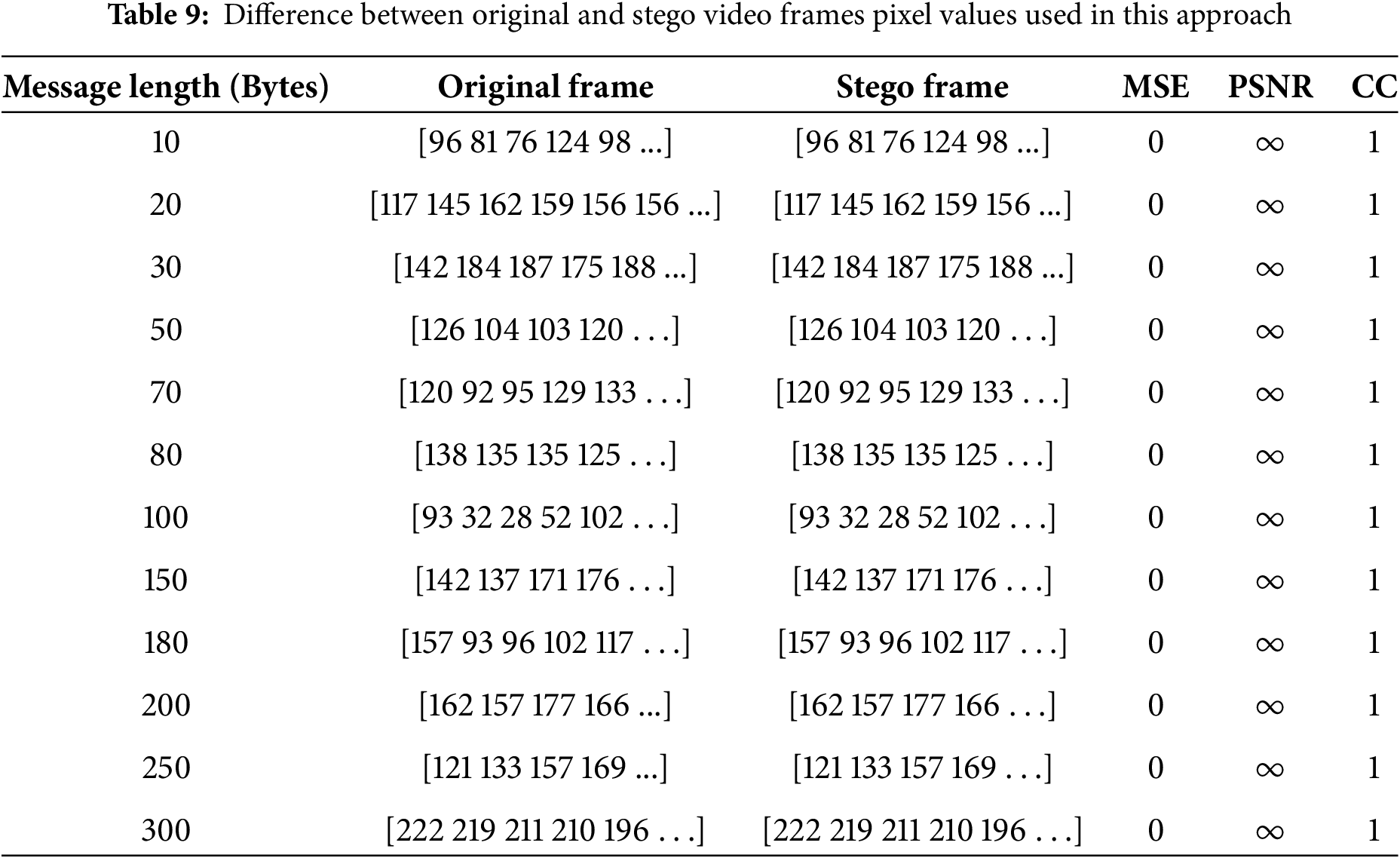

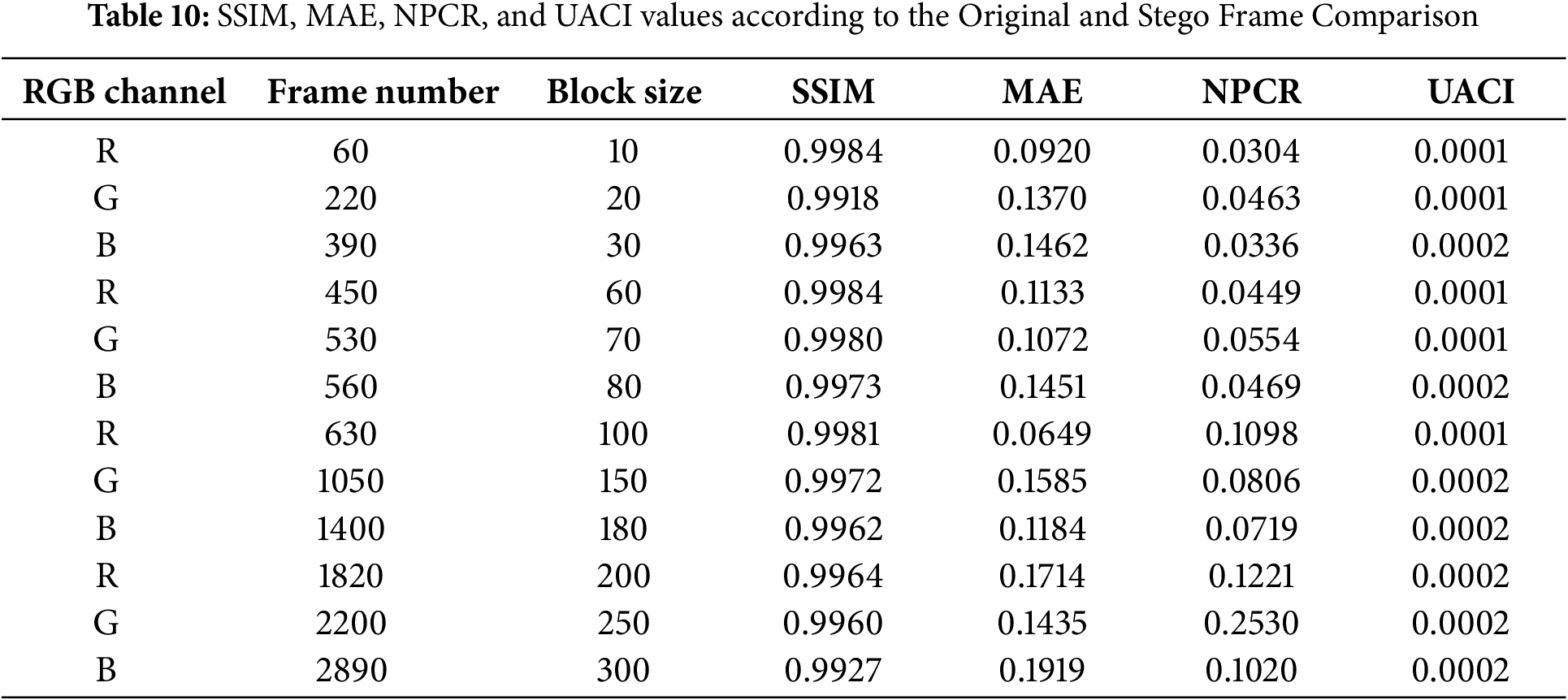

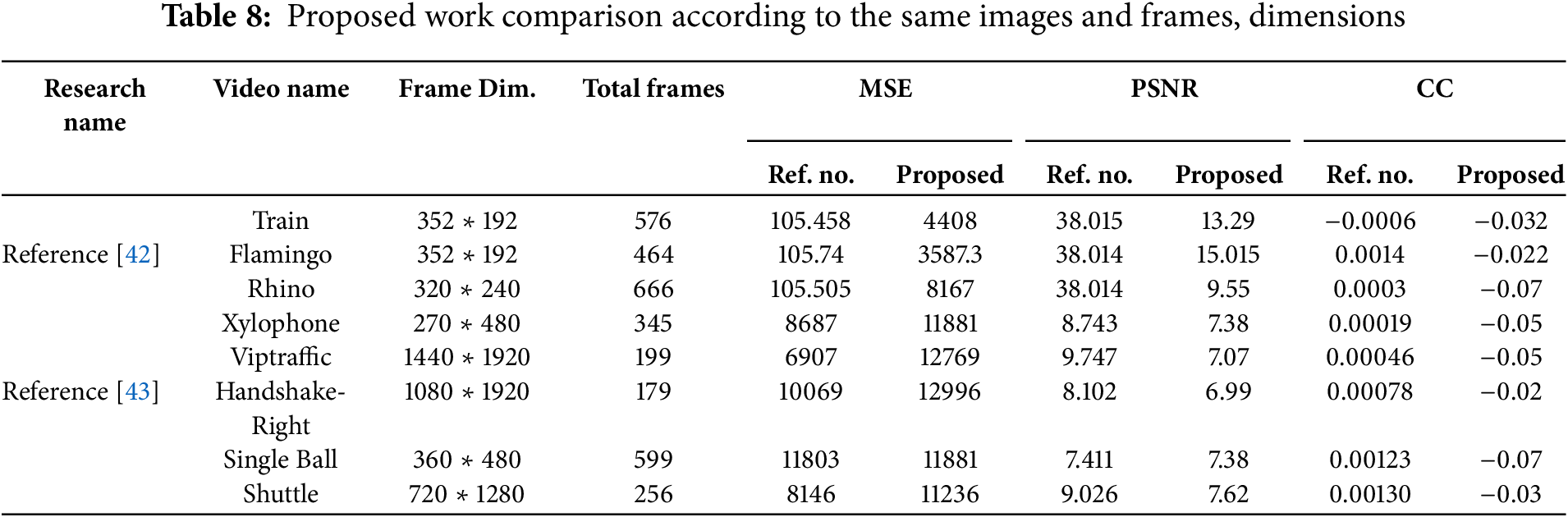

The same images and frames dimensions are compared as indicated in Table 8. The original video frame is identical to the stego frame according to the same pixel values of each frame, and the values of MSE, PSNR, and CC are 0 ∞ and 1, respectively, between the original frames and stego frames for the same message length as indicated in Table 9.

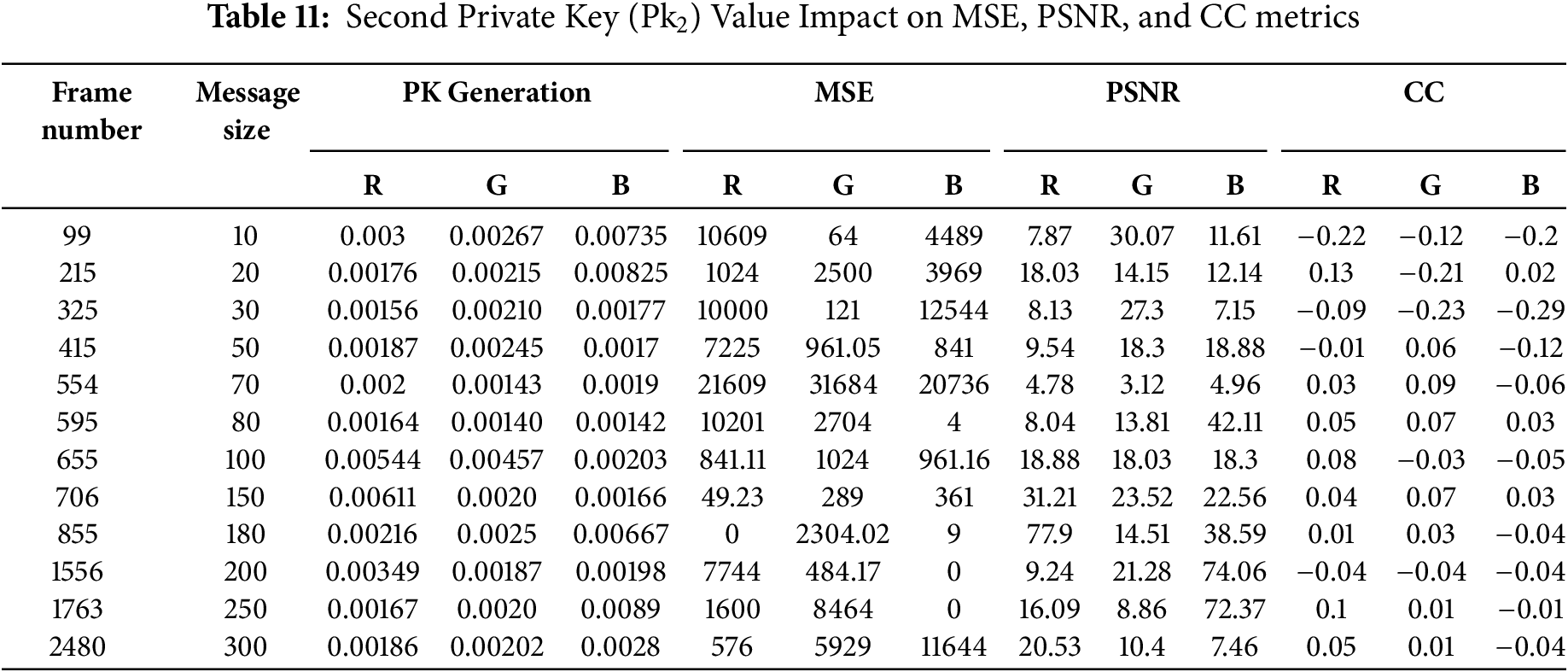

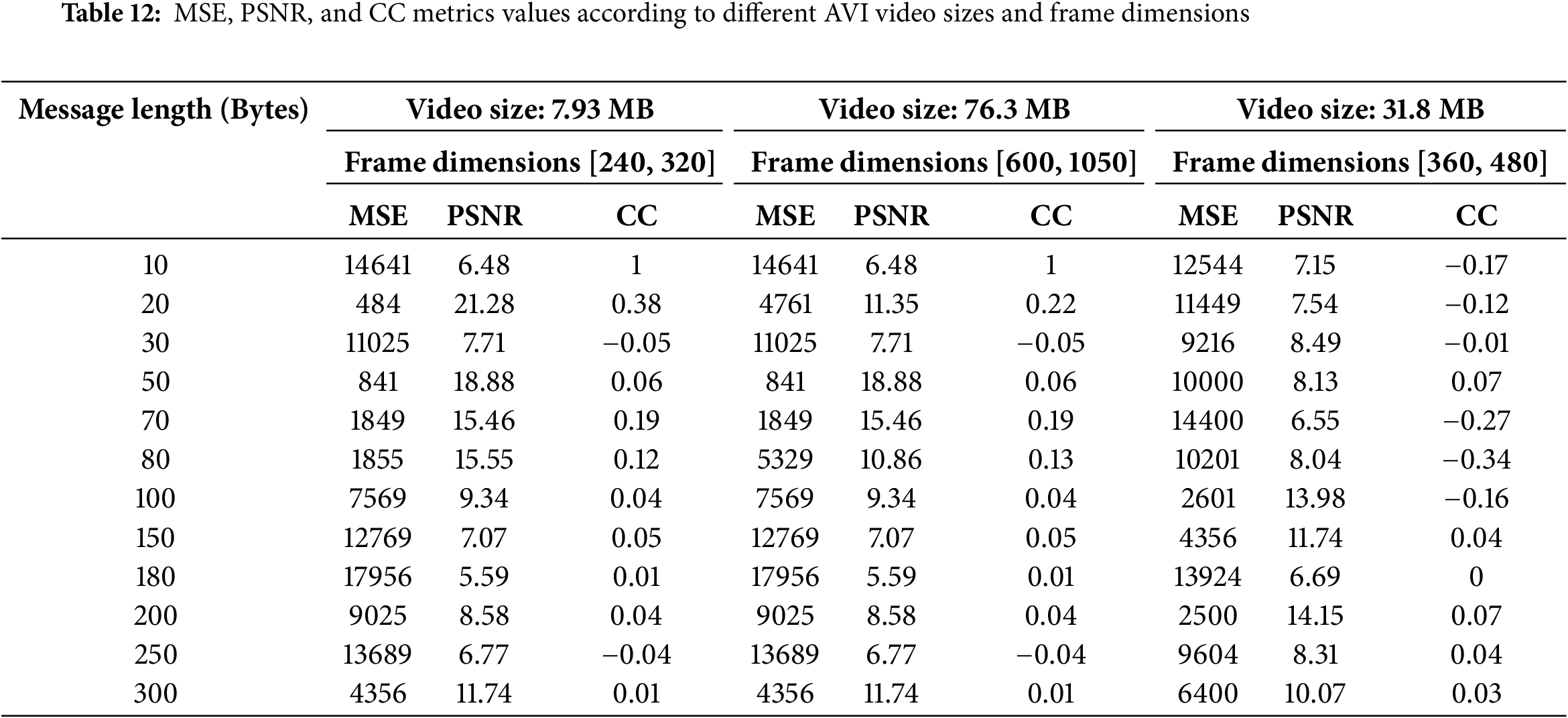

Additionally, the SSIM, MAE, NPCR, and UACI indicate the identically of the original and stego video frames as shown in Table 10. RGB values impact on MSE, PSNR, and CC values, so the optimization of these metrics depends on the private key value as indicated in Table 11. The suggested approach can be expanded to use other codecs, including AVI, in addition to MPEG video frames, as shown in Table 12.

This research has developed a robust triple lightweight model for concealing secret messages using HCT, RLD, and DWT processes. The proposed method employs two distinct private keys: the first is the Hill cipher key matrix (PK1), and the second is generated from video frames to create the second key (PK2). The secret message is initially encrypted with the Hill cipher, then encrypted again with the second key. This second encrypted message is resized into a one-row matrix with multiple columns, matching the size of the encrypted message, resulting in a rotated encrypted message that ranges from 10 to 300 bytes in this study. Finally, the Hill-encrypted secret message is further encrypted using RLDe and embedded into the video frame using the DWT insertion technique. Once the encrypted rotated secret message has been transmitted, it is first retrieved and decrypted using the same (PK2), RLDd to obtain the encrypted Hill message. The original text message is then obtained through a second decryption using (PK1)−1. According to metrics like MSE, PSNR, and CC, the suggested approach demonstrated exceptional performance in terms of encryption and decryption execution times as well as exceptional resistance to a variety of attacks. The original and stego frames were compared using SSIM, MAE, NPCR, and UACI metrics, which showed that they are almost the same. Combining HCT and RLD has been demonstrated to provide more secure data transmission in video frames as opposed to pictures.

The lightweight architecture of the approach supports its usability, allowing for efficient execution even on systems with limited resources. Confidentiality is maintained using the Hill cipher and RLD techniques, which shield the hidden data from unwanted access, while integrity is maintained by employing DWT to embed the encrypted message in an organized manner. However, when working with high-resolution videos like HD or Ultra HD, the computational overhead from frame extraction and key generation can become a bottleneck, even with its promising speed. Future work could focus on optimizing the model for lower power consumption, improving its performance for ultra-high-definition (4K/8K) videos, and further enhancing resistance to advanced cryptographic attacks.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank the Deanship of Scientific Research at Shaqra University for supporting this work.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Sara H. Elsayed, conceptualization, software, writing, and preparation; Rodaina Abdelsalam, data curation and investigation; Mahmoud A. Ismail Shoman, resources and project administration; Raed Alotaibi, writing and visualization; Omar Reyad, idea proposal, review and editing, and supervision. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The video file that supports the findings of this research is publicly available as indicated in the references. Source code and proposed work data is available in [44].

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Hosny KM, Zaki MA, Lashin NA, Fouda M, Hamza HM. Multimedia security using encryption: a survey. IEEE Access. 2023;11:63027–56. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3287858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Reyad O, Karar ME. Secure CT-image encryption for COVID-19 infections using HBBS-based multiple keystreams. Arab J Sci Eng. 2021;46(4):3581–93. doi:10.1007/s13369-020-05196-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Kadry H, Farouk A, Zanaty EA, Reyad O. Intrusion detection model using optimized quantum neural network and elliptical curve cryptography for data security. Alex Eng J. 2023;71(1):491–500. doi:10.1016/j.aej.2023.03.072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Mehta K, Dhingra G, Mangrulkar R. Enhancing multimedia security using shortest weight first algorithm and symmetric cryptography. J Appl Secur Res. 2024;19(2):276–99. doi:10.1080/19361610.2022.2157193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Reyad O, Mansour H, Zanaty E, Heshmat M. Medical image privacy enhancement using key extension of advanced encryption standard. Sohag J Sci. 2024;9(3):211–6. doi:10.21608/sjsci.2024.250176.1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Asghar A, Shifa A, Asghar MN. Survey on video security: examining threats, challenges, and future trends. Comput Mater Contin. 2024;80(3):3591–635. doi:10.32604/cmc.2024.05465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Muhammed Z, Anwar Z, Javed AR, Saleem B, Abbas S, Gadekallu TR, et al. Smartphone security and privacy: a Survey on apts, sensor-based attacks, side-channel attacks, google play attacks, and defenses. Technologies. 2023;11(3):76. doi:10.3390/technologies11030076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Kıran HE. A novel chaos-based encryption technique with parallel processing using CUDA for mobile powerful GPU control center. Chaos Fractals. 2024;1(1):6–18. doi:10.69882/adba.chf.2024072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Alaca Y, Celik Y, Goel S. Anomaly detection in cyber security with graph-based LSTM in log analysis. Chaos Theory Appl. 2023;5(3):188–97. doi:10.51537/chaos.1348302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Thomas G, André F, Matthias K. Forensic analysis of video file formats. Digit Investig. 2014;11:S68–76. doi:10.1016/j.diin.2014.03.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Potdar U, Talele KT, Gandhe ST. Comparison of MPEG video encryption algorithms. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communication and Control; 2009 Jan 23–24; Mumbai, India. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; 2009. p. 289–94. doi:10.1145/1523103.1523163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Dalal M, Juneja M. A survey on information hiding using video steganography. Artif Intell Rev. 2021;54(8):5831–95. doi:10.1007/s10462-021-09968-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Azanuddin A, Kartadie R, Erwis F, Boy AF, Nasyuha AH. A combination of Hill cipher and RC4 methods for text security. Telecommun Comput Electron Control. 2024;22(2):351–61. doi:10.12928/telkomnika.v22i2.25628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Hadi HHH, Neamah AA. An image encryption method based on modified elliptic curve Diffie-Hellman key exchange protocol and Hill Cipher. Open Eng. 2024;14(1):20220552. doi:10.1515/eng-2022-0552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Al-Batah MS, Alzboon MS, Alzyoud M, Al-Shanableh N. Enhancing image cryptography performance with block left rotation operations. Appl Comput Intell Soft Comput. 2024;1(1):3641927. doi:10.1155/2024/3641927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Wadho SA, Meghji AF, Yichiet A, Kumar R, Shaikh FB. Encryption techniques and algorithms to combat cybersecurity attacks: a review. Trans Comput Sci. 2023;11(1):295–305. doi:10.21015/vtcs.v11i1.1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Abubakar AM, Kauthar K. Hybrid of least significant bits and most significant bits for improving security and quality of digital image steganography. WSEAS Trans Comput. 2023;22:253–62. doi:10.37394/23205.2023.22.29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Rabie T, Baziyad M. The pixogram: addressing high payload demands for video steganography. IEEE Access. 2019;7:21948–219. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2898838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Suhail AT, Ayoub HG. A new method for hiding a secret file in several WAV files depends on circular secret key. Egypt Inform J. 2022;23(4):33–43. doi:10.1016/j.eij.2022.06.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Vergara GF, Giacomelli P, Serrano ALM, Mendonça FLLD, Rodrigues GAP, Bispo GD. Stego-STFAN: a novel neural network for video steganography. Computers. 2024;13(7):180. doi:10.3390/computers13070180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Dutta S, Saini K. Securing data: a study on different transform domain techniques. WSEAS Trans Syst Control. 2021;16:23203–2021. doi:10.37394/23203.2021.16.8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Oudah MK, Abed AN, Khudhair RS, Kaleefah SM. Improvement of image steganography using discrete wavelet transform. Eng Technol J. 2022;38(1):83–7. doi:10.30684/etj.v38i1A.266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Durafe A, Patidar V. Development and analysis of IWT-SVD and DWT-SVD steganography using fractal cover. J King Saud Univ—Comput Inf Sci. 2022;34(7):4483–98. doi:10.1016/j.jksuci.2020.10.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Karim NA, Ali SA, Jawad MJ. A coverless image steganography based on robust image wavelet hashing. TELKOMNIKA (Telecommun Comput Electron Control). 2022;20(6):1317–25. doi:10.12928/telkomnika.v20i6.23596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Murari TV, KC R, ME R. Selective encryption of video frames using the one-time random key algorithm and permutation techniques for secure transmission over the content delivery network. Multimed Tools Appl. 2024;83(35):82303–42. doi:10.1007/s11042-024-18613-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Mao X, Hu X, Peng W, Gan Z, Ying Q, Qian Z, et al. From covert hiding to visual editing: robust generative video steganography. In: Proceedings of the MM’24: The 32nd ACM International Conference on Multimedia; 2024 Oct 28–Nov 1; Melbourne, VIC, Australia. doi:10.1145/3664647.3681149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Ibrahim A. Video steganography using least significant bit in frequency domain. Int J Intell Comput Inf Sci. 2016;16(1):89–98. doi:10.21608/ijicis.2016.10012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Zareai D, Balafar M, FeiziDerakhshi M. EGPIECLMAC: efficient grayscale privacy image encryption with chaos logistics maps and Arnold Cat. Evol Syst. 2023;14(6):993–1023. doi:10.1007/s12530-022-09482-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Guan M, Yang X, Hu W. Chaotic image encryption algorithm using frequency-domain DNA encoding. IET Image Process. 2019;13(9):1535–9. doi:10.1049/iet-ipr.2019.0051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Ur Rehman A, Liao X, Ashraf R, Ullah S, Wang H. A color image encryption technique using exclusive-OR with DNA complementary rules based on chaos theory and SHA-2. Optik. 2018;159:348–67. doi:10.1016/j.ijleo.2018.01.064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Niyat AY, Moattar MH, Torshiz MN. Color image encryption based on hybrid hyper-chaotic system and cellular automata. Opt Lasers Eng. 2017;90(9):225–37. doi:10.1016/j.optlaseng.2016.10.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Faragallah OS, El-Sayed HS, El-Shafai W. Efficient opto MVC/HEVC cybersecurity framework based on arnold map and discrete cosine transform. J Ambient Intell Humaniz Comput. 2023;14(3):1591–606. doi:10.1007/s12652-021-03382-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Alarifi A, Sankar S, Altameem T, Jithin KC, Amoon M, El-Shafai W, et al. A novel hybrid cryptosystem for secure streaming of high efficiency H.265 compressed videos in IoT multimedia applications. IEEE Access. 2020;8:128548–73. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3008644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Salama WM, Elkamchouchi H, Saleh Y. New video encryption schemes based on chaotic maps. Let Image Process. 2019;14(2):1–16. doi:10.1049/iet-ipr.2018.5250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Hosny KM, Zaki MA, Hamza HM, Fouda MM, Lashin NA. Privacy protection in surveillance videos using block scrambling-based encryption and DCNN-based face detection. IEEE Access. 2022;10:106750–69. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3211657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Adeniyi AE, Misra S, Daniel E, Bokolo AJr. Computational complexity of modified blowfish cryptographic algorithm on video data. Algorithms. 2022;15(10):373. doi:10.3390/a15100373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Kumar V, Mali SS, Rajender G, Medikondu NR. A secure system for digital video applications using an intelligent crypto model. Multimed Tools Appl. 2024;83(6):16395–415. doi:10.1007/s11042-023-16223-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Al-Khafaji BJ, Rahma AMS. A modern encryption approach to improve video security as an advanced standard adopted. Ibn AL-Haitham J Pure Appl Sci. 2024;37(2):460–70. doi:10.30526/37.2.3907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Ojo O, Kareem M, Oyinloye O, Ikumpayi O. Stegovideo: an efficient mechanism for securing video data using steganography and cryptography techniques. J Sci Technol. 2024;42(2):50–63. doi:10.4314/just.v42i2.4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Abu-Faraj MA, Al-Hyari A, Aldebei K, Alqadi ZA, Al-Ahmad B. Rotation left digits to enhance the security level of message blocks cryptography. IEEE Access. 2022;10(12):69388–97. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3187317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Alzyoud M, Saleh Alomar A, Al-shanableh N, Al-Batah M, Alqadi Z, Al-Hawary S, et al. The cryptography of secret messages using block rotation left operation. Appl Math Inf Sci. 2024;18(2):395–402. doi:10.18576/amis/180214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Dhingra D, Dua M. A chaos-based novel approach to video encryption using dynamic S-box. Multimed Tools Appl. 2024;83(1):1693–723. doi:10.1007/s11042-023-15593-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Jaafar A, Mohammed AA. A colour video encryption scheme based on chaotic maps. Taiz Univ Res J. 2024;39(39). [Google Scholar]

44. Hamdy S. Lightweight-multi-layered-research [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jul 1]. Available from: https://github.com/shamdy1993/Lightweight-Multi-Layered-Research. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools