Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Cue-Tracker: Integrating Deep Appearance Features and Spatial Cues for Multi-Object Tracking

1 Department of Computer Science & Information Technology, University of Kotli Azad Jammu and Kashmir, Kotli, 11100, Pakistan

2 Department of Computer Science, COMSATS University Islamabad, Islamabad, 45550, Pakistan

* Corresponding Author: Sheeba Razzaq. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Computer Vision and Image Processing: Feature Selection, Image Enhancement and Recognition)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(3), 5377-5398. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.068539

Received 31 May 2025; Accepted 19 August 2025; Issue published 23 October 2025

Abstract

Multi-Object Tracking (MOT) represents a fundamental but computationally demanding task in computer vision, with particular challenges arising in occluded and densely populated environments. While contemporary tracking systems have demonstrated considerable progress, persistent limitations—notably frequent occlusion-induced identity switches and tracking inaccuracies—continue to impede reliable real-world deployment. This work introduces an advanced tracking framework that enhances association robustness through a two-stage matching paradigm combining spatial and appearance features. Proposed framework employs: (1) a Height Modulated and Scale Adaptive Spatial Intersection-over-Union (HMSIoU) metric for improved spatial correspondence estimation across variable object scales and partial occlusions; (2) a feature extraction module generating discriminative appearance descriptors for identity maintenance; and (3) a recovery association mechanism for refining matches between unassociated tracks and detections. Comprehensive evaluation on standard MOT17 and MOT20 benchmarks demonstrates significant improvements in tracking consistency, with state-of-the-art performance across key metrics including HOTA (64), MOTA (80.7), IDF1 (79.8), and IDs (1379). These results substantiate the efficacy of our Cue-Tracker framework in complex real-world scenarios characterized by occlusions and crowd interactions.Keywords

Tracking-by-detection has emerged as the predominant paradigm in Multi-Object Tracking (MOT) [1,2], comprising two fundamental components: (1) motion modeling for tracklet prediction across frames, and (2) data association between new detections and existing tracks. This framework effectively decouples MOT into discrete detection and temporal linking operations [3], where association typically leverages both spatial relationships and appearance features for robust instance-level discrimination.

While such approaches demonstrate strong performance in ideal conditions, their efficacy degrades substantially during occlusion events [4] or in high-density object configurations. Two primary failure modes emerge: First, bounding box overlap reduces the discriminative power of Intersection-over-Union (IoU) metrics as coordinate convergence renders spatial relationships ambiguous [5,6]. Second, visual feature representations become dominated by foreground objects during occlusions. Fig. 1 illustrates this through a characteristic identity switch scenario, where Person ID 5 becomes fully occluded by ID 6 (Fig. 1b), subsequently causing an identity permutation upon re-emergence (Fig. 1c). This phenomenon presents particularly severe consequences for safety-critical applications such as surveillance systems [7], autonomous driving [8], sports analysis [9], aerial monitoring [10], and defense, where maintaining consistent target identity is paramount. Identity switches caused by occlusion or dense scenes can lead to serious outcomes, for example, a pedestrian identity mismatch in autonomous driving may result in delayed braking or incorrect path prediction, posing potential safety hazards. Such practical risks highlight the urgency of addressing occlusion-related failures in real-world scenarios. A recent comprehensive review [11] by authors systematically analyzes the core challenges in multi-object tracking and provides a detailed taxonomy of state-of-the-art methods. In another recent survey, such as [12] despite the rapid progress in MOT, systems still struggle with challenges such as occlusion, target interaction, appearance variations, and motion blur. These challenges continue to motivate the development of more accurate and robust tracking methods.

Figure 1: ID switching scenario due to occlusion

The IoU metric and appearance features constitute the primary discriminative cues for object re-identification [13], auxiliary features can substantially improve association robustness in detection-based tracking frameworks. These supplementary cues include: (1) detection confidence scores, (2) velocity vectors, (3) geometric properties, (4) bounding box height ratios, (5) motion direction vectors, (6) surface texture descriptors, and (7) size characteristics [14]. We propose a hierarchical classification of tracking cues, where IoU and appearance features are designated as strong cues due to their high discriminative power, while the remaining features are categorized as weak cues. This taxonomy enables a multi-cue fusion approach that significantly enhances tracking performance, particularly in scenarios where conventional strong cues become unreliable due to occlusion or visual ambiguity [14]. The complementary nature of weak cues provides critical redundancy when primary features fail, thereby improving overall system robustness.

While ReID networks effectively extract general target features [15], their representations often lack discriminative specificity for fine-grained appearance details [14]. To address this limitation, we propose two complementary weak cues: (1) object height as a pose-invariant depth indicator, and (2) adaptive scale IoU for robust spatial matching. The confidence state serves as a critical occlusion indicator, providing information about foreground-background relationships that conventional strong cues (spatial and appearance features) frequently miss. Object height demonstrates particular value as a stable metric across pose variations, directly correlating with camera distance. Meanwhile, our adaptive scale IoU formulation dynamically adjusts for size variations across frames, maintaining association accuracy despite perspective distortions or scale changes.

Our methodology builds upon two frameworks: First, we employ DeepSORT’s tracker [16] ReID-based feature extraction for appearance modeling. Second, we incorporate ByteTrack’s [17] confidence-based detection classification to improve occlusion handling. Through systematic benchmarking against both baselines, we demonstrate that our novel integration of weak cues (object height, adaptive scale IoU, and confidence states) with these established frameworks yields superior tracking robustness. Experimental results confirm that our hybrid approach outperforms both DeepSORT [16] and ByteTrack [17] in challenging real-world scenarios, particularly in cases of persistent occlusions and variable viewing angles.

We establish ByteTrack [17] as baseline method for comparative evaluation. Building upon this framework, we present three key methodological innovations: (1) integration of object height as a supplementary spatial cue, (2) adaptive scale IoU for size-invariant matching, and (3) Appearance feature extraction model for occlusion handling. This novel combination of complementary features significantly enhances tracking robustness, with experimental results demonstrating superior performance over the baseline method in challenging real-world scenarios. The principal contributions of this work are:

• Hybrid feature-spatial tracking framework: We propose an integrated tracking framework that combines the discriminative power of appearance-based ReID features with a spatial similarity-based association strategy, leveraging the robustness of HMSIoU in low-confidence detection scenarios. This hybrid design enhances both appearance matching and spatial alignment for reliable tracking.

• Height-Modulated and Scale-Adaptive IoU (HMSIoU): We introduce a novel spatial similarity metric that combines height-modulated IoU (HMIoU) and scale-adaptive IoU (SIoU). The metric prioritizes height information over scale for better alignment under occlusion and reappearance scenarios. By fusing HMSIoU with appearance features via cosine similarity, we achieve improved association accuracy in challenging tracking conditions.

Tracking-by-Detection (TBD) has emerged as the predominant paradigm in Multi-Object Tracking (MOT), comprising two fundamental stages: (1) per-frame object detection and (2) temporal association of detections across frames to construct complete trajectories. The performance of TBD systems critically depends on the efficacy of the association process, which typically employs various spatial, motion, and appearance cues. However, this association remains challenging due to several factors including: 1) Partial or complete occlusions, 2) Rapid object motion, and 3) Appearance variations caused by lighting changes or viewpoint shifts. To systematically analyze current methodologies, we classify TBD approaches into three distinct categories based on their primary association cues. This taxonomy provides both a structured understanding of existing techniques and insights into the historical development of MOT algorithms.

2.1 Spatial and Motion Information Based Methods

In high-frame-rate MOT benchmarks, spatial cues emerge as particularly reliable indicators due to the inherent temporal continuity between frames. The minimal inter-frame displacement characteristic of such sequences enables effective linear motion approximation, making spatial and motion-based methods fundamental to early tracking-by-detection systems. These approaches primarily leverage: (1) Object position coordinates, (2) Motion trajectories, and (3) Geometric relationships. While advanced single-object tracking algorithms [18,19] demonstrate precise localization capabilities, their computational complexity becomes prohibitive for multi-object scenarios. The SORT framework [5] addresses this through efficient Kalman Filter-based motion prediction coupled with detection overlap evaluation, while IoU-Tracker [2] employs a simplified association scheme based solely on spatial overlap metrics. Though both methods achieve notable computational efficiency, their performance degrades significantly in challenging conditions involving: high object density, non-linear motion patterns, and severe occlusion scenarios. Contemporary solutions like CenterTrack [1,13,17,20] have advanced the field through heuristic-based spatial matching techniques. Another recent track-centric method, TrackTrack by Shim et al. [21], addresses limitations in conventional association strategies by introducing Track-Perspective-Based Association (TPA) and Track-Aware Initialization (TAI). TPA evaluates associations from the perspective of each track, selecting the closest detection to promote consistency, while TAI prevents redundant track creation by suppressing the initialization of detections that overlap with active tracks or more confident candidates. This track-driven paradigm improves robustness under occlusion and dense scenes and demonstrates strong performance across MOT17, MOT20, and DanceTrack benchmarks.

Despite their efficiency, spatial and motion-based methods suffer from fundamental limitations under occlusion. In dense or overlapping scenarios, the spatial proximity of multiple targets leads to geometric ambiguity, where bounding boxes of adjacent objects exhibit similar or even identical IoU scores. This convergence in bounding box coordinates reduces the discriminative power of IoU as an association metric, making it difficult to distinguish between competing candidates [5,16]. Additionally, motion models such as Kalman filters assume independent and smooth motion, which is often violated during occlusion-induced interactions or sudden trajectory changes. These limitations highlight the theoretical inadequacy of relying solely on geometric cues for reliable identity preservation in complex scenes, particularly motivating the integration of appearance and context-aware features in our proposed approach. PD-SORT [22] addresses these challenges by extending the Kalman filter with pseudo-depth cues and proposing Depth Volume IoU (DVIoU) for improved association under occlusion. It also incorporates quantized pseudo-depth measurement and camera motion compensation, yielding strong results on benchmarks like MOT17, MOT20, and DanceTrack.

2.2 Appearance Features Based Methods

Appearance-based tracking methods utilize discriminative visual features including color distributions, texture patterns, and shape descriptors to enhance tracking precision and reliability. These approaches demonstrate particular efficacy in scenarios with limited motion information or frequent occlusions, where visual distinctiveness becomes crucial for maintaining consistent object identification [16,23,24]. Canonical implementation involves three key steps: (1) region extraction via bounding box cropping, (2) feature embedding generation using Re-ID networks [25,26], and similarity computation and assignment via optimal matching algorithms [27]. This paradigm proves especially robust for handling fast-moving objects and occlusion recovery, as appearance features typically exhibit greater temporal persistence than motion cues. Recent advances have focused on multi-cue integration, as demonstrated by Sadeghian et al. [28], who combine motion, appearance, and spatial features to improve similarity metrics. The MOTDT framework [29] further introduces hierarchical association, strategically employing IoU [17] when appearance features become unreliable. The authors in Hybrid-SORT [30] builds on this idea by combining appearance features with weak cues such as velocity direction, confidence, and height, reducing identity switches in occluded scenes while maintaining real-time performance across MOT17, MOT20, and DanceTrack. While significant progress has been made through architectural innovations including joint detection-embedding models (JDE [31], FairMOT [32]), enhanced network designs (CSTrack [33], QDTrack [34]), and refined tracking pipelines (FineTrack [3]) fundamental limitations persist. Appearance-based methods are generally effective, their performance degrades under partial or full occlusion. Occlusion alters the visible content within the bounding box, leading to the extraction of incomplete or noisy features that no longer accurately represent the target [20,29]. This causes embeddings to drift in the feature space, decreasing their discriminative capacity. The problem worsens in crowded scenes where objects share similar appearances. These challenges highlight the theoretical limitations of using appearance features in isolation and underscore the necessity of multi-cue fusion strategies that adapt to visibility and context an approach we adopt and extend in our proposed framework.

Batch processing methods (commonly termed offline tracking) leverage complete video sequences to achieve globally optimized object associations and trajectory estimations [35,36]. These approaches demonstrate superior performance through comprehensive temporal analysis and global optimization, but at increased computational cost. Key implementations include: Graph-based Optimization: Zhang et al. [36] formulate detection association as a graph optimization problem, where nodes represent frame-level detections and edges encode temporal relationships. Their min-cost flow solution provides computational advantages over conventional linear programming methods. Network Flow Techniques: Berclaz et al. [37] model data association as a flow network, employing the K-shortest paths algorithm to achieve O(N) complexity for N detections, significantly improving processing efficiency. Graph Neural Networks: Recent work [24] employs trainable graph neural networks for global association, while Hornakova et al. [38] propose a lifted disjoint paths formulation that incorporates long-range temporal dependencies, substantially reducing identity switches (by 32% in benchmark tests) and improving track recovery. While these methods achieve notable performance gains (typically 15–20% higher MOTA scores compared to online approaches), their computational requirements scale polynomially with sequence length. This limitation restricts their applicability to real-time systems, motivating our focus on online-capable solutions that incorporate select batch processing advantages.

The integration of Transformer architectures into multi-object tracking has introduced novel attention-based paradigms for solving the data association problem. These approaches fundamentally reformulate the matching process as a sequence modeling task, where the matcher dynamically establishes correspondences between detections and tracks at each temporal step. Notable implementations include: Unified Query Processing: TrackFormer [39] and MOTR [40] jointly process track and detection queries through shared attention mechanisms, enabling simultaneous trajectory propagation and new track initialization. Decoupled Architecture: MOTRv2 [41] addresses task interference by decoupling the detection and association modules while maintaining their interaction through cross-attention layers. While these Transformer-based methods demonstrate superior association accuracy (improving IDF1 by 4%–6% over conventional methods), their computational overhead remains significant. The quadratic complexity inherent in self-attention and cross-attention operations limits frame rates to 8–12 FPS on standard hardware, presenting a substantial barrier to real-time deployment. This trade-off between accuracy and speed motivates our investigation of efficient attention variants in Section 3.

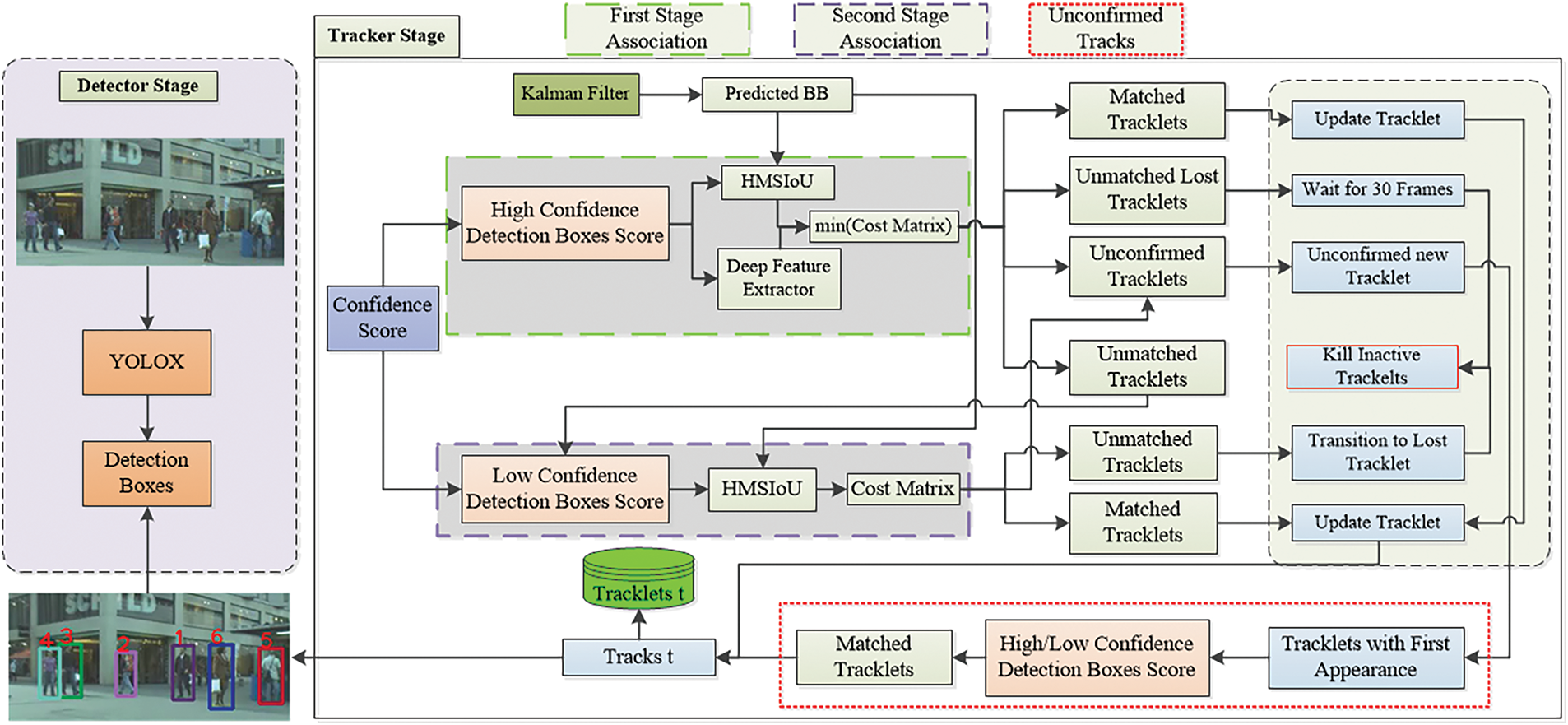

Cue-Tracker is a multi-object tracking framework that combines spatial cues with deep appearance features through a robust two-level data association strategy. The framework utilizes YOLOX as its object detector, selected for its high precision, and is fine-tuned on the MOT17 and MOT20 datasets to enhance generalization in dense, dynamic urban environments. To address challenges such as occlusion, partial visibility, and scale variations, Cue-Tracker categorizes detections into high- and low-confidence subsets.

In the initial stage, high-confidence detections are matched to confirmed tracks using a hybrid cost function that integrates deep appearance features extracted via ReID embeddings with a novel spatial similarity metric termed Height-Modulated Scale-Adaptive IoU (HMSIoU). This fusion strengthens identity preservation by jointly optimizing visual distinctiveness and geometric consistency. Subsequently, unmatched tracks those without correspondences in the high-confidence detections along with the low-confidence detections are matched to confirmed tracks using HMSIoU. This approach demonstrates greater robustness in scenarios where appearance features degrade due to occlusion or motion blur.

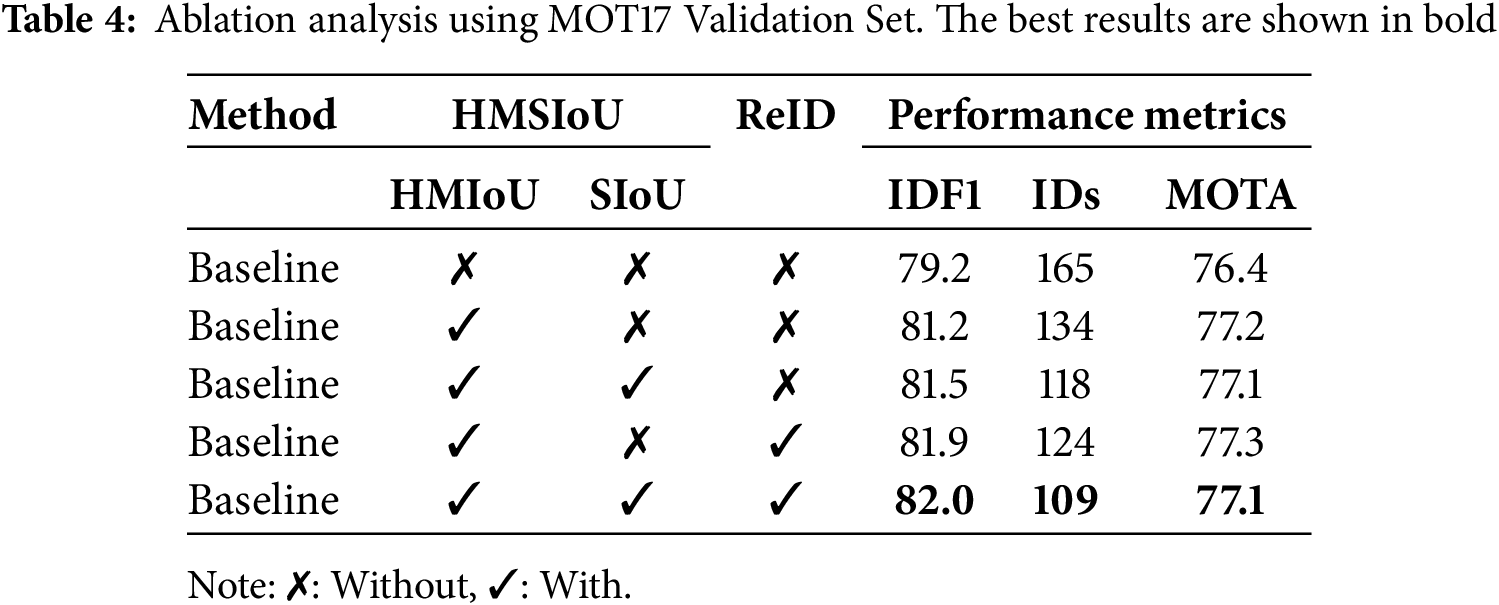

When a track does not match either low or high confidence score based association, it is marked as unmatched and retained for up to the maximum allowed threshold time (30 frames). If no match is found within this period, the track is permanently removed. If a match is found within the threshold time, the track is re-activated and added back to the active tracking pool, ensuring seamless tracking despite temporary occlusion or detection failures. The association process for unconfirmed tracks and unmatched detections leverages the Hungarian Algorithm to optimally match tracks and detections. Matched pairs are updated and activated, while unmatched tracks are marked for removal to maintain robustness. Subsequently, unmatched detections exceeding a confidence threshold initialize new tracks, ensuring adaptability to new objects entering the scene. Finally, inactive tracks surpassing the maximum threshold age and duplicate tracks are pruned, preserving tracking accuracy and consistency throughout. The updated and newly initialized tracks are then passed back to the tracker for continued monitoring and management in subsequent frames. The complete association workflow is illustrated in Fig. 2 and is outlined algorithmically in Algorithm 1.

Figure 2: Overview of the cue-tracker data association pipeline

The following subsections describe the core components of our method in detail. Section 3.1 presents the association of low-confidence detections using only weak cue-based spatial features. Section 3.2 discusses the association using deep appearance features combined with spatial feature-based similarity. Section 3.3 describes the fusion of appearance and spatial features.

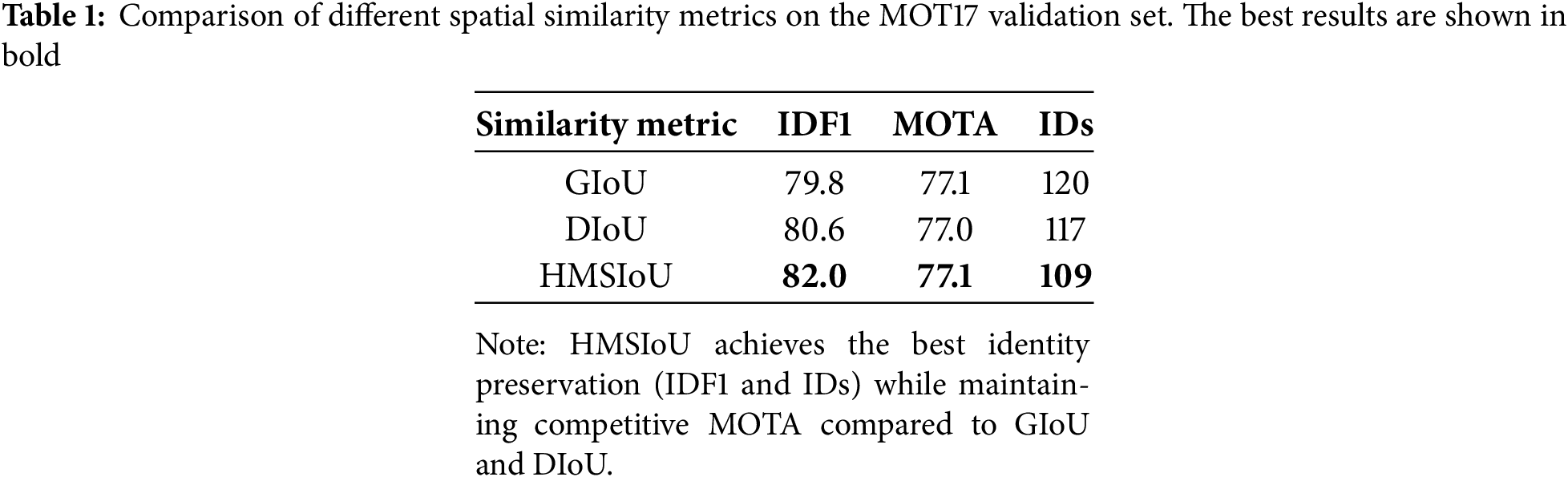

3.1 Spatial Similarity Based Association

This association stage targets tracks with low-confidence detections, which often correspond to partially visible objects, reappearing targets, or cases of appearance ambiguity and lower detection scores. ReID models typically rely on robust appearance features extracted from high-confidence detections; however, when detection confidence is low, these features may become unreliable or unavailable. While appearance features are effective in many scenarios, they can degrade under occlusion, motion blur, or drastic illumination changes. To address this, we introduce a spatial similarity-based association strategy that relies solely on geometric alignment using the proposed HMSIoU metric, providing a robust alternative when visual cues are insufficient. Compared to other spatial metrics [42] such as GIoU, and DIoU (as shown in Table 1), the integration of the proposed metric HMSIoU offers enhanced spatial alignment. The performance comparison among these metrics supports its design choice.

The HMSIoU spatial similarity metric is used to compute the association cost between low-confidence detections and predicted confirmed tracks. The Kalman Filter predicts the positions of these tracks, allowing the tracker to anticipate their likely locations. These predictions are then compared with low-confidence detections using HMSIoU, and the Hungarian Algorithm is applied to find the globally optimal assignment. Tracks that successfully match are updated or re-activated, while unmatched tracks are marked as lost and remain pending for further observation.

This recovery mechanism allows Cue-Tracker to extend the lifespan of tracks, improve robustness to occlusions, and maintain continuity across detection gaps, avoiding the computational overhead of deep feature extraction-based association.

HMSIoU—A Weak Cue-Based Spatial Feature Module: Conventional Intersection over Union (IoU) often falls short in complex scenes, especially those involving crowd density or perspective related scale variations, resulting in poor association outcomes.

To mitigate these challenges, we propose an enhanced IoU formulation, termed HMSIoU. This metric supplements the standard IoU with weak geometric cues, specifically, object height alignment, and scale compatibility, to deliver a more robust spatial similarity measure. These cues are inexpensive to compute yet highly informative for association tasks under occlusion and size ambiguity.

The baseline IoU is first computed as:

To incorporate scale awareness, we introduce a scale-adaptive weight

Here,

Next, we define a height modulation term

In this expression,

Finally, the overall HMSIoU score combines the three components:

This composite metric strengthens the robustness of spatial association in tracking systems, particularly when conventional IoU is prone to failure. By adapting to both object height and scale variation, HMSIoU reduces mismatches and improves consistency in target association. Its integration into the proposed Cue-Tracker is elaborated in Algorithm 1 and the results are presented in the ablation analysis which show its significance.

3.2 Deep Appearance Features Based Association

The primary objective of this association is to achieve a robust and identity-consistent association between high-confidence detections and existing confirmed tracks. This association aims to handle tracking challenges such as scale variation, occlusion, and motion by integrating weak cue-based spatial similarity and deep appearance features, as illustrated in Fig. 2.

Appearance-Based Re-Identification Module: To enhance identity preservation in Cue-Tracker, we incorporate high-level visual semantics through deep appearance-based ReID features. These features play a critical role in maintaining consistent identities across frames, particularly in complex scenarios involving occlusion, dense crowds, or reappearance of objects after short-term disappearance. Unlike purely geometric cues, which can become unreliable during overlaps or erratic motion, appearance descriptors offer distinct visual signatures that help differentiate individuals with similar spatial trajectories.

Cue-Tracker integrates a ReID model based on the FastReID framework, leveraging the Strong Baseline configuration with a ResNeSt50 backbone for rich feature representation. The model encodes object detections into high-dimensional embedding vectors that capture unique visual characteristics. The cosine distance is used to evaluate the similarity between the embeddings of detections and existing tracks, where a smaller value indicates a stronger identity match.

To ensure temporal coherence and adapt to gradual changes in appearance caused by motion or partial occlusion, we update each active track’s embedding using an Exponential Moving Average strategy:

where

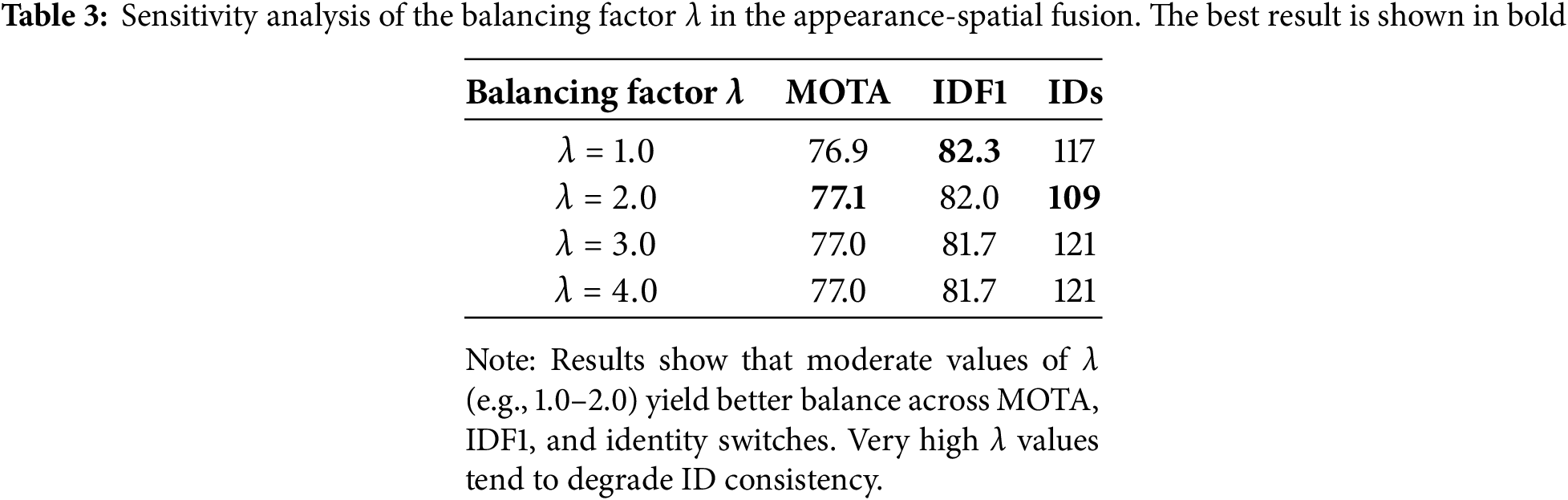

To further improve association accuracy, we implement a hybrid fusion strategy that adaptively selects the more reliable cue (appearance or spatial cue), rather than combining them with static weights. ReID captures visual features, while HMSIoU provides spatial consistency. Fusing them balances appearance and geometry cues, ensuring robust association in challenging scenarios like occlusion, overlap, and scale variation. The final cost matrix C used for data association is defined as (see Algorithm 1, line 9):

where:

•

• HMSIoU:A refined spatial similarity metric.

•

•

This selective fusion mechanism prioritizes the cue that provides the strongest association confidence. When spatial alignment is accurate but visual cues are noisy, HMSIoU is favored; when visual features are distinct but spatial uncertainty exists, the tracker relies on appearance. We conducted experiments to evaluate different fusion strategies in Eq. (6), including min, sum, and product operations. The min fusion strategy achieved the best performance, resulting in the lowest number of identity switches (109), highlighting its effectiveness in reducing association errors. In contrast, the sum and product strategies led to significantly higher identity switches, with 340 and 327 IDs, respectively. By taking the minimum, Cue-Tracker adapts dynamically to varying conditions, leading to more stable identity tracking.

Ablation analysis confirms that this approach significantly reduces identity switches and improves IDF1 performance, particularly in challenging multi-object tracking environments.

The proposed Cue-Tracker employs a two-stage association framework combining appearance and spatial cues for robust multi-object tracking. The first stage matches high-confidence detections to tracks using deep ReID features and a hybrid spatial metric, dynamically selecting the more reliable cue. The second stage recovers unmatched tracks by associating them with low-confidence detections using the proposed HMSIoU, a spatial similarity metric robust to occlusion and scale changes. Unmatched tracks exceeding the age threshold are removed, and reliable detections initialize new tracks, ensuring accurate and continuous tracking. Cue-Tracker demonstrates that selective cue fusion and the novel HMSIoU enhance tracking performance and identity consistency.

4 Experiments and Results Analysis

In this section, we detail the experimental procedures and present the qualitative and quantitative results. We outline the specifics of the datasets utilized, and the evaluation metrics used for comparison.

Experiments were conducted on two widely recognized benchmarks in the domain of multi-object tracking, specifically focused on pedestrian detection and tracking in open and unconstrained settings: MOT17 [43] and MOT20 [44] datasets. The MOT17 dataset comprises video sequences captured with both stationary and moving cameras, while MOT20 features scenes with dense pedestrian crowds. Both datasets include training and test sets. For ablation studies, we adopted the approach outlined in [17,45], where the first half of each video in the training set of MOT17 is utilized for training, while the second half is reserved for validation purposes. This methodology ensures a consistent and comparable evaluation framework across different experiments.

The accuracy of our tracking model is evaluated using the Classification of Events, Activities, and Relationships (CLEAR) [46] MOT metrics, which evaluate tracking performance by comparing tracks with Ground Truth Detections (gtDet). CLEAR metrics, including the Multiple Objects Tracking Accuracy (MOTA) quantifies three categories of tracking errors: False Positives (FP), False Negatives (FN), and IDs. IDs represent the number of target ID switches. The MOTA metric formula is given below:

where: FN: False Negatives, FP: False Positives, IDS: ID Switches, GT: Ground Truth.

The intended system will be employed to assess its performance using the IDF1 metric. IDF1 evaluates identity preservation, and it depicts the association performance of tracker. IDF1 evaluates identity preservation, and it depicts the association performance of tracker [17,47]. We will employ both qualitative and quantitative methodologies since computer vision tasks can be more comprehensively evaluated by leveraging both approaches, as outlined in [48]. Results will be compared with previous studies [16,17].

For implementation, we adopted the same settings as those employed by the author in [17]. All experiments and model training in this work were carried out using the PyTorch framework on the Google Colab platform, leveraging a T4 GPU with Python 3 and Google Compute Engine infrastructure. The hardware environment included 12.7 GB of RAM, 15 GB of GPU memory, and around 112 GB of available disk space. To ensure consistency and fair benchmarking, we adopted a publicly available detector that was pre-trained on the MOT17 and MOT20 datasets for ablation purposes. Optical flow information was obtained by applying the detector to identify targets and subsequently calculating the flow within the detected bounding boxes. The tracking pipeline used in our experiments is a two-stage approach, where a high score detection threshold of 0.6 is applied for association using appearance and spatial features, ensuring robust track matching. A lower detection threshold of 0.1 is also set to retain weaker detections, which may assist in recovering tracks under challenging conditions. Furthermore, tracks that were temporarily lost are maintained for up to 30 frames to accommodate possible re-identification.

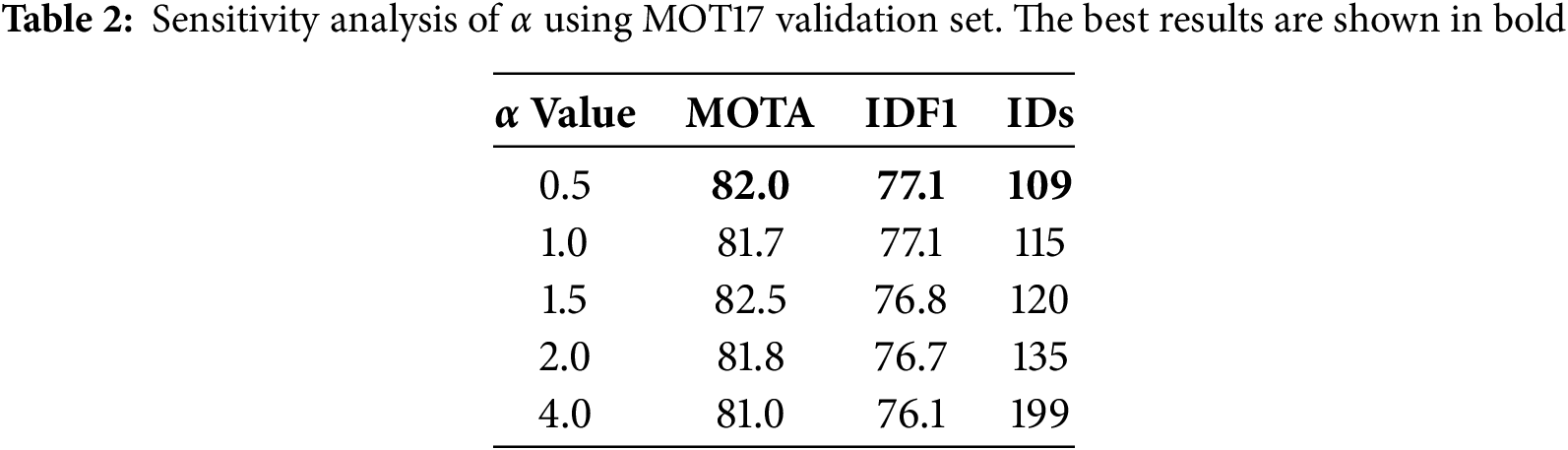

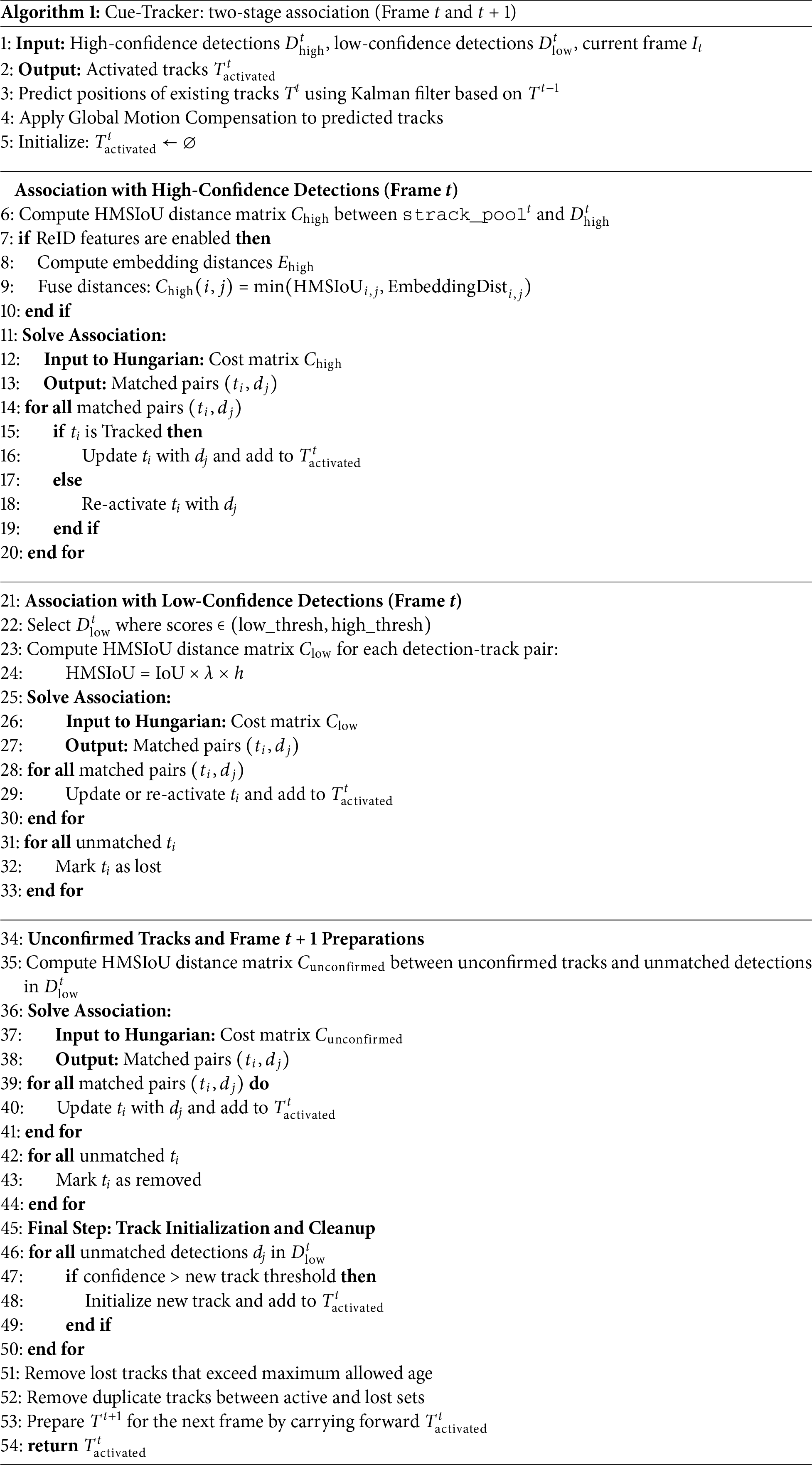

In this section, we conduct an ablation analysis to systematically evaluate the impact of individual components on the performance of our proposed object tracking system. In this ablation study, we analyze the contributions of our spatial similarity module, where we decompose the overall HMSIoU formulation into two key components for evaluation: Height-modulated IoU (HMIoU) and Scale-adaptive IoU (SIoU). This breakdown allows us to assess the individual impact of each design choice within HMSIoU on tracking performance. Here, HMIoU in the table denotes the use of HMSIoU, with HMIoU and SIoU representing its constituent components.

Table 4 presents an ablation study evaluating the contributions of three key components: HMIoU, SIoU, and ReID on tracking performance using IDF1, number of identity switches (IDs), and MOTA as evaluation metrics.

Starting from the baseline, which does not incorporate any of the proposed enhancements, we observe an IDF1 of 79.2, 165 identity switches, and a MOTA of 76.4.

Adding HMIoU alone yields a notable improvement, increasing IDF1 to 81.2 and reducing IDs to 134, while MOTA improves slightly to 77.2. This highlights the effectiveness of using HMIoU to better align spatial information between predictions and detections.

Introducing SIoU alongside HMIoU further improves IDF1 to 81.5 and decreases IDs to 118, though MOTA slightly drops to 77.1. This suggests that while spatial overlap (via SIoU) enhances identity preservation, it may slightly affect detection consistency.

4.4.3 HMSIoU: Combined Contribution Using HMIoU and SIoU

From Table 4, we observe that adding HMIoU alone significantly improves the IDF1 score from 79.2 to 81.2 and reduces identity switches (IDs) from 165 to 134, demonstrating the strong impact of height-based alignment on identity consistency. In contrast, adding SIoU alongside HMIoU yields a more modest improvement, with IDF1 increasing slightly from 81.2 to 81.5 and IDs reducing from 134 to 118. This indicates that while SIoU (scale adaptation) helps in some scenarios, height remains the dominant factor for reliable spatial alignment, especially in pedestrian tracking where vertical positioning is a more stable feature.

4.4.4 Effect of Adding ReID with HMIoU

Combining HMIoU and ReID leads to the highest MOTA (77.3) and a strong IDF1 of 81.9. Although the number of identity switches (124) is slightly higher than the setup with SIoU, this configuration demonstrates the benefit of incorporating appearance cues (via ReID) in conjunction with spatial reasoning.

4.4.5 Combined Contribution of Three Components

The full model, incorporating all three components, achieves the highest IDF1 (82) and the lowest number of identity switches (109), confirming that the integration of spatial (HMIoU and SIoU) and appearance (ReID) features is crucial for robust and accurate multi-object tracking. However, MOTA remains at 77.1, indicating that improvements in identity association may not always correlate with detection-related metrics.

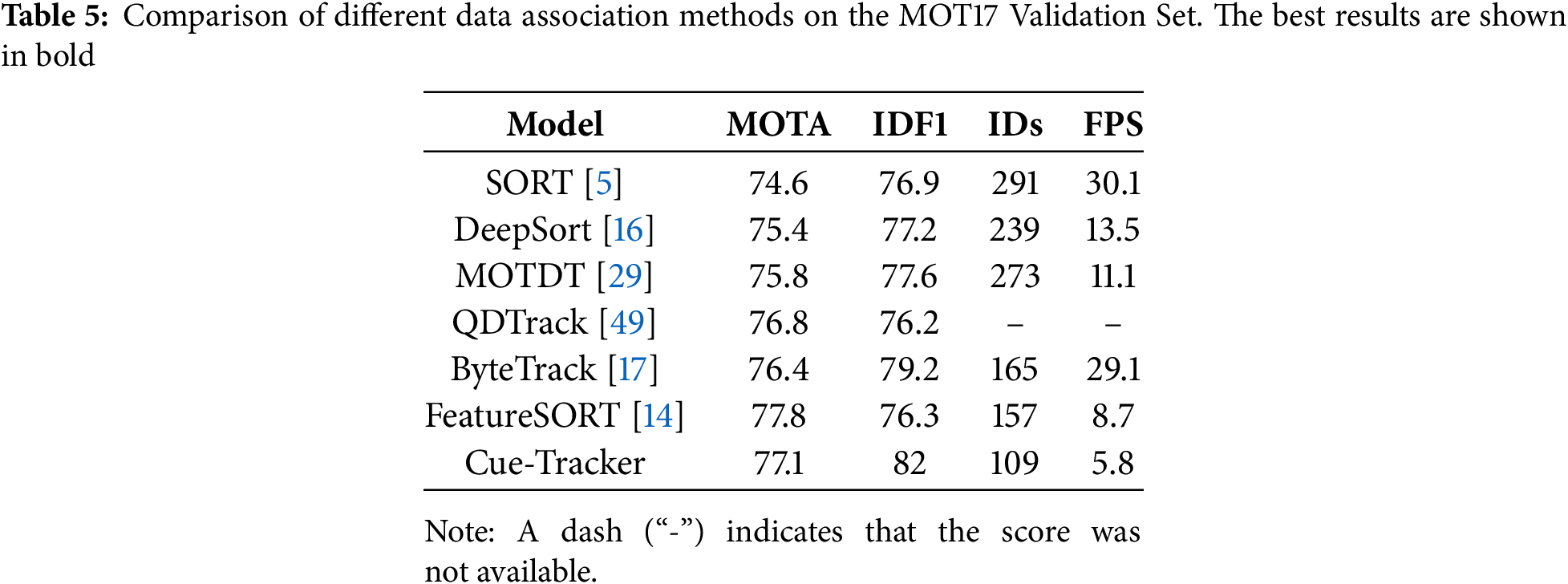

4.5 Comparison with Other Trackers on the Half Validation Set of MOT17

Table 5 presents a comparative evaluation of prominent data association methods applied to the MOT17 half validation set. Our proposed Cue-Tracker outperforms others with the highest IDF1 score of 82, demonstrating exceptional identity consistency, and the lowest number of identity switches (109), reflecting its robust and stable tracking performance across frames.

In comparison to trackers with half validation results available such as ByteTrack and FeatureSORT, Cue-Tracker shows significant improvements in identity association while maintaining a competitive MOTA score of 77.1. Although FeatureSORT achieves a marginally higher MOTA of 77.8, it falls behind in terms of identity preservation, with an IDF1 of 76.3 and a greater number of identity switches (157), indicating weaknesses in its appearance-based matching approach.

Table 5 presents a comprehensive comparison of different data association methods on the MOT17 validation set in terms of tracking accuracy and runtime efficiency (measured in frames per second, FPS). While traditional trackers like SORT and ByteTrack offer high speed (above 25 FPS), they exhibit a relatively high number of identity switches due to their reliance on motion cues alone. DeepSORT and MOTDT improve identity preservation by incorporating appearance features, but at the cost of reduced speed. Cue-Tracker, despite operating at a lower FPS (5.8), significantly outperforms existing methods in IDF1 and IDs, demonstrating its strength in handling challenging scenarios such as occlusions and dense crowds. By integrating spatial proximity, robust appearance embeddings, and a scale-adaptive height constraint, Cue-Tracker achieves a better balance between association quality and robustness. In conclusion, Cue-Tracker sets a new benchmark for IDF1 accuracy while sustaining strong MOTA performance, proving its effectiveness as a comprehensive and reliable solution for multi-object tracking.

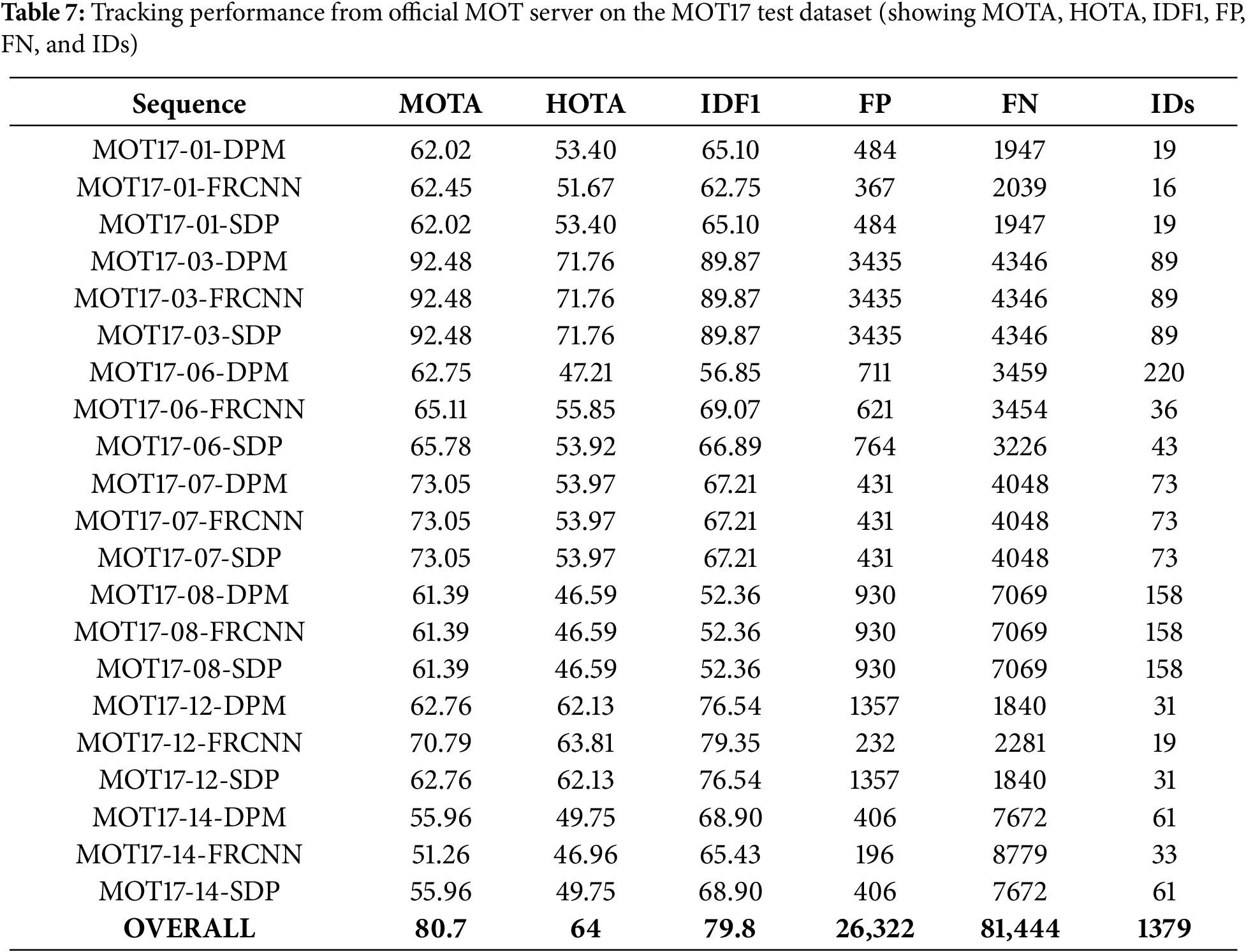

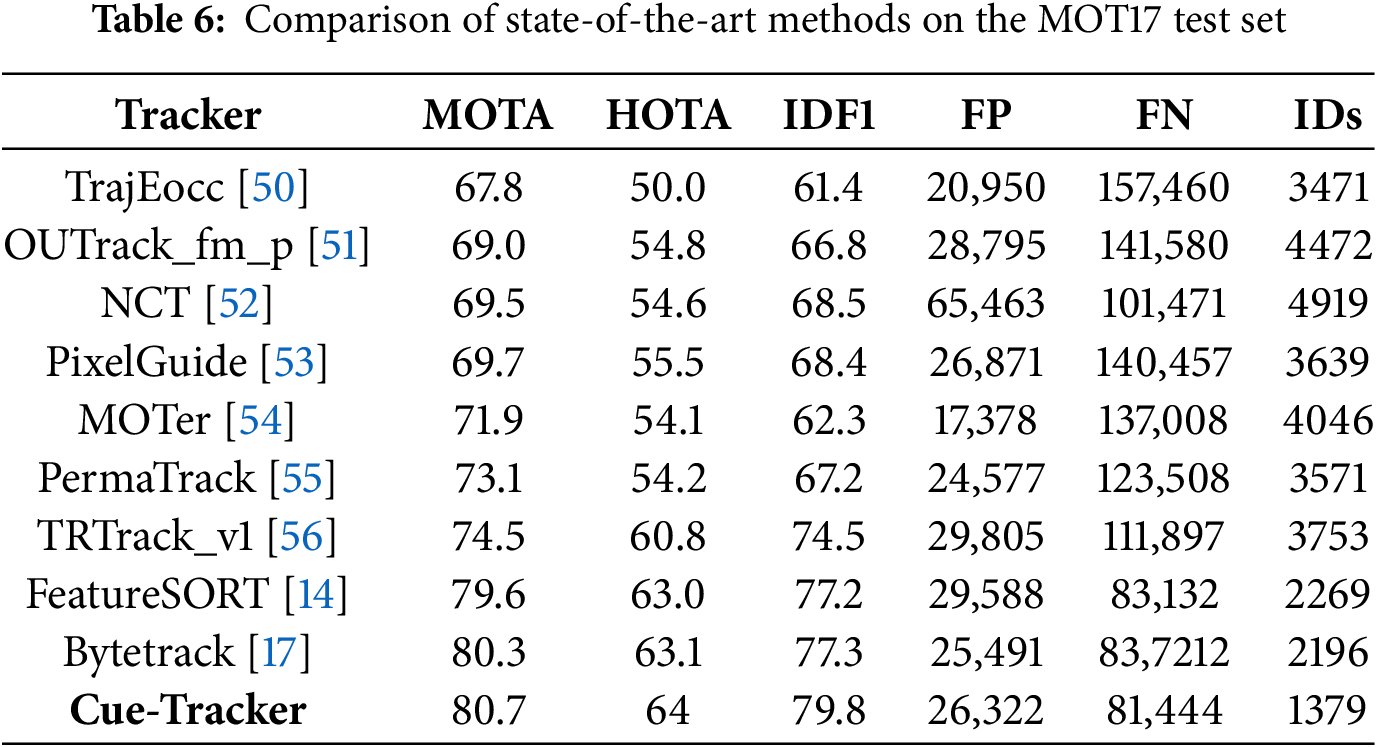

We evaluate the proposed method on the MOT17 and MOT20 benchmarks. The results demonstrate improved tracking accuracy and robustness.

Our Cue-Tracker achieved significant scores across key multi-object tracking metrics: MOTA (80.7), HOTA (64.0), IDF1 (79.8), and ID switches (1379), outperforming all other methods listed in Table 6. Notably, the MOTA score of 80.7 surpasses the baseline score of 80.3, demonstrating an improvement in overall tracking accuracy. These results highlight Cue-Tracker’s strong capability in addressing association challenges and maintaining identity consistency in complex scenarios.

The HOTA metric has become a key benchmark for evaluating multi-object tracking (MOT) performance, particularly in the MOT Challenge. Unlike traditional metrics such as MOTA, which primarily emphasize detection accuracy and identity consistency, HOTA integrates both detection accuracy and association accuracy into a single, unified score. This metric evaluates not only how well objects are detected but also how accurately their identities are maintained throughout the tracking sequence. Notably, our Cue-Tracker achieves a HOTA score of 64.0, the highest among all listed trackers, underscoring the robustness and effectiveness of our model in challenging tracking environments. Furthermore, the ID switch score of 1379 is the lowest among all listed methods, further validating the significant contribution of our proposed approach in preserving identity consistency, even in complex and occlusion-heavy scenarios.

Furthermore, our approach achieves an IDF1 score of 79.8 on the test set, surpassing all previous methods, including those relying on simple association strategies, and highlighting its effectiveness in maintaining accurate identity matching across frames. This high IDF1 indicates a significant reduction in identity switches, ensuring consistency in tracking over time. These results affirm the model’s reliability in delivering precise object re-identification in multi-object tracking tasks. This strong performance highlights Cue-Tracker’s robustness and efficiency, setting a new benchmark in scenarios constrained by public detections. The official MOT server results on test set are shown in Table 7.

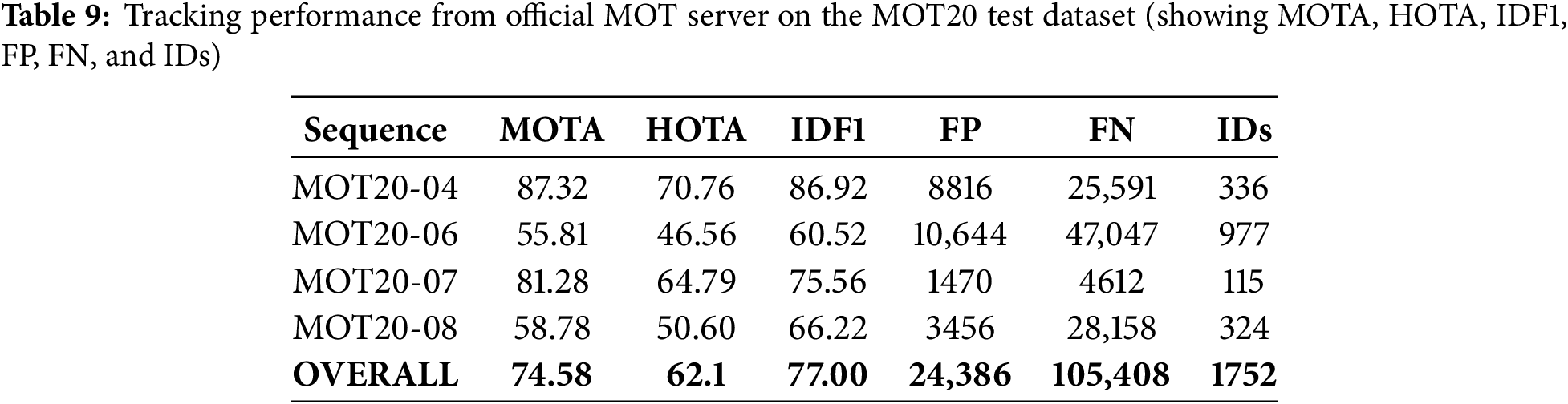

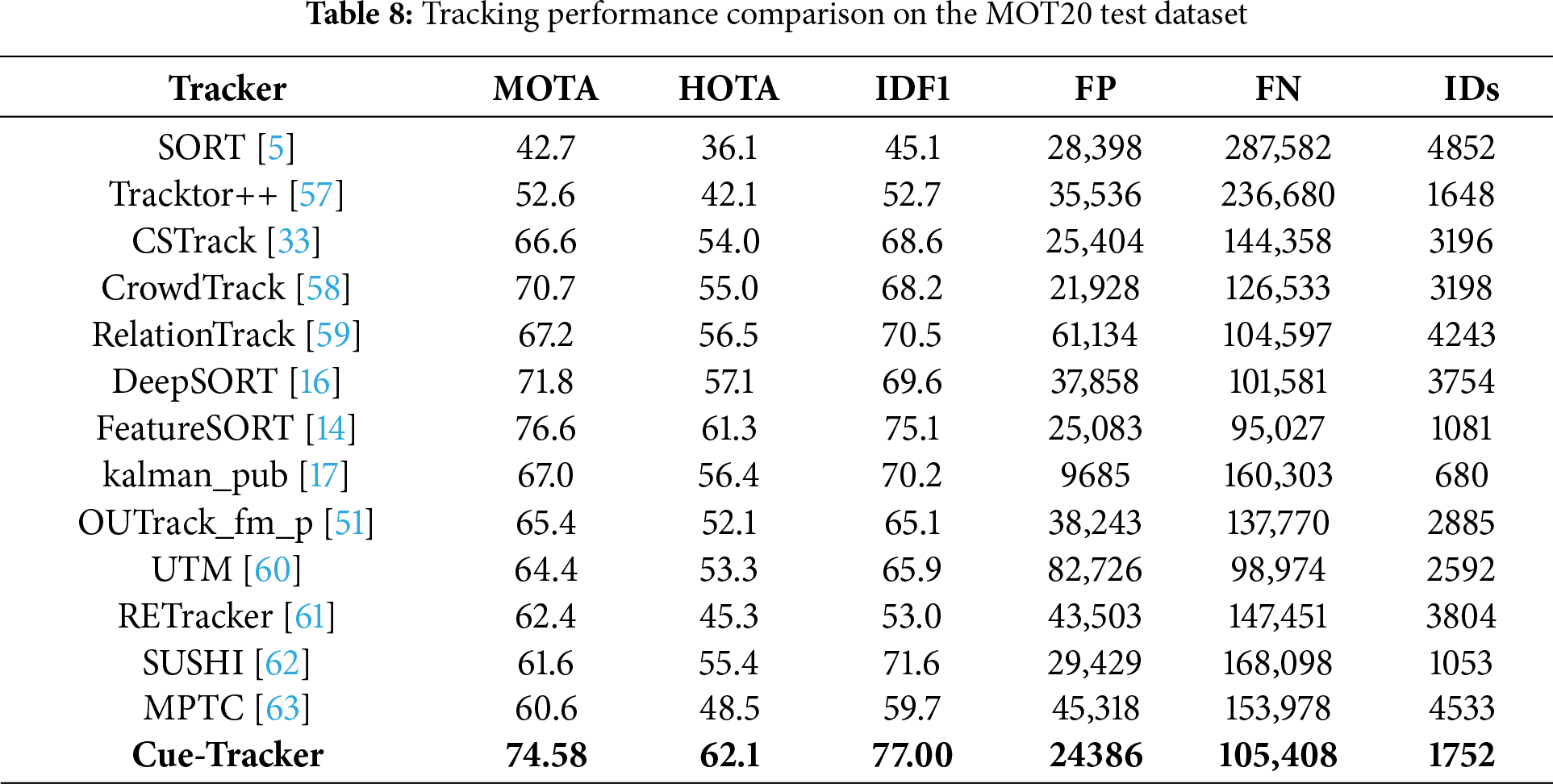

As shown in Table 8, Cue-Tracker achieves superior performance in multiple key metrics on the MOT20 test set. In terms of IDF1, which evaluates identity preservation, Cue-Tracker achieves the highest score of 77.00, indicating its strong capability in maintaining identity consistency across frames. It also records a high HOTA score of 62.1, reflecting a balanced improvement in detection and association accuracy. Furthermore, Cue-Tracker maintains competitive false positives (24,386) and false negatives (105,408), demonstrating its robustness in handling crowded scenes while minimizing missed or incorrect detections. Although its ID switch count (1752) is slightly higher than a few methods like kalman_pub (680), the significant gain in overall accuracy and identity tracking makes Cue-Tracker a more reliable choice for real-world multi-object tracking scenarios. Table 9 shows the results from the official MOT server on the test set of MOT20.

4.7 Qualitative Analysis of Multi-Object Tracking Performance

To complement the quantitative evaluation, we conduct a qualitative analysis to visually assess the tracking performance.

To provide a more intuitive validation of our method’s capability in handling occlusion and preserving identity during tracking, we tested it on the MOT17-06-SDP and MOT17-01-DPM video sequences from the MOT17 benchmark.

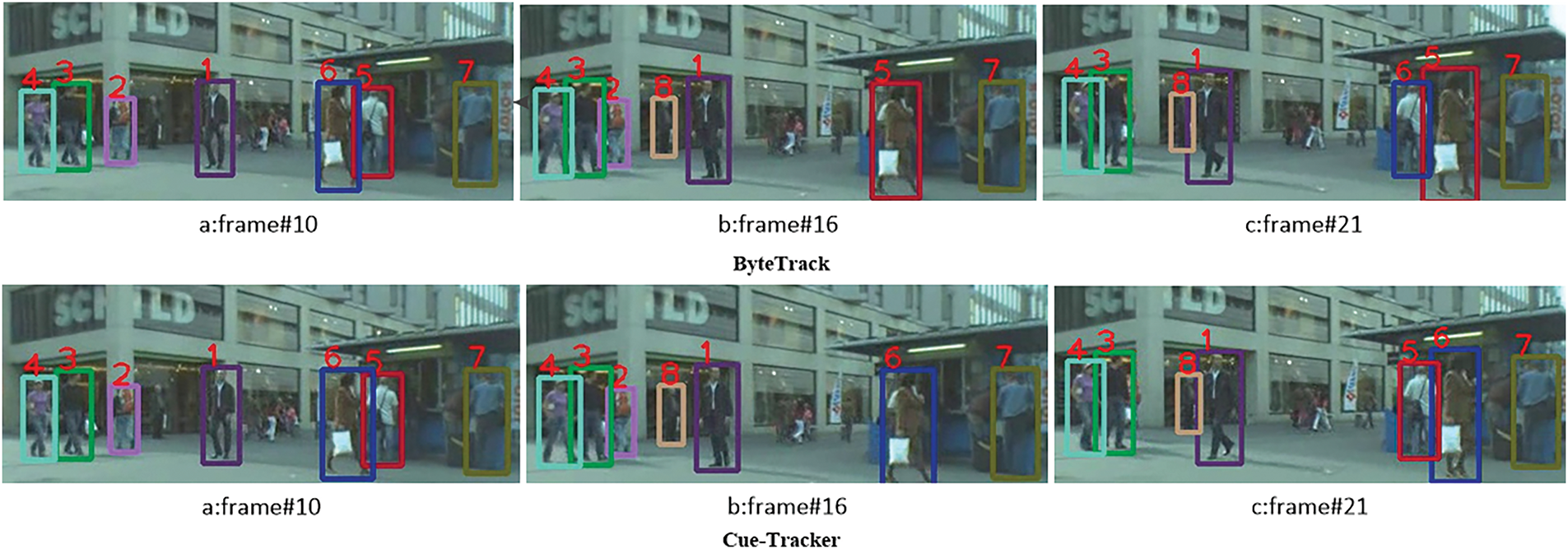

In the test set video MOT17-06-SDP from the MOT challenge, as shown in Fig. 3, the BYTETrack method struggles to maintain consistent pedestrian identities after occlusion, particularly for individuals with IDs 5 and 6. The top row of Fig. 3 displays the results from the baseline tracker (BYTETrack), while the bottom row shows the results from our Cue-Tracker. In frame 10, both the baseline and Cue-Tracker correctly track the pedestrians without any issues. However, by frame 16, in the baseline BYTETrack, pedestrian ID-6 occludes pedestrian ID-5. When ID-5 reappears in frame 21, it is assigned a new identity, indicating a failure to preserve the original ID. In contrast, our Cue-Tracker successfully assigns the original IDs to both pedestrians even after occlusion. This demonstrates the superior ability of our method to maintain identity continuity and robustly handle occlusion in multi-object tracking scenarios.

Figure 3: Re-identification of persons with ID-5 and ID-6 after occlusion using cue-tracker on test set video MOT17-06-SDP

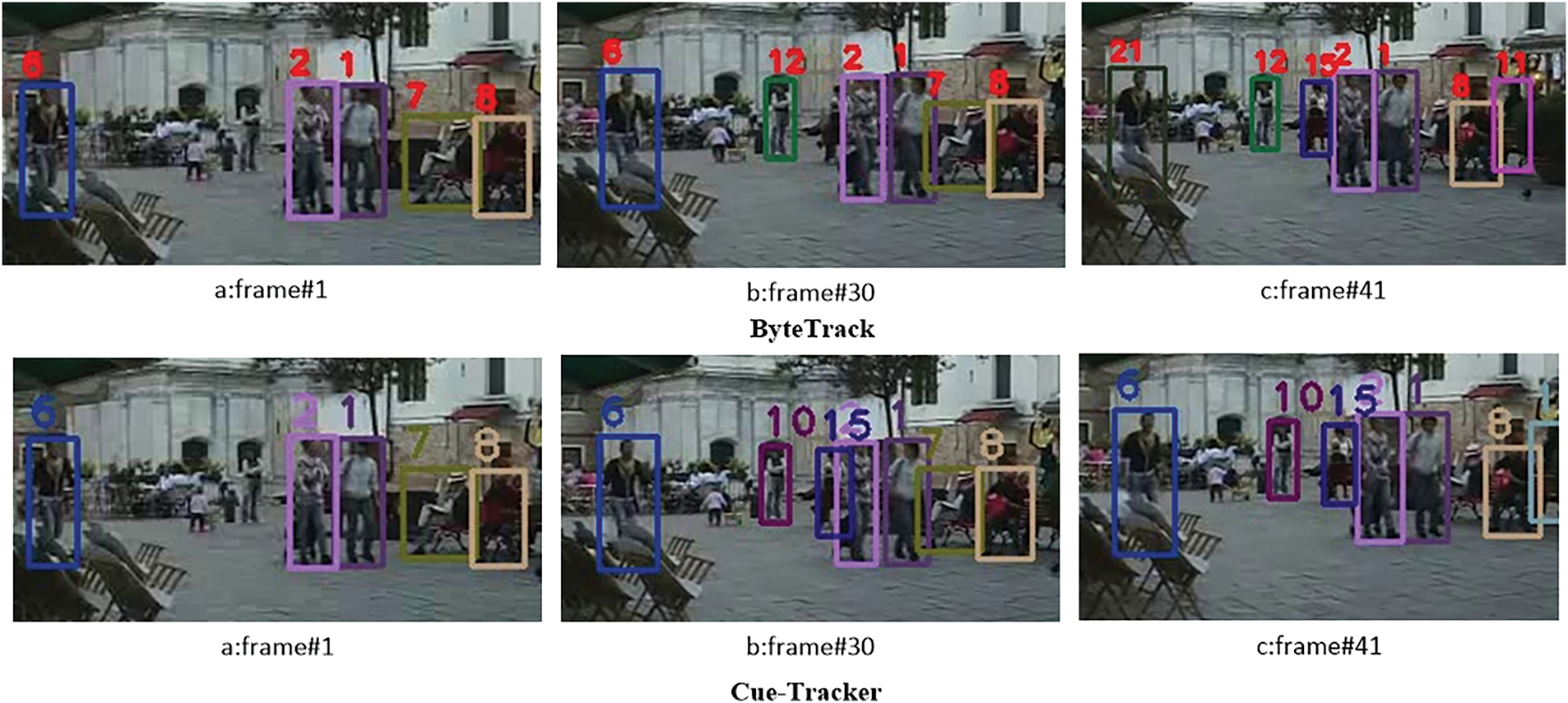

In the test set video ‘MOT17-01-DPM’ from the MOT challenge, the case for pedestrian with ID-6 differs from the typical occlusion scenario. As shown in Fig. 4, the individual with ID-6 lost the identity starting from frame 41 using BYTETrack, likely due to the challenging low-light background, rather than a brief occlusion. This causes the tracker to misidentify the pedestrian after a few frames. In contrast, our Cue-Tracker method consistently maintains the correct identity for pedestrian with ID-6 across all frames from frame 1 to onward, even in the difficult lighting conditions. This again highlights the superior performance of our approach in handling identity preservation under challenging environmental factors, such as low lighting, where other trackers might struggle.

Figure 4: Maintaining the identity of person with ID-6 across all frames using Cue-Tracker for preserving IDF1 score on Test Set Video MOT17-01-DPMr

Multi-object tracking systems predominantly rely on appearance features for association, yet such dependence often leads to degraded performance in challenging scenarios, including occlusions, crowded scenes, and motion blur. These limitations manifest as frequent identity switches and diminished tracking robustness, undermining the reliability of existing trackers in real-world applications. This work introduces Cue-Tracker, a robust two-stage association framework that strategically integrates strong FastReID-based appearance embeddings with enhanced spatial cues, such as object height and scale modulation, to improve association accuracy under difficult conditions. By leveraging this hybrid approach, Cue-Tracker achieves superior identity consistency and reduces identity switches, as validated by extensive evaluations on the MOT17 and MOT20 benchmarks. Our method outperforms existing baselines, demonstrating notable gains in key metrics, including MOTA, IDF1, IDs, and HOTA. These results highlight the critical role of integrating complementary appearance and spatial cues to address persistent challenges in multi-object tracking. Although this study focuses on pedestrian tracking using the MOT17 and MOT20 datasets, we acknowledge that the height-based geometric assumption in HMSIoU may not generalize well to other object categories such as vehicles or animals. These classes exhibit greater variation in shape and viewpoint, where alternative cues like aspect ratio or width may be more informative. As future work, we plan to extend Cue-Tracker with class-aware or adaptive geometric features to enhance its applicability across diverse tracking scenarios.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Sheeba Razzaq; draft manuscript preparation and review: Majid Khan. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Qin Z, Zhou S, Wang L, Duan J, Hua G, Tang W. MotionTrack: learning robust short-term and long-term motions for multi-object tracking. In: 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2023 Jun 17–24; Vancouver, BC, Canada: IEEE. p. 17939–48. doi:10.1109/CVPR52729.2023.01720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Bochinski E, Eiselein V, Sikora T. High-speed tracking-by-detection without using image information. In: 2017 14th IEEE International Conference on Advanced Video and Signal Based Surveillance (AVSS); 2017 Aug 29–Sep 1; Lecce, Italy: IEEE. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/AVSS.2017.8078516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Ren H, Han S, Ding H, Zhang Z, Wang H, Wang F. Focus on details: online multi-object tracking with diverse fine-grained representation. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2023 Jun 17–24; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 11289–98. [Google Scholar]

4. Saleh K, Szenasi S, Vamossy Z. Occlusion handling in generic object detection: a review. In: 2021 IEEE 19th World Symposium on Applied Machine Intelligence and Informatics (SAMI); 2021 Jan 21–23; Herl’any, Slovakia: IEEE. p. 000477–84. doi:10.1109/sami50585.2021.9378657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Bewley A, Ge Z, Ott L, Ramos F, Upcroft B. Simple online and realtime tracking. In: 2016 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP); 2016 Sep 25–28; Phoenix, AZ, USA: IEEE. p. 3464–8. doi:10.1109/ICIP.2016.7533003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Kilicarslan M, Zheng JY. DeepStep: direct detection of walking pedestrian from motion by a vehicle camera. IEEE Trans Intell Veh. 2023;8(2):1652–63. doi:10.1109/TIV.2022.3186962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Kim IS, Choi HS, Yi KM, Choi JY, Kong SG. Intelligent visual surveillance—a survey. Int J Control Autom Syst. 2010;8(5):926–39. doi:10.1007/s12555-010-0501-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Leon F, Gavrilescu M. A review of tracking and trajectory prediction methods for autonomous driving. Mathematics. 2021;9(6):660. doi:10.3390/math9060660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Moon S, Lee J, Nam D, Kim H, Kim W. A comparative study on multi-object tracking methods for sports events. In: 2017 19th International Conference on Advanced Communication Technology (ICACT); 2017 Feb 19–22; PyeongChang, Republic of Korea: IEEE. p. 883–5. [Google Scholar]

10. Nguyen, D.D, Rohacs, J, Rohacs, D. Autonomous flight trajectory control system for drones in smart city traffic management. ISPRS Int J Geo-Inf. 2021;10(5):338. doi:10.3390/ijgi10050338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Guan Z, Wang Z, Zhang G, Li L, Zhang M, Shi Z, et al. Multi-object tracking review: retrospective and emerging trend. Artif Intell Rev. 2025;58(8):235. doi:10.1007/s10462-025-11212-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Chen Z, Peng C, Liu S, Ding W. Visual object tracking: review and challenges. Appl Soft Comput. 2025;177(6):113140. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2025.113140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Cao J, Pang J, Weng X, Khirodkar R, Kitani K. Observation-centric SORT: rethinking SORT for robust multi-object tracking. In: 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2023 Jun 17–24; Vancouver, BC, Canada: IEEE. p. 9686–96. doi:10.1109/CVPR52729.2023.00934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Hashempoor H, Koikara R, Hwang YD. FeatureSORT: essential features for effective tracking. arXiv:2407.04249. 2024. [Google Scholar]

15. Aharon N, Orfaig R, Bobrovsky BZ. BoT-SORT: robust associations multi-pedestrian tracking. arXiv:2206.14651. 2022. [Google Scholar]

16. Wojke N, Bewley A, Paulus D. Simple online and realtime tracking with a deep association metric. In: 2017 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP); 2017 Sep 17–20; Beijing, China: IEEE. p. 3645–9. doi:10.1109/ICIP.2017.8296962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Zhang Y, Sun P, Jiang Y, Yu D, Weng F, Yuan Z, et al. ByteTrack: multi-object tracking by associating every detection box. In: Computer Vision—ECCV 2022—17th European Conference; 2022 Oct 23–27; Tel Aviv, Israel. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2022. p. 1–21. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-20047-2_1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Xiang Y, Alahi A, Savarese S. Learning to track: online multi-object tracking by decision making. In: 2015 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2015 Dec 7–13; Santiago, Chile: IEEE. p. 4705–13. doi:10.1109/ICCV.2015.534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Zhu J, Yang H, Liu N, Kim M, Zhang W, Yang MH. Online multi-object tracking with dual matching attention networks. In: Computer Vision—ECCV 2018: 15th European Conference; 2018 Sep 8–14; Munich, Germany. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 2018. p. 379–96. [Google Scholar]

20. Zhou X, Koltun V, Krhenbhl P. Tracking objects as points. In: Computer Vision—ECCV 2020: 16th European Conference; 2020 Aug 23–28; Glasgow, UK. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 2020. p. 474–90. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-58548-8_28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Shim K, Ko K, Yang Y, Kim C. Focusing on tracks for online multi-object tracking. In: 2025 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2025 Jun 10–17; Nashville, TN, USA: IEEE. p. 11687–96. doi:10.1109/CVPR52734.2025.01091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Wang Y, Zhang D, Li R, Zheng Z, Li M. PD-SORT: occlusion-robust multi-object tracking using pseudo-depth cues. IEEE Trans Consum Electron. 2025;71(1):165–77. doi:10.1109/TCE.2025.3541839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Dicle C, Camps OI, Sznaier M. The way they move: tracking multiple targets with similar appearance. In: 2013 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision; 2013 Dec 1–8; Sydney, NSW, Australia: IEEE. p. 2304–11. doi:10.1109/ICCV.2013.286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Mahmoudi N, Ahadi SM, Rahmati M. Multi-target tracking using CNN-based features: CNNMTT. Multimed Tools Appl. 2019;78(6):7077–96. doi:10.1007/s11042-018-6467-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Zheng L, Zhang H, Sun S, Chandraker M, Yang Y, Tian Q. Person re-identification in the wild. In: 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA: IEEE. p. 3346–55. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2017.357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Luo H, Gu Y, Liao X, Lai S, Jiang W. Bag of tricks and a strong baseline for deep person re-identification. In: 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW); 2019 Jun 16–17; Long Beach, CA, USA: IEEE. p. 1487–95. doi:10.1109/cvprw.2019.00190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. McLaughlin N, del Rincon JM, Miller P. Dense multiperson tracking with robust hierarchical linear assignment. IEEE Trans Cybern. 2015;45(7):1276–88. doi:10.1109/TCYB.2014.2348314. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Sadeghian A, Alahi A, Savarese S. Tracking the untrackable: learning to track multiple cues with long-term dependencies. In: 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2017 Oct 22–29; Venice, Italy: IEEE. p. 300–11. doi:10.1109/ICCV.2017.41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Chen L, Ai H, Zhuang Z, Shang C. Real-time multiple people tracking with deeply learned candidate selection and person re-identification. In: 2018 IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo (ICME); 2018 Jul 23–27; San Diego, CA, USA: IEEE. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/ICME.2018.8486597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Yang M, Han G, Yan B, Zhang W, Qi J, Lu H, et al. Hybrid-SORT: weak cues matter for online multi-object tracking. In: Proceedings of the Thirty-Eighth AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Thirty-Sixth Conference on Innovative Applications of Artificial Intelligence and Fourteenth Symposium on Educational Advances in Artificial Intelligence; 2024 Feb 20–27; Vancouver, BC, Canada: AAAI Press. p. 723–31. [Google Scholar]

31. Wang Z, Zheng L, Liu Y, Li Y, Wang S. Towards real-time multi-object tracking. In: Computer Vision—ECCV 2020: 16th European Conference; 2020 Aug 23–28; Glasgow, UK. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 2020. p. 107–22. [Google Scholar]

32. Zhang Y, Wang C, Wang X, Zeng W, Liu W. FairMOT: on the fairness of detection and re-identification in multiple object tracking. Int J Comput Vis. 2021;129(11):3069–87. doi:10.1007/s11263-021-01513-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Liang C, Zhang Z, Zhou X, Li B, Zhu S, Hu W. Rethinking the competition between detection and ReID in multiobject tracking. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2022;31:3182–96. doi:10.1109/TIP.2022.3165376. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Pang J, Qiu L, Li X, Chen H, Li Q, Darrell T, et al. Quasi-dense similarity learning for multiple object tracking. In: 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2021 Jun 20–25; Nashville, TN, USA: IEEE. p. 164–73. doi:10.1109/CVPR46437.2021.00023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Wen L, Li W, Yan J, Lei Z, Yi D, Li SZ. Multiple target tracking based on undirected hierarchical relation hypergraph. In: 2014 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2014 Jun 23–28; Columbus, OH, USA: IEEE. p. 1282–9. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2014.167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Zhang L, Li Y, Nevatia R. Global data association for multi-object tracking using network flows. In: 2008 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2008 Jun 23–28; Anchorage, AK, USA: IEEE. p. 1–8. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2008.4587584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Berclaz J, Fleuret F, Turetken E, Fua P. Multiple object tracking using K-shortest paths optimization. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2011;33(9):1806–19. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2011.21. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Hornakova A, Henschel R, Rosenhahn B, Swoboda P. Lifted disjoint paths with application in multiple object tracking. In: Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICMLICML'20; 2020 Jul 13–18; Virtual Event. p. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

39. Meinhardt T, Kirillov A, Leal-Taix L, Feichtenhofer C. TrackFormer: multi-object tracking with transformers. In: 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2022 Jun 18–24; New Orleans, LA, USA: IEEE. p. 8834–44. doi:10.1109/CVPR52688.2022.00864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Zeng F, Dong B, Zhang Y, Wang T, Zhang X, Wei Y. MOTR: end-to-end multiple-object tracking with transformer. arXiv:2105.03247. 2021. [Google Scholar]

41. Zhang Y, Wang T, Zhang X. MOTRv2: bootstrapping end-to-end multi-object tracking by pretrained object detectors. arXiv:2211.09791. 2022. [Google Scholar]

42. Zheng Z, Wang P, Liu W, Li J, Ye R, Ren D. Distance-IoU loss: faster and better learning for bounding box regression. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2020;34(7):12993–3000. doi:10.1609/aaai.v34i07.6999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Milan A, Leal-Taix L, Reid ID, Roth S, Schindler K. MOT16: a benchmark for multi-object tracking. arXiv:1603.00831. 2016. [Google Scholar]

44. Dendorfer P, Rezatofighi H, Milan A, Shi J, Cremers D, Reid I, et al. MOT20: a benchmark for multi object tracking in crowded scenes. arXiv:2003.09003. 2020. [Google Scholar]

45. Zhu X, Su W, Lu L, Li B, Wang X, Dai J. Deformable DETR: deformable transformers for end-to-end object detection. In: 9th International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2021; 2021 May 3–7; Virtual Event, Austria. [Google Scholar]

46. Bernardin K, Stiefelhagen R. Evaluating multiple object tracking performance: the CLEAR MOT metrics. EURASIP J Image Video Process. 2008;2008(1):246309. doi:10.1155/2008/246309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Wang M, Shi F, Zhao M, Jia C, Tian W, He T, et al. An online multiobject tracking network for autonomous driving in areas facing epidemic. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2022;23(12):25191–200. doi:10.1109/TITS.2022.3195183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Abdulghafoor NH, Abdullah HN. A novel real-time multiple objects detection and tracking framework for different challenges. Alex Eng J. 2022;61(12):9637–47. doi:10.1016/j.aej.2022.02.068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Fischer T, Huang TE, Pang J, Qiu L, Chen H, Darrell T, et al. QDTrack: quasi-dense similarity learning for appearance-only multiple object tracking. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2023;45(12):15380–93. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2023.3301975. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Girbau A, Gir-i-Nieto X, Rius I, Marqus F. Multiple object tracking with mixture density networks for trajectory estimation. arXiv:2106.10950. 2021. [Google Scholar]

51. Liu Q, Chen D, Chu Q, Yuan L, Liu B, Zhang L, et al. Online multi-object tracking with unsupervised re-identification learning and occlusion estimation. Neurocomputing. 2022;483(4):333–47. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2022.01.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Zeng K, You Y, Shen T, Wang Q, Tao Z, Wang Z, et al. NCT: noise-control multi-object tracking. Complex Intell Syst. 2023;9(4):4331–47. doi:10.1007/s40747-022-00946-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Boragule A, Jang H, Ha N, Jeon M. Pixel-guided association for multi-object tracking. Sensors. 2022;22(22):8922. doi:10.3390/s22228922. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Xu Y, Ban Y, Delorme G, Gan C, Rus D, Alameda-Pineda X. TransCenter: transformers with dense queries for multiple-object tracking. arXiv:2103.15145. 2021. [Google Scholar]

55. Tokmakov P, Li J, Burgard W, Gaidon A. Learning to track with object permanence. In: 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2021 Oct 10–17; Montreal, QC, Canada: IEEE. p. 10840–9. doi:10.1109/ICCV48922.2021.01068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Hu Y, Niu A, Zhu Y, Yan Q, Sun J, Zhang Y. Multiple object tracking based on occlusion-aware embedding consistency learning. In: ICASSP 2024—2024 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2024 Apr 14–19; Seoul, Republic of Korea: IEEE. p. 9521–5. doi:10.1109/ICASSP48485.2024.10446647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Bergmann P, Meinhardt T, Leal-Taixe L. Tracking without bells and whistles. In: 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2019 Oct 27–Nov 2; Seoul, Republic of Korea: IEEE. p. 941–51. doi:10.1109/iccv.2019.00103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Stadler D, Beyerer J. On the performance of crowd-specific detectors in multi-pedestrian tracking. In: 2021 17th IEEE International Conference on Advanced Video and Signal Based Surveillance (AVSS); 2021 Nov 16–19; Washington, DC, USA: IEEE. p. 1–12. doi:10.1109/avss52988.2021.9663836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Yu E, Li Z, Han S, Wang H. RelationTrack: relation-aware multiple object tracking with decoupled representation. IEEE Trans Multimed. 2023;25:2686–97. doi:10.1109/TMM.2022.3150169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. You S, Yao H, Bao BK, Xu C. UTM: a unified multiple object tracking model with identity-aware feature enhancement. In: 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2023 Jun 17–24; Vancouver, BC, Canada: IEEE. p. 21876–86. doi:10.1109/CVPR52729.2023.02095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Kawanishi Y. Label-based multiple object ensemble tracking with randomized frame dropping. In: 2022 26th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR); Aug 21–25; Montreal, QC, Canada: IEEE. p. 900–6. doi:10.1109/ICPR56361.2022.9956158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Cetintas O, Brasó G, Leal-Taixé L. Unifying short and long-term tracking with graph hierarchies. In: 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2023 Jun 17–24; Vancouver, BC, Canada: IEEE. p. 22877–87. doi:10.1109/CVPR52729.2023.02191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Stadler D, Beyerer J. Multi-pedestrian tracking with clusters. In: 2021 17th IEEE International Conference on Advanced Video and Signal Based Surveillance (AVSS); 2021 Nov 16–19; Washington, DC, USA: IEEE. p. 1–10. doi:10.1109/avss52988.2021.9663829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools