Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Prompt-Guided Dialogue State Tracking with GPT-2 and Graph Attention

1 School of Computer Science and Engineering, Southeast University, Nanjing, 211189, China

2 Department of AI and Data Science, Sejong University, Seoul, 05006, Republic of Korea

3 Department of Electronics and Communication Engineering, National Institute of Technology, Rourkela, 769008, India

4 Department of Computer Science, Shaheed Benazir Bhutto University, Sheringal, 18050, Pakistan

5 Department of Computer Science, University of Engineering and Technology, Mardan, 23200, Pakistan

6 School of Computing, Gachon University, Seongnam, 13120, Republic of Korea

7 Department of Informatics, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, 54124, Greece

* Corresponding Authors: Jawad Khan. Email: ; Yeong Hyeon Gu. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(3), 5451-5468. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.069134

Received 15 June 2025; Accepted 29 August 2025; Issue published 23 October 2025

Abstract

Dialogue State Tracking (DST) is a critical component of task-oriented spoken dialogue systems (SDS), tasked with maintaining an accurate representation of the conversational state by predicting slots and their corresponding values. Recent advances leverage Large Language Models (LLMs) with prompt-based tuning to improve tracking accuracy and efficiency. However, these approaches often incur substantial computational and memory overheads and typically address slot extraction implicitly within prompts, without explicitly modeling the complex dependencies between slots and values. In this work, we propose PUGG, a novel DST framework that constructs schema-driven prompts to fine-tune GPT-2 and utilizes its tokenizer to implement a memory encoder. PUGG explicitly extracts slot values via GPT-2 and employs Graph Attention Networks (GATs) to model and reason over the intricate relationships between slots and their associated values. We evaluate PUGG on four publicly available datasets, where it achieves state-of-the-art performance across multiple evaluation metrics, highlighting its robustness and generalizability in diverse conversational scenarios. Our results indicate that the integration of GPT-2 substantially reduces model complexity and memory consumption by streamlining key processes. Moreover, prompt tuning enhances the model’s flexibility and precision in extracting relevant slot-value pairs, while the incorporation of GATs facilitates effective relational reasoning, leading to improved dialogue state representations.Keywords

Spoken Dialogue Systems (SDS) have witnessed significant advancements, transforming human-computer interaction by enabling natural and seamless communication [1,2]. These systems support a wide range of applications, from simple inquiries to complex information retrieval tasks, by interpreting and responding to spoken inputs [3]. Core components of SDS include Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR) for transcribing speech, Spoken Language Understanding (SLU) for semantic interpretation, Dialogue State Tracking (DST) for maintaining and updating the dialogue context, Dialogue Policy for deciding system actions, Natural Language Generation (NLG) for producing conversational text, and Text-to-Speech (TTS) for vocalizing responses [4,5]. Among these, DST plays a pivotal role by continuously extracting slots and their associated values to represent the user’s goals and intentions, ensuring coherent dialogue management across diverse interactions [6,7].

DST has evolved from early single-domain systems [8], designed for specific tasks such as restaurant reservations [9] or flight bookings, to sophisticated multidomain approaches that handle multiple topics simultaneously [10,11]. This shift addresses the growing demand for flexible, scalable SDS capable of tracking user preferences across diverse domains within a single conversation, thereby enhancing user experience [12,13].

More recently, Large Language Models (LLMs) have substantially advanced DST by enabling nuanced, context-aware dialogue management [14]. These models generate human-like text and improve dialogue coherence and accuracy [12], facilitating effective user goal tracking across domains [15]. ECDG-DST [16] and HS2DG-DST [17] focus on efficient context modeling and hierarchical slot selection but do not integrate prompt-based tuning or lightweight LLMs. Our method uniquely combines schema-guided prompting with GPT-2 and Graph Attention Networks, enabling explicit slot extraction and interpretable reasoning with reduced computational cost. Prompt tuning has emerged as a powerful fine-tuning technique that adapts LLMs to DST with minimal labeled data, leveraging pre-trained knowledge efficiently. However, prompt sensitivity remains a challenge, often causing performance variability and underscoring the need for robust prompt design [7,18].

Despite these advances, current prompt-based LLM approaches exhibit limitations. Many models jointly extract slots and values without explicitly modeling slots as distinct entities, which can propagate errors and degrade performance [6,10,19]. For example, while prompt-based few-shot methods [12,20,21] demonstrate promising results, they often lack mechanisms for separate slot extraction. End-to-end prompt tuning frameworks [7,15,22] further overlook explicit slot handling, which can limit interpretability and accuracy. Additionally, prompt designs that rely on implicit slot-value extraction or simplistic instructions introduce variability and inconsistency in results.

Moreover, state-of-the-art LLMs such as LLaMA, GPT-3, GPT-3.5 Turbo, and ChatGPT demand substantial computational resources due to their large parameter counts [14,15], and some are closed-source, restricting customization [12]. Furthermore, these models may occasionally produce inconsistent outputs, such as misrepresenting time values (e.g., “4:00 p.m.” as “16:00”) [12].

Coreference resolution in DST remains challenging due to the dynamic nature of dialogue and the requirement for deep contextual reasoning [7,23]. Prior work has addressed this by employing dynamically adjusted prompt tuning [7] and entity-adaptive pre-training [23] to improve reference linking. Nonetheless, the core objective of DST—to accurately extract slots and values—necessitates frameworks that not only tackle coreference but also explicitly optimize slot-value extraction.

Motivated by these gaps, we propose a novel framework extending our prior work [19] by integrating prompt tuning algorithms that automatically optimize prompts across tasks and domains. Our approach leverages Graph Attention Networks (GATs) to explicitly model complex slot-value relationships, enhancing interpretability and relational reasoning within DST. Unlike large LLMs, we utilize GPT-2, which offers a favorable balance between performance and computational efficiency, making the approach practical for real-time deployment. We further adopt a separate slot extraction strategy [6,10,24] to better handle multiple slots and reduce computational overhead.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first work to combine prompt-based GPT-2 with GATs for dialogue state tracking. Our key contributions are summarized as follows:

• We design a schema-based prompt template that improves slot-value extraction with GPT-2 by explicitly separating slot extraction, thereby enhancing handling of multiple slots and increasing robustness through reduced model complexity.

• We employ Graph Attention Networks to model intricate slot-value interactions using an embedding aggregator and residual blocks, which refine predictions by jointly optimizing GAT and GPT-2 outputs.

• We conduct extensive evaluations against state-of-the-art baselines across four benchmark datasets, demonstrating significant improvements in joint goal accuracy, slot accuracy, average goal accuracy, and joint turn accuracy.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews recent related studies; Section 3 details the proposed methodology; Section 4 describes experimental setup and evaluation protocols; Section 5 presents and analyzes results; finally, Section 6 concludes the paper.

The recent literature on dialogue state tracking (DST) can be broadly categorized into three main paradigms: static traditional approaches (rule-based and statistical), deep learning (DL) methods (neural networks leveraging large language models), and hybrid frameworks that combine DL with graph-based techniques. This section reviews seminal and state-of-the-art contributions under these categories, emphasizing their key methodologies, strengths, and limitations.

2.1 Static Traditional Approaches

Early DST systems predominantly employed rule-based and statistical methodologies [25]. Rule-based approaches, such as the GENR belief tracker [26], relied on handcrafted, domain-independent rules without requiring external knowledge sources. Similarly, the SJTU system [27], introduced during the second DST Challenge (DSTC), combined rule-based heuristics with a statistical semantic parser and integrated classifiers including Maximum Entropy and deep neural networks. Unlike pure rule-based models [26], SJTU leveraged data-driven insights for enhanced state tracking. Statistical models based on Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) and Partially Observable Markov Decision Processes (POMDPs) [28] provided probabilistic dialogue state estimation but faced scalability challenges when addressing large state spaces. Bayesian Update of Dialogue State (BUDS) [29] improved expressiveness using Bayesian networks, while Conditional Random Fields (CRFs) [30] enabled joint modeling of dialogue states and acts, enhancing prediction accuracy by exploiting sequence dependencies. Despite their foundational role, traditional approaches often suffer from limited capacity to model complex, multi-turn dialogues due to reliance on sparse representations and handcrafted features. In contrast, our method employs dense contextual embeddings via GPT-2 and leverages Graph Attention Networks (GATs) to explicitly model intricate slot-value relationships, enabling more robust and coherent dialogue state representations.

Neural network-based methods have revolutionized DST by leveraging contextual embeddings and attention mechanisms. Pre-trained models such as BERT [31] have been effectively applied for slot filling and intent detection across diverse, schema-guided dialogues, demonstrating improved generalization and robustness. Hong et al. [32] proposed a unified multi-task framework to jointly learn domain knowledge and user intents, enhancing comprehension of complex dialogues. In-context learning techniques [33] have shown promise in adapting to novel tasks with limited data, addressing low-resource constraints. Attention-based models such as MA-DST [34] employ multi-attention layers to capture dependencies between dialogue components, improving multi-domain state tracking.

Furthermore, DST approaches of the cross model [35] and multimodal LLM [36,37] incorporate visual and textual inputs for enriched dialogue context modeling. However, these methods typically demand significant computational resources and careful tuning, limiting their applicability in real-time or resource-constrained environments. The emergence of large language models (LLMs) has further advanced DST by enabling adaptive fine-tuning through prompt tuning [12,20]. Techniques such as continual and dual prompt tuning [21,22] dynamically adapt models to evolving dialogue contexts, while parameter-efficient tuning [18] supports low-resource adaptation. Models like DSTEA [23] utilize entity-adaptive pre-training to improve entity relationship modeling, thereby enhancing slot-value extraction accuracy. Nevertheless, these LLM-based approaches may face challenges in consistency, scalability, and computational efficiency, particularly when handling multi-domain, multi-turn dialogues. Related work on structured motion generation [38] and multilingual attention [39] highlights the need for schema-guided alignment in complex generative tasks. Our approach addresses these limitations by combining GATs with prompt-tuned GPT-2, focusing on precise and separate extraction of slots and values, while capturing complex inter-slot dependencies dynamically. This integration promotes efficient and interpretable DST without the heavy computational footprint of larger LLMs. Unlike vision-language or physics-based foundation model applications [36,37], our work focuses on structured language understanding for dialogue systems, where schema-guided prompting and slot-value alignment are central.

Hybrid methods integrate graph neural networks (GNNs), such as Graph Attention Networks (GATs) [40] and Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs), with neural language models to leverage structural dialogue information. Lin et al. [41] enriched GPT-2 with external knowledge graphs to resolve ambiguity and enhance dialogue state accuracy. Similarly, Yu and Ko [42] employed discourse graphs to represent syntactic dependencies, facilitating improved dialogue state prediction. Schema and context fusion networks [43] utilized GCNs to integrate multi-domain dialogue information effectively, enhancing robustness and scalability. Zhao et al. [44] proposed a multi-task framework employing GATs to maintain dialogue coherence across tasks. Huang et al. [45] combined multi-perspective graph convolution with multi-agent reinforcement learning and gated recurrent units (GRUs) to model diverse dialogue perspectives. While these hybrid models better capture complex dialogue structures, they often demand extensive annotated data and suffer from high computational complexity. Our framework advances this line of work by employing prompt tuning to mitigate data dependency and GPT-2 to ensure computational efficiency. Crucially, we adopt a separate slot extraction mechanism within a unified GPT-2 architecture, thereby reducing memory usage and computational cost without sacrificing accuracy.

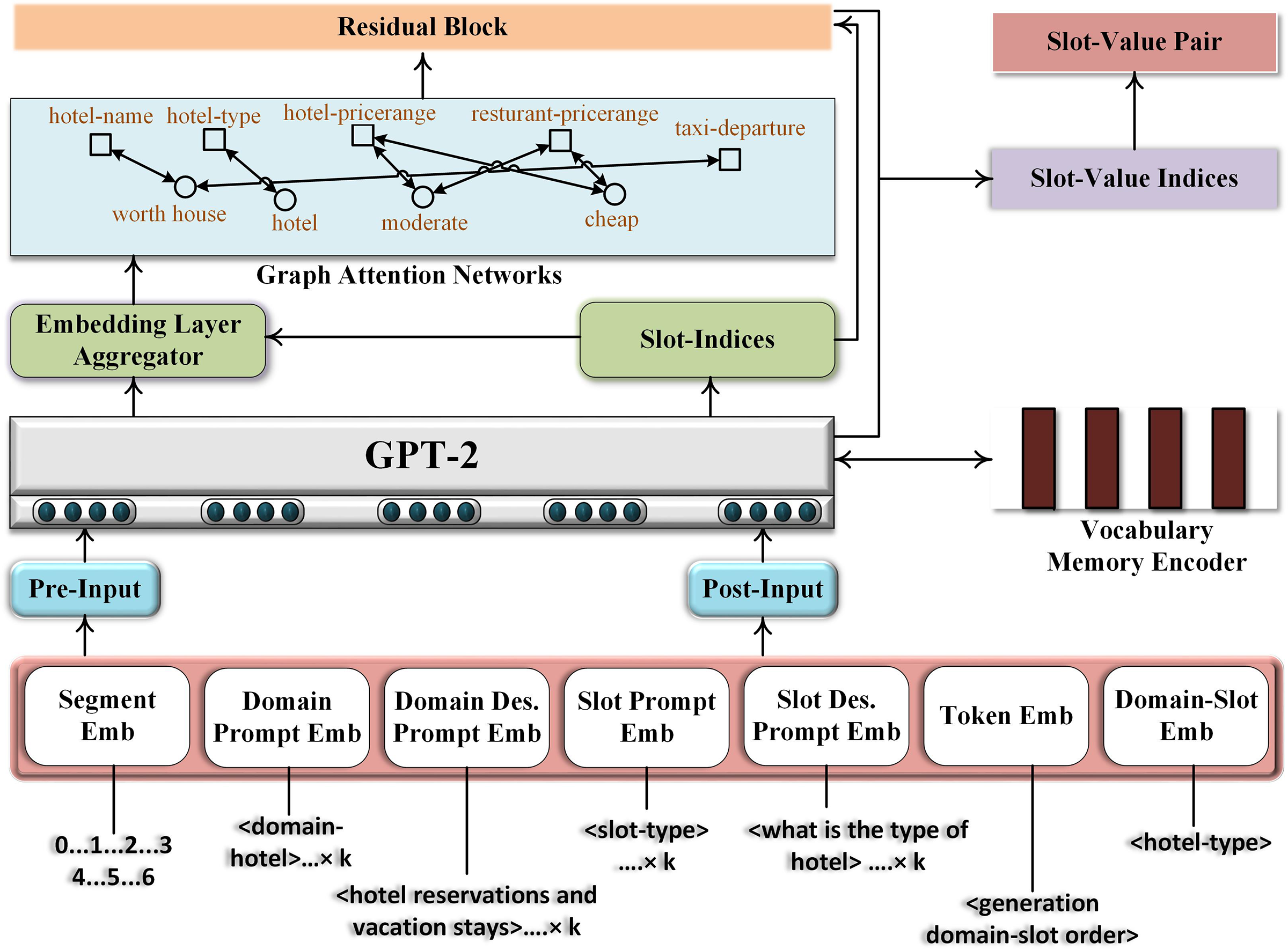

This section presents our proposed model, depicted in Fig. 1. The model processes the following tasks: (1) prompt tuning generates prompts for domains and slots. (2) GPT-2 creates a vocabulary memory encoder and extracts slot and slot-values. (3) GAT creates the relationship among the slots and values using an embedding layer aggregator. (4) The residual block handles the slots based on the output from the slot indices and GAT. (5) The indexer for slot-values retain the slots among their values generated by GPT-2 and GAT. (6) The losses for GPT-2 and GAT are calculated and added together.

Figure 1: A schematic view of the proposed model

The goal of the prompt tuning is to prompt a function that influences the GPT-2’s final extraction of slots and values. We construct the input sequence by concatenating the domain name, domain description, slot name, and slot description to formalize slot S for all examples. Each prompt has

We introduce domain detection technique to design prompt template

Domain descriptions, such as find touristy stuff to do around you, hotel reservations and vacation stays, are used from schema introduced by [46,47] for each domain.

For slot detection, prompt template

The results of domain and slot detection are aggregated to create a structured representation of token embedding

Aggregation may also involve additional processing steps such as normalization (e.g., converting dates to a standard format), validation (e.g., ensuring that the detected slots are semantically valid), and handling ambiguous or incomplete information.

The GPT-2 [48] tokenizer uses a Vocabulary Memory Encoder (VME) to enhance classification tasks by leveraging GPT-2’s extensive vocabulary. This approach addresses lexical and morphological ambiguities with specialized tokens for various dialogue elements, including system and user utterances, sentence boundaries, masking, and slot names followed by [19]. By integrating the entire lexicon from pre-trained GPT-2 model, the tokenizer benefits from GPT-2’s linguistic knowledge and can handle specialized terminology. A permanent vocabulary, once exported, can be reused across different datasets, reducing computational demands and enhancing consistency. The model can automatically process new values without pre-training, making it adaptable to unseen words and well-suited for cross-lingual and multilingual DST. This adaptability reflects trends observed in wearable voice authentication tasks [49], where flexible handling of user-dependent input is essential. The vocabulary captures key information such as current and historical dialogue context, slot information, and belief state, with a CLS-Label-Dict organizing slot values. This methodology streamlines model adaptation and enhances its versatility in processing diverse linguistic nuances.

GPT-2 is constructed based on the transformer architecture [48], which heavily relies on self-attention mechanisms. The transformer utilizes stacks of self-attention layers and feedforward neural networks to process utterances

The GPT-2 language model (LM) head then utilizes the last hidden state

In this expression, the

within this mathematical expression, the vector

To improve state prediction, an additional input is provided, which comprises system and user utterances represented as

where

We then use the GPT-2 language model (LM) head, similar to Eq. (5), to compute

Here, the GPT-2 language model generates the vocabulary output probabilities for each token at position

Graph Attention Networks (GATs) [40] link values associated with related slots from H, utilizing recursion with both current and prior states. Representing the graph as

where

where

Our model uses two recursive GAT layers with a fixed ontology size to match GPT-2’s vocabulary dimensions. This recursive representation design is conceptually similar to feature-aware triplet extraction with GCNs [50], and our use of uniform input shapes through padding ensures efficiency across training batches. The GAT input consists of same-size batches created via padding, slightly different than single batch [40].

3.7 Residual Blocks and Slot-Value Indexing

Residual blocks enable the model to learn slot features effectively by allowing gradients to flow through skip connections. For slot embedding

where F is a residual function (e.g., convolution or fully connected layers with activation) parameterized by

The slot-value indexer then associates slots with their values, maintaining consistency in the belief state across turns.

To jointly optimize the GPT-2 and GAT components, the total loss L is the sum of the individual losses:

where

This section details the experimental setup, including the datasets employed, baseline models for comparison, parameter configurations, and evaluation metrics.

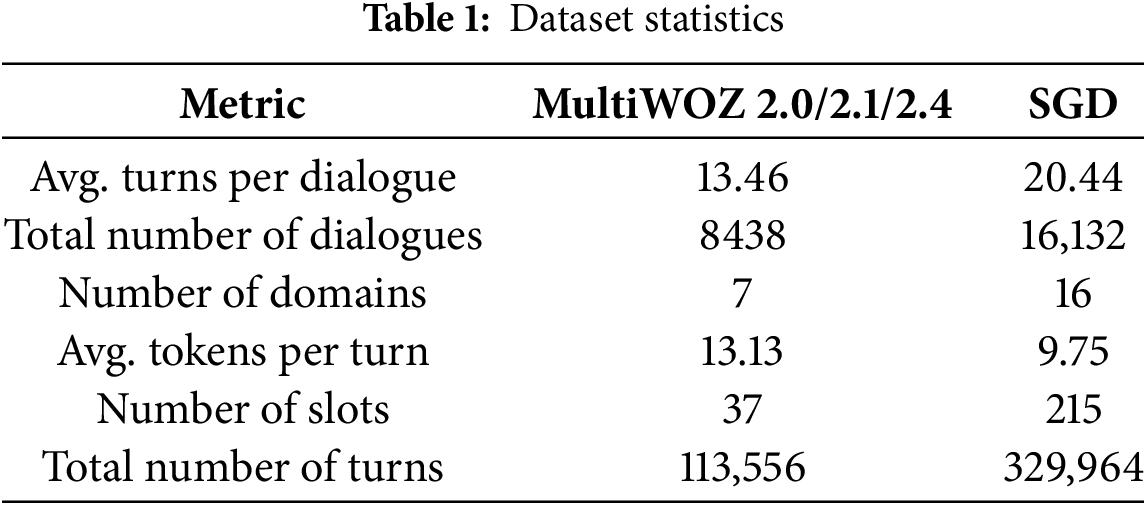

We conduct experiments on four publicly available multi-domain Dialogue State Tracking (DST) datasets: Schema-Guided Dialogue (SGD) [47], MultiWOZ 2.0 [51], MultiWOZ 2.1 [1], and MultiWOZ 2.4 [52]. The MultiWOZ datasets have been preprocessed following established protocols: MultiWOZ 2.0 and 2.1 as per [24], and MultiWOZ 2.4 according to [6]. These datasets contain over 10,000 dialogues spanning seven domains and 35 domain-slot pairs. MultiWOZ 2.0 is among the largest task-oriented dialogue datasets but contains annotation errors, which were progressively corrected in MultiWOZ 2.1 and further refined in MultiWOZ 2.4, especially for validation and test splits.

For our experiments, we focus on five domains and 30 domain-slot pairs following the protocols of [6,10,13], excluding the police and hospital domains due to their sparsity in training data and absence in validation/test sets. The SGD dataset comprises over 16,000 annotated multi-domain dialogues spanning 26 services and 16 domains, designed specifically to evaluate zero-shot generalization capabilities to unseen services.

Table 1 summarizes key dataset statistics relevant to DST evaluation.

Our model leverages the GPT-2 architecture1 with 12 transformer layers, hidden dimension size of 768, 12 attention heads, and approximately 117 million parameters for pre-training. The learning rates were set to

We employ a range of established metrics to evaluate DST performance, with particular emphasis on Joint Goal Accuracy (JGA), the primary benchmark in DST. The metrics are defined as follows:

• Slot Accuracy (SA): Measures the system’s ability to correctly identify the presence or absence of each slot, independent of the slot’s value [10]. It is computed as the macro-averaged accuracy across all slots

• Joint Goal Accuracy (JGA): A key DST metric that measures the percentage of dialogue turns for which the model correctly predicts the entire set of slot-value pairs, reflecting complete and accurate dialogue state tracking [6,12,27].

• Average Turn Accuracy (ATA): The percentage of dialogue turns where the predicted dialogue state exactly matches the ground truth [10].

• Average Goal Accuracy (AGA): Measures the percentage of dialogue turns where the user’s intentions or goals are correctly predicted over the conversation [12].

• Classification Accuracy (CA): Assesses slot prediction precision by computing the ratio of correct predictions over total predictions for each slot [19].

• Not-None Classification Accuracy (NCA): Similar to CA but excludes predictions labeled as “none”, focusing on slots with assigned values [19].

4.4 Evaluation against Baseline Models

We benchmark our proposed model against a set of state-of-the-art (SOTA) DST approaches to validate its effectiveness:

• SOM-Assist [10] selectively updates dialogue state rather than rewriting it fully each turn, retaining previously accurate slot information unless new reliable updates occur.

• AUX-Assist [10] incorporates auxiliary loss functions on specific dialogue state components, such as domain and slot prediction, to stabilize and enhance training.

• STAR-Assist [24] combines self-training and auxiliary randomization techniques to mitigate label noise and improve robustness in DST.

• SOM-Meta [6] applies meta-learning to fine-tune SOM-DST’s selective memory mechanism for faster adaptation to dialogue variations.

• STAR-Meta [6] extends STAR with meta-learning to maintain high performance across diverse dialogue scenarios.

• Assist-Meta [6] leverages meta-learning to optimize auxiliary mechanisms under noisy or limited data conditions.

• ChatGPT [12] uses contextual embeddings from ChatGPT as input for dialogue state tracking to improve understanding of user intents and dialogue context.

• LDST variants such as LDST-LLaMa2-7B and LDST-LLaMa-30B [12] explore the effect of model scale on DST performance, with larger models capturing more complex state transitions.

• Instructtods-GPT4 [11] exploits large language model capabilities to extract intents and slot values directly from user utterances.

• LLaMa-2 [14] integrates LLaMa2 models (7, 13, 70B) with function calling for zero-shot DST, including FNCTOD-LLaMa2-13B and ChatGPT-GPT4, enhancing dialogue state updating.

• Proposed PUGG Model: Our model generates slot prompts and memory vocabularies, feeding dialogue context into GPT-2 to generate slot and slot-value pairs. These are further processed with embeddings through a GAT to model inter-slot relationships, and combined outputs update the slot-value indexer to maintain an accurate belief state.

This section presents a comprehensive evaluation of the proposed PUGG model compared with established baselines across three major datasets. We analyze overall performance metrics, domain-specific joint goal accuracy (JGA), confusion matrices, and classification accuracy measures including Not-None Accuracy (NCA) and Classification Accuracy (CA).

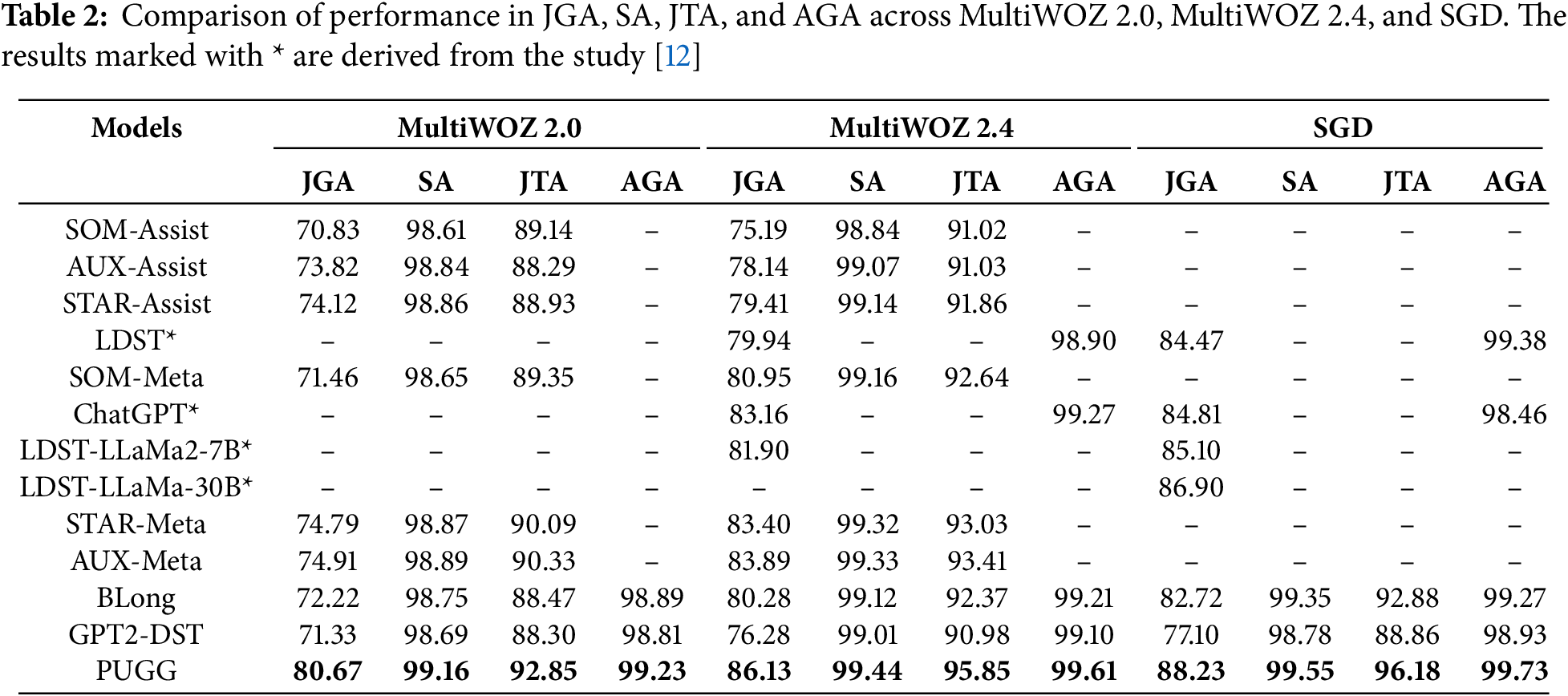

5.1 Comparative Results Analysis

Table 2 demonstrates that PUGG consistently outperforms all baselines across all datasets and metrics. Particularly on MultiWOZ 2.0, PUGG achieves improvements of 5.76% in JGA, 0.27% in SA, and 2.52% in JTA over the second-best model, underscoring its efficacy in joint slot-value tracking. The enhanced performance is attributed to PUGG’s innovative vocabulary memory encoder facilitating multilingual token representation and a Graph Attention Network (GAT) module that models complex slot-value dependencies. While SOM-Assist and GPT2-DST exhibit relatively lower performance, primarily due to open-vocabulary DST strategies and the absence of prompt tuning, respectively, BLong’s use of a Longformer backbone yields improved sequence modeling but still falls short of PUGG’s comprehensive approach. On MultiWOZ 2.4, baselines generally improve over their MultiWOZ 2.0 results. LDST’s employment of slot instructions and prompt templates contributes to notable gains, while ChatGPT leverages implicit slot generation through prompt engineering. Despite these advances, PUGG’s attention mechanisms and memory encoder maintain superiority, validating the model’s robustness. In the SGD dataset, PUGG again outperforms all competitors, including large-scale LDST variants and ChatGPT, achieving the highest scores. This is especially significant considering SGD’s domain diversity and complexity. PUGG’s modular architecture effectively mitigates error propagation and enables accurate implicit slot-value modeling.

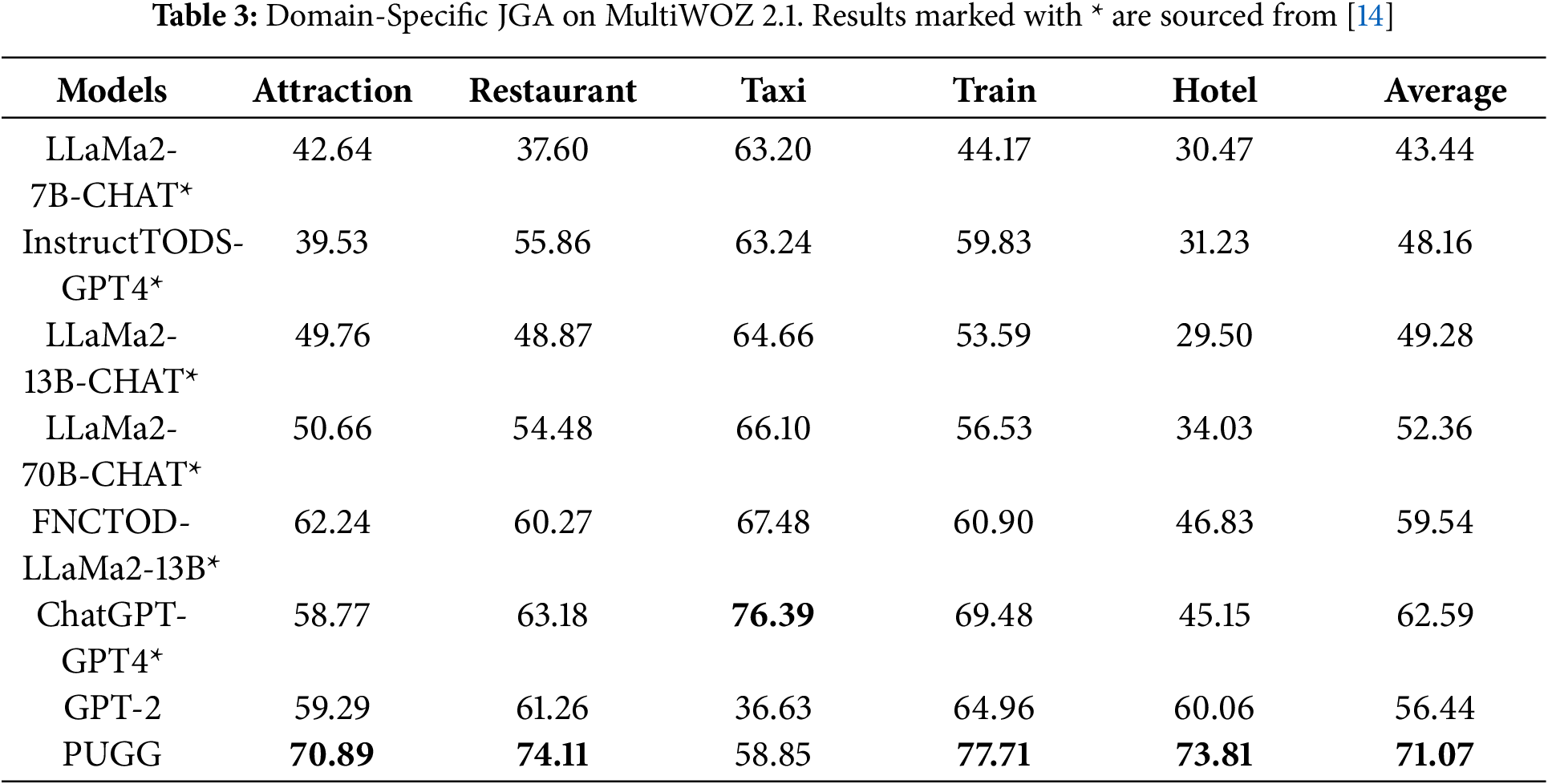

5.2 Domain-Specific Joint Goal Accuracy

Table 3 reports domain-specific JGA results on MultiWOZ 2.1 across seven models. PUGG attains the highest average JGA of 71.07%, excelling in four out of five domains. The model’s superior domain discrimination stems from its domain-wise slot separation strategy and efficient noise handling via the vocabulary memory encoder. LLaMa2-7B-CHAT underperforms due to limited model capacity for nuanced dialogue understanding, whereas larger models like ChatGPT-GPT4 achieve competitive but lower scores than PUGG. Models relying heavily on function calls or computationally intensive architectures (e.g., FNCTOD-LLaMa2-13B) face scalability constraints, limiting their deployment.

These results underscore the benefit of using GPT-2 as the language model backbone. While larger models like ChatGPT-GPT4 and FNCTOD-LLaMa2-13B offer stronger contextual representations, they incur significant inference latency, GPU memory usage, and deployment complexity. In contrast, GPT-2 (117M parameters) enables real-time tracking with lower computational cost while still achieving superior JGA across all domains. This demonstrates that PUGG’s prompt-guided extraction and GAT-based reasoning architecture effectively compensate for the smaller model size, striking a favorable balance between accuracy and efficiency. Comparable strategies have been employed in DAG-structured translation [54], emphasizing domain separation and representation control to boost task accuracy.

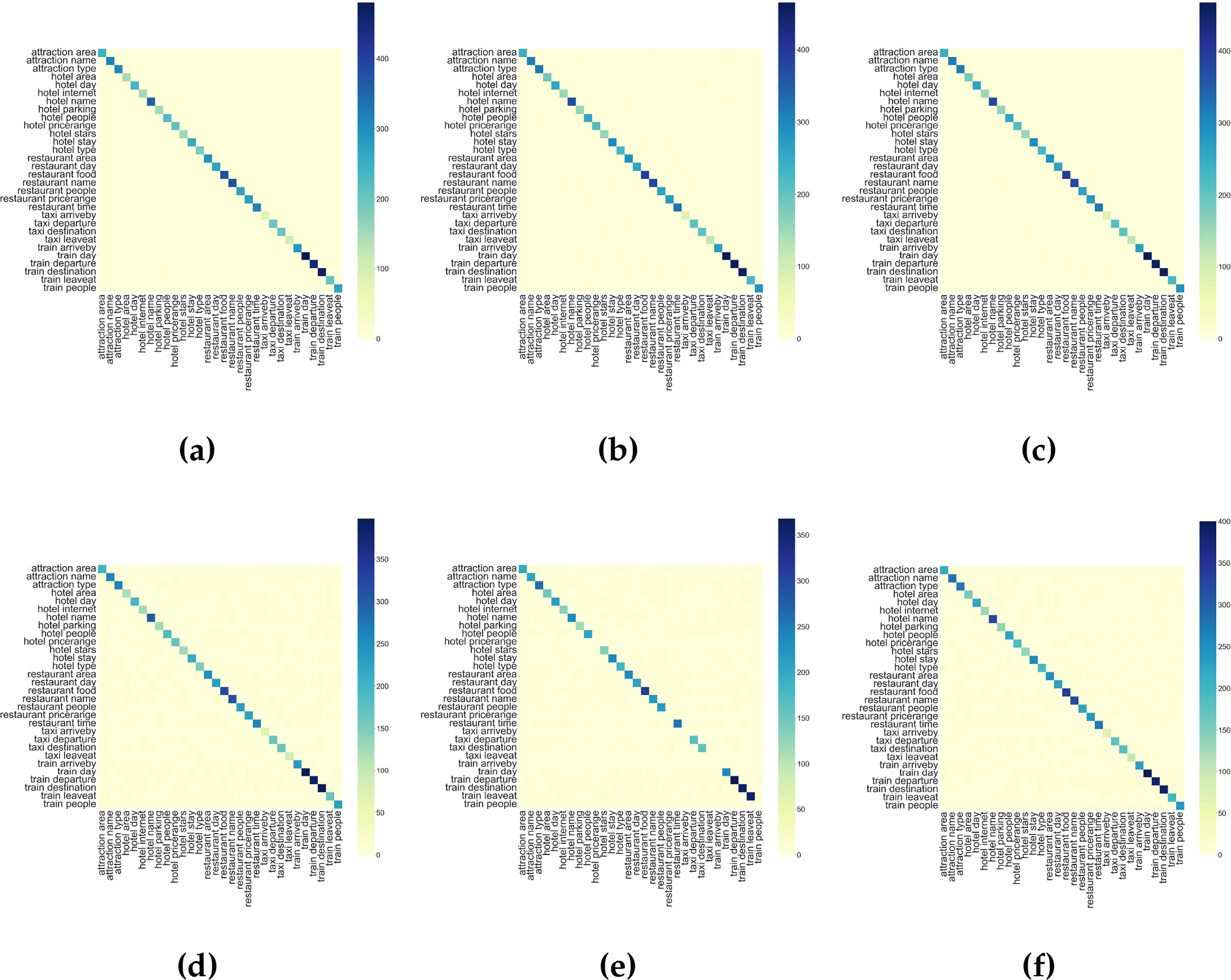

Fig. 2 illustrates standardized confusion matrices for slot accuracy (SA) and joint goal accuracy (JGA) across MultiWOZ 2.0, 2.1, and 2.4. The model shows high precision in predicting attraction-related slots, with only minimal misclassifications. However, confusions persist among hotel-related attributes (e.g., parking, pricing, star ratings) and certain restaurant and train slots. Notably, the model achieves perfect accuracy in predicting hotel internet access and taxi arrivals, underscoring its capacity for reliable slot classification in these domains.

Figure 2: Standardized Confusion Matrices: 1) (a)–(c) for SA, and 2) (d)–(f) for JGA

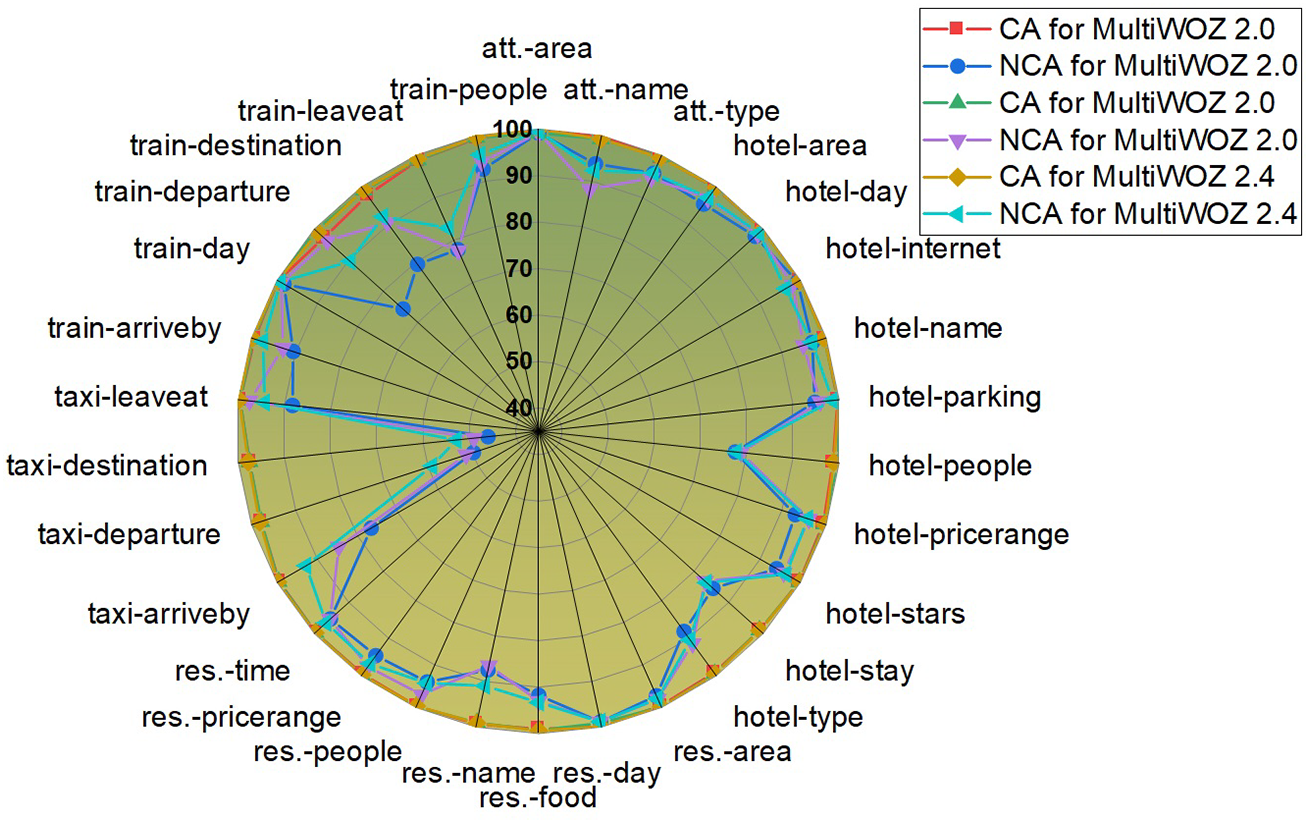

5.4 Classification Accuracy and Not-None Classification Accuracy

In this section, we evaluate the model’s ability to accurately classify specific slots as well as to detect the absence of classifiable features, as illustrated in Fig. 3. For Not-None Classification Accuracy (NCA) on the MultiWOZ 2.0 dataset, the model exhibited lower performance on two slots, with accuracy ranging between 45% and 50%. Five slots achieved NCA scores between 70% and 80%, four slots ranged between 80% and 90%, nine slots were between 90% and 95%, and ten slots attained NCA values from 95% up to 99.5%.

Figure 3: NCA and CA results for MultiWOZ 2.0 and MultiWOZ 2.4 datasets

Regarding Classification Accuracy (CA), the model demonstrated consistently strong performance, achieving accuracies between 97% and 99.98% across all slots in MultiWOZ 2.0, 2.1, and 2.4 datasets. Notably, CA on MultiWOZ 2.1 and 2.4 surpassed that of MultiWOZ 2.0, with two slots scoring between 49% and 60%, two slots between 77% and 83%, and four slots on MultiWOZ 2.1 (and three on MultiWOZ 2.4) falling within 83% to 90%. Additionally, eight slots for MultiWOZ 2.1 and seven slots for MultiWOZ 2.4 achieved NCA values in the range of 90% to 95%. The remaining slots scored between 95% and 99.58%. Such classification consistency across languages and datasets aligns with performance stability shown in anti-noise dialogue systems [55] and adversarial diffusion-based text-to-image models [56].

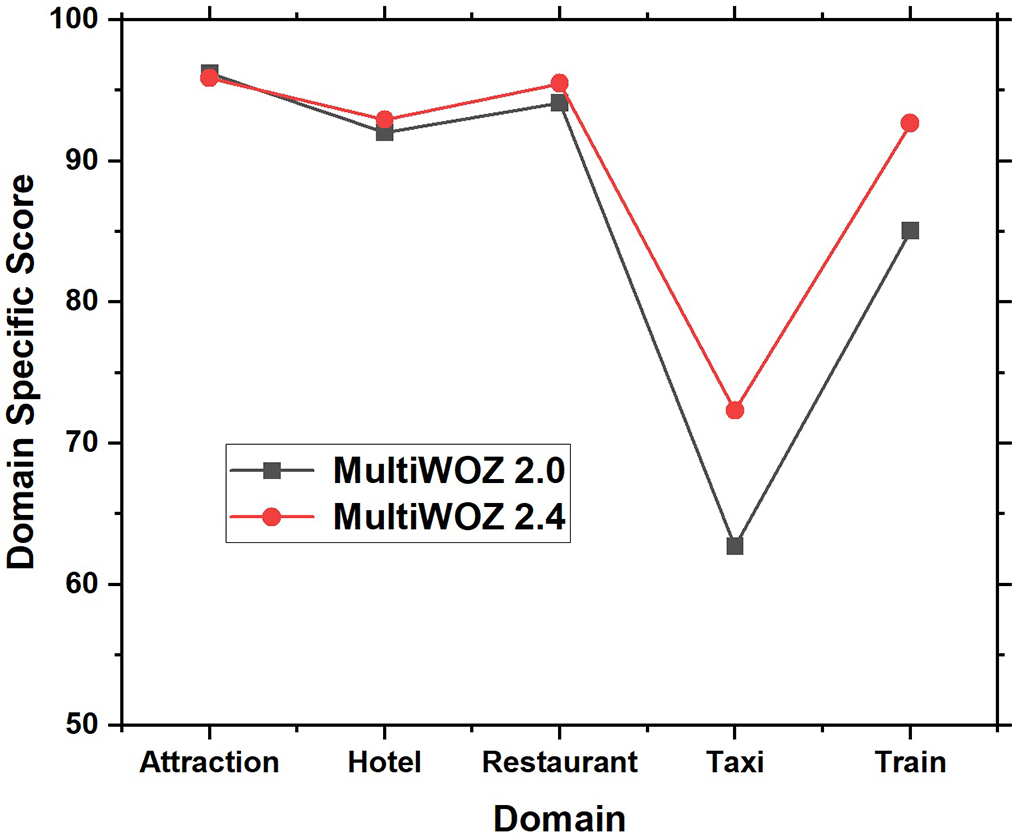

We further assessed our model’s performance on individual domains using the domain-specific score metric [10], as depicted in Fig. 4. This metric isolates domain-level performance by aggregating results across all slots within each domain and was computed using the PUGG approach on MultiWOZ 2.0 and MultiWOZ 2.4 datasets. In these evaluations, the attraction domain consistently scored lower than the taxi domain, with differences of 1.74% on MultiWOZ 2.0 and 0.24% on MultiWOZ 2.4. Conversely, the hotel and restaurant domains outperformed both the taxi and attraction domains.

Figure 4: Domain-specific score for MultiWOZ 2.0 and MultiWOZ 2.4

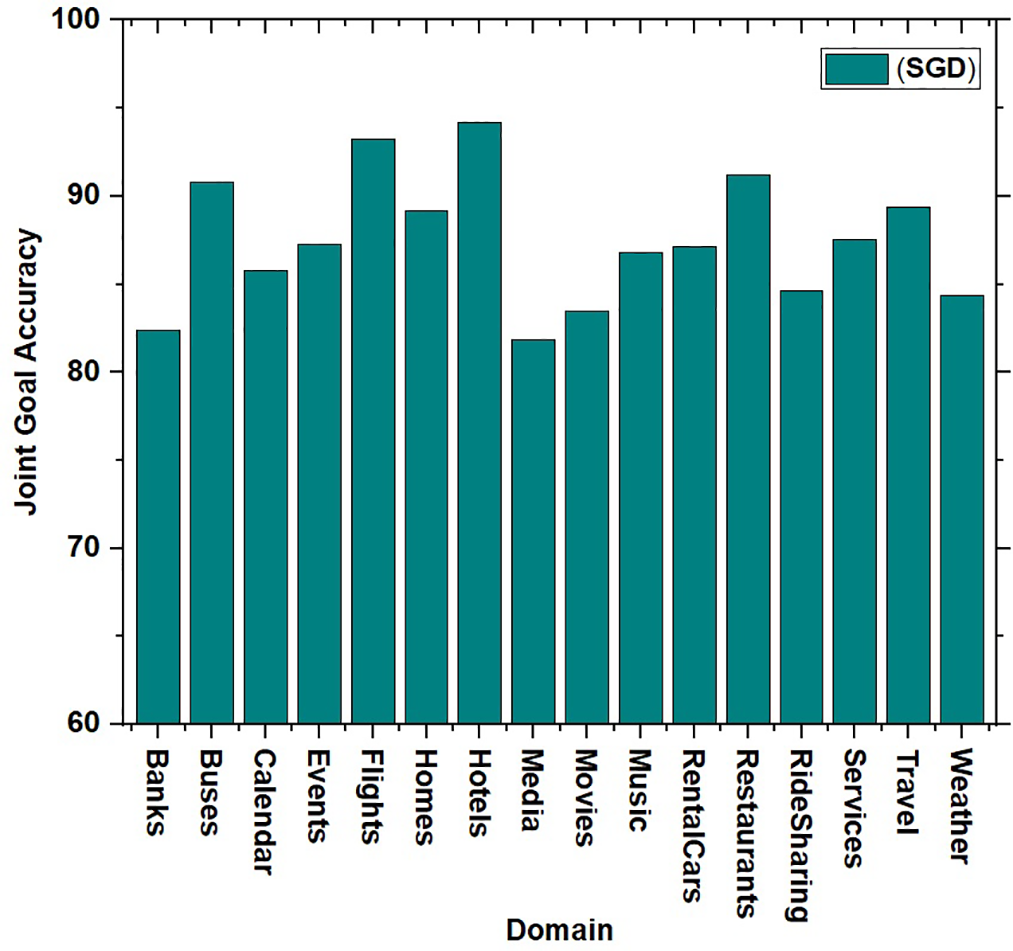

Fig. 5 presents the domain-specific scores for the SGD dataset. Here, the bank and media domains demonstrated comparatively lower scores, whereas the hotel and flight domains exceeded 90%, indicating robust performance in these areas.

Figure 5: Domain-specific score for SGD

Dialogue state tracking (DST) has undergone substantial advancements, evolving from traditional statistical methods to sophisticated deep learning and hybrid approaches. While foundational, traditional methods struggled with scalability and flexibility limitations. The advent of deep learning models, particularly those based on BERT and large language models (LLMs), has significantly improved contextual understanding and adaptability, boosting DST accuracy across multi-domain and low-resource settings. Hybrid models integrating graph-based techniques with neural networks have further enhanced DST by effectively capturing complex inter-slot relationships within dialogues.

In this work, we proposed the PUGG model, which synergistically combines Graph Attention Networks (GATs) with GPT-2 using prompt tuning to address these challenges effectively. By leveraging dense contextual word representations and dynamic adaptability, our approach offers a robust, scalable solution for accurate dialogue state tracking, marking a significant advancement in the field. The main findings of this study are summarized as follows:

• Prompt tuning enables GPT-2 to better adapt to the nuanced dialogue context, thereby enhancing its capability to accurately track dialogue states and predict slot-value pairs across diverse domains and tasks.

• Model accuracy often declines as input sequence length increases because longer inputs typically contain a high proportion of padding tokens, which add computational overhead and memory usage without providing meaningful context. For this reason, most existing dialogue state tracking models, including those based on traditional neural networks and large language models such as ChatGPT and LLaMa, limit the input length to 512 tokens. In contrast, our model utilizes GPT-2 with a 1024-token input length, which allows it to retain more dialogue history and maintain richer contextual understanding across turns. This enhanced capacity has led to significantly better performance across all benchmark datasets and has outperformed even larger LLM-based models.

• Graph Attention Networks improve interpretability by modeling complex relationships between slots and values, leading to better context comprehension and decision-making. This addresses limitations of prior models that struggle with such dependencies.

• Employing a separate slot extraction technique facilitates handling a large number of slots more effectively, resulting in a more organized and scalable approach for multi-domain dialogue systems.

• Careful tuning of hyper-parameters, particularly the tuning rates for both GPT-2 and GATs, is critical for optimizing model performance. Independent adjustment of these parameters significantly influences overall results, highlighting the importance of meticulous fine-tuning.

These findings underscore the benefits of integrating graph-based methodologies with LLMs to enhance DST performance and the ongoing need for innovation to tackle remaining challenges.

Despite the progress achieved with prompt tuning, GPT-2, and GATs, challenges remain—especially in adapting the model for broader, open-source frameworks such as LLaMa-2. The current system requires manual hyper-parameter tuning, which is cumbersome for diverse domains and varying dialogue lengths. Future work could focus on developing adaptive learning rate mechanisms within an open-source DST framework for LLaMa-2, enabling dynamic adjustment to different conversational contexts. Such advancements would improve scalability, reduce manual intervention, and increase efficiency across various domains and dialogue complexities.

Acknowledgement: This research was supported by the MSIT (Ministry of Science and ICT), Korea, under the ITRC (Information Technology Research Centre) support program (IITP-2024-RS-2024-00437191) supervised by the IITP (Institute for Information & Communications Technology Planning & Evaluation).

Funding Statement: This research was supported by the MSIT (Ministry of Science and ICT), Republic of Korea, under the ITRC (Information Technology Research Centre) support program (IITP-2024-RS-2024-00437191) supervised by the IITP (Institute for Information & Communications Technology Planning & Evaluation).

Author Contributions: Muhammad Asif Khan: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Writing, Data curation. Dildar Hussain: Writing, Review, Editing. Bhuyan Kaibalya Prasad: Software, Methodology. Irfan Ullah: Validation, Writing, Review, Editing. Inayat Khan: Review, Editing. Jawad Khan: Conceptualization, Review, Editing. Yeong Hyeon Gu: Supervision, Conceptualization. Pavlos Kefalas: Editing, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Review. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets used in this research can be found in [1,47,51,52]. For the code of the proposed model, readers may refer to the corresponding authors.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

1https://huggingface.co/openai-community/gpt2/tree/main (accessed on 28 August 2025)

References

1. Eric M, Goel R, Paul S, Sethi A, Agarwal S, Gao S, et al. MultiWOZ 2.1: a consolidated multi-domain dialogue dataset with state corrections and state tracking baselines. In: Proceedings of the 12th Language Resources and Evaluation Conference. Marseille, France: European Language Resources Association; 2020. p. 422–8. [Google Scholar]

2. Kim S, Yang S, Kim G, Lee SW. Efficient dialogue state tracking by selectively overwriting memory. In: Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics. Association for Computational Linguistics; 2020. p. 567–82. [Google Scholar]

3. Jacqmin L, Rojas Barahona LM, Favre B. “Do you follow me?”: a survey of recent approaches in dialogue state tracking. In: Proceedings of the 23rd Annual Meeting of the Special Interest Group on Discourse and Dialogue. Edinburgh, UK; 2022. p. 336–50. [Google Scholar]

4. Ouyang Y, Chen M, Dai X, Zhao Y, Huang S, Chen J. Dialogue state tracking with explicit slot connection modeling. In: Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics. Association for Computational Linguistics; 2020. p. 34–40. [Google Scholar]

5. Abro WA, Qi G, Aamir M, Ali Z. Joint intent detection and slot filling using weighted finite state transducer and BERT. Appl Intell. 2022;52(15):17356–70. doi:10.1007/s10489-022-03295-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Ye F, Wang X, Huang J, Li S, Stern S, Yilmaz E. MetaASSIST: robust dialogue state tracking with meta learning. In: Proceedings of the Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; 2022 Dec 7–11; Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2022. p. 1157–69. [Google Scholar]

7. Xu HD, Mao XL, Yang P, Sun F, Huang H. Cross-domain coreference modeling in dialogue state tracking with prompt learning. Knowl Based Syst. 2024;283:111189. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2023.111189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Jiao F, Guo Y, Huang M, Nie L. Enhanced multi-domain dialogue state tracker with second-order slot interactions. IEEE/ACM Transact Audio Speech Lang Process. 2022;31:265–76. doi:10.1109/taslp.2022.3221044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Zhong V, Xiong C, Socher R. Global-locally self-attentive encoder for dialogue state tracking. In: Proceedings of the 56th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers). Melbourne, Australia; 2018. p. 1458–67. [Google Scholar]

10. Ye F, Feng Y, Yilmaz E. ASSIST: towards label noise-robust dialogue state tracking. In: Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2022; 2022 May 22–27; Dublin, Ireland; 2022. p. 2719–31. [Google Scholar]

11. Chung W, Cahyawijaya S, Wilie B, Lovenia H, Fung P. InstructTODS: large language models for end-to-end task-oriented dialogue systems. In: Proceedings of the Second Workshop on Natural Language Interfaces. Bali, Indonesia: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2023. p. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

12. Feng Y, Lu Z, Liu B, Zhan L, Wu XM. Towards LLM-driven dialogue state tracking. In: Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP); 2023 Dec 6–10; Singapore; 2023. p. 739–55. [Google Scholar]

13. Li Q, Zhang W, Huang M, Feng S, Wu Y. RSP-DST: revisable state prediction for dialogue state tracking. Electronics. 2023;12(6):1494. doi:10.3390/electronics12061494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Li Z, Chen ZZ, Ross M, Huber P, Moon S, Lin Z, et al. Large language models as zero-shot dialogue state tracker through function calling. arXiv:2402.10466. 2024. [Google Scholar]

15. Niu C, Wang X, Cheng X, Song J, Zhang T. Enhancing dialogue state tracking models through LLM-backed user-agents simulation. arXiv:2405.13037. 2024. [Google Scholar]

16. Zhu M, Xu X. ECDG-DST: a dialogue state tracking model based on efficient context and domain guidance for smart dialogue systems. Comput Speech Lang. 2025;90(9):101741. doi:10.1016/j.csl.2024.101741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Gong Y, Kim H, Hwang S, Kim D, Lee KH. Multi-domain dialogue state tracking via dual dynamic graph with hierarchical slot selector. Knowl Based Syst. 2025;308(10):112754. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2024.112754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Ma MD, Kao JY, Gao S, Gupta A, Jin D, Chung T, et al. Parameter-efficient low-resource dialogue state tracking by prompt tuning. arXiv:2301.10915. 2023. [Google Scholar]

19. Khan MA, Prasad BK, Qi G, Song W, Ye F, Ali Z, et al. UTMGAT: a unified transformer with memory encoder and graph attention networks for multidomain dialogue state tracking. Appl Intell. 2024;54(17):8347–66. doi:10.1007/s10489-024-05571-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Saha D, Santra B, Goyal P. A study on prompt-based few-shot learning methods for belief state tracking in task-oriented dialog systems. arXiv:2204.08167. 2022. [Google Scholar]

21. Yang Y, Lei W, Huang P, Cao J, Li J, Chua TS. A Dual prompt learning framework for few-shot dialogue state tracking. In: Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference; 2023 Apr 30; Austin, TX, USA: ACM; 2023. p. 1468–77. [Google Scholar]

22. Zhu Q, Li B, Mi F, Zhu X, Huang M. Continual prompt tuning for dialog state tracking. In: Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers); 2022 May 22–27; Dublin, Ireland: ACL. p. 1124–37. [Google Scholar]

23. Lee Y, Kim T, Yoon H, Kang P, Bang J, Kim M. DSTEA: improving dialogue state tracking via entity adaptive pre-training. Knowl Based Syst. 2024;290(10):111542. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2024.111542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Ye F, Manotumruksa J, Zhang Q, Li S, Yilmaz E. Slot self-attentive dialogue state tracking. In: Proceedings of the Web Conference; 2021 Apr 19–23; Ljubljana, Slovenia: ACM. p. 1598–608. [Google Scholar]

25. Khan MA, Huang Y, Feng J, Prasad BK, Ali Z, Ullah I, et al. A multi-attention approach using BERT and stacked bidirectional LSTM for improved dialogue state tracking. Appl Sci. 2023;13(3):1775. doi:10.3390/app13031775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Lee S. Extrinsic evaluation of dialog state tracking and predictive metrics for dialog policy optimization. In: Proceedings of the 15th Annual Meeting of the Special Interest Group on Discourse and Dialogue (SIGDIAL). Philadelphia, PA, USA. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: ACL; 2014. p. 310–7. [Google Scholar]

27. Sun K, Chen L, Zhu S, Yu K. The SJTU system for dialog state tracking challenge 2. In: Proceedings of the 15th Annual Meeting of the Special Interest Group on Discourse and Dialogue (SIGDIAL). Philadelphia, PA, USA. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: ACL; 2014. p. 318–26. [Google Scholar]

28. Young S, Gašic M, Thomson B, Williams JD. POMDP-based statistical spoken dialog systems: a review. Proc IEEE. 2013;101(5):1160–79. doi:10.1109/jproc.2012.2225812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Thomson B, Young S. Bayesian update of dialogue state: a POMDP framework for spoken dialogue systems. Comput Speech Lang. 2010;24(4):562–88. doi:10.1016/j.csl.2009.07.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Ren H, Xu W, Zhang Y, Yan Y. Dialog state tracking using conditional random fields. In: Proceedings of the SIGDIAL 2013 Conference; 2013 Aug 22–24; Metz, France; 2013. p. 457–61. [Google Scholar]

31. Noroozi V, Zhang Y, Bakhturina E, Kornuta T. A fast and robust BERT-based dialogue state tracker for schema-guided dialogue dataset. arXiv:2008.12335. 2020. [Google Scholar]

32. Hong T, Cho J, Yu H, Ko Y, Seo J. Knowledge-grounded dialogue modelling with dialogue-state tracking, domain tracking, and entity extraction. Comput Speech Lang. 2023;78:101460. doi:10.1016/j.csl.2022.101460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Hu Y, Lee CH, Xie T, Yu T, Smith NA, Ostendorf M. In-context learning for few-shot dialogue state tracking. In: Findings of the Association for Computational. Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates: EMNLP; 2022. p. 2627–43. [Google Scholar]

34. Kumar A, Ku P, Goyal A, Metallinou A, Hakkani-Tur D. MA-DST: multi-attention-based scalable dialog state tracking. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2020;34(05):8107–14. doi:10.1609/aaai.v34i05.6322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Mou X, Sigouin B, Steenstra I, Su H. Multimodal dialogue state tracking by QA approach with data augmentation. arXiv:2007.09903. 2020. [Google Scholar]

36. Nie W, Chen R, Wang W, Lepri B, Sebe N. T2TD: text-3D generation model based on prior knowledge guidance. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2025;47(1):172–89. doi:10.1109/tpami.2024.3463753. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Wang G, Cheng S. Can foundation language models predict fluid dynamics? Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2025;144(2):111427. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2025.111427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Wang Y, Li M, Liu J, Leng Z, Li FW, Zhang Z, et al. Fg-T2M++: LLMs-augmented fine-grained text driven human motion generation. Int J Comput Vis. 2025;133(7):4277–93. doi:10.1007/s11263-025-02392-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Zhao H-H, Ji T-L, Rosin PL, Lai Y-K, Meng W-L, Wang Y-N. Cross-lingual font style transfer with full-domain convolutional attention. Pattern Recognit. 2024;155(2):110709. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2024.110709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Velickovic P, Cucurull G, Casanova A, Romero A, Lio P, Bengio Y, et al. Graph attention networks. arXiv:1710.10903. 2017. [Google Scholar]

41. Lin W, Tseng BH, Byrne B. Knowledge-aware graph-enhanced GPT-2 for dialogue state tracking. In: Proceedings of the Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing. Online and Punta Cana, Dominican Republic; 2021. p. 7871–81. [Google Scholar]

42. Yu H, Ko Y. Enriching the dialogue state tracking model with a asyntactic discourse graph. Patt Recognit Lett. 2023;169(05):81–6. doi:10.1016/j.patrec.2023.03.024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Zhu S, Li J, Chen L, Yu K. Efficient context and schema fusion networks for multi-domain dialogue state tracking. In: Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2020. Online. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: ACL; 2020. p. 766–81. [Google Scholar]

44. Zhao M, Wang L, Jiang Z, Li R, Lu X, Hu Z. Multi-task learning with graph attention networks for multi-domain task-oriented dialogue systems. Knowl Based Syst. 2023;259(19):110069. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2022.110069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Huang Z, Li F, Yao J, Chen Z. MGCRL: multi-view graph convolution and multi-agent reinforcement learning for dialogue state tracking. Neural Comput Appl. 2024;36(9):4829–46. doi:10.1007/s00521-023-09328-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Zang X, Rastogi A, Sunkara S, Gupta R, Zhang J, Chen J. MultiWOZ 2.2: a dialogue dataset with additional annotation corrections and state tracking baselines. In: Proceedings of the 2nd Workshop on Natural Language Processing for Conversational AI. Association for Computational Linguistics; 2020. p. 109–17. [Google Scholar]

47. Rastogi A, Zang X, Sunkara S, Gupta R, Khaitan P. Schema-guided dialogue state tracking task at DSTC8. arXiv:2002.01359. 2020. [Google Scholar]

48. Radford A, Wu J, Child R, Luan D, Amodei D, Sutskever I, et al. Language models are unsupervised multitask learners. OpenAI Blog. 2019;1(8):9. [Google Scholar]

49. Han F, Yang P, Du H, Li XY. Accuth+: accelerometer-based anti-spoofing voice authentication on wrist-worn wearables. IEEE Transact Mobile Comput. 2023;23(5):5571–88. doi:10.1109/tmc.2023.3314837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Jiang H, Chen X, Miao D, Zhang H, Qin X, Gu X, et al. Fpa-GCN: enhancing aspect sentiment triplet extraction with feature-rich prediction-aware graph convolutional networks. Appl Intell. 2025;55(9):740. doi:10.1007/s10489-025-06313-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Budzianowski P, Wen TH, Tseng BH, Casanueva I, Ultes S, Ramadan O, et al. MultiWOZ—a large-scale multi-domain wizard-of-oz dataset for task-oriented dialogue modelling. In: Proceedings of the Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing. Brussels, Belgium; 2018. p. 5016–26. [Google Scholar]

52. Ye F, Manotumruksa J, Yilmaz E. MultiWOZ 2.4: a multi-domain task-oriented dialogue dataset with essential annotation corrections to improve state tracking evaluation. In: Proceedings of the 23rd Annual Meeting of the Special Interest Group on Discourse and Dialogue. Edinburgh, UK; 2022. p. 351–60. [Google Scholar]

53. Kingma DP, Ba J. Adam: a method for stochastic optimization. In: Bengio Y, LeCun Y, editors. 3rd International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR; 2015 May 7–9; San Diego, CA, USA: Conference Track Proceedings. [Google Scholar]

54. Lv S, Yang B, Wang R, Lu S, Tian J, Zheng W, et al. Dynamic multi-granularity translation system: dag-structured multi-granularity representation and self-attention. Systems. 2024;12(10):420. doi:10.3390/systems12100420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Liu F, Zhao X, Zhu Z, Zhai Z, Liu Y. Dual-microphone active noise cancellation paved with Doppler assimilation for TADS. Mech Syst Signal Process. 2023;184(9):109727. doi:10.1016/j.ymssp.2022.109727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Song W, Ye Z, Sun M, Hou X, Li S, Hao A. AttriDiffuser: adversarially enhanced diffusion model for text-to-facial attribute image synthesis. Pattern Recognit. 2025;163(8):111447. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2025.111447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools