Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

An Active Safe Semi-Supervised Fuzzy Clustering with Pairwise Constraints Based on Cluster Boundary

1 Graduate University of Science and Technology, Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology, Hanoi, 100000, Vietnam

2 FPT Software Company Limited, Hanoi, 100000, Vietnam

3 Institute of Information Technology, Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology, Hanoi, 100000, Vietnam

4 Faculty of Information Technology, Electric Power University, Hanoi, 100000, Vietnam

5 School of Information and Communications Technology, Hanoi University of Industry, Hanoi, 100000, Vietnam

* Corresponding Author: Luong Thi Hong Lan. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(3), 5625-5642. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.069636

Received 27 June 2025; Accepted 28 August 2025; Issue published 23 October 2025

Abstract

Semi-supervised clustering techniques attempt to improve clustering accuracy by utilizing a limited number of labeled data for guidance. This method effectively integrates prior knowledge using pre-labeled data. While semi-supervised fuzzy clustering (SSFC) methods leverage limited labeled data to enhance accuracy, they remain highly susceptible to inappropriate or mislabeled prior knowledge, especially in noisy or overlapping datasets where cluster boundaries are ambiguous. To enhance the effectiveness of clustering algorithms, it is essential to leverage labeled data while ensuring the safety of the previous knowledge. Existing solutions, such as the Trusted Safe Semi-Supervised Fuzzy Clustering Method (TS3FCM), struggle with random centroid initialization, fixed neighbor radius formulas, and handling outliers or noise at cluster overlaps. A new framework called Active Safe Semi-Supervised Fuzzy Clustering with Pairwise Constraints Based on Cluster Boundary (AS3FCPC) is proposed in this paper to deal with these problems. It does this by combining pairwise constraints and active learning. AS3FCPC uses active learning to query only the most informative data instances close to the cluster boundaries. It also uses pairwise constraints to enforce the cluster structure, which makes the system more accurate and robust. Extensive test results on diverse datasets, including challenging noisy and overlapping scenarios, demonstrate that AS3FCPC consistently achieves superior performance compared to state-of-the-art methods like TS3FCM and other baselines, especially when the data is noisy and overlaps. This significant improvement underscores AS3FCPC’s potential for reliable and accurate semi-supervised fuzzy clustering in complex, real-world applications, particularly by effectively managing mislabeled data and ambiguous cluster boundaries.Keywords

Fuzzy clustering is a basic yet powerful clustering method that seeks to deal with vague and overlapping grouping boundaries while also providing comprehensive membership degree information. In the Industry 4.0 era, leveraging the exponential growth of data is critical, making knowledge discovery techniques essential. Clustering, which groups similar data points, is widely used, especially for complex data like text and images [1,2]. However, traditional “crisp” clustering struggles with complex data where points can belong to multiple clusters. When dealing with data distributions that call for overlapping cluster structures or with instances of ambiguous cluster delineations, the utilization of a fuzzy theory for cluster allocation results in a configuration that is more favorable. To solve this issue, Bezdek introduced Fuzzy C-Means (FCM) [3] that examines the partial membership of samples in specific clusters to execute a soft clustering process. To date, numerous FCM-based methods [4–6] have been introduced, building upon conventional fuzzy clustering techniques.

Despite its wide application, FCM has limitations in handling complex, overlapping clusters, particularly at ambiguous boundaries common in real-world datasets like image segmentation and bioinformatics. This challenge is particularly evident in real-world datasets, such as those in image segmentation or bioinformatics, where boundary clusters may blur or represent overlapping functions, complicating classification. Furthermore, FCM is highly sensitive to the initialization of cluster centroids, and poor initialization can result in suboptimal clustering. Because FCM is sensitive to initialization, and it’s hard to figure out the best number of clusters at boundaries, more advanced methods are needed. To overcome the limitations of FCM, numerous pertinent SSFC methods [7–11] have been proposed to enhance the clustering performance of SSC by leveraging prior knowledge. In most cases, it is presumed that having previous information is advantageous in order to achieve the desired outcomes. Nevertheless, it is possible to acquire inappropriate prior knowledge in certain situations, such as the use of incorrect cluster designations. Within this scenario, clustering efficacy may decline as a consequence of previous knowledge.

The SSFC comprises three categories of pre-defined knowledge: labeled data, link constraints, and prior membership degrees. Labeled data refer to a limited number of information points that are annotated to guide the clustering process, whereas link constraints illustrate the relationships among information points within the same cluster and those across different clusters. Previous membership degrees would utilize fuzzy membership values of specific data points to inform the calculation of the final cluster centers and memberships. Examples include Constraint FCM [12] and MMR-FCM [13], utilizing labeled data and pairwise constraints, respectively. Despite these advancements, challenges remain in effectively clustering complex, overlapping data, especially at cluster boundaries and in noisy scenarios. Moreover, these semi-supervised algorithms often incorporate additional optimization mechanisms, such as weighting functions and adaptive strategies [14–18], to refine the clustering process. Gan et al. [17] introduced a weighting mechanism to assess the reliability of labeled samples and mitigate the impact of mislabeled instances. Subsequent research, CS3FCM by Gan [18], expanded on this approach, but challenges persist in handling pairwise constraints and assessing risk between labeled and unlabeled data points.

The main goal of FCM is to find the best decision boundary that effectively separates the clusters while taking into account both correctly and incorrectly labeled data. This will improve the performance of both classification and clustering. To address mislabeled data, Thong et al. [19] introduced the Trusted Safe Semi-Supervised Fuzzy Clustering Method (TS3FCM). TS3FCM uses a two-phase approach: first, it filters the data labeled for reliability, and second, it performs SSFC using trusted labels and prior memberships

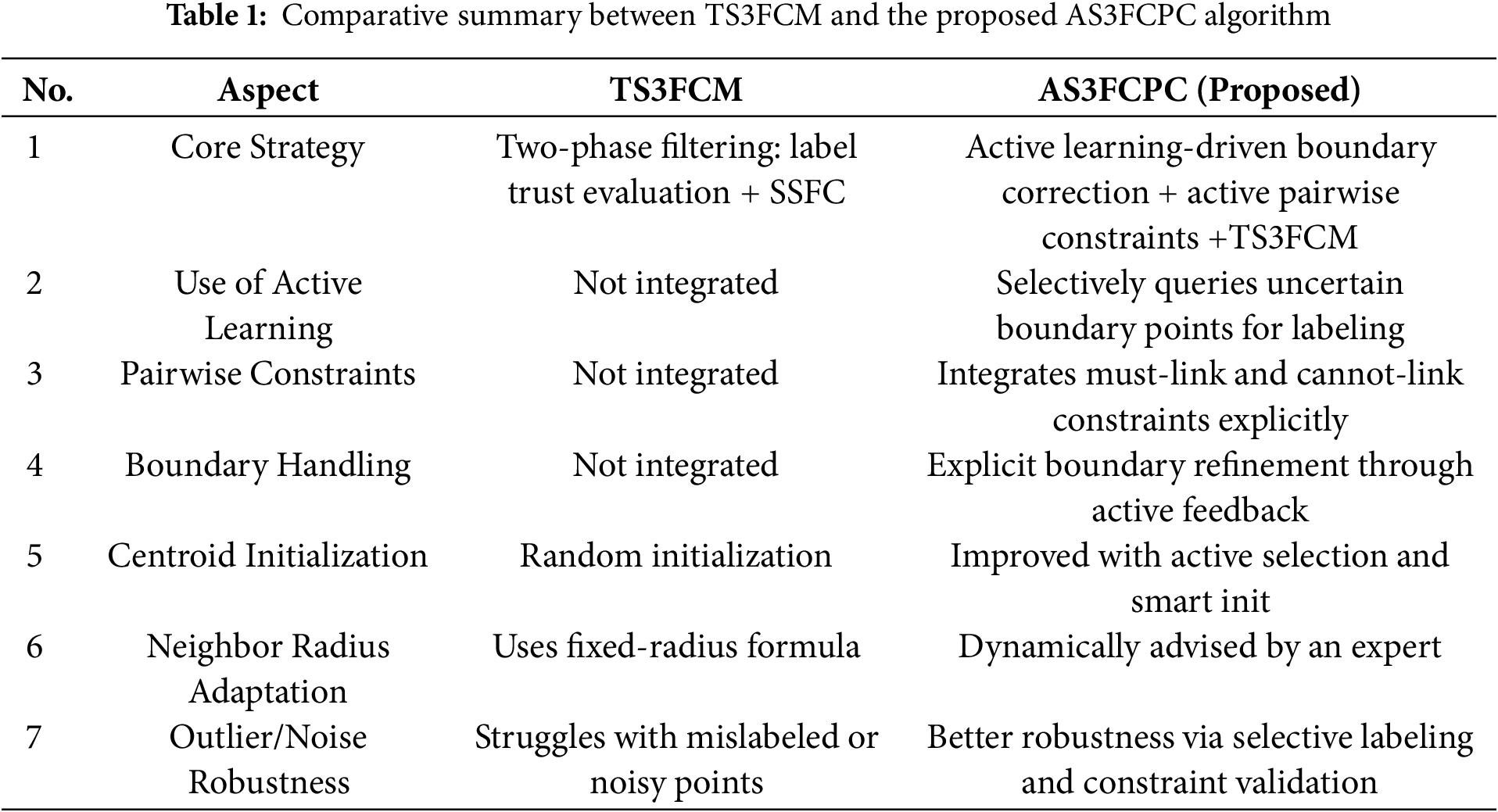

To build upon and improve the TS3FCM framework, this paper proposes a novel method called Active Safe Semi-Supervised Fuzzy Clustering with Pairwise Constraints Based on Cluster Boundary (AS3FCPC). AS3FCPC integrates several improvements over TS3FCM, addressing its limitations while leveraging its strengths. First, it introduces a more robust strategy for cluster boundary refinement, using actively queried data and pairwise constraints to better separate overlapping clusters. Second, instead of relying on random labeled data initialization as in FCM and TS3FCM, the model employs a k-means++ [29] inspired approach that intelligently selects initial labeled points based on neighborhood structure. Third, it replaces the static neighbor radius with an active expert-driven radius selection, allowing for more flexible and context-aware clustering adjustments. Fourth, the model introduces an adaptive correction mechanism to detect and mitigate the influence of mislabeled data points. These innovations enable AS3FCPC to outperform traditional clustering methods in handling noisy, boundary-ambiguous, and sparsely labeled datasets, and make it well-suited for real-world applications such as medical diagnosis, flood area segmentation, and social network analysis, where uncertainty and data complexity are significant challenges. Table 1 presents a comparison analysis that underscores the principal differences between AS3FCPC and TS3FCM.

The key contributions of this work are as follows:

• Active Safe Semi-Supervised Fuzzy Clustering with Pairwise Constraints Based on Cluster Boundary (AS3FCPC): A new method that combines active learning with pairwise constraints to enhance clustering efficiency and accuracy, particularly in noisy and overlapping regions.

• Active Radius Selection via Expert Query (Alpha-Parameter): Instead of a fixed radius, the active radius selection is introduced that contains actively queried from an expert. This active approach enables dynamic and data-aware neighbor definitions.

• Handling of Mislabeled Data: An adaptive approach that identifies and adjusts misclassified data points to reduce their negative impact on clustering.

• Enhanced Cluster Boundary Determination: A more accurate definition of cluster separation, particularly in overlapping regions, using pairwise constraints.

• Computational Efficiency: The method is computationally efficient, combining FCM, SSFCM, and ASSFCFM techniques to enhance performance without significantly increasing computational cost.

Through these contributions, our proposed method improves clustering results in noisy and overlapping datasets, enhances the accuracy of semi-supervised fuzzy clustering, and provides a new direction for future research in this field.

The paper is structured as follows: Section 1 presents the basic concepts used in researching and developing the proposed model; Section 2 describes the construction of an Active Safe Semi-Supervised Fuzzy Clustering with Pairwise Constraints Based on Cluster Boundary; Section 3 presents test results validating the proposed model; and the Section 4 provides conclusions and recommendations. This new approach actively corrects the dependencies of boundary elements to improve clustering accuracy by first identifying the boundary regions using fuzzy semi-supervised clustering and then applying active learning to refine these boundaries. For detailed information, refer to the sections in the document where the main contributions are described and explained in context.

2 The Proposed Active Semi-Supervised Fuzzy Clustering Model

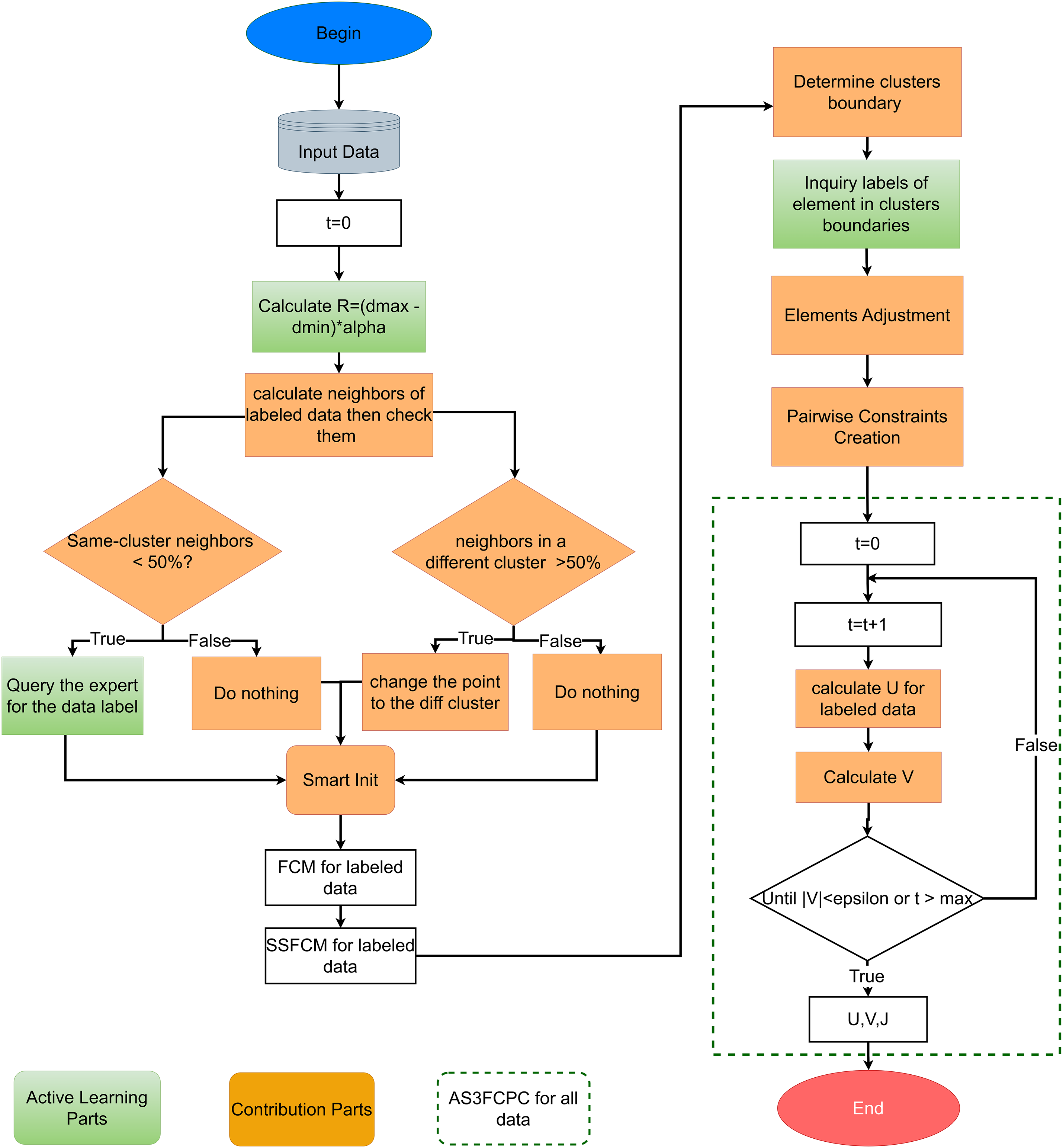

The proposed model integrates fuzzy clustering, semi-supervised learning, and active learning to improve clustering performance, especially in scenarios with sparse labels and complex or ambiguous data distributions. Active learning in this framework is embedded to enhance confidence assessment and weighting of labeled data, building upon TS3FCM. By analyzing local neighborhood structures, active learning evaluates the reliability of initial labels and dynamically adjusts their confidence, ensuring a stronger initialization of membership values and cluster centers. Fig. 1 describes details of the proposed Active Semi-Supervised Safe Fuzzy Clustering Based on Clusters Boundary model that combines active learning with pairwise constraints to enhance clustering quality.

Figure 1: The active semi-supervised safe fuzzy clustering based on the clusters boundary model

The model begins by combining labeled and unlabeled data, balancing supervised guidance with unsupervised learning. It focuses on ambiguous regions—where data points lie near cluster boundaries or have uncertain memberships—using active learning to query or adjust labels based on neighborhood patterns. This reduces initial uncertainty and improves clustering accuracy from the start. To further strengthen clustering, the method incorporates pairwise constraints (must-link and cannot-link), capturing domain-specific relationships between data points. These constraints guide cluster formation, particularly in overlapping or ambiguous areas, improving robustness and interpretability. By tightly integrating fuzzy clustering, semi-supervised learning, and active learning, the model creates an adaptive process well-suited for complex datasets. Its combined flexibility and supervision make it effective for applications with limited labeled data, leveraging expert knowledge to achieve high clustering accuracy.

The proposed AS3FCPC method comprises four sequential phases: (1) active learning initialization combined with FCM for labeled data; (2) iterative semi-supervised fuzzy clustering for the whole dataset; (3) active refinement of cluster boundaries and selective generation of pairwise constraints; and (4) final iterative optimization and convergence. Details of each phase are described as follows:

Phase 1: Active Learning Initialization and FCM for Labeled Data. The process begins with active learning initialization, focusing on identifying ambiguous or uncertain data points by analyzing neighborhood relationships. Specifically, for each data point, a neighborhood radius

where

Phase 2: Iterative Semi-Supervised Fuzzy Clustering. Using the initialized membership matrix

Phase 3: Active Boundary Refinement and Pairwise Constraint Generation. This phase focuses on refining the clustering structure by analyzing cluster boundaries and actively identifying critical data points for constraint generation. First, the boundaries of the preliminary clusters are determined to identify data points with uncertain membership degrees, which are typically located in ambiguous regions near cluster borders. Active learning is then applied to these boundary points to assess label reliability. By examining local neighborhood relationships, the model either confirms existing labels, queries additional information, or adjusts label assignments to improve consistency. This focused assessment ensures that boundary points are accurately represented in the clustering structure, strengthening the model’s initial confidence levels.

Once label reliability is refined, the model proceeds to generate pairwise constraints following the strategy from Bajpai et al. [30]. Must-link (

Phase 4: Final Optimization and Convergence. In the final phase, the model enters the optimization loop, where clustering is progressively refined by minimizing the objective function until convergence is achieved. The optimization process iteratively updates the membership matrix

At each iteration, membership values are recalculated to balance data proximity to cluster centers, prior membership confidence, and adherence to must-link and cannot-link constraints. Cluster centers are subsequently updated to reflect the refined membership assignments, improving cluster compactness and separation. This iterative process continues until convergence criteria are satisfied, defined by minimal changes in cluster centers or reaching the maximum number of iterations. The result is an optimized clustering solution that effectively integrates all available supervision and data structure insights, ensuring robust and accurate final cluster configurations.

The overall objective function optimized by AS3FCPC is defined as:

With the constraints:

Eq. (2) defines the core optimization objective of the AS3FCPC model. This objective function is minimized subject to the given constraints, which include normalization of fuzzy membership degrees, adherence to pairwise relational constraints, and integration of active learning-based supervision. Together, these components form a constrained optimization problem that guides the iterative update of both membership values and cluster centroids, particularly refining boundary points through actively queried expert feedback. We can consider four parts of the objective function:

With the aim of enforcing this constraint, a Lagrange multiplier

To find the optimal membership values

The derivative of the second term with respect to

In which the derivative values with respect to

Combine all the derivative terms, we have:

Group terms involving

Combine the terms on the left-hand side:

Then, divide both sides by

With the constraint

Rearranging this expression, we can solve for

Substitute

Hence, to find the centroids

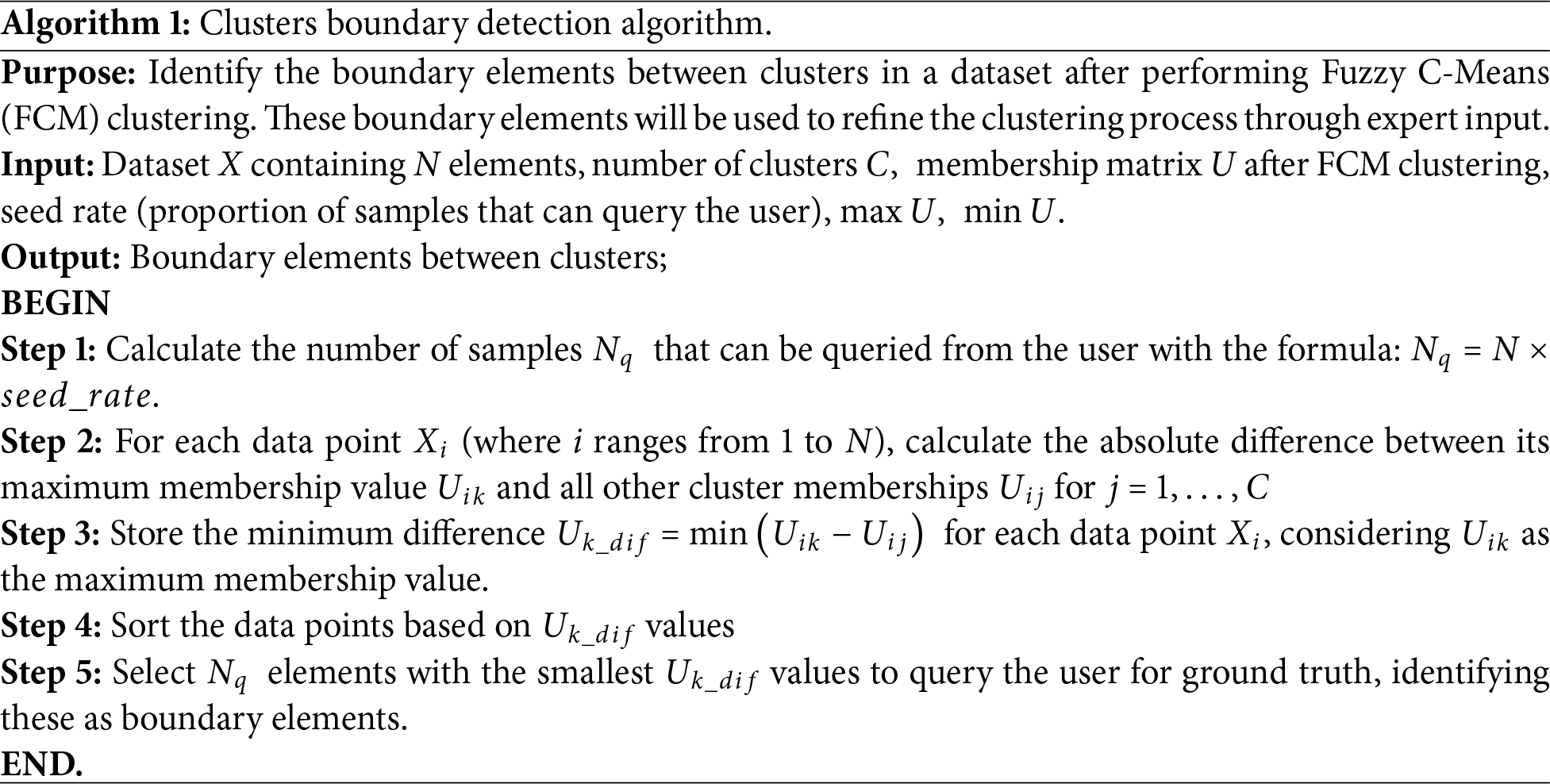

Algorithm 1 begins by calculating the number of samples

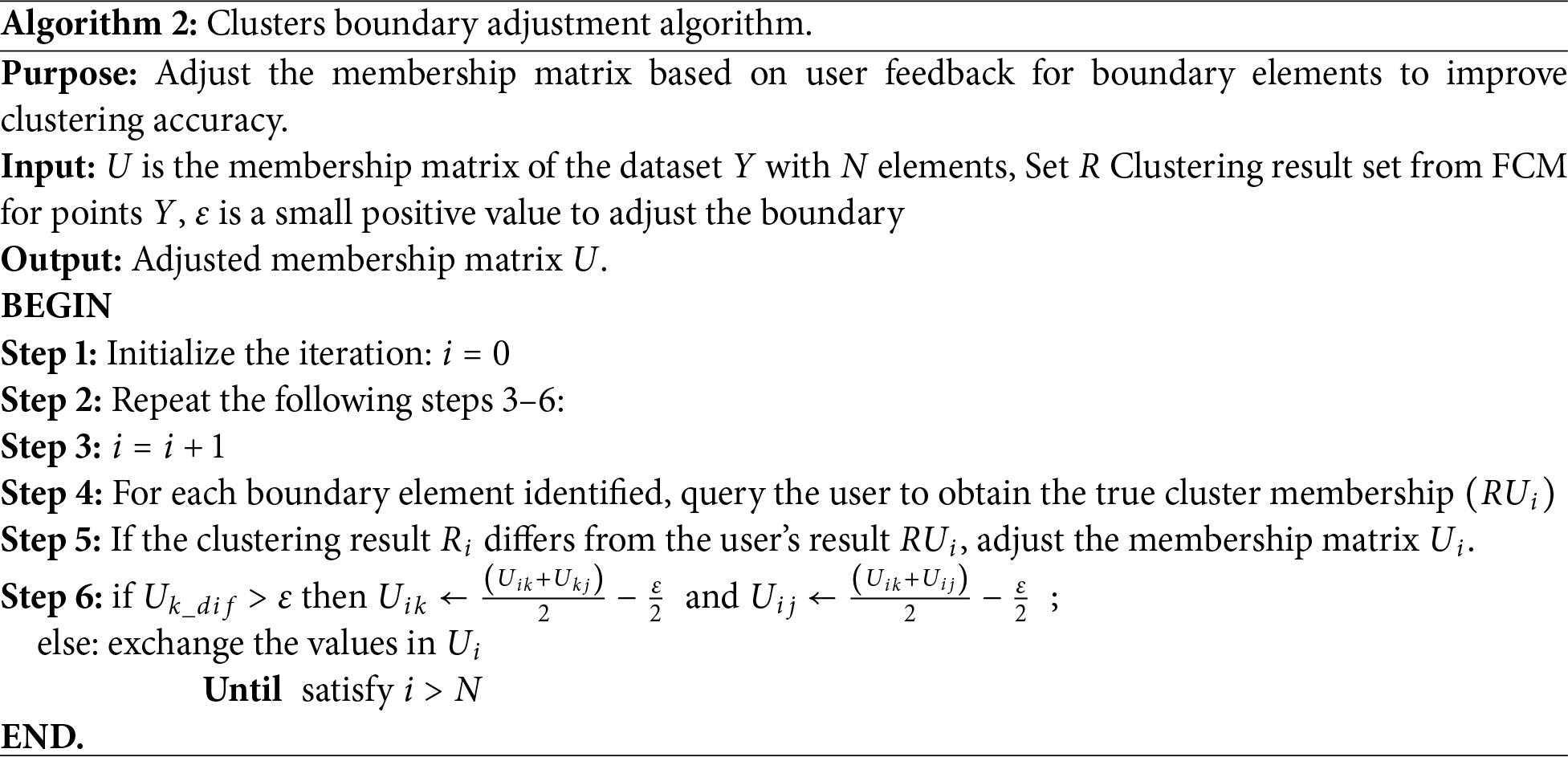

Algorithm 2 operates by iteratively refining the membership matrix based on user feedback. In each iteration, the algorithm compares the clustering results with the user’s ground truth for boundary elements. Adjustments are made by modifying the membership values according to a predefined epsilon threshold, ensuring that the clustering adapts to the user’s corrections.

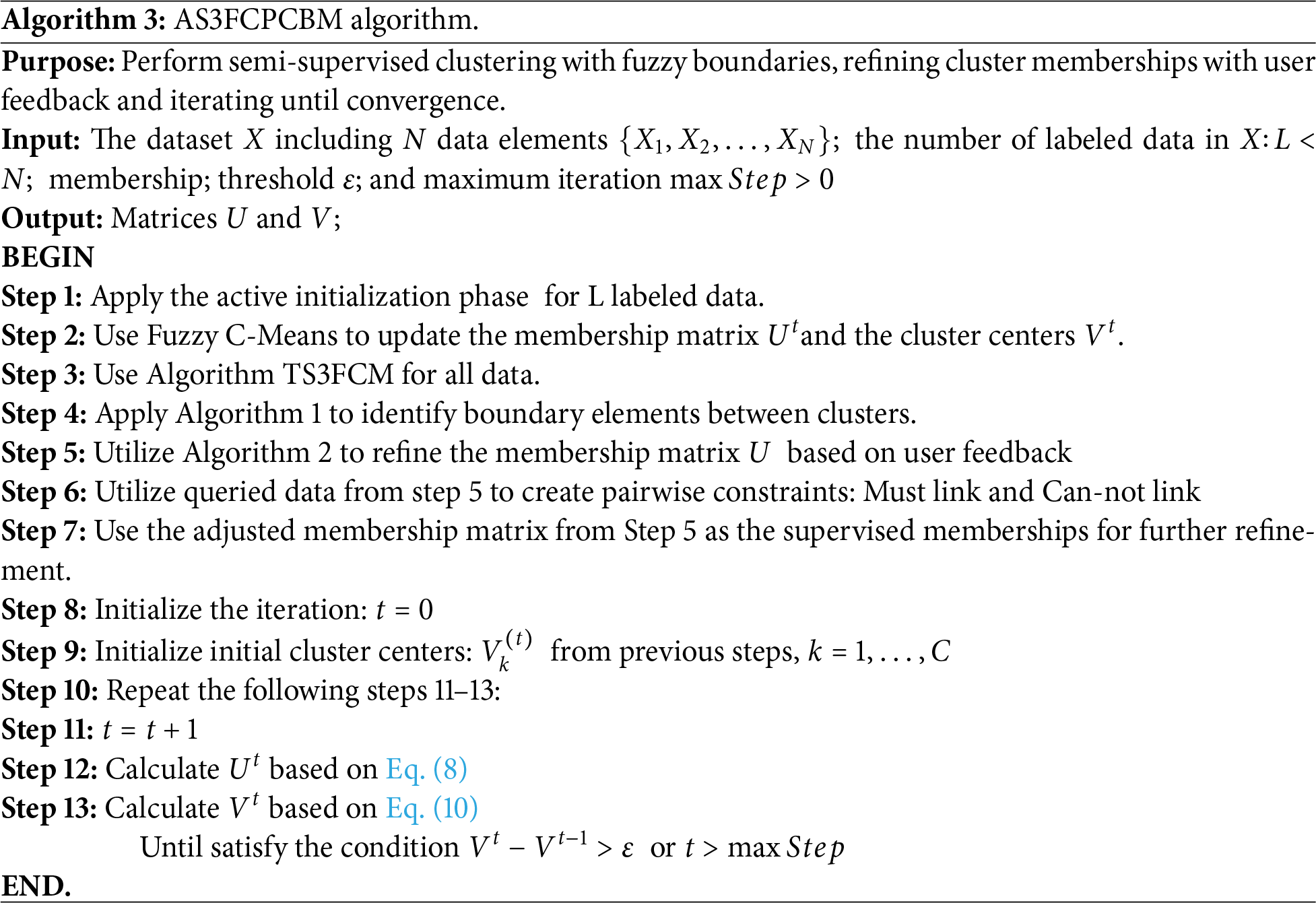

Algorithm 3 is a comprehensive approach that integrates FCM clustering with semi-supervised adjustments based on boundary elements. After initial clustering, the algorithm detects boundary elements and refines them with user feedback. The final steps involve iterating through membership and cluster center updates until convergence is achieved, ensuring the clustering is accurate and well-adapted to the provided data.

The computational complexity of the proposed AS3FCPC algorithm is driven by multiple fuzzy clustering phases and refinement steps. In Step 2, Fuzzy C-Means (FCM) is applied only to the small set of initially labeled data (

here,

Compared to TS3FCM, the proposed AS3FCPC algorithm achieves higher clustering accuracy by explicitly refining boundary points using active learning and pairwise constraints. While this results in improved robustness and precision—particularly in overlapping clusters—it introduces additional computational overhead due to repeated membership updates and expert-guided refinement. The trade-off is a modest increase in complexity for a significant gain in clustering quality under challenging conditions.

This section presents test results to demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed method compared to other fuzzy semi-supervised methods for the problem of assessing the quality of clusters.

The Test compares and suggests test scenarios on two types of data: UCI standard dataset and a flood satellite image dataset. The goal is to show that the success of the proposed method works even when there are a lot of noise points. We selected these datasets to thoroughly assess the performance of our algorithm in various data types and clustering scenarios. Testing on both tabular and image data allows for rigorous evaluation, ensuring the effectiveness of the clustering model in many different real-life situations.

3.1.1 The UCI Benchmark Data Sets

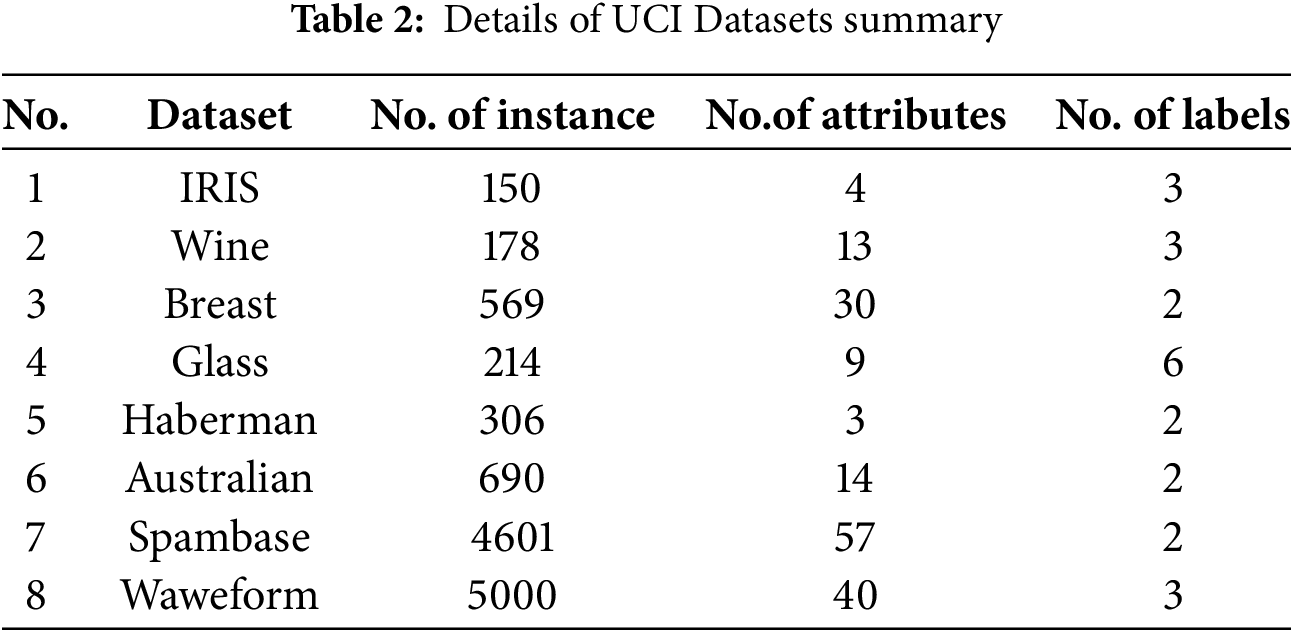

There are six datasets taken from the UCI standard database, from the UCI Machine Learning Repository [31], including IRIS, Wine, Breast, Thyroid, Soybean, and Glass. Details of the UCI benchmark data sets are described in Table 2 as follows.

The Standard UCI benchmark datasets were selected for their diversity in sample size, feature dimensionality, class imbalance, and the presence of noise and overlapping decision boundaries, which make them well-suited for evaluating the robustness of clustering algorithms like AS3FCPC.

3.1.2 Flood Area Segmentation Dataset

To evaluate our method, we employed a dataset designed for flood area segmentation [32]. An illustrative example of a satellite image is shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Illustration of the satellite image flood detection

This dataset consists of 290 images illustrating flood-stricken locations, accompanied by corresponding pixel-level mask annotations that were self-generated using the Label Studio open-source tool. The dataset was designed to demonstrate the algorithm’s effectiveness in complex and noisy scenarios with real application relevance. The annotations delineate water regions, enabling binary segmentation into “flood area” and “no flood area” classes. Our proposed approach aims to achieve this binary segmentation, thereby facilitating automated flood area detection within the images.

3.2 Evaluation Metrics and Test Environments

The tests were implemented in C using the Dev-C++ IDE and run on a Surface laptop with an Intel(R) Core(TM) i5-1135G7 CPU (2.40 GHz) and 16 GB RAM. This setup ensures consistent testing conditions and reproducibility. We evaluate the performance of the proposed AS3FCPC algorithm by comparing it with five existing fuzzy clustering methods: FCM, SSFCM [33], CS3FCM, TS3FCM, and AFFC [34]. To assess clustering quality under noisy boundary conditions, we use four standard evaluation metrics: Rand Index (RI) [35], F1-score [36], Normalized Mutual Information (NMI) [37], and Davies-Bouldin Index (DB) [38].

3.3 Test Results and Some Discussions

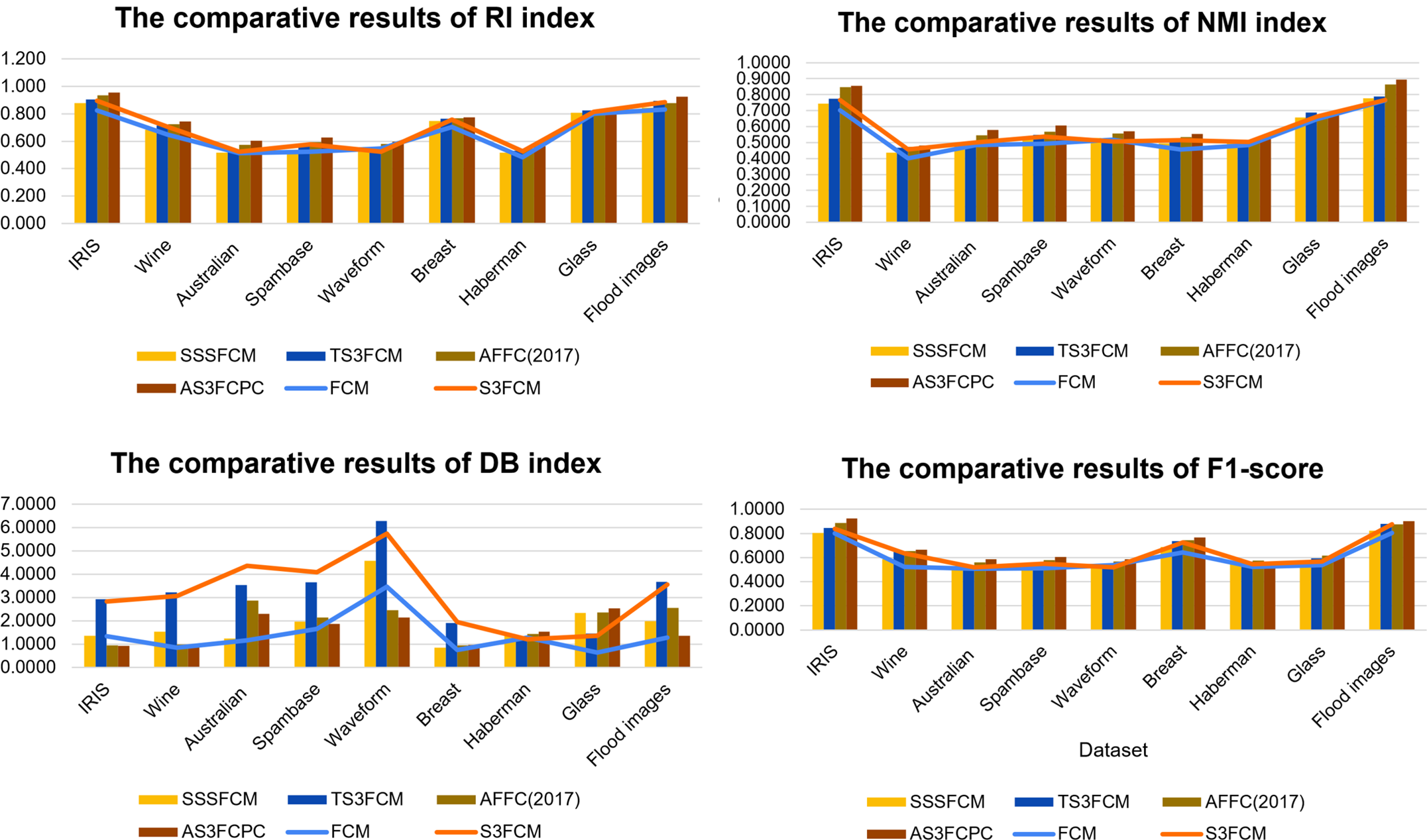

After conducting the tests, we observed that the proposed algorithm converges within 10 to 25 iterations, depending on the complexity and noise level of each dataset. For most benchmark datasets (e.g., Wine, Iris, and Flood Segmentation), convergence was achieved efficiently and well below the maximum iteration threshold. The comparative results illustrating the clustering performance of the proposed AS3FCPC model against related methods—evaluated using RI, F1-score, NMI, and DB index are presented in Fig. 3:

Figure 3: The comparison results of methods on each criterion

First of all, the performance of the AS3FCPC algorithm is evaluated and contrasted with other well-known clustering techniques using the RI measure. The test results indicate that AS3FCPC outperforms the different clustering algorithms in terms of the RI across all datasets. In the IRIS dataset, AS3FCPC got an RI score of 0.956 compared to 0.904 for TS3FCM, which is much higher than the scores of the other algorithms, like AFFC (2017), which got a score of 0.936. This suggests that, in comparison to its rivals, AS3FCPC is especially good at accurately classifying the data points and reducing errors, producing more precise clustering results. On more complex datasets such as Australian and Spambase, AS3FCPC attains RI scores of 0.605 and 0.625, respectively, while TS3FCM reaches only 0.526 and 0.563. The advantage is also evident in the real-world Flood Images dataset, where AS3FCPC scores 0.925, outperforming TS3FCM’s 0.893. Also, the AS3FCPC algorithm can handle various datasets with ease. For instance, AS3FCPC outperformed the other algorithms once more with a score of 0.925 in the Flood dataset. This consistency across different data types demonstrates AS3FCPC’s dependability and exceptional clustering task performance. According to these findings, the AS3FCPC algorithm is a valuable tool for clustering analysis tasks since it is a very reliable and efficient way to achieve high-quality clustering.

By analyzing the F1-score, the test findings show that the AS3FCPC algorithm works better than other clustering methods. It exceeds algorithms such as TS3FCM (0.845636), AFFC (2017) (0.8853), and S3FCM (0.8375) and attains the highest F1 scores across multiple datasets, including IRIS (0.9253). This pattern is evident in all examined datasets, demonstrating the algorithm’s resilience. The F1-score equilibrates precision and recall, which are essential for efficient clustering, particularly in imbalanced datasets. AS3FCPC is successful in accurately identifying clusters and capturing all genuine clusters. Its elevated F1 scores across various datasets indicate that it circumvents overfitting and underfitting, demonstrating its adaptability in clustering tasks. Compared to other algorithms like FCM (0.80261) and TS3FCM (0.87831), AS3FCPC achieves a high F1-score of 0.90137 in challenging datasets, such as the Flood dataset. This demonstrates the algorithm’s capacity to manage intricate clustering jobs, rendering it a dependable and practical option for real applications. This clearly illustrates that, even when compared with strong baselines like TS3FCM, AS3FCPC offers a better balance between precision and recall—making it a more reliable and practical option for real-world clustering applications, especially under noisy or overlapping conditions.

NMI is a commonly used metric to evaluate clustering quality by measuring the agreement between predicted clusters and accurate class labels. Higher NMI values indicate more substantial alignment with the ground truth. AS3FCPC consistently outperforms baseline methods across all evaluated datasets. The IRIS dataset achieves an NMI score of 0.8556, outperforming FCM (0.7023), SSFCM (0.7437), and CS3FCM (0.7647) as well as TS3FCM (0.7736). Similarly, on the Australian dataset, AS3FCPC reaches 0.5783, higher than CS3FCM (0.5007) and TS3FCM (0.5053). The method also demonstrates robustness on more complex and high-dimensional datasets. On Flood Images, AS3FCPC achieves 0.8932, surpassing TS3FCM (0.7885), FCM (0.7641), SSFCM (0.7762), and CS3FCM (0.7670). For Spambase and Waveform, AS3FCPC yields NMI scores of 0.6065 and 0.5711, respectively, outperforming both FCM and SSFCM, and improving upon TS3FCM’s performance (0.5475 and 0.5158). Across all datasets, AS3FCPC maintains consistently higher NMI values, regardless of data complexity. This indicates its capability to generate cluster structures that closely reflect the underlying data distribution. Its consistent performance on both complex and straightforward datasets highlights its reliability for diverse real-world clustering tasks, even in scenarios where TS3FCM already showed strong baseline accuracy.

Finally, the Davies-Bouldin Index (DB) score is a widely used metric that evaluates the balance between intra-cluster compactness and inter-cluster separation, with lower values indicating better clustering performance. Test results demonstrate that the proposed AS3FCPC consistently achieves lower DB values across a wide range of datasets, reflecting its ability to form compact and well-separated clusters. For instance, AS3FCPC outperforms other methods such as TS3FCM (2.9246), FCM (1.3348), SSFCM (1.3654), and CS3FCM (2.8324) in the IRIS dataset, achieving a DB value of 0.9244. An important measure of successful clustering is a lower DB value, which indicates that the clusters created by AS3FCPC are more compact and well-separated.

Similarly, AS3FCPC (0.9451) performs better than SSFCM (1.5327) and CS3FCM (3.0645) in the Wine dataset, indicating that it can create clusters that are more distinct and coherent. One of the most striking aspects of AS3FCPC is the fact that it performs exceptionally well on more complicated datasets. In the Australian dataset, for example, AS3FCPC gets a DB value of 2.2984, significantly lower than TS3FCM (3.5437) and CS3FCM (4.3658), demonstrating its superiority in managing intricate, high-dimensional data structures. Additionally, AS3FCPC performs well under challenging conditions, such as in the Flood images dataset, where it achieves a DB value of 1.3544, surpassing FCM (1.2836) and SSFCM (1.9805). This demonstrates its resilience and effectiveness, even in more complex clustering scenarios.

The extensive test results provide strong evidence of the effectiveness of AS3FCPC in improving semi-supervised fuzzy clustering performance. The integration of confidence-based learning, active query selection, and pairwise constraints allow for more accurate, interpretable, and stable clustering outcomes. Across all evaluation metrics (RI, F1-score, and NMI), AS3FCPC consistently outperforms competing methods while achieving lower DB values, ensuring compact, well-separated clusters. This study firmly establishes AS3FCPC as a state-of-the-art method for semi-supervised fuzzy clustering, particularly in scenarios involving sparsely labeled data, noisy environments, and complex distributions. Our approach’s ability to adaptively refine clustering structures and enhance trust-based clustering decisions makes it a robust and scalable solution for various real-world applications. Future work could explore extending this methodology to high-dimensional and streaming data environments, further enhancing its applicability in dynamic and evolving datasets.

In summary, the proposed AS3FCPC method presents a novel approach that synergistically integrates fuzzy clustering, semi-supervised learning, and active learning to tackle the challenges of clustering in scenarios with limited labeled data and ambiguous boundary regions. By initially leveraging both labeled and unlabeled data through an active learning initialization phase, the method effectively identifies and refines ambiguous data points, ensuring that the cluster centers are robustly established. The subsequent iterative semi-supervised fuzzy clustering phase, enhanced with pairwise constraints, further refines the membership values and cluster boundaries, leading to a clustering configuration that closely aligns with domain-specific relationships.

The test results across benchmark datasets demonstrate that AS3FCPC consistently achieves superior performance, as evidenced by higher Rand Index, F1 scores, and Normalized Mutual Information, as well as lower Davies-Bouldin indices compared to TS3FCM, as well as traditional fuzzy clustering, and other semi-supervised approaches. These findings confirm that the dynamic integration of active learning and fuzzy clustering not only enhances clustering accuracy but also produces well-separated and compact clusters, making AS3FCPC highly effective for complex, real-world applications such as flood area segmentation. While this paper demonstrates the effectiveness of AS3FCPC through comparisons with several established semi-supervised fuzzy clustering methods, future work will focus on extending this evaluation to include more recent models published in 2024–2025.

Looking ahead, several promising future research directions can further elevate the capabilities and applicability of AS3FCPC. Enhancing scalability and computational efficiency remains a key priority, with potential solutions including parallel processing, distributed computing frameworks, and algorithmic optimizations to handle large-scale datasets without compromising performance. From an optimization perspective, future work may explore the integration of metaheuristic algorithms—such as Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), Genetic Algorithms (GA), or Ant Colony Optimization (ACO)—to dynamically optimize cluster center initialization, constraint weighting, or membership updates, thereby reducing convergence time and improving clustering quality. Additionally, integrating deep learning techniques models (e.g., CNNs or GNNs) for feature extraction and representation learning is anticipated to enrich data representations, thereby further improving the accuracy of boundary refinement and membership assignments. Moreover, advancing automated boundary detection and correction methods would significantly reduce reliance on manual interventions, streamlining the clustering process and enhancing robustness in noisy or uncertain environments. While effective, AS3FCPC currently depends on fixed neighborhood radius settings, expert feedback for labeling, and predefined pairwise constraints. Future work may address these limitations by incorporating adaptive neighborhood estimation, automated constraint selection, and weak or self-supervised alternatives to reduce labeling dependency. Exploring a broader array of active learning strategies—such as uncertainty sampling, query-by-committee, or diversity-based approaches—could provide deeper insights into optimizing the selection of ambiguous data points, thereby fine-tuning the model’s adaptability across various data scenarios. In addition, for fuzzy clustering contexts, we also considered metrics that incorporate membership degrees—such as Partition Coefficient (PC) and Partition Entropy (PE)—in our preliminary tests to analyze fuzziness in membership distribution. Finally, extending the application of AS3FCPC to diverse domains—ranging from medical imaging and remote sensing to social network analysis—will not only validate its versatility but also reveal domain-specific challenges that can inspire further innovations, paving the way for its adoption in a wide range of complex, real-world clustering tasks.

Acknowledgement: The authors acknowledge the use of ChatGPT (OpenAI) for assistance with grammar checking, language polishing and minor improvements to sentence structure. All outputs were carefully reviewed and verified by the authors to ensure accuracy and originality.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Study conceptualization: Duong Tien Dung, Ha Hai Nam, Nguyen Long Giang, Luong Thi Hong Lan; data collection and experiment: Duong Tien Dung, Nguyen Long Giang; analysis and interpretation of results: Duong Tien Dung, Luong Thi Hong Lan; draft manuscript preparation: Duong Tien Dung, Ha Hai Nam, Luong Thi Hong Lan. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available on request from the authors.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Qu F, Shi Y, Yang Y, Hu Y, Liu Y. Coordinate descent K-means algorithm based on split-merge. Comput Mater Contin. 2024;81(3):4875–93. doi:10.32604/cmc.2024.060090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Xia Y, Li X, Liu Y, Zhou W, Tang Y. Relative-density-viewpoint-based weighted kernel fuzzy clustering (RDVWKFC). Comput Mater Contin. 2025;84(1):625–51. doi:10.32604/cmc.2025.065358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Bezdek JC. Pattern recognition with fuzzy objective function algorithms. New York, NY, USA: Springer Science & Business Media; 2013. doi:10.1007/978-1-4757-0450-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Xing R, Li C. Fuzzy C-means algorithm automatically determining optimal number of clusters. Comput Mater Contin. 2019;60(2):767–80. doi:10.32604/cmc.2019.04500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Hussain I, Sinaga KP, Yang MS. Unsupervised multiview fuzzy c-means clustering algorithm. Electronics. 2023;12(21):4467. doi:10.3390/electronics12214467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Daneshfar F, Soleymanbaigi S, Yamini P, Amini MS. A survey on semi-supervised graph clustering. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2024;133(Part B):108215. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2024.108215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Thong PH, Canh HT, Lan LTH, Huy NT, Giang NL. Multi-view picture fuzzy clustering: a novel method for partitioning multi-view relational data. Comput Mater Contin. 2025;83(3):5461–85. doi:10.32604/cmc.2025.065127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Xu S, Hao Z, Zhu Y, Wang Z, Xiao Y, Liu B. Semi-supervised fuzzy clustering algorithm based on prior membership degree matrix with expert preference. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;238(5):121812. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2023.121812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Kmita K, Kaczmarek-Majer K, Hryniewicz O. Explainable impact of partial supervision in semi-supervised fuzzy clustering. IEEE Trans Fuzzy Syst. 2024;32(5):3189–98. doi:10.1109/TFUZZ.2024.3370768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Oskouei AG, Samadi N, Tanha J. Feature-weight and cluster-weight learning in fuzzy c-means method for semi-supervised clustering. Appl Soft Comput. 2024;161(2):111712. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2024.111712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Santos GM, Julia RMS, Do Nascimento MZ. K-GBS3FCM-KNN graph-based safe semi-supervised fuzzy c-means. In: 2024 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (BigData); 2024 Dec 15–18; Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE. p. 3498–507. doi:10.1109/BigData62323.2024.10825467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Li K, Cao Z, Cao L, Zhao R. A novel semi-supervised fuzzy c-means clustering method. In: 2009 Chinese Control and Decision Conference; 2009 Jun 17–19; Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE. p. 3761–5. doi:10.1109/CCDC.2009.5191706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Wang Y, Chen L, Zhou J, Li T, Yu Y. Pairwise constraints-based semi-supervised fuzzy clustering with multi-manifold regularization. Inf Sci. 2023;638(2):118994. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2023.118994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Chen HR, Wang XP, Wu JX, Wang HZ. Adaptive semi-supervised fuzzy C-means method with local spatial information and pre-clustering for image segmentation. IEEE Access. 2024;12:196328–46. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3521595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Samadi N, Tanha J, Jalili M. A weighted semi-supervised Possibilistic Fuzzy c-Means algorithm for data stream classification and emerging class detection. Knowl Based Syst. 2025;309(5):112831. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2024.112831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Triguero I, García S, Herrera F. Self-labeled techniques for semi-supervised learning: taxonomy, software and empirical study. Knowl Inf Syst. 2015;42(2):245–84. [Google Scholar]

17. Gan H, Fan Y, Luo Z, Zhang Q. Local homogeneous consistent safe semi-supervised clustering. Expert Syst Appl. 2018;97:384–93. [Google Scholar]

18. Gan H, Fan Y, Luo Z, Huang R, Yang Z. Confidence-weighted safe semi-supervised clustering. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2019;81:107–16. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2019.02.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Huan PT, Thong PH, Tuan TM, Hop DT, Thai VD, Minh NH, et al. TS3FCM: trusted safe semi-supervised fuzzy clustering method for data partition with high confidence. Multimed Tools Appl. 2022;81(9):12567–98. doi:10.1007/s11042-022-12133-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Sener O, Savarese S. Active learning for convolutional neural networks: a core-set approach. arXiv:1708.00489. 2017. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1708.00489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Li D, Wang Z, Chen Y, Jiang R, Ding W, Okumura M. A survey on deep active learning: recent advances and new frontiers. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2024;36(4):5879–99. doi:10.1109/TNNLS.2024.3396463. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Atwa W, Almazroi AA, Aldhahr EA, Janbi NF. Active semi-supervised clustering algorithm for multi-density datasets (ASS-DBSCAN). Int J Adv Comput Sci Appl. 2024;15(10):2014. doi:10.14569/IJACSA.2024.0151052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Agrawal A, Tripathi S, Vardhan M. Active learning approach using a modified least confidence sampling strategy for named entity recognition. Prog Artif Intell. 2021;10(2):113–28. doi:10.1007/s13748-021-00230-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Tharwat A, Schenck W. A survey on active learning: state-of-the-art, practical challenges and research directions. Mathematics. 2023;11(4):820. doi:10.3390/math11040820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Memarzadeh M, Matthews B, Templin T, Sharif Rohani A, Weckler D. Semi-supervised active learning for anomaly detection in aviation. J Aerosp Inf Syst. 2023;20(4):181–94. doi:10.2514/1.I011083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Grira N, Crucianu M, Boujemaa N. Active semi-supervised fuzzy clustering. Pattern Recognit. 2008 May;41(5):1834–44. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2007.10.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Jasim AK, Tanha J, Balafar MA. Neighborhood information based semi-supervised fuzzy C-means employing feature-weight and cluster-weight learning. Chaos Solitons Frac. 2024;181(1):114670. doi:10.1016/j.chaos.2024.114670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Qiao J, Sun Z, Meng X. Interval type-2 fuzzy neural network based on active semi-supervised learning for non-stationary industrial processes. IEEE Trans Autom Sci Eng. 2023;21(2):1151–62. doi:10.1109/TASE.2023.3237840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Arthur D, Vassilvitskii S. k-means++: the advantages of careful seeding. In: Proceedings of the Eighteenth Annual ACM-SIAM Symposium on Discrete Algorithms (SODA). Philadelphia, PA, USA: Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics; 2007. p. 1027–35. [cited 2025 Aug 1]. Available from: 10.5555/1283383.1283494. [Google Scholar]

30. Bajpai N, Paik JH, Sarkar S. A stratified seed selection algorithm for K-means clustering on big data. IEEE Trans Artif Intell. 2025 May;6(5):1334–44. doi:10.1109/TAI.2024.3524370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Markelle Kelly KN, Rachel L. The UCI machine learning repository [Internet]. [cited 2025 May 15]. Available from: https://archive.ics.uci.edu. [Google Scholar]

32. Karim MF, Sharma K, Niyar R, Barman NR. Flood area segmentation [Dataset]. Kaggle. 2022; [cited 2025 May 15]. Available from: https://www.kaggle.com/dsv/4732950. [Google Scholar]

33. Yasunori E, Yukihiro H, Makito Y, Sadaaki M. On semi-supervised fuzzy c-means clustering. In: 2009 IEEE International Conference on Fuzzy Systems; 2009 Aug 20–24; Jeju, Republic of Korea. p. 1119–24. doi:10.1109/FUZZY.2009.5277177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Novoselova N, Tom I. Fuzzy semi-supervised clustering with active constraint selection. In: International Conference on Pattern Recognition and Information Processing. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2016. p. 132–9. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-54220-1_14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Rand WM. Objective criteria for the evaluation of clustering methods. J Am Stat Assoc. 1971;66(336):846–50. doi:10.2307/2284239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Li S, Kou P, Ma M, Yang H, Huang S, Yang Z. Application of semi-supervised learning in image classification: research on fusion of labeled and unlabeled data. IEEE Access. 2024;12:27331–27343. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3367772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Mahmoudi A, Jemielniak D. Proof of biased behavior of normalized mutual information. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):9021. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-59073-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Ros F, Riad R, Guillaume S. PDBI: a partitioning Davies-Bouldin index for clustering evaluation. Neurocomputing. 2023;528(2):178–99. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2023.01.043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools