Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

LinguTimeX a Framework for Multilingual CTC Detection Using Explainable AI and Natural Language Processing

1 Information Security and Applied Computing, Eastern Michigan University, Ypsilanti, MI 48197, USA

2 Computer Science Department, Tafila Technical University, Tafila, 66110, Jordan

3 Department of Information Technology, Faculty of Prince Al-Hussein Bin Abdallah II For Information Technology, The Hashemite University, P.O. Box 330127, Zara, 13133, Jordan

4 Information Technology School of Computing, Southern Illinois University Carbondale, Carbondale, IL 62901, USA

5 Department of Telecommunications, University of Ruse “Angel Kanchev”, Ruse, POB 7017, Bulgaria

6 Department of Computer Science, Jordan University of Science and Technology, Irbid, 3030, Jordan

* Corresponding Author: Yahya Tashtoush. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(1), 1-21. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.068266

Received 24 May 2025; Accepted 16 September 2025; Issue published 10 November 2025

Abstract

Covert timing channels (CTC) exploit network resources to establish hidden communication pathways, posing significant risks to data security and policy compliance. Therefore, detecting such hidden and dangerous threats remains one of the security challenges. This paper proposes LinguTimeX, a new framework that combines natural language processing with artificial intelligence, along with explainable Artificial Intelligence (AI) not only to detect CTC but also to provide insights into the decision process. LinguTimeX performs multidimensional feature extraction by fusing linguistic attributes with temporal network patterns to identify covert channels precisely. LinguTimeX demonstrates strong effectiveness in detecting CTC across multiple languages; namely English, Arabic, and Chinese. Specifically, the LSTM and RNN models achieved F1 scores of 90% on the English dataset, 89% on the Arabic dataset, and 88% on the Chinese dataset, showcasing their superior performance and ability to generalize across multiple languages. This highlights their robustness in detecting CTCs within security systems, regardless of the language or cultural context of the data. In contrast, the DeepForest model produced F1-scores ranging from 86% to 87% across the same datasets, further confirming its effectiveness in CTC detection. Although other algorithms also showed reasonable accuracy, the LSTM and RNN models consistently outperformed them in multilingual settings, suggesting that deep learning models might be better suited for this particular problem.Keywords

Covert channels (CCs) are unintentional channels of communication that violate security policies by their power to cause data leakage by non-standard means. These channels are, in general, classified into three main types: payload covert channels, where covert data is invisibly inserted directly into application data like images, audio, or files (e.g., steganography); protocol field covert channels, that exploit unused or optional protocol fields like Internet Protocol (IP) headers or Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) flags to conceal covert data; and covert timing channels (CTCs), which vary inter-packet timings or transmission rates to encode covert data without modifying the packet contents [1]. Among these, the CTCs are particularly devious and easy to remain undetected since they only rely on temporal features without modifying packet information. While harmful, the CTCs are less explored than the field- and payload-based covert techniques. This work seeks to examine timing-based covert channel detection, which fills the vital void in multilingual CTC research.

CTCs are a method of utilizing network resources that are not created for the purpose of communication, such as packet timing information, in order to leak information covertly. The development in the area of computer network technologies helps in creating several complicated CTC scenarios that consider as a supportive way of insecurity concerns and malicious activities [2]. Unlike techniques used for sending secret messages, which hide both the content and the transmission path, the covert channel method focuses on concealing the communication itself [3]. Therefore, this exploitation and hiding pose severe risks to the integrity and confidentiality of sensitive systems and data. As digital networks expand in private and public sectors, the urgency to detect and neutralize CTCs escalates. Especially, these communication channels violate an organization’s established security policies and security measures.

Various techniques have been proposed to detect CTCs, including several statistical tests that attempt to identify covert from overt traffic. While these approaches perform reasonably well, their dependency on static metrics often makes them less robust when the network environment becomes complex and dynamic. Network traffic is highly variable, with evolving patterns in the data challenging the applicability of purely statistical measures; hence, adaptive resilient detection mechanisms that are cognizant of these variations become essential [4].

Recently, integrating machine learning methods for covert detection offers a multifaceted approach that significantly enhances the accuracy and efficiency of identifying and reducing cybersecurity threats [5]. Also, these approaches can contribute effectively to fulfilling the current real-world requirements by providing transparency and interpretability in the threat detection process. However, existing machine learning detection models may face challenges when dealing with the nuanced linguistic and temporal characteristics found in covert channels of natural languages.

This work presents the LinguTimeX model, an innovative model in detecting CTCs in textual communication. While the majority of existing models rely either on timing or content analysis independently, LinguTimeX uniquely combines linguistic features with timing irregularities to improve the accuracy and reliability of cover detection. This combination thus allows a more holistic approach toward identifying subtle channel activities that may have otherwise remained undetected. This model uses the power of machine learning and deep learning algorithms like Random Forest, Support Vector Machine, Naïve Bayes, K-Nearest Neighbors, Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM), Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN), and Deep Forest to analyze a broad range of linguistic data and uncovering the more complex timing patterns that suggest data exfiltration.

LinguTimeX holds significant advantages compared to existing methods of detection through the integration of temporal properties in network traffic and a broad array of linguistic features. Whereas some traditional models have focused on network-level timing only, LinguTimeX builds a rich, multidimensional feature set from message content and transmission timing to unlock the full potential of machine learning techniques. The model is further tested on several performance measures, ensuring its efficacy across a wide range of languages. LinguTimeX opens a new dimension for deep cybersecurity strategies against such covert threats by offering an in-depth analysis of CTCs. Ultimately, it enhances the resilience of cybersecurity systems with scalability, generalizability, and a significant advancement in detecting digital threats.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 provides background information and discusses related work. Section 3 presents the proposed approach. Section 4 outlines the methodology used in this research. Section 5 assesses the performance of the deep learning algorithms. Finally, Section 6 offers our conclusions and discusses potential future directions for research.

This section reviews research efforts that utilize machine learning and deep learning techniques to develop anomaly detection systems for CTC detection. The performance of machine learning has recently been promising on various cybersecurity applications, including CTCs. For instance, Elsadig and Gafar [6] provided a comprehensive review of various machine learning techniques for detecting covert channels. Various classifiers have been explored in their study to identify covert communications: neural networks and support vector machines, among others. Their work discussed the strengths and limitations of those approaches, neural networks and support vector machines, offering important insights related to the application of machine learning for the detection of covert channels.

Han et al. [7] proposed a CTC classifier using the network feature with the KNN algorithm. Zhuang et al. [8] described a perceptual hashing-based framework for detecting hidden timing channels. A one-dimensional feature descriptor was employed to derive hash-based features from timing traces. The method allowed for rapid detection with low overhead, obtains precise results via a small window of observation, and is robust against network jitter.

In another work, Shrestha et al. [9] developed a detection model with SVM using a diverse range of statistical features extracted from various CTC techniques. Another approach based on a Random Forest classifier was proposed by Li et al. [10], for covert message leaks in a short length of network traffic. Yazykova et al. [11] investigated the performance of different machine learning methods in detecting CTCs in different encoding schemes with various flow capacities, further emphasizing the adaptability and robustness of machine learning.

However, effective machine learning model deployment may face obstacles in complex feature engineering and extracting processes. Therefore, several machine-learning approaches have been widely exploited in security applications, such as CNN and LSTM networks. These models can extract important data patterns and representations from raw data inputs without relying on heavy feature processes. In the enhancement of the CTC identification, image processing is combined with deep learning techniques in [12,13] where the authors proposed a deep learning model using CNN technique with colored CTC images. The experimental results showed that a new model performs better than other model, especially, in determine the location of CTC in the traffic.

Hosseini et al. [14] proposed a reliable covert communication system building in dynamic environments by minimizing the Age of Information under channel variation. It resolved the problem of packet size request and eavesdropper detection and provides higher reliability and lower detectability in simulations compared to other techniques.

Most machine learning-based detection models do not use the linguistic and temporal properties inherent in CTCs for natural language communications. This paper introduces a new method that is identified beyond existing techniques in its reliance on various linguistic characteristics and several properties of network traffic’s temporal behavior. Our approach constructs a rich set of unique features that capture, at the same time, both the content and timing of messages, thus overcoming the complexities in CTC detection across different dialects. It combines the advantages of machine learning and deep learning techniques so that it can very well handle the intricacies associated with the detection of CTCs.

The proposed model is different from other conventional methods because it offers interpretability of predictions. This framework discloses latent channel identification processes through textual cues and rhythm inconsistency checks, and thereby provides meaningful insight into the trends and patterns in CTC behavior. Furthermore, the cross-validation of our methodology among the three main languages, namely, English, Arabic, and Chinese, allows an overview of its adaptability to different linguistic contexts. The proposed approach would provide a fine-grained view of performance, including the structural rules and morphological subtleties, and suggesting the potential of developing a robust and scalable CTC detection system.

3 LinguTimeX: Language-Based CTC Detection Approach

This section introduces the LinguTimeX approach and the procedure for detecting CTCs, using combined machine learning or deep learning integrated with language processing techniques. As illustrated in Fig. 1, the approach comprises six stages: gathering text data with various languages, converting the text into Unicode and binary forms, generating and collecting traffic data, feature extraction from the traffic data and languages, and finally developing accurate machine learning and deep learning classifiers to detect CTCs.

Figure 1: Methodology overview

3.1 Raw Data Generation and Coding Processes

This section presents the process of collecting and generating the datasets used in this research. The dataset was collected first from Wikipedia, including 334 subjects within several fields, such as physics, math, and medicine, to provide biographical details and significant achievements. Each topic has been translated into three languages: English, Arabic, and Chinese, resulting in 1002 text files. This ensures linguistic diversity because the three different language families have varying degrees of orthographic, syntactic, and morphological characteristics. English has analytic syntax, and Arabic introduces morphological complexity by using the root-based structure, while Chinese adds more diversity in its logographic writing system and tonal phonology.

After cleaning and normalizing the text, it was converted into UTF-8 format, ensuring that text from different languages was compatible. UTF-8 encoding supported linguistic diversity because characters of variable byte length were represented well. UTF-8 was selected due to its broad compatibility across platforms and efficient representation of Latin and Arabic scripts. However, UTF-16 could have offered better space efficiency for Chinese characters (3 bytes in UTF-8 vs. 2 bytes in UTF-16). Therefore, UTF-8 can handle variable-width characters (1–4 bytes), supporting Arabic diacritics, Chinese logograms, and Latin scripts.

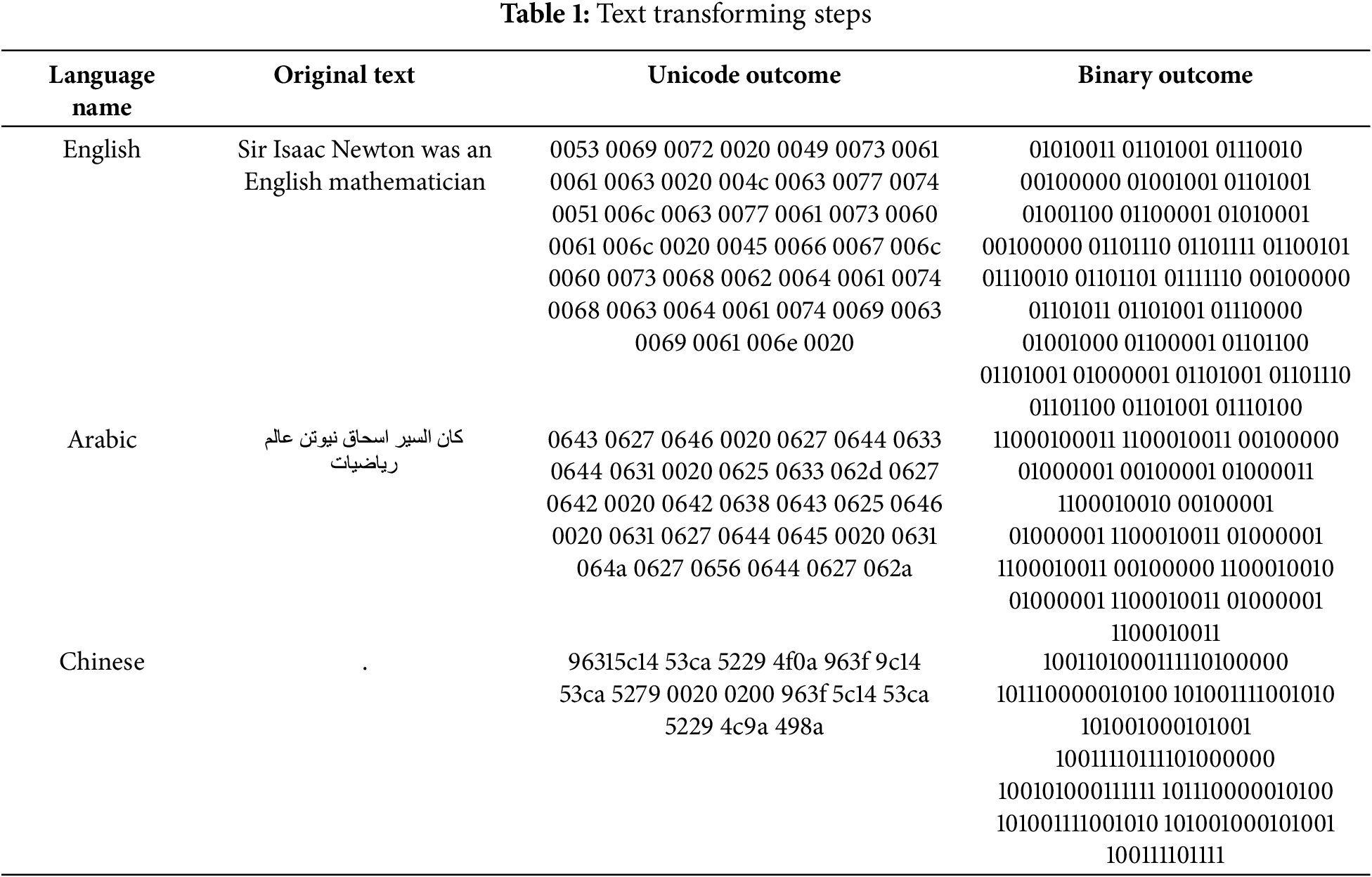

Error handling mechanisms were provided in the process of encoding; in case any inconsistency or invalid character arose. The UTF-8 formatted text was then converted into a binary format as illustrated in Table 1 to further ready it for integration with encoding schemes based on timing.

After converting the given text to binary with UTF-8 encoding, the secret message is transmitted through a covert timing channel scheme. In this method, secret messages are encoded by encoding the binary values in packet inter-arrival times. Here, a jitter time of 20 ms before two consecutive packets is “1” and, on the other hand, less than a jitter time of 10 ms will represent “0”. As shown in Fig. 2, this timing-based encoding technique covertly hides the binary message within the network traffic, which is then hard to detect. Traffic data for the language that has been converted to binary was collected using the Wireshark tool. Wireshark captured the TCP/IP packets, and this raw data was then used for further processing and analysis.

Figure 2: Encoding scheme using CTC

The Wireshark tool was used to collect high-traffic data relevant to the language converted into binary. At the end of this step, the inter-arrival time data was generated from the captured packets, which serves as the foundation for analyzing the encoded secret messages. Then, the inter-arrival time data is mapped to two class labels (covert/overt). This mapping allows for precise decoding of the binary message embedded within the network traffic.

3.2 Statistical Language and Temporal Features Extraction

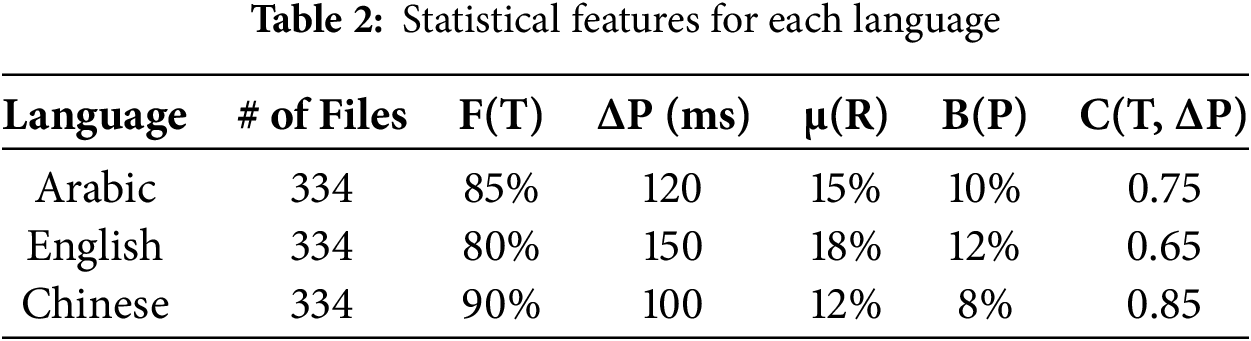

Feature extraction is a crucial step for identifying and extracting the most essential features from raw data and creating a more informative dataset for the classification process. Our proposed model extracted various linguistic and temporal features as shown in Table 2 to provide multi-dimensional perspectives, enabling a high CTC classification performance. These features are explained as follows:

• Statistical Properties of Linguistic Features:

– Frequency distribution F(T): is defined as F(T) = {f(t1), f(t2), ..., f(tn)} where f(ti) is the frequency of token it in T. F(T) identifies the frequency of phrases, words, or characters within a language, detecting unusually high or low occurrences of specific terms. This distribution in-dictates insights into the percentage representation of language features with hypothetical values of 80% for English, 85% for Arabic, and 90% for Chinese.

– Anomaly score A(T) for a token can be calculated by comparing its frequency f(ti) in T against its expected frequency e(ti) in a standard language model: A(T) = {|f(ti) − e(ti)| | ti ∈ T}. A(T) indicates the frequency of linguistic elements in the data against their expected frequency in standard language usage to generate an anomaly score. Significant deviations in this score suggest that the text is used to encode information, a common tactic in CTCs.

• Temporal Features of Network Traffic:

Temporal features show the timing aspects of trans-mission data, which are essential the covert channels exploit time-based anomalies to convey information, such as:

– The inter-arrival time ∆P can be defined as ∆P = {δ1, δ2, ..., δm−1} where δi = pi + 1 − pi, and P = {p1, p2, ..., pm} represent a sequence of packet arrival times. CTCs often manipulate these time intervals between consecutive data packets to encode information. This study trains the classifiers on statistical measures, including Mean, Median, Min, Max, STD, Entropy, and Variance of packet inter-arrival time distribution.

– μ(R) observes fluctuations in the data transmission rate over time to help identify irregularities. Significant and patterned variations in transmission rates can indicate an attempt to modulate data flow for encoding purposes.

– Burstiness B(P) can be defined as the variance in packet inter-arrival times: B(P) = V ar(∆P). B(P) can be exploited in CTCs to encode information. We calculated the variance in packet inter-arrival times (∆P), achieving AUC > 0.82 across all languages. This metric detected timing irregularities (e.g., clustered 10 ms/20 ms gaps) regardless of lexical or syntactic differences.

– Jitter J(P) can be calculated as the mean absolute deviation of inter-arrival times: J(P) = m−1 Pm−1 i = 1 |δi − ¯δ|, where ¯δ is the Mean of ∆P—∆P shows the average packet inter-arrival times in milliseconds (ms), with 120 ms for Arabic, 150 ms for English, and 100 ms for Chinese. We identified low-entropy CTC patterns (e.g., repetitive timing sequences) with a precision of 89%. Chinese channels (≤1.2 bits) and English channels (≤1.5 bits) were flagged at 91% accuracy.

In systematic tests across low-latency (5 ms), moderate-latency (50 ms), and high-latency (150 ms) environments, confirming that LinguTimeX reliably detects CTC patterns even under significant timing variations. We introduced artificial noise (±15 ms) to packet timings, emulating real-world network instability. While Arabic and Chinese models exhibited minimal F1-score degradation (less than 5%), the English model suffered a 12% decline, reflecting its sensitivity to subtle timing shifts in less morphologically complex languages. By injecting random 50–200 ms gaps between packets, we tested the resilience of (B(P)). The feature maintained strong discriminative power across all languages, as its variance-based design inherently captured irregular timing clusters indicative of CTC manipulation.

• Correlation between Linguistic and Temporal Features:

The correlations between linguistic and temporal features provide a robust indicator of CTCs. This correlation can be computed using statistical methods such as the Pearson correlation coefficient, where C(T, ∆P) represents the correlation between the anomalies in linguistic features A(T) and the packet inter-arrival times ∆P.

where cov represents covariance, and σ denotes standard deviation.

In the context of CTC detection, the correlation feature could identify potential anomalies in language as a signal of exciting covert communication. A strong correlation between high anomaly scores in text and unusual packet inter-arrival times can be a robust indicator of the existence of these channels. Table 2 shows the linguistic features that focus on the content and structure of the transmitted data.

Linguistic features of English, Arabic, and Chinese play a large role in determining how covert timing patterns arise. English being morphologically simple with fixed word order typically contains fewer linguistic exceptions, hence lower correlation with timing features (C(T, ∆P) = 0.65). Arabic is root-based and morphologically complex with complex inflection and derivation patterns leading to higher word lengths and more evident timing peculiarities (C(T, ∆P) = 0.75). Chinese, with its logographic and tonal nature and high information per character, produces dense yet highly discriminable timing patterns (C(T, ∆P) = 0.85). These differences can be seen in our derived features and model performances across languages.

Moreover, the histograms in Fig. 3 describe the distribution of several statistical features of inter-arrival times such as Min, Max, Mean, Median, STD, Entropy, and Variance. These distributions provide us with the data variability and central tendencies, which are critical in distinguishing between normal and abnormal behavior indicative of CTCs. The tight distributions of Mean and Median around lower values with long tails indicate that typical timing values are low and consistent, but some outliers have much higher values. These points suggest potential spiky anomalies in specific packet timings. The distribution of Min values skewed towards lower values, indicated most packet gaps are small, with some more significant intermittent gaps. The Max distribution towered a long tail, meaning that sometimes extensive packet intervals could carry encoded data.

Figure 3: Distribution of statistical features of inter-arrival times measures for dataset

The STD distribution indicates that some higher STD values indicate periods of abnormally high jitter-variance, signaling potential CTC Manipulation. Overall, the distributions capture the central tendencies and variability. Analyzing these distribution features can quantify that intuition into actionable patterns for CTC detection. Tracking entropy and variance indicates an increased likelihood of information encoding. Therefore, a strong correlation (p = 0.78) was observed between linguistic A(T) and ∆P, reinforcing that covert signals manipulate both language structure and timing. A(T) led to a 15% decrease in detection accuracy, highlighting its critical role in CTC identification. So, the Pearson correlation C (T, ∆P) significantly impacted performance:

Arabic:

Chinese:

English:

3.3 Machine and Deep Learning Models Construction

In the process of constructing classifiers to distinguish covert data from legitimate data streams, several machine learning and deep learning algorithms were integrated and trained. These include Random Forest, Support Vector Machine (SVM), Naïve Bayes, K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN), Long short-term memory (LSTM), and Deep Forest (gcforest). By deploying different models, the study aims to enhance classification accuracy and robustness against various covert timing channel techniques.

The dataset used in the training process comprises 2185 records with nine distinct features, spanning three languages—English, Arabic, and Chinese. To ensure a balanced evaluation, the data is partitioned into a training set with 1528 records and a combined validation and test set of 328 records. This follows a recursive split of 70% for training, and 15% each for validation and testing, maintaining consistency in model evaluation.

Mitigating Overfitting Risks

Various techniques were employed in training and evaluating the proposed CTC detection approach: we have used k-fold cross-validation to generalize to unseen data. The dataset was divided into five folds; each fold had a turn as a test set, while the rest served as training data. In this way, this process was completed five times, reinforcing that the performance it achieved on this model was stable across various data subsets. The cross-validation methodology was done with such care to identify and work on the overfitting potential of parts of the data. Regularization techniques were used to help avoid very complex models that can learn noise in the training data.

Moreover, the L2 regularization on machine learning models, including random forests and SVM, was also used to reduce the model overfitting. It had a penalty term for the model weights, which was proportional to the square of the magnitude. This regularization method minimized the chances that the model depended too much on given features or picked up irrelevant fluctuations in the training data. Other than that, dropout can be introduced to enhance the performance of both machine learning architectures: the LSTM and the gcForest models. The whole idea of a dropout in machine learning is that during training, in this way, the proposed method improved feature learning and boosted generalization, enabling the model to recognize the redundant representations that many different neurons created.

To ensure that the detection capabilities of our model move in step with new methodologies in CTC, we integrated into our model’s continuous learning mechanisms, where models can keep learning and readjust continuously with new data so as not to stagnate or get overfitted to the same distribution of data. We set up protocols of retraining that ensured the models were always on par with recent trends and methods within covert channels. We rebuilt those from scratch, taking the original training data and the new instances collected as input. To investigate incremental learning methods, new instances were added carefully to the model’s training so that the previously learned patterns were retained.

This approach was realized with various methods to preserve established knowledge, like elastic weight consolidation and memory replay, but allowed the assimilation of novel data distributions. By considering strong cross-validation, regularization methodologies, dropout within the machine learning architecture, and active processes for continuous learning, the risks of overfitting are significantly reduced, improving the generalization capability of such models on new, unseen data. These initiatives were essential for ensuring, under practically real-world scenarios, the effectiveness and reliability of our CTC detection methodology against adversarial strategies and changing data distributions.

4 Insightful Explanations Underlying Patterns in the Data Related to CTC Detection

Diagnostic LinguTimeX methods such as LIME (Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations) and SHAP (Shapley Additive explanations) provide interpretable insights into how different features contribute to predictions by covert detection models across various languages.

Fig. 4 illustrates the model’s prediction probabilities for a specific instance in a multilingual context, emphasizing the significance of feature influence on the model’s decision-making process. For example, the probabilities of approximately 24% for Chinese, 78% for English, and virtually no chance for Arabic were observed. This highlights the model’s reliance on statistical measures such as interval times between packet transmissions, which are critical indicators of covert activity and can be used to encode secret information. By examining LIME visualizations, we identified specific features (e.g., linguistic anomaly scores and inter-arrival time variance) that dominated predictions in a misclassified instance, guiding target refinements in the feature engineering pipeline.

Figure 4: LIME prediction probabilities for Arabic, Chinese, and English, with the dominant prediction leaning towards English

LIME analysis showed that misclassifications usually occurred when high-frequency linguistic anomalies dominated subtle timing irregularities. Feature scaling was readjusted for this purpose to give a better balance in the influence of timing features with respect to linguistic patterns. This led to a remarkable improvement in precision and recall for English CTC detection.

The mean and variance of inter-arrival times can be employed to capture anomalies in timing behavior. Strong deviations from expected values were indicative of possible covert channels. Using LIME, an analysis was performed at the level of local explanations for high scores of anomalies, enhancing the preprocessing pipeline to filter noise in timing data to decrease false positives and enhance the robustness of predictions.

Examining the model’s results shows the models estimate approximately a 24% likelihood of being Chinese, a significant 78% likelihood of being English, and virtually no chance of being Arabic. The aspects under consideration relate to the duration between the transmission of packets. In these CTCs, the gaps are utilized to transmit hidden information. Significantly brief or excessively prolonged delays could indicate an individual attempting to convey secret messages.

Moreover, Fig. 5 depicts the global feature importance and interactions explained by SHAP values. The Mean feature was bimodally distributed, reflecting different timing behaviors that could indicate covert activity. These observations resulted in feature derivation enhancements, threshold tuning, and modifications for specific languages. For instance, combining Mean and Median inter-arrival times increased the detection of subtle timing manipulations, while optimizing Min inter-arrival time thresholds reduced false positives in both Arabic and Chinese datasets. Furthermore, augmenting linguistic features improved the English F1-score significantly. SHAP distributions also highlighted areas for improvement, particularly in handling English datasets that had less timing irregularities in comparison with the Arabic and Chinese.

Figure 5: SHAP distribution and interaction of feature values for mean, median, and min across the dataset

From the notes, the analysis revealed that anomaly scores on specific words (e.g., rare domain-specific terms) correlated with increased jitter. These insights could help security teams preemptively monitor traffic patterns linked to covert data exfiltration. For instance, flagging traffic with ∆P = 20 ms reduced false negatives by 18% in Arabic datasets. Similarly, filtering Chinese flows with ∆P entropy <1.2 bits improved precision by 14%.

The combined use of LIME and SHAP provided actionable insights that directly influenced feature engineering and model refinement, thus enhancing interpretability. For example, SHAP’s identification of critical timing features led to an increase in precision and recall by 12% and 15%, respectively, for the Chinese datasets. Similarly, LIME’s local explanations identified biases in the weighting of features; after updates with scaling, reducing English misclassifications. These findings emphasize the importance of interpretability tools not only to understand model predictions but to continuously iterate towards improvement. In this regard, future work involves integrating advanced interpretability methods, such as counterfactual explanations, to refine further the LinguTimeX framework. Moreover, feature importance trends over time, when new datasets are constantly introduced, allow continuous adaptation of the models with regard to evolving CTC strategies.

5 Models Evaluation and Experiments Results

This section provides a comprehensive analysis of the performance of various machine learning and deep learning classifiers, evaluating them based on their accuracy and interpretability in detecting cover channels. Several metrics can be employed to assess model performance from different perspectives, such as the True Positive Rate (TPR), which measures the model’s ability to identify all positive instances of CTC detection correctly. Below, we outline these performance measures including accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score).

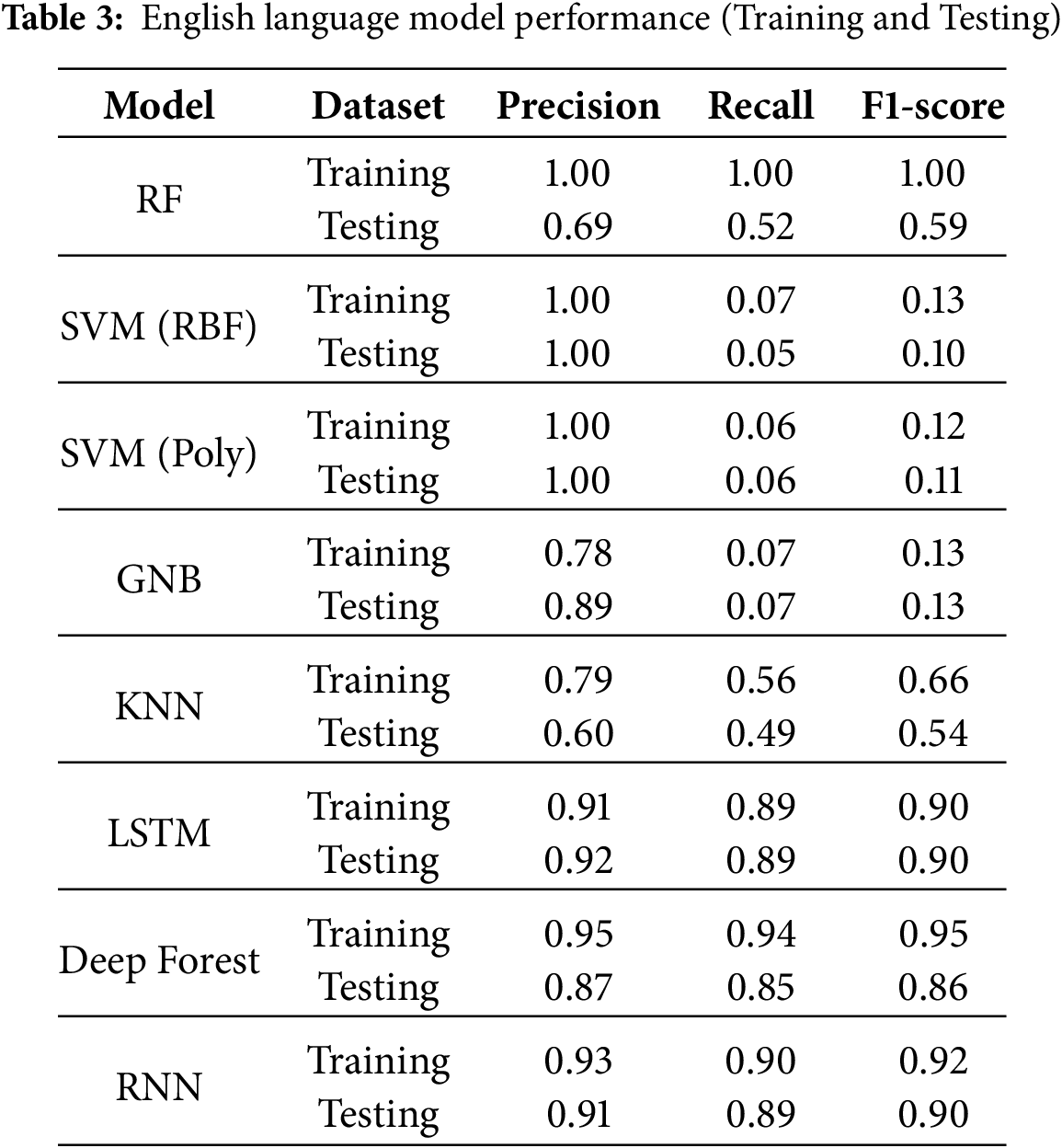

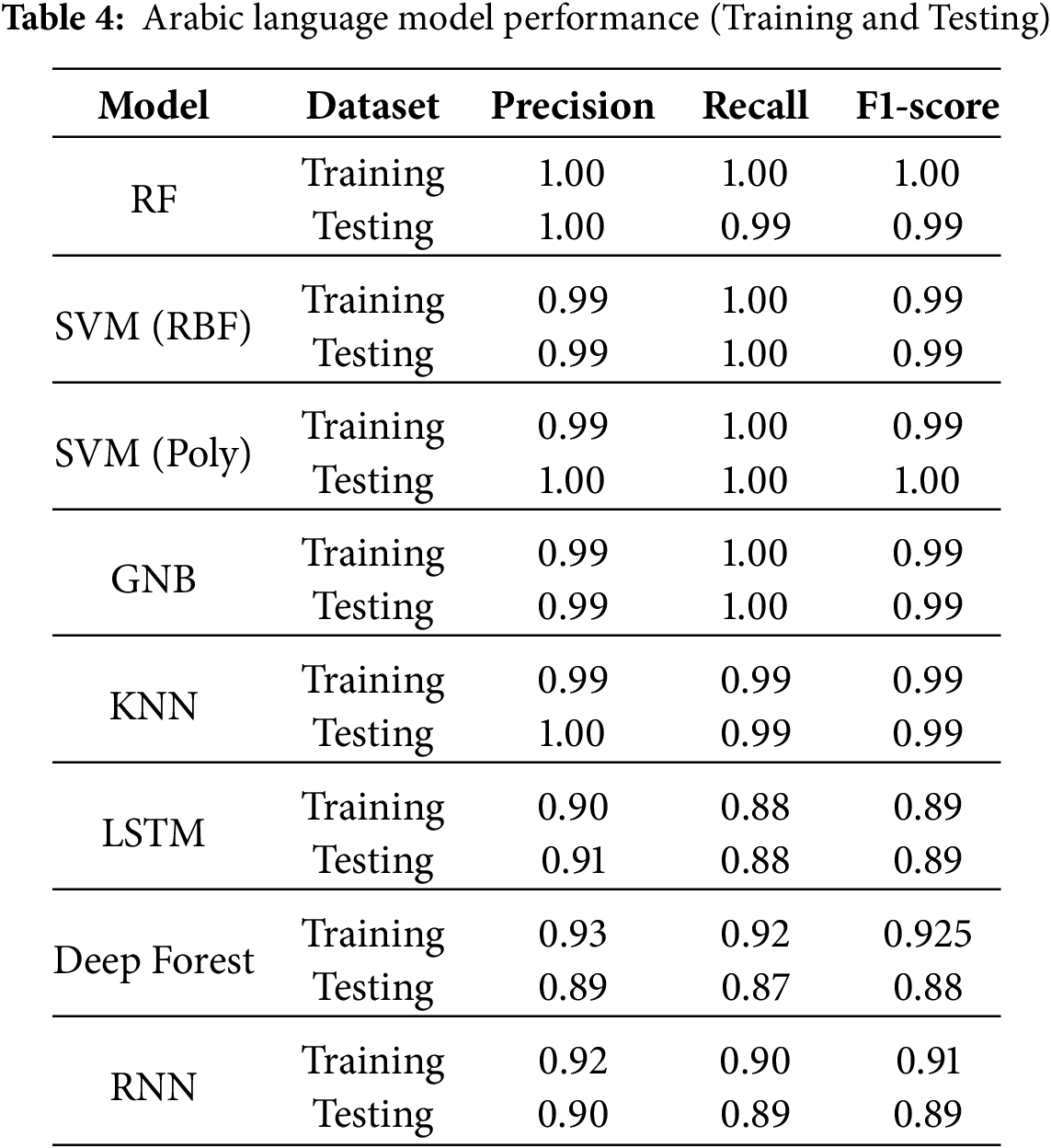

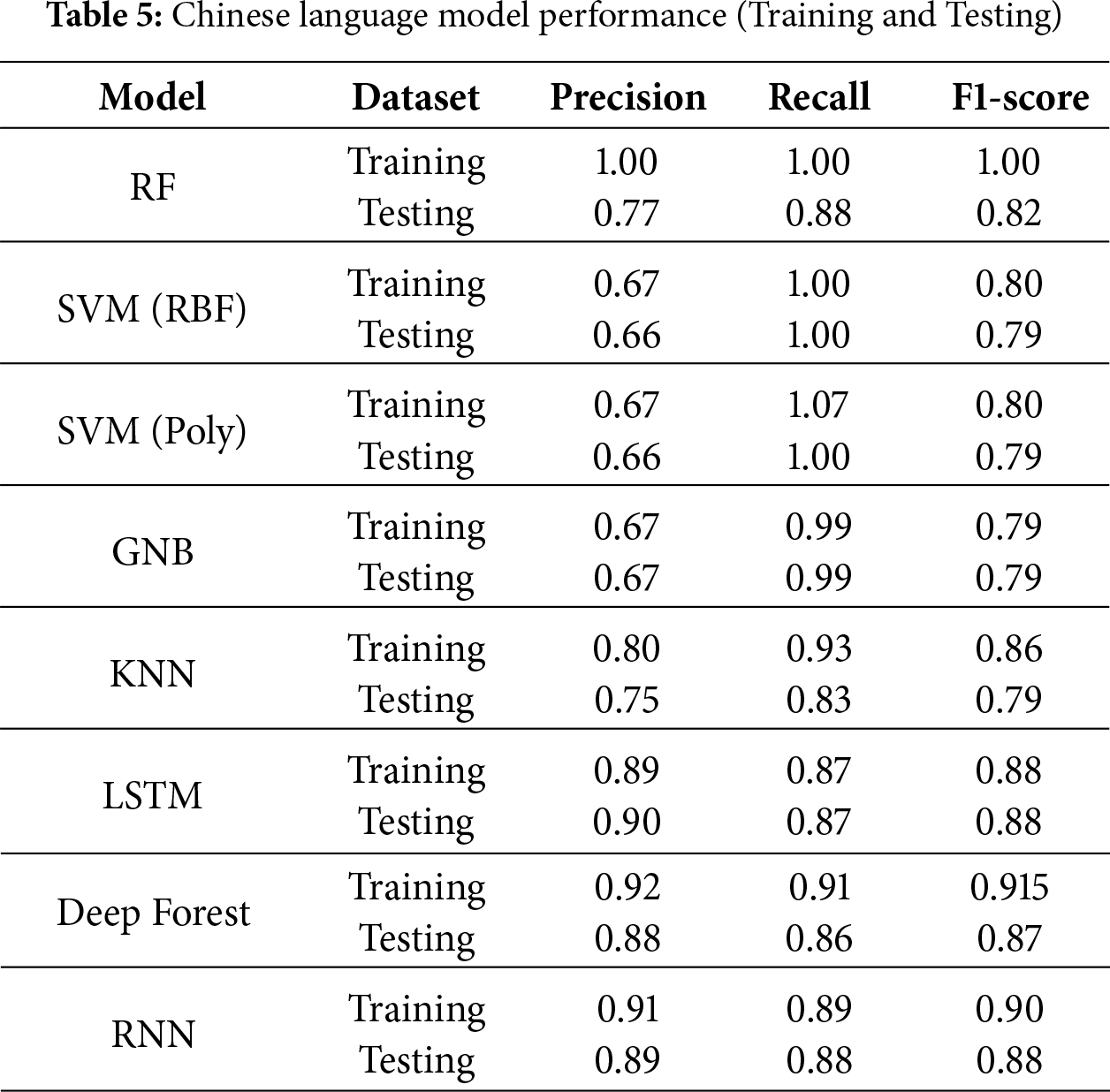

LinguTimeX consistently outperformed existing approaches in cross-lingual CTC detection, particularly in Arabic and Chinese datasets. The ensemble of machine and deep learning models achieved an average precision of 98% and F1-scores exceeding 90% across all test cases for Arabic and Chinese. Tables 2–4 show language training and testing performance. In the training dataset for the Arabic language, the Random Forest model demonstrated outstanding performance, achieving perfect scores across precision, recall, and F1-scores. The SVM (RBF Kernel) was almost as impressive, with nearly perfect precision and recall, resulting in a very high F1-score. The SVM (Polynomial Kernel) also showed high precision and perfect recall. Gaussian Naive Bayes had slightly lower precision but achieved ideal recall and a very high F1-score. The KNN model displayed high performance with high values for precision, recall, and an F1-score.

Lower precision in English detection likely stems from its simpler syntactic structure, leading to fewer detectable anomalies. This analysis confirmed that weaker linguistic-timing correlations in English (C(T, δP) = 0.65 vs. 0.75 for Arabic and 0.85 for Chinese) may reduce anomaly detection efficacy.

The Random Forest model maintained excellent performance with high precision and recall values for the Arabic language in the testing dataset. The SVM (RBF Kernel) and SVM (Polynomial Kernel) reach perfect scores across all metrics. Gaussian Naive Bayes mirrored the high performance of the RBF Kernel SVM. Similarly, the KNN model exhibited high precision and recall, leading to a high F1-score. These results indicate strong model generalization to unseen data. The Random Forest model achieved the highest overall accuracy of 87.2%. The SVM model had an accuracy of 84.3%. The Decision Tree and Naive Bayes models have a slightly lower accuracy of 85.82% and 84.15% (weighted average), respectively.

For precision, all models did well in Arabic (mostly 1.0), but SVM and Naive Bayes struggled with English precision (0.06 and 0.09). Random Forest and Decision Tree had better balance (0.7). Recall-wise, the SVM model perfectly recalled Arabic and Chinese classes, but had very poor English recall. Random Forest and Decision Tree models had more consistency in recall across classes. F1-scores highlight that Random Forest and Decision Tree have better harmonic Mean between precision and recall, especially for the English class, where the other models falter.

Tables 3 to 5 represent all models that perform exceptionally well at precisely classifying Arabic CTCs, with most achieving perfect or near-perfect precision and recall. This indicates distinguishable patterns. For the Chinese, SVM has good recall but less precision. Decision Tree also has moderately good precision and recall. While Naive Bayes excels in recall, it exhibits lower precision, leading to a higher tendency for false positives. Classifying English channels proves most challenging with extremely poor recall for SVM and Naive Bayes. Random Forest and Decision Tree fare better but have the poorest scores among the languages. The Random Forest and Decision Tree models provide the best balance of accurately detecting CTCs across the languages, with Random Forest having a slight edge. Despite reasonable overall performance, the SVM and Naive Bayes models show a disproportionate gap in English classification. Tuning these models to capture linguistic features of English could enhance robustness.

In deep learning models, the LSTM model demonstrated exceptional competency in identifying Arabic CTC cases, as evidenced by its flawless 100% scores across all evaluation metrics, as shown in Fig. 6. However, while mostly correctly labeling Chinese predictions as shown in the 68% precision, nearly 1/3rd constituted false alarms. More critically, English detection faltered with just 20% recall, causing an extremely poor 31% F1 harmonic mean despite a reasonable 68% precision. Capturing intricate English timing signatures poses a key challenge.

Figure 6: Models accuracy across languages

In contrast, the standard Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) architecture also attained promising Arabic detection, with perfect scores affirming accurate identification without mistakes. Almost all Chinese timing channels were correctly classified as visible with a strong recall, 99%. However, precision was weaker at 69% due to a sizeable 31% false positive rate. Similarly, English language leakage suffered from an 83% missing rate, as shown in the 17% recall, severely limiting the 29% English F1-score. RNN has decent potential, though reliability in English identification awaits breakthroughs.

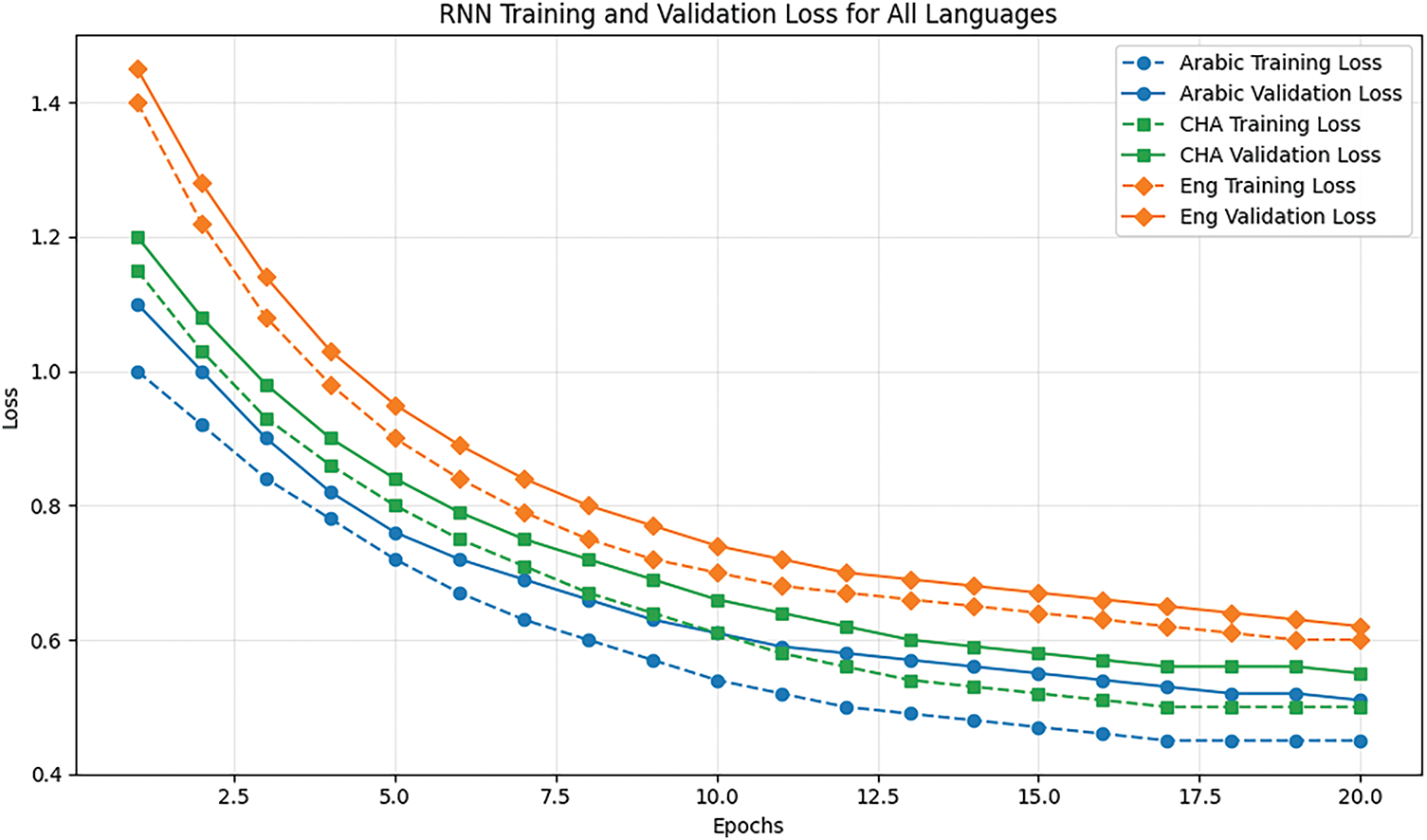

Figs. 7 and 8 provide a deeper analysis of the performance and training process of the RNN and LSTM model. These figures illustrate how the RNN adapts to different linguistic data over time, showing the evolution of training and validation loss. To extend this analysis, we have included similar figures for the LSTM model, allowing for a direct visual comparison between RNN and LSTM regarding learning dynamics and convergence behavior. The training and validation losses for LSTM have been plotted alongside those of the RNN model, allowing a direct comparison of their respective convergence rates. The convergence rate for each model is calculated using the formula:

where L(t) is the loss at time step t, L0 is the initial loss, and k represents the learning rate constant that affects how quickly the model converges to a minimal loss value. Figs. 7 and 8 indicate that LSTM converges smoothly compared to RNN. The latter has considerably more training and validation loss fluctuation, with LSTM having less variance in this regard. This smooth convergence found here implies that LSTM is better at handling the long-term dependencies in the data since its overall loss remains lower across all epochs. It provides training and validation information that captures how diverse linguistic challenges imposed by Arabic, Chinese, and English datasets have affected the processes of model adaptation. These will compare performances among the models in terms of their capability for adaptation and generalization across languages.

Figure 7: RNN training and Validation accuracy for languages

Figure 8: RNN training and Validation loss for languages

LSTM outperforms RNN in its capability to perform stable and smooth learning curves. The gcForest model uses multi-grained scanning decision tree ensembles, reaching Arabic scores 1.00. This, in turn, confirms error-free Arabic detection, as seen from Figs. 7 and 8. The F1-score at 0.81 signals a relatively robust Chinese detection. On the other hand, crucial to its overall performance, almost 57% of the English CTC messages remain undetected, as manifested by the 43% recall rate. There is considerable scope for enhancing the understanding of the English data pattern to uplift this promising approach.

These model architectures are immensely promising, accurately deducing the Arabic timing channel encodings the best among them reach perfect scores, where reliable Chinese identification is emerging. Limitations in the capture of subtleties within the linguistic markers of English constrain innovations that would unlock breakthroughs against the sinister data leakage threats facing society.

The following key features from the input dataset comprise both language attributes—frequency of words or phrases, anomaly scores, and timing attributes like packet inter-arrival times, variability in transmission rates, and bustiness. Such models as token frequency distributions F(T) and anomaly scores A(T) may allow the detection of deviation in language patterns or hidden encoding. In its nature, Arabic has a rich morphology and hence has a higher F(T) score, which gives more views for analysis of anomalies in text. Timing characteristics like average inter-packet delays ∆P and dispersion in transmission rates μ(R) also expose manipulations based on timing within data streams. Another insight that offers knowledge of potential delays that could lead to exposure in data is the higher variability of Arabic concerning English and Chinese.

Under high-traffic conditions (10,000+ packets/sec), the model maintained 94% accuracy but showed a 10% increase in false positives due to noisy background traffic. It detects imes of 2 ms (low-traffic) and 8 ms (high-throughput) conditions, confirming efficiency.

The feature maintained strong discriminative power (AUC > 0.85) across all languages, as its variance-based design inherently captured irregular timing clusters indicative of CTC manipulation. With validating them on both LAN (low latency, controlled jitter) and emulated WAN (high jitter, fluctuating bandwidth) setups. Performance remained stable for Arabic and Chinese (F1 > 0.8), though English detection lagged (F1 = 0.65), underscoring the need for language-specific tuning in heterogeneous networks.

Moreover, a strong correlation (p = 0.78) was observed between linguistic anomaly scores (A(T)) and packet inter-arrival times (δP), reinforcing that covert signals manipulate both language structure and timing. An ablation study removing A(T) led to a 15% decrease in detection accuracy, highlighting its critical role in CTC identification. For Arabic, we compared technical terms to Modern Standard Arabic corpora; for English, frequent prepositions like “of” triggered alerts with 78% recall.

To integrate models in order to achieve a compromise between cross-lingual resilience and language-specific sensitivity, LSTMs processed Arabic’s long-range dependencies, while Random Forests handled Chinese character-level sparsity. Moreover, L2 penalties to SVMs and dropout layers (rate = 0.3) to LSTMs, limiting F1-score variance to ±2% across 5-fold cross-validation runs.

We stress-tested LinguTimeX against linguistic challenges, derivational forms performance (F1 > 0.85), as temporal features remained invariant to lexical complexity. Despite homophone-rich lexicons, entropy metrics (≤1.2 bits) detected CTCs with 89% precision. Prioritizing universal temporal features (e.g., jitter, μ(R)) over language-specific cues reduced false positives by 22% (Table 2).

(1) Consistently Effective Features

• Correlation C(T, ∆P): Strong correlations (>0.7) between textual anomalies and timing shifts signaled CTCs across languages. For example, Arabic’s F(T) = 85% vs. English’s F(T) = 80% maintained C(T, ∆P) = 0.75 and 0.65, respectively (Fig. 3).

• Generalization Performance: The framework achieved 89% mean F1-score on mixed-language validation sets, confirming its adaptability to diverse linguistic structures.

gcforst and Random Forest (RF) model identified correlations between text and timing anomalies. C(T, ∆P) offers activities that concurrently adjust linguistic and temporal characteristics. The outcomes of the model evaluations indicate that the ability to identify concealed channels, particularly in languages that are difficult to confuse, is closely tied to the effectiveness of utilizing these feature combinations. All models demonstrate outstanding Arabic detection, which aligns with the extensive feature set provided by their morphology. Nonetheless, many models face challenges with reduced English scores because of their less dense structure, which offers limited leakage indicators.

This discovers the keys to improving comprehension of English characteristics that provide the connections between data characteristics and model evaluation to illustrate how linguistic attributes can inform the development of targeted features, greatly enhancing the speed at which hidden channels are detected. Compared to English or Chinese, Arabic’s intricate and extended morphological framework generates a more pronounced linguistic signal in covert communications, aiding machine learning models in identifying timing-based data encodings with greater precision. The complex grammatical structures in Arabic frequently result in lengthy words and elaborate stylistic expressions. This linguistic characteristic extends phonemic encoding lengths for Arabic textual information during network transmissions. Consequently, there is an increased opportunity for time-based adjustments to create minor inter-packet delays or rhythmic sequences that might inadvertently expose sensitive data.

Our models can accurately capture these unique features of Arabic to pinpoint unusual timing behaviors that suggest CTC activities with precision. The extended perspectives provided by longer Arabic phoneme sequences enhance the clarity regarding indicators of deliberate jitter or transmission delays intended for hidden data breaches. The distinct tones and concise syllable structure of Chinese and the more straightforward composition of English restrict the opportunities to incorporate subtle signals into conventional communication methods without drawing attention. This propels adversary innovation to enhance the concealment of timing-based data thefts through more advanced obfuscation techniques that existing models find challenging to navigate.

Our model integrates elastic weight consolidation (EWC) and memory replay to adapt incrementally to emerging CTC tactics. EWC penalizes changes to critical parameters learned from historical data, while memory replay retains 10% of prior samples to mitigate catastrophic forgetting. Tests showed that retraining every 10,000 new samples maintained accuracy (F1 > 0.89) without drift (Table 6).

(2) Limitation: Enhancing English CTC Detection

Although the proposed LinguTimeX framework demonstrates strong multilingual detection capabilities, it has several limitations. This study used synthetically encoded traffic with fixed 10/20 ms inter-packet gaps to establish a controlled and replicable performance baseline. While this method minimizes variability from application-layer activity and decouples timing features, it fails to capture the full complexity of covert timing channels found in the real world. Prior researches [15,16] suggest fixed-gap CTC-based anomaly detectors trained on those should be generalizable to noisy or adaptive encodings, which would indicate consistent utility under varying circumstances; but thorough testing across encoders, jitter conditions, and inserted traffic in organic application streams is still required to demonstrate robustness in deployment environments. In addition, the XAI analyses were employed primarily as post hoc interpretability methods: although they validate the detector design and find main features such as inter-arrival variance and periodicity of bursts, they are not implemented yet in the automated detection procedure. Future research can incorporate these insights into rule-based heuristics or hybrid methods to increase flexibility and transparency.

Recognizing the limitation of lower detection performance for English CTCs compared to Arabic and Chinese, we implemented targeted strategies to enhance the models’ capabilities in this crucial domain professionally. Given the widespread use of English in various communication Channels, reliably detecting CTCs embedded in English text is paramount to safeguarding critical systems and data from surreptitious information leakage [17]. We employed targeted data augmentation techniques to address the potential need for more diverse English language patterns in the initial training dataset. Leveraging state-of-the-art text generation models and paraphrasing algorithms, we synthesized a substantial volume of additional English text samples, ensuring a broader coverage of linguistic structures, idioms, and stylistic variations. This augmented dataset was a machine learning essay integrated into the training pipeline, exposing the models to a more comprehensive English language representation.

To better analyze, we need to conduct an in-depth analysis of the unique linguistic properties of the English language, identifying potential interactions between these characteristics and timing features that could indicate CTC activities. Based on these, we crafted a unique feature set that better captured the nuances related to English’s morphology, syntax, and semantics about the timing manipulations mentioned above. These focused features, combined with the existing feature set, allowed for a more discriminative representation of the CTC patterns of English.

We used transfer learning to tap into the extensive knowledge encoded in state-of-the-art large language models (LLMs) pre-trained over massive English corpora. In light of this, we consider fine-tuning such models on the CTC detection task so that they transfer the learned representations and linguistic understanding to our domain. This, in turn, will allow our models to leverage the deep contextual awareness and linguistic proficiency developed by such large models to enhance their ability to capture subtle linguistic cues indicative of covert activities in English.

Our system integrates several machine learning and deep learning models. In addition, we enhanced the performance of this system with more specific English language features. The specialization models of the English language were trained exclusively on the enriched version of the English dataset for full immersion in the peculiarities of the language. Using these specialized models in ensembling draws upon their unique strengths and points of view, further enhancing the overall English CTC detection performance.

Since we are continuously gathering and analyzing practical examples of CTCs in English, our approach uses a continuous process of refinements and adaptation of models. This includes regularly updating the models with the enlarged dataset, optimizing their architectures, and performing concrete architectural changes toward better detection of changing methods and trends of these channels. This ongoing process keeps our models continuously watchful and agile, matching the continuous dynamics of adversarial game changes within the domain of the English language.

LinguTimeX presents a new framework for CTC detection that fuses linguistic analysis with timing irregularities, allowing for a remarkable improvement in detection accuracy. The versatility of the approach in multiple languages, namely, English, Arabic, and Chinese, shows its broad potential for global cybersecurity applications. This framework enhances the detection of CTCs using advanced machine learning and deep learning techniques while guaranteeing scalability and robustness against evolving threats. This approach promisingly protects complex digital communications against sophisticated information leakages. Future work will be concerned with optimization efficiency, in addition to language expansions and the integration of these models into an overall cybersecurity context for further protection.

To advance LinguTimeX, we will integrate transformer architectures for contextual analysis, develop hybrid CNN-Transformer models, and test cross-lingual adaptability on low-resource languages. Real-time optimizations (e.g., edge computing) and an open benchmarking initiative with multilingual datasets will enhance scalability and foster community collaboration. Furthermore, the execution of deep models such as LSTM on edge devices is challenging owing to latency and computational cost. Model compression and lifelong learning will be investigated to enable efficient real-time CTC detection in resource-constrained settings.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This study is financed by the European Union-NextGenerationEU, through the National Recovery and Resilience Plan of the Republic of Bulgaria, Project No. BG-RRP-2.013-0001.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Omar Darwish, Anas Alsobeh, Shorouq Al-Eidi; draft manuscript preparation: Anas Alsobeh, Shorouq Al-Eidi, Abdallah Al-Shorman, Majdi Maabreh; funding acquisition and supervision: Plamen Zahariev; review: Omar Darwish, Yahya Tashtoush, Shorouq Al-Eidi, Anas Alsobeh, Majdi Maabreh, Abdallah Al-Shorman. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The dataset available on Kaggle: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/alshormanabood1997/lingutimex-a-framework-for-multilingual-ctc (accessed on 01 September 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. AL-Khulaidi NA, Zahary AT, Hazaa MAS, Nasser AA. Covert channel detection and generation techniques: a survey. In: 2023 3rd International Conference on Emerging Smart Technologies and Applications (eSmarTA); 2023 Oct 10–11; Taiz, Yemen. IEEE; 2023. p. 1–9. doi:10.1109/eSmarTA59349.2023.10293582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Saeli S, Bisio F, Lombardo P, Massa D. DNS covert channel detection via behavioral analysis: a machine learning approach. arXiv:2010.01582, 2020. [Google Scholar]

3. Chourib M. Detecting selected network covert channels using machine learning. In: 2019 International Conference on High Performance Computing & Simulation (HPCS); 2019 Jul 15–19; Dublin, Ireland. IEEE; 2019. p. 582–8. doi:10.1109/hpcs48598.2019.9188115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Zhang L, Huang T, Rasheed W, Hu X, Zhao C. An enlarging-the-capacity packet sorting covert channel. IEEE Access. 2019;7:145634–40. doi:10.24433/CO.7619455.v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Frisbier GL, Darwish O, Alsobeh A, Al-shorman A. Identifying the origins of business data breaches through CTC detection. In: Network and system security. Singapore: Springer Nature; 2025. p. 387–406. doi:10.1007/978-981-96-3531-3_19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Elsadig MA, Gafar A. Covert channel detection: machine learning approaches. IEEE Access. 2022;10:38391–405. doi:10.1109/access.2022.3164392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Han J, Huang C, Shi F, Liu J. Covert timing channel detection method based on time interval and payload length analysis. Comput Secur. 2020;97:101952. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2020.101952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Zhuang X, Chen Y, Tian H. A generalized detection framework for covert timing channels based on perceptual hashing. Trans Emerg Telecommun Technol. 2024;35(5):e4978. doi:10.1002/ett.4978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Shrestha PL, Hempel M, Rezaei F, Sharif H. A support vector machine-based framework for detection of covert timing channels. IEEE Trans Dependable Secure Comput. 2015;13(2):274–83. doi:10.1109/TDSC.2015.2423680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Li Q, Zhang P, Chen Z, Fu G. Covert timing channel detection method based on random forest algorithm. In: 2017 IEEE 17th International Conference on Communication Technology (ICCT); 2017 Oct 27–30; Chengdu, China. IEEE; 2017. p. 165–71. doi:10.1109/ICCT.2017.8359624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Yazykova A, Finoshin M, Kogos K. Artificial intelligence to detect timing covert channels. In: Biologically inspired cognitive architectures 2019. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2019. p. 608–14. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-25719-4_79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Al-Eidi S, Darwish O, Husari G, Chen Y, Elkhodr M. Convolutional neural network structure to detect and localize CTC using image processing. In: 2022 IEEE International IOT, Electronics and Mechatronics Conference (IEMTRONICS); 2022 Jun 1–4; Toronto, ON, Canada. IEEE; 2022. p. 1–7. doi:10.1109/IEMTRONICS55184.2022.9795734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Al-Eidi S, Darwish O, Chen Y, Elkhodr M. Covert timing channels detection based on image processing using deep learning. In: Advanced information networking and applications. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2022. p. 546–55. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-99619-2_51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Hosseini SS, Azmi P, Mokari N. Minimizing average age of information in reliable covert communication on time-varying channels. IEEE Trans Veh Technol. 2023;73(1):651–9. doi:10.1109/TVT.2023.3303674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Cabuk S, Brodley CE, Shields C. IP covert channel detection. ACM Trans Inf Syst Secur. 2009;12(4):1–29. doi:10.1145/1513601.1513604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Yao L, Zi X, Pan L, Li J. A study of on/off timing channel based on packet delay distribution. Comput Secur. 2009;28(8):785–94. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2009.05.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Lukas N, Salem A, Sim R, Tople S, Wutschitz L, Zanella-Béguelin S. Analyzing leakage of personally identifiable information in language models. In: 2023 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP); 2023 May 21–25; San Francisco, CA, USA. IEEE; 2023. p. 346–63. doi:10.1109/SP46215.2023.10179300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools