Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

HS-APF-RRT*: An Off-Road Path-Planning Algorithm for Unmanned Ground Vehicles Based on Hierarchical Sampling and an Enhanced Artificial Potential Field

School of Equipment Engineering, Shenyang Ligong University, Shenyang, 110159, China

* Corresponding Author: Qingquan Liu. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(1), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.068780

Received 06 June 2025; Accepted 18 August 2025; Issue published 10 November 2025

Abstract

Rapidly-exploring Random Tree (RRT) and its variants have become foundational in path-planning research, yet in complex three-dimensional off-road environments their uniform blind sampling and limited safety guarantees lead to slow convergence and force an unfavorable trade-off between path quality and traversal safety. To address these challenges, we introduce HS-APF-RRT*, a novel algorithm that fuses layered sampling, an enhanced Artificial Potential Field (APF), and a dynamic neighborhood-expansion mechanism. First, the workspace is hierarchically partitioned into macro, meso, and micro sampling layers, progressively biasing random samples toward safer, lower-energy regions. Second, we augment the traditional APF by incorporating a slope-dependent repulsive term, enabling stronger avoidance of steep obstacles. Third, a dynamic expansion strategy adaptively switches between 8 and 16 connected neighborhoods based on local obstacle density, striking an effective balance between search efficiency and collision-avoidance precision. In simulated off-road scenarios, HS-APF-RRT* is benchmarked against RRT*, Goal-Biased RRT*, and APF-RRT*, and demonstrates significantly faster convergence, lower path-energy consumption, and enhanced safety margins.Keywords

Path planning for unmanned vehicles in off-road environments represents a fundamental challenge in the field of intelligent autonomous systems. Unlike structured road networks, unstructured terrains—such as wilderness and mountainous regions—exhibit highly heterogeneous surface properties, random obstacle distributions, and rapidly varying slopes, all of which can invalidate classical planners that assume deterministic terrain models [1]. Frequent terrain changes and the risk of slippage on inclines further undermine the feasibility of planned routes.

In three-dimensional off-road settings, planners typically fall into three categories: grid-based methods, intelligent model-based approaches, and sampling-based algorithms [2]. Grid-based techniques discretize space into regular voxels and search over the resulting lattice [3], but they suffer from high computational and memory costs in large, cluttered 3D scenes. Intelligent methods (e.g., deep-learning planners) can adapt to dynamic environments [4], yet they demand extensive training data and complex models. By contrast, sampling-based planners avoid exhaustive discretization, exploring only a subset of the configuration space via random or heuristic samples. This leads to significantly lower computation and memory requirements, enabling rapid discovery of feasible paths in large-scale, obstacle-rich terrains [5]. Moreover, sampling-based approaches do not rely on pre-collected training data and can flexibly capture spatial structure in changing conditions [6].

Among sampling-based methods, the Rapidly-exploring Random Tree (RRT) is particularly popular for real-time path planning, as it grows a search tree via random node sampling to efficiently find feasible trajectories in complex spaces [7]. However, vanilla RRT often produces jagged, suboptimal paths filled with redundant waypoints [8]. To overcome these drawbacks, Karaman and Frazzoli introduced RRT*, which guarantees asymptotic optimality by rewiring the tree as it grows [9]. Gammell et al. further accelerated convergence with Informed-RRT*, using heuristic-guided sampling within an informed subset of the space [10], though its performance remains sensitive to initial paths and environmental complexity [11].

To enhance collision-avoidance, the Artificial Potential Field (APF) method is frequently integrated with RRT [12], but classical APF can become trapped in local minima and fail to find global routes. Hybrid strategies—such as Bi-APF-RRT, which blends bidirectional tree growth with potential-field guidance—have demonstrated improved path quality and faster convergence [13].

Despite these advances, existing sampling-based planners typically treat terrain as deterministic and neglect critical off-road variables such as surface type and gradient [14]. Researchers have begun to address this gap: Pu et al. proposed a 3D-RRT* variant with heuristic sampling and evolutionary search for terrain-aware route optimization [15]; Yin et al. coupled RRT* with adaptive surrogate models (ER-RRT*) to iteratively refine both the tree and its guiding model [16]; Ramirez-Robles et al. developed a semantic-segmentation-driven framework combining DeepLab and LiDAR point clouds to generate occupancy maps for RRT* [17]; Lee and Seo introduced a Q-learning–augmented APF for path planning under battlefield constraints [18]; and Jiang et al. formulated R2-RRT*, incorporating reliability metrics into the sampling process to balance path cost and mission success probability [19].

With the expanding use of unmanned vehicles in reconnaissance, geological survey, and other off-road applications [20], there is an urgent need for planners that jointly optimize path cost and safety under terrain uncertainty. To this end, we propose HS-APF-RRT*, which integrates hierarchical terrain sampling, a slope-aware APF, and a dynamic 8/16-neighborhood expansion mechanism. By quantifying terrain, morphology, gradient, and energy consumption in a layered manner, HS-APF-RRT* achieves both efficient and safe tree growth, offering a theoretically grounded and practically effective solution for off-road unmanned vehicle path planning.

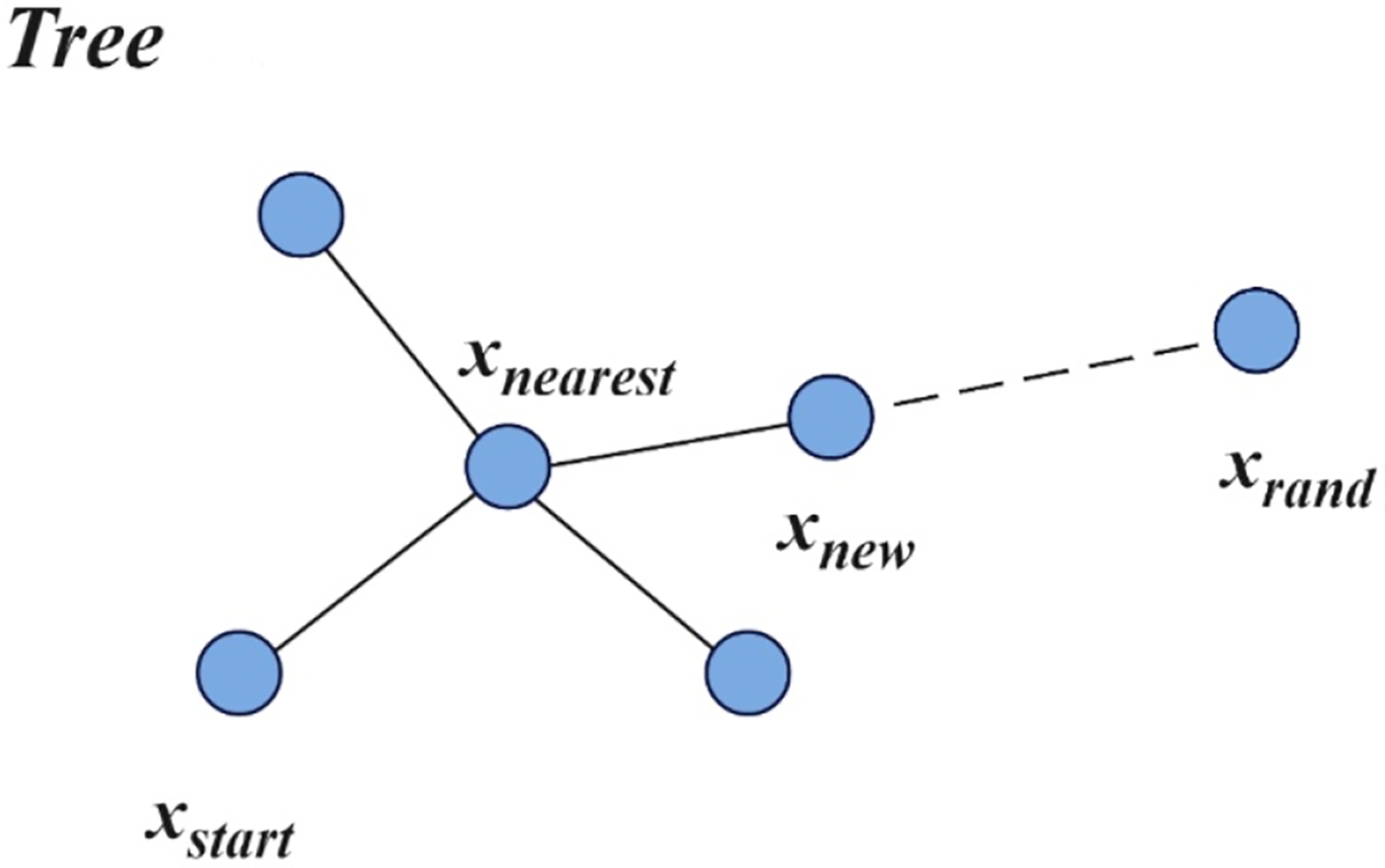

To appreciate the enhancements embodied in RRT*, it is helpful to first review the core Rapidly-exploring Random Tree (RRT) method. RRT incrementally builds a tree rooted at the start configuration by repeatedly sampling the planning space at random. In each iteration, a new sample point is drawn uniformly; the algorithm then identifies the nearest existing tree node and attempts to extend from that node toward the sample by a fixed step length (Fig. 1). If the straight-line segment connecting these two points does not intersect any obstacles, the new node is added to the tree; otherwise, the sample is discarded and a new iteration begins. This simple yet powerful sampling strategy allows RRT to rapidly explore high-dimensional and cluttered workspaces, making it well suited for three-dimensional off-road path planning where the combinatorial explosion of possible configurations can otherwise overwhelm grid- or graph-based planners.

Figure 1: Random tree expansion process

While standard RRT excels at quickly finding a feasible route, it offers no guarantees of optimality and often produces jagged, suboptimal paths packed with redundant waypoints. RRT* overcomes these shortcomings by introducing a cost-aware expansion and a local “rewiring” mechanism. Rather than always connecting a new sample to its single nearest neighbor, RRT* considers all tree nodes within a specified neighborhood radius and selects the parent that minimizes the cumulative cost from the root to the new node. After insertion, RRT* also revisits nearby vertices to determine whether rerouting them through the new node would reduce their overall path cost, and, if so, “rewires” the tree accordingly. These two innovations—neighbor-based parent selection and iterative rewiring—preserve RRT’s exploration efficiency while ensuring that, as the number of samples grows, the cost of the discovered path converges asymptotically toward the global optimum.

The APF-RRT* algorithm is an improved version of RRT* that incorporates the Artificial Potential Field (APF) method. Although RRT* can rapidly explore high-dimensional spaces, its purely random expansion often produces blind growth and fails to maintain sufficient clearance from obstacles. APF-RRT* remedies this by integrating an enhanced APF: it brings the APF concepts of attractive force toward the goal and repulsive force away from obstacles into the RRT* node-generation process. Under the influence of this potential field, new nodes are no longer chosen solely by random sampling but are biased to grow toward the goal while avoiding obstacle regions. This guided sampling reduces the number of invalid nodes, speeds up tree expansion toward the target, improves planning efficiency, and yields higher-quality, safer paths for off-road unmanned vehicles. The attractive and repulsive components of the APF are defined in Eqs. (1)–(3), where denotes the current node of the vehicle.

Here,

Although RRT* can asymptotically approach the optimal path, it exhibits pronounced shortcomings in off-road scenarios. Its purely random sampling scheme converges slowly over rugged terrain and generates many invalid samples, which both inflate computational cost and ignore the influence of heterogeneous ground conditions on vehicle energy consumption. At the same time, the fixed-step tree-expansion strategy cannot adapt to varying obstacle distributions—using large steps near steep or side slopes increases collision risk, while small steps impede exploration—so RRT* struggles to rapidly produce feasible, smooth, and safe routes in complex three-dimensional landscapes.

To address these issues, we introduce a series of enhancements to RRT*. First, a hierarchical sampling strategy integrates terrain complexity, surface vegetation, and estimated energy cost to guide random samples progressively toward safer, lower-energy regions. Second, the artificial potential field is strengthened by dynamically adjusting the repulsive gain according to local slope magnitude, balancing the attractive pull toward the goal with stronger avoidance of impassable areas and mitigating local minima. Finally, a dynamic neighborhood expansion mechanism switches between 8-connected and 16-connected tree-growth modes based on local obstacle density—using an 8-neighbor in cluttered regions to maximize safety and precision, and a 16-neighbor in open spaces to accelerate exploration. Together, these modifications yield more efficient and reliable tree growth, delivering faster convergence and higher-quality, safer paths for unmanned vehicles in off-road environments.

3.1 Hierarchical Sampling Strategy Incorporating Complex Terrain Factors

In off-road environments, path planning for unmanned ground vehicles must explicitly account for terrain undulations, since local elevation changes directly affect traversability, energy consumption, and safety. A grid-based digital elevation model can faithfully reconstruct the terrain by discretizing the workspace into uniform cells, each annotated with precise relative height information and flagged if its slope exceeds a traversable threshold. This allows the planner to accurately compute elevation-change costs and exclude impassable regions at the adjacency level. Furthermore, off-road surfaces—rock, grass, bare soil, and so on—differ markedly in terms of rolling resistance and allowable speed. By assigning a traversal cost to each cell based on its surface type, the algorithm can enforce both safety constraints and smoothness requirements, yielding routes that better reflect the vehicle’s true on-ground capabilities.

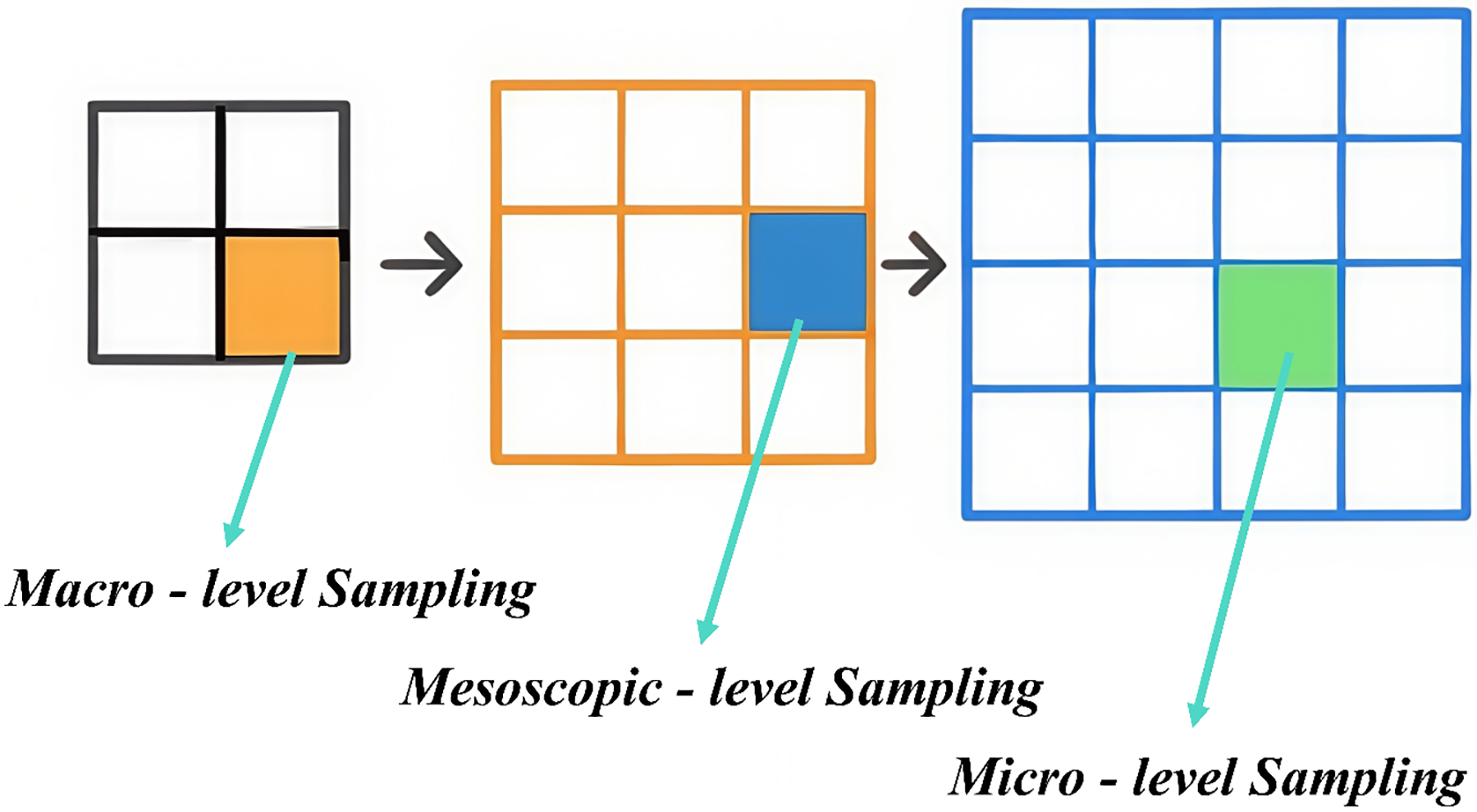

To exploit these rich terrain and surface data and steer the random-tree growth more efficiently, we introduce a hierarchical sampling strategy with macro, meso, and micro layers. Each random sample is generated in three sequential stages: first by choosing a “macro” module with gentle slopes and low energy cost, then by refining selection within a “meso” submodule of that region, and finally by probing the precise “micro” cell where the new node will be placed. This coarse-to-fine scheme dramatically reduces wasted samples, accelerates convergence, and produces smoother, safer trajectories by focusing exploration on zones that satisfy combined criteria of terrain complexity, vegetation cover, and estimated energy consumption.

Grid discretization underpins our hierarchical sampling scheme. To accurately model the vehicle’s footprint, we set each micro-cell to a

Figure 2: Hierarchical sampling process

We begin by sampling at the macro layer, where primary attention is given to ground traversability and, critically, both longitudinal and lateral slope constraints. In off-road contexts, excessive incline can exceed a vehicle’s climbing capability or induce rollback, while steep side slopes dramatically increase rollover risk. Therefore, each macro-cell module is evaluated not only on conventional surface-type metrics but also on its average grade and cross-slope calculated from terrain data. Modules whose longitudinal slope exceeds the vehicle’s design threshold or whose transverse slope poses stability hazards are excluded outright, leaving only “friendly” regions with gentle grades and stable cross-slopes for further sampling. To quantify passability, we treat water bodies as impassable obstacles and classify any region with a longitudinal incline over

Here,

Because surface type strongly affects vehicle mobility—bare soil is far more navigable than grass, and water is completely impassable—we also compute a traversal-suitability index

Eqs. (11) and (12) define the raw sampling probability and its normalized form, respectively. First, we compute a sampling probability for each macro-grid region and then normalize these values to guide the actual sampling. In these expressions,

At the meso layer, sampling is driven by a detailed slope–energy coupling analysis that quantifies how uphill and downhill segments differentially impact vehicle power demands. Unlike the coarse terrain filtering of the macro layer, this stage treats each intermediate cell as a separate evaluation unit and employs a refined energy–slope model. When climbing, the vehicle must overcome the gravitational component of its weight, requiring extra motor or engine output and substantially increasing energy consumption. Conversely, on descents, while gravity assists motion, frequent braking or regenerative actions also affect net energy use. Accordingly, we construct both an uphill energy-increment model and a downhill compensation model. Regions exhibiting steep gradients or excessive cumulative energy cost have their sampling probability dynamically reduced, whereas gently sloped, low-energy cells are favored as candidates. This slope-aware mechanism thus steers sampling away from high-cost terrain and toward routes that balance traversal efficiency with energy economy.

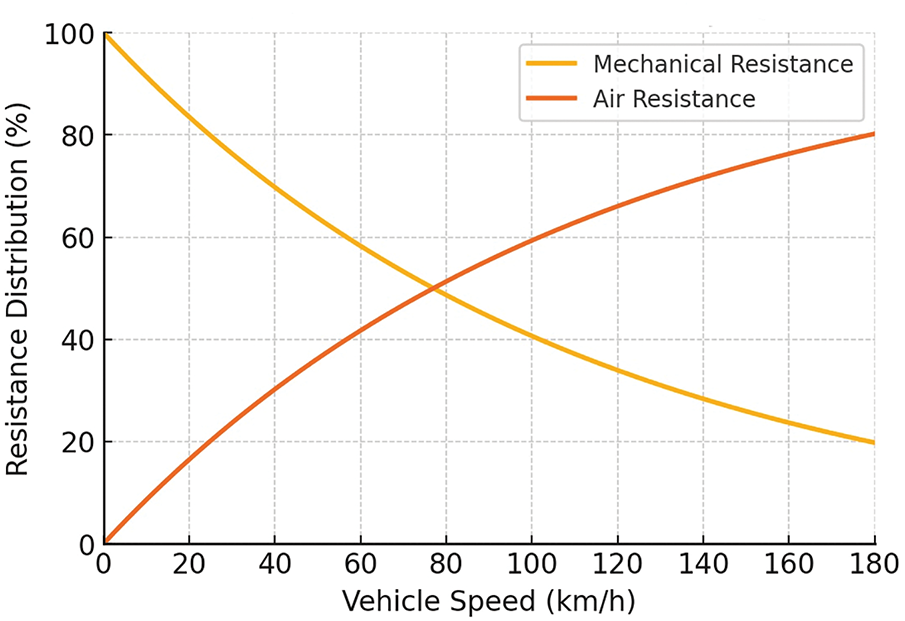

In our analysis, total vehicle energy use is approximated from steady-speed operation on flat, uphill, and downhill segments, considering kinetic energy, rolling resistance work, potential-energy work, and aerodynamic drag—while internal mechanical friction is negligible and treated as part of rolling resistance.

We denote the subscript

Here,

Figure 3: Relationship between mechanical resistance and aerodynamic drag at different vehicle speeds

Here,

The gravitational energy consumptions

We reciprocally normalize the mean energy consumption of each meso-grid and then select grids according to the resulting probability distribution, as defined by the following equation.

In the micro layer, we balance exploratory randomness with practical feasibility by combining uniform random sampling within each small grid cell and a multi-criteria validation step. Unlike the macro and meso layers, which filter regions based on coarse terrain and energy costs, the micro layer treats every 5 m

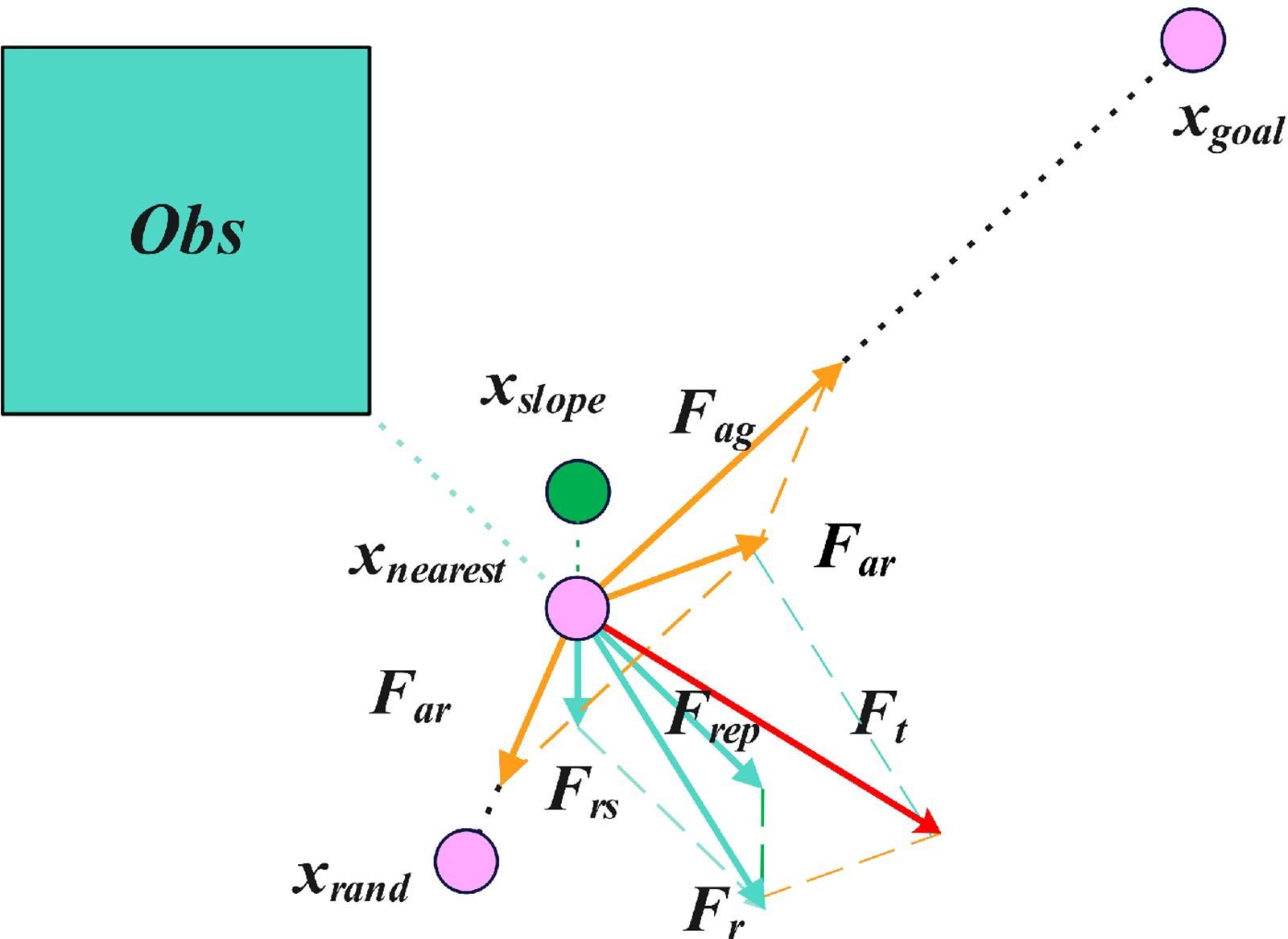

This section adjusts the attractive and repulsive components of the Artificial Potential Field (APF) and presents an APF variant tailored for off-road environments. We redefine the attractive potential so that, within the RRT* framework, both the goal and each randomly sampled point exert an attractive force on the current node. The total attractive force

In Eq. (25),

Different obstacle types should generate correspondingly different repulsive forces on the unmanned vehicle. To model each obstacle’s impact more precisely, we assign a unique weight

Here,

Additionally, to further enhance off-road path planning quality, we propose a slope-adaptive repulsion regulation mechanism. This mechanism uses the vehicle’s maximum traversable slope as a safety threshold and establishes a continuous mapping between local gradient and repulsive force magnitude, enabling differentiated handling of terrains with varying inclines. Specifically, when a sampled point’s slope remains below the threshold, the system dynamically scales the repulsive force in proportion to how close the slope is to the maximum: the steeper the incline, the stronger the repulsion, thereby steering the planner away from high-grade regions; conversely, gentler slopes incur only mild repulsive forces to preserve overall path optimality.

We compute the local slope—up to the vehicle’s maximum allowable gradient—in the current region and proportionally amplify the repulsive force. This simple linear mapping links slope to repulsion: the steeper the incline, the higher the weighting factor and the stronger the resulting repulsive force.

The core advantage of this mechanism lies in its quantitative treatment of slope-dependent repulsion: the repulsive field not only accounts for impassable areas but also scales according to local incline, so that terrain steepness and obstacle presence jointly guide the planner in a multi-factor coupling framework. By adaptively adjusting repulsive forces in this way, the approach ensures the safety of unmanned vehicles in off-road conditions and markedly enhances overall path-planning performance in complex terrain environments.

As illustrated in Fig. 4, the forces acting on the current node are shown, and the growth direction of the random tree is determined by the direction of the resulting force

Figure 4: Force analysis on the current node

In off-road environments, extending an unmanned vehicle’s path is a complex task that requires great care. The terrain is highly varied and can change suddenly—ranging from gentle slopes to abrupt cliffs—so choosing the right expansion step size is critical. If the step is too large, the vehicle may be unable to react in time to unexpected terrain changes and risk becoming immobilized; by contrast, selecting a terrain-adaptive step length based on local conditions ensures that the vehicle can negotiate all types of off-road obstacles safely and reliably.

Owing to the intricate terrain of off-road environments, and to balance search speed with traversal safety, we introduce a dynamic neighborhood-switching mechanism during the random-tree expansion. This mechanism continuously assesses local obstacle density in real time and adaptively adjusts the connectivity radius: in sparsely obstructed areas, it enlarges the neighborhood to accelerate tree growth and thus expedite path discovery; conversely, in densely cluttered regions, it contracts the neighborhood to enhance obstacle avoidance, thereby ensuring the unmanned vehicle can navigate complex off-road terrain both swiftly and safely.

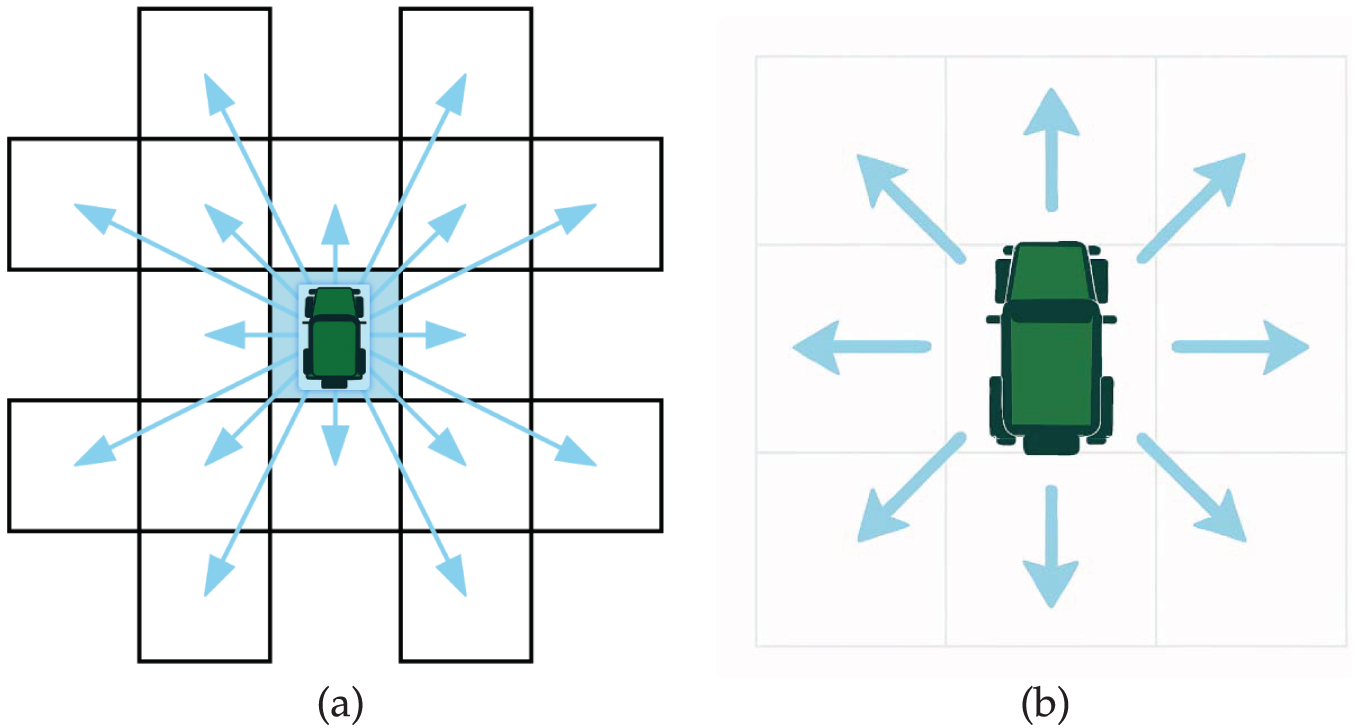

In selecting the neighborhood connectivity for tree expansion, multiple options exist; however, in the context of complex off-road terrain—where both vehicle safety and planning efficacy are paramount—we adopt a maximum 16-connected neighborhood (Fig. 5a). This 16-neighbor scheme offers a rich set of expansion directions that align naturally with the guidance provided by our enhanced APF, enabling rapid, flexible exploration across open, favorable regions. Conversely, when the tree encounters densely packed obstacles, the algorithm seamlessly switches to an 8-connected neighborhood (Fig.5b) to strengthen collision avoidance. By dynamically toggling between 8- and 16-neighborhoods based on local obstacle density, our method obviates the need to predefine a fixed connectivity pattern and delivers both fast convergence and robust, context-aware path growth.

Figure 5: Neighborhood expansion modes: (a) 16-connected expansion; (b) 8-connected expansion.

4.1 Simulation Environment Setup

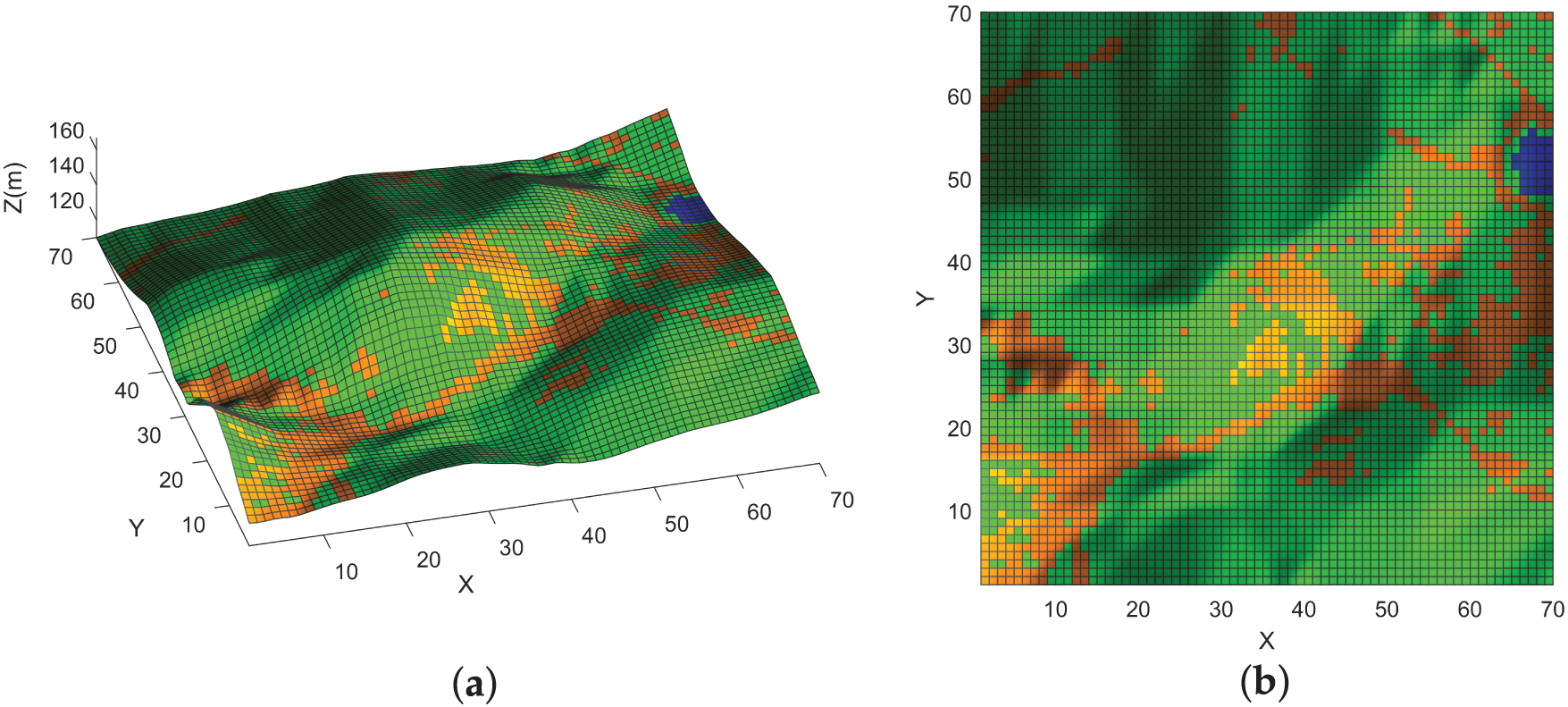

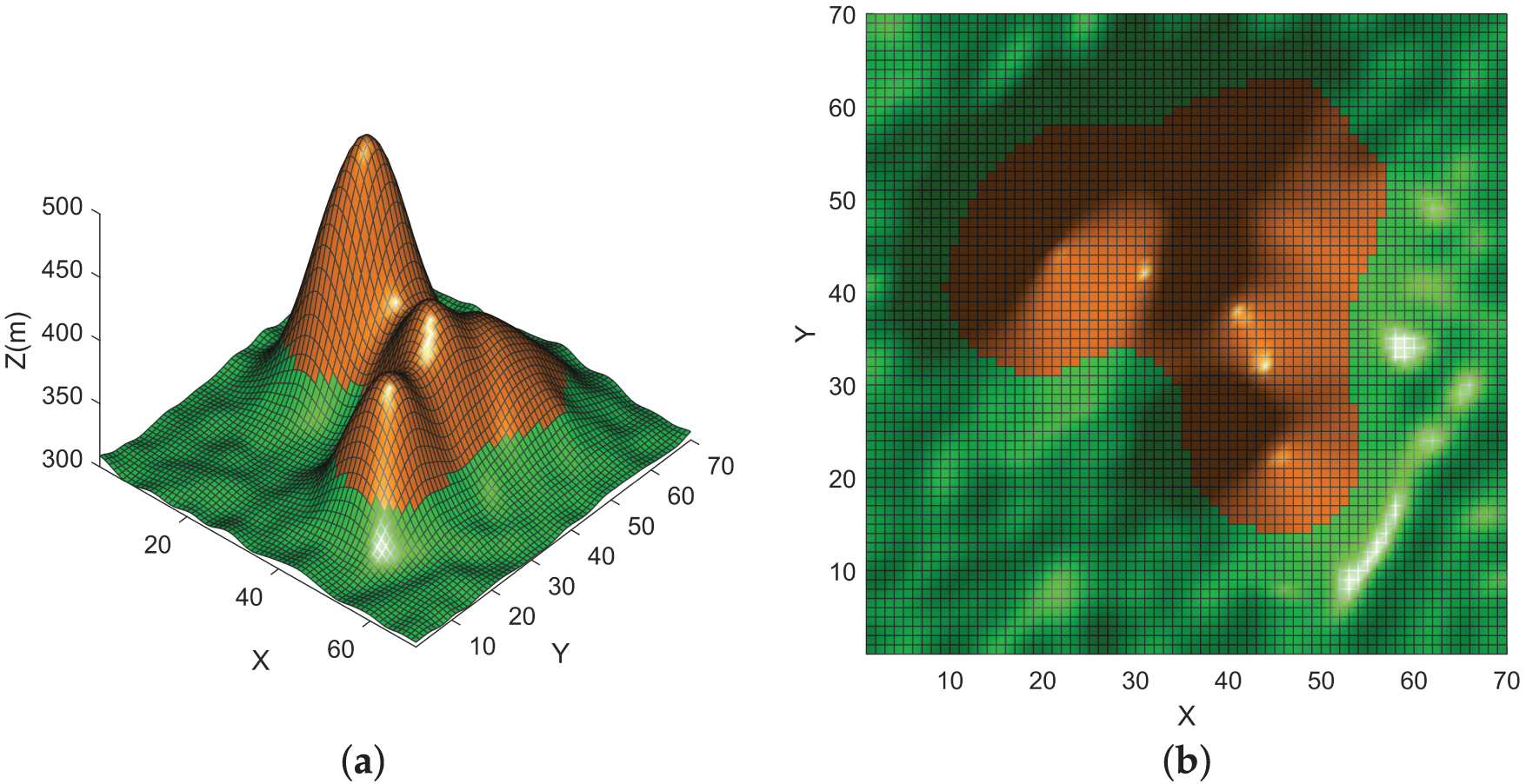

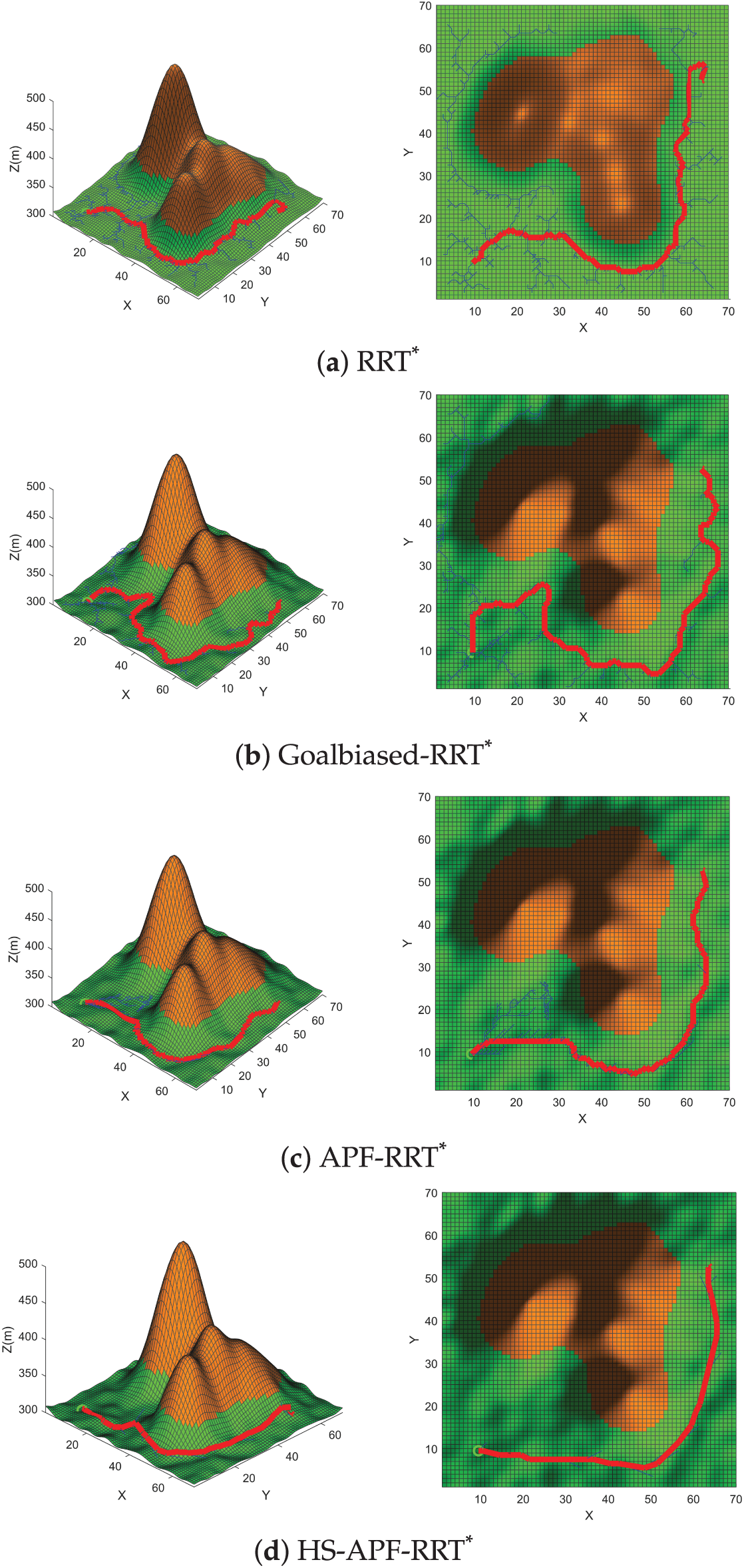

We acquired aerial imagery of a target region from a geographic information platform and applied supervised classification—using representative land-cover samples—to categorize the surface into water bodies, bare soil, and grassland, iteratively refining the classification through manual validation. These land-cover labels were then merged with a digital elevation model (DEMs obtained from NASA SRTM Global DEM via the USGS EarthExplorer portal) to recreate realistic terrain undulations. Finally, the combined elevation and land-cover data were discretized into a uniform grid, with each cell assigned both a surface type and an elevation value. This gridded environment forms the basis for off-road path planning, and the resulting simulation scenarios are shown in Figs. 6 and 7. All experiments were conducted on a computer equipped with an Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-7700HQ CPU @ 2.80 GHz, an NVIDIA GeForce GTX 1060 GPU (6 GB), and 16 GB of DDR4 RAM, using MATLAB R2022b.

Figure 6: Off-road Environment A: (a) 3D view; (b) plan view.

Figure 7: Off-road Environment B: (a) 3D view; (b) plan view.

4.2 Simulation Results Analysis

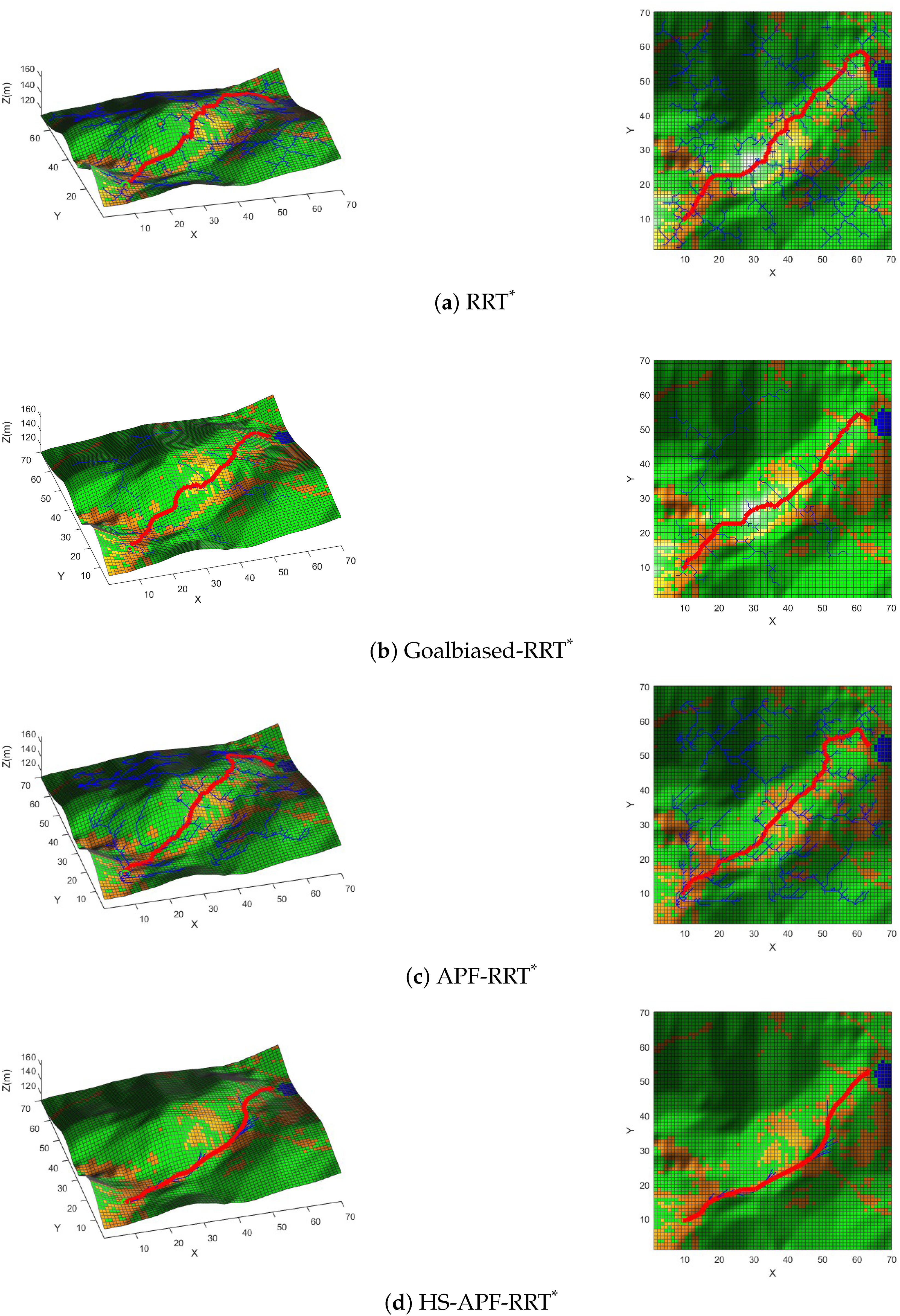

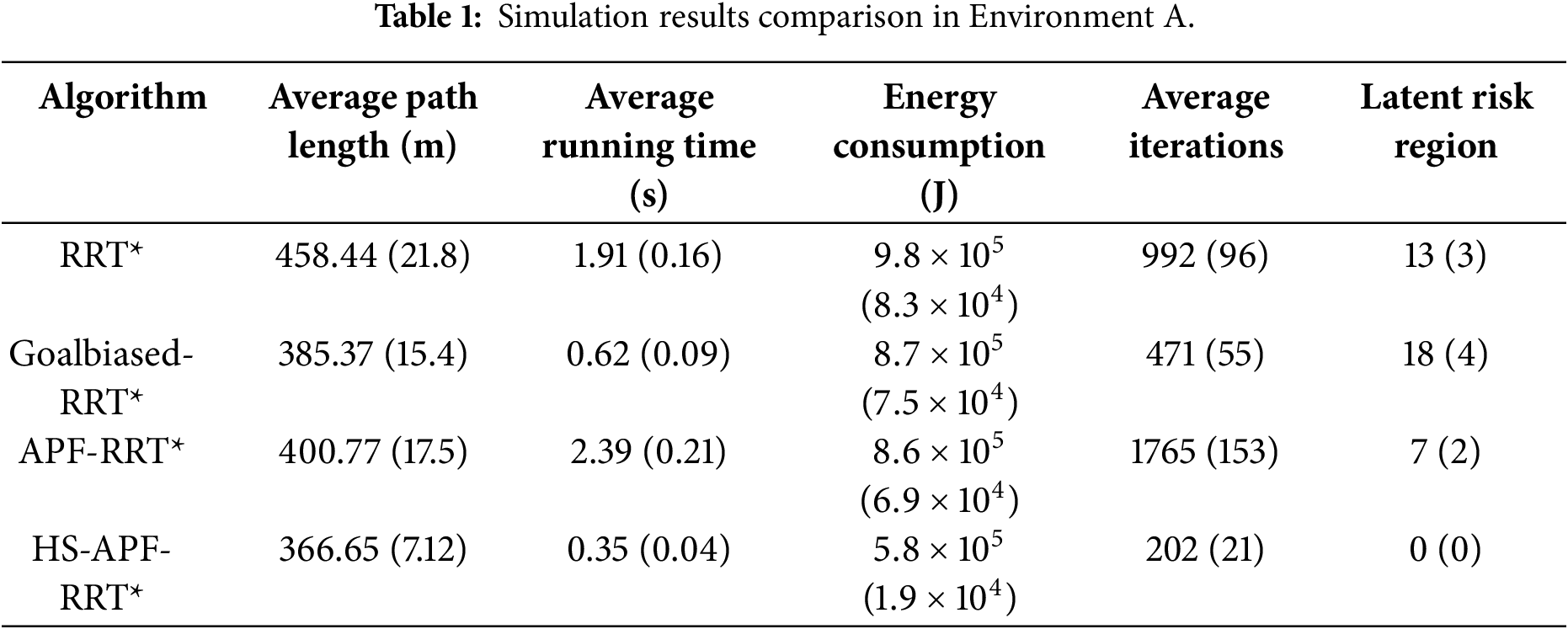

In our simulation experiments, we selected a relatively flat area for the vehicle’s start and goal positions, with the unmanned vehicle traveling from (10, 10) to (63, 53). Impassable cells are shown in blue, and the vehicle’s trajectory is indicated by the red line. Cells with longitudinal slopes exceeding

Simulation Environment A is characterized by a predominantly flat topography with minimal elevation undulations and uniformly low slope angles. This environment is designed to emulate off-road driving under gentle-incline conditions, enabling systematic evaluation of path-planning algorithms in terms of driving efficiency, stability, and energy-consumption performance.

The results are illustrated in the Fig. 8. In Fig. 8d, the proposed HS-APF-RRT* algorithm, leveraging the hierarchical sampling strategy, concentrates node generation in regions of gentle slope—thereby markedly reducing invalid samples. Combined with the enhanced APF that introduces slope-dependent repulsive forces, this approach not only ensures effective obstacle avoidance but also significantly improves computational efficiency, ultimately yielding safe and reliable paths.

Figure 8: Simulation results in Environment A.

Data in Table 1 show that, compared with RRT*, HS-APF-RRT* achieves a 20.02% reduction in path length, an 81.68% decrease in average runtime, and a 40.85% drop in energy consumption; the mean iteration count falls by 79.64%, and the number of traversed hazardous cells is reduced from 13 to 0. Against Goal-Biased RRT*, HS-APF-RRT* shortens the path by 4.85%, cuts runtime by 43.55%, lowers energy use by 32.41%, and reduces iterations by 57.11%, while eliminating all hazardous-cell crossings (from 18 to 0). Relative to APF-RRT*, it delivers an 8.52% shorter path, an 85.36% faster runtime, a 32.28% reduction in energy consumption, and an 88.56% decrease in iterations, with hazardous-cell traversals dropping from 7 to 0. These results demonstrate that HS-APF-RRT* markedly outperforms the compared methods in planning efficiency, energy economy, iteration count, and safety under off-road conditions.

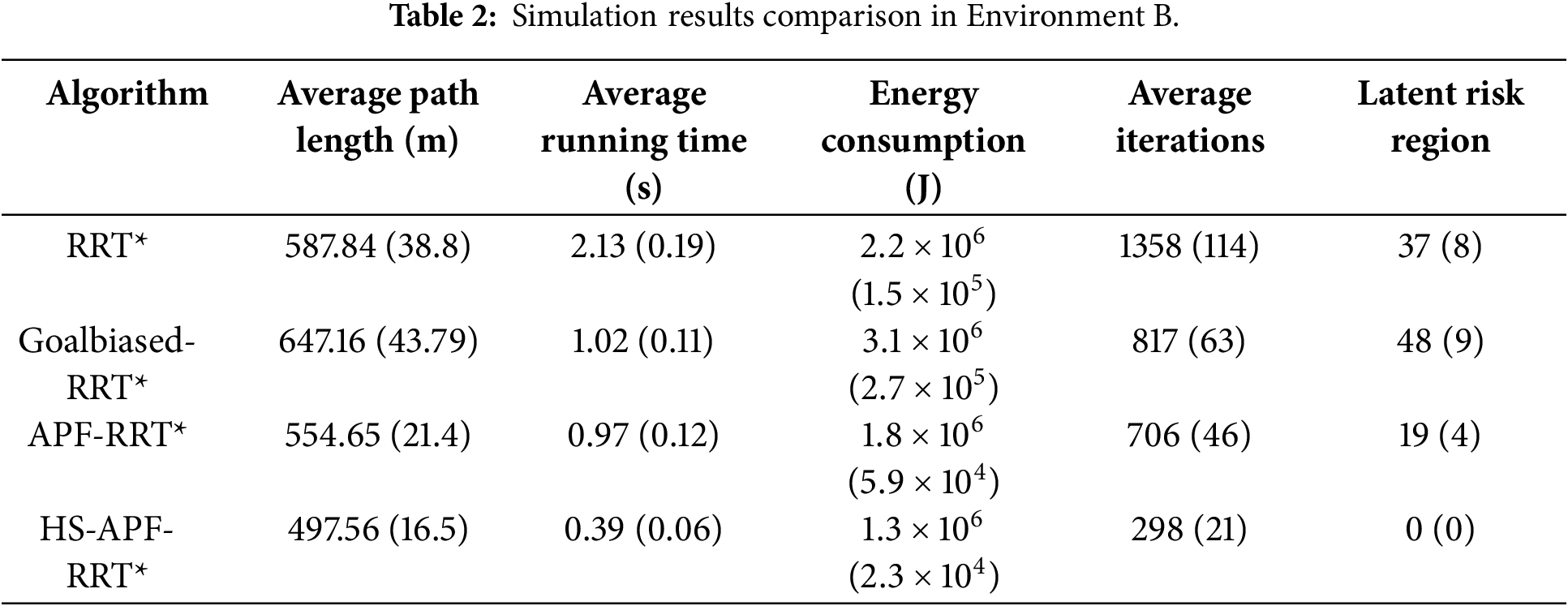

Simulation Environment B is characterized by a complex mountainous topology with pronounced elevation undulations and widely varying slope gradients. This scenario is designed to replicate off-road conditions featuring alternating steep inclines and terrain undulations, enabling the evaluation of path-planning algorithms under high-gradient conditions with respect to path feasibility, operational stability, and energy-consumption efficiency.

Fig. 9 illustrates the simulation results for Environment B. As shown in Fig. 9d, in this rugged off-road scenario characterized by severe terrain undulations and steep slope fluctuations, the proposed HS-APF-RRT* algorithm first implements a hierarchical sampling strategy weighted by both slope and energy-consumption metrics, effectively suppressing the generation of invalid nodes in high-gradient regions. It then integrates the enhanced APF model with an adaptive neighborhood expansion mechanism, significantly improving the computational efficiency of node sampling and path search. Ultimately, the algorithm successfully generates off-road trajectories that optimally balance safety, trajectory smoothness, and energy-consumption efficiency under complex terrain conditions.

Figure 9: Simulation results in Environment B

From the simulation results presented in Table 2, under highly undulating terrain with significant slope variation, the proposed HS-APF-RRT* algorithm exhibits outstanding performance in planning efficiency, path quality and safety. Specifically, compared with RRT*, HS-APF-RRT* achieves a 15.36% reduction in path length, an 81.69% decrease in average runtime, a 40.91% reduction in energy consumption, a 78.06% decrease in mean iteration count, and eliminates hazardous-cell traversals (from 37 to 0). Against Goal-Biased RRT*, it shortens path length by 23.12%, cuts runtime by 61.76%, lowers energy consumption by 58.06%, reduces iterations by 63.53%, and reduces hazardous-cell crossings from 48 to 0. Relative to APF-RRT*, HS-APF-RRT* delivers a 10.29% shorter path, a 59.79% faster runtime, a 27.78% reduction in energy consumption, a 57.79% decrease in iterations, and decreases hazardous-cell traversals from 19 to 0. These results demonstrate that HS-APF-RRT* markedly outperforms the benchmark methods in complex, variable off-road environments.

4.3 Ablation and Sensitivity Analysis

For the sensitivity analysis of the repulsion coefficient

We conducted a quantitative sensitivity analysis on the slope-weight parameter

We also performed an ablation study by disabling the slope-repulsion term and running 20 trials in the more challenging Environment B. Without this component, the average path length increased from 497.56 m to 515.32 m (≈3.5%), the number of traversed hazardous cells rose from 0 to 6, and energy consumption grew from

4.4 Statistical Significance Testing

To quantify the performance gains of HS-APF-RRT* over baseline methods in distinct off-road scenarios, we conducted two-sided paired Student’s

We then computed the sample mean

In Environment A, for example, the average planning time of HS-APF-RRT* was

In Environment B, every metric comparison again produced

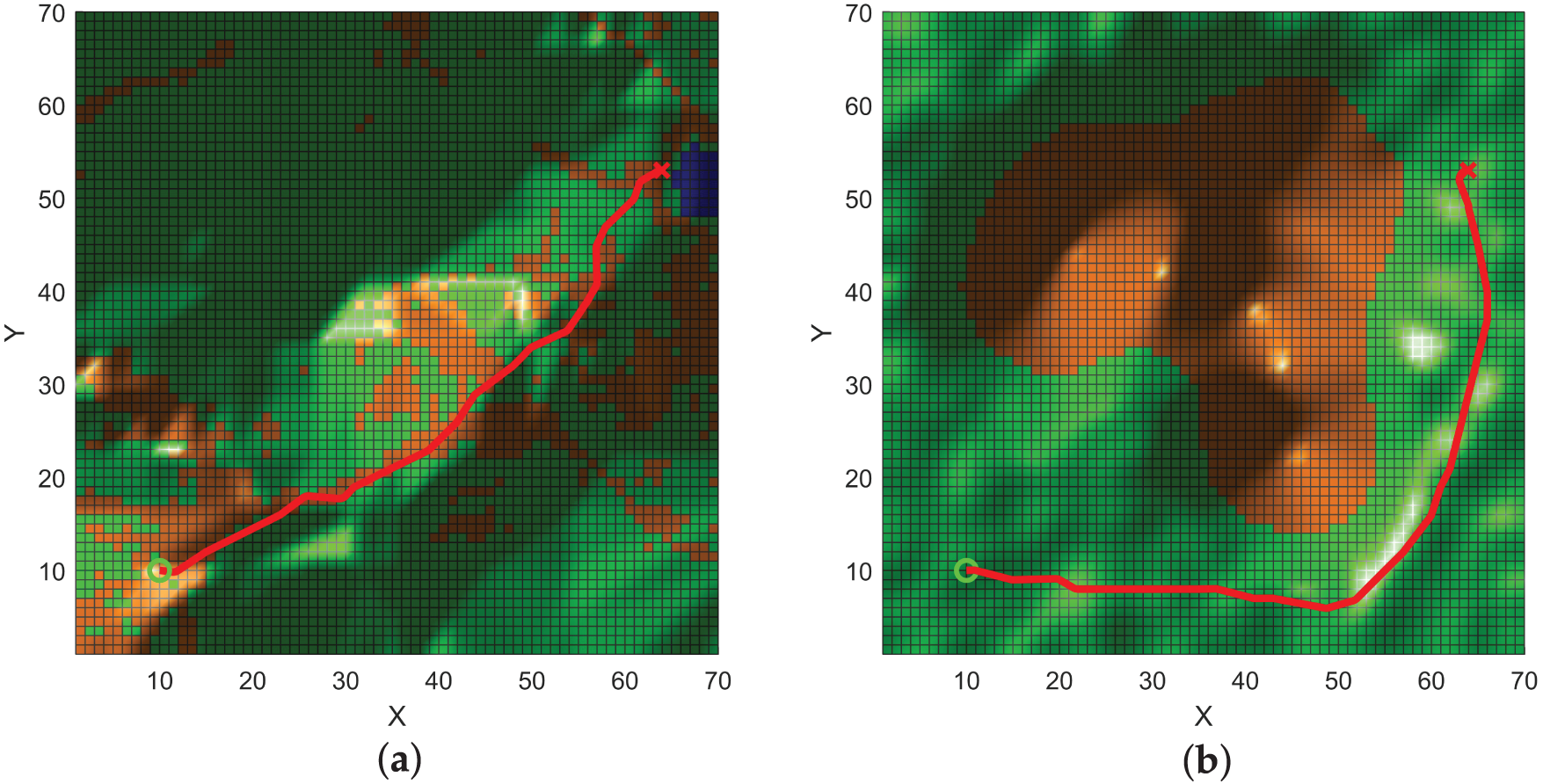

4.5 Vehicle Steering Constraints and Path Smoothing

The proposed algorithm is agnostic to the specific steering mechanism and is applicable to both front-wheel-steering and differential-drive platforms. While front-wheel vehicles inherently enforce a minimum turning radius through their kinematic model, differential-drive UGVs—despite being capable of zero-radius in-place rotations—suffer from side-slip and tracking errors when performing frequent sharp turns in highly undulating off-road terrain, and therefore also require a minimum turning radius constraint. Based on the safe turning requirements of typical off-road UGVs, we set a uniform minimum turning radius of

To eliminate the non-executable sharp corners produced by grid-based global planning and to ensure kinematic feasibility, we apply a Dubins-curve smoothing post-processing step. As illustrated in Fig. 10, this Dubins smoothing converts the discrete piecewise-linear path into a continuous trajectory composed of “constant-curvature

Figure 10: Dubins curve: (a) Environment A; (b) Environment B.

This paper has presented HS-APF-RRT*, a novel off-road path-planning algorithm that integrates a three-layer hierarchical sampling strategy with an enhanced Artificial Potential Field (APF). Building on the RRT* framework, our method first segments the workspace into macro, meso, and micro layers: the macro layer filters out impassable regions; the meso layer biases sampling according to slope and energy-cost estimates; and the micro layer preserves randomness while enforcing safety constraints. This coarse-to-fine sampling hierarchy greatly accelerates convergence by focusing random samples on feasible, low-cost areas. We further augment the conventional APF by introducing a slope-dependent repulsive term, which adaptively scales repulsion intensity with local gradient to steer the tree toward gentle, safe terrain. Finally, a dynamic neighborhood-expansion mechanism switches between 8- and 16-connected growth based on obstacle density, balancing computational efficiency with collision avoidance.

Simulation comparisons confirm that HS-APF-RRT* consistently produces the shortest, highest-quality paths across all tested scenarios. It also generates initial solutions more rapidly, requires fewer iterations, and consumes substantially less energy, while entirely avoiding hazardous regions. These results demonstrate that HS-APF-RRT* offers an efficient, safe, and robust solution for unmanned vehicle navigation in challenging off-road environments.

Acknowledgement: We sincerely thank all individuals and institutions that have provided support and assistance for this research.

Funding Statement: This work was supported in part by 14th Five Year National Key R & D Program Project (Project Number: 2023YFB3211001) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (62273339, U24A201397).

Author Contributions: Conceptualization: Zhenpeng Jiang; Methodology: Zhenpeng Jiang; Software: Zhenpeng Jiang; Validation: Zhenpeng Jiang; Formal analysis: Zhenpeng Jiang; Investigation: Zhenpeng Jiang; Resources: Zhenpeng Jiang; Data curation: Zhenpeng Jiang; Writing—original draft preparation: Zhenpeng Jiang; Writing—review and editing: Qingquan Liu; Visualization: Zhenpeng Jiang; Supervision: Qingquan Liu, Ende Wang; Project administration: Qingquan Liu, Ende Wang; Funding acquisition: Qingquan Liu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Akay R, Yildirim MY. SBA*: an efficient method for 3D path planning of unmanned vehicles. Math Comput Simul. 2025;231(3):294–317. doi:10.1016/j.matcom.2024.12.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Mazaheri H, Goli S, Nourollah A. A survey of 3D space path-planning methods and algorithms. ACM Comput Surv. 2025;57(1):1–32. doi:10.1145/3673896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Wang J, Wu Z, Tan M, Yu J. 3-D path planning with multiple motions for a gliding robotic dolphin. IEEE Trans Syst Man Cybern Syst. 2021;51(5):2904–15. doi:10.1109/tsmc.2019.2917635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Wang W, Li X, Tian J. UAV formation path planning for mountainous forest terrain utilizing an artificial rabbit optimizer incorporating reinforcement learning and thermal conduction search strategies. Adv Eng Inform. 2024;62(D):102947. doi:10.1016/j.aei.2024.102947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Lindqvist B, Patel A, Löfgren K, Nikolakopoulos G. A tree-based next-best-trajectory method for 3-D UAV exploration. IEEE Trans Robot. 2024;40:3496–513. doi:10.1109/tro.2024.3422052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Martínez-Rozas S, Alejo D, Caballero F, Merino L. Path and trajectory planning of a tethered UAV-UGV marsupial robotic system. IEEE Robot Autom Lett. 2023;8(10):6475–82. doi:10.1109/lra.2023.3301292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Fan J, Chen X, Wang Y, Chen X. UAV trajectory planning in cluttered environments based on PF-RRT algorithm with goal biased strategy. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2022;114(2):105182. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2022.105182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Li J, Li C, Chen T, Zhang Y. Improved RRT algorithm for AUV target search in unknown 3D environment. J Mar Sci Eng. 2022;10(6):826. doi:10.3390/jmse10060826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Karaman S, Frazzoli E. Sampling-based algorithms for optimal motion planning. Int J Robot Res. 2011;30(7):846–94. doi:10.1177/0278364911406761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Gammell JD, Srinivasa SS, Barfoot TD. Informed RRT: optimal sampling-based path planning focused via direct sampling of an admissible ellipsoidal heuristic. In: 2014 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems; 2014 Sep 14–18; Chicago, IL, USA. p. 2997–3004. [Google Scholar]

11. Li Y, Wei W, Gao Y, Wang D, Fan Z. PQ-RRT*: an improved path planning algorithm for mobile robots. Expert Syst Appl. 2020;152(2):113425. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2020.113425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Pan Z, Zhang C, Xia Y, Xiong H, Shao X. An improved artificial potential field method for path planning and formation control of the multi-UAV systems. IEEE Trans Circuits Syst II Express. 2022;69(3):1129–33. doi:10.1109/tcsii.2021.3112787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Fan J, Chen X, Liang X. UAV trajectory planning based on bi-directional APF-RRT* algorithm with goal-biased. Expert Syst Appl. 2023;213(101376):119137. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2022.119137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Gao Q, Yuan Q, Sun Y, Xu L. Path planning algorithm of robot arm based on improved RT* and BP neural network algorithm. J King Saud Univ—Comput Inf Sci. 2024;35(8):101650. doi:10.1016/j.jksuci.2023.101650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Pu H, Wan X, Song T, Schonfeld P, Peng L. A 3D-RRT-star algorithm for optimizing constrained mountain railway alignments. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2024;130(1):107770. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2023.107770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Yin J, Hu Z, Mourelatos ZP, Gorsich D, Singh A, Tau S. Efficient reliability-based path planning of off-road autonomous ground vehicles through the coupling of surrogate modeling and RRT*. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2023;24(12):15035–50. doi:10.1109/tits.2023.3296651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Ramirez-Robles E, Starostenko O, Alarcon-Aquino V. Real-time path planning for autonomous vehicle off-road driving. PeerJ Comput Sci. 2024;10(12):e2209. doi:10.7717/peerj-cs.2209. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Lee J, Seo Y. Q-learning based on strategic artificial potential field for path planning enabling concealment and cover in ground battlefield environments. Appl Intell. 2024;54(13):7170–200. doi:10.1007/s10489-024-05436-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Jiang C, Hu Z, Mourelatos ZP, Gorsich D, Jayakumar P, Fu Y, et al. R2-RRT*: reliability-based robust mission planning of off-road autonomous ground vehicle under uncertain terrain environment. IEEE Trans Autom Sci Eng. 2022;19(2):1030–46. doi:10.1109/tase.2021.3050762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Zhang R, Xu Q, Su Y, Chen R, Sun K, Li F, et al. CPP: a path planning method taking into account obstacle shadow hiding. Complex Intell Syst. 2025;11(2):129. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools