Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Multi-Objective Deep Reinforcement Learning Algorithm for Computation Offloading in Internet of Vehicles

1 School of Computer and Big Data Engineering, Zhengzhou Business University, Zhengzhou, 451400, China

2 School of Computer and Information Engineering, Henan University, Kaifeng, 475000, China

3 School of Joint Innovation Industry, Quanzhou Vocational and Technical University, Quanzhou, 362268, China

4 School of Computer Science and Technology, Xidian University, Xi’an, 710071, China

* Corresponding Author: Dong Yuan. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(1), 1-26. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.068795

Received 06 June 2025; Accepted 06 June 2025; Issue published 10 November 2025

Abstract

Vehicle Edge Computing (VEC) and Cloud Computing (CC) significantly enhance the processing efficiency of delay-sensitive and computation-intensive applications by offloading compute-intensive tasks from resource-constrained onboard devices to nearby Roadside Unit (RSU), thereby achieving lower delay and energy consumption. However, due to the limited storage capacity and energy budget of RSUs, it is challenging to meet the demands of the highly dynamic Internet of Vehicles (IoV) environment. Therefore, determining reasonable service caching and computation offloading strategies is crucial. To address this, this paper proposes a joint service caching scheme for cloud-edge collaborative IoV computation offloading. By modeling the dynamic optimization problem using Markov Decision Processes (MDP), the scheme jointly optimizes task delay, energy consumption, load balancing, and privacy entropy to achieve better quality of service. Additionally, a dynamic adaptive multi-objective deep reinforcement learning algorithm is proposed. Each Double Deep Q-Network (DDQN) agent obtains rewards for different objectives based on distinct reward functions and dynamically updates the objective weights by learning the value changes between objectives using Radial Basis Function Networks (RBFN), thereby efficiently approximating the Pareto-optimal decisions for multiple objectives. Extensive experiments demonstrate that the proposed algorithm can better coordinate the three-tier computing resources of cloud, edge, and vehicles. Compared to existing algorithms, the proposed method reduces task delay and energy consumption by 10.64% and 5.1%, respectively.Keywords

The Internet of Vehicles (IoV) extends the Internet of Things (IoT) paradigm into the vehicular domain [1], and has great potential in enabling intelligent capabilities onboard terminals [2]. With the rapid progress of current artificial intelligence technologies, a large number of intelligent applications have emerged, including collaborative navigation systems, vehicle collision detection, and augmented reality/virtual reality [3,4]. These applications impose stringent requirements on task delay and energy consumption, posing significant challenges for resource-constrained in vehicle computing platforms [5]. To address this, Vehicle Edge Computing (VEC) has emerged as a pivotal solution. By constructing network topological relationships through vehicles, Roadside Units (RSUs) [6], tasks can be offloaded to RSUs for computation in a vehicle-to-infrastructure (V2I) manner, thus meeting the stringent requirements of intelligent applications [7]. This allows vehicles to obtain efficient and secure services [8].

Facing a large number of heterogeneous tasks from vehicles, RSUs struggle with inadequate computing resources. In response, a joint cloud computing (CC) approach can be used to offload computation tasks from RSUs to cloud servers [9]. Utilizing the powerful computing power of the cloud, RSU computational pressure is alleviated, and the Quality of Experience (QoE) of users can be improved [10].

The specific programs required for edge device computing tasks are usually defined as service caches. Taking vehicle environment perception as an example, the input data includes sensor data such as radar, cameras, and lidar around the vehicle. The execution of the task requires caching the corresponding environment perception service program into the vehicle or edge server, whose input data is usually unique and difficult to reuse [11], but the relevant service program data can be reused in future executions of similar tasks.

For RSUs, they need to parallel process significant volumes of vehicular requests, and the vehicle density on the road is random [12], which results in dynamically changing computational resources [13]. Given constrained RSU storage capacity, only a portion of service programs can be hosted locally at a time, making selective caching imperative. In addition, computing resources across RSUs often exhibit disparate allocation dynamically, thus requiring collaborative offloading to balance the computing load. Since service cache decisions are closely related to computing offloading decisions, when a service program has already been cached on RSUs, we tend to choose to offload the execution of tasks. However, existing approaches fail to resolve critical challenges: 1) How to optimize conflicting objectives such as delay, energy consumption, load balancing, and privacy entropy in a dynamic vehicular environment. 2) How to jointly optimize service caching and computation offloading decisions. 3) Adaptive adjustment of the weights among objectives in multi-objective optimization.

We propose a cloud-edge collaborative Internet of Vehicles (IoV) scenario aimed at optimizing computation offloading and service caching strategies. Considering the dynamic nature of network structures and real-time changes in task requests within road environments, we introduce a Multi-Objective Reinforcement Learning (MORL) algorithm based on Reinforcement Learning (RL). This algorithm leverages storage space and computing resources from vehicles and RSUs to collaborate with the cloud for computation offloading while ensuring the privacy and security of tasks. By integrating Radial Basis Function Networks (RBFN) with Chebyshev scalarization, our approach dynamically adjusts the weights among multiple objectives in multi-objective optimization. The contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

1. We design a joint service caching and computational offloading model for cloud-edge collaborative IoV, formulating task delay, device energy consumption, RSU load balancing, and task privacy entropy as a multi-objective optimization problem, which is optimized in a unified manner.

2. We propose a Multi-Objective DDQN-Based Edge Caching and Offloading Algorithm (MODDQN-ECO), which integrates a Radial Basis Function Network (RBFN) with Chebyshev scalarization. This hybrid approach dynamically adjusts weights by learning the value changes among multiple objectives and can also incorporate predefined preference values to guide decision making.

3. Through extensive simulation experiments comparing with benchmark algorithms and recent multi-objective optimization methods, the proposed approach demonstrates superior performance across multiple metrics, including task delay, energy consumption, RSU computational load, and task privacy entropy.

The remaining parts of this paper are as follows. Section 2 surveys state-of-the-art VEC computational frameworks. Section 3 describes the system model in detail. Section 4 elaborates the Multi-Objective Reinforcement Learning (MORL) methodology. Section 5 evaluates the performance of the algorithm through simulation experiments. Section 6 concludes the research findings of this paper.

This section summarize prior work on computation offloading in IoV. Bai et al. studied the vehicle task planning problem with priority constraints and proposed a new strategy heuristic algorithm based on topological sorting to minimize vehicle travel distance and quickly obtain near-optimal solutions [14]. Zhu et al. designed an improved NSGA-III algorithm by constructing models of latency and energy consumption in the Internet of Vehicles, achieving multi-objective joint optimization of system delay and energy consumption [15]. Hussain et al. established an optimization framework examining infrastructure deployment in vehicular fog networks for latency and energy reduction [16]. Materwala et al. proposed an energy-aware offloading strategy and used an evolutionary algorithm to optimize the energy consumption of edge cloud devices [17]. Sun et al. propose a predictive computation offloading method for vehicles, offloading computation tasks to edge servers using vehicle-to-vehicle (V2V) and V2I communication, then performing multi-objective optimization of energy consumption and delay using a genetic algorithm [18]. Wu et al.’s cloud-edge collaboration work establishes a multi-objective formulation minimizing processing delay, device energy consumption, and costs [19]. Cui et al. developed an edge and terminals collaborative offloading scheme with multi-objective optimization model, addressing task latency and energy efficiency [20].

Most existing research on IoV computation offloading has focused on using genetic algorithms. However, traditional MOEAs may not perform well in real-time changing road environments as they require significant computational time to find Pareto-optimal solutions. DRL, on the other hand, can make real-time decisions in dynamic vehicle environments, making it more suitable for optimizing problems in IoV. Moghaddasi et al. proposed a task offloading method based on Rainbow Deep Q-Network (DQN) to optimize task allocation in a three-tier architecture consisting of device-to-device (D2D), edge, and cloud computing [21] Lin et al. employed a DRL framework to optimize real-time offloading decisions between mobile vehicles and RSUs, significantly reducing vehicle delay [22]. Lu et al. investigated a multi-objective edge server deployment strategy based on DRL, which reduces task delay while improving IoV coverage and load-balancing capabilities [23]. Liu et al. defined peak and off-peak unloading modes, combining a simulated annealing genetic algorithm with DQN to alleviate vehicle system delay [24]. Geng et al. designed a distributed DRL algorithm in order to reduce the task delay and device energy consumption in the computational offloading problem [25]. To address the high computational complexity and poor real-time performance of genetic algorithms, we employ a DRL algorithm as the multi-objective optimization approach in the IoV model.

The aforementioned studies predominantly focus on optimizing individual metrics, with insufficient exploration of multi-objective collaborative optimization. Amir Masoud Rahmani et al. reviewed integration approaches of cloud computing, fog computing, and edge computing in the Internet of Things (IoT) environment, with a focus on the application of meta-heuristic algorithms in task offloading optimization. They pointed out that these algorithms effectively reduce system delay, energy consumption, and cost by optimizing task allocation, and also outlined current research challenges and future directions [26]. Yao et al. formulated the delay and energy consumption optimization problem in dynamic IoV computation offloading as a Markov Decision Process (MDP) to achieve dual minimization [27]. Liu et al. integrated convex optimization algorithms with Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) to effectively reduce both delay and energy consumption in computation offloading [28]. Qiu et al. designed a vehicular network model considering stochastic task arrivals, time-varying channels, and vehicle mobility, and proposed a deep reinforcement learning-based computation offloading and power allocation scheme to minimize the total delay and energy consumption in VEC networks [29]. Shang et al. studied the problem of offloading non-orthogonal multi-access computation with joint resource allocation and optimized the weighted posterior of energy consumption and delay [30]. Ullah et al. comprehensively reviewed the current development of multi-agent task allocation strategies and multi-agent reinforcement learning (MARL) methods in the Internet of Vehicles (IoV), highlighting the key roles of intelligent learning architectures, security issues, and computing platforms. They also identified the main challenges in current multi-agent task allocation, including scalability, complexity, communication overhead, resource allocation, security, and privacy protection, and proposed potential directions for future research [31]. Most research on IoV computation offloading simply weight task delay and energy consumption into scalar objectives, which may not satisfy the preference requirements of different offloading tasks. To address this, we design a constrained multi-objective reinforcement learning algorithm with dynamically adjusted weights, targeting multiple optimization goals including delay, load balancing, energy consumption, and task privacy entropy.

Caching the relevant programs required to execute computational tasks is referred to as service caching. Jointly optimizing service caching and computation offloading decisions can significantly improve the efficiency of task offloading, effectively reducing server computational pressure and the delay of intensive tasks. Yan et al. proposed a low-complexity heuristic algorithm with a service cache to control the computational offloading behavior [32]. Ko et al. propose a joint offloading and service caching strategy that considers heterogeneous service preferences, maximizing the total utility of the MEC system [33]. Zhu et al. designed an edge caching scheme for the Internet of Vehicles. By pre-dividing and caching content segments, it reduces the load on the central server and alleviates network pressure [34]. Tang et al. proposed a computational offloading scheme in conjunction with service caching [35]. In the above studies, some researchers explore the relationship between computation offloading and caching, but there are still some shortcomings. For example, Yan’s MEC environment is significantly different from the VEC environment. Zhu et al. study content caching rather than service caching. Tang’s research does not consider the problem of limited resources. This paper integrates edge intelligence to achieve the coordination of caching and computing resources under resource-constrained conditions.

In summary, regarding the multi-objective optimization research in IoV models, many scholars tend to employ multi-objective evolutionary algorithms to optimize various performance metrics. However, such algorithms often fall short in performance when dealing with dynamic changes in road environments. On the other hand, while reinforcement learning-based methods have been applied for model optimization, these studies mostly concentrate on enhancing individual performance indicators, with insufficient exploration into comprehensively addressing multi-objective optimization problems. Furthermore, despite the significant role of service caching mechanisms in improving system efficiency, recent research that adequately considers this aspect in model design remains relatively scarce. Therefore, we propose a dynamic adaptive multi-objective reinforcement learning algorithm for joint computational offloading and service caching in a cloud-edge collaborative IoV model. The algorithm uses an RBFN network to dynamically update target weights while optimizing for delay, load balancing, energy consumption, and task privacy entropy. This effectively solves the complex scheduling problem in cloud-edge collaboration, maximizing utilization of resource-constrained vehicles and RSUs infrastructure through cloud-assisted delay optimization. Table 1 summarizes the research contents of related work.

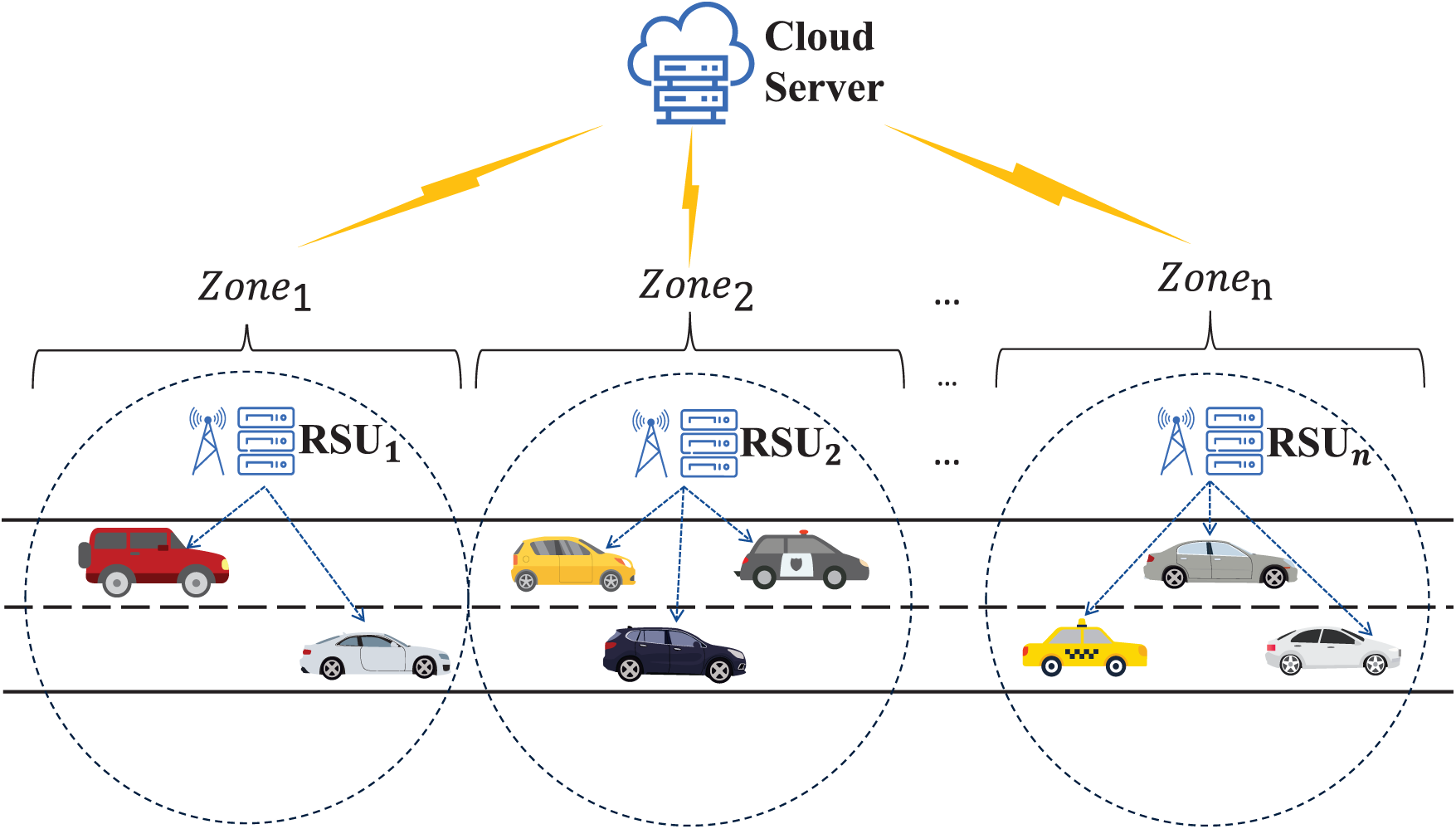

3.1 Cloud-Edge Collaborative IoV Model

We study an IoV system consisting of vehicles, RSUs and the cloud. There are

Figure 1: Cloud-edge collaborative IoV model

There are

The

3.1.1 Task and Communication Model

We define the task corresponding to the vehicle as

The RSUs in each region can cover all vehicles within their region, where the total bandwidth of the RSUs in each region is

where,

At time slot

where the binary variables

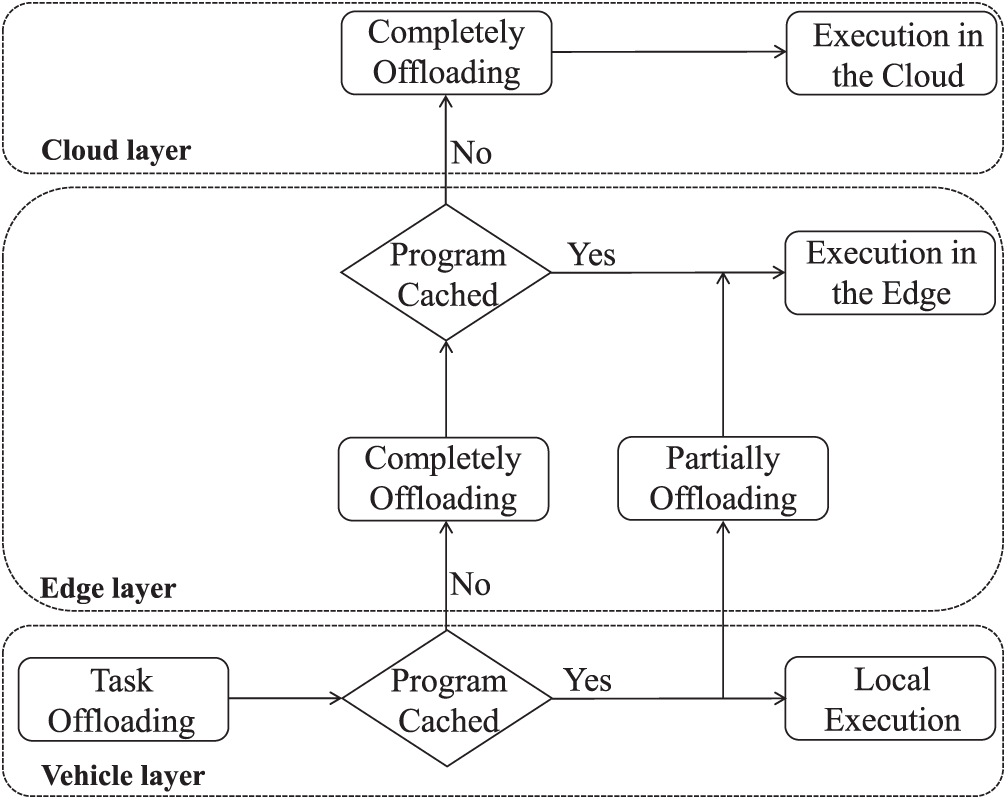

As shown in Fig. 2, in this paper, the computing tasks of vehicles adopt a partial offloading strategy. When the relevant programs of the computing tasks requested by vehicle

Figure 2: The computation offloading flowchart

3.2.1 Local Computational Model

The vehicle can leave the

The computational consumption of locally executing tasks can be derived as follows, where

3.2.2 Offloading Execution Mode

When the vehicle

a) Decision stage: When vehicle

b) Transmission stage: When the vehicle offloads the task to the corresponding RSU, then the time required to upload the task

c) Processing stage: The RSU processes the offloaded tasks based on the allocated computational resources, where

d) Results return stage: When the RSU completes the computation of task

With the above four stages, the total delay

The energy consumption for executing the offloaded task is calculated as follows [40]:

where

When the vehicle and RSU have no cached tasks or insufficient computing resources, the RSU can offload tasks to the cloud. Due to the abundant computational resources available in the cloud, the delay of cloud computing can be negligible. Therefore, the computational delay of task

where

where

There is a possibility of data leakage when offloading some privacy-sensitive tasks on the vehicular terminal. Therefore, we use privacy entropy as an indicator of security in the task data transfer process [42]. When the value of privacy entropy is higher, it indicates that the transmission process of the task is more secure, and we set the task arrivals to conform to the Poisson distribution:

where

The privacy entropy of

In this paper, since the Cache and computing resources of RSUs are unchanged, the rise of workload in some time periods will lead to a large fluctuation in the load balancing rate of RSUs, and the quality of service (QoS) of users deteriorates consequently, and optimization of the load balancing can effectively improve the resource utilization rate of RSUs [43]. We define the computational load of RSUs serving vehicle

where

Based on the above introduction of the local and offloaded computing models, the delay and energy consumption of

This study aims to minimize application delay, reduce energy consumption and the computational load on Roadside Units (RSUs), while balancing user experience and maximizing privacy entropy. That is, formulas (16)–(19). A conflicting relationship exists among these objectives: reducing delay inevitably requires consuming more computational resources, leading to increased energy consumption on devices, and maximizing privacy entropy introduces additional task transmission delay. To address this, this paper establishes a multi-objective framework through the joint optimization of computation offloading and service caching:

s,t:

where constraint

3.4 Extreme Value Analysis for T and E

The maximum and minimum values of

1) Case1:

2) Case2:

3) Case3:

4) Case4:

It can be concluded from the above:

Since Case2 has the nature of a segmented function, we can derive its minimum delay:

where

From the above it can be obtained that the delay of the task is related to the communication, computation, and caching capabilities of the device. Therefore, in order to minimize the delay, one should try to avoid choosing the decision that will lead to the highest delay.

Similarly, the maximum and minimum values of

1) Case1:

2) Case2:

3) Case3:

4) Case4:

Based on the above, we can conclude:

By performing an extreme value analysis on

4 Service Caching and Offloading Algorithms Based on Multi-Objective Reinforcement Learning

In this paper, Simultaneous optimization of multiple factors task delay, load balancing rate, and privacy entropy is required. Regarding multi-objective optimization (MOO), evolutionary algorithms remain the predominant approach in existing studies. However, their slow convergence speed impedes applicability in real-time dynamic vehicular offloading scenarios. DRL emerges as an effective methodology for dynamic environment optimization, maximizing expected cumulative rewards to achieve objectives. It aggregates demand-resource information within vehicular networks, subsequently executing actions to optimize joint offloading policies alongside resource distribution.

We formulate the problem as a Markov Decision Process (MDP) and propose an multi-objective Reinforcement Learning algorithm combining RBFN network with Chebyshev method. By dynamically adjusting the weights of objectives including task delay, device energy consumption, device computation load, and privacy entropy, find the optimal caching and offloading strategy.

An MDP in the usual case is defined as a quintuple

• State Space: We denote the state at a

• Action Space: The agent makes a decision strategy based on

• Reward: The reward at time

• Transition probability: The probability of the environment moving from

We complete the optimization problem by learning the policy

where

Compared to standard single-objective reinforcement learning, multi-objective reinforcement learning [45] can obtain multiple reward values as feedback from the environment when an agent takes an action. In this paper, the task delay, device energy consumption, privacy entropy and computing load rate of vehicular tasks are all reward values. Therefore, the feedback reward is a vector corresponding to multiple objectives, rather than a scalar value:

Since there are conflicting relationships among the multiple objectives to be optimized in this paper, the algorithm needs to find the strategy that maximizes the gain of the system among these conflicting relationships. We use a nonlinear scalarization method to solve this multi-objective optimization problem.

4.2.1 Multi-Objective DRL Based on Chebyshev’s Scalarization Method

Considering the issue that linear weighting method cannot approximate all Pareto frontiers, we adopt the Chebyshev scalarization method, taking the ideal point

The

where

Intelligent bodies make the value of the action constantly close to the optimum, and eventually the system is able to obtain the optimal computational offloading gain.

4.2.2 Multi-Objective DDQN Computational Offloading Algorithm

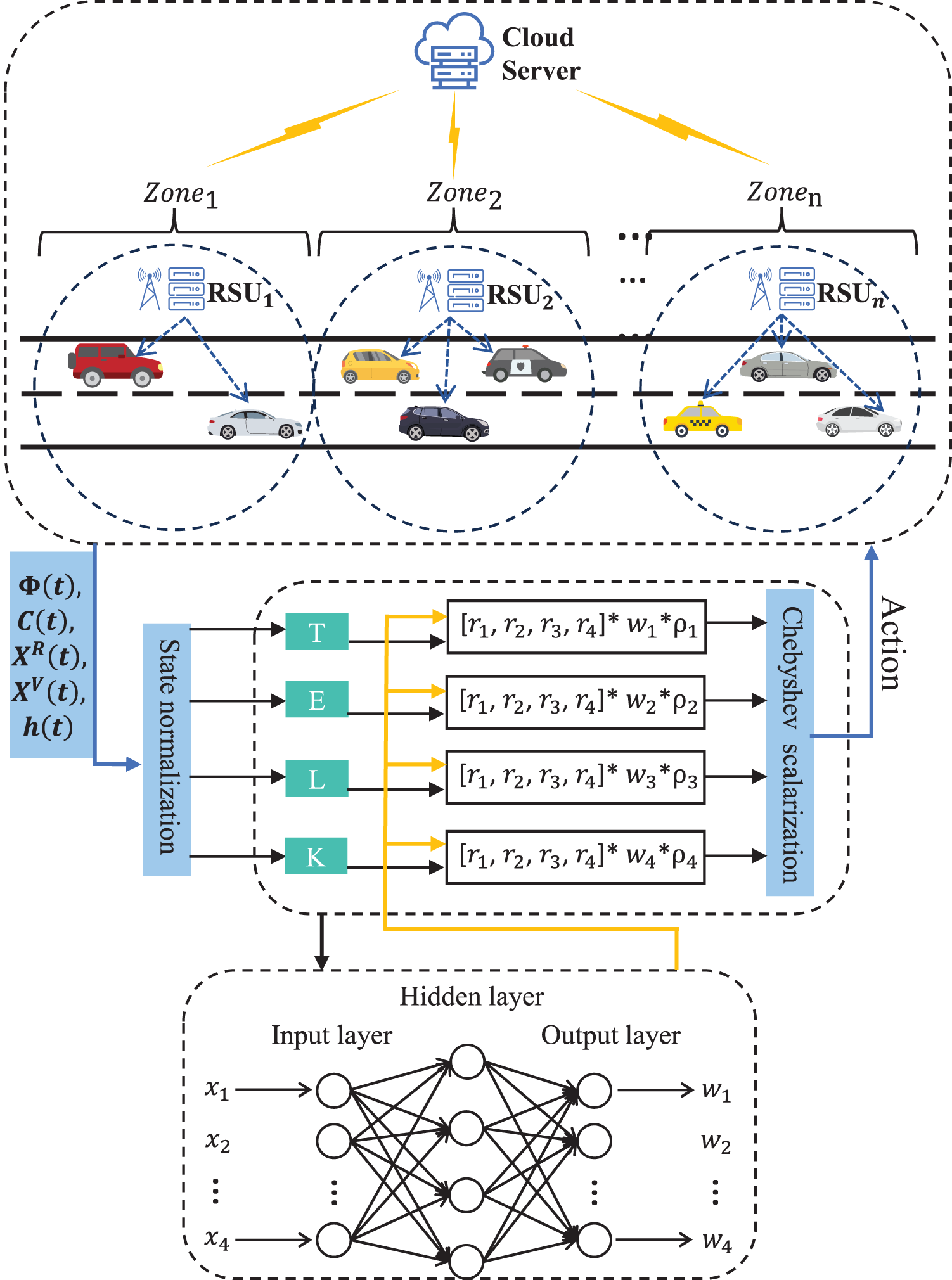

In multi-objective double deep Q-network (DDQN) reinforcement learning computational offloading algorithm, where RBFN network is used to learn multiple different objective values to better adapt to weight changes, while also better addressing the Q-value overestimation issue in DQN. As shown in Fig. 3. Each DDQN is denoted by DDQNT, DDQNE, DDQNL, and DDQNK, and its intelligences are rewarded based on different optimization objectives. In this paper, we set the reward function based on delay, energy consumption, computational load, and privacy entropy factor sub-objectives separately to obtain a better multi-objective solution. We correspond to the value of each objective by defining a dynamic weight

Figure 3: MODDQN-ECO algorithmic frameworkm

We denote

With

4.2.3 RBF Neural Network Update

The RBFN network [46], consisting of an input layer, a hidden layer, and an output layer as shown in Fig. 3, is a feedforward neural network. It has a large number of hidden neurons and can accurately approximate continuous functions. The Gaussian function of the RBFN network is defined:

where

Each DDQN corresponds to a Q function for the optimization objective, in which

where

In this section, we experimentally evaluate the performance of the proposed MODDQN-ECO algorithm in the IoV model. Previous studies [48,49] provide empirical references for parameter settings, with detailed experimental parameters summarized in Table 3. We implement the IoV simulation environment using TensorFlow 1.15.0 and Python 3.7. The simulation establishes a 1000-meter-long two-lane road with five roadside servers deployed, each covering a 200-meter range to divide the road into five segments. Task sizes are set within [20, 25] Mb and vehicle CPU frequencies are configured at

Multi-objective DQN Computational Offloading Algorithm (DQN) [50]: multi-objective DQN computational offloading algorithm using linear scalarization method is very reliable to solve computational offloading problems in dynamically changing environments using DQN. Its approximates the value function through a convolutional neural network. agent obtains the corresponding Q-value based on the state of the IoV environment and selects an action using a greedy strategy, then updates the network parameters of the value function based on the feedback reward value and the new state. The intelligents use an empirical playback method [51] to improve data efficiency and enhance training stability.

Improved Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm (INSGA-II) [52]: An improved NSGA-II algorithm is employed to solve the model in this paper. The algorithm retains the fast non-dominated sorting mechanism. In the genetic operations, it adopts Simulated Binary Crossover (SBX) and Simulated Binary Mutation (SBM) to generate offspring with good diversity. This enhancement effectively improves the convergence speed of the algorithm, the uniformity of solution distribution, and the robustness in handling complex multi-objective optimization problems, making it well-suited for the conflicting optimization objectives addressed in this work.

Cloud Computing (CO): all on-board tasks are offloaded to the cloud to perform computation.

Random offload policy (RO): service caching and computation offload policies are randomly generated for each time period.

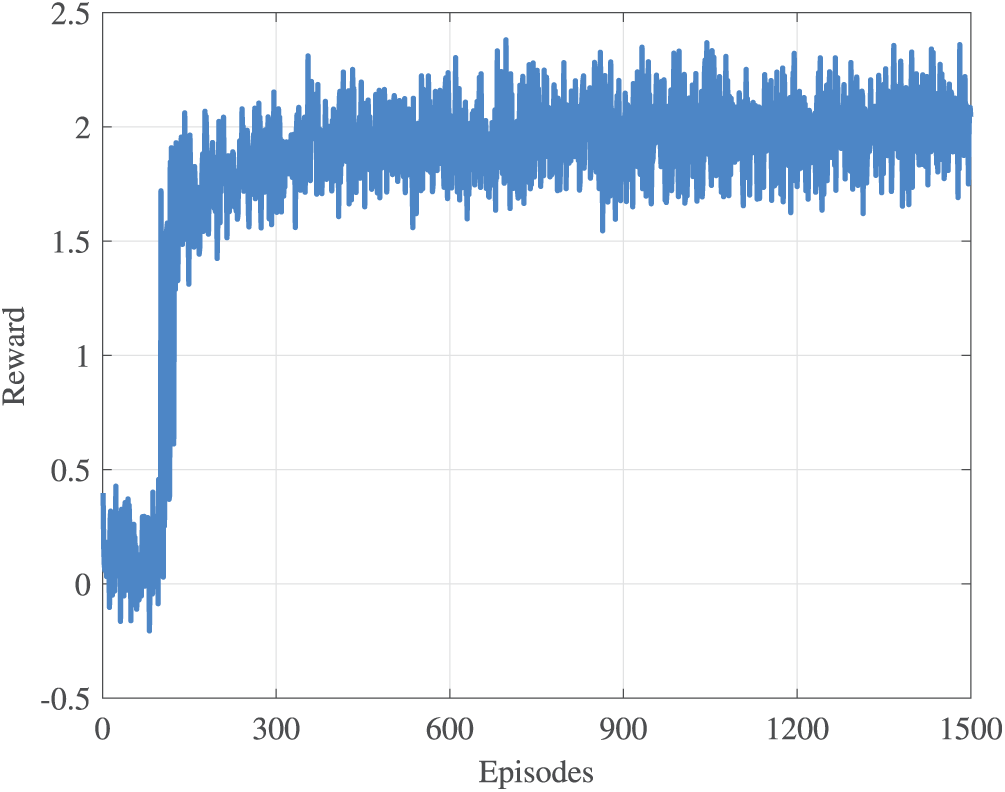

Fig. 4 shows the reward curve of MODDQN-ECO algorithm, and the result verifies that MODDQN-ECO algorithm can converge quickly while satisfying multiple objective balances, and then get the optimal offloading gain value. And it requires fewer iterations than some classical evolutionary algorithms, which can better cope with the time-varying road environment.

Figure 4: This is a figure example. Please remove all non-English terms or add a definition for them

5.1.1 Influence of Vehicle Number on IoV System

Fig. 5 experimentally evaluates algorithmic performance under varying vehicular density. In Fig. 5a,b, when the total number of vehicles on the road is relatively low, the performance gap between the MODDQN-ECO algorithm and DQN is not significant, and both tend to maintain balance across multiple objectives. However, they outperform the evolutionary algorithm INSGA-II in most scenarios, which is attributed to the faster convergence characteristics of reinforcement learning algorithms under the same number of iterations. MODDQN-ECO dynamically adjusts the weighting of each objective through the RBF network, enabling it to achieve a more balanced advantage in delay performance. This mechanism allows the algorithm to rapidly adapt to the environment and derive superior offloading decisions. As the number of vehicles increases, the task volume rises accordingly, leading to reduced per-vehicle bandwidth allocation and decreased task transmission rate, which consequently increases the task offloading delay. When the number of vehicles further increases, the delay advantage of task execution by RSUs weakens. At this point, the algorithm employs two key strategies to cope with the pressure: (1) Offloading some tasks to the cloud server to alleviate the computational resource pressure on the RSUs; (2) Some tasks are forced to execute locally. Although these strategies result in an increase in total task execution delay and device energy consumption, the rate of increase for MODDQN-ECO is significantly lower than that of the comparative algorithms. In high-density scenarios, by sensing the intensity of resource competition in the environment, the algorithm automatically adjusts the weight distribution among the various objectives, maintaining its performance advantage in terms of both delay and energy consumption. Compared to INSGA-II and DQN in terms of delay performance, MODDQN-ECO achieves average improvements of 10.64% and 8.71%, respectively. In terms of energy consumption, it shows improvements of 5.05% and 3.87% over the two algorithms, respectively.

Figure 5: Performance of MODDQN-ECO algorithm with different number of vehicles

Fig. 5c demonstrates the performance of RSU load-balancing. MODDQN-ECO, under different vehicle densities, can dynamically adjust the weighting for load balancing to steer tasks toward underutilized nodes, exhibiting superior load-balancing capability. Compared to INSGA-II and DQN, it achieves average improvements of 11.07% and 3.11%, respectively. The MODDQN-ECO algorithm proposed in this paper significantly outperforms NSGA3 and DQN on key performance metrics such as delay and energy consumption. Furthermore, this advantage expands with an increasing number of vehicles, validating the effectiveness of its dynamic weighting mechanism in high-density IoV scenarios. Table 4 shows the core data of Fig. 5. The MODDQN-ECO algorithm proposed in this paper significantly outperforms the INSGA-II and DQN algorithms in key performance metrics, and this advantage becomes larger with the number of vehicles.

5.1.2 Performance of Task Privacy Entropy

Fig. 6 verifies the MODDQN-ECO algorithm’s performance in terms of privacy entropy. When the vehicle number reaches 40, offloaded tasks are split into more parts, increasing transmission time and delay. Despite this, the algorithm maintains low delay and high privacy entropy in the mid and late iterations. This shows that the MODDQN-ECO with the Chebyshev scalar approach can dynamically approximate optimal decisions in multi-objective optimization. In contrast, DQN and INSGA-II with fixed weights fail to effectively approach the Pareto front, resulting in lower privacy entropy.

Figure 6: Task privacy entropy performance for different number of iterations

5.1.3 Performance under Different Task Sizes

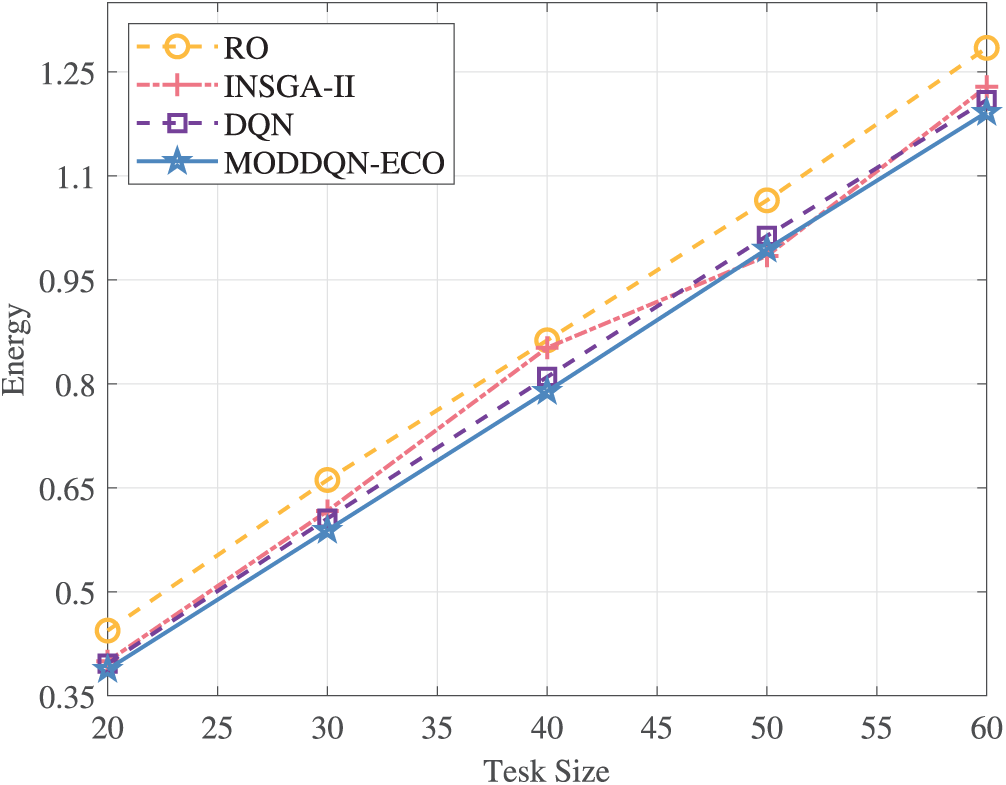

In Figs. 7 and 8, we conduct an in-depth investigation into the impact of task size on delay and energy consumption. Fig. 7 illustrates the trend of task delay vs. task size, revealing a linear increase attributable to the proportional relationship between delay and input data volume. As task scales expand, the surge in data transmission and computational demands elevates overall system delay. To mitigate this, the system dynamically increases cloud offloading ratios, alleviating computational pressures on RSUs and vehicles while reallocating freed resources to accelerate processing of tasks already offloaded to RSUs—thereby achieving synergistic optimization and reducing delay impacts.

Figure 7: The performance of delay under different task sizes

Figure 8: The performance of energy consumption under different task sizes

Fig. 8 further demonstrates a strong correlation between energy consumption and task scale. Larger tasks substantially increase data transmission and computational energy costs. Under these conditions, both DQN and MODDQN-ECO algorithms effectively orchestrate three-tier computing resources (local vehicles, RSUs, and cloud) to collaboratively fulfill offloading requests, yielding significant energy consumption advantages. Moreover, MODDQN-ECO’s core capability of dynamically adjusting multi-objective weights through its RBFN network enables sustained optimal balance between delay and energy consumption during task scaling variations. This approach significantly outperforms static-policy algorithms in maximizing offloading gains. The comprehensive improvement in delay and energy consumption achieves enhancements of 10.26% and 4.33% compared to INSGA-II and DQN, respectively.

5.1.4 Delay Performance at Different Cycle Frequencies

Fig. 9 illustrates the impact of RSU computational frequency on total task delay, with the number of vehicles fixed at 40. It is evident from the figure that higher RSU computational frequencies significantly reduce system delay. This is because RSUs can rapidly process a larger number of offloaded tasks, effectively shortening the task response cycle. Consequently, the algorithm preferentially offloads more tasks to edge servers for computation. In this optimized scenario, all three intelligent algorithms demonstrate improved delay performance. However, unlike other static strategy algorithms, MODDQN-ECO distinguishes itself through its dynamic objective weight adjustment capability, enabling greater adaptability to such conditions by re-prioritizing task offloading. This mechanism maximizes the utilization of RSU computing resources while optimizing task distribution ratios, thereby fulfilling the low-delay requirements of complex tasks.

Figure 9: Total delay performance at different cycle frequencies of RSUs

5.1.5 Delay Performance at Different Speed Range

Fig. 10 illustrates the impact of vehicles traveling at various speed ranges on latency. In this section, the number of vehicles is set to 40, and the latency performance is compared for tasks where vehicle speeds fall within the ranges of [40–60] km/h, [60–80] km/h, and comprehensively [40–80] km/h. Observably from the graph, vehicles operating at lower speed ranges generally experience less delay. As vehicle speeds increase, some tasks may be offloaded or completed while the vehicle has already moved into another server’s coverage area, thereby increasing inter-server communication time. All three intelligent algorithms exhibit minimal performance variation, attributed to the high efficiency of communication between servers. Compared to the classical evolutionary algorithm INSGA-II and the reinforcement learning algorithm DQN, the MODDQN-ECO algorithm demonstrates greater stability and more effectively minimizes latency associated with service caching and computational offloading in dynamic vehicular scenarios.

Figure 10: Delay performance at different speed range

Aiming at the real-time varying vehicular network scenarios, this paper designs a novel computational offloading model and derives critical threshold values for task delay and energy consumption under different network conditions. By integrating delay, device energy consumption, RSU computing load, and task privacy entropy into a multi-objective optimization framework, the MODDQN-ECO algorithm with dynamic RBFN-based weighting achieves significant improvements: compared to INSGA-II and DQN, the average delay is reduced by 10.64% and 8.71%, while energy consumption decreases by 5.1% and 3.9%, respectively. MODDQN-ECO effectively coordinates caching resources and RSU computing capabilities, maintaining robust performance during dynamic fluctuations in RSU frequency, thereby validating its efficiency.

Our approach still has certain limitations in terms of model architecture. For instance, it relies on the V2I communication paradigm for task transmission and does not fully utilize the task delivery capabilities of V2V communication, especially in forming service gaps within RSU coverage blind spots; the dynamic weighting mechanism may lead to policy instability in cases of extreme objective conflicts. In future research, we will explore homomorphic encryption-supported secure V2V task sharing protocols to enable safe reuse of cached tasks among vehicles; develop hierarchical scheduling mechanisms for concurrent computation-intensive tasks targeting vehicle clusters; and investigate federated learning approaches to enhance privacy protection capabilities in distributed edge environments.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by Key Science and Technology Program of Henan Province, China (Grant Nos. 242102210147, 242102210027); Fujian Province Young and Middle aged Teacher Education Research Project (Science and Technology Category) (No. JZ240101) (Corresponding author: Dong Yuan).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Junjun Ren; methodology, Guoqiang Chen and Zheng-Yi Chai; software, Guoqiang Chen; validation, Junjun Ren, Guoqiang Chen and Zheng-Yi Chai; formal analysis, Dong Yuan; investigation, Dong Yuan; resources, Junjun Ren; data curation, Dong Yuan; writing—original draft preparation, Guoqiang Chen and Zheng-Yi Chai; writing—review and editing, Junjun Ren; visualization, Zheng-Yi Chai; supervision, Junjun Ren; project administration, Junjun Ren; funding acquisition, Guoqiang Chen and Zheng-Yi Chai. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Luo Q, Li C, Luan TH, Shi W, Wu W. Self-learning based computation offloading for internet of vehicles: model and algorithm. IEEE Trans Wireless Commun. 2021;20(9):5913–25. doi:10.1109/twc.2021.3071248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Zhai Y, Sun W, Wu J, Zhu L, Shen J, Du X, et al. An energy aware offloading scheme for interdependent applications in software-defined IoV with fog computing architecture. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2021;22(6):3813–23. doi:10.1109/tits.2020.3044177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Liu J, Guo H, Xiong J, Kato N, Zhang J, Zhang Y. Smart and resilient EV charging in SDN-enhanced vehicular edge computing networks. IEEE J Selected Areas Commun. 2020;38(1):217–28. doi:10.1109/jsac.2019.2951966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Zhou H, Jiang K, Liu X, Li X, Leung VCM. Deep reinforcement learning for energy-efficient computation offloading in mobile-edge computing. IEEE Internet of Things J. 2022;9(2):1517–30. doi:10.1109/jiot.2021.3091142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Malektaji S, Ebrahimzadeh A, Elbiaze H, Glitho RH, Kianpisheh S. Deep reinforcement learning-based content migration for edge content delivery networks with vehicular nodes. IEEE Trans Netw Serv Manage. 2021;18(3):3415–31. doi:10.1109/tnsm.2021.3086721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Binh TH, Son DB, Vo H, Nguyen BM, Binh HTT. Reinforcement learning for optimizing delay-sensitive task offloading in vehicular edge-cloud computing. IEEE Internet of Things J. 2024;11(2):2058–69. doi:10.1109/jiot.2023.3292591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Guo H, Zhou X, Liu J, Zhang Y. Vehicular intelligence in 6G: networking, communications, and computing. Veh Commun. 2022;33:100399. doi:10.1016/j.vehcom.2021.100399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Hazarika B, Singh K, Biswas S, Li CP. DRL-based resource allocation for computation offloading in IoV networks. IEEE Trans Ind Inform. 2022;18(11):8027–38. doi:10.1109/tii.2022.3168292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Chen C, Liu B, Wan S, Qiao P, Pei Q. An edge traffic flow detection scheme based on deep learning in an intelligent transportation system. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2021;22(3):1840–52. doi:10.1109/tits.2020.3025687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Ju Y, Chen Y, Cao Z, Liu L, Pei Q, Xiao M, et al. Joint secure offloading and resource allocation for vehicular edge computing network: a multi-agent deep reinforcement learning approach. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2023;24(5):5555–69. doi:10.1109/tits.2023.3242997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Xu J, Chen L, Zhou P. Joint service caching and task offloading for mobile edge computing in dense networks. In: IEEE INFOCOM 2018-IEEE Conference on Computer Communications; 2018 Apr 15–19; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 207–15. [Google Scholar]

12. Lyu F, Yang P, Wu H, Zhou C, Ren J, Zhang Y, et al. Service-oriented dynamic resource slicing and optimization for space-air-ground integrated vehicular networks. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2022;23(7):7469–83. doi:10.1109/tits.2021.3070542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Huang J, Wan J, Lv B, Ye Q, Chen Y. Joint computation offloading and resource allocation for edge-cloud collaboration in internet of vehicles via deep reinforcement learning. IEEE Syst J. 2023;17(2):2500–11. doi:10.1109/jsyst.2023.3249217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Bai X, Cao M, Yan W, Ge SS, Zhang X. Efficient heuristic algorithms for single-vehicle task planning with precedence constraints. IEEE Trans Cybern. 2020;51(12):6274–83. doi:10.1109/tcyb.2020.2974832. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Zhu S, Song Z, Huang C, Zhu H, Qiao R. Dependency-aware cache optimization and offloading strategies for intelligent transportation systems. J Supercomput. 2025;81(1):45. doi:10.1007/s11227-024-06596-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Hussain MM, Azar AT, Ahmed R, Umar Amin S, Qureshi B, Dinesh Reddy V, et al. SONG: a multi-objective evolutionary algorithm for delay and energy aware facility location in vehicular fog networks. Sensors. 2023;23(2):667. doi:10.3390/s23020667. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Materwala H, Ismail L, Shubair RM, Buyya R. Energy-SLA-aware genetic algorithm for edge-cloud integrated computation offloading in vehicular networks. Future Gen Comput Syst. 2022;135:205–22. doi:10.1016/j.future.2022.04.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Sun Y, Wu Z, Shi D, Hu X. Task offloading method of internet of vehicles based on cloud-edge computing. In: 2022 IEEE International Conference on Services Computing (SCC); 2022 Jul 11–16; Barcelona, Spain. p. 315–20. [Google Scholar]

19. Wu X, Dong S, Hu J, Hu Q. Multi-objective computation offloading based on invasive tumor growth optimization for collaborative edge-cloud computing. Soft Comput. 2023;27(23):17747–61. doi:10.1007/s00500-023-09051-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Cui Z, Xue Z, Fan T, Cai X, Zhang W. A many-objective evolutionary algorithm based on constraints for collaborative computation offloading. Swarm Evol Comput. 2023;77:101244. doi:10.1016/j.swevo.2023.101244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Moghaddasi K, Rajabi S, Gharehchopogh FS, Ghaffari A. An advanced deep reinforcement learning algorithm for three-layer D2D-edge-cloud computing architecture for efficient task offloading in the Internet of Things. Sustain Comput Inform Syst. 2024;43:100992. doi:10.1016/j.suscom.2024.100992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Lin J, Huang S, Zhang H, Yang X, Zhao P. A deep reinforcement learning based computation offloading with mobile vehicles in vehicular edge computing. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023;10(17):15501–14. doi:10.1109/jiot.2023.3264281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Lu J, Jiang J, Balasubramanian V, Khosravi MR, Xu X. Deep reinforcement learning-based multi-objective edge server placement in Internet of Vehicles. Comput Commun. 2022;187:172–80. doi:10.1016/j.comcom.2022.02.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Liu L, Yuan X, Zhang N, Chen D, Yu K, Taherkordi A. Joint computation offloading and data caching in multi-access edge computing enabled internet of vehicles. IEEE Trans Veh Technol. 2023;72(11):14939–54. doi:10.1109/tvt.2023.3285073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Geng L, Zhao H, Wang J, Kaushik A, Yuan S, Feng W. Deep-reinforcement-learning-based distributed computation offloading in vehicular edge computing networks. IEEE Internet of Things J. 2023;10(14):12416–33. doi:10.1109/jiot.2023.3247013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Rahmani AM, Haider A, Khoshvaght P, Gharehchopogh FS, Moghaddasi K, Rajabi S, et al. Optimizing task offloading with metaheuristic algorithms across cloud, fog, and edge computing networks: a comprehensive survey and state-of-the-art schemes. Sustain Comput Inform Syst. 2025;45:101080. doi:10.1016/j.suscom.2024.101080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Yao L, Xu X, Bilal M, Wang H. Dynamic edge computation offloading for internet of vehicles with deep reinforcement learning. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2023;24(11):12991–9. doi:10.1109/tits.2022.3178759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Liu Z, Jia Z, Pang X. DRL-based hybrid task offloading and resource allocation in vehicular networks. Electronics. 2023;12(21):4392. doi:10.3390/electronics12214392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Qiu B, Wang Y, Xiao H, Zhang Z. Deep reinforcement learning-based adaptive computation offloading and power allocation in vehicular edge computing networks. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2024;25(10):13339–49. doi:10.1109/tits.2024.3391831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Shang C, Sun Y, Luo H, Guizani M. Computation offloading and resource allocation in NOMA-MEC: a deep reinforcement learning approach. IEEE Internet of Things J. 2023;10(17):15464–76. doi:10.1109/jiot.2023.3264206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Ullah I, Singh SK, Adhikari D, Khan H, Jiang W, Bai X. Multi-agent reinforcement learning for task allocation in the internet of vehicles: exploring benefits and paving the future. Swarm Evol Comput. 2025;94:101878. doi:10.1016/j.swevo.2025.101878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Yan J, Bi S, Duan L, Zhang YJA. Pricing-driven service caching and task offloading in mobile edge computing. IEEE Trans Wireless Commun. 2021;20(7):4495–512. doi:10.1109/twc.2021.3059692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Ko SW, Kim SJ, Jung H, Choi SW. Computation offloading and service caching for mobile edge computing under personalized service preference. IEEE Trans Wireless Commun. 2022;21(8):6568–83. doi:10.1109/twc.2022.3151131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Zhu S, Tian X, Zhang Z, Qiao R, Zhu H. Content placement and edge collaborative caching scheme based on deep reinforcement learning for internet of vehicles. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2025;26(6):8050–64. doi:10.1109/tits.2025.3558898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Tang C, Zhu C, Wu H, Li Q, Rodrigues JJ. Toward response time minimization considering energy consumption in caching-assisted vehicular edge computing. IEEE Internet of Things J. 2021;9(7):5051–64. doi:10.1109/jiot.2021.3108902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Xue Z, Liu Y, Han G, Ayaz F, Sheng Z, Wang Y. Two-layer distributed content caching for infotainment applications in VANETs. IEEE Internet of Things J. 2022;9(3):1696–711. doi:10.1109/jiot.2021.3089280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Chen W, Su Z, Xu Q, Luan TH, Li R. VFC-based cooperative UAV computation task offloading for post-disaster rescue. In: IEEE INFOCOM 2020-IEEE Conference on Computer Communications; 2020 Jul 6–9; Online. p. 228–36. doi:10.1109/infocom41043.2020.9155397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Bi S, Huang L, Zhang YJA. Joint optimization of service caching placement and computation offloading in mobile edge computing systems. IEEE Trans Wireless Commun. 2020;19(7):4947–63. doi:10.1109/twc.2020.2988386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Yu S, Chen X, Yang L, Wu D, Bennis M, Zhang J. Intelligent edge: leveraging deep imitation learning for mobile edge computation offloading. IEEE Wireless Commun. 2020;27(1):92–9. doi:10.1109/mwc.001.1900232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Zhang Y, Liu T, Zhu Y, Yang Y. A deep reinforcement learning approach for online computation offloading in mobile edge computing. In: 2020 IEEE/ACM 28th International Symposium on Quality of Service (IWQoS); 2020 Jun 15–17; Hangzhou, China. p. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

41. Mao Y, Zhang J, Letaief KB. Dynamic computation offloading for mobile-edge computing with energy harvesting devices. IEEE J Selected Areas Commun. 2016;34(12):3590–605. doi:10.1109/jsac.2016.2611964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Xu Z, Liu X, Jiang G, Tang B. A time-efficient data offloading method with privacy preservation for intelligent sensors in edge computing. EURASIP J Wireless Commun Netw. 2019;2019(1):1–12. doi:10.1186/s13638-019-1560-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Ye Q, Shi W, Qu K, He H, Zhuang W, Shen X. Joint RAN slicing and computation offloading for autonomous vehicular networks: a learning-assisted hierarchical approach. IEEE Open J Veh Technol. 2021;2:272–88. doi:10.1109/ojvt.2021.3089083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Van Moffaert K, Drugan MM, Nowé A. Scalarized multi-objective reinforcement learning: novel design techniques. In: 2013 IEEE Symposium on Adaptive Dynamic Programming and Reinforcement Learning (ADPRL); 2013 Apr 16–19; Singapore. p. 191–9. [Google Scholar]

45. Brys T, Harutyunyan A, Vrancx P, Nowé A, Taylor ME. Multi-objectivization and ensembles of shapings in reinforcement learning. Neurocomputing. 2017;263:48–59. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2017.02.096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Gorbachenko VI, Alqezweeni MM. Learning radial basis functions networks in solving boundary value problems. In: 2019 International Russian Automation Conference (RusAutoCon); 2019 Sep 8–14; Sochi, Russia. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

47. Alqezweeni MM, Gorbachenko V. Approximation of functions and approximate solution of partial differential equations using radial basis functions networks. In: 2020 1st. Information Technology To Enhance e-learning and Other Application (IT-ELA); 2020 Jul 12–13; Baghdad, Iraq. p. 25–30. doi:10.1109/it-ela50150.2020.9253069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Li H, Chen C, Shan H, Li P, Chang YC, Song H. Deep deterministic policy gradient-based algorithm for computation offloading in IoV. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2024;25(3):2522–33. doi:10.1109/tits.2023.3325267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Wu J, Wang J, Chen Q, Yuan Z, Zhou P, Wang X, et al. Resource allocation for delay-sensitive vehicle-to-multi-edges (V2Es) communications in vehicular networks: a multi-agent deep reinforcement learning approach. IEEE Trans Netw Sci Eng. 2021;8(2):1873–86. doi:10.1109/tnse.2021.3075530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Liu X, Feng L, Zhang P, Yu Y, Wang J. An efficient computational offloading method using deep reinforcement learning in edge-end-cloud. Ad Hoc Netw. 2025;178:103941. doi:10.1016/j.adhoc.2025.103941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Mossalam H, Assael YM, Roijers DM, Whiteson S. Multi-objective deep reinforcement learning. arXiv:1610.02707. 2016. [Google Scholar]

52. Zhu S, Tian X, Chen H, Zhu H, Qiao R. Edge collaborative caching solution based on improved NSGA II algorithm in Internet of Vehicles. Comput Netw. 2024;244:110307. doi:10.1016/j.comnet.2024.110307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools